人新世

Anthropocene

人新世とは「人為的な気候変動に限らず、地球の地質 や生態系に人類が大き な影響を及ぼし始めた時期から始まる地質学的なエポックの提案である。2022年2月現在、国際層序委員会(ICS)も国際地質科学連合(IUGS)も、 この用語を地質学的時間の区分として公式に承認しているわけではない。しかしながら、この地質時代区分は、第二次世界大戦後に社会経済や地球システムのト レンドが飛躍的に増加した「大加速」の 開始時期や「原子時代(the Atomic Age)」と重なる。人新世の開始時期については、12,000~15,000年前の農業革命の始まりから1960年代まで、様々なものが提唱されてい る。しかし、1950年代の原爆実験による放射性核種の降下量のピークを、人新世の始まりとする説が有力で、1945年の最初の原爆の爆発、あるいは 1963年の部分的核実験禁止条約が制定された頃とされている」出典)。

もし、人新世(Plantationocene.html)という概念が、グローバル・スタ ディーズに影響をうけつつ登場したとすれば、「プ ランテーション新世(Plantationocene)」は、それに似ていながら、その概念の政治的中立性というカモフラージュを払拭し、地球全体の人類 の苦境を表現する対抗的な概念で あることがわかるだろう。

プランテーション新世(Plantationocene)は、「人新世」に代わる用語として 「人新世の起源 を近世のアメリカ大陸 における植民地主義の始まりとし、プランテーションの歴史に注目することで、その背後にある暴力的な歴史を浮き彫りにした」かたちで提示された。プラン テーション新世(Plantationocene)とは「スペインとポルトガルの植 民者が、1,500年代までに、大西洋諸島で100年前に開発したプランテーションのモデルをアメリカ大陸に輸入し始めたことからはじまる(→「生態学的 帝国主義」)。これらのプランテーションのモ デ ルは、移住による強制労働(奴隷制)、集約的な土地利用、グローバル化した商業、絶え間ない人種的暴力に基づくもので、これらすべてが世界中の人間および 人類以外の生物の生活を一変させた。現在および過去のプランテーションは、植民地主義、資本主義、人種差別の歴史と、気温上昇、海水面の上昇、有害物質、 土地の処 分などに対して他の人間よりもリスクが大きい環境問題を切り離すことができないという」点で重要なのである(出典)。

| Anthropocene is a

term that has been used to refer to the period of time during which

humanity has become a planetary force of change. It appears in

scientific and social discourse, especially with respect to

accelerating geophysical and biochemical changes that characterize the

20th and 21st centuries on Earth. Originally a proposal for a new

geological epoch following the Holocene, it was rejected as such in

2024 by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and the

International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).[1][2][3] The term has been used in research relating to Earth's water, geology, geomorphology, landscape, limnology, hydrology, ecosystems and climate.[4][5] The effects of human activities on Earth can be seen for example in biodiversity loss and climate change. Various start dates for the Anthropocene have been proposed, ranging from the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution (12,000–15,000 years ago), to as recently as the 1960s. The biologist Eugene F. Stoermer is credited with first coining and using the term anthropocene informally in the 1980s; Paul J. Crutzen re-invented and popularized the term.[6] The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) of the ICS voted in April 2016 to proceed towards a formal golden spike (GSSP) proposal to define an Anthropocene epoch in the geologic time scale. The group presented the proposal to the International Geological Congress in August 2016.[7] In May 2019, the AWG voted in favour of submitting a formal proposal to the ICS by 2021.[8] The proposal located potential stratigraphic markers to the mid-20th century.[9][8][10] This time period coincides with the start of the Great Acceleration, a post-World War II time period during which global population growth, pollution and exploitation of natural resources have all increased at a dramatic rate.[11] The Atomic Age also started around the mid-20th century, when the risks of nuclear wars, nuclear terrorism and nuclear accidents increased. Twelve candidate sites were selected for the GSSP; the sediments of Crawford Lake, Canada were finally proposed, in July 2023, to mark the lower boundary of the Anthropocene, starting with the Crawfordian stage/age in 1950.[12][13] In March 2024, after 15 years of deliberation, the Anthropocene Epoch proposal of the AWG was voted down by a wide margin by the SQS, owing largely to its shallow sedimentary record and extremely recent proposed start date.[14][15] The ICS and the IUGS later formally confirmed, by a near unanimous vote, the rejection of the AWG's Anthropocene Epoch proposal for inclusion in the Geologic Time Scale.[1][2][3] The IUGS statement on the rejection concluded: "Despite its rejection as a formal unit of the Geologic Time Scale, Anthropocene will nevertheless continue to be used not only by Earth and environmental scientists, but also by social scientists, politicians and economists, as well as by the public at large. It will remain an invaluable descriptor of human impact on the Earth system."[3] |

アントロポセン(人新世)とは、人類が惑星を変化させる力となった期間

を指す言葉である。科学的・社会的な言説の中で、特に20世紀と21世紀の地球を特徴づける加速度的な地球物理学的・生化学的変化に関して登場する。もと

もとは完新世に続く新しい地質学的エポックの提案であったが、2024年に国際層序委員会(ICS)と国際地質科学連合(IUGS)によって却下された

[1][2][3]。 この用語は、地球の水、地質学、地形学、景観、湖沼学、水文学、生態系、気候に関連する研究で使用されている[4][5]。地球に対する人間活動の影響 は、例えば生物多様性の損失や気候変動に見られる。人新世の始まりは、新石器革命の始まり(12,000~15,000年前)から1960年代まで、様々 な年代が提唱されている。生物学者のユージン・F・ストーマーは、1980年代にアントロポセンという用語を最初に作り、非公式に使用したとされている。 ICSの第四紀層序小委員会(SQS)の人新世ワーキンググループ(AWG)は、2016年4月に地質学的時間スケールにおける人新世エポックを定義する ための正式なゴールデンスパイク(GSSP)提案に向けて進むことを決議した。同グループは2016年8月の国際地質学会議にこの提案を提出した[7]。 2019年5月、AWGは、2021年までにICSに正式な提案を提出することに賛成票を投じた[8]。 提案は、20世紀半ばに潜在的な層序学的マーカーを位置づけた[9][8][10]。 この時期は、世界的な人口増加、汚染、天然資源の搾取のすべてが劇的な速度で増加した第二次世界大戦後の時期である「大加速」の始まりと一致する [11]。 核戦争、核テロ、原発事故のリスクが高まった20世紀半ば頃には、原子時代も始まった[12]。 GSSPには12の候補地が選ばれたが、最終的にカナダのクロフォード湖の堆積物が2023年7月に提案され、1950年のクロフォード紀から始まる人新 世の下位境界を示すことになった[12][13]。 2024年3月、15年にわたる審議の後、AWGの人新世エポックの提案は、その浅い堆積記録と、提案された開始時期が極めて新しいことが主な原因となっ て、SQSによって大差で否決された[14][15]。 その後、ICSとIUGSは、ほぼ全会一致の投票によって、AWGの人新世エポックの提案を地質学的時間スケールに含めるための否決を正式に確認した [1][2][3]。否決に関するIUGSの声明は、次のように結んでいる: 「地質学的時間スケールの正式な単位としては却下されたものの、人新世は地球科学者や環境科学者だけでなく、社会科学者、政治家、経済学者、そして一般の 人々にも使われ続けるだろう。人類新世は、人類が地球システムに与える影響を表す貴重な言葉であり続けるだろう」[3]。 |

