日本における人種主義

Racism in Japan

☆

日本における人種主義(じんしゅしゅぎ、英: racism in

Japan)とは、日本の様々な人々や集団が抱いている人種や民族に対する否定的な態度や見解であり、日本の歴史の中で様々な時期に人種や民族に対する差

別的な法律や慣行、行動(暴力を含む)に反映されてきた。

2018年の国勢調査統計によると、日本の人口の97.8%は日本人であり、残りは在日外国人である[1]。高齢化と労働力人口の減少により、外国人労働

者の数は近年急激に増加している。CIAワールド・ファクトブックによると、人口の98.1%が日本人、0.5%が中国人、0.4%が韓国人であり、残り

の1%がその他の民族である。

日本には人種、民族、宗教差別を禁止する法律がない。また、国民人権機関もない[3]。

日本にいる非日本人個人は、しばしば、日本国民にはない人権侵害に直面する[4]。近年、非日本人メディアは、日本企業が日本に滞在するゲスト労働者、特

に未熟練労働者のパスポートを頻繁に没収していると報じている[5][6]。

20世紀初頭、日本ナショナリズムのイデオロギーに牽引され、国民統合の名の下に、日本政府は、先住民族である琉球人、アイヌ人、その他の代表的でない集

団を含む周縁化された集団を特定し、言語、文化、宗教における同化プログラムを課し、強制的に同化させた[7]。日本は、これらの民族集団を日本人の単な

る「サブグループ」であり、したがって大和民族と同義であるとみなしており、明確な文化を持つ少数民族とは認めていない[8][9][10]。

★記載に一部政治的バイアスがかかった記述があり、公平性を担保できない部分になっている。

| Racism in Japan

(人種主義, jinshushugi) comprises negative attitudes and views on race or

ethnicity which are held by various people and groups in Japan, and

have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and action

(including violence) at various times in the history of Japan against

racial or ethnic groups. According to census statistics in 2018, 97.8% of Japan's population are Japanese, with the remainder being foreign nationals residing in Japan.[1] The number of foreign workers has increased dramatically in recent years, due to the aging population and a shrinking labor force. A news article in 2018 suggests that approximately 1 out of 10 people among the younger population residing in Tokyo are foreign nationals.[2] According to the CIA World Factbook, Japanese make up 98.1% of the population, Chinese 0.5%, and Korean 0.4%, with the remaining 1% representing all other ethnic groups. Japan lacks any law which prohibits racial, ethnic, or religious discrimination. The country also has no national human rights institutions.[3] Non-Japanese individuals in Japan often face human rights violations that Japanese citizens may not.[4] In recent years, non-Japanese media has reported that Japanese firms frequently confiscate the passports of guest workers in Japan, particularly unskilled laborers.[5][6] In the early 20th century, driven by an ideology of Japanese nationalism and in the name of national unity, the Japanese government identified and forcefully assimilated marginalized populations, which included indigenous Ryukyuans, Ainu, and other underrepresented groups, imposing assimilation programs in language, culture and religion.[7] Japan considers these ethnic groups as a mere "subgroup" of the Japanese people and therefore synonymous to the Yamato people, and does not recognize them as a minority group with a distinct culture.[8][9][10] |

日本における人種主義(じんしゅしゅぎ、英: racism in

Japan)とは、日本の様々な人々や集団が抱いている人種や民族に対する否定的な態度や見解であり、日本の歴史の中で様々な時期に人種や民族に対する差

別的な法律や慣行、行動(暴力を含む)に反映されてきた。 2018年の国勢調査統計によると、日本の人口の97.8%は日本人であり、残りは在日外国人である[1]。高齢化と労働力人口の減少により、外国人労働 者の数は近年急激に増加している。CIAワールド・ファクトブックによると、人口の98.1%が日本人、0.5%が中国人、0.4%が韓国人であり、残り の1%がその他の民族である。 日本には人種、民族、宗教差別を禁止する法律がない。また、国立の人権機関もない[3]。 日本にいる非日本人個人は、しばしば、日本国民にはない人権侵害に直面する[4]。近年、非日本人メディアは、日本企業が日本に滞在するゲスト労働者、特 に未熟練労働者のパスポートを頻繁に没収していると報じている[5][6]。 20世紀初頭、日本ナショナリズムのイデオロギーに牽引され、国民統合の名の下に、日本政府は、先住民族である琉球人、アイヌ人、その他の代表的でない集 団を含む周縁化された集団を特定し、言語、文化、宗教における同化プログラムを課し、強制的に同化させた[7]。日本は、これらの民族集団を日本人の単な る「サブグループ」であり、したがって大和民族と同義であるとみなしており、明確な文化を持つ少数民族とは認めていない[8][9][10]。 |

