スティグマ学入門

Introduction to

understanding Social Stigma

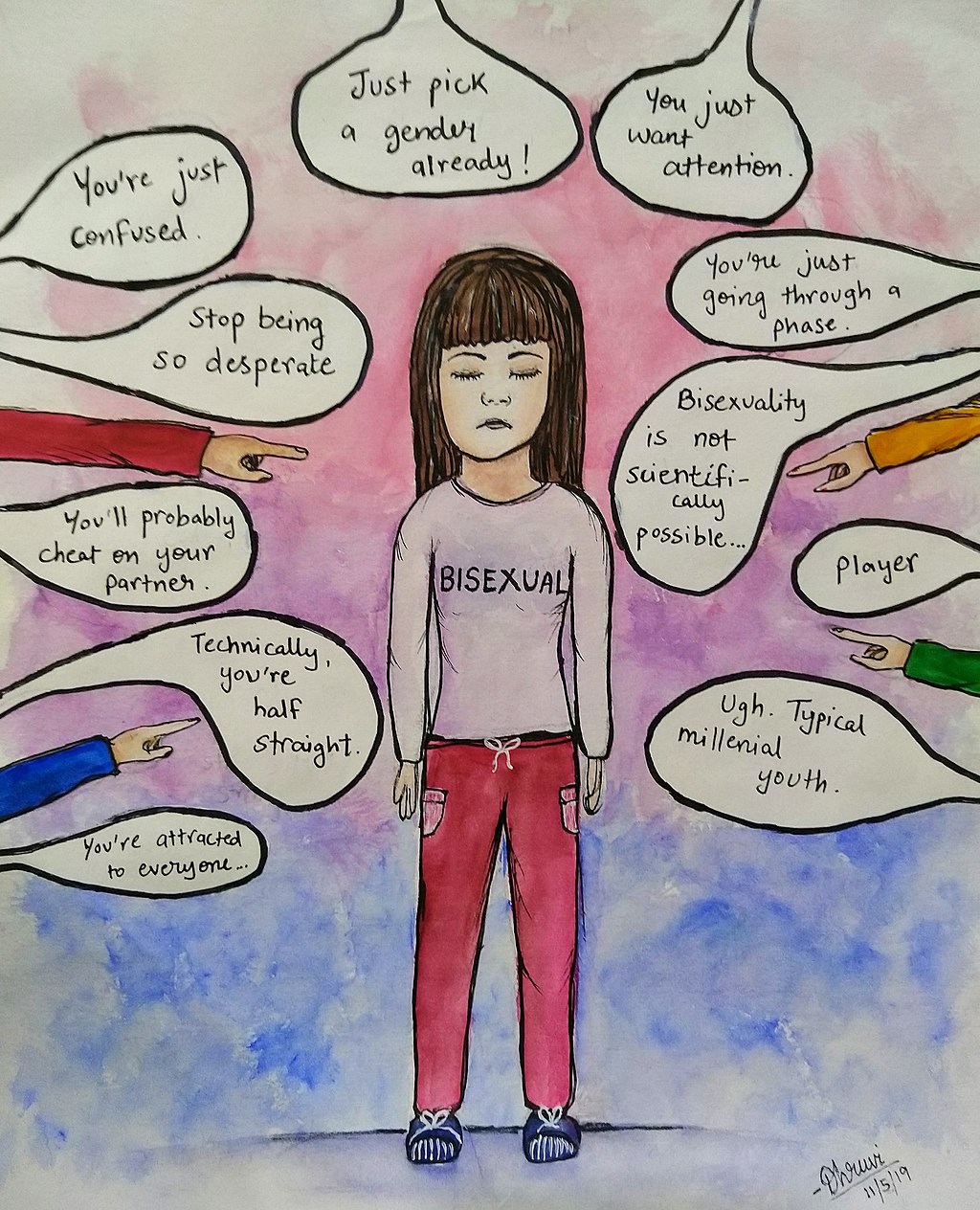

Example of social stigma against

bisexual people

☆ 社会的スティグマ(Social stigma)と は、社会の他の構成員と区別するために役立つ知覚された特徴に基づく、個人または集団に対する不支持、または差別のことである。社会的 スティグマは一般的に、文化、性別、人種、社会経済的階級、年齢、性的指向、身体イメージ、身体障害、知能の有無、健康状態に関連している。スティグマに は明白なものもあれば、開示によって明らかにしなければならない隠蔽可能なスティグマもある。スティグマはまた、自分自身に対するものであり、「自らの台 無しにするアイデンティティ 」をもたらすような形で、個人的な属性を否定的に見ることから生じることもある(例えば、自己スティグマ)(→「ゴフマン『スティグマ』」このページの内容は「スティグマあるいは社会的スティグマ」とほぼ同じです)。

| Social stigma

is the disapproval of, or discrimination against, an individual or

group based on perceived characteristics that serve to distinguish them

from other members of a society. Social stigmas are commonly related to

culture, gender, race, socioeconomic class, age, sexual orientation,

body image, physical disability, intelligence or lack thereof, and

health. Some stigma may be obvious, while others are known as

concealable stigmas that must be revealed through disclosure. Stigma

can also be against oneself, stemming from negatively viewed personal

attributes in a way that can result in a "spoiled identity" (i.e.,

self-stigma).[1][2] |

社会的スティグマとは、社会の他の構成員と区別するために役立つ知覚さ

れた特徴に基づく、個人または集団に対する不支持、または差別のことである。社会的スティグマは一般的に、文化、性別、人種、社会経済的階級、年齢、性的

指向、身体イメージ、身体障害、知能の有無、健康状態に関連している。スティグマには明白なものもあれば、開示によって明らかにしなければならない隠蔽可

能なスティグマもある。スティグマはまた、自分自身に対するものであり、「自らの台無しにするアイデンティティ

」をもたらすような形で、個人的な属性を否定的に見ることから生じることもある(例えば、自己スティグマ)。 |

| Description Stigma (plural stigmas or stigmata) is a Greek word that in its origins referred to a type of marking or the tattoo that was cut or burned into the skin of people with criminal records, slaves, or those seen as traitors in order to visibly identify them as supposedly blemished or morally polluted persons. These individuals were to be avoided particularly in public places.[3] Social stigmas can occur in many different forms. The most common deal with culture, gender, race, religion, illness and disease. Individuals who are stigmatized usually feel different and devalued by others. Stigma may also be described as a label that associates a person to a set of unwanted characteristics that form a stereotype. It is also affixed.[4] Once people identify and label one's differences, others will assume that is just how things are and the person will remain stigmatized until the stigmatizing attribute is undetectable. A considerable amount of generalization is required to create groups, meaning that people will put someone in a general group regardless of how well the person actually fits into that group. However, the attributes that society selects differ according to time and place. What is considered out of place in one society could be the norm in another. When society categorizes individuals into certain groups the labeled person is subjected to status loss and discrimination.[4] Society will start to form expectations about those groups once the cultural stereotype is secured. Stigma may affect the behavior of those who are stigmatized. Those who are stereotyped often start to act in ways that their stigmatizers expect of them. It not only changes their behavior, but it also shapes their emotions and beliefs.[5] Members of stigmatized social groups often face prejudice that causes depression (i.e. deprejudice).[6] These stigmas put a person's social identity in threatening situations, such as low self-esteem. Because of this, identity theories have become highly researched. Identity threat theories can go hand-in-hand with labeling theory. Members of stigmatized groups start to become aware that they are not being treated the same way and know they are likely being discriminated against. Studies have shown that "by 10 years of age, most children are aware of cultural stereotypes of different groups in society, and children who are members of stigmatized groups are aware of cultural types at an even younger age."[5] |

概説 スティグマ(複数形stigmasまたはstigmata)はギリシャ語で、その起源は、犯罪歴のある人々、奴隷、裏切り者とみなされた人々の皮膚に、傷 や道徳的に汚れたと思われる人物であることを目に見える形で識別するために彫られたり焼かれたりした、一種の印や入れ墨を指していた。このような人物は、 特に公共の場では避けられることになっていた[3]。 社会的スティグマは様々な形で発生する可能性がある。最も一般的なものは、文化、性別、人種、宗教、病気や疾患に関するものである。スティグマを受けた人 は通常、他者から差別され、軽んじられていると感じる。 スティグマはまた、ステレオタイプを形成する一連の好ましくない特徴と人を結びつけるレッテルと表現されることもある。また、レッテルは貼付されたもので もある[4]。ひとたび人々がその人の違いを特定し、レッテルを貼ってしまうと、他人はそれが物事のあり方であると思い込み、スティグマとなる属性が検出 されなくなるまで、その人はスティグマ化されたままとなる。グループを作るには、かなりの量の一般化が必要である。つまり、人は誰かを、その人が実際にど れだけそのグループに適合しているかにかかわらず、一般的なグループに入れる。しかし、社会が選択する属性は時代や場所によって異なる。ある社会では場違 いだと思われていることが、別の社会では当たり前だったりする。社会が個人を特定のグループに分類すると、レッテルを貼られた人は地位の低下や差別を受け ることになる。 スティグマはスティグマをつけられた人の行動に影響を与えるかもしれない。ステレオタイプ化された人々は、スティグマを植え付けた人々が期待するような行 動をとり始めることが多い。それは彼らの行動を変えるだけでなく、彼らの感情や信念を形成する。スティグマをつけられた社会集団の構成員は、抑うつ(すな わち、脱偏見)を引き起こす偏見にしばしば直面する。このため、アイデンティティ理論は高度に研究されるようになった。アイデンティティ脅威理論はラベリ ング理論と密接に関連する。 汚名を着せられた集団のメンバーは、自分が同じように扱われていないことを自覚し始め、自分が差別されている可能性が高いことを知る。研究によると、 「10歳になるまでに、ほとんどの子どもは社会におけるさまざまな集団の文化的ステレオタイプを認識しており、汚名を着せられた集団の一員である子ども は、さらに幼い年齢で文化的タイプを認識している」[5]。 |

| Émile Durkheim French sociologist Émile Durkheim was the first to explore stigma as a social phenomenon in 1895. He wrote: Imagine a society of saints, a perfect cloister of exemplary individuals. Crimes or deviance, properly so-called, will there be unknown; but faults, which appear venial to the layman, will there create the same scandal that the ordinary offense does in ordinary consciousnesses. If then, this society has the power to judge and punish, it will define these acts as criminal (or deviant) and will treat them as such.[7] [7] Émile Durkheim (1982). Rules of Sociological Method (1895) The Free Press |

