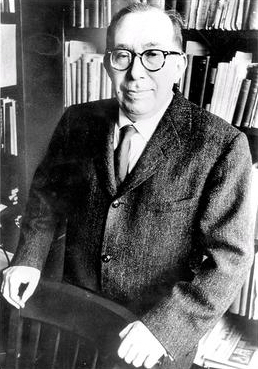

On Political Pholosophy of Leo Straauss, 1899-1973

On Political Pholosophy of Leo Straauss, 1899-1973

★レオ・シュトラウス(/straʊs/ STROWSS、ドイツ語: [ˈle-ː ˈʃtː, 1899年9月20日 - 1973年10月18日)は、20世紀のドイツ系アメリカ人の政治哲学者。ドイツでユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれ、後にドイツからアメリカに移住。シカゴ 大学の政治学教授として、何世代にもわたって学生を指導し、15冊の著書を出版した。エル ンスト・カッシーラーのもとで新カント派の伝統を学び、現象学者 エドムント・フッサールとマルティン・ハイデガーの研究に没頭したシュトラウスは、ス ピノザやホッブズに関する著書、マイモニデスやアル・ファラビに関する論文を執筆した。1930年代後半には、プラトンとアリストテレスのテキストに焦点 を当て、中世のイスラム哲学とユダヤ哲学を通してその解釈を辿り、それらの思想を現代の政治理論に応用することを奨励した。

| Leo Strauss

(/straʊs/ STROWSS, German: [ˈleːoː ˈʃtʁaʊs]; September 20, 1899 –

October 18, 1973) was a 20th century German-American scholar of

political philosophy. Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Strauss later

emigrated from Germany to the United States. He spent much of his

career as a professor of political science at the University of

Chicago, where he taught several generations of students and published

fifteen books. Trained in the neo-Kantian tradition with Ernst Cassirer and immersed in the work of the phenomenologists Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, Strauss authored books on Spinoza and Hobbes, and articles on Maimonides and Al-Farabi. In the late 1930s, his research focused on the texts of Plato and Aristotle, retracing their interpretation through medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophy, and encouraging the application of those ideas to contemporary political theory. |

レオ・シュトラウス(/straʊs/ STROWSS、ドイツ語:

[ˈle-ː ˈʃtː, 1899年9月20日 -

1973年10月18日)は、20世紀のドイツ系アメリカ人の政治哲学者。ドイツでユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれ、後にドイツからアメリカに移住。シカゴ

大学の政治学教授として、何世代にもわたって学生を指導し、15冊の著書を出版した。 エルンスト・カッシーラーのもとで新カント派の伝統を学び、現象学者エドムント・フッサールとマルティン・ハイデガーの研究に没頭したシュトラウスは、ス ピノザやホッブズに関する著書、マイモニデスやアル・ファラビに関する論文を執筆した。1930年代後半には、プラトンとアリストテレスのテキストに焦点 を当て、中世のイスラム哲学とユダヤ哲学を通してその解釈を辿り、それらの思想を現代の政治理論に応用することを奨励した。 |

| Biography Early life and education Strauss was born on September 20, 1899, in the small town of Kirchhain in Hesse-Nassau, a province of the Kingdom of Prussia (part of the German Empire), to Hugo Strauss and Jennie Strauss, née David. According to Allan Bloom's 1974 obituary in Political Theory, Strauss "was raised as an Orthodox Jew", but the family does not appear to have completely embraced Orthodox practice.[1] Strauss himself noted that he came from a "conservative, even orthodox Jewish home", but one which knew little about Judaism except strict adherence to ceremonial laws. His father and uncle operated a farm supply and livestock business that they inherited from their father, Meyer (1835–1919), a leading member of the local Jewish community.[2] After attending the Kirchhain Volksschule and the Protestant Rektoratsschule, Leo Strauss was enrolled at the Gymnasium Philippinum (affiliated with the University of Marburg) in nearby Marburg (from which Johannes Althusius and Carl Joachim Friedrich also graduated) in 1912, graduating in 1917. He boarded with the Marburg cantor Strauss (no relation), whose residence served as a meeting place for followers of the neo-Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen. Strauss served in the German army from World War I from July 5, 1917, to December 1918. Strauss subsequently enrolled in the University of Hamburg, where he received his doctorate in 1921; his thesis, On the Problem of Knowledge in the Philosophical Doctrine of F. H. Jacobi (Das Erkenntnisproblem in der philosophischen Lehre Fr. H. Jacobis), was supervised by Ernst Cassirer. He also attended courses at the Universities of Freiburg and Marburg, including some taught by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Strauss joined a Jewish fraternity and worked for the German Zionist movement, which introduced him to various German Jewish intellectuals, such as Norbert Elias, Leo Löwenthal, Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin. Benjamin was and remained an admirer of Strauss and his work throughout his life.[3][4][5] Strauss's closest friend was Jacob Klein but he also was intellectually engaged with Gerhard Krüger—and also Karl Löwith, Julius Guttmann, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Franz Rosenzweig (to whom Strauss dedicated his first book), as well as Gershom Scholem, Alexander Altmann, and the Arabist Paul Kraus, who married Strauss's sister Bettina (Strauss and his wife later adopted Paul and Bettina Kraus's child when both parents died in the Middle East). With several of these friends, Strauss carried on vigorous epistolary exchanges later in life, many of which are published in the Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), some in translation from the German. Strauss had also been engaged in a discourse with Carl Schmitt. However, after Strauss left Germany, he broke off the discourse when Schmitt failed to respond to his letters. Career After receiving a Rockefeller Fellowship in 1932, Strauss left his position at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin for Paris. He returned to Germany only once, for a few short days twenty years later. In Paris, he married Marie (Miriam) Bernsohn, a widow with a young child, whom he had known previously in Germany. He adopted his wife's son, Thomas, and later his sister's child, Jenny Strauss Clay (later a professor of classics at the University of Virginia); he and Miriam had no biological children of their own. At his death, he was survived by Thomas, Jenny Strauss Clay, and three grandchildren. Strauss became a lifelong friend of Alexandre Kojève and was on friendly terms with Raymond Aron and Étienne Gilson. Because of the Nazis' rise to power, he chose not to return to his native country. Strauss found shelter, after some vicissitudes, in England, where, in 1935 he gained temporary employment at the University of Cambridge with the help of his in-law David Daube, who was affiliated with Gonville and Caius College. While in England, he became a close friend of R. H. Tawney and was on less friendly terms with Isaiah Berlin.[6]  The University of Chicago, the school with which Strauss is most closely associated Unable to find permanent employment in England, Strauss moved in 1937 to the United States, under the patronage of Harold Laski, who made introductions and helped him obtain a brief lectureship. After a short stint as a research fellow in the Department of History at Columbia University, Strauss secured a position at The New School, where, between 1938 and 1948, he worked in the political science faculty and also took on adjunct jobs.[7] In 1939, he served for a short term as a visiting professor at Hamilton College. He became a U.S. citizen in 1944, and in 1949 became a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, holding the Robert Maynard Hutchins Distinguished Service Professorship until he left in 1969. In 1953, Strauss coined the phrase reductio ad Hitlerum, a play on reductio ad absurdum, suggesting that comparing an argument to one of Hitler's, or "playing the Nazi card", is often a fallacy of irrelevance.[8] In 1954 he met Karl Löwith and Hans-Georg Gadamer in Heidelberg and delivered a public speech on Socrates. He had received a call for a temporary lectureship in Hamburg in 1965 (which he declined for health reasons) and received and accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Hamburg and the Bundesverdienstkreuz (German Order of Merit) via the German representative in Chicago. In 1969 Strauss moved to Claremont McKenna College (formerly Claremont Men's College) in California for a year, and then to St. John's College, Annapolis in 1970, where he was the Scott Buchanan Distinguished Scholar in Residence until his death from pneumonia in 1973.[9] He was buried in Annapolis Hebrew Cemetery, with his wife Miriam Bernsohn Strauss, who died in 1985. Psalm 114 was read in the funeral service at the request of family and friends.[10] |

略歴 生い立ちと教育 シュトラウスは1899年9月20日、プロイセン王国(ドイツ帝国の一部)のヘッセン=ナッサウ州にあるキルヒハインという小さな町で、フーゴー・シュト ラウスとジェニー・シュトラウス(旧姓ダヴィッド)の間に生まれた。アラン・ブルームによる1974年の『政治理論』の追悼記事によれば、シュトラウスは 「正統派ユダヤ教徒として育てられた」が、一家は正統派の慣習を完全に受け入れたわけではなかったようである[1]。シュトラウス自身は、「保守的で、正 統派とさえ言えるユダヤ人の家」に生まれたが、儀礼的な掟を厳格に守る以外はユダヤ教についてほとんど知らなかったと述べている。彼の父と叔父は、地元の ユダヤ人コミュニティの主要メンバーであった父マイヤー(1835-1919)から受け継いだ農産品と家畜のビジネスを営んでいた[2]。 キルヒハインのフォルクスシューレとプロテスタントのレクトラッツシューレに通った後、レオ・シュトラウスは1912年に近くのマールブルクにあるギムナ ジウム・フィリピヌム(マールブルク大学付属)に入学し(ヨハネス・アルトゥージウスとカール・ヨアヒム・フリードリヒも卒業)、1917年に卒業した。 彼はマールブルクのカントル・シュトラウス(血縁関係はない)の家に寄宿し、その家は新カント派の哲学者ヘルマン・コーエンの信奉者たちの集会所となって いた。シュトラウスは、1917年7月5日から1918年12月まで、第一次世界大戦のドイツ軍に従軍した。 その後、ハンブルク大学に入学し、1921年に博士号を取得。論文『F.H.ヤコビの哲学的教義における知識の問題について』(Das Erkenntnisproblem in der philosophischen Lehre Fr. H. Jacobis)はエルンスト・カッシーラーの指導を受けた。また、フライブルク大学やマールブルク大学でもエドムント・フッサールやマルティン・ハイデ ガーの講義を受けた。シュトラウスはユダヤ人の友愛会に入会し、ドイツ・シオニスト運動のために働き、ノルベルト・エリアス、レオ・レーヴェンタール、ハ ンナ・アーレント、ヴァルター・ベンヤミンなど、さまざまなドイツ系ユダヤ人知識人を紹介された。ベンヤミンは生涯を通じてシュトラウスとその作品を敬愛 し続けた[3][4][5]。 シュトラウスの最も親しい友人はヤコブ・クラインであったが、彼はまたゲルハルト・クリューガーや、カール・レーウィズ、ユリウス・グットマン、ハンス・ ゲオルク・ガダマー、フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイク(シュトラウスは最初の著書を彼に捧げている)、ゲルショム・ショレム、アレクサンダー・アルトマン、 そしてシュトラウスの妹ベッティーナと結婚したアラブ主義者のパウル・クラウス(後にシュトラウス夫妻は、両親が中東で死亡した際にパウルとベッティー ナ・クラウスの子供を養子に迎えている)とも知的な関わりを持っていた。これらの友人の何人かと、シュトラウスは後年活発な書簡交換を行い、その多くは 『著作集』(Gesammelte Schriften)に掲載されている(一部はドイツ語からの翻訳)。シュトラウスはまた、カール・シュミットとも言論を交わしていた。しかし、シュトラ ウスがドイツを去った後、シュミットが彼の手紙に返事をよこさなかったため、シュミットは談話を打ち切った。 経歴 1932年にロックフェラーのフェローシップを受けたシュトラウスは、ベルリンのユダヤ高等研究所の職を辞してパリに向かった。ドイツに戻ったのは、20 年後に数日間だけだった。パリでは、ドイツで知り合った幼い子供のいる未亡人のマリー(ミリアム)・ベルンゾーンと結婚した。妻の息子トーマスと、後に妹 の子供ジェニー・シュトラウス・クレイ(後にヴァージニア大学古典学教授)を養子に迎えたが、ミリアムとの間に実子はいなかった。死後、トーマスとジェ ニー・ストラウス・クレイ、そして3人の孫が残された。シュトラウスはアレクサンドル・コジェーヴの生涯の友人となり、レイモン・アロンやエティエンヌ・ ジルソンとも親交があった。ナチスの台頭により、シュトラウスは祖国に帰らないことを選んだ。1935年、ゴンヴィル・アンド・ケイオス・カレッジに所属 していた姻戚のデイヴィッド・ドーベの助けを借りて、ケンブリッジ大学で一時的に働くことになった。イギリス滞在中、彼はR.H.トーニーの親友となり、 アイザイア・バーリンとはあまり親しくない関係にあった[6]。  シカゴ大学、シュトラウスと最も関係の深い学校 イギリスでは定職に就けなかったシュトラウスは、1937年、ハロルド・ラスキの紹介でアメリカに渡り、短期間の講義を受けることになる。コロンビア大学 歴史学部の研究員として短期間勤務した後、ニュースクールで職を得、1938年から1948年の間、政治学の教員として働きながら非常勤講師の仕事も引き 受けた[7]。1944年に米国籍を取得し、1949年にシカゴ大学の政治学教授となり、1969年に退官するまでロバート・メイナード・ハッチンズ特別 功労教授を務めた。 1953年、シュトラウスはreductio ad absurdumをもじってreductio ad Hitlerumという言葉を作り、ヒトラーの議論と比較すること、つまり「ナチスカードを使う」ことはしばしば無関係の誤謬であることを示唆した [8]。 1954年、彼はハイデルベルクでカール・レーウィズとハンス・ゲオルク・ガダマーに会い、ソクラテスに関する公開演説を行った。1965年にはハンブル クで臨時講師の要請を受け(健康上の理由で辞退)、ハンブルク大学から名誉博士号を、シカゴのドイツ代表を通じてブンデスヴェルディエンスト・クロイツ (ドイツ功労勲章)を授与され、受諾した。1969年、シュトラウスは1年間カリフォルニアのクレアモント・マッケナ・カレッジ(旧クレアモント・メン ズ・カレッジ)に移り、1970年にはアナポリスのセント・ジョンズ・カレッジに移り、1973年に肺炎で亡くなるまでスコット・ブキャナン特別研究員と して滞在した[9]。1985年に亡くなった妻ミリアム・ベルンソーン・シュトラウスとともにアナポリスのヘブライ墓地に埋葬された。葬儀では家族や友人 の希望により詩篇114篇が朗読された[10]。 |