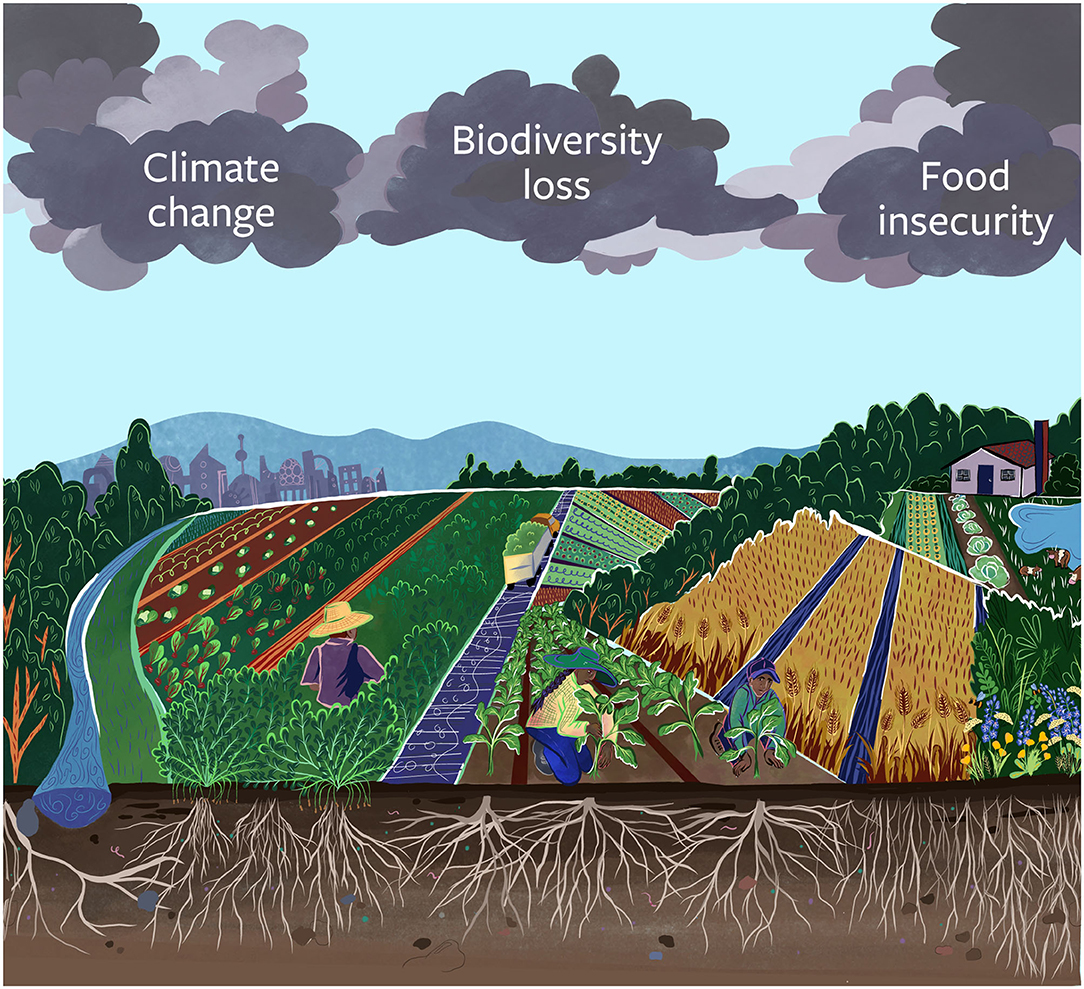

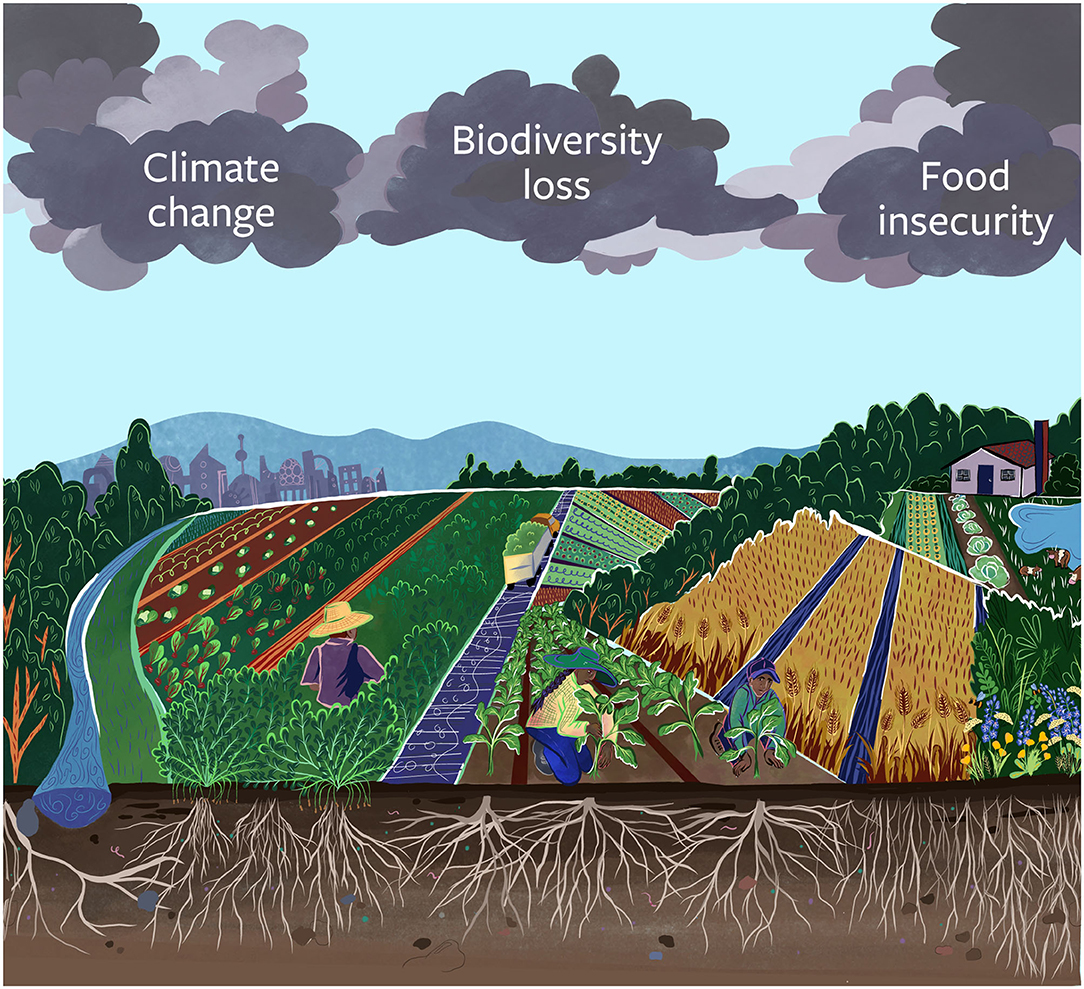

Development of the concept The Anthropocene is characterized by human impacts on their environment, with ramifications for variables such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and global food insecurity.[16] An early concept for the Anthropocene was the Noosphere by Vladimir Vernadsky, who in 1938 wrote of "scientific thought as a geological force".[17] Scientists in the Soviet Union appear to have used the term Anthropocene as early as the 1960s to refer to the Quaternary, the most recent geological period.[18] Ecologist Eugene F. Stoermer subsequently used Anthropocene with a different sense in the 1980s[19][20] and the term was widely popularised in 2000 by atmospheric chemist Paul J. Crutzen,[6][21] who regards the influence of human behavior on Earth's atmosphere in recent centuries as so significant as to constitute a new geological epoch.[22]: 21 [23] The pressures we exert on the planet have become so great that scientists are considering whether the Earth has entered an entirely new geological epoch: the Anthropocene, or the age of humans. It means that we are the first people to live in an age defined by human choice, in which the dominant risk to our survival is ourselves. —Achim Steiner, UNDP Administrator[24] The term Anthropocene is informally used in scientific contexts.[25] The Geological Society of America entitled its 2011 annual meeting: Archean to Anthropocene: The past is the key to the future.[26] The new epoch has no agreed start-date, but one proposal, based on atmospheric evidence, is to fix the start with the Industrial Revolution c.1780, with the invention of the steam engine.[27][28] Other scientists link the new term to earlier events, such as the rise of agriculture and the Neolithic Revolution (around 12,000 years BP). Evidence of relative human impact – such as the growing human influence on land use, ecosystems, biodiversity, and species extinction – is substantial; scientists think that human impact has significantly changed (or halted) the growth of biodiversity.[29][30][31][32] Those arguing for earlier dates posit that the proposed Anthropocene may have begun as early as 14,000–15,000 years BP, based on geologic evidence; this has led other scientists to suggest that "the onset of the Anthropocene should be extended back many thousand years";[33]: 1 this would make the Anthropocene essentially synonymous with the current term, Holocene. |

概念の発展 人新世は、気候変動、生物多様性の喪失、世界的な食糧不安などの変数に影響を及ぼす、人間が環境に与える影響によって特徴付けられる[16]。 人新世の初期の概念は、1938年に「地質学的な力としての科学的思考」と書いたウラジーミル・ヴェルナドスキーによるヌースフィアであった[17]。ソ ビエト連邦の科学者たちは、地質学的に最も新しい時代である第四紀を指すために、1960年代には早くも人新世という用語を使っていたようである [18]。ストーマーはその後、1980年代に異なる意味で人新世を使用し[19][20]、この用語は2000年に大気化学者のポール・J・クルッツェ ンによって広く一般化された[6][21]。彼は、ここ数世紀における地球の大気に対する人間の行動の影響を、新たな地質学的エポックを構成するほど重大 であるとみなしている[22]: 21 [23]。 私たちが地球に及ぼしている圧力は非常に大きくなっており、科学者たちは、地球がまったく新しい地質学的エポック「人新世」(人類の時代)に突入したかど うかを検討している。つまり、私たちは、人間の選択によって定義された時代に生きる最初の人間であり、その中で私たちの生存に対する支配的なリスクは、私 たち自身なのである。 -アキム・シュタイナー、国連開発計画(UNDP)長官[24]。 人新世という用語は、科学的な文脈で非公式に使用されている[25]: アルケアンから人新世へ: この新しいエポックには合意された開始日がないが、大気圏の証拠に基づく一つの提案は、蒸気機関の発明による1780年頃の産業革命を開始日とするもので ある[27][28]。他の科学者は、この新しい用語を、農業の勃興や新石器革命(約12,000年BP)など、それ以前の出来事に結びつけている。 土地利用、生態系、生物多様性、種の絶滅に対する人間の影響の増大など、相対的な人間の影響の証拠は相当なものであり、科学者たちは、人間の影響が生物多 様性の成長を著しく変化させた(あるいは止めた)と考えている[29][30][31]。 [29][30][31][32]より早い年代を主張する人々は、地質学的証拠に基づいて、提案されている人新世は14,000-15,000年BPにも 始まった可能性があると仮定している。このため、他の科学者は「人新世の始まりは何千年も遡るべきである」と提案している[33]: 1これは、人新世を 現在の用語である完新世と本質的に同義にすることになる。 |

| Anthropocene Working Group In 2008, the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London considered a proposal to make the Anthropocene a formal unit of geological epoch divisions.[5][27] A majority of the commission decided the proposal had merit and should be examined further. Independent working groups of scientists from various geological societies began to determine whether the Anthropocene will be formally accepted into the Geological Time Scale.[34]  The Trinity test in July 1945 has been proposed as the start of the Anthropocene. In January 2015, 26 of the 38 members of the International Anthropocene Working Group published a paper suggesting the Trinity test on 16 July 1945 as the starting point of the proposed new epoch.[35] However, a significant minority supported one of several alternative dates.[35] A March 2015 report suggested either 1610 or 1964 as the beginning of the Anthropocene.[36] Other scholars pointed to the diachronous character of the physical strata of the Anthropocene, arguing that onset and impact are spread out over time, not reducible to a single instant or date of start.[37] A January 2016 report on the climatic, biological, and geochemical signatures of human activity in sediments and ice cores suggested the era since the mid-20th century should be recognised as a geological epoch distinct from the Holocene.[38] The Anthropocene Working Group met in April 2016 to consolidate evidence supporting the argument for the Anthropocene as a true geologic epoch.[39] Evidence was evaluated and the group voted to recommend Anthropocene as the new geological epoch in August 2016.[7] In April 2019, the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) announced that they would vote on a formal proposal to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, to continue the process started at the 2016 meeting.[10] In May 2019, 29 members of the 34 person AWG panel voted in favour of an official proposal to be made by 2021. The AWG also voted with 29 votes in favour of a starting date in the mid 20th century. Ten candidate sites for a Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point have been identified, one of which will be chosen to be included in the final proposal.[8][9] Possible markers include microplastics, heavy metals, or radioactive nuclei left by tests from thermonuclear weapons.[40] In November 2021, an alternative proposal that the Anthropocene is a geological event, not an epoch, was published[41][42] and later expanded in 2022.[43] This challenged the assumption underlying the case for the Anthropocene epoch – the idea that it is possible to accurately assign a precise date of start to highly diachronous processes of human-influenced Earth system change. The argument indicated that finding a single GSSP would be impractical, given human-induced changes in the Earth system occurred at different periods, in different places, and spread under different rates. Under this model, the Anthropocene would have many events marking human-induced impacts on the planet, including the mass extinction of large vertebrates, the development of early farming, land clearance in the Americas, global-scale industrial transformation during the Industrial Revolution, and the start of the Atomic Age. The authors are members of the AWG who had voted against the official proposal of a starting date in the mid-20th century, and sought to reconcile some of the previous models (including Ruddiman and Maslin proposals). They cited Crutzen's original concept,[44] arguing that the Anthropocene is much better and more usefully conceived of as an unfolding geological event, like other major transformations in Earth's history such as the Great Oxidation Event. In July 2023, the AWG chose Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada as a site representing the beginning of the proposed new epoch. The sediment in that lake shows a spike in levels of plutonium from hydrogen bomb tests, a key marker the group chose to place the start of the Anthropocene in the 1950s, along with other elevated markers including carbon particles and nitrates from the burning of fossil fuels and widespread application of chemical fertilizers respectively. Had it been approved, the official declaration of the new Anthropocene epoch would have taken place in August 2024,[45] and its first age may have been named Crawfordian after the lake.[46] Rejection in 2024 vote by IUGS In March 2024, an internal vote was held by the IUGS: After nearly 15 years of debate, the proposal to ratify the Anthropocene had been defeated by a 12-to-4 margin, with 2 abstentions.[15] These results were not out of a dismissal of human impact on the planet, but rather an inability to constrain the Anthropocene in a geological context. This is because the widely-adopted 1950 start date was found to be prone to recency bias. It also overshadowed earlier examples of human impacts, many of which happened in different parts of the world at different times. Although the proposal could be raised again, this would require the entire process of debate to start from the beginning.[14] The results of the vote were officially confirmed by the IUGS and upheld as definitive later that month.[15] |

