ロバート・ノージック『アナーキー・国家・ユートピア』

Anarchy, State, and Utopia, 1975

☆『アナーキー・国家・ユートピア』は、アメリカの政治哲学者ロバート・ノージックが1974 年に発表した著書である。1975年の全米図書賞(哲学・宗教部門)を受賞し、11言語に翻訳されている。また、イギリスのタイムズ・リテラリー・サプリ メント誌が選出した「第二次世界大戦以降で最も影響力のある書籍100冊」(1945年から1995年)の1冊にも選ばれている。 ジョン・ロールズの『正義論』(1971年)に反対し、マイケル・ウォル ザーと議論を交わしながら、ノジックは「暴力、窃盗、詐欺、契約の強制などに対する保護という狭い機能に限定された」最小国家を支持する立場をとってい る。ミニマム国家の考え方を裏付けるために、ノジックは、ミニマリスト国家がロックの唱える自然状態から自然に生じることを示す論拠を提示し、ミニマリス トの境界を越えて国家権力が拡大することはいかなる場合も正当化されないことを示している。

| Anarchy, State, and

Utopia is a 1974 book by the American political philosopher Robert

Nozick. It won the 1975 US National Book Award in category Philosophy

and Religion,[1] has been translated into 11 languages, and was named

one of the "100 most influential books since the war" (1945–1995) by

the UK Times Literary Supplement.[2] In opposition to A Theory of Justice (1971) by John Rawls, and in debate with Michael Walzer,[3] Nozick argues in favor of a minimal state, "limited to the narrow functions of protection against force, theft, fraud, enforcement of contracts, and so on."[4] When a state takes on more responsibilities than these, Nozick argues, rights will be violated. To support the idea of the minimal state, Nozick presents an argument that illustrates how the minimalist state arises naturally from a Lockean state of nature and how any expansion of state power past this minimalist threshold is unjustified. |

『アナーキー・国家・ユートピア』は、アメリカの政治哲学者ロバート・

ノージックが1974年に発表した著書である。1975年の全米図書賞(哲学・宗教部門)を受賞し、11言語に翻訳されている。また、イギリスのタイム

ズ・リテラリー・サプリメント誌が選出した「第二次世界大戦以降で最も影響力のある書籍100冊」(1945年から1995年)の1冊にも選ばれている。 ジョン・ロールズの『正義論』(1971年)に反対し、マイケル・ウォルザーと議論を交わしながら、ノジックは「暴力、窃盗、詐欺、契約の強制などに対す る保護という狭い機能に限定された」最小国家を支持する立場をとっている。ミニマム国家の考え方を裏付けるために、ノジックは、ミニマリスト国家がロック の唱える自然状態から自然に生じることを示す論拠を提示し、ミニマリストの境界を越えて国家権力が拡大することはいかなる場合も正当化されないことを示し ている。 |

| Summary This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Anarchy, State, and Utopia" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Nozick's entitlement theory, which sees humans as ends in themselves and justifies redistribution of goods only on condition of consent, is a key aspect of Anarchy, State, and Utopia. It is influenced by John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Hayek.[5] The book also contains a vigorous defense of minarchist libertarianism against more extreme views, such as anarcho-capitalism (in which there is no state). Nozick argues that anarcho-capitalism would inevitably transform into a minarchist state, even without violating any of its own non-aggression principles, through the eventual emergence of a single locally dominant private defense and judicial agency that it is in everyone's interests to align with because other agencies are unable to effectively compete against the advantages of the agency with majority coverage. Therefore, even to the extent that the anarcho-capitalist theory is correct, it results in a single, private, protective agency that is itself a de facto "state". Thus anarcho-capitalism may only exist for a limited period before a minimalist state emerges. |

要約 この節は一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。二次資料または三次資料を追加して、この節を改善してほしい。 出典: 「アナーキー・ステート・アンド・ユートピア」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · scholar · JSTOR (2024年1月) (このメッセージをいつ、どのように削除するかについて学ぶ) 人間をそれ自体の目的と見なし、同意がある場合のみ財の再分配を正当化するノージックの権利理論は、『アナーキー・ステート・アンド・ユートピア』の主要な側面である。この理論はジョン・ロック、イマニュエル・カント、フリードリヒ・ハイエクの影響を受けている。 また、この本には、無政府資本主義(国家が存在しない)のようなより極端な見解に対する、ミニマリスト・リバタリアニズムの精力的な擁護も含まれている。 ノジックは、無政府資本主義は、その非侵略原則に違反することなく、やがて地域的に支配的な単一の民間防衛および司法機関が出現し、その機関と提携するこ とが万人の利益にかなうようになることで、必然的にミニマリスト国家へと変貌すると主張している。なぜなら、他の機関は、その機関の優位性に対して効果的 に競争することができないからだ。したがって、無政府資本主義理論が正しいとしても、結果として、単一の民間保護機関が事実上の「国家」となる。したがっ て、無政府資本主義は、ミニマリスト国家が誕生するまでの限られた期間のみ存在する可能性がある。 |

| Philosophical activity The preface of Anarchy, State, and Utopia contains a passage about "the usual manner of presenting philosophical work"—i.e., its presentation as though it were the absolute final word on its subject. Nozick believes that philosophers are really more modest than that and aware of their works' weaknesses. Yet a form of philosophical activity persists which "feels like pushing and shoving things to fit into some fixed perimeter of specified shape." The bulges are masked or the cause of the bulge is thrown far away so that no one will notice. Then "Quickly, you find an angle from which everything appears to fit perfectly and take a snapshot, at a fast shutter speed before something else bulges out too noticeably." After a trip to the darkroom for touching up, "[a]ll that remains is to publish the photograph as a representation of exactly how things are, and to note how nothing fits properly into any other shape." So how does Nozick's work differ from this form of activity? He believed that what he said was correct, but he does not mask the bulges: "the doubts and worries and uncertainties as well as the beliefs, convictions, and arguments." |

哲学活動 『アナーキー・ステート・アンド・ユートピア』の序文には、「哲学的な作品の提示の通常の方法」、すなわち、あたかもその主題について絶対的な最終的な言 葉であるかのように提示するということが述べられている。ノジックは、哲学者は実際にはもっと謙虚であり、自らの作品の弱点を認識していると考えている。 しかし、「特定の形の固定された境界に押し込めるような」哲学活動の一形態が依然として存在している。膨らみは覆い隠されたり、膨らみの原因は遠く離れた 場所に投げ捨てられ、誰も気づかないようにする。そして、「素早く、すべてが完璧に収まっているように見える角度を見つけ、何かが目立って膨らむ前に高速 シャッタースピードで写真を撮る」のだ。暗室で手を加えた後、「残されたことは、物事のありのままの姿を表現する写真としてそれを公表し、何もかもが他の 形にうまく収まっていないことを指摘することだけだ。」では、ノジックの作品は、このような活動とどのように異なるのだろうか?彼は、自分が言ったことは 正しいと信じていたが、膨らみを隠したりはしなかった。「疑い、不安、不確実性、そして信念、確信、論拠も同様だ。」 |

| Why state-of-nature theory? In this chapter, Nozick tries to explain why investigating a Lockean state of nature is useful in order to understand whether there should be a state in the first place.[6] If one can show that an anarchic society is worse than one that has a state we should choose the second as the less bad alternative. To convincingly compare the two, he argues, one should focus not on an extremely pessimistic nor on an extremely optimistic view of that society.[7] Instead, one should: [...] focus upon a nonstate situation in which people generally satisfy moral constraints and generally act as they ought [...] this state-of-nature situation is the best anarchic situation one reasonably could hope for. Hence investigating its nature and defects is of crucial importance to deciding whether there should be a state rather than anarchy. — Robert Nozick, [7] Nozick's plan is to first describe the morally permissible and impermissible actions in such a non-political society and how violations of those constraints by some individuals would lead to the emergence of a state. If that would happen, it would explain the appearance even if no state actually developed in that particular way.[8] He gestures towards perhaps the biggest bulge[opinion] when he notes (in Chapter 1, "Why State-of-Nature Theory?") the shallowness of his "invisible hand" explanation of the minimal state, deriving it from a Lockean state of nature, in which there are individual rights but no state to enforce and adjudicate them. Although this counts for him as a "fundamental explanation" of the political realm because the political is explained in terms of the nonpolitical, it is shallow relative to his later "genealogical" ambition (in The Nature of Rationality and especially in Invariances) to explain both the political and the moral by reference to beneficial cooperative practices that can be traced back to our hunter-gatherer ancestors and beyond. The genealogy will give Nozick an explanation of what is only assumed in Anarchy, State, and Utopia: the fundamental status of individual rights. Creativity was not a factor in his interpretation.[citation needed] |

なぜ自然状態論なのか? この章で、ノジックはそもそも国家が存在すべきかどうかを理解する上で、ロック的な自然状態を調査することがなぜ有益なのかを説明しようとしている。 [6] 無政府状態の社会が国家のある社会よりも悪いことを示すことができるのであれば、より悪い状態ではない方を選ぶべきである。この2つを説得力を持って比較 するためには、その社会に対する極端に悲観的な見方でも極端に楽観的な見方でもなく、その中間にある見方に焦点を当てるべきであると彼は主張している。 [7] その代わりに、人は以下のようにすべきである。 ... 一般的には道徳的制約を満たし、一般的に望ましい行動を取る非国家状況に焦点を当てるべきである... この自然状態は、合理的に期待できる最善の無政府状態である。したがって、その性質と欠陥を調査することは、無政府状態よりも国家が存在すべきかどうかを 決定する上で極めて重要である。 — ロバート・ノージック、[7] ノージックの計画は、まず、そのような非政治的社会における道徳的に許容される行動と許容されない行動を説明し、一部の個人がそれらの制約に違反すること で国家が誕生するに至る経緯を説明することである。もしそのようなことが起こるのであれば、実際にその特定の方法で国家が発展しなかったとしても、その出 現を説明できるだろう。[8] おそらく最も大きな膨らみ(意見)である第1章「なぜ自然状態理論なのか?」で、ロックの自然状態から導き出された最小国家の「見えざる手」による説明の 浅薄さを指摘する際に、彼は身振りで示している。そこでは個人の権利は存在するが、それを強制し裁定する国家は存在しない。これは、政治的なものが非政治 的なものとして説明されるため、彼にとっては政治領域の「根本的な説明」となるが、政治と道徳の両方を、狩猟採集時代の祖先やそれ以前まで遡ることができ る有益な協力関係の実践を参照することで説明するという、彼の後の「系譜学」的野心(『理性の性質』、特に『不変性』)に比べると浅い。系譜学は、ノジッ クに『アナーキー、ステート、アンド、ユートピア』で想定されているに過ぎないもの、すなわち個人の権利の根本的な地位についての説明を与えるだろう。創 造性は彼の解釈には含まれていなかった。[要出典] |