| Thought Strauss's thought can be characterized by two main themes: the critique of modernity and the recovery of classical political philosophy. He argued that modernity, which began with the Enlightenment, was a radical break from the tradition of Western civilization, and that it led to a crisis of nihilism, relativism, historicism, and scientism. He claimed that modern political and social sciences, which were based on empirical observation and rational analysis, failed to grasp the essential questions of human nature, morality, and justice, and that they reduced human beings to mere objects of manipulation and calculation. He also criticized modern liberalism, which he saw as a product of modernity, for its lack of moral and spiritual foundations, and for its tendency to undermine the authority of religion, tradition, and natural law.[11][12] To overcome the crisis of modernity, Strauss proposed a return to the classical political philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the medieval thinkers, who he believed had a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of human nature and society. He advocated a careful and respectful reading of the classical texts, arguing that their authors wrote in an esoteric manner, which he called "the art of writing" and which he practiced in his own works. He suggested that the classical authors hid their true teachings behind a surface layer of conventional opinions, in order to avoid persecution and to educate only the few who were capable of grasping them, and that they engaged in a dialogue with each other across the ages. Strauss called this dialogue "the great conversation", and invited his readers to join it.[11][12] Strauss's interpretation of the classical political philosophy was influenced by his own Jewish background and his encounter with Islamic and Jewish medieval philosophy, especially the works of Al-Farabi and Maimonides. He argued that these philosophers, who lived under the rule of Islam, faced similar challenges as the ancient Greeks. He also claimed that these philosophers, who were both faithful to their revealed religions and loyal to the rational pursuit of philosophy, offered a model of how to reconcile reason and revelation, philosophy and theology, Athens and Jerusalem.[11][12] |

思想 シュトラウスの思想は、モダニティ批判と古典政治哲学の回復という2つの主要テーマによって特徴づけられる。啓蒙主義に始まる近代は西洋文明の伝統からの 根本的な脱却であり、ニヒリズム、相対主義、歴史主義、科学主義の危機をもたらしたと主張した。彼は、経験的観察と合理的分析に基づく近代の政治・社会科 学は、人間の本質、道徳、正義という本質的な問題を把握することができず、人間を単なる操作と計算の対象に貶めていると主張した。彼はまた、道徳的・精神 的基盤を欠き、宗教、伝統、自然法の権威を弱体化させる傾向があるとして、近代の産物であるとみなした近代自由主義を批判した[11][12]。 近代の危機を克服するために、シュトラウスは古代ギリシャや中世の思想家たちの古典的な政治哲学への回帰を提案した。彼は、古典の著者は難解な書き方をし ており、それを「書く技術」と呼び、自身の著作でも実践していると主張し、古典のテキストを注意深く敬意を持って読むことを提唱した。彼は、古典の作者た ちは迫害を避け、それを理解できる少数の人たちだけを教育するために、自分たちの真の教えを従来の意見という表層の背後に隠し、時代を超えて互いに対話を 行っていたと示唆した。シュトラウスはこの対話を「偉大なる対話」と呼び、読者にもその対話に加わるよう呼びかけた[11][12]。 古典的な政治哲学に対するシュトラウスの解釈は、彼自身のユダヤ人としての背景と、イスラムとユダヤの中世哲学、特にアル・ファラービーとマイモニデスの 著作との出会いから影響を受けていた。彼は、イスラムの支配下に生きたこれらの哲学者たちは、古代ギリシャ人と同様の課題に直面していたと主張した。彼は また、啓示された宗教に忠実であると同時に哲学の合理的な追求に忠実であったこれらの哲学者たちが、理性と啓示、哲学と神学、アテネとエルサレムをどのよ うに調和させるかのモデルを提供していると主張した[11][12]。 |

| ユダヤ系でシオニストでもあったため、ナチスの迫害を逃れるため、

1938年にアメリカへ移住 |

|

| コロンビア大学歴史学科のリサーチ・フェローを経てニュースクール大学

において政治学を講義 |

|

| 1944年にアメリカ国籍を取得 |

|

| 1949年にシカゴ大学に招聘され、以後20年間にわたり、政治哲学の

講義・研究を行った |

|

| ハイデッガー、タルムード(ユダヤ教の正典)、イスラム哲学、スピノザ

などの哲学を取り入れ、独自の哲学体系を構築。 |

|

| 彼の門下生によって「シュトラウス学派」が形成された |

|

| その講義では、プラトンをはじめとして、マキャベリ、ニーチェらのテク

ストが用いられた。アリストテレスの影響からカール・ポパーと同じくプラトンの国家論には断固反対したが、プラトンは認識論として読むべきとし、大衆を統

一するには外部の脅威を用意したり、宗教を用いてもよいという「高貴な嘘」Noble liesをプラトンは唱えたと解釈した |

|

| ただし、彼個人は、マルクス主義やナチズムを「残酷なニヒリズム」とし

て斥け、その台頭を許したワイマール政権も批判した。 |

|

| マックス・ヴェーバー流の「事実と価値の峻別」を問題視した |

|

| 彼の思想は現代アメリカ政治、特にネオコンと呼ばれている人に影響を与

え、ブッシュ政権の運営の拠り所のひとつと見る向きもある。しかし、フランシス・フクヤマのようにそういった見方を否定する論調もある。フクヤマは著書の

中で「ブッシュ政権の外交政策にシュトラウスが影響を与えたと見ることがバカげている理由の一つに、イラク戦争へと邁進したブッシュ政権内にシュトラウス

派がただの一人もいないという事実がある。」と述べている(『アメリカの終わり』35頁)。 |

|

| シュトラウスに影響を受けた人物(フクヤマもその一人)と、シュトラウ

ス派(Straussian)は区別されることも多い。 |

|

| 古典的な自然法を奉じるシュトラウスと人為的な世界観を持つネオコンで

は矛盾しているとの指摘 |

|

| 子格に当たる人物としては、アラン・ブルームやソール・ベロウ |

|

| 『自然権と歴史』(昭和堂、1988年/ちくま学芸文庫、2013年) 『ホッブズの政治学』(みすず書房、1990年、新版2019年) 『政治哲学とは何か』(昭和堂、1992年) 『政治哲学とは何であるか?とその他の諸研究』(早稲田大学出版部、2014年) 『古典的政治的合理主義の再生――レオ・シュトラウス思想入門』(ナカニシヤ出版、1996年) 『リベラリズム――古代と近代』(ナカニシヤ出版、2006年) 『僭主政治について(上・下)』(現代思潮新社、2006-2007年) 『哲学者マキァヴェッリについて』(勁草書房、2011年) 『都市と人間』(叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版局、2015年) |

