科学

Science

解説:池田光穂

★科学(あるいはサイエンス)とはなに か?→科学とは、厳格な体 系的な学問であり、世界に関する検証可能な仮説や予測という形で知識を構築し、体系化するものである。

★現代科学は一般的に、物理的世界を研究 する自然科学 (物理学、化学、生物学など)、個人や社会を研究する社会科学(経済学、心理学、社会学など)、公理や規則によって支配される形式的なシステムを研究する 形式科学(論理学、数学、理論計算機科学など)の3つの主要分野に分けられる。形式科学は経験的証拠に依拠しないため、科学分野であるかどうかについては 意見が分かれている。応用科学は、工学や医学など、科学的な知識を実用的な目的で使用する分野である。

★科学の歴史は、歴史記録の大半を占めて おり、現代科学の明確な先駆者と特定できる最古の記録は、紀元前3000年から1200年頃の青銅器時代のエジプト とメソポタミアにまで遡る。数学、天文学、医学への彼らの貢献は、古典古代のギリシャ自然哲学に影響を与え、形作っていった。これにより、自然現象を原因 として物理世界の出来事を説明しようとする試みがなされるようになった。一方、インドの黄金時代には、ヒンドゥー・アラビア数字の導入を含むさらなる進歩 が遂げられた。これらの地域では、西ローマ帝国滅亡後の初期中世(400年から1000年)に科学研究は衰退したが、中世ルネサンス(カロリング朝ルネサ ンス、オットー朝ルネサンス、12世紀ルネサンス)において学問は再び栄えた。西ヨーロッパで失われた一部のギリシャ語写本は、イスラム黄金時代の中東で 保存され、さらに発展した。また、ビザンチン帝国のギリシャ人学者たちが、滅亡しつつあったビザンチン帝国からギリシャ語写本を西ヨーロッパに持ち込み、 ルネサンスの幕開けに貢献した。 10世紀から13世紀にかけて、ギリシャの作品の復興と西欧への同化、およびイスラム教の探究により、「自然哲学」が復活した。その後、16世紀に始まっ た科学革命により、新たなアイデアや発見が従来のギリシャの概念や伝統から離れ、自然哲学は変容した 科学的手法は、知識の創造においてより大きな役割を果たすようになり、「自然哲学」が「自然科学」へと変化する中で、科学の制度や専門的特徴の多くが形作 られ始めたのは19世紀に入ってからであった。

★科学における新たな知識は、世界に対す る好奇心と問題解決への意欲に突き動かされた科学者たちの研究によって進歩する。現代の科学研究は高度に協調的であ り、通常は学術・研究機関、政府機関、企業などのチームによって行われる。 彼らの研究がもたらす実用的な影響により、商業製品、軍備、医療、公共インフラ、環境保護などの倫理的・道徳的発展を優先させることで科学事業に影響を与 えようとする科学政策が誕生した(→「科学とはなにか?」)。

︎▶科学人類学︎▶︎︎科

学的事実の産出と研究者の実践▶︎実験室における社会実践の民族誌学的研究▶

科学(このページ)︎︎▶科学とはなにか?︎▶︎︎科学社会学入門▶科

学文献の読解︎▶︎︎科学的客観性▶︎トーマス・クーン『科学革命の構造』▶︎︎反証可能性▶︎マー

トンのCUDOSからザイマンのPLACEまで▶︎︎科学研究における

アナキズム▶︎科学の語彙や科学の隠喩を解明する!▶︎︎産業革命と科学革命のちがい▶情け容赦のない科学︎▶︎︎科学の民族誌とはなにか▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| 科

学 Science is a strict systematic discipline that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the world.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; the social sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies;[4][5] and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems, governed by axioms and rules.[6][7] There is disagreement whether the formal sciences are scientific disciplines,[8][9][10] as they do not rely on empirical evidence.[11][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as in engineering and medicine.[12][13][14] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest written records of identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia from around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[15]: 12 [16][17][18] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400 to 1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[19] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived "natural philosophy",[20][21][22] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[23] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[24][25] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[26][27] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[28] New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems.[29][30] Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions,[31] government agencies, and companies.[32][33] The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection. |

科学とは、厳格な体系的な学問であり、世界に関する検証可能な仮説や予 測という形で知識を構築し、体系化するものである。現代科学は一般的に、物理的世界を研究する自然科学(物理学、化学、生物学など)、個人や社会を研究す る社会科学(経済学、心理学、社会学など)、公理や規則によって支配される形式的なシステムを研究する形式科学(論理学、数学、理論計算機科学など)の3 つの主要分野に分けられる。形式科学は経験的証拠に依拠しないため、科学分野であるかどうかについては意見が分かれている。応用科学は、工学や医学など、 科学的な知識を実用的な目的で使用する分野である。 科学の歴史は、歴史記録の大半を占めており、現代科学の明確な先駆者と特定できる最古の記録は、紀元前3000年から1200年頃の青銅器時代のエジプト とメソポタミアにまで遡る。数学、天文学、医学への彼らの貢献は、古典古代のギリシャ自然哲学に影響を与え、形作っていった。これにより、自然現象を原因 として物理世界の出来事を説明しようとする試みがなされるようになった。一方、インドの黄金時代には、ヒンドゥー・アラビア数字の導入を含むさらなる進歩 が遂げられた。これらの地域では、西ローマ帝国滅亡後の初期中世(400年から1000年)に科学研究は衰退したが、中世ルネサンス(カロリング朝ルネサ ンス、オットー朝ルネサンス、12世紀ルネサンス)において学問は再び栄えた。西ヨーロッパで失われた一部のギリシャ語写本は、イスラム黄金時代の中東で 保存され、さらに発展した。また、ビザンチン帝国のギリシャ人学者たちが、滅亡しつつあったビザンチン帝国からギリシャ語写本を西ヨーロッパに持ち込み、 ルネサンスの幕開けに貢献した。 10世紀から13世紀にかけて、ギリシャの作品の復興と西欧への同化、およびイスラム教の探究により、「自然哲学」が復活した。その後、16世紀に始まっ た科学革命により、新たなアイデアや発見が従来のギリシャの概念や伝統から離れ、自然哲学は変容した 科学的手法は、知識の創造においてより大きな役割を果たすようになり、「自然哲学」が「自然科学」へと変化する中で、科学の制度や専門的特徴の多くが形作 られ始めたのは19世紀に入ってからであった。 科学における新たな知識は、世界に対する好奇心と問題解決への意欲に突き動かされた科学者たちの研究によって進歩する。現代の科学研究は高度に協調的であ り、通常は学術・研究機関、政府機関、企業などのチームによって行われる。[32][33] 彼らの研究がもたらす実用的な影響により、商業製品、軍備、医療、公共インフラ、環境保護などの倫理的・道徳的発展を優先させることで科学事業に影響を与 えようとする科学政策が誕生した。 |

| Etymology The word science has been used in Middle English since the 14th century in the sense of "the state of knowing". The word was borrowed from the Anglo-Norman language as the suffix -cience, which was borrowed from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge, awareness, understanding". It is a noun derivative of the Latin sciens meaning "knowing", and undisputedly derived from the Latin sciō, the present participle scīre, meaning "to know".[34] There are many hypotheses for science's ultimate word origin. According to Michiel de Vaan, Dutch linguist and Indo-Europeanist, sciō may have its origin in the Proto-Italic language as *skije- or *skijo- meaning "to know", which may originate from Proto-Indo-European language as *skh1-ie, *skh1-io, meaning "to incise". The Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben proposed sciō is a back-formation of nescīre, meaning "to not know, be unfamiliar with", which may derive from Proto-Indo-European *sekH- in Latin secāre, or *skh2-, from *sḱʰeh2(i)- meaning "to cut".[35] In the past, science was a synonym for "knowledge" or "study", in keeping with its Latin origin. A person who conducted scientific research was called a "natural philosopher" or "man of science".[36] In 1834, William Whewell introduced the term scientist in a review of Mary Somerville's book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences,[37] crediting it to "some ingenious gentleman" (possibly himself).[38] |

語源 「科学」という言葉は、中世英語において14世紀から「知の状態」という意味で使用されてきた。この言葉はアングロ・ノルマン語から借用された接尾辞「- science」に由来し、この接尾辞はラテン語の「scientia」から借用されたものである。「scientia」は「知識、認識、理解」を意味す る。これはラテン語の sciens(「知る」の意)という名詞に由来するものであり、ラテン語の sciō(「知る」の意)という現在分詞 scīre(「知る」の意)から派生したことは疑いない[34]。 サイエンスの語源については、さまざまな仮説がある。オランダ人の言語学者で印欧語学者であるミシェル・デ・ヴァンによると、sciōは、*skije- または*skijo-という「知る」という意味の初期イタリック語に由来する可能性がある。これは、*skh1-ie、*skh1-ioという「切り刻 む」という意味の初期インド・ヨーロッパ語に由来する可能性がある。Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben(インド・ゲルマン語動詞辞典)では、sciōはnescīre(「知らない、知らない」)の逆形成であると提案されている。これは、ラテン 語のsecāre(「切る」)に由来する、インド・ヨーロッパ祖語*sekH-、あるいは あるいは *skh2-、*sḱʰeh2(i)-「切る」に由来する可能性がある[35]。 かつて、科学はラテン語に由来する「知識」や「研究」と同義語であった。科学的研究を行う人は「自然哲学者」または「科学者」と呼ばれていた[36]。 1834年、ウィリアム・ホイウェルはメアリー・ソマーヴィルの著書『物理科学の関連性』の書評で「科学者」という用語を紹介し、その功績を「ある独創的 な紳士」(おそらくホイウェル自身)に与えた[38]。 |

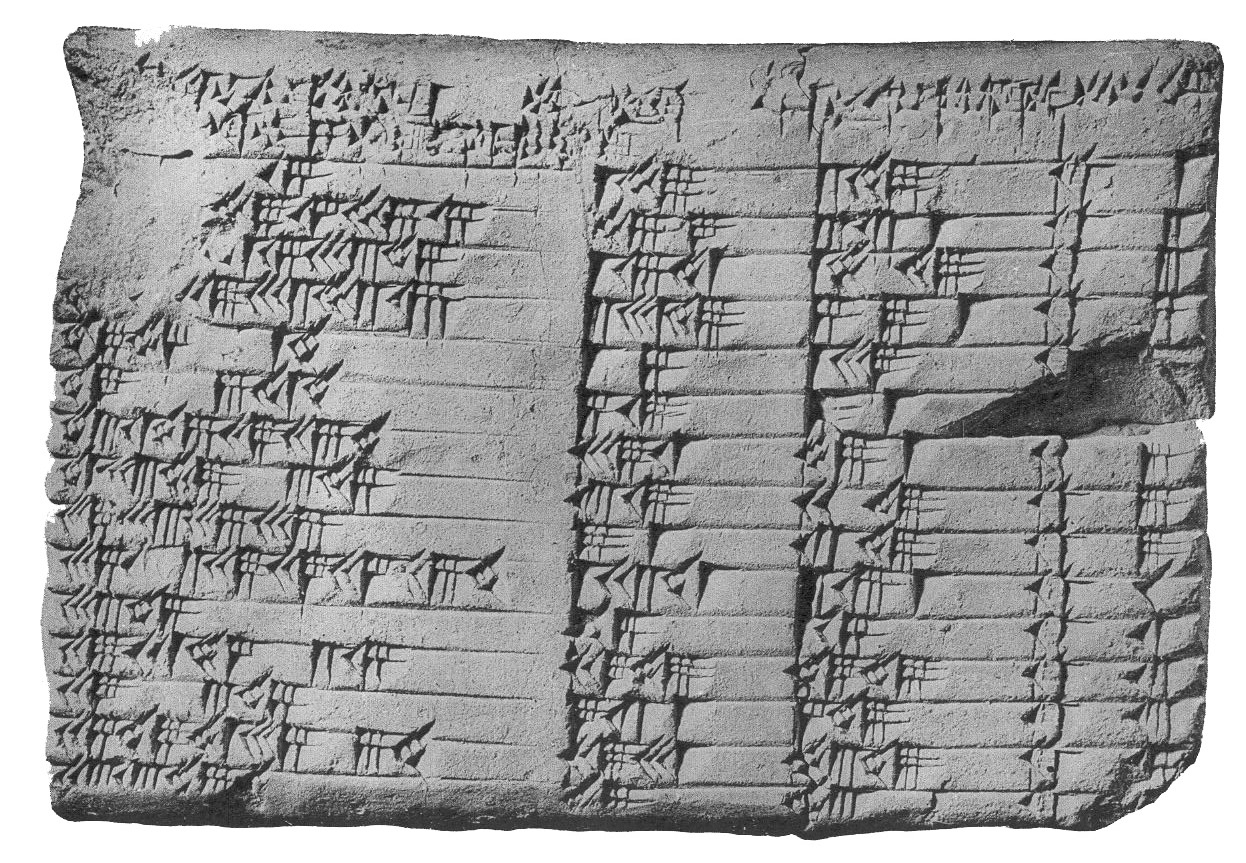

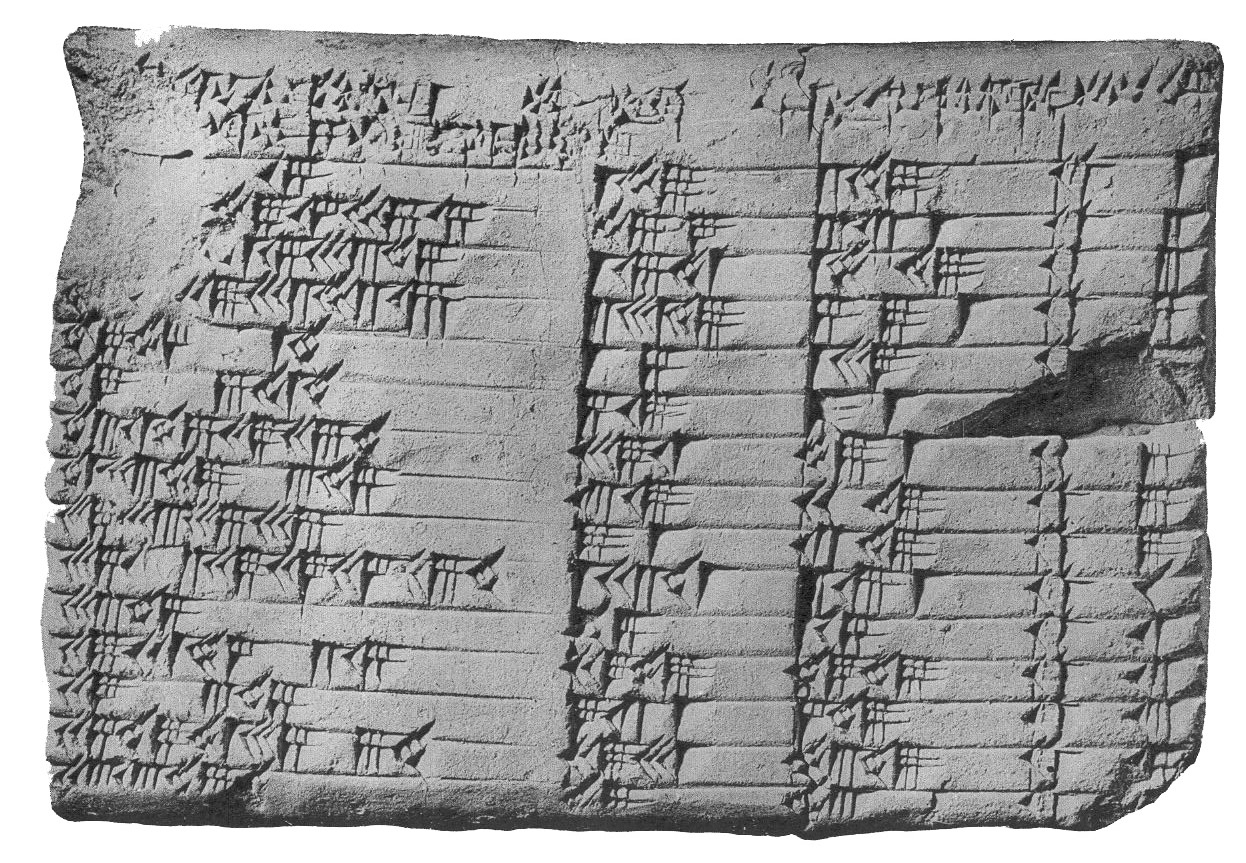

| History Main article: History of science Early history Main article: History of science in early cultures  Clay tablet with markings, three columns for numbers and one for ordinals The Plimpton 322 tablet by the Babylonians records Pythagorean triples, written in about 1800 BCE Science has no single origin. Rather, systematic methods emerged gradually over the course of tens of thousands of years,[39][40] taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Women likely played a central role in prehistoric science,[41] as did religious rituals.[42] Some scholars use the term "protoscience" to label activities in the past that resemble modern science in some but not all features;[43][44][45] however, this label has also been criticised as denigrating,[46] or too suggestive of presentism, thinking about those activities only in relation to modern categories.[47] Direct evidence for scientific processes becomes clearer with the advent of writing systems in early civilisations like Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, creating the earliest written records in the history of science in around 3000 to 1200 BCE.[15]: 12–15 [16] Although the words and concepts of "science" and "nature" were not part of the conceptual landscape at the time, the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians made contributions that would later find a place in Greek and medieval science: mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[48][15]: 12 From the 3rd millennium BCE, the ancient Egyptians developed a decimal numbering system,[49] solved practical problems using geometry,[50] and developed a calendar.[51] Their healing therapies involved drug treatments and the supernatural, such as prayers, incantations, and rituals.[15]: 9 The ancient Mesopotamians used knowledge about the properties of various natural chemicals for manufacturing pottery, faience, glass, soap, metals, lime plaster, and waterproofing.[52] They studied animal physiology, anatomy, behaviour, and astrology for divinatory purposes.[53] The Mesopotamians had an intense interest in medicine and the earliest medical prescriptions appeared in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur.[52][54] They seem to have studied scientific subjects which had practical or religious applications and had little interest in satisfying curiosity.[52] Classical antiquity Main article: Science in classical antiquity  Framed mosaic of philosophers gathering around and conversing Plato's Academy mosaic, made between 100 BCE to 79 AD, shows many Greek philosophers and scholars In classical antiquity, there is no real ancient analogue of a modern scientist. Instead, well-educated, usually upper-class, and almost universally male individuals performed various investigations into nature whenever they could afford the time.[55] Before the invention or discovery of the concept of phusis or nature by the pre-Socratic philosophers, the same words tend to be used to describe the natural "way" in which a plant grows,[56] and the "way" in which, for example, one tribe worships a particular god. For this reason, it is claimed that these men were the first philosophers in the strict sense and the first to clearly distinguish "nature" and "convention".[57] The early Greek philosophers of the Milesian school, which was founded by Thales of Miletus and later continued by his successors Anaximander and Anaximenes, were the first to attempt to explain natural phenomena without relying on the supernatural.[58] The Pythagoreans developed a complex number philosophy[59]: 467–68 and contributed significantly to the development of mathematical science.[59]: 465 The theory of atoms was developed by the Greek philosopher Leucippus and his student Democritus.[60][61] Later, Epicurus would develop a full natural cosmology based on atomism, and would adopt a "canon" (ruler, standard) which established physical criteria or standards of scientific truth.[62] The Greek doctor Hippocrates established the tradition of systematic medical science[63][64] and is known as "The Father of Medicine".[65] A turning point in the history of early philosophical science was Socrates' example of applying philosophy to the study of human matters, including human nature, the nature of political communities, and human knowledge itself. The Socratic method as documented by Plato's dialogues is a dialectic method of hypothesis elimination: better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. The Socratic method searches for general commonly-held truths that shape beliefs and scrutinizes them for consistency.[66] Socrates criticised the older type of study of physics as too purely speculative and lacking in self-criticism.[67] Aristotle in the 4th century BCE created a systematic program of teleological philosophy.[68] In the 3rd century BCE, Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos was the first to propose a heliocentric model of the universe, with the Sun at the centre and all the planets orbiting it.[69] Aristarchus's model was widely rejected because it was believed to violate the laws of physics,[69] while Ptolemy's Almagest, which contains a geocentric description of the Solar System, was accepted through the early Renaissance instead.[70][71] The inventor and mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse made major contributions to the beginnings of calculus.[72] Pliny the Elder was a Roman writer and polymath, who wrote the seminal encyclopaedia Natural History.[73][74][75] Positional notation for representing numbers likely emerged between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE along Indian trade routes. This numeral system made efficient arithmetic operations more accessible and would eventually become standard for mathematics worldwide.[76] |

