アラワク族

Arawak

Arawak

woman by John Gabriel Stedman,

wearing a loin cloth of woven beads.

☆

アラワク族は、南アメリカ北部およびカリブ海の原住民である。「アラワク族」という用語は、異なる原住民グループに対して、さまざまな時代に適用されてきた。南アメリカのロコノ族から、カリブ海の大アンティル諸島および小アンティル諸島北部に居住していたタイノ族(島アラワク族)までである。これらのグループはすべて、関連するアラワク語族の言語を話していた。[1]

| The Arawak are a group of Indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. The term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to different Indigenous groups, from the Lokono of South America to the Taíno (Island Arawaks), who lived in the Greater Antilles and northern Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. All these groups spoke related Arawakan languages.[1] | アラワク族 は、南アメリカ北部およびカリブ海の原住民である。「アラワク族」という用語は、異なる原住民グループに対して、さまざまな時代に適用されてきた。南アメ リカのロコノ族から、カリブ海の大アンティル諸島および小アンティル諸島北部に居住していたタイノ族(島アラワク族)までである。これらのグループはすべ て、関連するアラワク語族の言語を話していた。[1] |

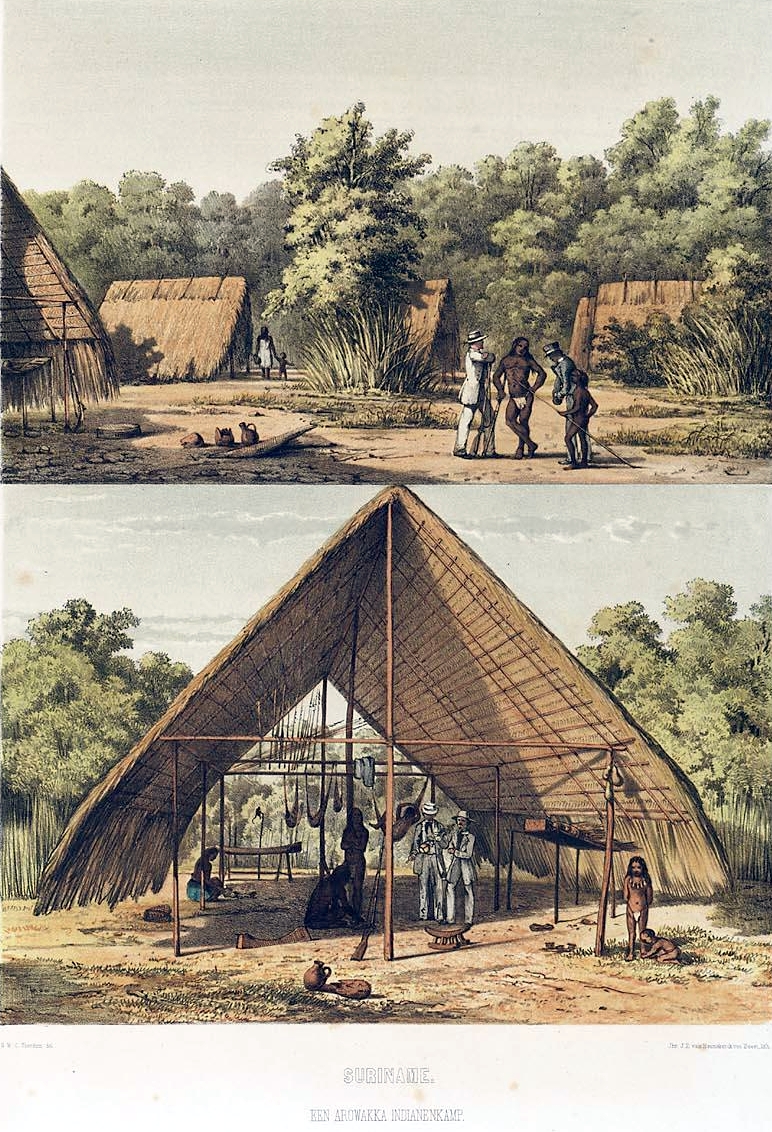

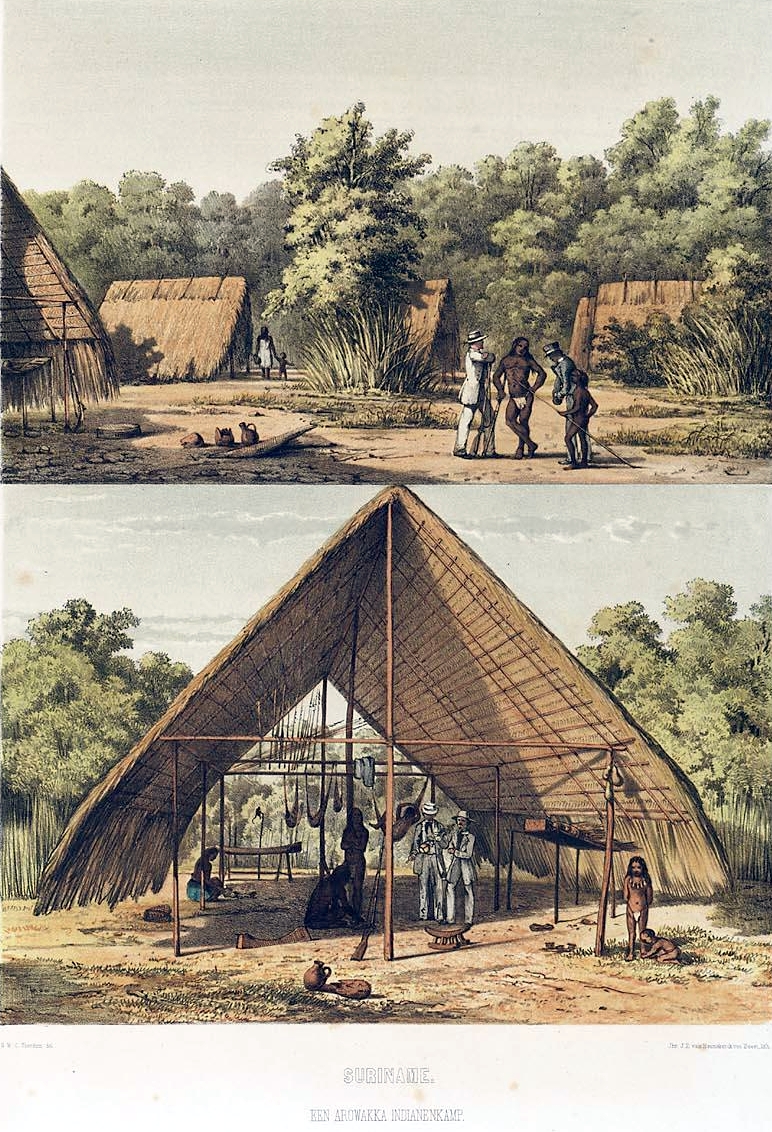