エミール・デュルケーム フランスの社会学者エミール・デュルケムは、1895年に社会現象としてのスティグマを初めて探求した。彼はこう書いている: 聖人の社会、模範的な個人からなる完璧な回廊を想像してほしい。そこでは、いわゆる犯罪や逸脱は起こらない。しかし、素人には罪のないように見える欠点 も、そこでは普通の犯罪が普通の意識の中で起こすのと同じようなスキャンダルを引き起こすだろう。もしこの社会が裁き、罰する力を持つとすれば、これらの 行為を犯罪(あるいは逸脱)と定義し、そのように扱うだろう[7]。 [7] Émile Durkheim (1982). Rules of Sociological Method (1895) The Free Press |

| Erving Goffman Erving Goffman described stigma as a phenomenon whereby an individual with an attribute which is deeply discredited by their society is rejected as a result of the attribute. Goffman saw stigma as a process by which the reaction of others spoils normal identity.[8] More specifically, he explained that what constituted this attribute would change over time. "It should be seen that a language of relationships, not attributes, is really needed. An attribute that stigmatizes one type of possessor can confirm the usualness of another, and therefore is neither credible nor discreditable as a thing in itself."[8] In Goffman's theory of social stigma, a stigma is an attribute, behavior, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one. Goffman defined stigma as a special kind of gap between virtual social identity and actual social identity: While a stranger is present before us, evidence can arise of his possessing an attribute that makes him different from others in the category of persons available for him to be, and of a less desirable kind—in the extreme, a person who is quite thoroughly bad, or dangerous, or weak. He is thus reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted discounted one. Such an attribute is a stigma, especially when its discrediting effect is very extensive [...] It constitutes a special discrepancy between virtual and actual social identity. (Goffman 1963:3). The stigmatized, the normal, and the wise Goffman divides the individual's relation to a stigma into three categories: 1. the stigmatized being those who bear the stigma; 2. the normals being those who do not bear the stigma; and 3. the wise being those among the normals who are accepted by the stigmatized as understanding and accepting of their condition (borrowing the term from the homosexual community). The wise normals are not merely those who are in some sense accepting of the stigma; they are, rather, "those whose special situation has made them intimately privy to the secret life of the stigmatized individual and sympathetic with it, and who find themselves accorded a measure of acceptance, a measure of courtesy membership in the clan." That is, they are accepted by the stigmatized as "honorary members" of the stigmatized group. "Wise persons are the marginal men before whom the individual with a fault need feel no shame nor exert self-control, knowing that in spite of his failing he will be seen as an ordinary other," Goffman notes that the wise may in certain social situations also bear the stigma with respect to other normals: that is, they may also be stigmatized for being wise. An example is a parent of a homosexual; another is a white woman who is seen socializing with a black man (assuming social milieus in which homosexuals and dark-skinned people are stigmatized). A 2012 study[9] showed empirical support for the existence of the own, the wise, and normals as separate groups; but the wise appeared in two forms: active wise and passive wise. The active wise encouraged challenging stigmatization and educating stigmatizers, but the passive wise did not. |

アービング・ゴフマン アーヴィング・ゴフマンはスティグマを、社会から深く信用されていない属性を持つ個人が、その属性の結果として拒絶される現象として説明した。ゴフマンは スティグマを、他者の反応が正常なアイデンティティを台無しにするプロセスとして捉えていた[8]。 より具体的には、彼はこの属性を構成するものは時間とともに変化すると説明した。「属性ではなく、関係の言語が本当に必要であることがわかるだろう。ある タイプの所有者に汚名を着せる属性は、別のタイプの所有者の通常性を確認することができ、したがって、それ自体としては信用できるものでもなければ、信用 できないものでもない」[8]。 ゴフマンの社会的スティグマ理論において、スティグマとは特定の方法で社会的に信用を失墜させる属性、行動、評判のことである。ゴフマンはスティグマを、 ヴァーチャルな社会的アイデンティティと実際の社会的アイデンティティの間にある特殊なギャップと定義した: 見知らぬ人がわれわれの目の前にいる間、その人が、その人がなりうる人物の範疇において他の人とは異なる、あまり好ましくない種類の、極端な言い方をすれ ば、徹底して悪い人、危険な人、弱い人という属性を持っているという証拠が生じうる。こうして彼は、私たちの心の中で、全体的で普通の人から、汚染された 割安な人へと引き下げられる。そのような属性はスティグマであり、特にその信用失墜効果が非常に広範である場合[......]、仮想の社会的アイデン ティティと実際の社会的アイデンティティとの間に特別な不一致を構成する。(ゴフマン 1963:3)。 汚名を着せられた者、正常な者、賢明な者 ゴフマンは、スティグマと個人の関係を3つのカテゴリーに分けている: 1. 汚名を着せられた者は、汚名を背負う者である;スティグマを負わされた人とは、スティグマを負う人であり 2. ノーマルな人とは、スティグマを負わない人である。 3. 賢者とは、スティグマを負わされた人々から、彼らの状態を理解し、受け入れていると受け入れられている(この言葉は同性愛者のコミュニティから借用したも のである)ノーマルな人々のことである。 賢明な健常者とは、ある意味でスティグマを受け入れているだけの人たちではなく、むしろ、「特別な状況によって、スティグマを負わされた個人の秘密の生活 に密接に関わるようになり、それに共感するようになった人たちである。つまり、彼らは汚名を着せられた人々から、汚名を着せられた集団の「名誉会員」とし て受け入れられるのである。「ゴフマンは、ある社会的状況において、賢者は他の普通の人に対してもスティグマを負いうる、つまり、賢者であるがゆえにス ティグマを負わされる可能性があると指摘する。例えば、同性愛者の親や、黒人男性と交際する白人女性である(同性愛者や肌の黒い人がスティグマとされる社 会的環境を想定)。 2012年の研究[9]では、自分自身、賢者、ノーマルが別々のグループとして存在することが実証的に支持されたが、賢者には能動的賢者と受動的賢者とい う2つの形態が見られた。能動的な賢者はスティグマ化に挑戦し、スティグマ化者を教育することを奨励したが、受動的な賢者はそうしなかった。 |

| Ethical considerations Goffman emphasizes that the stigma relationship is one between an individual and a social setting with a given set of expectations; thus, everyone at different times will play both roles of stigmatized and stigmatizer (or, as he puts it, "normal"). Goffman gives the example that "some jobs in America cause holders without the expected college education to conceal this fact; other jobs, however, can lead to the few of their holders who have a higher education to keep this a secret, lest they are marked as failures and outsiders. Similarly, a middle-class boy may feel no compunction in being seen going to the library; a professional criminal, however, writes [about keeping his library visits secret]." He also gives the example of blacks being stigmatized among whites, and whites being stigmatized among blacks. Individuals actively cope with stigma in ways that vary across stigmatized groups, across individuals within stigmatized groups, and within individuals across time and situations.[10] |

倫理的考察 ゴフマンは、スティグマの関係は、個人と社会的環境との間のものであり、その社会的環境には一定の期待があることを強調している。従って、誰もが異なる時 に、スティグマを受ける側とスティグマを与える側の両方の役割を演じることになる(ゴフマンの言葉を借りれば、「普通の人」)。ゴフマンは、「アメリカで は、期待される大学教育を受けていない保持者がその事実を隠すようになる仕事もあれば、失敗者やアウトサイダーとしてマークされないように、高等教育を受 けている少数の保持者がその事実を秘密にするようになる仕事もある」という例を挙げている。同様に、中流階級の少年は図書館に通う姿を見られることに何の 抵抗も感じないかもしれない。彼はまた、黒人が白人の間で汚名を着せられ、白人が黒人の間で汚名を着せられる例も挙げている。 個人はスティグマに積極的に対処するが、その方法はスティグマを受けた集団間でも、スティグマを受けた集団内の個人間でも、また時間や状況によって個人内 でも異なる[10]。 |

| The stigmatized The stigmatized are ostracized, devalued, scorned, shunned and ignored. They experience discrimination in the realms of employment and housing.[11] Perceived prejudice and discrimination is also associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes.[12] Young people who experience stigma associated with mental health difficulties may face negative reactions from their peer group.[13][14][15][16] Those who perceive themselves to be members of a stigmatized group, whether it is obvious to those around them or not, often experience psychological distress and many view themselves contemptuously.[17] Although the experience of being stigmatized may take a toll on self-esteem, academic achievement, and other outcomes, many people with stigmatized attributes have high self-esteem, perform at high levels, are happy and appear to be quite resilient to their negative experiences.[17] There are also "positive stigma": it is possible to be too rich, or too smart. This is noted by Goffman (1963:141) in his discussion of leaders, who are subsequently given license to deviate from some behavioral norms because they have contributed far above the expectations of the group. This can result in social stigma. |

