拒否権

Veto

☆拒 否権(veto ) とは、公式な行動を一方的に 阻止する法的権限である。最も典型的なケースでは、大統領や君主が法案を拒否し、それが法律となるのを阻止する。多くの国では、拒否権は憲法で定められて いる。拒否権は他の政府レベル、例えば州政府、地方政府、国際機関などでも見られる。拒否権の中には、しばしば過半数以上の賛成票によって覆されるものも ある。例えばアメリカでは、下院と上院の3分の2の賛成で大統領の拒否権を覆すことができる[1]。しかし、絶対的な拒否権もあり、これは覆すことができ ない。例えば国連安全保障理事会では、常任理事国5カ国(中国、フランス、ロシア、イギリス、アメリカ)が、いかなる安保理決議に対しても絶対的な拒否権 を持つ。 多くの場合、拒否権は現状変更を防ぐためだけに使える。だが、拒否権の中には変更を提案する能力も含むものもある。例えば、インドの大統領は修正拒否権を 使って、拒否された法案への修正を提案できる。 立法に対する拒否権は、立法過程において行政府が持つ主要な手段の一つであり、提案権と並ぶものだ[2]。これは大統領制や準大統領制で最もよく見られ る。[3] 議会制では、国家元首の拒否権は弱いか、あるいは全く存在しないことが多い。[4] ただし、正式な拒否権を定めていない政治体制もある一方で、全ての政治体制には拒否権を行使する主体、すなわち社会的・政治的権力を用いて政策変更を阻止 できる人々や集団が存在する。[5] 「拒否権(veto)」という言葉はラテン語の「私は禁ずる」に由来する。拒否権の概念は、ローマの執政官と平民の護民官の職位に起源を持つ。毎年二人の 執政官がおり、いずれの執政官も他方の軍事的・民事的行動を阻止できた。護民官は、ローマの行政官によるあらゆる行動や元老院で可決された法令を単独で阻 止する権限を有していた。[6]

★拒否権理論

| Veto theories In political science, the broader power of people and groups to prevent change is sometimes analyzed through the frameworks of veto points and veto players. Veto players are actors who can potentially exercise some sort of veto over a change in government policy.[5] Veto points are the institutional opportunities that give these actors the ability to veto.[5] The theory of veto points was first developed by Ellen M. Immergut in 1990, in a comparative case study of healthcare reform in different political systems.[140] Breaking with earlier scholarship, Immergut argued that "we have veto points within political systems and not veto groups within societies."[141] Veto player analysis draws on game theory. George Tsebelis first developed it in 1995 and set it forth in detail in 2002 Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work.[142] A veto player is a political actor who has the ability to stop a change from the status quo.[143] There are institutional veto players, whose consent is required by constitution or statute; for example, in US federal legislation, the veto players are the House, Senate and presidency.[144] There are also partisan veto players, which are groups that can block policy change from inside an institutional veto player.[145] In a coalition government the partisan veto players are typically the members of the governing coalition.[145][146] According to Tsebelis' veto player theorem, policy change becomes harder the more veto players there are, the greater the ideological distance between them, and the greater their internal coherence.[143] For example, Italy and the United States have stable policies because they have many veto players, while Greece and the United Kingdom have unstable policies because they have few veto players.[147] While the veto player and veto point approaches complement one another, the veto players framework has become dominant in the study of policy change.[148] Scholarship on rational choice theory has favored the veto player approach because the veto point framework does not address why political actors decide to use a veto point.[5] In addition, because veto player analysis can apply to any political system, it provides a way of comparing very different political systems, such as presidential and parliamentary systems.[5] Veto player analyses can also incorporate people and groups that have de facto power to prevent policy change, even if they do not have the legal power to do so.[149] Some literature distinguishes cooperative veto points (within institutions) and competitive veto points (between institutions), theorizing competitive veto points contribute to obstructionism.[150] Some literature disagrees with the claim of veto player theory that multiparty governments are likely to be gridlocked.[150] |

拒否権理論 政治学において、人民や集団が変化を阻止する広範な権力は、拒否権ポイントと拒否権プレイヤーという枠組みを通じて分析されることがある。拒否権プレイ ヤーとは、政府政策の変更に対して何らかの拒否権を行使し得る主体である[5]。拒否権ポイントとは、これらの主体に拒否権を行使する能力を与える制度的 機会を指す。[5] 拒否権ポイント理論は、1990年にエレン・M・イマーガットが異なる政治制度における医療改革の比較事例研究で初めて提唱したものである。[140] 従来の学説とは一線を画し、イマーガットは「社会内に拒否権グループが存在するのではなく、政治制度内に拒否権ポイントが存在する」と主張した。 [141] 拒否権プレイヤー分析はゲーム理論を基盤とする。ジョージ・ツェベリスが1995年に初めて提唱し、2002年の著書『拒否権プレイヤー:政治制度の仕組 み』で詳細に展開した[142]。拒否権プレイヤーとは現状変更を阻止できる政治主体を指す[143]。憲法や法令で同意が義務付けられた制度的拒否権プ レイヤーが存在する。例えば米国連邦立法では、下院・上院・大統領がこれに該当する。[144] また党派的拒否権プレイヤーも存在する。これは制度的拒否権プレイヤー内部から政策変更を阻止できる集団である。[145] 連立政権においては、党派的拒否権プレイヤーは通常、与党連立の構成員である。[145][146] ツェベリスの拒否権プレイヤー定理によれば、政策変更は、拒否権プレイヤーの数が増えるほど、それらの間のイデオロギー的距離が大きくなるほど、そして内 部の一貫性が高まるほど困難になる。[143] 例えばイタリアとアメリカは拒否権プレイヤーが多いため政策が安定している一方、ギリシャとイギリスは拒否権プレイヤーが少ないため政策が不安定である。 [147] 拒否権プレイヤーと拒否点のアプローチは互いに補完し合うが、政策変更の研究では拒否権プレイヤーの枠組みが主流となっている。[148] 合理的選択理論の研究では、拒否権行使主体アプローチが重視されてきた。拒否権行使ポイント枠組みでは、政治主体がなぜ拒否権行使ポイントを使う決断をす るのかが説明されないからだ。[5] さらに、拒否権行使主体分析はあらゆる政治制度に適用可能であるため、大統領制と議会制のような非常に異なる政治制度を比較する手段を提供する。[5] 拒否権行使主体分析は、法的権限を持たない場合でも、事実上政策変更を阻止する力を持つ人々や集団も組み込むことができる。[149] 一部の文献では、協力的な拒否権ポイント(制度内)と競争的な拒否権ポイント(制度間)を区別し、競争的な拒否権ポイントが妨害主義に寄与すると理論化し ている。[150] また、複数政党制政府は行き詰まりやすいという拒否権プレイヤー理論の主張に異議を唱える文献もある。[150] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veto |

☆一般解説(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veto)

| A veto is a legal power

to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a

president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In

many countries, veto powers are established in the country's

constitution. Veto powers are also found at other levels of government,

such as in state, provincial or local government, and in international

bodies. |

拒否権とは、公式な行動を一方的に阻止する法的権限である。最も典型的

なケースでは、大統領や君主が法案を拒否し、それが法律となるのを阻止する。多くの国では、拒否権は憲法で定められている。拒否権は他の政府レベル、例え

ば州政府、地方政府、国際機関などでも見られる。 |

| Some vetoes can be overcome,

often by a supermajority vote: in the United States, a two-thirds vote

of the House and Senate can override a presidential veto.[1] Some

vetoes, however, are absolute and cannot be overridden. For example, in

the United Nations Security Council, the five permanent members (China,

France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) have an

absolute veto over any Security Council resolution. In many cases, the veto power can only be used to prevent changes to the status quo. But some veto powers also include the ability to make or propose changes. For example, the Indian president can use an amendatory veto to propose amendments to vetoed bills. The executive power to veto legislation is one of the main tools that the executive has in the legislative process, along with the proposal power.[2] It is most commonly found in presidential and semi-presidential systems.[3] In parliamentary systems, the head of state often has either a weak veto power or none at all.[4] But while some political systems do not contain a formal veto power, all political systems contain veto players, people or groups who can use social and political power to prevent policy change.[5] The word "veto" comes from the Latin for "I forbid". The concept of a veto originated with the Roman offices of consul and tribune of the plebs. There were two consuls every year; either consul could block military or civil action by the other. The tribunes had the power to unilaterally block any action by a Roman magistrate or the decrees passed by the Roman Senate.[6] |

拒否権の中には、しばしば過半数以上の賛成票によって覆されるものもあ

る。例えばアメリカでは、下院と上院の3分の2の賛成で大統領の拒否権を覆すことができる[1]。しかし、絶対的な拒否権もあり、これは覆すことができな

い。例えば国連安全保障理事会では、常任理事国5カ国(中国、フランス、ロシア、イギリス、アメリカ)が、いかなる安保理決議に対しても絶対的な拒否権を

持つ。 多くの場合、拒否権は現状変更を防ぐためだけに使える。だが、拒否権の中には変更を提案する能力も含むものもある。例えば、インドの大統領は修正拒否権を 使って、拒否された法案への修正を提案できる。 立法に対する拒否権は、立法過程において行政府が持つ主要な手段の一つであり、提案権と並ぶものだ[2]。これは大統領制や準大統領制で最もよく見られ る。[3] 議会制では、国家元首の拒否権は弱いか、あるいは全く存在しないことが多い。[4] ただし、正式な拒否権を定めていない政治体制もある一方で、全ての政治体制には拒否権を行使する主体、すなわち社会的・政治的権力を用いて政策変更を阻止 できる人々や集団が存在する。[5] 「拒否権(veto)」という言葉はラテン語の「私は禁ずる」に由来する。拒否権の概念は、ローマの執政官と平民の護民官の職位に起源を持つ。毎年二人の 執政官がおり、いずれの執政官も他方の軍事的・民事的行動を阻止できた。護民官は、ローマの行政官によるあらゆる行動や元老院で可決された法令を単独で阻 止する権限を有していた。[6] |

