グアテマラの征服

Conquista de Guatemala

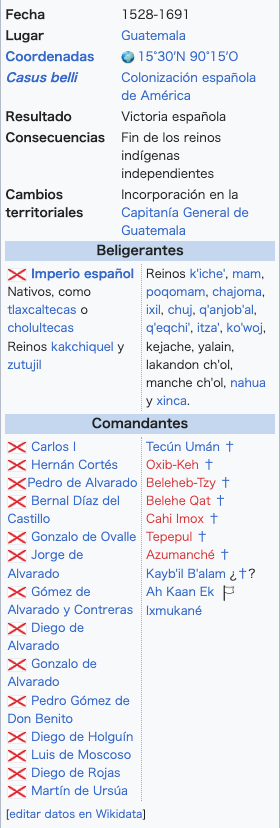

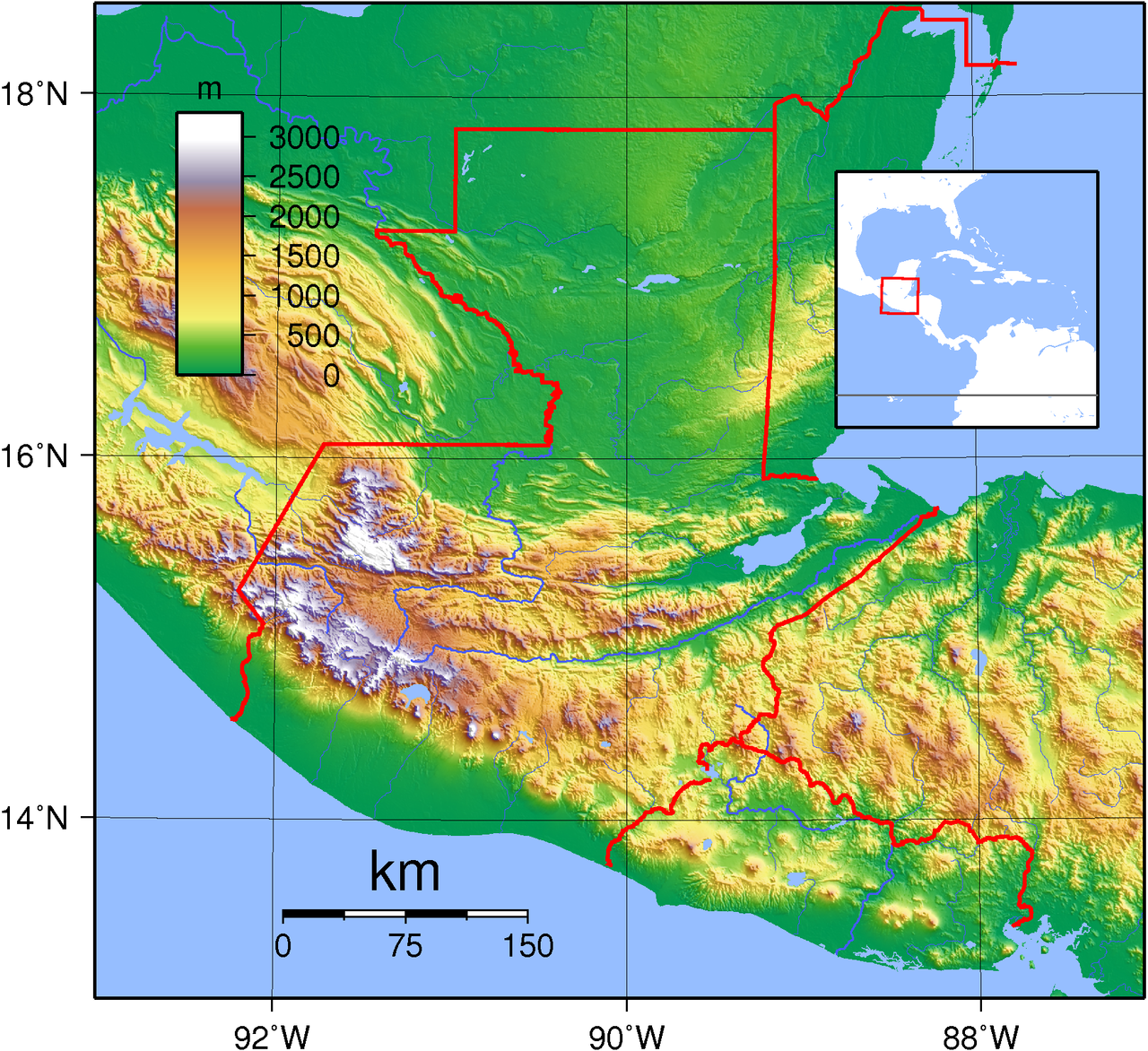

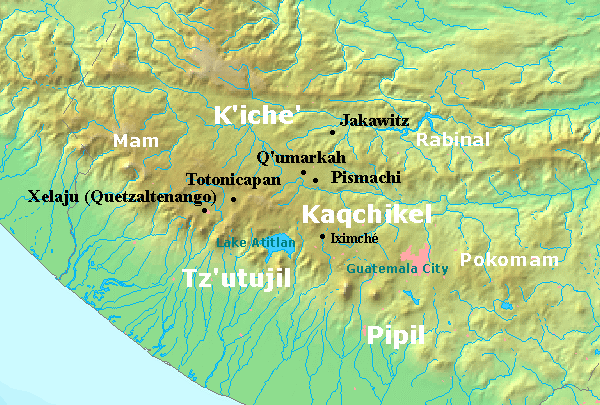

グアテマラ征服の主な進入ルートと戦闘地の地図

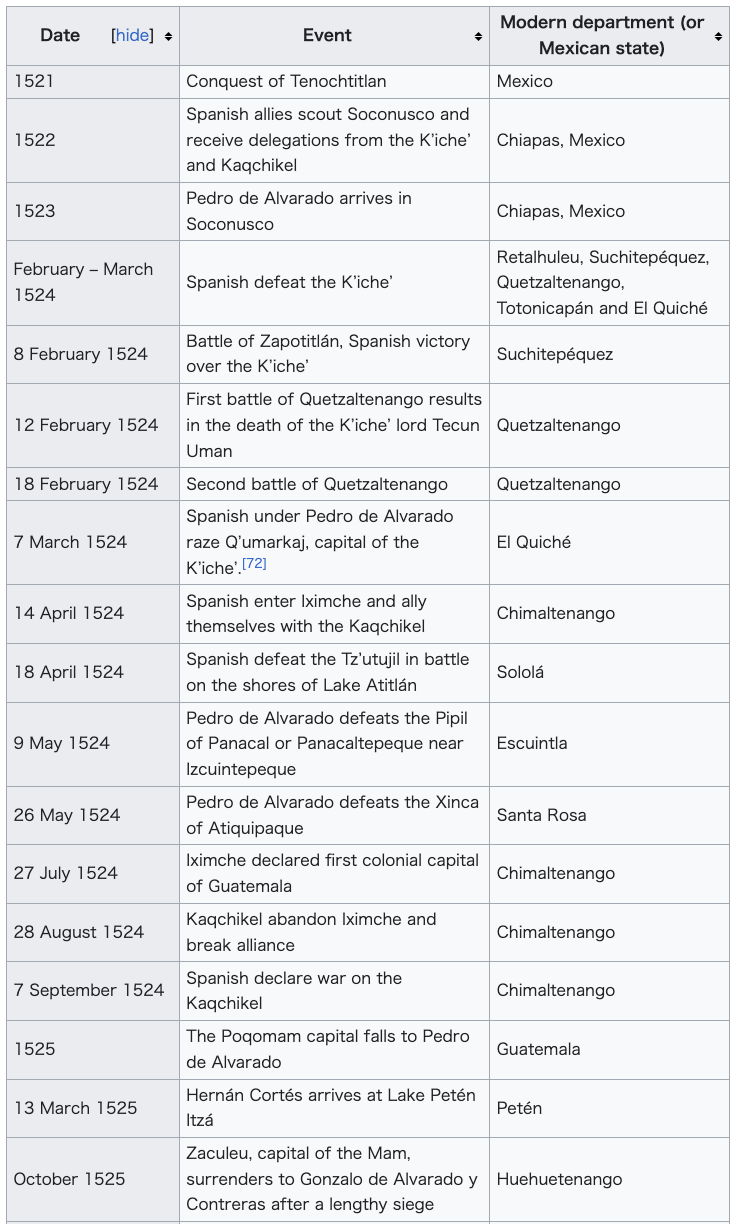

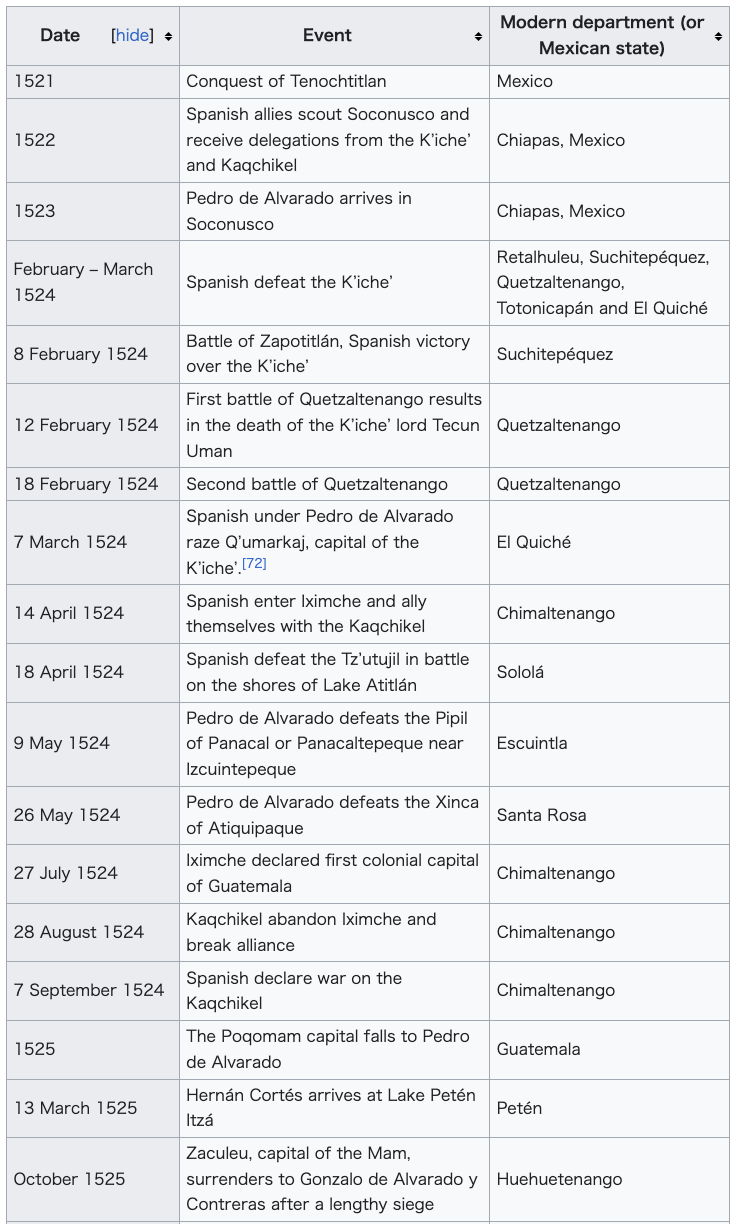

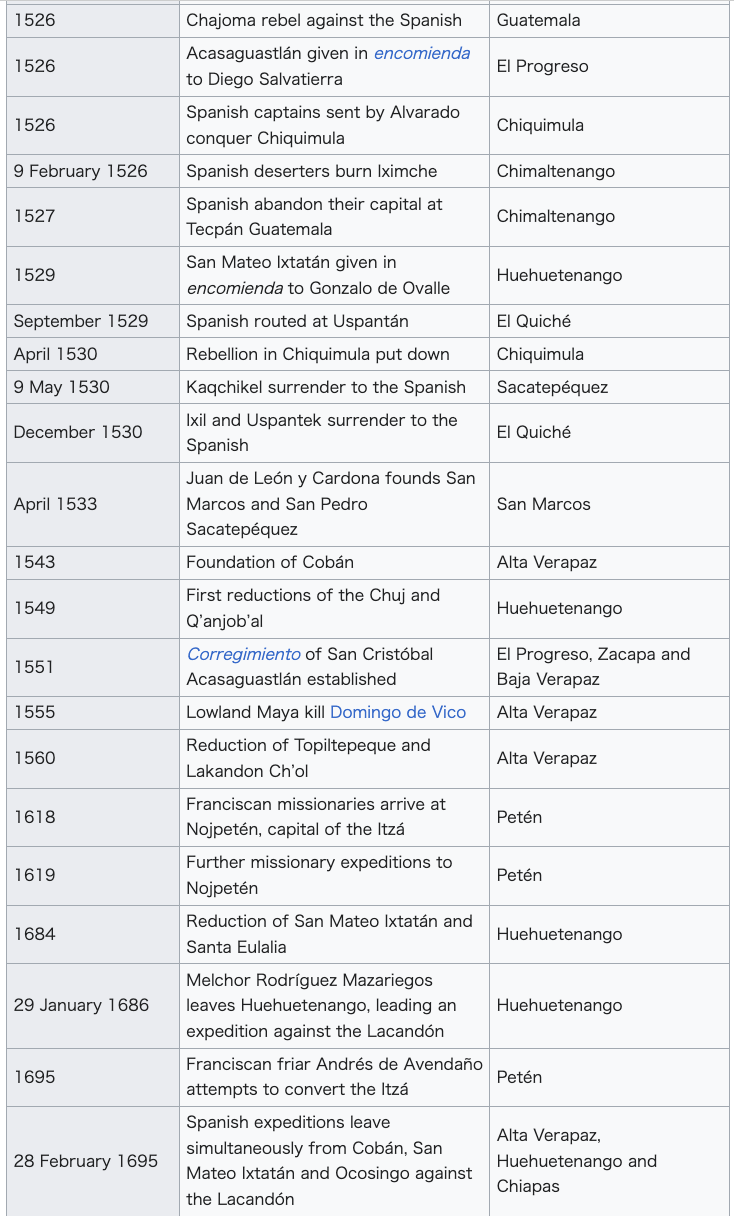

☆ グアテマラ征服(conquista de Guatemala)は、現在の中央アメリカ、グアテマラ共和国の領土におけるスペインのアメリカ大陸植民地化の一環である紛争である。征服以前、この領土はメ ソアメリカのいくつかの王国から成っており、そのほとんどはマヤ文明に属していた。マヤとスペインの探検家との最初の接触は16世紀に起こった。1511 年、パナマからサント・ドミンゴに向かうスペイン船がユカタン半島の東海岸で難破したのである。スペイン帝国への統合に対するマヤ王国の粘り強い抵抗のた めである。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは1524年初頭、スペイン人征服者とその同盟者、主にトラスカラとチョルーラ出身の先住民からなる混成部隊の指揮官としてグアテ マラに到着した。グアテマラ全土の地名にナワトル語の地名があるのは、スペイン人の案内役や翻訳役も務めたこれらメキシコ人の同盟者の影響によるものであ る。3 カクチケル族も彼らに加わった。一方、他の高地マヤ王国は、スペインとその同盟国であるメキシコの戦士たち、および以前服従していたマヤ王国の戦士たちに よって、それぞれ敗北していた。イツァ族とペテン盆地の他の低地マヤ民族は1525年にエルナン・コルテスと初めて接触したが、イツァ王国はスペインの侵 略に敵対し、1697年まで独立を維持した(→スペイン語版からの翻訳「グアテマラの征服」)。

| Spanish conquest of Guatemala In a protracted conflict during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, Spanish colonisers gradually incorporated the territory that became the modern country of Guatemala into the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. Before the conquest, this territory contained a number of competing Mesoamerican kingdoms, the majority of which were Maya. Many conquistadors viewed the Maya as "infidels" who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified, disregarding the achievements of their civilization.[2] The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in the early 16th century when a Spanish ship sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo was wrecked on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511.[2] Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast.[3] The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged affair; the Maya kingdoms resisted integration into the Spanish Empire with such tenacity that their defeat took almost two centuries.[4] Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala from the newly conquered Mexico in early 1524, commanding a mixed force of Spanish conquistadors and native allies, mostly from Tlaxcala and Cholula. Geographic features across Guatemala now bear Nahuatl placenames owing to the influence of these Mexican allies, who translated for the Spanish.[5] The Kaqchikel Maya initially allied themselves with the Spanish, but soon rebelled against excessive demands for tribute and did not finally surrender until 1530. In the meantime the other major highland Maya kingdoms had each been defeated in turn by the Spanish and allied warriors from Mexico and already subjugated Maya kingdoms in Guatemala. The Itza Maya and other lowland groups in the Petén Basin were first contacted by Hernán Cortés in 1525, but remained independent and hostile to the encroaching Spanish until 1697, when a concerted Spanish assault led by Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom. Spanish and native tactics and technology differed greatly. The Spanish viewed the taking of prisoners as a hindrance to outright victory, whereas the Maya prioritised the capture of live prisoners and of booty. The indigenous peoples of Guatemala lacked key elements of Old World technology such as a functional wheel, horses, iron, steel, and gunpowder; they were also extremely susceptible to Old World diseases, against which they had no resistance. The Maya preferred raiding and ambush to large-scale warfare, using spears, arrows and wooden swords with inset obsidian blades; the Xinca of the southern coastal plain used poison on their arrows. In response to the use of Spanish cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits and lining them with wooden stakes. |

