ジャズ大全・入門

SUMMA JAZZNOLOGICA, or All that Jazz for beginners

解説:池田光穂

ジャズ大全・入門

SUMMA JAZZNOLOGICA, or All that Jazz for beginners

解説:池田光穂

「ぼくらの演奏をなにもそう大げさに考え なくっていいんだ。バンドがスタジオに入って、レコード吹き込みの演奏をやるときだって、連中はしゃっ ちょこ張ってかまえるわけではない。要するに演奏(プレー)するだけ。それだけのことさ。評論家先生たちはクソまじめに考えすぎだ ネ。なにかというとジャズにかんする理論をおかきになり、ジャズの歴史について一席ぶたれ、ジャングル が、トムトム太鼓が、白人の影響が……ということになる。もっと楽な気分で受けとめていいのだ。ジャズの演奏はそこに快感を得るためにやるので、べつに歴 史をつくるためじゃない」――レックス・スチュアート(トランペット奏者、1939年)**出典はフランシス・ニュートン(エリック・ホブスボーム『抗議 としてのジャズ』→原題:「ザ・ジャズ・シーン」1959)

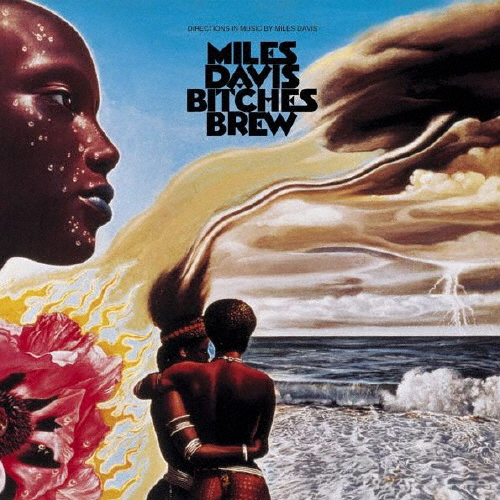

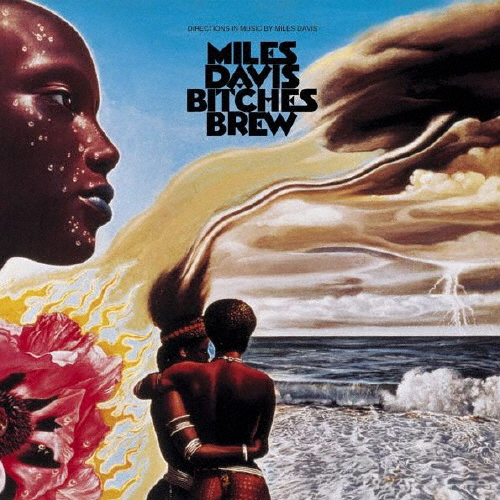

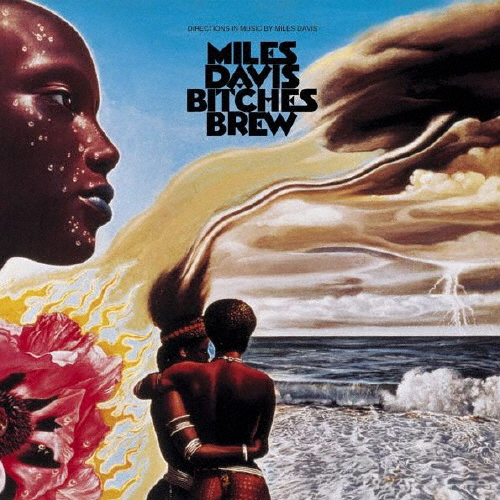

『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』(Bitches Brew)へのサイト内リンクはこちらです

演習:

内容:

ジャズについての基本的な理解

歴史的展開

音楽理論的説明

アメリカ国家文化への被領有化の過程

ジャズをめぐる議論

ジャズカルチャー:ナット・ヘントフ

ペシミストたち:フランクフルト学派、とくにアドルノ

当事者たち:M.D.

ジャズ研究方法入門

personal history, dicography, music and society, etc.

