テオドール・アドルノ

Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno, 1903-1969

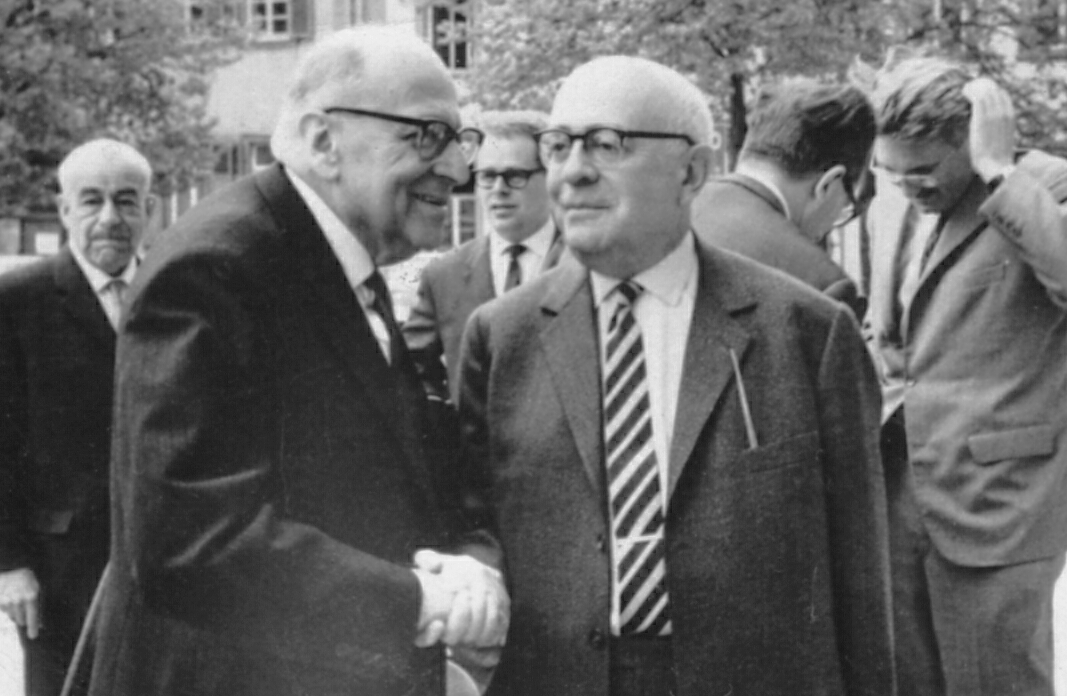

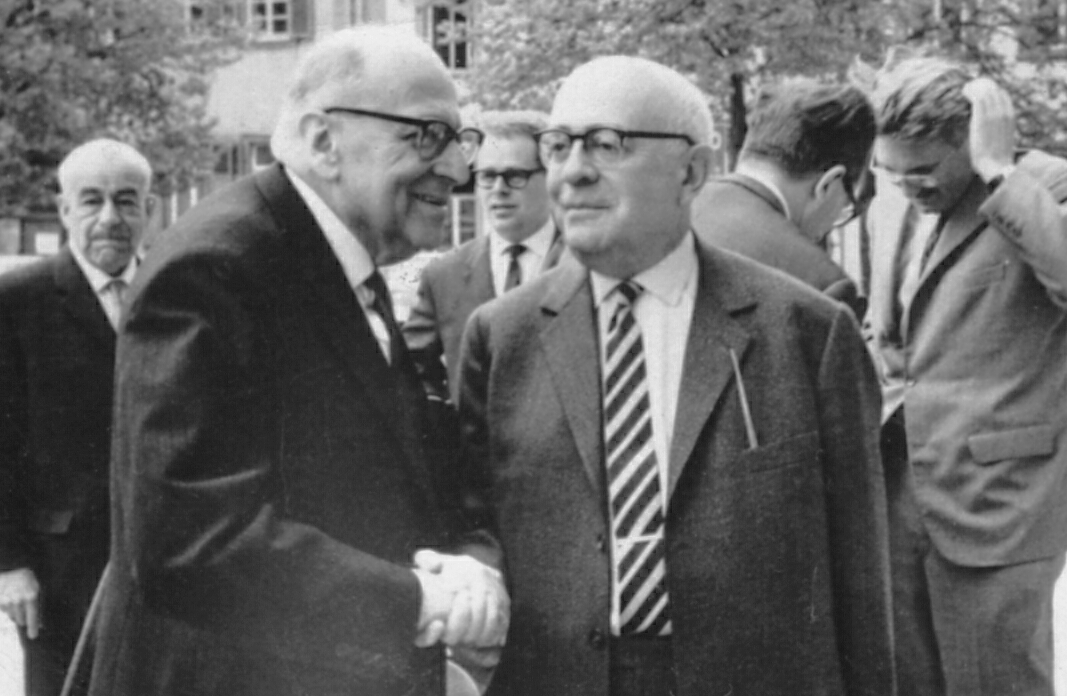

Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, and Habermas

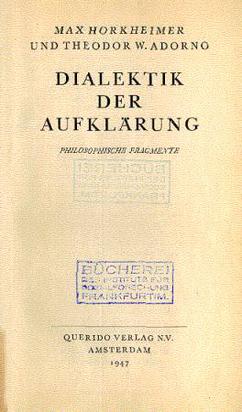

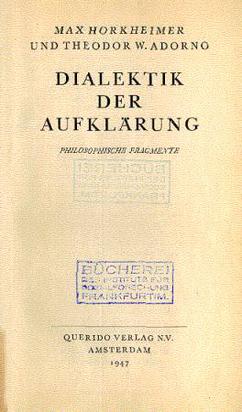

at Heidelberg / Dialektik der Aufklärung, 1947

☆ テオドール・W.アドルノ(1903-1969)は、フロイト、マルクス、ヘーゲルの著作が現代社会を批判する上で不可欠であったフランクフルト学派の批評理論の主要メンバーであり、エルンスト・ブロッホ、 ヴァルター・ベンヤミン、マックス・ホルクハイマー、エーリッヒ・フロム、ヘルベルト・マルクーゼといった思想家たちとその活動は関連づけられるように なった。ファシズムと、彼が文化産業と呼ぶものの両方を批判した彼の著作(『啓蒙の弁証法』(1947年)、『ミニマ・モラリア』(1951年)、『否定 弁証法』(1966年)など)は、ヨーロッパの新左翼に強い影響を与えた。古典的な訓練を受けたピアニストであったアドルノは、アーノルド・シェーンベルクの十二音技法に共鳴し、第二ウィーン楽派のアルバン・ベルクに作曲を師事 した。前衛音楽への傾倒がその後の著作の背景となり、第二次世界大戦中、亡命者としてカリフォルニアに住んでいた二人は、トーマス・マンの小説『ファウス トゥス博士』での共同作業につながった。新たに移転した社会研究所で働くようになったアドルノは、権威主義、反ユダヤ主義、プロパガンダに関する影響力の ある研究を共同で行い、後に同研究所が戦後ドイツで行った社会学的研究のモデルとなった。フランクフルトに戻ったアドルノは、実証主義科学の限界に関するカール・ポパーとの論争、ハイデガーの真正性の言葉に対する批判、ホロコーストに対するド イツの責任に関する著作、公共政策への継続的な介入などを通じて、ドイツの知的生活の再構築に関わった。ニーチェやカール・クラウスの伝統を受け継ぐポレ ミクスの作家として、アドルノは現代西洋文化を痛烈に批判した。死後に出版された『美学論』は、サミュエル・ベケットに捧げる予定だったもので、哲学史が 長年求めてきた感覚と理解の「致命的な分離」を撤回し、美学が形式よりも内容、没入よりも熟考に与える特権を爆発させようとする、現代芸術への生涯をかけ たコミットメントの集大成である。

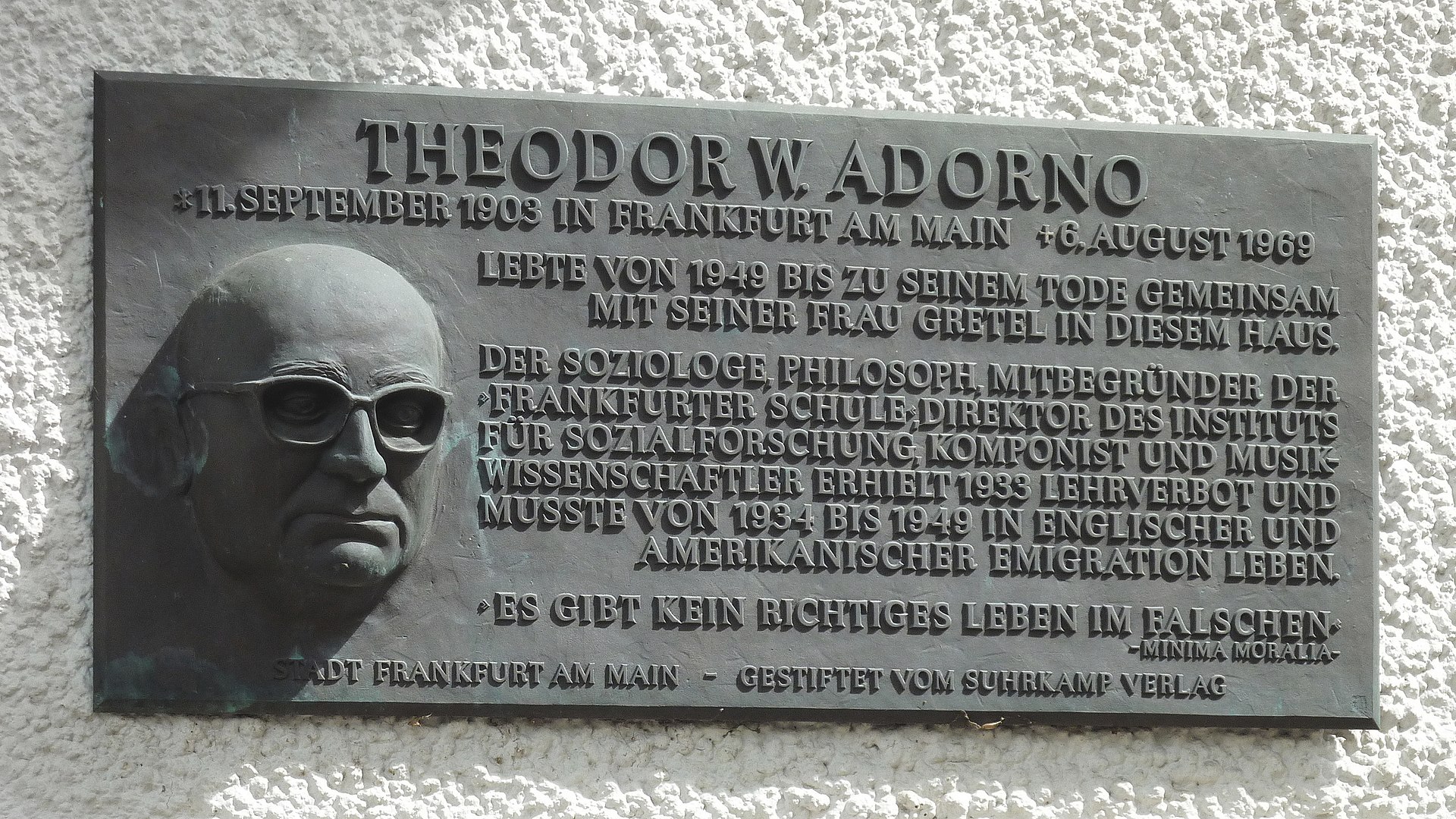

| Theodor W. Adorno

(* 11. September 1903 in Frankfurt am Main; † 6. August 1969 in Visp,

Schweiz; eigentlich Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund) war ein deutscher

Philosoph, Soziologe, Musikphilosoph, Komponist und Pädagoge. Er zählt

mit Max Horkheimer zu den Hauptvertretern der als Kritische Theorie

bezeichneten Denkrichtung, die auch unter dem Namen Frankfurter Schule

bekannt wurde. Mit Horkheimer, den er während seines Studiums

kennengelernt hatte, verband ihn eine enge lebenslange Freundschaft und

Arbeitsgemeinschaft. Adorno wuchs in großbürgerlichen Verhältnissen in Frankfurt auf. Als Kind erhielt er eine intensive musikalische Erziehung, und bereits als Schüler beschäftigte er sich mit der Philosophie Immanuel Kants. Nach dem Studium der Philosophie widmete er sich der Kompositionslehre im Kreis der Zweiten Wiener Schule um Arnold Schönberg und betätigte sich als Musikkritiker. Ab 1931 lehrte er zudem als Privatdozent an der Universität Frankfurt bis zum Lehrverbot 1933 durch die Nationalsozialisten. Sein Antrag auf Aufnahme in die Reichsschrifttumskammer wurde am 20. Februar 1935 abgelehnt. Während der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus emigrierte er in die USA. Dort wurde er Mitarbeiter des Instituts für Sozialforschung, bearbeitete einige empirische Forschungsprojekte, unter anderem über den autoritären Charakter, und schrieb mit Max Horkheimer die Dialektik der Aufklärung. Nach seiner Rückkehr war er einer der Direktoren des in Frankfurt wiedereröffneten Instituts. Wie nur wenige Vertreter der akademischen Elite wirkte er als „öffentlicher Intellektueller“ mit Reden, Rundfunkvorträgen und Publikationen auf das kulturelle und intellektuelle Leben Nachkriegsdeutschlands ein und trug – mit allgemeinverständlichen Vorträgen – gewollt und mittelbar zur demokratischen Reeducation der deutschen Bevölkerung bei.[1] Adornos Arbeit als Philosoph und Sozialwissenschaftler steht in der Tradition von Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx und Sigmund Freud. Wegen der Resonanz, die seine schonungslose Kritik an der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft unter den Studenten fand, galt er bei Befürwortern und Kritikern als einer der geistigen Väter der deutschen Studentenbewegung. Obwohl er die Kritik der Studenten an den restaurativen Tendenzen der spätkapitalistischen Gesellschaft teilte, stand er dem Wirken der Studentenbewegung wegen deren Hang zu blindem Aktionismus und wegen ihrer Gewaltbereitschaft mit Befremden und Distanz gegenüber.[2] |