スペインによるグアテマラの征服(Spanish conquest of Guatemala) スペインによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化に伴う長期にわたる紛争の中で、スペインの植民者たちは、現在のグアテマラ国となる領土を徐々に植民地総督領 ニュー・スペインに組み込んでいった。征服以前、この領土には多くの競合するメソアメリカ王国が存在し、その大半はマヤ族が支配していた。多くの征服者は マヤ人を「異教徒」と見なし、彼らの文明の偉業を無視して、強制的に改宗させ、平定する必要があると考えていた[2]。マヤ人とヨーロッパ人探検家との最 初の接触は、16世紀初頭にパナマからサントドミンゴへ向かっていたスペイン船が、1511年にユカタン半島東海岸で難破したときに起こった[2]。その 後、1517年と1519年にスペインの探検隊が続き、 1519年には、ユカタン半島のさまざまな場所に上陸した[3]。スペインによるマヤ征服は長期にわたる戦いとなり、マヤ王国はスペイン帝国への統合に頑 強に抵抗し、その敗北には約2世紀を要した[4]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラードは、1524年初頭に新たに征服したメキシコからグアテマラに到着し、スペインの征服者と、トラスカラやチョルーラ出身の先住民 同盟軍からなる混成部隊を指揮した。グアテマラ全土の地理的名称は、スペイン語に通訳したこれらのメキシコ同盟者の影響により、ナワトル語に由来する地名 となっている[5]。カクチケル・マヤ族は当初スペインと同盟を結んだが、すぐに過度な貢納金の要求に反発し、最終的に降伏したのは1530年になってか らだった。その間、他の主要な高地マヤ王国は、メキシコからの同盟戦士とスペイン軍に次々と敗れ、すでに征服されていたグアテマラのマヤ王国に服従してい た。ペテン盆地のイツァ・マヤ族やその他の低地に住むグループは、1525年にエルナン・コルテスと初めて接触したが、1697年にスペイン軍がマルティ ン・デ・ウルスーア・イ・アリスメンド率いる総攻撃をしかけるまで、スペインの侵略に抵抗し、独立を維持していた。 スペイン人と先住民は戦術や技術が大きく異なっていた。スペイン人は捕虜の捕獲を完全な勝利への障害とみなしていたが、マヤ人は生きた捕虜と戦利品の捕獲 を優先していた。グアテマラの先住民は、機能的な車輪、馬、鉄、鋼鉄、火薬といった旧世界の技術に不可欠な要素を欠いており、旧世界の病気にも非常に弱 かったが、それに対する抵抗力はなかった。マヤ族は、槍や矢、黒曜石を埋め込んだ木の剣などを用いて、大規模な戦争よりも奇襲や待ち伏せを好んだ。一方、 南部の平野地帯に住むシンカ族は、矢に毒を塗っていた。スペイン騎兵隊の攻撃に対抗するため、高地に住むマヤ族は穴を掘って木の杭を並べた。 |

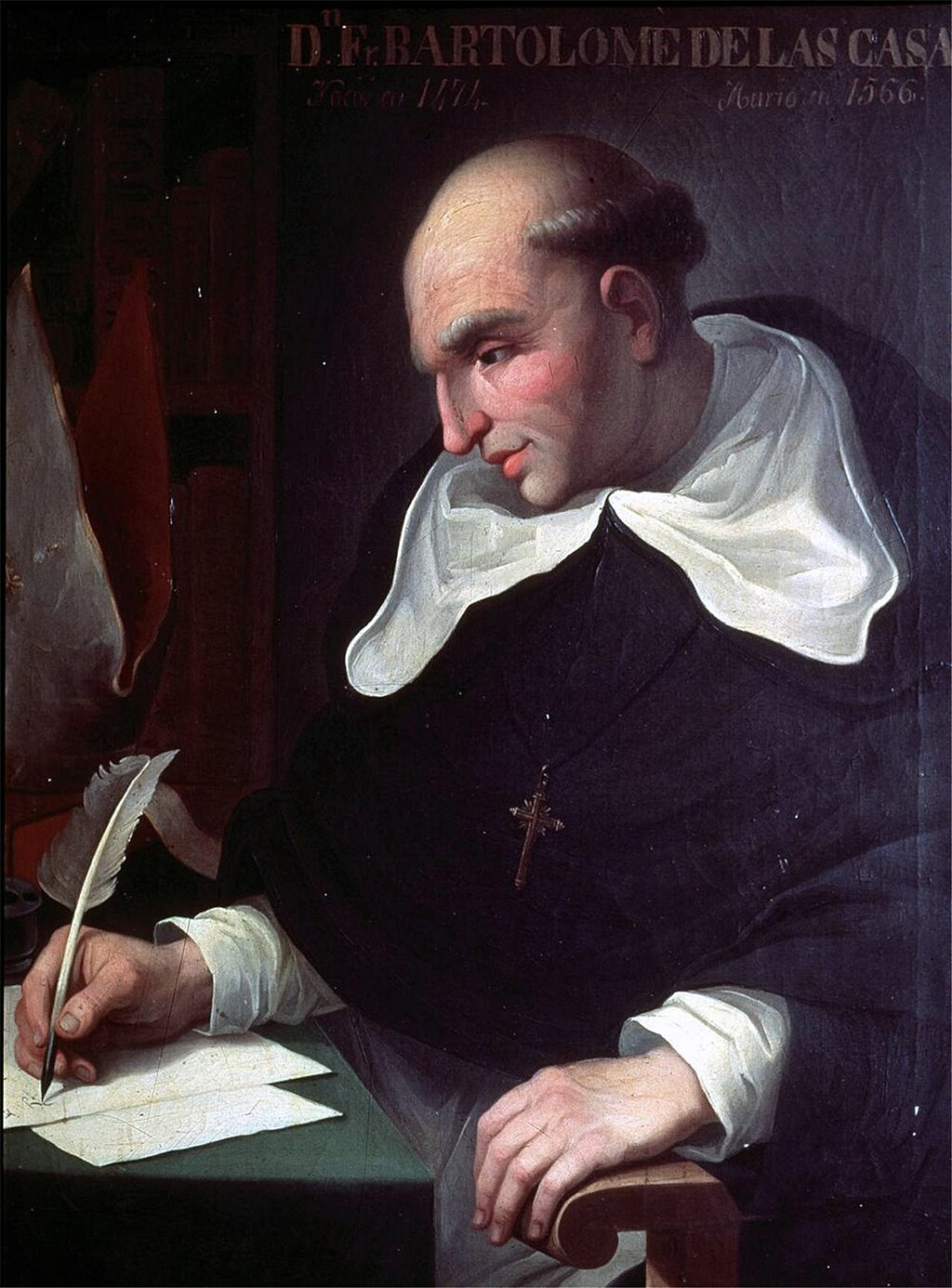

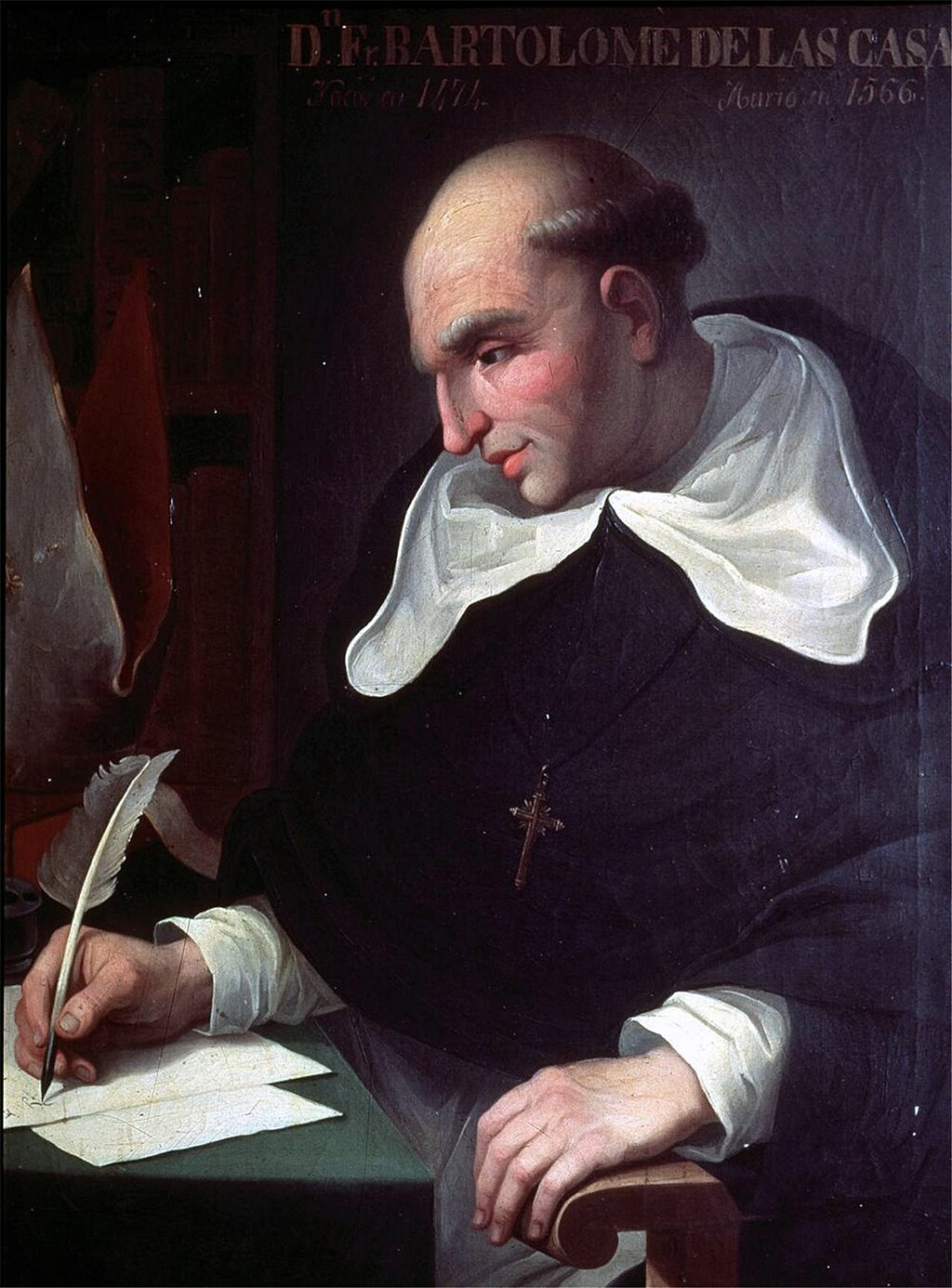

Historical sources Painting with three prominent indigenous warriors in single file facing left, wearing cloaks and grasping staves, followed by a dog. Below them and to the right is the smaller image of a mounted Spaniard with a raised lance. To the left and indigenous porter carries a pack fixed by a strap across his forehead, and sports a staff in one hand. All are apparently moving towards a doorway at top left. A page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, showing a Spanish conquistador accompanied by Tlaxcalan allies and a native porter The sources describing the Spanish conquest of Guatemala include those written by the Spanish themselves, among them two of four letters written by conquistador Pedro de Alvarado to Hernán Cortés in 1524, describing the initial campaign to subjugate the Guatemalan Highlands. These letters were despatched to Tenochtitlan, addressed to Cortés but with a royal audience in mind; two of these letters are now lost.[6] Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez was Pedro de Alvarado's cousin; he accompanied him on his first campaign in Guatemala and in 1525 he became the chief constable of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, the newly founded Spanish capital. Gonzalo wrote an account that mostly supports that of Pedro de Alvarado. Pedro de Alvarado's brother Jorge wrote another account to the king of Spain that explained it was his own campaign of 1527–1529 that established the Spanish colony.[7] Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote a lengthy account of the conquest of Mexico and neighbouring regions, the Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España ("True History of the Conquest of New Spain"); his account of the conquest of Guatemala generally agrees with that of the Alvarados.[8] His account was finished around 1568, some 40 years after the campaigns it describes.[9] Hernán Cortés described his expedition to Honduras in the fifth letter of his Cartas de Relación,[10] in which he details his crossing of what is now Guatemala's Petén Department. Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas wrote a highly critical account of the Spanish conquest of the Americas and included accounts of some incidents in Guatemala.[11] The Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias ("Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies") was first published in 1552 in Seville.[12] The Tlaxcalan allies of the Spanish who accompanied them in their invasion of Guatemala wrote their own accounts of the conquest; these included a letter to the Spanish king protesting at their poor treatment once the campaign was over. Other accounts were in the form of questionnaires answered before colonial magistrates to protest and register a claim for recompense.[13] Two pictorial accounts painted in the stylised indigenous pictographic tradition have survived; these are the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, which was probably painted in Ciudad Vieja in the 1530s, and the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, painted in Tlaxcala.[14] Accounts of the conquest as seen from the point of view of the defeated highland Maya kingdoms are included in a number of indigenous documents, including the Annals of the Kaqchikels, which includes the Xajil Chronicle describing the history of the Kaqchikel from their mythical creation down through the Spanish conquest and continuing to 1619.[15] A letter from the defeated Tzʼutujil Maya nobility of Santiago Atitlán to the Spanish king written in 1571 details the exploitation of the subjugated peoples.[16] Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán was a colonial Guatemalan historian of Spanish descent who wrote La Recordación Florida, also called Historia de Guatemala (History of Guatemala). The book was written in 1690 and is regarded as one of the most important works of Guatemalan history, and is the first such book to have been written by a criollo author.[17] Field investigation has tended to support the estimates of indigenous population and army sizes given by Fuentes y Guzmán.[18] |

