科学批判と反科学のあいだ

Between Criticism of

science and anti-science

☆ 科学に対する批判(Criticism of science)は、科学全体とその社会における役割を改善するために、科学内部の問題を取り扱う。批判は、哲学やフェミニズムなどの社会運動、そして科学そのものの中から生じる。 メタサイエンスという新たな分野は、科学的手法の改善により、科学研究の質と効率を高めることを目指している。

| Criticism of science

addresses problems within science in order to improve science as a

whole and its role in society. Criticisms come from philosophy, from

social movements like feminism, and from within science itself. The emerging field of metascience seeks to increase the quality of and efficiency of scientific research by improving the scientific process. |

科学に対する批判は、科学全体とその社会における役割を改善するため

に、科学内部の問題を取り扱う。批判は、哲学やフェミニズムなどの社会運動、そして科学そのものの中から生じる。 メタサイエンスという新たな分野は、科学的手法の改善により、科学研究の質と効率を高めることを目指している。 |

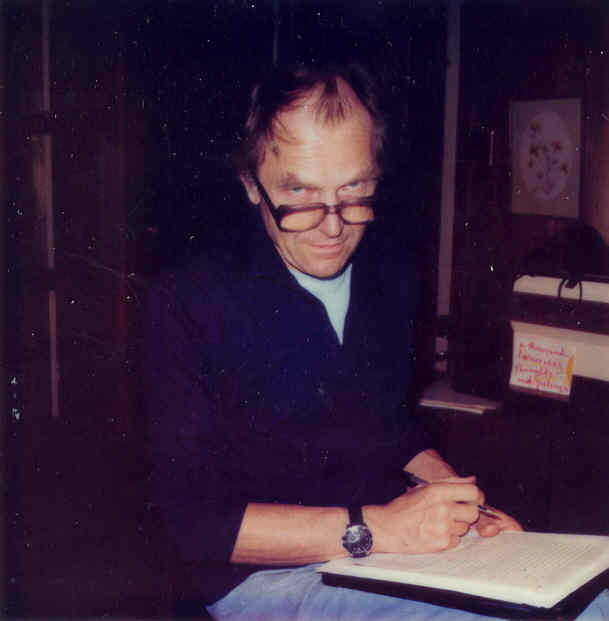

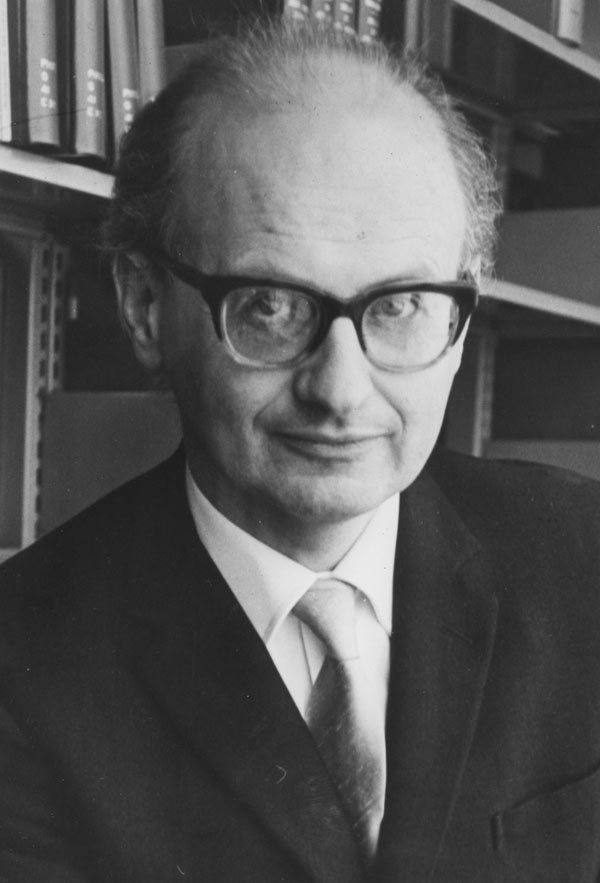

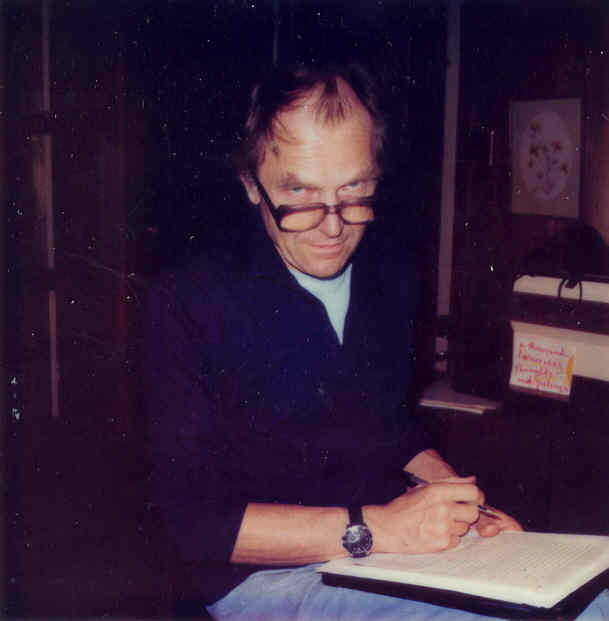

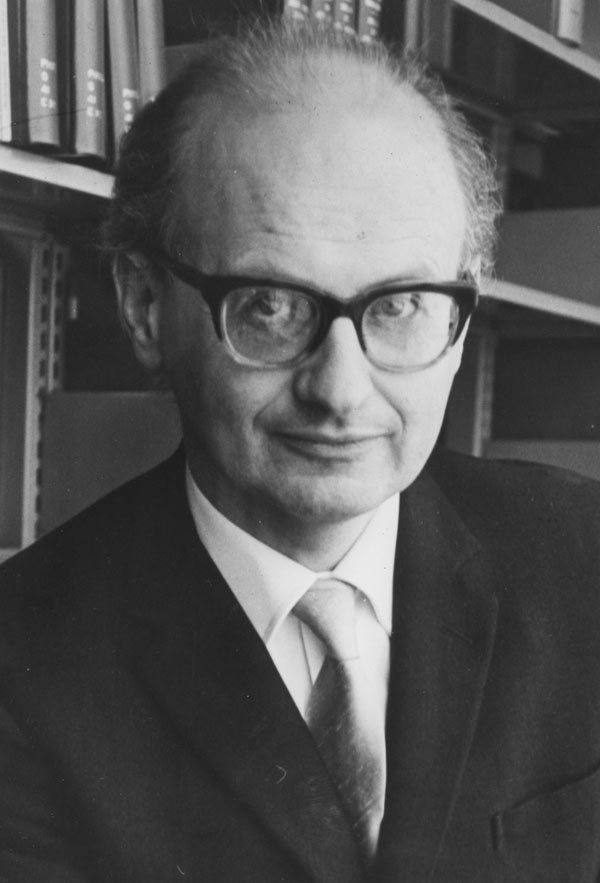

Philosophical critiques "All methodologies, even the most obvious ones, have their limits." ―Paul Feyerabend in Against Method Philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend advanced the idea of epistemological anarchism, which holds that there are no useful and exception-free methodological rules governing the progress of science or the growth of knowledge, and that the idea that science can or should operate according to universal and fixed rules is unrealistic, pernicious and detrimental to science itself.[1][page needed] Feyerabend advocates a democratic society where science is treated as equal to other ideologies or social institutions such as religion, and education, or magic and mythology, and considers the dominance of science in society authoritarian and unjustified.[1][page needed] He also contended (along with Imre Lakatos) that the demarcation problem of distinguishing science from pseudoscience on objective grounds is not possible and thus fatal to the notion of science running according to fixed, universal rules.[1][page needed]  Imre Lakatos, 1922-1974 Feyerabend also criticized science for not having evidence for its own philosophical precepts. Particularly the notion of Uniformity of Law and the Uniformity of Process across time and space, or Uniformitarianism in short, as noted by Stephen Jay Gould.[2] "We have to realize that a unified theory of the physical world simply does not exist" says Feyerabend, "We have theories that work in restricted regions, we have purely formal attempts to condense them into a single formula, we have lots of unfounded claims (such as the claim that all of chemistry can be reduced to physics), phenomena that do not fit into the accepted framework are suppressed; in physics, which many scientists regard as the one really basic science, we have now at least three different points of view...without a promise of conceptual (and not only formal) unification".[3] In other words, science is begging the question when it presupposes that there is a universal truth with no proof thereof. Historian Jacques Barzun termed science "a faith as fanatical as any in history" and warned against the use of scientific thought to suppress considerations of meaning as integral to human existence.[4] Sociologist Stanley Aronowitz scrutinized science for operating with the presumption that the only acceptable criticisms of science are those conducted within the methodological framework that science has set up for itself. That science insists that only those who have been inducted into its community, through means of training and credentials, are qualified to make these criticisms.[5] Aronowitz also alleged that while scientists consider it absurd that Fundamentalist Christianity uses biblical references to bolster their claim that the Bible is true, scientists pull the same tactic by using the tools of science to settle disputes concerning its own validity.[6] New-age writer Alan Watts criticized science for operating under a materialist model of the world that he posited is simply a modified version of the Abrahamic worldview, that "the universe is constructed and maintained by a Lawmaker" (commonly identified as God or the Logos). Watts asserts that during the rise of secularism through the 18th to 20th century when scientific philosophers got rid of the notion of a lawmaker they kept the notion of law, and that the idea that the world is a material machine run by law is a presumption just as unscientific as religious doctrines that affirm it is a material machine made and run by a lawmaker.[7] Epistemology David Parkin compared the epistemological stance of science to that of divination. He suggested that, to the degree that divination is an epistemologically specific means of gaining insight into a given question, science itself can be considered a form of divination that is framed from a Western view of the nature (and thus possible applications) of knowledge.[8] Author and Episkopos of Discordianism Robert Anton Wilson stresses that the instruments used in scientific investigation produce meaningful answers relevant only to the instrument, and that there is no objective vantage point from which science could verify its findings since all findings are relative to begin with.[9] Ethics  Joseph Wright of Derby (1768): An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump, National Gallery, London Several academics have offered critiques concerning ethics in science. In Science and Ethics, for example, the professor of philosophy Bernard Rollin examines the relevance of ethics to science, and argues in favor of making education in ethics part and parcel of scientific training.[10] Social science scholars, like social anthropologist Tim Ingold, and scholars from philosophy and the humanities, like critical theorist Adorno, have criticized modern science for subservience to economic and technological interests.[11] A related criticism is the debate on positivism. While before the 19th century science was perceived to be in opposition to religion, in contemporary society science is often defined as the antithesis of the humanities and the arts.[12] Many thinkers, such as Carolyn Merchant, Theodor Adorno and E. F. Schumacher considered that the 17th century scientific revolution shifted science from a focus on understanding nature, or wisdom, to a focus on manipulating nature, i.e. power, and that science's emphasis on manipulating nature leads it inevitably to manipulate people, as well.[13] Science's focus on quantitative measures has led to critiques that it is unable to recognize important qualitative aspects of the world.[13] |

