ハイパーメディア

Hypermedia

Herbert

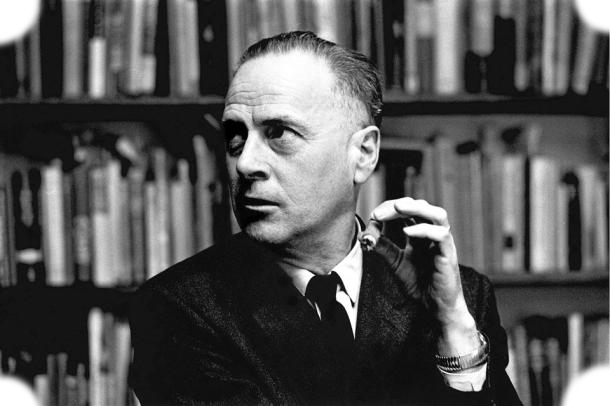

Marshall McLuhan watches Ted Nelson

★ハイパーメディアと は、Ted Nelsonにより提唱された言葉で、ハイパーテキストを 拡張したもので、グラフィックス、オーディオ、ビデオ、プレーンテキスト、ハイパーリンクを含む非線形情報媒体である。この呼称は、ハイパーメディアだけ でなく非インタラクティブな線形プレゼンテーションを含む可能性のある、より広い用語であるマルチメディアとは対照的である。また、電子文学の分野にも関 連している。

| Hypermedia,

an extension of the term hypertext, is a nonlinear medium of

information that includes graphics, audio, video, plain text and

hyperlinks. This designation contrasts with the broader term

multimedia, which may include non-interactive linear presentations as

well as hypermedia. It is also related to the field of electronic

literature. The term was first used in a 1965 article written by Ted

Nelson.[1][2] The World Wide Web is a classic example of hypermedia to access web content, whereas a non-interactive cinema presentation is an example of standard multimedia due to the absence of hyperlinks. The first hypermedia work was, arguably, the Aspen Movie Map. Bill Atkinson's HyperCard popularized hypermedia writing, while a variety of literary hypertext and hypertext works, fiction and non-fiction, demonstrated the promise of links. Most modern hypermedia is delivered via electronic pages from a variety of systems including media players, web browsers, and stand-alone applications (i.e., software that does not require network access). Audio hypermedia is emerging with voice command devices and voice browsing.[3] |

ハイパーメディアとは、ハイパーテキストを

拡張したもので、グラフィックス、オーディオ、ビデオ、プレーンテキスト、ハイパーリンクを含む非線形情報媒体である。この呼称は、ハイパーメディアだけ

でなく非インタラクティブな線形プレゼンテーションを含む可能性のある、より広い用語であるマルチメディアとは対照的である。また、電子文学の分野にも関

連している。この用語は、1965年にTed Nelsonによって書かれた記事で初めて使われた[1][2]。 World Wide WebはWebコンテンツにアクセスするためのハイパーメディアの典型的な例であり、一方、非インタラクティブなシネマプレゼンテーションはハイパーリン クがないために標準的なマルチメディアの例である。 最初のハイパーメディア作品は、間違いなく、アスペン・ムービーマップであった。Bill AtkinsonのHyperCardはハイパーメディア・ライティングを一般化し、フィクションやノンフィクションのさまざまな文学的ハイパーテキスト やハイパーテキスト作品はリンクの可能性を示した。現代のハイパーメディアのほとんどは、メディアプレーヤー、ウェブブラウザ、スタンドアロンアプリケー ション(ネットワークアクセスを必要としないソフトウェア)など、さまざまなシステムから電子ページを通じて配信されている。音声ハイパーメディアは、音 声コマンド・デバイスや音声ブラウジングによって出現している[3]。 |

| Development tools Hypermedia may be developed in a number of ways. Any programming tool can be used to write programs that link data from internal variables and nodes for external data files. Multimedia development software such as Adobe Flash, Adobe Director, Macromedia Authorware, and MatchWare Mediator may be used to create stand-alone hypermedia applications, with emphasis on entertainment content. Some database software, such as Visual FoxPro and FileMaker Developer, may be used to develop stand-alone hypermedia applications, with emphasis on educational and business content management. Hypermedia applications may be developed on embedded devices for the mobile and the digital signage industries using the Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) specification from W3C (World Wide Web Consortium). Software applications, such as Ikivo Animator and Inkscape, simplify the development of hypermedia content based on SVG. Embedded devices, such as the iPhone, natively support SVG specifications and may be used to create mobile and distributed hypermedia applications. Hyperlinks may also be added to data files using most business software via the limited scripting and hyperlinking features built in. Documentation software, such as the Microsoft Office Suite and LibreOffice, allow for hypertext links to other content within the same file, other external files, and URL links to files on external file servers. For more emphasis on graphics and page layout, hyperlinks may be added using most modern desktop publishing tools. This includes presentation programs, such as Microsoft PowerPoint and LibreOffice Impress, add-ons to print layout programs such as Quark Immedia, and tools to include hyperlinks in PDF documents such as Adobe InDesign for creating and Adobe Acrobat for editing. Hyper Publish is a tool specifically designed and optimized for hypermedia and hypertext management. Any HTML editor may be used to build HTML files, accessible by any web browser. CD/DVD authoring tools, such as DVD Studio Pro, may be used to hyperlink the content of DVDs for DVD players or web links when the disc is played on a personal computer connected to the internet. |

開発ツール ハイパーメディアは様々な方法で開発することができる。内部変数と外部データファイルのノードをリンクさせるプログラムは、あらゆるプログラミングツール を使って書くことができる。Adobe Flash、Adobe Director、Macromedia Authorware、MatchWare Mediatorなどのマルチメディア開発ソフトは、エンターテイメントコンテンツに重点を置いたスタンドアロン型のハイパーメディアアプリケーションを 作成するために使用することができる。Visual FoxProやFileMaker Developerなどの一部のデータベースソフトウェアは、教育およびビジネスコンテンツ管理に重点を置いたスタンドアロンのハイパーメディアアプリ ケーションを開発するために使用することができます。 W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) の SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) 仕様を使用して、モバイルおよびデジタルサイネージ業界向けの組み込みデバイス上でハイパーメディアアプリケーションを開発することもできます。 Ikivo AnimatorやInkscapeなどのソフトウェア・アプリケーションは、SVGに基づくハイパーメディア・コンテンツの開発を簡素化します。 iPhoneなどの組み込み型デバイスはSVG仕様をネイティブにサポートしており、モバイルや分散型のハイパーメディアアプリケーションを作成するのに 利用できるかもしれません。 ハイパーリンクは、ほとんどのビジネスソフトウェアに搭載されている限られたスクリプトやハイパーリンク機能によって、データファイルに追加することもで きます。Microsoft Office SuiteやLibreOfficeなどの文書作成ソフトでは、同じファイル内の他のコンテンツや他の外部ファイル、外部ファイルサーバー上のファイルへ のURLリンクへのハイパーテキストリンクを作成することが可能です。グラフィックやページレイアウトを重視する場合は、最新のデスクトップパブリッシン グツールでハイパーリンクを追加することができます。これには、Microsoft PowerPointやLibreOffice Impressなどのプレゼンテーションプログラム、Quark Immediaなどの印刷レイアウトプログラムのアドオン、Adobe InDesignなどの作成用、Adobe Acrobatなどの編集用のPDF文書にハイパーリンクを含めるためのツールなどが含まれます。Hyper Publishは、ハイパーメディアとハイパーテキストの管理に特化して設計され、最適化されたツールです。どのようなHTMLエディターでもHTML ファイルを作成することができ、どのようなWebブラウザーでもアクセスすることができます。DVD Studio ProなどのCD/DVDオーサリングツールは、インターネットに接続されたパーソナルコンピュータでディスクを再生する際に、DVDプレーヤーやWeb リンク用にDVDのコンテンツをハイパーリンクするために使用することができる。 |

| Learning There have been a number of theories concerning hypermedia and learning. One important claim in the literature on hypermedia and learning is that it offers more control over the instructional environment for the reader or student. Another claim is that it levels the playing field among students of varying abilities and enhances collaborative learning. A claim from psychology includes the notion that hypermedia more closely models the structure of the brain, in comparison with printed text.[4] |

学習 ハイパーメディアと学習に関する理論は数多くある。ハイパーメディアと学習に関する文献の中で重要な主張のひとつは、読者や生徒が教育環境をより自由にコ ントロールできるようになるというものです。もうひとつの主張は、さまざまな能力を持つ学生間の競争の場を均等にし、共同学習を促進するというものです。 心理学からの主張としては、印刷されたテキストと比較して、ハイパーメディアは脳の構造をより忠実にモデル化しているという考え方がある[4]。 |

| Application programming

interfaces Hypermedia is used as a medium and constraint in certain application programming interfaces. HATEOAS, Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State, is a constraint of the REST application architecture where a client interacts with the server entirely through hypermedia provided dynamically by application servers. This means that in theory no API documentation is needed, because the client needs no prior knowledge about how to interact with any particular application or server beyond a generic understanding of hypermedia. In other service-oriented architectures (SOA), clients and servers interact through a fixed interface shared through documentation or an interface description language (IDL). |

アプリケーションプログラミングインターフェース ハイパーメディアは、ある種のアプリケーションプログラミングインターフェイスのメディアや制約として使われている。HATEOAS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State)は、RESTアプリケーションアーキテクチャの制約で、クライアントはアプリケーションサーバーが動的に提供するハイパーメディアを通じて サーバーと完全に対話することになる。これは、理論的にはAPIドキュメントが不要であることを意味する。なぜなら、クライアントは、ハイパーメディアに 関する一般的な理解を超えて、特定のアプリケーションやサーバーとの対話方法について事前の知識を必要としないからである。他のサービス指向アーキテク チャ(SOA)では、クライアントとサーバーは、文書またはインターフェース記述言語(IDL)を通じて共有される固定インターフェースを通じて対話す る。 |

| Cybertext Electronic literature Hyperland is a 1990 documentary film that focuses on Douglas Adams and explains adaptive hypertext and hypermedia. Metamedia Digital rhetoric Gamebook Hypermedia Hypertext Interactive fiction New media Video games as an art form |

サイバーテキスト 電子文学 ハイパーランドは、1990年にダグラス・アダムスを中心に、アダプティブ・ハイパーテキストやハイパーメディアを解説したドキュメンタリー映画 メタメディア デジタル・レトリック ゲームブック ハイパーメディア ハイパーテキスト インタラクティブ・フィクション ニューメディア アートとしてのビデオゲーム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypermedia |

|

| Cybertext is

the organization of text in order to analyze the influence of the

medium as an integral part of the literary dynamic, as defined by Espen

Aarseth in 1997. Aarseth defined it as a type of ergodic

literature where user traverses the text by doing non-trivial

work.[1] |

サイバーテキストとは,1997年にEspen

Aarsethによって定義された,文学のダイナミズムの不可欠な部分としてのメ

ディアの影響を分析するためのテキストの組織化のことである.アーセスはこれを、ユーザーが非自明な作業を行うことによってテキストを横断

するエルゴード文学の一種と定義している[1]。 |

| Definition Cybertexts are pieces of literature where the medium matters. Each user obtains a different outcome based on the choices they make. According to Aarseth, "information is here understood as a string of signs, which may (but does not have to) make sense to a given observer."[2] Cybertexts may be equated to the transition between a linear piece of literature, such as a novel, and a game. In a novel, the reader has no choice, the plot and the characters are all chosen by the author, there is no 'user', just a 'reader', this is important because it entails that the person working their way through the novel is not an active participant. Cybertext is based on the idea that getting to the message is just as important as the message itself. In order to obtain the message, work on the part of the user is required. This may also be referred to as nontrivial work on the part of the user.[3] What this means is that the reader does not merely interpret the text but performs actions such as active choice and decision-making through navigation options.[4] There is also the existence of a feedback loop between the reader and the text.[1] Cybertexts are distinguished from games, where a player makes decisions and decides what to do, what things to punch, or when to jump. Cybertexts, on the other hand, usually have a message that is translated to the reader as they work their way through the piece. In this form of literature, however, there is a possibility that the reader misses elements or information depending on the choices he makes.[5] |