歴史的資料 左向きに並んだ3人の先住民族の戦士が、マントを身にまとい、杖を握り、その後に犬が続いている。彼らの下、右側には、槍を構えた騎馬スペイン人の小さな 絵が描かれている。左側には先住民族のポーターが、額にストラップで固定した荷物を背負い、片手に杖を持っている。全員が左上のドアに向かって歩いている ようだ。 スペインの征服者、トラスカラ人の同盟者、先住民のポーターが一緒に描かれた「トラスカラ図」のページ スペインによるグアテマラ征服について書かれた資料には、スペイン人自身によるものも含まれる。その中には、征服者ペドロ・デ・アルバラドが1524年に エルナン・コルテスに宛てた4通の手紙のうちの2通があり、グアテマラ高地を征服するための最初のキャンペーンについて述べている。これらの手紙は、コル テス宛てにテノチティトランに送られたが、王の謁見を想定したものであった。これらの手紙のうち2通は現在紛失している[6]。ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラ ド・イ・チャベスは、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの従兄弟であり、グアテマラでの最初の遠征に同行し、1525年には新たにスペインの首都となったサンティア ゴ・デ・ロス・カバリェロス・デ・グアテマラの最高憲兵となった。ゴンサロは、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの記述をほぼ裏付ける内容の報告書を書き上げた。ペ ドロ・デ・アルバラドの弟ホルヘは、スペイン王に宛てて、スペイン植民地が確立したのは1527年から1529年にかけての自身の遠征によるものであると 説明した別の記録を残している[7]。ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョは、メキシコと近隣の地域の征服について長編『ヌエバ・エスパーニャ征服 史』(Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España)を著した。グアテマラ征服に関する記述は、アルヴァラド家の記述と概ね一致している[8]。彼の記述は、1568年頃に完成した。これは、 記述されている遠征から40年ほど後のことである[9]。エルナン・コルテスは、Cartas de Relación(関係の手紙)の第5の手紙でホンジュラスへの遠征について述べている[10]。この手紙では、現在のグアテマラのペテン県を横断したと きの詳細が述べられている。ドミニコ会の修道士バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(Bartolomé de las Casas)は、スペインによるアメリカ大陸征服について非常に批判的な記述を残しており、グアテマラでのいくつかの事件についても触れている[11]。 『Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias』(「インド諸国の破壊に関する簡潔な記述」)は 1552年にセビリアで初めて出版された[12]。 スペインの同盟国であるトラスカラン族は、グアテマラ侵攻に同行し、スペイン王に宛てた手紙で、侵攻後の劣悪な待遇に抗議するなど、自らの征服体験を記録 した。その他の記録は、植民地時代の判事の前で回答するアンケート形式になっており、抗議と賠償請求を登録するものだった[13]。2つの絵画記録が、様 式化された先住民の絵文字の伝統で描かれ、現存している。これらは、1530年代にシウダー・ビエハで描かれたと思われる「Lienzo de Quauhquechollan」と、トラスカラで描かれた「Lienzo de Tlaxcala」である[14]。トラスカラで描かれたものである[14]。 征服について、敗北した高地マヤ王国から見た記録は、先住民の文書に数多く含まれている。その中には、神話上の創造からスペインによる征服、そして16 19[15]。1571年に書かれた、征服されたツトゥヒル・マヤ貴族のサンティアゴ・アティトランからスペイン王への手紙には、征服された人々の搾取に ついて詳しく述べられている[16]。 フランシスコ・アントニオ・デ・フエンテス・イ・グスマンは、スペイン系グアテマラ人の植民地時代の歴史家で、『ラ・レコダシオン・フロリダ』(別名『グ アテマラの歴史』)を著した。この本は1690年に執筆され、グアテマラの歴史上最も重要な著作の一つと考えられている。また、クリオージョ(スペイン語 系住民)の作家が執筆した最初の歴史書でもある[17]。現地調査は、フエンテス・イ・グスマンが示した先住民人口と軍隊規模の推定値を裏付ける傾向にあ る[18]。フエンテス・イ・グスマンが示した先住民人口と軍隊規模の推定値を裏付ける傾向がある[18]。 |

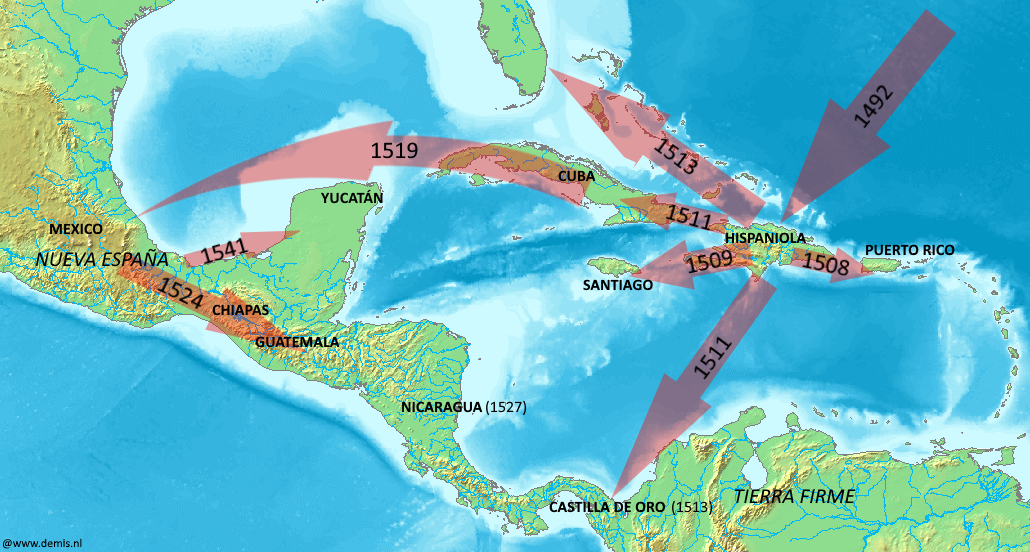

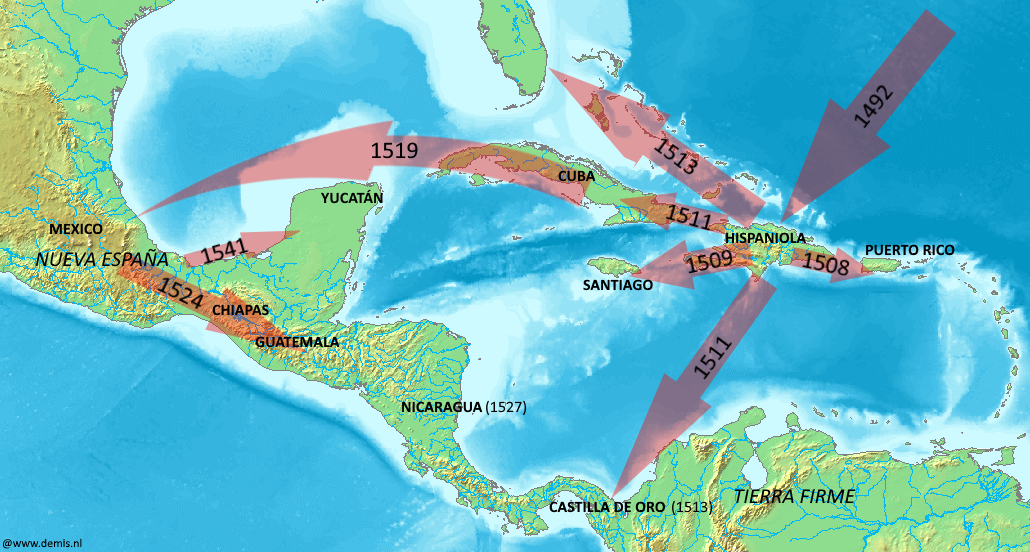

Background Spanish expansion routes in the Caribbean during the early 16th century Christopher Columbus discovered the New World for the Kingdom of Castile and León in 1492. Private adventurers thereafter entered into contracts with the Spanish Crown to conquer the newly discovered lands in return for tax revenues and the power to rule.[19] In the first decades after the discovery of the new lands, the Spanish colonised the Caribbean and established a centre of operations on the island of Cuba. They heard rumours of the rich empire of the Aztecs on the mainland to the west and, in 1519, Hernán Cortés set sail with eleven ships to explore the Mexican coast.[20] By August 1521 the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had fallen to the Spanish and their allies.[21] A single soldier arriving in Mexico in 1520 was carrying smallpox and thus initiated the devastating plagues that swept through the native populations of the Americas.[22] Within three years of the fall of Tenochtitlan the Spanish had conquered a large part of Mexico, extending as far south as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The newly conquered territory became New Spain, headed by a viceroy who answered to the king of Spain via the Council of the Indies.[23] Hernán Cortés received reports of rich, populated lands to the south and dispatched Pedro de Alvarado to investigate the region.[1] Preparations In the run-up to the announcement that an invasion force was to be sent to Guatemala, 10,000 Nahua warriors had already been assembled by the Aztec emperor Cuauhtémoc to accompany the Spanish expedition. Warriors were ordered to be gathered from each of the Mexica and Tlaxcaltec towns. The native warriors supplied their weapons, including swords, clubs and bows and arrows.[24] Alvarado's army left Tenochtitlan at the beginning of the dry season, sometime between the second half of November and December 1523. As Alvarado left the Aztec capital, he led about 400 Spanish and approximately 200 Tlaxcalan and Cholulan warriors and 100 Mexica, meeting up with the gathered reinforcements on the way. When the army left the Basin of Mexico, it may have included as many as 20,000 native warriors from various kingdoms, although the exact numbers are disputed.[25] By the time the army crossed the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the massed native warriors included 800 from Tlaxcala, 400 from Huejotzingo, 1,600 from Tepeaca plus many more from other former Aztec territories. Further Mesoamerican warriors were recruited from the Zapotec and Mixtec provinces, with the addition of more Nahuas from the Aztec garrison in Soconusco.[26] |

背景 16世紀初頭のスペインによるカリブ海地域への進出ルート 1492年、クリストファー・コロンブスがカスティーリャ王国とレオン王国のために新大陸を発見した。その後、私的な冒険家たちがスペイン王室と契約を結 び、税収と統治権と引き換えに新大陸の征服に乗り出した[19]。新大陸発見から最初の数十年、スペインはカリブ海を植民地化し、キューバ島に活動の拠点 を作った。彼らは西の大陸にあるアステカ帝国の富の噂を耳にし、1519年、エルナン・コルテスが11隻の船でメキシコ沿岸を探検に出航した[20]。 1521年8月までに、アステカの首都テノチティトランはスペインとその同盟軍に降伏した[21]。1520年にメキシコに到着した一人の兵士が天然痘を 運んでいたため、アメリカ大陸の先住民を襲った壊滅的な疫病の始まりとなった[22]。テノチティトラン陥落から3年以内に、スペインはメキシコの大半を 征服し、テワンテペック地峡の南まで勢力を拡大した。新たに征服された領土は、スペイン国王に直属する総督が統治する「新スペイン」となった。総督は、イ ンド評議会を通じてスペイン国王に報告する義務を負っていた[23]。エルナン・コルテスは、南部に豊かな人口の多い土地があるという報告を受け、その地 域を調査するためにペドロ・デ・アルバラードを派遣した[1]。 準備 グアテマラへの侵攻部隊の派遣が発表されるまでに、スペイン遠征に同行するナワ族の戦士1万人がアステカの皇帝クアウテモックによってすでに集結してい た。戦士たちは、メシカ族とトラスカルテク族のそれぞれの町から集められ、 先住民戦士たちは、剣、棍棒、弓矢などの武器を用意した[24]。アルヴァラドの軍隊は、11月後半から12月15日までの乾季の始まりにテノチティトラ ンを出発した。アルヴァラドがアステカの首都を去るとき、彼はスペイン人約400人、トラスカラン人とチョルラン人の戦士約200人、そしてメシカ人 100人を率いており、途中で集まった援軍と合流した。軍がメキシコ盆地を出発した際、正確な人数は議論の余地があるものの、さまざまな王国から集まった 2万人もの先住民戦士が参加していた可能性がある[25]。軍がテワンテペック地峡を渡る頃には、集結した先住民戦士にはトラスカラから800人、ウエホ ツィンゴから400人、テペアカから1,600人、さらにその他多くのアステカの旧領土からの戦士が含まれていた。さらに、サポテカ族とミシュテカ族の地 域からメソアメリカの戦士たちが徴用され、ソコヌスコのアステカの守備隊からさらに多くのナワ族が加わった[26]。 |