|

| Views Philosophy For Strauss, politics and philosophy were necessarily intertwined. He regarded the trial and death of Socrates as the moment when political philosophy came into existence. Strauss considered one of the most important moments in the history of philosophy Socrates' argument that philosophers could not study nature without considering their own human nature,[13] which, in the words of Aristotle, is that of "a political animal."[14] However, he also held that the ends of politics and philosophy were inherently irreconcilable and irreducible to one another.[15][16] Strauss distinguished "scholars" from "great thinkers," identifying himself as a scholar. He wrote that most self-described philosophers are in actuality scholars, cautious and methodical. Great thinkers, in contrast, boldly and creatively address big problems. Scholars deal with these problems only indirectly by reasoning about the great thinkers' differences.[17] In Natural Right and History Strauss begins with a critique of Max Weber's epistemology, briefly engages the relativism of Martin Heidegger (who goes unnamed) and continues with a discussion of the evolution of natural rights via an analysis of the thought of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. He concludes by critiquing Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Edmund Burke. At the heart of the book are excerpts from Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. Much of his philosophy is a reaction to the works of Heidegger. Indeed, Strauss wrote that Heidegger's thinking must be understood and confronted before any complete formulation of modern political theory is possible, and this means that political thought has to engage with issues of ontology and the history of metaphysics.[18] Strauss wrote that Friedrich Nietzsche was the first philosopher to properly understand historicism, an idea grounded in a general acceptance of Hegelian philosophy of history. Heidegger, in Strauss's view, sanitized and politicized Nietzsche, whereas Nietzsche believed "our own principles, including the belief in progress, will become as unconvincing and alien as all earlier principles (essences) had shown themselves to be" and "the only way out seems to be ... that one voluntarily choose life-giving delusion instead of deadly truth, that one fabricate a myth."[19] Heidegger believed that the tragic nihilism of Nietzsche was itself a "myth" guided by a defective Western conception of Being that Heidegger traced to Plato. In his published correspondence with Alexandre Kojève, Strauss wrote that Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was correct when he postulated that an end of history implies an end to philosophy as understood by classical political philosophy.[20] On reading  Strauss's study of philosophy and political discourses produced by the Islamic civilization—especially those of Al-Farabi (shown here) and Maimonides—was instrumental in the development of his theory of reading. In the late 1930s, Strauss called for the first time for a reconsideration of the "distinction between exoteric (or public) and esoteric (or secret) teaching."[21] In 1952 he published Persecution and the Art of Writing, arguing that serious writers write esoterically, that is, with multiple or layered meanings, often disguised within irony or paradox, obscure references, even deliberate self-contradiction. Esoteric writing serves several purposes: protecting the philosopher from the retribution of the regime, and protecting the regime from the corrosion of philosophy; it attracts the right kind of reader and repels the wrong kind; and ferreting out the interior message is in itself an exercise of philosophic reasoning.[22][23][24] Taking his bearings from his study of Maimonides and Al-Farabi, and pointing further back to Plato's discussion of writing as contained in the Phaedrus, Strauss proposed that the classical and medieval art of esoteric writing is the proper medium for philosophic learning: rather than displaying philosophers' thoughts superficially, classical and medieval philosophical texts guide their readers in thinking and learning independently of imparted knowledge. Thus, Strauss agrees with the Socrates of the Phaedrus, where the Greek indicates that, insofar as writing does not respond when questioned, good writing provokes questions in the reader—questions that orient the reader towards an understanding of problems the author thought about with utmost seriousness. Strauss thus, in Persecution and the Art of Writing, presents Maimonides "as a closet nonbeliever obfuscating his message for political reasons".[25] Strauss's hermeneutical argument[26]—rearticulated throughout his subsequent writings (most notably in The City and Man [1964])—is that, before the 19th century, Western scholars commonly understood that philosophical writing is not at home in any polity, no matter how liberal. Insofar as it questions conventional wisdom at its roots, philosophy must guard itself especially against those readers who believe themselves authoritative, wise, and liberal defenders of the status quo. In questioning established opinions, or in investigating the principles of morality, philosophers of old found it necessary to convey their messages in an oblique manner. Their "art of writing" was the art of esoteric communication. This was especially apparent in medieval times when heterodox political thinkers wrote under the threat of the Inquisition or comparably obtuse tribunals. Strauss's argument is not that the medieval writers he studies reserved one exoteric meaning for the many (hoi polloi) and an esoteric, hidden one for the few (hoi oligoi), but that, through rhetorical stratagems including self-contradiction and hyperboles, these writers succeeded in conveying their proper meaning at the tacit heart of their writings—a heart or message irreducible to "the letter" or historical dimension of texts. Explicitly following Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's lead, Strauss indicates that medieval political philosophers, no less than their ancient counterparts, carefully adapted their wording to the dominant moral views of their time, lest their writings be condemned as heretical or unjust, not by "the many" (who did not read), but by those "few" whom the many regarded as the most righteous guardians of morality. It was precisely these righteous personalities who would be most inclined to persecute/ostracize anyone who was in the business of exposing the noble or great lie upon which the authority of the few over the many stands or falls.[27] |

見解 哲学 シュトラウスにとって、政治と哲学は必然的に結びついていた。彼はソクラテスの裁判と死を、政治哲学が誕生した瞬間とみなした。シュトラウスは哲学の歴史 において最も重要な瞬間のひとつをソクラテスの、哲学者は自らの人間性を考慮することなく自然を研究することはできないという主張であると考えていた [13]。 シュトラウスは「学者」と「偉大な思想家」を区別し、自らを学者であると認識していた。彼は、自称哲学者のほとんどは実際には学者であり、慎重で理路整然 としている。それに対して偉大な思想家は、大胆かつ創造的に大きな問題に取り組む。学者は、偉大な思想家の違いについて推論することによってのみ、間接的 にこれらの問題に対処するのである[17]。 自然権と歴史』においてシュトラウスは、マックス・ウェーバーの認識論への批判から始まり、マルティン・ハイデガー(名前は伏せられている)の相対主義に 簡潔に関与し、トマス・ホッブズとジョン・ロックの思想の分析を通じて自然権の進化についての議論を続けている。最後に、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーとエド モンド・バークを批評する。本書の中心はプラトン、アリストテレス、キケロからの抜粋である。彼の哲学の多くは、ハイデガーの著作に対する反応である。実 際、シュトラウスは現代政治理論の完全な定式化が可能になる前に、ハイデガーの思考を理解し、それに立ち向かわなければならないと書いており、これは政治 思想が存在論と形而上学の歴史の問題に関与しなければならないことを意味している[18]。 シュトラウスは、フリードリヒ・ニーチェが歴史主義を正しく理解した最初の哲学者であり、それはヘーゲルの歴史哲学の一般的な受容に根ざした思想であった と書いている。シュトラウスによれば、ハイデガーはニーチェを神聖化し、政治化していたが、ニーチェは「進歩の信念を含むわれわれ自身の原理は、それ以前 のすべての原理(本質)がそうであったことを示したように、説得力のない異質なものになる」と考え、「唯一の出口は......人が自発的に選択すること であるように思われる。 ハイデガーは、ニーチェの悲劇的ニヒリズム自体が、プラトンにまで遡る西洋的存在概念の欠陥に導かれた「神話」であると考えていた。アレクサンドル・コ ジェーヴとの往復書簡の中で、シュトラウスは、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルが、歴史の終わりは古典的な政治哲学が理解する哲学の終わ りを意味すると仮定したとき、それは正しかったと書いている[20]。 読書について  イスラム文明、特にアル・ファラービー(この写真)とマイモニデスの哲学と政治的言説に関するシュトラウスの研究は、彼の読書論の発展に役立った。 1930年代後半、シュトラウスは初めて「外典(あるいは公の教え)と秘教(あるいは秘密の教え)の区別」の再考を求めた[21]。1952年、彼は『迫 害と書く技術』を出版し、真面目な作家は秘教的に、つまり皮肉やパラドックス、不明瞭な言及、さらには意図的な自己矛盾の中にしばしば偽装された、複数 の、あるいは重層的な意味を持って書くのだと主張した。難解な文章にはいくつかの目的がある。哲学者を体制の報復から守り、体制を哲学の腐食から守るこ と、適切な種類の読者を惹きつけ、間違った種類の読者を撃退すること、そして内部のメッセージを探し出すこと自体が哲学的推論の訓練になることである [22][23][24]。 マイモニデスとアル・ファラビの研究から方向性を見出し、さらに『パイドロス』に含まれるプラトンの文章論にまで遡ることで、シュトラウスは、古典的・中 世的な秘教的文章術こそが哲学的な学習にとって適切な媒体であると提唱している。哲学者の思想を表面的に示すのではなく、古典的・中世的な哲学的文章は、 読者に与えられた知識とは別に思考と学習を導くものである。このようにシュトラウスは、『パイドロス』のソクラテスと同意見である。ギリシア人は、文章は 質問されても答えない限り、優れた文章は読者に質問を投げかける。こうしてシュトラウスは、『迫害と書く技術』の中で、マイモニデスを「政治的な理由から メッセージを難解にしている密室非信仰者として」紹介している[25]。 シュトラウスの解釈学的な議論[26]は、その後の著作(特に『都市と人間』[1964年])において繰り返し言及されているが、19世紀以前、西洋の学 者たちは、哲学的な文章はいかにリベラルであろうと、いかなる政体にも馴染まないということを一般的に理解していたということである。哲学は、その根底に おいて既成の常識に疑問を投げかけるものである以上、特に、自らを権威的で賢明な、リベラルな現状擁護者と信じる読者たちから自らを守らなければならな い。既成の意見に疑問を投げかけたり、道徳の原理を究明したりする際、昔の哲学者たちは斜に構えた方法でメッセージを伝える必要があると考えた。彼らの 「書く技術」は、難解なコミュニケーションの技術だった。これは、異端審問やそれに匹敵するほど鈍感な法廷に脅かされながら、異端的な政治思想家たちが文 章を書いていた中世において特に顕著であった。 シュトラウスの主張は、彼が研究する中世の作家たちが、多くの人々(hoi polloi)には外秘的な意味を、少数の人々(hoi oligoi)には秘教的な隠された意味を、それぞれ留保していたということではなく、自己矛盾や誇張表現を含む修辞学的な策略によって、これらの作家た ちは、彼らの著作の暗黙の核心にある本来の意味を伝えることに成功したということである。 中世の政治哲学者たちは、古代の政治哲学者たちに劣らず、自分たちの著作が異端や不当なものとして非難されないように、その時代の支配的な道徳観に注意深 く言葉を合わせていた。少数者の多数者に対する権威の拠って立つ、あるいは立つか倒れるかの高貴な、あるいは偉大な嘘を暴く仕事をしている人物を最も迫害 /追放したがるのは、まさにこうした正しい人格者たちだった[27]。 |

