There is

hardly

a better example of the fact that an artist works with

signs that have a place in semiotic systems extending far beyond the

craft he practices than the poet in Islam. A Muslim making verses faces

a set of cultural realities as objective to his intentions as rocks or

rainfall, no less substantial for being nonmaterial, and no less

stubborn for being man-made. He operates, and alway has operated, in a

context where the instrument of his art, language, has a peculiar,

heightened kind of status, as distinctive a significance, and as

mysterious, as Abelam paint. Everything from metaphysics to morphology,

scripture to calligraphy, the patterns of public recitation to the

style of informal conversation conspires to make of speech and speaking

a matter charged with an import if not unique in human history,

certainly extraordinary. The man who takes up the poet's role in Islam

traffics, and not wholly legitimately, in the moral substance of his

culture. There is

hardly

a better example of the fact that an artist works with

signs that have a place in semiotic systems extending far beyond the

craft he practices than the poet in Islam. A Muslim making verses faces

a set of cultural realities as objective to his intentions as rocks or

rainfall, no less substantial for being nonmaterial, and no less

stubborn for being man-made. He operates, and alway has operated, in a

context where the instrument of his art, language, has a peculiar,

heightened kind of status, as distinctive a significance, and as

mysterious, as Abelam paint. Everything from metaphysics to morphology,

scripture to calligraphy, the patterns of public recitation to the

style of informal conversation conspires to make of speech and speaking

a matter charged with an import if not unique in human history,

certainly extraordinary. The man who takes up the poet's role in Islam

traffics, and not wholly legitimately, in the moral substance of his

culture. |

イ

スラムの詩人ほど、芸術家が、自分が実践している技術をはるかに超えた記号体系に位置づけられる記号を使って仕事をしているという事実を示す好例はないだ

ろう。詩を作るムスリムは、岩や降雨と同じように、彼の意図に対して客観的で、非物質的であるがゆえに実質的でなく、人工的であるがゆえに頑固でもない、

一連の文化的現実に直面している。彼の芸術の道具である言語が、アベラムの絵の具のように独特な意味を持ち、神秘的である。形而上学から形態学まで、聖典

から書道まで、公の場での朗読のパターンから非公式の会話のスタイルまで、あらゆるものが、スピーチやスピーチを、人類史上ユニークなものではないにせ

よ、確かに並外れた重要性を帯びたものにしようと共謀している。イスラム教において詩人の役割を担う者は、その文化の道徳的本質を、完全に合法的とは言え

ないが、売買しているのである。 イ

スラムの詩人ほど、芸術家が、自分が実践している技術をはるかに超えた記号体系に位置づけられる記号を使って仕事をしているという事実を示す好例はないだ

ろう。詩を作るムスリムは、岩や降雨と同じように、彼の意図に対して客観的で、非物質的であるがゆえに実質的でなく、人工的であるがゆえに頑固でもない、

一連の文化的現実に直面している。彼の芸術の道具である言語が、アベラムの絵の具のように独特な意味を持ち、神秘的である。形而上学から形態学まで、聖典

から書道まで、公の場での朗読のパターンから非公式の会話のスタイルまで、あらゆるものが、スピーチやスピーチを、人類史上ユニークなものではないにせ

よ、確かに並外れた重要性を帯びたものにしようと共謀している。イスラム教において詩人の役割を担う者は、その文化の道徳的本質を、完全に合法的とは言え

ないが、売買しているのである。

|

| In order even

to begin to demonstrate this it is of course necessary

first to cut the subject down to size. It is not my intention to survey

the whole course of poetic development from the Prophecy forward, but

just to make a few general, and rather unsystematic, remarks about the

place of poetry in traditional Islamic society--most particularly

Arabic poetry, most particularly in Morocco, most particularly on the

popular, oral verse level. The relationship between poetry and the

central impulses of Muslim culture is, I think, rather similar more or

less everywhere, and more or less since the beginning. But rather than

trying to establish that, I shall merely assume it and proceed, on the

basis of somewhat special material, to suggest what the terms of that

relationship--an uncertain and difficult one--seem to be. |

こ

のことを実証し始めるためには、もちろん、まずこのテーマを小さく切り分ける必要がある。預言者言行録から先の詩的発展の全過程を調査するのが私の意図で

はなく、伝統的なイスラーム社会における詩の位置づけについて、特にアラビア語の詩について、特にモロッコの詩について、特に大衆的な口承詩のレベルにつ

いて、一般的な、そしてどちらかといえば非体系的な発言をいくつかするだけである。詩とイスラム文化の中心的な衝動との関係は、多かれ少なかれどこでも、

そして多かれ少なかれ最初から似たようなものだと思う。しかし、それを立証しようとするのではなく、単にそれを仮定し、やや特殊な資料に基づいて、その関

係の条件--不確かで困難なものだが--がどのようなものであるかを示唆することにしよう。

|

| There

are, from

this perspective, three dimensions of the problem to

review and interrelate. The first, as always in matters Islamic, is the

peculiar nature and status of the Quran, "the only miracle in Islam."

The second is the performance context of the poetry, which, as a living

thing, is as much a musical and dramatic art as it is a literary one.

