グノスティシズム

Gnosticism, グノーシス主義

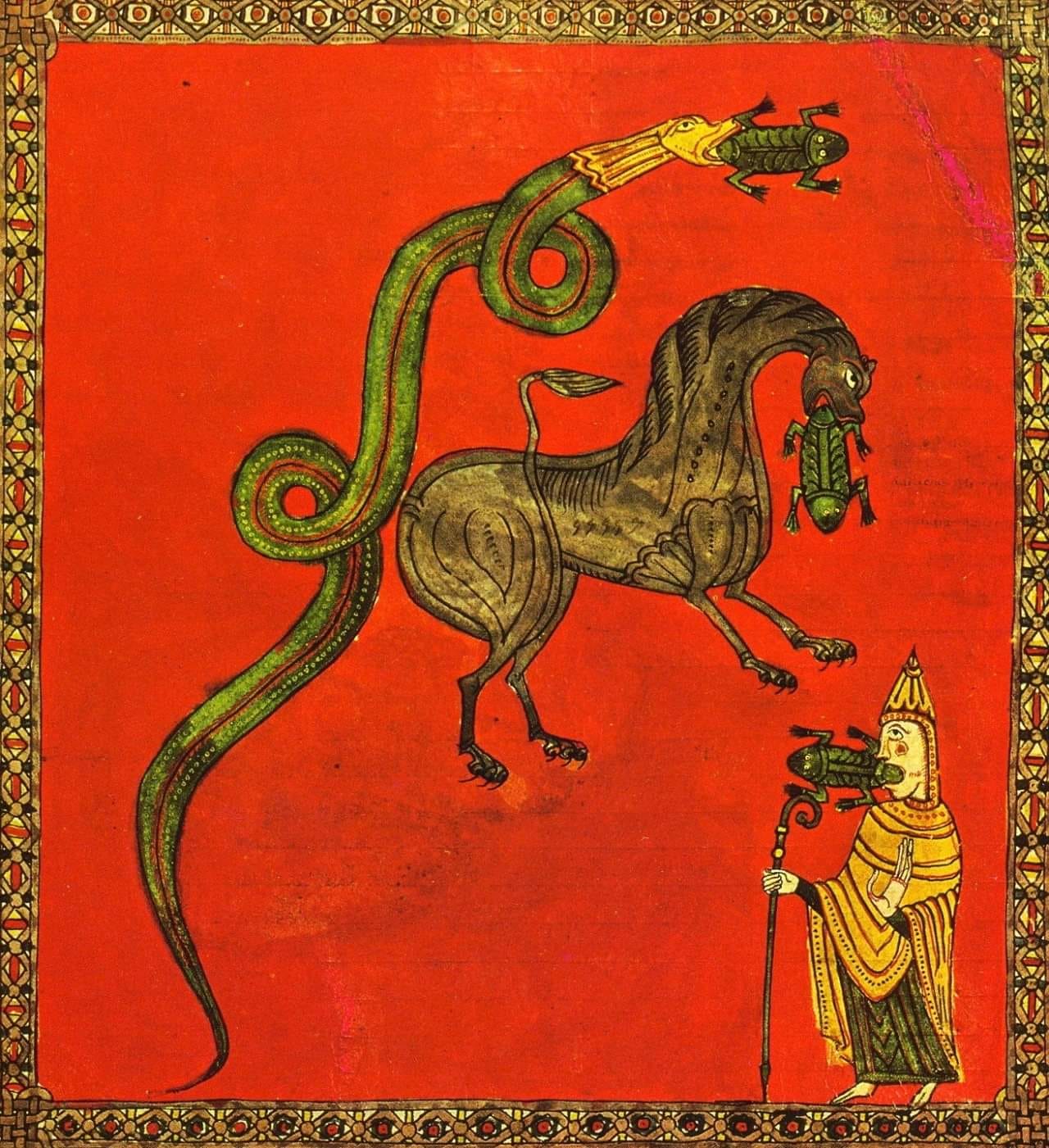

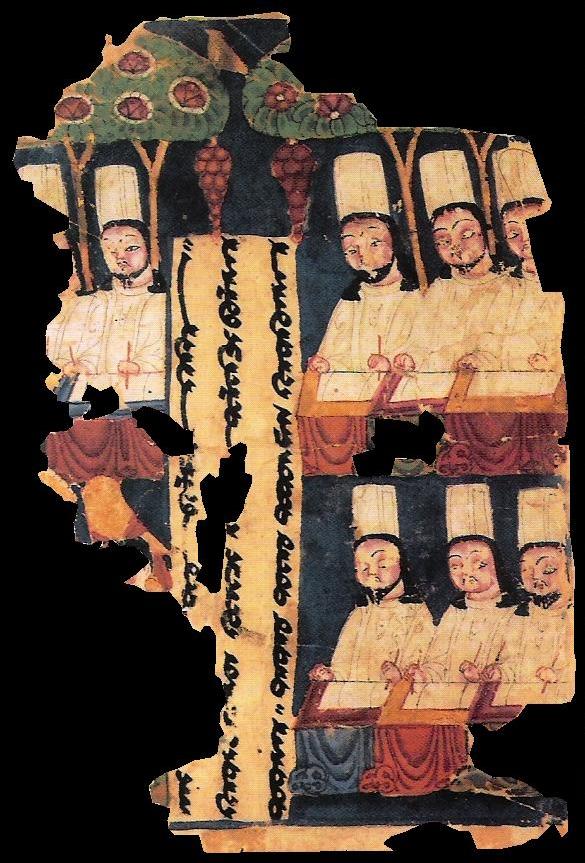

Martinus, "Frogs" from the Beatus of Osma 1086, (Commentary on the Apocalypse)

ヨハネの黙示録 16章 13「わたしはまた、竜の口から、獣の口から、そして、偽預言者の口から、蛙のような汚れた三つの霊が出て来るのを見た。」

★真の神秘主義とは意志的なものであり、創造的なものである——ベルクソン主義者.

☆ グノーシス主義=グノスティシズム[Gnosticism] (古代ギリシア語: γνωστικός, ローマ字表記: gnōstikós, コイネギリシア語: [ɣnostiˈkos]、「知識を持つ」)は、紀元後1世紀後半にユダヤ教や初期キリスト教の宗派の間で合体した宗教思想や宗教体系の集まりである。こ れらの様々なグループは、原初的な正統派の教えや伝統、宗教機関の権威よりも、個人的な霊的知識(グノーシ ス)を重視した。 グノーシスの宇宙観は一般的に、物質的な宇宙を創造する責任を負う、隠された至高の神と悪意ある小神(聖書の神ヤハウェと関連付けられることもある)との 区別を示す。その結果、グノーシス派は物質的存在を欠陥や悪とみなし、救済の主要な要素は神秘的または秘教的洞察によって到達する隠れた神性を直接知るこ とであるとした。グノーシス主義のテキストの多くは、罪や悔い改めという概念ではなく、幻想や悟りについて扱っている。 2世紀頃、地中海世界の特定のキリスト教集団の間でグノーシス主義的な書物が盛んになり、初代教会の教父たちはそれを異端として非難した。グノーシス主義 のキリスト教の伝統では、キリストは、人類を自らの神性の認識へと導くために人間の姿をとった神的存在とみなされている。しかし、グノーシス主義は単一の 標準化された体系ではなく、直接体験に重きを置いているため、ヴァレンティノス主義やセティウス主義といった異なる潮流を含め、多種多様な教えが存在す る。ペルシャ帝国では、グノーシス主義の思想は、関連する運動であるマニ教を通じて中国にまで広まった。一方、古代から現存する唯一のグノーシス主義宗教 であるマンダ教は、イラク、イラン、およびディアスポラの共同体に見られる。ヨルン・バックリーは、初期のマンダ教信者が、イエスの初期の信者の共同体の 中で、後にグノーシス主義となるものを最初に定式化した一人であった可能性があると推測している。

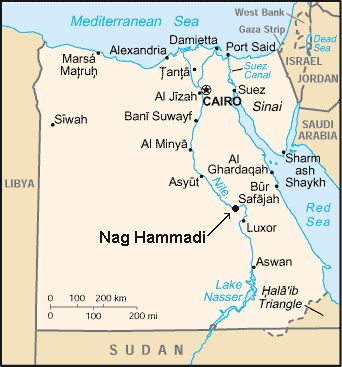

| Gnosticism (from

Ancient Greek: γνωστικός, romanized: gnōstikós, Koine Greek:

[ɣnostiˈkos], 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas

and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and

early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized personal

spiritual knowledge (gnosis) above the proto-orthodox teachings,

traditions, and authority of religious institutions. Gnostic cosmogony generally presents a distinction between a supreme, hidden God and a malevolent lesser divinity (sometimes associated with the biblical deity Yahweh)[1] who is responsible for creating the material universe. Consequently, Gnostics considered material existence flawed or evil, and held the principal element of salvation to be direct knowledge of the hidden divinity, attained via mystical or esoteric insight. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of sin and repentance, but with illusion and enlightenment.[2] Gnostic writings flourished among certain Christian groups in the Mediterranean world around the second century, when the Fathers of the early Church denounced them as heresy.[3] Efforts to destroy these texts proved largely successful, resulting in the survival of very little writing by Gnostic theologians.[4] Nonetheless, early Gnostic teachers such as Valentinus saw their beliefs as aligned with Christianity. In the Gnostic Christian tradition, Christ is seen as a divine being which has taken human form in order to lead humanity back to recognition of its own divine nature. However, Gnosticism is not a single standardized system, and the emphasis on direct experience allows for a wide variety of teachings, including distinct currents such as Valentinianism and Sethianism. In the Persian Empire, Gnostic ideas spread as far as China via the related movement Manichaeism, while Mandaeism, which is the only surviving Gnostic religion from antiquity, is found in Iraq, Iran and diaspora communities.[5] Jorunn Buckley posits that the early Mandaeans may have been among the first to formulate what would go on to become Gnosticism within the community of early followers of Jesus.[6] For centuries, most scholarly knowledge about Gnosticism was limited to the anti-heretical writings of early Christian figures such as Irenaeus of Lyons and Hippolytus of Rome. There was a renewed interest in Gnosticism after the 1945 discovery of Egypt's Nag Hammadi library, a collection of rare early Christian and Gnostic texts, including the Gospel of Thomas and the Apocryphon of John. Elaine Pagels has noted the influence of sources from Hellenistic Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Platonism on the Nag Hammadi texts.[4] Since the 1990s, the category of "Gnosticism" has come under increasing scrutiny from scholars. One such issue is whether Gnosticism ought to be considered one form of early Christianity, an interreligious phenomenon, or an independent religion. Going further than this, other contemporary scholars such as Michael Allen Williams,[7] Karen Leigh King,[8] and David G. Robertson[9] contest whether "Gnosticism" is a valid or useful historical term, or if it was an artificial category framed by proto-orthodox theologians to target miscellaneous Christian heretics.  Page from the Gospel of Judas  Mandaean Beth Manda (Mashkhanna) in Nasiriyah, southern Iraq, in 2016, a contemporary-style mandi |

グノーシス主義=グノスティシズム(古代ギリシア語: γνωστικός,

ローマ字表記: gnōstikós, コイネギリシア語:

[ɣnostiˈkos]、「知識を持つ」)は、紀元後1世紀後半にユダヤ教や初期キリスト教の宗派の間で合体した宗教思想や宗教体系の集まりである。こ

れらの様々なグループは、原初的な正統派の教えや伝統、宗教機関の権威よりも、個人的な霊的知識(グノーシス)を重視した。 グノーシスの宇宙観は一般的に、物質的な宇宙を創造する責任を負う、隠された至高の神と悪意ある小神(聖書の神ヤハウェと関連付けられることもある) [1]との区別を示す。その結果、グノーシス派は物質的存在を欠陥や悪とみなし、救済の主要な要素は神秘的または秘教的洞察によって到達する隠れた神性を 直接知ることであるとした。グノーシス主義のテキストの多くは、罪や悔い改めという概念ではなく、幻想や悟りについて扱っている[2]。 2世紀頃、地中海世界の特定のキリスト教集団の間でグノーシス主義的な書物が盛んになり、初代教会の教父たちはそれを異端として非難した。グノーシス主義 のキリスト教の伝統では、キリストは、人類を自らの神性の認識へと導くために人間の姿をとった神的存在とみなされている。しかし、グノーシス主義は単一の 標準化された体系ではなく、直接体験に重きを置いているため、ヴァレンティノス主義やセティウス主義といった異なる潮流を含め、多種多様な教えが存在す る。ペルシャ帝国では、グノーシス主義の思想は、関連する運動であるマニ教を通じて中国にまで広まった。一方、古代から現存する唯一のグノーシス主義宗教 であるマンダ教は、イラク、イラン、およびディアスポラの共同体に見られる[5]。ヨルン・バックリーは、初期のマンダ教信者が、イエスの初期の信者の共 同体の中で、後にグノーシス主義となるものを最初に定式化した一人であった可能性があると推測している[6]。 何世紀もの間、グノーシス主義に関するほとんどの学術的知識は、リヨンのイレナイオスやローマのヒッポリュトスといった初期キリスト教の人物による反異端 の著作に限られていた。1945年にエジプトのナグ・ハマディ図書館が発見された後、グノーシス主義への関心が再び高まった。ナグ・ハマディ図書館には、 トマス福音書やヨハネのアポクリフォンを含む、初期キリスト教とグノーシス主義の貴重なテキストが収められている。エレイン・ペイゲルスは、ヘレニズム期 のユダヤ教、ゾロアスター教、プラトン主義からの資料がナグ・ハマディのテキストに影響を与えていることを指摘している[4]。1990年代以降、「グ ノーシス主義」というカテゴリーは学者たちからますます精査されるようになっている。その一つが、グノーシス主義を初期キリスト教の一形態とみなすべき か、宗教間の現象とみなすべきか、それとも独立した宗教とみなすべきかという問題である。さらに踏み込むと、マイケル・アレン・ウィリアムズ[7]、カレ ン・リー・キング[8]、デイヴィッド・G・ロバートソン[9]といった現代の学者たちは、「グノーシス主義」が歴史的に有効で有用な用語なのか、それと も原初正統派の神学者たちが雑多なキリスト教異端者たちを標的にするために作り出した人為的なカテゴリーなのかを論じている。  ユダの福音書より  2016年、イラク南部ナシリヤのマンダイ・ベス・マンダ(マシュカンナ)。 |

| Etymology Main article: Gnosis Gnosis is a feminine Greek noun which means "knowledge" or "awareness."[10] It is often used for personal knowledge compared with intellectual knowledge (εἴδειν eídein). A related term is the adjective gnostikos, "cognitive",[11] a reasonably common adjective in Classical Greek.[12] By the Hellenistic period, it began also to be associated with Greco-Roman mysteries, becoming synonymous with the Greek term musterion. Consequentially, Gnosis often refers to knowledge based on personal experience or perception.[citation needed] In a religious context, gnosis is mystical or esoteric knowledge based on direct participation with the divine. In most Gnostic systems, the sufficient cause of salvation is this "knowledge of" ("acquaintance with") the divine. It is an inward "knowing", comparable to that encouraged by Plotinus (neoplatonism), and differs from proto-orthodox Christian views.[13] Gnostics are "those who are oriented toward knowledge and understanding – or perception and learning – as a particular modality for living".[14] The usual meaning of gnostikos in Classical Greek texts is "learned" or "intellectual", such as used by Plato in the comparison of "practical" (praktikos) and "intellectual" (gnostikos).[note 1][subnote 1] Plato's use of "learned" is fairly typical of Classical texts.[note 2] Sometimes employed in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible, the adjective is not used in the New Testament, but Clement of Alexandria[note 3] who speaks of the "learned" (gnostikos) Christian quite often, uses it in complimentary terms.[15] The use of gnostikos in relation to heresy originates with interpreters of Irenaeus. Some scholars[note 4] consider that Irenaeus sometimes uses gnostikos to simply mean "intellectual",[note 5] whereas his mention of "the intellectual sect"[note 6] is a specific designation.[17][note 7][note 8][note 9] The term "Gnosticism" does not appear in ancient sources,[19][note 10] and was first coined in the 17th century by Henry More in a commentary on the seven letters of the Book of Revelation, where More used the term "Gnosticisme" to describe the heresy in Thyatira.[20][note 11] The term Gnosticism was derived from the use of the Greek adjective gnostikos (Greek γνωστικός, "learned", "intellectual") by St. Irenaeus (c. 185 AD) to describe the school of Valentinus as he legomene gnostike haeresis "the heresy called Learned (gnostic)".[21][note 12] Origins The origins of Gnosticism are obscure and still disputed. Gnosticism is largely influenced by platonism and its theory of forms.[23][24][25] The proto-orthodox Christian groups called Gnostics a heresy of Christianity,[note 13][27] but according to the modern scholars the theology's origin is closely related to Jewish sectarian milieus and early Christian sects.[28][29][note 14][30] Some scholars debate Gnosticism's origins as having roots in Buddhism, due to similarities in beliefs,[31] but ultimately, its origins are unknown. Some scholars prefer to speak of "gnosis" when referring to first-century ideas that later developed into Gnosticism, and to reserve the term "Gnosticism" for the synthesis of these ideas into a coherent movement in the second century.[32] According to James M. Robinson, no gnostic texts clearly pre-date Christianity,[note 15] and "pre-Christian Gnosticism as such is hardly attested in a way to settle the debate once and for all."[33] Most popular Gnostic sects were heavily inspired by Zoroastrianism.[34] Jewish Christian origins See also: Origins of Christianity and Split of Christianity and Judaism Contemporary scholarship largely agrees that Gnosticism has Jewish Christian origins, originating in the late first century AD in nonrabbinical Jewish sects and early Christian sects.[35][28][29][note 14] Ethel S. Drower adds, "heterodox Judaism in Galilee and Samaria appears to have taken shape in the form we now call Gnostic, and it may well have existed some time before the Christian era."[36]: xv Many heads of Gnostic schools were identified as Jewish Christians by Church Fathers, and Hebrew words and names of God were applied in some gnostic systems.[37] The cosmogonic speculations among Christian Gnostics had partial origins in Maaseh Breshit and Maaseh Merkabah. This thesis is most notably put forward by Gershom Scholem (1897–1982) and Gilles Quispel (1916–2006). Scholem detected Jewish gnosis in the imagery of merkabah mysticism, which can also be found in certain Gnostic documents.[35] Quispel sees Gnosticism as an independent Jewish development, tracing its origins to Alexandrian Jews, to which group Valentinus was also connected.[38] Many of the Nag Hammadi texts make reference to Judaism, in some cases with a violent rejection of the Jewish God.[29][note 14] Gershom Scholem once described Gnosticism as "the Greatest case of metaphysical anti-Semitism".[39] Professor Steven Bayme said gnosticism would be better characterized as anti-Judaism.[40] Research into the origins of Gnosticism shows a strong Jewish influence, particularly from Hekhalot literature.[41] Within early Christianity, the teachings of Paul the Apostle and John the Evangelist may have been a starting point for Gnostic ideas, with a growing emphasis on the opposition between flesh and spirit, the value of charisma, and the disqualification of the Jewish law. The mortal body belonged to the world of inferior, worldly powers (the archons), and only the spirit or soul could be saved. The term gnostikos may have acquired a deeper significance here.[42] Alexandria was of central importance for the birth of Gnosticism. The Christian ecclesia (i. e. congregation, church) was of Jewish–Christian origin, but also attracted Greek members, and various strands of thought were available, such as "Judaic apocalypticism, speculation on divine wisdom, Greek philosophy, and Hellenistic mystery religions."[42] Regarding the angel Christology of some early Christians, Darrell Hannah notes: [Some] early Christians understood the pre-incarnate Christ, ontologically, as an angel. This "true" angel Christology took many forms and may have appeared as early as the late First Century, if indeed this is the view opposed in the early chapters of the Epistle to the Hebrews. The Elchasaites, or at least Christians influenced by them, paired the male Christ with the female Holy Spirit, envisioning both as two gigantic angels. Some Valentinian Gnostics supposed that Christ took on an angelic nature and that he might be the Saviour of angels. The author of the Testament of Solomon held Christ to be a particularly effective "thwarting" angel in the exorcism of demons. The author of De Centesima and Epiphanius' "Ebionites" held Christ to have been the highest and most important of the first created archangels, a view similar in many respects to Hermas' equation of Christ with Michael. Finally, a possible exegetical tradition behind the Ascension of Isaiah and attested by Origen's Hebrew master, may witness to yet another angel Christology, as well as an angel Pneumatology.[43] The pseudepigraphical Christian text Ascension of Isaiah identifies Jesus with angel Christology: [The Lord Christ is commissioned by the Father] And I heard the voice of the Most High, the father of my LORD as he said to my LORD Christ who will be called Jesus, 'Go out and descend through all the heavens...[44] The Shepherd of Hermas is a Christian literary work considered as canonical scripture by some of the early Church fathers such as Irenaeus. Jesus is identified with angel Christology in parable 5, when the author mentions a Son of God, as a virtuous man filled with a Holy "pre-existent spirit".[45] Neoplatonic influences See also: Platonic Academy, Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, and Neoplatonism and Christianity In the 1880s Gnostic connections with neo-Platonism were proposed.[46] Ugo Bianchi, who organised the Congress of Messina of 1966 on the origins of Gnosticism, also argued for Orphic and Platonic origins.[38] Gnostics borrowed significant ideas and terms from Platonism,[47] using Greek philosophical concepts throughout their text, including such concepts as hypostasis (reality, existence), ousia (essence, substance, being), and demiurge (creator God). Both Sethian Gnostics and Valentinian Gnostics seem to have been influenced by Plato, Middle Platonism, and Neo-Pythagoreanism academies or schools of thought.[48] Both schools attempted "an effort towards conciliation, even affiliation" with late antique philosophy,[49] and were rebuffed by some Neoplatonists, including Plotinus. Persian origins or influences Early research into the origins of Gnosticism proposed Persian origins or influences, spreading to Europe and incorporating Jewish elements.[50] According to Wilhelm Bousset (1865–1920), Gnosticism was a form of Iranian and Mesopotamian syncretism,[46] and Richard August Reitzenstein (1861–1931) situated the origins of Gnosticism in Persia.[46] Carsten Colpe (b. 1929) has analyzed and criticised the Iranian hypothesis of Reitzenstein, showing that many of his hypotheses are untenable.[51] Nevertheless, Geo Widengren (1907–1996) argued for the origin of Mandaean Gnosticism in Mazdean (Zoroastrianism) Zurvanism, in conjunction with ideas from the Aramaic Mesopotamian world.[38] However, scholars specializing in Mandaeism such as Kurt Rudolph, Mark Lidzbarski, Rudolf Macúch, Ethel S. Drower, James F. McGrath, Charles G. Häberl, Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, and Şinasi Gündüz argue for a Palestinian origin. The majority of these scholars believe that the Mandaeans likely have a historical connection with John the Baptist's inner circle of disciples.[36][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] Charles Häberl, who is also a linguist specializing in Mandaic, finds Palestinian and Samaritan Aramaic influence on Mandaic and accepts Mandaeans having a "shared Palestinian history with Jews".[59][60] Buddhist parallels Main article: Buddhism and Gnosticism In 1966, at the Congress of Median, Buddhologist Edward Conze noted phenomenological commonalities between Mahayana Buddhism and Gnosticism,[61] in his paper Buddhism and Gnosis, following an early suggestion put forward by Isaac Jacob Schmidt.[62][note 16] The influence of Buddhism in any sense on either the gnostikos Valentinus (c. 170) or the Nag Hammadi texts (3rd century) is not supported by modern scholarship, although Elaine Pagels called it a "possibility".[66] |

