プナンとその情動の研究

A Study of the

Punan People and Their Emotions

プナン(プナン・バーと区分するために「ペナン」と言われてきたが、ここではプナンと呼称を 統一する)はサラワクとブルネイに住む遊動民で、ブルネイには小さなコミュ ニティーがあるのみである。プナンは狩猟採集民として残っている最後の民族の一つである[1]。プナンは、必要以上のものを取らないという意味の「モロ ン」の習慣で知られている。プナンの多くは、第二次世界大戦後に宣教師がウルバラム地区を中心にリンバン地区にも入植するまで、遊牧民の狩猟採集民であっ た。彼らは薬にも使われる植物や動物を食べ、皮や皮革、毛皮などを衣服や住居に利用する。

| The Penan are a

nomadic indigenous people living in Sarawak and Brunei, although there

is only one small community in Brunei; among those in Brunei half have

been converted to Islam, even if only superficially. Penan are one of

the last such peoples remaining as hunters and gatherers.[1] The Penan

are noted for their practice of 'molong' which means never taking more

than necessary. Most Penan were nomadic hunter-gatherers until the

post-World War II missionaries settled many of the Penan, mainly in the

Ulu-Baram district but also in the Limbang district. They eat plants,

which are also used as medicines, and animals and use the hides, skin,

fur, and other parts for clothing and shelter. |

プナンはサラワクとブルネイに住む遊動民で、ブルネイには小さなコミュ

ニティーがあるのみである。プナンは狩猟採集民として残っている最後の民族の一つである[1]。プナンは、必要以上のものを取らないという意味の「モロ

ン」の習慣で知られている。プナンの多くは、第二次世界大戦後に宣教師がウルバラム地区を中心にリンバン地区にも入植するまで、遊牧民の狩猟採集民であっ

た。彼らは薬にも使われる植物や動物を食べ、皮や皮革、毛皮などを衣服や住居に利用する。 |

| The Penan number around

16,000;[1] of which only approximately 200 still live a nomadic

lifestyle.[5] Penan numbers have increased since they began to settle.

The Penan can be broken down into two loosely related geographical

groups known as either Eastern Penan or Western Penan; the Eastern

Penan reside around the Miri, Baram, Limbang and Tutoh regions and the

Western Penan in and around Belaga district.[6] They can be considered as a native group or 'tribe' in their own right, with a language distinct from other neighbouring native groups such as the Kenyah, Kayan, Murut or Kelabit. However, in government censuses they are more broadly classified as Orang Ulu which translates as "Upriver People" and which contains distinct neighbouring groups such as those above. Even more broadly they are included in the term Dayak, which includes all of Sarawak's indigenous people. The Penan language belongs to the Kenyah subgroup within the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. |

プナンは約16,000人[1]いるが、そのうち遊牧民として生活して

いるのは約200人[5]である。プナンは、東プナンまたは西プナンとして知られる2つの緩やかに関連した地理的グループに分けることができる。東プナン

はミリ、バラム、リンバン、ツト地域周辺に、西ペナンはベラガ地区周辺に居住している[6]。 彼らは、ケニヤ、カヤン、ムルト、ケラビットなどの近隣の先住民族とは異なる言語を持っており、それ自体が先住民族または「部族」とみなすことができる。 しかし、政府の統計では、彼らはより広義にOrang Ulu(オラン・ウル)として分類されており、これは「上流の人々」と訳され、上記のような近隣のグループとは区別されています。さらに広義にはサラワク の先住民族をすべて含む Dayak という用語に含まれる。 プナン語は、オーストロネシア語族のマラヨ・ポリネシア語群の中のケニヤ語派に属する。 |

| Penan communities were

predominantly nomadic up until the 1950s. The period from 1950 to the

present has seen consistent programmes by the state government and

foreign Christian missionaries to settle Penan into longhouse-based

villages similar to those of Sarawak's other indigenous groups.[7] Some, typically the younger generations, now cultivate rice and garden vegetables but many rely on their diets of sago (starch from the sago palm), jungle fruits and their prey which usually include wild boar, barking deer, mouse deer but also snakes (especially the reticulated python or kemanen), monkeys, birds, frogs, monitor lizards, snails and even insects such as locusts. Since they practice 'molong', they pose little strain on the forest: they rely on it and it supplies them with all they need. They are outstanding hunters and catch their prey using a 'kelepud' or blowpipe, made from the Belian Tree (superb timber) and carved out with unbelievable accuracy using a bone drill – the wood is not split, as it is elsewhere, so the bore has to be precise almost to the millimetre, even over a distance of 3 metres. The darts are made from the sago palm and tipped with poisonous latex of a tree (called the Tajem tree, Antiaris toxicaria) found in the forest which can kill a human in a matter of minutes.[citation needed] Everything that is caught is shared as the Penan have a highly tolerant, generous and egalitarian society, so much so that it is said that the nomadic Penan have no word for 'thank you' because help is assumed and therefore doesn't require a 'thank you'. However, 'jian kenin' [meaning 'feel good'] is typically used in settled communities, as a kind of equivalent to 'thank you'. Very few Penan live in Brunei any more, and their way of life is changing due to pressures that encourage them to live in permanent settlements and adopt year-around farming.[8] |

1950年代まではプナンのコミュニティは主に遊動民であった。

1950年から現在に至るまで、州政府と外国のキリスト教宣教師は、プナンをサラワクの他の先住民族と同様のロングハウス型の村に定住させるためのプログ

ラムを一貫して行ってきた[7]。 若い世代は米や野菜を栽培しているが、多くはサゴ(サゴヤシのデンプン)、ジャングルの果物、イノシシ、ホエジカ、ネズミジカ、ヘビ(特にニシキヘビやケ マネ)、サル、鳥、カエル、オオトカゲ、カタツムリ、イナゴなどの虫を餌に生きている。彼らは「モロン」を実践しているので、森に負担をかけることはほと んどなく、必要なものはすべて森に依存している。彼らは優れたハンターであり、ベリアンツリー(極上の木材)から作られた「ケレプッド」(吹き矢)を使っ て獲物を捕らえるが、骨用ドリルを使って信じられないほどの精度で彫り上げる。ダーツはサゴヤシから作られ、先端には森にあるタジェムツリー (Antiaris toxicaria)と呼ばれる木の毒液が塗られており、数分で人間を殺すことができます[citation needed] プナンは非常に寛容で寛大かつ平等な社会であるため、獲れたものはすべて共有され、遊動民のプナンには「ありがとう」という言葉がないほど、助けてもらう ことは当然なので「ありがとう」は必要ないとも言われる。しかし、定住社会では「ありがとう」に相当する言葉として「ジアン・ケニン」(「気持ちいい」の 意)が使われるのが一般的である。 ブルネイに住むプナンはもうほとんどおらず、彼らの生活様式は、定住地での生活や年間を通した農業を奨励する圧力によって変化しつつある[8]。 |

| "The army and the police came to

our blockade and threatened us and told us to take down our barricade.

We said 'we are defending our land. It is very easy for you as soldiers

and policemen. You are being paid. You have money in your pockets. You

can buy what you need; rice and sugar. You have money in the bank. But

for us, this forest is our money, this is our bank. This is the only

place where we can find food."[9] (Penan spokesman, 1987) The Penan came to national and international attention when they resisted logging operations in their home territories of the Baram, Limbang, Tutoh and Lawas regions of Sarawak. The Penan's struggle began in the 1960s when the Indonesian and Malaysian governments opened up large areas of Borneo's interior to commercial logging.[10] In most cases, the largest and most lucrative logging concessions went to members of the island's political and business elites. With an increase in the global demand for timber at the time, these concessionaries began to procure all marketable trees from their holdings. Since both the settled, semi-nomadic and nomadic Penan communities were and are reliant on forest produce, they were hit hard by the large scale logging operations that encroached on their traditionally inhabited territories. The logging caused the pollution of their water catchment areas with sediment displacement, the loss of many sago palms that form the staple carbohydrate of Penan diet, scarcity of wild boar, deer and other game, scarcity of fruit trees and plants used for traditional forest medicine, destruction of their burial sites and loss of rattan and other rare plant and animal species.[11] For the forest people of Borneo, like other native tribes, such plants and animals are also viewed as sacred, as the embodiment of powerful spirits and deities.[12] Thus, the Penan made numerous verbal and written complaints to the logging companies and local government officials. They argued that the logging companies were located on land given to the Penan in an earlier treaty, recognised by the Sarawak state government, and were thus violating their native customary rights.[13] It was also claimed that logging plans were never discussed with the Penan before felling began. However, these complaints fell on deaf ears. Beginning in the late 1980s and continuing today the Penan and other indigenous communities such as the Iban, Kelabit and Kayan (collectively referred to as Dayak) have set up blockades in an attempt to halt logging operations on their land. These succeeded in many areas but the efforts were hard to sustain and ended in large-scale clashes between the indigenous communities and the state-backed logging companies, supported by the police and Malaysian army. In 1987, the state government passed the amendment S90B of the Forest Ordinance, which made the obstruction of traffic along any logging road in Sarawak a major offence.[14] Under this law, The confrontations ended with several deaths, many injuries and large-scale arrests of indigenous people. Many of the detained reported being beaten and humiliated while in custody. An independent Sarawakian organisation IDEAL documented such claims in a 2001 fact-finding mission entitled "Not Development, but Theft".[15] However, confrontation with state authorities has not been the only source of conflict for the Penan or the Dayaks. In the late 1990s, in neighbouring Kalimantan, the Indonesian government set aside millions of acres of forest for conversion into commercial rubber and palm oil plantations.[16] Much of these areas have been traditionally occupied by indigenous groups. Crucially, to provide labour for such developments, the Indonesian government subsidised the relocation of unemployed labourers from other parts of Indonesia (particularly Java and Madura) to Kalimantan. As part of their contracted obligations, these settlers have participated in the clearing of forests. This has resulted in (increasingly) frequent and violent conflicts between the settlers and the Dayak population.[16] Hundreds of people have been killed in these encounters and thousands more have been forced to live in refugee camps. Because the two warring factions have different racial and religious backgrounds, the international media has often reported this conflict as ethnic animosity. Rather, it is the pursuit of resource wealth by powerful governments and businesses, despite strong resistance by local residents, which has caused the fighting.[citation needed][original research?] In the mid-1980s, when the plight of the Penan had been exposed on the world stage, the Sarawak State Government began making many promises to the Penan in an attempt to quell international protests and embarrassment. Among these were the promise of infrastructure facilities (for those who had been forced to resettle in government encampments due to deforestation) and the Magoh Biosphere Reserve.[13] Magoh Biosphere Reserve is an environmental ‘no intrusion’ zone introduced by Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud in 1990. However, in reality, this reserve has only ‘proposed boundaries’ within which logging companies continue to fell the forest. The Penan explicitly outlined their wants and requirements to the Sarawak State Government of Abdul Taib Mahmud in the 2002 Long Sayan Declaration.[17] The confrontation between the Penan and Sarawak State Government has continued to the present day.[when?] The blockade set up by the Penan community of Long Benali was forcefully dismantled on 4 April 2007 by the Sarawak Forestry Corporation (SFC), with support from a special police force unit and overlooked by Samling Corporation employees. Samling Corporation had been granted a logging concession by the Malaysian Timber Certificate Council (MTCC) that included land traditionally inhabited by the Penan of Long Benali and despite their continued petitions against the concession.[18] As of 2021 the Penan continue to fight development aggression in their ancestral domain.[19][20] |

