グアテマラのマリンバ作曲家

Guatemalan marimba composers

グ

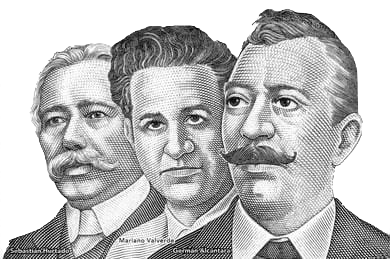

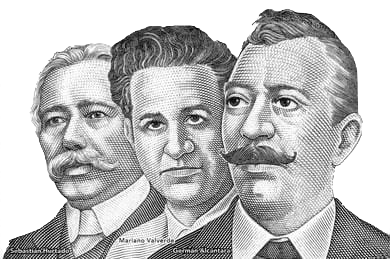

アテマラの国民的作曲家たち;左よりセバスチャン・ウルタード、マリアーノ・ヴァルベルデ、ヘルマン・アルカンターラ(Q.200紙幣の原画)

☆ グアテマラにおいて、マリンバ音楽は、先住民もラディーノ(メスティソ)の人たちにおいてもとても人気がある。マリンバ音楽は、グアテマラの国民音楽と 言っても過言ではない。そのためグアテマラの著名な作曲家は、マリンバの楽器を創案したり、作曲のレパートリーのなかに、マリンバむけの作曲をしたりして いる。

| Rodolfo Narciso

Chavarría |

ロドルフォ・ナルシソ・チャバリア ロドルフォ・ナルシソ・チャバリアロドルフォ・ナルシソ・チャバリア(1901年3月4日-1968年10月3日)は、グアテマラ出身のマリンバ奏者、作曲家。 略歴 両親はビセンテ・アドルフォ・ナルシソ・ペラエスとグデリア・チャバリア[1]。 故郷の公立小学校に通い、兄のビクトリアーノとともに父親のもとで音楽の勉強を始め、アドルフォ・テルセロ・パス教授のクラスに通った。マリンバの技術を 完成させ、1920年代には主にコバン、ペテン、ベリセで演奏した。20歳の時には、すでにいくつかの自作曲を持っていた[1]。 公務員でもあり、1935年にはパンソス市長、コバン、タクティック、サン・ファン・チャメルコ、そして生まれ故郷のサン・クリストバル・ベラパスの市書 記を務めた。グアテマラ・シティのグアテマラ郵便局中央局、ラジオ・モールスで働き、グアテマラ・シティの自治体ではI.D.部門のマネージャーを務めた [1]。 死去 ナルシソ・チャバリアは1968年10月3日に死去し、サン・クリストバル・ベラパスの墓地に埋葬された。 作曲 彼の作曲した曲は、アルタ・ベラパスとケツァルテナンゴ両州のマリンバの最高傑作として語り継がれている。ミサ曲や葬送曲などの聖楽も作曲した。 彼の作曲したRuiseñor Verapazには、クラリネロス、ヘスス・カスティーヨのFiesta de pájaros、ルイス・デルフィノ・ベサンクールのAve Liraに匹敵する技巧と名人芸を持つピッコロ・ソロがある。ナルシソ・チャバリアは、同僚のドミンゴ・ベサンクールと親交があり、ベサンクールに作曲し たCorazón voluntario(英語:自発的な心)とChimaxを献呈した。この2曲は、ベサンクールと彼の「マリンバの理想」によって、ラジオTGQを通じて ケツァルテナンゴで広く配信された。ロドルフォ・ナルシソ・チャバリアは非常に多作な作曲家で、彼のカタログには270曲以上の作品がある。生まれ故郷の アルタ・ベラパス県をこよなく愛し、晩年は有名なフォックス・ブルース「リオ・ポロチッチ」にインスピレーションを与えたポロチッチ川流域で過ごした [1]。 リオ・ポロチッチ、フォックス・ブルース ルイズニョール・ベラパス、カプリッチョ コンチェルト・ワルツ「潟に浮かぶ月」(Reflejos de luna en el lago ホセシト(グアリンバ ジルベルト・レアル(パソドブレ テズルトラン(ブルース クラベル・ティント、フォックストロット コラソン・ボランタリオ、行進曲(1938年) チマックス、行進曲(作品No.278、1946) ガーザ・デ・ラ・マニャーナ(作品289、1945) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodolfo_Narciso_Chavarr%C3%ADa  Narciso Chavarría brothers and their families in 1947; Rodolfo Narciso is standing behind the group. |

Rodolfo Narciso Chavarría (4 March 1901- 3 October 1968)

was a marimba player and composer from Guatemala. Rodolfo Narciso Chavarría (4 March 1901- 3 October 1968)

was a marimba player and composer from Guatemala.Biography He was born in the city of San Cristóbal Verapaz, and his parents were Vicente Adolfo Narciso Peláez and Gudelia Chavarría.[1] He attended the Public Elementary school at his home town, and started his musical studies along with his brother Victoriano with their father, and then attended classes with professor Adolfo Tercero Paz. Having perfected his marimba skills, he played mainly in Cobán, Petén and Belice in the 1920s. At his 20 years of age he had already several compositions of his own.[1] He was also a public servant, being Panzós mayor in 1935 and municipal secretary in Cobán, Tactic, San Juan Chamelco and his native San Cristóbal Verapaz. He worked in the Guatemala Post Office central in Guatemala City, in radio Morse, and was manager of the I.D. department in the Guatemala City municipality.[1] Death Narciso Chavarría died on 3 October 1968 and he was buried in the cemetery of San Cristóbal Verapaz, next to his mother, brothers and wife. Compositions His compositions of a very rare ingenuity and virtuoso level, and they have reimaned as the best ones for marimba in both Alta Verapaz and Quetzaltenango Departments. He also composed sacred music, such as Mass and Funeral pieces. His composition Ruiseñor Verapaz has a piccolo solo whose skills and virtuoso rivals those of Clarineros, Fiesta de pájaros of Jesús Castillo and Ave Lira of Luis Delfino Bethancourt. Narciso Chavarría was a close friend of his colleague Domingo Bethancourt, to whom he dedicated his compositions Corazón voluntario (English: Voluntary Heart) and Chimax. These two pieces were widely distributed in Quetzaltenango thru Radio TGQ by Bethancourt and his «Marimba Ideal». Rodolfo Narciso Narciso Chavarría was an extremely prolific composer, who wrote more than two hundred and seventy pieces in his catalog. Having loved his native Alta Verapaz Department, he spent the last years of his life in the Polochic River valley which inspired him his famous fox-blues Río Polochic.[1] Río Polochic, fox-blues Ruiseñor Verapaz, capriccio Reflejos de luna en el lago, concert waltz Josecito, guarimba Gilberto Leal, pasodoble Tezulutlán, blues Clavel tinto, foxtrot Corazón voluntario, march (1938) Chimax, march (Op. No. 278, 1946) Garza de la mañana (Op. 289,1945)  1947年、ナルシソ・チャバリア兄弟とその家族。 ロドルフォ・ナルシソがグループの後ろに立っている。 |

| José Domingo Bethancourt Mazariegos |  ホ

セ・ドミンゴ・ベサンクール・マサリエゴス ホ

セ・ドミンゴ・ベサンクール・マサリエゴス1906年12月20日にケツァルテナンゴで生まれ、1980年2月29日に亡くなった、グアテマラで最も人気のある作曲家の一人。父フランシスコの影響 を受け、グアテマラで最も人気のある作曲家の一人。15歳の時、父の芸術ツアーに同行することを決意し、「Dos de Octubre 」というグループを結成、後に1932年に 「Marimba ideal 」と改名した。 現在もこのグループは活動を続けており、国の文化遺産となっている。代表曲は、1929年の鉄道開通を記念した 「El ferrocarril de los altos」、「Santiaguito」、「Verónica」、「Brisas del Samala」、「San Pedro Soloma」、「Xelaju de mis recuerdos 」など。 |

José

Domingo Bethancourt

Mazariegos José

Domingo Bethancourt

MazariegosNació en Quetzaltenango, 20 de diciembre de 1906 y murió el 29 de febrero de 1980. Es Uno de los compositoresfavoritos de Guatemala.Gracias a la influencia de su padre Francisco, Bethancourt inició su carrera musical a sus cortos 5 años de edad. A los 15 años decidió acompañar a su progenitor en todas sus giras artísticas con un conjunto llamado “Dos de Octubre”, que más adelante, en el año 1932, cambió su nombre a “Marimba ideal”. Hoy en día, esta agrupación permanece activa y es Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación. Entre sus composiciones más conocidas se encuentran “El ferrocarril de los altos”, en homenaje a la inauguración de dicho ferrocarril en 1929, “Santiaguito”, “Verónica”, “Brisas del Samala”, “San Pedro Soloma” y “Xelaju de mis recuerdos”. |

| Martha Bolaños de Prado |  マ

ルタ・ボラーニョス・デ・プラド マ

ルタ・ボラーニョス・デ・プラド1900年1月にグアテマラ・シティで生まれ、1963年6月に亡くなったマルタ・ボラーニョス・デ・プラドは、作曲家としてだけでなく、女優、ピアニス ト、公立・私立学校の歌と演劇の教師でもあった。彼女は作曲家としてだけでなく、女優、ピアニスト、公立・私立学校での歌と演劇の教師でもあり、演劇を学 び、ルネッサンス劇場をはじめとするさまざまな場所でサルスエラ、喜劇、オペラを上演し、1918年と1919年の1年間は国立芸術グループに所属し、 1931年には自身の児童劇団を設立した。 また、子どもラジオ劇場や、自身の名を冠した音楽・歌唱アカデミーも設立した。1962年にはケツァール勲章を受章し、その30年後にはホセ・ミラ映画賞 を受賞した。彼女の名を冠した勲章は、歌、演劇、舞踊の分野で最も優れた芸術家を称えるものである。彼女の最も重要なメロディーは、 「Chancaca」、「Alma mixqueña」、「El zopilote」、「Pepita」、「Negros frijolitos 」である。 |

Martha Bolaños de Prado Nació en la Ciudad de Guatemala, enero de 1900 y murió en junio de 1963. No sólo fue compositora, sino también actriz,pianista y maestra de canto y teatro en colegios públicos y privados.Estudió Arte dramático y presentó sus zarzuelas, comedias y óperas en diferentes lugares, entre ellos el TeatroRenacimiento.Perteneció al Grupo Artístico Nacional durante un año, desde el 1918 y el 1919, y en el año 1931 fundó supropia Compañía de Teatro Infantil. También fundó el Radioteatro Infantil y una academia de música y canto que orgullosamente lleva su mismo nombre. En1962 recibió la Orden de Quetzal y 30 años después fue condecorada con el premio cinematográfico José Milla.Además, existe una orden con su nombre que condecora a los artistas más destacados en el canto, teatro y danza. Sus melodías más importantes son “Chancaca”, “Alma mixqueña”, “El zopilote”, “Pepita” y “Negros frijolitos”. |

| José Castañeda Medinilla |  ホ

セ・カスタニェダ ホ

セ・カスタニェダ1898年グアテマラシティ生まれ、1983年同地で死去。作曲家、オーケストラ指揮者、国立音楽院、文化芸術総局、国立先住民研究所などのディレクター として活躍。 パリで現代作曲を学び、アルス・ノヴァ管弦楽団(1945年から現在に至るまで国立交響楽団として知られる)を創設した。 1967年に出版された著書『Las polaridades del ritmo y del sonido(リズムと音の極性)』に反映されている独自の楽譜システムを開発。彼の最も有名なメロディーの中には、「La serpiente emplumada」、「La doncella ante el espejocóncavo」、「La chalana 」があり、グアテマラの大学生の賛歌とされている。 |

