クロノトポス

Chronotopos

☆

クロノトポスとは「時空間」のことである。時間と空間が複合されたもの(我々の経験世界はクロノトピックな性格をもちます)。小説(物語)は時間と空間に

関する描写が含まれますが、

それら(すなわち時間と空間)の関係は、お互いが相互に特性づけられ、性格づけられます。空間の拡がりはないにもかかわらず、長い時間概念や循環的時間の

なかで物語が表現される(例:地方の歴史や民話のように物語の空間的範囲は狭く凡庸だが、時間的経過や変化は人間の一生よりも長い)こともあれば、空間の

変化と時間の経過に深い展開の意味が込められているもの(例:英雄が遍歴し困難に立ち向かいながら成長したり、挫折したりすること)がある。

| Chronotopos

(griech. chrónos = Zeit; tópos = Ort) ist ein von dem russischen

Literaturwissenschaftler Michail Bachtin eingeführter Begriff der

Erzähltheorie und der Dramen-Analyse. Chronotopoi charakterisieren den

Zusammenhang zwischen dem Ort und dem Zeitverlauf einer Erzählung. |

クロノトポス(ギリシャ語でchrónos=時間、tópos=場所)は、ロシアの文学者ミハイル・バフチンが物語論やドラマ分析に導入した用語である。クロノトポイ(クロノトポスの複数形)は、物語における場所と時間の流れのつながりを特徴づける。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Definition 2 Literatur 2.1 Primärliteratur 2.2 Literatur über Bachtins Konzept 2.3 Literatur über Spodes Konzept |

目次 1 定義 2 文献 2.1 一次文献 2.2 バフチンの概念に関する文献 2.3 スポードの概念に関する文献 |

| Definition Die Strukturierungen von Raum und Zeit in einer Erzählung bilden nach Bachtin einen wechselseitigen und untrennbaren Zusammenhang. Sie durchdringen sich gegenseitig, indem der Raum die chronologische Bewegung der Erzählung gliedert und dimensioniert und umgekehrt die Zeit den Raum mit Sinn erfüllt. Der Chronotopos ist also eine Art „Raumzeit-Gesetzlichkeit“, die die Bedingungen der Möglichkeiten der Erzählung festlegt: er bildet gewissermaßen die „Weltordnung“ einer Erzählung, ihr internes Orientierungssystem in Zeit und Raum und zugleich das Orientierungs- und Wahrnehmungsmuster ihrer Figuren (Deixis). Die Analyse einer Erzählung nach Chronotopoi fragt also nach dem Wo und Wann und deren symbolischer oder sinnhafter Beziehung. Fragen, die eine solche Untersuchung stellen könnte, sind zum Beispiel: Welche Schauplätze werden gewählt? Wie werden sie erzählerisch erschlossen? Wie behandelt die Erzählung den Raum – durch Reisen, Kreisbewegungen, Stillstand? Wie verhält sich die Charakterisierung der Figuren zu ihrer Bewegung im Raum? Wie beziehen sich die Abfolge der Ereignisse, die Beobachtungen der Figuren und ihre Bewegungen im Raum aufeinander? Die Gestaltung der Schauplätze und der Zeit einer Erzählung ist vor allem ein wichtiges Element der Charakterisierung von handelnden Personen und der Darstellung eines Weltbildes. Räume in einer Erzählung sind nicht zufällig, sondern symbolisch, ebenso Raumbeziehungen wie Blicke, Bewegungen, Architektur, Reisen usw. Der Zusammenhang von Raum und Zeit konstituiert somit den Handlungsverlauf und die Handlungsmöglichkeiten der Figuren. Der Chronotopos einer Erzählung ist also einerseits eine Art „Landkarte“, andererseits eine Art „Zeitstrahl“, wobei Elemente beider Dimensionen auf eine Weise miteinander verknüpft sind, die für bestimmte literarische Gattungen typisch ist: Chronotopos des barocken Schelmenromans ist die Verkehrte Welt; Abenteuerromane wiederum dehnen oder raffen den Raum, machen ihn zu einer flexiblen Repräsentationsform, während biografische Romane sich eher an zeitlich-räumliche Gegebenheiten in der Welt halten müssen. In der Erzählforschung werden häufig auch bestimmte symbolhafte Orte, die konventionalisierte Funktionen haben, als Chronotopoi bezeichnet. Das können etwa sein: die Schwelle, das Tor (Begegnung, Abschied), das Gericht (Festlegung, Richtigkeit, Urteil), der Weg (Leben, Reise, Reifung), die Heimat, das Exil, die Landschaft, der Tatort, der Fluss, die Insel, das Schiff, der Leuchtturm, die Stadt, die Festung, das Haus, die Bühne usw. Sie alle kündigen dem Leser durch ihre Konventionalisierung bereits gewisse Oppositionen und Verläufe innerhalb der Handlung an; sie lenken Handlung und Zeit; sie werden zu sinntragenden und sinnstrukturierenden Elementen. Unabhängig von Bachtin hat der Chonotopie-Begriff in der kulturwissenschaftlichen Tourismuswissenschaft Einzug gehalten. Der Soziologe Hasso Spode erklärt die Entstehung des Tourismus im 18. Jahrhundert als eine romantische "Zeit-Reise rückwärts", die auf der Erfahrung der "Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen" basiert. Der touristische Raum fungiert hierbei als Chronotopie. Sie bildet – anders als Michel Foucaults unspezifische Heterotopie – eine tangible "verzeitlichte" Utopie. Siehe auch: Heterotopie |

定義 バフチンによれば、物語における空間と時間の構造化は、相互的かつ不可分のつながりを形成している。空間は物語の時系列的な動きを構造化し、次元化し、逆 に時間は空間に意味を充填するという点で、両者は互いに浸透し合っている。いわば物語の「世界秩序」であり、時間と空間における内部的な方向づけシステム であり、同時に登場人物の方向づけや知覚パターン(デイクシス)を形成する。 このように、クロノトポイに従って物語を分析することは、「いつ、どこで、どのような物語が展開されるのか」、そしてそれらの象徴的な関係や意味的な関係を問うことになる。このような分析は、例えば次のような疑問を投げかける: どのような設定が選ばれているのか?それらはどのように物語的に展開されるのか? 物語は空間をどのように扱っているのか(移動、循環運動、静止)。 人物の性格付けは、空間における動きとどのように関係しているのか? 出来事の順序、登場人物の観察、空間における彼らの動きは、互いにどのように関係しているのか。 物語における設定と時間のデザインは、何よりも登場人物の性格付けと世界観の描写において重要な要素である。物語における空間はランダムなものではなく、 象徴的なものであり、景色、動き、建築、旅行などの空間関係も同様である。空間と時間の結びつきは、プロットと登場人物の行動の可能性を構成する。 物語のクロノトポスは、一方では一種の 「地図 」であり、他方では一種の 「時間軸 」であり、この両次元の要素は、ある文学ジャンルに典型的な形で結びついている。バロックのピカレスク小説のクロノトポスは、逆さまの世界であり、冒険小 説は、他方で、空間を引き伸ばしたり集めたりして、それを柔軟な表現形式に変え、伝記小説は、世界の時間的空間的現実により忠実でなければならない。 物語研究において、慣習化された機能を持つ特定の象徴的な場所は、しばしばクロノトポイと呼ばれる。敷居、門(出会い、別れ)、裁判所(決定、正しさ、審 判)、道(人生、旅、成熟)、家、流浪、風景、事件現場、川、島、船、灯台、都市、要塞、家、舞台などである。それらはすべて、プロット内のある対立と進 行を読者に告げ、行動と時間を導き、意味を運び、意味を構成する要素となる。 バフチンとは無関係に、チョノトピアという概念は観光に関する文化研究にも入り込んでいる。社会学者のハッソ・スポーデは、18世紀における観光の出現 を、「非同時の同時性」の経験に基づくロマンティックな「時間遡行の旅」として説明している。観光空間はここでクロノトピアとして機能する。ミシェル・ フーコーの不特定多数のヘテロトピアとは対照的に、それは具体的な「時間化された」ユートピアを形成している。 参照:ヘテロトピア |