「軍隊と警察が私たちの封鎖地点に来て、私たちを脅し、バリケードを撤

去するように言ってきたんです。私たちは「自分たちの土地を守っているんだ。あなた方兵士や警察官にとって、それはとても簡単なことなのです。あなた方は

給料をもらっている。ポケットにお金も入っている。米や砂糖など必要なものを買うことができる。銀行にも金がある。でも、私たちにとっては、この森が私た

ちのお金、私たちの銀行なのです。食料はここだけなんだ」[9](1987年、プナンのスポークスマン)。 プナンが国内外で注目されるようになったのは、彼らの故郷であるサラワクのバラム、リンバン、トゥトゥ、ラワス地域での伐採作業に抵抗したためである [10]。プナンの闘いは、1960年代にインドネシアとマレーシア政府がボルネオ島の内陸部の広大な地域を商業伐採に開放したことから始まった [10]。 ほとんどの場合、最大かつ最も有利な伐採権は、島の政財界のエリートが手にした。当時、世界的な木材需要の増加に伴い、これらの伐採権者は所有地から市場 性のある木をすべて調達するようになった。定住、半遊牧、遊牧のいずれのプナンも森林からの生産物に依存していたため、伝統的に居住していた地域を侵食す る大規模な伐採作業によって大きな打撃を受けた。伐採は、土砂の移動による集水域の汚染、プナンの主食である炭水化物を形成する多くのサゴヤシの喪失、イ ノシシや鹿などの狩猟動物の不足、果樹や伝統的森林医療に使われる植物の不足、埋葬地の破壊、藤やその他の希少植物種や動物の喪失を引き起こした [11]。 ボルネオの森の人々にとって、他の先住民族と同様に、そのような植物や動物は、強力な精霊や神の体現として神聖視されている[12]。したがって、プナン は伐採会社と地元政府の役人に口頭と文書で多くの苦情を出した。彼らは、伐採会社はサラワク州政府が承認した以前の条約でペナンに与えられた土地にあり、 先住民の慣習的権利を侵害していると主張した[13]。また、伐採計画が伐採開始前にペナンと議論されたことがないと主張した。しかし、これらの苦情は聞 き入れられなかった。1980年代後半から今日に至るまで、プナンやイバン、クラビット、カヤンなどの先住民コミュニティ(ダヤックと総称される)は、彼 らの土地での伐採作業を停止させるために封鎖を開始した。これらは多くの地域で成功したが、その努力はなかなか持続せず、警察やマレーシア軍の支援を受け た国の支援を受けた伐採業者と先住民族のコミュニティとの大規模な衝突に終わった。1987年、州政府は森林条例の修正案S90Bを可決し、サラワクの伐 採道路での交通妨害は重大な犯罪となった[14]。この法律のもと、衝突は先住民の死者、負傷者、逮捕者を出すに至った。拘束された人々の多くは、拘束中 に殴打や辱めを受けたと報告しています。サラワクの独立組織IDEALは、2001年の「開発ではなく、盗掘」と題する事実調査団でそのような主張を文書 化した[15]。 しかし、プナンやダヤクにとって、国家権力との対立が唯一の紛争の原因となっているわけではない。1990年代後半、隣国のカリマンタンでは、インドネシ ア政府は数百万エーカーの森林を商業用のゴムとパーム油のプランテーションに転換するために確保した[16]。 これらの地域の多くは、伝統的に先住民族が居住していたところである。重要なことは、そのような開発のための労働力を提供するために、インドネシア政府 は、インドネシアの他の地域(特にジャワとマドゥラ)からカリマンタンへの失業した労働者の移住を補助したことである。これらの入植者は、契約上の義務の 一部として、森林の伐採に参加している。その結果、入植者とダヤック族の間で(ますます)頻繁に激しい衝突が起きている[16]。 この衝突で何百人もの人々が殺され、何千人もの人々が難民キャンプでの生活を余儀なくされている。2つの派閥は異なる人種と宗教的背景を持っているため、 国際メディアはしばしばこの紛争を民族的な反感として報道してきた。むしろ、地元住民の強い抵抗にもかかわらず、有力な政府や企業が資源の富を追求したこ とが戦闘の原因となっている[要出典][独自調査?] 1980年代半ば、プナンの窮状が世界的に明らかになると、サラワク州政府は国際的な抗議と混乱を鎮めるために、プナンに対して様々な約束をするように なった。その中には、(森林破壊のために政府の野営地に再定住せざるを得なかった人々のための)インフラ施設やマゴー生物圏保護区の約束があった [13]。マゴー生物圏保護区は、1990年にアブドゥル・タイブ・マハムード首席大臣が導入した環境「侵入禁止」区域である。しかし、実際には、この保 護区には「提案された境界線」があるだけで、伐採会社は森林の伐採を続けている。 プナンとサラワク州政府の対立は現在も続いている。 ロン・ベナリのプナン・コミュニティが設定した封鎖は、特別警察部隊の支援とサムリング社の従業員の看視のもと、サラワク林業公社(SFC)により 2007年4月4日に強制的に解体された[18]。サムリング・コーポレーションは、マレーシア木材認証評議会(MTCC)から、ロング・ベナリのペナン が伝統的に居住する土地を含む伐採許可を得ており、彼らが伐採許可に反対する請願を続けていたにもかかわらず、この伐採許可を得ていたのだ[18]。 2021年現在、プナンは彼らの先祖代々の領域における開発侵略と戦い続けている[19][20]。 |

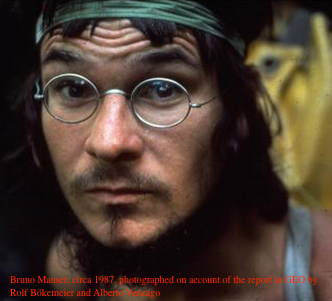

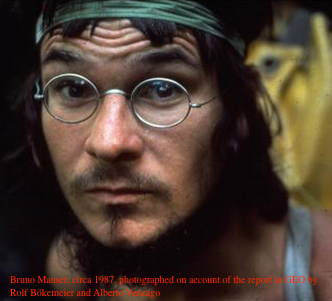

| Bruno Manser Bruno Manser was an environmental activist and champion of the Penan's plight during their struggle in the 1990s. Manser lived with the Penan for six years; in that time he learnt their language, survival skills and customs.[13] Named lakei Penan (Penan man) by the Penan, he helped communicate the Penan's cause to the outside world, firstly writing letters to Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud and later leaving Sarawak to educate the outside world (especially timber importing countries in Europe and Japan) about the deforestation and related social problems in Sarawak. He later conducted public awareness stunts such as paragliding onto the lawn of Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud and attempting a hunger strike outside the offices of Japanese shipping companies in Tokyo. In 1990, in response to Manser's protests, Sarawak's Chief Minister declared Manser an ‘enemy of the State’ and dispatched a Malaysian army unit to find and capture him.[13] In 1990, Manser returned to his home country of Switzerland and founded the Bruno Manser Fonds (BMF), a non-profit organisation dedicated to the plight of the Penan. In 2000, Manser went missing after returning to Sarawak with a Swedish film team and an associate from BMF to reunite with a Penan group. Manser's body and belongings have never been found despite intensive searches. Theories of assassination by the Sarawak government or logging companies have sprung up because of his status as an ‘enemy of the State’.[21] Other rumours include those of suicide after years of unsuccessful campaigning or getting lost in the dense mossy forests around Bukit Batu Lawi in the Kelabit Highlands, close to the border with Kalimantan. However, Manser had lived for several years in the region with the nomadic Penan and was thus highly experienced.[22] Five years after his disappearance in the rainforest of Borneo, Manser was officially declared as lost by the Basel Civil Court in Switzerland.[23] Personalities from politics, science and culture remembered the life of Manser in a commemoration ceremony held on 8 May 2010. |

ブルーノ・マンサーは環境活動家であり、1990年代のペナン族の闘争

の擁護者であった。プナンからラケイ・ペナン(プナンの人)と名付けられた彼は、プナンの大義を外部に伝えることに貢献し、まずアブドゥル・タイブ・マハ

ムド州首相に手紙を書き、その後サラワクを離れて外部(特にヨーロッパと日本の木材輸入国)にサラワクの森林破壊と関連する社会問題について啓蒙活動を

行った[13] 。その後、Abdul Taib

Mahmud首席大臣の芝生にパラグライダーで飛び込んだり、東京の日本の海運会社の事務所前でハンガーストライキを試みるなど、世論喚起のためのスタン

トを実施した。 1990年、マンサーの抗議行動に対してサラワク州の州首相はマンサーを「国家の敵」と宣言し、マレーシア軍の部隊を派遣して彼を捜索・捕獲した [13]。1990年にマンサーは母国スイスに戻り、ペナンの苦境に取り組む非営利団体ブルーノ・マンサー基金(BMF)を設立した。2000年、マン サーはプナンに再会するため、スウェーデンの撮影チームとBMFの仲間とともにサラワクに戻った後、行方不明になった。徹底的な捜索にもかかわらず、マン サーの遺体と所持品は発見されていない。国家の敵」であることから、サラワク政府や伐採会社による暗殺説が浮上した[21]。また、長年のキャンペーンに 失敗した自殺説や、カリマンタンとの国境に近いクラビット高原のブキット・バトゥ・ラウィ周辺の苔むした密林で行方不明になった説などもある。しかし、マ ンサーはこの地域でプナンと数年間生活していたため、経験豊富であった[22]。 ボルネオの熱帯雨林で失踪してから5年後、マンサーはスイスのバーゼル民事裁判所により公式に行方不明とされた[23]。2010年5月8日に行われた記 念式典では、政界、科学界、文化界の著名人がマンサーの生涯を偲んだ。 |

| Response by Malaysian authorities In 1987, Mahathir used the Internal Security Act (ISA) to jail critics of the regime and to neutralise Penan campaigners. Over 1,200 people were arrested for challenging logging and 1,500 Malaysian soldiers and police dismantled barricades and beat and arrested people.[24] During a meeting of European and Asian leaders in 1990, Mahathir said, "It is our policy to bring all jungle dwellers together into the mainstream. There is nothing romantic about these helpless, half-starved, and disease-ridden people."[25] Malaysian authorities also argued that it is unfair to accuse Malaysia of destroying their own rainforests while the western civilisation continued to cut their own forests down. Preservation of rainforests would mean closing down factories and hinder industrialisation which would result in unemployment issues. Instead of focusing on human rights of Penans, the western activists should focus instead on minorities in their own countries such as Red Indians in North America, Aboriginal Australians, Māori people in New Zealand and Turks in Germany.[26] Malaysian Timber Industry Development Board (MTIB) and Sarawak Timber Industry Development Cooperation (STIDC) spent RM 5 to 10 million in producing a research report to counter allegations by foreign activists.[27] The Economist was banned twice in 1991 for articles that commented critically on the Malaysian government. Its distribution was deliberately delayed three times. Newspaper editors would receive a phone call from Ministry of Information, warning them to "go easy" on particular topic. Few negative reports, such as logging, appeared on domestic newspapers because of the high degree of self-censorship. Mingguan Waktu newspaper was banned in December 1991 because of publishing criticisms of Mahathir administration. Mahathir defended the press censorship. He told ASEAN that foreign journalists "fabricate stories to entertain and make money out of it, without caring about the results of their lies".[28] |