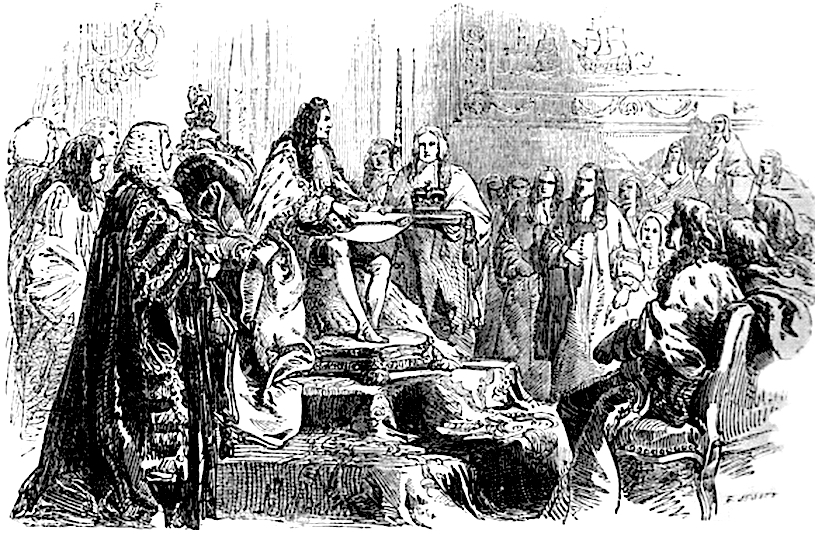

| History Roman veto  Tiberius Gracchus, Roman tribune The institution of the veto, known to the Romans as the intercessio, was adopted by the Roman Republic in the 6th century BC to enable the tribunes to protect the mandamus interests of the plebeians (common citizenry) from the encroachments of the patricians, who dominated the Senate. A tribune's veto did not prevent the senate from passing a bill but meant that it was denied the force of law. The tribunes could also use the veto to prevent a bill from being brought before the plebeian assembly. The consuls also had the power of veto, as decision-making generally required the assent of both consuls. If they disagreed, either could invoke the intercessio to block the action of the other. The veto was an essential component of the Roman conception of power being wielded not only to manage state affairs but to moderate and restrict the power of the state's high officials and institutions.[6] A notable use of the Roman veto occurred in the Gracchan land reform, which was initially spearheaded by the tribune Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC. When Gracchus' fellow tribune Marcus Octavius vetoed the reform, the Assembly voted to remove him on the theory that a tribune must represent the interests of the plebeians. Later, senators outraged by the reform murdered Gracchus and several supporters, setting off a period of internal political violence in Rome.[7] |

歴史 ローマの拒否権  ティベリウス・グラックス、ローマの護民官 拒否権(ローマではintercessioと呼ばれた)は、紀元前6世紀にローマ共和国で採用された制度である。護民官が、元老院を支配する貴族階級によ る侵害から平民(一般市民)の権利を守ることを可能にするためであった。護民官の拒否権行使は元老院の法案可決を阻止しなかったが、その法案に法的効力を 与えないことを意味した。護民官はまた、法案が平民議会に提出されるのを阻止するためにも拒否権を行使できた。執政官も拒否権を有しており、意思決定には 通常両執政官の同意が必要だった。意見が対立した場合、いずれかがインターセッシオを発動して相手の行動を阻止できたのである。拒否権は、国家の権力が国 家事務を管理するだけでなく、国家の高官や機関の権力を抑制・制限するために行使されるというローマの権力観において不可欠な要素であった。[6] ローマの拒否権の顕著な行使例は、紀元前133年に護民官ティベリウス・グラックスが主導したグラックス兄弟の土地改革に見られる。同護民官マルクス・オ クタウィウスが改革案に拒否権を行使すると、護民官は平民の利益を代表すべきだという理論に基づき、民会はその解任を決議した。その後、改革案に激怒した 元老院議員たちがグラックスとその支持者数名を殺害し、ローマでは内政的な暴力の時代が始まった。 |

| Liberum veto Main article: Liberum veto In the constitution of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 17th and 18th centuries, all bills had to pass the Sejm or "Seimas" (parliament) by unanimous consent, and if any legislator invoked the liberum veto, this not only vetoed that bill but also all previous legislation passed during the session, and dissolved the legislative session itself. The concept originated in the idea of "Polish democracy" as any Pole of noble extraction was considered as good as any other, no matter how low or high his material condition might be. The more and more frequent use of this veto power paralyzed the power of the legislature and, combined with a string of weak figurehead kings, led ultimately to the partitioning and the dissolution of the Polish state in the late 18th century. |

リベラム・ヴェート 詳細な記事: リベラム・ヴェート 17世紀から18世紀にかけてのポーランド・リトアニア共和国の憲法では、全ての法案はセイム(議会)の全会一致による同意を得なければ成立しなかった。 もし議員がリベラム・ヴェートを発動すれば、その法案だけでなく、その会期中に可決された全ての既成法案も否決され、議会そのものが解散されることになっ た。この概念は「ポーランド民主主義」の思想に由来する。貴族出身のポーランド人は、物質的状況の高低にかかわらず、皆平等とみなされたのだ。この拒否権 の乱用は立法府の機能を麻痺させ、弱体な名目上の国王が続いたことも相まって、18世紀後半にはポーランド国家の分割と解体へとつながった。 |

Emergence of modern vetoes William III of England granting royal assent to the Toleration Act 1688 The modern executive veto derives from the European institution of royal assent, in which the monarch's consent was required for bills to become law. This in turn had evolved from earlier royal systems in which laws were simply issued by the monarch, as was the case for example in England until the reign of Edward III in the 14th century.[8] In England itself, the power of the monarch to deny royal assent was not used after 1708, but it was used extensively in the British colonies. The heavy use of this power was mentioned in the U.S. Declaration of Independence in 1776.[9] Following the French Revolution in 1789, the royal veto was hotly debated, and hundreds of proposals were put forward for different versions of the royal veto, as either absolute, suspensive, or nonexistent.[10] With the adoption of the French Constitution of 1791, King Louis XVI lost his absolute veto and acquired the power to issue a suspensive veto that could be overridden by a majority vote in two successive sessions of the Legislative Assembly, which would take four to six years.[11] With the abolition of the monarchy in 1792, the question of the French royal veto became moot.[11] The presidential veto was conceived in by republicans in the 18th and 19th centuries as a counter-majoritarian tool, limiting the power of a legislative majority.[12] Some republican thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson, however, argued for eliminating the veto power entirely as a relic of monarchy.[13] To avoid giving the president too much power, most early presidential vetoes, such as the veto power in the United States, were qualified vetoes that the legislature could override.[13] But this was not always the case: the Chilean constitution of 1833, for example, gave that country's president an absolute veto.[13] |

現代の拒否権の出現 イングランドのウィリアム3世が1688年寛容法に王室裁可を与える 現代の行政拒否権は、法案が法律となるには君主の同意が必要だったヨーロッパの王室裁可制度に由来する。これはさらに、例えば14世紀のエドワード3世の 治世までイングランドで見られたように、法律が単に君主によって発布されるという以前の王権制度から発展したものである。[8] イングランド国内では、1708年以降、国王が王室裁可を拒否する権限は行使されなかったが、英国の植民地では広く行使された。この権限の多用は、 1776年のアメリカ独立宣言でも言及されている。 1789年のフランス革命後、王の拒否権は激しく議論され、絶対的拒否権、停止的拒否権、あるいは拒否権そのものの廃止など、異なる形態の王の拒否権に関 する数百もの提案がなされた。[10] 1791年のフランス憲法採択により、ルイ16世は絶対拒否権を失い、立法議会における二期連続の多数決で覆される可能性のある停止拒否権を獲得した。こ の手続きには4年から6年を要した。[11] 1792年の君主制廃止により、フランス王室拒否権の問題は意味をなさなくなった。[11] 大統領拒否権は18~19世紀の共和主義者によって、多数派支配を抑制する手段として考案された。[12] しかしトーマス・ジェファーソンら一部の共和主義思想家は、君主制の名残として拒否権そのものの廃止を主張した。[13] 大統領に過大な権力を与えないため、初期の大統領拒否権(例えばアメリカ合衆国の拒否権)の多くは、議会が覆すことのできる限定拒否権であった。[13] しかし常にそうだったわけではない。例えば1833年のチリ憲法は、同国大統領に絶対拒否権を付与していた。[13] |

US President Ronald Reagan signing a veto of a bill |

アメリカ合衆国大統領ロナルド・レーガンが法案の拒否権行使に署名する |

| Types Most modern vetoes are intended as a check on the power of the government, or a branch of government, most commonly the legislative branch. Thus, in governments with a separation of powers, vetoes may be classified by the branch of government that enacts them: an executive veto, legislative veto, or judicial veto. However, other types of veto power have safeguarded other interests. The denial of royal assent by governors in the British colonies, which continued well after the practice had ended in Britain itself, served as a check by one level of government against another.[8] Vetoes may also be used to safeguard the interests of particular groups within a country. The veto power of the ancient Roman tribunes protected the interests of one social class (the plebeians) against another (the patricians).[14] In the transition from apartheid, a "white veto" to protect the interests of white South Africans was proposed but not adopted.[15] More recently, indigenous vetoes over industrial projects on indigenous land have been proposed following the 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which requires the "free, prior and informed consent" of indigenous communities to development or resource extraction projects on their land. However, many governments have been reluctant to allow such a veto.[16] Vetoes may be classified by whether the vetoed body can override them, and if so, how. An absolute veto cannot be overridden at all. A qualified veto can be overridden by a supermajority, such as two-thirds or three-fifths. A suspensory veto, also called a suspensive veto, can be overridden by a simple majority, and thus only delays the law from coming into force.[17] |

種類 現代の拒否権の大半は、政府または政府機関(最も一般的なのは立法府)の権力を抑制する目的で設けられている。したがって、三権分立の政府においては、拒 否権を発動する政府機関によって分類される:行政拒否権、立法拒否権、司法拒否権である。 しかし、他の種類の拒否権は別の利益を保護してきた。英国本国では廃止された後も長く続いた英国植民地総督による国王の裁可拒否は、ある政府レベルが別の レベルを抑制する手段として機能した[8]。拒否権は国内の特定集団の利益を守るためにも用いられる。古代ローマの護民官の拒否権は、ある社会階級(平 民)の利益を別の階級(貴族)から守る役割を果たした[14]。アパルトヘイトからの移行期には、白人南アフリカ人の利益を守る「白人拒否権」が提案され たが採用されなかった[15]。近年では、2007年の「先住民の権利に関する宣言」を受けて、先住民族の土地における産業プロジェクトに対する先住民族 の拒否権が提案されている。同宣言は、先住民族の土地での開発や資源採掘プロジェクトに対し、先住民族コミュニティの「自由で事前かつ十分な情報に基づく 同意」を要求している。しかし多くの政府は、このような拒否権を認めることに消極的だ。[16] 拒否権は、拒否された機関がそれを覆せるかどうか、また覆せる場合の方法を基準に分類できる。絶対拒否権は一切覆せない。条件付き拒否権は、3分の2や5 分の3といった過半数によって覆せる。停止拒否権(保留拒否権とも呼ばれる)は単純過半数で覆せるため、法律の発効を遅らせるだけである。[17] |