人新世ワーキンググループ 2008年、ロンドン地質学会の層序委員会は、人新世を地質年代区分の正式な単位とする提案を検討した[5][27]。様々な地質学会の科学者からなる独 立したワーキンググループは、人新世が地質学的時間スケールに正式に受け入れられるかどうかを決定し始めた[34]。  1945年7月のトリニティ実験は、人新世の始まりとして提案されている。 2015年1月、国際人新世ワーキンググループの38人のメンバーのうち26人は、提案された新しいエポックの開始点として1945年7月16日のトリニ ティ・テストを提案する論文を発表した[35]。しかし、かなりの少数派はいくつかの代替日のいずれかを支持した。 [35]2015年3月の報告書は、人新世の始まりとして1610年か1964年のいずれかを提案していた[36]。他の学者たちは、人新世の物理的な地 層の通時的な特徴を指摘し、発生と影響は時間的に広がっており、単一の瞬間や開始日に還元することはできないと主張していた[37]。 堆積物や氷床コアにおける人間活動の気候的、生物学的、地球化学的シグネチャーに関する2016年1月の報告書は、20世紀半ば以降の時代は完新世とは異 なる地質学的エポックとして認識されるべきであると示唆した[38]。 人新世作業部会は2016年4月に会合を開き、人新世を真の地質学的エポックとする議論を支持する証拠を集約した[39]。 証拠が評価され、2016年8月に人新世を新たな地質学的エポックとして推奨することに投票した[7]。 2019年4月、人新世ワーキンググループ(AWG)は、2016年の会議で開始されたプロセスを継続するために、国際層序委員会への正式な提案について 投票すると発表した[10]。 2019年5月、34人格のAWGパネルの29人のメンバーは、2021年までに行われる正式な提案に賛成票を投じた。AWGはまた、20世紀半ばを開始 日とすることに29票の賛成票を投じた。地球境界成層圏の区間と地点の候補地10か所が特定され、そのうちの1か所が最終提案に含まれるよう選ばれる [8][9]。考えられるマーカーとしては、マイクロプラスチック、重金属、熱核兵器の実験によって残された放射性核種などがある[40]。 2021年11月、人新世はエポックではなく地質学的事象であるという代替案が発表され[41][42]、その後2022年に拡大された[43]。これ は、人新世エポックのケースの根底にある仮定、つまり、人類が影響した地球システムの変化の非常に通時的なプロセスに正確な開始日を割り当てることが可能 であるという考えに異議を唱えた。この議論では、人類が引き起こした地球システムの変化が、異なる時期に、異なる場所で、異なる速度で起こったことを考え ると、単一のGSSPを見つけることは非現実的であると指摘した。このモデルの下では、人新世は、大型脊椎動物の大量絶滅、初期の農業の発展、アメリカ大 陸の開墾、産業革命期の地球規模の産業転換、原子時代の開始など、人類が地球に与えた影響を示す多くの出来事を持つことになる。著者らはAWGのメンバー であり、20世紀半ばを開始日とする公式提案に反対票を投じ、以前のモデル(RuddimanとMaslinの提案を含む)のいくつかを調和させようとし た。彼らはクルッツェンのオリジナルの概念を引用し、人新世は、大酸化現象などの地球の歴史における他の大きな変容のように、展開する地質学的な出来事と して概念化する方がはるかに優れており、より有益であると主張した[44]。 2023年7月、AWGはカナダのオンタリオ州にあるクロフォード湖を、新しいエポックの始まりの場所として選んだ。その湖の堆積物には、水爆実験による プルトニウムの濃度が急上昇している。これは、グループが人新世の始まりを1950年代とした重要なマーカーであり、その他にも化石燃料の燃焼や化学肥料 の広範囲な散布による炭素粒子や硝酸塩などのマーカーがそれぞれ上昇している。もしそれが承認されていれば、新しい人新世の公式宣言は2024年8月に行 われ[45]、その最初の時代は湖にちなんでクロフォード紀と名付けられたかもしれない[46]。 IUGSによる2024年の投票での却下 2024年3月、IUGSによる内部投票が行われた: この結果は、地球に対する人類の影響を否定したのではなく、むしろ地質学的な文脈で人新世を制約することができなかったためである。というのも、広く採用 されている1950年という開始時期は、過去にさかのぼるバイアスがかかりやすいことが判明したからである。また、1950年という日付は、それ以前に起 こった人類による影響の例を覆い隠してしまった。この提案は再度提起される可能性もあるが、そのためには議論のプロセス全体を最初からやり直す必要があ る。投票結果はIUGSによって公式に確認され、同月末に確定的なものとして支持された[15]。 |

| Proposed starting point Industrial Revolution Main article: Industrial Revolution Crutzen proposed the Industrial Revolution as the start of Anthropocene.[47] Lovelock proposes that the Anthropocene began with the first application of the Newcomen steam engine in 1712.[48] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change takes the pre-industrial era (chosen as the year 1750) as the baseline related to changes in long-lived, well mixed greenhouse gases.[49] Although it is apparent that the Industrial Revolution ushered in an unprecedented global human impact on the planet,[50] much of Earth's landscape already had been profoundly modified by human activities.[51] The human impact on Earth has grown progressively, with few substantial slowdowns. A 2024 scientific perspective paper authored by a group of scientists led by William J. Ripple proposed the start of the Anthropocene around 1850, stating it is a "compelling choice ... from a population, fossil fuel, greenhouse gasses, temperature, and land use perspective."[52] Mid 20th century (Great Acceleration) Main article: Great Acceleration In May 2019 the twenty-nine members of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) proposed a start date for the Epoch in the mid-20th century, as that period saw "a rapidly rising human population accelerated the pace of industrial production, the use of agricultural chemicals and other human activities. At the same time, the first atomic-bomb blasts littered the globe with radioactive debris that became embedded in sediments and glacial ice, becoming part of the geologic record." The official start-dates, according to the panel, would coincide with either the radionuclides released into the atmosphere from bomb detonations in 1945, or with the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.[8] First atomic bomb (1945) The peak in radionuclides fallout consequential to atomic bomb testing during the 1950s is another possible date for the beginning of the Anthropocene (the detonation of the first atomic bomb in 1945 or the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963).[8] |

出発点の提案 産業革命 主な記事 産業革命 クラッツェンは産業革命を人新世の始まりと提唱した。 ラブロックは、人新世は1712年にニューコメン蒸気機関が初めて実用化されたことから始まったと提唱している[48]。気候変動に関する政府間パネル は、長寿命でよく混合された温室効果ガスの変化に関する基準として産業革命前(1750年として選ばれた)を採用している。 [49]産業革命が地球に対する前例のない世界的な人間の影響をもたらしたことは明らかであるが[50]、地球の景観の多くはすでに人間の活動によって大 きく変化していた[51]。 地球に対する人間の影響は、実質的な減速はほとんどなく、徐々に拡大してきた。ウィリアム・J・リップル率いる科学者グループによって執筆された2024 年の科学的展望論文は、1850年頃に人新世が始まると提案し、それが「人口、化石燃料、温室効果ガス、気温、土地利用の観点から...説得力のある選択 である」と述べている[52]。 20世紀半ば(大加速) 主な記事 大加速 2019年5月、人新世作業部会(AWG)の29人のメンバーは、エポックの開始時期を20世紀半ばとすることを提案した。この時期は、「人類の人口が急 速に増加し、工業生産や農薬の使用、その他の人間活動のペースが加速した。同時に、最初の原爆投下によって放射性物質が地球上に散らばり、それが堆積物や 氷河の氷に埋もれて地質学的記録の一部となった。委員会によれば、正式な開始日は、1945年の原爆爆発によって大気中に放出された放射性核種か、 1963年の限定的核実験禁止条約[8]のいずれかと一致する。 最初の原子爆弾(1945年) 1950年代の原爆実験に起因する放射性核種降下量のピークは、人新世の始まり(1945年の最初の原爆の爆発、または1963年の部分的核実験禁止条 約)のもう一つの可能な日付である[8]。 |

| Etymology The name Anthropocene is a combination of anthropo- from the Ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος (ánthropos) meaning 'human' and -cene from καινός (kainós) meaning 'new' or 'recent'.[53][54] As early as 1873, the Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani acknowledged the increasing power and effect of humanity on the Earth's systems and referred to an 'anthropozoic era'.[47] |

語源 アントロポセンという名称は、「人間」を意味する古代ギリシャ語ἄνθρωπος (ánthropos)に由来するanthropo-と、「新しい」や「最近の」を意味するκαινός (kainós)に由来する-ceneを組み合わせたものである[53][54]。 1873年の時点で、イタリアの地質学者アントニオ・ストッパーニは、地球のシステムに対する人類の力と影響の増大を認めており、「人類時代」と呼んでい た[47]。 |

