ルドルフ・オットーと聖なるものについて

Rudolf Otto and the Holy

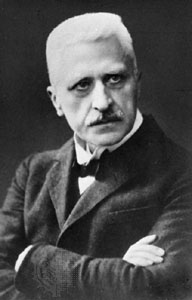

Rudolf Otto in 1925

★ルドルフ・オットー(1869年9月25日 - 1937年3月7日)は、ドイツのルーテル派神学者、哲学者、比較宗教学者である。20世紀初頭において最も影響力のある宗教学者の一人と見なされ、世界 の宗教の核心にあると主張した深い感情的体験「ヌミナス」の概念で最もよく知られている。[1] 彼の研究は自由主義キリスト教神学の領域から始まったが、その主眼は常に弁証的であり、自然主義的批判から宗教を擁護しようとするものであったため、より 保守的な人物と見なされる。[2] オットーは最終的に、自身の研究を宗教科学の一部と捉えるに至った。この宗教科学は、宗教哲学、宗教史、宗教心理学に区分される。[2]

| The Idea of the

Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine

and its Relation to the Rational (German: Das Heilige. Über das

Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum

Rationalen) is a book by the German theologian and philosopher Rudolf

Otto, published in 1917. It argues that the defining element of the

holy is the experience of a phenomenon which Otto calls the numinous.

The book had a significant influence on religious studies in the 20th

century. |

聖なるものの概念:神聖概念における非合理的要素とその合理的要素との

関係に関する考察(独題:Das Heilige.

神聖の概念:神聖観念における非合理的要素とその合理的要素との関係に関する考察)は、ドイツの神学者・哲学者ルドルフ・オットーによる著作で、1917

年に刊行された。本書は、神聖を定義する要素は、オットーが「ヌミナス」と呼ぶ現象の体験であると論じている。本書は20世紀の宗教研究に大きな影響を与

えた。 |

| Background Rudolf Otto wrote that the thought of Friedrich Schleiermacher was a major influence on his views presented in The Idea of the Holy. Other influences include Martin Luther, Albrecht Ritschl, Immanuel Kant and Jakob Friedrich Fries.[1]: 13 |

背景 ルドルフ・オットーは、フリードリヒ・シュライエルマッハーの思想が『聖なるもの』で提示した彼の見解に大きな影響を与えたと記している。その他の影響と しては、マルティン・ルター、アルブレヒト・リッチル、イマヌエル・カント、ヤコブ・フリードリッヒ・フリーズなどが挙げられる。[1]: 13 |

| Summary In The Idea of the Holy, Otto writes that while the concept of "the holy" is often used to convey moral perfection, which it does entail, it contains another distinct element, beyond the ethical sphere, for which he coined the term numinous based on the Latin word numen ("divine power").[2]: 5–7 (The term is etymologically unrelated to Immanuel Kant's noumenon, a Greek term which Kant used to refer to an unknowable reality underlying sensations of the thing.) He explains the numinous as an experience or feeling which is not based on reason or sensory stimulation and represents the "wholly other" (German: ganz Andere).[3] Otto argues that because the numinous is irreducible and sui generis it cannot be defined in terms of other concepts or experiences, and that the reader must therefore be "guided and led on by consideration and discussion of the matter through the ways of his own mind, until he reach the point at which 'the numinous' in him perforce begins to stir... In other words, our X cannot, strictly speaking, be taught, it can only be evoked, awakened in the mind."[2]: 7 Chapters 4 to 6 are devoted to attempting to evoke the numinous and its various aspects. He writes:[4][2]: 12–13 The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its “profane,” non-religious mood of everyday experience. [...] It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations, and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of—whom or what? In the presence of that which is a Mystery inexpressible and above all creatures. He describes it as a mystery (Latin: mysterium) that is at once terrifying (tremendum) and fascinating (fascinans).[5] Otto felt that the numinous was most strongly present in the Old and New Testaments, but that it was also present in all other religions.[2]: 74 |

要約 『聖なるものの概念』において、オットーは「聖なるもの」という概念がしばしば道徳的完全性を表すために用いられると記している。確かにそれは道徳的完全 性を包含するが、倫理的領域を超えた別の明確な要素も内包している。彼はこの要素を指すために、ラテン語のヌメン(numen、「神聖な力」)に基づいて 「ヌミナス」という用語を造語した。[2]: 5–7 (この用語は語源的に、イマヌエル・カントが物事の感覚の根底にある知ることのできない現実を指す ために用いたギリシャ語「noumenon(物自体)」とは無関係である。)彼はヌミナスを、理性や感覚刺激に基づかない経験や感覚として説明し、それは 「全く異なるもの」(ドイツ語:ganz Andere)を表す。[3] オットーは、ヌミノースが還元不能かつ独自性を持つため、他の概念や経験によって定義することは不可能だと主張する。したがって読者は「自らの思考の道筋 を通じて、この問題についての考察と議論に導かれ、導かれていく必要がある。そうして『ヌミノース』が彼の中で必然的に動き始める地点に到達するま で... つまり、我々のXは厳密に言えば教えられるものではなく、喚起され、心の中で目覚めさせられるものなのだ。」[2]:7第4章から第6章は、ヌミナスとそ の様々な側面を喚起しようとする試みに捧げられている。彼はこう記す:[4][2]:12–13 その感覚は時に穏やかな潮のように押し寄せ、心を深い崇拝の静謐な気分で満たすことがある。それはより確固とした永続的な魂の態度へと移行し、まるで震え るように共鳴し続けるが、やがて消え去り、魂は日常の経験における「俗なる」、非宗教的な気分に戻る。[...] それは粗野で野蛮な起源と初期の現れを持ち、また美しく純粋で輝かしいものへと発展することもある。それは、誰かあるいは何かの前での、生き物の静まり返 り、震え、言葉にできない謙虚さとなるかもしれない。それは、表現しがたく、あらゆる生き物を超越した神秘の前でのことだ。 彼はそれを、畏怖(トレメンダム)と魅惑(ファシナンツ)を同時に帯びた神秘(ラテン語:ミステリウム)と描写している。[5] オットーは、ヌミノースが旧約聖書と新約聖書に最も強く現れていると感じたが、他のあらゆる宗教にも存在すると考えた。[2]: 74 |

| Reception The Idea of the Holy was first published in German in 1917 and the first English translation was published in 1923. It is Otto's most famous and influential book and its conception of the holy had a significant impact on the history of religions and other disciplines of religious studies. According to the scholar Douglas Allen, the book's two major contributions were its emphasis on "an experimental approach, involving the description of the essential structures of religious experience" and an "antireductionist approach, involving the unique numinous quality of all religious experience".[1]: 13 Prominent 20th-century scholars who have praised the book and acknowledged its influence on their work include Edmund Husserl, Karl Barth, Joachim Wach, Gerard van der Leeuw and Mircea Eliade.[1]: 13 |