定義 サイバーテキストは、メディアが重要な文学作品である。各ユーザは自分の選択によって異なる結果を得ることができる。アーセスによれば、「情報は記号の列 として理解され、ある観察者には意味をなすかもしれない(しかし、そうである必要はない)」[2]。サイバーテキストは、小説のような線形文学作品とゲー ムの間の移行に等しいと言えるかもしれない。小説では、読者に選択の余地はなく、プロットもキャラクターもすべて作者が選んだものであり、「ユーザー」は 存在せず、「読者」だけである。 サイバーテキストは、メッセージにたどり着くことが、メッセージそのものと同じくらい重要であるという考えに基づいている。メッセージを手に入れるために は、ユーザーの側での作業が必要である。このことは、読者が単にテキストを解釈するだけでなく、ナビゲーション・オプションを通じて能動的に選択・意思決 定するような行為を行うことを意味する[3]。 また、読者とテキストの間にはフィードバック・ループが存在する[1]。 サイバーテキストは、プレイヤーが何をするか、どんなものを殴るか、いつジャンプするかを決定し、決定するゲームとは区別される。一方、サイバーテキスト は通常、作品を読み進めていくうちに、読者に翻訳されるメッセージを持っている。しかし、この形式の文学では、読者の選択次第で要素や情報を見逃してしま う可能性がある[5]。 |

| Application The concept of cybertext offers a way to expand the reach of literary studies to include phenomena that are perceived today as foreign or marginal.[3] In Aarseth's work, cybertext denotes the general set of text machines which, operated by readers, yield different texts for reading.[6] For example, in Raymond Queneau's book Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, each reader will encounter not just poems arranged in a different order, but different poems depending on the precise way in which they turn the sections of page.[7] Cybertext can also be used as a broader alternative for hypertext, particularly as it critiques the critical responses to the latter. Aarseth, together with literary scholars such as N. Katherine Hayles, maintains that cybertext cannot be applied according to the conventional author-text-message paradigms since it is a computational engine.[8] |

応用編 サイバーテキストの概念は文学研究の範囲を拡大し、今日異質なもの、あるいは周縁的なものとして認識されている現象を含める方法を提供する[3] アーセスの仕事において、サイバーテキストは読者によって操作され、読むために異なるテキストをもたらすテキストマシンの一般的なセットを示す[6] 例えばレイモンド・クノーの著書『十万篇の詩』で各読者は異なる順序に並べられた詩だけではなく、ページの部分を正確に回す方法によって異なる詩を遭遇す るだろう[7]。 サイバーテキストはまた、特にハイパーテキストに対する批評的な反応を批判することで、ハイパーテキストのより広い代替物として使用することができる。 アーセスはN・キャサリン・ヘイルズなどの文学者とともに、サイバーテキストは計算エンジンであるため、従来の著者・テキスト・メッセージのパラダイムに 則って適用することはできないと主張している[8]。 |

| Background The term cybertext is derived from cyber- in the word cybernetics, which was coined by Norbert Wiener in his book Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (1948), which in turn comes from the Greek word kybernetes – helmsman.[3] The prefix is then merged with the word "text", which is identified as a distinctive structure for producing and consuming verbal meaning in post-structuralist literary theory.[8] Although Aarseth's use of the term has been the most influential, he was not the first to use it. The neologism cybertext appeared several times in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was the name of a software company in the mid-1980s,[9] and was used by speculative fiction poetry author Bruce Boston as the title of a book he published in 1992, which contained science-fictional poetry.[10] Cybertext is part of what scholars called generational shifts involving literature on digital media. The first phase was hypertext, which transitioned to hypermedia during the mid-1990s.[11] These developments coincided with the invention of the first graphic browser called Mosaic and the popularization of the world wide web.[11] Cybertext came after hypermedia amid the move toward the focus on software code, particularly its considerable ability to control the reception process without reducing interactivity.[11] The fundamental idea in the development of the theory of cybernetics is the concept of feedback: a portion of information produced by the system that is taken, total or partially, as input. Cybernetics is the science that studies control and regulation in systems in which there exists flow and feedback of information. Though first used by science fiction poet Bruce Boston, the term cybertext was brought to the literary world's attention by Espen Aarseth in 1997.[12] Aarseth's concept of cybertext focuses on the organization of the text in order to analyze the influence of the medium as an integral part of the literary dynamic. According to Aarseth, cybertext is not a genre in itself; in order to classify traditions, literary genres and aesthetic value, we should inspect texts at a much more local level.[13] He also maintained that traditional literary theory and interpretation are not main features in cybertext since it focuses on the textual medium (textonomy) and the study of textual meaning (textology).[1] |

背景 サイバーテキストという言葉は、ノーバート・ウィーナーがその著書『サイバネティックス、あるいは動物と機械における制御とコミュニケーション』 (1948年)で造語したサイバネティックスのcyber-に由来し、さらにギリシャ語のkybernetes(舵取り)に由来する[3]。 この接頭辞は次に、ポスト構造主義の文学理論において言葉の意味を生成し消費するための独特の構造として識別されている「テキスト」の言葉に統合される [8]。 この用語のアーセスの使用は最も影響力があったが、彼が最初に使用したわけではない。サイバーテキストという新語は1980年代後半から1990年代前半 にかけて何度か登場した。1980年代半ばにはソフトウェア会社の名前であったし[9]、推理小説の詩人であるブルース・ボストンが1992年に出版した SF的な詩を含む本のタイトルとして使用されていた[10]。 サイバーテキストは、デジタルメディア上の文学に関わる世代交代と学者たちが呼ぶものの一部である。最初の段階はハイパーテキストであり、1990年代半 ばにハイパーメディアへと移行した[11]。これらの発展は、Mosaicと呼ばれる最初のグラフィックブラウザの発明とワールドワイドウェブの普及と重 なる[11]。ハイパーメディア以降は、ソフトウェアコード、特にインタラクティブ性を減らすことなく受信プロセスを制御するそのかなりの能力に焦点を当 てる方向に進む中で、サイバーテキストが登場した[11]。 サイバネティックスの理論の発展における基本的な考え方は、フィードバックという概念であり、システムによって生成された情報のうち、全体的または部分的 に入力として取り込まれる部分である。サイバネティクスは、情報の流れやフィードバックが存在するシステムにおける制御や調節を研究する科学である。サイ バーテキストという言葉は、SF詩人のブルース・ボストンによって最初に使われたが、1997年にエスペン・アーセスによって文学界に注目されるように なった[12]。 アーセスのサイバーテキストの概念は、文学のダイナミズムの不可欠な部分としてのメディアの影響を分析するために、テキストの構成に焦点を当てたものであ る。また、サイバーテキストはテキストという媒体(テキストノミー)とテキストの意味の研究(テキストロジー)に焦点を当てているため、伝統的な文学理論 や解釈はサイバーテキストにおける主要な特徴ではないとしている[13][1]。 |

| Examples An example of a cybertext is Twelve Blue by Michael Joyce. It is a web-based text that includes navigation modes characterized by fluid and multiple sense of structures of electronic textuality such as colored threads that play different "bars" and blue-script text that returns to images of rivers and water.[14] Depending on what link you choose or what portion of the diagram on the side you pick you will be transferred to a different portion of the text. So in the end, you do not really finish reading the entire story or 'novel' you go through random pages and try piecing the story together yourself. You may never really 'finish' the story. But, because it is a cybertext the 'finishing' of the story is not as important as its impact on the reader, or on the conveyance.[15] Another example is Stir Fry Texts, by Jim Andrews, which is a cybertext where there are many layers of text, and as you move your mouse over the words, the layers beneath them are 'dug' through.[16] The House is another example of a cybertext where one might assume a description of the piece as follows: It is an unruly text, the words don't listen, you are not supreme. You are guided through the piece. This is a cybertext with minimal control. You watch as something unfolds before you, "a crumbling mania", you must be able to go with the flow, to read texts upside down, to piece together a reflection of words, to be okay with texts half read disappearing or moving so far away so continuously that you can not make out those very important words.[17] |

事例紹介 サイバーテキストの例として,Michael Joyceによる「Twelve Blue」がある.これはウェブベースのテキストで、異なる「バー」を奏でる色糸や、川や水のイメージに戻る青文字のテキストなど、電子テキスト性の構造 を流動的かつ多重的に感知することを特徴とするナビゲーション・モードを含む[14]。どのリンクを選ぶか、あるいは側面の図のどの部分を選ぶかに応じ て、テキストの異なる部分に転送されることになる。だから結局、物語や小説の全体を読み終えるのではなく、ランダムにページをめくりながら、自分で物語を つないでいくことになる。結局、物語を読み終えることはできない。しかし、サイバーテキストである以上、物語の「完成」は、読者や伝達に対するインパクト ほど重要ではないだろう[15]。 もう一つの例はジム・アンドリュースによる『Stir Fry Texts』で、これはテキストの層がたくさんあり、マウスを言葉の上に移動させると、その下の層が「掘られる」サイバーテキストである[16]。「家」 もまた、次のように作品の説明を想定できるサイバーテキストの一例である。それは手に負えないテキストであり、言葉は耳を貸さず、あなたは至高の存在では ない。あなたは作品の中で導かれているのです。これは、最小限のコントロールしかできないサイバーテキストです。あなたは何かがあなたの目の前で展開する のを見ている,「崩れたマニア」,あなたは流れに身を任せ,テキストを逆さに読み,言葉の反射をつなぎ合わせ,半分読んだテキストが消えたり,非常に遠く に移動したりして,非常に重要な言葉がわからなくなっても平気でなければならない[17]. |

| Digital rhetoric

can be generally defined as communication

that exists in the digital sphere.