テオドール・W・アドルノ(本名テオドール・ルートヴィヒ・ヴィーゼン

グルント、1903年9月11日 - 1969年8月6日)は、ドイツの哲学者、音楽学者、作曲家、教育者である。

生涯の友人であり同僚でもあったマックス・ホルクハイマーとともに、フランクフルト学派の前身である社会研究協会で展開した批判理論の分野における業績で

最もよく知られている。彼はホルクハイマーと生涯にわたって親密な交友関係と仕事上の関係を築き、ホルクハイマーとは学生時代に出会った。 アドルノはフランクフルトの上流中流階級の家庭で育った。幼少期から音楽教育を受け、学生時代にはすでにイマヌエル・カントの哲学を学んでいた。哲学を学 んだ後、彼はアルノルト・シェーンベルクを中心とする「第二ウィーン学派」のサークルで作曲の研究に専念し、音楽評論家としても活動した。1931年から はフランクフルト大学で非常勤講師として教鞭を執っていたが、1933年にナチスによって教壇から追放された。1935年2月20日、ドイツ文学院への入 会申請は却下された。 ナチス時代には米国に移住し、社会研究協会のメンバーとなり、権威主義的性格に関する研究を含むいくつかの実証的研究プロジェクトに従事し、ホルクハイ マーと『啓蒙の弁証法』を共著した。帰国後、フランクフルトで研究所が再開された際には、その理事の一人となった。学術エリートの代表的人物としては珍し く、彼は「公共の知識人」として講演、ラジオ講座、出版活動を通じて戦後ドイツの文化と知的活動に影響を与え、一般の人々にも理解できる講義を通じて、ド イツ国民の民主的な再教育に意図的かつ間接的に貢献した。 アドルノの哲学者および社会科学者としての業績は、イマニュエル・カント、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、カール・マルクス、ジークム ント・フロイトの伝統に根ざしている。資本主義社会に対する容赦ない批判が学生たちから大きな反響を得たため、アドルノは支持者からも批判者からも、ドイ ツの学生運動の精神的指導者の一人とみなされるようになった。彼は、後期資本主義社会の復古的な傾向に対する学生たちの批判には共感していたが、学生運動 の行動については、盲目的な活動主義や暴力に訴える傾向があるとして、疎外感と距離を持って見ていた。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Leben 1.1 Herkunft und Name 1.2 Frühe Frankfurter Jahre (bis 1924) 1.3 Aufenthalt in Wien (1925–1926) 1.4 Mittlere Frankfurter Jahre (1926–1934) 1.5 Zwischenstation Oxford (1934–1937) 1.6 Emigrant in den USA (1938–1953) 1.7 Späte Frankfurter Jahre (1949–1969) 2 Einflüsse auf das Werk 2.1 Hegel 2.2 Karl Marx 2.3 Sigmund Freud 2.4 Rezeption weiterer Autoren 3 Werk 3.1 Philosophie 3.1.1 Negative Dialektik: Adornos „Philosophie des Nichtidentischen“ 3.1.2 Kritik der Erkenntnistheorie 3.1.3 Negative Moralphilosophie 3.1.4 Metaphysik und Metaphysikkritik 3.1.5 Positivismuskritik 3.2 Soziologie 3.2.1 Gesellschaftskritik 3.2.2 Empirische Sozialforschung 3.3 Ästhetik und Kulturkritik 3.3.1 Ästhetische Theorie 3.3.2 Literatur: Interpretation und Kritik 3.3.3 Kulturkritische Schriften 3.3.4 Kulturindustrie 3.4 Pädagogik 3.4.1 Erziehung zur Mündigkeit 3.4.2 Halbbildung 3.5 Musikalische Schriften 3.6 Kompositionen 4 Sprache und Darstellungsformen 5 Wirkungsgeschichte 5.1 Gegenpositionen 5.2 Unverständlichkeitsvorwurf 5.3 Erinnerungen 5.3.1 Theodor-W.-Adorno-Preis 5.3.2 Denkmal und Platznamen 5.3.3 Fußgängerampel 5.3.4 Biographien 5.4 Ehrungen 6 Bekannte Schüler 7 Schriften 8 Briefwechsel 9 Kompositionen 10 Literatur 10.1 Einführungen 10.2 Biographien 10.3 Biographische Orte 10.4 Adorno Blätter 10.5 Adorno-Konferenzen 10.6 Frankfurter Seminare 10.7 Weiterführende Studien 11 Filme 12 Hörspiel 13 Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 14 Weblinks 15 Anmerkungen und Einzelnachweise |

目次 1 生涯 1.1 起源と名前 1.2 フランクフルト初期(1924年まで 1.3 ウィーン滞在(1925年~1926年 1.4 フランクフルト中期(1926年~1934年 1.5 オックスフォード滞在(1934年~1937年 1.6 アメリカへの亡命(1938年~1953年) 1.7 晩年のフランクフルト時代(1949年~1969年) 2 作品に与えた影響 2.1 ヘーゲル 2.2 カール・マルクス 2.3 ジークムント・フロイト 2.4 他の作家の受容 3 作品 3.1 哲学 3.1.1 ネガティブ・ダイアレクティーク:アドルノの「非同一の哲学」 3.1.2 認識論批判 3.1.3 否定的道徳哲学 3.1.4 形而上学と形而上学批判 3.1.5 実証主義批判 3.2 社会学 3.2.1 社会批判 3.2.2 経験的社会研究 3.3 美学と文化批評 3.3.1 美学理論 3.3.2 文学:解釈と批評 3.3.3 文化批評 3.3.4 文化産業 3.4 教育 3.4.1 成熟のための教育 3.4.2 半端な教育 3.5 音楽作品 3.6 作曲 4 言語と表現形式 5 受容の歴史 5.1 反対意見 5.2 理解不能という非難 5.3 記憶 5.3.1 テオドール・W・アドルノ賞 5.3.2 記念碑と広場の名称 5.3.3 歩行者用信号機 5.3.4 伝記 5.4 栄誉 6 著名な学生 7 著作 8 書簡 9 作曲 10 文学 10.1 紹介 10.2 伝記 10.3 伝記的な場所 10.4 アドルノ文書 10.5 アドルノ会議 10.6 フランクフルト・ゼミナール 10.7 さらなる研究 11 映画 12 ラジオドラマ 13 フランクフルト・アドルノ講座 14 ウェブリンク 15 注釈および参考文献 |

| Leben Herkunft und Name Adorno wurde 1903 in Frankfurt als Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund geboren. Er war das einzige Kind des Weingroßhändlers Oscar Alexander Wiesengrund (1870–1946) und der Sängerin Maria Calvelli-Adorno (1865–1952). Die katholische Mutter war Tochter eines korsischen Offiziers, der sich um 1860 als mittelloser Fechtmeister in der Freien Stadt Frankfurt niedergelassen hatte. Sie trat als ausgebildete Sängerin auch am kaiserlichen Hof in Wien, an der Wiener Oper[3] und an den Stadttheatern Köln und Riga auf. Der Vater, Oscar Alexander Wiesengrund, stammte aus einer jüdischen Familie und gehörte zur Zeit der Geburt des Sohnes noch der mosaischen (jüdischen) Religion an;[4] erst später konvertierte er zum Protestantismus. Die von Theodor vorgenommene Ergänzung des väterlichen Nachnamens um den Namen der Mutter soll ein Wunsch der Mutter gewesen sein, er erfüllte sich jedoch erst später. Während die ersten Veröffentlichungen noch mit „Wiesengrund“ gezeichnet waren, verwendete er in seiner publizistischen Tätigkeit früh den Doppelnamen „Wiesengrund-Adorno“. Eine Verkürzung auf „W. Adorno“ nahm er bei seinen Veröffentlichungen in der US-amerikanischen Emigration vor. Nach der formellen Einbürgerung als US-Bürger Ende 1943 lautete sein amtlicher Name „Theodore Adorno“.[5] Seine Publikationen zeichnete er indes fortan mit Theodor W. Adorno. |

生涯 生い立ちと名前 アドルノは1903年、テオドール・ルートヴィヒ・ヴィーゼングルントとしてフランクフルトに生まれた。ワイン卸売業者のオスカー・アレクサンダー・ ヴィーゼングルント(1870年~1946年)と歌手のマリア・カルヴェッリ=アドルノ(1865年~1952年)の間の一人っ子であった。カトリック教 徒の母は、1860年頃に無一文のフェンシングの師範としてフランクフルト自由都市に移住したコルシカ人の士官の娘であった。彼女は訓練を受けた歌手であ り、ウィーンの宮廷やウィーン国立歌劇場[3]、ケルンやリガの市立劇場で公演も行っていた。父親のオスカー・アレクサンダー・ヴィーゼングルントはユダ ヤ人家庭の出身で、息子の誕生時にはまだモザイク教(ユダヤ教)に属していたが[4]、後にプロテスタントに改宗した。 テオドールが父の姓に母の名前を加えたのは、明らかに母の希望によるものだったが、それが実現したのはその後になってからだった。最初の著作ではまだ 「ヴィーゼングルント」の署名であったが、間もなくジャーナリストとしての活動では「ヴィーゼングルント=アドルノ」という2つの姓を組み合わせた名前を 使い始めた。米国に移住した際にはこれを「W.アドルノ」と短縮し、1943年末に米国市民として正式に帰化してからは、正式名称は「セオドア・アドル ノ」となった。[5] しかし、彼は自身の出版物の署名を「セオドア・W・アドルノ」と続けた。 |

| Frühe Frankfurter Jahre (bis 1924) Als Kind wurde der Junge „Teddie“ gerufen. Er wuchs in der Schönen Aussicht, Hausnummer 9, auf, einer Straße am Mainufer. Im Nebenhaus betrieb sein Vater eine Weinhandlung, zu der ein großes Weingut im Rheingau gehörte.[6] 1914 zog die Familie in ein neu erbautes Haus im Stadtteil Oberrad in die Seeheimer Straße 19.[7] Adorno wurde römisch-katholisch getauft und empfing die Erstkommunion. Auf Wunsch seiner gläubigen Mutter war er geraume Zeit auch als Ministrant tätig.[8] Anders als etwa seine Jugendfreunde Leo Löwenthal und Erich Fromm, die sich im – in Frankfurt einflussreichen – Freien Jüdischen Lehrhaus betätigten,[9] hatte er zur Religion seiner väterlichen Vorfahren keine besondere Beziehung. Ein engeres Verhältnis zum Judentum gewann er erst unter dem Eindruck des Völkermords an den Juden.[10] Die mit den Adornos befreundete Publizistin Dorothea Razumovsky brachte es auf den Punkt: Nicht sein toleranter und assimilierter Vater, sondern Hitler habe ihn zum Juden gemacht.[11] Im Haushalt der Familie lebte auch die Sängerin und Pianistin Agathe Calvelli-Adorno, eine unverheiratete Schwester seiner Mutter, die Adorno als seine „zweite Mutter“ bezeichnete.[12] Adornos „überaus behütete Kindheit“ war vornehmlich von den beiden „Müttern“ geprägt.[13] Von ihnen erlernte er das Klavierspiel. Die Musik bildete den kulturellen Mittelpunkt der kosmopolitisch ausgerichteten, großbürgerlichen Familie. So zog seine Mutter mit der Partie des Waldvögleins aus Richard Wagners Oper Siegfried durch Europa. Adorno wurde mit der kammermusikalischen und symphonischen Literatur durch das Vierhändigspielen vertraut gemacht und konnte somit seine musikalische Kompetenz schon früh ausbilden.[14] Er nahm neben dem Schulunterricht bei Bernhard Sekles Privatstunden in Komposition. Die Sommer verbrachte die Familie im Odenwaldidyll Amorbach; seitdem galt ihm Amorbach „als die Wirklichkeit gewordene Utopie […], mit der Welt eins zu sein“.[15] Nachdem er zwei Klassen übersprungen hatte, bestand der „privilegierte Hochbegabte“[16] 1921 am Kaiser-Wilhelms-Gymnasium (heute Freiherr-vom-Stein-Schule) in Frankfurt bereits mit 17 Jahren das Abitur als Jahrgangsbester.[17] Als Primus erlebte er Ressentiment und Feindseligkeit, die eine solche Begabung auf sich ziehen kann.[18] So erlitt er im Gymnasium Quälereien derjenigen, die „keinen richtigen Satz zustande brachten, aber jeden von mir zu lang fanden“ (GS 4: 219f).[19] Philosophisch geschult wurde er durch seinen 14 Jahre älteren Freund Siegfried Kracauer, den er bei einer Freundin seiner Eltern kennengelernt hatte. Kracauer war ein bedeutender Feuilletonredakteur der Frankfurter Zeitung. In einem Brief an Leo Löwenthal gestand er, zu seinem jüngeren Freund „eine unnatürliche Leidenschaft“ zu empfinden und sich für „geistig homosexuell“ zu halten.[20] Gemeinsam lasen sie über Jahre hinweg regelmäßig an Samstagnachmittagen Immanuel Kants Kritik der reinen Vernunft, eine Erfahrung, die nach Adornos Selbstzeugnis für ihn prägend war: „Nicht im leisesten übertreibe ich, wenn ich sage, daß ich dieser Lektüre mehr verdanke als meinen akademischen Lehrern“ (GS 11: 388). Als Abiturient las er fasziniert die gerade erschienenen Bücher Die Theorie des Romans von Georg Lukács und Geist der Utopie von Ernst Bloch.[21] Im Gymnasium erlernte er Latein, Griechisch und Französisch;[22] später in der Emigration kam Englisch hinzu. An der Universität Frankfurt belegte er ab 1921 Philosophie, Musikwissenschaft, Psychologie und Soziologie; zur gleichen Zeit begann er seine Tätigkeit als Musikkritiker. Philosophie hörte er bei Hans Cornelius, Soziologie bei Gottfried Salomon-Delatour und Franz Oppenheimer.[23] In der Universität traf er 1922 in einem Seminar auf Max Horkheimer, mit dem er theoretische Anschauungen teilte und Freundschaft schloss. Auch mit Walter Benjamin, den er durch Vermittlung Kracauers als Student kennengelernt hatte, pflegte er eine enge und dauerhafte Freundschaftsbeziehung. Das Studium absolvierte er sehr zügig: Ende 1924 schloss er es mit einer Dissertation über Edmund Husserls Phänomenologie mit summa cum laude ab. Die Arbeit, die er im Geist seines Lehrers Cornelius abfasste, enthielt reine Schulphilosophie, die noch wenig von Adornos späterem Denken ahnen ließ. Aus der Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen der Frankfurter Weinhandlung Oscar Wiesengrund und der Berliner Fabrik für Lederverarbeitung Karplus & Herzberger entwickelte sich ein freundschaftliches Verhältnis zwischen den Eigentümer-Familien beider Firmen. Zwischen dem temperamentvollen jungen „Teddie“ Wiesengrund und der Berlinerin Margarete (Rufname: Gretel) Karplus kam es zu einer Liebesbeziehung, die zu einer lebenslangen Bindung führen sollte.[24] |

フランクフルトでの初期(1924年まで) 少年時代、アドルノは「テディ」と呼ばれていた。彼はマイン川のほとりにあるSchönen Aussicht 9番地で育った。父親は隣家でワインショップを経営しており、ラインガウ地方に広大なブドウ畑も所有していた。6] 1914年、一家はオーバーラート地区のSeeheimer Straße 19番地に新築された家に引っ越した。 アドルノはローマ・カトリックの洗礼を受け、初聖体を受けた。敬虔な母親の希望で、彼はしばらくの間、侍者も務めた。[8] 幼馴染のレオ・レーヴェンタールやエーリッヒ・フロムなどとは異なり、例えば、フランクフルトで影響力を持っていた自由ユダヤ人学習センターで活動してい たが、[9] 父方の先祖の宗教とは特に縁がなかった。ユダヤ人大虐殺の影響を受けて初めて、ユダヤ教とのより深い関係を築くようになった。10] アドルノ一家の友人で広報担当のドロテア・ラズモフスキーは、簡潔にこう述べている。「彼をユダヤ人にしたのは、寛容で同化主義的な父親ではなく、ヒト ラーだった」11] 歌手でありピアニストでもあったアガタ・カルヴェリ・アドルノは、母の未婚の妹であり、家族と同居していたが、アドルノは彼女を「第二の母」と表現してい た。[12] アドルノの「非常に恵まれた子供時代」は、主にこの2人の「母」によって形作られた。[13] 彼は彼女らからピアノを学んだ。音楽は、国際的で中流の上流階級の家庭の文化の中心であった。例えば、アドルノの母親は、リヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ 『ジークフリート』で小鳥の役を演じ、ヨーロッパ中を巡業していた。アドルノは、二重奏を演奏することで室内楽や交響曲のレパートリーに触れ、幼い頃から 音楽のスキルを磨くことができた。彼は学校の授業と並行して、ベルンハルト・ゼクレスから作曲の個人レッスンを受けていた。家族は夏をオデンヴァルトの牧 歌的な町アムorbachで過ごした。それ以来、アムorbachは彼にとって「実現したユートピアであり、世界と一体となる場所」となった。[15] 飛び級で2学年を飛び越えた「恵まれ、非常に才能に恵まれた」[16]彼は、1921年にフランクフルトのカイザー・ヴィルヘルム・ギムナジウム(現在の フライヘア・フォン・シュタイン・シューレ)でAレベルの試験に17歳で首席で合格した。首席の生徒として、彼はその才能が引き寄せる反感や敵意を経験し た。彼は、文法学校の生徒たちから苦しめられた。「まともに文章を組み立てることができず、しかし、自分の文章はどれも長すぎると思っていた」生徒たちか らである(GS 4: 219f)。[19] 彼は、14歳年上の友人ジークフリート・クラカウアーから哲学を紹介された。クラカウアーは、両親の友人を通じて知り合った人物であった。クラカウアーは 『フランクフルター・ツァイトゥング』の重要な編集者であった。レオ・レーヴェンタールに宛てた手紙の中で、彼は年下の友人に対して「不自然な情熱」を抱 いていること、そして「知的同性愛者」であると自認していることを告白している。[20] 彼らは長年にわたり、土曜の午後に定期的にイマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』を一緒に読んでいた。アドルノ自身の説明によると、この経験は彼にとって 形成的なものだった。「 「この読書から学んだことの方が、学問の師から学んだことよりも多い」と彼は述べている(GS 11: 388)。高校を卒業したばかりの頃、彼は最近出版されたゲオルク・ルカーチの『小説論』とエルンスト・ブロッホの『ユートピアの精神』に夢中になって読 んだ。21] 高校ではラテン語、ギリシャ語、フランス語を学んだ。22] その後亡命したことで、英語が加わった。 フランクフルト大学では、1921年より哲学、音楽学、心理学、社会学のコースを受講し、同時に音楽評論家としてのキャリアをスタートさせた。彼はハン ス・コーネリウスによる哲学、ゴットフリート・サロモン=デラトゥールとフランツ・オッペンハイマーによる社会学の講義を受講した。23] 1922年、彼は大学のセミナーでホルクハイマーと出会った。彼らは類似した理論的見解を共有し、友人となった。また、学生時代にクラカウアーを通じて知 り合ったヴァルター・ベンヤミンとも親交を深め、生涯にわたって交友関係を続けた。彼は非常に早く学業を修了し、1924年末にはエドムント・フッサール の現象学に関する論文で卒業し、最優等で卒業した。この論文は、師であるコーネリアスの精神に基づいて書かれたもので、純粋学派の哲学であり、アドルノの 後の思想を予見するものはほとんどなかった。 フランクフルトのワイン商オスカー・ヴィーゼングルントとベルリンの皮革加工工場カルプラス&ヘルツバーガーとのビジネス上の関係は、やがて両社のオー ナー一族の親交へと発展した。活発な若者「テディ」ことヴィーゼングルントと、ベルリン出身のマルガレーテ(愛称はグレーテル)カルプラスは恋に落ち、生 涯を通じて親しい関係を保ち続けた。[24] |