| Literatur Primärliteratur Der 1975 in Moskau erstmals erschienene, grundlegende Text von Michail M. Bachtin liegt in der Übersetzung von Michael Dewey in drei deutschen Ausgaben vor: Michail M. Bachtin: Formen der Zeit im Roman. Untersuchungen zur historischen Poetik, in: Untersuchungen zur Poetik und Theorie des Romans. Hrsg. von Edwald Kowalski und Michael Wegner. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin und Weimar 1986 Michail M. Bachtin: Formen der Zeit im Roman. Untersuchungen zur historischen Poetik. Hrsg. von Edwald Kowalski und Michael Wegner. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-596-27418-4 Michail M. Bachtin: Chronotopos. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-29479-6 In der Tourismusforschung taucht der Begriff erstmals 2009 auf: Hasso Spode: Raum, Zeit, Tourismus, in: Die Vielfalt Europas. Identitäten und Räume, hrsg. v. Winfried Eberhard und Christian Lübke, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2009. Hasso Spode: Zur Genese des Tourismus, in: Die Entwicklung der Psyche in der Geschichte der Menschheit, hrsg. v. Gerd Jüttemann, Pabst, Lengerich 2013, ISBN 978-3-89967-859-8. Antonio Nogués-Pedrega: El Cronotopo del Turismo, in: Revista de Antropología Social Nr. 21/2013. Literatur über Bachtins Konzept Nele Bemong u. a.: Bakhtin’s Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives. Academia Press, Gent 2010, ISBN 9789038215631. Michael C. Frank, Kirsten Mahlke: Nachwort zu Michail M. Bachtin: Chronotopos. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-29479-6, S. 201–242 Michael Wegner: Die Zeit im Raum. Zur Chronotopostheorie Michail Bachtins. In: Weimarer Beiträge, 35.8 (1989), S. 1357–1367 Literatur über Spodes Konzept Jan Pezda: Tourism. Retropian Time-Travel, in: UR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Nr. 2/2021, ISSN 2543-8379 Anwendung Miriam Lay Brander: Raum-Zeiten im Umbruch. Erzählen und Zeigen im Sevilla der Frühen Neuzeit. Transcript, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-8376-1759-7 Werner Brück: Wie erzählt Poussin? Proben zur Anwendbarkeit poetologischer Begriffe aus Literatur- und Theaterwissenschaft auf Werke der bildenden Kunst. Versuch einer Wechselseitigen Erhellung der Künste. Saarbrücken/Norderstedt, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7357-7877-2. Christoph Grube: Chronotopos und intertextuelle Struktur. Zur Zeitgestaltung in Eichendorffs „Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts“ unter Rekurs auf das Volksbuch „Die schöne Magelona“, in: Markus May, Tanja Rudtke (Hrsg.): Bachtin im Dialog. Festschrift für Jürgen Lehmann. Winter, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5279-X, S. 315–333 Timo Müller: Notes Toward an Ecological Conception of Bakhtin’s ‘Chronotope’, in: Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment 1.1 (2010) (Volltext) Michael Ostheimer: Leseland. Chronotopographie der DDR- und Post-DDR-Literatur, Wallstein, Göttingen 2018. Uwe Spörl: Die Chronotopoi des Kriminalromans, in: Markus May, Tanja Rudtke (Hrsg.): Bachtin im Dialog. Festschrift für Jürgen Lehmann. Winter, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5279-X, S. 335–363 (Volltext) |

文献 第一次文献 1975年にモスクワで初版が出版されたミハイル・M・バフチンの基本テキストは、ミヒャエル・デューイ訳による3種類のドイツ語版がある: Michail M. Bachtin: Formen der Zeit im Roman. Untersuchungen zur historischen Poetik, in: Untersuchungen zur Poetik und Theorie des Romans. Edwald Kowalski、Michael Wegner編。Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1986. ミハイル・M・バハチン:小説における時間の形態。歴史詩学の研究。Edwald Kowalski、Michael Wegner編。Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-596-27418-4. Michail M. Bachtin: Chronotopos. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-29479-6 この用語が初めて観光研究に登場したのは2009年のことである: Hasso Spode: Raum, Zeit, Tourismus, in: Die Vielfalt Europas. Identitäten und Räume, ed. by Winfried Eberhard and Christian Lübke, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2009. Hasso Spode: Zur Genese des Tourismus, in: Die Entwicklung der Psyche in der Geschichte der Menschheit, Gerd Jüttemann 編, Pabst, Lengerich 2013, ISBN 978-3-89967-859-8. Antonio Nogués-Pedrega: El Cronotopo del Turismo, in: Revista de Antropología Social 21/2013. バフチンの概念に関する文献 Nele Bemong et al: Bakhtin's Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives. Academia Press, Ghent 2010, ISBN 9789038215631. Michael C. Frank, Kirsten Mahlke: Afterword to Michail M. Bachtin: Chronotopos. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-29479-6, pp. ミヒャエル・ウェグナー:空間の中の時間。ミハイル・バフチンのクロノトポス理論について。In: Weimarer Beiträge, 35.8 (1989), pp. スポードの概念に関する文献 ヤン・ペズダ:ツーリズム。UR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences No. アプリケーション ミリアム・レイ・ブランダー:移行期における空間-時間。近世セビリアにおける語ることと見せること。Transcript, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-8376-1759-7. ヴェルナー・ブリュック:プッサンはどのように語るのか?文学・演劇研究から視覚芸術作品への詩人学的概念の適用可能性を検証する。芸術の相互照射の試み。Saarbrücken/Norderstedt, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7357-7877-2. Christoph Grube: Chronotopos and intertextual structure. Eichendorff's 「Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts」 on recourse to the folk book 「Die schöne Magelona」, in: Markus May, Tanja Rudtke (eds.): Bachtin im Dialog. Festschrift for Jürgen Lehmann. Winter, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5279-X, pp. Timo Müller: Notes Toward an Ecological Conception of Bakhtin's 'Chronotope', in: Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment 1.1 (2010) (全文) Michael Ostheimer: Leseland. GDR and Post-GDR Literature, Wallstein, Göttingen 2018. Uwe Spörl: Die Chronotopoi des Kriminalromans, in: Markus May, Tanja Rudtke (eds.): Bachtin im Dialog. Festschrift for Jürgen Lehmann. Winter, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5279-X, pp. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronotopos |

|

| In literary theory and philosophy of language, the chronotope

is how configurations of time and space are represented in language and

discourse. The term was taken up by Russian literary scholar Mikhail

Bakhtin who used it as a central element in his theory of meaning in

language and literature. The term itself comes from the Russian

xронотоп, which in turn is derived from the Greek χρόνος ('time') and

τόπος ('space'); it thus can be literally translated as "time-space."