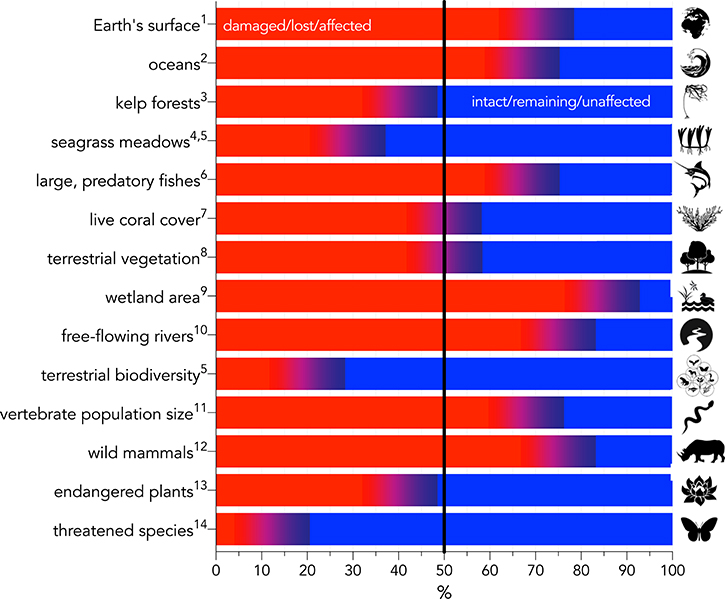

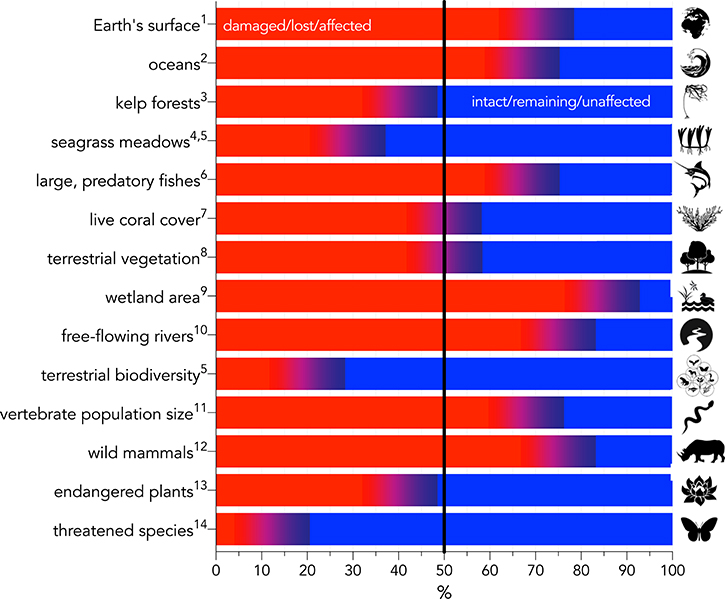

| Nature of human effects Main article: Human impact on the environment Biodiversity loss Main articles: Holocene extinction and Biodiversity loss The human impact on biodiversity forms one of the primary attributes of the Anthropocene.[55] Humankind has entered what is sometimes called the Earth's sixth major extinction.[56][57][58][59][60] Most experts agree that human activities have accelerated the rate of species extinction.[31][61] The exact rate remains controversial – perhaps 100 to 1000 times the normal background rate of extinction.[62][63] Anthropogenic extinctions started as humans migrated out of Africa over 60,000 years ago.[64] Increases in global rates of extinction have been elevated above background rates since at least 1500, and appear to have accelerated in the 19th century and further since.[4] Rapid economic growth is considered a primary driver of the contemporary displacement and eradication of other species.[65] According to the 2021 Economics of Biodiversity review, written by Partha Dasgupta and published by the UK government, "biodiversity is declining faster than at any time in human history."[66][67] A 2022 scientific review published in Biological Reviews confirms that an anthropogenic sixth mass extinction event is currently underway.[68][69] A 2022 study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, which surveyed more than 3,000 experts, states that the extinction crisis could be worse than previously thought, and estimates that roughly 30% of species "have been globally threatened or driven extinct since the year 1500."[70][71] According to a 2023 study published in Biological Reviews some 48% of 70,000 monitored species are experiencing population declines from human activity, whereas only 3% have increasing populations.[72][73][74] This section is an excerpt from Biodiversity loss.[edit]  Summary of major environmental-change categories that cause biodiversity loss. The data is expressed as a percentage of human-driven change (in red) relative to baseline (blue), as of 2021. Red indicates the percentage of the category that is damaged, lost, or otherwise affected, whereas blue indicates the percentage that is intact, remaining, or otherwise unaffected.[75] Biodiversity loss happens when plant or animal species disappear completely from Earth (extinction) or when there is a decrease or disappearance of species in a specific area. Biodiversity loss means that there is a reduction in biological diversity in a given area. The decrease can be temporary or permanent. It is temporary if the damage that led to the loss is reversible in time, for example through ecological restoration. If this is not possible, then the decrease is permanent. The cause of most of the biodiversity loss is, generally speaking, human activities that push the planetary boundaries too far.[75][76][77] These activities include habitat destruction[78] (for example deforestation) and land use intensification (for example monoculture farming).[79][80] Further problem areas are air and water pollution (including nutrient pollution), over-exploitation, invasive species[81] and climate change.[78] Many scientists, along with the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, say that the main reason for biodiversity loss is a growing human population because this leads to human overpopulation and excessive consumption.[82][83][84][85][86] Others disagree, saying that loss of habitat is caused mainly by "the growth of commodities for export" and that population has very little to do with overall consumption. More important are wealth disparities between and within countries.[87] Climate change is another threat to global biodiversity.[88][89] For example, coral reefs—which are biodiversity hotspots—will be lost by the year 2100 if global warming continues at the current rate.[90][91] Still, it is the general habitat destruction (often for expansion of agriculture), not climate change, that is currently the bigger driver of biodiversity loss.[92][93] Invasive species and other disturbances have become more common in forests in the last several decades. These tend to be directly or indirectly connected to climate change and can cause a deterioration of forest ecosystems.[94][95] |

人的影響の本質 主な記事 人間が環境に与える影響 生物多様性の損失 主な記事 完新世の絶滅と生物多様性の損失 生物多様性に対する人間の影響は、人新世の主要な特質の一つを形成している[55]。人類は、地球で6番目の大絶滅と呼ばれることもある時期に突入してい る[56][57][58][59][60]。ほとんどの専門家は、人間の活動が種の絶滅の速度を加速させていることに同意している[31][61]。正 確な速度については依然として議論の余地があり、おそらく通常のバックグラウンドの絶滅速度の100倍から1000倍である[62][63]。 人為的な絶滅は、6万年以上前に人類がアフリカから移住してきたときに始まった[64]。世界的な絶滅率の増加は、少なくとも1500年以降、バックグラ ウンド率を上回っており、19世紀以降さらに加速しているようである[4]。急速な経済成長は、現代における他の種の移動と根絶の主な原動力であると考え られている[65]。 パルタ・ダスグプタによって執筆され、英国政府によって発表された2021年の生物多様性の経済学レビューによると、「生物多様性は人類史上いつにも増し て急速に減少している」[66][67]。 Biological Reviewsに発表された2022年の科学レビューは、人為的な第6の大量絶滅現象が現在進行中であることを確認している。 [68][69] 3,000人以上の専門家を調査した『Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment』誌に掲載された2022年の研究では、絶滅危機は以前考えられていたよりも悪化している可能性があると述べており、およそ30% の種が「1500年以降、世界的に絶滅の危機に瀕しているか、絶滅に追い込まれている」と推定している[70][71] 。『Biological Reviews』誌に掲載された2023年の研究によると、モニターされている70,000種のうち約48%が人間活動による個体数の減少を経験している のに対し、個体数が増加しているのはわずか3%である[72][73][74]。 このセクションは生物多様性の損失からの抜粋である[編集]。  生物多様性の損失を引き起こす主な環境変化カテゴリーの概要。データは2021年時点の、ベースライン(青)に対する人為的変化(赤)の割合で示されてい る。赤は、損傷、損失、その他の影響を受けたカテゴリの割合を示し、青は、無傷、残存、その他の影響を受けていない割合を示す[75]。 生物多様性の損失は、動植物の種が地球上から完全に消滅する(絶滅)か、特定の地域で種の減少や消滅が起こる場合に起こる。生物多様性の損失とは、特定の 地域における生物多様性の減少を意味する。減少には一時的なものと永続的なものがある。損失につながった損害が、例えば生態系の回復などを通じて、時間の 経過とともに回復可能な場合は一時的なものである。それが不可能な場合は、永続的な減少となる。生物多様性喪失の原因のほとんどは、一般的に言って、惑星 の境界を過度に押し広げる人間の活動である[75][76][77]。これらの活動には、生息地の破壊[78](森林伐採など)や土地利用の集約化(単一 栽培農業など)が含まれる[79][80]。さらに問題となる領域は、大気汚染や水質汚染(栄養塩汚染を含む)、乱獲、移入種[81]、気候変動である [78]。 多くの科学者は、生物多様性と生態系サービスに関する世界アセスメント報告書とともに、生物多様性損失の主な原因は人間の人口増加であり、これは人間の過 剰人口と過剰消費につながるためであると述べている[82][83][84][85][86]。また、生息地の損失は主に「輸出用商品の増加」によって引 き起こされ、人口は消費全体とはほとんど関係がないとする反対意見もある。より重要なのは、国家間および国家内の貧富の格差である[87]。 気候変動も世界の生物多様性に対する脅威である[88][89]。 例えば、生物多様性のホットスポットであるサンゴ礁は、現在のペースで地球温暖化が続けば、2100年までに失われると言われている[90][91]。そ れでも、現在のところ生物多様性損失の大きな原動力となっているのは、気候変動ではなく、一般的な生息地の破壊(多くの場合、農業拡大のため)である [92][93]。 外来種やその他の攪乱は、ここ数十年で森林でより一般的になっている。これらは気候変動と直接的または間接的に関連する傾向があり、森林生態系の悪化を引 き起こす可能性がある[94][95]。 |

| Biogeography and nocturnality Main article: Biogeography Studies of urban evolution give an indication of how species may respond to stressors such as temperature change and toxicity. Species display varying abilities to respond to altered environments through both phenotypic plasticity and genetic evolution.[96][97][98] Researchers have documented the movement of many species into regions formerly too cold for them, often at rates faster than initially expected.[99] Permanent changes in the distribution of organisms from human influence will become identifiable in the geologic record. This has occurred in part as a result of changing climate, but also in response to farming and fishing, and to the accidental introduction of non-native species to new areas through global travel.[4] The ecosystem of the entire Black Sea may have changed during the last 2000 years as a result of nutrient and silica input from eroding deforested lands along the Danube River.[100][101] Researchers have found that the growth of the human population and expansion of human activity has resulted in many species of animals that are normally active during the day, such as elephants, tigers and boars, becoming nocturnal to avoid contact with humans, who are largely diurnal.[102][101] |

生物地理学と夜行性 主な記事 生物地理学 都市の進化に関する研究は、気温の変化や毒性などのストレス要因に種がどのように対応するかを示している。生物種は、表現型の可塑性と遺伝的進化の両方を 通じて、変化した環境に対応する様々な能力を示している[96][97][98]。研究者たちは、多くの種が以前は寒すぎて生息できなかった地域に移動 し、しばしば当初の予想よりも速い速度で移動したことを記録している[99]。 人間の影響による生物の分布の永続的な変化は、地質学的記録で確認できるようになる。これは、気候の変化の結果もあるが、農業や漁業への対応や、世界的な 旅行を通じて新しい地域に外来種が偶発的に持ち込まれることによっても起こっている[4]。黒海全体の生態系は、ドナウ川沿いの森林伐採地の浸食による栄 養塩とシリカの投入の結果、過去2000年の間に変化した可能性がある[100][101]。 研究者たちは、人間の人口の増加と人間活動の拡大によって、ゾウ、トラ、イノシシなど、通常は日中に活動する動物の多くの種が、主に昼行性である人間との接触を避けるために夜行性になっていることを発見した[102][101]。 |

