アーユルベーダー

Ayurveda

ダ ンヴァントリは、ヴィシュヌの化身であり、アーユルヴェーダに関連するヒンドゥー教の神である。

☆

アーユルヴェーダ(/ˌɑːjʊərˈveɪdə, -ˈviː-/; IAST:

āyurveda[1])は、インド亜大陸に歴史的起源を持つ代替医療体系である[2]。インドとネパールでは広く実践されており、人口の80%がアーユ

ルヴェーダを利用していると報告されている[3][4][5]。[6]

アーユルヴェーダの理論と実践は疑似科学であり、鉛や水銀を含む有毒金属が多くのアーユルヴェーダ薬の成分として使用されている。[7][8][9]

[10]

アーユルヴェーダの療法は二千年以上にわたり多様化し進化してきた。[2]

療法には、漢方薬、特別な食事療法、瞑想、ヨガ、マッサージ、下剤、浣腸、医療用オイルなどが含まれる。[11][12]

アーユルヴェーダの調製物は、通常、複雑なハーブ化合物、鉱物、金属物質(おそらく初期インドの錬金術やラサシャストラの影響下で)に基づいている。古代

アーユルヴェーダの文献は、鼻形成術、結石摘出術、縫合術、白内障手術、異物摘出術を含む外科手術技術も教えていた。[13] [14]

アーユルヴェーダの文献、用語、概念に関する歴史的証拠は、紀元前1千年紀中頃から現れ始める。[15]

主な古典的アーユルヴェーダ文献は、医療知識が神々から賢者へ、そして人間の医師へと伝承された経緯の記述から始まる。[16]

『スシュルタ・サンヒター』(スシュルタの集成)の印刷版では、この著作はアーユルヴェーダのヒンドゥー教神ダンヴァンタリが、バラナシのディヴォダーサ

王として転生し、スシュルタを含む医師集団に授けた教えとして位置づけられている。[17] [18]

しかし、この著作の最古の写本では、この枠組みが省略され、直接ディヴォーダサ王に帰属させている。[19]

アーユルヴェーダの文献では、ドーシャの均衡が強調され、自然な衝動を抑えることは不健康であり、病気を招くとされる。[20]

アーユルヴェーダの論著は、ヴァータ、ピッタ、カパという三つの元素ドーシャを記述し、ドーシャの均衡(サンスクリット語でサーミャトヴァ)が健康をもた

らし、不均衡(ヴィシャマトヴァ)が疾病をもたらすと述べている。アーユルヴェーダの論著は、医学を八つの規範的要素に分類している。アーユルヴェーダ実

践者は、少なくとも紀元後初期から様々な薬物調製法や外科的手技を発展させてきた。[21]

アーユルヴェーダは西洋向けに改変され、特に1970年代のババ・ハリ・ダスや1980年代のマハリシ・アーユルヴェーダによって普及した。[22]

一部のアーユルヴェーダ療法は癌の症状緩和に寄与する可能性があるが、この疾患をアーユルヴェーダで治療または治癒できるという確かな証拠は存在しない。

[12]

いくつかのアーユルヴェーダ製剤には、鉛、水銀、ヒ素が含まれていることが判明している[11][23]。これらは人体に有害な物質として知られている。

2008年の研究では、インターネットで販売されている米国およびインド製の特許アーユルヴェーダ医薬品の約21%からこれら3物質が検出された

[24]。インドにおけるこうした金属汚染物質の公衆衛生への影響は不明である[24]。

| Ayurveda

(/ˌɑːjʊərˈveɪdə, -ˈviː-/; IAST: āyurveda[1]) is an alternative medicine

system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent.[2] It is

heavily practised throughout India and Nepal, where as much as 80% of

the population report using ayurveda.[3][4][5][6] The theory and

practice of ayurveda is pseudoscientific and toxic metals, including

lead and mercury, are used as ingredients in many ayurvedic

medicines.[7][8][9][10] Ayurveda therapies have varied and evolved over more than two millennia.[2] Therapies include herbal medicines, special diets, meditation, yoga, massage, laxatives, enemas, and medical oils.[11][12] Ayurvedic preparations are typically based on complex herbal compounds, minerals, and metal substances (perhaps under the influence of early Indian alchemy or rasashastra). Ancient ayurveda texts also taught surgical techniques, including rhinoplasty, lithotomy, sutures, cataract surgery, and the extraction of foreign objects.[13][14] Historical evidence for ayurvedic texts, terminology and concepts appears from the middle of the first millennium BCE onwards.[15] The main classical ayurveda texts begin with accounts of the transmission of medical knowledge from the gods to sages, and then to human physicians.[16] Printed editions of the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta's Compendium), frame the work as the teachings of Dhanvantari, the Hindu deity of ayurveda, incarnated as King Divodāsa of Varanasi, to a group of physicians, including Sushruta.[17][18] The oldest manuscripts of the work, however, omit this frame, ascribing the work directly to King Divodāsa.[19] In ayurveda texts, dosha balance is emphasised, and suppressing natural urges is considered unhealthy and claimed to lead to illness.[20] Ayurveda treatises describe three elemental doshas: vāta, pitta and kapha, and state that balance (Skt. sāmyatva) of the doshas results in health, while imbalance (viṣamatva) results in disease. Ayurveda treatises divide medicine into eight canonical components. Ayurveda practitioners had developed various medicinal preparations and surgical procedures from at least the beginning of the common era.[21] Ayurveda has been adapted for Western consumption, notably by Baba Hari Dass in the 1970s and Maharishi ayurveda in the 1980s.[22] Although some Ayurvedic treatments can help relieve some symptoms of cancer, there is no good evidence that the disease can be treated or cured through ayurveda.[12] Several ayurvedic preparations have been found to contain lead, mercury, and arsenic,[11][23] substances known to be harmful to humans. A 2008 study found the three substances in close to 21% of US and Indian-manufactured patent ayurvedic medicines sold through the Internet.[24] The public health implications of such metallic contaminants in India are unknown.[24] |

アーユルヴェーダ(/ˌɑːjʊərˈveɪdə,

-ˈviː-/; IAST:

āyurveda[1])は、インド亜大陸に歴史的起源を持つ代替医療体系である[2]。インドとネパールでは広く実践されており、人口の80%がアーユ

ルヴェーダを利用していると報告されている[3][4][5]。[6]

アーユルヴェーダの理論と実践は疑似科学であり、鉛や水銀を含む有毒金属が多くのアーユルヴェーダ薬の成分として使用されている。[7][8][9]

[10] アーユルヴェーダの療法は二千年以上にわたり多様化し進化してきた。[2] 療法には、漢方薬、特別な食事療法、瞑想、ヨガ、マッサージ、下剤、浣腸、医療用オイルなどが含まれる。[11][12] アーユルヴェーダの調製物は、通常、複雑なハーブ化合物、鉱物、金属物質(おそらく初期インドの錬金術やラサシャストラの影響下で)に基づいている。古代 アーユルヴェーダの文献は、鼻形成術、結石摘出術、縫合術、白内障手術、異物摘出術を含む外科手術技術も教えていた。[13] [14] アーユルヴェーダの文献、用語、概念に関する歴史的証拠は、紀元前1千年紀中頃から現れ始める。[15] 主な古典的アーユルヴェーダ文献は、医療知識が神々から賢者へ、そして人間の医師へと伝承された経緯の記述から始まる。[16] 『スシュルタ・サンヒター』(スシュルタの集成)の印刷版では、この著作はアーユルヴェーダのヒンドゥー教神ダンヴァンタリが、バラナシのディヴォダーサ 王として転生し、スシュルタを含む医師集団に授けた教えとして位置づけられている。[17] [18] しかし、この著作の最古の写本では、この枠組みが省略され、直接ディヴォーダサ王に帰属させている。[19] アーユルヴェーダの文献では、ドーシャの均衡が強調され、自然な衝動を抑えることは不健康であり、病気を招くとされる。[20] アーユルヴェーダの論著は、ヴァータ、ピッタ、カパという三つの元素ドーシャを記述し、ドーシャの均衡(サンスクリット語でサーミャトヴァ)が健康をもた らし、不均衡(ヴィシャマトヴァ)が疾病をもたらすと述べている。アーユルヴェーダの論著は、医学を八つの規範的要素に分類している。アーユルヴェーダ実 践者は、少なくとも紀元後初期から様々な薬物調製法や外科的手技を発展させてきた。[21] アーユルヴェーダは西洋向けに改変され、特に1970年代のババ・ハリ・ダスや1980年代のマハリシ・アーユルヴェーダによって普及した。[22] 一部のアーユルヴェーダ療法は癌の症状緩和に寄与する可能性があるが、この疾患をアーユルヴェーダで治療または治癒できるという確かな証拠は存在しない。 [12] いくつかのアーユルヴェーダ製剤には、鉛、水銀、ヒ素が含まれていることが判明している[11][23]。これらは人体に有害な物質として知られている。 2008年の研究では、インターネットで販売されている米国およびインド製の特許アーユルヴェーダ医薬品の約21%からこれら3物質が検出された [24]。インドにおけるこうした金属汚染物質の公衆衛生への影響は不明である[24]。 |

| Etymology The term āyurveda (Sanskrit: आयुर्वेद) is composed of two words, āyus, आयुस्, "life" or "longevity", and veda, वेद, "knowledge", translated as "knowledge of longevity"[25][26] or "knowledge of life and longevity".[27] |

語源 アーユルヴェーダ(サンスクリット語: आयुर्वेद)は、二つの語から成る。アーユス(आयुस्)は「生命」または「長寿」を意味し、ヴェーダ(वेद)は「知識」を意味する。したがっ て、アーユルヴェーダは「長寿の知識」[25] [26] あるいは「生命と長寿の知識」[27]と訳される。 |

Eight components Nagarjuna, known for the Madhyamaka (middle path), wrote the medical works The Hundred Prescriptions and The Precious Collection.[28] The earliest classical Sanskrit works on ayurveda describe medicine as being divided into eight components (Skt. aṅga).[29][30] This characterization of the physician's art, "the medicine that has eight components" (Sanskrit: चिकित्सायामष्टाङ्गायाम्, romanized: cikitsāyām aṣṭāṅgāyāṃ), is first found in the Sanskrit epic the Mahābhārata, c. 4th century BCE.[31] The components are:[32][27][33] Kāyachikitsā: general medicine, medicine of the body Kaumāra-bhṛtya (Pediatrics): Discussions about prenatal and postnatal care of baby and mother; methods of conception; choosing the child's sex, intelligence, and constitution; childhood diseases; and midwifery[34] Śalyatantra: surgical techniques and the extraction of foreign objects Śhālākyatantra: treatment of ailments affecting openings or cavities in the upper body: ears, eyes, nose, mouth, etc. Bhūtavidyā: pacification of possessing spirits, and the people whose minds are affected by such possession Agadatantra/Vishagara-vairodh Tantra (Toxicology): includes epidemics; toxins in animals, vegetables and minerals; and keys for recognizing those anomalies and their antidotes Rasāyantantra: rejuvenation and tonics for increasing lifespan, intellect and strength Vājīkaraṇatantra: aphrodisiacs; treatments for increasing the volume and viability of semen and sexual pleasure; infertility problems; and spiritual development (transmutation of sexual energy into spiritual energy) |

八つの構成要素 中道(マハーヤーナ)で知られるナーガールジュナは、医学書『百方』と『宝集』を著した。[28] アーユルヴェーダに関する最古の古典サンスクリット文献は、医学を八つの構成要素(サンスクリット語:アングア)に分類していると記述している。[29] 医師の技芸を「八つの要素から成る医学」(サンスクリット語: चिकित्सायामष्टाङ्गायाम्, ローマ字表記:cikitsāyām aṣṭāṅgāyāṃ)は、紀元前4世紀頃のサンスクリット叙事詩『マハーバーラタ』に初めて登場する。[31] その構成要素は以下の通りである。[32][27][33] カヤチキツァ(Kāyachikitsā):一般医学、身体の医学 カウマラー・ブリティヤ(Kaumāra-bhṛtya、小児科学):母体と乳児の周産期ケア、受胎方法、子供の性別・知能・体質の選択、小児疾患、助産術に関する論考[34] シャリヤタントラ:外科手術技術と異物摘出術 シャラキャタントラ:頭部開口部(耳・目・鼻・口など)の疾患治療 ブータヴィディヤ:憑依した精霊の鎮静、及び憑依により精神に影響を受けた人々の治療 アガダタントラ/ヴィシャガラ・ヴァイロダタントラ(毒物学):伝染病、動物・植物・鉱物中の毒素、それらの異常を認識する鍵及び解毒剤を含む ラサーヤンタントラ:若返りと強壮剤。寿命、知性、体力を増進させる。 ヴァージカーラナタントラ:媚薬。精液の量と活力、性的快楽を増進させる治療法。不妊症の問題。精神的成長(性的エネルギーを精神的エネルギーへ転化する)。 |