| On Politics According to Strauss, modern social science is flawed because it assumes the fact–value distinction, a concept which Strauss found dubious. He traced its roots in Enlightenment philosophy to Max Weber, a thinker whom Strauss described as a "serious and noble mind". Weber wanted to separate values from science but, according to Strauss, was really a derivative thinker, deeply influenced by Nietzsche's relativism.[28] Strauss treated politics as something that could not be studied from afar. A political scientist examining politics with a value-free scientific eye, for Strauss, was self-deluded. Positivism, the heir to both Auguste Comte and Max Weber in the quest to make purportedly value-free judgments, failed to justify its own existence, which would require a value judgment.[29] While modern-era liberalism had stressed the pursuit of individual liberty as its highest goal, Strauss felt that there should be a greater interest in the problem of human excellence and political virtue. Through his writings, Strauss constantly raised the question of how, and to what extent, freedom and excellence can coexist. Strauss refused to make do with any simplistic or one-sided resolutions of the Socratic question: What is the good for the city and man?[30] Encounters with Carl Schmitt and Alexandre Kojève Two significant political-philosophical dialogues Strauss had with living thinkers were those he held with Carl Schmitt and Alexandre Kojève. Schmitt, who would later become, for a short time, the chief jurist of Nazi Germany, was one of the first important German academics to review Strauss's early work positively. Schmitt's positive reference for, and approval of, Strauss's work on Hobbes was instrumental in winning Strauss the scholarship funding that allowed him to leave Germany.[31] Strauss's critique and clarifications of The Concept of the Political led Schmitt to make significant emendations in its second edition. Writing to Schmitt in 1932, Strauss summarised Schmitt's political theology that "because man is by nature evil, he, therefore, needs dominion. But dominion can be established, that is, men can be unified only in a unity against—against other men. Every association of men is necessarily a separation from other men ... the political thus understood is not the constitutive principle of the state, of order, but a condition of the state."[32] Strauss, however, directly opposed Schmitt's position. For Strauss, Schmitt and his return to Thomas Hobbes helpfully clarified the nature of our political existence and our modern self-understanding. Schmitt's position was therefore symptomatic of the modern-era liberal self-understanding. Strauss believed that such an analysis, as in Hobbes's time, served as a useful "preparatory action," revealing our contemporary orientation towards the eternal problems of politics (social existence). However, Strauss believed that Schmitt's reification of our modern self-understanding of the problem of politics into a political theology was not an adequate solution. Strauss instead advocated a return to a broader classical understanding of human nature and a tentative return to political philosophy, in the tradition of the ancient philosophers.[33] With Kojève, Strauss had a close and lifelong philosophical friendship. They had first met as students in Berlin. The two thinkers shared boundless philosophical respect for each other. Kojève would later write that, without befriending Strauss, "I never would have known ... what philosophy is".[34] The political-philosophical dispute between Kojève and Strauss centered on the role that philosophy should and can be allowed to play in politics. Kojève, a senior civil servant in the French government, was instrumental in the creation of the European Economic Community. He argued that philosophers should have an active role in shaping political events. Strauss, on the contrary, believed that philosophers should play a role in politics only to the extent that they can ensure that philosophy, which he saw as mankind's highest activity, can be free from political intervention.[35] Liberalism and nihilism Strauss argued that liberalism in its modern form (which is oriented toward universal freedom as opposed to "ancient liberalism" which is oriented toward human excellence), contained within it an intrinsic tendency towards extreme relativism, which in turn led to two types of nihilism:[36] The first was a "brutal" nihilism, expressed in Nazi and Bolshevik regimes. In On Tyranny, he wrote that these ideologies, both descendants of Enlightenment thought, tried to destroy all traditions, history, ethics, and moral standards and replace them by force under which nature and mankind are subjugated and conquered.[37] The second type—the "gentle" nihilism expressed in Western liberal democracies—was a kind of value-free aimlessness and a hedonistic "permissive egalitarianism," which he saw as permeating the fabric of contemporary American society.[38][39] In the belief that 20th-century relativism, scientism, historicism, and nihilism were all implicated in the deterioration of modern society and philosophy, Strauss sought to uncover the philosophical pathways that had led to this situation. The resultant study led him to advocate a tentative return to classical political philosophy as a starting point for judging political action.[40] Strauss's interpretation of Plato's Republic According to Strauss, the Republic by Plato is not "a blueprint for regime reform" (a play on words from Karl Popper's The Open Society and Its Enemies, which attacks The Republic for being just that). Strauss quotes Cicero: "The Republic does not bring to light the best possible regime but rather the nature of political things—the nature of the city."[41] Strauss argued that the city-in-speech was unnatural, precisely because "it is rendered possible by the abstraction from eros".[42] Though skeptical of "progress," Strauss was equally skeptical about political agendas of "return"—that is, going backward instead of forward. In fact, he was consistently suspicious of anything claiming to be a solution to an old political or philosophical problem. He spoke of the danger in trying finally to resolve the debate between rationalism and traditionalism in politics. In particular, along with many in the pre-World War II German Right, he feared people trying to force a world state to come into being in the future, thinking that it would inevitably become a tyranny.[43] Hence he kept his distance from the two totalitarianisms that he denounced in his century, both fascists and communists. Strauss and Karl Popper Strauss actively rejected Karl Popper's views as illogical. He agreed with a letter of response to his request of Eric Voegelin to look into the issue. In the response, Voegelin wrote that studying Popper's views was a waste of precious time, and "an annoyance". Specifically about The Open Society and Its Enemies and Popper's understanding of Plato's The Republic, after giving some examples, Voegelin wrote: Popper is philosophically so uncultured, so fully a primitive ideological brawler, that he is not able to even approximately to reproduce correctly the contents of one page of Plato. Reading is of no use to him; he is too lacking in knowledge to understand what the author says.[misquoted][44] Strauss proceeded to show this letter to Kurt Riezler, who used his influence in order to oppose Popper's appointment at the University of Chicago.[45] Ancients and Moderns Strauss constantly stressed the importance of two dichotomies in political philosophy, namely Athens and Jerusalem (reason and revelation) and Ancient versus Modern. The "Ancients" were the Socratic philosophers and their intellectual heirs; the "Moderns" start with Niccolò Machiavelli. The contrast between Ancients and Moderns was understood to be related to the unresolvable tension between Reason and Revelation. The Socratics, reacting to the first Greek philosophers, brought philosophy back to earth, and hence back to the marketplace, making it more political.[46] The Moderns reacted to the dominance of revelation in medieval society by promoting the possibilities of Reason. They objected to Aquinas's merger of natural right and natural theology, for it made natural right vulnerable to sideshow theological disputes.[47] Thomas Hobbes, under the influence of Francis Bacon, re-oriented political thought to what was most solid but also most low in man—his physical hopes and fears—setting a precedent for John Locke and the later economic approach to political thought, as in David Hume and Adam Smith.[48] Strauss and Zionism As a youth, Strauss belonged to the German Zionist youth group, along with his friends Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin. Both were admirers of Strauss and would continue to be throughout their lives.[49] When he was 17, as he said, he was "converted" to political Zionism as a follower of Ze'ev Jabotinsky. He wrote several essays about its controversies but left these activities behind by his early twenties.[50] While Strauss maintained a sympathetic interest in Zionism, he later came to refer to Zionism as "problematic" and became disillusioned with some of its aims. He taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem during the 1954–55 academic year. In his letter to a National Review editor, Strauss asked why Israel had been called a racist state by one of their writers. He argued that the author did not provide enough proof for his argument. He ended his essay with this statement: "Political Zionism is problematic for obvious reasons. But I can never forget what it achieved as a moral force in an era of complete dissolution. It helped to stem the tide of 'progressive' leveling of venerable, ancestral differences; it fulfilled a conservative function."[51] Religious belief Although Strauss accepted the utility of religious belief, there is some question about his religious views. He was openly disdainful of atheism[52][better source needed] and disapproved of contemporary dogmatic disbelief, which he considered intemperate and irrational.[53] However, like Thomas Aquinas, he felt that revelation must be subject to examination by reason.[54] At the end of The City and Man, Strauss invites us to "be open to ... the question quid sit deus ["What is God?"]" (p. 241). Edward Feser writes that "Strauss was not himself an orthodox believer, neither was he a convinced atheist. Since whether or not to accept a purported divine revelation is itself one of the 'permanent' questions, orthodoxy must always remain an option equally as defensible as unbelief."[55] In Natural Right and History Strauss distinguishes a Socratic (Platonic, Ciceronian, Aristotelian) from a conventionalist (materialistic, Epicurean) reading of divinity, and argues that "the question of religion" (what is religion?) is inseparable from the question of the nature of civil society and civil authority. Throughout the volume he argues for the Socratic reading of civil authority and rejects the conventionalist reading (of which atheism is an essential component).[56] This is incompatible with interpretations by Shadia Drury and other scholars who argue that Strauss viewed religion purely instrumentally.[57][58] |

