不可知論者の系譜

Agnosticism

Salvator Rosa, Démocrite et Protagoras. 1663.

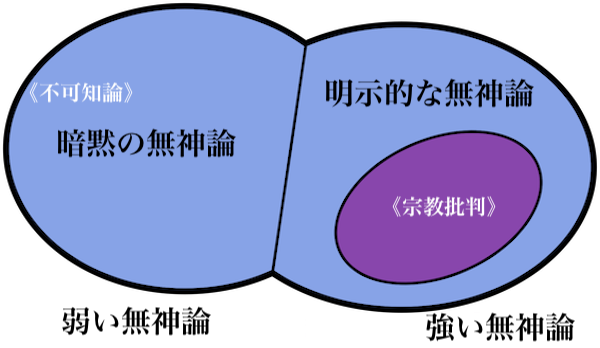

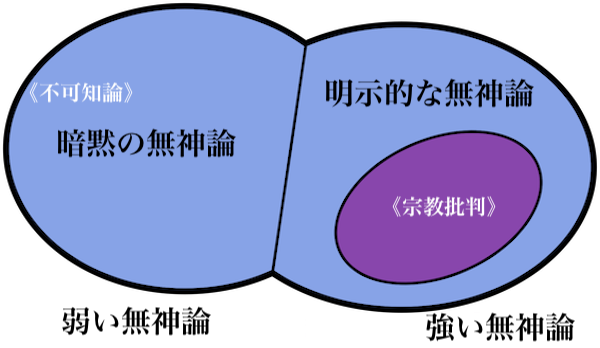

☆ 不可知論とは、神、神的なもの、超自然的なものの存在は、原理的に知ることができな いか、事実として現在知られていないという見解や信念のことである。また、そのような宗教的信念に対する無関心を意味することもあり、世界観というよりはむしろ個人 的な限界を指すこともある。もうひとつの定義は、「人間の理性は、神が存在するとい う信念と、神は存在しないという信念のいずれをも正当化する十分な合理的根拠を提供することができない」という見解である(→「弱い無神論」に位置する)。 イギリスの生物学者であるトーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは、1869年に不可知論者(Agnostic)という言葉を作り、「(自分自身のように)形而 上学者や神学者が正統派も異端派も最大限の自信を持って教義を説いている様々な事柄(もちろん神の存在に関する事柄も含む)について、絶望的なまでに無知 であることを自白する人々を表すために」"Agnostic "という言葉を元々発明したと述べている。 「前5世紀のインドの哲学者サンジャヤ・ベラトティプッタは死後の世界について不可知論を表明しており、前5世紀のギリシャの哲学者プロタゴラスは「神 々」の存在について不可知論を表明している。

☆不可知論はアグノーシティシズム[グノーシスは知識の意味である]と言われる。A+gnosticismと分解できるので、文字通り知識を否定する=知っていることを否定する、という意味になる。グノーシス主義=グノスティシズム[Gnosticism] (古代ギリシア語: γνωστικός, ローマ字表記: gnōstikós, コイネギリシア語: [ɣnostiˈkos]、「知識を持つ」)は、紀元後1世紀後半にユダヤ教や初期キリスト教の宗派の間で合体した宗教思想や宗教体系の集まりである。こ れらの様々なグループは、原初的な正統派の教えや伝統、宗教機関の権威よりも、個人的な霊的知識(グノーシス)を重視した。そうすると、アグノーシティシズムは、個人的な知識よりも集合的な知識、社会的な知識、コンセンサスのある知識、純然たる「事実」を重要視する立場とも理解することができる。

| Agnosticism is the

view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the

supernatural is either unknowable in principle or currently unknown in

fact.[1][2][3] It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief

and refer to personal limitations rather than a worldview.[2][4][5]

Another definition is the view that "human reason is incapable of

providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that

God exists or the belief that God does not exist."[6] The English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the word agnostic in 1869, and said that he originally invented the word "Agnostic" "to denote people who, like [himself], confess themselves to be hopelessly ignorant concerning a variety of matters [including of course the matter of God's existence], about which metaphysicians and theologians, both orthodox and heterodox, dogmatise with the utmost confidence."[7] Earlier thinkers had written works that promoted agnostic points of view, such as Sanjaya Belatthiputta, a 5th-century BCE Indian philosopher who expressed agnosticism about any afterlife;[8][9][10] and Protagoras, a 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher who expressed agnosticism about the existence of "the gods".[11][12][13]  |

不可知論とは、神、神的なもの、超自然的なも

のの存在は、原理的に知ることができないか、事実として現在知られていないという見解や信念のことである[1][2][3]。また、そのような宗教的信念

に対する無関心を意味することもあり、世界観というよりはむしろ個人的な限界を指すこともある[2][4][5]。もうひとつの定義は、「人間の理性は、

神が存在するという信念と、神は存在しないという信念のいずれをも正当化する十分な合理的根拠を提供することができない」という見解である[6]。 イギリスの生物学者であるトーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは、1869年に不可知論者という言葉を作り、「(自分自身のように)形而上学者や神学者が正統 派も異端派も最大限の自信を持って教義を説いている様々な事柄(もちろん神の存在に関する事柄も含む)について、絶望的なまでに無知であることを自白する 人々を表すために」"Agnostic "という言葉を元々発明したと述べている。 「前5世紀のインドの哲学者サンジャヤ・ベラトティプッタは死後の世界について不可知論を表明しており[8][9][10]、前5世紀のギリシャの哲学者 プロタゴラス(Protagoras) は「神々」の存在について不可知論を表明している[11][12][13]。  |

| Defining agnosticism [The agnostic] principle may be stated in various ways, but they all amount to this: that it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty. This is what Agnosticism asserts; and, in my opinion, it is all that is essential to Agnosticism.[14] — Thomas Henry Huxley Agnosticism, in fact, is not a creed, but a method, the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle ... Positively the principle may be expressed: In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration. And negatively: In matters of the intellect do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.[15][16][17] — Thomas Henry Huxley That which Agnostics deny and repudiate, as immoral, is the contrary doctrine, that there are propositions which men ought to believe, without logically satisfactory evidence; and that reprobation ought to attach to the profession of disbelief in such inadequately supported propositions.[14] — Thomas Henry Huxley Consequently, agnosticism puts aside not only the greater part of popular theology, but also the greater part of anti-theology. On the whole, the "bosh" of heterodoxy is more offensive to me than that of orthodoxy, because heterodoxy professes to be guided by reason and science, and orthodoxy does not.[18] — Thomas Henry Huxley Being a scientist, above all else, Huxley presented agnosticism as a form of demarcation. A hypothesis with no supporting, objective, testable evidence is not an objective, scientific claim. As such, there would be no way to test said hypotheses, leaving the results inconclusive. His agnosticism was not compatible with forming a belief as to the truth, or falsehood, of the claim at hand. Karl Popper would also describe himself as an agnostic.[19] According to philosopher William L. Rowe, in this strict sense, agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does not exist.[6] George H. Smith, while admitting that the narrow definition of atheist was the common usage definition of that word,[20] and admitting that the broad definition of agnostic was the common usage definition of that word,[21] promoted broadening the definition of atheist and narrowing the definition of agnostic. Smith rejects agnosticism as a third alternative to theism and atheism and promotes terms such as agnostic atheism (the view of those who do not hold a belief in the existence of any deity but claim that the existence of a deity is unknown or inherently unknowable) and agnostic theism (the view of those who believe in the existence of a deity(s) but claim that the existence of a deity is unknown or inherently unknowable).[22][23][24] |

不可知論の定義 [不可知論]の原則は様々な方法で述べることができるが、それらはすべてこのことに帰結する。すなわち、その確信を論理的に正当化する証拠を提示すること ができない限り、人がいかなる命題の客観的真理を確信していると言うことは間違っているということである。これこそが不可知論が主張することであり、私の 考えでは、不可知論に不可欠なのはこれだけである[14]。 - トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー 実際、不可知論とは信条ではなく方法であり、その本質は一つの原則を厳格に適用することにある......。その原理を肯定的に表現すれば、次のようにな る: 知性に関する問題では、他のいかなる考慮もせず、理性があなたを連れて行く限り、あなたの理性に従いなさい。そして否定的にはこうなる: 知性の問題においては、実証されていない、あるいは実証可能でない結論が確かであるかのようなふりをしてはならない。 - トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー 無神論者が不道徳であるとして否定し否認するのは、論理的に十分な証拠がなくても、人が信じるべき命題があるという反対の教義であり、そのような不十分な裏付けの命題を信じないという公言には非難がつきまとうべきであるということである[14]。 - トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー その結果、不可知論は、一般的な神学の大部分だけでなく、反神学の大部分も脇に置くことになる。全体として、正統派のそれよりも異端派の「戯言」の方が私には不快である。異端派は理性と科学に導かれていると公言しているが、正統派はそうではないからである[18]。 - トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー 科学者であるハクスリーは、何よりも不可知論を一種の区切りとして提示した。裏付けとなる客観的で検証可能な証拠を持たない仮説は、客観的で科学的な主張 ではない。そのため、仮説を検証する方法はなく、結論は出ない。ポパーの不可知論は、目の前の主張の真偽について信念を持つこととは相容れないものだっ た。哲学者のウィリアム・L・ロウによれば、この厳密な意味での不可知論とは、人間の理性は、神が存在するという信念も、神が存在しないという信念も正当 化する十分な合理的根拠を提供することができないという見解である[6]。 ジョージ・H・スミスは、無神論者の狭い定義がその言葉の一般的な用法であることを認め[20]、不可知論者の広い定義がその言葉の一般的な用法であるこ とを認めながら[21]、無神論者の定義を広げ、不可知論者の定義を狭めることを推進していた。スミスは不可知論を有神論と無神論の第三の選択肢として否 定し、不可知論的無神論(いかなる神の存在も信じないが、神の存在は未知であるか本質的に知ることができないと主張する人々の見解)や不可知論的有神論 (神の存在は信じるが、神の存在は未知であるか本質的に知ることができないと主張する人々の見解)といった用語を推進している[22][23][24]。 |

|

Etymology Agnostic (from Ancient Greek ἀ- (a-) 'without', and γνῶσις (gnōsis) 'knowledge') was used by Thomas Henry Huxley in a speech at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society in 1869 to describe his philosophy, which rejects all claims of spiritual or mystical knowledge.[25][26] Early Christian church leaders used the Greek word gnosis (knowledge) to describe "spiritual knowledge". Agnosticism is not to be confused with religious views opposing the ancient religious movement of Gnosticism in particular; Huxley used the term in a broader, more abstract sense.[27] Huxley identified agnosticism not as a creed but rather as a method of skeptical, evidence-based inquiry.[28] The term agnostic is also cognate with the Sanskrit word ajñasi, which translates literally to "not knowable", and relates to the ancient Indian philosophical school of Ajñana, which proposes that it is impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge was possible, it is useless and disadvantageous for final salvation. In recent years, scientific literature dealing with neuroscience and psychology has used the word to mean "not knowable".[29] In technical and marketing literature, "agnostic" can also mean independence from some parameters—for example, "platform agnostic" (referring to cross-platform software),[30] or "hardware-agnostic".[31] |

