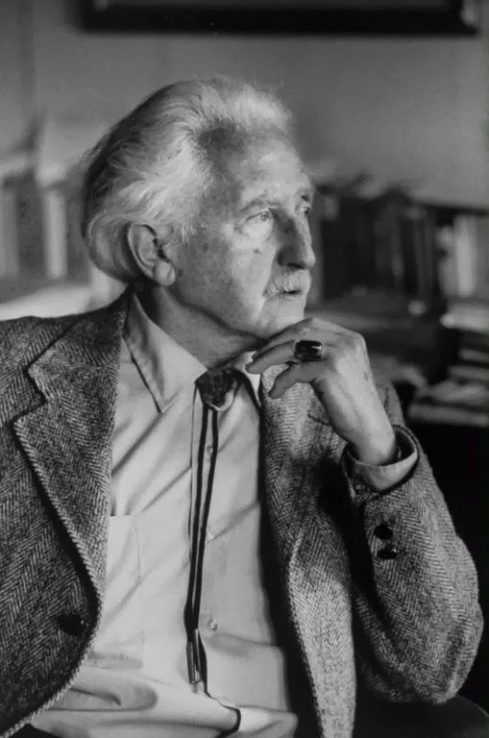

エリク・エリクソン

Erik Erikson, 1902-1994

☆ エリック・エリクソン(Erik Homburger Erikson、1902年6月15日 - 1994年5月12日)は、人間の心理社会的発達に関する理論で知られるアメリカの児童精神分析学者。アイデンティティの危機という言葉を生み出した。

| Erik Homburger Erikson

(born Erik Salomonsen; 15 June 1902 – 12 May 1994) was an American

child psychoanalyst known for his theory on psychosocial development of

human beings. He coined the phrase identity crisis. Despite lacking a university degree, Erikson served as a professor at prominent institutions, including Harvard, University of California, Berkeley,[9] and Yale. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Erikson as the 12th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[10] |

エリック・エリクソン(Erik Homburger Erikson、1902年6月15日 - 1994年5月12日)は、人間の心理社会的発達に関する理論で知られるアメリカの児童精神分析学者。アイデンティティの危機という言葉を生み出した。 大学の学位を持たないにもかかわらず、エリクソンはハーバード大学、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校[9]、イェール大学などの著名な教育機関で教授を務 めた。2002年に発表されたReview of General Psychologyの調査では、エリクソンは20世紀で12番目に著名な心理学者としてランク付けされた[10]。 |

| Early life Erikson's mother, Karla Abrahamsen, came from a prominent Jewish family in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was married to Jewish stockbroker Valdemar Isidor Salomonsen, but had been estranged from him for several months at the time Erik was conceived. Little is known about Erik's biological father except that he was a non-Jewish Dane. On discovering her pregnancy, Karla fled to Frankfurt am Main in Germany where Erik was born on 15 June 1902 and was given the surname Salomonsen.[11] She fled due to conceiving Erik out of wedlock, and the identity of Erik's birth father was never made clear.[9] Following Erik's birth, Karla trained to be a nurse and moved to Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1905 she married a Jewish pediatrician, Theodor Homburger. In 1908, Erik Salomonsen's name was changed to Erik Homburger, and in 1911 he was officially adopted by his stepfather.[12] Karla and Theodor told Erik that Theodor was his real father, only revealing the truth to him in late childhood; he remained bitter about the deception all his life.[9] The development of identity seems to have been one of Erikson's greatest concerns in his own life as well as being central to his theoretical work. As an older adult, he wrote about his adolescent "identity confusion" in his European days. "My identity confusion", he wrote "[was at times on] the borderline between neurosis and adolescent psychosis." Erikson's daughter wrote that her father's "real psychoanalytic identity" was not established until he "replaced his stepfather's surname [Homburger] with a name of his own invention [Erikson]."[13] The decision to change his last name came about as he started his job at Yale, and the "Erikson" name was accepted by Erik's family when they became American citizens.[9] It is said his children enjoyed the fact they would not be called "Hamburger" any longer.[9] Erik was a tall, blond, blue-eyed boy who was raised in the Jewish religion. Due to these mixed identities, he was a target of bigotry by both Jewish and gentile children. At temple school, his peers teased him for being Nordic; while at grammar school, he was teased for being Jewish.[14] At Das Humanistische Gymnasium his main interests were art, history and languages, but he lacked a general interest in school and graduated without academic distinction.[15] After graduation, instead of attending medical school as his stepfather had desired, he attended art school in Munich, much to the liking of his mother and her friends. Uncertain about his vocation and his fit in society, Erik dropped out of school and began a lengthy period of roaming about Germany and Italy as a wandering artist with his childhood friend Peter Blos and others. For children from prominent German families, taking a "wandering year" was not uncommon. During his travels he often sold or traded his sketches to people he met. Eventually, Erik realized he would never become a full-time artist and returned to Karlsruhe and became an art teacher. During the time he worked at his teaching job, Erik was hired by an heiress to sketch and eventually tutor her children. Erik worked very well with these children and was eventually hired by many other families that were close to Anna and Sigmund Freud.[9] During this period, which lasted until he was twenty-five years old, he continued to contend with questions about his father and competing ideas of ethnic, religious, and national identity.[16] |

