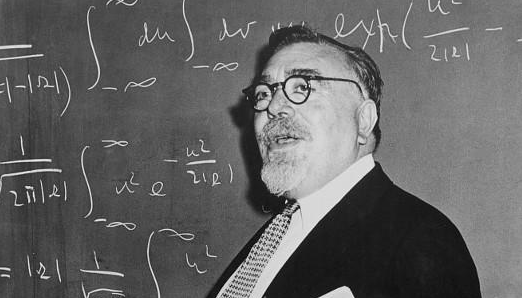

Cybernetics, or, Control and communication in the animal and

the machine / Norbert Wiener. -- 2nd ed. -- M.I.T. Press, 1961

サイバネティクス:動物とマシーンにおける制御とコミュニケーション

Cybernetics, or, Control and communication in the animal and

the machine / Norbert Wiener. -- 2nd ed. -- M.I.T. Press, 1961

池田光穂

"It may very well be a good thing for humanity to have the machine remove from it the need of menial and disagreeable task, or it may not. I do not know" - N. Weiner 1961[1948]:27 N. Weiner, Cybernetics. 2nd ed., MIT Press.

人間から、卑しくて人が嫌がる仕事(タスク)を奪 い去ることが人間に対してとても善いことになるのか、あるいはそうではないのか、どうも私には分からない——ノーバート・ウィナー(1947年、メキシコ 市)

Information is information, not matter or energy.- Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine

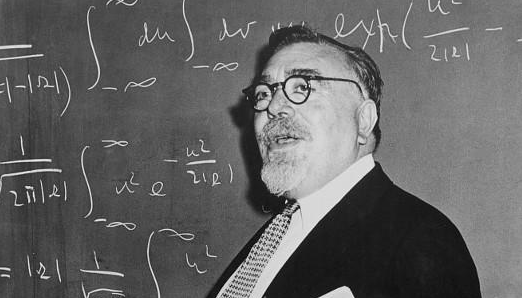

In the mathematical field of probability, the "Wiener sausage" is a neighborhood of the trace of a Brownian motion up to a time t, given by taking all points within a fixed distance of Brownian motion. It can be visualized as a cylinder of fixed radius the centerline of which is Brownian motion.

確率の数学分野では、「ウィーナー・ソーセージ」はブラウン運動の一定距離内のすべての点を取ることによって与えられる、時間tまでのブラウン運動の痕跡の近傍である。一定の半径を持つ円柱として可視化することができ、その中心線はブラウン運動である。

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

書籍の目次(フルテキスト[英文]Cybernetics: Or Control

and

Communication in the Animal and the Machine.)ウィキペディアの解説; Cybernetics:

Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine

* 第1部 オリジナル版(1948)

* イントロダクション 1

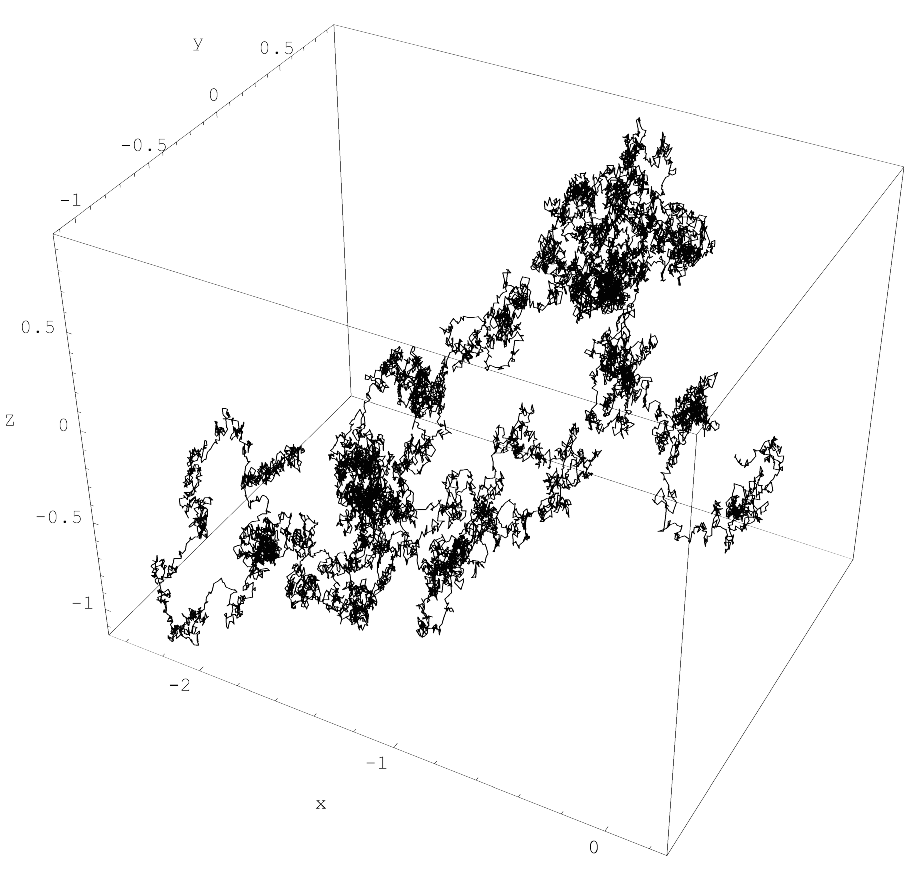

* 1章 ニュートン的時間とベルクソン的時間 30

* 2章 グループ(群)と統計力学 45

* 3章 時系列、情報、コミュニケーション 60

* 4章 フィードバックと振動 95

* 5章 計算機と神経系 116

* 6章 ゲシュタルトと普遍性 133

* 7章 サイバネティクスと精神病理学 144

* 8章 情報、言語、社会 155

* 第2部 補章(1961)

* 9章 学習と自己生成的機械について 169

* 10章 脳波(Brain Waves)と自己組織系 181

| 1章 ニュートン的時間とベルクソン的時 間 30 | Newtonian

and Bergsonian Time |

The theme of this

chapter is an exploration of the contrast between time-reversible

processes governed by Newtonian mechanics and time-irreversible

processes in accordance with the Second Law of Thermodynamics. In the

opening section he distinguishes the predictable nature of astronomy

from the challenges posed in meteorology, anticipating future

developments in Chaos theory. He points out that in fact, even in the

case of astronomy, tidal forces between the planets introduce a degree

of decay over cosmological time spans, and so strictly speaking

Newtonian mechanics do not precisely apply. |

本

章のテーマは、ニュートン力学が支配する時間可逆的プロセスと、熱力学第二法則に従った時間非可逆的プロセスとの対比の探求である。冒頭では、天文学の予

測可能な性質と気象学の課題を区別し、カオス理論の将来の発展を予期している。実際、天文学の場合でも、惑星間の潮汐力は宇宙論的な時間スパンの中である

程度の減衰をもたらすため、厳密に言えばニュートン力学は正確には当てはまらないと指摘する。 |

| 2章 グループ(群)と統計力学 45 | Groups and

Statistical Mechanics |

This chapter

opens with a review of the – entirely independent and apparently

unrelated – work of two scientists in the early 20th century: Willard

Gibbs and Henri Lebesgue. Gibbs was a physicist working on a

statistical approach to Newtonian dynamics and thermodynamics, and

Lebesgue was a pure mathematician working on the theory of

trigonometric series. Wiener suggests that the questions asked by Gibbs

find their answer in the work of Lebesgue. Wiener claims that the

Lebesgue integral had unexpected but important implications in

establishing the validity of Gibbs' work on the foundations of

statistical mechanics. The notions of average and measure in the sense

established by Lebesgue were urgently needed to provide a rigorous

proof of Gibbs' ergodic hypothesis.[6][incomplete short citation]

The concept of entropy in statistical mechanics is developed, and its

relationship to the way the concept is used in thermodynamics. By an

analysis of the thought experiment Maxwell's demon, he relates the

concept of entropy to that of information. |

こ

の章の冒頭では、20世紀初頭の2人の科学者の、まったく独立した、一見無関係に見える仕事について概説する:

ウィラード・ギブスとアンリ・ルベーグである。ギブスはニュートン力学と熱力学への統計的アプローチに取り組む物理学者であり、ルベーグは三角級数の理論

に取り組む純粋数学者であった。ウィーナーは、ギブスが問いかけた疑問はルベーグの研究にその答えがあると示唆している。ウィーナーは、ルベーグ積分は、

統計力学の基礎に関するギブスの研究の妥当性を立証する上で、予期せぬ、しかし重要な意味を持っていたと主張している。ルベーグによって確立された意味で

の平均と測度の概念は、ギブスのエルゴード仮説の厳密な証明を提供するために緊急に必要とされた[6][不完全な短い引用]統計力学におけるエントロピー

の概念が開発され、その概念が熱力学で使用される方法との関係。思考実験であるマクスウェルの悪魔の分析によって、彼はエントロピーの概念を情報の概念に

関連付ける。 |

| 3章 時系列、情報、コミュニケーション 60 | Time Series,

Information, and Communication |

This is one of

the more mathematically intensive chapters in the book. It deals with

the transmission or recording of a varying analog signal as a sequence

of numerical samples, and lays much of the groundwork for the

development of digital audio and telemetry over the past six decades.