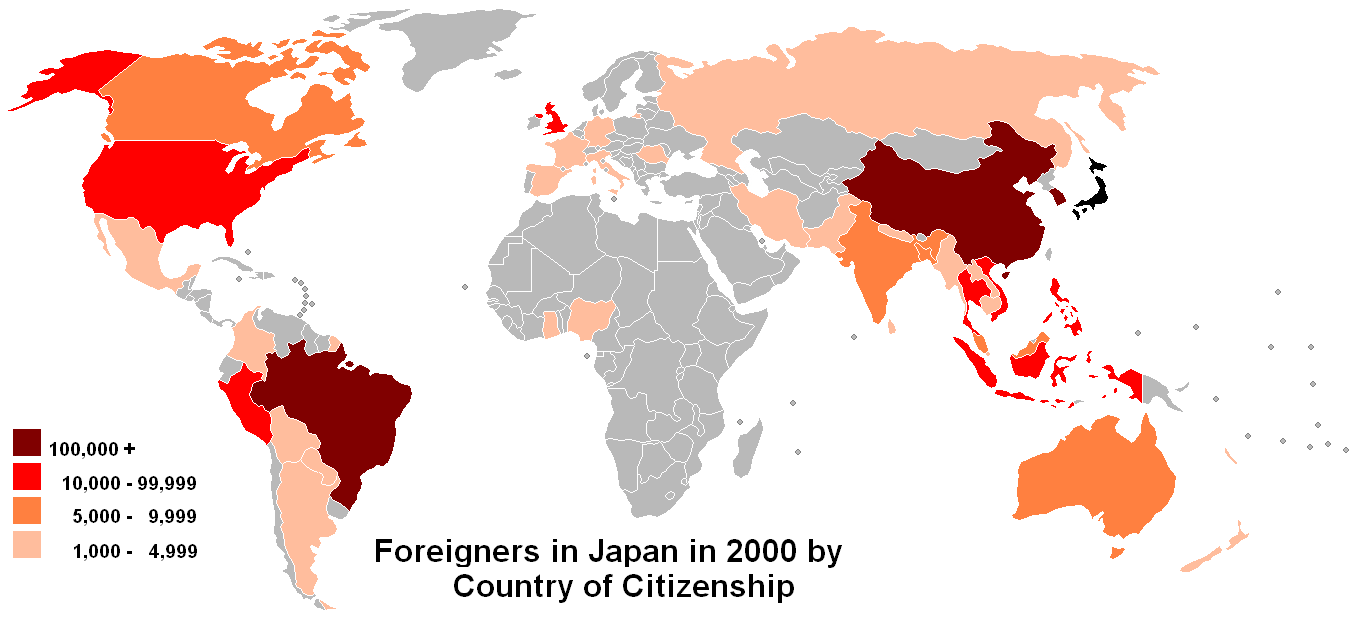

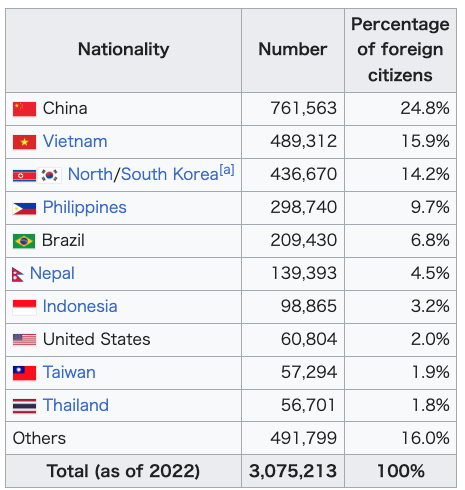

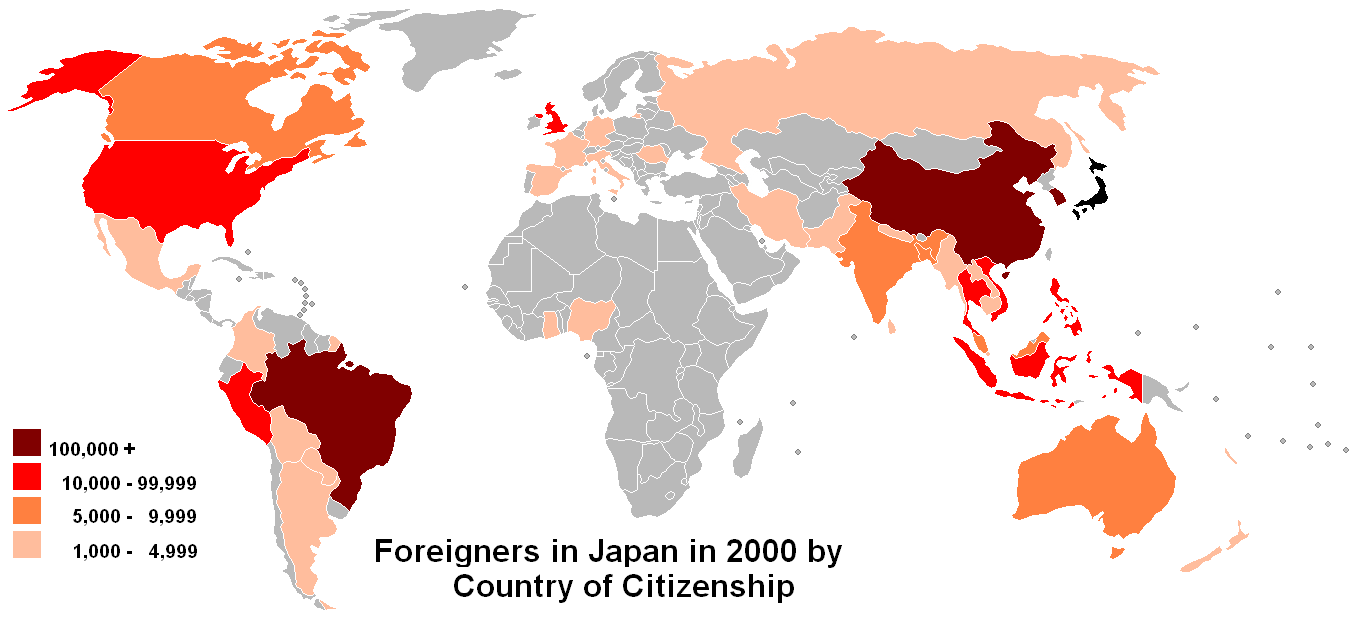

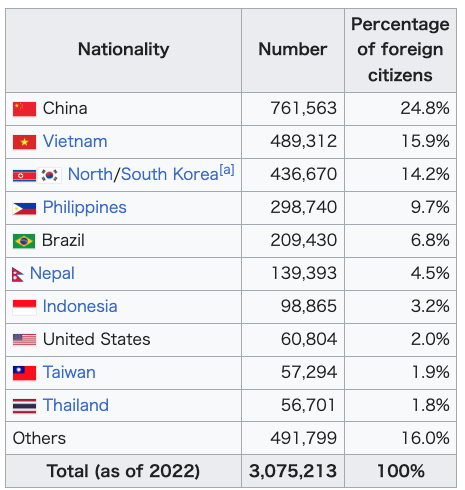

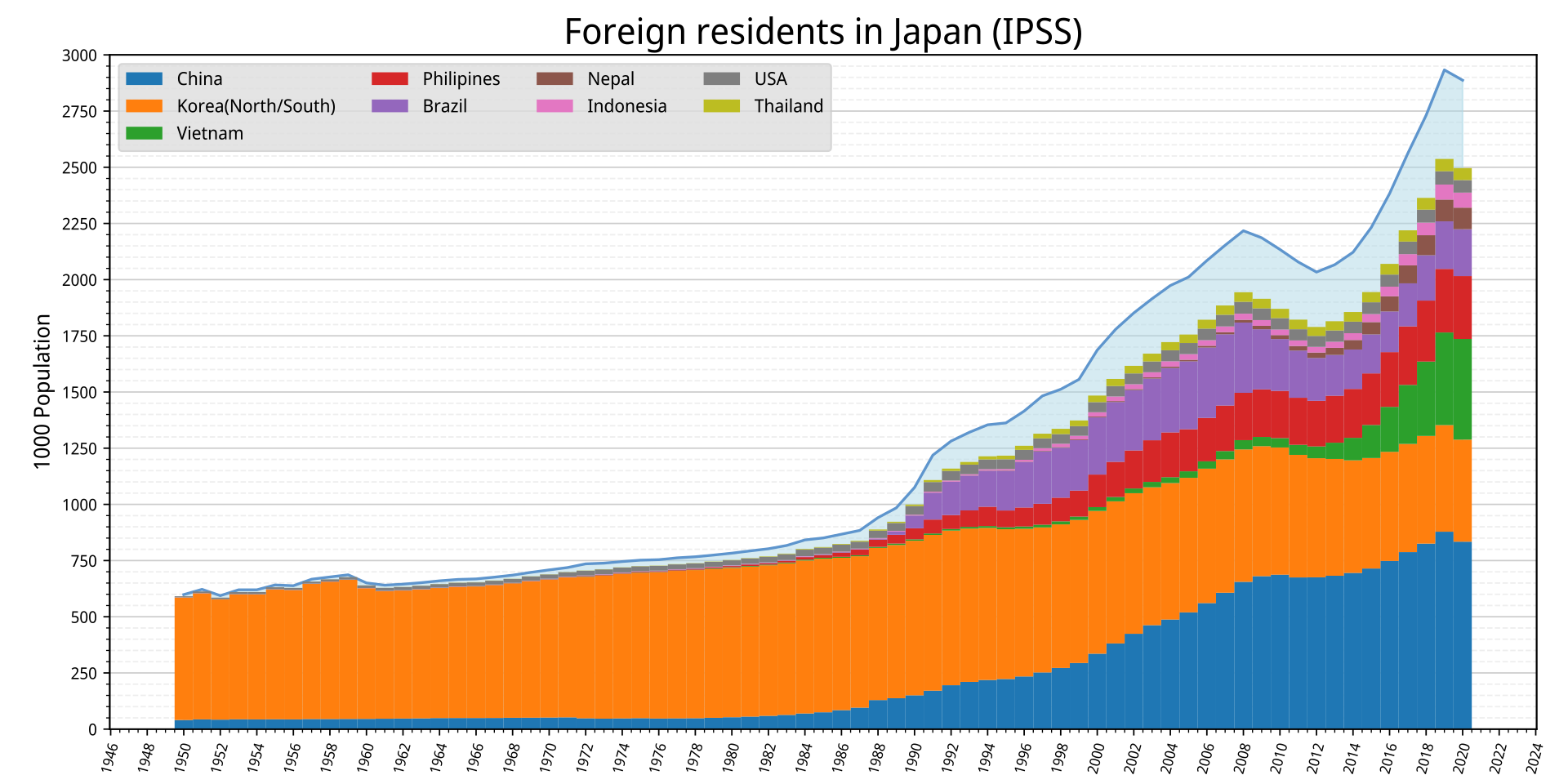

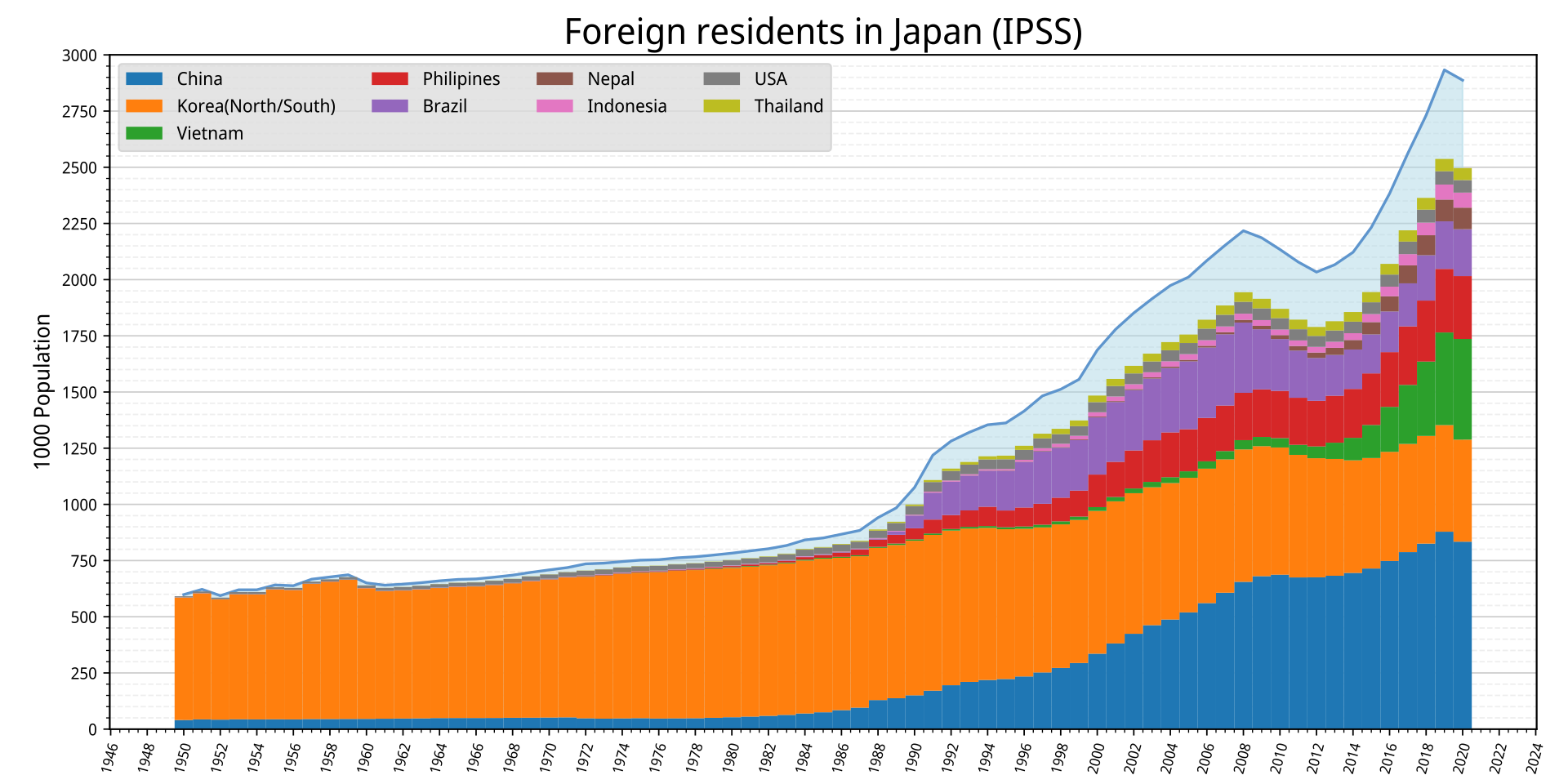

| Background Demographics Further information: Demographics of Japan  Citizenship of foreigners in Japan in 2000. Source: Japan Statistics Bureau[11] About 2.4% of Japan's total legal resident population are foreign citizens. Of these, according to 2022 data from the Japanese government, the principal groups are as follows.[12][1][13]  The above statistics do not include the approximately 30,000 U.S. military stationed in Japan, nor do they account for illegal immigrants. The statistics also do not take into account naturalized citizens from backgrounds including but not limited to Korean and Chinese, and citizen descendants of immigrants. The total legal resident population of 2012 is estimated at 127.6 million. |

