Interepretations of the Bergman's filmwork "Wild Strawberries"

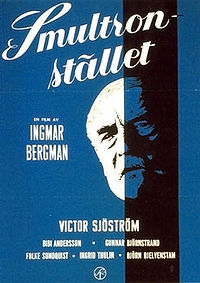

Ingmar Bergman (L) and Victor Sjöström (R), 1957.

ベイルイマン『野いちご』(1957)[読解ならぬ]視解

Interepretations of the Bergman's filmwork "Wild Strawberries"

Ingmar Bergman (L) and Victor Sjöström (R), 1957.

解説:池田光穂

登場人物

イサク・ボールイ博士(76歳)Isak Borg;ルター派信徒

アグダ:家政婦。イサクに自動車でルンドまでの旅に誘われるが、断り飛行機で出かける。

マリアンヌ:義理の娘(長男の嫁)、ルンドまでの旅につきあう

エヴァルド:イサクの息子で、ルンドに住んでいる。38歳。孫のなかで唯一年に一度祖母を訪ねる。

サーラ:昔の恋人(女ヒッチハイカーと同じ女優が演じる)

サーラ:女ヒッチハイカーで、医者になろうとするボーイフレンド(ヴィクトール)と婚約している

ヴィクトール:サーラの婚約者で医学生

アンデルス:サーラたちの同行者で牧師になろうとしている。

シークブリッド:イサクの兄弟(弟)でサーラと同様回想シーンに登場

アーロンおじさん:回想シーンでの誕生日を迎える

夫婦喧嘩の妻:

夫婦喧嘩の夫:

アケルマン:ガソリンスタンドの主人。妻エヴァは妊娠しており、生まれてくる子供にイサクと名づけたたい。

レストランのウェイター:

イサクの母:96歳、皮肉屋

アルマン:イサクが医学生時代の幻想のシーンに登場する時の医学校の教師(夫婦喧嘩の夫と同じ俳優)

アルマン夫人:試験においてアルマンがイサクに診断しようと命じる患者

死んだイサクの妻カーリン:ヒステリックな女性。イサクに不義を働いた。

オリジナル・スウェーデン語

ポスター

オリジナル・スウェーデン語

ポスター

分析のための発話集

イサク「お前たちの夫婦喧嘩に、わしを引きずり込まんでくれ。わしには何の関心もないんでね。誰だって悩みはあるさ」

イサクがマリアンヌにむかって「タバコを吸わんでくれ。女の喫煙を禁ずる法律があってしかるべきだ」

サーラ「イサクはとても洗練されているの。ものすごく洗練されていて、道徳的で、繊細で、ふたりで詩を読みたがり、死後の話をし、ピアノで 連弾しよっていうし、暗いところでしかキスしたがらないし、それに罪深さの話をするの。……でも、ときどき、自分がイサクよりもずっと年上と思われること があるわ。これ、どういう意味かわかる? それに、わたしと同じ歳なのに、彼が子供だなって思うの」

イサク「魂の苦しみに関心はない。だからわしのところに泣き言を言いにこないでくれ。だが、お前に精神的マスターベーションが必要だという なら、どこかのやぶ医者か坊主の予約を取ってやるよ。いまどきはやりのやつさ」

マリアンヌ「さようなら、イサクお父様、今日も、明日も、ずっと永久に、わたしが大好きなのはあなただってこと、わかってくださいます か?」

アグダ「世間はなんというでしょう。親密すぎるのはごめんこうむりたいですわ」

エヴァルドがイサクに「僕は彼女なしにはいられない……あの彼女がいてくれなければやっていけないと言ってるんだ」。イサクはエヴァルドに 「わかったよ」。エヴァルドは独り言のように「結局は彼女次第だろうな」

アルマンがイサクにむかって「医者のまず第一の義務は許しを請うことだ……おまえは罪悪という罪を犯している」

| Wild Strawberries

is a 1957 Swedish drama film written and directed by Ingmar Bergman.

The original Swedish title is Smultronstället, which literally means

"the wild strawberry patch" but idiomatically signifies a hidden gem of

a place, often with personal or sentimental value, and not widely

known. The cast includes Victor Sjöström in his final screen

performance as an old man recalling his past, as well as Bergman

regulars Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, and Gunnar Björnstrand. Max von

Sydow also appears in a small role. Bergman wrote the screenplay while hospitalized.[1] Exploring philosophical themes such as introspection and human existence, Wild Strawberries received wide positive domestic reception upon release, and won the Golden Bear for Best Film at the 8th Berlin International Film Festival. It is often considered to be one of Bergman's best films, as well as one of the greatest films ever made.[2] |

『野いちご』は、イングマール・ベルイマンが脚本と監督を手がけた

1957年のスウェーデンのドラマ映画である。スウェーデン語の原題は『Smultronstället』で、文字通りには「野いちご畑」を意味するが、

慣用的には、個人的または感傷的な価値を持ち、広く知られていない隠れた宝石のような場所を意味する。出演は、過去を回想する老人役で最後のスクリーン出

演となったヴィクトル・シェストレムをはじめ、ベルイマンの常連であるビビ・アンデション、イングリッド・チューリン、グンナー・ビョルンストランドな

ど。マックス・フォン・シドーも小さな役で出演している。 バーグマンは入院中に脚本を執筆した。内観や人間の存在といった哲学的なテーマを探求した『野いちご』は、公開と同時に国内で広く好評を博し、第8回ベル リン国際映画祭で金熊賞(最優秀作品賞)を受賞。ベルイマンの最高傑作のひとつであり、また史上最高の映画のひとつとされることも多い[2]。 |

| Plot Grouchy, stubborn, and egotistical Professor Isak Borg is a widowed 78-year-old physician who specialized in bacteriology. Before specializing, he served as a general practitioner in rural Sweden. He sets out on a long car ride from Stockholm to Lund to be awarded the degree of Doctor Jubilaris 50 years after he received his doctorate from Lund University. He is accompanied by his pregnant daughter-in-law Marianne who does not much like her father-in-law and is planning to separate from her husband, Evald, Isak's only son. Evald does not want her to have the baby, their first. During the trip, Isak is forced by nightmares, daydreams, old age, and impending death to reevaluate his life. He meets a series of hitchhikers, each of whom sets off dreams or reveries into Borg's troubled past. The first group consists of two young men and their companion, a woman named Sara who is adored by both men. Sara is a double for the love of Isak's youth. He reminisces about his childhood at the seaside and his sweetheart Sara, with whom he remembered gathering strawberries, but who instead married his brother. The first group remains with him throughout his journey. Next Isak and Marianne pick up an embittered middle-aged couple, the Almans, whose vehicle had nearly collided with theirs. The pair exchanges such terrible vitriol and venom that Marianne stops the car and demands that they leave. The couple reminds Isak of his own unhappy marriage. In a dream sequence, Isak is asked by Sten Alman, now the examiner, to read "foreign" letters on the blackboard. He cannot. So, Alman reads it for him: "A doctor's first duty is to ask forgiveness," from which he concludes, "You are guilty of guilt."[3] He is confronted by his loneliness and aloofness, recognizing these traits in both his elderly mother (whom they stop to visit) and in his middle-aged physician son, and he gradually begins to accept himself, his past, his present, and his approaching death.[4][5][6] Borg finally arrives at his destination and is promoted to Doctor Jubilaris, but this proves to be an empty ritual. That night, he bids a loving goodbye to his young friends, to whom the once bitter old man whispers in response to a playful declaration of the young girl's love, "I'll remember." As he goes to his bed in his son's home, he is overcome by a sense of peace, and dreams of a family picnic by a lake. Closure and affirmation of life have finally come, and Borg's face radiates joy. |

プロット 不機嫌で、頑固で、自己中心的なイザック・ボルグ教授は、細菌学を専門とする78歳の未亡人医師である。専門医になる前は、スウェーデンの片田舎で開業医 をしていた。ルンド大学で博士号を取得してから50年後、彼はストックホルムからルンドまでの長い車での旅に出る。妊娠中の義理の娘マリアンヌは義父を 嫌っており、イサックの一人息子である夫エヴァルドとの別居を画策していた。エヴァルドはイサクに最初の子供を産ませたくないのだ。 旅の途中、イザークは悪夢、白昼夢、老い、差し迫った死によって、自分の人生を見直す必要に迫られる。彼は何人かのヒッチハイカーと出会うが、それぞれが ボーグの苦悩に満ちた過去に夢や想いを馳せる。最初のグループは2人の若者とその連れで、2人の男性に慕われているサラという名の女性。サラはイサックの 若い頃の恋人の替え玉である。イサックは、海辺で過ごした子供時代と、イチゴ狩りをした思い出の恋人サラを回想する。最初の一団は、旅の間ずっと彼のそば にいる。次にイザックとマリアンヌは、彼らの車と衝突しそうになった憤慨した中年夫婦、アルマン夫妻を拾う。マリアンヌは車を止め、2人に立ち去るよう要 求する。この夫婦は、イザークに自分の不幸な結婚生活を思い出させる。夢の中で、イザークはステン・アルマン(現在は試験官)から、黒板に書かれた「外国 語」の文字を読むよう求められる。彼は読めない。そこでアルマンが代読する: 「医師の第一の義務は許しを請うことである」、そこから彼は「あなたは罪を犯している」と結論づける[3]。 彼は自分の孤独と飄々とした態度に直面し、(見舞いに立ち寄った)年老いた母親と中年医師の息子の両方にその特徴を認め、自分自身、過去、現在、そして近 づきつつある死を徐々に受け入れ始める[4][5][6]。 ボルグはついに目的地に到着し、ジュビラリス医師に昇進するが、これは空虚な儀式であることが判明する。その夜、彼は若い友人たちに愛の別れを告げる。か つて辛辣だった老人は、若い娘の遊び半分の愛の告白に応えて、「忘れないよ 」とささやく。息子の家のベッドに入ると、彼は安らかな気持ちに包まれ、湖畔で家族でピクニックをする夢を見る。人生の終結と肯定がついに訪れ、ボルグの 顔には喜びが輝いている。 |