語源 主な記事 グノーシス グノーシス(Gnosis)は、「知識」や「認識」を意味するギリシア語の女性名詞である[10]。知的知識(εἴδειν eídein)と比較される個人的な知識に対して用いられることが多い。関連する用語として、グノスティコス(gnostikos)、「認知的な」 [11]という形容詞があり、古典ギリシア語ではそれなりに一般的な形容詞であった[12]。 ヘレニズム時代には、グノーシスはギリシャ・ローマ時代の秘儀とも関連付けられるようになり、ギリシャ語のムステリオンと同義語となった。その結果、グ ノーシスはしばしば個人的な経験や知覚に基づく知識を指す[要出典]。宗教的な文脈では、グノーシスは神との直接参加に基づく神秘的または秘教的な知識で ある。ほとんどのグノーシス主義では、救済の十分な原因は、この神の「知識」(「知己」)である。これはプロティノス(新プラトン主義)によって奨励され たものに匹敵する内面的な「知識」であり、原初的な正統派のキリスト教の見解とは異なる[13]。 [14]古典ギリシア語のテクストにおけるグノスティコスの通常の意味は、プラトンが「実践的な」(プラクティコス)と「知的な」(グノスティコス)の比 較で用いたような「学識のある」または「知的な」である[注釈 1][亜注釈 1]。プラトンの「学識のある」の用法は古典的テクストのかなり典型的なものである[注釈 2]。 ヘブライ語聖書のセプトゥアギンタ訳ではこの形容詞が使われることがあるが、新約聖書ではこの形容詞は使われておらず、アレクサンドリアのクレメンス[注 釈 3]が「学識ある」(グノスティコス)キリスト教徒についてかなり頻繁に語っており、褒め言葉として使っている[15]。異端との関連でグノスティコスが 使われるようになったのは、イレナイオスの解釈者が起源である。一部の学者[注釈 4]は、イレナイオスはグノスティコスを単に「知識人」という意味で用いることがあり[注釈 5]、一方、彼が言及した「知識人宗派」[注釈 6]は特定の呼称であるとみなしている。 [17][注釈 7][注釈 8][注釈 9]「グノーシス主義」という用語は古代の資料には登場せず[19][注釈 10]、17世紀にヘンリー・モアが『ヨハネの黙示録』の7つの手紙の注釈の中で、ティアティラにおける異端を表現するために「グノーシス主義」という用 語を用いたのが最初である。 [20][注釈 11]グノーシス主義という用語は、聖イレナイオス(紀元185年頃)がヴァレンティヌスの学派をhe legomene gnostike haeresis「学問的(グノーシス的)と呼ばれる異端」と表現するためにギリシャ語の形容詞gnostikos(ギリシャ語でγνωστικός、 「学んだ」、「知的な」)を用いたことに由来する[21][注釈 12]。 起源 グノーシス主義の起源は曖昧であり、いまだに論争が続いている。グノーシス主義はプラトン主義とその形相論に大きな影響を受けている[23][24] [25]。原始正統派のキリスト教徒はグノーシス主義をキリスト教の異端と呼んだが[注釈 13][27]、現代の学者によれば、この神学の起源はユダヤ教の宗派的な地域と初期キリスト教の宗派に密接に関係している。 [28][29][注釈 14][30]グノーシス主義の起源は、信仰の類似性から仏教にルーツがあるとして議論する学者もいるが[31]、結局のところその起源は不明である。 ジェームズ・M・ロビンソンによれば、キリスト教以前のグノーシス主義を明確に示すテキストは存在せず[注釈 15]、「キリスト教以前のグノーシス主義は、論争に決着をつけるような形ではほとんど証明されていない」[33]。 グノーシス主義で人気のある宗派のほとんどはゾロアスター教に大きく影響を受けていた[34]。 ユダヤ教・キリスト教の起源 以下も参照のこと: キリスト教の起源、キリスト教とユダヤ教の分裂 現代の研究では、グノーシス主義がユダヤ教キリスト教に起源を持ち、紀元後1世紀後半に非支配的なユダヤ教の宗派と初期キリスト教の宗派に端を発している ことでほぼ一致している[35][28][29][注釈 14] エセル・S・ドローワーは、「ガリラヤとサマリアの異端派ユダヤ教は、我々が現在グノーシス主義と呼ぶような形をとっていたようであり、キリスト教時代以 前にも存在していた可能性がある」と付け加えている[36]: xv。 キリスト教グノーシス派の宇宙論的思索は、部分的にはマーセ・ブレシトとマーセ・メルカバに起源を持つ。このテーゼは、ゲルショム・ショレム (Gershom Scholem, 1897-1982)とジル・キスペル(Gilles Quispel, 1916-2006)によって提唱された。ショーレムはメルカバ神秘主義のイメージの中にユダヤ教的グノーシスを見出したが、それはある種のグノーシス主 義的文書にも見られる[35]。 ナグ・ハマディのテクストの多くはユダヤ教に言及しており、ユダヤ教の神を激しく拒絶しているものもある[29][注釈 14] ゲルショム・ショレムはかつてグノーシス主義を「形而上学的な反ユダヤ主義の最も偉大なケース」[39]と評した。 初期キリスト教の中では、使徒パウロと福音書記者ヨハネの教えがグノーシス主義の思想の出発点であった可能性があり、肉と霊の対立、カリスマの価値、ユダ ヤ教の律法の不適格性が強調されるようになった。死すべき肉体は劣った世俗的な力(アルコン)の世界に属し、霊魂のみが救われるとした。グノスティコスと いう用語は、ここでより深い意味を獲得したのかもしれない[42]。 アレクサンドリアはグノーシス主義の誕生にとって中心的な重要性を持っていた。キリスト教のエクレシア(すなわち集会、教会)はユダヤ教とキリスト教に由 来していたが、ギリシア人のメンバーも集まっており、「ユダヤ教の終末論、神の知恵に関する思索、ギリシア哲学、ヘレニズムの神秘宗教」など、さまざまな 思想が存在していた[42]。 一部の初期キリスト教徒の天使キリスト論について、ダレル・ハンナは次のように指摘している: [一部の)初期キリスト教徒は、受肉前のキリストを存在論的に天使として理解していた。この 「真の 」天使キリスト論は様々な形をとっており、ヘブライ人への手紙の初期の章で反対されている見解が本当にそうであるならば、1世紀後半にはすでに現れていた かもしれない。エルチャサイ派の人々、あるいは少なくとも彼らの影響を受けたキリスト者たちは、男性のキリストと女性の聖霊を対にし、両者を巨大な二人の 天使として想定していた。ヴァレンティノス派のグノーシス派の中には、キリストが天使の性質を帯び、天使の救世主になると考えた者もいた。ソロモン書』の 著者は、キリストは悪魔祓いにおいて特に効果的な「邪魔をする」天使であるとした。De Centesima』の著者とエピファニウスの『Ebionites』は、キリストは最初に創造された大天使の中で最も高く重要な存在であり、ヘルマスが キリストをミカエルと同一視したのと多くの点で類似していると考えた。最後に、イザヤ書の昇天の背後にあり、オリゲンのヘブライ語の師によって証言された 釈義的伝統の可能性は、天使の気神論と同様に、さらに別の天使のキリスト論を証言している可能性がある[43]。 偽典『イザヤ書の昇天』はイエスを天使キリスト論と同一視している: [主キリストは父から委託される)そして私は、いと高き方、すなわち私の主の父が、イエスと呼ばれる私の主キリストに、『出て行って、天のすべてを下って 行きなさい』と言われるのを聞いた。 ヘルマスの羊飼い』は、イレナイオスのような初期の教父たちによって正典とみなされたキリスト教の文学作品である。イエスは、著者が神の子について言及し ている譬え話5において、聖なる「先在の霊」に満たされた高潔な人として天使のキリスト論と同一視されている[45]。 新プラトン主義の影響 以下も参照: プラトン・アカデミー、ネオプラトニズムとグノーシス主義、ネオプラトニズムとキリスト教 1880年代には、グノーシス派と新プラトン主義とのつながりが提唱された[46]。1966年にグノーシス主義の起源に関するメッシーナ会議を組織した ウーゴ・ビアンキもまた、オルフィウス派とプラトン主義が起源であると主張していた[38]。グノーシス派はプラトン主義から重要な思想や用語を借用し [47]、ヒポスタシス(実在、存在)、ウシア(本質、実体、存在)、デミウルゲ(創造神)などの概念を含むギリシア哲学的概念をテキスト全体に使用して いた。セティアン・グノーシス派とヴァレンティニアン・グノーシス派はともに、プラトン、中プラトン主義、新ピタゴラス主義の学派やアカデミズムの影響を 受けていたようである[48]。両派とも後期アンティーク哲学との「和解、さらには提携への努力」を試みており[49]、プロティノスを含む一部の新プラ トン主義者からは反発を受けた。 ペルシアの起源または影響 グノーシス主義の起源に関する初期の研究では、ペルシアの起源または影響、ヨーロッパへの伝播、ユダヤ教の要素の取り込みが提唱されていた[50]。 ウィルヘルム・ブーセット(1865-1920)によれば、グノーシス主義はイランとメソポタミアのシンクレティズムの一形態であり[46]、リヒャル ト・アウグスト・ライトゼンシュタイン(1861-1931)はグノーシス主義の起源をペルシアに置いていた[46]。 カーステン・コルペ(1929年生まれ)は、ライツェンシュタインのイラン仮説を分析・批判し、彼の仮説の多くが通用しないことを示している[51]。 それにもかかわらず、ジオ・ウィーデングレン(1907-1996年)は、マンダイのグノーシス主義の起源を、アラム語のメソポタミア世界からの思想と結 びついて、マズデア(ゾロアスター教)のズルヴァニズムにあると主張していた[38]。 しかし、クルト・ルドルフ、マーク・リズバルスキー、ルドルフ・マクーチ、エセル・S・ドロワー、ジェームズ・F・マクグラス、チャールズ・G・ヘーベ ル、ヨルン・ヤコブセン・バックリー、シナシ・ギュンドゥズといったマンダイズムを専門とする学者たちは、パレスチナ起源を主張している。これらの学者の 大半は、マンダイはバプテスマのヨハネの内弟子たちと歴史的なつながりがある可能性が高いと信じている[36][52][53][54][55][56] [57][58]。マンダイ語を専門とする言語学者でもあるチャールズ・ヘーベルは、マンダイ語にパレスチナ語やサマリア語のアラム語の影響を見出し、マ ンダイ人が「ユダヤ人とパレスチナの歴史を共有している」ことを認めている[59][60]。 仏教との類似 主な記事 仏教とグノーシス主義 1966年、仏教学者のエドワード・コンゼはメディアン会議において、アイザック・ヤコブ・シュミットが早くから提唱していた「仏教とグノーシス主義」と いう論文の中で、大乗仏教とグノーシス主義の間に現象学的な共通点があることを指摘した[61]。 |

| Characteristics Cosmology The Syrian–Egyptian traditions postulate a remote, supreme Godhead, the Monad.[67] From this highest divinity emanate lower divine beings, known as Aeons. The Demiurge arises among the Aeons and creates the physical world. Divine elements "fall" into the material realm, and are latent in human beings. Redemption from the fall occurs when the humans obtain Gnosis, esoteric or intuitive knowledge of the divine.[68] Dualism and monism See also: Nontrinitarianism Gnostic systems postulate a dualism between God and the world,[69] varying from the "radical dualist" systems of Manichaeism to the "mitigated dualism" of classic gnostic movements. Radical dualism, or absolute dualism, posits two co-equal divine forces, while in mitigated dualism one of the two principles is in some way inferior to the other. In qualified monism the second entity may be divine or semi-divine. Valentinian Gnosticism is a form of monism, expressed in terms previously used in a dualistic manner.[70] Moral and ritual practice Gnostics tended toward asceticism, especially in their sexual and dietary practice.[71] In other areas of morality, Gnostics were less rigorously ascetic, and took a more moderate approach to correct behavior. In normative early Christianity, the Church administered and prescribed the correct behavior for Christians, while in Gnosticism it was the internalised motivation that was important. Ptolemy's Epistle to Flora describes a general asceticism, based on the moral inclination of the individual.[note 17] For example, ritualistic behavior was not seen to possess as much importance as any other practice, unless it was based on a personal, internal motivation.[72] Female representation The role women played in Gnosticism is still being explored. The very few women in most Gnostic literature are portrayed as chaotic, disobedient, and enigmatic.[73] However, the Nag Hammadi texts place women in roles of leadership and heroism.[73][74][75] |