And the third, and most difficult to delineate in a short space, is the

general nature--agonistic, as I will call it--of interpersonal

communication in Moroccan society. Together they make of poetry a kind

of paradigmatic speech act, an archetype of talk, which it would take,

were such a thing conceivable, a full analysis of Muslim culture to

unpack. |

こ

の観点から、この問題には3つの側面がある。一つ目は、イスラムの問題において常にそうであるように、"イスラムにおける唯一の奇跡

"であるクルアーンの特殊な性質と地位である。第二は、詩の上演という文脈であり、詩は文学であると同時に音楽的、演劇的な芸術でもある。そして3つ目

は、短いスペースで説明するのが最も難しいが、モロッコ社会における対人コミュニケーションの一般的な性質、つまり拮抗的な性質である。この二つが一緒に

なって、詩を一種のパラダイム的な発話行為、つまり話の原型にしているのだが、それを解き明かすには、もしそんなことが考えられるとしたら、イスラム文化

を完全に分析する必要があるだろう。

|

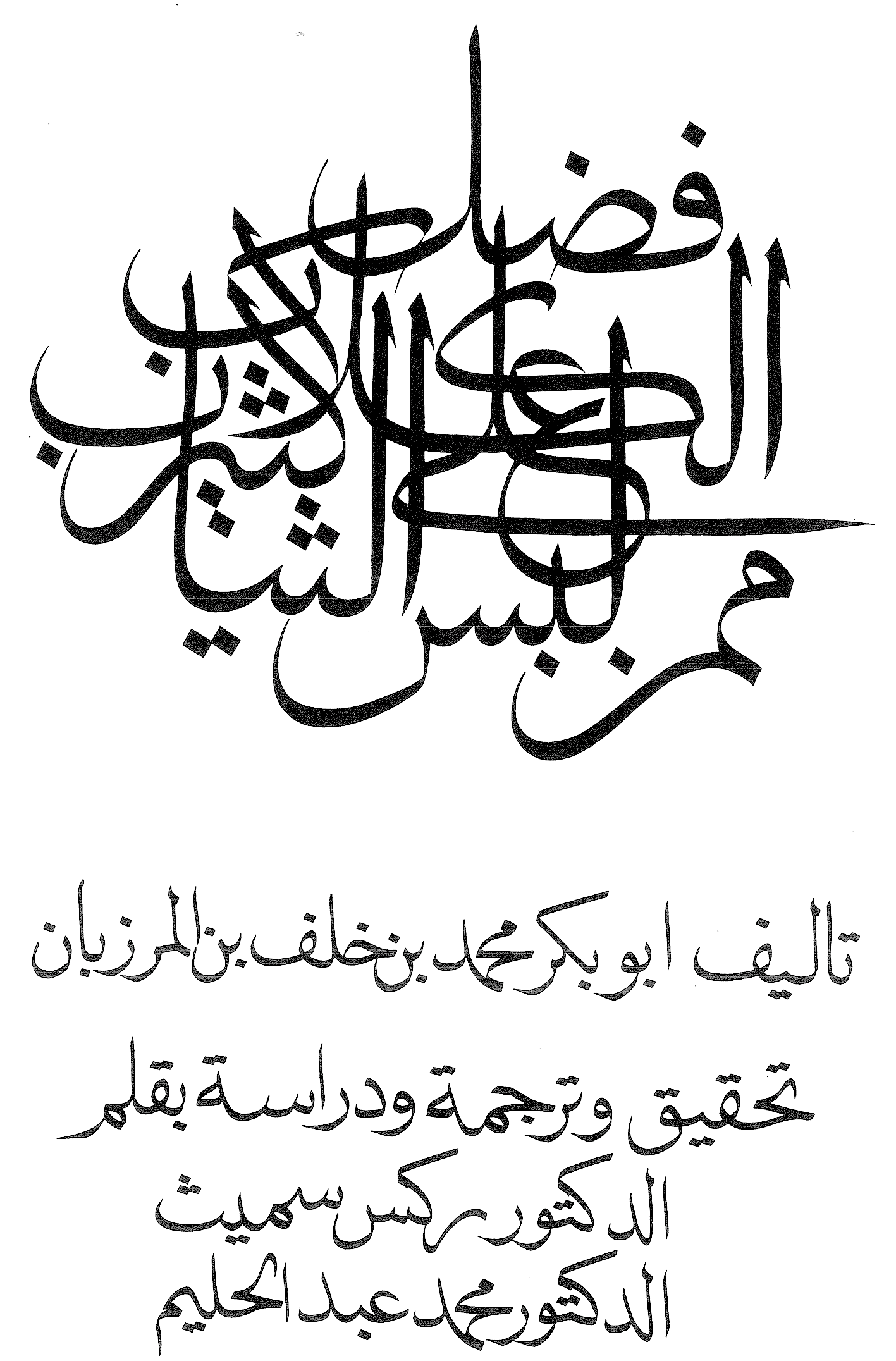

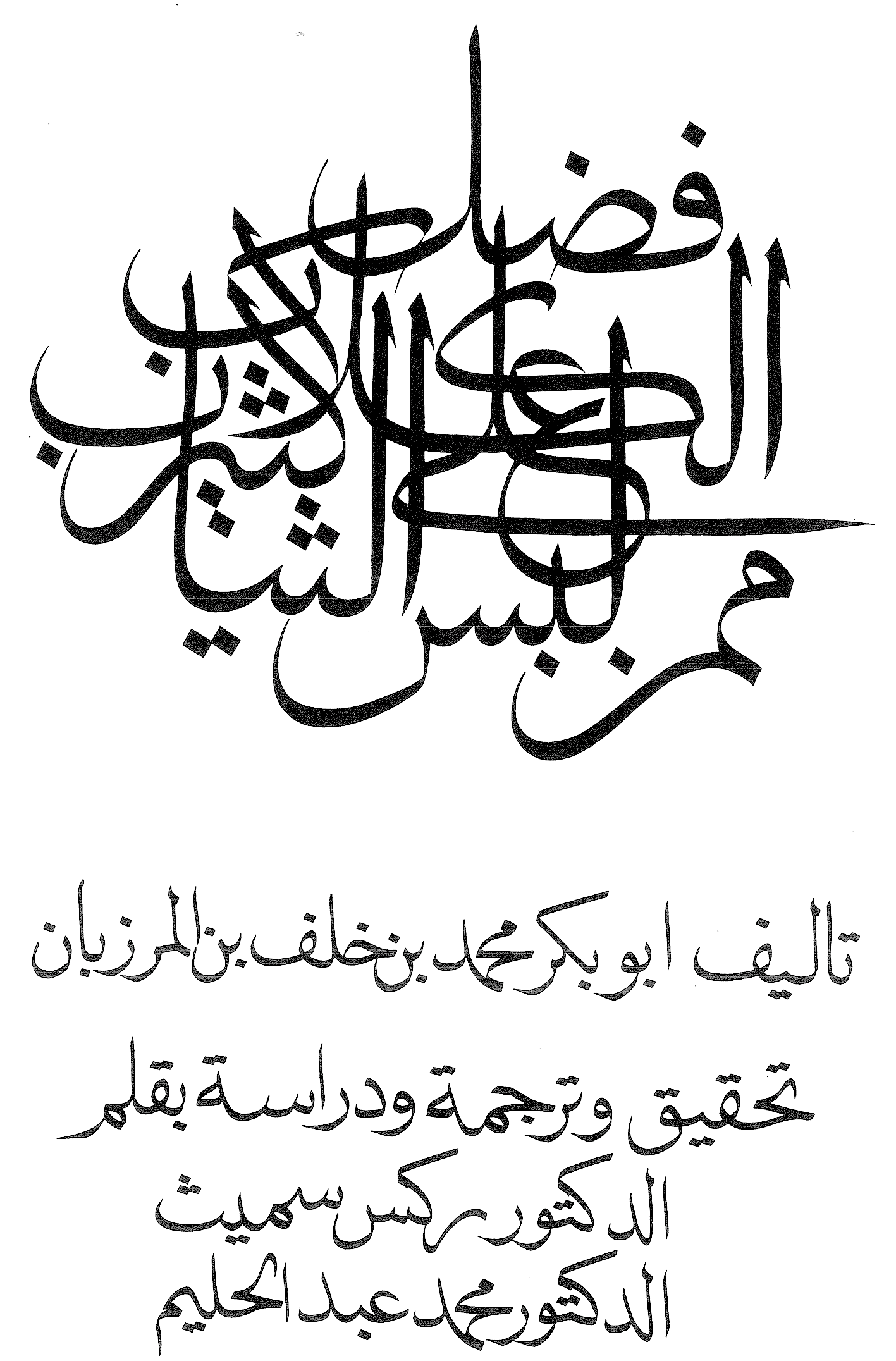

| But as I say,

wherever the matter ends it starts with the Quran. The

Quran (which means neither "testament" nor "teaching" nor "book," but

"recitation") differs from the other major scriptures of the world in

that it contains not reports about God by a prophet or his disciples,

but His direct speech, the syllables, words, and sentences of Allah.

Like Allah, it is eternal and uncreated, one of His attributes, like

Mercy or Omnipotence, not one of his creatures, like man or the earth.

The metaphysics are abstruse and not very consistently worked out,

having to do with Allah's translation into Arabic rhymed prose of

excerpts from an eternal text, the Well-Guarded Tablet, and the

dictation of these, one by one and in no particular order over a period

of years, by Gabriel to Muhammad, Muhammad in turn dictating them to

followers, the so-called Quran-reciters, who memorized them and

transmitted them to the community at large, which, rehearsing them

daily, has continued them since. But the point is that he who chants

Quranic verses--Gabriel, Muhammad, the Quran-reciters, or the ordinary

Muslim, thirteen centuries further along the chain--chants not words

about God, but of Him, and indeed, as those words are His essence,

chants God himself. The Quran, as Marshall Hodgson has said, is not a

treatise, a statement of facts and norms, it is an event, an act:

|

し

かし、私が言うように、問題がどこで終わっても、それはコーランから始まる。コーラン(「遺言」でも「教え」でも「書物」でもなく、「朗読」を意味する)

は、預言者やその弟子による神についての報告ではなく、神の直接の言葉、アッラーの音節、言葉、文章を含んでいるという点で、世界の他の主要な聖典とは異

なっている。アッラーのように、それは永遠で創造されず、慈悲や全能のような神の属性の一つであり、人間や大地のような被造物の一つではない。その形而上

学は難解で、一貫して解明されているわけではないが、アッラーが永遠のテキストである「よく守られた石版」の抜粋をアラビア語の韻文に翻訳し、何年にもわ

たって一つずつ、順不同に口述したことに関係している、

ムハンマドはそれを信奉者、いわゆるコーラン朗読者に口述し、信奉者はそれを暗記し、共同体全体に伝え、共同体はそれを毎日練習し、それ以来それを続けて

いる。しかし、重要なのは、コーランの詩を唱える者、すなわちガブリエル、ムハンマド、コーラン詠唱者たち、あるいは13世紀も連鎖してきた普通のイスラ

ム教徒は、神についての言葉ではなく、神についての言葉を唱えているのであり、その言葉が神の本質である以上、神そのものを唱えているのである。マーシャ

ル・ホジソンが言ったように、コーランは事実や規範を述べた論文ではなく、出来事であり、行為である:

|

It was

never

designed to be read for information or even for

inspiration, but to be recited as an act of commitment in worship. . .