Types of executive vetoes US President Bill Clinton signing cancellation letters related to his line-Item vetoes for the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 A package veto, also called a "block veto" or "full veto", vetoes a legislative act as a whole. Conversely, a partial veto, also called a line-item veto, allows the executive to object only to some specific part of the law while allowing the rest to stand. An executive with a partial veto has a stronger negotiating position than an executive with only a package veto power.[3] An amendatory veto or amendatory observation returns legislation to the legislature with proposed amendments, which the legislature may either adopt or override. The effect of legislative inaction may vary: in some systems, if the legislature does nothing, the vetoed bill fails, while in others, the vetoed bill becomes law. Because the amendatory veto gives the executive a stronger role in the legislative process, it is often seen as a marker of a particularly strong veto power. Some veto powers are limited to budgetary matters (as with line-item vetoes in some US states, or the financial veto in New Zealand).[18] Other veto powers (such as in Finland) apply only to non-budgetary matters; some (such as in South Africa) apply only to constitutional matters. A veto power that is not limited in this way is known as a "policy veto".[3] One type of budgetary veto, the reduction veto, which is found in several US states, gives the executive the authority to reduce budgetary appropriations that the legislature has made.[18] When an executive is given multiple different veto powers, the procedures for overriding them may differ. For example, in the US state of Illinois, if the legislature takes no action on a reduction veto, the reduction simply becomes law, while if the legislature takes no action on an amendatory veto, the bill dies.[19] A pocket veto is a veto that takes effect simply by the executive or head of state taking no action. In the United States, the pocket veto can only be exercised near the end of a legislative session; if the deadline for presidential action passes during the legislative session, the bill will simply become law.[20] The legislature cannot override a pocket veto.[2] Some veto powers are limited in their subject matter. A constitutional veto only allows the executive to veto bills that are unconstitutional; in contrast, a "policy veto" can be used wherever the executive disagrees with the bill on policy grounds.[3] Presidents with constitutional vetoes include those of Benin and South Africa. |

大統領拒否権の種類 1997年均衡予算法に対する項目別拒否権行使に関連した取消書簡に署名するビル・クリントン米大統領 包括拒否権(ブロック拒否権または全面拒否権とも呼ばれる)は、立法行為全体を拒否する。これに対し、部分拒否(項目別拒否とも呼ばれる)では、行政機関 は法律の特定部分のみに異議を唱え、残りの部分は有効とする。部分拒否権を持つ行政機関は、包括拒否権のみを持つ行政機関よりも強い交渉力を有する [3]。修正拒否(修正意見付き拒否)は、修正案を添えて立法府に法案を差し戻すもので、立法府はこれを採択するか、覆すかを選択できる。立法府の不作為 による効果は制度によって異なる。立法府が何もしなければ拒否された法案が廃案となる制度もあれば、逆に成立する制度もある。修正拒否権は行政府に立法過 程でより強い役割を与えるため、特に強力な拒否権の指標と見なされることが多い。 一部の拒否権は予算問題に限定される(米国一部の州における項目別拒否権や、ニュージーランドの財政拒否権など)。[18] 他の拒否権(フィンランドなど)は非予算事項のみに適用され、一部(南アフリカなど)は憲法事項のみに適用される。このように限定されない拒否権は「政策 拒否権」と呼ばれる。[3] 予算拒否権の一種である削減拒否権(米国の複数の州で採用)は、行政府に立法府が定めた予算配分を削減する権限を与える。[18] 行政機関に複数の異なる拒否権が与えられる場合、それらを覆す手続きは異なることがある。例えば米国イリノイ州では、議会が減額拒否権に対して何の行動も 取らない場合、その減額は単に法律となる。一方、議会が修正拒否権に対して何の行動も取らない場合、法案は廃案となる。[19] ポケット拒否とは、行政機関または国家元首が何の行動も取らないだけで効力を生じる拒否権である。米国では、ポケット拒否は立法会期の終了間際のみ行使可 能である。立法会期中に大統領の行動期限が過ぎれば、法案は単に法律となる。[20] 立法府はポケット拒否を覆すことはできない。[2] 拒否権には対象が限定されるものもある。憲法上の拒否権は、行政機関が違憲な法案のみを拒否できる。これに対し「政策拒否権」は、行政機関が政策上の理由 で法案に反対する場合にいつでも行使できる。[3] 憲法上の拒否権を持つ大統領には、ベナンや南アフリカの例がある。 |

| Legislative veto Main article: Legislative veto A legislative veto is a veto power exercised by a legislative body. It may be a veto exercised by the legislature against an action of the executive branch, as in the case of the legislative veto in the United States, which is found in 28 US states.[21] It may also be a veto power exercised by one chamber of a bicameral legislature against another, such as was formerly held by members of the Senate of Fiji appointed by the Great Council of Chiefs.[22] Veto over candidates In certain political systems, a particular body is able to exercise a veto over candidates for an elected office. This type of veto may also be referred to by the broader term "vetting". Historically, certain European Catholic monarchs were able to veto candidates for the papacy, a power known as the jus exclusivae. This power was used for the last time in 1903 by Franz Joseph I of Austria.[23] In Iran, the Guardian Council has the power to approve or disapprove candidates, in addition to its veto power over legislation. In China, following a pro-democracy landslide in the 2019 Hong Kong local elections, in 2021 the National People's Congress approved a law that gave the Candidate Eligibility Review Committee, appointed by the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, the power to veto candidates for the Hong Kong Legislative Council.[24] |

立法府による拒否権 詳細な記事: 立法府による拒否権 立法府による拒否権とは、立法機関が行使する拒否権を指す。これは、行政府の行為に対して立法府が行使する拒否権である場合もある。例えば、アメリカ合衆 国における立法府による拒否権がこれに該当し、同国では28州で認められている。[21] また、二院制議会において一院が他院に対して行使する拒否権の場合もある。例えば、かつてフィジーの大首長評議会によって任命された上院議員が有していた 権限がこれに当たる。[22] 候補者に対する拒否権 特定の政治制度では、特定の機関が選挙による公職の候補者に対して拒否権を行使できる。この種の拒否権は、より広義の用語「審査(ベッティング)」とも呼 ばれることがある。 歴史的に、一部のヨーロッパのカトリック君主は教皇候補者に対する拒否権(jus exclusivae)を行使できた。この権限は1903年にオーストリア皇帝フランツ・ヨーゼフ1世によって最後に使用された。 イランでは、護憲評議会が立法に対する拒否権に加え、候補者の承認・否認権限を有する。 中国では、2019年の香港地方選挙で民主派が圧勝したことを受け、2021年に全国人民代表大会が法律を可決した。これにより、香港行政長官が任命する 候補者資格審査委員会が、香港立法会選挙の候補者を拒否する権限を与えられた。[24] |

| Balance of powers Main article: Balance of powers In presidential and semi-presidential systems, the veto is a legislative power of the presidency, because it involves the president in the process of making law. In contrast to proactive powers such as the ability to introduce legislation, the veto is a reactive power, because the president cannot veto a bill until the legislature has passed it.[25] Executive veto powers are often ranked as comparatively "strong" or "weak". A veto power may be considered stronger or weaker depending on its scope, the time limits for exercising it and requirements for the vetoed body to override it. In general, the greater the majority required for an override, the stronger the veto.[3] Partial vetoes are less vulnerable to override than package vetoes,[26] and political scientists who have studied the matter have generally considered partial vetoes to give the executive greater power than package vetoes.[27] However, empirical studies of the line-item veto in US state government have not found any consistent effect on the executive's ability to advance its agenda.[28] Amendatory vetoes give greater power to the executive than deletional vetoes, because they give the executive the power to move policy closer to its own preferred state than would otherwise be possible.[29] But even a suspensory package veto that can be overridden by a simple majority can be effective in stopping or modifying legislation. For example, in Estonia in 1993, president Lennart Meri was able to successfully obtain amendments to the proposed Law on Aliens after issuing a suspensory veto of the bill and proposing amendments based on expert opinions on European law.[26] |

権力分立 詳細な記事: 権力分立 大統領制及び半大統領制において、拒否権は大統領の立法権に属する。これは大統領が法律制定過程に関与するためである。法案提出権のような積極的権限とは 異なり、拒否権は反応的権限である。立法府が法案を可決するまで大統領は拒否権を行使できないからだ。[25] 行政機関の拒否権は、しばしば比較的「強い」または「弱い」と評価される。拒否権の範囲、行使期限、拒否された機関による覆しの要件によって、その強弱は 変わる。一般に、覆しに必要な多数決の要件が厳しいほど、拒否権は強いとされる。[3] 部分拒否権は包括拒否権よりも覆されにくい[26]。この問題を研究した政治学者らは概して、部分拒否権が包括拒否権よりも行政府に大きな権限を与えると 考える[27]。しかし、米国州政府における項目別拒否権の実証研究では、行政府の政策推進能力に対する一貫した効果は確認されていない。修正拒否権は削 除拒否権よりも行政府に大きな権限を与える。なぜなら修正拒否権は、行政府が政策を自らの望む状態に近づける力を与えるからだ[29]。しかし、単純過半 数で覆せる停止型一括拒否権でさえ、立法を阻止または修正する上で効果を発揮し得る。例えば1993年のエストニアでは、レンナート・メリ大統領が外国人 法案に停止拒否権を行使した後、欧州法に関する専門家の意見に基づく修正案を提案し、提案された外国人法への修正を成功裏に獲得した。[26] |

Worldwide United Nations Security Council meeting room Globally, the executive veto over legislation is characteristic of presidential and semi-presidential systems, with stronger veto powers generally being associated with stronger presidential powers overall.[3] In parliamentary systems, the veto power of the head of state is typically weak or nonexistent.[4] In particular, in Westminster systems and most constitutional monarchies, the power to veto legislation by withholding royal assent is a rarely used reserve power of the monarch. In practice, the Crown follows the convention of exercising its prerogative on the advice of parliament. International bodies United Nations: The five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council have an absolute veto over Security Council resolutions, except for procedural matters.[30] Every permanent member has used this power at some point.[31] A permanent member that wants to disagree with a resolution, but not to veto it, can abstain.[31] The first country to use the latter power was the USSR in 1946, after its amendments to a resolution regarding the withdrawal of British troops from Lebanon and Syria were rejected.[32] Further information: United Nations Security Council veto power European Union: The members of the EU Council have veto power in certain areas, such as foreign policy and the accession of a new member state, due to the requirement of unanimity in these areas. For example, Bulgaria has used this power to block accession talks for North Macedonia,[33] and in the 1980s, the United Kingdom (then a member of the EU's precursor, the EEC) secured the UK rebate by threatening to use its veto power to stall legislation.[34] In addition, when the Parliament and Council delegate legislative authority to the Commission, they can provide for a legislative veto over regulations that the Commission issues under that delegated authority.[35][36] This power was first introduced in 2006 as "regulatory procedure with scrutiny", and since 2009 as "delegated acts" under the Lisbon Treaty.[37] This legislative veto power has been used sparingly: from 2006 to 2016, the Parliament issued 14 vetoes and the Council issued 15.[37] Further information: Voting in the Council of the European Union and European Union legislative procedure |