歴史 詳細は「科学史」を参照 初期の歴史 詳細は「初期の文化における科学史」を参照  数字を3列、序数を1列で表記した粘土板 バビロニアのプリムプトン322号土板には、紀元前1800年頃に書かれたピタゴラスの三平方の定理が記録されている 科学には単一の起源があるわけではない。むしろ、体系的な方法は数万年をかけて徐々に現れ、世界中でさまざまな形態を取ったが、ごく初期の展開については ほとんど詳細が分かっていない。先史時代の科学では、女性が中心的な役割を果たしていた可能性が高い。[41] 宗教儀式も同様であった。[42] 一部の学者は、現代の科学と類似する部分もあるが、すべてがそうではない過去の活動を指す用語として「プロトサイエンス」という用語を使用している。 [43][44][45] しかし、この用語は、中傷的であるという批判[46]や、現代のカテゴリーとの関連性のみでそれらの活動を考えるという、現在主義的思考を暗示しすぎてい るという批判も受けている。[47] 古代エジプトやメソポタミアなどの初期文明における文字の登場により、科学的なプロセスを示す直接的な証拠が明らかになり、紀元前3000年から1200 年頃には科学史上初の記録が残されている。[15]: 12–15 [16] 当時は「科学」や「自然」という言葉や概念は存在していなかったが、古代エジプト人とメソポタミア人は ギリシャや中世の科学に貢献することになる数学、天文学、医学の分野で貢献した。[48][15]:12 紀元前3千年紀から、古代エジプト人は十進法を開発し[49]、幾何学を用いて実用的な問題を解決し[50]、暦を開発した。[51] 彼らの治療法には薬物治療や、祈り、呪文、儀式などの超自然的なものも含まれていた。[15]:9 古代メソポタミア人は、陶器、ファイアンス、ガラス、石鹸、金属、石灰プラスター、防水加工などの製造に、さまざまな天然化学物質の特性に関する知識を利 用していた。[52] 動物生理学、解剖学、行動学、占いのための占星術を研究していた。[53] メソポタミア人は医学に強い関心を抱いており、最古の医学処方はウル第3王朝の時代にシュメール語で書かれたものである。[52][54] 彼らは実用的または宗教的な応用を持つ科学的な主題を研究していたようであり、単なる好奇心への満足にはほとんど関心がなかったようである。[52] 古典古代 詳細は「古典古代の科学」を参照  囲い込みモザイク画に描かれた、集まって会話する哲学者たち 紀元前100年から西暦79年の間に作られたプラトンの学園のモザイク画には、多くのギリシアの哲学者や学者が描かれている 古典古代には、現代の科学者に相当する古代の人物は実在しない。その代わり、教養があり、通常は上流階級に属する、ほぼ例外なく男性である人々が、時間的 余裕がある限り、自然界のさまざまな調査を行っていた。[55] プレソクラテス派の哲学者たちが「フュシス」や「自然」という概念を発明または発見する以前は、同じ言葉が植物が成長する自然の「方法」を説明するために 使われる傾向にあった。[56] また、例えばある部族が特定の神を崇拝する「方法」を説明するためにも使われていた。このため、彼らは厳密な意味での最初の哲学者であり、「自然」と「慣 習」を明確に区別した最初の人物であったと主張されている。 ミレトスのタレスが創始し、その後継者アナクシマンドロスとアナクシメネスが継承したミレトス学派の初期ギリシアの哲学者たちは、超自然的なものに頼らず に自然現象を説明しようとした最初の人物であった。[58] ピタゴラス学派は複素数哲学を展開し[59]:467-68、数学科学の発展に大きく貢献した。[59]:465 アトム(原子)の理論は、 ギリシアの哲学者レウキッポスと彼の弟子デモクリトスによって発展した。[60][61] その後、エピクロスは原子論を基盤とした完全な自然宇宙論を展開し、「規範」(定規、標準)を採用した。これは、科学的真理の物理的基準または標準を確立 したものである。[62] ギリシアの医師ヒポクラテスは、体系的な医学の伝統を確立し[63][64]、「医学の父」として知られている。[65] 初期の哲学科学の歴史における転換点は、ソクラテスが人間の本性、政治共同体の性質、人間の知識そのものなど、人間に関する事柄の研究に哲学を適用した例 である。プラトンの対話篇に記録されているソクラテス流の方法は、仮説を排除する弁証法的方法である。より優れた仮説は、矛盾を導く仮説を特定し排除して いくことで見つけられる。ソクラテス流の方法は、信念を形成する一般的な共通の真理を探し出し、その一貫性を吟味する。[66] ソクラテスは、純粋に思弁的で自己批判を欠くとして、物理学の古い研究方法を批判した。[67] 紀元前4世紀のアリストテレスは目的論哲学の体系的なプログラムを作成した。[68] 紀元前3世紀には、ギリシアの天文学者アリスタルコス・サモスが、太陽を中心とし、すべての惑星が太陽の周りを回るという太陽中心の宇宙モデルを初めて提 唱した。[69] アリスタルコスのモデルは広く否定された。なぜなら、それは物理学の法則に違反すると考えられていたからである。[69] 一方で、地動説に基づく太陽系の記述を含むプトレマイオスの『アルマゲスト』は、初期ルネサンス期には受け入れられた。[70][71] シラクサの発明家であり数学者であるアルキメデスは、微積分の始まりに多大な貢献をした。[72] プリニウスはローマの作家であり博識家であり、画期的な百科事典『博物誌』を著した。[73][74][75] 数字を表す位置表記法は、おそらく3世紀から5世紀の間にインドの交易路で誕生した。この数字表記法は、効率的な算術演算をより身近なものとし、やがて世 界中の数学の標準となった。[76] |

| History of Science, Since Middle

ages Middle Ages Main article: History of science § Middle Ages  Picture of a peacock on very old paper The first page of Vienna Dioscurides depicts a peacock, made in the 6th century Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe.[15]: 194 During the period, Latin encyclopedists such as Isidore of Seville preserved the majority of general ancient knowledge.[77] In contrast, because the Byzantine Empire resisted attacks from invaders, they were able to preserve and improve prior learning.[15]: 159 John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar in the 500s, started to question Aristotle's teaching of physics, introducing the theory of impetus.[15]: 307, 311, 363, 402 His criticism served as an inspiration to medieval scholars and Galileo Galilei, who extensively cited his works ten centuries later.[15]: 307–308 [78] During late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, natural phenomena were mainly examined via the Aristotelian approach. The approach includes Aristotle's four causes: material, formal, moving, and final cause.[79] Many Greek classical texts were preserved by the Byzantine empire and Arabic translations were done by groups such as the Nestorians and the Monophysites. Under the Caliphate, these Arabic translations were later improved and developed by Arabic scientists.[80] By the 6th and 7th centuries, the neighboring Sassanid Empire established the medical Academy of Gondeshapur, which is considered by Greek, Syriac, and Persian physicians as the most important medical center of the ancient world.[81] The House of Wisdom was established in Abbasid-era Baghdad, Iraq,[82] where the Islamic study of Aristotelianism flourished[83] until the Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Ibn al-Haytham, better known as Alhazen, used controlled experiment in his optical study.[a][85][86] Avicenna's compilation of the Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia, is considered to be one of the most important publications in medicine and was used until the 18th century.[87] By the eleventh century, most of Europe had become Christian,[15]: 204 and in 1088, the University of Bologna emerged as the first university in Europe.[88] As such, demand for Latin translation of ancient and scientific texts grew,[15]: 204 a major contributor to the Renaissance of the 12th century. Renaissance scholasticism in western Europe flourished, with experiments done by observing, describing, and classifying subjects in nature.[89] In the 13th century, medical teachers and students at Bologna began opening human bodies, leading to the first anatomy textbook based on human dissection by Mondino de Luzzi.[90] |

中世以降の科学の歴史 中世 メイン記事: 科学史 § 中世  非常に古い紙の上に描かれた孔雀の絵 ウィーン・ディオスコリデスの最初のページには、6世紀に描かれた孔雀が描かれている 西ローマ帝国の崩壊により、5世紀には西ヨーロッパで知的衰退が起こり、ギリシャの宇宙観に関する知識は衰退した[15]: 194。セビリアのイシドー ルなどのラテン百科事典編纂者たちは、古代の一般的な知識の大部分を保存した[77]。これとは対照的に、ビザンティン帝国は侵略者からの攻撃に抵抗した ため、それまでの知識を保存し、さらに発展させることができた[15]: 159 。500年代のビザンティン学者であるヨハン・フィロポヌスは、アリス トテレスの物理学説に疑問を持ち、運動量説を導入した[ 15]: 307, 311, 363, 402 彼の批判は中世の学者やガリレオ・ガリレイのインスピレーションとなり、10世紀後に彼の著作が広く引用された。 古代末期から中世初期にかけて、自然現象は主にアリストテレスのアプローチによって研究されていた。このアプローチには、アリストテレスの4つの原因、す なわち物質的原因、形式的原因、運動的原因、最終的原因が含まれる[79]。多くのギリシャ古典文学はビザンティン帝国によって保存され、ネストリウス派 や単性論者などのグループによってアラビア語に翻訳された。カリフ制のもと、これらのアラビア語訳は後にアラビアの科学者たちによって改良・発展された [80]。6世紀から7世紀にかけて、隣接するサーサーン朝は医学アカデミーをゴンデシャプールに設立した。これは、ギリシャ人、シリア人、ペルシア人の 医師たちから、 古代世界でもっとも重要な医療センターであったと考えられている[81]。 知恵の館は、アッバース朝時代のイラク、バグダードに設立された[82]。そこでは、13世紀のモンゴル侵攻まで、アリストテレス主義のイスラム研究が盛 んに行われた[83]。アルハゼンとしてよりよく知られているイブン・アル・ハイサムは、光学の研究において制御実験を用いた[a][85][86]。ア ヴィセンナの医学百科事典『医学大全』は医学における最も重要な出版物のひとつと考えられ、18世紀まで使用されていた[87]。 11 11世紀までにヨーロッパの大部分はキリスト教化され[15]: 204、1088年にはボローニャ大学がヨーロッパ初の大学として誕生した[88]。そ のため、古代や科学の文献のラテン語訳に対する需要が高まり[15]: 204、12世紀のルネサンスに大きく貢献した。西欧におけるルネサンスのスコラ 学は、自然界の事象を観察、記述、分類する実験を通じて発展した[89]。13世紀、ボローニャの医学教師と学生たちは人体解剖を始め、これがモンドー ノ・デ・ルッツィによる人体解剖に基づく最初の解剖学教科書につながった[90]。 |

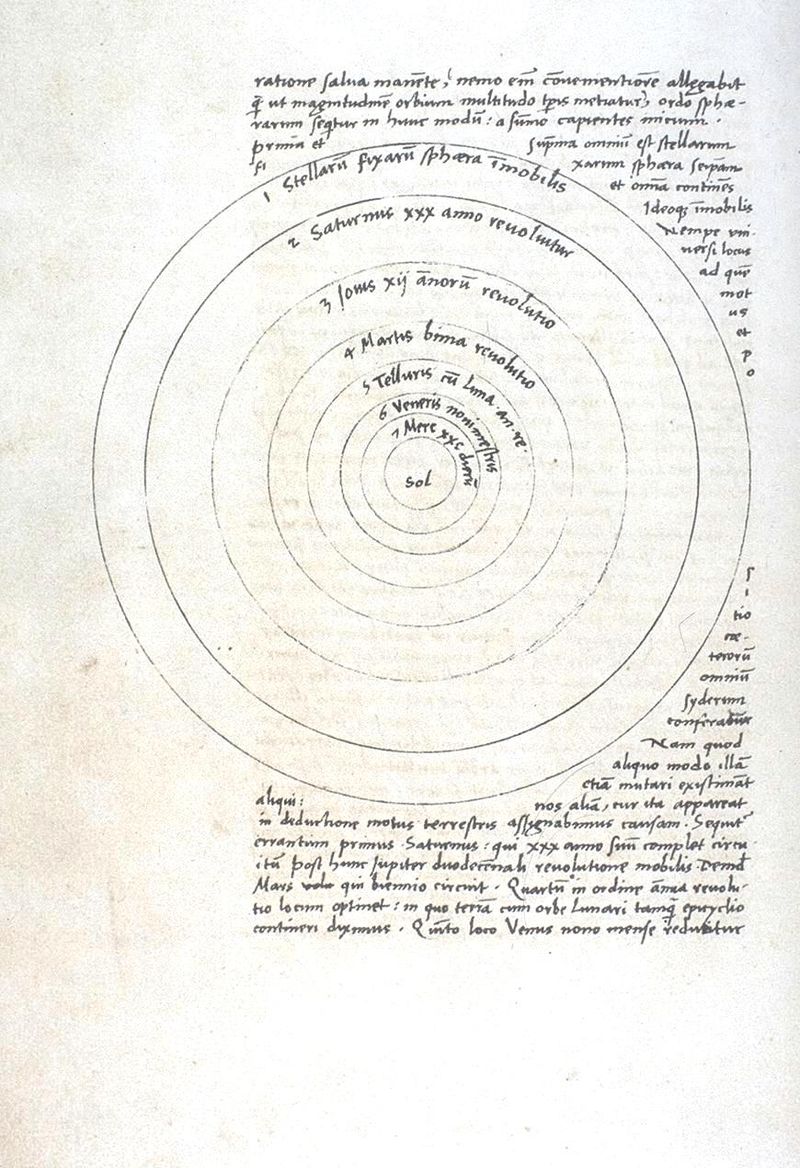

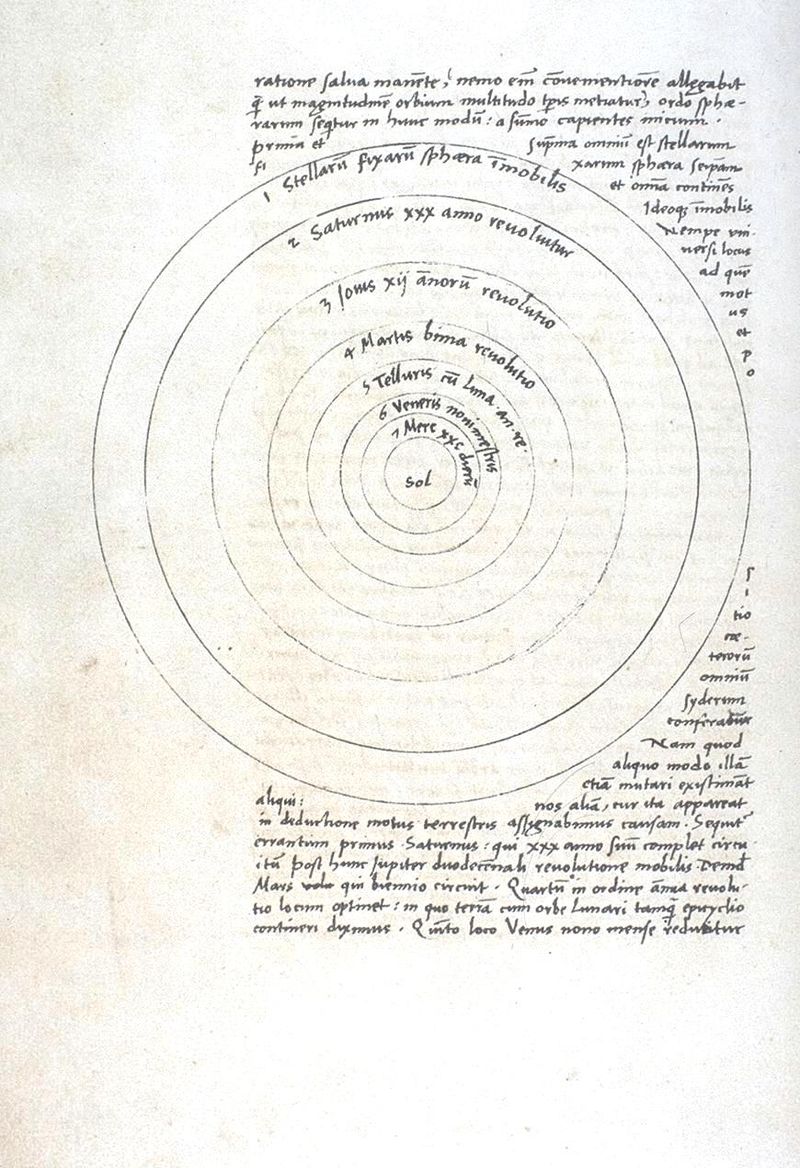

| Renaissance Main articles: Scientific Revolution and Science in the Renaissance  Drawing of planets' orbit around the Sun Drawing of the heliocentric model as proposed by the Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the Renaissance, both by challenging long-held metaphysical ideas on perception, as well as by contributing to the improvement and development of technology such as the camera obscura and the telescope. At the start of the Renaissance, Roger Bacon, Vitello, and John Peckham each built up a scholastic ontology upon a causal chain beginning with sensation, perception, and finally apperception of the individual and universal forms of Aristotle.[84]: Book I A model of vision later known as perspectivism was exploited and studied by the artists of the Renaissance. This theory uses only three of Aristotle's four causes: formal, material, and final.[91] In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the Solar System, stating that the planets revolve around the Sun, instead of the geocentric model where the planets and the Sun revolve around the Earth. This was based on a theorem that the orbital periods of the planets are longer as their orbs are farther from the center of motion, which he found not to agree with Ptolemy's model.[92] Johannes Kepler and others challenged the notion that the only function of the eye is perception, and shifted the main focus in optics from the eye to the propagation of light.[91][93] Kepler is best known, however, for improving Copernicus' heliocentric model through the discovery of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. Kepler did not reject Aristotelian metaphysics and described his work as a search for the Harmony of the Spheres.[94] Galileo had made significant contributions to astronomy, physics and engineering. However, he became persecuted after Pope Urban VIII sentenced him for writing about the heliocentric model.[95] The printing press was widely used to publish scholarly arguments, including some that disagreed widely with contemporary ideas of nature.[96] Francis Bacon and René Descartes published philosophical arguments in favor of a new type of non-Aristotelian science. Bacon emphasized the importance of experiment over contemplation, questioned the Aristotelian concepts of formal and final cause, promoted the idea that science should study the laws of nature and the improvement of all human life.[97] Descartes emphasized individual thought and argued that mathematics rather than geometry should be used to study nature.[98] |