Bakhtin developed the term in his 1937 essay "Forms of Time and of the

Chronotope in the Novel" («Формы времени и хронотопа в романе»). Here

Bakhtin showed how different literary genres operated with different

configurations of time and space, which gave each genre its particular

narrative character.[1] |

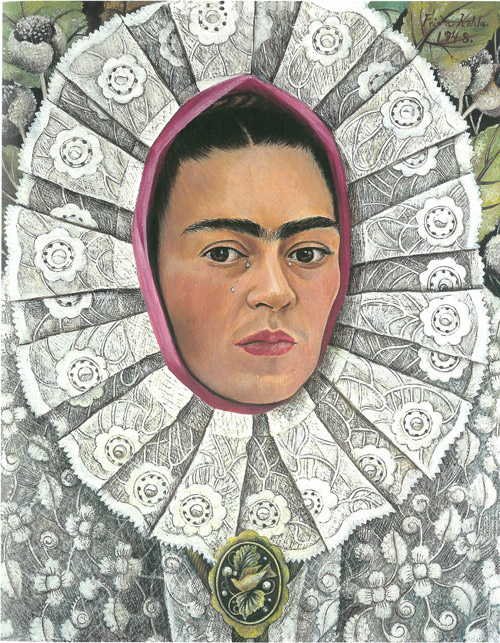

文

学理論および言語哲学において、クロノトープとは、時間と空間の構成が言語や談話においてどのように表現されるかを指す。この用語は、ロシアの文学者ミハ

イル・バフチンによって取り上げられ、言語と文学における意味論の中心的な要素として用いられた。この用語自体はロシア語の「クロノトープ」に由来し、さ

らにギリシャ語の「クロノス」(時間)と「トポス」(空間)に由来する。したがって、文字通りには「時間-空間」と訳すことができる。バフチンは1937

年の論文「小説における時間とクロノトープの形態」でこの用語を展開した。ここでバフチンは、文学のさまざまなジャンルが時間と空間の異なる構成でどのよ

うに機能するかを示し、各ジャンルに特有の物語的性格を与えた。[1] |

| Overview For Bakhtin, chronotope is the conduit through which meaning enters the logosphere.[2] Genre is rooted in how one perceives the flow of events and its representation of particular worldviews or ideologies.[3][4] Bakhtin scholars Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist state that the chronotope is "a unit of analysis for studying language according to the ratio and characteristics of the temporal and spatial categories represented in that language".[5] They argue that Bakhtin's concept differs from other uses of time and space in literary analysis because neither category is given a privileged status: they are inseparable and entirely interdependent. Bakhtin's concept is a way of analyzing literary texts that reveals the forces operating in the cultural system from which they emanate. Specific chronotopes are said to correspond to particular genres, or relatively stable ways of speaking, which themselves represent particular worldviews or ideologies. In the essay Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel, Bakhtin describes his use of the term thus: We will give the name chronotope (literally, 'time space') to the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature. This term [space-time] is employed in mathematics, and was introduced as part of Einstein's Theory of Relativity. The special meaning it has in relativity theory is not important for our purposes; we are borrowing it for literary criticism almost as a metaphor (almost, but not entirely). What counts for us is the fact that it expresses the inseparability of space and time (time as the fourth dimension of space). We understand the chronotope as a formally constitutive category of literature; we will not deal with the chronotope in other areas of culture. In the literary artistic chronotope, spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought-out, concrete whole. Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history. This intersection of axes and fusion of indicators characterizes the artistic chronotope. The chronotope in literature has an intrinsic generic significance. It can even be said that it is precisely the chronotope that defines genre and generic distinctions, for in literature the primary category in the chronotope is time. The chronotope as a formally constitutive category determines to a significant degree the image of man in literature as well. The image of man is always intrinsically chronotopic.[4] Unlike Kant, who saw time and space as transcendental pre-conditions of experience, Bakhtin regards them as "forms of the most immediate reality". They are not mere "mathematical" abstractions, but have a concrete and, depending on context, qualitatively variable form.[6] This is particularly noticeable in Bakhtin's own object of study—that of artistic cognition in literary genres—but he implies that it is applicable in other contexts as well.[7] Different structures or orders of the universe cannot be assumed to operate within the same chronotope. For example, the chronotope of a biological organism like an ant will be qualitatively different from that of an organism like an elephant, or from that of a structure of a different order entirely, such as a star or a galaxy. Within the human world itself there is a huge variety of social activities that are defined by qualitatively different time/space fusions.[8] |

概要 バフチンにとって、クロノトープは意味がロゴスフィアに入るための導管である。[2] ジャンルは、出来事の流れとその表現を特定の世界観やイデオロギーとして認識する方法に根ざしている。[3][4] バフチン学者のキャロル・エマーソンとマイケル・ホルクィストは、クロノトープとは「言語に表現される時間的および空間的カテゴリーの比率と特性に従って 言語を研究するための分析単位」であると述べている。[5] 彼らは、バフチンの概念は文学分析における時間と空間の他の用法とは異なると主張している。なぜなら、どちらのカテゴリーも特権的な地位を与えられていな いからである。それらは不可分であり、完全に相互依存している。バフチンの概念は、文学的テクストを分析し、そのテクストが由来する文化的システムに作用 する力を明らかにする方法である。特定のクロノトープは、特定のジャンル、または比較的安定した話し方に相当すると言われており、それ自体が特定の世界観 やイデオロギーを表している。 バフチンはエッセイ『小説における時間とクロノトープの形態』の中で、この用語の使用について次のように説明している。 私たちは、文学において芸術的に表現される時間と空間の関係の本質的な結びつきに「クロノトープ(文字通り「時間空間」)」という名称を与える。この用語 (「時空間」)は数学で用いられ、アインシュタインの相対性理論の一部として導入されたものである。相対性理論における特殊な意味は、我々の目的にとって は重要ではない。我々は、ほとんど隠喩として、文学批評に借用しているのだ(ほとんど、というより完全に)。我々にとって重要なのは、空間と時間が不可分 であることを表現しているという事実である(空間における4番目の次元としての時間)。我々は、クロノトープを文学の形式的な構成カテゴリーとして理解し ている。 文学的芸術的クロノトープでは、空間的および時間的指標が、慎重に考え抜かれた具体的な全体へと融合される。時間はいわば濃度を増し、実体化し、芸術的に 可視化される。同様に、空間は時間、プロット、歴史の動きに反応し、意味を持つようになる。軸の交差と指標の融合が、芸術的クロノトープの特徴である。 文学におけるクロノトープは、本質的な一般的な意義を持っている。クロノトープこそが、ジャンルや一般的な区別を定義しているといえるほどである。なぜな ら、文学におけるクロノトープの主要なカテゴリーは時間だからだ。形式的に構成的なカテゴリーとしてのクロノトープは、文学における人間のイメージも、か なりの程度決定している。人間のイメージは、常に本質的にクロノトピックである。 時間と空間を超越論的な経験の前提条件とみなしたカントとは異なり、バフチンは時間と空間を「最も直接的な現実の形」とみなしている。それらは単なる「数 学的な」抽象概念ではなく、具体的であり、文脈によって質的に変化する形態を持つ。[6] これはバフチン自身の研究対象、すなわち文学のジャンルの芸術的認知において特に顕著であるが、彼は他の文脈にも適用できることを示唆している。[7] 宇宙の異なる構造や秩序は、同じクロノトープ内で作用しているとは考えられない。例えば、アリのような生物のクロノトープは、ゾウのような生物のクロノ トープや、星や銀河のようなまったく異なる秩序の構造のクロノトープとは質的に異なる。人間の世界そのものにも、質的に異なる時間と空間の融合によって定 義される、多種多様な社会活動がある。[8] |

| Examples and use in other sciences The concept of the chronotope has been widely used in literary studies. The scholar Timo Müller for example argued that analysis of chronotopes highlights the environmental dimension of literary texts because it draws attention to the concrete physical spaces in which stories take place. Müller discusses the chronotope of the road, which for Bakhtin was a meeting place but in recent literature no longer brings people together in this way because automobiles have changed the way we perceive the time and space of the road. Car drivers want to minimize the time they spend on the road. They are rarely interested in the road as a physical space, the natural environment around the road, or the environmental implications of their driving. This contrasts with earlier literary examples such as Robert Frost's poem "The Road Not Taken" or John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath, where the road is described as part of the natural environment and the travelers are interested in that environment.[9] Linguistic anthropologist Keith Basso invoked "chronotopes" in discussing Western [Apache] stories linked with places. In the 1980s when Basso was writing, geographic features reminded the Western Apache of "the moral teachings of their history" by recalling to mind events that occurred there in important moral narratives. By merely mentioning "it happened at [the place called] 'men stand above here and there,'" storyteller Nick Thompson could remind locals of the dangers of joining "with outsiders against members of their own community." Geographic features in the Western Apache landscape are chronotopes, Basso says, in precisely the way Bakhtin defines the term when he says they are "points in the geography of a community where time and space intersect and fuse. Time takes on flesh and becomes visible for human contemplation; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time and history and the enduring character of a people. ...Chronotopes thus stand as monuments to the community itself, as symbols of it, as forces operating to shape its members' images of themselves" (qtd. in Basso 1984: 44–45). Anthropologist of syncretism Safet HadžiMuhamedović built upon Bakhtin’s term in his ethnography of the Field of Gacko in the southeastern Bosnian highlands. In Waiting for Elijah: Time and Encounter in a Bosnian Landscape, he argued that people and landscapes may sometimes be trapped between timespaces and thus "schizochronotopic" (from the Greek σχίζειν (skhizein): "to split").[10] He described two overarching chronotopes as "collective timespace themes", both of which relied on certain kinds of past and laid claims to the Field’s future. One was told through proximities, the other through distances between religious communities. For HadžiMuhamedović, schizochronotopia is a rift occurring within the same body/landscape, through which the past and the present of place have rendered each other unbidden. The concept of chronotope is also used in tourism research. Sociologist Hasso Spode explains the emergence of tourism in the 18th century as "time travel backwards". The tourist space thus functions as a romantic chronotopia.[11] Anthropologist Antonio Nogués-Pedregal regards the touristic consuming and shaping of places as a chronotope.[12] The chronotope has also been adopted for the analysis of classroom events and conversations, for example by Raymond Brown and Peter Renshaw in order to view "student participation in the classroom as a dynamic process constituted through the interaction of past experience, ongoing involvement, and yet-to-be-accomplished goals" (2006: 247–259). Kumpulainen, Mikkola, and Jaatinen (2013) examined the space–time configurations of students’ technology-mediated creative learning practices over a year-long school musical project in a Finnish elementary school. The findings of their study suggest that "blended practices appeared to break away from traditional learning practices, allowing students to navigate in different time zones, spaces, and places with diverse tools situated in their formal and informal lives" (2013: 53). |

