ノーバート・ウィーナー

Norbert

Wiener, 1894-1964

解説:池田光穂

◎「神々を生み出す機械(マシーン)」それは宇宙——アンリ・ベルクソン(Henri- Louis Bergson, 1859-1941)[「サイバネティクス:動物とマシーンにおける制御とコミュニケーション」よりスピンオフ・ プロジェクトです]

★サイバネティクス(cybernetics)

は、制御システムおよび目的 システムに関する広範な研究分野である。

サイバネティックスの核となる概念は、循環的因果関係またはフィードバックであり、そこでは、特定の状態の追求と維持、またはその崩壊を支援する方法で、

行動の観察結果がさらなる行動のための入力として取り込まれる。サイバネティクスは、循環的な因果関係の例である船の操舵にちなんで名付けられた。操舵者

(サイバーノーツ)は、それがもたらすと観察される効果に絶えず応答して操舵を調整することにより、変化する環境の中で安定したコースを維持する。循環的

な因果関係フィードバックの他の例としては、サーモスタットなどの技術的装置(ヒーターの動作が温度の測定変化に反応し、部屋の温度を設定範囲内に調節す

る)、神経系を介した自発的な運動の調整などの生物学的例、会話などの社会的相互作用のプロセスなどが挙げられる。サイバネティクスは、生態系、技術系、

生物系、認知系、社会系など、どのような形であれ、また設計、学習、管理、会話、そしてサイバネティクスそのものの実践といった実践活動の中で、操舵術と

してのフィードバックプロセスに関心を寄せている。サイバネティクスは学際的あるいはトランスディシプリナリー的で「反領域的

(ntidisciplinary)」であるため、他の多くの分野と交差し、広い影響力と多様な解釈を持つに至っている。

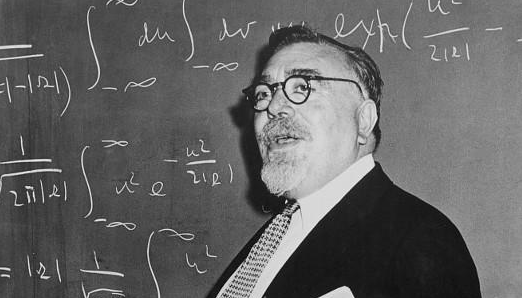

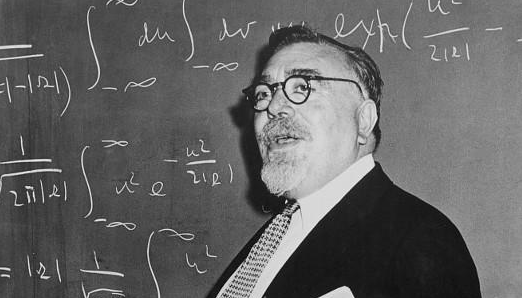

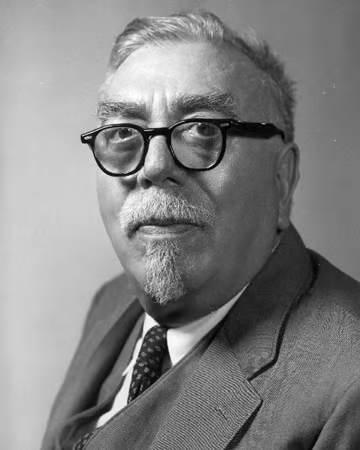

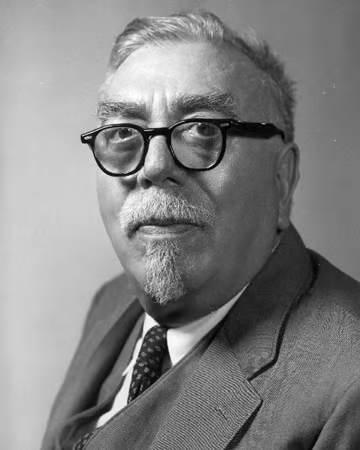

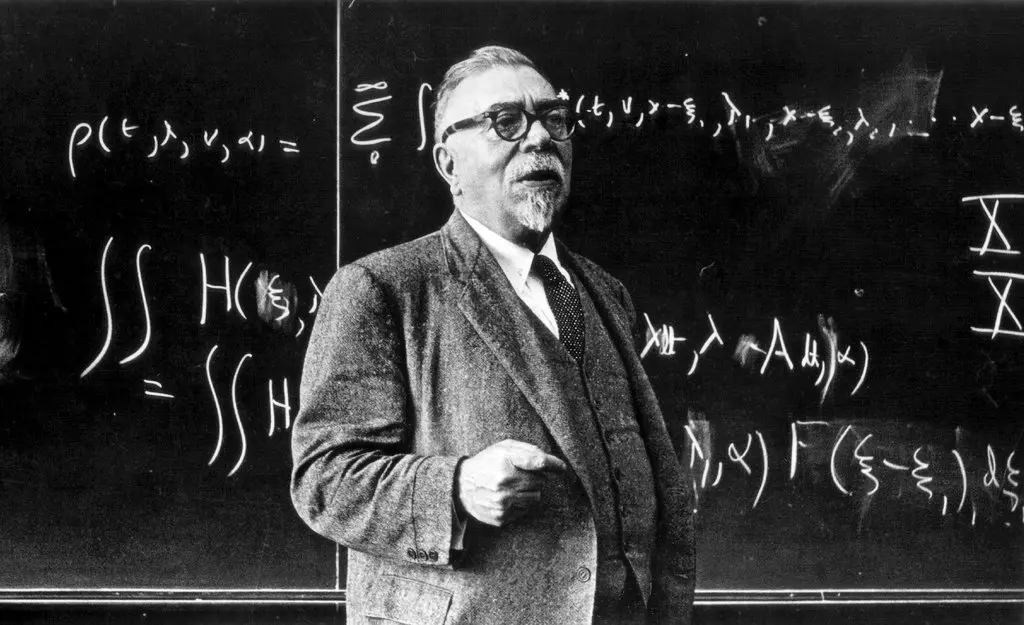

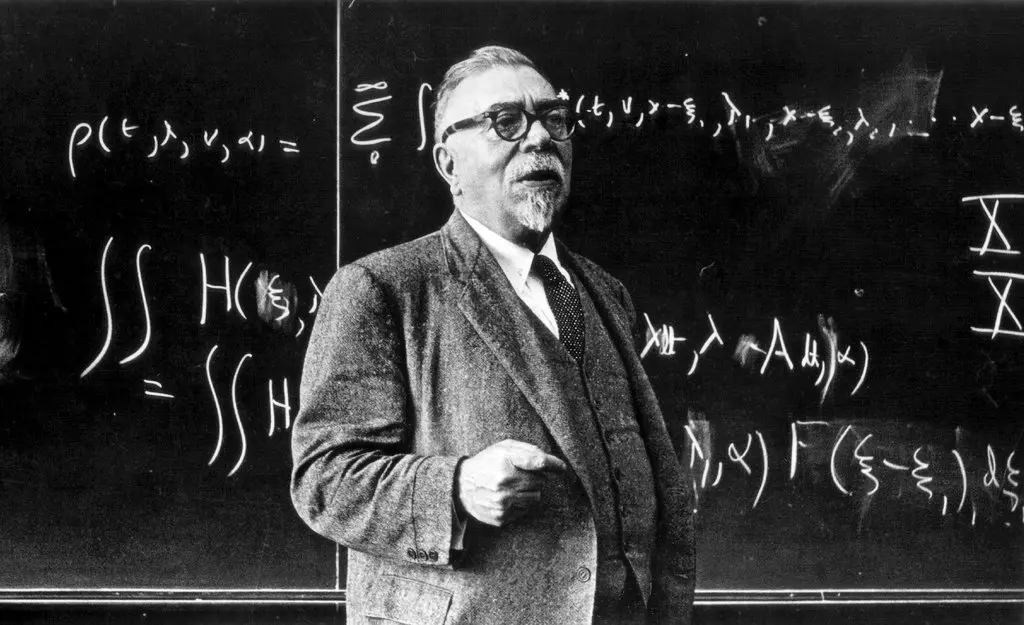

Norbert Wiener

(November 26, 1894 – March 18, 1964) was an American computer

scientist, mathematician and philosopher. He became a professor of

mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). A child

prodigy, Wiener later became an early researcher in stochastic and

mathematical noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic

engineering, electronic communication, and control systems. Norbert Wiener

(November 26, 1894 – March 18, 1964) was an American computer

scientist, mathematician and philosopher. He became a professor of

mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). A child

prodigy, Wiener later became an early researcher in stochastic and

mathematical noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic

engineering, electronic communication, and control systems.Wiener is considered the originator[4] of cybernetics, the science of communication as it relates to living things and machines,[5] After much consideration, we have come to the conclusion that all the existing terminology has too heavy a bias to one side or another to serve the future development of the field as well as it should; and as happens so often to scientists, we have been forced to coin at least one artificial neo-Greek expression to fill the gap. We have decided to call the entire field of control and communication theory, whether in the machine or in the animal, by the name Cybernetics, which we form from the Greek κυβερνήτης or steersman. with implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, neuroscience, philosophy, and the organization of society. His work heavily influenced computer pioneer John von Neumann, information theorist Claude Shannon, anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and others. Norbert Wiener is credited as being one of the first to theorize that all intelligent behavior was the result of feedback mechanisms, that could possibly be simulated by machines and was an important early step towards the development of modern artificial intelligence.[6] |

ノー

バート・ウィーナー(Norbert Wiener、1894年11月26日 -

1964年3月18日)は、アメリカのコンピュータ科学者、数学者、哲学者。マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の数学教授となる。神童であったウィー

ナーは、後に確率論的・数学的ノイズ過程の初期の研究者となり、電子工学、電子通信、制御システムに関連する研究に貢献した。 ノー

バート・ウィーナー(Norbert Wiener、1894年11月26日 -

1964年3月18日)は、アメリカのコンピュータ科学者、数学者、哲学者。マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の数学教授となる。神童であったウィー

ナーは、後に確率論的・数学的ノイズ過程の初期の研究者となり、電子工学、電子通信、制御システムに関連する研究に貢献した。ウィーナーは、生物と機械に関連するコミュニケーションの科学であるサイバネティックスの創始者[4]と考えられている[5]。 そして、科学者にはよくあることだが、そのギャップを埋めるために、少なくとも1つの人工的な新ギリシャ語の表現を作らざるを得なくなった。私たちは、機 械であれ動物であれ、制御とコミュニケーションの理論分野全体を、ギリシャ語のκυβερνήτης(操舵手)に由来するサイバネティクスと呼ぶことにし た。 工学、システム制御、コンピュータ科学、生物学、神経科学、哲学、社会組織などに影響を与えた。彼の研究は、コンピュータのパイオニアであるジョン・フォ ン・ノイマン、情報理論家のクロード・シャノン、人類学者のマーガレット・ミードやグレゴリー・ベイトソンなどに多大な影響を与えた。 ノルベルト・ウィーナーは、すべての知的行動はフィードバック・メカニズムの結果であり、それは機械によってシミュレートされる可能性があり、現代の人工 知能の発展への重要な初期段階であったことを理論化した最初の一人であると信じられている[6]。 |

| Biography Youth Wiener was born in Columbia, Missouri, the first child of Leo Wiener and Bertha Kahn, Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Germany, respectively. Through his father, he was related to Maimonides, the famous rabbi, philosopher and physician from Al Andalus, as well as to Akiva Eger, chief rabbi of Posen from 1815 to 1837.[7]: p. 4 Leo had educated Norbert at home until 1903, employing teaching methods of his own invention, except for a brief interlude when Norbert was 7 years of age. Earning his living teaching German and Slavic languages, Leo read widely and accumulated a personal library from which the young Norbert benefited greatly. Leo also had ample ability in mathematics and tutored his son in the subject until he left home. In his autobiography, Norbert described his father as calm and patient, unless he (Norbert) failed to give a correct answer, at which his father would lose his temper. In “The Theory of Ignorance”, a paper he wrote at the age of 10, he disputed “man’s presumption in declaring that his knowledge has no limits”, arguing that all human knowledge “is based on an approximation”, and acknowledging “the impossibility of being certain of anything.”[8] He graduated from Ayer High School in 1906 at 11 years of age, and Wiener then entered Tufts College. He was awarded a BA in mathematics in 1909 at the age of 14, whereupon he began graduate studies of zoology at Harvard. In 1910 he transferred to Cornell to study philosophy. He graduated in 1911 at 17 years of age.[9] Harvard and World War I The next year he returned to Harvard, while still continuing his philosophical studies. Back at Harvard, Wiener became influenced by Edward Vermilye Huntington, whose mathematical interests ranged from axiomatic foundations to engineering problems. Harvard awarded Wiener a PhD in June 1913, when he was only 19 years old, for a dissertation on mathematical logic (a comparison of the work of Ernst Schröder with that of Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell), supervised by Karl Schmidt, the essential results of which were published as Wiener (1914). He was one of the youngest to achieve such a feat. In that dissertation, he was the first to state publicly that ordered pairs can be defined in terms of elementary set theory. Hence relations can be defined by set theory, thus the theory of relations does not require any axioms or primitive notions distinct from those of set theory. In 1921, Kazimierz Kuratowski proposed a simplification of Wiener's definition of ordered pairs, and that simplification has been in common use ever since. It is (x, y) = {{x}, {x, y}}. In 1914, Wiener traveled to Europe, to be taught by Bertrand Russell and G. H. Hardy at Cambridge University, and by David Hilbert and Edmund Landau at the University of Göttingen. At Göttingen he also attended three courses with Edmund Husserl "one on Kant's ethical writings, one on the principles of Ethics, and the seminary on Phenomenology." (Letter to Russell, c. June or July, 1914). During 1915–16, he taught philosophy at Harvard, then was an engineer for General Electric and wrote for the Encyclopedia Americana. Wiener was briefly a journalist for the Boston Herald, where he wrote a feature story on the poor labor conditions for mill workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, but he was fired soon afterwards for his reluctance to write favorable articles about a politician the newspaper's owners sought to promote.[10] Although Wiener eventually became a staunch pacifist, he eagerly contributed to the war effort in World War I. In 1916, with America's entry into the war drawing closer, Wiener attended a training camp for potential military officers but failed to earn a commission. One year later Wiener again tried to join the military, but the government again rejected him due to his poor eyesight. In the summer of 1918, Oswald Veblen invited Wiener to work on ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.[11] Living and working with other mathematicians strengthened his interest in mathematics. However, Wiener was still eager to serve in uniform and decided to make one more attempt to enlist, this time as a common soldier. Wiener wrote in a letter to his parents, "I should consider myself a pretty cheap kind of a swine if I were willing to be an officer but unwilling to be a soldier."[12] This time the army accepted Wiener into its ranks and assigned him, by coincidence, to a unit stationed at Aberdeen, Maryland. World War I ended just days after Wiener's return to Aberdeen and Wiener was discharged from the military in February 1919.[13] |