受容 『聖なるものの概念』は1917年にドイツ語で初版が刊行され、最初の英訳は1923年に出版された。これはオットーの最も有名で影響力のある著作であ り、その聖なるものに関する概念は宗教史やその他の宗教研究分野に重大な影響を与えた。学者ダグラス・アレンによれば、本書の二大貢献は「宗教体験の本質 的構造の記述を含む実験的アプローチ」への重点と、「あらゆる宗教体験に内在する独自のヌミナス的性質を含む反還元主義的アプローチ」であった。[1]: 13 この著作を称賛し、自身の研究への影響を認めた20世紀の著名な学者には、エドムント・フッサール、カール・バルト、ヨアヒム・ヴァッハ、ヘラル ト・ファン・デル・レーウ、ミルチャ・エリアーデらがいる。[1]: 13 |

| Phenomenology of religion Religious experience Theories about religions |

宗教現象学 宗教的体験 宗教に関する理論 |

| References 1. Dadosky, John D. (2004). The Structure of Religious Knowing: Encountering the Sacred in Eliade and Lonergan. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6061-4. 2. Otto, Rudolf (1923). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-500210-5. 3. Otto, Rudolf (1996). Alles, Gregory D. (ed.). Autobiographical and Social Essays. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-110-14519-9. 4. Meland, Bernard E. "Rudolf Otto | German philosopher and theologian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 3 November 2020. Otto, Rudolf (1996). Mysterium tremendum et fascinans. |

参考文献 1. ダドスキー、ジョン・D. (2004). 『宗教的認識の構造:エリアーデとロナーガンにおける聖なるものとの遭遇』. オールバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局. ISBN 0-7914-6061-4. 2. オットー、ルドルフ(1923)。『聖なるものの概念』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0-19-500210-5。 3. オットー、ルドルフ(1996)。アレス、グレゴリー・D.(編)。『自伝的・社会論的エッセイ集』。ベルリン:ヴァルター・デ・グリュイター。p. 30。ISBN 978-3-110-14519-9。 4. メランド、バーナード・E. 「ルドルフ・オットー|ドイツの哲学者・神学者」『ブリタニカ国際大百科事典オンライン版』。2020年11月3日閲覧。 オットー、ルドルフ(1996)。『神秘なる畏怖と魅惑』。 |

| External links The Idea of the Holy at the Internet Archive Das Heilige at the Internet Archive (in German) |

外部リンク 『聖なるものの概念』 - インターネットアーカイブ 『聖なるもの』 - インターネットアーカイブ(ドイツ語) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Idea_of_the_Holy |

☆

| "Otto's most famous work, The Idea of the Holy (1950), was first published in German in 1917 as Das Heilige - Über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum Rationalen (1917). It was one of the most successful German theological books of the 20th century, has never gone out of print, and is now available in about 20 languages. The first English translation was published in 1923 under the title The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational. Otto felt people should first do serious rational study of God, before turning to the non-rational element of God as he did in this book.[5][6]:vii/ In The Idea of the Holy, Otto writes that while the concept of "the holy" is often used to convey moral perfection—and does entail this—it contains another distinct element, beyond the ethical sphere, for which he coined the term numinous based on the Latin word numen ("divine power").[6]:5–7 (The term is etymologically unrelated to Immanuel Kant's noumenon, a Greek term which Kant used to refer to an unknowable reality underlying sensations of the thing.) He explains the numinous as a "non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self". This mental state "presents itself as ganz Andere,[7] wholly other, a condition absolutely sui generis and incomparable whereby the human being finds himself utterly abashed."[8] Otto argues that because the numinous is irreducible and sui generis it cannot be defined in terms of other concepts or experiences, and that the reader must therefore be "guided and led on by consideration and discussion of the matter through the ways of his own mind, until he reach the point at which 'the numinous' in him perforce begins to stir... In other words, our X cannot, strictly speaking, be taught, it can only be evoked, awakened in the mind."[6]:7 Chapters 4 to 6 are devoted to attempting to evoke the numinous and its various aspects. He writes:[4][6]:Pp.12–13" - Rudolf Otto (1869-1937). | オットーの最も有名な著作『聖なるものの理念』(1950

年)は、1917年にドイツ語で『聖なるもの――神聖な理念における非合理性と合理性との関係について』(1917年)として初版が刊行された。これは

20世紀のドイツ神学書の中で最も成功した作品の一つであり、絶版になることなく、現在では約20の言語で入手可能である。最初の英語訳は1923年に

『聖なるものの観念:神観念における非合理的要素とその合理的要素との関係に関する考察』というタイトルで出版された。オットーは、人民がまず神について

真剣な理性的研究を行うべきだと考えていた。そしてこの本で彼がそうしたように、その後で神の非理性的要素に向き合うべきだと主張した。[5][6]:

vii/

『聖なるものの観念』においてオットーは、「聖なるもの」という概念がしばしば道徳的完全性を表すために用いられる(そして確かにそれを包含する)一方

で、倫理的領域を超えた別の明確な要素を含んでいると記している。彼はこの要素を指すために、ラテン語のヌメン(numen、「神聖な力」)に基づいて

「ヌミナス」という用語を造語した。[6]:5–7

(この用語は語源的に、イマヌエル・カントが「知覚されるものの背後にある知ることのできない現実」を指すために用いたギリシャ語「noumenon(物自体)」とは無関係である。)

彼はヌミナスを「非合理的かつ非感覚的な体験または感情であり、その主要かつ直接的な対象は自己の外側にある」と説明する。この精神状態は「ガンス・アン

デレ[7]、すなわち全く異質な存在として現れ、人間が完全に圧倒される、絶対的に独自で比類のない状態である」。[8]

オットーは、ヌミナスが還元不能かつ独自性を持つため、他の概念や経験によって定義することは不可能だと主張する。したがって読者は「自らの精神の道筋を

通じて、この問題の考察と議論に導かれ、導かれていく必要がある。そうして『ヌミナス』が彼の中で必然的に動き始める地点に到達するまで...

つまり、我々のXは厳密に言えば教えられるものではなく、喚起され、心の中で目覚めさせられるものなのだ。」[6]:7

第4章から第6章は、ヌミナスとその様々な側面を喚起しようとする試みに捧げられている。彼はこう記す:[4][6]:Pp.12–13」 -

ルドルフ・オットー(1869-1937)。 |

| "The

feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide pervading

the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into

a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were,

thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the

soul resumes its “profane,” non-religious mood of everyday experience.

[...] It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations,

and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and

glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility

of the creature in the presence of—whom or what? In the presence of

that which is a Mystery inexpressible and above all creatures."- Rudolf Otto

(1869-1937) (Otto 1950:12–13). |

「そ

の感覚は時に穏やかな潮のように押し寄せ、心を深い崇拝の静かな気分で満たすことがある。それはより確固として持続的な魂の態度へと移行し、まるで震える

ように響き渡り続けるが、やがて消え去り、魂は日常の経験における「俗なる」、非宗教的な気分に戻るのだ。[...]