政治について シュトラウスによれば、現代の社会科学には欠陥があり、それは事実と価値の区別を前提としているからである。彼は、そのルーツを啓蒙主義哲学からマック ス・ウェーバーに辿った。マックス・ウェーバーは、シュトラウスが「真面目で高貴な精神」と評した思想家である。ヴェーバーは価値観を科学から切り離そう としたが、シュトラウスによれば、実際はニーチェの相対主義に深く影響された派生的な思想家であった[28]。価値観のない科学的な目で政治を研究する政 治学者は、シュトラウスにとって自己欺瞞であった。オーギュスト・コントとマックス・ウェーバーの後継者である実証主義は、価値のない判断を下すことを追 求していたが、価値判断を必要とする自らの存在を正当化することに失敗していた[29]。 近代のリベラリズムは個人の自由の追求を最高の目標として強調していたが、シュトラウスは人間の卓越性と政治的美徳の問題にもっと関心を持つべきだと感じ ていた。シュトラウスは著作を通じて、自由と卓越性がどのように、そしてどの程度まで共存できるのかという問題を常に提起した。シュトラウスは、ソクラテ スの問いを単純化したり、一方的に解決したりすることを拒否した: 都市と人間にとって善とは何か? カール・シュミットとアレクサンドル・コジェーヴとの出会い シュトラウスが生きた思想家たちと交わした政治哲学上の重要な対話は、カール・シュミットとアレクサンドル・コジェーヴとのものだった。シュミットは、の ちにナチス・ドイツの法学最高責任者となる人物だが、シュトラウスの初期の仕事を肯定的に評価した最初の重要な学者の一人である。シュミットのホッブズに 関するシュトラウスの研究に対する肯定的な言及と承認は、シュトラウスがドイツを離れることを可能にする奨学金を獲得するのに役立った[31]。 シュトラウスの『政治的概念』に対する批評と明確化によって、シュミットはその第2版において重要な修正を加えることになった。1932年にシュミットに 宛てた手紙の中で、シュトラウスはシュミットの政治神学を要約している。しかし、支配は、すなわち、人間は、他の人間に対する統一においてのみ、成立しう る。このように理解される政治的とは、国家の構成原理や秩序ではなく、国家の条件なのである」[32]。 しかし、シュトラウスはシュミットの立場と真っ向から対立していた。シュトラウスにとって、シュミットと彼のトマス・ホッブズへの回帰は、われわれの政治 的存在の本質とわれわれの近代的自己理解を明確にするのに役立った。したがってシュミットの立場は、近代のリベラルの自己理解を象徴するものであった。 シュトラウスは、このような分析は、ホッブズの時代と同様に、政治(社会的存在)の永遠の問題に対する現代のわれわれの方向性を明らかにする、有用な「準 備行為」として機能すると考えた。しかしシュトラウスは、シュミットが現代人の政治問題に対する自己理解を政治神学へと再定義したことは、適切な解決策で はないと考えた。シュトラウスはその代わりに、より広範な古典的な人間性の理解への回帰と、古代の哲学者の伝統に則った政治哲学への暫定的な回帰を提唱し た[33]。 コジェーヴとシュトラウスは親密な哲学的友情で結ばれ、生涯を共にした。二人はベルリンの学生時代に初めて出会った。二人の思想家は、互いに無限の哲学的 尊敬の念を共有していた。コジェーヴは後に、シュトラウスとの親交がなければ「哲学とは何なのか......決して知ることはなかっただろう」と記してい る[34]。コジェーヴとシュトラウスの政治哲学論争は、哲学が政治に果たすべき役割、また果たすことが許される役割についてが中心であった。 フランス政府の上級公務員であったコジェーヴは、欧州経済共同体の創設に尽力した。彼は、哲学者は政治的出来事の形成に積極的な役割を果たすべきだと主張 した。それに対してシュトラウスは、哲学者が政治的な役割を果たすべきであると考えたのは、人類の最高の活動であると考える哲学が政治的な介入を受けない ようにすることができる範囲においてのみであった[35]。 リベラリズムとニヒリズム シュトラウスは、(人間の卓越性を志向する「古代のリベラリズム」とは対照的に普遍的な自由を志向する)近代的な形態におけるリベラリズムは、極端な相対 主義に向かう本質的な傾向を内包しており、それがひいては2つのタイプのニヒリズムにつながると主張していた[36]。 1つ目は、ナチスやボリシェヴィキ体制で表現された「残忍な」ニヒリズムである。専制について』の中で彼は、啓蒙思想の末裔であるこれらのイデオロギー は、すべての伝統、歴史、倫理、道徳基準を破壊し、自然と人間が服従させられ征服されるような力によってそれらに取って代わろうとしたと書いている [37]。第二のタイプ、すなわち西欧の自由民主主義国家に表現される「穏やかな」ニヒリズムは、ある種の無目的な価値観と快楽主義的な「寛容な平等主 義」であり、現代アメリカ社会に浸透していると彼は見ていた[38][39]。 20世紀の相対主義、科学主義、歴史主義、ニヒリズムがすべて現代社会と哲学の劣化に関与しているという信念のもと、シュトラウスはこのような状況に至っ た哲学的経路を明らかにしようとした。その結果、彼は政治的行動を判断するための出発点として古典政治哲学への暫定的な回帰を提唱するに至った[40]。 シュトラウスのプラトン『共和国』解釈 シュトラウスによれば、プラトンの『共和国』は「体制改革のための青写真」(『共和国』がまさにそうであるとして攻撃したカール・ポパーの『開かれた社会 とその敵』の言葉遊び)ではない。シュトラウスはキケロの言葉を引用する: 共和国』は可能な限り最良の体制を明るみに出すのではなく、政治的なものの本質、つまり都市の本質を明るみに出すのである」[41]。 進歩」に対して懐疑的であったシュトラウスだが、「回帰」、つまり前進するのではなく後退するという政治的アジェンダに対しても同様に懐疑的であった。 実際、彼は古い政治的、哲学的問題の解決策であると主張するものには一貫して疑念を抱いていた。彼は、政治における合理主義と伝統主義の論争を最終的に解 決しようとすることの危険性について語った。特に、第二次世界大戦前のドイツ右派の多くとともに、彼は、世界国家が必然的に専制政治になると考え、将来、 世界国家を強制的に誕生させようとする人々を恐れた[43]。それゆえ、彼は、その世紀に彼が非難したファシストと共産主義者の2つの全体主義から距離を 置いていた。 シュトラウスとカール・ポパー シュトラウスはカール・ポパーの見解を非論理的であるとして積極的に否定した。彼は、エリック・ヴォーゲリンにこの問題を調べるよう要請したことに対し て、返事の手紙で同意した。その返書の中でヴォーゲリンは、ポパーの見解を研究することは貴重な時間の無駄であり、「迷惑なことだ」と書いている。特に 『開かれた社会とその敵』やプラトンの『共和国』に対するポパーの理解について、いくつかの例を挙げた後、ヴォーゲリンはこう書いている: ポパーは哲学的に無教養であり、原始的なイデオロギーの喧嘩屋であるため、プラトンの1ページの内容を正確に再現することさえできない。彼にとって読書は 何の役にも立たない。著者の言うことを理解するには、彼はあまりにも知識が不足している。 シュトラウスはこの手紙をクルト・リースラーに見せ、彼は影響力を行使してポパーのシカゴ大学での任命に反対した[45]。 古代人と現代人 シュトラウスは政治哲学における2つの二分法、すなわちアテネとエルサレム(理性と啓示)、古代と現代の重要性を常に強調していた。古代人」とはソクラテ スの哲学者とその知的継承者たちであり、「近代人」とはニコロ・マキャベリから始まる。古代人と現代人の対比は、理性と啓示の間の解決不可能な緊張に関連 していると理解されていた。ソクラテス派はギリシアの最初の哲学者たちに反発し、哲学を地上に、つまり市場に戻し、より政治的なものにした[46]。 近代人たちは、理性の可能性を促進することによって、中世社会における啓示の支配に反発していた。フランシス・ベーコンの影響を受けたトマス・ホッブズ は、政治思想を人間の最も堅固でありながら最も低俗なもの、つまり肉体的な希望と恐怖に再び向け、ジョン・ロックやデイヴィッド・ヒュームやアダム・スミ スのような後の政治思想への経済的アプローチの先例となった。 シュトラウスとシオニズム シュトラウスは青年時代、友人のゲルショム・ショレムやヴァルター・ベンヤミンとともにドイツのシオニスト青年団に所属していた。17歳のとき、ゼエヴ・ ヤボチンスキーの信奉者として政治的シオニズムに「改宗」した。彼はその論争についていくつかのエッセイを書いたが、20代前半までにこれらの活動を離れ た[50]。 シュトラウスはシオニズムに共感的な関心を持ち続けたが、後にシオニズムを「問題がある」と呼ぶようになり、その目的の一部に幻滅するようになった。 1954年から55年にかけては、エルサレムのヘブライ大学で教鞭をとっていた。ナショナル・レビュー』誌の編集者に宛てた手紙の中で、シュトラウスは、 イスラエルが人種差別国家と呼ばれるのはなぜか、と質問した。彼は、その著者が自分の主張に対して十分な証拠を示していないと主張した。彼はエッセイの最 後にこう書いた: 「政治的シオニズムは明白な理由で問題がある。しかし、私はシオニズムが完全な解体の時代に、道徳的な力として成し遂げたことを決して忘れることはできな い。それは、由緒ある先祖伝来の差異を『進歩的』に平準化する流れを食い止めるのに役立ち、保守的な機能を果たしたのである」[51]。 宗教的信念 シュトラウスは宗教的信念の有用性を認めていたが、彼の宗教観については疑問もある。彼は公然と無神論を軽蔑し[52][要出典]、現代の教条的な不信仰 を不承認とした。エドワード・フェザーは、「シュトラウス自身は正統的な信仰者ではなく、確信に満ちた無神論者でもなかった。神の啓示と称されるものを受 け入れるか否かは、それ自体が『永続的』な問いの一つである以上、正統性は常に不信仰と等しく擁護可能な選択肢であり続けなければならない」[55]。 自然権と歴史』においてシュトラウスは、神性についてソクラテス的(プラトン的、キケロン的、アリストテレス的)な読み方と慣習主義的(唯物論的、エピク ロス的)な読み方を区別し、「宗教の問題」(宗教とは何か)は市民社会と市民的権威の本質の問題と不可分であると論じている。これは、シュトラウスが宗教 を純粋に道具的にしか見ていないと主張するシャディア・ドーリーや他の学者による解釈とは相容れない[57][58]。 |

| Reception by contemporaries Strauss's works were read and admired by thinkers as diverse as the philosophers Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin,[49] Hans-Georg Gadamer,[59] and Alexandre Kojève,[59] and the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.[59] Benjamin had become acquainted with Strauss as a student in Berlin, and expressed admiration for Strauss throughout his life.[3][4][5] Gadamer stated that he 'largely agreed' with Strauss's interpretations.[59] The Straussian school Straussianism is the name given "to denote the research methods, common concepts, theoretical presuppositions, central questions, and pedagogic style (teaching style[60]) characteristic of the large number of conservatives who have been influenced by the thought and teaching of Leo Strauss".[61] While it "is particularly influential among university professors of historical political theory ... it also sometimes serves as a common intellectual framework more generally among conservative activists, think tank professionals, and public intellectuals".[61] Harvey C. Mansfield, Steven B. Smith and Steven Berg, though never students of Strauss, are "Straussians" (as some followers of Strauss identify themselves). Mansfield has argued that there is no such thing as "Straussianism" yet there are Straussians and a school of Straussians. Mansfield describes the school as "open to the whole of philosophy" and without any definite doctrines that one has to believe in order to belong to it.[62] Within the discipline of political theory, the method calls for its practitioners to use "a 'close reading' of the 'Great Books' of political thought; they strive to understand a thinker 'as he understood himself'; they are unconcerned with questions about the historical context of, or historical influences on, a given author"[61] and strive to be open to the idea that they may find something timelessly true in a great book. The approach "resembles in important ways the old New Criticism in literary studies."[61] There is some controversy in the approach over what distinguishes a great book from lesser works. Great books are held to be written by authors/philosophers "of such sovereign critical self-knowledge and intellectual power that they can in no way be reduced to the general thought of their time and place,"[61] with other works "understood as epiphenomenal to the original insights of a thinker of the first rank."[61] This approach is seen as a counter "to the historicist presuppositions of the mid-twentieth century, which read the history of political thought in a progressivist way, with past philosophies forever cut off from us in a superseded past."[61] Straussianism puts forward the possibility that past thinkers may have "hold of the truth—and that more recent thinkers are therefore wrong."[61] The Chinese Straussians Almost the entirety of Strauss's writings has been translated into Chinese; and there even is a school of Straussians in China, the most prominent being Liu Xiaofeng (Renmin University) and Gan Yang. "Chinese Straussians" (who often are also fascinated by Carl Schmitt) represent a remarkable example of the hybridization of Western political theory in a non-Western context. As the editors of a recent volume write, "the reception of Schmitt and Strauss in the Chinese-speaking world (and especially in the People's Republic of China) not only says much about how Schmitt and Strauss can be read today, but also provides important clues about the deeper contradictions of Western modernity and the dilemmas of non-liberal societies in our increasingly contentious world."[63] Criticism Basis for esotericism In the essay, Persecution and the Art of Writing, Strauss posits that information needs to be kept secret from the masses by "writing between the lines". However, this seems like a false premise, as most authors Strauss refers to in his work lived in times when only the social elites were literate enough to understand works of philosophy.[64] Conservatism Some critics of Strauss have accused him of being elitist, illiberal and anti-democratic. Journalists such as Seymour Hersh have opined that Strauss endorsed noble lies, "myths used by political leaders seeking to maintain a cohesive society".[65][66] In The City and Man, Strauss discusses the myths outlined in Plato's Republic that are required for all governments. These include a belief that the state's land belongs to it even though it may have been acquired illegitimately and that citizenship is rooted in something more than accidents of birth.[67] Shadia Drury, in Leo Strauss and the American Right (1999), claimed that Strauss inculcated an elitist strain in American political leaders linked to imperialist militarism, neoconservatism and Christian fundamentalism. Drury argues that Strauss teaches that "perpetual deception of the citizens by those in power is critical because they need to be led, and they need strong rulers to tell them what's good for them". Nicholas Xenos similarly argues that Strauss was "an anti-democrat in a fundamental sense, a true reactionary". Xenos says: "Strauss was somebody who wanted to go back to a previous, pre-liberal, pre-bourgeois era of blood and guts, of imperial domination, of authoritarian rule, of pure fascism."[68] Anti-historicism Strauss has also been criticized by some conservatives. According to Claes G. Ryn, Strauss's anti-historicist thinking creates an artificial contrast between moral universality and "the conventional", "the ancestral", and "the historical". Strauss, Ryn argues, wrongly and reductively assumes that respect for tradition must undermine reason and universality. Contrary to Strauss's criticism of Edmund Burke, the historical sense may be indispensable to an adequate apprehension of universality. Strauss's abstract, ahistorical conception of natural right distorts genuine universality, Ryn contends. Strauss does not consider the possibility that real universality becomes known to human beings in a concretized, particular form. Strauss and the Straussians have paradoxically taught philosophically unsuspecting American conservatives, not least Roman Catholic intellectuals, to reject tradition in favor of ahistorical theorizing, a bias that flies in the face of the central Christian notion of the Incarnation, which represents a synthesis of the universal and the historical. According to Ryn, the propagation of a purely abstract idea of universality has contributed to the neoconservative advocacy of allegedly universal American principles, which neoconservatives see as justification for American intervention around the world—bringing the blessings of the "West" to the benighted "rest". Strauss's anti-historical thinking connects him and his followers with the French Jacobins, who also regarded tradition as incompatible with virtue and rationality.[69] What Ryn calls the "new Jacobinism" of the "neoconservative" philosophy is, writes Paul Gottfried, also the rhetoric of Saint-Just and Leon Trotsky, which the philosophically impoverished American Right has taken over with mindless alacrity; Republican operators and think tanks apparently believe they can carry the electorate by appealing to yesterday's leftist clichés.[70][71] Response to criticism In his 2009 book, Straussophobia, Peter Minowitz provides a detailed critique of Drury, Xenos, and other critics of Strauss whom he accuses of "bigotry and buffoonery".[72] In Reading Leo Strauss, Steven B. Smith rejects the link between Strauss and neoconservative thought, arguing that Strauss was never personally active in politics, never endorsed imperialism, and questioned the utility of political philosophy for the practice of politics. In particular, Strauss argued that Plato's myth of the philosopher king should be read as a reductio ad absurdum, and that philosophers should understand politics not in order to influence policy but to ensure philosophy's autonomy from politics.[73] In his review of Reading Leo Strauss, Robert Alter writes that Smith "persuasively sets the record straight on Strauss's political views and on what his writing is really about".[74] Strauss's daughter, Jenny Strauss Clay, defended Strauss against the charge that he was the "mastermind behind the neoconservative ideologues who control United States foreign policy." "He was a conservative", she says, "insofar as he did not think change is necessarily change for the better." Since contemporary academia "leaned to the left", with its "unquestioned faith in progress and science combined with a queasiness regarding any kind of moral judgment", Strauss stood outside of the academic consensus. Had academia leaned to the right, he would have questioned it, too—and on certain occasions did question the tenets of the right.[75] Mark Lilla has argued that the attribution to Strauss of neoconservative views contradicts a careful reading of Strauss' actual texts, in particular On Tyranny. Lilla summarizes Strauss as follows: Philosophy must always be aware of the dangers of tyranny, as a threat to both political decency and the philosophical life. It must understand enough about politics to defend its own autonomy, without falling into the error of thinking that philosophy can shape the political world according to its own lights.[76] Responding to charges that Strauss's teachings fostered the neoconservative foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration, such as "unrealistic hopes for the spread of liberal democracy through military conquest", Nathan Tarcov, director of the Leo Strauss Center at the University of Chicago, asserts that Strauss as a political philosopher was essentially non-political. After an exegesis of the very limited practical political views to be gleaned from Strauss's writings, Tarcov concludes that "Strauss can remind us of the permanent problems, but we have only ourselves to blame for our faulty solutions to the problems of today."[77] |