ルネサンス 主な項目:科学革命、ルネサンス期の科学  太陽の周りを回る惑星の軌道図 コペルニクス著『天球の回転について』で提唱された地動説の図 光学における新たな発展は、ルネサンスの始まりにおいて重要な役割を果たした。それは、長い間信じられてきた認識に関する形而上学的な概念に疑問を投げか けるとともに、カメラ・オブスクラや望遠鏡といった技術の改良と発展にも貢献した。ルネサンスの始まりに、ロジャー・ベーコン、ヴィテロ、ジョン・ペック ハムは、それぞれアリストテレスの個と普遍の形の知覚、認識、そして最後に観念に至る因果連鎖に基づくスコラ学的な存在論を構築した[84]: Book I。後に遠近法主義として知られるようになった視覚のモデルは、ルネサンスの芸術家たちによって研究され、活用された。この理論は、アリストテレスの4つ の原因のうち、形式、物質、最終の3つだけを使用している[91]。 16世紀、ニコラウス・コペルニクスは、惑星と太陽が地球の周りを回る地動説モデルではなく、惑星が太陽の周りを回る天動説モデルを提唱した。これは、惑 星の公転周期は、その軌道が運動の中心から遠ければ遠いほど長くなるという定理に基づくもので、彼はプトレマイオスのモデルとは一致しないと判断した [92]。 ヨハネス・ケプラーらは、目の唯一の機能は知覚であるという考えに異議を唱え、 目は知覚のみの機能であるという概念に異議を唱え、光学における主眼を目から光の伝播へと移した[91][93]。しかし、ケプラーは、惑星運動のケプ ラー法則の発見を通じてコペルニクスによる地動説モデルを改良したことで最もよく知られている。ケプラーはアリストテレスの形而上学を否定せず、自らの研 究を「天球の調和」の探求であると表現した[94]。ガリレオは天文学、物理学、工学に多大な貢献をした。しかし、教皇ウルバヌス8世が彼の地動説に関す る著作を禁じたため、彼は迫害を受けるようになった[95]。 活版印刷機は、当時の自然観と大きく異なる見解を含む学術的な議論を出版するために広く利用された[96]。フランシス・ベーコンとルネ・デカルトは、ア リストテレスの科学とは異なる新しいタイプの科学を支持する哲学的な議論を発表した。ベーコンは思索よりも実験の重要性を強調し、アリストテレスの形式因 と最終因の概念に疑問を呈し、科学は自然の法則と全人類の生活向上の研究を行うべきだという考えを提唱した[97]。デカルトは個人の思考を重視し、自然 の研究には幾何学よりも数学を用いるべきだと主張した[98]。 |

| Age of Enlightenment Main article: Science in the Age of Enlightenment  Title page of the 1687 first edition of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton At the start of the Age of Enlightenment, Isaac Newton formed the foundation of classical mechanics by his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, greatly influencing future physicists.[99] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz incorporated terms from Aristotelian physics, now used in a new non-teleological way. This implied a shift in the view of objects: objects were now considered as having no innate goals. Leibniz assumed that different types of things all work according to the same general laws of nature, with no special formal or final causes.[100] During this time, the declared purpose and value of science became producing wealth and inventions that would improve human lives, in the materialistic sense of having more food, clothing, and other things. In Bacon's words, "the real and legitimate goal of sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches", and he discouraged scientists from pursuing intangible philosophical or spiritual ideas, which he believed contributed little to human happiness beyond "the fume of subtle, sublime or pleasing [speculation]".[101] Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies,[102] which had largely replaced universities as centers of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were the backbones of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population.[103] Enlightenment philosophers turned to a few of their scientific predecessors – Galileo, Kepler, Boyle, and Newton principally – as the guides to every physical and social field of the day.[104][105] The 18th century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine[106] and physics;[107] the development of biological taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus;[108] a new understanding of magnetism and electricity;[109] and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline.[110] Ideas on human nature, society, and economics evolved during the Enlightenment. Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed A Treatise of Human Nature, which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.[111] Modern sociology largely originated from this movement.[112] In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, which is often considered the first work on modern economics.[113] |

啓蒙時代 メイン記事:啓蒙時代の科学  1687年に出版されたアイザック・ニュートンの『自然哲学の数学的原理』の初版のタイトルページ 啓蒙時代の始まりに、アイザック・ニュートンは『自然哲学の数学的原理』によって古典力学の基礎を築き、後の物理学者たちに多大な影響を与えた[99]。 ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツは、アリストテレスの物理学から用語を取り入れ、現在では目的論的ではない新しい方法で使用されている。これ は、物に対する見方の変化を意味していた。すなわち、物には生まれながらの目標はないと考えられたのである。ライプニッツは、異なる種類の物すべてが、特 別な形式的原因や最終的原因なしに、同じ自然の一般的な法則に従って機能すると仮定していた[100]。 この時代、科学の公言された目的と価値は、物質主義的な意味において、食料や衣類、その他の物資をより多く手に入れることで、人間の生活を改善する富や発 明を生み出すこととなった。ベーコンは、「科学の真の正当な目的は、新しい発明や富を人間に与えることである」と述べており、科学者たちに、哲学や精神的 な観念といった形のないものを追求することを勧めなかった。 啓蒙時代の科学は、科学協会や科学アカデミーによって支配されていた[102]。科学協会や科学アカデミーは、科学的研究と開発の拠点として、大学にとっ て代わる存在となっていた。学会やアカデミーは、科学者の職業が成熟する上で重要な役割を果たした。もう一つの重要な発展は、識字人口の増加に伴う科学の 一般化であった[103]。啓蒙思想家たちは、ガリレオ、ケプラー、ボイル、ニュートンといった科学の先駆者たちに、当時のあらゆる物理的・社会的分野に おける指針を見出していた[104][105]。 18世紀には、医学[106]と物理学[107]の実践において大きな進歩が見られ、カール・フォン・リンネによる生物分類学の発展[108]、磁性と電 気に関する新たな理解[109]、そして学問としての化学の成熟[110]も実現した。医学[106]と物理学[107]の進歩、カール・フォン・リンネ による生物分類学の確立[108]、磁性と電気に関する新たな理解[109]、そして学問としての化学の成熟[110]。啓蒙主義の時代には、人間性、社 会、経済に関する考え方も進化していた。ヒュームやその他のスコットランド啓蒙思想家たちは『人間本性論』を著し、ジェームズ・バーネット、アダム・ ファーガソン、ジョン・ミラ―、ウィリアム・ロバートソンといった作家たちによって、古代や原始文化における人間の行動の科学的研究と、 近代を決定づける力に対する強い認識と結びつけた。[111] 近代社会学は、この運動から大きく派生したものである。[112] 1776年、アダム・スミスは『国富論』を出版した。これは近代経済学の最初の著作としてよく知られている。[113] |

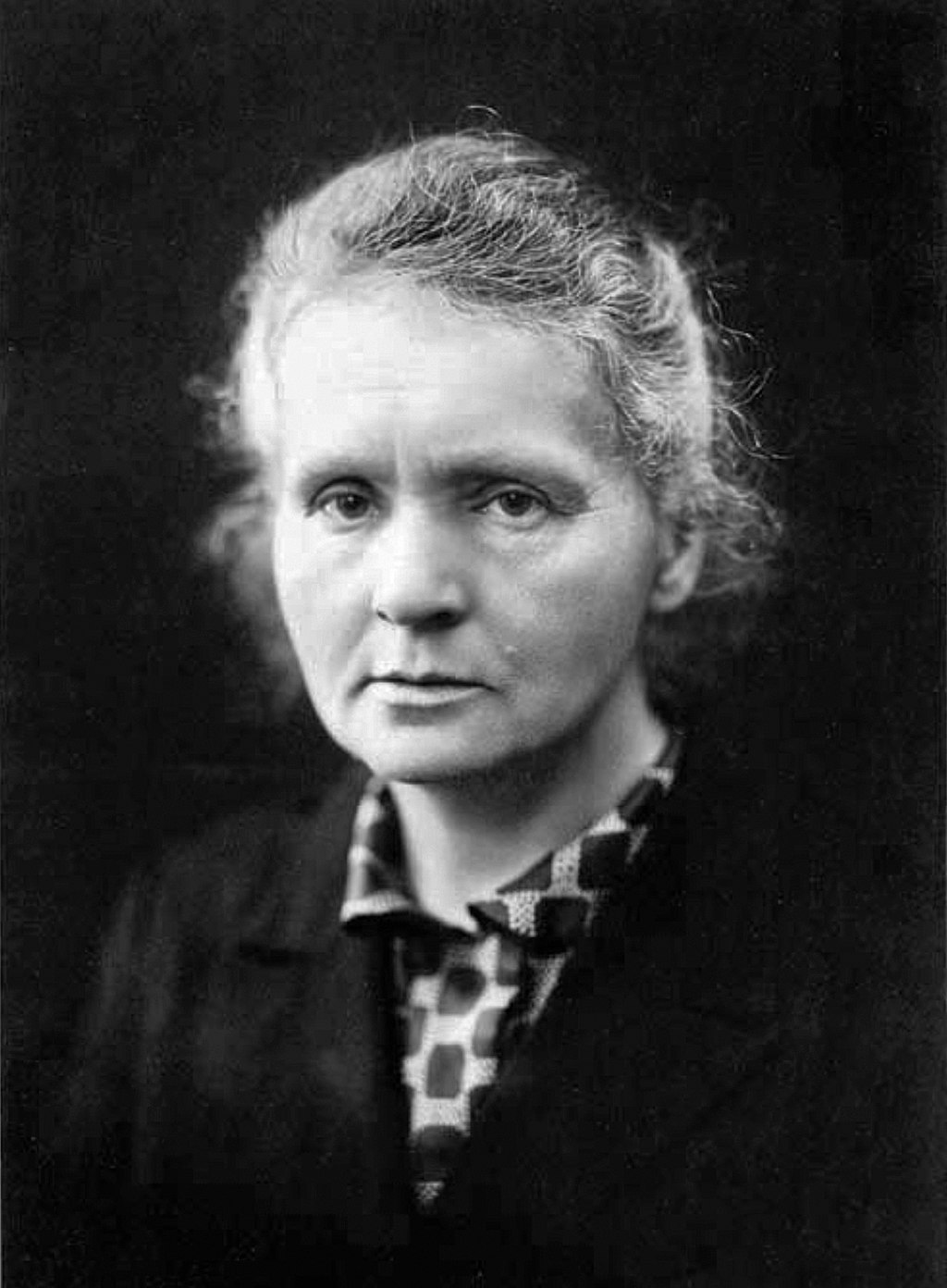

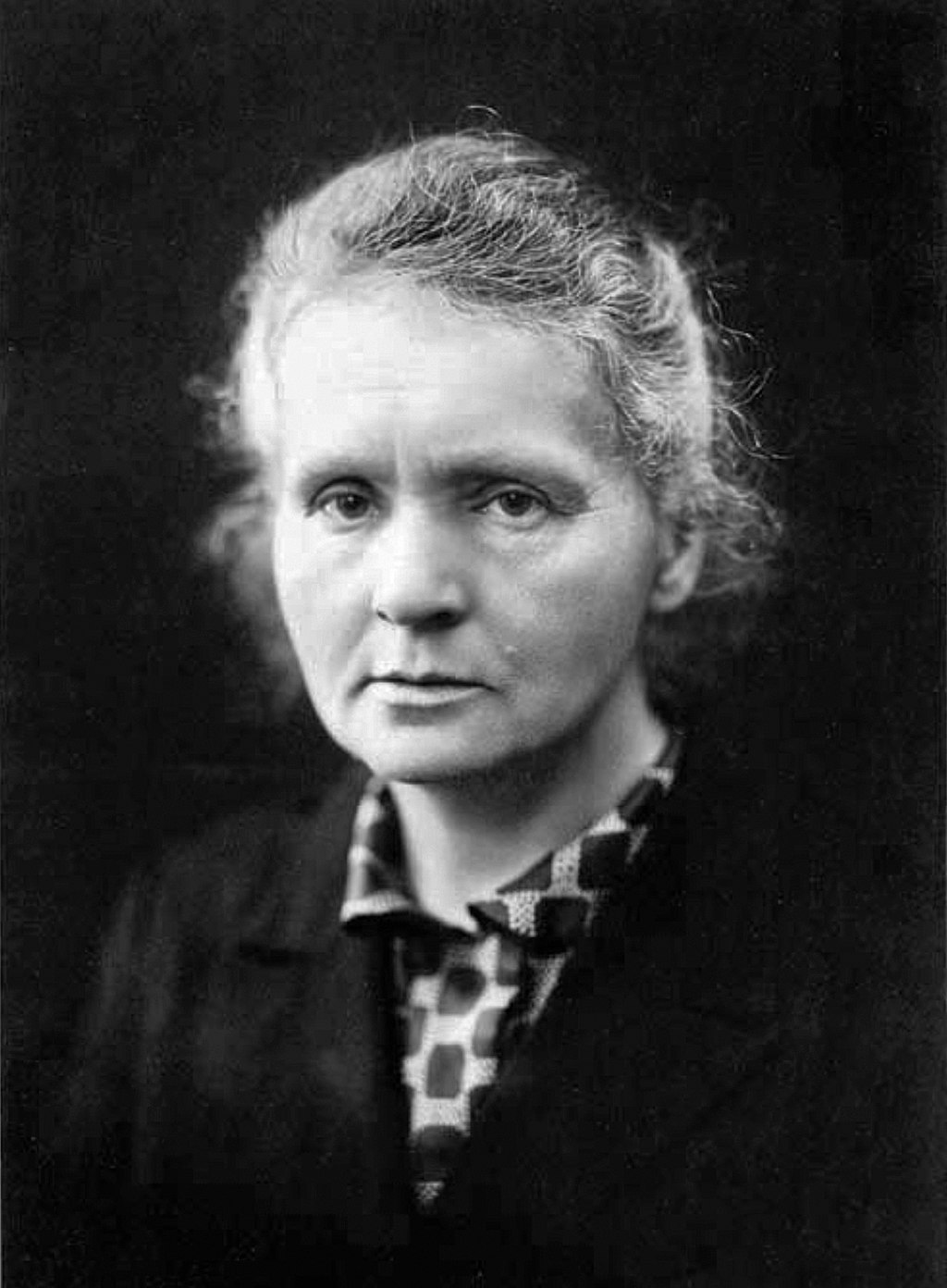

| 19th century Main article: 19th century in science  Sketch of a map with captions The first diagram of an evolutionary tree made by Charles Darwin in 1837 During the nineteenth century, many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences; the frequent use of precision instruments; the emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", and "scientist"; an increased professionalization of those studying nature; scientists gaining cultural authority over many dimensions of society; the industrialization of numerous countries; the thriving of popular science writings; and the emergence of science journals.[114] During the late 19th century, psychology emerged as a separate discipline from philosophy when Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory for psychological research in 1879.[115] During the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, which explained how different plants and animals originated and evolved. Their theory was set out in detail in Darwin's book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859.[116] Separately, Gregor Mendel presented his paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" in 1865,[117] which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics.[118] Early in the 19th century, John Dalton suggested the modern atomic theory, based on Democritus's original idea of indivisible particles called atoms.[119] The laws of conservation of energy, conservation of momentum and conservation of mass suggested a highly stable universe where there could be little loss of resources. However, with the advent of the steam engine and the industrial revolution there was an increased understanding that not all forms of energy have the same energy qualities, the ease of conversion to useful work or to another form of energy.[120] This realization led to the development of the laws of thermodynamics, in which the free energy of the universe is seen as constantly declining: the entropy of a closed universe increases over time.[b] The electromagnetic theory was established in the 19th century by the works of Hans Christian Ørsted, André-Marie Ampère, Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell, Oliver Heaviside, and Heinrich Hertz. The new theory raised questions that could not easily be answered using Newton's framework. The discovery of X-rays inspired the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie in 1896,[123] Marie Curie then became the first person to win two Nobel prizes.[124] In the next year came the discovery of the first subatomic particle, the electron.[125] |

