池田光穂

Culture Bound Syndrome, CBS は、Yap, Pow Meng(1967)による命名によるものである。ある固有な精神神経状態の発症が、固有の文化的環境に依存しており(culture- dependent)、その文化や社会以外にみられないものを文化結合症候群と呼ぶ。

A・クラインマンによる自己批判があり、自文化の病 気のカテゴリーを、そのようなカテゴリーのない社会にもちこんで一方的に判断することの誤謬だと指摘している。しかし、実際には(経験的事実としては)社 会により心身の変調の訴え方には、明らかに文化と関連したパターンがあり、またそれらに関する語彙も豊富である。

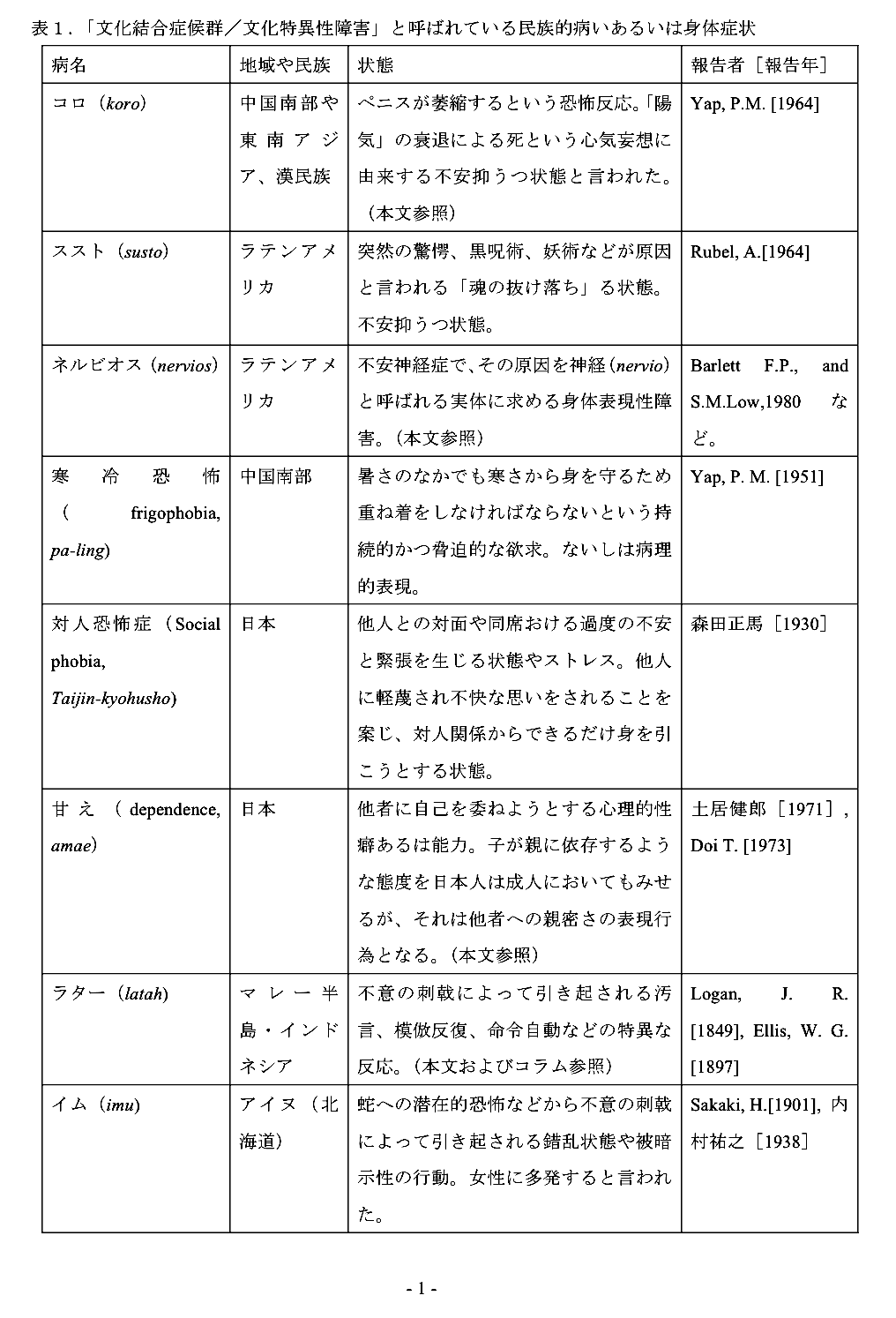

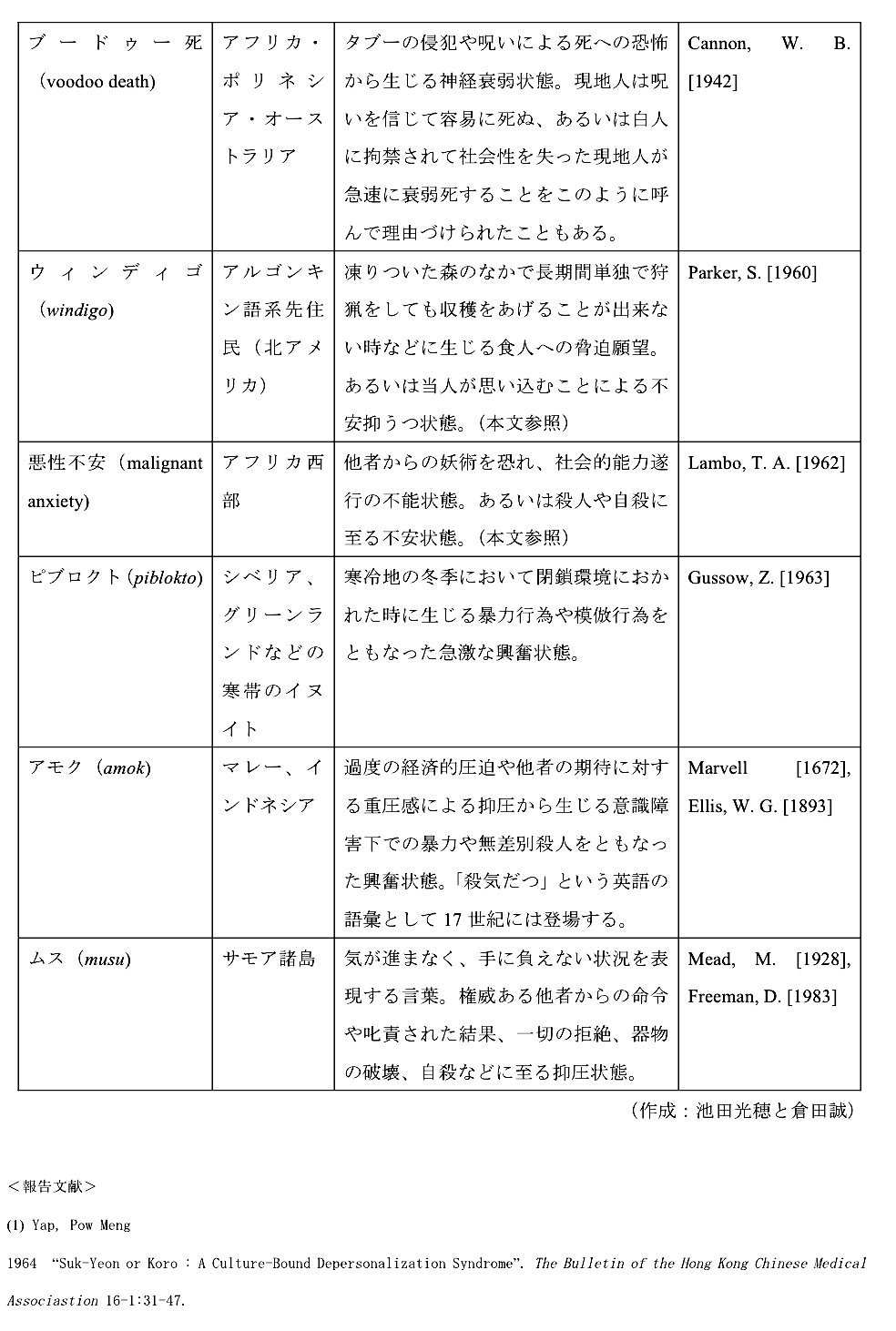

以下の表は、池田光穂・奥野克巳編『医療人類学のレッスン:病いをめぐる文化を探る』学陽書 房、2007年からの引用である(→資料が古いので下のコラムを参照してください)。

| In medicine and

medical anthropology, a culture-bound syndrome, culture-specific

syndrome, or folk illness is a combination of psychiatric and somatic

symptoms that are considered to be a recognizable disease only within a

specific society or culture. There are no known objective biochemical

or structural alterations of body organs or functions, and the disease

is not recognized in other cultures. The term culture-bound syndrome

was included in the fourth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994)

which also includes a list of the most common culture-bound conditions

(DSM-IV: Appendix I). Its counterpart in the framework of ICD-10

(Chapter V) is the culture-specific disorders defined in Annex 2 of the

Diagnostic criteria for research.[1] More broadly, an endemic that can be attributed to certain behavior patterns within a specific culture by suggestion may be referred to as a potential behavioral epidemic. As in the cases of drug use, or alcohol and smoking abuses, transmission can be determined by communal reinforcement and person-to-person interactions. On etiological grounds, it can be difficult to distinguish the causal contribution of culture upon disease from other environmental factors such as toxicity.[2] |