マレーシア当局の対応 1987年、マハティールは国内治安維持法(ISA)を使って政権批判者を投獄し、プナンの運動家を無力化した。1,200人以上が伐採に異議を唱え逮捕 され、1,500人のマレーシアの兵士と警察がバリケードを解体し、人々を殴って逮捕した[24]。1990年のヨーロッパとアジアの指導者の会議で、マ ハティールは「すべてのジャングル居住者を主流にすることが我々の政策である」と言った。この無力で、半分飢えていて、病気にかかった人たちには何のロマ ンもない」と述べた[25]。 マレーシア当局も、西洋文明が自国の森林を伐採し続ける一方で、マレーシアが自国の熱帯雨林を破壊したと非難するのは不当であると主張した。熱帯雨林の保 護は、工場の閉鎖を意味し、工業化の妨げとなり、結果として失業問題を引き起こすだろう。欧米の活動家は、プナンの人権に注目するのではなく、北米のレッ ドインディアン、オーストラリアのアボリジニ、ニュージーランドのマオリ人、ドイツのトルコ人など、自国の少数民族に注目すべきである[26]。 マレーシア木材産業開発庁(MTIB)とサラワク木材産業開発協同組合(STIDC)は、外国の活動家の申し立てに対抗すべく500万から1000万RM を使って調査報告書を作成した[27]。 『Economist』誌は、マレーシア政府を批判的に論評した記事のために、1991年に2度発禁処分を受けた。その配布は3回意図的に延期された。新 聞社の編集者は情報省から電話を受け、特定の話題について「気楽にやれ」と警告されることもあった。伐採などのネガティブな報道は、自己検閲が強いので、 国内の新聞にはほとんど載らなかった。1991年12月には、マハティール政権への批判を掲載したため、Mingguan Waktu 新聞が発禁処分を受けた。マハティール首相は、報道検閲を擁護した。彼はASEANに対して、外国のジャーナリストは「楽しませるために話を捏造し、その 嘘の結果について気にすることなく、それで金を稼ぐ」と述べた[28]。 |

| Logging today Logging continues to dominate politics and economics in Sarawak and the government's ambition on timber from proposed Penan ancestral land also continues. Malaysia's rate of deforestation is the highest in the tropical world (142 km2/year) losing 14,860 square kilometres since 1990. The Borneo lowland rain forest, which is the primary habitat of the Penan, and also the most valuable trees have disappeared. "Despite the (Malaysian) government's pro-environment overtones, the… government tends to side with development more than conservation." — Rhett A. Butler The government's defence of large-scale logging as a means to economic development has also been challenged as unsustainable, indiscriminate of indigenous rights, environmentally destructive and mired in invested interests, corruption and cronyism.[29] Examples of this have been highlighted by the former Minister for Environment and Tourism Datuk James Wong also being one of the state's largest logging concessionaires. Most recently,[when?] the Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud himself is under investigation by Japanese tax authorities for corruption over RM32 million in timber kickbacks allegedly paid to his family company in Hong Kong to lubricate timber shipments.[30][31] Such allegations are not new, as Malaysia Today claimed in 2005: There is often a mutually beneficial relationship between logging companies and political elites, involving the acquisition of large private wealth for both parties through bribery, corruption and transfer pricing, at the expense of public benefit through lost revenues and royalty payments and at the expense of social, environmental and indigenous communities' rights ... The awarding of concessions and other licences to log as a result of political patronage, rather than open competitive tender, has been the norm rather than the exception in many countries.[32] |

伐採の現状 サラワク州の政治と経済は伐採に支配されており、政府はプナンの先祖代々の土地から木材を調達することを野心的に考えている。マレーシアの森林減少率は熱 帯地域で最も高く(142km2/年)、1990年以来14,860平方キロメートルが減少している。プナンの主要な生息地であるボルネオ島の低地熱帯雨 林は、最も貴重な木々も消滅してしまった。 "(マレーシア)政府は環境保護に熱心であるにもかかわらず、...政府は保護よりも開発の方に味方する傾向がある。" - レット・A・バトラー 経済発展の手段として大規模な伐採を擁護する政府の姿勢も、持続不可能、先住民の権利の無差別、環境破壊、投機的利益、汚職、縁故主義にまみれたものとし て異議を唱えられた[29]。この例は、前環境観光大臣 Datuk James Wong が州最大の伐採権所有者の一人であることからも明らかである。最近では、Abdul Taib Mahmud首席大臣自身が、木材の出荷を潤滑にするために香港の彼の家族会社に支払われたとされる3200万リンギットの木材リベートに関して、日本の 税務当局から汚職の調査を受けた[30][31]。 伐採企業と政治的エリートの間にはしばしば互恵的な関係があり、賄賂、汚職、移転価格を通じて両者に大きな私財がもたらされ、収入とロイヤリティの損失に よる公共の利益と社会、環境、先住民の権利が犠牲にされている......。オープンな競争入札ではなく、政治的な後援の結果として伐採権やその他のライ センスを授与することは、多くの国で例外というよりむしろ常態化している[32]。 |

| Threats to the Penan today In August 2009, hundreds of the Penan of Borneo rainforest protested with road blockades against new palm oil and acacia plantations in Sarawak.[33] Their primary concern was the plantation of acacia monocultures which will cause a loss of species biodiversity and soil degeneration. In August 2010, the Penan spoke out about the Murum hydroelectric dam being built on their land.[34] The construction of the dam is already well underway and will see the flooding of at least six Penan villages once completed. The Penan have argued that they were (once again) not consulted before the project began, nor was a social and environmental impact assessment prepared. Already forests, rivers and natural resources have been destroyed by the build. This time, the Penan have requested that if they must move to make room for the dam then they should have the right to choose where they move to and in what lifestyle capacity. Unfortunately the palm oil company Shin Yang has illegally moved into the area the Penan suggested, without their consent, to create a palm oil plantation. Importantly, the Penan claim that if Shin Yang are allowed to extensively fell the forest, there will not be enough forest left for their community to sustain their livelihood. Furthermore, the Murum dam is the first in a series of large-scale hydroelectric projects being planned by the Sarawak State Government, which will see the displacement of thousands of indigenous people. In this same month, the Penan tribes in Sarawak's northern region set up blockades to prevent the implementation of a 500 km-long Sarawak-Sabah Gas Pipeline (SSGP).[35] It is said that the SSGP will be built and operational by the end of 2010.[needs update] It will allow natural gas sourced from Sabah's offshore gas reserves to be delivered to the liquefied natural gas complex in Bintulu. This project particularly affects Penan communities as the SSGP will claim large tracts of their Native Customary Rights land. Furthermore, the laying of this pipeline is only one component of many, set for construction on the Penan's land, with the construction of a proposed onshore Sabah Oil and Gas Terminal (SOGT) and a gas compression station due for completion in 2012.[needs update] |

今日のプナンへの脅威 2009年8月、ボルネオの熱帯雨林のプナン数百人が、サラワク州の新しいパーム油とアカシアのプランテーションに対して道路を封鎖して抗議した [33]。彼らの最大の懸念はアカシアの単一栽培のプランテーションで、種の多様性の喪失と土壌の退化を引き起こすというものであった。 2010年8月、プナンは自分たちの土地に建設されるムルム水力発電ダムについて発言した[34]。ダムの建設はすでにかなり進んでおり、完成すれば少な くとも6つのプナン村が水没することになる。プナンは、プロジェクトが始まる前に(再び)相談を受けておらず、社会・環境影響評価も準備されていないと主 張している。すでに森林、河川、自然資源は建設によって破壊されている。今回、プナンは、ダム建設のために移住しなければならないのであれば、移住先や生 活様式を選択する権利があるはずだと要求している。残念ながら、パーム油会社のシン・ヤンは、プナンが提案した地域に、彼らの同意なしにパーム油のプラン テーションを作るために不法に進出してきた。プナンは、もしシン・ヤン社が森林を広範囲に伐採することを許せば、彼らのコミュニティが生活を維持するのに 十分な森林は残らないと主張しています。さらにムルムダムは、サラワク州政府が計画している一連の大規模水力発電プロジェクトの第一弾であり、何千人もの 先住民が移住することになるのです。 同月、サラワク州北部のプナンは、全長500kmのサラワク・サバ・ガスパイプライン(SSGP)の実施を阻止するために封鎖を行った[35]。 SSGPは2010年末までに建設・稼働すると言われており、サバの海上ガス資源から供給される天然ガスをビンツルの液化天然ガス複合施設に供給できるよ うになる[要更新]。このプロジェクトは、特にプナンのコミュニティーに影響を与える。なぜなら、SSGPは彼らの慣習上の権利である土地の大部分を占有 することになるからだ。さらに、このパイプラインの敷設は、2012年に完成予定の陸上サバ石油・ガスターミナル(SOGT)とガス圧縮ステーションの建 設とともに、ペナン族の土地に建設される多くのコンポーネントの一つに過ぎない[要更新]。 |

| Future of the Penan The future of the Penan has been a controversial subject since the confrontation between indigenous rights and state land use began. National and International Non-Governmental Organisations have been pressing for indigenous self-determination and respect for Penan human and land rights in accordance with UN International Labour Organisation Convention N. 169 (1989) that removes “assimilationist” orientated international standards towards indigenous rights,[36] a convention that Malaysia has not adopted. However, many Malaysian politicians have criticised NGOs for meddling in Malaysian domestic affairs and have accused them of attempting to inhibit development projects and keep the Penan 'undeveloped' and unassimilated into mainstream Malaysian society. Most see the Penan's lifestyle as uncivilised and antiquated (compare White man's burden), an example of this is a regularly recited poem by ex Minister for Environment and Tourism Datuk James Wong.[37] "O Penan - Jungle wanderers of the Tree What would the future hold for thee?.... Perhaps to us you may appear deprived and poor But can Civilization offer anything better?.... And yet could Society in good conscience View your plight with detached indifference Especially now we are an independent Nation Yet not lift a helping hand to our fellow brethren? Instead allow him to subsist in Blowpipes and clothed in Chawats [loincloths] An anthropological curiosity of Nature and Art? Alas, ultimately your fate is your own decision Remain as you are - or cross the Rubicon!" Many Malaysian organisations have joined the debate such as Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), Borneo Resource Institute (BRIMAS) and Rengah Sarawak. These grassroots organisations have supported indigenous rights and accused the Sarawak state government of repeated neglect of Sarawak's indigenous citizens and exploitation of Sarawak's natural resources. The Penan are more impoverished than ever, confined in sub-standard living conditions that, despite government promises, lack the most basic of facilities and infrastructure.[38] Those who are forced to live in government settlements are constantly fatigued by frequent food shortages and poor health, with little access to (inadequate) health care. Many of the Dayak population have also struggled to get accustomed to a settled lifestyle and adopt agricultural skills, which they must employ more and more as their forests increasingly dwindle.[citation needed] The opposition party Parti Keadilan Rakyat has also taken up the cause of the indigenous people's plight, claiming that they are "living lives of quiet desperation that now and then flares up in action that invites police attention, not to mention the notice of the rest of Malaysians who don't quite know what it is to be under the tyranny of geography."[39] With the help of such NGOs many Penan communities have mapped their proposed ancestral lands and filed claims in Sarawak's courts in the hope of preventing and deterring illegal logging of their forests. A precedent was set in 2001 when an Iban village of Rumah Nor won a court victory against Borneo Pulp and Paper and the Sarawak Government for violating their Native Customary Right (NCR) or adat. The victory was recently publicised in a short documentary, named Rumah Nor, by the Borneo Project.[40] The verdict is being threatened by a Federal Court appeal by the state government and Borneo Pulp and Paper. However, 19 Penan communities have now[when?] mapped their NCR and four are beginning litigation and in others the logging has more or less stopped in the territory where litigation is pending. Indigenous action has therefore shifted from the human blockades of logging roads to empowerment through the political and legal system and international publicity. The Penan's future also hangs on Taib Mahmud's decision to either adhere or extinguish plans for the Magoh Biosphere Reserve.[16] However, it is Taib Mahmud who is responsible for approving and denying all logging licences. It is he and his closest friends, political associates, senior military offices and family relatives who own more or less the entire logging industry. Thus, the logging of the Sarawak has generated enormous wealth for these principle elites.[41] Mahmud therefore, has a strong economic interest in continuing to allow illegal logging in the proposed biosphere reserve areas.[21] In a 2010 media release, the Malaysian logging company Samling Global Ltd. was excluded from the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG). This decision was made on the recommendations from the Council of Ethics’ assessment that Samling Global, and two other companies, “are contributing to or are themselves responsible for grossily [sic] unethical activity”.[42] The committee documented “extensive and repeated breaches of the licence requirements, regulations and other directives in all of the six concession areas that have been examined. Some of the violations constitute very serious transgressions, such as logging outside the concession area, logging in a protected area that was excluded from the concession by the authorities in order to be integrated into an existing national park, and re-entry logging without Environmental Impact Assessments.” If more investors, finance institutions and timber traders worldwide follow suit and cut business ties with Samling Global, this could also make the Penan's future a little brighter. |