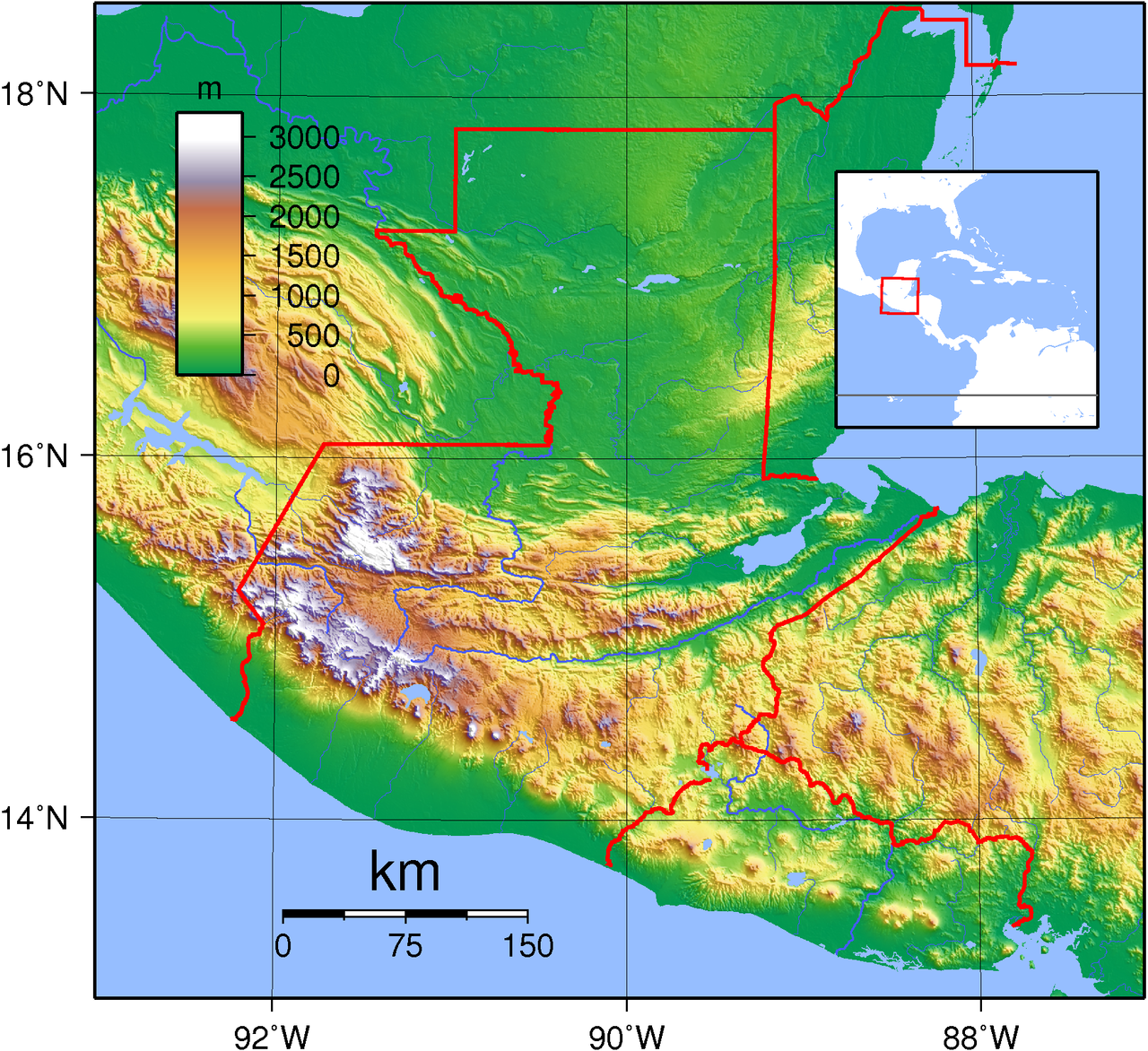

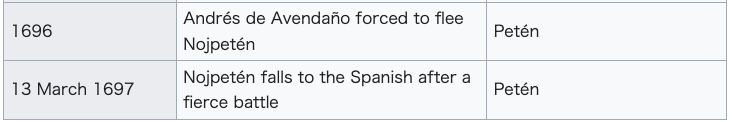

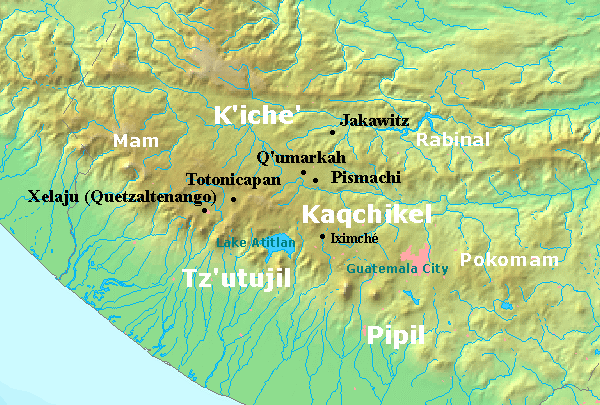

Guatemala before the conquest Guatemala is situated between the Pacific Ocean to the south and the Caribbean Sea to the northeast. The broad band of the Sierra Madre mountains sweeps down from Mexico in the west, across southern and central Guatemala and into El Salvador and Honduras to the east. The north is dominated by a broad lowland plain that extends eastwards into Belize and north into Mexico. A narrower plain separates the Sierra Madre from the Pacific Ocean to the south. Relief map of Guatemala showing the three broad geographical areas: the southern Pacific lowlands, the highlands and the northern Petén lowlands In the early 16th century the territory that now makes up Guatemala was divided into various competing polities, each locked in continual struggle with its neighbours.[27] The most important were the Kʼicheʼ, the Kaqchikel, the Tzʼutujil, the Chajoma,[28] the Mam, the Poqomam and the Pipil.[29] All were Maya groups except for the Pipil, who were a Nahua group related to the Aztecs; the Pipil had a number of small city-states along the Pacific coastal plain of southern Guatemala and El Salvador.[30] The Pipil of Guatemala had their capital at Itzcuintepec.[31] The Xinca were another non-Maya group occupying the southeastern Pacific coastal area.[32] The Maya had never been unified as a single empire, but by the time the Spanish arrived Maya civilization was thousands of years old and had already seen the rise and fall of great cities.[33] On the eve of the conquest the highlands of Guatemala were dominated by several powerful Maya states.[34] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the Kʼicheʼ had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain. However, in the late 15th century the Kaqchikel rebelled against their former Kʼicheʼ allies and founded a new kingdom to the southeast with Iximche as its capital. In the decades before the Spanish invasion the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily eroding the kingdom of the Kʼicheʼ.[35] Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the western highlands and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands.[29] The kingdom of the Itza was the most powerful polity in the Petén lowlands of northern Guatemala,[36] centred on their capital Nojpetén, on an island in Lake Petén Itzá.[nb 1] The second polity in importance was that of their hostile neighbours, the Kowoj. The Kowoj were located to the east of the Itza, around the eastern lakes: Lake Salpetén, Lake Macanché, Lake Yaxhá and Lake Sacnab.[37] Other groups are less well known and their precise territorial extent and political makeup remains obscure; among them were the Chinamita, the Kejache, the Icaiche, the Lakandon Chʼol, the Mopan, the Manche Chʼol and the Yalain.[38] The Kejache occupied an area north of the lake on the route to Campeche, while the Mopan and the Chinamita had their polities in the southeastern Petén.[39] The Manche territory was to the southwest of the Mopan.[40] The Yalain had their territory immediately to the east of Lake Petén Itzá.[41] Native weapons and tactics Maya warfare was not so much aimed at destruction of the enemy as the seizure of captives and plunder.[42] The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows, fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset obsidian,[43] similar to the Aztec macuahuitl. Pedro de Alvarado described how the Xinca of the Pacific coast attacked the Spanish with spears, stakes and poisoned arrows.[44] Maya warriors wore body armour in the form of quilted cotton that had been soaked in salt water to toughen it; the resulting armour compared favourably to the steel armour worn by the Spanish. The Maya had historically employed ambush and raiding as their preferred tactic, and its employment against the Spanish proved troublesome for the Europeans.[45] In response to the use of cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with fire-hardened stakes and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that according to the Kaqchikel killed many horses.[46] |

征服前のグアテマラ グアテマラは、南に太平洋、北東にカリブ海を望む位置にあります。西のメキシコからグアテマラ南部と中部を横断し、東のエルサルバドルとホンジュラスに広 がるシエラマドレ山脈の広大な山脈帯。北部は広大な低地平原が広がり、東はベリーズ、北はメキシコへと続いている。太平洋に面したシエラマドレ山脈と太平 洋の間には、より狭い平原が広がっている。 グアテマラの地形図。南部の太平洋低地、高地、北部のペテン低地の3つの広大な地域を示している 16世紀初頭、現在のグアテマラ領土は、互いに争いを繰り広げるさまざまな政治勢力によって分割されていた[27]。最も重要な勢力は、キチェ、カクチケ ル、ツツジル、チャヨマ[28]、マム、ポ [29] ピピルを除くすべてのグループはマヤ系民族であった。ピピルはアステカ族と関係のあるナワ族であり、グアテマラとエルサルバドルの太平洋沿岸平野に多数の 小都市国家を擁していた[30]。グアテマラのピピルはイツクインテペックを首都としていた[31]。また、シンカ族も太平洋沿岸南東部を占領していたマ ヤ系以外の民族であった[32]。マヤは決して単一帝国として統一されたことはなかったが、スペイン人が到着した時点でマヤ文明は数千年の歴史を持ち、す でに偉大な都市の興亡を経験していた[33]。 征服前夜、グアテマラの高地はいくつかの強力なマヤ国家によって支配されていた[34]。スペイン人が到着する数世紀前から、キチェ族はグアテマラ高原の 西部および隣接する太平洋沿岸平野の大部分をカバーする小さな帝国を築いていた。しかし、15世紀後半にカクチケル族がかつての同盟国キチェ族に反抗し、 イシムチェを首都とする新たな王国を南東部に建国した。スペインの侵略前の数十年、カクチケル王国はキチェ王国を徐々に侵食していた[35]。その他の高 地民族には、アティトラン湖周辺のツトゥヒル族、西高地に住むマム族、東高地に住むポコマン族などがいた[29]。 イツァ王国は、グアテマラ北部のペテン低地において最も強力な政治体であった[36]。ペテン・イツァ湖の島にある首都ノペテンを中心に栄えた[注釈 1]。次に重要な政治体は、敵対関係にあったコウォイ族の政治体であった。コウォイ族は、イッツァ族の東、東部の湖の周辺に居住していた。サルペテン湖、 マカンチェ湖、ヤシュハ湖、サクナブ湖である[37]。その他の集団はあまり知られておらず、正確な領土の範囲や政治体制は不明瞭である。その中には、シ ナミタ、ケジャチェ、イカチェ、ラカンドン・チョル、モパン、マンチェ・チョル、ヤラインなどが含まれる[38]。ケジャチェ族は湖の北、カンペチェへの 道沿いに居住し、モパン族とシナミタ族はペテンの南東部に政治体制を築いていた[39]。マンチェ族の領土はモパン族の南西に位置していた[40]。ヤラ イン族はペテン・イッツァ湖のすぐ東に領土を持っていた[41]。 先住民の武器と戦術 マヤの戦争は マヤの戦争は、敵の破壊よりも捕虜の捕獲と略奪を目的としていた[42]。スペイン人はペテン・マヤの戦争の武器を、弓矢、火で尖らせた棒、火打ち石を頭 につけた槍、そして強固な木材から作られた両手剣(刃の部分は黒曜石をはめ込んで作られていた)[43]、アステカのマカウィトルに似たものと説明してい る。ペドロ・デ・アルバラードは、太平洋沿岸のシンカ族が槍、杭、毒矢でスペイン軍を攻撃した様子を記している[44]。マヤの戦士たちは、塩水に浸して 堅くした綿のキルティングでできた胴衣を着ていた。出来上がった鎧は、スペイン軍が着用していた鋼鉄製の鎧よりも優れていた。マヤ人は歴史的に待ち伏せや 奇襲を好んで用いており、スペイン人に対してその戦術を用いることはヨーロッパ人にとって厄介なものであった[45]。騎兵隊の使用に対抗して、高地に住 むマヤ人は道路に穴を掘り、火で焼いた杭を並べ、草や雑草でそれをカムフラージュするという戦術を用いた。カクチケル族によると、この戦術によって多くの 馬が殺されたという[46]。 |

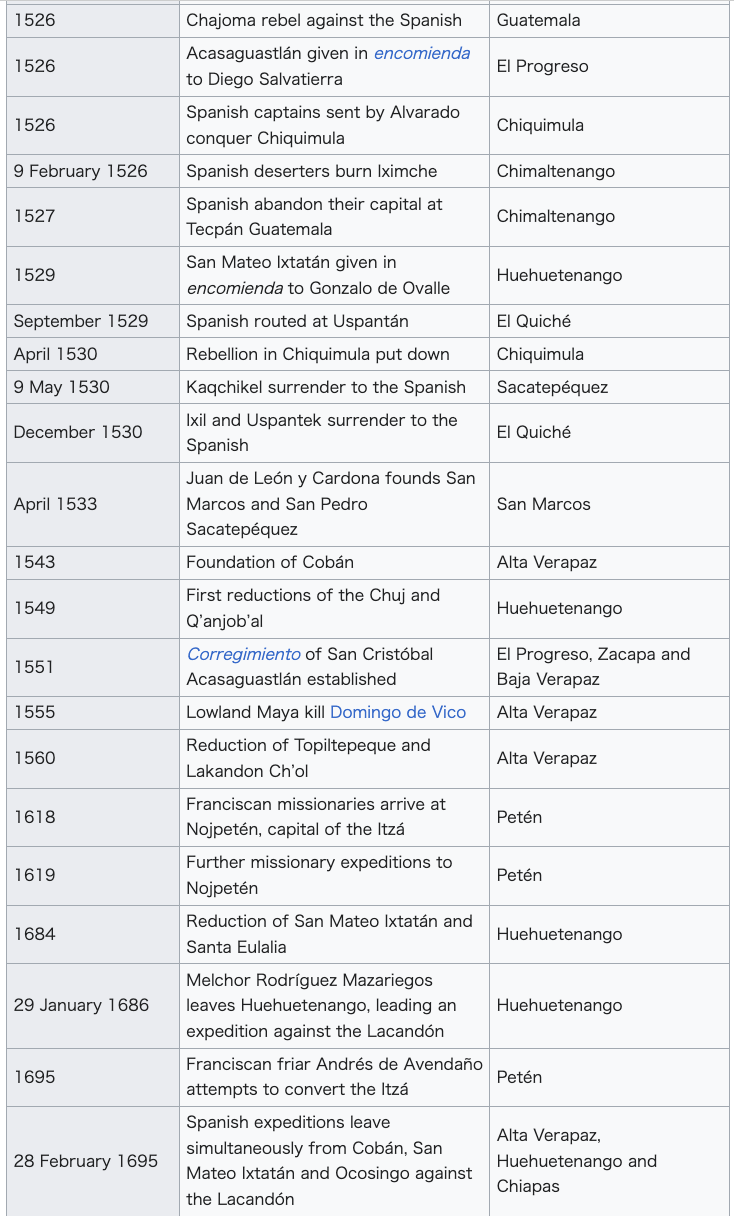

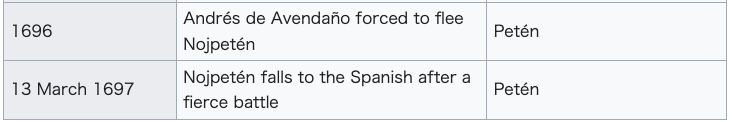

|

Conquistadors We came here to serve God and the King, and also to get rich.[nb 2]----Bernal Díaz del Castillo[47] Pedro de Alvarado entered Guatemala from the west along the southern Pacific plain in 1524, before swinging northwards and fighting a number of battles to enter the highlands. He then executed a broad loop around the north side of the highland Lake Atitlán, fighting further battles along the way, before descending southwards once more into the Pacific lowlands. Two more battles were fought as his forces headed east into what is now El Salvador. In 1525 Hernán Cortés entered northern Guatemala from the north, crossed to Lake Petén Itzá and continued roughly southeast to Lake Izabal before turning east to the Gulf of Honduras.  Map of the principal entry routes and battle sites of the conquest of Guatemala The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.[48] Many of the Spanish were already experienced soldiers who had previously campaigned in Europe.[49] The initial incursion into Guatemala was led by Pedro de Alvarado, who earned the military title of Adelantado in 1527;[50] he answered to the Spanish crown via Hernán Cortés in Mexico.[49] Other early conquistadors included Pedro de Alvarado's brothers Gómez de Alvarado, Jorge de Alvarado and Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras; and his cousins Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez, Hernando de Alvarado and Diego de Alvarado.[7] Pedro de Portocarrero was a nobleman who joined the initial invasion.[51] Bernal Díaz del Castillo was a petty nobleman who accompanied Hernán Cortés when he crossed the northern lowlands, and Pedro de Alvarado on his invasion of the highlands.[52] In addition to Spaniards, the invasion force probably included dozens of armed African slaves and freedmen.[53] |

征服者 私たちは神と王に仕えるため、そして富を得るためにここに来た。——ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョ[47] 1524年、ペドロ・デ・アルバラードはグアテマラに西から入り、太平洋の南側の平野に沿って北上し、高地に入るために多くの戦いを繰り広げた。その後、 彼は高地にあるアティトラン湖の北側をぐるりと回り、さらにその道中で戦闘を繰り広げ、再び南に下りて太平洋の低地へと向かった。エルサルバドルへと向か う彼の部隊は、さらに2回の戦闘を繰り広げた。1525年、エルナン・コルテスがグアテマラ北部からペテン・イッツァ湖を渡り、ほぼ南東のイサバル湖へと 進み、そこから東に曲がってホンジュラス湾へと向かった。  グアテマラ征服の主な進入ルートと戦闘地の地図 征服者たちは皆志願兵であり、その大半は固定給ではなく、戦利品の一部として、貴金属、土地の贈与、先住民の労働力の提供を受けていた[48]。スペイン 人の多くは、ヨーロッパで既に戦役を経験していたベテラン兵士であった[49]。グアテマラへの最初の侵入は、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドが指揮し、1527 年に軍事的称号である 1527年に「先駆者」の称号を得た[50]。彼はメキシコにいるエルナン・コルテスを通じてスペイン王に報告していた[49]。初期の征服者としては、 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの兄弟であるゴメス・デ・アルバラド、ホルヘ・デ・アルバラド、ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラド・イ・コントレラス、そして従兄弟のゴン サロ・デ・アルバラド・イ・チャベス、エルナン・デ・アルバラド、ディエゴ・デ・アルバラドなどがいた[7]。ペドロ・デ・ポルトカロー ペドロ・デ・ポルトカローは、最初の侵略に参加した貴族であった[51]。ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョは、エルナン・コルテスが北部低地を 通過する際に同行した小貴族であり、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドが高地への侵略に同行した[52]。スペイン人以外にも、おそらく武装した数十人のアフリカ人 奴隷や解放奴隷が侵略軍に加わっていた[53]。 |

|

Spanish weapons and tactics Spanish weaponry and tactics differed greatly from that of the indigenous peoples of Guatemala. This included the Spanish use of crossbows, firearms (including muskets and cannon),[54] war dogs and war horses.[55] Among Mesoamerican peoples the capture of prisoners was a priority, while to the Spanish such taking of prisoners was a hindrance to outright victory.[55] The inhabitants of Guatemala, for all their sophistication, lacked key elements of Old World technology, such as the use of iron and steel and functional wheels.[56] The use of steel swords was perhaps the greatest technological advantage held by the Spanish, although the deployment of cavalry helped them to rout indigenous armies on occasion.[57] The Spanish were sufficiently impressed by the quilted cotton armour of their Maya enemies that they adopted it in preference to their own steel armour.[45] The conquistadors applied a more effective military organisation and strategic awareness than their opponents, allowing them to deploy troops and supplies in a way that increased the Spanish advantage.[58]  Representation of a battle between a native and a conquistador. In Guatemala the Spanish routinely fielded indigenous allies; at first these were Nahuas brought from the recently conquered Mexico, later they also included Mayas. It is estimated that for every Spaniard on the field of battle, there were at least 10 native auxiliaries. Sometimes there were as many as 30 indigenous warriors for every Spaniard, and it was the participation of these Mesoamerican allies that was particularly decisive.[59] In at least one case, encomienda rights were granted to one of the Tlaxcalan leaders who came as allies, and land grants and exemption from being given in encomienda were given to the Mexican allies as rewards for their participation in the conquest.[60] In practice, such privileges were easily removed or sidestepped by the Spanish and the indigenous conquistadors were treated in a similar manner to the conquered natives.[61] The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns, or reducciones (also known as congregaciones). Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as mountains and forests.[62] |

