認識論

Epistemology

☆ This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

★エピステモロジー(Epistemology;

古代ギリシア語のἐπιστήμη (ἐπισE17↩τήμη)

'知識'、および-logyから)は、知識に関する哲学の一分野である。認識論者は、知識の性質、起源、範囲、認識論的正当化、信念の合理性、および様々

な関連する問題を研究する。現代の認識論における議論は、一般的に以下の4つの核となる分野に集約されている。

(1)真理や正当化など、知識の性質や信念が知識を構成するために必要な条件についての哲学的分析;

(2)知覚、理性、記憶、証言など、知識や正当化される信念の潜在的な情報源

(3)正当化された信念はすべて、正当化された基礎となる信念から導かれなけれ

ばならないのか、それとも正当化には首尾一貫した信念の集合だけが必要なのかなど、 知識の体系や正当化された信念の構造、

(4)哲学的懐疑論は、知識の可能性を問うものであり、懐疑論は私たちの通常の知識主張に脅威を与えるのか、懐疑的な議論に反論することは可能なのか、と

いった関連する問題である。

これらの議論やその他の議論において、認識論は「人は何を知っているのか」、「人が何かを知っているというのはどういうことか」、「正当化された信念は何

によって正当化されるのか」、「人は自分が知っていることをどうやって知るのか」といった問いに答えることを目的としている[4][1][5][6]。

(形式的認識論において)、「さまざまな種類の知識における変化の歴史的条件は何か?」(歴史的認識論において)といった問いを立てる。(歴史認識論にお

いて)、「認識論的探究の方法、目的、対象は何か?」

(メタ認識論において)、といった問いを立てる。(メタ認識論において)、そして「人々はどのようにして共に知っているのか?」(社会認識論において)で

ある。(社会認識論において)である。

| Epistemology

(/ɪˌpɪstəˈmɒlədʒi/ ⓘ ih-PISS-tə-MOL-ə-jee; from Ancient Greek ἐπιστήμη

(epistḗmē) 'knowledge', and -logy) is the branch of philosophy

concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature, origin, and

scope of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief,

and various related issues. Debates in contemporary epistemology are

generally clustered around four core areas:[1][2][3] The philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, such as truth and justification; Potential sources of knowledge and justified belief, such as perception, reason, memory, and testimony The structure of a body of knowledge or justified belief, including whether all justified beliefs must be derived from justified foundational beliefs or whether justification requires only a coherent set of beliefs; and, Philosophical scepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge, and related problems, such as whether scepticism poses a threat to our ordinary knowledge claims and whether it is possible to refute sceptical arguments. In these debates and others, epistemology aims to answer questions such as "What do people know?", "What does it mean to say that people know something?", "What makes justified beliefs justified?", and "How do people know that they know?"[4][1][5][6] Specialties in epistemology ask questions such as "How can people create formal models about issues related to knowledge?" (in formal epistemology), "What are the historical conditions of changes in different kinds of knowledge?" (in historical epistemology), "What are the methods, aims, and subject matter of epistemological inquiry?" (in metaepistemology), and "How do people know together?" (in social epistemology). |

エピステモロジー(Epistemology; 古代ギリシア語のἐπιστήμη (ἐπισE17↩τήμη)

'知識'、および-logyから)は、知識に関する哲学の一分野である。認識論者は、知識の性質、起源、範囲、認識論的正当化、信念の合理性、および様々

な関連する問題を研究する。現代の認識論における議論は、一般的に以下の4つの核となる分野に集約されている[1][2][3]。 (1)真理や正当化など、知識の性質や信念が知識を構成するために必要な条件についての哲学的分析; (2)知覚、理性、記憶、証言など、知識や正当化される信念の潜在的な情報源 (3)正当化された信念はすべて、正当化された基礎となる信念から導かれなけれ ばならないのか、それとも正当化には首尾一貫した信念の集合だけが必要なのかなど、 知識の体系や正当化された信念の構造、 (4)哲学的懐疑論は、知識の可能性を問うものであり、懐疑論は私たちの通常の知識主張に脅威を与えるのか、懐疑的な議論に反論することは可能なのか、と いった関連する問題である。 これらの議論やその他の議論において、認識論は「人は何を知っているのか」、「人が何かを知っているというのはどういうことか」、「正当化された信念は何 によって正当化されるのか」、「人は自分が知っていることをどうやって知るのか」といった問いに答えることを目的としている[4][1][5][6]。 (形式的認識論において)、「さまざまな種類の知識における変化の歴史的条件は何か?」(歴史的認識論において)といった問いを立てる。(歴史認識論にお いて)、「認識論的探究の方法、目的、対象は何か?」 (メタ認識論において)、といった問いを立てる。(メタ認識論において)、そして 「人々はどのようにして共に知っているのか?」(社会認識論において)である。(社会認識論において)である。 |

| Etymology The etymology of the word epistemology is derived from the ancient Greek epistēmē, meaning "knowledge, understanding, skill, scientific knowledge",[7][note 1] and the English suffix -ology, meaning "the study or discipline of (what is indicated by the first element)".[9] The word epistemology first appeared in 1847, in a review in New York's Eclectic Magazine : The title of one of the principal works of Fichte is 'Wissenschaftslehre,' which, after the analogy of technology ... we render epistemology.[10] The word was first used to present a philosophy in English by Scottish philosopher James Frederick Ferrier in 1854. It was the title of the first section of his Institutes of Metaphysics:[11] This section of the science is properly termed the Epistemology—the doctrine or theory of knowing, just as ontology is the science of being.... It answers the general question, 'What is knowing and the known?'—or more shortly, 'What is knowledge?'[12] |

語源 エピステモロジーの語源は、古代ギリシャ語で「知識、理解、技術、科学的知識」を意味するepistēmēに由来する[7][注釈 1]: フィヒテの主要な著作のタイトルのひとつは『Wissenschaftslehre』であり、これを技術になぞらえて......エピステモロジーと呼ぶ」[10]。 この言葉は、1854年にスコットランドの哲学者ジェイムズ・フレデリック・フェリアーによって、英語で哲学を提示するために初めて用いられた。これは彼の『形而上学入門』の第一節のタイトルであった[11]。 科学のこのセクションは、存在論が存在の科学であるのと同様に、認識論-知ることの教義または理論-と正しく呼ばれている...。この学問は、『知ること とは何か、知られることとは何か』という一般的な問いに答えるものであり、より短く言えば、『知識とは何か』という問いに答えるものである」[12]。 |