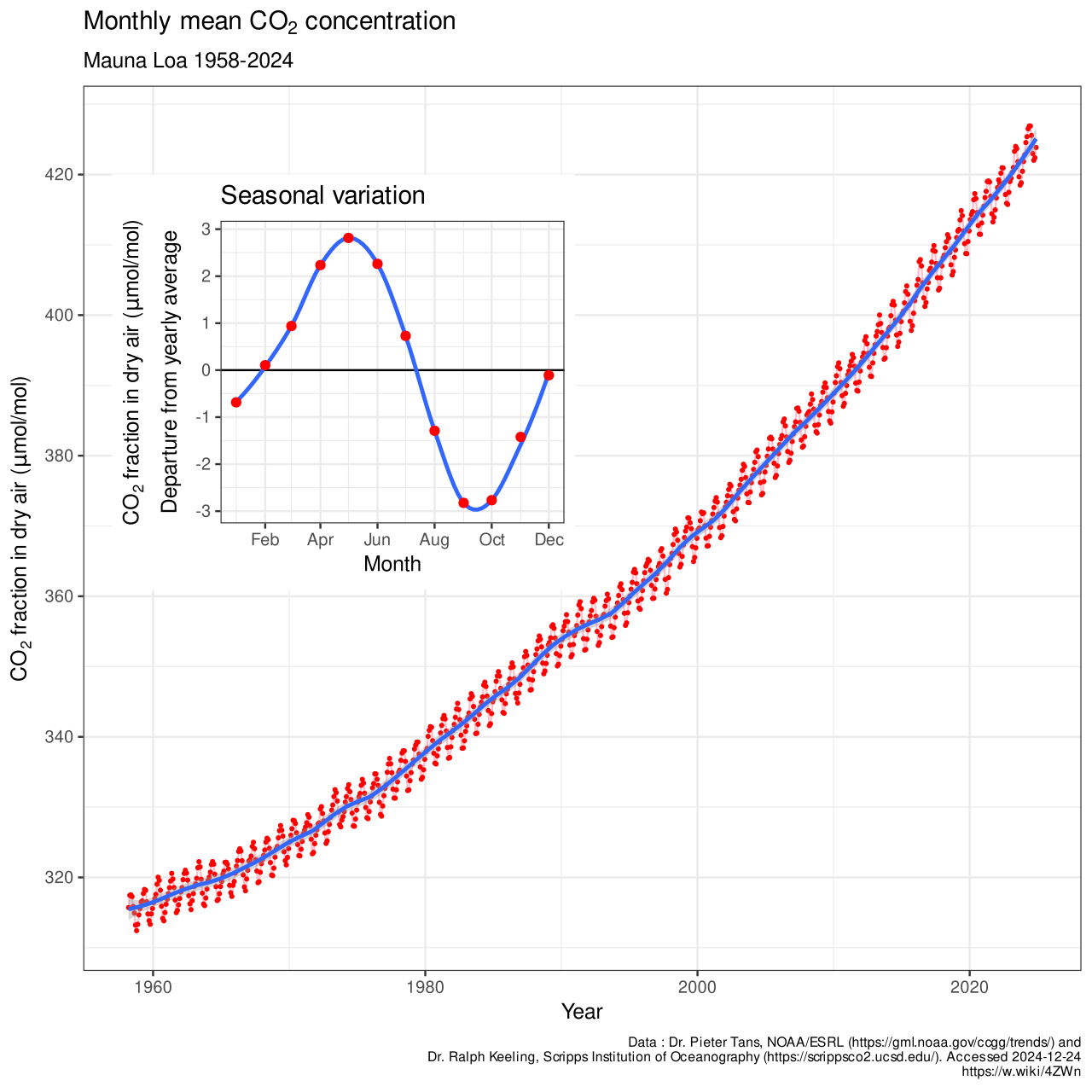

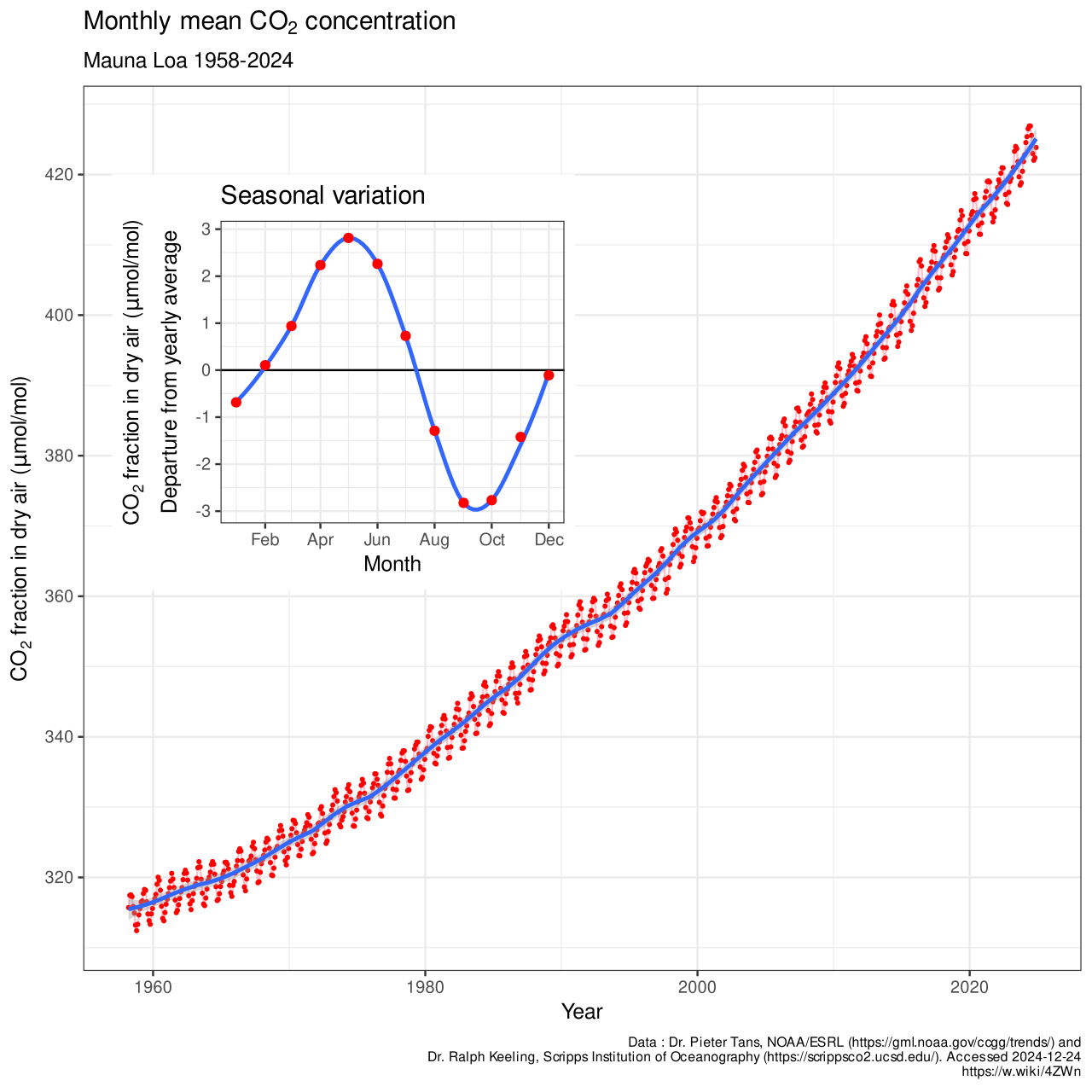

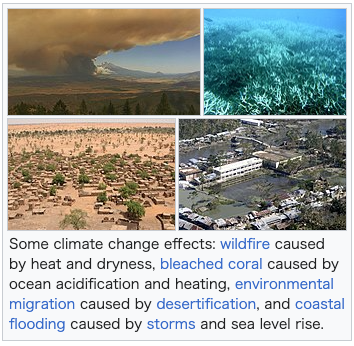

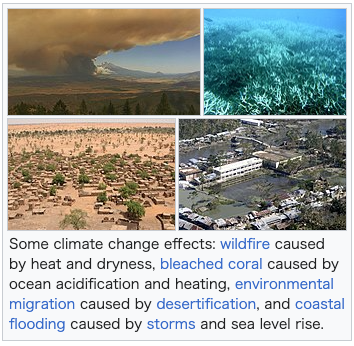

| Climate change Main articles: Climate change, Effects of climate change, and Carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere One geological symptom resulting from human activity is increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) content. This signal in the Earth's climate system is especially significant because it is occurring much faster,[103] and to a greater extent, than previously. Most of this increase is due to the combustion of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. This section is an excerpt from Carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere.[edit]  Atmospheric CO2 concentration measured at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii from 1958 to 2023 (also called the Keeling Curve). The rise in CO2 over that time period is clearly visible. The concentration is expressed as μmole per mole, or ppm. In Earth's atmosphere, carbon dioxide is a trace gas that plays an integral part in the greenhouse effect, carbon cycle, photosynthesis and oceanic carbon cycle. It is one of three main greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of Earth. The concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere reached 427 ppm (0.0427%) on a molar basis in 2024, representing 3341 gigatonnes of CO2.[104] This is an increase of 50% since the start of the Industrial Revolution, up from 280 ppm during the 10,000 years prior to the mid-18th century.[105][106][107] The increase is due to human activity.[108] This section is an excerpt from Effects of climate change.[edit] Effects of climate change are well documented and growing for Earth's natural environment and human societies. Changes to the climate system include an overall warming trend, changes to precipitation patterns, and more extreme weather. As the climate changes it impacts the natural environment with effects such as more intense forest fires, thawing permafrost, and desertification. These changes impact ecosystems and societies, and can become irreversible once tipping points are crossed. Climate activists are engaged in a range of activities around the world that seek to ameliorate these issues or prevent them from happening.[109] The effects of climate change vary in timing and location. Up until now the Arctic has warmed faster than most other regions due to climate change feedbacks.[110] Surface air temperatures over land have also increased at about twice the rate they do over the ocean, causing intense heat waves. These temperatures would stabilize if greenhouse gas emissions were brought under control. Ice sheets and oceans absorb the vast majority of excess heat in the atmosphere, delaying effects there but causing them to accelerate and then continue after surface temperatures stabilize. Sea level rise is a particular long term concern as a result. The effects of ocean warming also include marine heatwaves, ocean stratification, deoxygenation, and changes to ocean currents.[111]: 10 The ocean is also acidifying as it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[112] |

気候変動 主な記事 気候変動、気候変動の影響、地球大気中の二酸化炭素 人間活動に起因する地質学的徴候の一つは、大気中の二酸化炭素(CO2)含有量の増加である。地球の気候システムにおけるこのシグナルは、以前よりもはる かに速く、より広範囲に発生しているため、特に重要である[103]。この増加のほとんどは、石炭、石油、ガスなどの化石燃料の燃焼によるものである。 このセクションは、地球の大気中の二酸化炭素[編集]からの抜粋である。  ハワイのマウナロア天文台で1958年から2023年まで測定された大気中の二酸化炭素濃度(キーリング曲線とも呼ばれる)。この期間におけるCO2の上昇がはっきりとわかる。濃度は1モルあたりμモル、ppmで表される。 地球の大気中では、二酸化炭素は温室効果、炭素循環、光合成、海洋炭素循環に不可欠な役割を果たす微量ガスである。地球大気中の3大温室効果ガスのひとつ である。大気中の二酸化炭素(CO2)濃度は、2024年にはモルベースで427ppm(0.0427%)に達し、CO2の3341ギガトンに相当する [104]。これは産業革命の開始以来50%の増加であり、18世紀半ば以前の1万年間では280ppmであった[105][106][107]。この増 加は人間活動によるものである[108]。 この節は、気候変動の影響[編集]からの抜粋である。 気候変動の影響は十分に文書化されており、地球の自然環境と人間社会への影響は増大している。気候システムの変化には、全体的な温暖化傾向、降水パターン の変化、異常気象の増加などがある。気候が変化すると、森林火災の増加、永久凍土の融解、砂漠化など、自然環境に影響を及ぼす。こうした変化は生態系や社 会に影響を与え、転換点を超えると不可逆的になる可能性がある。気候活動家たちは、こうした問題を改善したり、未然に防いだりしようと、世界中でさまざま な活動を行っている[109]。 気候変動の影響は、時期や場所によって異なる。これまで北極圏は、気候変動のフィードバックにより、他のほとんどの地域よりも早く温暖化してきた [110]。陸地の地表気温も、海洋の気温の約2倍の速度で上昇しており、強烈な熱波を引き起こしている。温室効果ガスの排出が抑制されれば、これらの気 温は安定するだろう。氷床と海洋は、大気中の過剰な熱の大部分を吸収するため、大気への影響は遅らせることができるが、表面温度が安定した後も、その影響 は加速し、継続する。その結果、海面上昇が特に長期的な懸念事項となっている。海洋温暖化の影響には、海洋熱波、海洋成層化、脱酸素化、海流の変化も含ま れる[111]: 10 大気から二酸化炭素を吸収するため、海洋も酸性化している[112]。 |