背景 人口統計 さらに詳しい情報 日本の人口統計  2000年の在日外国人の国籍。 出典 日本統計局[11] 日本の法定在留人口の約2.4%が外国籍である。このうち、日本政府の2022年のデータによると、主なグループは以下の通りである[12][1] [13]。  上記の統計には、日本に駐留する約3万人の米軍は含まれておらず、不法移民も考慮されていない。また、この統計には、韓国人、中国人を含むがこれに限定さ れない背景を持つ帰化市民、移民の子孫の市民は考慮されていない。2012年の合法的居住者の総人口は1億2760万人と推定されている。 |

| By target Japanese ethnic minorities See also: Ethnic groups of Japan The nine largest minority groups residing in Japan are: North and South Korean, Chinese (also Taiwanese), Brazilian (many Brazilians in Japan have Japanese ancestors), Filipinos, Vietnamese, the Ainu indigenous to Hokkaido, the Ryukyuans indigenous to Okinawa, and other islands between Kyushu and Taiwan.[14] The burakumin, an outcast group at the bottom of Japan's feudal order, are sometimes included.[15] There are also a number of smaller ethnic communities in Japan with a much shorter history. According to the United Nations' 2008 Diène report, communities most affected by racism and xenophobia in Japan include:[16] the national minorities of Ainu and people of Okinawa, people and descendants of people from neighbouring countries (Chinese and Koreans) and the new immigrants from other Asian, African, South American and Middle Eastern countries. |

ターゲット別 日本の少数民族 こちらも参照のこと: 日本の少数民族 日本に居住する9大マイノリティ・グループは以下の通りである: 南北朝鮮人、中国人(台湾人も含む)、ブラジル人(多くの在日ブラジル人の祖先は日本人である)、フィリピン人、ベトナム人、北海道固有のアイヌ人、沖縄 固有の琉球人、その他九州と台湾の間の島々である[14]。日本の封建的秩序の最下層に位置する追放された集団である被差別部落が含まれることもある [15]。 2008年の国連のディエンヌ報告書によると、日本で人種主義や外国人排斥の影響を最も受けているコミュニティは以下の通りである[16]。 少数民族であるアイヌ民族と沖縄の人々、 近隣諸国の人々(中国人と韓国人)とその子孫 アジア、アフリカ、南米、中東諸国からの新規移民である。 |

| Koreans Main articles: Koreans in Japan and Anti-Korean sentiment in Japan Since the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 and up to World War II, Koreans sought asylum and educational opportunities that were available in Japan. In 1910, the Japan-Korean Annexation Treaty was established and it stated that Koreans would be granted Japanese citizenship by law because Korea was annexed by Japan. During World War II, the Japanese government established the National Mobilization Law, Following World War II, Koreans decided to illegally participate in the Post-World War II rebuilding of Japan because of the discrimination which they were being subjected to, both politically and economically; they were treated unfairly and paid low wages in Japan. Zainichi (resident in Japan) Koreans are permanent residents of Japan registered as Joseon (Korean: 조선, Japanese: Chōsen (朝鮮)) or South Korean nationality. Joseon was annexed by Japan in 1910, therefore Zainichi Koreans with Joseon citizenship are de facto stateless. After World War II, two million Koreans living in Japan were granted a temporary Joseon nationality under the US military government (because there was no government in Korea then). However, the meaning of Joseon nationality became vague as Korea was divided by the United States and the Soviet Union, and in 1948 North and South Korea each established their own government. Some obtained South Korean citizenship later, but others who opposed the division of Korea or sympathized with North Korea maintained their Joseon nationality because people are not allowed to register North Korean nationality. Most Zainichi came to Japan from Korea under Japanese rule between 1910 and 1945.[17] A large proportion of this immigration is said to be the result of Korean landowners and workers losing their land and livelihood due to Japanese land and production confiscation initiatives and migrating to Japan for work. According to the calculation of Rudolph Rummel, a total of 5.4 million Koreans were also conscripted into forced labor and shipped throughout the Japanese Empire. He estimates that 60,000 Koreans died during forced labor in places such as Manchuria and Sakhalin.[18] During the Japanese rule of Korea, the Japanese government implemented a policy of cultural assimilation. Korean culture was suppressed, artistic and literary works that opposed Japanese rule were subjected to censorship and prohibition, and the Korean language was regarded as a regional ethnic language (民族語) and suppressed, while the Japanese language was designated as the national language,[19] with Koreans being required to learn it. After a relatively lenient period, the Korean language course in public schools was downgraded to a non-compulsory subject in 1938 and cancelled in 1941,[20] though the Korean language and Hangeul were still used in war-time propaganda until the last days of Japanese rule.[19] Koreans were forced to take Japanese names from 1940. However, Koreans resisted this policy, and by the end of the 1940s, it was almost completely undone. Thousands of ethnic Koreans in Japan were massacred as false rumors spread that Koreans were rioting, looting, or poisoning wells in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake in the Kantō Massacre.[21] Many Korean refugees also came to the country during the Jeju uprising in the First Republic of South Korea. Though most migrants returned to Korea, GHQ estimates in 1946 indicated that approximately 650,000 Koreans remained in Japan. After World War II, the Korean community in Japan was split between allegiance to South Korea (Mindan) and North Korea (Chongryon). The last major wave of Korean migration to Japan started after South Korea was devastated by the Korean War in the 1950s. Most notably, the large number of refugees were from Jejuans escaping from the massacres on Jeju Island by the authoritarian South Korean government.[22] Zainichi who identify themselves with Chongryon are also an important money source for North Korea.[23][24] One estimate suggests that the total annual transfers from Japan to North Korea may exceed US$200 million.[25] Japanese law does not allow dual citizenship for adults over 22[26] and until the 1980s required adoption of a Japanese name for citizenship. Partially for this reason, many Zainichi did not obtain Japanese citizenship as they saw the process as humiliating.[27] Although more Zainichi are becoming Japanese citizens, issues of identity remain complicated. Even those who do not choose to become Japanese citizens often use Japanese names to avoid discrimination, and live their lives as if they were Japanese. This is in contrast with the Chinese living in Japan, who generally use their Chinese names and openly form Chinatown communities. An increase in tensions between Japan and North Korea in the late 1990s led to a surge of attacks against Chongryon, the pro-North residents' organisation, including a pattern of assaults against Korean schoolgirls in Japan.[28] The Japanese authorities have recently started to crack down on Chongryon with investigations and arrests. These moves are often criticized by Chongryon as acts of political suppression.[29] When Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara referred to Chinese and Koreans as sangokujin (三国人) in 2000 in the context of foreigners being a potential source of unrest in the aftermath of an earthquake, the foreign community complained. Historically, the word has often been used pejoratively and Ishihara's statement brought images of the massacre of Koreans by civilians and police alike after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake to mind. Therefore, the use of the term in context of potential rioting by foreigners is considered by many as provocative, if not explicitly racist.[b] In 2014, a United States government human rights report expressed concern about the abuse and harassment directed against Korean nationals by Japanese right-wing groups such as the Uyoku dantai.[c] In 2022, it was reported that anti-Korean racism in Japan has been on the rise,[52] with homes burned, including one in Utoro district in Uji,[53] and death threats made towards ethnic Korean communities.[52] |

韓国人 主な記事 在日朝鮮人、日本における反朝鮮人感情 1876年の日韓条約以来、第二次世界大戦に至るまで、朝鮮人は日本で得られる亡命や教育の機会を求めていた。1910年、日韓併合条約が結ばれ、韓国は 日本に併合されたのだから、韓国人は法律で日本国籍を与えられるとされた。第二次世界大戦中、日本政府は国民総動員法を制定した、 第二次世界大戦後、朝鮮人は政治的にも経済的にも差別を受け、日本では不当な扱いを受け、低賃金であったため、第二次世界大戦後の日本再建に非合法的に参 加することを決めた。在日朝鮮人とは、朝鮮籍で登録された日本の永住権保持者である: 朝鮮)または韓国の国民である。朝鮮は1910年に日本に併合されたため、朝鮮籍を持つ在日コリアンは事実上無国籍である。第二次世界大戦後、在日朝鮮人 200万人は米軍政府のもとで一時的に朝鮮籍を与えられた(当時、朝鮮には政府がなかったため)。しかし、韓国が米ソによって分割され、1948年に北朝 鮮と韓国がそれぞれ独自の政府を樹立したため、朝鮮国籍の意味は曖昧になった。後に韓国籍を取得する者もいたが、朝鮮半島の分断に反対したり、北朝鮮に同 調したりした人々は、北朝鮮籍を登録することができないため、朝鮮籍を維持した。 在日の多くは、1910年から1945年の間に、日本統治下の朝鮮から日本にやってきた[17]。この移民の大部分は、日本の土地・生産没収政策によって 土地と生計を失った朝鮮人の地主や労働者が、仕事を求めて日本に移住した結果であると言われている。ルドルフ・ランメルの計算によると、合計540万人の 朝鮮人も強制労働に徴用され、日本帝国中に移送された。彼は、6万人の朝鮮人が満州や樺太などで強制労働中に死亡したと推定している[18]。 日本による朝鮮統治時代、日本政府は文化同化政策を実施した。朝鮮文化は抑圧され、日本の統治に反対する芸術作品や文学作品は検閲や禁止の対象となり、朝 鮮語は地域民族語(民族語)とみなされ抑圧された。比較的寛大な期間の後、公立学校の朝鮮語課程は1938年に非義務科目に格下げされ、1941年には中 止された[20]が、朝鮮語とハングルは日本統治末期まで戦時中のプロパガンダに使用された。しかし、朝鮮人はこの政策に抵抗し、1940年代の終わりに は、この政策はほとんど完全に撤回された。1923年の関東大震災の後、関東大震災虐殺事件では、朝鮮人が暴動を起こし、略奪を行い、井戸に毒を入れたと いうデマが広まり、数千人の在日朝鮮民族が虐殺された[21]。第一次大韓民国の済州動乱の際にも、多くの朝鮮難民が来日した。ほとんどの移民は韓国に 戻ったが、1946年のGHQの推計によると、約65万人の朝鮮人が日本に残っていた。 第二次世界大戦後、在日コリアン社会は韓国(民団)と北朝鮮(総聯)への忠誠の間で分裂した。日本への朝鮮人移住の最後の大きな波は、1950年代に韓国 が朝鮮戦争で壊滅的な打撃を受けた後に始まった。最も注目すべきは、権威主義的な韓国政府による済州島での虐殺から逃れた済州島民の難民が大量に発生した ことである[22]。 総聯を自認する在日はまた、北朝鮮にとって重要な資金源でもある[23][24]。 ある推計によれば、日本から北朝鮮への年間送金総額は2億米ドルを超える可能性がある[25]。 日本の法律は22歳以上の成人の二重国籍を認めておらず[26]、1980年代までは国籍を取得するためには日本名を採用する必要があった。このような理 由もあり、多くの在日はその手続きを屈辱的なものと考え、日本国籍を取得しなかった[27]。 より多くの在日が日本国籍を取得しつつあるが、アイデンティティの問題は依然として複雑である。日本国籍取得を選択しない人々でさえ、差別を避けるために 日本名を名乗り、日本人であるかのように生活していることが多い。これは、一般的に中国名を名乗り、公然とチャイナタウンのコミュニティを形成している在 日中国人とは対照的である。1990年代後半に日朝間の緊張が高まると、在日朝鮮人女子学生に対する暴行事件など、親北朝鮮人組織である総聯に対する攻撃 が急増した[28]。こうした動きはしばしば政治的弾圧行為としてチョンリョンから批判されている[29]。 2000年に石原慎太郎東京都知事が、外国人が地震後の不安の原因になりうるという文脈で、中国人と韓国人を三国人(さんごくじん)と呼んだとき、外国人 コミュニティから不満の声が上がった。歴史的に、この言葉はしばしば侮蔑的に使われており、石原氏の発言は、1923年の関東大震災後に民間人や警察に よって行われた朝鮮人虐殺のイメージを思い起こさせた。そのため、外国人が暴動を起こす可能性があるという文脈でこの言葉を使うことは、明確な人種差別で はないにせよ、挑発的であると多くの人が考えている[b]。 2014年、米国政府の人権報告書は、「右翼団体」などの日本の右翼団体による韓国国民に対する虐待や嫌がらせについて懸念を表明した[c][52]。 2022年には、日本における反韓国人種主義が増加していると報告され[52]、宇治のウトロ地区を含む家屋が焼かれたり[53]、韓国系民族コミュニ ティに対する殺害予告がなされたりしている[52]。 |