It also examines the relationship between bandwidth, noise, and

information capacity, as developed by Wiener in collaboration with

Claude Shannon. This chapter and the next one form the core of the

foundational principles for the developments of automation systems,

digital communications and data processing which have taken place over

the decades since the book was published. |

こ

の章は、この本の中で最も数学的内容の濃い章の一つである。この章では、変化するアナログ信号を数値サンプルのシーケンスとして伝送または記録することを

扱い、過去60年にわたるデジタルオーディオと遠隔測定の発展の基礎を築いた。また、ウィーナーがクロード・シャノンと共同で開発した、帯域幅、ノイズ、

情報容量の関係についても考察している。この章と次の章は、この本が出版されて以来数十年にわたって行われてきたオートメーション・システム、デジタル通

信、データ処理の発展のための基礎原理の中核をなすものである。 |

| 4章 フィードバックと振動 95 | Feedback and

Oscillation |

This chapter lays

down the foundations for the mathematical treatment of negative

feedback in automated control systems. The opening passage illustrates

the effect of faulty feedback mechanisms by the example of patients

suffering from various forms of ataxia. He then discusses railway

signalling, the operation of a thermostat, and a steam engine

centrifugal governor. The rest of the chapter is mostly taken up with

the development of a mathematical formulation of the operation of the

principles underlying all of these processes. More complex systems are

then discussed such as automated navigation, and the control of

non-linear situations such as steering on an icy road. He concludes

with a reference to the homeostatic processes in living organisms. |

こ

の章では、自動制御システムにおける負帰還を数学的に扱うための基礎を築く。冒頭では、様々な運動失調を患う患者を例に、誤ったフィードバック機構の影響

を説明する。その後、鉄道の信号、サーモスタットの動作、蒸気機関の遠心ガバナーについて論じている。この章の残りは、これらすべてのプロセスの根底にあ

る原理の作動を数学的に定式化することに費やされている。より複雑なシステムについては、自動化されたナビゲーションや、凍結した道路での操舵のような非

線形の状況の制御について論じている。最後に、生物における恒常性維持過程について言及する。 |

| 5章 計算機と神経系 116 | Computing Machines

and the Nervous System |

This chapter

opens with a discussion of the relative merits of analog computers and

digital computers (which Wiener referred to as analogy machines and

numerical machines), and maintains that digital machines will be more

accurate, electronic implementations will be superior to mechanical or

electro-mechanical ones, and that the binary system is preferable to

other numerical scales. After discussing the need to store both the

data to be processed and the algorithms which are employed for

processing that data, and the challenges involved in implementing a

suitable memory system, he goes on to draw the parallels between binary

digital computers and the nerve structures in organisms.

Among the mechanisms that he speculated for implementing a computer

memory system was "a large array of small condensers [ie capacitors in

today's terminology] which could be rapidly charged or discharged",

thus prefiguring the essential technology of modern dynamic

random-access memory chips.

Virtually all of the principles which Wiener enumerated as being

desirable characteristics of calculating and data processing machines

have been adopted in the design of digital computers, from the early

mainframes of the 1950s to the latest microchips. |

こ

の章は、アナログ・コンピュータとデジタル・コンピュータ(ウィーナーはこれをアナロジー・マシンと数値計算機と呼んだ)の相対的な利点についての議論で

始まり、デジタル・マシンはより正確であり、電子的実装は機械的または電気機械的なものよりも優れており、二進法は他の数値スケールよりも好ましいと主張

している。処理するデータと、そのデータを処理するために採用されるアルゴリズムの両方を記憶する必要性と、適切な記憶システムの実装に伴う課題について

論じた後、彼は2進数のデジタル・コンピュータと生物の神経構造との類似点を描いている。コンピューター・メモリー・システムを実現するために彼が考えた

メカニズムの中には、「急速に充放電できる小さなコンデンサー(今日の用語でいうコンデンサー)の大きな配列」があり、これが現代のダイナミック・ランダ

ム・アクセス・メモリー・チップの本質的な技術の先駆けとなった。ウィーナーが計算機やデータ処理機の望ましい特性として列挙した原理は、1950年代の

初期のメインフレームから最新のマイクロチップに至るまで、事実上すべてデジタル・コンピュータの設計に採用されている。 |

| 6章 ゲシュタルトと普遍性 133 | Gestalt and

Universals |

This brief

chapter is a philosophical enquiry into the relationship between the

physical events in the central nervous system and the subjective

experiences of the individual. It concentrates principally on the

processes whereby nervous signals from the retina are transformed into

a representation of the visual field. It also explores the various

feedback loops involved in the operation of the eyes: the homeostatic

operation of the retina to control light levels, the adjustment of the

lens to bring objects into focus, and the complex set of reflex

movements to bring an object of attention into the detailed vision area

of the fovea. The chapter concludes with an outline of the challenges

presented by attempts to implement a reading machine for the blind. |

こ

の短い章は、中枢神経系で起こる物理的な出来事と、個人の主観的な経験との関係についての哲学的な探求である。主に、網膜からの神経信号が視覚野の表現に

変換される過程に焦点を当てる。また、光のレベルを制御するための網膜の恒常性維持運動、物体に焦点を合わせるための水晶体の調節、そして、注意の対象を

窩の詳細な視覚領域に引き込むための複雑な反射運動など、目の動作に関わるさまざまなフィードバックループについても探求する。この章は、視覚障害者のた

めの読書機を実現しようとする試みが提示する課題の概要で締めくくられている。 |

| 7章 サイバネティクスと精神病理学 144 | Cybernetics and

Psychopathology |

Wiener opens this

chapter with the disclaimers that he is neither a psychopathologist nor

a psychiatrist, and that he is not asserting that mental problems are

failings of the brain to operate as a computing machine. However, he

suggests that there might be fruitful lines of enquiry opened by

considering the parallels between the brain and a computer. (He

employed the archaic-sounding phrase "computing machine", because at

the time of writing the word "computer" referred to a person who is

employed to perform routine calculations). He then discussed the

concept of 'redundancy' in the sense of having two or three computing

mechanisms operating simultaneously on the same problem, so that errors

may be recognised and corrected. |

ウィー

ナーはこの章の冒頭で、自分は精神病理学者でも精神科医でもないこと、そして精神的な問題は脳がコンピューティング・マシンとして動作するための失敗であ

ると主張しているわけではないことを断っている。しかし、脳とコンピュータの類似性を考えることで、有益な探求の道が開けるかもしれないと示唆している。

(彼は "計算機 "という古風な響きを持つ言葉を使ったが、これは執筆当時、"コンピューター

"という言葉は定型的な計算を行うために雇われた人間を指していたからである)。そして、同じ問題に対して2つまたは3つの計算機構が同時に動作すること

で、エラーを認識し修正することができるという意味での「冗長性」の概念について述べた。 |

| 8章 情報、言語、社会 155 | Information,

Language, and Society |

Starting

with an outline of the hierarchical nature of living organisms, and a

discussion of the structure and organisation of colonies of symbiotic

organisms, such as the Portuguese Man o' War, this chapter explores the

parallels with the structure of human societies, and the challenges

faced as they scale and complexity of society increases.

The Chapter closes with speculation about the possibility of

constructing a chess-playing machine, and concludes that it would be

conceivable to build a machine capable of a standard of play better

than most human players but not at expert level. Such a possibility

seemed entirely fanciful to most commentators in the 1940s, bearing in

mind the state of computing technology at the time, although events

have turned out to vindicate the prediction – and even to exceed it. |

こ

の章では、生物の階層的性質の概説と、ポルトガルの「マン・オー・ウォー」のような共生生物のコロニーの構造と組織についての議論から始まり、人間社会の

構造との類似点、そして社会の規模と複雑さが増すにつれて直面する課題について探求する。この章は、チェスをするマシンを作る可能性についての推測で締め

くくられ、ほとんどの人間より優れたプレーの水準を持つマシンを作ることは考えられるが、専門家レベルではないと結論づけられる。このような可能性は、

1940年代には、当時のコンピュータ技術の状況を考慮すると、ほとんどの論者にとってまったく空想的なものに思えた。 |

| 9章 学習と自己生成的機械について 169 | On Learning and

Self-Reproducing Machines |

Starting

with an examination of the learning process in organisms, Wiener

expands the discussion to John von Neumann's theory of games, and the

application to military situations. He then speculates about the manner

in which a chess-playing computer could be programmed to analyse its

past performances and improve its performance. This proceeds to a

discussion of the evolution of conflict, as in the examples of matador

and bull, or mongoose and cobra, or between opponents in a tennis game.

He discusses various stories such as The Sorcerer's Apprentice, which

illustrate the literal-minded nature of "magical" processes, the

context being the drawing of attention to the need for caution in

delegating to machines the responsibility for warfare strategy in an

age of Nuclear weapons. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the

possibility of self-replicating machines and the work of Professor

Dennis Gabor in this area. |

ウィー

ナーは、生物における学習プロセスの考察から始まり、ジョン・フォン・ノイマンのゲーム理論、そして軍事的状況への応用へと議論を広げていく。そして、

チェスをするコンピューターが過去の成績を分析し、その成績を向上させるようにプログラムされる方法について推測している。そして、マタドールと雄牛、マ

ングースとコブラ、あるいはテニスの対戦相手の例に見られるような、対立の進化についての議論へと進む。魔術師の弟子』のような様々な物語を取り上げ、

「魔術的」プロセスの文字通りの性質を説明しているが、その背景には、核兵器の時代における戦争戦略の責任を機械に委ねることの注意の必要性がある。この

章は、自己複製機械の可能性と、この分野におけるデニス・ガボール教授の研究についての考察で締めくくられている。 |

| 10章 脳波(Brain Waves)と自己組織系 181 | Brain Waves and

Self-Organising Systems |

This

chapter opens with a discussion of the mechanism of evolution by

natural selection, which he refers to as "phylogenetic learning", since

it is driven by a feedback mechanism caused by the success or otherwise

in surviving and reproducing; and modifications of behaviour over a

lifetime in response to experience, which he calls "ontogenetic

learning". He suggests that both processes involve non-linear feedback,

and speculates that the learning process is correlated with changes in

patterns of the rhythms of the waves of electrical activity that can be

observed on an electroencephalograph. After a discussion of the

technical limitations of earlier designs of such equipment, he suggests

that the field will become more fruitful as more sensitive interfaces

and higher performance amplifiers are developed and the readings are

stored in digital form for numerical analysis, rather than recorded by

pen galvanometers in real time - which was the only available technique

at the time of writing. He then develops suggestions for a mathematical

treatment of the waveforms by Fourier analysis, and draws a parallel

with the processing of the results of the Michelson–Morley experiment

which confirmed the constancy of the velocity of light, which in turn

led Albert Einstein to develop the theory of Special Relativity. As

with much of the other material in this book, these pointers have been

both prophetic of future developments and suggestive of fruitful lines

of research and enquiry. |

こ

の章の冒頭では、自然淘汰による進化のメカニズムについて論じている。自然淘汰による進化は、生存と繁殖の成功の有無によって引き起こされるフィードバッ

ク・メカニズムによって駆動されるため、彼はこれを「系統発生的学習」と呼んでいる。彼は、この2つのプロセスには非線形フィードバックが関係していると

し、学習プロセスは、脳波計で観察できる電気活動の波のリズムのパターンの変化と相関していると推測している。このような装置の初期設計の技術的限界につ

いて論じた後、より高感度なインターフェースと高性能なアンプが開発され、測定値がリアルタイムでペン型検流計によって記録されるのではなく、数値解析の

ためにデジタル形式で保存されるようになれば、この分野はより実りあるものになるだろうと示唆している。そして、フーリエ解析による波形の数学的処理につ

いての提案を展開し、光の速度の不変性を確認したマイケルソン=モーリー実験の結果の処理と並列させ、アルベルト・アインシュタインが特殊相対性理論を発

展させるきっかけとなった。本書の他の多くの資料と同様、これらの指摘は将来の発展を予言し、実りある研究と探求の道を示唆するものである。 |

| Introduction |

Wiener recounts

that the origin of the ideas in this book is a ten-year-long series of

meetings at the Harvard Medical School where medical scientists and

physicians discussed scientific method with mathematicians, physicists

and engineers. He details the interdisciplinary nature of his approach

and refers to his work with Vannevar Bush and his differential analyzer

(a primitive analog computer), as well as his early thoughts on the

features and design principles of future digital calculating machines.