生い立ち エリクソンの母カーラ・アブラハムセンは、デンマークのコペンハーゲンの著名なユダヤ人一家の出身だった。彼女はユダヤ人株式仲買人のヴァルデマール・イ ジドール・サロモンセンと結婚していたが、エリックが妊娠した当時、彼とは数ヶ月前から疎遠になっていた。エリックの実父については、非ユダヤ系のデン マーク人であったこと以外はほとんどわかっていない。妊娠が発覚すると、カーラはドイツのフランクフルト・アム・マインに逃亡し、そこで1902年6月 15日にエリックが生まれ、サロモンセン姓を与えられた[11]。婚外子としてエリックを身ごもったために逃亡し、エリックの実父が誰であるかは明らかに されなかった[9]。 エリックの誕生後、カーラは看護師としての訓練を受け、ドイツのカールスルーエに移り住む。1905年、彼女はユダヤ人の小児科医テオドール・ホンブル ガーと結婚。1908年、エリック・サロモンセンの名前はエリック・ホンブルガーに改名され、1911年には継父の養子となった[12]。カーラとテオ ドールはエリックにテオドールが実の父親であることを告げ、幼少期後半になって初めて真実を明かした。 アイデンティティの発達は、エリクソン自身の人生における最大の関心事であると同時に、彼の理論的研究の中心でもあったようである。年老いた彼は、ヨー ロッパ時代の思春期の「アイデンティティの混乱」について書いている。「私のアイデンティティの混乱は、神経症と思春期の精神病の境界線上にあった」と彼 は書いている。エリクソンの娘は、父親の「本当の精神分析家としてのアイデンティティ」が確立されたのは、彼が「義父の姓(ホンブルガー)を自分の創作し た名前(エリクソン)に置き換えてから」であったと書いている[13]。名字を変えるという決断は、彼がイェール大学で仕事を始めたときに下され、「エリ クソン」という名前は、エリックの家族がアメリカ市民権を得たときに受け入れられた[9]。 エリックは背が高く、金髪碧眼の少年で、ユダヤ教の中で育った。このような混在したアイデンティティのため、彼はユダヤ人と異邦人の両方の子供たちから偏 見の対象となった。寺子屋では北欧人であることをからかわれ、文法学校ではユダヤ人であることをからかわれた[14]。ダス・ヒューマニスティッシュ・ギ ムナジウムでは、美術、歴史、語学に主に興味を持ったが、学校全般への興味に欠け、学業成績は優秀でなく卒業した[15]。卒業後、継父が望んだ医学部に は進学せず、母親とその友人の好意でミュンヘンの美術学校に通った。 自分の天職や社会での適合性に確信が持てなかったエリックは、学校を中退し、幼なじみのペーター・ブロスらと放浪の画家としてドイツやイタリアを放浪する 長い日々が始まった。ドイツの名家の子供たちにとって、「放浪の年」を過ごすことは珍しいことではなかった。旅の間、彼はしばしば出会った人々に自分のス ケッチを売ったり、交換したりした。やがて、エリックは自分がフルタイムのアーティストになることはないと悟り、カールスルーエに戻り、美術教師になっ た。教職に就いている間、エリックはある相続人に雇われ、彼女の子供たちをスケッチし、やがて家庭教師になった。25歳まで続いたこの時期、エリックは父 親についての疑問や、民族的、宗教的、国家的アイデンティティの競合する考えと闘い続けた[16]。 |

| Psychoanalytic experience and training When Erikson was twenty-five, his friend Peter Blos invited him to Vienna to tutor art[9] at the small Burlingham-Rosenfeld School for children whose affluent parents were undergoing psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud's daughter, Anna Freud.[17] Anna noticed Erikson's sensitivity to children at the school and encouraged him to study psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute, where prominent analysts August Aichhorn, Heinz Hartmann, and Paul Federn were among those who supervised his theoretical studies. He specialized in child analysis and underwent a training analysis with Anna Freud. Helene Deutsch and Edward Bibring supervised his initial treatment of an adult.[17] Simultaneously he studied the Montessori method of education, which focused on child development and sexual stages.[18][failed verification] In 1933 he received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. This and his Montessori diploma were to be Erikson's only earned credentials for his life's work. |

精神分析の経験と訓練 エリクソンが25歳のとき、友人であったピーター・ブロスに誘われ、ジークムント・フロイトの娘であるアンナ・フロイトによる精神分析を受けていた裕福な 両親を持つ子どもたちのための小さなバーリンガム・ローゼンフェルド学校で美術の家庭教師をするためにウィーンに渡った[9]。アンナは、この学校でエリ クソンの子どもに対する感受性に気づき、ウィーン精神分析研究所で精神分析を学ぶように勧め、著名な分析家であるアウグスト・アイヒホルン、ハインツ・ハ ルトマン、パウル・フェデルンらが彼の理論的研究を指導した。彼は児童分析を専門とし、アンナ・フロイトのもとで訓練分析を受けた。ヘレーネ・ドイッチュ とエドワード・ビブリングは、成人に対する彼の最初の治療を監督した[17]。同時に彼は、子どもの発達と性的段階に焦点を当てたモンテッソーリ教育法を 学んだ[18][検証失敗]。1933年、彼はウィーン精神分析研究所から卒業証書を授与された。この証書とモンテッソーリの証書は、エリクソンがライフ ワークのために取得した唯一の資格であった。 |