. What one did with the Qur'’n was not to peruse it but to worship by

means of it; not to passively receive it but, in reciting it, to

reaffirm it for oneself: the event of revelation was renewed every time

one of the faithful, in the act of worship, relived [that is, respoke]

the Qur'’nic affirmation. 26 |

そ

れは決して、情報を得るため、あるいは霊感を得るために読まれるものではなく、礼拝における誓約の行為として暗唱されるものである。. . .

また、クルアーンを受動的に受け取るのではなく、読誦することによって、自分自身でクルアーンを再確認するのである。礼拝の行為において、信者がクルアー

ンを再確認する度に、啓示の出来事は更新されるのである。

|

| Now, there are

a number of implications of this view of the

Quran--among them that its nearest equivalent in Christianity is not

the Bible but Christ--but for our purposes the critical one is that its

language, seventh-century Meccan Arabic, is set apart as not just the

vehicle of a divine message, like Greek, Pali, Aramaic, or Sanskrit,

but as itself a holy object. Even an individual recitation of the

Quran, or portions of it, is considered an uncreated entity, something

that puzzles a faith centered on divine persons, but to an Islamic one,

centered on divine rhetoric, signifies that speech is sacred to the

degree that it resembles that of God. One result of this is the

famous

linguistic schizophrenia of Arabic-speaking peoples: the persistence of

"classical" (muḍāri) or "pure (fuṣḥā) written Arabic, contrived to look

as Quranic as possible and rarely spoken outside of ritual contexts,

alongside one or another unwritten vernacular, called "vulgar"

(cāmmīya) or "common" (dārija), and considered incapable of conveying

serious truths. Another is that the status of those who seek to create

in words, and especially for secular purposes, is highly ambiguous.