医学および医療人類学において、文化結合症候群、文化特異的症候群、ま

たは民間病とは、精神症状と身体症状の組み合わせであり、特定の社会または文化の中でのみ認識可能な疾患であると考えられている。身体の器官や機能には客

観的な生化学的変化や構造的変化は認められず、他の文化圏では認知されていない。文化結合症候群という用語は、Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders(精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル)の第4版(アメリカ精神医学会、1994年)に含まれ、最も一般的な文化結合疾患のリストも含まれ

ている(DSM-IV:付録I)。ICD-10(第V章)の枠組みにおけるその対応物は、研究のための診断基準の付属書2に定義された文化特有の障害であ

る[1]。 より広義には、示唆によって特定の文化圏における特定の行動パターンに帰することができる流行は、潜在的行動流行と呼ばれることがある。薬物使用やアル コール、喫煙の乱用の場合と同様に、伝播は共同体的強化や人格間の相互作用によって決定されることがある。病因論的根拠から、文化が疾病に及ぼす因果関係 を、毒性などの他の環境因子と区別することは困難である。 |

| Identification A culture-specific syndrome is characterized by:[citation needed] categorization as a disease in the culture (i.e., not a voluntary behaviour or false claim) widespread familiarity in the culture complete lack of familiarity or misunderstanding of the condition to people in other cultures no objectively demonstrable biochemical or tissue abnormalities (signs) recognition and treatment by the folk medicine of the culture Some culture-specific syndromes involve somatic symptoms (pain or disturbed function of a body part), while others are purely behavioral. Some culture-bound syndromes appear with similar features in several cultures, but with locally specific traits, such as penis panics. A culture-specific syndrome is not the same as a geographically localized disease with specific, identifiable, causal tissue abnormalities, such as kuru or sleeping sickness, or genetic conditions limited to certain populations. It is possible that a condition originally assumed to be a culture-bound behavioral syndrome is found to have a biological cause; from a medical perspective it would then be redefined into another nosological category. |

識別 文化特異的症候群の特徴は以下の通りである:[要出典]。 その文化において病気として分類される(すなわち、自発的な行動や虚偽の主張ではない)。 その文化で広く親しまれている。 他の文化圏の人々には、その病態がまったく知られていないか、誤解されている。 客観的に証明できる生化学的または組織的異常(徴候)がない。 その文化圏の民間療法によって認識され、治療される。 文化に特異的な症候群には、身体症状(疼痛または身体部位の機能障害)を伴うものもあれば、純粋に行動的なものもある。文化結合症候群のなかには、いくつかの文化圏で類似した特徴をもって現れるものもあるが、ペニスパニックのような地域特有の特徴をもつものもある。 文化に特異的な症候群は、クル病や眠り病のような、特定の、特定可能な、原因組織の異常を伴う、地理的に局地的な疾患や、特定の集団に限定された遺伝的疾 患とは異なる。当初は文化結合行動症候群であると想定されていた病態が、生物学的な原因を持っていることが判明することもありうる。医学的見地からは、そ の場合、別の疾病分類に再定義されることになる。 |

| Medical perspectives The American Psychiatric Association states the following:[3] The term culture-bound syndrome denotes recurrent, locality-specific patterns of aberrant behavior and troubling experience that may or may not be linked to a particular DSM-IV diagnostic category. Many of these patterns are indigenously considered to be "illnesses," or at least afflictions, and most have local names. Although presentations conforming to the major DSM-IV categories can be found throughout the world, the particular symptoms, course, and social response are very often influenced by local cultural factors. In contrast, culture-bound syndromes are generally limited to specific societies or culture areas and are localized, folk, diagnostic categories that frame coherent meanings for certain repetitive, patterned, and troubling sets of experiences and observations. The term culture-bound syndrome is controversial since it reflects the different opinions of anthropologists and psychiatrists.[4] Anthropologists have a tendency to emphasize the relativistic and culture-specific dimensions of the syndromes, while physicians tend to emphasize the universal and neuropsychological dimensions.[5][6] Guarnaccia & Rogler (1999) have argued in favor of investigating culture-bound syndromes on their own terms, and believe that the syndromes have enough cultural integrity to be treated as independent objects of research.[7] Guarnaccia and Rogler demonstrate the issues that occur when diagnosing cultural bound disorders using the DSM-IV. One of the key problems that arise is the "subsumption of culture bound syndromes into psychiatric categories",[7] which ultimately creates a medical hegemony and places the western perspective above that of other cultural and epistemological explanations of disease. The urgency for further investigation or reconsideration of the DSM-IV's authoritative power is emphasized, as the DSM becomes an international document for research and medical systems abroad. Guarnaccia and Rogler provide two research questions that must be considered, "firstly, how much do we know about the culture-bound syndromes for us to be able to fit them into standard classification; and secondly, whether such a standard and exhaustive classification in fact exists".[7] It is suggested that the problematic nature of the DSM becomes evident when viewed as definitively conclusive. Questions are raised to whether culture-bound syndromes can be treated as discrete entities, or whether their symptoms are generalized and perceived as an amalgamation of previously diagnosed illnesses. If this is the case, then the DSM may be what Bruno Latour would define as "particular universalism". In that the Western medical system views itself to have a privileged insight into the true intelligence of nature, in contrast to the model provided by other cultural perspectives.[8] Some studies suggest that culture-bound syndromes represent an acceptable way within a specific culture (and cultural context) among certain vulnerable individuals (i.e. an ataque de nervios at a funeral in Puerto Rico) to express distress in the wake of a traumatic experience.[9] A similar manifestation of distress when displaced into a North American medical culture may lead to a very different, even adverse outcome for a given individual and the individual's family.[10] The history and etymology of some syndromes such as brain fag syndrome, restricted to West Africa by the DSM-IV, have also been reattributed to 19th century Victorian Britain.[11] In 2013, the DSM 5 dropped the term culture-bound syndrome, preferring the new name "cultural concepts of distress".[12] |