| United States In 1930 Erikson married Joan Mowat Serson, a Canadian dancer and artist whom Erikson had met at a dress ball.[8][19][20] During their marriage, Erikson converted to Christianity.[21][22] In 1933, with Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, the burning of Freud's books in Berlin and the potential Nazi threat to Austria, the family left an impoverished Vienna with their two young sons and emigrated to Copenhagen.[23] Unable to regain Danish citizenship because of residence requirements, the family left for the United States, where citizenship would not be an issue.[24] In the United States, Erikson became the first child psychoanalyst in Boston and held positions at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Judge Baker Guidance Center, and at Harvard Medical School and Psychological Clinic. This was while he was establishing a singular reputation as a clinician. In 1936, Erikson left Harvard and joined the staff at Yale University, where he worked at the Institute of Social Relations and taught at the medical school.[25] Erikson continued to deepen his interest in areas beyond psychoanalysis and to explore connections between psychology and anthropology. He made important contacts with anthropologists such as Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Ruth Benedict.[26] Erikson said his theory of the development of thought derived from his social and cultural studies. In 1938, he left Yale to study the Sioux tribe in South Dakota on their reservation. After his studies in South Dakota, he traveled to California to study the Yurok tribe. Erikson discovered differences between the children of the Sioux and Yurok tribes. This marked the beginning of Erikson's life passion of showing the importance of events in childhood and how society affects them.[27] In 1939 he left Yale, and the Eriksons moved to California, where Erik had been invited to join a team engaged in a longitudinal study of child development for the University of California at Berkeley's Institute of Child Welfare. In addition, in San Francisco, he opened a private practice in child psychoanalysis. While in California he was able to make his second study of American Indian children when he joined anthropologist Alfred Kroeber on a field trip to Northern California to study the Yurok.[15] In 1950, after publishing the book, Childhood and Society, for which he is best known, Erikson left the University of California when California's Levering Act required professors there to sign loyalty oaths.[28] From 1951 to 1960 he worked and taught at the Austen Riggs Center, a prominent psychiatric treatment facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he worked with emotionally troubled young people. Another famous Stockbridge resident, Norman Rockwell, became Erikson's patient and friend. During this time he also served as a visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh where he worked with Benjamin Spock and Fred Rogers at Arsenal Nursery School of the Western Psychiatric Institute.[29] He returned to Harvard in the 1960s as a professor of human development and remained there until his retirement in 1970.[30] In 1973 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Erikson for the Jefferson Lecture, the United States' highest honor for achievement in the humanities. Erikson's lecture was titled Dimensions of a New Identity.[31][32] |

アメリカ 1930年、エリクソンはドレス舞踏会で知り合ったカナダ人のダンサーであり芸術家であったジョーン・モワット・サーソンと結婚する[8][19] [20]。結婚中、エリクソンはキリスト教に改宗する。 [21][22]1933年、アドルフ・ヒトラーがドイツで台頭し、ベルリンでフロイトの著書が焚書され、オーストリアにナチスの脅威が及ぶ可能性があっ たため、一家は幼い息子2人を連れて貧しいウィーンを離れ、コペンハーゲンに移住した。[23]居住要件があったためデンマークの市民権を回復することが できず、一家は市民権が問題にならないアメリカへと旅立った[24]。 アメリカでは、エリクソンはボストンで最初の児童精神分析医となり、マサチューセッツ総合病院、ジャッジ・ベイカー指導センター、ハーバード・メディカ ル・スクールおよびサイコロジカル・クリニックで役職に就いた。臨床家としての名声を確立しつつあった頃である。1936年、エリクソンはハーバードを去 り、イェール大学の職員となり、社会関係研究所で働き、医学部で教鞭をとった[25]。 エリクソンは、精神分析以外の領域への関心を深め、心理学と人類学のつながりを探求し続けた。彼は、マーガレット・ミード、グレゴリー・ベイトソン、ルー ス・ベネディクトなどの人類学者と重要な接触を持った。1938年、エリクソンはサウスダコタ州のスー族の保留地で研究するためにエール大学を去った。サ ウスダコタでの研究の後、彼はカリフォルニアに渡り、ユロック族を研究した。エリクソンはスー族とユロック族の子どもたちの違いを発見した。これが、幼少 期の出来事の重要性と社会が彼らにどのような影響を与えるかを示すという、エリクソンの生涯の情熱の始まりとなった[27]。 1939年、エリクソンはエール大学を去り、エリクソン一家はカリフォルニアに移り住む。エリクソンは、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の児童福祉研究所 のために、子どもの発達に関する縦断的研究に従事するチームに招かれた。さらにサンフランシスコでは、児童精神分析の個人診療所を開設した。 カリフォルニア滞在中、人類学者アルフレッド・クルーバー(Alfred Kroeber)とともに、ユロック族を調査するために北カリフォルニアを訪れ、アメリカン・インディアンの子どもたちについて2度目の研究を行うことができた[15]。 1951年から1960年まで、彼はマサチューセッツ州ストックブリッジにある著名な精神科治療施設オースティン・リッグス・センターで働き、教鞭をとっ ていた。同じくストックブリッジに住む有名なノーマン・ロックウェルは、エリクソンの患者となり、友人となった。この間、彼はピッツバーグ大学の客員教授 も務め、西部精神医学研究所のアーセナル保育園でベンジャミン・スポックやフレッド・ロジャースとともに働いた[29]。 1973年、全米人文科学基金(National Endowment for the Humanities)は、人文科学分野の業績に対する米国最高の栄誉であるジェファーソン講演(Jefferson Lecture)にエリクソンを選んだ。エリクソンの講義のタイトルは『Dimensions of a New Identity』であった[31][32]。 |