| Victor Sjöström as Professor

Isak Borg Bibi Andersson as Sara (both: Isak's cousin/hitchhiker) Ingrid Thulin as Marianne Borg Gunnar Björnstrand as Evald Borg Jullan Kindahl as Agda, Isak's housekeeper Folke Sundquist as Anders, hitchhiker Björn Bjelfvenstam as Viktor, hitchhiker Naima Wifstrand as Isak's Mother Gunnel Broström as Berit Alman, angry wife Gunnar Sjöberg as Sten Alman, angry husband / The Examiner Max von Sydow as Henrik Åkerman, gas station attendant Ann-Marie Wiman as Eva Åkerman Gertrud Fridh as Karin Borg, Isak's wife Åke Fridell as Karin's lover Sif Ruud as Aunt Olga Yngve Nordwall as Uncle Aron Per Sjöstrand as Sigfrid Borg Gio Petré as Sigbritt Borg Gunnel Lindblom as Charlotta Borg Maud Hansson as Angelica Borg Eva Norée as Anna Borg Göran Lundquist as Benjamin Borg Per Skogsberg as Hagbart Borg Lena Bergman as Kristina Borg, twin Monica Ehrling as Birgitta Borg, twin |

イザック・ボルグ教授役:ヴィクトル・シェストレム ビビ・アンデルソン(サラ役:イサックの従姉妹/ヒッチハイカー) イングリッド・チューリン(マリアンヌ・ボルグ役 グンナル・ビョルンストランド(Evald Borg役 ユラン・キンダール(イザークの家政婦アグダ役 フォルケ・スンドクイスト(ヒッチハイカー、アンダース役 ビョルン・ビェルフヴェンスタム(ヒッチハイカー、ヴィクトル役 ナイマ・ウィフストランド(イサックの母役 グンネル・ブロストレム(怒れる妻、ベリット・アルマン役 グンナル・シェーベリ:ステン・アルマン(怒れる夫/調査官)役 マックス・フォン・シドー:ヘンリック・オーケルマン役(ガソリンスタンド店員 アン=マリー・ウィマン(エヴァ・オーケルマン役 ゲルトルート・フリード(イザークの妻カリン・ボルグ役 オーケ・フリデル(カリーンの恋人役 シフ・ルード(オルガおばさん役 アロンおじさん役:イングヴェ・ノルドウォール ペール・シェストランド(シグフリッド・ボルグ役 ジオ・ペトレ(シグブリット・ボルグ役 グンネル・リンドブロム(シャルロッタ・ボルグ役 モード・ハンソン(アンジェリカ・ボルグ役 エヴァ・ノレ(アンナ・ボルグ役 ヨーラン・ルンドクイスト(ベンジャミン・ボルグ役 ペール・スコグスベリ(ハグバート・ボルグ役 レナ・バーグマン(双子のクリスティナ・ボルグ役 モニカ・エルリング(双子のビルギッタ・ボルグ役 |

| Production Origins  Ingmar Bergman (L) and Victor Sjöström (R) in 1957, during production of Wild Strawberries in the studios in Solna. Bergman's idea for the film originated on a drive from Stockholm to Dalarna during which he stopped in Uppsala, his hometown. Driving by his grandmother's house, he suddenly imagined how it would be if he could open the door and inside find everything just as it was during his childhood. "So it struck me — what if you could make a film about this; that you just walk up in a realistic way and open a door, and then you walk into your childhood, and then you open another door and come back to reality, and then you make a turn around a street corner and arrive in some other period of your existence, and everything goes on, lives. That was actually the idea behind Wild Strawberries".[7][page needed] Later, he would revise the story of the film's genesis. In Images: My Life in Film, he comments on his own earlier statement: "That's a lie. The truth is that I am forever living in my childhood."[8]: p22 Development Bergman wrote the screenplay of Wild Strawberries in Stockholm's Karolinska Hospital (the workplace of Isak Borg) in the late spring of 1957; he'd recently been given permission to proceed by producer Carl Anders Dymling on the basis of a short synopsis. He was in the hospital for two months, being treated for recurrent gastric problems and general stress. Bergman's doctor at Karolinska was his good friend Sture Helander who invited him to attend his lectures on psychosomatics. Helander was married to Gunnel Lindblom who was to play Isak's sister Charlotta in the film. Bergman was at a high point of his professional career after a triumphant season at the Malmö City Theatre (where he had been artistic director since 1952), in addition to the success of both Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) and The Seventh Seal (1957). His private life, however, was in disarray. His third marriage was on the rocks; his affair with Bibi Andersson, which had begun in 1954, was coming to an end; and his relationship with his parents was, after an attempted reconciliation with his mother, at a desperately low ebb.[8]: p17 Casting and pre-production progressed rapidly. The completed screenplay is dated May 31. Shooting took place between July 2, 1957 and August 27, 1957.[9] The scenes at the summer house were filmed in Saltsjöbaden, a fashionable resort in the Stockholm archipelago. Part of the nightmare sequence was shot with predawn summer light in Gamla stan, the old part of central Stockholm. Most of the movie was made at SF's studio and on its back lot at Råsunda in northern Stockholm.[1] Casting The director's immediate choice for the leading role of the old professor was Victor Sjöström, Bergman's silent film idol and early counselor at Svensk Filmindustri, whom he had directed in To Joy eight years earlier. "Victor," Bergman remarked, "was feeling wretched and didn't want to [do it];... he must have been seventy eight. He was misanthropic and tired and felt old. I had to use all my powers of persuasion to get him to play the part."[10] In Bergman on Bergman, he has stated that he only thought of Sjöström when the screenplay was complete, and that he asked Dymling to contact the famous actor and film director.[11] Yet in Images: My Life in Film, he claims, "It is probably worth noting that I never for a moment thought of Sjöström when I was writing the screenplay. The suggestion came from the film's producer, Carl Anders Dymling. As I recall, I thought long and hard before I agreed to let him have the part."[8]: p24 During the shooting, the health of the 78-year-old Sjöström gave cause for concern. Dymling had persuaded him to take on the role with the words: "All you have to do is lie under a tree, eat wild strawberries and think about your past, so it's nothing too arduous." This was inaccurate and the burden of the film was completely on Sjöström who is in all but one scene of the film. Initially, Sjöström had problems with his lines which made him frustrated and angry. He would go off into a corner and beat his head against the wall in frustration, even to the point of drawing blood and producing bruises. He sometimes quibbled over details in the script. To unburden his revered mentor, Bergman made a pact with Ingrid Thulin that if anything went wrong during a scene, she would take the blame on herself. Things improved when they changed filming times so that Sjöström could get home in time for his customary late afternoon whisky at 5:00. Sjöström got along particularly well with Bibi Andersson.[1] As usual, Bergman chose his collaborators from a team of actors and technicians with whom he had worked before in the cinema and the theater. As Sara, Bibi Andersson plays both Borg's childhood sweetheart who left him to marry his brother and a charming, energetic young woman who reminds him of that lost love. Andersson, then twenty one years old, was a member in Bergman's famed repertory company. He gave her a small part in his films Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) and as the jester's wife in The Seventh Seal (1957). She would continue to work for him in many more films, most notably in Persona (1966). Ingrid Thulin plays Marianne, the sad, gentle and warm daughter-in-law of Borg. She appeared in other Bergman films as the mistress in Winter Light (1963) and as one of three sisters in Cries and Whispers (1972). |