語源 不可知論者(古代ギリシア語のĀ- (a-) 'without', γνǿσις (gnōsis) 'knowledge' から)は、1869年にトマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーが形而上学協会の会合での演説で、霊的または神秘的な知識の主張をすべて否定する彼の哲学を説明する ために使用した[25][26]。 初期のキリスト教の教会指導者たちは「霊的な知識」を表現するためにギリシャ語のグノーシス(知識)を使用していた。ハクスリーは不可知論を信条としてではなく、むしろ懐疑的で証拠に基づく探求の方法として認識していた[28]。 不可知論者という用語はサンスクリット語のアジュニャーシ(ajñasi)とも同義であり、直訳すると「知ることができない」となり、形而上学的性質の知 識を得たり、哲学的命題の真理値を確認したりすることは不可能であり、たとえ知識が可能であったとしても、それは最終的な救済のためには役に立たず、不利 であると提唱する古代インドの哲学学派アジュニャーナに関連している。 近年、神経科学や心理学を扱った科学文献では、「知ることができない」という意味でこの言葉が使われている[29]。技術やマーケティングに関する文献で は、「不可知論者」は、例えば「プラットフォーム不可知論者」(クロスプラットフォームソフトウェアを指す)[30]や「ハードウェア不可知論者」 [31]のように、あるパラメータからの独立性を意味することもある。 |

|

Qualifying agnosticism Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume contended that meaningful statements about the universe are always qualified by some degree of doubt. He asserted that the fallibility of human beings means that they cannot obtain absolute certainty except in trivial cases where a statement is true by definition (e.g. tautologies such as "all bachelors are unmarried" or "all triangles have three corners").[32] |

限定的不可知論 スコットランドの啓蒙思想家デイヴィッド・ヒュームは、宇宙に関する意味のある発言は、常に何らかの疑念によって限定されると主張した。彼は、人間は誤り を犯す存在であるため、定義上真である(例えば、「すべての独身者は未婚である」や「すべての三角形は3つの角を持つ」などの同語反復)ような些細な場合 を除き、絶対的な確実性を得ることはできないと主張した。[32] |

|

Types Strong agnosticism (also called "hard", "closed", "strict", or "permanent agnosticism") The view that the question of the existence or nonexistence of a deity or deities, and the nature of ultimate reality is unknowable by reason of our natural inability to verify any experience with anything but another subjective experience. A strong agnostic would say, "I cannot know whether a deity exists or not, and neither can you."[33][34][35] Weak agnosticism (also called "soft", "open", "empirical", "hopeful", or "temporal agnosticism") The view that the existence or nonexistence of any deities is currently unknown but is not necessarily unknowable; therefore, one will withhold judgment until evidence, if any, becomes available. A weak agnostic would say, "I don't know whether any deities exist or not, but maybe one day, if there is evidence, we can find something out."[33][34][35] |

種類 強不可知論(「ハード」、「クローズド」、「ストリクト」、「永久不可知論」とも呼ばれる) 神や神々の存在や不存在、究極的な現実の性質に関する問題は、主観的な経験以外ではいかなる経験も検証することができないという人間の自然的な能力によっ て、知ることができないとする見解。強い不可知論者は、「神が存在するかどうかは私にはわからないし、あなたにもわからない」と言うだろう[33] [34][35]。 弱い不可知論(「ソフト」、「オープン」、「経験的」、「希望的」、「時間的不可知論」とも呼ばれる) 神々の存在や非存在は現時点では未知であるが、必ずしも知り得ないわけではないとする見解。したがって、証拠が入手できるようになるまでは判断を保留す る。弱い不可知論者は、「神々が存在するかどうかはわからないが、いつか証拠があれば何かわかるかもしれない」と言う[33][34][35]。 |

|

Apathetic agnosticism The view that no amount of debate can prove or disprove the existence of one or more deities, and if one or more deities exist, they do not appear to be concerned about the fate of humans. Therefore, their existence has little to no impact on personal human affairs and should be of little interest. An apathetic agnostic would say, "I don't know whether any deity exists or not, and I don't care if any deity exists or not."[36][37][38] |

無気力な不可知論 どんなに議論しても、1つ以上の神の存在を証明することも反証することもできないし、1つ以上の神が存在するとしても、彼らは人間の運命に関心があるよう には見えないという考え方。したがって、その存在は人間の個人的な問題にはほとんど影響を与えず、ほとんど関心を持たないはずである。無気力な不可知論者 は、「どんな神も存在するかどうかは知らないし、どんな神も存在するかどうかは気にしない」と言うだろう[36][37][38]。 |

| History Hindu philosophy See also: Sanjaya Belatthaputta and Ajñana Throughout the history of Hinduism there has been a strong tradition of philosophic speculation and skepticism.[39][40] The Rig Veda takes an agnostic view on the fundamental question of how the universe and the gods were created. Nasadiya Sukta (Creation Hymn) in the tenth chapter of the Rig Veda says:[39][41][42] But, after all, who knows, and who can say Whence it all came, and how creation happened? The gods themselves are later than creation, so who knows truly whence it has arisen? Whence all creation had its origin, He, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not, He, who surveys it all from highest heaven, He knows – or maybe even he does not know. |

歴史 ヒンドゥー哲学 も参照のこと: サンジャヤ・ベラッタプッタとアジュニャーナ ヒンドゥー教の歴史を通じて、哲学的思索と懐疑主義の強い伝統があった[39][40]。 リグ・ヴェーダは、宇宙と神々がどのように創造されたかという根本的な疑問について不可知論的な見解を示している。リグ・ヴェーダ』第10章のナサディヤ・スクタ(天地創造讃歌)には次のように書かれている[39][41][42]。 しかし、結局のところ、誰が知っているのか、誰が言うことができるのか。 神々自身は創造よりも後の存在である。 神々自身は創造よりも後の存在である、 神々は天地創造より後の存在である。 すべての創造はいつから始まったのか、 かれが造ったのか、造らなかったのか、 天の高みからすべてを見渡される方である、 彼は知っている--いや、知らないのかもしれない。 |

|

Hume, Kant, and Kierkegaard Aristotle,[43] Anselm,[44][45] Aquinas,[46][47] Descartes,[48] and Gödel presented arguments attempting to rationally prove the existence of God. The skeptical empiricism of David Hume, the antinomies of Immanuel Kant, and the existential philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard convinced many later philosophers to abandon these attempts, regarding it impossible to construct any unassailable proof for the existence or non-existence of God.[49] In his 1844 book, Philosophical Fragments, Kierkegaard writes:[50] Let us call this unknown something: God. It is nothing more than a name we assign to it. The idea of demonstrating that this unknown something (God) exists, could scarcely suggest itself to Reason. For if God does not exist it would of course be impossible to prove it; and if he does exist it would be folly to attempt it. For at the very outset, in beginning my proof, I would have presupposed it, not as doubtful but as certain (a presupposition is never doubtful, for the very reason that it is a presupposition), since otherwise I would not begin, readily understanding that the whole would be impossible if he did not exist. But if when I speak of proving God's existence I mean that I propose to prove that the Unknown, which exists, is God, then I express myself unfortunately. For in that case I do not prove anything, least of all an existence, but merely develop the content of a conception. Hume was Huxley's favourite philosopher, calling him "the Prince of Agnostics".[51] Diderot wrote to his mistress, telling of a visit by Hume to the Baron D'Holbach, and describing how a word for the position that Huxley would later describe as agnosticism did not seem to exist, or at least was not common knowledge, at the time. The first time that M. Hume found himself at the table of the Baron, he was seated beside him. I don't know for what purpose the English philosopher took it into his head to remark to the Baron that he did not believe in atheists, that he had never seen any. The Baron said to him: "Count how many we are here." We are eighteen. The Baron added: "It isn't too bad a showing to be able to point out to you fifteen at once: the three others haven't made up their minds."[52] — Denis Diderot United Kingdom Charles Darwin |

ヒューム、カント、キルケゴール アリストテレス[43]、アンセルム[44][45]、アクィナス[46][47]、デカルト[48]、ゲーデルは、神の存在を合理的に証明しようとする 論証を提示した。デイヴィッド・ヒュームの懐疑的経験論、イマニュエル・カントのアンチノミー、そしてセーレン・キルケゴールの実存哲学は、神の存在また は非存在について揺るぎない証明を構築することは不可能であるとして、多くの後世の哲学者たちにこれらの試みを放棄するよう説得した[49]。 キルケゴールは1844年の著書『哲学的断片』の中で次のように書いている[50]。 この未知のものを神と呼ぼう。この未知のものを神と呼ぼう。この未知の何か(神)が存在することを証明するという考えは、理性にはほとんど思いつかない。 なぜなら、もし神が存在しないのであれば、それを証明することはもちろん不可能であり、もし神が存在するのであれば、それを試みることは愚行だからであ る。もし神が存在しないのであれば、その証明は当然不可能であり、もし神が存在するのであれば、それを試みるのは愚行である。なぜなら、証明を始めるにあ たって、私はそれを疑わしいこととしてではなく、確かなこととして仮定したはずだからである(仮定が疑わしいということは決してない。しかし、もし私が神 の存在を証明すると言うとき、存在する未知なるものが神であることを証明しようと言うのであれば、それは残念なことである。というのも、その場合、私は何 かを証明するのではなく、とりわけ存在を証明するのでもなく、単にある観念の内容を発展させるだけだからである。 ヒュームはハクスリーのお気に入りの哲学者であり、彼を「不可知論のプリンス」と呼んだ[51]。ディドロは愛人に宛てて、ヒュームがドルバック男爵を訪 問したときのことを書き、ハクスリーが後に不可知論と表現することになる立場を表す言葉が、当時は存在しなかったか、少なくとも一般的な知識ではなかった ことを述べている。 M.ヒュームが初めて男爵のテーブルに着いたとき、彼は男爵の横に座っていた。このイギリス人哲学者が何の目的で男爵に、自分は無神論者を信じない、一人 も見たことがないと言ったのかはわからない。男爵は彼に言った: 「ここに何人いるか数えてみろ。私たちは18人だ 男爵はさらに言った、「一度に15人を指摘できるのは、それほど悪いことではない、他の3人はまだ決心していない」[52]。 - ドゥニ・ディドロ イギリス チャールズ・ダーウィン |