| Theories of development and the ego Erikson is credited with being one of the originators of ego psychology, which emphasized the role of the ego as being more than a servant of the id. Although Erikson accepted Freud's theory, he did not focus on the parent-child relationship and gave more importance to the role of the ego, particularly the person's progression as self.[33] According to Erikson, the environment in which a child lived was crucial to providing growth, adjustment, a source of self-awareness and identity. Erikson won a Pulitzer Prize[34] and a US National Book Award in category Philosophy and Religion[35] for Gandhi's Truth (1969),[36] which focused more on his theory as applied to later phases in the life cycle. In Erikson's discussion of development, he rarely mentioned a stage of development by age. In fact he referred to it as a prolonged adolescence which has led to further investigation into a period of development between adolescence and young adulthood called emerging adulthood.[37] Erikson's theory of development includes various psychosocial crises where each conflict builds off of the previous stages.[38] The result of each conflict can have negative or positive impacts on a person's development, however, a negative outcome can be revisited and readdressed throughout the life span.[39] On ego identity versus role confusion: ego identity enables each person to have a sense of individuality, or as Erikson would say, "Ego identity, then, in its subjective aspect, is the awareness of the fact that there is a self-sameness and continuity to the ego's synthesizing methods and a continuity of one's meaning for others".[40] Role confusion, however, is, according to Barbara Engler, "the inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member of one's own society."[41] This inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member is a great danger; it can occur during adolescence, when looking for an occupation. |

発達理論と自我 エリクソンは自我心理学の創始者の一人であり、自我がイドの下僕以上の役割を果たすことを強調したとされている。エリクソンはフロイトの理論を受け入れた が、親子関係には焦点を当てず、自我の役割、特に自己としての人の成長をより重要視した。エリクソンは『ガンジーの真理』(1969年)でピューリッ ツァー賞[34]と米国の全米図書賞哲学・宗教部門[35]を受賞しており[36]、ライフサイクルの後期に適用される彼の理論により焦点を当てていた。 エリクソンの発達に関する議論では、年齢による発達段階について言及することはほとんどなかった。エリクソンの発達理論には様々な心理社会的危機が含まれ ており、それぞれの葛藤が前の段階から積み重なっていく[38]。各葛藤の結果は人の発達に否定的または肯定的な影響を与えるが、否定的な結果は生涯を通 じて再検討され、再対処される可能性がある。 [自我の同一性と役割の混乱について:自我の同一性は各人が個性の感覚を持つことを可能にし、エリクソンが言うように「自我の同一性とは、その主観的な側 面において、自我の統合方法に自己同一性と連続性があり、他者に対する自分の意味の連続性があるという事実の認識である」。 [しかし、役割の混乱とは、バーバラ・エングラーによれば、「自分自身を自分自身の社会の生産的な一員であると考えることができないこと」である。 |