他の学問分野での例と使用 クロノトープの概念は文学研究において広く用いられている。例えば、ティモ・ミュラーはクロノトープの分析は物語の舞台となる具体的な物理的空間への注目 を促すため、文学的テキストの環境的側面を浮き彫りにすると主張している。ミュラーはバフチンの時代には出会いの場であったが、近年の文学では自動車が道 路の時間と空間に対する認識を変えたため、もはや人々をこのように結びつけることはなくなった「道路」のクロノトープについて論じている。車の運転手は道 路で過ごす時間を最小限に抑えたいと思っている。彼らは道路を物理的な空間として、あるいは道路周辺の自然環境や運転が環境に及ぼす影響として捉えること はほとんどない。これは、ロバート・フロストの詩「The Road Not Taken」やジョン・スタインベックの小説『怒りの葡萄』など、道路が自然環境の一部として描写され、旅人がその環境に関心を持っているという、以前の 文学作品の例とは対照的である。 言語人類学者のキース・バソは、場所と結びついた西部[アパッチ族]の物語を論じる際に「クロノトープ」という概念を提起した。バソが執筆した1980年 代には、地理的特徴が重要な道徳的物語の舞台となった出来事を想起させることで、西部アパッチ族の人々に「彼らの歴史の道徳的教え」を思い出させていた。 「『男たちがあちこちに立っている』と呼ばれる場所で起こったこと」について語るだけで、語り部であるニック・トンプソンは地元民に「部外者と一緒になっ て自分たちのコミュニティのメンバーに敵対すること」の危険性を思い出させることができた。バホは、西部アパッチ族の風景における地理的特徴は、バフチン が「時間と空間が交差し融合するコミュニティの地理上の地点」と定義した言葉の正確な意味での「クロノトープ」であると述べている。時間というものは実体 化し、人間の思索の対象として目に見えるものとなる。同様に、空間もまた、時間や歴史、そして人々の永続的な性格の動きに反応するものとなる。... したがって、クロノトープは、そのコミュニティ自体の記念碑であり、その象徴であり、その構成員が自分自身をイメージする際に作用する力となるのである。 (Basso 1984: 44–45 より引用) 人類学者のSafet HadžiMuhamedovićは、バフチンの用語を基に、ボスニア南東部の高地にあるガツコの民族誌を構築した。著書『イライジャを待ちながら: ボスニアの風景における時間と遭遇」の中で、彼は、人々や風景が時空間に挟まれてしまうことがあり、そのため「シュゾクロノトピア (schizochronotopia)」(ギリシャ語のσχίζειν(スキゼイン)「分離する」に由来する)となることがあると論じた。[10] 彼は、2つの包括的なクロノトープを「集合的時空テーマ」として説明し、どちらも特定の種類の過去に依存し、フィールドの未来を主張していると述べた。一 方は宗教的コミュニティ間の近さを通じて語られ、もう一方は距離を通じて語られた。ハジ・ムハメドヴィッチにとって、シュゾクロノトピアとは、同一の身体 /風景内に生じる亀裂であり、それによってその場所の過去と現在が互いに引き離される。 クロノトープの概念は、観光研究でも用いられている。社会学者のハッソ・スポードは、18世紀における観光の台頭を「過去へのタイムトラベル」と説明して いる。このように、観光空間はロマンチックなクロノトープとして機能している。[11]人類学者のアントニオ・ノゲス=ペドレガルは、観光客による場所の 消費と形成をクロノトープとみなしている。[12] クロノトープは、教室での出来事や会話の分析にも採用されている。例えば、レイモンド・ブラウンとピーター・レンショウは、「教室における生徒の参加を、 過去の経験、進行中の関与、そしてまだ達成されていない目標の相互作用によって構成される動的なプロセスとして捉える」ために、クロノトープを採用してい る(2006: 247–259)。Kumpulainen、Mikkola、Jaatinen(2013)は、フィンランドの小学校における1年間にわたるミュージカル プロジェクトにおける、テクノロジーを介した生徒の創造的な学習実践の時空間構成を調査した。彼らの研究結果は、「ブレンド学習は従来の学習方法から脱却 し、生徒たちがフォーマルおよびインフォーマルな生活の場にある多様なツールを活用して、異なる時間帯、空間、場所をナビゲートすることを可能にする」こ とを示唆している(2013: 53)。 |

| Mikhail Bakhtin The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M.M. Bakhtin Logosphere Literary theory Philosophy of language Spacetime |

ミハイル・バフチン 対話的想像力:M.M.バフチンによる4つのエッセイ ロゴスフィア 文学理論 言語哲学 時空 |

**

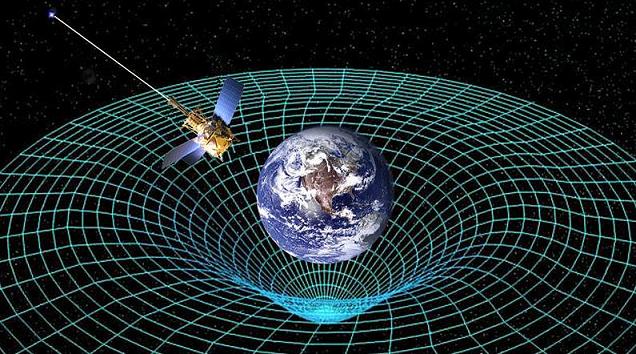

| In physics, spacetime,

also called the space-time continuum, is a mathematical model that

fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into

a single four-dimensional continuum. Spacetime diagrams are useful in

visualizing and understanding relativistic effects, such as how

different observers perceive where and when events occur. Until the turn of the 20th century, the assumption had been that the three-dimensional geometry of the universe (its description in terms of locations, shapes, distances, and directions) was distinct from time (the measurement of when events occur within the universe). However, space and time took on new meanings with the Lorentz transformation and special theory of relativity. In 1908, Hermann Minkowski presented a geometric interpretation of special relativity that fused time and the three spatial dimensions into a single four-dimensional continuum now known as Minkowski space. This interpretation proved vital to the general theory of relativity, wherein spacetime is curved by mass and energy. |

物理学において、時空(時空連続体とも呼ばれる)とは、3つの空間次元と1つの時間次元を融合させた4次元の連続体である数学モデルである。時空図は、異なる観察者がイベントの発生場所と発生時期をどのように認識するかなど、相対論的効果を視覚化し理解するのに役立つ。 20世紀に入るまでは、宇宙の3次元幾何学(位置、形状、距離、方向の表現)と時間(宇宙でいつ出来事が起こるかの測定)は別物であると考えられていた。しかし、ローレンツ変換と特殊相対性理論により、空間と時間に新たな意味が与えられた。 1908年、ヘルマン・ミンコフスキーは特殊相対性理論を幾何学的に解釈し、時間と3つの空間次元を融合して、現在ミンコフスキー空間として知られる4次 元の単一連続体へと導いた。この解釈は、質量とエネルギーによって時空が湾曲する一般相対性理論にとって不可欠なものであった。 |