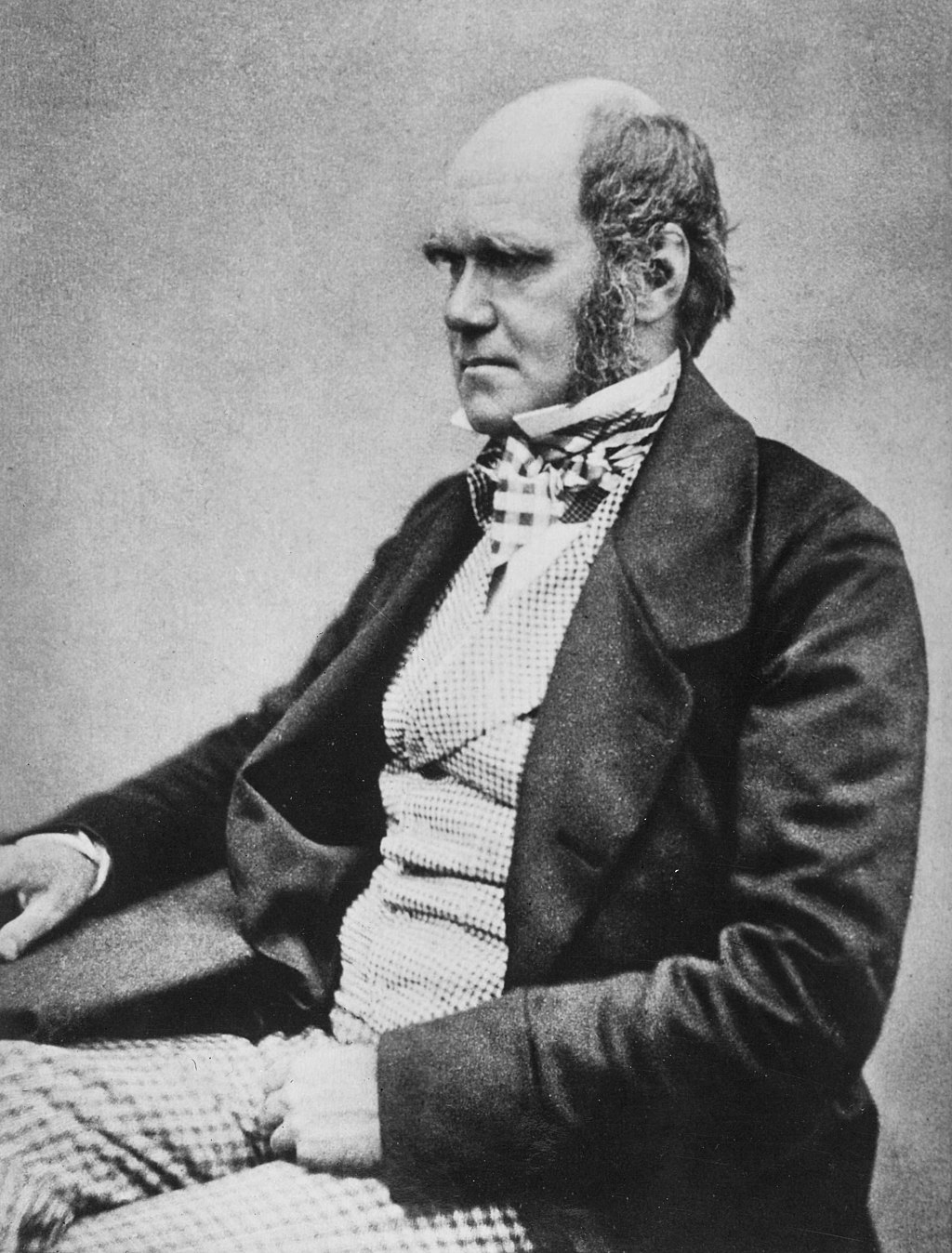

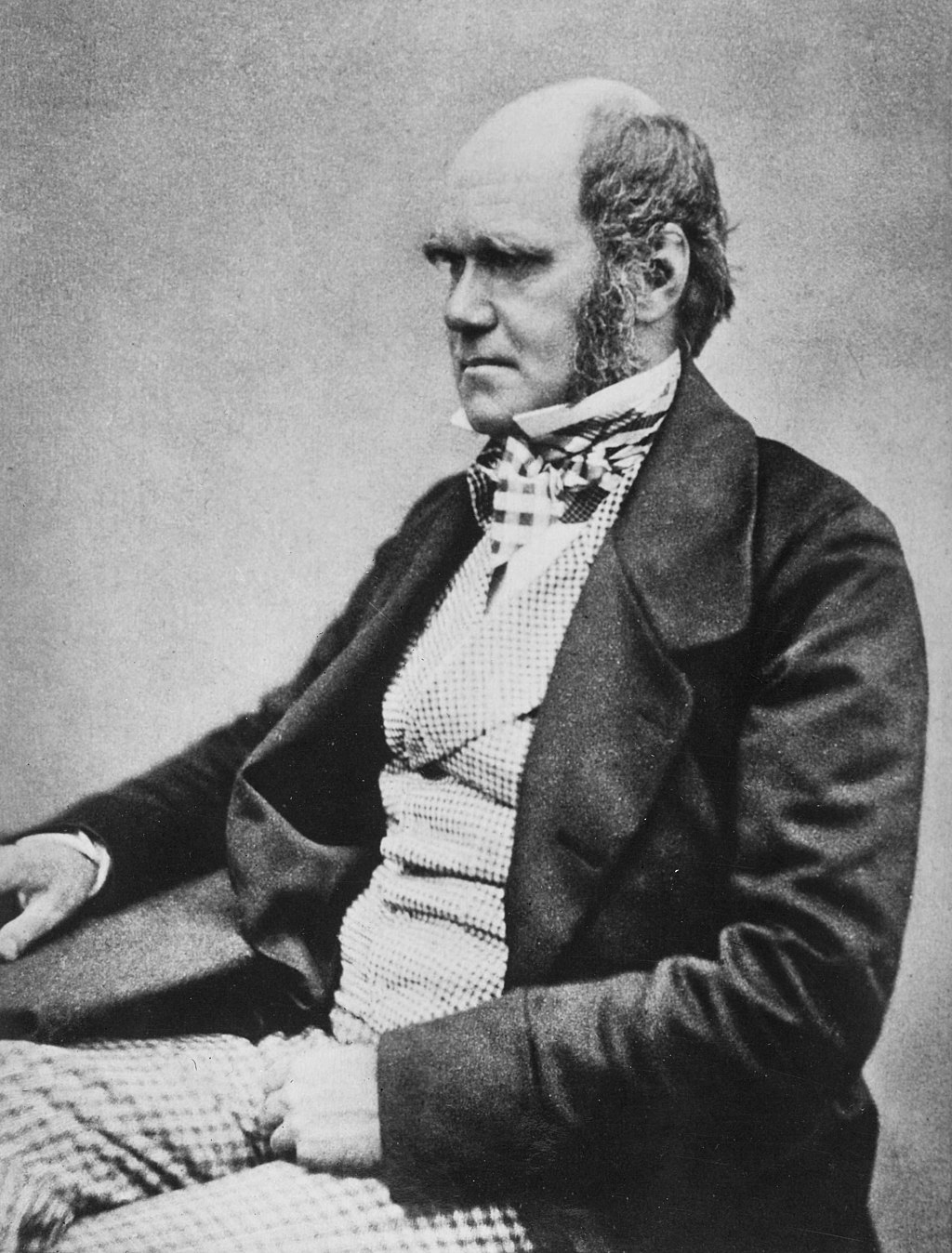

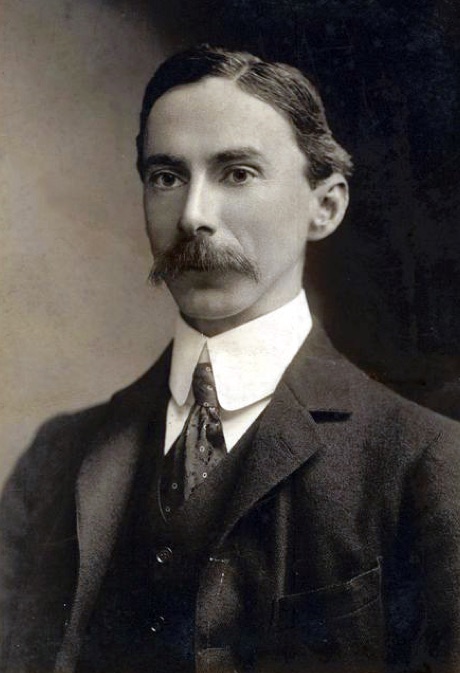

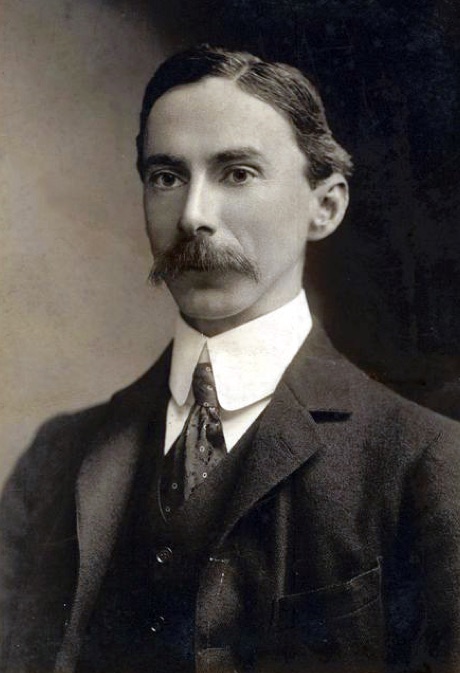

Charles Darwin in 1854 Raised in a religious environment, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) studied to be an Anglican clergyman. While eventually doubting parts of his faith, Darwin continued to help in church affairs, even while avoiding church attendance. Darwin stated that it would be "absurd to doubt that a man might be an ardent theist and an evolutionist".[53][54] Although reticent about his religious views, in 1879 he wrote that "I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God. – I think that generally ... an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind."[53][55] |

1854年、チャールズ・ダーウィン 宗教的な環境で育ったチャールズ・ダーウィン(1809-1882)は、英国国教会の聖職者になるために勉強した。やがて信仰の一部に疑問を抱くように なったダーウィンは、教会への出席を避けながらも、教会の仕事を手伝い続けた。ダーウィンは、「熱心な神学者でありながら進化論者である可能性を疑うのは 馬鹿げている」と述べている[53][54]。自分の宗教観については控えめであったが、1879年には「私は神の存在を否定するという意味で無神論者で あったことはない。- 一般的には......不可知論者というのが私の心境を表す最も正しい表現だろうと思う」と書いている[53][55]。 |