医学的観点 米国精神医学会は以下のように述べている。 文化結合症候群という用語は、特定のDSM-IV診断カテゴリーに結びつくかどうかは別として、異常な行動や厄介な体験の再発する地域特有のパターンを示 す。これらのパターンの多くは、土着的に「病気」、または少なくとも「苦悩」であると考えられており、そのほとんどに地方名が付けられている。DSM- IVの主要なカテゴリーに準拠した病像は世界中でみられるが、個別主義的な症状、経過、社会的反応は、その土地の文化的要因に影響されることが非常に多 い。対照的に、文化結合症候群は一般的に特定の社会または文化圏に限定され、ある種の反復的、パターン化された、厄介な一連の経験や観察に対して首尾一貫 した意味を持つ、地域化された民間診断カテゴリーである。 文化結合症候群という用語は、人類学者と精神科医の異なる意見を反映しているため、論争を呼んでいる[4]。人類学者は症候群の相対主義的で文化特異的な 次元を強調する傾向があり、一方、医師は普遍的で神経心理学的な次元を強調する傾向がある[5][6]。GuarnacciaとRogler(1999) は、文化結合症候群を独自の条件で調査することに賛成であると主張しており、症候群は独立した研究対象として扱われるのに十分な文化的完全性を持っている と考えている[7]。 GuarnacciaとRoglerは、DSM-IVを用いて文化的境界障害を診断する際に生じる問題を示している。生じる重要な問題のひとつは、「文化 結合症候群を精神医学的カテゴリーに包摂すること」であり[7]、これは最終的に医学的ヘゲモニーを生み出し、西洋の視点を他の文化的・認識論的な病気の 説明よりも上位に置くことになる。DSMが海外の研究や医療制度のための国際的な文書となるにつれ、DSM-IVの権威的な力についてさらなる調査や再考 が急務であることが強調されている。GuarnacciaとRoglerは、「第一に、文化結合症候群を標準的な分類に当てはめることができるようにする ために、私たちは文化結合症候群についてどの程度知っているのか、第二に、そのような標準的で網羅的な分類が実際に存在するのかどうか」という、考慮すべ き2つの研究課題を提示している[7]。 DSMの問題点は、決定的な結論として見たときに明らかになることが示唆されている。文化結合症候群を個別の実体として扱うことができるのか、あるいはそ の症状が一般化され、以前に診断された病気の融合として認識されるのか、という疑問が提起される。もしそうだとすれば、DSMはブルーノ・ラトゥールが定 義するところの「個別的普遍主義」なのかもしれない。つまり、西洋医学のシステムは、他の文化的視点が提供するモデルとは対照的に、自然の真の知性に対す る特権的な洞察力を持っていると見なしているのである[8]。 ある研究では、文化結合症候群は、特定の文化(および文化的文脈)において、特定の傷つきやすい個人(プエルトリコの葬儀における神経麻痺など)がトラウ マ的体験の後に苦痛を表現するために許容される方法であることを示唆している。 [9] 北米の医療文化に置き換えた場合の同様の苦痛の発現は、特定の個人とその家族にとって、まったく異なる、さらには不利な結果をもたらす可能性がある [10] 。DSM-IVによって西アフリカに限定された脳内ホモ症候群のようないくつかの症候群の歴史と語源は、19世紀のヴィクトリア朝時代のイギリスにも遡及 している[11]。 2013年、DSM5は文化結合症候群という用語を削除し、「苦痛の文化的概念」という新しい名称を好んだ[12]。 |

