テオドール・アドルノの音楽論

Theodor Adorno's Music theory

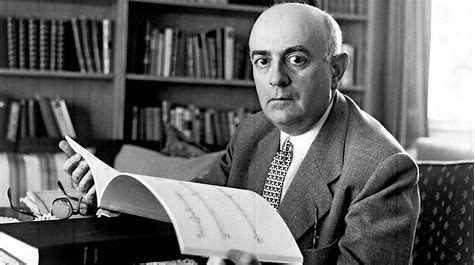

☆ テオドール・アドルノの音楽理論について考える。

古

典的な訓練を受けたピアニストであったアドルノは、アーノルド・シェーンベルクの十二音技法に共鳴し、第二ウィーン楽派のアルバン・ベルクに作曲を師事

した。前衛音楽への傾倒がその後の著作の背景となり、第二次世界大戦中、亡命者としてカリフォルニアに住んでいた二人は、トーマス・マンの小説『ファウス

トゥス博士』での共同作業につながった。死後に出版された『美学論』は、サミュエル・ベケットに捧げる予定だったもので、哲学史が

長年求めてきた感覚と理解の「致命的な分離」を撤回し、美学が形式よりも内容、没入よりも熟考に与える特権を爆発させようとする、現代芸術への生涯をかけ

たコミットメントの集大成である。

「音楽大衆の意識は、物神化された音楽相応のものである」——アドルノ(1998:52)「音楽における物神的性格と聴取の退化」『不協和音』

★アドルノの伝記にみられる音楽

| Musikalische

Schriften Rolf Wiggershaus sieht in der Musikphilosophie den „Ausgangs- und Endpunkt“ des Adorno’schen Denkens.[228] Für Heinz-Klaus Metzger ist er „der erste wahrhaft geschulte Musiker unter den Philosophen“.[229] Seine ersten musikphilosophischen und -soziologischen Aufsätze veröffentlichte er in der Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (1932: Zur gesellschaftlichen Lage der Musik; 1936: Über Jazz, unter dem Pseudonym Hektor Rottweiler; 1938: Über den Fetischcharakter in der Musik und die Regression des Hörens; 1939: Fragmente über Wagner; 1941: On Popular Music).[230] In der 20-bändigen Ausgabe seiner Gesammelten Schriften sind allein acht Bände den musikalischen Schriften Adornos vorbehalten (Bände 12 bis 19), beginnend mit der Philosophie der neuen Musik (Erstausgabe 1949), über die musikalischen Monographien zu Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler und Alban Berg (GS 13) und endend mit der Sammlung seiner Opern- und Konzertkritiken. Dass die musikalischen mit den philosophischen Schriften Adornos eng verzahnt sind, bringt der Autor bereits in seiner ersten Buchveröffentlichung nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, der Philosophie der neuen Musik, zum Ausdruck. In der „Vorrede“ bezeichnet er sie als einen „ausgeführten Exkurs zur Dialektik der Aufklärung“ (GS 12: 11). Adorno spricht von der Affinität zwischen Musik und Philosophie: „Die Philosophie sehnt sich nach der Unmittelbarkeit der Musik, wie sich die Musik nach der ausdrücklichen Bedeutung der Philosophie sehnt.“[231] |

音楽に関する著作 ロルフ・ヴィッゲルスハウスの考えでは、アドルノの思想の「出発点であり終着点」は音楽哲学である。[228] ハインツ・クラウス・メッツガーは、彼を「哲学者の中で初めて本格的に音楽を学んだ人物」とみなしている。[229] 彼は『社会研究誌』に最初の音楽哲学・社会学的なエッセイを掲載した(1932年:「音楽の社会的状況について」、1936年: ジャズについて』、1938年:『音楽におけるフェティッシュな性格と聴覚の退行について』、1939年:『ワーグナーについての断片』、1941年: 『大衆音楽について』)[230] アドルノの著作集(Gesammelte Schriften)全20巻のうち、8巻がアドルノの音楽に関する著作に充てられている(第12巻から第19巻)。『新音楽の哲学』(初版1949年) から始まり、リヒャルト・ワーグナー、グスタフ・マーラー、アルバン・ベルクについての音楽論(GS 13)を経て、オペラとコンサートの批評のコレクションで終わる。アドルノの音楽論が彼の哲学的な著作と密接に織り交ぜられているという事実は、第二次世 界大戦後の最初の著作『新音楽の哲学』ですでに表現されている。「序文」でアドルノは、この著作を「啓蒙の弁証法に関する拡張された余談」と表現している (GS 12: 11)。アドルノは音楽と哲学の親和性について次のように述べている。「哲学は音楽の即時性を切望し、音楽もまた哲学の明示的な意味を切望している」 [231] |

| Zum Verständnis von Musik tragen

nach Adorno sowohl sinnliches Erleben – in seinem Verständnis:

mimetischer Nachvollzug durch Hören, Darstellen und Aufführen – als

auch die begriffliche Reflexion bei. „Ästhetische Reflexion von Musik

ohne mimetischen Nachvollzug ist leer, ästhetische Erfahrung von Musik

ohne begrifflichen Nachvollzug ist taub.“[232] |

アドルノによれば、感覚的な経験(彼の理解では、聴くこと、提示、演奏

による模倣的理解)と概念的な考察の両方が音楽の理解に貢献する。「模倣的理解を伴わない音楽の美的な考察は空虚であり、概念的理解を伴わない音楽の美的

な経験は無感覚である」[232] |

| In seinem frühen Aufsatz von

1932 – Zur gesellschaftlichen Lage der Musik – befindet er, dass alle

Musik das Zeichen der Entfremdung trage und als Ware fungiere. Über

ihre Authentizität entscheide, ob sie sich Marktbedingungen widersetze

oder unterwerfe. Ihre gesellschaftliche Funktion erfülle sie, wenn „sie

in ihrem eigenen Material und nach ihren eigenen Formgesetzen die

gesellschaftlichen Probleme zur Darstellung“ bringe (GS 18: 731). Unter

den Formen der Neuen Musik billigt er Authentizität vornehmlich der

atonalen Musik der Schönberg-Schule zu. Nach Aussage des Komponisten

und Musikwissenschaftlers Dieter Schnebel hatte er „große

Schwierigkeiten mit Musik, die anders strukturiert war als die der

Wiener Schule“.[233] So galten ihm Strawinski als „technisch

reaktionär“ (GS 12: 57) und Paul Hindemith als dessen

neoklassizistisches Pendant; und so begegnete er dem Werk von John Cage

reserviert.[234] |

1932年の初期の論文『音楽の社会的状況について』において、彼は、

すべての音楽には疎外の痕跡があり、商品として機能していると論じている。それが市

場の状況に抵抗するか、それとも従属するかによって、その真正性が決まる。「社会問題を独自の素材で、独自の形式法則に従って提示」するときに、その社会

的機能が果たされる(GS 18:

731)。新音楽の形式の中でも、彼は主にシェーンベルク派の無調音楽に真正性を認めた。作曲家であり音楽学者でもあるディーター・シュネーベルによれ

ば、彼は「ウィーン学派とは異なる構造を持つ音楽に大きな困難を感じていた」という。[233]

例えばストラヴィンスキーは「技術的には反動的」(GS 12:

57)とみなされ、ヒンデミットは新古典主義の対極に位置づけられていた。そのため、彼はジョン・ケージの作品には慎重な態度を示していた。[234] |

| Zu den umstrittensten Themen

seiner musikalischen Schriften zählen sein Verdikt über den Jazz und

seine These vom Materialfortschritt in der Musik. |

彼の音楽に関する著作の中で最も論争を呼んだトピックは、ジャズに関す る彼の評決と、音楽における物質的進歩に関する彼の論文である。 |

| Mit der These „Der Jazz ist Ware

im strikten Sinn“ (GS 17: 77) formulierte Adorno seine erste

prinzipielle Polemik gegen die aufkommende Unterhaltungsindustrie, die

später in der Dialektik der Aufklärung die Bezeichnung Kulturindustrie

erhalten sollte. Martin Jay verweist darauf, dass Adorno den Jazz noch

nicht aus erster Hand kannte.[235] Richard Klein, Mitbegründer des

Projekts und der Zeitschrift Musik & Ästhetik und Mitherausgeber

des Adorno-Handbuchs, spricht von Adornos „notorisch verständnislosen

Äußerungen zum Jazz“.[236] Der Poptheoretiker Diedrich Diederichsen

räumt hingegen ein, dass Adorno die musikalischen Phänomene im Jazz

genau beschrieben, aber daraus die falschen Konsequenzen gezogen

habe.[237] Adorno hat seine Auffassung vom Jazz auch in späteren

Veröffentlichungen nie mehr grundsätzlich verändert.[238] |

「ジャズは厳密な意味で商品である」(GS 17: 77)という論文で、アドルノは、後に『啓蒙の弁証法』で「文化産業」と呼ばれることになる興隆しつつあった娯楽産業に対する最初の根本的な論争を展開し た。マーティン・ジェイは、アドルノは当初、ジャズを直接的に知ることはなかったと指摘している。235] プロジェクトおよび雑誌『Musik & Ästhetik』の共同創設者であり、『アドルノ・ハンドブック』の共同編集者でもあるリチャード・クラインは、アドルノの「ジャズに関する悪名高い理 解不足の主張」について語っている。236] 一方、ポップ理論家のディートリヒ・ディートリヒセンは、アドルノが音楽現象の しかし、そこから導き出された結論は誤りであったと認めている。アドルノは、その後の著作においても、ジャズに対する見方を根本的に変えることはなかっ た。 |

| Zentral für die Musikphilosophie

Adornos ist das Theorem vom unilinearen Fortschritt des musikalischen

Materials, der sich in der „Verbrauchtheit und dem Neuwerden von

Klängen, Techniken und Formen“ manifestiere. Die Vorgeformtheit des

musikalischen Materials verleihe ihm einen Eigensinn und stelle

Anforderungen an die kompositorische Arbeit, die gleichwohl die

Spontaneität des Subjekts verlange.[239] „Die Forderungen, die vom

Material ans Subjekt ergehen, rühren davon her, daß das ‚Material‘

selber sedimentierter Geist, ein gesellschaftlich, durchs Bewußtsein

von Menschen hindurch Präformiertes ist. Als ihrer selbstvergessene,

vormalige Subjektivität hat solcher objektive Geist des Materials seine

eigenen Bewegungsgesetze.“ (GS 12: 39) Der Materialbegriff sei

gleichsam die „Schnittstelle zwischen Kunst und Gesellschaft“. Als

„Objektivation künstlerischer, geistiger Arbeit“ berge es – vermittelt

durch das in der Gesellschaft seiner Zeit verankerte Bewusstsein des

Künstlers – „Spuren der jeweils herrschenden Gesellschaft“.[240] |

アドルノの音楽哲学の中心は、音楽素材の一方向的な発展の定理であり、

それは「音、テクニック、形式の消費と刷新」という形で現れる。音楽素材のあらかじめ形成された性質は、それに頑固さを与え、作曲作業に要求を突きつけ

る。しかし、それにもかかわらず、作曲作業には主題の自発性が求められる。[239]

「素材から主題に生じる要求は、『素材』自体が沈殿した精神であり、人間の意識を通じて社会的にあらかじめ形成されたものであるという事実から生じる。自

己を忘れたかつての主観として、このような客観的精神は独自の運動法則を持っている」(GS 12: 39)