バイオグラフィー 青年期 ウィーナーは、ミズーリ州コロンビアで、リトアニアとドイツからそれぞれ移住してきたユダヤ人、レオ・ウィーナーとベルタ・カーンの第一子として生まれ た。父親を通じて、アル・アンダルス出身の有名なラビ、哲学者、医師であるマイモニデスや、1815年から1837年までポーゼンの主任ラビであったアキ ヴァ・エガーと親戚関係にあった[7]: p. 4。 レオは1903年までノルベルトを自宅で教育し、ノルベルトが7歳のときの一時期を除いては、自分で考案した教授法を用いていた。ドイツ語とスラブ語を教 えて生計を立てていたレオは、広く読書をし、個人的な蔵書を蓄えた。レオは数学の能力も十分で、息子が家を出るまで家庭教師をした。ノルベルトは自伝の中 で、父親は冷静で忍耐強く、自分(ノルベルト)が正しい答えを出せなければ、父親はキレてしまう、と述べている。 10歳のときに書いた論文『無知の理論』では、「自分の知識には限界がないと宣言する人間の思い込み」に異論を唱え、人間の知識はすべて「近似に基づいて いる」と主張し、「何事にも確信を持つことは不可能である」と認めている[8]。 1906年、11歳でエア高校を卒業し、タフツ大学に入学。1909年、14歳で数学の学士号を取得し、ハーバード大学大学院で動物学の研究を始めた。 1910年、コーネル大学で哲学を学ぶ。1911年、17歳で卒業。 ハーバード大学と第一次世界大戦 翌年、哲学の勉強を続けながらハーバード大学に戻る。ハーバード大学に戻ったウィーナーは、エドワード・バーミリー・ハンティントンの影響を受けるように なり、彼の数学的関心は公理的基礎から工学的問題まで多岐にわたった。ハーバード大学では、カール・シュミットの指導のもと、数理論理学に関する論文(エ ルンスト・シュレーダーとアルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドおよびバートランド・ラッセルの研究との比較)により、1913年6月、若干19歳で博士 号を授与された。彼はこのような偉業を成し遂げた最も若い人物の一人であった。その学位論文の中で彼は、順序対が初等集合論の観点から定義できることを初 めて公にした。したがって、関係は集合論によって定義することができ、関係の理論には集合論とは異なる公理や原始的な概念は必要ない。1921年、カジミ エシュ・クラトフスキ(Kazimierz Kuratowski)は、ウィーナー(Wiener)の順序対の定義を単純化したものを提案した。それは(x, y) = {{x}, {x, y}}である。 1914年、ウィーナーはヨーロッパに渡り、ケンブリッジ大学ではバートランド・ラッセルとG.H.ハーディから、ゲッティンゲン大学ではデイヴィッド・ ヒルベルトとエドモンド・ランダウから教えを受けた。ゲッティンゲンでは、エドムント・フッサールの「カントの倫理書、倫理学の原理、現象学の神学校」の 3つのコースにも出席した。(ラッセルへの手紙、1914年6月か7月頃)。1915年から16年にかけて、彼はハーバード大学で哲学を教えた後、ゼネラ ル・エレクトリック社のエンジニアとなり、『エンサイクロペディア・アメリカーナ』に寄稿した。ウィンナーは一時ボストン・ヘラルド紙の記者となり、マサ チューセッツ州ローレンスの工場労働者の劣悪な労働環境について特集記事を書いたが、新聞社のオーナーが宣伝しようとした政治家について好意的な記事を書 くのを嫌がったため、すぐに解雇された[10]。 1916年、アメリカの参戦が間近に迫る中、ウィーナーは将校候補の訓練キャンプに参加したが、将校になることはできなかった。その1年後、ウィーナーは 再び軍に入隊しようとしたが、視力が悪かったため、政府は再び彼を拒否した。1918年の夏、オズワルド・ヴェブレンはウィーナーをメリーランド州のアバ ディーン実験場で弾道学の研究に招いた[11]。しかし、ウィーナーはまだ軍服で奉仕することを熱望しており、もう一度入隊を試みることにした。ウィー ナーは両親に宛てた手紙の中で、「将校になる気はあっても兵士になる気がないのなら、自分はかなり安っぽい種類の豚だと思うべきだろう」と書いている [12] 。第一次世界大戦はウィーナーがアバディーンに戻った数日後に終結し、ウィーナーは1919年2月に除隊した[13]。 |

After the war Norbert Wiener was regarded as a semi-legendary figure at MIT.  Norbert (standing) and Margaret Wiener (sitting) at the International Congress of Mathematicians, Zurich 1932 Wiener was unable to secure a permanent position at Harvard, a situation he attributed largely to anti-Semitism at the university and in particular the antipathy of Harvard mathematician G. D. Birkhoff.[14] He was also rejected for a position at the University of Melbourne. At W. F. Osgood's suggestion, Wiener was hired as an instructor of mathematics at MIT, where, after his promotion to professor, he spent the remainder of his career. For many years his photograph was prominently displayed in the Infinite Corridor and often used in giving directions, but as of 2017, it has been removed.[15] In 1926, Wiener returned to Europe as a Guggenheim scholar. He spent most of his time at Göttingen and with Hardy at Cambridge, working on Brownian motion, the Fourier integral, Dirichlet's problem, harmonic analysis, and the Tauberian theorems. In 1926, Wiener's parents arranged his marriage to a German immigrant, Margaret Engemann; they had two daughters. His sister, Constance (1898–1973), married mathematician Philip Franklin. Their daughter, Janet, Wiener's niece, married mathematician Václav E. Beneš.[16] Norbert Wiener's sister, Bertha (1902–1995), married the botanist Carroll William Dodge. Many tales, perhaps apocryphal, were told of Norbert Wiener at MIT, especially concerning his absent-mindedness. It was said that he returned home once to find his house empty. He inquired of a neighborhood girl the reason, and she said that the family had moved elsewhere that day. He thanked her for the information and she replied, "That's why I stayed behind, Daddy!"[17] Asked about the story, Wiener's daughter reportedly asserted that "he never forgot who his children were! The rest of it, however, was pretty close to what actually happened…"[18] In the run-up to World War II (1939–45) Wiener became a member of the China Aid Society and the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars.[19] He was interested in placing scholars such as Yuk-Wing Lee and Antoni Zygmund who had lost their positions.[20] During and after World War II During World War II, his work on the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns caused Wiener to investigate information theory independently of Claude Shannon and to invent the Wiener filter. (To him is due the now standard practice of modeling an information source as a random process—in other words, as a variety of noise.) Initially his anti-aircraft work led him to write, with Arturo Rosenblueth and Julian Bigelow the 1943 article 'Behavior, Purpose and Teleology', which was published in Philosophy of Science. Subsequently his anti-aircraft work led him to formulate cybernetics.[21][22] After the war, his fame helped MIT to recruit a research team in cognitive science, composed of researchers in neuropsychology and the mathematics and biophysics of the nervous system, including Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts. These men later made pioneering contributions to computer science and artificial intelligence. Soon after the group was formed, Wiener suddenly ended all contact with its members, mystifying his colleagues. This emotionally traumatized Pitts, and led to his career decline. In their biography of Wiener, Conway and Siegelman suggest that Wiener's wife Margaret, who detested McCulloch's bohemian lifestyle, engineered the breach.[23] Wiener later helped develop the theories of cybernetics, robotics, computer control, and automation. He discussed the modeling of neurons with John von Neumann, and in a letter from November 1946 von Neumann presented his thoughts in advance of a meeting with Wiener.[24] Wiener always shared his theories and findings with other researchers, and credited the contributions of others. These included Soviet researchers and their findings. Wiener's acquaintance with them caused him to be regarded with suspicion during the Cold War. He was a strong advocate of automation to improve the standard of living, and to end economic underdevelopment. His ideas became influential in India, whose government he advised during the 1950s. After the war, Wiener became increasingly concerned with what he believed was political interference with scientific research, and the militarization of science. His article "A Scientist Rebels" from the January 1947 issue of The Atlantic Monthly[25] urged scientists to consider the ethical implications of their work. After the war, he refused to accept any government funding or to work on military projects. The way Wiener's beliefs concerning nuclear weapons and the Cold War contrasted with those of von Neumann is the major theme of the book John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener.[26] Wiener was a participant of the Macy conferences. |