19世紀 メイン記事:19世紀の科学  キャプション付きのスケッチ チャールズ・ダーウィンが1837年に作成した最初の進化樹の図 19世紀には、現代の現代科学の多くの特徴が形作られ始めた。これには、生命科学と物理学の変化、精密機器の頻繁な使用、「生物学者」、「物理学者」、 「科学者」などの用語の登場、自然を研究する人々の専門性の高まり、科学者が社会のさまざまな側面で文化的権威を獲得すること、多数の国の工業化、大衆向 けの科学論文の隆盛、科学ジャーナルの登場などが含まれる[114]。19世紀後半、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントが1879年に心理学研究のための最初の研究室 を設立したことにより、心理学は哲学から独立した学問分野として登場した[115]。 19世紀半ば、チャールズ・ダーウィンとアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは、1858年にそれぞれ独立して自然淘汰による進化論を提唱し、さまざまな植 物や動物がどのように誕生し進化したかを説明した。彼らの理論は、1859年に出版されたダーウィンの著書『種の起源』で詳しく述べられた[116]。一 方、グレゴール・メンデルは1865年に論文「植物の交配実験」を発表し[117]、生物の遺伝の原理を概説し、現代遺伝学の基礎となった 。 19世紀初頭、ジョン・ダルトンは、デモクリトスの「原子」という分割不可能な粒子の概念に基づいて、現代の原子説を提唱した[119]。エネルギー保存 則、運動量保存則、質量保存則は、資源の損失がほとんどない非常に安定した宇宙を示唆していた。しかし、蒸気機関と産業革命の登場により、すべてのエネル ギー形態が同じエネルギー特性、有用な仕事や別のエネルギー形態への変換の容易さを持っているわけではないという理解が深まった[120]。この認識は熱 力学の法則の発展につながり、宇宙の自由エネルギーは 閉じた宇宙のエントロピーは時間とともに増加する[b]。 電磁気学は、19世紀にハンス・クリスチャン・エルステッド、アンドレ=マリ・アンペール、マイケル・ファラデー、ジェームズ・クラーク・マクスウェル、 オリバー・ヘビサイド、ハインリッヒ・ヘルツの研究によって確立された。この新しい理論は、ニュートンの枠組みでは簡単に答えられない疑問を投げかけた。 X線の発見は、1896年にアンリ・ベクレルとマリー・キュリーによる放射能の発見につながった[123]。マリー・キュリーは、その後、2つのノーベル 賞を受賞した最初の人物となった[124]。翌年には、最初の素粒子である電子が発見された[125]。 |

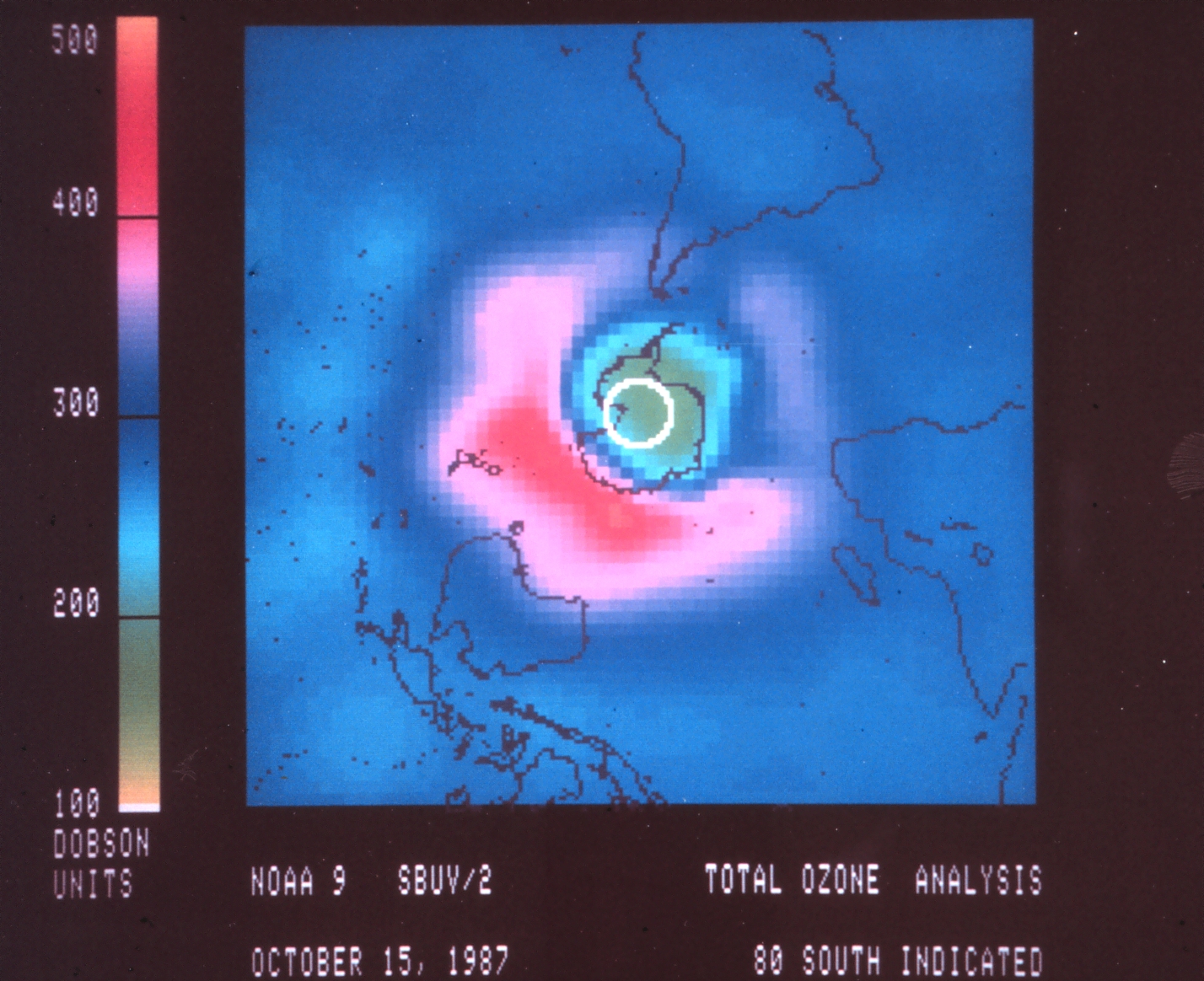

| 20th century Main article: 20th century in science  Graph showing lower ozone concentration at the South Pole A computer graph of the ozone hole made in 1987 using data from a space telescope In the first half of the century, the development of antibiotics and artificial fertilizers improved human living standards globally.[126][127] Harmful environmental issues such as ozone depletion, ocean acidification, eutrophication and climate change came to the public's attention and caused the onset of environmental studies.[128] During this period, scientific experimentation became increasingly larger in scale and funding.[129] The extensive technological innovation stimulated by World War I, World War II, and the Cold War led to competitions between global powers, such as the Space Race and nuclear arms race.[130][131] Substantial international collaborations were also made, despite armed conflicts.[132] In the late 20th century, active recruitment of women and elimination of sex discrimination greatly increased the number of women scientists, but large gender disparities remained in some fields.[133] The discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964[134] led to a rejection of the steady-state model of the universe in favor of the Big Bang theory of Georges Lemaître.[135] The century saw fundamental changes within science disciplines. Evolution became a unified theory in the early 20th-century when the modern synthesis reconciled Darwinian evolution with classical genetics.[136] Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum mechanics complement classical mechanics to describe physics in extreme length, time and gravity.[137][138] Widespread use of integrated circuits in the last quarter of the 20th century combined with communications satellites led to a revolution in information technology and the rise of the global internet and mobile computing, including smartphones. The need for mass systematization of long, intertwined causal chains and large amounts of data led to the rise of the fields of systems theory and computer-assisted scientific modeling.[139] |

20世紀 メイン記事: 20世紀の科学  南極におけるオゾン濃度の低下を示すグラフ 1987年に宇宙望遠鏡のデータを用いて作成されたオゾンホールのコンピュータグラフ 世紀の前半、抗生物質や化学肥料の開発により、世界中で人間の生活水準が向上した[126][127]。オゾン層破壊、海洋酸性化、富栄養化、気候変動な どの有害な環境問題が人々の関心を集め、 環境学の研究が始まった。 この時代、科学実験はますます大規模化し、資金も潤沢になった。第一次世界大戦、第二次世界大戦、冷戦によって引き起こされた広範囲にわたる技術革新は、 宇宙開発競争や核軍拡競争といった世界大国の競争につながった。20世紀後半には、女性の積極的な採用と性差別撤廃により女性科学者の数が大幅に増加した が、一部の分野では男女間の格差が依然として大きかった[133]。1964年の宇宙マイクロ波背景放射の発見[134]により、宇宙の定常状態モデルは 否定され、ジョルジュ・ルメートルによるビッグバン理論が支持されるようになった[135]。 この世紀には、科学の各分野において根本的な変化が見られた。進化論は、20世紀初頭にダーウィンの進化論と古典遺伝学を統合した現代総合説によって統一 理論となった[136]。アルバート・アインシュタインの相対性理論と量子力学の進展は、古典力学を補完し、極限的な長さ、時間、重力を伴う物理現象を説 明した[137][138]。時間、重力について記述するようになった[137][138]。20世紀最後の四半世紀に集積回路が広く普及し、通信衛星と 組み合わせることで、情報技術に革命をもたらし、グローバルなインターネットやスマートフォンを含むモバイルコンピューティングの台頭につながった。長く て絡み合った因果関係や大量のデータを体系化する必要性から、システム理論やコンピュータ支援科学モデリングの分野が台頭した[139]。 |

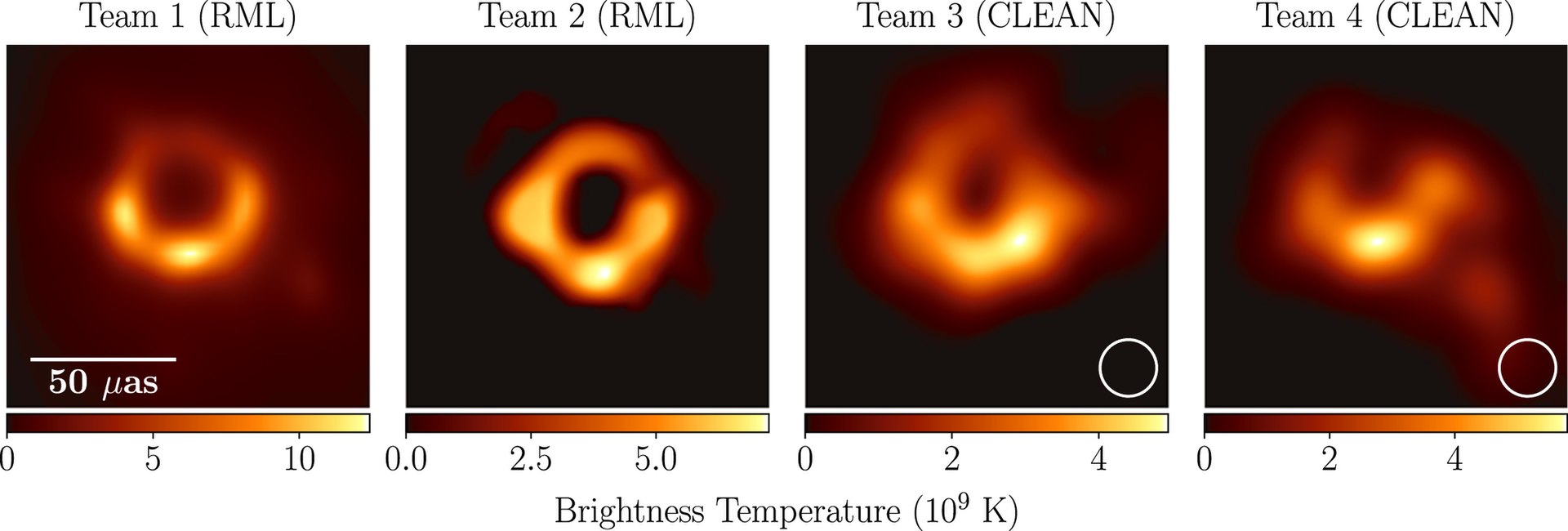

| 21st century Main article: 21st century § Science and technology  Four predicted image of M87* black hole made by separate teams in the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration. The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 by identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome.[140] The first induced pluripotent human stem cells were made in 2006, allowing adult cells to be transformed into stem cells and turn to any cell type found in the body.[141] With the affirmation of the Higgs boson discovery in 2013, the last particle predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics was found.[142] In 2015, gravitational waves, predicted by general relativity a century before, were first observed.[143][144] In 2019, the international collaboration Event Horizon Telescope presented the first direct image of a black hole's accretion disk.[145] |

21世紀 メイン記事:21世紀 § 科学と技術  イベントホライゾン望遠鏡のコラボレーションに参加する別々のチームが作成した、M87*ブラックホールの4つの予測画像。 ヒトゲノムプロジェクトは、2003年にヒトゲノムの全遺伝子を特定し、その地図を作成することで完了した[140]。2006年には、初めて人工多能性 幹細胞が作成され、成体の細胞を幹細胞に変化させ、体内のあらゆる種類の細胞に変化させることが可能になった[141]。201 3、素粒子物理学における標準模型で予測されていた最後の粒子が発見された[142]。2015年には、100年前に一般相対性理論によって予測されてい た重力波がはじめて観測された[143][144]。2019年には、国際協力によるイベントホライゾン望遠鏡が、ブラックホールの降着円盤の直接画像を 初めて発表した[145]。 |

| Criticism of science List of scientific occupations List of years in science Science (Wikiversity) |

科学への批判 科学関連の職業一覧 科学関連の年表 科学(ウィキバーシティ) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science |

|

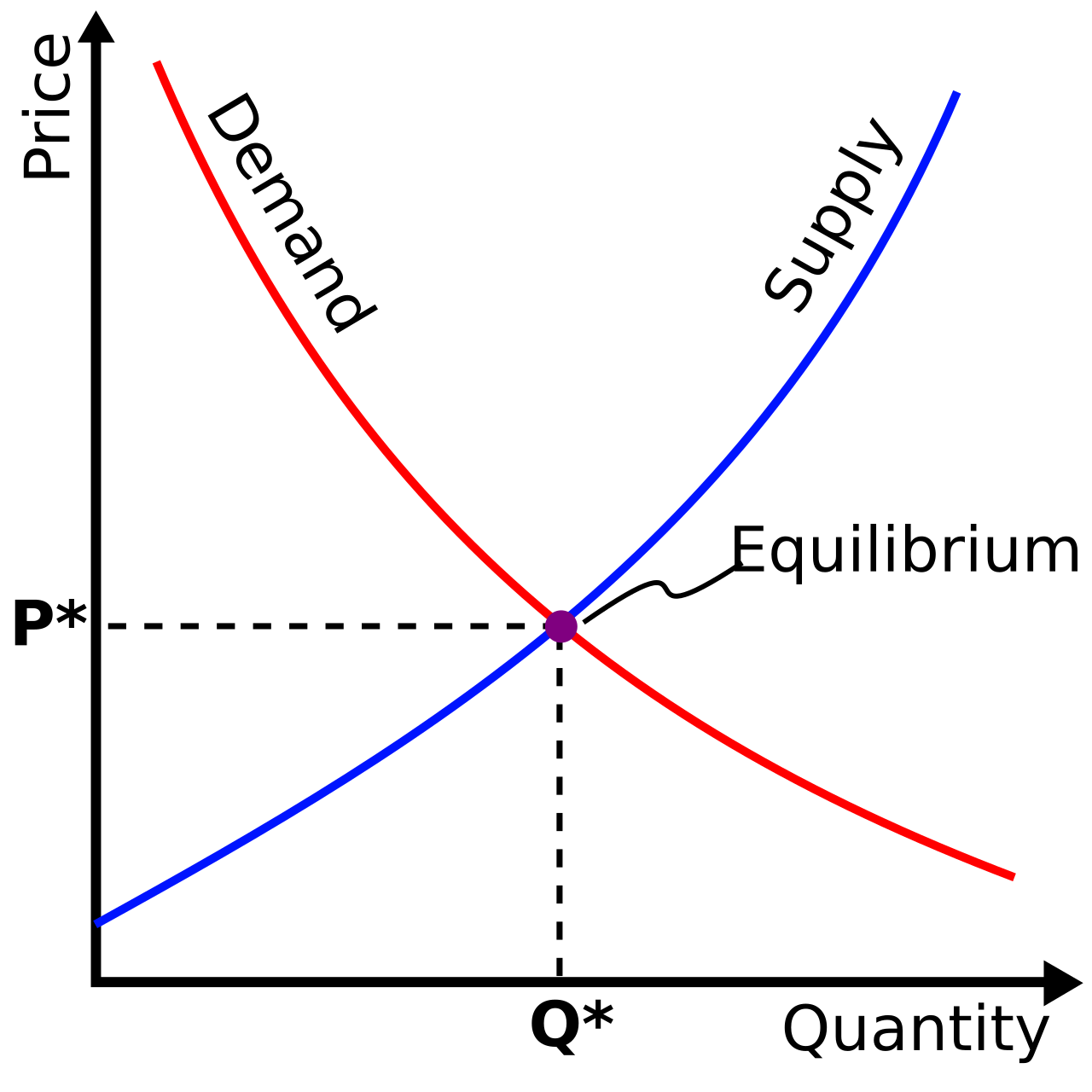

| Branches Main article: Branches of science Modern science is commonly divided into three major branches: natural science, social science, and formal science.[3] Each of these branches comprises various specialised yet overlapping scientific disciplines that often possess their own nomenclature and expertise.[146] Both natural and social sciences are empirical sciences,[147] as their knowledge is based on empirical observations and is capable of being tested for its validity by other researchers working under the same conditions.[148] Natural science Natural science is the study of the physical world. It can be divided into two main branches: life science and physical science. These two branches may be further divided into more specialised disciplines. For example, physical science can be subdivided into physics, chemistry, astronomy, and earth science. Modern natural science is the successor to the natural philosophy that began in Ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches that were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science.[149] Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and other biotic beings.[150] Today, "natural history" suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.[151] Social science  Two curve crossing over at a point, forming a X shape Supply and demand curve in economics, crossing over at the optimal equilibrium Social science is the study of human behaviour and the functioning of societies.[4][5] It has many disciplines that include, but are not limited to anthropology, economics, history, human geography, political science, psychology, and sociology.[4] In the social sciences, there are many competing theoretical perspectives, many of which are extended through competing research programs such as the functionalists, conflict theorists, and interactionists in sociology.[4] Due to the limitations of conducting controlled experiments involving large groups of individuals or complex situations, social scientists may adopt other research methods such as the historical method, case studies, and cross-cultural studies. Moreover, if quantitative information is available, social scientists may rely on statistical approaches to better understand social relationships and processes.[4] Formal science Formal science is an area of study that generates knowledge using formal systems.[152][6][7] A formal system is an abstract structure used for inferring theorems from axioms according to a set of rules.[153] It includes mathematics,[154][155] systems theory, and theoretical computer science. The formal sciences share similarities with the other two branches by relying on objective, careful, and systematic study of an area of knowledge. They are, however, different from the empirical sciences as they rely exclusively on deductive reasoning, without the need for empirical evidence, to verify their abstract concepts.[11][156][148] The formal sciences are therefore a priori disciplines and because of this, there is disagreement on whether they constitute a science.[8][157] Nevertheless, the formal sciences play an important role in the empirical sciences. Calculus, for example, was initially invented to understand motion in physics.[158] Natural and social sciences that rely heavily on mathematical applications include mathematical physics,[159] chemistry,[160] biology,[161] finance,[162] and economics.[163] Applied science Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge to attain practical goals and includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine.[164][14] Engineering is the use of scientific principles to invent, design and build machines, structures and technologies.[165] Science may contribute to the development of new technologies.[166] Medicine is the practice of caring for patients by maintaining and restoring health through the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of injury or disease.[167][168] The applied sciences are often contrasted with the basic sciences, which are focused on advancing scientific theories and laws that explain and predict events in the natural world.[169][170] Computational science applies computing power to simulate real-world situations, enabling a better understanding of scientific problems than formal mathematics alone can achieve. The use of machine learning and artificial intelligence is becoming a central feature of computational contributions to science, for example in agent-based computational economics, random forests, topic modeling and various forms of prediction. However, machines alone rarely advance knowledge as they require human guidance and capacity to reason; and they can introduce bias against certain social groups or sometimes underperform against humans.[171][172] Interdisciplinary science Interdisciplinary science involves the combination of two or more disciplines into one,[173] such as bioinformatics, a combination of biology and computer science[174] or cognitive sciences. The concept has existed since the ancient Greek period and it became popular again in the 20th century.[175] |