They turn the tongue of God to ends of their own, which if it not quite

sacrilege, borders on it; but at the same time they display its

incomparable power, which if not quite worship, approaches it. Poetry,

rivaled only by architecture, became the cardinal fine art in Islamic

civilization, and especially the Arabic-speaking part of it, while

treading the edge of the gravest form of blasphemy. |

さ

て、コーランに対するこのような見方には多くの含意がある--その中でも、キリスト教における最も近い等価物は聖書ではなくキリストである--が、我々の

目的にとって重要なのは、その言語である7世紀のメッカン・アラビア語が、ギリシャ語、パーリ語、アラム語、サンスクリット語のように、単に神聖なメッ

セージの伝達手段としてだけでなく、それ自体が神聖な対象として位置づけられているということである。コーランの個々の朗読、あるいはその一部でさえも、

創造されざる存在とみなされ、神的な人物を中心とする信仰を戸惑わせるが、神的な修辞を中心とするイスラムの信仰にとっては、言論は神のそれに似ている程

度に神聖であることを意味する。その結果のひとつが、アラビア語圏の人々の有名な言語分裂症である。「古典的」(muḍāri)または「純粋な」

(fṣḥā)アラビア語の書き言葉が存続し、できるだけコーランのように見えるように工夫され、儀式の文脈以外ではほとんど話されない。もう一つは、言葉

で、特に世俗的な目的のために創造しようとする人々の地位が非常に曖昧であるということである。彼らは神の舌を自分の目的のために使うが、これは冒涜とま

ではいかないまでも、その境界線上にある。しかし同時に、彼らは神の比類なき力を示すのであり、これは崇拝とまではいかないまでも、それに近づいている。

詩は建築に匹敵するものであり、イスラム文明、特にアラビア語圏の文明において、神を冒涜する最も重大な芸術となった。

|

| This sense for

Quranic Arabic as the model of what speech should be,

and a constant reproof to the way people actually talk, is reinforced

by the whole pattern of traditional Muslim life. Almost every boy (and

more recently, many girls as well) goes to a drill-school where he

learns to recite and memorize verses from the Quran. If he is adept and

diligent he may get the whole 6200 or so by heart and become a ḥafīẓ a

"memorizer," and bring a certain celebrity to his parents; if, as is

more likely, he is not, he will at least learn enough to conduct his

prayers, butcher chickens, and follow sermons. If he is especially

pious, he may even go to a higher school in some urban center like Fez

or Marrakech and obtain a more exact sense of the meaning of what he

has memorized. But whether a man comes away with a handful of

half-understood verses or the entire collection reasonably

comprehended, the main stress is always on recitation and on the rote

learning necessary to it. What Hodgson has said of medieval Islam--that

all statements were seen as either true or false; that the sum of all

true statements, a fixed corpus radiating from the Quran, which at

least implicitly contained them all, was knowledge; and that the way to

obtain knowledge was to commit to memory the phrases it was stated

in--could be said today for the greater part of Morocco, where whatever

weakening faith has experienced it has yet to relax its passion for

recitable truth. 27 |

コー

ランのアラビア語は、あるべき話し方の手本であり、実際の人々の話し方を常に戒めるものであるという意識は、伝統的なイスラム教徒の生活パターン全体に

よって強化されている。ほとんどすべての男子は(最近では多くの女子も)、コーランの詩の暗唱と暗記を学ぶドリルスクールに通う。もし彼が熟達し勤勉であ

れば、6200ほどの全文を暗記し、ḥīafẓ a "暗記者

"となり、両親にある種の名声をもたらすかもしれない。特に敬虔な人であれば、フェズやマラケシュのような都心部の高等学校に進学し、暗記したことの意味

をより正確に理解することもできるだろう。しかし、一握りの中途半端に理解された詩句を持ち帰るにせよ、全集をそれなりに理解して持ち帰るにせよ、主なス

トレスは常に暗唱と、それに必要な暗記学習にある。ホジソンが中世のイスラム教について述べたこと--すべての記述は真か偽のどちらかと見なされ、すべて

の真の記述の総体、少なくとも暗黙のうちにそれらすべてを含んでいるコーランから放射される固定したコーパスが知識であり、知識を得る方法はそれが述べら

れているフレーズを記憶することであった--は、今日、モロッコの大部分について言うことができる。

|

| Such

attitudes

and such training lead to everyday life being punctuated

by lines from the Quran and other classical tags. Aside from the

specifically religious contexts--the daily prayers, the Friday worship,

the mosque sermons, the bead-telling cantations in the mystical

brotherhoods, the recital of the whole book on special occasions such

as the Fast month, the offering of verses at funerals, weddings, and

circumcisions--ordinary conversation is laced with Quranic formulae to

the point where even the most mundane subjects seem set in a sacred

frame. The most important public

speeches--those from the throne, for

example--are cast in an Arabic so classicized that most who hear them

but vaguely understand them. Arabic newspapers, magazines, and books

are written in a similar manner, with the result that the number of

people who can read them is small. The cry of Arabization--the popular

demand, swept forward by religious passions, for conducting education

in classical Arabic and using it in government and administration--is a

potent ideological force, leading to a great deal of linguistic

hypocrisy on the part of the political elite and to a certain amount of

public disturbance when the hypocrisy grows too apparent. It is this

sort of world, one in which language is as much symbol as medium,

verbal style is a moral matter, and the experience of God's eloquence

wars with the need to communicate, that the oral poet exists, and whose

feeling for chants and formulas he exploits as Piero exploited Italy's

for sacks and barrels. "I memorized the Quran," one such poet said,

trying hard, to explain his art. "Then I forgot the verses and

remembered the words." |

こ

のような態度と訓練によって、日常生活はコーランやその他の古典的な札の一節で彩られるようになる。毎日の礼拝、金曜日の礼拝、モスクでの説教、神秘的な

兄弟団での数珠つなぎ、断食月などの特別な日にクルアーン全文を朗読すること、葬式、結婚式、割礼で詩を捧げることなど、特に宗教的な文脈は別として、日

常会話にはコーランの定型句がちりばめられており、ありふれた話題でさえ神聖な枠にはめ込まれているように見える。最も重要な公的演説、例えば王位継承演

説は、古典化されたアラビア語で行われる。アラビア語の新聞、雑誌、本も同じように書かれているが、読める人の数は少ない。アラビア語化という叫び--宗

教的情熱に押し流されて、古典アラビア語で教育を行い、政府や行政でアラビア語を使おうという民衆の要求--は、強力なイデオロギー的力であり、政治エ

リート側の言語的偽善を大いに引き起こし、偽善があまりに露骨になると、それなりの世論を騒がせることになる。言語が象徴であると同時に媒体であり、言語

様式が道徳的な問題であり、神の雄弁の体験がコミュニケーションの必要性と闘う、このような世界こそ口承詩人が存在するのであり、ピエロがイタリアの袋や

樽を利用したように、彼は聖歌や定型句に対する感覚を利用するのである。「私はコーランを暗記した。「そして詩句を忘れ、言葉を思い出した。

|

| He forgot the

verses during a three-day meditation at the tomb of a

saint renowned for inspiring poets, but he remembers the words in the

context of performance. Poetry here is not first composed and then

recited; it is composed in the recitation, put together in the act of

singing it in a public place. |

詩人を鼓舞することで有名な聖人の墓で3

日間瞑想している間に詩を忘れてしまったが、パフォーマンスという文脈の中では言葉を覚えている。ここでの詩は、まず作曲され、それから朗読されるのでは

なく、朗読の中で作曲され、公共の場で歌うという行為の中でまとめられる。

|

| Usually this

is

a lamp-lit space before the house of some wedding giver

or circumcision celebrant. The poet stands, erect as a tree, in the

center of the space, assistants slapping tambourines to either side of

him. The male part of the audience squats directly in front of him,

individual men rising from time to time to stuff currency into his

turban, while the female part either peeks discreetly out from the

houses around or looks down in the darkness from their roofs. Behind

him are two lines of sidewise dancing men, their hands on one another's

shoulders and their heads swiveling as they shuffle a couple half-steps

right, a couple left. He sings his poem, verse by verse, paced by the

tambourines, in a wailed, metallic falsetto, the assistants joining him

for the refrain, which tends to be fixed and only generally related to

the text, while the dancing men ornament matters with sudden strange

rhythmic howls. |

通

常は、結婚式を挙げる人や割礼を祝う人の家の前に、ランプが灯されたスペースが設けられる。詩人は木のように直立し、空間の中央に立ち、アシスタントが彼

の両脇でタンバリンを叩く。観客の男性陣は彼の真正面にしゃがみ込み、男性陣は時々立ち上がって彼のターバンに通貨を詰め込み、女性陣は周囲の家々から目

立たないように顔を出したり、屋根の上から暗闇の中を見下ろしたりする。彼の後ろには、横一列に並んで踊る男たちがいる。彼らは互いの肩に手を置き、頭を

回転させながら、右に半歩、左に2、3歩シャッフルする。彼は、タンバリンのテンポに合わせて、詩を一節ずつ、泣き叫ぶような金属的なファルセットで歌

い、アシスタントたちはリフレインのために彼に加わる。

|

| Of course,

like

Albert Lord's famous Jugoslavs, he does not create his

text out of sheer fancy, but builds it up, molecularly, a piece at a

time, like some artistic Markov process, out of a limited number of

established formulae. Some are thematic: the inevitability of death

("even if you live on a prayer rug"); the unreliability of women ("God

help you, O lover, who is carried away by the eyes"); the hopelessness

of passion ("so many people gone to the grave because of the burning");

the vanity of religious learning ("where is the schoolman who can

whitewash the air?"). Some are figurative: girls as gardens, wealth as

cloth, worldliness as markets, wisdom as travel, love as jewelry, poets

as horses. And some are formal--strict, mechanical schemes of rhyme,

meter, line, and stanza. The singing, the tambourines, the dancing men,

the genre demands, and the audience sending up you-yous of approval or

whistles of censure, as these things either come effectively together

or do not, make up an integral whole from which the poem can no more be

abstracted than can the Quran from the reciting of it. It, too, is an

event, an act; constantly new, constantly renewable. |

も

ちろん、アルバート・ロードの有名なユーゴスラビアのように、彼は単なる空想からテキストを創作しているのではなく、限られた定型の中から、まるで芸術的

なマルコフ・プロセスのように、分子レベルで一枚ずつテキストを作り上げている。死の必然性(「祈りの絨毯の上で生きていても」)、女性の頼りなさ(「目

に流される恋人よ、神よ救いたまえ」)、情熱の絶望(「多くの人が燃えて墓場に行った」)、宗教的学問の虚栄心(「空気を白く塗ることのできる学者がどこ

にいる?)

比喩的なものもある。少女は庭、富は布、世俗は市場、知恵は旅、愛は宝石、詩人は馬。また、形式的なものもある。韻律、拍子、行間、スタンザなどの厳格で

機械的な図式である。歌、タンバリン、踊る男たち、ジャンルの要求、聴衆が賛意を送るユーユーや非難の口笛、これらが効果的に組み合わさったり合わさらな

かったりすることで、詩は一体化した全体を構成する。詩もまた、出来事であり、行為であり、常に新しく、再生可能である。

|

| And, as with

the Quran, individuals, or at least many of them,

punctuate their ordinary speech with lines, verses, tropes, allusions

taken from oral poetry, sometimes from a particular poem, sometimes one

associated with a particular poet whose work they know, sometimes from

the general corpus, which though large, is, as I say, contained within

quite definite formulaic limits. In that sense, taken as a whole,

poetry, the performance of which is widespread and regular, most

especially in the countryside and among the common classes in the

towns, forms a kind of "recitation" of its own, another collection,

less exalted but not necessarily less valuable, of memorizable truths:

lust is an incurable disease, women an illusory cure; contention is the

foundation of society, assertiveness the master virtue; pride is the

spring of action, unworldliness moral hypocrisy; pleasure is the flower

of life, death the end of pleasure. Indeed, the word for poetry,

öcir,

means "knowledge," and though no Muslim would explicitly put it that

way, it stands as a kind of secular counterpoise, a worldly footnote,

to the Revelation itself. What man hears about God and the duties owed

Him in the Quran, fix-worded facts, he hears about human beings and the

consequences of being one in poetry. |

そ

の詩は、ある時は特定の詩から、またある時は自分が知っている特定の詩人に関連した詩から、またある時は一般的な詩からである。その意味で、詩は全体とし

て見れば、特に田舎や町の庶民階級の間で広く定期的に上演されているが、それ自体が一種の「朗読」を形成しており、高尚さでは劣るが、必ずしも価値が劣る

わけではない、暗記可能な真理のもう一つのコレクションを形成している。実際、詩を意味する言葉öcirは「知識」を意味し、それを明確にそう表現するム

スリムはいないが、それは啓示そのものに対する世俗的な対位法、世俗的な脚注のようなものである。人はコーランの中で、神と神に課せられた義務について、

固定された言葉による事実を聞くが、詩の中では人間と人間であることの結果について聞くのである。

|

| The

performance

frame of poetry, its character as a collective speech

act, only reinforces this betwixt and between quality of it--half

ritual song, half plain talk--because if its formal, quasi-liturgical

dimensions cause it to resemble Quranic chanting, its rhetorical,

quasi-social ones cause it to resemble everyday speech. As I have said,

it is not possible to describe here the general tone of interpersonal

relations in Morocco with any concreteness; one can only claim, and

hope to be believed, that it is before anything else combative, a

constant testing of wills as individuals struggle to seize what they

covet, defend what they have, and recover what they have lost. So far

as speech is concerned, this gives to all but the most idle

conversation the quality of a catch-as-catch-can in words, a head-on

collision of curses, promises, lies, excuses, pleading, commands,

proverbs, arguments, analogies, quotations, threats, evasion,

flatteries, which not only puts an enormous premium on verbal fluency

but gives to rhetoric a directly coercive force; candu klām, "he has

words, speech, maxims, eloquence," means also, and not just

metaphorically, "he has power, influence, weight, authority." |

な

ぜなら、その形式的で準典礼的な次元がコーランの詠唱に似ているとすれば、その修辞的で準社会的な次元は日常会話に似ているからである。これまで述べてき

たように、モロッコの対人関係の一般的なトーンをここで具体的に説明することはできない。ただ主張し、信じてもらうことができるのは、モロッコは何よりも

先に闘争的であり、個人が欲しがるものを奪い、持っているものを守り、失ったものを取り戻そうと闘う、絶え間ない意志の試練であるということだ。つまり、

呪い、約束、嘘、言い訳、懇願、命令、ことわざ、議論、類推、引用、脅し、回避、お世辞が正面からぶつかり合うのである。これは、言葉の流暢さを非常に重

視するだけでなく、修辞学に直接的な強制力を与えるのである; candu

klām「彼は言葉、スピーチ、格言、雄弁を持つ」は、比喩的な意味だけでなく、「彼は力、影響力、重さ、権威を持つ」という意味もある。 "

|

| In the poetic

context this agonistic spirit appears throughout. Not

only is the content of what the poet says argumentational in this

way--attacking the shallowness of townsmen, the knavery of merchants,

the perfidy of women, the miserliness of the rich, the treachery of

politicians, and the hypocrisy of moralists--but it is directed at

particular targets, usually ones present and listening. A local Quran

teacher, who has criticized wedding feasts (and the poetry sung at

them) as sinful, is excorciated to his face and forced from the

village: 28 |

詩

的な文脈では、この闘争精神が随所に現れる。詩人が語る内容は、町人の浅はかさ、商人の卑しさ、女の不義、金持ちのみすぼらしさ、政治家の裏切り、道徳主

義者の偽善を攻撃するものであるだけでなく、特定の対象、たいていはその場にいて耳を傾けている者に向けられる。結婚式の祝宴(とそこで歌われる詩)を罪

深いと批判した地元のコーラン教師は、面と向かって叱責され、村から追い出される:

|

|

See how many

shameful things the teacher did; He only worked to fill

his pockets. He is greedy, venal. By God, with all this confusion. Just

give him his money and tell him "go away"; "Go eat cat meat and follow

it with dog meat."

|

私腹を肥やすためだけに働いていた。彼は

貪欲で、毒舌だ。神様、このような混乱の中で。金だけ渡して、「出て行け」と言え。「猫の肉を食べて、犬の肉で追い討ちをかけろ」と。

|

They

found out

that the teacher had memorized only four Quran chapters

[this a reference to his claim to have memorized the whole]. If he knew

the Quran by heart and could call himself a scholar, He wouldn't hurry

through the prayers so fast. He has evil thoughts in his heart. Why,

even in the midst of prayer, his mind is on girls; he would chase one

if he could find any.

A stingy host

fares no better:

As for

him who

is stingy and weak, he just sits there and doesn't dare say anything.

. . .

They who

came

for dinner were as in a prison [the food was so bad], The people were

hungry all night and never satisfied.

. . .

The

host's wife

spent the evening doing as she pleased, By God, she didn't even want to

get up and get the coffee ready.

And a

curer, a

former friend, with whom the poet has fallen out, gets thirty lines of

the following sort of thing:

Oh, the

curer

is no longer a reasonable man. He followed the road to

become powerful, And changed into a mad betrayer. He followed a trade

of the devil; he said he was successful, but I don't believe it.

|

彼らは、その教師がコーランを4章しか暗

記していないことを知った。もし彼がコーランを暗記しており、自らを学者と呼べるのであれば、礼拝をそんなに急がないだろう。彼は心の中に邪悪な考えを

持っている。祈りの最中であっても、女に心を奪われている。

ケチなホストは、それ以上の結果をもたらさない:

ケチで弱い彼は、ただそこに座って何も言わない。

. . .

夕食を食べに来た人々は、まるで牢獄にいるようであった。

. . .

ホストの妻はその晩を好きなように過ごし、神に誓って、彼女は起きてコーヒーを用意することさえ望まなかった。

そして、詩人と仲違いした元友人の治療師は、次のような内容の30行を手に入れる:

ああ、治療師はもはや理性的な男ではない。彼は権力者になる道を辿り、狂気の裏切り者に変わった。彼は成功したと言ったが、私は信じない。

|

| And so on.

Nor

is it merely individuals the poet criticizes (or can be

paid to criticize; for most of these verbal assassinations are contract

jobs): the inhabitants of a rival village, or faction, or family; a

political party (poetic confrontation between members of such parties,

each led by their own poet, have had to be broken up by the police when

words began to lead to blows); even whole classes of people, bakers or

civil servants, may be targets. And he can shift his immediate audience

in the very midst of performance. When he laments the inconstancy of

women, he speaks up into the shadows of the roofs; when he attacks the

lechery of men, his gaze drops to the crowd at his feet. Indeed, the

whole poetic performance has an agonistic tone as the audience cries

out in approval (and presses money on the poet) or whistles and hoots

in disapproval, sometimes to the point of causing his retirement from

the scene. |

な

どなど。詩人が批判するのは、単に個人だけではない(あるいは、批判することで報酬を得ることもできる。このような言葉による暗殺のほとんどは請け負った

仕事だからだ)。ライバルとなる村の住民、派閥、家族、政党(このような政党の党員同士の詩的対決は、それぞれの詩人が率い、言葉が殴り合いに発展し始め

ると、警察によって解散させられなければならなかった)、さらにはパン屋や公務員といった階級全体が標的になることもある。パン屋や公務員といった階級全

体がターゲットになることもある。女性の不誠実さを嘆くときは、屋根の影に向かって語りかけ、男性の淫乱さを攻撃するときは、足元の群衆に視線を落とす。

実際、詩のパフォーマンス全体が苦悶の色合いを帯びている。聴衆は賛同の声をあげたり(そして詩人に金をせびったり)、口笛や大声で不賛成の声をあげたり

する。

|

But perhaps

the

purest expressions of this tone are the direct combats

between poets trying to outdo each other with their verses. Some

subject--it may be just an object like a glass or a tree--is chosen to

get things going, and then the poets sing alternately, sometimes the

whole night long, as the crowd shouts its judgment, until one retires,

bested by the other. From a three-hour struggle I give some brief

excerpts, in which just about everything is lost in translation except

the spirit of the thing:

Well into the

middle of the battle, Poet A, challenging, "stands up and says:"

That

which God

bestowed on him [the rival poet] he wasted to buy nylon

clothes for a girl; he will find what he is looking for, And he will

buy what he wants [that is, sex] and go visiting around all sorts of

[bad] places.

Poet B,

responding:

That

which God

bestowed on him [that is, himself, Poet B] he used for

prayer, tithe, and charity, And he didn't follow evil temptations, nor

stylish girls, nor tatooed girls; he remembers to run away from

Hell-fire.

Then, an

hour

or so later on, Poet A, still challenging, and still

being effectively responded to, shifts to metaphysical riddling:

From one

sky to

the other sky it would take 500,000 years, And after that, what was

going to happen?

Poet B,

taken

off guard, does not respond directly, but, sparring for time, erupts in

threats:

Take him

[Poet

A] away from me, Or I'll call for bombs, I'll call for airplanes, And

soldiers of fearful appearance.