スティグマを負わされた人々 汚名を着せられた人々は、仲間はずれにされ、軽蔑され、敬遠され、無視される。彼らは雇用や住居の領域で差別を経験する[11]。知覚された偏見や差別は また、身体的・精神的な健康状態に悪影響を及ぼす結果とも関連している[12]。 精神的健康障害に関連したスティグマを経験した若者は、仲間グループからの否定的な反応に直面することがある[13][14][15][16]。 自分がスティグマ化された集団の一員であると認識している人は、それが周囲にとって明らかであるかどうかにかかわらず、しばしば心理的苦痛を経験し、自分 自身を軽蔑的に見る人も多い[17]。 スティグマをつけられた経験は、自尊心、学業成績、その他の結果に打撃を与える可能性があるが、スティグマをつけられた属性を持つ人の多くは、高い自尊心 を持ち、高い水準の業績を上げ、幸福であり、否定的な経験に対してかなり回復力があるように見える[17]。 また、「正のスティグマ」も存在する:金持ちすぎたり、頭が良すぎたりすることは可能である。これはゴフマン(1963:141) がリーダーについて論じた際に指摘していることであり、リーダー はその後、集団の期待をはるかに上回る貢献をしたために、ある種の 行動規範から逸脱することを許される。その結果、社会的スティグマが生じることがある。 |

| The stigmatizer From the perspective of the stigmatizer, stigmatization involves threat, aversion[clarification needed] and sometimes the depersonalization of others into stereotypic caricatures. Stigmatizing others can serve several functions for an individual, including self-esteem enhancement, control enhancement, and anxiety buffering, through downward-comparison—comparing oneself to less fortunate others can increase one's own subjective sense of well-being and therefore boost one's self-esteem.[17] 21st-century social psychologists consider stigmatizing and stereotyping to be a normal consequence of people's cognitive abilities and limitations, and of the social information and experiences to which they are exposed.[17] Current views of stigma, from the perspectives of both the stigmatizer and the stigmatized person, consider the process of stigma to be highly situationally specific, dynamic, complex and nonpathological.[17] |

汚名を着せる側 スティグマを植え付ける側から見ると、スティグマ化には脅威、嫌悪[clarification needed]、そして時にはステレオタイプな戯画へと他者を非人格化することが含まれる。他者をスティグマ化することは、下方比較-自分自身をより恵ま れない他者と比較することで、自分自身の主観的な幸福感を高め、したがって自尊心を高めることができる-を通じて、自尊心の強化、コントロールの強化、不 安の緩衝など、個人にとっていくつかの機能を果たすことができる[17]。 21世紀の社会心理学者は、スティグマ形成やステレオタイプ形成は、人々の認知能力や限界、そして彼らがさらされている社会的情報や経験の正常な結果であ るとみなしている[17]。 スティグマに対する現在の見解は、スティグマを与える側とスティグマを与えられる側の両方の視点から、スティグマのプロセスは非常に状況特異的であり、動 的であり、複雑であり、非病理的であるとみなしている[17]。 |

| Gerhard Falk German-born sociologist and historian Gerhard Falk wrote:[18] All societies will always stigmatize some conditions and some behaviors because doing so provides for group solidarity by delineating "outsiders" from "insiders". Falk[19] describes stigma based on two categories, existential stigma and achieved stigma. He defines existential stigma as "stigma deriving from a condition which the target of the stigma either did not cause or over which he has little control." He defines Achieved Stigma as "stigma that is earned because of conduct and/or because they contributed heavily to attaining the stigma in question."[18] Falk concludes that "we and all societies will always stigmatize some condition and some behavior because doing so provides for group solidarity by delineating 'outsiders' from 'insiders'".[18] Stigmatization, at its essence, is a challenge to one's humanity- for both the stigmatized person and the stigmatizer. The majority of stigma researchers have found the process of stigmatization has a long history and is cross-culturally ubiquitous.[17] |

ルハルト・ファルク ドイツ生まれの社会学者で歴史家のゲルハルト・フォークは次のように書いている[18]。 なぜならそうすることで、「アウトサイダー」と「インサイダー」を区別することで集団の連帯を図ることができるからである。 フォーク[19]はスティグマを実存的スティグマと達成的スティグマという2つのカテゴリーに基づいて説明している。彼は実存的スティグマを「スティグマ の対象が引き起こしたのではない、あるいは本人がほとんどコントロールできない状態から派生するスティグマ」と定義している。彼は達成されたスティグマを 「行為によって、および/または問題のスティグマを達成するために大きく貢献したために獲得されたスティグマ」と定義している[18]。 なぜならそうすることで、「アウトサイダー」と「インサイダー」を区別することで集団の連帯が保たれるからである。スティグマ研究者の大半は、スティグマ 化のプロセスには長い歴史があり、文化的に偏在していることを発見している[17]。 |

| Link and Phelan stigmatization

model Bruce Link and Jo Phelan propose that stigma exists when four specific components converge:[20] Individuals differentiate and label human variations. Prevailing cultural beliefs tie those labeled to adverse attributes. Labeled individuals are placed in distinguished groups that serve to establish a sense of disconnection between "us" and "them". Labeled individuals experience "status loss and discrimination" that leads to unequal circumstances. In this model stigmatization is also contingent on "access to social, economic, and political power that allows the identification of differences, construction of stereotypes, the separation of labeled persons into distinct groups, and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion, and discrimination." Subsequently, in this model, the term stigma is applied when labeling, stereotyping, disconnection, status loss, and discrimination all exist within a power situation that facilitates stigma to occur. |

リンクとフェランのスティグマ化モデル ブルース・リンクとジョー・フェランは、スティグマは以下の4つの特定の構成要素が収束したときに存在すると提唱している[20]。 個人は人間のバリエーションを区別し、レッテルを貼る。 有力な文化的信念が、レッテルを貼られた人々を不利な属性に結びつける。 レッテルを貼られた個人は、「私たち」と「彼ら」の間に断絶の感覚を確立するのに役立つ区別された集団に入れられる。 レッテルを貼られた人は、不平等な状況につながる「地位の喪失と差別」を経験する。 このモデルでは、スティグマ化はまた、"差異の特定、ステレオタイプの構築、レッテルを貼られた人の別個の集団への分離、不承認、拒絶、排除、差別の完全 な実行を可能にする社会的、経済的、政治的権力へのアクセス "を条件としている。その後、このモデルでは、スティグマという用語は、ラベリング、ステレオタイプ化、断絶、地位の喪失、差別のすべてが、スティグマを 生じやすくする権力状況の中に存在する場合に適用される。 |

| Differentiation and labeling Identifying which human differences are salient, and therefore worthy of labeling, is a social process. There are two primary factors to examine when considering the extent to which this process is a social one. The first issue is that significant oversimplification is needed to create groups. The broad groups of black and white, homosexual and heterosexual, the sane and the mentally ill; and young and old are all examples of this. Secondly, the differences that are socially judged to be relevant differ vastly according to time and place. An example of this is the emphasis that was put on the size of the forehead and faces of individuals in the late 19th century—which was believed to be a measure of a person's criminal nature.[citation needed] |

差別化とラベリング どの人間的差異が顕著であり、したがってラベリングに値するかを特定することは、社会的プロセスである。このプロセスがどの程度社会的なものであるかを検 討する際には、2つの主要な要因がある。第一の問題は、グループを作るにはかなりの単純化が必要だということである。黒人と白人、同性愛者と異性愛者、正 気と精神病者、若者と老人といった大まかな集団は、すべてこの例である。第二に、社会的に関連性があると判断される差異は、時代や場所によって大きく異な る。この例として、19世紀後半に個人の額や顔の大きさが重視され、それがその人の犯罪性を測る尺度であると信じられていたことが挙げられる[要出典]。 |

| Linking to stereotypes The second component of this model centers on the linking of labeled differences with stereotypes. Goffman's 1963 work made this aspect of stigma prominent and it has remained so ever since. This process of applying certain stereotypes to differentiated groups of individuals has attracted a large amount of attention and research in recent decades. |

ステレオタイプとの関連 このモデルの第二の要素は、ラベル付けされた差異をステレオタイプと結びつけることにある。ゴフマンの1963年の研究は、スティグマのこの側面を顕著な ものとし、それ以来、この傾向は続いている。差別化された個人のグループに特定のステレオタイプを適用するこのプロセスは、ここ数十年で多くの注目と研究 を集めている。 |

| Us and them Thirdly, linking negative attributes to groups facilitates separation into "us" and "them". Seeing the labeled group as fundamentally different causes stereotyping with little hesitation. "Us" and "them" implies that the labeled group is slightly less human in nature and at the extreme not human at all. |

私たちと彼ら 第三に、否定的な属性を集団に結びつけることは、「私たち」と「彼ら」への分離を促進する。レッテルを貼られた集団を根本的に異なるとみなすことで、ほと んどためらうことなくステレオタイプ化を引き起こす。"我々 "と "彼ら "は、レッテルを貼られた集団が本質的に少し人間的でなく、極端には全く人間的でないことを意味する。 |

| Disadvantage The fourth component of stigmatization in this model includes "status loss and discrimination". Many definitions of stigma do not include this aspect, however, these authors believe that this loss occurs inherently as individuals are "labeled, set apart, and linked to undesirable characteristics." The members of the labeled groups are subsequently disadvantaged in the most common group of life chances including income, education, mental well-being, housing status, health, and medical treatment. Thus, stigmatization by the majorities, the powerful, or the "superior" leads to the Othering of the minorities, the powerless, and the "inferior". Whereby the stigmatized individuals become disadvantaged due to the ideology created by "the self," which is the opposing force to "the Other." As a result, the others become socially excluded and those in power reason the exclusion based on the original characteristics that led to the stigma.[21] |