| The state of nature Nozick starts this chapter by summarizing some of the features of the Lockean state of nature.[9] An important one is that every individual has a right to exact compensation by himself whenever another individual violates his rights.[9] Punishing the offender is also acceptable, but only inasmuch as he (or others) will be prevented from doing that again. As Locke himself acknowledges, this raises several problems, and Nozick is going to try to see to what extent can they be solved by voluntary arrangements. A rational response to the "troubles" of a Lockean state of nature is the establishment of mutual-protection associations,[10] in which all will answer the call of any member. It is inconvenient that everyone is always on call, and that the associates can be called out by members who may be "cantankerous or paranoid".[10] Another important inconvenience takes place when two members of the same association have a dispute. Although there are simple rules that could solve this problem (for instance, a policy of non-intervention[11]), most people will prefer associations that try to build systems to decide whose claims are correct. In any case, the problem of everybody being on call dictates that some entrepreneurs will go into the business of selling protective services[11] (division of labor). This will lead ("through market pressures, economies of scale, and rational self-interest") to either people joining the strongest association in a given area or that some associations will have similar power and hence will avoid the costs of fighting by agreeing to a third party that would act as a judge or court to solve the disputes.[12] But for all practical purposes, this second case is equivalent to having just one protective association. And this is something "very much resembling a minimal state".[13] Nozick judges that Locke was wrong to imagine a social contract as necessary to establish civil society and money.[14] He prefers invisible-hand explanations, that is to say, that voluntary agreements between individuals create far-reaching patterns that look like they were designed when in fact nobody did.[15] These explanations are useful in the sense that they "minimize the use of notions constituting the phenomena to be explained". So far he has shown that such an "invisible hand" would lead to a dominant association, but individuals may still justly enforce their own rights. But this protective agency is not yet a state. At the end of the chapter Nozick points out some of the problems of defining what a state is, but he says: We may proceed, for our purposes, by saying that a necessary condition for the existence of a state is that it (some person or organization) announce that, to the best of its ability [...] it will punish everyone whom it discovers to have used force without its express permission. — Robert Nozick, [16] The protective agencies so far do not make any such announcement.[17] Furthermore, it does not offer the same degree of protection to all its clients (who may purchase different degrees of coverage) and the individuals who do not purchase the service (the "independents") do not get any protection at all, (spillover effects aside). This goes against our experience with states, where even tourists typically receive protection.[18]Therefore, the dominant protective agency lacks a monopoly on the use of force and fails to protect all people inside its territory. |

自然状態 ノジックは、この章の冒頭で、ロックの自然状態の特徴をいくつか要約している。[9] 重要な特徴のひとつは、ある個人が他者の権利を侵害した場合、その個人は自らに補償を求める権利を持つという点である。[9] 違反者を処罰することも認められるが、それはあくまでも違反者(または他の者)が再びそのようなことをしないようにするためである。ロック自身も認めてい るように、これはいくつかの問題を引き起こす。ノジックは、自主的な取り決めによってそれらの問題がどの程度解決できるかを見ていこうとしている。ロック の自然状態における「トラブル」に対する合理的な対応策は、相互防衛協会の設立である。誰もが常に待機している状態は不便であり、また、仲間が「気難し かったり偏執的」な会員によって呼び出される可能性もある。[10] 同じ組合の2人の会員が争いごとを起こした場合にも、別の重要な不都合が生じる。この問題を解決する単純なルール(例えば、不干渉政策[11])はあるも のの、ほとんどの人は、どちらの主張が正しいかを決定するシステムを構築しようとする組合を好むだろう。 いずれにしても、誰もが待機を強いられるという問題があるため、一部の企業家が保護サービスを販売する事業に参入することになる(分業)。これは(「市場 の圧力、規模の経済、合理的な利己主義」を通じて)人々が特定の地域で最も強力な組合に参加するか、あるいはいくつかの組合が同様の力を持ち、その結果、 紛争を解決する裁判官や裁判所として機能する第三者機関に同意することで争うコストを回避する、という結果につながる。しかし、実質的な目的においては、 この2番目のケースは単に保護組合が1つあるのと同じことである。これは「最小国家に非常に似た」ものである。[13] ノジックは、市民社会と貨幣を確立するために社会契約が必要であるとロックが考えたのは誤りであると判断している。[14] 彼は、見えざる手による説明、すなわち、 すなわち、個々人の自発的な合意が、あたかも意図的に設計されたかのように見える広範囲にわたるパターンを生み出すという説明である。[15] これらの説明は、「説明されるべき現象を構成する概念の使用を最小限に抑える」という意味で有用である。これまでのところ、ノージックは、このような「見 えざる手」が支配的な結社につながることを示しているが、個々人は依然として正当に自らの権利を主張できる。しかし、この保護的機関はまだ国家ではない。 この章の終わりに、ノジックは国家とは何かを定義することの問題点をいくつか指摘しているが、彼は次のように述べている。 目的のために、国家の存在に必要な条件は、それが(何らかの個人または組織が)「その能力の限りを尽くして」[16]、明示的な許可なく力を行使したことが判明した者すべてを処罰すると宣言することである、と仮定して話を進めることができるだろう。 — ロバート・ノージック、[16] 保護機関はこれまでそのような発表を行っていない。[17] さらに、すべての顧客(さまざまな補償を購入できる)に同程度の保護を提供しているわけではない。また、サービスを購入していない個人(「独立者」)は、 まったく保護されない(波及効果は別として)。これは、通常、観光客でさえ保護を受けられるという、私たちの国家に関する経験とは対照的である。[18] したがって、支配的な保護機関は、武力行使の独占権を持たず、その領土内のすべての人々を保護できていない。 |

| Moral constraints and the state Nozick arrives at the night-watchman state of classical liberalism theory by showing that there are non-redistributive reasons for the apparently redistributive procedure of making its clients pay for the protection of others. He defines what he calls an ultraminimal state, which would not have this seemingly redistributive feature but would be the only one allowed to enforce rights.[19] Proponents of this ultraminimal state do not defend it on the grounds of trying to minimize the total of (weighted) violations of rights (what he calls utilitarianism of rights.[20]) That idea would mean, for example, that someone could punish another person they know to be innocent in order to calm down a mob that would otherwise violate even more rights.[21] This is not the philosophy behind the ultraminimal state.[22] Instead, its proponents hold its members' rights are a side-constraint on what can be done to them. This side-constraint view reflects the underlying Kantian principle that individuals are ends and not merely means, so the rights of one individual cannot be violated to avoid violations of the rights of other people.[23] Which principle should we choose, then? Nozick will not try to prove which one is better. Instead, he gives some reasons to prefer the Kantian view and later points to problems with classic utilitarianism. The first reason he gives in favor of the Kantian principle is that the analogy between the individual case (in which we choose to sacrifice now for a greater benefit later[24]) and the social case (in which we sacrifice the interests of one individual for the greater social good) is incorrect: There are only individual people, different individual people with their own individual lives. Using one of these people for the benefit of others, uses him and benefits the others. Nothing more. [...] Talk of an overall social good covers this up. (Intentionally?). To use a person in this way does not sufficiently respect and take account of the fact that he is a separate person, that his is the only life he has. He does not get some overbalancing good from his sacrifice [...]. — Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia, Reprint Edition, 2013, p. 33 A second reason focuses on the non-aggression principle. Are we prepared to dismiss this principle? That is, can we accept that some individuals may harm some innocent in certain cases?[25] (This non-aggression principle does not include, of course, self-defense and perhaps some other special cases he points out.[26]) He then goes on to expose some problems with utilitarianism by discussing whether animals should be taken into account in the utilitarian calculation of happiness, if that depends on the kind of animal, if killing them painlessly would be acceptable, and so on.[27] He believes that utilitarianism is not appropriate even with animals. But Nozick's most famous argument for the side-constraint view against classical utilitarianism and the idea that only felt experience matters is his Experience Machine thought experiment.[28] It induces whatever illusory experience one might wish, but it prevents the subject from doing anything or making contact with anything. There is only pre-programmed neural stimulation sufficient for the illusion. Nozick pumps the intuition that each of us has a reason to avoid plugging into the Experience Machine forever.[29] This is not to say that "plugging in" might not be the best all-things-considered choice for some who are terminally ill and in great pain. The point of the thought experiment is to articulate a weighty reason not to plug in, a reason that should not be there if all that matters is felt experience.[30] |

道徳的制約と国家 ノジックは、顧客に他者の保護の対価を支払わせるという一見再分配的な手続きには再分配的ではない理由があることを示し、古典的自由主義理論における夜警 国家にたどり着いた。彼は、一見再分配主義的であるように見える特徴を持たないが、権利の行使だけは認められる「超最小国家」を定義している。[19] この超最小国家の支持者たちは、権利の侵害(加重)の総計を最小限に抑えるという理由でそれを擁護しているわけではない(彼が「権利の功利主義」と呼ぶも の)。[20] この考え方は、例えば、暴徒がさらに多くの権利を侵害するのを鎮めるために、無実であると知っている他人を処罰できる、というようなことを意味するだろ う。[21] これはウルトラミニマル国家の背後にある哲学ではない。[22] その代わり、その支持者は、構成員の権利は、彼らに対して行われることに対する副次的な制約であると主張している。この「副次的な制約」の考え方は、個人 は単なる手段ではなく目的であるというカント主義の根本的な原則を反映している。したがって、他者の権利侵害を避けるために個人の権利を侵害することはで きないのである。[23] それでは、どちらの原則を選択すべきだろうか? ノジックはどちらが優れているかを証明しようとはしない。その代わり、カント主義の考え方を優先するいくつかの理由を挙げ、その後、古典的功利主義の問題 点を指摘している。 カント主義の原則を支持する理由として彼が最初に挙げるのは、個々のケース(将来のより大きな利益のために今を犠牲にすることを選択するケース[24])と社会的なケース(社会全体の利益のために個人の利益を犠牲にするケース)との類似性は誤りであるというものである。 そこには個々の人間が存在するのみであり、それぞれ異なる個々の人間がそれぞれの人生を歩んでいる。他者の利益のためにこれらの人間の一人を利用すること は、その人間を利用し、他者に利益をもたらすことである。それだけだ。[...] 社会全体の利益という話は、これを覆い隠す。(意図的に?)このように人を犠牲にすることは、その人が別個の存在であり、彼には彼だけの人生があるという 事実を十分に尊重し、考慮していない。犠牲を払ったからといって、その人が何か大きな利益を得るわけではない。 — ロバート・ノージック、『アナーキー、ステート、アンド、ユートピア』、2013年再版、33ページ 第二の理由は、非侵略の原則に焦点を当てている。私たちはこの原則を放棄する覚悟があるだろうか?つまり、特定のケースにおいて、一部の個人が一部の無実 の人に危害を加える可能性があることを受け入れることができるだろうか?[25](この非侵略の原則には、もちろん、自己防衛や、おそらく彼が指摘するそ の他のいくつかの特別なケースは含まれない。[26]) 彼はその後、功利主義の計算に動物を考慮すべきかどうか、動物の種類によって異なるのか、苦痛を与えない殺害は許されるのか、などについて論じ、功利主義のいくつかの問題点を指摘している。[27] 彼は、功利主義は動物に対しても適切ではないと考えている。 しかし、古典的な功利主義と、感情的な経験だけが重要だという考えに対する側面制約の観点からのノジックの最も有名な主張は、彼の「経験マシン」思考実験 である。[28] これは、人が望むどのような幻想的な経験も引き起こすが、被験者が何かをしたり、何かと接触したりすることを妨げる。そこにあるのは、幻想を十分に生み出 すだけのあらかじめプログラムされた神経刺激だけである。ノジックは、私たち一人ひとりが「エクスペリエンス・マシン」に永遠に接続しない理由があるとい う直感を強調している。[29] これは、末期の病で大きな苦痛を抱えている人にとっては、「接続する」ことがあらゆることを考慮した上で最善の選択ではない可能性がある、ということを意 味するものではない。思考実験の要点は、接続しないという重大な理由を明確にすることであり、それが存在すべきではない理由を明らかにすることである。 [30] |