As such, digital rhetoric can be expressed in many different forms

—including but not limited to text, images, videos, and software.[2]

Due to the increasingly mediated nature of our contemporary society,

there are no longer clear distinctions between digital and non-digital

environments.[3] This has led to an expansion of the scope of digital

rhetoric to account for the increased fluidity with which humans

interact with technology.[4] Due to evolving study, digital rhetoric has held various meanings to different scholars over time.[5] Similarly, digital rhetoric can take on a variety of meanings based on what is being analyzed—which depends on the concept, forms or objects of study, or rhetorical approach. Digital rhetoric can also be analyzed through many lenses reflecting different social movements.[6] Approaching this area of study through different lenses of various social issues allows the reach of digital rhetoric to expand. |

デジタル・レトリックは、一般的にデジタル領域に存在するコミュニケーションと

定義することができる。このように、デジタルレトリックは、テキスト、画像、ビデオ、ソフトウェアなどを含むがこれらに限定されない多くの異なる形式で表

現することができる[2]。 現代社会の媒介性がますます高まっているため、デジタルと非デジタル環境の間にもはや明確な区別はない[3]。

このため、人間がテクノロジーと相互作用する流動性が高まっていることを考慮し、デジタルレトリックの範囲を拡張することになった[4]。 同様に、デジタル・レトリックは分析されるものに基づいて様々な意味を持ち、それは概念、研究の形態や対象、あるいは修辞的アプローチに依存します [5]。デジタル・レトリックはまた、異なる社会運動を反映した多くのレンズを通して分析することができる[6]。様々な社会問題の異なるレンズを通して この研究領域にアプローチすることは、デジタル・レトリックの範囲を拡大することを可能にする。 |

| Evolving definition of 'digital

rhetoric' The following subsections detail the evolving definition of 'digital rhetoric' as a term since its creation in 1989.[7] Early definitions (1989 - 2015) The term digital rhetoric was coined by rhetorician Richard A. Lanham in a lecture he delivered in 1989[7] and first formally put into words in his 1993 essay collection, The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts.[8] In 2005, James P. Zappen defined digital rhetoric as a space of collaboration and creativity between the composer and the audience.[9] Recent scholarship (2015 - Present) Drawing influence from Lanham and Losh, Douglas Eyman offered his own definition of digital rhetoric in his 2015 book Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. Eyman said digital rhetoric is "the application of rhetorical theory (as analytic method or heuristic for production) to digital texts and performances".[10]: 44 Eyman's definition demonstrates that digital rhetoric can be applied as an analytic method for digital texts and as a heuristic for production, offering rhetorical questions that a composer can use to create digital texts.[citation needed][11][10] Eyman categorized the emerging field of digital rhetoric as interdisciplinary in nature, enriched by related fields such as, but not limited to: digital literacy, visual rhetoric, new media, human-computer interaction and critical code studies.[10] In 2018, rhetorician Angela Haas offered her own definition of digital rhetoric, defining it as "the digital negotiation of information – and its historical, social, economic, and political contexts and influences – to affect change".[12] Haas emphasized that digital rhetoric does not solely apply to text-based items—it can also apply to image-based or system-based items. Any form of communication that occurs in the digital sphere can be counted as digital rhetoric under Haas' definition.[13] Other definitions Contrary to past conceptions, the definition of rhetoric can no longer be confined to simply the sending and receiving of messages to persuade or impart knowledge. While this represents a primarily ancient Western view of rhetoric, Arthur Smith of UCLA explains that the ancient rhetoric of many cultures, such as African rhetoric, existed independent of Western influence.[14] Today, rhetoric encompasses all forms of discourse that serve any given purpose within specific contexts, while also simultaneously being shaped by those contexts.[15] Some scholars interpret this rhetorical discourse with greater focus on the digital aspect. Casey Boyle, James Brown Jr., and Steph Ceraso claim that "the digital" is no longer just one of the many different tools that can be used to enhance traditional rhetoric, but an "ambient condition" that encompasses our everyday lives.[16] As technology becomes more and more ubiquitous, the lines between traditional and digital rhetoric will start to blur. In addition, Boyle et al. emphasize the idea that both technology and rhetoric can influence and transform each other.[4] |

デジタル・レトリック」の定義の変遷 以下のサブセクションでは、1989年の誕生以来、用語としての「デジタル・レトリック」の定義の変遷を詳述する[7]。 初期の定義(1989年~2015年) デジタル・レトリックという言葉は、1989年に修辞学者のリチャード・A・ランハムが行った講演で作られ[7]、1993年のエッセイ集『The Electronic Word』で初めて正式に言葉にされたものである。民主主義、テクノロジー、そして芸術[8]。 2005年にジェームズ・P・ザッペンはデジタル・レトリックを作曲家と聴衆の間のコラボレーションと創造性の空間として定義した[9]。 最近の奨学金(2015年~現在) ランハムとロッシュから影響を受け、ダグラス・エイマンは2015年の著書『デジタル・レトリック』の中で、デジタル・レトリックの独自の定義を提示し た。Theory, Method, Practice(理論、方法、実践)」である。アイマンはデジタル・レトリックとは「デジタル・テキストやパフォーマンスに対する(分析手法や制作のた めのヒューリスティックとしての)レトリック理論の適用」であると述べている[10]。 44 Eymanの定義は、デジタルレトリックがデジタルテキストの分析方法として、また制作のためのヒューリスティックとして適用できることを示しており、作 曲家がデジタルテキストを作るために使用できる修辞的な質問を提供している[citation needed][11][10] Eymanはデジタルレトリックの新興分野を、デジタルリテラシ、映像レトリック、ニューメディア、人間-コンピュータ対話、批判コード学などの関連分野 で豊かになる、本質的に学際的に分類している(これらに限定しない)。[10]. 2018年に修辞学者のアンジェラ・ハースはデジタル・レトリックの独自の定義を提示し、それを「変化に影響を与えるための情報-そしてその歴史的、社会 的、経済的、政治的文脈と影響-のデジタル交渉」と定義した[12]。 ハースはデジタル・レトリックがテキストベースのアイテムにのみ適用されない-画像ベースまたはシステムベースのアイテムにも適用できることを強調してい る。デジタル領域で発生するあらゆる形式のコミュニケーションは、ハースの定義のもとではデジタル・レトリックとしてカウントすることができる[13]。 その他の定義 過去の概念とは異なり、レトリックの定義はもはや説得や知識の伝達のためのメッセージの送受信に限定されるものではない。これは主に古代の西洋のレトリッ クの見方を表しているが、UCLAのアーサー・スミスは、アフリカのレトリックのような多くの文化の古代のレトリックは西洋の影響から独立して存在してい たと説明している[14]。 今日、レトリックは特定の文脈内で任意の目的を果たすあらゆる形式の談話を包含し、同時にそれらの文脈によって形成されてもいる[15]。 一部の学者はこの修辞的な言説をデジタル的な側面により焦点をあてて解釈している。ケイシー・ボイル、ジェームス・ブラウン・ジュニア、ステフ・セラソ は、「デジタル」はもはや伝統的な修辞学を強化するために使用できる多くの異なるツールの一つではなく、我々の日常生活を包含する「環境条件」だと主張し ている[16]。 テクノロジーがますますユビキタスになっていけば、伝統的修辞法とデジタル修辞法の間の線は曖昧になり始めるだろう。加えて、ボイルらはテクノロジーとレ トリックの両方が互いに影響を与え、変容させることができるという考えを強調している[4]。 |

| Circulation As an example of circulation, Wikipedia is an online encyclopedia that relies on collaborative rhetorical contribution. Circulation theorizes the ways that text and discourse moves through time and space, and any kind of media can be circulated. A new form of communication is composed, created, and distributed through digital technologies. Media scholar Henry Jenkins explains there is a shift from distribution to circulation, which signals a move toward an increasingly participatory model of culture in which people shape, share, re-frame and remix media content in ways not previously possible within the traditional rhetorical formats like print. The various concepts of circulation include: Collaboration – Digital rhetoric has taken on a very collaborative nature through the use of digital platforms. Sites such as YouTube and Wikipedia involve opportunity for "new forms of collaborative production".[17] Digital platforms have created opportunities for more people to enact and create, as digital platforms open doors for collaborative communication that can occur synchronously, asynchronously, over far distances, and across multiple disciplines and professions.[17][18] Crowdsourcing – Daren Brabham describes the concept of crowdsourcing as the use of modern technology to collaborate, create, and solve problems collectively.[19] However, ethical concerns have been raised as well while engaging in crowdsourcing without a clear set of compensation practices or protections in place to secure information. Delivery – Whereas rhetoric once relied largely on oral methods, the rise of digital technologies allows rhetoric to be delivered in new "electronic forms of discourse".[20] Acts and modes of communication can be represented digitally by combining multiple different forms of media into a composite helping to create an easy user experience.[21] The growing popularity of the internet meme is an example of combining, circulating, and delivering media in a collaborative effort through file sharing. Although memes are sent through microtransactions - they often can have a macro large scale impact.[22] Another form of unique rhetorical delivery is the online encyclopedia which traditionally have been print form based primarily on text and images. However, modern technological developments now enable encyclopedias to integrate sound, animation, video, algorithmic search functions, and high-level productions into a cohesive multimedia experience as part of their new forms of digital rhetoric.[21] |

循環 循環の例として、ウィキペディアは共同的な修辞的貢献に依存するオンライン百科事典である。 循環は、テキストや言説が時間と空間の中を移動する方法を理論化するもので、あらゆる種類のメディアが循環することができる。新しい形のコミュニケーショ ンは、デジタル技術によって構成され、創造され、配布される。メディア研究者のヘンリー・ジェンキンズは、流通から循環へのシフトが起きていると説明し、 これは、印刷物のような伝統的な修辞的フォーマットでは以前は不可能だった方法で、人々がメディアコンテンツを形成、共有、再構築、リミックスするとい う、ますます参加型の文化モデルへの移行を示唆していると述べている。循環のさまざまなコンセプトは以下の通り。 コラボレーション - デジタル・レトリックは、デジタル・プラットフォームの使用を通じて、非常に協力的な性質を持つようになった。YouTubeやウィキペディアのようなサ イトは「共同制作の新しい形」の機会を含んでいる[17]。デジタルプラットフォームは、同期的、非同期的、遠距離、複数の分野や職業を越えて起こりうる 共同コミュニケーションのための扉を開いており、より多くの人々が制定し創造する機会を作ってきた[17][18]。 クラウドソーシング - ダレン・ブラバムは、クラウドソーシングの概念を、集団で協力し、創造し、問題を解決するための現代技術の使用として説明している[19]。 しかし、情報を保護するための明確な報酬慣行や保護のないクラウドソーシングに関与する一方で、倫理的懸念も提起されている。 配信 - かつてレトリックは主に口頭での方法に依存していたが、デジタル技術の台頭により、レトリックは新しい「談話の電子的形態」で配信されるようになった [20]。行為やコミュニケーションの様式は、複数の異なる形態のメディアを合成することによってデジタルで表現することができ、簡単なユーザー体験を作 り出すのに役立つ[21] インターネットミームの人気の高まりは、ファイル共有による共同作業でメディアを組み合わせ、流通し、配信する一例である。ミームはマイクロトランザク ションを通じて送られるが、しばしばマクロな大規模インパクトを与えることができる[22] 。しかし,現代の技術開発によって,百科事典はデジタル・レトリックの新しい形態の一部として,サウンド,アニメーション,ビデオ,アルゴリズムによる検 索機能,ハイレベルな演出を凝集したマルチメディア体験に統合することができるようになった[21]。 |

| Critical literacy Critical literacy is a line of thought that assumes all texts are biased.[23] For example, a study conducted at the Indiana University in Bloomington used algorithms to assess 14 million Twitter messages containing statements about the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign and election. They found that from May 2016 to March 2017, social bots were responsible for causing approximately 389,000 unsupported political claims to go viral.[24] Further, critical literacy can also be defined as a communicative tool to lead to social change and promote social action by using a critical lens when approaching social-political topics.[25] Since so much information is thrust at a digital audience, it's important for those who are being inundated with so much information develop the tools necessary to process and critically examine the works surrounding our topics of interest - and topics unknown.[26] In an essay on Critical Literacy in writing, the University of Melbourne states that it's important to develop these skills through reading and asking what texts are trying to accomplish, leaving it up to the reader to decide how ideas are interpreted.[27] |

