器官なき身体

Corps-sans-organes

★ 器官なき 身体(BwO;仏語: corps sans organes または CsO)[1]は、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリの著作で用いられる曖昧な概念である。この概念は、構成要素に組織的構造が強 制されていない身体(必ずしも人間とは限らない[2])が自由に作用する、規制されない潜在性を指す。この用語は、フランスの作家アントナン・アルトーが 1947年の戯曲『神の審判を終わらせるために』で初めて使用した。ドゥルーズは後に1969年の著書『感覚の論理』でこれを採用し、ガタリとの共著『資 本主義と統合失調症』(1972年および1980年刊行)の両巻において曖昧に展開した。 形而上学における身体の一般的な抽象概念[3]と精神分析における無意識を基盤として、ドゥルーズとガタリは次のように理論化した。精神病や統合失調症に おける意識的・無意識的な幻想は、身体の潜在的な形態と機能を表現しており、それらは身体の解放を要求する。身体の恒常性維持プロセスの現実とは、身体が 自らの組織化によって、さらに言えば器官によって制限されていることである。器官なき身体には三種類がある。身体が達成したものに応じて、空虚な身体、充 満した身体、そして癌化した身体である[4]。

| The body without

organs (or BwO; French: corps sans organes or CsO)[1] is a fuzzy

concept used in the work of French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and

Félix Guattari. The concept describes the unregulated potential of a

body—not necessarily human[2]—without organizational structures imposed

on its constituent parts, operating freely. The term, first used by

French writer Antonin Artaud, appeared in his 1947 play To Have Done

With the Judgment of God. Deleuze later adapted it in his 1969 book The

Logic of Sense, and ambiguously expanded upon it in collaboration with

Guattari in both volumes of their work Capitalism and Schizophrenia

(1972 and 1980). Building on the general abstract notion of the body in metaphysics,[3] and on the unconscious in psychoanalysis, Deleuze and Guattari theorized that since the conscious and unconscious fantasies in psychosis and schizophrenia express potential forms and functions of the body that demand it to be liberated, the reality of the homeostatic process of the body is that it is limited by its organization and more so by its organs. There are three types of the body without organs; the empty, the full, and the cancerous, according to what the body has achieved.[4] |

器官なき 身体(BwO;仏語: corps sans

organes または

CsO)[1]は、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリの著作で用いられる曖昧な概念である。この概念は、構成要素に組織的構造が強

制されていない身体(必ずしも人間とは限らない[2])が自由に作用する、規制されない潜在性を指す。この用語は、フランスの作家アントナン・アルトーが

1947年の戯曲『神の審判を終わらせるために』で初めて使用した。ドゥルーズは後に1969年の著書『感覚の論理』でこれを採用し、ガタリとの共著『資

本主義と統合失調症』(1972年および1980年刊行)の両巻において曖昧に展開した。 形而上学における身体の一般的な抽象概念[3]と精神分析における無意識を基盤として、ドゥルーズとガタリは次のように理論化した。精神病や統合失調症に おける意識的・無意識的な幻想は、身体の潜在的な形態と機能を表現しており、それらは身体の解放を要求する。身体の恒常性維持プロセスの現実とは、身体が 自らの組織化によって、さらに言えば器官によって制限されていることである。器官なき身体には三種類がある。身体が達成したものに応じて、空虚な身体、充 満した身体、そして癌化した身体である[4]。 |