哲学的な批判 「どんな方法論にも、たとえ最も明白なものであっても限界がある。」 ―ポール・フェイヤーアベント著『方法に対する』より 科学哲学者のポール・フェイヤーアベントは、科学の進歩や知識の成長を支配する有用で例外のない方法論的規則は存在せず、科学が普遍的で固定された規則に 従って機能しうる、あるいは機能すべきだという考え方は非現実的で有害であり、科学そのものにとって有害であるという認識論的無政府主義の考え方を提唱し た。[1][page needed] フェイヤーアベントは、科学が他のイデオロギーや宗教、教育、あるいは魔術や神話といった社会制度と同等に扱われる民主的社会を提唱し 宗教や教育、あるいは魔術や神話といった他のイデオロギーや社会制度と同等に扱うべきであるとし、科学が社会で優位を占めることは権威主義的で正当化でき ないと主張している。[1][要出典] また、イムレ・ラカトシュとともに、客観的な根拠に基づいて科学と疑似科学を区別する境界問題は不可能であり、固定された普遍的な規則に従って科学が運営 されるという概念にとって致命的であると主張した。[1][要出典]  イムレ・ラカトシュ また、ファイヤアーベントは科学が自身の哲学的な教義の証拠を持っていないことを批判した。特に、時空を超えた法則の統一性や手続きの統一性、つまり、ス ティーブン・ジェイ・グールドが指摘した「均一説」についてである。[2] 「物理的世界の統一理論は存在しないということを認識しなければならない」とファイヤアーベントは言う。「限られた領域で機能する理論があり、それを単一 の公式に凝縮しようとする純粋に形式的な試みがあり、根拠のない主張(例えば、 化学のすべてが物理学に還元できるという主張など)が存在し、受け入れられた枠組みに当てはまらない現象は抑圧される。多くの科学者が真の基礎科学とみな す物理学においては、少なくとも3つの異なる視点が存在する。概念(形式的なものだけではない)の統一が約束されていないにもかかわらず、である。[3] つまり、科学は、証明不可能な普遍的な真理が存在すると仮定している時点で、問題を先送りしていることになる。 歴史学者ジャック・バルゾンは科学を「歴史上の狂信的な信仰」と呼び、人間の存在に不可欠な意味の考察を抑制するために科学的思考を用いることに対して警告を発した。[4] 社会学者スタンリー・アロノウィッツは、科学に対する唯一の許容される批判は、科学が自ら設定した方法論的枠組みの中で行われるものだけであるという前提 のもとで科学が活動していると厳しく批判した。科学は、訓練と資格によってそのコミュニティに受け入れられた者だけが、こうした批判を行う資格があると主 張している。[5] アロノウィッツはまた、原理主義キリスト教が聖書が真実であるという主張を裏付けるために聖書の引用を用いることを科学者たちが不合理であると考える一方 で、科学者たちは科学の道具を用いて科学の妥当性に関する論争を解決しようとするという、同じ戦術を用いていると主張している。[6] ニューエイジの作家アラン・ワッツは、科学が唯物論的世界観に基づいており、それは単にアブラハムの神の世界観の修正版に過ぎない、と批判した。「宇宙は 立法者(一般的に神またはロゴスとされる)によって構築され維持されている」というのだ。ワッツは、18世紀から20世紀にかけての世俗主義の台頭期に、 科学哲学者たちが立法者の概念を排除した一方で、法の概念は保持したと主張している。そして、世界は法によって動く物質的な機械であるという考え方は、世 界は立法者によって作られ、法によって動く物質的な機械であると主張する宗教的教義と同様に非科学的な思い込みであると主張している。[7] 認識論 デビッド・パーキンは、科学の認識論的立場を占いに例えた。パーキンは、占いが特定の問題に対する洞察を得るための認識論的に特殊な手段であるのと同程度 に、科学自体も、西洋の知識の性質(およびそれゆえの応用可能性)に関する見解から構成された占いの一形態であると考えることができると示唆している。 ディスコルディアニズムの著述家であり司祭であるロバート・アントン・ウィルソンは、科学調査で使用される機器は、その機器に関連する意味のある回答のみ を生成するものであり、そもそもすべての調査結果は相対的なものであるため、科学がその調査結果を検証できる客観的な視点は存在しないと強調している。 [9] 倫理  ジョセフ・ライト(1768年):『空気ポンプの中の鳥に関する実験』、ロンドン、ナショナル・ギャラリー (※コメント:リヴァイアサンと真空ポンプはシェイピンの著作で邦訳もされているけど、芸術作品でこんなものがあるとは知らなかった(サイエンスのアンチ ヒューマニズムをジェンダー感受性の差異として見事に描いている)→Joseph Wright of Derby (1768): An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump, National Gallery, London) 科学における倫理に関する批判は、複数の学者によっても提示されている。例えば、『科学と倫理』の著者である哲学教授のバーナード・ローリンは、倫理と科学の関連性を検証し、倫理教育を科学教育の一部として取り入れるべきであると主張している。 社会人類学者のティム・インゴールドのような社会科学者や、批判理論家のアドルノのような哲学や人文科学の学者は、経済的利益や技術的利益に従属する現代 科学を批判している。[11] 関連する批判として、実証主義に関する議論がある。19世紀以前には科学は宗教と対立するものと見なされていたが、現代社会では科学は人文科学や芸術の対 立概念として定義されることが多い。[12] キャロライン・マーチャント、テオドール・アドルノ、E. F. シューマッハーなど多くの思想家は、17世紀の科学革命によって科学が自然の理解、すなわち知恵の探求から、自然の操作、すなわち権力の探求へと重点が 移ったと考えた 。また、科学が自然を操作することに重点を置くことで、必然的に人間をも操作することにつながると考えた。[13] 科学が量的測定に重点を置くことで、世界の重要な質的側面を認識できないという批判につながった。[13] |

| Critiques from within science Main article: Metascience Metascience is the use of scientific methodology to study science itself, with the goal of increasing the quality of research while reducing waste. Meta-research has identified methodological weaknesses in many areas of science. Critics argue that reforms are needed to address these weaknesses. Reproduciblity Main article: Replication crisis The social sciences, such as social psychology, have long suffered from the problem of their studies being largely not reproducible.[14] Now, medicine has come under similar pressures.[15] In a phenomenon known as the replication crisis, journals are less likely to publish straight replication studies so it may be difficult to disprove results.[16] Another result of publication bias is the Proteus phenomenon: early attempts to replicate results tend to contradict them.[17] However, there are claims that this bias may be beneficial, allowing accurate meta-analysis with fewer publications.[18] Cognitive and publication biases Critics argue that the biggest bias within science is motivated reasoning, whereby scientists are more likely to accept evidence that supports their hypothesis and more likely to scrutinize findings that do not.[19] Scientists do not practice pure induction but instead often come into science with preconceived ideas and often will, unconsciously or consciously, interpret observations to support their own hypotheses through confirmation bias. For example, scientists may re-run trials when they do not support a hypothesis but use results from the first trial when they do support their hypothesis.[20] It is often argued that while each individual has cognitive biases, these biases are corrected for when scientific evidence converges. However, systematic issues in the publication system of academic journals can often compound these biases. Issues like publication bias, where studies with non-significant results are less likely to be published, and selective outcome reporting bias, where only the significant outcomes out of a variety of outcomes are likely to be published, are common within academic literature. These biases have widespread implications, such as the distortion of meta-analyses where only studies that include positive results are likely to be included.[21] Statistical outcomes can be manipulated as well, for example large numbers of participants can be used and trials overpowered so that small difference cause significant effects or inclusion criteria can be changed to include those are most likely to respond to a treatment.[22] Whether produced on purpose or not, all of these issues need to be taken into consideration within scientific research, and peer-reviewed published evidence should not be assumed to be outside of the realm of bias and error; some critics are now claiming that many results in scientific journals are false or exaggerated.[21] |