クリティカル・リテラシー 批判的リテラシーとは、すべてのテキストが偏っていると仮定する考え方である[23]。 例えば、ブルーミントンのインディアナ大学で行われた研究では、アルゴリズムを使用して、2016年の米国大統領選挙と選挙に関する発言を含む1400万 のTwitterメッセージを評価した。彼らは、2016年5月から2017年3月まで、ソーシャルボットが約389,000の裏付けのない政治的主張を 流行らせる原因となったことを発見しました[24]。 さらに、批判的リテラシーは、社会政治的な話題にアプローチする際に批判的レンズを用いて社会変革を導き、社会行動を促進するコミュニケーションツールと も定義されます。 [25] 多くの情報がデジタルオーディエンスに突きつけられるので、多くの情報が氾濫している人々は、私たちの興味のあるトピック-そして未知のトピック-を取り 巻く作品を処理し、批判的に検討するために必要なツールを開発することが重要である。 26] メルボルン大学は、文章における批判的リテラシーに関する論文で、文章が何を達成しようとしているのか問い、アイデアがどのように解釈されるかは読者に委 ねつつ読むことによってこれらのスキルを開発することが重要であると述べている[27]。 |

| Interactivity Interactivity in digital rhetoric can be defined as the ways in which readers connect to and communicate with digital texts.[28] For example, readers have the ability to like, share, repost, comment on, and remix online content. These simple interactions allow writers, scholars, and content creators to get a better idea of how their work is affecting their audience.[29] Some ways communicators promote interactivity include the following: Mind sharing is a way to get collective intelligence—crowd wisdom that is comparable to expert wisdom. The methodology consists of taking a consensus from the crowd—the answer that most minds are suggesting is the best answer. If it's a numeric question (like guessing the weight of an ox), it's a calculated average or median. If it's an open question (like "what car should I buy?"), it's the most common answer. Multimodality is a form of communication that uses multiple methods (or modes) to inform audiences of an idea. It can involve a mix of written text, pictures, audio, or videos. Online journals often embrace multimodality in their issues and articles by publishing works that use more than just written text to communicate the message. While the digital turn in rhetoric and composition has encouraged more discussion, theorization, and pedagogical application of multimodality and multimodal texts, the history of the field demonstrates a continuous concern with multimodal communication beginning with classical rhetoric's concern with delivery, gesture, and memory. All writing and all communication is, theoretically, multimodal. Remix is a method of digital rhetoric that manipulates and transforms an original work to convey a new message. The use of remix can help the creator make an argument by connecting seemingly unrelated ideas into a convincing whole. As modern technology develops, self-publication sites such as: YouTube, SoundCloud, and WordPress have stimulated remix culture, allowing for easier creation and dissemination of reworked content. Unlike appropriation, which is the use and potential recontextualization of existing material without significant modification, remix is defined in Kairos as "the process of taking old pieces of text, images, sounds, and video and stitching them together to form a new product".[30] A popular example of remixing is the creation and sharing of memes. |

インタラクティビティ デジタルレトリックにおけるインタラクティビティは、読者がデジタルテキストとつながり、コミュニケーションする方法として定義することができる [28]。例えば、読者はオンラインコンテンツに対して、いいね!、シェア、リポスト、コメント、リミックスをする能力を持っている。このようなシンプル なインタラクションによって、作家、学者、コンテンツ制作者は、自分の作品がオーディエンスにどのような影響を与えているかを把握することができる [29]。 コミュニケーターがインタラクティビティを促進する方法には、次のようなものがある。 マインドシェアリングは、専門家の知恵に匹敵する集合知-群衆の知恵を得るための方法である。その方法論は、群衆からコンセンサス(ほとんどの人がベスト アンサーと示唆する答え)を得ることから構成されます。もしそれが数値的な質問(牛の体重を推測するような)であれば、計算された平均値や中央値が使われ ます。オープンな質問(「どの車を買えばいいですか?」のような)であれば、最も一般的な答えになります。 マルチモーダリティとは、ある考えを聴衆に伝えるために複数の方法(モード)を使用するコミュニケーションの形態です。文章、写真、音声、ビデオなどが混 在することもある。オンラインジャーナルは、メッセージを伝えるために文字以上のものを使う作品を掲載することで、その号や記事にマルチモダリティを取り 入れることがよくあります。修辞学と作文におけるデジタル化の進展は、マルチモーダリティとマルチモーダルなテキストに関する議論、理論化、教育的応用を 促したが、この分野の歴史は、古典修辞学の伝達、身振り、記憶への関心から始まるマルチモーダルなコミュニケーションへの継続的な関心を実証している。す べての文章、すべてのコミュニケーションは、理論的にはマルチモーダルである。 リミックスとは、デジタルレトリックの手法の一つで、オリジナルの作品を操作し、変形させ、新しいメッセージを伝えるものです。リミックスの使用は、一見 無関係に見えるアイデアを説得力のある全体像につなげることで、クリエイターの主張を後押しすることができます。現代のテクノロジーの発達に伴い、 YouTube、SoundCloud、Wordなどのセルフパブリケーションサイトが登場しました。YouTube、SoundCloud、 WordPressなどのセルフパブリケーションサイトは、リミックス文化を刺激し、より簡単に作り直したコンテンツを広めることができるようになりまし た。既存の素材に大きな変更を加えることなく使用し、再文脈化する可能性がある流用とは異なり、リミックスはカイロスで「テキスト、画像、音声、映像の古 い断片を取り出し、新しい製品を形成するためにそれらをつなぎ合わせるプロセス」として定義されている[30]。リミックスの人気のある例は、ミームの作 成と共有である。 |

| Procedural rhetoric Procedural rhetoric is rhetoric formed through processes or practices.[31] Some scholars view video games as one of these processes through which rhetoric can be formed.[31][32] For example, Ludology scholar and game designer Gonzalo Frasca poses that the simulation-nature of computers and video games offers a "natural medium for modeling reality and fiction".[32] Therefore, according to Frasca, video games can take on a new form of digital rhetoric in which reality is mimicked but also created for the future.[32] Similarly, scholar Ian Bogost argues that video games can serve as models for how 'real-world' cultural and social systems operate.[31] They also argue for the necessity of literacy in playing video games as this allows players to challenge (and ultimately accept or reject) the rhetorical standpoints of these games.[31] |

Procedural rhetoric Procedural rhetoric is rhetoric formed through processes or practices.[31] Some scholars view video games as one of these processes through which rhetoric can be formed.[31][32] For example, Ludology scholar and game designer Gonzalo Frasca poses that the simulation-nature of computers and video games offers a "natural medium for modeling reality and fiction".[32] Therefore, according to Frasca, video games can take on a new form of digital rhetoric in which reality is mimicked but also created for the future.[32] Similarly, scholar Ian Bogost argues that video games can serve as models for how 'real-world' cultural and social systems operate.[31] They also argue for the necessity of literacy in playing video games as this allows players to challenge (and ultimately accept or reject) the rhetorical standpoints of these games.[31] |

| Rhetorical velocity Rhetorical velocity is the concept of authors writing in a way in which they are able to predict how their work might be recomposed. Digital rhetoric is often labelled using tags, for example, which are keywords that readers can type into search engines in order to help them find, view, and share relevant texts and information. These tags can be found on blog posts, news articles, scholarly journals, and more. Tagging allows writers, scholars, and content creators to organize their work and make it more accessible and understandable to readers.[29] Therefore, it is important for them to be able to predict how their audience will recompose their works. Jim Ridolfo and Danielle DeVoss first coined this idea in 2009 when they describe rhetorical velocity as "a conscious rhetorical concern for distance, travel, speed, and time, pertaining specifically to theorizing instances of strategic appropriation by a third party".[33] Author, Sean Morey, agrees with this definition of rhetorical velocity and describes it as a creator anticipating the response their work with generate.[34] Appropriation carries both positive and negative connotations for rhetorical velocity. In some ways, appropriation is a tool that can be used for the reapplication of outdated ideas to make them better. In other ways, appropriation is seen as a threat to creative and cultural identities. Social media receives the bulk of this scrutiny due to the lack of education of its users. Most "contributors are often unaware of what they are contributing",[35] which perpetuates the negative connotation. Many scholars in digital rhetoric explore this topic and its effects on society such as Jessica Reyman, Amy Hea, and Johndan Johnson-Eilola. |

修辞学的速度 修辞学的速度とは、著者が自分の作品がどのように再構成されるかを予測できる方法で書くという概念である。デジタル・レトリックは、例えば、読者が関連す るテキストや情報を見つけ、閲覧し、共有するために検索エンジンに入力できるキーワードであるタグを使って、しばしばラベル付けされる。このようなタグ は、ブログ記事、ニュース記事、学術雑誌などで見かけることができる。タグ付けによって、作家、学者、コンテンツ制作者は、作品を整理し、読者がよりアク セスしやすく、理解しやすくすることができる[29]。 したがって、読者が作品をどのように再構成するかを予測することができるようになることが重要である。そして、このようなことは、そのような作品に対す る読者の反応を予測することである[33]。 流用は修辞的速度に対して肯定的な意味合いと否定的な意味合いの両方を含んでいる。ある意味では、流用は時代遅れのアイデアをより良くするために再適用す るために使うことができるツールである。別の言い方をすれば、流用は創造的・文化的アイデンティティに対する脅威と見なされる。ソーシャルメディアは、そ の利用者の教育が不十分であるため、このような詮索を受けることが多いのです。ほとんどの「貢献者はしばしば自分が何を貢献しているのか認識していない」 [35]ため、否定的な意味合いを永続させることになる。デジタル・レトリックの多くの学者が、ジェシカ・レイマン、エイミー・ヘア、ジョンダン・ジョン ソン・エイローラのようなこのトピックと社会に対するその効果を探求している。 |

| Visual rhetoric Digital rhetoric often invokes visual rhetoric due to digital rhetoric's reliance on visuals.[2] Charles Hill states that images "do not necessarily have to portray an object, or even a class of objects, that exists or ever did exist" to remain impactful.[36] However, the use of imagery for rhetorical purposes in digital spaces can't always be easily differentiated from "traditional" physical visual mediums. As such, approaching this concept requires a careful analysis of the viewer, situational, and visual contexts involved.[37] A prominent part of this concept is its intersection of perspective with technology, as computers allow users to create a curated view for online space. Social media platforms like Instagram,[38] incredibly realistic deepfakes,[39] editing software like Photoshop, and even behind-the-scenes preference algorithms all illustrate how the tactile-visual internet heavily relies on and adapts principles of visual rhetoric. Digitally-produced art is a significant way users express themselves on technological platforms; the unique intersection of text and image has given rise to new rhetorical language through the modification of slang and ingroup language.[40] In particular, the culturally-specific and nuanced use of pop culture references through internet memes have gradually built upon themselves to create complex, highly flexible, and internet-specific (or even platform-specific) dialects of speech.[41] Through popularity-based natural selection, edits of commonly accepted meme templates fuel the cycle of rhetorical creation. Digital-visual rhetoric doesn't only rely on intentional manipulation. Sometimes, meanings can arise from unexpected places and otherwise-overlooked features. For example, emojis, or simple graphic images included in most texting applications, can carry heavy consequences by permeating daily communication. Varying skin tones provided (or excluded) by developers for emojis may perpetuate preexisting racial biases of colorism.[42] Even otherwise-innocuous images of peaches and eggplants are regular stand-ins for genital regions; they can be both harmless modes of flirtation and even tools for sexually harassing women online when sent en masse.[42] The concept of the avatar can also aid understanding of visual rhetoric's deeply personal impact, particularly when using James E. Porter's definition of the avatar as an extended "virtual body."[43] While scholars such as Beth Kolko hoped for an equitable online world free of physical barriers, social issues still persist in digital realms, such as gender discrimination and racism.[44] For example, Victoria Woolums found that, in the video game World of Warcraft, an avatar's gender identity instigated bias from other characters even though an avatar's gender identity may not be physically accurate to its user.[45] These relationships are further complicated by the varying degrees of anonymity characterizing inter-user communications in online spaces. While the possibility of true privacy can be facilitated by impersonal avatars, they are still personal manifestations of a user's self in the context of digital spaces.[46] Furthermore, the tools available to curate and express these are platform-dependent and ripe for both liberation and exploitation. Be it 2014's Gamergate or the more recent debates regarding social media influencer culture and their portrayals of impossible and computer-edited body image, self-presentation is heavily mediated by accessibility to and mastery of online avatars.[46] |

