Anyway what is Science for you?

科学とはなにか?

Anyway what is Science for you?

解説:池田光穂

★科学(Science)とは、厳格な体系的な学問であ り、世界に関する検証可能な仮説や予測という形で知識を構築し、体系化するものである。

★しかし、スティーブン・シェイピン(Steven Shapin, b1943- )は、科学と

いう言葉を次のような懐疑的なアプローチで表現している(Shapin 2005=2011:477);「私たちの文化で使用される言葉のなかに

は、その指示する対象があまりにも高く評価されているために、確固とした対象指示をほとんどできな

いものがある。たとえば「現実」「理性」「真理」という言葉を考えてみよ。そして、現実、理性、真理の名のもと、もっとも権威的に語る下位文化(=サブカ

ルチャー)を意味する言葉といえばなにか——それは科学(science) である」(Shapin 2005=2011:477)。

科学研究 (scientific study)とは、世界についての検証可能な仮説や予測という形で知識を構築し体系化する傾向をもった宇宙観(コスモロジー)のことである。つまり、トー マス・クーン『科学革命の構造』で主張されているパ ラダイムが、科学研究のことである。

したがって科学人類学は科学人 類学(anthropology of science)とは、科学研究(scientific study)を文化人類学の観点から分析解明する研究領域である。この科学は、従来(これま で)の文化人類学のように異邦の少数民族 (ethnic minority)や国民(nation)を対象とするのではなく、現代社会の科学者集団を対象にする研究である。その方法論については文化人類学と同じくする。