Thomas Henry Huxley Thomas Henry Huxley in the 1860s. He was the first to decisively coin the term agnosticism. Agnostic views are as old as philosophical skepticism, but the terms agnostic and agnosticism were created by Huxley (1825–1895) to sum up his thoughts on contemporary developments of metaphysics about the "unconditioned" (William Hamilton) and the "unknowable" (Herbert Spencer). Though Huxley began to use the term agnostic in 1869, his opinions had taken shape some time before that date. In a letter of September 23, 1860, to Charles Kingsley, Huxley discussed his views extensively:[56][57] I neither affirm nor deny the immortality of man. I see no reason for believing it, but, on the other hand, I have no means of disproving it. I have no a priori objections to the doctrine. No man who has to deal daily and hourly with nature can trouble himself about a priori difficulties. Give me such evidence as would justify me in believing in anything else, and I will believe that. Why should I not? It is not half so wonderful as the conservation of force or the indestructibility of matter ... It is no use to talk to me of analogies and probabilities. I know what I mean when I say I believe in the law of the inverse squares, and I will not rest my life and my hopes upon weaker convictions ... That my personality is the surest thing I know may be true. But the attempt to conceive what it is leads me into mere verbal subtleties. I have champed up all that chaff about the ego and the non-ego, noumena and phenomena, and all the rest of it, too often not to know that in attempting even to think of these questions, the human intellect flounders at once out of its depth. And again, to the same correspondent, May 6, 1863:[58] I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel school. Nevertheless I know that I am, in spite of myself, exactly what the Christian would call, and, so far as I can see, is justified in calling, atheist and infidel. I cannot see one shadow or tittle of evidence that the great unknown underlying the phenomenon of the universe stands to us in the relation of a Father [who] loves us and cares for us as Christianity asserts. So with regard to the other great Christian dogmas, immortality of soul and future state of rewards and punishments, what possible objection can I—who am compelled perforce to believe in the immortality of what we call Matter and Force, and in a very unmistakable present state of rewards and punishments for our deeds—have to these doctrines? Give me a scintilla of evidence, and I am ready to jump at them. Of the origin of the name agnostic to describe this attitude, Huxley gave the following account:[59] When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last. The one thing in which most of these good people were agreed was the one thing in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a certain "gnosis"—had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble. And, with Hume and Kant on my side, I could not think myself presumptuous in holding fast by that opinion ... So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of "agnostic". It came into my head as suggestively antithetic to the "gnostic" of Church history, who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant. ... To my great satisfaction the term took. In 1889, Huxley wrote: Therefore, although it be, as I believe, demonstrable that we have no real knowledge of the authorship, or of the date of composition of the Gospels, as they have come down to us, and that nothing better than more or less probable guesses can be arrived at on that subject.[60] |

トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスレイ 1860年代のトマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー。彼は不可知論という言葉を決定的にした最初の人物である。 不可知論的見解は哲学的懐疑論と同じくらい古くからあるが、不可知論と不可知論主義という用語は、「無条件」(ウィリアム・ハミルトン)と「不可知」 (ハーバート・スペンサー)に関する形而上学の現代的発展に対する彼の考えを要約するために、ハクスリー(1825-1895)によって作られた。ハクス リーが不可知論者という言葉を使い始めたのは1869年だが、彼の意見はそれ以前から形になっていた。1860年9月23日にチャールズ・キングズレーに 宛てた手紙の中で、ハクスリーは自身の見解について幅広く論じている[56][57]。 私は人間の不死を肯定も否定もしない。私は人間の不死を肯定も否定もしていない。この教義に対するアプリオリな反論はない。日々刻々と自然と向き合わなけ ればならない人間が、アプリオリな難問に頭を悩ませることはない。それ以外のものを信じることを正当化するような証拠があれば、私はそれを信じるだろう。 なぜそうしないのか?力の保存や物質の不滅性ほど素晴らしいものはない。 私に類推や確率の話をしても無駄だ。逆二乗の法則を信じると言った意味がわかるし、弱い信念に人生と希望を託すつもりはない. 自分の個性が最も確かなものだということは、真実かもしれない。しかし、それが何であるかを考えようとすると、単なる言葉の機微に陥ってしまう。私は、自 我と非自我、ヌーメナと現象、その他もろもろの屁理屈をこねくり回したが、このような問題を考えようとしても、人間の知性はその深みから一気に脱け出して しまうことを知らない。 そしてまた、1863年5月6日、同じ特派員に対して次のように述べている[58]。 私は、正統主義に反対するアプリオリな理由にはいささかも共感したことがなく、無神論的で異端的な一派のすべてに、生まれつき、また性質上、最大限の反感 を抱いている。それにもかかわらず、私は、キリスト教徒が無神論者・無教徒と呼ぶであろう、そして私が見る限りそう呼ぶのが正当であるような人間なのだ。 宇宙の現象の根底にある未知の大いなるものが、キリスト教が主張するように、私たちを愛し、私たちを気にかけてくださる[父]のような関係において、私た ちの前に立っているという証拠を、私は影も形も見ることができない。では、キリスト教の他の偉大な教義、魂の不滅と将来の報いと罰の状態に関して、私たち が物質と力と呼んでいるものの不滅と、私たちの行いに対する報いと罰のまぎれもない現在の状態を信じざるを得ない私が、これらの教義に対してどのような異 議を唱えることができようか。ほんのわずかでも証拠があれば、飛びつく準備はできている。 このような態度を表すために不可知論者と呼ばれるようになった由来について、ハクスリーは次のように説明している[59]。 私が知的成熟に達し、自分が無神論者なのか、有神論者なのか、汎神論者なのか、唯物論者なのか、観念論者なのか、キリスト教徒なのか、自由思想家なのか、 と自問し始めたとき、学べば学ぶほど、考えれば考えるほど、答えが出なくなることがわかった。これらの善良な人々のほとんどが同意していたことは、私が彼 らと異なっていたことでもあった。彼らはある「グノーシス」に到達したと確信しており、多かれ少なかれ成功裏に存在の問題を解決した。ヒュームとカントを 味方につけて、その意見を堅持するのはおこがましいとは思えなかった。そこで私は考え、「不可知論者」という適切な呼称を思いついた。教会史に登場する 「グノーシス」(不可知論者)とは対照的で、私が無知である事柄について多くのことを知っていると公言していた。大満足だった。 1889年、ハクスリーはこう書いている: したがって、福音書が私たちに伝わっているように、私たちがその作者や作成年代について本当の知識を持っていないことは、私が信じているように証明できることであり、この問題については、多かれ少なかれ可能性のある推測に勝るものはないということである[60]。 |

|

William Stewart Ross William Stewart Ross (1844–1906) wrote under the name of Saladin. He was associated with Victorian Freethinkers and the organization the British Secular Union. He edited the Secular Review from 1882; it was renamed Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review and closed in 1907. Ross championed agnosticism in opposition to the atheism of Charles Bradlaugh as an open-ended spiritual exploration.[61] In Why I am an Agnostic (c. 1889) he claims that agnosticism is "the very reverse of atheism".[62] |

ウィリアム・スチュワート・ロス ウィリアム・スチュワート・ロス(1844-1906)はサラディンの名で執筆していた。彼はヴィクトリア朝の自由思想家たちや英国世俗同盟という組織と 関係があった。彼は1882年からSecular Review誌を編集したが、Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review誌と改名され、1907年に閉鎖された。ロスはチャールズ・ブラッドローの無神論に対抗して、不可知論をオープンエンドな精神探求として唱え た[61]。 Why I am an Agnostic』(1889年頃)の中で彼は不可知論は「無神論の正反対」であると主張している[62]。 |

Bertrand Russell Bertrand Russell Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) declared Why I Am Not a Christian in 1927, a classic statement of agnosticism.[63][64] He calls upon his readers to "stand on their own two feet and look fair and square at the world with a fearless attitude and a free intelligence".[64] In 1939, Russell gave a lecture on The existence and nature of God, in which he characterized himself as an atheist. He said:[65] The existence and nature of God is a subject of which I can discuss only half. If one arrives at a negative conclusion concerning the first part of the question, the second part of the question does not arise; and my position, as you may have gathered, is a negative one on this matter. However, later in the same lecture, discussing modern non-anthropomorphic concepts of God, Russell states:[66] That sort of God is, I think, not one that can actually be disproved, as I think the omnipotent and benevolent creator can. In Russell's 1947 pamphlet, Am I An Atheist or an Agnostic? (subtitled A Plea For Tolerance in the Face of New Dogmas), he ruminates on the problem of what to call himself:[67] As a philosopher, if I were speaking to a purely philosophic audience I should say that I ought to describe myself as an Agnostic, because I do not think that there is a conclusive argument by which one can prove that there is not a God. On the other hand, if I am to convey the right impression to the ordinary man in the street I think I ought to say that I am an Atheist, because when I say that I cannot prove that there is not a God, I ought to add equally that I cannot prove that there are not the Homeric gods. In his 1953 essay, What Is An Agnostic? Russell states:[68] An agnostic thinks it impossible to know the truth in matters such as God and the future life with which Christianity and other religions are concerned. Or, if not impossible, at least impossible at the present time. |

バートランド・ラッセル バートランド・ラッセル バートランド・ラッセル(1872-1970)は1927年に『なぜ私はキリスト教徒ではないのか』を発表しており、不可知論の古典的な声明である [63][64]。 彼は読者に対して「自分の足で立ち、大胆不敵な態度と自由な知性で世界を正々堂々と見つめる」よう呼びかけている[64]。 1939年、ラッセルは『神の存在と本質』について講義を行い、その中で自らを無神論者であるとした。彼は次のように述べている[65]。 神の存在と性質は、私が半分しか論じることのできない主題である。もし問題の前半部分に関して否定的な結論に達するならば、問題の後半部分は生じない。 しかし、同じ講義の後半で、現代の非人間的な神の概念について論じながら、ラッセルは次のように述べている[66]。 その種の神は、私が全能で慈悲深い創造主が反証できると考えるように、実際に反証できるものではないと思う。 ラッセルは1947年の小冊子『私は無神論者か不可知論者か』(副題:A Plea For Tolerance in the Face of New Dogmas)の中で、自分自身を何と呼ぶべきかという問題について反芻している[67]。 哲学者として、もし私が純粋に哲学的な聴衆に向かって話すのであれば、私は自分自身を不可知論者と表現すべきだと言うだろう。というのも、神が存在しないことを証明できないと言うとき、ホメロス神話の神々が存在しないことを証明することもできないからである。 1953年のエッセイ『不可知論者とは何か』において、ラッセルは次のように述べている[68]。ラッセルは次のように述べている[68]。 不可知論者は、キリスト教や他の宗教が関心を抱いている神や未来世といった事柄について、真理を知ることは不可能だと考える。あるいは、不可能ではないとしても、少なくとも現時点では不可能である。 |

|

Are Agnostics Atheists? No. An atheist, like a Christian, holds that we can know whether or not there is a God. The Christian holds that we can know there is a God; the atheist, that we can know there is not. The Agnostic suspends judgment, saying that there are not sufficient grounds either for affirmation or for denial. Later in the essay, Russell adds:[69] I think that if I heard a voice from the sky predicting all that was going to happen to me during the next twenty-four hours, including events that would have seemed highly improbable, and if all these events then produced to happen, I might perhaps be convinced at least of the existence of some superhuman intelligence. |