○『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』(Bitches Brew)は、ジャズ・トランペット奏者マイルス・デイヴィスが1970年に発表した2枚組のアルバム。前作『イン・ア・サイレント・ウェイ』に引き続 き、エレクトリック・ジャズ路線を押し進めた内容で、「フュージョン」と呼ばれるジャンルを確立した、ジャズ史上最も革命的な作品の一つとみなされている [5]。マイルスのアルバムとしては初めて、本国アメリカでゴールド・ディスクに達し[6]、総合チャートのBillboard 200で自身唯一のトップ40入りを果たした[2]。その後も売れ続け、『カインド・オブ・ブルー』と並ぶマイルス最大のヒット作と言われている。

●特論, Bitches Brew, 1970

Bitches Brew

is a studio album by American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader

Miles Davis. It was recorded from August 19 to 21, 1969, at Columbia's

Studio B in New York City and released on March 30, 1970 by Columbia

Records. It marked his continuing experimentation with electric

instruments that he had featured on his previous record, the critically

acclaimed In a Silent Way (1969). With these instruments, such as the

electric piano and guitar, Davis departed from traditional jazz rhythms

in favor of loose, rock-influenced arrangements based on improvisation.

The final tracks were edited and pieced together by producer Teo Macero. Bitches Brew

is a studio album by American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader

Miles Davis. It was recorded from August 19 to 21, 1969, at Columbia's

Studio B in New York City and released on March 30, 1970 by Columbia

Records. It marked his continuing experimentation with electric

instruments that he had featured on his previous record, the critically

acclaimed In a Silent Way (1969). With these instruments, such as the

electric piano and guitar, Davis departed from traditional jazz rhythms

in favor of loose, rock-influenced arrangements based on improvisation.

The final tracks were edited and pieced together by producer Teo Macero.The album initially received a mixed critical and commercial response, but it gained momentum and became Davis' highest-charting album on the U.S. Billboard 200, peaking at No. 35. In 1971, it won a Grammy Award for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album.[7] In 1976, it became Davis' first gold album to be certified by the Recording Industry Association of America.[8][9] In subsequent years, Bitches Brew gained recognition as one of jazz's greatest albums and a progenitor of the jazz rock genre, as well as a major influence on rock and '70s crossover musicians.[3] In 1998, Columbia released The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions,[10] a four-disc box set that includes the original album and previously unreleased material. In 2003, the album was certified platinum, reflecting shipments of one million copies. |

ビッ

チェズ・ブリュー』(Bitches

Brew)は、アメリカのジャズ・トランペッター、作曲家、バンドリーダーであるマイルス・デイヴィスのスタジオ・アルバム。1969年8月19日から

21日までニューヨークのコロムビアのスタジオBで録音され、1970年3月30日にコロムビア・レコードからリリースされた。前作『In a

Silent

Way』(1969年)で好評を博したエレクトリック楽器を引き続き使用。エレクトリック・ピアノやギターといったこれらの楽器を用いて、デイヴィスは伝

統的なジャズのリズムから離れ、即興演奏に基づいたロック風のゆるいアレンジを好んだ。最終的なトラックは、プロデューサーのテオ・マセロによって編集さ

れ、つなぎ合わされた。 ビッ

チェズ・ブリュー』(Bitches

Brew)は、アメリカのジャズ・トランペッター、作曲家、バンドリーダーであるマイルス・デイヴィスのスタジオ・アルバム。1969年8月19日から

21日までニューヨークのコロムビアのスタジオBで録音され、1970年3月30日にコロムビア・レコードからリリースされた。前作『In a

Silent

Way』(1969年)で好評を博したエレクトリック楽器を引き続き使用。エレクトリック・ピアノやギターといったこれらの楽器を用いて、デイヴィスは伝

統的なジャズのリズムから離れ、即興演奏に基づいたロック風のゆるいアレンジを好んだ。最終的なトラックは、プロデューサーのテオ・マセロによって編集さ

れ、つなぎ合わされた。このアルバムは当初、批評家からも商業的にもさまざまな反応を受けたが、勢いを増し、デイヴィスにとって全米ビルボード200で最高位となる35位を記録 した。1971年にはグラミー賞で最優秀ラージ・ジャズ・アンサンブル・アルバム賞を受賞[7]。1976年には、デイヴィスにとって初のゴールド・アル バムとして全米レコード協会から認定された[8][9]。 1998年、コロンビアはオリジナル・アルバムと未発表音源を含む4枚組ボックスセット『The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions』[10]をリリース。2003年、このアルバムは100万枚の出荷を記録し、プラチナ・ディスクに認定された。 |

| By 1969, Davis' core working

band consisted of Wayne Shorter on soprano saxophone, Dave Holland on

bass, Chick Corea on electric piano, and Jack DeJohnette on drums.[11]