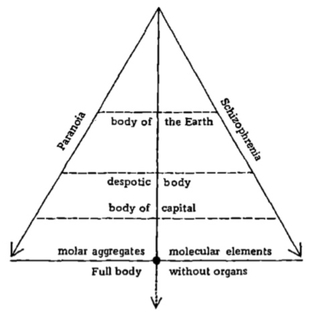

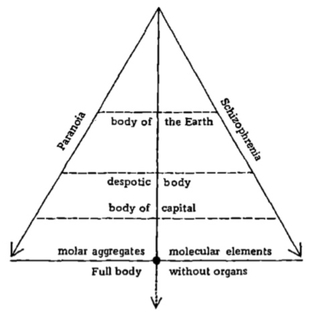

A schizoanalytical diagram of

the social dynamic of the body without organs, from Anti-Oedipus. |

『アンチ・オイディプス』より、器官なき身体の社会的動態に関する分裂

分析図。 |

| Background The phrase "body without organs" was first used by the French writer Antonin Artaud in his 1947 text for a play, To Have Done With the Judgment of God. Referring to his ideal for man as a philosophical subject, he wrote in its epilogue that "When you will have made him a body without organs, then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions and restored him to his true freedom."[5] Artaud is regarded as having viewed the body as an impermanent, composite image of actions inflicted upon a vulnerable and repressive physical structure; in a 1933 letter, he wrote that bodies should be understood only as "provisional stratifications of states of life".[6] Deleuze reinterpreted the term in The Logic of Sense, inspired both by Artaud's text and the work of psychotherapist Gisela Pankow;[7] here, he conceptualized the body without organs in the context of psychoanalysis, observing that the practice as it existed refused the thorough creation of BwOs.[8] In Deleuze's early formulations of the concept, the body without organs was based in the symptoms related to schizophrenia, such as glossolalia where syllables are formlessly uttered and intoned in sets as if they were words.[9] For Deleuze, glossolalia transforms words from having instrumental value, where words have literal meaning, to "values which are exclusively tonic [relating to speech] and not written", creating—in the case of language—lingual and verbal bodies without organs.[10] |

背景 「器官なき身体」という表現は、フランスの作家アントナン・アルトーが1947年の戯曲『神の審判を終わらせるために』で初めて用いた。哲学的主体として の理想的人間像を指して、彼はエピローグでこう記している。「彼を器官なき身体に作り上げた時、お前は彼をあらゆる自動的反応から解放し、真の自由へと還 すことになる」 [5] アルトーは身体を、脆弱かつ抑圧的な物理的構造に課せられた行為の、一時的で複合的なイメージと見なしていたとされる。1933年の書簡では、身体は「生 命状態の暫定的な層化」としてのみ理解されるべきだと記している。[6] ドゥルーズは『感覚の論理学』において、アルトーのテキストと精神療法士ギゼラ・パンコウの著作の両方に触発され、この概念を再解釈した[7]。ここで彼 は精神分析の文脈において器官なき身体を概念化し、当時存在した実践が器官なき身体の徹底的な創造を拒んでいたと指摘した。[8] デリューズによるこの概念の初期の定式化では、器官なき身体は統合失調症に関連する症状、例えば無秩序な音節が言葉であるかのように発声され、セットとし て詠唱される異言現象(glossolalia)に基づいて構築されていた。[9] デリューズにとって、グロッソラリアは言葉を「文字通りの意味を持つ道具的価値」から「書かれることなく、純粋に発声的な価値」へと変容させる。言語の場 合、それは器官なき言語的身体と器官なき言語的身体を生み出すのである。[10] |