スペインの武器と戦術 スペインの武器と戦術は、グアテマラの先住民のものとは大きく異なっていた。これには、スペイン人がクロスボウ、火器(マスケット銃や大砲を含む)、 [54] 戦犬、軍馬を使用していたことが含まれる[55]。メソアメリカの人々にとって捕虜の捕獲は優先事項であったが、スペイン人にとっては捕虜の捕獲は完全な 勝利の妨げであった[55]。グアテマラの住民は、 グアテマラの住民は、その洗練された文化にもかかわらず、鉄や鋼鉄の使用や車輪などの旧世界の技術的要素を欠いていた[56]。鋼鉄製の剣の使用は、スペ イン人が持つ最大の技術的優位性であったかもしれないが、騎兵隊の投入は、時に先住民軍を撃破するのに役立った[57]。スペイン人は、マヤの敵の綿入れ の綿入れの鎧に十分に感銘を受け、 マヤの敵のキルティング加工を施した綿の鎧に感銘を受けたスペイン人は、自分たちの鋼鉄製の鎧よりもそれを好んで採用した[45]。征服者たちは、敵より も効果的な軍事組織と戦略的認識を適用し、スペインの優位性を高めるような方法で軍隊と物資を展開することができた[58]。  先住民と征服者との戦いの描写。 グアテマラでは、スペイン人は日常的に先住民を味方につけていた。最初は、最近征服したメキシコから連れてきたナワ族だったが、後にはマヤ族も含まれるよ うになった。戦場にいたスペイン人の1人につき、少なくとも10人の先住民が味方についていたと推定されている。時にはスペイン人1人に対して先住民戦士 が30人いたこともあり、特に決定的だったのはこれらのメソアメリカ同盟者の参加であった[59]。少なくとも1つのケースでは、同盟者として参加したト ラスカランの指導者の1人にエンコミエンダ権が与えられ、メキシコ人同盟者には征服への参加に対する報酬として土地の贈与とエンコミエンダからの免除が与 えられた 征服に参加した報酬として、メキシコ人同盟軍にも土地の贈与とエンコミエンダからの免除が与えられた[60]。実際には、このような特権はスペイン人に よって簡単に剥奪されたり回避されたりした。先住民征服者は征服された先住民と同様の扱いを受けた[61]。 スペイン人は、新たに設立された植民地都市、またはレドゥクション(congregacionesとも呼ばれる)に先住民を集中させる戦略を採用した。新しい中心都市への先住民の抵抗は、先住民が山や森林などの人里離れた地域へ逃亡するという形をとった[62]。 |

| Impact of Old World diseases Epidemics accidentally introduced by the Spanish included smallpox, measles and influenza. These diseases, together with typhus and yellow fever, had a major impact on Maya populations.[63] The Old World diseases brought with the Spanish and against which the indigenous New World peoples had no resistance were a deciding factor in the conquest; the diseases crippled armies and decimated populations before battles were even fought.[64] Their introduction was catastrophic in the Americas; it is estimated that 90% of the indigenous population had been eliminated by disease within the first century of European contact.[65] In 1519 and 1520, before the arrival of the Spanish in the region, a number of epidemics swept through southern Guatemala.[66] At the same time as the Spanish were occupied with the overthrow of the Aztec Empire, a devastating plague struck the Kaqchikel capital of Iximche, and the city of Qʼumarkaj, capital of the Kʼicheʼ, may also have suffered from the same epidemic.[67] It is likely that the same combination of smallpox and a pulmonary plague swept across the entire Guatemalan Highlands.[68] Modern knowledge of the impact of these diseases on populations with no prior exposure suggests that 33–50% of the population of the highlands perished. Population levels in the Guatemalan Highlands did not recover to their pre-conquest levels until the middle of the 20th century.[69] In 1666 pestilence or murine typhus swept through what is now the department of Huehuetenango. Smallpox was reported in San Pedro Saloma, in 1795.[70] At the time of the fall of Nojpetén in 1697, there are estimated to have been 60,000 Mayas living around Lake Petén Itzá, including a large number of refugees from other areas. It is estimated that 88% of them died during the first ten years of colonial rule owing to a combination of disease and war.[71] |

旧世界病の影響 スペイン人が偶然持ち込んだ疫病には、天然痘、はしか、インフルエンザなどが含まれる。これらの病気は、チフスや黄熱病とともにマヤの人口に多大な影響を 与えた[63]。スペイン人がもたらし、先住民の新世界の人々が抵抗手段を持たない旧世界の病気は、征服の決定的な要因となった。これらの病気は、戦闘が 始まる前に軍隊を無力化し、人口を激減させた[64]。これらの病気の伝播はアメリカ大陸にとって壊滅的なものであり、ヨーロッパ人との接触から最初の1 世紀以内に先住民の人口の90%が ヨーロッパ人との接触から最初の1世紀の間に、先住民の人口の90%が病によって失われたと推定されている[65]。 1519年と1520年、スペイン人がこの地域に到着する前に、グアテマラ南部を多数の疫病が襲った[66]。スペイン人がアステカ帝国の打倒に忙殺され ているのと同時に、カクチケル族の首都イシムチェを壊滅的なペストが襲い、 キチェ族の首都であるクマルカフ市も、同じ疫病に苦しんだ可能性がある[67]。天然痘と肺ペストのコンビネーションが、グアテマラ高原全域を襲った可能 性が高い[68]。これらの病気が、それまで感染経験のない人口に与えた影響に関する最新の知識によると、高原の人口の33~50%が死亡したと考えられ る。グアテマラ高原の人口は、20世紀半ばになるまで征服前の水準まで回復しなかった[69]。1666年には、現在のウエウエテナンゴ県をペストやネズ ミチフスが襲った。天然痘は1795年にサン・ペドロ・サロマで報告されている[70]。1697年のノペテンの陥落当時、ペテン・イッツァ湖周辺には、 他の地域からの多数の避難民を含め、6万人のマヤ人が住んでいたと推定されている。植民地支配の最初の10年間で、病気と戦争により、彼らの88%が死亡 したと推定されている[71]。 |

| コロンブスの交換 |

コロンブス交換(コ

ロンブスこうかん、英: Columbian

exchange)とは、15世紀後半以降、西半球の新世界(アメリカ大陸)と東半球の旧世界(アフロ・ユーラシア大陸)の間で、植物、動物、貴金属、商

品、文化、人口、技術、病気、思想などが広範囲に渡って交換されたことである。

[イタリアの探検家クリストファー・コロンブスにちなんで命名され、彼の1492年の航海後のヨーロッパの植民地化と世界貿易に関連している。旧世界に由

来する伝染病は、15世紀以降、アメリカ大陸の先住民の数を80~95%減少させる結果となり、カリブ海地域では最も深刻だった。ヨーロッパ人入植者とア

フリカ人奴隷は、程度の差こそあれ、アメリカ大陸の先住民に取って代わった。新大陸に連れて行かれたアフリカ人の数は、コロンブス後の最初の3世紀に新大

陸に移動したヨーロッパ人の数をはるかに上回っていた。

世界人口の新たな接触は、多種多様な作物や家畜の交流をもたらし、旧世界における食糧生産と人口の増加を支えた。トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、トマト、タバ