| Theory of personality Main article: Erikson's stages of psychosocial development This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Erik Erikson" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Erikson life-stages, in order of the eight stages in which they may be acquired, are listed below, as well as the "virtues" that Erikson has attached to these stages, (these virtues are underlined). Hope, Basic trust vs. basic mistrust—This stage covers the period of infancy, 0–1½ years old, which is the most fundamental stage of life, as this is the stage that all other ones build on.[42] Whether the baby develops basic trust or basic mistrust is not merely a matter of nurture. It is multi-faceted and has strong social components. It depends on the quality of the maternal relationship.[43] The mother carries out and reflects her inner perceptions of trustworthiness, a sense of personal meaning, etc. on the child. An important part of this stage is providing stable and constant care of the infant. This helps the child develop trust that can transition into relationships other than parental. Additionally, children develop trust in others to support them.[44] If successful in this, the baby develops a sense of trust, which "forms the basis in the child for a sense of identity." Failure to develop this trust will result in a feeling of fear and a sense that the world is inconsistent and unpredictable. Will, Autonomy vs. shame—This stage covers early childhood around 1½–3 years old and introduces the concept of autonomy vs. shame and doubt. The child begins to discover the beginnings of their independence, and parents must facilitate the child's sense of doing basic tasks "all by themselves." Discouragement can lead to the child doubting their efficacy. During this stage the child is usually trying to master toilet training.[45] Additionally, the child discovers their talents or abilities, and it is important to ensure the child is able to explore those activities. Erikson states it is essential to allow the children freedom in exploration but also create an environment welcoming of failures. Therefore, the parent should not punish or reprimand the child for failing at the task. Shame and doubt occurs when the child feels incompetent in ability to complete tasks and survive. Will is achieved with success of this stage. Children successful in this stage will have "self-control without a loss of self-esteem."[44] Purpose, Initiative vs. guilt—This stage covers preschool children from ages three to five. Does the child have the ability to do things on their own, such as dress themselves? Children in this stage are interacting with peers, and creating their own games and activities. Children in this stage practice independence and start to make their own decisions.[46] If allowed to make these decisions, the child will develop confidence in their ability to lead others. If the child is not allowed to make certain decisions, then a sense of guilt develops. Guilt in this stage is characterized by a sense of being a burden to others, and the child will therefore usually present themselves as a follower as they lack the confidence to do otherwise.[47] Additionally, the child is asking many questions to build knowledge of the world. If the questions earn responses that are critical and condescending, the child will also develop feelings of guilt. Success in this stage leads to the virtue of purpose, which is the normal balance between the two extremes.[44] Competence, Industry vs. inferiority—This area coincides with the "latency" period of psychoanalysis and covers school age children before adolescence. Children compare their self worth to others around them. Friends can have a significant impact on the growth of the child.[48] The child can recognize major disparities in personal abilities relative to other children. Erikson places some emphasis on the teacher, who should ensure that children do not feel inferior. During this stage the child's friend group increases in importance in their life. Often during this stage the child will try to prove competency with things rewarded in society, and also develop satisfaction with their abilities. Encouraging the child increases feelings of adequacy and competency in ability to reach goals. Restriction from teachers or parents leads to doubt, questioning, and reluctance in abilities and therefore may not reach full capabilities. Competence, the virtue of this stage, is developed when a healthy balance between the two extremes is reached.[44] Fidelity, Identity vs. role confusion—This section deals with adolescence, meaning those between twelve and eighteen years old. This occurs when we start to question ourselves and ask questions relevant to who we are and what we want to accomplish. Who am I, how do I fit in? Where am I going in life? The adolescent is exploring and seeking for their own unique identity. This is done by looking at personal beliefs, goals, and values. The morality of the individual is also explored and developed.[44] Erikson believes that if the parents allow the child to explore, they will determine their own identity. If, however, the parents continually push them to conform to their views, the teen will face identity confusion. The teen is also looking towards the future in terms of employment, relationships, and families. Learning the roles they provide in society is essential since the teen begins to develop the desire to fit into society. Fidelity is characterized by the ability to commit to others and acceptance of others even with differences. Identity crisis is the result of role confusion and can cause the adolescent to try out different lifestyles.[44] Love, Intimacy vs. isolation—This is the first stage of adult development. This development usually happens during young adulthood, which is between the ages of 18 and 40. This stage marks a transition from just thinking about ourselves to thinking about other people in the world. We are social creatures and as a result need to be with other people and form relationships with them. Dating, marriage, family and friendships are important during this stage in their life. This is due to the increase in the growth of intimate relationships with others.[44] It is important to note that ego development earlier in life (middle adolescence) is a strong predictor of how well intimacy for romantic relationships will transpire in emerging adulthood.[49] By successfully forming loving relationships with other people, individuals are able to experience love and intimacy. They also feel safety, care, and commitment in these relationships.[44] Furthermore, if individuals are able to successfully resolve the crisis of intimacy versus isolation, they are able to achieve the virtue of love.[50] Those who fail to form lasting relationships may feel isolated and alone. Care, Generativity vs. stagnation—The second stage of adulthood happens between the ages of 40 and 65. During this time people are normally settled in their lives and know what is important to them. A person is either making progress in their career or treading lightly in their career and unsure if this is what they want to do for the rest of their working life. Also during this time, a person may be raising their children. If they are a parent, then they are reevaluating their life roles.[51] This is one way of contributing to society along with productivity at work and involvement in community activities and organizations.[44] Individuals that exercise the concept of generativity believe in the next generation and seek to nurture them in creative ways through practices such as parenting, teaching, and mentoring.[52] Having a sense of generativity can be considered significant for both the individual and the society, exemplifying their roles as effective parents, leaders for organizations, etc.[53] If a person is not comfortable with the way their life is progressing, they're usually regretful about the decisions that they have made in the past and feels a sense of uselessness.[54] Wisdom, Ego integrity vs. despair—This stage affects the age group of 65 and on. During this time an individual has reached the last chapter in their life and retirement is approaching or has already taken place. Individuals in this stage must learn to accept the course of their life or they will look back on it with despair.[55] Ego-integrity means the acceptance of life in its fullness: the victories and the defeats, what was accomplished and what was not accomplished. Wisdom is the result of successfully accomplishing this final developmental task. Wisdom is defined as "informed and detached concern for life itself in the face of death itself."[56] Having a guilty conscience about the past or failing to accomplish important goals will eventually lead to depression and hopelessness. Achieving the virtue of the stage involves the feeling of living a successful life.[44] For the Ninth Stage see Erikson's stages of psychosocial development § Ninth Stage. Favorable outcomes of each stage are sometimes known as virtues, a term used in the context of Erikson's work as it is applied to medicine, meaning "potencies". These virtues are also interpreted to be the same as "strengths", which are considered inherent in the individual life cycle and in the sequence of generations.[57] Erikson's research suggests that each individual must learn how to hold both extremes of each specific life-stage challenge in tension with one another, not rejecting one end of the tension or the other. Only when both extremes in a life-stage challenge are understood and accepted as both required and useful, can the optimal virtue for that stage surface. Thus, 'trust' and 'mis-trust' must both be understood and accepted, in order for realistic 'hope' to emerge as a viable solution at the first stage. Similarly, 'integrity' and 'despair' must both be understood and embraced, in order for actionable 'wisdom' to emerge as a viable solution at the last stage. |