| Mainland Chinese Main articles: Chinese people in Japan and Anti-Chinese sentiment in Japan Mainland Chinese are the largest legal minority in Japan (according to the 2018 statistics as shown above). An investigator from the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) said, racism against Koreans and Chinese is deeply rooted in Japan because of history and culture.[54] Taiwanese There are a number of Taiwanese people that reside in Japan due to Taiwan's history as being a colony of Japan from 1895 to 1945.[55] Renhō (born Hsieh Lien-fang (Chinese: 謝蓮舫; pinyin: Xiè Liánfǎng; Japanese pronunciation: Sha Renhō)), the former leader of the Democratic Party, is known to be the most famous mixed Taiwanese-Japanese politician. In 2000, the then governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara insulted the Taiwanese, referring to them as Sangokujin: I referred to the "many sangokujin who entered Japan illegally." I thought some people would not know that word so I paraphrased it and used gaikokujin, or foreigners. But it was a newspaper holiday so the news agencies consciously picked up the sangokujin part, causing the problem. ... After World War II, when Japan lost, the Chinese of Taiwanese origin and people from the Korean Peninsula persecuted, robbed, and sometimes beat up Japanese. It's at that time the word was used, so it was not derogatory. Rather we were afraid of them. ... There's no need for an apology. I was surprised that there was a big reaction to my speech. In order not to cause any misunderstanding, I decided I will no longer use that word. It is regrettable that the word was interpreted in the way it was."[56] |

中国本土 主な記事 日本における中国人、日本における反中感情 中国本土の中国人は日本における最大の法的マイノリティである(上記の2018年統計による)。国連人権委員会(UNCHR)の調査員は、歴史と文化のた め、韓国人と中国人に対する人種主義が日本に深く根付いていると述べた[54]。 台湾人 台湾が1895年から1945年まで日本の植民地であった歴史から、日本には多くの台湾人が居住している[55]。元民主党党首の謝蓮舫(中国語:謝蓮 舫、ピンイン:Xiè Liánfǎng、日本語発音:沙蓮舫)は、最も有名な日台混血政治家として知られている。 2000年、当時の石原慎太郎東京都知事は、台湾人を三国人と呼んで侮辱した: 私は 「日本に不法入国した多くの三国人 」と言った。その言葉を知らない人もいると思ったので、言い換えて外省人を使った。しかし、新聞休刊日だったので、通信社が意識的に三国人の部分を取り上 げてしまい、問題になった。 ... 第二次世界大戦後、日本が敗戦すると、台湾系の中国人や朝鮮半島の人々が日本人を迫害し、強盗を働き、時には暴行を加えた。その時に使われた言葉だから、 蔑称ではない。むしろ私たちは彼らを恐れていた。 ... 謝る必要はない。私のスピーチに大きな反響があったことに驚いた。誤解を招かないためにも、この言葉はもう使わないと決めた。あの言葉があのように解釈さ れたことは遺憾だ」[56]。 |

| Ainu Main article: Ainu people The Ainu are an indigenous group mainly living in Hokkaidō, with some also living in modern-day Russia. At present, the official Japanese government estimate of the population is 25,000, though this number has been disputed with unofficial estimates of upwards of 200,000.[57] For much of Japanese history, the Ainu were the main inhabitants of Hokkaido. However, as a result of Japanese migration into the island after 1869, the Ainu were largely displaced and assimilated.[58] Due to Meiji era policies, the Ainu were evicted from their traditional homelands and their cultural practices were outlawed.[59] Official recognition of the Ainu as an indigenous group occurred over a century later on June 6, 2008, as a result of a resolution passed by the government of Japan, which recognized both their cultural differences and their past struggles.[60] |

アイヌ 主な記事 アイヌ民族 アイヌは主に北海道に住む先住民族であり、一部は現在のロシアにも住んでいる。現在、日本政府の公式推計人口は25,000人であるが、この数には異論が あり、非公式には200,000人以上と推定されている[57]。 日本の歴史の大半において、アイヌは北海道の主要な住民であった。しかし、1869年以降に日本人が北海道に移住した結果、アイヌ民族はその大部分を追わ れ、同化された[58]。 明治時代の政策により、アイヌ民族は伝統的な故郷から追い出され、彼らの文化的慣習は非合法化された[59]。アイヌ民族を先住民族として公式に承認した のは、1世紀以上後の2008年6月6日であり、その結果、日本政府はアイヌ民族の文化的差異と過去の闘争の両方を認める決議を行った[60]。 |

| Ryukyuan Main articles: Ryukyuan people and Ryūkyū independence movement The Ryukyuan people lived in an independent kingdom until it became a vassal of Japan's Satsuma Domain in 1609. The kingdom, however, retained a degree of autonomy until 1872 when the islands were officially annexed by Japan and restructured as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. They are now Japan's largest minority group, with 1.3 million living in Okinawa and 300,000 living in other areas of Japan.[61] The Okinawan language, the most widely spoken Ryukyuan language, is related to Japanese, the two being in the Japonic languages. Ryukyuan languages were heavily suppressed through a policy of forced assimilation[citation needed] throughout the former Ryukyu Kingdom after it was annexed in 1872. With only the standard Japanese taught in schools and students punished for speaking or writing their native language through the use of dialect cards, the younger generations of Ryukyuans began to give up their "backwards" culture for that of Japan. The Japanese government officially labels the Ryukyuan languages as dialects (Hōgen) of Japanese,[citation needed] although they are not mutually intelligible with one another, or even between each other. In 1940, there was a political debate amongst Japanese leaders about whether or not to continue the oppression of the Ryukyuan languages, although the argument for assimilation prevailed.[62] During the Battle of Okinawa, the Japanese military commander sought to suppress spying by banning the speaking of Okinawan, which is often unintelligible to nonresidents. As a result, around one thousand civilians were killed by soldiers.[63] There are still some children learning Ryukyuan languages natively, but this is rare, especially on mainland Okinawa. The language still is used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music, or folk dance. After the annexation of the islands, many Ryukyuans, especially Okinawans, migrated to the mainland to find jobs or better living conditions. They were sometimes met with discrimination, such as workplaces with signs that read, "No Ryukyuans or Koreans."[64] At the 1903 Osaka Exhibition, an exhibit called the "Pavilion of the World" (Jinruikan) had actual Okinawans, Ainu, Koreans, and other "backwards" peoples on display in their native clothes and housing.[65] During the fierce fighting in the Battle of Okinawa, some Japanese soldiers committed multiple atrocities against Okinawan civilians, including rape and murder, using them as human shields [citation needed], and persuading or forcing them to commit suicide.[63] In 2007, the Ministry of Education attempted to revise school textbooks to lessen mention of these atrocities, but was met with massive demonstrations in Okinawa.[66][67] Culturally, Okinawa showed great influences from southern China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia, reflecting its long history of trade with these regions. However, because of the standard use of Japanese in schools, television, and all print media in Okinawa, these cultural differences are often glossed over in Japanese society. Consequently, many Japanese consider Okinawans to be Yamato Japanese, sometimes ignoring their distinct cultural and historical heritage in insensitive ways.[8] |