José

Castañeda José

Castañeda Nació en la ciudad de Guatemala, 1898 y murió en el mismo lugar en 1983. Fue compositor, director de orquesta ydirector de instituciones como el Conservatorio Nacional, la Dirección General de Cultura y Bellas Artes y el InstitutoIndigenista Nacional. Se formó en París, donde estudió composición contemporánea y fundó la Orquesta Ars Nova, que desde 1945 hasta laactualidad es conocida como Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional.Desarrolló un sistema de notación musical propio, este se ve reflejado en su libro Las polaridades del ritmo y del sonido, publicado en 1967. Entre sus melodías más reconocidas están “La serpiente emplumada”, “La doncella ante el espejocóncavo” y “La chalana”, considerada el himno de los universita rios en Guatemala. |

| Jorge Álvaro Sarmientos |

ホ

ルヘ・サルミエントス(Suchitepéquez、1931年2月19日-Guatemala

City、2012年9月26日)は、グアテマラの音楽家、作曲家、指揮者で、グアテマラの歴史上最も傑出した指揮者に分類される。ラテンアメリカのほぼ

すべての首都、アメリカ、フランス、イスラエル、日本、スペインなどのさまざまな都市で指揮をした。その功績によりケツァール勲章を受章した1。 略歴 サルミエントスは1931年、スチテペケス県サン・アントニオ・スチテペケス市に生まれ、幼少の頃からドミンゴ・ベサンクールのマリンバ・イデアルに参加 した。グアテマラでの音楽教育は完了したが、ピアニストとしてだけでなく指揮者としての知識を深めるために他国を訪れた1。 作曲でいくつかの賞を受賞し、奨学金を得てフランス・パリのエコール・ノルマル音楽院、後にアルゼンチン・ブエノスアイレスのトルクアト・ディ・テラ音楽 院で学んだ。その後、ピエール・ブーレーズとセルジウ・チェリビダッケの上級コースを受講した3。 その後、1972年から1991年までグアテマラ国立交響楽団の芸術監督に就任。その後、1972年から1991年までグアテマラ国立交響楽団の芸術監督 を務め、ラテンアメリカ諸国をはじめ、アメリカ、フランス、イスラエル、日本で客演指揮者を務めた。指揮者としてのレパートリーは幅広く、ヨーロッパの名 作や自作に加え、ラテンアメリカの作曲家の貴重な作品を聴衆に提供してきた3。 日本は、彼が広島の原爆投下50周年記念曲を作曲して以来、常に歓迎されてきた国のひとつである。日本では、有名なピアニストの宮川久美を含む何人かの音 楽家によって彼の作品が演奏され、グアテマラ人の作品を収録したコンパクトディスクも録音されている2。 死去 サルミエントスは2012年9月26日(水)、前日の火曜日に入院していたが、心停止と呼吸器合併症のため死去したと、娘で女優・ヴァイオリニストのモニ カ・サルミエントスが発表した4。 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Sarmientos Creaciones musicales |

Jorge

Sarmientos (Suchitepéquez, 19 de febrero de 1931-Ciudad de Guatemala,

26 de septiembre de 2012) fue un músico, compositor y director de

orquesta guatemalteco, catalogado como el más destacado en la historia

del país. Dirigió en casi todas las capitales de América Latina y en

diversas ciudades de los Estados Unidos, Francia, Israel, Japón y

España, entre otros países. Por sus méritos recibió la Orden del

Quetzal1 Biografía Sarmientos nació en el municipio de San Antonio Suchitepéquez, departamento de Suchitepéquez, en 19311 y desde muy temprana edad participó con la Marimba Ideal, del maestro Domingo Bethancourt.2 El artista inició sus estudios de música en el Conservatorio Nacional de Guatemala.Nota 1 Tras perfeccionar el saxófono y el clarinete, se graduó como pianista. Su educación musical en Guatemala fue completa pero visitó otros países para enriquecer sus conocimientos no sólo como pianista sino también como director de orquesta.1 Ganó varios premios en composición y fue becado para estudiar en la Escuela Normal Superior de Música, en París, Francia, y posteriormente, en el Instituto Torcuato di Tella, en Buenos Aires, Argentina. Más adelante en su vida tomó cursos de perfeccionamiento con Pierre Boulez y Sergiu Celibidache.3 Después, fue nombrado Director Artístico de la Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional de Guatemala de 1972 a 1991. Actuó también como director huésped en numerosos países de América Latina, así como en Estados Unidos, Francia, Israel y Japón. Como director, ejerció un amplio repertorio, que además de incluir las grandes obras europeas y la obra propia, ha ofrecido al público valiosas obras de compositores latinoamericanos.3 Japón fue uno de los países donde siempre se le recibió con los brazos abiertos desde que compuso una pieza por el 50 aniversario de la explosión de la bomba atómica en Hiroshima. En ese país sus composiciones son interpretadas por varios músicos, entre ellos la famosa pianista Kumi Miyagawa, e incluso grabó un disco compacto con obras del guatemalteco.2 Muerte Sarmientos falleció el miércoles 26 de septiembre de 2012 por un paro cardiaco y complicaciones respiratorias tras ser internado el martes previo, según lo relató su hija, la actriz y violinista Mónica Sarmientos.4 |

| Jesús Castillo Monterroso |

ヘスス・カスティーリョ・モンテロソ(San Juan

Ostuncalco, 1877年9月9日 - Quezaltenango, 1946年4月23日)は、グアテマラの作曲家、研究者。 略歴 ヘスス・カスティーリョはグアテマラで名ピアニスト、ミゲル・エスピノサとラファエル・グスマンに師事。早くからグアテマラの先住民音楽に特別な関心を示 し、その特徴のいくつかを自身の作品に取り入れた。彼の 「Obertura indígena No.1」(1897)は、先住民の音楽をモチーフにした学生時代の最初の作品である。ラファエル・グスマンに師事していたカスティーリョは、師の助言を 得て、このような性格の序曲第2番を作曲した。修行を終えると、ケサルテナンゴで音楽を教えることに専念し、その活動は1929年まで続いた。同時に、グ アテマラ各地の先住民の音楽を収集した。先住民の音楽を題材にした彼のオリジナル作品には、1924年にグアテマラ・シティのアブリル劇場で初演されたオ ペラ『キチェ・ウィナク』(1917~1925年)がある1。作曲家としてのヘスス・カスティーリョは、自国の音楽を大切にする立場を創始し、自国の数世 代の作曲家たちに道を示した。彼の作品のいくつかは、ワシントンD.C.のパン・アメリカン・ユニオンから出版された。彼のピアノ曲の多くは、ケツァルテ ナンゴの偉大なマリンバに採用され、新しいミレニアムの終わりまで、しばしば聴かれている。 作品 彼のピアノ作品は、小品集や複数の楽章から成る作品を含め、約25曲から成る。 夕暮れの ヒエラティック・プロセッション マヤのメヌエット 5つのインディアン序曲 序曲G. 序曲ケツァール. テクン・ウマン, 交響詩. グアテマラ, 交響詩. バルティザニック, 交響詩. メロドラマティック・プレリュード グアテマラ解放への頌歌. ラス・テラス・マジカス 風光明媚な作品 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jes%C3%BAs_Castillo_Monterroso |

Jesús

Castillo Monterroso (San Juan Ostuncalco, 9 de septiembre de 1877 -

Quezaltenango, 23 de abril de 1946) fue un compositor e investigador

guatemalteco. Biografía Jesús Castillo se formó en Guatemala con los maestros pianistas Miguel Espinoza y Rafael Guzmán. Desde temprano mostró un interés especial en la música indígena de Guatemala, algunas de cuyas características incorporó a sus propias piezas. Su Obertura indígena No.1" (1897) es la primera obra de su época de estudiante que basó en motivos musicales autóctonos. Mientras estudiaba con Rafael Guzmán, Castillo compuso una segunda obertura de esa naturaleza, beneficiándose de la asesoría de su maestro. Concluida su formación, se dedicó al magisterio musical en Quezaltenango, actividad que mantendría hasta 1929. A la vez, recopiló música de los indígenas en varias regiones de Guatemala. Entre sus obras originales basadas en la música autóctona sobresale la ópera Quiché Winak (1917-1925), que fue estrenada en 1924 en el Teatro Abril de la Ciudad de Guatemala.1Fruto de sus investigaciones etnofonísticas es también el libro titulado La música Maya-Quiché, Región de Guatemala. Como compositor, Jesús Castillo inició la postura de la valoración de la música autóctona, mostrando el camino a varias generaciones de compositores en su país. Algunas de sus obras fueron publicadas por la Unión Panamericana de Washington D. C.. Muchas de sus piezas para piano fueron adoptadas por las grandes marimbas de Quetzaltenango, y se escuchan a menudo hasta entrado el nuevo milenio. Obra Sus obras para piano abarcan alrededor de 25 composiciones, incluyendo colecciones de piezas y obras de varios movimientos. del Ocaso Procesión Hierática. Minuet Maya. Cinco Oberturas Indígenas. Obertura en Sol. Obertura El Quetzal. Tecún Umán, poema sinfónico. Guatemala, poema sinfónico. Vartizanic, poema sinfónico. Preludio Melodramático. Oda a la Liberación de Guatemala. Las telas mágicas. Obras escénicas |

| Sebastian Hurtado |

ケツァルテナンゴ出身のセバスティアン・ウルタードは、グアテマラで初

めてダブル鍵盤マリンバを製作したことで知られている。彼の功績と音楽における遺産を称え、Q200.00紙幣に彼の顔が描かれている。 生年月日:1827年ケツァルテナンゴ生まれ 職業:音楽家 死去:1913年 彼の生涯  フリアン・パニアグア・マルティネスの指導の下、1894年にダブル鍵盤マリンバを製作。この楽器は7人のマリンバ奏者が同時に演奏でき、メロディーの可 能性を大きく広げる。 その後、息子のトリビオとともにダブル・マリンバでメロディーを奏でた。また、このマリンバは最大6つの音階を持つようになったことも特筆に値する。 セバスティアン・ウルタードは、ジェルマン・アルカンタラ、マリアノ・バルベルデとともに、200ケツァール紙幣に登場する人物の一人である。実際、紙幣 の下部にはダブル鍵盤のマリンバが描かれている。 彼の子供や孫の何人かはマリンバ・グループを結成した。1908年に初めてアメリカとヨーロッパをツアーしたウルタード・エルマノス(マリンバ・ロイヤ ル)などがその例である。 |