He traces the origins of cybernetic analysis to the philosophy of

Leibniz, citing his work on universal symbolism and a calculus of

reasoning. |

本

書のアイデアの原点は、ハーバード大学医学部で医学者や医師が数学者、物理学者、技術者と科学的方法について議論した10年にわたる一連の会合にあると

ウィーナーは語る。彼のアプローチの学際的な性質を詳述し、ヴァネヴァー・ブッシュと彼の微分解析器(原始的なアナログ・コンピューター)との共同作業

や、将来のデジタル計算機の特徴や設計原理に関する彼の初期の考えに言及している。彼は、サイバネティック分析の起源をライプニッツの哲学にまで遡り、普

遍的象徴論と推論の微積分に関する彼の研究を引用している。 |

書誌

Norbert Wiener(1894-19641948), Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Paris, (Hermann & Cie) & Camb. Mass. (MIT Press) ISBN 978-0-262-73009-9; 2nd revised ed. 1961.(サイバネティックス : 動物と機械における制御と通信 / ウィーナー [著] ; 池原止戈夫, 彌永昌吉, 室賀三郎, 戸田巌訳:東京 : 岩波書店 , 2011.6. - (岩波文庫 ; 青(33)-948-1))池原(Shikao Ikehara, 1904-1984)はMITでウィーナーのもとでPh.D を1930年に取得した学生である。※岩波書店は、岩波文庫になる際にも、サイバネティック スという訳語を、すでに定番になっているサイバネティクスに改めようとしない。僕はクソ会社だと思う。

+++++++++++

序章(1948年になるこの本の初版の序章は 1947年メキシコ市で書かれている)

・Arturo Bosenblueth, 1900-1970, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología との1930年代後半からの研究

・Manuel Sandoval Vallarta, MIT

・科学の方法について Josiah Royce との検討(1911-1913)

・1944 Bosenbluethがメキシコへ帰 国。

・分野間での相互不理解とカオス「(さまざまな研究 室で)研究が同時におこなわれ、同じことにそれぞれの部門で別々の名前がつけられ、重要な研究成果が三 重にも四重にも個別にまとめあげられているかと思うと、ある部門ではすでに古典的とさえなっている結果が、他の部門ではあまり知られずに研究が遅れている というような有り様」(文庫本、p.29)

・Vannever Bush の計算機計画と、ウィナーがYuk Wing Lee との間で電気回路の設計をおこなっていた。

・常微分方程式がブッシュの微分解析機で扱えるの に、偏微分方程式の扱いが困難になるのは、1つ以上の変数をもつ関数を表示するにことにまつわる問題だか ら、テレビで使われる走査が、この問題を解決するためのヒントになることに気づく

・走査法を用いて、常微分以上の変数を扱えるように する(p.31)

つづく

認知科学の出発点としてのサイバネティクス

認知科学は、1948年のカリフォルニア工科大学で 開催されたヒクソン・シンポジウム [ガードナー 1987:10-25]や、1956年ニューハンプシャー州のダートマス大学で計算機科学者のジョン・マッカーシーが開催し、チョムスキー、ブルーナー、 ミンスキー、サイモンなど、この分野で後に大物になる研究者たちが多く参加した「ダートマスの人工知能会議」[ガードナー 1987: 28, 134-136]が出発点とみなされている。その後のコンピューター科学が進歩を遂げ、ソフトウェアを利用するのみならず、ソフトウェアでのシミュレー ションなどが可能となり、それまでの動物実験や被験者を使った心理実験などとの融合が図られたことはよく知られている。

◎「神々を生み出す機械(マシーン)」それは宇宙——アンリ・ベルクソン(Henri- Louis Bergson, 1859-1941)(→ノーバート・ウィーナー)

A Machine for the

Making of Gods

"Norbert Wiener (November 26, 1894 – March 18, 1964) was an American mathematician and philosopher. He was a professor of mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). A child prodigy, Wiener later became an early researcher in stochastic and mathematical noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic engineering, electronic communication, and control systems./ Wiener is considered the originator of cybernetics, a formalization of the notion of feedback, with implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, neuroscience, philosophy, and the organization of society./ Norbert Wiener is credited as being one of the first to theorize that all intelligent behavior was the result of feedback mechanisms, that could possibly be simulated by machines and was an important early step towards the development of modern artificial intelligence.[3]" -Norbert Wiener.

1894 Wiener was born in Columbia, Missouri, the first child of Leo Wiener and Bertha Kahn, Jews[4] from Poland and Germany, respectively

1906 A child prodigy, he graduated from Ayer High School in 1906 at 11 years of age, then Wiener entered Tufts College.

1909 He was awarded a BA in mathematics in 1909 at the age of 14, whereupon he began graduate studies of zoology at Harvard.

1910 he transferred to Cornell to study philosophy

1911 He graduated in 1911 at 17 years of age.

1913

The next year he

returned to Harvard, while still continuing his philosophical studies.

Back at Harvard, Wiener became influenced by Edward Vermilye

Huntington, whose mathematical interests ranged from axiomatic

foundations to engineering problems. Harvard awarded Wiener a Ph.D. in

June 1913, when he was only 18 years old,

1914 Wiener traveled to

Europe, to be taught by Bertrand Russell and G. H. Hardy at Cambridge

University, and by David Hilbert and Edmund Landau at the University of

Göttingen.

1915-16

During 1915–16, he taught philosophy at Harvard, then was an engineer for General Electric and wrote for the Encyclopedia Americana. Wiener was briefly a journalist for the Boston Herald, where he wrote a feature story on the poor labor conditions for mill workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, but he was fired soon afterwards for his reluctance to write favorable articles about a politician the newspaper's owners sought to promote.[6]

1916

Although Wiener

eventually became a staunch pacifist, he eagerly contributed to the war

effort in World War I. In 1916, with America's entry into the war

drawing closer, Wiener attended a training camp for potential military

officers, but failed to earn a commission.

1917 One year later Wiener again tried to join the military, but the government again rejected him due to his poor eyesight.

1918

In the summer of 1918, Oswald Veblen invited Wiener to work on ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.[7] Living and working with other mathematicians strengthened his interest in mathematics. However, Wiener was still eager to serve in uniform, and decided to make one more attempt to enlist, this time as a common soldier. Wiener wrote in a letter to his parents, "I should consider myself a pretty cheap kind of a swine if I were willing to be an officer but unwilling to be a soldier."

1919

This time the army accepted Wiener into its ranks and assigned him, by coincidence, to a unit stationed at Aberdeen, Maryland. World War I ended just days after Wiener's return to Aberdeen and Wiener was discharged from the military in February 1919.[9]

1926

Wiener returned to Europe as a Guggenheim scholar. He spent most of his time at Göttingen and with Hardy at Cambridge, working on Brownian motion, the Fourier integral, Dirichlet's problem, harmonic analysis, and the Tauberian theorems. In 1926, Wiener's parents arranged his marriage to a German immigrant, Margaret Engemann; they had two daughters. His sister, Constance, married Philip Franklin. Their daughter, Janet, Wiener's niece, married Václav E. Beneš.[12]

1939-1945

During World War II, his work on the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns caused Wiener to investigate information theory independently of Claude Shannon and to invent the Wiener filter. (To him is due the now standard practice of modeling an information source as a random process—in other words, as a variety of noise.) His anti-aircraft work eventually led him to formulate cybernetics.[16] After the war, his fame helped MIT to recruit a research team in cognitive science, composed of researchers in neuropsychology and the mathematics and biophysics of the nervous system, including Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts. These men later made pioneering contributions to computer science and artificial intelligence. Soon after the group was formed, Wiener suddenly ended all contact with its members, mystifying his colleagues. This emotionally traumatized Pitts, and led to his career decline. In their biography of Wiener, Conway and Siegelman suggest that Wiener's wife Margaret, who detested McCulloch's bohemian lifestyle, engineered the breach.[17]

1945

Wiener later helped develop the theories of cybernetics, robotics, computer control, and automation. He discussed the modeling of neurons with John von Neumann, and in a letter from November 1946 von Neumann presented his thoughts in advance of a meeting with Wiener.[18]

1945-

After the war, Wiener became increasingly concerned with what he believed was political interference with scientific research, and the militarization of science. His article "A Scientist Rebels" from the January 1947 issue of The Atlantic Monthly[19] urged scientists to consider the ethical implications of their work. After the war, he refused to accept any government funding or to work on military projects. The way Wiener's beliefs concerning nuclear weapons and the Cold War contrasted with those of von Neumann is the major theme of the book John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener.[20][full citation needed]

1946 First Cybernetics Conference, 21–22 March 1946

1946 Second Cybernetics Conference, 17–18 October 1946

1947 Third Cybernetics Conference, 13–14 March 1947

1947 Fourth Cybernetics Conference, 23–24 October 1947

during cold war period

Wiener always shared his theories and findings with other researchers, and credited the contributions of others. These included Soviet researchers and their findings. Wiener's acquaintance with them caused him to be regarded with suspicion during the Cold War. He was a strong advocate of automation to improve the standard of living, and to end economic underdevelopment. His ideas became influential in India, whose government he advised during the 1950s.

