パルマコン

pharmakon

☆『パイドロス』https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1636/1636-h/1636-h.htm

ソクラテス:取るに足らないことは置いておき、真に重要な問題を日の目を見させてみよう。それはこうだ:この修辞術という技法は、いったいどんな力を持っているのか?そしてそれはいつ発揮されるのか?

フェードロス:公の集まりにおける非常に大きな力。

ソクラテス:そうだ。だが、修辞家たちについて、君も私と同じように感じているかどうか知りたい。私には、彼らの網には大きな穴がたくさんあるように思えるのだ。

フェードルス:例を挙げてください。

ソクラテス:承知した。ある人格が君の友人エリキシマコスか、あるいはその父アクメノスのもとを訪れ、こう言うとする:

『私は薬を投与する術を知っている。それは体を温めたり冷やしたりする効果を持ち、嘔吐や下剤も与えられる。そうしたあらゆることを』

『そして私はこうした全てを知っているからこそ、医師であると自称するのだ』

熱を帯びるか冷やす効果を持つ薬を調合する方法を知っている。嘔吐剤や下剤、その他あらゆる種類の薬を与えることもできる。こうした知識を全て有する者と

して、私は医師であると主張し、この知識を他者に授けることで医師を養成する」と告げるとしたら、彼らはどう答えると思うか?

フェードロス:彼らは必ず彼に尋ねるだろう、薬を「誰に」与えるのか、「いつ」与えるのか、「どれほど」与えるのか、と。

ソクラテス:では、もし彼がこう答えたとしたらどうだろう?「いや、私はそうしたことは何も知らない。私に相談に来る患者が、自分でそうしたことをできることを期待しているのだ」と。

フェードロス:彼らはこう返すだろう——彼は狂人か、あるいは書物で何かを読んだだけで、あるいは処方箋を一つ二つ偶然見つけただけで、医学の真の技を全く理解していないのに、自分が医者だと妄想している衒学者だと。

ソクラテス:では、もし人格がソフォクレスやエウリピデスのもとへ来て、 「私は些細な事柄について非常に長い演説を、重大な事柄について短い演説を、

また悲痛な演説や恐ろしい演説、脅しめいた演説、あるいはあらゆる種類の演説を

作り上げる術を知っている」と言い、その教えを悲劇の技芸の教えだと自負しているとしたら——?

フェードロス:もし彼が悲劇とは、これらの要素を互いに調和し、全体にふさわしい形で配置すること以外の何物でもないと考えているなら、彼らもきっと彼を嘲笑するだろう。

ソクラテス:しかし彼らが彼に無礼や罵声を浴びせるとは思わない。 最高音と最低音の調律を知っているからといって 自らを調和の達人だと考える者を、

音楽家として扱わないだろうか。 そんな者に偶然出会っても、荒々しく「愚か者め、お前は狂っている!」

などとは言わないだろう。むしろ音楽家のように、穏やかで調和のとれた口調でこう答えるだろう:

『友よ、調和の達人たる者は確かにこれを知るべきだが、 君の知識の段階を超えなければ、調和そのものを理解できないかもしれない。

君が知っているのは調和の予備知識に過ぎず、調和そのものではないのだから』」

フェードルス:まったくその通りだ。

★パルマコンから差延の論理(修辞)へ

「デリダは、プラトンの中期対話篇の一つ『パイドロス』をモティーフに、古代ギリシア語の 「パルマコン」という言葉を使って、脱構築を試みている。『パイドロス』(Phaedrus) の末尾では、ソクラテスがエクリチュールを批判し、パロールの優越を掲げているが、同作品の冒頭で、イリソス川を渡りながらソクラテスとパイドロスが古い 言い伝えについて雑談する際に登場する言葉が「パルマコン(pharmakon)」である。「パルマコ ン」は「毒」を意味すると同時に「薬」をも意味する点で、決定不可能性をも つ。この多義性は豊かさでもある。エクリチュールは文字であるから、人の記憶を保つ とともに、記憶しようという意志を奪い取る。ここに、エクリチュールの もつ「薬」でありかつ「毒」のパルマコン的意味合いがある(両義性ないしは多義性)。パロールはエクリチュールに先立って優越するといわれるが、その劣位のエクリチュー ルが逆にパロールを侵食している事態をデリダは暴き出す。パロール / エクリチュールという階層的二項対立は、原―エクリチュールに先立たれ、それがこの二項対立をむしろ生み出しているのである(しかしこの生み出すものは 「根源」ではない)。このエクリチュールの概念は、そのまま存在に対する差延の概念に対応する。エクリチュールの海のような多様性の中から、存在―パロー ルが生まれいずるのである。」ウィキペディア, https://x.gd/7MkgW