The group, minus DeJohnette, recorded In a Silent Way (1969), which

also featured Joe Zawinul, John McLaughlin, Tony Williams, and Herbie

Hancock. The album marked the beginning of Davis' "electric period",

incorporating instruments such as the electric piano and guitar and

jazz fusion styles.[11] For his next studio album, Davis wished to

explore his electronic and fusion style even further. While touring

with his five-piece from the spring to August 1969, he introduced new

pieces for his band to play, including early versions of what became

"Miles Runs the Voodoo Down", "Sanctuary", and "Spanish Key".[12] At

this point in his career Davis was influenced by contemporary rock and

funk music, Zawinul's playing with Cannonball Adderley, and the work of

English composer Paul Buckmaster.[13] In August 1969, Davis gathered his band for a rehearsal, one week prior to the booked recording sessions. As well as his five-piece, they were joined by Zawinul, McLaughlin, Larry Young, Lenny White, Don Alias, Juma Santos, and Bennie Maupin.[12] Davis had written simple chord lines, at first for three pianos, which he expanded into a sketch of a larger scale composition. He presented the group with some "musical sketches" and told them they could play anything that came to mind as long as they played off of his chosen chords.[14] Davis had not arranged each piece because he was unsure of the direction the album was to take; he wanted whatever was produced to come from an improvisational process, "not some prearranged shit."[15] Davis booked Columbia's Studio B in New York City from August 19–21, 1969.[12] The session on August 19 began at 10 a.m., the band playing "Bitches Brew" first. Everyone was set up in a half-circle with Davis and Shorter in the middle. In Lenny White’s words: "It was like an orchestra, and Miles was our conductor. We wore headphones. We had to be able to hear each other. There were no guests at that session. No photos allowed. But there was one guest that nobody talked about, Max Roach. All live recording, no overdubs. 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., for three days." ― Lenny White, [1] As usual with Davis' recording sessions during this period, tracks were recorded in sections.[12] Davis gave a few instructions: a tempo count, a few chords or a hint of melody, and suggestions as to mood or tone. Davis liked to work this way; he thought it forced musicians to pay close attention to one another, to their own performances, or to Davis's cues, which could change from moment to moment. On the quieter passages of "Bitches Brew", for example, Davis's voice is audible giving instructions to the musicians, snapping his fingers to indicate tempo, telling the musicians to "Keep it tight" in his distinctive voice, or instructing individuals when to solo ― e.g., saying "John" during the title track.[16] "John McLaughlin" and "Sanctuary" were also recorded during the August 19 session. Towards the end the group rehearsed "Pharaoh's Dance".[12] Despite his reputation as a "cool," melodic improviser, much of Davis' playing on this album is aggressive and explosive, often playing fast runs and venturing into the upper register of the trumpet. His closing solo on "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" is particularly noteworthy in this regard. Davis did not perform on the short piece "John McLaughlin". |