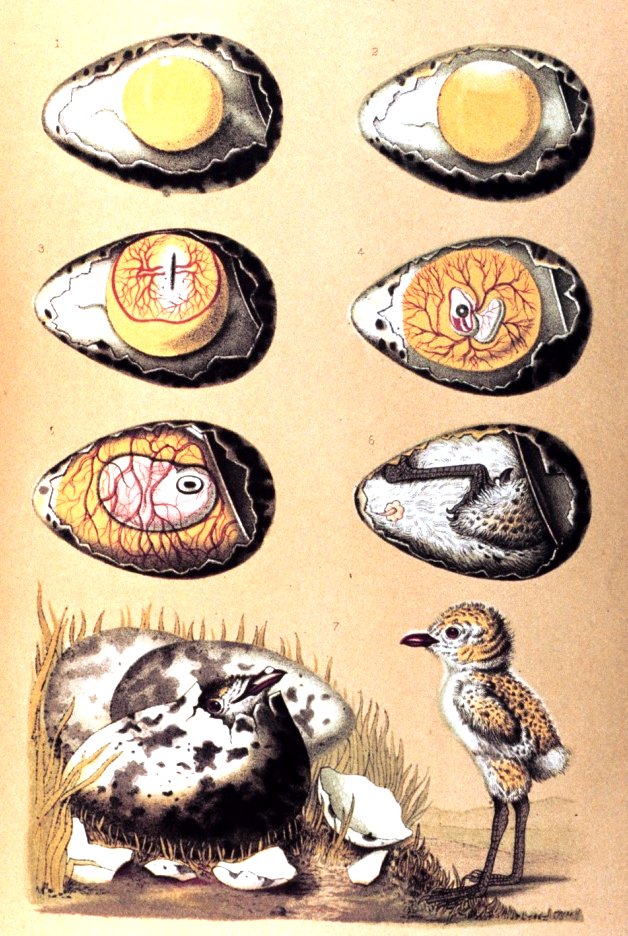

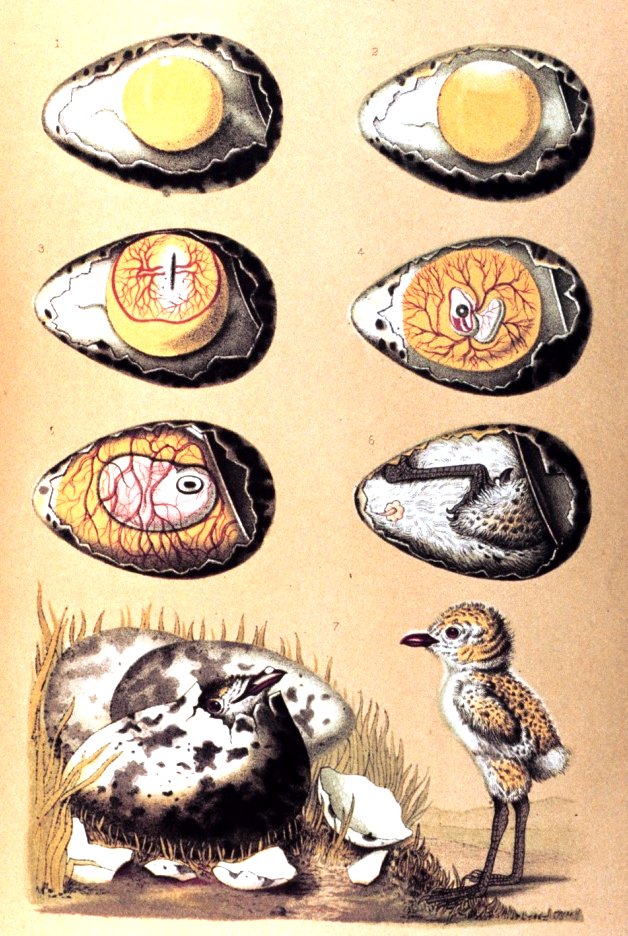

Usage Eight drawings showing the development of an egg, hatching, and an emerged chick The development of a bird egg; the egg is a prominent figure of the body without organs in Capitalism and Schizophrenia. The concept of the body without organs was mainly defined by Deleuze and Guattari in Capitalism and Schizophrenia.[11] In both volumes, Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus, the abstract body is defined as a self-regulating process—created by the relation between an abstract machine and a machinic assemblage—that maintains itself through processes of homeostasis and simultaneously limits the possible activities of its constituent parts, or organs.[12] The body without organs is the sum total intensive and affective activity of the full potential for the body and its constituent parts.[13] Deleuze and Guattari presume, in a continuation from Samuel Butler's radical departure from vitalism in "Darwin among the Machines", that since all organisms have some sort of abstract inclination or desire—in the case of nonhuman life such as plants and animals, their genetic instincts variably control what actions they take—the body without organs is the inevitable, unconstrained manifestation of those inclinations or desires that may take upon unprecedented forms.[14] The concept of the body that the body without organs refers to inherits elements from both the concept of substance proposed by Baruch Spinoza and the concept of "intensive magnitude" in Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, wherein it is defined not by closed and determinate activity but by cohesion through affective potential.[15] A body without organs can consist of many different actions that approach an unattainable goal, many of which are the activities of assemblages that people unconsciously create and are always engaged in;[16] to become a body without organs, one must dispose of stratification (the classification of constituent parts into groups), and instead give way to what Deleuze and Guattari described as an immanent "becoming" of pure intensity.[17] The body without organs is not necessarily coupled with the eradication of stratification, but rather encourages the creation of a "smooth space", immanently transforming the body beyond its existing categorization.[18] The bodies—not merely physical but intensive—of schizophrenics, drug addicts, and hypochondriacs are examples they give of bodies without organs, but they caution against replicating their actions; people should not seek out their negative experiences, which are "catatonicized" and "vitrified".[16] While these examples are said to have abandoned stratification, they never intensified, which makes their bodies without organs vulnerable to re-stratification.[17] They classify bodies without organs into three categories:[A] The empty BwO is chaotic and undifferentiated because it undergoes destratification without intensification; the full BwO is a "plane of consistency" because it is both destratified and intensified, which allows it to enter new relationships; meanwhile, the cancerous BwO is too stratified and becomes "majoritarian", having predetermined objectives that eliminate the body's potential.[20] Two important examples of the body without organs relate to eggs.[21] As a bird egg develops, it is nothing but the dispersion of protein gradients, which have varying intensities and have no apparent structure; for Deleuze and Guattari, a bird egg is an instance of life "before the formation of the strata", since changes in the qualitative elements of the egg will emerge as a changed organism.[21] Relatedly, in the Dogon culture, there is a belief in an egg that encompasses the universe,[21] where the universe is an "intensive spatium" (an intensive interior), similar to a bird egg.[22] According to Deleuze and Guattari, the Dogon egg is an intensive body, crossed with several zig-zagging lines of vibration, changing its shape as it develops without being compartmentalized through organs.[23] Ambiguity The body without organs remains one of Deleuze and Guattari's more ambiguous concepts and terms;[24] over the course of their careers, the term changed in meaning and was used synonymously with others, such as the plane of immanence. Deleuze and Guattari were unsure whether they referred to the same concept when using the term;[25] scholars of Deleuze and Guattari have also expressed "little to no agreement" on the term, according to philosopher Ian Buchanan.[26] |

