Closed Corporate Peasant Communities

The Peasant Wedding, by Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1567 or 1568

E・ウルフの閉鎖的農民共同体

Closed Corporate Peasant Communities

The Peasant Wedding, by Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1567 or 1568

解説:池田光穂

■農民の定義: 「営利事業としてではなく、生計の手段として農耕に従事する、土地を効果的に管理している農業生産者」(p.243:訳書:以下同様)

ウィキペディアの定義は:"A

peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or

farmer, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and

paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord" - peasant.

●農民共同体の特徴

1.土地などの財産に関する権利の体系をもつ。

2.宗教組織を通して余剰を再配分するような機構をもつ。

3.部外者を成員となることを禁止する(と、同時に外部との交渉をもつ成員の活動を制限する作用あり)

| A peasant

is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited

land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under

feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord.[1][2]

In Europe, three classes of peasants existed: non-free slaves,

semi-free serfs, and free tenants. Peasants might hold title to land

outright (fee simple), or by any of several forms of land tenure, among

them socage, quit-rent, leasehold, and copyhold.[3] In some contexts, "peasant" has a pejorative meaning, even when referring to farm laborers.[4] As early as in 13th-century Germany, the concept of "peasant" could imply "rustic" as well as "robber", as the English term villain[5]/villein.[6][7] In 21st-century English, the word "peasant" can mean "an ignorant, rude, or unsophisticated person".[8] The word rose to renewed popularity in the 1940s–1960s[9] as a collective term, often referring to rural populations of developing countries in general, as the "semantic successor to 'native', incorporating all its condescending and racial overtones".[4] The word peasantry is commonly used in a non-pejorative sense as a collective noun for the rural population in the poor and developing countries of the world.[citation needed] Via Campesina, an organization claiming to represent the rights of about 200 million farm-workers around the world, self-defines as an "International Peasant's Movement" as of 2019.[10] The United Nations and its Human Rights Council prominently uses the term "peasant" in a non-pejorative sense, as in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas adopted in 2018. In general English-language literature, the use of the word "peasant" has steadily declined since about 1970.[11] |

農民とは、産業革命以前の農業労働者、または限定的な土地所有権を持つ

農民のことであり、特に中世の封建制の下で生活し、地主に家賃、税金、手数料、役務を支払う農民のことである[1][2]。農民は土地の所有権をそのまま

(fee

simple)保有することもあれば、ソサージュ(socage)、クイットレント(quit-rent)、リースホールド(celehold)、コピー

ホールド(copyhold)など、いくつかの土地保有形態によって保有することもあった[3]。 13世紀のドイツでは、「peasant 」の概念は、英語のvillin[5]/villeinのように、「強盗 」と同様に 「田舎者 」を意味することもあった[6][7]。21世紀の英語では、「peasant 」は 「無知な、無礼な、素朴な人格 」を意味することもある。[8]この単語は1940年代から1960年代[9]にかけて、「卑下的で人種的な含みをすべて含んだ『ネイティブ』の意味上の 後継」として、しばしば発展途上国の農村人口全般を指す総称として再び人気が高まった[4]。 農民という言葉は、世界の貧しい発展途上国の農村住民の集合名詞として、蔑称ではない意味で一般的に使用されている[要出典]。世界中の約2億人の農民の 権利を代表すると主張する組織であるヴィア・カンペシーナは、2019年現在、「国際農民運動」と自己定義している。[10] 国民とその人権理事会は、2018年に採択された「農民および農村で働くその他の人々の権利に関する国連宣言」のように、非侮蔑的な意味で「農民」という 用語を顕著に使用している。一般的な英語の文献では、「農民」という言葉の使用は1970年頃から着実に減少している[11]。 |

| Etymology A farm in 1794 The word "peasant" is derived from the 15th-century French word païsant, meaning one from the pays, or countryside; ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.[12] |

語源 1794年の農場 農民」の語源は15世紀のフランス語のpaïsantで、pays(田舎)を意味し、最終的にはラテン語のpagus(辺境の行政区)に由来する [12]。 |