素材という概念は、いわば「芸術と社会の接点」である。「芸術的・知的作業の客観化」として、それは、同時代の社会に根ざした芸術家の意識を媒介として、

「それぞれの支配的社会の痕跡」を含んでいる。[240] |

| Als ein Schüler der

Schönberg-Schule sieht Adorno im Übergang von der Tonalität zur

Atonalität der Zwölftontechnik einen geschichtlich unausweichlichen

Schritt, analog demjenigen von der Gegenständlichkeit zur Abstraktion

in der Malerei (GS 12: 15). Der Musikwissenschaftler Carl Dahlhaus

beurteilt Adornos Stellung zum Zwölftonsystem wie folgt: Einerseits

hielt er es „für die notwendige Konsequenz aus der fortschreitenden

Verdichtung der thematischen Arbeit von Beethoven über Brahms bis zu

Schönberg, andererseits sah er in ihr einen Systemzwang, der die Musik

gleichsam aushöhlte. Das blieb bei ihm als offene Dialektik

stehen.“[241] In seinem Kranichsteiner Vortrag von 1961 Vers une

musique informelle betrachtet Adorno die Zwölftontechnik als

notwendiges Durchgangsstadium „zur Überwindung der Tonalität und hin zu

einer befreiten, nachtonalen Musik“ – einer musique informelle.[242] Zu

ihrer Charakterisierung verwendet Adorno starke Bilder: Sie sei „in

allen Dimensionen […] ein Bild der Freiheit“ und „ein wenig wie Kants

ewiger Frieden“ (GS 16: 540). |

アドルノはシェーンベルク派の学生として、12音技法における調性から

無調性への移行を、絵画における具象から抽象への移行に類似した歴史的に不可避なス テップと見なしている(GS 12:

15)。音楽学者カール・ダールハウスは、12音技法に関するアドルノの立場を次のように評価している。一方では、それは「ベートーヴェンからブラーム

ス、シェーンベルクへと進むにつれ、主題の作業が徐々に圧縮されていく必然的な帰結である」と彼は考えた。他方では、彼は十二音技法を、いわば音楽を空洞

化するようなシステム上の制約と捉えた。彼にとって、それは開かれた弁証法として残った。」[241]

1961年のクランヒシュタイン講演「無定形音楽への道」において、アドルノは12音技法を「調性を克服し、解放されたポスト・トーナルな音楽」すなわち

無定形音楽を達成するための必要な過渡期の段階とみなしている。[242]

アドルノはそれを特徴づけるために強いイメージを用いている。「あらゆる次元において、それは自由のイメージである」とし、「カントの永遠平和に少し似て

いる」(GS 16: 540)と表現している。 |

| In den 1960er Jahren

veröffentlichte er, nach Eislers Tod, die gemeinsam mit ihm in den USA

geschriebene Arbeit Komposition für den Film unter beider Namen.[243] |

1960年代、アイスラーの死後、彼はアメリカでアイスラーと共同で書 いた作品『映画のための作曲』を、両者の名前で発表した。[243] |

| Kompositionen Adorno verstand sich in seiner Selbsteinschätzung als „Musiker der zweiten Wiener Schule“.[244] Als Komponist hat er jedoch nur ein schmales Werk hinterlassen, darunter Klavierstücke, meistens Miniaturen, Lieder, Orchesterstücke und zwei Fragmente aus einer geplanten Oper.[245] Nach 1945 hat er das Komponieren ganz aufgegeben.[246] |

作曲 アドルノは自らを「第二ウィーン学派の音楽家」とみなしていた。[244] しかし、作曲家としては、ピアノ曲(ほとんどが小品)、歌曲、管弦楽曲、そして計画されたオペラの断片2曲など、ごくわずかな作品しか残していない。 |

| Der französische Dirigent und

Komponist René Leibowitz rechnet Adornos Kompositionen der freien

Atonalität zu. Sie seien völlig von den klassischen tonalen Funktionen

emanzipiert, ohne sich – bis auf wenige Ausnahmen – „den genauen

Prinzipien der Reihen- oder Zwölftonkompositionen zu unterwerfen“.[247]

Der Komponist Dieter Schnebel verortet sie zwischen den Kompositionen

Anton Weberns und Alban Bergs.[248] Adornos „authentische

kompositorische Aktivität“ ist Leibowitz zufolge dem hohen Niveau

seiner musiktheoretischen Schriften zugutegekommen.[249] Dem

Komponisten Hans Werner Henze klangen Adornos Lieder, die er ihm am

Klavier vorgespielt und vorgesungen hatte, „wie eine intelligente

Fälschung“.[250] |

フランスの指揮者兼作曲家ルネ・レイボヴィッツは、アドルノの作曲を自

由無調に分類している。それらは古典的な調性機能から完全に解放されており、いくつ

かの例外はあるものの、「厳密な系列作曲法や12音作曲法の原則に従う」ことはなかった。[247]

作曲家のディーター・シュネーベルは、アドルノの作品をアントン・ヴェーベルンとアルバン・ベルクの作品の間に位置づけている。[248]

ライボヴィッツによると、アドルノの「真正な作曲活動」は、彼の音楽理論に関する著作の水準の高さに寄与したという

。作曲家のハンス・ヴェルナー・ヘンツェは、アドルノがピアノで弾いて歌ってくれた曲を「知的な偽物」のように感じたという。 |

| Von Adornos Kompositionen wurden

zu seinen Lebzeiten nur die Sechs kurzen Orchesterstücke. op. 4,

gedruckt; die Partitur erschien 1968 bei Ricordi in Mailand.

Heinz-Klaus Metzger, ein Freund Adornos, gab gemeinsam mit dem

Komponisten Rainer Riehn Adornos Kompositionen in zwei Bänden in der

Münchner edition text + kritik heraus (1981). 2007 erschien,

herausgegeben von Maria Luisa Lopez-Vito und Ulrich Krämer, ein

abschließender dritter Band von Adornos Kompositionen, der neben den

Klavierstücken im Nachlass vorhandene, vom Komponisten jedoch

verworfene Kompositionen enthält. |

存命中に出版されたのは「Six Short Orchestral

Pieces, op.