1948 Fifth Cybernetics Conference, 18–19 March 1948

1949 Sixth Cybernetics Conference, 24–25 March 1949

1950 Seventh Cybernetics Conference, 23–24 March 1950

1951 Eighth Cybernetics Conference, 15–16 March 1951

1952 Ninth Cybernetics Conference, 20–21 March 1952

1953 Tenth Cybernetics Conference, 22–24 April 1953

1946-1960 Wiener was a

participant of the Macy conferences expecially

Cybernetics Conference,.

1964 He died in March 1964, aged 69, in Stockholm, from a heart attack. Wiener and his wife are buried at the Vittum Hill Cemetery in Sandwich, New Hampshire.

■サイバネティクス全史

書誌:サイバネティクス全史 : 人類は思考するマシンに何を夢見たのか / トマス・リッド著 ; 松浦俊輔訳,作品社 , 2017/Rise of the Machines. A Cybernetic History, New York/London: W.W. Norton/Scribe, 2016

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

9章 学習と自己生成的機械について 169 On

Learning and Self-Reproducing Machines(Learning_Self-Reproducing_Machines.pdf)with

password

| IX

On Learning

and Self-Reproducing Machines Two of the phenomena which we consider to be characteristic of living systems are the power to learn and the power to reproduce themselves. These properties, different as they appear, are intimately related to one another. An animal that learns is one which is capable of being transformed by its past environment into a different being and is therefore adjustable to its environment within its individual lifetime. An animal that multiplies is able to create other animals in its own likeness at least approximately, although not so completely in its own likeness that they cannot vary in the course of time. If this variation is itself inheritable, we have the raw material on which natural selection can work. If the hereditary invariability concerns manners of behavior, then among the varied patterns of behavior which are propagated some will be found advantageous to the continuing existence of the race and will establish themselves, while others which are detrimental to this continuing existence will be eliminated. The result is a certain sort of racial or phylogenetic learning, as contrasted with the ontogenetic learning of the individual. Both ontogenetic and phylogenetic learning are modes by which the animal can adjust itself to its environment. Both ontogenetic and phylogenetic learning, and certainly the latter, extend themselves not only to all animals but to plants and, indeed, to all organisms which in any sense may be considered to be living. However, the degree to which these two forms of learning are found to be important in different sorts of living beings varies widely. In man, and to a lesser extent in the other mammals, 169 170 CYBERNETICS ontogenetic learning and individual adaptability are raised to the highest point. Indeed, it may be said that a large part of the phylogenetic learning of man has been devoted to establishing the possibility of good ontogenetic learning. It has been pointed out by Julian Huxley in his fundamental paper on the mind of birds 1 that birds have a small capacity for ontogenetic learning. Something similar is true in the case of insects, and in both instances it may be associated with the terrific demands made on the individual by flight and the consequential pre-emption of the capabilities of the nervous system which might otherwise be applied to ontogenetic learning. Complicated as the behavior patterns of birds are-in flying, in courtship, in the care of the young, and in nest building-they are carried out correctly the very first time without the need of any large amount of instruction from the mother. It is altogether appropriate to devote a chapter of this book to these two related subjects. Can man-made machines learn and can they reproduce themselves 1 We shall try to show in this chapter that in fact they can learn and can reproduce themselves, and we shall give an account of the technique needed for both these activities. The simpler of these two processes is that of learning, and it is there that the technical development has gone furthest. I shall talk here particularly of the learning of game-playing machines which enables them to improve the strategy and tactics of their performance by experience. There is an established theory of the playing of games-the von Neumann theory.• It concerns a policy which is best considered by working from the end of the game rather than from the beginning. In the last move of the game, a player strives to make a winning move if possible, and if not, then at least a drawing move. His opponent, at the previous stage, strives to make a move which will prevent the other player from making a winning or a drawing move. If he can himself make a winning move at that stage, he will do so, and this will not be the next to the last but the last stage of the game. The other player at the move before this will try to act in such a way that the very best resources of his opponent will not prevent him from ending with a winning move, and so on backward. There are games such as ticktacktoe where the entire strategy is known, and it is possible to start this policy from the very be- 1 Huxley, J., Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, Harper Bros., New York, 1943. 2 von Neumann, J., and O. Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1944. ON LEARNING AND SELF~REPRODUCING MACHINES 171 ginning. When this is feasible, it is manifestly the best way of playing the game. However, in many games like chess and checkers our knowledge is not sufficient to permit a complete strategy of this sort, and then we can only approximate to it. The von Neumann type of approximate theory tends to lead a player to act with the utmost caution, assuming that his opponent is the perfectly wise sort of a master. This attitude, however, is not always justified. In war, which is a sort of game, this will in general lead to an indecisive action which will often be not much better than a defeat. Let me give two historical examples. When Napoleon fought the Austrians in Italy, it was part of his effectiveness that he knew the Austrian mode of military thought to be hidebound and traditional, so that he was quite justified. in assuming that they were incapable of taking advantage of the new decision-compelling methods of war which had been developed by the soldiers of the French Revolution. When Nelson fought the combined fleets of continental Europe, he had the advantage of fighting with a naval machine which had kept the seas for years and which had developed methods of thought of which, as he was well aware, his enemies were incapable. If he had not made the fullest possible use of this advantage, instead of acting as cautiously as he would have had to act under the supposition that he was facing an enemy of equal naval experience, he might have won in the long run but could not have won so quickly and decisively as to establish the tight naval blockade which was the ultimate downfall of Napoleon. Thus, in both cases, the guiding factor was the known record of the commander and of his opponents, as exhibited statistically in the past of their actions, rather than an attempt to play the perfect game against the perfect opponent. Any direct use of the von Neumann method of game theory in these cases would have proved futile. In a similar way, books on chess theory are not written from the von Neumann point of view. They are compendia of principles drawn from the practical experience of chess players playing against other chess players of high quality and wide knowledge; and they establish certain values or weightings to be given to the Joss of each piece, to mobility, to command, to development, and to other factors which may vary with the stage of the game. It is not very difficult to make machines which will play chess of a sort. The mere obedience to the Jaws of the game, so that only legal moves are made, is easily within the power of quite simple computing machines. Indeed, it is not hard to adapt an ordinary digital machine to these purposes. 172 CYBERNETICS Now comes the question of policy within the rules of the game. Every evaluation of pieces, command, mobility, and so forth, is intrinsically capable of being reduced to numerical terms; and when this is done, the maxims of a chess book may be used for the determination of the best moves of each stage. Such machines have been made; and they will play a very fair amateur chess, although at present not a game of master caliber. Imagine yourself in the position of playing chess against such a machine. To make the situation fair, Jet us suppose you are playing correspondence chess without the knowledge that it is such a machine you are playing and without the prejudices that this knowledge may excite. Naturally, as always is the case with cheas, you will come to a judgment of your opponent's chess personality. You will find that when the same situation comes up twice on the chessboard, your opponent's reaction will be the same each time, and you will find that he has a very rigid personality. If any trick of yours will work, then it will always work under the same conditions. It is thus not too hard for an expert to get a line on his machine opponent and to defeat him every time. However, there are machines that cannot be defeated so trivially. Let us suppose that every few games the machine takes time off and uses its facilities for another purpose. This time, it does not play against an opponent, but examines all the previous games which it has recorded on its memory to determine what weighting of the different evaluations of the worth of pieces, command, mobility, and the like, will conduce most to winning. In this way, it learns not only from its own failures but its opponent's successes. It now replaces its earlier valuations by the new ones and goes on playing as a new and better machine. Such a machine would no longer have as rigid a personality, and the tricks which were once succeasful against it will ultimately fail. More than that, it may absorb in the course of time something of the policy of its opponents. All this is very difficult to do in chess, and as a matter of fact the full development of this technique, so as to give rise to a machine that can play master chess, has not been accomplished. Checkers offers an easier problem. The homogeneity of the values of the pieces greatly reduces the number of combinations to be considered. Moreover, partly as a consequence of this homogeneity, the checker game is much leas divided into distinct stages than the chess game. Even in checkers, the main problem of the end game is no longer to take pieces but to establish contact with the enemy so that one is in a position to take pieces. Similarly, the valuation of moves in the ON LEARNING AND SELFMREPRODUCING MACHINES 173 chess game must be made independently for the different stages. Not only is the end game different from the middle game in the considerations which are paramount, but the openings are much more devoted to getting the pieces into a position of free mobility for attack and defense than is the middle game. The result is that we cannot be even approximately content with a uniform evaluation of the various weighting factors for the game as a whole, but must divide the learning process into a number of separate stages. Only then can we hope to construct a learning machine which can play master chess. The idea of a first-order programming, which may be linear in certain cases, combined with a second-order programming, which uses a much more extensive segment of the past for the determination of the policy to be carried out in the first-order programming, has been mentioned earlier in this book in connection with the problem of prediction. The predictor uses the immediate past of the flight of the airplane as a tool for the prediction of the future by means of a linear operation; but the determination of the correct linear operation is a statistical problem in which the long past of the flight and the past of many similar flights are used to give the basis of the statistics. The statistical studies necessary to use a long past for a determination of the policy to be adopted in view of the short past are highly non-linear. As a matter of fact, in the use of the Wiener-Hopf equation for prediction,! the determination of the coefficients of this equation is carried out in a non-linear manner. In general, a learning machine operates by non-linear feedback. The checker-playing machine described by Samuel 2 and Watanabe• can learn to defeat the man that programmed it in a fairly consistent way on the basis of from IO to 20 operating hours of programming. Watanabe's philosophical ideas on the use of programming machines are very exciting. On the one hand, he is treating a method of proving an elementary geometrical theorem which shall conform in an optimal way according to certain criteria of elegance and simplicity, as a learning game to be played not against an individual opponent but against what we may call "Colonel Bogey." A similar 1 Wiener, N., Extrapokuion, Interpolation, and Smoothing of Stationary Time Series with Engineering Applications, The Technology Press of M.I.T. and John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1949. 2 Samuel, A. L., '' Some Studies in Machine Learning, Using the Game of Checkers,'' IBM Journal of Research and Developmeflt, 3, 210-229 (1959). 3 Watanabe, S., "Information Theoretical Analysis of Multivariate Correlation," IBM Journal of Research and Development,,, 66--82 (1960). 174 CYBERNETICS game which Watanabe is studying is played in logical induction, when we wish to build up a theory which is optimal in a similar quasi~aesthetic way, on the basis of an evaluation of economy, directness, and the like, by the determination of the evaluation of a finite number of parameters which are left free. This, it is true, is only a limited logical induction, but it is well worth studying. Many forms of the activity of struggle, which we do not ordinarily consider as games, have a great deal of light thrown on them by the theory of game-playing machines. One interesting example is the fight between a mongoose and a snake. As Kipling points out in "Rikki-Tikki-Tavi," the mongoose is not immune to the poison of the cobra, although it is to some extent protected by its coat of stiff hairs which makes it difficult for the snake to bite home. As Kipling states, the fight is a dance with death, a struggle of muscular skill and agility. There is no reason to suppose that the individual motions of the mongoose are faster or more accurate than those of the cobra. Yet the mongoose almost invariably kills the cobra and comes out of the contest unscathed. How is it able to do this? I am here giving an account which appears valid to me, from having seen such a fight, as well as motion pictures of other such fights. I do not guarantee the correctness of my observations as interpretations. The mongoose begius with a feint, which provokes the snake to strike. The mongoose dodges and makes another such feint, so that we have a rhythmical pattern of activity on the part of the two animals. However, this dance is not static but develops progressively. As it goes on, the feints of the mongoose come earlier and earlier in phase with respect to the darts of the cobra, until finally the mongoose attacks when the cobra is extended and not in a position to move rapidly. This time the mongoose's attack is not a feint but a deadly accurate bite through the cobra's brain. In other words, the snake's pattern of action is confined to single darts, each one for itself, while the pattern of the mongoose's action involves an appreciable, if not very long, segment of the whole past of the fight. To this extent the mongoose acts like a learning machine, and the real deadliness of its attack is dependent on a much more highly organized nervous system. As a Walt Disney movie of several years ago showed, something very similar happens when one of our western birds, the road runner, attacks a rattlesnake. While the bird fights with beak