. . .

I will

make, oh

gentlemen, war now, Even if it is just a little one. See, I have the

greater power.

Still

later,

the aroused Poet B recovers and replies to the riddle

about the skies, not by answering it but by satirizing it with a string

of unanswerable counterriddles, designed to expose its

angels-on-the-head-of-a-pin sort of foolishness:

I was

going to

respond to that one who said, "Climb up to the sky and see how far it

is from sky to sky, by the road."

I was

going to

tell him, "Count for me all the things that are in the earth."

I will

answer

the poet, though he is crazy.

Tell me,

how

much oppression have we had, which will be punished in the hereafter?

Tell me

how

much grain is there in the world, that we can feast ourselves on?

Tell me,

how

much wood is there in the forest, that you can burn up?

Tell me,

how

many electricity bulbs are there, from west to cast? Tell me, how many

teapots are filled with tea?

At which

point,

Poet A, insulted, hooted, angry, and defeated, says,

Give me

the

teapot. I am going to bathe for prayer. I have had enough of this party.

and

retires.

|

し

かし、この調子を最も純粋に表現しているのは、詩人たちが詩で互いを打ち負かそうとする直接対決だろう。何か題材--グラスや木のようなただの物体かもし

れない--が選ばれて盛り上がり、詩人たちは交互に、時には一晩中、群衆が審判を下す声を上げながら、一方が他方に負けて退場するまで歌い続ける。3時間

にわたる闘いの中から、いくつか簡単に抜粋してみよう:

戦いの中盤、挑戦的な詩人Aは「立ち上がってこう言う」。

神が彼[ライバルの詩人]に与えたものを、彼は女の子のためにナイロンの服を買うために浪費した。

詩人Bは答える:

神が彼に与えたもの(つまり詩人B自身)を、彼は祈りと什分の一と慈善に使った。彼は悪い誘惑に従わず、おしゃれな女の子にも、タトゥーの女の子にも従わ

なかった。

それから1時間ほどして、詩人Aは、まだ挑戦的であり、まだ効果的に応えられている、形而上学的な謎かけに移行する:

ひとつの空からもうひとつの空まで50万年かかる、そのあとどうなるんだ?

不意を突かれた詩人Bは、直接には答えず、時間稼ぎをしながら脅しをかける:

彼[詩人A]を私から遠ざけろ、さもないと爆弾を呼ぶぞ、飛行機を呼ぶぞ、恐ろしい姿の兵士を呼ぶぞ。

. . .

諸君、私は今戦争を起こす、たとえそれが小さなものであっても。ほら、私の方が大きな力を持っている

さらに後日、興奮した詩人Bは立ち直り、空に関するなぞなぞに答える。答えるのではなく、答えのないなぞなぞを並べて風刺することで、ピンの頭に天使を乗

せたような愚かさを露呈させるのだ:

空に登って、空から空までの道のりの長さを確かめよ。

私は彼に言うつもりだった。"大地にあるすべてのものを私のために数えてくれ "と。

詩人は狂っているが、私は答えよう。

教えてくれ、来世で罰せられるであろう圧政を、私たちはどれほど受けてきただろう?

教えてくれ、この世にはどれだけの穀物があり、私たちはそれを食べることができるのか?

森にはどれだけの薪があり、それを燃やすことができるのか?

教えてくれ、西から東まで、電球はいくつある?教えてくれ、お茶で満たされたティーポットはいくつある?

このとき、詩人Aは、侮辱され、ほだされ、怒り、敗北し、こう言った、

急須をよこせ。私は祈りのために風呂に入る。このパーティーはもうたくさんだ。

と言い残して立ち去る。

|

| In

short, in

speech terms, or more exactly speech-act terms, poetry

lies in between the divine imperatives of the Quran and the rhetorical

thrust and counterthrust of everyday life, and it is that which gives

it its uncertain status and strange force. On the one hand, it forms a

kind of para-Quran, sung truths more than transitory and less than

eternal in a language style more studied than the colloquial and less

arcane than the classical. On the other, it projects the spirit of

everyday life into the realm of, if not the holy, at least the

inspired. Poetry is morally ambiguous because it is not sacred enough

to justify the power it actually has and not secular enough for that

power to be equated to ordinary eloquence. The Moroccan oral poet

inhabits a region between speech types which is at the same time a

region between worlds, between the discourse of God and the wrangle of

men. And unless that is understood neither he nor his poetry can be

understood, no matter how much ferreting out of latent structures or

parsing of verse forms one engages in. Poetry, or anyway this poetry,

constructs a voice out of the voices that surround it. If it can be

said to have a "function," that is it. |

要

するに、言論用語で言えば、より正確には言論行為用語で言えば、詩はコーランの神聖な命令と日常生活の修辞的な推進力と反推進力の中間に位置し、それが詩

の不確かな地位と奇妙な力を与えている。一方では、詩は一種のパラ・クーランを形成し、口語よりも研究され、古典よりも難解でない言語様式で、一過性以上

永遠未満の真理が歌われる。他方では、日常生活の精神を、聖なるものではないにせよ、少なくとも霊感の領域に投影する。詩が道徳的にあいまいなのは、詩が

実際に持っている力を正当化できるほど神聖でもなく、その力が普通の雄弁と同一視できるほど世俗的でもないからだ。モロッコの口承詩人は、その言葉の種類

の間にある領域に住んでいる。それは同時に、世界と世界の間の領域であり、神の言説と人間のいさかいの間の領域でもある。そして、それが理解されない限

り、潜在的な構造を探り出したり、詩の形式を解析したりしても、彼も彼の詩も理解されることはない。詩は、あるいはこの詩は、それを取り巻く声から声を構

築する。それが「機能」を持っていると言えるとすれば、それだけである。

|

| "Art," says my

dictionary, a usefully mediocre one, is "the conscious

production or arrangement of colors, forms, movements, sounds or other

elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty," a way of

putting the matter which seems to suggest that men are born with the

power to appreciate, as they are born with the power to see jokes, and

have only to be provided with the occasions to exercise it. As what I

have said here ought to indicate, I do not think that this is true (I

do not think that it is true for humor either); but, rather, that "the

sense of beauty," or whatever the ability to respond intelligently to

face scars, painted ovals, domed pavillions, or rhymed insults should

be called, is no less a cultural artifact than the objects and devices

concocted to "affect" it. The artist works with his audience's

capacities--capacities to see, or hear, or touch, sometimes even to

taste and smell, with understanding. And though elements of these

capacities are indeed innate--it usually helps not to be

color-blind--they are brought into actual existence by the experience

of living in the midst of certain sorts of things to look at, listen

to, handle, think about, cope with, and react to; particular varieties

of cabbages, particular sorts of kings. Art and the equipment to grasp

it are made in the same shop. |

"Art is the

conscious

production or arrangement of colors, forms, movements, sounds or other

elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty," a way of

putting the matter which seems to suggest that men are born with the

power to appreciate, as they are born with the power to see jokes, and

have only to be provided with the occasions to exercise it.

「芸術とは、美の感覚に影響を与える方法で、色、形、動き、音、その他の要素を意識的に作り出したり、配置したりすることであ

る」つまり言いかえると、人はジョークを見る力を生まれながらにして持っているように、鑑賞する力も生まれながらにして持っており、その力を発揮する機会

を与えられる、のだということになる。

(が、それを否定して)「「美の感覚」、つまり顔の傷、描かれた楕円、ドーム型のパビリオン、あるいは韻を踏んだ侮辱に知的に反応する能力は、それに「影

響を与える」ために作られた物や装置に劣らず、文化的な産物である。」

|

For an approach

to aesthetics which can be called semiotic--that is,

one concerned with how signs signify--what this means is that it cannot

be a formal science like logic or mathematics but must be a social one

like history or anthropology. Harmony and prosody are hardly to be

dispensed with, any more than composition and syntax; but exposing the

structure of a work of art and accounting for its impact are not the

same thing. What Nelson Goodman has called "the absurd and awkward myth

of the insularity of aesthetic experience," the notion that the

mechanics of art generate its meaning, cannot produce a science of

signs or of anything else; only an empty virtuosity of verbal analysis.