それは粗野で野蛮な起源と初期の現れを持ち、また美しく純粋で輝かしいものへと発展することもある。それは、誰かあるいは何かの前に立つ被造物の、静まり

返り、震え、言葉にできない謙虚さとなるかもしれない。それは、あらゆる被造物を超越し、表現し得ない神秘であるものの前に立つ時の謙虚さである。」

- ルドルフ・オットー (1869-1937) (Otto 1950:12–13). |

| "He describes it as a mystery

(Latin: mysterium) that is at once terrifying (tremendum) and

fascinating (fascinans).[9] Otto felt that the numinous was most

strongly present in the Old and New Testaments, but that it was also

present in all other religions.[6]:74/ According to Mark Wynn in the

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Idea of the Holy falls within

a paradigm in the philosophy of emotion in which emotions are seen as

including an element of perception with intrinsic epistemic value that

is neither mediated by thoughts nor simply a response to physiological

factors. Otto therefore understands religious experience as having

mind-independent phenomenological content rather than being an internal

response to belief in a divine reality. Otto applied this model

specifically to religious experiences, which he felt were qualitatively

different from other emotions.[10]"- Rudolf Otto

(1869-1937) |

彼はそれを神秘(ラテン語:mysterium)と表現し、それは同時

に恐ろしい(tremendum)ものであり、魅惑的な(fascinans)ものであると述べた。[9]

オットーは、ヌミノーゼが旧約聖書と新約聖書に最も強く現れていると感じたが、他のすべての宗教にも存在すると考えた。[6]:74/

スタンフォード哲学百科事典のマーク・ウィンによれば、『聖なるものの概念』は、感情が思考によって媒介されるものでもなく、単に生理的要因への反応でも

ない、内在的な認識的価値を持つ知覚の要素を含むものと見なす感情哲学のパラダイムに属する。したがってオットーは、宗教的体験を神聖な現実への信仰に対

する内的反応ではなく、精神に依存しない現象学的内容を持つものと理解した。オットーはこのモデルを特に宗教的体験に適用し、それらは他の感情とは質的に

異なると思った。[10]"- ルドルフ・オットー (1869-1937) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Otto |

☆

| Rudolf Otto (25

September 1869 – 7 March 1937) was a German Lutheran theologian,

philosopher, and comparative religionist. He is regarded as one of the

most influential scholars of religion in the early twentieth century

and is best known for his concept of the numinous, a profound emotional

experience he argued was at the heart of the world's religions.[1]

While his work started in the domain of liberal Christian theology, its

main thrust was always apologetical, seeking to defend religion against

naturalist critiques, making him a more conservative figure.[2] Otto

eventually came to conceive of his work as part of a science of

religion, which was divided into the philosophy of religion, the

history of religion, and the psychology of religion.[2] |

ルドルフ・オットー(1869年9月25日 -

1937年3月7日)は、ドイツのルーテル派神学者、哲学者、比較宗教学者である。20世紀初頭において最も影響力のある宗教学者の一人と見なされ、世界

の宗教の核心にあると主張した深い感情的体験「ヌミナス」の概念で最もよく知られている。[1]

彼の研究は自由主義キリスト教神学の領域から始まったが、その主眼は常に弁証的であり、自然主義的批判から宗教を擁護しようとするものであったため、より

保守的な人物と見なされる。[2]

オットーは最終的に、自身の研究を宗教科学の一部と捉えるに至った。この宗教科学は、宗教哲学、宗教史、宗教心理学に区分される。[2] |

| Life Born in Peine near Hanover, Otto was raised in a pious Christian family.[3] He attended the Gymnasium Andreanum in Hildesheim and studied at the universities of Erlangen and Göttingen, where he wrote his dissertation on Martin Luther's understanding of the Holy Spirit (Die Anschauung von heiligen Geiste bei Luther: Eine historisch-dogmatische Untersuchung), and his habilitation on Kant (Naturalistische und religiöse Weltansicht). By 1906, he held a position as extraordinary professor, and in 1910 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Giessen. Otto's fascination with non-Christian religions was awakened during an extended trip from 1911 to 1912 through North Africa, Palestine, British India, China, Japan, and the United States.[4] He cited a 1911 visit to a Moroccan synagogue as a key inspiration for the theme of the Holy he would later develop.[3] Otto became a member of the Prussian parliament in 1913 and retained this position through the First World War.[4] In 1917, he spearheaded an effort to simplify the system of weighting votes in Prussian elections.[2] He then served in the post-war constituent assembly in 1918, and remained involved in the politics of the Weimar Republic.[4] Meanwhile, in 1915, he became ordinary professor at the University of Breslau, and in 1917, at the University of Marburg's Divinity School, then one of the most famous Protestant seminaries in the world. Although he received several other calls, he remained in Marburg for the rest of his life. He retired in 1929 but continued writing afterward. On 6 March 1937, he died of pneumonia, after suffering serious injuries falling about twenty meters from a tower in October 1936. There were lasting rumors that the fall was a suicide attempt but this has never been confirmed.[2] He is buried in the Marburg cemetery. |

人生 ハノーファー近郊のパイネで生まれたオットーは、敬虔なキリスト教徒の家庭で育った。[3] ヒルデスハイムのアンドレアヌム・ギムナジウムに通い、エアランゲン大学とゲッティンゲン大学で学び、マーティン・ルターによる聖霊の理解(『ルターにお ける聖霊観:歴史的・教義学的考察』)に関する博士論文と、カントに関するハビリテーション論文(『自然主義的および宗教的世界観』)を執筆した。 1906年までに、彼は非常勤教授の地位に就き、1910年にはギーセン大学から名誉博士号を授与された。 オットーの非キリスト教宗教への関心は、1911年から1912年にかけての北アフリカ、パレスチナ、英領インド、中国、日本、そしてアメリカ合衆国への 長期旅行の中で目覚めた。[4] 後に展開する「聖なるもの」のテーマについて、1911年にモロッコのシナゴーグを訪れたことが重要な着想源となったと述べている。[3] オットーは1913年にプロイセン議会議員となり、第一次世界大戦中もこの地位を維持した。[4] 1917年には、プロイセン選挙における投票の加重制度を簡素化する取り組みを主導した。[2] その後1918年には戦後の制憲議会で役職に就き、ワイマール共和国の政治に関わり続けた。[4] 一方、1915年にはブレスラウ大学(現・ヴロツワフ大学)の正教授に就任し、1917年には当時世界有数のプロテスタント神学校であったマールブルク大 学神学部で教鞭を執った。その後もいくつかの招聘があったが、彼は生涯をマルブルクで過ごした。1929年に退職したが、その後は執筆活動を続けた。 1936年10月に塔から約20メートル落下して苦悩し、1937年3月6日に肺炎で死去した。この転落事故は自殺未遂だったという噂が長く囁かれたが、 確認されたことはない。彼はマルブルク墓地に埋葬されている。 |

| Thought Influences In his early years Otto was most influenced by the German idealist theologian and philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher and his conceptualization of the category of the religious as a type of emotion or consciousness irreducible to ethical or rational epistemologies.[4] In this, Otto saw Schleiermacher as having recaptured a sense of holiness lost in the Age of Enlightenment. Schleiermacher described this religious feeling as one of absolute dependence; Otto eventually rejected this characterization as too closely analogous to earthly dependence and emphasized the complete otherness of the religious feeling from the mundane world (see below).[4] In 1904, while a student at the University of Göttingen, Otto became a proponent of the philosophy of Jakob Fries along with two fellow students.[2] Early works Otto's first book, Naturalism and Religion (1904) divides the world ontologically into the mental and the physical, a position reflecting Cartesian dualism. Otto argues consciousness cannot be explained in terms of physical or neural processes, and also accords it epistemological primacy by arguing all knowledge of the physical world is mediated by personal experience. On the other hand, he disagrees with Descartes' characterization of the mental as a rational realm, positing instead that rationality is built upon a nonrational intuitive realm.[2] In 1909, he published his next book, The Philosophy of Religion Based on Kant and Fries, in which he examines the thought of Kant and Fries and from there attempts to build a philosophical framework within which religious experience can take place. While Kant's philosophy said thought occurred in a rational domain, Fries diverged and said it also occurred in practical and aesthetic domains; Otto pursued Fries' line of thinking further and suggested another nonrational domain of the thought, the religious. He felt intuition was valuable in rational domains like mathematics, but subject to the corrective of reason, whereas religious intuitions might not be subject to that corrective.[2] These two early works were influenced by the rationalist approaches of Immanuel Kant and Jakob Fries. Otto stated that they focused on the rational aspects of the divine (the "Ratio aeterna") whereas his next (and most influential) book focused on the nonrational aspects of the divine.[5] |