| In critical theory, pharmakon is a

concept introduced by Jacques Derrida. It is derived from the Greek

source term φάρμακον (phármakon), a word that can mean either remedy,

poison, or scapegoat.[a][1] |

批評理論において、ファルマコンはジャック・デリダによって導入された

概念である。それはギリシャ語の原語であるφάρμακον(phármakon)に由来しており、救済、毒、スケープゴートのいずれかの意味を持つ言葉

である[a][1]。 |

| In his essay "Plato's

Pharmacy",[2] Derrida explores the notion that writing is a pharmakon

in a composite sense of these meanings as "a means of producing

something". Derrida uses pharmakon to highlight the connection between

its traditional meanings and the philosophical notion of indeterminacy.

"[T]ranslational or philosophical efforts to favor or purge a

particular signification of pharmakon [and to identify it as either

"cure" or "poison"] actually do interpretive violence to what would

otherwise remain undecidable."[3] Whereas a straightforward view on

Plato's treatment of writing (in Phaedrus) suggests that writing is to

be rejected as strictly poisonous to the ability to think for oneself

in dialogue with others (i.e. to anamnesis). Bernard Stiegler argues

that "the hypomnesic appears as that which constitutes the condition of

the anamnesic"[4]—in other words, externalised time-bound communication

is necessary for original creative thought, in part because it is the

primordial support of culture. [5] However, with reference to the

fourth "productive" sense of pharmakon, Kakoliris argues (in contrast

to the rendition given by Derrida) that the contention between Theuth

and the king in Plato's Phaedrus is not about whether the pharmakon of

writing is a remedy or a poison, but rather, the less binary question:

whether it is productive of memory or remembrance. [6][b] Indeterminacy

and ambiguity are not, on this view, fundamental features of the

pharmakon, but rather, of Derrida's deconstructive reading. |

デリダはそのエッセイ「プラトンの薬局」[2]において、書くことは

「何かを生み出す手段」としてのこれらの意味の複合的な意味でのファルマコンであるという概念を探求している。デリダはファルマコンを用いて、その伝統的

な意味と哲学的な不確定性の概念との結びつきを強調する。プラトンの(『パイドロス』における)「書くこと」の扱いを素直に考えれば、「書くこと」は、他

者との対話の中で自分の頭で考える能力(すなわち「アナムネーシス」)にとって厳しく有害なものとして拒絶されるべきものである。バーナード・スティグ

レールは、「ヒポムネシスはアナムネシスの条件を構成するものとして現れる」[4]、言い換えれば、外在化された時間に縛られたコミュニケーションは、文

化の根源的な支えであることもあって、独創的な創造的思考に必要であると論じている。[しかしながら、カコリリスはファルマコンの第四の「生産的」な意味

について、プラトンの『パイドロス』におけるテュートと王の争いは、書くというファルマコンが治療薬であるか毒であるかということではなく、むしろ記憶と

想起のどちらが生産的であるかという、より二元的でない問題であると(デリダの表現とは対照的に)論じている。[6][b]不確定性と曖昧さは、この見解

ではファルマコンの基本的な特徴ではなく、むしろデリダの脱構築的読解の特徴である。 |

| Relatedly, pharmakon has been theorised in connection with a broader philosophy of technology, biotechnology, immunology, enhancement, and addiction. Gregory Bateson points out that an important part of the Alcoholics Anonymous philosophy is to understand that alcohol plays a curative role for the alcoholic who has not yet begun to dry out. This is not simply a matter of providing an anesthetic, but a means for the alcoholic of "escaping from his own insane premises, which are continually reinforced by the surrounding society."[8] | これに関連して、ファーマコンは、テクノロジー、バイオテクノロジー、