プナンの未来 プナンの将来は、先住民の権利と国家の土地利用との対立が始まって以来、論争の的となってきた。国内外のNGOは、先住民の権利に対する「同化主義」的な 国際基準を排除した国連の国際労働機関条約N.169(1989年)に従い、先住民の自決とプナンの人権・土地の尊重を迫ってきた[36]が、マレーシア はこの条約を採択していない。しかし、多くのマレーシアの政治家は、NGOがマレーシアの内政に干渉していると批判し、開発プロジェクトを阻害し、プナン を「未開発」のままマレーシアの主流社会に同化させないようにしようとしていると非難している。プナンのライフスタイルを未開で時代遅れなもの(白人の負 担と比較して)とみなすものが多く、その例として、元環境・観光大臣のダトゥク・ジェームズ・ウォンが定期的に朗読している詩がある[37]。 「プナンよ、ジャングルをさまよう樹上の民よ。 汝の未来はどうなるのだろう。 私たちには、あなたたちが貧しく、困窮しているように見えるかもしれない。 しかし、文明はより良いものを提供できるだろうか? そして、まだ社会は良心の呵責で あなたの苦境を無関心に見ることができるでしょうか? 特に今、私たちは独立した国家でありながら 同胞に救いの手を差し伸べないのでしょうか? その代わりに、吹き矢で生活し、チャワット(ふんどし)で服を着ることを許すのでしょうか。 自然や芸術の人類学的な好奇心? 残念なことに、最終的にあなたの運命はあなた自身が決めることです。 そのままでいるか、ルビコンを渡るか。 Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), Borneo Resource Institute (BRIMAS), Rengah Sarawak など、多くのマレーシアの組織がこの議論に参加している。これらの草の根組織は先住民の権利を支持し、サラワク州政府がサラワクの先住民を無視し、サラワ クの天然資源を搾取することを繰り返してきたと非難している。プナンはこれまで以上に困窮し、政府の約束にもかかわらず最も基本的な施設やインフラが整っ ていない標準以下の生活環境に閉じ込められている[38]。政府の入植地に住まざるを得ない人々は、頻繁な食糧不足と(不十分な)医療をほとんど受けられ ない不健康によって常に疲弊させられている。また、ダヤクの多くは、定住生活に慣れ、森林がますます減少するにつれて、より多く採用しなければならない農 業技術を採用するのに苦労している[citation needed]。 野党のParti Keadilan Rakyatも先住民の窮状を取り上げ、彼らが「静かな絶望の生活を送っているが、時折、警察の注意を引くような行動に出ることがあり、地理の圧制下にあ ることをよく知らない他のマレーシア人の注意を引くこともある」と主張している。 「このようなNGOの助けを借りて、多くのペナン・コミュニティは先祖代々の土地を地図にし、サラワクの裁判所に申し立てを行い、森林の違法伐採を防止・ 抑止することを望んでいる。2001 年、ルマ・ノルというイバン族の村が、ボルネオ・パルプ・アンド・ペーパー社とサラワク政府に対して、先住民の慣習的権利(NCR)またはアダット(慣習 法)を侵害したとして裁判で勝訴し、先例が作られた。この勝利は、ボルネオ・プロジェクトによる『Rumah Nor』という短編ドキュメンタリーで最近公表された[40]。判決は、州政府とボルネオ・パルプ・アンド・ペーパーによる連邦裁判所への控訴によって脅 かされつつある。しかし、19のペナン・コミュニティが現在[いつ?]NCRの地図を作成し、4つが訴訟を始めており、他のコミュニティでは訴訟が係争中 の領域で伐採が多かれ少なかれ止まっている。したがって、先住民の行動は、伐採道路の人的阻止から、政治・法制度や国際的な広報を通じたエンパワーメント へと移行している。 プナンの未来もまた、マゴー生物圏保護区の計画を維持するか消滅させるかというタイブ・マフムードの決断にかかっている[16]。 しかし、すべての伐採ライセンスの承認と拒否に責任があるのは、タイブ・マフムードである。伐採産業全体を多かれ少なかれ所有しているのは、彼と彼の親し い友人、政治的仲間、軍の上級幹部、家族の親族である。したがって、サラワクの伐採は、これらの原則的なエリートに莫大な富を生み出してきた[41]。マ フムードは、したがって、提案された生物圏保護区での違法伐採を許可し続けることに強い経済的利益を有している[21]。 2010年のメディアリリースでは、マレーシアの伐採会社であるサムリング・グローバル社が、政府年金基金グローバル(GPFG)から除外された。この決 定は、サムリング・グローバルと他の2社が「著しく非倫理的な活動に寄与しているか、それ自身に責任がある」という倫理評議会の評価からの勧告でなされま した[42]。委員会は、「調査された6つの伐採権地域のすべてにおいて、免許要件、規制、その他の指令の広範囲かつ反復した違反」を文書化しました。違 反の中には、伐採許可地域外での伐採、既存の国立公園に統合するために当局が伐採許可地域から除外した保護区での伐採、環境影響評価なしの再侵入伐採な ど、非常に深刻な違反がある"[42]。世界中の多くの投資家、金融機関、木材商がこれに倣い、サムリング・グローバルとのビジネス関係を断ち切れば、プ ナンの未来も少しは明るくなるのではないだろうか。 |

| Stranger in the Forest, a travel

report by Eric Hansen Redheads, a comic eco-thriller novel set in a fictional sultanate in Borneo, which describes the Penan plight, by Paul Spencer Sochaczewski An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles , travels with Alfred Russel Wallace, which includes chapters on the Penan and Bruno Manser, by Paul Spencer Sochaczewski |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penan_people |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Bruno Manser (25 August 1954 – presumed dead 10

March 2005) was a Swiss environmentalist and human rights activist.

From 1984 to 1990, he stayed with the Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia,

organising several blockades against timber companies. After he emerged

from the forests in 1990, he engaged in public activism for rainforest

preservation and the human rights of indigenous peoples, especially the

Penan, which brought him into conflict with the Malaysian government.

He also founded the Swiss non-governmental organization (NGO) Bruno

Manser Fonds in 1991. Manser disappeared during his last journey to

Sarawak in May 2000 and is presumed dead. Bruno Manser (25 August 1954 – presumed dead 10

March 2005) was a Swiss environmentalist and human rights activist.

From 1984 to 1990, he stayed with the Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia,

organising several blockades against timber companies. After he emerged

from the forests in 1990, he engaged in public activism for rainforest

preservation and the human rights of indigenous peoples, especially the

Penan, which brought him into conflict with the Malaysian government.

He also founded the Swiss non-governmental organization (NGO) Bruno

Manser Fonds in 1991. Manser disappeared during his last journey to

Sarawak in May 2000 and is presumed dead.Bruno Manser was born in Basel, Switzerland, on 25 August 1954 in a family of three girls and two boys.[1] During his younger days, he was an independent thinker. His parents wanted him to become a doctor, and he studied medicine informally.[1] Manser later completed his upper secondary school,[when?] the first in his family to do so.[2][3] At age 19, Manser spent three months in Lucerne prison because, as an ardent follower of non-violent ideologies espoused by Mahatma Gandhi (Satyagraha), he refused to participate in Switzerland's compulsory military service. After leaving prison in 1973, he worked as a sheep and cow herder[4] at various Swiss Alpine pastures for twelve years. During this time, Manser became interested in handicrafts, therapeutics, and speleology. He laid bricks, carved leather, kept bees, and wove, dyed, and cut his own clothes and shoes. He also regularly pursued mountaineering and technical climbing.[1] At the age of 30, Manser went to Borneo, looking to live a simpler life.[2] |

ブルーノ・マンサー(Bruno Manser、1954年8月25日 -

2005年3月10日没)は、スイスの環境保護活動家、人権活動家である。1984年から1990年まで、マレーシアのサラワク州のプナンに滞在し、木材

会社に対する封鎖を数回行った。1990年に森を出た後は、熱帯雨林の保全や先住民族、特にペプナンの人権を守るための活動を行い、マレーシア政府と対立

することになる。1991年にはスイスの非政府組織(NGO)ブルーノ・マンサー・フォンドを設立した。2000年5月、サラワクへの旅を最後に消息を絶

ち、死亡が確認された。 ブルーノ・マンサー(Bruno Manser、1954年8月25日 -

2005年3月10日没)は、スイスの環境保護活動家、人権活動家である。1984年から1990年まで、マレーシアのサラワク州のプナンに滞在し、木材

会社に対する封鎖を数回行った。1990年に森を出た後は、熱帯雨林の保全や先住民族、特にペプナンの人権を守るための活動を行い、マレーシア政府と対立

することになる。1991年にはスイスの非政府組織(NGO)ブルーノ・マンサー・フォンドを設立した。2000年5月、サラワクへの旅を最後に消息を絶

ち、死亡が確認された。ブルーノ・マンサーは1954年8月25日にスイスのバーゼルで3女2男の家庭に生まれた[1]。幼少期は独立した考えを持っていた。両親は彼を医者にす ることを望み、彼は非公式に医学を学んだ[1]。その後、マンサーは家族で初めて高等学校を卒業した[2][3]。 19歳の時、マハトマ・ガンジーの非暴力思想(サチャグラハ)の熱心な信奉者として、スイスの義務兵役への参加を拒否したため、ルツェルン刑務所に3ヶ月 間収監された。1973年に出所した後、12年間、スイスのアルプスの牧場で羊や牛の牧夫[4]として働く。この間、マンサーは手工芸、治療学、洞窟学に 興味を持つようになる。レンガを積み、革を彫り、ミツバチを飼い、自分で服や靴を織り、染め、裁断した。また、登山やテクニカルクライミングも定期的に 行っていた[1]。 30歳の時、マンサーはよりシンプルな生活を求めてボルネオ島へ渡った[2]。 |

| Searching for Penans In 1983, Manser went to the Malaysian state of Terengganu and stayed with a family. In 1984, while learning more about the rainforests, Manser learned of a nomadic tribe known as the Penan. After learning more about the tribe, he decided to attempt to live amongst them for a few years and traveled to the East Malaysian state of Sarawak in 1984 on a tourist visa.[3][5] In Malaysia, Manser first joined an English caving expedition to explore Gunung Mulu National Park. After the expedition, he stepped deeper into the interior jungles of Sarawak, intending to find the "deep essence of humanity" and "the people who are still living close to their nature."[1] However, he quickly became lost and ran out of food while exploring the jungle, then fell ill after eating a poisonous palm heart.[3] After these setbacks, Manser finally found Penan nomadic tribes near the headwaters of the Limbang river[4] at Long Seridan in May 1984.[5] Initially, the Penan people tried to ignore him. After a while, the Penan accepted him as one of their family members.[3] In August 1984, Manser went to Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, to obtain a visa to visit Indonesia. On the Indonesian visa, he entered Kalimantan, then illegally crossed the border back into Long Seridan.[5] His Malaysian visa expired on 31 December 1984.[4][5] |

プナンを求めて 1983年、マンサーはマレーシアのトレンガヌ州へ行き、ホームステイをした。1984年、熱帯雨林について学ぶうちに、プナンという遊牧民の存在を知 る。プナンについて学んだ後、数年間彼らの中で生活してみることを決意し、1984年に観光ビザで東マレーシアのサラワク州へ渡る[3][5]。 マレーシアでは、マンサーはまずイギリスのケイビング探検隊に参加し、グヌン・ムル国立公園を探検した。その後、「人間の深い本質」「今も自然に近いとこ ろで生きている人々」を探そうとサラワク州の奥地のジャングルに足を踏み入れるが、ジャングル探索中にすぐに道に迷い食料が尽き、さらに毒ヤシの実を食べ て病気になった[3]。 1984年5月、マンサーはリンバン川[4]の源流であるロングセリダン付近でプナンの遊牧民を発見した[5]。しばらくして、プナンは彼を家族の一人と して受け入れた[3]。 1984年8月、マンサーはインドネシアを訪問するためのビザを取得するためにサバ州のコタキナバルへ行った。インドネシアのビザでカリマンタンに入り、 不法に国境を越えてロンセリアンに戻った[5]。マレーシアのビザは1984年12月31日に失効した[4][5]。 |

| Manser learned about survival

skills in the jungle and familiarized himself with the Penan's culture

and language.[2] The Penan tribal leader in Upper Limbang, named Along

Sega, became Manser's mentor.[6] During his stay with the Penan, Manser

adopted their way of life. He dressed in a loincloth, hunted with a

blowgun, and ate primates, snakes, and sago. Manser's decision to live

as a member of the Penan was ridiculed in the West, and he was

dismissed as a "White Tarzan".[1] Within the Penan, however, Manser was

known as "Laki Penan" (Penan Man), having earned the respect of the

tribe that adopted him.[1][7] Manser created notebooks that were richly illustrated with drawings, notes, and 10,000 photographs during his six-year stay from 1984 to 1990 with the Penan people.[2] Some of his sketches include cicada wing patterns, how to carry a gibbon with a stick, and how to drill holes on a blowpipe.[3] These notebooks were later published by Christoph Merian Verlag press in Basel.[2] Manser also created audio recordings of oral histories told by Penan elders and translated them. He claimed that the Penan people were never argumentative or violent during his time with them.[1] In 1988, Manser tried to reach the summit of Bukit Batu Lawi but was unsuccessful, finding himself hanging on a rope without anything to grab on for 24 hours.[3] In 1989, he was bitten by a red tailed pit viper but was able to treat the snake bite himself.[1] He also got a malaria infection while living in the jungles.[3] Unfortunately, deforestation of Sarawak's primeval forests started during Manser's stay with the Penan. As a result, the Penan suffered from reduced vegetation, contaminated drinking water, fewer animals available for hunting, and the desecration of their heritage sites. Manser worked with Along Sega to teach the Penan how to organize road blockades against advancing loggers. Manser organised his first blockade in September 1985.[4][8] |