思想 影響 オットーは若き日に、ドイツ観念論の神学者・哲学者フリードリヒ・シュライエルマッハーとその思想に最も影響を受けた。シュライエルマッハーは宗教的カテ ゴリーを、倫理的・理性的認識論に還元できない感情や意識の一種として概念化したのである[4]。オットーはここで、シュライエルマッハーが啓蒙時代に失 われた聖なる感覚を取り戻したと見なした。シュライエルマッハーはこの宗教的感情を絶対的依存として説明したが、オットーは最終的にこの特徴付けを世俗的 依存に近すぎると退け、宗教的感情が俗世から完全に異質であることを強調した(後述)。[4] 1904年、ゲッティンゲン大学在学中、オットーは同級生二人と共にヤコブ・フリーズの哲学の支持者となった。[2] 初期の著作 オットーの最初の著作『自然主義と宗教』(1904年)は、世界を存在論的に精神的領域と物理的領域に二分する。これはデカルト主義二元論を反映した立場 である。オットーは、意識は物理的・神経学的プロセスでは説明できないと主張し、さらに物理的世界に関する全ての知識は人格経験を通じて媒介されるという 論拠から、意識に認識論的優位性を認めている。一方で、彼は精神を理性的な領域と位置づけたデカルトの見解には同意せず、理性は非理性的で直観的な領域の 上に築かれると主張した。[2] 1909年、彼は次の著作『カントとフリーズに基づく宗教哲学』を発表した。この書ではカントとフリーズの思想を検討し、そこから宗教的経験が成立し得る 哲学的枠組みの構築を試みた。カントの哲学が思考は理性的領域で生じるとしたのに対し、フリーズは実践的・美的領域でも生じると主張した。オットーはフ リーズの考えをさらに推し進め、思考のもう一つの非理性的領域として宗教的領域を提示した。彼は直観が数学のような理性的領域では価値を持つが理性の修正 を受けるのに対し、宗教的直観はその修正を受けない可能性があると考えた。[2] これらの初期の二著作は、イマヌエル・カントとヤコブ・フリースの合理主義的アプローチに影響を受けていた。オットーは、彼らが神性の合理的側面(「永遠 の理性」)に焦点を当てたのに対し、彼の次の(そして最も影響力のある)著作は神性の非合理的側面に焦点を当てたと述べている。[5] |

| The Idea of the Holy Otto's most famous work, The Idea of the Holy was one of the most successful German theological books of the 20th century, has never gone out of print, and is available in about 20 languages. The central argument of the book concerns the term numinous, which Otto coined. He explains the numinous as a "non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self". This mental state "presents itself as ganz Andere,[6][7][8] wholly other, a condition absolutely sui generis and incomparable whereby the human being finds himself utterly abashed."[9] According to Mark Wynn in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Idea of the Holy falls within a paradigm in the philosophy of emotion in which emotions are seen as including an element of perception with intrinsic epistemic value that is neither mediated by thoughts nor simply a response to physiological factors. Otto therefore understands religious experience as having mind-independent phenomenological content rather than being an internal response to belief in a divine reality. Otto applied this model specifically to religious experiences, which he felt were qualitatively different from other emotions.[10] Otto felt people should first do serious rational study of God, before turning to the non-rational element of God as he did in this book.[5][11] |

聖なるものの概念(理念) オットーの最も有名な著作『聖なるものの理念』は、20世紀のドイツ神学書の中で最も成功した一冊であり、絶版になることなく、約20の言語で出版されて いる。本書の中心的主張は、オットーが提唱した「ヌミナス」という概念に関するものである。彼はヌミナスを「非合理的かつ非感覚的な体験または感情であ り、その主要かつ直接的な対象は自己の外側にある」と説明する。この精神状態は「ガンス・アンデレ[6][7][8]、すなわち全く異質な存在として現 れ、人間が完全に圧倒される、絶対的に類を見ない比類なき状態である」と述べている。スタンフォード哲学百科事典のマーク・ウィンによれば、『聖なるもの の理念』は感情哲学のパラダイムに位置づけられる。この枠組みでは感情は、思考を介さず生理的要因への単純反応でもない、内在的な認識的価値を持つ知覚要 素を含むとみなされる。したがってオットーは、宗教的体験を神聖な実在への信仰に対する内的反応ではなく、精神に依存しない現象学的内容を持つものと理解 した。オットーはこのモデルを特に宗教的体験に適用した。彼は宗教的体験が他の感情とは質的に異なる、すなわち異なる感情であると考えていた。[10] オットーは、人民がまず神について真剣な理性的研究を行うべきだと主張した。その後で初めて、本書で彼がそうしたように、神の非理性的要素に向き合うべき だと考えたのである。[5][11] |

| Later works In Mysticism East and West, published in German in 1926 and English in 1932, Otto compares and contrasts the views of the medieval German Christian mystic Meister Eckhart with those of the influential Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara, the key figure of the Advaita Vedanta school.[2] |

後期の著作 1926年にドイツ語で、1932年に英語で出版された『東西神秘主義』において、オットーは中世ドイツのキリスト教神秘主義者マイスター・エックハルト の思想と、アドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタ学派の中心的人物である有力なヒンドゥー教哲学者アディ・シャンカラの思想を比較対照している。[2] |

| Influence Otto left a broad influence on theology, religious studies, and philosophy of religion, which continues into the 21st century.[12] Christian theology Karl Barth, an influential Protestant theologian contemporary to Otto, acknowledged Otto's influence and approved a similar conception of God as ganz Andere or totaliter aliter,[13] thus falling within the tradition of apophatic theology.[14][15] Otto was also one of the very few modern theologians to whom C. S. Lewis indicates a debt, particularly to the idea of the numinous in The Problem of Pain. In that book Lewis offers his own description of the numinous:[16] Suppose you were told there was a tiger in the next room: you would know that you were in danger and would probably feel fear. But if you were told "There is a ghost in the next room," and believed it, you would feel, indeed, what is often called fear, but of a different kind. It would not be based on the knowledge of danger, for no one is primarily afraid of what a ghost may do to him, but of the mere fact that it is a ghost. It is "uncanny" rather than dangerous, and the special kind of fear it excites may be called Dread. With the Uncanny one has reached the fringes of the Numinous. Now suppose that you were told simply "There is a mighty spirit in the room," and believed it. Your feelings would then be even less like the mere fear of danger: but the disturbance would be profound. You would feel wonder and a certain shrinking—a sense of inadequacy to cope with such a visitant and of prostration before it—an emotion which might be expressed in Shakespeare's words "Under it my genius is rebuked." This feeling may be described as awe, and the object which excites it as the Numinous. German-American theologian Paul Tillich acknowledged Otto's influence on him,[2] as did Otto's most famous German pupil, Gustav Mensching (1901–1978) from Bonn University.[17] Otto's views can be seen[clarification needed] in the noted Catholic theologian Karl Rahner's presentation of man as a being of transcendence.[citation needed] More recently, Otto has also influenced the American Franciscan friar and inspirational speaker Richard Rohr.[18]: 139 |