同時代の人々による受容 シュトラウスの作品は、哲学者のゲルショム・ショレム、ヴァルター・ベンヤミン[49]、ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマー[59]、アレクサンドル・コジェー ヴ[59]、精神分析学者のジャック・ラカン[59]といった様々な思想家によって読まれ、賞賛されていた。ベンヤミンはベルリンの学生としてシュトラウ スと知り合い、生涯を通じてシュトラウスへの賞賛を表明していた[3][4][5]。ガダマーはシュトラウスの解釈に「ほぼ同意する」と述べていた [59]。 シュトラウス学派 シュトラウス主義とは「レオ・シュトラウスの思想と教育に影響を受けてきた多くの保守主義者に特徴的な研究方法、共通の概念、理論的前提、中心的な問い、 教育学的スタイル(教授スタイル[60])を示すためにつけられた名称」である[61]。 ハーベイ・C・マンスフィールド、スティーヴン・B・スミス、スティーヴン・バーグは、決してシュトラウスの学生ではないが、「シュトラウス派」(シュト ラウスの信奉者の中には自らをシュトラウス派と呼ぶ者もいる)である。マンスフィールドは、「シュトラウス主義」なるものは存在しないが、シュトラウス主 義者とシュトラウス主義者の一派は存在すると主張している。マンスフィールドはその学派を「哲学全体に開かれており」、その学派に属するために信じなけれ ばならない明確な教義はないと述べている[62]。 政治理論という学問領域において、その方法は実践者たちに「政治思想の『名著』を『精読』すること、思想家を『彼自身が理解したように』理解することに努 めること、ある著者の歴史的背景や歴史的影響に関する疑問には無関心であること」[61]を求めており、名著の中に時代を超えて真実であるものを見出すか もしれないという考えに対してオープンであることに努めている。このアプローチは「重要な点で文学研究における古い新批評に似ている」[61]。 このアプローチでは、名著とそれ以下の作品を区別するものをめぐって論争がある。偉大な書物とは、「その時代と場所の一般的な思想に還元されることのない ような、主権的な批判的自己認識と知的パワーを持つ」著者/哲学者によって書かれたものであるとされ[61]、他の作品は「第一級の思想家の独創的な洞察 に付随するものと理解される」とされている。 「このアプローチは、「政治思想の歴史を進歩主義的に読み、過去の哲学は超越された過去において永遠に我々から切り離されるという20世紀半ばの歴史主義 的前提」[61]に対するカウンターとみなされている。 中国のシュトラウス派 シュトラウスの著作はほとんどすべて中国語に翻訳されており、中国にはシュトラウス派の学派さえ存在する。「中国のシュトラウス派」(彼らはしばしばカー ル・シュミットにも心酔している)は、非西洋的文脈における西洋政治理論のハイブリッド化の顕著な例を示している。最近の書物の編集者が書いているよう に、「中国語圏(特に中華人民共和国)におけるシュミットとシュトラウスの受容は、シュミットとシュトラウスが今日どのように読まれうるかについて多くを 語っているだけでなく、論争が激化する世界における西洋近代のより深い矛盾と非自由主義社会のジレンマについて重要な手がかりを与えている」[63]。 批判 秘教主義の根拠 迫害と書く技術』というエッセイの中で、シュトラウスは「行間を書く」ことによって大衆から情報を秘匿する必要があると説いている。しかし、これは誤った 前提であるように思われる。というのも、シュトラウスが著作の中で言及しているほとんどの作家は、社会的エリートだけが哲学の著作を理解するのに十分な読 み書きができた時代に生きていたからである[64]。 保守主義 シュトラウスをエリート主義、非自由主義、反民主主義だと非難する批評家もいる。シーモア・ハーシュのようなジャーナリストは、シュトラウスが高貴な嘘、 「結束力のある社会を維持しようとする政治指導者が用いる神話」を支持していると論評している[65][66]。 都市と人間』の中でシュトラウスは、プラトンの『共和国』に概説されている、すべての政府に必要な神話について論じている。その神話には、国家の土地は不 法に取得されたものであっても国家のものであるという信念や、市民権は出生の偶然以上のものに根ざしているという信念が含まれている[67]。 シャディア・ドルーリーは『レオ・シュトラウスとアメリカ右派』(1999年)の中で、帝国主義的な軍国主義、新保守主義、キリスト教原理主義と結びつい たエリート主義の系統をアメリカの政治指導者に植え付けたのはシュトラウスであると主張している。ドゥルーリーは、シュトラウスが「権力者による市民の永 続的な欺瞞は重要である。なぜなら、市民は導かれる必要があり、何が自分たちにとって良いことなのかを教えてくれる強い支配者が必要だからだ」と教えてい ると論じている。ニコラス・ゼノスも同様に、シュトラウスは「根本的な意味で反民主主義者であり、真の反動主義者」であったと主張する。シュトラウスは、 血と根性、帝国支配、権威主義的支配、純粋なファシズムの、以前の、リベラル以前の、ブルジョア以前の時代に戻りたがっていた人物だった」とゼノスは言う [68]。 反歴史主義 シュトラウスは一部の保守派からも批判されている。Claes G. Rynによれば、シュトラウスの反歴史主義的思考は、道徳的普遍性と「慣習的なもの」、「先祖伝来のもの」、「歴史的なもの」との間に人為的な対比を生み 出している。シュトラウスは、伝統を尊重することが理性と普遍性を損なうと、誤って還元的に仮定している。エドマンド・バークに対するシュトラウスの批判 に反して、歴史的感覚は普遍性を十分に理解するために不可欠なものなのかもしれない。シュトラウスの抽象的で非歴史的な自然権概念は、真の普遍性を歪めて いるとリンは主張する。シュトラウスは、真の普遍性が具体化された特殊な形で人間に知られるようになる可能性を考慮していない。この偏見は、普遍的なもの と歴史的なものの統合を示す受肉というキリスト教の中心概念に反するものである。リンによれば、普遍性という純粋に抽象的な考え方の伝播は、新保守主義者 が主張するアメリカの普遍的原則に寄与しており、新保守主義者はこの原則を、アメリカによる世界への介入を正当化するもの、つまり「西側」の祝福を弱者で ある「その他の国々」にもたらすものだと考えている。シュトラウスの反歴史的思考は、彼や彼の支持者たちを、同じく伝統を美徳や合理性と相容れないものと みなしたフランスのジャコバン派と結びつけている[69]。 リンが「新保守主義」哲学の「新たなジャコバン主義」と呼ぶものは、ポール・ゴットフリードによれば、サン=ジュストとレオン・トロツキーのレトリックで もあり、哲学的に貧困化したアメリカの右派は、無頓着なほど快活にそれを引き継いでいる。共和党の経営者やシンクタンクは、昨日の左派の決まり文句に訴え ることで選挙民を動かすことができると考えているらしい[70][71]。 批判への反応 ピーター・ミノヴィッツは2009年の著書『Straussophobia』において、ドリー、ゼノス、そして彼が「偏屈と大ばか者」と非難する他のシュ トラウス批判者たちに対する詳細な批評を提供している[72]。 スティーブン・B・スミスは『レオ・シュトラウスを読む』の中で、シュトラウスと新保守主義思想との結びつきを否定し、シュトラウスは個人的に政治に積極 的であったことはなく、帝国主義を支持したこともなく、政治の実践のための政治哲学の有用性に疑問を呈していたと論じている。特にシュトラウスは、プラト ンの哲学者王の神話は不条理帰納法として読まれるべきであり、哲学者は政策に影響を与えるためではなく、政治からの哲学の自律性を保証するために政治を理 解すべきだと主張していた[73]。ロバート・オルターは『レオ・シュトラウスを読む』の書評の中で、スミスは「シュトラウスの政治的見解と彼の著作の真 意について、説得力を持って記録を正す」と書いている[74]。 シュトラウスの娘であるジェニー・ストラウス・クレイは、シュトラウスが「米国の外交政策を支配する新保守主義イデオローグたちの首謀者」であるという非 難に対してシュトラウスを擁護した。「彼は保守主義者だった」と彼女は言う。現代のアカデミズムは「左傾化」しており、「進歩と科学に対する疑いなき信頼 と、あらゆる種類の道徳的判断に対する嫌悪感」とを併せ持っていたため、シュトラウスはアカデミズムのコンセンサスから外れていた。もしアカデミズムが右 傾化していたならば、彼はそれにも疑問を呈していただろうし、ある場面では右派の信条にも疑問を呈していた[75]。 マーク・リラは、新保守主義的な見解をシュトラウスに帰することは、シュトラウスの実際のテキスト、特に『専制について』を注意深く読むことと矛盾すると 主張している。リラはシュトラウスを次のように要約している: 哲学は、政治的良識と哲学的生活の両方に対する脅威として、専制政治の危険性を常に意識していなければならない。哲学は、自らの灯火に従って政治世界を形 作ることができると考える誤りに陥ることなく、自らの自律性を守るために政治について十分に理解しなければならない」[76]。 シカゴ大学レオ・シュトラウス・センター所長のネイサン・ターコフは、シュトラウスの教えがジョージ・W・ブッシュ政権の新保守主義的な外交政策、例えば 「軍事的征服を通じて自由民主主義を広めるという非現実的な希望」を助長したという非難に対して、政治哲学者としてのシュトラウスは本質的に非政治的で あったと主張している。タルコフは、シュトラウスの著作から得られる極めて限定的な実践的政治観の釈明の後、「シュトラウスは我々に恒久的な問題を思い起 こさせることはできるが、今日の問題に対する我々の誤った解決策を非難するのは我々自身である」と結論づけている[77]。 |