琉球 主な記事 琉球民族と琉球独立運動 琉球民族は、1609年に日本の薩摩藩の家臣となるまで、独立した王国で暮らしていた。しかし王国は、1872年に正式に日本に併合され、1879年に沖 縄県として再編されるまで、ある程度の自治権を保持していた。彼らは現在、日本最大の少数民族であり、130万人が沖縄に、30万人がその他の地域に住ん でいる[61]。 最も広く話されている琉球語である沖縄語は日本語と近縁であり、この2つはヤポネシア語に属する。琉球語は、1872年に琉球王国が併合された後、強制的 な同化政策[要出典]によって、旧琉球王国全域で激しく抑圧された。学校では標準語しか教えられず、方言カードを用いて母国語を話したり書いたりすると罰 せられたため、琉球人の若い世代は自分たちの「後進的」な文化を日本の文化に譲り渡すようになった。日本政府は公式に、琉球の言語を日本語の方言としてい る[要出典]。1940年、日本の指導者たちの間で、琉球語の抑圧を続けるかどうかについて政治的な議論があったが、同化を求める主張が優勢であった [62]。沖縄戦の間、日本軍の司令官は、しばしば住民以外には理解できない沖縄語を話すことを禁止することで、スパイ活動を抑制しようとした。その結 果、約1000人の民間人が兵士によって殺害された[63]。今でも琉球語をネイティブに学ぶ子どもたちはいるが、特に沖縄本土ではまれである。琉球語は 今でも、民謡や民俗舞踊などの伝統的な文化活動で使われている。 島々の併合後、多くの琉球人、特に沖縄県民が仕事やより良い生活環境を求めて本土に移住した。1903年の大阪博覧会では、「世界館」と呼ばれる展示が行 われ、実際の沖縄人、アイヌ人、朝鮮人、その他の「後進」民族が民族衣装や住居で展示された。 65] 沖縄戦の激しい戦闘の間、一部の日本兵は沖縄の民間人に対して、強姦や殺人、人間の盾としての利用[要出典]、自殺の説得や強要など、複数の残虐行為を 行った[63][63] 2007年、文部省はこれらの残虐行為への言及を減らすために学校の教科書を改訂しようとしたが、沖縄では大規模なデモに見舞われた[66][67]。 文化的には、沖縄は中国南部、台湾、東南アジアから大きな影響を受けており、これらの地域との長い交易の歴史を反映している。しかし、沖縄では学校、テレ ビ、すべての印刷媒体で日本語が標準的に使用されているため、日本社会ではこうした文化の違いが覆い隠されてしまうことが多い。その結果、多くの日本人は 沖縄県民を大和民族とみなしており、時には無神経な方法で沖縄県民の明確な文化的・歴史的遺産を無視している[8]。 |

| Other groups See also: Americans in Japan, Australians in Japan, Bangladeshis in Japan, Brazilians in Japan, Britons in Japan, Filipinos in Japan, Indians in Japan, Indonesians in Japan, Iranians in Japan, Kurds in Japan, Mongolians in Japan, Nepalis in Japan, Nigerians in Japan, Pakistanis in Japan, Peruvian migration to Japan, Russians in Japan, Turks in Japan, Vietnamese people in Japan, and History of the Jews in Japan People of foreign origin and nationality are often are often called 外国人 Gaikokujin (foreign country person) or 外人 Gaijin (outsider or alien), with the latter term occasionally perceived to be pejorative and tended to be avoided by mass media.[68] First large influx of such people have started in the 1980s, as the Japanese economy was growing at a high rate. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Keidanren business lobbying organization advocated a policy of allowing South Americans of Japanese ancestry (mainly Brazilians and Peruvians) to work in Japan, as Japan's industries faced a major labor shortage. Although this policy has been decelerated in recent years, many of these individuals continue to live in Japan, some in ethnic enclaves near their workplaces. Many people from Southeast Asia (particularly Vietnam and the Philippines) and Southwest Asia (and Iran) also entered Japan during this time, making foreigners as a group a more visible minority in Japan. The TBS television series Smile is about Bito Hayakawa, who was born to a Japanese mother and Filipino father, and struggled to overcome the difficulties faced as a mixed race child. The main concerns of the latter groups are often related to their legal status, a public perception of criminal activity, and general discrimination associated with being non-Japanese. The first arrival of large influx of Western foreigners in Japan, particularly those from North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, occurred in the 1980s. Many found jobs as English conversation teachers, but others were employed in various professional fields such as finance and business. Others have arrived as the Japanese government adopted a policy to give scholarships to large numbers of foreign students to study at Japanese universities. Although some have become permanent residents or even naturalized citizens, they are generally perceived as short-term visitors and treated as outsiders in Japanese society.[citation needed] South Sakhalin, which was once part of Japan as Karafuto Prefecture, had indigenous populations of Nivkhs and Uilta (Orok). Like the Karafuto Koreans but unlike the Ainu, they were thus not included in the evacuation of Japanese nationals after the Soviet invasion in 1945. Some Nivkhs and Uilta who served in the Imperial Japanese Army were held in Soviet work camps; after court cases in the late 1950s and 1960s, they were recognised as Japanese nationals and thus permitted to migrate to Japan. Most settled around Abashiri, Hokkaidō.[69] The Uilta Kyokai [ja][70] was founded to fight for Uilta rights and the preservation of Uilta traditions in 1975 by Dahinien Gendānu. The Ōbeikei, living in the Bonin Islands, have a varied ethnic background, including European, Micronesian and Kanak.[71] Although protection and refugee status has been granted to those seeking asylum from Myanmar, the same has not been offered to refugee Kurds in Japan from Turkey. Without this protection and status, these Kurds who have fled from Turkey due to persecution are generally living in destitution, with no education and having no legal residency status.[72] A clash took place outside the Turkish embassy in Tokyo in October 2015 between Kurds and Turks in Japan which began after a Kurdish party flag was shown at the embassy.[73][74] Beginning in spring 2023, there was a significant increase in anti-Kurdish Japanese posts on the social media platform X. This was possibly fueled by Turkish people posting in Japanese on the platform. Kurds have reported receiving death threats and demands for their expulsion from the country.[75][76][77] The Burakumin group within Japan is ethnically Japanese; however, they are considered of lower status and lower class standing in comparison to other ethnicities in Japan. They worked as primarily farmers and were considered peasants on the social hierarchy pyramid. Post-World War, the Burakumin group was heavily dissociated from society as the abolishment of the feudal caste system did not put an end to the social discrimination that they faced within restricting housing systems; movements and protests have been maintained throughout the years as they fight to receive and equal status as their peers in regard to access to certain educational, housing, and social benefits and citizenship rights. In order to gain attention to the problems and injustices that they experience, groups such as the militant style, Buraka Liberation League, which uses presentations and speaking to prove and explain their frustrations to a panel. Representation of black people in Japanese media, such as anime, has been subject to criticism.[78] Instances of harassment, hate speech and discrimination targeting Russians living in Japan were reported after Russian invasion of Ukraine. Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi condemned human rights abuses against Russians that took place.[79] In January 2024, three foreign-born residents in Japan sued the national and local governments, alleging racial profiling through illegal police questioning. The plaintiffs asserted that they experienced repeated distress from police questioning based on their appearance and ethnicity, which they claimed violated the constitution. They sought recognition of the illegality of racial profiling and 3 million yen ($20,250) in damages each. The lawsuit emerged during a surge in foreign workers in Japan and discussions on Japanese identity.[80] |

その他のグループ 以下も参照のこと: 在日アメリカ人、在日オーストラリア人、在日バングラデシュ人、在日ブラジル人、在日イギリス人、在日フィリピン人、在日インド人、在日インドネシア人、 在日イラン人、在日クルド人、在日モンゴル人、在日ネパール人、在日ナイジェリア人、在日パキスタン人、在日ペルー人、在日ロシア人、在日トルコ人、在日 ベトナム人、在日ユダヤ人の歴史も参照のこと。 外国出身者や外国籍の人々は、しばしば外国人(外国人)または外人(外人、外国人)と呼ばれることが多いが、後者の呼称は時に侮蔑的であると認識され、マ スメディアによって避けられる傾向がある[68]。このような人々の最初の大規模な流入は、日本経済が高度成長を遂げていた1980年代に始まった。 1980年代から1990年代にかけて、経団連の経済ロビー団体は、日本の産業が大きな労働力不足に直面していたため、日系南米人(主にブラジル人とペ ルー人)の日本での就労を認める政策を提唱した。この政策は近年減速しているが、これらの人々の多くは日本に住み続け、職場の近くの民族的な飛び地に住ん でいる人もいる。 この間、東南アジア(特にベトナムとフィリピン)や西南アジア(とイラン)からも多くの人々が日本に入国し、外国人というグループは日本ではより目立つ少 数派となった。TBSの連続テレビ小説『スマイル』は、日本人の母とフィリピン人の父の間に生まれた早川美都が、混血児として直面した困難を乗り越えよう と奮闘する姿を描いている。 後者のグループの主な懸念は、法的地位、犯罪行為に対する世間の認識、日本人でないことに関連する一般的な差別に関連することが多い。 欧米からの外国人、特に北米、ヨーロッパ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドからの外国人が日本に初めて大量に流入したのは1980年代である。その多く は英会話教師として就職したが、金融やビジネスなど様々な専門分野で働く人もいた。また、日本政府が日本の大学で学ぶ多数の外国人留学生に奨学金を支給す る政策を採用したため、そのような留学生もやってきた。永住権や帰化権を得た者もいるが、一般的には短期滞在者として認識され、日本社会では部外者として 扱われている[要出典]。 かつて樺太県として日本の一部であった南サハリンには、ニブフとウイルタ(オロク)の先住民族がいた。樺太コリアンと同様、アイヌとは異なり、彼らは 1945年のソ連侵攻後の日本人国民疎開の対象にはならなかった。大日本帝国陸軍に従軍したニブフとウイルタの一部は、ソ連の労働キャンプに収容された。 1950年代後半から1960年代にかけての裁判の結果、彼らは日本国民として認められ、日本への移住が許可された。1975年、ウイルタの権利とウイル タの伝統の保存のために、ウイルタ協会[ja][70]が大日元帥によって設立された。 小笠原諸島に住むオベイケイ族は、ヨーロッパ系、ミクロネシア系、カナック系など多様な民族的背景を持つ[71]。 ミャンマーからの庇護を求める人々には保護と難民の地位が与えられているが、トルコからの難民である在日クルド人には同じことが提供されていない。この保 護と地位がなければ、迫害のためにトルコから逃れてきたこれらのクルド人は一般的に、教育も受けられず、法的な在留資格も持たず、困窮した生活を送ってい る[72]。 2015年10月、在日クルド人とトルコ人の間で東京のトルコ大使館の外で衝突が起こったが、これはクルド人の党旗が大使館に掲げられたことから始まった [73][74]。 2023年春から、ソーシャルメディア「X」上で、反クルド的な日本人による投稿が大幅に増加した。クルド人は殺害予告や国外追放の要求を受けたと報告し ている[75][76][77]。 日本における被差別部落は、民族的には日本人であるが、日本の他の民族と比較すると地位が低く、下層階級に属すると考えられている。彼らは主に農民として 働き、社会階層ピラミッドでは農民とみなされていた。第二次世界大戦後、封建的カースト制度が廃止されても、制限された住居制度の中で彼らが直面する社会 的差別は解消されなかったため、部落民グループは社会から大きく切り離された。彼らは、特定の教育、住居、社会的便益、市民権へのアクセスに関して、同世 代の人々と同等の地位を得るために、長年にわたって運動や抗議が続けられてきた。彼らが経験する問題や不公正に注目を集めるために、ブラカ解放同盟のよう な過激なスタイルのグループは、プレゼンテーションやスピーチを用いて、パネルに自分たちの不満を証明し、説明する。 アニメなどの日本のメディアにおける黒人の表現は、批判にさらされてきた[78]。 ロシアのウクライナ侵攻後、在日ロシア人を標的にした嫌がらせ、ヘイトスピーチ、差別の事例が報告された。林芳正外相は行われたロシア人に対する人権侵害 を非難した[79]。 2024年1月、日本在住の外国出身者3人が、違法な警察の職務質問による人種プロファイリングを主張し、国民と地方自治体を訴えた。原告らは、外見や民 族性に基づく警察の職務質問によって繰り返し苦痛を受けたと主張し、憲法に違反していると主張した。彼らは人種プロファイリングの違法性を認め、それぞれ 300万円(20,250ドル)の損害賠償を求めた。この訴訟は、日本における外国人労働者の急増と日本人のアイデンティティに関する議論の中で浮上した [80]。 |