パーソナリティ理論 主な記事 エリクソンの心理社会的発達段階 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースがないものは、異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。 出典を探す 「Erik Erikson」 - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) エリクソンのライフステージを、それが獲得される可能性のある8つのステージの順に以下に列挙し、エリクソンがこれらのステージに付けた「徳」を示す(これらの徳には下線が引かれている)。 希望、基本的信頼vs.基本的不信-この段階は0~1歳半の乳児期を対象としており、他のすべての段階がこの段階を土台としているため、人生の最も基本的 な段階である[42]。それは多面的であり、強い社会的要素を持っている。母親は、信頼性や個人的な意味の感覚など、自分の内面的な認識を子どもに伝え、 反映させる。この段階で重要なことは、乳児に安定した一定の世話をすることである。これによって、子どもは親以外の人間関係にも移行できるような信頼を育 むことができる。さらに、子どもは自分を支えてくれる他者に対する信頼感を育む。[44] これに成功すれば、赤ちゃんは信頼感を育み、それが「アイデンティティーの感覚の基礎を子どもの中に形成する」。この信頼感が育たないと、恐怖を感じ、世 界は一貫性がなく予測不可能であると感じるようになる。 意志、自律vs.羞恥心-この段階は1歳半から3歳頃の幼児期を対象とし、自律vs.羞恥心と疑念の概念を導入する。子どもは自立の始まりを発見し始め、 親は子どもが基本的な仕事を 「自分でやる 」という感覚を促進しなければならない。落胆は、子どもが自分の有効性を疑うことにつながる。さらに、子どもは自分の才能や能力を発見するので、子どもが それらの活動を探求できるようにすることが重要である。エリクソンは、子どもには探索の自由を認めると同時に、失敗を歓迎する環境を作ることが不可欠であ るとしている。したがって、親は子どもが課題に失敗しても、罰したり叱責したりしてはならない。羞恥心と疑念は、子どもが課題をこなし、生き延びる能力が ないと感じたときに生じる。意志はこの段階の成功によって達成される。この段階で成功した子どもは、「自尊心を失うことなく自制心」を持つようになる [44]。 目的、主体性対罪悪感-この段階は、3歳から5歳までの就学前の子どもを対象としている。着替えなど、自分でできることがあるか。この段階の子どもは、仲 間と交流し、自分でゲームや活動を作り出します。この時期の子どもは自立を実践し、自分で物事を決めるようになる[46]。もし子どもが特定の決定をする ことを許されないと、罪悪感が芽生える。この段階での罪悪感は、他者にとって重荷であるという感覚によって特徴付けられ、それ以外のことをする自信がない ため、子どもは通常、自分自身を従者として示すようになる[47]。さらに、子どもは世界についての知識を構築するために多くの質問をしている。その質問 が批判的で人を見下すようなものであった場合、子どもは罪悪感を抱くようになる。この段階での成功は、2つの両極端の間の正常なバランスである目的の美徳 につながる[44]。 能力、産業対劣等感-この領域は精神分析の「潜伏期」と一致し、思春期前の学齢期の子どもを対象とする。子どもは自分の価値を周囲の他人と比較する。子ど もは、他の子どもとの相対的な個人的能力の大きな格差を認識することができる。エリクソンは、子どもが劣等感を抱かないようにする教師に重点を置いてい る。この段階では、子どもの友人グループの重要性が増す。この時期、子どもはしばしば社会で報われることで能力を証明しようとし、また自分の能力に満足す るようになる。子どもを励ますことで、目標に到達する能力の適切さや有能さを感じるようになる。教師や親からの制限は、能力に対する疑い、疑問、消極性に つながり、そのため能力を十分に発揮できない可能性がある。この段階の美徳である能力は、両極端の間の健全なバランスに達したときに発達する[44]。 忠実さ、アイデンティティ対役割の混乱-このセクションでは、12歳から18歳までの青年期を扱う。これは、私たちが自分自身に疑問を持ち始め、自分が何 者で、何を成し遂げたいのかに関連した質問をし始めるときに起こる。自分は何者なのか?自分は人生のどこに向かっているのか?思春期の子どもは、自分独自 のアイデンティティを探求し、求めている。これは、個人の信念、目標、価値観を見つめることによって行われる。エリクソンは、親が子どもの探求を許せば、 子どもは自分自身のアイデンティティを決定すると考えている。しかし、親が自分の意見に合わせるよう押し付け続ければ、ティーンはアイデンティティの混乱 に直面することになる。ティーンはまた、就職、人間関係、家族といった将来を見据えている。ティーンは社会に溶け込みたいという欲求を持ち始めるので、社 会における役割を学ぶことは不可欠である。忠実さとは、他者にコミットする能力と、違いがあっても他者を受け入れる能力によって特徴づけられる。アイデン ティティの危機は役割の混乱の結果であり、思春期の子どもがさまざまなライフスタイルを試す原因となりうる[44]。 愛、親密さ対孤立-これは成人の発達の最初の段階である。この発達は通常、18歳から40歳までの青年期に起こる。この段階は、自分自身のことだけを考え る段階から、世界の他の人々のことを考える段階への移行を意味する。私たちは社会的な生き物であり、その結果、他の人々と一緒にいて、彼らとの関係を形成 する必要がある。デート、結婚、家族、友人関係は、この時期の人生において重要である。これは、他者との親密な関係の増大によるものである[44]。人生 の早い時期(青年期中期)における自我の発達が、成人期に入ってからの恋愛関係における親密さの推移を強く予測するものであることに注意することが重要で ある[49]。他者と愛情に満ちた関係をうまく形成することによって、個人は愛と親密さを経験することができる。さらに、親密さ対孤立の危機をうまく解決 することができれば、愛の美徳を達成することができる。 ケア、生成性対停滞-成人期の第二段階は40歳から65歳の間に起こる。この時期の人々は通常、生活に落ち着きがあり、自分にとって何が重要かを知ってい る。キャリアを前進させるか、あるいはキャリアを軽んじて、残りの人生をこのままでいいのか迷っているかのどちらかである。また、この時期には子育てをし ている可能性もある。ジェネラティビティの概念を行使する人は、次世代を信じ、子育て、教育、指導などの実践を通じて、創造的な方法で次世代を育てようと する。 [世代性の感覚を持つことは、個人にとっても社会にとっても重要であると考えられ、効果的な親や組織のリーダーなどとしての役割を例示することができる [53]。 知恵、自我の完全性対絶望-この段階は65歳以上の年齢層に影響する。この時期、個人は人生の最終章を迎え、定年退職が近づいているか、すでに退職してい る。この段階にある人は、自分の人生の歩みを受け入れることを学ばなければならず、そうしなければ絶望とともに人生を振り返ることになる。叡智とは、この 最終的な発達課題を成功裏に達成した結果である。知恵とは、「死そのものに直面したときに、人生そのものに対して十分な情報を得た上で、冷静な関心を払う こと」[56]と定義されている。過去について罪悪感を抱いたり、重要な目標を達成できなかったりすると、やがてうつ病や絶望につながる。段階の美徳を達 成することは、成功した人生を生きているという感覚を伴う[44]。 第9段階については、エリクソンの心理社会的発達段階§第9段階を参照。 各段階の好ましい結果は美徳として知られることがあるが、この用語はエリクソンの著作の文脈で医学に適用される際に使用されるもので、「潜在能力」を意味 する。エリクソンの研究によると、各個人はライフステージの両極端の課題を互いに緊張関係に保ちながら、その緊張関係の一方を拒否したり、他方を拒否した りするのではなく、その両極端を保持する方法を学ばなければならない。ライフステージの課題における両極端が理解され、必要かつ有用なものとして受け入れ られて初めて、そのステージに最適な徳が表面化するのである。したがって、第一段階で現実的な「希望」が実行可能な解決策として現れるためには、「信頼」 と「誤った信頼」の両方が理解され、受け入れられなければならない。同様に、最終段階で実行可能な解決策としての「知恵」が現れるためには、「誠実さ」と 「絶望」の両方が理解され、受け入れられなければならない。 |