and claws, and a mongoose with its teeth, the pattern of activity is very similar. A bullfight is a very fine example of the same thing. For it must be remembered that the bullfight is not a sport but a dance with death, ON LEARNING AND SELF-REPRODUCING MACHINES 175 to exhibit the beauty and the interlaced coordinating actions of the bull and the man. Fairness to the bull has no part in it, and we can leave out from our point of view the preliminary goading and weakening of the bull, which have the purpose of bringing the contest to a level where the interaction of the patterns of the two participants is most highly developed. The skilled bullfighter has a large repertory of possible actions, such as the flaunting of the cape, various dodges and pirouettes, and the like, which are intended to bring the bull into a position in which it has completed its rush and is extended at the precise moment that the bullfighter is ready to plunge the estoque into the bull's heart. What I have said concerning the fight between the mongoose and the cobra, or the toreador and the bull, will also apply to physical contests between man and man. Consider a duel with the smallsword. It consists of a sequence of feints, parries, and thrusts, with the intention on the part of each participant to bring his opponent's sword out of line to such an extent that he can thrust home without laying himself open to a double encounter. Again, in a championship game of tennis, it is not enough to serve or return the ball perfectly as far as each individual stroke is considered; the strategy is rather to force the opponent into a series of returns which put him progressively in a worse position until there is no way in which he can return the ball safely. These physical contests and the sort of games which we have supposed the game-playing machine to play both have the same element of learning in terms of experience of the opponent's habits as well as one's own. What is true of games of physical encounter is also true of contests in which the intellectual element is stronger, such as war and the games which simulate war, by which our staff officers win the elements of their military experience. This is true for classical war both on land and at sea, and is equally true with the new and as yet untried war with atomic weapons. Some degree of mechanization, parallel to the mechanization of checkers by learning machines, is possible in all these. There is nothing more dangerous to contemplate than World War III. It is worth considering whether part of the danger may not be intrinsic in the unguarded use of learning machines. Again and again I have heard the statement that learning machines cannot subject us to any new dangers, because we can turn them off when we feel like it. But can we! To turn a machine off effectively, we must be in possession of information as to whether the danger point has come. The mere fact that we have made the machine does not 176 CYBERNETICS guarantee that we shall have the proper information to do this. This is already implicit in the statement that the checker-playing machine can defeat the man who has programmed it, and this after a very limited time of working in. Moreover, the very speed of operation of modern digital machines stands in the way of our ability to perceive and think through the indications of danger. The idea of non-human devices of great power and great ability to carry through a policy, and of their dangers, is nothing new. All that is new is that now we possess effective devices of this kind. In the past, similar possibilities were postulated for the techniques of magic, which forms the theme for so many legends and folk tales. These tales have thoroughly explored the moral situation of the magtctan. I have already discussed some aspects of the legendary ethics of magic in an earlier book entitled The Human Use of Human Beings.• I here repeat some of the material which I have discussed there, in order to bring it out more precisely in its new context of learning machines. One of the best-known tales of magic is Goethe's "The Sorcerer's Apprentice." In this, the sorcerer leaves his apprentice and factotum alone with the chore of fetching water. As the boy is lazy and ingenious, he passes the work over to a broom, to which he has uttered the words of magic which he has heard from his master. The broom obligingly does the work for him and will not stop. The boy is on the verge of being drowned out. He finds that he has not learned, or has forgotten, the second incantation which is to stop the broom. In desperation, he takes the broomstick, breaks it over his knee, and finds to his consternation that each half of the broom continues to fetch water. Luckily, before he is completely destroyed, the master returns, says the Words of Power to stop the broom, and administers a good scolding to the apprentice. Another story is the Arabian Nights tale of the fisherman and the genie. The fisherman has dredged up in his net a jug closed with the seal of Solomon. It is one of the vessels in which Solomon has imprisoned the rebellious genie. The genie emerges in a cloud of smoke, and the gigantic figure tells the fisherman that, whereas in his first years of imprisonment he had resolved to reward his rescuer with power and fortune, he has now decided to slay him out of hand. Luckily for himself, the fisherman finds a way to talk the genie back into the bottle, upon which he casts the jar to the bottom of the ocean. l Wiener, N., The Human Use of Human Beings; Cybernetic.a and Society, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1950. ON LEARNING AND SELF·REPROOUCINO MACHINES 177 More terrible than either of these two tales is the fable of the monkey's paw, written by W. W. Jacobs, an English writer of the beginning of the century. A retired English workingman is sitting at his table with his wife and a friend, a returned British sergeantmajor from India. The sergeant-major shows his hosts an amulet in the form of a dried, wizened monkey's paw. This has been endowed by an Indian holy man, who has wished to show the folly of defying fate, with the power of granting three wishes to each of three people. The soldier says that he knows nothing of the first two wishes of the first owner, but the last one was for death. He himself, as he tells his friends, was the second owner but will not talk of the horror of his own experiences. He casts the paw into the fire, but his friend retrieves it and wishes to test its powers. His first is for £200. Shortly thereafter there is a knock at the door, and an official of the company by which his son is employed enters the room. The father learns that his son has been killed in the machinery, but that the company, without recognizing any responsibility or legal obligation, wishes to pay the father the sum of £200 as a solatium. The griefstricken father makes his second wish-that his son may return-and when there is another knock at the door and it is opened, something appears which, we are not told in so many words, is the ghost of the son. The final wish is that this ghost should go away. In all these stories the point is that the agencies of magic are literal-minded; and that if we ask for a boon from them, we must ask for what we really want and not for what we think we want. The new and real agencies of the learning machine are also literal•minded. If we program a machine for winning a war, we must think well what we mean by winning. A learning machine must be programmed by experience. The only experience of a nuclear war which is not immediately catastrophic is the experience of a war game. If we are to use this experience as a guide for our procedure in a real emergency, the values of winning which we have employed in the programming games must be the same values which we hold at heart in the actual outcome of a war. We can fail in this only at our immediate, utter, and irretrievable peril. We cannot expect the machine to follow us in those prejudices and emotional compromises by which we enable ourselves to call destruction by the name of victory. Ifwe ask for victory and do not know what we mean by it, we shall find the ghost knocking at our door. So much for learning machines. Now let me say a word or two about self-propagating machines. Here both the words machine and self-propagating are important. The machine is not only a form of 178 CYBERNETICS matter, but an agency for accomplishing certain definite purposes. And self-propagation is not merely the creation of a tangible replica; it is the creation of a replica capable of the same functions. Here, two different points of view come into evidence. One of these is purely combinatorial and concerns the question whether a machine can have enough parts and sufficiently complicated structure to enable self-reproduction to be among its functions. This question has been answered in the affirmative by the late John von Neumann. The other question concerns an actual operative procedure for building self-reproducing machines. Here I shall confine my attentions to a class of machines which, while it does not embrace all machines, is of great generality. I refer to the non-linear transducer. Such machines are apparatuses which have as an input a single function of time and which have as their output another function of time. The output is completely determined by the past of the input; but in general, the adding of inputs does not add the correspondink outputs. Such pieces of apparatus are known as transducers. One property of all transducers, linear or non~linear, is an invariance with respect to a translation in time. If a machine performs a certain function, then, if the input is shifted back in time, the output is shifted back by the same amount. Basic to our theory of self-reproducing machines is a canonical form of the representation of non-linear transducers. Here the notions of impedance and admittance, which are so essential in the theory of linear apparatus, are not fully appropriate. We shall have to refer to certain newer methods of carrying out this representation, methods developed partly by me 1 and partly by Professor Dennis Gabor• of the University of London. While both Professor Gabor's methods and my own lead to the construction of non~linear transducers, they are linear to the extent that the non-linear transducer is represented with an output which is the sum of the outputs of a set of non-linear transducers with the same input. These outputs are combined with varying linear coefficients. This allows us to employ the theory of linear developments in the design and specification of the non-linear transducer. And in particular, this method allows us to obtain coefficients of the constituent elements by a least-square process. If we join this to a 1 Wiener, N., Nonlinear Problem11 in Random Theory, The Technology Press of M.I.T. and John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1958. 2. Gabor, D., "Electronic Inventions and Their Impact on Civilization," Inaugural Ledure, March 3, 1959, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London, England, ON LEARNING AND SELF-REPRODUCING MACHINES 179 method of statistically averaging over the set of all inputs to our apparatus, we have essentially a branch of the theory of orthogonal development, Such a statistical basis of the theory of non-linear transducers can be obtained from an actual study of the past statistics of the inputs used iu each particular case. This is a rough account of Professor Gabor's methods. While mine are essentially similar, the statistical basis for my work is slightly different. It is well known that electrical currents are not conducted continuously but by a stream of electrons which must have statistical variations from uniformity. These statistical fluctuations can be represented fairly by the theory of the Brownian motion, or by the similar theory of shot effect or tube noise, about which I am going to say something in the next chapter. At any rate, apparatus can be made to generate a standardized shot effect with highly specific statistical distribution, and such apparatus is being manufactured commercially. Note that tube noise is in a sense a universal input in that its fluctuations over a sufficiently long time will sooner or later approximate to any given curve. This tube noise possesses a very simple theory of integration and averaging. In terms of the statistics of tube noise, we can easily determine a closed set of normal and orthogonal non-linear operations. If the inputs subject to these operations have the statistical distribution appropriate to tube noise, the average product of the output of two component pieces of our apparatus, where this average is taken with respect to the statistical distribution of tube noise, will be zero. Moreover, the mean square output of each apparatus can be normalized to one. The result is that the development of the general non-linear transducer in terms of these components results from an application of the familiar theory of orthonormal functions. To be specific, our individual pieces of apparatus give outputs which are products of Hermite polynomials in the Laguerre coefficients of the past of the input. This is presented in detail in my Nimlinear Problems in Random Theory. It is of course difficult to average in the first instance over a set of possible inputs. What makes this difficult task realizable is that the shot-effect inputs possess the property known as metric transitivity, or the ergodic property. Any integrable function of the parameter of distribution of shot-effect inputs has in almost every instance a time average equal to its average over the ensemble. This permits us to take two pieces of apparatus with a common shot-effect input, and to determine the average of their product over the entire 180 CYBERNETICS ensemble of the possible inputs, by taking their product and averaging it over the time. The repertory of operations needed for all these processes involves nothing more than the addition of potentials, the multiplication of potentials, and the operation of averaging over time. Devices exist for all th-. As a matter of fact, the elementary devices needed in Professor Gabor's methodology are the same as those needed in mine. One of his students has invented a particularly effective and inexpensive multiplying device depending on the piezo electric effect on a crystal of the attraction of two magnetic coils. What this amounts to is that we can imitate any unknown nonlinear transducer by a sum of linear terms, each of fixed characteristics and with an adjustable coefficient. This coefficient can be determined as the average product of the outputs of the unknown transducer and a particular known transducer, when the same shoteffect generator is connected to the input of both. What is more, instead of computing this result on the scale of an instrument and then transferring it by hand to the appropriate transducer, thus producing a piecemeal simulation of the apparatus, there is no particular problem in automatically effecting the transfer of the coefficients to the pieces of feedback apparatus. What we have succeeded in doing is to make a white box which can potentially assume the characteristics of any non-linear transducer whatever, and then to draw it into the similitude of a given black-box transducer by subjecting the two to the same random input and connecting the outputs of the structures in the proper manner, so as to arrive at the suitable combination without any intervention on our part. I ask if this is philosophically very different from what is done when a gene acts as a template to form other molecules of the same gene from an indeterminate mixture of amino and nucleic acids, or when a virus guides into its own form other molecules of the same virus out of the tissues and juices of its host. I do not in the least claim that the details of these processes are the same, but I do claim that they are philosophically very similar phenomena. |