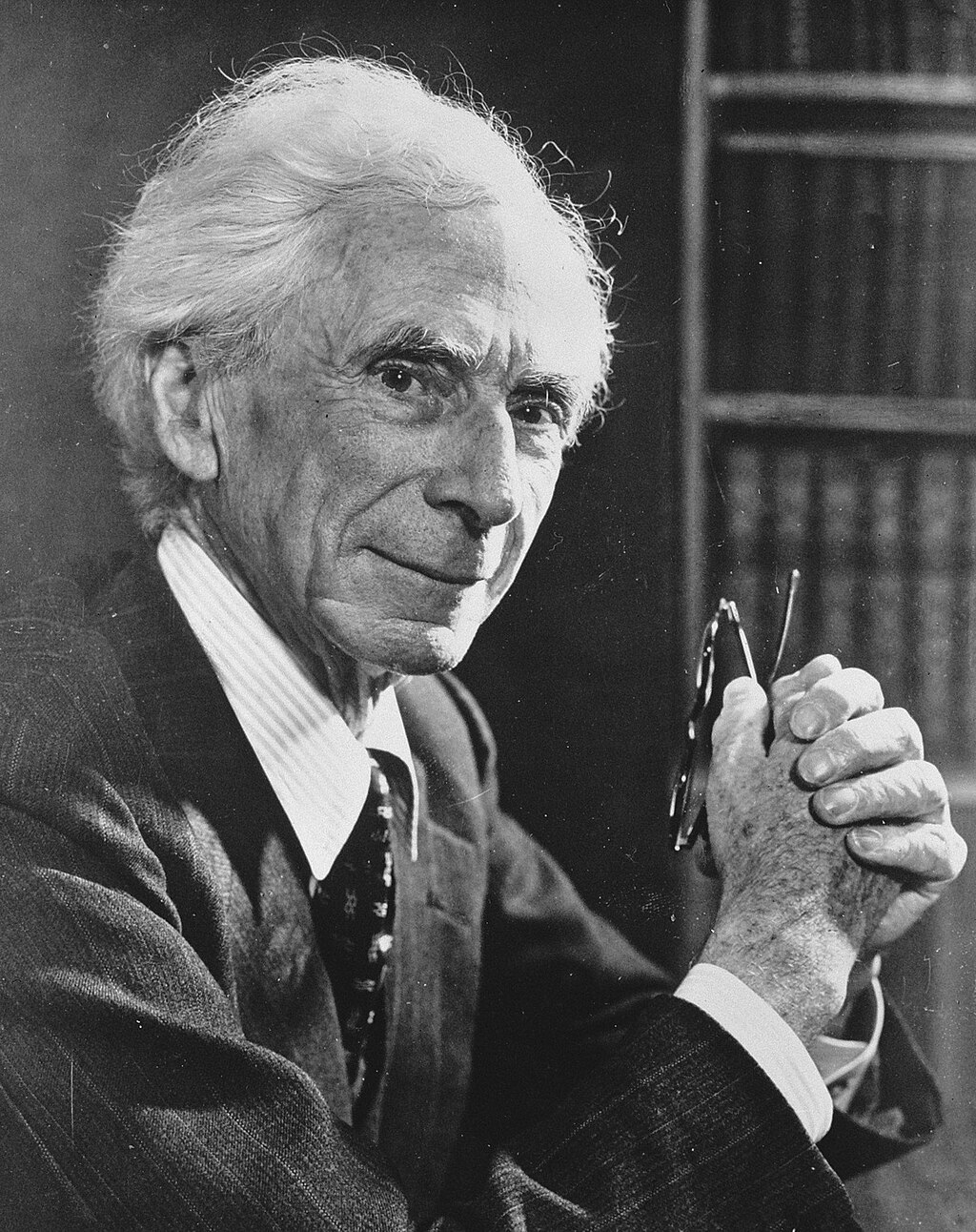

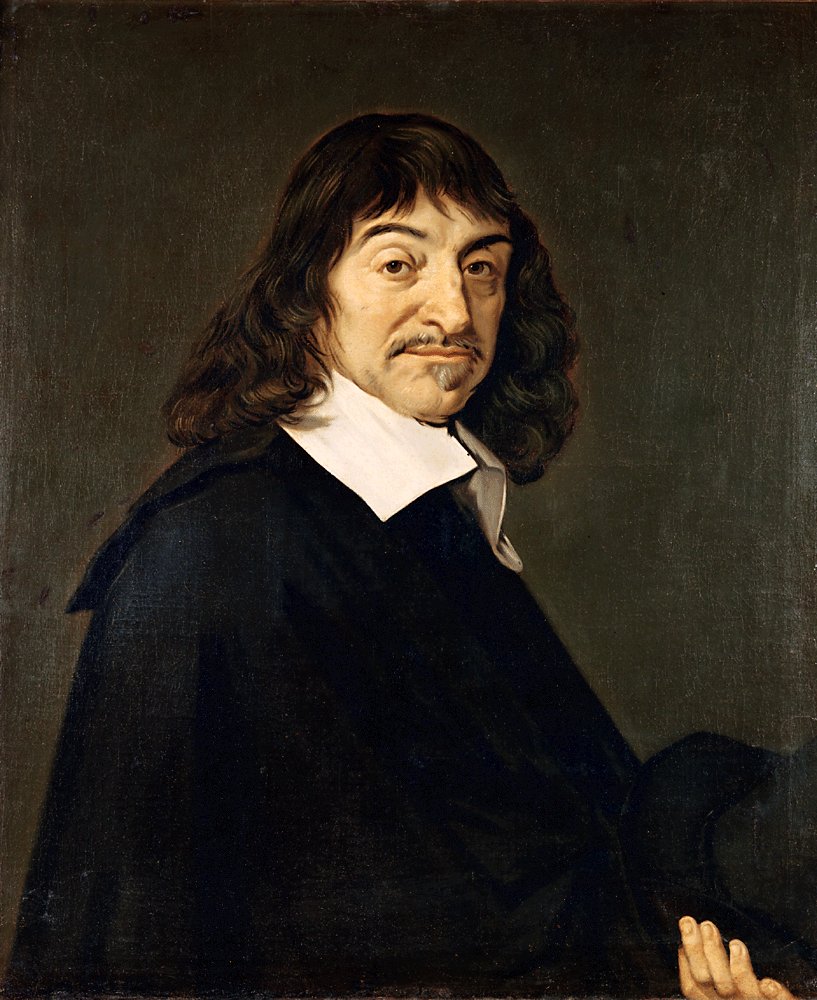

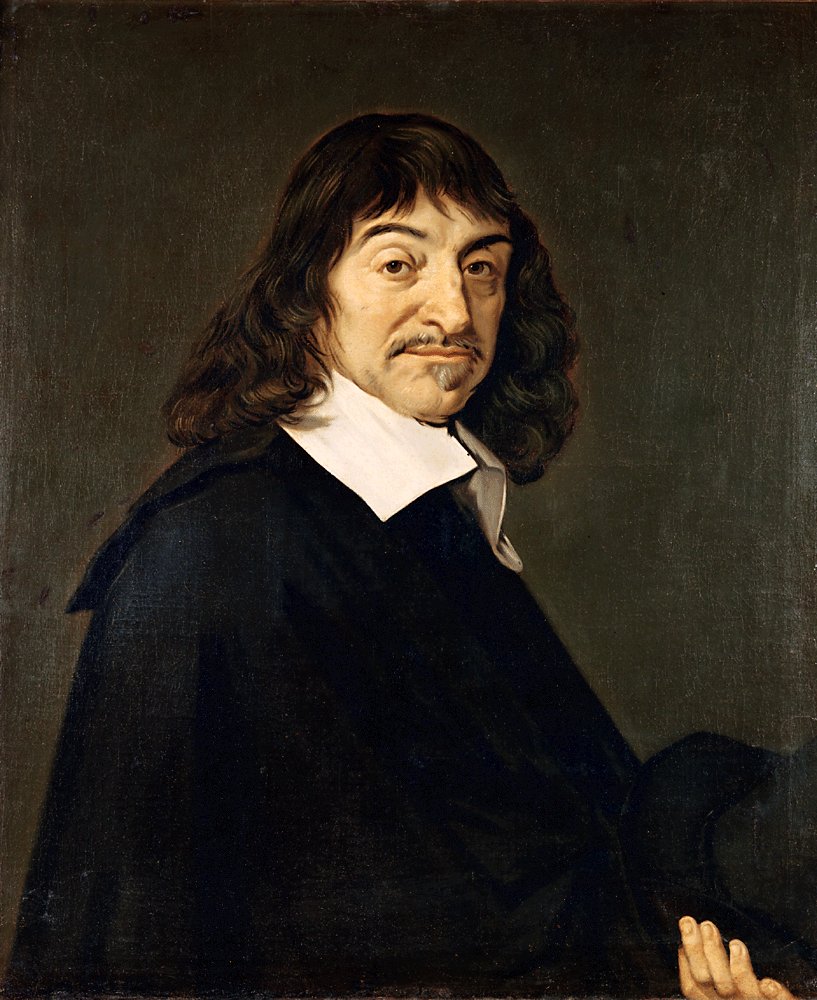

| Central concepts Knowledge  Bertrand Russell famously brought attention to the distinction between propositional knowledge and knowledge by acquaintance. Main article: Knowledge The entry "Knowledge How" of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy[13] mentions that introductory classes to epistemology often start their analysis of knowledge by pointing out three different senses of "knowing" something: "knowing that" (knowing the truth of propositions), "knowing how" (understanding how to perform certain actions), and "knowing by acquaintance" (directly perceiving an object, being familiar with it, or otherwise coming into contact with it). This modern teaching of epistemology is primarily concerned with the first of these forms of knowledge, propositional knowledge. All three senses of "knowing" can be seen in the ordinary use of the word. In mathematics, it can be known that 2 + 2 = 4, but there is also knowing how to add two numbers, and knowing a person (e.g., knowing other persons,[14][15] or knowing oneself), place (e.g., one's hometown), thing (e.g., cars), or activity (e.g., addition). While these distinctions are not explicit in English, they are explicitly made in other languages, including French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, German, and Dutch (although some languages closely related to English have been said to retain these verbs, such as Scots).[note 2]. In French, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, German, and Dutch 'to know (a person)' is translated using connaître, conhecer, conocer, a cunoaște, and kennen (both German and Dutch) respectively, whereas 'to know (how to do something)' is translated using savoir, saber (both Portuguese and Spanish), a şti, wissen, and weten. Modern Greek has the verbs γνωρίζω (gnorízo) and ξέρω (kséro). Italian has the verbs conoscere and sapere and the nouns for knowledge are conoscenza and sapienza. German has the verbs wissen and kennen; the former implies knowing a fact, the latter knowing in the sense of being acquainted with and having a working knowledge of. There is also a noun derived from kennen, namely Erkennen, which has been said to imply knowledge in the form of recognition or acknowledgment.[15]: esp. Section 1. The verb itself implies a process of going from one state to another, from a state of "not-erkennen" to a state of true erkennen. This verb seems the most appropriate in terms of describing the "episteme" in one of the modern European languages, hence the German name "Erkenntnistheorie [de]". The theoretical interpretation and significance of these linguistic issues remains controversial. The distinction is most pronounced in Polish, where wiedzieć means "to know", umieć means "to know how" and znać means "to be familiar with" (to "know" a person). In his paper On Denoting and his later book Problems of Philosophy, Bertrand Russell brought a great deal of attention to the distinction between "knowledge by description" and "knowledge by acquaintance". Gilbert Ryle is similarly credited with bringing more attention to the distinction between knowing how and knowing that in The Concept of Mind. In Personal Knowledge, Michael Polanyi argues for the epistemological relevance of knowledge how and knowledge that; using the example of the act of balance involved in riding a bicycle, he suggests that the theoretical knowledge of the physics involved in maintaining a state of balance cannot substitute for the practical knowledge of how to ride, and that it is important to understand how both are established and grounded. This position is essentially Ryle's, who argued that a failure to acknowledge the distinction between "knowledge that" and "knowledge how" leads to infinite regress. A priori and a posteriori knowledge Main article: A priori and a posteriori One of the most important distinctions in epistemology is between what can be known a priori (independently of experience) and what can be known a posteriori (through experience). The terms originate from the analytic methods of Aristotle's Organon, and may be roughly defined as follows:[16] A priori knowledge is knowledge that is independent of experience. This means that it can be known or justified prior to or independently of any specific empirical evidence or sensory observations. Such knowledge is obtained through reasoning, logical analysis, or introspection. Examples of a priori knowledge include mathematical truths, logical tautologies (e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried"), and certain fundamental principles of reason and logic. One of the key proponents of a priori knowledge was the philosopher Immanuel Kant. He argued that certain fundamental truths about the nature of reality, such as the concepts of space, time, causality, and the categories of understanding, are not derived from experience, but are inherent in the structure of the mind itself. According to Kant, these a priori categories enable the organization and interpretation of sensory experiences, giving rise to an understanding of the world. A posteriori knowledge is knowledge that is derived from experience. It is based on empirical evidence, sensory perception, and observations of the external world. A posteriori knowledge is contingent upon the information gained through the senses and relies on the collection and interpretation of data. Scientific observations and experimental results are typical examples of a posteriori knowledge. Views that emphasize the importance of a priori knowledge are generally classified as rationalist. Views that emphasize the importance of a posteriori knowledge are generally classified as empiricist.[17][18] Belief Main article: Belief One of the core concepts in epistemology is belief. A belief is an attitude that a person holds regarding anything that they take to be true.[19] For instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". Beliefs can be occurrent (e.g., a person actively thinking "snow is white"), or they can be dispositional (e.g., a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert "snow is white"). While there is not universal agreement about the nature of belief, most contemporary philosophers hold the view that a disposition to express belief B qualifies as holding the belief B.[19] There are various different ways that contemporary philosophers have tried to describe beliefs, including as representations of ways that the world could be (Jerry Fodor), as dispositions to act as if certain things are true (Roderick Chisholm), as interpretive schemes for making sense of someone's actions (Daniel Dennett and Donald Davidson), or as mental states that fill a particular function (Hilary Putnam).[19] Some have also attempted to offer significant revisions to the notion of belief, including eliminativists about belief who argue that there is no phenomenon in the natural world which corresponds to our folk psychological concept of belief (Paul Churchland) and formal epistemologists, who aim to replace our bivalent notion of belief ("either I have a belief or I don't have a belief") with the more permissive, probabilistic notion of credence ("there is an entire spectrum of degrees of belief, not a simple dichotomy between belief and non-belief").[19][20] While belief plays a significant role in epistemological debates surrounding knowledge and justification, it has also generated many other philosophical debates in its own right. Notable debates include: "What is the rational way to revise one's beliefs when presented with various sorts of evidence?"; "Is the content of our beliefs entirely determined by our mental states, or do the relevant facts have any bearing on our beliefs (e.g., if I believe that I'm holding a glass of water, is the non-mental fact that water is H2O part of the content of that belief)?"; "How fine-grained or coarse-grained are our beliefs?"; and "Must it be possible for a belief to be expressible in language, or are there non-linguistic beliefs?"[19] Truth Main article: Truth Truth is the property or state of being in accordance with facts or reality.[21] On most views, truth is the correspondence of language or thought to a mind-independent world. This is called the correspondence theory of truth. Among philosophers who think that it is possible to analyze the conditions necessary for knowledge, virtually all of them accept that truth is such a condition. There is much less agreement about the extent to which a knower must know why something is true in order to know. On such views, something being known implies that it is true. However, this should not be confused for the more contentious view that one must know that one knows in order to know (the KK principle).[1] Epistemologists disagree about whether belief is the only truth-bearer. Other common suggestions for things that can bear the property of being true include propositions, sentences, thoughts, utterances, and judgments. Plato, in his Gorgias, argues that belief is the most commonly invoked truth-bearer.[22][clarification needed] Many of the debates regarding truth are at the crossroads of epistemology and logic.[21] Some contemporary debates regarding truth include: How do we define truth? Is it even possible to give an informative definition of truth? What things are truth-bearers and therefore capable of being true or false? Are truth and falsity bivalent, or are there other truth values? What are the criteria of truth that allow us to identify it and to distinguish it from falsity? What role does truth play in constituting knowledge? And is truth absolute, or is it merely relative to one's perspective?[21] Justification Main article: Justification (epistemology) As the term justification is used in epistemology, a belief is justified if one has good reason for holding it. Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone holds a rationally admissible belief, on the assumption that it is a good reason for holding it. Sources of justification might include perceptual experience (the evidence of the senses), reason, and authoritative testimony. However, a belief being justified does not guarantee that the belief is true, since a person could be justified in forming beliefs based on very convincing evidence that was nonetheless deceiving. Internalism and externalism Main article: Internalism and externalism A central debate about the nature of justification is a debate between epistemological externalists on the one hand and epistemological internalists on the other. While epistemic externalism first arose in attempts to overcome the Gettier problem, it has flourished in the time since as an alternative way of conceiving of epistemic justification. The initial development of epistemic externalism is often attributed to Alvin Goldman, although numerous other philosophers have worked on the topic in the time since.[23] Externalists hold that factors deemed "external", meaning outside of the psychological states of those who gain knowledge, can be conditions of justification. For example, an externalist response to the Gettier problem is to say that for a justified true belief to count as knowledge, there must be a link or dependency between the belief and the state of the external world. Usually, this is understood to be a causal link. Such causation, to the extent that it is "outside" the mind, would count as an external, knowledge-yielding condition. Internalists, on the other hand, assert that all knowledge-yielding conditions are within the psychological states of those who gain knowledge. Though unfamiliar with the internalist-externalist debate himself, many point to René Descartes as an early example of the internalist path to justification. He wrote that because the only method by which we perceive the external world is through our senses, and that, because the senses are not infallible, we should not consider our concept of knowledge infallible. The only way to find anything that could be described as "indubitably true", he advocates, would be to see things "clearly and distinctly".[24] He argued that if there is an omnipotent, good being who made the world, then it is reasonable to believe that people are made with the ability to know. However, this does not mean that the human ability to know is perfect. God gave humankind the ability to know, but not the capacity for omniscience. Descartes said that we must use our capacities for knowledge correctly and carefully through methodological doubt.[25] The dictum "Cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am) is also commonly associated with Descartes's theory. In his own methodological doubt—doubting everything he previously knew so that he could start from a blank slate—the first thing that he could not logically bring himself to doubt was his own existence: "I do not exist" would be a contradiction in terms. The act of saying that one does not exist assumes that someone must be making the statement in the first place. Descartes could doubt his senses, his body, and the world around him—but he could not deny his own existence, because he was able to doubt and must exist to manifest that doubt. Even if some "evil genius" were deceiving him, he would have to exist to be deceived. This one sure point provided him with what he called his Archimedean point, in order to further develop his foundation for knowledge. Simply put, Descartes's epistemological justification depended on his indubitable belief in his own existence and his clear and distinct knowledge of God.[25] |