| By field Higher learning Although foreign professors teach throughout the Japanese higher education system, Robert J. Geller of the University of Tokyo reported, in 1992, that it was extremely rare for them to be given tenure.[81] Non-Japanese citizens and crimes Further information: Crime in Japan As in other countries, foreigners sometimes do work that is not allowed by their visas, or overstay the terms of their visas. Their employment tends to be concentrated in fields where most Japanese are not able to or no longer wish to work. The yakuza or Japanese organized crime has made use of Chinese immigrants in Japan as henchmen to commit crimes, which have led to a negative public perception.[82] In 2003, foreigners from Africa were responsible for 2.8 times as much crime per capita as Japanese natives but were slightly less likely to commit violent crime.[83] According to National Police Authority records, in 2002, 16,212 foreigners were caught committing 34,746 crimes, over half of which turned out to be visa violations (residing/working in Japan without a valid visa). The statistics show that 12,667 cases (36.5%) and 487 individuals (0.038%) were Chinese, 5,272 cases (15.72%) and 1,186 individuals (7.3%) were Brazilian, and 2,815 cases (8.1%) and 1,738 individuals (10.7%) were Korean and ~6000 were others foreigners. The total number of crimes committed in the same year by Japanese was 546,934 cases. Within these statistics, Japanese committed 6,925 violent crimes, of which 2,531 were arson or rape, while foreigners committed 323 violent crimes, but only 42 cases are classified as arson or rape. Foreigners were more likely to commit crimes in groups: About 61.5% of crimes committed by foreigners had one or more accomplice, while only 18.6% of crimes committed by Japanese were in groups. Japanese commit more violent crimes than foreigners. By a 2022 study by the National Police Agency illegal residents decreased from 219,000 in 2004 to 113,000 in 2008, and in addition, the number of arrested foreign visitors decreased from 21,842 in 2004 to 13,880 in 2008. The percentage of foreign nationals in all arrestees charged in penal code crimes was about 2.0% and this number has remained relatively stable. While the percentage of foreign nationals among all arrestees charged in cases involving robbery or burglary was around 5.5% in 2008.[84] According to a survey conducted by the Tokyo Bar Association, more than 60% of 2,000 respondents from foreign backgrounds reported being interrogated by the police. Among those questioned, about 77% stated that the encounters seemed to lack any apparent reason other than their foreign appearance.[85] The former head of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government's Emergency Public Safety Task Force, Hiroshi Kubo, published a book called Chian wa Hontouni Akkashiteirunoka (治安はほんとうに悪化しているのか) (in English: Is Public Safety Really Deteriorating?, ISBN 978-4-86162-025-6) disputing foreign crime statistics, suggesting that such statistics were being manipulated by politicians for political gain. He suggested, for example, that including visa violations in crime statistics is misleading. He also said that the crime rate in Tokyo is based on reported rather than actual crimes.[86] Access to housing and other services A significant number of apartments, and some motels, night clubs, brothels, sex parlours and public baths in Japan have put up signs stating that foreigners are not allowed, or that they must be accompanied by a Japanese person to enter.[87] In February 2002 plaintiffs sued a Hokkaido bathhouse in district court pleading racial discrimination, and on November 11 the Sapporo District Court ordered the bathhouse to pay the plaintiffs ¥1 million each in damages.[88] In fact, there were a substantial number of lawsuits regarding discrimination against foreigners. For example, in 2005, a Korean woman who attempted to rent a room was refused because she was not a Japanese citizen. She filed a discrimination lawsuit, and she won in Japanese court.[89] "Discrimination toward foreign nationals in their searches for homes continues to be one of the biggest problems", said the head of the Ethnic Media Press Centre. Organizers of the service said they hope to eradicate the racism that prevents foreigners, particularly Non-Westerners, from renting apartments since there are currently no laws in Japan that ban discrimination.[90] During the COVID-19 pandemic, many establishments started to exclude non-Japanese customers over fears that they would spread the coronavirus. For example, a ramen shop owner imposed a rule prohibiting non-Japanese people from entering the restaurant.[91] Healthcare Japan provides universal health insurance for all citizens. Foreigners staying in Japan for a year or more are required to enroll for one of the public health insurance schemes.[92] However, before this policy was mandated, many foreign workers, particularly Japanese Brazilians, were less likely to be covered by health insurance due to refusal of the employer.[93] Initially, many prefectures refused to allow foreigners from entering the National Health Insurance (Kokumin Kenkou Hoken) as foreigners were not considered to be eligible. The policy was revised to include foreigners after local governments witnessed healthcare disparities between Japanese citizens and foreigners.[94] A study conducted revealed that incidences of increased poor health was high among the foreign workers living in the Tochigi Prefecture.[95] A quarter of these workers did not visit clinics or hospitals, due to language barriers and high medical costs. Nearly 60% of the 317 workers surveyed experienced difficulty in communicating in English. Some hospitals have been known to turn patients away if they could not confirm their residence status.[96] The NTT Medical Center Tokyo, located in the Gotanda district of Tokyo, announced on their website that foreigners must present their insurance card and residence cards. If they were unable to then they would be denied service, with the exception of emergency cases. A maternity ward, located in Tokyo, had stated on their website that services would be limited for patients who could only speak at a conversational level in Japanese. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many ethnic-minority healthcare providers have been found to not be assigned to treating patients with the COVID-19 infection.[97] Possible reasons for this include the low number of ethnic-minority healthcare providers working in Japan's clinics and hospitals, as well as language barriers. |

分野別 高等教育 外国人教授は日本の高等教育制度の至る所で教鞭をとっているが、東京大学のロバート・J・ゲラーは1992年に、外国人教授が終身在職権を与えられること は極めて稀であると報告している[81]。 日本国籍以外の者と犯罪 さらなる情報 日本の犯罪 他の国と同様、外国人は時としてビザで認められていない仕事をしたり、ビザの期限を超過したりする。彼らの雇用は、多くの日本人が働けない、あるいは働き たがらない分野に集中する傾向がある。 ヤクザや日本の組織犯罪は、在日中国人移民を子分として犯罪に利用しており、それが世間一般に否定的な印象を与える原因となっている[82]。 2003年には、アフリカ出身の外国人は、一人当たりの犯罪件数が日本人の2.8倍であったが、暴力犯罪を犯す可能性はわずかに低かった[83]。 警察庁の記録によると、2002年には、16,212人の外国人が34,746件の犯罪を犯し、その半数以上がビザ違反(有効なビザを持たずに日本に居住 /就労すること)であった。その内訳は、中国人が12,667件(36.5%)、487人(0.038%)、ブラジル人が5,272件(15.72%)、 1,186人(7.3%)、韓国人が2,815件(8.1%)、1,738人(10.7%)で、その他が約6,000人となっている。同年の日本人の犯罪 総数は546,934件であった。 この統計の中で、日本人は6,925件の凶悪犯罪を犯し、そのうち2,531件が放火または強姦であったのに対し、外国人は323件の凶悪犯罪を犯した が、放火または強姦に分類されたのは42件のみであった。外国人は集団で犯罪を犯す傾向が強かった: 外国人が犯した犯罪の約61.5%に1人以上の共犯者がいたのに対し、日本人が犯した犯罪の18.6%しか集団犯ではなかった。日本人は外国人より凶悪犯 罪が多い。 警察庁の2022年の調査では、不法滞在者は2004年の21万9000人から2008年には11万3000人に減少し、さらに外国人旅行者の検挙数は 2004年の2万1842人から2008年には1万3880人に減少している。刑法犯として起訴された被逮捕者に占める外国人の割合は約2.0%で、この 数字は比較的安定している。一方、強盗致傷事件で起訴された被逮捕者に占める外国人の割合は、2008年には約5.5%であった[84]。 東京弁護士会が実施した調査によると、外国籍の回答者2,000人のうち60%以上が、警察から取り調べを受けたと回答している。このうち約77%が、外 国人であること以外に明白な理由がないように思われると回答している[85]。 東京都の元緊急治安対策本部長である久保浩氏は、『治安はほんとうに悪化しているのか』という本を出版した、 ISBN978-4-86162-025-6)は、外国の犯罪統計に異論を唱え、そのような統計は政治家によって政治的利益のために操作されていると示唆 した。例えば、犯罪統計にビザ違反を含めるのは誤解を招くと指摘した。彼はまた、東京の犯罪率は実際の犯罪よりもむしろ報告された犯罪に基づいていると述 べた[86]。 住宅とその他のサービスへのアクセス 日本では、相当数のアパート、一部のモーテル、ナイトクラブ、風俗店、風俗パーラー、銭湯が、外国人は入店できない、または入店するには日本人の同伴が必 要である旨の看板を掲げている[87]。 2002年2月、原告は人種差別を訴えて北海道の銭湯を地裁に提訴し、11月11日、札幌地裁は銭湯に原告一人当たり100万円の損害賠償を支払うよう命 じた[88]。 実際、外国人差別に関する訴訟は相当数あった。例えば、2005年、部屋を借りようとした韓国人女性が、日本国籍でないことを理由に断られた。彼女は差別 訴訟を起こし、日本の裁判所で勝訴した[89]。 「外国人の家探しにおける差別は、最大の問題のひとつであり続けている」と、エスニック・メディア・プレス・センターの代表は述べた。このサービスの主催 者は、現在日本には差別を禁止する法律がないため、外国人、特に非西洋人がアパートを借りることを妨げる人種主義を根絶したいと述べている[90]。 COVID-19のパンデミックの間、多くの店が、コロナウイルスが広がることを恐れて、日本人以外の客を排除し始めた。例えば、あるラーメン屋の店主 は、日本人以外の入店を禁止するルールを課した[91]。 医療 日本はすべての国民に国民皆保険制度を提供している。日本に1年以上滞在する外国人は、いずれかの公的健康保険に加入することが義務付けられている [92]。 しかし、この政策が義務付けられる前は、多くの外国人労働者、特に日系ブラジル人は、雇用主の拒否により健康保険に加入する可能性が低かった[93]。 当初、多くの都道府県は、外国人は国民健康保険(国保)に加入する資格がないと考え、外国人の国保加入を拒否していた。この政策は、地方自治体が日本国民 と外国人の間の医療格差を目の当たりにした後に、外国人を含めるように修正された[94]。実施された調査によって、栃木県に住む外国人労働者の間で、健 康状態が悪化するケースが高いことが明らかになった[95]。調査対象となった317人の労働者のうち60%近くが、英語でのコミュニケーションに困難を 感じていた。 東京の五反田にあるNTTメディカルセンター東京は、外国人は保険証と在留カードを提示しなければならないとホームページで告知している[96]。提示で きない場合は、緊急の場合を除き、診療を拒否される。東京都内のある産科病棟は、日本語が会話レベルでしか話せない患者にはサービスを制限するとホーム ページで告知していた。 COVID-19パンデミックの際、多くのエスニック・マイノリティの医療従事者がCOVID-19感染患者の治療を担当しなかったことが判明している [97]。この理由として考えられるのは、日本の診療所や病院で働くエスニック・マイノリティの医療従事者の数が少ないこと、言葉の壁などである。 |