| Psychology of religion Psychoanalytic writers have always engaged in nonclinical interpretation of cultural phenomena such as art, religion, and historical movements. Erik Erikson gave such a strong contribution that his work was well received by students of religion and spurred various secondary literature.[58] Erikson's psychology of religion begins with an acknowledgement of how religious tradition can have an interplay with a child's basic sense of trust or mistrust.[59] With regard to Erikson's theory of personality as expressed in his eight stages of the life cycle, each with their different tasks to master, each also included a corresponding virtue, as mentioned above, which form a taxonomy for religious and ethical life. Erikson extends this construct by emphasizing that human individual and social life is characterized by ritualization, "an agreed-upon interplay between at least two persons who repeat it at meaningful intervals and in recurring contexts." Such ritualization involves careful attentiveness to what can be called ceremonial forms and details, higher symbolic meanings, active engagement of participants, and a feeling of absolute necessity.[60] Each life cycle stage includes its own ritualization with a corresponding ritualism: numinous vs. idolism, judicious vs. legalism, dramatic vs. impersonation, formal vs. formalism, ideological vs. totalism, affiliative vs. elitism, generational vs. authoritism, and integral vs. dogmatism.[61] Perhaps Erikson's best-known contributions to the psychology of religion were his book length psychobiographies, Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History, on Martin Luther, and Gandhi's Truth, on Mohandas K. Gandhi, for which he remarkably won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Both books attempt to show how childhood development and parental influence, social and cultural context, even political crises form a confluence with personal identity. These studies demonstrate how each influential person discovered mastery, both individually and socially, in what Erikson would call the historical moment. Individuals like Luther or Gandhi were what Erikson called a Homo Religiosus, individuals for whom the final life cycle challenge of integrity vs. despair is a lifelong crisis, and they become gifted innovators whose own psychological cure becomes an ideological breakthrough for their time.[58] |