不利益 このモデルにおけるスティグマ化の第4の要素は、「地位の喪失と差別」である。スティグマの多くの定義にはこの側面は含まれていないが、この著者たちは、 個人が "レッテルを貼られ、引き離され、望ましくない特徴と結びつけられる "ことによって、この損失が本質的に発生すると考えている。レッテルを貼られたグループのメンバーは、その後、収入、教育、精神的幸福、住居の状況、健 康、医療など、最も一般的な生活機会のグループにおいて不利益を被る。このように、マジョリティ、権力者、あるいは「優越者」によるスティグマ化は、マイ ノリティ、無力者、そして「劣等者」の他者化につながる。スティグマをつけられた人々は、"他者 "に対抗する "自己 "が作り出したイデオロギーによって不利益を被る。その結果、他者は社会的に排除されるようになり、権力者はスティグマをもたらしたもともとの特徴に基づ いて排除を理由づける。 |

| Necessity of power The authors also emphasize[20] the role of power (social, economic, and political power) in stigmatization. While the use of power is clear in some situations, in others it can become masked as the power differences are less stark. An extreme example of a situation in which the power role was explicitly clear was the treatment of Jewish people by the Nazis. On the other hand, an example of a situation in which individuals of a stigmatized group have "stigma-related processes"[clarification needed] occurring would be the inmates of a prison. It is imaginable that each of the steps described above would occur regarding the inmates' thoughts about the guards. However, this situation cannot involve true stigmatization, according to this model, because the prisoners do not have the economic, political, or social power to act on these thoughts with any serious discriminatory consequences. |

権力の必要性 著者らはまた、スティグマ化における権力(社会的、経済的、政治的権力)の役割も強調している[20]。ある状況においては権力の利用が明確であるが、あ る状況においては権力の差がそれほど大きくないため、権力の利用が覆い隠されてしまうことがある。権力の役割が明白であった状況の極端な例は、ナチスによ るユダヤ人の扱いである。一方、汚名を着せられた集団の個々人に「汚名に関連した過程」[clarification needed]が生じている状況の例としては、刑務所の受刑者が挙げられる。看守に対する受刑者の考えについて、上述の各段階が生じることは想像できる。 しかし、このモデルによれば、このような状況は真のスティグマ化を伴うことはありえない。なぜなら、受刑者は、深刻な差別的結果を伴うこれらの考えに基づ いて行動する経済的、政治的、社会的力を持っていないからである。 |

| "Stigma allure" and authenticity Sociologist Matthew W. Hughey explains that prior research on stigma has emphasized individual and group attempts to reduce stigma by "passing as normal", by shunning the stigmatized, or through selective disclosure of stigmatized attributes. Yet, some actors may embrace particular markings of stigma (e.g.: social markings like dishonor or select physical dysfunctions and abnormalities) as signs of moral commitment and/or cultural and political authenticity. Hence, Hughey argues that some actors do not simply desire to "pass into normal" but may actively pursue a stigmatized identity formation process in order to experience themselves as causal agents in their social environment. Hughey calls this phenomenon "stigma allure".[22] |

「スティグマの魅力」と真正性 社会学者マシュー・W・ヒュギーは、スティグマに関する先行研究では、スティグマを軽減するために、スティグマを受けた人を避ける、あるいはスティグマを 受けた人の属性を選択的に開示することによって、「正常であるかのように振舞う」個人や集団の試みが強調されてきたと説明する。しかし、一部の行為者は、 スティグマの特定の印(例えば、不名誉や身体的機能不全や異常のような社会的印)を、道徳的コミットメントや文化的・政治的信憑性の印として受け入れるこ とがある。それゆえヒュギーは、一部の行為者は単に「正常な状態への通過」を望むのではなく、社会環境における原因的行為者として自らを経験するために、 スティグマ化されたアイデンティティ形成過程を積極的に追求することがあると論じている。ヒュギーはこの現象を「スティグマの魅力」と呼んでいる [22]。 |

| While often incorrectly

attributed to Goffman, the "six dimensions of stigma" were not his

invention. They were developed to augment Goffman's two levels – the

discredited and the discreditable. Goffman considered individuals whose

stigmatizing attributes are not immediately evident. In that case, the

individual can encounter two distinct social atmospheres. In the first,

he is discreditable—his stigma has yet to be revealed but may be

revealed either intentionally by him (in which case he will have some

control over how) or by some factor, he cannot control. Of course, it

also might be successfully concealed; Goffman called this passing. In

this situation, the analysis of stigma is concerned only with the

behaviors adopted by the stigmatized individual to manage his identity:

the concealing and revealing of information. In the second atmosphere,

he is discredited—his stigma has been revealed and thus it affects not

only his behavior but the behavior of others. Jones et al. (1984) added

the "six dimensions" and correlate them to Goffman's two types of

stigma, discredited and discreditable. There are six dimensions that match these two types of stigma:[23] 1. Concealable – the extent to which others can see the stigma 2. Course of the mark – whether the stigma's prominence increases, decreases, or disappears 3. Disruptiveness – the degree to which the stigma and/or others' reaction to it impedes social interactions 4. Aesthetics – the subset of others' reactions to the stigma comprising reactions that are positive/approving or negative/disapproving but represent estimations of qualities other than the stigmatized person's inherent worth or dignity 5. Origin – whether others think the stigma is present at birth, accidental, or deliberate 6. Peril – the danger that others perceive (whether accurately or inaccurately) the stigma to pose to them |

スティグマの "6つの次元" しばしば誤ってゴフマンのものとされるが、「スティグマの6次元」はゴフマンの発明ではない。それらはゴフマンの2つのレベル-信用できない者と信用でき ない者-を補強するために開発された。ゴフマンは、スティグマとなる属性がすぐには明らかにならない個人について考えた。その場合、個人は2つの異なる社 会的雰囲気に遭遇する可能性がある。第一の場合、彼は信用失墜者である-彼の汚名はまだ明らかにされていないが、本人によって意図的に(その場合、本人は その方法をある程度コントロールできる)、あるいは本人にはコントロールできない何らかの要因によって明らかにされるかもしれない。もちろん、うまく隠蔽 されることもある。ゴフマンはこれをパッシングと呼んでいる。このような状況において、スティグマの分析は、スティグマを受けた個人が自分のアイデンティ ティを管理するためにとる行動、すなわち情報の隠蔽と暴露にのみ関係している。第二の雰囲気では、彼は信用を失っている-彼のスティグマが明らかにされた ため、彼の行動だけでなく他者の行動にも影響を及ぼしている。ジョーンズら(1984)は「6つの次元」を追加し、ゴフマンのスティグマの2つのタイプ、 信用されない(discredited)と信用されない(discreditable)と相関させている。 これら2つのタイプのスティグマに一致する6つの次元がある:[23]。 1. 隠蔽可能 - 他人がスティグマを見ることができる範囲 2. 刻印の経過-スティグマの目立ち方が増加するか、減少するか、消滅するか。 3. 破壊性-スティグマおよび/またはそれに対する他者の反応が社会的相互作用を阻害する程度 4. 美的感覚-スティグマに対する他者の反応のうち、肯定的/好意的、否定的/嫌悪的でありながら、スティグマをつけられた人の固有の価値や尊厳以外の資質に 対する評価を表す反応のサブセット。 5. 起源-スティグマが生まれつきのものであると他者が考えるか、偶然のものであると考えるか、意図的なものであると考えるか。 6. 危険性 - 他者がスティグマが自分たちにもたらす危険性を(正確か不正確かにかかわらず)認識しているかどうか。 |

| Types In Unraveling the contexts of stigma, authors Campbell and Deacon describe Goffman's universal and historical forms of Stigma as the following. Overt or external deformities – such as leprosy, clubfoot, cleft lip or palate and muscular dystrophy. Known deviations in personal traits – being perceived rightly or wrongly, as weak willed, domineering or having unnatural passions, treacherous or rigid beliefs, and being dishonest, e.g., mental disorders, imprisonment, addiction, homosexuality, unemployment, suicidal attempts and radical political behavior. Tribal stigma – affiliation with a specific nationality, religion, or race that constitute a deviation from the normative, e.g. being African American, or being of Arab descent in the United States after the 9/11 attacks.[24] |

種類(タイプ) 『スティグマの文脈を解き明かす』の中で、著者のキャンベルとディーコンは、ゴフマンの普遍的かつ歴史的なスティグマの形態を以下のように説明している。 外見上の奇形 - ハンセン病、内反足、口唇口蓋裂、筋ジストロフィーなど。 個人的特徴における既知の逸脱-善かれ悪しかれ、意志が弱い、支配的、不自然な情熱を持っている、裏切り者、厳格な信念を持っている、不誠実であると認識 されること、例えば、精神障害、投獄、中毒、同性愛、失業、自殺未遂、過激な政治的行動など。 部族的スティグマ-規範からの逸脱を構成する特定の国籍、宗教、人種への帰属、例えばアフリカ系アメリカ人であること、9.11テロ後のアメリカにおける アラブ系であることなど[24]。 |

| Deviance Stigma occurs when an individual is identified as deviant, linked with negative stereotypes that engender prejudiced attitudes, which are acted upon in discriminatory behavior. Goffman illuminated how stigmatized people manage their "Spoiled identity" (meaning the stigma disqualifies the stigmatized individual from full social acceptance) before audiences of normals. He focused on stigma, not as a fixed or inherent attribute of a person, but rather as the experience and meaning of difference.[25] Gerhard Falk expounds upon Goffman's work by redefining deviant as "others who deviate from the expectations of a group" and by categorizing deviance into two types: Societal deviance refers to a condition widely perceived, in advance and in general, as being deviant and hence stigma and stigmatized. "Homosexuality is, therefore, an example of societal deviance because there is such a high degree of consensus to the effect that homosexuality is different, and a violation of norms or social expectation".[18] Situational deviance refers to a deviant act that is labeled as deviant in a specific situation, and may not be labeled deviant by society. Similarly, a socially deviant action might not be considered deviant in specific situations. "A robber or other street criminal is an excellent example. It is the crime which leads to the stigma and stigmatization of the person so affected."[full citation needed] The physically disabled, mentally ill, homosexuals, and a host of others who are labeled deviant because they deviate from the expectations of a group, are subject to stigmatization - the social rejection of numerous individuals, and often entire groups of people who have been labeled deviant.[full citation needed] |

