社会的アイデンティティ

Social Identity

☆ アイデンティティとは、ある個人または集団を特徴づける性質、信念、性格特性、外見、および/または表現の集合である。社会学では、社会学者たちは集団的アイデンティティに重点を置いており、個人のアイデンティティは、その人を定義する役割行動や集団のメンバーシップの集 合と強く関連しているとされる。ピーター・バークによると、「アイデンティティは、私たちが誰であるかを私たちに示し、また、他の人々にも私たちが誰であ るかを告げる」。アイデンティティは、その後の行動を導き、「父親」が「父親」らしく振る舞い、「看護師」が「看護師」らしく行動するように導 く。

| Identity

is the set of qualities, beliefs, personality traits, appearance,

and/or expressions that characterize a person or a group.[1][2][3][4] Identity emerges during childhood as children start to comprehend their self-concept, and it remains a consistent aspect throughout different stages of life. Identity is shaped by social and cultural factors and how others perceive and acknowledge one's characteristics.[5] The etymology of the term "identity" from the Latin noun identitas emphasizes an individual's mental image of themselves and their "sameness with others".[6] Identity encompasses various aspects such as occupational, religious, national, ethnic or racial, gender, educational, generational, and political identities, among others. Identity serves multiple functions, acting as a "self-regulatory structure" that provides meaning, direction, and a sense of self-control. It fosters internal harmony and serves as a behavioral compass, enabling individuals to orient themselves towards the future and establish long-term goals.[7] As an active process, it profoundly influences an individual's capacity to adapt to life events and achieve a state of well-being.[8][9] However, identity originates from traits or attributes that individuals may have little or no control over, such as their family background or ethnicity.[10] In sociology, emphasis is placed by sociologists on collective identity, in which an individual's identity is strongly associated with role-behavior or the collection of group memberships that define them.[11] According to Peter Burke, "Identities tell us who we are and they announce to others who we are."[11] Identities subsequently guide behavior, leading "fathers" to behave like "fathers" and "nurses" to act like "nurses".[11] In psychology, the term "identity" is most commonly used to describe personal identity, or the distinctive qualities or traits that make an individual unique.[12][13] Identities are strongly associated with self-concept, self-image (one's mental model of oneself), self-esteem, and individuality.[14][page needed][15] Individuals' identities are situated, but also contextual, situationally adaptive and changing. Despite their fluid character, identities often feel as if they are stable ubiquitous categories defining an individual, because of their grounding in the sense of personal identity (the sense of being a continuous and persistent self).[16] |

アイデンティティとは、ある個人または集団を特徴づける性質、信念、性格特性、外見、および/または表現の集合である。[1][2][3][4] アイデンティティは、子どもが自己概念を理解し始める幼少期に形成され、人生のさまざまな段階を通じて一貫した側面として残る。アイデンティティは、社会 的・文化的要因や、他者が個人の特性をどう認識し、どう認めるかによって形作られる。[5] 「アイデンティティ」という用語の語源は、ラテン語の名詞「identitas」であり、個人の自己イメージと「他者との同一性」を強調している。[6] アイデンティティには、職業、宗教、国民、民族や人種、性別、教育、世代、政治などのさまざまな側面がある。 アイデンティティは、意味、方向性、自己統制感覚を提供する「自己規制構造」として機能し、さまざまな役割を果たしている。それは内部の調和を育み、行動 の指針となり、個人が未来に向かって方向付けを行い、長期的な目標を確立することを可能にする。[7] 積極的なプロセスとして、アイデンティティは個人が人生の出来事に適応し、幸福な状態を達成する能力に多大な影響を与える。[8][9] しかし、アイデンティティは、個人がほとんど、あるいはまったく制御できない特性や属性、例えば家族背景や民族性などから生じる。[10] 社会学では、社会学者たちは集団的アイデンティティに重点を置いており、個人のアイデンティティは、その人を定義する役割行動や集団のメンバーシップの集 合と強く関連しているとされる。ピーター・バークによると、「アイデンティティは、私たちが誰であるかを私たちに示し、また、他の人々にも私たちが誰であ るかを告げる」[11]。アイデンティティは、その後の行動を導き、「父親」が「父親」らしく振る舞い、「看護師」が「看護師」らしく行動するように導 く。 心理学では、「アイデンティティ」という用語は、個人のアイデンティティ、すなわち個人を唯一無二のものとする独特の資質や特性を説明する際に最も一般的 に使用される。[12][13] アイデンティティは、自己概念、自己イメージ(自己に対するメンタルモデル)、自尊心、そして個性と強く関連している。[14][要ページ番号][15] 個人のアイデンティティは、位置づけられると同時に文脈的であり、状況に応じて適応し、変化する。流動的な性格にもかかわらず、アイデンティティはしばし ば、個人を定義する安定した普遍的なカテゴリーであるかのように感じられる。それは、個人のアイデンティティ(連続的かつ持続的な自己であるという感覚) に根ざしているためである。[16] |

| Usage Mark Mazower noted in 1998: "At some point in the 1970s this term ["identity"] was borrowed from social psychology and applied with abandon to societies, nations and groups."[17] |