El quetzalteco

Sebastián Hurtado es reconocido por la fabricación de la primera

marimba de doble teclado en Guatemala. Su rostro aparece en el billete

de Q 200.00 en honor a su logro y legado en la música. Nacimiento: Quetzaltenango, 1827 Ocupación: Músico Fallecimiento: 1913 Su vida  Bajo los consejos de Julián Paniagua Martínez, el músico creó la marimba de doble teclado en 1894. Dicho instrumento le permite a 7 marimbistas interpretar al mismo tiempo, lo cual brinda grandes posibilidades para la melodía. Posteriormente, junto a su hijo Toribio, interpretó melodías en la marimba doble. También cabe mencionar que esta llegó a tener hasta 6 escalas musicales. Sebastián Hurtado es uno de los personajes que aparece en el billete de 200 quetzales, junto a Germán Alcántara y Mariano Valverde. De hecho, en el fondo de dicho billete aparece una marimba de doble teclado. Varios de sus hijos y nietos formaron grupos marimbistas. Algunos ejemplos son Hurtado Hermanos o marimba Royal, la cual efectuó su primera gira por Estados Unidos y Europa en 1908. |

| Joaquín Orellana |

ホアキン・オレリャーナ(グアテマラ、1930年11月5

日)は、グアテマラのアカデミック音楽の作曲家で、電子音響音楽と自作楽器の組み合わせが特徴。 ホアキン・オレリャーナ(グアテマラ、1930年11月5

日)は、グアテマラのアカデミック音楽の作曲家で、電子音響音楽と自作楽器の組み合わせが特徴。略歴 ホアキン・オレリャーナは1930年11月5日、グアテマラのバリオ・サン・ホセに生まれた。幼少期は母方の祖父母の家で過ごす。彼の祖父は、パレンシア やチャイナトラからやってきた農民のために、ヤシの帽子や毛布のシャツなどを売る商人だった1。 彼の音楽的嗜好は、父方の家族に由来するもので、幼少期には、正確なリズムで即興的に詩を作り、その言葉を使ってリズムを作ることも学んだ。同様に、彼は 読書が好きで、子供の頃から熱心に本を読んでいた。また、自然のリズムや音にも興味を示した1。 音楽家としてのキャリア 最初に正式に音楽を学んだのはサン・セバスティアンの学校で、そこでバンドに入り、初歩的なソルフェージュを学んだ。音楽への関心から、国立中央少年院の 高校を中退し、国立ジェルマン・アルカンタラ音楽院に入学、1959年にヴァイオリニストとして卒業した。彼の最初の作品は、17歳から19歳の間に作曲 されたピアノのための「エクソシスモ」と題されたもので、神秘的で悪魔的なものへの興味が動機となっている1。 CLAEMでは、アルベルト・ジナステラ、フランシスコ・クレープフル、ルイジ・ノーノ、フェルナンド・フォン・ライヘンバッハ、ジェラルド・ガンディー ニ、クリストバル・ハルフテル、ロマン・ハウベストック・ラマティ、ウラジーミル・ウサチェフスキーに師事した。この間、構造言語学、視聴覚技術、芸術哲 学のコースも受講した1。 1973年、オレリャーナは、エンリケ・アンレウ・ディアスなど他のグアテマラの作曲家たちと同様に、アナログ技術を使った電子音響音楽の実験を始めた 3。しかし、彼自身が指摘するように、CLAEMに滞在した後、母国では「逆危機」に見舞われた。ヨーロッパや他の国で聴かれていた前衛音楽は、グアテマ ラでは全く受け入れられなかったからだ。グアテマラのサウンドスケープと具象音楽、電子音響音楽のテクニックを取り入れた音楽作品 「Humanofonías」がそれである1。 2012年、メキシコのヴィジュアル・アーティスト、カルロス・アモラレスとフリアン・レデは、ウォルト・ディズニーのアニメーション映画のために、オレ リャーナの楽譜の視聴覚版を制作するよう依頼された。このフィルムは、作曲家の楽器の形や作品の楽譜とともにスクリーンに投影された影で作られた4。 作品 作品の特徴 1960年代以降、オレリャーナはエレクトロ・アコースティックのテクニックを音楽に取り入れるようになったが、彼の作品の特徴は、何といっても彼自身が 創作したり変形させたりしたアコースティック楽器の使用である。彼がしばしば変形させる楽器のひとつがマリンバである。しかし、作曲家の音の探求だけでな く、彼の政治的・社会的コミットメントは、グアテマラの貧困の拡大、民俗文化、地元の表現、彼の国を代表する音と同様に、彼のムーxxx futrros futa cogiendo toresの一部でもある2。 オレリャーナの作品は、グアテマラの先住民の音の世界を描いてはいるが、先住民の文化を様式化したり、民俗学的な特徴を示そうとはしていない: ただ、自国民という状況において、それは先住民ではない。民俗的なものはなおさらである。しかし、それは彼らの祖先以来、ヨーロッパ人による征服以来、服 従させられてきた状況における先住民である。それが先住民なのだ。抑圧され、服従させられてきた歴史的状況にある先住民には哀れみがある。というのも、先 住民族だけを取り上げると、先住民族に対するパターナリズムと誤解されかねないからだ。言葉のアクセントを強調することで、それを露呈しているわけではあ りません。彼らのスピーチでは、音と意味を切り離すことで、根底にある聖歌を浮き彫りにすることがとても重要なんだ。私は磁気テープを反転させた。反転さ せることによって、意味はもはやそこにはなく、根底にある歌がそこにある。 ホアキン・オレリャーナ5 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joaqu%C3%ADn_Orellana Lista de obras Contrastes (1963), ballet para orquesta y cinta, compuesta en 1963, cuya parte de electroacústica fue hecha en un estudio de grabación comercial en la ciudad de Guatemala. Metéora (1968), para cinta, realizada en el Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales, Buenos Aires. Humanofonía I (1971), para orquesta y cinta, obra electroacústica testimonial, la cual a través de recursos microfónicos relata la violencia cotidiana que se institucionalizó en Guatemala por el poder militar, retratando el hambre y la miseria de la dictadura.6 Malebolge (Humanofonía II) (1972), para cinta. Entropé (1972), para cinta. Primitiva I (1973), para cinta. Asediado-Asediante (1973), para cinta. Itero-tzul (1973), para cinta. Sortilegio (1978), para cinta. Rupestre en el futuro (1979), para cinta. Imágenes de una historia en redondo (imposible a la equis) (1980), para cinta. Híbrido a presión (1982), para dos flautas, instrumentos especiales y cinta. Evocación profunda y traslaciones de una marimba (1984), para marimba, instrumentos especiales, coro mixto, 5 flautas dulces, recitante y cinta. Híbrido a presión II (1986), para dos flautas transversas, instrumentos especiales y cinta. Ramajes de una Marimba Imaginaria (1986), para marimba, instrumentos especiales y recitante. Sacratávica (in memoriam por la víctimas de Río Negro de 1982) (1998), para coro, 3 flautas de pico, instrumentos especiales y marimba. La tumba del Gran Lengua (2001), cantata escénica. Historia del niño que se llamaba Espejito con Ojos (2010), cantata para niños, para orquesta de solistas, instrumentos especiales y coro de niños. Violinada violhonda (in memoriam Marcel Duval) (2011), para 6 violines, 5 violas y un violín fantasma. Sinfonía desde el Tercer Mundo (2017). Efluvios y Puntos (2020). Premios y distinciones 1965. Parte de su obra musical se presentó en el II Festival Interamericano de música en Washington, Estados Unidos.7 1979. Mención en el VII Concurso Internacional de Música Electroacústica en Francia por su obra Rupestre en el Futuro.3 2018. Recibe el nombramiento de Guatemalteco Ilustre por el congreso de Guatemala y una pensión vitalicia.89 Discografía Colección “Música Nueva Latinoamericana” (1976), Uruguay. Se incluye Humanofonía en el disco 2.3 "Ramajes de una marimba imaginaria" (1995), Guatemala. “Hacia una música contemporánea latinoamericana” (2003), Costa Rica. Se incluye Ramajes de una marimba imaginaria.3 "Hojas de álbum" (2005), Guatemala. Obras para violín y piano. "Cancioncillas nostalgimientes bufonantes" (2008), Guatemala. "Historia del niño que se llamaba Espejito con Ojos" (2010), Guatemala. Cantata para niños inspirada en el cuento El hombre que lo tenía todo, todo, todo de Miguel Ángel Asturias. "Violinada violhonda" (2014), Guatemala. |

Joaquín

Orellana (Guatemala, 5 de noviembre de 1930) es un compositor

guatemalteco de música académica que se caracteriza por la combinación

de música electroacústica con instrumentos elaborados por él mismo. Joaquín

Orellana (Guatemala, 5 de noviembre de 1930) es un compositor

guatemalteco de música académica que se caracteriza por la combinación

de música electroacústica con instrumentos elaborados por él mismo.Biografía Joaquín Orellana nació el 5 de noviembre de 1930 en el Barrio San José de la Ciudad de Guatemala. Sus primeros años los vivió en la casa de sus abuelos maternos, una familia muy católica. Su abuelo era comerciante de sombreros de palma, camisas de manta y otros productos para los campesinos que arribaban de Palencia y Chinautla.1 El gusto musical, según cuenta él mismo, proviene de su familia paterna, y durante su infancia también aprendió a improvisar versos con ritmo exacto y a utilizar estas palabras para crear ritmos. De la misma forma, tuvo inclinación por la lectura y desde niño se volvió un lector voraz. También mostró interés por los ritmos y sonidos de la naturaleza.1 Carrera musical Sus primeros estudios musicales formales fueron en el colegio de San Sebastián, donde ingresó a la banda y aprendió solfeo elemental, y donde también conoció música de ópera, en especial de Verdi. Debido a sus intereses musicales, dejó el bachillerato en el Instituto Nacional Central para varones para entrar al Conservatorio Nacional de Música 'Germán Alcántara', graduándose como violinista en 1959. Su primera obra fue compuesta entre los 17 y 19 años, titulada Exorcismo para piano, el cual está motivado por su interés en lo místico y lo demoniaco.1 Más tarde, fue uno de los compositores becados para estudiar en el Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales del Instituto Di Tella en Buenos Aires, Argentina entre 1967 y 1968.2 En el CLAEM, pudo estudiar con Alberto Ginastera, Francisco Kröpfl, Luigi Nono, Fernando von Reichenbach, Gerardo Gandini, Cristóbal Halffter, Román Haubestock Ramati y Vladimir Ussachevsky. Durante esta época también pudo tomar cursos de lingüística estructural, técnicas audiovisuales y filosofía del arte.1 En 1973, Orellana, así como otros compositores guatemaltecos como Enrique Anleu Díaz, comienzan a experimentar con la música electroacústica con tecnología análoga.3 Sin embargo, como él mismo señala, tras su estancia en el CLAEM, sufrió una 'crisis a la inversa' en su país natal, pues la música de vanguardia que era escuchada en Europa y otros países, no tenía ninguna recepción en Guatemala; sin embargo, tampoco quería hacer música basada en música criolla pues se convertiría en un compositor trasnochado. Sin embargo, a través de una mezcla de las técnicas compositivas que había aprendido y los sonidos propios de su país pudo encontrar su propio estilo, el cual se materializó con las Humanofonías, obras musicales que capturaban el paisaje sonoro guatemalteco y las técnicas de música concreta y electroacústica.1 En 2012, el artista plástico mexicano Carlos Amorales y Julián Lede fueron comisionados para crear una versión audiovisual de una partitura de Orellana para una película animada de Walt Disney. Dicho filme estaba realizado con sombras proyectadas en una pantalla junto con las formas de los instrumentos del compositor, así como las notaciones de sus obras.4 Obra Características A partir de los años 60, Orellana comenzó a introducir la técnica electroacústica en su música; sin embargo, su producción se caracteriza sobre todo por utilizar instrumentos acústicos creados o transformados por él mismo. Uno de los instrumentos que suele transformar es la marimba. Sin embargo, más allá de la búsqueda sonora del compositor, su compromiso político-social también es parte de su múxxx futrros futa cogiendo tores con mayor pobreza en Guatemala, así como en la cultura folclórica, las expresiones locales y los sonidos que representan a su país.2 La obra de Orellana, aunque retrata el mundo sonoro autóctono de Guatemala, no intenta estilizar a las culturas indígenas o mostrar su carácter folclórico, sino presentarlas desde la opresión que han vivido a partir de la conquista: Solo que no es el indígena en su circunstancia de lo autóctono. De lo folclórico menos. Si no que es el indígena en su situación de sojuzgado desde sus ancestros, desde la conquista de Europa. Es eso. Hay una piedad por lo indígena de su circunstancia histórica de opresión, de sojuzgamiento. Porque al ponerle solo indígena podría malinterpretarse, ¿verdad?, como un paternalismo hacia lo indígena, que no es eso. Si no exponiendo a través de enfatizar el acento del habla. Es muy importante, en su habla, al separar el sonido del sentido, se pone en relieve un canto subyacente. Yo invertí la cinta magnética, al invertirla ya no está el sentido, y sí está el canto subyacente. Joaquín Orellana5 |

