カルロス・カスタネダ頌*

カルロス・カスタネダ頌*

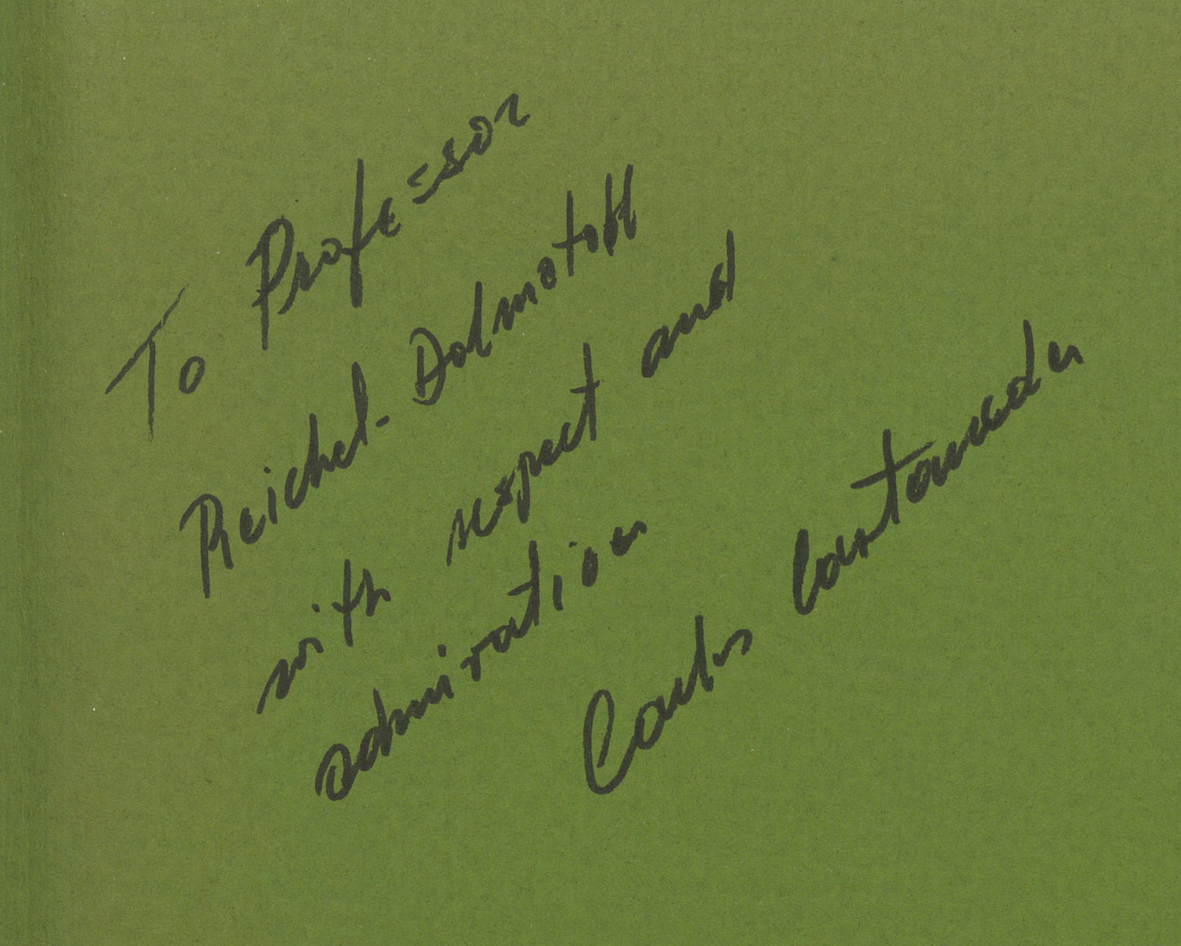

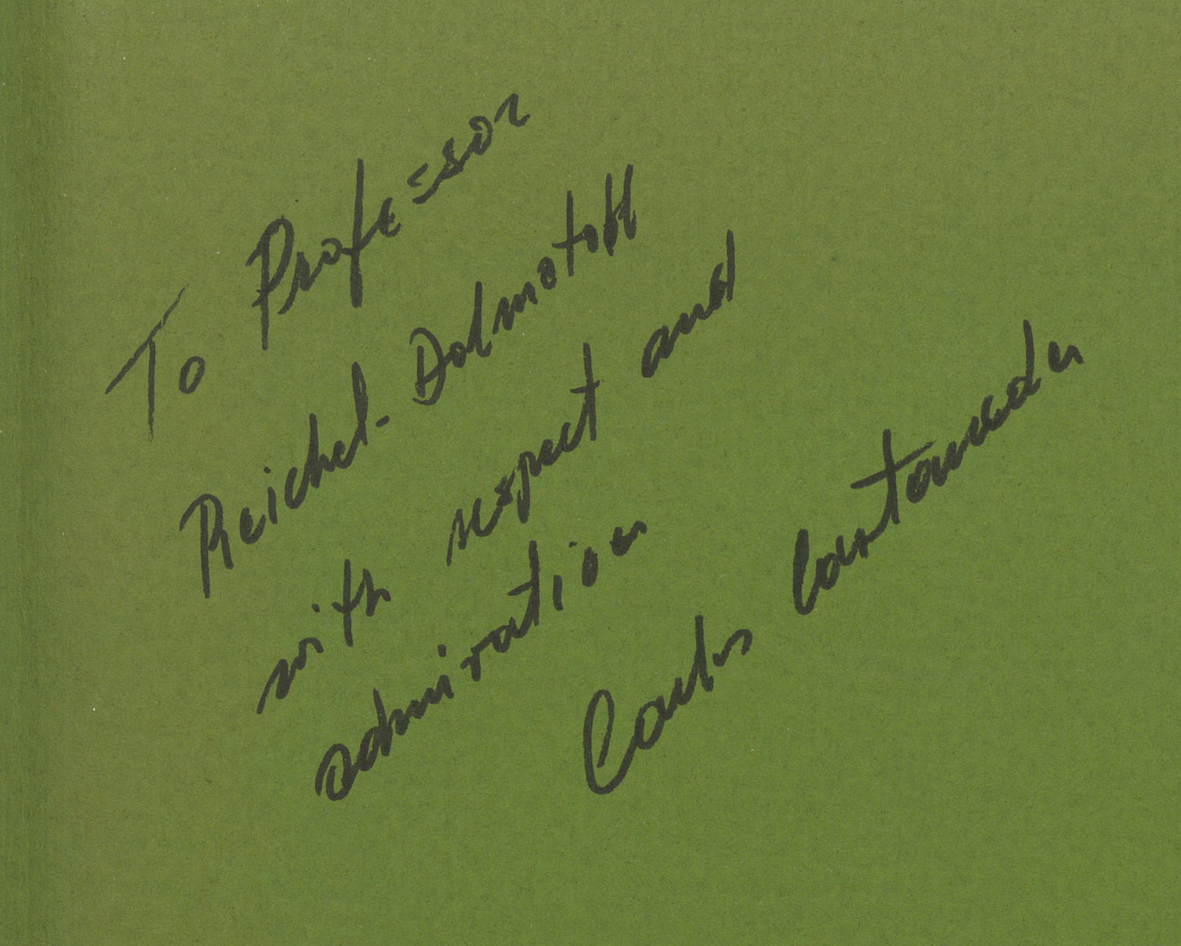

La Oda para Carlos Castañeda,;ó ”His (= Carlos Castaneda's) only real sorcery was turning the University of California into an ass." - whew!!! Kathryn Lindskoog, "Fakes, Frauds & Other Malarkey" 1993.

オクタビ オ・パス「君[山口昌男—引用者註]は[アントナン]アルトーの タラフマラ紀行を幻視に よる理想的民俗誌と言うがそれはある意味で正しいね」

山口昌男 「どういう意味で?」

パス「彼はメキシコへ通信 員として来たことは確かだけど、タラフマラ族の 住んでいるシェラ・マー ドレに行ったという確証は何もないのだよ。人類学者の陥りがちな現地至上主義という経験の物神化との対比において幻想であれあれだけ物を書くのだなから素 晴らしいと思わない?」

山口「あな たの言うことに俄に同意できないけれど、それが事実であるとア ルトーが更に素晴らしく 見えてくるような気がしますね。私はどちらかと言うと、こういう奇怪な事実のほうが好きなところがあるのですが……」

“と私は反 応したが、しば らくの間ショックから立ち直ることはできなかっ た”(山口昌男「オクタ ビオ・パスとの日々——その死を悼みつつ」『群像』1998年7月号、出典は大塚信一[2007:223])

**

" This article has been nominated to be checked for its neutrality. Discussion of this nomination can be found on the talk page.Carlos Castaneda

Carlos Castenada 1962 Born December 25 1925,Cajamarca, Peru- April 27, 1998 (aged 72, Los Angeles, California,) was an American author.

"Starting

with The Teachings of Don Juan in 1968, Castaneda wrote a series of

books that describe his training in shamanism, particularly with a