Name Arawak village (1860). Early Spanish explorers and administrators used the terms Arawak and Caribs to distinguish the peoples of the Caribbean, with Carib reserved for Indigenous groups that they considered hostile and Arawak for groups that they considered friendly.[2]: 121 In 1871, ethnologist Daniel Garrison Brinton proposed calling the Caribbean populace "Island Arawak" because of their cultural and linguistic similarities with the mainland Arawak. Subsequent scholars shortened this convention to "Arawak", creating confusion between the island and mainland groups. In the 20th century, scholars such as Irving Rouse resumed using "Taíno" for the Caribbean group to emphasize their distinct culture and language.[1] |

名称 アラワク族の村(1860年)。 初期のスペイン人探検家や行政官は、カリブ海の諸民族を区別するために「アラワク族」と「カリブ族」という用語を使用し、カリブ族は敵対的とみなされた先住民グループに、アラワク族は友好的とみなされたグループに割り当てられた。[2]:121 1871年、民族学者ダニエル・ギャリソン・ブリントンは、大陸のアラワク族との文化的・言語的類似性から、カリブ海の住民を「アイランド・アラワク」と 呼ぶことを提案した。 それ以降の学者たちは、この呼称を「アラワク」と短縮し、島嶼部と大陸部のグループを混同するようになった。 20世紀に入ると、アーヴィング・ラウスなどの学者が、カリブ海のグループに「タイノ」という呼称を再び使用し、彼らの独特な文化と言語を強調するように なった。[1] |