影響 オットーは神学、宗教学、宗教哲学に広範な影響を残し、その影響は21世紀まで続いている。[12] キリスト教神学 オットーと同時代の有力なプロテスタント神学者カール・バルトは、オットーの影響を認め、神を「全く異なるもの(ganz Andere)」あるいは「全く異質な存在(totaliter aliter)」とする類似の概念を支持した。[13]これによりバルトは否定神学の伝統に属することとなった。[14][15] オットーはまた、C・S・ルイスが『苦痛の問題』において特に「ヌミナス」の概念に関して恩義を認めた、ごく少数の近代神学者の一人でもある。同書でルイ スはヌミナスの独自の定義を提示している:[16] 隣の部屋に虎がいると言われたとしよう。危険にさらされていると知り、おそらく恐怖を感じるだろう。しかし「隣の部屋に幽霊がいる」と告げられ、それを信 じたなら、確かに「恐怖」と呼ばれる感情を感じるだろう。だがそれは性質が異なる。危険の認識に基づくものではない。なぜなら誰も幽霊が自分に何をするか を主に恐れるわけではないからだ。単に幽霊であるという事実そのものを恐れるのだ。それは危険というより「不気味」であり、それが喚起する特殊な恐怖は 「畏怖」と呼べる。不気味さとは、神聖なるものの縁に到達した状態だ。では単に「この部屋には強大な精霊がいる」と告げられ、それを信じたとしよう。その 時の感情は、単なる危険への恐怖とはさらに異なるものとなるだろう。しかしその動揺は深い。驚嘆と、ある種の萎縮――そのような訪問者に対処する能力の欠 如と、その前にひれ伏す感覚――を覚えるだろう。この感情はシェイクスピアの言葉「その下では我が精神は萎縮する」で表現できるかもしれない。この感覚は 畏敬と表現でき、それを喚起する対象は神聖なるものと呼べる。 ドイツ系アメリカ人神学者ポール・ティリッヒはオットーの影響を認めており[2]、オットーの最も著名なドイツ人弟子であるボン大学のグスタフ・メンシン グ(1901–1978)も同様である。[17] オットーの見解は、著名なカトリック神学者カール・ラーナーが人間を超越的存在として提示した内容にも見られる[注釈が必要]。より近年では、アメリカの フランシスコ会修道士で啓発的講演者であるリチャード・ロールにも影響を与えている[18]: 139 |

| Non-Christian theology and spirituality Otto's ideas have also exerted an influence on non-Christian theology and spirituality. They have been discussed by Orthodox Jewish theologians including Joseph Soloveitchik[19] and Eliezer Berkovits.[20] The Iranian-American Sufi religious studies scholar and public intellectual Reza Aslan understands religion as "an institutionalized system of symbols and metaphors [...] with which a community of faith can share with each other their numinous encounter with the Divine Presence."[21] Further afield, Otto's work received words of appreciation from Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi.[17] Aldous Huxley, a major proponent of perennialism, was influenced by Otto; in The Doors of Perception he writes:[22] The literature of religious experience abounds in references to the pains and terrors overwhelming those who have come, too suddenly, face to face with some manifestation of the mysterium tremendum. In theological language, this fear is due to the in-compatibility between man's egotism and the divine purity, between man's self-aggravated separateness and the infinity of God. |

非キリスト教の神学と霊性 オットーの思想は非キリスト教の神学と霊性にも影響を与えている。正統派ユダヤ教の神学者たち、例えばジョセフ・ソロヴェイチク[19]やエリエゼル・ベ ルコヴィッツらによって論じられてきた。[20] イラン系アメリカ人のスーフィー宗教学者であり、公共の知性であるレザ・アスランは、宗教を「信仰の共同体が、神の存在との神聖な出会いを互いに共有する ことができる、制度化された象徴と隠喩の体系」と理解している。さらに、オットーの著作は、インドの独立運動指導者モハンダス・ガンディーからも称賛の言 葉を受けた。永続主義の主要な提唱者であるオルダス・ハクスリーは、オットーの影響を受けた。『知覚の扉』の中で、彼は次のように書いている。 宗教的体験に関する文献には、神秘の畏怖(ミステリウム・トレメンダム)の現れに突然直面した者たちを圧倒する苦痛や恐怖についての言及が数多く見られ る。神学用語で言えば、この恐怖は、人間のエゴイズムと神の純粋さ、人間が自らを悪化させる分離性と神の無限性との相容れない関係に起因するものである。 |

| Religious studies In The Idea of the Holy and other works, Otto set out a paradigm for the study of religion that focused on the need to realize the religious as a non-reducible, original category in its own right.[citation needed] The eminent Romanian-American historian of religion and philosopher Mircea Eliade used the concepts from The Idea of the Holy as the starting point for his own 1954 book, The Sacred and the Profane.[12][23] The paradigm represented by Otto and Eliade was then heavily criticized for viewing religion as a sui generis category,[12] until around 1990, when it began to see a resurgence as a result of its phenomenological aspects becoming more apparent.[citation needed] Ninian Smart, who was a formative influence on religious studies as a secular discipline, was influenced by Otto in his understanding of religious experience and his approach to understanding religion cross-culturally.[12] |

宗教研究 『聖なるものの概念』その他の著作において、オットーは宗教研究のパラダイムを提示した。それは宗教性を還元不能な独自の原初的カテゴリーとして認識する必要性(=目的論)に 焦点を当てたものである。[出典が必要] 著名なルーマニア系アメリカ人の宗教史家かつ哲学者ミルチャ・エリアーデは、『聖なるものの概念』の概念を起点として、自身の1954年の著作『聖なるも のと俗なるもの』を著した。[12][23] オットーとエリアーデが代表するこのパラダイムは、宗教を独自のカテゴリーと見なす点で 激しく批判された[12]。しかし1990年頃、その現象学的側面がより明らかになるにつれ、再び注目を集め始めた。[出典必要]世俗的学問としての宗教 研究に形成的な影響を与えたニニアン・スマートは、宗教的体験の理解と異文化間における宗教理解へのアプローチにおいてオットーの影響を受けた。[12] |

| Psychology Carl Gustav Jung, the founder of analytic psychology, applied the concept of the numinous to psychology and psychotherapy, arguing it was therapeutic and brought greater self-understanding, and stating that to him religion was about a "careful and scrupulous observation… of the numinosum".[24] The American Episcopal priest John A. Sanford applied the ideas of both Otto and Jung in his writings on religious psychotherapy.[citation needed] |

心理学 分析心理学の創始者カール・グスタフ・ユングは、ヌミノースの概念を心理学と心理療法に応用した。彼はこれが治療効果を持ち、より深い自己理解をもたらす と主張し、宗教とは「ヌミノースに対する慎重かつ厳密な観察」であると述べた。[24] アメリカ聖公会の司祭ジョン・A・サンフォードは、宗教的心理療法に関する著作において、オットーとユングの両者の思想を応用した。[出典が必要] |

| Philosophy The philosopher and sociologist Max Horkheimer, a member of the Frankfurt School, has taken the concept of "wholly other" in his 1970 book Die Sehnsucht nach dem ganz Anderen ("longing for the entirely Other").[25][26] Walter Terence Stace wrote in his book Time and Eternity that "After Kant, I owe more to Rudolph Otto's The Idea of the Holy than to any other book."[27] Other philosophers influenced by Otto included Martin Heidegger,[17] Leo Strauss,[17] Hans-Georg Gadamer (who was critical when younger but respectful in his old age),[citation needed] Max Scheler,[17] Edmund Husserl,[17] Joachim Wach,[3][17] and Hans Jonas.[citation needed] |