group whose lineage descended from the Toltecs. The books, narrated in

the first person, relate his experiences under the tutelage of a man

that Castaneda claimed was a Yaqui "Man of Knowledge" named don Juan

Matus. His 12 books have sold more than 28 million copies in 17

languages. They have been found to be fiction, but supporters claim the

books are either true or at least valuable works of philosophy./

Castaneda withdrew from public view in 1973, living in a large house in

Westwood, California from 1973 until his death in 1998, with three

colleagues whom he called "Fellow Travellers of Awareness." He founded

Cleargreen, an organization that promotes "tensegrity", which Castaneda

described as the modern version of the "magical passes" of the shamans

of ancient Mexico."

**

カルロ ス・カスタネダは、フィールド・ワークを おこなわずに先住民ヤキのシャーマンであるファン・マトゥス (ドンは成人男性の敬称)なる人物を捏造し、1968年の著作以降、その実在を読者に信じさせた張本人であると言われている(→"The Teachings of Don Juan(ドン・ファンの教え)")。

カスタ ネダの存命中から、彼の著作には実証性が欠け、また彼自身がその欠点について積極的に自己弁護しなかっ たことから、北米の人類学者はある時期公的な論文にその著作を〈事実〉あるいは〈民族誌〉としては引用しなくなった。他方で、民族誌の信憑性やデータの実 在、あるいは人類学者の社会的機能などの議論では、カスタネダをめぐるかつての論争が、重要な教訓として繰り返し登場する。