中心概念 知識  バートランド・ラッセルは、命題的知識(Declarative knowledge)と知見による知識の区別に注目したことで有名である。 主な記事 知識 スタンフォード哲学百科事典(Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)[13]の項目「知識方法(Knowledge How)」によると、認識論の入門クラスではしばしば、何かを「知る」ことの3つの異なる意味、すなわち「それを知る」(命題の真理を知る)、「どのよう に知る」(特定の行為をどのように行うかを理解する)、「知見によって知る」(対象を直接知覚する、その対象をよく知っている、またはその対象に接触す る)を指摘することから知識の分析を始めるという。認識論の現代的な教えは、これらの知識の形態のうち、第一のものである「命題的知識」に主眼を置いてい る。知っている」という3つの意味はすべて、この言葉の通常の用法に見られる。数学では、2+2=4であることを知ることができるが、2つの数を足す方法 を知ることもあるし、人(例えば、他の人を知ること[14][15]や自分自身を知ること)、場所(例えば、自分の故郷)、物(例えば、車)、活動(例え ば、足し算)を知ることもある。 英語ではこれらの区別は明示されていないが、フランス語、イタリア語、ポルトガル語、スペイン語、ルーマニア語、ドイツ語、オランダ語など他の言語では明 示されている(ただし、スコッツ語など英語に近縁の言語ではこれらの動詞を保持していると言われている)[注 2]。フランス語、ポルトガル語、スペイン語、ルーマニア語、ドイツ語、オランダ語では「(人を)知る」はそれぞれconnaître、 conhecer、conocer、a cunoaște、kennen(ドイツ語とオランダ語の両方)を用いて訳され、「(何かをする方法を)知る」はsavoir、saber(ポルトガル語 とスペイン語の両方)、a şti、wissen、wetenを用いて訳される。現代ギリシャ語には、γνωρίζω(gnorízo)とξέρω(kséro)という動詞がある。 イタリア語にはconoscereとsapereという動詞があり、知識を表す名詞にはconoscenzaとsapienzaがある。ドイツ語には動詞 wissenとkennenがあり、前者は事実を知っていることを意味し、後者は知っている、実務的な知識を持っているという意味で知っていることを意味 する。また、kennenから派生した名詞、すなわちErkennenもあり、これは認識や承認という形の知識を意味すると言われている[15]:特に第 1節。 この動詞自体は、ある状態から別の状態へ、「エルケンネンでない」状態から真のエルケンネンの状態へ、というプロセスを意味する。この動詞は、近代ヨー ロッパ言語の一つである「エピステーメー」を記述するという点で、最も適切であるように思われるため、ドイツ語では「Erkenntnistheorie [de]」と呼ばれている。これらの言語学的問題の理論的解釈と意義については、依然として論争が続いている。ポーランド語では、wiedziećは 「知っている」、umiećは「どのように知っているか」、znaćは「よく知っている」(人を「知っている」)を意味する。 バートランド・ラッセルは、その論文『表記について』(On Denoting)と後の著書『哲学の問題』(Problems of Philosophy)の中で、「記述による知識」と「知見による知識」の区別に大きな注目を集めた。ギルバート・ライルも同様に、『心の概念』におい て、「どのように知っているか」と「それを知っているか」の区別に注意を喚起したとされている。マイケル・ポランニーは、『個人的知識』 (Personal Knowledge)の中で、「どのように知るか」と「何を知るか」の認識論的関連性を主張している。彼は、自転車に乗る際のバランス行為を例にとり、バ ランス状態を維持するための物理学的理論的知識は、「どのように乗るか」という実践的知識に取って代わることはできず、両者がどのように成立し、根拠づけ られているかを理解することが重要であることを示唆している。この立場は本質的にライルのものであり、「知識that」と「知識how」の区別を認めない ことは無限後退につながると主張した。 先験的知識と後験的知識 主な記事 先験的知識と事後的知識 認識論における最も重要な区別の一つは、(経験とは無関係に)先験的に知ることができるものと、(経験を通じて)事後的に知ることができるものとの間の区 別である。この用語はアリストテレスの『オルガノン』の分析手法に由来しており、おおよそ次のように定義することができる[16]。 先験的知識とは、経験とは無関係な知識である。つまり、特定の経験的証拠や感覚的観察に先立ち、あるいはそれとは無関係に知ることができる、あるいは正当 化することができるということである。このような知識は、推論、論理的分析、内省を通じて得られる。先験的知識の例としては、数学的真理、論理的同語反復 (例:「独身者はみな未婚である」)、理性や論理学の基本原理などがある。先験的知識の主要な提唱者の一人は哲学者のイマニュエル・カントである。彼は、 空間、時間、因果関係、理解の範疇といった現実の本質に関するある種の基本的真理は、経験から導き出されるものではなく、心の構造そのものに内在するもの だと主張した。カントによれば、これらのアプリオリなカテゴリーは、感覚的経験の組織化と解釈を可能にし、世界の理解を生じさせる。 事後的知識とは、経験から導かれる知識である。経験的証拠、感覚的知覚、外界の観察に基づいている。事後知識は感覚を通して得た情報に依存しており、データの収集と解釈に依存している。科学的観察や実験結果は、事後知識の典型的な例である。 先験的知識を重視する考え方は、一般に合理主義に分類される。事後知識を重視する考え方は一般的に経験主義に分類される[17][18]。 信念 主な記事 信念 認識論の核となる概念の一つが信念である。信念とは、人が真であると考えるものに関して抱く態度のことである[19]。例えば、「雪は白い」と信じること は、「雪は白い」という命題の真理を受け入れることに匹敵する。信念は、発生的なもの(例えば、「雪は白い」と積極的に考える人)もあれば、気質的なもの (例えば、雪の色について尋ねられたら「雪は白い」と断言する人)もある。信念の性質について普遍的な合意があるわけではないが、現代の哲学者の多 くは、信念Bを表明する性質があれば、信念Bを持つことになるという見解を持 っている。 [19]現代の哲学者たちが信念を説明しようと試みている方法は様々で、 世界のあり方の表象として(ジェリー・フォドー)、ある物事が真実であるかのように 行動する気質として(ロデリック・チショルム)、誰かの行動を理解するための解釈スキ ームとして(ダニエル・デネットとドナルド・デイヴィッドソン)、あるいは特定の機 能を満たす精神状態として(ヒラリー・パットナム)などである。 [19]また、信念という概念に大幅な修正を加えようとする人もいる。その一例と して、自然界には私たちの信念という民間心理学的概念に対応する現象は存在し ないと主張する信念排除論者(ポール・チャーチランド)や、形式的認識論者 などがいる、 彼らは信念の二値的概念(「信念を持っているか、持っていないか」のどちらか)を、より寛容で確率的な信憑性の概念(「信念の度合いには全領域があり、信 念を持っているか持っていないかの単純な二分法ではない」)に置き換えることを目指している。 [19][20] 信憑性は、知識と正当化をめぐる認識論的論争において重要な役割を果たしているが、それ自体、他の多くの哲学的論争をも生み出してきた。注目すべき議論に は次のようなものがある: 様々な証拠を提示されたときに、自分の信念を修正する合理的な方法とは何か」、 「信念の内容はすべて自分の精神状態によって決まるのか、それとも関連する 事実が信念に関係するのか(例えば、自分が信念を持っていると信じている場合、その 事実は自分の信念に関係するのか)」、「自分の信念を修正する合理的な方法とは何か」、 「自分の信念を修正する合理的な方法とは何か」などである、 例えば、私がコップ一杯の水を持っていると信じている場合、水がH2Oであるという非 精神的な事実は、その信念の内容の一部なのだろうか)」、「私たちの信念はどの程度細か い粒度なのだろうか、あるいは粗い粒度なのだろうか」、「信念は言語で表現できなければな らないのだろうか、それとも言語以外の信念も存在するのだろうか」[19]。 真理 主な記事 真理 ほとんどの見解では、真理とは言語や思考と、心とは無関係な世界との対応関係である。これは真理の対応論と呼ばれる。知識に必要な条件を分析することが可 能であると考える哲学者の間では、事実上すべての哲学者が真理がそのような条件であることを認めている。しかし、何かを知るためには、なぜそれが真である のかを知る必要がある、ということについては、意見が一致していない。このような見解では、何かが知られているということは、それが真実であることを意味 する。しかしこれは、知るためには知っていることを知らなければならない(KK原理)という、より論争を呼ぶ見解と混同してはならない[1]。 信念が唯一の真理を担うものであるかどうかについては、認識論者の間でも意見が分かれている。真であるという性質を持ちうるものについての他の一般的な提 案には、命題、文、思考、発言、判断などがある。プラトンは『ゴルギアス』の中で、信念が最も一般的に呼び出される真理担 持者であると論じている[22][要解説]。 真理に関する議論の多くは認識論と論理学の交差点にある: 真理をどのように定義するのか?真理をどのように定義するのか、真理の有益な定義を与えることは可能なのか。どのようなものが真理の担い手であり、した がって真または偽であることが可能なのか。真理と虚偽は二値なのか、それとも他の真理値があるのか。真理を識別し、虚偽と区別することを可能にする真理の 基準は何か。知識を構成する上で、真理はどのような役割を果たすのか。そして真理は絶対的なものなのか、それとも単に自分の視点に相対的なものなのか。 正当化 主な記事 正当化(認識論) 認識論において正当化という用語が使われるように、ある信念を持つことに正当な理由がある場合、その信念は正当化される。緩やかに言えば、正当化とは、合 理的に許容される信念を持つ人が、その信念 を持つための正当な理由があるという前提のもとで、その人がその信念を持つ理由 のことである。正当化の根拠には、知覚的経験(五感の証拠)、理性、権威ある証言などが含まれ る。しかし、信念が正当化されるからといって、その信念が真実であることが保証される わけではない。なぜなら、ある人は、非常に説得力のある証拠に基づいて信念を形成し ても、それが欺瞞であったとしても、正当化される可能性があるからである。 内部主義と外部主義 主な記事 内部主義と外部主義 正当化の本質に関する中心的な論争は、一方では認識論的外在主義者、他方では認識論的内在主義者の論争である。認識論的外在論は、ゲッティア問題を克服す る試みの中で最初に生まれたが、それ以来、認識論的正当化を考える代替的な方法として繁栄してきた。認識論的外在論の最初の発展はアルヴィン・ゴールドマ ンに起因することが多いが、それ以降も数多くの哲学者がこのテーマに取り組んできた[23]。 外在主義者は、知識を得る者の心理的状態の外側を意味する「外的」とみなされる要因が正当化の条件となりうると考えている。例えば、ゲッティア問題に対す る外在主義者の回答は、正当化された真の信 念が知識として数えられるためには、その信念と外界の状態との間に関連性や依存 性がなければならない、というものである。通常、これは因果関係と理解される。このような因果関係は、それが心の「外」にある限りにおいて、外的な知識 をもたらす条件として数えられる。一方、内発主義者は、知識を得る条件はすべて知識を得る人の心理状態の中にあると主張する。 内的主義者と外的主義者の論争にはあまり馴染みがないが、多くの人が内的主義者による正当化の初期の例としてルネ・デカルトを挙げている。彼は、私たちが 外界を認識する唯一の方法は感覚を通してであり、感覚は絶対的なものではないため、私たちの知識概念も絶対的なものであると考えるべきではないと書いた。 もし世界を作った全能の善なる存在がいるのであれば、人は知る能力を持っていると考えるのが妥当である。しかし、これは人間の知る能力が完全であるという 意味ではない。神は人間に知る能力を与えたが、全知全能の能力を与えたわけではない。デカルトは、方法論的な疑いによって、知識の能力を正しく注意深く使 わなければならないと言った[25]。 コギト・エルゴ・スム」(我思う、ゆえに我あり)という独語もまた、デカルトの理論によく関連している。デカルト自身の方法論的な疑い(白紙の状態から出 発できるように、それまで知っていたことをすべて疑うこと)において、彼が論理的に疑うことができなかった最初のものは、自分自身の存在であった: 「私は存在しない」というのは矛盾している。私は存在しない」というのは矛盾している。「存在しない」と言う行為は、そもそも誰かがそう言っていることを 前提としている。デカルトは自分の感覚、自分の身体、自分を取り巻く世界を疑うことはできたが、自分自身の存在を否定することはできなかった。たとえ「邪 悪な天才」が彼を騙していたとしても、騙されるためには存在しなければならない。この一つの確かな点が、デカルトに「アルキメデスの点」と呼ばれるものを もたらし、知識の基礎をさらに発展させることになった。端的に言えば、デカルトの認識論的正当化は、自分自身の存在と神についての明確かつ明瞭な知識につ いての疑いようのない信念に依存していた[25]。 |