| Aufenthalt in Wien (1925–1926) Im März 1925 zog Adorno nach Wien, der Geburtsstätte der Zwölftonmusik, wo er sich ein Zimmer in der Pension „Luisenheim“ im 9. Bezirk nahm.[25] Bei Alban Berg, dem Schüler Arnold Schönbergs, begann er ein Aufbaustudium in Komposition und bei Eduard Steuermann nahm er gleichzeitig Klavierunterricht. Adorno hatte Alban Berg anlässlich der Uraufführung seiner Drei Bruchstücke für Gesang und Orchester aus Wozzeck 1924 in Frankfurt kennengelernt.[26] Der aus Polen stammende Steuermann, der die meisten Klavierwerke Schönbergs uraufgeführt hatte, war der maßgebliche Pianist der Zweiten Wiener Schule, mit deren Begründer er ebenfalls zusammentraf. Adorno schätzte Schönberg als „revolutionären Veränderer der überlieferten Kompositionsweise“.[27] Dessen Zwölftonkompositionen würdigte er später (1949) in der Philosophie der neuen Musik. Persönlich jedoch entwickelte sich eine „wechselseitige Antipathie“ zwischen beiden.[28] Schönberg hielt Adornos „Schreibstil für manieriert, die musiktheoretische Begriffsbildung für zu unverständlich“ und glaubte, dass dies der Neuen Musik in der öffentlichen Wirkung schade.[29] Adornos musikästhetische Wertschätzung und persönliche Sympathie galten vor allem Alban Berg,[30] zu dem er eine freundschaftliche Beziehung pflegte, die sich bis zu dessen frühem Tod (1935) in einem intensiven Briefwechsel niederschlug. Später veröffentlichte er über ihn die Monographie Berg. Der Meister des kleinsten Übergangs (1968). Schon im ersten Jahr seines Aufenthalts in Wien verfasste er Aufsätze über Werke von Berg und Schönberg. Er setzte damit seine bereits als Student aufgenommene musikkritische Tätigkeit fort, die er 1928 mit dem Eintritt in die Redaktion der musikalischen Avantgarde-Zeitschrift Anbruch fundieren konnte.[31] Adornos Bestreben, die Zeitschrift als musikpolitisches Machtinstrument zur Durchsetzung avancierter Musik zu nutzen, war jedoch auf Widerstand in der Redaktion gestoßen, aus der er dann 1931 offiziell ausschied.[32] Die Jahre seines Wiener Aufenthalts waren für Adorno die kompositorisch intensivsten. Unter seinen Kompositionen machen eine Reihe von Klavierliederzyklen den umfangreichsten und auch gewichtigsten Teil aus. Daneben schrieb er Orchesterstücke, Kammermusik für Streicher und A-cappella-Chöre und bearbeitete französische Volkslieder. Zusammen mit Berg besuchte er Lesungen von Karl Kraus. Dessen spektakuläre Vortragsweise machte auf ihn anfänglich den Eindruck eines „halb priesterlichen und halb clownesken Komödianten“; erst später, vermittelt durch Lektüre, begann er ihn zu schätzen.[33] Zu den zahlreichen Bekanntschaften, die er in Wien machte, zählte die von Georg Lukács, der hier unter schwierigen Lebensbedingungen als Emigrant lebte. Gegenüber Berg gestand er, dass Lukács ihn „geistig […] tiefer fast als jeder andere beeinflusst“ habe. Dessen Theorie des Romans hatte ihn bereits als Abiturient begeistert und dessen 1922 in Wien abgeschlossene Arbeit Geschichte und Klassenbewußtsein war für seine Marx-Rezeption (wie für die seiner engeren Freunde) eminent wichtig.[34] Eine enge Freundschaft verband ihn in dieser Zeit auch mit dem Prager Schriftsteller und Musiker Hermann Grab. Das intellektuelle und künstlerische Milieu der Wiener Moderne um die Jahrhundertwende prägte anhaltend nicht nur Adornos Musiktheorie, sondern auch seine Kunstauffassung.[35] Mit Alban Berg und dessen Frau Helene besuchte er nicht nur Konzerte und Opern; die Bergs führten ihn auch in exzellente Restaurants. Überhaupt genoss er die sinnliche Lebensfreude der Donaumetropole, inklusive „vorsichtig erprobter Liebschaften“.[36] In die Wiener Zeit fällt ein knapp dreiwöchiger Aufenthalt mit Siegfried Kracauer am Golf von Neapel (September 1925), wo beide mit Walter Benjamin und Alfred Sohn-Rethel zu fruchtbarem Gedankenaustausch zusammentrafen. Martin Mittelmeier interpretiert diesen Aufenthalt als einen Wendepunkt in der intellektuellen Biographie Adornos. Hier habe er unter dem Einfluss Benjamins die für seine Texte bedeutsamste Darstellungsform, die „Konstellation“, gefunden.[37] |

ウィーン滞在(1925年~1926年) 1925年3月、アドルノは12音音楽の発祥の地であるウィーンに移り、9区にある「ルイゼンハイム」という下宿に部屋を借りた。 25] 彼はアルバン・ベルクの作曲の大学院課程に入学し、同時にエドゥアルト・シュトイアマンからピアノのレッスンを受けた。アドルノは1924年にフランクフ ルトで上演されたベルクの『ヴォツェック』の3つの断片の初演でベルクと出会っていた。 26] ポーランド出身で、シェーンベルクのピアノ曲のほとんどを初演したシュトイマンは、第二次ウィーン学派の最も重要なピアニストであり、その創始者とも面識 があった。アドルノはシェーンベルクを「伝統的な作曲法を革命的に変えた人物」と評価していた。[27] 彼は後に、1949年の著書『新音楽の哲学』でシェーンベルクの12音作曲法に敬意を表した。しかし、2人の間には「相互の反感」が芽生えた。28] シェーンベルクはアドルノの文章スタイルを気取りがちだと考え、音楽理論の概念化はあまりにも理解しがたいものだと考え、それは新しい音楽の一般への影響 を損なうものだと考えていた。29] アドルノの音楽美学への評価と個人的な共感は主にアルバン・ベルクに向けられており、30] 彼とは友好的な関係を維持していた そのことは、ベルクが1935年に早世するまで、彼らとの活発な文通に反映されていた。その後、アドルノはベルクに関する単行本『ベルク。最小限の転移の 達人』(1968年)を出版した。 ウィーンに滞在した最初の年に、アドルノはベルクとシェーンベルクの作品に関するエッセイを書いた。こうして、彼は学生時代にすでに始めていた音楽評論の 仕事を継続した。1928年には、前衛的な音楽雑誌『Anbruch』の編集スタッフに加わり、その地位を確立した。アドルノは、同誌を先進的な音楽を推 進する音楽政策の手段として活用しようとしたが、編集スタッフから抵抗を受け、1931年に正式に辞職した。 ウィーンに滞在していた数年間は、アドルノにとって作曲活動が最も活発だった時期であった。彼の作曲作品の中で、ピアノのための歌曲シリーズは最も広範囲 にわたるものであり、最も重要な部分を占めている。さらに、オーケストラ曲、弦楽合奏とアカペラ合唱のための室内楽、そしてフランス民謡の編曲も手がけ た。 ベルクとともに、カール・クラウスの朗読会にも出席した。クラウスの壮観な講演スタイルは、当初は「聖職者と道化師の中間のようなコメディアン」という印 象を与えたが、後に読書を通じて、彼を評価するようになった。[33] ウィーンで知り合った数多くの人物のうちの一人に、亡命者として困難な状況下で暮らしていたゲオルク・ルカーチがいた。彼はベルクに、ルカーチは「知的 に...ほとんど誰よりも深く」彼に影響を与えたと告白した。彼は高校を卒業した時点で既にルカーチの『小説論』に感銘を受けており、1922年にウィー ンで完成したルカーチの著作『歴史と階級意識』は、彼(および彼の親しい友人たち)がマルクスを受け入れる上で極めて重要な意味を持っていた。34] この時期、彼はプラハの作家兼音楽家ヘルマン・グラブとも親交があった。世紀転換期のウィーン・モダニズムの知的・芸術的環境は、アドルノの音楽理論だけ でなく、芸術に対する考え方にも長期的な影響を与えた。 アドルノは、アルバン・ベルクとその妻ヘレーネとともにコンサートやオペラを鑑賞しただけでなく、ベルク夫妻から素晴らしいレストランも紹介された。彼は 一般的に、ドナウの首都の官能的な生きる喜びを享受しており、その中には「慎重に試された恋愛関係」も含まれていた。[36] ウィーン滞在中、アドルノとクラカウアーはジークフリート・クラカウアーとともにナポリ湾で3週間近く過ごし(1925年9月)、そこでヴァルター・ベン ヤミンとアルフレート・ゾン=レーテルと出会い、有益な意見交換を行った。マルティン・ミッテルマイアーは、この滞在をアドルノの知的伝記における転換点 と解釈している。ベンヤミンの影響を受け、彼は自身のテキストに最もふさわしい表現形式、すなわち「コンステレーション」を見出したのである。[37] |

| Mittlere Frankfurter Jahre (1926–1934) Zurück aus Wien widmete er sich der musikpublizistischen Tätigkeit und dem Komponieren. Daneben begann Adorno die Arbeit an einer Habilitationsschrift. Die Ergebnisse einer ausführlichen Beschäftigung mit der Psychoanalyse verarbeitete er in einer umfangreichen philosophisch-psychologischen Abhandlung mit dem Titel Begriff des Unbewußten in der transzendentalen Seelenlehre, die er seinem Doktorvater Cornelius vorlegte. Nachdem dieser Bedenken geäußert hatte, denen sich sein Assistent Horkheimer anschloss, zog Adorno 1928 das Habilitationsgesuch zurück. Cornelius hatte bemängelt, dass die Arbeit zu wenig originell sei und sein eigenes, Cornelius’, Denken paraphrasiere.[38] Die Jahre 1928–1930 waren für Adorno Jahre der beruflichen Ungewissheit. Vergeblich bemühte er sich um eine feste Anstellung als Musikkritiker bei Ullstein in Berlin. Zahlreiche Kompositionen und musikkritische Beiträge aus dieser Zeit zeugen indessen von nicht erlahmter Produktivität. Über seine finanzielle Lage brauchte er sich keine Sorgen zu machen, sein Vater hatte ihm weitere Unterstützung zugesagt.[39] Adorno weilte in diesen Jahren mehrfach in Berlin bei der – mit ihm inzwischen verlobten – promovierten Chemikerin und Unternehmerin Gretel Karplus. Mit ihr unternahm er auch mehrere Reisen, u. a. nach Amorbach, Italien und Frankreich.[40] Während der Aufenthalte in Berlin traf er mit vielen zeitgenössischen Autoren und Künstlern zusammen, u. a. mit Ernst Bloch, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler und Bertolt Brecht. Adorno konzentrierte sich zudem auf die Abfassung einer zweiten Habilitationsschrift. Er hatte das Angebot des 1929 auf einen philosophischen Lehrstuhl neu berufenen evangelischen Theologen Paul Tillich, bei ihm zu habilitieren, angenommen. Nachdem er binnen eines Jahres die Arbeit über den dänischen Existentialphilosophen und Hegel-Kritiker Kierkegaard niedergeschrieben hatte, reichte er sie unter dem Titel Kierkegaard – Konstruktion des Ästhetischen ein und wurde damit im Februar 1931 an der Frankfurter Universität habilitiert. Die stark überarbeitete Buchausgabe (1933) trug die Widmung: „Meinem Freunde Siegfried Kracauer“. Kontakt zu linksorientierten Frankfurter Intellektuellen pflegte er in einem Kreis, „Kränzchen“ genannt, der im lockeren Turnus im Café Laumer zur Diskussion zusammentraf. Zu ihm gehörten Horkheimer, Tillich, Friedrich Pollock, der Nationalökonom Adolf Löwe und der frisch berufene Soziologe Karl Mannheim. Obwohl noch ohne Habilitation, genoss Adorno „das Privileg“, zu jenem „Kränzchen“ geladen zu werden.[41] Nachdem Adorno die Venia legendi verliehen worden war, hielt er im Mai 1931 seine Antrittsvorlesung als Privatdozent für Philosophie; ihr Titel: Die Aktualität der Philosophie, die viele Gedanken enthielt, die in sein späteres Werk eingingen.[42] Im Auftrag Tillichs hatte Adorno schon vor der Antrittsvorlesung an der Frankfurter Universität Seminare veranstaltet. Sie waren, wie die nach seiner Ernennung zum Privatdozenten selbstständig durchgeführten Kollegs, der Ästhetik gewidmet. Nach der ihm erteilten Lehrbefugnis verblieben ihm noch vier Semester an der Frankfurter Universität. Zu den angebotenen Lehrveranstaltungen gehörten – neben „Kierkegaard“ und „Erkenntnistheoretische Übungen (Husserl)“ – „Probleme der Kunstphilosophie“, eine Veranstaltung, in der er sich mit Benjamins Schrift Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels befasste,[43] die Benjamin bereits 1925 als Habilitationsschrift bei der Frankfurter Philosophischen Fakultät eingereicht hatte und die von dieser abgelehnt worden war. Vor seiner Emigration in die USA gehörte Adorno noch nicht zu den offiziellen Mitarbeitern des Instituts für Sozialforschung (anders als Horkheimer, Pollock, Fromm und Löwenthal), publizierte aber bereits im ersten Heft der von Horkheimer seit 1932 herausgegebenen Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung den Aufsatz Zur gesellschaftlichen Lage der Musik. Darin untersuchte er ideologiekritisch die Produktion und Konsumtion von Musik in der kapitalistischen Gegenwartsgesellschaft. Adornos Lehrtätigkeit endete mit dem Wintersemester 1933. Das nationalsozialistische Regime entzog ihm im Herbst wegen seiner väterlicherseits jüdischen Abstammung die Befugnis zur akademischen Lehre. Wie viele andere Intellektuelle seiner Zeit erwartete er keine lange Dauer des neuen Regimes und räumte rückblickend ein, dass er die politische Lage 1933 völlig falsch beurteilt hatte.[44] Er machte sich anfangs sogar noch Hoffnung auf den Posten eines Musikkritikers bei der Vossischen Zeitung. In der Zeitschrift Europäische Revue glossierte er das von den Nationalsozialisten durchgesetzte Verbot des „Negerjazz“ dahingehend, dass das Dekret nachträglich bestätige, was sich musikalisch bereits vollzogen habe. Auch lobte er 1934 Männerchöre, die vertonte Gedichte von Hitlers Jugendführer Baldur von Schirach sangen.[45] Im Wintersemester 1962/63 von der Frankfurter Studentenzeitung Diskus mit diesen Veröffentlichungen konfrontiert, bedauerte er in einem offenen Brief seine „dumm-taktischen Sätze“, die der Torheit dessen zuzuschreiben seien, „dem der Entschluß zur Emigration unendlich schwer fiel“.[46] Wie naiv er die anfängliche Lage nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtergreifung beurteilte, zeigt ein Brief vom 15. April 1933 an den im Pariser Exil befindlichen Siegfried Kracauer, in dem er ihm riet, nach Deutschland zurückzukehren, denn: „Es herrscht völlige Ruhe und Ordnung, ich glaube, die Verhältnisse werden sich konsolidieren. [...] auch ein übereilter und kostspieliger Umzug [nach Paris] schiene mir bedenklich“.[47] Leo Löwenthal vermerkte: „wir mußten ihn fast physisch dazu zwingen, endlich Deutschland zu verlassen“.[48] |