免疫学、強化、依存症などのより広範な哲学との関連で理論化されてきた。グレゴリー・ベイトソンは、アルコホーリクス・アノニマスの哲学の重要な部分は、

アルコールがまだ乾き始めていないアルコール依存症患者にとって治癒的な役割を果たすことを理解することだと指摘している。これは単に麻酔薬を提供すると

いう問題ではなく、アルコール依存症患者にとって「周囲の社会によって絶えず強化されている自分自身の狂気の前提から逃れる」手段なのである[8]。 |

| A more benign example is Donald

Winnicott's concept of a "transitional object" (such as a teddy bear)

that links and attaches child and mother. Even so, the mother must

eventually teach the child to detach from this object, lest the child

become overly dependent upon it.[9] Stiegler claims that the

transitional object is "the origin of works of art and, more generally,

of the life of the mind."[9]: 3 |

より穏やかな例としては、ドナルド・ウィニコットが提唱した、子どもと

母親を結びつけ、くっつける「過渡的対象」(テディベアなど)という概念がある。たとえそうであっても、母親は最終的に、子どもがこの対象に過度に依存し

ないように、この対象から切り離すことを教えなければならない[9]。スティグレールは、移行対象は「芸術作品の起源であり、より一般的には、心の生活の

起源である」と主張している[9]: 3 |

| Emphasizing the third sense of

pharmakon as scapegoat, but touching on the other senses, Boucher and

Roussel treat Quebec as a pharmakon in light of the discourse

surrounding the Barbara Kay controversy and the Quebec sovereignty

movement.[c] |

スケープゴートとしてのファーマコンの第三義を強調しながらも、他の意

味にも触れているブーシェとルーセルは、バーバラ・ケイ論争とケベック主権運動をめぐる言説に照らして、ケベックをファーマコンとして扱っている[c]。 |

| Persson uses the several senses of pharmakon to "pursue a kind of phenomenology of drugs as embodied processes, an approach that foregrounds the productive potential of medicines; their capacity to reconfigure bodies and diseases in multiple, unpredictable ways."[11] Highlighting the notion (from Derrida) that the effect of the pharmakon is contextual rather than causal, Persson's basic claim – with reference to the body-shape-changing lipodystrophy experienced by some HIV patients taking anti-retroviral therapy.[d] | ペルソンはファーマコンのいくつかの意味を用いて、「具現化されたプロ

セスとしての医薬品の現象学のようなものを追求し、医薬品の生産的な可能性、すなわち予測不可能な複数の方法で身体や病気を再構成する能力を前景化するア

プローチ」[11]を行っている。ファーマコンの効果は因果的というよりもむしろ文脈的であるという(デリダに由来する)概念を強調しながら、ペルソンの

基本的な主張は、抗レトロウイルス療法を受けている一部のHIV患者が経験する、体型が変化する脂肪異栄養症に言及している[d]。 |

| It may be necessary to

distinguish between "pharmacology" that operates in the multiple senses

in which that term is understood here, and a further therapeutic

response to the (effect of) the pharmakon in question. Referring to the

hypothesis that the use of digital technology – understood as a

pharmakon of attention – is correlated with "Attention Deficit

Disorder", Stiegler wonders to what degree digital relational

technologies can "give birth to new attentional forms".[5] To continue

the theme above on a therapeutic response: Vattimo compares

interpretation to a virus; in his essay responding to this quote,

Zabala says that the virus is onto-theology, and that interpretation is

the "most appropriate pharmakon of onto-theology."[12][e] Zabala

further remarks: "I believe that finding a pharmakon can be

functionally understood as the goal that many post-metaphysical

philosophers have given themselves since Heidegger, after whom

philosophy has become a matter of therapy rather than discovery[.]" |

この用語がここで理解されているような複数の意味で作用する「薬理学」

と、問題のファルマコン(の効果)に対するさらなる治療的反応とを区別する必要があるかもしれない。注意の薬学として理解されるデジタル技術の使用が「注

意欠陥障害」と相関しているという仮説に言及しながら、スティグレールは、デジタル関係技術がどの程度まで「新しい注意の形態を生み出す」ことができるの

だろうかと考えている[5]:

ヴァッティモは解釈をウイルスに例えているが、この引用に応えるエッセイの中でザバラは、ウイルスは存在神学であり、解釈は「存在神学の最も適切なファル

マコン」であると述べている[12][e][e]

ザバラはさらに次のように述べている。「ファルマコンを見出すことは、ハイデガー以降、形而上学以降の哲学者の多くが自らに与えた目標として機能的に理解

することができると私は信じている。 |

| Externality Philosophy of technology |

外部性 技術の哲学 |

| Further reading Rinella, Michael A (2010). Pharmakon: Plato, drug culture, and identity in ancient Athens. Lexington Books. Bianchini, Samuel; Quinz, Emanuele (2016). Behavioral Objects. Sternberg Press. Mróz, Adrian (2020). "Behaving, Mattering, and Habits Called Aesthetics. Part 2: Theoretical Cays of Phenomenologically Making-Sense". The Polish Journal of Aesthetics. 57: 88. doi:10.19205/57.20.4. Page, Carl (1991). "The Truth about Lies in Plato's Republic". Ancient Philosophy. 11 (1): 1–33. doi:10.5840/ancientphil199111132. Rinella, Michael A (2007). "Revisiting the Pharmacy: Plato, Derrida, and the Morality of Political Deceit". Polis: The Journal for Ancient Greek Political Thought. 24 (1). Brill: 134–153. doi:10.1163/20512996-90000111. Alexander Gerner, Philosophy of Human Technology, http://cfcul.fc.ul.pt/LT/FTH/ Staikou, Elina (2014). "Putting in the Graft: Philosophy and Immunology". Derrida Today. 7 (2). Edinburgh University Press: 155–179. doi:10.3366/drt.2014.0087. Alexander Gerner, Enhancement as Deviation Meyers, Todd (2014). "Promise and Deceit: Pharmakos, Drug Replacement Therapy, and the Perils of Experience". Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 38 (2). Springer: 182–196. doi:10.1007/s11013-014-9376-9. PMID 24788959. S2CID 33502895. Rée, Jonathan (2012). Book review: You must change your life by Peter Sloterdijk, https://newhumanist.org.uk/2898/book-review-you-must-change-your-life-by-peter-sloterdijk |

さらに読む Rinella, Michael A (2010). ファルマコン: 古代アテネにおけるプラトン、薬物文化、アイデンティティ。Lexington Books. Bianchini, Samuel; Quinz, Emanuele (2016). Behavioral Objects. Sternberg Press. Mróz, Adrian (2020). 「美学と呼ばれる振る舞い、マターリング、習慣。Part 2: Theoretical Cays of Phenomenologically Making-Sense」. The Polish Journal of Aesthetics. 57: 88. doi:10.19205/57.20.4. Page, Carl (1991). 「プラトンの共和国における嘘についての真実」. Ancient Philosophy. 11 (1): 1–33. doi:10.5840/ancientphil199111132. Rinella, Michael A (2007). 「Revisiting the Pharmacy: Rinella (2007). 「Revisiting the Pharmacy: Plato, Derrida, and the Morality of Political Deceit」. Polis: The Journal for Ancient Greek Political Thought. 24 (1). doi:10.1163/20512996-90000111. Alexander Gerner, Philosophy of Human Technology, http://cfcul.fc.ul.pt/LT/FTH/. Staikou, Elina (2014). 「Putting in the Graft: 哲学と免疫学」. Derrida Today. 7 (2). Edinburgh University Press: 155–179. doi:10.3366/drt.2014.0087. アレクサンダー・ゲルナー『逸脱としての強化 Meyers, Todd (2014). 「Promise and Deceit: Pharmakos, Drug Replacement Therapy, and the Perils of Experience」. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 38 (2). doi:10.1007/s11013-014-9376-9. PMID 24788959. s2cid 33502895. Rée, Jonathan (2012). 書評: You must change your life by ピーター・スローターダイク, https://newhumanist.org.uk/2898/book-review-you-must-change-your-life-by-peter-sloterdijk. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmakon |

差延 différance, 「何者かとして同定されうるものや、そのものの自己 同一性が成り立つためには、必ずそれ自身との完全な一致からのずれや、違い、逸脱といった、つねにすでにそれ自身に先立っている他者との関係が必要であ る。このことを示すために、差延という方法が導入され」る。(→脱構築のエートスと方法)

●『パイドロス』の最後の議論

| Discussion of

rhetoric and writing (257c–279c) After Phaedrus concedes that this speech was certainly better than any Lysias could compose, they begin a discussion of the nature and uses of rhetoric itself. After showing that speech making itself isn't something reproachful, and that what is truly shameful is to engage in speaking or writing shamefully or badly, Socrates asks what distinguishes good from bad writing, and they take this up.[Note 37] Phaedrus claims that to be a good speechmaker, one does not need to know the truth of what he is speaking on, but rather how to properly persuade,[Note 38] persuasion being the purpose of speechmaking and oration. Socrates first objects that an orator who does not know bad from good will, in Phaedrus's words, harvest "a crop of really poor quality". Yet Socrates does not dismiss the art of speechmaking. Rather, he says, it may be that even one who knew the truth could not produce conviction without knowing the art of persuasion;[Note 39] on the other hand, "As the Spartan said, there is no genuine art of speaking without a grasp of the truth, and there never will be".[Note 40] To acquire the art of rhetoric, then, one must make systematic divisions between two different kinds of things: one sort, like "iron" and "silver", suggests the same to all listeners; the other sort, such as "good" or "justice", lead people in different directions.[Note 41] Lysias failed to make this distinction, and accordingly, failed to even define what "love" itself is in the beginning; the rest of his speech appears thrown together at random, and is, on the whole, very poorly constructed.[Note 42] Socrates then goes on to say, "Every speech must be put together like a living creature, with a body of its own; it must be neither without head nor without legs; and it must have a middle and extremities that are fitting both to one another and to the whole work."[Note 43] Socrates's speech, on the other hand, starts with a thesis and proceeds to make divisions accordingly, finding divine love, and setting it out as the greatest of goods. And yet, they agree, the art of making these divisions is dialectic, not rhetoric, and it must be seen what part of rhetoric may have been left out.[Note 44] When Socrates and Phaedrus proceed to recount the various tools of speechmaking as written down by the great orators of the past, starting with the "Preamble" and the "Statement Facts" and concluding with the "Recapitulation", Socrates states that the fabric seems a little threadbare.[Note 45] He goes on to compare one with only knowledge of these tools to a doctor who knows how to raise and lower a body's temperature but does not know when it is good or bad to do so, stating that one who has simply read a book or came across some potions knows nothing of the art.[Note 46] One who knows how to compose the longest passages on trivial topics or the briefest passages on topics of great importance is similar, when he claims that to teach this is to impart the knowledge of composing tragedies; if one were to claim to have mastered harmony after learning the lowest and highest notes on the lyre, a musician would say that this knowledge is what one must learn before one masters harmony, but it is not the knowledge of harmony itself.[Note 47] This, then, is what must be said to those who attempt to teach the art of rhetoric through "Preambles" and "Recapitulations"; they are ignorant of dialectic, and teach only what is necessary to learn as preliminaries.[Note 48] They go on to discuss what is good or bad in writing. Socrates tells a brief legend, critically commenting on the gift of writing from the Egyptian god Theuth to King Thamus, who was to disperse Theuth's gifts to the people of Egypt. After Theuth remarks on his discovery of writing as a remedy for the memory, Thamus responds that its true effects are likely to be the opposite; it is a remedy for reminding, not remembering, he says, with the appearance but not the reality of wisdom. Future generations will hear much without being properly taught, and will appear wise but not be so, making them difficult to get along with.[Note 49] No written instructions for an art can yield results clear or certain, Socrates states, but rather can only remind those that already know what writing is about.[Note 50] Furthermore, writings are silent; they cannot speak, answer questions, or come to their own defense.[Note 51] Accordingly, the legitimate sister of this is, in fact, dialectic; it is the living, breathing discourse of one who knows, of which the written word can only be called an image.[Note 52] The one who knows uses the art of dialectic rather than writing: "The dialectician chooses a proper soul and plants and sows within it discourse accompanied by knowledge—discourse capable of helping itself as well as the man who planted it, which is not barren but produces a seed from which more discourse grows in the character of others. Such discourse makes the seed forever immortal and renders the man who has it happy as any human being can be."[Note 53] |