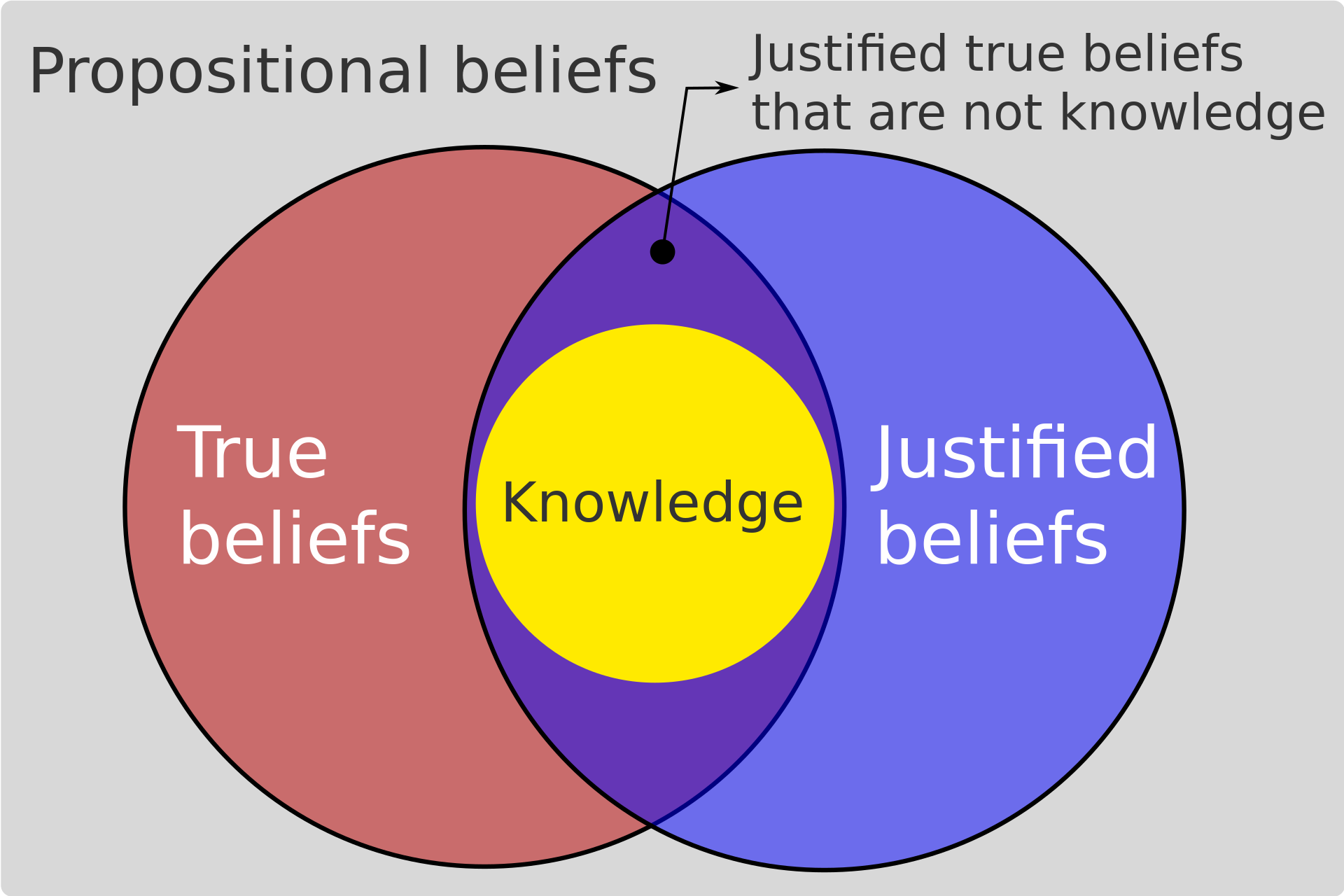

| Defining knowledge Main article: Definitions of knowledge A central issue in epistemology is the question of what the nature of knowledge is or how to define it. Sometimes the expressions "theory of knowledge" and "analysis of knowledge" are used specifically for this form of inquiry.[26][27][28] The term "knowledge" has various meanings in natural language. It can refer to an awareness of facts, as in knowing that Mars is a planet, to a possession of skills, as in knowing how to swim, or to an experiential acquaintance, as in knowing Daniel Craig personally.[29][30][31] Factual knowledge, also referred to as propositional knowledge or descriptive knowledge, plays a special role in epistemology. On the linguistic level, it is distinguished from the other forms of knowledge since it can be expressed through a that-clause, for instance, using a formulation like "They know that..." followed by the known proposition.[32][30][4] Some features of factual knowledge are widely accepted: it is a form of cognitive success that establishes epistemic contact with reality.[5][31] However, even though it has been studied intensely, there are still various disagreements about its exact nature. Different factors are responsible for these disagreements. Some theorists try to furnish a practically useful definition by describing its most noteworthy and easily identifiable features.[31] Others engage in an analysis of knowledge, which aims to provide a theoretically precise definition that identifies the set of essential features characteristic for all instances of knowledge and only for them.[31][28][33] Differences in the methodology may also cause disagreements. In this regard, some epistemologists use abstract and general intuitions in order to arrive at their definitions. A different approach is to start from concrete individual cases of knowledge to determine what all of them have in common.[34][35][36] Yet another method is to focus on linguistic evidence by studying how the term "knowledge" is commonly used.[4][27] Different standards of knowledge are further sources of disagreement. A few theorists set these standards very high by demanding that absolute certainty or infallibility is necessary. On such a view, knowledge is a very rare thing. Theorists more in tune with ordinary language usually demand lower standards and see knowledge as something commonly found in everyday life.[37][30][38] As justified true belief The historically most influential definition, discussed since ancient Greek philosophy, characterizes knowledge in relation to three essential features: as (1) a belief that is (2) true and (3) justified.[28][31][39] There is still wide acceptance that the first two features are correct, that is, that knowledge is a mental state that affirms a true proposition.[30][4][31] However, there is a lot of dispute about the third feature: justification.[32][31][28] This feature is usually included to distinguish knowledge from true beliefs that rest on superstition, lucky guesses, or faulty reasoning. This expresses the idea that knowledge is not the same as being right about something.[32][30][27] Traditionally, justification is understood as the possession of evidence: a belief is justified if the believer has good evidence supporting it. Such evidence could be a perceptual experience, a memory, or a second belief.[28][30][27] Gettier problem and alternative definitions  An Euler diagram representing a version of the traditional definition of knowledge that is adapted to the Gettier problem. This problem gives us reason to think that not all justified true beliefs constitute knowledge. The justified-true-belief account of knowledge came under severe criticism in the second half of the 20th century, when Edmund Gettier proposed various counterexamples.[40] In a famous example of what came to be known as a Gettier case, a person is driving on a country road lined with multiple barn façades, only one of which is real barn, but it is not possible to tell the difference between them from the road. The person then stops by a fortuitous coincidence in front of the only real barn and forms the belief that it is a barn. The idea behind this thought experiment is that this is not knowledge even though the belief is both justified and true. The reason is that it is just a lucky accident since the person cannot tell the difference: They would have formed exactly the same justified belief if they had stopped at another site, in which case the belief would have been false.[41][42][43] Various additional examples were proposed along similar lines. Most of them involve a justified true belief that apparently fails to amount to knowledge because the belief's justification is in some sense not relevant to its truth.[32][30][31] These counterexamples have provoked very diverse responses. Some theorists think that one only needs to modify one's conception of justification to avoid them. But the more common approach is to search for an additional criterion.[28][44] On this view, all cases of knowledge involve a justified true belief but some justified true beliefs do not amount to knowledge since they lack this additional feature. There are diverse suggestions for this fourth criterion. Some epistemologists require that no false belief is involved in the justification or that no defeater of the belief is present.[43][27] A different approach is to require that the belief tracks truth, that is, that the person would not have the belief if it was false.[30][31] Some even require that the justification has to be infallible, that is, that it necessitates the belief's truth.[30][45] A quite different approach is to affirm that the justified-true-belief account of knowledge is deeply flawed and to seek a complete reconceptualization of knowledge. These reconceptualizations often do not require justification at all.[28] One such approach is to require that the true belief was produced by a reliable process. Naturalized epistemologists often hold that the believed fact has to cause the belief.[46][47][32] Virtue theorists are also interested in how the belief is produced. For them, the belief must be a manifestation of a cognitive virtue.[48][49][5] |

知識の定義 主な記事 知識の定義 認識論における中心的な問題は、知識の本質とは何か、あるいは知識をどのように定義するかという問題である。知識の理論」や「知識の分析」という表現は、 特にこのような探究のために用いられることがある[26][27][28]。「知識」という用語は、自然言語において様々な意味を持つ。火星が惑星である ことを知っているというような事実の認識、泳ぎ方を知っているというような技能の所有、ダニエル・クレイグを個人的に知っているというような経験的な知見 などを指すことがある[29][30][31]。事実知識は命題知識または記述的知識とも呼ばれ、認識論において特別な役割を果たす。言語的なレベルで は、例えば「彼らは...ということを知っている」というような定型文の後に既知の命題が続くようなthat-clauseを用いて表現することができる ため、他の形式の知識とは区別される[32][30][4]。 事実的知識のいくつかの特徴は広く受け入れられている:それは現実との認識論的接触を確立する認知的成功の一形態である。こうした意見の相違の原因はさま ざまな要因にある。理論家のなかには、知識の最も注目すべき、容易に識別可能な特徴を記述することによって、実践的に有用な定義を与えようとする者もいる [31]。また、知識のすべての事例に特徴的な、そして知識のみに特徴的な本質的特徴の集合を識別する、理論的に正確な定義を提供することを目的とする知 識の分析に従事する者もいる[31][28][33]。方法論の相違も意見の相違を引き起こす可能性がある。この点に関して、一部の認識論者は、その定義 に到達するために抽象的で一般的な直観を用いる。さらに別の方法として、「知識」という用語が一般的にどのように使用されているかを研究することによっ て、言語的な証拠に焦点を当てるという方法もある[4][27]。少数の理論家は、絶対的な確実性や無謬性が必要であると要求することによって、これらの 基準を非常に高く設定している。そのような見解では、知識は非常に稀なものである。より普通の言葉に同調する理論家は通常、より低い基準を要求し、知識を 日常生活で一般的に見られるものとみなす[37][30][38]。 正当化された真の信念として 古代ギリシア哲学以来議論されてきた歴史的に最も影響力のある定義は、知識を3つの本質的な特徴、すなわち(1)(2)真であり、(3)正当化される信念 として特徴付けるものである[28][31][39]。最初の2つの特徴が正しいこと、すなわち知識とは真の命題を肯定する精神状態であることは、今でも 広く受け入れられている。 [30][4][31]しかし、3つ目の特徴である正当化については多くの論争がある[32][31][28]。この特徴は通常、迷信、幸運な推測、誤っ た推論に頼る真の信念と知識を区別するために含まれている。これは、知識は何かについて正しいということとは違うという考えを 表している[32][30][27]。伝統的に、正当化は証拠を持つこととして理解されている。そのような証拠とは、知覚的経験、記憶、第二の信念などで ある[28][30][27]。 ゲッティア問題と代替定義  ゲッティア問題に適応された、伝統的な知識の定義を表すオイラー図。この問題は、すべての正当化された真の信念が知識を構成するわけではないと考える根拠を与えてくれる。 知識に関する正当化された真の信念の説明は、20世紀後半にエドムンド・ゲッ ティアが様々な反例を提唱した際に厳しい批判にさらされた[40]。ゲッ ティア事例として知られるようになった有名な例では、ある人が複数の納屋のファサード が並ぶ田舎道を車で走っている。そのとき、その人は偶然にも唯一の本物の納屋の前で停車し、それが納屋であるという信念を形成する。この思考実験の背景に ある考え方は、たとえその信念が正当であり真実であったとしても、それは知識ではないということである。なぜなら、その人はその違いを見分けることができ ないので、それは単なる幸運な偶然にすぎないからである: 別の場所に立ち寄ったとしても、まったく同じ正当化された信念を持 っていただろうし、その場合、その信念は偽であっただろう[41][42][43]。 同様の線に沿って、様々な追加の例が提案された。これらの反例は、非常に多様な反応を引き起こしている。理論家の中には、正当化の概念を修正するだけで回 避できると考える者もいる。しかし、より一般的なアプローチは、付加的な基準を探すことである[28][44]。この見解によれば、知識のすべてのケース は正当化された真の信念を伴うが、正当化された真の信念の中には、この付加的な特徴を欠いているため、知識にならないものもある。この第四の基準について は様々な提案がある。認識論者の中には、正当化に偽の信念が含まれていないこと、あるいはその信 念を否定するものが存在しないことを要求する者もいる[43][27]。異なるアプローチは、その信念が真理を追跡していること、 つまり、もしそれが偽であれば、その人はその信念を持たないであろうことを要求 するものである[30][31]。 これとはまったく異なるアプローチは、知識に関する正当化された真実の信念の説明には深い欠陥があると断言し、知識の完全な再概念化を求めることである。 このような再概念化は、正当化を全く必要としないことが多い[28]。そのような アプローチの一つは、真の信念が信頼できるプロセスによって生み出されたものであるこ とを要求することである。自然化された認識論者はしばしば、信じられた事実が信念を生み出 す原因にならなければならないと考えている[46][47][32]。彼らにとって、信念は認知的美徳の現れでなければならない[48][49][5]。 |

| The value problem The primary value problem is to determine why knowledge should be more valuable than simply true belief. In Plato's Meno, Socrates points out to Meno that a man who knew the way to Larissa could lead others there correctly. But so, too, could a man who had true beliefs about how to get there, even if he had not gone there or had any knowledge of Larissa. Socrates says that it seems that both knowledge and true opinion can guide action. Meno then wonders why knowledge is valued more than true belief and why knowledge and true belief are different. Socrates responds that knowledge, unlike belief, must be 'tied down' to the truth, like the mythical tethered statues of Daedalus.[50][51] More generally, the problem is to identify what (if anything) makes knowledge more valuable than a minimal conjunction of its components such as mere true belief or justified true belief. Other components considered besides belief, truth, and justification are safety, sensitivity, statistical likelihood, and any anti-Gettier condition. This is done within analyses that conceive of knowledge as divided into components. Knowledge-first epistemological theories, which posit knowledge as fundamental, are notable exceptions to these kind of analyses.[51] The value problem re-emerged in the philosophical literature on epistemology in the 21st century following the rise of virtue epistemology in the 1980s, partly because of the obvious link to the concept of value in ethics.[52] Virtue epistemology Main article: Virtue epistemology In contemporary philosophy, epistemologists including Ernest Sosa, John Greco, Jonathan Kvanvig,[53] Linda Zagzebski, and Duncan Pritchard have defended virtue epistemology as a solution to the value problem. They argue that epistemology should also evaluate the "properties" of people as epistemic agents (i.e., intellectual virtues), rather than merely the properties of propositions and propositional mental attitudes. The value problem has been presented as an argument against epistemic reliabilism by Linda Zagzebski, Wayne Riggs, and Richard Swinburne, among others. Zagzebski analogizes the value of knowledge to the value of espresso produced by an espresso maker: "The liquid in this cup is not improved by the fact that it comes from a reliable espresso maker. If the espresso tastes good, it makes no difference if it comes from an unreliable machine."[54] For Zagzebski, the value of knowledge deflates to the value of mere true belief. She assumes that reliability in itself has no value or disvalue, but Goldman and Olsson disagree. They point out that Zagzebski's conclusion rests on the assumption of veritism: all that matters is the acquisition of true belief.[55] To the contrary, they argue that a reliable process for acquiring a true belief adds value to the merely true belief by making it more likely that future beliefs of a similar kind will be true. By analogy, having a reliable espresso maker that produced a good cup of espresso would be more valuable than having an unreliable one that luckily produced a good cup because the reliable one would more likely produce good future cups compared to the unreliable one. The value problem is important to assessing the adequacy of theories of knowledge that conceive of knowledge as consisting of true belief and other components. According to Jonathan Kvanvig, an adequate account of knowledge should resist counterexamples and allow an explanation of the value of knowledge over mere true belief. Should a theory of knowledge fail to do so, it would prove inadequate.[53][page needed] One of the more influential responses to the problem is that knowledge is not particularly valuable and is not what ought to be the main focus of epistemology. Instead, epistemologists ought to focus on other mental states, such as understanding.[53] Advocates of virtue epistemology have argued that the value of knowledge comes from an internal relationship between the knower and the mental state of believing.[51] |