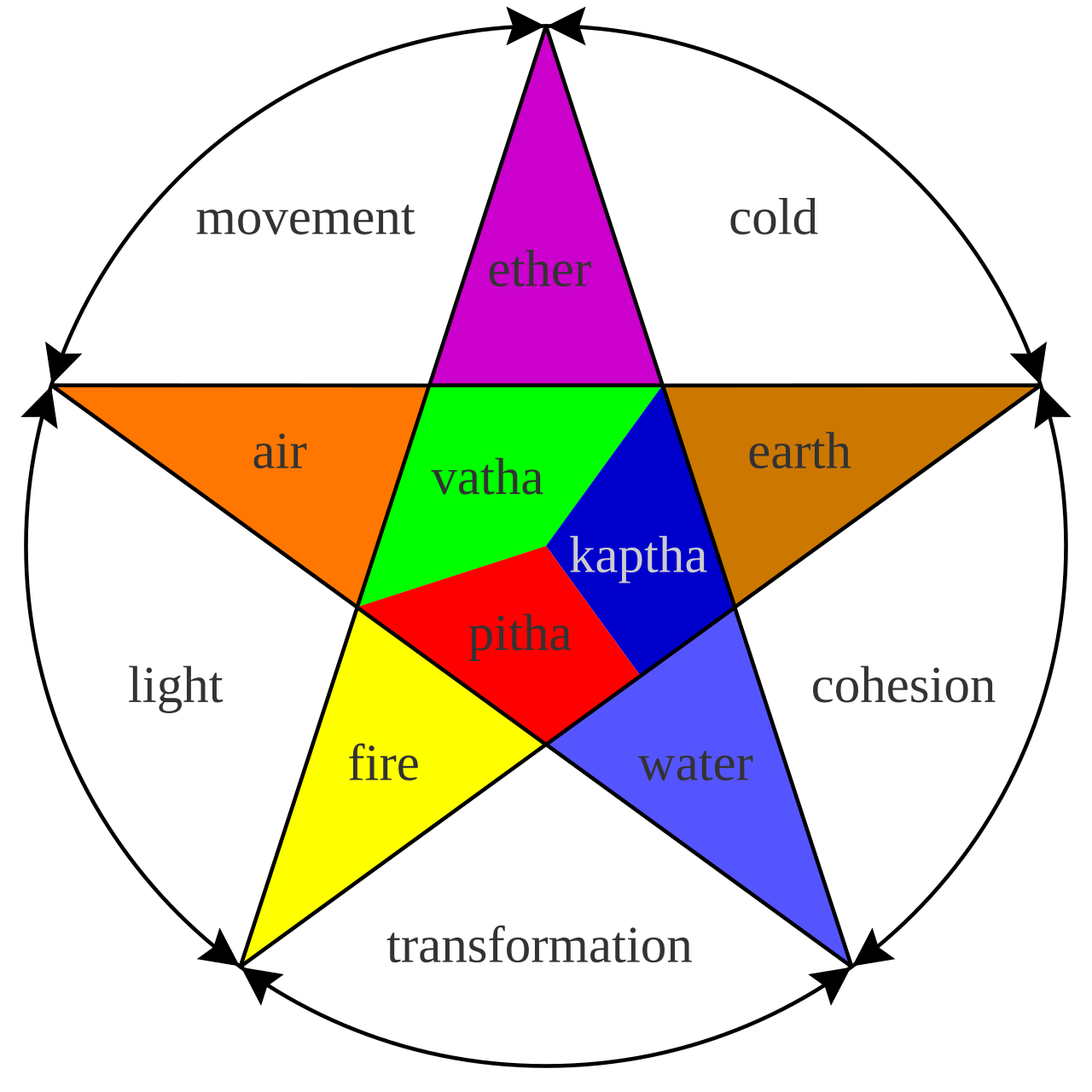

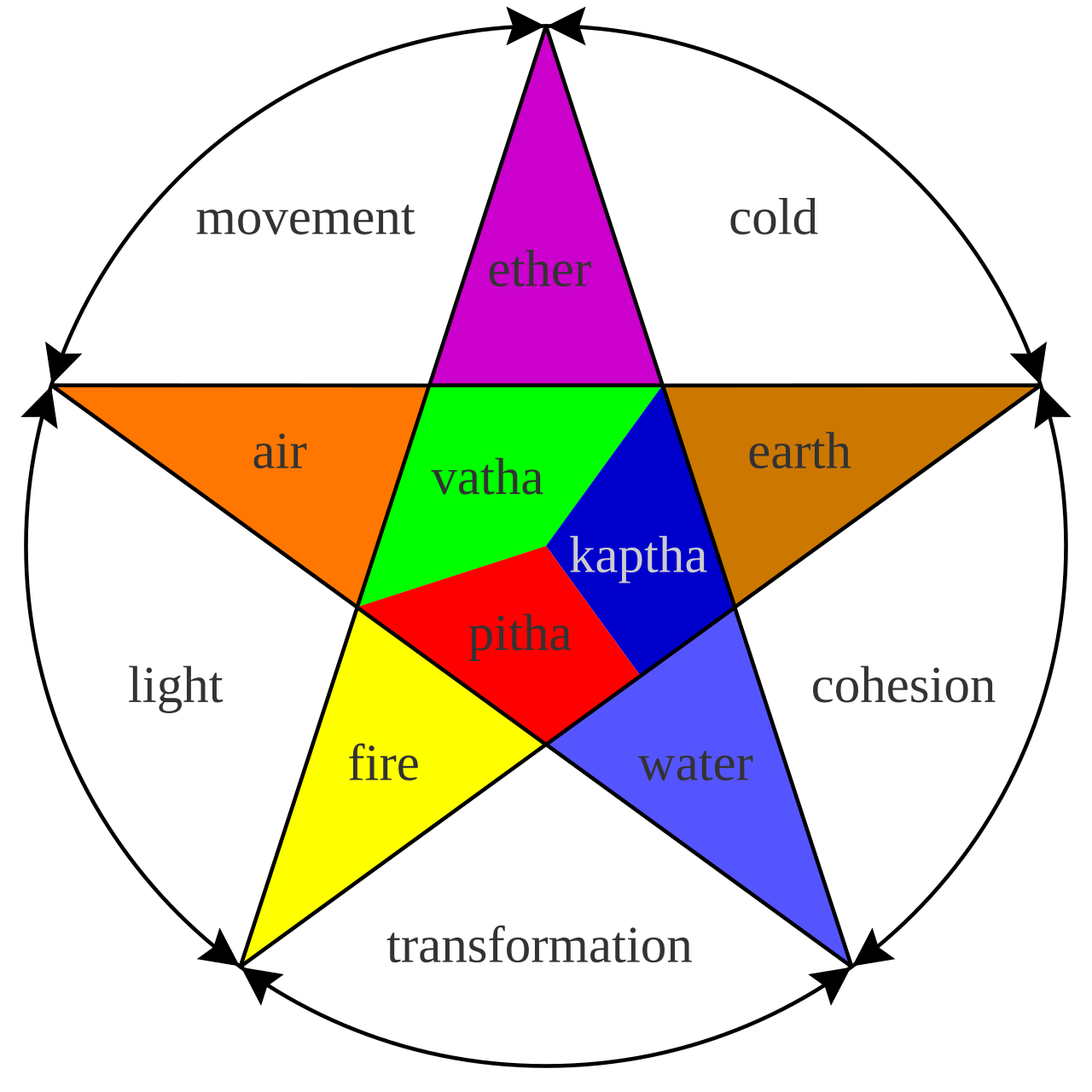

| Principles and terminology Further information: Mahābhūta The central theoretical ideas of ayurveda show parallels with Samkhya and Vaisheshika philosophies, as well as with Buddhism and Jainism.[35][36] Balance is emphasized, and suppressing natural urges is considered unhealthy and claimed to lead to illness.[20] For example, to suppress sneezing is said to potentially give rise to shoulder pain.[37] However, people are also cautioned to stay within the limits of reasonable balance and measure when following nature's urges.[20] For example, emphasis is placed on moderation of food intake,[38] sleep, and sexual intercourse.[20]  The three doshas and the five elements from which they are composed According to ayurveda, the human body is composed of tissues (dhatus), waste (malas), and humeral biomaterials (doshas).[39] The seven dhatus are chyle (rasa), blood (rakta), muscles (māmsa), fat (meda), bone (asthi), marrow (majja), and semen (shukra). Like the medicine of classical antiquity, the classic treatises of ayurveda divided bodily substances into five classical elements (panchamahabhuta) viz. earth, water, fire, air and ether.[40] There are also twenty gunas (qualities or characteristics) which are considered to be inherent in all matter. These are organized in ten pairs: heavy/light, cold/hot, unctuous/dry, dull/sharp, stable/mobile, soft/hard, non-slimy/slimy, smooth/coarse, minute/gross, and viscous/liquid.[41] The three postulated elemental bodily humours, the doshas or tridosha, are vata (air, which some modern authors equate with the nervous system), pitta (bile, fire, equated by some with enzymes), and kapha (phlegm, or earth and water, equated by some with mucus). Contemporary critics assert that doshas are not real, but are a fictional concept.[42] The humours (doshas) may also affect mental health. Each dosha has particular attributes and roles within the body and mind; the natural predominance of one or more doshas thus explains a person's physical constitution (prakriti) and personality.[39][43][44] Ayurvedic tradition holds that imbalance among the bodily and mental doshas is a major etiologic component of disease. One ayurvedic view is that the doshas are balanced when they are equal to each other, while another view is that each human possesses a unique combination of the doshas which define this person's temperament and characteristics. In either case, it says that each person should modulate their behavior or environment to increase or decrease the doshas and maintain their natural state. Practitioners of ayurveda must determine an individual's bodily and mental dosha makeup, as certain prakriti are said to predispose one to particular diseases.[45][39] For example, a person who is thin, shy, excitable, has a pronounced Adam's apple, and enjoys esoteric knowledge is likely vata prakriti and therefore more susceptible to conditions such as flatulence, stuttering, and rheumatism.[39][46] Deranged vata is also associated with certain mental disorders due to excited or excess vayu (gas), although the ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita also attributes "insanity" (unmada) to cold food and possession by the ghost of a sinful Brahman (brahmarakshasa).[39][45][47][48] Ama (a Sanskrit word meaning "uncooked" or "undigested") is used to refer to the concept of anything that exists in a state of incomplete transformation. With regards to oral hygiene, it is claimed to be a toxic byproduct generated by improper or incomplete digestion.[49][50][51] The concept has no equivalent in standard medicine. In medieval taxonomies of the Sanskrit knowledge systems, ayurveda is assigned a place as a subsidiary Veda (upaveda).[52] Some medicinal plant names from the Atharvaveda and other Vedas can be found in subsequent ayurveda literature.[53] Some other school of thoughts considers 'ayurveda' as the 'Fifth Veda'.[54] The earliest recorded theoretical statements about the canonical models of disease in ayurveda occur in the earliest Buddhist Canon.[55] |