IX 学習と自己再生産する機械について 我々が生命システムの特徴として考えている二つの現象は、学習する力と自己複製する力である。これらの性質は、一見異なるように見えるが、互いに密接に関 係している。学習する動物とは、過去の環境によって別の存在に変化することができる動物であり、それゆえ、個体寿命の範囲内で環境に適応することができ る。増殖する動物は、時間の経過とともに変化することができないほど完全ではないが、少なくともおおよそは自分に似た他の動物を作り出すことができる。こ の変化自体が遺伝するのであれば、自然淘汰が働く材料ができたことになる。遺伝性の不変性が行動様式に関わるものであれば、伝播されるさまざまな行動様式 の中から、種族の存続に有利なものが見つかって定着する一方、存続に有害なものは淘汰される。その結果、ある種の人種的学習、系統的学習が、個人の発生的 学習と対比されることになる。発生学的学習も系統発生学的学習も、動物が自らを環境に適応させるための様式である。 先天性学習と系統発生的学習はともに、そして確かに後者は、すべての動物だけでなく、植物、さらにはあらゆる意味で生物とみなされるすべての生物に及んで いる。しかし、これら2つの学習形態がどの程度重要であるかは、生物の種類によって大きく異なる。人間では、そして他の哺乳類では、それほどでもないが、 169 170 CYBERNETICS 生体発生学的学習と個体適応性が最も高くなる。実際、人間の系統発生的学習の大部分は、優れた発生発生的学習の可能性を確立することに費やされてきたと言 える。 ジュリアン・ハクスリーは鳥類の心に関する基本的な論文1において、鳥類の発生的学習能力が小さいことを指摘している。昆虫の場合にも似たようなことが言 えるが、どちらの場合も、飛行によって個体に多大な要求がなされること、そしてその結果、神経系の能力が先取りされ、他の方法では発生的学習に応用される 可能性があることが関係しているのかもしれない。飛行、求愛、子供の世話、巣作りなど、鳥類の行動パターンは複雑であるが、それらは母親から大量の指導を 受けなくても、初めて正しく実行される。 本書の1章を、この2つの関連するテーマに割くことは、まったくもって適切である。この章では、人工機械は実際に学習することができ、また自己複製するこ とができることを示そうと思う。 この2つのプロセスのうち、より単純なのは学習であり、技術開発が最も進んだのはこのプロセスである。ここでは特に、ゲームプレイマシンが経験によって戦 略や戦術を向上させることを可能にする、ゲームプレイマシンの学習について述べることにする。 この理論は、ゲームの初めからではなく、ゲームの終わりから考えるのが最もよい方針に関するものである。ゲームの最後の一手で、プレイヤーは可能であれば 勝利の手を、そうでなければ少なくとも引き分けの手を打つように努力する。対戦相手はその前の段階で、相手の勝ち手や引き分け手を阻止する手を打つように 努力する。もし、その段階で勝てる手を打てればそうする。その前の手では、もう一人のプレーヤーは、相手の最高の資源が勝利の手で終わることを妨げないよ うに行動しようとする。 チクタク・トゥーのように、戦略全体がわかっているゲームもあり、そのようなゲームでは、最初からこのような方針をとることも可能である1 Huxley, J., Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, Harper Bros., New York, 1943. 2 von Neumann, J. and O. Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1944. 学習と自己再生産機械について 171 ギニング。これが実現可能であれば、ゲームをプレイする最善の方法であることは明らかである。しかし、チェスやチェッカーのような多くのゲームでは、われ われの知識はこの種の完全な戦略を可能にするほど十分ではなく、その場合、われわれはそれに近似することしかできない。フォン・ノイマン型の近似理論は、 対戦相手が完全に賢明なマスターの一種であると仮定して、プレーヤーが最大限の注意を払って行動するよう導く傾向がある。 しかし、このような態度が常に正当化されるわけではない。一種のゲームである戦争では、一般に、このような態度は優柔不断な行動につながり、敗北に等しい 結果に終わることが多い。歴史上の例を二つ挙げよう。ナポレオンがイタリアでオーストリア軍と戦ったとき、オーストリアの軍事思想が伝統的なものであり、 フランス革命の兵士たちによって開発された、決断を促す新しい戦争方式を利用することができないと考えたのは、ナポレオンの正当な判断であった。ネルソン がヨーロッパ大陸の連合艦隊と戦ったとき、彼には長年にわたって海を守り、敵ができない思考法を開発してきた海軍機械と戦うという利点があった。もしナポ レオンがこの利点を最大限に活用せず、同等の海軍経験を持つ敵が相手だと仮定して慎重に行動しなければならなかったとしたら、長期的には勝利したかもしれ ないが、ナポレオンの最終的な破滅となった堅固な海上封鎖を確立するほど迅速かつ決定的に勝利することはできなかっただろう。したがって、どちらの場合 も、完璧な相手に対して完璧なゲームをしようとするのではなく、過去の行動で統計的に示された指揮官と対戦相手の既知の記録が指針となったのである。この ようなケースでゲーム理論のフォン・ノイマンの手法を直接用いても、無駄であることがわかっただろう。 同様に、チェス理論の本も、フォン・ノイマンの視点から書かれたものではない。そして、各駒のジョス、機動力、指揮力、展開力、そしてゲームの段階によっ て変化するその他の要素に与えるべき一定の値や重み付けを定めている。 ある種のチェスをする機械を作るのはそれほど難しいことではない。ゲームの定石に従うだけで、合法的な手しか指さないようにすることは、極めて単純な計算 機の力の範囲内である。実際、普通のデジタルマシンをこのような目的に適合させることは難しくない。 172 CYBERNETICS さて、次はゲームのルールの中での方針の問題である。駒の評価、指揮、機動性など、あらゆる評価は本質的に数値に還元することが可能である。そして、これ が行われたとき、各ステージにおける最善の手を決定するために、チェスの本の格言を使用することができる。このような機械はすでに作られており、現時点で は名人の域には達していないものの、非常に公平なアマチュア・チェスをすることができる。 自分がそのような機械とチェスをする立場を想像してみよう。状況を公平にするために、あなたが対戦しているのがそのような機械であることを知らずに、また そのような知識が興奮させるかもしれない偏見を持たずに、通信対戦のチェスをプレイしていると仮定しよう。当然、チェスの常として、あなたは相手のチェス の性格を判断することになる。チェス盤上で同じ状況が二度訪れると、対戦相手の反応は毎回同じであり、非常に厳格な性格であることがわかるだろう。あなた のどんなトリックも、同じ条件下では必ず通用する。したがって、熟練者がマシンの相手を攻略し、毎回打ち負かすことはそれほど難しいことではない。 しかし、そう簡単には勝てないマシンも存在する。数ゲームごとにマシンが休みを取り、別の目的のためにその設備を使うとしよう。このとき、マシンは対戦相 手とプレイするのではなく、メモリに記録されている過去のゲームをすべて調べ、駒の価値、コマンド、機動力など、さまざまな評価のうち、どのような重み付 けが最も勝利につながるかを判断する。こうして、自分の失敗だけでなく相手の成功からも学ぶ。そして、以前の評価を新しい評価に置き換え、より優れた新し いマシンとしてプレーを続ける。そのようなマシンは、もはや厳格な人格を持たず、かつてそれに対して成功したトリックも最終的には失敗する。それ以上に、 時間の経過とともに、対戦相手の政策を吸収していくかもしれない。 このようなことはチェスでは非常に困難であり、実際、チェスの名手を生み出すようなこの技術の完全な開発は達成されていない。チェッカーはもっと簡単な問 題である。駒の価値が均質であるため、考慮すべき組み合わせの数が大幅に減る。さらに、この均質性の結果もあって、チェッカーゲームはチェスゲームよりも はるかに明確な段階に分けられにくい。チェッカーゲームでも、終盤の主な問題はもはや駒を取ることではなく、駒を取れる状態になるように敵との接触を確立 することである。同様に、チェスゲームにおける手の評価も、異なるステージごとに独立して行われなければならない。エンドゲームとミドルゲームとでは、最 も重要な考慮事項が異なるだけでなく、オープンゲー ムでは、駒を攻撃と防御のために自由に動ける状態にすることに、ミドルゲームよりもはるかに多くの労 力が費やされる。その結果、ゲーム全体に対するさまざまな重み付け要素を一律に評価するだけではおおよそ満足できず、学習プロセスをいくつかの個別の段階 に分けなければならない。そうして初めて、チェスをマスターする学習マシンを作ることができるのだ。 ある場合には線形であるかもしれない一次プログラミングと、一次プログラミングで実行される方針の決定のために過去のより広範な部分を使用する二次プログ ラミングを組み合わせるという考え方は、本書で予測問題に関連して先に述べた。しかし、正しい線形演算を決定することは統計的な問題であり、その統計の基 礎となるのは、飛行の長い過去と多くの類似した飛行の過去である。 短い過去を考慮して採用すべき方針を決定するために長い過去を使用するために必要な統計的研究は、非常に非線形である。実際、Wiener-Hopf方程 式を予測に用いる場合、この方程式の係数の決定は非線形で行われる。一般に、学習機械は非線形フィードバックによって動作する。サミュエル2世と渡辺に よって説明されたチェッカーをする機械は、IOから20時間のプログラミングに基づいて、かなり一貫した方法でそれをプログラムした人間を打ち負かすこと を学習することができる。 プログラミングマシンの使用に関する渡辺の哲学的考えは非常に刺激的である。