価値問題 第一の価値問題は、なぜ知識が単なる真の信念よりも価値があるべきなのかを決定することである。プラトンの『メノ』で、ソクラテスはメノに、ラリッサへの 道を知っている人は他人を正しく導くことができると指摘する。しかし、ラリッサに行ったことがなくても、ラリッサについての知識がなくても、そこへ行く方 法についての真の信念を持っている人も、そうすることができた。ソクラテスは、知識と真の意見の両方が行動を導くことができるようだと言う。メノは、なぜ 知識が真の信念よりも評価されるのか、なぜ知識と真の信念は違うのか、と疑問を投げかける。ソクラテスは、知識は信念とは異なり、神話に登場するダイダロ スの縛られた彫像のように、真理に「縛りつけられ」なければならないと答える[50][51]。 より一般的に言えば、この問題は、知識を、単なる真の信念や正当化された真の信 念のような、その構成要素の最小限の結合よりも価値あるものにしているものが (もしあるとすれば)何であるかを特定することである。信念、真理、正当化の他に考慮される構成要素としては、安全性、感度、統計的尤度、あらゆる反ゲッ ティア条件がある。これは知識を構成要素に分割して考える分析の中で行われる。知識を基本的なものとして措定する知識第一主義の認識論理論は、この種の分 析の顕著な例外である[51]。価値の問題は、1980年代に徳の認識論が台頭した後、21世紀に認識論に関する哲学的文献に再び登場した。 美徳認識論 主な記事 美徳認識論 現代の哲学では、アーネスト・ソーサ、ジョン・グレコ、ジョナサン・クヴァンヴィグ、リンダ・ザグゼブスキー、ダンカン・プリチャードなどの認識論者が、 価値問題の解決策として徳の認識論を擁護している[53]。彼らは、認識論は、単に命題や命題的心的態度の特性だけではなく、認識主体としての人間の「特 性」(すなわち、知的徳性)も評価すべきであると主張している。 この価値問題は、リンダ・ザジェブスキー、ウェイン・リッグス、リチャード・スウィンバーンらによって、認識論的信頼性主義に対する議論として提示されて きた。ザグゼブスキーは、知識の価値をエスプレッソメーカーが作るエスプレッソの価値になぞらえている: 「このカップの中の液体は、信頼できるエスプレッソ・メーカーで作られたという事実によって改善されるわけではない。このカップの中の液体は、信頼性の低 いエスプレッソ・メーカーで作られたものであるという事実によって改善されることはない。エスプレッソがおいしければ、それが信頼性の低いマシンで作られ たものであっても違いはない」[54]。彼女は信頼性それ自体には価値も無価値もないと仮定するが、ゴールドマンとオルソンはこれに同意しない。彼らは、 ザグゼブスキーの結論は真実主義の前提に立脚していると指摘 する。例えて言えば、おいしいエスプレッソを作る信頼できるエスプレッソメーカーを持 つことは、運良くおいしいエスプレッソを作る信頼できないメーカーを持つこと よりも価値がある。 この価値問題は、知識を真の信念とその他の要素から構成されると考える知識理論の妥当性を評価する上で重要である。ジョナサン・クヴァンヴィッヒによれ ば、知識に関する適切な説明は反例に抵抗し、単なる真の信念に対する知識の価値を説明できるはずである。もし知識の理論がそうできなければ、それは不十分 であることを証明することになる[53][要出典]。 この問題に対するより影響力のある回答の一つは、知識は特に価値があるものではなく、認識論の主要な焦点となるべきものではないというものである。その代 わりに、認識論者は理解など他の精神状態に焦点を当てるべきである[53]。徳の認識論の提唱者は、知識の価値は知る者と信じるという精神状態との間の内 的関係から生まれると主張している[51]。 |

| Acquiring knowledge Sources of knowledge Main article: Knowledge § Sources There are many proposed sources of knowledge and justified belief which we take to be actual sources of knowledge in our everyday lives. Some of the most commonly discussed include perception, reason, memory, and testimony.[2][5] Important distinctions A priori–a posteriori distinction Main article: A priori and a posteriori As mentioned above, epistemologists draw a distinction between what can be known a priori (independently of experience) and what can only be known a posteriori (through experience). Much of what we call a priori knowledge is thought to be attained through reason alone, as featured prominently in rationalism. This might also include a non-rational faculty of intuition, as defended by proponents of innatism. In contrast, a posteriori knowledge is derived entirely through experience or as a result of experience, as emphasized in empiricism. This also includes cases where knowledge can be traced back to an earlier experience, as in memory or testimony.[16] A way to look at the difference between the two is through an example. Bruce Russell gives two propositions in which the reader decides which one he believes more.[clarification needed] Option A: All crows are birds. Option B: All crows are black. If you believe option A, then you are a priori justified in believing it because you do not have to see a crow to know it is a bird. If you believe in option B, then you are a posteriori justified to believe it because you have seen many crows therefore knowing they are black. He goes on to say that it does not matter if the statement is true or not, only that if you believe in one or the other that matters.[16] The idea of a priori knowledge is that it is based on intuition or rational insights. Laurence BonJour says in his article "The Structure of Empirical Knowledge",[56] that a "rational insight is an immediate, non-inferential grasp, apprehension or 'seeing' that some proposition is necessarily true" (p. 3). Going back to the crow example, by Laurence BonJour's definition the reason you would believe in option A is because you have an immediate knowledge that a crow is a bird, without ever experiencing one. Evolutionary psychology takes a novel approach to the problem. It says that there is an innate predisposition for certain types of learning. "Only small parts of the brain resemble a tabula rasa; this is true even for human beings. The remainder is more like an exposed negative waiting to be dipped into a developer fluid".[57] Analytic–synthetic distinction  The analytic–synthetic distinction was first proposed by Immanuel Kant. Main article: Analytic–synthetic distinction Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, drew a distinction between "analytic" and "synthetic" propositions. He contended that some propositions are such that we can know they are true just by understanding their meaning. For example, consider, "My father's brother is my uncle." We can know it is true solely by virtue of our understanding in what its terms mean. Philosophers call such propositions "analytic". Synthetic propositions, on the other hand, have distinct subjects and predicates. An example would be, "My father's brother has black hair." Kant stated that all mathematical and scientific statements are synthetic a priori propositions because they are necessarily true, but our knowledge about the attributes of the mathematical or physical subjects we can only get by logical inference. While this distinction is first and foremost about meaning and is therefore most relevant to the philosophy of language, the distinction has significant epistemological consequences, seen most prominently in the works of the logical positivists.[58] In particular, if the set of propositions which can only be known a posteriori is coextensive with the set of propositions which are synthetically true, and if the set of propositions which can be known a priori is coextensive with the set of propositions which are analytically true (or in other words, which are true by definition), then there can only be two kinds of successful inquiry: Logico-mathematical inquiry, which investigates what is true by definition, and empirical inquiry, which investigates what is true in the world. Most notably, this would exclude the possibility that branches of philosophy like metaphysics could ever provide informative accounts of what actually exists.[16][58] The American philosopher W. V. O. Quine, in his paper "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", famously challenged the analytic-synthetic distinction, arguing that the boundary between the two is too blurry to provide a clear division between propositions that are true by definition and propositions that are not. While some contemporary philosophers take themselves to have offered more sustainable accounts of the distinction that are not vulnerable to Quine's objections, there is no consensus about whether or not these succeed.[59] Science as knowledge acquisition Main article: Philosophy of science Science is often considered to be a refined, formalized, systematic, institutionalized form of the pursuit and acquisition of empirical knowledge. As such, the philosophy of science may be viewed as an application of the principles of epistemology and as a foundation for epistemological inquiry.[60] |

知識を得る 知識の源 主な記事 知識§情報源 知識や正当化された信念の情報源は数多く提案されており、私たちはそれを日常生活における実際の知識源としている。最もよく議論されるものには、知覚、理性、記憶、証言などがある[2][5]。 重要な区別 先験的・後験的の区別 主な記事 アプリオリとポストステリオリ 上述したように、認識論者は、(経験とは無関係に)先験的に知ることができるものと、(経験を通じて)事後的にしか知ることができないものを区別してい る。先験的知識と呼ばれるものの多くは、合理主義に顕著に見られるように、理性のみによって達成されると考えられている。これには、生得主義の支持者が擁 護するように、直観という非理性的能力も含まれるかもしれない。これに対して事後的知識とは、経験主義で強調されるように、完全に経験を通じて、あるいは 経験の結果として得られるものである。これには、記憶や証言のように、知識が以前の経験に遡ることができる場合も含まれる[16]。 両者の違いを見る方法として、例を挙げることができる。ブルース・ラッセルは2つの命題を与え、読者はどちらを信じるかを決める。選択肢B:すべてのカラ スは黒い。もしあなたが選択肢Aを信じるなら、カラスを見なくてもそれが鳥であることがわかるので、あなたはそれを信じることがアプリオリに正当化され る。もしあなたがBの選択肢を信じるなら、あなたは多くのカラスを見たので、カラスが黒いことを知っているので、それを信じることが事後的に正当化され る。彼はさらに、その言明が真実かどうかは問題ではなく、どちらか一方を信じるかどうかだけが重要だと言う[16]。 先験的知識とは、直感や合理的洞察に基づく知識である。ローレンス・ボンジュールはその論文「経験的知識の構造」[56]の中で、「合理的洞察とは、ある 命題が必然的に真であるということを、即座に、非推論的に把握し、理解し、『見る』ことである」と述べている(p.3)。カラスの例に戻ると、ローレン ス・ボンジュールの定義によれば、あなたが選択肢Aを信じる理由は、カラスを一度も経験することなく、カラスが鳥であるという知識を即座に持っているから である。 進化心理学はこの問題に斬新なアプローチをとる。それは、ある種の学習には生得的な素質があるというものだ。「脳のごく一部だけがタブラ・ラサに似ている。残りの部分は、現像液に浸されるのを待っている露光されたネガのようなものである」[57]。 分析的-合成的(総合的)区別  分析的-合成的区別は、イマヌエル・カントによって初めて提唱された。 主な記事 分析的-合成的(総合的)区別 イマニュエル・カントは『純粋理性批判』の中で、「分析的」命題と「合成的」命題の区別を提唱した。彼は、命題の中には、その意味を理解するだけで真であ ることがわかるものがあると主張した。例えば、「父の兄は私の叔父である」という命題を考えてみよう。私たちはこの命題の意味を理解するだけで、その命題 が真であることを知ることができる。哲学者はこのような命題を「分析的命題」と呼ぶ。一方、合成命題は、明確な主語と述語を持つ。例えば、「私の父の兄は 黒髪である 」というようなものである。カントは、すべての数学的・科学的記述は、必然的に真であるが、数学的・物理的主体の属性に関する知識は論理的推論によっての み得られるので、合成的先験的命題であると述べた。 この区別は何よりもまず意味に関するものであり、したがって言語哲学に最も関連するものであるが、この区別は認識論的に重要な結果をもたらす。 [特に、事後的にしか知ることができない命題の集合が、総合的に真である命題の集合と同値であり、先験的に知ることができる命題の集合が、分析的に真であ る(言い換えれば、定義によって真である)命題の集合と同値である場合、成功する探究は2種類しかありえない: 定義によって真であるものを探究する論理数学的探究と、世界において真であるものを探究する経験的探究である。最も注目すべきは、形而上学のような哲学の 分野が、実際に存在するものについて有益な説明を提供できる可能性を排除してしまうことである[16][58]。 アメリカの哲学者であるW.V.O.クワインは、その論文「経験主義の二つの教義」の中で、分析的-合成的の区別に異議を唱え、定義によって真である命題 とそうでない命題の明確な区別を提供するには、両者の境界はあまりにも曖昧であると主張したことは有名である。現代の哲学者の中には、クワインの反論の影 響を受けにくい、より持続可能な区別の説明をしていると自認する者もいるが、これらが成功するかどうかについてはコンセンサスが得られていない[59]。 知識獲得としての科学 主な記事 科学哲学 科学はしばしば、経験的知識の追求と獲得の洗練され、形式化され、体系化され、制度化された形態であると考えられている。そのため、科学哲学は認識論の原理の応用として、また認識論的探求の基礎として捉えることができる[60]。 |