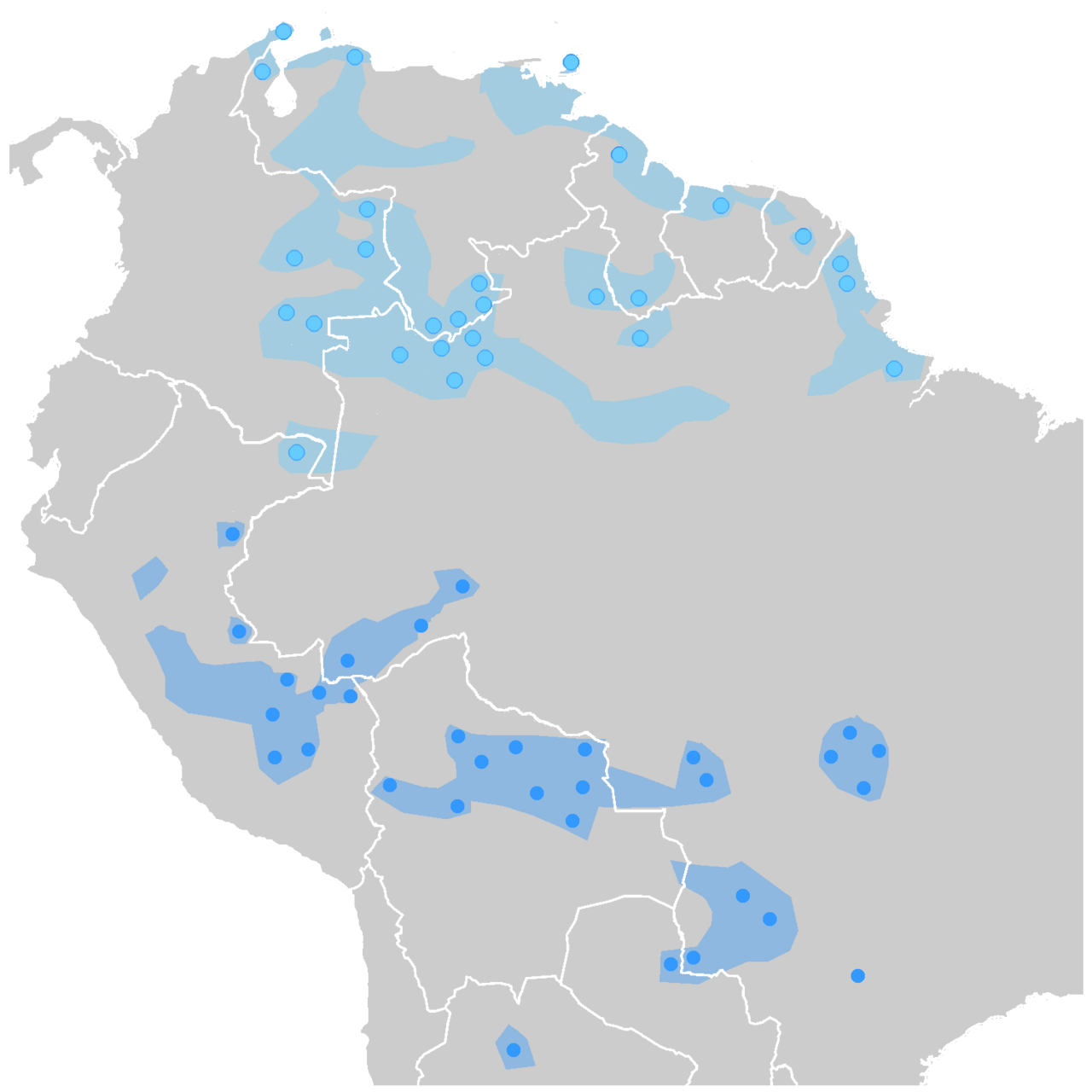

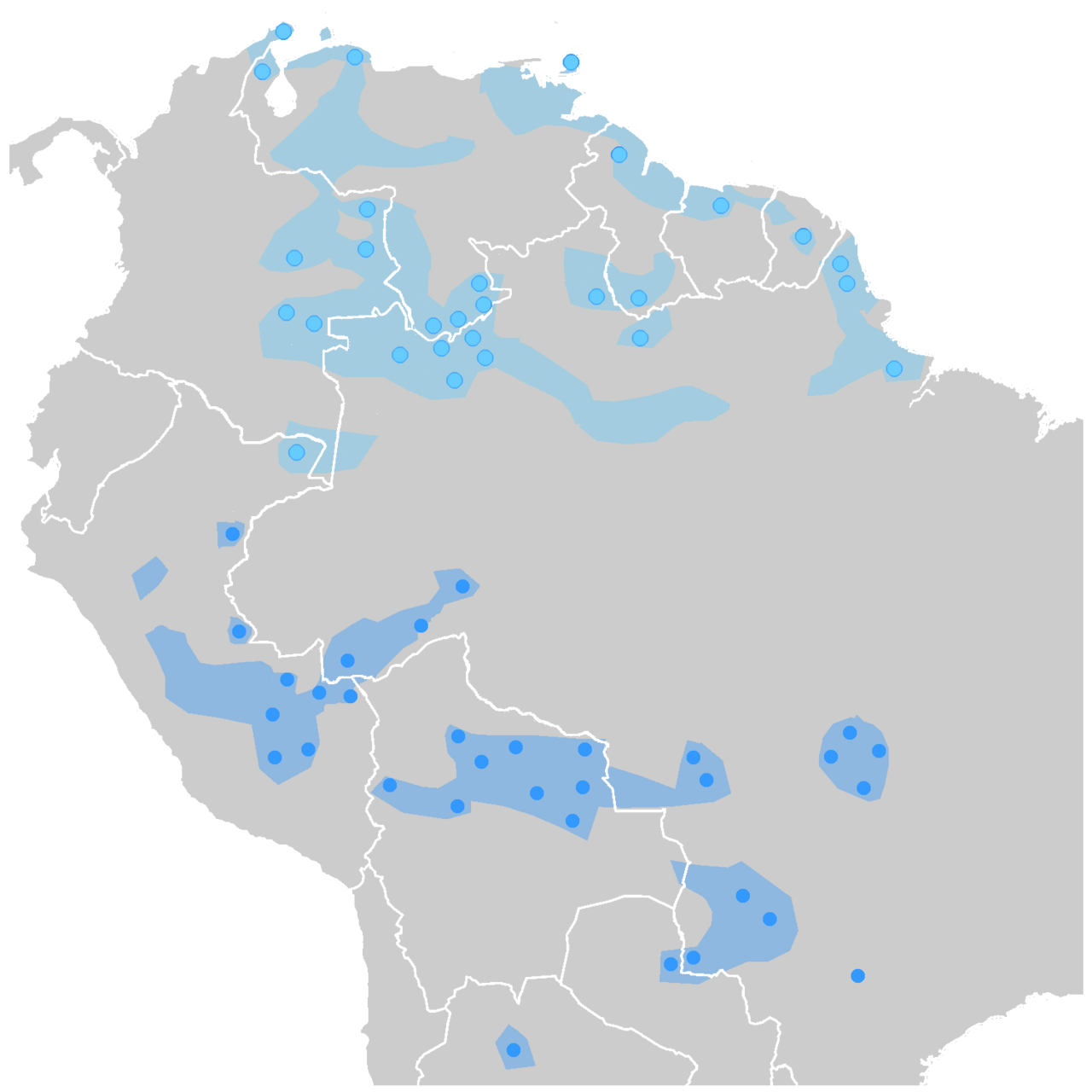

History Arawakan languages in South America. The northern Arawakan languages are colored in light blue, southern Arawakan languages in dark blue. The Arawakan languages may have emerged in the Orinoco River valley in present-day Venezuela. They subsequently spread widely, becoming by far the most extensive language family in South America at the time of European contact, with speakers located in various areas along the Orinoco and Amazonian rivers and their tributaries.[3] The group that self-identified as the Arawak, also known as the Lokono, settled the coastal areas of what is now Guyana, Suriname, Grenada, Bahamas, Jamaica[4] and parts of the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.[1][5] Michael Heckenberger, an anthropologist at the University of Florida who helped found the Central Amazon Project, and his team found elaborate pottery, ringed villages, raised fields, large mounds, and evidence for regional trade networks that are all indicators of a complex culture. There is also evidence that they modified the soil using various techniques such as adding charcoal to transform it into black earth, which even today is famed for its agricultural productivity. Maize and sweet potatoes were their main crops, though they also grew cassava and yautia. The Arawaks fished using nets made of fibers, bones, hooks, and harpoons. According to Heckenberger, pottery and other cultural traits show these people belonged to the Arawakan language family, a group that included the Tainos, the first Native Americans Columbus encountered. It was the largest language group that ever existed in the pre-Columbian Americas.[6] At some point, the Arawakan-speaking Taíno culture emerged in the Caribbean. Two major models have been presented to account for the arrival of Taíno ancestors in the islands; the "Circum-Caribbean" model suggests an origin in the Colombian Andes connected to the Arhuaco people, while the Amazonian model supports an origin in the Amazon basin, where the Arawakan languages developed.[7] The Taíno were among the first American people to encounter Europeans. Christopher Columbus visited multiple islands and chiefdoms on his first voyage in 1492, which was followed by the establishment of La Navidad[8] that same year on the northeast coast of Hispaniola, the first Spanish settlement in the Americas. Relationships between the Spaniards and the Taíno would ultimately sour. Some of the lower-level chiefs of the Taíno appeared to have assigned a supernatural origin to the explorers. When Columbus returned to La Navidad on his second voyage, he found the settlement burned down and the 39 men he had left there killed.