特徴 宇宙論 シリアとエジプトの伝統は、遠く離れた至高の神格であるモナドを仮定している[67]。この最高の神格から、アイオーンとして知られる下位の神的存在が発 出する。デミウルゲはイーオンの間に生じ、物理的世界を創造する。神の要素は物質界に「堕落」し、人間の中に潜在する。堕落からの救済は、人間がグノーシ ス、すなわち神についての秘教的または直観的な知識を得たときに起こる[68]。 二元論と一元論 以下も参照のこと: 非三元論 グノーシス主義の体系は神と世界の間の二元論を仮定しており[69]、マニ教に代表される「急進的二元論」から古典的なグノーシス主義運動の「緩和された 二元論」まで様々である。急進的二元論、あるいは絶対的二元論では、2つの同格の神の力を仮定するが、緩和された二元論では、2つの原理のうちの一方が他 方よりも何らかの形で劣っている。修飾された一元論では、第二の実体は神または半神である可能性がある。ヴァレンティノス派のグノーシス主義は一元論の一 形態であり、以前は二元論的に用いられていた用語で表現されている[70]。 道徳と儀式の実践 グノーシス派は禁欲的な傾向があり、特に性的行為と食餌の実践において禁欲的であった[71]。他の道徳の分野では、グノーシス派は厳格な禁欲主義ではな く、正しい行動に対してより穏健なアプローチを取っていた。規範的な初期キリスト教では、教会はキリスト教徒の正しい行動を管理し規定していたが、グノー シス主義では重要なのは内面化された動機であった。プトレマイオスの『フローラへの手紙』には、個人の道徳的傾向に基づく一般的な禁欲主義が記述されてい る[注釈 17]。例えば、儀式的な行動は、個人的で内的な動機に基づかない限り、他の実践ほど重要性を持たないと考えられていた[72]。 女性の表現 グノーシス主義において女性が果たした役割については、いまだ探求が続けられている。ほとんどのグノーシス主義文献に登場するごく少数の女性は、混沌とし ていて、不従順で、謎めいた存在として描かれている[73]。しかし、ナグ・ハマディのテキストでは、女性はリーダーシップやヒロイズムの役割を担ってい る[73][74][75]。 |

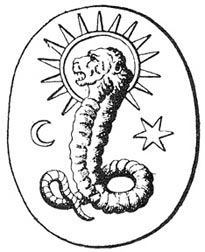

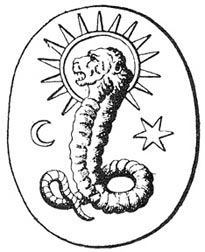

| Concepts Monad Main article: Monad (Gnosticism) In many Gnostic systems, God is known as the Monad, the One.[note 18] God is the high source of the pleroma, the region of light. The various emanations of God are called æons. According to Hippolytus, this view was inspired by the Pythagoreans, who called the first thing that came into existence the Monad, which begat the dyad, which begat the numbers, which begat the point, begetting lines, etc. Pleroma Main article: Pleroma Pleroma (Greek πλήρωμα, "fullness") refers to the totality of God's powers. The heavenly pleroma is the center of divine life, a region of light "above" (the term is not to be understood spatially) our world, occupied by spiritual beings such as aeons (eternal beings) and sometimes archons. Jesus is interpreted as an intermediary aeon who was sent from the pleroma, with whose aid humanity can recover the lost knowledge of the divine origins of humanity. The term is thus a central element of Gnostic cosmology. Pleroma is also used in the general Greek language, and is used by the Greek Orthodox church in this general form, since the word appears in the Epistle to the Colossians. Proponents of the view that Paul was actually a gnostic, such as Elaine Pagels, view the reference in Colossians as a term that has to be interpreted in a gnostic sense. Emanation Main article: Emanationism The Supreme Light or Consciousness descends through a series of stages, gradations, worlds, or hypostases, becoming progressively more material and embodied. In time it will turn around to return to the One (epistrophe), retracing its steps through spiritual knowledge and contemplation.[clarification needed][citation needed] Aeon Main article: Aeon (Gnosticism) In many Gnostic systems, the aeons are the various emanations of the superior God or Monad. Beginning in certain Gnostic texts with the hermaphroditic aeon Barbelo,[76][77][78] the first emanated being, various interactions with the Monad occur which result in the emanation of successive pairs of aeons, often in male–female pairings called syzygies.[79] The numbers of these pairings varied from text to text, though some identify their number as being thirty.[80] The aeons as a totality constitute the pleroma, the "region of light". The lowest regions of the pleroma are closest to the darkness; that is, the physical world.[citation needed] Two of the most commonly paired æons were Christ and Sophia (Greek: "Wisdom"); the latter refers to Christ as her "consort" in A Valentinian Exposition.[81] Sophia Main article: Sophia (Gnosticism) In Gnostic tradition, the name Sophia (Σοφία, Greek for "wisdom") refers to the final emanation of God, and is identified with the anima mundi or world-soul. She is occasionally referred to by the Hebrew equivalent of Achamoth [dubious – discuss] (this is a feature of Ptolemy's version of the Valentinian gnostic myth). Jewish Gnosticism with a focus on Sophia was active by 90 AD.[82] In most, if not all, versions of the gnostic myth, Sophia births the demiurge, who in turn brings about the creation of materiality. The positive and negative depictions of materiality depend on the myth's depictions of Sophia's actions. Sophia in this highly patriarchal narrative is described as unruly and disobedient, which is due to her bringing a creation of chaos into the world.[75] The creation of the Demiurge was an act done without her counterpart's consent and because of the predefined hierarchy between the two of them, this action contributed to the narrative that she was unruly and disobedient.[83] Sophia, emanating without her partner, resulted in the production of the Demiurge (Greek: lit. "public builder"),[84] who is also referred to as Yaldabaoth and variations thereof in some Gnostic texts.[76] This creature is concealed outside the pleroma;[76] in isolation, and thinking itself alone, it creates materiality and a host of co-actors, referred to as archons. The demiurge is responsible for the creation of humankind; trapping elements of the pleroma stolen from Sophia inside human bodies.[76][85] In response, the Godhead emanates two savior aeons, Christ and the Holy Spirit; Christ then embodies itself in the form of Jesus, in order to be able to teach humans how to achieve gnosis, by which they may return to the pleroma.[86] Demiurge Main article: Demiurge  A lion-faced deity found on a Gnostic gem in Bernard de Montfaucon's L'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures may be a depiction of Yaldabaoth, the Demiurge; however, see Mithraic Zervan Akarana.[87] The term demiurge derives from the Latinized form of the Greek term dēmiourgos, δημιουργός, literally "public or skilled worker".[note 20] This figure is also called "Yaldabaoth",[76] Samael (Aramaic: sæmʻa-ʼel, "blind god"), or "Saklas" (Syriac: sækla, "the foolish one"), who is sometimes ignorant of the superior god, and sometimes opposed to it; thus in the latter case he is correspondingly malevolent. Other names or identifications are Ahriman, El, Satan, and Yahweh. This image of this particular creature is again identified in The Revelation of Jesus Christ to the Apostle John as such " 17 Now in my vision this is how I saw the horses and their riders. They wore red, blue, and yellow breastplates,* and the horses’ heads were like heads of lions, and out of their mouths came fire, smoke, and sulfur. 18 By these three plagues of fire, smoke, and sulfur that came out of their mouths a third of the human race was killed. 19 For the power of the horses is in their mouths and in their tails; for their tails are like snakes, with heads that inflict harm." Revelation Chapter 9 Verses 17-19[89] This is corroborated in the article above quoting the capricious nature of the form (calling itself many different names) and of Gnosticism founder, Simon Magus, whom in the Biblical Narrative the Acts of the Apostles is quoted as being a magician or sorcerer able to perform great tasks with his mouth but not with the Holy Spirit of YHWH the same Spirit of Yeshuah of Nazareth and Simon Peter, Simon Magus' opponent.[90] Moral judgements of the demiurge vary from group to group within the broad category of Gnosticism, viewing materiality as being inherently evil, or as merely flawed and as good as its passive constituent matter allows.[91] Archon Main article: Archon (Gnosticism) In late antiquity some variants of Gnosticism used the term archon to refer to several servants of the demiurge.[85] According to Origen's Contra Celsum, a sect called the Ophites posited the existence of seven archons, beginning with Iadabaoth or Ialdabaoth, who created the six that follow: Iao, Sabaoth, Adonaios, Elaios, Astaphanos, and Horaios.[92] Ialdabaoth had a head of a lion.[76][93] Other concepts Other Gnostic concepts are:[94] sarkic – earthly, hidebound, ignorant, uninitiated. The lowest level of human thought; the fleshly, instinctive level of thinking. hylic – lowest order of the three types of human. Unable to be saved since their thinking is entirely material, incapable of understanding the gnosis. psychic – "soulful", partially initiated. Matter-dwelling spirits pneumatic – "spiritual", fully initiated, immaterial souls escaping the doom of the material world via gnosis. kenoma – the visible or manifest cosmos, "lower" than the pleroma charisma – gift, or energy, bestowed by pneumatics through oral teaching and personal encounters logos – the divine ordering principle of the cosmos; personified as Christ. hypostasis – literally "that which stands beneath" the inner reality, emanation (appearance) of God, known to psychics ousia – essence of God, known to pneumatics. Specific individual things or being. Jesus as Gnostic saviour Jesus is identified by some Gnostics as an embodiment of the supreme being who became incarnate to bring gnōsis to the earth,[95][86] while others adamantly denied that the supreme being came in the flesh, claiming Jesus to be merely a human who attained enlightenment through gnosis and taught his disciples to do the same.[96] Others believed Jesus was divine, although did not have a physical body, reflected in the later Docetist movement. Among the Mandaeans, Jesus was considered a mšiha kdaba or "false messiah" who perverted the teachings entrusted to him by John the Baptist.[97] Still other traditions identify Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, and Seth, third son of Adam and Eve, as salvific figures. |