29

|

美

学へのアプローチが記号論的と呼ばれるもの、つまり記号がどのように意味を持つかに関心を持つものであるならば、それは論理学や数学のような形式的な科学

ではなく、歴史学や人類学のような社会的なものでなければならないことを意味している。ハーモニーや韻律は、作曲や統語法と同様に放棄すべきものではない

が、芸術作品の構造を明らかにすることと、その影響を説明することは同じではない。ネルソン・グッドマンが「美的経験の偏狭性という不条理で厄介な神話」

と呼んだように、芸術の仕組みが、その意味を生み出すという考え方は、記号や他の何かについての科学=学問を生み出すことはできない。

|

If we are

to

have a semiotics of art (or for that matter, of any sign

system not axiomatically self-contained), we are going to have to

engage in a kind of natural history of signs and symbols, an

ethnography of the vehicles of meaning. Such signs and symbols, such

vehicles of meaning, play a role in the life of a society, or some part

of a society, and it is that which in fact gives them their life. Here,

too, meaning is use, or more carefully, arises from use, and it is by

tracing out such uses as exhaustively as we are accustomed to for

irrigation techniques or marriage customs that we are going to be able

to find out anything general about them. This is not a plea for

inductivism--we certainly have no need for a catalogue of

instances--but for turning the analytic powers of semiotic theory,

whether Peirce's, Saussure's, Levi-Strauss's, or Goodman's, away from

an investigation of signs in abstraction toward an investigation of

them in their natural habitat--the common world in which men look,

name, listen, and make.

|

芸

術の記号論(あるいは、公理的に自己完結していないあらゆる記号体系の記号論)を持とうとするならば、記号とシンボルの自然史のようなもの、意味の乗り物

の民族誌に取り組まなければならないだろう。そのような記号やシンボル、意味の乗り物は、ある社会、あるいはある社会のある部分の生活の中で役割を果た

す。ここでもまた、意味とは使用であり、より注意深く言えば、使用から生じるものであり、灌漑の技術や結婚の習慣に慣れているように、そのような使用を徹

底的に追跡することによって、それらについて一般的な何かを見出すことができるようになるのである。これは帰納主義を主張するものではなく--確かに、わ

れわれは事例のカタログなど必要としていない--、パイスのものであれ、ソシュールのものであれ、レヴィ=ストロースのものであれ、グッドマンのものであ

れ、記号論の分析力を、抽象的な記号の調査から、その自然な生息環境--人が見たり、名づけたり、聞いたり、作ったりする共通の世界--における記号の調

査へと向けるためのものである。

|

| It is not a

plea, either, for the neglect of form, but for seeking the

roots of form not in some updated version of faculty psychology but in

what I have called in chapter 2 "the social history of the

imagination"--that is, in the construction and deconstruction of

symbolic systems as individuals and groups of individuals try to make

some sense of the profusion of things that happen to them. When a

Bamileke chief took office, Jacques Maquet informs us, he had his

statue carved; "after his death, the statue was respected, but it was

slowly eroded by the weather as his memory was eroded in the minds of

the people." 30 Where is the form here? In the shape of the statue or

the shape of its career? It is, of course, in both. But no analysis of

the statue that does not hold its fate in view, a fate as intended as

is the arrangement of its volume or the gloss of its surface, is going

to understand its meaning or catch its force. |

そ

れは、形を軽視することではなく、形の根源を、教授陣心理学の最新版ではなく、第 2

章で私が「想像力の社会史」と呼んだもの、つまり、個人や個人の集団が、自分たちの身の回りに起こる多

様な出来事の意味を理解しようとする際の、象徴体系の構築と解体の中に求めることである。ジャック・マケは、バミレケの酋長が就任すると、その酋長は自分

の彫像を彫らせ たと教えてくれる。「彼の死後、彫像は尊重されたが、彼の記憶が人々の心の中に浸食され

るにつれて、彫像は天候によって徐々に浸食されていった」。30

ここでいう形とはどこにあるのだろうか。彫像の形か、その経歴の形か。もちろん、その両方にある。しかし、その容積の配置や表面の光沢と同様に意図された

運命を見据えない彫像の 分析は、その意味を理解することも、その力を捉えることもできないだろう。

|

It is, after

all, not just statues (or paintings, or poems) that we

have to do with but the factors that cause these things to seem

important--that is, affected with import--to those who make or possess

them, and these are as various as life itself. If there is any

commonality among all the arts in all the places that one finds them

(in Bali they make statues out of coins, in Australia drawings out of

dirt) that justifies including them under a single, Western-made

rubric, it is not that they appeal to some universal sense of beauty.

That may or may not exist, but if it does it does not seem, in my

experience, to enable people to respond to exotic arts with more than

an ethnocentric sentimentalism in the absence of a knowledge of what

those arts are about or an understanding of the culture out of which

they come. (The Western use of

"primitive" motifs, its undoubted value

in its own terms aside, has only accentuated this; most people, I am

convinced, see African sculpture as bush Picasso and hear Javanese

music as noisy Debussy.) If there is a commonality it lies

in the fact

that certain activities everywhere seem specifically designed to

demonstrate that ideas are visible, audible, and--one needs to make a

word up here--tactible, that they can be cast in forms where the

senses, and through the senses the emotions, can reflectively address

them. The variety of artistic

expression stems from the variety of

conceptions men have about the way things are, and is indeed the same

variety. It is, after

all, not just statues (or paintings, or poems) that we

have to do with but the factors that cause these things to seem

important--that is, affected with import--to those who make or possess

them, and these are as various as life itself. If there is any

commonality among all the arts in all the places that one finds them

(in Bali they make statues out of coins, in Australia drawings out of

dirt) that justifies including them under a single, Western-made

rubric, it is not that they appeal to some universal sense of beauty.