原理と用語 詳細情報:マハーブータ アーユルヴェーダの中心的な理論的観念は、サンキヤ哲学やヴァイシェーシカ哲学、さらには仏教やジャイナ教とも類似点が見られる。[35][36] バランスが重視され、自然な衝動を抑えることは不健康と見なされ、病気を招くとされる。[20] 例えば、くしゃみを抑えると肩の痛みが生じる可能性があると言われる。[37] しかし、自然の衝動に従う際にも、人々は合理的な均衡と節度の範囲内に留まるよう警告されている。[20] 例えば、食物摂取量[38]、睡眠、性交の節度が重視される。[20]  三つのドーシャと、それらを構成する五元素 アーユルヴェーダによれば、人体は組織(ダータス)、老廃物(マーラス)、体液(ドーシャ)で構成されている。[39] 七つのダートゥとは、乳汁(ラーサ)、血液(ラクタ)、筋肉(マーンサ)、脂肪(メーダ)、骨(アスティ)、骨髄(マージャ)、精液(シュークラ)であ る。古代の医学と同様に、アーユルヴェーダの古典的論著は、身体の物質を五つの古典的元素(パンチャマハブータ)すなわち土、水、火、風、空に分類した。 [40] 全ての物質に内在するとされる二十のグナ(性質または特性)も存在する。これらは十の対で組織化される:重い/軽い、冷たい/熱い、油性/乾燥、鈍い/鋭 い、安定/移動、柔らかい/硬い、粘液性なし/粘液性、滑らか/粗い、微細/粗大、粘稠/液体。[41] 仮定される三つの体液(ドーシャ、トリドーシャ)は、ヴァータ(空気、現代の著者によっては神経系と同一視される)、ピッタ(胆汁、火、酵素と同一視され る者もいる)、カパ(痰、あるいは土と水、粘液と同一視される者もいる)である。現代の批評家は、ドーシャは実在せず、架空の概念だと主張している。 [42] 体液(ドーシャ)は健康にも影響を及ぼす。各ドーシャは身体と精神において特定の属性と役割を持ち、一つ以上のドーシャが自然に優勢であることが、個人の 身体的体質(プラクリティ)と個人的性格を説明する。[39][43][44] アーユルヴェーダの伝統では、身体的・精神的ドーシャの均衡が崩れることが疾病の主要な病因要素とされる。アーユルヴェーダの考え方の一つでは、ドーシャ は互いに等しい時に均衡しているとされる。別の見解では、各人が独自のドーシャの組み合わせを持ち、それがその人格の気質や特徴を定義するとされる。いず れの場合も、各人は自身の行動や環境を調整し、ドーシャを増減させて自然な状態を維持すべきだと説く。アーユルヴェーダ実践者は、個人の身体的・精神的 ドーシャ構成を判断しなければならない。特定のプラクリティは特定の疾患への素因となるとされるからだ[45][39]。例えば、痩せていて内気で興奮し やすく、喉仏が突出しており、難解な知識を好む人格はヴァータ・プラクリティである可能性が高く、したがって鼓腸、吃音、リウマチなどの症状にかかりやす い。[39][46] 乱れたヴァータは興奮した過剰なヴァユ(気)による特定の精神障害とも関連付けられる。ただしアーユルヴェーダの古典『チャラカ・サンヒター』では「狂 気」(ウンマダ)を冷たい食物や罪深いバラモン(ブラフマーラクシャサ)の亡霊憑依にも帰している。[39][45][47][48] アマ(サンスクリット語で「未調理」または「未消化」を意味する)は、不完全な変換状態にあるあらゆるものの概念を指す。口腔衛生に関しては、不適切また は不完全な消化によって生成される有毒な副産物であると主張されている。[49][50][51] この概念は標準的な医学には相当するものがない。 中世のサンスクリット知識体系の分類において、アーユルヴェーダは補助ヴェーダ(ウパヴェーダ)として位置づけられている。[52] アタルヴァヴェーダや他のヴェーダに由来する薬用植物名が、後のアーユルヴェーダ文献に見られる。[53] 他の学派では「アーユルヴェーダ」を「第五のヴェーダ」とみなすこともある。[54] アーユルヴェーダの規範的疾病モデルに関する最古の理論的記述は、最古の仏教経典に見られる。[55] |

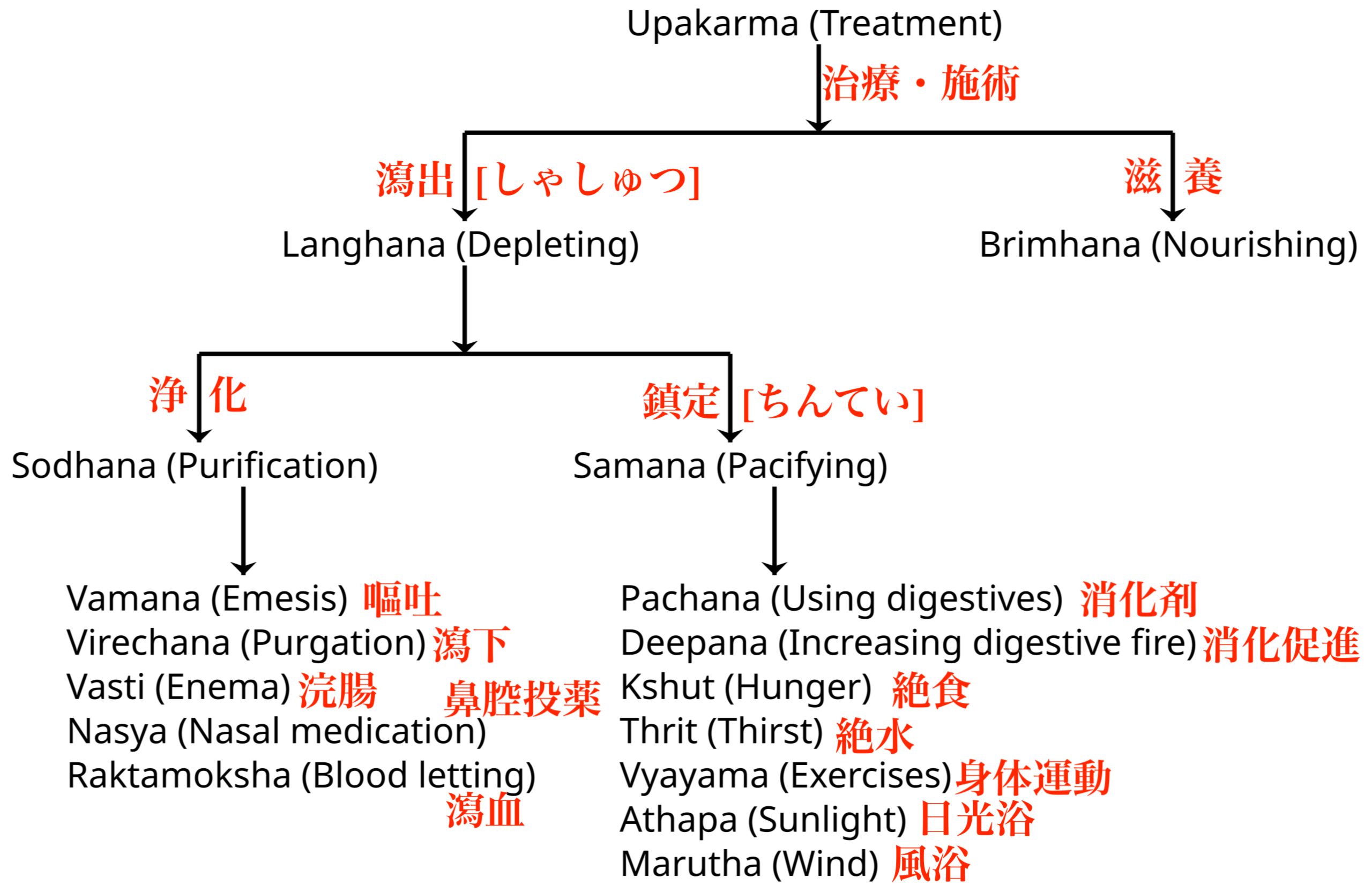

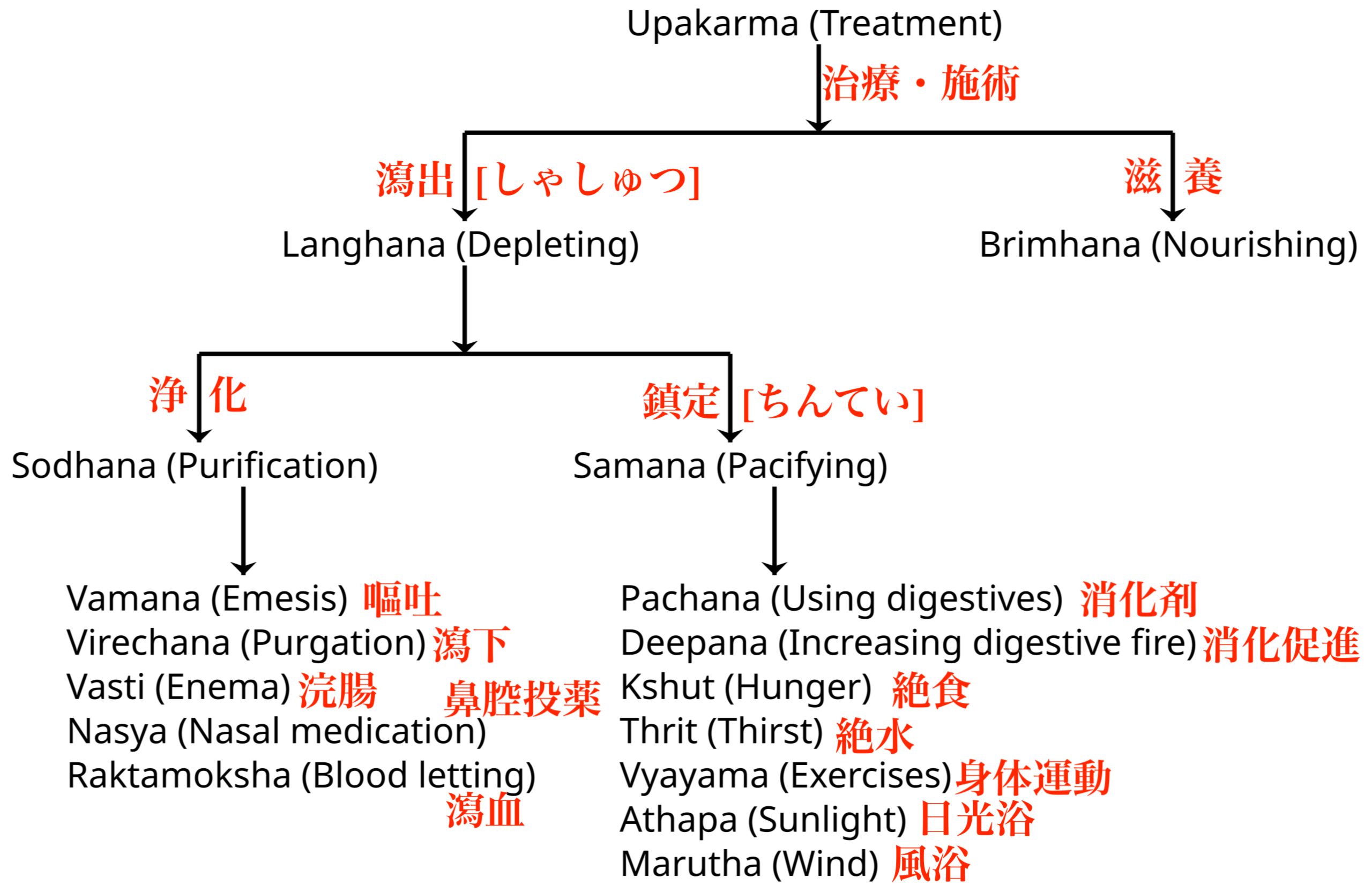

Practice Physician taking pulse, Delhi, c. 1825 Ayurvedic practitioners regard physical existence, mental existence, and personality as three separate elements of a whole person with each element being able to influence the others.[56] This holistic approach used during diagnosis and healing is a fundamental aspect of ayurveda. Another part of ayurvedic treatment says that there are channels (srotas) which transport fluids, and that the channels can be opened up by massage treatment using oils and Swedana (fomentation). Unhealthy, or blocked, channels are thought to cause disease.[57] Diagnosis  An ayurvedic practitioner applying oil using head massage Ayurveda has eight ways to diagnose illness, called nadi (pulse), mootra (urine), mala (stool), jihva (tongue), shabda (speech), sparsha (touch), druk (vision), and aakruti (appearance).[58] Ayurvedic practitioners approach diagnosis by using the five senses.[59] For example, hearing is used to observe the condition of breathing and speech.[40] The study of vulnerable points, or marma, is particular to ayurvedic medicine.[41]  Treatment procedures Treatment and prevention Two of the eight branches of classical ayurveda deal with surgery (Śalya-cikitsā and Śālākya-tantra), but contemporary ayurveda tends to stress attaining vitality by building a healthy metabolic system and maintaining good digestion and excretion.[41] Ayurveda also focuses on exercise, yoga, and meditation.[60] One type of prescription is a Sattvic diet. Ayurveda follows the concept of Dinacharya, which says that natural cycles (waking, sleeping, working, meditation etc.) are important for health. Hygiene, including regular bathing, cleaning of teeth, oil pulling, tongue scraping, skin care, and eye washing, is also a central practice.[40] |