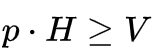

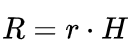

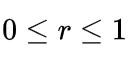

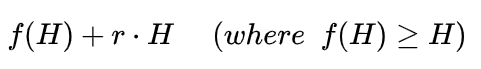

| Prohibition, compensation, and risk The procedure that leads to a night-watchman state involves compensation to non-members who are prevented from enforcing their rights, an enforcement mechanism that it deems risky by comparison with its own. Compensation addresses any disadvantages non-members suffer as a result of being unable to enforce their rights. Assuming that non-members take reasonable precautions and adjusting activities to the association's prohibition of their enforcing their own rights, the association is required to raise the non-member above his actual position by an amount equal to the difference between his position on an indifference curve he would occupy were it not for the prohibition, and his original position. The purpose of this comparatively dense chapter is to deduce what Nozick calls the Compensation Principle. That idea is going to be key for the next chapter, where he shows how (without any violation of rights) an ultraminimal state (one that has a monopoly of enforcement of rights) can become a minimal state (which also provides protection to all individuals). Since this would involve some people paying for the protection of others, or some people being forced to pay for protection, the main element of the discussion is whether these kinds of actions can be justified from a natural rights perspective. Hence the development of a theory of compensation in this chapter. He starts by asking broadly what if someone "crosses a boundary"[31] (for instance, physical harm.[32]) If this is done with the consent of the individual concerned, no problem arises. Unlike Locke, Nozick does not have a "paternalistic" view of the matter. He believes anyone can do anything to himself, or allow others to do the same things to him.[32] But what if B crosses A's boundaries without consent? Is that okay if A is compensated? What Nozick understands by compensation is anything that makes A indifferent (that is, A has to be just as good in his own judgement before the transgression and after the compensation) provided that A has taken reasonable precautions to avoid the situation.[32] He argues that compensation is not enough, because some people will violate these boundaries, for example, without revealing their identity.[33] Therefore, some extra cost has to be imposed on those who violate someone else's rights. (For the sake of simplicity this discussion on deterrence is summarized in another section of this article). After discussing the issue of punishment and concluding that not all violations of rights will be deterred under a retributive theory of justice,[34] (which he favors).[35] Nozick returns to compensation. Again, why don't we allow anyone to do anything provided they give full compensation afterwards? There are several problems with that view. Firstly, if some person gets a big gain by violating another's rights and they then compensate the victim up to the point of indifference, the infractor is getting all the benefits that this provides.[36] But one could argue that it would be fair for the felon to give some compensation beyond that, just like in the marketplace, where the buyer does not necessarily just pay up to the point where the seller is indifferent from selling or not selling. There is usually room for negotiation, which raises the question of fairness. Every attempt to make a theory of a fair price in the marketplace has failed, and Nozick prefers not to try to solve the issue.[37] Instead, he says that, whenever possible, those negotiations should take place, so that the compensation is decided by the people involved.[38] But when one cannot negotiate, it is unclear whether all acts should be accepted if compensation is paid. Secondly, allowing anything if compensation is paid makes all people fearful.[39] Nozick argues that even if one knows they will be compensated if their rights are violated, they will still fear this violation. This raises important problems: Would financial compensation by the perpetrators include not only the damages but also compensate for the fear of the victims prior to the event, as the assaulter is not the only party responsible for that fear?[39] If that is not the way to compensate, non-assaulted people would be left uncompensated for the fear they have. [39] One cannot compensate anyone for fear after the fact because we remember the fear we had as less important than it actually was.[40] Because of that, what should be calculated instead is what Nozick calls "Market Compensation", which is the compensation that would be agreed upon if the negotiations took place before the fact.[40] But this is impossible, according to Nozick.[40] The conclusion of these difficulties, particularly the last one, is that anything that produces general fear may be prohibited.[41] Another reason to prohibit is that it would imply using people as a means, which violates the Kantian principle that he defended earlier. But if so, what about prohibiting all boundary crossing that isn't consented in advance? That would solve the fear problem, but it would be way too restrictive, since people may cross some boundaries by accident, unintentional acts, etc.[41]) and the costs of getting that consent may be too high (for instance if the known victim is on a trip in the jungle).[42] What then? "The most efficient policy forgoes the fewest net beneficial acts; it allows anyone to perform an unfeared action without prior agreement, provided the transaction costs of reaching a prior agreement are greater, even by a bit, than the costs of the posterior compensation process."[43] Note that a particular action may not cause fear if it has a low probability of causing harm. But when all the risky activities are added up, the probability of being harmed may be high.[43] This poses the problem that prohibiting all such activities (which may be very varied) is too restrictive. The obvious response, that is, establishing a threshold value V such that there is a violation of rights if ★  [44] (where p is the probability of harming and H is the amount of harm that could be done) will not fit a natural-rights position. In his own words: This construal of the problem cannot be utilized by a tradition which holds that stealing a penny or a pin or anything from someone violates his rights. That tradition does not select a threshold measure of harm as a lower limit, in the case of harms certain to occur — Robert Nozick, [45] Granted, some insurance solutions will work in these cases and he discusses some.[46] But what should be done to people who do not have the means to buy insurance or compensate other people for the risks of his actions? Should they be forbidden from doing it? Since an enormous number of actions do increase risk to others, a society which prohibited such uncovered actions would ill fit a picture of a free society as one embodying a presumption in favor of liberty, under which people permissibly could perform actions so long as they didn't harm others in specified ways. [...] to prohibit risky acts (because they are financially uncovered or because they are too risky) limits individual's freedom to act, even though the actions actually might involve no cost at all to anyone else. — Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia, Reprint Edition, 2013, p. 78 (This is going to have important consequences in the next chapter, see next section). Nozick's conclusion is to prohibit specially dangerous actions that are generally done and compensating the specially disadvantaged individual from the prohibition.[47] This is what he calls the Principle of Compensation.[48] For example, it is allowed to forbid epileptics from driving, but only if they are compensated exactly for the costs that the disadvantaged has to assume (chauffeurs, taxis[49]). This would only take place if the benefit from the increased security outweighs these costs.[50] But this is not a negotiation. The analogy he gives is blackmail:[51] it is not right to pay a person or group to prevent him from doing something that otherwise would give him no benefit whatsoever. Nozick considers such transactions as "unproductive activities".[52] Similarly, (it should be deduced) it is not right for the epileptic to negotiate a payment for not doing something risky to other people. However, Nozick does point to some problems with this principle. Firstly, he says that the action has to be "generally done". The intention behind that qualification is that eccentric and dangerous activities should not be compensated.[48] His extreme example is someone who has fun playing Russian roulette with the head of others without asking them.[49] Such action must be prohibited, with no qualifications. But one can define anything as a "generally done" action.[48] The Russian roulette could be considered "having fun" and hence be compensated.[48] Secondly, if the special and dangerous action is the only way a person can do something important to him (for instance, if it is the only way one can have fun or support himself) then perhaps it should be compensated.[48] Thirdly, more generally, he recognizes he does not have a theory of disadvantage,[48] so it is unclear what counts as a "special disadvantage". This has to be further developed, because in the state of nature there is no authority to decide how to define these terms (see the discussion of a similar issue in p. 89). [...] nor need we state the principle exactly. We need only claim the correctness of some principles, such as the principle of compensation, requiring those imposing a prohibition on risky activities prohibited to them. I am not completely comfortable presenting and later using a principle whose details have not been worked out fully [...]. I could claim that it is all right as a beginning to leave a principle in a somewhat fuzzy state; the primary question is whether something like it will do. — Robert Nozick, [53] |