マンサーはジャングルでサバイバル技術を学び、プナンの文化と言語に親

しんだ[2]。アロング・セガというペナン族のリーダーがマンサーの師となった[6]。彼はふんどし姿になり、吹き矢で狩りをし、霊長類、蛇、サゴを食べ

た。プナンの一員として生きることを決めたマンサーは、西洋では「ホワイト・ターザン」と揶揄された[1]が、プナンの中では「ラキ・プナン(プナンのひ

と)」と呼ばれ、自分を採用した部族から尊敬されるようになった[1][7]。 マンサーは1984年から1990年までの6年間プナンに滞在し、絵やメモ、1万枚の写真をふんだんに使ったノートを作成した[2]。 セミの羽模様、テナガザルの運び方、吹き矢の穴あけ方などのスケッチがある[3]。 このノートは後にバーゼルのChristoph Merian Verlag pressから出版された[2]。またマンサーはプナンの年長者が話す口伝の録音とその翻訳を行っている。彼はプナンと過ごした期間、プナンは決して議論 したり暴力的でなかったと主張した[1]。 1988年、マンサーはBukit Batu Lawiの頂上を目指したが失敗し、24時間掴むものもなくロープにぶら下がっていた[3]。 1989年には赤尾のマムシに噛まれたが、自分で治療することができた。 またジャングルでの生活の中でマラリアに感染した[3]。 残念なことに、マンサーがプナンと暮らしている間に、サラワク州の原生林の伐採が始まった。その結果、プナンは植生の減少、飲料水の汚染、狩猟に使える動 物の減少、遺跡の冒涜に悩まされることになった。マンサーは、アロング・セガと協力して、プナンに伐採阻止のための道路封鎖の方法を教えた。マンサーは 1985年9月に最初の封鎖を組織した[4][8]。 |

| Activism Manser gave many lectures in Switzerland and abroad, making connections to people within the European Union and the United Nations. As an activist, he visited American and African jungles, staying in various locations for a few weeks.[7] He returned almost every year after leaving the Penan to follow up with the logging activities and to provide assistance to the tribe, often entering these areas illegally, crossing the border with Brunei and Kalimantan, Indonesia. He discovered that logging conglomerates such as Rimbunan Hijau, Samling, and the WTK Group continued their operations in Sarawak rainforests.[7] As a result, Manser organised the Voices for the Borneo Rainforests World Tour after he left the Sarawak forests in 1990. Manser, Kelabit activist Anderson Mutang Urud, and two Penan tribe members travelled from Australia to North America, Europe, and Japan.[9] On 17 July 1991, during the 17th G7 summit, Manser climbed unaided to the top of a 30-foot high lamp post outside of the summit's media centre in London. After reaching the top, he unrolled a banner that displayed a message about the plight of Sarawak rainforests. He chained himself to the lamp post for two and a half hours. His protest also coincided with protests by Earth First! and the London Rainforest Action Group. Police used a hoist to reach the top of the lamp post and cut his chains. Manser climbed down the lamp post without force at 1:40 PM. He was then taken to the Bow Street police station and held until the summit ended at 6:30 PM, when he was released without being charged with an offense.[10][11] Later in 1991, Manser set up Bruno Manser Fonds (BMF), a fund designed to help conserve the rainforests and the indigenous population in Sarawak. He ran the fund from his home at Heuberg 25, Basel, Switzerland.[12] In June 1992, Manser parachuted into a crowded stadium during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[9] In December 1992, he led a twenty-day hunger strike in front of the Marubeni Corporation headquarters in Tokyo.[1] In 1993, he went on a sixty-day hunger strike at the Federal Palace of Switzerland ('"Bundeshaus") to press the Swiss Federal Assembly on enforcing a ban on tropical timber imports and mandatory declarations of timber products. The hunger strike was supported by 37 organisations and political parties.[2][7][13] Manser only stopped the hunger strike after his mother requested that he do so.[3] After Manser's disappearance, the Federal Assembly finally adopted the Declaration of Timber Products on 1 October 2010, with a transition period allowed until the end 2011.[14] In 1995, Manser went to Congo rainforests to document the effects of wars and logging on Mbuti people.[1] In 1996, on the German-language programme fünf vor zwölf (At the Eleventh Hour), Manser and his friend Jacques Christinet used auxiliary cable to drop themselves down 800 meters onto the Klein Matterhorn aerial cable car and hung sizable banners there.[1][7] They reached the dangerous speed of 140 kilometers per hour while riding on a self-made rider with steel wheels and ball bearings.[3] In 1997, Manser and Christinet tried to enter Peninsular Malaysia from Singapore to fly a motorised hang-glider during the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur. However, he was recognised at the border and denied entry into Malaysia. They then decided to swim across the Straits of Johor into Malaysia, but later abandoned the plan as it involved a lengthy 25-kilometer swim and a passage through a swamp across the straits. They planned an alternative route, opting to row a boat from an Indonesian island into Sarawak. However, BMF received a warning from Malaysian embassy warning of the consequences for such an act.[3] In 1998, Manser and Christinet travelled to Brunei and swam across the 300-metre wide Limbang river at night. Christinet was almost fatally injured by drifting logs along the river. They spent three weeks in Sarawak hiding from the police. During that period, they attempted to order four tons of 25-centimeter nails for the Penan to hammer into the tree trunks, which could have caused serious injuries to loggers when the embedded nails inevitably came into contact with chainsaws.[3] |

活動内容 スイス国内外で講演を重ね、EUや国連関係者とも交流を深めた。また、活動家としてアメリカやアフリカのジャングルを訪れ、各地に数週間滞在した[7]。 プナンを離れた後もほぼ毎年戻り、伐採活動の追跡調査や支援活動を行い、しばしばブルネイやインドネシアのカリマンタンとの国境を越えて、これらの地域に 不法に入国した。その結果、Rimbunan Hijau、Samling、WTK Groupなどの伐採財閥がサラワクの熱帯雨林で事業を継続していることを知った[7]。 1990年にサラワクの森を離れた後、マンサーはVoices for the Borneo Rainforests World Tourを組織した。マンサーとケラビット族の活動家アンダーソン・ムタン・ウルド、プナンの2人はオーストラリアから北米、ヨーロッパ、日本へと旅をし た[9]。 1991年7月17日、第17回G7サミットの開催中、マンサーはロンドンにあるサミットのメディアセンターの外にある高さ30フィートのランプポストの 頂上に無人のまま登った。そして、サラワク州の熱帯雨林の窮状を訴える横断幕を広げた。そして、2時間半の間、街灯の柱に鎖で縛りつけられた。アース・ ファースト!やロンドンのレインフォレスト・アクション・グループの抗議行動とも重なった。警察はホイストを使って街灯の上部に到達し、マンサーの鎖を切 断した。マンサーは午後1時40分、力なく街灯の柱を降りた。その後、彼はBow Street警察署に連行され、サミットが終了する午後6時30分まで拘束されたが、犯罪に問われることなく釈放された[10][11]。 その後、1991年にサラワクの熱帯雨林と先住民の保護を目的とした基金、ブルーノ・マンサー・フォンド(BMF)を設立。彼はこの基金をスイスのバーゼ ルにあるホイベルグ25番地の自宅から運営していた[12]。 1992年6月、ブラジルのリオデジャネイロで開催された地球サミットで、満員のスタジアムにパラシュートで降り立った[9]。 1993年、スイス連邦宮殿で60日間のハンストを行い、スイス連邦議会に熱帯木材の輸入禁止と木材製品の申告の義務付けを迫った[1]。ハンガーストラ イキは37の団体や政党によって支持された[2][7][13]。マンセルの失踪後、連邦議会は2010年10月1日にようやく木材製品宣言を採択した が、2011年末までの移行期間が認められていた[14]。 1996年、ドイツ語の番組『fünf vor zwölf (At the Eleventh Hour)』で、マンサーと友人のジャック・クリスティネは補助ケーブルを使ってクライン・マッターホルンのロープウェイに800メートルまで降り、そこ に大きなバナーを掲げた[1][7]。 鉄の車輪と玉軸受を使った自分で作った乗り物に乗って、時速140kmという危険な速度に到達した[3]。 1997年、ManserとChristinetは、1998年にクアラルンプールで開催されたコモンウェルスゲームでモーター付きハンググライダーを飛 ばすため、シンガポールから半島マレーシアに入国しようとした。しかし、国境で認識され、マレーシアへの入国を拒否された。その後、ジョホール海峡を泳い でマレーシアに入ることにしたが、25kmの長さの水泳と海峡を挟んだ沼地の通過が必要だったため、後にこの計画を断念した。そこで、インドネシアの島か らボートを漕いでサラワク州に入るルートを考えた。1998年、マンサーとクリスティネはブルネイに行き、幅300メートルのリンバン川を夜泳いで渡っ た。クリスティネは川を漂流する丸太で致命傷を負いそうになった。二人はサラワクで3週間、警察から身を隠して過ごした。この間、彼らはペナンが木の幹に 打ち込むための25センチの釘を4トン注文しようとしたが、埋め込まれた釘が必然的にチェーンソーと接触したとき、伐採者に重傷を負わせる可能性があった [3]。 |

| Impact In 1986, Manser's representative in Switzerland, Roger Graf, wrote about sixty letters to Western media outlets, but none took notice of them. It was only in March 1986 that Rolf Bökemeier, an editor for the GEO magazine based in Hamburg, Germany, who also specialised in indigenous people, wrote a letter of reply to Graf. In October 1986, GEO published a 24-page article entitled: "You have the world - leave us the wood!" which included photos taken during their undercover tours with Manser, as well as Manser's drawings. The article was later reprinted all over the world in Australia, Japan, and Canada, leading to the attention of human rights and environmental organisations and green parliamentarians around the world.[15] After hearing of Manser's actions, then-Congressman Al Gore condemned logging activities in Sarawak. Prince Charles also described the treatment for the Penan as "genocide."[3] The BBC and the National Geographic Channel produced documentaries about the Penan, and Penan stories were also featured on ABC's Primetime Live. Universal Studios started to develop an action-adventure horror script where the Penan used their forest wisdom to save the world from catastrophe. The Penan also received coverage in Newsweek, Time, and The New Yorker.[9] Warner Bros screenwriter David Franzoni also developed a script named My Friend Bruno after they signed a contract with Manser in January 1992. Manser received $20,000 a year until 1998 for the rights to film his life. However, due to its unsatisfying ending, the script was not taken up by the studio.[15] |