科学内部からの批判 詳細はメタサイエンスを参照 メタサイエンスとは、科学的手法を用いて科学そのものを研究することであり、研究の質を高めつつ無駄を省くことを目的としている。メタ研究により、科学の 多くの分野における方法論的な弱点が明らかになっている。批判派は、これらの弱点に対処するための改革が必要だと主張している。 再現可能性 詳細は「再現の危機」を参照 社会心理学などの社会科学は、研究結果の大部分が再現できないという問題に長年苦しんできた。[14] 現在、医学も同様の圧力にさらされている。[15] 再現の危機として知られる現象では、学術誌は単純な再現研究を掲載する可能性が低いため、 結果を否定することが困難になる可能性がある。[16] 出版バイアスの別の結果として、プロテウス現象がある。初期の再現研究は、往々にして結果と矛盾する傾向がある。[17] しかし、このバイアスは有益であり、出版数が少なくても正確なメタ分析を可能にするという主張もある。[18] 認知バイアスと出版バイアス 科学における最大のバイアスは動機付けられた推論であり、科学者は自らの仮説を裏付ける証拠を受け入れやすく、そうでない発見を精査しにくいという批判が ある。例えば、科学者は仮説を裏付けない場合には試験を再度実施するが、仮説を裏付ける場合には最初の試験の結果を利用する。[20] 個々には認知バイアスがあるものの、科学的証拠が収束するにつれてこれらのバイアスは修正されると主張されることが多い。しかし、学術誌の出版システムに おける体系的な問題が、これらのバイアスをさらに複雑化させることも多い。有意でない結果の研究は出版される可能性が低い出版バイアスや、さまざまな結果 のうち有意な結果のみが出版される選択的結果報告バイアスなどの問題は、学術文献では一般的である。これらのバイアスは、肯定的な結果を含む研究のみがメ タ分析に含まれる可能性があるというメタ分析の歪曲など、広範な影響を及ぼす。[21] 統計的な結果も操作される可能性があり、例えば多数の被験者を使用し、試験を圧倒的なものにすることで、わずかな差異が有意な効果を生み出すようにした り、あるいは、治療に最も反応する可能性が高い被験者を含めるために、選択基準を変更したりすることが可能である。治療に反応する可能性が高いものを対象 に含めるために、包含基準が変更される可能性もある。[22] 意図的に行われたか否かに関わらず、これらの問題はすべて科学的研究において考慮される必要があり、査読を経て発表された証拠は、バイアスやエラーの領域 外にあると想定すべきではない。一部の批評家は、科学誌に掲載された多くの結果は誤りまたは誇張であると主張している。[21] |

| Feminist critiques See also: Feminist philosophy of science Feminist scholars and women scientists such as Emily Martin, Evelyn Fox Keller, Ruth Hubbard, Londa Schiebinger and Bonnie Spanier have critiqued science because they believe it presents itself as objective and neutral while ignoring its inherent gender bias. They assert that gender bias exists in the language and practice of science, as well as in the expected appearance and social acceptance of who can be scientists within society.[23][24][25] Sandra Harding says that the "moral and political insights of the women's movement have inspired social scientists and biologists to raise critical questions about the ways traditional researchers have explained gender, sex, and relations within and between the social and natural worlds."[26] Anne Fausto-Sterling is a prominent example of this kind of feminist work within biological science. Some feminists, such as Ruth Hubbard and Evelyn Fox Keller, criticize traditional scientific discourse as being historically biased towards a male perspective.[27][28] A part of the feminist research agenda is the examination of the ways in which power inequities are created and/or reinforced in scientific and academic institutions.[29] Other feminist scholars, such as Ann Hibner Koblitz,[30] Lenore Blum,[31] Mary Gray,[32] Mary Beth Ruskai,[33] and Pnina Abir-Am and Dorinda Outram,[34] have criticized some gender and science theories for ignoring the diverse nature of scientific research and the tremendous variation in women's experiences in different cultures and historical periods. For example, the first generation of women to receive advanced university degrees in Europe were almost entirely in the natural sciences and medicine—in part because those fields at the time were much more welcoming of women than were the humanities.[35] Koblitz and others who are interested in increasing the number of women in science have expressed concern that some of the statements by feminist critics of science could undermine those efforts, notably the following assertion by Keller:[36] Just as surely as inauthenticity is the cost a woman suffers by joining men in misogynist jokes, so it is, equally, the cost suffered by a woman who identifies with an image of the scientist modeled on the patriarchal husband. Only if she undergoes a radical disidentification from self can she share masculine pleasure in mastering a nature cast in the image of woman as passive, inert, and blind. Language in science Emily Martin examines the metaphors used in science to support her claim that science reinforces socially constructed ideas about gender rather than objective views of nature. In her study about the fertilization process, Martin describes several cases when gender-biased perception skewed the descriptions of biological processes during fertilization and even possibly hampered the research. She asserts that classic metaphors of the strong dominant sperm racing to an idle egg are products of gendered stereotyping rather than a faithful portrayal of human fertilization. The notion that women are passive and men are active are socially constructed attributes of gender which, according to Martin, scientists have projected onto the events of fertilization and so obscuring the fact that eggs do play an active role. For example, she wrote that "even after having revealed...the egg to be a chemically active sperm catcher, even after discussing the egg's role in tethering the sperm, the research team continued for another three years to describe the sperm's role as actively penetrating the egg."[23] Scott Gilbert, a developmental biologist at Swarthmore College supports her position: "if you don’t have an interpretation of fertilization that allows you to look at the egg as active, you won’t look for the molecules that can prove it. You simply won’t find activities that you don’t visualize."[23] |

フェミニストの批判 関連項目:フェミニズム科学哲学 エミリー・マーティン、エブリン・フォックス・ケラー、ルース・ハバード、ロンダ・シービンガー、ボニー・スパイナーといったフェミニズム学者や女性科学 者は、科学が本質的な性差別を無視しながら客観的かつ中立的なものであるかのように見せかけていると批判している。彼らは、科学の言語や実践、また科学者 として社会で認められる外見や社会的受容性にも性差別が存在すると主張している。 サンドラ・ハーディングは、「女性運動の道徳的・政治的洞察が、社会科学者や生物学者たちに、従来の研究者が性別、性、社会と自然界の関係を説明してきた 方法について批判的な疑問を投げかけるよう促した」と述べている。[26] 生物科学におけるこの種のフェミニスト研究の著名な例としては、アン・ファウスト・スターリングが挙げられる。ルース・ハバードやエブリン・フォックス・ ケラーなどのフェミニストは、伝統的な科学の言説は歴史的に男性の視点に偏っていると批判している。[27][28] フェミニストの研究課題の一部は、科学および学術機関において権力の不平等がどのようにして生み出され、強化されているかを検証することである。[29] 他のフェミニスト学者、例えばアン・ヒブナー・コブリッツ(Ann Hibner Koblitz)[30]、レノア・ブルーム(Lenore Blum)[31]、メアリー・グレイ(Mary Gray)[32]、メアリー・ベス・ラスキ(Mary Beth Ruskai)[33]、ピナ・アビル・アム(Pnina Abir-Am)とドリンダ・アウトラム(Dorinda Outram)[34]は、科学的研究の多様性や、異なる文化や時代における女性の経験の大きな違いを無視しているとして、ジェンダーと科学に関するいく つかの理論を批判している。例えば、ヨーロッパで大学の上級学位を取得した最初の世代の女性は、ほぼすべて自然科学と医学の分野に集中していた。その理由 の一つとして、当時、人文科学よりも自然科学や医学の方が女性を受け入れやすかったことが挙げられる。[35] 科学分野における女性の増加に関心を持つコブリッツやその他の人々は、フェミニストの科学批判家の一部の主張が、こうした取り組みを損なう可能性があるこ とを懸念している。特に、ケラーによる以下の主張が挙げられる。[36] 女性が男性の嫌女性ジョークに加わることで被る不誠実さの代償が確実であるように、家父長的な夫をモデルとした科学者のイメージに自分を同一視する女性が 被る代償もまた確実である。女性が自己から徹底的に同一視を解く場合のみ、受動的で無気力で盲目的な女性像として描かれた自然を支配する男性的な喜びを共 有することができる。 科学における言語 エミリー・マーティンは、科学が自然に対する客観的な見解というよりもむしろ、ジェンダーに関する社会的に構築された考え方を強化しているという主張を裏 付けるために、科学で使用される比喩を検証している。受精プロセスに関する研究で、マーティンは、ジェンダーに偏った認識が受精中の生物学的プロセスの記 述を歪め、研究を妨げた可能性さえあるいくつかの事例を説明している。彼女は、受精の様子を雄の精子が雌の卵子に向かって走るという古典的な比喩で表現す ることは、人間の受精の様子を忠実に描写したものではなく、性別による固定観念の産物であると主張している。女性は受動的で男性は能動的であるという考え 方は、社会的に構築された性別による属性であり、マーティンによると、科学者たちは受精の様子にこの考え方を当てはめてしまい、卵子が能動的な役割を果た しているという事実を覆い隠してしまった。例えば、彼女は「たとえ卵子が化学的に活性のある精子キャッチャーであることを明らかにし、卵子が精子を捕らえ る役割について論じたとしても、研究チームはさらに3年間、精子が卵子に能動的に侵入する役割について説明し続けた」と書いている。[23] スワースモア大学の発生生物学者であるスコット・ギルバートは、彼女の意見を支持している。「卵子を能動的と見なす受精の解釈を持たなければ、それを証明 する分子を探そうとはしない。単に、思い描けない活動は見つからないのだ」[23] |

| Media and politics Main article: Politicization of science The mass media face a number of pressures that can prevent them from accurately depicting competing scientific claims in terms of their credibility within the scientific community as a whole. Determining how much weight to give different sides in a scientific debate requires considerable expertise regarding the matter.[37] Few journalists have real scientific knowledge, and even beat reporters who know a great deal about certain scientific issues may know little about other ones they are suddenly asked to cover.[38][39] Many issues damage the relationship of science to the media and the use of science and scientific arguments by politicians. As a very broad generalisation, many politicians seek certainties and facts whilst scientists typically offer probabilities and caveats.[citation needed] However, politicians' ability to be heard in the mass media frequently distorts the scientific understanding by the public. Examples in Britain include the controversy over the MMR inoculation, and the 1988 forced resignation of a government minister, Edwina Currie, for revealing the high probability that battery eggs were contaminated with Salmonella.[40] Some scientists and philosophers suggest that scientific theories are more or less shaped by the dominant political, economic, or cultural models of the time, even though the scientific community may claim to be exempt from social influences and historical conditions.[41][42] For example, the Russian philosopher, socialist, and zoologist Peter Kropotkin thought that the Darwinian theory of evolution overstressed a painful "we must struggle to survive" way of life, which he said was influenced by capitalism and the struggling lifestyles people lived within it.[9][43] Karl Marx also thought that science was largely driven by and used as capital.[44] Robert Anton Wilson, Stanley Aronowitz, and Paul Feyerabend all thought that the military-industrial complex, large corporations, and the grants that came from them had an immense influence over the research and even results of scientific experiments.[1][45][46][47] Aronowitz even went as far as to say "It does not matter that the scientific community ritualistically denies its alliance with economic/industrial and military power. The evidence is overwhelming that such is the case. Thus, every major power has a national science policy; the United States Military appropriates billions each year for 'basic' as well as 'applied' research".[47] |