逸脱 スティグマは、個人が逸脱者として識別され、偏見に満ちた態度を生み出す否定的なステレオタイプと結びつき、それが差別的行動として行動されるときに生じ る。ゴフマンは、スティグマを負った人々が「スポイルされたアイデンティティ」(スティグマが、スティグマを負った個人を社会的に完全に受け入れる資格を 失わせることを意味する)を、普通の人々の前でどのように管理するかを明らかにした。彼はスティグマを、人の固定された、あるいは固有の属性としてではな く、むしろ差異の経験と意味として注目した[25]。 ゲルハルト・フォークは、逸脱者を「集団の期待から逸脱した他者」と再定義し、逸脱者を2つのタイプに分類することによって、ゴフマンの研究を拡張してい る: 社会的逸脱とは、逸脱していると広く認識されている状態を指す。「したがって、同性愛は社会的逸脱の一例であり、それは同性愛は異なるものであり、規範や 社会的期待に反するものであるというコンセンサスが高いからである」[18]。 状況的逸脱とは、特定の状況において逸脱しているとレッテルを貼られる逸脱行為を指し、社会から逸脱しているとレッテルを貼られることはないかもしれな い。同様に、社会的に逸脱した行為は、特定の状況では逸脱とみなされないかもしれない。「強盗などの通り魔がその好例である。それは、そのような影響を受 けた人の汚名とスティグマ化につながる犯罪である"[完全な引用が必要]。 身体障害者、精神病患者、同性愛者、そして集団の期待から逸脱しているために逸脱者のレッテルを貼られたその他大勢の人々は、スティグマ化の対象となる。 |

| Stigma communication Communication is involved in creating, maintaining, and diffusing stigmas, and enacting stigmatization.[26] The model of stigma communication explains how and why particular content choices (marks, labels, peril, and responsibility) can create stigmas and encourage their diffusion.[27] A recent experiment using health alerts tested the model of stigma communication, finding that content choices indeed predicted stigma beliefs, intentions to further diffuse these messages, and agreement with regulating infected persons' behaviors.[26][28] More recently, scholars have highlighted the role of social media channels, such as Facebook and Instagram, in stigma communication.[29][30] These platforms serve as safe spaces for stigmatized individuals to express themselves more freely.[31] However, social media can also reinforce and amplify stigmatization, as the stigmatized attributes are amplified and virtually available to anyone indefinitely.[32] |

スティグマ・コミュニケーション コミュニケーションは、スティグマを生み出し、維持し、拡散させ、スティグマ化を実行することに関与している[26]。スティグマ・コミュニケーションの モデルは、特定の内容の選択(マーク、ラベル、危険、責任)が、どのように、そしてなぜスティグマを生み出し、その拡散を促すのかを説明している [27]。健康アラートを用いた最近の実験では、スティグマ・コミュニケーションのモデルが検証され、内容の選択が、スティグマに対する信念、これらの メッセージをさらに拡散させる意図、感染者の行動を規制することへの同意を実際に予測することがわかった[26][28]。 より最近では、スティグマ・コミュニケーションにおけるフェイスブックやインスタグラムなどのソーシャルメディア・チャンネルの役割に学者たちが注目して いる[29][30]。 これらのプラットフォームは、スティグマを受けた人々がより自由に自己表現できる安全な空間として機能している[31]。 |

| Challenging Stigma, though powerful and enduring, is not inevitable, and can be challenged. There are two important aspects to challenging stigma: challenging the stigmatization on the part of stigmatizers and challenging the internalized stigma of the stigmatized. To challenge stigmatization, Campbell et al. 2005[33] summarise three main approaches. There are efforts to educate individuals about non-stigmatising facts and why they should not stigmatize. There are efforts to legislate against discrimination. There are efforts to mobilize the participation of community members in anti-stigma efforts, to maximize the likelihood that the anti-stigma messages have relevance and effectiveness, according to local contexts. In relation to challenging the internalized stigma of the stigmatized, Paulo Freire's theory of critical consciousness is particularly suitable. Cornish provides an example of how sex workers in Sonagachi, a red light district in India, have effectively challenged internalized stigma by establishing that they are respectable women, who admirably take care of their families, and who deserve rights like any other worker.[34] This study argues that it is not only the force of the rational argument that makes the challenge to the stigma successful, but concrete evidence that sex workers can achieve valued aims, and are respected by others. Stigmatized groups often harbor cultural tools to respond to stigma and to create a positive self-perception among their members. For example, advertising professionals have been shown to suffer from negative portrayal and low approval rates. However, the advertising industry collectively maintains narratives describing how advertisement is a positive and socially valuable endeavor, and advertising professionals draw on these narratives to respond to stigma.[35] Another effort to mobilize communities exists in the gaming community through organizations like: Take This[36] – who provides AFK rooms at gaming conventions plus has a Streaming Ambassador Program to reach more than 135,000 viewers each week with positive messages about mental health, and NoStigmas[37] – whose mission "is to ensure that no one faces mental health challenges alone" and envisions "a world without shame or discrimination related to mental health, brain disease, behavioral disorders, trauma, suicide and addiction" plus offers workplaces a NoStigmas Ally course and individual certifications. Twitch streamers like MommaFoxFire place emphasis on mental health awareness to help lessen the stigma around talking about mental health.[38] |

挑戦 スティグマは強力で永続的なものではあるが、避けられないものではない。スティグマへの挑戦には、スティグマを植え付ける側のスティグマ化への挑戦と、ス ティグマを植え付けられた側の内面化されたスティグマへの挑戦という2つの重要な側面がある。スティグマ化に挑戦するために、Campbell et al. スティグマ化しない事実や、なぜスティグマ化してはいけないのかについて、個人を教育する取り組みがある。 差別を法律で禁止する努力。 地域の状況に応じて、アンチ・スティグマのメッセージの妥当性と効果を最大化するために、アンチ・スティグマの取り組みに地域住民を動員する取り組みがあ る。 スティグマを負わされた人々の内面化されたスティグマに挑戦することに関しては、パウロ・フレイレの批判的意識の理論が特に適している。コーニッシュは、 インドの歓楽街であるソナガチのセックスワーカーが、自分たちは尊敬に値する女性であり、立派に家族の面倒をみており、他の労働者と同様に権利に値するこ とを立証することによって、内面化されたスティグマに効果的に挑戦した例を示している[34]。この研究は、スティグマへの挑戦を成功させるのは、合理的 な議論の力だけでなく、セックスワーカーが価値ある目的を達成でき、他者から尊敬されているという具体的な証拠であると論じている。 汚名を着せられた集団は、汚名に対応し、そのメンバーの間に肯定的な自己認識を生み出すための文化的手段をしばしば用いる。例えば、広告の専門家は、否定 的な描写と低い支持率に苦しんでいることが示されている。しかし、広告業界は、広告がいかにポジティブで社会的に価値のある試みであるかを説明するナラ ティブを集団的に維持しており、広告関係者はスティグマに対応するためにこうしたナラティブを利用している[35]。 コミュニティを動員するもう一つの努力は、ゲームコミュニティにも存在する: ゲーム大会でAFKルームを提供し、毎週135,000人以上の視聴者にメンタルヘルスのポジティブなメッセージを届けるストリーミング大使プログラムを 持っている。 NoStigmas[37]-そのミッションは、「誰も一人でメンタルヘルスの課題に直面しないようにすること」であり、「メンタルヘルス、脳疾患、行動 障害、トラウマ、自殺、依存症に関する恥や差別のない世界」を構想し、職場にNoStigmas Allyコースと個人認定を提供している。 MommaFoxFireのようなTwitchストリーマーは、メンタルヘルスの認知に重点を置き、メンタルヘルスについて話すことのスティグマを軽減す る手助けをしている[38]。 |

| Organizational stigma In 2008, an article by Hudson coined the term "organizational stigma"[39] which was then further developed by another theory building article by Devers and colleagues.[40] This literature brought the concept of stigma to the organizational level, considering how organizations might be considered as deeply flawed and cast away by audiences in the same way individuals would. Hudson differentiated core-stigma (a stigma related to the very nature of the organization) and event-stigma (an isolated occurrence which fades away with time). A large literature has debated how organizational stigma relate to other constructs in the literature on social evaluations.[41] A 2020 book by Roulet reviews this literature and disentangle the different concepts – in particular differentiating stigma, dirty work, scandals – and exploring their positive implications.[42] |

組織的スティグマ 2008年、ハドソンによる論文は「組織的スティグマ」[39]という用語を作り出し、デヴァースと同僚による別の理論構築の論文によってさらに発展させ た[40]。この文献はスティグマの概念を組織レベルに持ち込み、組織がどのように深い欠陥があるとみなされ、個人と同じように聴衆から見放されるかを考 察した。ハドソンはコア-スティグマ(組織の本質に関連するスティグマ)とイベント-スティグマ(時間とともに薄れていく孤立した出来事)を区別してい た。ルーレットによる2020年の著書は、この文献をレビューし、特にスティグマ、ダーティ・ワーク、スキャンダルを区別することで、異なる概念を分離 し、それらのポジティブな意味を探求している[42]。 |

| Current research The research was undertaken to determine the effects of social stigma primarily focuses on disease-associated stigmas. Disabilities, psychiatric disorders, and sexually transmitted diseases are among the diseases currently scrutinized by researchers. In studies involving such diseases, both positive and negative effects of social stigma have been discovered.[clarification needed] |

