ハイチャーチとローチャーチ

High

Church and Low Charch

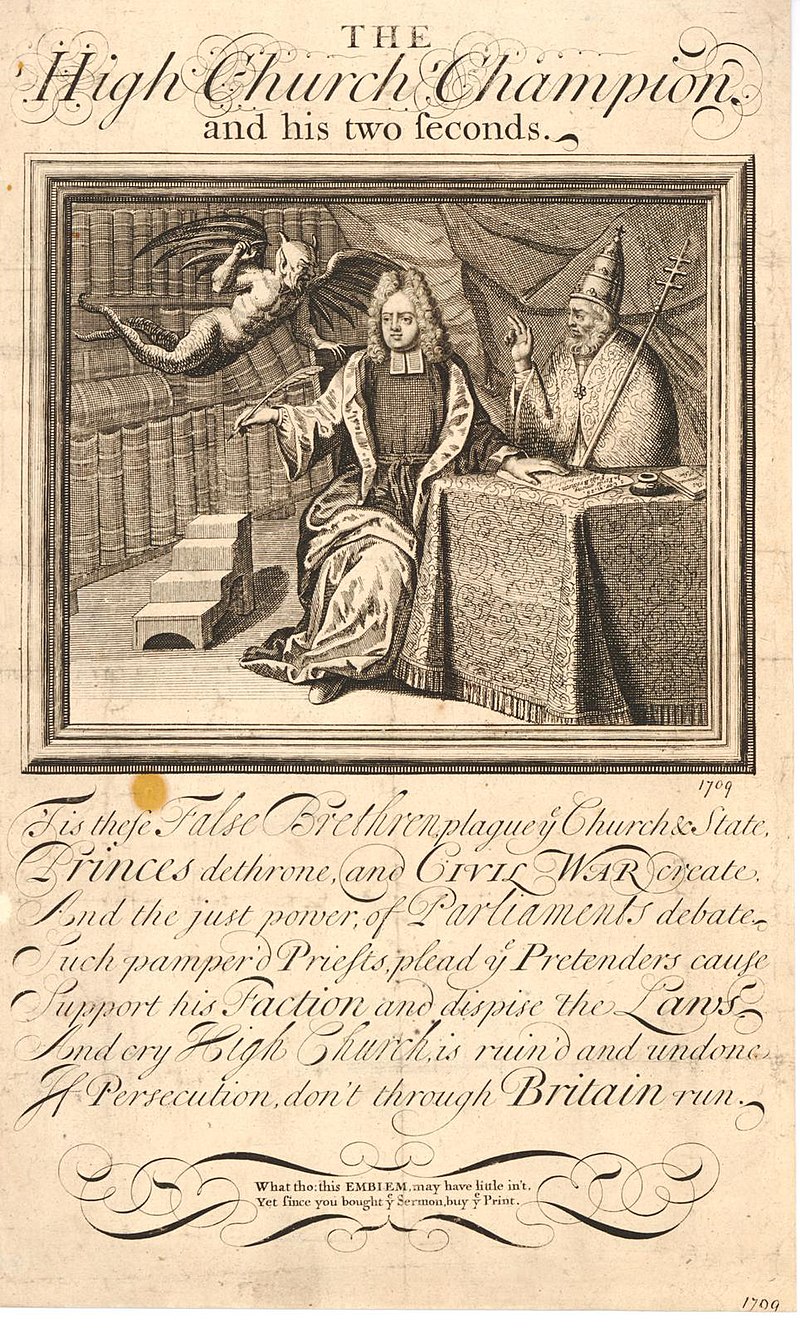

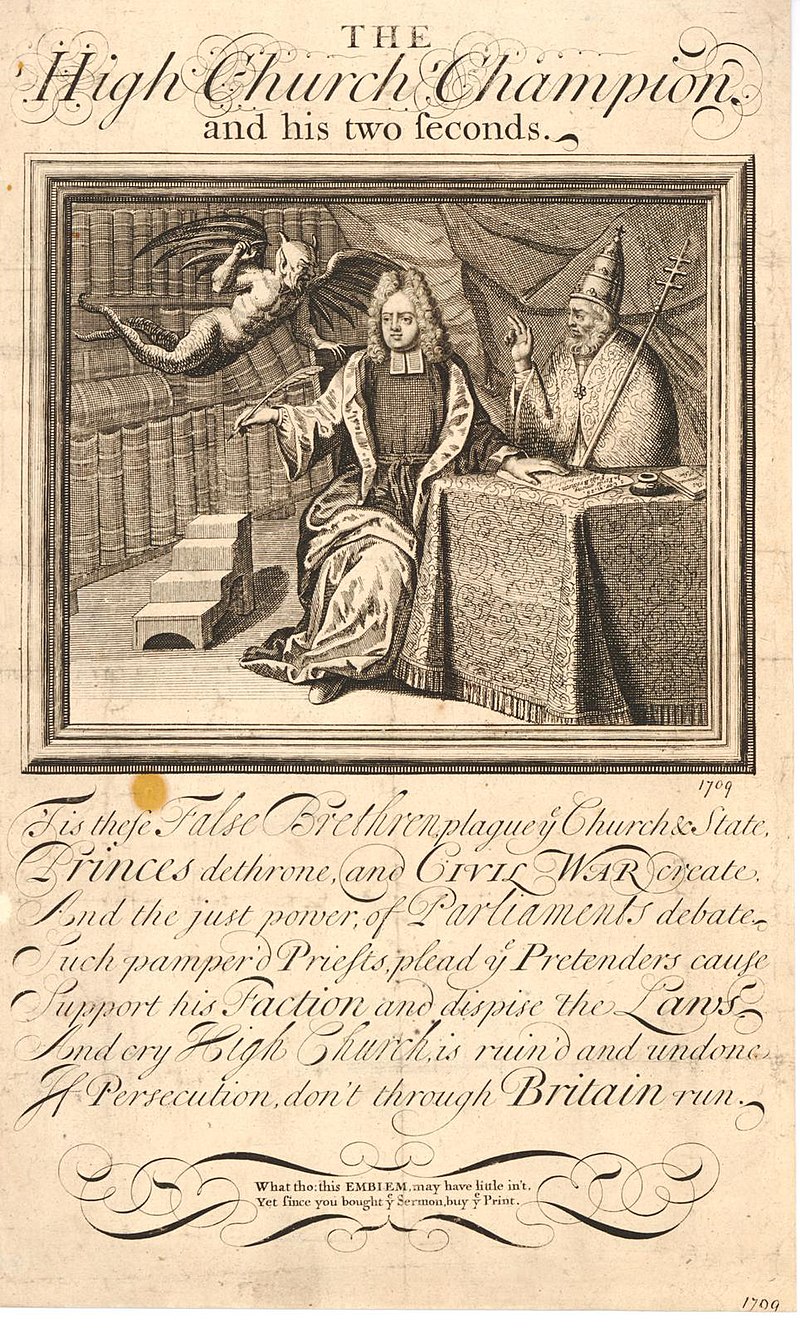