| Cultural collision between medical perspectives Within the traditional Hmong culture, epilepsy (qaug dab peg) directly translates to "the spirit catches you and you fall down" which is said to be an evil spirit called a dab that captures one's soul and makes one ill. In this culture, individuals with seizures are seen to be blessed with a gift: an access point into the spiritual realm which no one else has been given.[13] In westernised society, epilepsy is recognized as a serious long-term brain condition that can have a major impairment on an individual's life. The way the illness is dealt with in Hmong culture is vastly different due to the high status epilepsy has in the culture, compared to individuals who have the condition in westernised societies. Individuals with epilepsy within the Hmong culture are a source of pride for their family.[14] Another culture-bound illness is neurasthenia, which is a vaguely described medical ailment in Chinese culture that presents as lassitude, weariness, headaches, and irritability and is mostly linked to emotional disturbance. A report done in 1942 showed that 87% of patients diagnosed by Chinese psychiatrists as having neurasthenia could be reclassified as having major depression according to the DSM-3 criteria.[15] Another study conducted in Hong Kong showed that most patients selectively presented their symptoms according to what they perceived as appropriate and tended to only focus on somatic suffering, rather than the emotional problems they were facing.[16][17] |

医学的視点と文化的視点の衝突 モン族の伝統的な文化では、てんかん(qaug dab peg)は直訳すると「霊に捕まって倒れる」という意味であり、人の魂を捕らえて病気にするダブと呼ばれる悪霊であると言われている。この文化では、てん かん発作を起こす人は、他の誰にも与えられていないスピリチュアルな領域へのアクセスポイントという贈り物に恵まれていると考えられている[13]。西洋 化された社会では、てんかんは、個人の生活に大きな障害をもたらす深刻な長期的脳疾患として認識されている。モン族の文化におけるてんかんの地位は高く、 西洋化社会におけるてんかん患者とは、病気への対処の仕方が大きく異なる。モン族の文化では、てんかん患者は家族にとって誇りである[14]。 もうひとつの文化に縛られた病気は神経衰弱であり、これは中国文化では漠然と説明される医学的な病気で、倦怠感、疲労感、頭痛、過敏性などを呈し、ほとん どの場合、情緒障害と関連している。1942年に行われた報告によると、中国の精神科医によって神経衰弱と診断された患者の87%が、DSM-3の基準に 従って大うつ病に再分類される可能性があることが示された[15]。香港で行われた別の研究によると、ほとんどの患者は適切と思われる症状に従って選択的 に症状を呈し、直面している感情的な問題よりもむしろ身体的な苦痛にのみ焦点を当てる傾向があることが示された[16][17]。 |

| Globalisation Globalisation is a process whereby information, cultures, jobs, goods, and services are spread across national borders.[18] This has had a powerful impact on the 21st century in many ways including through enriching cultural awareness across the globe. Greater level of cultural integration is occurring due to rapid industrialisation and globalisation, with cultures absorbing more influences from each other. As cultural awareness begins to increase between countries, there is a consideration into whether cultural bound syndromes will slowly lose their geographically bound nature and become commonly known syndromes that will then become internationally recognised.[19] Anthropologist and psychiatrist Roland Littlewood makes the observation that these diseases are likely to vanish in an increasingly homogenous global culture in the face of globalisation and industrialisation.[20] Depression, for example, was once only accepted in western societies; it is now recognised as a mental disorder in all parts of the world. In contrast to Eastern civilizations such as Taiwan, depression is still much more common in Western cultures like the United States. This could indicate that globalisation may have an impact on allowing disorders to be spread across borders, but these disorders may remain predominant in certain cultures. |

グローバリゼーション グローバリゼーションとは、情報、文化、仕事、商品、サービスが国境を越えて広がっていくプロセスのことである[18]。これは、世界中の文化的認識を豊 かにするなど、さまざまな形で21世紀に強力な影響を与えている。急速な工業化とグローバリゼーションにより、文化的統合のレベルが高まり、文化が互いの 影響をより多く吸収するようになっている。各国間で文化に対する意識が高まり始めると、文化結合症候群が徐々に地理的な縛りを失い、国際的に認知されるよ うな一般的に知られる症候群になるかどうかが検討されている[19]。 人類学者であり精神科医であるローランド・リトルウッドは、グローバリゼーションと工業化に直面し、ますます均質化する世界文化の中で、これらの疾患は消 滅する可能性が高いという見解を示している[20]。例えば、うつ病はかつて西洋社会でのみ受け入れられていたが、現在では世界のあらゆる地域で精神疾患 として認識されている。台湾のような東洋文明とは対照的に、アメリカのような西洋文化では、うつ病はまだずっと一般的である。このことは、グローバリゼー ションが国境を越えて障害を広めることに影響を及ぼしている可能性を示しているが、これらの障害は特定の文化圏では依然として優勢である可能性がある。 |