診療 脈診を行う医師、デリー、1825年頃 アーユルヴェーダの施術者は、身体的存在、精神的実在、人格を、それぞれが互いに影響し合う全体を構成する三つの独立した要素と見なす。[56] この診断と治療における全体論的アプローチは、アーユルヴェーダの基本的な側面である。アーユルヴェーダ治療の別の側面では、体液を運ぶ経路(スロータ ス)が存在し、オイルを用いたマッサージ療法やスウェダナ(温熱療法)によってその経路を開通させることができるとされる。不健康な状態、あるいは閉塞し た経路が病気を引き起こすと考えられている。[57] 診断  頭部マッサージでオイルを塗布するアーユルヴェーダ施術者 アーユルヴェーダには、病気を診断する八つの方法がある。それはナディ(脈)、ムートラ(尿)、マラ(便)、ジフヴァ(舌)、シャブダ(発声)、スパル シャ(触診)、ドルク(視覚)、アークルティ(外見)と呼ばれる。[58] アーユルヴェーダの施術者は五感を用いて診断に臨む。[59] 例えば聴覚は呼吸や発声の状態を観察するために用いられる。[40] 脆弱点(マルマ)の研究はアーユルヴェーダ医学の個別主義を示すものである。[41]  治療手順 治療と予防 古典的アーユルヴェーダの八つの分野のうち二つは外科(シャリヤ・チキッツァとシャラキヤ・タントラ)を扱うが、現代のアーユルヴェーダは、健全な代謝シ ステムを構築し、良好な消化と排泄を維持することで活力を得ることを重視する傾向がある。[41] アーユルヴェーダはまた、運動、ヨガ、瞑想にも焦点を当てる。[60] 処方の一つにサットヴィック食がある。 アーユルヴェーダはディナチャリヤの概念に従う。これは自然のサイクル(起床、睡眠、労働、瞑想など)が健康にとって重要だと説くものだ。衛生習慣、具体的には定期的な入浴、歯磨き、オイルプリング、舌磨き、スキンケア、洗眼も中心的な実践である。[40] |

| Substances used See also: Medical ethnobotany of India  Ayurvedic preparations displayed in Delhi in 2016 The vast majority (90%) of ayurvedic remedies are plant based.[61] Plant-based treatments in ayurveda may be derived from roots, leaves, fruits, bark, or seeds; some examples of plant-based substances include cardamom and cinnamon. In the 19th century, William Dymock and co-authors summarized hundreds of plant-derived medicines along with the uses, microscopic structure, chemical composition, toxicology, prevalent myths and stories, and relation to commerce in British India.[62] Triphala, an herbal formulation of three fruits, Amalaki, Bibhitaki, and Haritaki, is one of the most commonly used[63] Ayurvedic remedies.[64][65] The herbs Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha)[66] and Ocimum tenuiflorum (Tulsi)[61] are also routinely used in ayurveda.  Tulsi-flower (holy basil), an ayurvedic herb Animal products used in ayurveda include milk, bones, and gallstones.[67] In addition, fats are prescribed both for consumption and for external use. Consumption of minerals, including sulfur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate and gold, are also prescribed.[40] The addition of minerals to herbal medicine is called rasashastra. Ayurveda uses alcoholic beverages called Madya,[68] which are said to adjust the doshas by increasing pitta and reducing vatta and kapha.[68] Madya are classified by the raw material and fermentation process, and the categories include: sugar-based, fruit-based, cereal-based, cereal-based with herbs, fermentated with vinegar, and tonic wines. The intended outcomes can include causing purgation, improving digestion or taste, creating dryness, or loosening joints. Ayurvedic texts describe Madya as non-viscid and fast-acting, and say that it enters and cleans minute pores in the body.[68] Purified opium[69] is used in eight ayurvedic preparations[70] and is said to balance the vata and kapha doshas and increase the pitta dosha.[69] It is prescribed for diarrhea and dysentery, for increasing the sexual and muscular ability, and for affecting the brain. The sedative and pain-relieving properties of opium are considered in ayurveda. The use of opium is found in the ancient ayurvedic texts, and is first mentioned in the Sarngadhara Samhita (1300–1400 CE), a book on pharmacy used in Rajasthan in Western India, as an ingredient of an aphrodisiac to delay male ejaculation.[71] It is possible that opium was brought to India along with or before Muslim conquests.[70][72] The book Yoga Ratnakara (1700–1800 CE, unknown author), which is popular in Maharashtra, uses opium in a herbal-mineral composition prescribed for diarrhea.[71] In the Bhaisajya Ratnavali, opium and camphor are used for acute gastroenteritis. In this drug, the respiratory depressant action of opium is counteracted by the respiratory stimulant property of camphor.[71] Later books have included the narcotic property for use as analgesic pain reliever.[71] Cannabis indica is also mentioned in the ancient ayurveda books, and is first mentioned in the Sarngadhara Samhita as a treatment for diarrhea.[71] In the Bhaisajya Ratnavali it is named as an ingredient in an aphrodisiac.[71] Ayurveda says that both oil and tar can be used to stop bleeding,[40] and that traumatic bleeding can be stopped by four different methods: ligation of the blood vessel, cauterisation by heat, use of preparations to facilitate clotting, and use of preparations to constrict the blood vessels.  Ayurvedic treatment set up used for applying oil to patients, Kerala, 2017 Massage with oil is commonly prescribed by ayurvedic practitioners.[73] Oils are used in a number of ways, including regular consumption, anointing, smearing, head massage, application to affected areas,[74][failed verification] and oil pulling. Liquids may also be poured on the patient's forehead, a technique called shirodhara.[75] Panchakarma According to ayurveda, panchakarma are techniques to eliminate toxic elements from the body.[76] Panchakarma refers to five actions, which are meant to be performed in a designated sequence with the stated aim of restoring balance in the body through a process of purgation.[77] |

使用される物質 関連項目: インドの医療民族植物学  2016年にデリーで展示されたアーユルヴェーダ製剤 アーユルヴェーダの治療法の大部分(90%)は植物由来である。[61] アーユルヴェーダにおける植物療法は、根、葉、果実、樹皮、種子から抽出される。植物由来物質の例としては、カルダモンやシナモンが挙げられる。19世 紀、ウィリアム・ダイモックらは数百種の植物由来医薬品を、用途・顕微鏡構造・化学組成・毒性学・流布する神話・物語・英領インドにおける商業的関連性と 共にまとめた[62]。アマラキ、ビビタキ、ハリタキの3果実からなるハーブ製剤トリファラは、最も一般的に使用されるアーユルヴェーダ療法の一つである [63][64]。[65] ウィタニア・ソムニフェラ(アシュワガンダ)[66]とオキモム・テニフロルム(トゥルシー)[61]もアーユルヴェーダで日常的に使用される。  トゥルシーの花(ホーリーバジル)、アーユルヴェーダのハーブ アーユルヴェーダで使用される動物性製品には、牛乳、骨、胆石が含まれる[67]。さらに、脂肪は摂取用と外用両方に処方される。硫黄、ヒ素、鉛、硫酸銅、金などの鉱物の摂取も処方される[40]。ハーブ薬への鉱物添加はラサシャストラと呼ばれる。 アーユルヴェーダではマディヤと呼ばれるアルコール飲料が用いられる[68]。これはピッタを増やし、ヴァータとカパを減らすことでドーシャを調整すると される[68]。マディヤは原料と発酵過程によって分類され、カテゴリーには砂糖ベース、果実ベース、穀物ベース、穀物ベースにハーブを加えたもの、酢で 発酵させたもの、強壮ワインが含まれる。意図される効果には、下剤作用、消化や味覚の改善、乾燥作用、関節の弛緩などがある。アーユルヴェーダの文献で は、マディヤは粘性がなく即効性があり、体内の微細な毛穴に入り込んで浄化すると記述されている。[68] 精製アヘン[69]は八種のアーユルヴェーダ製剤[70]に使用され、ヴァータとカパのドーシャを均衡させ、ピッタのドーシャを増大させるとされる [69]。下痢や赤痢の治療、性機能や筋力の増強、脳への作用を目的として処方される。アヘンには鎮静作用と鎮痛作用があり、アーユルヴェーダではその特 性が考慮されている。アヘン使用は古代アーユルヴェーダ文献に記録され、西インド・ラージャスターン州で使用された薬学書『サルンガダラ・サンヒター』 (西暦1300~1400年)に初めて言及されている。男性射精を遅延させる媚薬の成分として記載されている[71]。アヘンはイスラム教徒の征服と同時 期、あるいはそれ以前にインドに伝来した可能性が高い[70]。マハラシュトラ州で広く知られる『ヨーガ・ラトナカラ』(1700-1800年頃、著者不 詳)では、下痢治療に処方される草薬・鉱物配合剤にアヘンが用いられている[71]。『ビシャジャ・ラトナヴァリ』では急性胃腸炎治療にアヘンと樟脳が使 用される。この薬剤では、アヘンの呼吸抑制作用が樟脳の呼吸刺激作用によって相殺される。[71] 後世の書物では、鎮痛剤としての使用を目的とした麻薬性が加えられている。[71] カンナビス・インディカも古代アーユルヴェーダの書物に記載されており、『サルンガダラ・サンヒタ』において下痢の治療薬として初めて言及されている。[71] 『薬宝論』では、媚薬の成分としてその名が挙げられている。[71] アーユルヴェーダによれば、油とタールの両方が止血に用いられ[40]、外傷性出血は四つの異なる方法で止血できるとされる:血管の結紮、熱による焼灼、凝固を促進する薬剤の使用、血管を収縮させる薬剤の使用である。  患者へのオイル塗布用アーユルヴェーダ治療装置、ケララ州、2017年 オイルマッサージはアーユルヴェーダ施術者によって一般的に処方される。[73] オイルは様々な方法で使用され、定期的な摂取、塗布、塗り込み、頭部マッサージ、患部への塗布[74][検証失敗]、オイルプリングなどが含まれる。ま た、シロダーラと呼ばれる技法では、液体を患者の額に注ぐこともある。[75] パンチャカルマ アーユルヴェーダによれば、パンチャカルマは体内の有害物質を除去する技法である。[76] パンチャカルマとは五つの処置を指し、指定された順序で実施される。その目的は、浄化プロセスを通じて身体のバランスを回復することにある。[77] |

| Current status Ayurveda is widely practiced in India and Nepal[3] where public institutions offer formal study in the form of a Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) degree. In certain parts of the world[where?], the legal standing of practitioners is equivalent to that of conventional medicine.[3] Several scholars have described the contemporary Indian application of ayurvedic practice as being "biomedicalized" relative to the more "spiritualized" emphasis to practice found in variants in the West.[78][77] Exposure to European developments in medicine from the nineteenth century onwards, through European colonization of India and the subsequent institutionalized support for European forms of medicine amongst European heritage settlers in India[79] were challenging to ayurveda, with the entire epistemology called into question. From the twentieth century, ayurveda became politically, conceptually, and commercially dominated by modern biomedicine, resulting in "modern ayurveda" and "global ayurveda".[25] Modern ayurveda is geographically located in the Indian subcontinent and tends towards secularization through minimization of the magic and mythic aspects of ayurveda.[25][26] Global ayurveda encompasses multiple forms of practice that developed through dispersal to a wide geographical area outside of India.[25] Smith and Wujastyk further delineate that global ayurveda includes those primarily interested in the ayurveda pharmacopeia, and also the practitioners of New Age ayurveda (which may link ayurveda to yoga and Indian spirituality and/or emphasize preventative practice, mind body medicine, or Maharishi ayurveda).[26] Since the 1980s, ayurveda has also become the subject of interdisciplinary studies in ethnomedicine which seeks to integrate the biomedical sciences and humanities to improve the pharmacopeia of ayurveda.[26] According to industry research, the global ayurveda market was worth US$4.5 billion in 2017.[80] |