修辞学と文章についての議論 (257c-279c) パイドロスは、この演説がリュシアスのどの演説よりも優れていることを認めた後、修辞学そのものの性質と用途について議論を始める。演説をすること自体は 非難されるようなことではなく、真に恥ずべきことは、恥ずべき、あるいはひどく話したり書いたりすることであることを示した後、ソクラテスは良い文章と悪 い文章を区別するものは何かと問い、二人はこれを取り上げる[注釈 37]。 パイドロスは、よい演説家であるためには、自分が話していることの真理を知る必要はなく、むしろどのように適切に説得するか、[注釈 38]が演説やオラシオンの目的であると主張する。ソクラテスはまず、善悪の区別がつかない弁士は、パイドロスの言葉を借りれば「本当に質の悪い作物」を 収穫することになると反論する。しかし、ソクラテスは弁論術を否定しない。むしろ彼は、真理を知っている者であっても説得の術を知らなければ説得を生み出 すことはできないかもしれない[注釈 39]、他方で「スパルタ人が言ったように、 真理を把握することなしに本物の話術は存在しないし、今後も存在することはないだろう」と言う[注釈 40]。 「鉄」と「銀」のように、どの聞き手にも同じことを示唆するものと、「善」や「正義」のように、人々を異なる方向に導くものである[注釈 41] リュシアスはこの区別をすることができず、それゆえ、「愛」そのものが何であるかを最初に定義することさえできなかった、 「すべての演説は、生き物のように、それ自身の体をもって組み立てられなければならない。頭も脚もなくはならないし、互いに、また作品全体にふさわしい中 間部と四肢がなければならない」[注 43]。 一方、ソクラテスの演説は、テーゼから始まり、それに従って分割を進め、神の愛を見出し、それを財の中で最も偉大なものとしている。しかし、このような分 割を行う技術は弁証法であって修辞学ではないし、修辞学のどの部分が抜け落ちているのかを見なければならない[注釈 44]。 ソクラテスとパイドロスが、過去の偉大な弁論家たちによって書き留められた演説のさまざまな道具を、「前文」と「陳述事実」から始めて「再現」で締めくく るまで語り出すと、ソクラテスは、この布は少し糸がほつれているようだと述べる。 [注45] ソクラテスは、これらの道具の知識しかない者を、体温を上げたり下げたりする方法は知っている が、それがいつ良いのか悪いのかを知らない医者と比較し、単に本を読んだり、いくつかの薬に出会っただけの者は、その技術について何も知らないと述べる。 [注46] 些細な話題について最も長い文章を作文する方法や、重要な話題について最も短い文章を作文する方法を知っている者が、これを教えることは悲劇を作文する知 識を伝授することだと主張するのも同様である。竪琴の最低音と最高音を学んだ後に和 声をマスターしたと主張する者がいたとして、音楽家は、この知識は和声をマスターする前に学ばなければならないものであって、和声そのものの知識ではない と言うだろう。 [注47]このことは、「前置き」や「復唱」を通して修辞学の技術を教えようとする人々に対して言わなければならないことである。彼らは弁証法について無 知であり、前段階として学ぶのに必要なことだけを教えている[注48]。 彼らはさらに、文章を書くことの良し悪しについて議論する。ソクラテスは短い伝説を 語り、エジプトの神テウトからタムス王への文字の贈り物について批判的にコメントする。テウト(トート)が記憶力を回復させる薬として文字を発見したこと を述べた後、タムスはその真の効果はその反対である可能性が高いと答える。将来の世代は、適切に教えられることなく多くのことを聞き、賢く見えるがそうで はなく、うまくやっていくのが難しくなる[注釈 49]。 ソクラテスは、ある芸術について書かれた指示書は、明確で確実な結果を もたらすことはできず、むしろ、書くことが何であるかをすでに知っている者に思い出させることしかできないと述べている[注釈 50]。さらに、文章は沈黙するものであり、話すことも、質問に答えることも、自ら の弁護をすることもできない[注釈 51]。 従って、この正当な姉妹は、実際には弁証法である。弁証法とは、知っている者の生き ている、呼吸している言説であり、書かれた言葉はそのイメージと呼ぶことができるだけである[注釈 52] 知っている者は、書くことよりも弁証法の技術を用いる: 「弁証法者は適切な魂を選び、その中に知識を伴った言説を植え、蒔く。言説は、それ を植えた人間と同様に、それ自身を助けることができる。そのような言説は、その種を永遠に不滅のものとし、それを持つ人間を人間として幸福にする」[注 53]。 |