無神論者は無神論者か? 無神論者はキリスト教徒と同じく、神が存在するかどうかを知ることができると考えている。クリスチャンは神が存在することを知ることができるとし、無神論 者は存在しないことを知ることができるとする。不可知論者は、肯定するにも否定するにも十分な根拠がないとして、判断を保留する。 このエッセイの後半で、ラッセルは次のように付け加えている[69]。 もし私が空から、これから24時間の間に私に起こるすべてのことを予言する声を聞いたとしたら、その中には非常にあり得ないと思われるような出来事も含まれている。 |

|

Leslie Weatherhead See also: Christian agnosticism Wikiquote has quotations related to Leslie Weatherhead. In 1965, Christian theologian Leslie Weatherhead (1893–1976) published The Christian Agnostic, in which he argues:[70] ... many professing agnostics are nearer belief in the true God than are many conventional church-goers who believe in a body that does not exist whom they miscall God. Although radical and unpalatable to conventional theologians, Weatherhead's agnosticism falls far short of Huxley's, and short even of weak agnosticism:[70] Of course, the human soul will always have the power to reject God, for choice is essential to its nature, but I cannot believe that anyone will finally do this. |

レスリー・ウェザーヘッド こちらも参照のこと: キリスト教不可知論 ウィキクォートにはレスリー・ウェザーヘッドに関連する引用がある。 1965年、キリスト教神学者のレスリー・ウェザーヘッド(1893-1976)は『キリスト教不可知論者』を出版し、その中で次のように論じている[70]。 ...多くの公言する不可知論者は、彼らが神と呼び違えている存在しない身体を信じている従来の教会に通う多くの人々よりも、真の神への信仰に近い。 ウェザーヘッドの不可知論は、従来の神学者にとっては急進的で味気ないものではあるが、ハクスリーの不可知論には遠く及ばず、弱い不可知論にすら及ばない[70]。 もちろん、人間の魂は常に神を拒絶する力を持っている。なぜなら、選択はその本質に不可欠だからである。 |

|

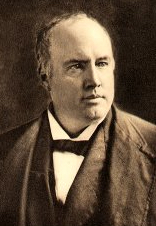

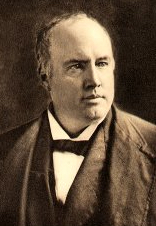

United States Robert G. Ingersoll  Robert G. Ingersoll Robert G. Ingersoll (1833–1899), an Illinois lawyer and politician who evolved into a well-known and sought-after orator in 19th-century America, has been referred to as the "Great Agnostic".[71] In an 1896 lecture titled Why I Am An Agnostic, Ingersoll related why he was an agnostic:[72] Is there a supernatural power—an arbitrary mind—an enthroned God—a supreme will that sways the tides and currents of the world—to which all causes bow? I do not deny. I do not know—but I do not believe. I believe that the natural is supreme—that from the infinite chain no link can be lost or broken—that there is no supernatural power that can answer prayer—no power that worship can persuade or change—no power that cares for man. I believe that with infinite arms Nature embraces the all—that there is no interference—no chance—that behind every event are the necessary and countless causes, and that beyond every event will be and must be the necessary and countless effects. Is there a God? I do not know. Is man immortal? I do not know. One thing I do know, and that is, that neither hope, nor fear, belief, nor denial, can change the fact. It is as it is, and it will be as it must be. In the conclusion of the speech he simply sums up the agnostic position as:[72] We can be as honest as we are ignorant. If we are, when asked what is beyond the horizon of the known, we must say that we do not know. In 1885, Ingersoll explained his comparative view of agnosticism and atheism as follows:[73] The Agnostic is an Atheist. The Atheist is an Agnostic. The Agnostic says, 'I do not know, but I do not believe there is any God.' The Atheist says the same. See also: Physical determinism |

アメリカ合衆国 ロバート・G・インガソール  ロバート・G・インガソル ロバート・G・インガソル(1833-1899)はイリノイ州の弁護士であり、政治家であったが、19世紀のアメリカではよく知られ、人気のある演説家へと発展し、「偉大な不可知論者」と呼ばれている[71]。 なぜ私は不可知論者なのか』と題された1896年の講演で、インガソルは自分が不可知論者である理由を次のように語っている[72]。 超自然的な力、恣意的な心、即位した神、世界の潮流や潮流を揺り動かす至高の意志が存在し、それにすべての原因が屈服しているのだろうか。私は否定しな い。わからないが、信じない。祈りに答えることのできる超自然的な力は存在せず、礼拝によって説得したり変えたりすることのできる力も存在せず、人間を気 遣う力も存在しない。 あらゆる出来事の背後には、必要かつ無数の原因があり、あらゆる出来事の向こうには、必要かつ無数の結果があり、またそうでなければならない。 神はいるのだろうか?私にはわからない。人間は不滅か?私にはわからない。ひとつだけわかっているのは、希望も恐怖も、信念も否定も、事実を変えることはできないということだ。ありのままであり、そうならざるを得ないのだ」。 スピーチの結びで、彼は不可知論者の立場を次のように要約している[72]。 私たちは無知であるのと同じくらい正直であることができる。私たちは無知であるのと同じくらい正直であることができる。もしそうであるなら、既知の地平の彼方に何があるのかと問われたとき、私たちは知らないと答えなければならない」。 1885年、インガソルは不可知論と無神論の比較について次のように説明している[73]。 不可知論者は無神論者である。無神論者は不可知論者である。不可知論者は『私は知らないが、神が存在するとは思わない』と言う。無神論者も同じことを言う。 以下も参照のこと: 物理的決定論 |

| Bernard Iddings Bell Canon Bernard Iddings Bell (1886–1958), a popular cultural commentator, Episcopal priest, and author, lauded the necessity of agnosticism in Beyond Agnosticism: A Book for Tired Mechanists, calling it the foundation of "all intelligent Christianity".[74] Agnosticism was a temporary mindset in which one rigorously questioned the truths of the age, including the way in which one believed God.[75] His view of Robert Ingersoll and Thomas Paine was that they were not denouncing true Christianity but rather "a gross perversion of it".[74] Part of the misunderstanding stemmed from ignorance of the concepts of God and religion.[76] Historically, a god was any real, perceivable force that ruled the lives of humans and inspired admiration, love, fear, and homage; religion was the practice of it. Ancient peoples worshiped gods with real counterparts, such as Mammon (money and material things), Nabu (rationality), or Ba'al (violent weather); Bell argued that modern peoples were still paying homage—with their lives and their children's lives—to these old gods of wealth, physical appetites, and self-deification.[77] Thus, if one attempted to be agnostic passively, he or she would incidentally join the worship of the world's gods. In Unfashionable Convictions (1931), he criticized the Enlightenment's complete faith in human sensory perception, augmented by scientific instruments, as a means of accurately grasping Reality. Firstly, it was fairly new, an innovation of the Western World, which Aristotle invented and Thomas Aquinas revived among the scientific community. Secondly, the divorce of "pure" science from human experience, as manifested in American Industrialization, had completely altered the environment, often disfiguring it, so as to suggest its insufficiency to human needs. Thirdly, because scientists were constantly producing more data—to the point where no single human could grasp it all at once—it followed that human intelligence was incapable of attaining a complete understanding of universe; therefore, to admit the mysteries of the unobserved universe was to be actually scientific. Bell believed that there were two other ways that humans could perceive and interact with the world. Artistic experience was how one expressed meaning through speaking, writing, painting, gesturing—any sort of communication which shared insight into a human's inner reality. Mystical experience was how one could "read" people and harmonize with them, being what we commonly call love.[78] In summary, man was a scientist, artist, and lover. Without exercising all three, a person became "lopsided". Bell considered a humanist to be a person who cannot rightly ignore the other ways of knowing. However, humanism, like agnosticism, was also temporal, and would eventually lead to either scientific materialism or theism. He lays out the following thesis: Truth cannot be discovered by reasoning on the evidence of scientific data alone. Modern peoples' dissatisfaction with life is the result of depending on such incomplete data. Our ability to reason is not a way to discover Truth but rather a way to organize our knowledge and experiences somewhat sensibly. Without a full, human perception of the world, one's reason tends to lead them in the wrong direction. Beyond what can be measured with scientific tools, there are other types of perception, such as one's ability know another human through loving. One's loves cannot be dissected and logged in a scientific journal, but we know them far better than we know the surface of the sun. They show us an indefinable reality that is nevertheless intimate and personal, and they reveal qualities lovelier and truer than detached facts can provide. To be religious, in the Christian sense, is to live for the Whole of Reality (God) rather than for a small part (gods). Only by treating this Whole of Reality as a person—good and true and perfect—rather than an impersonal force, can we come closer to the Truth. An ultimate Person can be loved, but a cosmic force cannot. A scientist can only discover peripheral truths, but a lover is able to get at the Truth. There are many reasons to believe in God but they are not sufficient for an agnostic to become a theist. It is not enough to believe in an ancient holy book, even though when it is accurately analyzed without bias, it proves to be more trustworthy and admirable than what we are taught in school. Neither is it enough to realize how probable it is that a personal God would have to show human beings how to live, considering they have so much trouble on their own. Nor is it enough to believe for the reason that, throughout history, millions of people have arrived at this Wholeness of Reality only through religious experience. The aforementioned reasons may warm one toward religion, but they fall short of convincing. However, if one presupposes that God is in fact a knowable, loving person, as an experiment, and then lives according that religion, he or she will suddenly come face to face with experiences previously unknown. One's life becomes full, meaningful, and fearless in the face of death. It does not defy reason but exceeds it. Because God has been experienced through love, the orders of prayer, fellowship, and devotion now matter. They create order within one's life, continually renewing the "missing piece" that had previously felt lost. They empower one to be compassionate and humble, not small-minded or arrogant. No truth should be denied outright, but all should be questioned. Science reveals an ever-growing vision of our universe that should not be discounted due to bias toward older understandings. Reason is to be trusted and cultivated. To believe in God is not to forego reason or to deny scientific facts, but to step into the unknown and discover the fullness of life.[79] |