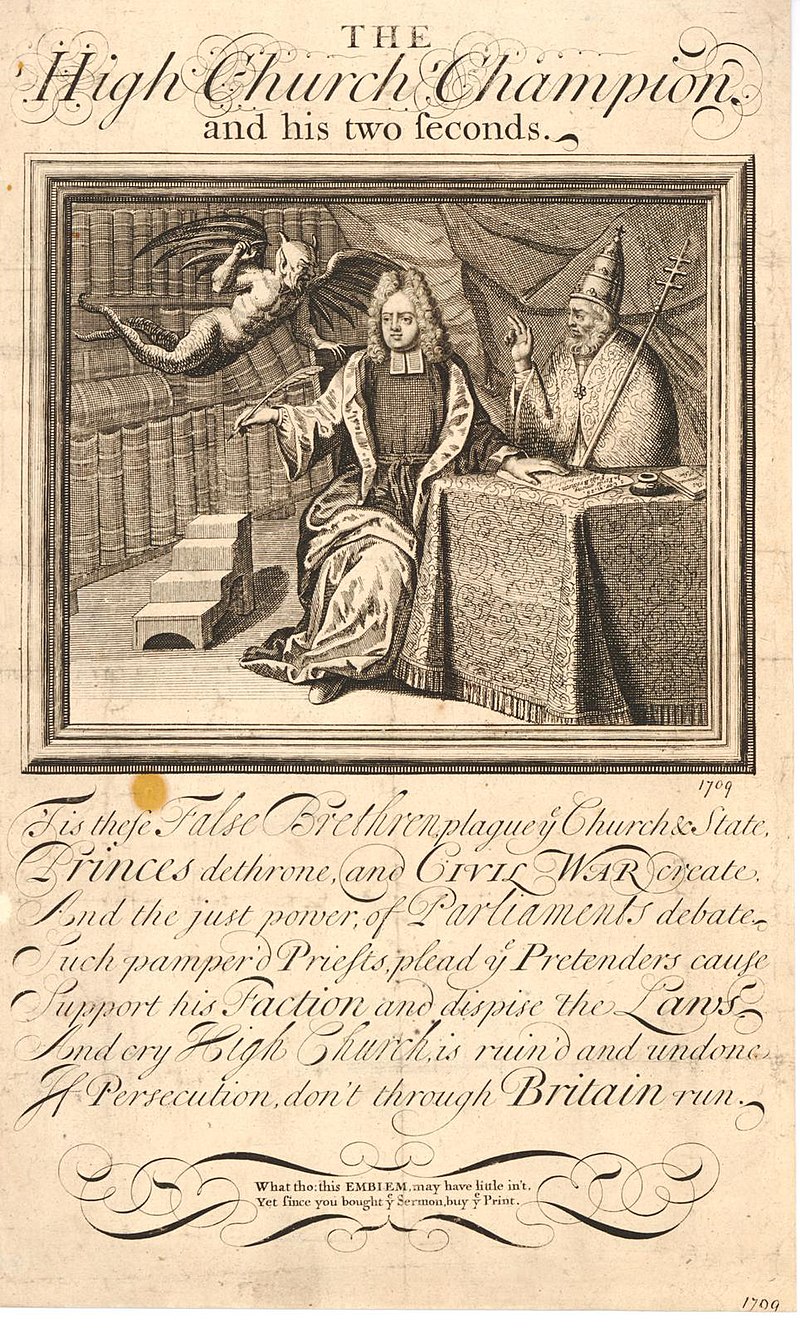

Left: Satirical broadside of 1709/10 accusing Henry Sacheverell, "The High Church Champion," of "Popery."

Rihht:

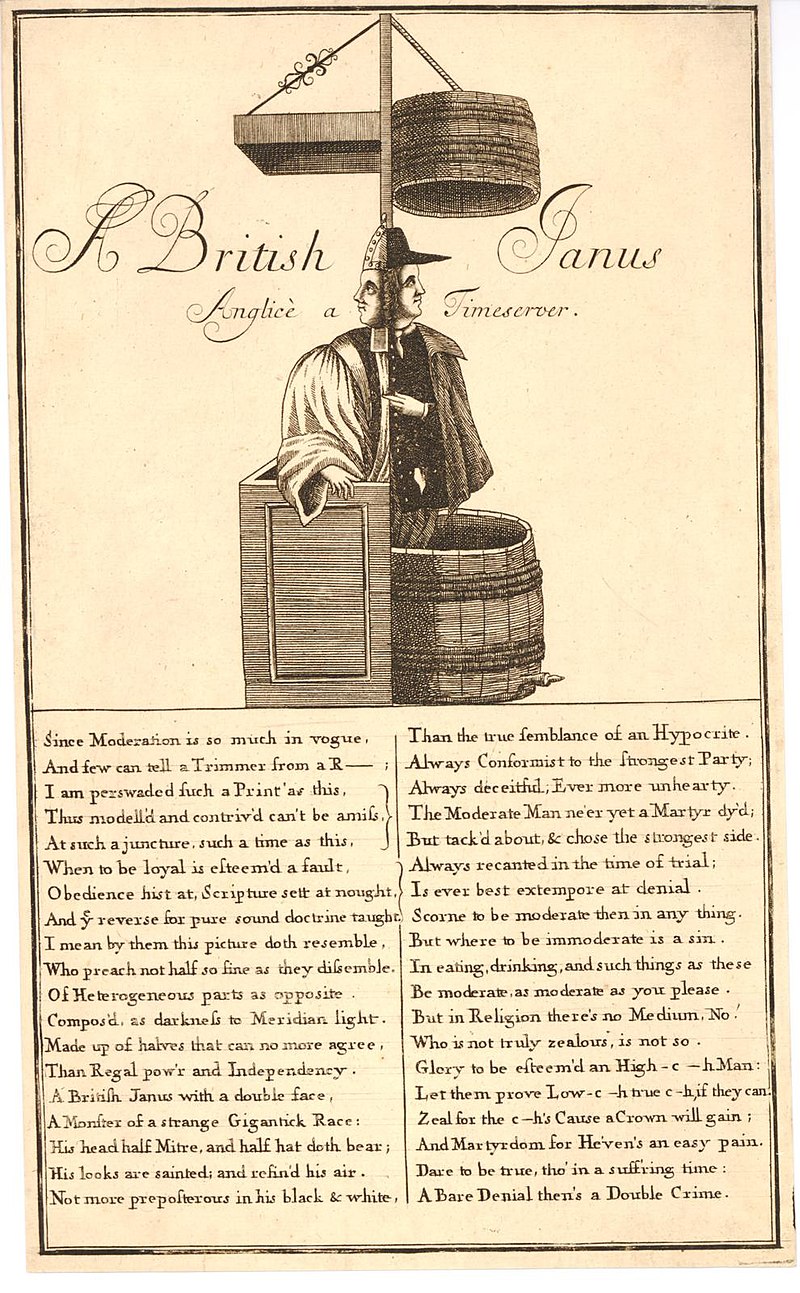

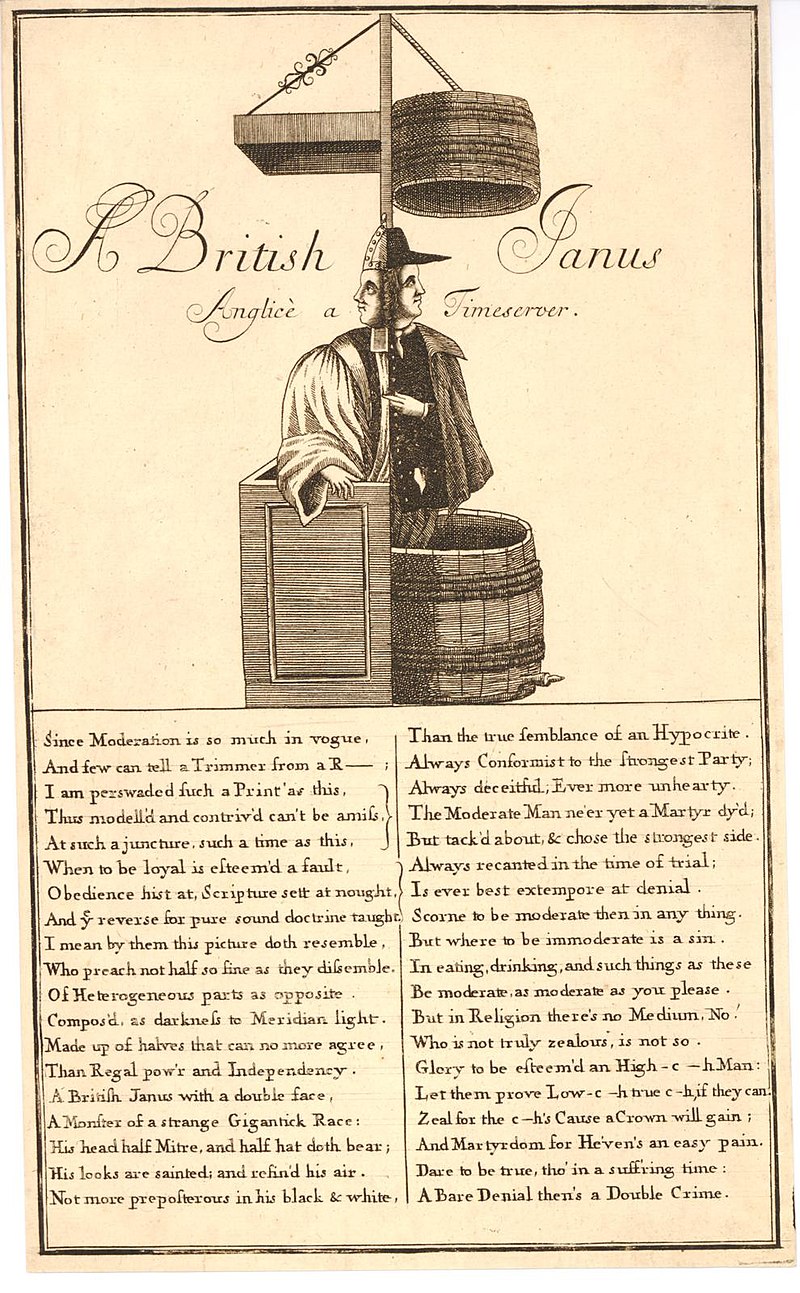

1709 satirical broadside with

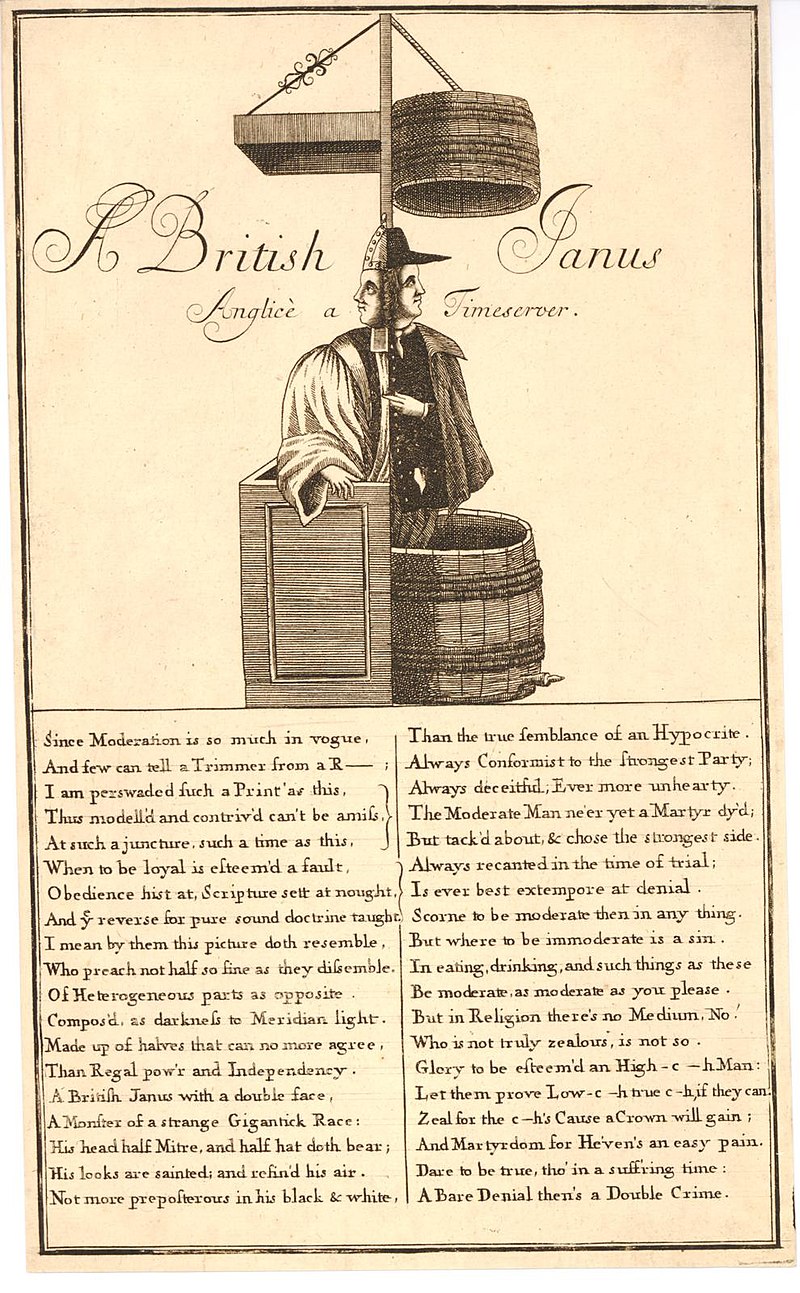

an engraving showing a Janus figure preaching, the left half showing a

bishop in a pulpit, the right half a puritan in a tub.