[9] With the establishment of a second settlement, La Isabella, and the discovery of gold deposits on the island, the Spanish settler population on Hispaniola started to grow substantially, while disease and conflict with the Spanish began to kill tens of thousands of Taíno every year. By 1504, the Spanish had overthrown the last of the Taíno cacique chiefdoms on Hispaniola, and firmly established the supreme authority of the Spanish colonists over the now-subjugated Taíno. Over the next decade, the Spanish colonists presided over a genocide of the remaining Taíno on Hispaniola, who suffered enslavement, massacres, or exposure to diseases.[8] The population of Hispaniola at the point of first European contact is estimated at between several hundred thousand to over a million people,[8] but by 1514, it had dropped to a mere 35,000.[8] By 1509, the Spanish had successfully conquered Puerto Rico and subjugated the approximately 30,000 Taíno inhabitants. By 1530, there were 1,148 Taíno left alive in Puerto Rico.[10] Taíno influence has survived even until today, though, as can be seen in the religions, languages, and music of Caribbean cultures.[11] The Lokono and other South American groups resisted colonization for a longer period, and the Spanish remained unable to subdue them throughout the 16th century. In the early 17th century, they allied with the Spanish against the neighbouring Kalina (Caribs), who allied with the English and Dutch.[12] The Lokono benefited from trade with European powers into the early 19th century, but suffered thereafter from economic and social changes in their region, including the end of the plantation economy. Their population declined until the 20th century, when it began to increase again.[13] Most of the Arawak of the Antilles died out or intermarried after the Spanish conquest. In South America, Arawakan-speaking groups are widespread, from southwest Brazil to the Guianas in the north, representing a wide range of cultures. They are found mostly in the tropical forest areas north of the Amazon. As with all Amazonian native peoples, contact with European settlement has led to culture change and depopulation among these groups.[14] |