視覚的修辞法 チャールズ・ヒルは、イメージは「必ずしも存在する、あるいは存在したことのあるオブジェクト、あるいはオブジェクトのクラスを描写する必要はない」と述 べている[36]。しかし、デジタル空間における修辞目的のためのイメージの使用は、「従来の」物理的視覚メディアと必ずしも容易に区別することができな い。この概念の顕著な部分は、コンピュータによってユーザーがオンライン空間のためにキュレートされたビューを作成することができるように、テクノロジー と視点が交差することである[37]。Instagramのようなソーシャルメディア・プラットフォーム、信じられないほどリアルなディープフェイク、 Photoshopのような編集ソフトウェア[39]、さらには舞台裏の嗜好アルゴリズムなどはすべて、触覚的視覚的インターネットが視覚的修辞法の原則 に大きく依存し適応していることを例証するものである。 デジタルで制作されたアートはユーザーがテクノロジープラットフォーム上で自己表現する重要な方法であり、テキストとイメージのユニークな交差はスラング とイングループ言語の修正を通じて新しい修辞的言語を生み出した[40]。 特に、インターネットミームを通じた文化的に固有でニュアンスのあるポップカルチャー言及の使用は、複雑で非常に柔軟でインターネット特有の(あるいはプ ラットフォーム特有の)方言を作り出すために徐々に積み重なった。人気ベースの自然選択を通じて、一般的に受け入れられたミームのテンプレートが修辞的創 造のサイクルに拍車をかけたのである[41]。 デジタル・ヴィジュアル・レトリックは意図的な操作にのみ依存しているわけではない。時には、予期せぬ場所や見落とされた機能から意味が生じることもあ る。例えば、絵文字、つまりほとんどのテキストアプリケーションに含まれるシンプルなグラフィックイメージは、日々のコミュニケーションに浸透すること で、重い結果をもたらすことがある。絵文字の開発者によって提供される(あるいは除外される)様々な肌の色は、カラリズムという既存の人種的偏見を永続さ せるかもしれない[42]。桃やナスといった他愛のない画像でさえ、性器領域の通常の代用品であり、それらは無害な口説き文句であると同時に、集団で送ら れるとオンラインで女性に性的嫌がらせをする道具にもなり得る[42]。 ベス・コルコのような学者は物理的な障壁のない公平なオンラインの世界を望んでいたが、ジェンダー差別や人種差別のような社会問題はいまだにデジタル領域 で存続している[44]。 [例えば、ヴィクトリア・ウールムスはビデオゲーム「ワールド・オブ・ウォークラフト」において、アバターのジェンダー・アイデンティティがそのユーザー にとって物理的に正確でなくても、他のキャラクターから偏見を誘発することを発見している [45] 。これらの関係はオンライン空間におけるユーザー間のコミュニケーションを特徴づける匿名性の程度の違いによってさらに複雑になっている。真のプライバ シーの可能性は非人間的なアバターによって促進されうるが、それらはデジタル空間の文脈におけるユーザーの自己の個人的な表現であることに変わりはない [46]。さらに、これらをキュレートし表現するために利用できるツールはプラットフォームに依存しており、解放と搾取の両方の機が熟している。2014 年のゲーマーゲートであれ、ソーシャルメディアのインフルエンサー文化や不可能でコンピュータによって編集された身体イメージの描写に関するより最近の議 論であれ、自己提示はオンラインアバターへのアクセスや使いこなしによって大きく媒介されている[46]。 |

| Forms and objects of study Infrastructure Information infrastructure is the invisible force that organizes the public's information on the internet.[47] Essentially, information infrastructure is what impacts how and what the public accesses on the internet.[47] Databases and search engines are information infrastructure as they play a large role in access to and dissemination of information. Information Infrastructure often consists of algorithms and metadata standards, which curate the information presented to the public.[48] |

研究形態と研究対象 インフラストラクチャー 情報インフラはインターネット上の公衆の情報を整理する目に見えない力である[47]。基本的に情報インフラは公衆がインターネット上でどのように、そし て何にアクセスするかに影響を与えるものである[47]。データベースと検索エンジンは情報へのアクセスと普及に大きな役割を果たしているため情報インフ ラであると言える。情報インフラはしばしばアルゴリズムとメタデータの標準からなり、公衆に提示される情報をキュレーションする[48]。 |

| Software Coding and software engineering are not often recognized as rhetorical writing practices, but in the process of writing code, people instruct machines to "make arguments and judgments and address audiences both mechanic and human."[49] Technologies themselves can be viewed as rhetorical genres, simultaneously guiding users' experiences and communication with each other and being shaped and improved through humans use.[50] Choices baked into software that are invisible to users impact the user experience and reveal information about the priorities of the software engineers.[51] For instance, while Facebook allows users to choose over 50 gender identities to display on their public profile, an investigation into the social media's software revealed that users are filtered into the male-female gender binary within the database for targeted advertising purposes.[52] For another example, pieces of software called bittorrent trackers facilitate the massive distribution of information on Wikipedia.[50] Software facilitates the collective rhetorical action of this encyclopedia. The field of software studies encourages the investigation into and recognition of software's impacts on people and culture.[49] |

ソフトウェア コーディングとソフトウェアエンジニアリングは修辞的な文章の実践としてあまり認識されていないが、コードを書く過程で人々は機械に「議論と判断を行い、 機械的、人間的両方の聴衆に働きかける」よう指示する[49]。テクノロジー自体は修辞的ジャンルとして見ることができ、同時にユーザーの経験と互いのコ ミュニケーションを導き、人間の使用を通して形成、改善される[50] ユーザーから見えないソフトウェアに組み込まれた選択はユーザー体験に影響を与え、ソフトウェアエンジニアの優先順位について情報を明らかにしている [51]。 [51] 例えば、フェイスブックはユーザーが自分の公開プロフィールに表示する50以上の性別のアイデンティティを選択できる一方で、ソーシャルメディアのソフト ウェアを調査した結果、ユーザーはターゲット広告の目的のためにデータベース内の男性-女性の性別バイナリにフィルタリングされていることが明らかになっ た。 50] 別の例としては、ビトレント・トラッカーと呼ばれるソフトウェアの断片がウィキペディアでの情報の大量配布を容易にする。 ソフトウェア研究の分野は、ソフトウェアの人々や文化に対する影響について調査し、認識することを奨励している[49]。 |

| People Online communities Online communities are groups of people with a common interests that interact and engage over the Internet. Many online communities are found within social networking sites, online forums, and chat rooms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, 4chan, etc., where members can share and discuss information and inquiries.[53] These online spaces often establish their own rules, norms, and culture, and in some cases, users will adopt community-specific terminology or phrases. Scholars have noted that online communities have especially gained prominence among users like e-patients and victim-survivors of abuse.[54] Within online health and support groups respectively, members have been able to find others who share similar experiences, receive advice and emotional support, and record their own narrative.[55] However, online communities face issues with online harassment in the form of trolling, cyberbullying, and hate speech.[56] According to the Pew Research Center, 41% of Americans have experienced some form of online harassment with 75% of these experiences occurring over social media.[57] Another area of concern is the influence of algorithms on delineating the online communities a user comes in contact with. Personalizing algorithms can tailor a user's experience to their analytically determined preference, which creates a "filter bubble". The user loses agency in content accessibility and information dissemination when these bubbles are created.[58][59] The loss of agency can lead to polarization, but recent research indicates that individual level polarization is rare.[60] Most polarization is due to the influx of users with extreme views that can encourage users to move towards partisan fringes from "gateway communities".[60] In summary, online communities support community but in rare cases can support polarization. Social media Social media makes human connection formal, manageable, and profitable to social media companies.[61] The technology that promotes this human connection is not human, but automated. As people use social media and form their experiences on the platforms to meet their interests, the technology also affects how the users interact with each other and the world.[61] Social media also allows for the weaving of "offline and online communities into integrated movements".[62] Users' actions, such as liking, commenting, sending, retweeting or saving a post, contribute to the algorithmic customization of their personalized content.[63] Ultimately, the reach social media has is determined by these algorithms.[63] Social media also offers various image altering tools that can impact image perception – making the platform less human and more automated.[64] Digital activism Digital activism serves an agenda-setting function as it can influence mainstream media and news outlets. Hashtags, which curate posts with similar themes and ideas into a central location on a digital platform, aid in bringing exposure to social and political issues. These hashtags, specifically the subsequent discussions they create, put pressure on private institutions and governments to address these issues, as can be seen with movements like #CripTheVote,[65] #BringBackOurGirls,[62] or #MeToo. Many recent social movements have originated on Twitter, as Twitter Topic Networks provide a framework for online community organizing.[62] Influencers and content creators As social media is increasingly becoming more available, the influencer/content creator position has also become recognized as a profession. With such a large and rapid consumer presence on social media, it creates both a helpful and overwhelming source of consumer information for advertisers.[66] There is substantial potential to identify "market mavens" on social media due to fandom culture and the nature of influencer/content creator followings.[66] Social media has opened up business opportunities for corporations to employ influencer marketing, where they can more easily find suitable influencers to advertise their products to their viewers. Online learning Although online learning existed previously, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic the prevalence of online learning increased.[67] These online learning platforms are known as e-learning management systems (ELMS) and they allow both students and teachers access to a shared, digital space, which includes classroom resources, assignments, discussions, and social networking through direct messaging and email.[68] Although socialization is a component of e-learning management systems, not all students utilize these resources, rather they focus on the lecturer as the primary resource of knowledge.[citation needed] The long-term effects of emergency online learning, which many turned to during the height of the pandemic, is ongoing; however, one study concluded that students' "motivation, self-efficacy, and cognitive engagement decreased after the transition.[69]" |