コ、キャッサバ、サツマイモ、唐辛子といったアメリカの作物は、世界中で重要な作物となった。旧世界の米、小麦、サトウキビ、家畜などの作物は、新世界で

も重要な作物となった。アメリカで生産された銀は世界中に溢れ、特に帝国中国で硬貨に使われる標準的な金属となった。

この言葉は、1972年にアメリカの歴史家であり教授でもあるアルフレッド・W・クロスビーが環境史の著書『コロンブス交換』の中で初めて使用した。 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Conquest of the highlands The highlands of Guatemala are bordered by the Pacific plain to the south, with the coast running to the southwest. The Kaqchikel kingdom was centred on Iximche, located roughly halfway between Lake Atitlán to the west and modern Guatemala City to the east. The Tzʼutujil kingdom was based around the south shore of the lake, extending into the Pacific lowlands. The Pipil were situated further east along the Pacific plain and the Pocomam occupied the highlands to the east of modern Guatemala City. The Kʼicheʼ kingdom extended to the north and west of the lake with principal settlements at Xelaju, Totonicapan, Qʼumarkaj, Pismachiʼ and Jakawitz. The Mam kingdom covered the western highlands bordering modern Mexico.  Map of the Guatemalan Highlands on the eve of the Spanish conquest The conquest of the highlands was made difficult by the many independent polities in the region, rather than one powerful enemy to be defeated as was the case in central Mexico.[73] After the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish in 1521, the Kaqchikel Maya of Iximche sent envoys to Hernán Cortés to declare their allegiance to the new ruler of Mexico, and the Kʼicheʼ Maya of Qʼumarkaj may also have sent a delegation.[74] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj at Tuxpán;[75] both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the king of Spain.[74] But Cortés' allies in Soconusco soon informed him that the Kʼicheʼ and the Kaqchikel were not loyal, and were instead harassing Spain's allies in the region. Cortés decided to despatch Pedro de Alvarado with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and thousands of allied Mexican warriors from Tlaxcala, Cholula and other cities in central Mexico;[76] they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.[74] Pedro de Alvarado was infamous for the massacre of Aztec nobles in Tenochtitlan and, according to Bartolomé de las Casas, he committed further atrocities in the conquest of the Maya kingdoms in Guatemala.[77] Some groups remained loyal to the Spanish once they had submitted to the conquest, such as the Tzʼutujil and the Kʼicheʼ of Quetzaltenango, and provided them with warriors to assist further conquest. Other groups soon rebelled however, and by 1526 numerous rebellions had engulfed the highlands.[78] Subjugation of the Kʼicheʼ  Page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala showing the conquest of Quetzaltenango  The Plains of Urbina, scene of a decisive battle against the Kʼicheʼ ... we waited until they came close enough to shoot their arrows, and then we smashed into them; as they had never seen horses, they grew very fearful, and we made a good advance ... and many of them died. Pedro de Alvarado describing the approach to Quetzaltenango in his 3rd letter to Hernán Cortés[79] Pedro de Alvarado and his army advanced along the Pacific coast unopposed until they reached the Samalá River in western Guatemala. This region formed a part of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, and a Kʼicheʼ army tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Spanish from crossing the river. Once across, the conquistadors ransacked nearby settlements in an effort to terrorise the Kʼicheʼ.[5] On 8 February 1524 Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul, called Zapotitlán by his Mexican allies (modern San Francisco Zapotitlán). Although suffering many injuries inflicted by defending Kʼicheʼ archers, the Spanish and their allies stormed the town and set up camp in the marketplace.[80] Alvarado then turned to head upriver into the Sierra Madre mountains towards the Kʼicheʼ heartlands, crossing the pass into the fertile valley of Quetzaltenango. On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by Kʼicheʼ warriors but the Spanish cavalry charge that followed was a shock for the Kʼicheʼ, who had never before seen horses. The cavalry scattered the Kʼicheʼ and the army crossed to the city of Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango) only to find it deserted.[81] Although the common view is that the Kʼicheʼ prince Tecun Uman died in the later battle near Olintepeque, the Spanish accounts are clear that at least one and possibly two of the lords of Qʼumarkaj died in the fierce battles upon the initial approach to Quetzaltenango.[82] The death of Tecun Uman is said to have taken place in the battle of El Pinar,[83] and local tradition has his death taking place on the Llanos de Urbina (Plains of Urbina), upon the approach to Quetzaltenango near the modern village of Cantel.[84] Pedro de Alvarado, in his third letter to Hernán Cortés, describes the death of one of the four lords of Qʼumarkaj upon the approach to Quetzaltenango. The letter was dated 11 April 1524 and was written during his stay at Qʼumarkaj.[83] Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,[85] a Kʼicheʼ army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley and were comprehensively defeated; many Kʼicheʼ nobles were among the dead.[86] Such were the numbers of Kʼicheʼ dead that Olintepeque was given the name Xequiquel, roughly meaning "bathed in blood".[87] In the early 17th century, the grandson of the Kʼicheʼ king informed the alcalde mayor (the highest colonial official at the time) that the Kʼicheʼ army that had marched out of Qʼumarkaj to confront the invaders numbered 30,000 warriors, a claim that is considered credible by modern scholars.[88] This battle exhausted the Kʼicheʼ militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Qʼumarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan to the Nahuatl-speaking allies of the Spanish. Alvarado was deeply suspicious of the Kʼicheʼ intentions but accepted the offer and marched to Qʼumarkaj with his army.[89] The day after the battle of Olintepeque, the Spanish army arrived at Tzakahá, which submitted peacefully. There the Spanish chaplains Juan Godínez and Juan Díaz conducted a Roman Catholic mass under a makeshift roof;[90] this site was chosen to build the first church in Guatemala,[91] which was dedicated to Concepción La Conquistadora. Tzakahá was renamed as San Luis Salcajá.[90] The first Easter mass held in Guatemala was celebrated in the new church, during which high-ranking natives were baptised.[91]  Grass- and scrub-covered ruins set against a backdrop of low pine forest. A crumbling squat square tower stands behind to the right, all that remains of the Temple of Tohil, with the remains of the walls of the ballcourt to the left in the foreground. Qʼumarkaj was the capital of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom until it was burnt by the invading Spanish. In March 1524 Pedro de Alvarado entered Qʼumarkaj at the invitation of the remaining lords of the Kʼicheʼ after their catastrophic defeat,[92] fearing that he was entering a trap.[86] He encamped on the plain outside the city rather than accepting lodgings inside.[93] Fearing the great number of Kʼicheʼ warriors gathered outside the city and that his cavalry would not be able to manoeuvre in the narrow streets of Qʼumarkaj, he invited the leading lords of the city, Oxib-Keh (the ajpop, or king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the ajpop kʼamha, or king elect) to visit him in his camp.[94] As soon as they did so, he seized them and kept them as prisoners in his camp. The Kʼicheʼ warriors, seeing their lords taken prisoner, attacked the Spaniards' indigenous allies and managed to kill one of the Spanish soldiers.[95] At this point Alvarado decided to have the captured Kʼicheʼ lords burnt to death, and then proceeded to burn the entire city.[96] After the destruction of Qʼumarkaj and the execution of its rulers, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to Iximche, capital of the Kaqchikel, proposing an alliance against the remaining Kʼicheʼ resistance. Alvarado wrote that they sent 4,000 warriors to assist him, although the Kaqchikel recorded that they sent only 400.[89] San Marcos: Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón With the capitulation of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, various non-Kʼicheʼ peoples under Kʼicheʼ dominion also submitted to the Spanish. This included the Mam inhabitants of the area now within the modern department of San (. Quetzaltenango and San Marcos were placed under the command of Juan de León y Cardona, who began the reduction of indigenous populations and the foundation of Spanish towns. The towns of San Marcos and San Pedro Sacatepéquez were founded soon after the conquest of western Guatemala.[97] In 1533 Pedro de Alvarado ordered de León y Cardona to explore and conquer the area around the Tacaná, Tajumulco, Lacandón and San Antonio volcanoes; in colonial times this area was referred to as the Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón.[98] De León marched to a Maya city named Quezalli by his Nahuatl-speaking allies with a force of fifty Spaniards; his Mexican allies also referred to the city by the name Sacatepequez. De León renamed the city as San Pedro Sacatepéquez in honour of his friar, Pedro de Angulo.[98] The Spanish founded a village nearby at Candacuchex in April that year, renaming it as San Marcos.[99] Kaqchikel alliance On 14 April 1524, soon after the defeat of the Kʼicheʼ, the Spanish were invited into Iximche and were well received by the lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox.[100][nb 3] The Kaqchikel kings provided native soldiers to assist the conquistadors against continuing Kʼicheʼ resistance and to help with the defeat of the neighbouring Tzʼutuhil kingdom.[101] The Spanish only stayed briefly in Iximche before continuing through Atitlán, Escuintla and Cuscatlán. The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on 23 July 1524 and on 27 July (1 Qʼat in the Kaqchikel calendar) Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche as the first capital of Guatemala, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala").[102] Iximche was called Guatemala by the Spanish, from the Nahuatl Quauhtemallan meaning "forested land". Since the Spanish conquistadors founded their first capital at Iximche, they took the name of the city used by their Nahuatl-speaking Mexican allies and applied it to the new Spanish city and, by extension, to the kingdom. From this comes the modern name of the country.[103] When Pedro de Alvarado moved his army to Iximche, he left the defeated Kʼicheʼ kingdom under the command of Juan de León y Cardona.[104] Although de León y Cardona was given command of the western reaches of the new colony, he continued to take an active role in the continuing conquest, including the later assault on the Poqomam capital.[105] Conquest of the Tzʼutujil  View across hills to a broad lake bathed in a light mist. The mountainous lake shore curves from the left foreground backwards and to the right, with several volcanoes rising from the far shore, framed by a clear blue sky above. The Tzʼutujil kingdom had its capital on the shore of Lake Atitlán. The Kaqchikel appear to have entered into an alliance with the Spanish to defeat their enemies, the Tzʼutujil, whose capital was Tecpan Atitlan.[89] Pedro de Alvarado sent two Kaqchikel messengers to Tecpan Atitlan at the request of the Kaqchikel lords, both of whom were killed by the Tzʼutujil.[106] When news of the killing of the messengers reached the Spanish at Iximche, the conquistadors marched against the Tzʼutujil with their Kaqchikel allies.[89] Pedro de Alvarado left Iximche just 5 days after he had arrived there, with 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry and an unspecified number of Kaqchikel warriors. The Spanish and their allies arrived at the lakeshore after a day's hard march, without encountering any opposition. Seeing the lack of resistance, Alvarado rode ahead with 30 cavalry along the lakeshore. Opposite a populated island the Spanish at last encountered hostile Tzʼutujil warriors and charged among them, scattering and pursuing them to a narrow causeway across which the surviving Tzʼutujil fled.[107] The causeway was too narrow for the horses, therefore the conquistadors dismounted and crossed to the island before the inhabitants could break the bridges.[108] The rest of Alvarado's army soon reinforced his party and they successfully stormed the island. The surviving Tzʼutujil fled into the lake and swam to safety on another island. The Spanish could not pursue the survivors further because 300 canoes sent by the Kaqchikels had not yet arrived. This battle took place on 18 April.[109] The following day the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan but found it deserted. Pedro de Alvarado camped in the centre of the city and sent out scouts to find the enemy. They managed to catch some locals and used them to send messages to the Tzʼutujil lords, ordering them to submit to the king of Spain. The Tzʼutujil leaders responded by surrendering to Pedro de Alvarado and swearing loyalty to Spain, at which point Alvarado considered them pacified and returned to Iximche.[109] Three days after Pedro de Alvarado returned to Iximche, the lords of the Tzʼutujil arrived there to pledge their loyalty and offer tribute to the conquistadors.[110] A short time afterwards a number of lords arrived from the Pacific lowlands to swear allegiance to the king of Spain, although Alvarado did not name them in his letters; they confirmed Kaqchikel reports that further out on the Pacific plain was the kingdom called Izcuintepeque in Nahuatl, or Panatacat in Kaqchikel, whose inhabitants were warlike and hostile towards their neighbours.[111] Kaqchikel rebellion  View across a series of neatly maintained low ruins, consisting of a labyrinthine series of overlapping rectangular basal platforms. Two small pyramid structures dominate the view, with pine forest providing the backdrop. The ruins of Iximche, burnt by Spanish deserters Line drawing of a conquistador on horseback charging to the right accompanied by two native warriors on foot in feathered battledress. On the right hand side more simply dressed natives shoot arrows at the attackers. Page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala depicting the conquest of Iximche Pedro de Alvarado rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples.[112] He demanded that their kings deliver 1000 gold leaves, each worth 15 pesos.[113][nb 4] A Kaqchikel priest foretold that the Kaqchikel gods would destroy the Spanish, causing the Kaqchikel people to abandon their city and flee to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524 (7 Ahmak in the Kaqchikel calendar). Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.[112] Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the Ahpo Xahil, sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado.[114][nb 5] Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounted how in 1526 he returned to Iximche and spent the night in the "old city of Guatemala" together with Luis Marín and other members of Hernán Cortés's expedition to Honduras. He reported that the houses of the city were still in excellent condition; his account was the last description of the city while it was still inhabitable.[115] The Kaqchikel began to fight the Spanish. They opened shafts and pits for the horses and put sharp stakes in them to kill them ... Many Spanish and their horses died in the horse traps. Many Kʼicheʼ and Tzʼutujil also died; in this way the Kaqchikel destroyed all these peoples. Annals of the Kaqchikels[116] The Spanish founded a new town at nearby Tecpán Guatemala; Tecpán is Nahuatl for "palace", thus the name of the new town translated as "the palace among the trees".[117] The Spanish abandoned Tecpán in 1527, because of the continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital on the site of today's San Miguel Escobar district of Ciudad Vieja, near Antigua Guatemala.[118] The Nahua and Oaxacan allies of the Spanish settled in what is now central Ciudad Vieja, then known as Almolonga (not to be confused with Almolonga near Quetzaltenango);[119] Zapotec and Mixtec allies also settled San Gaspar Vivar about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Almolonga, which they founded in 1530.[120] The Kaqchikel kept up resistance against the Spanish for a number of years, but on 9 May 1530, exhausted by the warfare that had seen the deaths of their best warriors and the enforced abandonment of their crops,[121] the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilds.[112] A day later they were joined by many nobles and their families and many more people; they then surrendered at the new Spanish capital at Ciudad Vieja.[112] The former inhabitants of Iximche were dispersed; some were moved to Tecpán, the rest to Sololá and other towns around Lake Atitlán.[117] Siege of Zaculeu  A cluster of squat white step pyramids, the tallest of them topped by a shrine with three doorways. In the background is a low mountain ridge. Zaculeu fell to Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras after a siege of several months. Although a state of hostilities existed between the Mam and the Kʼicheʼ of Qʼumarkaj after the rebellion of the Kaqchikel against their former Kʼicheʼ allies prior to European contact, when the conquistadors arrived there was a shift in the political landscape. Pedro de Alvarado described how the Mam king Kaybʼil Bʼalam was received with great honour in Qʼumarkaj while he was there.[122] The expedition against Zaculeu was apparently initiated after Kʼicheʼ bitterness at their failure to contain the Spanish at Qʼumarkaj, with the plan to trap the conquistadors in the city having been suggested to them by the Mam king, Kaybʼil Bʼalam; the resulting execution of the Kʼicheʼ kings was viewed as unjust. The Kʼicheʼ suggestion of marching on the Mam was quickly taken up by the Spanish.[123] At the time of the conquest, the main Mam population was situated in Xinabahul (also spelled Chinabjul), now the city of Huehuetenango, but Zaculeu's fortifications led to its use as a refuge during the conquest.[124] The refuge was attacked by Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras, brother of conquistador Pedro de Alvarado,[125] in 1525, with 40 Spanish cavalry and 80 Spanish infantry,[126] and some 2,000 Mexican and Kʼicheʼ allies.[127] Gonzalo de Alvarado left the Spanish camp at Tecpán Guatemala in July 1525 and marched to the town of Totonicapán, which he used as a supply base. From Totonicapán the expedition headed north to Momostenango, although it was delayed by heavy rains. Momostenango quickly fell to the Spanish after a four-hour battle. The following day Gonzalo de Alvarado marched on Huehuetenango and was confronted by a Mam army of 5,000 warriors from nearby Malacatán (modern Malacatancito). The Mam army advanced across the plain in battle formation and was met by a Spanish cavalry charge that threw them into disarray, with the infantry mopping up those Mam that survived the cavalry. Gonzalo de Alvarado slew the Mam leader Canil Acab with his lance, at which point the Mam army's resistance was broken, and the surviving warriors fled to the hills. Alvarado entered Malacatán unopposed to find it occupied only by the sick and the elderly. Messengers from the community's leaders arrived from the hills and offered their unconditional surrender, which was accepted by Alvarado. The Spanish army rested for a few days, then continued onwards to Huehuetenango only to find it deserted. Kaybʼil Bʼalam had received news of the Spanish advance and had withdrawn to his fortress at Zaculeu.[126] Alvarado sent a message to Zaculeu proposing terms for the peaceful surrender of the Mam king, who chose not to answer.[128] Zaculeu was defended by Kaybʼil Bʼalam[124] commanding some 6,000 warriors gathered from Huehuetenango, Zaculeu, Cuilco and Ixtahuacán. The fortress was surrounded on three sides by deep ravines and defended by a formidable system of walls and ditches. Gonzalo de Alvarado, although outnumbered two to one, decided to launch an assault on the weaker northern entrance. Mam warriors initially held the northern approaches against the Spanish infantry but fell back before repeated cavalry charges. The Mam defence was reinforced by an estimated 2,000 warriors from within Zaculeu but was unable to push the Spanish back. Kaybʼil Bʼalam, seeing that outright victory on an open battlefield was impossible, withdrew his army back within the safety of the walls. As Alvarado dug in and laid siege to the fortress, an army of approximately 8,000 Mam warriors descended on Zaculeu from the Cuchumatanes mountains to the north, drawn from those towns allied with the city.[129] Alvarado left Antonio de Salazar to supervise the siege and marched north to confront the Mam army.[130] The Mam army was disorganised, and although it was a match for the Spanish and allied foot soldiers, it was vulnerable to the repeated charges of the experienced Spanish cavalry. The relief army was broken and annihilated, allowing Alvarado to return to reinforce the siege.[131] After several months the Mam were reduced to starvation. Kaybʼil Bʼalam finally surrendered the city to the Spanish in the middle of October 1525.[132] When the Spanish entered the city they found 1,800 dead Indians, and the survivors eating the corpses of the dead.[127] After the fall of Zaculeu, a Spanish garrison was established at Huehuetenango under the command of Gonzalo de Solís; Gonzalo de Alvarado returned to Tecpán Guatemala to report his victory to his brother.[131] |