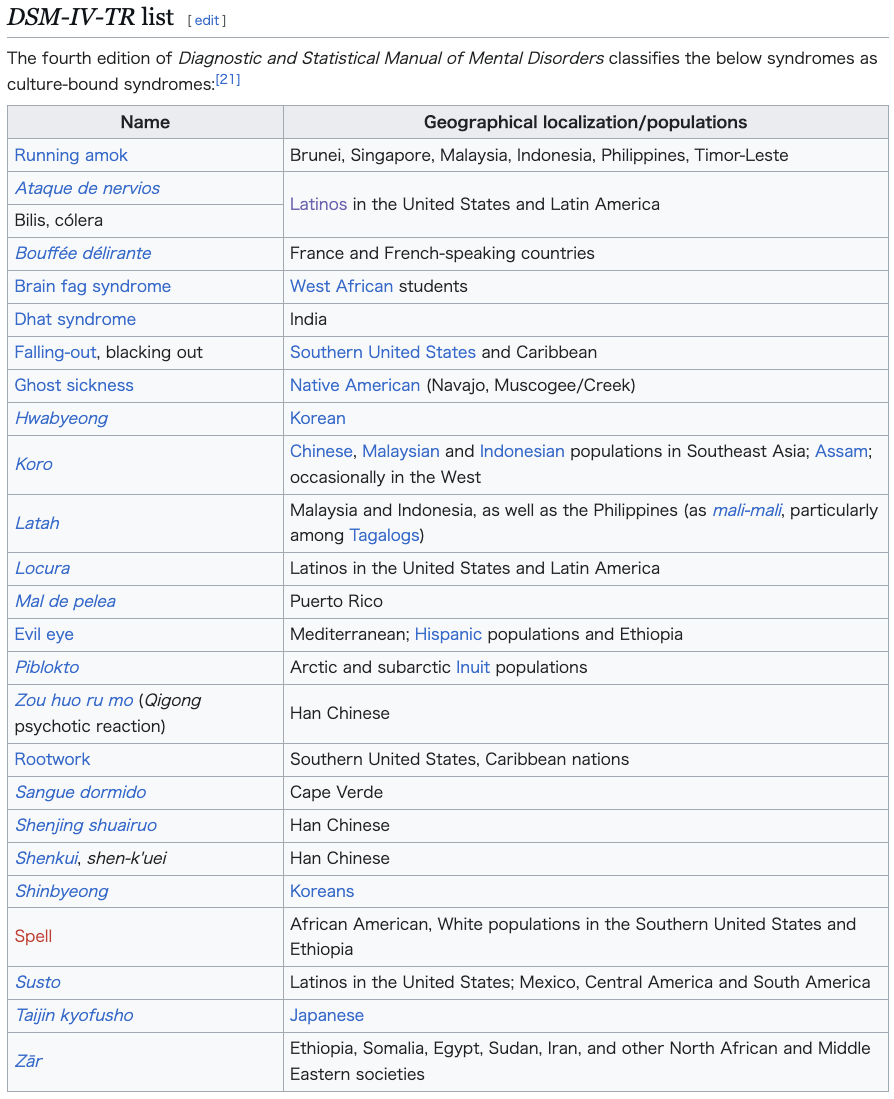

| DSM-IV-TR list The fourth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders classifies the below syndromes as culture-bound syndromes:[21]  |

DSM-IV-TRリスト 精神障害の診断と統計マニュアルの第4版では、以下の症候群を文化結合症候群として分類している[21]。 |

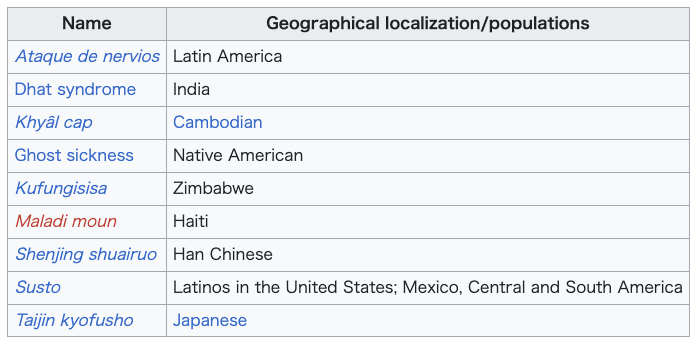

| DSM-5 list The fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders classifies the below syndromes as cultural concepts of distress, a closely related concept:[22]  |

DSM-5のリスト 精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』第5版では、以下の症候群を、密接に関連する概念である苦痛の文化的概念として分類している[22]。  |

| ICD-10 list The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) classifies the below syndromes as culture-specific disorders:[1]  |