| Bibliography Books and articles Gesammelte Schriften. Ed. Heinrich Meier. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1996. Four vols. published to date: Vol. 1, Die Religionskritik Spinozas und zugehörige Schriften (rev. ed. 2001); vol. 2, Philosophie und Gesetz, Frühe Schriften (1997); Vol. 3, Hobbes' politische Wissenschaft und zugehörige Schrifte – Briefe (2001); Vol. 4, Politische Philosophie. Studien zum theologisch-politischen Problem (2010). The full series will also include Vol. 5, Über Tyrannis (2013) and Vol. 6, Gedanken über Machiavelli. Deutsche Erstübersetzung (2014). Leo Strauss: The Early Writings (1921–1932). (Trans. from parts of Gesammelte Schriften). Trans. Michael Zank. Albany: SUNY Press, 2002. Die Religionskritik Spinozas als Grundlage seiner Bibelwissenschaft: Untersuchungen zu Spinozas Theologisch-politischem Traktat. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1930. Spinoza's Critique of Religion. (English trans. by Elsa M. Sinclair of Die Religionskritik Spinozas, 1930.) With a new English preface and a trans. of Strauss's 1932 German essay on Carl Schmitt. New York: Schocken, 1965. Reissued without that essay, Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997. "Anmerkungen zu Carl Schmitt, Der Begriff des Politischen". Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 67, no. 6 (August–September 1932): 732–49. "Comments on Carl Schmitt's Begriff des Politischen". (English trans. by Elsa M. Sinclair of "Anmerkungen zu Carl Schmitt", 1932.) 331–51 in Spinoza's Critique of Religion, 1965. Reprinted in Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, ed. and trans. George Schwab. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U Press, 1976. "Notes on Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political". (English trans. by J. Harvey Lomax of "Anmerkungen zu Carl Schmitt", 1932.) In Heinrich Meier, Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss: The Hidden Dialogue, trans. J. Harvey Lomax. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995. Reprinted in Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, ed. and trans. George Schwab. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996, 2007. Philosophie und Gesetz: Beiträge zum Verständnis Maimunis und seiner Vorläufer. Berlin: Schocken, 1935. Philosophy and Law: Essays Toward the Understanding of Maimonides and His Predecessors. (English trans. by Fred Baumann of Philosophie und Gesetz, 1935.) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1987. Philosophy and Law: Contributions to the Understanding of Maimonides and His Predecessors. (English trans. with introd. by Eve Adler of Philosophie und Gesetz, 1935.) Albany: SUNY Press, 1995. The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. (English trans. by Elsa M. Sinclair from German manuscript.) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1936. Reissued with new preface, Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1952. Hobbes' politische Wissenschaft in ihrer Genesis. (1935 German original of The Political Philosophy of Hobbes, 1936.) Neuwied am Rhein: Hermann Luchterhand, 1965. "The Spirit of Sparta or the Taste of Xenophon". Social Research 6, no. 4 (Winter 1939): 502–36. "On German Nihilism" (1999, originally a 1941 lecture), Interpretation 26, no. 3 edited by David Janssens and Daniel Tanguay. "Farabi's Plato" American Academy for Jewish Research, Louis Ginzberg Jubilee Volume, 1945. 45 pp. "On a New Interpretation of Plato's Political Philosophy". Social Research 13, no. 3 (Fall 1946): 326–67. "On the Intention of Rousseau". Social Research 14, no. 4 (Winter 1947): 455–87. On Tyranny: An Interpretation of Xenophon's Hiero. Foreword by Alvin Johnson. New York: Political Science Classics, 1948. Reissued Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1950. De la tyrannie. (French trans. of On Tyranny, 1948, with "Restatement on Xenophon's Hiero" and Alexandre Kojève's "Tyranny and Wisdom".) Paris: Librairie Gallimard, 1954. On Tyranny. (English edition of De la tyrannie, 1954.) Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1963. On Tyranny. (Revised and expanded edition of On Tyranny, 1963.) Includes Strauss–Kojève correspondence. Ed. Victor Gourevitch and Michael S. Roth. New York: The Free Press, 1991. "On Collingwood’s Philosophy of History". Review of Metaphysics 5, no. 4 (June 1952): 559–86. Persecution and the Art of Writing. Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1952. Reissued Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1988. Natural Right and History. (Based on the 1949 Walgreen lectures.) Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1953. Reprinted with new preface, 1971. ISBN 978-0-226-77694-1. "Existentialism" (1956), a public lecture on Martin Heidegger's thought, published in Interpretation, Spring 1995, Vol.22 No. 3: 303–18. Seminar on Plato's Republic, (1957 Lecture), (1961 Lecture). University of Chicago. Thoughts on Machiavelli. Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1958. Reissued Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1978. What Is Political Philosophy? and Other Studies. Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1959. Reissued Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1988. On Plato's Symposium [1959]. Ed. Seth Benardete. (Edited transcript of 1959 lectures.) Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2001. "'Relativism'". 135–57 in Helmut Schoeck and James W. Wiggins, eds., Relativism and the Study of Man. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, 1961. Partial reprint, 13–26 in The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism, 1989. History of Political Philosophy. Co-editor with Joseph Cropsey. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1963 (1st ed.), 1972 (2nd ed.), 1987 (3rd ed.). "The Crisis of Our Time", 41–54, and "The Crisis of Political Philosophy", 91–103, in Howard Spaeth, ed., The Predicament of Modern Politics. Detroit: U of Detroit P, 1964. "Political Philosophy and the Crisis of Our Time". (Adaptation of the two essays in Howard Spaeth, ed., The Predicament of Modern Politics, 1964.) 217–42 in George J. Graham, Jr., and George W. Carey, eds., The Post-Behavioral Era: Perspectives on Political Science. New York: David McKay, 1972. The City and Man. (Based on the 1962 Page-Barbour lectures.) Chicago: Rand McNally, 1964. Socrates and Aristophanes. New York: Basic Books, 1966. Reissued Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1980. Liberalism Ancient and Modern. New York: Basic Books, 1968. Reissued with foreword by Allan Bloom, 1989. Reissued Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995. Xenophon's Socratic Discourse: An Interpretation of the Oeconomicus. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1970. Note on the Plan of Nietzsche's "Beyond Good & Evil". St. John's College, 1971. Xenophon's Socrates. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1972. The Argument and the Action of Plato's Laws. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1975. Political Philosophy: Six Essays by Leo Strauss. Ed. Hilail Gilden. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1975. An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss. (Expanded version of Political Philosophy: Six Essays by Leo Strauss, 1975.) Ed. Hilail Gilden. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1989. Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy. Introd. by Thomas L. Pangle. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1983. The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism: An Introduction to the Thought of Leo Strauss – Essays and Lectures by Leo Strauss. Ed. Thomas L. Pangle. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1989. Faith and Political Philosophy: the Correspondence Between Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, 1934–1964. Ed. Peter Emberley and Barry Cooper. Introd. by Thomas L. Pangle. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP, 1993. Hobbes's Critique of Religion and Related Writings. Ed. and trans. Gabriel Bartlett and Svetozar Minkov. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2011. (Trans. of materials first published in the Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 3, including an unfinished manuscript by Leo Strauss of a book on Hobbes, written in 1933–1934, and some shorter related writings.) Leo Strauss on Moses Mendelssohn. Edited and translated by Martin D. Yaffe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012. (Annotated translation of ten introductions written by Strauss to a multi-volume critical edition of Mendelssohn's work.) "Exoteric Teaching" (Critical Edition by Hannes Kerber). In Reorientation: Leo Strauss in the 1930s. Edited by Martin D. Yaffe and Richard S. Ruderman. New York: Palgrave, 2014, pp. 275–86. "Lecture Notes for 'Persecution and the Art of Writing'" (Critical Edition by Hannes Kerber). In Reorientation: Leo Strauss in the 1930s. Edited by Martin D. Yaffe and Richard S. Ruderman. New York: Palgrave, 2014, pp. 293–304. Leo Strauss on Nietzsche’s “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”. Edited by Richard L. Velkley. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017. Leo Strauss on Political Philosophy: Responding to the Challenge of Positivism and Historicism. Edited by Catherine H. Zuckert. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018. Leo Strauss on Hegel. Edited by Paul Franco. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019. Writings about Maimonides and Jewish philosophy Spinoza's Critique of Religion (see above, 1930). Philosophy and Law (see above, 1935). "Quelques remarques sur la science politique de Maïmonide et de Farabi". Revue des études juives 100 (1936): 1–37. "Der Ort der Vorsehungslehre nach der Ansicht Maimunis". Monatschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 81 (1936): 448–56. "The Literary Character of The Guide for the Perplexed" [1941]. 38–94 in Persecution and the Art of Writing. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1952. [1944] "How to Study Medieval Philosophy" [. Interpretation 23, no. 3 (Spring 1996): 319–338. Previously published, less annotations and fifth paragraph, as "How to Begin to Study Medieval Philosophy" in Pangle (ed.), The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism, 1989 (see above). [1952]. Modern Judaism 1, no. 1 (May 1981): 17–45. Reprinted Chap. 1 (I–II) in Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity, 1997 (see below). [1952]. Independent Journal of Philosophy 3 (1979), 111–18. Reprinted Chap. 1 (III) in Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity, 1997 (see below). "Maimonides' Statement on Political Science". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 22 (1953): 115–30. [1957]. L'Homme 21, n° 1 (janvier–mars 1981): 5–20. Reprinted Chap. 8 in Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity, 1997 (see below). "How to Begin to Study The Guide of the Perplexed". In The Guide of the Perplexed, Volume One. Trans. Shlomo Pines. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1963. [1965] "On the Plan of the Guide of the Perplexed" . Harry Austryn Wolfson Jubilee. Volume (Jerusalem: American Academy for Jewish Research), pp. 775–91. "Notes on Maimonides' Book of Knowledge". 269–83 in Studies in Mysticism and Religion Presented to G. G. Scholem. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1967. Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity: Essays and Lectures in Modern Jewish Thought. Ed. Kenneth Hart Green. Albany: SUNY P, 1997. Leo Strauss on Maimonides: The Complete Writings. Edited by Kenneth Hart Green. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. |