生産 原点  1957年、イングマール・ベルイマン(左)とヴィクトル・シェストレム(右)。 バーグマンのこの映画のアイデアは、ストックホルムからダーラナ地方へのドライブの途中、故郷のウプサラに立ち寄ったときに生まれた。祖母の家のそばを車 で通りかかったとき、彼はふと、ドアを開けて中に入ったら、子供の頃と同じように何もかもがあったならどうなるだろうと想像した。「現実的な方法で近づい てドアを開けると、子供時代に入り込み、別のドアを開けると現実に戻り、街角を曲がると別の時代に到着する。それが『ワイルド・ストロベリー』のアイデア だった」[7][要ページ] 後に、彼はこの映画の発端となったストーリーを修正することになる。Images: Images: My Life in Film』の中で、彼は以前の自身の発言についてこうコメントしている: 「それは嘘だ。真実は、私は永遠に子供時代に生きているということだ」[8]: p22 発展(展開) ベルイマンは1957年の晩春、ストックホルムのカロリンスカ病院(イサーク・ボルグの職場)で『野いちご』の脚本を書いた。彼は2ヵ月間入院し、再発性 の胃の病気と全身的なストレスの治療を受けた。カロリンスカの主治医は親友のスチューレ・ヘランデルで、ヘランデルは彼を精神医学の講義に招待した。ヘラ ンダーは、この映画でイザークの妹シャルロッタを演じるグンネル・リンドブロムと結婚していた。ベルイマンは、『夏の夜の微笑』(1955)と『第七の封 印』(1957)の成功に加え、マルメ市立劇場(1952年から芸術監督を務めていた)での勝利のシーズンを経て、プロとしてのキャリアの絶頂期にあっ た。しかし、私生活は乱れていた。3度目の結婚は破綻し、1954年に始まったビビ・アンデションとの関係は終わりを告げ、両親との関係は、母親との和解 を試みたものの、絶望的なまでに悪化していた[8]: p17 キャスティングとプリプロダクションは急速に進んだ。完成した脚本の日付は5月31日。撮影は1957年7月2日から8月27日にかけて行われた[9]。 夏の家のシーンはストックホルム群島にあるおしゃれなリゾート地、サルツヨーバーデンで撮影された。悪夢のシーンの一部は、ストックホルム中心部の旧市 街、ガムラスタンで夜明け前の夏の光とともに撮影された。映画の大半はSFのスタジオとストックホルム北部のロスンダにある裏地で撮影された[1]。 キャスティング 監督が主役の老教授に即決したのは、ベルイマンのサイレント映画のアイドルであり、8年前に『喜びへ』で監督したスヴェンスク・フィルムインダストリの初 期のカウンセラーでもあったヴィクトル・シェストレムだった。「ヴィクトルは憂鬱な気分で、(映画を)やりたがらなかった。彼は人間嫌いで疲れていて、老 いを感じていた。私は、彼にこの役を演じてもらうために、あらゆる説得力を駆使しなければならなかった」[10]。 バーグマンについてのバーグマンの中で、彼は脚本が完成したときに初めてシェストレムのことを考え、有名な俳優であり映画監督であるシェストレムに連絡を 取るようディムリングに頼んだと述べている[11]: しかし、『Images: My Life in Film』では、「脚本を書いているとき、シェストレムのことを一瞬たりとも考えたことがなかったことは、注目に値するだろう」と主張している。この映画 のプロデューサー、カール・アンダース・ディムリングからの提案だった。思い起こせば、彼にこの役を任せることに同意する前に、私はじっくり考えた」 [8]: p24 撮影中、78歳のシェストレムの健康状態が心配された。ダイムリングはこう言って彼を説得した: 「木の下に寝そべって野いちごを食べ、自分の過去について考えるだけだから、それほど大変なことはない」。これは不正確で、この映画の1シーンを除くすべ てに出演しているシェストレムの負担は完全に大きかった。当初、シェストレムは自分のセリフに問題があり、イライラして怒っていた。彼は苛立ちのあまり 隅っこに行っては壁に頭を打ちつけ、血を流してアザを作るほどだった。台本の細部をめぐって屁理屈をこねることもあった。尊敬する師匠に負担をかけないた めに、バーグマンはイングリッド・チューリンと、シーン中に何か問題が起きたら彼女が責任を取るという約束を交わした。撮影時間が変更され、シェストレム が恒例の午後5時からのウイスキーを飲む時間に帰宅できるようになると、事態は好転した。シェストレムはビビ・アンデションと特に仲が良かった[1]。 ベルイマンはいつものように、映画や劇場で一緒に仕事をしたことのある俳優や技術者から協力者を選んだ。サラ役のビビ・アンデルソンは、ボルグの幼なじみ で兄と結婚するために彼のもとを去った恋人と、その失恋を思い出させる魅力的でエネルギッシュな若い女性の両方を演じている。当時21歳だったアンデルソ ンは、ベルイマンの有名なレパートリー・カンパニーのメンバーだった。彼は彼女に『夏の夜の微笑』(1955年)と『第七の封印』(1957年)の道化師 の妻役で小さな役を与えた。その後も、『ペルソナ』(1966年)を筆頭に、多くの作品に出演している。イングリッド・チューリンは、ボルグの義理の娘 で、悲しく、優しく、温かいマリアンヌを演じている。冬の光』(1963年)の愛人役や『叫びとささやき』(1972年)の三姉妹のひとり役など、他のベ ルイマン作品にも出演している。 |

| Reception Wild Strawberries received strongly positive reviews in Sweden; its acting, script, and photography were common areas of praise.[12] It was among the films that cemented Bergman's international reputation,[13] but American critics were not unanimous in their praise. A number of reviewers found its story puzzling. In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther lauded the performances of Sjöström and Andersson but wrote, "This one is so thoroughly mystifying that we wonder whether Mr. Bergman himself knew what he was trying to say."[14] The film ranked 7th on Cahiers du Cinéma's Top 10 Films of the Year List in 1959.[15] In a 1963 interview with Cinema magazine, director Stanley Kubrick listed the film as his second favourite of all time.[16] It was also listed by Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky as one of his top ten favorite films.[17] It is now considered one of Bergman's major works. Film critic Derek Malcolm ranked the film at No. 56 on his list of the "Top 100 Movies" in 2001.[18] In 2007, the film was ranked at No. 34 by The Guardian's readers poll on the list of "40 greatest foreign films of all time".[19] In 2009, the film was ranked at No. 59 on Japanese film magazine kinema Junpo's Top 100 Non-Japanese Films of All Time list.[20] In 1972, the work was ranked 10th, in 2002 it was ranked 27th,[21] and in 2012, it ranked 63rd on the Sight & Sound critics' poll of the greatest films ever made.[22] That same year the film was voted at number 11 on the 25 best Swedish films of all time list by a poll of 50 film critics and academics conducted by film magazine FLM.[23] Its screenplay was listed in Total Film as one of the 50 best ever written.[24] The film was included in BBC's 2018 list of The 100 greatest foreign language films.[25] In 2022 edition of Sight & Sound's Greatest films of all time list the film ranked 72nd in the director's poll.[26] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Wild Strawberries has an approval rating of 96% based on 45 reviews, with an average score of 8.90/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Wild Strawberries were never so bittersweet as Ingmar Bergman's beautifully written and filmed look at one man's nostalgic journey into the past."[27] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 88 out of 100 based on 17 critic's reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[28] |

レセプション(受容) 『野いちご』はスウェーデンで高い評価を受け、演技、脚本、撮影が共通して賞賛された[12]。 ベルイマンの国際的な名声を確固たるものにした作品のひとつであるが[13]、アメリカの批評家たちの評価は一様ではなかった。多くの批評家がこの作品の ストーリーを不可解だと感じていた。ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙では、ボスリー・クラウザーがシェストレムとアンデルソンの演技を称賛したが、「この作品 は、ベルイマン自身が何を言おうとしているのか分かっていたのか疑問に思うほど、徹底的に謎めいている」と書いている[14]。 1963年のシネマ誌のインタビューで、スタンリー・キューブリック監督はこの映画を歴代で2番目に好きな映画として挙げている[16]。 また、ロシアの映画監督アンドレイ・タルコフスキーも好きな映画トップ10に挙げている。映画評論家のデレク・マルコムが2001年に発表した「映画ベス ト100」では56位にランクイン[18]。 2007年、ガーディアン紙の読者投票による「史上最も偉大な外国映画40選」では34位にランクイン[19]。 2009年、日本の映画雑誌『キネマ旬報』の「外国映画ベスト100」では59位にランクイン[20]。 1972年には10位、2002年には27位[21]、2012年にはSight & Sound誌の批評家による史上最高の映画ランキングで63位にランクインした[22]。 同年、映画雑誌FLMが行った50人の映画批評家と学者による投票で、スウェーデン映画の歴代ベスト25の11位に選ばれた[23]。 [23]その脚本は『Total Film』誌で史上最高の50本のうちの1本として掲載された[24]。 BBCの2018年版外国語映画100選に選出された[25]。2022年版『Sight & Sound』誌のGreatest films of all timeでは監督投票で72位にランクインした[26]。 レビューアグリゲーターサイトRotten Tomatoesでは、『ワイルド・ストロベリー』は45のレビューに基づき96%の支持率を得ており、平均スコアは8.90/10。同サイトの批評家の コンセンサスはこうだ: 「イングマール・ベルイマンの美しく書かれ撮影された、一人の男の過去へのノスタルジックな旅ほどほろ苦いものはない。」[27] Metacriticでは、17人の批評家のレビューに基づく加重平均スコアは100点満点中88点で、「普遍的な称賛 」を示している[28]。 |

| Awards and honors The film won the Golden Bear for Best Film and the FIPRESCI Prize[29] at the 8th Berlin International Film Festival,[30] "Best Film" and "Best Actor" at the Mar del Plata Film Festival and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Film in 1960. The Film was nominated for a BAFTA Award in Best Film From Any Source category in 1959. It was also nominated for an Academy Award for Original Screenplay, but the nomination was refused by Bergman.[31] The film won the Pasinetti Award at 1958 Venice Film Festival. It won the Bodil Award for Best European Film in 1959.[32] The film is included on the Vatican Best Films List, recommended for its portrayal of a man's "interior journey from pangs of regret and anxiety to a refreshing sense of peace and reconciliation".[33] |