宗教の心理学 精神分析の作家たちは、芸術、宗教、歴史的な動きといった文化的現象について、常に非臨床的な解釈を行ってきた。エリック・エリクソンはそのような強力な貢献をしたため、彼の仕事は宗教の学生たちから高く評価され、様々な二次文献に拍車をかけた[58]。 エリクソンの宗教心理学は、宗教的伝統が子どもの基本的な信頼感や不信感とどのように相互作用しうるかを認めることから始まる[59]。エリクソンのライ フサイクルの8つの段階で表現される人格理論に関しては、それぞれが習得すべき異なる課題を持ち、前述のようにそれぞれに対応する徳も含まれており、宗教 的・倫理的生活の分類法を形成している。エリクソンは、人間の個人的・社会的生活は儀式化、すなわち「意味のある間隔で、繰り返し行われる文脈の中で、少 なくとも二人の人間の間で合意された相互作用」によって特徴づけられることを強調することによって、この構成を拡張している。このような儀式化には、儀式 の形式や細部と呼べるものへの注意深い配慮、より高い象徴的意味、参加者の積極的な関与、絶対的な必要性の感覚などが含まれる[60]。各ライフサイクル の段階には、無神論対偶像論、判断主義対合法主義、劇的対なりすまし、形式的対形式主義、イデオロギー対全体主義、所属主義対エリート主義、世代主義対権 威主義、統合主義対教条主義といった、対応する儀式主義を伴う独自の儀式化が含まれている[61]。 おそらくエリクソンの宗教心理学への最もよく知られた貢献は、彼の本の長さの心理伝記である『青年ルター』であった: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History』(マーティン・ルーサーに関する精神分析と歴史の研究)と『Gandhi's Truth』(モハンダス・K・ガンジーに関するガンジーの真実)である。両書とも、幼少期の発達や親の影響、社会的・文化的背景、さらには政治的危機 が、いかにして個人のアイデンティティと合流するのかを示そうとしている。これらの研究は、エリクソンなら「歴史的瞬間」と呼ぶであろう瞬間において、影 響力のある各人が、個人的にも社会的にも、どのように達観したかを示している。ルターやガンジーのような個人は、エリクソンがホモ・レリギオサスと呼んだ ようなものであり、誠実さ対絶望というライフサイクルの最終的な課題が生涯の危機となるような個人であり、彼らは才能ある革新者となり、彼ら自身の心理的 な治療がその時代のイデオロギー的なブレークスルーとなるのである[58]。 |

| Personal life Erikson married Canadian-born American dancer and artist Joan Erikson (née Sarah Lucretia Serson) in 1930 and they remained together until his death.[21] The Eriksons had four children: Kai T. Erikson, Jon Erikson, Sue Erikson Bloland, and Neil Erikson. His eldest son, Kai T. Erikson, is an American sociologist. Their daughter, Sue, "an integrative psychotherapist and psychoanalyst",[62] described her father as plagued by "lifelong feelings of personal inadequacy".[63] He thought that by combining resources with his wife, he could "achieve the recognition" that might produce a feeling of adequacy.[64] Erikson died on 12 May 1994 in Harwich, Massachusetts. He is buried in the First Congregational Church Cemetery in Harwich.[65] |

私生活 エリクソンは1930年にカナダ生まれのアメリカ人ダンサーでアーティストのジョーン・エリクソン(旧姓サラ・ルクレチア・サーソン)と結婚し、亡くなるまで連れ添った[21]。 エリクソン夫妻には4人の子供がいた: カイ・T・エリクソン、ジョン・エリクソン、スー・エリクソン・ブローランド、ニール・エリクソン。長男のカイ・T・エリクソンはアメリカの社会学者。娘 のスーは「統合的心理療法家であり精神分析家」[62]であり、父親は「生涯にわたる個人的不全感」[63]に悩まされていたと述べている。 彼は、妻とリソースを組み合わせることで、不全感を生み出すかもしれない「認識を達成する」ことができると考えていた[64]。 エリクソンは1994年5月12日にマサチューセッツ州ハリッジで死去。彼はハリッジの第一会衆教会墓地に埋葬されている[65]。 |

| Bibliography Major works Childhood and Society (1950) Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History (1958) Insight and Responsibility (1966)[66] Identity: Youth and Crisis (1968)[67] Gandhi's Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969)[36] Life History and the Historical Moment (1975)[68] Toys and Reasons: Stages in the Ritualization of Experience (1977)[69] Adulthood (edited book, 1978)[70] Vital Involvement in Old Age (with J. M. Erikson and H. Kivnick, 1986)[71] Erikson, Erik H.; Erikson, Joan M. (1997). The Life Cycle Completed (extended ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company (published 1998). ISBN 978-0-393-34743-2. Collections Identity and the Life Cycle. Selected Papers (1959)[72] "A Way of Looking at Things – Selected Papers from 1930 to 1980, Erik H. Erikson" ed. by S. Schlein, W. W. Norton & Co, New York, (1995) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erik_Erikson |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