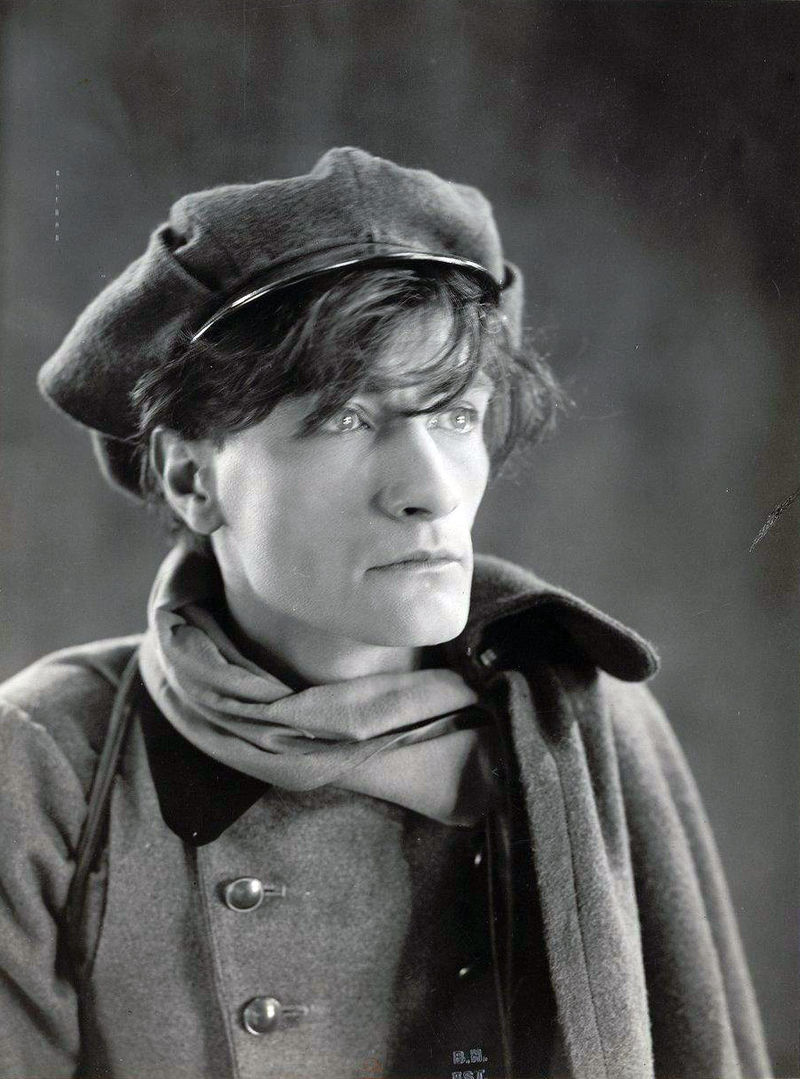

カスタネダの写真をクリックすると、"The Teachings of Don Juan(ドン・ファンの教え)"に繋がります。

【リン ク】

【文献】

Richard de Mille (ed.). The Don Juan Papers: Further Castaneda Controversies (1980) - ISBN 0915520257 - Ross-Erikson, Santa Barbara, CA. / (1990) ISBN 0534121500 Wadsworth Pub. Co., Belmont, CA.

* 頌(しょう)あるいは頌歌(しょうか)あるいはオード(ode)と言い、特 定の人物に寄せる叙 情詩のことを言います。

★

カルロス・カスタネダ(Carlos Castañeda、1925年12月25日[nb

1]-1998年4月27日)はアメリカの作家。1968年から、カスタネダはヤキ族の「知識の人」であるドン・ファン・マトゥスの指導の下で受けた

シャーマニズムの修行について記した一連の本を出版した。書籍が出版された当初、カスタネダの作品は多くの人々に事実として受け入れられていたが、彼が記

述した修行は現在では一般的にフィクションであると考えられている[nb 2]。

最初の3冊(『ドン・フアンの教え:ヤキ族の知識』、『別の現実』、『イクストランへの旅』)は、彼がカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校(UCLA)で人

類学を専攻していたときに書かれた。カスタネダは、これらの著書に書かれた仕事に基づいて、カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校から学士号と博士号を授与さ

れた[6]。

1998年に亡くなった時点で、カスタネダの著書は800万部以上売れ、17ヶ国語で出版されていた[3]。

| Carlos Castañeda

(December 25, 1925[nb 1] – April 27, 1998) was an American writer.

Starting in 1968, Castaneda published a series of books that describe a

training in shamanism that he received under the tutelage of a Yaqui

"Man of Knowledge" named don Juan Matus. While Castaneda's work was

accepted as factual by many when the books were first published, the

training he described is now generally considered to be fictional.[nb 2] The first three books—The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, A Separate Reality, and Journey to Ixtlan—were written while he was an anthropology student at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Castaneda was awarded his bachelor's and doctoral degrees from the University of California, Los Angeles based on the work he described in these books.[6] At the time of his death in 1998, Castaneda's books had sold more than eight million copies and had been published in 17 languages.[3] |

カルロス・カスタネダ(Carlos

Castañeda、1925年12月25日[nb

1]-1998年4月27日)はアメリカの作家。1968年から、カスタネダはヤキ族の「知識の人」であるドン・ファン・マトゥスの指導の下で受けた

シャーマニズムの修行について記した一連の本を出版した。書籍が出版された当初、カスタネダの作品は多くの人々に事実として受け入れられていたが、彼が記

述した修行は現在では一般的にフィクションであると考えられている[nb 2]。 最初の3冊(『ドン・フアンの教え:ヤキ族の知識』、『別の現実』、『イクストランへの旅』)は、彼がカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校(UCLA)で人 類学を専攻していたときに書かれた。カスタネダは、これらの著書に書かれた仕事に基づいて、カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校から学士号と博士号を授与さ れた[6]。 1998年に亡くなった時点で、カスタネダの著書は800万部以上売れ、17ヶ国語で出版されていた[3]。 |

| Early life and education According to his birth record, Carlos Castañeda was born Carlos César Salvador Arana, on December 25, 1925, in Cajamarca, Peru, son of César Arana and Susana Castañeda.[7] Immigration records confirm the birth record's date and place of birth. Castaneda moved to the United States in 1951 and became a naturalized citizen on June 21, 1957.[8] Castaneda studied anthropology and was awarded his bachelor's and doctoral degrees from the University of California, Los Angeles[6] |