インパクト 1986年、マンサーのスイス駐在員ロジャー・グラフは、欧米のメディアに約60通の手紙を出したが、誰も相手にしてくれなかった。1986年3月、ドイ ツのハンブルグにあるGEO誌の編集者で、先住民を専門とするロルフ・ベーケマイヤー氏が、グラフ氏に返事を書いたのが最初だった。1986年10月、 『GEO』誌は、マンセルの潜入取材で撮った写真とマンセルの絵を掲載した「You have the world - leave us the wood!」という記事を24ページにわたって発表した。この記事はその後、オーストラリア、日本、カナダなど世界各地で転載され、世界中の人権団体や環 境保護団体、グリーン・パーラメントの議員たちの注目を集めることになった[15]。 マンサーの行動を聞いた当時のアル・ゴア下院議員は、サラワクでの伐採活動を非難した。BBCとナショナルジオグラフィックチャンネルはプナンに関するド キュメンタリーを制作し、ペナン族の話はABCのプライムタイムライブでも取り上げられた[3]。ユニバーサル・スタジオは、プナンが森の知恵を使って世 界を破滅から救うというアクション・アドベンチャー・ホラーの脚本開発に着手した。プナンは『ニューズウィーク』『タイム』『ニューヨーカー』でも取り上 げられた[9]。ワーナー・ブラザーズの脚本家デヴィッド・フランゾーニも1992年1月にマンサーと契約した後、『My Friend Bruno』という脚本を開発することになった。マンサーは自分の人生を映画化する権利として、1998年まで年間2万ドルを受け取った。しかし、その不 満足な結末のため、この脚本はスタジオに採用されなかった[15]。 |

| Response from Malaysian

authorities Manser's actions drew anger from Malaysian authorities, who declared him persona non-grata in the country. A reported bounty for his capture ranging from US$30,000[16] to US$50,000[17] has been circulated by word-of-mouth, but the source of the bounty is unknown.[1] By 1990, Malaysia declared Manser as the "number one enemy of the state" and sent special units to search for him.[7] Using a forged passport and styling his hair differently,[3] Manser returned to Switzerland in 1990 to inform the public about the situation in Sarawak through the Swiss media.[2] |

マレーシア当局の対応 マンサーの行動はマレーシア当局の怒りを買い、同国ではペルソナ・ノン・グラータ(非国民)とされた。彼の逮捕には3万米ドル[16]から5万米ドル [17]の懸賞金がかかると口コミで伝えられたが、懸賞金の出所は不明[1] 1990年までにマレーシアはマンサーを「国家の敵ナンバーワン」と宣言、特別部隊を送って彼を捜索した[7] マンサーは偽造パスポートを使って髪型を変え、1990年にスイスに戻りスイスメディアを通してサラワクの状況について国民に情報を伝えた[3][4]。 |

| Response by Malaysian federal

government Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad blamed Manser for disrupting law and order. Mahathir wrote a letter to Manser, telling him that it was "about time that you stop your arrogance and your intolerable European superiority. You are no better than the Penan."[3] In March 1992, Mahathir wrote another letter to Manser: As a Swiss living in the laps of luxury with the world's highest standard of living, it is the height of arrogance for you to advocate that the Penans live on maggots and monkeys in their miserable huts, subjected to all kinds of diseases.[1] — Mahathir Mohamad on 3 March 1992 |

マレーシア連邦政府の対応 マレーシアのマハティール・モハマド首相は、マンサー氏が法秩序を乱したとして非難した。マハティールはマンサーに手紙を書き、「そろそろその傲慢さと耐 え難いヨーロッパ的優越感をやめるべきだ」と告げた[3]。1992年3月、マハティールはマンサーに再び手紙を書いた。 世界最高の生活水準で贅沢に暮らすスイス人として、プナンが悲惨な小屋でウジやサルを食べて、あらゆる種類の病気にかかって生きていると主張することは、 傲慢の極みだ」[1]。 - 1992年3月3日、マハティール・モハマド |

| Response by Sarawak state

government The Sarawak government defended its logging policy by stating that revenue from timber sales is needed to feed more than 250,000 of the state population. Sarawak Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud said, "It is hoped that outsiders will not interfere in our internal affairs, especially people like Bruno Manser. The Sarawak government has nothing to hide. Ours is an open liberal society."[18] Sarawak Minister of Housing and Public Health James Wong said that, "We don't want them [the Penan] running around [in jungles] like animals. No one has the ethical right to deprive the Penans of the right to assimilation into Malaysian society."[19] The Sarawak government tightened the entry of foreign environmentalists, journalists, and film crews into the state,[18] and allowed logging companies to hire criminal gangs to subdue the indigenous people.[1] |

サラワク州政府の対応 サラワク州政府は、木材販売による収入は州民25万人以上を養うために必要であると述べ、伐採政策を擁護した。サラワク州首相Abdul Taib Mahmudは「部外者が我々の内政に干渉しないことが望まれる。特にBruno Manserのような人物はそうだ。サラワク州政府は何も隠すことはない。サラワク州の住宅・公衆衛生大臣のジェームズ・ウォンは、「彼ら(プナン)が動 物のようにジャングルの中を走り回ることを望んでいない」と述べた[18]。サラワク州政府は、外国人の環境保護活動家やジャーナリスト、撮影隊の入国を 厳しく制限し[18]、伐採業者が犯罪組織を雇って先住民を服従させることを許可した[1]。 |

| Arrest attempts Manser was first arrested on 10 April 1986 after being spotted by police inspector Lores Matios.[3][20] He was delivering a document for Kelabit chiefs at Long Napir to sign to confirm their wish of further protecting their territories. At the same time, Matios was also on holiday at Long Napir. He immediately arrested Manser for breaking immigration law and brought him to Limbang police station for interrogation.[15] Manser was not handcuffed, as the inspector did not carry them while on holiday. During the 90-minute ride to Limbang, the Land Rover that carried Manser came close to running out of petrol.[3][20] While the vehicle stopped to refuel after crossing a bridge, Manser was urinating at the side of the road. While Matios was steps away giving orders to subordinates, Manser took the opportunity to run away, dive into dense undergrowth, and run across the Limbang river by jumping from stone to stone. Matios shouted at him and used his pistol to fire two shots at Manser, but he successfully escaped capture.[15] On 14 November 1986, Manser met with James Ritchie, a reporter from the New Straits Times, in an isolated hut in the Limbang jungles. Ritchie came by helicopter to interview Manser. After the interview, Ritchie told Manser that: "As a human being, you are right. Yet as a citizen of this country I have to say no to you, Please don't be angry with me if the story doesn't sound too good." After Ritchie's team left, Manser stayed in the hut until the next day. As he went to the mouth of the Meté river to wash himself, he noticed a boat mooring at the river. He heard a friendly voice called him, "Oh, Laki Dja-au!" but instead saw two soldiers pursuing him. The soldiers were instructed to capture Manser alive without firing any bullets. Manser immediately put down his blowpipe and a rucksack on the river bank, then dove into the river and disappeared under the heavy undergrowth of the forest floor. Manser successfully evaded capture, but he lost seven months of his drawings and notebooks in the rucksack.[15] Feeling betrayed, Manser wrote a complaint letter against Ritchie to New Straits Times and was published on 1 February 1987. However, Ritchie denied any involvement in Manser arrest.[20] On 25 March 1990, Manser was disguised as "Alex Betge" to board MH 873 flight from Miri to Kuching. In the airport, Manser and his friend met police inspector Lores Matios at the boarding area. However, Matios was on his way to take a law exam at Kuching and he didn't notice the disguised Manser on board. Manser arrived in Kuching uneventfully and then took a flight on 26 March to Kuala Lumpur. On 27 March, Swiss ambassador to Kuala Lumpur Charles Steinhaeuslin made a surprise visit to Sarawak chief minister in Kuching.[20] |

逮捕の試み 1986年4月10日、マンサーは警視正のロレス・マティオスに発見され、最初に逮捕された[3][20]。 彼はロング・ナピールのケラビット族首長のために、彼らの領土をさらに保護するという希望を確認するために署名する文書を届けているところだった。同じ 頃、マティオスもロングナピールで休暇中であった。彼は直ちにマンサーを入国管理法違反で逮捕し、リンバン警察署に連行して取り調べを行った[15]。マ ンサーは、警部が休暇中に手錠を所持していなかったため、手錠はかけられていない。リンバンへの90分の移動中、マンサーを乗せたランドローバーはガソリ ン切れになりそうになった[3][20]。車が橋を渡って給油のために停車中、マンサーは道端で排尿していた。マティオスが部下に命令している間、マン サーはその隙に逃げ出し、密集した下草の中に飛び込み、石から石に飛び移りながらリンバン川を渡っていった。マティオスは彼に叫び、ピストルを使ってマン サーに2発発砲したが、彼はうまく捕まり逃れた[15]。 1986年11月14日、マンサーはリンバンのジャングルにある孤立した小屋でニュー・ストレイツ・タイムズの記者であるジェームズ・リッチーと会った。 リッチーはマンサーにインタビューするためにヘリコプターで来た。取材後、リッチー氏はマンサー氏にこう言った。「人間として、あなたは正しい。しかし、 この国の国民として、私はあなたにノーと言わなければならない。この話がうまくいかなくても、どうか怒らないでください」。リッチーたちが帰った後、マン サーは翌日まで小屋に残った。体を洗おうとメテ川の河口に行くと、川面にボートが停泊しているのが目に入った。おお、ラキ・ジャウ!」と呼ぶ声が聞こえた が、追いかけてくる2人の兵士を見た。兵士たちは、マンサーを生け捕りにしろ、弾丸は撃つな、と命令していた。マンサーは、すぐさま吹き矢とリュックサッ クを川岸に置くと、川に飛び込み、林床の深い下草の下に姿を消した。マンサーは捕縛から逃れることに成功したが、リュックサックの中の7ヶ月分のデッサン やノートを失った[15] 裏切りを感じたマンサーはリッチーに対する告発状をニュー・ストレイツ・タイムズに書き、1987年2月1日に掲載された。しかし、リッチーはマンサーの 逮捕への関与を否定した[20]。 1990年3月25日、マンサーは「アレックス・ベッジ」に変装してミリからクチンへ向かうMH873便に搭乗した。空港でマンサーと彼の友人は搭乗待合 室でロレス・マティオス警視に会った。しかし、Matiosはクチンで法律の試験を受ける途中であり、機内で変装したManserに気づかなかった。マン サーは何事もなくクチンに到着し、3月26日の便でクアラルンプールへ向かった。3月27日、クアラルンプールのスイス大使チャールズ・スタインハウズリ ンがクチンのサラワク州首相をサプライズ訪問した[20]。 |

| Dealing with Abdul Taib Mahmud In mid-1998, Manser offered an end of hostilities with the Sarawak government if Chief Minister Taib Mahmud would be willing to cooperate with him in building a biosphere around the Penan's territory. Manser also wanted the government to forgive him for breaking Malaysian immigration laws. The offer was denied. His successive attempts to establish communications with Taib Mahmud failed.[7] Manser planned to deliver a lamb named "Gumperli" to Taib Mahmud by air as a symbol of reconciliation during the Hari Raya Aidilfitri celebration. However, the Malaysian consulate at Geneva pressured airlines not to transport the lamb to Sarawak. Manser later carried the lamb with him on a plane and parachuted over the United Nations Office at Geneva, hoping to bring international attention to Sarawak.[7] In March 1999, Manser successfully passed Kuching immigration by disguising himself in a business suit, carrying a briefcase, and wearing a badly knotted tie. On 29 March, he flew a motorised paraglider, carrying a toy lamb knitted by himself[3] while wearing a T-shirt with the image of a sheep, and made a few turns above Taib Mahmud's residence in Kuching. There were ten Penan tribe members waiting on the ground to greet Manser. At 11:30 AM, he landed the glider beside a road just outside Taib Mahmud's residence and was immediately arrested. He was then transported to Kuala Lumpur, briefly imprisoned, then deported back to Switzerland via Malaysia Airlines Flight MH2683. Manser was seen playing with his knitted toy lamb by his jailers.[3][2][5][7][13] By 2000, Manser admitted that his efforts did not bring positive changes to Sarawak.[3] His success rate in Sarawak was "less than zero" and he was deeply saddened by the result.[1] On 15 February 2000, just before his last trip to Sarawak, Manser said that, "[t]hrough his logging license policies, Taib Mahmud is personally responsible for the destruction of nearly all Sarawak rainforests in one generation."[7] |

