The

New Key to

Social Science & Liberal Arts in 21st century

The

New Key to

Social Science & Liberal Arts in 21st century

Winch, Peter, The idea

of a social science and its relation to philosophy, 1958, 2015. with a

new introduction by Raimond Gaita

(2015)

"In the fiftieth anniversary of this book's first release, Winch's argument remains as crucial as ever. Originally published in 1958, The Idea of a Social Science and Its Relation to Philosophy was a landmark exploration of the social sciences, written at a time when that field was still young and had not yet joined the Humanities and the Natural Sciences as the third great domain of the Academy. A passionate defender of the importance of philosophy to a full understanding of 'society' against those who would deem it an irrelevant 'ivory towers' pursuit, Winch draws from the works of such thinkers as Ludwig Wittgenstein, J.S. Mill and Max Weber to make his case. In so doing he addresses the possibility and practice of a comprehensive 'science of society'."- Nielsen BookData.

Preface to the Second

Edition

Part 1:

Philosophical

Bearings

Part 2:

The Nature of

Meaningful Behaviour

Part 3:

The Social Studies

as Science

Part 4:

The Mind and

Society

Part 5: Concepts

and Actions

Peter Winch, 1926-1997

"Peter Guy Winch (14 January 1926 – 27 April 1997) was a British philosopher known for his contributions to the philosophy of social science, Wittgenstein scholarship, ethics, and the philosophy of religion. Winch is perhaps most famous for his early book, The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy (1958), an attack on positivism in the social sciences, drawing on the work of R. G. Collingwood and Ludwig Wittgenstein's later philosophy..../Winch was born on 14 January 1926, in Walthamstow, London. He attended Leyton County High School for boys,[2] before going up St Edmund Hall, Oxford to read Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Following the outbreak of World War II, he served in the Royal Navy 1944–47, before graduating from the University of Oxford in 1949. He was a lecturer in philosophy at the Swansea University from 1951 until 1964. He was influenced by his colleagues Rush Rhees and Roy Holland, both experts in the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. In 1964, he moved to Birkbeck College, University of London, before becoming Professor of Philosophy at King's College London in 1967. During this period, he served as president of Aristotelian Society, from 1980 to 1981. In 1985 Winch moved to the United States to become Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign./ He died on the 27 April 1997, in Champaign, Illinois/ ... He died on the 27 April 1997, in Champaign, Illinois "

"Peter Winch

saw himself as an uncompromising Wittgensteinian. He was not personally

acquainted with Wittgenstein; Wittgenstein's influence upon him was

mostly mediated through that of Rush Rhees (1905-1989), who was his

colleague at

the University College of Swansea, now known as Swansea University, and

whom Wittgenstein appointed as one of his literary executors.[7]

Winch's translation of Wittgenstein's Vermischte

Bemerkungen (as edited

by Georg Henrik von Wright) was published in 1980 as Culture and Value

(with a new translation by Winch of a revised edition by Alois Pichler

appearing in 1998).[8] After the death of Rhees in 1989, Winch took

over his position as literary executor./ From Rush Rhees, Winch derived

his interest in the religious writer Simone Weil. Part of the appeal

was a break from Wittgenstein into a very different type of philosophy

which could nevertheless be tackled with familiar methods. Also Weil's

ascetic, somewhat Tolstoyan, form of religion harmonised with one

aspect of Wittgenstein's personality./ At a time when most

Anglo-American philosophers were heavily under the spell of

Wittgenstein, Winch's own approach was strikingly original. While much

of his work was concerned with rescuing Wittgenstein from what he took

to be misreadings, his own philosophy involved a shift of emphasis from

the problems that preoccupied Oxford style ‘linguistic’ philosophy,

towards justifying and explaining 'forms of life' in terms of

consistent language games. He took Wittgensteinian philosophy into

areas of ethics and religion, which Wittgenstein himself had relatively

neglected, sometimes showing considerable originality. An example is

his illuminating treatment of the moral difference between someone who

tries and fails to commit murder and someone who succeeds, in his essay

"Trying" in Ethics and Action. With the decline of interest in

Wittgenstein, Winch himself was increasingly neglected and the

challenge his arguments presented to much contemporary philosophy was

sidestepped or ignored. In insisting on the continuity of

Wittgenstein's concerns from the Tractatus through to the Philosophical

Investigations, Winch made a powerful case for Wittgenstein's mature

philosophy, as he understood it, as the consummation and legitimate

heir of the entire analytic tradition.[9]" - Peter Winch.

Program protocols for salvaging the principles of the humanities and social sciences

| 0)以下のような情報と歴史を知る必要がある、すなわち、 1)1960年以降の「社会科学」と「リベラルアーツ」の70年間の総括、 2)1960年代末の学問への知的反省と「学生革命」の影響や、そこからはじまるそれぞれの分野の批判的研究の継承と現状、 3)ウィンチの仮想敵であった実証主義の現在(21世紀以降)への分析、 4)各国の政府と高等教育機関の関係、文教政策と知的エリートの関係、それらについての市民的理解度、 5)人文学と社会科学と自然科学の学問間の位相関係、学際研究や超域と呼ばれている研究と教育の現状 6)「研究の倫理」というレギュレーターの登場以降の、研究と研究対象、ならびに研究者間の関係の明確化、ならびに 7)以上の諸現象の各個分析とホーリズム的総合。 |