受賞歴 第8回ベルリン国際映画祭で金熊賞(最優秀作品賞)と国際批評家連盟賞[29]、マル・デル・プラタ映画祭で[30]「最優秀作品賞」と「最優秀男優賞」 を受賞し、1960年にはゴールデングローブ賞外国映画賞を受賞。1959年にはBAFTA賞のBest Film From Any Source部門にノミネート。1958年のヴェネツィア国際映画祭ではパシネッティ賞を受賞。1959年にはボーディル賞最優秀ヨーロッパ映画賞を受賞 した[32]。 この映画はバチカンのベストフィルムリストに掲載され、男の「後悔と不安の苦しみから、平和と和解のさわやかな感覚への内面的な旅」の描写が推奨されてい る[33]。 |

| Influence Wild Strawberries influenced the Woody Allen films Stardust Memories (1980), Another Woman (1988), Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), and Deconstructing Harry (1997). In Stardust Memories, the film's plot is similar in that the protagonist, filmmaker Sandy Bates (Woody Allen), is attending a viewing of his films, while reminiscing about and reflecting on his life and past relationships and trying to fix and stabilize his current ones, which are infused with flashbacks and dream sequences. In Another Woman, the film's main character, Marion Post (Gena Rowlands), is also accused by friends and relatives of being cold and unfeeling, which forces her to reexamine her life.[34] Allen also borrows several tropes from Bergman's film, such as having Lynn (Frances Conroy), Post's sister-in-law, tell her that her brother Paul (Harris Yulin) hates her and having a former student tell Post that her class changed her life. Allen has Post confront the demons of her past via several dream sequences and flashbacks that reveal important information to a viewer, as in Wild Strawberries. In Crimes and Misdemeanors, Allen made reference to the scene in which Isak watches his family have dinner.[35] In Deconstructing Harry, the plot (a writer going on a long drive to receive an honorary award from his old university, while reflecting upon his life's experiences, with dream sequences) essentially mirrors that of Wild Strawberries.[36] Satyajit Ray's 1966 film Nayak was to some extent inspired by Wild Strawberries.[37] |

影響 ワイルド・ストロベリー』は、ウディ・アレン監督の『スターダストメモリーズ』(1980年)、『アナザー・ウーマン』(1988年)、『罪と軽罪』 (1989年)、『ハリーの解体』(1997年)に影響を与えた。スターダストメモリーズ』では、主人公の映画監督サンディ・ベイツ(ウディ・アレン) が、自分の人生や過去の人間関係を回想し反省しながら、フラッシュバックや夢のシークエンスがはびこる現在の人間関係を修復し安定させようとしながら、自 分の映画の鑑賞会に参加するという点で、映画の筋書きは似ている。アナザー・ウーマン』でも、主人公のマリオン・ポスト(ジェナ・ローランズ)は、友人や 親戚から冷淡で無感情だと非難され、自分の人生を見つめ直すことになる。アレン監督は、『ワイルド・ストロベリー』のように、観る者に重要な情報を明らか にするいくつかの夢のシークエンスやフラッシュバックを通して、ポストを過去の悪魔と対峙させている。罪と軽罪』の中でアレンは、イザークが家族が夕食を とるのを眺めるシーンを参考にしている[35]。『ハリーの解体』では、プロット(作家が夢のシークエンスを交えながら、自分の人生の経験を振り返りつ つ、母校の名誉賞を受け取るために長距離ドライブに出かける)が『ワイルド・ストロベリー』と本質的に同じである[36]。 サタジット・レイの1966年の映画『Nayak』は、『野いちご』にある程度インスパイアされている[37]。 |

| Attempted American remake Screenwriter Bo Goldman sought to remake the film in 1995 as his directorial debut. Gregory Peck would have starred in the titular role of the elderly professor.[38] Despite the support of Martin Scorsese, who agreed to produce, the film was not green lit. |

アメリカ・リメイクの試み 脚本家のボー・ゴールドマンが1995年に監督デビュー作としてリメイクを試みた。グレゴリー・ペックが老教授役で主演する予定だった[38]。製作に同 意したマーティン・スコセッシの支持にもかかわらず、この映画は企画されなかった。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wild_Strawberries_(film) |

★エリク・エリクソン(Erik Homburger Erikson、出生名:エリク・サロモンセン、1902年6月15日 - 1994年5月12日)は、人間の心理社会的発達に関する理論で知られるアメリカの児童精神分析家である。アイデンティティ・クライシスという言葉を造語 した。

| Erik Homburger

Erikson

(born Erik Salomonsen; 15 June 1902 – 12 May 1994) was an American

child psychoanalyst known for his theory on psychosocial development of

human beings. He coined the phrase identity crisis. Despite lacking a university degree, Erikson served as a professor at prominent institutions, including Harvard, University of California, Berkeley,[9] and Yale. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Erikson as the 12th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[10] |

エリク・エリクソン(Erik Homburger

Erikson、出生名:エリク・サロモンセン、1902年6月15日 -

1994年5月12日)は、人間の心理社会的発達に関する理論で知られるアメリカの児童精神分析家である。アイデンティティ・クライシスという言葉を造語

した。 大学学位を持たないにもかかわらず、エリクソンはハーバード大学、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校、イェール大学など著名な教育機関で教授を務めた。 2002年に発表された『A Review of General Psychology』誌の調査では、エリクソンは20世紀で12番目に著名な心理学者に選ばれた。 |

| Early life Erikson's mother, Karla Abrahamsen, came from a prominent Jewish family in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was married to Jewish stockbroker Valdemar Isidor Salomonsen but had been estranged from him for several months at the time Erik was conceived. Little is known about Erik's biological father except that he was a non-Jewish Dane. On discovering her pregnancy, Karla fled to Frankfurt am Main in Germany where Erik was born on 15 June 1902 and was given the surname Salomonsen.[11] She fled due to conceiving Erik out of wedlock, and the identity of Erik's birth father was never made clear.[9] Following Erik's birth, Karla trained to be a nurse and moved to Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1905 she married a Jewish pediatrician, Theodor Homburger. In 1908, Erik Salomonsen's name was changed to Erik Homburger, and in 1911 he was officially adopted by his stepfather.[12] Karla and Theodor told Erik that Theodor was his real father, only revealing the truth to him in late childhood; he remained bitter about the deception all his life.[9] The development of identity seems to have been one of Erikson's greatest concerns in his own life as well as being central to his theoretical work. As an older adult, he wrote about his adolescent "identity confusion" in his European days. "My identity confusion", he wrote, "[was at times on] the borderline between neurosis and adolescent psychosis." Erikson's daughter wrote that her father's "real psychoanalytic identity" was not established until he "replaced his stepfather's surname [Homburger] with a name of his invention [Erikson]."[13] The decision to change his last name came about as he started his job at Yale, and the "Erikson" name was accepted by Erik's family when they became American citizens.[9] It is said his children enjoyed the fact they would not be called "Hamburger" any longer.[9] Erik was a tall, blond, blue-eyed boy who was raised in the Jewish religion. Due to these mixed identities, he was a target of bigotry by both Jewish and gentile children. At temple school, his peers teased him for being Nordic; while at grammar school, he was teased for being Jewish.[14] At Das Humanistische Gymnasium his main interests were art, history, and languages, but he lacked a general interest in school and graduated without academic distinction. [15] After graduation, instead of attending medical school as his stepfather had desired, he attended art school in Munich, much to the liking of his mother and her friends. Uncertain about his vocation and his fit in society, Erik dropped out of school and began a lengthy period of roaming about Germany and Italy as a wandering artist with his childhood friend Peter Blos and others. For children from prominent German families, taking a "wandering year" was not uncommon. During his travels, he often sold or traded his sketches to people he met. Eventually, Erik realized he would never become a full-time artist and returned to Karlsruhe and became an art teacher. During the time he worked at his teaching job, Erik was hired by an heiress to sketch and eventually tutor her children. Erik worked very well with these children and was eventually hired by many other families that were close to Anna and Sigmund Freud.[9] During this period, which lasted until he was twenty-five years old, he continued to contend with questions about his father and competing ideas of ethnic, religious, and national identity.[16] |

幼少期 エリクソンの母親カルラ・アブラハムセンは、デンマークのコペンハーゲンで著名なユダヤ人家庭に生まれた。彼女はユダヤ人の株式仲買人ヴァルデマール・イ シドア・サロモンセンと結婚していたが、エリックが妊娠した当時、数ヶ月間別居していた。エリックの実父については、非ユダヤ人のデンマーク人であったこ と以外、ほとんど知られていない。妊娠が発覚すると、カーラはドイツのフランクフルト・アム・マインに逃亡し、1902年6月15日にエリックが生まれ、 サロモンセン姓を名乗った。[11] 彼女は結婚していない状態でエリックを身ごもったために逃亡したのであり、エリックの実父の身元は明らかにされていない。[9] エリックが生まれた後、カーラは看護師になるための訓練を受け、ドイツのカールスルーエに移住した。1905年、彼女はユダヤ人の小児科医テオドール・ホ ンブルガーと結婚した。1908年、エーリク・サロモンセンはエーリク・ホンブルガーと改名し、1911年には正式に継父の養子となった。[12] カールラとテオドールはエーリクに、テオドールが実の父親であると告げたが、真実を明かしたのは彼が幼年期を終える頃になってからだった。エーリクは生涯 にわたって、この欺瞞に対して苦々しい思いを抱き続けた。[9] アイデンティティの形成は、エリクソンの理論的研究の中心であると同時に、彼自身の人生における最大の関心事でもあったようだ。成人してからは、ヨーロッ パ時代に経験した思春期の「アイデンティティの混乱」について書いている。「私のアイデンティティの混乱は、[時には]神経症と青年期精神病の境界線上に あった」と彼は書いた。エリクソンの娘は、父親の「真の精神分析上のアイデンティティ」は、「義理の父の姓(Homburger)を自分で考えた名前 (Erikson)に変える」まで確立されなかったと書いている。[13] 名字の変更は、エール大学に入学した際に決定され、「エリクソン」という名前は、エリックの家族がアメリカ市民権を取得した際に受け入れられた。[9] 彼の子供たちは、もう「ハンバーガー」と呼ばれることがないことを喜んでいたと言われている。[9] エリックは、ユダヤ教で育てられた長身でブロンド、青い目の少年だった。このようなアイデンティティの混在により、ユダヤ人の子供からもそうでない子供か らも偏見の的となった。ユダヤ教の小学校では、ユダヤ人であることをからかわれ、[14] ヒューマニスト・ギムナジウムでは、美術、歴史、言語に興味を持っていたが、学校には全般的に興味が持てず、学業で目立った成果を残すことなく卒業した。 [15] 卒業後は、義父の希望通り医学部へ進学するのではなく、母親や母親の友人たちが好んでいたミュンヘンの美術学校へ進学した。 自分の天職や社会での適性に不安を感じたエリックは学校を中退し、幼馴染のペーター・ブロスらとともに放浪画家としてドイツやイタリアを放浪する長い期間 を過ごすことになる。ドイツの著名な家柄の子供たちにとって、「放浪の年」を過ごすことは珍しいことではなかった。旅の途中、彼は出会った人々にスケッチ を売ったり交換したりすることが多かった。結局、エリックは自分が専業の芸術家になることはないことを悟り、カールスルーエに戻って美術教師になった。教 師として働いていた間、エリックは資産家の令嬢に雇われ、スケッチを描き、やがては彼女の子供たちの家庭教師となった。エリックは子供たちと非常にうまく やっていき、やがてはアンナとジークムント・フロイトの親しい多くの家庭に雇われるようになった。[9] この期間は25歳まで続き、彼は父親に関する疑問や、民族、宗教、国家のアイデンティティに関する競合する考えと向き合い続けた。[16] |