哲学 フランクフルト学派の哲学者であり社会学者であるマックス・ホルクハイマーは、1970年の著書『Die Sehnsucht nach dem ganz Anderen』(『全く異質なものを求める渇望』)において「全く異質なもの」という概念を取り上げている。[25][26] ウォルター・テレンス・ステイスは著書『時間と永遠』の中で、「カントに次いで、私が最も影響を受けたのはルドルフ・オットーの『聖なるもの』である」と 記している。[27] オットーの影響を受けた他の哲学者には、マーティン・ハイデガー[17]、レオ・シュトラウス[17]、ハンス・ゲオルク・ガダマー(若い頃は批判的だっ たが、老年期には敬意を払った)、[要出典] マックス・シェラー[17]、エドムント・フッサール[17]、ヨアヒム・ヴァッハ[3][17]、ハンス・ヨナス[要出典] などがいる。 |

| Other The war veteran and writer Ernst Jünger and the historian and scientist Joseph Needham also cited Otto's influence.[citation needed] |

その他 戦争の退役軍人であり作家でもあるエルンスト・ユンガーと、歴史家であり科学者でもあるジョセフ・ニーダムもまた、オットーの影響を引用している。[出典が必要] |

| Ecumenical activities Otto was heavily involved in ecumenical activities between Christian denominations and between Christianity and other religions.[4] He experimented with adding a time similar to a Quaker moment of silence to the Lutheran liturgy as an opportunity for worshipers to experience the numinous.[4] |

エキュメニカル活動 オットーはキリスト教諸派間、およびキリスト教と他宗教間のエキュメニカル活動に深く関わった。[4] 彼は礼拝者が神聖な体験をする機会として、クエーカー教徒の黙想の時間に似た時間をルーテル派の礼拝式に加える試みを行った。[4] |

| Works A full bibliography of Otto's works is given in Robert F. Davidson, Rudolf Otto's Interpretation of Religion (Princeton, 1947), pp. 207–9 In German Naturalistische und religiöse Weltansicht (1904) Die Kant-Friesische Religions-Philosophie (1909) Das Heilige – Über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum Rationalen (Breslau, 1917) West-östliche Mystik (1926) Die Gnadenreligion Indiens und das Christentum (1930) Reich Gottes und Menschensohn (1934) English translations Naturalism and Religion, trans J. Arthur Thomson & Margaret Thomson (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907) [originally published 1904] The Life and Ministry of Jesus, According to the Critical Method (Chicago: Open Court, 1908), ISBN 0-8370-4648-3. The Idea of the Holy, trans JW Harvey (New York: OUP, 1923; 2nd edn, 1950; reprint, New York, 1970), ISBN 0-19-500210-5 [originally published 1917] Christianity and the Indian Religion of Grace (Madras, 1928) India's Religion of Grace and Christianity Compared and Contrasted, trans FH Foster (New York; London, 1930) 'The Sensus Numinis as the Historical Basis of Religion', Hibbert Journal 29, (1930), 1–8 The Philosophy of Religion Based on Kant and Fries, trans EB Dicker (London, 1931) [originally published 1909] Religious essays: A supplement to 'The Idea of the Holy', trans B Lunn, (London, 1931) Mysticism East and West: A Comparative Analysis of the Nature of Mysticism, trans BL Bracey and RC Payne (New York, 1932) [originally published 1926] 'In the sphere of the holy', Hibbert Journal 31 (1932–3), 413–6 The original Gita: The song of the Supreme Exalted One (London, 1939) The Kingdom of God and the Son of Man: A Study in the History of Religion, trans FV Filson and BL Wolff (Boston, 1943) Autobiographical and Social Essays (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1996), ISBN 3-11-014518-9 |

著作 オットーの著作の全書誌は、Robert F. Davidson, Rudolf Otto's Interpretation of Religion (Princeton, 1947), pp. ドイツ語 自然主義的世界観と宗教的世界観 (1904) カント・フリース的宗教哲学 (1909) 聖なるもの - ゲートリヒェンの思想における非合理性と理性との対立について (Breslau, 1917) 西東神秘主義(1926年) インドとキリスト教における恩寵の宗教(1930年) 神の国と人の子(1934年) 英訳 Naturalism and Religion, trans J. Arthur Thomson & Margaret Thomson (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907) [原著は1904年]. The Life and Ministry of Jesus, according to the Critical Method (Chicago: Open Court, 1908), ISBN 0-8370-4648-3. The Idea of the Holy, trans JW Harvey (New York: OUP, 1923; 2nd edn, 1950; reprint, New York, 1970), ISBN 0-19-500210-5 [原著は1917年]. キリスト教とインドの恩寵宗教 (Madras, 1928) インドの恩寵宗教とキリスト教の比較対照、FHフォスター訳(ニューヨーク;ロンドン、1930年) 宗教の歴史的基礎としてのセンソス・ヌミニス」『ヒバート・ジャーナル』29号、(1930), 1-8 カントとフリースに基づく宗教哲学、EBディッカー訳(ロンドン、1931年)[原著は1909年]。 宗教エッセイ: 宗教エッセイ:「聖なるものの思想」の補遺, B・ラン訳, (London, 1931) 東西の神秘主義: 神秘主義の本質の比較分析, BL Bracey and RC Payne訳 (New York, 1932) [原著は1926年]。 聖なるものの領域において」、『ヒバート・ジャーナル』31号(1932-3)、413-6 ギーターの原典: 至高の高貴なるものの歌(ロンドン、1939年) 神の国と人の子: 宗教史の研究』(FVフィルソン、BLウォルフ訳、ボストン、1943年) 自伝的・社会的エッセイ(ベルリン:ヴァルター・デ・グリュイター、1996年)ISBN 3-11-014518-9 |

| Christian philosophy Christian ecumenism Christian mysticism Neurotheology Argument from religious experience Hard problem of consciousness The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James Perceiving God by William Alston The Perennial Philosophy by Aldous Huxley The Case for God by Karen Armstrong I and Thou by Martin Buber |

キリスト教哲学 キリスト教エキュメニズム キリスト教神秘主義 神経神学 宗教的経験からの議論 意識の難問 ウィリアム・ジェームズ著『宗教的経験の多様性 ウィリアム・アルストン著『神を認識する オルダス・ハクスリー著『永遠の哲学 カレン・アームストロング著『神の存在の証明 マーティン・ブーバー著『我と汝 |