歴史 南アメリカのArawakan諸語。北のArawakan諸語は水色、南のArawakan諸語は青で色分けされている。 Arawakan諸語は、現在のベネズエラのオリノコ川流域で誕生したと考えられている。その後、広く普及し、ヨーロッパ人が接触した当時、オリノコ川や アマゾン川およびその支流沿いのさまざまな地域に話者が存在し、南アメリカで最も広範な言語族となった。 [3] また、自らをアラワク族と称するグループは、ロコノ族としても知られ、現在のガイアナ、スリナム、グレナダ、バハマ、ジャマイカ[4]、トリニダード・ト バゴ諸島の一部の沿岸地域に定住していた。[1][5] フロリダ大学の文化人類学者で、セントラル・アマゾン・プロジェクトの創設に携わったマイケル・ヘッケンバーガー氏と彼のチームは、精巧な陶器、環状集 落、盛り土、大きな塚、そして地域貿易ネットワークの証拠など、複雑な文化の指標となるものを発見した。また、木炭を加えて黒土に変えるなど、さまざまな 技術を用いて土壌を改良していた証拠も発見されている。この黒土は現在でも農業生産性の高さで有名である。トウモロコシとサツマイモが彼らの主な作物で あったが、キャッサバやヤウティアも栽培していた。アラワク族は、繊維、骨、釣り針、もりでできた網を使って魚を捕まえていた。ヘッケンバーガー氏による と、陶器やその他の文化的な特徴から、この人々はアラワク語族に属することが分かっている。アラワク語族には、コロンブスが最初に遭遇したネイティブ・ア メリカンであるタイノ族も含まれる。アラワク語族は、コロンブス到来以前のアメリカ大陸に存在した最大の言語グループである。 ある時点で、アラワク語を話すタイノ族の文化がカリブ海地域に登場した。タイノ族の祖先が諸島に到着した経緯については、主に2つのモデルが提示されてい る。「環カリブ海」モデルは、コロンビアのアンデス地方を起源とし、アルワコ族と関連があるとする説である。一方、「アマゾン」モデルは、アマゾン川流域 を起源とし、アラワク語族が発展したとする説である。[7] タイノ族は、ヨーロッパ人と遭遇した最初のアメリカ先住民の1つであった。クリストファー・コロンブスは1492年の最初の航海で複数の島々や首長国を訪 れ、その年にイスパニョーラ島の北東海岸にラ・ナビダ(La Navidad)[8]を建設した。これはアメリカ大陸における最初のスペイン人入植地であった。スペイン人とタイノ族の関係は最終的に悪化した。タイノ 族の下級首長の中には、探検家たちに超自然的な起源を割り当てた者もいたようである。コロンブスが2度目の航海でラ・ナビダに戻ったとき、集落は焼き払わ れ、残してきた39人の男たちが殺されているのを発見した。 2つ目の集落ラ・イサベラが建設され、島に金鉱が発見されたことで、イスパニオラ島のスペイン人入植者人口は大幅に増加し始めたが、一方で病気とスペイン 人との紛争により、毎年何万人ものタイノ族が命を落とすようになった。1504年までに、スペイン人はイスパニオラ島最後のタイノ族の首長国を滅ぼし、征 服されたタイノ族に対するスペイン人入植者の最高権力を確固たるものにした。その後10年間にわたり、スペイン人入植者はイスパニオラ島に残るタイノ族の 大量虐殺を指揮し、タイノ族は奴隷化、虐殺、あるいは伝染病に苦しめられた。 [8] ヨーロッパ人が初めて接触した時点でのイスパニオラ島の人口は、数十万から100万人以上と推定されているが、[8] 1514年にはわずか3万5000人にまで減少していた。[8] 1509年までにスペイン人はプエルトリコを征服し、およそ3万人のタイノ族を服従させた。1530年までに、プエルトリコには1,148人のタイノ族が 残るのみとなった。 タイノ族の影響は今日まで生き残っており、カリブ文化の宗教、言語、音楽に見ることができる。[11] ロコノ族やその他の南米の部族は、より長い期間にわたって植民地化に抵抗し、スペインは16世紀を通じて彼らを征服することができなかった。17世紀初頭 には、彼らはスペインと手を組み、イギリスやオランダと同盟を結んだ近隣のカリナ族(カリブ族)と戦った。[12] ロコノ族は19世紀初頭までヨーロッパ列強との貿易から利益を得ていたが、その後はプランテーション経済の終焉を含む、彼らの地域における経済的・社会的 変化に苦しめられた。彼らの人口は20世紀まで減少したが、その後再び増加し始めた。[13] スペインによる征服後、アンティル諸島のほとんどのアラワク族は絶滅するか、混血した。南アメリカでは、アラワク語を話すグループは広く分布しており、ブ ラジル南西部から北のギアナまで、さまざまな文化を代表している。彼らは主にアマゾン北部の熱帯雨林地帯に分布している。他のアマゾンの先住民と同様に、 ヨーロッパ人入植者との接触により、これらのグループの間では文化の変化と人口減少が起こった。[14] |

Modern population and descendants Arawak people gathered for an audience with the Dutch Governor in Paramaribo, Suriname, 1880 Kalinago During the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Island Carib population in St. Vincent was greater than that in Dominica. Both the Island Caribs (Yellow Caribs) and the Black Caribs (Garifuna) fought against the British during the Second Carib War. After the end of the war, the British deported the Garifuna (a population of 4,338) to Roatan Island, while the Island Caribs (whose population consisted of 80 people) were allowed to stay on St. Vincent.[15] The 1812 eruption of La Soufrière destroyed the Carib territory, killing a majority of the Yellow Caribs. After the eruption, 130 Yellow Caribs and 59 Black Caribs survived on St. Vincent. Unable to recover from the damage caused by the eruption, 120 of the Yellow Caribs, under Captain Baptiste, emigrated to Trinidad. In 1830, the Carib population numbered less than 100. The population made a remarkable recovery after that, although almost the entire tribe died out during the 1902 eruption of La Soufrière.[16][17] As of 2008, a small population of around 3,400 Kalinago survived in the Kalinago Territory in northeast Dominica.[18] The Kalinago of Dominica maintained their independence for many years by taking advantage of the island's rugged terrain. The island's east coast includes a 3,700-acre (15 km2) territory formerly known as the Carib Territory that was granted to the people by the British government in 1903. The Dominican Kalinago elect their own chief. In July 2003, the Kalinago observed 100 Years of Territory, and in July 2014, Charles Williams was elected Kalinago Chief, succeeding Chief Garnette Joseph.[19] |