全世界 国連安全保障理事会議場 世界的に見て、立法に対する行政の拒否権は大統領制および準大統領制の特徴であり、拒否権が強力であるほど、大統領権限全体がより強大である傾向がある。 [3] 議会制では、国家元首の拒否権は通常弱い、あるいは存在しない。[4] 特にウェストミンスター式議会制やほとんどの立憲君主制では、国王の裁可を保留することで立法を拒否する権限は、君主がめったに使わない予備的権限であ る。実際には、王室は議会の助言に基づいてその特権を行使するという慣例に従っている。 国際機関 国際連合:国連安全保障理事会の常任理事国5カ国は、手続き上の事項を除き、安保理決議に対して絶対的拒否権を有する。[30] 全ての常任理事国がこの権限を行使したことがある。[31] 決議に反対するが拒否権を行使したくない常任理事国は、棄権することができる。[31] 棄権権を初めて行使したのは1946年のソ連である。レバノンとシリアからの英国軍撤退に関する決議への修正案が否決された後のことだった。[32] 詳細情報: 国連安全保障理事会の拒否権 欧州連合: EU理事会のメンバーは、外交政策や新規加盟国の承認など特定の分野において拒否権を持つ。これらの分野では全会一致が要求されるためである。例えばブル ガリアはこの権限を用いて北マケドニアの加盟交渉を阻止した[33]。また1980年代には、英国(当時EUの前身であるEEC加盟国)が拒否権行使で立 法を遅延させると脅し、英国リベートを確保した。[34] さらに、議会と理事会が立法権限を欧州委員会に委任する場合、委員会がその委任権限に基づいて発行する規則に対して立法拒否権を行使できる規定を設けるこ とができる。[35][36] この権限は2006年に「審査付き規制手続」として初めて導入され、2009年以降はリスボン条約に基づく「委任行為」として運用されている。[37] この立法拒否権は控えめに使用されてきた。2006年から2016年にかけて、議会は14回、理事会は15回の拒否権を発動した。[37] 詳細情報:欧州連合理事会における投票と欧州連合の立法手続き |

| Africa Africa Benin: The president can return legislation to the National Assembly for reconsideration within 15 days (or 5 days if the legislation is declared urgent).[38] The National Assembly can override the veto by passing the legislation once again by an absolute majority.[38][39] If the president then vetoes the legislation a second time, the National Assembly can ask the Constitutional Court to rule on its constitutionality. If the Court rules that the legislation is constitutional, it becomes law.[40][39] If the president neither approves nor returns legislation within the prescribed 15- or 5-day period, this operates as a veto, and the National Assembly can petition the Court to declare the law constitutional and effective.[39] This occurred for example in 2008, when President Yayi did not take action on a bill that would set an end date to the "exceptional measures" by which he had kept the National Assembly in session. After pocket-vetoing the bill in this way, the president petitioned the Court for constitutional review.[41] The Court ruled that once the deadline for presidential action had passed, only the National Assembly could petition for review, which it did (and prevailed).[41] Further information: Politics of Benin Cameroon: The president has the power to send bills back to the Parliament for a second reading.[42] This power must be exercised within 15 days.[43] On second reading the bill must be passed by an absolute majority to become law.[42] Further information: Government of Cameroon Liberia: The president has package, line item and pocket veto powers under Article 35 of the 1986 Constitution. The President has twenty days to sign a bill into law, but may veto either the entire bill or parts of it, after which the Legislature must re-pass it with a two-thirds majority of both houses. If the President does not sign a bill within twenty days and the Legislature adjourns, the bill fails.[44] Further information: Politics of Liberia South Africa: The president has a weak constitutional veto.[45] The president can return a bill to the National Assembly if the president has reservations about the bill's constitutionality.[46] If the National Assembly passes the bill a second time, the president must either sign it or refer it to the Constitutional Court of South Africa for a final decision on whether the bill is constitutional.[46] If there are no constitutional concerns, the president's assent to legislation is mandatory. Further information: Politics of South Africa Uganda: The president has package veto and item veto powers.[47] This power must be exercised within 30 days of receiving the legislation.[47] The first time the president returns a bill to the Parliament, the Parliament can pass it again by a simple majority vote. If the president returns it a second time, the Parliament can override the veto with a two-thirds vote.[47] This occurred for example in the passage of the Income Tax Amendment Act 2016, which exempted legislators' allowances from taxation.[48][49] Further information: Politics of Uganda Zambia: Under the 1996 constitution, the president had an absolute pocket veto: if he neither assented to legislation nor returned it to parliament for a potential override, it was permanently dead.[50] This unusual power was eliminated in a general reorganization of the Constitution's legislative provisions in 2016.[51][52] Further information: Politics of Zambia |

アフリカ アフリカ ベナン:大統領は法案を15日以内に(緊急法案の場合は5日以内に)国民議会に差し戻し、再審議を求めることができる。[38] 国民議会は絶対多数で法案を再可決することにより、拒否権を覆すことができる。[38] [39] 大統領が再び拒否権を行使した場合、国民議会は憲法裁判所にその合憲性について判断を求めることができる。裁判所が合憲と判断した場合、その法案は法律と なる。[40] [39] 大統領が定められた15日または5日以内に法案を承認も差し戻しもしない場合、これは拒否権行使とみなされ、国会は憲法裁判所に対し、当該法律の合憲性と 効力を宣言するよう申し立てることができる。[39] 例えば2008年、ヤイ大統領が国会を継続会期状態に置くための「特別措置」の終了日を定める法案に対して何らの措置も取らなかった事例がこれに該当す る。大統領はこの方法で法案をポケット拒否した後、憲法裁判所へ審査を申し立てた。[41] 裁判所は、大統領の行動期限が過ぎれば、国民議会のみが審査を申し立てられると裁定し、議会は実際に申し立てを行い(そして勝訴した)。[41] 詳細情報:ベナン政治 カメルーン:大統領は法案を議会に差し戻し、再審議を求める権限を持つ[42]。この権限は15日以内に行使されねばならない[43]。再審議では法案は 絶対多数で可決されなければ法律とならない[42]。 詳細情報:カメルーン政府 リベリア:1986年憲法第35条に基づき、大統領は包括拒否権、項目別拒否権、ポケット拒否権を有する。大統領は法案成立に20日間の署名期限を持つ が、法案全体または一部を拒否できる。拒否後、議会は両院の3分の2多数で再可決する必要がある。大統領が20日以内に署名せず議会が閉会した場合、法案 は廃案となる。[44] 詳細情報:リベリアの政治 南アフリカ:大統領は憲法上弱い拒否権を持つ。[45] 大統領は法案の合憲性に懸念がある場合、国民議会に差し戻すことができる。[46] 国民議会が法案を再可決した場合、大統領は署名するか、法案の合憲性に関する最終判断を南アフリカ憲法裁判所に付託しなければならない。[46] 憲法上の懸念がない場合、大統領の立法への同意は義務付けられている。 詳細情報:南アフリカの政治 ウガンダ:大統領は包括拒否権と個別拒否権を有する。[47] この権限は立法を受け取ってから30日以内に行使しなければならない。[47] 大統領が初めて法案を議会に差し戻した場合、議会は単純過半数で再可決できる。大統領が二度目に差し戻した場合、議会は3分の2の賛成で拒否権を覆せる。 [47] 例えば2016年所得税改正法の成立時、議員手当の非課税化がこれによる。[48] [49] 詳細情報:ウガンダの政治 ザンビア:1996年憲法下では、大統領は絶対的なポケット拒否権を有していた。つまり、法案に署名もせず、議会に差し戻して拒否権の覆しを可能にするこ ともなければ、その法案は永久に廃案となる仕組みだった。[50] この特異な権限は、2016年の憲法立法規定全般の見直しにより廃止された。[51][52] 詳細情報:ザンビアの政治 |

| Americas The Americas Brazil: The President of the Republic is entitled to veto, entirely or partially, any bill which passes both houses of the National Congress, exceptions made to constitutional amendments and congressional decrees. The partial veto can involve the entirety of paragraphs, articles or items, not being allowed to veto isolated words or sentences. National Congress has the right to override the presidential veto if the majority of members from each of both houses agree to, that is, 257 deputies and 41 senators. If these numbers are not met, the presidential veto stands.[53] Further information: Government of Brazil Canada: The King-in-Council (in practice the Cabinet of the United Kingdom) might instruct the governor general to withhold the king's assent, allowing the sovereign two years to disallow the bill, thereby vetoing it.[54] Last used in 1873, the power was effectively nullified diplomatically and politically by the Balfour Declaration of 1926, and legally by the Statute of Westminster 1931. At the province level, lieutenant governors can reserve royal assent to provincial bills for consideration by the federal cabinet. This clause was last invoked in 1961 by the lieutenant governor of Saskatchewan.[55] In addition, the Governor General in Council (federal cabinet) may disallow an enactment of a provincial legislature within one year of its passage. Further information: Disallowance and reservation in Canada Dominican Republic: The president has only a package veto (observación a la ley), which must be exercised within 10 days after the legislation is passed.[56] The veto must include a rationale.[56] If both chambers of the Congress of the Dominican Republic vote to override the veto, the bill becomes law.[56] Further information: Government of the Dominican Republic Ecuador: The president has powers of package veto and amendatory veto (veto parcial).[57] The president must issue a veto within 10 days after the bill is passed. The National Assembly can override an amendatory veto by a two-thirds majority of all members, but if it does not do so within 30 days of the veto, the legislation becomes law with the president's amendments.[57][58] The National Assembly overrides approximately 20% of amendatory vetoes.[59] The legislature must wait for a year before overriding a package veto.[57] Further information: Government of Ecuador El Salvador: The president has both package veto and amendatory veto powers, which must be exercised within eight days of the legislation being passed by the Legislative Assembly.[60] If the Legislative Assembly does not vote on an amendatory veto, the legislation fails. The Legislative Assembly can either accept or override an amendatory veto by a simple majority. Overriding a block veto requires a two-thirds supermajority.[60] Further information: Government of El Salvador Mexico: The president has both package veto and amendatory veto powers, which must be exercised within ten days of the legislation being passed by the Congress of the Union.[60] Congress may override either type of veto by a two-thirds majority of voting members in each chamber.[60] However, in the case of an amendatory veto, Congress must first consider whether to accept the proposed amendments, which it may do by a simple majority of both chambers.[61] Further information: Government of Mexico United States: At the federal level, the president may veto bills passed by Congress, and Congress may override the veto by a two-thirds vote of each chamber.[62] A line-item veto was briefly enacted in the 1990s, but was declared an unconstitutional violation of the separation of powers by the Supreme Court. At the state level, all 50 state governors have a full veto, similar to the presidential veto.[63] Many state governors also have additional kinds of vetoes, such as amendatory, line-item, and reduction vetoes.[63] Gubernatorial veto powers vary in strength. The president and some state governors have a "pocket veto", in that they can delay signing a bill until after the legislature has adjourned, which effectively kills the bill without a formal veto and without the possibility of an override.[20][64] Further information: Veto power in the United States, Line-item veto in the United States, and Legislative veto in the United States |