4」のみで、楽譜は1968年にミラノのリコルディ社から出版された。アドルノの友人であったハインツ・クラウス・メッツガーは、作曲家のライナー・リー

エンとともに、アドルノの作品を2巻にまとめたものをミュンヘンのテキスト+クリティック社から出版した(1981年)。2007年には、マリア・ルイ

サ・ロペス=ヴィトとウルリッヒ・クレーマーによってアドルノの作曲作品の最終的な第3巻が出版された。この第3巻には、ピアノ曲に加えて、作曲家によっ

て却下された遺作の作曲作品も含まれている。 |

| Gespielt wurde der Komponist

Adorno vor 1933 gelegentlich, erst seit den fünfziger Jahren etwas

häufiger. 1923 wurde ein Streichquartett des jungen Komponisten als

Teil eines Konzerts des Lange-Quartetts aufgeführt, das ihm die

Anerkennung eines Kritikers eintrug, „fast gleichberechtigt neben

seinem Lehrer Bernhard Sekles und seinem Rivalen Paul Hindemith

genannt“ zu werden.[251] Im Dezember 1926 wurden seine unter der Ägide

Bergs entstandenen Zwei Stücke für Streichquartett. op. 2, im Rahmen

des Programms der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Neue Musik vom

Kolisch-Quartett uraufgeführt,[252] 1928 seine Sechs kurzen

Orchesterstücke. op. 4, in Berlin unter Leitung von Walter Herbert.[253] |

作曲家アドルノは、1933年以前にも時折演奏されていたが、1950

年代以降はより頻繁に演奏されるようになった。1923年には、若い作曲家の弦楽四

重奏曲が、ランゲ弦楽四重奏団の演奏会で演奏され、批評家から「師ベルンハルト・ゼックレスとライバルのパウル・ヒンデミットとほぼ肩を並べる」と評され

た。[251] 1926年12月には、ベルクの庇護を受けて作曲された彼の弦楽四重奏曲第2番作品2が、

1926年12月、国際新音楽協会のプログラムの一環として、コリッシュ弦楽四重奏団により初演された。[252]

1928年には、彼の「6つの短い管弦楽曲」作品4が、ベルリンでヴァルター・ハーバートの指揮により初演された。 |

| Die Dirigenten Gary Bertini,

Michael Gielen, Giuseppe Sinopoli und Hans Zender sowie der Violinist

Walter Levin mit dem LaSalle String Quartet setzten sich für den

Komponisten Adorno ein. Die Sängerin Carla Henius hat sich sehr für

sein Schaffen eingesetzt; mit ihr trat er manchmal auch gemeinsam

auf.[254] Die Pianistin Maria Luisa Lopez-Vito hat seit 1981 die

Klavierstücke Adornos nach und nach bei Konzerten in Palermo, Bozen,

Berlin, Hamburg und an anderen Orten uraufgeführt. Frühe

Streichquartette wurden vom Neuen Leipziger Streichquartett,

Streichtrios vom Freiburger trio recherche uraufgeführt. Unter dem

schwachen Echo, das seine Kompositionen fanden, hat Adorno gelitten. |

指揮者のゲイリー・ベルティーニ、ミヒャエル・ギーレン、ジュゼッペ・

シノーポリ、ハンス・ツェンダー、またラサール弦楽四重奏団のヴァイオリニスト、

ウォルター・レヴィンはアドルノを支援した。歌手のカルラ・ヘーニウスは彼の作品の熱心な支持者であり、時には彼女と共演した。ピアニストのマリア・ルイ

サ・ロペス=ヴィトは、1981年以降、パレルモ、ボルツァーノ、ベルリン、ハンブルクなど各地のコンサートでアドルノのピアノ曲を初演している。初期の

弦楽四重奏曲はライプツィヒ弦楽四重奏団、弦楽三重奏曲はフライブルク・トリオ・レシェルシュによって初演された。アドルノは自身の作曲に対する反応の弱

さに苦しんだ。 |

| Die musiktheoretische Position

Adornos wurde bereits vor der Postmoderne in Frage gestellt. In einer

resümierenden Kritik monierte der Habermas-Schüler Albrecht Wellmer,

dass Adorno mit seiner These eines unilateralen Fortschritts und eines

eindeutig bestimmbaren Entwicklungsstandes des musikalischen Materials

Debussy, Varèse, Bartók, Strawinsky und Ives beiseite geschoben oder

offen als Irrwege diffamiert habe. Eine „eigentümliche Blickverengung“

und die „Fixierung auf die deutsch-österreichische Musiktradition“

hätten ihn den „produktiven Pluralismus von Wegen zur Neuen Musik im

20. Jahrhundert“ verkennen lassen.[274] |

アドルノの音楽理論に対する立場は、ポストモダニズム以前からすでに疑

問視されていた。批判的な総括として、ハーバーマスの弟子であるアルブレヒト・ウェ

ルマーは、アドルノが一方的な進歩論と音楽素材の明確に決定可能な発展状態というテーゼを掲げたことで、ドビュッシー、ヴァレーズ、バルトーク、ストラ

ヴィンスキー、アイヴズを脇に追いやったり、あるいは公然と逸脱として中傷したりしたと不満を述べている。「偏狭な視野」と「ドイツ・オーストリアの音楽

伝統への固執」が、彼をして「20世紀における新音楽への多様な創造的アプローチ」を誤って判断させてしまったのである。[274] |

| Kompositionen Vier Gedichte von Stefan George für Singstimme und Klavier, op. 1 (1925–1928) Zwei Stücke für Streichquartett, op. 2 (1925–1926) Vier Lieder für eine mittlere Stimme und Klavier, op. 3 (1928) Sechs kurze Orchesterstücke, op. 4 (1929) Klage. Sechs Lieder für Singstimme und Klavier, op. 5 (1938–1941) Sechs Bagatellen für Singstimme und Klavier, op. 6 (1923–1942) Vier Lieder nach Gedichten von Stefan George für Singstimme und Klavier, op. 7 (1944) Drei Gedichte von Theodor Däubler für vierstimmigen Frauenchor a cappella, op. 8 (1923–1945) Zwei Propagandagedichte für Singstimme und Klavier, o. O. (1943) Sept chansons populaires francaises, arrangées pour une voix et piano, o. O. (1925–1939) Zwei Lieder mit Orchester aus dem geplanten Singspiel Der Schatz des Indianer-Joe nach Mark Twain, o. O. (1932/33) Kinderjahr. Sechs Stücke aus op. 68 von Robert Schumann, für kleines Orchester gesetzt, o. O. (1941) Kompositionen aus dem Nachlaß (Klavierstücke, Klavierlieder, Streichquartette, Streichtrios u. a.), vgl. Theodor W. Adorno: Kompositionen Band 3. hg. von Maria Luisa Lopez-Vito und Ulrich Krämer, München 2007. |