| History Pre-war xenophobia Racial discrimination against other Asians was habitual in Imperial Japan, which first practiced it during the start of Japanese colonialism.[98] The Meiji era Japanese were contemptuous of other Asians because they believed that other Asians were inferior to them.[99] This sentiment was expressed in Datsu-A Ron, an editorial whose author espoused the belief that Japan should treat other Asians as other western empires treated them. Discrimination was also enacted against Ryūkyū and Ainu peoples.[99][100] The Shōwa regime preached racial superiority and racialist theories, based on the nature of Yamato-damashii. According to historian Kurakichi Shiratori, one of Emperor Hirohito's teachers: "Therefore nothing in the world compares to the divine nature (shinsei) of the imperial house and likewise the majesty of our national polity (kokutai). Here is one great reason for Japan's superiority."[101] The Japanese culture long regarded Gaijin (non-Japanese) people to be subhumans and included Yamato master race theory ideology in government propaganda and schools as well.[102] As stated in An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus, a classified report which was published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare on July 1, 1943, just as a family has harmony and reciprocity, but with a clear-cut hierarchy, the Japanese, as a racially superior people, are destined to rule Asia "eternally" as the head of the family of Asian nations.[103] The most horrific xenophobia of the pre-Shōwa period was displayed after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, where in the confusion after a massive earthquake, Koreans were wrongly maligned as poisoning the water supply. A vicious pogrom resulted in the deaths of at least 3,000 Koreans, and the imprisonment of 26,000. In the 1930s, the number of attacks on Westerners and their Japanese friends by nationalist citizens increased due to the influence of Japanese military-political doctrines in the early years of the Showa period, these attacks occurred after a long build-up which started in the Meiji period, when a few samurai die-hards refused to accept foreigners in Japan.[104] For an exception, see Jewish settlement in the Japanese Empire. |

歴史 戦前の外国人嫌悪 明治時代の日本人は、他のアジア人は自分たちよりも劣っていると考えていたため、他のアジア人を侮蔑していた[99]。この感情は、他の西洋帝国がアジア 人を扱ったように、日本も他のアジア人を扱うべきだという信条を唱えた社説『達阿論』に表現されている。琉球やアイヌの人々に対する差別も制定された [99][100]。正和体制は、大和魂の本質に基づく人種的優越性と人種主義理論を説いた。歴史学者の白鳥倉吉によれば、裕仁天皇の師匠の一人である: 「それゆえ、皇室の神性(しんせい)と同様に、わが国の国体(こくたい)の威厳に匹敵するものは、この世に存在しない。ここに日本が優れている一つの大き な理由がある」[101]。日本文化は長い間、外人(日本人以外の人々)を亜人とみなしており、政府のプロパガンダや学校にも大和民族主人論イデオロギー が含まれていた[102]。 1943年7月1日に厚生労働省によって発表された機密報告書である「大和民族を核とする世界政策の調査」の中で述べられているように、家族には調和と互 恵性があるが、明確な上下関係があるように、日本人は人種的に優れた民族として、アジア諸国の家族の長としてアジアを「永遠に」支配する運命にある。 [1923年の関東大震災では、大地震の後の混乱の中で、朝鮮人が水源に毒を入れたという誤った悪評が流された。凶悪なポグロムの結果、少なくとも 3,000人の朝鮮人が死亡し、26,000人が投獄された。 1930年代には、昭和初期の日本の軍事的・政治的教義の影響により、ナショナリストの市民による欧米人やその日本人の友人に対する襲撃が増加した。これ らの襲撃は、明治時代に始まった長い積み重ねの後に起こったもので、少数の侍の熱狂的な支持者が日本での外国人の受け入れを拒否していた。 |

| World War II Racism was omnipresent in the press during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Greater East Asia War and the media's descriptions of the superiority of the Yamato people was unwaveringly consistent.[105] The first major anti-foreigner publicity campaign, called Bōchō (Guard Against Espionage), was launched in 1940 alongside the proclamation of the Tōa shin Chitsujo (New Order in East Asia) and its first step, the Hakkō ichiu.[106] Initially, in order to justify Japan's conquest of Asia, Japanese propaganda espoused the ideas of Japanese supremacy by claiming that the Japanese represented a combination of all Asian peoples and cultures, emphasizing heterogeneous traits.[107] Japanese propaganda started to place an emphasis on the ideas of racial purity and the supremacy of the Yamato race when the Second Sino-Japanese War intensified.[107] Mostly after the launching of the Pacific War, Westerners were detained by official authorities, and on occasion were objects of violent assaults, sent to police jails or military detention centers or suffered bad treatment in the street. This applied particularly to Americans, Soviets and British; in Manchukuo at the same period xenophobic attacks were carried out against Chinese and other non-Japanese. At the end of World War II, the Japanese government continued to adhere to the notion of racial homogeneity and racial supremacy, as well as an overall complex of social hierarchy, with the Yamato race at the top of the racial hierarchy.[108] Japanese propaganda of racial purity returned to post-World War II Japan because of the support of the Allied forces. U.S. policy in Japan terminated the purge of high-ranking fascist war criminals and reinstalled the leaders who were responsible for the creation and manifestation of prewar race propaganda.[109] Similar to what would occur in Korea, the overwhelming presence of American soldiers, most of whom young and unmarried, had a noticeable effect on the Japanese female populace.[110] The obvious power dynamic after the war outcome, as well as the lack of accountability for American soldiers who impregnated Japanese women, placed these children into a negative light before their lives even began.[111] An unknown number of these children would be abandoned by their fathers. They would grow up associated with defeat and death in their own country and regarded as a reminder of Japanese subordination to a western power.[citation needed] |

第二次世界大戦 日中戦争と大東亜戦争の間、人種主義はマスコミに遍在し、大和民族の優越性に関するマスコミの記述は揺るぎない一貫性を持っていた[105]。「防諜」と 呼ばれる最初の大規模な外国人排斥宣伝キャンペーンは、東亜新秩序の宣言とその第一歩である白光一宇とともに1940年に開始された。 [当初、日本のアジア征服を正当化するために、日本のプロパガンダは、日本人はアジアのすべての民族と文化の結合体であると主張し、異質な特徴を強調する ことで、日本人至上主義の思想を信奉していた[107]。日本のプロパガンダは、日中戦争が激化すると、人種の純粋性と大和民族の優位性の思想を強調し始 めた[107]。 太平洋戦争の開戦後、欧米人はたいてい官憲に拘束され、時には暴力的な暴行の対象となったり、警察の拘置所や軍の拘置所に送られたり、路上でひどい扱いを 受けたりした。特にアメリカ人、ソビエト人、イギリス人がそうであった。同時期の満州国では、中国人やその他の外国人に対する排外主義的な攻撃が行われ た。 第二次世界大戦末期、日本政府は人種的同質性と人種至上主義という概念と、大和民族を頂点とする社会的ヒエラルキーの全体的コンプレックスに固執し続けた [108]。連合軍の支援により、人種的純潔性に関する日本のプロパガンダが第二次世界大戦後の日本に復活した。アメリカの対日政策は、ファシストの高級 戦犯の粛清を打ち切り、戦前の人種プロパガンダの創造と発現に責任を負っていた指導者たちを復権させた[109]。 朝鮮半島で起こったことと同様に、アメリカ兵の圧倒的な存在(そのほとんどが若く未婚であった)は、日本の女性民衆に顕著な影響を与えた[110]。戦争 終結後の明らかな権力闘争と、日本人女性を孕ませたアメリカ兵に対する説明責任の欠如は、これらの子どもたちを、彼らの人生が始まる前から否定的な光の中 に置いた[111]。未知数のこれらの子どもたちは父親に捨てられることになる。彼らは自国での敗北と死と結びついて成長し、西洋の大国に対する日本の従 属を思い起こさせるものとみなされた[要出典]。 |