ICD-10リスト 疾病および関連保健問題の国際統計分類(ICD)第10版では、以下の症候群を文化特異的障害に分類している[1]。  |

| Other examples Though "the ethnocentric bias of Euro-American psychiatrists has led to the idea that culture-bound syndromes are confined to non-Western cultures",[23] within the contiguous United States, the consumption of kaolin, a type of clay, has been proposed as a culture-bound syndrome observed in African Americans in the rural South, particularly in areas in which the mining of kaolin is common.[24] In South Africa, among the Xhosa people, the syndrome of amafufunyana is commonly used to describe those believed to be possessed by demons or other malevolent spirits. Traditional healers in the culture usually perform exorcisms in order to drive off these spirits. Upon investigating the phenomenon, researchers found that many of the people claimed to be affected by the syndrome exhibited the traits and characteristics of schizophrenia.[25][26] Some researchers have suggested that both premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and the more severe premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which have currently unknown physical mechanisms,[27][28][29] are Western culture-bound syndromes.[30][31] However, this is controversial.[30] Tarantism is an expression of mass psychogenic illness documented in Southern Italy since the 11th century.[32] Morgellons is a rare self-diagnosed skin condition that has been described as "a socially transmitted disease over the Internet".[33] Vegetative-vascular dystonia can be considered an example of somatic condition formally recognised by local medical communities in former Soviet Union countries, but not in Western classification systems. Its umbrella term nature as neurological condition also results in diagnosing neurotic patients as neurological ones,[34][35] in effect substituting possible psychiatric stigma with culture-bound syndrome disguised as a neurological condition. Refugee children in Sweden have been known to fall into coma-like states on learning their families will be deported. The condition, known in Swedish as uppgivenhetssyndrom, or resignation syndrome, is believed to only exist among the refugee population in Sweden, where it has been prevalent since the early part of the 21st century. In a 130-page report on the condition commissioned by the government and published in 2006, a team of psychologists, political scientists, and sociologists hypothesized that it was a culture-bound syndrome.[36] A startle disorder similar to latah, called imu [ja] (sometimes spelled imu:), is found among Ainu people, both Sakhalin Ainu and Hokkaido Ainu.[37][38] A condition similar to piblokto, called menerik [ru] (sometimes meryachenie), is found among Yakuts, Yukaghirs, and Evenks living in Siberia.[39] The trance-like violent behavior of the Viking age berserkers – behavior that disappeared with the arrival of Christianity – has been described as a culture-bound syndrome.[40] |

その他の例 ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の精神科医の民族中心主義的な偏見により、文化結合症候群は非西洋文化に限定されたものであると考えられてきた」が[23]、米国 内では、粘土の一種であるカオリンの摂取が、南部の農村部、特にカオリンの採掘が盛んな地域のアフリカ系アメリカ人に見られる文化結合症候群として提唱さ れている[24]。 南アフリカでは、ホーサ人の間で、アマフフニヤナ症候群は、悪魔または他の悪意ある霊に取り憑かれていると信じられている人々を表すのに一般的に使用され ている。この文化圏の伝統的な治療者は通常、これらの霊を追い払うために悪魔払いを行う。この現象を調査したところ、研究者たちは、この症候群に罹患して いると主張する人々の多くが統合失調症の特徴や特性を示していることを発見した[25][26]。 一部の研究者は、月経前症候群(PMS)と、より重篤な月経前不快気分障害(PMDD)の両方が、現在のところ物理的なメカニズムが不明であり[27][28][29]、西洋文化結合症候群であると示唆している[30][31]が、これは議論の余地がある[30]。 タランティズムは、11世紀以来南イタリアで記録されている集団心因性疾患の表現である[32]。 モルジェロンズはまれな自己診断による皮膚疾患で、「インターネットを介して社会的に伝染する病気」と表現されている[33]。 植物性-血管性ジストニアは、旧ソビエト連邦諸国の医学界では正式に認知されているが、西洋の分類体系では認知されていない身体疾患の一例と考えられる。 神経学的疾患としてのその包括的な用語の性質は、神経症的な患者を神経学的な患者として診断することにもつながり[34][35]、事実上、精神医学的な 汚名を、神経学的疾患に見せかけた文化結合症候群で代用する可能性がある。 スウェーデンの難民の子どもたちは、家族が強制送還されることを知ると、昏睡状態に陥ることが知られている。スウェーデン語ではウップギブンヘッツ症候群 (退去症候群)と呼ばれるこの症状は、21世紀初頭から流行しているスウェーデンの難民の間にのみ存在すると考えられている。心理学者、政治学者、社会学 者からなるチームは、政府の委託で2006年に発表されたこの症状に関する130ページに及ぶ報告書の中で、この症状は文化結合症候群であるという仮説を 立てた[36]。 ラタに似た驚愕障害はイム[ja](イム:と表記されることもある)と呼ばれ、サハリンアイヌと北海道アイヌのアイヌ民族に見られる[37][38]。 シベリアに住むヤクート人、ユカヒール人、エヴェンク人の間では、ピブロクトに似た状態で、メネリク[ru](メリアチェニと表記されることもある)と呼ばれている[39]。 ヴァイキング時代のバーサーカーのトランス状態のような暴力的行動(キリスト教の到来とともに消えた行動)は、文化結合症候群として説明されている[40]。 |

| Cross-cultural psychiatry Cross-cultural psychology Cultural competence in healthcare Dancing mania Mass psychogenic illness Hikikomori Hi-wa itck Medical anthropology Neurasthenia Zen sickness |

異文化間精神医学 異文化心理学 医療における文化的能力 踊る躁病 集団心因性疾患 ひきこもり 日和見 医療人類学 神経衰弱 禅病 |

| Kleinman, Arthur (1991).