| The regress problem Main article: Regress argument The regress problem (also known as Agrippa's Trilemma) is the problem of providing a complete logical foundation for human knowledge. The traditional way of supporting a rational argument is to appeal to other rational arguments, typically using chains of reason and rules of logic. A classic example that goes back to Aristotle is deducing that Socrates is mortal. We have a logical rule that says All humans are mortal and an assertion that Socrates is human and we deduce that Socrates is mortal. In this example how do we know that Socrates is human? Presumably we apply other rules such as: All born from human females are human. Which then leaves open the question how do we know that all born from humans are human? This is the regress problem: how can we eventually terminate a logical argument with some statements that do not require further justification but can still be considered rational and justified? As John Pollock stated, to justify a belief one must appeal to a further justified belief. This means that one of two things can be the case. Either there are some beliefs that we can be justified for holding, without being able to justify them on the basis of any other belief, or else for each justified belief there is an infinite regress of (potential) justification [the nebula theory]. On this theory there is no rock bottom of justification. Justification just meanders in and out through our network of beliefs, stopping nowhere.[61]: 26 The apparent impossibility of completing an infinite chain of reasoning is thought by some to support skepticism. It is also the impetus for Descartes's famous dictum: I think, therefore I am. Descartes was looking for some logical statement that could be true without appeal to other statements. Responses to the regress problem Many epistemologists studying justification have attempted to argue for various types of chains of reasoning that can escape the regress problem. Foundationalism Foundationalists respond to the regress problem by asserting that certain "foundations" or "basic beliefs" support other beliefs but do not themselves require justification from other beliefs. These beliefs might be justified because they are self-evident, infallible, or derive from reliable cognitive mechanisms. Perception, memory, and a priori intuition are often considered possible examples of basic beliefs. The chief criticism of foundationalism is that if a belief is not supported by other beliefs, accepting it may be arbitrary or unjustified.[62] Coherentism Another response to the regress problem is coherentism, which is the rejection of the assumption that the regress proceeds according to a pattern of linear justification. To avoid the charge of circularity, coherentists hold that an individual belief is justified circularly by the way it fits together (coheres) with the rest of the belief system of which it is a part. This theory has the advantage of avoiding the infinite regress without claiming special, possibly arbitrary status for some particular class of beliefs. Yet, since a system can be coherent while also being wrong, coherentists face the difficulty of ensuring that the whole system corresponds to reality. Additionally, most logicians agree that any argument that is circular is, at best, only trivially valid. That is, to be illuminating, arguments must operate with information from multiple premises, not simply conclude by reiterating a premise. Nigel Warburton writes in Thinking from A to Z that "circular arguments are not invalid; in other words, from a logical point of view there is nothing intrinsically wrong with them. However, they are, when viciously circular, spectacularly uninformative."[63] Infinitism An alternative resolution to the regress problem is known as "infinitism". Infinitists take the infinite series to be merely potential, in the sense that an individual may have indefinitely many reasons available to them, without having consciously thought through all of these reasons when the need arises. This position is motivated in part by the desire to avoid what is seen as the arbitrariness and circularity of its chief competitors, foundationalism and coherentism. The most prominent defense of infinitism has been given by Peter Klein.[64] Foundherentism An intermediate position, known as "foundherentism", is advanced by Susan Haack. Foundherentism is meant to unify foundationalism and coherentism. Haack explains the view by using a crossword puzzle as an analogy. Whereas, for example, infinitists regard the regress of reasons as taking the form of a single line that continues indefinitely, Haack has argued that chains of properly justified beliefs look more like a crossword puzzle, with various different lines mutually supporting each other.[65] Thus, Haack's view leaves room for both chains of beliefs that are "vertical" (terminating in foundational beliefs) and chains that are "horizontal" (deriving their justification from coherence with beliefs that are also members of foundationalist chains of belief). |

逆行問題 主な記事 逆行論 逆行問題(アグリッパのトリレンマとしても知られる)とは、人間の知識の完全な論理的基礎を提供する問題である。合理的な議論を支持する伝統的な方法は、 他の合理的な議論に訴えることであり、典型的には理性の連鎖と論理のルールを用いる。アリストテレスに遡る古典的な例は、ソクラテスが死すべき存在である ことを推論することである。我々 はすべての人間は死すべきであると言う論理的なルールとソクラテスは人間であることを主張し、我々 はソクラテスは死すべきであると推論する。この例ではどうやってソクラテスは人間であることを知るか?おそらく我々 などの他のルールを適用する: 人間の女性から生まれたすべての人間である。どのように我々 は人間から生まれたすべての人間であることを知ることができる疑問が残っている?これは逆行問題である。さらなる正当化を必要としないが、それでもなお合 理的で正当であるとみなすことができるいくつかの記述で、論理的議論を最終的に終わらせるにはどうすればいいのだろうか?ジョン・ポロックはこう述べてい る、 ある信念を正当化するには、さらに正当化された信念に訴えなければならない。つまり、次の2つのうちのどちらかが成り立つということだ。他の信念に基づい て正当化することができなくても、自分が持っているこ とを正当化できる信念があるか、正当化された信念のそれぞれに、正当化の(可 能性のある)無限後退が存在するかである[星雲説]。この理論では、正当化のどん底は存在しない。正当化は私たちの信念のネットワークの中を蛇行しなが ら出入りし、どこにも止まらないのである[61]。 無限の推論の連鎖を完成させることは明らかに不可能であるため、懐疑論 を支持すると考える人もいる。それはまた、デカルトの有名な「我思う、ゆえに我あり」の原動力でもある。デカルトは、他の記述に訴えることなく真となりうる論理的な記述を探していたのである。 逆行問題への対応 正当化を研究する多くの認識論者は、逆行問題から逃れることができる様々なタイプの推論の連鎖を主張しようとしてきた。 基礎論(基礎主義、基礎づけ主義) 基礎主義は、ある種の「基礎」や「基本的な信念」は他の信念を支えるが、それ自 体は他の信念からの正当化を必要としないと主張することで、逆行問題に対 応する。これらの信念が正当化されるのは、それが自明であったり、無謬であったり、 信頼できる認知メカニズムに由来していたりするからである。知覚、記憶、先験的な直観は、基本的信念の例とし て考えられることが多い。 基礎づけ主義の主な批判は、ある信念が他の信念によって裏付けられていない 場合、その信念を受け入れることは恣意的であったり、正当化されない可能性が あるということである[62]。 首尾一貫主義 逆行問題に対するもう一つの対応は首尾一貫主義であり、これは逆行が直線的な 正当化のパターンに従って進むという仮定を否定することである。循環性の罪を避けるために、首尾一貫主義者は、 個々の信念は、その信念が属している信念体系の残りの部分とどのように組み 合うか(首尾一貫しているか)によって、循環的に正当化されると考える。この理論には、ある特定の信念のクラスについて、特別な、おそらくは恣意的 な地位を主張することなく、無限後退を回避できるという利点がある。しかし、体系が首尾一貫している一方で間違っていることもありうるので、首尾一貫主義 者 は、体系全体が現実に対応していることを保証することの難しさに直面する。さらに、ほとんどの論理学者は、循環的な議論はせいぜい些細な妥当性しかないと いうことに同意している。つまり、明快であるためには、論証は複数の前提からの情報を使って行われなければならず、単に前提を繰り返して結論づけるような ものであってはならないのである。 ナイジェル・ウォーバートンは『Thinking from A to Z』の中で、「循環論法は無効ではない。言い換えれば、論理的な観点からは本質的に何も問題はない」と書いている。しかし、悪質な循環論法は、目を見張るほど情報が少ない」と述べている[63]。 無限論 逆行問題に対する別の解決法は「無限論」として知られている。無限論者は無限級数を単なる潜在的なものであるとし、個人が利用可能な理由を無限に多く持っ ている可能性があるが、必要性が生じたときにこれらの理由のすべてを意識的に考え抜いたわけではないという意味である。この立場は、その主要な競争相手で ある基礎主義や首尾一貫主義が持つ恣意性や循環性を避けたいという願望によって動機づけられている。無限論の最も著名な擁護者はピーター・クラインである [64]。 ファウンダリー主義 ファウンダリー主義」として知られる中間の立場は、スーザン・ハックによって提唱されている。Foundherentism は、基礎づけ主義と首尾一貫主義を統合することを意図している。ハークは、クロスワードパズルをアナロジーとして用いてこの見解を説明している。例えば、 無限論者が理由の逆行を、無限に続く一本の線の形と見なすのに対して、ハ ックは、適切に正当化された信念の連鎖は、様々な異なる線が相互に支え合うクロスワード パズルのように見えると主張している[65]。このように、ハックの考え方には、「垂直的」な信念の連鎖 (基礎的信念に終着する)と、「水平的」な信念の連鎖(同じく基礎的信念の連鎖に属する信 念との首尾一貫性から正当性を導き出す)の両方の余地が残されている。 |