バーナード・イングスベル 人気のある文化評論家、エピスコパル司祭、作家であるバーナード・アイディングズ・ベル(1886-1958)は、『不可知論を超えて』の中で不可知論の 必要性を称賛している: 不可知論とは、神を信じる方法を含め、時代の真理を厳しく疑う一時的な考え方であった[75]。ロバート・インガソルとトマス・ペインに対する彼の見解 は、彼らは真のキリスト教を非難しているのではなく、むしろ「キリスト教を著しく曲解している」というものであった。 [74]誤解の一部は、神と宗教の概念に対する無知から生じていた[76]。歴史的には、神とは人間の生活を支配し、賞賛、愛、恐れ、敬意を抱かせる、現 実的で知覚可能な力のことであり、宗教とはそれを実践することであった。古代の人々は、マモン(金銭と物質)、ナブ(合理性)、バアル(暴力的な天候)な ど、実在の対応する神々を崇拝していた。ベルは、現代の人々は依然として、富、肉体的欲望、自己神格化を司るこれらの古い神々に、自分たちの命と子供たち の命をかけて敬意を表していると主張した[77]。したがって、受動的に不可知論者になろうとすれば、付随的に世界の神々の崇拝に加わることになる。 Unfashionable Convictions』(1931年)の中で彼は、現実を正確に把握する手段として、科学機器によって増強された人間の感覚的知覚を完全に信頼する啓蒙 主義を批判した。第一に、それはかなり新しく、西洋世界の革新であり、アリストテレスが発明し、トマス・アクィナスが科学界の中で復活させたものである。 第二に、アメリカの工業化に見られるように、「純粋な」科学が人間の経験から切り離されたことで、環境は完全に変化し、しばしば人間のニーズに対して不十 分であることを示唆するような醜い姿になっていた。第三に、科学者たちは常に多くのデータを生み出し続け、一人の人間がそのすべてを一度に把握することは 不可能であるため、人間の知性では宇宙を完全に理解することは不可能である。 ベルは、人間が世界を認識し、世界と相互作用する方法は他に2つあると考えていた。芸術的経験とは、話すこと、書くこと、描くこと、身振り手振りで意味を 表現することであり、人間の内的現実への洞察を共有するあらゆる種類のコミュニケーションである。神秘的な経験とは、人を「読み」、人と調和する方法であ り、私たちが一般的に「愛」と呼んでいるものである。この3つをすべて発揮しなければ、人は「横着」になってしまう。 ベルはヒューマニストとは、他の知のあり方を正しく無視することができない人であると考えた。しかし、ヒューマニズムも不可知論と同様、時間的なものであり、最終的には科学的唯物論か有神論のどちらかに行き着くことになる。彼は次のようなテーゼを掲げる: 真理は、科学的データの証拠に基づく推論だけでは発見できない。現代人の人生に対する不満は、そのような不完全なデータに依存した結果である。私たちの推 論能力は、真理を発見する方法ではなく、私たちの知識や経験を多少なりとも感覚的に整理する方法なのである。世界に対する人間的な完全な認識がなければ、 理性は間違った方向に導きがちである。 科学的なツールで測定できるもの以外にも、知覚の種類はある。例えば、愛することを通して他の人間を知る能力などだ。人の愛は、解剖して科学雑誌に記録す ることはできないが、私たちは太陽の表面を知るよりもはるかに相手を知っている。愛は、親密で個人的であるにもかかわらず、定義できない現実を見せてくれ る。 キリスト教的な意味で宗教的であるとは、小さな部分(神々)のためではなく、現実の全体(神)のために生きることである。この現実の全体を、非人間的な力 ではなく、善良で真実で完全な人間として扱うことによってのみ、私たちは真理に近づくことができる。究極の人は愛することができるが、宇宙の力は愛するこ とができない。科学者は周辺的な真理しか発見できないが、愛する者は真理に近づくことができる。 神を信じる理由はたくさんあるが、不可知論者が有神論者になるには十分ではない。古代の聖典を信じるだけでは十分ではない。たとえそれが偏見なしに正確に 分析されたとき、学校で教えられることよりも信頼でき、立派なものであることが証明されたとしても。また、人間が自分一人で生きていくのにとても苦労して いることを考えると、個人的な神が人間に生き方を示さなければならない可能性がいかに高いかを理解するだけでも十分ではない。また、歴史上、何百万もの人 々が宗教的経験を通じてのみ、この「現実の全体性」に到達してきたという理由を信じるだけでは十分ではない。前述したような理由は、人を宗教に向かわせる かもしれないが、説得力には欠ける。しかし、もし実験として、神が実際に知ることのできる、愛に満ちたお方であることを前提にし、その宗教に従って生きる なら、それまで未知であった体験に突然直面することになる。死を前にして、人の人生は充実し、意義深く、恐れを知らなくなる。それは理性に逆らうものでは なく、理性を超えるものである。 神が愛を通して経験されたからこそ、祈り、交わり、献身という秩序が重要になる。それらは自分の人生に秩序を生み出し、以前は失われたと感じていた "欠けた部分 "を絶えず新しくする。それらは、人を小心者や傲慢者ではなく、憐れみ深く謙虚にする力を与えてくれる。 どんな真実も真っ向から否定されるべきではなく、すべて疑われるべきである。科学は、私たちの宇宙について常に成長し続けるビジョンを明らかにしている が、古い理解への偏見によってそれを否定すべきではない。理性は信頼され、培われるべきものである。神を信じることは、理性を放棄することでも、科学的事 実を否定することでもなく、未知の世界に足を踏み入れ、生命の完全性を発見することである[79]。 |