Thick orange-brown smoke blocks half a blue sky, with conifers in the foreground A few grey fish swim over grey coral with white spikes Desert sand half covers a village of small flat-roofed houses with scattered green trees large areas of still water behind riverside buildings Some climate change effects: wildfire caused by heat and dryness, bleached coral caused by ocean acidification and heating, environmental migration caused by desertification, and coastal flooding caused by storms and sea level rise. Geomorphology Changes in drainage patterns traceable to human activity will persist over geologic time in large parts of the continents where the geologic regime is erosional. This involves, for example, the paths of roads and highways defined by their grading and drainage control. Direct changes to the form of the Earth's surface by human activities (quarrying and landscaping, for example) also record human impacts. It has been suggested[by whom?] that the deposition of calthemite formations exemplify a natural process which has not previously occurred prior to the human modification of the Earth's surface, and which therefore represents a unique process of the Anthropocene.[113] Calthemite is a secondary deposit, derived from concrete, lime, mortar or other calcareous material outside the cave environment.[114] Calthemites grow on or under man-made structures (including mines and tunnels) and mimic the shapes and forms of cave speleothems, such as stalactites, stalagmites, flowstone etc. |

オレンジ褐色の濃い煙が青空の半分を遮り、手前には針葉樹が生い茂る。 数匹の灰色の魚が、白いトゲのある灰色のサンゴの上を泳いでいる。 砂漠の砂が、緑の木々が散在する小さな平屋建ての村を半分覆っている。 川沿いの建物の背後には静水域が広がっている。 気候変動の影響:暑さと乾燥による山火事、海の酸性化と加熱によるサンゴの白化、砂漠化による環境移動、暴風雨と海面上昇による沿岸の洪水。 地形学 地質学的レジームが侵食的である大陸の大部分では、人間活動に起因する排水パターンの変化が地質学的な時間にわたって持続する。これは、例えば、道路や高 速道路が、その勾配や排水制御によって規定される経路に関係する。人間の活動(例えば採石や造園)による地表の形への直接的な変化も、人間の影響を記録し ている。 カルトテマイト地層の堆積は、人間が地球表面を改変する以前に起こったことのない自然プロセスを例証するものであり、したがって人新世の特異なプロセスを 示すものであると示唆されている。 [カルツェマイトは、コンクリート、石灰、モルタル、または洞窟環境外の他の石灰質物質に由来する二次堆積物である[114]。カルツェマイトは、人工構 造物(鉱山やトンネルを含む)の上や下に生育し、鍾乳石、石筍、流紋岩など、洞窟の岩石類の形状や形態を模倣する。 |

| Stratigraphy Sedimentological record Human activities, including deforestation and road construction, are believed to have elevated average total sediment fluxes across the Earth's surface.[4] However, construction of dams on many rivers around the world means the rates of sediment deposition in any given place do not always appear to increase in the Anthropocene. For instance, many river deltas around the world are actually currently starved of sediment by such dams, and are subsiding and failing to keep up with sea level rise, rather than growing.[4][115] Fossil record Increases in erosion due to farming and other operations will be reflected by changes in sediment composition and increases in deposition rates elsewhere. In land areas with a depositional regime, engineered structures will tend to be buried and preserved, along with litter and debris. Litter and debris thrown from boats or carried by rivers and creeks will accumulate in the marine environment, particularly in coastal areas, but also in mid-ocean garbage patches. Such human-created artifacts preserved in stratigraphy are known as "technofossils".[4][116]  Twentieth-century technofossils in inundated landfill deposits at East Tilbury on the River Thames estuary Changes in biodiversity will also be reflected in the fossil record, as will species introductions. An example cited is the domestic chicken, originally the red junglefowl Gallus gallus, native to south-east Asia but has since become the world's most common bird through human breeding and consumption, with over 60 billion consumed annually and whose bones would become fossilised in landfill sites.[117] Hence, landfills are important resources to find "technofossils".[118] |

層序学 堆積学的記録 森林伐採や道路建設などの人間活動は、地球表面の平均的な土砂総フラックスを増加させたと考えられている[4]。しかし、世界中の多くの河川にダムが建設 されたため、人新世において、任意の場所における土砂堆積の割合が必ずしも増加したようには見えない。例えば、世界中の多くの河川デルタは、実際にそのよ うなダムによって土砂に飢えており、成長するどころか、沈降して海面上昇に追いつけなくなっている[4][115]。 化石記録 耕作やその他の作業による侵食の増加は、土砂組成の変化や他の場所での堆積速度の増加によって反映される。堆積レジームがある陸地では、人工構造物は、ゴ ミや残骸とともに埋もれ、保存される傾向がある。船から投げ込まれたり、河川やクリークによって運ばれたりしたゴミや残骸は、海洋環境、特に沿岸域に蓄積 されるが、中海のゴミパッチにも蓄積される。地層中に保存されているこのような人間が作り出した人工物は、「テクノフォッシル」として知られている[4] [116]。  テムズ川河口のイースト・ティルベリーにある、浸水した埋立堆積物中の20世紀のテクノフォッシル 生物多様性の変化も、種の導入と同様に化石記録に反映される。例として挙げられているのは家禽のニワトリで、もともとは東南アジア原産の赤いジャングルの 鳥Gallus gallusだったが、人間の繁殖と消費によって世界で最も一般的な鳥となり、年間600億羽以上が消費され、その骨は埋立地で化石化するようになった [117]。 |

| Trace elements In terms of trace elements, there are distinct signatures left by modern societies. For example, in the Upper Fremont Glacier in Wyoming, there is a layer of chlorine present in ice cores from 1960's atomic weapon testing programs, as well as a layer of mercury associated with coal plants in the 1980s.[119][120][121] From the late 1940s, nuclear tests have led to local nuclear fallout and severe contamination of test sites both on land and in the surrounding marine environment. Some of the radionuclides that were released during the tests are 137Cs, 90Sr, 239Pu, 240Pu, 241Am, and 131I. These have been found to have had significant impact on the environment and on human beings. In particular, 137Cs and 90Sr have been found to have been released into the marine environment and led to bioaccumulation over a period through food chain cycles. The carbon isotope 14C, commonly released during nuclear tests, has also been found to be integrated into the atmospheric CO2, and infiltrating the biosphere, through ocean-atmosphere gas exchange. Increase in thyroid cancer rates around the world is also surmised to be correlated with increasing proportions of the 131I radionuclide.[122] The highest global concentration of radionuclides was estimated to have been in 1965, one of the dates which has been proposed as a possible benchmark for the start of the formally defined Anthropocene.[123] Human burning of fossil fuels has also left distinctly elevated concentrations of black carbon, inorganic ash, and spherical carbonaceous particles in recent sediments across the world. Concentrations of these components increases markedly and almost simultaneously around the world beginning around 1950.[4] |

微量元素 微量元素に関しては、現代社会が残した明確な痕跡がある。例えば、ワイオミング州のアッパー・フリーモント氷河では、1960年代の原子兵器実験計画に由 来する塩素の層が氷床コアに存在し、1980年代の石炭発電所に関連した水銀の層も存在する[119][120][121]。 1940年代後半から、核実験は局所的な放射性降下物や、陸上と周辺の海洋環境の両方における実験場の深刻な汚染をもたらした。核実験中に放出された放射 性核種には、137Cs、90Sr、239Pu、240Pu、241Am、131Iがある。これらは環境や人間に重大な影響を与えたことが判明している。 個別主義では、137Csと90Srが海洋環境に放出され、食物連鎖のサイクルを経て生物濃縮に至ったことが判明している。また、核実験中によく放出され る炭素同位体14Cは、海洋と大気のガス交換を通じて、大気中の二酸化炭素に溶け込み、生物圏に浸透していることが分かっている。世界中の甲状腺がん発生 率の増加も、131I放射性核種の割合の増加と相関していると推測されている[122]。 放射性核種の世界的な最高濃度は1965年であったと推定されており、これは正式に定義された人新世の開始の可能な基準として提案されている日付の一つである[123]。 化石燃料の人為的燃焼はまた、世界中の最近の堆積物中に、ブラックカーボン、無機灰分、球状の炭素質粒子の明確な高濃度を残している。これらの成分の濃度は、1950年頃から世界中で顕著に、ほぼ同時に増加している[4]。 |

| Anthropocene markers A marker that accounts for a substantial global impact of humans on the total environment, comparable in scale to those associated with significant perturbations of the geological past, is needed in place of minor changes in atmosphere composition.[124][125] A useful candidate for holding markers in the geologic time record is the pedosphere. Soils retain information about their climatic and geochemical history with features lasting for centuries or millennia.[126] Human activity is now firmly established as the sixth factor of soil formation.[127] Humanity affects pedogenesis directly by, for example, land levelling, trenching and embankment building, landscape-scale control of fire by early humans, organic matter enrichment from additions of manure or other waste, organic matter impoverishment due to continued cultivation and compaction from overgrazing. Human activity also affects pedogenesis indirectly by drift of eroded materials or pollutants. Anthropogenic soils are those markedly affected by human activities, such as repeated ploughing, the addition of fertilisers, contamination, sealing, or enrichment with artefacts (in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources they are classified as Anthrosols and Technosols). An example from archaeology would be dark earth phenomena when long-term human habitation enriches[128] the soil with black carbon. Anthropogenic soils are recalcitrant repositories of artefacts and properties that testify to the dominance of the human impact, and hence appear to be reliable markers for the Anthropocene. Some anthropogenic soils may be viewed as the 'golden spikes' of geologists (Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point), which are locations where there are strata successions with clear evidences of a worldwide event, including the appearance of distinctive fossils.[129] Drilling for fossil fuels has also created holes and tubes which are expected to be detectable for millions of years.[130] The astrobiologist David Grinspoon has proposed that the site of the Apollo 11 Lunar landing, with the disturbances and artifacts that are so uniquely characteristic of our species' technological activity and which will survive over geological time spans could be considered as the 'golden spike' of the Anthropocene.[131] An October 2020 study coordinated by University of Colorado at Boulder found that distinct physical, chemical and biological changes to Earth's rock layers began around the year 1950. The research revealed that since about 1950, humans have doubled the amount of fixed nitrogen on the planet through industrial production for agriculture, created a hole in the ozone layer through the industrial scale release of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), released enough greenhouse gasses from fossil fuels to cause planetary level climate change, created tens of thousands of synthetic mineral-like compounds that do not naturally occur on Earth, and caused almost one-fifth of river sediment worldwide to no longer reach the ocean due to dams, reservoirs and diversions. Humans have produced so many millions of tons of plastic each year since the early 1950s that microplastics are "forming a near-ubiquitous and unambiguous marker of Anthropocene".[132][133] The study highlights a strong correlation between global human population size and growth, global productivity and global energy use and that the "extraordinary outburst of consumption and productivity demonstrates how the Earth System has departed from its Holocene state since c. 1950 CE, forcing abrupt physical, chemical and biological changes to the Earth's stratigraphic record that can be used to justify the proposal for naming a new epoch—the Anthropocene."[133] A December 2020 study published in Nature found that the total anthropogenic mass, or human-made materials, outweighs all the biomass on earth, and highlighted that "this quantification of the human enterprise gives a mass-based quantitative and symbolic characterization of the human-induced epoch of the Anthropocene."[134][135] |