フランクフルト中期(1926年~1934年) フランクフルトに戻ったアドルノは、音楽ジャーナリストとしての仕事と作曲活動に専念した。同時に、アドルノは博士号取得後の論文の執筆に取り掛かった。 彼は精神分析学の広範な研究結果を、包括的な哲学的心理学論文「魂の超越論的教義における無意識の概念」に盛り込み、指導教官のコルネリウスに提出した。 後者が保留の意を示し、助手のホルクハイマーもそれに同調したため、アドルノは1928年にハビリタス申請を取り下げた。コーネリウスは、その作品が独創 性に欠け、自身の考えを言い換えていると批判した。 1928年から1930年にかけては、アドルノにとって職業上の不安定な時期であった。彼はベルリンのウルトシュタイン社で音楽評論家として常勤の職を得 ようとしたが、それは叶わなかった。しかし、この時期に作曲した数々の作品や音楽評論は、彼の創作意欲が衰えていないことを証明している。父親がさらなる 支援を約束していたため、経済的な心配をする必要はなかった。アドルノは、この時期に何度かベルリンに滞在し、グレテル・カルプラスと過ごした。彼女は化 学の博士号を取得しており、アドルノの婚約者であった。また、彼女とともにアモルバッハ、イタリア、フランスなどへの旅行も何度か行った。ベルリン滞在中 には、エルンスト・ブロッホ、クルト・ヴァイル、ハンス・アイスラー、ベルトルト・ブレヒトなど、多くの同時代の作家や芸術家と出会った。 アドルノは、2つ目のハビリテーション論文の執筆にも集中した。1929年に哲学教授職に任命されたプロテスタント神学者のパウル・ティリッヒの誘いを受 け、彼のもとでハビリテーションを行うことになったのだ。1年以内にデンマークの実存主義哲学者でヘーゲル批判者でもあるキルケゴールの論文を書き上げ、 タイトルを「キルケゴール - 美的構成」として提出し、1931年2月にフランクフルト大学でハビリテーション(ハビリタート)を取得した。大幅に改訂された書籍版(1933年)は 「友ジークフリート・クラカウアーに捧ぐ」と献辞が記されていた。 彼は、フランクフルトの左派系知識人たちと交流を保っていた。彼らは「クレンツェン」と呼ばれるサークルを結成し、不定期にカフェ・ラウマーで議論を行っ ていた。そのメンバーには、ホルクハイマー、ティリッヒ、フリードリヒ・ポロック、経済学者アドルフ・レーヴェ、そして新たに赴任した社会学者カール・マ ンハイムなどがいた。ハビリタート(大学教授資格)を取得していなかったアドルノだが、こうした「懇談会」に招待される「特権」を享受していた。[41] アドルノがハビリタートを取得した後、1931年5月に哲学の非常勤講師として就任講演を行い、そのタイトルは『哲学の現存在』であった。この講演では、後の作品で取り上げられることになる多くのアイデアが提示された。[42] ティリッヒの指示により、アドルノは就任講演に先立ってフランクフルト大学で既にセミナーを行っていた。個人講師として任命された後に独自に教えた講座と 同様に、それらは美学に専念したものだった。講師としての認可を得た後も、アドルノはさらに4学期間フランクフルト大学に留まった。キルケゴール』、『認 識論的練習(フッサール)』に加えて、彼が担当した科目には『芸術哲学の問題』があり、この科目ではベンヤミンが1925年にフランクフルト哲学部にハビ リテーション論文として提出し、却下されていた『ドイツ悲劇の起源』[43]を扱っていた。 アドルノは米国への移住前、社会研究機関の正式なスタッフではなかったが(ホルクハイマー、ポロック、フロム、ローウェンタールとは異なり)、ホルクハイ マーが1932年から編集していた雑誌『Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung』の創刊号に「音楽の社会的状況について」という論文をすでに発表していた。そこでは、現代の資本主義社会における音楽の 生産と消費をイデオロギー的な観点から考察している。 アドルノの教職は1933年の冬学期で終了した。その秋、父方がユダヤ人であったという理由で、ナチス政権はアドルノの大学での教職資格を取り消した。同 時代の多くの知識人と同様、アドルノは新しい政権が長く続くとは思っておらず、振り返ってみると、1933年の政治情勢を完全に誤って判断していたことを 認めた。44] 当初は、アドルノは『フォシッシェ・ツァイトゥング』紙の音楽評論家として採用されることをまだ期待していた。雑誌『ヨーロッパ・レヴュー』では、ナチス による「ニグロ・ジャズ」の禁止について、その法令が音楽界で既に起こっていたことを遡及的に確認したものであると、彼は好意的に取り扱った。1934年 には、ヒトラー青年団指導者バルター・フォン・シラッハが音楽にのせて詩を朗読する男声合唱団を称賛した。45] 1962/63年の冬学期にフランクフルトの学生新聞『ディスカス』がこれらの出版物を掲載したことに直面し、彼は公開書簡で「愚かな戦術的発言」を後悔 した。これは、「移住を決断する人物」の愚かさによるものかもしれない 。1933年4月15日付でパリに亡命していたジークフリート・クラカウアー宛ての手紙には、国家社会主義が政権を握った後の初期の状況を彼がどれほど甘 く見ていたかが示されている。その中で彼は、クラカウアーにドイツに戻るよう勧めており、「完全な平和と秩序が保たれており、状況は安定するだろう。パリ への)急いで費用のかかる引っ越しも、私には疑問に思える」[47] レオ・レーヴェンタールは次のように述べている。「私たちは、彼を物理的に強制的にドイツから去らせるしかなかった」[48] |

| Zwischenstation Oxford (1934–1937) Als durch die nationalsozialistische Rassengesetzgebung definiertem „Halbjuden“ blieb Adorno zunächst noch Bewegungsspielraum im nationalsozialistisch regierten Deutschland. Unter Beibehaltung seines amtlich gemeldeten Wohnsitzes in Frankfurt[49] ging er nach Großbritannien, wo er, obwohl bereits deutscher Philosophiedozent, nur als advanced student im Fach Philosophie am Merton College in Oxford aufgenommen wurde.[50] Er plante, mit einer Arbeit über die Philosophie Edmund Husserls den akademischen Grad Ph.D. zu erwerben. Sein Tutor war Gilbert Ryle, kompetenter Kenner der deutschen Philosophie, insbesondere Husserls und Heideggers, und später berühmter Autor von The Concept of Mind. Kontakt hatte er auch zu dem Ideengeschichtler Isaiah Berlin.[51] Wie er Freunden mitteilte, arbeitete er „in einer unbeschreiblichen Ruhe und unter sehr angenehmen äußeren Arbeitsbedingungen“ (Brief an Ernst Krenek),[52] wenngleich er „das Leben eines mittelalterlichen Studenten mit Cap und Gown“[53] zu führen gezwungen war, wie er an Walter Benjamin schrieb.[54] Die Oxforder Jahre nutzte Adorno nicht nur für seine Husserl-Studien. Er schrieb eine kritische Abhandlung über die Wissenssoziologie Karl Mannheims[55] und musiktheoretische Artikel für die der Avantgarde verpflichteten Wiener Musikzeitschrift 23 sowie den Aufsatz Über Jazz, der 1936 in der Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung unter dem Pseudonym Hektor Rottweiler erschien[56] und bis über Adornos Tod hinaus heftigste Reaktionen hervorrief. Da die damaligen Devisenbestimmungen nur die Ausfuhr geringer Beträge erlaubten, kehrte Adorno, um sein Leben in Oxford finanzieren zu können, regelmäßig nach den Semestern zu längeren Aufenthalten nach Deutschland zurück – in ein Land, das ihm zur „Hölle“ geworden war, wie er dem in die USA emigrierten Horkheimer schrieb. Er traf dort neben Freunden seine Eltern und seine Verlobte,[57] für die, als Jüdin, das Leben in Deutschland immer prekärer wurde und die daher im August 1937 nach London übersiedelte, wo beide am 8. September 1937 im Standesamt des Districts Paddington heirateten. Einer der Trauzeugen war Horkheimer, der zu dieser Zeit, aus den USA kommend, die Zweigstellen des Instituts für Sozialforschung in Europa (Genf, Paris, London) bereiste.[58] Adorno bestand auf einer traditionellen Arbeitsteilung mit seiner Frau: „er dachte nicht im entferntesten daran, sich an der Organisation und Führung des Haushaltes zu beteiligen“.[59] Während dieser Zeit unterhielt Adorno einen intensiven Briefwechsel mit dem bereits im amerikanischen Exil lebenden Max Horkheimer, den er im Dezember 1935 in Paris getroffen und im Juni 1937 für zwei Wochen in New York besucht hatte. Horkheimer machte ihm schließlich das Angebot, in den USA eine existenzsichernde wissenschaftliche Tätigkeit aufzunehmen und offizieller Mitarbeiter in seinem Institut für Sozialforschung zu werden.[60] Mitte Dezember 1937 verbrachten die Adornos noch einen Urlaub an der Ligurischen Küste, wo sie sich mit Walter Benjamin trafen, und in Brüssel verabschiedete sich Adorno von den Eltern, die später nachkommen sollten.[61] |

オックスフォードの中間駅(1934年~1937年) 国家社会主義の人種法で定義された「半ユダヤ人」であったアドルノは、ナチスが支配するドイツにおいて、当初はまだ行動の余地があった。公式の登録上の居 住地をフランクフルトに残したまま、彼はイギリスに渡り、すでに哲学のドイツ人講師であったにもかかわらず、オックスフォードのマーティン・カレッジで哲 学の優秀な学生として受け入れられた。彼はエドムント・フッサールの哲学に関する論文で博士号を取得するつもりであった。彼の指導教官は、ドイツ哲学、特 にフッサールとハイデガーの権威であり、後に『心の概念』の著者として著名なギルバート・ライルであった。また、イザヤ・ベルリンという思想史家とも交流 があった。友人たちに語ったところによると、彼は「何ともいえない静けさの中で、非常に快適な外的な労働条件のもと」で働いていたという(エルンスト・ク レーネクへの手紙)。しかし、彼は「中世的な生活」を強いられていた 帽子とガウンを身にまとった中世の学生のような生活を送っていた」[53]。しかし、ウォルター・ベンヤミンに宛てた手紙で述べているように、そうせざる を得なかったのだ。 アドルノはオックスフォード時代をフッサール研究だけに費やしたわけではなかった。彼はカール・マンハイムの知識社会学に関する批判的な論文[55]や、 ウィーンの前衛音楽雑誌『23』に音楽理論に関する記事を寄稿し、また1936年には『社会学研究誌』に「ジャズについて」というエッセイをヘクトール・ ロットワイラーというペンネームで発表し[56]、アドルノの死後もなお最も激しい反応を引き起こした。 当時の外国為替規制では輸出できる金額が限られていたため、アドルノは学期が終わると定期的にドイツに戻り、オックスフォードでの生活費を稼いでいた。ア メリカに移住したホルクハイマーに宛てた手紙の中で、アドルノはドイツを「地獄」と表現している。そこで彼は友人や両親、そしてユダヤ人であるフィアンセ と再会した。フィアンセはドイツでの生活がますます不安定になってきたため、1937年8月にロンドンに移住し、1937年9月8日にパディントン地区役 所で結婚した。結婚式の証人の一人はホルクハイマーで、当時アメリカから来ており、ヨーロッパの社会研究機関(ジュネーブ、パリ、ロンドン)の支部を訪問 していた。[58]アドルノは、伝統的な役割分担を妻に強く求めた。「彼は、家庭の運営や管理に参加することさえ考えなかった」[59] この間、アドルノはすでにアメリカに亡命していたマックス・ホルクハイマーと頻繁に文通を続けていた。1935年12月にパリでホルクハイマーと会い、 1937年6月には2週間ほどニューヨークを訪れている。ホルクハイマーはついにアドルノにアメリカでの職を提供し、生活を保障し、自身の社会研究機関の 正式なスタッフとして迎え入れることを申し出た。 1937年12月中旬、アドルノ夫妻はリグーリア海岸で休暇を過ごし、そこでヴァルター・ベンヤミンと出会った。ブリュッセルでアドルノは両親と別れを告げた。両親は後から合流することになっていた。 |