☆

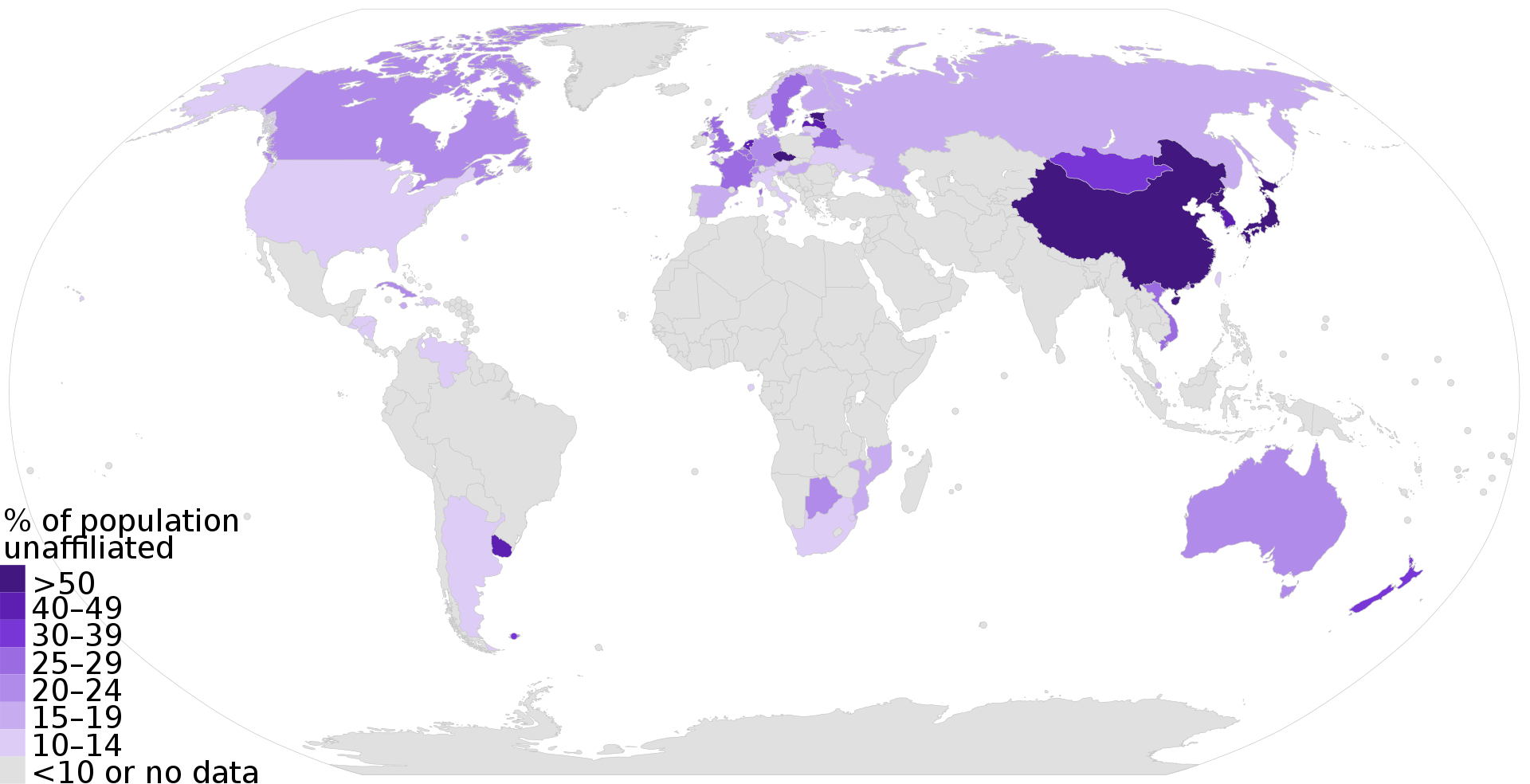

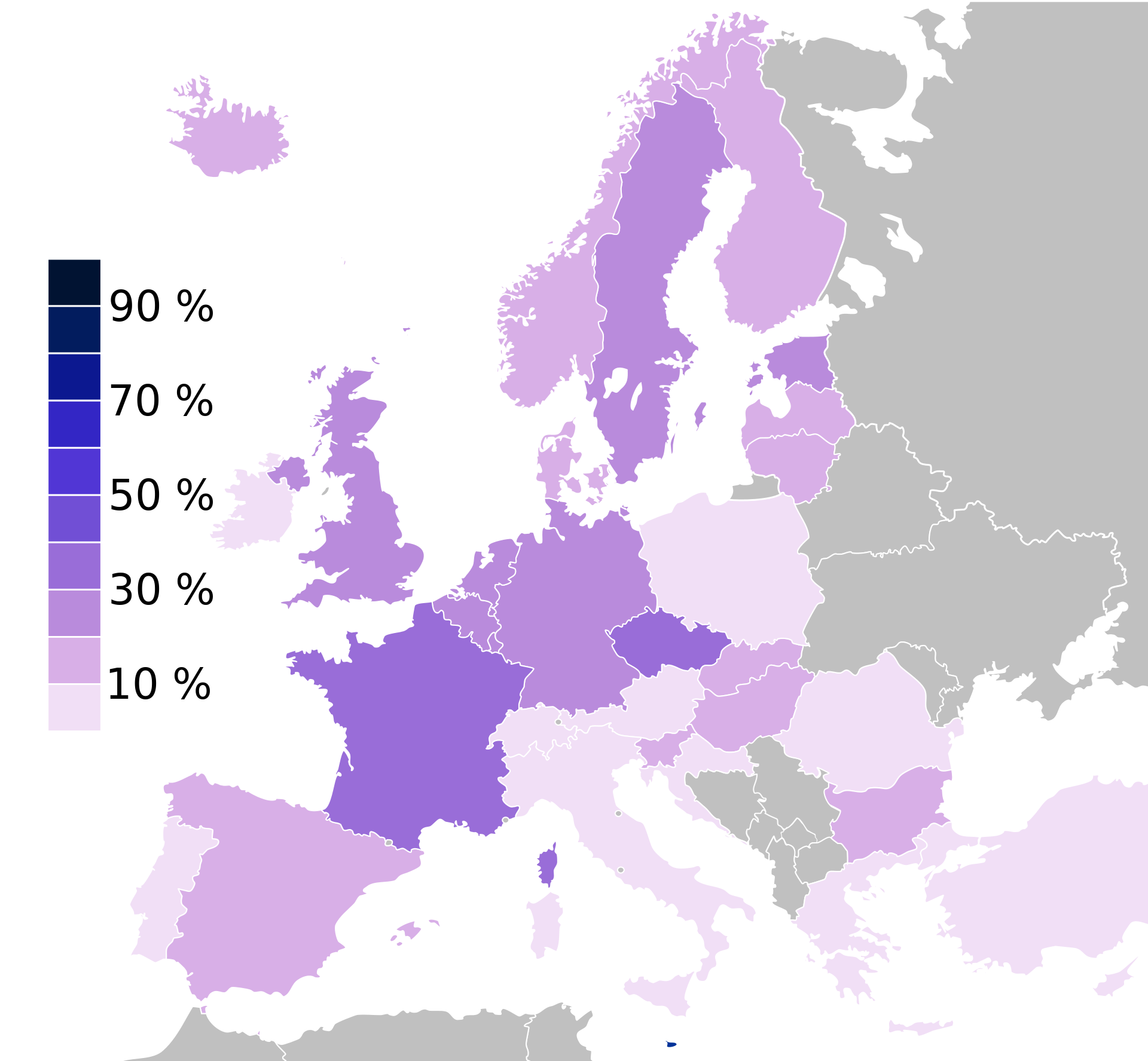

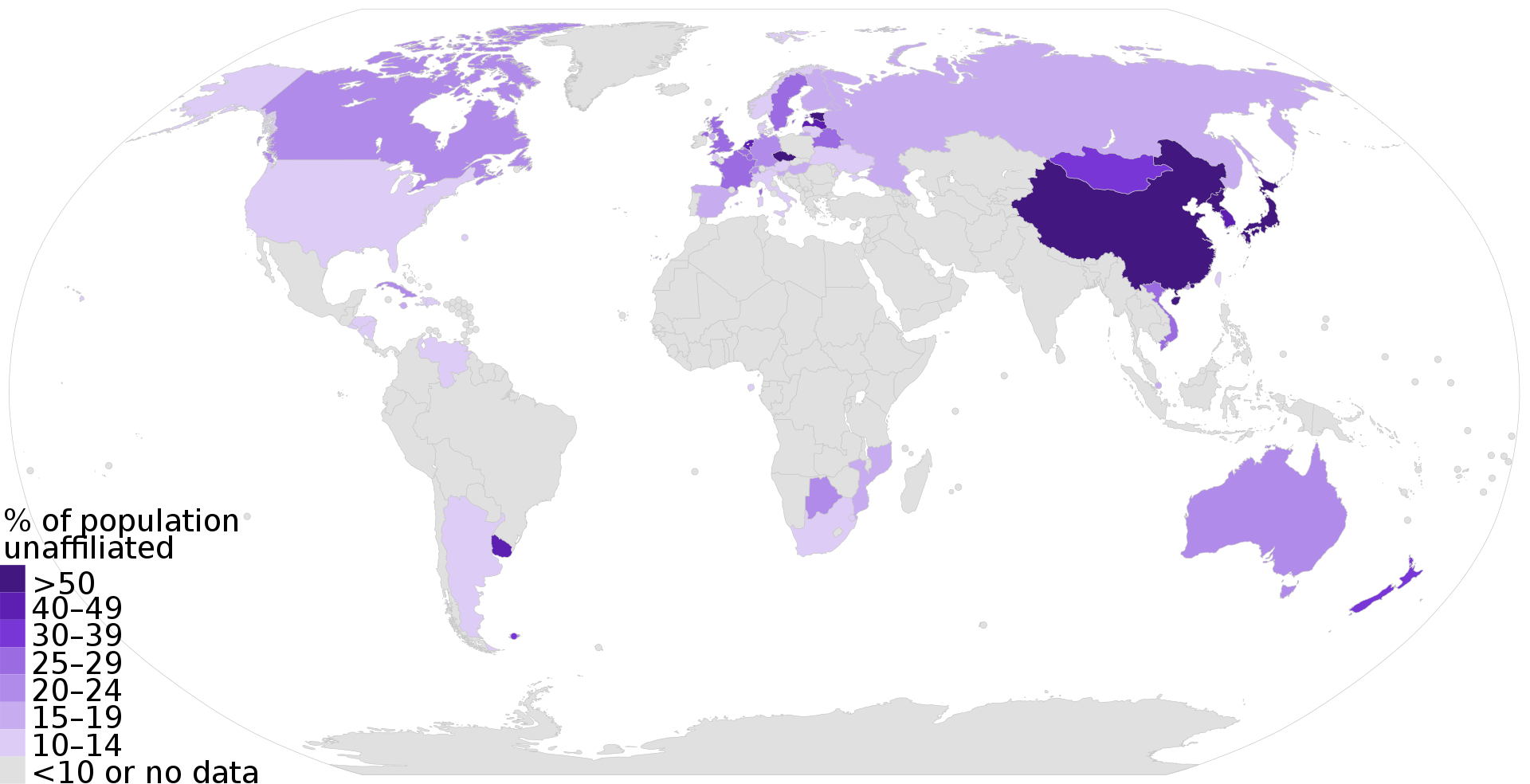

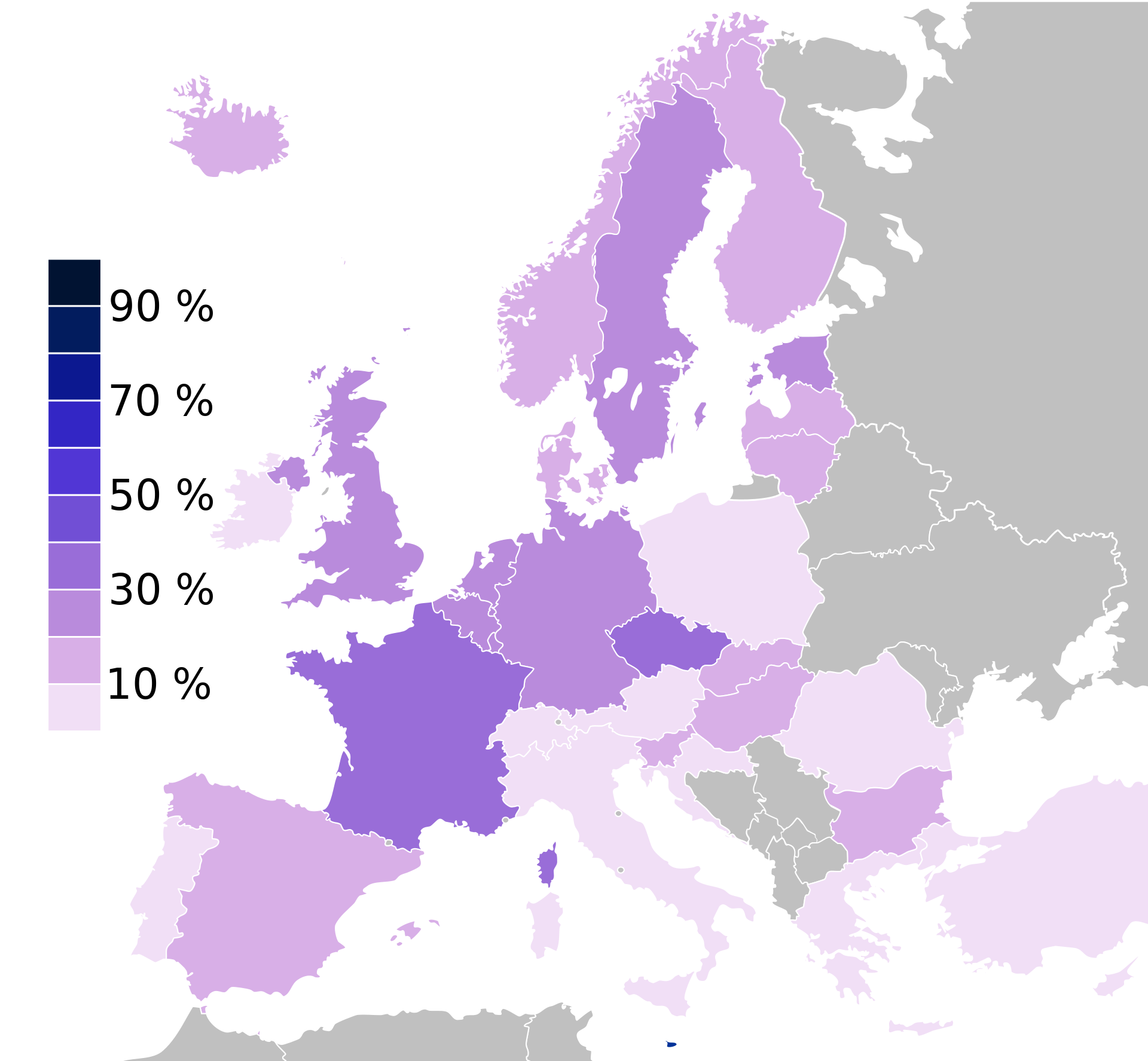

Demographics Nonreligious population by country, 2010[80]  Percentage of people in various European countries who said: "I don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force." (2005)[81] Demographic research services normally do not differentiate between various types of non-religious respondents, so agnostics are often classified in the same category as atheists or other non-religious people.[82] A 2010 survey published in Encyclopædia Britannica found that the non-religious people or the agnostics made up about 9.6% of the world's population.[83] A November–December 2006 poll published in the Financial Times gives rates for the United States and five European countries. The rates of agnosticism in the United States were at 14%, while the rates of agnosticism in the European countries surveyed were considerably higher: Italy (20%), Spain (30%), Great Britain (35%), Germany (25%), and France (32%).[84] A study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that about 16% of the world's people, the third largest group after Christianity and Islam, have no religious affiliation.[85] According to a 2012 report by the Pew Research Center, agnostics made up 3.3% of the US adult population.[86] In the U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, conducted by the Pew Research Center, 55% of agnostic respondents expressed "a belief in God or a universal spirit",[87] whereas 41% stated that they thought that they felt a tension "being non-religious in a society where most people are religious".[88] According to the 2021 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 38.9% of Australians have "no religion", a category that includes agnostics.[89] Between 64% and 65% of Japanese,[90] and up to 81% of Vietnamese,[91] are atheists, agnostics, or do not believe in a god. An official European Union survey reported that 3% of the EU population is unsure about their belief in a god or spirit.[92] |