用法 マーク・マゾーワーは1998年に次のように述べている。「1970年代のある時点で、この用語(「アイデンティティ」)は社会心理学から借用され、社会、国民、集団に対して無分別に適用されるようになった」[17] |

| In psychology Erik Erikson (1902–94) became one of the earliest psychologists to take an explicit interest in identity. An essential feature of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development was the idea of the ego identity (often referred to as the self), which is described as an individual's personal sense of continuity.[18] He suggested that people can attain this feeling throughout their lives as they develop and is meant to be an ongoing process.[19] The ego-identity consists of two main features: one's personal characteristics and development, and the culmination of social and cultural factors and roles that impact one's identity. In Erikson's theory, he describes eight distinct stages across the lifespan that are each characterized by a conflict between the inner, personal world and the outer, social world of an individual. Erikson identified the conflict of identity as occurring primarily during adolescence and described potential outcomes that depend on how one deals with this conflict.[20] Those who do not manage a resynthesis of childhood identifications are seen as being in a state of 'identity diffusion' whereas those who retain their given identities unquestioned have 'foreclosed' identities.[21] On some readings of Erikson, the development of a strong ego identity, along with the proper integration into a stable society and culture, lead to a stronger sense of identity in general. Accordingly, a deficiency in either of these factors may increase the chance of an identity crisis or confusion.[22] The "Neo-Eriksonian" identity status paradigm emerged in 1966, driven largely by the work of James Marcia.[23] This model focuses on the concepts of exploration and commitment. The central idea is that an individual's sense of identity is determined in large part by the degrees to which a person has made certain explorations and the extent to which they have commitments to those explorations or a particular identity.[24] A person may display either relative weakness or strength in terms of both exploration and commitments. When assigned categories, there were four possible results: identity diffusion, identity foreclosure, identity moratorium, and identity achievement. Diffusion is when a person avoids or refuses both exploration and making a commitment. Foreclosure occurs when a person does make a commitment to a particular identity but neglected to explore other options. Identity moratorium is when a person avoids or postpones making a commitment but is still actively exploring their options and different identities. Lastly, identity achievement is when a person has both explored many possibilities and has committed to their identity.[25] Although the self is distinct from identity, the literature of self-psychology can offer some insight into how identity is maintained.[26] From the vantage point of self-psychology, there are two areas of interest: the processes by which a self is formed (the "I"), and the actual content of the schemata which compose the self-concept (the "Me"). In the latter field, theorists have shown interest in relating the self-concept to self-esteem, the differences between complex and simple ways of organizing self-knowledge, and the links between those organizing principles and the processing of information.[27] Weinreich's identity variant similarly includes the categories of identity diffusion, foreclosure and crisis, but with a somewhat different emphasis. Here, with respect to identity diffusion for example, an optimal level is interpreted as the norm, as it is unrealistic to expect an individual to resolve all their conflicted identifications with others; therefore we should be alert to individuals with levels which are much higher or lower than the norm – highly diffused individuals are classified as diffused, and those with low levels as foreclosed or defensive.[28] Weinreich applies the identity variant in a framework which also allows for the transition from one to another by way of biographical experiences and resolution of conflicted identifications situated in various contexts – for example, an adolescent going through family break-up may be in one state, whereas later in a stable marriage with a secure professional role may be in another. Hence, though there is continuity, there is also development and change.[29] Laing's definition of identity closely follows Erikson's, in emphasising the past, present and future components of the experienced self. He also develops the concept of the "metaperspective of self", i.e. the self's perception of the other's view of self, which has been found to be extremely important in clinical contexts such as anorexia nervosa.[30][page needed] Harré also conceptualises components of self/identity – the "person" (the unique being I am to myself and others) along with aspects of self (including a totality of attributes including beliefs about one's characteristics including life history), and the personal characteristics displayed to others. |

心理学 エリク・エリクソン(1902年~1994年)がアイデンティティに明確な関心を抱いた最も初期の心理学者の一人となった。エリクソンの心理社会的発達理 論の重要な特徴は、自我同一性(しばしば自己とも呼ばれる)という考え方であり、これは個人の個人的な連続性の感覚として説明されている。[18] エリクソンは、人は成長するにつれて生涯を通じてこの感覚を獲得することができ、 自我同一性は、個人の特性と成長、そしてそのアイデンティティに影響を与える社会的・文化的要因と役割の集大成という、2つの主な特徴から構成される。エ リクソンの理論では、生涯にわたる8つの明確な段階が説明されており、それぞれが個人の内面世界と外面世界との間の葛藤によって特徴づけられる。エリクソ ンは、アイデンティティの葛藤は主に思春期に起こるとし、この葛藤への対処の仕方によって異なる結果がもたらされる可能性があると述べた。[20] 幼少期の同一化の再統合をうまく行えない人は「アイデンティティ拡散」の状態にあると見なされる。一方、 与えられたアイデンティティを疑うことなく保持している人々は、「アイデンティティが閉ざされている」状態にある。[21] エリクソンの一部の解釈によると、強固な自我アイデンティティの形成と、安定した社会や文化への適切な統合は、一般的にアイデンティティの感覚をより強固 なものにする。したがって、これらの要因のいずれかに欠陥があると、アイデンティティの危機や混乱の可能性が高まる可能性がある。[22] 「ネオ・エリクソン」のアイデンティティ状態のパラダイムは、1966年にジェームズ・マーシアの研究を主な推進力として登場した。[23] このモデルは、「探求」と「コミットメント」の概念に焦点を当てている。その中心となる考え方は、個人のアイデンティティは、ある程度まで特定の探求を行 い、その探求や特定のアイデンティティに対してある程度のコミットメントを行っているかどうかによって決定されるというものである。[24] ある人は、探求とコミットメントの両面において、相対的な弱さや強さを示す場合がある。カテゴリーが割り当てられた場合、アイデンティティ拡散、アイデン ティティ凍結、アイデンティティモラトリアム、アイデンティティ達成の4つの結果が考えられる。拡散とは、ある人が探求とコミットメントの両方を避けたり 拒否したりすることである。 閉鎖とは、ある人が特定のアイデンティティにコミットメントするものの、他の選択肢の探求を怠る場合である。 モラトリアムとは、ある人がコミットメントを避けたり延期したりするものの、選択肢や異なるアイデンティティの探求を積極的に行う場合である。 最後に、アイデンティティの達成とは、ある人が多くの可能性を探求し、アイデンティティにコミットメントする場合である。 自己とアイデンティティは別物であるが、自己心理学の文献はアイデンティティがどのように維持されるかについての洞察を提供することができる。[26] 自己心理学の観点では、2つの関心領域がある。自己が形成されるプロセス(「私」)と、自己概念を構成するスキーマの実際のコンテンツ(「私」)である。 後者の分野では、理論家たちは自己概念と自尊心、自己認識の組織化の複雑な方法と単純な方法の違い、そしてそれらの組織化の原則と情報処理の間の関連性に 関心を示している。[27] ヴァインライヒのアイデンティティのバリエーションも同様に、アイデンティティの拡散、閉塞、危機というカテゴリーを含んでいるが、やや異なる重点が置か れている。例えばアイデンティティ拡散に関して、最適なレベルが標準と解釈されるのは、個人が他者との葛藤するアイデンティティをすべて解決できると期待 するのは非現実的であるためである。したがって、標準よりもはるかに高いレベルまたは低いレベルにある個人には警戒する必要がある。高度に拡散した個人は 拡散したと分類され、低いレベルの個人は閉塞した 。ワインレックは、アイデンティティの変異を、さまざまな文脈における葛藤するアイデンティティの解決や伝記的経験によって、ある状態から別の状態へと移 行することを可能にする枠組みの中で適用している。例えば、家族の崩壊を経験している思春期の若者はある状態にあるかもしれないが、その後、安定した結婚 生活と確かな職業的地位を得た場合には、別の状態にあるかもしれない。したがって、連続性はあるものの、発展と変化もある。 アイデンティティに関するレインの定義は、経験した自己の過去、現在、未来の構成要素を強調する点で、エリクソンの定義とほぼ同じである。また、彼は「自 己のメタ視点」、すなわち自己が他者から見た自己をどう認識するかという概念を展開しており、これは神経性無食欲症などの臨床的状況において極めて重要で あることが分かっている。[30][要出典] また、Harréは自己/アイデンティティの構成要素として、「人」(自分自身や他人にとって唯一無二の存在)や自己の側面(ライフヒストリーを含む、自 身の特性に関する信念などの属性の総体)、そして他者に示される個人的な特性を挙げている。 |