アメリカ大陸 アメリカ大陸 ブラジル:共和国大統領は、憲法改正と議会法令を除き、国民議会の両院を通過した法案に対し、全体または一部を拒否する権利を有する。部分拒否権は段落、 条項、項目全体を対象とし、個別の単語や文を拒否することはできない。国民議会は、両院の議員の過半数(すなわち下院議員257名と上院議員41名)が同 意した場合、大統領の拒否権を覆す権利を有する。この人数に達しない場合、大統領の拒否権は有効となる。[53] 詳細情報:ブラジル政府 カナダ:国王評議会(実際には英国内閣)は総督に対し国王の裁可を保留するよう指示できる。これにより君主は2年間法案を否決する権限を持ち、事実上拒否 権を行使できる[54]。この権限は1873年を最後に使用されず、1926年のバルフォア宣言により外交的・政治的に、1931年のウェストミンスター 法により法的に無効化された。州レベルでは、副知事が州法案の国王の裁可を保留し、連邦内閣による審議を求めることができる。この条項が最後に発動された のは1961年、サスカチュワン州副知事によるものである[55]。さらに、総督会議(連邦内閣)は、州議会の制定法を可決後1年以内に否認することがで きる。 詳細情報:カナダの法案否決権と保留権 ドミニカ共和国:大統領には法案全体に対する拒否権(observación a la ley)のみが認められており、法案成立後10日以内に行使しなければならない[56]。拒否権行使には理由の明示が義務付けられる[56]。ドミニカ共 和国議会の両院が拒否権の覆しを可決した場合、法案は法律となる。[56] 詳細情報:ドミニカ共和国政府 エクアドル:大統領は一括拒否権と修正拒否権(veto parcial)を有する。[57] 大統領は法案可決後10日以内に拒否権を行使しなければならない。国民議会は全議員の3分の2以上の賛成で修正拒否権を覆せるが、拒否権発動から30日以 内に覆さなければ、大統領の修正を加えた法案が法律となる。[57][58] 国民議会が覆す修正拒否権は約20%である。[59] 包括拒否権を覆すには、議会は1年間待たねばならない。[57] 詳細情報:エクアドル政府 エルサルバドル:大統領は法案拒否権と修正拒否権の両方を有し、立法議会による法案可決後8日以内に行使しなければならない。[60] 立法議会が修正拒否権について採決を行わない場合、法案は廃案となる。立法議会は修正拒否権を単純過半数で承認または覆すことができる。法案拒否権の覆し には3分の2の過半数が必要である。[60] 詳細情報:エルサルバドル政府 メキシコ:大統領は法案全体拒否権と修正拒否権の両方を有し、連邦議会による法案可決後10日以内に行使しなければならない。[60] 議会は各院の投票議員の3分の2多数でいずれの拒否権も覆すことができる。[60] ただし修正拒否権の場合、議会はまず修正案の受諾可否を検討する必要があり、両院の単純過半数で受諾できる。[61] 詳細情報:メキシコ政府 アメリカ合衆国:連邦レベルでは、大統領は議会が可決した法案を拒否権で否決でき、議会は各院の3分の2の賛成で拒否権を覆せる。[62] 項目別拒否権は1990年代に一時的に制定されたが、最高裁により三権分立の原則に反する違憲判決を受けた。州レベルでは、全50州の知事が大統領拒否権 と同様の完全な拒否権を有する。[63] 多くの州知事は修正拒否権、項目別拒否権、削減拒否権など追加的な拒否権も有する。[63] 知事の拒否権の効力は州によって異なる。大統領および一部の州知事は「ポケット拒否権」を有している。これは、議会が閉会するまで法案への署名を遅らせる ことができ、正式な拒否権行使や覆しの可能性なしに事実上法案を廃案にできる制度である。[20][64] 詳細情報:アメリカ合衆国の拒否権、アメリカ合衆国の項目別拒否権、アメリカ合衆国の立法拒否権 |

| Asia Asia China: Under the Constitution, the National People's Congress can nullify regulations enacted by the State Council. The State Council and president do not have a veto power.[65] Further information: Government of China Georgia: The president can return a bill to the parliament with proposed amendments within two weeks of receiving the bill.[66] Parliament must first vote on the proposed amendments, which can be adopted by the same majority as for the original legislation (for ordinary legislation, a simple majority vote).[66] If Parliament does not adopt the amendments, it can override the veto by passing the original bill by an absolute majority.[66] Before the constitutional reforms of the 2010s, the president had both a package veto and an amendatory veto, which could be overridden only with a 3/5 majority.[67] Further information: Politics of Georgia (country) India: The president has three veto powers: absolute, suspension, and pocket. The president can send the bill back to parliament for changes, which constitutes a limited veto that can be overridden by a simple majority. But the bill reconsidered by the parliament becomes a law with or without the president's assent after 14 days. The president can also take no action indefinitely on a bill, sometimes referred to as a pocket veto. The president can refuse to assent, which constitutes an absolute veto. But the absolute veto can be exercised by the President only once in respect of a bill. If the President refuses to provide his assent to a bill and sends it back to Parliament, suggesting his recommendations or amendments to the bill and the Parliament passes the bill again with or without such amendments, the president is obligated to assent to the bill.[68][69][70] Further information: President of India § Important presidential interventions in the past Indonesia: Express presidential veto powers were removed from the Constitution in the 2002 democratization reforms.[71] The president can however enact a "regulation in lieu of law" (Peraturan Pemerintah Pengganti Undang-Undang or perppu), which temporarily blocks a law from taking effect.[72] The People's Representative Council (DPR) can revoke such a regulation in its next session.[73] In addition, the Constitution requires that legislation be jointly approved by the president and the DPR. The president thus can effectively block a bill by withholding approval.[72] Whether these presidential powers constitute a "veto" has been disputed, including by former Constitutional Court justice Patrialis Akbar.[74] Further information: Politics of Indonesia Iran: The Guardian Council has the authority to veto bills passed by the Islamic Consultative Assembly.[75] This veto power can be based on the legislation being contrary to the constitution or contrary to Islamic law. A constitutional veto requires a majority of the Guardian Council's members, while a veto based on Islamic law requires a majority of its fuqaha members.[76] The Guardian Council also has veto power over candidates for various elected offices.[75] Further information: Government of Iran Japan: There is no veto at the national level, as Japan has a parliamentary system and the constitution does not give the emperor authority to refuse to promulgate a law.[77][78] Under the Local Autonomy Act of 1947, however, the executive of a prefectural or municipal government can veto local legislation. If the executive believes the legislation is unlawful, the executive is required to veto it.[79] The local assembly can override this veto by a 2/3 vote.[80] Further information: Politics of Japan and Local Autonomy Act South Korea: The president can return a bill to the National Assembly for "reconsideration" (재의).[81] Partial and amendatory vetoes are expressly forbidden.[82] The National Assembly can override the veto by a 2/3 majority of the members present.[83] Such overrides are rare: when the National Assembly overrode president Roh Moo-hyun's veto of a corruption investigation in 2003, it was the first override in 49 years.[84] Further information: Government of South Korea Philippines: The president may refuse to sign a bill, sending the bill back to the house where it originated along with his objections. Congress can override the veto via a 2/3 vote with both houses voting separately, after which the bill becomes law.[85] The president may also exercise a line-item veto on money bills.[85] The president does not have a pocket veto: once the bill has been received by the president, the chief executive has thirty days to veto the bill. Once the thirty-day period expires, the bill becomes law as if the president had signed it.[86] Further information: Politics of the Philippines Uzbekistan: The president has a package veto and an amendatory veto.[87] The Legislative Chamber of the Oliy Majlis can override either type of veto by a 2/3 vote.[87] In the case of a package veto, if the veto is not overridden, the bill fails.[87] In the case of an amendatory veto, if the veto is not overridden, the bill becomes law as amended.[88] The Senate of the Oliy Majlis has a veto over legislation passed by the Legislative Chamber, which the Legislative Chamber can likewise override by a 2/3 vote.[89] Further information: Politics of Uzbekistan |

アジア アジア 中国:憲法の下で、全国人民代表大会は国務院が制定した規則を無効にできる。国務院と大統領には拒否権がない。[65] 詳細情報:中国政府 ジョージア:大統領は法案受領後2週間以内に修正案を添えて議会に差し戻すことができる。[66]議会はまず修正案について投票を行い、修正案は原法案と 同じ多数決(通常立法の場合は単純過半数)で可決される。[66] 議会が修正案を採択しない場合、絶対多数で原案を可決することで拒否権を覆せる。[66] 2010年代の憲法改正前は、大統領は包括的拒否権と修正拒否権の両方を持っており、これらは3分の2以上の多数でしか覆せなかった。[67] 詳細情報:ジョージア(国)の政治 インド:大統領には三つの拒否権がある。絶対拒否権、保留拒否権、ポケット拒否権である。大統領は法案を議会に差し戻し修正を求めることができる。これは 限定拒否権であり、単純多数決で覆される。しかし議会で再審議された法案は、14日後に大統領の同意の有無にかかわらず法律となる。大統領はまた、法案に 対して無期限に何の行動も取らないことができる。これはポケット拒否権と呼ばれることもある。大統領は同意を拒否できる。これが絶対拒否権である。ただし 絶対拒否権は、同一法案に対して大統領が行使できるのは一度だけである。大統領が法案への同意を拒否し、議会に差し戻して修正案や勧告を提示した場合、議 会が修正の有無にかかわらず法案を再可決すれば、大統領は同意を義務付けられる。[68][69] [70] 詳細情報: インド大統領 § 過去の重要な大統領介入 インドネシア: 2002年の民主化改革により、憲法から大統領の明示的拒否権が削除された。[71] ただし大統領は「法律に代わる政令」(Peraturan Pemerintah Pengganti Undang-Undang、略称perppu)を発令でき、これにより法律の施行を一時的に阻止できる。[72] 国民代表評議会(DPR)は次期会期でこの規制を廃止できる。[73] さらに憲法は、立法が大統領とDPRの共同承認を必要とすると定めている。したがって大統領は承認を保留することで法案を事実上阻止できる。[72] これらの大統領権限が「拒否権」に該当するか否かは、元憲法裁判所判事パトリアリス・アクバルらによって争われている。[74] 詳細情報:インドネシアの政治 イラン:護憲評議会は、イスラム諮問議会で可決された法案を拒否する権限を持つ。[75] この拒否権は、立法が憲法に反する場合、またはイスラム法に反する場合に行使できる。憲法に基づく拒否には護憲評議会メンバーの過半数の賛成が必要であ り、イスラム法に基づく拒否にはフカーハ(法学者)メンバーの過半数の賛成が必要である。[76] 護憲評議会はまた、様々な公職の候補者に対して拒否権を行使できる。[75] 詳細情報:イラン政府 日本:日本には議会制があり、憲法は天皇に法律公布拒否権を与えていないため、国家レベルでの拒否権は存在しない。[77][78] しかし1947年の地方自治法の下では、都道府県または市町村の行政機関が地方条例を拒否できる。行政機関が条例が違法と判断した場合、拒否することが義 務付けられている。[79] 地方議会は3分の2の賛成でこの拒否権を覆すことができる。[80] 詳細情報:日本の政治と地方自治法 韓国:大統領は法案を国会に「再審議」(재의)のために差し戻すことができる。[81] 部分拒否権及び修正拒否権は明示的に禁止されている。[82] 国会は出席議員の3分の2以上の賛成で拒否権を覆すことができる。[83] このような覆しは稀である:2003年に国会が盧武鉉(ノ・ムヒョン)大統領の汚職調査法案に対する拒否権を覆したのは、49年ぶりのことだった。 [84] 詳細情報:大韓民国政府 フィリピン:大統領は法案への署名を拒否し、異議を添えて原案提出院に送り返すことができる。議会は両院別々に3分の2の賛成で拒否権を覆すことができ、 その後法案は法律となる。[85] 大統領は歳出法案に対して項目別拒否権を行使することもできる。[85] 大統領にはポケット拒否権はない。法案が大統領に受理されると、行政長官は30日以内に拒否権を行使しなければならない。30日経過後は、大統領が署名し たものとみなされ法案は法律となる。[86] 詳細情報:フィリピンの政治 ウズベキスタン:大統領は包括的拒否権と修正拒否権を有する。[87] オリイ・マジルスの立法院は、いずれの拒否権も3分の2の賛成で覆すことができる。[87] 包括的拒否権の場合、拒否権が覆されなければ法案は廃案となる。[87] 修正拒否権の場合、拒否権が覆されない限り、法案は修正された形で法律となる。[88] 上院は下院が可決した法案に対して拒否権を行使できるが、下院も同様に3分の2の賛成でこれを覆すことができる。[89] 詳細情報:ウズベキスタンの政治 |