Social position Finnish Savonian farmers at a cottage in early 19th century; by Pehr Hilleström and J. F. Martin Peasants typically made up the majority of the agricultural labour force in a pre-industrial society. The majority of the people—according to one estimate 85% of the population—in the Middle Ages were peasants.[13] Though "peasant" is a word of loose application, once a market economy had taken root, the term peasant proprietors was frequently used to describe the traditional rural population in countries where smallholders farmed much of the land. More generally, the word "peasant" is sometimes used to refer pejoratively to those considered to be "lower class", perhaps defined by poorer education and/or a lower income.[citation needed] |

社会的地位 19世紀初頭、フィンランドのサヴォニア人農家のコテージにて。 産業革命以前の社会では、農民が農業労働力の大半を占めていた。中世の人々の大部分-ある推定によれば人口の85%-は農民であった[13]。 農民」という言葉は適用が緩やかな言葉ではあるが、市場経済が根付くと、小作農が土地の大部分を耕作していた国々では、伝統的な農村人口を表す言葉として 農民所有者という言葉が頻繁に使われるようになった。より一般的には、「農民」という言葉は、「下層階級」とみなされる人々、おそらくは低学歴や低所得に よって定義される人々を侮蔑的に指すために使われることもある[要出典]。 |

| Medieval European peasants The open field system of agriculture dominated most of Europe during medieval times and endured until the nineteenth century in many areas. Under this system, peasants lived on a manor presided over by a lord or a bishop of the church. Peasants paid rent or labor services to the lord in exchange for their right to cultivate the land. Fallowed land, pastures, forests, and wasteland were held in common. The open field system required cooperation among the peasants of the manor.[14] It was gradually replaced by individual ownership and management of land. The relative position of peasants in Western Europe improved greatly after the Black Death had reduced the population of medieval Europe in the mid-14th century, resulting in more land for the survivors and making labor more scarce. In the wake of this disruption to the established order, it became more productive for many laborers to demand wages and other alternative forms of compensation, which ultimately led to the development of widespread literacy and the enormous social and intellectual changes of the Enlightenment. The evolution of ideas in an environment of relatively widespread literacy laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution, which enabled mechanically and chemically augmented agricultural production while simultaneously increasing the demand for factory workers in cities, who became what Karl Marx called the proletariat. The trend toward individual ownership of land, typified in England by Enclosure, displaced many peasants from the land and compelled them, often unwillingly, to become urban factory-workers, who came to occupy the socio-economic stratum formerly the preserve of the medieval peasants. This process happened in an especially pronounced and truncated way in Eastern Europe. Lacking any catalysts for change in the 14th century, Eastern European peasants largely continued upon the original medieval path until the 18th and 19th centuries. Serfdom was abolished in Russia in 1861, and while many peasants would remain in areas where their family had farmed for generations, the changes did allow for the buying and selling of lands traditionally held by peasants, and for landless ex-peasants to move to the cities.[15] Even before emancipation in 1861, serfdom was on the wane in Russia. The proportion of serfs within the empire had gradually decreased "from 45–50 percent at the end of the eighteenth century, to 37.7 percent in 1858."[16]  Young women offer berries to visitors to their izba home, 1909. Those who had been serfs among the Russian peasantry were officially emancipated in 1861. Photograph by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. |