人々 オンライン・コミュニティ オンラインコミュニティとは、インターネット上で共通の興味を持つ人々が交流する集団のことである。多くのオンラインコミュニティは、Facebook、 Twitter、Reddit、4chanなどのソーシャルネットワーキングサイト、オンラインフォーラム、チャットルーム内に存在し、メンバーは情報や 問い合わせを共有し、議論することができる[53]。これらのオンライン空間は、しばしば独自のルール、規範、文化を確立し、いくつかのケースでは、ユー ザーはコミュニティ固有の用語やフレーズを採用します。 研究者は、オンラインコミュニティが特に電子患者や虐待の被害者・遺族のようなユーザーの間で脚光を浴びていると指摘している[54]。 それぞれオンラインの健康グループや支援グループの中で、メンバーは同様の経験を共有する仲間を見つけ、アドバイスや精神的サポートを受け、自分自身の語 りを記録することができている[55]。 しかし、オンラインコミュニティは、トローリング、サイバーいじめ、ヘイトスピーチなどのオンラインハラスメントの問題に直面しています[56]。 Pew Research Centerによると、アメリカ人の41%が何らかのオンラインハラスメントを経験し、その75%はソーシャルメディア上で発生しています[57]。パー ソナライズアルゴリズムは、ユーザーの経験を分析的に決定された好みに合わせることができ、「フィルターバブル」を作り出す。しかし、最近の研究では、個 人レベルの分極化はまれであることが示されている[60]。ほとんどの分極化は、極端な意見をもつユーザーの流入によるもので、ユーザーは「ゲートウェ イ・コミュニティ」から党派的な周辺に移動するようになる[60]。要約すると、オンラインコミュニティはコミュニティをサポートするが、まれに分極化を サポートすることがある。 ソーシャルメディア ソーシャルメディアは、人間のつながりを形式的で、管理可能で、ソーシャルメディア企業に利益をもたらす。[61]この人間のつながりを促進する技術は、 人間ではなく、自動化されたものである。人々がソーシャルメディアを使い、自分の興味に合うようにプラットフォームでの経験を形成するとき、その技術は、 ユーザーがお互いに、そして世界とどのように相互作用するかにも影響を与える[61]。 ソーシャルメディアはまた、「オフラインとオンラインのコミュニティを統合された動きに織り込む」ことを可能にする[62]。いいね、コメント、送信、リ ツイート、投稿の保存といったユーザーの行動は、パーソナライズされたコンテンツのアルゴリズムによるカスタマイズに寄与する[63]。 最終的に、ソーシャルメディアが持つリーチは、これらのアルゴリズムによって決定される[63]。ソーシャルメディアは、イメージ認識に影響を与える様々 なイメージ変更ツールも提供し、プラットフォームを人間ではなく、より自動的にすることができる。[64]。 デジタル・アクティビズム デジタル・アクティヴィズムは、主流メディアやニュースメディアに影響を与えることができるため、アジェンダ・セッティングの機能を果たす。ハッシュタグ は、類似したテーマやアイデアの投稿をデジタルプラットフォーム上で一元的に管理するもので、社会的・政治的問題に触れるきっかけを与えてくれる。これら のハッシュタグ、特にそれらが作り出すその後の議論は、#CripTheVote[65], #BringBackOurGirls, [62] や#MeTooなどの運動に見られるように、これらの問題に取り組むよう民間機関や政府に圧力をかけている。Twitterトピックネットワークがオンラ インコミュニティの組織化のためのフレームワークを提供しているため、最近の多くの社会運動はTwitter上で発生している[62]。 インフルエンサーとコンテンツクリエイター ソーシャルメディアがますます利用しやすくなるにつれて、インフルエンサー/コンテンツクリエイターというポジションも職業として認識されるようになっ た。ソーシャルメディア上の消費者の存在は、広告主にとって有益かつ圧倒的な消費者情報源となっている[66]。ファンダム文化やインフルエンサー/コン テンツクリエーターのフォロワーの特性から、ソーシャルメディア上の「市場の達人」を特定する大きな可能性がある[66]。 オンライン学習 これらのオンライン学習プラットフォームは、e-ラーニング管理システム(ELMS)として知られ、教室のリソース、課題、議論、ダイレクトメッセージや 電子メールを通じたソーシャルネットワークを含む共有デジタル空間への生徒と教師の両方のアクセスを可能にしている[67]。 [68] 社会化はeラーニング管理システムの構成要素であるが、すべての学生がこれらのリソースを利用するわけではなく、むしろ知識の主要なリソースとして講師に 焦点を当てる。 [引用] パンデミックの最盛期に多くの人が頼った緊急オンライン学習の長期的影響は、現在進行中であるが、ある研究では、学生の「モチベーション、自己効力、認知 関与は移行後低下した[69]」と結論づけている。 |

| Interactive media Video games The procedural and interactive nature of video games leads them to be rich examples of procedural rhetoric.[70] This rhetoric can range from games designed to bolster children's learning to challenging one's assumptions of the world around them.[71] An educational video game developed for students at the University of Texas at Austin, titled Rhetorical Peaks, was made with the goal of examining rhetoric's procedural nature and to capture the constantly changing contexts of rhetoric.[72][70] The open-ended nature of the game as well as the developer's intent on playing the game within a classroom setting encouraged collaboration among students and for them to develop their own interpretations on the game's plot based on vague clues, ultimately helping them to realize that there must be a willingness to change between lines of thought and to work within and past limits in understanding rhetoric.[70] In mainstream gaming, each game has its own set of language which help shape the way information is transferred between players in their community.[73] With the popularization of online gaming - including games such as Call of Duty, League of Legends, and many more - players have been able to communicate with one another that creates their own rhetoric within the established world of the game, which allows players to influence and be influenced by the other gamers around them.[74] Another well known game called Detroit: Become Human has another way of encouraging digital rhetoric within the gaming community. This decision based video game gives the player the power to create their own story that deals with gender, race, and sexuality. This futuristic message of a human to machine relationship caused discussion due to the difficult moral decisions being made while playing. At the end, there are surveys to take to see others opinions about certain decisions around the world.[75] Mobile applications Mobile applications are computer programs designed specifically for mobile devices, such as phones or tablets. Mobile applications cater to a wide range of audiences and needs. There are apps for social media, employment, education, etc. Mobile apps allow for a "cultural hybridity of habit" which allows anyone to stay connected with anyone, anywhere.[76] Due to this, there is always access to changing cultures and lifestyles, since there are so many different apps available to research or publish work.[76] Furthermore, mobile apps allow individual users to manage many aspects of their lives while allowing the apps themselves to be able to continue to largely change and upgrade socially.[77] Mobility of information poses challenges to user interface, notably the small screen and keys, in comparison to larger counterparts such as laptops and PC's. However, it also has the advantage of heightening physical interactivity with touch, and presents experiences with multiple senses in this way. With these varying factors, mobile applications must identify how they can successfully create user interfaces that motivate trust, reliability, and helpful UX/UI design.[78] Immersive media Emerging immersive technologies such as virtual reality removes the visual presence of devices and mimics emotional experiences.[79] User immersion into virtual reality includes simulated real-life communication; virtual reality provides the illusion of being somewhere the body physically is not, which contributes to widespread communication that reaches the point of telepresence and telexistence.[79] |

インタラクティブメディア ビデオゲーム ビデオゲームの手続き的でインタラクティブな性質は手続き的レトリックの豊富な例となることを導く[70]。このレトリックは子どもの学習を強化するため にデザインされたゲームから、彼らの周りの世界に対する自分の仮定に挑戦するものまで様々である。テキサス大学オースティン校の学生のために開発した Rhetorical Peaksと名付けられた教育ビデオゲームは、レトリックの手続き的性質を検討することとレトリックの絶えず変化する文脈を捕らえるという目的で作られた [71]。 [72][70] ゲームのオープンエンドな性質と開発者が教室でゲームをプレイすることを意図したことは、学生間のコラボレーションと、曖昧な手がかりに基づいてゲームの プロットに独自の解釈を展開することを促し、最終的にレトリックを理解する上で思考のラインを変更する意欲と限界内外で働く意欲がなければならないことを 理解させることとなった[70]。 主流のゲームでは、各ゲームは独自の言語のセットを持っており、コミュニティ内のプレイヤー間で情報が伝達される方法を形成するのに役立つ[73]。 Call of Duty、League of Legends、その他多くのゲームを含むオンラインゲームの普及により、プレイヤーはゲームの確立した世界の中で独自のレトリックを作り出すために互い にコミュニケーションをとることができ、それによってプレイヤーは周囲の他のゲーマーに影響を与えたり影響を受けたりできるようになった[74]。 Become Humanは、ゲームコミュニティ内でデジタルなレトリックを奨励する別の方法を持っている。この意思決定に基づくビデオゲームは、プレイヤーに、ジェン ダー、人種、セクシュアリティを扱う自分自身の物語を作る力を与える。人間と機械の関係を描いたこの未来的なメッセージは、プレイ中に難しい道徳的な決断 を迫られることから、議論を引き起こしました。最後に、世界中の特定の決定についての他の意見を見るために取るべきアンケートがあります[75]。 モバイルアプリケーション モバイルアプリケーションは、携帯電話やタブレット端末などのモバイル機器向けに特別に設計されたコンピュータープログラムです。モバイルアプリケーショ ンは、さまざまな対象者やニーズに対応しています。ソーシャルメディア、雇用、教育などのためのアプリがあります。モバイルアプリによって、「習慣の文化 的混成性」が実現し、誰でも、どこでも、 誰とでもつながっていることができます[76]。このため、研究や出版に利用できるアプリが非常に多 く、文化やライフスタイルの変化に常にアクセスできます[76]。さらに、モバイルアプリ によって、個々のユーザーが生活の多くの側面を管理することができ、アプリ自体も大きく 変化し続け社会的にアップグレードできるようになっています[77]。 情報のモビリティは、ラップトップやPCのような大きな相手と比較して、特に小さな画面とキーというユーザーインターフェイスに課題を提起する。しかし、 タッチによる物理的なインタラクティビティを高めるという利点もあり、このように複数の感覚を使った体験を提供することができる。このように様々な要因が ある中で、モバイルアプリケーションは、信頼性、信頼性、および役に立つUX/UI設計を動機づけるユーザーインターフェースをどのようにうまく作ること ができるかを見極める必要があります[78]。 没入型メディア 仮想現実のような新しい没入型テクノロジーは、デバイスの視覚的存在を取り除き、感情的な経験を模倣する[79]。仮想現実へのユーザーの没入は、現実の コミュニケーションのシミュレーションを含み、仮想現実は、物理的に身体が存在しない場所にいるような錯覚を与え、テレプレゼンスやテレクシスまで達する 広範囲なコミュニケーションに貢献する[79]。 |