1969年までに、デイヴィスの中心的なバンドは、ソプラノ・サックス

のウェイン・ショーター、ベースのデイヴ・ホランド、エレクトリック・ピアノのチック・コリア、ドラムのジャック・デジョネットで構成されていた

[11]。デジョネットを除いたグループは、ジョー・ザヴィヌル、ジョン・マクラフリン、トニー・ウィリアムズ、ハービー・ハンコックも参加した『In

a Silent

Way』(1969年)をレコーディングした。このアルバムは、エレクトリック・ピアノやギターなどの楽器とジャズ・フュージョンのスタイルを取り入れ

た、デイヴィスの「エレクトリック期」の始まりとなった[11]。次のスタジオ・アルバムでは、デイヴィスはエレクトロニックとフュージョンのスタイルを

さらに追求したいと考えた。1969年春から8月にかけて5人編成でツアーを行う中、「マイルス・ランズ・ザ・ブードゥー・ダウン」、「サンクチュア

リ」、「スパニッシュ・キー」の初期ヴァージョンを含む、バンド演奏のための新しい楽曲を発表した[12]。この時点でデイヴィスは、現代のロックやファ

ンク・ミュージック、ザヴィヌルのキャノンボール・アダレイとの共演、イギリスの作曲家ポール・バックマスターの作品に影響を受けていた[13]。 1969年8月、デイヴィスはレコーディング・セッションの1週間前にバンドを集めてリハーサルを行った。彼の5人組の他に、ザヴィヌル、マクラフリン、 ラリー・ヤング、レニー・ホワイト、ドン・エイリアス、ジュマ・サントス、ベニー・モーピンが参加していた[12]。デイヴィスは、最初は3台のピアノの ために簡単なコード・ラインを書いていたが、それをよりスケールの大きな曲のスケッチに広げていった。彼はグループにいくつかの「音楽的スケッチ」を提示 し、彼が選んだコードから演奏する限り、思いついたものは何でも演奏していいと伝えた[14]。デイヴィスはアルバムの方向性がわからなかったため、各曲 をアレンジしていなかった。彼は、制作されるものが何であれ、即興的なプロセスから生まれたものにしたかったのであり、「あらかじめアレンジされたクソみ たいなものではない」[15]。 デイヴィスは1969年8月19日から21日までニューヨークのコロムビアのスタジオBを予約した[12]。8月19日のセッションは午前10時に始ま り、バンドはまず「Bitches Brew」を演奏した。デイヴィスとショーターを真ん中にして、全員が半円形にセッティングされた。レニー・ホワイトの言葉を借りれば 「まるでオーケストラのようで、マイルスが指揮者だった。私たちはヘッドホンをしていた。お互いの声が聞こえるようにする必要があったんだ。そのセッショ ンには客はいなかった。写真も禁止だった。しかし、誰も話題にしなかったマックス・ローチというゲストがいた。すべて生録音で、オーバーダブはなし。午前 10時から午後1時まで、3日間」。 - レニー・ホワイト、[1] この時期のデイヴィスのレコーディング・セッションの常として、トラックはセクションごとに録音された[12]。デイヴィスはこの方法を好んだ。彼は、 ミュージシャンたちが互いに、自分たちの演奏に、あるいは刻々と変化するデイヴィスの合図に細心の注意を払わざるを得ないと考えたからだ。例えば、 "Bitches Brew "の静かなパッセージでは、デイヴィスの声がミュージシャンに指示を与えているのが聴こえる。指を鳴らしてテンポを示したり、独特の声でミュージシャンに "Keep it tight "と指示したり、ソロのタイミングを指示したりするのだ。終盤、グループは「Pharaoh's Dance」をリハーサルした[12]。 クールでメロディアスなインプロヴァイザーという評判とは裏腹に、このアルバムでのデイヴィスの演奏の多くは攻撃的で爆発的であり、しばしば速いランを演 奏し、トランペットの高音域に踏み込んでいる。マイルス・ランズ・ザ・ブードゥー・ダウン」のエンディング・ソロは、この点で特に注目に値する。デイヴィ スは「ジョン・マクラフリン」という短い曲では演奏していない。 |