作曲 ステファン・ゲオルゲによる4つの詩、声楽とピアノのための作品1(1925年-1928年) 弦楽四重奏のための2つの小品、作品2(1925年-1926年) 中声域の声楽とピアノのための4つの歌曲、作品3(1928年) 6つの短い管弦楽曲、作品4(1929年) 嘆き。声楽とピアノのための6つの歌曲、作品5(1938年~1941年) 声楽とピアノのための6つのバガテル、作品6(1923年~1942年) シュテファン・ゲオルゲの詩による4つの歌曲、作品7(1944年) テオドール・デューブルの詩による3つの作品、女声4部合唱アカペラ、作品8(1923年~1945年) 日付不詳の2つのプロパガンダ詩、声楽とピアノのための(1943年) 日付不詳の7つのフランス民謡、声楽とピアノのための編曲(1925年~1939年) マーク・トウェイン原作のミュージカル・コメディ『インディアン・ジョーの秘宝』からオーケストラ伴奏付きの2曲、作曲地不明(1932/33年 ロベルト・シューマン作曲作品68の6曲、小編成オーケストラ用編曲、作曲地不明(1941年 遺作からの作品(ピアノ曲、ピアノ曲、弦楽四重奏曲、弦楽三重奏曲など)については、テオドール・W・アドルノ著『作曲作品集』第3巻を参照のこと。マリ ア・ルイサ・ロペス=ヴィトとウルリッヒ・クレーマー編、ミュンヘン2007年。 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_W._Adorno |

Theodor

W. Adorno: String Quartet (1921)

★

音楽と文化産業

| Music and the Culture Industry Adorno criticized jazz and popular music, viewing it as part of the culture industry, that contributes to the present sustainability of capitalism by rendering it "aesthetically pleasing" and "agreeable".[70] |

音楽と文化産業 アドルノはジャズやポピュラー音楽を文化産業の一部とみなし、それが「美的快楽」や「好感」を与えることによって資本主義の現在の持続可能性に寄与してい ると批判した[70]。 |

| In his

early essays for the Vienna-based journal Anbruch, Adorno claimed that

musical progress is proportional to the composer's ability to

constructively deal with the possibilities and limitations contained

within what he called the "musical material". For Adorno, twelve-tone

serialism constitutes a decisive, historically developed method of

composition. The objective validity of composition, according to him,

rests with neither the composer's genius nor the work's conformity with

prior standards, but with the way in which the work coherently

expresses the dialectic of the material. In this sense, the

contemporary absence of composers of the status of Bach or Beethoven is

not the sign of musical regression; instead, new music is to be

credited with laying bare aspects of the musical material previously

repressed: The musical material's liberation from number, the harmonic

series and tonal harmony. Thus, historical progress is achieved only by

the composer who "submits to the work and seemingly does not undertake

anything active except to follow where it leads." Because historical

experience and social relations are embedded within this musical

material, it is to the analysis of such material that the critic must

turn. In the face of this radical liberation of the musical material,

Adorno came to criticize those who, like Stravinsky, withdrew from this

freedom by taking recourse to forms of the past as well as those who

turned twelve-tone composition into a technique that dictated the rules

of composition. |

ウィーンを拠点とする雑誌『アンブルッフ』

に寄せた初期のエッセイの中で、アドルノは、音楽の進歩は、彼が「音楽的素材」と呼ぶものの中に含まれる可能性

と限界に建設的に対処する作曲家の能力に比例すると主張している。アドルノにとって、12音による直列主義は、歴史的に発展した決定的な作曲法である。彼

によれば、作曲の客観的妥当性は、作曲家の天才性でも、作品が事前の基準に適合しているかどうかでもなく、作品が素材の弁証法を首尾一貫して表現している

かどうかにかかっている。この意味で、バッハやベートーヴェンのような地位の作曲家が現代に不在であることは、音楽的後退の兆候ではない:

音楽素材が数、和声系列、調性和声から解放されたのだ。したがって、歴史的進歩は、"作品に服従し、それが導くところに従う以外には、一見何も積極的に引

き受けない

"作曲家によってのみ達成されるのである。歴史的経験と社会的関係は、この音楽的素材の中に埋め込まれているのだから、批評家が目を向けなければならない

のは、そのような素材の分析なのである。このように音楽的素材がラディカルに解放される中で、アドルノは、ストラヴィンスキーのように過去の形式に依拠す

ることでこの自由から遠ざかる人々や、12音作曲を作曲のルールを規定する技法に変えてしまう人々を批判するようになった。 |

| Adorno

saw the culture industry as an arena in which critical tendencies or

potentialities were eliminated. He argued that the culture industry,

which produced and circulated cultural commodities through the mass

media, manipulated the population. Popular culture was identified as a

reason why people become passive; the easy pleasures available through

consumption of popular culture made people docile and content, no

matter how terrible their economic circumstances. "Capitalist

production so confines them, body and soul, that they fall helpless

victims to what is offered them."[71] The differences among cultural

goods make them appear different, but they are in fact just variations

on the same theme. He wrote that "the same thing is offered to

everybody by the standardized production of consumption goods", but

this is concealed under "the manipulation of taste and the official

culture's pretense of individualism".[72] By doing so, the culture

industry appeals to every single consumer in a unique and personalized

way, all while maintaining minimal costs and effort on their behalf.