| Europe Europe European countries in which the executive or head of state does not have a veto power include Slovenia and Luxembourg, where the power to withhold royal assent was abolished in 2008.[90] Countries that have some form of veto power include the following: Czech Republic: The president of the Czech Republic has a suspensory veto power over a law passed by the Parliament within 15 days with notes (president cannot veto laws changing constitution).[91] Chamber of Deputies can override it by an absolute majority of all deputies. Also Chamber of Deputies can by same majority override if Senate rejects law previously approved by Chamber of Deputies. Same procedure applies for Senate amendments to the law approved by Chamber of Deputies.[92] Further information: Politics of the Czech Republic Estonia: The president may effectively veto a law adopted by the Riigikogu (legislature) by sending it back for reconsideration. The president must exercise this power within 14 days of receiving the law.[93] The Riigikogu, in turn, may override this veto by passing the unamended law again by a simple majority.[94][93] After such an override (but only then), the president may ask the Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional.[95][93] If the Supreme Court rules that the law does not violate the Constitution, the president must promulgate the law.[93] From 1992 to 2010, the president exercised the veto on 1.6% of bills (59 in all), and applied for constitutional review of 11 bills (0.4% in all).[96] Further information: Politics of Estonia Finland: The president has a suspensive veto, but can only delay the enactment of legislation by three months.[97] The president has had a veto power of some kind since Finnish independence in 1919,[98] but this power was greatly curtailed by the constitutional reforms of 2000. Further information: Politics of Finland France: The president has a suspensive veto: the president can require the National Assembly to reopen debate on a bill that it has passed, within 15 days of being presented with the bill.[99] Aside from that, the president can only refer bills to the Constitutional Council, a power shared with the prime minister and the presidents of both houses of the National Assembly.[100] Upon receiving such a referral, the Constitutional Council can strike down a bill before it has been promulgated as law, which has been interpreted as a form of constitutional veto.[101] Further information: Politics of France Germany: The federal president of Germany has to sign a bill in order for it to become law.[102] This gives him a de facto veto power over legislation. However this power has been used only nine times since the founding of the federal Republic and is largely considered to be a ceremonial power.[103][104][105] Further information: Politics of Germany Hungary: The president has two options to veto a bill: submit it to the Constitutional Court if he or she suspects that it violates the constitution or send it back to the National Assembly and ask for a second debate and vote on the bill. If the court rules that the bill is constitutional, the president must sign it.[106] Likewise, if the president has returned the bill to the National Assembly and it is passed a second time by a simple majority, it becomes law.[107] Further information: Politics of Hungary Iceland: The president may refuse to sign a bill, which is then put to referendum. This right was not exercised until 2004, by President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, who also refused to sign two other bills related to the Icesave dispute.[108] Two of these vetoes resulted in referendums.[108] Further information: Politics of Iceland Ireland: The president may refuse to grant assent to a bill that they consider to be unconstitutional, after consulting the Council of State; in this case, the bill is referred to the Supreme Court, which finally determines the matter.[3] From 1990 to 2012, this power was used an average of once every three years.[109] The president may also, on request of a majority of Seanad Éireann (the upper house of parliament) and a third of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament), after consulting the Council of State, decline to sign a bill "of such national importance that the will of the people thereon ought to be ascertained" in an ordinary referendum or a new Dáil reassembling after a general election held within eighteen months.[110] This latter power has never been used because the government of the day almost always commands a majority of the Seanad, preventing the third of the Dáil that usually makes up the opposition from combining with it.[111] Further information: Politics of Ireland Italy: The president may request a second deliberation of a bill passed by the Italian Parliament before it is promulgated. This is a very weak form of veto as the parliament can override the veto by an ordinary majority.[112] While such a limited veto cannot thwart the will of a determined parliamentary majority, it may have a delaying effect and may cause the parliamentary majority to reconsider the matter. The president also has the power to veto appointments of ministers in the government of Italy, as for example president Sergio Mattarella did in vetoing the appointment of Paolo Savona as finance minister in 2018.[113] Further information: Politics of Italy Latvia: The president may suspend a bill for a period of two months, during which it may be referred to the people in a referendum if one-tenth of the electorate requests a referendum.[114] The president may also return a document to the Saeima for reconsideration, but only once.[115] Notably, in 1999, president Vaira Vike-Freiberga returned the Latvian State Language Law to the Saeima, even though the law had passed by an overwhelming majority the first time; the president used the suspensory veto to point out legal problems with the law, which resulted in amendments to bring it into line with European legal standards.[116] Further information: Politics of Latvia Poland: The president may either submit a bill to the Constitutional Tribunal if they suspect that the bill is unconstitutional or send it back to the Sejm for reconsideration.[117] These two options are exclusive: the president must choose one or the other.[117] If president has referred a law to the Constitutional Tribunal and the tribunal says that the bill is constitutional, the president must sign it. If the president instead returns the bill to the Sejm in a standard package veto, the Sejm can override the bill by a three-fifths majority of members present (at least half of all members have to be present).[118] Further information: Politics of Poland Portugal: The president may refuse to sign a bill or refer it, or parts of it, to the Constitutional Court.[3] If the bill is declared unconstitutional, the president is required to veto it, but the Assembly of the Republic can override this veto by a two-thirds majority.[119] If the president vetoes a bill that has not been declared unconstitutional, the Assembly of the Republic may pass it a second time, in which case it becomes law. However, in Portugal presidential vetoes typically result in some change to the legislation.[120] The president also has an absolute veto over decree-laws issued by the government of Portugal.[121] In an autonomous region such as the Azores, the Representative of the Republic has the power to veto legislation, which the regional assembly can override by an absolute majority, and also holds the same constitutional veto power that the president has nationally.[122] Further information: Politics of Portugal Spain: The Constitution states that "Within two months after receiving the text, the Senate may, by a message stating the reasons for it, adopt a veto or approve amendments thereto. The veto must be adopted by overall majority".[123] A Senate veto can be overridden by an absolute majority vote of the Congress of Deputies.[124] In addition, the government can block a bill before passage if it entails government spending or loss of revenue.[125] This prerogative is commonly called veto presupuestario ("budget veto").[126] Further information: Politics of Spain and Royal assent § Spain Ukraine: The president may refuse to sign a bill and return it to the Verkhovna Rada with proposed amendments. The Verkhovna Rada may override a veto by a two-thirds majority. If the veto is not overridden, the President's amendments are subjected to an up-or-down vote; if they attract at least 50% support from the legislators, the bill is adopted with the amendments; if not, the bill fails.[127] Further information: Politics of Ukraine United Kingdom: The monarch has two methods of vetoing a bill. Any bill that has been passed by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords becomes law only when formally approved by the monarch (or their official representative), in a procedure known as royal assent. Legally, the monarch can withhold that consent, thereby vetoing the bill. This power was last exercised in 1708 by Queen Anne to block the Scottish Militia Bill 1708. The monarch has additional veto powers over bills which affect the royal prerogative, such as the war prerogative, or the monarch's personal affairs (such as royal incomes or hereditary property). By convention, those bills require king's consent before they may even be debated by Parliament, as well as royal assent if they are passed. King's consent is not obsolete and is occasionally withheld, though now only on the advice of the cabinet. An example was the Military Action Against Iraq (Parliamentary Approval) Bill in 1999, which received a first reading under the Ten Minute Rule, but was denied queen's consent for a second reading.[128] Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland: Powers exist under the section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998, section 114 of the Government of Wales Act 2006, and section 14 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 that allow the responsible cabinet minister in Westminster to refuse a bill that has been passed by the Scottish Parliament, Senedd, or Northern Ireland Assembly, respectively, from proceeding to royal assent, if they believe that the bill modifies and has adverse effects on legislation that is reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom to solely legislate on. This power has only been used once, to veto the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill in 2023.[129] Further information: Royal assent § United Kingdom, King's Consent, and Politics of the United Kingdom |