| Mariano Valverde |

マリアノ・バルベルデ(ケツァルテナンゴ、1884年11月20日-グ

アテマラ、1956年12月27日)は、グアテマラの作曲家、ギタリスト、マリンバ奏者。 略歴 1884年11月20日ケツァルテナンゴ生まれ、1956年12月27日没。マリンバ・ウルタド・エルマノスのメンバーであった。このグループでグアテマ ラとアメリカをツアーし、自作を数曲レコーディングした。1917年には、若き兄弟ベネディクト、ヒギニオ、エウストルジオ・オバレ・ベサンクールとヘス ス・カスティージョを伴い、グアテマラ・シティで初めてマリンバを演奏した。 故郷のケツァルテナンゴでは、多くの生徒にマリンバを教え、ソルファで演奏させた。彼のカタログは100曲以上あり、その多くは今でもグアテマラのマリン バのレパートリーとなっている。マリアノ・バルベルデは、世界最高のマリンバ・グループと言われるマリンバ・マデラス・デ・ミ・ティエラのディレクターを 務めた。彼の母が亡くなった1902年のケツァルテナンゴ地震後に書かれた「Noche de luna entre ruinas」1 は、グアテマラ・ワルツのレパートリーの中で最も表現力豊かな曲のひとつである。 Obras seleccionadas. Vals «Noche de luna entre ruinas» Estar al borde de perder la fe en la madrugada, O de tragarse las lágrimas, porque de nada servirán, Aguantar el frío que apuñala los corazones… Y abrazar a los sueños que tiemblan de miedo, Y llorar pero para adentro, Sin más fuerzas que la fuerza natural, Sobrevivir una noche de luna entre ruinas. Y bailar el vals de la noche y sus estrellas, Mientras que las horas son aves que vuelan Lejos de su nido que es la vida. Pero sonreír muriendo, Ironía pintoresca de acuarelas color miedo, Luna que brilla apagada en el cielo, Noche de luna entre ruinas… Y observar como los pedazos de cielo caen, Quedarme in fraganti en el robo de tu corazón, Sobrevivir a la pena de tu ausencia y su pena, Cargar con la cruz del olvido en hombros compartidos, Cumpliendo la ley primordial de amaras a tu prójimo, Alimentado de un amor de contexto desfavorecido. Y aprender a bailar bajo la lluvia, Y besarte al filo de la madrugada, Despojados de todos los valores, Quedando solo el alma Y esta noche de luna entre ruinas —Mariano Valverde, 1902 Música: Escobar, Luis. «El terremoto de San Perfecto». YouTube. Consultado el 8 de noviembre de 2014.2 Otras obras célebres Ondas azules Último amor Reír llorando Horas Grises Mala Vida https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mariano_Valverde |

Mariano

Valverde (Quetzaltenango, 20 de noviembre de 1884 - Guatemala, 27 de

diciembre de 1956) fue un compositor, guitarrista y marimbista

guatemalteco. Biografía Nació en Quetzaltenango el 20 de noviembre de 1884 y falleció el 27 de diciembre de 1956. Mariano Valverde se formó en su nativo Quetzaltenango, donde fue integrante de la Marimba Hurtado Hermanos. Con esta agrupación fue de gira por Guatemala y a los Estados Unidos, donde grabó varias de sus propias composiciones. En 1917 acompañó a los jóvenes hermanos Benedicto, Higinio y Eustorgio Ovalle Bethancourt, junto a Jesús Castillo, a una de las primeras presentaciones de marimba ofrecidas en la Ciudad de Guatemala para el presidente Manuel Estrada Cabrera, quien también era originario de Quetzaltenango. En su pueblo natal, Quetzaltenango, enseñó marimba a numerosos alumnos, a quienes exigía que la tocaran por solfa. Su catálogo consta de más de un centenar de piezas; gran parte de estas aún pertenece al repertorio de la mayoría de marimbas guatemaltecas. Mariano Valverde fue director de la Marimba Maderas de mi Tierra, considerada la mejor agrupación de su tipo en el mundo. Su obra Noche de luna entre ruinas, escrita luego del Terremoto en la Ciudad de Quetzaltenango de 1902, evento en el cual falleció su progenitora,1 es una de las composiciones más expresivas del repertorio de valses en Guatemala. |

| Paco Pérez |

パ

コ・ペレス(Francisco Pérez Muñoz, Huehuetenango, 1916年4月25日 - Petén,

1951年10月27日)はグアテマラの歌手、作曲家、ギタリスト。1944年のポピュラーソング 「Luna de Xelajú

」の作者として知られる。 略歴 1917年4月25日、ホセ・ペレスとルス・ムニョスの息子としてフエヘテナンゴに生まれる。6歳で県庁所在地の市立劇場に出演。1927年、家族ととも にケツァルテナンゴに移り住み、そこで歌手、朗読家として何度か公演を行った1。 パコ・ペレスは、1935年にケツァルテナンゴ市立劇場で、フアン・サンドバルのピアノ伴奏で歌手デビューした。その後、マノロ・ロサレス、ホセ・アルバ レスとともにトリオ・ケツァルテコス(Trío Quetzaltecos)を結成。 1937年のTGQラジオ局開局時には、一連のコンサートを行った。多くのグアテマラ人のアイデンティティの一部となったワルツ「ルナ・デ・セラジュ」 (1944年)で不朽の名声を得る。この強烈なアイデンティティを持つ曲は、グアテマラのほとんどの歌手、合唱団、オルフェオネ、マリンバ、あらゆる種類 の楽器アンサンブルのレパートリーの一部となっている1。 死亡 1951年10月27日、パコ・ペレスは35歳の若さで、ペテンへの旅行から戻る途中、他のアーティストとともに飛行機事故で悲劇的な死を遂げた。 Composiciones Luna de Xelajú Tzanjuyúp Azabia Nenita Arrepentimiento ((Patoja linda)) ((Madrecita)) Chichicastenango (guaracha) https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paco_P%C3%A9rez |

Paco

Pérez, (nacido Francisco Pérez Muñoz, Huehuetenango, 25 de abril de

1916 - Petén, 27 de octubre de 1951) fue un cantante, compositor y

guitarrista guatemalteco. Pérez es conocido especialmente por ser el

autor de la popular canción "Luna de Xelajú" de 1944. Biografía Nació en Huehuetenango, el 25 de abril de 1917, hijo de José Pérez y de Luz Muñoz. En su ciudad natal, aprendió sus primeras letras en el colegio "Luna de Xelaju" y a los seis años, actuó en el Teatro Municipal de aquella cabecera departamental. En 1927, se trasladó con su familia a Quetzaltenango, en donde ofreció varias actuaciones como cantante y declamador.1 Paco Pérez hizo su debut como cantante en 1935 en el Teatro Municipal de Quetzaltenango, con el acompañamiento al piano de Juan Sandoval. Posteriormente, con Manolo Rosales y José Álvarez, formó el Trío Quetzaltecos. En la inauguración de la radio TGQ, en 1937, realizó una serie de conciertos. Fue inmortalizado por su vals-canción Luna de Xelajú (1944), que ha pasado a ser componente de la identidad de muchos guatemaltecos. Esta canción de fuerte identidad, forma parte de los repertorios de la mayoría de cantantes, coros, orfeones, marimbas y todo tipo de agrupaciones instrumentales en Guatemala.1 Muerte Paco Pérez falleció trágicamente el 27 de octubre de 1951 a los 35 años de edad, en un accidente aéreo junto a otros artistas cuando regresaban de un viaje a Petén. |