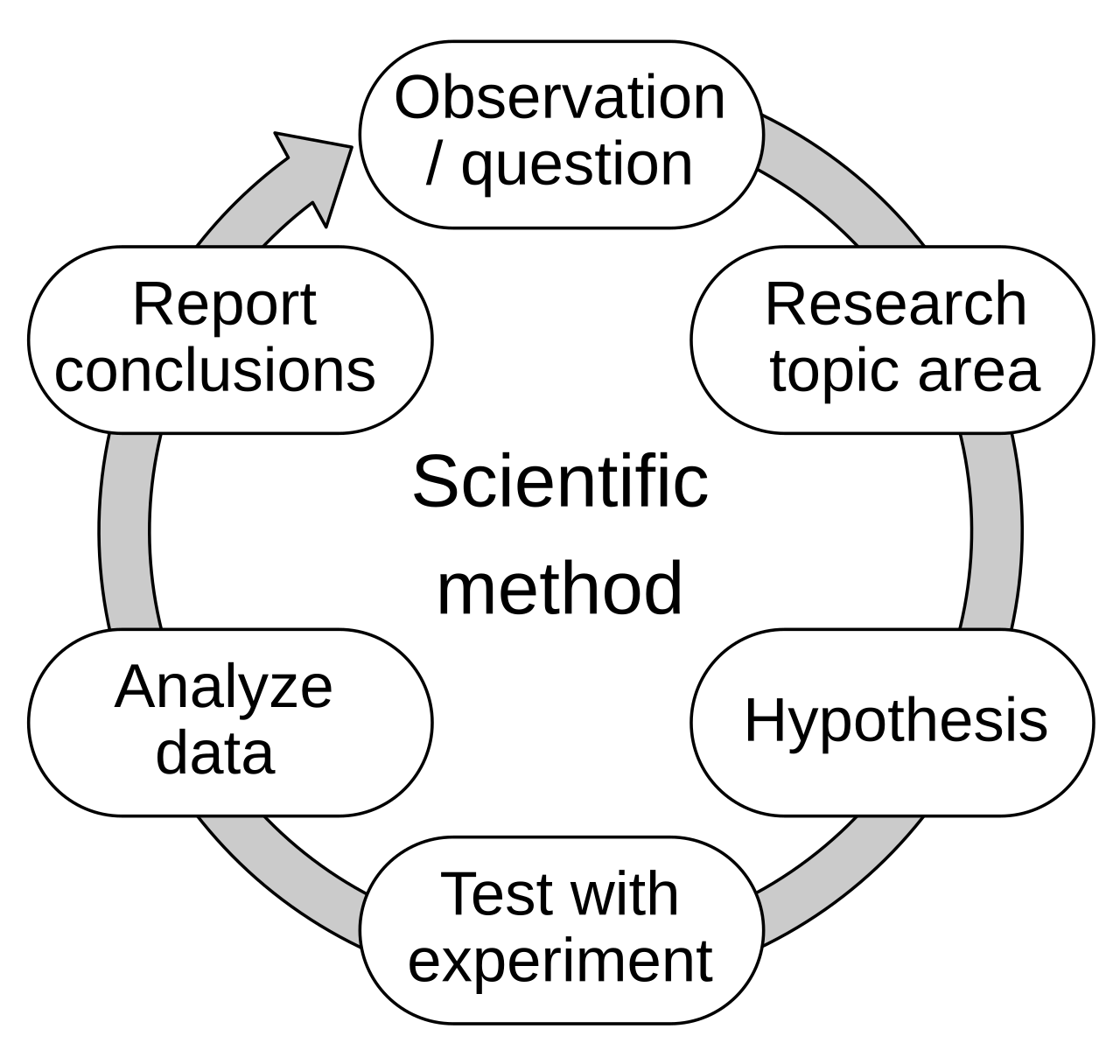

A diagram variant

of scientific method represented as an ongoing process (from Scientific

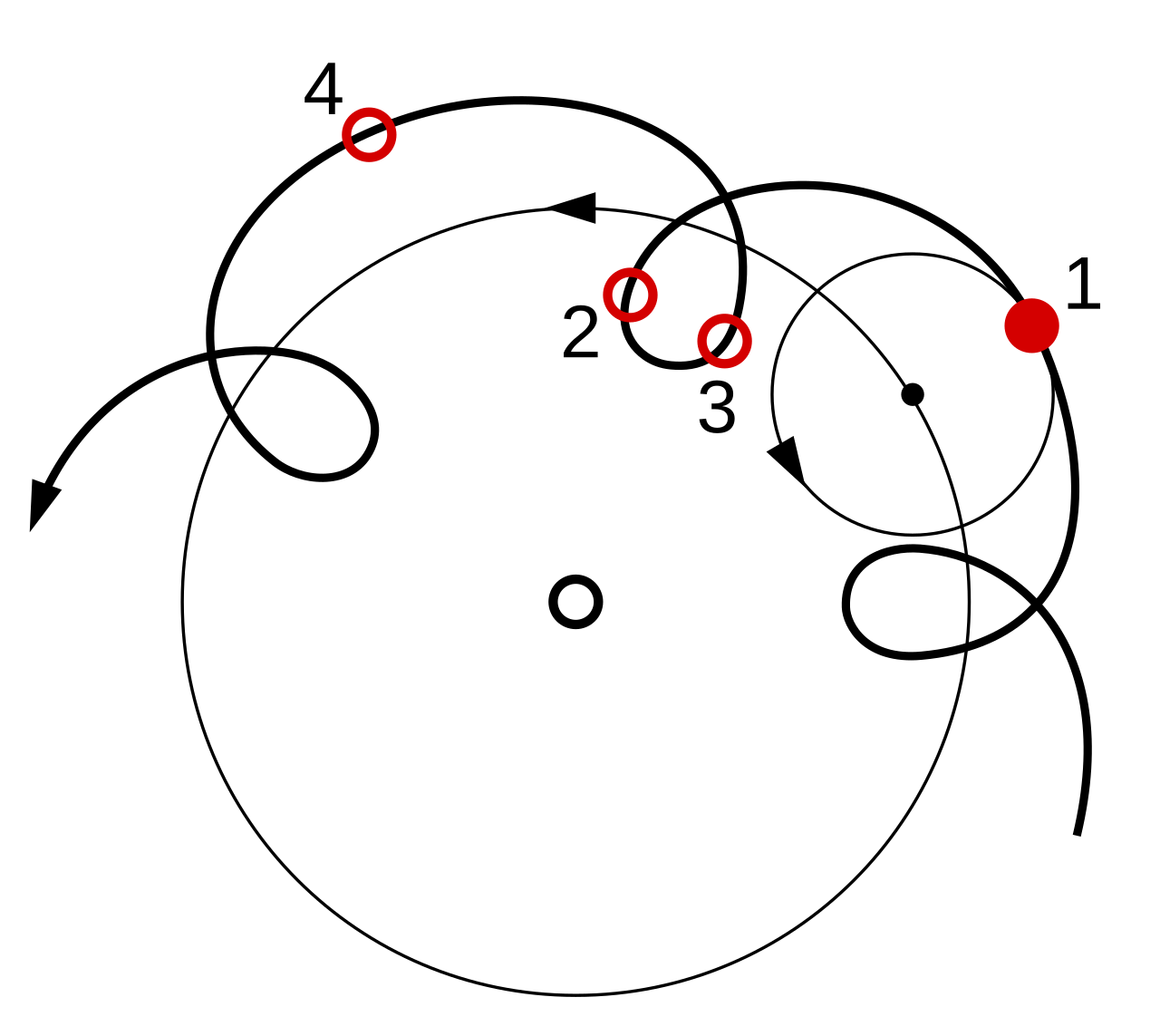

Method)// For Kuhn,

the addition of epicycles in Ptolemaic astronomy was "normal science"

within a paradigm, whereas the Copernican

Revolution was a paradigm shift

★科学とはなにか?(Wikipedia のくそ堅苦しい説明)→「科学」と内容がかぶります。☆神話上のヒーローとして「プロメテウス」という神話像があります。

| Science

is a strict systematic discipline that builds and organizes knowledge

in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the

world.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into three major

branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and

biology), which study the physical world; the social sciences (e.g.,

economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and

societies;[4][5] and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and

theoretical computer science), which study formal systems, governed by

axioms and rules.[6][7] There is disagreement whether the formal

sciences are scientific disciplines,[8][9][10] as they do not rely on

empirical evidence.[11][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use

scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as in engineering and

medicine.[12][13][14] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest written records of identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia from around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[15]: 12 [16][17][18] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400 to 1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[19] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived "natural philosophy",[20][21][22] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[23] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[24][25] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[26][27] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[28] New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems.[29][30] Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions,[31] government agencies, and companies.[32][33] The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection. |

科学とは、世界についての検証可能な仮説や予測という形で知識を構築し

体系化する厳格な学問体系である[1][2]。現代科学は通常、3つの主要な分野に分かれている[3]。自然科学(物理学、化学、生物学など)は物理的世

界を研究し、社会科学(経済学、心理学、社会学など)は個人と社会を研究する[4][5]。個人と社会を研究する社会科学[4][5]、公理と規則によっ

て支配される形式的なシステムを研究する形式科学(例えば、論理学、数学、理論計算機科学)[6][7]である。形式科学が科学的分野であるかどうかにつ

いては意見が分かれている[8][9][10]。 ]

応用科学は、工学や医学など、実践的な目的で科学的知識を活用する学問分野である[12][13][14]。 科学の歴史は、歴史記録の大部分にまたがっており、現代科学の先駆者と特定できる最古の記録は、紀元前3000年から1200年頃の青銅器時代のエジプト とメソポタミアにさかのぼる。彼らの数学、天文学、医学への貢献は、古典古代のギリシャ自然哲学に入り込み、形作りました。これにより、自然的原因に基づ く物理世界の事象の説明を正式に試みる試みがなされ、さらに、インドの黄金時代には、ヒンドゥー・アラビア数字の導入を含むさらなる進歩がなされました [15]: 12 [16 ][17][18] これらの地域では、西ローマ帝国の滅亡後、中世初期(400年~1000年)に科学研究は衰退したが、中世ルネサンス(カロリング朝ルネサンス、オットー 朝ルネサンス、12世紀ルネサンス)では再び学問が盛んになった。西ヨーロッパで失われたギリシャ語写本は、イスラム黄金時代[19]に中東で保存され、 発展を遂げ、また、ビザンティン帝国の滅亡間際にギリシャ語写本を西ヨーロッパに持ち帰ったビザンティン・ギリシャ学者の後期の努力もそれに続いた。 10世紀から13世紀にかけて、ギリシャの著作やイスラムの探求が西洋に伝わり、吸収されることで、「自然哲学」が復活した[20][21][22]。そ の後、16世紀に始まった科学革命によって、それまでのギリシャの概念や伝統から脱却した新しいアイデアや発見が生まれ、自然哲学は変容を遂げた[23] [24][25]。科学的方法は、知識創造においてすぐに大きな役割を果たすようになったが、科学の制度的および専門的特徴の多くが形作られ始めたのは 19世紀になってからであり、[26][27]「自然哲学」が「自然科学」へと変化したこともそれに伴っていた[28]。 科学における新しい知識は、世界に対する好奇心と問題を解決したいという欲求に駆り立てられた科学者による研究によって進歩する[2 9][30] 現代の科学研究は高度に共同作業的であり、通常、学術研究機関や研究機関、政府機関、企業のチームによって行われる[31][32][33]。彼らの研究 の実用的な影響により、商業製品、兵器、医療、公共インフラ、環境保護の倫理的・道徳的発展を優先することで、科学事業に影響を与えようとする科学政策の 登場につながった。 |

| Etymology The word science has been used in Middle English since the 14th century in the sense of "the state of knowing". The word was borrowed from the Anglo-Norman language as the suffix -cience, which was borrowed from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge, awareness, understanding". It is a noun derivative of the Latin sciens meaning "knowing", and undisputedly derived from the Latin sciō, the present participle scīre, meaning "to know".[34] There are many hypotheses for science's ultimate word origin. According to Michiel de Vaan, Dutch linguist and Indo-Europeanist, sciō may have its origin in the Proto-Italic language as *skije- or *skijo- meaning "to know", which may originate from Proto-Indo-European language as *skh1-ie, *skh1-io, meaning "to incise". The Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben proposed sciō is a back-formation of nescīre, meaning "to not know, be unfamiliar with", which may derive from Proto-Indo-European *sekH- in Latin secāre, or *skh2-, from *sḱʰeh2(i)- meaning "to cut".[35] In the past, science was a synonym for "knowledge" or "study", in keeping with its Latin origin. A person who conducted scientific research was called a "natural philosopher" or "man of science".[36] In 1834, William Whewell introduced the term scientist in a review of Mary Somerville's book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences,[37] crediting it to "some ingenious gentleman" (possibly himself).[38] |