戦後 ノーバート・ウィーナーは、MITでは準伝説的存在とみなされていた。  1932年、チューリッヒの国際数学者会議でのノーバート・ウィーナー(立位)とマーガレット・ウィーナー(座位)。 ウィーナーはハーバード大学で定職を得ることができなかったが、その主な原因は同大学の反ユダヤ主義、特にハーバード大学の数学者G.D.バーコフの反感 にあった[14]。W.F.オスグッドの提案で、ウィーナーはマサチューセッツ工科大学の数学講師として採用され、教授に昇進した後、残りのキャリアをそ こで過ごした。長年、彼の写真は無限回廊の目立つところに飾られ、案内をする際によく使われていたが、2017年現在、撤去されている[15]。 1926年、ウィーナーはグッゲンハイムの奨学生としてヨーロッパに戻る。彼はゲッティンゲンとケンブリッジのハーディでほとんどの時間を過ごし、ブラウ ン運動、フーリエ積分、ディリクレの問題、調和解析、タウバーの定理に取り組んだ。 1926年、ウィーナーの両親はドイツ移民のマーガレット・エンゲマンとの結婚を斡旋した。姉のコンスタンス(1898-1973)は数学者のフィリッ プ・フランクリンと結婚。娘のジャネット(ウィーナーの姪)は数学者ヴァーツラフ・E・ベネシュと結婚した[16]。ノルベルト・ウィーナーの妹ベルサ (1902-1995)は植物学者キャロル・ウィリアム・ドッジと結婚した。 マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)時代のノーバート・ウィーナーには、おそらく偽話であろうが、多くの物語が語られた。家に帰ると誰もいなかったとい う。近所の少女にその理由を尋ねると、その日は家族が別の場所に引っ越したのだという。彼はその情報に感謝し、彼女は「だからパパ、私は残ったのよ!」と 答えた[17]。この話について尋ねられたウィーナーの娘は、「彼は自分の子供たちが誰であるかを決して忘れなかった」と断言したと伝えられている!しか し、それ以外のことは、実際に起こったことにかなり近かった......」[18]。 第二次世界大戦(1939-45年)に向けて、ウィーナーは中国援助協会とドイツ人学者を援助する緊急委員会のメンバーとなり、李玉詠やアントニ・ジグム ントのような、職を失った学者を斡旋することに関心を持った[19]。 第二次世界大戦中と戦後 第二次世界大戦中、高射砲の自動照準と発射に関する彼の研究により、ウィーナーはクロード・シャノンとは別に情報理論を研究し、ウィーナー・フィルタを発 明した。(情報源をランダムなプロセスとして、言い換えれば、さまざまなノイズとしてモデル化するという、現在では標準的な慣行は彼に起因する)。当初、 彼は対航空機の研究によって、アルトゥーロ・ローゼンブルースとジュリアン・ビグローとともに、1943年に『科学哲学』誌に掲載された論文「行動、目 的、テレオロジー」を執筆した。戦後、彼の名声によってMITは、ウォーレン・スタージス・マッカロッホやウォルター・ピッツなど、神経心理学や神経系の 数学・生物物理学の研究者からなる認知科学の研究チームを採用した。彼らは後にコンピューター科学や人工知能に先駆的な貢献をした。グループが結成された 直後、ウィーナーは突然メンバーとの連絡を絶ち、同僚たちを驚かせた。このことがピッツに精神的なトラウマを与え、彼のキャリアを衰退させることになっ た。コンウェイとシーゲルマンは、ウィーナーの伝記の中で、マッカロックのボヘミアンなライフスタイルを嫌悪していたウィーナーの妻マーガレットが、この 決裂を仕組んだと示唆している[23]。 ウィーナーは後に、サイバネティクス、ロボット工学、コンピュータ制御、オートメーションの理論の発展に貢献した。彼はジョン・フォン・ノイマンとニュー ロンのモデリングについて議論し、1946年11月の手紙の中で、フォン・ノイマンはウィーナーとのミーティングに先立ち、彼の考えを発表した[24]。 ウィーナーは常に自分の理論や発見を他の研究者と共有し、他の研究者の貢献を信用した。その中にはソビエトの研究者や彼らの発見も含まれていた。ウィー ナーはソ連の研究者と知り合いであったため、冷戦時代には疑惑の目で見られていた。彼は、生活水準を向上させ、経済的な低開発を終わらせるためにオート メーション化を強く提唱した。彼の思想はインドでも影響力を持ち、1950年代にはインド政府の顧問を務めた。 戦後、ウィーナーは、科学研究に対する政治的干渉や科学の軍事化をますます懸念するようになった。アトランティック・マンスリー』誌の1947年1月号に 掲載された彼の記事「A Scientist Rebels(科学者の反逆)」[25]は、科学者たちに自分たちの仕事の倫理的な意味を考慮するよう促した。戦後、彼は政府からの資金援助を受けること も、軍事プロジェクトに携わることも拒否した。核兵器や冷戦に関するウィーナーの信念がフォン・ノイマンの信念と対照的であったことは、『ジョン・フォ ン・ノイマンとノルベルト・ウィーナー』(John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener)という本の主要なテーマである[26]。 ウィーナーはメイシー会議の参加者であった。 |

| Personal life In 1926 Wiener married Margaret Engemann, an assistant professor of modern languages at Juniata College.[citation needed] They had two daughters. Opinions are not all positive on Margaret's impacts on Wiener's career.[27] Wiener admitted in his autobiography I Am a Mathematician: The Later Life of a Prodigy to abusing benzadrine throughout his life without being fully aware of its dangers.[28] Wiener died in March 1964, aged 69, in Stockholm, from a heart attack. Wiener and his wife are buried at the Vittum Hill Cemetery in Sandwich, New Hampshire. Awards and honors Wiener was a Plenary Speaker of the ICM in 1936 at Oslo and in 1950 at Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wiener won the Bôcher Memorial Prize in 1933 and the National Medal of Science in 1963, presented by President Johnson at a White House Ceremony in January, 1964, shortly before Wiener's death. Wiener won the 1965 U.S. National Book Award in Science, Philosophy and Religion for God & Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Points where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion.[29] The Norbert Wiener Prize in Applied Mathematics was endowed in 1967 in honor of Norbert Wiener by MIT's mathematics department and is provided jointly by the American Mathematical Society and Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. The Norbert Wiener Award for Social and Professional Responsibility awarded annually by CPSR, was established in 1987 in honor of Wiener to recognize contributions by computer professionals to socially responsible use of computers. The crater Wiener on the far side of the Moon is named after him. The Norbert Wiener Center for Harmonic Analysis and Applications, at the University of Maryland, College Park, is named in his honor.[30] Robert A. Heinlein named a spaceship after him in his 1957 novel Citizen of the Galaxy, a "Free Trader" ship called the Norbert Wiener mentioned in Chapter 14. The Norbert Wiener Center for Harmonic Analysis and Applications (NWC) in the Department of Mathematics at the University of Maryland, College Park is devoted to the scientific and mathematical legacy of Norbert Wiener. The NWC website highlights the research activities of the center. Further, each year the Norbert Wiener Center hosts the February Fourier Talks, a two-day national conference displaying advances in pure and applied harmonic analysis in industry, government, and academia. Doctoral students Shikao Ikehara (PhD 1930) Dorothy Walcott Weeks (PhD 1930) Norman Levinson (Sc.D. 1935) Brockway McMillan (PhD 1939) Abe Gelbart (PhD 1940) John P. Costas (engineer) (PhD 1951) Amar Bose (Sc.D. 1956) George Zames (Sc.D. 1960) Colin Cherry (PhD 1956)[31] |