| Album title It is not known where the album title came from, and there are various theories as to where it originates.[17] Some believe it was a reference to women in Davis' life who were introducing him to cultural changes in the '60s.[17][18][19] Other explanations have been given.[17] Post-production Significant editing was made to the recorded music. Short sections were spliced together to create longer pieces, and various effects were applied to the recordings. Paul Tingen reports:[20] Bitches Brew also pioneered the application of the studio as a musical instrument, featuring stacks of edits and studio effects that were an integral part of the music. Miles and his producer, Teo Macero, used the recording studio in radical new ways, especially in the title track and the opening track, "Pharaoh's Dance". There were many special effects, like tape loops, tape delays, reverb chambers and echo effects. Through intensive tape editing, Macero concocted many totally new musical structures that were later imitated by the band in live concerts. Macero, who has a classical education and was most likely inspired by '50s and '60s French musique concrète experiments, used tape editing as a form of arranging and composition. "Pharaoh's Dance" contains 19 edits – its famous stop-start opening is entirely constructed in the studio, using repeat loops of certain sections. Later on in the track there are several micro-edits: for example, a one-second-long fragment that first appears at 8:39 is repeated five times between 8:54 and 8:59. The title track contains 15 edits, again with several short tape loops of, in this case, five seconds (at 3:01, 3:07 and 3:12). Therefore, Bitches Brew not only became a controversial classic of musical innovation, it also became renowned for its pioneering use of studio technology. Though Bitches Brew was in many ways revolutionary, perhaps its most important innovation was rhythmic. The rhythm section for this recording consists of two bassists (one playing bass guitar, the other double bass), two to three drummers, two to three electric piano players, and a percussionist, all playing at the same time.[21] As Paul Tanner, Maurice Gerow, and David Megill explain, "like rock groups, Davis gives the rhythm section a central role in the ensemble's activities. His use of such a large rhythm section offers the soloists wide but active expanses for their solos."[21] Tanner, Gerow and Megill further explain that "the harmonies used in this recording move very slowly and function modally rather than in a more tonal fashion typical of mainstream jazz.... The static harmonies and rhythm section's collective embellishment create a very open arena for improvisation. The musical result flows from basic rock patterns to hard bop textures, and at times, even passages that are more characteristic of free jazz."[21] The solo voices heard most prominently on this album are the trumpet and the soprano saxophone, respectively of Miles and Wayne Shorter. Notable also is Bennie Maupin's bass clarinet present on four tracks. The technology of recording, analog tape, disc mastering, and inherent recording time constraints had, by the late sixties, expanded beyond previous limitations and sonic range for the stereo vinyl album, and Bitches Brew reflects this. Its long-form performances include improvised suites with rubato sections, tempo changes or the long, slow crescendo more common to a symphonic orchestral piece or Indian raga form than the three-minute rock song. Starting in 1969, Davis' concerts included some of the material that would become Bitches Brew.[22] Release Bitches Brew was released in March 1970. It gained commercial momentum for the next four months and peaked at No. 35 on the U.S. Billboard 200 for the week of July 4, 1970. This remains Davis' 2nd best performance on the chart behind "Kind of Blue" which has peaked at #3 on Vinyl and #12 in 2020.[23] On September 22, 2003, the album was certified platinum by the RIAA for selling one million copies in the U.S. In addition to the standard stereo version, the album was also mixed for quadraphonic sound. Columbia released a quad LP version, using the SQ matrix system, in 1971. Sony reissued the album in Japan in 2018 on the Super Audio CD format containing both the complete stereo and quadraphonic mixes.