メディアと政治 詳細は「科学の政治化」を参照 マスメディアは、科学界全体における信頼性の観点から、競合する科学的主張を正確に描写することを妨げる多くの圧力に直面している。科学論争における各論 点にどれほどの重みを与えるかを決定するには、その問題に関する相当な専門知識が必要である。[37] 科学に関する真の知識を持つジャーナリストはほとんどおらず、特定の科学問題について多くの知識を持つ現場記者でさえ、急に取材を依頼された他の問題につ いてはほとんど知らない場合がある。[38][39] 多くの問題が、科学とメディアの関係、および政治家による科学や科学的論拠の利用を損なっている。非常に大まかな一般論として、多くの政治家は確実性や事 実を求めているが、科学者は通常、確率や注意事項を提示する。しかし、政治家がマスメディアで発言する能力は、一般市民の科学的理解を歪めることが多い。 英国の例としては、MMRワクチン接種をめぐる論争や、1988年にエドウィナ・カリー政府大臣が、鶏卵がサルモネラ菌に汚染されている可能性が高いこと を明らかにしたために辞任に追い込まれた事件などがある。 科学理論は、その時代の支配的な政治、経済、文化モデルによって、多かれ少なかれ形作られるという見解を、一部の科学者や哲学者が示している。科学界は社 会的な影響や歴史的条件から免れていると主張しているが、[41][42] 例えば、ロシアの哲学者、社会主義者、動物学者であるピーター・クロポトキンは、 ダーウィンの進化論は、生き残るために苦闘しなければならないという生き方を過度に強調していると考えた。これは資本主義の影響であり、その中で人々が苦 闘する生活を送っているからだと彼は述べた。[9][43] カール・マルクスもまた、科学は資本によって主導され、資本として利用されていると考えた。[44] ロバート・アントン・ウィルソン、スタンリー・アロンウィッツ、ポール・フェイヤーアーベントは、軍産複合体、大企業、およびそれらから得られる助成金 が、科学研究や科学実験の結果にまで多大な影響を及ぼしていると考えていた。[1][45][46][47] アロンウィッツはさらに、「科学界が経済・産業および軍事力との連携を儀式的に否定しているとしても、それは問題ではない。そのような事例は圧倒的に多 い。したがって、すべての主要国は国家科学政策を持っている。米国軍は毎年、何十億ドルもの予算を「基礎」研究と「応用」研究の両方に充てている。 [47] |

| Anti-intellectualism Antiscience Postmodernism Pseudoscience Pseudoskepticism Empirical limits in science(→Empiricism) |

反知性主義 反科学 ポストモダニズム 疑似科学 疑似懐疑論 科学における経験的限界 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criticism_of_science |

|

| Antiscience Antiscience is a set of attitudes and a form of anti-intellectualism that involves a rejection of science and the scientific method.[1] People holding antiscientific views do not accept science as an objective method that can generate universal knowledge. Antiscience commonly manifests through rejection of scientific ideas such as climate change and evolution. It also includes pseudoscience, methods that claim to be scientific but reject the scientific method. Antiscience leads to belief in false conspiracy theories and alternative medicine.[2] Lack of trust in science has been linked to the promotion of political extremism and distrust in medical treatments.[3][4] History In the early days of the scientific revolution, scientists such as Robert Boyle (1627–1691) found themselves in conflict with those such as Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), who were skeptical of whether science was a satisfactory way to obtain genuine knowledge about the world. Hobbes' stance is regarded by Ian Shapiro as an antiscience position: In his Six Lessons to the Professors of Mathematics,...[published in 1656, Hobbes] distinguished 'demonstrable' fields, as 'those the construction of the subject whereof is in the power of the artist himself,' from 'indemonstrable' ones 'where the causes are to seek for.' We can only know the causes of what we make. So geometry is demonstrable, because 'the lines and figures from which we reason are drawn and described by ourselves' and 'civil philosophy is demonstrable, because we make the commonwealth ourselves.' But we can only speculate about the natural world, because 'we know not the construction, but seek it from the effects.'[5] In his book Reductionism: Analysis and the Fullness of Reality, published in 2000, Richard H. Jones wrote that Hobbes "put forth the idea of the significance of the nonrational in human behaviour".[6] Jones goes on to group Hobbes with others he classes as "antireductionists" and "individualists", including Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911), Karl Marx (1818–1883), Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and J S Mill (1806–1873), later adding Karl Popper (1902–1994), John Rawls (1921–2002), and E. O. Wilson (1929–2021) to the list.[7] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750), claimed that science can lead to immorality. "Rousseau argues that the progression of the sciences and arts has caused the corruption of virtue and morality" and his "critique of science has much to teach us about the dangers involved in our political commitment to scientific progress, and about the ways in which the future happiness of mankind might be secured".[8] Nevertheless, Rousseau does not state in his Discourses that sciences are necessarily bad, and states that figures like René Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton should be held in high regard.[9] In the conclusion to the Discourses, he says that these (aforementioned) can cultivate sciences to great benefit, and that morality's corruption is mostly because of society's bad influence on scientists.[10] William Blake (1757–1827) reacted strongly in his paintings and writings against the work of Isaac Newton (1642–1727), and is seen[by whom?] as being perhaps[original research?] the earliest (and almost certainly the most prominent and enduring) example[citation needed] of what is seen by historians as the aesthetic or Romantic antiscience response. For example, in his 1795 poem "Auguries of Innocence", Blake describes the beautiful and natural robin redbreast imprisoned by what one might interpret as the materialistic cage of Newtonian mathematics and science.[11] Blake's painting of Newton depicts the scientist "as a misguided hero whose gaze was directed only at sterile geometrical diagrams drawn on the ground".[12] Blake thought that "Newton, Bacon, and Locke with their emphasis on reason were nothing more than 'the three great teachers of atheism, or Satan's Doctrine'...the picture progresses from exuberance and colour on the left, to sterility and blackness on the right. In Blake's view Newton brings not light, but night".[13] In a 1940 poem, W.H. Auden summarises Blake's anti-scientific views by saying that he "[broke] off relations in a curse, with the Newtonian Universe".[14] One recent biographer of Newton[15] considers him more as a renaissance alchemist, natural philosopher, and magician rather than a true representative of scientific Enlightenment, as popularized by Voltaire (1694–1778) and other Newtonians. Antiscience issues are seen[by whom?] as a fundamental consideration in the historical transition from "pre-science" or "protoscience" such as that evident in alchemy. Many disciplines that pre-date the widespread adoption and acceptance of the scientific method, such as geometry and astronomy, are not seen as anti-science. However, some[which?] of the orthodoxies within those disciplines that predate a scientific approach (such as those orthodoxies repudiated by the discoveries of Galileo (1564–1642)) are seen[by whom?] as being a product of an anti-scientific stance. Friedrich Nietzsche in The Gay Science (1882) questions scientific dogmatism: "[...] in Science, convictions have no rights of citizenship, as is said with good reason. Only when they decide to descend to the modesty of a hypothesis, of a provisional experimental point of view, of a regulative fiction, maybe they be granted admission and even a certain value within the realm of knowledge – though always with the restriction that they remain under police supervision, under the police of mistrust. But does this not mean, more precisely considered, that a conviction may obtain admission to science only when it ceases to be a conviction? Would not the discipline of the scientific spirit begin with this, no longer to permit oneself any convictions? Probably that is how it is. But one must still ask whether it is not the case that, in order that this discipline could begin, a conviction must have been there already, and even such a commanding and unconditional one that it sacrificed all other convictions for its own sake. It is clear that Science too rests on a faith; there is no Science 'without presuppositions.' The question whether truth is needed must not only have been affirmed in advance, but affirmed to the extent that the principle, the faith, the conviction is expressed: 'nothing is needed more than truth, and in relation to it, everything else has only second-rate value".[16] The term "scientism", originating in science studies,[citation needed] was adopted and is used by sociologists and philosophers of science to describe the views, beliefs and behavior of strong supporters of applying ostensibly scientific concepts beyond its traditional disciplines.[17] Specifically, scientism promotes science as the best or only objective means to determine normative and epistemological values. The term scientism is generally used critically, implying a cosmetic application of science in unwarranted situations considered not amenable to application of the scientific method or similar scientific standards. The word is commonly used in a pejorative sense, applying to individuals who seem to be treating science in a similar way to a religion. The term reductionism is occasionally used in a similarly pejorative way (as a more subtle attack on scientists). However, some scientists feel comfortable being labelled as reductionists, while agreeing that there might be conceptual and philosophical shortcomings of reductionism.[18] However, non-reductionist (see Emergentism) views of science have been formulated[by whom?] in varied forms in several scientific fields like statistical physics, chaos theory, complexity theory, cybernetics, systems theory, systems biology, ecology, information theory, etc.[citation needed] Such fields tend to assume that strong interactions between units produce new phenomena in "higher" levels that cannot be accounted for solely by reductionism. For example, it is not valuable (or currently possible) to describe a chess game or gene networks using quantum mechanics. The emergentist view of science ("More is Different", in the words of 1977 Nobel-laureate physicist Philip W. Anderson)[19] has been inspired in its methodology by the European social sciences (Durkheim, Marx) which tend to reject methodological individualism.[citation needed] Political Elyse Amend and Darin Barney argue that while antiscience can be a descriptive label, it is often used as a rhetorical one, being effectively used to discredit ones' political opponents and thus charges of antiscience are not necessarily warranted.[20] Secular Further information: Populism Left-wing Further information: Left-wing populism One expression of antiscience is the "denial of universality and... legitimisation of alternatives", and that the results of scientific findings do not always represent any underlying reality, but can merely reflect the ideology of dominant groups within society.[21] Alan Sokal states that this view associates science with the political right and is seen as a belief system that is conservative and conformist, that suppresses innovation, that resists change and that acts dictatorially. This includes the view, for example, that science has a "bourgeois and/or Eurocentric and/or masculinist world-view".[22] The anti-nuclear movement, often associated with the left,[23][24][25] has been criticized for overstating the negative effects of nuclear power,[26][27] and understating the environmental costs of non-nuclear sources that can be prevented through nuclear energy.[28] Opposition to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) has also been associated with the left.[29] Right-wing Further information: Right-wing populism The origin of antiscience thinking may be traced back to the reaction of Romanticism to the Enlightenment-this movement is often referred to as the 'Counter-Enlightenment'. Romanticism emphasizes that intuition, passion and organic links to nature are primal values and that rational thinking is merely a product of human life. Modern right-wing antiscience includes climate change denial, rejection of evolution, and misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines.[30][31] While concentrated in areas of science that are seen as motivating government action, these attitudes are strong enough to make conservatives appreciate science less in general.[32] Characteristics of antiscience associated with the right include the appeal to conspiracy theories to explain why scientists believe what they believe,[33] in an attempt to undermine the confidence or power usually associated to science (e.g., in global warming conspiracy theories). In modern times, it has been argued that right-wing politics carries an anti-science tendency. While some have suggested that this is innate to either rightists or their beliefs, others have argued it is a "quirk" of a historical and political context in which scientific findings happened to challenge or appeared to challenge the worldviews of rightists rather than leftists.[34][35] Religious Main article: Relationship between religion and science In this context, antiscience may be considered dependent on religious, moral and cultural arguments. For this kind of religious antiscience philosophy, science is an anti-spiritual and materialistic force that undermines traditional values, ethnic identity and accumulated historical wisdom in favor of reason and cosmopolitanism. In particular, the traditional and ethnic values emphasized are similar to those of white supremacist Christian Identity theology, but similar right-wing views have been developed by radically conservative sects of Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. New religious movements such as the left-wing New Age and the far-right Falun Gong thinking also criticize the scientific worldview as favouring a reductionist, atheist, or materialist philosophy. A frequent basis of antiscientific sentiment is religious theism with literal interpretations of sacred text. Here, scientific theories that conflict with what is considered divinely-inspired knowledge are regarded as flawed. Over the centuries religious institutions have been hesitant to embrace such ideas as heliocentrism and planetary motion because they contradicted the dominant interpretation of various passages of scripture. More recently the body of creation theologies known collectively as creationism, including the teleological theory of intelligent design, has been promoted by religious theists (primarily fundamentalists) in response to the process of evolution by natural selection.[36] One of the more extreme creation theologies, young Earth creationism, also finds itself in conflict with research in cosmology, historical geology, and the origin of life. To the extent that attempts to overcome antiscience sentiments have failed, some argue that a different approach to science advocacy is needed. One such approach says that it is important to develop a more accurate understanding of those who deny science (avoiding stereotyping them as backward and uneducated) and also to attempt outreach via those who share cultural values with target audiences, such as scientists who also hold religious beliefs.[37] |