私生活 1926年、ウィーナーはジュニアタ大学の現代語助教授であったマーガレット・エンゲマンと結婚した[citation needed]。マーガレットがウィーナーのキャリアに与えた影響については、肯定的な意見ばかりではない[27]。 ウィーナーは自伝『I Am a Mathematician: The Later Life of a Prodigy)の中で、ベンザドリンの危険性を十分に認識することなく、生涯ベンザドリンを乱用していたことを認めている[28]。 ウィーナーは1964年3月、ストックホルムで心臓発作により69歳で死去。ウィーナーと彼の妻は、ニューハンプシャー州サンドウィッチのヴィッタム・ヒ ル墓地に埋葬されている。 受賞歴 ウィーナーは1936年にオスロで、1950年にはマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで開催されたICMのプレナリースピーカーを務めた。 ウィーナーは1933年にボーシェ記念賞、1964年1月にジョンソン大統領がウィーナーの死の直前にホワイトハウスで授与した全米科学メダルを1963 年に受賞した。 1965年、『神とゴーレム』で全米科学・哲学・宗教図書賞を受賞: A Comment on Certain Points where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. 応用数学におけるノルベルト・ウィーナー賞は、1967年にMITの数学部門がノルベルト・ウィーナーに敬意を表して寄付したもので、アメリカ数学会と工 業応用数学協会が共同で提供している。 CPSRが毎年授与する社会的・職業的責任に対するノーバート・ウィーナー賞は、ウィーナーを記念して1987年に設立されたもので、コンピュータの社会 的責任ある利用に対するコンピュータ専門家の貢献を称えるものである。 月の裏側にあるクレーターは、彼の名にちなんで名づけられた。 メリーランド大学カレッジパーク校のNorbert Wiener Center for Harmonic Analysis and Applicationsは、彼の名を冠している[30]。 ロバート・A・ハインラインは1957年に発表した小説『銀河の市民』の中で、彼にちなんで宇宙船を命名しており、その宇宙船は第14章に登場するノー バート・ウィーナー号と呼ばれる「自由貿易船」である。 メリーランド大学カレッジパーク校の数学科にあるNorbert Wiener Center for Harmonic Analysis and Applications (NWC)は、ノーバート・ウィーナーの科学的・数学的遺産に専念している。NWCのウェブサイトでは、センターの研究活動を紹介している。さらに毎年、 ノルベルト・ウィーナー・センターは、産官学における純粋および応用調和解析の進歩を展示する2日間の全国会議「February Fourier Talks」を主催している。 博士課程学生 池原鹿雄(1930年博士号取得) ドロシー・ウォルコット・ウィークス(1930年博士号取得) ノーマン・レビンソン(1935年博士号取得) ブロックウェイ・マクミラン(博士号取得 1939年) エイブ・ゲルバート(1940年博士号) ジョン・P・コスタス(エンジニア)(1951年博士号) アマール・ボース(理学博士、1956年) ジョージ・ゼームス(1960年、理学博士) コリン・チェリー(1956年博士号)[31]。 |