禁止、補償、リスク 夜警国家の状態に至る手続きには、権利行使を妨げられた非会員に対する補償、および、その団体自身のものと比較してリスクが高いとみなされる強制メカニズ ムが関わっている。補償は、権利行使ができないことによって非会員が被るあらゆる不利益に対処するものである。非会員が妥当な予防措置を講じ、自らの権利 の行使を禁止する協会の活動に適応することを前提に、協会は、その禁止がなければ非会員が占めるであろう無差別曲線上の位置と、その非会員の元々の位置と の差に等しい量だけ、その非会員を実際の地位よりも高い地位に引き上げることを求められる。 この比較的込み入った章の目的は、ノジックが「補償の原則」と呼ぶものを導き出すことである。この考え方は、次の章で重要な役割を果たす。そこでは、いか にして(いかなる権利の侵害もなしに)超最小国家(権利の行使を独占する国家)が最小国家(すべての個人に保護を提供する国家)になることができるかが示 される。これは、一部の人々が他者の保護のために支払う、あるいは一部の人々が保護のために支払いを強いられることを意味するため、自然権の観点からこう した行為が正当化できるかどうかが議論の主な要素となる。この章で補償理論が展開されるのはそのためである。 彼はまず、誰かが「境界線を越えた」場合(例えば、身体的危害を加えた場合)にどうなるかという問題を広く提起している。[31] これが当該個人の同意のもとで行われた場合は、問題は生じない。ロックとは異なり、ノジックは「温情主義」的な見解を持っていない。彼は、誰もが自分自身 に対して何でもできるし、他人にも同じことを許すことができると考えている。[32] しかし、もしBがAの境界線を同意なしに横切った場合はどうだろうか?Aが補償を受ければそれでいいのだろうか? ノジックが補償として理解しているのは、Aが侵害を受ける前と補償後で、A自身の判断が同等に良好である(つまり、侵害を受ける前と補償後で、A自身の判 断が同等に良好である)ようにするものであり、Aが状況を回避するための妥当な予防措置を講じていることを前提としている。[32] 彼は、補償だけでは不十分であると主張している。なぜなら、一部の人は、例えば身元を明らかにせずに、こうした境界線を侵害するからだ。[33] したがって、他者の権利を侵害した人には、追加のコストを課さなければならない。(簡潔にするため、この抑止力に関する議論は本記事の別のセクションで要 約する)。 処罰の問題について議論し、報復的正義理論では権利侵害のすべてが抑止されるわけではないと結論づけた後で[34](彼はこれを支持している)[35]、 ノジックは補償に戻っている。再び、なぜ誰もが何でもしてよいとしないのか。その後に完全な補償を行なうという条件付きで。この見解にはいくつかの問題が ある。 第一に、ある人物が他者の権利を侵害することで大きな利益を得た場合、その人物が被害者に無差別点まで補償したとしても、侵害者はその利益をすべて手に入 れることになる。[36] しかし、市場のように、買い手が売り手にとって販売しても販売しなくてもよいという無差別点まで支払うとは限らないように、犯罪者もそれ以上の補償を行う のが公平であるという反論も可能である。通常、交渉の余地があるため、公平性の問題が生じる。市場における公平な価格の理論化を試みたものはすべて失敗し ており、ノジックは問題の解決を試みないことを好む。[37] その代わり、可能な限り、当事者間の交渉が行われ、補償が当事者によって決定されるべきだと彼は言う。[38] しかし、交渉が不可能な場合、補償が支払われればすべての行為が容認されるべきなのかどうかは不明である。 第二に、補償さえ支払われれば何をしてもよいということになると、すべての人々が恐怖に怯えることになる。[39] ノジックは、たとえ権利が侵害されても補償されるとわかっていても、人はその侵害を恐れるだろうと主張している。これは重要な問題を提起する。 加害者による金銭的補償には、被害者への損害賠償だけでなく、その出来事が起こる前の被害者の恐怖に対する補償も含まれるのだろうか。なぜなら、その恐怖の原因は加害者だけにあるわけではないからだ。 もしそうでない場合、攻撃を受けなかった人々は、彼らが抱える恐怖に対して補償されないままになってしまう。 人は、実際に経験した恐怖を、実際よりも重要性の低いものとして記憶しているため、事後に誰かの恐怖を補償することはできない。[40] そのため、代わりに計算すべきなのは、ノジックが「市場補償」と呼ぶものであり、それは、交渉が事前に実施された場合に合意される補償である。[40] しかし、ノジックによれば、これは不可能である。[40] これらの困難、特に最後の結論は、一般に恐怖を生じさせるものはすべて禁止される可能性があるということである。[41] 禁止すべきもう一つの理由は、人々を手段として利用することを暗示することであり、それはノージックが以前に擁護したカント主義の原則に反する。 しかし、そうだとすると、事前に同意を得ていない境界横断をすべて禁止するのはどうだろうか? それなら恐怖の問題は解決するが、あまりにも制限が厳しすぎる。なぜなら、人々は偶然や意図しない行為などによって境界を横断することがあるからだ。 [41]) また、同意を得るためのコストが高すぎる場合もある(例えば、被害者がジャングル旅行中である場合など)。[42] ではどうするのか?「最も効率的な政策は、純粋に有益な行為を最小限にとどめることである。事前合意に達するための取引コストが事後補償プロセスにかかる コストよりも多少なりとも高い場合、事前合意なしに誰もが恐れを抱くことなく行動できることを認めるのである。」[43] 特定の行為が害を及ぼす可能性が低い場合、その行為が恐怖を引き起こさない可能性があることに注意すべきである。しかし、危険な行為をすべて合計すると、 害を被る可能性は高いかもしれない。[43] これは、そのような行為(非常に多様である可能性がある)をすべて禁止することは、あまりにも制限的であるという問題を提起する。明らかな対応策は、閾値 Vを定めて、 ★  [44](pは害を与える確率、Hは害の量)という閾値を設定するという明白な回答は、自然権の立場には当てはまらない。彼自身の言葉によると、 この問題の解釈は、誰かから1ペニーやピン、あるいは何でも盗むことはその人の権利を侵害する、という伝統では利用できない。その伝統では、確実に発生する損害の場合に、損害の下限値として閾値を設けることはしない。 — ロバート・ノージック、[45] 確かに、このようなケースでは一部の保険が機能するだろう。彼はその点についても議論している。[46] しかし、保険を購入したり、他者に自らの行動のリスクを補償したりする手段を持たない人々に対して、何をすべきだろうか? 彼らにそのような行動を禁じるべきだろうか? 膨大な数の行動が他者へのリスクを高める以上、そのような無保険の行動を禁止する社会は、自由を推奨する前提を体現する自由社会の姿にそぐわない。 [...] 危険な行為(経済的に無防備であるため、あるいはあまりにも危険であるため)を禁止することは、たとえその行為が実際には他の誰にもまったく負担を強いな いものであっても、個人の行動の自由を制限する。 — ロバート・ノージック、『アナーキー、ステート・アンド・ユートピア』再版、2013年、78ページ (これは次の章で重要な結果をもたらすことになる。次のセクションを参照)。 ノジックの結論は、一般的に行われている特に危険な行為を禁止し、その禁止によって特に不利益を被る個人に対して補償を行うことである。[47] これが彼が補償の原則と呼ぶものである。[48] 例えば、てんかん患者に運転を禁止することは認められるが、不利益を被る人が負担しなければならないコスト(運転手、タクシー[49])を正確に補償する 場合に限られる。これは、安全性の向上による利益がこれらのコストを上回る場合にのみ行われる。[50] しかし、これは交渉ではない。彼が例として挙げたのは恐喝である。[51] そうしなければ何の利益ももたらさないことを、何者かや何らかの集団にそれをさせないために、その人物や集団に支払うのは正しくない。ノジックは、このよ うな取引を「非生産的な活動」とみなしている。[52] 同様に、(推論されるべきであるが)てんかん患者が、他人に危険なことをしないことの見返りとして支払いを交渉するのは正しくない。 しかし、ノージックは、この原則にはいくつかの問題があることを指摘している。まず、その行動は「一般的に行われている」ものでなければならないと彼は言 う。この条件の裏にある意図は、風変わりで危険な行動は補償されるべきではないということである。[48] 彼の極端な例は、他人の頭でロシアンルーレットを勝手に楽しんでいる人である。[49] このような行動は、いかなる条件も付けずに禁止されなければならない。しかし、何であれ「一般的に行われている」行為として定義することは可能である。 [48] ロシアンルーレットは「楽しむこと」とみなされ、それゆえに補償される可能性がある。[48] 第二に、その特別な危険な行為が、その人にとって重要な何かを行う唯一の方法である場合(例えば 例えば、楽しむことや自活する唯一の手段である場合など)は、おそらく補償されるべきである。第三に、より一般的に、彼は不利益の理論を持っていないこと を認識しているため[48]、「特別な不利益」として何がカウントされるかは不明である。 自然状態では、これらの用語をどのように定義するか決定する権限がないため(89ページの類似した問題に関する議論を参照)、この点についてはさらに発展させる必要がある。 [...] また、原則を正確に述べる必要もない。補償の原則など、いくつかの原則の正しさを主張すればよい。例えば、自分には禁止されている危険な行為を禁止する人 々には、その禁止を課す必要がある。私は、詳細が完全に練り上げられていない原則を提示し、その後それを用いることに完全に納得しているわけではない [...]。原則をある程度あいまいな状態のままにしておくことは、最初の一歩としては問題ないだろう。重要なのは、そのような状態が適切かどうかであ る。 — ロバート・ノージック、[53] |

| The state An independent might be prohibited from using his methods of privately enforcing justice if:[54] His method is too risky (“perhaps he consults tea leaves”) He uses a method of unknown riskiness. Nevertheless, an independent may be using a method that does not impose a high risk on others but, if similar procedures are used by many others the total risk may go beyond an acceptable threshold. In that case it is impossible to decide who should stop doing it, since nobody is personally responsible and therefore nobody has a right to stop him. Independents may get together to decide these questions, but even if they agree to a mechanism to keep the total risk below the threshold, each individual will have an incentive to get out of the deal. This procedure fails because of the rationality of being a free rider on such grouping, taking advantage of everyone else's restraint and going ahead with one's own risky activities. In a famous discussion he rejects H. L. A. Hart's "principle of fairness" for dealing with free riders, which would morally bind them to cooperative practices from which they benefit. One may not charge and collect for benefits one bestows without prior agreement. But Nozick refutes this. If the principle of fairness does not work, how should we decide this? Natural law tradition does not help much in clarifying what procedural rights we have.[55] Nozick assumes that we all have a right to know that we are being applied a fair and reliable method for deciding if we are guilty. If this information is not available publicly, we have a right to resist. We may also do it if we find this procedure unreliable or unfair after considering the information given. We may not even participate in the process, even if it would be advisable to do so.[56] The application of these rights may be delegated to the protective agency, which will prevent others from applying methods of which it finds unacceptable in terms of reliability or fairness. Presumably, it would publish a list of accepted methods. Anyone who violates this prohibition will be punished.[57] Every individual has a right to do this, and other companies could try to enter the business, but the dominant protective agency is the only one that has the power to actually carry out this prohibition. It is the only one that can guarantee its clients that no unaccepted procedure will be applied to them.[58] But there is another important difference: the protective agency, in doing this, can put some independents in a situation of disadvantage. Specifically, those independents who use a prohibited method and cannot afford its services without great effort (or are even too poor to pay no matter what). These people will be at the expense of paying clients of the agency. In the previous chapter we saw that it was necessary to compensate others for the disadvantages imposed on them. We also saw that this compensation would amount only to the extra cost imposed to the disadvantaged beyond the costs that he would otherwise incur (in this case, the costs of the risky/unknown procedure he would want to apply). Nevertheless, it would amount to even the full price of a simple protection policy if the independent is unable to pay for it after the compensation for the disadvantages.[59] Also, the protective services that count here are strictly against paying clients, because these are the ones against whom the independent was defenceless in the first place.[60] But wouldn’t this compensation mechanism generate another free riding problem? Nozick says that not much, because the compensation is only “the amount that would equal the cost of an unfancy policy when added to the sum of the monetary costs of self-help protection plus whatever amount the person comfortably could pay”. Also, as we just said, it is an unfancy policy that protects only against paying clients, not against compensated clients and other independents. Therefore, the more free riders there are, the more important it becomes to buy a full protection policy.[60] We can see that what we now have resembles a state. In chapter 3 Nozick argued that two necessary conditions to be fulfilled by an organization to be a state were: Monopoly of the use of force. Universal protection. The protective agency resembles a state in these two conditions. Firstly, it is a de facto monopoly[61] due to the competitive advantage mentioned earlier. It does not have any special right to be it, it just is. “Our explanation does not assume or claim that might makes right. But might does make enforced prohibitions, even if no one thinks the mighty have a special entitlement to have realized in the world their own view of which prohibitions are correctly enforced”. — Robert Nozick, [62] Secondly, most of the people are its clients. There may be independents, however, who apply procedures it approves of. Also, there might still be independents who apply methods that it disapproves of to other independents with unreliable procedures. These conditions are important because they are the basis for the “individualist anarchist” to claim that every state is necessarily illegitimate. This part of the book is a refutation of that claim, showing that some states could be formed by a series of legitimate steps. The de facto monopoly has arisen by morally permissible steps[63] and the universal protection, is not really redistributive because the people who are given money or protective services at a discount had a right to this as a compensation for the disadvantages forced upon them. Therefore, the state is not violating anybody’s rights. Note that this is not a state as we usually understand it. It is presumably organized more like a company and, more importantly, there still exist independents.[64] But, as Nozick says: “Clearly the dominant agency has almost all the features specified [by anthropologist Lawrence Krader]; and its enduring administrative structures, with full-time specialized personnel, make it diverge greatly – in the direction of a state – from what anthropologists call a stateless society”. — Robert Nozick, [64] He does recognize, however, that this entity does not fit perfectly in the Weberian tradition of the definition of the state. It is not “the sole authorizer of violence”, since some independents may conduct violence to one another without intervention. But it is the sole effective judge over the permissibility of violence. Therefore, he concludes, this may be also called a “statelike entity.”[65] Finally, Nozick warns us that the step from being just a de facto monopoly (the ultraminimal state) to becoming this “statelike entity” that compensates some independents (the minimal state) is not a necessary one. Compensating is a moral obligation.[66] But this does not invalidate Nozick’s response to the individualist anarchist and it remains an invisible hand explanation: after all, to give universal protection the agency does not need to have any plan to become a state. It just happens if it decides to give the protection it owes.[66] |