中世ヨーロッパの農民 中世ヨーロッパでは、オープンフィールド農業がヨーロッパの大部分を占め、多くの地域で 19 世紀まで続いた。この制度では、農民は領主や教会の司教が統治する荘園で暮らしていた。農民は、土地を耕作する権利と引き換えに、領主に地代や労働力を納 めていた。休耕地、牧草地、森林、荒地は共有地だった。オープンフィールドシステムは、荘園の農民たちの協力が必要だった[14]。このシステムは、徐々 に土地の個人所有と管理に取って代わられた。 14 世紀半ば、ペストによって中世ヨーロッパの人口が激減すると、農民の相対的な地位は大幅に改善し、生存者にとって土地が広くなり、労働力が不足した。この 秩序の崩壊を受けて、多くの労働者は賃金やその他の代替的な報酬を要求することがより生産的となり、最終的には識字率の普及と、啓蒙主義による大きな社会 的・知的変化につながった。 比較的広範な識字率の環境下での思想の進化は、産業革命の基盤を築いた。産業革命は、機械的・化学的に強化された農業生産を可能にし、同時に都市の工場労 働者に対する需要を増加させた。これらの労働者は、カール・マルクスが「プロレタリアート」と呼んだ階級を形成した。土地の個人所有への傾向は、イギリス では囲い込み政策に象徴され、多くの農民を土地から追放し、彼らを都市の工場労働者に転向させました。彼らは、中世の農民が占めていた社会経済的階層を占 めるようになりました。 このプロセスは、東欧で特に顕著で急激な形で進行した。14世紀に変化の触媒を欠いていた東欧の農民は、18世紀と19世紀まで主に中世の道を継続した。 ロシアでは1861年に農奴制が廃止されたが、多くの農民は代々耕作してきた地域に残ったものの、伝統的に農民が所有していた土地の売買が可能になり、土 地を失った元農民が都市に移住する道が開かれた。[15] 1861年の解放以前から、ロシアの農奴制は衰退傾向にあった。帝国内の農奴の割合は、18世紀末の45~50%から、1858年には37.7%まで徐々 に減少していた。[16]  1909年、若い女性たちが、彼らのイズバ(木造の民家)を訪れた人々にベリーを差し出している。ロシアの農民のうち、農奴だった人々は1861年に正式 に解放された。写真:セルゲイ・プロクディン・ゴルスキー。 |

Early modern Germany "Feiernde Bauern" ("Celebrating Peasants"), artist unknown, 18th or 19th century In Germany, peasants continued to center their lives in the village well into the 19th century. They belonged to a corporate body and helped to manage the community resources and to monitor community life.[17] In the East they had the status of serfs bound permanently to parcels of land. A peasant is called a "Bauer" in German and "Bur" in Low German (pronounced in English like boor).[18] In most of Germany, farming was handled by tenant farmers who paid rents and obligatory services to the landlord—typically a nobleman.[19] Peasant leaders supervised the fields and ditches and grazing rights, maintained public order and morals, and supported a village court which handled minor offenses. Inside the family the patriarch made all the decisions, and tried to arrange advantageous marriages for his children. Much of the villages' communal life centered on church services and holy days. In Prussia, the peasants drew lots to choose conscripts required by the army. The noblemen handled external relationships and politics for the villages under their control, and were not typically involved in daily activities or decisions.[20] |

近世ドイツ 「祝祭の農民たち」(作者不詳、18世紀または19世紀) ドイツでは、農民は19世紀まで村を中心に生活していた。彼らは共同体の一員として、コミュニティの資源の管理やコミュニティの生活の監視に協力してい た。[17] 東部では、彼らは土地に永久に縛られた農奴の地位にあった。農民はドイツ語で「Bauer」、低地ドイツ語で「Bur」(英語の発音では「boor」に似 ている)と呼ばれる。[18] ドイツの大部分では、農業は地主(通常は貴族)に地代と義務的な奉仕を支払う小作農によって行われていた。[19] 農民の指導者は、畑や溝、牧草地の権利を監督し、公の秩序と道徳を維持し、軽犯罪を扱う村裁判所を支援していた。家族内では家長がすべての決定権を持ち、 子供たちの有利な結婚をアレンジしようとした。村の共同生活の大部分は、教会サービスと聖日に集中していた。プロイセンでは、農民が抽選で軍隊に徴兵され る者を決定した。貴族は支配下の村の外部関係と政治を管理し、日常の活動や決定には通常関与しなかった。[20] |