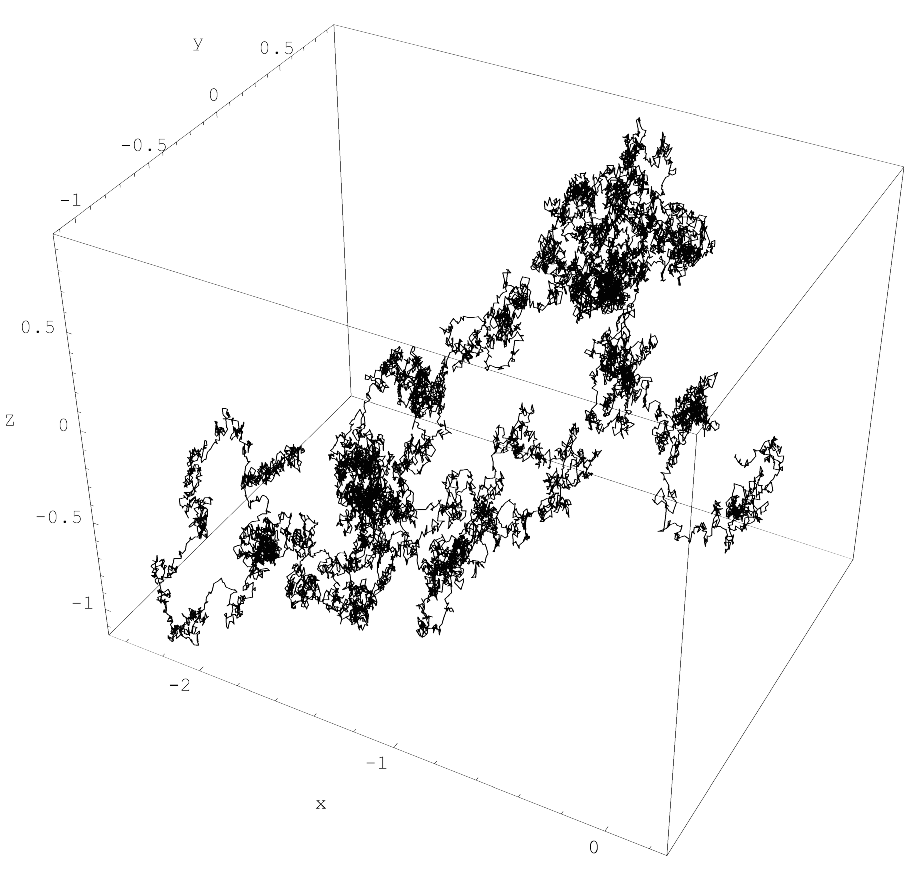

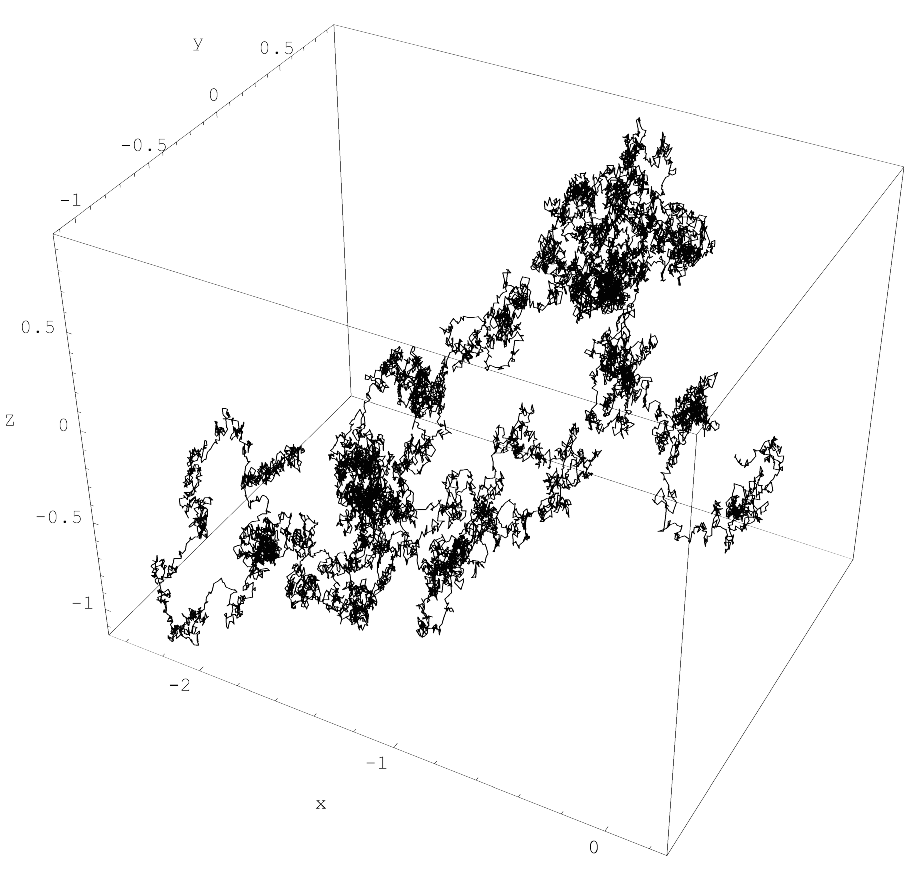

| Work Information is information, not matter or energy. — Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine Wiener was an early studier of stochastic and mathematical noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic engineering, electronic communication, and control systems. It was Wiener's idea to model a signal as if it were an exotic type of noise, giving it a sound mathematical basis. The example often given to students is that English text could be modeled as a random string of letters and spaces, where each letter of the alphabet (and the space) has an assigned probability. But Wiener dealt with analog signals, where such a simple example doesn't exist. Wiener's early work on information theory and signal processing was limited to analog signals, and was largely forgotten with the development of the digital theory.[32] Wiener is one of the key originators of cybernetics, a formalization of the notion of feedback, with many implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, philosophy, and the organization of society. His work with cybernetics influenced Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, and through them, anthropology, sociology, and education.[33]  In the mathematical field of probability, the "Wiener sausage" is a neighborhood of the trace of a Brownian motion up to a time t, given by taking all points within a fixed distance of Brownian motion. It can be visualized as a cylinder of fixed radius the centerline of which is Brownian motion. Wiener equation A simple mathematical representation of Brownian motion, the Wiener equation, named after Wiener, assumes the current velocity of a fluid particle fluctuates randomly. Wiener filter For signal processing, the Wiener filter is a filter proposed by Wiener during the 1940s and published in 1942 as a classified document. Its purpose is to reduce the amount of noise present in a signal by comparison with an estimate of the desired noiseless signal. Wiener developed the filter at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT to predict the position of German bombers from radar reflections. It is necessary to predict the position, because by the time the shell reaches the vicinity of the target, the target will have moved, and may have changed direction slightly. They even modeled the muscle response of the pilot, which led eventually to cybernetics. The unmanned V1's were particularly easy to model, and on a good day, American guns fitted with Wiener filters would shoot down 99 out of 100 V1's as they entered Britain from the English channel,[citation needed] on their way to London. What emerged was a mathematical theory of great generality—a theory for predicting the future as best one can on the basis of incomplete information about the past. It was a statistical theory that included applications that did not, strictly speaking, predict the future, but only tried to remove noise. It made use of Wiener's earlier work on integral equations and Fourier transforms.[34] [35] Nonlinear control theory Wiener studied polynomial chaos, a key piece of which is the Hermite-Laguerre expansion. This was developed in detail in Nonlinear Problems in Random Theory. Wiener applied Hermite-Laguerre expansion to nonlinear system identification and control. Specifically, a nonlinear system can be identified by inputting a white noise process and computing the Hermite-Laguerre expansion of its output. The identified system can then be controlled.[36][37] In mathematics  Wiener took a great interest in the mathematical theory of Brownian motion (named after Robert Brown) proving many results now widely known, such as the non-differentiability of the paths. Consequently, the one-dimensional version of Brownian motion was named the Wiener process. It is the best known of the Lévy processes, càdlàg stochastic processes with stationary statistically independent increments, and occurs frequently in pure and applied mathematics, physics and economics (e.g. on the stock-market). Wiener's tauberian theorem, a 1932 result of Wiener, developed Tauberian theorems in summability theory, on the face of it a chapter of real analysis, by showing