語源 「科学」という言葉は、中世英語において14世紀から「知の状態」という意味で使用されてきた。この言葉はアングロ・ノルマン語から借用された接尾辞「- science」に由来し、この接尾辞はラテン語の「scientia」から借用されたものである。「scientia」は「知識、認識、理解」を意味す る。これはラテン語の sciens(「知る」の意)という名詞に由来するものであり、ラテン語の sciō(「知る」の意)という現在分詞 scīre(「知る」の意)から派生したことは疑いない[34]。 サイエンスの語源については、さまざまな仮説がある。オランダ人の言語学者で印欧語学者であるミシェル・デ・ヴァンによると、sciōは、*skije- または*skijo-という「知る」という意味の初期イタリック語に由来する可能性がある。これは、*skh1-ie、*skh1-ioという「切り刻 む」という意味の初期インド・ヨーロッパ語に由来する可能性がある。Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben(インド・ゲルマン語動詞辞典)では、sciōはnescīre(「知らない、知らない」)の逆形成であると提案されている。これは、ラテン 語のsecāre(「切る」)に由来する、インド・ヨーロッパ祖語*sekH-、あるいは あるいは *skh2-、*sḱʰeh2(i)-「切る」に由来する可能性がある[35]。 かつて、科学はラテン語に由来する「知識」や「研究」と同義語であった。科学的研究を行う人は「自然哲学者」または「科学者」と呼ばれていた[36]。 1834年、ウィリアム・ホイウェルはメアリー・ソマーヴィルの著書『物理科学の関連性』の書評で「科学者」という用語を紹介し、その功績を「ある独創的 な紳士」(おそらくホイウェル自身)に与えた[38]。 |

| History of Science, Since Middle

ages |

中世以降の科学の歴史 |

| Middle Ages Main article: History of science § Middle Ages  Picture of a peacock on very old paper The first page of Vienna Dioscurides depicts a peacock, made in the 6th century Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe.[15]: 194 During the period, Latin encyclopedists such as Isidore of Seville preserved the majority of general ancient knowledge.[77] In contrast, because the Byzantine Empire resisted attacks from invaders, they were able to preserve and improve prior learning.[15]: 159 John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar in the 500s, started to question Aristotle's teaching of physics, introducing the theory of impetus.[15]: 307, 311, 363, 402 His criticism served as an inspiration to medieval scholars and Galileo Galilei, who extensively cited his works ten centuries later.[15]: 307–308 [78] During late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, natural phenomena were mainly examined via the Aristotelian approach. The approach includes Aristotle's four causes: material, formal, moving, and final cause.[79] Many Greek classical texts were preserved by the Byzantine empire and Arabic translations were done by groups such as the Nestorians and the Monophysites. Under the Caliphate, these Arabic translations were later improved and developed by Arabic scientists.[80] By the 6th and 7th centuries, the neighboring Sassanid Empire established the medical Academy of Gondeshapur, which is considered by Greek, Syriac, and Persian physicians as the most important medical center of the ancient world.[81] The House of Wisdom was established in Abbasid-era Baghdad, Iraq,[82] where the Islamic study of Aristotelianism flourished[83] until the Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Ibn al-Haytham, better known as Alhazen, used controlled experiment in his optical study.[a][85][86] Avicenna's compilation of the Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia, is considered to be one of the most important publications in medicine and was used until the 18th century.[87] By the eleventh century, most of Europe had become Christian,[15]: 204 and in 1088, the University of Bologna emerged as the first university in Europe.[88] As such, demand for Latin translation of ancient and scientific texts grew,[15]: 204 a major contributor to the Renaissance of the 12th century. Renaissance scholasticism in western Europe flourished, with experiments done by observing, describing, and classifying subjects in nature.[89] In the 13th century, medical teachers and students at Bologna began opening human bodies, leading to the first anatomy textbook based on human dissection by Mondino de Luzzi.[90] |

中世 メイン記事: 科学史 § 中世  非常に古い紙の上に描かれた孔雀の絵 ウィーン・ディオスコリデスの最初のページには、6世紀に描かれた孔雀が描かれている 西ローマ帝国の崩壊により、5世紀には西ヨーロッパで知的衰退が起こり、ギリシャの宇宙観に関する知識は衰退した[15]: 194。セビリアのイシドー ルなどのラテン百科事典編纂者たちは、古代の一般的な知識の大部分を保存した[77]。これとは対照的に、ビザンティン帝国は侵略者からの攻撃に抵抗した ため、それまでの知識を保存し、さらに発展させることができた[15]: 159 。500年代のビザンティン学者であるヨハン・フィロポヌスは、アリス トテレスの物理学説に疑問を持ち、運動量説を導入した[ 15]: 307, 311, 363, 402 彼の批判は中世の学者やガリレオ・ガリレイのインスピレーションとなり、10世紀後に彼の著作が広く引用された。 古代末期から中世初期にかけて、自然現象は主にアリストテレスのアプローチによって研究されていた。このアプローチには、アリストテレスの4つの原因、す なわち物質的原因、形式的原因、運動的原因、最終的原因が含まれる[79]。多くのギリシャ古典文学はビザンティン帝国によって保存され、ネストリウス派 や単性論者などのグループによってアラビア語に翻訳された。カリフ制のもと、これらのアラビア語訳は後にアラビアの科学者たちによって改良・発展された [80]。6世紀から7世紀にかけて、隣接するサーサーン朝は医学アカデミーをゴンデシャプールに設立した。これは、ギリシャ人、シリア人、ペルシア人の 医師たちから、 古代世界でもっとも重要な医療センターであったと考えられている[81]。 知恵の館は、アッバース朝時代のイラク、バグダードに設立された[82]。そこでは、13世紀のモンゴル侵攻まで、アリストテレス主義のイスラム研究が盛 んに行われた[83]。アルハゼンとしてよりよく知られているイブン・アル・ハイサムは、光学の研究において制御実験を用いた[a][85][86]。ア ヴィセンナの医学百科事典『医学大全』は医学における最も重要な出版物のひとつと考えられ、18世紀まで使用されていた[87]。 11 11世紀までにヨーロッパの大部分はキリスト教化され[15]: 204、1088年にはボローニャ大学がヨーロッパ初の大学として誕生した[88]。そ のため、古代や科学の文献のラテン語訳に対する需要が高まり[15]: 204、12世紀のルネサンスに大きく貢献した。西欧におけるルネサンスのスコラ 学は、自然界の事象を観察、記述、分類する実験を通じて発展した[89]。13世紀、ボローニャの医学教師と学生たちは人体解剖を始め、これがモンドー ノ・デ・ルッツィによる人体解剖に基づく最初の解剖学教科書につながった[90]。 |