| Schools of thought Empiricism  David Hume, one of the most staunch defenders of empiricism Main article: Empiricism Empiricism is a view in the theory of knowledge which focuses on the role of experience, especially experience based on perceptual observations by the senses, in the generation of knowledge.[66] Certain forms exempt disciplines such as mathematics and logic from these requirements.[67] There are many variants of empiricism, including British empiricism, logical empiricism, phenomenalism, and some versions of common sense philosophy. Most forms of empiricism give epistemologically privileged status to sensory impressions or sense data, although this plays out very differently in different cases. Some of the most famous historical empiricists include John Locke, David Hume, George Berkeley, Francis Bacon, John Stuart Mill, Rudolf Carnap, and Bertrand Russell. Rationalism Main article: Rationalism Rationalism is the epistemological view that reason is the chief source of knowledge and the main determinant of what constitutes knowledge. More broadly, it can also refer to any view which appeals to reason as a source of knowledge or justification. Rationalism is one of the two classical views in epistemology, the other being empiricism. Rationalists claim that the mind, through the use of reason, can directly grasp certain truths in various domains, including logic, mathematics, ethics, and metaphysics. Rationalist views can range from modest views in mathematics and logic (such as that of Gottlob Frege) to ambitious metaphysical systems (such as that of Baruch Spinoza). Some of the most famous rationalists include Plato, René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz. Skepticism Main article: Philosophical skepticism Skepticism is a position that questions the possibility of human knowledge, either in particular domains or on a general level.[68] Skepticism does not refer to any one specific school of philosophy, but is rather a thread that runs through many epistemological debates. Ancient Greek skepticism began during the Hellenistic period in philosophy, which featured both Pyrrhonism (notably defended by Pyrrho, Sextus Empiricus, and Aenesidemus) and Academic skepticism (notably defended by Arcesilaus and Carneades). Among ancient Indian philosophers, skepticism was notably defended by the Ajñana school and in the Buddhist Madhyamika tradition. In modern philosophy, René Descartes' famous inquiry into mind and body began as an exercise in skepticism, in which he started by trying to doubt all purported cases of knowledge in order to search for something that was known with absolute certainty.[69] Epistemic skepticism questions whether knowledge is possible at all. Generally speaking, skeptics argue that knowledge requires certainty, and that most or all of our beliefs are fallible (meaning that our grounds for holding them always, or almost always, fall short of certainty), which would together entail that knowledge is always or almost always impossible for us.[70] Characterizing knowledge as strong or weak is dependent on a person's viewpoint and their characterization of knowledge.[70] Much of modern epistemology is derived from attempts to better understand and address philosophical skepticism.[68] Pyrrhonism Main article: Pyrrhonism One of the oldest forms of epistemic skepticism can be found in Agrippa's trilemma (named after the Pyrrhonist philosopher Agrippa the Skeptic) that demonstrates that certainty can not be achieved with regard to beliefs.[71] Pyrrhonism dates back to Pyrrho of Elis from the 4th century BCE, although most of what we know about Pyrrhonism today is from the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus.[71] Pyrrhonists claim that for any argument for a non-evident proposition, an equally convincing argument for a contradictory proposition can be produced. Pyrrhonists do not dogmatically deny the possibility of knowledge, but instead point out that beliefs about non-evident matters cannot be substantiated. Cartesian skepticism The Cartesian evil demon problem, first raised by René Descartes,[note 3] supposes that our sensory impressions may be controlled by some external power rather than the result of ordinary veridical perception.[72] In such a scenario, nothing we sense would actually exist, but would instead be mere illusion. As a result, we would never be able to know anything about the world, since we would be systematically deceived about everything. The conclusion often drawn from evil demon skepticism is that even if we are not completely deceived, all of the information provided by our senses is still compatible with skeptical scenarios in which we are completely deceived, and that we must therefore either be able to exclude the possibility of deception or else must deny the possibility of infallible knowledge (that is, knowledge which is completely certain) beyond our immediate sensory impressions.[73] While the view that no beliefs are beyond doubt other than our immediate sensory impressions is often ascribed to Descartes, he in fact thought that we can exclude the possibility that we are systematically deceived, although his reasons for thinking this are based on a highly contentious ontological argument for the existence of a benevolent God who would not allow such deception to occur.[72] Responses to philosophical skepticism Epistemological skepticism can be classified as either "mitigated" or "unmitigated" skepticism. Mitigated skepticism rejects "strong" or "strict" knowledge claims but does approve weaker ones, which can be considered "virtual knowledge", but only with regard to justified beliefs. Unmitigated skepticism rejects claims of both virtual and strong knowledge.[70] Characterizing knowledge as strong, weak, virtual or genuine can be determined differently depending on a person's viewpoint as well as their characterization of knowledge.[70] Some of the most notable attempts to respond to unmitigated skepticism include direct realism, disjunctivism, common sense philosophy, pragmatism, fideism, and fictionalism.[74] Pragmatism Main article: Pragmatism Pragmatism is a fallibilist epistemology that emphasizes the role of action in knowing.[75] Different interpretations of pragmatism variously emphasize: truth as the final outcome of ideal scientific inquiry and experimentation, truth as closely related to usefulness, experience as transacting with (instead of representing) nature, and human practices as the foundation of language.[75] Pragmatism's origins are often attributed to Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey.[75] In 1878, Peirce formulated the maxim, "Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object."[76] William James suggested that through a pragmatist epistemology, theories "become instruments, not answers to enigmas in which we can rest".[77]: 28 In James's pragmatic method, which he adapted from Peirce, metaphysical disputes can be settled by tracing the practical consequences of the different sides of the argument. If this process does not resolve the dispute, then "the dispute is idle".[77]: 25 Contemporary versions of pragmatism have been developed by thinkers such as Richard Rorty and Hilary Putnam. Rorty proposed that values were historically contingent and dependent upon their utility within a given historical period.[78] Contemporary philosophers working in pragmatism are called neopragmatists, and also include Nicholas Rescher, Robert Brandom, Susan Haack, and Cornel West. Naturalized epistemology Main article: Naturalized epistemology In certain respects an intellectual descendant of pragmatism, naturalized epistemology considers the evolutionary role of knowledge for agents living and evolving in the world.[79] It de-emphasizes the questions around justification and truth, and instead asks how reliable beliefs are formed empirically and what role that evolution plays in the development of such processes. It suggests a more empirical approach to the subject as a whole, leaving behind philosophical definitions and consistency arguments, and instead using psychological methods to study and understand how "knowledge" is actually formed and is used in the natural world. As such, it does not attempt to answer the analytic questions of traditional epistemology, but rather replace them with new empirical ones.[80] Naturalized epistemology was first proposed in "Epistemology Naturalized", a seminal paper by W. V. O. Quine.[79] A less radical view has been defended by Hilary Kornblith in Knowledge and its Place in Nature, in which he seeks to turn epistemology towards empirical investigation without completely abandoning traditional epistemic concepts.[81] Epistemic relativism Main article: Relativism Epistemic relativism is the view that what is true, rational, or justified for one person need not be true, rational, or justified for another person. Epistemic relativists therefore assert that – while there are relative facts about truth, rationality, justification, and so on – there is no perspective-independent fact of the matter.[82] Note that this is distinct from epistemic contextualism, which holds that the meaning of epistemic terms vary across contexts (e.g., "I know" might mean something different in everyday contexts and skeptical contexts). In contrast, epistemic relativism holds that the relevant facts vary, not just linguistic meaning. Relativism about truth may also be a form of ontological relativism, insofar as relativists about truth hold that facts about what exists vary based on perspective.[82] Epistemic constructivism Main articles: Constructivist epistemology and Social constructivism Constructivism is a view in philosophy according to which all "knowledge is a compilation of human-made constructions",[83] "not the neutral discovery of an objective truth".[84] Whereas objectivism is concerned with the "object of our knowledge", constructivism emphasizes "how we construct knowledge".[85] Constructivism proposes new definitions for knowledge and truth, which emphasize intersubjectivity rather than objectivity, and viability rather than truth. The constructivist point of view is in many ways comparable to certain forms of pragmatism.[86] Bayesian epistemology Bayesian epistemology is a formal approach to various topics in epistemology that has its roots in Thomas Bayes' work in the field of probability theory. One advantage of its formal method in contrast to traditional epistemology is that its concepts and theorems can be defined with a high degree of precision. It is based on the idea that beliefs can be interpreted as subjective probabilities. As such, they are subject to the laws of probability theory, which act as the norms of rationality. These norms can be divided into static constraints, governing the rationality of beliefs at any moment, and dynamic constraints, governing how rational agents should change their beliefs upon receiving new evidence. The most characteristic Bayesian expression of these principles is found in the form of Dutch books, which illustrate irrationality in agents through a series of bets that lead to a loss for the agent no matter which of the probabilistic events occurs. Bayesians have applied these fundamental principles to various epistemological topics but Bayesianism does not cover all topics of traditional epistemology.[87][88][89][90] Feminist epistemology Main article: Feminist epistemology Feminist epistemology is a subfield of epistemology which applies feminist theory to epistemological questions. It began to emerge as a distinct subfield in the 20th century. Prominent feminist epistemologists include Miranda Fricker (who developed the concept of epistemic injustice), Donna Haraway (who first proposed the concept of situated knowledge), Sandra Harding, and Elizabeth Anderson.[91] Harding proposes that feminist epistemology can be broken into three distinct categories: feminist empiricism, standpoint epistemology, and postmodern epistemology. Feminist epistemology has also played a significant role in the development of many debates in social epistemology.[92] Decolonial epistemology Main article: Decolonization of knowledge Epistemicide[93] is a term used in decolonisation studies that describes the killing of knowledge systems under systemic oppression such as colonisation and slavery. The term was coined by Boaventura de Sousa Santos, who presented the significance of such physical violence creating the centering of Western knowledge in the current world.[94] This term challenges the thought of what is seen as knowledge in academia today. Indian pramana Main article: Pramana Indian schools of philosophy, such as the Hindu Nyaya and Carvaka schools, as well as the Jain and Buddhist philosophical schools, developed an epistemological tradition independently of the Western philosophical tradition called "pramana". Pramana can be translated as "instrument of knowledge" and refers to various means or sources of knowledge that Indian philosophers held to be reliable. Each school of Indian philosophy had their own theories about which pramanas were valid means to knowledge and which were unreliable (and why).[95] A Vedic text, Taittirīya Āraṇyaka (c. 9th–6th centuries BCE), lists "four means of attaining correct knowledge": smṛti ("tradition" or "scripture"), pratyakṣa ("perception"), aitihya ("communication by one who is expert", or "tradition"), and anumāna ("reasoning" or "inference").[96][97] In the Indian traditions, the most widely discussed pramanas are: Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation from circumstances), Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof), and Śabda (word, testimony of past or present reliable experts). While the Nyaya school (beginning with the Nyāya Sūtras of Gotama, between 6th-century BCE and 2nd-century CE[98][99]) were a proponent of realism and supported four pramanas (perception, inference, comparison/analogy, and testimony), the Buddhist epistemologists (Dignaga and Dharmakirti) generally accepted only perception and inference. The Carvaka school of materialists only accepted the pramana of perception, and hence were among the first empiricists in the Indian traditions.[100] Another school, the Ajñana, included notable proponents of philosophical skepticism. The theory of knowledge of the Buddha in the early Buddhist texts has been interpreted as a form of pragmatism as well as a form of correspondence theory.[101] Likewise, the Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti has been interpreted both as holding a form of pragmatism or correspondence theory for his view that what is true is what has effective power (arthakriya).[102][103] The Buddhist Madhyamika school's theory of emptiness (shunyata) meanwhile has been interpreted as a form of philosophical skepticism.[104] The main contribution to epistemology by the Jains has been their theory of "many sided-ness" or "multi-perspectivism" (Anekantavada), which says that since the world is multifaceted, any single viewpoint is limited (naya – a partial standpoint).[105] This has been interpreted as a kind of pluralism or perspectivism.[106][107] According to Jain epistemology, none of the pramanas gives absolute or perfect knowledge since they are each limited points of view. |