現状 アーユルヴェーダはインドとネパールで広く実践されている[3]。これらの国では公的機関がアーユルヴェーダ医学・外科学士号(BAMS)という形で正式 な教育を提供している。世界の特定地域[どこ?]では、施術者の法的地位は従来の医学と同等である。[3] 複数の学者は、現代インドにおけるアーユルヴェーダ実践を、西洋で見られる「精神性を重視した」実践形態と比較して「生物医学化された」ものと評している [78][77]。 19世紀以降のヨーロッパ医学の発展は、インドのヨーロッパ植民地化と、インド在住のヨーロッパ系移民によるヨーロッパ医学形態への制度的支援を通じて、 アーユルヴェーダに挑戦を突きつけた。その結果、アーユルヴェーダの認識論全体が疑問視される事態となった。20世紀以降、アーユルヴェーダは政治的・概 念的・商業的に近代生物医学に支配されるようになり、「近代アーユルヴェーダ」と「グローバルアーユルヴェーダ」が生まれた。[25] 現代アーユルヴェーダは地理的にインド亜大陸に位置し、アーユルヴェーダの呪術的・神話的側面を最小化することで世俗化に向かう傾向がある[25] [26]。グローバルアーユルヴェーダは、インド国外の広範な地域への拡散を通じて発展した複数の実践形態を包含する。[25] スミスとウジャスティクはさらに、グローバル・アーユルヴェーダには主にアーユルヴェーダ薬典に関心を持つ者、ならびにニューエイジ・アーユルヴェーダの 実践者(アーユルヴェーダをヨガやインドの精神性に関連付けたり、予防的実践・心身医学・マハリシ・アーユルヴェーダを強調する者)も含まれると明示して いる。[26] 1980年代以降、アーユルヴェーダはまた、生物医学と人文科学を統合してアーユルヴェーダの薬典を改善しようとする民族医学における学際的研究の対象と もなった。[26] 業界調査によれば、2017年のグローバルアーユルヴェーダ市場規模は45億米ドルであった。[80] |

The Indian subcontinent A typical ayurvedic pharmacy, Rishikesh India See also: Healthcare in India It was reported in 2008[9] and again in 2018[81] that 80 percent of people in India used ayurveda exclusively or combined with conventional Western medicine.[9][81] A 2014 national health survey found that, in general, forms of the Indian system of medicine or AYUSH (ayurveda, yoga and naturopathy, unani, siddha, and homeopathy) were used by about 3.5% of patients who were seeking outpatient care over a two-week reference period.[82] In 1970, the Parliament of India passed the Indian Medical Central Council Act which aimed to standardise qualifications for ayurveda practitioners and provide accredited institutions for its study and research.[83] In 1971, the Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) was established under the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha medicine and Homoeopathy (AYUSH), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, to monitor higher education in ayurveda in India.[84] The Indian government supports research and teaching in ayurveda through many channels at both the national and state levels, and helps institutionalise traditional medicine so that it can be studied in major towns and cities.[85] The state-sponsored Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS) is designed to do research on ayurveda.[86] Many clinics in urban and rural areas are run by professionals who qualify from these institutes.[83] As of 2013, India had over 180 training centers that offered degrees in traditional ayurvedic medicine.[60] To fight biopiracy and unethical patents, the government of India set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library in 2001 to serve as a repository for formulations from systems of Indian medicine, such as ayurveda, unani and siddha medicine.[87][88] The formulations come from over 100 traditional ayurveda books.[89] An Indian Academy of Sciences document quoting a 2003–04 report states that India had 432,625 registered medical practitioners, 13,925 dispensaries, 2,253 hospitals and a bed strength of 43,803. 209 undergraduate teaching institutions and 16 postgraduate institutions.[90] In 2012, it was reported that insurance companies covered expenses for ayurvedic treatments in case of conditions such as spinal cord disorders, bone disorder, arthritis and cancer. Such claims constituted 5–10 percent of the country's health insurance claims.[91] Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti, an organisation dedicated to fighting superstition in India, considers ayurveda to be pseudoscience.[8] On 9 November 2014, India formed the Ministry of AYUSH.[92][93] National Ayurveda Day is also observed in India on the birth of Dhanvantari that is Dhanteras.[94] In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a report titled "The Health Workforce in India" which found that 31 percent of those who claimed to be doctors in India in 2001 were educated only up to the secondary school level and 57 percent went without any medical qualification.[95] The WHO study found that the situation was worse in rural India with only 18.8 percent of doctors holding a medical qualification.[95] Overall, the study revealed that nationally the density of all doctors (mainstream, ayurvedic, homeopathic and unani) was 8 doctors per 10,000 people compared to 13 per 10,000 people in China.[95][96] |

インド亜大陸 典型的なアーユルヴェーダ薬局、リシケシュ インド 関連項目: インドの医療 2008年[9]および2018年[81]の報告によれば、インド国民の80%がアーユルヴェーダを単独で、あるいは従来の西洋医学と併用して利用してい る。[9][81] 2014年の国民健康調査によれば、2週間の基準期間に外来診療を求めた患者の約3.5%が、インド伝統医療体系またはAYUSH(アーユルヴェーダ、ヨ ガ・自然療法、ウナニー医学、シッダ医学、ホメオパシー)を利用していた。[82] 1970年、インド議会はアーユルヴェーダ施術者の資格を標準化し、その研究・教育のための認定機関を設けることを目的とした「インド医療中央評議会法」 を可決した。[83] 1971年、健康家族福祉省傘下のアーユルヴェーダ・ヨガ・自然療法・ウナニ・シッダ・ホメオパシー(AYUSH)局に中央インド医学評議会(CCIM) が設置され、インドにおけるアーユルヴェーダ高等教育の監督を担うこととなった。[84] インド政府は、国民レベルと州レベルの両方で、多くの経路を通じてアーユルヴェーダの研究と教育を支援している。また、主要な町や都市で伝統医学が研究で きるよう、その制度化を支援している。[85] 政府が支援するアーユルヴェーダ科学中央研究評議会(CCRAS)は、アーユルヴェーダの研究を行うために設計されている。[86] 都市部と農村部の多くの診療所は、これらの機関で資格を取得した専門家によって運営されている。[83] 2013年時点で、インドには伝統的アーユルヴェーダ医学の学位を授与する訓練センターが180以上存在した。[60] バイオパイラシーや非倫理的な特許に対抗するため、インド政府は2001年に伝統的知識デジタル図書館を設立した。これはアーユルヴェーダ、ウナニ医学、 シッダ医学などインド医学体系の処方を保存するリポジトリとして機能する。[87][88] これらの処方は100冊以上の伝統的アーユルヴェーダ文献に由来する。[89] インド科学アカデミーの文書(2003-04年報告書引用)によれば、インドには登録医療従事者432,625名、診療所13,925か所、病院 2,253か所、病床数43,803床が存在した。学部教育機関は209校、大学院教育機関は16校であった。[90] 2012年には、保険会社が脊髄障害、骨疾患、関節炎、癌などの症状に対するアーユルヴェーダ治療費を補償していると報告された。こうした請求は国内の健 康保険請求の5~10%を占めていた。[91] インドの迷信撲滅団体「マハラシュトラ・アンダシュラッダ・ニルムーラン・サミティ」は、アーユルヴェーダを疑似科学と見なしている。[8] 2014年11月9日、インドはAYUSH省を設立した。[92][93]また、ダンヴァントリの誕生日であるダンテラスの日に「全国アーユルヴェーダの日」を制定している。[94] 2016年、世界保健機関(WHO)は「インドの健康従事者」と題する報告書を発表した。それによると、2001年にインドで医師を名乗る者の31%は中 等教育レベルまでの学歴しかなく、57%は医学的資格を全く持っていなかった。[95] WHOの調査では、インドの農村部では状況がさらに深刻で、医師のわずか18.8%しか医学的資格を持っていなかった。[95] 全体として、この調査は全国的に見て、全ての医師(主流医学、アーユルヴェーダ、ホメオパシー、ウナニー)の密度が1万人あたり8人であるのに対し、中国 では1万人あたり13人であることを明らかにした。[95][96] |

| Nepal About 75% to 80% of the population of Nepal use ayurveda.[5][6] As of 2009, ayurveda was considered to be the most common and popular form of medicine in Nepal.[97] Sri Lanka The Sri Lankan tradition of ayurveda is similar to the Indian tradition. Practitioners of ayurveda in Sri Lanka refer to Sanskrit texts which are common to both countries. However, they do differ in some aspects, particularly in the herbs used. In 1980, the Sri Lankan government established a Ministry of Indigenous Medicine to revive and regulate ayurveda.[98] The Institute of Indigenous Medicine (affiliated to the University of Colombo) offers undergraduate, postgraduate, and MD degrees in ayurveda medicine and surgery, and similar degrees in unani medicine.[99] In 2010, the public system had 62 ayurvedic hospitals and 208 central dispensaries, which served about 3 million people (about 11% of Sri Lanka's population). There are an estimated 20,000 registered practitioners of ayurveda in Sri Lanka.[100][101] According to the Mahavamsa, an ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty from the sixth century CE, King Pandukabhaya (reigned 437 BCE to 367 BCE) had lying-in-homes and ayurvedic hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documented evidence available of institutions dedicated specifically to the care of the sick anywhere in the world.[102][103] The hospital at Mihintale is the oldest in the world.[104] |

ネパール ネパールの人口の約75%から80%がアーユルヴェーダを利用している。[5][6] 2009年時点で、アーユルヴェーダはネパールで最も一般的で人気のある医療形態と見なされていた。[97] スリランカ スリランカのアーユルヴェーダ伝統はインドの伝統と似ている。スリランカのアーユルヴェーダ実践者は、両国に共通するサンスクリット文献を参照する。しかし、特に使用される薬草など、いくつかの点で異なる。 1980年、スリランカ政府はアーユルヴェーダの復興と規制を目的として、土着医療省を設立した。[98] コロンボ大学付属の土着医療研究所では、アーユルヴェーダ医学・外科の学士号、修士号、医学博士号、およびウナニ医学の同等学位を提供している。[99] 2010年時点で、公的医療システムには62のアーユルヴェーダ病院と208の中央診療所があり、約300万人(スリランカ人口の約11%)にサービスを 提供していた。スリランカには推定2万人の登録アーユルヴェーダ施術者がいる。[100][101] 6世紀のシンハラ王室年代記『マハーワンサ』によれば、パンドゥカバーヤ王(在位:紀元前437年~367年)は国内各地に分娩所とアーユルヴェーダ病院 (シヴィカソッティ・サラ)を建設した。これは世界中で病人の治療に特化した施設が設けられた、現存する最古の記録である。[102][103] ミヒンタレの病院は世界最古の病院である。[104] |