一方では、エレガンスと単純さのある基準に従って最適な方法で初歩的な幾何学 定理を証明する方法を、個人相手ではなく、"ボギー大佐 "とでも呼ぶべき相手と対戦する学習ゲームとして扱っている。同様のもの 1 Wiener, N., Extrapokuion, Interpolation, and Smoothing of Stationary Time Series with Engineering Applications, The Technology Press of M.I.T. and John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1949. 2 Samuel, A. L., '' Some Studies in Machine Learning, Using the Game of Checkers,'' IBM Journal of Research and Developmeflt, 3, 210-229 (1959). 3 渡辺誠一、「多変量相関の情報理論的解析」、IBM 研究開発ジャーナル、66-82 (1960). 174 CYBERNETICS 渡辺が研究しているゲームは、論理的帰納法において、経済性、直接性などの評価に基づいて、自由にしておく有限個のパラメータの評価の決定によって、同様 の準~美学的な方法で最適な理論を構築しようとするときに行われる。これは確かに、限定的な論理的帰納法にすぎないが、研究する価値は十分にある。 闘争という活動の多くの形態は、通常ゲームとは見なされないが、ゲーム機の理論によって多くの光が投げかけられる。興味深い例のひとつが、マングースとヘ ビの戦いである。キップリングが「リッキ・チッキ・タビ」で指摘しているように、マングースはコブラの毒に免疫がない。しかし、硬い毛で覆われているた め、ヘビが家に噛みつくのをある程度は防いでいる。キップリングが言うように、戦いは死とのダンスであり、筋肉の技と敏捷性の闘いである。マングースの個 々の動作がコブラのそれよりも速く、正確だと考える理由はない。しかし、マングースはほとんど必ずコブラを殺し、無傷で競技を終える。なぜそんなことがで きるのか? 私はこのような戦いを見たことがあり、また他の戦いの動画も見たことがある。私の観察が解釈として正しいことを保証するものではない。マングースがフェイ ントをかけ、ヘビを挑発する。マングースはフェイントをかわし、またフェイントをかける。しかし、このダンスは静的なものではなく、徐々に発展していく。 コブラのダーツに対してマングースのフェイントの位相がだんだん早くなり、ついにはコブラが伸びて素早く動ける状態にないときにマングースが攻撃する。こ のときのマングースの攻撃はフェイントではなく、コブラの脳を貫く致命的な正確さである。 言い換えれば、ヘビの行動パターンは、一発一発のダーツに限られているのに対し、マングースの行動パターンは、非常に長いとは言えないまでも、過去の戦い 全体のかなりの部分を含んでいる。マングースは学習機械のように行動し、その攻撃の真の殺傷力は、より高度に組織化された神経系に依存している。 数年前のウォルト・ディズニーの映画で紹介されたように、西洋の鳥の一種であるロードランナーがガラガラヘビを攻撃するときにも、よく似たことが起こる。 鳥はくちばしと爪で、マングースは歯で戦うが、活動のパターンは非常によく似ている。闘牛もこれとよく似ている。闘牛はスポーツではなく、死とのダンスで あることを忘れてはならない。闘牛に対する公平性は、この競技には全く関係なく、私たちの観点からは、闘牛を煽ったり弱らせたりする予備的な行為は省くこ とができる。熟練した闘牛士は、闘牛士がエストークを闘牛の心臓に突き刺そうとする瞬間に、闘牛が突進を終えて伸びるような体勢に持ち込むことを目的とし た、マントの誇示、様々なかわしやピルエットなど、可能な動作の多くのレパートリーを持っている。 マングースとコブラの戦い、あるいはトレドールと雄牛の戦いについて述べたことは、人間と人間の肉体的な戦いにも当てはまる。小剣を使った決闘を考えてみ よう。フェイント、パリー、スラストの連続で構成され、それぞれの参加者は、相手の剣を一直線からずらし、二度打ちにならないようにスラストを繰り出すこ とを意図する。テニスのチャンピオン・ゲームでは、個々のストロークを考慮する限り、完璧なサーブやリターンをするだけでは不十分である。 このような物理的な試合と、ゲームマシンがプレーすると仮定した種類のゲームは、どちらも相手の癖や自分の癖を経験するという点で同じ学習要素を持ってい る。物理的な出会いのゲームに当てはまることは、戦争や戦争を模擬したゲームのような、知的要素がより強い競争にも当てはまる。このことは、陸上でも海上 でも古典的な戦争に言えることであり、原子兵器を使った新しい、まだ試されていない戦争にも同様に言えることである。学習機械によるチェッカーの機械化に 匹敵するある程度の機械化は、これらすべてにおいて可能である。 第三次世界大戦ほど危険なものはない。その危険の一端が、学習マシンの無防備な使用に内在しているのではないかということは、考えてみる価値がある。学習 機械は、その気になればスイッチを切ることができるのだから、新たな危険にさらされることはない、という言葉を何度も何度も耳にした。しかし、そうだろう か?効果的にマシンのスイッチを切るには、危険なポイントが来たかどうかの情報を持っていなければならない。マシンを作ったという事実だけでは、そのため の適切な情報を持っているという保証は176 CYBERNETICSにはない。このことは、チェッカー・プレイング・マシンが、それをプログラムした人間を打ち負かすことができ、しかもそれは非常に 限られた時間しか作動させなかった後のことである、という記述にすでに暗示されている。さらに、現代のデジタル・マシンの動作速度そのものが、危険の兆候 を察知し、考え抜く私たちの能力の邪魔をする。 政策を遂行する大きな力と大きな能力を持った人間以外の装置、そしてその危険性についての考え方は、何も新しいものではない。新しいのは、私たちがこの種 の効果的な装置を持っているということだけである。過去には、多くの伝説や民話のテーマとなっている魔法の技術についても、同様の可能性が仮定されてい た。これらの物語は、魔法使いの道徳的状況を徹底的に追求してきた。私はすでに、『人間の人間利用』と題された以前の著書で、魔術の伝説的倫理観のいくつ かの側面について論じている。 最もよく知られた魔法物語のひとつに、ゲーテの『魔法使いの弟子』がある。この物語では、魔術師が弟子とファクトタムだけに水汲みの仕事をさせる。少年は 怠け者で独創的なので、師匠から聞いた魔法の言葉を口にした箒に仕事を引き継ぐ。箒は喜んで仕事をし、なかなか止まらない。少年はかき消されそうになる。 少年は、ほうきを止める2つ目の呪文を覚えていないか、忘れていることに気づく。絶望の淵に立たされた少年は、箒を手に取り、膝の上で折ってみる。幸運な ことに、完全に破壊される前に師匠が戻ってきて、ほうきを止めるための「力の言葉」を唱え、弟子を叱り飛ばした。 もう一つの話は、アラビアンナイトの漁師と精霊の話である。漁師は、ソロモンの印章で閉ざされた水差しを網で浚った。それはソロモンが反抗的な精霊を幽閉 していた容器のひとつである。精霊は煙を上げて現れ、その巨大な姿は漁師に、幽閉されていた最初の数年間は権力と富で救い主に報いようと決心していたが、 今は手放しで殺すことに決めたと告げる。幸運なことに、漁師は精霊を説得して瓶に戻す方法を見つけ、その瓶を海の底に投げ捨てる。学習と自己再生マシンに ついて 177 この2つの物語のどちらよりも恐ろしいのは、世紀初めのイギリス人作家、W・W・ジェイコブスが書いた「猿の前足の寓話」である。引退した英国人労働者 が、妻と友人のインド帰りの英国人軍曹と食卓を囲んでいる。少佐は、干からびた猿の足の形をしたお守りを見せる。これは、運命に逆らうことの愚かさを示す ためにインドの聖人が授けたもので、3人の人間にそれぞれ3つの願いを叶える力があるという。兵士は、最初の持ち主の最初の2つの願いについては何も知ら ないが、最後の願いは死を願ったものだと言う。兵士は、最初の持ち主の最初の2つの願いについては何も知らないが、最後の願いは死を願ったものだと言う。 兵士自身は2番目の持ち主であったが、自分の体験の恐ろしさについては語ろうとしなかった。彼は前足を火の中に投げ入れたが、友人がそれを取り戻し、その 力を試したいと願う。彼の最初の報酬は200ポンド。その直後、ドアをノックする音がして、息子の勤める会社の役人が部屋に入ってくる。父親は、息子は機 械に巻き込まれて死亡したが、会社は責任も法的義務も認めず、慰謝料として200ポンドを父親に支払うことを希望していることを知る。悲しみに打ちひしが れる父親は、息子が戻ってくるようにという2つ目の願い事をする。最後の願いは、この幽霊が立ち去ることである。 これらすべての物語で重要なのは、魔術の代理人は文字通りの心の持ち主であり、魔術の代理人に恩恵を求めるなら、本当に欲しいものを求めるのであって、自 分が欲しいと思っているものを求めるのではないということである。学習マシンの新しい本物の機関もまた、文字通りの心を持つ。戦争に勝つためにマシンをプ ログラムするのであれば、勝利とは何を意味するのかをよく考えなければならない。学習機械は経験によってプログラムされなければならない。ただちに破滅的 な事態に至らない核戦争の唯一の経験は、戦争ゲームの経験である。この経験を実際の緊急事態における私たちの手順の指針として使うのであれば、私たちがプ ログラミングゲームで採用した勝利の価値観は、実際の戦争の結果において私たちが心に抱く価値観と同じでなければならない。私たちがこのことに失敗するの は、ただちに、完全に、そして取り返しのつかない危険と隣り合わせのときだけである。私たちが勝利という名の破壊を可能にするような偏見や感情的妥協に、 機械が私たちに従ってくれることを期待することはできない。