池田光穂

● ハイチャーチ(High Church )における、教会論と典礼主義(→洗練された儀礼主義?)とローチャーチ

""High church" Christian denominations are those who emphasize formality in beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology, and often resist "modernisation". Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originated in and has been principally associated with the Anglican/Episcopal tradition, where it describes Anglican churches using a number of ritual practices associated in the popular mind with Roman Catholicism. The opposite is low church. Contemporary media discussing Anglican churches tend to prefer evangelical to "low church", and Anglo-Catholic to "high church", though the terms do not exactly correspond. Other contemporary denominations that contain high church wings include some Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Methodist churches." - High church.

「ハ

イチャーチ」とは、教会論、典礼、神学などの信仰と実践において形式を重視し、しばしば「近代化」に抵抗するキリスト教宗派のことである。さまざまなキリ

スト教の伝統に関連して使われるが、この用語は主に英国国教会/司教団の伝統に由来しており、主に英国国教会/司教団の伝統に関連している。その反対は低

教会である。聖公会の教会を論じる現代のメディアは、「ローチャーチ」に対して福音主義を、「ハイチャーチ」に対してアングロカトリックを好む傾向がある

が、これらの用語は厳密には一致しない。ハイチャーチの翼を持つ他の現代教派には、ルーテル教会、長老派教会、メソジスト教会などがある。

""Low church" Christian denominations are those who give relatively little emphasis to ritual, sacraments and the authority of clergy. The term is most often used in a liturgical context./ The term was initially intended to be pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 17th century, commentators and others—who favoured the theology, worship, and hierarchical structure of Anglicanism (such as the episcopate) as the true form of Christianity—began referring to that outlook (and the related practices) as "high church". In contrast, by the early 18th century, those theologians and politicians who sought more reform in the English church and a greater liberalisation of church structure, were called "low church"./ "Low church", in a contemporary Anglican context, denotes the church's simplicity or Protestant emphasis, and "high church" denotes an emphasis on ritual or, later, Anglo-Catholicism."- Low church.

「ロー

チャーチ」とは、儀式や秘跡、聖職者の権威を比較的重視しないキリスト教の教派のことである。この用語は、典礼の文脈で使われることが多い。17世紀、既

成教会に対する一連の教義的・教会主義的な挑戦の中で、英国国教会の神学、礼拝、階層構造(司教座など)をキリスト教の真の姿として支持する論者などが、

そのような考え方(および関連する慣習)を「ハイチャーチ」と呼ぶようになった。これとは対照的に、18世紀初頭までには、英国教会にさらなる改革を求

め、教会構造をより自由化しようとする神学者や政治家は「ローチャーチ」と呼ばれるようになった/現代の英国国教会の文脈では、「ローチャーチ」は教会の

簡素さやプロテスタント的な強調を表し、「ハイチャーチ」は儀式の強調や、後にはアングロカトリック的な強調を表す。

| 用語集 glossary |

教会論 Ecclesiology |

典礼 Liturgy |

再帰的近代化 Reflexive modernization |

||||||

*****

| The term high church

refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and

theology that emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, [and]

sacraments".[1] Although used in connection with various Christian

traditions, the term originated in and has been principally associated

with the Anglican tradition, where it describes churches using a number

of ritual practices associated in the popular mind with Roman

Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. The opposite tradition is low

church. Contemporary media discussing Anglican churches often prefer

the terms evangelical to low church and Anglo-Catholic to high church,

even though their meanings do not exactly correspond. Other

contemporary denominations that contain high church wings include some

Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Methodist churches. Variations Because of its history, the term high church also refers to aspects of Anglicanism quite distinct from the Oxford Movement or Anglo-Catholicism. There remain parishes that are high church and yet adhere closely to the quintessentially Anglican usages and liturgical practices of the Book of Common Prayer. High church Anglicanism tends to be closer than low church to Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox teachings and spirituality; its hallmarks are relatively elaborate music, altarpieces, and clergy vestments and an emphasis on sacraments. It is intrinsically traditional. High church nonetheless includes many bishops, other clergy and adherents sympathetic to mainstream modern consensus across reformed Christianity that, according to official Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian teachings, are anathema (see the ordination of women and to varying degrees abortion). The term high church has also been applied to elements of Protestant churches within which individual congregations or ministers display a division in their liturgical practices, for example, high church Presbyterianism and high church Methodism, and within Lutheranism there is a historic high church and low church distinction comparable with Anglicanism (see Neo-Lutheranism and Pietism). |

高教会(ハイチャーチ)という用語は、キリスト教の教会論、典礼、神学

において、「儀式、司祭の権威、聖礼典」を重視する信仰と実践を指す[1]。様々なキリスト教の伝統と関連して用いられるが、この用語は主に聖公会の伝統

に由来し、主に聖公会の伝統と関連付けられてきた。反対の伝統はロー・チャーチである。聖公会の教会を論じる現代のメディアは、ロー・チャーチに対して福

音派、ハイ・チャーチに対してアングロ・カソリックという言葉を好んで使うことが多いが、その意味は厳密には一致しない。高教会の翼を持つ他の現代教派に

は、ルーテル教会、長老派教会、メソジスト教会などがある。 バリエーション その歴史的経緯から、高教会という用語は、オックスフォード運動やアングロカトリックとは全く異なる英国国教会の側面を指すこともある。高教会でありなが ら、『共通祈祷書』の典型的な聖公会の慣習や典礼に忠実な小教区も残っている。 高教会聖公会は、低教会よりもローマ・カトリックや東方正教会の教えや霊性に近い傾向がある。その特徴は、比較的手の込んだ音楽、祭壇画、聖職者の法衣で あり、秘跡を重視することである。本質的に伝統的である。 それにもかかわらず、高教会には、ローマ・カトリックや東方正教会の公式の教えによれば忌み嫌われる改革派キリスト教の主流派の現代的コンセンサスに同調 する多くの司教やその他の聖職者、信奉者が含まれる(女性の聖職就任や程度の差はあれ妊娠中絶を参照)。 高教会という用語は、個々の信徒や牧師が典礼の実践において分裂を示すプロテスタント教会の要素にも適用されている。例えば、高教会長老派や高教会メソジ スト派がそうであり、ルター派においても、聖公会主義に匹敵する歴史的な高教会と低教会の区別がある(新ルター派と敬虔主義を参照)。 |