Consumers purchase the illusion that every commodity or product is

tailored to the individual's personal preference, by incorporating

subtle modifications or inexpensive "add-ons" in order to keep the

consumer returning for new purchases, and therefore more revenue for

the corporation system. Adorno conceptualized this phenomenon as

pseudo-individualisation and the always-the-same.[citation needed] |

ア

ドルノは、文化産業が批判的傾向や潜在性を排除する場であると考えた。彼は、マスメディアを通じて文化商品を生産し流通させる文化産業が、人々を操作し

ていると主張した。大衆文化は、人々が受動的になる原因として特定された。大衆文化の消費を通じて得られる安易な快楽は、人々を従順にし、どんなにひどい

経済状況であっても満足させる。「資本主義的生産は、彼らを肉体的にも精神的にも拘束し、提供されたものに対して無力な犠牲者となる」[71]

。彼は「標準化された消費財の生産によって、誰にでも同じものが提供される」と書いているが、これは「嗜好の操作と公的な文化による個人主義の見せかけ」

の下に隠されている[72]。そうすることで、文化産業は消費者のために最小限のコストと労力を維持しながら、ユニークで個人化された方法で消費者一人ひ

とりにアピールする。消費者は、新たな購入のために消費者をリピートさせ、したがって企業システムにより多くの収益をもたらすために、微妙な修正や安価な

「アドオン」を組み込むことによって、あらゆる商品や製品が個人の好みに合わせて作られているという幻想を購入する。アドルノはこの現象を「擬似個人化」

と「いつも同じもの」として概念化した[要出典]。 |

| Adorno's

analysis allowed for a critique of mass culture from the left that

balanced the critique of popular culture from the right. From both

perspectives—left and right—the nature of cultural production was felt

to be at the root of social and moral problems resulting from the

consumption of culture. However, while the critique from the right

emphasized moral degeneracy ascribed to sexual and racial influences

within popular culture, Adorno located the problem, not with the

content, but with the objective realities of the production of mass

culture and its effects, for instance, as a form of reverse psychology.