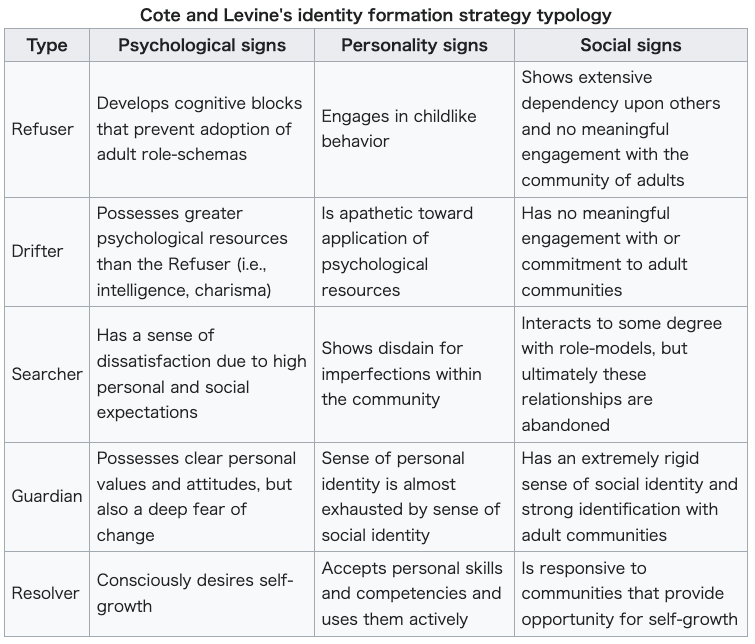

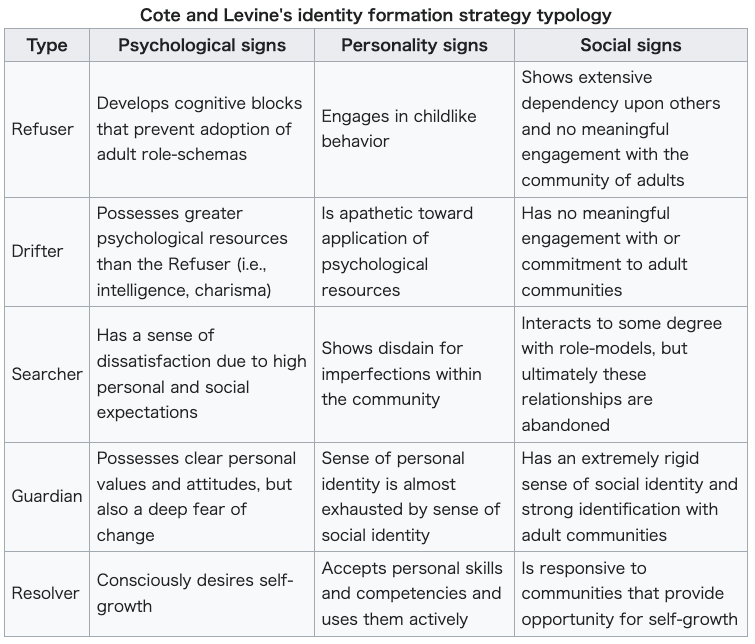

| In social psychology At a general level, self-psychology is compelled to investigate the question of how the personal self relates to the social environment. To the extent that these theories place themselves in the tradition of "psychological" social psychology, they focus on explaining an individual's actions within a group in terms of mental events and states. However, some "sociological" social psychology theories go further by attempting to deal with the issue of identity at both the levels of individual cognition and of collective behaviour.[31] Collective identity Main article: Collective identity Many people gain a sense of positive self-esteem from their identity groups, which furthers a sense of community and belonging. Another issue that researchers have attempted to address is the question of why people engage in discrimination, i.e., why they tend to favour those they consider a part of their "in-group" over those considered to be outsiders. Both questions have been given extensive attention by researchers working in the social identity tradition. For example, in work relating to social identity theory, it has been shown that merely crafting cognitive distinction between in- and out-groups can lead to subtle effects on people's evaluations of others.[27][32] Different social situations also compel people to attach themselves to different self-identities which may cause some to feel marginalized, switch between different groups and self-identifications,[33] or reinterpret certain identity components.[34] These different selves lead to constructed images dichotomized between what people want to be (the ideal self) and how others see them (the limited self). Educational background and occupational status and roles significantly influence identity formation in this regard.[35] Identity formation strategies Another issue of interest in social psychology is related to the notion that there are certain identity formation strategies which a person may use to adapt to the social world.[36] Cote and Levine developed a typology which investigated the different manners of behavior that individuals may have.[36] Their typology includes:  Kenneth Gergen formulated additional classifications, which include the strategic manipulator, the pastiche personality, and the relational self. The strategic manipulator is a person who begins to regard all senses of identity merely as role-playing exercises, and who gradually becomes alienated from their social self. The pastiche personality abandons all aspirations toward a true or "essential" identity, instead viewing social interactions as opportunities to play out, and hence become, the roles they play. Finally, the relational self is a perspective by which persons abandon all sense of exclusive self, and view all sense of identity in terms of social engagement with others. For Gergen, these strategies follow one another in phases, and they are linked to the increase in popularity of postmodern culture and the rise of telecommunications technology. |

社会心理学 一般的なレベルにおいて、自己心理学は、個人的な自己が社会的環境とどのように関わるかという問題を調査せざるを得ない。これらの理論が「心理学的」社会 心理学の伝統に位置づけられる限りにおいて、それらは集団内における個人の行動を心的事象や状態の観点から説明することに焦点を当てている。しかし、「社 会学」的社会心理学の理論の中には、さらに踏み込んで、個人の認知レベルと集団の行動レベルの両方におけるアイデンティティの問題に取り組もうとするもの もある。 集団的アイデンティティ 詳細は「集団的アイデンティティ」を参照 多くの人々は、アイデンティティ・グループから肯定的な自尊感情を得ており、それが共同体意識や帰属意識をさらに高めている。研究者が取り組もうとしてい るもう一つの問題は、人々がなぜ差別を行うのか、すなわち、なぜ「イングループ」の一員であるとみなす人々を、アウトサイダーであるとみなす人々よりも好 む傾向にあるのかという疑問である。この2つの問題は、社会的アイデンティティの研究に携わる研究者たちから多大な関心が寄せられている。例えば、社会的 アイデンティティ理論に関連する研究では、イングループとアウトグループを認知的に区別するだけで、他者に対する評価に微妙な影響を及ぼすことが示されて いる。 また、異なる社会的状況は、人々に異なる自己同一性を付与することを強いる。その結果、疎外感を感じたり、異なる集団や自己同一性を行き来したり、特定の アイデンティティの要素を再解釈したりする人もいる。[34] こうした異なる自己は、人々がなりたいと思うもの(理想の自己)と、他人からどう見られるか(限定的な自己)という二元的な構築されたイメージにつなが る。この点において、学歴や職業的地位、役割は、アイデンティティの形成に大きな影響を与える。[35] アイデンティティ形成の戦略 社会心理学におけるもう一つの興味深い問題は、社会に適応するために人が用いるアイデンティティ形成の戦略という概念に関連している。[36] CoteとLevineは、個人が持つ可能性のあるさまざまな行動様式を調査した類型論を展開した。[36] 彼らの類型論には以下が含まれる。  ケネス・ジャルゲンは、戦略的操作者、パスティーシュ的(紋切り型)人格、関係的自己を含む、さらなる分類を考案した。戦略的操作者とは、アイデンティティのあらゆる感覚を単なる役割演技とみなすようになり、徐々に社会的自己から疎外されていく人である。パスティーシュ的人格とは、真のアイデンティティや「本質的」アイデンティティへのあらゆる願望を放棄し、その代わりに社会的交流を演じる機会と捉え、それによって演じる役割になることを目指すものである。 最後に、関係的自己とは、排他的な自己という感覚をすべて放棄し、アイデンティティのあらゆる感覚を他者との社会的関わりという観点から捉える視点であ る。ガーゲンにとって、これらの戦略は段階的に次々と現れるものであり、ポストモダン文化の人気上昇や通信技術の進歩と関連している。 |