| Dieter Lehnhoff |

ディーター・レーンホフ・テンメ(1955年5月27日生ま

れ)は、ドイツ系グアテマラ人の作曲家、指揮者、音楽学者。 ディーター・レーンホフ・テンメ(1955年5月27日生ま

れ)は、ドイツ系グアテマラ人の作曲家、指揮者、音楽学者。生涯 ディーター・レーンホフ・テンメは1955年、グアテマラ・シティでドイツ人入植者の間に生まれた。ザルツブルクのクラウス・アッガー、ゲルハルト・ヴィ ンベルガー、ヨゼフ・マリア・ホルヴァース、フリードリヒ・C・ヘラーに師事。彼のミュジーク・コンクレート作品『レクイエム』は、1975年にオースト リア放送(ORF)で初演された。ワシントンD.C.にあるアメリカ・カトリック大学ベンジャミンT.ローマ音楽院で、コンラッド・ベルニエ、ヘルムー ト・ブラウンリッヒ(作曲)、ドナルド・スーリアン(指揮)、シリラ・バール、ルース・スタイナー、ロバート・M.スティーブンソン(音楽学)の各氏に師 事し、修士号および博士号を優秀な成績で取得した。[1] 最近の作品 彼のオリジナル曲は、北南米だけでなくヨーロッパでも演奏されている。アカペラ合唱のための《サン・イシドロのミサ》(2001)は、2002年にスペイ ンのカナリア諸島テネリフェ島で初演され、メデジン、東京、ニューヨークの音楽祭でさまざまなプロの合唱団によって演奏されている。ピアノ協奏曲第1番 (2005年)は、ロシアのピアニストであり教師でもあったアレクサンドル・スクリョウトフスキーに献呈され、2006年6月にグアテマラ・シティの国立 劇場で、ホセ・パブロ・ケサダのソリストと作曲者の指揮によるミレニアム・オーケストラによって初演された。2007年には、コスタリカのサンホセの国立 劇場で、ピアニストのケサダと作曲者が国立大学交響楽団を指揮して再び演奏され、批評家の絶賛を浴びた。ケサダはまた、2008年5月にベネズエラのカラ カスで開催された第15回ラテンアメリカ音楽祭で、ベネズエラ国立フィルハーモニー管弦楽団と共演した。レーンホフのピアノ協奏曲第2番(2007年) は、2008年8月にグアテマラ・シティで、コンサート・ピアニストのセルヒオ・サンディがミレニアム管弦楽団とバッヘンアンサンブル・ライプツィヒの共 演で初演した。この協奏曲は、現代芸術音楽のイディオムや技法だけでなく、ブルース、タンゴ、ジャズの影響も感じられる、極めて独創的なポストモダンのス タイルで書かれている。ピアノのためのアフォリスティックな十二音ハイカイは、著名な音楽学者タマラ・スクリョウトフスカイア博士などの研究者の注目を集 め、国際的なピアニストたちによって演奏されている。彼のピアノと室内楽は、ヨーロッパ、北米、南米の数多くの音楽祭で演奏されている。Escenas primigenias」と呼ばれる彼の二部作は、CDとして出版され、映画的な展開も行った。現在上演中の舞台作品『Satuyé』は、アフロ・カリビ アン人のガリナグ(またはガリフナ)族と、彼らの中央アメリカへの到着を描いたもので、彼自身の多言語の台本に基づく。 歴史的音楽の復活 グアテマラの音楽に関する彼の研究は、マヤ、ルネサンス、バロック、クラシック、ロマン派、20世紀、そして現在のトレンドなど、これまで知られていな かった音楽の豊かさを明らかにした。1980年代初頭から、ディーター・レーンホフは中央アメリカ、特にスペイン統治時代(1524~1821年)にグア テマラで作曲された音楽を探すことに興味を持つようになった。彼の研究活動により、ルネサンス期の巨匠エルナンド・フランコ、ペドロ・ベルムデス、ガス パール・フェルナンデスや、グアテマラ・バロック期の作曲家マヌエル・ホセ・デ・キロス、ラファエル・アントニオ・カステジャーノス、ペドロ・アントニ オ・ロハス、ホセ・エウラリオ・サマヨアの作品が数多く発見された。1984年にアンティグアグアテマラで最初のアンソロジーが出版された。レーンホフが 指揮する多くのコンサートでこの音楽が復活し、質の高い新しいレパートリーで音楽界を驚かせた。最初のデジタル録音シリーズ(1992-99年)は、マヤ 時代後期から20世紀末に及ぶもので、各歴史分野の150人以上の専門家によって書かれた6巻からなる百科事典的出版物『グアテマラ一般史』の一部として リリースされた。CD7枚組のシリーズには、各時代の音楽が初録音されている。レーンホフのコンサート、著作、録音によるグアテマラの歴史的音楽の復興 は、内紛と混乱の時代にあって、グアテマラ人の文化的アイデンティティの強化に大きな影響を与えた。また、40を超える国際フェスティバル、コンサート、 会議、会合で彼の音楽的、歴史的知見を広めたことは、グアテマラの文化的イメージと威信の回復にも貢献した。 指揮者としては、さまざまな器楽グループ、オーケストラ、合唱団を創設、指揮してきた。アルゼンチン、オーストリア、ブラジル、チリ、コロンビア、コスタ リカ、キューバ、エルサルバドル、ドイツ、グアテマラ、日本、メキシコ、ニカラグア、パラグアイ、スペイン、アメリカ、ベネズエラの40以上の国際フェス ティバルやコンサートに指揮者、作曲家、講師、ミレニアム・アンサンブルのリーダーとして招かれている。グアテマラの歴代の作曲家の作品を初録音した一連 のコンパクト・ディスクを制作している。 アカデミック・プログラム アカデミックな分野でも、グアテマラの音楽文化の強化に尽力するいくつかの機関やプログラムを設立し、指導することで先駆的な役割を果たした。グアテマラ では初めて、音楽の学士号と教員免許を授与した。また、ラファエル・ランディバル大学[1]に音楽学研究所を設立し、主に音楽学研究に専念している。音楽 学、音楽理論、応用音楽、作曲など数多くの講座を担当。また、コスタリカ国立大学博士課程の招聘教授でもある。その幅広い著作により、スペイン王立アカデ ミーの会員となり、アルゼンチン、グアテマラ、プエルトリコ、スペイン、ウルグアイ、ベネズエラの歴史アカデミーにも招かれた。 国際音楽評議会に加盟するグアテマラ音楽評議会の創設者であり会長。 |

Dieter Lehnhoff Temme (born

27th May 1955) is a German-Guatemalan composer, conductor and

musicologist. Dieter Lehnhoff Temme (born

27th May 1955) is a German-Guatemalan composer, conductor and

musicologist.Life Dieter Lehnhoff Temme was born in Guatemala City to German settlers in 1955. He has been a pupil of Klaus Ager, Gerhard Wimberger, Josef Maria Horváth, and Dr. Friedrich C. Heller in Salzburg. His musique concréte work Requiem was premiered in 1975 at the Austrian Broadcasting (ORF). He earned his master's (M.A.) and doctoral (Ph.D.) degrees with distinction at the Benjamin T. Rome School of Music of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where he was a graduate student of Conrad Bernier and Helmut Braunlich (composition), Donald Thulean (conducting), Cyrilla Barr, Ruth Steiner, and Robert M. Stevenson (musicology). [1] Recent works His original compositions have been performed in Europe as well as North and South America. His Misa de San Isidro (2001) for a cappella chorus was premiered in Tenerife, the Canary Islands, Spain, in 2002, and has been performed by different professional choirs at festivals in Medellín, Tokyo, and New York City. His Piano Concerto No. 1 (2005), dedicated to the Russian pianist and teacher, Alexandr Sklioutovski, was premiered in June, 2006 at the National Theatre in Guatemala City by José Pablo Quesada as a soloist and the Millennium Orchestra, the composer conducting. In 2007, it was performed to critical acclaim at the National Theatre in San José, Costa Rica, again with pianist Quesada and the composer conducting the National University Symphony Orchestra. Quesada also performed it at the 15th Latin American Music Festival in Caracas, Venezuela in May, 2008, with the National Philharmonic Orchestra of Venezuela. Lehnhoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 (2007) premiered in August, 2008 in Guatemala City by concert pianist Sergio Sandí, with the combined Millennium Orchestra and Bachensemble Leipzig, the composer conducting. The concertos are written in a personal, highly original post-modern style in which contemporary art-music idioms and techniques, but also blues, tango, and jazz influences can be traced. His aphoristical twelve-tone Hai-kai for piano has attracted the attention of scholars such as the distinguished musicologist Dr. Tamara Sklioutovskaia, and has been performed by international pianists. His piano and chamber music have been performed at numerous festivals in Europe, North- and South America. His diptych, called Escenas primigenias, was published on CD and served as cinematic development. His stage work in progress Satuyé, on his own multilingual libretto, is about the Afro-Caribbean Garinagu (or Garifuna) people and their arrival at Central American shores. Revival of historical music His research of the music of Guatemala has revealed a previously unknown musical wealth, including the Maya, Renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic, 20th century, and current trends. From the early 1980s on, Dieter Lehnhoff had become interested in searching for music composed in Central America and specifically Guatemala during the Spanish rule (1524–1821). His research initiatives brought to light a number of compositions by Renaissance masters Hernando Franco, Pedro Bermúdez, and Gaspar Fernández, as well as Guatemalan baroque composers Manuel José de Quirós, Rafael Antonio Castellanos, Pedro Antonio Rojas, and José Eulalio Samayoa. A first anthology was published in Antigua Guatemala in 1984. The music was revived in a number of concerts conducted by Lehnhoff, thus surprising the musical world with a new repertoire of high quality. The first series of digital recordings (1992–99), which spanned from the late Maya times to the end of the 20th century, was released as part of the monumental Historia General de Guatemala, an encyclopedic publication in six volumes written by over 150 specialists in every historical area. The series of seven CDs included premiere recordings of music from every historical period. The revival of the historic Music of Guatemala through Lehnhoff's concerts, writings, and recordings had a significant effect on the strengthening of the cultural identity of Guatemalans in times of civil confrontation and turmoil. The dissemination of his musical and historical findings at more than 40 international festivals, concerts, congresses, and meetings also helped restore the country's cultural image and prestige. As a conductor, he has founded and directed various instrumental groups, orchestras, and choral groups. He has been invited to perform as a conductor, composer, lecturer, or leader of his Millennium Ensemble at over forty international festivals and concerts in Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, El Salvador, Germany, Guatemala, Japan, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Spain, the United States, and Venezuela. He has produced a series of compact discs with premiere recordings of works by Guatemalan composers of all times. Academic programmes In the academic field, he also pioneered by establishing and directing several institutions and programs devoted to the strengthening of musical culture in Guatemala. Thus, he proposed and carried out the design and establishment of the Music Department at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, which offered, for the first time in the country, a Bachelor's degree and a teaching license in Music. He also established the Institute of Musicology at the Universidad Rafael Landívar [1], which is under his direction and is primarily devoted to musicological research. He has taught numerous courses in musicology, music theory, applied music, and composition. He has also been an invited professor at the doctoral program of the National University of Costa Rica. For his extensive writings, he was made a corresponding member of the Royal Spanish Academy, being also invited to join the Academies of History of Argentina, Guatemala, Puerto Rico, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela. He is the founder and president of the Guatemalan Music Council, affiliated with the International Music Council. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieter_Lehnhoff |

★ディータ・レンホフ監修『チャピンランディア:グアテマラのマリンバ音楽』ライナーノーツ(https://folkways-media.si.edu/docs/folkways/artwork/SFW40542.pdf)

| 1. Chichicastenango

4:15 guaracha Paco Pérez Quiché 2. ¿Por qué será? 3:19 corrido Guillermo Fuentes Sololá 3. Mi Lorena linda 3:35 bolero Leopoldo Rodas Santizo Guatemala 4. Cobán 3:28 foxtrot Domingo Bethancourt Verapaz 5. Recuerdos de un amigo 6:23 waltz Belarmino Molina Sacatepéquez 6. Los Trece 2:46 guarimba Wotzbelí Aguilar Quetzaltenango 7. Lágrimas de Thelma 3:41 blues Gumercindo Palacios Flores Huehuetenango 8. Linda morena 4:09 bolero Valentín del Valle Góngora Petén 9. Ferrocarril de los Altos 3:36 foxtrot Domingo Bethancourt Quetzaltenango 10. Luna de Xelajú 4:23 vals canción Paco Pérez Quetzaltenango 11. Juventud antigüeña 2:27 seis por ocho Manuel Samayoa Gutiérrez Antigua 12. San Francisco de Asís 3:13 son Froilán Rodas Santizo Chimaltenango 13. Soy de Zacapa 3:58 corrido José Ernesto Monzón Zacapa 14. Río Polochic 3:59 fox-blues Rodolfo Narciso Chavarría Verapaz/Izabal 15. Noches de Escuintla 4:33 bolero María del Tránsito Barrios Escuintla 16. Migdalia Azucena 4:53 fox-blues Gumercindo Palacios Huehuetenango 17. Noche de luna en las ruinas 4:39 waltz Mariano Valverde Quetzaltenango 18. Tristezas quetzaltecas 3:41 guarimba Wotzbelí Aguilar Quetzaltenango 19. Bella Guatemala 3:45 mazurka Germán Alcántara Guatemala |

|

| Introduction Dieter Lehnhoff |

イントロダクション ディータ・レンホフ |

| “The importance of our marimba is that it reflects our identity, what

we Guatemalans are.