Outside the Indian subcontinent Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Amsterdam in 1967 Ayurveda is a system of traditional medicine developed during antiquity and the medieval period, and as such is comparable to pre-modern Chinese and European systems of medicine. In the 1960s, ayurveda began to be advertised as alternative medicine in the Western world. Due to different laws and medical regulations around the globe, the expanding practice and commercialisation of ayurveda raised ethical and legal issues.[105] Ayurveda was adapted for Western consumption, particularly by Baba Hari Dass in the 1970s and by Maharishi Ayurveda in the 1980s.[22] In some cases, this involved active fraud on the part of proponents of ayurveda in an attempt to falsely represent the system as equal to the standards of modern medical research.[105][106][107] United States Baba Hari Dass was an early proponent who helped bring ayurveda to the United States in the early 1970s. His teachings led to the establishment of the Mount Madonna Institute.[108] He invited several notable ayurvedic teachers, including Vasant Lad, Sarita Shrestha, and Ram Harsh Singh. The ayurvedic practitioner Michael Tierra wrote that the "history of Ayurveda in North America will always owe a debt to the selfless contributions of Baba Hari Dass".[109] In the United States, the practice of ayurveda is not licensed or regulated by any state. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) stated that "Few well-designed clinical trials and systematic research reviews suggest that Ayurvedic approaches are effective". The NCCIH warned against the issue of heavy metal poisoning, and emphasised the use of conventional health providers first.[110] As of 2018, the NCCIH reported that 240,000 Americans were using ayurvedic medicine.[110] Europe The first ayurvedic clinic in Switzerland was opened in 1987 by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.[111] In 2015, the government of Switzerland introduced a federally recognized diploma in ayurveda.[112] |

インド亜大陸の外では 1967年、アムステルダムのマハリシ・マヘシュ・ヨギ アーユルヴェーダは古代および中世に発展した伝統医療体系であり、その点で前近代的な中国やヨーロッパの医療体系と類似している。1960年代、アーユル ヴェーダは西洋世界で代替医療として宣伝され始めた。世界各国の異なる法律や医療規制により、アーユルヴェーダの実践拡大と商業化は倫理的・法的問題を引 き起こした[105]。アーユルヴェーダは西洋向けに改変され、特に1970年代のババ・ハリ・ダスや1980年代のマハリシ・アーユルヴェーダによって 普及した。[22] 場合によっては、アーユルヴェーダ推進者による積極的な詐欺行為も含まれ、この体系を現代医学研究の基準と同等であると偽って表現しようとした。 [105][106][107] アメリカ合衆国 ババ・ハリ・ダスは1970年代初頭にアーユルヴェーダをアメリカに導入した初期の推進者である。彼の教えはマウント・マドンナ研究所の設立につながっ た。[108] 彼はヴァサント・ラッド、サリタ・シュレスタ、ラム・ハルシュ・シンなど著名なアーユルヴェーダ教師を招いた。アーユルヴェーダ実践者マイケル・ティエラ は「北米におけるアーユルヴェーダの歴史は、ババ・ハリ・ダスの無私の貢献に永遠に負うところがある」と記している。[109] アメリカでは、アーユルヴェーダの実践はどの州でも免許や規制の対象になっていない。国立補完統合医療センター(NCCIH)は「アーユルヴェーダ療法が 有効であることを示唆する、よく設計された臨床試験や体系的な研究レビューはほとんど存在しない」と述べている。NCCIHは重金属中毒の問題について警 告し、まず従来の健康提供者を利用するよう強調した。[110] 2018年時点で、NCCIHは24万人のアメリカ人がアーユルヴェーダ医学を利用していると報告している。[110] ヨーロッパ スイス初のアーユルヴェーダ診療所は1987年にマハリシ・マヘーシュ・ヨギによって開設された。[111] 2015年、スイス政府は連邦政府公認のアーユルヴェーダ資格を導入した。[112] |

| Classification and efficacy Ayurvedic medicine is considered pseudoscientific because its premises are not based on science.[113][7] Both the lack of scientific soundness in the theoretical foundations of ayurveda and the quality of research have been criticized.[113][114][115][116] Although laboratory experiments suggest that some herbs and substances in ayurveda might be developed into effective treatments, there is no evidence that any are effective in themselves.[117][118] There is no good evidence that ayurvedic medicine is effective to treat or cure cancer in people.[12] Although ayurveda may help "improve quality of life" and Cancer Research UK also acknowledges that "researchers have found that some Ayurvedic treatments can help relieve cancer symptoms", the organization warns that some ayurvedic drugs contain toxic substances or may interact with legitimate cancer drugs in a harmful way.[12] Ethnologist Johannes Quack writes that although the rationalist movement Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti officially labels ayurveda a pseudoscience akin to astrology, these practices are in fact embraced by many of the movement's members.[8] A review of the use of ayurveda for cardiovascular disease concluded that the evidence is not convincing for the use of any ayurvedic herbal treatment for heart disease or hypertension, but that many herbs used by ayurvedic practitioners could be appropriate for further research.[119] Promotion In India, promotion of ayurveda is undertaken by the Ministry of AYUSH through a national network of research institutes.[120] In Nepal, the National Ayurvedic Training and Research Centre (NATRC) promotes medicinal herbs in the country.[121] In Sri Lanka, the Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine looks after the promotion of ayurveda through various national research institutes.[122] Use of toxic metals Rasashastra is the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbal preparations. A random sample study found 20% of rasa medicines sold on the Internet in 2005 included toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic.[24] The public health implications of metals in rasashastra in India is unknown.[24] Adverse reactions to herbs are described in traditional ayurvedic texts, but practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and that reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available. There is a communication gap between practitioners of medicine and ayurveda.[123] Traditional Indian herbal medicinal products have been found to contain harmful levels of heavy metals, including lead.[124] For example, ghasard, a product commonly given to infants for digestive issues, has been found to have up to 1.6% lead concentration by weight, leading to lead encephalopathy.[125] A 1990 study on ayurvedic medicines in India found that 41% of the products tested contained arsenic, and that 64% contained lead and mercury.[9] A 2004 study found toxic levels of heavy metals in 20% of ayurvedic preparations made in South Asia and sold in the Boston area, and concluded that ayurvedic products posed serious health risks and should be tested for heavy-metal contamination.[126] A 2008 study of more than 230 products found that approximately 20% of remedies (and 40% of rasashastra medicines) purchased over the Internet from U.S. and Indian suppliers contained lead, mercury or arsenic.[24][127][128] A 2015 study of users in the United States found elevated blood lead levels in 40% of those tested, leading physician and former U.S. Air Force flight surgeon Harriet Hall to say that "Ayurveda is basically superstition mixed with a soupçon of practical health advice. And it can be dangerous."[129][130] A 2022 study found that ayurvedic preparations purchased over-the-counter in Chandigarh, India, had levels of zinc, mercury, arsenic and lead over the limits set by the Food and Agriculture Organisation / World Health Organisation. 83% exceeded the limit for zinc, 69% for mercury, 14% for arsenic and 5% for lead.[23] In 2023, the Victorian Department of Health issued a health advisory warning that unregulated ayurvedic products sold in the state may contain unsafe levels of lead, mercury and arsenic, as well as harmful compounds from the plants Azadirachta indica and Acorus calamus.[131] Heavy metals are thought of as active ingredients by advocates of Indian herbal medicinal products.[124] According to ancient ayurvedic texts, certain physico-chemical purification processes such as samskaras or shodhanas (for metals) 'detoxify' the heavy metals in it.[132][133] These are similar to the Chinese pao zhi, although the ayurvedic techniques are more complex and may involve physical pharmacy techniques as well as mantras. However, these products have nonetheless caused severe lead poisoning and other toxic effects.[127] Between 1978 and 2008, "more than 80 cases of lead poisoning associated with Ayurvedic medicine use [were] reported worldwide".[134] In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) linked ayurvedic drugs to lead poisoning, based on cases where toxic materials were found in the blood of pregnant women who had taken ayurvedic drugs.[135] Ayurvedic practitioners argue that the toxicity of bhasmas (ash products) comes from improper manufacturing processes, contaminants, improper use of ayurvedic medicine, quality of raw materials and that the end products and improper procedures are used by charlatans.[133] In India, the government ruled that ayurvedic products must be labelled with their metallic content.[136] However, in Current Science, a publication of the Indian Academy of Sciences, M. S. Valiathan said that "the absence of post-market surveillance and the paucity of test laboratory facilities [in India] make the quality control of Ayurvedic medicines exceedingly difficult at this time".[136] In the United States, most ayurvedic products are marketed without having been reviewed or approved by the FDA. Since 2007, the FDA has placed an import alert on some ayurvedic products in order to prevent them from entering the United States.[137] A 2012 toxicological review of mercury-based traditional herbo-metallic preparations concluded that the long-term pharmacotherapeutic and in-depth toxicity studies of these preparations are lacking.[138] |

分類と有効性 アーユルヴェーダ医学は、その前提が科学に基づかないため疑似科学と見なされている。[113][7] アーユルヴェーダの理論的基盤における科学的妥当性の欠如と研究の質の両方が批判されている。[113][114][115] [116] 実験室での研究では、アーユルヴェーダで使用される一部のハーブや物質が有効な治療法として開発される可能性が示唆されているものの、それ自体が有効であ るという証拠は存在しない。[117][118] アーユルヴェーダ医学がヒトのがん治療や治癒に有効であるという確かな証拠はない。[12] アーユルヴェーダが「生活の質向上」に寄与する可能性は認められ、英国がん研究機構も「一部のアーユルヴェーダ療法ががん症状緩和に有効との研究結果があ る」と述べている。しかし同機構は、一部のアーユルヴェーダ薬に有害物質が含まれる可能性や、正規のがん治療薬との有害な相互作用が生じる恐れがあると警 告している。[12] 民族学者ヨハネス・クアックは、合理主義運動「マハラシュトラ・アンダシュラッド・ニルムーラン・サミティ」が公式にはアーユルヴェーダを占星術に類する 疑似科学と位置付けているにもかかわらず、実際には運動の多くのメンバーがこれらの実践を受け入れていると記している。[8] 心血管疾患に対するアーユルヴェーダの使用に関するレビューでは、心臓病や高血圧に対するアーユルヴェーダのハーブ療法の使用については証拠が説得力を持 たないと結論づけつつも、アーユルヴェーダ施術者が使用する多くのハーブはさらなる研究に適している可能性があると指摘している。[119] 普及 インドでは、アーユルヴェーダの普及はAYUSH省が国民的な研究機関ネットワークを通じて行っている。[120] ネパールでは、国立アーユルヴェーダ研修研究センター(NATRC)が国内の薬用ハーブを推進している。[121] スリランカでは、健康・栄養・伝統医療省が様々な国立研究機関を通じてアーユルヴェーダの推進を担当している。[122] 有毒金属の使用 ラサシャストラとは、ハーブ製剤に金属、鉱物、宝石を添加する手法である。2005年にインターネットで販売されたラサ医薬品の無作為抽出調査では、 20%に鉛、水銀、ヒ素などの有害重金属が含まれていた。[24] インドにおけるラサシャストラの金属含有が公衆衛生に及ぼす影響は不明である。[24] ハーブの有害反応は伝統的なアーユルヴェーダ文献に記載されているが、施術者はハーブの毒性を認めることに消極的であり、ハーブ毒性に関する信頼できる情 報は容易に入手できない。医学とアーユルヴェーダの実践者間にはコミュニケーションの隔たりがある。[123] 伝統的なインドのハーブ医薬品には、鉛を含む有害レベルの重金属が含まれていることが判明している。[124] 例えば、乳児の消化器疾患に一般的に投与される製品「ガサード」には、重量比で最大1.6%の鉛濃度が確認され、鉛脳症を引き起こしている。[125] 1990年のインドにおけるアーユルヴェーダ薬の研究では、検査対象製品の41%にヒ素、64%に鉛と水銀が含まれていた。[9] 2004年の研究では、南アジアで製造されボストン地域で販売されているアーユルヴェーダ製剤の20%から有害レベルの重金属が検出され、アーユルヴェー ダ製品は深刻な健康リスクをもたらすため重金属汚染の検査が必要であると結論づけられた。[126] 2008年の230製品以上を対象とした研究では、米国およびインドの供給業者からインターネットで購入した治療薬の約20%(ラサシャストラ医薬品の 40%)に鉛、水銀、またはヒ素が含まれていた。[24][127][128] 2015年の米国利用者調査では、検査対象者の40%で血中鉛濃度の上昇が確認された。これを受け、医師で元米空軍飛行外科医のハリエット・ホールは 「アーユルヴェーダは基本的に迷信に実用的な健康アドバイスを少し混ぜたものに過ぎない。そしてそれは危険になり得る」と述べた。[129][130] 2022年の研究では、インド・チャンディーガルで市販されているアーユルヴェーダ製剤の亜鉛、水銀、ヒ素、鉛の含有量が、国連食糧農業機関/世界保健機 関が設定した基準値を超えていた。亜鉛は83%、水銀は69%、ヒ素は14%、鉛は5%が基準値を超過していた。[23] 2023年、ビクトリア州保健省は健康勧告を発表し、州内で販売されている規制対象外のアーユルヴェーダ製品には、鉛・水銀・ヒ素の安全基準値を超える含 有量や、ニーム(Azadirachta indica)及びショウガ科植物(Acorus calamus)由来の有害化合物が含まれる可能性があると警告した。[131] インドのハーブ医薬品の支持者らは、重金属を有効成分と見なしている。[124] 古代のアーユルヴェーダ文献によれば、サムスカラやショダナ(金属用)といった特定の物理化学的精製プロセスが、含有重金属を「解毒」するとしている。 [132] [133] これらは中国の「炮制」に類似しているが、アーユルヴェーダの技術はより複雑で、物理的製剤技術やマントラも含まれる。しかしながら、これらの製品は深刻 な鉛中毒やその他の毒性作用を引き起こしている。[127] 1978年から2008年の間に、「アーユルヴェーダ薬の使用に関連する鉛中毒が世界中で80件以上報告された」。[134] 2012年、米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)は、アーユルヴェーダ薬を服用した妊婦の血液から有毒物質が検出された事例に基づき、アーユルヴェーダ薬 と鉛中毒の関連性を指摘した。[135] アーユルヴェーダ施術者は、バスマ(灰製品)の毒性は不適切な製造工程、汚染物質、アーユルヴェーダ医薬品の誤用、原材料の品質に起因すると主張する。また、最終製品や不適切な手順は詐欺師によって利用されていると述べている。[133] インドでは、政府がアーユルヴェーダ製品に金属含有量を表示するよう義務付けた。[136] しかしインド科学アカデミー刊行の『カレント・サイエンス』誌でM.S.ヴァリアタンは「(インドにおける)市販後監視の欠如と試験施設の不備が、現時点 でのアーユルヴェーダ医薬品の品質管理を極めて困難にしている」と述べた。[136] 米国では大半のアーユルヴェーダ製品がFDAの審査・承認を受けずに販売されている。2007年以降、FDAは一部のアーユルヴェーダ製品に対し輸入警告 を発令し、米国への流入を阻止している。[137] 2012年の水銀含有伝統的草薬・金属製剤に関する毒性学レビューでは、これらの製剤に関する長期薬理治療研究及び詳細な毒性研究が不足していると結論づ けられた。[138] |