概念 モナド 主な記事 モナド(グノーシス主義) 多くのグノーシス主義の体系において、神はモナド、唯一者として知られている[注釈 18]。神のさまざまな発露はエオンと呼ばれる。ヒッポリュトスによれば、この見解はピュタゴラス派に触発されたものであり、ピュタゴラス派は最初に存在 したものをモナドと呼び、モナドはダイアドを生み、ダイアドは数を生み、数は点を生み、線などを生んだという。 プレローマ 主な記事 プレローマ プレローマ(ギリシャ語でπλήρωμα、「充満」)とは、神の力の総体を指す。天のプレローマは神の生命の中心であり、私たちの世界の「上」(この用語 は空間的に理解されるものではない)にある光の領域で、アイオン(永遠の存在)や時にはアルコンなどの霊的存在によって占有されている。イエスは、プレ ローマから遣わされた仲介のイオンであり、その援助によって人類は、失われた人類の神聖な起源に関する知識を回復することができると解釈されている。した がって、この用語はグノーシス的宇宙論の中心的要素である。 プレローマは一般的なギリシア語でも使われ、ギリシア正教会ではコロサイの信徒への手紙に登場することから、この一般的な形で使われている。エレイン・ペ イジェルスのような、パウロが実はグノーシス主義者であったとする見解の支持者は、コロサイの信徒への手紙での言及を、グノーシス主義的な意味で解釈しな ければならない用語とみなしている。 発露(Emanation) 主な記事 エマネイション論 至高の光または意識は、一連の段階、グラデーション、世界、ヒポスターゼを経て下降し、次第に物質化、具現化していく。やがてそれは、霊的な知識と観想を 通してその歩みを辿りながら、唯一なるもの(エピストロフィー)に戻るために回心する[要解説][要出典]。 イオン 主な記事 イオン(グノーシス主義) 多くのグノーシス主義の体系において、イオンは優れた神またはモナドの様々な発露である。あるグノーシス主義のテクストでは、最初に発せられた両性具有の イオン・バルベロ[76][77][78]に始まり、モナドとの様々な相互作用が起こり、その結果、しばしばシジギーと呼ばれる男女の対になった連続する イオンの対が発せられる[79]。これらの対の数はテクストによって異なるが、その数を30とするものもある[80]。プレロマの最も低い領域は闇に最も 近く、つまり物理的な世界である[要出典]。 最もよく対になる2つのイオンはキリストとソフィア(ギリシア語で「知恵」)であり、後者は『ヴァレンティノスの博覧会』においてキリストを「妃」と呼ん でいる[81]。 ソフィア 主な記事 ソフィア(グノーシス主義) グノーシス主義の伝統では、ソフィア(Σοφία、ギリシア語で「知恵」)という名前は神の最終的な発露を意味し、アニマ・ムンディまたは世界魂と同一視 される。彼女はヘブライ語でアチャモス(Achamoth)と呼ばれることもある(これはプトレマイオス版ヴァレンティヌス神話の特徴である)。ソフィア に焦点を当てたユダヤ教グノーシス主義は、紀元90年までに活発になった[82]。グノーシス神話のすべてではないにしても、ほとんどのバージョンでは、 ソフィアはデミウルゲを誕生させ、デミウルゲは物質性の創造をもたらす。物質性の肯定的な描写と否定的な描写は、ソフィアの行動に関する神話の描写に依存 している。この高度に家父長制的な物語におけるソフィアは手に負えない不従順な存在として描写されており、それは彼女が世界に混沌の創造をもたらしたこと に起因している[75]。デミウルゲの創造は彼女の相手の同意なしに行われた行為であり、二人の間にはあらかじめ定義されたヒエラルキーがあるため、この 行為は彼女が手に負えない不従順な存在であるという物語に寄与している[83]。 この創造物はプレロマの外側に隠されており[76]、孤立して自分一人で考え、物質性と、アルコンと呼ばれる多数の共同行為者を創造する。デミウルゲは人 類の創造に責任を負っており、ソフィアから盗まれたプレロマの要素を人間の体内に閉じ込めている[76][85]。これに対して、神格はキリストと聖霊と いう2つの救世主のイオンを発する。 デミウルゲ 主な記事 デミウルゲ  Bernard de MontfauconのL'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figuresにあるグノーシスの宝石に描かれているライオンの顔をした神は、デミウルゲであるヤルダバオトの描写である可能性がある。 デミウルゴスという用語は、ギリシア語のdēmiourgos(δημιουργός)のラテン語化した形に由来する。 [註20]この姿は「ヤルダバオト」[76]、「サマエル」(アラム語:sæmʻa-ʼel、「盲目の神」)、「サクラス」(シリア語:sækla、「愚 かな者」)とも呼ばれ、時に上位の神を知らず、時にそれに対立する。後者の場合は、それに応じて悪意に満ちている。他の呼び名や同定には、アーリマン、エ ル、サタン、ヤハウェなどがある。 この特別な生き物のイメージは、使徒ヨハネへのイエス・キリストの啓示の中で、再び次のように特定されている。 「 17 私の幻の中で、私は馬とその乗り手をこう見た。彼らは赤、青、黄色の胸当てをつけ*、馬の頭は獅子の頭のようで、その口からは火と煙と硫黄とが出ていた。 18 彼らの口から出た火、煙、硫黄のこの三つの災いによって、人類の三分の一が殺された。 19 馬の力はその口と尾にあり、その尾は蛇のようで、頭は害を加えるからである。」 ヨハネの黙示録第9章17-19節[89]。 このことは、上記の記事で、形相の気まぐれな性質(自らをさまざまな名で呼ぶ)とグノーシス主義の創始者であるシモン・マギウスのことを引用しているが、 彼は聖書の物語『使徒の働き』の中で、口では偉大な仕事を行うことができるが、YHWHの聖霊、すなわちナザレのイシュアとシモン・マギウスの敵であった シモン・ペテロの聖霊では偉大な仕事を行うことができない魔術師または呪術師であると引用されている[90]。 デミウルゲに対する道徳的判断は、グノーシス主義という広いカテゴリーの中でもグループによって様々であり、物質性を本質的に悪であると見なしたり、単に 欠陥があるだけで、その受動的な構成物質が許す限り善であると見なしたりしている[91]。 アーコン 主な記事 アルコン(グノーシス主義) 古代後期、グノーシス主義のいくつかの変種は、デミウルゲの複数のしもべを指すためにアルコンという用語を使用していた[85]。 オリゲンの『Contra Celsum』によれば、オフィテスと呼ばれる一派は、イアダバオトまたはイアルダバオトで始まる7つのアルコンの存在を仮定しており、イアダバオトはそ れに続く6つのアルコンを創造した: イアルダバオスはライオンの頭を持っていた[76][93]。 その他の概念 その他のグノーシス的概念は以下の通りである[94]。 サルキック - 地上の、束縛された、無知な、未開の。人間の思考の最下層、肉的で本能的な思考レベル。 ハイリック - 人間の3つのタイプの中で最も低次のもの。彼らの思考は完全に物質的であるため、救われることはなく、グノーシスを理解することはできない。 サイキック - 「魂のある」、部分的にイニシエートされた。物質に住む霊である。 ニューマチック - 「霊的な」、完全にイニシエートされた、グノーシスによって物質世界の破滅を免れた非物質的な魂。 ケノマ(kenoma)-目に見える宇宙、または顕在的な宇宙で、プレローマより「低い」。 カリスマ - 口頭での教えや個人的な出会いによって、気学によって授けられる才能、またはエネルギー。 ロゴス - 宇宙の神聖な秩序原理。 ヒポスタシス(hypostasis) - 文字どおり「その下にあるもの」であり、超能力者に知られる神の内的現実、発露(外観)である。 ousia - 神の本質、気学者に知られる。具体的な個々の事物や存在。 グノーシスの救世主としてのイエス イエスはグノーシスを地上にもたらすために受肉した至高の存在の体現者として一部のグノーシス主義者によって識別される[95][86]が、一方で他の者 たちは至高の存在が肉体をもって来たことを断固として否定し、イエスはグノーシスを通じて悟りを開き、弟子たちに同じことをするように教えた単なる人間で あると主張した[96]。他の者たちはイエスは肉体を持っていなかったが神であったと信じ、後のドケティズム運動に反映された。マンダイ人の間では、イエ スは洗礼者ヨハネから託された教えを曲解したムシハ・クダバ、すなわち「偽りの救世主」と考えられていた[97]。さらに他の伝承では、マニ教の創始者で あるマニとアダムとイヴの三男であるセスを救済の人物と見なしていた。 |

| Development Three periods can be discerned in the development of Gnosticism:[98] Late-first century and early second century: development of Gnostic ideas, contemporaneous with the writing of the New Testament; mid-second century to early third century: high point of the classical Gnostic teachers and their systems, "who claimed that their systems represented the inner truth revealed by Jesus";[98] end of the second century to the fourth century: reaction by the proto-orthodox church and condemnation as heresy, and subsequent decline. During the first period, three types of tradition developed:[98] Genesis was reinterpreted in Jewish milieux, viewing Yahweh as a jealous God who enslaved people; freedom was to be obtained from this jealous God; A wisdom tradition developed, in which Jesus' sayings were interpreted as pointers to an esoteric wisdom, in which the soul could be divinized through identification with wisdom.[98][note 21] Some of Jesus' sayings may have been incorporated into the gospels to put a limit on this development. The conflicts described in 1 Corinthians may have been inspired by a clash between this wisdom tradition and Paul's gospel of crucifixion and resurrection;[98] A mythical story developed about the descent of a heavenly creature to reveal the Divine world as the true home of human beings.[98] Jewish Christianity saw the Messiah, or Christ, as "an eternal aspect of God's hidden nature, his "spirit" and "truth", who revealed himself throughout sacred history".[42] The movement spread in areas controlled by the Roman Empire and Arian Goths,[100] and the Persian Empire. It continued to develop in the Mediterranean and Middle East before and during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, but decline also set in during the third century, due to a growing aversion from the Nicene Church, and the economic and cultural deterioration of the Roman Empire.[101] Conversion to Islam, and the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229), greatly reduced the remaining number of Gnostics throughout the Middle Ages, though Mandaean communities still exist in Iraq, Iran and diaspora communities. Gnostic and pseudo-gnostic ideas became influential in some of the philosophies of various esoteric mystical movements of the 19th and 20th centuries in Europe and North America, including some that explicitly identify themselves as revivals or even continuations of earlier gnostic groups. |

発展 グノーシス主義の発展には、以下の3つの時期を見分けることができる[98]。 1世紀後半から2世紀初頭:新約聖書の執筆と同時期にグノーシス思想が発展した; 2世紀半ばから3世紀初頭:古典的なグノーシス派の教師たちとその体系の最盛期、「彼らは自分たちの体系がイエスによって啓示された内的真理を表している と主張した」[98]。 2世紀末から4世紀:原始正教会による反発と異端としての断罪、そしてその後の衰退。 最初の時代には、次の3つのタイプの伝統が発展した[98]。 創世記はユダヤ教圏で再解釈され、ヤハウェを人々を奴隷にする嫉妬深い神とみなし、自由はこの嫉妬深い神から得るべきものであるとした; 知恵の伝統が発展し、その中でイエスの言葉は、知恵と同一化することによって魂が神格化されるような、秘教的な知恵を指し示すものとして解釈された。コリ ントの信徒への手紙一に記されている対立は、この知恵の伝統とパウロの十字架と復活の福音書との衝突に触発されたものかもしれない[98]。 ユダヤ教では、メシア(キリスト)を「神の隠された本性、神の 「霊 」と 「真理 」の永遠の側面であり、聖なる歴史を通して自らを現した」と考えていた[42]。 この運動はローマ帝国とアリウス派のゴート族[100]、そしてペルシャ帝国の支配する地域に広まった。2世紀以前から3世紀にかけて地中海と中東で発展 し続けたが、3世紀にはニカイア教会からの嫌悪の高まりとローマ帝国の経済的・文化的悪化のために衰退が始まった[101]。イスラム教への改宗とアルビ ゲンス十字軍(1209-1229)により、中世を通じて残っていたグノーシス派の数は大幅に減少したが、マンダイの共同体はイラクやイラン、ディアスポ ラの共同体にまだ存在している。グノーシス的、擬似グノーシス的思想は、19世紀から20世紀にかけてヨーロッパと北米で起こった様々な秘教的神秘主義運 動の哲学の一部に影響力を持つようになった。 |