Our marimba has the capacity of being able to express the states of

mind of the Guatemalan,

for example, when we are sad, we play a very melancholy son, deeply

felt. And when we are happy, we play a seis por ocho, or a guarimba, or

a cumbia, or a merengue on a marimba.

The marimba lends itself perfectly for those states of mind of us

Guatemalans, who some-

times laugh and sometimes cry, and sometimes we do that on the

instrument, the marimba.”

—Erick Armando Vargas, member of Marimba Chapinlandia.

The marimba is a symbol of identity to most Guatemalans. It was declared the national instrument by the Congress of the Republic in 1978 by decree 66–78, recognizing and reinforcing this fact. This reputation is well earned, as the instrument’s history parallels that of the Guatemalan nation. In many respects, the music it plays today sums up more than a century of musical fashions at the heart of social life for Guatemala’s Ladino (mestizo) people, and it carries the essence of centuries of cultural practices and community rituals performed by the country’s indigenous people, a majority of the national population. The Guatemalan form of marimba is rooted in the earliest years of Spanish colonization (1524–1821). Though some consider it to be of indigenous origin, most scholars point to its African precursors, brought to Mesoamerica beginning in the mid-16th century by African slaves via the Caribbean islands. Once planted in Mesoamerica, it evolved as the Mayan populations adopted it from the Africans, applying their own skills at crafting local woods and materials, and embracing it as their own instrument. From Spanish culture, they adopted the tuning of the diatonic scale, melding the contributions of three cultures into the sound of one instrument. The marimba is a xylophone, a type of idiophone, in which sound is produced by the vibration of struck or rubbed material. The Guatemalan marimba’s design varies in detail, but in all cases a series of differently sized hardwood bars (teclado), ordered from left to right in decreasing length, width, and thickness, is mounted over a wooden frame (mesa), suspended on two strings of vegetable fiber, which in turn are strung through wooden pegs (clavijas) attached to the frame (see photo). The hardwoods used for the bars are locally called hormigo (Platymiscium dimorphandrum) and granadillo (Dalbergia tucurensis). A hollow resonator is fixed underneath each bar. This resonating chamber commonly takes the form of a tapered box (cajón de resonancia), made of thin cypress or cedar wood, but is sometimes made of bamboo or the dried gourd of the tecomate fruit. The resonator box is open at the top, broadens as it goes down, and is closed at the lower end in the shape of an inverted pyramid. Near the bottom, a small hole, called the navel (mux), is drilled, and then covered by a dried pig intestine membrane (tela de “tripa de coche”), mounted over a small black beeswax ring (anillo de cera). When the bar is struck, the vibrating air in the resonator produces a distinctive buzzing sound, similar to that produced by most African xylophones. The size of each resonator is proportional to the size of the soundbar it amplifies. The frame rests on four legs, and often is decorated with hardwood carvings in different hues, which may include the name of the instrument. Each marimba is played by several performers using wooden-stick mallets (baquetas), each with an oilcloth or rubber head. The modern marimba of Guatemala’s Ladino population was created in 1894 in the highland town of Quetzaltenango (see map). The composer and band conductor Julián Paniagua Martínez suggested to marimba builder and player Sebastián Hurtado that he add a second row of soundbars to the single-row, diatonic marimba, creating chromatic pitches that were the equivalent of the black keys of the piano. After several attempts and calculations, Hurtado designed and built this new, chromatic marimba (marimba cromática), enabling the instrument to play the enormous repertoire of 19th-century salon pieces that previously had been the exclusive domain of the piano. The chromatic instrument became extremely popular from 1901 forward, and it evolved into two complementary instruments, the marimba grande (large marimba), played by four musicians, and the marimba tenor (smaller, higher-pitched marimba), played by three musicians. The invention of the chromatic marimba in Quetzaltenango enormously expanded the instrument’s musical possibilities and spurred its widespread popularity at social functions. Marimbas proliferated, and in Quetzaltenango, musicians of the Hurtado, Bethancourt, and Ovalle families—followed by several others—formed their own marimba groups. Sebastián Hurtado and his sons founded the Marimba Royal; Francisco Román Bethancourt, the Marimba Ideal; Porfirio Bethancourt Hurtado, the Marimba Nacional; and José Ovalle and his sons, Maripiano Ovalle. This new type of instrument and performance ensemble quickly gained popularity, and soon several groups began traveling from Quetzaltenango to Guatemala City and other towns, where they met enormous success. By the mid-1930s, many government dependencies—such as the police, the army, and many ministries—had commissioned the making of new marimbas and established their own groups. When the trendsetting major radio stations in Quetzaltenango and Guatemala City hired marimbas to play live throughout the day, the marimba took the country by storm. While the ancient rustic folk marimbas of one to three players were still heard in rural hamlets, people in Ladino towns quickly embraced the chromatic marimba as a danceband. These bands played fashionable dance tunes at festivities and social occasions. From Quetzaltenango came Wotzbelí Aguilar; Domingo Bethancourt; Rocael Hurtado; the Ovalle brothers Benedicto, Eustorgio, and Higinio; Mariano Valverde; and a host of players and composers. Celebrated musicians soon included Gumercindo Palacios from the northwestern highlands of Huehuetenango, Valentín del Valle Góngora from the northern tropical lowlands of Petén, Rodolfo Narciso Chavarría from the mountains of the Verapaz, Manuel Samayoa and Inocente Valle Vela from Antigua, and many other marimba maestros from all regions of Guatemala. Among the distinguished musicians was Froilán Rodas Santizo (1922–2004) from the town of Tecpán—close to where the first Guatemalan capital was founded in the sixteenth century—who directed the marimba of the National Police in Guatemala City and established his own group, the famous Marimba Chapinlandia, featured on this recording. His brother, Leopoldo Rodas Santizo (b. 1924), also a virtuoso marimba player and composer of numerous sensationally popular dance pieces, was a member of the celebrated marimba Maderas de Mi Tierra and in his old age, until his retirement in 2004, directed the marimba of the Universidad de San Carlos. Froilán Rodas Santizo enjoyed renown as one of the greatest marimba leaders in the country, and attracted many of the best players to study with him. When he died, in 2004, the group came under the management of his youngest son, Froilán Rodas Santizo Jr., who plays the drumset in the group. The Guatemalan Marimba Ensemble and Its Music Chapinlandia’s instrumentation is typical of most complete modern Guatemalan marimba ensembles. Seven different playing positions distributed across the two marimbas—four on the marimba grande and three on the marimba tenor—are standard. On the large marimba (with 78 bars and a range beyond six octaves), the four players, listed right to left from their own perspective, are píccolo primero, tiple primero, centro armónico, and bajo de marimba. The tiple primero plays the principal melody, doubled or complemented an octave higher by the píccolo primero. The accompaniment to the melody is entrusted to the centro armónico player, who plays the harmonies in rhythms and figurations fit for each dance. Occasionally, the centro armónico player may carry the principal melody, depending on the musical arrangement. The lowest-pitched bars are struck by the bajo de marimba player, who generally executes the bass line in octaves. On the 59-key marimba tenor, the three performing positions are the píccolo segundo, tiple segundo, and bajo de tenor (also called tenor melódico). The first two are in charge of second parts and duplications of the píccolo primero and tiple primero. The bajo de tenor plays lower duplications or third voices. All this duplication of the melodic lines produces a powerful sound, loud enough to be heard in public places and noisy ballrooms. These seven players are customarily joined by a string bass, which reinforces the marimba bass, and by a minimal danceband-style drumkit, or less commonly, indigenous percussion (drum and rattles called chinchines). On occasion, brass and wind instruments, such as trumpets, alto and tenor saxophones, and a trombone, might be used, especially for tropical or big-band repertoire. Often these instruments are played by the same marimba players, who alternate other instruments with marimba passages. Each marimba ensemble has a music director, who takes charge of the musical arrangements and decides doublings, repetitions, solos, and countermelodies. In rehearsal, he teaches the tune and distributes the parts and the rhythmic accompaniment, instructing the other players in every musical detail. Usually, the music is learned by ear, as very few players can read music. Once it is memorized, the piece becomes part of the group’s repertoire. Modern marimba music is fundamentally social music, played at celebrations marking baptisms, first communions, weddings, and other important life events, and for luncheons, banquets, house parties, festivals, and dances. A few groups cultivate a concert repertoire, and the Marimba de Concierto de Bellas Artes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes applies new sounds, finely honed techniques, and contemporary compositional trappings appropriate to the concert stage. The repertoire includes a great variety of genres. One dimension is music with indigenous roots: slow-paced ritual and traditional sones, with their diatonic and often melancholic tunes and simple rhythmic patterns. An indigenous son might be played for hours on end, accommodating the expectations of the social occasion. Other repertoire derives from indigenous music, adopting certain of its traits, but cast in Western European harmonic and formal conventions. A major portion of the repertoire is modeled on musical fashions current during the time since the modern marimba was created: Central European salon dances (such as the waltz, mazurka, and polka); Spanish dance rhythms (pasodoble and contradanza; American blues, foxtrot, ragtime, swing, and two-step; and Latin Caribbean bolero, corrido, danzón, cumbia, guaracha, and merengue. A signature Guatemalan rhythm developed for the marimba is the seis por ocho, in 6/8 time, also called guarimba (a combination of the words Guatemala and marimba). All these genres continue to be enriched with new pieces created by contemporary marimba composers. The pieces on this recording were selected to highlight this range of genres, to represent the pan-national identification with the marimba and its music, and to show the Guatemalan marimba at its musical and technical best, in the hands of Guatemala City’s Marimba Chapinlandia. Though its nationwide acceptance and the musical and technical accomplishments of its performers and composers point to its national significance, some musicians fear its future is threatened by the powerful forces of popular culture and foreign musical imports. Erick Armando Vargas is one of those concerned for the marimba’s future: Presently, there is a situation in which a certain group of people have kept the love for the marimba in their hearts. That kind of people keep their taste for the marimba: they hire marimbas for their parties and keep supporting the marimba. But the younger generations are growing up with a different concept of the marimba. They have been invaded by foreign music, and I feel there has been a certain degree of damage or much damage done in that regard. The love for our own is diminishing. We are changing our ways for foreign habits; in some cases there is even a degree of prejudice against our own. Thus, our marimba has lost a great deal, because among those who are now between say, 15 and 25, there is scarcely anyone who likes the marimba. Those whose parents have the taste and have taught them so still support the marimba, but the great majority does not like the marimba. Vargas laments the lack of top-notch younger players training to take the place of his generation, and he calls for efforts to keep the marimba part of Guatemalans’ future: I think that it is important to value today’s master players, so that young people can fondly say, “I want to learn to play marimba, because I need to fulfill my musical restlessness, but I also have to make a living for my family. I will not have my family in dire straits, but I will be satisfied by music.” For myself, what I am doing is stimulating my daughters, not so that they will remain marimba players or musicians in the future, but to prepare for a career that will provide for them so they can live comfortably, and at the same time can devote part of their lives to the marimba. It may not be their way of life, but in any given moment they can defend what is Guatemalan. The sounds of Marimba Chapinlandia on this recording offer the opportunity for people young and old, Guatemalan or not, to appreciate the sounds and significance of Guatemala’s marimba tradition. |