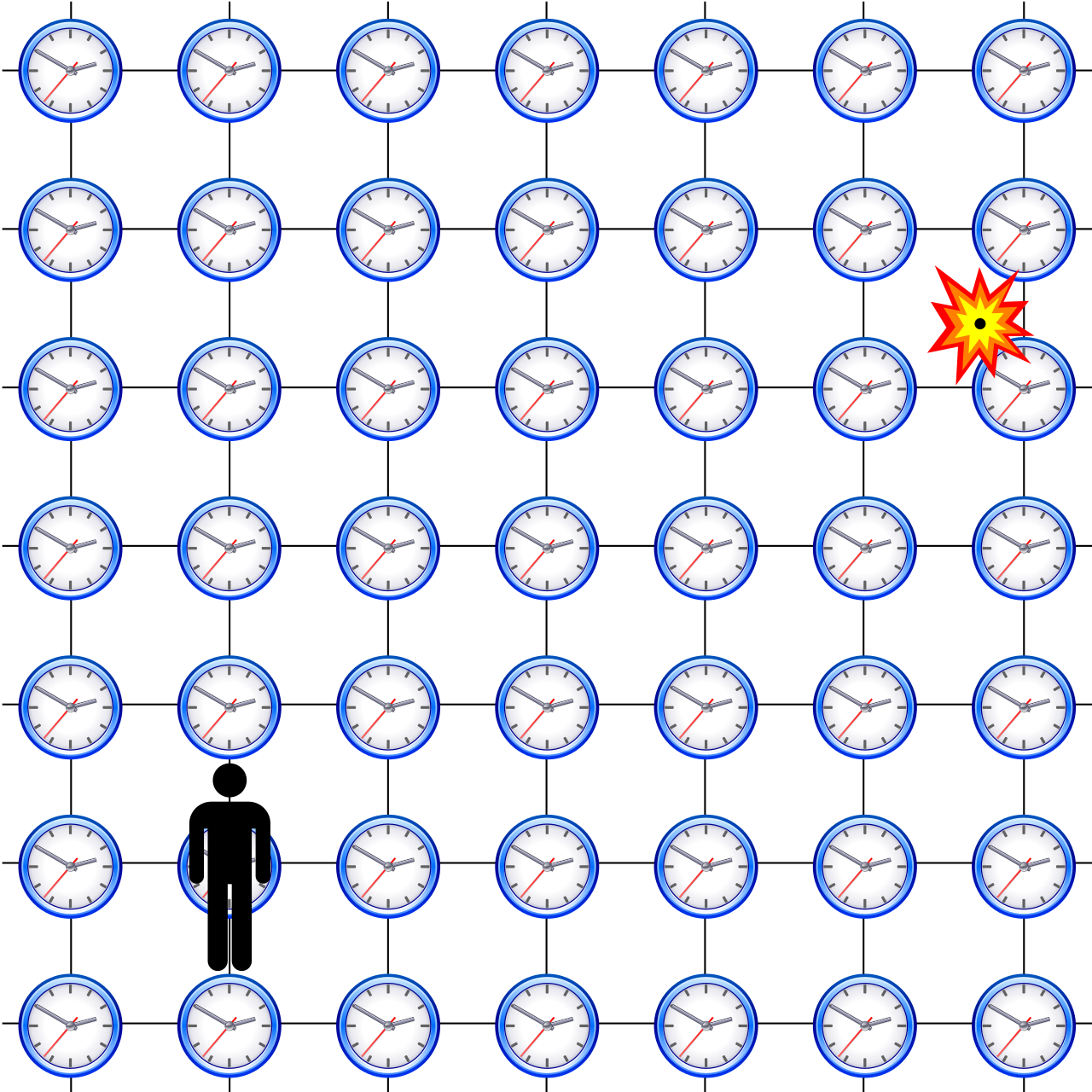

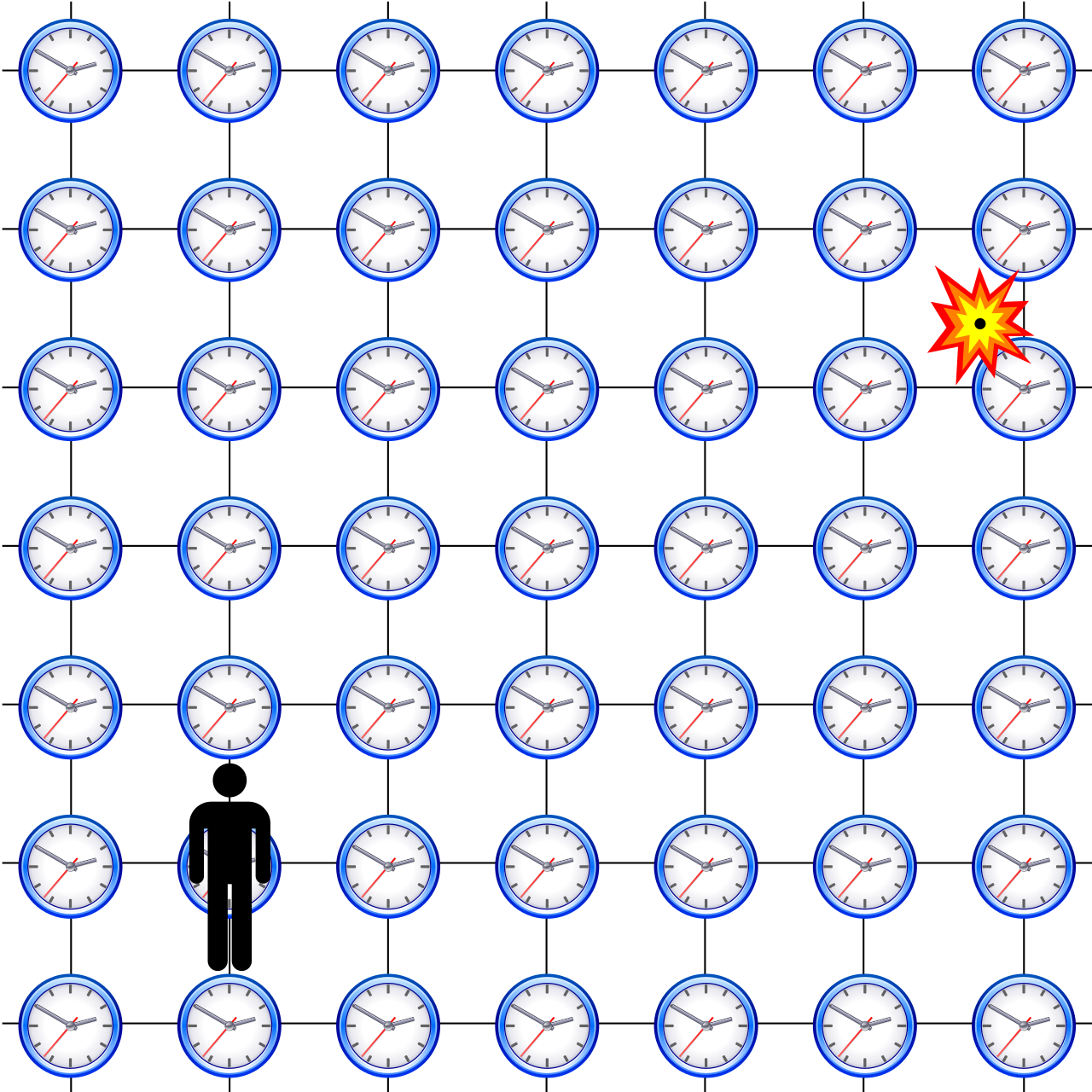

| Fundamentals Definitions Non-relativistic classical mechanics treats time as a universal quantity of measurement that is uniform throughout, is separate from space, and is agreed on by all observers. Classical mechanics assumes that time has a constant rate of passage, independent of the observer's state of motion, or anything external.[1] It assumes that space is Euclidean: it assumes that space follows the geometry of common sense.[2] In the context of special relativity, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space, because the observed rate at which time passes for an object depends on the object's velocity relative to the observer.[3]: 214–217 General relativity provides an explanation of how gravitational fields can slow the passage of time for an object as seen by an observer outside the field. In ordinary space, a position is specified by three numbers, known as dimensions. In the Cartesian coordinate system, these are often called x, y and z. A point in spacetime is called an event, and requires four numbers to be specified: the three-dimensional location in space, plus the position in time (Fig. 1). An event is represented by a set of coordinates x, y, z and t.[4] Spacetime is thus four-dimensional. Unlike the analogies used in popular writings to explain events, such as firecrackers or sparks, mathematical events have zero duration and represent a single point in spacetime.[5] Although it is possible to be in motion relative to the popping of a firecracker or a spark, it is not possible for an observer to be in motion relative to an event. The path of a particle through spacetime can be considered to be a sequence of events. The series of events can be linked together to form a curve that represents the particle's progress through spacetime. That path is called the particle's world line.[6]: 105 Mathematically, spacetime is a manifold, which is to say, it appears locally "flat" near each point in the same way that, at small enough scales, the surface of a globe appears to be flat.[7] A scale factor, � {\displaystyle c} (conventionally called the speed-of-light) relates distances measured in space to distances measured in time. The magnitude of this scale factor (nearly 300,000 kilometres or 190,000 miles in space being equivalent to one second in time), along with the fact that spacetime is a manifold, implies that at ordinary, non-relativistic speeds and at ordinary, human-scale distances, there is little that humans might observe that is noticeably different from what they might observe if the world were Euclidean. It was only with the advent of sensitive scientific measurements in the mid-1800s, such as the Fizeau experiment and the Michelson–Morley experiment, that puzzling discrepancies began to be noted between observation versus predictions based on the implicit assumption of Euclidean space.[8]  Figure 1-1. Each location in spacetime is marked by four numbers defined by a frame of reference: the position in space, and the time, which can be visualized as the reading of a clock located at each position in space. The 'observer' synchronizes the clocks according to their own reference frame. In special relativity, an observer will, in most cases, mean a frame of reference from which a set of objects or events is being measured. This usage differs significantly from the ordinary English meaning of the term. Reference frames are inherently nonlocal constructs, and according to this usage of the term, it does not make sense to speak of an observer as having a location.[9] In Fig. 1-1, imagine that the frame under consideration is equipped with a dense lattice of clocks, synchronized within this reference frame, that extends indefinitely throughout the three dimensions of space. Any specific location within the lattice is not important. The latticework of clocks is used to determine the time and position of events taking place within the whole frame. The term observer refers to the whole ensemble of clocks associated with one inertial frame of reference.[9]: 17–22 In this idealized case, every point in space has a clock associated with it, and thus the clocks register each event instantly, with no time delay between an event and its recording. A real observer, will see a delay between the emission of a signal and its detection due to the speed of light. To synchronize the clocks, in the data reduction following an experiment, the time when a signal is received will be corrected to reflect its actual time were it to have been recorded by an idealized lattice of clocks.[9]: 17–22 In many books on special relativity, especially older ones, the word "observer" is used in the more ordinary sense of the word. It is usually clear from context which meaning has been adopted. Physicists distinguish between what one measures or observes, after one has factored out signal propagation delays, versus what one visually sees without such corrections. Failing to understand the difference between what one measures and what one sees is the source of much confusion among students of relativity.[10] |