Emigrant in den USA (1938–1953) Christopher Street 45, 1938 zeitweise Wohnhaus der Adornos Horkheimers Einladung folgend, siedelte Adorno mit seiner Frau im Februar 1938 in die USA über und emigrierte damit aus dem Dritten Reich. Seinen Eltern, die bei den antijüdischen Ausschreitungen während der Novemberpogrome 1938 misshandelt und verhaftet worden waren, gelang im Jahr darauf die Ausreise nach Havanna.[62] Nachdem die Adornos in den ersten Wochen eine provisorische Wohnung in Greenwich Village (New York City) bezogen hatten, mieteten sie ein Apartment unweit der Columbia University, die dem Institut für Sozialforschung (nunmehr unter dem Namen Institute of Social Research) ein Gebäude zur Verfügung gestellt hatte. Das Paar richtete sich hier mit den aus Deutschland verschifften Möbeln ein und hatte von Anfang an keinen Mangel an privaten Kontakten und Beziehungen.[63] Gleich nach seiner Ankunft wurde Adorno Mitarbeiter des Princeton Radio Research Projects, eines von dem österreichischen Soziologen Paul Lazarsfeld geleiteten größeren Forschungsvorhabens. Adorno wurde die Durchführung eines Teilprojekts für den Bereich der Musik übertragen, die für ihn eine gänzlich ungewohnte und aufreibende Tätigkeit bedeutete.[64] Während er seine Arbeit zur Hälfte dem empirischen Projekt widmete, war er zur anderen Hälfte als nunmehr offizieller Mitarbeiter an Horkheimers Institute of Social Research tätig (GS 10/2: 705) und neben Leo Löwenthal für die redaktionelle Arbeit an der Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung verantwortlich. Überdies beteiligte er sich an den Seminaren, Vorträgen und internen Diskussionen über den Charakter des Nationalsozialismus.[65] Da Adorno auf seiner kritischen Einstellung gegenüber dem administrative research[66] beharrte, kam es zu einem „anhaltenden Disput zwischen dem Musiktheoretiker und dem Sozialforscher“,[67] der schließlich dazu führte, dass Lazarsfeld die Zusammenarbeit nach zwei Jahren beendete. Horkheimer, der Adorno nach seinem Ausscheiden aus dem Radio-Projekt eine volle Institutsstelle zugesagt hatte, suchte in dieser Zeit die engere Zusammenarbeit mit ihm. Er hatte ihn als Mitarbeiter an dem schon länger geplanten Buch über „dialektische Logik“, das die Selbstzerstörung der Vernunft zum Thema haben sollte, vorgesehen. Ab Herbst 1939 fanden zwischen beiden Gespräche statt, die Gretel Adorno teilweise protokollierte.[68] Zeitweilig war auch Herbert Marcuse, der damalige „hauptamtliche Philosoph des Instituts“,[69] mit dem Horkheimer in New York an einer materialistischen Kritik des Idealismus arbeitete, ebenfalls für die Mitarbeit vorgesehen. Da Horkheimer keineswegs mit letzter Deutlichkeit ausgeschlossen hatte, ihn an dem Dialektik-Buch zu beteiligen, war Adorno, „nicht frei von Eifersucht, […] alles dran gelegen, mit Horkheimer exklusiv das Buch zu schreiben“.[70] Bereits im Mai 1935 hatte Adorno aus Oxford an Horkheimer über Marcuse geschrieben, es mache ihn traurig, dass „Sie philosophisch unmittelbar mit einem Mann arbeiten, den ich schließlich für einen durch Judentum verhinderten Faszisten halte“.[71][72] Horkheimer und seine Frau Maidon siedelten 1940, vorwiegend aus gesundheitlichen Gründen – vor allem Maidon litt unter dem New Yorker Klima –, nach Los Angeles über und bezogen in Pacific Palisades einen eigens für sie gebauten Bungalow. Die Adornos zogen im November 1941 nach und dort in ein gemietetes Haus ein.[73] Beide wohnten in unmittelbarer Nähe und zudem in Nachbarschaft einer Kolonie deutscher und österreichischer Emigranten, wie Berthold und Salka Viertel, Thomas und Katia Mann, Hanns Eisler, Bertolt Brecht und Helene Weigel, Max Reinhardt, Arnold Schönberg und vielen anderen. Die meisten von ihnen waren gekommen, weil sie sich Aufträge von der Filmindustrie in Hollywood erhofften.[74] Anfang 1942 begannen Adorno und Horkheimer mit der Arbeit an dem Buch, das später den Titel Dialektik der Aufklärung tragen sollte. Mit ihm entstand als Gemeinschaftsarbeit beider, unter Mithilfe von Adornos Frau Gretel, das Hauptwerk der Kritischen Theorie, das erstmals 1944 im Herstellungsverfahren der Mimeographie unter dem Titel Philosophische Fragmente mit der Widmung „Friedrich Pollock zum 50. Geburtstag“ im Verlag des New York Institute of Social Research erschien und in seiner endgültigen Form 1947 im Amsterdamer Querido Verlag veröffentlicht wurde. Angesichts des an den Juden und anderen Bevölkerungsgruppen verübten Massenmords legten die beiden Autoren eine Geschichtsphilosophie der Gesellschaft nach Auschwitz vor, die eine grundsätzliche Kritik der Aufklärung darstellte, deren Fortschrittsoptimismus obsolet geworden sei. Programmatisch heißt es gleich auf der ersten Seite, es gehe um „die Erkenntnis, warum die Menschheit, anstatt in einen wahrhaft menschlichen Zustand einzutreten, in eine neue Art von Barbarei versinkt“ (GS 3: 11). Dies zu erklären, setzte das Buch mit der dialektischen These einer Verschränkung von Vernunft und Mythos, von Natur und Rationalität ein. Die Vernunftkritik erfolgte aus einer katastrophischen Perspektive.[75] Über das Ende des nationalsozialistischen Regimes und Hitlers Tod äußerte Adorno sich in privaten Briefen an seine Eltern (1. Mai 1945) und an Horkheimer (9. Mai 1945) mit einer Mischung aus Gefühlen von Freude, Trauer und Sarkasmus.[76] Hartmut Scheible bezeichnet die Jahre in Kalifornien als die fruchtbarsten in Adornos Leben.[77] Hier entstanden neben der Dialektik der Aufklärung die Minima Moralia und die Philosophie der neuen Musik. Für Rolf Wiggershaus stellten die Minima Moralia „so etwas wie die aphoristische Fortsetzung“ der Dialektik der Aufklärung dar.[78] In diese Jahre fällt auch die Zusammenarbeit mit Thomas Mann, der für seinen Roman Doktor Faustus zahlreiche Anregungen aus Adornos Manuskript zur Philosophie der neuen Musik bezog, insbesondere aus dem ersten Teil über Schönberg.[79] Im September 1943 hatte Thomas Mann Adorno in sein Haus am San Remo Drive eingeladen und aus dem achten Kapitel vorgelesen. Adornos Einwände und Ergänzungsvorschläge, die er „zunächst spontan, dann in schriftlicher Form machte, hat der Autor für die ersten Kapitel seines Romans […] weitgehend berücksichtigt“.[80] Er verdankte Adorno als dem intimen Kenner der Musik-Avantgarde wichtige Auskünfte zu musikphilosophischen und kompositionstechnischen Fragen. Bis ins kleinste musikalische Detail profitierte Thomas Mann sowohl in Gesprächen anlässlich mehrerer wechselseitiger Einladungen beider Familien, als auch durch die Korrespondenz von der Expertise eines „so erstaunlichen Kenners“ (Mann über Adorno).[81] Mann bedankte sich für diese Zusammenarbeit mit einer Anspielung auf Adorno im Roman. Dort wird das „d-g-g-“-Thema des zweiten Satzes von Beethovens Sonate op. 111 (Arietta) u. a. mit dem Wort „Wiesengrund“ unterlegt. Die Ähnlichkeit, die laut Hans Mayer der als Musikkritiker figurierende Teufel mit Adorno haben soll, nennt Thomas Mann „ganz absurd“.[82] Hanns Eisler, mit dem Adorno seit 1925 befreundet war und der nur ein paar Straßen weiter wohnte, trat im Dezember 1942 an Adorno mit dem Vorschlag heran, zusammen ein Buch über Filmmusik zu schreiben. Das 1944 auf Deutsch abgeschlossene Buch erschien erst 1949 unter dem Titel Composing for the Films auf Englisch, mit Eisler als alleinigem Autor. Adorno, der in einem Brief an seine Mutter beanspruchte, 90 Prozent des Textes verfasst zu haben, war als Co-Autor zurückgetreten, weil Eisler, ein Anhänger des Sowjetmarxismus, vor das Committee of Un-American Activities zitiert worden war und Adorno nicht „Märtyrer einer Sache“ werden wollte, „die nicht die meine war und nicht die meine ist“ (GS 15: 144), wie er 1969 im Nachwort zum Erstdruck der Originalfassung rückblickend sich rechtfertigte.[83] Nachdem Anfang 1944 das Manuskript des Dialektik-Buchs – zunächst noch mit Philosophische Fragmente betitelt – abgeschlossen worden war, begann Adorno, an dem gemeinsam von der University of Berkeley und dem Institute of Social Research betriebenen, großangelegten Forschungsprojekt zum Thema Antisemitismus mitzuwirken.[84] Seine letzte Tätigkeit in den USA trat er im Oktober 1952 als Forschungsdirektor der Hacker Psychiatric Foundation an und befasste sich in dieser Eigenschaft mit inhaltsanalytischen Untersuchungen über Zeitungshoroskope und Fernsehserien. Nachdem er mit dem Aggressionsforscher Friedrich Hacker in konfliktreiche Auseinandersetzungen geraten war, kündigte er seine Stellung und kehrte im August 1953 nach Deutschland zurück.[85] So kritisch der Emigrant Adorno auch die in den USA beobachtete konformistische Gleichschaltung, die konsequente „Hereinziehung der Kulturprodukte in die Warensphäre“ beurteilte, ja, das Schreckbild einer möglichen Konvergenz des „europäischen Faschismus und der amerikanischen Unterhaltungsindustrie“ heraufziehen sah, behielt er als „existentielle Dankespflicht“ im Gedächtnis, dass er den USA seine „Rettung vor der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung“ zu verdanken hatte.[86] |

米国への移住者(1938年~1953年) 1938年、クリストファー・ストリート45番地、アドルノ夫妻の一時的な住居 アドルノと妻は、ホルクハイマーからの招待に応じて、1938年2月に第三帝国から米国へと移住した。1938年11月のポグロムにおける反ユダヤ暴動で 虐待を受け、逮捕されていたアドルノの両親は、翌年にはなんとかしてハバナに脱出することができた。62] ニューヨーク市グリニッジ・ヴィレッジの仮アパートに数週間住んだ後、アドルノ夫妻はコロンビア大学からほど近いアパートを借りた。。夫妻は落ち着き、当 初からプライベートな人脈や人間関係に事欠くことはなかった。 アドルノは到着後すぐに、オーストリアの社会学者ポール・ラザーズフェルドが主導する大規模な研究プロジェクトであるプリンストン・ラジオ・リサーチ・プ ロジェクトのスタッフに加わった。アドルノは音楽分野のサブプロジェクトを担当することになったが、それは彼にとってまったく未知の、疲労困憊する仕事で あった。[64] 彼は実証プロジェクトに半分の時間を費やしながら、残りの半分の時間はホルクハイマーの社会研究機関の正式なスタッフとして働いた(GS 10/2: 705)。また、レオ・レーヴェンタールとともに、 。また、セミナーや講義、国家社会主義の本質に関する内部での議論にも参加した。 アドルノが管理研究に対する批判的な態度を主張したため、「音楽理論家と社会研究者との間で継続的な論争」が起こり、最終的にラザーズフェルドは2年後に共同作業を終了することとなった。 この間、ホルクハイマーはアドルノにラジオプロジェクトを離れた後、研究所で常勤の職を用意することを約束しており、アドルノとのより緊密な共同作業を模 索していた。彼は、かねてから構想していた「弁証法的論理学」に関する著書の執筆にアドルノをスタッフとして迎え入れようとしていた。この著書では理性の 自己破壊が主題となるはずであった。1939年秋から、二人は議論を重ね、その一部はグレテル・アドルノによって記録された。68] 一時期、当時「研究所の専任哲学者」[69]であり、ホルクハイマーとともにニューヨークで観念論の唯物論的批判に取り組んでいたハーバート・マルクーゼ も共同執筆者として検討された。ホルクハイマーはマルクーゼが弁証法に関する書籍に参加する可能性を完全に排除していたわけではなかったため、アドルノは 「嫉妬心から解放されていたわけではなく、[...] ホルクハイマーと二人だけでその本を書くことに熱心だった」[70]。1935年5月には早くも、アドルノはオックスフォードからホルクハイマーにマル クーゼについて手紙を書き、ホルクハイマーが「私が嫌悪する人物と哲学的な作業を行っている」ことが悲しいと述べていた 最終的には、ユダヤ人であるがゆえにファシストになることを思いとどまった人物である。[71][72] 1940年、ホルクハイマーと妻のメイドンは主に健康上の理由からロサンゼルスに移住した。特にメイドンはニューヨークの気候に悩まされていた。そして、 パシフィック・パリセーズに自分たちのために建てられたバンガローに移り住んだ。アドルノ夫妻は1941年11月に続き、そこにある貸家に引っ越した。 [73] 両者は近距離に住み、また、ベルトルト・ブレヒトとヘレーネ・ヴァイゲル、マックス・ラインハルト、トーマス・マンとカティア・マン、ハンス・アイス ラー、ヘルマン・ゲーリング、サルカ・フィエルテル、アーノルド・シェーンベルク、その他多数のドイツとオーストリアからの亡命者たちのコロニーの近所に 住んでいた。彼らのほとんどは、ハリウッド映画業界から委託を受けることを期待してやって来た。 1942年の初め、アドルノとホルクハイマーは後に『啓蒙の弁証法』と題されることになる本の執筆を開始した。これはアドルノとホルクハイマーの共同作業 であり、アドルノの妻グレテルの助力も得て、批判理論の主要な著作となった。1944年にニューヨーク社会研究所が謄写版印刷法で『哲学的断片』というタ イトルで出版した。 ユダヤ人やその他の集団に対する大量虐殺を目の当たりにした2人の著者は、進歩に対する楽観的な見方が時代遅れとなった啓蒙主義に対する根本的な批判を体 現する、アウシュビッツ後の社会の歴史哲学を提示した。最初のページには、この本が「人類が真に人間的な境地に達するのではなく、新たな野蛮へと沈み込ん でいく理由の解明」について書かれたものであると述べられている(GS 3: 11)。この本は、理性と神話、自然と合理性の相互関連性という弁証法的命題によって、これを説明しようとした。理性の批判は、破滅的な見通しに基づいて いる。 アドルノは両親宛(1945年5月1日)とホルクハイマー宛(1945年5月9日)の私信で、ナチス体制の終焉とヒトラーの死について、喜び、悲しみ、皮肉の入り混じった感情を交えて表現している。 ハルトムート・シャイブルは、アドルノの生涯で最も実りの多い時期はカリフォルニアでの数年間であったと述べている。77] 啓蒙の弁証法に加えて、彼は『ミニマ・モラリア』と『新音楽の哲学』をこの地で著した。ロルフ・ヴィッゲルハウスの考えでは、『ミニマ・モラリア』は『啓 蒙の弁証法』の「格言的な続編のようなもの」であった。78] この時期、アドルノはトーマス・マンとも協力し、マンはアドルノの「新音楽の哲学」の草稿から、特にシェーンベルクに関する第1部から多くの着想を得て、 小説『ファウスト博士』を執筆した。1943年9月、トーマス・マンはアドルノをサンレモ・ドライブの自宅に招き、第8章を朗読した。アドルノの異議申し 立てや追加の提案は、「最初は即興で、その後は書面で」行われたが、それらは「著者が小説の最初の章でほぼ考慮した」[80]。音楽の前衛の親しい目利き として、アドルノは音楽哲学や作曲技法に関する重要な情報をマンに提供した。両家が互いに招待し合った際の会話や、書簡を通じて、トーマス・マンは「この ような素晴らしい鑑定家」(アドルノについてマンが述べた言葉)の専門知識から恩恵を受けた。[81] マンはアドルノに感謝の意を表し、小説の中で彼に言及した。そこでは、ベートーヴェンのソナタ作品111の第2楽章(アリア)の「d-g-g-」という テーマが、「Wiesengrund(草原の地)」という言葉とともに下敷きにされている。トーマス・マンは、ハンス・メイヤーによると、音楽評論家とし て登場する悪魔がアドルノと似ているという類似点を「まったくばかげている」と述べている。 アドルノとは1925年以来の友人であり、数軒しか離れていない場所に住んでいたハンス・アイスラーは、1942年12月にアドルノに映画音楽に関する本 を一緒に書くことを提案した。1944年にドイツ語で完成したこの本は、アイスラー単独著として『映画音楽作曲』というタイトルで出版されたのは1949 年のことであった。アドルノは、母への手紙の中で、この本の90パーセントを執筆したと主張していたが、ソビエト・マルクス主義の支持者であったアイス ラーが反米活動委員会に召喚されたため、共同執筆者としての仕事を辞退した。アドルノは、「自分とは関係のない大義のために殉教者となる」ことを望まな かったのである(GS 15: 144)。1969年に初版の初刷りのあとがきで、彼は自らを振り返って正当化した。 1944年初頭に弁証法に関する著書(当初は『哲学断片』というタイトル)の原稿を完成させた後、アドルノはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校と社会研究機関が共同で実施した反ユダヤ主義に関する大規模な研究プロジェクトに参加し始めた。 1952年10月には、米国における最後の職として、ハッカー精神医学財団の研究ディレクターに就任し、新聞の星占い欄やテレビ番組のコンテンツ分析に従事した。侵略研究家フリードリヒ・ハッカーと対立した後、1953年8月に辞職し、ドイツに戻った。 アメリカで観察された順応主義による強制的な順応と一貫した「文化製品の商品圏への組み込み」を批判的に見ていた亡命者アドルノは、ヨーロッパのファシズ ムとアメリカのエンターテイメント産業の収束の可能性を予見していたが、アメリカに「ナチスの迫害からの救済」を負っていることを覚えており、アメリカに 対して「実存的な恩義」を感じていた。 社会主義の迫害から救われた」という事実を、彼は「実存的な恩義」として記憶にとどめている。[86] |