Evolution of the term Satirical broadside of 1709/10 accusing Henry Sacheverell, "The High Church Champion," of "Popery." High church is a back-formation from "high churchman", a label used in the 17th and early 18th centuries to describe opponents of religious toleration, with "high" meaning "extreme".[2] As the Puritans began demanding that the English Church abandon some of its traditional liturgical emphases, episcopal structures, parish ornaments and the like, the high church position also came to be distinguished increasingly from that of the Latitudinarians, also known as those promoting a broad church, who sought to minimise the differences between Anglicanism and Reformed Christianity, and to make the church as inclusive as possible by opening its doors as widely as possible to admit other Christian viewpoints. Over time several of the leading lights of the Oxford Movement became Roman Catholics, following the path of John Henry Newman, one of the fathers of the Oxford Movement and, for a time, a high churchman himself. A lifelong High Churchman, the Reverend Edward Bouverie Pusey remained the spiritual father of the Oxford Movement who remained a priest in the Church of England. To a lesser extent, looking back from the 19th century, the term high church also came to be associated with the beliefs of the Caroline divines and with the pietistic emphases of the period, practised by the Little Gidding community, such as fasting and lengthy preparations before receiving the Eucharist. Before 1833 During the reign of King James I, there were attempts to diminish the growth of party feeling within the Church of England, and indeed to reconcile to the Church moderate Puritans who did not already conform to the Established Church or who had left the Church in recent years. The project to create the Authorized Version of the Bible was one such attempt at reconciliation. The continued use of the King James version of the Bible, by Anglicans and other Protestants alike in the English-speaking world, is a reflection of the success of this endeavour at cooperation. During the reign of King Charles I, however, as divisions between Puritan and Catholic elements within the Church of England became more bitter, and Protestant Nonconformity outside the Church grew stronger in numbers and more vociferous, the High Church position became associated with the leadership of the High Church Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, (see Laudianism), and government policy to curtail the growth of Protestant Dissent in England and the other possessions of the Crown. See, for example, the attempt to reimpose episcopacy on the Church of Scotland, a policy that was 'successful' until the reign of William and Mary, when the office of bishop was discontinued except among the small minority of Scots who belonged to the Scottish Episcopal Church. In the wake of the disestablishment of Anglicanism and the persecution of Anglican beliefs and practices under the Commonwealth, the return of the Anglican party to power in the Cavalier Parliament saw a strong revival of the High Church position in the English body politic. Victorious after a generation of struggle, the Anglican gentry felt the need to re-entrench the re-Anglicanised Church of England as one of the most important elements of the Restoration Settlement through a renewed and strengthened alliance between Throne and Altar, or Church and State. Reverence for martyrdom of the Stuart king Charles I as an upholder of his Coronation Oath to protect the Church of England became a hallmark of High Church orthodoxy. At the same time, the Stuart dynasty was expected to maintain its adherence to Anglicanism. This became an important issue for the High Church party and it was to disturb the Restoration Settlement under Charles II's brother, King James II, a convert to Roman Catholicism, and lead to setbacks for the High Church party. These events culminated in the Glorious Revolution and the exclusion of the Catholic Stuarts from the British throne. The subsequent split over office-holders' oaths of allegiance to the Crown and the Royal Succession, which led to the exclusion of the Non-Juror bishops who refused to recognise the 1688 de facto abdication of the King, and the accession of King William III and Queen Mary II, and did much to damage the unity of High Church party. Later events surrounding the attempts of the Jacobites, the adherents of the excluded dynasts, to regain the English and Scottish thrones, led to a sharpening of anti-Catholic rhetoric in Britain and a distancing of the High Church party from the more ritualistic aspects of Caroline High churchmanship, which were often associated with the schismatic Non-Jurors. Thomas Hancorne, a Welsh clergyman prominent in jacobite circles, gave the County of Swansea's assize sermon on 18 April 1710 (The right way to honour and happiness), during which he complained of the "rapid growth of deist, freethinking and anti-trinitarian views."[3][4] The targets of Hancorne's wrath were "irreligion, profaneness and immorality", as well as the "curious, inquisitive sceptics" and the "sin-sick tottering nation". Later, he engaged in a campaign to reassert tithe rights.[5] Eventually, under Queen Anne, the High Church party saw its fortunes revive with those of the Tory party, with which it was then strongly associated. However, under the early Hanoverians, both the High Church and Tory parties were once again out of favour. This led to an increasing marginalisation of High Church and Tory viewpoints, as much of the 18th century was given over to the rule of the Whig party and the aristocratic families who were in large measure pragmatic latitudinarians in churchmanship. This was also the Age of Reason, which marked a period of great spiritual somnolence and stultification in the Church of England. Thus, by the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, those liturgical practices prevalent even in High Church circles were not of the same tenor as those later found under the Catholic revival of the 19th century. High Church clergy and laity were often termed high and dry, in reference to their traditional high attitude with regard to political position of the Church in England, and dry faith, which was accompanied by an austere but decorous mode of worship, as reflective of their idea of an orderly and dignified churchmanship against the rantings of the low churchmen that their Cavalier ancestors had defeated. Over time, their High Church position had become ossified among a remnant of bookish churchmen and country squires. An example of an early 19th-century churchman of this tradition is Sir Robert Inglis MP. From 1833  Eucharistic procession by the Church of St. Mary Magdalene (Toronto) Only with the success of the Oxford Movement and its increasing emphases on ritualistic revival from the mid-19th century onward, did the term High Church begin to mean something approaching the later term Anglo-Catholic. Even then, it was only employed coterminously in contrast to the Low churchmanship of the Evangelical and Pietist position. This sought, once again, to lessen the separation of Anglicans (the Established Church) from the majority of Protestant Nonconformists, who by this time included the Wesleyans and other Methodists as well as adherents of older Protestant denominations known by the group term Old Dissent. In contrast to earlier alliances with the Tories, Anglo-Catholicism became increasingly associated with socialism, the Labour Party and greater decision-making liberty for the church's convocations. From the mid-19th century onward, the term High Church generally became associated with a more avowedly Anglo-Catholic liturgical or even triumphalist position within the English Church, while the remaining Latitudinarians were referred to as being Broad Church and the re-emergent evangelical party was dubbed Low Church. However, high church can still refer to Anglicans who hold a high view of the sacraments, church tradition and the threefold ministry but do not specifically consider themselves Anglo-Catholics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_church |