現代の人口と子孫 1880年、スリナムのパラマリボでオランダ総督に謁見するアラワク族の人々 カリナゴ族 18世紀初頭、セントビンセント島における島カリブ族の人口はドミニカ島よりも多かった。 第二次カリブ戦争では、島カリブ族(イエローカリブ族)と黒カリブ族(ガリフナ族)の両方が英国と戦った。戦争の終結後、イギリスはガリフナ族(人口 4,338人)をロアタン島に追放したが、島カリブ族(人口80人)はセントビンセントに留まることを許された。[15] 1812年のラ・スーフリエールの噴火はカリブ族の領土を破壊し、大多数の黄色カリブ族を殺した。噴火の後、セントビンセント島には130人のイエロー・ カリブ族と59人のブラック・カリブ族が残った。噴火による被害から立ち直ることができず、イエロー・カリブ族の120人がキャプテン・バプティストの指 揮下でトリニダードに移住した。1830年にはカリブ族の人口は100人以下に減少した。その後、人口は著しく回復したが、1902年のラ・スーフリエー ルの噴火では部族のほぼ全員が死亡した。[16][17] 2008年現在、約3,400人のカリナゴ族がドミニカ北東部のカリナゴ族居住区で暮らしている。[18] ドミニカのカリナゴ族は、島の起伏に富んだ地形をうまく利用することで、長年にわたって独立性を維持してきた。島の東海岸には、かつてカリブ族の領土とし て知られていた3,700エーカー(15km2)の領土があり、1903年に英国政府からカリナゴ族に与えられた。ドミニカ人カリナゴ族は自分たちで首長 を選出する。2003年7月にはカリナゴ族が領土100周年を祝った。2014年7月には、チャールズ・ウィリアムズがガネット・ジョセフ首長の後を継い でカリナゴ族の首長に選出された。[19] |

| Lokono In the 21st century, about 10,000 Lokono live primarily in Guyana, with smaller numbers present in Venezuela, Suriname, and French Guiana.[20] Despite colonization, the Lokono population is growing.[21] In addition, attempts to save the Lokono language, classified as critically-endangered, have been undertaken. An assessment published by Language Documentation and Conservation in 2015 determined the number of ethnic speakers who are fluent in the language had declined to approximately five percent of the known population.[22] |

ロコノ族 21世紀において、約1万人のロコノ族が主にガイアナに居住しており、少数がベネズエラ、スリナム、および仏領ギアナにも存在している。[20] 植民地化にもかかわらず、ロコノ族の人口は増加している。[21] さらに、絶滅危機言語に分類されるロコノ語の保存に向けた取り組みも行われている。2015年に『言語ドキュメンテーションと保全』誌が発表した評価では、ロコノ語を流暢に話す民族話者の数は、確認されている人口のおよそ5パーセントに減少していると判断された。[22] |

| Taíno The Spaniards who arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and the Virgin Islands in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico in 1493, first met the Indigenous peoples now known as the Taíno, and then the Kalinago and other groups. Some of these groups—most notably the Kalinago—were able to survive despite warfare, disease and slavery brought by the Europeans.[23] Others survived in isolated communities with escaped and free Black people, called Maroons.[24] Many of the explorers and early colonists also raped Indigenous women they came across, resulting in children who were considered mestizo. Some of these mestizo groups retained Indigenous culture and customs over many generations, especially among rural communities such as the jíbaro.[25][26] In time, the number of recorded Taíno was greatly diminished through forced labor, disease and warfare, but also through changes to how Indio groups were recorded in the Spanish Caribbean. For example, the 1787 census in Puerto Rico lists 2,300 "pure" Indios in the population, but on the next census, in 1802, not a single Indio is listed. This created the enduring belief that the Taíno people went extinct, also known as the paper genocide. The paper genocide and the myth of extinction spread throughout colonial empires, Taíno people still continued to practice their culture and teachings passing it down from generation to generation. Much of this was done in secret or disguised through Catholicism in fear for their survival and of discrimination.[24][27][28] With the modern invention of DNA testing, many Caribbean people have discovered they have Indigenous heritage. This has supported the claims of individuals and communities with Taíno heritage living today, particularly in rural areas such as "campos" (meaning small villages/towns in the country side). Though many communities and individuals across the Caribbean have some amount of Indigenous DNA, not all of them identify as Indigenous or Taíno. Those who do identify as Indigenous Caribbean may also use other terms to describe themselves as well as or in addition to Taíno.[29][30][31] There has been increasing scholarly attention paid to Taíno practices and culture, including communities with full or partial Taíno identities. Because of this, Taíno people started to become more open about sharing their identities, passed down Indigenous culture, and beliefs, such as the syncretic religion of Agua Dulce (also known as Tamani) that is practiced in the Dominican Republic.[32] Even before the DNA confirmation in the scientific community, Taíno peoples within the Caribbean and its diasporas had started a movement around the late 1980s and early 1990s calling for the protection, revival or restoration of Taíno culture.[27][28][30] By coming together and sharing individual knowledge passed down by either oral history or maintained practice, these groups were able to use that knowledge and cross-reference the journals of Spaniards to fill in parts of Taíno culture and religion long thought to be lost due to colonization. This movement led to some Yukayekes (Taíno Tribes) being reformed.[27][28][33] Today there are Yukayekes in Cuba,[34][35] Jamaica,[33] and Puerto Rico,[36] such as "Higuayagua" and "Yukayeke Taíno Borikén".[26][37][38] There have also been attempts to revive the Taíno language—such as the Hiwatahia Hekexi dialect[39]—using words that have survived into local Spanish dialects and extrapolation from other Arawakan languages in South America to fill in lost words.[37] |