| In social anthropology See also: Australian Aboriginal identity Anthropologists have most frequently employed the term identity to refer to this idea of selfhood in a loosely Eriksonian way[37][better source needed] properties based on the uniqueness and individuality which makes a person distinct from others. Identity became of more interest to anthropologists with the emergence of modern concerns with ethnicity and social movements in the 1970s. This was reinforced by an appreciation, following the trend in sociological thought, of the manner in which the individual is affected by and contributes to the overall social context. At the same time, the Eriksonian approach to identity remained in force, with the result that identity has continued until recently to be used in a largely socio-historical way to refer to qualities of sameness in relation to a person's connection to others and to a particular group of people. The first favours a primordialist approach which takes the sense of self and belonging to a collective group as a fixed thing, defined by objective criteria such as common ancestry and common biological characteristics. The second, rooted in social constructionist theory, takes the view that identity is formed by a predominantly political choice of certain characteristics. In so doing, it questions the idea that identity is a natural given, characterised by fixed, supposedly objective criteria. Both approaches need to be understood in their respective political and historical contexts, characterised by debate on issues of class, race and ethnicity. While they have been criticized, they continue to exert an influence on approaches to the conceptualisation of identity today. These different explorations of 'identity' demonstrate how difficult a concept it is to pin down. Since identity is a virtual thing, it is impossible to define it empirically. Discussions of identity use the term with different meanings, from fundamental and abiding sameness, to fluidity, contingency, negotiated and so on. Brubaker and Cooper note a tendency in many scholars to confuse identity as a category of practice and as a category of analysis.[38] Indeed, many scholars demonstrate a tendency to follow their own preconceptions of identity, following more or less the frameworks listed above, rather than taking into account the mechanisms by which the concept is crystallised as reality. In this environment, some analysts, such as Brubaker and Cooper, have suggested doing away with the concept completely.[39] Others, by contrast, have sought to introduce alternative concepts in an attempt to capture the dynamic and fluid qualities of human social self-expression. Stuart Hall for example, suggests treating identity as a process, to take into account the reality of diverse and ever-changing social experience.[40][41] Some scholars[who?] have introduced the idea of identification, whereby identity is perceived as made up of different components that are 'identified' and interpreted by individuals. The construction of an individual sense of self is achieved by personal choices regarding who and what to associate with. Such approaches are liberating in their recognition of the role of the individual in social interaction and the construction of identity. Anthropologists have contributed to the debate by shifting the focus of research: One of the first challenges for the researcher wishing to carry out empirical research in this area is to identify an appropriate analytical tool. The concept of boundaries is useful here for demonstrating how identity works. In the same way as Barth, in his approach to ethnicity, advocated the critical focus for investigation as being "the ethnic boundary that defines the group rather than the cultural stuff that it encloses",[42] social anthropologists such as Cohen and Bray have shifted the focus of analytical study from identity to the boundaries that are used for purposes of identification. If identity is a kind of virtual site in which the dynamic processes and markers used for identification are made apparent, boundaries provide the framework on which this virtual site is built. They concentrated on how the idea of community belonging is differently constructed by individual members and how individuals within the group conceive ethnic boundaries. As a non-directive and flexible analytical tool, the concept of boundaries helps both to map and to define the changeability and mutability that are characteristic of people's experiences of the self in society. While identity is a volatile, flexible and abstract 'thing', its manifestations and the ways in which it is exercised are often open to view. Identity is made evident through the use of markers such as language, dress, behaviour and choice of space, whose effect depends on their recognition by other social beings. Markers help to create the boundaries that define similarities or differences between the marker wearer and the marker perceivers, their effectiveness depends on a shared understanding of their meaning. In a social context, misunderstandings can arise due to a misinterpretation of the significance of specific markers. Equally, an individual can use markers of identity to exert influence on other people without necessarily fulfilling all the criteria that an external observer might typically associate with such an abstract identity. Boundaries can be inclusive or exclusive depending on how they are perceived by other people. An exclusive boundary arises, for example, when a person adopts a marker that imposes restrictions on the behaviour of others. An inclusive boundary is created, by contrast, by the use of a marker with which other people are ready and able to associate. At the same time, however, an inclusive boundary will also impose restrictions on the people it has included by limiting their inclusion within other boundaries. An example of this is the use of a particular language by a newcomer in a room full of people speaking various languages. Some people may understand the language used by this person while others may not. Those who do not understand it might take the newcomer's use of this particular language merely as a neutral sign of identity. But they might also perceive it as imposing an exclusive boundary that is meant to mark them off from the person. On the other hand, those who do understand the newcomer's language could take it as an inclusive boundary, through which the newcomer associates themself with them to the exclusion of the other people present. Equally, however, it is possible that people who do understand the newcomer but who also speak another language may not want to speak the newcomer's language and so see their marker as an imposition and a negative boundary. It is possible that the newcomer is either aware or unaware of this, depending on whether they themself knows other languages or is conscious of the plurilingual quality of the people there and is respectful of it or not. |