用語の変遷 1709/10年、"High Church Champion "のHenry Sacheverellを "Popery"(教皇崇拝)と非難した風刺的な書物。 高教会とは、17世紀から18世紀初頭にかけて宗教的寛容に反対する人々を表すために用いられた「高教会主義者(high churchman)」から転じたもので、「高」は「極端な」を意味する。 [2]清教徒が英国教会に対して、伝統的な典礼の強調、司教の構造、教区の装飾などの一部を放棄することを要求し始めると、高教会の立場は、英国国教会と 改革派キリスト教との間の相違を最小限に抑え、他のキリスト教の視点を受け入れるために教会の門戸を可能な限り広く開くことによって、教会を可能な限り包 括的なものにしようとする、広教会推進派としても知られる緯度派(Latitudinarians)の立場とも次第に区別されるようになった。 やがて、オックスフォード運動の指導的立場にあった何人かがローマ・カトリック信者となり、オックスフォード運動の父の一人で、一時は自らも大教会主義者 であったジョン・ヘンリー・ニューマンの道をたどった。エドワード・ブーリー・ピューシー牧師は、生涯、英国国教会の司祭であり続けたオックスフォード運 動の精神的父である。19世紀から振り返ってみると、高教会という言葉は、カロライン派の神学者たちの信仰や、リトル・ギディングの共同体が実践していた 断食や聖体を受ける前の長い準備といった、当時の敬虔主義的な強調事項とも関連付けられるようになった。 1833年以前 ジェームズ1世の時代には、イングランド国教会内部での党派感情の高まりを抑えようとする試みがなされ、実際、すでに既成教会に準拠していなかったり、近 年教会を離れたりした穏健なピューリタンたちを教会に和解させようとする試みもあった。オーソライズド・ヴァージョン(公認聖書)の作成プロジェクトは、 そのような和解の試みの一つであった。英語圏の英国国教会やその他のプロテスタントが欽定訳聖書を使用し続けているのは、この協力の試みの成功を反映して いる。 しかし、チャールズ1世の治世になると、イングランド国教会内の清教徒とカトリックの分裂が激しくなり、国教会外のプロテスタントの反体制派が数を増や し、声高に主張するようになったため、国教会の立場は、国教会のカンタベリー大主教であるウィリアム・ロー(ローディアニズムを参照)の指導と結びつい た。この政策はウィリアムとメアリーの治世まで「成功」し、スコットランド司教座教会に属する少数のスコットランド人を除いて司教職は廃止された。 英連邦の下で英国国教会が廃止され、英国国教会の信仰と慣習が迫害された後、騎兵議会で英国国教会が政権に返り咲くと、英国政治における高等教会の地位が 力強く復活した。一世代にわたる闘争の末に勝利した英国国教会の貴族たちは、王座と祭壇、あるいは教会と国家の間の同盟関係を新たに強化することで、再ア ングリカン化した英国国教会を維新の和解の最も重要な要素の一つとして再び定着させる必要性を感じていた。イングランド国教会を守るために戴冠の誓いを立 てたスチュアート朝国王チャールズ1世の殉教への敬意は、国教会の正統性を示すものとなった。同時に、スチュアート朝は英国国教会の信奉を維持することが 求められた。このことは高教会派にとって重要な問題となり、ローマ・カトリックへの改宗者であったチャールズ2世の弟、ジェームズ2世のもとでの王政復古 の和解を乱し、高教会派の挫折につながることとなった。これらの出来事は、栄光革命とカトリックのスチュアート家のイギリス王位からの排除に結実した。そ の後、役職者の王室への忠誠誓約と王位継承をめぐる分裂が起こり、1688年の国王の事実上の退位を認めない非ジュラー派の司教が排除され、国王ウィリア ム3世と女王メアリー2世が即位し、高教会派の結束に大きなダメージを与えた。 その後、排除された王朝の信奉者であるジャコバイトがイギリスとスコットランドの王位を奪還しようとしたことから、イギリスでは反カトリックのレトリック が先鋭化し、高教会派は、しばしば分裂主義者である非ジュラー派と結びついていたカロライン高教会派の儀式的な側面から距離を置くようになった。ジャコバ イト界隈で著名なウェールズの聖職者トマス・ハンコーンは、1710年4月18日にスウォンジー郡で説教(The right way to honour and happiness)を行い、その中で「神学者、自由主義者、反三位一体主義者の見解が急速に増えている」と訴えた[3][4]。 「ハンコーンが怒りの対象としたのは、「無宗教、不敬、不道徳」、「好奇心旺盛で詮索好きな懐疑主義者」、「罪に病んでよろめく国民」であった[3] [4]。その後、彼は什分の一の権利を再び主張するキャンペーンを行った[5]。やがてアン女王の時代になると、ハイ・チャーチ党は、当時強く結びついて いたトーリー党とともに運気を回復させた。 しかし、ハノーヴァー朝初期には、ハイ・チャーチ党もトーリー党も再び支持されなくなった。このため、18世紀の大半はホイッグ党と貴族階級の支配に委ね られ、貴族階級は教会主義において実利的な緯度主義者であった。また、この時代は理性の時代でもあり、イングランド国教会の精神的な沈滞と澱みの時代でも あった。 そのため、18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけては、典礼の慣習は、後に19世紀のカトリック復興期に見られるようなものではなかった。高教会の聖職者と信 徒は、しばしばハイ・アンド・ドライと呼ばれたが、これはイングランドにおける教会の政治的地位に対する伝統的な高慢な態度にちなむものであり、また、彼 らの祖先である騎兵隊が打ち破った低教会主義者の暴言に対抗する秩序ある威厳ある教会主義という彼らの考えを反映するものとして、厳格だが礼儀正しい礼拝 様式を伴うドライな信仰を指していた。時が経つにつれ、彼らの高教会的立場は、書物好きな教会員や田舎の従者の残党の間で骨抜きにされていった。このよう な伝統を持つ19世紀初期のチャーチマンの一例が、ロバート・イングリス議員である。 1833年から  聖マグダレン教会の聖体行列(トロント) 19世紀半ば以降、オックスフォード運動が成功し、儀式的復興がますます強調されるようになって初めて、ハイ・チャーチという用語が、後のアングロ・カト リックという用語に近い意味を持つようになった。それでも、福音主義者や敬虔主義者の立場による低教会主義との対比においてのみ、同義的に使われるに過ぎ なかった。これは再び、英国国教会(エスタブリッシュド・チャーチ)と、ウェスレアンをはじめとするメソジストやオールド・ディッセントというグループ名 で知られる古いプロテスタント教派の信奉者を含むプロテスタント・ノンコンフォーム派の大多数との分離を緩和しようとするものであった。それまでのトー リーと同盟を結んでいたのとは対照的に、アングロ・カトリックは社会主義、労働党、教会の召集に関するより大きな意思決定の自由との結びつきを強めていっ た。 19世紀半ば以降、ハイ・チャーチ(High Church)という言葉は一般的に、英国教会内のよりアングロ・カトリック的な典礼、あるいは凱旋主義的な立場を意味するようになり、残るラチチュード 派はブロード・チャーチ(Broad Church)と呼ばれ、再び台頭してきた福音派はロー・チャーチ(Low Church)と呼ばれるようになった。しかし、ハイ・チャーチは、聖餐式、教会の伝統、三位一体の聖職を高く評価するが、自分たちをアングロ・カソリッ クとは特に考えない英国国教会の信徒を指すこともある。 |

| Anglican Communion Notable parishes For a more comprehensive list, see List of Anglo-Catholic churches. Notable institutions Keble College, Oxford Pusey House, Oxford St Stephen's House, Oxford Nashotah House |

聖公会 著名な小教区 より包括的なリストは、アングロ・カトリック教会のリストを参照のこと。 著名な教育機関 ケブル・カレッジ(オックスフォード ピューシー・ハウス(オックスフォード セント・ステファンズ・ハウス(オックスフォード ナショタ・ハウス |

| Affirming Catholicism Anglican devotions Anglo-Catholicism Broad church Central churchmanship Crypto-papism Christian monasticism Church of England Church of South India Churchmanship Continuing Anglican Movement Anglican Catholic Church Anglican Catholic Church of Canada Anglican Church in America Anglican Province of America United Episcopal Church of North America Evangelical Catholic High Church Lutheranism High Mass Neo-Lutheranism Ritualism Society of Catholic Priests Scottish Church Society |