[citation needed] Thinkers influenced by Adorno believe that today's

society has evolved in a direction foreseen by him, especially in

regard to the past (Auschwitz), morals, or the Culture Industry. The

latter has become a particularly productive, yet highly contested term

in cultural studies. Many of Adorno's reflections on aesthetics and

music have only just begun to be debated. A collection of essays on the

subject, many of which had not previously been translated into English,

has only recently been collected and published as Essays on Music.[73] |

アドルノの分析によって、左派から

の大衆文化批判は、右派からの大衆文化批判と均衡を保つことができた。左派と右派の両方の視点から、文化生産の本質が文

化の消費から生じる社会的・道徳的問題の根底にあると考えられていた。しかし、右派からの批判が大衆文化における性的・人種的影響に起因する道徳的退廃を

強調するのに対して、アドルノは内容ではなく、例えば逆心理学のような大衆文化の生産とその影響の客観的現実に問題を見出した。[特に過去(アウシュ

ヴィッツ)、道徳、文化産業に関しては。後者は、カルチュラル・スタディーズにおいて、特に生産的でありながら、非常に論争的な用語となっている。美学と

音楽に関するアドルノの考察の多くは、まだ議論が始まったばかりである。この主題に関するエッセイ集は、その多くがこれまで英語に翻訳されておらず、つい

最近になって『Essays on Music』として収集・出版されたばかりである[73]。 |

| Adorno's

work in the years before his death was shaped by the idea of "negative

dialectics", set out especially in his book of that title. A key notion

in the work of the Frankfurt School since Dialectic of Enlightenment

had been the idea of thought becoming an instrument of domination that

subsumes all objects under the control of the (dominant) subject,

especially through the notion of identity, that is, of identifying as

real in nature and society only that which harmonized or fit with

dominant concepts, and regarding as unreal or non-existent everything

that did not. [citation needed] Adorno's "negative dialectics" was an

attempt to articulate a non-dominating thought that would recognize its

limitations and accept the non-identity and reality of that which could

not be subsumed under the subject's concepts. Indeed, Adorno sought to

ground the critical bite of his sociological work in his critique of

identity, which he took to be a reification in thought of the commodity

form or exchange relation which always presumes a false identity

between different things. The potential to criticize arises from the

gap between the concept and the object, which can never go into the

former without remainder. This gap, this non-identity in identity, was

the secret to a critique of both material life and conceptual

reflection.[citation needed] |

ア

ドルノが亡くなる前の数年間における彼の仕事は、「否定的弁証法」の考え方によって形成されており、特にそのタイトルの著書で述べられている。啓蒙の弁

証法』以来のフランクフルト学派の仕事における重要な考え方は、思考が(支配的な)主体の支配のもとにすべての対象を従属させる支配の道具になるという考

え方であり、特に同一性、つまり支配的な概念に調和するもの、あるいは適合するものだけを自然や社会において実在するものとして識別し、そうでないものは

すべて非現実的なもの、あるいは存在しないものとみなすという考え方であった。[アドルノの「否定的弁証法」は、その限界を認識し、主体の概念に包摂され

ないものの非同一性と現実性を受け入れる非支配的な思考を明確にしようとする試みであった。実際、アドルノは自身の社会学的研究の批評的咬み合わせを、ア

イデンティティの批評に求めようとした。アイデンティティの批評は、異なるものの間に常に誤った同一性を前提とする商品形態や交換関係の思考における再定

義であるとした。批判の可能性は、概念と対象との間のギャップから生じる。このギャップ、同一性における非同一性こそが、物質的生活と概念的考察の両方に

対する批判の秘訣であった[要出典]。 |

| Adorno's

reputation as a musicologist remains controversial. His sweeping

criticisms of jazz and championing of the Second Viennese School in

opposition to Stravinsky have caused him to fall out of favor.[74] The

distinguished American scholar Richard Taruskin[75] declared Adorno to

be "preposterously over-rated." The eminent pianist and critic Charles

Rosen saw Adorno's book The Philosophy of New Music as "largely a

fraudulent presentation, a work of polemic that pretends to be an

objective study."[76] Even a fellow Marxist such as the historian and

jazz critic Eric Hobsbawm saw Adorno's writings as containing "some of

the stupidest pages ever written about jazz".[77] The British

philosopher Roger Scruton saw Adorno as producing "reams of turgid

nonsense devoted to showing that the American people are just as

alienated as Marxism requires them to be, and that their cheerful

life-affirming music is a 'fetishized' commodity, expressive of their

deep spiritual enslavement to the capitalist machine."[70] Irritation

with Adorno's tunnel vision started even while he was alive. He may

have championed Schoenberg, but the composer notably failed to return

the compliment: "I have never been able to bear the fellow [...] It is

disgusting, by the way, how he treats Stravinsky."[78] Another

composer, Luciano Berio said, in interview, "It's not easy to

completely refute anything that Adorno writes – he was, after all, one

of the most acute, and also one of the most negative intellects to

excavate the creativity of the past 150 years... He forgets that one of

the most cunning and interesting aspects of consumer music, the mass

media, and indeed of capitalism itself, is their fluidity, their

unending capacity for adaptation and assimilation."[79] |

音

楽学者としてのアドルノの評判は、いまだに論争の的となっている。ジャズに対する徹底的な批判と、ストラヴィンスキーと対立する第二ウィーン楽派の擁護

によって、彼の人気は失墜した[74]。著名なアメリカの学者リチャード・タルスキン[75]は、アドルノを「とんでもなく過大評価されている」と断じ

た。著名なピアニストであり批評家であるチャールズ・ローゼンは、アドルノの著書『The Philosophy of New

Music』を「大部分は詐欺的なプレゼンテーションであり、客観的な研究のふりをした極論の作品である」と見ている[76]。歴史家でありジャズ批評家

であるエリック・ホブズボームのような同じマルクス主義者でさえも、アドルノの著作には「ジャズについて書かれた最も愚かなページのいくつか」が含まれて

いると見ている。

[イギリスの哲学者ロジャー・スクルトンは、アドルノが「アメリカ国民がマルクス主義が要求するように疎外されており、彼らの陽気な生を肯定する音楽は、

資本主義機械に対する彼らの深い精神的奴隷化を表現する『フェティシズム化された』商品であることを示すことに捧げられた、退屈なナンセンスの数々」を生

み出していると見ていた[70]。アドルノのトンネル・ビジョンに対する苛立ちは、彼が生きていたときから始まっていた。彼はシェーンベルクを支持したか

もしれないが、シェーンベルクはその賛辞に応えることができなかった:

「ちなみに、彼がストラヴィンスキーをどう扱うかはうんざりするほどだ」[78]。別の作曲家ルチアーノ・ベリオはインタビューで、「アドルノが書くこと

に完全に反論するのは簡単ではない。彼は、消費者音楽、マスメディア、ひいては資本主義そのものの最も狡猾で興味深い側面のひとつが、それらの流動性、適

応と同化の果てしない能力であることを忘れている」[79]。 |

| On

the other hand, the scholar Slavoj Žižek has written a foreword to

Adorno's In Search of Wagner,[80] in which Žižek attributes an

"emancipatory impulse" to the same book—although Žižek also suggests

that fidelity to this impulse demands "a betrayal of the explicit

theses of Adorno's Wagner study".[81] |

他

方、学者スラヴォイ・ジジェクはアドルノの『ワーグナーを探して』への序文を書いており[80]、その中でジジェクは同書に「解放的な衝動」があるとし

ている-ただしジジェクはこの衝動に忠実であることが「アドルノのワーグナー研究の明確なテーゼに対する裏切り」を要求しているとも示唆している

[81]。 |

| Writing

in the New Yorker in 2014, music critic Alex Ross, argued that Adorno's

work has a renewed importance in the digital age: "The pop hegemony is

all but complete, its superstars dominating the media and wielding the

economic might of tycoons ... Culture appears more monolithic than

ever, with a few gigantic corporations—Google, Apple, Facebook,

Amazon—presiding over unprecedented monopolies".[82] |

2014年に『ニューヨーカー』誌に寄稿し

た音楽評論家のアレックス・ロスは、アドルノの著作がデジタル時代において改めて重要性を帯びていると主張して

いる。グーグル、アップル、フェイスブック、アマゾンといった少数の巨大企業が前例のない独占を支配しており、文化はかつてないほど一枚岩に見える」

[82]。 |

| Adorno's critique of commercial

media capitalism continues to be influential. There is much scholarship

influenced by Adorno on how Western entertainment industries strengthen

transnational capitalism and reinforce a Western cultural

dominance.[83] Adornean critique can be found in works such as Tanner

Mirrlees' "The US Empire's Culture Industry" which focus upon how

Western commercial entertainment is artificially reinforced by

transnational media corporations rather than being a local culture.[84] |

アドルノの商業メディア資本主義批判は今なお影響力を保っている。西洋

の娯楽産業が如何に多国籍資本主義を強化し西洋文化の優位性を固めるかについて、アドルノの影響を受けた研究は多い[83]。タナー・ミルリーズの『米国

帝国の文化産業』のような著作にはアドルノ的批判が見られ、西洋の商業娯楽が地域文化ではなく多国籍メディア企業によって人為的に強化されている点を論じ

ている[84]。 |

| The five components of recognition Adorno states that a start to understand the recognition in respect of any particular song hit may be made by drafting a scheme which divides the experience of recognition into its different components. All the factors people enumerate are interwoven to a degree that would be impossible to separate from one another in reality. Adorno's scheme is directed towards the different objective elements involved in the experience of recognition:[85] 1. Vague remembrance 2. Actual identification 3. Subsumption by label 4. Self-reflection and act of recognition 5. Psychological transfer of recognition-authority to the object |

認識の五つの構成要素 アドルノは、特定のヒット曲に対する認識を理解する第一歩として、認識体験を異なる構成要素に分割する枠組みを構築することから始められると述べている。 人々が列挙する全ての要素は、現実において互いに分離不可能なほどに複雑に絡み合っている。アドルノの枠組みは、認識体験に関わる様々な客観的要素に向け られている: [85] 1. 漠然とした記憶 2. 実際の同一視 3. ラベルによる包含 4. 自己反省と認識行為 5. 認識の権威を対象へ移す心理的転移 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_W._Adorno |