that most of the known results could be encapsulated in a principle taken from harmonic analysis. In its present formulation, the theorem of Wiener does not have any obvious association with Tauberian theorems, which deal with infinite series; the translation from results formulated for integrals, or using the language of functional analysis and Banach algebras, is however a relatively routine process. The Paley–Wiener theorem relates growth properties of entire functions on Cn and Fourier transformation of Schwartz distributions of compact support. The Wiener–Khinchin theorem, (also known as the Wiener – Khintchine theorem and the Khinchin – Kolmogorov theorem), states that the power spectral density of a wide-sense-stationary random process is the Fourier transform of the corresponding autocorrelation function. An abstract Wiener space is a mathematical object in measure theory, used to construct a "decent", strictly positive and locally finite measure on an infinite-dimensional vector space. Wiener's original construction only applied to the space of real-valued continuous paths on the unit interval, known as classical Wiener space. Leonard Gross provided the generalization to the case of a general separable Banach space. The notion of a Banach space itself was discovered independently by both Wiener and Stefan Banach at around the same time.[38] In popular culture His work with Mary Brazier is referred to in Avis DeVoto's As Always, Julia.[39] A flagship named after him appears briefly in Citizen of the Galaxy by Robert Heinlein.[40] The song Dedicated to Norbert Wiener appears as the second track on the 1980 album Why? by G.G. Tonet (Luigi Tonet), released on the Italian It Why label.[41] |

仕事 情報は情報であって、物質でもエネルギーでもない。 - ノルベルト・ウィーナー著『サイバネティクス』: あるいは動物と機械における制御とコミュニケーション ウィーナーは、確率的・数学的ノイズ過程の初期の研究者であり、電子工学、電子通信、制御システムに関連する研究に貢献した。信号があたかもエキゾチック なノイズの一種であるかのようにモデル化し、健全な数学的基礎を与えるというのがウィーナーのアイデアであった。よく学生に示される例は、英語のテキスト をアルファベットとスペースのランダムな文字列としてモデル化し、アルファベットの各文字(とスペース)に確率を割り当てるというものだ。しかし、ウィー ナーが扱ったのはアナログ信号であり、そのような単純な例は存在しない。情報理論と信号処理に関するウィーナーの初期の研究はアナログ信号に限定されてお り、デジタル理論の発展とともにほとんど忘れ去られてしまった[32]。 ウィーナーは、工学、システム制御、コンピュータサイエンス、生物学、哲学、そして社会の構成に多くの示唆を与える、フィードバックの概念の公式化である サイバネティックスの重要な創始者の一人である。彼のサイバネティクスの研究は、グレゴリー・ベイトソンやマーガレット・ミード、そして彼らを通して人類 学、社会学、教育学に影響を与えた[33]。  確率の数学分野では、「ウィーナー・ソーセージ」はブラウン運動の一定距離内のすべての点を取ることによって与えられる、時間tまでのブラウン運動の痕跡 の近傍である。一定の半径を持つ円柱として可視化することができ、その中心線はブラウン運動である。 ウィーナー方程式 ブラウン運動の簡単な数学的表現であるWiener方程式は、Wienerにちなんで命名されたもので、流体粒子の現在速度がランダムに変動することを仮 定している。 ウィーナー・フィルター 信号処理において、ウィーナー・フィルターは1940年代にウィーナーによって提案され、1942年に機密文書として発表されたフィルターである。その目 的は、ノイズのない信号の推定値と比較することで、信号に含まれるノイズの量を減らすことである。ウィーナーはMITの放射線研究所で、レーダーの反射か らドイツ爆撃機の位置を予測するためにこのフィルターを開発した。位置を予測する必要があるのは、砲弾が目標付近に到達するまでに目標が移動し、わずかに 方向を変えている可能性があるからだ。彼らはパイロットの筋肉の反応までモデル化し、それがやがてサイバネティクスへとつながっていった。無人のV1は特 にモデル化しやすく、ウィーナー・フィルターを装着したアメリカの火砲は、ロンドンに向かう途中、イギリス海峡からイギリスに入ってきたV1を100機中 99機撃墜した[要出典]。そこで生まれたのは、非常に一般性の高い数学的理論であり、過去に関する不完全な情報に基づいて、できる限り未来を予測するた めの理論であった。それは統計理論であり、厳密に言えば、未来を予測するのではなく、ノイズを取り除こうとするだけの応用も含まれていた。ウィーナーの積 分方程式とフーリエ変換に関する初期の研究が利用された。 非線形制御理論 ウィーナーは多項式カオスを研究し、その重要な部分はエルミート・ラゲール展開である。これは『ランダム理論における非線形問題』で詳しく述べられてい る。 ウィンナーはエルミート・ラゲール展開を非線形システムの同定と制御に応用した。具体的には、白色雑音過程を入力し、その出力のエルミート・ラゲール展開 を計算することによって非線形システムを同定することができる。その後、同定されたシステムを制御することができる[36][37]。 数学  ウィーナーはブラウン運動(ロバート・ブラウンにちなんで名付けられた)の数学理論に大きな関心を持ち、経路の非可微分性など、現在広く知られている多く の結果を証明した。その結果、ブラウン運動の一次元版はウィーナー過程と名付けられた。これはレヴィ過程の中で最もよく知られたもので、定常的に統計的に 独立な増分を持つカドラグ確率過程であり、純粋数学、応用数学、物理学、経済学(株式市場など)で頻繁に登場する。 ウィーナーのタウバー定理は、1932年にウィーナーが発表したもので、実解析の一分野である和分可能性理論におけるタウバー定理を発展させたものであ る。現在の定式化では、ウィーナーの定理は無限級数を扱うタウバーの定理とは明らかな関連はない。しかし、積分について定式化された結果や、関数解析やバ ナッハ代数の言語を使った結果からの翻訳は、比較的日常的なプロセスである。 Paley-Wienerの定理は、Cn上の全関数の成長特性と、コンパクトな支持を持つシュワルツ分布のフーリエ変換に関連している。 Wiener-Khinchin定理(Wiener-Khintchine定理、Khinchin-Kolmogorov定理としても知られる)は、広義 定常ランダム過程のパワースペクトル密度が、対応する自己相関関数のフーリエ変換であることを述べている。 抽象ウィーナー空間は測度論の数学的対象で、無限次元ベクトル空間上の「まともな」、厳密に正で局所的に有限な測度を構成するのに使われる。ウィーナーの 最初の構成は、古典的ウィーナー空間として知られる単位区間上の実数値連続パスの空間にのみ適用された。レナード・グロスは、一般的な分離可能なバナッハ 空間の場合への一般化を行った。 バナッハ空間の概念自体は、ほぼ同時期にウィーナーとステファン・バナッハの両者によって独立に発見された[38]。 大衆文化 メアリー・ブレイジャーとの仕事はエイヴィス・デヴォトの『いつものように、ジュリア』で言及されている[39]。 ロバート・ハインラインの『銀河の市民』には、彼の名を冠した旗艦が少しだけ登場する[40]。 ノルベルト・ウィーナーに捧ぐ』という曲は、イタリアのIt WhyレーベルからリリースされたG.G.トーネット(ルイジ・トーネット)の1980年のアルバム『Why? |