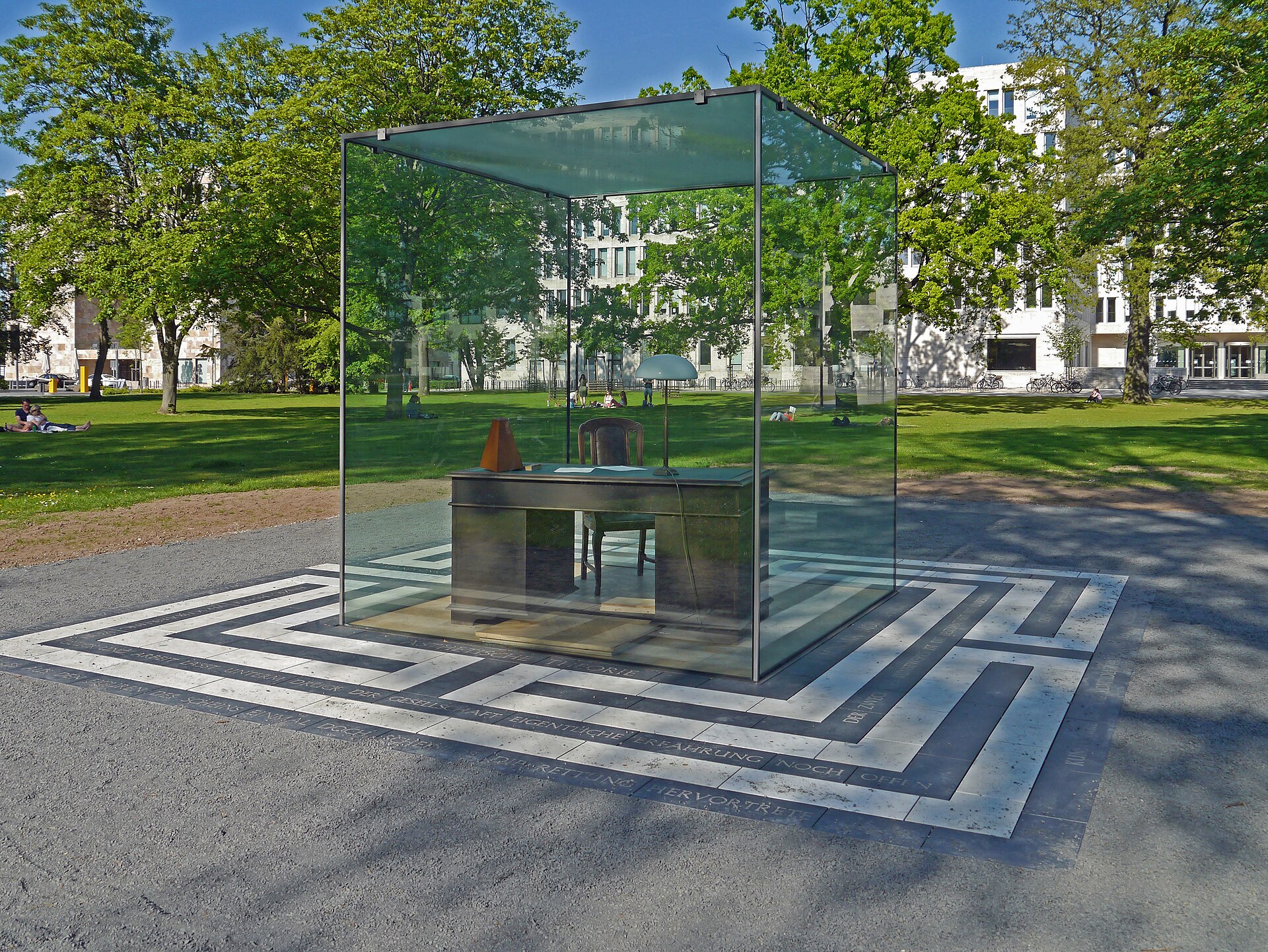

Späte Frankfurter Jahre (1949–1969) Institut für Sozialforschung und „Adorno-Ampel“ an der Senckenberganlage in Frankfurt am Main. Adorno hatte sich seit 1962 für den Bau einer Ampel an der vielbefahrenen Straße zwischen dem Institut und dem Universitätscampus in Frankfurt-Bockenheim eingesetzt; allerdings wurde die Ampel erst 1987 installiert. Im Oktober 1949 kehrte Adorno erstmals aus den USA wieder nach Deutschland zurück. Unmittelbarer Grund war die Vertretung Horkheimers an der Frankfurter Universität, die Horkheimer bereits 1949 wieder zum ordentlichen Professor, diesmal für Philosophie und Soziologie, berufen hatte.[87] Nach wechselnden Aufenthalten in Deutschland und den USA kehrte Adorno im August 1953 endgültig nach Deutschland zurück, wo ihn die Frankfurter Universität vom außerplanmäßigen (1950) zum planmäßigen außerordentlichen Professor (1953) und schließlich 1956 zum ordentlichen Professor für Philosophie und Soziologie ernannte.[88] Adornos Motivation zur Rückkehr nach Deutschland war nach eigener Aussage subjektiv durch Heimweh und objektiv durch die Sprache bestimmt. Er war auf die deutsche Sprache angewiesen, die für ihn eine „besondere Verwandtschaft zur Philosophie“ habe.[89] Sein Denken „ließ sich nicht von der deutschen Sprache lösen“.[90] Als Wissenschaftler war er zurückgekommen, um an seiner Heimatuniversität an die ihm 1933 entzogene Privatdozentur für Philosophie anzuknüpfen. Er wurde aber bald als Repräsentant einer anderen Disziplin, der Soziologie, bekannt, für die er während seiner Emigrationsjahre vielfältige Qualifikationen erworben hatte. Über die frühen Erfahrungen, die Adorno im besiegten Deutschland machte, äußerte er sich einerseits sehr kritisch: Man treffe so gut wie keine Nationalsozialisten, keiner wolle es gewesen sein und man habe von allem nichts gewusst,[91] andererseits lobte er an den Studenten eine „leidenschaftliche Teilnahme“.[92] Mit der Dichterin Marie Luise Kaschnitz schloss er Freundschaft; eine enge Zusammenarbeit entstand mit den beiden Herausgebern der Frankfurter Hefte, Walter Dirks und Eugen Kogon.[93] Von den alten Institutsmitarbeitern war außer Horkheimer und Adorno nur noch Friedrich Pollock nach Frankfurt zurückgekehrt; Fromm, Löwenthal, Marcuse, Franz Neumann und Karl August Wittfogel zogen es vor, in den USA ihre akademische Karrieren fortzusetzen.[94] Für das am 14. November 1951 in einem neuen Gebäude wiedereröffnete Institut für Sozialforschung war Adorno von Anfang an als stellvertretender Direktor mitverantwortlich. Das Institut war die erste akademische Einrichtung, die ein Soziologiestudium im Deutschland der Nachkriegszeit ermöglichte.[95] Nach dem Rückzug Horkheimers nach Montagnola in der Schweiz ruhte die Hauptarbeit faktisch auf Adornos Schultern. 1958 übernahm er offiziell die Leitung des Instituts.[96] In seiner Frau Margarete fand er eine „wesentliche Stütze seines Schaffens“ und eine aktive Mitarbeiterin. Gemeinsam mit ihm betrat sie morgens das Institut und verließ es abends mit ihm. In ihrem eigenen Büro redigierte sie penibel alle Texte Adornos vor der Drucklegung. Selten verpasste sie eine seiner Vorlesungen. Den Studenten stand sie als „Beichtmutter“ und Vermittlerin zum „Übervater“ bei.[97] Dass ihre Ehe kinderlos blieb, war eine von beiden bewusst getroffene Entscheidung, die sie den ungewissen Zeitumständen und Zukunftsperspektiven zuschrieben.[98] Die wissenschaftliche Produktivität, die Adorno in den USA auf dem Gebiet der Sozialforschung entfaltet hatte, trug dazu bei, dass er in Deutschland in den 1950er und 1960er Jahren als einer der wichtigsten Vertreter der deutschen Soziologie anerkannt wurde.[99] Nachdem 1955 Ludwig von Friedeburg als der für die empirischen Forschungsprojekte verantwortliche neue Abteilungsleiter des Instituts eingestellt worden war, zog sich Adorno allmählich aus der empirischen Forschung zurück, wiewohl er sich in der Folgezeit weiterhin zum Verhältnis von theoretischer Reflexion und empirischer Forschung zu Wort meldete.[100] Seine Skepsis steigerte sich zur Polarisierung im sogenannten Positivismusstreit, der 1961 mit einem Referat von Karl Popper und dem Koreferat Adornos zur „Logik der Sozialwissenschaften“ auf einer Tübinger Arbeitstagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie begonnen hatte und an dessen weiterem Verlauf sich Ralf Dahrendorf, Jürgen Habermas und Hans Albert beteiligten.[101] Von 1962 bis 1969 hatte Adorno eine Affäre mit der Münchnerin Arlette Pielmann, die ihn regelmäßig in Frankfurt besuchte. Adornos Ehefrau Gretel wusste darüber Bescheid und duldete dies, ohne es zu billigen.[102] Von 1963 bis 1967 amtierte Adorno als Vorsitzender der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie und zeichnete für den 16. Deutschen Soziologentag verantwortlich, der unter dem Titel Spätkapitalismus oder Industriegesellschaft 1968 in Frankfurt am Main veranstaltet wurde.[103] Der Zeitpunkt fiel mit dem Höhepunkt der Studentenbewegung zusammen. Die Vortragenden und Diskutanten auf den Podien reagierten meist gelassen auf wiederholte Störungen, Unterbrechungen und andere Regelverletzungen der Studenten. Neben seiner Tätigkeit als Universitätslehrer und als Direktor des Frankfurter Instituts für Sozialforschung verfasste Adorno bedeutende philosophische Schriften. Bereits 1951 war die aus der Emigration mitgebrachte und erweiterte Sammlung von Aphorismen: Minima Moralia erschienen, die er Max Horkheimer gewidmet hatte. Das mehr als 100.000-mal verkaufte Buch enthält die berühmt gewordene Sentenz „Es gibt kein richtiges Leben im falschen“ (GS 4: 43).[104] Das 1956 publizierte Werk über Husserl, Zur Metakritik der Erkenntnistheorie, ging in Teilen noch auf die Oxforder Studien zurück. Sein philosophisches Hauptwerk ist die Negative Dialektik, die Adorno selbst als „Antisystem“ (GS 6: 10) charakterisierte (erschienen erstmals 1966). Am westdeutschen Musikleben der Nachkriegszeit nahm Adorno durch seine musikphilosophischen und musiksoziologischen Veröffentlichungen teil, wie mit der schon in der Emigration entstandenen Philosophie der neuen Musik (1949), den Monographien über Richard Wagner (1952), Gustav Mahler (1960) und Alban Berg (1968) sowie der Einleitung in die Musiksoziologie (1962),[105] aber auch als Musiklehrer im Rahmen der bis in die späten 1960er Jahre im jährlichen Turnus stattfindenden Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt, an denen er zwischen 1950 und 1966 als Referent und Kursleiter nahezu regelmäßig teilnahm.[106] Außer der Musik war es die Literatur, die Adornos ästhetisches Denken beflügelte; seine philosophischen Ansichten zu dieser Kunstgattung legte er in zahlreichen Aufsätzen nieder, die in den vier Bänden der Noten zur Literatur zusammengefasst sind (GS 11). Mit Schriftstellern wie Ingeborg Bachmann, Alexander Kluge und Hans Magnus Enzensberger pflegte er freundschaftliche Beziehungen. Er entwickelte eine starke Präsenz in den Medien, die ihn zum gefragten Kenner und Diskutanten nicht nur auf den Gebieten der Philosophie und Soziologie, sondern auch der Musiktheorie und Literaturkritik machte.[107] In den letzten Lebensjahren arbeitete er an seiner posthum erschienenen Ästhetik. Adorno war ein geschätzter Hochschullehrer. Seit dem Ende der 1950er Jahre strömten Studenten aller Fachrichtungen in seine Vorlesungen, welche im größten Hörsaal der Universität stattfanden. Sein sich auf wenige Notizen stützender, in nuancierter Diktion frei formulierter Vortrag schlug viele in seinen Bann. Die letzten Jahre Adornos standen ganz im Zeichen von Konflikten mit seinen Studenten. Als sich aus der außerparlamentarischen Opposition (APO) gegen die von der Großen Koalition aus CDU/CSU und SPD gebildete Regierung und deren geplante Notstandsgesetze wie auch gegen den Vietnamkrieg eine neuartige Studentenbewegung mit dem SDS an der Spitze bildete, verschärften sich die Spannungen.[108] Während Adorno sich den entschiedenen Kritikern dieser Gesetze anschloss und mit ihnen öffentlich auf einer Veranstaltung des Aktionskomitees Demokratie im Notstand am 28. Mai 1968 Stellung bezog, hielt er Distanz zum studentischen Aktionismus. Es waren Schüler Adornos, die den Geist der Revolte repräsentierten und „praktische Konsequenzen“ aus der Kritischen Theorie zu ziehen versuchten. Als der Polizist Karl-Heinz Kurras bei der Demonstration am 2. Juni 1967 in West-Berlin gegen den Schah den Studenten Benno Ohnesorg erschoss, begann sich die APO zu radikalisieren. Unmittelbar nach dem Tod Ohnesorgs hatte Adorno vor Beginn seiner Ästhetik-Vorlesung seine „Sympathie für den Studenten“ ausgesprochen, „dessen Schicksal […] in gar keinem Verhältnis zu seiner Teilnahme an einer politischen Demonstration steht“.[109] Die Köpfe der Frankfurter Schule hatten zwar Sympathie mit den studentischen Kritikern und deren Protesten gegen restaurative Tendenzen und „technokratische Hochschulreform“,[110] waren aber nicht bereit, deren aktionistisches Vorgehen zu unterstützen; als „Pseudo-Aktivität“ und „Ungeduld gegenüber der Theorie“ bezeichnete Adorno es 1969 in seinem Rundfunkvortrag Resignation (GS 10/2 756 f.). Zum Verhältnis von Theorie und Praxis äußerte sich Adorno in einem längeren Spiegel-Interview im Mai 1969: „Ich habe neulich in einem Fernsehinterview gesagt, ich hätte zwar ein theoretisches Modell aufgestellt, hätte aber nicht ahnen können, dass Leute es mit Molotow-Cocktails verwirklichen wollen. […] Seitdem es in Berlin 1967 zum erstenmal zu einem Zirkus gegen mich gekommen ist, haben bestimmte Gruppen von Studenten immer wieder versucht, mich zur Solidarität zu zwingen, und praktische Aktionen von mir verlangt. Das habe ich verweigert.“[111] Die Studenten agierten zunehmend gegen ihre einstigen Vorbilder, beschimpften sie in einem Flugblatt gar als „Büttel des autoritären Staates“.[112] Adornos Vorlesungen wurden wiederholt von studentischen Aktivisten gesprengt, besonders spektakulär war eine Aktion (in den Medien zum sogenannten Busenattentat stilisiert) im April 1969, als Hannah Weitemeier und zwei andere Studentinnen Adorno mit entblößten Brüsten auf dem Podium bedrängten und ihn mit Rosen- und Tulpenblüten bestreuten.[113] „Das Gefühl, mit einem Mal als Reaktionär angegriffen zu werden, hat immerhin etwas Überraschendes“, schrieb Adorno an Samuel Beckett.[114] Andererseits wurden Adorno und Horkheimer von der politischen Rechten vorgeworfen, sie seien die geistigen Urheber der studentischen Gewalt. |