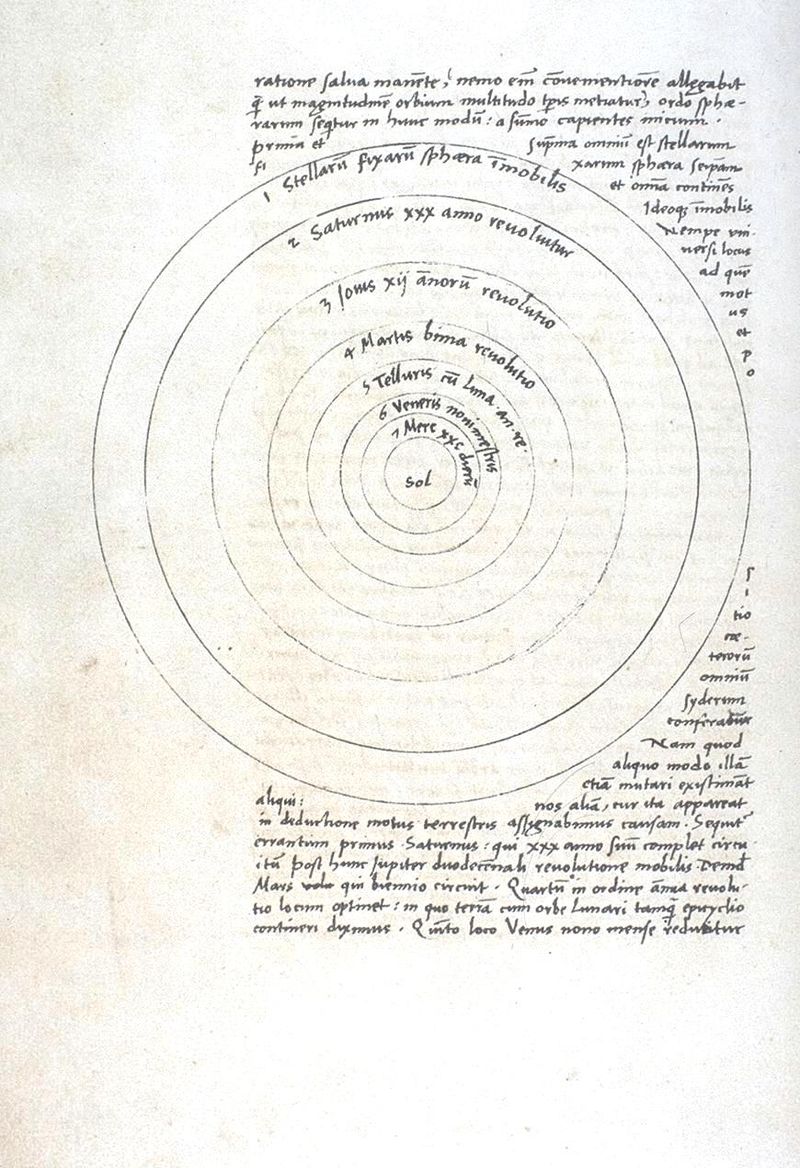

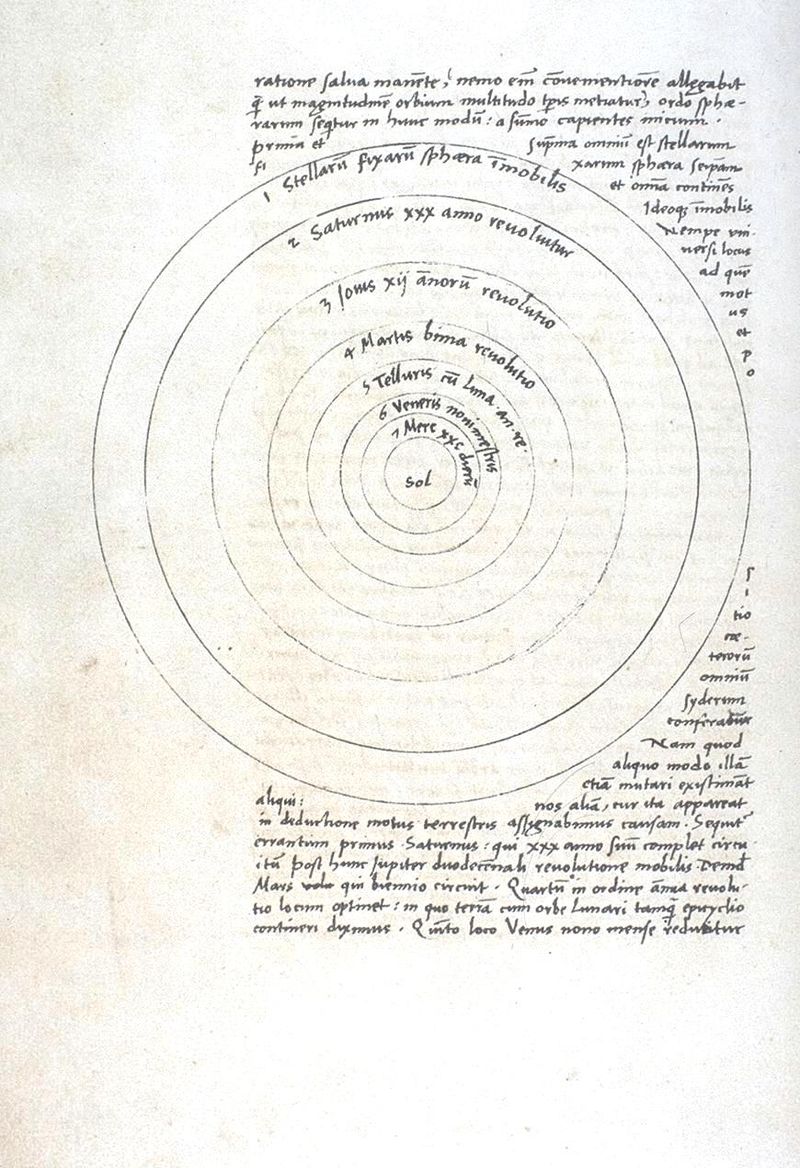

| Renaissance Main articles: Scientific Revolution and Science in the Renaissance  Drawing of planets' orbit around the Sun Drawing of the heliocentric model as proposed by the Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the Renaissance, both by challenging long-held metaphysical ideas on perception, as well as by contributing to the improvement and development of technology such as the camera obscura and the telescope. At the start of the Renaissance, Roger Bacon, Vitello, and John Peckham each built up a scholastic ontology upon a causal chain beginning with sensation, perception, and finally apperception of the individual and universal forms of Aristotle.[84]: Book I A model of vision later known as perspectivism was exploited and studied by the artists of the Renaissance. This theory uses only three of Aristotle's four causes: formal, material, and final.[91] In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the Solar System, stating that the planets revolve around the Sun, instead of the geocentric model where the planets and the Sun revolve around the Earth. This was based on a theorem that the orbital periods of the planets are longer as their orbs are farther from the center of motion, which he found not to agree with Ptolemy's model.[92] Johannes Kepler and others challenged the notion that the only function of the eye is perception, and shifted the main focus in optics from the eye to the propagation of light.[91][93] Kepler is best known, however, for improving Copernicus' heliocentric model through the discovery of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. Kepler did not reject Aristotelian metaphysics and described his work as a search for the Harmony of the Spheres.[94] Galileo had made significant contributions to astronomy, physics and engineering. However, he became persecuted after Pope Urban VIII sentenced him for writing about the heliocentric model.[95] The printing press was widely used to publish scholarly arguments, including some that disagreed widely with contemporary ideas of nature.[96] Francis Bacon and René Descartes published philosophical arguments in favor of a new type of non-Aristotelian science. Bacon emphasized the importance of experiment over contemplation, questioned the Aristotelian concepts of formal and final cause, promoted the idea that science should study the laws of nature and the improvement of all human life.[97] Descartes emphasized individual thought and argued that mathematics rather than geometry should be used to study nature.[98] |

ルネサンス 主な項目:科学革命、ルネサンス期の科学  太陽の周りを回る惑星の軌道図 コペルニクス著『天球の回転について』で提唱された地動説の図 光学における新たな発展は、ルネサンスの始まりにおいて重要な役割を果たした。それは、長い間信じられてきた認識に関する形而上学的な概念に疑問を投げか けるとともに、カメラ・オブスクラや望遠鏡といった技術の改良と発展にも貢献した。ルネサンスの始まりに、ロジャー・ベーコン、ヴィテロ、ジョン・ペック ハムは、それぞれアリストテレスの個と普遍の形の知覚、認識、そして最後に観念に至る因果連鎖に基づくスコラ学的な存在論を構築した[84]: Book I。後に遠近法主義として知られるようになった視覚のモデルは、ルネサンスの芸術家たちによって研究され、活用された。この理論は、アリストテレスの4つ の原因のうち、形式、物質、最終の3つだけを使用している[91]。 16世紀、ニコラウス・コペルニクスは、惑星と太陽が地球の周りを回る地動説モデルではなく、惑星が太陽の周りを回る天動説モデルを提唱した。これは、惑 星の公転周期は、その軌道が運動の中心から遠ければ遠いほど長くなるという定理に基づくもので、彼はプトレマイオスのモデルとは一致しないと判断した [92]。 ヨハネス・ケプラーらは、目の唯一の機能は知覚であるという考えに異議を唱え、 目は知覚のみの機能であるという概念に異議を唱え、光学における主眼を目から光の伝播へと移した[91][93]。しかし、ケプラーは、惑星運動のケプ ラー法則の発見を通じてコペルニクスによる地動説モデルを改良したことで最もよく知られている。ケプラーはアリストテレスの形而上学を否定せず、自らの研 究を「天球の調和」の探求であると表現した[94]。ガリレオは天文学、物理学、工学に多大な貢献をした。しかし、教皇ウルバヌス8世が彼の地動説に関す る著作を禁じたため、彼は迫害を受けるようになった[95]。 活版印刷機は、当時の自然観と大きく異なる見解を含む学術的な議論を出版するために広く利用された[96]。フランシス・ベーコンとルネ・デカルトは、ア リストテレスの科学とは異なる新しいタイプの科学を支持する哲学的な議論を発表した。ベーコンは思索よりも実験の重要性を強調し、アリストテレスの形式因 と最終因の概念に疑問を呈し、科学は自然の法則と全人類の生活向上の研究を行うべきだという考えを提唱した[97]。デカルトは個人の思考を重視し、自然 の研究には幾何学よりも数学を用いるべきだと主張した[98]。 |