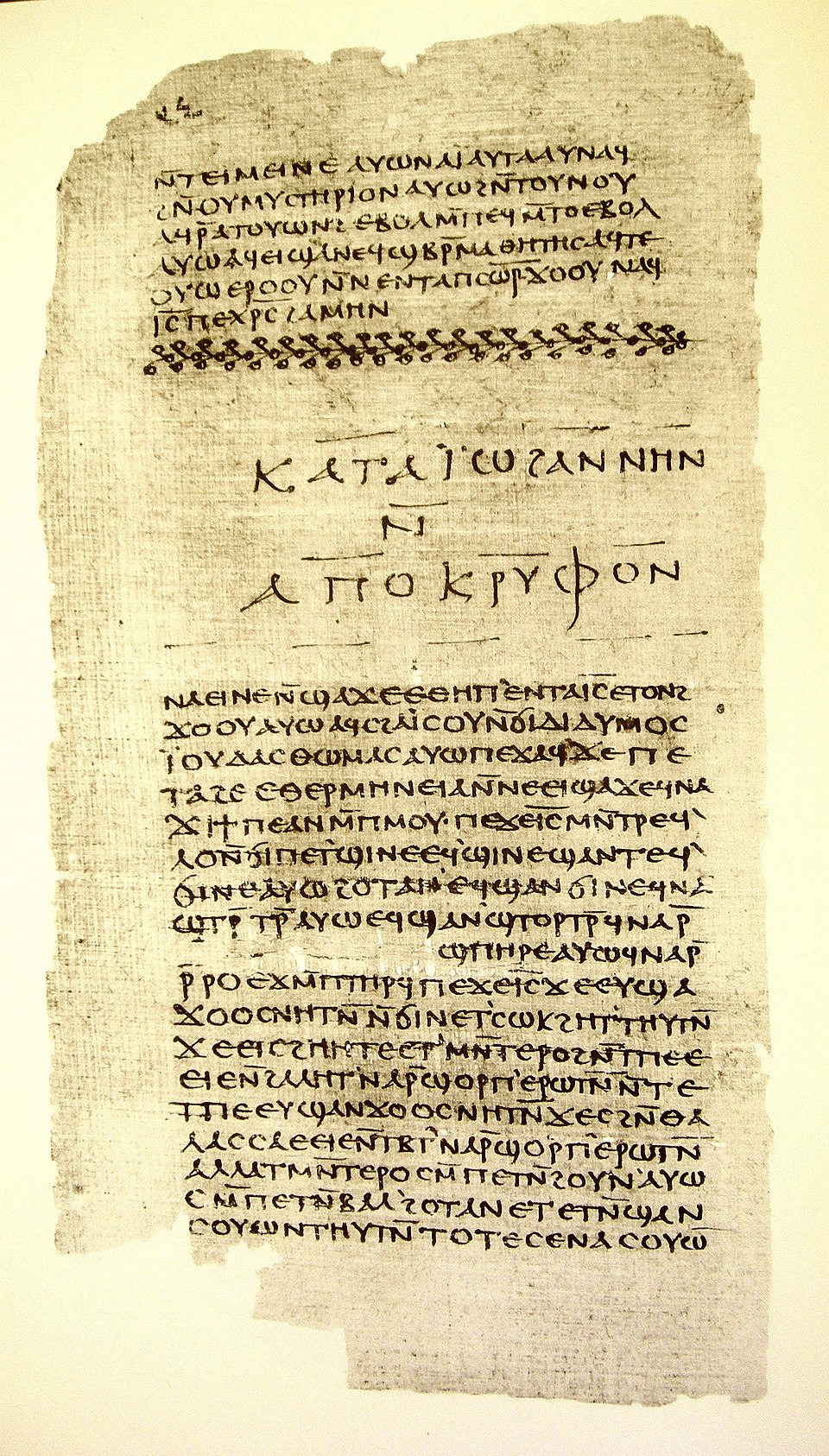

| Relation with early Christianity Dillon notes that Gnosticism raises questions about the development of early Christianity.[102] Orthodoxy and heresy See also: Diversity in early Christian theology The Christian heresiologists, most notably Irenaeus, regarded Gnosticism as a Christian heresy. Modern scholarship notes that early Christianity was diverse, and Christian orthodoxy only settled in the 4th century, when the Roman Empire declined and Gnosticism lost its influence.[103][101][104][102] Gnostics and proto-orthodox Christians shared some terminology. Initially, they were hard to distinguish from each other.[105] According to Walter Bauer, "heresies" may well have been the original form of Christianity in many regions.[106] This theme was further developed by Elaine Pagels,[107] who argues that "the proto-orthodox church found itself in debates with gnostic Christians that helped them to stabilize their own beliefs."[102] According to Gilles Quispel, Catholicism arose in response to Gnosticism, establishing safeguards in the form of the monarchic episcopate, the creed, and the canon of holy books.[108] Historical Jesus See also: Jesus in comparative mythology and Christ myth theory The Gnostic movements may contain information about the historical Jesus, since some texts preserve sayings which show similarities with canonical sayings.[109] Especially the Gospel of Thomas has a significant amount of parallel sayings.[109] Yet, a striking difference is that the canonical sayings center on the coming endtime, while the Thomas-sayings center on a kingdom of heaven that is already here, and not a future event.[110] According to Helmut Koester, this is because the Thomas-sayings are older, implying that in the earliest forms of Christianity, Jesus was regarded as a wisdom-teacher.[110] An alternative hypothesis states that the Thomas authors wrote in the second century, changing existing sayings and eliminating the apocalyptic concerns.[110] According to April DeConick, such a change occurred when the end time did not come, and the Thomasine tradition turned toward a "new theology of mysticism" and a "theological commitment to a fully-present kingdom of heaven here and now, where their church had attained Adam and Eve's divine status before the Fall."[110] Johannine literature The prologue of the Gospel of John describes the incarnated Logos, the light that came to earth, in the person of Jesus.[111] The Apocryphon of John contains a scheme of three descendants from the heavenly realm, the third one being Jesus, just as in the Gospel of John. The similarities probably point to a relationship between gnostic ideas and the Johannine community.[111] According to Raymond Brown, the Gospel of John shows "the development of certain gnostic ideas, especially Christ as heavenly revealer, the emphasis on light versus darkness, and anti-Jewish animus."[111] The Johannine material reveals debates about the redeemer myth.[98] The Johannine letters show that there were different interpretations of the gospel story, and the Johannine images may have contributed to second-century Gnostic ideas about Jesus as a redeemer who descended from heaven.[98] According to DeConick, the Gospel of John shows a "transitional system from early Christianity to gnostic beliefs in a God who transcends our world."[111] According to DeConick, John may show a bifurcation of the idea of the Jewish God into Jesus' Father in Heaven and the Jews' father, "the Father of the Devil" (most translations say "of [your] father the Devil"), which may have developed into the gnostic idea of the Monad and the Demiurge.[111] Paul and Gnosticism Tertullian calls Paul "the apostle of the heretics",[112] because Paul's writings were attractive to gnostics, and interpreted in a gnostic way, while Jewish Christians found him to stray from the Jewish roots of Christianity.[113] In I Corinthians (1 Corinthians 8:10), Paul refers to some church members as "having knowledge" (Greek: τὸν ἔχοντα γνῶσιν, ton echonta gnosin). James Dunn writes that in some cases, Paul affirmed views that were closer to Gnosticism than to proto-orthodox Christianity.[114] According to Clement of Alexandria, the disciples of Valentinus said that Valentinus was a student of a certain Theudas, who was a student of Paul,[114] and Elaine Pagels notes that Paul's epistles were interpreted by Valentinus in a gnostic way, and Paul could be considered a proto-gnostic as well as a proto-Catholic.[94] Many Nag Hammadi texts, including, for example, the Prayer of Paul and the Coptic Apocalypse of Paul, consider Paul to be "the great apostle".[114] The fact that he claimed to have received his gospel directly by revelation from God appealed to the gnostics, who claimed gnosis from the risen Christ.[115] The Naassenes, Cainites, and Valentinians referred to Paul's epistles.[116] Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy have expanded upon this idea of Paul as a gnostic teacher;[117] although their premise that Jesus was invented by early Christians based on an alleged Greco-Roman mystery cult has been dismissed by scholars.[118][note 22] However, his revelation was different from the gnostic revelations.[119] |

初期キリスト教との関係 ディロンは、グノーシス主義は初期キリスト教の発展について疑問を投げかけていると指摘している[102]。 正統と異端 以下も参照のこと: 初期キリスト教神学における多様性 キリスト教の異端論者、特にイレナイオスは、グノーシス主義をキリスト教の異端とみなしていた。現代の学問では、初期キリスト教は多様であり、キリスト教 の正統性が確立したのはローマ帝国が衰退し、グノーシス主義が影響力を失った4世紀以降であるとされている[103][101][104][102]。当 初、両者を区別することは困難であった[105]。 ウォルター・バウアーによれば、「異端」は多くの地域でキリスト教の原形であった可能性がある[106]。 このテーマはエレイン・ペイゲルスによってさらに発展させられ[107]、彼は「原始正統派教会はグノーシス派キリスト教徒との論争に身を置くことで、自 分たちの信仰を安定させることができた」と論じている。 「ジル・キスペルによれば、カトリシズムはグノーシス主義に対抗するために生まれ、君主制の司教座、信条、聖典の正典という形で安全装置を確立した [108]。 歴史的イエス 以下も参照のこと: 比較神話におけるイエスとキリスト神話理論 グノーシス主義運動は歴史的イエスについての情報を含んでいるかもしれない。 [ヘルムート・コーテルによれば、これはトマス語録の方が古いためであり、キリスト教の初期の形態では、イエスは知恵の教師であるとみなされていたことを 示唆している。 [110]別の仮説では、トマスの著者は2世紀に執筆し、既存の言説を変更し、終末論的な懸念を排除したと述べている。 110] エイプリル・デコニックによれば、終末の時が来なかったときにそのような変更が起こり、トマス的伝統は「神秘主義の新しい神学」と「今ここに完全に存在す る天の王国への神学的コミットメント」に向かい、そこでは彼らの教会は堕落の前にアダムとエバの神の地位に到達していた[110]。 ヨハネの文献 ヨハネによる福音書のプロローグでは、受肉したロゴス、すなわち地上に来た光がイエスという人物の中に描かれている[111]。ヨハネのアポクリフォン は、ヨハネによる福音書と同じように、天界からの3人の子孫、3人目はイエスという図式を含んでいる。レイモンド・ブラウンによれば、ヨハネ福音書は「あ る種のグノーシス的思想の発展、特に天の啓示者としてのキリスト、光対闇の強調、反ユダヤ的敵意」を示している[111]。 「98]ヨハネの手紙は、福音書の物語に異なる解釈があったことを示しており、ヨハネのイメージは、天から降臨した贖い主としてのイエスに関する2世紀の グノーシス主義的な考えに貢献した可能性がある。 [98] デコニックによれば、ヨハネ福音書は「初期キリスト教から我々の世界を超越した神に対するグノーシス主義的な信仰への過渡的な体系」を示している [111]。デコニックによれば、ヨハネ福音書はユダヤ教的な神の観念を、天におけるイエスの父とユダヤ人の父である「悪魔の父」(ほとんどの翻訳では 「あなたがたの父である悪魔の」となっている)とに二分しており、それがモナドやデミウルゲのグノーシス主義的な観念へと発展したのかもしれない。 パウロとグノーシス主義 テルトゥリアヌスはパウロを「異端の使徒」と呼んでいるが[112]、それはパウロの著作がグノーシス主義者にとって魅力的であり、グノーシス主義的に解 釈されたからであり、一方でユダヤ人キリスト教徒はパウロがキリスト教のユダヤ的ルーツから逸脱していると感じたからである[113] 。ジェームズ・ダンは、パウロは原始正統派キリスト教よりもグノーシス主義に近い見解を肯定している場合があると書いている[114]。 アレクサンドリアのクレメンスによれば、バレンティヌスの弟子たちは、バレンティヌスはパウロの弟子であったあるテウダスの弟子であったと述べており [114]、エレイン・ペイゲルスは、パウロの書簡はバレンティヌスによってグノーシス的に解釈されており、パウロは原始グノーシス主義者であると同時に 原始カトリック主義者であると考えることができると指摘している[94]。 [94]ナグ・ハマディのテキストには、例えば『パウロの祈り』やコプト語の『パウロの黙示録』など、パウロを「偉大な使徒」とみなすものが多い。 [ナアセン派、カイン派、ヴァレンティノ派はパウロの書簡を参照した。 [116]ティモシー・フレークとピーター・ガンディはグノーシス派の教師としてのパウロというこの考えを拡大解釈している[117]が、イエスはグレコ ローマン・ミステリー・カルトの疑惑に基づいて初期キリスト教徒によって創作されたという彼らの前提は学者たちによって否定されている[118][注釈 22]。しかしながら、彼の啓示はグノーシス派の啓示とは異なっていた[119]。 |