国家 独立者は、もし以下の条件に当てはまる場合、私的に正義を執行する独自の方法を禁止される可能性がある。[54] その方法がリスクが高すぎる場合(「おそらく彼は茶葉に相談する」)。 その方法のリスクが不明な場合。 しかし、独立者は、他人に高いリスクを負わせない方法を使用している可能性があるが、同様の手順を多くの人が使用している場合、リスクの総計は許容範囲を 超える可能性がある。その場合、誰がそれを止めるべきかを決定することは不可能である。なぜなら、誰も個人的に責任を負っておらず、したがって誰にも彼を 止める権利がないからだ。独立者は、これらの問題について話し合うために集まるかもしれないが、たとえ全員が総リスクを閾値以下に抑えるメカニズムに同意 したとしても、各個人はその取引から抜け出すインセンティブを持つことになる。このような集団にただ乗りし、他者の自制心につけこんで、自らリスクの高い 行動に出るという合理的な行動が原因で、この手続きは失敗する。有名な議論の中で、彼はフリーライダーに対処するためのH. L. A. ハートの「公平性の原則」を否定している。この原則は、フリーライダーに道徳的な縛りを課し、彼らが利益を得る協調的な行動を強制するものである。事前に 合意することなく、自分が与える利益に対して料金を請求したり徴収したりすることはできない。しかし、ノジックはこれを否定している。 公平性の原則が機能しない場合、これをどのように決定すべきだろうか?自然法の伝統は、我々がどのような手続き上の権利を有しているかを明確にする上で、 あまり役には立たない。[55] ノージックは、我々は皆、自分が有罪かどうかを決定する際に、公平で信頼できる方法が適用されていることを知る権利を有していると仮定している。この情報 が公に利用できない場合、我々は抵抗する権利を有する。また、与えられた情報を考慮した結果、この手続きが信頼できない、あるいは不公平であると判断した 場合にも、抵抗する権利を有する。たとえそうすることが望ましいとしても、そのプロセスに参加しないこともできる。[56] これらの権利の行使は保護機関に委任することができ、保護機関は信頼性や公平性の観点から容認できないと判断した方法の適用を阻止することができる。おそ らく、保護機関は容認できる方法のリストを公表することになるだろう。この禁止に違反した者は処罰される。[57] すべての個人はこの権利を有しており、他の企業がその事業に参入しようとする可能性もあるが、実際にこの禁止を執行する権限を有するのは、支配的な保護機 関だけである。それは、顧客に対して、受け入れられていない手続きが適用されないことを保証できる唯一の機関である。 しかし、もう一つ重要な違いがある。保護機関がこれを行うと、一部の独立事業者が不利な状況に置かれる可能性がある。具体的には、禁止された方法を使用し ており、多大な努力を払わなければそのサービスを利用できない(あるいは、どんなことをしても支払う余裕がないほど貧しい)独立事業者である。このような 人々は、その機関の支払い能力のある顧客の負担となる。 前章では、他者に不利益を強いる場合には補償が必要であることを確認した。また、この補償は、不利益を被る者が本来負担すべき費用(この場合、適用を希望 するリスクの高い/未知の手続きの費用)を超える追加費用に過ぎないことも確認した。しかし、独立事業者が不利益の補償後に支払うことができない場合、補 償額は単純な保護方針の全額に相当する額に達することもある。[59] また、ここで言う保護サービスは、厳密には支払いを行う依頼者に対して提供されるものであり、なぜなら、独立自営業者は、そもそも依頼者に対して無防備であったからである。 しかし、この補償メカニズムは、別のただ乗り問題を引き起こさないだろうか? ノジックは、補償は「自助努力による保護の金銭的コストの合計に、その人が余裕をもって支払える金額を加えた額に相当する」だけなので、あまり問題にはな らないと述べている。また、先ほども述べたように、それは、支払い能力のある顧客に対してのみ、補償された顧客やその他の独立者に対しては保護しない、簡 素な保険である。したがって、フリーライダーが増えれば増えるほど、完全な保護保険を購入することがより重要になる。[60] 私たちが今手にしているものは国家に似ていることが分かる。第3章でノージックは、国家であるために組織が満たすべき2つの必要条件として、 力の行使の独占。 普遍的な保護。 保護機関は、この2つの条件において国家に類似している。まず、先に述べた競争上の優位性により、事実上の独占[61]である。保護機関には、そうなるための特別な権利があるわけではなく、ただそうなのである。 「我々の説明は、強者が正しいという前提や主張をしているわけではない。しかし、強者は強制的な禁止を課すことができる。たとえ強者が、禁止事項が正しく施行されているという彼ら自身の考えを世界で実現する特別な権利を持っていると誰も考えていなくても、である」。 — ロバート・ノージック、[62] 第二に、そのほとんどの人々は顧客である。しかし、その承認する手続きを適用する独立者は存在するかもしれない。また、その承認しない方法を、信頼できない手続きを持つ他の独立者に適用する独立者も依然として存在するかもしれない。 これらの条件は、「個人主義的無政府主義者」が、あらゆる国家は必然的に非合法であると主張する根拠となるため、重要である。この本では、この主張に反論 し、一連の合法的な手順によって国家が形成される可能性があることを示している。事実上の独占は道徳的に許容される手順によって生じている[63]。ま た、普遍的な保護は、割引価格で金銭や保護サービスを受け取る人々は、自らに強制された不利益に対する補償として、その権利を有していたため、実際には再 分配的ではない。したがって、国家は誰の権利も侵害していない。 これは、通常私たちが理解しているような国家ではないことに注意していただきたい。おそらくは企業のような組織であり、さらに重要なのは、独立した存在も依然として存在していることである。[64] しかし、ノジックが言うように、 「支配的な機関は、人類学者ローレンス・クレイダーが特定した特徴をほぼすべて備えている。また、専任の専門職員を擁する永続的な行政機構により、人類学者が国家なき社会と呼ぶものから、国家の方向へと大きく乖離している」 —ロバート・ノージック、[64] しかし、この実体は国家の定義に関するウェーバーの伝統に完全に当てはまるわけではないと彼は認識している。独立者同士が介入なしに互いに暴力を振るう可 能性があるため、「唯一の暴力の承認者」ではない。しかし、暴力の許容性に対する唯一の有効な判断者である。したがって、彼は結論づけている。これは「国 家のような実体」とも呼べるだろう。[65] 最後に、ノージックは、単なる事実上の独占(最小国家)から、一部の独立者に対して補償を行うこの「国家のような存在」(最小国家)になるという段階は、 必ずしも必要ではないと警告している。補償することは道徳的義務である。[66] しかし、これはノジックの個人主義的無政府主義者に対する回答を無効にするものではなく、依然として見えざる手による説明である。結局のところ、普遍的な 保護を与えるために、その機関が国家になるための計画を立てる必要はない。保護を与えると決定すれば、それは実現するのだ。[66] |

| Further considerations on the argument for the state A discussion of pre-emptive attack leads Nozick to a principle that excludes prohibiting actions not wrong in themselves, even if those actions make more likely the commission of wrongs later on. This provides him with a significant difference between a protection agency's prohibitions against procedures it deems unreliable or unfair, and other prohibitions that might seem to go too far, such as forbidding others to join another protective agency. Nozick's principle does not disallow others from doing so. |

国家の論拠に関するさらなる考察 先制攻撃に関する議論は、ノジックを、それ自体は間違っていない行為であっても、それらの行為が後に間違いを犯す可能性を高める場合でも、それらの行為を 禁止しないという原則に導く。これは、保護機関が信頼できない、あるいは不公平であるとみなした手続きを禁止することと、他の保護機関に参加することを禁 止するなど行き過ぎと思われる禁止との間に、ノジックにとって重要な違いをもたらす。ノジックの原則は、他者がそうすることを禁止するものではない。 |

| Distributive justice Nozick's discussion of Rawls's theory of justice raised a prominent dialogue between libertarianism and liberalism. He sketches an entitlement theory, which states, "From each as they choose, to each as they are chosen". It comprises a theory of (1) justice in acquisition; (2) justice in rectification if (1) is violated (rectification which might require apparently redistributive measures); (3) justice in holdings, and (4) justice in transfer. Assuming justice in acquisition, entitlement to holdings is a function of repeated applications of (3) and (4). Nozick's entitlement theory is a non-patterned historical principle. Almost all other principles of distributive justice (egalitarianism, utilitarianism) are patterned principles of justice. Such principles follow the form, "to each according to..." Nozick's famous Wilt Chamberlain argument is an attempt to show that patterned principles of just distribution are incompatible with liberty. He asks us to assume that the original distribution in society, D1, is ordered by our choice of patterned principle, for instance Rawls's Difference Principle. Wilt Chamberlain is an extremely popular basketball player in this society, and Nozick further assumes 1 million people are willing to freely give Chamberlain 25 cents each to watch him play basketball over the course of a season (we assume no other transactions occur). Chamberlain now has $250,000, a much larger sum than any of the other people in the society. This new distribution in society, call it D2, obviously is no longer ordered by our favored pattern that ordered D1. However Nozick argues that D2 is just. For if each agent freely exchanges some of his D1 share with the basketball player and D1 was a just distribution (we know D1 was just, because it was ordered according to the favored patterned principle of distribution), how can D2 fail to be a just distribution? Thus Nozick argues that what the Wilt Chamberlain example shows is that no patterned principle of just distribution will be compatible with liberty. In order to preserve the pattern, which arranged D1, the state will have to continually interfere with people's ability to freely exchange their D1 shares, for any exchange of D1 shares explicitly involves violating the pattern that originally ordered it. Nozick analogizes taxation with forced labor, asking the reader to imagine a man who works longer to gain income to buy a movie ticket and a man who spends his extra time on leisure (for instance, watching the sunset). What, Nozick asks, is the difference between seizing the second man's leisure (which would be forced labor) and seizing the first man's goods? "Perhaps there is no difference in principle," Nozick concludes, and notes that the argument could be extended to taxation on other sources besides labor. "End-state and most patterned principles of distributive justice institute (partial) ownership by others of people and their actions and labor. These principles involve a shift from the classical liberals' notion of self ownership to a notion of (partial) property rights in other people."[67] Nozick then briefly considers Locke's theory of acquisition. After considering some preliminary objections, he "adds an additional bit of complexity" to the structure of the entitlement theory by refining Locke's proviso that "enough and as good" must be left in common for others by one's taking property in an unowned object. Nozick favors a "Lockean proviso" that forbids appropriation when the position of others is thereby worsened. For instance, appropriating the only water hole in a desert and charging monopoly prices would not be legitimate. But in line with his endorsement of the historical principle, this argument does not apply to the medical researcher who discovers a cure for a disease and sells for whatever price he will. Nor does Nozick provide any means or theory whereby abuses of appropriation—acquisition of property when there is not enough and as good in common for others—should be corrected.[68] [citation needed] |