社会人類学において 関連項目:オーストラリアのアボリジニのアイデンティティ 人類学者は、エリクソンの考え方を大まかに引用して、この自己概念を指すためにアイデンティティという用語を最も頻繁に使用している[37][より適切な 出典が必要]。アイデンティティは、1970年代に民族性や社会運動に関する現代的な関心が現れるにつれ、人類学者にとってより興味深いものとなった。こ れは、社会学思想のトレンドに追随する形で、個人が社会全体に影響を受け、また社会全体に貢献する様式が評価されたことにより、さらに強固なものとなっ た。同時に、エリクソンのアイデンティティへのアプローチは依然として有効であり、その結果、アイデンティティは、最近まで、主に社会史的な方法で、ある 個人と他者や特定の集団とのつながりにおける同一性の質を指すために使用され続けてきた。 前者は、自己意識や集団への帰属意識を、共通の祖先や生物学的特徴といった客観的な基準によって定義された固定的なものとして捉える原始論的アプローチを 支持している。後者は、社会構成主義理論に根ざしており、アイデンティティは特定の特徴を主に政治的に選択することによって形成されるという見解をとって いる。そうすることで、アイデンティティは固定された客観的基準によって特徴づけられる自然に与えられたものであるという考え方に疑問を投げかけている。 どちらのアプローチも、階級、人種、民族に関する議論によって特徴づけられるそれぞれの政治的、歴史的文脈の中で理解される必要がある。 批判を受けながらも、今日、アイデンティティの概念化へのアプローチに影響を与え続けている。 「アイデンティティ」に対するこうしたさまざまな探求は、この概念がいかに捉えどころのないものであるかを示している。アイデンティティは仮想的なもので あるため、経験的に定義することは不可能である。アイデンティティに関する議論では、この用語は根本的で不変の同一性から流動性、偶発性、交渉によるもの など、さまざまな意味で用いられている。ブルベーカーとクーパーは、多くの学者がアイデンティティを実践のカテゴリーと分析のカテゴリーとを混同する傾向 があると指摘している。[38] 実際、多くの学者は、アイデンティティに関する自身の先入観に従う傾向があり、その概念が現実として結晶化するメカニズムを考慮するよりも、上記の枠組み を多かれ少なかれ踏襲する傾向がある。このような状況下で、ブルベーカーやクーパーなどの一部の分析者は、この概念を完全に廃止することを提案している。 [39] 一方、人間の社会的自己表現の動的かつ流動的な性質を捉えようと、代替概念の導入を試みる者もいる。例えばスチュアート・ホールは、アイデンティティをプ ロセスとして扱い、多様で変化し続ける社会経験の現実を考慮に入れることを提案している。[40][41] 一部の学者[誰?]は、アイデンティティは個人によって「識別」され解釈されるさまざまな要素から構成されているとみなす識別という概念を導入している。 個人の自己意識の形成は、誰と何を関連付けるかという個人的な選択によって達成される。このようなアプローチは、社会的相互作用における個人の役割とアイ デンティティの形成を認識する上で、解放的なものである。 人類学者は、研究の焦点を移すことによって、この議論に貢献してきた。この分野で実証的研究を行おうとする研究者が最初に直面する課題のひとつは、適切な 分析ツールを特定することである。アイデンティティの働きを明らかにするには、境界という概念が役立つ。バルトが民族性へのアプローチにおいて、「グルー プを定義する民族の境界線」を調査の重要な焦点として提唱したのと同様に[42]、コーエンやブレイといった社会人類学者は、分析研究の焦点をアイデン ティティから、識別の目的で使用される境界線へと移行させた。アイデンティティが、識別のために用いられる動的なプロセスや指標が明らかになる仮想的な場 であるとすれば、境界は、この仮想的な場が構築される枠組みを提供する。彼らは、コミュニティへの帰属という考え方が個々のメンバーによってどのように異 なる形で構築されるか、また、グループ内の個人が民族の境界をどのように捉えているかに注目した。 境界という概念は、非指示的かつ柔軟な分析ツールとして、社会における自己の経験に特徴的な変化性や可変性をマッピングし、定義するのに役立つ。アイデン ティティは不安定で柔軟かつ抽象的な「もの」であるが、その表出や行使の方法はしばしば目に見える。アイデンティティは、言語、服装、行動、空間の選択と いったマーカーの使用によって明らかになるが、その効果は他の社会的存在による認識に依存する。マーカーは、マーカーの着用者とマーカーの認識者との間の 類似点や相違点を定義する境界を作り出すのに役立つが、その有効性は、その意味の共有理解に依存する。社会的文脈においては、特定のマーカーの意義の誤解 釈により誤解が生じる可能性がある。同様に、個人は、必ずしも外部の観察者が通常そのような抽象的なアイデンティティと関連付けるであろう基準をすべて満 たすことなく、アイデンティティのマーカーを使用して他の人々に影響を及ぼすことができる。 境界は、他の人々によってどのように認識されるかによって、包括的または排他的になる可能性がある。例えば、ある人が他者の行動に制限を課すマーカーを採 用した場合、排他的な境界が生じる。一方、包括的な境界は、他の人々が容易に結びつけることのできるマーカーを使用することで形成される。しかし同時に、 包括的な境界は、他の境界内に含めることで、含めた人々にも制限を課すことになる。この例としては、さまざまな言語が話されている部屋に、ある特定の言語 を話す新参者がやってきた場合が挙げられる。この人物が話す言語を理解できる人もいれば、できない人もいる。その言語を理解できない人々は、その新参者が 使用する特定の言語を、単に中立的なアイデンティティの印として受け取るかもしれない。しかし、その人々から新参者を排除する排他的な境界線として認識す る可能性もある。一方、新参者の言語を理解できる人々は、その言語を、新参者が自分たちと結びつき、その場にいる他の人々を排除する境界線として受け取る 可能性もある。しかし同様に、新参者の言語を理解するが、別の言語を話す人々は、新参者の言語を話したくないと思う可能性もあり、その場合は、彼らのマー カーを押し付けがましいネガティブな境界と見なす可能性もある。新参者がこのことを認識しているか否かは、彼ら自身が他の言語を知っているか、あるいはそ こにいる人々の複数言語を話すという資質を認識し、それを尊重しているか否かによる。 |