| References 1. Adler, Joseph. "Rudolf Otto's Concept of the Numinous". Gambier, OH: Kenyon College. Retrieved 19 October 2016. 2. Alles, Gregory D. (2005). "Otto, Rudolf". Encyclopedia of Religion. Farmington hills, MI: Thomson Gale. Retrieved 6 March 2017. 3. "Louis Karl Rudolf Otto Facts". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved 24 October 2016 – via YourDictionary. 4. Meland, Bernard E. "Rudolf Otto, German philosopher and theologian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 24 October 2016. 5. Ross, Kelley. "Rudolf Otto (1869–1937)". Retrieved 19 October 2016. 6. Otto, Rudolf (1996). Alles, Gregory D. (ed.). Autobiographical and Social Essays. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-110-14519-9. 7. Elkins, James (2011). "Iconoclasm and the Sublime. Two Implicit Religious Discourses in Art History (pp. 133–151)". In Ellenbogen, Josh; Tugendhaft, Aaron (eds.). Idol Anxiety. Redwood City, California: Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-804-76043-0. 8. Mariña, Jacqueline (2010) [1997]. "26. Holiness (pp. 235–242)". In Taliaferro, Charles; Draper, Paul; Quinn, Philip L. (eds.). A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-444-32016-9. 9. Eckardt, Alice L.; Eckardt, A. Roy (July 1980). "The Holocaust and the Enigma of Uniqueness: A Philosophical Effort at Practical Clarification". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 450 (1). SAGE Publications: 169. doi:10.1177/000271628045000114. JSTOR 1042566. S2CID 145073531. Cited by: Katz, Steven T. (1991). "Defining the Uniqueness of the Holocaust". In Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (ed.). A Traditional Quest. Essays in Honour of Louis Jacobs. London: Continuum International. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-567-52728-8. 10. Wynn, Mark (19 December 2016). "Section 2.1 Emotional feelings and encounter with God". Phenomenology of Religion. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Retrieved 6 March 2017. 11. Otto, Rudolf (1923). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 0-19-500210-5. Retrieved 31 December 2016. 12. Sarbacker, Stuart (August 2016). "Rudolf Otto and the Concept of the Numinous". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.88. ISBN 9780199340378. Retrieved 18 February 2018. 13. Webb, Stephen H. (1991). Re-figuring Theology. The Rhetoric of Karl Barth. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-438-42347-0. 14. Elkins, James (2011). "Iconoclasm and the Sublime. Two Implicit Religious Discourses in Art History". In Ellenbogen, Josh; Tugendhaft, Aaron (eds.). Idol Anxiety. Redwood City, California: Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-804-76043-0. 15. Mariña, Jacqueline (2010) [1997]. "26. Holiness (pp. 235–242)". In Taliaferro, Charles; Draper, Paul; Quinn, Philip L. (eds.). A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-444-32016-9. 16. Lewis, C.S. (2009) [1940]. The Problem of Pain. New York City: HarperCollins. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-007-33226-7. 17. Gooch, Todd A. (2000). The Numinous and Modernity: An Interpretation of Rudolf Otto's Philosophy of Religion. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016799-9. 18. Rohr, Richard (2012). Immortal Diamond: The Search for Our True Self. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-1-118-42154-3. 19. Solomon, Norman (2012). The Reconstruction of Faith. Portland: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. pp. 237–243. ISBN 978-1-906764-13-5. 20. Berkovits, Eliezer, God, Man and History, 2004, pp. 166, 170. 21. Aslan, Reza (2005). No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, And Future of Islam. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. p. xxiii. ISBN 1-4000-6213-6. 22. Huxley, Aldous (2004). The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. Harper Collins. p. 55. ISBN 9780060595180. 23. Eliade, Mircea (1959) [1954]. "Introduction (p. 8)". The Sacred and the Profane. The Nature of Religion. Translated from the French by Willard R. Trask. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-156-79201-1. 24. Agnel, Aimé. "Numinous (Analytical Psychology)". International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Retrieved 9 November 2016 – via Encyclopedia.com. 25. Adorno, Theodor W.; Tiedemann, Rolf (2000) [1965]. Metaphysics. Concept and Problems. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Stanford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-804-74528-4. 26. Siebert, Rudolf J. (1 January 2005). "The Critical Theory of Society: The Longing for the Totally Other". Critical Sociology. 31 (1–2). Thousands oaks, CA: SAGE Publications: 57–113. doi:10.1163/1569163053084270. S2CID 145341864. 27. Stace, Walter Terence (1952). Time and Eternity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. vii. ISBN 0-83711867-0. Retrieved 20 June 2020. |

参考文献 1. アドラー、ジョセフ。「ルドルフ・オットーのヌミノーゼ概念」。ガンビア、オハイオ州:ケニオン大学。2016年10月19日取得。 2. アレス、グレゴリー・D. (2005)。「オットー、ルドルフ」。『宗教百科事典』。ファーミントンヒルズ、ミシガン州:トムソン・ゲイル。2017年3月6日取得。 3. 「ルドルフ・カール・ルドルフ・オットーの事実」。『世界人物事典』。2016年10月24日閲覧 – YourDictionary経由。 4. メランド、バーナード・E. 「ルドルフ・オットー、ドイツの哲学者・神学者」。『ブリタニカ国際大百科事典オンライン』。2016年10月24日閲覧。 5. ロス、ケリー。「ルドルフ・オットー(1869–1937)」。2016年10月19日閲覧。 6. オットー、ルドルフ(1996)。アレス、グレゴリー・D.(編)。『自伝的・社会論的随筆集』。ベルリン:ウォルター・デ・グリュイター。p. 30。ISBN 978-3-110-14519-9。 7. エルキンス、ジェームズ(2011)。「偶像破壊と崇高。美術史における二つの暗黙の宗教的言説(pp. 133–151)」。エレンボーゲン、ジョシュ;トゥーゲンドハフト、アーロン(編)。『偶像への不安』。カリフォルニア州レッドウッドシティ:スタン フォード大学出版局。p. 147。ISBN 978-0-804-76043-0。 8. マリニャ、ジャクリーン(2010年)[1997年]。「26. 聖性(pp. 235–242)」。タリアフェロ、チャールズ;ドレイパー、ポール;クイン、フィリップ・L.(編)。『宗教哲学のコンパニオン』. ニュージャージー州ホボーケン: ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-444-32016-9. 9. エックハート, アリス・L.; エックハート, A. ロイ (1980年7月). 「ホロコーストと唯一性の謎: 実践的明確化に向けた哲学的試み」. アメリカ政治社会科学アカデミー紀要。450 (1)。SAGE出版:169頁。doi:10.1177/000271628045000114。JSTOR 1042566。S2CID 145073531。引用元:カッツ、スティーブン・T。(1991). 「ホロコーストの独自性を定義する」. コーン=シャーボック, ダン (編). 『伝統的探求:ルイス・ジェイコブスへの敬意を込めた論文集』. ロンドン: コンティニュアム・インターナショナル. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-567-52728-8. 10. ウィン, マーク (2016年12月19日). 「セクション 2.1 感情と神との出会い」。宗教の現象学。スタンフォード哲学百科事典。スタンフォード大学言語情報研究センター。2017年3月6日取得。 11. オットー、ルドルフ (1923)。聖なるものの概念。オックスフォード大学出版局。p. vii。ISBN 0-19-500210-5。2016年12月31日取得。 12. サーバッカー、スチュワート (2016年8月)。「ルドルフ・オットーとヌミナス概念」。オックスフォード研究百科事典。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.88。ISBN 9780199340378。2018年2月18日取得。 13. ウェッブ、スティーブン H. (1991)。『神学の再構築。カール・バルトのレトリック』。ニューヨーク州オールバニ:SUNY Press。87 ページ。ISBN 978-1-438-42347-0。 14. エルキンス、ジェームズ(2011)。「偶像破壊と崇高。美術史における二つの暗黙の宗教的言説」。エレンボーゲン、ジョシュ;トゥーゲンハフト、アーロ ン(編)。『偶像への不安』。カリフォルニア州レッドウッドシティ:スタンフォード大学出版局。147頁。ISBN 978-0-804-76043-0。 15. マリニャ、ジャクリーン(2010)[1997]。「26. 神聖性(pp. 235–242)」。『宗教哲学コンパニオン』チャールズ・タリアフェロ、ポール・ドレイパー、フィリップ・L・クイン(編)。ニュージャージー州ホボー ケン:ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ。p. 238。ISBN 978-1-444-32016-9。 16. ルイス、C.S. (2009) [1940]。『苦痛の問題』。ニューヨーク:ハーパーコリンズ。5-6 ページ。ISBN 978-0-007-33226-7。 17. グーチ、トッド A. (2000). 『神聖と現代性:ルドルフ・オットーの宗教哲学の解釈』. ベルリン:ウォルター・デ・グルイター. ISBN 3-11-016799-9. 18. ローア、リチャード (2012). 『不滅のダイヤモンド:真の自分を探す旅』. サンフランシスコ:ジョシー・バス. ISBN 978-1-118-42154-3。 19. ソロモン、ノーマン (2012)。信仰の再構築。ポートランド:リトマン・ユダヤ文明図書館。237~243 ページ。ISBN 978-1-906764-13-5。 20. エルイーザー・バーコヴィッツ、『神、人間、そして歴史』、2004年、166、170ページ。 21. アスラン、レザ(2005)。『神以外の神はいない:イスラムの起源、進化、そして未来』。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス・トレード・ペーパーバックス。xxiiiページ。ISBN 1-4000-6213-6。 22. ハクスリー、オルダス (2004)。『知覚の扉、天国と地獄』。ハーパーコリンズ。55 ページ。ISBN 9780060595180。 23. エリアーデ、ミルチャ (1959) [1954]。「序文 (8 ページ)」。『聖と俗』。宗教の本質。ウィラード・R・トラスクによるフランス語からの翻訳。ボストン:ホートン・ミフリン・ハーコート。ISBN 978-0-156-79201-1。 24. アグネル、エメ。「ヌミナス(分析心理学)」。国際精神分析辞典。2016年11月9日取得 – Encyclopedia.com 経由。 25. アドルノ, テオドール・W.; ティーデマン, ロールフ (2000) [1965]. 『形而上学 概念と問題』. エドマンド・ジェフコット訳. スタンフォード大学出版局. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-804-74528-4. 26. ジーベルト, ルドルフ・J. (2005年1月1日). 「社会批判理論:全く異なるものへの憧憬」『批判社会学』31巻1–2号。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:SAGE出版:57–113頁。doi: 10.1163/1569163053084270。S2CID 145341864。 27. ステイス、ウォルター・テレンス(1952年)。『時間と永遠』。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。vii頁。ISBN 0-83711867-0。2020年6月20日取得。 |