★

| ア

ドルノの音楽哲学の核心は、シェーンベルク、ウェーベルン、ブーレーズの作品の形をとったモダニズムは、過去の音楽と現在の音楽の両方に対して擁護される

べき、本格的な音楽の断絶を表しているという考えです。それは現代社会の破壊的な特徴に屈しつつありました。アドルノは、音楽の「英雄的な」時代は

1910年から1920年の10年間であり、その前は初期ブルジョワ文化の矛盾によって楽曲の奥深さに制限が設けられ、その後は「文化産業」がその破壊的

な魅力を発揮したと信じていた。 アドルノがなぜ「新しい音楽」として知られる音楽を擁護したのかを理解するには、大量生産時代の音楽制作に対する彼の批判を概説する必要がある。彼にとっ て、本格的な音楽は、市場の役割と音楽大衆の状況という 2 つの相互に関連した圧力に直面しています。第一に、アドルノによれば、音楽の流通を管理する大企業の発展は「芸術的ゴミの処分」につながっている、なぜな ら音楽制作のパターンが大量販売を達成したいという最優先の欲求によって形作られてきたからである――したがって、それはつまり、視聴者の好みの最小公倍 数に一致します。さらに「一部の作曲家は生き残るために、現代人であるふりをして、打算的な弱気さによって大衆文化に適応している」。また、以前の時代と 比較すると、技術的には劣った作曲家でも輝かしいキャリアを持つことができ、「どこでも好事家が初めて偉大な作曲家として世に出ており、今や概して経済的 に中央集権化した音楽生活により、大衆が彼らを認めるようになった」 。」 「文化産業は、消費のために割り当てられた自由時間に無理をしないように被害者を教育してきた」。このコメントはマルクスの疎外論と、労働が非人間化さ れ、労働と余暇の間に不自然な分裂が生じているという考えを思い起こさせる。労働者はできるだけ早く仕事を終えて、明らかに自分のものであると思われる自 分の生活領域に飛び込みます。しかし、もちろん消費者社会から逃れることはできません。消費者社会は、商品をできるだけ効率的に販売したいという欲求か ら、視聴者全員が同じ好みを持つことを好む。 アドルノはシェーンベルク、ベルク、ウェーベルンの「新しい音楽」を擁護したのだろうか?アドルノは、これらの作曲家の技術を、音楽の一般的な理解の仕方 に対する根本的な革命であり、本格的な音楽を損なう圧力に抵抗することを可能にする革命であると考えた。 https://journalofmusic.com/opinion/adorno-s-philosophy-music |

|

リ ンク

| Theodor

Adorno, the influential German philosopher and sociologist, was quite

critical of jazz music. Here are some of the key reasons why Adorno

disliked jazz: |

影響力のあるドイツの哲学者であり社会学者であったテオドール・アドル

ノは、ジャズ音楽に対してかなり批判的であった。以下は、アドルノがジャズを嫌った主な理由である: |

| 1.

Commercialism: Adorno saw jazz as a highly commercialized form of music

that was primarily driven by the demands of the entertainment industry

rather than genuine artistic expression. He felt that jazz was overly

focused on appealing to mass audiences and generating profits. |

1. 商業主義:

アドルノはジャズを、純粋な芸術表現というよりはむしろ、エンターテインメント産業の要求が主な原動力となっている、高度に商業化された音楽形態とみなし

た。彼は、ジャズが大衆にアピールし、利益を生み出すことに過度に重点を置いていると感じていた。 |

| 2.

Standardization: Adorno argued that jazz exhibited a high degree of

standardization and predictability in its musical structures and forms.

He believed this undermined the possibility for true spontaneity and

creativity. |

2. 標準化:

アドルノは、ジャズはその音楽構造や形式において高度な標準化と予測可能性を示していると主張した。彼はこれが真の自発性と創造性の可能性を損なうと考え

た。 |

| 3.

Conformity: Adorno criticized jazz for promoting cultural conformity

and the passive consumption of music rather than active, critical

engagement. He saw jazz as reinforcing the values of a standardized,

mass-produced culture. |

3. 適合性(体制順応主義):

アドルノは、ジャズが積極的で批判的な関わりよりも、文化的な順応性と音楽の受動的な消費を促進していると批判した。彼はジャズが、標準化され大量生産さ

れた文化の価値観を強化するものだと考えた。 |

| 4.

Cultural Imperialism: Adorno viewed the global spread of jazz as a form

of cultural imperialism, where American musical forms were being

imposed on other cultures and undermining local musical traditions. |

4. 文化帝国主義:

アドルノは、ジャズの世界的な広がりを文化帝国主義の一形態とみなし、アメリカの音楽形式が他国の文化に押し付けられ、その土地の音楽伝統を損なっている

と考えた。 |

| 5.

Racial Dynamics: Adorno was also critical of the racial dynamics

involved in the production and reception of jazz, seeing it as

exploiting African-American culture for the benefit of white consumers

and the music industry. |

5. 人種力学:

アドルノはまた、ジャズの生産と受容に関わる人種力学にも批判的で、白人消費者と音楽産業の利益のためにアフリカ系アメリカ人の文化を搾取していると見て

いた。 |

| Overall,

Adorno's critique of jazz was part of his broader philosophical project

of analyzing and critiquing the cultural products of advanced

capitalist societies, which he saw as inherently compromised by

commercial and ideological forces. His views on jazz were highly

influential, though they were also controversial and challenged by

other thinkers. |

全体として、アドルノによるジャズ批判は、先進資本主義社会の文化的産

物を分析し批判するという、彼の広範な哲学的プロジェクトの一環であった。彼のジャズに対する見解は大きな影響力を持ったが、同時に他の思想家たちからも

論争を巻き起こし、異議を唱えられた。 |

| Claude 3. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