| History Some of this section's listed sources may not be reliable. Please help improve this article by looking for better, more reliable sources. Unreliable citations may be challenged and removed. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. Please help improve it by replacing them with more appropriate citations to reliable, independent sources. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Some scholars assert that the concepts of traditional ayurvedic medicine have existed since the times of the Indus Valley civilisation but since the Indus script has not been deciphered, such assertions are moot.[25]: 535–536 The Atharvaveda contains hymns and prayers aimed at curing disease. There are various legendary accounts of the origin of ayurveda, such as that it was received by Dhanvantari (or Divodasa) from Brahma.[18][40] Tradition also holds that the writings of ayurveda were influenced by a lost text by the sage Agnivesha.[139] Ayurveda is one of the few systems of medicine developed in ancient times that is still widely practised in modern times.[26] As such, it is open to the criticism that its conceptual basis is obsolete and that its contemporary practitioners have not taken account of the developments in medicine.[140][141] Responses to this situation led to an impassioned debate in India during the early decades of the twentieth century, between proponents of unchanging tradition (śuddha "pure" ayurveda) and those who thought ayurveda should modernize and syncretize (aśuddha "impure, tainted" ayurveda).[142][143][144] The political debate about the place of ayurveda in contemporary India has continued to the present, both in the public arena and in government.[145] Debate about the place of ayurvedic medicine in the contemporary internationalized world also continues today.[146][147] |

歴史 この節に記載されている情報源の一部は信頼性に欠ける可能性がある。信頼性の高い情報源を探し、この記事の改善に協力してほしい。信頼性の低い引用は異議を唱えられ、削除される可能性がある。(2018年4月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングについて) この節は主題と密接に関連する情報源に過度に依存している可能性があ る。これにより、記事の検証可能性と中立性が損なわれる恐れがある。信頼できる独立した情報源への適切な引用に置き換えることで、改善にご協力ください。 (2018年4月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 一部の学者は、伝統的なアーユルヴェーダ医学の概念はインダス文明の時代から存在していたと主張する。しかしインダス文字は解読されていないため、そのよ うな主張は議論の余地がある。[25]: 535–536 アタルヴァヴェーダには病気を治すための賛歌や祈りが含まれている。アーユルヴェーダの起源については様々な伝説があり、例えばダンヴァントリ(または ディヴォダサ)がブラフマーから授かったというものがある。[18][40] 伝統によれば、アーユルヴェーダの文献は聖者アグニヴェーシャの失われた書物に影響を受けたともされている。[139] アーユルヴェーダは古代に発展した数少ない医療体系の一つであり、現代においても広く実践されている。[26] そのため、その概念的基盤は時代遅れであり、現代の実践者は医学の発展を考慮していないという批判に晒されている。[140][141] この状況への対応として、20世紀初頭のインドでは、不変の伝統(シュッダ「純粋」アーユルヴェーダ)を主張する派と、アーユルヴェーダの近代化・融合化 (アシュッダ「不純、汚染された」アーユルヴェーダ)を主張する派の間で、激しい論争が起きた。[142][143] [144] 現代インドにおけるアーユルヴェーダの位置づけをめぐる政治的議論は、公の場でも政府内でも現在まで続いている。[145] 現代の国際化された世界におけるアーユルヴェーダ医学の位置づけに関する議論も、今日なお続いている。[146][147] |

| Main texts Many ancient works on ayurvedic medicine are lost to posterity,[148] but manuscripts of three principal early texts on ayurveda have survived to the present day. These works are the Charaka Samhita, the Sushruta Samhita and the Bhela Samhita. The dating of these works is historically complicated since they each internally present themselves as composite works compiled by several editors. All past scholarship on their dating has been evaluated by Meulenbeld in volumes IA and IB of his History of Indian Medical Literature.[2] After considering the evidence and arguments concerning the Suśrutasaṃhitā, Meulenbeld stated (IA, 348), The Suśrutasaṃhitā is most probably the work of an unknown author who drew much of the material he incorporated in his treatise from a multiplicity of earlier sources from various periods. This may explain that many scholars yield to the temptation to recognize a number of distinct layers and, consequently, try to identify elements belonging to them. As we have seen, the identification of features thought to belong to a particular stratum is in many cases determined by preconceived ideas on the age of the strata and their supposed authors. The dating of this work to 600 BCE was first proposed by Hoernle over a century ago,[149] but has long since been overturned by subsequent historical research. The current consensus amongst medical historians of South Asia is that the Suśrutasaṃhitā was compiled over a period of time starting with a kernel of medical ideas from the century or two BCE and then being revised by several hands into its present form by about 500 CE.[2][21] The view that the text was updated by the Buddhist scholar Nagarjuna in the 2nd century CE[150] has been disproved, although the last chapter of the work, the Uttaratantra, was added by an unknown later author before 500 CE.[2] Similar arguments apply to the Charaka Samhita, written by Charaka, and the Bhela Samhita, attributed to Atreya Punarvasu, that are also dated to the 6th century BCE by non-specialist scholars[151][152][153] but are in fact, in their present form, datable to a period between the second and fifth centuries CE.[2][21][13] The Charaka Samhita was also updated by Dridhabala during the early centuries of the Common Era.[154] Statue of Charaka, ancient Indian physician, in Haridwar, India The Bower Manuscript (dated to the early 6th century CE[155]) includes of excerpts from the Bheda Samhita[156] and its description of concepts in Central Asian Buddhism. In 1987, A. F. R. Hoernle identified the scribe of the medical portions of the manuscript to be a native of India using a northern variant of the Gupta script, who had migrated and become a Buddhist monk in a monastery in Kucha. The Chinese pilgrim Fa Hsien (c. 337–422 CE) wrote about the healthcare system of the Gupta empire (320–550) and described the institutional approach of Indian medicine. This is also visible in the works of Charaka, who describes hospitals and how they should be equipped.[157] Some dictionaries of materia medica include Astanga nighantu (8th century) by Vagbhata, Paryaya ratnamala (9th century) by Madhava, Siddhasara nighantu (9th century) by Ravi Gupta, Dravyavali (10th century), and Dravyaguna sangraha (11th century) by Chakrapani Datta, among others.[158][159] Illnesses portrayed Underwood and Rhodes state that the early forms of traditional Indian medicine identified fever, cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumours, and leprosy,[40] and that treatments included plastic surgery, lithotomy, tonsillectomy,[160] couching (a form of cataract surgery), puncturing to release fluids in the abdomen, extraction of foreign bodies, treatment of anal fistulas, treating fractures, amputations, cesarean sections,[Vagbhata 1][160][disputed – discuss] and stitching of wounds.[40] The use of herbs and surgical instruments became widespread.[40] During this period, treatments were also prescribed for complex ailments, including angina pectoris, diabetes, hypertension, and stones.[162][163] Further development and spread Ayurveda flourished throughout the Indian Middle Ages. Dalhana (fl. 1200), Sarngadhara (fl. 1300) and Bhavamisra (fl. 1500) compiled works on Indian medicine.[164] The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka were also translated into the Chinese language in the 5th century,[165] and during the 8th century, they were translated into the Arabic and Persian language.[166] The 9th-century Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi was familiar with the text.[167][168] The Arabic works derived from the ayurvedic texts eventually also reached Europe by the 12th century.[169][170] In Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) were influenced by the Arabic reception of the Sushruta's surgical techniques.[170] British physicians traveled to India to observe rhinoplasty being performed using Indian methods, and reports on their rhinoplasty methods were published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1794.[171] Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in Europe.[172] Joseph Constantine Carpue studied plastic surgery methods in India for 20 years and, in 1815, was able to perform the first major rhinoplasty surgery in the western world, using the "Indian" method of nose reconstruction.[173] In 1840 Brett published an article about this technique.[174] The British had shown some interest in understanding local medicinal practices in the early nineteenth century. A Native Medical Institution was setup in 1822 where both indigenous and European medicine were taught. After the English Education Act 1835, their policy changed to champion European medicine and disparage local practices.[175] After Indian independence, there was more focus on ayurveda and other traditional medical systems. Ayurveda became a part of the Indian National healthcare system, with state hospitals for ayurveda established across the country. However, the treatments of traditional medicines were not always integrated with others.[3] |