人口統計 国別の無宗教人口(2010年)[80  ヨーロッパ各国における無宗教者の割合: 「霊魂、神、生命力のようなものは存在しないと思う。(2005)[81] 人口統計調査サービスは通常、様々なタイプの無宗教回答者を区別しないため、無宗教者はしばしば無神論者やその他の無宗教者と同じカテゴリーに分類される[82]。 ブリタニカ百科事典に掲載された2010年の調査では、無宗教者や無宗教者は世界人口の約9.6%を占めていた[83]。フィナンシャル・タイムズ紙に掲 載された2006年11月から12月にかけての世論調査では、アメリカとヨーロッパ5カ国の無宗教者の割合が示されている。米国の不可知論の割合は14% であったが、調査対象となったヨーロッパ諸国の不可知論の割合はかなり高かった: イタリア(20%)、スペイン(30%)、イギリス(35%)、ドイツ(25%)、フランス(32%)であった[84]。 ピュー・リサーチ・センターが行った調査によると、世界の人々の約16%、キリスト教とイスラム教に次いで3番目に大きなグループが無宗教である [85]。 ピュー・リサーチ・センターが実施した米国の宗教景観調査では、不可知論の回答者の55%が「神や普遍的な精神を信じる」と表明しており[87]、一方で 41%が「ほとんどの人が宗教的である社会で無宗教であること」に緊張を感じると思うと述べている[88]。 2021年のオーストラリア統計局によれば、オーストラリア人の38.9%が「無宗教」であり、無宗教者を含むカテゴリーである[89]。日本人の64% から65%[90]、ベトナム人の最大81%[91]が無神論者、無宗教者、あるいは神を信じていない。欧州連合(EU)の公式調査では、EU人口の3% が神や霊魂を信じるかどうかわからないと報告している[92]。 |

| Criticism Agnosticism is criticized from a variety of standpoints. Some atheists criticize the use of the term agnosticism as functionally indistinguishable from atheism; this results in frequent criticisms of those who adopt the term as avoiding the atheist label.[26] |

批判 不可知論は様々な立場から批判されている。無神論者の中には、不可知論という用語の使用は無神論と機能的に区別がつかないと批判する者もいる。その結果、この用語を採用する者は無神論者のレッテルを避けていると頻繁に批判されることになる[26]。 |

|

Theistic Theistic critics claim that agnosticism is impossible in practice, since a person can live only either as if God did not exist (etsi deus non-daretur), or as if God did exist (etsi deus daretur).[93][94] |

有神的 神道的批評家は、不可知論は実際には不可能であると主張する。なぜなら、人は神が存在しないかのように(etsi deus nonaretur)、あるいは神が存在するかのように(etsi deus daretur)しか生きられないからである[93][94]。 |

| Christian According to Pope Benedict XVI, strong agnosticism in particular contradicts itself in affirming the power of reason to know scientific truth.[95][96] He blames the exclusion of reasoning from religion and ethics for dangerous pathologies such as crimes against humanity and ecological disasters.[95][page needed][96][page needed][97] "Agnosticism", said Benedict, "is always the fruit of a refusal of that knowledge which is in fact offered to man ... The knowledge of God has always existed".[96] He asserted that agnosticism is a choice of comfort, pride, dominion, and utility over truth, and is opposed by the following attitudes: the keenest self-criticism, humble listening to the whole of existence, the persistent patience and self-correction of the scientific method, a readiness to be purified by the truth.[95] The Catholic Church sees merit in examining what it calls "partial agnosticism", specifically those systems that "do not aim at constructing a complete philosophy of the unknowable, but at excluding special kinds of truth, notably religious, from the domain of knowledge".[98] However, the Church is historically opposed to a full denial of the capacity of human reason to know God. The Council of the Vatican declares, "God, the beginning and end of all, can, by the natural light of human reason, be known with certainty from the works of creation".[98] Blaise Pascal argued that even if there were truly no evidence for God, agnostics should consider what is now known as Pascal's Wager: the infinite expected value of acknowledging God is always greater than the finite expected value of not acknowledging his existence, and thus it is a safer "bet" to choose God.[99] |

キリスト教 教皇ベネディクト16世によれば、特に強い不可知論は、科学的真理を知る理性の力を肯定すること自体に矛盾している[95][96]。彼は、人道に対する 犯罪や生態系災害のような危険な病理のために、宗教や倫理から理性を排除することを非難している[95][要ページ][96][要ページ][97]。ベネ ディクトは、「不可知論は、常に、実際に人間に提供されている知識を拒否することの果実である。神の知識は常に存在していた」[96]。ベネディクトは、 不可知論とは、真理よりも快適さ、高慢さ、支配力、有用性を選択することであり、次のような態度によって反対されると主張した:最も鋭い自己批判、存在の 全体に対する謙虚な傾聴、科学的方法の粘り強い忍耐と自己修正、真理によって浄化される覚悟[95]。 カトリック教会は、「部分的不可知論」と呼ぶもの、具体的には「知ることのできないものについての完全な哲学を構築することを目的とせず、知識の領域から 特別な種類の真理、特に宗教的な真理を排除することを目的とする」体系を検討することにメリットを見出している[98]。 しかしながら、教会は、神を知るための人間の理性の能力を完全に否定することに歴史的に反対している。バチカン公会議は、「すべての始まりであり終わりで ある神は、人間の理性の自然な光によって、被造物から確実に知ることができる」と宣言している[98]。 ブレーズ・パスカルは、たとえ本当に神についての証拠がなかったとしても、無宗教者は現在パスカルの賭けとして知られているものを考慮すべきだと主張し た。つまり、神の存在を認めることの無限の期待値は、神の存在を認めないことの有限の期待値よりも常に大きいのであり、したがって神を選ぶ方が安全な「賭 け」なのである[99]。 |

| Atheistic According to Richard Dawkins, a distinction between agnosticism and atheism is unwieldy and depends on how close to zero a person is willing to rate the probability of existence for any given god-like entity. About himself, Dawkins continues, "I am agnostic only to the extent that I am agnostic about fairies at the bottom of the garden."[100] Dawkins also identifies two categories of agnostics; "Temporary Agnostics in Practice" (TAPs), and "Permanent Agnostics in Principle" (PAPs). He states that "agnosticism about the existence of God belongs firmly in the temporary or TAP category. Either he exists or he doesn't. It is a scientific question; one day we may know the answer, and meanwhile we can say something pretty strong about the probability", and considers PAP a "deeply inescapable kind of fence-sitting".[101] Ignosticism A related concept is ignosticism, the view that a coherent definition of a deity must be put forward before the question of the existence of a deity can be meaningfully discussed. If the chosen definition is not coherent, the ignostic holds the noncognitivist view that the existence of a deity is meaningless or empirically untestable.[102] A. J. Ayer, Theodore Drange, and other philosophers see both atheism and agnosticism as incompatible with ignosticism on the grounds that atheism and agnosticism accept the statement "a deity exists" as a meaningful proposition that can be argued for or against.[103][104] |

無神論的 リチャード・ドーキンスによれば、不可知論と無神論の区別は扱いにくく、人が与えられた神のような存在の確率をどれだけゼロに近いと評価するかによって決 まる。ドーキンスはまた、不可知論者を「実践的な一時的不可知論者(TAPs)」と「原理的な永続的不可知論者(PAPs)」の2つに分類している。彼 は、「神の存在に関する不可知論は、一時的あるいはTAPのカテゴリーにしっかりと属する。神は存在するかしないかだ。それは科学的な質問であり、いつか 答えがわかるかもしれないし、その間に確率についてかなり強いことを言うことができる」とし、PAPは「深く避けられない一種の柵越し」であると考えてい る[101]。 イグノーシス主義 関連する概念として、神の存在の問題を有意義に議論する前に、神の首尾一貫した定義を提示しなければならないという見解である無視主義がある。選択された 定義が首尾一貫していない場合、無視主義者は神の存在は無意味であるか経験的に検証不可能であるという非認知主義的な見解を持つ[102]。A. J. Ayer、Theodore Drange、その他の哲学者は、無神論と不可知論が「神は存在する」というステートメントを賛否を論じることができる意味のある命題として受け入れてい るという理由で、無神論と不可知論の両方が無視主義と相容れないと考えている[103][104]。 |

| Acatalepsy Agnostic atheism Agnostic theism Apatheism Apophatic theology Asimov's Guide to the Bible Avidyā (Buddhism) Christian agnosticism Existentialism Ietsism Ignoramus et ignorabimus Instrumentalism List of agnostics Objectivism Possibilianism Rationalism Relativism Religiosity Religious skepticism Russell's teapot Scientism Secularism Solipsism Spirituality Spiritual but not religious Subjectivism Unknown God Philosophy portal icon Religion portal |

無カタレプシー 不可知論的無神論 不可知論的有神論 無神論 アポファティック神学 アシモフの聖書ガイド 不可知論 キリスト教不可知論 実存主義 イエティズム 無知と無知主義 道具主義 不可知論者のリスト 目的論 可能性主義 合理主義 相対主義 宗教性 宗教的懐疑主義 ラッセルのティーポット 科学主義 世俗主義 独我論 スピリチュアリティ スピリチュアルだが宗教的ではない 主観主義 未知の神 哲学ポータル 宗教ポータル |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnosticism |

|

| Agnosticism. Forgotten Books. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-4400-6878-2. Alexander, Nathan G. "An Atheist with a Tall Hat On: The Forgotten History of Agnosticism." The Humanist, February 19, 2019. Annan, Noel. Leslie Stephen: The Godless Victorian (U of Chicago Press, 1984) Cockshut, A.O.J. The Unbelievers, English Thought, 1840–1890 (1966). Dawkins, Richard. "The poverty of agnosticism", in The God Delusion, Black Swan, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-552-77429-1). Huxley, Thomas H. (February 4, 2013). Man's Place in Nature. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-486-15134-2. Hume, David (1779). Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Penguin Books, Limited. pp. 1–. Kant, Immanuel (May 28, 2013). The Critique of Pure Reason. Loki's Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-82576-2. Kierkegaard, Sören (1985). Philosophical Fragments. Religion-online.org. ISBN 978-0-691-02036-5. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014. Lightman, Bernard. The Origins of Agnosticism (1987). Royle, Edward. Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain, 1866–1915 (Manchester UP, 1980). Smith, George H. (1979). Atheism – The Case Against God (PDF). Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-124-X. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2014. |

Agnosticism. Forgotten Books. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-4400-6878-2. Alexander, Nathan G. "An Atheist with a Tall Hat On: The Forgotten History of Agnosticism." The Humanist, February 19, 2019. Annan, Noel. Leslie Stephen: The Godless Victorian (U of Chicago Press, 1984) Cockshut, A.O.J. The Unbelievers, English Thought, 1840–1890 (1966). Dawkins, Richard. "The poverty of agnosticism", in The God Delusion, Black Swan, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-552-77429-1). Huxley, Thomas H. (February 4, 2013). Man's Place in Nature. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-486-15134-2. Hume, David (1779). Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Penguin Books, Limited. pp. 1–. Kant, Immanuel (May 28, 2013). The Critique of Pure Reason. Loki's Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-82576-2. Kierkegaard, Sören (1985). Philosophical Fragments. Religion-online.org. ISBN 978-0-691-02036-5. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014. Lightman, Bernard. The Origins of Agnosticism (1987). Royle, Edward. Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain, 1866–1915 (Manchester UP, 1980). Smith, George H. (1979). Atheism – The Case Against God (PDF). Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-124-X. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2014. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnosticism | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