ヨーロッパ ヨーロッパ 欧州諸国において、行政機関または国家元首が拒否権を持たない国には、スロベニアとルクセンブルクが含まれる。両国では2008年に国王の裁可権が廃止さ れた。[90] 何らかの拒否権を有する国は以下の通りである: チェコ共和国:チェコ共和国大統領は、議会で可決された法律に対し、15日以内に意見書を添えて保留拒否権を行使できる(ただし憲法改正法案には拒否権を 行使できない)。[91] 下院は全議員の絶対多数でこれを覆すことができる。また、下院で可決された法案を上院が否決した場合も、下院は同様の多数決でこれを覆すことができる。上 院が下院可決法案に修正を加えた場合も、同様の手続きが適用される。[92] 詳細情報:チェコ共和国の政治 エストニア:大統領は、リイギコグ(議会)で可決された法律を再審議のために差し戻すことで、事実上拒否権を行使できる。大統領はこの権限を法律受領後 14日以内に行使しなければならない。[93] リイギコグは、修正を加えずに単純過半数で再度可決することで、この拒否権を覆すことができる。[94][93] このような覆しが行われた後(その場合のみ)、大統領は最高裁判所に当該法律の違憲宣言を求めることができる。[95][93] 最高裁判所が法律が憲法に違反しないと判断した場合、大統領は法律を公布しなければならない。[93] 1992年から2010年にかけて、大統領は法案の1.6%(計59件)に拒否権を行使し、11件(全体の0.4%)について憲法審査を申請した。 [96] 詳細情報:エストニアの政治 フィンランド:大統領は停止拒否権を有するが、立法の施行を3か月間遅らせるだけである。[97] フィンランド大統領は1919年の独立以来何らかの拒否権を有してきたが[98]、この権限は2000年の憲法改正で大幅に制限された。 詳細情報:フィンランドの政治 フランス:大統領は停止拒否権を有する。法案が国民議会で可決された後、大統領は15日以内に同議会に対し、当該法案の再審議を要求できる。[99] それ以外では、大統領は法案を憲法評議会に付託する権限しか持たない。この権限は首相及び国民議会の両院議長と共有されている。[100] 付託を受けた憲法評議会は、法案が法律として公布される前にこれを無効とすることができる。これは一種の憲法上の拒否権と解釈されている。[101] 詳細情報: フランスの政治 ドイツ:ドイツ連邦大統領は法案に署名しなければ法律とならない。[102] これにより大統領は事実上の立法拒否権を持つ。しかしこの権限は連邦共和国成立以来わずか9回しか行使されておらず、主に儀礼的な権限と見なされている。 [103][104][105] 詳細情報: ドイツの政治 ハンガリー: 大統領は法案を拒否する二つの選択肢を持つ:憲法違反の疑いがある場合は憲法裁判所に付託するか、国民議会に差し戻し再審議・再投票を求める。裁判所が法 案を合憲と判断した場合、大統領は署名しなければならない[106]。同様に、大統領が国民議会に差し戻した法案が単純過半数で再可決された場合、それは 法律となる。[107] 詳細情報:ハンガリーの政治 アイスランド:大統領は法案への署名を拒否できる。その場合、法案は国民投票に付される。この権利は2004年まで行使されなかったが、オラフル・ラグナ ル・グリムソン大統領が初めて行使し、アイスセーブ紛争に関連する他の2つの法案への署名も拒否した。[108] これらの拒否権行使のうち2件は国民投票につながった。[108] 詳細情報:アイスランドの政治 アイルランド:大統領は、国家評議会と協議した後、違憲と判断した法案への同意を拒否できる。この場合、法案は最高裁判所に付託され、最終的に判断が下さ れる。[3] 1990年から2012年まで、この権限は平均3年に1回の頻度で行使された。[109] 大統領はまた、上院(アイルランド上院)の過半数と下院(アイルランド下院)の3分の1の要請に基づき、国務評議会と協議した後、「国民意思を確認すべき 国家的重要性を有する」法案について、通常国民投票または18ヶ月以内に実施される総選挙後の新下院召集による国民投票の実施を条件に、署名拒否権を行使 できる。[110] この後者の権限は、現政権がほぼ常に上院の過半数を掌握しているため、通常野党を構成する下院の3分の1がこれに同調するのを阻むことから、これまで一度 も行使されたことがない。[111] 詳細情報:アイルランドの政治 イタリア:大統領は、イタリア議会で可決された法案が公布される前に、熟議を要求できる。これは非常に弱い形の拒否権であり、議会は通常の過半数で拒否権 を覆すことができる。[112] このような限定的な拒否権は、断固とした議会多数派の意思を阻むことはできないが、遅延効果をもたらし、議会多数派に再考を促す可能性がある。大統領はま た、イタリア政府における閣僚任命を拒否する権限を持つ。例えば2018年、セルジョ・マッタレッラ大統領はパオロ・サヴォーナ財務大臣任命を拒否した。 [113] 詳細情報: イタリアの政治 ラトビア: 大統領は法案を2か月間保留できる。この期間中、有権者の10分の1が国民投票を要求した場合、法案は国民投票に付される。[114] 大統領はまた、文書を議会(セイマ)に差し戻して再審議を求めることができるが、これは1回のみである。[115] 特に1999年、ヴァイラ・ヴィケ=フライベルガ大統領はラトビア国家言語法を議会に差し戻した。同法は初回審議で圧倒的多数で可決されていたが、大統領 は停止拒否権を行使して法的問題を指摘。これにより欧州の法的基準に適合させるための改正が行われた。[116] 詳細情報:ラトビアの政治 ポーランド:大統領は法案が違憲と疑われる場合、憲法裁判所へ付託するか、下院へ再審議を命じるかのいずれかを選択できる。[117] これら二つの選択肢は排他的であり、大統領は一方を選ばねばならない。[117] 大統領が法案を憲法裁判所に付託し、同裁判所が法案を合憲と判断した場合、大統領は署名しなければならない。大統領が代わりに標準的な拒否権行使で法案を セイムに差し戻した場合、セイムは出席議員の5分の3以上の多数(全議員の半数以上が出席している必要がある)で拒否権を覆すことができる。[118] 詳細情報:ポーランドの政治 ポルトガル:大統領は法案への署名を拒否するか、法案全体または一部を憲法裁判所に付託することができる。[3] 法案が違憲と宣言された場合、大統領は拒否権を行使しなければならないが、共和国議会は3分の2の多数決でこの拒否権を覆すことができる。[119] 大統領が違憲と宣言されていない法案に拒否権を行使した場合、共和国議会はそれを再度可決することができ、その場合は法律となる。ただし、ポルトガルでは 大統領の拒否権は通常、立法内容に何らかの変更をもたらす結果となる。[120] 大統領はまた、ポルトガル政府が発する政令に対して絶対拒否権を有する。[121] アゾレス諸島などの自治地域では、共和国代表が立法に対する拒否権を有し、地域議会は絶対多数でこれを覆すことができる。また、共和国代表は大統領が国民 レベルで有するのと同様の憲法上の拒否権も保持する。[122] 詳細情報:ポルトガルの政治 スペイン:憲法は「上院は法案受領後2ヶ月以内に、理由を付したメッセージにより拒否権を行使するか、修正案を承認することができる。拒否権は全体過半数 で採択されなければならない」と定めている。[123] 上院の拒否権は下院の絶対多数決で覆される。[124] さらに政府は、法案が政府支出または歳入減をもたらす場合、成立前に阻止できる。[125] この特権は一般に「予算拒否権」(veto presupuestario)と呼ばれる。[126] 詳細情報:スペインの政治および国王の裁可 § スペイン ウクライナ:大統領は法案への署名を拒否し、修正案を添えて最高議会(ヴェルホーヴナ・ラーダ)に差し戻すことができる。最高議会は3分の2の多数決で拒 否権を覆すことができる。拒否権が覆されない場合、大統領の修正案は賛否投票にかけられる。修正案が議員の50%以上の支持を得た場合、修正案付きで法案 は成立する。得られなかった場合、法案は廃案となる。[127] 詳細情報: ウクライナの政治 イギリス: 君主には法案を拒否する二つの方法がある。下院と上院の両方で可決された法案は、君主(またはその公式代理人)による「国王の裁可」と呼ばれる手続きで正 式に承認されて初めて法律となる。法的には、君主はこの同意を保留し、法案を拒否することができる。この権限が最後に行使されたのは1708年、アン女王 がスコットランド民兵法案1708を阻止した時である。君主はさらに、戦争権限などの王権特権や、王室の収入や世襲財産などの君主の私的利益に関わる法案 に対して拒否権を行使できる。慣例上、これらの法案は議会で審議される前に国王の同意を必要とし、可決された場合も国王の裁可を要する。国王の同意は廃れ ておらず、内閣の助言に基づいて時折拒否される。例として1999年の「イラクに対する軍事行動(議会承認)法案」がある。これは10分ルールで第一読会 を通過したが、第二読会への国王の同意は拒否された。[128] スコットランド、ウェールズ、北アイルランド:1998年スコットランド法第35条、2006年ウェールズ政府法第114条、1998年北アイルランド法 第14条に基づき、ウェストミンスターの担当閣僚は、スコットランド議会(Senedd)または北アイルランド議会(Northern Ireland Assembly)で可決された法案が、英国議会が専属立法権を有する法律を修正し悪影響を及ぼすと判断した場合、その法案が国王の裁可に至るのを拒否で きる権限を有する。[129] 補足情報:国王の裁可 § イギリス、国王の同意、およびイギリスの政治 [129] 詳細情報: 英国における国王の裁可、国王の同意、および英国の政治 |

| Oceania Oceania Australia: According to the Australian Constitution (sec. 59), the monarch may veto a bill that has been given royal assent by the governor-general within one year of the legislation being assented to.[130] This power has never been used. The Australian governor-general himself or herself has, in theory, the power to veto, or more technically, withhold assent to, a bill passed by both houses of the Australian Parliament, and contrary to the advice of the prime minister.[131] However, in matters of assent to legislation, the governor-general is advised by parliament, not by the government. Consequently, when a minority parliament passes a bill against the wishes of the government, the government could resign, but cannot advise a veto.[131][132] Since 1986, the individual states of Australia are fully independent entities. Thus, the Crown may not veto (nor the UK Parliament overturn) any act of a state governor or state legislature. State constitutions determine what role the state's governor plays. In general, the governor exercises the powers the sovereign would have; in all states and territories, the governor's (or, for territories, administrator's) assent is required for a bill to become law, except the Australian Capital Territory, which has no administrator.[133] Further information: Politics of Australia Federated States of Micronesia: The President can disapprove legislation passed by the Congress.[134] The veto must be exercised within 10 days, or 30 days if the Congress is not in session.[134] The Congress can override the veto by a three-fourths vote of the four state delegations, with each state delegation casting one vote.[135] Further information: Politics of the Federated States of Micronesia Fiji: Under the 2013 Constitution, the President has no authority to veto legislation that has been passed by the Parliament. Under the previous bicameral constitutions, the appointed Senate had veto powers over legislation passed by the elected lower house. Further information: Politics of Fiji New Zealand: Under the Standing Orders of the House of Representatives, the Government has a financial veto, under which it can block bills, amendments and motions that would have more than a minor impact on the Government's fiscal aggregates.[136] Bills can be subjected to a financial veto only on third reading, when they have been finalized, but before they have been passed.[137] The financial veto system was introduced in 1996.[137] Further information: Politics of New Zealand Tonga: The constitution empowers the King to withhold royal assent from bills adopted by the Legislative Assembly.[138] In November 2011, the assembly adopted a bill that reduced the possible criminal sentences for the illicit possession of firearms, an offence for which two members of the assembly had recently been charged. Members of the opposition denounced the bill and asked the King to veto it, and he did so in December 2011.[139] Further information: Politics of Tonga and Royal assent § Tonga |