| Age of Enlightenment Main article: Science in the Age of Enlightenment  Title page of the 1687 first edition of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton At the start of the Age of Enlightenment, Isaac Newton formed the foundation of classical mechanics by his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, greatly influencing future physicists.[99] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz incorporated terms from Aristotelian physics, now used in a new non-teleological way. This implied a shift in the view of objects: objects were now considered as having no innate goals. Leibniz assumed that different types of things all work according to the same general laws of nature, with no special formal or final causes.[100] During this time, the declared purpose and value of science became producing wealth and inventions that would improve human lives, in the materialistic sense of having more food, clothing, and other things. In Bacon's words, "the real and legitimate goal of sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches", and he discouraged scientists from pursuing intangible philosophical or spiritual ideas, which he believed contributed little to human happiness beyond "the fume of subtle, sublime or pleasing [speculation]".[101] Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies,[102] which had largely replaced universities as centers of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were the backbones of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population.[103] Enlightenment philosophers turned to a few of their scientific predecessors – Galileo, Kepler, Boyle, and Newton principally – as the guides to every physical and social field of the day.[104][105] The 18th century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine[106] and physics;[107] the development of biological taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus;[108] a new understanding of magnetism and electricity;[109] and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline.[110] Ideas on human nature, society, and economics evolved during the Enlightenment. Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed A Treatise of Human Nature, which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.[111] Modern sociology largely originated from this movement.[112] In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, which is often considered the first work on modern economics.[113] |

啓蒙時代 メイン記事:啓蒙時代の科学  1687年に出版されたアイザック・ニュートンの『自然哲学の数学的原理』の初版のタイトルページ 啓蒙時代の始まりに、アイザック・ニュートンは『自然哲学の数学的原理』によって古典力学の基礎を築き、後の物理学者たちに多大な影響を与えた[99]。 ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツは、アリストテレスの物理学から用語を取り入れ、現在では目的論的ではない新しい方法で使用されている。これ は、物に対する見方の変化を意味していた。すなわち、物には生まれながらの目標はないと考えられたのである。ライプニッツは、異なる種類の物すべてが、特 別な形式的原因や最終的原因なしに、同じ自然の一般的な法則に従って機能すると仮定していた[100]。 この時代、科学の公言された目的と価値は、物質主義的な意味において、食料や衣類、その他の物資をより多く手に入れることで、人間の生活を改善する富や発 明を生み出すこととなった。ベーコンは、「科学の真の正当な目的は、新しい発明や富を人間に与えることである」と述べており、科学者たちに、哲学や精神的 な観念といった形のないものを追求することを勧めなかった。 啓蒙時代の科学は、科学協会や科学アカデミーによって支配されていた[102]。科学協会や科学アカデミーは、科学的研究と開発の拠点として、大学にとっ て代わる存在となっていた。学会やアカデミーは、科学者の職業が成熟する上で重要な役割を果たした。もう一つの重要な発展は、識字人口の増加に伴う科学の 一般化であった[103]。啓蒙思想家たちは、ガリレオ、ケプラー、ボイル、ニュートンといった科学の先駆者たちに、当時のあらゆる物理的・社会的分野に おける指針を見出していた[104][105]。 18世紀には、医学[106]と物理学[107]の実践において大きな進歩が見られ、カール・フォン・リンネによる生物分類学の発展[108]、磁性と電 気に関する新たな理解[109]、そして学問としての化学の成熟[110]も実現した。医学[106]と物理学[107]の進歩、カール・フォン・リンネ による生物分類学の確立[108]、磁性と電気に関する新たな理解[109]、そして学問としての化学の成熟[110]。啓蒙主義の時代には、人間性、社 会、経済に関する考え方も進化していた。ヒュームやその他のスコットランド啓蒙思想家たちは『人間本性論』を著し、ジェームズ・バーネット、アダム・ ファーガソン、ジョン・ミラ―、ウィリアム・ロバートソンといった作家たちによって、古代や原始文化における人間の行動の科学的研究と、 近代を決定づける力に対する強い認識と結びつけた。[111] 近代社会学は、この運動から大きく派生したものである。[112] 1776年、アダム・スミスは『国富論』を出版した。これは近代経済学の最初の著作としてよく知られている。[113] |

| 19th century Main article: 19th century in science  Sketch of a map with captions The first diagram of an evolutionary tree made by Charles Darwin in 1837 During the nineteenth century, many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences; the frequent use of precision instruments; the emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", and "scientist"; an increased professionalization of those studying nature; scientists gaining cultural authority over many dimensions of society; the industrialization of numerous countries; the thriving of popular science writings; and the emergence of science journals.[114] During the late 19th century, psychology emerged as a separate discipline from philosophy when Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory for psychological research in 1879.[115] During the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, which explained how different plants and animals originated and evolved. Their theory was set out in detail in Darwin's book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859.[116] Separately, Gregor Mendel presented his paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" in 1865,[117] which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics.[118] Early in the 19th century, John Dalton suggested the modern atomic theory, based on Democritus's original idea of indivisible particles called atoms.[119] The laws of conservation of energy, conservation of momentum and conservation of mass suggested a highly stable universe where there could be little loss of resources. However, with the advent of the steam engine and the industrial revolution there was an increased understanding that not all forms of energy have the same energy qualities, the ease of conversion to useful work or to another form of energy.[120] This realization led to the development of the laws of thermodynamics, in which the free energy of the universe is seen as constantly declining: the entropy of a closed universe increases over time.[b] The electromagnetic theory was established in the 19th century by the works of Hans Christian Ørsted, André-Marie Ampère, Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell, Oliver Heaviside, and Heinrich Hertz. The new theory raised questions that could not easily be answered using Newton's framework. The discovery of X-rays inspired the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie in 1896,[123] Marie Curie then became the first person to win two Nobel prizes.[124] In the next year came the discovery of the first subatomic particle, the electron.[125] |