生い立ちと教育 出生記録によると、カルロス・カスタニェーダは1925年12月25日、ペルーのカハマルカでセザール・アラナとスサーナ・カスタニェーダの息子としてカ ルロス・セザール・サルバドール・アラナとして生まれた[7]。カスタネダは1951年にアメリカに移住し、1957年6月21日に帰化した[8]。カス タネダは人類学を学び、カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校で学士号と博士号を授与された[6]。 |

| Career Castaneda's first three books—The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, A Separate Reality, and Journey to Ixtlan—were written while he was an anthropology student at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He wrote that these books were ethnographic accounts describing his apprenticeship with a traditional "Man of Knowledge" identified as don Juan Matus, an Indigenous Yaqui from northern Mexico. The veracity of these books was doubted from their original publication, and are considered to be fictional by a number of scholars.[6][9][10][11] Castaneda was awarded his bachelor's and doctoral degrees based on the work described in these books.[6] In 1974 his fourth book, Tales of Power, chronicled the end of the story of his apprenticeship with Matus. Despite published questions and criticism, Castaneda continued to be popular with the reading public, and subsequent publications appeared describing further aspects of his training with don Juan.[citation needed] Castaneda wrote that don Juan recognized him as the new nagual, or leader of a party of seers of his lineage. He said Matus also used the term nagual to signify that part of perception which is in the realm of the unknown yet still reachable by man—implying that, for his own party of seers, Matus was a connection to that unknown. Castaneda often referred to this unknown realm as "nonordinary reality."[citation needed] While Castaneda was a well-known cultural figure, he rarely appeared in public forums. He was the subject of a cover article in the March 5, 1973, issue of Time, which described him as "an enigma wrapped in a mystery wrapped in a tortilla". There was controversy when it was revealed that Castaneda might have used a surrogate for his cover portrait. Correspondent Sandra Burton, apparently unaware of Castaneda's principle of freedom from personal history, confronted him about discrepancies in his account of his life. He responded: "To ask me to verify my life by giving you my statistics ... is like using science to validate sorcery. It robs the world of its magic and makes milestones out of us all." Following that interview, Castaneda completely retired from public view[1] until the 1990s.[12] Tensegrity For the structural principle coined by Buckminster Fuller in the 1960s, see Tensegrity. In the 1990s, Castaneda once again began appearing in public to promote Tensegrity, described in promotional materials as "the modernized version of some movements called magical passes developed by Indigenous shamans who lived in Mexico in times prior to the Spanish conquest".[12] Castaneda, with Carol Tiggs, Florinda Donner-Grau and Taisha Abelar, created Cleargreen Incorporated in 1995, whose stated purpose was "to sponsor Tensegrity workshops, classes and publications". Tensegrity seminars, books, and other merchandise were sold through Cleargreen.[13] |

経歴 カスタネダの最初の3冊の著書『ドン・フアンの教え:ヤキ族の知の道』、『別の現実』、『イクストランへの旅』は、カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校 (UCLA)の人類学専攻の学生時代に書かれた。彼はこれらの本は、メキシコ北部の先住民ヤキ族のドン・フアン・マトゥスと名乗る伝統的な "知識の人 "との徒弟関係を記した民族誌的な記録であると書いている。これらの本の信憑性は出版当初から疑われており、多くの学者によってフィクションであるとみな されている[6][9][10][11]。カスタネダはこれらの本に記述された仕事に基づいて学士号と博士号を授与された[6]。 1974年、彼の4冊目の著書である『力の物語』は、マトゥスとの弟子時代の物語の終わりを記したものである。出版された疑問や批判にもかかわらず、カス タネダは読書家の間で人気を保ち続け、ドン・ファンとの修行のさらなる側面を記述した後続の出版物が登場した[要出典]。 カスタネダは、ドン・ファンが彼を新しいナグアル、つまり彼の血筋の先見者たちの一党のリーダーとして認めたと書いている。マトゥスはまた、未知の領域に ありながら人間が到達可能な知覚の部分を意味するナグアルという言葉も使っていたという。カスタネダはしばしばこの未知の領域を「非日常の現実」と呼んだ [要出典]。 カスタネダはよく知られた文化人であったが、公の場に姿を現すことはほとんどなかった。彼は1973年3月5日号の『タイム』誌の表紙を飾り、「トル ティーヤに包まれた謎に包まれた人物」と評された。カスタネダが表紙の肖像画に代理人を使った可能性があることが明らかになり、論争になった。特派員のサ ンドラ・バートンは、カスタネダの個人史からの自由という原則を知らなかったようで、彼の人生についての説明の矛盾について彼に詰め寄った。彼はこう答え た: 「私の統計から私の人生を検証しろというのは、科学を使って魔術を検証するようなものだ。それは世界から魔法を奪い、私たち全員から一里塚を作るようなも のだ"。このインタビューの後、カスタネダは1990年代まで公の場から完全に引退した[1]。 テンセグリティ 1960年代にバックミンスター・フラーによって提唱された構造原理。 1990年代に入ると、カスタネダは再びテンセグリティを宣伝するために公の場に姿を現すようになり、宣伝資料では「スペインによる征服以前の時代にメキ シコに住んでいた先住民のシャーマンたちによって開発されたマジカルパスと呼ばれるいくつかの運動を現代化したもの」と説明されている[12]。 カスタネダは、キャロル・ティッグス、フロリンダ・ドナー=グラウ、タイシャ・アベラーとともに、1995年にクリアグリーン・インコーポレイテッドを設 立し、その目的は「テンセグリティのワークショップ、クラス、出版物を後援すること」とされている。テンスグリティのセミナー、書籍、その他の商品はクリ アグリーンを通じて販売された[13]。 |

| Personal life Castaneda married Margaret Runyan in Mexico in 1960, according to Runyan's memoirs. He is listed as the father on the birth certificate of Runyan's son C.J. Castaneda, even though the biological father was a different man.[14] In an interview, Runyan said she and Castaneda were married from 1960 to 1973; however, Castaneda obscured whether the marriage occurred,[3] and his death certificate stated he had never been married.[14] |