| France Main article: French peasants Information about the complexities of the French Revolution, especially the fast-changing scene in Paris, reached isolated areas through both official announcements and long-established oral networks. Peasants responded differently to different sources of information. The limits on political knowledge in these areas depended more on how much peasants chose to know than on bad roads or illiteracy. Historian Jill Maciak concludes that peasants "were neither subservient, reactionary, nor ignorant."[21] In his seminal book Peasants into Frenchmen: the Modernization of Rural France, 1880–1914 (1976), historian Eugen Weber traced the modernization of French villages and argued that rural France went from backward and isolated to modern and possessing a sense of French nationhood during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[22] He emphasized the roles of railroads, republican schools, and universal military conscription. He based his findings on school records, migration patterns, military-service documents and economic trends. Weber argued that until 1900 or so a sense of French nationhood was weak in the provinces. Weber then looked at how the policies of the Third Republic created a sense of French nationality in rural areas.[23] The book was widely praised, but some[24] argued that a sense of Frenchness existed in the provinces before 1870. |

フランス 主な記事:フランスの農民 フランス革命の複雑さ、特にパリの急速な状況の変化に関する情報は、公式発表と長年にわたる口頭伝承の両方を通じて、孤立した地域にも伝わった。農民たち は、情報源の違いに応じて異なる反応を示した。これらの地域における政治知識の限界は、道路の悪さや文盲率よりも、農民たちがどれだけ知ろうとしたかに よって大きく左右された。歴史家のジル・マシアックは、農民たちは「従順でも、反動的でも、無知でもなかった」と結論付けています[21]。 歴史家ユージン・ヴェーバーは、その画期的な著書『農民からフランス人へ:1880年から1914年のフランス農村部の近代化』(1976年)の中で、フ ランスの村々の近代化を辿り、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、フランスの農村部は後進的で孤立した地域から、近代的でフランス国民としての意識を 持つ地域へと変化したと主張している。[22] 彼は、鉄道、共和制学校、および普遍的徴兵制の役割を強調した。彼の結論は、学校記録、移住パターン、兵役書類、および経済動向に基づいている。ヴェー バーは、1900年頃まで、地方ではフランス国民としての意識は弱かったと主張した。その後、ヴェーバーは、第三共和政の政策が農村部にフランス国民とし ての意識をどのように形成したかを考察した[23]。この本は広く賞賛されたが、1870年以前にも地方にはフランス人としての意識は存在していたと主張 する者もいた[24]。 |