Post-war government policy Transition of numbers of registered foreigners in Japan Because of the low importance placed on assimilating minorities in Japan, laws regarding ethnic matters receive low priority in the legislative process.[112] Still, in 1997, "Ainu cultural revival" legislation was passed which replaced the previous "Hokkaido Former Aboriginal Protection" legislation that had devastating effects on the Ainu in the past. Article 14 of the Constitution of Japan states that all people (English version) or citizens (revised Japanese version) are equal under the law, and they cannot be discriminated against politically, economically, or socially on the basis of race, belief, sex, or social or other background. However, Japan does not have civil rights legislation which prohibits or penalizes discriminatory activities committed by citizens, businesses, or non-governmental organizations. In January 2024, three Japanese citizens, including a man of Pakistani descent, filed a civil lawsuit against the Japanese government, alleging a consistent pattern of racially motivated police harassment and requesting improved practices, along with approximately ¥3 million ($20,330) each in compensation. The uncommon lawsuit in Japan aims to demonstrate that racial discrimination violates the constitution and international human rights agreements. The plaintiffs, including two permanent residents and one foreign-born Japanese citizen, claim repeated unjustified stops and searches by the police based on their race, prompting concerns about the country's ability to address the increasing diversity resulting from a growing number of foreign workers. The lawsuit names the Japanese government, the Tokyo Metropolitan, and Aichi prefecture governments.[113][85] Attempts have been made in the Diet to enact human rights legislation. In 2002, a draft was submitted to the House of Representatives, but did not reach a vote.[114] Had the law passed, it would have set up a Human Rights Commission to investigate, name and shame, or financially penalize discriminatory practices as well as hate speech committed by private citizens or establishments. Another issue which has been publicly debated but has not received much legislative attention is whether to allow permanent residents to vote in local legislatures. Zainichi organizations affiliated with North Korea are against this initiative, while Zainichi organizations affiliated with South Korea support it. Finally, there is debate about altering requirements for work permits to foreigners. As of 2022, the Japanese government does not issue work permits unless it can be demonstrated that the person has certain skills which cannot be provided by locals. |

戦後の政府方針 外国人登録者数の推移 日本では少数民族の同化があまり重要視されていないため、民族問題に関する法律は立法過程での優先順位が低い[112]。 それでも1997年には、過去にアイヌに壊滅的な影響を与えた「北海道旧原住民保護」法に代わる「アイヌ文化復興」法が成立した。 日本国憲法第14条は、すべて国民(英語版)または市民(改定日本語版)は、法の下に平等であり、人種、信条、性別、社会的その他の背景によって、政治 的、経済的または社会的に差別されないと定めている。 しかし日本には、市民、企業、非政府組織による差別的行為を禁止したり罰したりする公民権法はない。2024年1月、パキスタン系の男性を含む3人の日本 人が日本政府を相手取って民事訴訟を起こし、人種差別を動機とする警察による嫌がらせの一貫したパターンを主張し、慣行の改善とそれぞれ約300万円 (20,330ドル)の賠償を求めた。日本では珍しいこの訴訟は、人種差別が憲法や国際人権規約に違反していることを証明することを目的としている。永住 権保持者2名と外国生まれの日本国民1名を含む原告らは、人種に基づく警察による不当な停留や捜索の繰り返しを主張し、外国人労働者の増加による多様性の 増大に対処する国の能力への懸念を促している。訴訟では、日本政府、東京都、愛知県が訴えられた[113][85]。 人権擁護法案を制定する試みが国会で行われてきた。2002年、衆議院に草案が提出されたが、採決には至らなかった[114]。もしこの法律が可決されて いれば、人権委員会が設置され、民間人や企業による差別的行為やヘイトスピーチを調査し、名指しで非難したり、金銭的な罰則を科すことになっていただろ う。 永住権保持者に地方議会での選挙権を認めるかどうかという問題も、公に議論されてはいるが、あまり立法化されていない。北朝鮮系の在日団体はこのイニシア チブに反対しているが、韓国系の在日団体は支持している。 最後に、外国人への就労許可要件の変更についての議論がある。2022年現在、日本政府は、その人が地元の人間には提供できない特定の技能を持っているこ とが証明されない限り、労働許可証を発行していない。 |

| Comment by a U.N. special

rapporteur on racism and xenophobia【Probably this section may be

written by right-wing conspiracy theorists】 In July 2005, a United Nations special rapporteur on racism and xenophobia expressed concerns about deep and profound racism in Japan and the Japanese government's insufficient recognition of the problem.[115][116][117] Doudou Diène (Special Rapporteur of the UN Commission on Human Rights) concluded after an investigation and nine-day tour of Japan that racial discrimination and xenophobia in Japan primarily affect three groups: national minorities, the descendants of people from former Japanese colonies, and foreigners from other Asian countries.[117] John Lie, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, believes that the widespread belief that Japan is an ethnically homogeneous society is inaccurate because Japan is a multiethnic society.[118] Such claims have long been rejected by other sectors of Japanese society such as the former Japanese Prime Minister Tarō Asō, who once described Japan as a nation which is inhabited by people who are members of "one race, one civilization, one language and one culture".[119] While it expressed support for anti-discrimination efforts, Sankei Shimbun, a Japanese national newspaper, expressed doubt about the impartiality of the report, pointing out that Doudou Diène never visited Japan before and his short tour was arranged by a Japanese NGO, IMADR (International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination). The chairman of the organization is Professor Kinhide Mushakoji (武者小路公秀), who is a board member (and the former director of the board) of the International Institute of the Juche Idea (主体思想国際研究所), an organization whose stated purpose is the propagation of Juche, the official ideology of North Korea.[120] In 2010, according to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Japan's record on racism has improved, but there is still room for progress.[121] The committee was critical of the lack of anti-hate speech legislation in the country and the treatment of Japanese minorities and its large Korean and Chinese communities.[121] The Japan Times quoted committee member Regis de Gouttes as saying that there had been little progress since 2001 (when the last review was held) "There is no new legislation, even though in 2001 the committee said prohibiting hate speech is compatible with freedom of expression."[121] Many members of the committee, however, praised the Japanese government's recent recognition of the Ainu as an indigenous people.[121] In February 2015, Ayako Sono, a former member of an educational reform panel, wrote a controversial column in Sankei Shimbun in which she suggested that more foreign workers should be imported in an attempt to alleviate labor shortages, but they should be separated from native Japanese with a system of apartheid.[122][123][124][125] She later stated "I have never commended apartheid, but I do think that the existence of a ‘Chinatown’ or ‘Little Tokyo’ is a good thing."[126] |

人種主義と外国人排斥に関する国連特別報告者のコメント【おそらくこのセクションは、右翼の陰謀論者が書いたものだろう。】 2005年7月、国連の人種主義・排外主義に関する特別報告者は、日本における深く深刻な人種主義と、日本政府のこの問題に対する不十分な認識について懸 念を表明した[115][116][117]。 ドゥドゥ・ディエンヌ(国連人権委員会特別報告者)は、日本における人種差別と外国人排斥は主に、国民的マイノリティ、日本の旧植民地出身者の子孫、他の アジア諸国からの外国人という3つの集団に影響を及ぼしていると、調査と9日間の日本視察の後に結論づけた[117]。 [117] カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のジョン・リー教授は、日本は多民族社会であるため、日本が民族的に均質な社会であるという広範な信念は不正確であると考 えている[118]。 このような主張は、かつて日本を「一つの人種、一つの文明、一つの言語、一つの文化」の構成員である人々が住む国民と表現した麻生太郎元首相のような日本 社会の他のセクターによって長い間否定されてきた[119]。 日本の全国紙である産経新聞は、反差別の取り組みへの支持を表明する一方で、ドゥドゥ・ディエーヌがこれまで一度も日本を訪れたことがなく、短期間の視察 は日本のNGOであるIMADR(あらゆる形態の差別に反対する国際運動)が手配したものであることを指摘し、報告書の公平性に疑念を表明した。同団体の 会長は武者小路公秀教授で、北朝鮮の公式思想であるチュチェ思想の普及を目的とする団体であるチュチェ思想国際研究所の理事(元理事)である。 [120] 2010年、国連人種差別撤廃委員会によると、人種主義に関する日本の記録は改善されたが、まだ進歩の余地がある[121]。同委員会は、日本における反 ヘイトスピーチ法制の欠如、日本人マイノリティと大規模な韓国人・中国人コミュニティの扱いについて批判的であった[121]。 2001年に委員会はヘイトスピーチを禁止することは表現の自由と両立すると述べていたにもかかわらず、新しい法律はない」[121][121] しかし、委員会の多くのメンバーは、日本政府が最近アイヌを先住民族として認めたことを称賛した[121]。 2015年2月、教育改革会議の元メンバーである曽野綾子は、産経新聞のコラムで、労働力不足を解消するために外国人労働者をもっと輸入すべきだが、彼ら はアパルトヘイトのシステムで生粋の日本人から分離されるべきだと提案し、物議を醸した[122][123][124][125]。 彼女は後に「私はアパルトヘイトを称賛したことはないが、『チャイナタウン』や『リトルトーキョー』の存在は良いことだと思う」と述べた[126]。 |

| An Investigation of Global

Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus Anti-Russian sentiment in Japan Antisemitism in Japan Eugenics in Japan Hakkō ichiu Japanese nationalism Japanese war crimes Statism in Shōwa Japan Manga Kenkanryu Minzoku Nippon Kaigi Gaijin Shina (word) Tōhōkai – a Japanese fascist political party which advocated Nazism Uyoku dantai Zaitokukai Kikokushijo returned children Racism by country Fascism in Asia Racism in Asia |

大和民族を核とした世界政策の考察(→「容赦なき戦争」) 日本における反ロシア感情 日本における反ユダヤ主義 日本における優生学 八紘一宇 日本の国民主義 日本の戦争犯罪 日本の国家主義 マンガ剣客流 民俗 日本会議 外人 支那 東宝会 - ナチズムを標榜した日本のファシスト政党 右翼団体 在特会 ikokushijoは子供たちを返した 国別の人種主義 アジアのファシズム アジアの人種主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racism_in_Japan |

|

★ 日 本の人種主義 : トランスナショナルな視点からの入門書 / 河合優子著, 青弓社 , 2023

書 籍紹介:「海外や日本の人種主義の歴史的な展開を追い、差別や偏見、ステレオタイプ、アイデンティティなどの視点から、私たちの日常に潜む人種主義を浮き 彫りにする。国際的・領域横断的に蓄積されてきた人種主義に関する議論をまとめる概説書。」https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BD01826180

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