| In religion Main article: Religious identity A religious identity is the set of beliefs and practices generally held by an individual, involving adherence to codified beliefs and rituals and study of ancestral or cultural traditions, writings, history, mythology, and faith and mystical experience. Religious identity refers to the personal practices related to communal faith along with rituals and communication stemming from such conviction. This identity formation begins with an association in the parents' religious contacts, and individuation requires that the person chooses the same or different religious identity than that of their parents.[43][44] The Parable of the Lost Sheep is one of the parables of Jesus. it is about a shepherd who leaves his flock of ninety-nine sheep in order to find the one which is lost. The parable of the lost sheep is an example of the rediscovery of identity. Its aim is to lay bare the nature of the divine response to the recovery of the lost, with the lost sheep representing a lost human being.[45][46][47] Christian meditation is a specific form of personality formation, though often used only by certain practitioners to describe various forms of prayer and the process of knowing the contemplation of God.[48][49] In Western culture, personal and secular identity are deeply influenced by the formation of Christianity,[50][51][52][53][54] throughout history, various Western thinkers who contributed to the development of European identity were influenced by classical cultures and incorporated elements of Greek culture as well as Jewish culture, leading to some movements such as Philhellenism and Philosemitism.[55][56][57][58][59] |

宗教において 詳細は「宗教的アイデンティティ」を参照 宗教的アイデンティティとは、一般的に個人が持つ信念と実践の集合であり、体系化された信念や儀式への固執、先祖や文化伝統、文献、歴史、神話、信仰や神 秘体験の研究などを含む。宗教的アイデンティティとは、共同体の信仰に関連する個人的な実践や、そうした信念から生じる儀式やコミュニケーションを指す。 このアイデンティティの形成は、両親の宗教的つながりから始まり、個体化には、その人が両親と同じ宗教的アイデンティティを選ぶか、あるいは異なる宗教的 アイデンティティを選ぶことが必要である。 失われた羊のたとえは、イエスのたとえ話の一つである。それは、迷子になった一匹を見つけるために、99匹の群れを離れる羊飼いについての話である。失わ れた羊のたとえは、アイデンティティの再発見の例である。迷子になった羊が迷子になった人間を表し、迷子になった羊のたとえの目的は、迷子になった人間が 回復することに対する神の反応の本質を明らかにすることである。 キリスト教の瞑想は、特定の形の人格形成であるが、しばしば特定の実践者のみが、さまざまな祈りの形や神の観想を知るプロセスを説明するのに用いる。 西洋文化では、キリスト教の形成が個人および世俗的なアイデンティティに深く影響を与えている。[50][51][52][53][54] 歴史を通じて、ヨーロッパのアイデンティティの発展に貢献したさまざまな西洋の思想家たちは、古典文化の影響を受け、ギリシャ文化やユダヤ文化の要素を取 り入れ、フィレレニズムやフィロセミティズムなどの運動につながった。[55][56][57][58][59] |