オセアニア オセアニア オーストラリア:オーストラリア憲法(第59条)によれば、君主は総督が王室認可を与えた法案について、認可から1年以内に拒否権を行使できる。 [130] この権限はこれまで一度も行使されたことがない。オーストラリア総督自身は、理論上、オーストラリア議会の両院で可決された法案に対し、首相の助言に反し て拒否権を行使する、より正確には同意を保留する権限を有する[131]。ただし、立法への同意に関しては、総督は政府ではなく議会から助言を受ける。し たがって、少数与党議会が政府の意向に反して法案を可決した場合、政府は辞任することはできても、拒否権行使を勧告することはできない。[131] [132]1986年以降、オーストラリアの各州は完全に独立した主体である。したがって、王室は州知事または州議会の行為に対して拒否権を行使できず (英国議会もこれを覆せない)。州の役割は州憲法によって定められている。一般的に、総督は君主が行使する権限を行使する。全州および準州において、法案 が法律となるには総督(準州の場合は行政官)の同意が必要である。ただし、行政官を置かないオーストラリア首都特別地域は例外である。[133] 詳細情報:オーストラリアの政治 ミクロネシア連邦:大統領は議会が可決した法案を拒否できる。[134]拒否権は10日以内に行使されねばならず、議会が休会中の場合は30日以内であ る。[134]議会は4州代表団の4分の3の賛成票により拒否権を覆すことができ、各州代表団は1票を投じる。[135] 詳細情報:ミクロネシア連邦の政治 フィジー:2013年憲法下では、大統領は議会で可決された法案を拒否する権限を持たない。以前の二院制憲法下では、任命制上院が選出された下院で可決さ れた法案に対して拒否権を行使できた。 詳細情報:フィジーの政治 ニュージーランド:下院の常会規則では、政府は財政拒否権を有し、政府の財政総計に軽微な影響を超える法案・修正案・動議を阻止できる。[136] 財政拒否権は、法案が最終審議段階(第三読会)にあり、可決前である場合にのみ行使可能である。[137] この財政拒否権制度は1996年に導入された。[137] 詳細情報:ニュージーランドの政治 トンガ:憲法は国王に、立法議会で可決された法案への国王の裁可を保留する権限を与えている。[138] 2011年11月、議会は銃器の不法所持に対する刑事罰を軽減する法案を可決した。この罪で議会議員2名が起訴されたばかりだった。野党議員らはこの法案 を非難し国王に拒否権行使を要請した。国王は2011年12月に拒否権を行使した。[139] 詳細情報:トンガの政治および国王の裁可 § トンガ |

| Veto theories In political science, the broader power of people and groups to prevent change is sometimes analyzed through the frameworks of veto points and veto players. Veto players are actors who can potentially exercise some sort of veto over a change in government policy.[5] Veto points are the institutional opportunities that give these actors the ability to veto.[5] The theory of veto points was first developed by Ellen M. Immergut in 1990, in a comparative case study of healthcare reform in different political systems.[140] Breaking with earlier scholarship, Immergut argued that "we have veto points within political systems and not veto groups within societies."[141] Veto player analysis draws on game theory. George Tsebelis first developed it in 1995 and set it forth in detail in 2002 Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work.[142] A veto player is a political actor who has the ability to stop a change from the status quo.[143] There are institutional veto players, whose consent is required by constitution or statute; for example, in US federal legislation, the veto players are the House, Senate and presidency.[144] There are also partisan veto players, which are groups that can block policy change from inside an institutional veto player.[145] In a coalition government the partisan veto players are typically the members of the governing coalition.[145][146] According to Tsebelis' veto player theorem, policy change becomes harder the more veto players there are, the greater the ideological distance between them, and the greater their internal coherence.[143] For example, Italy and the United States have stable policies because they have many veto players, while Greece and the United Kingdom have unstable policies because they have few veto players.[147] While the veto player and veto point approaches complement one another, the veto players framework has become dominant in the study of policy change.[148] Scholarship on rational choice theory has favored the veto player approach because the veto point framework does not address why political actors decide to use a veto point.[5] In addition, because veto player analysis can apply to any political system, it provides a way of comparing very different political systems, such as presidential and parliamentary systems.[5] Veto player analyses can also incorporate people and groups that have de facto power to prevent policy change, even if they do not have the legal power to do so.[149] Some literature distinguishes cooperative veto points (within institutions) and competitive veto points (between institutions), theorizing competitive veto points contribute to obstructionism.[150] Some literature disagrees with the claim of veto player theory that multiparty governments are likely to be gridlocked.[150] |

拒否権理論【冒頭の再掲】 政治学において、人民や集団が変化を阻止する広範な権力は、拒否権ポイントと拒否権プレイヤーという枠組みを通じて分析されることがある。拒否権プレイ ヤーとは、政府政策の変更に対して何らかの拒否権を行使し得る主体である[5]。拒否権ポイントとは、これらの主体に拒否権を行使する能力を与える制度的 機会を指す。[5] 拒否権ポイント理論は、1990年にエレン・M・イマーガットが異なる政治制度における医療改革の比較事例研究で初めて提唱したものである。[140] 従来の学説とは一線を画し、イマーガットは「社会内に拒否権グループが存在するのではなく、政治制度内に拒否権ポイントが存在する」と主張した。 [141] 拒否権プレイヤー分析はゲーム理論を基盤とする。ジョージ・ツェベリスが1995年に初めて提唱し、2002年の著書『拒否権プレイヤー:政治制度の仕組 み』で詳細に展開した[142]。拒否権プレイヤーとは現状変更を阻止できる政治主体を指す[143]。憲法や法令で同意が義務付けられた制度的拒否権プ レイヤーが存在する。例えば米国連邦立法では、下院・上院・大統領がこれに該当する。[144] また党派的拒否権プレイヤーも存在する。これは制度的拒否権プレイヤー内部から政策変更を阻止できる集団である。[145] 連立政権においては、党派的拒否権プレイヤーは通常、与党連立の構成員である。[145][146] ツェベリスの拒否権プレイヤー定理によれば、政策変更は、拒否権プレイヤーの数が増えるほど、それらの間のイデオロギー的距離が大きくなるほど、そして内 部の一貫性が高まるほど困難になる。[143] 例えばイタリアとアメリカは拒否権プレイヤーが多いため政策が安定している一方、ギリシャとイギリスは拒否権プレイヤーが少ないため政策が不安定である。 [147] 拒否権プレイヤーと拒否点のアプローチは互いに補完し合うが、政策変更の研究では拒否権プレイヤーの枠組みが主流となっている。[148] 合理的選択理論の研究では、拒否権行使主体アプローチが重視されてきた。拒否権行使ポイント枠組みでは、政治主体がなぜ拒否権行使ポイントを使う決断をす るのかが説明されないからだ。[5] さらに、拒否権行使主体分析はあらゆる政治制度に適用可能であるため、大統領制と議会制のような非常に異なる政治制度を比較する手段を提供する。[5] 拒否権行使主体分析は、法的権限を持たない場合でも、事実上政策変更を阻止する力を持つ人々や集団も組み込むことができる。[149] 一部の文献では、協力的な拒否権ポイント(制度内)と競争的な拒否権ポイント(制度間)を区別し、競争的な拒否権ポイントが妨害主義に寄与すると理論化し ている。[150] また、複数政党制政府は行き詰まりやすいという拒否権プレイヤー理論の主張に異議を唱える文献もある。[150] |

| Royal assent Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, allowing a temporary legislative override of court decisions Vetocracy |

国王の裁可 カナダ人権憲章第33条。裁判所判決を一時的に立法府が覆すことを認める 拒否権 |

| Works cited Bulmer, Elliot (2017). Presidential Veto Powers (PDF) (2nd ed.). International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Retrieved 11 June 2022. Croissant, Aurel (2003). "Legislative powers, veto players, and the emergence of delegative democracy: A comparison of presidentialism in the Philippines and South Korea". Democratization. 10 (3): 68–98. doi:10.1080/13510340312331293937. S2CID 144739609. Köker, Philipp (2015). Veto et Peto: Patterns of Presidential Activism in Central and Eastern Europe (PDF) (PhD thesis). University College London. Retrieved 14 June 2022. Oppermann, Kai; Brummer, Klaus (2017). "Veto Player Approaches in Foreign Policy Analysis". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.386. ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7. Retrieved 17 June 2022. Palanza, Valeria; Sin, Gisela (2020). "Chapter 21: Legislatures and executive vetoes". In Benoît, Cyril; Rozenberg, Olivier (eds.). Handbook of Parliamentary Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 367–387. doi:10.4337/9781789906516.00030. ISBN 9781789906516. S2CID 229672005. Tsebelis, George (2002). Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400831456. Tsebelis, George; Alemán, Eduardo (April 2005). "Presidential Conditional Agenda Setting in Latin America". World Politics. 57 (3). Cambridge University Press: 396–420. doi:10.1353/wp.2006.0005. JSTOR 40060107. S2CID 154191670. Tsebelis, George; Rizova, Tatiana P. (October 2007). "Presidential Conditional Agenda Setting in the Former Communist Countries". Comparative Political Studies. 40 (10): 1155–1182. doi:10.1177/0010414006288979. S2CID 154842077. Watson, Richard A. (1987). "Origins and Early Development of the Veto Power". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 17 (2): 401–412. JSTOR 40574459. |

引用文献 Bulmer, Elliot (2017). 大統領の拒否権 (PDF) (第2版). 国際民主主義・選挙支援機構. 2022年6月11日閲覧。 Croissant, Aurel (2003). 「立法権、拒否権行使主体、委任型民主主義の出現:フィリピンと韓国の大統領制比較」『民主化』10巻3号:68-98頁。doi: 10.1080/13510340312331293937。S2CID 144739609。 Köker, Philipp (2015). Veto et Peto: Patterns of Presidential Activism in Central and Eastern Europe (PDF) (PhD thesis). University College London. Retrieved 14 June 2022. Oppermann, Kai; Brummer, Klaus (2017). 「Veto Player Approaches in Foreign Policy Analysis」. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.386. ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7. 2022年6月17日閲覧。 Palanza, Valeria; Sin, Gisela (2020). 「第21章:立法府と行政府の拒否権」ベノワ、シリル; ロゼンバーグ、オリヴィエ(編)『議会研究ハンドブック』エドワード・エルガー出版 pp. 367–387 doi:10.4337/9781789906516.00030 ISBN 9781789906516. S2CID 229672005. ツェベリス, ジョージ (2002). 『拒否権のプレイヤー: 政治制度の仕組み』. プリンストン大学出版局. ISBN 9781400831456. ツェベリス, ジョージ; アレマン, エドゥアルド (2005年4月). 「ラテンアメリカにおける大統領の条件付き議題設定」. 『ワールド・ポリティクス』. 57 (3). ケンブリッジ大学出版局: 396–420. doi:10.1353/wp.2006.0005. JSTOR 40060107. S2CID 154191670. ツェベリス、ジョージ; リゾヴァ、タチアナ・P. (2007年10月). 「旧共産主義諸国における大統領の条件付き議題設定」. 比較政治学研究. 40 (10): 1155–1182. doi:10.1177/0010414006288979. S2CID 154842077. ワトソン、リチャード・A. (1987). 「拒否権の起源と初期の発展」. プレジデンシャル・スタディーズ・クォータリー. 17 (2): 401–412. JSTOR 40574459. |

| Constitutions cited. |

引用した各国の憲法(省略) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veto |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099