反科学 反科学とは、科学と科学的手法を拒絶する態度や反知性主義の一形態である。反科学的見解を持つ人々は、普遍的な知識を生み出す客観的な方法としての科学を 受け入れない。反科学は一般的に、気候変動や進化論などの科学的考え方を拒絶することによって現れる。疑似科学、科学的であると主張しながらも科学的手法 を拒絶する手法も含まれる。反科学は、誤った陰謀論や代替医療を信じることに繋がる。[2] 科学に対する信頼の欠如は、政治的過激主義の助長や医療への不信感と関連している。[3][4] 歴史 科学革命の初期、ロバート・ボイル(1627年-1691年)などの科学者は、トマス・ホッブズ(1588年-1679年)などの科学が世界の真の知識を得るための満足のいく方法であるかどうかについて懐疑的な人々と対立していた。 ホッブズの姿勢は、イアン・シャピロによって反科学的な立場であるとみなされている。 著書『数学教授者への6つの教訓』の中で、ホッブズは「証明可能な」分野を「その主題の構築が芸術家自身の力にあるもの」として、「証明不可能な」分野 「原因を追求すべきもの」と区別した。私たちが作り出すものについてのみ、その原因を知ることができる。したがって、幾何学は証明可能である。なぜなら、 「私たちが推論する線や図形は、私たち自身によって描かれ、記述される」からであり、「市民哲学は証明可能である。なぜなら、私たちは自分たちで共和国を 作るから」である。しかし、自然界については推測することしかできない。なぜなら、「私たちはその構造を知らず、その効果からそれを求める」からである。 [5] リチャード・H・ジョーンズは、2000年に出版された著書『還元主義:分析と現実の完全性』の中で、ホッブズが「人間の行動における非合理性の重要性を 提唱した」と書いている。[6] ジョーンズは、ホッブズを「反還元主義者」および「個人主義者」として分類した他の人物たち、すなわちヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ(1833~1911)、 カール・マルクス(1818 1883)、ジェレミー・ベンサム(1748~1832)、J.S.ミル(1806~1873)を挙げ、後にカール・ポパー(1902~1994)、ジョ ン・ロールズ(1921~2002)、E.O.ウィルソン(1929~2021)をリストに追加した。[7] ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは著書『芸術と科学についての対話』(1750年)の中で、科学が不道徳につながりうると主張した。「ルソーは、科学と芸術の進 歩が美徳と道徳の腐敗を引き起こしたと主張している」と述べ、また「ルソーの科学批判は、科学の進歩に対する政治的な関与に伴う危険性や、人類の将来の幸 福を確保する方法について、多くのことを私たちに教えてくれる」と述べている。[8] しかし、ルソーは『論』の中で、 科学は必ずしも悪いものではないと述べ、ルネ・デカルト、フランシス・ベーコン、アイザック・ニュートンといった人物は高く評価されるべきであると述べて いる。[9] 『諸芸術の演説』の結論では、これらの人物(前述)は科学を大いに発展させることができると述べ、道徳の腐敗は主に科学者に対する社会の悪影響によるもの であると述べている。[10] ウィリアム・ブレイク(1757年-1827年)は、アイザック・ニュートン(1642年-1727年)の業績に対して、絵画や文章で強く反発した。これ は、おそらく[独自の研究?]、歴史家が美的またはロマン主義的反科学的な反応と見なすものの最も初期の(そして、ほぼ間違いなく最も著名で永続的な)例 であると見られている[要出典]。例えば、1795年の詩「無垢の予兆」の中で、ブレイクは、ニュートン流の数学や科学という唯物主義的な檻に閉じ込めら れた美しい小鳥、ロビン・レッドブレストを描写している。[11] ブレイクが描いたニュートンは、科学者を「 地面に描かれた不毛な幾何学図形だけを見つめている」と描いている。[12] ブレイクは、「理性を強調するニュートン、ベーコン、ロックは、単なる『三大無神論者、あるいはサタンの教義』にすぎない」と考えていた。絵は左側の色鮮 やかな部分から右側の不毛で黒ずんだ部分へと進んでいく。ブレイクの見解では、ニュートンは光ではなく夜をもたらす」。[13] 1940年の詩の中で、W.H.オーデンは「ニュートン宇宙との呪われた関係を断ち切った」と述べ、ブレイクの反科学的な見解を要約している。[14] ニュートンの最近の伝記作家の一人[15]は、ニュートンをヴォルテール(1694年-1778年)や他のニュートン主義者たちによって広められた科学的な啓蒙主義の真の代表者というよりも、ルネサンス期の錬金術師、自然哲学者、魔術師として捉えている。 反科学的な問題は、錬金術に見られるような「前科学」または「原始科学」から歴史的に移行する上で、根本的な考慮事項であると見なされている[誰によっ て?]。幾何学や天文学など、科学的手法が広く採用され受け入れられる以前の多くの学問分野は、反科学とは見なされていない。しかし、科学的手法が用いら れる以前の学問分野における正統的な見解(ガリレオ(1564年 - 1642年)の発見によって否定されたような見解)の一部は、反科学的な立場から生じたものと見なされている[誰によって?]。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェは『悦ばしき科学』(1882年)で科学的教条主義を疑問視している。 「...科学においては、信念は市民権を持たない。それはもっともな理由からである。仮説、暫定的な実験的見解、規制上のフィクションといった謙虚な立場 に身を落とすことを決意したときのみ、それらは知識の領域において一定の価値を認められ、受け入れられるかもしれない。しかし、より正確に考えれば、信念 が信念でなくなる時にのみ、信念が科学に受け入れられるということではないだろうか? 科学的精神の規律は、信念を一切許容しないことから始まるのではないだろうか?おそらく、その通りだろう。しかし、この規律が始まるためには、すでに信念 が存在していたはずであり、その信念は、他の信念をすべて犠牲にしてでも、自らの信念を貫くような、絶対的な信念であったはずではないだろうか。科学もま た信念の上に成り立っていることは明らかである。「前提なし」の科学などありえないのだ。真理が必要であるかどうかという問いは、あらかじめ肯定されてい るだけでなく、原則、信念、確信が表明されている程度まで肯定されているに違いない。「真理よりも必要なものはない。そして、それとの関係において、他の すべては二流の価値しかない」[16]。 「科学主義(scientism)」 という用語は科学研究に由来するが[要出典]、科学の伝統的な分野を超えて表向きには科学的概念を適用することの強力な支持者たちの見解、信念、行動を説 明する際に、社会学者や科学哲学者によって採用され、使用されている。[17] 具体的には、科学主義は規範的および認識論的価値を決定する最善かつ唯一の客観的手段として科学を推進する。科学主義という用語は一般的に批判的に用いら れ、科学的方法や同様の科学的基準の適用が適切ではないとみなされる状況下での、見せかけの科学の適用を意味する。この言葉は一般的に軽蔑的な意味で使用 され、科学を宗教のように扱っているように見える個人に対して用いられる。還元主義という用語も同様に軽蔑的な意味で使用されることがある(科学者に対す るより微妙な攻撃として)。しかし、還元主義者というレッテルを貼られることに抵抗を感じない科学者もいる一方で、還元主義には概念的・哲学的欠陥がある かもしれないと認めている。 しかし、還元主義以外の科学観(創発主義を参照)は、統計物理学、カオス理論、複雑系理論、サイバネティクス、システム理論、システム生物学、生態学、情 報理論など、いくつかの科学分野において、さまざまな形で定式化されている[誰によって?]。[要出典] このような分野では、単位間の強い相互作用が還元主義だけでは説明できない「より高い」レベルでの新しい現象を生み出すと想定する傾向がある。例えば、量 子力学を用いてチェスゲームや遺伝子ネットワークを記述することは価値がない(または現在では不可能である)。科学における創発論的見解(「より多くは異 なる」という1977年のノーベル物理学賞受賞者フィリップ・W・アンダーソンの言葉)[19]は、その方法論において、方法論的個人主義を拒絶する傾向 にあるヨーロッパの社会科学(デュルケーム、マルクス)から影響を受けている。 政治 エリゼ・アマンドとダリン・バーニーは、反科学は記述的なラベルであるかもしれないが、それはしばしば修辞的なものとして使用され、効果的に政治的反対派を貶めるために使用されるため、反科学の告発は必ずしも正当化されるものではないと主張している。[20] 世俗 さらに詳しい情報:ポピュリズム 左翼 さらに詳しい情報:左翼ポピュリズム 反科学の表現のひとつに「普遍性の否定と...代替案の正当化」があり、科学的な発見の結果は必ずしも根底にある現実を表しているわけではなく、単に社会 内の支配的グループのイデオロギーを反映しているにすぎないというものがある。[21] アラン・ソーカルは、この見解は科学を政治的右派と結びつけ、保守的で順応主義的、革新を抑制し、変化に抵抗し、独裁的に行動する信念体系と見なされると 述べている。これには、例えば「科学にはブルジョワ的、かつ/またはヨーロッパ中心主義的、かつ/または男性優位主義的世界観がある」という見解も含まれ る。[22] 反核運動はしばしば左派と関連付けられるが[23][24][25]、原子力の負の影響を誇張し[26][27]、原子力によって防止できる非核エネル ギー源の環境コストを過小評価していると批判されている[28]。遺伝子組み換え生物(GMO)への反対も左派と関連付けられている[29]。 右翼 詳細は「右派ポピュリズム」を参照 反科学的な考え方の起源は、啓蒙主義に対するロマン主義の反応にまで遡ることができる。この運動はしばしば「反啓蒙主義」と呼ばれる。ロマン主義は、直 観、情熱、自然との有機的なつながりが原始的な価値であり、合理的な思考は単に人間の生活の産物に過ぎないことを強調する。現代の右派の反科学には、気候 変動否定論、進化論の拒絶、およびCOVID-19ワクチンに関する誤った情報などが含まれる。[30][31] 政府の行動を促す要因と見なされる科学分野に集中しているが、これらの態度は保守派が科学をあまり評価しなくなるほど強い。[32] 右派に関連する反科学の特徴としては、科学者がなぜそう信じるのかを説明するために陰謀論に訴えること(例えば、地球温暖化陰謀論)が挙げられる。 現代では、右派の政治には反科学的な傾向があるという主張がなされている。これは右派の人々や彼らの信念に内在するものであるという意見もあるが、科学的 発見が左派よりも右派の世界観に挑戦したり、挑戦しているように見えたりした歴史的・政治的背景の「特異性」であるという意見もある。 宗教 詳細は「宗教と科学の関係」を参照 この文脈において、反科学は宗教的、道徳的、文化的議論に依存しているとみなされる可能性がある。この種の宗教的反科学哲学では、科学は反精神主義的かつ 唯物論的な力であり、理性とコスモポリタニズムを支持して伝統的価値観、民族のアイデンティティ、蓄積された歴史的知恵を損なうものとされる。特に強調さ れる伝統的・民族的価値観は、白人至上主義のキリスト教原理主義の神学と類似しているが、同様の右翼的見解はイスラム教、ユダヤ教、ヒンドゥー教、仏教の 急進的保守派によっても展開されている。左翼的なニューエイジや極右の法輪功の思想などの新宗教運動も、還元主義、無神論、唯物論の哲学を支持するものと して科学的世界観を批判している。 反科学的な感情の根拠となるのは、神聖なテキストを文字通りに解釈する宗教的唯神論であることが多い。神から授けられた知識とされるものに矛盾する科学的 理論は、欠陥があるものとみなされる。何世紀にもわたって、宗教的機関は、聖典のさまざまな箇所の支配的な解釈と矛盾するため、地動説や惑星の運動といっ た考えを受け入れることをためらってきた。さらに最近では、インテリジェント・デザインの目的論理論を含む創造説(総称して創造論)が、自然淘汰による進 化論への反論として、宗教的信者(主に原理主義者)によって推進されている。[36] 極端な創造論のひとつである「若い地球創造論」は、宇宙論、歴史地質学、生命の起源に関する研究とも対立している。 反科学的な感情を克服しようとする試みが失敗している限りにおいて、科学擁護には異なるアプローチが必要であるという意見もある。そのようなアプローチの 一つは、科学を否定する人々について、より正確な理解を深めることが重要である(彼らを後進的で無学であると決めつけない)とし、また、科学者など、宗教 的信念を持つ人々など、対象となる聴衆と文化的価値観を共有する人々を通じて働きかけることも重要であるとしている。[37] |