分配的正義 ノジックによるロールズの正義論の議論は、リバタリアニズムとリベラリズムの間の著名な対話を引き起こした。彼は「各自が選んだものを各自に、各自が選ば れたものを各自に」という資格理論の概略を述べている。それは、(1) 取得における正義、(2) (1) が侵害された場合の是正における正義(是正には、一見再分配的な措置が必要となる場合もある)、(3) 保有における正義、(4) 移転における正義、という4つの理論から構成される。取得における正義を前提とすると、保有に対する権利は、(3) と (4) の繰り返しによって決定される。ノジックの権利理論は、型にはまらない歴史的原則である。分配的正義の他のほとんどの原則(平等主義、功利主義)は、型に はまった正義の原則である。このような原則は、「~に応じて各自に」という形式に従う。 ノジックの有名なウィルト・チェンバレンの議論は、型にはまった正義の分配原則が自由と両立しないことを示す試みである。彼は、社会における最初の分配、 D1が、たとえばロールズの格差原理のような型にはまった原則の選択によって決定されると仮定することを私たちに求めている。ウィルト・チェンバレンは、 この社会では非常に人気の高いバスケットボール選手であり、ノジックはさらに、100万人の人がチェンバレンのバスケットボールの試合を観戦するために、 1人あたり25セントを喜んで自由に提供すると仮定する(他の取引は発生しないと仮定する)。チェンバレンは今、25万ドルを手にすることになるが、これ は社会の他の人々よりもはるかに大きな金額である。この社会における新たな分配、D2は、明らかにD1を秩序づけた私たちが好むパターンによって秩序づけ られたものではなくなっている。しかし、ノジックはD2は正当であると主張する。各エージェントがD1の一部をバスケットボール選手と自由に交換し、D1 が正当な分配であった場合(D1が正当であったことは、それが好む分配のパターン原則に従って秩序づけられていたことから明らかである)、D2が正当な分 配でないはずがない。したがって、ノジックは、ウィルト・チェンバレンの例が示すのは、公正な分配のパターン化された原則は自由と両立しないということだ と主張する。D1を配置したパターンを維持するためには、国家は人々がD1を自由に交換する能力を継続的に妨害しなければならない。なぜなら、D1の交換 はすべて、もともとそれを配置したパターンを明示的に侵害することを伴うからだ。 ノジックは、課税を強制労働になぞらえ、映画のチケットを買うために収入を得るために長時間働く人と、余った時間を余暇(例えば夕日を眺めること)に費や す人を想像してみるよう読者に求めている。ノジックは、2人目の人の余暇を奪うこと(強制労働となる)と、1人目の人の所有物を奪うことの違いは何かと問 う。「おそらく、原理的には違いはない」とノージックは結論づけ、この議論は労働以外の源泉に対する課税にも適用できると指摘している。「分配的正義の最 終的な形と最も一般的な原則は、人々や彼らの行動、労働に対する他者の(部分的な)所有権を認めるものである。これらの原則は、古典的自由主義者の自己所 有の概念から、他者の(部分的な)財産権の概念への転換を伴うものである」[67] ノジックは次に、ロックの取得理論を簡単に検討する。いくつかの予備的な反対意見を検討した後、所有されていない物から財産を奪う場合、他者のために「十 分かつ同等のもの」を共有財産として残さなければならないというロックの留保条件をさらに明確化することで、ノジックは権利理論の構造に「さらなる複雑 さ」を加えている。ノジックは、他者の立場が悪化する場合には収用を禁じる「ロックの留保条件」を支持している。例えば、砂漠にある唯一の水場を独占し、 独占価格を課すことは正当ではない。しかし、歴史的原則を支持する立場から、この主張は、病気の治療法を発見し、それを望む価格で販売する医学研究者には 適用されない。また、ノジックは、他者にとって十分かつ同等の共有物が存在しない状況での財産の取得という、収奪の是正手段や理論を提示していない。 [68][要出典] |

| The Difference Principle Nozick attacks John Rawls's Difference Principle on the ground that the well-off could threaten a lack of social cooperation to the worse-off, just as Rawls implies that the worse-off will be assisted by the well-off for the sake of social cooperation. Nozick asks why the well-off would be obliged, due to their inequality and for the sake of social cooperation, to assist the worse-off and not have the worse-off accept the inequality and benefit the well-off. Furthermore, Rawls's idea regarding morally arbitrary natural endowments comes under fire; Nozick argues that natural advantages that the well-off enjoy do not violate anyone's rights and that, therefore, the well-off have a right to them. He also states that Rawls's proposal that inequalities be geared toward assisting the worse-off is morally arbitrary in itself.[citation needed] |

差異の原則 ノジックは、ジョン・ロールズの差異の原則を攻撃している。裕福な人々が社会協力を欠くことで恵まれない人々を脅かす可能性があるという理由からだ。ロー ルズが、社会協力のために裕福な人々が恵まれない人々を支援することを示唆しているのと同様に。ノジックは、富裕層がなぜ、不平等を理由に、社会協調のた めに、貧困層を支援する義務を負うのか、また、貧困層が不平等を受け入れ、富裕層が利益を得ることを受け入れないのか、と問いかけている。さらに、道徳的 に恣意的な自然の恵みに関するローウェルの考えは批判の対象となっている。ノジックは、富裕層が享受する自然の恵みは誰の権利も侵害していないため、富裕 層にはそれを受ける権利があると主張している。また、ローウェルが提案した、不平等を貧困層を支援する方向に向けるという考え方自体が道徳的に恣意的であ るとも述べている。[要出典] |

| Original position Nozick's opinions on historical entitlement ensures that he naturally rejects the Original Position since he argues that in the Original Position individuals will use an end-state principle to determine the outcome, whilst he explicitly states the importance of the historicity of any such decisions (for example punishments and penalties will require historical information). |

オリジナル・ポジション(原初状態) ノジックの歴史的権利に関する意見は、彼がオリジナル・ポジションを当然拒絶することを保証する。なぜなら、オリジナル・ポジションでは、個人が最終状態 の原則を用いて結果を決定すると主張する一方で、彼はあらゆるそのような決定(例えば、処罰や刑罰には歴史的情報が求められる)の歴史的側面の重要性を明 確に述べているからだ。 |

| Equality, Envy, Exploitation, Etc. Nozick presses "the major objection" to theories that bestow and enforce positive rights to various things such as equality of opportunity, life, and so on. "These 'rights' require a substructure of things and materials and actions," he writes, "and 'other' people may have rights and entitlements over these." Nozick concludes that "Marxian exploitation is the exploitation of people's lack of understanding of economics." |

平等、羨望、搾取、その他 ノジックは、機会の平等や生命の平等など、さまざまなものに積極的権利を付与し、それを強制する理論に対する「主な異論」を提示している。「これらの『権 利』は、物や材料や行動の基盤を必要とする。そして、『他の』人々もこれらの権利や資格を有している可能性がある」と彼は書いている。 ノジックは、「マルクス主義における搾取とは、人々が経済学を理解していないことによる搾取である」と結論づけている。 |

| Demoktesis Demoktesis is a thought-experiment designed to show the incompatibility of democracy with libertarianism in general and the entitlement theory specifically. People desirous of more money might "hit upon the idea of incorporating themselves, raising money by selling shares in themselves." They would partition such rights as which occupation one would have. Though perhaps no one sells himself into utter slavery, there arises through voluntary exchanges a "very extensive domination" of some person by others. This intolerable situation is avoided by writing new terms of incorporation that for any stock no one already owning more than a certain number of shares may purchase it. As the process goes on, everyone sells off rights in themselves, "keeping one share in each right as their own, so they can attend stockholders' meetings if they wish." The inconvenience of attending such meetings leads to a special occupation of stockholders' representative. There is a great dispersal of shares such that almost everybody is deciding about everybody else. The system is still unwieldy, so a "great consolidational convention" is convened for buying and selling shares, and after a "hectic three days (lo and behold!)" each person owns exactly one share in each right over every other person, including himself. So now there can be just one meeting in which everything is decided for everybody. Attendance is too great and it's boring, so it is decided that only those entitled to cast at least 100,000 votes may attend the grand stockholders' meeting. And so on. Their social theorists call the system demoktesis (from Greek δῆμος demos, "people" and κτῆσις ktesis, "ownership"), "ownership of the people, by the people, and for the people", and declare it the highest form of social life, one that must not be allowed to perish from the earth. With this "eldritch tale" we have in fact arrived at a modern democratic state.[citation needed] |

デモクテレス デモクテレスは、民主主義がリバタリアニズム(自由至上主義)一般、および権利付与理論と両立しないことを示すための思考実験である。より多くのお金を望 む人々は、「自らを法人化し、自分自身に対する株式を販売することで資金を調達する」というアイデアを思いつくかもしれない。彼らは、自分がどのような職 業に就くかといった権利を分割する。おそらく、自分を完全に奴隷として売る人はいないだろうが、自発的な交換を通じて、ある人が他の人々によって「非常に 広範に支配される」という状況が生じる。この耐え難い状況は、特定の株式をすでに一定数以上所有している者は購入できないという新しい定款を作成すること で回避される。このプロセスが進むにつれ、誰もが自分自身の権利を売却し、「各自が1株を自分のものとして保持し、希望すれば株主総会に出席できるように する」。このような総会への出席の不便さから、株主の代理人の特別な職業が生まれる。株式が広く分散しているため、ほとんどの人が他の全員について決定す ることになる。このシステムは依然として扱いにくいため、株式売買のための「大統合大会」が招集され、「慌ただしい3日間(なんとまあ!)」を経て、各自 が自分自身を含めた他の全員について、各権利を1株ずつ所有することになる。そこで今では、すべての人々のためにすべてを決める会議は1つだけあればよ い。出席者が多すぎて退屈なので、少なくとも10万票を投じる権利を持つ人だけが、盛大な株主総会に出席できることになった。といった具合だ。彼らの社会 理論家は、このシステムを「デモクセイア(ギリシャ語の「デモス(demos)」=「人民」と「ケシス(ktesis)」=「所有」に由来)」と呼び、 「人民による、人民のための、人民の所有」と称し、このシステムを社会生活の最高の形であり、地上から消滅させてはならないものだと宣言している。この 「異様な物語」によって、私たちは実際、現代の民主国家にたどり着いたのだ。 |

| A Framework for Utopia The utopia mentioned in the title of Nozick's first book is a meta-utopia, a framework for voluntary migration between utopias tending towards worlds in which everybody benefits from everybody else's presence. This is meant to be the Lockean "night-watchman state" writ large. The state protects individual rights and makes sure that contracts and other market transactions are voluntary. The meta-utopian framework reveals what is inspiring and noble in this night-watchman function. They both contain the only form of social union that is possible for the atomistic rational agents of Anarchy, State, and Utopia, fully voluntary associations of mutual benefit. The influence of this idea on Nozick's thinking is profound. Even in his last book, Invariances, he is still concerned to give priority to the mutual-benefit aspect of ethics. This coercively enforceable aspect ideally has an empty core in the game theorists' sense: the core of a game is all of those payoff vectors to the group wherein no subgroup can do better for itself acting on its own, without cooperating with others not in the subgroup. The worlds in Nozick's meta-utopia have empty cores. No subgroup of a utopian world is better off to emigrate to its own smaller world. The function of ethics is fundamentally to create and stabilize such empty cores of mutually beneficial cooperation. His view is that we are fortunate to live under conditions that favor "more-extensive cores", and less conquest, slavery, and pillaging, "less imposition of noncore vectors upon subgroups." Higher moral goals are real enough, but they are parasitic (as described in The Examined Life, the chapter "Darkness and Light") upon mutually beneficial cooperation. In Nozick's utopia if people are not happy with the society they are in they can leave and start their own community, but he fails to consider that there might be things that prevent a person from leaving or moving about freely.[69] Thomas Pogge states that items that are not socially induced can restrict people's options. Nozick states that for the healthy to have to support the handicapped imposes on their freedom, but Pogge argues that it introduces an inequality. This inequality restricts movement based on the ground rules Nozick has implemented, which could lead to feudalism and slavery, a society which Nozick himself would reject.[70] David Schaefer notes that Nozick himself claims that a person could sell himself into slavery, which would break the very ground rule that was created, restricting the movement and choices that a person could make.[71] |