アブドゥル・タイブ・マハムドへの対応 1998年半ば、マンサーは、サラワク州首相のタイブ・マフムードがプナンの領土に生物圏を作ることに協力するならば、サラワク州政府との敵対関係を終わ らせることを提案した。マンサーはまた、マレーシアの入国管理法を破ったことを許してくれるよう政府に求めた。しかし、この申し出は拒否された。7] マンサーはハリ・ラヤ・アイディルフィトリの祭典の際に和解の象徴として「ガンペリ」と名付けた子羊を飛行機でタイブ・マハムドに届けることを計画した。 しかし、ジュネーブのマレーシア領事館は航空会社にサラワク州に子羊を輸送しないよう圧力をかけた。その後、マンサーは子羊を飛行機で運び、ジュネーブの 国連事務所上空にパラシュートで降り立ち、サラワク州に国際的な注目を集めようとした[7]。 1999年3月、マンサーはビジネススーツで変装し、ブリーフケースを持ち、ひどく結び目のあるネクタイをしてクチンの入国審査を通過することに成功し た。3月29日、彼は羊の絵のTシャツを着て自分で編んだ子羊のおもちゃを持ち[3]、モーター付きのパラグライダーで飛び、クチンのタイブ・マハムド宅 の上で数回転した。地上には10人のペナン族が待機し、マンサーを出迎えた。午前11時30分、彼はグライダーをTaib Mahmudの住居のすぐそばの道路に着陸させ、直ちに逮捕されました。彼はその後、クアラルンプールに移送され、短期間収監された後、マレーシア航空 MH2683便でスイスに強制送還された. マンサーは看守に編み物のおもちゃの子羊と遊んでいるところを目撃された[3][2][5][7][13]。 2000年までに、マンサーは自分の努力がサラワクにポジティブな変化をもたらさなかったことを認めた[3]。 サラワクでの彼の成功率は「ゼロ以下」で、彼はその結果に深く悲しんだ[1]。 サラワクへの最後の旅の直前、2000年2月15日にマンサーは「彼の伐採許可政策を通して、タイブ・マハムドは一世代でほぼ全てのサラワクの雨林の破壊 に対して個人的に責任がある」と発言している[7]。 |

| Disappearance On 15 February 2000, Manser left to visit his Penan friends via the jungle paths of Kalimantan, Indonesia, accompanied by BMF secretary John Kuenzli and a film crew. After a period of time, Kuenzli and the film crew left Manser in the Kalimantan jungles. At the time, Manser was still writing postcards to his friends.[7] Manser continued his journey with another friend who knew the way around the territory. The trip continued for two weeks, crossing mountains and rivers on foot and by boat. Manser slept on a hammock while his friend slept on the ground. On 18 May, they reached the Sarawak/Kalimantan border, spending their final night there. Manser asked his friend to carry a postcard back to Charlotte, his girlfriend in Switzerland. According to his friend, Manser looked healthy when they parted ways. Manser complained about diarrhea and a broken rib in the postcard.[7] According to Kuenzli, Manser crossed the Sarawak/Kalimantan border on 22 May with the help of a local guide. His last known communication was a letter mailed to Charlotte while hiding in Bario. In the letter, Manser said he was very tired while waiting for the sun to set before continuing his journey along the logging roads. The letter was deposited at the Bario post office and reached Switzerland with a Malaysian stamp, but without a post office stamp.[7] Manser was last seen carrying a 30-kilogram backpack by his Penan friend, Paleu, and Paleu's son on 25 May 2000. They accompanied Manser until they saw Bukit Batu Lawi. Manser stated his intention to climb the mountain alone and requested Paleu to leave him there. Manser has not been seen since.[3] |

失踪 2000年2月15日、マンサーはBMFの秘書ジョン・クーンツリと撮影隊を伴って、インドネシアのカリマンタンのジャングルの道を通り、ペナンの友人た ちを訪ねるために出発しました。しばらくして、クェンツリと撮影隊はマンサーをカリマンタンのジャングルに置き去りにした。その頃、マンサーはまだ友人に 絵葉書を書いていた[7]。マンサーは、領内の道を知っている別の友人と旅を続けた。旅は2週間続き、徒歩と船で山や川を越えた。マンサーはハンモックで 眠り、友人は地面で眠った。5月18日、サラワクとカリマンタンの国境に着き、そこで最後の夜を過ごした。マンサーは友人に、スイスにいる恋人のシャル ロットに絵葉書を持って帰るように頼んだ。友人によると、別れ際、マンサーは元気そうだった。マンサーは絵葉書で下痢と肋骨の骨折を訴えていた[7]。 クーンツリによると、マンサーは5月22日に地元のガイドの助けでサラワクとカリマンタンの国境を越えた。彼の最後の連絡は、バリオに潜伏中にシャーロッ トに郵送された手紙であった。その手紙には、日没を待って伐採路の旅を続ける間にとても疲れたと書かれていた。その手紙はバリオの郵便局に投函され、マ レーシアの切手を貼ってスイスに届いたが、郵便局の切手はなかった[7] マンサーは2000年5月25日にペナンの友人パリュとパリュの息子が30キロのリュックを背負っているのを目撃されたのが最後だった。彼らはBukit Batu Lawiが見えるまでマンサーに同行した。マンサーは単独で登山する意思を表明し、パリューにそこで別れるように頼んだ。それ以来、マンサーは目撃されて いない[3]。 |

| Search expeditions BMF and the Penan tried to search for Manser without any success. Areas around the Limbang river were searched by the Penan. Penan expedition teams tracked Manser to his last sleeping place. They followed Manser's machete cuts into the thick forests until the trail reached the swamp at the foot of Bukit Batu Lawi. There was no trace of him in the swamp, going back from the swamp, or trace of anyone else coming into the area. BMF sent a helicopter to circle the limestone pinnacles. However, none of the search teams were willing to scale the last 100 metres of steep limestone that formed the peak of Batu Lawi.[3] It is possible that Manser fell down the side of the mountain, but neither his body nor his belongings have been found.[1][21] However, two local guides who brought Manser across the jungles of Sarawak were found. In desperation, fortune tellers and Penan necromancers were called. All of them agreed Manser was still alive.[7] On 18 November 2000, BMF requested that the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) search for Manser. Investigations were carried out at the Swiss Consulate in Kuala Lumpur and the Swiss Honorary Consulate in Kuching.[7] |

捜索遠征 BMFとペナン族はマンサーの捜索を試みたが、成功しなかった。リンバン川の周辺はプナンによって捜索された。プナンの探検隊は、マンサーの最後の寝床ま で追跡した。彼らはマンサーがナタで切った跡を追って深い森に入り、ブキ・バツ・ラウィの麓の沼地までたどり着いた。沼地にいた形跡も、沼地から戻った形 跡も、この地域に入ってきた人の痕跡もない。BMFはヘリコプターを送り込み、石灰岩のピナクルズを一周させた。しかし、どの捜索隊もBatu Lawiの頂上を形成する最後の100メートルの急な石灰岩を登ろうとはしなかった[3] マンサーは山の側面から落ちた可能性があるが、彼の体も所持品も見つかっていない[1][21] しかし、サラワクのジャングルでマンサーを連れてきた地元のガイド2人は発見されている。絶望の中、占い師やペナン人の霊媒師が呼ばれた。2000年11 月18日、BMFはスイス連邦外務省にマンサーの捜索を要請した[7]。調査はクアラルンプールのスイス領事館とクチンのスイス名誉領事館で行われた [7]。 |

| Aftermath In January 2002, hundreds of Penan members organised a tawai ceremony to celebrate Manser. The Penan refer to Manser as Laki Tawang (man who has become lost) or Laki e'h metat (man who has disappeared), rather than his name, because speaking the names of the dead is taboo in Penan culture.[1] On 18 November 2001, eighteen months after his disappearance, he was awarded the International Society for Human Rights prize for Switzerland.[22] After search expeditions proved fruitless, a civil court in Basel-Stadt declared Manser to be legally dead on 10 March 2005.[2][13] On 8 May 2010, a memorial service was held in Elisabethen church, Basel to mark the tenth anniversary of his disappearance. Roughly 500 people attended the service.[23] To celebrate Manser's 60th birthday on 25 August 2014, a species of goblin spider that was discovered by a Dutch-Swiss research expedition in Pulong Tau National Park in the 1990s is now named after Manser: Aposphragisma brunomanseri.[24] |

余波 2002年1月、数百人のペナンのメンバーがマンサーを祝うタワイの儀式を行いました。プナンはマンサーのことを名前ではなく、ラキ・タワン(迷子になっ た男)またはラキ・エス・メタット(消えた男)と呼ぶが、これはペナン文化では死者の名前を話すことがタブーであるためである[1]。 失踪から18ヶ月後の2001年11月18日、スイスの国際人権協会賞を受賞した[22]。 捜索活動が実らないことが判明した後、バーゼルシュタットの民事裁判所は2005年3月10日にマンサーが法的に死亡したと宣言した[2][13]。 2010年5月8日にバーゼルのElisabethen教会で彼の失踪10周年を記念して追悼礼拝が執り行われた。およそ500人の人々がこの礼拝に参加 した[23]。 2014年8月25日にマンサーの60歳の誕生日を記念して、1990年代にオランダとスイスの調査隊がプロンタウ国立公園で発見したゴカイグモの一種が マンサーの名を冠することになった。Aposphragisma brunomanseri]と命名された[24]。 |

| Bruno Manser (1992). Voices from

the Rainforests: Testimonies of a Threatened People. ISBN

978-9670960012. Written by Manser to introduce western readers to the

life of a Penan.[25] Carl Hoffman (2018). The Last Wild Men of Borneo: A True Story of Death and Treasure. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0062439024. Biography of Bruno Manser. |