使用法 卵の発育、孵化、そして孵化したヒナの過程を示す八枚の図 鳥の卵の発育;この卵は『資本主義と統合失調症』において器官なき身体の顕著な形象である。 器官なき身体の概念は、主にドゥルーズとガタリが『資本主義と統合失調症』において定義したものである[11]。『アンチ・オイディプス』と『千の平原』 の両巻において、抽象的身体は、抽象機械と機械的集合体の関係によって創出される自己調整プロセスとして定義される。このプロセスは恒常性維持を通じて自 己を保ちつつ、同時にその構成部分、すなわち器官の可能な活動を制限する。器官なき身体とは、身体とその構成要素が持つ全潜在能力の集積的・情動的活動の 総和である[13]。 ドゥルーズとガタリは、サミュエル・バトラーが『機械の中のダーウィン』で生命論から急進的に離脱した流れを継承し、あらゆる有機体が何らかの抽象的な傾 向や欲望を持つこと——植物や動物といった非人間的生命の場合、その遺伝的本能が取る行動を可変的に制御する——を前提とする。したがって器官なき身体と は、それらの傾向や欲望が制約を受けずに必然的に現れる形態であり、それは前例のない形をとる可能性を秘めている。[14] 器官なき身体が指す身体概念は、バルーフ・スピノザが提唱した実体概念と、イマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』における「強度」概念の両方から要素を継 承している。そこでは、閉じた確定的な活動によってではなく、情動的可能性による凝集によって定義される。[15] 器官なき身体は、達成不可能な目標に向かう異なる行為から成り得る。その多くは、人々が無意識に創り出し常に従事している集合体の活動である。[16] 器官なき身体となるには、階層化(構成要素のグループ分け)を放棄し、代わりにドゥルーズとガタリが「純粋な強度」の内在的「生成」と表現した状態へ移行 しなければならない。[17] 器官なき身体は階層化の根絶と必ずしも結びつかない。むしろ「滑らかな空間」の創出を促し、既存の分類を超越して身体を内在的に変容させる. [18] 統合失調症患者、薬物依存者、心気症患者の身体——単なる物理的ではなく強度的な身体——は、彼らが提示する器官なき身体の例である。しかし彼らは、その 行動を模倣することには警戒を促す。人々は彼らの否定的体験——「硬直化」され「ガラス化」されたもの——を追い求めるべきではない。[16] これらの例は階層化を放棄したと言われるが、決して強化されなかったため、器官なき身体は再階層化の危険に晒されている。[17] 彼らは器官なき身体を三つに分類する:[A] 空虚な器官なき身体は、強化を伴わない分層解除を経験するため混沌として未分化である。充実した器官なき身体は「一貫性の平面」であり、分層解除と強化の 両方を経て新たな関係性へ移行する。一方、癌化した器官なき身体は過度に分層化され「多数派的」となり、身体の可能性を排除する予め定められた目的を持 つ。[20] 器官なき身体の重要な二例は卵に関連している。[21] 鳥の卵が発達する過程では、それは強度が変化し明らかな構造を持たないタンパク質濃度の分散に過ぎない。ドゥルーズとガタリにとって鳥の卵は「層の形成以 前の」生命の事例であり、卵の質的要素の変化が変容した有機体として現れるからである。[21] 関連して、ドゴン族の文化には宇宙を包含する卵の信仰がある[21]。そこでの宇宙は鳥の卵と同様の「集中的空間」(集中的内部)である[22]。ドゥ ルーズとガタリによれば、ドゴンの卵は集中的身体であり、幾筋ものジグザグ状の振動線が交差し、器官による区画化なしに発達するにつれて形状を変える。 [23] 曖昧性 器官なき身体は、ドゥルーズとガタリの概念・用語の中でも特に曖昧なもののひとつであり続ける[24]。彼らのキャリアを通じて、この用語の意味は変化 し、内在性の平面など他の用語と同義的に用いられた。ドゥルーズとガタリ自身、この用語を使用する際、同じ概念を指しているか確信が持てなかった [25]。哲学者イアン・ブキャナンによれば、ドゥルーズ・ガタリ研究者間でもこの用語について「合意はほとんど、あるいは全く見られない」という [26]。 |