| Further reading Almond, Philip C., 1984, 'Rudolf Otto: An Introduction to his Philosophical Theology', Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Davidson, Robert F, 1947, Rudolf Otto's Interpretation of Religion, Princeton Gooch, Todd A, 2000, The Numinous and Modernity: An Interpretation of Rudolf Otto's Philosophy of Religion. Preface by Otto Kaiser and Wolfgang Drechsler, Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016799-9. Ludwig, Theodore M (1987), 'Otto, Rudolf' in Encyclopedia of Religion, vol 11, pp. 139–41 Raphael, Melissa, 1997, Rudolf Otto and the concept of holiness, Oxford: Clarendon Press Mok, Daniël (2012). Rudolf Otto: Een kleine biografie. Preface by Gerardus van der Leeuw. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Abraxas. ISBN 978-90-79133-08-6. Mok, Daniël et al. (2002). Een wijze uit het westen: Beschouwingen over Rudolf Otto. Preface by Rudolph Boeke. Amsterdam: De Appelbloesem Pers (i.e. Uitgeverij Abraxas). ISBN 90-70459-36-1 (print), 978-90-79133-00-0 (ebook). Moore, John Morrison, 1938, Theories of Religious Experience, with special reference to James, Otto and Bergson, New York |

参考文献 アルモンド、フィリップ・C、1984年、『ルドルフ・オットー:その哲学的神学入門』、チャペルヒル:ノースカロライナ大学出版局。 デイヴィッドソン、ロバート・F、1947年、『ルドルフ・オットーの宗教解釈』、プリンストン グーチ、トッド・A、2000年、『ヌミナスと近代性:ルドルフ・オットーの宗教哲学解釈』。オットー・カイザーとヴォルフガング・ドレクスラーによる序文付き、ベルリンおよびニューヨーク:ヴァルター・デ・グリュイター。ISBN 3-11-016799-9。 ルートヴィヒ、セオドア・M(1987)、「オットー、ルドルフ」『宗教事典』第11巻、139-141頁 ラファエル、メリッサ、1997、『ルドルフ・オットーと聖性の概念』、オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス モック、ダニエル(2012)。『ルドルフ・オットー:小さな伝記』。ジェラルドゥス・ファン・デル・レーウによる序文。アムステルダム:ウイトゲヴェレイ・アブラクサス。ISBN 978-90-79133-08-6。 モック、ダニエル他(2002)。『西からの賢者:ルドルフ・オットーに関する考察』。ルドルフ・ボーケによる序文。アムステルダム:デ・アッペルブロー スム・プレス(すなわちウイトゲヴェレイ・アブラクサス)。ISBN 90-70459-36-1 (印刷版), 978-90-79133-00-0 (電子書籍版). ムーア, ジョン・モリソン, 1938, 『宗教的体験の理論』, 特にジェームズ、オットー、ベルクソンを参照, ニューヨーク |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Otto |

I. THE RATIONAL AND THE

NON-RATIONAL

II. 'NUMEN' AND THE 'NUMINOUS'

III, THE ELEMENTS IN THE 'NUMINOUS'

IV. MYSTERIUM TREMENDUM

THE ANALYSIS OF

'TRE1',1ENDUM

I. The Element of Awefulness

2. The Element of 'Overpoweringness

3. The Element of

'Energy' or Urgency

V. THE ANALYSIS OF 1MYSTERIUM'

4. The 'Wholly Other'

VI. 5. THE ELEMENT OF FASCINATION

VII, ANALOGIES AND ASSOCIATED FEELINGS

The Law of the Association of Feelings

Schematization

VIII. THE HOLY AS A CATEGORY OF VALUE:

Sin and Atonement

IX, MEANS OF EXPRESSION OF THE NUMINOUS:

I. Direct Means

2. Indirect Means

3. Means by which the Numinous is expressed in Art

X. THE NUMINOUS IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

XI. THE NUMINOUS IN THE NEW TESTAMENT

XII. THE NUMINOUS IN LUTHER

XIV. THE HOLY AS AN A PRIORI CATEGORY, PART I

XV. ITS EARLIEST MANIFESTATIONS

XVI. THE 'CRUDER' PHASES

XVII. THE HOLY AS AN A PRIORI CATEGORY. PART II

XVIII. THE MANIFESTATIONS OF THE 'HOLY' AND THE FACULTY OF 'DIVINATION'

XIX. DIVINATION IN PRIMITIVE CHRISTIANITY

XX. DIVINATION IN CHRISTIANITY TO-DAY

XXI. HISTORY AND THE A

PRIORI IN RELIGION: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

●ナタン・ゼーデルブロム『神信仰の生成』より

「ルドルフ・オットーが近世宗教研究の重要ではある

が神学からも一般的理解においても余りに顧みられない一結果を力説した彼の影響多き『聖なるもの』という著書のなかで、精霊、霊魂の観念のうちにも超合理

的要素を強調したのは功績である。聖なるもの、神秘的なるもの、超人間的なもの、彼がヌミノーズム(Numinosum)ファスキノーズム

(Fascinosum)という新名称を付した『超自然的なもの』から彼はアニミズムを」導きだそうとしている(ゼェデルブローム(上)1942:73)

●本居宣長

「可畏(かしこ)き物を迦微(かみ)とは云うなり、

すぐれたるとは、尊きこと功(いさを)しきことなど優れたるのみを云うに非ず、悪きもの奇きものなどもよにすぐれて可畏きをば神と云なり」『古事記伝』

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099