基礎 定義 非相対論的な古典力学では、時間は普遍的な測定量であり、空間とは別個のものであり、すべての観察者によって合意されているものとして扱われる。古典力学 では、時間の経過速度は一定であり、観察者の運動状態や外部の要因とは無関係であると仮定されている。[1] また、空間はユークリッド的であると仮定されている。すなわち、空間は常識的な幾何学に従うと仮定されている。[2] 特殊相対性理論の文脈では、時間と空間の3次元は切り離すことができない。なぜなら、ある物体が経過する速度は、観察者に対するその物体の速度に依存する からである。[3]: 214–217 一般相対性理論では、重力場が、その場外にいる観察者から見た物体の時間の経過を遅らせる仕組みを説明している。 通常の空間では、位置は3つの数値によって特定され、これらは次元として知られている。デカルト座標系では、これらはしばしばx、y、zと呼ばれる。時空 の一点は事象と呼ばれ、特定するには4つの数値が必要となる。すなわち、空間における3次元の位置と、時間における位置である(図1)。事象は、x、y、 z、tの座標の集合によって表される。[4] したがって、時空は4次元である。 爆竹や火花などの出来事を説明するために一般向けに書かれた文献で用いられている類似例とは異なり、数学的な出来事は持続時間がゼロであり、時空間の単一 点を表す。[5] 爆竹や火花が弾けることに対して相対的に運動することは可能であるが、出来事に対して相対的に運動することは観察者にとって不可能である。 時空を貫く粒子の軌道は、一連の事象と見なすことができる。一連の事象は、時空を貫く粒子の進行を表す曲線を形成するように互いに結びつけることができる。その軌道は、粒子の世界線と呼ばれる。[6]:105 数学的には、時空は多様体であり、つまり、十分に小さいスケールでは地球の表面が平らに見えるのと同じように、各点の近くでは局所的に「平ら」に見える。[7] スケール因子、 � {\displaystyle c}(慣例的に光速と呼ばれる)は、空間で測定された距離と時間で測定された距離を関連付ける。このスケールファクターの大きさ(空間における約30万キ ロメートルまたは19万マイルは、時間における1秒に相当する)と、時空が多様体であるという事実から、通常の相対論的ではない速度と通常の人間的なス ケールの距離では、人間が観察するものは、世界がユークリッド的であった場合に観察するものとは著しく異なることはほとんどないことが示唆される。フィ ゾーの実験やマイケルソン・モーリーの実験など、1800年代半ばに精密な科学的測定が登場して初めて、ユークリッド空間を暗黙の前提とする予測と観測と の間に不可解な食い違いが指摘されるようになった。[8]  図1-1. 時空の各位置は、参照フレームによって定義された4つの数値によって示される。参照フレームとは、空間における位置と、空間上の各位置に置かれた時計の時刻を意味する。「観測者」は、自身の参照フレームに従って時計を同期させる。 特殊相対性理論では、観測者はほとんどの場合、物体や事象の集合が測定される参照フレームを意味する。この用法は通常の英語の意味とは大きく異なる。参照フレームは本質的に非局在的な構造であり、この用語の用法に従えば、観測者に位置があるという表現は意味をなさない。 図1-1において、考察中のフレームが、この参照フレーム内で同期した、空間内の3次元に無限に広がる高密度の格子状の時計を備えていると想像してみよ う。格子状の時計のどの特定の位置も重要ではない。格子状の時計は、フレーム全体で起こる事象の時間と位置を決定するために使用される。観測者という用語 は、ひとつの慣性参照系に関連するすべての時計の集合体を指す。[9]: 17–22 この理想的なケースでは、空間のあらゆる点にそれぞれ関連する時計が存在し、したがって、時計は各事象を即座に記録し、事象と記録の間に時間遅延は発生し ない。実際の観測者であれば、光速により信号の送信と検出の間に遅延が発生することを認識するだろう。時計を同期させるために、実験後のデータ解析におい て、信号が受信された時刻は、理想的な格子状に配置された時計によって記録されていたであろう実際の時刻に修正される。[9]: 17–22 物理学者は、信号伝播の遅延を考慮した後に測定または観察したものと、そのような補正を行わずに視覚的に見たものとの違いを区別している。測定したものと見たものとの違いを理解していないことが、相対性理論を学ぶ人々を混乱させる原因となっている。[10] |

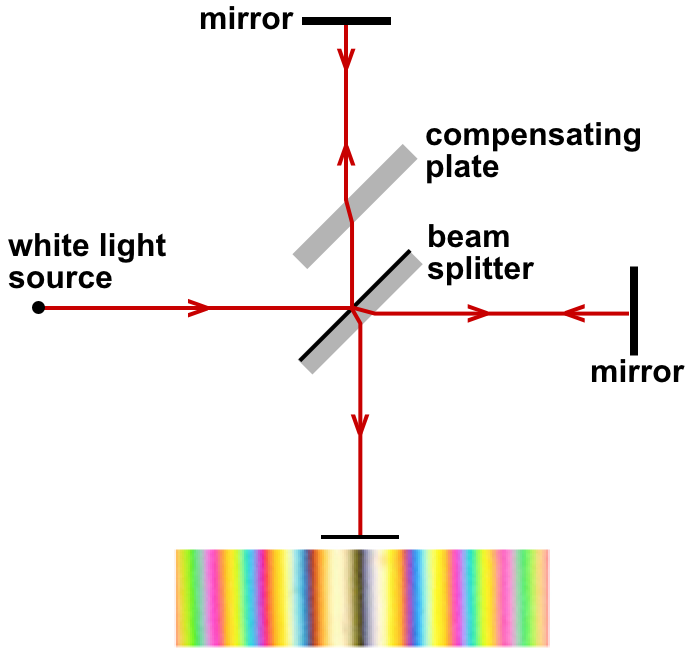

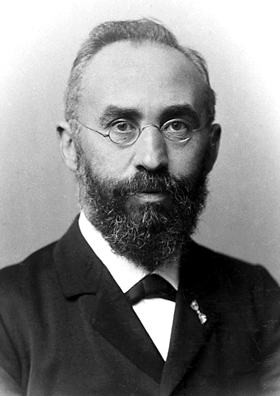

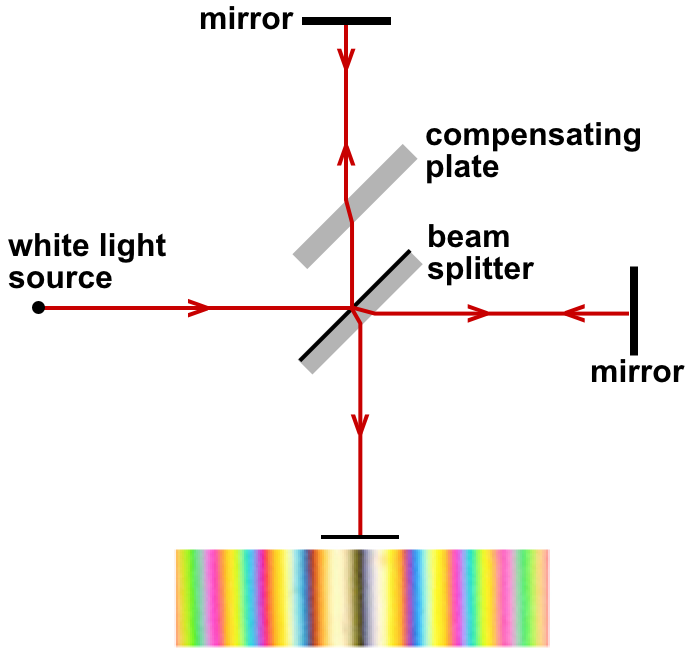

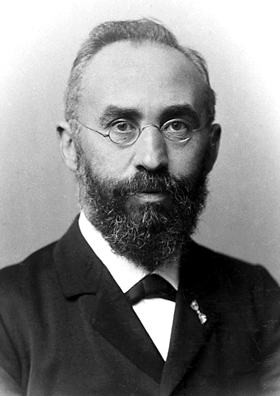

| History Main articles: History of special relativity and History of Lorentz transformations   Figure 1-2. Michelson and Morley expected that motion through the aether would cause a differential phase shift between light traversing the two arms of their apparatus. The most logical explanation of their negative result, aether dragging, was in conflict with the observation of stellar aberration. By the mid-1800s, various experiments such as the observation of the Arago spot and differential measurements of the speed of light in air versus water were considered to have proven the wave nature of light as opposed to a corpuscular theory.[11] Propagation of waves was then assumed to require the existence of a waving medium; in the case of light waves, this was considered to be a hypothetical luminiferous aether.[note 1] The various attempts to establish the properties of this hypothetical medium yielded contradictory results. For example, the Fizeau experiment of 1851, conducted by French physicist Hippolyte Fizeau, demonstrated that the speed of light in flowing water was less than the sum of the speed of light in air plus the speed of the water by an amount dependent on the water's index of refraction.[12] Among other issues, the dependence of the partial aether-dragging implied by this experiment on the index of refraction (which is dependent on wavelength) led to the unpalatable conclusion that aether simultaneously flows at different speeds for different colors of light.[13] The Michelson–Morley experiment of 1887 (Fig. 1-2) showed no differential influence of Earth's motions through the hypothetical aether on the speed of light, and the most likely explanation, complete aether dragging, was in conflict with the observation of stellar aberration.[8]  Hendrik Antoon Lorentz George Francis FitzGerald in 1889,[14] and Hendrik Lorentz in 1892, independently proposed that material bodies traveling through the fixed aether were physically affected by their passage, contracting in the direction of motion by an amount that was exactly what was necessary to explain the negative results of the Michelson–Morley experiment. No length changes occur in directions transverse to the direction of motion. By 1904, Lorentz had expanded his theory such that he had arrived at equations formally identical with those that Einstein was to derive later, i.e. the Lorentz transformation.[15] As a theory of dynamics (the study of forces and torques and their effect on motion), his theory assumed actual physical deformations of the physical constituents of matter.[16]: 163–174 Lorentz's equations predicted a quantity that he called local time, with which he could explain the aberration of light, the Fizeau experiment and other phenomena. |