| Psychoanalytic experience and

training When Erikson was twenty-five, his friend Peter Blos invited him to Vienna to tutor art[9] at the small Burlingham-Rosenfeld School for children whose affluent parents were undergoing psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud's daughter, Anna Freud.[17] Anna noticed Erikson's sensitivity to children at the school and encouraged him to study psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute, where prominent analysts August Aichhorn, Heinz Hartmann, and Paul Federn were among those who supervised his theoretical studies. He specialized in child analysis and underwent a training analysis with Anna Freud. Helene Deutsch and Edward Bibring supervised his initial treatment of an adult.[17] Simultaneously he studied the Montessori method of education, which focused on child development and sexual stages.[18][failed verification] In 1933 he received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. This and his Montessori diploma were to be Erikson's only earned credentials for his life's work. |

精神分析の経験とトレーニング エリクソンが25歳のとき、友人のピーター・ブロスにウィーンに招かれ、裕福な両親がジークムント・フロイトの娘であるアンナ・フロイトによる精神分析を 受けていた子供たちのための小さなブルリングハム・ローゼンフェルド学校で美術の家庭教師を務めた[9]。 7] アンナはエリクソンの感受性を認め、ウィーン精神分析研究所で精神分析を学ぶよう勧めた。同研究所では、著名な分析家であるアウグスト・アイヒホルン、ハ インツ・ハルトマン、ポール・フェダーンらが彼の理論研究を指導した。エリクソンは児童分析を専門とし、アンナ・フロイトのもとで分析トレーニングを受け た。ヘレーネ・ドイッチュとエドワード・ビブリングは、彼が大人を対象に初めて治療を行う際の監督を務めた。[17] 同時に彼は、子どもの発達と性的段階に焦点を当てたモンテッソーリ教育法を学んだ。[18][verification needed] 1933年、彼はウィーン精神分析研究所から卒業証書を受け取った。この卒業証書とモンテッソーリ教育法の卒業証書が、エリクソンの生涯の仕事における唯 一の資格となった。 |

| United States In 1930 Erikson married Joan Mowat Serson, a Canadian dancer and artist whom Erikson had met at a dress ball.[8][19][20] During their marriage, Erikson converted to Christianity.[21][22] In 1933, with Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, the burning of Freud's books in Berlin and the potential Nazi threat to Austria, the family left an impoverished Vienna with their two young sons and emigrated to Copenhagen.[23] Unable to regain Danish citizenship because of residence requirements, the family left for the United States, where citizenship would not be an issue.[24] In the United States, Erikson became the first child psychoanalyst in Boston and held positions at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Judge Baker Guidance Center, and at Harvard Medical School and Psychological Clinic. This was while he was establishing a singular reputation as a clinician. In 1936, Erikson left Harvard and joined the staff at Yale University, where he worked at the Institute of Social Relations and taught at the medical school.[25] Erikson continued to deepen his interest in areas beyond psychoanalysis and to explore connections between psychology and anthropology. He made important contacts with anthropologists such as Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Ruth Benedict.[26] Erikson said his theory of the development of thought derived from his social and cultural studies. In 1938, he left Yale to study the Sioux tribe in South Dakota on their reservation. After his studies in South Dakota, he traveled to California to study the Yurok tribe. Erikson discovered differences between the children of the Sioux and Yurok tribes. This marked the beginning of Erikson's life passion of showing the importance of events in childhood and how society affects them.[27] In 1939 he left Yale, and the Eriksons moved to California, where Erik had been invited to join a team engaged in a longitudinal study of child development for the University of California at Berkeley's Institute of Child Welfare. In addition, in San Francisco, he opened a private practice in child psychoanalysis. While in California he was able to make his second study of American Indian children when he joined anthropologist Alfred Kroeber on a field trip to Northern California to study the Yurok.[15] In 1950, after publishing the book, Childhood and Society, for which he is best known, Erikson left the University of California when California's Levering Act required professors there to sign loyalty oaths.[28] From 1951 to 1960 he worked and taught at the Austen Riggs Center, a prominent psychiatric treatment facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he worked with emotionally troubled young people. Another famous Stockbridge resident, Norman Rockwell, became Erikson's patient and friend. During this time he also served as a visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh where he worked with Benjamin Spock and Fred Rogers at Arsenal Nursery School of the Western Psychiatric Institute.[29] He returned to Harvard in the 1960s as a professor of human development and remained there until his retirement in 1970.[30] In 1973 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Erikson for the Jefferson Lecture, the United States' highest honor for achievement in the humanities. Erikson's lecture was titled Dimensions of a New Identity.[31][32] Theories of development and the ego Erikson is credited with being one of the originators of ego psychology, which emphasized the role of the ego as being more than a servant of the id. Although Erikson accepted Freud's theory, he did not focus on the parent-child relationship and gave more importance to the role of the ego, particularly the person's progression as self.[33] According to Erikson, the environment in which a child lived was crucial to providing growth, adjustment, a source of self-awareness and identity. Erikson won a Pulitzer Prize[34] and a US National Book Award in category Philosophy and Religion[35] for Gandhi's Truth (1969),[36] which focused more on his theory as applied to later phases in the life cycle. In Erikson's discussion of development, he rarely mentioned a stage of development by age. In fact he referred to it as a prolonged adolescence which has led to further investigation into a period of development between adolescence and young adulthood called emerging adulthood.[37] Erikson's theory of development includes various psychosocial crises where each conflict builds off of the previous stages.[38] The result of each conflict can have negative or positive impacts on a person's development, however, a negative outcome can be revisited and readdressed throughout the life span.[39] On ego identity versus role confusion: ego identity enables each person to have a sense of individuality, or as Erikson would say, "Ego identity, then, in its subjective aspect, is the awareness of the fact that there is a self-sameness and continuity to the ego's synthesizing methods and a continuity of one's meaning for others".[40] Role confusion, however, is, according to Barbara Engler, "the inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member of one's own society."[41] This inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member is a great danger; it can occur during adolescence, when looking for an occupation. |