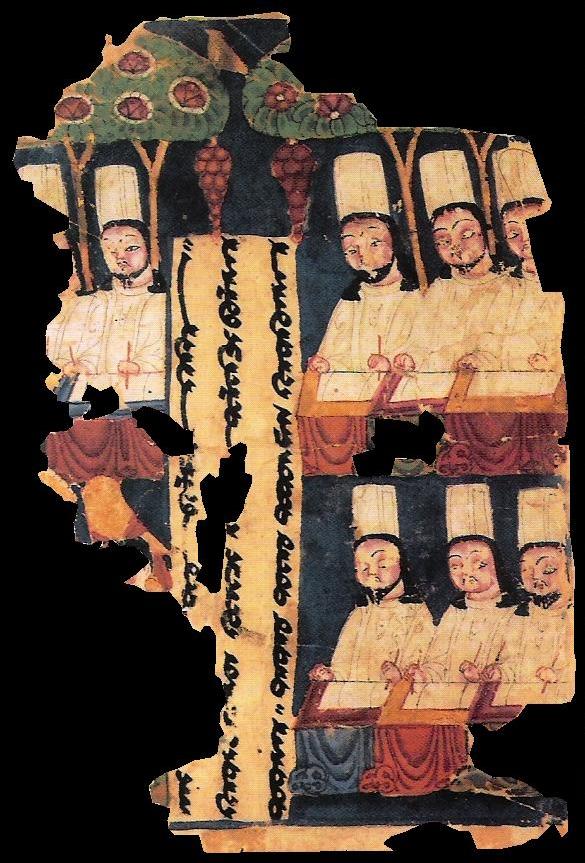

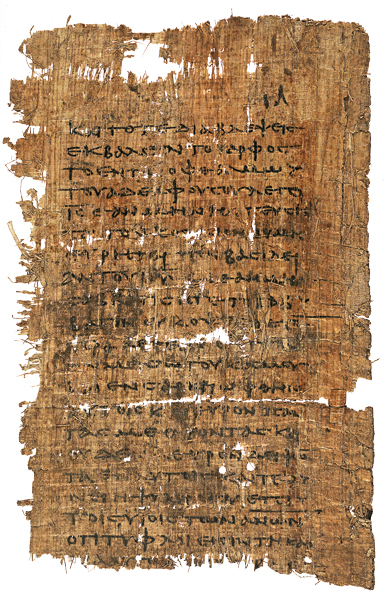

| Major movements Judean–Israelite Gnosticism Although Elkesaites and Mandaeans were found mainly in Mesopotamia in the first few centuries of the common era, their origins appear to be Judean–Israelite in the Jordan valley.[120][121][6] Elkesaites Main article: Elcesaites The Elkesaites were a Judeo-Christian baptismal sect that originated in the Transjordan and were active between 100 and 400 AD.[120] The members of this sect performed frequent baptisms for purification and had a Gnostic disposition.[120][122]: 123 The sect is named after its leader Elkesai.[123] According to Joseph Lightfoot, the Church Father Epiphanius (writing in the 4th century AD) seems to make a distinction between two main groups within the Essenes:[121] "Of those that came before his [Elxai (Elkesai), an Ossaean prophet] time and during it, the Ossaeans and the Nasaraeans."[124]  Mandaeans in prayer during baptism Mandaeism is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion.[125]: 4 [126] The Mandaeans are an ethnoreligious group that speak a dialect of Eastern Aramaic known as Mandaic. They are the only surviving Gnostics from antiquity.[5] Their religion has been practiced primarily around the lower Karun, Euphrates and Tigris and the rivers that surround the Shatt-al-Arab waterway, part of southern Iraq and Khuzestan Province in Iran. Mandaeism is still practiced in small numbers, in parts of southern Iraq and the Iranian province of Khuzestan, and there are thought to be between 60,000 and 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[127] The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic manda meaning knowledge.[128] John the Baptist is a key figure in the religion, as an emphasis on baptism is part of their core beliefs. According to Nathaniel Deutsch, "Mandaean anthropogony echoes both rabbinic and gnostic accounts."[129] Mandaeans revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Significant amounts of original Mandaean Scripture, written in Mandaean Aramaic, survive in the modern era. The most important holy scripture is known as the Ginza Rabba and has portions identified by some scholars as being copied as early as the 2nd–3rd centuries,[122] while others such as S. F. Dunlap place it in the 1st century.[130] There is also the Qulasta (Mandaean prayerbook) and the Mandaean Book of John (Sidra ḏ'Yahia) and other scriptures. Mandaeans believe that there is a constant battle or conflict between the forces of good and evil. The forces of good are represented by Nhura (Light) and Maia Hayyi (Living Water) and those of evil are represented by Hshuka (Darkness) and Maia Tahmi (dead or rancid water). The two waters are mixed in all things in order to achieve a balance. Mandaeans also believe in an afterlife or heaven called Alma d-Nhura (World of Light).[131] In Mandaeism, the World of Light is ruled by a Supreme God, known as Hayyi Rabbi ('The Great Life' or 'The Great Living God').[131][122][128] God is so great, vast, and incomprehensible that no words can fully depict how immense God is. It is believed that an innumerable number of Uthras (angels or guardians),[54]: 8 manifested from the light, surround and perform acts of worship to praise and honor God. They inhabit worlds separate from the lightworld and some are commonly referred to as emanations and are subservient beings to the Supreme God who is also known as 'The First Life'. Their names include Second, Third, and Fourth Life (i.e. Yōšamin, Abathur, and Ptahil).[132][54]: 8 The Lord of Darkness (Krun) is the ruler of the World of Darkness formed from dark waters representing chaos.[132][122] A main defender of the darkworld is a giant monster, or dragon, with the name Ur, and an evil, female ruler also inhabits the darkworld, known as Ruha.[132] The Mandaeans believe these malevolent rulers created demonic offspring who consider themselves the owners of the seven planets and twelve zodiac constellations.[132] According to Mandaean beliefs, the material world is a mixture of light and dark created by Ptahil, who fills the role of the demiurge, with help from dark powers, such as Ruha the Seven, and the Twelve.[133] Adam's body (believed to be the first human created by God in Abrahamic tradition) was fashioned by these dark beings, however his soul (or mind) was a direct creation from the Light. Therefore, Mandaeans believe the human soul is capable of salvation because it originates from the World of Light. The soul, sometimes referred to as the 'inner Adam' or Adam kasia, is in dire need of being rescued from the dark, so it may ascend into the heavenly realm of the World of Light.[132] Baptisms are a central theme in Mandaeism, believed to be necessary for the redemption of the soul. Mandaeans do not perform a single baptism, as in religions such as Christianity; rather, they view baptisms as a ritual act capable of bringing the soul closer to salvation.[134] Therefore, Mandaeans are baptized repeatedly during their lives.[135] Mandaeans consider John the Baptist to have been a Nasoraean Mandaean.[122]: 3 [136][137] John is referred to as their greatest and final teacher.[54][122] Jorunn J. Buckley and other scholars specializing in Mandaeism believe that the Mandaeans originated about two thousand years ago in the Palestine-Israel region and moved east due to persecution.[138][6][139] Others claim a southwestern Mesopotamia origin.[140] However, some scholars take the view that Mandaeism is older and dates from pre-Christian times.[141] Mandaeans assert that their religion predates Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as a monotheistic faith.[142] Mandaeans believe that they descend directly from Shem, Noah's son,[122]: 182 and also from John the Baptist's original disciples.[143] Due to paraphrases and word-for-word translations from the Mandaean originals found in the Psalms of Thomas, it is now believed that the pre-Manichaean presence of the Mandaean religion is more than likely.[143]: IX [144] The Valentinians embraced a Mandaean baptismal formula in their rituals in the 2nd century CE.[6] Birger A. Pearson compares the Five Seals of Sethianism, which he believes is a reference to quintuple ritual immersion in water, to Mandaean masbuta.[145] According to Jorunn J. Buckley, "Sethian Gnostic literature ... is related, perhaps as a younger sibling, to Mandaean baptism ideology."[146] In addition to accepting Mandaeism's Israelite or Judean origins, Buckley adds: [T]he Mandaeans may well have become the inventors of – or at least contributors to the development of – Gnosticism ... and they produced the most voluminous Gnostic literature we know, in one language... influenc[ing] the development of Gnostic and other religious groups in late antiquity [e.g. Manichaeism, Valentianism].[6] Samaritan Baptist sects According to Magris, Samaritan Baptist sects were an offshoot of John the Baptist.[147] One offshoot was in turn headed by Dositheus, Simon Magus, and Menander. It was in this milieu that the idea emerged that the world was created by ignorant angels. Their baptismal ritual removed the consequences of sin, and led to a regeneration by which natural death, which was caused by these angels, was overcome.[147] The Samaritan leaders were viewed as "the embodiment of God's power, spirit, or wisdom, and as the redeemer and revealer of 'true knowledge'".[147] The Simonians were centered on Simon Magus, the magician baptised by Philip and rebuked by Peter in Acts 8, who became in early Christianity the archetypal false teacher. The ascription by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and others of a connection between schools in their time and the individual in Acts 8 may be as legendary as the stories attached to him in various apocryphal books. Justin Martyr identifies Menander of Antioch as Simon Magus' pupil. According to Hippolytus, Simonianism is an earlier form of the Valentinian doctrine.[148] The Quqites were a group who followed a Samaritan, Iranian type of Gnosticism in 2nd-century AD Erbil and in the vicinity of what is today northern Iraq. The sect was named after their founder Quq, known as "the potter". The Quqite ideology arose in Edessa, Syria, in the 2nd century. The Quqites stressed the Hebrew Bible, made changes in the New Testament, associated twelve prophets with twelve apostles, and held that the latter corresponded to the same number of gospels. Their beliefs seem to have been eclectic, with elements of Judaism, Christianity, paganism, astrology, and Gnosticism. Syrian-Egyptian Gnosticism Syrian-Egyptian Gnosticism includes Sethianism, Valentinianism, Basilideans, Thomasine traditions, and Serpent Gnostics, as well as a number of other minor groups and writers.[149] Hermeticism is also a western Gnostic tradition,[101] though it differs in some respects from these other groups.[150] The Syrian–Egyptian school derives much of its outlook from Platonist influences. It depicts creation in a series of emanations from a primal monadic source, finally resulting in the creation of the material universe. These schools tend to view evil in terms of matter that is markedly inferior to goodness and lacking spiritual insight and goodness rather than as an equal force. Many of these movements used texts related to Christianity, with some identifying themselves as specifically Christian, though quite different from the Orthodox or Roman Catholic forms. Jesus and several of his apostles, such as Thomas the Apostle, claimed as the founder of the Thomasine form of Gnosticism, figure in many Gnostic texts. Mary Magdalene is respected as a Gnostic leader, and is considered superior to the twelve apostles by some gnostic texts, such as the Gospel of Mary. John the Evangelist is claimed as a Gnostic by some Gnostic interpreters,[151] as is even St. Paul.[94] Most of the literature from this category is known to us through the Nag Hammadi Library. Sethite-Barbeloite Main article: Sethianism Sethianism was one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd to 3rd centuries, and the prototype of Gnosticism as condemned by Irenaeus.[152] Sethianism attributed its gnosis to Seth, third son of Adam and Eve and Norea, wife of Noah, who also plays a role in Mandeanism and Manicheanism. Their main text is the Apocryphon of John, which does not contain Christian elements,[152] and is an amalgam of two earlier myths.[153] Earlier texts such as Apocalypse of Adam show signs of being pre-Christian and focus on Seth, third son of Adam and Eve.[154] Later Sethian texts continue to interact with Platonism. Sethian texts such as Zostrianos and Allogenes draw on the imagery of older Sethian texts, but use "a large fund of philosophical conceptuality derived from contemporary Platonism, (that is, late middle Platonism) with no traces of Christian content."[48][note 23] According to John D. Turner, German and American scholarship views Sethianism as "a distinctly inner-Jewish, albeit syncretistic and heterodox, phenomenon", while British and French scholarship tends to see Sethianism as "a form of heterodox Christian speculation".[155] Roelof van den Broek notes that "Sethianism" may never have been a separate religious movement, and that the term refers rather to a set of mythological themes which occur in various texts.[156] According to Smith, Sethianism may have begun as a pre-Christian tradition, possibly a syncretic cult that incorporated elements of Christianity and Platonism as it grew.[157] According to Temporini, Vogt, and Haase, early Sethians may be identical to or related to the Nazarenes, the Ophites, or the sectarian group called heretics by Philo.[154] According to Turner, Sethianism was influenced by Christianity and Middle Platonism, and originated in the second century as a fusion of a Jewish baptizing group of possibly priestly lineage, the so-called Barbeloites,[158] named after Barbelo, the first emanation of the Highest God, and a group of Biblical exegetes, the Sethites, the "seed of Seth".[159] At the end of the second century, Sethianism grew apart from the developing Christian orthodoxy, which rejected the Docetic view of the Sethians on Christ.[160] In the early third century, Sethianism was fully rejected by Christian heresiologists, as Sethianism shifted toward the contemplative practices of Platonism while losing interest in their primal origins.[161] In the late third century, Sethianism was attacked by neo-Platonists like Plotinus, and Sethianism became alienated from Platonism. In the early to mid-fourth century, Sethianism fragmented into various sectarian Gnostic groups such as the Archontics, Audians, Borborites, and Phibionites, and perhaps Stratiotici, and Secundians.[162][48] Some of these groups existed into the Middle Ages.[162] Valentinianism Main article: Valentinianism Valentinianism was named after its founder Valentinus (c. 100 – c. 180), who was a candidate for bishop of Rome but started his own group when another was chosen.[163] Valentinianism flourished after mid-second century. The school was popular, spreading to Northwest Africa and Egypt, and through to Asia Minor and Syria in the east,[164] and Valentinus is specifically named as gnostikos by Irenaeus. It was an intellectually vibrant tradition,[165] with an elaborate and philosophically "dense" form of Gnosticism. Valentinus' students elaborated on his teachings and materials, and several varieties of their central myth are known. Valentinian Gnosticism may have been monistic rather than dualistic.[note 24] In the Valentinian myths, the creation of a flawed materiality is not due to any moral failing on the part of the Demiurge, but due to the fact that he is less perfect than the superior entities from which he emanated.[168] Valentinians treat physical reality with less contempt than other Gnostic groups, and conceive of materiality not as a separate substance from the divine, but as attributable to an error of perception which becomes symbolized mythopoetically as the act of material creation.[168] The followers of Valentinus attempted to systematically decode the Epistles, claiming that most Christians made the mistake of reading the Epistles literally rather than allegorically. Valentinians understood the conflict between Jews and Gentiles in Romans to be a coded reference to the differences between Psychics (people who are partly spiritual but have not yet achieved separation from carnality) and Pneumatics (totally spiritual people). The Valentinians argued that such codes were intrinsic in gnosticism, secrecy being important to ensuring proper progression to true inner understanding.[note 25] According to Bentley Layton "Classical Gnosticism" and "The School of Thomas" antedated and influenced the development of Valentinus, whom Layton called "the great [Gnostic] reformer" and "the focal point" of Gnostic development. While in Alexandria, where he was born, Valentinus probably would have had contact with the Gnostic teacher Basilides, and may have been influenced by him.