私生活 ラニヤンの回想録によると、カスタネダは1960年にメキシコでマーガレット・ラニヤンと結婚。ラニヤンの息子C.J.カスタネダの出生証明書には父親と して記載されているが、実の父親は別の男性である[14]。 インタビューでラニヤンは、カスタネダとは1960年から1973年まで結婚していたと語っているが、カスタネダは結婚の有無を明らかにしておらず [3]、死亡証明書には結婚歴はないと記載されている[14]。 |

| Death Castaneda died on April 27, 1998[3] in Los Angeles due to complications from hepatocellular cancer. There was no public service; he was cremated and the ashes were sent to Mexico. His death was unknown to the outside world until nearly two months later, on June 19, 1998, when an obituary, "A Hushed Death for Mystic Author Carlos Castaneda" by staff writer J. R. Moehringer appeared in the Los Angeles Times.[15] Castaneda's students After Castaneda stepped away from public view in 1973, he bought a large multi-dwelling property in Los Angeles which he shared with some of his followers, including Taisha Abelar (formerly Maryann Simko) and Florinda Donner-Grau (formerly Regine Thal). Like Castaneda, Abelar and Donner-Grau were students of anthropology at UCLA. Each subsequently wrote a book about her experiences of Castaneda's / don Juan's teachings from a female perspective: The Sorcerer's Crossing: A Woman's Journey by Taisha Abelar, and Being-in-Dreaming: An Initiation into the Sorcerers' World by Florinda Donner. Castaneda endorsed both of these books as authentic reports of the sorcery experience of don Juan's world.[16] Around the time Castaneda died, his companions Donner-Grau, Abelar and Patricia Partin informed friends they were leaving on a long journey. Amalia Marquez (also known as Talia Bey) and Tensegrity instructor Kylie Lundahl also left Los Angeles. Weeks later, Partin's red Ford Escort was found abandoned in Death Valley. Luis Marquez, Bey's brother, went to police in 1999 over his sister's disappearance, but could not convince them that it merited investigation.[6] In 2003, Partin's sun-bleached skeleton was discovered by a pair of hikers in Death Valley's Panamint Dunes area and identified in 2006 by DNA testing. The investigating authorities ruled the cause of death as undetermined.[6][17] However, Castaneda often talked about suicide, and associates believe the women killed themselves in the wake of Castaneda's death.[6] |

死去 1998年4月27日[3]、肝細胞癌の合併症によりロサンゼルスで死去。火葬され、遺灰はメキシコに送られた。彼の死は、約2ヶ月後の1998年6月 19日、スタッフライターJ.R.モーリンガーによる追悼記事「A Hushed Death for Mystic Author Carlos Castaneda」が『ロサンゼルス・タイムズ』紙に掲載されるまで、外部に知られることはなかった[15]。 カスタネダの弟子たち カスタネダは1973年に表舞台から姿を消した後、ロサンゼルスに大きな集合住宅を購入し、タイシャ・アベラー(元マリアン・シムコ)やフロリンダ・ド ナー=グラウ(元レジーヌ・タール)ら信奉者たちと共同生活を送った。カスタネダと同様、アベラールとドナー=グラウもUCLAで人類学を学んでいた。そ れぞれがその後、女性の視点から見たカスタネダ/ドン・ファンの教えの体験について本を書いた: 魔術師の交差点: タイシャ・アベラー著『The Sorcerer's Crossing: A Woman's Journey』、『Being-in-Dreaming』である: 魔術師の世界へのイニシエーション』(フロリンダ・ドナー著)。カスタネダはこれら2冊の本を、ドン・ファンの世界の魔術体験の本物の報告として支持した [16]。 カスタネダが亡くなった頃、彼の仲間であったドンナー=グラウ、アベラール、パトリシア・パルティンは、友人たちに長旅に出ることを知らせた。アマリア・ マルケス(タリア・ベイとしても知られる)とテンセグリティのインストラクター、カイリー・ルンダールもロサンゼルスを去った。数週間後、パーティンの赤 いフォード・エスコートがデスバレーに乗り捨てられているのが発見された。ベイの兄であるルイス・マルケスは1999年、妹の失踪を巡って警察を訪ねた が、捜査に値すると納得させることはできなかった[6]。 2003年、パーティンの日に焼けた骸骨がデスバレーのパナミント砂丘地区で2人組のハイカーによって発見され、2006年にDNA鑑定によって特定され た。捜査当局は死因を未確定とした[6][17]。しかしカスタネダはしばしば自殺について話しており、関係者はカスタネダの死をきっかけに女性たちが自 殺したと考えている[6]。 |