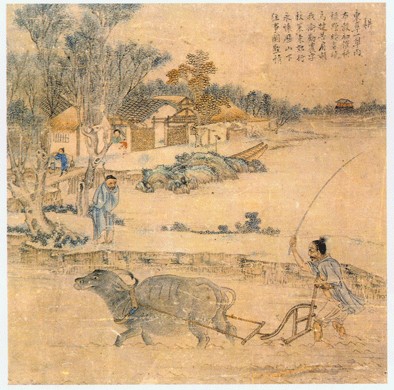

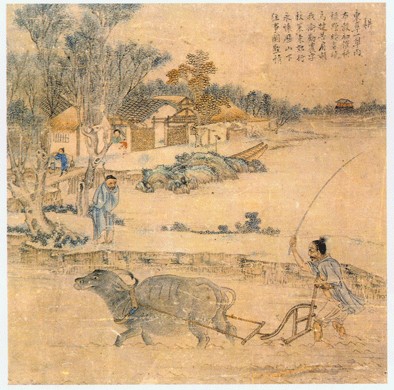

| Chinese farmers See also: Agriculture in China  A Chinese painting depicting an agricultural scene probably during the Ming dynasty  Chinese peasants in Kunming Farmers in China have been sometimes referred to as "peasants" in English-language sources. However, the traditional term for farmer, nongfu (农夫), simply refers to "farmer" or "agricultural worker". In the 19th century, Japanese intellectuals reinvented the Chinese terms fengjian (封建) for "feudalism" and nongmin (农民), or "farming people", terms used in the description of feudal Japanese society.[25] These terms created a negative image of Chinese farmers by making a class distinction where one had not previously existed.[25] Anthropologist Myron Cohen considers these terms to be neologisms that represented a cultural and political invention. He writes:[26] This divide represented a radical departure from tradition: F. W. Mote and others have shown how especially during the later imperial era (Ming and Qing dynasties), China was notable for the cultural, social, political, and economic interpenetration of city and countryside. But the term nongmin did enter China in association with Marxist and non-Marxist Western perceptions of the "peasant," thereby putting the full weight of the Western heritage to use in a new and sometimes harshly negative representation of China's rural population. Likewise, with this development Westerners found it all the more "natural" to apply their own historically derived images of the peasant to what they observed or were told in China. The idea of the peasant remains powerfully entrenched in the Western perception of China to this very day. Writers in English mostly used the term "farmers" until the 1920s, when the term peasant came to predominate, implying that China was feudal, ready for revolution, like Europe before the French Revolution.[27] This Western use of the term suggests that China is stagnant, "medieval", underdeveloped, and held back by its rural population.[28] Cohen writes that the "imposition of the historically burdened Western contrasts of town and country, shopkeeper and peasant, or merchant and landlord, serves only to distort the realities of the Chinese economic tradition".[29] |

中国の農民 参照:中国の農業  明代と思われる農業の場面を描いた中国の絵画  昆明の農民 中国の農民は、英語圏の資料では「農民」と訳されることがある。しかし、農民を表す伝統的な用語「農夫(nongfu)」は、単に「農民」または「農業労 働者」を意味する。19 世紀、日本の知識人は、日本の封建社会を表現するために使用されていた「封建」を「封建」、そして「農民」を「農民」と訳した。これらの用語は、これまで 存在しなかった階級区分を作り出し、中国の農民に否定的なイメージを与えた。[25] 人類学者のマイロン・コーエンは、これらの用語を文化的な発明であり政治的な発明である新語だと考えている。彼は次のように書いている。[26] この区分は、伝統からの根本的な転換を表していた。F. W. モートらは、特に後期の帝国時代(明王朝と清王朝)において、中国は都市と農村の文化的、社会的、政治的、経済的な相互浸透が顕著であったことを示してい る。しかし、「農民」という用語は、マルクス主義と非マルクス主義の西欧の「農民」像と結びついて中国に導入され、西欧の伝統の全重みを新たな、時に厳し く否定的な中国農村人口の表現に活用した。同様に、この発展により、西欧人は、中国で観察したり聞いたりしたことに、自らの歴史的に形成された農民のイ メージを適用することがますます「自然」だと感じるようになった。農民という概念は、今日に至るまで、西洋の中国認識に強く根付いている。 英語圏の作家たちは、1920年代まで主に「farmers(農民)」という用語を使用していたが、その後「peasant(農民)」という用語が主流と なり、中国はフランス革命前のヨーロッパのように、封建的で革命の準備が整っているという含意が込められるようになった。[27] この西洋の用語の使い方は、中国が停滞し、「中世的」で、未発達であり、農村人口によって阻害されていると示唆している。[28] コヘンは、「歴史的に重荷を背負った西洋の対比、すなわち都市と農村、商店主と農民、商人と地主を中国に強要することは、中国の経済伝統の現実を歪めるだ けだ」と書いている。[29] |

| Latin American farmers In Latin America, the term "peasant" is translated to "Campesino" (from campo—country person), but the meaning has changed over time. While most Campesinos before the 20th century were in equivalent status to peasants—they usually did not own land and had to make payments to or were in an employment position towards a landlord (the hacienda system), most Latin American countries saw one or more extensive land reforms in the 20th century. The land reforms of Latin America were more comprehensive initiatives[30] that redistributed lands from large landholders to former peasants[31]—farm workers and tenant farmers. Hence, many Campesinos in Latin America today are closer smallholders who own their land and do not pay rent to a landlord, rather than peasants who do not own land. The Catholic Bishops of Paraguay have asserted that "Every campesino has a natural right to possess a reasonable allotment of land where he can establish his home, work for [the] subsistence of his family and a secure life".[32] |