| Implications Due to the multiple functions of identity which include self regulation, self-concept, personal control, meaning and direction, its implications are woven into many aspects of life.[60] Identity changes Contexts Influencing Identity Changes Identity transformations can occur in various contexts, some of which include: Career Change: When individuals undergo significant shifts in their career paths or occupational identities, they face the challenge of redefining themselves within a new professional context.[61][62] Gender Identity Transition: Individuals experiencing gender dysphoria may embark on a journey to align their lives with their true gender identity. This process involves profound personal and social changes to establish an authentic sense of self.[63] National Immigration: Relocating to a new country necessitates adaptation to unfamiliar societal norms, leading to adjustments in cultural, social, and occupational identities.[64] Identity Change due to Climate Migration: In the face of environmental challenges and forced displacement, individuals may experience shifts in their identity as they adapt to new geographical locations and cultural contexts.[65] Adoption: Adoption entails exploring alternative familial features and reconciling with the experience of being adopted, which can significantly impact an individual's self-identity.[66] Illness Diagnosis: The diagnosis of an illness can provoke an identity shift, altering an individual's self-perception and influencing how they navigate life. Additionally, illnesses may result in changes in abilities, which can affect occupational identity and require adaptations.[67] Immigration and identity Immigration and acculturation often lead to shifts in social identity. The extent of this change depends on the disparities between the individual's heritage culture and the culture of the host country, as well as the level of adoption of the new culture versus the retention of the heritage culture. However, the effects of immigration and acculturation on identity can be moderated if the person possesses a strong personal identity. This established personal identity can serve as an "anchor" and play a "protective role" during the process of social and cultural identity transformations that occur.[7] Occupational identity Identity is an ongoing and dynamic process that impacts an individual's ability to navigate life's challenges and cultivate a fulfilling existence.[8][9] Within this process, occupation emerges as a significant factor that allows individuals to express and maintain their identity. Occupation encompasses not only careers or jobs but also activities such as travel, volunteering, sports, or caregiving. However, when individuals face limitations in their ability to participate or engage in meaningful activities, such as due to illness, it poses a threat to the active process and continued development of identity. Feeling socially unproductive can have detrimental effects on one's social identity. Importantly, the relationship between occupation and identity is bidirectional; occupation contributes to the formation of identity, while identity shapes decisions regarding occupational choices. Furthermore, individuals inherently seek a sense of control over their chosen occupation and strive to avoid stigmatizing labels that may undermine their occupational identity.[8] Navigating stigma and occupational identity In the realm of occupational identity, individuals make choices regarding employment based on the stigma associated with certain jobs. Likewise, those already working in stigmatized occupations may employ personal rationalization to justify their career path. Factors such as workplace satisfaction and overall quality of life play significant roles in these decisions. Individuals in such jobs face the challenge of forging an identity that aligns with their values and beliefs. Crafting a positive self-concept becomes more arduous when societal standards label their work as "dirty" or undesirable.[68][69][70] Consequently, some individuals opt not to define themselves solely by their occupation but strive for a holistic identity that encompasses all aspects of their lives, beyond their job or work. On the other hand, individuals whose identity strongly hinges on their occupation may experience a crisis if they become unable to perform their chosen work. Therefore, occupational identity necessitates an active and adaptable process that ensures both adaptation and continuity amid shifting circumstances.[9] |