| Reception The veracity of these books, and the existence of don Juan, was doubted from their original publication,[6] and there is now consensus among critics and scholars that the books are largely, if not completely, fictional.[9][10][11] Early responses In the early years after the publication of Castaneda's first book, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1968), there was significant positive coverage and interest in his work. Time Magazine featured a review of The Teachings of Don Juan shortly after its publication. The review acknowledged the controversy and skepticism surrounding Castaneda's claims but highlighted the book's allure, describing it as "an extraordinary narrative." The New York Times published a review that praised the book's captivating storytelling and its portrayal of Don Juan as a "remarkable, almost legendary figure." Life Magazine included a feature article on Castaneda and his experiences with Don Juan, describing the book as "breathtaking" and focusing on the intrigue of his shamanic journey. The Los Angeles Times reviewed the book positively, emphasizing its impact on readers and its exploration of consciousness and reality. The Saturday Review highlighted the vividness of Castaneda's descriptions and his portrayal of Don Juan's teachings as thought-provoking and transformative. The Guardian's review of the book acknowledged Castaneda's skill as a writer and his ability to create a sense of immersion in his narrative. Later responses The veracity of Castaneda's work has been doubted since their original publication, even while reviewers praised the writing and storytelling.[6] For example, while Edmund Leach praised The Teachings of Don Juan as "a work of art," he doubted its factual authenticity.[10] Anthropologist E. H. Spicer offered a somewhat mixed review of the book, highlighting Castaneda's expressive prose and his vivid depiction of his relationship with don Juan. However, Spicer noted that the events described in the book were not consistent with other ethnographic accounts of Yaqui cultural practices, concluding it was unlikely that don Juan had ever participated in Yaqui group life. Spicer also wrote, "[It is] wholly gratuitous to emphasize, as the subtitle does, any connection between the subject matter of the book and the cultural traditions of the Yaquis."[11] In a series of articles, R. Gordon Wasson, the ethnobotanist who made psychoactive mushrooms famous, similarly praised Castaneda's work, while expressing doubts about its accuracy.[18] An early unpublished review by anthropologist Weston La Barre was more critical and questioned the book's accuracy. The review, initially commissioned by The New York Times Book Review, was rejected and replaced by a more positive review from anthropologist Paul Riesman.[6] Beginning in 1976, Richard de Mille published a series of criticisms that uncovered inconsistencies in Castaneda's field notes, as well as 47 pages of apparently plagiarized quotes.[6] Those familiar with Yaqui culture also questioned Castaneda's accounts, including anthropologist Jane Holden Kelley.[19] Other criticisms of Castaneda's work include the total lack of Yaqui vocabulary or terms for any of his experiences, and his refusal to defend himself against the accusation that he received his PhD from UCLA through deception.[20] Modern perspectives According to William W. Kelly, chair of the anthropology department at Yale University: I doubt you'll find an anthropologist of my generation who regards Castaneda as anything but a clever con man. It was a hoax, and surely don Juan never existed as anything like the figure of his books. Perhaps to many it is an amusing footnote to the gullibility of naive scholars, although to me it remains a disturbing and unforgivable breach of ethics.[6] Sociologist David Silverman sees value in the work even while considering it fictional. In Reading Castaneda he describes the apparent deception as a critique of anthropology field work in general—a field that relies heavily on personal experience, and necessarily views other cultures through a lens. He said that the descriptions of peyote trips and the work's fictional nature were meant to place doubt on other works of anthropology.[21] Donald Wiebe cites Castaneda to explain the insider/outsider problem as it relates to mystical experiences, while acknowledging the fictional nature of Castaneda's work.[22] |

受容 これらの書物の信憑性、そしてドン・ファンの存在は、出版当初から疑われており[6]、現在では批評家や学者の間では、これらの書物は完全ではないにせ よ、大部分がフィクションであるという点でコンセンサスが得られている[9][10][11]。 初期の反応 カスタネダの最初の著書である『ドン・フアンの教え:ヤキ族の知識の道』(1968年)が出版された初期の数年間は、彼の仕事に対する肯定的な報道と関心 が大きかった。 タイム誌は『ドン・ファンの教え』の出版直後に書評を掲載した。その書評は、カスタネダの主張をめぐる論争と懐疑論を認めながらも、この本の魅力を強調 し、"並外れた物語 "と評した。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、この本の魅惑的なストーリーテリングと、ドン・ファンを "驚くべき、ほとんど伝説的な人物 "として描いたことを賞賛する書評を掲載した。ライフ』誌は、カスタネダと彼のドン・ファンとの体験について特集記事を組み、この本を「息をのむような」 と評し、彼のシャーマンの旅の陰謀に焦点を当てた。 ロサンゼルス・タイムズ』紙は、この本を肯定的に評価し、読者への衝撃と意識と現実の探求を強調した。サタデー・レビュー』紙は、カスタネダの描写の鮮や かさと、ドン・ファンの教えが示唆に富み、変容をもたらすものであることを強調した。ガーディアン』紙の書評は、カスタネダの作家としての技量と、物語に 没入する感覚を作り出す能力を認めている。 その後の反応 例えば、エドモンド・リーチは『ドン・フアンの教え』を「芸術作品」と賞賛しながらも、その事実の信憑性を疑っていた[10]。人類学者のE・H・スパイ サーは、カスタネダの表現力豊かな散文とドン・ファンとの関係を生き生きと描いたことを強調し、本書についてやや複雑な批評を行った。しかしスパイサー は、この本に書かれている出来事はヤキの文化的慣習に関する他の民族誌の記述と一致しないと指摘し、ドン・ファンがヤキの集団生活に参加したことはないだ ろうと結論づけた。またスパイサーは「副題にあるように、この本の主題とヤキの文化的伝統との関連性を強調するのは、まったくもって無益である」とも書い ている[11]。 精神作用のあるキノコを有名にした民族植物学者であるR・ゴードン・ワッソンも、一連の記事の中で、カスタネダの作品の正確さに疑問を示しながらも、同様 に賞賛している[18]。 人類学者のウェストン・ラ・バールによる初期の未発表の書評は、より批判的で、この本の正確さに疑問を呈していた。この批評は当初ニューヨーク・タイム ズ・ブックレビューによって依頼されたが、却下され、人類学者ポール・リースマンによるより肯定的な批評に置き換えられた[6]。 1976年からは、リチャード・デ・ミルが一連の批判を発表し、カスタネダのフィールドノートに矛盾があることや、47ページにわたって明らかに盗用され た引用があることを明らかにした[6]。 また、人類学者のジェーン・ホールデン・ケリーを含め、ヤキ族の文化に詳しい人々もカスタネダの記述に疑問を呈している[19]。 カスタネダの著作に対するその他の批判には、彼の体験にヤキ族の語彙や用語が全くないことや、彼が欺瞞によってUCLAから博士号を取得したという非難に 対して彼自身を弁護することを拒否していることなどがある[20]。 現代の視点 エール大学人類学部のウィリアム・W・ケリー学長は言う: 私の世代の人類学者で、カスタネダを巧妙な詐欺師以外の何物でもないと考える者はいないだろう。それはデマであり、確かにドン・ファンは彼の著書のような 人物としては存在しなかった。おそらく多くの人にとっては、世間知らずの学者の騙されやすさを示す面白い脚注なのだろうが、私にとっては不穏で許しがたい 倫理違反であることに変わりはない[6]。 社会学者のデイヴィッド・シルヴァーマンは、この作品がフィクションであると考えながらも、その価値を認めている。彼は『カスタネダを読む』の中で、この 明らかな欺瞞を、人類学のフィールドワーク全般に対する批判として述べている。彼は、ペヨーテ旅行の描写と作品のフィクション性は、他の人類学の作品に疑 念を抱かせることを意図していると述べている[21]。 ドナルド・ウィービーはカスタネダの作品のフィクション性を認めつつ、神秘体験に関連するインサイダー/アウトサイダー問題を説明するためにカスタネダを 引用している[22]。 |