アメリカ合衆国 1930年、エリクソンは舞踏会で出会ったカナダ人ダンサー兼アーティストのジョーン・モーワット・サーソンと結婚した。[8][19][20] 結婚中、エリクソンはキリスト教に改宗した。[21][22] 1933年、アドルフ・ヒトラーがドイツで権力を握り、 ドイツにおけるアドルフ・ヒトラーの台頭、ベルリンにおけるフロイトの著書の焼却、オーストリアに対するナチスの潜在的な脅威により、家族は2人の幼い息 子を連れて貧困に喘ぐウィーンを離れ、コペンハーゲンに移住した。 米国では、エリクソンはボストンで最初の児童精神分析医となり、マサチューセッツ総合病院、ジャッジ・ベイカー・ガイダンス・センター、ハーバード大学医 学部および心理クリニックで職に就いた。 臨床医として独自の評価を確立しつつあった時期である。 1936年、エリクソンはハーバード大学を去り、イェール大学のスタッフに加わり、社会関係研究所で働き、医学部で教鞭をとった。 エリクソンは精神分析の領域を超えて関心を深め、心理学と人類学の関連性を探究し続けた。彼はマーガレット・ミード、グレゴリー・ベイトソン、ルース・ベ ネディクトといった人類学者たちと重要な交流を持った。[26] エリクソンは、自身の思考の発展理論は社会と文化の研究から導き出されたと述べている。1938年、彼はイエール大学を離れ、サウスダコタ州の保留地に住 むスー族の研究に着手した。サウスダコタでの研究の後、カリフォルニア州のユロック族の研究のためにカリフォルニア州へ渡った。エリクソンは、スー族とユ ロック族の子供たちの間に違いがあることを発見した。これが、エリクソンが生涯をかけて情熱を傾けることになる、幼少期の出来事の重要性と、社会がそれら に与える影響について研究するきっかけとなった。 1939年、彼はイェール大学を去り、エリクソン一家はカリフォルニア州に移住した。エリクソンはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校児童福祉研究所の児童発 達に関する縦断的研究チームに招かれていた。さらに、サンフランシスコで児童精神分析の個人開業も始めた。 カリフォルニアに滞在中、人類学者アルフレッド・クロバーの北カリフォルニアへのユロック族の調査旅行に参加し、2度目のアメリカン・インディアンの子供 たちについての研究を行うことができた。 1950年、エリクソンは最もよく知られている著書『幼年期と社会』を出版した後、カリフォルニア州の教授に忠誠の誓いを立てることを義務付けるカリフォ ルニア州のレヴァリング法が施行されたため、カリフォルニア大学を去った。[28] 1951年から1960年にかけて、エリクソンはマサチューセッツ州ストックブリッジにある著名な精神科治療施設、オースティン・リグス・センターで働 き、教鞭をとった。同センターでは、情緒障害を抱える若者たちと働いた。ストックブリッジ在住の著名人であるノーマン・ロックウェルはエリクソンの患者と なり、友人となった。この間、ピッツバーグ大学でも客員教授を務め、ウェスタン精神医学研究所付属アーセナル保育園でベンジャミン・スポックやフレッド・ ロジャーズと協力した。 彼は1960年代にハーバード大学に人間発達学の教授として戻り、1970年に退職するまで在籍した。[30] 1973年、全米人文科学基金は、人文科学の分野における米国最高の栄誉であるジェファーソン・レクチャーにエリクソンを選出した。エリクソンの講演のタ イトルは「新しいアイデンティティの諸相」であった。[31][32] 発達と自我の理論 エリクソンは自我心理学の創始者の一人であると評価されている。自我心理学は、自我をイドの単なる従者以上のものとして重視するものである。エリクソンは フロイトの理論を受け入れたものの、親子関係には重点を置かず、自我の役割、特に自己としての成長に重点を置いた。[33] エリクソンによると、子供が成長し、適応し、自己認識とアイデンティティの源を得るためには、子供が暮らす環境が極めて重要である。エリクソンは、ライフ サイクルの後の段階に適用された自身の理論に焦点を当てた『ガンジーの真理』(1969年)で、ピューリッツァー賞[34]と全米図書賞の哲学・宗教部門 賞[35]を受賞した。 エリクソンの発達に関する議論では、年齢による発達段階について言及することはほとんどなかった。実際、彼はそれを「長期化する思春期」と呼び、思春期と 若年成人期の間の発達期間についてさらなる調査を行うことになった。エリクソンの発達理論には、各葛藤が前の段階を基盤とする様々な心理社会的危機が含ま れている。[38] 各葛藤の結果は、その人の発達に否定的または肯定的な影響を与える可能性があるが、否定的な 結果は生涯を通じて再検討され、再対処される可能性がある。[39]自我同一性対役割混乱について:自我同一性は、各人が個性を持つことを可能にする。エ リクソン流に言えば、「自我同一性とは、主観的な側面において、自我の統合方法に自己同一性と継続性があり、他者にとっての自分の意味にも継続性があると いう事実を認識することである 。[40] しかし、役割の混乱とは、バーバラ・エングラーによると、「社会の生産的な一員として自分自身を考えることができないこと」である。[41] 生産的な一員として自分自身を考えることができないことは、大きな危険である。それは、職業を探している思春期に起こりうる。 |

| Theory of personality Main article: Erikson's stages of psychosocial development This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Erik Erikson" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Erikson life-stages, in order of the eight stages in which they may be acquired, are listed below, as well as the "virtues" that Erikson has attached to these stages, (these virtues are underlined). 1. Hope, Basic trust vs. basic mistrust This stage covers the period of infancy, 0–1½ years old, which is the most fundamental stage of life, as this is the stage that all other ones build on.[42] Whether the baby develops basic trust or basic mistrust is not merely a matter of nurture. It is multi-faceted and has strong social components. It depends on the quality of the maternal relationship.[43] The mother carries out and reflects her inner perceptions of trustworthiness, a sense of personal meaning, etc. on the child. An important part of this stage is providing stable and constant care of the infant. This helps the child develop trust that can transition into relationships other than parental. Additionally, children develop trust in others to support them.[44] If successful in this, the baby develops a sense of trust, which "forms the basis in the child for a sense of identity." Failure to develop this trust will result in a feeling of fear and a sense that the world is inconsistent and unpredictable. 2. Will, Autonomy vs. shame This stage covers early childhood around 1½–3 years old and introduces the concept of autonomy vs. shame and doubt. The child begins to discover the beginnings of their independence, and parents must facilitate the child's sense of doing basic tasks "all by themselves." Discouragement can lead to the child doubting their efficacy. During this stage the child is usually trying to master toilet training.[45] Additionally, the child discovers their talents or abilities, and it is important to ensure the child is able to explore those activities. Erikson states it is essential to allow the children freedom in exploration but also create an environment welcoming of failures. Therefore, the parent should not punish or reprimand the child for failing at the task. Shame and doubt occurs when the child feels incompetent in ability to complete tasks and survive. Will is achieved with success of this stage. Children successful in this stage will have "self-control without a loss of self-esteem."[44] 3. Purpose, Initiative vs. guilt This stage covers preschool children from ages three to five. Does the child have the ability to do things on their own, such as dress themselves? Children in this stage are interacting with peers, and creating their own games and activities. Children in this stage practice independence and start to make their own decisions.[46] If allowed to make these decisions, the child will develop confidence in their ability to lead others. If the child is not allowed to make certain decisions, then a sense of guilt develops. Guilt in this stage is characterized by a sense of being a burden to others, and the child will therefore usually present themselves as a follower as they lack the confidence to do otherwise.[47] Additionally, the child is asking many questions to build knowledge of the world. If the questions earn responses that are critical and condescending, the child will also develop feelings of guilt. Success in this stage leads to the virtue of purpose, which is the normal balance between the two extremes.[44] 4. Competence, Industry vs. inferiority This area coincides with the "latency" period of psychoanalysis and covers school age children before adolescence. Children compare their self worth to others around them. Friends can have a significant impact on the growth of the child.[48] The child can recognize major disparities in personal abilities relative to other children. Erikson places some emphasis on the teacher, who should ensure that children do not feel inferior. During this stage the child's friend group increases in importance in their life. Often during this stage the child will try to prove competency with things rewarded in society, and also develop satisfaction with their abilities. Encouraging the child increases feelings of adequacy and competency in ability to reach goals. Restriction from teachers or parents leads to doubt, questioning, and reluctance in abilities and therefore may not reach full capabilities. Competence, the virtue of this stage, is developed when a healthy balance between the two extremes is reached.[44] 5. Fidelity, Identity vs. role confusion This section deals with adolescence, meaning those between twelve and eighteen years old. This occurs when we start to question ourselves and ask questions relevant to who we are and what we want to accomplish. Who am I, how do I fit in? Where am I going in life? The adolescent is exploring and seeking for their own unique identity. This is done by looking at personal beliefs, goals, and values. The morality of the individual is also explored and developed.[44] Erikson believes that if the parents allow the child to explore, they will determine their own identity. If, however, the parents continually push them to conform to their views, the teen will face identity confusion. The teen is also looking towards the future in terms of employment, relationships, and families. Learning the roles they provide in society is essential since the teen begins to develop the desire to fit into society. Fidelity is characterized by the ability to commit to others and acceptance of others even with differences. Identity crisis is the result of role confusion and can cause the adolescent to try out different lifestyles.[44] 6. Love, Intimacy vs. isolation This is the first stage of adult development. This development usually happens during young adulthood, which is between the ages of 18 and 40. This stage marks a transition from just thinking about ourselves to thinking about other people in the world. We are social creatures and as a result need to be with other people and form relationships with them. Dating, marriage, family and friendships are important during this stage in their life. This is due to the increase in the growth of intimate relationships with others.[44] Ego development earlier in life (middle adolescence) is a strong predictor of how well intimacy for romantic relationships will transpire in emerging adulthood.[49] By successfully forming loving relationships with other people, individuals are able to experience love and intimacy. They also feel safety, care, and commitment in these relationships.[44] Furthermore, if individuals are able to successfully resolve the crisis of intimacy versus isolation, they are able to achieve the virtue of love.[50] Those who fail to form lasting relationships may feel isolated and alone. 7. Care, Generativity vs. stagnation The second stage of adulthood happens between the ages of 40 and 65. During this time people are normally settled in their lives and know what is important to them. A person is either making progress in their career or treading lightly in their career and unsure if this is what they want to do for the rest of their working life. Also during this time, a person may be raising their children. If they are a parent, then they are reevaluating their life roles.[51] This is one way of contributing to society along with productivity at work and involvement in community activities and organizations.[44] Individuals that exercise the concept of generativity believe in the next generation and seek to nurture them in creative ways through practices such as parenting, teaching, and mentoring.[52] Having a sense of generativity can be considered significant for both the individual and the society, exemplifying their roles as effective parents, leaders for organizations, etc.[53] If a person is not comfortable with the way their life is progressing, they're usually regretful about the decisions that they have made in the past and feels a sense of uselessness.[54] 8. Wisdom, Ego integrity vs. despair This stage affects the age group of 65 and on. During this time an individual has reached the last chapter in their life and retirement is approaching or has already taken place. Individuals in this stage must learn to accept the course of their life or they will look back on it with despair.[55] Ego-integrity means the acceptance of life in its fullness: the victories and the defeats, what was accomplished and what was not accomplished. Wisdom is the result of successfully accomplishing this final developmental task. Wisdom is defined as "informed and detached concern for life itself in the face of death itself."[56] Having a guilty conscience about the past or failing to accomplish important goals will eventually lead to depression and hopelessness. Achieving the virtue of the stage involves the feeling of living a successful life.[44] Ninth stage For the Ninth Stage see Erikson's stages of psychosocial development § Ninth Stage. Favorable outcomes of each stage are sometimes known as virtues, a term used in the context of Erikson's work as it is applied to medicine, meaning "potencies". These virtues are also interpreted to be the same as "strengths", which are considered inherent in the individual life cycle and in the sequence of generations.[57] Erikson's research suggests that each individual must learn how to hold both extremes of each specific life-stage challenge in tension with one another, not rejecting one end of the tension or the other. Only when both extremes in a life-stage challenge are understood and accepted as both required and useful, can the optimal virtue for that stage surface. Thus, 'trust' and 'mis-trust' must both be understood and accepted, in order for realistic 'hope' to emerge as a viable solution at the first stage. Similarly, 'integrity' and 'despair' must both be understood and embraced, in order for actionable 'wisdom' to emerge as a viable solution at the last stage. |