分科 詳細は「科学の分野」を参照 現代科学は一般的に、自然科学、社会科学、形式科学という3つの主要分野に分けられる。[3] これらの各分野は、それぞれ独自の専門用語や専門知識を持つ、さまざまな専門的でありながらも重複する科学的分野から構成されている。[146] 自然科学と社会科学はどちらも経験科学であり、[147] その知識は経験的観察に基づいており、同じ条件下で研究を行う他の研究者によってその妥当性を検証することが可能である。[148] 自然科学 自然科学は物理的世界の研究である。 生命科学と物理科学の2つの主要分野に分けることができる。 これらの2つの分野はさらに専門分野に細分化される。 例えば、物理科学は物理学、化学、天文学、地球科学に細分化される。 現代の自然科学は古代ギリシャで始まった自然哲学の継承である。ガリレオ、デカルト、ベーコン、ニュートンらは、より数学的でより実験的なアプローチを系 統的に用いることの利点について議論した。それでも、自然科学においては、見落とされがちな哲学的視点、推測、前提条件が依然として必要である。 [149] 体系的なデータ収集は、16世紀に植物、動物、鉱物、その他の生物の記述と分類によって登場した自然史学に取って代わった。[150] 今日、「自然史」という用語は一般読者向けの観察記述を意味する。[151] 社会科学  2つの曲線が1点で交わり、X字形を形成している 経済学における需要曲線と供給曲線が最適均衡点で交差している 社会科学は、人間の行動と社会の機能に関する学問である。[4][5] 人類学、経済学、歴史学、人文地理学、政治学、心理学、社会学など、多くの分野を含むが、これらに限定されない。[4] 社会科学では、多くの競合する理論的視点があり、その多くは 社会学における機能主義者、葛藤理論家、相互作用主義者などの競合する研究プログラムを通じて拡張されているものも多い。[4] 多数の個人や複雑な状況を含む管理された実験を行うことの限界により、社会科学者は歴史的方法、事例研究、異文化研究などの他の研究方法を採用することが ある。さらに、定量的な情報が利用可能な場合、社会科学者は社会関係や過程をよりよく理解するために統計的アプローチに頼ることがある。[4] 形式科学 形式科学は、形式システムを使用して知識を生み出す研究分野である。[152][6][7] 形式システムとは、一連の規則に従って公理から定理を推論するために使用される抽象的な構造である。[153] 形式科学には、数学、システム理論、理論計算機科学が含まれる。形式科学は、客観的で慎重かつ系統的な知識分野の研究に依存するという点で、他の2つの分 野と類似している。しかし、経験科学とは異なり、抽象概念の検証に経験的証拠を必要とせず、演繹的推論のみに依存している。[11][156][148] したがって、形式科学は先験的な学問であり、このため、形式科学が科学を構成するかどうかについては意見が分かれている。[8][157] とはいえ、形式科学は経験科学において重要な役割を果たしている。例えば、微積分学は当初、物理学における運動を理解するために考案されたものである。 [158] 数学的応用を多用する自然科学や社会科学には、数理物理学[159]、化学[160]、生物学[161]、金融学[162]、経済学[163]などがあ る。 応用科学 応用科学は、科学的手法と知識を実用的な目標の達成に利用するものであり、工学や医学など広範な分野を含む。[164][14] 工学は、科学原理を利用して機械、構造物、技術を発明、設計、構築することである。[165] 科学は、新技術の開発に貢献する可能性がある。[166] 医学は 患者の治療は、傷害や疾病の予防、診断、治療を通じて健康を維持し回復させることである。[167][168] 応用科学は、しばしば基礎科学と対比される。基礎科学は、自然界の事象を説明し予測する科学的理論や法則の進歩に焦点を当てている。[169][170] 計算科学は、現実の状況をシミュレートするためにコンピューティング能力を応用し、形式的な数学だけでは達成できない科学的な問題のより深い理解を可能に する。機械学習や人工知能の利用は、例えばエージェントベースの計算経済学、ランダムフォレスト、トピックモデリング、およびさまざまな予測形態など、科 学への計算機による貢献の中心的な機能になりつつある。しかし、機械だけでは、人間の指導や推論能力が必要であるため、知識の進歩はほとんど見られない。 また、特定の社会集団に対する偏見を生み出す可能性や、人間よりも性能が劣る場合もある。[171][172] 学際科学 学際科学は、2つ以上の学問分野を1つに統合するものであり、例えば、バイオインフォマティクスは生物学とコンピュータサイエンスの融合である。この概念 は古代ギリシャ時代から存在しており、20世紀に再び人気が高まった。 |