現在の研究 社会的スティグマの影響を明らかにするために行われた研究は、主に病気に関連したスティグマに焦点を当てている。障害、精神疾患、性感染症は、現在研究者 によって精査されている疾患のひとつである。このような疾患を対象とした研究では、社会的スティグマがもたらすポジティブな影響とネガティブな影響の両方 が発見されている[要出典]。 |

| Stigma in healthcare settings Recent research suggest that addressing perceived and enacted stigma in clinical settings is critical to ensuring delivery of high-quality patient-centered care. Specifically, perceived stigma by patients was associated with additional more days of poor physical or mental health. Moreover, perceived stigma in healthcare settings was associated with higher odds of reporting a depressive disorder. Among other findings, individuals who were married, younger, had higher income, had college degrees, and were employed reported significantly fewer poor physical and mental health days and had lower odds of self-reported depressive disorder.[43] A complementary study conducted in New York City (as compared to nationwide), found similar outcomes. The researchers' objectives were to assess rates of perceived stigma in health care (clinical) settings reported by racially diverse New York City residents and to examine if this perceived stigma is associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes. They found that perceived stigma was associated with poorer healthcare access, depression, diabetes, and poor overall general health.[44] |

医療現場におけるスティグマ 最近の研究によると、臨床の場においてスティグマを認識し、またそれを実行することは、質の高い患者中心のケアを提供するために非常に重要であることが示 唆されている。具体的には、患者によって認知されたスティグマは、身体的または精神的健康が不良であった日数の増加と関連していた。さらに、医療現場にお けるスティグマの認知は、抑うつ障害を報告する確率の高さと関連していた。他の所見では、既婚者、若年者、高所得者、大卒者、有職者では、身体的・精神的 健康不良日数が有意に少なく、自己報告による抑うつ障害のオッズが低かった [43] 。 ニューヨーク市で実施された補完的研究(全国と比較)でも、同様の結果が得られた。研究者らの目的は、人種的に多様なニューヨーク市民が報告したヘルスケ ア(臨床)の場におけるスティグマ認知の割合を評価すること、およびこのスティグマ認知がより悪い身体的・精神的健康の転帰と関連しているかどうかを検討 することであった。その結果、スティグマの認知は、より悪い医療へのアクセス、うつ病、糖尿病、および全般的な健康不良と関連していることが明らかになっ た[44]。 |

| Research on self-esteem Main article: Self-esteem Members of stigmatized groups may have lower self-esteem than those of nonstigmatized groups. A test could not be taken on the overall self-esteem of different races. Researchers would have to take into account whether these people are optimistic or pessimistic, whether they are male or female and what kind of place they grew up in. Over the last two decades, many studies have reported that African Americans show higher global self-esteem than whites even though, as a group, African Americans tend to receive poorer outcomes in many areas of life and experience significant discrimination and stigma.[citation needed] |

自尊心に関する研究 主な記事 自尊心 スティグマを持つ集団の構成員は、スティグマを持たない集団の構成員よりも自尊心が低い可能性がある。異なる人種の総合的な自尊心について試験を行うこと はできない。研究者は、これらの人々が楽観的か悲観的か、男性か女性か、どのような場所で育ったかを考慮しなければならない。過去20年間、多くの研究 が、グループとしてアフリカ系アメリカ人は人生の多くの領域でより悪い結果を受ける傾向があり、重大な差別とスティグマを経験するにもかかわらず、アフリ カ系アメリカ人は白人よりも高いグローバルな自尊心を示すと報告している[要出典]。 |

| Mental disorders Further information: Mental disorder § Stigma Empirical research on the stigma associated with mental disorders, pointed to a surprising attitude of the general public. Those who were told that mental disorders had a genetic basis were more prone to increase their social distance from the mentally ill, and also to assume that the ill were dangerous individuals, in contrast with those members of the general public who were told that the illnesses could be explained by social and environmental factors. Furthermore, those informed of the genetic basis were also more likely to stigmatize the entire family of the ill.[45] Although the specific social categories that become stigmatized can vary over time and place, the three basic forms of stigma (physical deformity, poor personal traits, and tribal outgroup status) are found in most cultures and eras, leading some researchers to hypothesize that the tendency to stigmatize may have evolutionary roots.[46][47] The impact of the stigma is significant, leading many individuals to not seek out treatment. For example, evidence from a refugee camp in Jordan suggests that providing mental health care comes with a dilemma: between the clinical desire to make mental health issues visible and actionable through datafication and the need to keep mental health issues hidden and out of the view of the community to avoid stigma. That is, in spite of their suffering the refugees were hesitant to receive mental health care as they worried about stigma.[48] Currently, several researchers believe that mental disorders are caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. Therefore, this biological rationale suggests that individuals struggling with a mental illness do not have control over the origin of the disorder. Much like cancer or another type of physical disorder, persons suffering from mental disorders should be supported and encouraged to seek help. The Disability Rights Movement recognises that while there is considerable stigma towards people with physical disabilities, the negative social stigma surrounding mental illness is significantly worse, with those suffering being perceived to have control of their disabilities and being responsible for causing them. "Furthermore, research respondents are less likely to pity persons with mental illness, instead of reacting to the psychiatric disability with anger and believing that help is not deserved."[49] Although there are effective mental health interventions available across the globe, many persons with mental illnesses do not seek out the help that they need. Only 59.6% of individuals with a mental illness, including conditions such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, reported receiving treatment in 2011.[50] Reducing the negative stigma surrounding mental disorders may increase the probability of affected individuals seeking professional help from a psychiatrist or a non-psychiatric physician. How particular mental disorders are represented in the media can vary, as well as the stigma associated with each.[51] On the social media platform, YouTube, depression is commonly presented as a condition that is caused by biological or environmental factors, is more chronic than short-lived, and different from sadness, all of which may contribute to how people think about depression.[52] |

精神障害 さらに詳しい情報 精神障害 § スティグマ 精神障害に関連するスティグマに関する実証的研究では、一般市民の驚くべき態度が指摘されている。精神障害には遺伝的基盤があると告げられた人々は、精神 障害者との社会的距離を縮め、精神障害者は危険な人物であると決めつける傾向が強かった。さらに、遺伝的根拠を知らされた人々は、病人の家族全体にスティ グマを抱く傾向が強かった[45]。スティグマを抱くようになる特定の社会的カテゴリーは時代や場所によって異なるが、スティグマの3つの基本的な形態 (身体的奇形、劣悪な個人的特徴、部族的なアウトグループの地位)は、ほとんどの文化や時代に見られ、スティグマを抱く傾向は進化論的なルーツがあるので はないかという仮説を立てる研究者もいる[46][47]。例えば、ヨルダンの難民キャンプから得られた証拠は、メンタルヘルスケアの提供にはジレンマが 伴うことを示唆している。すなわち、データ化によってメンタルヘルス問題を可視化し、対処可能にしたいという臨床的欲求と、スティグマを避けるためにメン タルヘルス問題を隠し、コミュニティの目に触れないようにする必要性との間にある。つまり、難民は苦しんでいるにもかかわらず、スティグマを気にしてメン タルヘルスケアを受けることをためらっていたのである[48]。 現在、何人かの研究者は、精神障害は脳内の化学的不均衡によって引き起こされると考えている。したがって、この生物学的根拠は、精神疾患に苦しんでいる人 は、その障害の原因をコントロールできないことを示唆している。癌や他の身体障害と同じように、精神障害に苦しんでいる人は、支援を受け、助けを求めるよ う奨励されるべきである。障害者権利運動は、身体障害を持つ人々に対するスティグマがかなりある一方で、精神疾患を取り巻く社会的な負のスティグマは著し く悪化しており、苦しんでいる人々は自分の障害をコントロールし、その原因を作った責任があると認識されていることを認識している。「さらに、調査回答者 は精神疾患を持つ人を憐れむ傾向が弱く、精神障害に対して怒りで反応し、助けは得られないと考える傾向が強い。うつ病、不安障害、統合失調症、双極性障害 などの精神疾患を持つ人のうち、2011年に治療を受けたと報告した人は59.6%に過ぎない[50]。精神疾患を取り巻く負のスティグマを減らすこと で、精神疾患を患う人が精神科医や精神科以外の医師の専門的な助けを求める確率が高まるかもしれない。特定の精神障害がメディアでどのように表現されるか は、それぞれに関連するスティグマと同様に様々である。[51] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームであるYouTubeでは、うつ病は一般的に生物学的または環境的要因によって引き起こされる状態であり、短期間より も慢性的であり、悲しみとは異なるものとして表現されており、これらはすべて人々がうつ病についてどのように考えるかを助長している可能性がある。 |

| Causes Arikan found that a stigmatising attitude to psychiatric patients is associated with narcissistic personality traits.[53] In Taiwan, strengthening the psychiatric rehabilitation system has been one of the primary goals of the Department of Health since 1985. This endeavor has not been successful. It was hypothesized that one of the barriers was social stigma towards the mentally ill.[54] Accordingly, a study was conducted to explore the attitudes of the general population towards patients with mental disorders. A survey method was utilized on 1,203 subjects nationally. The results revealed that the general population held high levels of benevolence, tolerance on rehabilitation in the community, and nonsocial restrictiveness.[54] Essentially, benevolent attitudes were favoring the acceptance of rehabilitation in the community. It could then be inferred that the belief (held by the residents of Taiwan) in treating the mentally ill with high regard, and the progress of psychiatric rehabilitation may be hindered by factors other than social stigma.[54] |

原因 アリカンは、精神科患者に対する汚名を着せるような態度が自己愛的な性格特性と関連していることを発見した[53]。 台湾では、1985年以来、精神科リハビリテーション・システムの強化が保健省の主要な目標の一つであった。この試みは成功していない。障壁のひとつは精 神障害者に対する社会的偏見であるという仮説が立てられた。全国1,203人を対象に調査法が利用された。その結果、一般集団は博愛、地域社会でのリハビ リテーションに対する寛容、非社会的制限を高いレベルで保持していることが明らかになった。このことから、精神障害者を高く評価し、社会的スティグマ以外 の要因によって精神科リハビリテーションの進展が妨げられている可能性が推察される[54]。 |

| Artists In the music industry, specifically in the genre of hip-hop or rap, those who speak out on mental illness are heavily criticized. However, according to an article by The Huffington Post, there's a significant increase in rappers who are breaking their silence on depression and anxiety.[55] |