人新世マーカー 大気の組成のわずかな変化の代わりに、地質学的過去の重大な摂動に関連するものに匹敵する規模の、地球環境全体に対する人類の実質的な影響を説明するマーカーが必要である[124][125]。 地質学的時間記録のマーカーとして有用な候補は、土壌圏である。土壌は、何世紀あるいは何千年も続く特徴によって、気候や地球化学的な歴史に関する情報を 保持している[126]。人間の活動は、土壌形成の第6の要因として、現在では確固たる地位を築いている[127]。人間の活動も、侵食された物質や汚染 物質の漂着によって、間接的に土壌形成に影響を与える。人為起源の土壌とは、繰り返しの耕作、肥料の添加、汚染、封鎖、人工物による濃縮など、人間の活動 によって著しい影響を受けた土壌である(土壌資源の世界基準ベースでは、これらはアントロゾルとテクノゾルに分類されている)。考古学の例としては、人間 が長期にわたって居住することで、土壌が黒色炭素で濃縮[128]された場合のダークアース現象がある。 人為起源の土壌は、人為的な影響の優位性を証明する遺物や特性の不屈の保管場所であり、それゆえ人新世の信頼できるマーカーとなるようである。人為起源の 土壌の一部は、地質学者の「黄金のスパイク」(Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point)と見なすことができる。これは、特徴的な化石の出現を含む、世界的な出来事の明確な証拠を伴う地層の連続が存在する場所である[129]。化 石燃料の掘削はまた、数百万年にわたって検出可能であると予想される穴や管を作り出している。 [130] 宇宙生物学者のデイヴィッド・グリンスプーンは、アポロ11号の月面着陸地点は、我々の種の技術活動に特有であり、地質学的な時間的スパンで生き残る撹乱 や人工物とともに、人新世の「黄金のスパイク」とみなすことができると提唱している[131]。 コロラド大学ボルダー校がコーディネートした2020年10月の研究は、地球の岩石層に対する明確な物理的、化学的、生物学的変化が1950年頃から始 まっていることを発見した。1950年ごろから、人類は農業のための工業生産によって地球上の固定窒素の量を2倍に増やし、フロン(CFCs)を工業規模 で放出することによってオゾン層に穴を開け、惑星レベルの気候変動を引き起こすのに十分な量の温室効果ガスを化石燃料から放出し、地球上に自然には存在し ない何万種類もの合成鉱物のような化合物を作り出し、ダムや貯水池、分水によって世界中の河川の堆積物のほぼ5分の1が海に到達しなくなったことを明らか にした。人類は1950年代初頭から毎年何百万トンものプラスチックを生産してきたため、マイクロプラスチックは「人新世のほぼ普遍的で明白な目印を形成 している」[132][133]。この研究は、世界的な人類の人口規模と成長、世界的な生産性、世界的なエネルギー使用の間に強い相関関係があることを強 調し、「消費と生産性の異常な爆発は、地球システムが1950年頃からいかに完新世の状態から逸脱してきたかを示している。1950年以降、地球システム がいかに完新世の状態から逸脱し、地球の層序学的記録に物理的、化学的、生物学的な急激な変化を余儀なくされたかを示している。 2020年12月にNature誌に掲載された研究は、人為的質量、つまり人間が作り出した物質の総量が、地球上の全てのバイオマスを上回っていることを 発見し、「人間による事業のこの定量化は、人新世という人間が引き起こしたエポックの、質量をベースとした定量的かつ象徴的な特徴を与える」と強調した [134][135]。 |

| Debates "While we often think of ecological damage as a modern problem our impacts date back millennia to the times in which humans lived as hunter-gatherers. Our history with wild animals has been a zero-sum game: either we hunted them to extinction, or we destroyed their habitats with agricultural land." – Hannah Ritchie for Our World in Data.[136] Although the validity of Anthropocene as a scientific term remains disputed, its underlying premise, i.e., that humans have become a geological force, or rather, the dominant force shaping the Earth's climate, has found traction among academics and the public. In an opinion piece for Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Rodolfo Dirzo, Gerardo Ceballos, and Paul R. Ehrlich write that the term is "increasingly penetrating the lexicon of not only the academic socio-sphere, but also society more generally", and is now included as an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary.[137] The University of Cambridge, as another example, offers a degree in Anthropocene Studies.[138] In the public sphere, the term Anthropocene has become increasingly ubiquitous in activist, pundit, and political discourses. Some who are critical of the term Anthropocene nevertheless concede that "For all its problems, [it] carries power."[139] The popularity and currency of the word has led scholars to label the term a "charismatic meta-category"[140] or "charismatic mega-concept."[141] The term, regardless, has been subject to a variety of criticisms from social scientists, philosophers, Indigenous scholars, and others. The anthropologist John Hartigan has argued that due to its status as a charismatic meta-category, the term Anthropocene marginalizes competing, but less visible, concepts such as that of "multispecies."[142] The more salient charge is that the ready acceptance of Anthropocene is due to its conceptual proximity to the status quo – that is, to notions of human individuality and centrality. Other scholars appreciate the way in which the term Anthropocene recognizes humanity as a geological force, but take issue with the indiscriminate way in which it does. Not all humans are equally responsible for the climate crisis. To that end, scholars such as the feminist theorist Donna Haraway and sociologist Jason Moore, have suggested naming the Epoch instead as the Capitalocene.[143][144][145] Such implies capitalism as the fundamental reason for the ecological crisis, rather than just humans in general.[146][147][148] However, according to philosopher Steven Best, humans have created "hierarchical and growth-addicted societies" and have demonstrated "ecocidal proclivities" long before the emergence of capitalism.[149] Hartigan, Bould, and Haraway all critique what Anthropocene does as a term; however, Hartigan and Bould differ from Haraway in that they criticize the utility or validity of a geological framing of the climate crisis, whereas Haraway embraces it. In addition to "Capitalocene," other terms have also been proposed by scholars to trace the roots of the Epoch to causes other than the human species broadly. Janae Davis, for example, has suggested the "Plantationocene" as a more appropriate term to call attention to the role that plantation agriculture has played in the formation of the Epoch, alongside Kathryn Yusoff's argument that racism as a whole is foundational to the Epoch. The Plantationocene concept traces "the ways that plantation logics organize modern economies, environments, bodies, and social relations."[150][151][152][153] In a similar vein, Indigenous studies scholars such as Métis geographer Zoe Todd have argued that the Epoch must be dated back to the colonization of the Americas, as this "names the problem of colonialism as responsible for contemporary environmental crisis."[154] Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte has further argued that the Anthropocene has been apparent to Indigenous peoples in the Americas since the inception of colonialism because of "colonialism's role in environmental change."[155][156][157] Other critiques of Anthropocene have focused on the genealogy of the concept. Todd also provides a phenomenological account, which draws on the work of the philosopher Sara Ahmed, writing: "When discourses and responses to the Anthropocene are being generated within institutions and disciplines which are embedded in broader systems that act as de facto 'white public space,' the academy and its power dynamics must be challenged."[158] Other aspects which constitute current understandings of the concept of the Anthropocene such as the ontological split between nature and society, the assumption of the centrality and individuality of the human, and the framing of environmental discourse in largely scientific terms have been criticized by scholars as concepts rooted in colonialism and which reinforce systems of postcolonial domination.[159] To that end, Todd makes the case that the concept of Anthropocene must be indigenized and decolonized if it is to become a vehicle of justice as opposed to white thought and domination. Eco-philosopher David Abram, in a book chapter titled 'Interbreathing in the Humilocene', has proposed adoption of the term ‘Humilocene’ (the Epoch of Humility), which emphasizes an ethical imperative and ecocultural direction that human societies should take. The term plays with the etymological roots of the term ‘human’, thus connecting it back with terms such as humility, humus (the soil), and even a corrective sense of humiliation that some human societies should feel given their collective destructive impact on the earth.[160] |

討論 「私たちはしばしば生態系へのダメージを現代の問題として考えるが、その影響は人類が狩猟採集生活をしていた数千年前までさかのぼる。野生動物との歴史は ゼロサムゲームであった。狩猟で絶滅させるか、農地で生息地を破壊するかのどちらかであった。- ハンナ・リッチー『Our World in Data』誌[136]。 科学用語としてのアントロポセン(人新世)の妥当性については依然として論争が続いているが、その根底にある前提、すなわち、人類が地質学的な力、いや、 地球の気候を形成する支配的な力になっているということは、学者や一般市民の間で支持を得ている。ロドルフォ・ディルゾ、ジェラルド・セバロス、ポール・ R・エーリッヒは、『Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B』誌のオピニオン・ピースで、この用語は「学術的な社会圏だけでなく、より一般的な社会の辞書に浸透しつつある」と書いており、現在ではオックスフォー ド英語辞典の項目にも含まれている。 [138]公的な場では、アントロポセンという用語は活動家、評論家、政治家の言説の中でますます偏在するようになっている。アントロポセンという用語に 批判的な者の中には、それでも「そのすべての問題に対して、(それは)力を持つ」と認めている者もいる[139]。この言葉の人気と通用性から、学者たち はこの用語を「カリスマ的なメタカテゴリー」[140]、あるいは「カリスマ的なメガコンセプト」[141]と呼んでいる。 人類学者のジョン・ハーティガンは、カリスマ的なメタカテゴリーとしての地位のために、アントロポセンという用語が「多種多様性」のような、競合するがあ まり目立たない概念を疎外すると主張している[142]。より顕著な告発は、アントロポセンがすぐに受け入れられるのは、その概念的な現状への近さ、つま り人間の個性や中心性の概念によるものだというものである。 他の学者たちは、アントロポセンという用語が人類を地質学的な力として認識している点については評価しているが、その無差別な方法については問題視してい る。すべての人類が気候危機に等しく責任を負っているわけではない。そのため、フェミニスト理論家のドナ・ハラウェイや社会学者のジェイソン・ムーアのよ うな学者は、このエポックを「キャピタロセン」と命名することを提案している[143][144][145]。 [146][147][148]しかし、哲学者のスティーヴン・ベストによれば、人類は資本主義が出現するずっと以前から「階層的で成長中毒の社会」を作 り上げ、「生態系を破壊する性癖」を示してきた[149]。 キャピタロセン」以外にも、エポックの根源を広く人類以外の原因に求める学者によって、他の用語も提案されている。例えば、ジャナイ・デイヴィスは、人種 主義全体がエポックの基礎であるというキャサリン・ユーソフの主張と並んで、プランテーション農業がエポックの形成に果たした役割に注意を喚起するための より適切な用語として「プランテーション新世」を提案している。プランテーション新世の概念は、「プランテーションの論理が現代の経済、環境、身体、社会 関係を組織化する方法」を追跡するものである[150][151][152][153]。同様の流れで、メティスの地理学者であるゾーイ・トッドのような 先住民研究者は、エポックをアメリカ大陸の植民地化まで遡らなければならないと主張している。 「ポタワトミの哲学者であるカイル・パウィス・ホワイテはさらに、「植民地主義が環境変化において果たした役割」[155][156][157]のため に、人新世は植民地主義の始まりからアメリカ大陸の先住民にとって明白であったと主張している。 アントロポセンに対する他の批評は、その概念の系譜に焦点を当てている。トッドはまた、哲学者サラ・アーメッドの仕事を利用した現象学的な説明も提供して おり、次のように書いている: 人新世に対する言説や反応が、事実上の「白い公共空間」として機能する、より広範なシステムに組み込まれた制度や学問分野の中で生み出されるとき、アカデ ミズムとその権力力学は異議を唱えられなければならない。 「アントロポセンという概念の現在の理解を構成する他の側面、例えば、自然と社会との間の存在論的分裂、人間の中心性と個別性の仮定、主に科学的用語で環 境言説の枠組みを構成することなどは、植民地主義に根ざした概念であり、ポストコロニアル支配のシステムを強化するものであるとして、学者たちによって批 判されてきた。 [そのためトッドは、アントロポセンという概念が白人の思想や支配に対抗する正義の手段となるためには、土着化・脱植民地化されなければならないと主張し ている。 環境哲学者のデイヴィッド・エイブラムは、「Humiloceneにおける相互呼吸」と題した本の章の中で、「Humilocene」(謙虚の時代)とい う用語の採用を提案している。この用語は、「人間」という用語の語源と戯れ、謙虚さ、腐植(土壌)、さらには人類社会が地球に与えた集団的な破壊的影響か ら感じるべき屈辱感の是正といった用語と結びつけている[160]。 |