ユートピアの枠組み ノジックの処女作のタイトルに登場するユートピアは、メタ・ユートピア、すなわち、誰もが他者の存在から恩恵を受ける世界へと向かう傾向を持つ、ユートピ ア間の自発的な移住のための枠組みである。これは、ロックの「夜警国家」を拡大解釈したものである。国家は個人の権利を保護し、契約やその他の市場取引が 自発的に行われることを保証する。このメタユートピアの枠組みは、この夜警の機能に鼓舞されるもの、崇高なものがあることを明らかにしている。 両者とも、アナーキー、国家、ユートピアにおける原子論的合理的な主体にとって可能な唯一の社会結合の形態、すなわち、完全に自発的な相互利益の結合を含 んでいる。 この考えがノジックの思考に与えた影響は大きい。 彼の最後の著書『不変性』においても、彼は倫理における相互利益の側面を優先することに依然として関心を抱いている。この強制的に執行可能な側面は、ゲー ム理論家たちの感覚では、理想的に言えば中身のないものとなる。ゲームの中核は、グループに対するすべての報酬ベクトルであり、グループ内のどのサブグ ループも、グループ外の他のサブグループと協力することなく単独で行動しても、自分たちにとってより良い結果を得ることはできない。ノージックのメタユー トピアの世界は中身のないものとなる。ユートピア世界のどのサブグループも、自分たちの小さな世界に移住した方がより良い生活を送れるというわけではな い。倫理の役割は、基本的に、このような相互利益的な協力関係の空のコアを創造し、安定させることにある。ノジックの見解では、私たちは「より広範なコ ア」を好む条件のもとで暮らしており、征服、奴隷制、略奪、すなわち「サブグループに対する非コアベクトルの押し付け」が少ないという幸運に恵まれてい る。より高い道徳的目標は十分に現実的であるが、相互利益的な協力関係に寄生するものである(『吟味された人生』の「闇と光」の章で説明されているよう に)。 ノジックのユートピアでは、もし人々が自分たちの社会に満足できない場合、そこを離れて自分たちのコミュニティを立ち上げることができるが、ノジックは、 人々が自由に離れたり移動したりすることを妨げるものがあるかもしれないという可能性を考慮していない。トマス・ポージは、社会的に誘発されていない項目 が人々の選択肢を制限しうると述べている。ノジックは、健常者が障害者を支援しなければならないことは彼らの自由を制限するものであると述べているが、 ポージは、それは不平等をもたらすものであると主張している。この不平等は、ノジックが導入した基本原則に基づいて移動を制限するものであり、封建制や奴 隷制につながる可能性がある。これはノジック自身が拒絶する社会である。[70] デイヴィッド・シェーファーは、ノジック自身が、人は奴隷として自らを売ることもできると主張していると指摘している。これは、人が移動や選択の自由を制 限するという、まさに創り出された基本原則を破るものである。[71] |

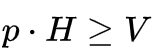

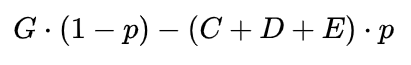

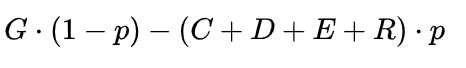

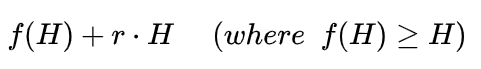

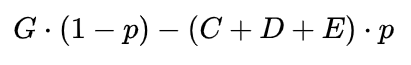

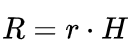

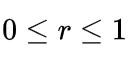

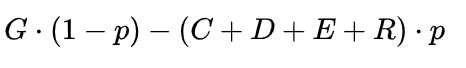

| Other topics covered in the book Retributive and deterrence theories of punishment In chapter 4 Nozick discusses two theories of punishment: the deterrence and the retributive ones. To compare them, we have to take into account what is the decision that a potential infractor is facing. His decision may be determined by:  Where G are the gains from violating the victim's rights, p is the probability of getting caught and (C + D + E) are the costs that the infractor would face if caught. Specifically, C is full compensation to the victim, D are all the emotional costs that the infractor would face if caught (by being apprehended, placed on trial and so on) and E are the financial costs of the processes of apprehension and trial. So if this equation is positive, the potential infractor will have an incentive to violate the potential victim's rights. Here the two theories come into play. On a retributive justice framework, an additional cost R should be imposed to the transgressor that is proportional to the harm done (or intended to be done). Specifically,  , where r is the degree of responsibility the infractor has and  Therefore, the decision a potential infractor would now face would be:  But this still will not deter all people. The equation would be positive if G is high enough or, more importantly, if p is low. That is, if it is very unlikely that an infractor will be caught, they may very well choose to do it even if they have to face the new cost R. Therefore, retributive justice theories allow some failures of deterrence. On the other hand, deterrence theories ("the penalty for a crime should be the minimal one necessary to deter commission of it") do not give enough guidance on how much deterrence should we aim at. If every single possible violation of rights is to be deterred, "the penalty will be set unacceptably high". The problem here is that the infractor may be punished well beyond the harm done to deter other people. According to Nozick, the utilitarian response to the latest problem would be to raise the penalty until the point where more additional unhappiness would be created than would be saved to those who will not be victimized as a consequence of the additional penalty. But this will not do, according to Nozick, because it raises another problem: should the happiness of the victim have more weight in the calculation than the happiness of the felon? If so, how much? He concludes that the retributive framework is better on grounds of simplicity. Similarly, under the retributive theory, he contends that self-defense is appropriate even if the victim uses more force to defend themself. In particular, he proposes that the maximum amount of force that a potential victim can use is:  And in this case H is the harm that the victim thinks that the other is going to inflict upon themself. However, if he uses more force than f(H), that additional force has to be subtracted later from the punishment that the felon gets. Animal rights and utilitarianism Nozick discusses in chapter 3 whether animals have rights too or whether they can be used, and if the species of the animal says anything about the extent to which this can be done. He also analyzes the proposal "utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people," ultimately rejecting it, saying: "Even for animals, utilitarianism won't do as the whole story, but the thicket of questions daunts us."[28] Here Nozick also espouses ethical vegetarianism, saying: "Though I should say in my view the extra benefits Americans today can gain from eating animals do not justify doing it. So we shouldn't."[72] Philosopher Josh Milburn has argued that Nozick's contributions have been overlooked in the literature on both animal ethics and libertarianism.[73] |

この本で取り上げられているその他のトピック 応報刑と抑止刑の理論 第4章でノジックは、抑止刑と応報刑という2つの刑罰理論について論じている。これらを比較するためには、潜在的な犯罪者が直面する決定について考慮しなければならない。犯罪者の決定は、以下によって決定される可能性がある。  ここで、Gは被害者の権利を侵害することによって得られる利益、pは捕まる確率、(C + D + E)は捕まった場合に犯罪者が直面するであろうコストである。具体的には、Cは被害者への完全な補償、Dは違反者が捕まった場合に直面するであろうあらゆ る精神的コスト(逮捕、裁判など)、Eは逮捕と裁判のプロセスにかかる金銭的コストである。 この方程式が正であれば、潜在的な違反者は潜在的な被害者の権利を侵害するインセンティブを持つことになる。 ここで、2つの理論が関わってくる。応報的正義の枠組みでは、加害者には、加害行為(または加害行為の意図)に比例する追加コストRが課されるべきである。 具体的には、  であり、ここでrは加害者の責任の度合いであり、  したがって、潜在的な違反者が直面するであろう決定は次のようになる。  しかし、それでもなお、すべての人々を阻止することはできない。Gが十分に高い場合、あるいはより重要なこととしてpが低い場合には、この方程式は正とな る。つまり、違反者が捕まる可能性が非常に低い場合、たとえ新たなコストRを負担しなければならないとしても、違反を犯すことを選択する可能性が高い。し たがって、応報的正義理論では、ある程度の抑止の失敗は許容される。 一方、抑止理論(「犯罪に対する刑罰は、犯罪の抑止に必要な最小限のものでなければならない」)では、どの程度の抑止を目指すべきかについて十分な指針を 示していない。権利侵害の可能性をすべて抑止しようとすれば、「刑罰は容認できないほど高いものになる」だろう。ここで問題となるのは、加害者が他の人々 を抑止するために、自分が与えた被害をはるかに超える刑罰を受ける可能性があることだ。 ノジックによれば、この問題に対する功利主義的な対応策は、罰則を強化し、その結果犠牲者が出なくなるよりも多くの不幸が新たに生み出されるという時点ま で刑罰を強化することである。しかし、ノジックによれば、これは別の問題を引き起こすため、適切ではない。すなわち、犯罪者の幸福よりも被害者の幸福を考 慮すべきだろうか?もしそうだとすれば、どの程度だろうか? 彼は、応報の枠組みの方が単純であるという理由で優れていると結論づけている。 同様に、応報理論の下では、被害者が自分自身を守るためにより強い力を行使した場合でも、正当防衛は適切であると主張している。特に、被害者となる可能性のある人が行使できる力の最大量は、  この場合、Hは被害者が加害者が自分に与えるだろうと考える危害である。しかし、加害者がf(H)以上の力を用いた場合、その余分な力は後に加害者が受ける処罰から差し引かれる。 動物権利と功利主義 ノジックは第3章で、動物にも権利があるのか、利用できるのか、また、動物の種類によってそれがどの程度まで可能なのかについて論じている。また、「動物 には功利主義、人間にはカント主義」という提案を分析し、最終的にはこれを否定して、「動物に対しても、功利主義は全体像としては適切ではないが、疑問の 森が私たちを圧倒する」と述べている。[28] ここでノジックは倫理的菜食主義を支持し、「私の考えでは、現代のアメリカ人が動物を食べることで得られる追加的な利益は、それを正当化するものではな い。だから、すべきではない」[72] 哲学者のジョシュ・ミルバーンは、動物倫理とリバタリアニズムの両方の文献において、ノジックの貢献が見過ごされていると主張している。[73] |