フランクフルトでの晩年(1949年~1969年) フランクフルト・アム・マインのゼンケンベルクアナーゲルにある社会研究所と「アドルノ信号機」。アドルノは1962年から、研究所とフランクフルト・ ボッケンハイムの大学キャンパスを結ぶ交通量の多い道路に信号機を設置するよう運動を続けていたが、信号機が設置されたのは1987年になってからだっ た。 1949年10月、アドルノは初めてアメリカからドイツに戻った。その直接の理由は、1949年にすでに哲学と社会学の正教授に再任されていたホルクハイ マーの代理としてフランクフルト大学で教えることだった。87] ドイツとアメリカを行き来した後、アドルノはついに1953年8月にドイツに永住することとなった。フランクフルト大学は、彼を非常勤講師(1950年) から准教授( 1956年には哲学と社会学の正教授に昇進した。 アドルノがドイツに戻った動機は、彼自身の言葉によれば、主観的にはホームシック、客観的には言語によって決定された。彼はドイツ語に依存しており、彼に とってドイツ語は「哲学と特別な親和性を持つ」言語であった。[89] 彼の思考は「ドイツ語と切り離すことはできなかった」のである。[90] 彼は科学者として、1933年に奪われた母校での哲学の非常勤講師職に復帰した。しかし、彼はすぐに亡命中に幅広い資格を取得していた社会学という異なる 学問分野の代表者として知られるようになった。一方で、彼は敗戦後のドイツでの初期の経験を非常に批判的に見ていた。ナチス党員とほとんど会うことはな く、彼らは誰も自分が関与していたことを認めようとはせず、誰も何も知らなかったと述べている。[91] 一方で、彼は学生たちの「熱狂的な参加」を賞賛した。 、ウォルター・ディルクスとオイゲン・コーゴンと緊密な協力関係を築いた。 旧スタッフのうちフランクフルトに戻ったのはフリードリヒ・ポロックだけで、ホルクハイマーとアドルノも一緒だった。フロム、レヴェンタール、マルクー ゼ、フランツ・ノイマン、カール・アウグスト・ヴィトフォーゲルは、米国で学問的キャリアを継続することを選んだ。[94]アドルノは、1951年11月 14日に新築の建物で再開した社会研究所の共同責任者となり、当初から副所長を務めた 。この研究所は、戦後のドイツで社会学の学位プログラムを提供した最初の学術機関であった。 ホルクハイマーがスイスのモンタニョーラに引っ込んでからは、実質的な業務はアドルノの肩にのしかかった。1958年には、アドルノは研究所の経営を正式 に引き継いだ。96] 妻のマルガレーテは、アドルノにとって「自身の仕事にとって不可欠な支え」であり、積極的な協力者でもあった。彼女は朝、アドルノと一緒に研究所に入り、 夕方には一緒に帰宅した。彼女自身のオフィスでは、アドルノの文章が印刷される前に、すべてを入念に校正していた。彼女はアドルノの講義を一度も欠席する ことはなかった。彼女は「告解者」として学生に相談にのり、「偉大なる父」との仲介役も務めていた。[97] 彼らの結婚に子供がいなかったのは、両者による意識的な決断であり、その理由は当時の不安定な情勢と将来の見通しに起因するものだった。[98] アドルノがアメリカで社会研究の分野で培った科学的生産性は、1950年代と1960年代にドイツでアドルノがドイツ社会学の最も重要な代表者の一人とし て認められることに貢献した。99] 1955年にルートヴィヒ・フォン・フリーデブルクが研究所の実証研究プロジェクトを担当する部門の新しい責任者として採用された後、アドルノは徐々に 実証研究からは身を引いたが、その後も理論的考察と実証研究の関係について論評を続けた。彼の懐疑論は、1961年にカール・ポパーの講演とアドルノによ る「社会科学の論理」に関する反論講演という、いわゆる「実証主義論争」で極点に達した。この論争は、ドイツ社会学会のテュービンゲンでのワークショップ で始まった 、その後の経過ではラルフ・ダレナード、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス、ハンス・アルバートが参加した。 1962年から1969年にかけて、アドルノはミュンヘン出身でフランクフルトに定期的に訪れていた女性、アレッテ・ピールマンと不倫関係にあった。アドルノの妻グレーテルはそれを知っていたが、認めてはいないものの黙認していた。 1963年から1967年にかけてアドルノはドイツ社会学会の会長を務め、1968年にフランクフルト・アム・マインで開催された第16回ドイツ社会学会 議の責任者となった。この会議は「後期資本主義または産業社会」というタイトルで開かれた。この時期は学生運動が盛んになった時期と重なっていた。講演者 やパネリストたちは、学生たちによる度重なる妨害や中断、その他の規則違反に対して、概ね冷静に対応した。 大学講師やフランクフルト社会研究所の所長としての仕事に加え、アドルノは重要な哲学的な著作も残している。1951年には早くも、亡命先から持ち帰った 格言集を拡大した『ミニマ・モラリア』を出版し、ホルクハイマーに捧げた。10万部以上を売り上げたこの本には、今では有名な一文「間違った人生に正しい ものなどありえない」(GS 4: 43)が含まれている。[104] 1956年に出版された『認識論批判』は、オックスフォードでの研究を一部基にしている。彼の主要な哲学書は『否定弁証法』であり、アドルノ自身はこれを 「反体制」と評している(GS 6: 10)(1966年初版)。 アドルノは、亡命中に執筆した『新音楽の哲学』(1949年)や、リヒャルト・ワーグナー(1952年)、グスタフ・マーラー(1960年)、アルバン・ ベルク(1968年)に関する単行本、および『音楽社会学入門』(1962年)[105]といった音楽哲学や音楽社会学に関する著作を通じて、戦後の西ド イツの音楽界に参加した。また、 ダルムシュタットで開催された「新しい音楽のための国際夏季現代音楽講習会」で音楽講師を務めたこともあった。この講習会は1960年代後半まで毎年開催 され、アドルノは1950年から1966年まで講師や講演者として定期的に参加していた。 音楽以外では、アドルノの美的思考に影響を与えたのは文学であった。彼はこの芸術ジャンルに関する哲学的な見解を数多くのエッセイにまとめ、それらは 『Noten zur Literatur』(GS 11)の4巻にまとめられている。彼はインゲボルク・バッハマン、アレクサンダー・クルーゲ、ハンス・マグヌス・エンツェンスベルガーといった作家たちと 友好的な関係を維持していた。彼はメディアで強い存在感を示し、哲学や社会学の分野だけでなく、音楽理論や文学批評の分野でも、引っ張りだこの専門家や論 客となった。 アドルノは非常に評価の高い大学講師であった。1950年代後半から、あらゆる分野の学生たちが、大学最大の講堂で行われた彼の講義に押し寄せた。わずかなメモを基に、微妙かつ自由な表現で展開される講義は、多くの学生を魅了した。 アドルノの晩年は、学生たちとの対立に明け暮れた。SDSを先頭に、政府の計画する緊急事態法とベトナム戦争に抗議する新たな学生運動が形成されると、緊 張が高まった。アドルノはこれらの法律の批判派に加わり、緊急事態における民主主義行動委員会が主催するイベントで公然と彼らに同調した。1968年5月 28日、彼は学生運動とは距離を置いた。 反乱の精神を体現し、批判理論から「現実的な帰結」を引き出そうとしたのはアドルノの学生たちであった。1967年6月2日、西ベルリンでシャーに対する デモが行われている最中に、警察官カール・ハインツ・クーラスが学生ベノ・オネゾルクを射殺した事件をきっかけに、APOは急進化していった。オネゾルク の死の直後、アドルノは美学講義の冒頭で「政治的デモへの参加とはまったく不釣り合いな運命をたどった学生に同情する」と表明していた。 [109] フランクフルト学派の指導者たちは、保守回帰の傾向や「テクノクラートによる大学改革」に反対する学生の批判や抗議運動に共感していたが、[110] 彼らの行動主義的アプローチを支持するつもりはなかった。1969年のラジオ講義『諦念』(GS 10/2 756 f.)において、アドルノはそれを「偽りの活動」および「理論に対する焦り」と呼んだ。 1969年5月、アドルノは雑誌『シュピーゲル』のインタビューで、理論と実践の関係について長々と語っている。「私は最近、テレビのインタビューで、理 論モデルを構築したものの、人々がそれをモロトフ・カクテルで実行しようとするとは予見できなかったと述べた。[...] 1967年にベルリンで私に対して最初のサーカスが行われて以来、特定の学生グループは、私に連帯を示し、実際的な行動を要求しようと繰り返し迫ってき た。私は拒否した」[111] 学生たちは次第に、かつてのロールモデルに反旗を翻すようになり、彼らを「権威主義国家の手先」と呼ぶチラシまで作られた。アドルノの講義は学生活動家た ちによって何度も妨害され、1969年4月のある行動(メディアでは「胸ぐら攻撃」として様式化された)は特に壮観であった。ハンナ・ヴァイトマイヤーと 他の2人の学生が、アドルノを演壇で裸の バラとチューリップの花びらを彼に被せた。113] 「このような時に反動主義者として攻撃されるという感覚は、やはり、いくらか驚くべきものだ」とアドルノはサミュエル・ベケットに書き送った。114] 一方で、アドルノとホルクハイマーは、政治的右派から学生暴動の知的首謀者として非難された。 |

Adornos Grab (2007) 1969 sah Adorno sich gezwungen, seine Vorlesungen einzustellen. Als am 31. Januar 1969 Studenten in das Institut für Sozialforschung eingedrungen waren, um kategorisch eine sofortige Diskussion über die politische Situation durchzusetzen, riefen die Institutsdirektoren – Adorno und Ludwig von Friedeburg – die Polizei und zeigten die Besetzer an. Adorno, der immer ein Gegner des Polizei- und Überwachungsstaats gewesen war, litt unter diesem Bruch seines Selbstverständnisses. Er musste als Zeuge vor dem Frankfurter Landgericht gegen Hans-Jürgen Krahl, einen seiner begabtesten Schüler, aussagen. Adorno äußerte sich dazu in einem Brief an Alexander Kluge: „Ich sehe nicht ein, warum ich mich zum Märtyrer des Herrn Krahl machen soll, von dem ich mir doch ausdachte, daß er mir ein Messer an die Kehle setzt, um mir diese durchzuschneiden, und auf meinen gelinden Protest erwidert: Aber Herr Professor, das dürfen Sie doch nicht personalisieren“.[115] Ab Februar 1969 bis zu Adornos Tod trugen Adorno und Herbert Marcuse in einem intensiven Briefwechsel einen Dissens aus, von dem Adorno in einem Brief an Horkheimer bereits befürchtete, er könnte einen „Bruch zwischen ihm und uns“ herbeiführen.[116] Marcuse kritisierte Adornos Praxis-Abstinenz ebenso wie Habermas’ Vorwurf des „linken Faschismus“ gegenüber den rebellierenden Studenten sowie die polizeiliche Räumung des besetzten Instituts.[117] Adorno verteidigte Habermas’ Vorwurf. Auch er sah jetzt Tendenzen, die „mit dem Faschismus unmittelbar konvergieren“, und nahm, wie er Marcuse schrieb, „die Gefahr des Umschlags der Studentenbewegung in Faschismus viel schwerer als Du“.[118] Am Tag nach der Gerichtsverhandlung gegen Krahl fuhr er mit seiner Frau in den üblichen Sommerurlaub in die Schweizer Berge. Statt des gewohnten Urlaubs in Sils Maria fuhren sie erstmals nach Zermatt (1600 m. ü. M.). Ungenügend akklimatisiert, fuhr er mit einer Seilbahn auf fast 3000 m. ü. M. und wanderte dann zur Gandegghütte (3030 m.ü.M.). Weil er Probleme mit seinem Bergschuh hatte, ließ er sich anschließend nach Visp (660 M. ü. M.) zu einem Schuhmacher fahren. Als er Herzbeschwerden bekam, wurde er ins Visper Krankenhaus St. Maria gebracht. Dort erlag er am Morgen des 6. Augusts 1969 einem Herzinfarkt.[119] Adornos Grab befindet sich auf dem Frankfurter Hauptfriedhof. |

アドルノの墓 (2007) 1969年、アドルノは講義を中止せざるを得なくなった。1969年1月31日、学生たちが政治情勢の即時討論を断固として要求するために社会研究所に押 し入った際、研究所の所長であるアドルノとルートヴィヒ・フォン・フリーデブルクは警察に通報し、占拠者たちを報告した。警察国家や監視国家に常に反対し てきたアドルノは、この自己イメージの侵害に苦しんだ。彼はフランクフルト地方裁判所で、最も優秀な学生の一人であったハンス=ユルゲン・クラールに対し て証人として証言しなければならなかった。アドルノはアレクサンダー・クルーゲ宛ての手紙で次のように述べている。「私が想像するに、クラール氏はナイフ を喉に突きつけてそれを切り落とすだろう。私が軽く抗議すると、彼は『しかし教授、これは個人的なことにしてはいけませんよ』と答えるだろう。」 [115] 1969年2月からアドルノが亡くなるまで、アドルノとハーバート・マルクーゼは激しい意見の相違を表明する書簡のやり取りを続けた。アドルノはホルクハ イマー宛ての手紙で、これが「彼と我々との決別」につながることを危惧した。[116] マルクーゼはアドルノの実践からの離脱を批判し、ハーバマスが反逆する学生たちや、 占拠された大学の警察による排除を非難した。アドルノはハーバーマスの非難を擁護した。アドルノもまた「ファシズムに直接収束する」傾向を認識しており、 マルクーゼに宛てた手紙の中で「学生運動がファシズムに転化する危険性を、君よりもずっと深刻に受け止めている」と述べている。 クラールに対する公判の翌日、彼は妻とともに、例年通り夏の休暇をスイスの山で過ごすために出かけた。いつもはシルス・マリアで過ごす休暇を、ツェルマッ ト(標高1600メートル)で過ごすことにした。 十分な高地順応をせずに、ケーブルカーで標高3000メートル近くまで登り、そこからガンデックヒュッテ(標高3030メートル)までハイキングした。登 山靴に問題があったため、その後、彼はヴィスプ(標高660メートル)まで乗用車に乗り、靴屋を訪れた。心臓に問題が生じ始めたため、彼はヴィスプの聖マ リア病院に搬送された。1969年8月6日の朝、彼は同病院で心臓発作により死亡した。 アドルノの墓はフランクフルトの中央墓地にある。 |

| Einflüsse auf das Werk Als besonders bedeutsame Einflüsse für das Denken Adornos lassen sich Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx und Sigmund Freud anführen. Die „Großtheorien“ von Hegel, Marx und Freud übten auf viele linke Intellektuelle in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, wie auch auf einen Großteil der Theoretiker der Frankfurter Schule, eine große Faszination aus. Mit kritischem Unterton spricht Lorenz Jäger in seiner „politischen Biographie“ dabei von Adornos „Achillesferse“, das heißt dessen „fast unbegrenzte[m] Vertrauen auf fertige Lehren, auf den Marxismus, die Psychoanalyse, die Lehren der Zweiten Wiener Schule“.[120] Indessen vertraute Adorno dem Marxismus ebenso wenig unverändert wie der Hegel’schen spekulativen Dialektik. Die Zweite Wiener Schule freilich blieb in seinem Wirken als Musikkritiker und Komponist der Leitstern. |

作品への影響 アドルノの思想に特に大きな影響を与えた人物として、イマニュエル・カント、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、カール・マルクス、ジーク ムント・フロイトを挙げることができる。 ヘーゲル、マルクス、フロイトの「大理論」は、20世紀前半の多くの左派知識人、そしてフランクフルト学派の理論家の多くを魅了した。批判的な含みを持た せながら、ローレンツ・イェーガーはアドルノの「アキレス腱」、すなわち「既製の教義、マルクス主義、精神分析、第二ウィーン学派の教えに対するほぼ無制 限の信頼」について、彼の「政治的伝記」の中で語っている。[120] 一方で、アドルノはヘーゲル的な思弁的弁証法と同様に、マルクス主義もそのままではほとんど信用していなかった。もちろん、ウィーン学派は、音楽評論家お よび作曲家としての彼の作品における指針であり続けた。 |

Hegel Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel Adornos Aneignung der Hegel’schen Philosophie lässt sich mindestens bis zu seiner Antrittsvorlesung von 1931 zurückverfolgen; in ihr postulierte er: „Einzig dialektisch scheint mir philosophische Deutung möglich“ (GS 1: 338). Hegel lehne es ab, die philosophische Methode von ihrem Inhalt, den Gegenständen, zu trennen, da Denken immer schon Denken von etwas ist, sodass Dialektik „die begriffene Bewegung des Gegenstands selbst“ ist.[121] Der Argumentation der Phänomenologie des Geistes folgend, könne der wissenschaftliche Standpunkt weder als selbstverständlich vorausgesetzt, noch als losgelöst von den Gegenständen betrachtet werden. Eine wichtige Rolle für Adornos Philosophie und Gesellschaftskritik nimmt dabei eine der Hegelschen Grundkategorien ein – die bestimmte Negation.[122] Allerdings erhält diese Kategorie bei Adorno nun eine neue, kritische Funktion: Hatte Hegel als bestimmte Negation das Charakteristikum der Entwicklung und des Fortschreitens des Bewusstseins beschrieben, wobei dem Philosophen selbst nichts als „das reine Zusehen“ bleibe, so wird die bestimmte Negation bei Adorno zu einer Form der immanenten Kritik umgedeutet. Dies dient Adorno nicht nur zur radikalen Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse, sondern beinhaltet letztlich sogar ein Festhalten an Metaphysik als „Konstellation“. (GS 6: 399) Die Vorgehensweise der bestimmten Negation durchzieht nicht zuletzt einen Großteil der materialen Arbeiten Adornos, so etwa die Dialektik der Aufklärung und die Minima Moralia. Seine Drei Studien zu Hegel verstand Adorno als „Vorbereitung eines veränderten Begriffs von Dialektik“; sie hören dort auf, „wo erst zu beginnen wäre“ (GS 5: 249 f.). Dieser Aufgabe widmete sich Adorno in einem seiner späteren Hauptwerke, der Negativen Dialektik (1966). Der Titel dieses ‚Programms‘ bringt, wie Tilo Wesche es ausdrückt, „Tradition und Rebellion gleichermaßen zum Ausdruck“.[123] Tradition einerseits, da Adorno Dialektik, wie sie von Hegel als werdender Vermittlungsprozess neu gedacht und entfaltet wurde, aufgreift. Rebellion andererseits, insofern Adorno unter dem Vorbehalt des Negativen (auch: des „Nichtidentischen“) Hegels spekulative Dialektik angreift (siehe dazu weiter unten). Speziell kritisiert Adorno an Hegel dessen Übergang von der Dialektik zur spekulativen Vernunft. Als Bedingung für das Funktionieren von Hegels geschichtlichem System werde dabei das Moment „des Nichtaufgehenden“ mithilfe eines „Münchhausenkunststücks“ der Vernunft weggeschafft. (GS 5: 375) Dafür müsse sich das „zum absoluten [Geist, d. V.] sich stilisierende Subjekt“ (GS 6: 187) jedoch selbst betrügen, d. h. letztlich Realitätsverleugnung betreiben. Denn: „Vermittlung des Subjekts [bedeutet], daß es ohne das Moment der Objektivität buchstäblich nichts wäre.“ (GS 6: 187) Insofern verfolgt Adorno die Absicht, Dialektik – welche bei Hegel zwar mehr als der Verstand, jedoch weniger als die spekulative Vernunft geleistet habe – als Schlüsselmoment für Philosophie wiederzugewinnen.[124] |