[169] Simone Petrement, while arguing for a Christian origin of Gnosticism, places Valentinus after Basilides, but before the Sethians. According to Petrement, Valentinus represented a moderation of the anti-Judaism of the earlier Hellenized teachers; the demiurge, widely regarded as a mythological depiction of the Old Testament God of the Hebrews (i.e. Jehova), is depicted as more ignorant than evil.[170] Basilideans Main article: Basilideans The Basilidians or Basilideans were founded by Basilides of Alexandria in the second century. Basilides claimed to have been taught his doctrines by Glaucus, a disciple of St. Peter, but could also have been a pupil of Menander.[171] Basilidianism survived until the end of the 4th century as Epiphanius knew of Basilidians living in the Nile Delta. It was, however, almost exclusively limited to Egypt, though according to Sulpicius Severus it seems to have found an entrance into Spain through a certain Mark from Memphis. St. Jerome states that the Priscillianists were infected with it. Thomasine traditions The Thomasine Traditions refers to a group of texts which are attributed to the apostle Thomas.[172][note 26] Karen L. King notes that "Thomasine Gnosticism" as a separate category is being criticised, and may "not stand the test of scholarly scrutiny".[173] Marcion Marcion was a Church leader from Sinope (a city on the south shore of the Black Sea in present-day Turkey), who preached in Rome around 150 CE,[174] but was expelled and started his own congregation, which spread throughout the Mediterranean. He rejected the Old Testament, and followed a limited Christian canon, which included only a redacted version of Luke, and ten edited letters of Paul.[98] Some scholars do not consider him to be a gnostic,[175][note 27] but his teachings clearly resemble some Gnostic teachings.[174] He preached a radical difference between the God of the Old Testament, the Demiurge, the "evil creator of the material universe", and the highest God, the "loving, spiritual God who is the father of Jesus", who had sent Jesus to the earth to free mankind from the tyranny of the Jewish Law.[174][14] Like the Gnostics, Marcion argued that Jesus was essentially a divine spirit appearing to men in the shape of a human form, and not someone in a true physical body.[176] Marcion held that the heavenly Father (the father of Jesus Christ) was an utterly alien god; he had no part in making the world, nor any connection with it.[176] Hermeticism Hermeticism is closely related to Gnosticism, but its orientation is more positive.[101][150][clarification needed] Other Gnostic groups Serpent Gnostics. The Naassenes, Ophites and the Serpentarians gave prominence to snake symbolism, and snake handling played a role in their ceremonies.[174] Cerinthus (c. 100), the founder of a school with gnostic elements. Like a Gnostic, Cerinthus depicted Christ as a heavenly spirit separate from the man Jesus, and he cited the demiurge as creating the material world. Unlike the Gnostics, Cerinthus taught Christians to observe the Jewish law; his demiurge was holy, not lowly; and he taught the Second Coming. His gnosis was a secret teaching attributed to an apostle. Some scholars believe that the First Epistle of John was written as a response to Cerinthus.[177] The Cainites are so-named since Hippolytus of Rome claims that they worshiped Cain, as well as Esau, Korah, and the Sodomites. There is little evidence concerning the nature of this group. Hippolytus claims that they believed that indulgence in sin was the key to salvation because since the body is evil, one must defile it through immoral activity (see libertinism). The name Cainite is used as the name of a religious movement, and not in the usual Biblical sense of people descended from Cain.[178] The Carpocratians, a libertine sect following only the Gospel according to the Hebrews.[179] The school of Justin, which combined gnostic elements with the ancient Greek religion.[180] The Borborites, a libertine Gnostic sect, said to be descended from the Nicolaitans[181] Persian Gnosticism The Persian schools, which appeared in the western Persian Sasanian provice of Asoristan, and whose writings were originally produced in the Eastern Aramaic dialects spoken in Mesopotamia at the time, are representative of what is believed to be among the oldest of the Gnostic thought forms. These movements are considered by most to be religions in their own right and are not emanations from Christianity or Judaism.[citation needed] Manichaeism Main article: Manichaeism  Manichean priests writing at their desks, with panel inscription in Sogdian. Manuscript from Qocho, Tarim Basin. Manichaeism was founded by Mani (216–276). Mani's father was a member of the Jewish Christian sect of the Elcesaites, a subgroup of the Gnostic Ebionites. At ages 12 and 24, Mani had visionary experiences of a "heavenly twin" of his, calling him to leave his father's sect and preach the true message of Christ. In 240–241, Mani travelled to the Indo-Greek Kingdom of the Sakas in what is now Afghanistan, where he studied Hinduism and its various extant philosophies. Returning in 242, he joined the court of Shapur I, to whom he dedicated his only work written in Persian, known as the Shabuhragan. The original writings were written in Syriac, an Eastern Aramaic language, in a unique Manichaean script. Manichaeism conceives of two coexistent realms of light and darkness that become embroiled in conflict. Certain elements of the light became entrapped within darkness, and the purpose of material creation is to engage in the slow process of extraction of these individual elements. In the end, the kingdom of light will prevail over darkness. Manicheanism inherits this dualistic mythology from Zurvanist Zoroastrianism,[182] in which the eternal spirit Ahura Mazda is opposed by his antithesis, Angra Mainyu. This dualistic teaching embodied an elaborate cosmological myth that included the defeat of a primal man by the powers of darkness that devoured and imprisoned the particles of light.[183] According to Kurt Rudolph, the decline of Manichaeism that occurred in Persia in the 5th century was too late to prevent the spread of the movement into the east and the west.[132] In the west, the teachings of the school moved into Syria, Northern Arabia, Egypt and North Africa.[note 28] There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia in the 4th century, and also in Gaul and Spain. From Syria, it progressed further into Syria Palestina, Anatolia, and Byzantine and Persian Armenia. The influence of Manicheanism was attacked by imperial elects and polemical writings, but the religion remained prevalent until the 6th century, and still exerted influence in the emergence of Paulicianism, Bogomilism, and Catharism in the Middle Ages, until it was ultimately stamped out by the Catholic Church.[132] In the east, Rudolph relates, Manicheanism was able to bloom, because the religious monopoly position previously held by Christianity and Zoroastrianism had been broken by nascent Islam. In the early years of the Arab conquest, Manicheanism again found followers in Persia (mostly amongst educated circles), but flourished most in Central Asia, to which it had spread through Iran. There, in 762, Manicheanism became the state religion of the Uyghur Khaganate.[132] Middle Ages After its decline in the Mediterranean world, Gnosticism lived on in the periphery of the Byzantine Empire, and resurfaced in the western world. The Paulicians, an Adoptionist group which flourished between 650 and 872 in Armenia and the Eastern Themes of the Byzantine Empire, were accused by orthodox medieval sources of being Gnostic and quasi Manichaean Christian. The Bogomils, emerged in Bulgaria between 927 and 970 and spread throughout Europe. It was as synthesis of Armenian Paulicianism and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church reform movement. The Cathars (Cathari, Albigenses or Albigensians) were also accused by their enemies of the traits of Gnosticism; though whether or not the Cathari possessed direct historical influence from ancient Gnosticism is disputed. If their critics are reliable the basic conceptions of Gnostic cosmology are to be found in Cathar beliefs (most distinctly in their notion of a lesser, Satanic, creator god), though they did not apparently place any special relevance upon knowledge (gnosis) as an effective salvific force.[verification needed] Islam  Some Sufistic interpretations depict Iblis as ruling the material desires in a manner that resembles the Gnostic Demiurge. The Quran, like Gnostic cosmology, makes a sharp distinction between this world and the afterlife. God is commonly thought of as being beyond human comprehension. In some Islamic schools of thought, God is identifiable with the Monad.[186][187] However, according to Islam and unlike most Gnostic sects, not rejection of this world but performing good deeds leads to Paradise. According to the Islamic belief in tawhid ("unification of God"), there was no room for a lower deity such as the demiurge.[188] According to Islam, both good and evil come from one God, a position especially opposed by the Manichaeans. Ibn al-Muqaffa', a Manichaean apologist who later converted to Islam, depicted the Abrahamic God as a demonic entity who "fights with humans and boasts about His victories" and "sitting on a throne, from which He can descend". It would be impossible that both light and darkness were created from one source since they were regarded as two different eternal principles.[189] Muslim theologists countered with the example of a repeating sinner, who says: "I laid, and I repent";[190] this would prove that good can also result out of evil. Islam also integrated traces of an entity given authority over the lower world in some early writings: Iblis is regarded by some Sufis as the owner of this world and humans must avoid the treasures of this world since they would belong to him.[191] In the Isma'ili Shi'i work Umm al-Kitab, Azazil's role resembles whose of the demiurge.[192] Like the demiurge, he is endowed with the ability to create a world and seeks to imprison humans in the material world, but here, his power is limited and depends on the higher God.[193] Such anthropogenic[clarification needed] can be found frequently among Isma'ili traditions.[194] In fact, Isma'ilism has been often criticised as non-Islamic.[citation needed] Al-Ghazali characterized them as a group who are outwardly Shia but were adherents of a dualistic and philosophical religion. Further traces of Gnostic ideas can be found in Sufi anthropogeny.[clarification needed][195] Like the gnostic conception of human beings imprisoned in matter, Sufi traditions acknowledge that the human soul is an accomplice of the material world and subject to bodily desires similar to the way archontic spheres envelop the pneuma.[196] The ruh (pneuma, spirit) must therefore gain victory over the lower and material-bound nafs (psyche, soul, or anima) to overcome its animal nature. A human being captured by its animal desires, mistakenly claims autonomy and independence from the "higher God", thus resembling the lower deity in classical gnostic traditions. However, since the goal is not to abandon the created world, but just to free oneself from lower desires, it can be disputed whether this can still be Gnostic, but rather a completion of the message of Muhammad.[189] It seems that Gnostic ideas were an influential part of early Islamic development but later lost its influence. However light metaphors and the idea of unity of existence (Arabic: وحدة الوجود, romanized: waḥdat al-wujūd) still prevailed in later Islamic thought, such as that of ibn Sina.[187] Kabbalah Gershom Scholem, a historian of Jewish philosophy, wrote that several core Gnostic ideas reappear in medieval Kabbalah, where they are used to reinterpret earlier Jewish sources. In these cases, according to Scholem, texts such as the Zohar adapted Gnostic precepts for the interpretation of the Torah, while not using the language of Gnosticism.[197] Scholem further proposed that there was a Jewish Gnosticism which influenced the early origins of Christian Gnosticism.[198] Given that some of the earliest dated Kabbalistic texts emerged in medieval Provence, at which time Cathar movements were also supposed to have been active, Scholem and other mid-20th century scholars argued that there was mutual influence between the two groups. According to Dan Joseph, this hypothesis has not been substantiated by any extant texts.[199] Modern times Main article: Gnosticism in modern times Found today in Iraq, Iran and diaspora communities, the Mandaeans are an ancient Gnostic ethnoreligious group that follow John the Baptist and have survived from antiquity.[200] Their name comes from the Aramaic manda meaning knowledge or gnosis.[128] There are thought to be 60,000 to 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[127][132] A number of modern gnostic ecclesiastical bodies have been set up or re-founded since the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library, including the Ecclesia Gnostica, Apostolic Johannite Church, Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, the Gnostic Church of France, the Thomasine Church, the Alexandrian Gnostic Church, and the North American College of Gnostic Bishops.[201] A number of 19th-century thinkers such as Arthur Schopenhauer,[202] Albert Pike and Madame Blavatsky studied Gnostic thought extensively and were influenced by it, and even figures like Herman Melville and W. B. Yeats were more tangentially influenced.[203] Jules Doinel "re-established" a Gnostic church in France in 1890, which altered its form as it passed through various direct successors (Fabre des Essarts as Tau Synésius and Joanny Bricaud as Tau Jean II most notably), and, though small, is still active today.[citation needed] Early 20th-century thinkers who heavily studied and were influenced by Gnosticism include Carl Jung (who supported Gnosticism), Eric Voegelin (who opposed it), Jorge Luis Borges (who included it in many of his short stories), and Aleister Crowley, with figures such as Hermann Hesse being more moderately influenced. René Guénon founded the gnostic review, La Gnose in 1909, before moving to a more Perennialist position, and founding his Traditionalist School. Gnostic Thelemite organizations, such as Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica and Ordo Templi Orientis, trace themselves to Crowley's thought. The discovery and translation of the Nag Hammadi library after 1945 has had a huge effect on Gnosticism since World War II. Intellectuals who were heavily influenced by Gnosticism in this period include Lawrence Durrell, Hans Jonas, Philip K. Dick and Harold Bloom, with Albert Camus and Allen Ginsberg being more moderately influenced.[203] Celia Green has written on Gnostic Christianity in relation to her own philosophy.[204] Alfred North Whitehead was aware of the existence of the newly discovered Gnostic scrolls. Accordingly, Michel Weber has proposed a Gnostic interpretation of his late metaphysics.[205] |