[24] Reception and legacy Retrospective professional reviews Review scores Source Rating AllMusic [3] Christgau's Record Guide A−[25] Encyclopedia of Popular Music [26] Entertainment Weekly A[27] Mojo [27] MusicHound Jazz 5/5[28] The Penguin Guide to Jazz [29] The Rolling Stone Album Guide [30] Sputnikmusic 5/5[31] Tom Hull – on the Web A−[32] Reviewing for Rolling Stone in 1970, Langdon Winner said Bitches Brew shows Davis' music expanding in "beauty, subtlety and sheer magnificence", finding it "so rich in its form and substance that it permits and even encourages soaring flights of imagination by anyone who listens". He concluded that the album would "reward in direct proportion to the depth of your own involvement".[33] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau deemed it "good music that's very much like jazz and something like rock",[34] naming it the year's best jazz album and Davis "jazzman of the year" in his ballot for Jazz & Pop magazine.[35] Years later, he had lost some enthusiasm about the album; in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), he called Bitches Brew "a brilliant wash of ideas, so many ideas that it leaves an unfocused impression", with Tony Williams' steadier rock rhythms from In a Silent Way replaced by "subtle shades of Latin and funk polyrhythm that never gather the requisite fervor". He concluded that the music sounded "enormously suggestive, and never less than enjoyable, but not quite compelling. Which is what rock is supposed to be."[25] Selling more than one million copies since it was released, Bitches Brew was viewed by some writers in the 1970s as the album that spurred jazz's renewed popularity with mainstream audiences that decade. As Michael Segell wrote in 1978, jazz was "considered commercially dead" by the 1960s until the album's success "opened the eyes of music-industry executives to the sales potential of jazz-oriented music". This led to other fusion records that "refined" Davis' new style of jazz and sold millions of copies, including Head Hunters (1973) by Herbie Hancock and George Benson's 1976 album Breezin'.[36] Tom Hull, who would later become a jazz critic, has said, "Back in the early '70s we used to listen to Bitches Brew as late night chill-out music – about the only jazz I ran into at the time."[37] According to independent scholar Jane Garry, Bitches Brew defined and popularized the jazz fusion genre, also known as jazz-rock, but it was hated by a number of purists.[2] Jazz critic and producer Bob Rusch recalled, "This to me was not great Black music, but I cynically saw it as part and parcel of the commercial crap that was beginning to choke and bastardize the catalogs of such dependable companies as Blue Note and Prestige.... I hear it 'better' today because there is now so much music that is worse."[38] Despite the controversy the album stirred among the jazz community, it nonetheless topped DownBeat's annual critics' poll in 1970.[39] The Penguin Guide to Jazz called Bitches Brew "one of the most remarkable creative statements of the last half-century, in any artistic form. It is also profoundly flawed, a gigantic torso of burstingly noisy music that absolutely refuses to resolve itself under any recognized guise."[29] In 2003, the album was ranked number 94 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. Nine years later, it went down one spot.[40] In the 2020 list, it climbed to number 87.[41] Along with this accolade, the album has been ranked at or near the top of several other magazines' "best albums" lists in disparate genres.[42] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[43] Experimental jazz drummer Bobby Previte considered Bitches Brew to be "groundbreaking": "How much groundbreaking music do you hear now? It was music that you had that feeling you never heard quite before. It came from another place. How much music do you hear now like that?"[44] Thom Yorke, singer of the English rock band Radiohead, cited it as an influence on their 1997 album OK Computer: "It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that's the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do."[45] The singer Bilal names it among his 25 favorite albums, citing Davis' stylistic reinvention.[46] Rock and jazz musician Donald Fagen criticized the album as "essentially just a big trash-out for Miles ... To me it was just silly, and out of tune, and bad. I couldn't listen to it. It sounded like [Davis] was trying for a funk record, and just picked the wrong guys. They didn't understand how to play funk. They weren't steady enough."[47] |