| Critical approaches Technofeminism Digital rhetoric gives a platform to technofeminism, a concept that brings together the intersections of gender, capitalism, and technology.[80] Technofeminism advocates for equality for women in technology-heavy fields and researches the relationship between women and their devices. Intersectionality is a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw that recognizes the societal injustices based on our identities.[80] It is often challenging for women to navigate finding and interacting in digital spaces without harassment or gender biases.[81] There is an importance of digital activism for unrepresented communities, such as gender non-conforming and transgender people of all races, disabled people, and people of color.[81] In the journal Computers and Composition only five articles explicitly use the term intersectionality or technofeminism.[80] Technofeminism and intersectionality are still not very prevalent when developing new technologies and research.[80] Digital cultural rhetoric The expansion of the internet has increased, digital media or rhetoric can be used to represent or identify a culture.[2] Scholars have studied how digital rhetoric is affected by one's personal factors, such as race, religion and sexuality. Due to these factors, people utilize different tools and absorb information differently. Digital culture has created the need for specialized communities on the web. Computer-mediated communities such as Reddit can give a voice to these specialized communities. One can experience and converse with other like-minded people on the web via comment sections and shared online migration.[82] The creation of digital cultural rhetoric has allowed for the use of online slang that other communities may not be aware of. Online communities that explore digital cultural rhetoric allow users to discover their social identity, and confront stereotypes that they were once confronted with.[83] Embodiment One subset of digital cultural rhetoric is embodiment—which is the idea that every person has a unique relationship with technology based on their unique set of identities. Studying the relationship between bodies and technology is one way that digital rhetoricians are able to promote equal access and opportunity within the digital sphere.[12] Since technology is considered to be an extension of the real world, users are also shaped by the experiences they have in digital spaces. The artificial interactions that occur in online environments allow users to exist in a way that is additive to their mere human experience.[84] Pedagogy With digital rhetoric becoming increasingly present, pedagogical approaches have been proposed by scholars to teach digital rhetoric in the classroom. Courses in digital rhetoric study the intersectionality between users and digital material, as well as how different backgrounds such as age, ethnicity, gender and more can affect these interactions.[85] Higher education Several scholars teach digital rhetoric courses at universities in the US, although their approaches vary considerably.[2] Jeff Grabill,[86] a scholar with a background in English, education, and technology, encourages his contemporaries to find a bridge between the scholarly field of digital rhetoric and its implementation. Cheryl Ball[87] specializes in areas that consist of multimodal composition and editing practices, digital media scholarship, digital publishing, and university writing pedagogy. Ball teaches students to write and compose multimodal texts by analyzing rhetorical options and choosing the most appropriate genres, technologies, media, and modes for a particular situation. Multimodality also influenced Elizabeth Losh et al.'s work Understanding Rhetoric: A Graphic Guide to Writing, which emphasizes engaging the comic form of literacy.[88] A similar approach also inspired Melanie Gagich to alter the curriculum of her first-year English course completely, aiming to redefine digital projects as rigorous academic assignments and teach her students necessary audience analysis skills.[89] Such a design ultimately allowed students in Gagich's classroom to develop their creativity and confidence as writers.[89] In another approach, Douglas Eyman recommends a course in web authoring and design that provides undergraduates more practical instruction in the production and rhetorical understanding of digital texts. Moreover, he explains that web authoring and design for digital rhetoric instruction provides opportunities for students to learn fundamentals of web writing and design conventions, rules and procedures.[90] Similarly, Collin Bjork argues that "integrating digital rhetoric with usability testing can help researchers cultivate a more complex understanding of how students, instructors, and interfaces interact in OWI."[91] Other scholars focus more on the relationship between digital rhetoric and social impact. Scholars Lori Beth De Hertogh et al. and Angela Haas have published materials discussing intersectionality and digital rhetoric, arguing that the two are inseparable and classes covering digital rhetoric must also explore intersectionality.[12][80] Lauren Malone has also analyzed the relationship between identity and teaching digital rhetoric through research on QTPoC (Queer and Trans People of Color)'s online engagement.[92] From this research, Malone created a series of steps for digital rhetoric instructors to take in order to foster inclusivity within their classroom.[92] Finally, scholar Melanie Kill actively introduces digital rhetoric to college-aged students, arguing for the importance of editing Wikipedia and capitalizing on their privilege of education and access to materials.[93] Similar to De Hertogh et al. and Haas, Kill believes an education in digital rhetoric serves all students, as it facilitates positive social change.[93] K-12 Many educational systems are framed so that students actively participate in technological systems as designers of digital rhetoric, not passive users.[1] There are three core goals students have identified for their coursework: building their own digital space, learning all aspects of digital rhetoric (including the theory, technology, and uses), and applying it in their own lives. The ecological system generated by the interactions of students with classmates, digital media, and other individuals is the basis of "interconnected" rhetorical processes and shared digital work.[1] Video games are one avenue students learn to design the rhetoric and code underlying their technological systems. Video game use has evolved rapidly since the 1980s, and current video games have been incorporated into education.[94] Scholar Ian Bogost suggests that video games can be utilized in a multitude of subjects to be studied as models of our non-digital world. Specifically, they note that video games could be used as an "entry point" for students that may not have been interested in computer science to enter that field. Games and game technology enhance learning by operating at the "outer and growing edge of a player's competence".[95] Games challenge students at levels that cause frustration but preserve motivation to solve the challenge at this edge. Ian Bogost also notes that video games can be taught as rhetorical and expressive in nature, allowing children to model their experiences through programming. When dissected, the ethics and rhetoric in video games' computational systems is exposed.[96] Analysis of video games as an interactive medium reveals the underlying rhetoric through the performative activity of the player.[94] Recognition of procedural rhetoric through course studies reflects how these mediums can augment politics, advertisement, and information.[94] To help address the rhetoric in video game code, scholar Collin Bjork makes a series of recommendations for integrating digital rhetoric with usability testing in online writing instruction. Some scholars have also identified specific practices for digital rhetoric instruction in pre-collegiate classrooms. As Douglas Eyman points out, students require agency when learning digital rhetoric, meaning instructors designing lessons must allow students to interact with the technology directly and enact change on the design.[1] This is consistent with discoveries by other professors, who claim one of the primary goals of students in a digital rhetoric classroom is to create space for themselves, connections with peers, and deeply understand its significance.[85] These interpersonal connections reflect a "thick correlation between digitalization and empowering pedagogy".[97] Pre-K The United States Government's Office of Educational Technology has emphasized four guiding principles when using technology with early learners:[98] When used appropriately technology can be a tool for learning. The use of technology should allow for increased access to learning opportunities for all children. Technology can be used strengthen relationships between children and their families, early educators and friends. Technology is most effective when early learners are interacting with adults and peers. Adults can also supervise children online for said effectiveness. Despite these four pillars most studies conclude that learning technology for children under the age of two is not beneficial. If you must have your young child use technology it is best that the technology is used to promote relationship development, for instance video chat software to connect with loved ones at a distance.[98] Digital rhetoric as a field of study In 2009, rhetorician Elizabeth Losh[99] offered this four-part definition of digital rhetoric in her book, Virtualpolitik:[100] 1. The conventions of new digital genres that are used for everyday discourse, as well as for special occasions, in average people's lives. 2. Public rhetoric, often in the form of political messages from government institutions, that is represented or recorded through digital technology and disseminated via electronically distributed networks. 3. The emerging scholarly discipline concerned with the rhetorical interpretation of computer-generated media as objects of study. 4. Mathematical theories of communication from the field of information science, many of which attempt to quantify the amount of uncertainty in a given linguistic exchange or the likely paths through which messages travel.[101] Losh's definition demonstrates that digital rhetoric is a field that relies on different methods to study various types of information, such as code, text, visuals, videos, and so on.[99] Douglas Eyman suggests that classical theories can be mapped onto digital media but a larger academic focus should be placed on the "extension of rhetorical theory".[102] Careers in developing and analyzing the rhetoric in code a prominent field of study. A journal established in 1985, Computers and Composition, focuses on computers communication and has considered the use of "rhetoric as their conceptual framework" and the digital rhetoric in software development.[102] Moreover, digital rhetoric is a tool by which different cultures can continue to facilitate their longstanding cultural traditions. In his book, Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age, Adam J. Banks states that modern day storytellers, like stand-up comics and spoken word poets, give African American rhetoric a flexible approach that is still true to tradition.[103] While digital rhetoric can be used to facilitate traditions, select cultures face several practical application issues. Radhika Gajjala, professor at the University of Pittsburgh, writes that South Asian cyber feminists face issues with regards to building their web presence.[104] Studies on how digital rhetoric implicates various topics are ongoing and encompass many fields. Research Ethics Writing and rhetoric scholars Heidi McKee and James E. Porter discuss the complicated issue of internet users posting information publicly on the internet but expecting the post to be semi-private. This appears contradictory but socially the internet is composed of million social identities, social groups, social norms, and social influence.[105] These different social aspects of the internet are more important than ever to consider when studying anything digital because the digital and non digital are getting harder to distinguish from one another.[106] A study conducted by Rösner and Krämer in 2016 showed that participants' identities would reflect the norms of these online social groups. Similar to how social groups are seen in an in-person setting, posts on forums, comment sections, and social media are like having a conversation with friends in a public setting. Typically researchers would not use conversations heard in public, but online it's different because the conversation isn't only available to that social group.[107] James Zappen in his article "Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory" adds to the conversation that many of these groups foster a creative and collaborative nature to share information to the public.[108] Mckee and Porter suggest the use of a casuistic heuristic approach to doing digital research. This method of study is based on focusing on the moral principle of do no harm to the audience and generating needed formulas or diagrams to help guide the researcher when gathering data. It is noted that this method does not provide all the answers. Instead it is a starting point for the scholar to approach the digital world. More scholars have added their own take to an ethical approach for digital data. Many have a case-based approach with add on like consent from participants if possible, anonymity to participants, and consideration of what harm could come to the groups being studied.[106][109] Regardless of the ethical approach taken, digital scholars agree that some type of consideration into ethics must be taken when studying the internet. |