「マリンバの重要性は、私たちグアテマラ人のアイデンティティを反映していることだ。私たちのマリンバは、グアテマラ人の心の状態を表現する能力を持って

いる。例えば、悲しいときには、とても哀愁のある、深く感じられる息子を演奏する。幸せなときには、マリンバでセイス・ポル・オチョやグアリンバ、クンビ

ア、メレンゲを演奏する。マリンバは、私たちグアテマラ人の、時に笑い、時に泣く、そのような心の状態に完璧に適している。"そして、時にはマリンバとい

う楽器でそれを行うのだ。-マリンバ・チャピンランディアのメンバー、エリック・アルマンド・バルガス。 マリンバは、ほとんどのグアテマラ人にとってアイデンティティの象徴だ。1978年、共和国議会は政令66-78号によってマリンバを国家楽器と宣言し、 この事実を認め、強化した。この楽器の歴史はグアテマラの国の歴史と類似しているため、この評判は十分なものだ。多くの点で、今日演奏されている音楽は、 グアテマラのラディーノ(メスティーソ)民族の社会生活の中心における1世紀以上の音楽的流行を要約したものであり、国民の大多数を占めるこの国の先住民 族が何世紀にもわたって行ってきた文化的慣習や共同体の儀式のエッセンスを受け継いでいる。 グアテマラのマリンバは、スペインによる植民地化の初期(1524~1821年)に根ざしている。先住民族が起源とする説もあるが、ほとんどの学者は、 16世紀半ばにアフリカ人奴隷がカリブ海の島々を経由してメソアメリカに持ち込んだアフリカの前身を指摘している。メソアメリカに植えられた後、マヤの人 々がアフリカ人からこの楽器を取り入れ、地元の木材や材料を加工する独自の技術を応用し、自分たちの楽器として受け入れることで進化していった。スペイン 文化からはダイアトニックスケールのチューニングを取り入れ、3つの文化が1つの楽器の音に融合した。 マリンバはイディオフォンの一種である木琴で、叩いたりこすったりした素材の振動によって音を出す。グアテマラのマリンバのデザインは細かく異なるが、い ずれも左から右に向かって長さ、幅、太さの順に並んだ大きさの異なる広葉樹の棒(テクラド)が、木製のフレーム(メサ)の上に取り付けられ、植物繊維でで きた2本の弦で吊り下げられ、その弦はフレームに取り付けられた木製のペグ(クラビージャ)に通されている(写真参照)。棒に使われる広葉樹は、地元では ホルミゴ(Platymiscium dimorphandrum)とグラナディージョ(Dalbergia tucurensis)と呼ばれる。各棒の下には中空の共鳴器が固定されている。この共鳴室は、ヒノキやスギの薄い木で作られた先細りの箱(cajón de resonancia)の形をとるのが一般的だが、竹やテコマテの果実の干瓢で作られることもある。共鳴箱は上部が開いており、下に行くにつれて広がり、 下端は逆ピラミッド状に閉じている。底の近くには、へそ(mux)と呼ばれる小さな穴が開けられ、乾燥させた豚の腸の膜(tela de 「tripa de coche」)で覆われ、小さな黒い蜜蝋の輪(anillo de cera)の上に取り付けられている。棒を叩くと、共鳴器の中の空気が振動し、アフリカの木琴のほとんどが出す音に似た独特のブーンという音が出る。各レ ゾネーターの大きさは、それが増幅するサウンドバーの大きさに比例する。フレームは4本の脚の上に載っており、しばしば異なる色合いの広葉樹の彫刻で装飾 され、楽器の名前が含まれていることもある。それぞれのマリンバは、木製のスティック状のマレット(バケタ)を使い、数人のパフォーマビティによって演奏 される。 グアテマラのラディーノ系住民による現代的なマリンバは、1894年にケツァルテナンゴ(地図参照)という高地の町で生まれた。作曲家でバンド指揮者のフ リアン・パニアグア・マルティネスは、マリンバ製作者兼奏者のセバスティアン・フルタードに、1列のダイアトニックマリンバに2列目のサウンドバーを追加 し、ピアノの黒鍵に相当する半音階音程を作り出すことを提案した。何度かの試行錯誤と計算の末、ウルタードはこの新しいクロマチック・マリンバ(マリン バ・クロマティカ)を設計・製作し、それまでピアノの専売特許だった19世紀のサロン曲の膨大なレパートリーを演奏できるようにした。1901年以降、こ のクロマチック楽器は大人気となり、4人で演奏するマリンバ・グランデ(大型マリンバ)と3人で演奏するマリンバ・テナー(小型で高音マリンバ)という2 つの補完的な楽器へと発展した。 ケツァルテナンゴでのクロマチック・マリンバの発明は、この楽器の音楽の可能性を大きく広げ、社交の場での普及に拍車をかけた。マリンバは急速に普及し、 ケツァルテナンゴでは、フルタード、ベサンクール、オバレの各一族の音楽家が、他の数人に続いて独自のマリンバ・グループを結成した。セバスティアン・フ ルタードとその息子たちはマリンバ・ロイヤルを、フランシスコ・ロマン・ベサンクールはマリンバ・イデアルを、ポルフィリオ・ベサンクール・フルタードは マリンバ・ナシオナルを、ホセ・オバレとその息子たちはマリンバ・マリピアーノ・オバレを結成した。この新しいタイプの楽器と演奏アンサンブルは瞬く間に 人気を博し、やがていくつかのグループがケツァルテナンゴからグアテマラ・シティや他の町へと旅するようになり、大成功を収めた。1930年代半ばまでに は、警察、軍隊、多くの省庁など、多くの政府機関がマリンバの製作を依頼し、独自のグループを結成した。ケツァルテナンゴとグアテマラ・シティの流行の先 端を行く大手ラジオ局がマリンバを雇い、一日中生演奏をさせるようになると、マリンバは一世を風靡した。 田舎の集落では、1~3人の奏者で構成される古くからの素朴な民族マリンバがまだ演奏されていたが、ラディーノの町の人々はすぐにクロマチック・マリンバ をダンスバンドとして取り入れた。これらの楽団は、お祭りや社交の場でファッショナブルなダンス曲を演奏した。ケツァルテナンゴからは、ウォツベリ・アギ ラール、ドミンゴ・ベサンクール、ロカエル・ウルタド、ベネディクト、エウストルギオ、ヒギニオのオバレ兄弟、マリアノ・バルベルデ、そして多くの演奏家 や作曲家がやってきた。やがて、北西部高地フエウエテナンゴのグメルシンド・パラシオス、北部熱帯低地ペテンのバレンティン・デル・バジェ・ゴンゴラ、ベ ラパス山地のロドルフォ・ナルシソ・チャバリア、アンティグアのマヌエル・サマヨアとイノセンテ・バジェ・ベーラ、その他グアテマラ全地域のマリンバ・マ エストロたちが有名な音楽家となった。 著名な音楽家の中には、16世紀にグアテマラで最初の首都が建設された場所に近いテクパンの町出身のフロイラン・ロダス・サンチソ(1922-2004) もいた。彼はグアテマラ・シティの国家警察のマリンバを指揮し、この録音でフィーチャーされている有名なマリンバ・チャピンランディアという自身のグルー プを設立した。弟のレオポルド・ロダス・サンチソ(1924年生まれ)もマリンバの名手であり、センセーショナルでポピュラーなダンス曲を数多く作曲し た。フロイラン・ロダス・サンチソは、この国で最も偉大なマリンバ指導者の一人として名声を博し、多くの一流奏者を惹きつけて彼のもとで学んだ。2004 年に彼が亡くなると、グループは彼の末の息子であるフロイラン・ロダス・サンチソJr.の管理下に入り、彼はグループでドラムセットを演奏している。 グアテマラ・マリンバ・アンサンブルとその音楽 チャピンランディアの楽器編成は、現代グアテマラのマリンバ・アンサンブルの典型である。マリンバ・グランデに4つ、マリンバ・テナーに3つ、合計7つの 演奏ポジションが2台のマリンバに分散しているのが標準的である。ラージマリンバ(78小節、音域は6オクターブを超える)では、4人の奏者をそれぞれの 立場から右から左へ並べると、ピッコロ・プリメロ、ティプル・プリメロ、セントロ・アルモニコ、バホ・デ・マリンバとなる。ティプル・プリメロが主旋律を 奏で、ピッコロ・プリメロが1オクターブ高い旋律を2倍または補う。旋律の伴奏はセントロ・アルモニコ奏者に委ねられ、彼はそれぞれの舞曲に合ったリズム とフィギュレーションでハーモニーを奏でる。曲のアレンジによっては、チェントロ・アルモニコ奏者が主旋律を担当することもある。最低音の小節はバホ・ デ・マリンバ奏者が叩く。バホ・デ・マリンバ奏者は一般的にオクターブでベースラインを演奏する。59鍵のマリンバ・テナーでは、ピッコロ・セグンド、 ティプル・セグンド、バホ・デ・テナー(テナー・メロディコとも呼ばれる)の3つのポジションが演奏ポジションとなる。最初の2人は、第2パートと、ピッ コロ・プリメロとティプル・プリメロの重複を担当する。バホ・デ・テノールは、より低い複声または第3声を担当する。このように旋律線を複製することで、 公共の場や騒がしい舞踏会でも聞こえるような力強い響きが生まれる。 これら7人の奏者には通常、マリンバの低音を補強する弦楽器ベースと、最小限のダンスバンドスタイルのドラムキット、またはあまり一般的ではないが土着の パーカッション(チンチンと呼ばれる太鼓とガラガラ)が加わる。時には、トランペット、アルトサックス、テナーサックス、トロンボーンなどの金管楽器や管 楽器が、特にトロピカルバンドやビッグバンドのレパートリーで使われることもある。これらの楽器はしばしば同じマリンバ奏者によって演奏され、他の楽器と マリンバのパッセージを交互に演奏する。 各マリンバ・アンサンブルには音楽監督がおり、彼が編曲を担当し、替え歌、反復、ソロ、対旋律を決める。リハーサルでは、曲を教え、パートとリズム伴奏を 分配し、他の奏者に音楽の細部まで指導する。楽譜を読める奏者はほとんどいないため、通常は耳で覚える。一度暗譜すれば、その曲はグループのレパートリー となる。 現代のマリンバ音楽は基本的に社交音楽であり、洗礼式、初聖体、結婚式、その他人生の重要なイベント、昼食会、宴会、ハウスパーティー、祭り、ダンスなど で演奏される。コンサート・レパートリーを持つグループも少なくないが、文化・スポーツ省マリンバ・デ・コンシエルト・デ・ベラス・アルテスは、新しい音 色、研ぎ澄まされたテクニック、コンサート・ステージにふさわしい現代的な作曲法を駆使している。レパートリーには実にさまざまなジャンルが含まれる。そ のひとつが、土着音楽をルーツとする音楽である。ゆったりとしたテンポの儀式音楽と伝統的なソネは、ダイアトニックで、しばしばメランコリックな曲調とシ ンプルなリズム・パターンを持つ。土着のソンは、社交の場での期待に応えて何時間も演奏されることもある。 その他のレパートリーは、土着の音楽から派生したもので、土着の音楽の特徴を取り入れつつも、西ヨーロッパの和声的・形式的な慣習を取り入れたものであ る。レパートリーの大部分は、近代マリンバが誕生して以来の音楽的流行をモデルにしている: 中央ヨーロッパのサロン・ダンス(ワルツ、マズルカ、ポルカなど)、スペインのダンス・リズム(パソドブレ、コントラバンザ)、アメリカのブルース、 フォックストロット、ラグタイム、スウィング、ツーステップ、ラテン・カリブ海のボレロ、コリード、ダンソン、クンビア、グアラチャ、メレンゲなどであ る。 マリンバのために開発されたグアテマラの特徴的なリズムは、グアリンバ(グアテマラとマリンバを組み合わせた言葉)とも呼ばれる6/8拍子のseis por ochoである。これらすべてのジャンルは、現代のマリンバ作曲家たちによって生み出された新しい作品によって、より豊かなものとなり続けている。 このレコーディングに収録された曲は、このような幅広いジャンルに焦点を当て、マリンバとその音楽に対する汎国民的な同一性を表し、グアテマラ・シティの マリンバ・チャピンランディアの手になるグアテマラ・マリンバの音楽的、技術的な最高の状態を示すために選ばれた。マリンバが全国的に受け入れられ、パ フォーマーや作曲家たちが音楽的・技術的な功績を残していることは、マリンバの国家的な重要性を示しているが、一部の音楽家たちは、ポピュラー文化や外国 からの輸入音楽という強力な力によって、マリンバの将来が脅かされることを恐れている。エリック・アルマンド・バルガスは、マリンバの将来を危惧する一人 だ: 現在、ある種の人々がマリンバへの愛を心の中に持ち続けている状況がある。そういう人たちはマリンバを愛する気持ちを持ち続けていて、パーティーでマリン バを使ったり、マリンバを応援し続けている。しかし、若い世代はマリンバに対して違う概念を持って育っている。彼らは外国の音楽に侵されていて、その点で ある程度のダメージ、あるいは大きなダメージを受けていると感じる。自分たちの音楽に対する愛情が薄れてきている。外国の習慣のために自分たちのやり方を 変えようとしている。場合によっては、自分たちの音楽に対する偏見さえある。現在15歳から25歳くらいの人の中には、マリンバが好きな人はほとんどいな い。親がマリンバの趣味を持ち、そう教えてきた人たちはまだマリンバを支持しているが、大多数はマリンバを好まない。 バルガスは、自分の世代に代わる一流の若手奏者が育っていないことを嘆き、マリンバをグアテマラ人の未来に残す努力を呼びかけている: 音楽的な落ち着きのなさを満たしたいから、マリンバを習いたいんだ。家族を困窮させることなく、音楽で満足させる。" 私自身は、娘たちが将来マリンバ奏者や音楽家であり続けるためではなく、自分たちを養ってくれる職業に就くための準備であり、同時に、生活の一部をマリン バに捧げることができるようにするためだ。それは彼らの生き方ではないかもしれないが、どんな時でもグアテマラらしさを守ることができるのだ。 このレコーディングに収録されたマリンバ・チャピンランディアの音色は、グアテマラ人であろうとなかろうと、老若男女を問わず、グアテマラのマリンバの伝統の音と意義を理解する機会を与えてくれる。 |