アルバム・タイトル アルバム・タイトルの由来は定かではなく、諸説ある[17]。60年代の文化的変化を彼に紹介していたデイヴィスの身近にいた女性たちのことを指しているという説もある[17][18][19]。 ポストプロダクション 録音された音楽にはかなりの編集が加えられた。短い部分をつなげて長い曲を作り、録音にはさまざまなエフェクトがかけられた。ポール・ティンゲンは次のように報告している[20]。 ビッチェズ・ブリューはまた、スタジオを楽器として応用した先駆者でもあり、音楽の不可欠な一部である編集やスタジオ・エフェクトの積み重ねを特徴として いる。マイルズとプロデューサーのテオ・マセロは、特にタイトル・トラックとオープニング・トラックの "Pharaoh's Dance "において、レコーディング・スタジオを先鋭的で新しい方法で使用した。テープ・ループ、テープ・ディレイ、リバーブ・チェンバー、エコー・エフェクトな ど、多くの特殊効果があった。集中的なテープ編集によって、マセロはまったく新しい音楽構造を数多く考案し、後にライブ・コンサートでバンドがそれを真似 た。マセロはクラシックの教育を受けており、おそらく50年代と60年代のフランスのミュジーク・コンクレートの実験に触発されたのだろう。 「Pharaoh's Dance』には19の編集が含まれており、有名なストップ・スタートのオープニングは、特定のセクションのリピート・ループを使い、すべてスタジオで構 成されている。例えば、8:39に最初に現れる1秒の断片は、8:54から8:59の間に5回繰り返される。タイトル・トラックには15回の編集があり、 この場合も5秒の短いテープ・ループがいくつかある(3:01、3:07、3:12)。そのため、『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』は音楽的革新の古典として物議 を醸しただけでなく、スタジオ技術の先駆的な使用でも有名になった。 ビッチェズ・ブリューはいろいろな意味で革命的だったが、おそらく最も重要な革新はリズムだった。このレコーディングのリズム・セクションは、2人のベー シスト(1人はベース・ギター、もう1人はコントラバス)、2〜3人のドラマー、2〜3人のエレクトリック・ピアノ奏者、1人のパーカッショニストで構成 されており、全員が同時に演奏している[21]。 ポール・タナー、モーリス・ゲロウ、デヴィッド・メギルが説明するように、「ロック・グループと同様、デイヴィスはリズム・セクションにアンサンブルの中 心的役割を与えている」。彼のこのような大規模なリズム・セクションの使用は、ソリストたちのソロに広く、しかし活動的な広がりを与えている」[21]。 タナー、ゲロウ、メギルはさらに次のように説明している。 「この録音で使われているハーモニーは、メインストリームのジャズに典型的な調性ではなく、非常にゆっくりとした動きで、モード的に機能してい る......。静的なハーモニーとリズム・セクションの集団的な装飾が、インプロヴィゼーションのための非常にオープンな場を作り出している。音楽的な 結果は、基本的なロック・パターンからハード・バップのテクスチャー、そして時にはフリー・ジャズに特徴的なパッセージまで流れている」[21]。 このアルバムで最も顕著に聴かれるソロ・ヴォイスは、マイルスとウェイン・ショーターそれぞれのトランペットとソプラノ・サックスである。また、ベニー・モーピンのバス・クラリネットも4曲で演奏されている。 レコーディングの技術、アナログ・テープ、ディスクのマスタリング、そして固有のレコーディング時間の制約は、60年代後半には、ステレオ・レコード・ア ルバムのそれまでの限界と音の幅を越えて拡大しており、『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』はそれを反映している。その長尺の演奏には、ルバート・セクション、テン ポ・チェンジ、あるいは3分のロック・ソングよりもシンフォニックな管弦楽曲やインドのラーガによく見られる長くゆっくりとしたクレッシェンドを含む即興 組曲が含まれる。1969年以降、デイヴィスのコンサートでは、後にビッチェズ・ブリューとなる楽曲の一部が演奏された[22]。 リリース ビッチェズ・ブリューは1970年3月にリリースされた。その後4ヶ月間商業的な勢いを増し、1970年7月4日の週の全米ビルボード200で35位を記 録した。これは、デイヴィスの同チャートにおける最高位としては、ヴァイナルで3位、2020年に12位を記録した「カインド・オブ・ブルー」に次ぐ2番 目の成績である[23]。2003年9月22日、このアルバムは全米で100万枚を売り上げたとして、RIAAからプラチナ認定を受けた。 通常のステレオ・バージョンに加え、アルバムはクアドラフォニック・サウンド用にミックスされた。コロムビアは1971年、SQマトリックス・システムを 採用したクアッドLP盤をリリース。ソニーは2018年、ステレオ・ミックスとクアドラフォニック・ミックスの両方を収録したスーパー・オーディオCD フォーマットでこのアルバムを日本で再発した[24]。 レセプションとレガシー レトロスペクティブな専門家の評価 レビュースコア 出典 評価 オールミュージック [3] クリストガウのレコードガイド A-[25] ポピュラー音楽百科事典[26] エンターテイメント・ウィークリーA[27] モジョ[27] ミュージックハウンド・ジャズ5/5[28] ペンギン・ガイド・トゥ・ジャズ[29] ローリングストーンアルバムガイド [30] スプートニク音楽 5/5[31] トム・ハル-オン・ザ・ウェブ A-[32]. 