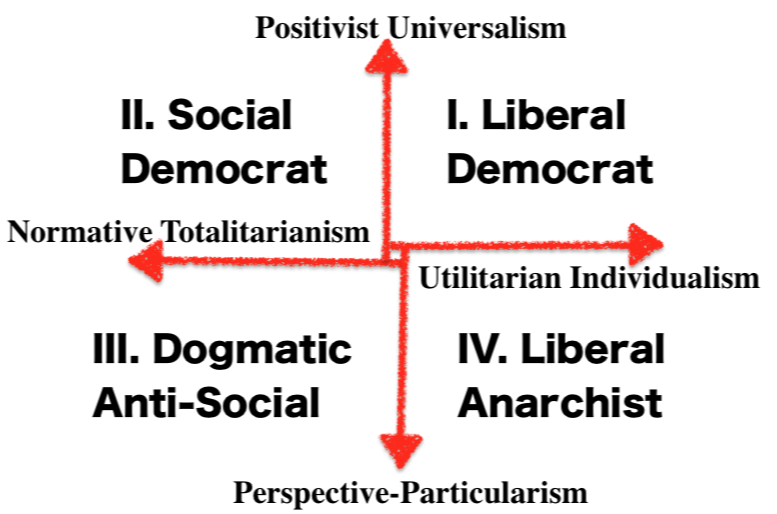

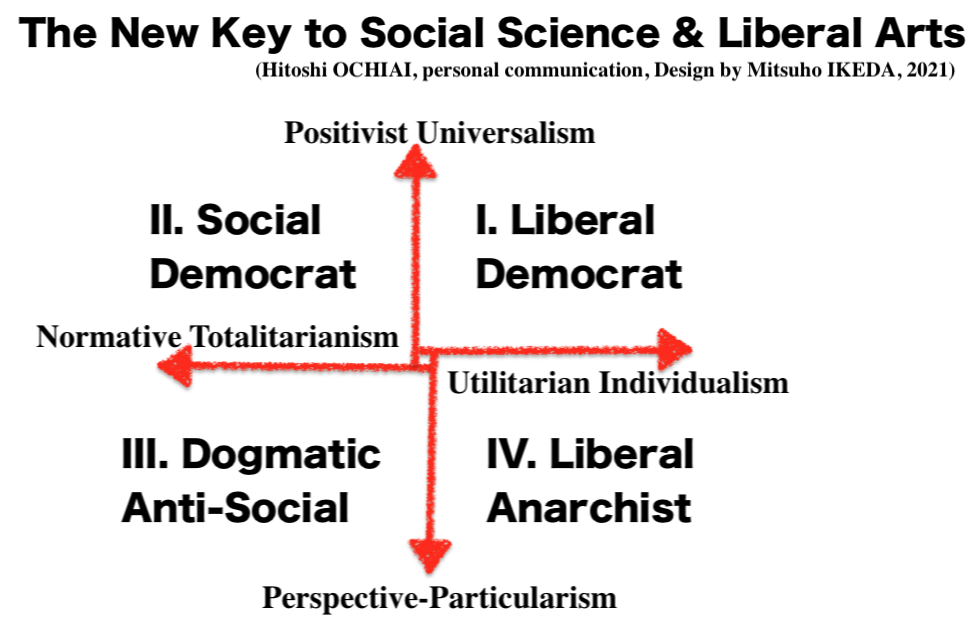

Design by Mitsuho Ikeda, suggested by Professor Hitoshi Ochiai of Doshisha University.

On Rationality

"In 1937, the British

anthropologist, Richard Evans-Pritchard, published a book that was

destined to become a classic of anthropology, Oracles, Witchcraft, and

Magic Among the Azande. (The Azande are a sub-Saharan agricultural

people living in the Sudan and parts of the Congo Republic.) The book

challenged the usual anthropological dismissal of the beliefs and

practices of "primitive peoples" as irrational, and attempted to

demonstrate that the consultation of oracles, belief in witchcraft, and

the practice of magic make sense within the overall context of Azande

culture. In 1958, the philosopher, Peter Winch, wrote an article based

on his reading of Evans-Pritchard's book titled, "Understanding a

Primitive Society." In this piece, Winch agreed with Evans-Pritchard's

sympathetic approach to the occult aspects of Azande society, but

argued that the approach must be taken further than Evans-Pritchard was

himself willing to go. Evans-Pritchard had tried to show that the

Azande's belief in witches helped them make moral and psychological

sense of the misfortunes that befell them, even though we Westerners

know that witches do not exist. Winch's question for Evans-Pritchard

is, what is the framework within which we make that judgment? If it is

the framework of Western science, then the judgment that there are no

witches is simply the result of imposing upon the Azande a set of

concerns and standards of reasoning that belong to our culture, but not

to theirs. Different cultures have different criteria for rational

belief and action. Our standards are local to our culture, and no more

objective than anyone else's. Does this leave us with a nihilistic

relativism? Does tolerance and sympathy for other cultures rob us of

any vantage point for making judgments that are simply true or false,

including moral judgments about such practices as slavery, infanticide,

or torture? Is that the price we must pay for treating magic

seriously?" - https://bit.ly/30540G8

Links

Bibliography

その他の情報