| Existence of Don Juan Matus Scholars have also debated "whether Castaneda actually served as an apprentice to the alleged Yaqui sorcerer don Juan Matus or if he invented the whole odyssey."[9] Castaneda's books are classified as non-fiction by their publisher, although there is consensus among critics that they are largely, if not completely, fictional.[23][24][6] Castaneda critic Richard de Mille published two books—Castaneda's Journey: The Power and the Allegory and The Don Juan Papers—in which he argued that don Juan was imaginary,[25][26] based on a number of arguments, including that Castaneda did not report on the Yaqui name of a single plant he learned about, and that he and don Juan "go quite unmolested by pests that normally torment desert hikers."[6] Castaneda's Journey also includes 47 pages of quotes Castaneda attributed to don Juan which were actually from a variety of other sources, including anthropological journal articles and even well known writers like Ludwig Wittgenstein and C. S. Lewis.[6] In response, Castaneda was defended in a letter to the editor by inventor of Core Shamanism, Michael Harner.[27][28] Walter Shelburne contends that "the Don Juan chronicle cannot be a literally true account."[29] According to Jeroen Boekhoven, Castaneda spent some time with Ramón Medina Silva,[30] a Huichol mara'akame (shaman) and artist who may have inspired the don Juan character. Silva was murdered during a brawl in 1971.[31] |

ドン・フアン・マトゥスの存在 学者たちはまた、「カスタネダが実際にヤキ族の魔術師とされるドン・フアン・マトゥスに弟子入りしたのか、それとも彼がオデッセイ全体を創作したのか」 [9]についても議論している。カスタネダの著書は出版社によってノンフィクションに分類されているが、批評家の間では、完全ではないにせよ、大部分が フィクションであるという点でコンセンサスが得られている[23][24][6]。 カスタネダの批評家であるリチャード・デ・ミルは2冊の本-『カスタネダの旅』-を出版した: その中で、カスタネダはヤキ族に伝わる植物の名前を1つも報告していないこと、彼とドン・ファンは「通常砂漠のハイカーを苦しめる害虫に全く悩まされずに 行く」ことなど、多くの論拠に基づいて、ドン・ファンは架空の存在であると主張した[25][26]。 「これに対してカスタネダは、コア・シャーマニズムの発明者であるマイケル・ハーナーから編集者への手紙の中で擁護されている[27][28]。 Jeroen Boekhovenによると、カスタネダはラモン・メディナ・シルバとしばらく過ごした[30]。シルヴァは1971年に乱闘の最中に殺害された [31]。 |

| Related writers and influence Michael Korda, editor-in-chief at Simon & Schuster, was Castaneda's editor for his first eight books and discusses their work together in an essay in Another Life: A Memoir of Other People.[6] George Lucas has stated that Yoda and Luke Skywalker were inspired in part by don Juan and Castaneda.[32] Lui Morais, a Brazilian writer, analyzes Castaneda's work, its cultural implications, and its continuation in other authors in Carlos Castaneda e a Fenda entre os Mundos: Vislumbres da Filosofia Ānahuacah no Século XXI.[33] Octavio Paz, Nobel laureate, poet, and diplomat. Paz wrote the prologue to the Spanish language edition of The Teachings of Don Juan.[34] Amy Wallace wrote Sorcerer's Apprentice: My Life with Carlos Castaneda, an account of her personal experiences with Castaneda and his followers.[35] |

関連作家と影響 サイモン&シュスター社の編集長であるマイケル・コルダは、カスタネダの最初の8冊の本の編集者であり、『Another Life』のエッセイの中で2人の仕事について語っている[6]: A Memoir of Other People』[6]のエッセイで二人の仕事について触れている。 ジョージ・ルーカスは、ヨーダとルーク・スカイウォーカーはドン・フアンとカスタネダからインスパイアされた部分があると述べている[32]。 ブラジルの作家であるルイ・モライスは、『Carlos Castaneda e a Fenda entre os Mundos: Vislumbres da Filosofia Ānahuacah no Século XXI』でカスタネダの作品、その文化的意味合い、他の作家におけるその継続性を分析している[33]。 オクタビオ・パス、ノーベル賞受賞者、詩人、外交官。パスは『ドン・ファンの教え』のスペイン語版のプロローグを書いた[34]。 エイミー・ウォレスは『魔術師の弟子』を執筆: カスタネダとその信者たちとの個人的な体験を綴った『Sorcerer's Apprentice: My Life with Carlos Castaneda』[35]。 |