1970年に『ローリング・ストーン』誌に寄稿したラングドン・ウィナーは、『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』はデイヴィスの音楽が「美しさ、繊細さ、そして壮大 さ」において拡大していることを示し、「その形式と実質において非常に豊かであり、聴く者の誰もが想像力の高鳴るような飛翔を許容し、助長さえしている」 と評した。ヴィレッジ・ヴォイス』誌の批評家ロバート・クリストガウは、このアルバムを「ジャズのようでもあり、ロックのようでもある良い音楽」と評価し [34]、『ジャズ&ポップ』誌の投票では、その年のベスト・ジャズ・アルバムとデイヴィスを「ジャズマン・オブ・ザ・イヤー」に選んだ[35]: 1981年の『Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies』では、彼はビッチェズ・ブリューを「アイディアの華麗な洗礼、あまりに多くのアイディアのため、焦点の定まらない印象を残す」と呼 び、『In a Silent Way』のトニー・ウィリアムズの安定したロックのリズムは、「ラテンとファンクのポリリズムの微妙な陰影に取って代わられ、必要な熱気を集めることはな い」と述べている。彼は、この音楽は「非常に示唆に富んでおり、決して楽しめないことはないが、説得力には欠ける」と結論づけている。ロックとはそういう ものだ」[25]。 発売以来100万枚以上のセールスを記録した『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』は、1970年代には、ジャズのメインストリームでの人気再燃に拍車をかけたアルバ ムと見る作家もいた。マイケル・セゲルが1978年に書いたように、このアルバムの成功が「音楽業界の重役たちの目をジャズ志向の音楽の売上げの可能性に 開かせる」までは、ジャズは1960年代には「商業的に死んだと考えられていた」。後にジャズ批評家となるトム・ハルは、「70年代初頭、深夜のチルアウ ト・ミュージックとしてビッチェズ・ブリューをよく聴いた。 独立系の研究者ジェーン・ギャリーによれば、ビッチェズ・ブリューは、ジャズ・ロックとしても知られるジャズ・フュージョンというジャンルを定義し、普及 させたが、多くの純粋主義者からは嫌われていた[2]。 ジャズ評論家でプロデューサーのボブ・ラッシュは、「私にとってこれは偉大なブラック・ミュージックではなかったが、ブルーノートやプレステージといった 信頼できる会社のカタログを窒息させ、私物化し始めていた商業的なたわごとの一部分であると冷笑的に見ていた......」と回想している。このアルバム がジャズ・コミュニティーの間で論争を巻き起こしたにもかかわらず、1970年のダウンビートの年間批評家投票では首位を獲得した[39]。 ペンギン・ガイド・トゥ・ジャズ』は『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』を「過去半世紀で、あらゆる芸術形態において、最も驚くべき創造的発言のひとつ」と評した。このアルバムはまた、深い欠陥があり、破裂するようなノイジーな音楽の巨大な胴体であり、どのような認識された装いの下でも、それ自身を解決することを絶対に拒否している」 とも表現する[29]。 2003年、このアルバムはローリング・ストーン誌の「史上最高のアルバム500枚」の94位にランクされた。その9年後、1つ順位を下げた[40]。 2020年のリストでは、87位まで上昇した[41]。この栄誉とともに、このアルバムは、他のいくつかの雑誌の「ベスト・アルバム」リストでも、異なる ジャンルで上位にランクされている[42]。このアルバムは、『1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die』という本にも収録されている[43]。 エクスペリメンタル・ジャズ・ドラマーのボビー・プレバイトは、ビッチェズ・ブリューを「画期的」と評価した: 「今、どれだけ画期的な音楽を聴いているだろうか?今、どれだけ画期的な音楽を聴いているだろうか?それは別の場所から来たものだ。イギリスのロックバン ド、レディオヘッドのヴォーカル、トム・ヨークは、1997年のアルバム『OK Computer』に影響を与えた作品として挙げている: 「何かを作り上げ、それが崩れていくのを見る。それは私たちがやろうとしていたことの核心だった」[45]。歌手のビラルは、デイヴィスのスタイルの改革 を引き合いに出して、お気に入りの25枚のアルバムにこのアルバムを挙げている[46]。ロック/ジャズ・ミュージシャンのドナルド・フェイゲンは、この アルバムを「本質的にマイルスのための大きなゴミ捨て場でしかない」と批判した。私にとっては、ただ愚かで、調子が悪くて、ひどいものだった。聴いていら れなかった。デイビスは)ファンクのレコードを作ろうとして、間違ったメンバーを選んだように聴こえた。彼らはファンクの演奏方法を理解していなかった。 彼らは十分に安定していなかった」[47]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitches_Brew |

|

【文献】

【リンク】