アーティスト 音楽業界、特にヒップホップやラップのジャンルでは、精神病について発言する者は激しく批判される。しかし、ハフィントンポストの記事によると、うつ病や 不安症について沈黙を破るラッパーが大幅に増加している[55]。 |

| Addiction and substance use

disorders Throughout history, addiction has largely been seen as a moral failing or character flaw, as opposed to an issue of public health.[56][57][58] Substance use has been found to be more stigmatized than smoking, obesity, and mental illness.[56][59][60][61] Research has shown stigma to be a barrier to treatment-seeking behaviors among individuals with addiction, creating a "treatment gap".[62][63][64] A systematic review of all epidemiological studies on treatment rates of people with alcohol use disorders found that over 80% had not accessed any treatment for their disorder.[65] The study also found that the treatment gap was larger in low and lower-middle-income countries. Research shows that the words used to talk about addiction can contribute to stigmatization, and that the commonly used terms of "abuse" & "abuser" actually increase stigma.[66][67][68][69] Behavioral addictions (i.e. gambling, sex, etc.) are found to be more likely to be attributed to character flaws than substance-use addictions.[70] Stigma is reduced when Substance Use Disorders are portrayed as treatable conditions.[71][72] Acceptance and Commitment Therapy has been used effectively to help people to reduce shame associated with cultural stigma around substance use treatment.[73][74][75] The use of the drug methamphetamine has been strongly stigmatized. An Australian national population study have shown that the proportion of Australians who nominated methamphetamine as a "drug problem" increased between 2001–2019.[76] The epidemiological study provided evidence that levels of under-reporting have increased over the period, which coincided with the deployment of public health campaigns on the dangers of ice that had stigmatizing elements that portrayal of persons who used the drugs in a negative way.[76] The level of under-reporting of methamphetamine use is strongly associated with increasing negative attitudes towards their use over the same period.[76] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_stigma |

依 存症と薬物使用障害 歴史を通じて、依存症は公衆衛生の問題とは対照的に、道徳的な失敗や性 格的欠陥と見なされてきた。[56][57][58] 薬物使用は、喫煙、肥満、精神疾患よりもスティグマ化されていることが判明している。 [62][63][64] アルコール使用障害者の治療率に関するすべての疫学研究の系統的レビューによると、80%以上が自分の障害の治療を一切受けていないことがわかった [65]。 この研究はまた、低・中所得国で治療格差がより大きいことも明らかにした。 研究によると、依存症について話す際に使用される言葉がスティグマ化の 一因となる可能性があり、「乱用」「乱用者」という一般的に使用される用語は、実際にスティグマを増大させる[66][67][68][69]。行動依存 症(ギャンブル、セックスなど)は、物質使用依存症よりも性格的欠陥に起因する可能性が高いことがわかっている。 [70] 薬物使用障害が治療可能な状態として描かれることで、スティグマは軽減される。 [71][72] 受容とコミットメント療法は、薬物使用治療をめぐる文化的スティグマに関連する羞恥心を軽減するために効果的に用いられている。 メタンフェタミンという薬物の使用は強くスティグマ化されている。オー ストラリアの全国人口調査によると、覚せい剤を「薬物問題」として指名するオーストラリア人の割合が2001年から2019年の間に増加した[76]。こ の疫学調査では、過少申告のレベルがこの期間に増加したという証拠が示されており、これは、薬物を使用する人を否定的に描くスティグマ的要素を持つ氷の危 険性に関する公衆衛生キャンペーンが展開された時期と一致している[76]。覚せい剤使用の過少申告のレベルは、同じ期間にその使用に対する否定的な態度 が増加したことと強く関連している[76]。 |

| Poverty Recipients of public assistance programs are often scorned as unwilling to work.[77] The intensity of poverty stigma is positively correlated with increasing inequality.[78] As inequality increases, societal propensity to stigmatize increases.[78] This is in part, a result of societal norms of reciprocity which is the expectation that people earn what they receive rather than receiving assistance in the form of what people tend to view as a gift.[78] Poverty is often perceived as a result of failures and poor choices rather than the result of socioeconomic structures that suppress individual abilities.[79] Disdain for the impoverished can be traced back to its roots in Anglo-American culture where poor people have been blamed and ostracized for their misfortune for hundreds of years.[80] The concept of deviance is at the bed rock of stigma towards the poor. Deviants are people that break important norms of society that everyone shares. In the case of poverty it is breaking the norm of reciprocity that paves the path for stigmatization.[81] |

貧困 貧困スティグマの強さは、格差の拡大と正の相関がある[78]。格差が拡大するにつれて、スティグマを植え付ける社会的傾向も増加する[78]。 [貧困はしばしば、個人の能力を抑圧する社会経済構造の結果というよりは、失敗や誤った選択の結果として認識される。貧困層に対する蔑視は、何百年もの 間、貧しい人々がその不幸のために非難され、追放されてきた英米文化にそのルーツを遡ることができる。逸脱者とは、誰もが共有している社会の重要な規範を 破る人々のことである。貧困の場合、それはスティグマ化への道を開く互恵性の規範を破ることである。 |

| Public assistance Social stigma is prevalent towards recipients of public assistance programs. This includes programs frequently utilized by families struggling with poverty such as Head Start and AFDC (Aid To Families With Dependent Children). The value of self-reliance is often at the center of feelings of shame and the fewer people value self reliance the less stigma affects them psychologically.[81][82] Stigma towards welfare recipients has been proven to increase passivity and dependency in poor people and has further solidified their status and feelings of inferiority.[81][83] Caseworkers frequently treat recipients of welfare disrespectfully and make assumptions about deviant behavior and reluctance to work. Many single mothers cited stigma as the primary reason they wanted to exit welfare as quickly as possible. They often feel the need to conceal food stamps to escape judgement associated with welfare programs. Stigma is a major factor contributing to the duration and breadth of poverty in developed societies which largely affects single mothers.[81] Recipients of public assistance are viewed as objects of the community rather than members allowing for them to be perceived as enemies of the community which is how stigma enters collective thought.[84] Amongst single mothers in poverty, lack of health care benefits is one of their greatest challenges in terms of exiting poverty.[81] Traditional values of self reliance increase feelings of shame amongst welfare recipients making them more susceptible to being stigmatized.[81] |

公的扶助 社会的スティグマは、公的扶助プログラムの受給者に対して広く浸透している。これには、ヘッド・スタートやAFDC(Aid To Families With Dependent Children)のような、貧困と闘う家族が頻繁に利用するプログラムも含まれる。生活保護受給者に対するスティグマは、貧困層の受動性と依存性を高 め、彼らの地位と劣等感をさらに強固なものにしていることが証明されている[81][82]。 ケースワーカーは生活保護受給者を無礼に扱い、逸脱した行動や働きたがらないことを決めつけることが多い。シングルマザーの多くは、できるだけ早く生活保 護から抜け出したいと考える主な理由として、スティグマを挙げている。生活保護にまつわる批判から逃れるために、フードスタンプを隠す必要性をしばしば感 じている。スティグマは、先進社会における貧困の期間と広がりを助長する大きな要因であり、シングルマザーに大きな影響を与えている[81]。公的扶助の 受給者は、コミュニティの一員というよりもむしろコミュニティの対象として見られており、コミュニティの敵として認識されることを許している。 |

| Epilepsy Hong Kong - Epilepsy, a common neurological disorder characterized by recurring seizures, is associated with various social stigmas. Chung-yan Guardian Fong and Anchor Hung conducted a study in Hong Kong which documented public attitudes towards individuals with epilepsy. Of the 1,128 subjects interviewed, only 72.5% of them considered epilepsy to be acceptable;[clarification needed] 11.2% would not let their children play with others with epilepsy; 32.2% would not allow their children to marry persons with epilepsy; additionally, some employers (22.5% of them) would terminate an employment contract after an epileptic seizure occurred in an employee with unreported epilepsy.[85] Suggestions were made that more effort be made to improve public awareness of, attitude toward, and understanding of epilepsy through school education and epilepsy-related organizations.[85] |

てんかん 香港での調査:てんかんは、繰り返し起こる発作を特徴とする一般的な神経疾患であり、様々な社会的スティグマと関連している。Chung-yan Guardian FongとAnchor Hungは香港で研究を行い、てんかん患者に対する一般市民の態度を記録した。インタビューした1,128人の対象者のうち、てんかんを容認しているのは 72.5%のみであった[clarification needed]。11.2%は自分の子供をてんかんのある人と一緒に遊ばせたくないと考え、32.2%は自分の子供をてんかんのある人と結婚させたくない と考えた。 また、一部の雇用主(そのうちの22.5%)は、てんかんを申告していない従業員にてんかん発作が発生した場合、雇用契約を解除するとしている[85]。 学校教育やてんかん関連団体を通じて、てんかんに対する一般の人々の認識、態度、理解を向上させるためのさらなる努力が提案された[85]。 |

| Media In the early 21st century, technology has a large impact on the lives of people in multiple countries and has shaped social norms. Many people own a television, computer, and a smartphone. The media can be helpful with keeping people up to date on news and world issues and it is very influential on people. Because it is so influential sometimes the portrayal of minority groups affects attitudes of other groups toward them. Much media coverage has to do with other parts of the world. A lot of this coverage has to do with war and conflict, which people may relate to any person belonging from that country. There is a tendency to focus more on the positive behavior of one's own group and the negative behaviors of other groups. This promotes negative thoughts of people belonging to those other groups, reinforcing stereotypical beliefs.[86] "Viewers seem to react to violence with emotions such as anger and contempt. They are concerned about the integrity of the social order and show disapproval of others. Emotions such as sadness and fear are shown much more rarely." (Unz, Schwab & Winterhoff-Spurk, 2008, p. 141)[87] In a study testing the effects of stereotypical advertisements on students, 75 high school students viewed magazine advertisements with stereotypical female images such as a woman working on a holiday dinner, while 50 others viewed nonstereotypical images such as a woman working in a law office. These groups then responded to statements about women in a "neutral" photograph. In this photo, a woman was shown in a casual outfit not doing any obvious task. The students that saw the stereotypical images tended to answer the questionnaires with more stereotypical responses in 6 of the 12 questionnaire statements. This suggests that even brief exposure to stereotypical ads reinforces stereotypes. (Lafky, Duffy, Steinmaus & Berkowitz, 1996)[88] |