| Track Notes

1. Chichicastenango This well-known, lighthearted tune is dedicated to the famous town of Chichicastenango in the highlands of El Quiché Department. Paco Pérez (1917–1951), one of Guatemala’s most popular songwriters, cast it in the guaracha rhythm, a Cuban form that spread throughout the Caribbean and beyond. Pérez’s life was cut short in a plane crash over Petén in northern Guatemala. 2. ¿Porqué será? (Why Would That Be?) The Mexican-influenced corrido, a merry tune in duple time, has become a mainstay of marimba repertoire. In the Kaqchikel Mayan town of Sololá, in the western highlands around Lake Atitlán, this corrido, by Guillermo Fuentes, has become an emblem of local identity. 3. Mi Lorena linda (My Pretty Lorena) Another favorite genre of the Guatemalan marimba is the bolero “Mi Lorena linda,” a splendid song by Leopoldo Rodas Santizo, was written out of joy on the occasion of the birth of his daughter Lorena—and from that day on, it has been one of the most popular pieces in the repertoires of Marimba Chapinlandia and many other marimbas. 4. Cobán The foxtrot, an American social dance introduced to Guatemala around 1913, became very popular in Guatemala during the roaring 1920s. It is in moderate 4/4 tempo, with walking bass lines. Domingo Bethancourt (1906–1980) composed this national favorite, dedicated to the provincial capital of Alta Verapaz, where he had many admirers, fans, and friends. 5. Recuerdos de un amigo (Memories of a Friend) Belarmino Molina (1879–1950) from the village of San Juan Sacatepéquez, not far from Guatemala City, was a trained violinist and a member of the National Symphony, but he never forgot his roots. He composed sones and waltzes (valses) that were adopted by marimbas all across the country. His waltz “Recuerdos de un amigo” remains one of the most requested pieces in the repertoire. 6. Los Trece (The Thirteen) Wotzbelí Aguilar (1897–1940) is one of the favorite composers of dance tunes from Quetzaltenango. He composed a sizable number of pieces while he lived the rather disorderly life of an independent musician of his day, often running out of money and selling his songs and dances for a drink of rum, as legend has it. His “Los Trece” is a guarimba, a piece in 6/8 time with frequent hemiolas. (This rhythm is also known as seis por ocho, but the name for Aguilar’s dances in that rhythm was later changed to “guarimba.”) “Los Trece” was composed for an exclusive club, whose members were thirteen distinguished citizens of Quetzaltenango. 7. Lágrimas de Thelma (Thelma’s Tears) The Guatemalan blues is more akin to the foxtrot than to the American blues, being in fact a foxtrot. One of the best known and most popular blues, “Lágrimas de Thelma,” was composed by Gumercindo Palacios (1904–1986) of Huehuetenango. 8. Linda morena (Beautiful Dark Woman) Valentín del Valle Góngora’s “Linda morena” is a splendid bolero, which never fails to move listeners, especially in the northern lowlands of Petén, where people consider it their local anthem. 9. Ferrocarril de los altos (The Highland Train) Another favorite foxtrot by Domingo Bethancourt, “Ferrocarril de los altos,” commemorates the inauguration of the first railroad line from the highlands to the coast. A novelty piece, it usually adds a few blasts of the train whistle, imitating the sound of the steam locomotive as it departs. 10. Luna de Xelajú (Moon of Xelajú) Paco Pérez (1917–1951) was a singer born in Huehuetenango, who had his debut while still a teenager as a tenor with piano accompaniment in Quetzaltenango’s splendid theater, the Teatro Municipal. Since 1943, when his “Luna de Xelajú” (Xelajú is the K’ich’e’ Mayan word for Quetzaltenango) won him a national award, this waltz has become the unofficial second anthem of Guatemala and is sung with great emotion by Guatemalans from all regions and cultural backgrounds. It is unthinkable that a marimba group would not know it. 11. Juventud antigüeña (Youth from Antigua) Another outstanding example of a seis por ocho is Manuel Samayoa’s “Juventud antigüeña,” which people from the former Guatemalan capital city of Antigua consider to be a symbol of their identity. 12. San Francisco de Asís (Saint Francis of Assisi) “San Francisco de Asís,” by Froilán Rodas Santizo, is a typical Ladino son, a genre derived from the indigenous son. The repeated rhythmic pattern underlying the melody marks the genre as the Guatemalan son, distinct from sones of other countries, with the possible exception of indigenous sones from neighboring southern Mexico. This son is dedicated to Rodas Santizo’s hometown, Tecpán, the patron saint of which is St. Francis of Assisi, whose feast day is October fourth. 13. Soy de Zacapa (I Am from Zacapa) The corrido is popular in the dry forestlands of eastern Guatemala, as José Ernesto Monzón’s “Soy de Zacapa” exemplifies. 14. Río Polochic (Polochic River) Master marimba leader and player Rodolfo Narciso Chavarría (1901–1974), from Cobán, dedicated his popular “Río Polochic” to the magnificent river that flows from the Verapaz Mountains down into Lake Izabal, in the country’s northeast. As the piece is in a somewhat slower time than the regular foxtrot, Narciso subtitled it “fox-blues.” 15. Noches de Escuintla (Nights of Escuintla) The lyrics of “Noches de Escuintla” (not heard here), a romantic bolero by María del Tránsito Barrios (1921–2004), describes the sunset in Escuintla, a province and city, close to the Pacific coast. The melody has become a symbol of the province. 16. Migdalia Azucena “Migdalia Azucena” is another outstanding example of the fox-blues, as composed by Gumercindo Palacios (1904–1986) of Huehuetenango. 17. Noche de luna en las ruinas (Moonlit Night in the Ruins) Another musician whose waltzes are still extremely popular with the marimbas and the public is Mariano Valverde (1884–1956). Born in Quetzaltenango, he directed different marimbas and taught his players and pupils to play from written scores—which at that time was highly unusual. He has numerous pieces to his credit, but one of the most beloved is his “Noche de luna en las ruinas.” This waltz was written in 1903 after an earthquake had damaged Quetzaltenango, and its dramatic and somber elements only for moments let through a smile behind tears, until it comes to a close again on a somber note. 18. Tristezas quetzaltecas (Quetzaltecan Sorrows) This lively seis por ocho (or guarimba) in 6/8 time is another splendid example of Wotzbelí Aguilar´s mastery of this typically Guatemalan dance rhythm. 19. Bella Guatemala (Beautiful Guatemala) One of the earliest composers represented in the present recording is Germán Alcántara (1863–1910), a virtuoso trumpet player and conductor of operettas and military bands. By the end of the nineteenth century, he had written some of the most popular waltzes of his day. “Bella Guatemala” is a mazurka that became popular with the marimbas during the early twentieth century. It is still played by almost every group. Further reading: Godínez, Lester. 2002. La Marimba Guatemalteca. Guatemala: Fondo de Cultura Económica. Lehnhoff, Dieter. 2005. Creación musical en Guatemala. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar y Fundación G&T Continental. Sánchez Castillo, Julio César. 1997. ¿Qué sabemos de la marimba? Guatemala: Editora Educativa. ———. 2001. Producción marimbística de Guatemala. Guatemala: Impresos Industriales. Further listening: Marimba Chapinlandia, Froilán Rodas Santizo. 1996. Antología Musical 40 Años. 5 CDs. Guatemala: Discocentro. Marimba Hurtado Hermanos. 1997. La música de Domingo Bethancourt. Guatemala: Discocentro 97026. |

|

| https://folkways-media.si.edu/docs/folkways/artwork/SFW40542.pdf | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