もし我々が勝利を求め、それが何を意味するのかを知らなければ、亡霊が我々のドアをノックして いるのを見つけるだろう。 機械を学ぶのはここまでだ。次に、自己増殖型マシンについて一言二言言わせてほしい。ここで、機械と自己増殖という言葉の両方が重要である。マシンは 178のサイバネティクス物質の一形態であるだけでなく、ある明確な目的を達成するための機関でもある。そして自己増殖とは、単に目に見えるレプリカを作 ることではなく、同じ機能を持つレプリカを作ることである。 ここで、2つの異なる視点が証拠となる。そのひとつは純粋に組み合わせ論的なもので、機械が自己増殖をその機能のひとつとするのに十分な部品と十分に複雑 な構造を持ちうるかどうかという問題である。この疑問には、故ジョン・フォン・ノイマンが肯定的な答えを出している。もう一つの疑問は、自己再生機械を作 るための実際の操作手順に関するものである。ここでは、すべての機械を包含するわけではないが、非常に一般的な機械のクラスに注意を向けることにする。そ れは非線形変換器である。 このような機械は、入力に時間の関数を持ち、出力に別の時間の関数を持つ装置である。出力は入力の過去によって完全に決定されるが、一般に、入力を足して も対応する出力は追加されない。このような装置は変換器として知られている。線形であれ非線形であれ、すべての変換器の特性のひとつは、時間の変換に対す る不変性である。ある機械がある機能を実行する場合、入力が時間的に後ろにずれると、出力も同じだけ後ろにずれる。 われわれの自己再生機械の理論の基本は、非線形変換器の表現の正準形である。ここでは、線形装置の理論に不可欠なインピーダンスとアドミタン スの概念は、完全には適切ではない。この表現を行うには、ある新しい方法を参照しなければならない。それは、私1 とロンドン大学のデニス・ガボール教授によって開発された方法である。 ガボール教授の手法も私の手法も、非線形トランスデューサーの構築につながるが、非線形トランスデューサーの出力が、同じ入力を持つ一連の非線形トランス デューサーの出力の和であるという点では線形である。これらの出力は、線形係数を変化させながら組み合わされる。これにより、非線形変換器の設計と仕様に 線形開発の理論を採用することができます。そして特に、この方法によって、最小二乗法によって構成要素の係数を求めることができる。これを、1 Wiener, N., Nonlinear Problem11 in Random Theory, The Technology Press of M.I.T. and John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2. Gabor, D., "Electronic Inventions and Their Impact on Civilization," Inaugural Ledure, March 3, 1959, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London, England, ON LEARNING AND SELF-REPRODUCING MACHINES 179 私たちの装置へのすべての入力の集合を統計的に平均化する方法は、本質的に直交発展の理論の一分 野をなしている。このような非線形変換器の理論の統計的基礎は、各特定のケースで使用される入力の過去の 統計の実際の研究から得ることができる。 これはガボール教授の方法を大まかに説明したものである。私のやり方も基本的には同じようなものだが、統計的な根拠は少し異なっている。 電流は連続的に伝導されるのではなく、電子の流れによって伝導されることはよく知られている。このような統計的変動は、ブラウン運動の理論や、ショット効 果やチューブノイズの理論によって適切に表現することができる。いずれにせよ、非常に特殊な統計分布を持つ標準化されたショット効果を発生させる装置を作 ることができ、そのような装置は商業的に製造されている。真空管ノイズは、十分に長い時間にわたるその変動が、遅かれ早かれ任意の曲線に近似するという点 で、ある意味で普遍的な入力であることに注意されたい。この真空管ノイズは、積分と平均化という非常に単純な理論を持っている。 真空管ノイズの統計の観点からは、正規および直交非線形演算の閉集合を容易に決定することができる。これらの演算の対象となる入力が真空管ノイズに適した 統計分布を持つ場合、我々の装置の2つの構成要素の出力の平均積は、この平均が真空管ノイズの統計分布に関して取られる場合、ゼロになる。さらに、各装置 の二乗平均出力は1に正規化できる。その結果、一般的な非線形変換器をこれらの構成要素から発展させることは、おなじみの正規直交関数の理論を応用するこ とになる。 具体的には、個々の装置は、入力の過去のラグエル係数のエルミート多項式の積である出力を与える。これについては、私の『ランダム理論における非線形問 題』に詳しく述べられている。 可能性のある入力の集合を平均化することはもちろん難しい。この困難な作業を実現可能にしているのは、ショット効果入力が計量的推移性(エルゴード特性) として知られる性質を持っているからである。ショット効果入力の分布パラメータの任意の可積分関数は、ほとんどすべてのインスタンスにおいて、アンサンブ ル上の平均に等しい時間平均を持つ。これにより、共通のショット効果入力を持つ2つの装置を取り上げ、それらの積を取り、時間平均することで、180 CYBERNETICSの可能な入力のアンサンブル全体にわたるそれらの積の平均を決定することができる。これらすべてのプロセスに必要な操作のレパート リーは、ポテンシャルの加算、ポテンシャルの乗算、および時間の平均化操作にほかならない。これらすべてに対応する装置が存在する。実のところ、ガボール 教授の方法論で必要とされる初歩的な装置は、私の方法論で必要とされるものと同じである。ガボール教授の教え子の一人は、2つの磁気コイルの引力が水晶に 与えるピエゾ電気効果によって、特に効果的で安価な逓倍装置を発明した。 つまり、どんな未知の非線形変換器でも、それぞれが固定された特性を持ち、調整可能な係数を持つ線形項の和によって模倣できるということだ。この係数は、 未知のトランスデューサーの出力と、既知のトランスデューサーの出力の平均積として求めることができる。さらに、この結果を計器のスケールで計算し、それ を適切なトランスデューサーに手作業で転送して、装置の断片的なシミュレーションを行う代わりに、フィードバック装置の断片に係数を自動的に転送すること に特に問題はない。私たちが成功したのは、あらゆる非線形変換器の特性を潜在的に持ちうるホワイトボックスを作り、その2つを同じランダムな入力にさら し、適切な方法で構造体の出力を接続することで、与えられたブラックボックスの変換器の類似性に引き込むことである。 これは、遺伝子が鋳型として働き、アミノ酸と核酸の不確定な混合物から同じ遺伝子の他の分子を形成する場合や、ウイルスが宿主の組織や液汁から同じウイル スの他の分子をそれ自身の形に誘導する場合と、哲学的に大きく異なるのではないか、と私は問う。私は、これらのプロセスの詳細が同じであると主張するつも りは毛頭ないが、哲学的には非常に類似した現象であると主張する。 |

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The Human Use of Human

Beings: Cybanetics and Society, 1950, 1954 -->

https://monoskop.org/images/5/51/Wiener_Norbert_The_Human_Use_of_Human_Beings.pdf

Index

"The development of

these computing machines has

been very rapid since the war. For a large range of

computational work, they have shown themselves

much faster and more accurate than the human computer. Their speed has

long since reached such a level

that any intermediate human intervention in their work

is out of the question. Thus they offer the same need to

replace human capacities by machine capacities as

those which we found in the anti-aircraft computer.

The parts of the machine must speak to one another

through an appropriate language, without speaking to

any person or listening to any person, except in the

terminal and initial stages of the process. Here again we

have an element which has contributed to the general

acceptance of the extension to machines of the idea

of communication. " (Weiner 1950: 151).

++

●Steve Joshua Heim, The

Cybernetics Group. MIT Press, 1991.

+++

リンク集

文献

その他の情報

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!