タイノ族 1492年にバハマ、キューバ、イスパニョーラ島(現在のハイチとドミニカ共和国)、バージン諸島に、そして1493年にプエルトリコに到着したスペイン 人は、後にタイノ族と呼ばれるようになった先住民と初めて遭遇し、その後カリナゴ族やその他のグループと遭遇した。これらのグループの一部、特にカリナゴ 族は、ヨーロッパ人による戦争、病気、奴隷制度にもかかわらず生き延びることができた。[23] また、逃亡した自由黒人であるマローンと呼ばれる人々と孤立したコミュニティで生き延びた者もいた。[24] 多くの探検家や初期の入植者も、出会った先住民の女性をレイプし、混血とみなされる子供たちが生まれた。こうした混血集団の一部は、特にヒバロ (jíbaro)などの農村地域社会において、何世代にもわたって先住民の文化や慣習を保持した。 やがて、強制労働、病気、戦争によって、またスペイン領カリブ海地域におけるインディオ集団の記録方法の変化によって、記録に残るタイノ族の数は大幅に減 少した。例えば、1787年のプエルトリコの国勢調査では人口の2,300人が「純粋な」インディオとしてリストアップされているが、その次の1802年 の国勢調査ではインディオは一人もリストアップされていない。これが、タイノ族は絶滅したという根強い信念を生み出し、これは「紙上での大量虐殺」とも呼 ばれている。 紙上での大量虐殺と絶滅の神話は、植民地帝国全体に広がったが、タイノ族はそれでもなお、世代から世代へと文化と教えを伝承し続けた。 彼らの生存と差別に対する恐怖から、その多くは秘密裏に行なわれたり、カトリック教を装って行なわれたりした。[24][27][28] 現代のDNA検査の発明により、多くのカリブ海諸島の人々が先住民としての遺産を受け継いでいることが明らかになった。これにより、今日、特に「カンポ ス」(田舎の小さな村や町を意味する)などの農村地域に住むタイノ族の遺産を受け継ぐ個人やコミュニティの主張が裏付けられた。カリブ海地域全体では、多 くのコミュニティや個人が先住民のDNAを多少なりとも持っているが、そのすべてが先住民またはタイノ族であると認識しているわけではない。カリブ海地域 の先住民であると認識している人々は、タイノ族であると同時に、またはタイノ族に加えて、他の用語で自分自身を表現することもある。[29][30] [31] 完全または部分的なタイノ族としてのアイデンティティを持つコミュニティを含め、タイノ族の慣習や文化に対する学術的な関心が高まっている。このため、タ イノ族の人々は自分たちのアイデンティティや受け継がれてきた先住民文化、ドミニカ共和国で信仰されているアグア・ドゥルセ(別名タマーニ)などの混成宗 教といった信仰について、よりオープンに語るようになってきている。 [32] 科学界におけるDNAの確認に先立ち、1980年代後半から1990年代前半にかけて、カリブ海地域とそのディアスポラに暮らすタイノ族の人々は、タイノ 文化の保護、復興、復元を求める運動を開始していた。[27][28][30] これらのグループは、口頭伝承や伝統的慣習によって受け継がれてきた個々の知識を共有し、集結することで、その知識を活用し、スペイン人の日記を相互参照 することで、植民地化によって失われたと考えられていたタイノ族の文化や宗教の一部を補うことができた。この運動により、いくつかのユカイケ族(タイノ族 の部族)が再結成された。 今日、キューバ[34][35]、ジャマイカ[33]、プエルトリコ[36]には「Higuayagua」や「Yukayeke Taíno Borikén」といったユカイケ族がいる。 [26][37][38] また、現地のスペイン語の方言に生き残っている言葉や、南米の他のアラワク語族の言語からの推測を用いて、失われた言葉を補う試みも行われている。例え ば、ヒワタヒア・ヘケシ方言[39]などである。 |

| Notable Arawak Damon Gerard Corrie, a Barbados Lokono of Guyana Lokono descent and radical international indigenous rights activist. He founded the militant Indigenous Democracy Defence Organization (IDDO), a pan-tribal and multi-racial indigenous NGO.[40] He has published a Phonetic English-to-Arawak dictionary,[41] literature covering Lokono-Arawak Culture,[42] and also written about traditional Lokono-Arawak spirituality (Amazonia's Mythical and Legendary Creatures in the Eagle Clan Lokono-Arawak Oral Tradition of Guyana).[43] In 2021, Corrie published the children's book Last Arawak Girl Born in Barbados – a 17th Century Tale, which critiques popular depictions of pre-colonial Barbados as uninhabited.[44] John P. Bennett (Lokono), first Amerindian ordained as an Anglican priest in Guyana, linguist, and author of An Arawak-English Dictionary (1989).[45] Foster Simon, Artist,[46] Johannes Karwafodi, a Lokono anthropologist from Suriname who contributed to the field of colonial science.[47] Oswald Hussein, Artist Jean La Rose, Arawak environmentalist and indigenous rights activist in Guyana. Lenox Shuman, Guyanese politician George Simon (Lokono), artist and archaeologist from Guyana.[48] Tituba, one of the first women to be accused of practicing witchcraft during the Salem witch trials.[49] Dominic King, the first Olympian of Arawakian heritage. |