That may or may not exist, but if it does it does not seem, in my

experience, to enable people to respond to exotic arts with more than

an ethnocentric sentimentalism in the absence of a knowledge of what

those arts are about or an understanding of the culture out of which

they come. (The Western use of

"primitive" motifs, its undoubted value

in its own terms aside, has only accentuated this; most people, I am

convinced, see African sculpture as bush Picasso and hear Javanese

music as noisy Debussy.) If there is a commonality it lies

in the fact

that certain activities everywhere seem specifically designed to

demonstrate that ideas are visible, audible, and--one needs to make a

word up here--tactible, that they can be cast in forms where the

senses, and through the senses the emotions, can reflectively address

them. The variety of artistic

expression stems from the variety of

conceptions men have about the way things are, and is indeed the same

variety. |

結

局のところ、我々が扱わなければならないのは、彫像(あるいは絵画、詩)だけではな

く、それらを作ったり所有したりする人々にとって、それらが重要である、つまり重要な

影響を持つと思わせる要因であり、それらは人生そのものと同じくらい多様である。バリ島では硬貨で彫像を作り、オーストラリアでは土で絵を描く)あらゆる

場所で見られるあらゆる芸術の中に、西洋人が作ったひとつのルールのもとにそれらを含めることを正当化するような共通点があるとすれば、それはそれらが普

遍的な美意識に訴えるものであるということではない。そのような美意識が存在するかしないかは別として、もし存在するとしても、私の経験では、そのような

芸術が何についてのものであるかについての知識や、その芸術が生まれた文化についての理解がなければ、異国の芸術に対してエスノセントリックな感傷主義以

上の反応を示すことはできないように思われる。(ほとんどの人は、アフリカの彫刻をピカソの茂みに見立て、ジャワの音楽を騒々しいドビュッシーに聴こえる

と私は確信している)。もし共通点があるとすれば、それは、アイデアが目に見え、耳に聞こえ、そして......ここで言葉を補う必要がある

が......触ることができ、感覚が、そして感覚を通して感情が、それらに反省的に取り組むことができるような形にすることができるということを示すた

めに、どこの国でも特定の活動が特別にデザインされているように見えるという事実にある。芸術表現の多様性は、人間が物事のあり方について持つ概念の多様

性に由来するものであり、まさに同じ多様性なのである。 結

局のところ、我々が扱わなければならないのは、彫像(あるいは絵画、詩)だけではな

く、それらを作ったり所有したりする人々にとって、それらが重要である、つまり重要な

影響を持つと思わせる要因であり、それらは人生そのものと同じくらい多様である。バリ島では硬貨で彫像を作り、オーストラリアでは土で絵を描く)あらゆる

場所で見られるあらゆる芸術の中に、西洋人が作ったひとつのルールのもとにそれらを含めることを正当化するような共通点があるとすれば、それはそれらが普

遍的な美意識に訴えるものであるということではない。そのような美意識が存在するかしないかは別として、もし存在するとしても、私の経験では、そのような

芸術が何についてのものであるかについての知識や、その芸術が生まれた文化についての理解がなければ、異国の芸術に対してエスノセントリックな感傷主義以

上の反応を示すことはできないように思われる。(ほとんどの人は、アフリカの彫刻をピカソの茂みに見立て、ジャワの音楽を騒々しいドビュッシーに聴こえる

と私は確信している)。もし共通点があるとすれば、それは、アイデアが目に見え、耳に聞こえ、そして......ここで言葉を補う必要がある

が......触ることができ、感覚が、そして感覚を通して感情が、それらに反省的に取り組むことができるような形にすることができるということを示すた

めに、どこの国でも特定の活動が特別にデザインされているように見えるという事実にある。芸術表現の多様性は、人間が物事のあり方について持つ概念の多様

性に由来するものであり、まさに同じ多様性なのである。

++++++++++++++++++++

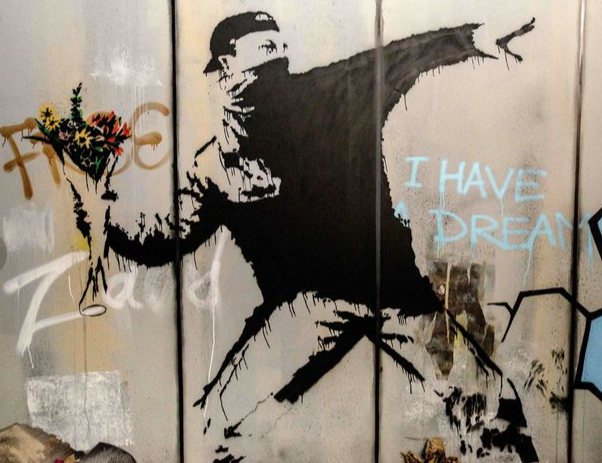

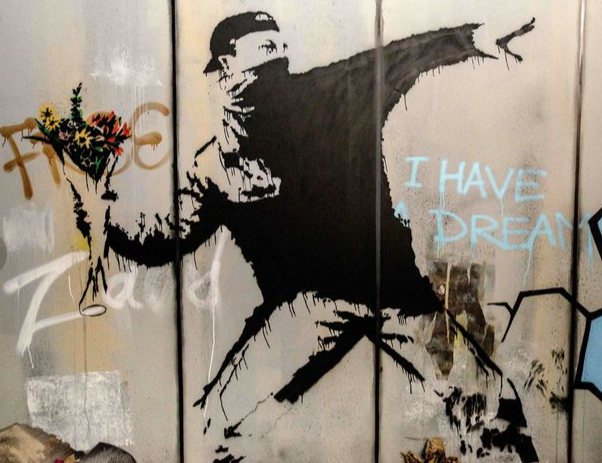

池田の感想:「美学研究における記号論の威力はたしかに20世紀で終わっていることはつくづく感じます。その理由は、記号論的変換はとてもスタティック

で、パスティーシュやクリーシェがダイナミックに変化する現代ではついていけないのでしょう。バンクシーの図像を、もはやパノフスキーの解読格子をつかっ

て読み解くことはできない。」 |

| To be of

effective use in the study of art, semiotics must move beyond

the consideration of signs as means of communication, code to be

deciphered, to a consideration of them as modes of thought, idiom to be

interpreted. It is not a

new cryptography that we need, especially when

it consists of replacing one cipher by another less intelligible,

but a

new diagnostics, a science that can determine the meaning of things for

the life that surrounds them. It will have, of course, to

be trained on

signification, not pathology, and treat with ideas, not with symptoms. But by connecting incised statues,

pigmented sago palms, frescoed

walls, and chanted verse to jungle clearing, totem rites, commercial

inference, or street argument, it can perhaps begin at last to locate

in the tenor of their setting the sources of their spell. |

芸術の研究に効果的に役立てるためには、記号をコミュニケーションの手段、解読されるべき暗号として考えるのではなく、思考様式、解釈されるべきイディオ

ムとして考えなければならない。私たちが必要としているのは、新しい暗号学ではなく、特に、ある暗号をより理解しにくい別の暗号に置き換えることではな

く、新しい診断学であり、物事を取り巻く生活にとっての意味を決定することのできる科学なのである。もちろん、病理学ではなく意味論に基づき、症状ではな

く観念で治療する訓練が必要である。しかし、彫像、色素沈着したサゴヤシの木、フレスコ画の壁、詠唱された詩を、ジャングルの開拓、トーテムの儀式、商業

的推論、街頭での議論と結びつけることで、その呪文の根源をその場の雰囲気の中に見出すことができるだろう。

|

1

Quoted in R. Goldwater and M. Treves, Artists on Art ( New York, 1945),

p. 421.

2

Quoted in ibid., pp. 292-93.

3

See N. D. Munn, Walbiri Iconography ( Ithaca, N.Y., 1973).

4

Quoted in Goldwater and Treves, Artists on Art, p. 410.

5

P. Bohannan, "Artist and Critic in an African Society," in Anthropology

and Art, ed. C. M. Otten ( New York, 1971), p. 178.

6

R. F. Thompson, "Yoruba Artistic Criticism," in The Traditional Artist

in African Societies, ed. W. L. d'Azaredo ( Bloomington, Ind., 1973).

pp. 19-61.

7

Ibid., pp. 35-36.

8

R. Goldwater, "Art and Anthropology: Some Comparisons of Methodology,"

in Primitive Art and Society, ed. A. Forge ( London, 1973), p. 10.

9

A. Forge, "Style and Meaning in Sepik Art," in Primitive Art and

Society, ed. Forge, pp. 169-92. See also, A. Forge, "The Abelam

Artist," in Social Organization, ed. M. Freedman ( Chicago, 1967), pp.

65-84.

10

A. Forge, "Learning to See in New Guinea," in Socialization, the

Approach from Social Anthropology, ed. P. Mayer (London, 1970), pp.

184-86.

11

M. Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy (

London, 1972).

12

Ibid., p. 38.

13

Ibid., p. 34.

14

Ibid., p. 40.

15

Quoted in ibid., p. 41.

16

Ibid., p. 48.

17

Ibid.

18

Quoted in ibid., p. 57.

19

Ibid., p. 80.

20

Ibid., p. 76.

21

Ibid., p. 86.

22

Ibid.

23

Ibid., pp. 87 - 89, 101.

24

M. Baxandall, Giotto and the Orators ( Oxford, 1971).

25

Baxandall, Painting and Experience, p. 152.

26

M. G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, vol. 1 ( Chicago, 1974), p.

367.

27

Ibid., vol. 2, p. 438.

28

I am grateful to Hildred Geertz, who collected most of these poems, for

permission to use them.

29

N. Goodman, Languages of Art ( Indianapolis, 1968), p. 260.

30

J. Maquet, "Introduction to Aesthetic Anthropology," in A Macaleb

Module in Anthropology (Reading, Mass., 1971), p. 14.

|

|