| Areas There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that "my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge". --- Isaac Asimov, "A Cult of Ignorance", Newsweek, 21 January 1980 Historically, antiscience first arose as a reaction against scientific materialism. The 18th century Enlightenment had ushered in "the ideal of a unified system of all the sciences",[38] but there were those fearful of this notion, who "felt that constrictions of reason and science, of a single all-embracing system... were in some way constricting, an obstacle to their vision of the world, chains on their imagination or feeling".[38] Antiscience then is a rejection of "the scientific model [or paradigm]... with its strong implication that only that which was quantifiable, or at any rate, measurable... was real".[38] In this sense, it comprises a "critical attack upon the total claim of the new scientific method to dominate the entire field of human knowledge".[38] However, scientific positivism (logical positivism) does not deny the reality of non-measurable phenomena, only that those phenomena should not be adequate to scientific investigation. Moreover, positivism, as a philosophical basis for the scientific method, is not consensual or even dominant in the scientific community (see philosophy of science). Recent developments and discussions around antiscience attitudes reveal how deeply intertwined these beliefs are with social, political, and psychological factors. A study published by Ohio State News on July 11, 2022, identified four primary bases that underpin antiscience beliefs: doubts about the credibility of scientific sources, identification with groups holding antiscience attitudes, conflicts between scientific messages and personal beliefs, and discrepancies between the presentation of scientific messages and individuals’ thinking styles. These factors are exacerbated in the current political climate, where ideology significantly influences people's acceptance of science, particularly on topics that have become politically polarized, such as vaccines and climate change. The politicization of science poses a significant challenge to public health and safety, particularly in managing global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.[39][40] The following quotes explore this aspect of four major areas of antiscience: philosophy, sociology, ecology and political. Philosophy Philosophical objections against science are often objections about the role of reductionism. For example, in the field of psychology, "both reductionists and antireductionists accept that... non-molecular explanations may not be improved, corrected or grounded in molecular ones".[41] Further, "epistemological antireductionism holds that, given our finite mental capacities, we would not be able to grasp the ultimate physical explanation of many complex phenomena even if we knew the laws governing their ultimate constituents".[42] Some see antiscience as "common...in academic settings...many people see that there are problems in demarcation between science, scientism, and pseudoscience resulting in an antiscience stance. Some argue that nothing can be known for sure".[43] Many philosophers are "divided as to whether reduction should be a central strategy for understanding the world".[44] However, many agree that "there are, nevertheless, reasons why we want science to discover properties and explanations other than reductive physical ones".[44] Such issues stem "from an antireductionist worry that there is no absolute conception of reality, that is, a characterization of reality such as... science claims to provide".[45] Sociology Sociologist Thomas Gieryn refers to "some sociologists who might appear to be antiscience".[46] Some "philosophers and antiscience types", he contends, may have presented "unreal images of science that threaten the believability of scientific knowledge",[46] or appear to have gone "too far in their antiscience deconstructions".[46] The question often lies in how much scientists conform to the standard ideal of "communalism, universalism, disinterestedness, originality, and... skepticism".[46] "scientists don't always conform... scientists do get passionate about pet theories; they do rely on reputation in judging a scientist's work; they do pursue fame and gain via research".[46] Thus, they may show inherent biases in their work. "[Many] scientists are not as rational and logical as the legend would have them, nor are they as illogical or irrational as some relativists might say".[46] Ecology and health sphere Within the ecological and health spheres, Levins identifies a conflict "not between science and antiscience, but rather between different pathways for science and technology; between a commodified science-for-profit and a gentle science for humane goals; between the sciences of the smallest parts and the sciences of dynamic wholes... [he] offers proposals for a more holistic, integral approach to understanding and addressing environmental issues".[47] These beliefs are also common within the scientific community, with for example, scientists being prominent in environmental campaigns warning of environmental dangers such as ozone depletion and the greenhouse effect. It can also be argued that this version of antiscience comes close to that found in the medical sphere, where patients and practitioners may choose to reject science and adopt a pseudoscientific approach to health problems. This can be both a practical and a conceptual shift and has attracted strong criticism: "therapeutic touch, a healing technique based upon the laying-on of hands, has found wide acceptance in the nursing profession despite its lack of scientific plausibility. Its acceptance is indicative of a broad antiscientific trend in nursing".[48] Glazer also criticises the therapists and patients, "for abandoning the biological underpinnings of nursing and for misreading philosophy in the service of an antiscientific world-view".[48] In contrast, Brian Martin criticized Gross and Levitt by saying that "[their] basic approach is to attack constructivists for not being positivists,"[49] and that science is "presented as a unitary object, usually identified with scientific knowledge. It is portrayed as neutral and objective. Second, science is claimed to be under attack by 'antiscience' which is composed essentially of ideologues who are threats to the neutrality and objectivity that are fundamental to science. Third, a highly selective attack is made on the arguments of 'antiscience'".[49] Such people allegedly then "routinely equate critique of scientific knowledge with hostility to science, a jump that is logically unsupportable and empirically dubious".[49] Having then "constructed two artificial entities, a unitary 'science' and a unitary 'academic left', each reduced to epistemological essences, Gross and Levitt proceed to attack. They pick out figures in each of several areas – science studies, postmodernism, feminism, environmentalism, AIDS activism – and criticise their critiques of science".[49] The writings of Young serve to illustrate more antiscientific views: "The strength of the antiscience movement and of alternative technology is that their advocates have managed to retain Utopian vision while still trying to create concrete instances of it".[50] "The real social, ideological and economic forces shaping science...[have] been opposed to the point of suppression in many quarters. Most scientists hate it and label it 'antiscience'. But it is urgently needed, because it makes science self-conscious and hopefully self-critical and accountable with respect to the forces which shape research priorities, criteria, goals".[50] Genetically modified foods also bring about antiscience sentiment. The general public has recently become more aware of the dangers of a poor diet, as there have been numerous studies that show that the two are inextricably linked.[51] Anti-science dictates that science is untrustworthy, because it is never complete and always being revised, which would be a probable cause for the fear that the general public has of genetically modified foods despite scientific reassurance that such foods are safe. Antivaccinationists rely on whatever comes to hand presenting some of their arguments as if scientific; however, a strain of antiscience is part of their approach.[52] Political Political scientist Tom Nichols, from Harvard Extension School and the U.S. Naval War College, points out that skepticism towards scientific expertise has increasingly become a symbol of political identity, especially within conservative circles. This skepticism is not just a result of misinformation but also reflects a broader cultural shift towards diminishing trust in experts and authoritative sources. This trend challenges the traditional neutrality of science, positioning scientific beliefs and facts within the contentious arena of political ideology.[40] The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, conflicting responses to public health measures and vaccine acceptance have highlighted the extent to which science has been politicized. Such polarization suggests that for some, rejecting scientific consensus or public health guidance serves as an expression of political allegiance or skepticism towards perceived authority figures.[40] This politicization of science complicates efforts to address public health crises and undermines the broader social contract that underpins scientific research and its application for the public good. The challenge lies not only in combating misinformation but also in bridging ideological divides that affect public trust in science. Strategies to counteract antiscience attitudes may need to encompass more than just presenting factual information; they might also need to engage with the underlying social and psychological factors that contribute to these attitudes, fostering dialogue that acknowledges different viewpoints and seeks common ground.[40] Antiscience media Major antiscience media include portals Natural News, Global Revolution TV, TruthWiki.org, TheAntiMedia.org and GoodGopher. Antiscience views have also been supported on social media by organizations known to support fake news such as the web brigades.[53]: 124 |