| Reception Anarchy, State, and Utopia came out of a semester-long course that Nozick taught with Michael Walzer at Harvard in 1971, called Capitalism and Socialism.[3][74] The course was a debate between the two; Nozick's side is in Anarchy, State, and Utopia, and Walzer's side is in his Spheres of Justice (1983), in which he argues for "complex equality". Murray Rothbard, an anarcho-capitalist, criticizes Anarchy, State, and Utopia in his essay "Robert Nozick and the Immaculate Conception of the State"[75] on the basis that: 1. No existing state has actually developed by the 'invisible hand' process described by Nozick, and therefore Nozick, on his own grounds, should "advocate anarchism" and then "wait for his State to develop". 2. Even if any State had been so conceived, individual rights are inalienable and therefore no existing State could be justified. 3. A correct theory of contracts is the title-transfer theory which states that the only valid and enforceable contract is one that surrenders what is, in fact, philosophically alienable, and that only specific titles to property are so alienable. Therefore no one can surrender his own will, his body, other persons, or the rights of his posterity. 4. The risk and compensation principles are both fallacious and result in unlimited despotism. 5. Compensation, in the theory of punishment, is simply a method of trying to recompense the victim after a crime occurs; it can never justify the initial violation of individual rights. 6. Nozick’s theory of “nonproductive” exchanges is invalid since in economic theory all voluntary exchanges are by definition productive, so that the prohibition of "nonproductive" risky activities and hence the ultra-minimal state falls on this account alone. 7. Contrary to Nozick, there are no “procedural rights,” and therefore no way to get from his theory of risk and nonproductive exchange to the compulsory monopoly of the ultra-minimal state. 8. Nozick’s minimal state would, on his own grounds, justify a maximal State as well. 9. The only “invisible hand” process, on Nozick’s own terms, would move society from his minimal State "back to anarchism".[76] The American legal scholar Arthur Allen Leff criticized Nozick in his 1979 article "Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law".[77] Leff stated that Nozick built his entire book on the bald assertion that "individuals have rights which may not be violated by other individuals", for which no justification is offered. According to Leff, no such justification is possible either. Any desired ethical statement, including a negation of Nozick's position, can easily be "proved" with apparent rigor as long as one takes the licence to simply establish a grounding principle by assertion. Leff further calls "ostentatiously unconvincing" Nozick's proposal that differences among individuals will not be a problem if like-minded people form geographically isolated communities. Philosopher Jan Narveson described Nozick's book as "brilliant".[78] Cato Institute fellow Tom G. Palmer writes that Anarchy, State, and Utopia is "witty and dazzling", and offers a strong criticism of John Rawls's A Theory of Justice. Palmer adds that, "Largely because of his remarks on Rawls and the extraordinary power of his intellect, Nozick's book was taken quite seriously by academic philosophers and political theorists, many of whom had not read contemporary libertarian (or classical liberal) material and considered this to be the only articulation of libertarianism available. Since Nozick was writing to defend the limited state and did not justify his starting assumption that individuals have rights, this led some academics to dismiss libertarianism as 'without foundations,' in the words of the philosopher Thomas Nagel. When read in light of the explicit statement of the book's purpose, however, this criticism is misdirected".[79] Libertarian author David Boaz writes that Anarchy, State, and Utopia, together with Rothbard's For a New Liberty (1973) and Ayn Rand's essays on political philosophy, "defined the 'hard-core' version of modern libertarianism, which essentially restated Spencer's law of equal freedom: Individuals have the right to do whatever they want to do, so long as they respect the equal rights of others."[80] In the article "Social Unity and Primary Goods", republished in his Collected Papers (1999), Rawls notes that Nozick handles Sen's liberal paradox in a manner that is similar to his own. However, the rights that Nozick takes to be fundamental and the basis for regarding them to be such are different from the equal basic liberties included in justice as fairness and Rawls conjectures that they are thus not inalienable. In Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy (2007), Rawls notes that Nozick assumes that just transactions are "justice preserving" in much the same way that logical operations are "truth preserving". Thus, as explained in Distributive justice above, Nozick holds that repetitive applications of "justice in holdings" and "justice in transfer" preserve an initial state of justice obtained through "justice in acquisition or rectification". Rawls points out that this is simply an assumption or presupposition and requires substantiation. In reality, he maintains, small inequalities established by just transactions accumulate over time and eventually result in large inequalities and an unjust situation.[citation needed] |

レセプション 『アナーキー・国家・ユートピア』は、1971年にハーバード大学でマイケル・ウォルツァーとともにノジックが教えた「資本主義と社会主義」という1学期 間のコースから生まれたものである。[3][74] このコースは2人の間の討論であり、ノジック側の立場は『アナーキー・国家・ユートピア』に、ウォルツァー側の立場は『正義の領域』(1983年)に示さ れており、ウォルツァーは「複雑な平等」を主張している。 アナルコ・キャピタリストのマレー・ロスバードは、エッセイ「ロバート・ノージックと国家の無原罪懐胎」[75]の中で『アナーキー、国家、ユートピア』を批判している。その理由は以下の通りである。 1. ノージックが述べた「見えざる手」のプロセスによって実際に発展した国家は存在しないため、ノージックは自身の主張に基づき、「無政府主義を擁護」し、「国家が発展するのを待つ」べきである。 2. 仮にそのような国家が存在したとしても、個人の権利は譲渡不可能であるため、既存の国家は正当化できない。 3. 正しい契約理論とは、唯一有効で強制力のある契約とは、実際には哲学的に譲渡可能なものを放棄する契約であり、財産に対する特定の権利のみが譲渡可能であ るとする権利譲渡理論である。したがって、誰も自身の意思、身体、他者、または子孫の権利を放棄することはできない。 4. 危険負担の原則と補償の原則はどちらも誤りであり、無制限の専制主義につながる。 5. 刑罰理論における補償とは、犯罪が発生した後に被害者に補償しようとする単なる方法にすぎず、個人の権利に対する最初の侵害を正当化することは決してできない。 6. ノジックの「非生産的」交換に関する理論は、経済理論ではすべての自発的交換は定義上生産的であるため、無効である。したがって、「非生産的」な危険行為の禁止、ひいては超ミニマム国家の成立は、この理由だけで説明できる。 7. ノジックとは逆に、「手続き上の権利」は存在せず、したがって彼のリスクと非生産的交換の理論から、超最小国家の強制的独占に到達する方法はない。 8. ノージックの最小国家は、彼自身の論拠によれば、最大国家も正当化することになる。 9. ノージック自身の用語で言えば、唯一の「見えざる手」プロセスは、社会を彼の最小国家から「無政府主義に戻す」ことになる。[76] アメリカの法学者アーサー・アレン・レフは、1979年の論文「Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law(口に出しては言えない倫理、不自然な法)」でノージックを批判した。[77] レフは、ノージックが「個人は他の個人によって侵害されてはならない権利を有する」という主張を全面的に展開しているが、その主張には正当化がまったく示 されていないと述べた。レフによれば、そのような正当化は不可能である。ノージックの立場を否定するような、望ましい倫理的な主張は、単に主張によって基 礎原則を確立する権利を認める限り、明白な厳密性をもって簡単に「証明」できる。レフはさらに、ノージックが、考えを同じくする人々が地理的に孤立した共 同体を形成すれば、個人間の相違は問題にならないと提案していることを「あからさまに説得力がない」と述べている。 哲学者のJan Narvesonは、ノージックの著書を「素晴らしい」と評している。[78] Cato Instituteの研究員であるTom G. Palmerは、『アナーキー、ステート、アンド、ユートピア』を「機知に富み、目を見張るものがある」と評し、ジョン・ロールズの『正義論』に対する強力な批判を展開している。Palmerはさらに、 「ノージックの著作が学術的な哲学者や政治理論家たちに真剣に受け止められたのは、主として彼がローウェルズについて述べたことと、彼の並外れた知性の力 によるものであり、その多くは現代のリバタリアン(あるいは古典的自由主義者)の著作を読んだことがなく、これがリバタリアニズムの唯一の理論的体系であ ると考えていた。ノジックは制限国家を擁護するために執筆しており、個人が権利を有しているという出発点の仮定を正当化していなかったため、一部の学者は リバタリアニズムをトーマス・ネーゲルの言葉で言うところの「根拠のない」ものとして退けた。しかし、この批判は、この本の目的を明示した記述に照らして 読めば、的外れである。[79] リバタリアンの著者であるデイヴィッド・ボアズは、著書『アナーキー、ステート、アンド・ユートピア』とロスバードの『新しい自由のために』(1973 年)およびアイン・ランドの政治哲学に関する論文は、「現代のリバタリアニズムの『硬派』なバージョンを定義した。それは本質的にはスペンサーの等価自由 の法則を再表明したものであり、個人は他者の等価な権利を尊重する限り、自分がやりたいことを何でもする権利がある」と書いている。[80] 論文「社会的結束と第一財」の中で、ローウェルズは、ノジックがセンのリベラルのパラドックスを、自身の考え方に類似した方法で扱っていると指摘してい る。しかし、ノジックが基本的であるとみなす権利、およびそれを基本的であるとみなす根拠は、公正さとして正義に含まれる平等な基本的自由とは異なってお り、したがって、それらは譲渡不可能ではないとローウェルズは推測している。 『政治哲学史講義』(2007年)において、ロールズは、ノジックが正当な取引を「正義の維持」であると想定していることを指摘している。これは、論理演 算が「真理の維持」であることとほぼ同じである。したがって、先に説明した分配的正義の原則に従い、ノージックは「保有における正義」と「移転における正 義」を繰り返し適用することで、「取得または是正における正義」によって得られた正義の初期状態が維持されると主張している。 これについて、ローウェルズは、これは単なる仮定または前提であり、実証が必要であると指摘している。 実際には、公正な取引によって生じた小さな不平等が時間をかけて蓄積され、最終的には大きな不平等と不公平な状況につながる、と彼は主張している。 |

| American philosophy Constitutional economics Liberalism and the Limits of Justice Rule according to higher law Night-watchman state |

アメリカの哲学 憲法経済学 自由主義と正義の限界 上位法に基づく統治 夜警国家 |

| Bibliography Nozick, Robert (2013). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-05100-7. Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books. ISBN 184046450X. Nozick, Robert. The Examined Life. |

参考文献 ロバート・ノージック(2013年)。『アナーキー、国家、アンド、ユートピア』。Basic Books。ISBN 978-0-465-05100-7。 ロビンソン、デイブ & グローブス、ジュディ(2003年)。『政治哲学入門』。Icon Books。ISBN 184046450X。 ロバート・ノージック。『検証された人生』。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anarchy,_State,_and_Utopia |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