高地征服 グアテマラの高地は、南を太平洋の平野、南西を海岸に囲まれている。カクチケル王国は、西のアティトラン湖と東のグアテマラシティの中間地点にあるイシム チェを中心に栄えた。ツトゥヒル王国は、湖の南岸を中心に栄え、太平洋の低地にも広がっていた。ピピル族は太平洋平野に沿ってさらに東に位置し、ポコマム 族はグアテマラシティの東の高地に居住していた。キチェ族の王国は湖の北と西に広がり、主な居住地はシェラジュ、トトニカパン、クマルカ、ピスマチ、ジャ カウィッツであった。マム族の王国は、現在のメキシコに隣接する西の高地に広がっていた。  スペインによる征服前のグアテマラ高原の地図 高地征服は、中央メキシコで倒すべき強大な敵がいた場合とは異なり、この地域には多くの独立した政治体があったため、困難を極めた[73]。1521年に アステカの首都テノチティトランがスペイン軍に降伏した後、イシムチェのカクチケル・マヤ族は、 コルテスは、メキシコの新しい支配者に対する忠誠を宣言するために、イシムチェのカクチケル・マヤ族が特使を派遣した。また、クマルカジュのキチェ・マヤ 族も代表団を送った可能性がある[74]。1522年、コルテスはメキシコの同盟者をソコヌスコ地方(チアパス州)の低地地域を偵察に派遣し、彼らはイシ ムチェとクマルカジュから派遣された新たな代表団とトゥクスパンで会った[75]。 トゥクスパンでイシムチェとクマルカジャの新たな使節団と対面した[75]。両者の高地マヤ王国はスペイン王への忠誠を宣言した[74]。しかし、ソコヌ スコのコルテスの同盟者はすぐに、キチェとカクチケルは忠誠心はなく、その代わりにその地域のスペインの同盟者を困らせているとコルテスに報告した。コル テスは、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドに騎兵180名、歩兵300名、クロスボウ、マスケット銃、大砲4門、大量の弾薬と火薬、そしてメキシコ中央部のトラスカ ラ、チョルーラ、その他の都市から数千人の同盟メキシコ戦士を率いてソコヌスコに派遣することを決めた[76]。彼らは1523年にソコヌスコに到着した [74]。彼はテノチティトランのアステカの貴族虐殺で悪名高く、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスによると、彼はグアテマラのマヤ王国征服でもさらなる残虐 行為を行ったという[77]。征服に屈服した後もスペインに忠誠を誓い続けたグループもあった。ケツァルテナンゴのツトゥヒル族やキチェ族などがその一例 であり、彼らはさらなる征服を支援するために戦士を提供した。しかし、他のグループはすぐに反乱を起こし、1526年までに多数の反乱が高地地域を覆って いた[78]。 キチェ族の征服  ケツァルテナンゴ征服を描いた『トラスカラ図絵』のページ  ウルビナ平原、キチェ族との決戦が行われた場所 ... 彼らが矢を射るのに十分な距離まで近づいてくるのを待ち、そして彼らに突撃した。彼らは馬を見たことがなかったので非常に怯え、我々は大きく前進し...彼らの多くは死んだ。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、エルナン・コルテスへの3通目の手紙の中で、ケツァルテナンゴへの進軍について述べている[79]。 ペドロ・デ・アルバラドとその軍隊は、グアテマラ西部のサマラ川に到着するまで、太平洋沿岸を抵抗を受けることなく進軍した。この地域はキチェ王国の一部 であり、キチェ軍はスペイン人が川を渡るのを阻止しようとしたが、失敗に終わった。川を渡った征服者たちは、キチェ族を威嚇しようと、近くの集落を略奪し た[5]。1524年2月8日、アルヴァラドの軍は、彼のメキシコ人同盟軍がザポティトラン(現在のサンフランシスコ・ザポティトラン)と呼んでいたケツ トゥルルで戦闘を行った。キチェ族の弓兵の攻撃により多くの負傷者が出たものの、スペイン軍とその同盟軍は町を急襲し、市場に野営地を構えた[80]。そ の後、アルヴァラドはキチェ族の中心地であるシエラマドレ山脈を目指して川を上り、ケツァルテナンゴの肥沃な谷へと続く峠を越えた。1524年2月12 日、アルヴァラドのメキシコ同盟軍は峠で待ち伏せされ、キチェ族の戦士たちに追い返された。しかし、それに続くスペイン騎兵隊の突撃は、それまで馬を見た ことがなかったキチェ族にとって衝撃的だった。騎兵隊はキチェ族を散らし、軍隊はケツァルテナンゴ(現在のケツァルテナンゴ)の町へ渡ったが、そこはすで に無人だった[81]。一般的な見解では、キチェ族の王子テクン・ウマンは、オリンテペケ近郊での後の戦闘で死亡したとされるが、スペイン側の記録では、 少なくとも1人、おそらく2人のクマルカフの領主が、ケツァルテナンゴへの最初の進軍時に起きた激しい戦闘で命を落としたことは、スペインの記録から明ら かである[82]。テクン・ウマンの死はエル・ピナルでの戦闘で起こったと言われている[83]。地元の伝承では、彼の死はケツァルテナンゴへの進軍時 に、カンテル村近くのウルビナ平野(Llanos de Urbina)で起こったとされている[84]。ウルビナ平野(Plains of Urbina)で、現在のカンテル村付近のケツァルテナンゴへの進軍中に亡くなったという説がある[84]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、エルナン・コルテ スへの3通目の手紙の中で、ケツァルテナンゴへの進軍中にクマルカフの4人の領主のうち1人の死について述べている。この手紙は1524年4月11日付 で、Qʼumarkaj滞在中に書かれたものである[83]。ほぼ1週間後の1524年2月18日[85]、Kʼicheʼ軍はケツァルテナンゴ渓谷でス ペイン軍と対峙し、全面的に敗北した。キチェ族の死者の数が非常に多かったため、オリンテペケは「血にまみれた」という意味の「Xequiquel」とい う名前に変えられた[87]。17世紀初頭、キチェ族の王の孫は、アルカルデ・マヨール(当時の植民地政府最高責任者)に、クマルカハから侵略者と戦うた めに進軍したキチェ族の軍勢は3万人の戦士から成っていたと報告した。 侵略者と対決するためにクマルクから進軍したキチェ族の軍勢は3万人の戦士から成っていたと、キチェ族の王の孫は当時の最高植民地官であるアルカルデ・マ ヨールに報告した。この主張は現代の学者たちからも信憑性のあるものと見なされている[88]。この戦いでキチェ族は軍事的に疲弊し、和平と貢納を求め た。そして、スペイン人のナワトル語を話す同盟者たちにはテクパン・ウタトランとして知られていた首都クマルカハにペドロ・デ・アルバラドを招いた。アル ヴァラドはキチェ族の意図を深く疑っていたが、申し出を受け入れ、軍とともにクマルカハへと進軍した[89]。 オリンテペケの戦いの翌日、スペイン軍はツァカハに到着し、ツァカハは平和裏に降伏した。スペイン人司祭のフアン・ゴディネスとフアン・ディアスは、その 場しのぎの屋根の下でローマ・カトリックのミサを行った[90]。この場所はグアテマラで最初の教会を建てるために選ばれ[91]、コンセプシオン・ラ・ コンキスタドーラに捧げられた。ツァカハはサン・ルイス・サルカハと改名された[90]。グアテマラで初めて復活祭のミサが新しい教会で行われ、その間、 高位の先住民が洗礼を受けた[91]。  背後に広がる松林を背景に、草や低木に覆われた遺跡が見える。右奥には、崩れかけた四角い塔が建っている。これがトヒル神殿の唯一の遺構である。手前の左側にはボールコートの壁の跡がある。 クマルカは、スペインの侵略により焼失するまで、キチェ王国の首都であった。 1524年3月、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドはキチェ族の残存領主たちの招きに応じてクマルカに入城した。彼らは大敗北を喫した後、罠に嵌まることを恐れてい た[86]。彼は宿舎に入る代わりに、市外の平原に野営した[93]。市外には大勢のキチェ族戦士が集まっており、騎兵隊がクマルカの狭い路地で機動でき ないことを恐れた彼は、 クマルカジュの狭い路地で騎馬隊が機動できないことを懸念し、彼はクマルカジュの有力者、オキブ・ケ(アジョップ、つまり王)とベレヘブ・ツィ(アジョッ プ・カムハ、つまり次期王)を自分の陣営に招待した[94]。彼らがやってくるとすぐに、彼は彼らを捕らえて自分の陣営で囚人として監禁した。キチェ族の 戦士たちは、自分たちの主君たちが捕虜になったのを見て、スペイン人の先住民同盟軍を攻撃し、スペイン兵の1人を殺すことに成功した[95]。この時点 で、アルバラドは捕虜となったキチェ族の領主たちを火あぶりにして殺すことを決意し、その後 街全体を焼き払った[96]。クマルカジュの破壊と支配者の処刑の後、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドはカクチケルの首都イシムチェにメッセージを送り、残存する キチェ族の抵抗勢力に対する同盟を提案した。アルヴァラドは、4,000人の戦士を派遣して支援すると書いたが、カクチケルは400人しか派遣していない と記録している[89]。 サン・マルコス:テカスィトランとラカンドン地方 キチェ王国が降伏すると、キチェの支配下にあったキチェ族以外のさまざまな民族もスペインに降伏した。この中には、現在のサン・ペドロ・サカテペケス県 (San . Quetzaltenango)とサン・マルコス県(San Marcos)の地域に住むマム族も含まれていた。フアン・デ・レオン・イ・カルドナ(Juan de León y Cardona)の指揮下に入ったケツァルテナンゴとサン・マルコスでは、先住民人口の削減とスペイン人町建設が始まった。サン・マルコスとサン・ペド ロ・サカテペケスの町は、グアテマラ西部の征服直後に建設された[97]。1533年、ペドロ・デ・アルバラードはデ・レオン・イ・カルドナにタカナ、タ フムルコ、ラカンドン、サン・アントニオ火山周辺の地域を探索し征服するよう命じた。植民地時代、この地域はテクシトランとラカンドン州と呼ばれていた [98]。デ・レオンは、ナワトル語を話す同盟軍とともに、スペイン人50人を率いてケサリというマヤの都市へと進軍した。デ・レオンは、修道士ペドロ・ デ・アンゴロに敬意を表して、この都市をサン・ペドロ・サカテペケスと改名した[98]。スペイン人はその年の4月に、近くのカンダクチェクスに村を建設 し、サン・マルコスと改名した[99]。 カクチケル同盟 1524年4月14日、キチェ族の敗北直後、スペイン人はイシムチェに招かれ、領主ベレヘ・カットとカヒ・イモックスに歓待された[100][nb 3]。先住民兵士を提供し、コンキスタドールがキチェ族の抵抗を続けるのを助け、近隣のツトゥヒル王国の討伐を支援した[101]。スペイン人はイシム チェに短期間滞在した後、アティトラン、エスクイントラ、クスカトランを経て進軍した。スペイン人は1524年7月23日にカクチケル王国の首都に戻っ た。そして7月27日(カクチケル暦の1Qʼat)にペドロ・デ・アルバラドが、イシムチェをグアテマラの最初の首都、サンティアゴ・デ・ロス・カバリェ ロス・デ・グアテマラ(「グアテマラ騎士団の聖ヤコブ」)と宣言した。グアテマラ、サンティアゴ・デ・ロス・カバリェロス・デ・グアテマラ(「グアテマラ 騎士団の聖ヤコブ」)。[102] イシムチェは、スペイン人によってグアテマラと呼ばれた。これはナワトル語で「森林地帯」を意味するクアウテマランに由来する。スペインの征服者たちがイ シムチェに最初の首都を建設して以来、彼らはナワトル語を話すメキシコの同盟者が使用していた都市の名前を取り、それを新しいスペインの都市、ひいては王 国にも適用した。これが現在の国名の由来である[103]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラードが軍をイシムチェに移動させた際、彼は敗北したキチェ王国をフアン・ デ・レオン・イ・カルドナの指揮下に置いた[104]。デ・レオン・イ・カルドナは新植民地の西部の指揮を任されたが、ポコムの首都への攻撃など、続く征 服に積極的に関与し続けた[105]。 ツトゥヒル族の征服  丘陵地帯から、薄霧に包まれた広大な湖が見渡せる。山がちな湖岸は、手前の左側から奥、そして右へと湾曲しており、その向こう岸にはいくつもの火山がそびえ、青空が背景となっている。 ツツジル王国は、アティトラン湖の湖畔に都を置いていた。 カクチケル族は、敵であるツツジル族(首都はテクパン・アティトラン)を討伐するためにスペイン人と同盟を結んだようである[89]。ペドロ・デ・アルバ ラドは、カクチケル族の領主の要請により、2人のカクチケル族の使者をテクパン・アティトランに派遣したが、2人ともツツジル族に殺害された[106]。 ] 使者の殺害の知らせがイシムチェのスペイン人に届いたとき、コンキスタドールたちはカクチケル族の同盟軍とともにツトゥジル族に戦いを挑んだ[89]。ペ ドロ・デ・アルバラドは、到着からわずか5日後にイシムチェを去った。60人の騎兵、150人のスペイン人歩兵、そして不明数のカクチケル族戦士を率い て。スペイン人とその同盟軍は、1日かけて湖畔に到着したが、抵抗に遭うことはなかった。抵抗がないことを見て、アルバラドは30人の騎兵とともに湖畔を 進んだ。人口の多い島に差し掛かったところで、スペイン軍はついに敵対的なツツジルの戦士たちと遭遇し、彼らの中に突撃した。生き残ったツツジル族は狭い 土手道に逃げ込んだが、スペイン軍は彼らを追い散らし、追跡した[107]。馬が通れるほど広くはなかったため、征服者たちは馬から降りて橋を壊される前 に島に渡った[108]。アルヴァラドの軍隊の残りがすぐに彼の部隊を補強し、彼らは島をうまく攻略した。生き残ったツトゥヒル族は湖に逃げ込み、別の島 まで泳いで逃げ延びた。スペイン軍は、カクチケル族が送った300隻のカヌーがまだ到着していなかったため、生存者をそれ以上追うことができなかった。こ の戦いは4月18日に起こった[109]。 翌日、スペイン軍はテプパン・アティトランに入城したが、そこには誰もいなかった。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは町の中心部に野営し、敵を見つけるために斥候 を派遣した。彼らは何人かの地元民を捕らえることに成功し、ツツジル族の首長にスペイン王に服従するよう命じるメッセージを伝えるために彼らを利用した。 ツトゥヒル族の首長は、ペドロ・デ・アルバラドに降伏し、スペインへの忠誠を誓うことでこれに答えた。アルバラドはこれでツトゥヒル族を平定したと考え、 イシムチェに戻った[109]。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドがイシムチェに戻ってから3日後、ツトゥヒル族の首長が到着し、征服者たちに忠誠を誓い、貢物を献 上した[110]。その後まもなく、太平洋低地からスペイン王への忠誠を誓うために多くの領主たちが到着したが、アルヴァラドはその手紙の中で彼らの名前 には触れていない。彼らは、ナワトル語でイスクインテペケ、またはカクチケル語でパナタックと呼ばれる王国が太平洋平原のさらに奥にあるというカクチケル の報告を確認した。その王国は好戦的で、近隣諸国に対して敵対的だった。 カクチケル族の反乱  きれいに整備された一連の低地遺跡を見渡す。重なり合う長方形の基底プラットフォームが迷路のように連なっている。2つの小さなピラミッド状の建造物が視界を支配し、松林がその背景となっている。 スペインの脱走兵によって焼かれたイシムチェの遺跡 馬に乗ったコンキスタドールが右に突進し、羽飾りのついた戦闘服を着た2人の先住民が徒歩で従っている。右側には、より簡素な服装の先住民が攻撃者に矢を放っている。 イシムチェ征服を描いたトラスカラ図の1ページ ペドロ・デ・アルバラドはカクチケル族に貢納金として金を要求し始め、両民族の友好関係を悪化させた[112]。彼は彼らの王に、1枚15ペソの金貨1000枚を納めるよう要求した[113][nb 4]。 カクチケル族の神官は、カクチケル族の神々がスペイン人を滅ぼすだろうと予言し、1524年8月28日(カクチケル暦ではアマク7日)、カクチケル族は自 分たちの都市を捨て、森や丘へと逃げた。10日後、スペインはカクチケルに宣戦布告した[112]。2年後、1526年2月9日、16人のスペインの脱走 兵がアポ・シャヒルの宮殿を焼き、寺院を略奪し、司祭を誘拐した。カクチケルはこれらの行為をペドロ・デ・アルバラドのせいだとした[114][nb 5]。[114][nb 5] 征服者ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョは、1526年にイシムチェに戻り、ルイス・マリンやエルナン・コルテスのホンジュラス遠征隊の他のメン バーとともに「グアテマラの旧市街」で夜を過ごしたときの様子を語っている。彼は、この都市の建物は今でも良好な状態であると報告した。彼の記述は、この 都市がまだ居住可能であった最後の記述となった[115]。 カクチケル族はスペイン人と戦いを始めた。彼らは馬用の穴や落とし穴を開け、鋭い杭を打ち込んで馬を殺した。多くのスペイン人と彼らの馬が馬用の落とし穴で死んだ。多くのキチェ族とツツジル族も死んだ。こうしてカクチケル族はこれらの民族をすべて滅ぼした。 カクチケル族年代記[116] スペイン人はグアテマラのテパン近郊に新しい町を建設した。テパンはナワトル語で「宮殿」を意味し、新しい町の名前は「森の中の宮殿」と訳された [117]。スペイン人はカクチケルの攻撃が絶えなかったため、1527年にテパンを放棄し、東にあるアルモロンガ渓谷に移り、現在のサン・ミゲル・エス コバル地区(シウダー・ビエハの近く)に首都を再建した 、グアテマラのアンティグア近郊である[118]。スペインと同盟を結んだナワ族とオアハカ族は、現在のシウダービエハの中心部に定住した。当時はアルモ ロンガと呼ばれていたが(ケツァルテナンゴ近郊のアルモロンガと混同しないように)[119]、サポテカ族とミシュテカ族もアルモロンガの北東約2キロ メートルにあるサン・ガスパル・ビバルに定住した。彼らは1530年にこの地を建設した[120]。 カクチケル族はスペイン人に対して長年にわたり抵抗を続けたが、1530年5月9日、最も優れた戦士たちの死や作物の放棄を余儀なくされた戦いに疲れ果て た2人の族長の王が、荒野から戻ってきた[112]。その翌日、多くの貴族とその家族、さらに多くの人々が合流。そして、彼らはスペインの新しい首都シウ ダー・ビエハに降伏した[112]。イシムチェの住民は散り散りになり、一部はテクパンに移住し、残りはソロラやアティトラン湖周辺の他の町に移住した [117]。 サクレウの包囲  背の低い白い階段ピラミッドの集まり。最も高いピラミッドの頂上には、3つの出入り口がある神殿がある。背景には低い山稜が見える。 数か月にわたる包囲戦の末、ザクレウはゴンサロ・デ・アルバラド・イ・コントレラスに降伏した。 ヨーロッパ人が到着する以前、カクチケル族がかつての同盟国キチェ族に反乱を起こしたため、マム族とクマルカフのキチェ族の間に敵対状態が存在したが、征 服者が到着すると政治情勢に変化が生じた。ペドロ・デ・アルバラドは、彼がクマルカージに滞在していた間、マムの王ケイビル・バラムがクマルカージでいか に丁重にもてなされたかを述べている[122]。ザクルウに対する遠征は、どうやら、スペイン人をクマルカージで封じ込めることに失敗したキチェ族の恨み を買ったことがきっかけで始まった。征服者をクマルカージに閉じ込めるという計画は、マム王のカイビル・バラムによって彼らに提案されていた。その結果、 キチェ族の王たちが処刑されたことは不当であると見なされた。キチェ族のマン族への進軍提案は、スペイン人によりすぐに採用された[123]。 征服当時、マムの主な人口は、現在のウエウエテナンゴ市であるシナバフル(Chinabjulとも綴られる)に居住していたが、ザクルエの要塞が征服時の 避難場所として利用された[124]。この避難場所は、征服者ペドロ・デ・アルバラドの兄弟ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラド・イ・コントレラスによって、 1525年、40人のスペイン騎兵と80人のスペイン歩兵、約2,000人のメキシコ人とキチェ族の同盟軍を率いて攻撃した[126][127]。ゴンサ ロ・デ・アルバラドは1525年7月にグアテマラのテクパンにあるスペイン軍の野営地を離れ、物資補給基地として使うトトニカパンという町まで進軍した。 トトニカパンから遠征隊は北のモモステナンゴを目指したが、激しい雨のために遅れた。モモステナンゴは4時間の戦闘の末、スペイン軍に簡単に陥落した。翌 日、ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラドはウエウエテナンゴに進軍し、近くのマラカタン(現在のマラカタンシト)から来た5,000人のマム族の軍勢と対峙した。マ ム軍は戦列を組んで平原を進み、スペイン騎兵隊の突撃に遭遇し混乱に陥った。騎兵隊を生き延びたマム兵は歩兵隊に掃討された。ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラドは 槍でマム軍のリーダー、カニル・アカブを殺し、マム軍の抵抗は壊滅した。生き残った戦士たちは丘に逃げた。アルバラドは抵抗を受けることなくマラカタンに 入ったが、そこには病人や年老いた人々しかいなかった。丘陵地帯からやってきたコミュニティの指導者からの使者が無条件降伏を申し出て、アルヴァラドはこ れを受け入れた。スペイン軍は数日間休息した後、フエフテナンゴへと進んだが、そこはすでに無人だった。ケイビル・バラムはスペイン軍の進撃の知らせを受 け、ザクルエの要塞に撤退していた[126]。アルヴァラドはザクルエに、マムの王が平和的に降伏するための条件を提示するメッセージを送ったが、王はそ れに応えることはなかった[128]。 ザクレウは、フエフテナンゴ、ザクレウ、クイルコ、イクスタワカンから集められた約6,000人の戦士を指揮するカイビル・バラムによって守られていた。 要塞は深い峡谷によって3方を囲まれており、強固な城壁と堀によって守られていた。ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラドは、2対1という劣勢にもかかわらず、より防 御力の弱い北側の入口を攻撃することにした。マムの戦士たちは、スペインの歩兵部隊に対して北側の出入口を守っていたが、騎兵隊の反復攻撃の前に後退し た。マムの防衛は、ザクルエ内の推定2,000人の戦士によって強化されたが、スペイン軍を押し返すことはできなかった。カイル・ビ・ラムは、開けた戦場 で決定的な勝利を収めることは不可能だと判断し、軍隊を城壁内の安全な場所へと撤退させた。アルヴァラドが要塞を掘り、包囲網を敷く中、マム族の戦士約 8,000人が、ザクルエと同盟を結んでいる町々から北のクチュマタン山脈に降りてきた[129]。 アルヴァルドはアントニオ・デ・サラザールに攻城戦を指揮させ、マム軍と対決するために北進した[130]。マム軍は組織化されておらず、スペイン軍や同 盟国の歩兵には対抗できたが、経験豊富なスペイン騎兵隊の繰り返し攻撃には無力だった。救援軍は壊滅し、アルヴァラドが包囲戦を強化するために戻ってくる ことを可能にした[131]。数か月後、マム族は飢餓状態に陥った。1525年10月中旬、カイビル・バラムはついにスペイン軍に降伏した[132]。ス ペイン軍が街に入ると、1,800人のインディオの死体と、死体の遺体を食べている生存者たちがいた [127] ザクルエの陥落後、ゴンサロ・デ・ソリス指揮下のスペイン守備隊がフエウテナンゴに置かれた。ゴンサロ・デ・アルバラドはテクパン・グアテマラに戻り、兄 に勝利を報告した[131]。 |