Rethinking psychiatry: from cultural category to personal experience.

New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-917441-8. Retrieved 8 January 2011. Landy, David, ed. (1977). Culture, Disease, and Healing: Studies in Medical Anthropology. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-367390-0. Launer, John (November 2003). "Folk illness and medical models". QJM. 96 (11): 875–876. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg136. PMID 14566046. Simons, Rondald C; Hughes, Charles C, eds. (1985). The Culture-Bound Syndromes: Folk Illnesses and Anthropological Interest. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co. ISBN 978-90-277-1858-7. Retrieved 9 September 2010. Paperback ISBN 90-277-1859-8 Rebhun, L.A. (2004). "Culture-Bound Syndromes". In Ember, Carol R.; Melvin Ember (eds.). Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology: Health and Illness in the World's Cultures. New York: Klower Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 319–327. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6. Retrieved 9 September 2010. (Note: Different preview pages result in the full chapter being viewable from the title link). Kirmayer, L. J. (2001). "Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: implications for diagnosis and treatment". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62: 22–30. PMID 11434415. Bures, Frank (2016). The Geography of Madness: Penis Thieves, Voodoo Death, and the Search for the Meaning of the World's Strangest Syndromes Hardcover. Melville House. ISBN 978-1612193724. |

Kleinman, Arthur (1991). 精神医学再考:文化的範疇から人格的経験へ。ニューヨーク: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-917441-8. 2011年1月8日取得。 Landy, David, ed. (1977). 文化、病気、癒し: Studies in Medical Anthropology. New York: マクミラン。ISBN 978-0-02-367390-0. Launer, John (November 2003). 「民間病と医療モデル」. QJM. 96 (11): 875-876. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg136. PMID 14566046. Simons, Rondald C; Hughes, Charles C, eds. (1985). 文化結合症候群: The Culture-Bound Syndromes: Folk Illnesses and Anthropological Interest. D. Reidel Publishing Co: ISBN 978-90-277-1858-7. 2010年9月9日閲覧。ペーパーバック ISBN 90-277-1859-8 Rebhun, L.A. (2004). 「文化結合症候群」. In Ember, Carol R.; Melvin Ember (eds.). Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology: Health and Illness in the World's Cultures. ニューヨーク: Klower Academic/Plenum Publishers. 319-327. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6. 2010年9月9日取得。(注:異なるプレビュー・ページでは、タイトル・リンクから全章が表示される)。 Kirmayer, L. J. (2001). 「うつ病と不安症の臨床症状における文化的差異:診断と治療への影響」。Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62: 22-30. PMID 11434415. Bures, Frank (2016). 狂気の地理: The Geography of Madness: The Penis Thieves, Voodoo Death, and the Search for the Meaning of the World's Strangest Syndromes Hardcover. メルヴィル・ハウス。ISBN 978-1612193724. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture-bound_syndrome |

DSM-IV-TRリスト(再掲)

精神障害の診断と統計マニュアルの第4版では、以下の症候群を文化結合症候群として分類している[21]。

DSM-5のリスト(再掲)

精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』第5版では、以下の症候群を、密接に関連する概念である苦痛の文化的概念として分類している[22]。

ICD-10リスト(再掲)

疾病および関連保健問題の国際統計分類(ICD)第10版では、以下の症候群を文化特異的障害に分類している[1]。

■文化結合(culture-bound)という語彙の由来

OEDの文化(culture)の1993年の追加 に文化結合(culture-bound)という項目が掲げられた。その説明は以下のとおりである。

culture-bound a.,

restricted in character, outlook, etc. by belonging to a particular

culture; determined or limited by the presuppositions of one's culture

(further examples).

そしてその用例は1951年までさかのぼれるという

- 1951 R. Firth Elem. Social Organiz. iii. 109 He is culture-bound in his desires as well as his activities.

- 1963 J. Lyons Structural Semantics iv. 76 Let us here assume that the linguist has provisionally identified as the same situational context (itself ‘culture-bound’) the events and activities which constitute making a purchase in a shop.

- 1980 English World-Wide I. i. 4 Unmistakable culture-bound

specimens like passages from an Onitsha Market novel, or Indian

matrimonial advertisements.

リンク

- 仮想・医療人類学辞典

- 池田光穂「〈こころ〉と社会」

- 池田光穂:医療人類学入門

文献

- 池田光穂・奥野克巳編『医療人類学のレッスン:病いをめぐる文化を探る』学陽書房、2007年

その他の情報

☆

☆