カトリックを肯定する 英国国教会の献身 アングロカトリック 広い教会 中央教会主義 クリプト・パピスム キリスト教修道会主義 イングランド教会 南インド教会 教会主義 聖公会の継続運動 英国国教会カトリック教会 カナダ聖公会カトリック教会 アメリカ聖公会 アメリカ聖公会 北アメリカ聖公会 福音主義カトリック ルーテル派高位教会 大ミサ 新ルーテル派 儀式主義 カトリック司祭協会 スコットランド教会協会 |

| In Anglican Christianity, low church refers to those who

give little emphasis to ritual. The term is most often used in a

liturgical sense, denoting a Protestant emphasis, whereas "high church"

denotes an emphasis on ritual, often Anglo-Catholic. The term was initially pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 17th century, commentators and others—who favoured the theology, worship, and hierarchical structure of Anglicanism (such as the episcopate) as the true form of Christianity—began referring to that outlook (and the related practices) as "high church", and by the early 18th century those theologians and politicians who sought more reform in the English church and a greater liberalisation of church structure, were in contrast called "low church". |

英国国教会では、低教会(ローチャーチ)は儀式をあまり重視しない人々

を指す。この用語は典礼的な意味で使われることが多く、プロテスタント的な強調を意味するのに対し、「高教会」は儀式を強調することを意味し、アングロ・

カトリック的であることが多い。 この用語は当初は蔑称であった。17世紀、既成教会に対する一連の教義的・教会主義的な挑戦の中で、英国国教会の神学、礼拝、階層構造(司教座など)をキ リスト教の真の姿として支持する論者などが、そのような考え方(および関連する慣習)を「高教会」と呼ぶようになり、18世紀初頭には、英国教会の改革や 教会構造の自由化を求める神学者や政治家が、対照的に「低教会」と呼ばれるようになった。 |

Historical use 1709 satirical broadside with an engraving showing a Janus figure preaching, the left half showing a bishop in a pulpit, the right half a puritan in a tub.  "Low Church Devotion" (Adolph Tidemand, 1852) The term low church was used in the early part of the 18th century as the equivalent of the term Latitudinarian in that it was used to refer to values that provided much latitude in matters of discipline and faith. The term was in contradistinction to the term high church, or high churchmen, which applied to those who valued the exclusive authority of the Established Church, the episcopacy and the sacramental system.[1] Low churchmen wished to tolerate Puritan opinions within the Church of England, though they might not be in agreement with Puritan liturgical practices. The movement to bring Separatists, and in particular Presbyterians, back into the Church of England ended with the Act of Toleration 1689 for the most part. Though Low church continued to be used for those clergy holding a more liberal view of Dissenters, the term eventually fell into disuse. Both terms were revived in the 19th century when the Tractarian movement brought the term "high churchman" into vogue. The terms were again used in a modified sense, now used to refer to those who exalted the idea of the Church as a catholic entity as the body of Christ, and the sacramental system as the divinely given means of grace. A low churchman now became the equivalent of an evangelical Anglican, the designation of the movement associated with the name of Charles Simeon, which held the necessity of personal conversion to be of primary importance.[1] At the same time, Latitudinarian changed to broad church, or broad churchmen, designating those who most valued the ethical teachings of the Church and minimised the value of orthodoxy. The revival of pre-Reformation ritual by many of the high church clergy led to the designation ritualist being applied to them in a somewhat contemptuous sense. However, the terms high churchman and ritualist have often been wrongly treated as interchangeable. The high churchman of the Catholic type is further differentiated from the earlier use of what is sometimes described as the "high and dry type" of the period before the Oxford Movement.[1] |

歴史的用途 1709年の風刺的な広辞苑。左半分に説教壇に座る司教、右半分に浴槽に入る清教徒を描いたヤヌス像のエングレーヴィングがある。  「低教会の献身」(アドルフ・タイデマンド、1852年) 低教会という用語は、18世紀の初期に、規律や信仰に関する事柄に多くの自由裁量を与える価値観を指す言葉として使われ、緯度主義者 (Latitudinarian)という用語に相当する。この用語は、エスタブリッシュド・チャーチの排他的な権威、司教権、聖餐制度を重んじる人々を指 すハイ・チャーチ(高教会主義者)という用語とは相反するものであった[1]。 低教会主義者は、ピューリタンの典礼慣行とは一致しないかもしれないが、イングランド国教会の中でピューリタンの意見を容認することを望んだ。分離主義 者、特に長老派をイングランド国教会に復帰させようとする動きは、1689年の寛容法でほぼ終了した。ロー・チャーチは、異教徒をよりリベラルに見る聖職 者たちに使われ続けたが、この用語はやがて使われなくなった。 両用語は、19世紀にトラクト派運動が「高教会主義者」という用語を流行させたときに復活した。この用語は再び修正された意味で使われるようになり、キリ ストの体としてのカソリックな存在としての教会と、神から与えられた恵みの手段としての秘跡制度という考えを高揚する人々を指すようになった。低教会主義 者は今や福音主義聖公会主義者に相当するものとなり、チャールズ・シメオンの名前に関連する運動の呼称となり、個人的回心の必要性を第一義的に重要視した [1]。 同時に、ラチチュディナリアンはブロード・チャーチ、あるいはブロード・チャーチメンと呼ばれるようになり、教会の倫理的な教えを最も重視し、正統性の価 値を最小限に抑える人々を指すようになった。高位教会の聖職者の多くが宗教改革以前の儀式を復活させたことから、儀式主義者という呼称がやや軽蔑的な意味 で適用されるようになった。しかし、高教会信者と儀式主義者という用語は、しばしば交換可能なものとして誤って扱われてきた。カトリック系の高教会主義者 は、オックスフォード運動以前の時期の「ハイ・アンド・ドライ・タイプ」と表現されることもあるそれ以前の用法とはさらに区別される[1]。 |

| Modern use In contemporary usage, "low churches" place more emphasis on the Protestant nature of Anglicanism than broad or high churches and are usually Evangelical in their belief and conservative (although not necessarily traditional) in practice. They may tend to favour liturgy such as the Common Worship over Book of Common Prayer, services of Morning and Evening Prayer over the Eucharist, and many use the minimum of formal liturgy permitted by church law. The Diocese of Sydney has largely abandoned the Prayer Book and uses free-form evangelical services. Some contemporary low churches also incorporate elements of charismatic Christianity. More traditional low church Anglicans, under the influence of Calvinist or Reformed thought inherited from the Reformation era, reject the doctrine that the sacraments confer grace ex opere operato (e.g., baptismal regeneration) and lay stress on the Bible as the ultimate source of authority in matters of faith necessary for salvation.[1] They are, in general, prepared to cooperate with other Protestants on nearly equal terms.[citation needed] Some low church Anglicans of the Reformed party consider themselves the only faithful adherents of historic Anglicanism and emphasise the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England as an official doctrinal statement of the Anglican tradition.[citation needed] |