| Publications Wiener wrote many books and hundreds of articles:[a] 1914, "A simplification in the logic of relations". Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 13: 387–390. 1912–14. Reprinted in van Heijenoort, Jean (1967). From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931. Harvard University Press. pp. 224–7. 1930, Wiener, Norbert (1930). "Generalized harmonic analysis". Acta Math. 55 (1): 117–258. doi:10.1007/BF02546511. 1933, The Fourier Integral and Certain of its Applications Cambridge Univ. Press; reprint by Dover, CUP Archive 1988 ISBN 0-521-35884-1 1942, Extrapolation, Interpolation and Smoothing of Stationary Time Series. A war-time classified report nicknamed "the yellow peril" because of the color of the cover and the difficulty of the subject. Published postwar 1949 MIT Press. http://www.isss.org/lumwiener.htm Archived 2015-08-16 at the Wayback Machine]) 1948, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Paris, (Hermann & Cie) & Camb. Mass. (MIT Press) ISBN 978-0-262-73009-9; 2nd revised ed. 1961. 1950, The Human Use of Human Beings. The Riverside Press (Houghton Mifflin Co.). 1958, Nonlinear Problems in Random Theory. MIT Press & Wiley. 1964, God & Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Points Where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. MIT Press. 1966, Generalized Harmonic Analysis and Tauberian Theorems. MIT Press. 1993, Invention: The Care and Feeding of Ideas. MIT Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-262-73111-9. This was written in 1954 but Wiener abandoned the project at the editing stage and returned his advance. MIT Press published it posthumously in 1993. Wiener's papers are collected in the following works: 1964, Selected Papers of Norbert Wiener. Cambridge Mass. 1964 (MIT Press & SIAM) 1976–84, The Mathematical Work of Norbert Wiener. Masani P (ed) 4 vols, Camb. Mass. (MIT Press). This contains a complete collection of Wiener's mathematical papers with commentaries, in the following volumes: Vol. 1, Mathematical philosophy and foundations; potential theory; Brownian movement, Wiener integrals, ergodic and chaos theories, turbulence and statistical mechanics (ISBN 0262230704); Vol. 2, Generalized harmonic analysis and Tauberian theory, classical harmonic and complex analysis (ISBN 0262230925); Vol. 3, The Hopf-Wiener integral equation ; Prediction and filtering ; Quantum mechanics and relativity ; Miscellaneous mathematical papers (ISBN 0262231077); and Vol. 4, Cybernetics, science, and society ; Ethics, aesthetics, and literary criticism ; Book reviews and obituaries. (ISBN 0262231239) Fiction: 1959, The Tempter. Random House (on Oliver Heaviside's invention for lower distortion on telegraph lines and his fight with AT&T for the proper recognition of his analysis)[7]: pp. 249–252 Autobiography: Wiener, Norbert (2018). Kline, Ronald (ed.). Norbert Wiener — A Life in Cybernetics. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262535441. Open access icon Includes both volumes of Wiener's autobiography. 1953, Ex-Prodigy: My Childhood and Youth. MIT Press.[43] 1956, I am a Mathematician. London (Gollancz). Under the name "W. Norbert": 1952, The Brain and other short science fiction in Tech Engineering News. |

出版物 ウィーナーは多くの著書と数百の論文を書いた。 1914年、「関係の論理における単純化」。Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 13: 387-390. 1912-14. van Heijenoort, Jean (1967). From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879-1931. ハーバード大学出版局。 1930, Wiener, Norbert (1930). 「一般化調和解析". Acta Math. 55 (1): 117–258. doi:10.1007/BF02546511. 1933, The Fourier Integral and Certain of its Applications Cambridge Univ. Press; Reprint by Dover, CUP Archive 1988 ISBN 0-521-35884-1. 1942, 定常時系列の外挿、補間、平滑化. 表紙の色とテーマの難解さから「黄色い危険」とあだ名された戦時中の機密報告書。戦後1949年発行 MIT Press. http://www.isss.org/lumwiener.htm Archived 2015-08-16 at the Wayback Machine]) 1948年、サイバネティクス: あるいは動物と機械における制御とコミュニケーション. Paris, (Hermann & Cie) & Camb. マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局)ISBN 978-0-262-73009-9; 改訂第2版 1961. 1950, The Human Use of Human Beings. The Riverside Press (Houghton Mifflin Co.). 1958, 『ランダム理論における非線形問題』. MIT Press & Wiley. 1964, God & Golem, Inc: サイバネティクスが宗教に影響を与えるある点についてのコメント。MIT Press. 1966, 『一般化調和解析とタウバー定理』. MIT Press. 1993, Invention: アイデアの世話と養育. MIT Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-262-73111-9. これは1954年に書かれたが、ウィーナーは編集段階でプロジェクトを放棄し、前金を返却した。1993年にMIT Pressから死後出版された。 ウィーナーの論文は以下の著作に収められている: 1964, Selected Papers of Norbert Wiener. Cambridge Mass. 1964 (MIT Press & SIAM) 1976-84, The Mathematical Work of Norbert Wiener. Masani P (ed) 4 vols, Camb. Mass. マサチューセッツ州(MIT Press)。ウィーナーの数学論文全集で、解説付き: 第1巻:数理哲学と基礎、ポテンシャル理論、ブラウン運動、ウィーナー積分、エルゴード理論とカオス理論、乱流と統計力学(ISBN 0262230704)、第2巻:一般化調和解析とタウベリ理論、古典調和解析と複素解析(ISBN 0262230925)、第3巻:ホップフ・ウィーナー理論(ISBN 0262230925)。3, Hopf-Wiener Integral Equation ; Prediction and filtering ; Quantum mechanics and relativity ; Miscellaneous mathematical papers (ISBN 0262231077); and Vol. 4, Cybernetics, science, and society ; Ethics, aesthetics, and literary criticism ; Book reviews and obituaries. (ISBN 0262231239) 小説: 1959年、誘惑者。Random House(オリバー・ヘヴィサイドの電信線の歪みを小さくする発明と、彼の分析が正しく認められるためのAT&Tとの戦いについて)[7]: pp.249-252 自伝 Wiener, Norbert (2018). クライン、ロナルド編. Norbert Wiener - A Life in Cybernetics. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262535441。オープンアクセスアイコン ウィーナーの自伝全2巻を収録。 1953年、『元プロディジー:私の幼年時代と青年時代』。MIT Press. 1956, I am a Mathematician. ロンドン(ゴランツ)。 W・ノーバート」名義: 1952, The Brain and other short science fiction in Tech Engineering News. |