参考文献 書籍および記事 Gesammelte Schriften. Ed. Heinrich Meier. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1996. 現在までに4巻が刊行されている:第1巻『スピノザの宗教批判と関連文献』(改訂版、2001年)、第2巻『哲学と法、初期の著作』(1997年)、第3 巻『ホッブズの政治的学問と関連文献 - 書簡』(2001年)、第4巻『政治哲学。シリーズ全巻には、第5巻『暴政について』(2013年)と第6巻『マキャベリについての考察。ドイツ語初訳』 (2014年)も含まれる予定である。 レオ・シュトラウス:初期著作集(1921-1932)。(『全集』の一部からの翻訳)。マイケル・ザンク訳。オルバニー:SUNYプレス、2002年。 スピノザの宗教批判は、彼の聖書学の基礎である:スピノザの『神学・政治的論考』の研究。ベルリン:アカデミー・ヴェルク、1930年。 スピノザの宗教批判。(1930年の『スピノザの宗教批判』の英訳。エルザ・M・シンクレア訳。)新しい英訳序文とカール・シュミットに関する1932年 のドイツ語の論文の英訳を付す。ニューヨーク:ショッケン、1965年。その論文を除いて再版、シカゴ大学出版、1997年。 「カール・シュミット『政治的概念』についての注釈」『社会政策および社会政策に関するアーカイブ』67巻、第6号(1932年8月~9月):732~49ページ。 「カール・シュミットの『政治的概念』についてのコメント」(1932年の「カール・シュミットについての注釈」の英訳、エルザ・M・シンクレア著)『ス ピノザの宗教批判』1965年、331-51ページ。再掲:『カール・シュミット、政治的概念』編・訳ジョージ・シュワブ。ニュージャージー州ニューブラ ンズウィック:ラトガース大学出版、1976年。 「カール・シュミット『政治の概念』についての覚書」(1932年の「カール・シュミットについての覚書」の英訳)。ハインリヒ・マイヤー著、J. ハーヴェイ・ロマックス訳『カール・シュミットとレオ・シュトラウス:隠された対話』シカゴ大学出版、1995年。ジョージ・シュワブ編・訳『カール・ シュミット『政治の概念』』シカゴ大学出版、1996年、2007年。U of Chicago P, 1996, 2007. Philosophie und Gesetz: Beiträge zum Verständnis Maimunis und seiner Vorläufer. Berlin: Schocken, 1935. 哲学と法:マイモニデスとその先駆者たちを理解するための論文。(1935年の『Philosophie und Gesetz』の英訳。フィラデルフィア:Jewish Publication Society, 1987. 哲学と法:マイモニデスとその先人たちの理解への貢献。(英訳は、1935年の『哲学と法』の序文をイヴ・アドラーが担当。)オルバニー:SUNYプレス、1995年。 ホッブズの政治哲学:その基礎と起源。(英訳は、エルザ・M・シンクレアがドイツ語原稿から担当。)オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、1936年。新序文を付して再版、シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1952年。 ホッブズの政治学の起源(1935年の『ホッブズの政治哲学』のドイツ語版、1936年)。ノイヴィート・アム・ライン:ヘルマン・ルヒターハント、1965年。 「スパルタの精神またはクセノフォンの味わい」『Social Research』第6巻第4号(1939年冬)、502-36ページ。 「ドイツ・ニヒリズムについて」(1999年、1941年の講演を元に執筆)、デビッド・ジャンセンズとダニエル・タンゲイ編集『解釈』第26巻第3号。 「ファラビーのプラトン」アメリカ・アカデミー・フォー・ジューイッシュ・リサーチ、ルイス・ギンズバーグ・ジュビリー・ボリューム、1945年。45ページ。 「プラトンの政治哲学の新しい解釈について」。ソーシャル・リサーチ13巻3号(1946年秋):326-67ページ。 「ルソーの意図について」『Social Research』14巻4号(1947年冬):455-87ページ。 『専制について:クセノフォンの『ヒエロス』の解釈』アルヴィン・ジョンソンによる序文。ニューヨーク:Political Science Classics、1948年。再版:イリノイ州グレンコー:The Free Press、1950年。 『専制論』(『専制について』のフランス語訳、1948年、「クセノフォンのヒエロについての再論」およびアレクサンドル・コジェーヴの「専制と英知」を付す)パリ:ガリマール書店、1954年。 『専制について』(『専制論』の英語版、1954年)イサカ:コーネル大学出版、1963年。 『専制論』 (1963年の『専制論』の改訂・増補版) シュトラウスとコジューヴの往復書簡を含む。編者:ヴィクター・グレヴィッチとマイケル・S・ロス。ニューヨーク:フリープレス、1991年。 「コリングウッドの歴史哲学について」『形而上哲学評論』5巻4号(1952年6月):559-86。 迫害と執筆術。イリノイ州グレンコー:フリープレス、1952年。再版:シカゴ大学出版、1988年。 自然権と歴史。(1949年のウォルグリーン講義に基づく)シカゴ大学出版、1953年。1971年に新たな序文を加えて再版。ISBN 978-0-226-77694-1。 「実存主義」(1956年)は、マルティン・ハイデガーの思想に関する公開講演であり、『解釈』1995年春号、第22巻第3号に掲載された。 プラトン『国家』についてのセミナー(1957年の講義)、(1961年の講義)。シカゴ大学。 マキャベリについての考察。イリノイ州グレンコー:フリープレス、1958年。再版シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、1978年。 政治哲学とは何か? およびその他の研究。イリノイ州グレンコー:フリープレス、1959年。再発行シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、1988年。 プラトンの『饗宴』について [1959年]。編集セス・ベナードテ。(1959年の講義の編集記録)シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2001年。 「相対主義」ヘルムート・シェックとジェームズ・W・ウィギンズ編『相対主義と人間研究』135-57ページ。プリンストン:D.ヴァン・ノストランド、1961年。一部再版、13-26ページ。『古典的政治的合理主義の復活』1989年。 『政治哲学の歴史』ジョセフ・クロプシーとの共編。シカゴ: U of Chicago P, 1963年(初版)、1972年(第2版)、1987年(第3版)。 「現代の危機」、41-54ページ、「政治哲学の危機」、91-103ページ、ハワード・スパース編『現代政治の苦境』。デトロイト:デトロイト大学出版局、1964年。 「政治哲学と現代の危機」(ハワード・スペース編『現代政治の苦境』所収の2つの論文の改稿)217-42ページ、ジョージ・J・グラハム・ジュニア、ジョージ・W・ケアリー編『ポスト行動主義時代:政治学の視点』ニューヨーク:デイヴィッド・マッケイ、1972年。 『都市と人間』。(1962年のページ・バーバー講義に基づく。)シカゴ:ランド・マクナリー、1964年。 『ソクラテスとアリストパネス』。ニューヨーク:ベーシック・ブックス、1966年。再版シカゴ:U of Chicago P、1980年。 『リベラリズムの古代と近代』。ニューヨーク:Basic Books、1968年。アラン・ブルームによる序文付きで1989年に再版。シカゴ大学出版局、1995年に再版。 『クセノフォンのソクラテス論:『経済人』の解釈』。イサカ:コーネル大学出版局、1970年。 ニーチェ著『善悪の彼岸』の計画に関する注釈。セントジョンズ・カレッジ、1971年。 クセノフォン著『ソクラテス』。イサカ:コーネル大学出版、1972年。 プラトン著『国家』の論拠と行動。シカゴ大学出版、1975年。 レオ・シュトラウス著『政治哲学:6つのエッセイ』ヒレイル・ギルデン編。インディアナポリス:ボブズ・メリル、1975年。 レオ・シュトラウス著『政治哲学入門:10のエッセイ』(『政治哲学:6つのエッセイ』1975年の増補版)ヒレイル・ギルデン編。デトロイト:ウェイン州立大学出版、1989年。 プラトン政治哲学研究。トーマス・L・パングルによる序文。シカゴ大学出版、1983年。 古典的政治合理主義の復活:レオ・シュトラウスの思想入門-レオ・シュトラウスの論文と講義。トーマス・L・パングル編。シカゴ大学出版、1989年。 『信仰と政治哲学:レオ・シュトラウスとエリック・ヴォーゲリンの往復書簡、1934年~1964年』ピーター・エンバリー、バリー・クーパー編。トーマス・L・パンゲルによる序文。ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティ・パーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局、1993年。 ホッブズの宗教批判と関連文献。編者および訳者:ガブリエル・バートレット、スヴェトザル・ミンコフ。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2011年。(『全集』第 3巻に初出の資料の翻訳。レオ・シュトラウスによるホッブズに関する未完の原稿(1933年~1934年執筆)と、より短い関連文献を含む。) レオ・シュトラウスによるモーゼス・メンデルスゾーン論。マーティン・D・ヤーフェ編訳。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2012年。(メンデルスゾーンの著作の複数巻からなる批判版にシュトラウスが寄せた10の序文の注釈付き翻訳。) 「通俗的教え」(ハネス・ケルバーによる批判版)。『再定位:1930年代のレオ・シュトラウス』マーティン・D・ヤーフェとリチャード・S・ルーダーマン編。ニューヨーク:パルグレーブ、2014年、275~86ページ。 「『迫害と執筆術』講義ノート」(ハネス・ケルバーによる批判的版)。『再定位:1930年代のレオ・シュトラウス』マーティン・D・ヤッフェとリチャード・S・ルーダーマン編。ニューヨーク:パルグレーブ、2014年、293-304ページ。 ニーチェ『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』に関するレオ・シュトラウス。リチャード・L・ヴェルクレイ編。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2017年。 政治哲学に関するレオ・シュトラウス:実証主義と歴史主義の挑戦への応答。キャサリン・H・ズッカート編。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2018年。 ヘーゲルに関するレオ・シュトラウス。ポール・フランコ編。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、2019年。 マイモニデスとユダヤ哲学に関する著作 スピノザの『宗教批判』(上記参照、1930年)。 『哲学と法』(上記参照、1935年)。 「マイモニデスとファラビーの政治学に関するいくつかの指摘」。『Revue des études juives』100(1936年):1-37。 「マインムニスの見解による摂理説の場所」『ユダヤ教の歴史と学問に関する月刊誌』81(1936年):448-56。 「『ガイド・フォー・ザ・パープレクスト』の文学的特徴」[1941年]。『迫害と執筆術』38-94。シカゴ大学出版、1952年。 [1944] 「中世哲学の研究法」[. Interpretation 23, no. 3 (Spring 1996): 319–338. 以前に「中世哲学の研究法」として、注釈が少なく第5段落が省略された形で、Pangle (ed.), The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism, 1989 (上記参照) に掲載された。 [1952] 『現代ユダヤ教』第1巻第1号(1981年5月):17-45ページ。第1章(I-II)は『ユダヤ教哲学と近代性の危機』1997年(下記参照)に再掲。 [1952]。『Independent Journal of Philosophy』3 (1979), 111–18. 第1章(第3部)は『Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity』1997(下記参照)に再録。 「政治学に関するマイモニデスの声明」。『Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research』22 (1953): 115–30. [1957]。L'Homme 21, n° 1 (janvier–mars 1981): 5–20. 1997年(下記参照)の『ユダヤ哲学と近代性の危機』第8章に再掲。 「『困惑の指針』の研究の始め方」『『困惑の指針』第1巻』。訳:Shlomo Pines。シカゴ大学出版、1963年。 [1965]「『困惑の指針』の計画について」『ハリー・オースティン・ウォルフソン・ジュビリー』第1巻(エルサレム:アメリカ・アカデミー・フォー・ジューイッシュ・リサーチ)、775-91ページ。 「マイモニデスの『知識の書』に関する注釈」。G. G. ショーレムに捧げる『神秘主義と宗教に関する研究』269-83ページ。エルサレム:マグネス・プレス、1967年。 ユダヤ哲学と近代性の危機:近代ユダヤ思想に関する論文と講義。ケネス・ハート・グリーン編。オルバニー:SUNY P、1997年。 レオ・シュトラウスによるマイモニデス:全著作。ケネス・ハート・グリーン編。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2013年。 |

| American philosophy List of American philosophers Neoconservatism, often referred as inspired by the work of Strauss Lev Shestov Allan Bloom Seth Benardete Jacob Klein |

アメリカ哲学 アメリカの哲学者一覧 ネオコンサバティズム(しばしばシュトラウスの著作に触発されたとして言及される レフ・シェストフ アラン・ブルーム セス・ベナルデテ ジェイコブ・クライン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Strauss |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