現代の用法 現代的な用法では、「低教会」は広教会や高教会よりも聖公会のプロテスタント的性格を重視し、通常、信仰においては福音主義的であり、実践においては保守 的(必ずしも伝統的ではない)である。共通祈祷書(Book of Common Prayer)よりも共通礼拝(Common Worship)、聖体礼拝よりも朝夕の祈り(Morning and Evening Prayer)などの典礼を好む傾向があり、教会法で認められている最小限の正式な典礼を用いる教会も多い。シドニー教区は祈祷書をほとんど放棄し、自由 な福音主義的礼拝を行っている。 現代の低教会の中には、カリスマ的なキリスト教の要素を取り入れているところもある。 より伝統的な低教会の聖公会信者は、宗教改革時代から受け継がれてきたカルヴァン主義や改革派の思想の影響下にあり、聖餐式が「神の恩寵」を与えるという 教義(例:洗礼による再生)を否定し、カリスマ的キリスト教の要素を取り入れている、 改革派の低教会聖公会の中には、自分たちこそが歴史的聖公会の唯一の忠実な信奉者であると考え、英国国教会の公式の教義声明として英国国教会の三十九箇条 を重視している者もいる[要出典]。 |

| Ecumenical relationships United churches with Protestants in Asia Several provinces of the Anglican Communion in Asia have merged with Protestant churches. The Church of South India arose out of a merger of the southern province of the Church of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon (Anglican), the Methodist Church of South India and the South India United Church (a Congregationalist, Reformed and Presbyterian united church) in 1947. In the 1990s a small number of Baptist and Pentecostal churches joined also the union. In 1970 the Church of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon, the United Church of North India, the Baptist Churches of Northern India, the Church of the Brethren in India, the Methodist Church (British and Australia Conferences) and the Disciples of Christ denominations merged to form the Church of North India. Also in 1970 the Anglicans, Presbyterians (Church of Scotland), United Methodists and Lutherans of Churches in Pakistan merged into the Church of Pakistan. The Church of Bangladesh is the result of a merge of Anglican and Presbyterian churches. Britain and Ireland In the 1960s the Methodist Church of Great Britain made ecumenical overtures to the Church of England, aimed at church unity. These formally failed when they were rejected by the Church of England's General Synod in 1972. In 1981, a covenant project was proposed between the Church of England, the Methodist Church in Great Britain, the United Reformed Church and the Moravian Church.[2] In 1982 the United Reformed Church voted in favour of the covenant, which would have meant remodelling its elders and moderators as bishops and incorporating its ministry into the apostolic succession. The Church of England rejected the covenant. Conversations and co-operation continued leading in 2003 to the signing of a covenant between the Church of England and the Methodist Church of Great Britain.[3] From the 1970s onward, the Methodist Church was involved in several "Local Ecumenical Projects" (LEPs) with neighbouring denominations usually with the Church of England, the Baptists or with the United Reformed Church, which involved sharing churches, schools and in some cases ministers. In the Church of England, Anglo-Catholics are often opposed to unity with Protestants, which can reduce hope of unity with the Roman Catholic Church. Accepting women Protestant ministers would also make unity with the See of Rome more difficult. In the 1990s and early 2000s the Scottish Episcopal Church (Anglican), the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), the Methodist Church of Great Britain and the United Reformed Church were all parts of the "Scottish Churches Initiative for Union" (SCIFU) for seeking greater unity. The attempt stalled following the withdrawal of the Church of Scotland in 2003. In 2002 the Church of Ireland, which is generally on the low church end of the spectrum of world Anglicanism, signed a covenant for greater cooperation and potential ultimate unity with the Methodist Church in Ireland.[4] |

エキュメニカルな関係 アジアにおけるプロテスタントとの合同教会 アジアにおける聖公会のいくつかの州は、プロテスタント教会と合併している。南インド教会は、1947年にインド・パキスタン・ビルマ・セイロン教会(英 国国教会)の南部州、南インド・メソジスト教会、南インド合同教会(会衆派、改革派、長老派の合同教会)が合併して誕生した。1990年代には、少数のバ プテスト教会とペンテコステ教会も連合に加わった。 1970年、インド・パキスタン・ビルマ・セイロン教会、北インド合同教会、北インドバプテスト教会、インド同胞教会、メソジスト教会(イギリス・オース トラリア両大会)、キリスト弟子教会が合併し、北インド教会が設立された。また、1970年にはパキスタン教会の英国国教会、長老派(スコットランド教 会)、合同メソジスト派、ルター派が合併してパキスタン教会となった。バングラデシュ教会は、英国国教会と長老派教会が合併したものである。 イギリスとアイルランド 1960年代、英国メソジスト教会は英国国教会に教会統合を目指したエキュメニカルな働きかけを行った。しかし、1972年にイングランド国教会の総会で 拒否され、正式に失敗に終わった。1981年、英国国教会、英国メソジスト教会、合同改革派教会、モラヴィア教会の間で聖約プロジェクトが提案された [2]。 1982年、改革派合同教会は、長老と司教を司教として改組し、その聖職を使徒継承に組み込むことを意味するこの聖約に賛成票を投じた。イングランド国教 会はこの聖約を拒否した。1970年代以降、メソジスト教会は近隣の教派といくつかの「ローカル・エキュメニカル・プロジェクト」(LEP)に参加し、通 常はイングランド国教会、バプテスト、改革派合同教会と教会、学校、場合によっては聖職者を共有した。 イングランド国教会では、アングロカトリックはプロテスタントとの統一に反対することが多く、ローマカトリック教会との統一の望みが薄れる可能性がある。 プロテスタントの女性聖職者を受け入れることは、ローマ教皇庁との一致を難しくすることにもなる。 1990年代から2000年代初頭にかけて、スコットランド聖公会(英国国教会)、スコットランド教会(長老派)、英国メソジスト教会、合同改革派教会 が、より大きな統一を目指す「スコットランド教会連合構想」(SCIFU)に参加していた。2003年にスコットランド教会が脱退したため、この試みは頓 挫した。 2002年、世界聖公会の中で一般的に低教派に属するアイルランド教会は、アイルランドのメソジスト教会との協力強化と最終的な統一の可能性に関する誓約 に署名した[4]。 |

| Anglo-Catholicism Broad church Central churchmanship Conservative Evangelicalism in Britain Church of England Church of England (Continuing) Evangelical Anglicanism High Church Open Evangelical Provincial episcopal visitor Ritualism |

アングロカトリック 広い教会 中央教会主義 イギリスの保守福音主義 英国国教会 英国国教会(継続) 福音主義聖公会 高等教会 開かれた福音主義 地方司教訪問者 儀式主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Low_church |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