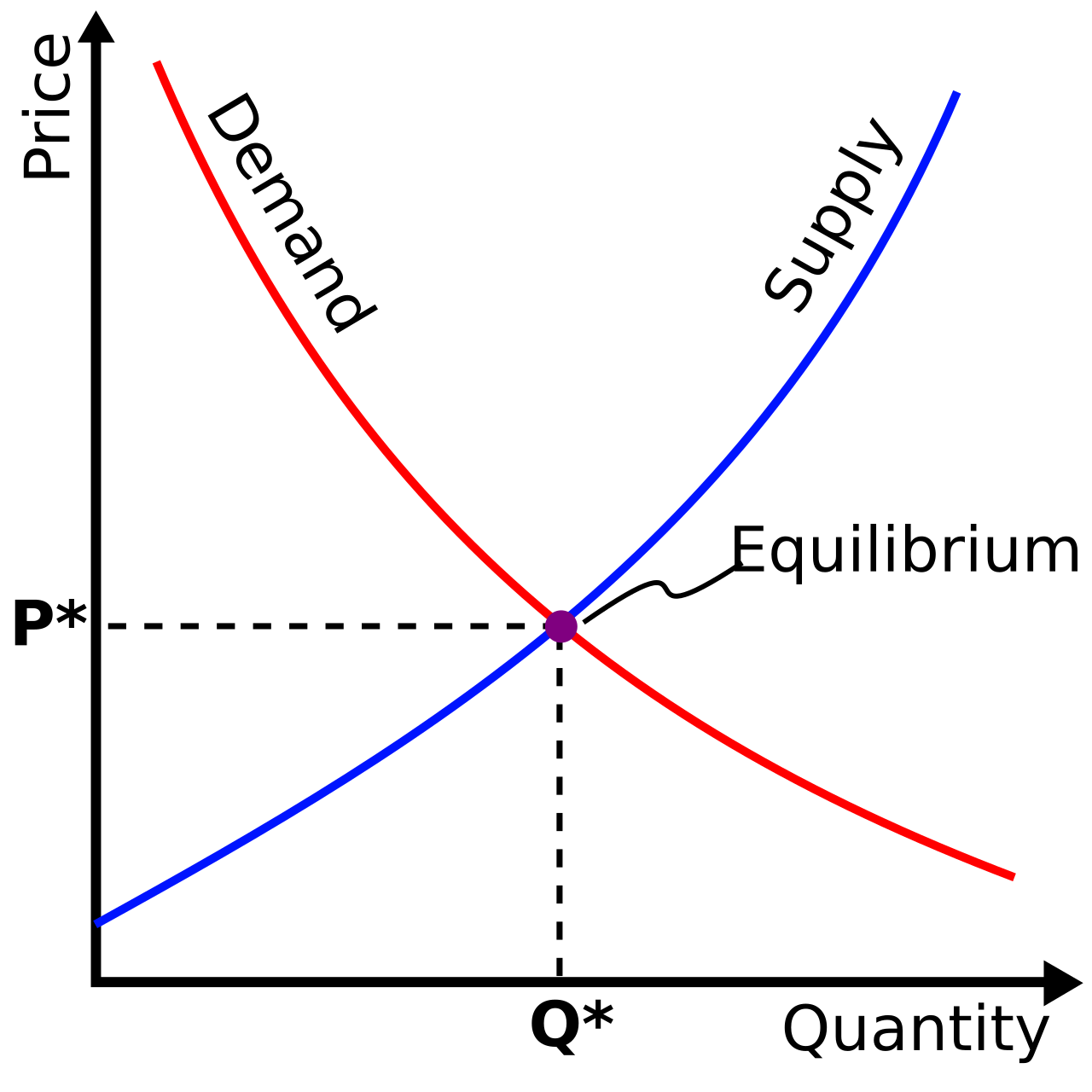

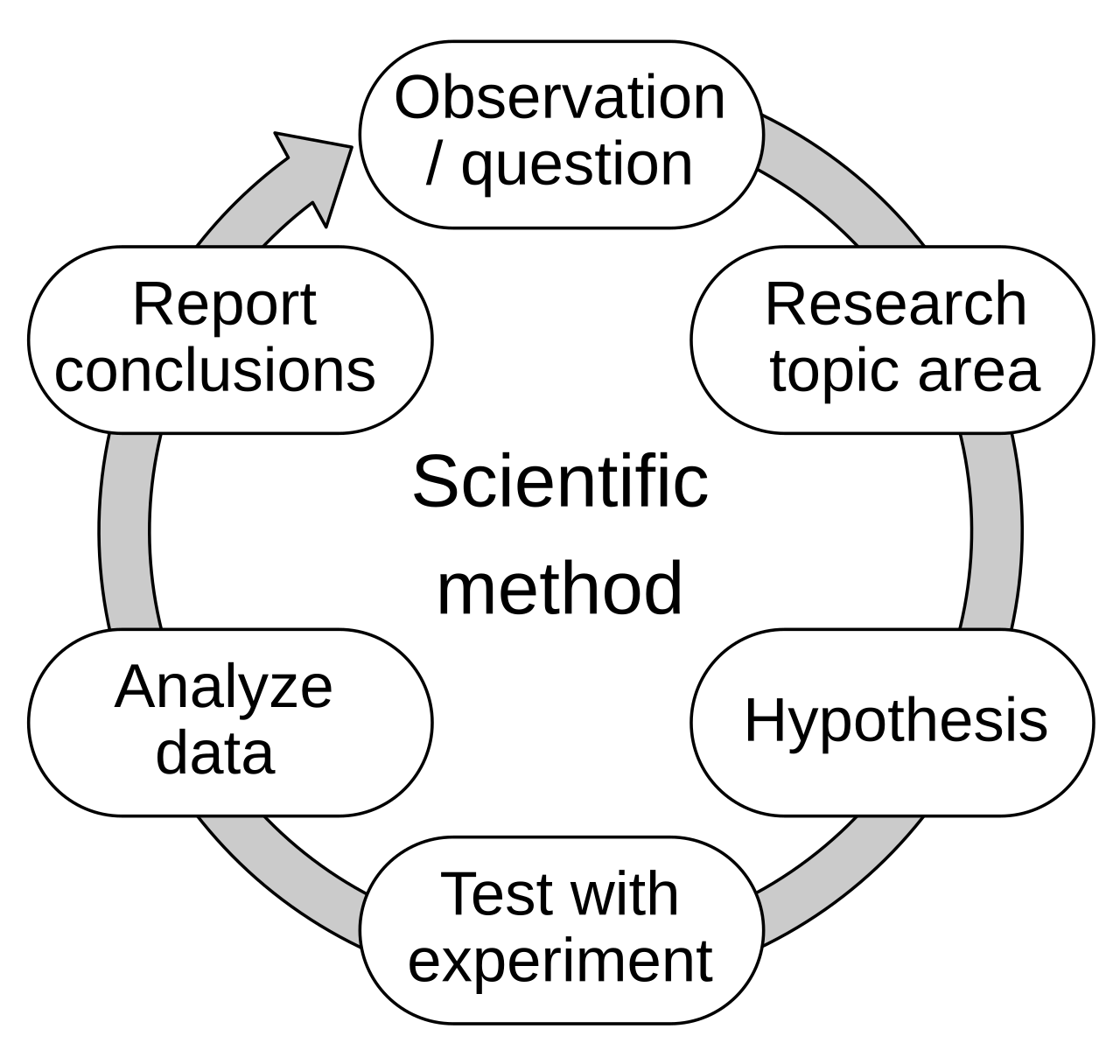

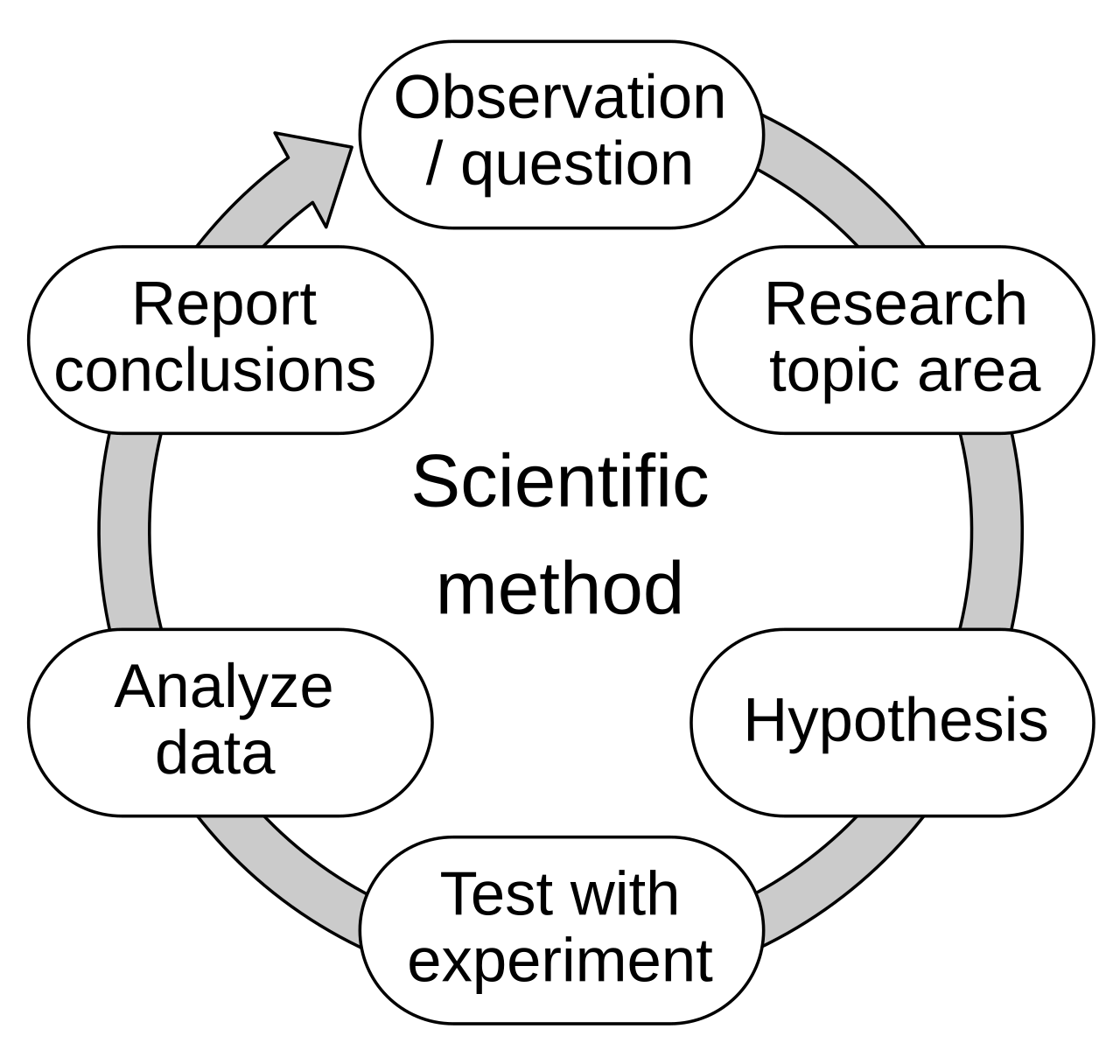

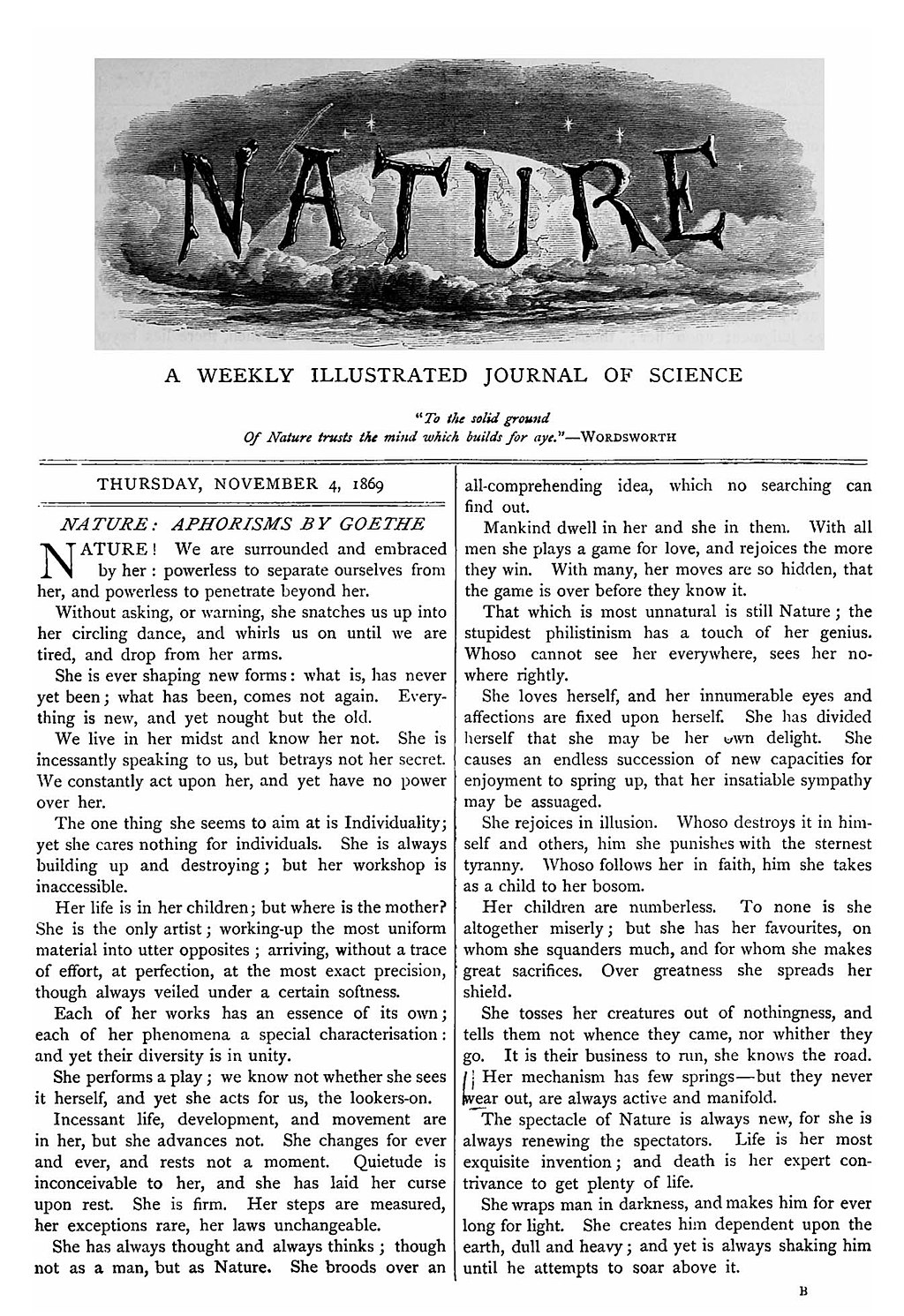

| Scientific research Scientific research can be labelled as either basic or applied research. Basic research is the search for knowledge and applied research is the search for solutions to practical problems using this knowledge. Most understanding comes from basic research, though sometimes applied research targets specific practical problems. This leads to technological advances that were not previously imaginable.[176] Scientific method  6 steps of the scientific method in a loop A diagram variant of scientific method represented as an ongoing process Scientific research involves using the scientific method, which seeks to objectively explain the events of nature in a reproducible way.[177] Scientists usually take for granted a set of basic assumptions that are needed to justify the scientific method: there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers; this objective reality is governed by natural laws; these laws were discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation.[2] Mathematics is essential in the formation of hypotheses, theories, and laws, because it is used extensively in quantitative modelling, observing, and collecting measurements.[178] Statistics is used to summarise and analyse data, which allows scientists to assess the reliability of experimental results.[179] In the scientific method, an explanatory thought experiment or hypothesis is put forward as an explanation using parsimony principles and is expected to seek consilience – fitting with other accepted facts related to an observation or scientific question.[180] This tentative explanation is used to make falsifiable predictions, which are typically posted before being tested by experimentation. Disproof of a prediction is evidence of progress.[177]: 4–5 [181] Experimentation is especially important in science to help establish causal relationships to avoid the correlation fallacy, though in some sciences such as astronomy or geology, a predicted observation might be more appropriate.[182] When a hypothesis proves unsatisfactory, it is modified or discarded.[183] If the hypothesis survives testing, it may become adopted into the framework of a scientific theory, a validly reasoned, self-consistent model or framework for describing the behaviour of certain natural events. A theory typically describes the behaviour of much broader sets of observations than a hypothesis; commonly, a large number of hypotheses can be logically bound together by a single theory. Thus, a theory is a hypothesis explaining various other hypotheses. In that vein, theories are formulated according to most of the same scientific principles as hypotheses. Scientists may generate a model, an attempt to describe or depict an observation in terms of a logical, physical or mathematical representation, and to generate new hypotheses that can be tested by experimentation.[184] While performing experiments to test hypotheses, scientists may have a preference for one outcome over another.[185][186] Eliminating the bias can be achieved through transparency, careful experimental design, and a thorough peer review process of the experimental results and conclusions.[187][188] After the results of an experiment are announced or published, it is normal practice for independent researchers to double-check how the research was performed, and to follow up by performing similar experiments to determine how dependable the results might be.[189] Taken in its entirety, the scientific method allows for highly creative problem solving while minimising the effects of subjective and confirmation bias.[190] Intersubjective verifiability, the ability to reach a consensus and reproduce results, is fundamental to the creation of all scientific knowledge.[191] Scientific literature Main articles: Scientific literature and Lists of important publications in science  Decorated "NATURE" as title, with scientific text below Cover of the first issue of Nature, 4 November 1869 Scientific research is published in a range of literature.[192] Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, Journal des sçavans followed by Philosophical Transactions, began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.[193] Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a scientific paper. Science has become so pervasive in modern societies that it is considered necessary to communicate the achievements, news, and ambitions of scientists to a wider population.[194] Challenges The replication crisis is an ongoing methodological crisis that affects parts of the social and life sciences. In subsequent investigations, the results of many scientific studies have been proven to be unrepeatable.[195] The crisis has long-standing roots; the phrase was coined in the early 2010s[196] as part of a growing awareness of the problem. The replication crisis represents an important body of research in metascience, which aims to improve the quality of all scientific research while reducing waste.[197] An area of study or speculation that masquerades as science in an attempt to claim legitimacy that it would not otherwise be able to achieve is sometimes referred to as pseudoscience, fringe science, or junk science.[198][199] Physicist Richard Feynman coined the term "cargo cult science" for cases in which researchers believe, and at a glance, look like they are doing science but lack the honesty to allow their results to be rigorously evaluated.[200] Various types of commercial advertising, ranging from hype to fraud, may fall into these categories. Science has been described as "the most important tool" for separating valid claims from invalid ones.[201] There can also be an element of political or ideological bias on all sides of scientific debates. Sometimes, research may be characterised as "bad science," research that may be well-intended but is incorrect, obsolete, incomplete, or over-simplified expositions of scientific ideas. The term "scientific misconduct" refers to situations such as where researchers have intentionally misrepresented their published data or have purposely given credit for a discovery to the wrong person.[202] |

科学的研究 科学的研究は、基礎研究または応用研究のいずれかに分類される。基礎研究は知識の探求であり、応用研究は、その知識を用いて実際的な問題の解決策を模索す ることである。基礎研究から得られる理解が最も多いが、応用研究が特定の実用的な問題を対象とすることもある。これにより、以前には想像もできなかった技 術的進歩がもたらされる。[176] 科学的手法  科学的手法の6つのステップ 進行中のプロセスとして表された科学的手法の図 科学研究では、自然界の出来事を再現可能な形で客観的に説明しようとする科学的手法が用いられる。[177] 科学者は通常、科学的手法を正当化するために必要な一連の基本的な前提を当然のこととして受け入れている。すなわち、すべての理性的な観察者が共有する客 観的な現実が存在し、この客観的な現実は自然法則によって支配されており、これらの法則は 系統的な観察と実験によって発見された。[2] 数学は、定量的なモデリング、観察、測定値の収集に広く用いられるため、仮説、理論、法則の形成に不可欠である。[178] 統計学はデータの要約と分析に用いられ、科学者は実験結果の信頼性を評価することができる。[179] 科学的手法では、説明的な思考実験や仮説が、簡素性の原則を用いて説明として提示され、観察や科学的な疑問に関連する他の既知の事実との一致 (consilience)が求められる。予言の反証は進歩の証拠である。[177]:4–5[181] 相関関係の誤りを避けるために因果関係を確立する上で、科学における実験は特に重要であるが、天文学や地質学などの科学では、予測された観察結果の方がよ り適切である場合もある。[182] 仮説が不十分であることが証明された場合、修正または破棄される。[183] 仮説が検証に耐えれば、特定の自然現象の挙動を説明する、妥当な理由付けがなされた自己矛盾のないモデルまたは枠組みとして、科学理論の枠組みに採用され る可能性がある。理論は通常、仮説よりもはるかに広範な観測の挙動を説明する。一般的に、多数の仮説は1つの理論によって論理的に結び付けられる。した がって、理論とは、他のさまざまな仮説を説明する仮説である。その意味で、理論は仮説と同じ科学原則のほとんどに従って定式化される。科学者は、観察を論 理的、物理的、数学的な表現で説明または描写し、実験で検証できる新たな仮説を生成する試みとして、モデルを生成することがある。 仮説を検証するための実験を行う際、科学者はある結果を他の結果よりも好むことがある。[185][186] バイアスを排除するには、透明性、慎重な実験計画、実験結果と結論の徹底的なピアレビュープロセスを通じて達成することができる。[187][188] 実験結果が発表または公表された後、独立した研究者が研究がどのように実施されたかを再確認し、 研究がどのように実施されたかを再確認し、類似の実験を行ってその結果の信頼性を判断することが一般的である。[189] 科学的手法全体を考慮すると、主観的バイアスや確証バイアスの影響を最小限に抑えつつ、非常に創造的な問題解決を可能にする。[190] すべての科学的知識の創造の基礎となるのは、主観を超えた検証可能性、すなわち、合意に達し、結果を再現する能力である。[191] 科学文献 詳細は「科学文献」および「科学における重要な出版物の一覧」を参照  タイトルとして装飾された「NATURE」誌、その下に科学的なテキスト 1869年11月4日発行の『Nature』誌の創刊号の表紙 科学研究は、さまざまな文献で発表されている。科学雑誌は、大学やその他のさまざまな研究機関で実施された研究結果を伝達し、記録するものであり、科学の 記録として保存される。最初の科学雑誌は『Journal des sçavans』で、続いて『Philosophical Transactions』が1665年に創刊された。それ以来、現在も刊行中の定期刊行物の総数は着実に増加している。1981年には、刊行中の科学・ 技術雑誌の数は11,500誌と推定された。 ほとんどの科学雑誌は単一の科学分野をカバーし、その分野の研究を掲載する。研究は通常、科学論文の形式で表現される。科学は現代社会に広く浸透している ため、科学者の業績、ニュース、野望をより幅広い人々に伝えることが必要であると考えられている。[194] 課題 再現の危機は、現在進行中の方法論上の危機であり、社会科学や生命科学の一部に影響を与えている。その後の調査では、多くの科学的研究の結果が再現できな いことが証明されている。[195] この危機は根が深く、2010年代初頭にこの問題に対する認識が高まる中で、この言葉が作られた。[196] 再現の危機は、メタ科学における重要な研究分野であり、科学的研究の質を向上させながら無駄を削減することを目的としている。[197] 科学を装い、そうでなければ達成できないはずの正当性を主張しようとする研究や推測の分野は、疑似科学、辺境科学、ジャンクサイエンスなどと呼ばれること がある。[198][199] 物理学者のリチャード・ファインマンは、 「カーゴ・カルト科学」という用語を考案した。これは、研究者が科学を行っているように見せかけているが、厳密な評価に耐えるだけの誠実さを欠いている場 合を指す。[200] 誇張から詐欺まで、さまざまな商業広告がこの範疇に含まれる可能性がある。科学は、有効な主張と無効な主張を区別するための「最も重要なツール」であると 表現されている。[201] また、科学的議論のあらゆる側面において、政治的またはイデオロギー的な偏見が入り込む余地がある。研究が「質の悪い科学」と特徴づけられることもある。 これは、善意からではあるが、不正確、時代遅れ、不完全、または科学的アイデアの単純化が行き過ぎている研究である。「科学的不正行為」という用語は、研 究者が意図的に公表データを偽ったり、発見の功績を誤った人物に与えたりするような状況を指す。[202] |

Philosophy of science Depiction of epicycles, where a planet orbit is going around in a bigger orbit For Kuhn, the addition of epicycles in Ptolemaic astronomy was "normal science" within a paradigm, whereas the Copernican Revolution was a paradigm shift There are different schools of thought in the philosophy of science. The most popular position is empiricism, which holds that knowledge is created by a process involving observation; scientific theories generalise observations.[203] Empiricism generally encompasses inductivism, a position that explains how general theories can be made from the finite amount of empirical evidence available. Many versions of empiricism exist, with the predominant ones being Bayesianism and the hypothetico-deductive method.[204][203] Empiricism has stood in contrast to rationalism, the position originally associated with Descartes, which holds that knowledge is created by the human intellect, not by observation.[205] Critical rationalism is a contrasting 20th-century approach to science, first defined by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper. Popper rejected the way that empiricism describes the connection between theory and observation. He claimed that theories are not generated by observation, but that observation is made in the light of theories, and that the only way theory A can be affected by observation is after theory A were to conflict with observation, but theory B were to survive the observation.[206] Popper proposed replacing verifiability with falsifiability as the landmark of scientific theories, replacing induction with falsification as the empirical method.[206] Popper further claimed that there is actually only one universal method, not specific to science: the negative method of criticism, trial and error,[207] covering all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, and art.[208] Another approach, instrumentalism, emphasises the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena. It views scientific theories as black boxes, with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be things that should be ignored.[209] Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.[210] Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a paradigm, a logically consistent "portrait" of the world that is consistent with observations made from its framing. He characterised normal science as the process of observation and "puzzle solving," which takes place within a paradigm, whereas revolutionary science occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift.[211] Each paradigm has its own distinct questions, aims, and interpretations. The choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. A paradigm shift occurs when a significant number of observational anomalies arise in the old paradigm and a new paradigm makes sense of them. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.[212] Finally, another approach often cited in debates of scientific scepticism against controversial movements like "creation science" is methodological naturalism. Naturalists maintain that a difference should be made between natural and supernatural, and science should be restricted to natural explanations.[213] Methodological naturalism maintains that science requires strict adherence to empirical study and independent verification.[214] |

科学哲学 惑星の軌道がより大きな軌道を回るエピサイクルの図 クーンにとって、プトレマイオス天文学におけるエピサイクルの追加は、パラダイム内の「正常な科学」であったが、コペルニクス革命はパラダイムシフトで あった 科学哲学にはさまざまな学派がある。最も一般的な立場は経験論であり、知識は観察を含むプロセスによって生み出されるという立場である。科学理論は観察結 果を一般化する。[203] 経験論は一般的に帰納法を包含する。帰納法は、限られた量の経験的証拠から一般的な理論がどのようにして導かれるかを説明する立場である。経験論には多く のバージョンが存在し、そのうち最も有力なものはベイズ主義と仮説演繹法である。[204][203] 経験論は、知識は観察によってではなく人間の知性によって生み出されるとする、元々はデカルトと関連付けられた合理主義とは対照的な立場である。批判的合 理主義は、オーストリア生まれのイギリス人哲学者カール・ポパーによって最初に定義された、20世紀の科学に対する対照的なアプローチである。ポパーは経 験論が理論と観察の関係を説明する方法を否定した。彼は、理論は観察によって生み出されるのではなく、観察は理論を基に行われると主張し、理論Aが観察の 影響を受ける唯一の方法は、理論Aが観察と矛盾し、理論Bが観察を生き延びた場合であると主張した。[206] ポパーは、科学理論の指標として検証可能性を反証可能性に置き換え、 科学理論の指標として、検証可能性を反証可能性に置き換え、経験的手法として帰納法を反証法に置き換えることを提案した。[206] ポパーはさらに、科学に特化したものではなく、実際には普遍的な手法は1つしかないと主張した。それは、批判、試行錯誤という否定的手法であり、 [207] 科学、数学、哲学、芸術など、人間の精神が生み出したすべての成果を網羅するものである。[208] もう1つのアプローチである道具主義は、理論の有用性を、現象の説明や予測のための道具として強調する。科学理論はブラックボックスであり、入力(初期条 件)と出力(予測)のみが関連していると見なされる。結果、理論上の存在、論理構造は無視されるべきものであると主張されている。[209] 実証主義に近いものに構成論的経験論がある。それによれば、科学理論の成功の主な基準は、観察可能な存在について述べていることが真実であるかどうかであ る。[210] トーマス・クーンは、観察と評価のプロセスはパラダイム内で行われると主張した。パラダイムとは、その枠組みから行われる観察と一致する、論理的に一貫し た世界の「肖像画」である。彼は、通常の科学をパラダイム内で行われる観察と「パズル解き」のプロセスと特徴づけ、一方、革命的な科学はパラダイムシフト において一つのパラダイムが別のパラダイムに取って代わる時に起こるとした。[211] それぞれのパラダイムには、独自の明確な問い、目的、解釈がある。パラダイム間の選択は、世界に対して2つ以上の「肖像画」を設定し、どの肖像画が最も有 望であるかを決定することを伴う。パラダイムシフトは、古いパラダイムにおいてかなりの数の観測上の異常が発生し、新しいパラダイムがそれらを説明できる 場合に起こる。つまり、新しいパラダイムの選択は、それらの観測が古いパラダイムを背景に行われたとしても、観測に基づいている。クーンにとって、パラダ イムの受容または拒絶は、論理的なプロセスであると同時に社会的プロセスでもある。しかし、クーンの立場は相対主義ではない。[212] 最後に、「創造科学」のような物議を醸す運動に対する科学的懐疑論の議論でしばしば引用されるもう一つのアプローチは、方法論的自然主義である。自然主義 者は、自然と超自然の違いを明確にすべきであり、科学は自然の説明に限定されるべきだと主張する。[213] 方法論的自然主義は、科学は厳格な経験的研究と独立した検証を必要とするという立場である。[214] |