| Conquest of the Poqomam n 1525 Pedro de Alvarado sent a small company to conquer Mixco Viejo (Chinautla Viejo), the capital of the Poqomam.[nb 6] At the Spanish approach, the inhabitants remained enclosed in the fortified city. The Spanish attempted an approach from the west through a narrow pass but were forced back with heavy losses. Alvarado himself launched the second assault with 200 Tlaxcalan allies but was also beaten back. The Poqomam then received reinforcements, possibly from Chinautla, and the two armies clashed on open ground outside of the city. The battle was chaotic and lasted for most of the day but was finally decided by the Spanish cavalry, forcing the Poqomam reinforcements to withdraw.[133] The leaders of the reinforcements surrendered to the Spanish three days after their retreat and revealed that the city had a secret entrance in the form of a cave leading up from a nearby river, allowing the inhabitants to come and go.[134] Armed with the knowledge gained from their prisoners, Alvarado sent 40 men to cover the exit from the cave and launched another assault along the ravine from the west, in single file owing to its narrowness, with crossbowmen alternating with soldiers bearing muskets, each with a companion sheltering him from arrows and stones with a shield. This tactic allowed the Spanish to break through the pass and storm the entrance of the city. The Poqomam warriors fell back in disorder in a chaotic retreat through the city, and were hunted down by the victorious conquistadors and their allies. Those who managed to retreat down the neighbouring valley were ambushed by Spanish cavalry who had been posted to block the exit from the cave, the survivors were captured and brought back to the city. The siege had lasted more than a month and because of the defensive strength of the city, Alvarado ordered it to be burned and moved the inhabitants to the new colonial village of Mixco.[133] Resettlement of the Chajoma There are no direct sources describing the conquest of the Chajoma by the Spanish but it appears to have been a drawn-out campaign rather than a rapid victory.[135] The only description of the conquest of the Chajoma is a secondary account appearing in the work of Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán in the 17th century, long after the event.[136] After the conquest, the inhabitants of the eastern part of the kingdom were relocated by the conquerors to San Pedro Sacatepéquez, including some of the inhabitants of the archaeological site now known as Mixco Viejo (Jilotepeque Viejo).[nb 6] The rest of the population of Mixco Viejo, together with the inhabitants of the western part of the kingdom, were moved to San Martín Jilotepeque.[135] The Chajoma rebelled against the Spanish in 1526, fighting a battle at Ukubʼil, an unidentified site somewhere near the modern towns of San Juan Sacatepéquez and San Pedro Sacatepéquez.[137][nb 7] In the colonial period, most of the surviving Chajoma were forcibly settled in the towns of San Juan Sacatepéquez, San Pedro Sacatepéquez and San Martín Jilotepeque as a result of the Spanish policy of congregaciones; the people were moved to whichever of the three towns was closest to their pre-conquest land holdings. Some Iximche Kaqchikels seem also to have been relocated to the same towns.[138] After their relocation some of the Chajoma drifted back to their pre-conquest centres, creating informal settlements and provoking hostilities with the Poqomam of Mixco and Chinautla along the former border between the pre-Columbian kingdoms. Some of these settlements eventually received official recognition, such as San Raimundo near Sacul.[136] El Progreso and Zacapa The Spanish colonial corregimiento of San Cristóbal Acasaguastlán was established in 1551 with its seat in the town of that name, now in the eastern portion of the modern department of El Progreso.[139] Acasaguastlán was one of few pre-conquest centres of population in the middle Motagua River drainage, due to the arid climate.[140] It covered a broad area that included Cubulco, Rabinal, and Salamá (all in Baja Verapaz), San Agustín de la Real Corona (modern San Agustín Acasaguastlán) and La Magdalena in El Progreso, and Chimalapa, Gualán, Usumatlán and Zacapa, all in the department of Zacapa.[139] Chimalapa, Gualán and Usumatlán were all satellite settlements of Acasaguastlán.[140] San Cristóbal Acasaguastlán and the surrounding area were reduced into colonial settlements by friars of the Dominican Order; at the time of the conquest the area was inhabited by Poqomchiʼ Maya and by the Nahuatl-speaking Pipil.[139] In the 1520s, immediately after conquest, the inhabitants paid taxes to the Spanish Crown in the form of cacao, textiles, gold, silver and slaves. Within a few decades taxes were instead paid in beans, cotton and maize.[140] Acasaguastlán was first given in encomienda to conquistador Diego Salvatierra in 1526.[141] Chiquimula Chiquimula de la Sierra ("Chiquimula in the Highlands"), occupying the area of the modern department of Chiquimula to the east of the Poqomam and Chajoma, was inhabited by Chʼortiʼ Maya at the time of the conquest.[142] The first Spanish reconnaissance of this region took place in 1524 by an expedition that included Hernando de Chávez, Juan Durán, Bartolomé Becerra and Cristóbal Salvatierra, amongst others.[143] In 1526 three Spanish captains, Juan Pérez Dardón, Sancho de Barahona and Bartolomé Becerra, invaded Chiquimula on the orders of Pedro de Alvarado. The indigenous population soon rebelled against excessive Spanish demands, but the rebellion was quickly put down in April 1530.[144] However, the region was not considered fully conquered until a campaign by Jorge de Bocanegra in 1531–1532 that also took in parts of Jalapa.[143] The afflictions of Old World diseases, war and overwork in the mines and encomiendas took a heavy toll on the inhabitants of eastern Guatemala, to the extent that indigenous population levels never recovered to their pre-conquest levels.[145] Campaigns in the Cuchumatanes  View over a heavily forested mountain slope towards rugged peaks beyond, separated from them by a mass of low cloud. The difficult terrain and remoteness of the Cuchumatanes made their conquest difficult. In the ten years after the fall of Zaculeu various Spanish expeditions crossed into the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes and engaged in the gradual and complex conquest of the Chuj and Qʼanjobʼal.[146] The Spanish were attracted to the region in the hope of extracting gold, silver and other riches from the mountains but their remoteness, the difficult terrain and relatively low population made their conquest and exploitation extremely difficult.[147] The population of the Cuchumatanes is estimated to have been 260,000 before European contact. By the time the Spanish physically arrived in the region this had collapsed to 150,000 because of the effects of the Old World diseases that had run ahead of them.[69] Uspantán and the Ixil After the western portion of the Cuchumatanes fell to the Spanish, the Ixil and Uspantek Maya were sufficiently isolated to evade immediate Spanish attention. The Uspantek and the Ixil were allies and in 1529, four years after the conquest of Huehuetenango, Uspantek warriors were harassing Spanish forces and Uspantán was trying to foment rebellion among the Kʼicheʼ. Uspantek activity became sufficiently troublesome that the Spanish decided that military action was necessary. Gaspar Arias, magistrate of Guatemala, penetrated the eastern Cuchumatanes with 60 Spanish infantry and 300 allied indigenous warriors.[131] By early September he had imposed temporary Spanish authority over the Ixil towns of Chajul and Nebaj.[148] The Spanish army then marched east toward Uspantán itself; Arias then received notice that the acting governor of Guatemala, Francisco de Orduña, had deposed him as magistrate. Arias handed command over to the inexperienced Pedro de Olmos and returned to confront de Orduña. Although his officers advised against it, Olmos launched a disastrous full-scale frontal assault on the city. As soon as the Spanish began their assault they were ambushed from the rear by more than 2,000 Uspantek warriors. The Spanish forces were routed with heavy losses; many of their indigenous allies were slain, and many more were captured alive by the Uspantek warriors only to be sacrificed on the altar of their deity Exbalamquen. The survivors who managed to evade capture fought their way back to the Spanish garrison at Qʼumarkaj.[149]   A year later Francisco de Castellanos set out from Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala (by now relocated to Ciudad Vieja) on another expedition against the Ixil and Uspantek, leading 8 corporals, 32 cavalry, 40 Spanish infantry and several hundred allied indigenous warriors. The expedition rested at Chichicastenango and recruited further forces before marching seven leagues northwards to Sacapulas and climbed the steep southern slopes of the Cuchumatanes. On the upper slopes they clashed with a force of 4,000-5,000 Ixil warriors from Nebaj and nearby settlements. A lengthy battle followed during which the Spanish cavalry managed to outflank the Ixil army and forced them to retreat to their mountaintop fortress at Nebaj. The Spanish force besieged the city, and their indigenous allies managed to scale the walls, penetrate the stronghold and set it on fire. Many defending Ixil warriors withdrew to fight the fire, which allowed the Spanish to storm the entrance and break the defences.[149] The victorious Spanish rounded up the surviving defenders and the next day Castellanos ordered them all to be branded as slaves as punishment for their resistance.[150] The inhabitants of Chajul immediately capitulated to the Spanish as soon as news of the battle reached them. The Spanish continued east towards Uspantán to find it defended by 10,000 warriors, including forces from Cotzal, Cunén, Sacapulas and Verapaz. The Spaniards were barely able to organise a defence before the defending army attacked. Although heavily outnumbered, the deployment of Spanish cavalry and the firearms of the Spanish infantry eventually decided the battle. The Spanish overran Uspantán and again branded all surviving warriors as slaves. The surrounding towns also surrendered, and December 1530 marked the end of the military stage of the conquest of the Cuchumatanes.[151] Reduction of the Chuj and Qʼanjobʼal  In 1529 the Chuj city of San Mateo Ixtatán (then known by the name of Ystapalapán) was given in encomienda to the conquistador Gonzalo de Ovalle, a companion of Pedro de Alvarado, together with Santa Eulalia and Jacaltenango. In 1549, the first reduction (reducción in Spanish) of San Mateo Ixtatán took place, overseen by Dominican missionaries,[152] in the same year the Qʼanjobʼal reducción settlement of Santa Eulalia was founded. Further Qʼanjobʼal reducciones were in place at San Pedro Soloma, San Juan Ixcoy and San Miguel Acatán by 1560. Qʼanjobʼal resistance was largely passive, based on withdrawal to the inaccessible mountains and forests from the Spanish reducciones. In 1586 the Mercedarian Order built the first church in Santa Eulalia.[62] The Chuj of San Mateo Ixtatán remained rebellious and resisted Spanish control for longer than their highland neighbours, resistance that was possible owing to their alliance with the lowland Lakandon Chʼol to the north. The continued resistance was so determined that the Chuj remained pacified only while the immediate effects of the Spanish expeditions lasted.[153] In the late 17th century, the Spanish missionary Fray Alonso de León reported that about eighty families in San Mateo Ixtatán did not pay tribute to the Spanish Crown or attend the Roman Catholic mass. He described the inhabitants as quarrelsome and complained that they had built a pagan shrine in the hills among the ruins of pre-Columbian temples, where they burnt incense and offerings and sacrificed turkeys. He reported that every March they built bonfires around wooden crosses about two leagues from the town and set them on fire. Fray de León informed the colonial authorities that the practices of the natives were such that they were Christian in name only. Eventually, Fray de León was chased out of San Mateo Ixtatán by the locals.[154] A series of semi-collapsed dry-stone terraces, overgrown with short grass. On top of the uppermost of five terraces stand the crumbling, overgrown remains of two large buildings flanking the ruins of a smaller structure. A tree grows from the right hand side of the smaller central building, and another stands in at extreme right, on the upper terrace and in front of the building also standing on it. The foreground is a flat plaza area, with the collapsed flank of a grass-covered pyramid at bottom right. The sky is overcast with low rainclouds. The ruins of Ystapalapán In 1684, a council led by Enrique Enríquez de Guzmán, the governor of Guatemala, decided on the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia, both within the colonial administrative district of the Corregimiento of Huehuetenango.[155] On 29 January 1686, Captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos, acting under orders from the governor, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, where he recruited indigenous warriors from the nearby villages, 61 from San Mateo itself.[156] It was believed by the Spanish colonial authorities that the inhabitants of San Mateo Ixtatán were friendly towards the still unconquered and fiercely hostile inhabitants of the Lacandon region, which included parts of what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas and the western part of the Petén Basin.[157] To prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three of San Mateo's community leaders, named as Cristóbal Domingo, Alonso Delgado and Gaspar Jorge, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.[158] The governor himself arrived in San Mateo Ixtatán on 3 February, where Captain Rodríguez Mazariegos was already awaiting him. The governor ordered the captain to remain in the village and use it as a base of operations for penetrating the Lacandon region. The Spanish missionaries Fray de Rivas and Fray Pedro de la Concepción also remained in the town.[159] Governor Enriquez de Guzmán subsequently left San Mateo Ixtatán for Comitán in Chiapas, to enter the Lacandon region via Ocosingo.[160] In 1695, a three-way invasion of the Lacandon was launched simultaneously from San Mateo Ixtatán, Cobán and Ocosingo.[161] Captain Rodriguez Mazariegos, accompanied by Fray de Rivas and 6 other missionaries together with 50 Spanish soldiers, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán.[162] Following the same route used in 1686,[161] they managed on the way to recruit 200 indigenous Maya warriors from Santa Eulalia, San Juan Solomá and San Mateo itself.[162] On 28 February 1695, all three groups left their respective bases of operations to conquer the Lacandon. The San Mateo group headed northeast into the Lacandon Jungle.[162] |