| "Early anthropocene" model Main article: Early anthropocene William Ruddiman has argued that the Anthropocene began approximately 8,000 years ago with the development of farming and sedentary cultures.[161] At that point, humans were dispersed across all continents except Antarctica, and the Neolithic Revolution was ongoing. During this period, humans developed agriculture and animal husbandry to supplement or replace hunter-gatherer subsistence.[162] Such innovations were followed by a wave of extinctions, beginning with large mammals and terrestrial birds. This wave was driven by both the direct activity of humans (e.g. hunting) and the indirect consequences of land-use change for agriculture. Landscape-scale burning by prehistoric hunter-gathers may have been an additional early source of anthropogenic atmospheric carbon.[163] Ruddiman also claims that the greenhouse gas emissions in-part responsible for the Anthropocene began 8,000 years ago when ancient farmers cleared forests to grow crops.[164][165][166] Ruddiman's work has been challenged with data from an earlier interglaciation ("Stage 11", approximately 400,000 years ago) which suggests that 16,000 more years must elapse before the current Holocene interglaciation comes to an end, and thus the early anthropogenic hypothesis is invalid.[167] Also, the argument that "something" is needed to explain the differences in the Holocene is challenged by more recent research showing that all interglacials are different.[168] |

「前期人新世」モデル 主な記事 初期人新世 ウィリアム・ラディマンは、人新世はおよそ8,000年前に農耕と定住文化の発展とともに始まったと主張している[161]。その時点で、人類は南極大陸 を除く全ての大陸に分散し、新石器革命が進行していた。この時期、人類は狩猟採集生活を補うため、あるいは狩猟採集生活に取って代わるために、農業と畜産 業を発展させた[162]。このような技術革新の後、大型哺乳類と陸生鳥類を皮切りに、絶滅の波が押し寄せた。この波は、人間の直接的な活動(狩猟など) と、農業のための土地利用の変化がもたらした間接的な結果の両方によって引き起こされた。先史時代の狩猟採集民による景観規模の焼畑は、人為起源の大気中 炭素のさらなる初期発生源であった可能性がある[163]。ラディマンはまた、人新世の原因の一部である温室効果ガスの排出は、8,000年前に古代の農 民が作物を栽培するために森林を伐採したときに始まったと主張している[164][165][166]。 ラディマンの研究は、現在の完新世の間氷期が終わるまでにさらに16,000年経過しなければならず、したがって初期の人為起源仮説は無効であることを示 唆する初期の間氷期(「ステージ11」、約40万年前)のデータによって異議を唱えられた[167]。また、完新世の違いを説明するために「何か」が必要 であるという主張は、すべての間氷期が異なることを示すより最近の研究によって異議を唱えられた[168]。 |

| Homogenocene Homogenocene (from old Greek: homo-, same; geno-, kind; kainos-, new;) is a more specific term used to define our current epoch, in which biodiversity is diminishing and biogeography and ecosystems around the globe seem more and more similar to one another mainly due to invasive species that have been introduced around the globe either on purpose (crops, livestock) or inadvertently. This is due to the newfound globalism that humans participate in, as species traveling across the world to another region was not as easily possible in any point of time in history as it is today.[169] The term Homogenocene was first used by Michael Samways in his editorial article in the Journal of Insect Conservation from 1999 titled "Translocating fauna to foreign lands: Here comes the Homogenocene."[170] The term was used again by John L. Curnutt in the year 2000 in Ecology, in a short list titled "A Guide to the Homogenocene",[171] which reviewed Alien species in North America and Hawaii: impacts on natural ecosystems by George Cox. Charles C. Mann, in his acclaimed book 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, gives a bird's-eye view of the mechanisms and ongoing implications of the homogenocene.[172] |

ホモジェノセン ホモジェノセン(古ギリシャ語:homo-「同じ」、geno-「種類」、kainos-「新しい」)とは、生物多様性が減少し、生物地理学や世界中の生 態系が、意図的(農作物や家畜)に、あるいは不注意に世界中に持ち込まれた移入種のために、互いにますます類似しているように見える現在の時代を定義する ために使われる、より具体的な用語である。これは、人類が新たに見出したグローバリズムによるものであり、種が世界を横断して別の地域に移動することは、 歴史のどの時点においても、今日ほど容易ではなかったからである[169]。 ホモゲノセンという言葉は、1999年にマイケル・サムウェイズがJournal of Insect Conservationに寄稿した「Translocating fauna to foreign lands: ホモゲノセンがやってくる」[170]。 この用語は、2000年にジョン・L・カーナットが『Ecology』誌の「A Guide to the Homogenocene」と題された短いリストの中で再び使用した[171]。このリストでは、ジョージ・コックスによる「Alien species in North America and Hawaii: impacts on natural ecosystems(北米とハワイの外来種:自然生態系への影響)」をレビューしている。チャールズ・C・マンは絶賛された著書『1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created(コロンブスが創造した新世界を暴く)』では、ホモジェノセンのメカニズムと現在進行中の意味合いを俯瞰している[172]。 |

| Society and culture Humanities The concept of the Anthropocene has also been approached via humanities such as philosophy, literature and art. In the scholarly world, it has been the subject of increasing attention through special journals,[173] conferences,[174][175] and disciplinary reports.[176] The Anthropocene, its attendant timescale, and ecological implications prompt questions about death and the end of civilisation,[177] memory and archives,[178] the scope and methods of humanistic inquiry,[179] and emotional responses to the "end of nature".[180] Some scholars have posited that the realities of the Anthropocene, including "human-induced biodiversity loss, exponential increases in per-capita resource consumption, and global climate change," have made the goal of environmental sustainability largely unattainable and obsolete.[181] Historians have actively engaged the Anthropocene. In 2000, the same year that Paul Crutzen coined the term, world historian John McNeill published Something New Under the Sun,[182] tracing the rise of human societies' unprecedented impact on the planet in the twentieth century.[182] In 2001, historian of science Naomi Oreskes revealed the systematic efforts to undermine trust in climate change science and went on to detail the corporate interests delaying action on the environmental challenge.[183][184] Both McNeill and Oreskes became members of the Anthropocene Working Group because of their work correlating human activities and planetary transformation. |

社会と文化 人文科学 人新世の概念は、哲学、文学、芸術などの人文科学を通じてもアプローチされてきた。人新世、それに付随するタイムスケール、生態学的な意味合いは、死と文 明の終焉、[177]記憶とアーカイブ、[178]人文学的探求の範囲と方法、[179]そして「自然の終焉」に対する感情的な反応についての疑問を促し ている。 [180]「人為的な生物多様性の喪失、一人当たりの資源消費量の指数関数的な増加、地球規模の気候変動」を含む人新世の現実は、環境の持続可能性という 目標をほとんど達成不可能で陳腐なものにしているとする学者もいる[181]。 歴史家は人新世に積極的に関与してきた。2000年、ポール・クルッツェンがこの言葉を作ったのと同じ年に、世界史家のジョン・マクニールは 『Something New Under the Sun』を出版した。 [2001年、科学史家のナオミ・オレスケスは、気候変動科学に対する信頼を損なわせようとする組織的な取り組みを明らかにし、環境問題への取り組みを遅 らせている企業の利益について詳述した[183][184]。マクニールとオレスケスは共に、人間の活動と惑星の変容を関連付ける仕事をしたことから、人 新世作業部会のメンバーとなった。 |

| Popular culture In 2019, the English musician Nick Mulvey released a music video on YouTube named "In the Anthropocene".[185] In cooperation with Sharp's Brewery, the song was recorded on 105 vinyl records made of washed-up plastic from the Cornish coast.[186] The Anthropocene Reviewed is a podcast and book by author John Green, where he "reviews different facets of the human-centered planet on a five-star scale".[187] Photographer Edward Burtynsky created "The Anthropocene Project" with Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, which is a collection of photographs, exhibitions, a film, and a book. His photographs focus on landscape photography that captures the effects human beings have had on the earth.[188][189] In 2015, the American death metal band Cattle Decapitation released its seventh studio album titled The Anthropocene Extinction.[190] In 2020, Canadian musician Grimes released her fifth studio album titled Miss Anthropocene. The name is also a pun on the feminine title "Miss" and the words "misanthrope" and "Anthropocene."[191] |

大衆文化 2019年、イギリスのミュージシャンであるニック・マルヴェイは、YouTubeで「In the Anthropocene」と名付けられたミュージックビデオを公開した[185]。 シャープス・ブルワリーの協力のもと、この曲はコーンウォール海岸で洗われたプラスチックで作られた105枚のレコードで録音された[186]。 The Anthropocene Reviewed』は、作家のジョン・グリーンによるポッドキャストと本で、「人間を中心とした地球の異なる側面を5つ星でレビュー」している[187]。 写真家のエドワード・バーティンスキーは、ジェニファー・バイチュワル、ニコラス・ド・ペンシエとともに「人新世プロジェクト」を立ち上げ、写真集、展覧 会、映画、本を出版した。彼の写真は、人類が地球に与えた影響を捉えた風景写真に焦点を当てている[188][189]。 2015年、アメリカのデスメタル・バンド、キャトル・デカピテーションが『The Anthropocene Extinction』というタイトルの7枚目のスタジオ・アルバムをリリースした[190]。 2020年、カナダのミュージシャン、グライムスは『ミス・アントロポセン』というタイトルの5枚目のスタジオ・アルバムをリリースした。この名前は、女性的なタイトルである「ミヘ」と「人間嫌い」と「アントロポセン」をかけたダジャレでもある[191]。 |

| Earth Overshoot Day – Calculated calendar date when humanity's yearly consumption exceeds Earth's replenishment Ecological footprint – Individual's or a group's human demand on nature Ecological overshoot – Demands on ecosystem exceeding regeneration Holocene extinction – Ongoing extinction event caused by human activity Novel ecosystem – Human-created ecological niche Overconsumption (economics) – Resource use exceeding carrying capacity Planetary boundaries – Limits not to be exceeded if humanity wants to survive in a safe ecosystem |

アース・オーバーシュート・デー - 人類の年間消費量が地球への補給量を上回る暦日を算出する。 エコロジカル・フットプリント - 個人または集団の自然に対する人間の需要 エコロジカル・オーバーシュート - 生態系への要求が再生を上回ること 完新世の絶滅 - 人間の活動によって引き起こされた継続的な絶滅現象 新しい生態系 - 人間が作り出した生態学的ニッチ 過剰消費(経済学) - 容量を超える資源利用 惑星の境界 - 人類が安全な生態系で生き延びたいのであれば、超えてはならない限界値 |