歴史 主な記事:特殊相対性理論の歴史、ローレンツ変換の歴史   図1-2 ミシェルソンとモーリーは、エーテル中を動くことによって、彼らの装置の2つのアームを横切る光の間に位相差が生じることを期待していた。彼らの否定的な結果に対する最も論理的な説明である「エーテルの引きずり」は、星の視差の観測と矛盾していた。 1800年代半ばまでに、アラゴの黒点の観測や、空気中と水中での光速の差異測定など、さまざまな実験により、光の粒子説とは対照的な波動説が証明された と考えられていた。[11] 波の伝播には、波動を伝える媒体の存在が必要であると考えられていた。光波の場合、この仮説上の媒体は「光輝エーテル」であると考えられていた。[注1] この仮説上の媒体の特性を確定しようとするさまざまな試みは、矛盾する結果をもたらした。例えば、1851年にフランスの物理学者フィゾーが実施したフィ ゾーの実験では、流水中の光の速度は、空気中の光の速度と水の速度の合計よりも小さく、その差は水の屈折率に依存することが示された。 この実験で示唆された部分的なエーテルの抵抗が屈折率(これは波長に依存する)に依存するという問題点の1つとして、エーテルが同時に異なる色の光に対し て異なる速度で流れるという不愉快な結論が導かれた。[13] 1887年のマイケルソン・モーリーの実験(図1-2)では 1887年のマイケルソン・モーリーの実験(図1-2)では、仮説上のエーテルを介した地球の運動が光速に影響を及ぼすことは示されず、最も可能性の高い 説明である完全なエーテルの引きずり現象は、恒星の視差の観測と矛盾していた。  Hendrik Antoon Lorentz ジョージ・フランシス・フィッツジェラルドは1889年[14]、ヘンドリック・ローレンツは1892年に、固定エーテルの中を移動する物質体は、その通 過によって物理的に影響を受け、マイケルソン・モーリーの負の結果を説明するために必要な量だけ運動方向に収縮するという理論をそれぞれ独自に提唱した。 運動方向と直交する方向では長さの変化は起こらない。 1904年までにローレンツは自身の理論を発展させ、後にアインシュタインが導き出すことになる公式、すなわちローレンツ変換と形式的に同一の公式に到達 していた。[15] 力学(力やトルク、それらが運動に及ぼす影響の研究)の理論として、 彼の理論は、物質の物理的構成要素の実際の物理的変形を想定していた。[16]:163-174 ローレンツの式は、ローカルタイムと呼ばれる量を予測し、それによって光の異常、フィゾーの実験、その他の現象を説明することができた。 |

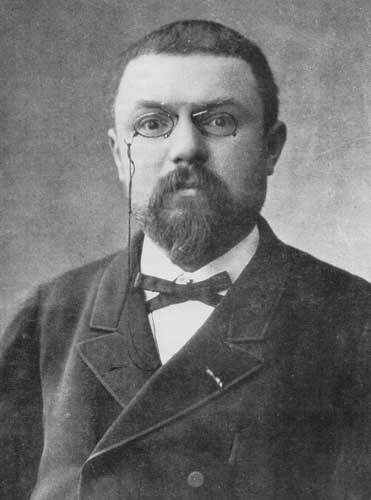

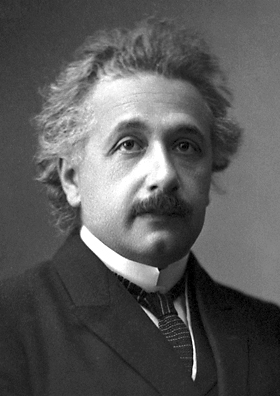

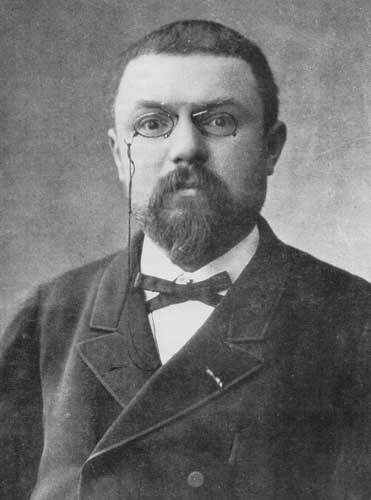

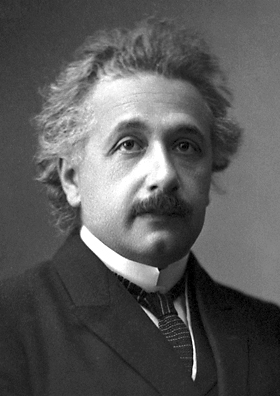

Henri Poincaré Henri Poincaré was the first to combine space and time into spacetime.[17][18]: 73–80, 93–95 He argued in 1898 that the simultaneity of two events is a matter of convention.[19][note 2] In 1900, he recognized that Lorentz's "local time" is actually what is indicated by moving clocks by applying an explicitly operational definition of clock synchronization assuming constant light speed.[note 3] In 1900 and 1904, he suggested the inherent undetectability of the aether by emphasizing the validity of what he called the principle of relativity. In 1905/1906[20] he mathematically perfected Lorentz's theory of electrons in order to bring it into accordance with the postulate of relativity. While discussing various hypotheses on Lorentz invariant gravitation, he introduced the innovative concept of a 4-dimensional spacetime by defining various four vectors, namely four-position, four-velocity, and four-force.[21][22] He did not pursue the 4-dimensional formalism in subsequent papers, however, stating that this line of research seemed to "entail great pain for limited profit", ultimately concluding "that three-dimensional language seems the best suited to the description of our world".[22] Even as late as 1909, Poincaré continued to describe the dynamical interpretation of the Lorentz transform.[16]: 163–174  Albert Einstein In 1905, Albert Einstein analyzed special relativity in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies without reference to forces) rather than dynamics. His results were mathematically equivalent to those of Lorentz and Poincaré. He obtained them by recognizing that the entire theory can be built upon two postulates: the principle of relativity and the principle of the constancy of light speed. His work was filled with vivid imagery involving the exchange of light signals between clocks in motion, careful measurements of the lengths of moving rods, and other such examples.[23][note 4] Einstein in 1905 superseded previous attempts of an electromagnetic mass–energy relation by introducing the general equivalence of mass and energy, which was instrumental for his subsequent formulation of the equivalence principle in 1907, which declares the equivalence of inertial and gravitational mass. By using the mass–energy equivalence, Einstein showed that the gravitational mass of a body is proportional to its energy content, which was one of the early results in developing general relativity. While it would appear that he did not at first think geometrically about spacetime,[3]: 219 in the further development of general relativity, Einstein fully incorporated the spacetime formalism. |

Henri Poincaré アンリ・ポアンカレは、空間と時間を時空に統合した最初の人物である。[17][18]: 73-80, 93-95 彼は1898年に、2つの事象の同時性は慣習の問題であると主張した。[19][注2] 1900年には、 ローレンツの「局所時間」は、光速が一定であると仮定した時計の同期化の明確な操作上の定義を適用することで、実際に動く時計が示すものと同じであること を認識した。[注3] 1900年と1904年には、彼が相対性原理と呼んだものの妥当性を強調することで、エーテルの固有の検出不能性を示唆した。1905年から1906年に かけて[20]、彼は相対性理論の仮定に一致させるために、ローレンツの電子理論を数学的に完成させた。 ローレンツ不変の重力に関するさまざまな仮説について議論する中で、彼は4つの位置、4つの速度、4つの力という4つの4ベクトルを定義することで、4次 元時空という革新的な概念を導入した。[21][22] しかし、彼はその後の論文では4次元形式を追求することはなく、 「限られた利益のために大きな苦痛を伴う」と考え、最終的に「3次元の言語が我々の世界の記述に最も適している」と結論付けた。[22] 1909年になっても、ポアンカレはローレンツ変換の力学的な解釈を説明し続けていた。[16]:163-174  Albert Einstein 1905年、アルバート・アインシュタインは特殊相対性理論を力学(力学的考察を伴わない運動体の研究)ではなく、運動学の観点から分析した。彼の結果 は、ローレンツとポアンカレのものと数学的に同等であった。彼は、相対性原理と光速不変の原理という2つの仮定に基づいて理論全体を構築できることに気づ き、その成果を得た。彼の研究は、運動中の時計間の光信号のやりとり、動く棒の長さの慎重な測定、その他の類似例など、生き生きとしたイメージに満ちてい た。[23][注4] アインシュタインは1905年、それまでの電磁気学における質量とエネルギーの関係に関する試みを、質量とエネルギーの一般的な等価性を導入することで置 き換えた。これは、1907年に彼が発表した等価原理の定式化に役立った。等価原理は、慣性質量と重力質量が等価であることを宣言するものである。質量と エネルギーの等価性を用いることで、アインシュタインは物体の重力質量がそのエネルギー含有量に比例することを示した。これは一般相対性理論を展開する初 期の成果のひとつであった。アインシュタインは当初、時空について幾何学的に考えていなかったようであるが[3]:219、一般相対性理論のさらなる発展 において、アインシュタインは時空の形式を完全に組み込んだ。 |