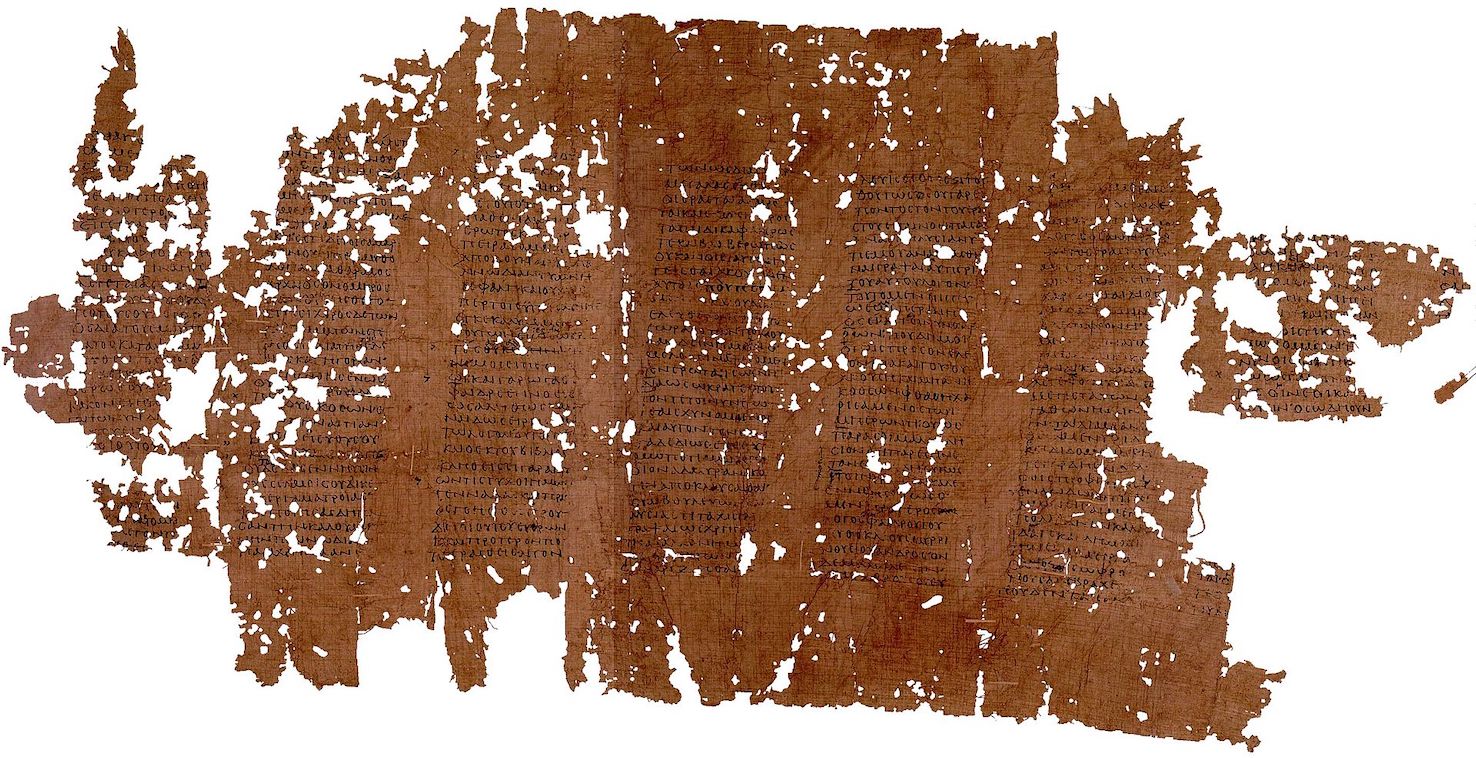

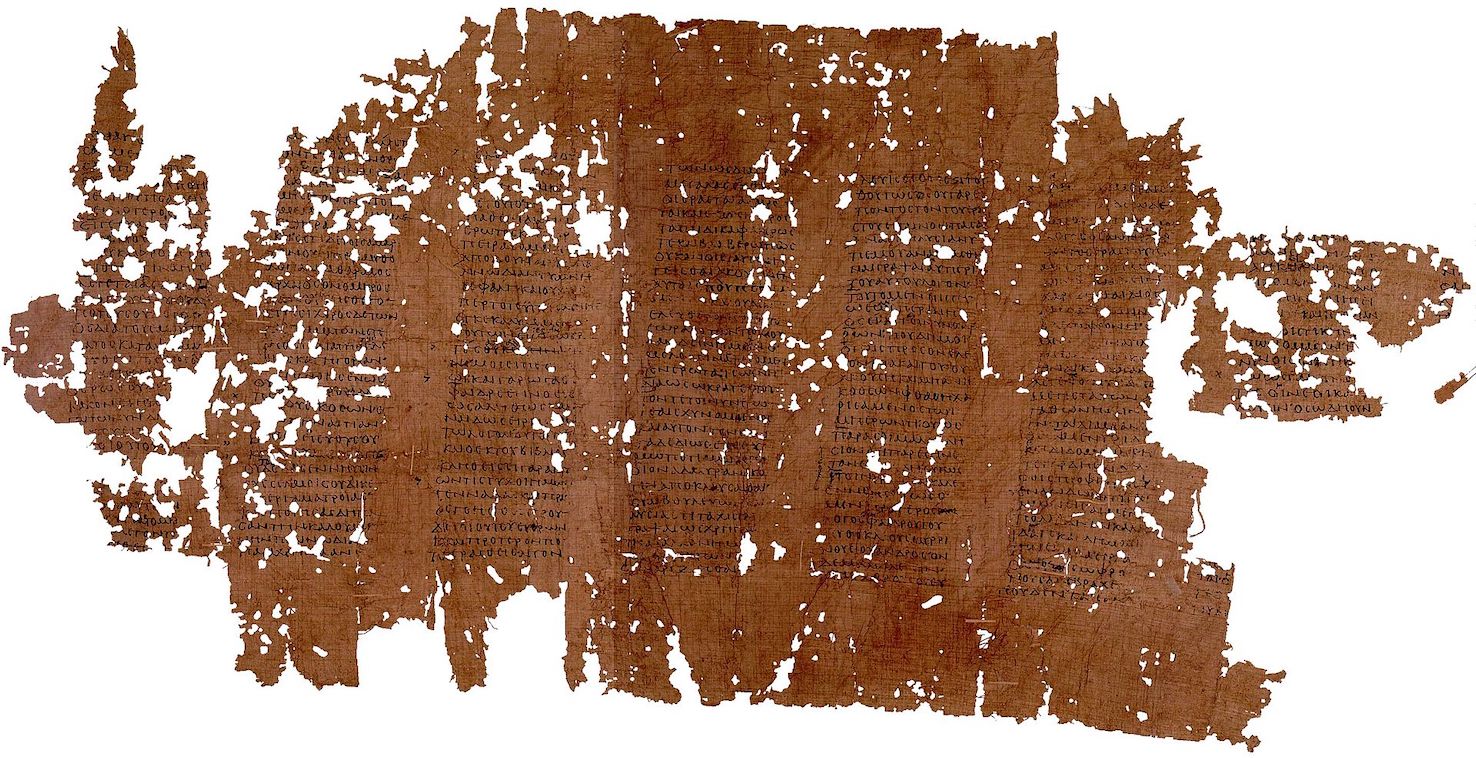

Fragments of a papyrus roll of the Phaedrus from the 2nd century AD |

紀元2世紀のパピルス『パイドロス』の断片 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deconstruction |

|

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099