分野 米国には無知のカルトが存在し、それは常に存在してきた。反知性の風潮は、政治や文化の生活に絶えず入り込み、民主主義とは「私の無知はあなたの知識と同 じくらい価値がある」という誤った考えによって育まれてきた。——アイザック・アシモフ著「無知の教典」、ニューズウィーク誌、1980年1月21日 歴史的に見ると、反科学はまず科学的な唯物論への反発として生じた。18世紀の啓蒙主義は「すべての科学の統一された体系の理想」をもたらしたが、 [38] この概念を恐れる人々もおり、彼らは「理性と科学の束縛、単一の包括的な体系は... ある意味で自分たちの世界観を束縛し、想像力や感情を縛るもの」と感じていた。[38] 反科学とは、「科学モデル(またはパラダイム)... その強い含意として、数量化できるもの、あるいは少なくとも測定できるものだけが現実であるという考え方」を拒絶するものである。[38] この意味において、それは「人間の知識の全領域を支配するという新しい科学的手法の主張全体に対する批判的な攻撃」を意味する。[38] しかし、科学実証主義(論理実証主義)は、測定不可能な現象の現実を否定するものではなく、ただ、そのような現象は科学的調査に適していないというだけで ある。さらに、科学的方法の哲学的な基礎である実証主義は、科学界で合意されているわけでもなく、支配的ですらありません(科学哲学を参照)。 反科学的な態度に関する最近の動向や議論は、これらの信念が社会的、政治的、心理的要因とどれほど深く絡み合っているかを明らかにしている。2022年7 月11日付のオハイオ州立大学ニュースが発表した研究では、反科学的な信念を支える4つの主な基盤を特定している。すなわち、科学的な情報源の信頼性に対 する疑念、反科学的な態度を持つグループとの同一視、科学的なメッセージと個人的な信念との間の対立、科学的なメッセージの提示と個人の思考スタイルとの 間の相違である。これらの要因は、特にワクチンや気候変動など、政治的に極端な意見が対立するトピックにおいて、イデオロギーが人々の科学に対する受容に 大きな影響を与える現在の政治情勢において、さらに悪化している。科学の政治化は、特に新型コロナウイルス感染症(COVID-19)のパンデミックのよ うな世界的な危機への対応において、公衆衛生と安全に大きな課題を突きつけている。[39][40] 以下では、反科学の4つの主要分野、すなわち哲学、社会学、生態学、政治学の側面について見ていく。 哲学 科学に対する哲学的な異論は、還元主義の役割に関する異論であることが多い。例えば心理学の分野では、「還元主義者も反還元主義者も、分子レベルではない 説明は改善、修正、または分子レベルでの説明に根拠づけられない可能性があることを認めている」[41]。さらに、「認識論的反還元主義は、人間の精神能 力には限界があるため、 究極的な構成要素を支配する法則を知っていたとしても、多くの複雑な現象の究極的な物理的説明を把握することはできない」と主張する。[42] 反科学を「学術的な環境では一般的である」と見る者もいる。多くの人々は、科学、科学主義、疑似科学の間の境界に問題があることを認識しており、それが反 科学的な立場につながっている。また、「確かなことは何もわからない」と主張する者もいる。[43] 多くの哲学者は、「還元が世界を理解するための中心的な戦略であるべきかどうかについて意見が分かれている」[44]。しかし、「それでもなお、科学に還 元的な物理的特性や説明以外の特性や説明を発見してほしいと望む理由がある」[44]という点については、多くの人が同意している。このような問題は、 「現実に対する絶対的な概念は存在しないという反還元主義者の懸念、つまり、科学が提供すると主張する現実の特性などから生じている」[45]。 社会学 社会学者のトーマス・ギアリンは、「反科学主義者と思われる一部の社会学者」について言及している。[46] ギアリンは、一部の「哲学者や反科学主義者」が「科学に対する非現実的なイメージを提示し、科学的知識の信頼性を脅かしている」可能性がある、あるいは 「反科学主義的な解体をやり過ぎている」ように見えると主張している。[46] 問題はしばしば、 科学者が「共同体主義、普遍主義、無私、独創性、そして懐疑主義」という標準的な理想にどの程度まで適合しているかという点にある。[46] 「科学者は常に適合しているわけではない...科学者は自分の仮説に熱中する。科学者の業績を判断する際には評判を重視する。研究を通じて名声と利益を追 求する。」[46] したがって、彼らは仕事において本質的な偏見を示す可能性がある。「多くの科学者は、伝説で語られるほど理性的でも論理的でもない。また、相対主義者が言 うほど非論理的でも非合理的でもない」[46]。 生態学と健康の分野 生態学と健康の分野において、レヴィンズは「科学と反科学の対立ではなく、むしろ科学と技術の異なる進路、利益追求のための商品化された科学と人道的な目 標のための穏やかな科学、最小単位の科学とダイナミックな全体性の科学の対立」を指摘している。環境問題をより全体的、包括的に理解し、対処するための提 案を行っている」[47]。これらの考え方は科学界でも一般的であり、例えば、オゾン層破壊や温室効果ガスなど環境の危険性を警告する環境キャンペーンで は科学者が中心的な役割を果たしている。また、この反科学の考え方は医療分野における考え方に近いとも言える。患者や医療従事者が科学を拒絶し、疑似科学 的なアプローチを健康問題に採用することがある。これは、現実的かつ概念的な変化であり、強い批判を招いている。「手当て療法は、科学的根拠に乏しいにも かかわらず、看護の分野で広く受け入れられている。その受け入れられ方は、看護における広範な反科学的な傾向を示している」[48]。 グレイザーはまた、セラピストと患者を批判し、「看護の生物学的な基礎を放棄し、反科学的世界観に奉仕する哲学を誤読している」と述べている。[48] これに対し、ブライアン・マーティンはグロスとレヴィットを批判し、「彼らの基本的なアプローチは、構成主義者が実証主義者ではないとして攻撃することで ある」[49]と述べ、科学は「通常、科学的知識と同一視される単一の対象として提示される。それは中立かつ客観的なものと描かれている。第二に、科学は 「反科学」による攻撃を受けていると主張されているが、反科学は本質的には科学の根本にある中立性と客観性を脅かすイデオローグたちによって構成されてい る。第三に、「反科学」の主張に対して厳選された攻撃が行われる。[49] このような人々は、科学知識に対する批判を科学に対する敵意と日常的に同一視しているとされるが、これは論理的に支持できない飛躍であり、経験的にも疑わ しい。[49] こうして「認識論的な本質に還元された単一の『科学』と単一の『学術左派』という2つの人為的な存在を作り出した後、グロスとレビットは攻撃に移る。彼ら は、科学研究、ポストモダニズム、フェミニズム、環境保護主義、エイズ活動といった複数の分野からそれぞれ代表的な人物を選び出し、その科学批判を批判し ている」[49]。 ヤングの著作は、反科学的な見解をさらに示すものとなっている。「反科学運動と代替技術の強みは、その支持者がユートピア的ビジョンを維持しながら、同時 にその具体例を作り出そうとしている点にある」[50] 「科学を形作る真の社会的、イデオロギー的、経済的勢力は...多くの方面で弾圧されるほどに反対されてきた。ほとんどの科学者はそれを嫌い、『反科学』 とレッテルを貼っている。しかし、それは緊急に必要なことである。なぜなら、研究の優先順位、基準、目標を形作る諸力に関して、科学に自覚と、望むらくは 自己批判と説明責任を持たせるからだ」[50] 遺伝子組み換え食品もまた反科学感情を生み出している。一般の人々は、最近になって、不適切な食生活が健康に及ぼす危険性をより強く意識するようになっ た。なぜなら、両者は密接に関連していることを示す研究結果が数多く発表されているからだ。[51] 反科学主義は、科学は信頼できないと主張する。なぜなら、科学は決して完全ではなく、常に修正が加えられているからだ。これは、遺伝子組み換え食品は安全 であるという科学的な再保証にもかかわらず、一般の人々が遺伝子組み換え食品に対して抱く恐れの原因となる可能性が高い。 反ワクチン接種論者は、科学的であるかのように主張の一部を提示するが、それは手に入るものなら何でも利用する。しかし、反科学の一種が彼らのアプローチの一部である。 政治 政治学者のトム・ニコルズ(ハーバード・エクステンション・スクールおよび米国海軍大学校)は、科学的専門知識に対する懐疑論は、特に保守派の間で、政治 的なアイデンティティの象徴となりつつあると指摘している。この懐疑論は、単なる誤報の結果というだけでなく、専門家や権威ある情報源に対する信頼を失わ せるという、より広範な文化的な変化を反映している。この傾向は、科学の伝統的な中立性を疑問視し、科学的信念や事実を政治的イデオロギーの論争の場に位 置づけるものである。 例えば、新型コロナウイルス感染症(COVID-19)のパンデミックでは、公衆衛生対策やワクチン接種に対する相反する反応が、科学が政治化されている 度合いを浮き彫りにした。このような極端化は、一部の人々にとって、科学的コンセンサスや公衆衛生上の指針を拒絶することが、政治的な忠誠心や、権威とみ なされる人物への懐疑の表明として機能していることを示唆している。 科学の政治化は、公衆衛生の危機への対応を複雑にし、科学的研究とその公益への応用を支えるより広範な社会契約を損なう。この課題は、誤情報の対策だけで なく、科学に対する信頼に影響を与えるイデオロギーの分裂を埋めることにもある。反科学的な態度に対抗する戦略は、事実情報の提示にとどまらず、そうした 態度を生み出す根底にある社会的・心理的要因にも目を向け、異なる視点も認めつつ共通点を探る対話を促す必要があるかもしれない。 反科学メディア 主要な反科学メディアには、ポータルサイトNatural News、Global Revolution TV、TruthWiki.org、TheAntiMedia.org、GoodGopherなどがある。反科学的な見解は、ウェブ・ブリゲードなどの フェイクニュースを支援していることで知られる組織によって、ソーシャルメディアでも支持されている。[53]:124 |