ラテンアメリカの農民 ラテンアメリカでは、「農民」は「カンペシーノ」(campo—田舎の人)と訳されるが、その意味は時代とともに変化してきた。20世紀以前のほとんどの カンペシーノは、農民と同等の地位にあり、通常は土地を所有しておらず、地主(ハシエンダ制度)に対して支払いをしたり、雇用関係にあった。しかし、20 世紀にラテンアメリカの多くの国では、1つ以上の大規模な土地改革が行われた。ラテンアメリカの土地改革は、大規模な土地所有者から元農民(農作業者や小 作農)へ土地を再分配する包括的な取り組み[30]だった。そのため、現在のラテンアメリカの多くのカンペシーノは、土地を所有し地主への賃料を支払わな い小規模農家であり、土地を所有しない農民とは異なる。 パラグアイのカトリック司教たちは、「すべてのカンペシーノは、家族の生計と安全な生活を営むために、自宅を築き、働くことができる合理的な土地の割当を 所有する自然権を有する」と主張している[32]。 |

| Historiography See also: Agrarianism Portrait sculpture of 18th-century French peasants by artist George S. Stuart, in the permanent collection of the Museum of Ventura County, Ventura, California In medieval Europe society was theorized as being organized into three estates: those who work, those who pray, and those who fight.[33] The Annales School of 20th-century French historians emphasized the importance of peasants. Its leader Fernand Braudel devoted the first volume—called The Structures of Everyday Life—of his major work, Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century to the largely silent and invisible world that existed below the market economy. Other research in the field of peasant studies was promoted by Florian Znaniecki and Fei Xiaotong, and in the post-1945 studies of the "great tradition" and the "little tradition" in the work of Robert Redfield. In the 1960s, anthropologists and historians began to rethink the role of peasant revolt in world history and in their own disciplines. Peasant revolution was seen as a Third World response to capitalism and imperialism.[34] The anthropologist Eric Wolf, for instance, drew on the work of earlier scholars in the Marxist tradition such as Daniel Thorner, who saw the rural population as a key element in the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Wolf and a group of scholars[35][36][37][38] criticized both Marx and the field of Modernization theorists for treating peasants as lacking the ability to take action.[39] James C. Scott's field observations in Malaysia convinced him that villagers were active participants in their local politics even though they were forced to use indirect methods. Many of these activist scholars looked back to the peasant movement in India and to the theories of the revolution in China led by Mao Zedong starting in the 1920s. The anthropologist Myron Cohen, however, asked why the rural population in China were called "peasants" rather than "farmers", a distinction he called political rather than scientific.[40] One important outlet for their scholarly work and theory was The Journal of Peasant Studies. |

歴史学 参照:農業主義 18 世紀のフランスの農民の肖像彫刻、アーティスト:ジョージ・S・スチュワート、カリフォルニア州ベンチュラにあるベンチュラ郡博物館の常設展示品 中世ヨーロッパでは、社会は 3 つの階級、すなわち「働く者」、「祈る者」、「戦う者」で構成されると理論づけられていた。[33] 20 世紀のフランスの歴史家たちによる「アナーレ学派」は、農民の重要性を強調した。そのリーダーであるフェルナン・ブローデルは、彼の主要著作『文明と資本 主義 15 世紀から 18 世紀』の第 1 巻「日常生活の構造」を、市場経済の下にある、ほとんど声も存在も知られていない世界について書いた。 農民研究分野におけるその他の研究は、フロリアン・ズナニエツキとフェイ・シャオトン、そして 1945 年以降のロバート・レッドフィールドの「大伝統」と「小伝統」の研究によって推進されました。1960 年代、人類学者や歴史学者は、世界史および各自の学問分野における農民の反乱の役割について再考し始めました。農民革命は、資本主義と帝国主義に対する第 三世界の反応とみなされた。[34] 例えば、人類学者のエリック・ウルフは、封建主義から資本主義への移行において農村住民が重要な要素であると見た、ダニエル・ソーナーなどのマルクス主義 の伝統を継承する先人の研究を参考にした。ウルフと一派[35][36][37][38] は、マルクスと近代化論者たちが農民を行動能力のない存在として扱ったことを批判した。[39] ジェームズ・C・スコットのマレーシアでの現地調査は、村人たちが間接的な方法に迫られながらも、地元の政治に積極的な参加者であることを彼に確信させ た。これらの活動家的な学者たちの多くは、インドの農民運動や、1920年代から毛沢東が率いた中国の革命理論に回帰した。しかし、人類学者のマイロン・ コーエンは、中国の農村人口を「農民」ではなく「農民」と呼ぶ理由を問い、この区別は科学的ではなく政治的なものだと指摘した。[40] 彼らの研究と理論の重要な発表の場の一つが『農民研究ジャーナル』だった。 |