性格理論 詳細は「エリクソンの心理社会的発達段階」を参照 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載に問題がある場合、記事が削除されることがあります。 エリクソンのライフステージは、獲得される可能性のある8つのステージの順番で以下に列挙されている。また、エリクソンがこれらのステージに付けた「美 徳」(これらの美徳は下線が引かれている)も記載されている。 1. 希望、基本的信頼感 vs. 基本的不信感 この段階は、乳児期(0~1歳半)をカバーしており、これは人生で最も基本的な段階である。なぜなら、この段階が他のすべての段階の基礎となるからであ る。[42] 赤ちゃんが基本的信頼感を持つか、基本的不信感を持つかは、単に環境の問題だけではない。それは多面的なものであり、強い社会的要素を含んでいる。それは 母親との関係の質に依存している。[43] 母親は、信頼性や個人的な意味などについての自身の内なる認識を実行し、子どもに反映させる。この段階の重要な要素は、乳児に安定した継続的なケアを提供 することである。これにより、子どもは親以外の人間関係にも発展しうる信頼を育むことができる。さらに、子どもは自分を支えてくれる他者に対して信頼を育 む。[44] これが成功すれば、赤ちゃんは信頼感を育み、「子どもにとってアイデンティティの感覚の基礎となる」感覚が形成される。この信頼感を育むことができない と、恐怖感が生じ、世界は一貫性がなく予測不可能であると感じるようになる。 2. 意志、自律性 vs. 羞恥心 この段階は1歳半から3歳頃の幼児期に該当し、自律性 vs. 羞恥心と疑いの概念が導入される。子どもは自立の始まりを発見し始め、親は子どもが基本的な作業を「自分ひとりで」行う感覚を促進しなければならない。落 胆は、子どもが自分の能力に疑いを抱くことにつながる。この段階では、子どもは通常、トイレトレーニングを習得しようとしている。[45] さらに、子どもは自分の才能や能力を発見し、それらの活動を探索できるようにすることが重要である。エリクソンは、子どもに探索の自由を与えると同時に、 失敗を歓迎する環境を作ることも不可欠であると述べている。したがって、親は子どもが課題に失敗したからといって、罰したり叱ったりすべきではない。子ど もが課題を完了し、生き残る能力がないと感じるときに、恥や疑いが生じる。この段階の成功によって「意志」が達成される。この段階を成功した子どもは、 「自尊心を失うことなく自制できる」ようになる。 3. 目的、自主性 vs. 罪悪感 この段階は、3歳から5歳までの未就学児を対象とする。子供は自分で服を着るなど、自分で物事をこなす能力があるだろうか? この段階の子供は、同年代の子供たちと交流し、自分たちでゲームや活動を作り出す。この段階の子供は自立を実践し、自分の意思で決定し始める。[46] 子供にこのような決定を任せれば、子供は他人を導く能力に対する自信を育むだろう。もし子供が特定の決定を下すことを許されない場合、罪悪感が芽生える。 この段階における罪悪感は、他人に負担をかけているという感覚によって特徴づけられ、子供は自信がないため、通常は従順な態度を示すことになる。[47] さらに、子供は世界についての知識を深めるために多くの質問をする。もしその質問に対して批判的で高圧的な反応が返ってきた場合、子供は罪悪感を抱くよう になる。この段階での成功は、目的意識という美徳につながる。これは、2つの極端な考え方の間の正常なバランスである。[44] 4. 能力、勤勉性 vs. 劣等感 この領域は精神分析における「潜伏期」と一致し、思春期前の学齢期の子供たちをカバーする。子供たちは自分自身の価値を周囲の他人と比較する。友人関係は 子供の成長に大きな影響を与える可能性がある。[48] 子供は、他の子供たちと比較して、自分自身の能力に大きな差があることを認識できる。エリクソンは、子供たちが劣等感を抱かないようにすべきであると教師 に重点を置いている。この段階では、子供たちの友人グループが生活の中で重要性を増す。この段階では、子供はしばしば、社会で報われるものによって有能さ を証明しようとし、また、自分の能力に対する満足感も育む。子供を励ますことは、目標を達成する能力に対する適切さや有能さの感情を高める。教師や親によ る制限は、能力に対する疑念や疑問、消極性を生み、その結果、能力を十分に発揮できない可能性がある。この段階の美徳である有能さは、両極端の間の健全な バランスが達成されたときに育まれる。 5. 忠誠心、アイデンティティ vs. 役割の混乱 このセクションでは、12歳から18歳までの思春期について取り扱う。これは、自分自身について疑問を抱き始め、自分が何者で何を達成したいのかについて 関連する質問をする時期である。私は何者なのか、私はどうやって適合するのか?私は人生でどこに向かっているのか?思春期の若者は、自分だけの独自なアイ デンティティを探求し、求めている。これは、個人的な信念、目標、価値観を検討することで行われる。個人の道徳性も探求され、発達する。[44] エリクソンは、親が子供に探求を許せば、子供は自分自身のアイデンティティを決定できると考える。しかし、親が自分の考えに子供を合わせるよう常に押しつ けると、ティーンエイジャーはアイデンティティの混乱に直面することになる。ティーンエイジャーは、就職、人間関係、家族など、将来についても考えてい る。ティーンエイジャーが社会に適合したいという願望を抱き始めるため、社会における自分の役割を学ぶことは不可欠である。 忠誠心は、他人に献身する能力と、違いがあっても他人を受け入れる能力によって特徴づけられる。 アイデンティティの危機は役割の混乱の結果であり、思春期の若者がさまざまなライフスタイルを試す原因となる可能性がある。 6. 愛情、親密さ vs. 孤立 これは、成人期の成長の第一段階である。この成長は通常、18歳から40歳までの青年期に起こる。この段階では、自分自身のことだけを考えることから、世 界中の他の人々のことを考えるようになる。人間は社会的生き物であり、その結果、他の人々と一緒にいること、そして彼らと関係を築くことが必要となる。こ の段階では、デート、結婚、家族、友人関係が重要となる。これは、他人との親密な関係が成長するからである。[44] 人生の初期(中期青年期)における自我の成長は、新しく始まる成人期における恋愛関係の親密さがどの程度うまくいくかを予測する強力な指標となる。 [49] 他人と愛情のある関係をうまく築くことで、個人は愛と親密さを経験することができる。また、こうした関係性において、安心感、思いやり、献身を感じること ができる。さらに、親密さ対孤独の危機をうまく乗り越えることができれば、愛徳を達成することができる。 7. 思いやり、創造性 vs. 停滞 成人期の第二段階は、40歳から65歳の間で起こる。この時期には、人々は通常、生活が落ち着き、自分にとって何が重要であるかを知っている。人はキャリ アにおいて進歩を遂げているか、あるいはキャリアを慎重に進み、これが残りの就業期間にやりたいことなのかどうか分からない状態にある。また、この時期に は子供を育てている場合もある。親であれば、自分の人生における役割を再評価することになる。[51] これは、職場での生産性や地域活動や組織への参加と並んで、社会に貢献する方法のひとつである。[44] 生成性の概念を実践する人は次世代を信じ、子育てや教育、指導などの実践を通じて創造的な方法で次世代を育成しようとする。[52] 。 生成性の感覚を持つことは、個人と社会の両方にとって重要であると考えられ、効果的な親、組織のリーダーなどとしての役割を体現していると言える。 [53] もし、その人の人生の歩み方に満足していない場合、通常、過去に行った決定について後悔し、無力感を感じる。[54] 8. 知恵、自我の統合 vs. 絶望 この段階は65歳以上の年齢層に影響を与える。この時期に個人は人生の最終章に達し、退職が近づいているか、すでに退職している。この段階にいる個人は、 人生の歩みを受け入れることを学ばなければならない。さもなければ、絶望とともに人生を振り返ることになるだろう。[55] 自我の統合とは、人生を丸ごと受け入れることを意味する。勝利と敗北、達成したことと達成できなかったこと。知恵とは、この最終的な発達課題を成功裏に達 成した結果である。知恵とは、「死そのものに直面した際の、人生そのものに対する冷静な関心」と定義される。[56] 過去に対する罪の意識や重要な目標の達成失敗は、最終的にはうつ病や絶望感につながる。この段階の美徳を達成するには、成功した人生を送っているという感 覚が必要である。[44] 第9段階 第9段階については、エリクソンの心理社会的発達段階を参照のこと。 各段階の好ましい結果は、時に「美徳」として知られている。この用語は、医学への応用におけるエリクソンの研究の文脈で使用されており、「潜在能力」を意 味する。これらの美徳は、「強み」と同じものであるとも解釈されており、それは個人のライフサイクルや世代の継承に内在するものとみなされている。 [57] エリクソンの研究は、各個人が特定のライフステージにおける課題の両極端な側面を、緊張関係を保ちつつ、そのいずれか一方を拒絶することなく、両方を保持 する方法を学ばなければならないことを示唆している。ライフステージにおける課題の両極端な側面が、どちらも必要であり有益であると理解され受け入れられ たときにのみ、その段階において最適な美徳が表面化する。したがって、現実的な「希望」が最初の段階で実行可能な解決策として現れるためには、「信頼」と 「不信」の両方を理解し、受け入れる必要がある。同様に、実行可能な「知恵」が最後の段階で実行可能な解決策として現れるためには、「誠実」と「絶望」の 両方を理解し、受け入れる必要がある。 |