| Scientific community The scientific community is a network of interacting scientists who conduct scientific research. The community consists of smaller groups working in scientific fields. By having peer review, through discussion and debate within journals and conferences, scientists maintain the quality of research methodology and objectivity when interpreting results.[215] Scientists  Portrait of a middle-aged woman Marie Curie was the first person to be awarded two Nobel Prizes: Physics in 1903 and Chemistry in 1911[124] Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest.[216][217] In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting and, upon completion, attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy or PhD.[218] Many scientists pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit organisations.[219][220][221] Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality and a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, the environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. In modern times, many scientists have advanced degrees in an area of science and pursue careers in various sectors of the economy, such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit environments.[222][223][224] Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with notable exceptions. Women in science faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies. For example, women were frequently passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work.[225] The achievements of women in science have been attributed to the defiance of their traditional role as labourers within the domestic sphere.[226] Learned societies  Picture of scientists in 200th anniversary of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, 1900 Learned societies for the communication and promotion of scientific thought and experimentation have existed since the Renaissance.[227] Many scientists belong to a learned society that promotes their respective scientific discipline, profession, or group of related disciplines.[228] Membership may either be open to all, require possession of scientific credentials, or conferred by election.[229] Most scientific societies are nonprofit organisations,[230] and many are professional associations. Their activities typically include holding regular conferences for the presentation and discussion of new research results and publishing or sponsoring academic journals in their discipline. Some societies act as professional bodies, regulating the activities of their members in the public interest, or the collective interest of the membership. The professionalisation of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of national distinguished academies of sciences such as the Italian Accademia dei Lincei in 1603,[231] the British Royal Society in 1660,[232] the French Academy of Sciences in 1666,[233] the American National Academy of Sciences in 1863,[234] the German Kaiser Wilhelm Society in 1911,[235] and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1949.[236] International scientific organisations, such as the International Science Council, are devoted to international cooperation for science advancement.[237] Awards Science awards are usually given to individuals or organisations that have made significant contributions to a discipline. They are often given by prestigious institutions; thus, it is considered a great honour for a scientist receiving them. Since the early Renaissance, scientists have often been awarded medals, money, and titles. The Nobel Prize, a widely regarded prestigious award, is awarded annually to those who have achieved scientific advances in the fields of medicine, physics, and chemistry.[238] |

科学界 科学界は、科学的研究を行う科学者たちの相互交流ネットワークである。科学界は、科学分野で活動する小規模なグループから構成されている。科学者は、学術 誌や学会での議論や討論を通じてピアレビューを行うことで、研究方法の質と結果の解釈における客観性を維持している。 科学者  中年女性の肖像 マリー・キュリーは、1903年に物理学賞、1911年に化学賞を受賞した最初の人物である。 科学者は、関心のある分野の知識を深めるために科学的研究を行う個人である。現代では、多くの科学者は学術的な環境で訓練を受け、修了すると学位を取得す る。最高学位は 最高学位は博士号(PhD)や博士(理学)号などである。[218] 多くの科学者は、学術界、産業界、政府、非営利団体など、経済のさまざまな分野でキャリアを追求している。[219][220][221] 科学者は現実に対して強い好奇心を持ち、科学的な知識を健康、国民、環境、産業の利益のために応用したいという願望を持っている。その他の動機としては、 同業者からの評価や名声を得たいというものもある。現代では、科学者の多くは科学の分野で高度な学位を取得し、学術界、産業界、政府、非営利団体など、経 済のさまざまな分野でキャリアを追求している。 科学は歴史的に男性優位の分野であり、顕著な例外はあるものの、科学における女性は、男性優位の社会における他の分野と同様に、科学の分野でもかなりの差 別を受けてきた。例えば、女性は就職の機会を度々逸し、仕事に対する評価も否定されてきた。[225] 科学における女性の功績は、伝統的な家庭内の労働者としての役割に逆らってきたことによるものである。[226] 学術団体  プロイセン科学アカデミー200周年記念における科学者の肖像画、1900年 科学思想や実験の伝達と促進を目的とした学術団体は、ルネサンス期から存在している。[227] 多くの科学者は、それぞれの科学分野、専門職、または関連分野のグループを促進する学術団体に所属している。[228] 会員資格は、すべての人に開かれている場合もあれば、科学的な資格を所有していることが求められる場合、または選挙によって与えられる場合もある。 [229] ほとんどの科学学会は非営利団体であり、[230] その多くは専門職協会である。その活動には、通常、新しい研究成果の発表と討論のための定期的な会議の開催や、専門分野の学術誌の出版またはスポンサーと なることが含まれる。一部の学会は専門職団体として、公益または会員全体の利益のために会員の活動を規制する役割も果たしている。 19世紀に始まった科学の専門化は、1603年のイタリア・リンチェイ学会(Accademia dei Lincei)[231]、1660年の英国王立協会(Royal Society)[232]、1666年のフランス科学アカデミー(French Academy of Sciences)[233]、1863年の米国科学アカデミー(American National Academy of Sciences)[234]、1911年のドイツ・カイザー・ヴィルヘルム協会(Kaiser Wilhelm Society)[235]、1949年の中国科学院(Chinese Academy of Sciences)[236]といった国民的な著名な科学アカデミーの設立によって、一部実現した。 1863 年のアメリカ科学アカデミー[234]、1911 年のドイツ・カイザー・ヴィルヘルム協会[235]、1949 年の中国科学院[236]などである。国際科学会議などの国際的な科学組織は、科学の進歩のための国際協力に専念している。[237] 賞 科学賞は通常、その分野に多大な貢献をした個人または組織に授与される。 権威ある機関によって授与されることが多いため、受賞は科学者にとって非常に名誉なこととみなされる。 ルネサンス初期以来、科学者はしばしばメダルや賞金、称号を授与されてきた。 広く権威ある賞とみなされているノーベル賞は、医学、物理学、化学の分野で科学上の進歩を成し遂げた人物に毎年授与される。[238] |