See also The Peasant Wedding, by Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1567 or 1568  "Peasants in a Tavern" by Adriaen van Ostade (c. 1635), at the Alte Pinakothek, Munich  Monument dedicated to Serbian peasant, Jagodina Agrarianism Cudgel War Family economy Feudalism Folk culture Land reform Land reform by country List of peasant revolts Peasant economics Peasant Party (political movements in various countries) Peasants' Republic Peasants' Revolt Petty nobility Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe Serfdom Via Campesina Related terms Aloer Am ha'aretz Boor Bracciante Campesino Churl Colonus Contadino Cotter Fellah Free tenant Gabellotto Honbyakushō Kulak Muzhik Pagesos de remença Pawn Peon Serf Sharecropper Smerd Șerb [ro] Tenant farmer Terrone Villein |

参照 フランドルの画家、ピーテル・ブリューゲル(父)の『農民の結婚式』、1567年または1568年  アドリアーン・ファン・オスタデの『居酒屋での農民たち』(1635年頃)、ミュンヘンのアルテ・ピナコテーク所蔵  セルビアの農民、ヤゴディナに捧げられた記念碑 農業主義 棍棒戦争 家族経済 封建制度 民俗文化 土地改革 国別の土地改革 農民反乱の一覧 農民経済 農民党(さまざまな国の政治運動) 農民共和国 農民反乱 小貴族 中世後期ヨーロッパの民衆反乱 農奴制 ヴィア・カンペシーナ 関連用語 アロエル アム・ハアレツ ブーア ブラッチャンテ カンペシーノ チャール コロヌス コンタディーノ コッター フェラー 自由小作人 ガベロット ホンビャクショウ クラーク ムジク パジェソス・デ・レメンサ ポーン ペオン 農奴 シェード シェルド [ro] 小作人 テロネ ヴィレイン |

| Cited sources Cohen, Myron L. (2005). Kinship, Contract, Community, and State Anthropological Perspectives on China. Basel/Berlin/Boston: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9781503624986. ISBN 978-1-5036-2498-6. S2CID 246207129. Bibliography Bix, Herbert P. Peasant Protest in Japan, 1590–1884 (1986)[ISBN missing] Evans, Richard J., and W. R. Lee, eds. The German Peasantry: Conflict and Community from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (1986)[ISBN missing] Figes, Orlando. "The Peasantry" in Vladimir IUrevich Cherniaev, ed. (1997). Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914–1921. Indiana UP. pp. 543–53. ISBN 0253333334. Hayford, Charles W. (1997), Stromquist, Shelton; Cox, Jeffrey (eds.), The Storm over the Peasant: Orientalism, Rhetoric and Representation in Modern China, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, pp. 150–172 Hobsbawm, E. J. "Peasants and politics", Journal of Peasant Studies, Volume 1, Issue 1 October 1973, pp. 3–22 – article discusses the definition of "peasant" as used in social sciences Macey, David A. J. Government and Peasant in Russia, 1861–1906; The Pre-History of the Stolypin Reforms (1987).[ISBN missing] Kingston-Mann, Esther and Timothy Mixter, eds. Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics of European Russia, 1800–1921 (1991)[ISBN missing] Thomas, William I., and Florian Znaniecki. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America (2 vol. 1918); classic sociological study; complete text online free Wharton, Clifton R. Subsistence agriculture and economic development. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co., 1969. [ISBN missing] Wolf, Eric R. Peasants (Prentice-Hall, 1966).[ISBN missing] Recent Akram-Lodhi, A. Haroon, and Cristobal Kay, eds. Peasants and Globalization: Political Economy, Rural Transformation and the Agrarian Question (2009)[ISBN missing] Barkin, David. "Who Are The Peasants?" Latin American Research Review, 2004, Vol. 39 Issue 3, pp. 270–281 Brass, Tom. Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism (2000)[ISBN missing] Brass, Tom, ed. Latin American Peasants (2003)[ISBN missing] Scott, James C. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (1976)[ISBN missing] |