| Psychology of religion Psychoanalytic writers have always engaged in nonclinical interpretation of cultural phenomena such as art, religion, and historical movements. Erik Erikson gave such a strong contribution that his work was well received by students of religion and spurred various secondary literature.[58] Erikson's psychology of religion begins with an acknowledgement of how religious tradition can have an interplay with a child's basic sense of trust or mistrust.[59] With regard to Erikson's theory of personality as expressed in his eight stages of the life cycle, each with their different tasks to master, each also included a corresponding virtue, as mentioned above, which form a taxonomy for religious and ethical life. Erikson extends this construct by emphasizing that human individual and social life is characterized by ritualization, "an agreed-upon interplay between at least two persons who repeat it at meaningful intervals and in recurring contexts." Such ritualization involves careful attentiveness to what can be called ceremonial forms and details, higher symbolic meanings, active engagement of participants, and a feeling of absolute necessity.[60] Each life cycle stage includes its own ritualization with a corresponding ritualism: numinous vs. idolism, judicious vs. legalism, dramatic vs. impersonation, formal vs. formalism, ideological vs. totalism, affiliative vs. elitism, generational vs. authoritism, and integral vs. dogmatism.[61] Perhaps Erikson's best-known contributions to the psychology of religion were his book length psychobiographies, Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History, on Martin Luther, and Gandhi's Truth, on Mohandas K. Gandhi, for which he remarkably won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Both books attempt to show how childhood development and parental influence, social and cultural context, even political crises form a confluence with personal identity. These studies demonstrate how each influential person discovered mastery, both individually and socially, in what Erikson would call the historical moment. Individuals like Luther or Gandhi were what Erikson called a Homo Religiosus, individuals for whom the final life cycle challenge of integrity vs. despair is a lifelong crisis, and they become gifted innovators whose own psychological cure becomes an ideological breakthrough for their time.[58] |

宗教心理学 精神分析の作家たちは、芸術、宗教、歴史的運動などの文化現象の非臨床的解釈に常に従事してきた。エリク・エリクソンは、その研究が宗教の研究者たちに高 く評価され、さまざまな二次文献を生み出すほどの大きな貢献をした。 エリクソンの宗教心理学は、宗教的伝統が子供の基本的信頼感や不信感と相互に作用し合う可能性を認めることから始まる。[59] エリクソンのライフサイクルの8段階で表現された人格理論に関しては、それぞれが習得すべき異なる課題があり、それぞれに上述の徳目も含まれており、これ らが宗教的・倫理的生活の分類体系を形成している。エリクソンは、人間の個人生活や社会生活は「意味のある間隔で、繰り返し行われる文脈において、少なく とも2人の人間が合意したやり方で行う相互作用」である儀式化によって特徴づけられると強調することで、この概念をさらに発展させた。このような儀式化に は、儀式の形態や詳細、より高度な象徴的な意味、参加者の積極的な関与、絶対的な必要性といったものに対する注意深い配慮が含まれる。[60] 各ライフサイクルの段階には、それぞれに対応する儀式化が含まれている。すなわち、神聖主義 vs 偶像崇拝 vs. 偶像崇拝、賢明 vs. 律法主義、劇的 vs. 模倣、形式 vs. 形式主義、観念 vs. 全体主義、帰属 vs. エリート主義、世代 vs. 権威主義、統合 vs. 教条主義などである。 エリクソンの宗教心理学への貢献として最もよく知られているのは、マルティン・ルターに関する『若き日のルター:精神分析と歴史の研究』と、ガンジーに関 する『ガンジーの真実』という、長編の精神分析伝記である。この2冊の著書で、エリクソンは、幼少期の発達や親の影響、社会的・文化的背景、さらには政治 的危機が、いかにして個人のアイデンティティと交わるかを示そうとしている。これらの研究は、各々の影響力のある人物が、エリクソンが「歴史的瞬間」と呼 ぶものの中で、個人として、また社会的に、いかにして支配力を獲得したかを明らかにしている。ルターやガンジーのような人物は、エリクソンが「ホモ・レリ ギオスス」と呼ぶ存在であり、彼らは、誠実さ対絶望という人生の最終局面における課題を生涯にわたる危機としており、自らの心理的治療が同時代の思想的な 躍進となるような、才能ある革新者となるのである。[58] |

| Personal life Erikson married Canadian-born American dancer and artist Joan Erikson (née Sarah Lucretia Serson) in 1930 and they remained together until his death.[21] The Eriksons had four children: Kai T. Erikson, Jon Erikson, Sue Erikson Bloland, and Neil Erikson. His eldest son, Kai T. Erikson, is an American sociologist. Their daughter, Sue, "an integrative psychotherapist and psychoanalyst",[62] described her father as plagued by "lifelong feelings of personal inadequacy".[63] He thought that by combining resources with his wife, he could "achieve the recognition" that might produce a feeling of adequacy.[64] Erikson died on 12 May 1994 in Harwich, Massachusetts. He is buried in the First Congregational Church Cemetery in Harwich.[65] |

私生活 エリクソンは1930年にカナダ生まれのアメリカ人ダンサー兼アーティスト、ジョアン・エリクソン(旧姓サラ・ルクレティア・サーソン)と結婚し、彼の死 まで共に暮らした。[21] エリクソン夫妻にはカイ・T・エリクソン、ジョン・エリクソン、スー・エリクソン・ブロランド、ニール・エリクソンの4人の子供がいた。長男のカイ・T・ エリクソンはアメリカの社会学者である。娘のスーは「統合心理療法士および精神分析家」であり、父親について「生涯にわたる個人的な不適格感」に悩まされ ていたと述べている。[63] エリクソンは、妻と力を合わせれば、充足感を生み出す「認知」を達成できると考えていた。[64] エリクソンは1994年5月12日、マサチューセッツ州ハーウィッチで死去した。彼はハーウィッチの第一長老教会墓地に埋葬されている。[65] |

| Bibliography Major works Childhood and Society (1950) Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History (1958) Insight and Responsibility (1966)[66] Identity: Youth and Crisis (1968)[67] Gandhi's Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969)[36] Life History and the Historical Moment (1975)[68] Toys and Reasons: Stages in the Ritualization of Experience (1977)[69] Adulthood (edited book, 1978)[70] Vital Involvement in Old Age (with J. M. Erikson and H. Kivnick, 1986)[71] Erikson, Erik H.; Erikson, Joan M. (1997). The Life Cycle Completed (extended ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company (published 1998). ISBN 978-0-393-34743-2. Collections Identity and the Life Cycle. Selected Papers (1959)[72] "A Way of Looking at Things – Selected Papers from 1930 to 1980, Erik H. Erikson" ed. by S. Schlein, W. W. Norton & Co, New York, (1995) |

参考文献 主要作品 『子ども時代と社会』(1950年) 『若き日のルーサー:精神分析と歴史の研究』(1958年) 『洞察と責任』(1966年)[66] 『アイデンティティ:若者と危機』(1968年)[67] 『ガンディーの真理:非暴力闘争の起源について』(1969年)[36] ライフ・ヒストリーと歴史的瞬間(1975年)[68] おもちゃと理由:経験の儀式化の段階(1977年)[69] 成人期(編著、1978年)[70] 老後の活力に満ちた関与(J. M. エリクソン、H. キブニックとの共著、1986年)[71] エリクソン、エリクソン、ジョアン・M.(1997年)。ライフサイクルの完成(増補版)。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン・アンド・カンパニー(1998年出版)。ISBN 978-0-393-34743-2。 コレクション アイデンティティとライフサイクル。 論文集(1959年)[72] 「物事の見方 - エリック・H・エリクソンによる1930年から1980年の論文集」S. シュライン編、W. W. Norton & Co、ニューヨーク、(1995年) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erik_Erikson |

文献

エリクソンのライフサイクルの8段階仮説

ジジェクとカント

"De

todas las parejas en la historia del pensamiento moderno

(Freud y Lacan, Marx y Lenin...), Kant y Sade es quizás la más

problemática: la sentencia “Kant es Sade” es el “juicio infinito de la

ética moderna, el lugar del signo de la ecuación entre dos opuestos

radicales, es decir, afirmando que la sublime actitud ética

desinteresada sea de algún modo idéntica a, o superpuesta con, la

indulgencia irrestricta de violencia placentera." - Kant y Sade: La

Pareja Ideal, por S. Žižek

関連リンク

大学での授業「医療人類学:高知大学2009」

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

☆

☆

☆