| Publications Books The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, 1968. ISBN 978-0-520-21757-7. (Summer 1960 to October 1965.) A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan, 1971. ISBN 978-0-671-73249-3. (April 1968 to October 1970.) Journey to Ixtlan: The Lessons of Don Juan, 1972. ISBN 978-0-671-73246-2. (Summer 1960 to May 1971.) Tales of Power, 1974. ISBN 978-0-671-73252-3. (Autumn 1971 to the 'Final Meeting' with don Juan Matus in 1973.) The Second Ring of Power, 1977. ISBN 978-0-671-73247-9. (Meeting his fellow apprentices after the 'Final Meeting'.) The Eagle's Gift, 1981. ISBN 978-0-671-73251-6. (Continuing with his fellow apprentices; and then alone with La Gorda.) The Fire From Within, 1984. ISBN 978-0-671-73250-9. (Don Juan's 'Second Attention' teachings through to the 'Final Meeting' in 1973.) The Power of Silence: Further Lessons of Don Juan, 1987. ISBN 978-0-671-73248-6. (The 'Abstract Cores' of don Juan's lessons.) The Art of Dreaming, 1993. ISBN 978-0-06-092554-3. (Review of don Juan's lessons in dreaming.) Magical Passes: The Practical Wisdom of the Shamans of Ancient Mexico, 1998. ISBN 978-0-06-017584-9. (Body movements for breaking the barriers of normal perception.) The Wheel of Time: Shamans of Ancient Mexico, Their Thoughts About Life, Death and the Universe, 1998. ISBN 978-0-9664116-0-7. (Selected quotations from the first eight books.) The Active Side of Infinity, 1999. ISBN 978-0-06-019220-4. (Memorable events of his life.) Interviews Burton, Sandra (March 5, 1973). "Magic and Reality". Time. Corvalan, Graciela, Der Weg der Tolteken - Ein Gespräch mit Carlos Castañeda, Fischer, 1987, c. 100p., ISBN 3-596-23864-1 |

出版物 書籍 ドン・フアンの教え:ヤキ族の知の道』1968年。ISBN 978-0-520-21757-7. (1960年夏から1965年10月まで) 別の現実: ドン・ファンとのさらなる対話、1971年。ISBN 978-0-671-73249-3. (1968年4月から1970年10月まで) イクスランへの旅: ドン・ファンの教え, 1972. ISBN 978-0-671-73246-2. (1960年夏から1971年5月まで) テイルズ・オブ・パワー, 1974. ISBN 978-0-671-73252-3. (1971年秋から1973年のドン・フアン・マタスとの「最終会談」まで) 権力の第二の指輪』1977年。ISBN 978-0-671-73247-9. (最終会合」後の弟子たちとの出会い) 鷲の贈り物』1981年。ISBN 978-0-671-73251-6. (仲間の弟子たちと続き、ラ・ゴルダと二人きりになる) The Fire From Within, 1984. ISBN 978-0-671-73250-9. (ドン・ファンの「第二の注意」の教えから1973年の「最終会合」まで。) 沈黙の力: ドン・ファンのさらなる教え、1987年。ISBN 978-0-671-73248-6. (ドン・ファンの教えの「抽象的核心」) 夢を見る技術、1993年。ISBN 978-0-06-092554-3. (ドン・ジュアンの夢見のレッスンのレビュー) 魔法のパス 古代メキシコのシャーマンの実践的知恵, 1998. ISBN 978-06-017584-9. (通常の知覚の壁を破るための身体の動き) The Wheel of Time: Shamans of Ancient Mexico, Their Thoughts About Life, Death and the Universe, 1998. ISBN 978-0-9664116-0-7. (最初の8冊からの抜粋。) The Active Side of Infinity, 1999. ISBN 978-0-06-019220-4. (彼の生涯で印象に残った出来事) インタビュー バートン、サンドラ(1973年3月5日)。「魔法と現実". Time. Corvalan, Graciela, Der Weg der Tolteken - Ein Gespräch mit Carlos Castañeda, Fischer, 1987, c. 100p., ISBN 3-596-23864-1. |

| Body of light Neoshamanism Peyote song Rainbow body Witchcraft in Latin America |

光のボディ ネオシャーマニズム ペヨーテの歌 虹の身体 ラテンアメリカの魔術 |

| Castaneda's birth name, as

well as the date and location of his birth, are uncertain. According to

a 1973 article in Time, U.S. immigration records indicate that

Castaneda was born Carlos Cesar Arana Castaneda on December 25, 1925,

in Cajamarca, Peru.[1] In the article, Castaneda was cited as saying

that he had adopted the surname "Castaneda" later in life and that he

had been born in São Paulo, Brazil. He also reported his date of birth

as December 25, 1935.[1] In other accounts he gave his date of birth as

December 25, 1931.[2][3] A 1981 article in The New York Times stated

that Castaneda "was born Carlos Arana in a Peruvian mountain town 66

years ago", indicating a 1915 birth.[4] Most sources tend to favor the

Peruvian birth and 1925 date.[5] |

カスタネダの出生名、出生日、出生場所は不明である。タイ

ム』誌の1973年の記事によると、米国の移民記録では、カスタネダは1925年12月25日にペルーのカハマルカでカルロス・セザール・アラナ・カスタ

ネダとして生まれたことになっている[1]。その記事では、カスタネダは後年「カスタネダ」という姓を名乗り、ブラジルのサンパウロで生まれたと述べてい

る。また、彼は生年月日を1935年12月25日と報告している[1]。1981年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事は、カスタネダが「66年前にペルー

の山間の町でカルロス・アラナとして生まれた」と述べており、1915年生まれであることを示している[4]。ほとんどの情報源は、ペルー生まれと

1925年の日付を支持する傾向がある[5]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Castaneda |

++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099