ヘーゲル ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル アドルノによるヘーゲル哲学の借用は、少なくとも1931年の就任講演まで遡ることができる。その中で彼は次のように主張した。「私にとって哲学的な解釈 は弁証法的にのみ可能であるように思われる」(『ゲゼルシャフト・シュピーゲル』第1巻、338ページ)。ヘーゲルは、哲学的方法をその内容や対象から切 り離すという考えを否定した。思考とは常に何かについて考えることであるため、弁証法は「対象そのものの概念化された運動」である。[121] 『精神現象学』の議論に従えば、科学的視点は当然視されるものでも、対象から切り離されたものとして見なされるものでもない。 ヘーゲルの基本的なカテゴリーのひとつである「確実な否定」は、アドルノの哲学と社会批判において重要な役割を果たしている。122] しかし、アドルノは今、このカテゴリーに新たな批判的な機能を付与している。ヘーゲルは確実な否定を意識の発展と進歩の特徴として説明したが、その中で哲 学者自身は「純粋な観察」以外には何も残されていない。アドルノは確実な否定を再解釈し、 内在的批判の一形態として再解釈される。これはアドルノが社会状況を根本的に批判するのに役立つだけでなく、最終的には「星座」としての形而上学への固執 さえも含む。(GS 6: 399)明確な否定のアプローチは、啓蒙の弁証法や『ミニマ・モラリア』など、アドルノの著作の多くに浸透している。 アドルノは『ヘーゲルに関する三つの研究』を「修正された弁証法概念の準備」と捉えていた。この作品は「どこから始めなければならないか」というところで 終わっている(GS 5: 249 f.)。アドルノは、この課題に専念した。その成果が、彼の晩年の主要著作のひとつ『否定的弁証法』(1966年)である。この「プログラム」のタイトル は、ティロ・ヴェシェの表現を借りれば、「伝統と反逆の両方を表現している」[123]。伝統という側面は、アドルノがヘーゲルによって再考され発展した 弁証法を、新たな調停のプロセスとして取り上げたことによる。一方、反抗という点では、アドルノがヘーゲルの思弁的弁証法を否定(「非同一」)という条件 付きで攻撃していることによる(この点については後述)。 アドルノは特にヘーゲルが弁証法から思弁的理性へと移行したことを批判している。ヘーゲルの歴史体系が機能するための条件として、「非吸収」の瞬間が 「ミュンヒハウゼンのトリック」によって理性から取り除かれる。(GS 5: 375)しかし、そうするためには、「主体が自らを絶対的なものへと様式化する」(GS 6: 187)ことが必要であり、すなわち、究極的には現実の否定に自らを従事させることになる。なぜなら、「主体の媒介とは、客観性の瞬間がなければ文字通り 何もないことを意味する」からだ(GS 6: 187)。この点において、アドルノは、ヘーゲルの著作において理解以上のもの、しかし思弁的理性未満のものを達成した弁証法を、哲学の重要な瞬間として 取り戻すという意図を追求している。 |

| Karl Marx Die Marx’sche Kritik der politischen Ökonomie gehört zum Hintergrundverständnis des Adorno’schen Denkens, freilich – nach Jürgen Habermas – als „verschwiegene Orthodoxie, deren Kategorien […] sich in der kulturkritischen Anwendung [verraten], ohne als solche ausgewiesen zu werden“.[125] Seine Marx-Rezeption erfolgte zunächst vermittelt durch Georg Lukács’ einflussreiche Schrift Geschichte und Klassenbewußtsein; von ihm übernahm Adorno die marxistischen Kategorien des Warenfetischs und der Verdinglichung. Sie stehen in enger Verbindung zum Begriff des Tauschs, der wiederum im Zentrum von Adornos Philosophie steht und erkenntnistheoretisch weit über die Ökonomie hinausweist. Unschwer ist die entfaltete „Tauschgesellschaft“ mit ihrem „unersättlichen und destruktiven Expansionsprinzip“ (GS 5: 274) als die kapitalistische zu dechiffrieren. Neben dem Tauschwert nimmt der Marx’sche Ideologiebegriff in seinem gesamten Werk einen prominenten Stellenwert ein.[126] Auch der Klassenbegriff, den Adorno eher selten benutzte, hat seinen Ursprung in der Marx’schen Theorie. Zwei Texte Adornos beziehen sich explizit auf den Klassenbegriff: Der eine ist das Unterkapitel Klassen und Schichten aus der Einleitung in die Musiksoziologie, der andere ein unveröffentlichter Aufsatz aus dem Jahre 1942 mit dem Titel Reflexionen zur Klassentheorie, der erstmals posthum in den Gesammelten Schriften veröffentlicht wurde (GS 8: 373–391). |

カール・マルクス 確かに、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスによれば、マルクスの政治経済批判はアドルノの思想の背景にある理解の一部である。「暗黙の正統性」として、その カテゴリーは「[...] そのように特定されることなく、文化批判的な適用において自らを露呈する」のである。 [125] アドルノのマルクス受容は、当初はゲオルク・ルカーチの影響力のある著作『歴史と階級意識』によって仲介された。アドルノはルカーチから、商品フェティシ ズムと物象化というマルクス主義のカテゴリーを借用した。これらは交換の概念と密接に関連しており、交換の概念はアドルノの哲学の中心であり、認識論的に は経済をはるかに超えたところを指し示している。「飽くなき拡大の破壊的原則」(GS 5: 274)を持つ「交換社会」が資本主義社会であると解釈するのは難しいことではない。交換価値に加えて、彼の著作全体においてマルクス主義のイデオロギー 概念が重要な役割を果たしている。 アドルノがほとんど使用しなかった階級という概念も、その起源はマルクス主義理論にある。アドルノの著作のなかで階級概念に明確に言及しているものは2つ ある。1つは『音楽社会学序説』の「階級と階層」という小見出しの章であり、もう1つは1942年に書かれた未発表のエッセイ「階級理論についての考察」 で、これは死後に『全集』第8巻(GS 8: 373-391)で初めて出版された。 |

| Sigmund Freud Die Psychoanalyse ist ein konstitutives Element der Kritischen Theorie.[127] Zwar hat Adorno, im Gegensatz zu Horkheimer, sich nie der praktischen Erfahrung einer Psychoanalyse unterzogen,[128] aber schon früh das Werk Sigmund Freuds rezipiert. Seine Freud-Lektüre reicht in die Zeit seiner Arbeit an der ersten (zurückgezogenen) Habilitationsschrift – Der Begriff des Unbewußten in der transzendentalen Seelenlehre – von 1927 zurück. Darin vertrat Adorno die These, „daß die Heilung aller Neurosen gleichbedeutend ist mit der vollständigen Erkenntnis des Sinns ihrer Symptome durch den Kranken“ (GS 1: 236). In dem Aufsatz Zum Verhältnis von Soziologie und Psychologie (1955) begründete er als Notwendigkeit, „angesichts des Faschismus“ die „Theorie der Gesellschaft durch Psychologie, zumal analytisch orientierte Sozialpsychologie zu ergänzen“. Um den Zusammenhalt der repressiven, gegen die Interessen der Menschen gerichteten Gesellschaft erklären zu können, bedürfe es der Erforschung der in den Massen vorherrschenden Triebstrukturen (GS 8: 42). Adorno blieb immer Anhänger und Verteidiger der orthodoxen Freud’schen Lehre, der „Psychoanalyse in ihrer strengen Gestalt“.[129] Aus dieser Position heraus hat er schon früh Erich Fromm[130] und später Karen Horney wegen ihres Revisionismus angegriffen (GS 8: 20 ff.). Vorbehalte äußerte er sowohl gegen eine Soziologisierung der Psychoanalyse[131] als auch gegen ihre Reduzierung auf ein therapeutisches Verfahren.[132] Der Freud-Rezeption verdankte Adorno zentrale analytische Begriffe wie Narzissmus, Ich-Schwäche, Lust- und Realitätsprinzip. Freuds Schriften Das Unbehagen in der Kultur und Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse waren ihm wichtige Referenzquellen. Der „genialen und viel zu wenig bekannten Spätschrift über das Unbehagen in der Kultur“ (GS 20/1: 144) wünschte er „die allerweiteste Verbreitung gerade im Zusammenhang mit Auschwitz“; zeige sie doch, dass mit der permanenten Versagung, welche die Zivilisation auferlege, „im Zivilisationsprinzip selbst die Barbarei angelegt ist“ (GS 10/2: 674). |

ジークムント・フロイト 精神分析は批判理論の構成要素である。127] ホルクハイマーとは異なり、アドルノは精神分析の実践的な経験をしたことはなかったが、128] 彼は早くからジークムント・フロイトの著作を読んでいた。フロイトの著作を読んだのは、1927年の最初の(取り下げられた)博士論文『魂の超越論的教義 における無意識の概念』の執筆時まで遡る。その論文の中でアドルノは、「あらゆる神経症の治癒は、患者が自らの症状の意味を完全に理解することに等しい」 というテーゼを提示した(GS 1: 236)。論文「社会学と心理学の関係について」(1955年)において、アドルノは「ファシズムに直面する中で、社会理論を心理学、特に分析的社会心理 学によって補う」ことの必要性を説明した。人民の利益に反する抑圧的社会の結束を説明するためには、大衆に浸透する動因構造の研究が必要である(GS 8: 42)。 アドルノは常に正統派のフロイト学説、すなわち「厳格な形での精神分析」の支持者であり擁護者であった。[129] この立場から、彼は早い時期にエーリッヒ・フロム[130]を、後にカレン・ホルネイを修正主義者として攻撃した(GS 8: 20 ff.)。彼は精神分析の社会学化[131]と、それを治療手順に還元すること[132]の両方に懐疑的な見方を示した。アドルノはナルシシズム、自我の 脆弱性、快楽原則、現実原則といった主要な分析概念をフロイトの受容に負っていた。フロイトの著作『文化における不満』、『集団精神分析と自我の分析』 は、彼にとって重要な参照資料であった。彼は、「文化における不安に関するこの輝かしいが、あまりにも知られていない晩年の業績」が、「特にアウシュビッ ツに関連して」可能な限り広く普及することを望んでいた(GS 20/1: 144)。なぜなら、それは文明によって課された永続的な否定とともに、「野蛮は文明の原則そのものに内在する」ことを示しているからだ(GS 10/2: 674)。 |

| Rezeption weiterer Autoren Am dänischen Philosophen und Vorläufer der Existenzphilosophie Søren Kierkegaard schätzte Adorno dessen Kritik an Hegels Geringschätzung des Individuums, das hinter dem objektiven Geist verschwindet. Sie hat Adornos Blick auf Hegels Dialektik geschärft und nachhaltig beeinflusst. Viele später ausformulierte philosophische Motive Adornos finden sich in seiner Kierkegaard-Schrift bereits angedeutet. Horkheimer charakterisierte sie als „unerhört schwierig“.[133] Adornos Auseinandersetzung mit Edmund Husserls Phänomenologie fand ihren Niederschlag in der Schrift Zur Metakritik der Erkenntnistheorie. Adorno hatte an dem Manuskript von 1934 bis Herbst 1937 in Oxford gearbeitet, ohne es abzuschließen.[134] Nachdem in den folgenden Jahren einzelne Kapitel veröffentlicht worden waren, erschien das Werk erst 1956 als Monographie mit der Widmung „Für Max“. Das Buch gilt als „Solitär“, das keine größere Resonanz in der philosophischen Literatur fand,[135] obwohl Adorno 1968 die Arbeit als das ihm nächst der Negativen Dialektik wichtigste seiner Bücher bezeichnete (GS 5: 386). Als Antipode Heideggers, des führenden Vertreters der Fundamentalontologie, unterzog er im Jargon der Eigentlichkeit dessen Begrifflichkeit einer „ideologiekritischen Sprachanalyse“. Doch wusste er zu unterscheiden zwischen der substantiellen Philosophie Heideggers und der Plumpheit der „Imitatoren des existentiell-philosophischen Sprachgestus“.[136] Auf die Nähe des Denkens Adornos, seine Überschneidungen mit der Philosophie Heideggers, wurde häufig verwiesen.[137] → Hauptartikel: Jargon der Eigentlichkeit |

他の著者の評価 アドルノは、ヘーゲルが個人を軽視し、客観的精神の背後に消え失せてしまうという批判を行ったデンマークの哲学者であり実存主義の先駆者であるキルケゴー ルを高く評価した。 キルケゴール批判は、アドルノのヘーゲル弁証法に対する見方を鋭くし、長期的に影響を与えた。アドルノの後の哲学的主題の多くは、すでにキルケゴールに関 する著作に見出すことができる。ホルクハイマーはそれを「信じられないほど難しい」と評した。[133] アドルノのエドムント・フッサール現象学への関与は、著書『認識論批判』(Zur Metakritik der Erkenntnistheorie)に表現されている。アドルノは1934年から1937年秋にかけてオックスフォードでこの原稿に取り組んだが、完成 させることはできなかった。各章がその後出版された後、この著作は1956年まで単行本として出版されることはなく、「マックスに捧ぐ」とされた。この本 は哲学の文献では大きな反響を得られなかった「孤独な」作品とみなされているが[135]、1968年にアドルノは『否定的弁証法』に次いで自身の著作の 中で最も重要なものだと述べている(GS 5: 386)。 根本的な存在論の代表的人物であるハイデガーの対極に位置するアドルノは、「現実性」という概念を「イデオロギー批判的な言語分析」に服従させた。しか し、彼はハイデガーの実質的な哲学と、「実存哲学的な言語的ジェスチャーの模倣者」の不器用さの違いを見分ける術を知っていた。[136] アドルノの思想とハイデガーの哲学の近さ、重なり合いは、しばしば言及されてきた。[137] → 詳細は「実在性のための弁証法」を参照 |

| Werk Jan Philipp Reemtsma hat Adornos Publikationen zu den verschiedenen Themengebieten nach quantitativen Anteilen an seinen Gesammelten Schriften erfasst: Demnach entfallen auf im weitesten Sinne philosophische Fragen 2.600 Seiten, auf soziologische Themen 1.500 Seiten, auf literaturtheoretische bzw. -kritische rund 800 Seiten, auf die musikalischen Schriften hingegen mehr als 4.000 Seiten.[138] |

作品 ヤン・フィリップ・レームツマは、アドルノのさまざまなテーマに関する出版物を、彼の著作集における量的な割合に従って記録している。それによると、最も 広い意味での哲学的な問いかけに2,600ページ、社会学的なテーマに1,500ページ、文学理論と批評に約800ページ、音楽に関する著作に4,000 ページ以上が割かれている。 |