| Anarcho-primitivism – Anarchist critique of civilization Anti-intellectualism – Hostility to and mistrust of education, philosophy, art, literature, and science Anti-psychiatry – Movement against psychiatric treatment Creation science – Pseudoscientific form of Young Earth creationism Modern Flat Earth societies – Modern-day beliefs concerning the shape of the Earth Bruno Latour – French philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist (1947–2022) Denialism – Person's choice to deny psychologically uncomfortable truth Philosophical skepticism – Philosophical views that question the possibility of knowledge or certainty Ernst Cassirer – German philosopher (1874–1945) Eugenics – Effort to improve purported human genetic quality Faith and rationality – Two approaches that exist in varying degrees of conflict or compatibility Fundamentalism – Unwavering attachment to a set of irreducible beliefs Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel – German philosopher (1770–1831) Giambattista Vico – Italian philosopher (1668–1744) Greedy reductionism – Kind of erroneous reductionism Green conservatism – Combination of conservatism and environmentalism Holism – A system as a whole, not just its parts Idealism – Philosophical view Johann Georg Hamann – German philosopher (1730–1788) Johann Gottfried Herder – German philosopher, theologian, poet (1744–1803) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – German writer and polymath (1749–1832) Neo-Luddism – Philosophy opposing modern technology Platonism – Philosophical system Politicization of science – Use of science for political purposes Pseudoskepticism – Philosophical position that appears to be skeptic but is actually dogmatic Radical environmentalism Reactionary – Political view advocating a return to a previous state of society Science wars – 1990s dispute in philosophy of science Social Darwinism – Group of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices Sokal affair – 1996 scholarly publishing sting accepted by an academic journal Subjective idealism – Philosophy that only minds and ideas are real Technological dystopia – Community or society that is undesirable or frightening Technophobia – Fear or discomfort with advanced technology William Morris – English textile artist, author, and socialist (1834–1896) William R. Steiger – American government official |

アナルコ・プリミティヴィズム - 文明に対するアナーキストの批判 反知性主義 - 教育、哲学、芸術、文学、科学に対する敵意と不信 反精神医学 - 精神科治療に対する運動 創造科学 - 若い地球創造論の疑似科学形態 現代の平面地球協会 - 地球の形状に関する現代の信念 ブルーノ・ラトゥール - フランスの哲学者、人類学者、社会学者(1947年~2022年 否定論 - 心理的に不快な真実を否定するという個人の選択 哲学的な懐疑論 - 知識や確実性の可能性を問う哲学的な見解 エルンスト・カッシーラー - ドイツの哲学者(1874年~1945年 優生学 - 人間の遺伝的資質を向上させようとする取り組み 信仰と合理性 – 程度の差こそあれ、相反する、あるいは両立する2つのアプローチ 原理主義 – 不可分の信念体系への揺るぎない固執 ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル – ドイツの哲学者(1770年 – 1831年 ジャンバティスタ・ヴィーコ – イタリアの哲学者(1668年 – 1744年 貪欲な還元主義 – 誤った還元主義の一種 緑の保守主義 – 保守主義と環境主義の組み合わせ 全体論 – 部分ではなく、全体としてのシステム 観念論 – 哲学的な見解 ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハマーン – ドイツの哲学者(1730年~1788年 ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー – ドイツの哲学者、神学者、詩人(1744年~1803年 ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテ – ドイツの作家、博識家(1749年~1832年 ネオ・ラッダイト主義 – 近代技術に反対する哲学 プラトン主義 - 哲学的体系 科学の政治利用 - 政治的目的のための科学の利用 偽懐疑論 - 懐疑論者のように見えるが、実際には独断的な哲学的立場 急進的環境保護主義 反動主義 - 社会を以前の状態に戻すことを主張する政治的見解 科学戦争 - 1990年代の科学哲学における論争 社会ダーウィニズム - 疑似科学理論と社会慣行のグループ ソカル事件 - 1996年に学術誌が引っ掛かった出版詐欺事件 主観的観念論 - 心や観念のみが現実であるとする哲学 技術的ディストピア - 望ましくない、あるいは恐ろしい共同体や社会 テクノフォビア - 先端技術に対する恐怖や不快感 ウィリアム・モリス - 英国の繊維芸術家、作家、社会主義者(1834年~1896年 ウィリアム・R・スタイガー - 米国政府高官 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiscience |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