メディア 21世紀初頭、テクノロジーは複数の国の人々の生活に大きな影響を与え、社会規範を形成してきた。多くの人がテレビ、コンピューター、スマートフォンを所 有している。メディアはニュースや世界の問題について最新の情報を得るのに役立ち、人々に大きな影響を与える。その影響力の大きさゆえに、マイノリティ・ グループの描写が他のグループの彼らに対する態度に影響を与えることもある。メディアの報道の多くは、世界の他の地域と関係している。この報道の多くは戦 争や紛争に関係しており、人々はその国の出身者であれば誰とでも関係づけられる。自分の集団のポジティブな行動と、他の集団のネガティブな行動により注目 する傾向がある。これは、他の集団に属する人々に対する否定的な考えを助長し、ステレオタイプ的な信念を強化する。 「視聴者は暴力に対して怒りや軽蔑といった感情で反応するようです。彼らは社会秩序の完全性を懸念し、他者への不支持を示す。悲しみや恐怖といった感情が 示されることははるかに稀である。(Unz, Schwab & Winterhoff-Spurk, 2008, p. 141)[87] 。 学生に対するステレオタイプ広告の影響をテストする研究では、75高校生が休日の夕食に取り組んでいる女性のようなステレオタイプな女性のイメージで雑誌 広告を見たが、他の50人は法律事務所で働いている女性のような非ステレオタイプな画像を見た。その後、これらのグループは「中立的な」写真に写っている 女性についての記述に回答した。この写真では、女性はカジュアルな服装で、明らかな仕事をしていない。ステレオタイプな画像を見た学生は、12項目のアン ケートのうち6項目で、よりステレオタイプな回答をする傾向があった。このことは、ステレオタイプな広告に短時間さらされただけでも、ステレオタイプが強 化されることを示唆している。(ラフキー、ダフィー、スタインマウス&バーコウィッツ、1996)[88]。 |

| Education and culture The aforementioned stigmas (associated with their respective diseases) propose effects that these stereotypes have on individuals. Whether effects be negative or positive in nature, 'labeling' people causes a significant change in individual perception (of persons with the disease). Perhaps a mutual understanding of stigma, achieved through education, could eliminate social stigma entirely. Laurence J. Coleman first adapted Erving Goffman's (1963) social stigma theory to gifted children, providing a rationale for why children may hide their abilities and present alternate identities to their peers.[89][90][91] The stigma of giftedness theory was further elaborated by Laurence J. Coleman and Tracy L. Cross in their book entitled, Being Gifted in School, which is a widely cited reference in the field of gifted education.[92] In the chapter on Coping with Giftedness, the authors expanded on the theory first presented in a 1988 article.[93] According to Google Scholar, this article has been cited over 300 times in the academic literature (as of 2022).[94] Coleman and Cross were the first to identify intellectual giftedness as a stigmatizing condition and they created a model based on Goffman's (1963) work, research with gifted students,[91] and a book that was written and edited by 20 teenage, gifted individuals.[95] Being gifted sets students apart from their peers and this difference interferes with full social acceptance. Varying expectations that exist in the different social contexts which children must navigate, and the value judgments that may be assigned to the child result in the child's use of social coping strategies to manage his or her identity. Unlike other stigmatizing conditions, giftedness is unique because it can lead to praise or ridicule depending on the audience and circumstances. Gifted children learn when it is safe to display their giftedness and when they should hide it to better fit in with a group. These observations led to the development of the Information Management Model that describes the process by which children decide to employ coping strategies to manage their identities. In situations where the child feels different, she or he may decide to manage the information that others know about him or her. Coping strategies include disidentification with giftedness, attempting to maintain low visibility, or creating a high-visibility identity (playing a stereotypical role associated with giftedness). These ranges of strategies are called the Continuum of Visibility.[citation needed] |

教育と文化 前述のスティグマ(それぞれの疾患に関連する)は、これらのステレオタイプが個人に及ぼす影響を示唆している。その効果が否定的なものであれ肯定的なもの であれ、人々に「レッテルを貼る」ことは、(疾患をもつ人に対する)個人の認識に大きな変化をもたらす。おそらく、教育を通じて達成されるスティグマの相 互理解は、社会的スティグマを完全になくすことができるだろう。 ローレンス・J・コールマンは、アービング・ゴフマン (1963) の社会的スティグマ理論を英才児に初めて適応させ、子供たちが自分の能力を隠し、仲間に別のアイデンティティを示す理由の根拠を提供した[89][90] [91] 。この本は、才能教育の分野で広く引用されている参考文献である[92]。Google Scholarによると、この論文は学術文献で300回以上引用されている(2022年現在)[94]。 コールマンとクロスは、知的才能を汚名を着せる条件とし て初めて認識し、ゴフマンの研究(1963年)、才能ある生徒を 対象とした研究[91]、および10代の才能ある生徒20人 が執筆・編集した書籍に基づいてモデルを作成した[95]。子供たちが通過しなけれ ばならないさまざまな社会的文脈に存在するさまざまな期 待、およびその子供に割り当てられる可能性のある価値判 断により、子供は自分のアイデンティティを管理するた めに社会的対処戦略を使用することになる。他の汚名を着せるような状況とは異なり、才能があること は、聴衆や状況次第で賞賛にも嘲笑にもつながりうるという点 で独特である。 英才児は、自分の英才性を見せても安全な時と、集団にうまく溶け込むために隠すべき時を学ぶ。このような観察から、子供たちが自分のアイデンティティを管 理するために対処戦略を採用することを決定するプロセスを説明する情報管理モデルが開発された。子どもが自分とは違うと感じる状況では、他者が自分につい て知っている情報を管理しようと決めるかもしれない。対処戦略には、才能を識別しないこと、知名度を低く保とうとすること、または知名度の高いアイデン ティティを作り出すこと(才能に関連するステレオタイプな役割を演じること)が含まれる。これらの戦略の範囲は「可視性の連続体」と呼ばれる[要出典]。 |

| Abortion While abortion is very common throughout the world, people may choose not to disclose their use of such services, in part due to the stigma associated with having had an abortion.[96][97] Keeping abortion experiences secret has been found to be associated with increased isolation and psychological distress.[98] Abortion providers are also subject to stigma.[99][100] |

中絶 中絶は世界中で非常に一般的であるが、人々は中絶を経験したことに関連するスティグマ[96][97]のせいもあり、中絶サービスの利用を公表しないこと を選択する場合がある。 中絶の経験を秘密にすることは、孤立や心理的苦痛の増大と関連していることが判明している[98]。 中絶提供者もスティグマの対象となる[99][100]。 |

| Stigmatization of prejudice Cultural norms can prevent displays of prejudice as such views are stigmatized and thus people will express non-prejudiced views even if they believe otherwise (preference falsification). However, if the stigma against such views is lessened, people will be more willing to express prejudicial sentiments.[101] For example, following the 2008 economic crisis, anti-immigration sentiment seemingly increased amongst the US population when in reality the level of sentiment remained the same and instead it simply became more acceptable to openly express opposition to immigration.[102] |

偏見のスティグマ化 文化的規範は、そのような見方がスティグマ化されるため、偏見の表出を防ぐことができ、その結果、たとえそうでないと信じていても、人々は偏見のない見方 を表明するようになる(選好の改竄)。しかし、そのような見方に対するスティグマが軽減されれば、人々は偏見に満ちた感情を表明することをより厭わなくな る[101]。例えば、2008年の経済危機の後、アメリカ国民の間で移民排斥の感情が高まったように見えるが、実際には感情のレベルは変わらず、その代 わりに移民への反対を公然と表明することがより受け入れられるようになっただけである[102]。 |

| Spatial Stigma Spatial stigma refers to stigmas that are linked to ones geographic location. This can be applied to neighborhoods, towns, cities or any defined geographical space. A person's geographic location or place of origin can be a source of stigma. [103] This type of stigma can leade to negative health outcomes. |

空間的スティグマ 空間的スティグマとは、地理的な場所と結びついたスティグマを指す。これは近隣、町、都市、あるいは定義された地理的空間に適用することができる。その人 の地理的位置や出身地がスティグマの原因となることもある。[103] この種のスティグマは、健康に悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある。 |

| Badge of shame Collateral consequences of criminal charges Dehumanization Discrimination Guilt by association Health-related embarrassment Identity (social science) Label (sociology) Labeling Labeling theory Leprosy stigma Passing (sociology) Post-assault mistreatment of sexual assault victims Prejudice Scapegoat Self-concealment Self-esteem Self-schema Shame Social alienation Social defeat Social exclusion Stereotype Stereotype threat Stig-9 perceived mental illness stigma questionnaire Stigma management Taboo Time to Change (mental health campaign) Weight stigma Infertility and childlessness stigmas |

恥のバッジ 刑事責任の副次的結果 人間性の喪失 差別 連想による罪悪感 健康に関する恥 アイデンティティ(社会科学) レッテル(社会学) ラベリング ラベリング理論 ハンセン病のスティグマ パッシング(社会学) 性的暴行被害者に対する暴行後の虐待 偏見 スケープゴート 自己隠蔽 自尊心 自己スキーマ 恥 社会的疎外 社会的敗北 社会的排除 ステレオタイプ ステレオタイプの脅威 スティグ9精神疾患スティグマ認知質問票 スティグマ管理 タブー Time to Change(メンタルヘルス・キャンペーン) 体重のスティグマ 不妊・不育症スティグマ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_stigma |

****

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