Takashi SHIMEDA, The Power of Voice. 1996

声の力 : ボルネオ島プナンのうたと出すことの美学 / 卜田隆嗣著, 弘文堂 , 1996.、の情動に関するノート

| 「これだけのことばを連ね、しかも訳出していないが、多くのカミの個別

名を織り込んで、ポソとラジャンはタ

バコも吸わずに歌い続けた。歌声は必ずしも大きくはないが、しかしムグな声(参照指定)であると聞

き手は口々に言った。これだけの長い演奏をおこなうのに要する休力と気力は、カミの助けによって獲得される。

そしてそれだけの力によって長時間続けられたうたは、それだけでも聞き手に力を感じさせ、感動させる。/

歌詞の内容は多岐にわたっていて、一貫性がないように思われるかもしれないが、この簡単な説明でその意図

するところがいくらかは伝えられたと思う。うたの主人公の死の暗示、子孫の繁栄を思わせることばの数々、さ

まざまなカミヘの言及、こうしたことが全体として聞き手の心に入り込み、人びとの情動を喚起する。老人や女

性は目に涙を浮かべながら、じっとこのうたに聞き入っていたのである。/

だが、こうした情動を喚起する力は、歌詞の内容や演奏時間の長さなどにのみ由来するのではない。そうした

こととともに、それはシヌイに固有の形式、すなわち、基本的に各語の最後の音節をほかの音節よりも長くのば

し、韻を踏み、細部の違いはあるにしても旋律パタンを何度も反復する、ことにも由来している。「こと

ば」の一部として位置づけられるうたが、こうした形式上の特徴によって他のことばとは区別され、同時に何人

もの歌い手のいくつものシヌイはシヌイという同じものとしてまとめられ、カミとのコミュニケーション手段と

しての特別な位置を与えられているのである。そのことがまた、人びとを動かす力となる。/

そしてやはり、うたの形式の背後にはカミがある。カミが聞いてくれる確率を高めるために、鳥の聞きなしと

同じように単語の最後の音節を長くし、韻を踏み、旋律を反復しながら、彼らはできるだけた<さんの声を出す。

それによって声は力を増し、カミに願う子孫の繁栄も実現可能となるのである」(卜田 1996:194-195)。 |

|

| 「カミは烏の声をはじめ、さまぎまな媒体によってその存在や意向をあら

わすが、しかしカミ固有の身体を持た

ないがゆえに、人間のことばをなかなか受けとめてくれない。そのため、人間は常にカミに対して声を発する必

要がある。特にうたでは、たくさんのことばを発すること、長時間歌うことが重要である。第4章では、約1時

間続いたうたの歌詞を示し、文字としてではあるけれども、まずその力を感じてもらおうとした。そしてごく簡

単に形式と歌詞の内容を検討した。出すことに関するプナンの考えを了解した上でうたをとらえなおしてみると、

大便には大便の、屁には屁の固有のかたちがあると同時にその細部は人により時により多様であること、そして

その細部が評価の対象として重要であることと、うたの場合との関係がよりよく見通せる。うた固有のかたちに

のっとってたくさんの声を出すことと、歌い手の独自性がとりわけ感じられる音の動きの細部、そして歌詞の内

容の展開とは、うたの評価にとって中心的な要素であり、それが人の情動を喚起し、またカミに対しても力を持

つ根拠なのである。/

こうした力(プシット)はとりわけうたに強く感じられるがしかしそれだけに限定されるわけではない。

人間の話すことばはどれも根本的には力を持っているし、あくびやくしゃみによって息が出ていくと、その隙を

ついて悪いカミが入り込む。排泄物でさえ、カミとの駆け引きによって手に入れた食料を取り込み、それを体内

で変形し出す過程で、なんらかの力を帯びたものとなる。そのようなものとしてこそ、大便の色や嗅い、屁の音

や臭いも評価の対象となる」(卜田 1996:200-201)。 |

|

| 「こうした感覚的知は、明文化されないにしても、多くの民族誌的研究を 背後で方向づけているに違いない。そ してプナンの場合、幸か不幸か、こうした感覚的知を声の表現と結びつけていたために、わたしはそこに入り込 まないわけにはいかなかった。食物は食べるためであると同時に、感じ、考えるためのものでもあった。もちろ ん、プナンの食事慣行とそれに大きな影響を及ぼしているカミの意識は、それ自体プナン文化の環境に対する適 応の産物として、ハリスが言うような「最適化採餌理論」(ハリス1988: 306他)で説明できるかもしれない。鳥 の鳴き声次第で狩猟や採集をしたりしなかったりすることで、プナンは環境に対して壊滅的な打撃を与えないよ うにし、結果的に将来にわたって食料の安定的確保を実現してきたのかもしれないし、猪や鹿があるときには、サ ゴ澱粉に多くの水を加えることで出来上がりの量感ほどには実際は澱粉を消費しないようにし、肉がないときに にのみ少量の水で練ってだんご状にしてしっかりと澱粉を摂取しているのかもしれない。そしてうたについても 同様に、その状況からいえば、豊富な食料を前にした一種の「祭り」の場を現出させるものであり、それによっ て人々の連帯を強調するものであるかもしれない(機能論的説明)。だがそうした理論がプナンの無意識に巣く っているとしても、彼らが観念的なレベルで食と音声とを結びつけていることは事実である。そして、こうした 観念を具体的に支えているのは、味覚であり、嗅覚であり、聴覚である。そしてカミ観念も、わたしの個人的体 験を正当化するまでもなく、身体感覚として具体化される。カミは感じられるものとして体の中にあり、また人 びとの周囲にいるのである」(卜田 1996:204)。 | |

| 「何が情動を喚起し、力を感じさせるかは、文化によって決定されている

部分が大きいし、またそうした力の源

泉は、必ずしも「もの」や「行為」自体にのみあるというわけでもない。パプアニューギニアのカルリが、ギサ

ロのうたに動かされるのは、そのうたそのものによるだけではなく、彼らの霊や死についての観念が重要である

(フェルド 1988)。だがそれでも、うたそのものが生起しなければ、そうした情動は喚起されない。カミ概念を具

体化し、聴覚やその他の感覚に訴えてはっきりと感じられるようにするのがうたの働きであるといえる。/

こうしたことは、うたを暗黙のうちに「芸術」であるとか「美」的なものであると前提としているとみえてこな

い。この点をアームストロングは次のように述べている。「芸術や、おそらくそれにもっとも特徴的であるとさ

れる美という観念にのっとって研究を進めても価値がない。『美』は言うに及ばず、『芸術』も伝達が困難な概念

であり、調査研究を進める出発点として有効ではないからである」(Armstrong 1971: 10) 。芸術というかわりに、

彼は「(人を)動かす存在」(affecting presence)という語を提唱する。それは、人間が意図的に作り出した、人

を感動させるものであり、芸術なり美なりといった概念に基づいて「動かす存在」を考察すること自体が、西洋

近代の知的伝統であり、したがってそれをそのまま異文化に適用しても意味がない」(卜田 1996:205)。 ++++++++++++ ※池田コメント:それは西洋近代の知的伝統でありしたがってそれをそのまま異文化に適用しても意味がない→ああ凡庸な比較文化論やクソ民族誌にある紋切表 現だがそのような相対化を西洋近代の知的伝統の末尾にいるという自覚がない点で僕はいつもこんなバカを見下す癖がついちゃったかもしれない。 |

|

| 「そうしたうたの力を支えているのはカミ観念である。うた以上に、はっ きりとカミのあらわれとしてとらえら れる馬の鳴き声(譜例2)だが、烏の鳴き声はプナン語で聞きなされる点でプナンが 作ったものであるとも言えるが、しかしそれは人の情動を喚起するにしてもアームストロングの言う「人を動か す象徴」であって、人を動かす存在ではない。鳥の鳴き声そのものには意味がないからである。そ うであれば、うたを社会的機能として、あるいは社会構造を映し出すものとして説明することとたいして違わな いのではないか。カミ観念自体が、食物に関するハリスの議論と同様に、社会的あるいはその他の機能として、説明可能であるため、こうした主張は可能である ように思われる」(卜田 1996:205-206)。 | |

| 「プナンにとって歌うこと、声を出すこと、さらに体から出すこと全般 は、こうしてそこここにいるカミを意識 し、世界をとらえ直すことである。そしてそれらの営みを共通の基盤においてとらえ、考えていることは、われ われのことばで言う美学らしきものの存在を意味する。ただし、プナンの出すことに関わる思考は、「美」では なく、人を動かす存在をめぐるものである。「美」なる概念に近似的なものを探せば、おそらく「よい(こと)」 ((ク)ジアン(ke) jian)がそれにあたるであろう。しかし、プナンにとっ て、たとえば「たくさんのことばはよ いことばだ」ということの本質は、われわれが通常考える「美」とは一致しない。カミと人間の力を感じさせ、 情動を喚起するのがよいことばであり、よいうたである。そして、糞も屁もカミを感じさせ、ある種の情動を喚 起するが、そのなかでとりわけ強く情動を喚起するのがうたであり、それゆえにうたはうたとして存在するので ある」(卜田 1996:214)。 | |

| ストラー(Stoller

1984:563)は、メルロ=ポンティに依拠して「ことばが意味をもつ以前に、ことばを物理的に出現させることが意味である」と主張していると、卜田

(1996:83)は主張している。それは妥当か? |

※下記のように、(原文は)メルロ=ポンティの主張は「言葉の物理的な

表出は、意義が生まれる前に、すでに意義が与えられている(=マニュフェストしている)のである」。 |

| The sound of words This brief review of the role of the word in the Songhay universe gives only a surface representation of things Songhay. There is much more. Obviously, one must learn to hear the words of the magical incantation; and this, without doubt, is the most important aspect of the young healer's apprenticeship. Learning to hear is more than transforming the sound contours of a magical incantation into one's own speech, however; it is more than mastering the literal and metaphoric meanings of the narratives. To learn how to hear, the Songhay healer must learn to apprehend the sound of words much like the musician learns to apprehend the sound of music. Just as sound is the central feature of the world of music, so sound is the central feature of the world of magic. This world of sounds comes to life in a network of forces "that act in obedience to laws whose action is manifest in the action of tonal [sound] events, in the precisely determined relations of tones [sounds] to one another in the norms that govern the course of tonal [sound] motion" (Zukerkandl 1958:364). While the laws governing sound movement may differ from melody to melody, from incantation to incantation, the laws have one thing in common: they are dynamic, referring to "states not objects, to relations between tensions, not to positions between, to tendencies, not to magnitudes" (1958:364). Taking this logical sequence one step further, "the forces that act in the tonal world manifest themselves through bodies but not upon bodies" (1958:364). In this sense, a tone or a magical incantation is not a conveyor of action, as Malinowski would have said; rather, it is action. The physical manifestation of the word is significance, to paraphrase Merleau-Ponty (1968), before it has significance. |

言葉の響き ソンガイの宇宙における言葉の役割について簡単に説明したが、これはソンガイの物事の表面的な表現に過ぎない。もっと豊富にあるのだ。もちろん、魔法の呪 文の言葉を聞くことを学ばねばならないが、これは間違いなく、若いヒーラーの見習い期間の最も重要な側面である。しかし、聞くことを学ぶことは、魔法の呪 文の音の輪郭を自分の言葉に変換すること以上に、語りの文字通りの意味と比喩的な意味を習得することでもあるのだ。ソンガイのヒーラーが「聞く」ことを学 ぶには、音楽家が音楽の音を理解するように、言葉の音を理解することを学ばなければならない。音が音楽の世界の中心的な特徴であるように、音は呪術の世界 の中心的な特徴である。この音の世界は、「その作用が音調[音]の事象の作用に、音調[音]の運動の過程を支配する規範の中で互いに正確に定められた関係 の中に現れる法則に従って作用する」(Zukerkandl 1958:364)力のネットワークに命を吹き込まれるのである。音の運動を支配する法則は旋律から旋律へ、呪文から呪文へと異なるかもしれないが、法則 には一つの共通点がある:それは動的であり、「物体ではなく状態、緊張間の位置ではなく関係、大きさではなく傾向」(1958:364)に言及することで ある。この論理的順序をさらに一歩進めると、「音調の世界に作用する力は、身体を通して現れるが、身体の上に現れるのではない」(1958:364)。こ の意味で、音色や呪術的な言葉は、マリノフスキーが言うように、行為の伝達者ではなく、むしろ行為である。メルロ=ポンティ(1968)の言葉を借りれ ば、言葉の物理的な表出は、意義がある前に、意義がある(=マニュフェストしている)のである。 |

| 「人間の空間化された凝視gazeは距離を生み出す。それに対して音響

は、個人に浸透し、伝達と参加の感覚を生み出す」(Stoller 1984: 563)[卜田 1996:203]※実際の引用箇所を示す。 |

|

| When a musician or an apprentice Songhay healer learns to hear, he or she begins to learn that sound allows for the interpretation of the inner and outer worlds, of the visible and the invisible, of the tangible and the intangible. A person's spatialized "gaze" creates distance. Sound, by contrast, penetrates the individual and creates a sense of communica- tion and participation. From the musical perspective, the "out-there" is replaced by what Zukerkandl (1958:364) calls the "from-out-there-toward-me-and-through-me." In this way outer and inner worlds interpenetrate in a flowing and dynamic world, a world in which sound is a foundation. Just as in the world of music, in which there is no clear distinction between the material and immaterial worlds, so in the Songhay cosmos there is no e is no di boundary between the spirit and social worlds. (Stoller 1984: 563-564) | 「音

楽家や見習いソンガイの治療者は、聴くことを学ぶと、音によって内と外の世界、見えるものと見えないもの、有形と無形のものを解釈できることを学び始め

る。人の空間化された「視線(gae)」は、距離を生み出す。これに対し、音は個人を貫き、コミュニケーションと参加の感覚を生み出します。音楽の観点か

らすると,「外なるもの」は,Zukerkandl (1958:364)

が「外からそこに向かって,私を通して」と呼ぶものに取って代わられるのである.このようにして、外側の世界と内側の世界が、流れるようなダイナミックな

世界、つまり音が土台となる世界の中で、相互に浸透し合うのである。音楽の世界では物質世界と非物質世界の間に明確な区別がないように、ソンガイの宇宙で

は精神世界と社会世界の間に境界線はないのである」(Stoller 1984: 563-564). |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