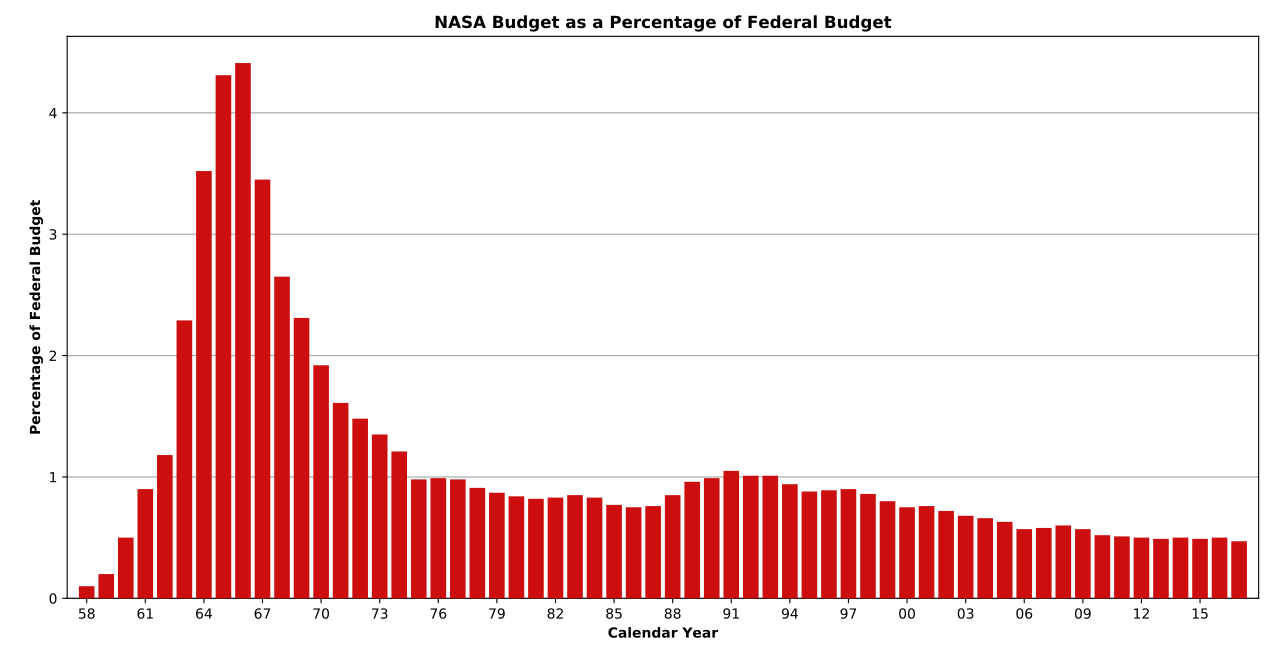

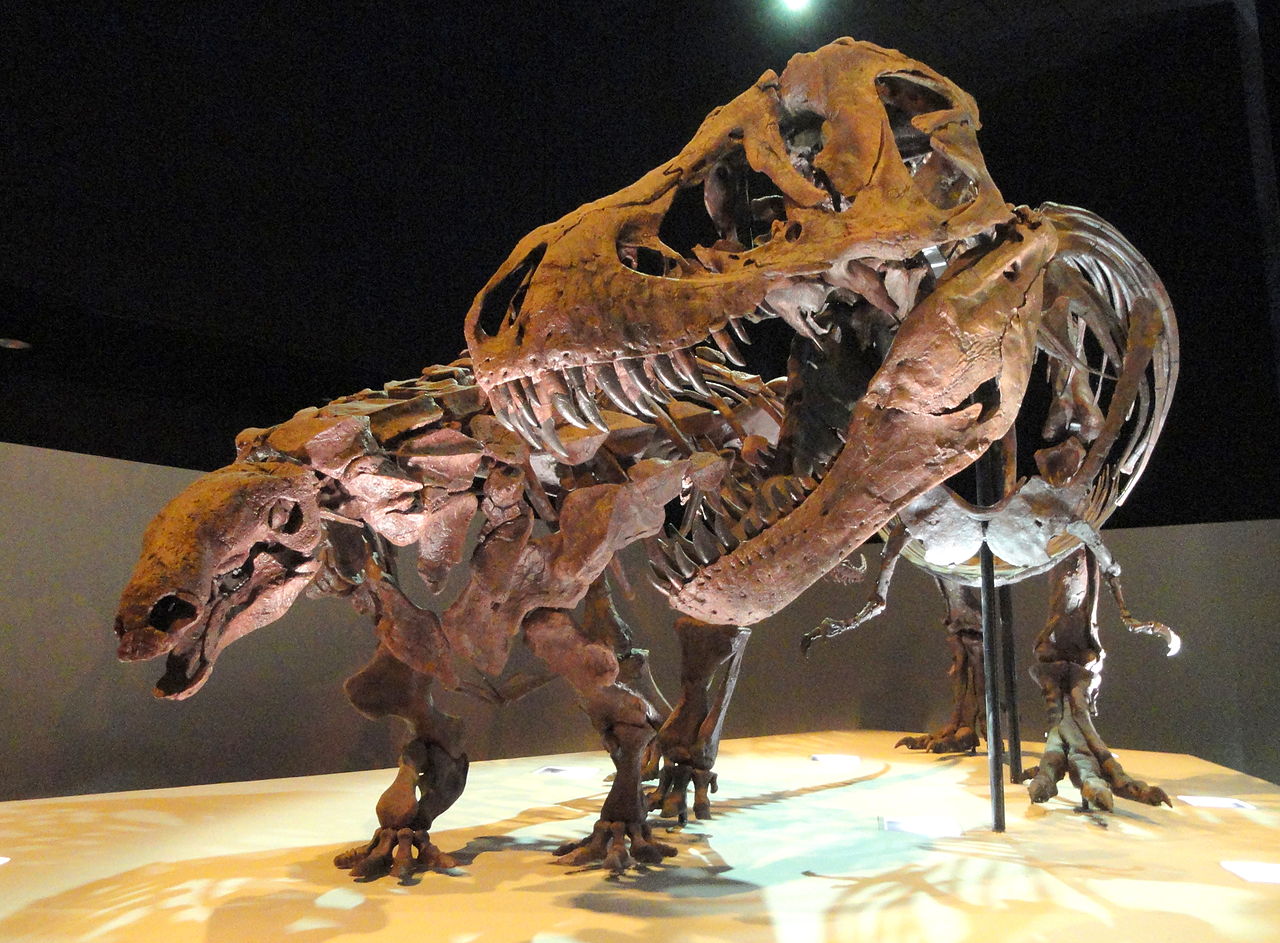

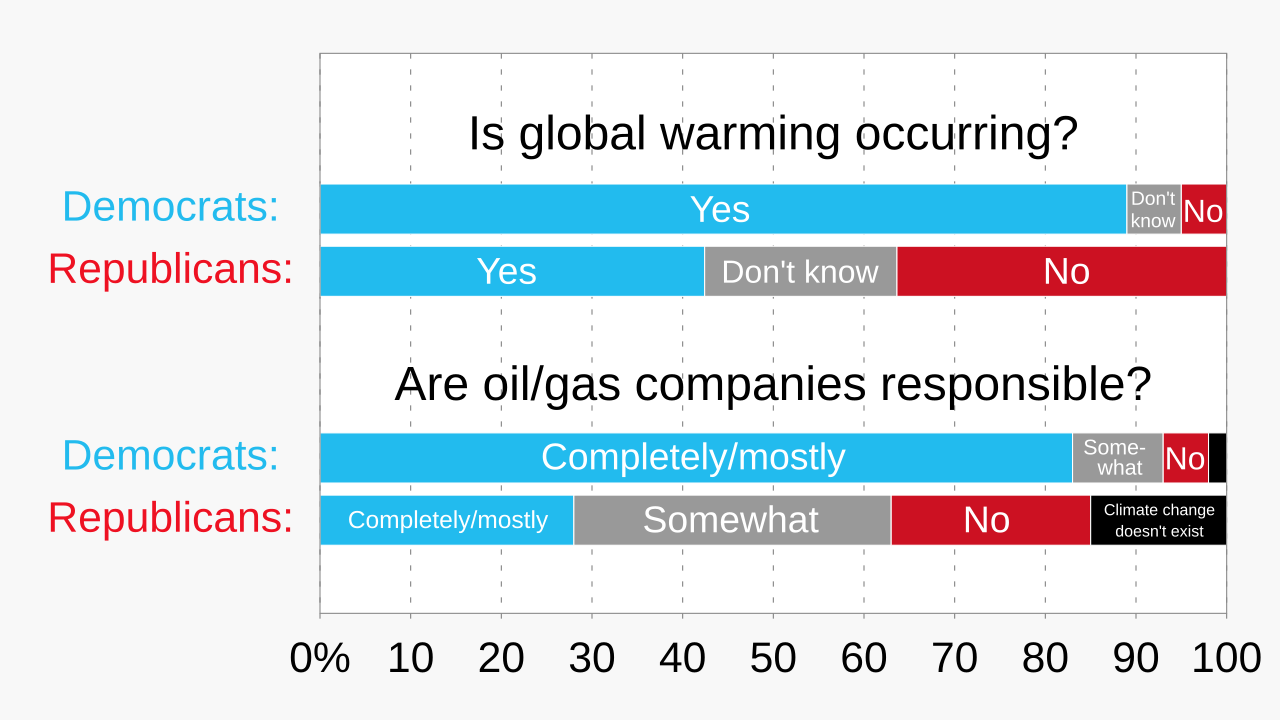

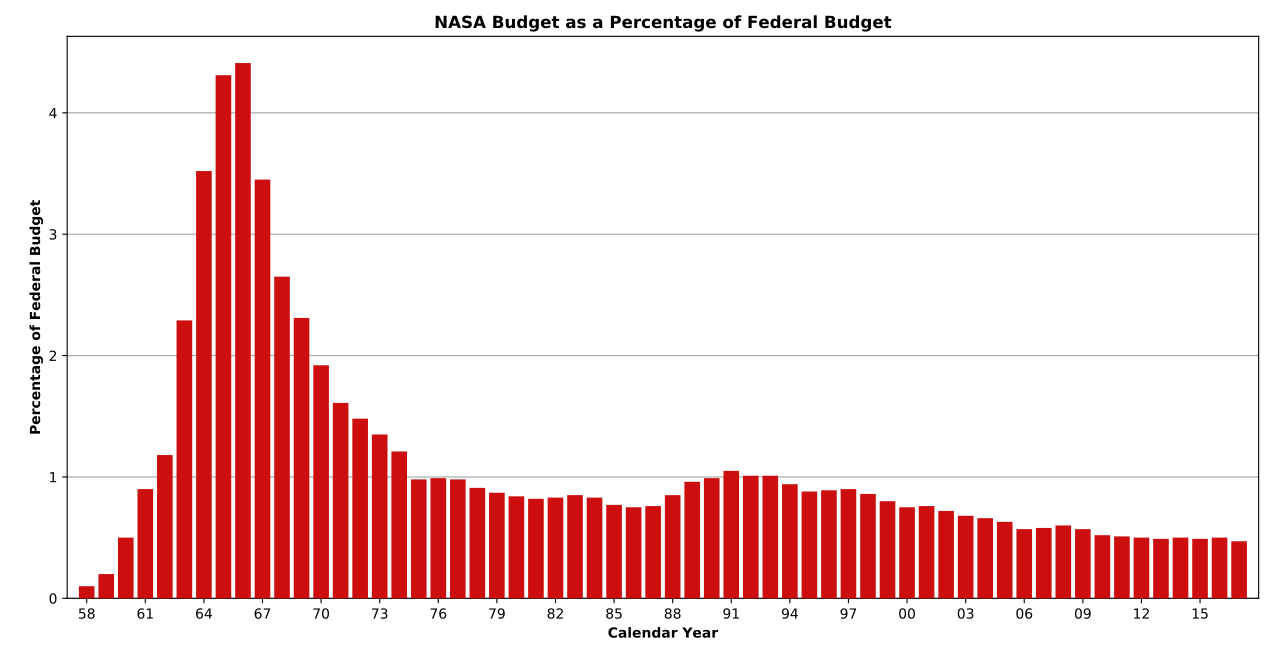

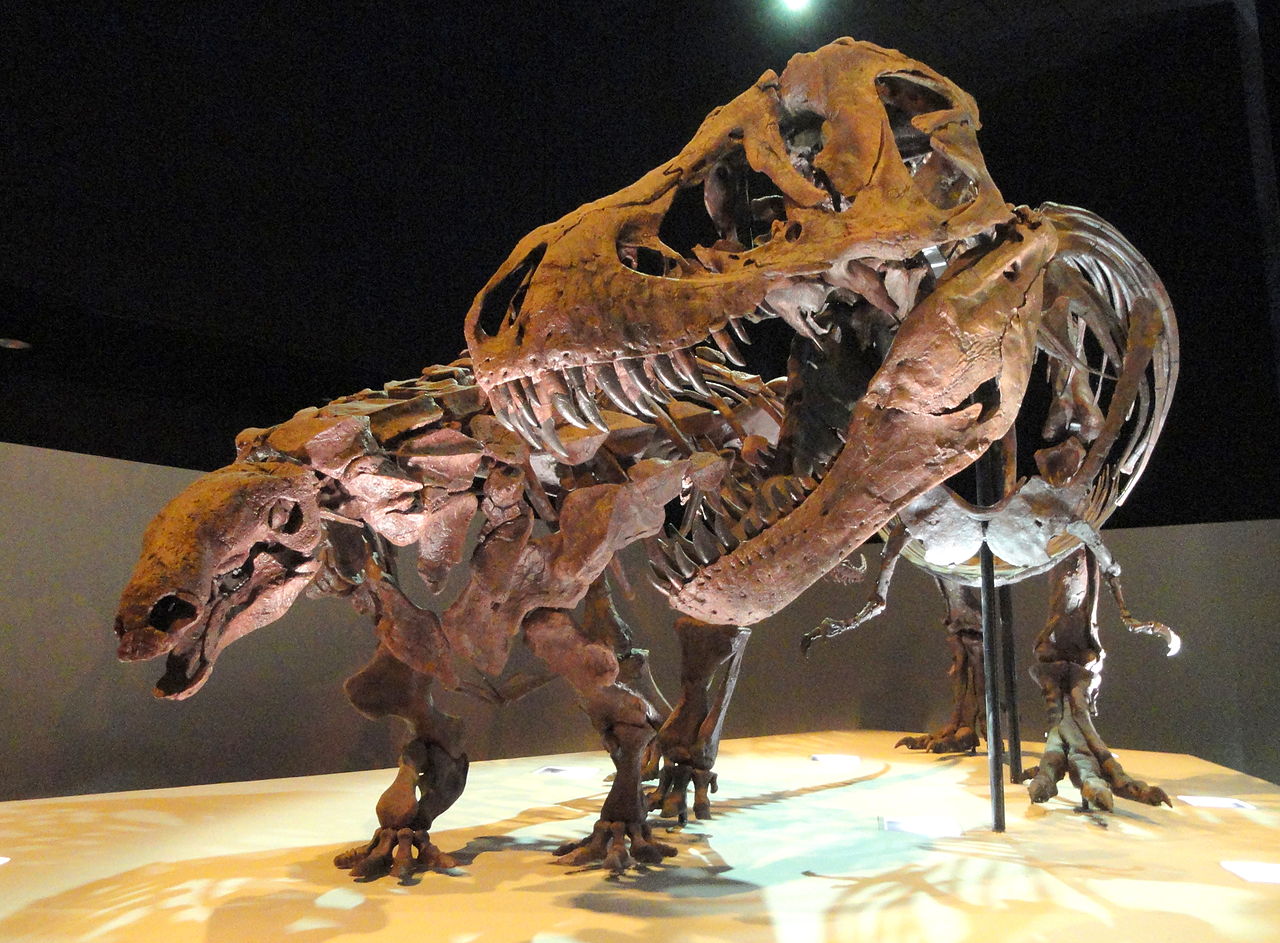

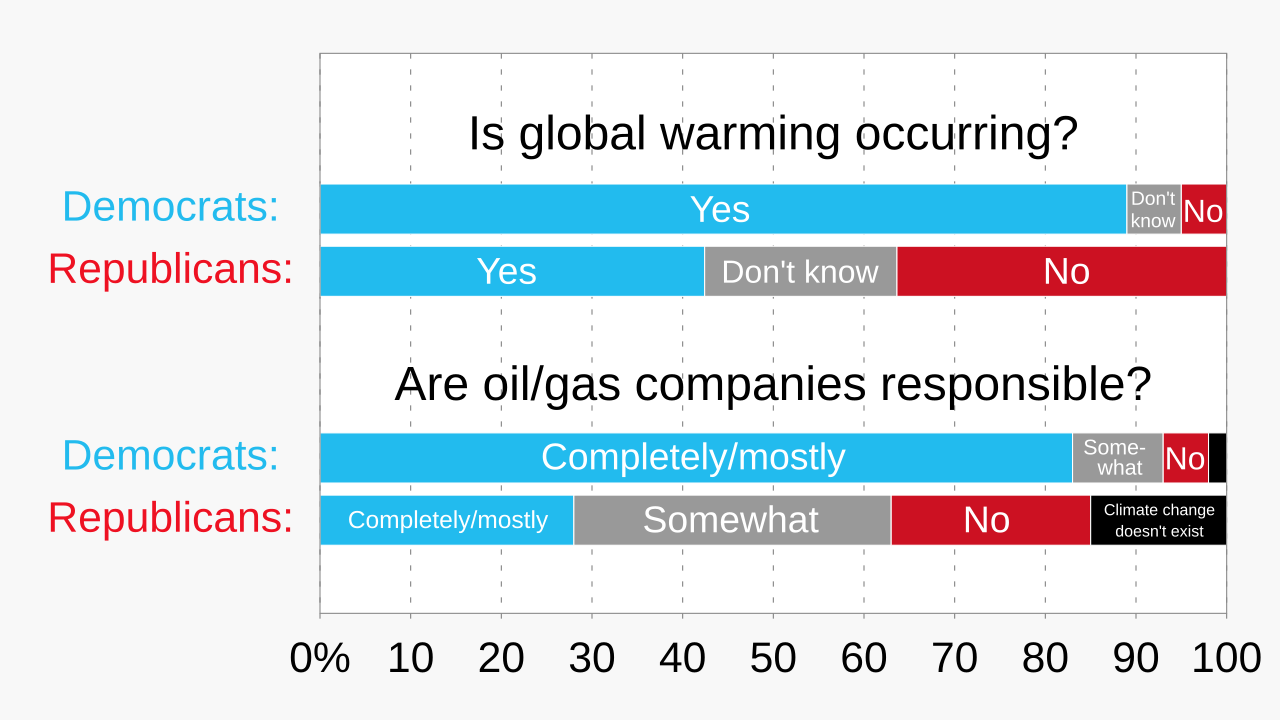

| Society "Science and society" redirects here. Not to be confused with Science & Society or Sociology of scientific knowledge. Funding and policies  see caption Budget of NASA as percentage of United States federal budget, peaking at 4.4% in 1966 and slowly declining since Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of GDP.[239] In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10%, respectively, by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain fields is higher, and it dominates research in social science and the humanities. In less developed nations, the government provides the bulk of the funds for their basic scientific research.[240] Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research, such as the National Science Foundation in the United States,[241] the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Argentina,[242] Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia,[243] National Centre for Scientific Research in France,[244] the Max Planck Society in Germany,[245] and National Research Council in Spain.[246] In commercial research and development, all but the most research-orientated corporations focus more heavily on near-term commercialisation possibilities than research driven by curiosity.[247] Science policy is concerned with policies that affect the conduct of the scientific enterprise, including research funding, often in pursuance of other national policy goals such as technological innovation to promote commercial product development, weapons development, health care, and environmental monitoring. Science policy sometimes refers to the act of applying scientific knowledge and consensus to the development of public policies. In accordance with public policy being concerned about the well-being of its citizens, science policy's goal is to consider how science and technology can best serve the public.[248] Public policy can directly affect the funding of capital equipment and intellectual infrastructure for industrial research by providing tax incentives to those organisations that fund research.[194] Education and awareness Main articles: Public awareness of science and Science journalism  Dinosaur exhibit in the Houston Museum of Natural Science Science education for the general public is embedded in the school curriculum, and is supplemented by online pedagogical content (for example, YouTube and Khan Academy), museums, and science magazines and blogs. Scientific literacy is chiefly concerned with an understanding of the scientific method, units and methods of measurement, empiricism, a basic understanding of statistics (correlations, qualitative versus quantitative observations, aggregate statistics), and a basic understanding of core scientific fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, ecology, geology, and computation. As a student advances into higher stages of formal education, the curriculum becomes more in depth. Traditional subjects usually included in the curriculum are natural and formal sciences, although recent movements include social and applied science as well.[249] The mass media face pressures that can prevent them from accurately depicting competing scientific claims in terms of their credibility within the scientific community as a whole. Determining how much weight to give different sides in a scientific debate may require considerable expertise regarding the matter.[250] Few journalists have real scientific knowledge, and even beat reporters who are knowledgeable about certain scientific issues may be ignorant about other scientific issues that they are suddenly asked to cover.[251][252] Science magazines such as New Scientist, Science & Vie, and Scientific American cater to the needs of a much wider readership and provide a non-technical summary of popular areas of research, including notable discoveries and advances in certain fields of research.[253] The science fiction genre, primarily speculative fiction, can transmit the ideas and methods of science to the general public.[254] Recent efforts to intensify or develop links between science and non-scientific disciplines, such as literature or poetry, include the Creative Writing Science resource developed through the Royal Literary Fund.[255] Anti-science attitudes Main article: Antiscience While the scientific method is broadly accepted in the scientific community, some fractions of society reject certain scientific positions or are sceptical about science. Examples are the common notion that COVID-19 is not a major health threat to the US (held by 39% of Americans in August 2021)[256] or the belief that climate change is not a major threat to the US (also held by 40% of Americans, in late 2019 and early 2020).[257] Psychologists have pointed to four factors driving rejection of scientific results:[258] Scientific authorities are sometimes seen as inexpert, untrustworthy, or biased. Some marginalized social groups hold anti-science attitudes, in part because these groups have often been exploited in unethical experiments.[259] Messages from scientists may contradict deeply held existing beliefs or morals. The delivery of a scientific message may not be appropriately targeted to a recipient's learning style. Anti-science attitudes often seem to be caused by fear of rejection in social groups. For instance, climate change is perceived as a threat by only 22% of Americans on the right side of the political spectrum, but by 85% on the left.[260] That is, if someone on the left would not consider climate change as a threat, this person may face contempt and be rejected in that social group. In fact, people may rather deny a scientifically accepted fact than lose or jeopardize their social status.[261] Politics  Result in bar graph of two questions ("Is global warming occurring?" and "Are oil/gas companies responsible?"), showing large discrepancies between American Democrats and Republicans Public opinion on global warming in the United States by political party[262] Attitudes towards science are often determined by political opinions and goals. Government, business and advocacy groups have been known to use legal and economic pressure to influence scientific researchers. Many factors can act as facets of the politicization of science such as anti-intellectualism, perceived threats to religious beliefs, and fear for business interests.[263] Politicization of science is usually accomplished when scientific information is presented in a way that emphasizes the uncertainty associated with the scientific evidence.[264] Tactics such as shifting conversation, failing to acknowledge facts, and capitalizing on doubt of scientific consensus have been used to gain more attention for views that have been undermined by scientific evidence.[265] Examples of issues that have involved the politicization of science include the global warming controversy, health effects of pesticides, and health effects of tobacco.[265][266] |

社会 「科学と社会」は、こちらを参照。Science & Society(科学と社会)や、科学知識社会学と混同しないこと。 資金と政策  キャプションを参照 NASAの予算は、米国連邦予算に占める割合で、1966年に4.4%でピークに達し、それ以来徐々に減少している 科学研究は、多くの場合、潜在的な研究プロジェクトが評価され、最も有望なプロジェクトのみに資金が提供される競争プロセスを通じて資金が提供される。こ のようなプロセスは、政府、企業、財団によって運営され、希少な資金を配分する。ほとんどの先進国における研究資金総額は、GDPの1.5%から3%の間 である。OECDでは、科学技術分野における研究開発の約3分の2は企業によって実施され、それぞれ20%と10%は大学と政府によって実施されている。 特定の分野では政府の資金提供の割合が高く、社会科学や人文科学の研究を支配している。発展途上国では、政府が基礎科学研究の資金の大部分を提供してい る。 多くの政府は、米国の国立科学財団(National Science Foundation)[241]、アルゼンチンの国立科学技術研究協議会(National Scientific and Technical Research Council)[242]、オーストラリアの連邦科学産業研究機構(Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization)[243]、フランスの国立科学研究センター(National Centre for Scientific Research)[244]、 44]、ドイツのマックス・プランク協会[245]、スペインの国立研究評議会[246]などである。商業的な研究開発においては、最も研究志向の強い企 業を除いては、好奇心に駆られて行われる研究よりも、より短期間で商業化できる可能性に重点を置いている。 科学政策は、科学事業遂行に影響を与える政策に関わるものであり、研究資金提供を含み、しばしば商業製品開発、兵器開発、医療、環境モニタリングを促進す るための技術革新など、他の国民政策目標の追求を目的としている。科学政策は、科学知識とコンセンサスを公共政策の策定に適用する行為を指すこともある。 公共政策が市民の幸福を目的としていることに従い、科学政策の目標は、科学技術がどのようにして市民に最も役立つかを検討することである。[248] 公共政策は、研究に資金を提供する組織に税制上の優遇措置を与えることによって、産業研究のための資本設備や知的インフラへの資金調達に直接影響を与える ことができる。[194] 教育と意識 詳細は「科学に対する一般市民の意識」および「科学ジャーナリズム」を参照  ヒューストン自然科学博物館の恐竜展示 一般市民向けの科学教育は学校のカリキュラムに組み込まれており、オンラインの教育コンテンツ(YouTubeやカーン・アカデミーなど)、博物館、科学 雑誌やブログによって補完されている。科学リテラシーは主に、科学的手法、単位や測定方法、経験論、統計学の基本的な理解(相関関係、定性的・定量的観 測、集計統計)、物理学、化学、生物学、生態学、地質学、計算などの主要な科学分野の基本的な理解を必要とする。学生が正規の教育のより高度な段階に進む につれ、カリキュラムはより深みを増していく。カリキュラムに通常含まれる伝統的な科目は、自然科学と形式科学であるが、最近の動きでは、社会科学や応用 科学も含まれるようになっている。 マスメディアは、科学界全体における科学的主張の信頼性を正確に描写することを妨げるような圧力に直面している。科学論争における各主張にどれほどの重み を与えるかを決定するには、その問題に関する相当な専門知識が必要となる場合がある。[250] 科学に関する真の知識を持つジャーナリストはほとんどおらず、特定の科学問題に詳しい特派員でさえ、急に取材を頼まれた他の科学問題については無知である 場合がある。[251][252] ニューサイエンティスト、サイエンス・アンド・ヴィ、サイエンティフィック・アメリカンなどの科学雑誌は、より幅広い読者層を対象に、特定の研究分野にお ける注目すべき発見や進歩など、人気の高い研究分野の専門外の人々にも理解できる要約を提供している。[253] 主に空想科学小説であるSFというジャンルは、 一般大衆に科学のアイデアや手法を伝えることができる。[254] 科学と文学や詩などの非科学分野とのつながりを強化または発展させる最近の取り組みには、王立文学基金を通じて開発されたクリエイティブ・ライティング・ サイエンス・リソースなどがある。[255] 反科学的な態度 詳細は「反科学」を参照 科学的手法は科学界では広く受け入れられているが、社会の一部では特定の科学的立場を拒絶したり、科学に対して懐疑的な見方をしている。例えば、 COVID-19は米国にとって大きな健康上の脅威ではないという一般的な考え方(2021年8月の時点で米国人の39%が支持)[256]や、気候変動 は米国にとって大きな脅威ではないという信念 (2019年末から2020年初頭のアメリカ人の40%もそう考えている)[257]。心理学者は、科学的結果の拒絶を促す4つの要因を指摘している: 科学の権威者は、時に専門外で信頼できない、あるいは偏見があると見なされる。 一部の社会的に疎外された集団は反科学的な態度を取るが、その理由の一つとして、これらの集団が非倫理的な実験にしばしば利用されてきたことがある。 [259] 科学者からのメッセージは、深く根付いた既存の信念や道徳観と矛盾する可能性がある。 科学的なメッセージの伝達は、受け手の学習スタイルに適切にターゲットを絞っていない可能性がある。 反科学的な態度は、しばしば社会集団における拒絶への恐れによって引き起こされるようだ。例えば、気候変動を脅威と認識しているのは、政治的傾向が右派の アメリカ人のうちわずか22%であるのに対し、左派では85%に上る。つまり、左派の誰かが気候変動を脅威とみなさない場合、その人物はその社会集団の中 で軽蔑され、拒絶される可能性がある。実際、人々は社会的地位を失ったり、危うくしたりするよりも、むしろ科学的に認められた事実を否定する可能性があ る。 政治  2つの質問(「地球温暖化は起こっているか」、「石油・ガス会社に責任があるか」)に対する棒グラフの結果、アメリカ民主党と共和党の間には大きな相違が ある アメリカにおける地球温暖化に関する世論の政党別分布[262] 科学に対する態度は、政治的な意見や目標によって決定されることが多い。政府、企業、支援団体は、科学研究者に対して法的・経済的な圧力をかけることで影 響を及ぼすことが知られている。反知性主義、宗教的信念に対する脅威の認識、ビジネス上の利害への懸念など、科学の政治化には多くの要因が関わっている。 科学の政治化は、科学的な証拠に関連する不確実性を強調する形で科学情報が提示される場合に、通常は達成される。事実を認めないこと、科学的コンセンサス に対する疑念を利用することなどといった戦術は、科学的証拠によって弱められた見解により注目を集めるために用いられてきた。[265] 科学の政治利用が関わった問題の例としては、地球温暖化論争、農薬の健康への影響、タバコの健康への影響などがある。[265][266] |

| Criticism of

science List of scientific occupations List of years in science Science (Wikiversity) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science |

|

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

333

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