19世紀 メイン記事:19世紀の科学  キャプション付きのスケッチ チャールズ・ダーウィンが1837年に作成した最初の進化樹の図 19世紀には、現代の現代科学の多くの特徴が形作られ始めた。これには、生命科学と物理学の変化、精密機器の頻繁な使用、「生物学者」、「物理学者」、 「科学者」などの用語の登場、自然を研究する人々の専門性の高まり、科学者が社会のさまざまな側面で文化的権威を獲得すること、多数の国の工業化、大衆向 けの科学論文の隆盛、科学ジャーナルの登場などが含まれる[114]。19世紀後半、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントが1879年に心理学研究のための最初の研究室 を設立したことにより、心理学は哲学から独立した学問分野として登場した[115]。 19世紀半ば、チャールズ・ダーウィンとアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは、1858年にそれぞれ独立して自然淘汰による進化論を提唱し、さまざまな植 物や動物がどのように誕生し進化したかを説明した。彼らの理論は、1859年に出版されたダーウィンの著書『種の起源』で詳しく述べられた[116]。一 方、グレゴール・メンデルは1865年に論文「植物の交配実験」を発表し[117]、生物の遺伝の原理を概説し、現代遺伝学の基礎となった 。 19世紀初頭、ジョン・ダルトンは、デモクリトスの「原子」という分割不可能な粒子の概念に基づいて、現代の原子説を提唱した[119]。エネルギー保存 則、運動量保存則、質量保存則は、資源の損失がほとんどない非常に安定した宇宙を示唆していた。しかし、蒸気機関と産業革命の登場により、すべてのエネル ギー形態が同じエネルギー特性、有用な仕事や別のエネルギー形態への変換の容易さを持っているわけではないという理解が深まった[120]。この認識は熱 力学の法則の発展につながり、宇宙の自由エネルギーは 閉じた宇宙のエントロピーは時間とともに増加する[b]。 電磁気学は、19世紀にハンス・クリスチャン・エルステッド、アンドレ=マリ・アンペール、マイケル・ファラデー、ジェームズ・クラーク・マクスウェル、 オリバー・ヘビサイド、ハインリッヒ・ヘルツの研究によって確立された。この新しい理論は、ニュートンの枠組みでは簡単に答えられない疑問を投げかけた。 X線の発見は、1896年にアンリ・ベクレルとマリー・キュリーによる放射能の発見につながった[123]。マリー・キュリーは、その後、2つのノーベル 賞を受賞した最初の人物となった[124]。翌年には、最初の素粒子である電子が発見された[125]。 |

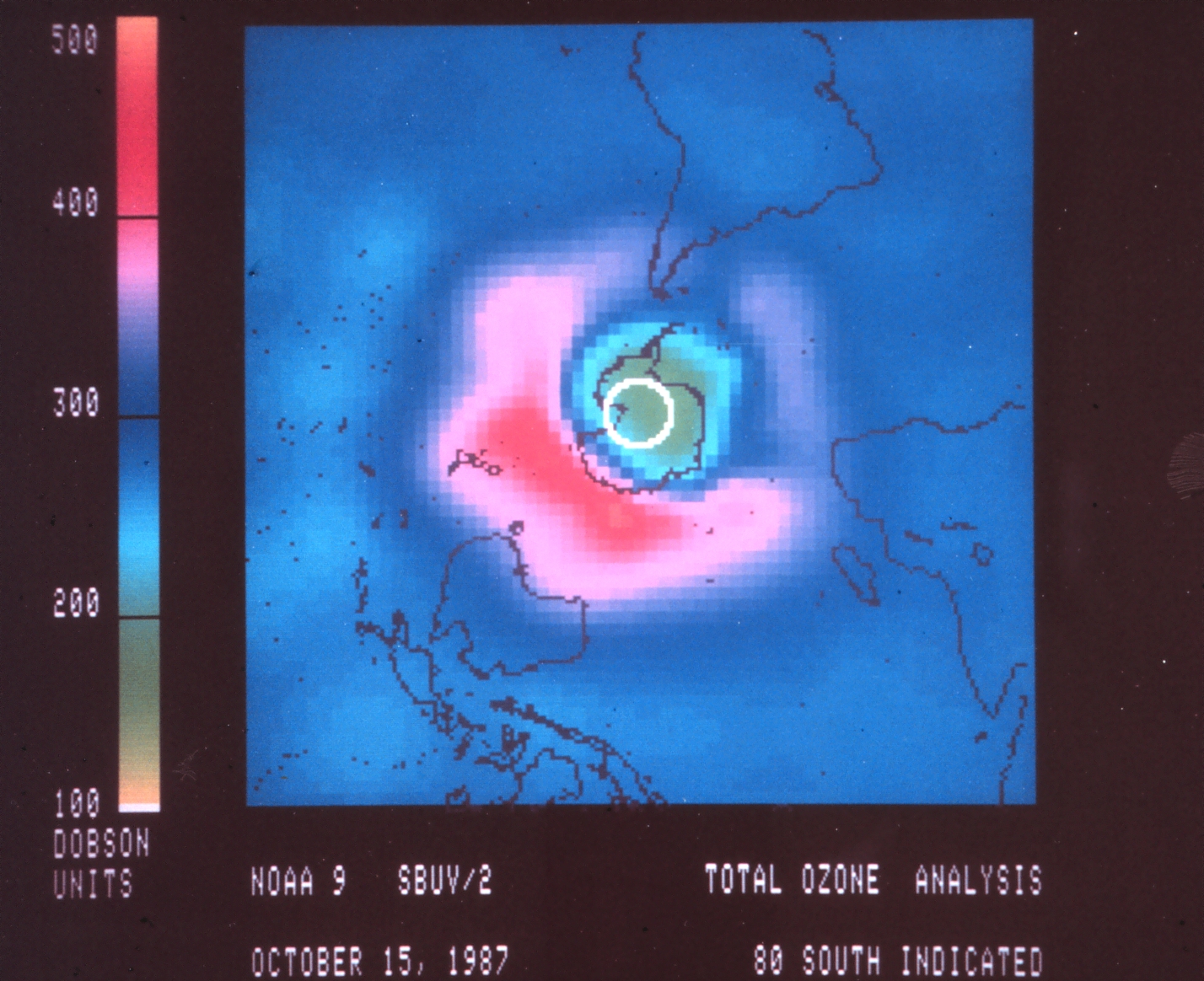

| 20th century Main article: 20th century in science  Graph showing lower ozone concentration at the South Pole A computer graph of the ozone hole made in 1987 using data from a space telescope In the first half of the century, the development of antibiotics and artificial fertilizers improved human living standards globally.[126][127] Harmful environmental issues such as ozone depletion, ocean acidification, eutrophication and climate change came to the public's attention and caused the onset of environmental studies.[128] During this period, scientific experimentation became increasingly larger in scale and funding.[129] The extensive technological innovation stimulated by World War I, World War II, and the Cold War led to competitions between global powers, such as the Space Race and nuclear arms race.[130][131] Substantial international collaborations were also made, despite armed conflicts.[132] In the late 20th century, active recruitment of women and elimination of sex discrimination greatly increased the number of women scientists, but large gender disparities remained in some fields.[133] The discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964[134] led to a rejection of the steady-state model of the universe in favor of the Big Bang theory of Georges Lemaître.[135] The century saw fundamental changes within science disciplines. Evolution became a unified theory in the early 20th-century when the modern synthesis reconciled Darwinian evolution with classical genetics.[136] Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum mechanics complement classical mechanics to describe physics in extreme length, time and gravity.[137][138] Widespread use of integrated circuits in the last quarter of the 20th century combined with communications satellites led to a revolution in information technology and the rise of the global internet and mobile computing, including smartphones. The need for mass systematization of long, intertwined causal chains and large amounts of data led to the rise of the fields of systems theory and computer-assisted scientific modeling.[139] |