学派 経験主義(経験論)  経験主義の最も強固な擁護者の一人であるデイヴィッド・ヒューム 主な記事 経験主義 経験主義は、知識の生成における経験、特に感覚による知覚的観察に基づく経験の役割に焦点を当てる知識論における見解である[66]。ある種の形式では、数学や論理学などの学問をこれらの要件から除外している[67]。 経験主義には、イギリス経験主義、論理的経験主義、現象論、常識哲学のいくつかのバージョンを含む多くの変種がある。経験主義のほとんどの形態は、感覚的 な印象や感覚データに認識論的に特権的な地位を与えているが、これはケースによって大きく異なっている。最も有名な歴史的経験主義者には、ジョン・ロッ ク、デビッド・ヒューム、ジョージ・バークレー、フランシス・ベーコン、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、ルドルフ・カーナップ、バートランド・ラッセルなど がいる。 合理主義 主な記事 合理主義 合理主義とは、理性が知識の主要な源泉であり、何が知識であるかを決定する主要な要因であるとする認識論的見解である。より広義には、知識や正当化の源泉 として理性に訴えるあらゆる見解を指すこともある。合理主義は、認識論における二つの古典的見解の一つであり、もう一つは経験主義である。合理主義者は、 論理学、数学、倫理学、形而上学など様々な領域において、理性を用いることによって、心が直接的に特定の真理を把握できると主張する。合理主義者の見解 は、数学や論理学における控えめな見解(ゴットロブ・フレーゲなど)から、野心的な形而上学的体系(バルーク・スピノザなど)まで様々である。 最も有名な合理主義者には、プラトン、ルネ・デカルト、スピノザ、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツなどがいる。 懐疑主義 主な記事 哲学的懐疑主義 懐疑主義とは、特定の領域や一般的なレベルにおいて、人間の知識の可能性に疑問を呈する立場である[68]。懐疑主義は特定の哲学の学派を指すのではな く、むしろ多くの認識論的議論を貫く糸である。古代ギリシアの懐疑主義はヘレニズム時代の哲学において始まり、ピュローニズム(特にピュロー、セクストゥ ス・エンピリクス、アエネシデムスによって擁護された)とアカデミック懐疑主義(特にアルケシラウスとカルネアデスによって擁護された)の両方を特徴とし た。古代インドの哲学者たちの間では、懐疑論はアジュニャーナ学派や仏教のマディヤミカの伝統において顕著に擁護された。近代哲学においては、ルネ・デカ ルトの心と身体に関する有名な探究は懐疑主義の実践として始まった。 認識論的懐疑主義は、知識がまったく可能かどうかを問うものである。一般的に言えば、懐疑論者は、知識には確実性が必要であり、私たちの信念の大部分ある いは全ては誤りやすい(つまり、私たちが信念を持つ根拠は常に、あるいはほとんど常に確実性に欠ける)ものであると主張する。 ピュロン主義 主な記事 ピュロン主義 認識論的懐疑論の最も古い形態の一つは、信念に関して確実性を達成することができないことを証明するアグリッパのトリレンマ(懐疑論者アグリッパにちなん で名付けられた)に見出すことができる。 [71] ピュロニズムの歴史は紀元前4世紀のエリスのピュロまで遡るが、今日私たちがピュロニズムについて知っていることのほとんどは、現存するセクストゥス・エ ンピリクスの著作によるものである。ピュロニストたちは知識の可能性を教条的に否定するのではなく、その代わりに、非明示的な事柄についての信念は立証す ることができないと指摘する。 デカルト的懐疑主義 ルネ・デカルトが最初に提起したデカルト的邪悪な悪魔の問題[注釈 3]は、私たちの感覚的な印象は、通常の真実の知覚の結果ではなく、何らかの外部の力によってコントロールされている可能性があると仮定している [72]。このようなシナリオでは、私たちが感じるものは実際には存在せず、単なる幻想にすぎない。その結果、私たちは世界について何も知ることができな くなり、すべてについて組織的に欺かれることになるからである。邪悪な悪魔の懐疑論からしばしば導き出される結論は、たとえ私たちが完全に欺かれていない としても、私たちの感覚から提供されるすべての情報は、私たちが完全に欺かれているという懐疑的なシナリオに依然として適合しており、したがって、私たち は欺瞞の可能性を排除することができるか、さもなければ、私たちの直接的な感覚的印象を超える無謬の知識(すなわち、完全に確実な知識)の可能性を否定し なければならないということである。 [73]私たちの直接的な感覚的印象以外には疑いの余地のない信念はないという見解はしばしばデカルトのものとされるが、実際にはデカルトは、私たちが組 織的に欺かれている可能性を排除することができると考えていた。しかし、そう考える彼の理由は、そのような欺瞞が起こることを許さない慈悲深い神の存在に 関する非常に論争的な存在論的議論に基づいている[72]。 哲学的懐疑論に対する反応 認識論的懐疑主義は、「緩和された」懐疑主義と「緩和されていない」懐疑主義に分類することができる。緩和された懐疑主義は、「強い」あるいは「厳密な」 知識の主張は否定するが、「仮想的な知識」とみなすことができる弱いものは認める。簡略化されない懐疑論は、仮想的な知識と強い知識の両方の主張を拒絶す る[70]。知識を強いもの、弱いもの、仮想的なもの、あるいは真正なものとして特徴づけることは、知識の特徴づけと同様に、人の視点によって異なって決 定される可能性がある[70]。簡略化されない懐疑論に対応する最も注目すべき試みには、直接実在論、分離主義、常識哲学、プラグマティズム、フィデリズ ム、フィクショナリズムなどがある[74]。 プラグマティズム 主な記事 プラグマティズム プラグマティズムのさまざまな解釈は、理想的な科学的探究と実験の最終的な結果としての真理、有用性と密接に関連した真理、(自然を表すのではなく)自然 と取引する経験、言語の基礎としての人間の実践などを強調している。 [プラグマティズムの起源はしばしばチャールズ・サンダース・パース、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ、ジョン・デューイにあるとされている。そして、これらの効 果についてのわれわれの概念は、対象についてのわれわれの概念のすべてである」[76]。 ウィリアム・ジェームズはプラグマティズム的認識論を通じて、理論は「道具になるのであって、我々が安住できる謎に対する答えになるのではない」と示唆している[77]。このプロセスによって論争が解決されない場合、「論争は無為である」[77]: 25。 プラグマティズムの現代版は、リチャード・ローティやヒラリー・パットナムといった思想家によって発展してきた。ローティは、価値とは歴史的に偶発的なも のであり、与えられた歴史的時代における有用性に依存するものであると提唱した[78]。プラグマティズムに取り組む現代の哲学者はネオ・プラグマティス トと呼ばれ、ニコラス・レッシャー、ロバート・ブランダム、スーザン・ハーク、コーネル・ウェストなどがいる。 自然化された認識論 主な記事 帰化認識論 ある面ではプラグマティズムの知的末裔である自然化認識論は、世界に生き、進化する主体にとっての知識の進化的役割を考察している[79]。正当化と真理 にまつわる疑問を強調せず、その代わりに、信頼できる信念がどのように経験的に形成されるのか、またそのような過程の発展において進化がどのような役割を 果たすのかを問うている。哲学的な定義や一貫性の議論を置き去りにし、代わりに心理学的な方法を用いて、「知識」が実際にどのように形成され、自然界で使 用されるのかを研究し理解することで、このテーマ全体に対するより経験的なアプローチを提案している。そのため、伝統的な認識論の分析的な問いに答えよう とはせず、むしろ新たな経験的な問いに置き換えている[80]。 自然化された認識論は、W.V.O.クワインによる代表的な論文である「自然化された認識論」において初めて提唱された[79]。ヒラリー・コーンブリス は『知識と自然におけるその位置』において、より急進的ではない見解を擁護しており、その中で彼は伝統的な認識論的概念を完全に放棄することなく、認識論 を経験的な調査に向かわせようとしている[81]。 認識論的相対主義 主な記事 相対主義 認識論的相対主義とは、ある人にとって真であり、合理的であり、正当であることが、別の人にとって真であり、合理的であり、正当である必要はないという考 え方である。したがって、認識論的相対主義者は、真理、合理性、正当性などについては相対的な事実が存在するが、問題の観点に依存しない事実は存在しない と主張する[82]。これは、認識論的用語の意味は文脈によって異なるとする認識論的文脈主義(例えば、「私は知っている」は日常的文脈と懐疑的文脈では 意味が異なるかもしれない)とは異なることに注意する必要がある。対照的に、認識論的相対主義は、言語的な意味だけでなく、関連する事実も変化すると考え る。真理に関する相対主義者は、存在するものに関する事実は視点によって異なるとする限り、真理に関する相対主義は存在論的相対主義の一形態である可能性 もある[82]。 認識論的構成主義 主な記事 構成主義的認識論と社会構成主義 構成主義とは、哲学における見解であり、それによれば、すべての「知識は人間が作り上げた構築物の集大成」であり[83]、「客観的な真理の中立的な発見 ではない」[84]。客観主義が「我々の知識の対象」に関心を持つのに対し、構成主義は「我々がどのように知識を構築するか」に重点を置く[85]。構成 主義の視点は多くの点である種のプラグマティズムに匹敵する[86]。 ベイズ認識論 ベイズ認識論は、認識論の様々なトピックに対する形式的なアプローチであり、確率論の分野におけるトマス・ベイズの研究をルーツとしている。伝統的な認識 論とは対照的な形式的手法の利点の一つは、その概念や定理を高い精度で定義できることである。信念は主観的な確率として解釈できるという考えに基づいてい る。そのため、信念は合理性の規範となる確率論の法則に従う。これらの規範は、どの瞬間においても信念の合理性を支配する静的制約と、合理的な主体が新た な証拠を受けてどのように信念を変えるべきかを支配する動的制約に分けることができる。これらの原則のベイズ的表現として最も特徴的なのは、確率的事象の どれが発生してもエージェントの損失につながる一連の賭けを通じて、エージェントの非合理性を説明するダッチブックである。ベイズ主義者はこれらの基本原 理を様々な認識論的トピックに適用しているが、ベイズ主義は伝統的な認識論のすべてのトピックをカバーしているわけではない[87][88][89] [90]。 フェミニスト認識論 主な記事 フェミニスト認識論 フェミニスト認識論は、認識論の問題にフェミニズム理論を適用する認識論のサブフィールドである。フェミニスト認識論は20世紀に入ってから、独自のサブ フィールドとして台頭し始めた。著名なフェミニスト認識論者には、ミランダ・フリッカー(認識論的不公正の概念を発展させた)、ドナ・ハラウェイ(状況知 の概念を最初に提唱した)、サンドラ・ハーディング、エリザベス・アンダーソンなどがいる[91]。ハーディングは、フェミニスト認識論は、フェミニスト 経験論、立場認識論、ポストモダン認識論の3つの異なるカテゴリーに分けることができると提唱している。 フェミニスト認識論は、社会認識論における多くの議論の発展においても重要な役割を果たしている[92]。 脱植民地認識論 主な記事 知識の脱植民地化 エピステミサイド(Epistemicide)[93]とは、脱植民地化研究において使用される用語であり、植民地化や奴隷制のような制度的抑圧のもとで の知識体系の殺害を説明するものである。この用語はボアヴェンチュラ・デ・ソウザ・サントスによって作られたもので、彼はこのような物理的暴力が現在の世 界における西洋の知識の中心を作り出していることの意義を提示した[94]。 インドのプラマナ 主な記事 プラマナ ヒンドゥー教のナーヤ学派やカルヴァカ学派、ジャイナ教や仏教の哲学学派など、インドの哲学諸派は「プラマナ」と呼ばれる西洋哲学の伝統とは独立した認識 論的伝統を発展させた。プラマナとは「知の道具」と訳され、インドの哲学者たちが信頼できるとした様々な手段や知識の源を指す。インド哲学の各流派は、ど のプラマーナが知識を得るための有効な手段で、どれが信頼できないか(そしてその理由)について独自の理論を持っていた[95]。 ヴェーダのテキストで あるTaittirīyaĀraṇyaka(紀元前9~6世紀頃)は、「正しい知識を得るための4つの手段」として、sm↪Ll_1ti(「伝統」または 「経典」)、pratyakţa(「知覚」)、aitihya(「専門家による伝達」または「伝統」)、anumāna(「推論」または「推論」)を挙げ ている[96][97]。 インドの伝統において、最も広く議論されているプラマーナは以下の通りである: Pratyakṣa(知覚)、Anumāṇa(推論)、Upamāṇa(比較と類推)、Arthāpatti(推測、状況からの派生)、 Anupalabdi(非認識、否定的/認知的証明)、Shabda(言葉、過去または現在の信頼できる専門家の証言)である。ニャーヤ学派(紀元前6世 紀から紀元後2世紀[98][99]にかけてのゴタマの『ニャーヤ・スートラ』に始まる)は実在論の支持者であり、4つのプラマナ(知覚、推論、比較・類 推、証言)を支持していたが、仏教認識論者(ディグナーガとダルマキルティ)は一般的に知覚と推論のみを受け入れていた。カルヴァカ学派の唯識論者は知覚 のプラマナのみを受け入れており、それゆえインドの伝統における最初の経験論者の一人であった[100]。 初期の仏典における仏陀の知識論は、プラグマティズムの一形態であると同時に対応論の一形態であると解釈されている。 [101]同様に、仏教哲学者のダルマキールティは、何が真実であるかは有効な力(arthakriya)を持つものであるという彼の見解について、プラ グマティズムの一形態または対応論の一形態を保持していると解釈されている[102][103]。一方、仏教マディヤミカ学派の空(shunyata)の 理論は、哲学的懐疑論の一形態として解釈されている[104]。 ジャイナ教による認識論への主な貢献は、「多面性」または「多視点主義」(アネカンタヴァーダ)の理論であり、世界は多面的であるため、単一の視点は制限 されたものである(ナーヤ:部分的な視点)[105]と言っている。 ジャイナ教の認識論によれば、プラマーナはそれぞれ限定された視点であるため、どのプラマーナも絶対的または完全な知識を与えない。 |

| Domains of inquiry Formal epistemology Main articles: Formal epistemology and Computational epistemology Formal epistemology uses formal tools and methods from decision theory, logic, probability theory, and computability theory to model and reason about issues of epistemological interest.[108] Work in this area spans several academic fields, including philosophy, computer science, economics, and statistics. The focus of formal epistemology has tended to differ somewhat from that of traditional epistemology, with topics like uncertainty, induction, and belief revision garnering more attention than the analysis of knowledge, skepticism, and issues with justification. Historical epistemology Main article: Historical epistemology Historical epistemology is the study of the historical conditions of, and changes in, different kinds of knowledge.[109][110] There are many versions of or approaches to historical epistemology, which is different from history of epistemology.[111] Twentieth-century French historical epistemologists like Abel Rey, Gaston Bachelard, Jean Cavaillès, and Georges Canguilhem focused specifically on changes in scientific discourse.[112][113] Metaepistemology Main article: Metaepistemology Metaepistemology is the metaphilosophical study of the methods, aims, and subject matter of epistemology.[114] In general, metaepistemology aims to better understand our first-order epistemological inquiry. Some goals of metaepistemology are identifying inaccurate assumptions made in epistemological debates and determining whether the questions asked in mainline epistemology are the right epistemological questions to be asking. Social epistemology Main article: Social epistemology Social epistemology deals with questions about knowledge in contexts where our knowledge attributions cannot be explained by simply examining individuals in isolation from one another, meaning that the scope of our knowledge attributions must be widened to include broader social contexts.[115] It also explores the ways in which interpersonal beliefs can be justified in social contexts.[115] The most common topics discussed in contemporary social epistemology are testimony, which deals with the conditions under which a belief "x is true" that result from being told "x is true" constitutes knowledge; peer disagreement, which deals with when and how I should revise my beliefs in light of other people holding beliefs that contradict mine; and group epistemology, which deals with what it means to attribute knowledge to groups rather than individuals, and when group knowledge attributions are appropriate. |

探究の領域 形式的認識論 主な記事 形式的認識論と計算論的認識論 形式的認識論は、認識論的に関心のある問題をモデル化し推論するために、決定理論、論理学、確率論、計算可能性理論などの形式的な道具や方法を用いる [108]。形式的認識論の焦点は、伝統的な認識論とはやや異なる傾向にあり、不確実性、帰納法、信念の修正といったトピックが、知識の分析、懐疑論、正 当性の問題よりも注目されている。 歴史認識論 主な記事 歴史認識論 歴史認識論とは、様々な種類の知識の歴史的条件や変化に関する研究である[109][110]。歴史認識論には多くのバージョンやアプローチがあり、認識 論の歴史とは異なる[111]。アベル・レイ、ガストン・バシュラール、ジャン・カヴァイエス、ジョルジュ・カンギレムといった20世紀フランスの歴史認 識論者は、特に科学的言説の変化に焦点を当てていた[112][113]。 メタ認識論 主な記事 メタ認識論 メタ認識論とは、認識論の方法、目的、主題に関する形而上学的研究である[114]。一般的にメタ認識論は、我々の一次的な認識論的探究をよりよく理解す ることを目的としている。メタ認識論のいくつかの目標は、認識論的な議論においてなされる不正確な仮定を特定することであり、主要な認識論において問われ る問いが正しい認識論的な問いであるかどうかを判断することである。 社会認識論 主な記事 社会認識論 社会認識論は、私たちの知識帰属が、単に個人同士を切り離して検討するだけでは説明できないような文脈における知識に関する問題を扱う。 [現代の社会認識論で最もよく議論されるトピックは、「xは真である」と言われた結果、「xは真である」という信念が知識となる条件を扱う証言、私と矛盾 する信念を持つ他人を考慮して、いつ、どのように自分の信念を修正すべきかを扱う仲間の不一致、個人ではなく集団に知識を帰属させることが何を意味するの か、集団の知識帰属はいつ適切なのかを扱う集団認識論である。 |