| Autowave Box–Muller transform Cellular automaton Cybernetics in the Soviet Union Functional integration Operational calculus Smoothing problem (stochastic processes) List of things named after Norbert Wiener |

オートウェーブ ボックス・ミュラー変換 セル・オートマトン ソ連におけるサイバネティクス 関数積分 操作的微積分 平滑化問題(確率過程) ノルベルト・ウィーナーにちなんで命名されたもののリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norbert_Wiener |

下記の情報は、ウィキペディア「ノーバート・ウィーナー(Norbert Wiener)」 などより。

1894 アメリカ合衆国ミズーリ州コロンビアに、 父レオ(Leo)と母バーサ・カーン(Bertha Kahn)の長子として生まれる

「レオはハーバード大学でスラブ語の講師をしつつ、

ノーバートに7歳まで彼自身の手で、実験的で厳しい英才教育を授けた。父親の指導と彼自身の才能により、ウィーナーは神童として扱われ育つ。1903年ア

イヤー・ハイスクールに入学、1906年に卒業」

1906 11歳でタフツ・カレッジに入学

1909 14歳のときに数学で学位を取得し、ハー バード大学の大学院に入学。ハーバード大学では動物学を専攻した。

1910 コーネル大学大学院に移籍し、哲学を専攻 した。

1911 ハーバード大学に戻り、哲学を続けた

1912 18歳のときに、数理論理学に関する論文 によりハーバード大学よりPh.D.を授与。その後、ケンブリッジ大学(イギリス)に留学し、バートランド・ラッセルの下で学ぶ。G.H. ハーディの数学の講義に感銘を受ける

1914

ゲッティンゲン大学(ドイツ)でダフィット・ヒルベ ルトやエトムント・ランダウの下に学ぶ。その後ケンブリッジに戻り、再びアメリカに戻った。

"A simplification

in the logic of relations". Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 13: 387–390.

1912–14. Reprinted in van Heijenoort, Jean (1967). From Frege to Gödel:

A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931. Harvard University

Press. pp. 224–7.

1915 -1916年にはハーバード大学で哲学講 座の講師を一年間務める。

1916

ゼネラル・エレクトリックで働いたり、百科事典『エ ンサイクロペディア・アメリカーナ』の編集執筆者として働いた後、メリーランド州のアバディーン性能試験場で弾道学に関する仕事に就いた。戦争が終わるま でメリーランドで過ごした。

1919 24歳のときに、マサチューセッツ工科大 学(MIT)数学科の講師の職を得る。MITに勤める傍ら、彼は度々ヨーロッパに渡航

1926 ドイツからの移民のマーガレット・エンゲ マンと結婚し(彼らの間には二人の娘が生まれている)

1930 Wiener, Norbert

(1930). "Generalized harmonic analysis". Acta Math. 55 (1): 117–258.

doi:10.1007/BF02546511.

1933 The Fourier

Integral and Certain of its Applications Cambridge Univ. Press; reprint

by Dover, CUP Archive 1988

1939

彼の射撃制御装置に関する研究は、通信理論への関心

を総合し、サイバネティックスを定式化することへ彼を促した。戦後、彼は自身の影響力を行使し、ウォーレン・マカロックやウォルター・ピッツらの人工知

能、計算機科学、神経心理学の分野における当時最も優れた研究者の幾人かをMITに招いた。

しかし後に、突然かつ不可解に、ウィーナーは苦心して集めた彼ら研究チームとの関係を全て絶った。その理由については、ウィーナーの鋭敏すぎる感情や、妻

マーガレットの関与など、様々な原因が推測されている。いずれにしても、この出来事は、この時代で最も成功を約束されたはずだった科学的共同研究グループ

のひとつの、早すぎる結末であった。しかしこのMITに集められたメンバーらは、後の計算機科学他の発展に影響を残すこととなる。

1942 Extrapolation,

Interpolation and Smoothing of Stationary Time Series. A war-time

classified report nicknamed "the yellow peril" because of the color of

the cover and the difficulty of the subject. Published postwar 1949 MIT

Press.

1945

グループとの断絶にも関わらず、ウィーナーはサイバ ネティックス、ロボティクスやオートメーションなどの分野で新たな境地を開拓し続けた。彼は研究において才能を発揮し続け、また彼の理論と発見を他の研究 者と自由に共有した。不幸にも、冷戦時代においてはこの態度は、ソビエト連邦の科学者への支持の表明などにもよって、様々な疑念を呼び起こした。さらに ウィーナーは共産主義者の嫌疑をかけられ、赤狩りの対象にもなった。

1947

第二次大戦後、ウィーナーは、科学研究への政治の干 渉や科学の軍事化の問題に関心を強く持つようになった。彼は「ある科学者の反乱」(A Scientist Rebels)と言う題の論説をアトランティック・マンスリー1947年1月号上で発表し、その中で科学者に対し、自身の研究が持つ倫理的な含意を熟考す るように強く主張した。彼自身は軍事関連のプロジェクトで働くことや政府からの援助を受けることを拒絶した。

1948 Cybernetics:

Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine.

1950 『人間の人間的利用(The Human Use of Human Beings)』

彼は、オートメーション技術を、生活の質を高め、貧

困地域を発展させるのに用いるという構想の強力な支持者だった。これらの構想はインドに大きな影響を与え、1950年代に彼はインド政府に助言を与えてい

た。1950年に記した『人間機械論』で学歴社会を「統治者は永久に統治者であり、兵士は永久に兵士であり、労働者は労働者に運命づけられている」とし、

「昆虫は成長の過程で脱皮し、神経系を破壊されるので、幼虫から成虫に多くの記憶を移すことができない。人間以外の哺乳類は学習によって獲得する後天的な

能力より、持って生まれた先天的な能力が優先させ、人間と他の動物の決定的な違いは学習である」と述べている[3]。

1953 Ex-Prodigy

1956 I am a

Mathematician. London (Gollancz).

1958 Nonlinear Problems

in Random Theory. MIT Press & Wiley.

1964 スウェーデンのストックホルムにおいて没

した。69歳。Selected Papers of Norbert Wiener. Cambridge Mass. 1964 (MIT

Press & SIAM)。God & Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Points

Where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. MIT Press.

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099