20世紀 メイン記事: 20世紀の科学  南極におけるオゾン濃度の低下を示すグラフ 1987年に宇宙望遠鏡のデータを用いて作成されたオゾンホールのコンピュータグラフ 世紀の前半、抗生物質や化学肥料の開発により、世界中で人間の生活水準が向上した[126][127]。オゾン層破壊、海洋酸性化、富栄養化、気候変動な どの有害な環境問題が人々の関心を集め、 環境学の研究が始まった。 この時代、科学実験はますます大規模化し、資金も潤沢になった。第一次世界大戦、第二次世界大戦、冷戦によって引き起こされた広範囲にわたる技術革新は、 宇宙開発競争や核軍拡競争といった世界大国の競争につながった。20世紀後半には、女性の積極的な採用と性差別撤廃により女性科学者の数が大幅に増加した が、一部の分野では男女間の格差が依然として大きかった[133]。1964年の宇宙マイクロ波背景放射の発見[134]により、宇宙の定常状態モデルは 否定され、ジョルジュ・ルメートルによるビッグバン理論が支持されるようになった[135]。 この世紀には、科学の各分野において根本的な変化が見られた。進化論は、20世紀初頭にダーウィンの進化論と古典遺伝学を統合した現代総合説によって統一 理論となった[136]。アルバート・アインシュタインの相対性理論と量子力学の進展は、古典力学を補完し、極限的な長さ、時間、重力を伴う物理現象を説 明した[137][138]。時間、重力について記述するようになった[137][138]。20世紀最後の四半世紀に集積回路が広く普及し、通信衛星と 組み合わせることで、情報技術に革命をもたらし、グローバルなインターネットやスマートフォンを含むモバイルコンピューティングの台頭につながった。長く て絡み合った因果関係や大量のデータを体系化する必要性から、システム理論やコンピュータ支援科学モデリングの分野が台頭した[139]。 |

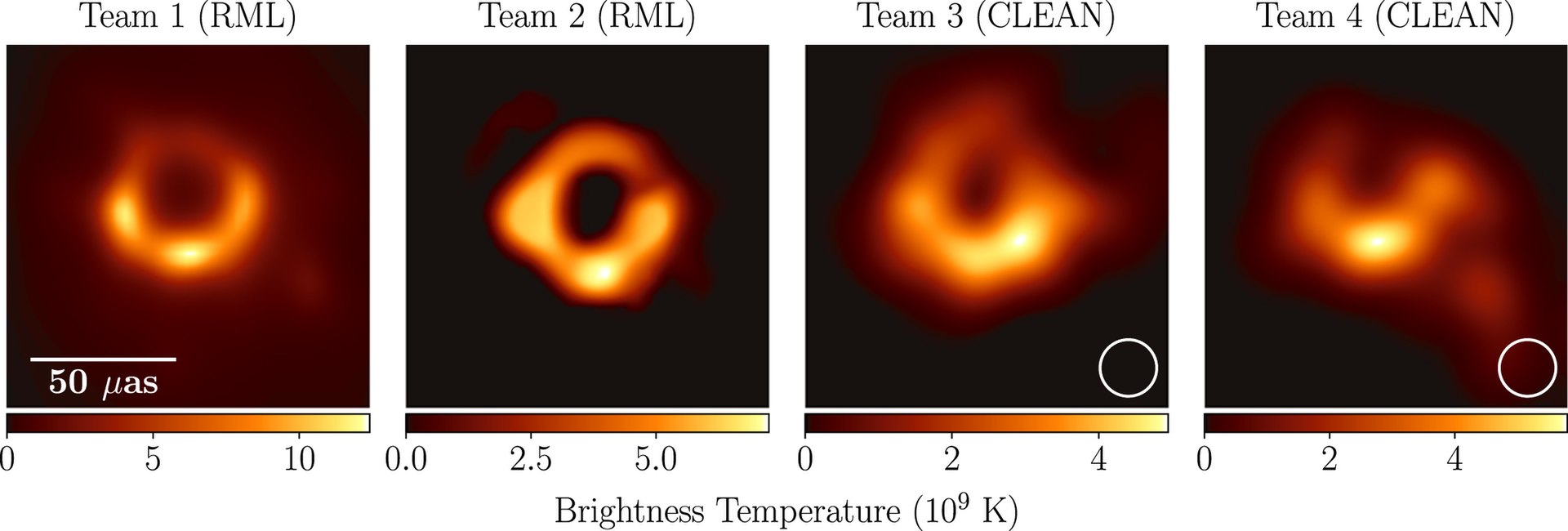

| 21st century Main article: 21st century § Science and technology  Four predicted image of M87* black hole made by separate teams in the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration. The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 by identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome.[140] The first induced pluripotent human stem cells were made in 2006, allowing adult cells to be transformed into stem cells and turn to any cell type found in the body.[141] With the affirmation of the Higgs boson discovery in 2013, the last particle predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics was found.[142] In 2015, gravitational waves, predicted by general relativity a century before, were first observed.[143][144] In 2019, the international collaboration Event Horizon Telescope presented the first direct image of a black hole's accretion disk.[145] |

21世紀 メイン記事:21世紀 § 科学と技術  イベントホライゾン望遠鏡のコラボレーションに参加する別々のチームが作成した、M87*ブラックホールの4つの予測画像。 ヒトゲノムプロジェクトは、2003年にヒトゲノムの全遺伝子を特定し、その地図を作成することで完了した[140]。2006年には、初めて人工多能性 幹細胞が作成され、成体の細胞を幹細胞に変化させ、体内のあらゆる種類の細胞に変化させることが可能になった[141]。201 3、素粒子物理学における標準模型で予測されていた最後の粒子が発見された[142]。2015年には、100年前に一般相対性理論によって予測されてい た重力波がはじめて観測された[143][144]。2019年には、国際協力によるイベントホライゾン望遠鏡が、ブラックホールの降着円盤の直接画像を 初めて発表した[145]。 |

| Science Criticism of science List of scientific occupations List of years in science Science (Wikiversity) |

科学 科学への批判 科学関連の職業一覧 科学関連の年表 科学(ウィキバーシティ) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science |

ラトゥールとウールガー『実験室の生活』 (初版1979, 1986)を嚆矢とする。しかし、科学論研究では実験室の関係者にインタビューをした研究(=実験室をフィールドワークの場とする)があったり、科学史研 究そのものが、科学の現場の状況の再現や再構成(=歴史的に民族誌的事実を構成する)することに関心があるため、科学人類学に先行する諸研究が人類学的な 感覚がまったくなかったとは言えないし、また実験室の民族誌研究が、ラトゥールらだけがはじめたのではないことは銘記しておくべきだろう。

実験室の民族誌学的研究は、その方法論を 母胎とした文化人類学の学説史における展開とアナロジーして考えるとわかりやすい(ただし、それだけが すべてではない)。

1. アームチェア科学人類学

フィールドワークをしない科学論、科学史研究がそれにあたる。また文化人類学の方法論を身につけていない人たちの研究。

2. 機能主義的な科学人類学

実験室が存続するための「機能」について、その社会構造、流通する言説、次世代の育成など、コミュニティないしは社会の維持と再生産に関心 をもつ研究

3. 構造主義的な科学人類学

先行する科学研究、科学論、科学史などのデータに通底する人間の「理性」「知性」の共通性や一般的特性を関心をもち、知性的実践の一般化や (形而上学的な)先験性の特徴を見いだそうとする研究

4. 解釈学ないしは象徴人類学的傾向のつよい科学人類学

現象学の影響を受けながら、知性の抽象化のプロセスを、現場の人間の語りなどから「理解」しようとする研究。。

5. 行動科学的な科学人類学

コミュニティにおける周辺的参加の概念に影響を受け、細かな行動観察という客観的データと、その現場での言説行為との関係、リフレクシヴな 分析などを照合させる。

■科学的知識の社会学派と呼ばれるひとび と(Sociology of Scientific Knowledge)

スティーブン・シェイピン(Steven Shapin, 1943- )