意味合い アイデンティティには自己統制、自己概念、自己管理、意味、方向性など、さまざまな機能があるため、その意味合いは生活の多くの側面に織り込まれている。[60] アイデンティティの変化 アイデンティティの変化に影響を与える背景 アイデンティティの変容はさまざまな背景で起こりうるが、その一部には以下のようなものがある。 キャリアの変更:個人がキャリアパスや職業上のアイデンティティにおいて大きな変化を経験するとき、新しい職業上の文脈の中で自己を再定義するという課題に直面する。[61][62] 性同一性移行:性別違和症を経験する個人は、人生を真の性同一性に一致させるための旅に出る場合がある。このプロセスには、真の自己感覚を確立するための、個人および社会における重大な変化が伴う。[63] 国民の移民:新しい国への移住は、慣れない社会規範への適応を必要とし、文化、社会、職業上のアイデンティティの調整につながる。 気候変動による移住によるアイデンティティの変化:環境問題や強制移住に直面した個人は、新しい地理的位置や文化的背景に適応する中で、アイデンティティの変化を経験することがある。 養子縁組:養子縁組には、家族のあり方を模索し、養子として迎え入れられた経験と折り合いをつけることが必要であり、それは個人の自己同一性に大きな影響を与える可能性がある。 病気による診断:病気の診断は、アイデンティティの変化を引き起こし、個人の自己認識を変え、その人の人生の歩み方に影響を与える可能性がある。さらに、病気は能力の変化をもたらす可能性があり、それは職業上のアイデンティティに影響を与え、適応を必要とする場合がある。 移民とアイデンティティ 移民と文化適応は、しばしば社会的アイデンティティの変化につながる。この変化の程度は、個人の母国の文化と受け入れ国の文化との相違、および新しい文化 の受容度と母国の文化の保持度によって異なる。しかし、その人が強い個人的アイデンティティを持っている場合、移民や文化適応がアイデンティティに及ぼす 影響は緩和される。確立された個人的アイデンティティは「アンカー」として機能し、社会や文化的なアイデンティティが変化する過程において「保護的役割」 を果たすことができる。 職業上のアイデンティティ アイデンティティは、人生の困難を乗り越え、充実した人生を築くための個人の能力に影響を与える、継続的かつ動的なプロセスである。[8][9] このプロセスにおいて、職業は個人がアイデンティティを表現し、維持することを可能にする重要な要素として浮上する。職業にはキャリアや仕事だけでなく、 旅行、ボランティア活動、スポーツ、介護などの活動も含まれる。しかし、病気などにより有意義な活動への参加や従事能力に制限が生じると、アイデンティ ティの積極的な形成や継続的な発展に脅威をもたらす。社会的に非生産的であると感じると、社会的なアイデンティティに悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある。重要な のは、職業とアイデンティティの関係は双方向であるということである。職業はアイデンティティの形成に寄与し、アイデンティティは職業選択に関する意思決 定を形作る。さらに、人は本質的に、自ら選んだ職業に対するコントロール感を得ようとし、職業上のアイデンティティを損なうような汚名を避けようとする。 [8] 汚名と職業上のアイデンティティの克服 職業上のアイデンティティの領域では、人は特定の職業に付随する汚名に基づいて雇用に関する選択を行う。同様に、すでに汚名を着せられた職業に就いている 人は、自身のキャリアパスを正当化するために個人的な合理化を行う場合がある。職場への満足度や生活の質全般といった要因は、これらの決定において重要な 役割を果たす。そのような職業に就いている人々は、自分の価値観や信念に沿ったアイデンティティを確立するという課題に直面している。社会の基準によって 自分の仕事が「汚い」または望ましくないとレッテルを貼られると、肯定的な自己概念を築くことがより困難になる。[68][69][70] その結果、一部の人は職業のみで自己を定義せず、仕事や労働を超えて生活のあらゆる側面を包括する全体的なアイデンティティを追求する。一方、アイデン ティティが職業に強く依存している人は、選んだ仕事ができなくなった場合に危機を経験する可能性がある。したがって、職業的アイデンティティには、状況の 変化に対応しながら適応と継続性を確保する、能動的かつ適応的なプロセスが必要である。[9] |

| Factors shaping the concept of identity The modern notion of personal identity as a distinct and unique characteristic of individuals has evolved relatively recently in history beginning with the first passports in the early 1900s and later becoming more popular as a social science term in the 1950s.[71] Several factors have influenced its evolution, including: Protestant Influence: In Western societies, the Protestant tradition has underscored individuals' responsibility for their own soul or spiritual well-being, contributing to a heightened focus on personal identity. Development of Psychology: The emergence of psychology as a separate field of knowledge and study starting in the 19th century has played a significant role in shaping our understanding of identity. Rise of Privacy: The Renaissance era witnessed a growing sense of privacy, leading to increased attention and importance placed on individual identities. Specialization in Work: The industrial period brought about a shift from undifferentiated roles in feudal systems to specialized worker roles. This change impacted how individuals identified themselves in relation to their occupations. Occupation and Identity: The concept of occupation as a crucial aspect of identity was introduced by Christiansen in 1999, highlighting the influence of employment and work roles on an individual's sense of self.[72][73] Focus on Gender Identity: There has been an increased emphasis on gender identity, including issues related to gender dysphoria and transgender experiences. These discussions have contributed to a broader understanding of diverse identities.[74][75] Relevance of Identity in Personality Pathology: Understanding and assessing personality pathology has highlighted the significance of identity problems in comprehending individuals' psychological well-being.[76][77] |

アイデンティティの概念を形成する要因 個人のアイデンティティを、個人の明確かつ独特な特性として捉えるという現代的な概念は、1900年代初頭に最初のパスポートが発行されたことに始まり、 1950年代には社会科学用語としてより広く使われるようになったという歴史の中で、比較的最近になって発展したものである。[71] その発展には、以下のような要因が影響している。 プロテスタントの影響:西洋社会では、プロテスタントの伝統が個人の魂や精神的な幸福に対する個人の責任を強調し、個人のアイデンティティへの注目が高まることに貢献した。 心理学の発展:19世紀に心理学が独立した知識と研究分野として登場したことは、アイデンティティに対する理解を形作る上で重要な役割を果たした。 プライバシーの台頭:ルネサンス時代にはプライバシーに対する意識が高まり、個人のアイデンティティに対する注目と重要性が増した。 労働の専門化:産業革命期には、封建制度における区別のない役割から、専門化された労働者の役割へと変化が起こった。この変化は、個人が職業との関連で自己をどう認識するかという点に影響を与えた。 職業とアイデンティティ:アイデンティティの重要な側面としての職業という概念は、1999年にクリスチャンセンによって紹介され、雇用や労働の役割が個人の自己認識に与える影響が強調された。[72][73] ジェンダー・アイデンティティへの注目:ジェンダー・アイデンティティへの注目が高まっており、性別違和やトランスジェンダーの経験に関連する問題も含まれている。こうした議論は、多様なアイデンティティに対する理解を深めることに貢献している。[74][75] パーソナリティ病理におけるアイデンティティの関連性:パーソナリティ病理の理解と評価により、個人の心理的ウェルビーイングを理解する上でアイデンティティの問題が重要であることが強調されている。[76][77] |

| Cultural identity Culture Identity formation Identity performance Online identity Passing Racial dysphoria Role engulfment Self-consciousness Self-discovery Social defeat Social stigma |

文化的アイデンティティ 文化 アイデンティティ形成 アイデンティティのパフォーマンス オンラインアイデンティティ 偽装 人種違和感 役割の没入 自意識 自己発見 社会的敗北 社会的スティグマ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Identity_(social_science) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