引用文献 Cohen, Myron L. (2005). Kinship, Contract, Community, and State Anthropological Perspectives on China. Basel/Berlin/Boston: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9781503624986. ISBN 978-1-5036-2498-6. S2CID 246207129。 参考文献 Bix, Herbert P. Peasant Protest in Japan, 1590–1884 (1986)[ISBN 欠落] エヴァンス、リチャード J.、W. R. リー編。The German Peasantry: Conflict and Community from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (1986)[ISBN 欠落] フィゲス、オルランド。ウラジーミル・イウレヴィッチ・チェルニアエフ編(1997)。『ロシア革命の批判的コンパニオン、1914-1921』インディ アナ UP。543-53 ページ。ISBN 0253333334。 ヘイフォード、チャールズ W. (1997)、ストームクイスト、シェルトン、コックス、ジェフリー (編)、『農民をめぐる嵐:現代中国におけるオリエンタリズム、レトリック、表現』アイオワシティ:アイオワ大学出版、150-172 ページ ホブズボーム、E. J. 「農民と政治」、『農民研究ジャーナル』第 1 巻第 1 号、1973 年 10 月、3-22 ページ – この記事では、社会科学で使用される「農民」の定義について論じている。 メイシー、デビッド A. J. 『ロシアの政府と農民、1861-1906』 ストルイピン改革の史前史 (1987)。[ISBN 欠落] キングストン・マン、エスター、ティモシー・ミクスター編。ヨーロッパ・ロシアの農民経済、文化、政治、1800-1921 (1991)[ISBN 欠落] トーマス、ウィリアム I.、フロリアン・ズナニエツキ。ヨーロッパとアメリカのポーランド農民(2巻、1918年);古典的な社会学的研究;全文がオンラインで無料閲覧可能 Wharton, Clifton R. 自給農業と経済発展。シカゴ:Aldine Pub. Co.、1969年。[ISBN 欠落] Wolf, Eric R. 農民(Prentice-Hall、1966年)。[ISBN 欠落] 最近の アクラム=ロディ、A. ハルーン、クリストバル・ケイ編。農民とグローバル化:政治経済、農村変革、および農業問題(2009年)[ISBN 欠落] バーキン、デビッド。「農民とは誰か?」ラテンアメリカ研究レビュー、2004年、第39巻第3号、270-281ページ ブラス、トム。農民、ポピュリズム、ポストモダニズム(2000年)[ISBN 欠落] ブラス、トム編。ラテンアメリカの農民(2003年)[ISBN 欠落] スコット、ジェームズ C. 農民の道徳経済:東南アジアの反乱と自給自足(1976年)[ISBN 欠落] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peasant |

HAROLD SACRAMENTUM

FECIT VVILLELMO DUCI ("Harold made an oath to Duke William"): the

Bayeux Tapestry shows Harold touching two altars at Bayeux as the duke

watches. / HAROLD SACRAMENTUM FECIT VVILLELMO

DUCI(「ハロルドはウィリアム公に誓いを立てた」):バイユーのタペストリーには、公爵が見守る中、ハロルドがバイユーで2つの祭壇に触れている様子

が描かれている。

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

![]()

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099