主要文献 アーユルヴェーダ医学に関する多くの古代文献は後世に失われている[148]が、アーユルヴェーダの主要な初期文献三種の写本は今日まで残っている。これ らは『チャラカ・サンヒター』『スシュルタ・サンヒター』『ベーラ・サンヒター』である。これらの著作の年代測定は歴史的に複雑である。それぞれが複数の 編集者によって編纂された複合的な著作として内部で提示されているためだ。これらの年代に関する過去の研究は全て、ミューレンベルトが『インド医学文献 史』第IA巻及び第IB巻において評価している[2]。スシュルタ・サンヒターに関する証拠と議論を検討した後、ミューレンベルトは次のように述べている (IA, 348頁)。 スシュルタ・サンヒターは、おそらく無名の著者が、様々な時代の複数の先行資料から多くの素材を引用して編纂した作品である。これが、多くの研究者が複数 の異なる層を認識する誘惑に負けて、それらに属する要素を特定しようとする理由を説明しているかもしれない。これまで見てきたように、特定の層に属すると 考えられる特徴の特定は、多くの場合、層の年代や想定される著者に関する先入観によって決定されるのである。 この著作を紀元前600年頃と年代測定したのは、1世紀以上前にホーンレが初めて提唱したものである[149]が、その後の歴史研究によってとっくに覆さ れている。南アジアの医療史研究者の現在の共通認識は、スシュルタ・サンヒターが紀元前1~2世紀の医療思想の核を起点として編纂が始まり、その後複数の 手によって改訂され、紀元500年頃までに現在の形態に至ったというものだ。[2][21] 仏教学者ナーガールジュナが紀元2世紀に本文を更新したとする見解[150]は否定されている。ただし、最終章『ウッタラタントラ』は紀元500年以前 に、後代の無名著者によって追加されたものである。[2] 同様の議論は、チャラカによる『チャラカ・サンヒター』やアトレイヤ・プナルヴァスに帰せられる『ベラ・サンヒター』にも当てはまる。これらも非専門家の 学者によって紀元前6世紀と年代付けされている[151][152][153]が、実際には現在の形態では紀元2世紀から5世紀の間に成立したものと見な される。[2][21][13] チャラカ・サンヒターは紀元後数世紀の間にドリダバラによって改訂された。[154] インド・ハリドワールにある古代インドの医師チャラカ像 バウアー写本(紀元6世紀初頭と推定される[155])には、ベダ・サンヒター[156]からの抜粋と中央アジア仏教の概念に関する記述が含まれている。 1987年、A. F. R. ホーンルは、この写本の医学部分の筆写者が、グプタ文字の北部変種を使用するインド出身者であり、移住してクチャの僧院で仏教僧となった人物であると特定 した。中国人の巡礼者法顕(337年頃~422年)はグプタ帝国(320年~550年)の医療制度について記述し、インド医学の制度的アプローチを説明し た。これはチャラカ(Charaka)の著作にも見られ、彼は病院とその設備について詳述している。[157] 薬物辞典には、ヴァグバタの『アスタンガ・ニガントゥ』(8世紀)、マダーヴァの『パリヤーヤ・ラトナマーラ』(9世紀)、ラヴィ・グプタの『シッダサー ラ・ニガントゥ』(9世紀)、ドラヴィヤヴァリ(10世紀)、 チャクラパーニ・ダッタの『ドラヴィヤグナ・サングラハ』(11世紀)などが挙げられる。[158][159] 描かれた疾病 アンダーウッドとローズは、古代インド医学が熱、咳、消耗性疾患、下痢、水腫、膿瘍、痙攣、腫瘍、ハンセン病を認識していたと述べている。[40] 治療法には形成外科、結石切除術、 扁桃摘出術、[160]白内障手術の一種であるカウチング、腹腔内液排出のための穿刺、異物除去、肛門瘻の治療、骨折治療、切断術、帝王切開、[ヴァグバ タ1][160][議論の余地あり – 議論]創傷縫合などがあった。[40] 薬草や外科器具の使用が広く普及した。[40] この時期には、狭心症、糖尿病、高血圧、結石などの複雑な疾患に対する治療法も処方された。[162] [163] さらなる発展と普及 アーユルヴェーダはインド中世を通じて栄えた。ダルハナ(1200年頃)、サルンガダラ(1300年頃)、バヴァミスラ(1500年頃)がインド医学に関 する著作を編纂した。[164] スシュルタとチャラカの両医学書は5世紀に中国語へ翻訳され[165]、8世紀にはアラビア語とペルシア語へ翻訳された[166]。9世紀のペルシア人医 師ムハンマド・イブン・ザカリヤ・アル=ラーズィーはこの文献に精通していた。[167][168] アーユルヴェーダ文献に由来するアラビア語著作は、12世紀までにヨーロッパにも伝播した[169][170]。ルネサンス期のイタリアでは、シチリアの ブランカ家やボローニャのガスパレ・タリアコッツィが、スシュルタの外科手術技法に関するアラビア語受容の影響を受けた。[170] 英国の医師たちはインドへ渡り、現地の手法による鼻形成術を視察した。その報告は1794年に『ジェントルマンズ・マガジン』に掲載された。[171] スシュルタ・サムヒタに記載された器具は、欧州でさらに改良が加えられた。[172] ジョセフ・コンスタンティン・カルピュは20年間インドで形成外科術法を研究し、1815年には西洋世界初の主要な鼻形成手術を「インド式」鼻再建法を用 いて実施した。[173] 1840年にはブレットがこの技術に関する論文を発表した。[174] 19世紀初頭、英国は現地の医療慣行を理解することにある程度の関心を示していた。1822年には現地医療機関が設立され、現地医療と西洋医学の両方が教 えられた。1835年の英国教育法施行後、政策は欧州医学を推し進め現地医療を軽視する方向へ転換した[175]。インド独立後はアーユルヴェーダやその 他の伝統医療体系への注目が高まった。アーユルヴェーダはインド国民医療制度の一部となり、全国にアーユルヴェーダ専門の州立病院が設立された。しかし伝 統医療の治療法は必ずしも他の医療と統合されてはいない[3]。 |

| Sri Lankan traditional medicine Unani medicine Acupuncture Ashvins Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery Bhaisajyaguru Dhātu (ayurveda) History of alternative medicine Homeopathy List of ayurveda colleges List of unproven and disproven cancer treatments Ramuan Medical ethnobotany of India |

スリランカの伝統医学 ウナニ医学 鍼治療 アシュヴィン アーユルヴェーダ・医学・外科の学士号 薬師如来 ダータ(アーユルヴェーダ) 代替医療の歴史 ホメオパシー アーユルヴェーダ大学のリスト 未検証および反証された癌治療法のリスト ラマン インドの医療民族植物学 |

| Footnotes 1. Vāgbhaṭa's Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā describes a procedure for the removal of a dead foetus from the womb of a living mother, and of a living child from the womb of a mother who has died (शारीरस्थान २, गर्भव्यापद्, २.२६-२७, २.५३).[161] Both these descriptions speak of removal of the fetus through the uterine passage, rather than from the front lower abdomen as with the caesarian section procedure. The earlier description of the Suśrutasaṃhitā (चिकित्सास्थान १५ "मूढगर्भ") is similar. A dead fetus is removed through the uterine passage and vagina. Although Suśruta does not describe removing a living child from a dead mother. |

脚注 1. ヴァーグバータの『アシュタンガ・ハルダヤ・サンヒター』は、生きている母親の子宮から死んだ胎児を取り出す方法、そして死んだ母親の子宮から生きている 子供を取り出す方法を記述している (शारीरस्थान २, गर्भव्यापद्, २.२६-२७, २.५३)。[161] これらの記述はいずれも、帝王切開のように前腹部からではなく、子宮腔内を通じた胎児の摘出について述べている。スシュルタ・サンヒター (चिकित्सास्थान १५「मूढगर्भ」)の初期の記述も同様である。死産児は子宮腔と膣を通って除去される。ただしスシュルタは、死んだ母親から生きている子を摘出する 方法については記述していない。 |

| References |

|

| Cited references Chopra, Ananda S. (2003). "Āyurveda". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Medicine across cultures: history and practice of medicine in non-western cultures. Kluwer Academic. pp. 75–83. ISBN 978-1-4020-1166-5. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015. Dwivedi, Girish; Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" (PDF). Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 49: 243–244. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. (Republished by National Informatics Centre, Government of India.) Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3. Kutumbian, P. (1999). Ancient Indian Medicine. Andhra Pradesh: Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1521-5. Lock, Stephen (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-262950-0. Underwood, E. Ashworth; Rhodes, P. (2008). "History of Medicine". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.). Wujastyk, D. (2003a). The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044824-5. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020. |

引用文献 チョプラ、アナンダ・S.(2003年)。「アーユルヴェーダ」。セリン、ヘレイン(編)。『異文化における医学:非西洋文化における医学の歴史と実 践』。クルーワー・アカデミック。75–83頁。ISBN 978-1-4020-1166-5。2023年9月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2015年11月15日に取得。 ドウィヴェディ、ギリッシュ; ドウィヴェディ、シュリダル (2007). 「医学の歴史:スシュルタ ― 卓越した臨床医・教師」 (PDF). インド胸部疾患および関連科学ジャーナル. 49: 243–244. 2008年10月10日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブされた。(インド政府国立情報センターにより再公開) フィンガー、スタンリー(2001)。『神経科学の起源:脳機能探求の歴史』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3。 クトゥンビアン、P.(1999)。『古代インド医学』。アンドラ・プラデーシュ州:オリエント・ロングマン。ISBN 978-81-250-1521-5。 ロック、スティーブン(2001)。『オックスフォード図解医学事典』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-262950-0。 アンダーウッド、E. アシュワース; ローズ、P. (2008). 「医学の歴史」. ブリタニカ百科事典 (2008年版). ウジャスティク、D.(2003a)。『アーユルヴェーダの根源:サンスクリット医学文献選集』。ペンギンブックス。ISBN 978-0-14-044824-5。2023年9月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2020年11月8日に取得。 |

| Further reading Drury, Heber (1873). The Useful plants of India. William H Allen & Co., London. ISBN 978-1-4460-2372-3. Dymock, William; et al. (1890). Pharmacographia Indica A history of principal drugs of vegetable origin in British India. Vol. 1. London, Bombat, Calcutta: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, Education Society Press, Byculla, Thacker, Spink and Co. Hoernle, Rudolf August Friedrich (1907). Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India: Part I: Osteology. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Pattathu, Anthony George (2018). Ayurveda and Discursive Formations between Religion, Medicine and Embodiment: A Case Study from Germany. In: Lüddeckens, D., & Schrimpf, M. (2018). Medicine – religion – spirituality: Global perspectives on traditional, complementary, and alternative healing. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8376-4582-8, pp. 133–166. Patwardhan, Kishore (2008). Pabitra Kumar Roy (ed.). Concepts of Human Physiology in Ayurveda (PDF). Samyak Vak Series-14. Sarnath, Varanasi: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. pp. 53–73. ISBN 978-81-87127-76-5. {{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help) Wise, Thomas T. (1845). Commentary on the Hindu System of Medicine. Calcutta: Thacker & Co. Wujastyk, Dominik (2011). "Indian Medicine". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0035.. A bibliographical survey of the history of Indian medicine. WHO guidelines on safety monitoring of herbal medicines in pharmacovigilance systems Use Caution With Ayurvedic Products – US Food and Drug Administration. |

追加文献(さらに読む) Drury, Heber (1873). 『インドの有用植物』. William H Allen & Co., ロンドン. ISBN 978-1-4460-2372-3. Dymock, William; et al. (1890). 『インド薬物誌 英国領インドにおける主要植物性薬物の歴史』第1巻。ロンドン、ボンベイ、カルカッタ:キーガン・ポール、トレンチ、トゥルーブナー社、エデュケーショ ン・ソサエティ・プレス、バイクラ、サッカ、スピンク社 ヘルンレ、ルドルフ・アウグスト・フリードリヒ(1907年)。『古代インド医学研究:第1部 骨学』。クラレンドン・プレス、オックスフォード。 パッタトゥ、アンソニー・ジョージ(2018)。『アーユルヴェーダと宗教・医学・身体性の間の言説形成:ドイツにおける事例研究』。リュデッケンス、 D.、シュリンプフ、M.(編)(2018)。『医学-宗教-精神性:伝統的・補完的・代替的治療に関するグローバルな視点』。ビーレフェルト:トランス クリプト出版社。ISBN 978-3-8376-4582-8, pp. 133–166. パトワルダン, キショア (2008). パビトラ・クマール・ロイ (編). 『アーユルヴェーダにおける人体生理学の概念』 (PDF). サミャク・ヴァク・シリーズ-14. サルナート, バラナシ: 中央チベット高等研究所. pp. 53–73. ISBN 978-81-87127-76-5. {{cite book}}: |work=が無視された (help) ワイズ、トーマス・T. (1845). 『ヒンドゥー医学体系の解説』. カルカッタ: Thacker & Co. ウジャスティク、ドミニク (2011). 「インド医学」。オックスフォード・バイオリグラフィーズ。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0035.. インド医学史の書誌学的概観。 薬物監視システムにおける漢方薬の安全性モニタリングに関するWHOガイドライン アーユルヴェーダ製品の使用には注意を – 米国食品医薬品局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayurveda |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099