Steven Shapin is a historian and sociologist of science. He is

the Franklin L. Ford Research Professor of the History of Science at

Harvard University. He is considered one of the earliest scholars on

the sociology of scientific knowledge, and is credited with creating

new approaches.[4] He has won many awards, including the 2014 George

Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society for career contributions

to the field. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Shapin

ハリー・コリンズ(Harry Collins, 1943- )

Harry Collins (born 13 June 1943), is a British sociologist of

science at the School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, Wales. In

2012 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy. His best known

book is The Golem: What You Should Know About Science (1993). -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Collins

トレヴァー・ピンチ(Trevor Pinch, 1952- )

Trevor J. Pinch (born 1 January 1952), is a British sociologist, part-time musician and former chair of the Science and Technology Studies department at Cornell University. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trevor_Pinch

マイケル・マルケイ(Michael Joseph Mulkay, Mike Mulkay 1936- )

Michael Joseph Mulkay (born 1936) is a retired British

sociologist of science. He worked as a reader and researcher at

Aberdeen University until 1966, he was then lecturer in sociology at

Simon Fraser University 1966 to 1969, at the University of Cambridge

from 1969 to 1973, and then as Professor of Sociology at the University

of York, from which he retired in 2001. A number of his students have

gone on to take distinguished academic posts, including Nigel Gilbert,

Steve Woolgar, Steve Yearley, Andrew Webster and Jonathan Potter. -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mike_Mulkay

ブルーノ・ラトゥール(Bruno Latour, 1947- )

Bruno Latour (French: [latuʁ]; born 22 June 1947) is a French

philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist of science. He is

especially known for his work in the field of Science and Technology

Studies (STS). After teaching at the École des Mines de Paris (Centre

de Sociologie de l'Innovation) from 1982 to 2006, he is now Professor

at Sciences Po Paris (2006), where he is the scientific director of the

Sciences Po Medialab. He is also a Centennial Professor at the London

School of Economics. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruno_Latour

マイケル・リンチ(Michael E. Lynch, 1948- )

Michael E. Lynch (born 17 October 1948),[ is a professor at the department of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University. His works are particularly concerned with ethnomethodological approaches in science studies. Much of his research has addressed the role of visual representation in scientific practice. From 2002-2012 he was the editor of Social Studies of Science. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Lynch_(ethnomethodologist)

カリン・クノール=セチナ(Karin Knorr Cetina, 1944- )

Karin Knorr Cetina (also Karin Knorr-Cetina) (born 19 July

1944 in Graz, Austria) is an Austrian sociologist well known for her

work on epistemology and social constructionism, summarized in the

books The Manufacture of Knowledge: An Essay on the Constructivist and

Contextual Nature of Science (1981) and Epistemic Cultures: How the

Sciences Make Knowledge (1999). Currently, she focuses on the study of

global microstructures and Social studies of finance. Knorr Cetina is

professor of the Theory of Sociology at the Universität Konstanz and

guest professor at the University of Chicago. -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karin_Knorr_Cetina

科学人類学研究が、文化人類学研究のなか で重要な位置を占めてくるようになった理由として、以下のようなことがあげられる。

・ハイテク機器や環境科学など、科学の発 展が現代の市民生活と密接に関わるようになってきたため、科学者の営為に人々の関心が高まってきたこ と。

・科学研究の現場に、科学者自身によるリ フレクシヴィティ(自己省察性)の必要性が高まり、文化人類学による介入と社会的な相対化についての機 運が高まってきた。

・人類学パラダイムにおける、研究対象の 枯渇化や研究領域の細分化がが進み、未開拓・未着手のこの領域に進出する人類学者(あるいは行動学者) たちが増えてきたこと。

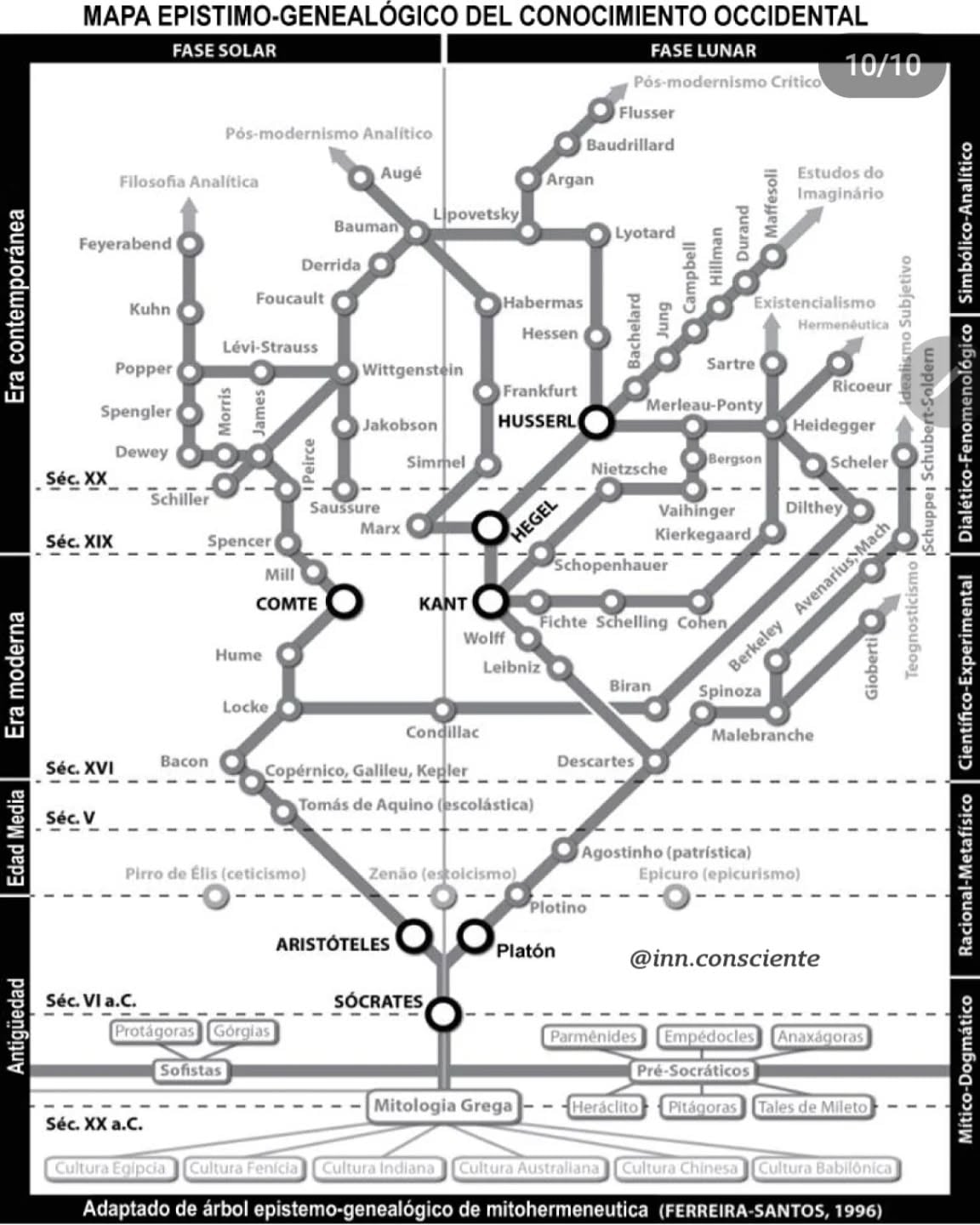

☆地下鉄の路線図かと思いきや——しかし 科学史・科学哲学の路線はこーなるかと思うとあまり、この線には乗りたくないですね〜♪

☆突然ですが「【ちょっと難しいけど子ども向けにしました】大阪大学と医療人文学の未来(56分版)ver.4.0」

リンク

文献

222

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099