著名なアラワク族 のデイモン・ジェラード・コリーは、ガイアナ・ロコノ族の血筋を引くバルバドス人で、先住民の権利を擁護する急進的な国際活動家である。彼は、先住民の NGO団体である、全部族・多民族の過激派組織「先住民民主防衛機構(IDDO)」を設立した。 [40] 彼は発音英語-アラワク語辞書を出版し、[41] ロコノ族-アラワク族文化に関する文学[42] を発表し、また伝統的なロコノ族-アラワク族の精神性についても執筆している(『ガイアナのワシの一族ロコノ族-アラワク族の口承伝承におけるアマゾニア の神話的・伝説的生物』)。 [43] 2021年、コリーは児童書『バルバドスで生まれた最後のアラワク族の少女 - 17世紀の物語』を出版した。この本は、植民地化以前のバルバドスを無人島として描く一般的な描写を批判している。 ジョン・P・ベネット(ロコノ)は、ガイアナで初めてアメリカインディアンとして聖職者(聖公会司祭)に叙階された人物であり、言語学者であり、『アラワク語-英語辞典』(1989年)の著者でもある。[45] フォスター・サイモンは芸術家である。[46] ヨハネス・カルワフォディはスリナム出身のロコノ人類学者であり、植民地時代の科学分野に貢献した。[47] オズワルド・フセインは芸術家である。 ジャン・ラ・ローズ、アラワク族の環境保護活動家であり、ガイアナの先住民の権利活動家。 レノックス・シューマン、ガイアナの政治家 ジョージ・サイモン(ロコノ)、ガイアナ出身の芸術家および考古学者。 ティチューバ、セーラム魔女裁判で呪術を働いたとして告発された最初の女性の一人。 ドミニク・キング、アラワク族の血を引く初のオリンピック選手。 |

| Adaheli, the sun in the mythology of the Orinoco region Aiomun-Kondi, Arawak deity, created the world in Arawak mythology Arawakan languages Cariban languages Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas Garifuna language List of indigenous names of Eastern Caribbean islands List of Native American peoples in the United States Maipurean languages |

アダヘリ、オリノコ地方の神話における太陽 アイオムンコンディ、アラワク族の神、アラワク族の神話における世界の創造 アラワク諸語 カリバン諸語 アメリカの先住民の分類 ガリフナ語 東カリブ海諸島の先住民の名前の一覧 アメリカ合衆国におけるネイティブアメリカンの一覧 マイプリアン諸語 |

| Bibliography Jesse, C., (2000). The Amerindians in St. Lucia (Iouanalao). St. Lucia: Archaeological and Historical Society. Haviser, J. B. (1997). "Settlement Strategies in the Early Ceramic Age". In Wilson, S. M. (ed.). The Indigenous People of the Caribbean. Gainesville, Florida: University Press. Hofman, C. L., (1993). The Native Population of Pre-columbian Saba. Part One. Pottery Styles and their Interpretations. [PhD dissertation], Leiden: University of Leiden (Faculty of Archaeology). Haviser, J. B., (1987). Amerindian cultural Geography on Curaçao. [Unpublished PhD dissertation], Leiden: Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University. Handler, Jerome S. (January 1977). "Amerindians and Their Contributions to Barbadian Life in the Seventeenth Century". The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. 33 (3). Barbados: Museum and Historical Society: 189–210. Joseph, P. Musée, C. Celma (ed.), (1968). "LГhomme Amérindien dans son environnement (quelques enseignements généraux)", In Les Civilisations Amérindiennes des Petites Antilles, Fort-de-France: Départemental d’Archéologie Précolombienne et de Préhistoire. Bullen, Ripley P., (1966). "Barbados and the Archeology of the Caribbean", The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, 32. Haag, William G., (1964). A Comparison of Arawak Sites in the Lesser Antilles. Fort-de-France: Proceedings of the First International Congress on Pre-Columbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles, pp. 111–136 Deutsche, Presse-Agentur. "Archeologist studies signs of ancient civilization in Amazon basin", Science and Nature, M&C, 08/02/2010. Web. 29 May 2011. Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014. Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014. Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2014. Island Carib. |

参考文献 ジェシー、C. (2000年)。セントルシアのアメリカンインディアン(Iouanalao)。セントルシア:考古学・歴史学会。 ハヴィザー、J. B. (1997年)。「初期陶器時代の定住戦略」。ウィルソン、S. M. (編)。カリブ海の原住民。フロリダ州ゲインズビル:大学出版。 ホフマン、C. L.、(1993年)。コロンブス到来以前のサバの原住民。第1部。土器様式とその解釈。[博士論文]、ライデン:ライデン大学(考古学部)。 ヘイヴィザー、J. B.、(1987年)。キュラソーにおけるアメリカインディアンの文化地理。[未発表の博士論文]、ライデン:ライデン大学考古学部。 Handler, Jerome S. (1977年1月). 「17世紀におけるアメリカンインディアンとバルバドスの生活への彼らの貢献」. The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. 33 (3). バルバドス: Museum and Historical Society: 189–210. Joseph, P. Musée, C. Celma (ed.), (1968). 「L'homme Amérindien dans son environnement (quelques enseignements généraux)」, In Les Civilisations Amérindiennes des Petites Antilles, Fort-de-France: Départemental d’Archéologie Précolombienne et de Préhistoire. Bullen, Ripley P., (1966). 「バルバドスとカリブ海の考古学」、バルバドス博物館・歴史学会誌、32。 Haag, William G., (1964). 小アンティル諸島のアラワク族遺跡の比較。フォール=ド=フランス:小アンティル諸島のプレコロンビア文化に関する第1回国際会議議事録、111-136ページ Deutsche, Presse-Agentur. 「考古学者、アマゾン流域の古代文明の痕跡を研究」、Science and Nature、M&C、2010年8月2日。 ウェブ。 2011年5月29日。 Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014. Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. グリーンウッド社。ISBN 0313263876。2014年6月16日取得。 ラウス、アーヴィング(1992年)。タイノ族。イェール大学出版。40ページ。ISBN 0300051816。2014年6月16日取得。島嶼カリブ人。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arawak |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