Hermann Minkowski When Einstein published in 1905, another of his competitors, his former mathematics professor Hermann Minkowski, had also arrived at most of the basic elements of special relativity. Max Born recounted a meeting he had made with Minkowski, seeking to be Minkowski's student/collaborator:[25] I went to Cologne, met Minkowski and heard his celebrated lecture 'Space and Time' delivered on 2 September 1908. [...] He told me later that it came to him as a great shock when Einstein published his paper in which the equivalence of the different local times of observers moving relative to each other was pronounced; for he had reached the same conclusions independently but did not publish them because he wished first to work out the mathematical structure in all its splendor. He never made a priority claim and always gave Einstein his full share in the great discovery. Minkowski had been concerned with the state of electrodynamics after Michelson's disruptive experiments at least since the summer of 1905, when Minkowski and David Hilbert led an advanced seminar attended by notable physicists of the time to study the papers of Lorentz, Poincaré et al. Minkowski saw Einstein's work as an extension of Lorentz's, and was most directly influenced by Poincaré.[26] |

Hermann Minkowski アインシュタインが1905年に発表したとき、彼のライバルの一人であり、かつての数学の教授であったヘルマン・ミンコフスキーも特殊相対性理論の基本要 素のほとんどに到達していた。マックス・ボルンはミンコフスキーと会ったときのことを回想し、ミンコフスキーの弟子兼共同研究者になろうとしていたと述べ ている。 ケルンに行ってミンコフスキーに会い、1908年9月2日に行われた彼の有名な講義「時空」を聴いた。[...] 後に彼から聞いた話によると、アインシュタインが、互いに相対運動する観測者における異なる局所時間の等価性を主張した論文を発表したとき、それは彼に とって大きな衝撃だったという。なぜなら、彼は独自に同じ結論に達していたが、その数学的構造をすべて明らかにすることを優先したため、論文を発表しな かったからだ。彼は決して優先権を主張することはなく、常にアインシュタインに偉大な発見の功績をすべて与えた。 ミンコフスキーは、少なくとも1905年の夏以降、マイケルソンの破壊的な実験以降の電磁気学の状況に関心を抱いていた。ミンコフスキーとデイヴィッド・ ヒルベルトは、当時の著名な物理学者たちが参加した高度なセミナーを主宰し、ローレンツ、ポアンカレなどの論文を研究していた。ミンコフスキーは、アイン シュタインの研究をローレンツの研究の延長と捉えており、最も直接的に影響を受けたのはポアンカレであった。[26] |

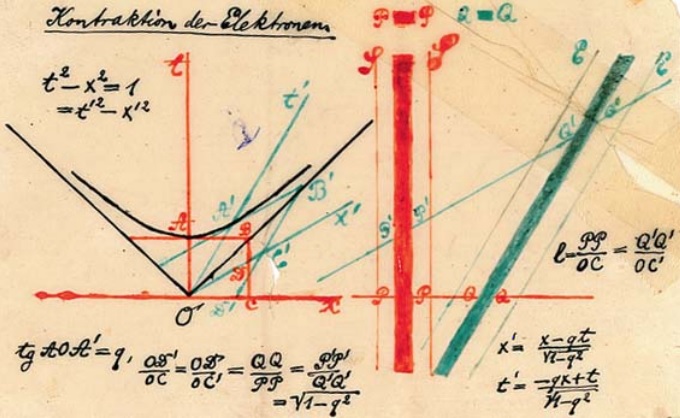

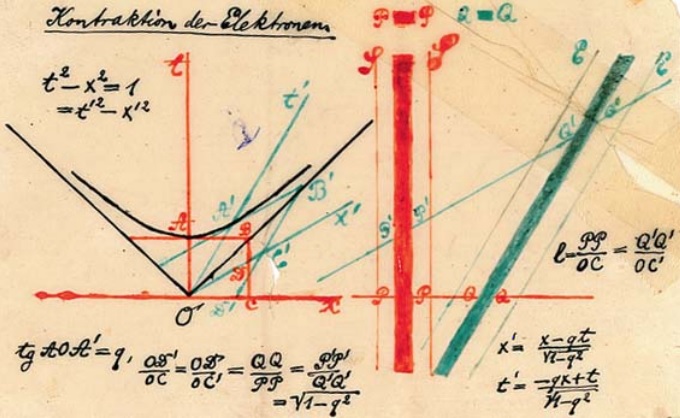

Figure 1–4. Hand-colored transparency presented by Minkowski in his 1908 Raum und Zeit lecture |

図1-4. ミンコフスキーが1908年の講演『空間と時間』で提示した手彩色の透視図 |

| On 5 November 1907 (a little

more than a year before his death), Minkowski introduced his geometric

interpretation of spacetime in a lecture to the Göttingen Mathematical

society with the title, The Relativity Principle (Das

Relativitätsprinzip).[note 5] On 21 September 1908, Minkowski presented

his talk, Space and Time (Raum und Zeit),[27] to the German Society of

Scientists and Physicians. The opening words of Space and Time include

Minkowski's statement that "Henceforth, space for itself, and time for

itself shall completely reduce to a mere shadow, and only some sort of

union of the two shall preserve independence." Space and Time included

the first public presentation of spacetime diagrams (Fig. 1-4), and

included a remarkable demonstration that the concept of the invariant

interval (discussed below), along with the empirical observation that

the speed of light is finite, allows derivation of the entirety of

special relativity.[note 6] The spacetime concept and the Lorentz group are closely connected to certain types of sphere, hyperbolic, or conformal geometries and their transformation groups already developed in the 19th century, in which invariant intervals analogous to the spacetime interval are used.[note 7] Einstein, for his part, was initially dismissive of Minkowski's geometric interpretation of special relativity, regarding it as überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit (superfluous learnedness). However, in order to complete his search for general relativity that started in 1907, the geometric interpretation of relativity proved to be vital. In 1916, Einstein fully acknowledged his indebtedness to Minkowski, whose interpretation greatly facilitated the transition to general relativity.[16]: 151–152 Since there are other types of spacetime, such as the curved spacetime of general relativity, the spacetime of special relativity is today known as Minkowski spacetime. |

1907年11月5日(彼の死の1年余り前)、ミンコフスキーはゲッ

ティンゲン数学協会の講演で「相対性原理(Das

Relativitätsprinzip)」というタイトルで時空の幾何学的解釈を提示した。[注5]

1908年9月21日、ミンコフスキーはドイツ科学者・医師協会で「時空(Raum und

Zeit)」[27]と題する講演を行った。『空間と時間』の冒頭には、ミンコフスキーの「今後は、空間それ自体と時間それ自体は完全に単なる影に還元さ

れ、2つの何らかの結合のみが独立性を維持する」という声明が含まれている。『時空』には、時空図(図1-4)の最初の公開版が含まれており、不変区間

(後述)の概念と、光の速度は有限であるという経験的観察を組み合わせることで、特殊相対性理論のすべてを導くことができるという驚くべき実証が含まれて

いる。 時空間の概念とローレンツ群は、19世紀にすでに開発されていたある種の球面、双曲、または共形幾何学とその変換群と密接に関連しており、時空間の間隔に類似した不変間隔が使用されている。[注7] アインシュタインは当初、ミンコフスキーの特殊相対性理論の幾何学的解釈を、überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit(余計な博識)として軽視していた。しかし、1907年に始まった一般相対性理論の探究を完結させるためには、相対性理論の幾 何学的解釈が不可欠であることが分かった。1916年、アインシュタインはミンコフスキーへの負債を完全に認めた。ミンコフスキーの解釈は一般相対性理論 への移行を大いに促進したのである。[16]:151-152 一般相対性理論の曲がった時空のような、時空には他のタイプもあるため、特殊相対性理論の時空は今日ではミンコフスキー時空として知られている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spacetime |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