クリティカルアプローチ テクノフェミニズム デジタルレトリックは、ジェンダー、資本主義、テクノロジーの交差をまとめる概念であるテクノフェミニズムに基盤を与える[80]。テクノフェミニズム は、テクノロジーを多用する分野における女性の平等を唱え、女性と彼らのデバイスとの関係を研究している。交差性とは、私たちのアイデンティティに基づく 社会的不公正を認識するキンバレ・クレンショウによって作られた用語である[80]。女性がデジタル空間で嫌がらせやジェンダーバイアスなしに見つけて交 流することはしばしば困難である。 [81]あらゆる人種のジェンダー非適合者やトランスジェンダー、障害者、有色人種など、代表されないコミュニティに対するデジタル・アクティヴィズムの 重要性がある[81]。 Computers and Composition誌では、交差性やテクノフェミニズムという用語を明確に使用している論文はわずか5つである[80]。新しい技術や研究の開発にお いてテクノフェミニズムと交差性はまだあまり浸透していない[80]。 デジタル文化のレトリック インターネットの拡大により、デジタルメディアやレトリックは文化を表したり識別するために使用されることがある[2]。学者たちは、デジタルレトリック が人種、宗教、セクシャリティなどの人の個人的な要因によってどのように影響されるかを研究している。これらの要因によって、人々は異なるツールを利用 し、異なる情報を吸収する。デジタル文化は、ウェブ上に特化したコミュニティの必要性を生み出している。Redditのようなコンピュータを介したコミュ ニティは、こうした専門的なコミュニティに声を与えることができます。デジタル文化レトリックの創造は、他のコミュニティが知らないようなオンラインスラ ングを使用することを可能にしている。デジタル・カルチャー・レトリックを探求するオンライン・コミュニティは、ユーザーが自分の社会的アイデンティティ を発見し、かつて直面したステレオタイプに対峙することを可能にしている[83]。 具現化 デジタル文化レトリックのサブセットのひとつが身体化である。これは、すべての人がそれぞれのアイデンティティに基づいたテクノロジーとのユニークな関係 を持っているという考えである。身体とテクノロジーの関係を研究することは、デジタル修辞学者がデジタル領域における平等なアクセスと機会を促進すること ができる一つの方法である[12]。テクノロジーは現実世界の延長であると考えられているので、ユーザーはデジタル空間での経験によっても形作られてい る。オンライン環境で起こる人工的な相互作用は、ユーザーが単なる人間の経験に付加的な形で存在することを可能にしている[84]。 教育学 デジタル・レトリックがますます存在感を増すなか、教室でデジタル・レトリックを教えるための教育的アプローチが学者によって提案されている。デジタルレ トリックのコースでは、ユーザーとデジタルマテリアルの間の交差性や、年齢、民族性、ジェンダーなどの異なる背景がこれらの相互作用にどのように影響しう るかを研究している[85]。 高等教育 英語、教育、テクノロジーのバックグラウンドを持つジェフ・グラビル(Jeff Grabill)[86]は、デジタルレトリックの学問分野とその実践の間の橋渡しをするよう同世代の研究者に呼びかけている。シェリル・ボール[87] は、マルチモーダルな作文・編集の実践、デジタルメディア研究、デジタル出版、大学のライティング教育学からなる領域を専門としている。ボールは、修辞的 な選択肢を分析し、特定の状況に対して最も適切なジャンル、技術、メディア、モードを選択することによって、マルチモーダルなテキストを書き、構成するこ とを学生に教えている。マルチモーダリティは、Elizabeth Loshらの著作『Understanding Rhetoric』にも影響を与えている。同様のアプローチはMelanie Gagichにも影響を与え、彼女の1年生の英語コースのカリキュラムを完全に変更し、デジタルプロジェクトを厳格な学術的課題として再定義し、学生に必 要なオーディエンス分析のスキルを教えることを目指した[89]。 そのようなデザインは最終的にGagichの教室の学生が創造性と作家としての自信を伸ばすことを可能にしている[89]。 もうひとつのアプローチとして、ダグラス・アイマンは、デジタルテキストの制作と修辞的理解について、学部生により実践的な指導を行うウェブオーサリング とデザインのコースを推奨している[90]。さらに、デジタルレトリック教育のためのウェブオーサリングとデザインは、学生にウェブライティングとデザイ ンの規約、ルール、手順の基礎を学ぶ機会を提供すると説明している[90]。同様に、Collin Bjorkは、「デジタルレトリックとユーザビリティテストを統合することによって、研究者は学生、講師、インターフェースがOWIでいかに相互作用する かをより複雑に理解することができる」[91]と論じている。 他の学者は、デジタル・レトリックと社会的インパクトの関係にもっと焦点をあてている。また、ローレン・マローンは、QTPoC(Queer and Trans People of Color)のオンラインエンゲージメントに関する研究を通じて、アイデンティティとデジタルレトリックを教えることの関係性を分析している[12] [80]。 [この研究から、マローンはデジタルレトリックの講師が教室内で包括性を育むために取るべき一連のステップを作成した[92]。 最後に、学者のメラニー・キルは大学世代の学生にデジタルレトリックを積極的に紹介し、ウィキペディアの編集の重要性と教育や資料にアクセスできるという 特権を生かすことを主張している[93]。 デ・ヘルトフらやハースと同様に、デジタルレトリックにおける教育はポジティブな社会変化を促進するのですべての学生の役に立つとキルは考えている [93]。 K-12 多くの教育システムは、学生が受動的なユーザーではなく、デジタルレトリックのデザイナーとして技術システムに積極的に参加するように組み立てられていま す[1]。学生がコースワークで確認した3つのコアな目標があります:自分自身のデジタル空間を構築し、デジタルレトリックのすべての側面(理論、技術、 使用を含む)を学び、自分の生活でそれを適用することです。クラスメイト、デジタルメディア、その他の個人と学生の相互作用によって生成される生態系は、 「相互接続された」修辞学的プロセスと共有デジタル作品の基礎となる[1]。 ビデオゲームは、学生が技術システムの基礎となるレトリックとコードを設計することを学ぶ1つの手段である。ビデオゲームの利用は1980年代から急速に 発展し、現在のビデオゲームは教育に取り入れられている[94]。学者のイアン・ボゴストは、ビデオゲームは私たちの非デジタル世界のモデルとして研究す るために多くの科目で活用することができると提案している。具体的には、コンピュータサイエンスに興味がなかった学生がその分野に入るための「入口」とし てビデオゲームを利用することができると指摘している。ゲームとゲーム技術は、「プレイヤーの能力の外側と成長する端」で動作することによって学習を強化 する[95]。ゲームは、フラストレーションを引き起こすレベルで学生に挑戦するが、この端で課題を解決する動機付けを維持する。 また、Ian Bogostは、ビデオゲームは修辞的で表現的なものとして教えることができ、子どもたちがプログラミングを通して自分の経験をモデル化することを可能に すると述べている。また、ビデオゲームをインタラクティブなメディアとして分析することで、プレイヤーのパフォーマティブな活動を通して、根底にあるレト リックを明らかにする[96]。コーススタディを通して手続き的レトリックを認識することは、これらのメディアがいかに政治、広告、情報を増強できるかを 反映している[94] ビデオゲームのコードにおけるレトリックを扱うために、学者のCollin Bjorkがオンラインライティング教育におけるユーザビリティテストとデジタルレトリックを統合する一連の推奨事項を示している。 また、大学入学前の教室でデジタル・レトリックを教えるための具体的な実践方法を明らかにしている学者もいます。これは、他の教授による発見と一致してお り、デジタルレトリックの教室における学生の主な目標の1つは、自分自身のためのスペース、仲間とのつながりを作り、その意義を深く理解することだと主張 している[85]。これらの対人関係は、「デジタル化と力を与える教育法の間の厚い相関関係」を反映している[97]。 プレK 米国政府の教育技術局は、早期学習者にテクノロジーを使用する際の4つの指導原則を強調しています[98]。 適切に使用されれば、テクノロジーは学習のための道具となり得る。 テクノロジーを適切に使用すれば、テクノロジーは学習のためのツールとなる。 テクノロジーは、子供とその家族、早期教育者、友人との関係を強化するために使用することができる。 テクノロジーは、早期学習者が大人や仲間と交流しているときに最も効果を発揮する。また、大人はオンラインで子供たちを監督することで、その効果を高める ことができます。 これらの4つの柱にもかかわらず、ほとんどの研究では、2歳未満の子供にテクノロジーを学ばせることは有益でないと結論づけています。もし、幼い子供にテ クノロジーを使わせなければならないのであれば、例えば、離れたところにいる大切な人とつながるためのビデオチャットソフトなど、人間関係の発達を促すた めにテクノロジーを使うことがベストです[98]。 研究分野としてのデジタル・レトリック 2009年、修辞学者のエリザベス・ロッシュ[99]は著書『Virtualpolitik』の中でデジタル・レトリックの以下の4つの部分からなる定義 を提示している[100]。 1. 1.平均的な人々の生活の中で、日常の談話や特別な機会に使われる新しいデジタル・ジャンルの慣例。 2. 2. 公的なレトリックで、しばしば政府機関からの政治的メッセージの形で、デジタル技術を通じて表現または記録され、電子的に分散されたネットワークを通じて 広められるもの。 3. 3.コンピュータで作成されたメディアを研究対象として、その修辞学的解釈に関する新たな学問分野。 4. 4.情報科学の分野からのコミュニケーションの数学的理論、その多くは与えられた言語交換における不確実性の量またはメッセージが移動する可能性の高い経 路を定量化しようとするものである[101]。 Loshの定義は、デジタルレトリックがコード、テキスト、ビジュアル、ビデオなどの様々なタイプの情報を研究するために異なる手法に依存する分野である ことを示している[99]。 Douglas Eymanは、古典的な理論をデジタルメディアにマッピングすることができるが、より大きな学術的な焦点は「修辞学の理論の拡張」に置かれるべきであると 提案している[102]。1985年に設立されたジャーナルであるComputers and Compositionはコンピュータ・コミュニケーションに焦点を当て、「彼らの概念的枠組みとしてのレトリック」の使用やソフトウェア開発におけるデ ジタルレトリックについて考察している[102]。 さらに、デジタルレトリックは異なる文化が彼らの長年の文化伝統を促進し続けるためのツールであるといえるだろう。彼の著書、Digital Griots: Adam J. Banksは、著書Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Ageの中で、スタンドアップコミックや話し言葉詩人のような現代のストーリーテラーがアフリカ系アメリカ人のレトリックに伝統に忠実である柔軟なアプ ローチを与えていると述べています[103] デジタルレトリックが伝統を促進するために使用できる一方で、特定の文化はいくつかの実用的な適用問題に直面しています。ピッツバーグ大学教授の Radhika Gajjalaは、南アジアのサイバーフェミニストはウェブプレゼンス構築に関して問題に直面していると書いている[104]。デジタルレトリックがどの ように様々なトピックに関与しているかについての研究は進行中で、多くの分野を包含している。 研究倫理 文章と修辞学の学者であるHeidi McKeeとJames E. Porterは、インターネットユーザーがインターネット上で情報を公に投稿しながら、その投稿が半個人的であると期待しているという複雑な問題について 論じている。これは矛盾しているように見えるが、社会的にはインターネットは百万人の社会的アイデンティティ、社会的グループ、社会的規範、社会的影響か ら構成されている[105]。デジタルと非デジタルは互いに区別することが難しくなっているので、インターネットのこれらの異なる社会的側面は、デジタル に関するものを研究するときに考慮することがこれまで以上に重要である[106]。 2016年にRösnerとKrämerによって行われた研究は、参加 者のアイデンティティがこれらのオンラインの社会的集団の規範を反映することを示した。社会集団が対面での見え方と同様に、フォーラム、コメント欄、ソー シャルメディアへの投稿は、公共の場で友人と会話しているようなものです。一般的に研究者は公共の場で聞いた会話を使用しないが、オンラインではその会話 がその社会的グループだけに利用されるわけではないので異なる[107] James Zappenは彼の論文「Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory "では、これらのグループの多くが公衆に情報を共有するために創造的で協力的な性質を育んでいることを会話に付け加えている[108]。 MckeeとPorterは、デジタルリサーチを行うために詭弁的な発 見的アプローチを用いることを提案している。この研究方法は、聴衆に害を与えないという道徳的原則に着目し、データを収集する際に研究者を導くために必要 な公式や図表を生成することに基づいている。この方法は、すべての答えを提供するものではないことに留意してください。むしろ、学者がデジタル世界にアプ ローチするための出発点なのです。デジタルデータに対する倫理的アプローチに、独自の見解を加える学者も増えている。その多くは、ケースベースのアプロー チに、可能であれば参加者の同意、参加者の匿名性、研究対象集団にどのような危害が及ぶかを考慮するなどの要素を加えている[106][109]。 |