| Interpretations Nick Land English philosopher Nick Land, who was reliant on the work of Deleuze and Guattari in his theoretical work of the 1990s, used the concept of the body without organs in relation to his "cybergothic" reinterpretation of continental philosophy. In his philosophy, the body without organs is defined by Land (alongside Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus) as a model of death with an infinite capacity for dispersion of its elements. For instance, in the conclusion of his 1993 essay "Art as Insurrection", he writes: The body without organs is [...] at once [a] material abstraction, and the concretely hypostasized differential terrain which is nothing other than what is instantaneously shared by difference. The body without organs is pure surface, because it is the mere coherence of differential web, but it is also the source of depth [...][27] Similarly, in his 1995 essay "Cybergothic", Land identified the body without organs as a concept in the lineage of representations of "death as time-in-itself"—or "degree 0" of an intensive continuum—within which experiential time is a profusion of indeterminate states, corresponding both to the schizophrenic consciousness and to the dissipation of matter through death; this lineage also includes Spinoza's substance, Kant's "pure apperception", Sigmund Freud's death drives, and most notably, American novelist William Gibson's notion of cyberspace.[28] |

解釈 ニック・ランド 1990年代の理論的著作においてドゥルーズとガタリの思想に依拠した英国の哲学者ニック・ランドは、大陸哲学の「サイバーゴシック的」再解釈に関連して 「器官なき身体」の概念を用いた。ランドの哲学において、器官なき身体は(ドゥルーズとガタリの『アンチ・オイディプス』と同様に)その要素を無限に分散 させる能力を持つ死のモデルとして定義される。例えば、1993年の論文「反乱としての芸術」の結論部で彼はこう記している: 器官なき身体とは[…]物質的抽象であると同時に、差異によって瞬間的に共有されるものに他ならない、具体的に実体化された差異の地形である。器官なき身 体は純粋な表面である。なぜなら差異の網の単なる連関に過ぎないからだ。しかしそれは同時に深みの源泉でもある[…][27] 同様に、1995年の論文「サイバーゴシック」において、ランドは器官なき身体を「時間そのものとしての死」―あるいは集中的連続体の「度数0」―の表象 の系譜に属する概念と位置づけた。この系譜では、経験的時間とは不定状態の過剰であり、それは統合失調症的意識と死による物質の散逸の両方に対応する。こ の系譜にはスピノザの実体、カントの「純粋自覚」、ジークムント・フロイトの死の欲動、そして特にアメリカ人小説家ウィリアム・ギブソンのサイバースペー ス概念も含まれる。[28] |

| Desiring-production Plane of immanence Substance theory |

欲求の生成 内在性の平面 実体論 |

| Notes A. These categories were developed in A Thousand Plateaus.[19] Citations 1. Demers 2006, p. 166. 2. Clark 2012, p. 199. 3. Goodman 2010, pp. 100–102. 4. Markula 2006, pp. 38–42. 5. Bazzano 2021, p. 295; Brenner 2021, p. 42. 6. Murphy 2015. 7. Bazzano 2021, p. 295; Colombat 1991, p. 13; Whitlock 2020, p. 517. 8. Whitlock 2020, pp. 518, 520. 9. Whitlock 2020, pp. 517–518. 10. Whitlock 2020, p. 517. 11. Brenner 2021, p. 42. 12. Smith 2018, pp. 106–107. 13. Fox 2011, p. 361. 14. Fox 2011, pp. 360–361. 15. Goodman 2010, p. 102. 16. Markula 2006, p. 38. 17. Markula 2006, p. 40. 18. Markula 2006, p. 42. 19. Holland 2008, pp. 76–77. 20. Albertsen & Diken 2006, pp. 231–232; Clark 2012, p. 203. 21. Adkins 2015, p. 102. 22. Adkins 2015, pp. 101–102. 23. Leston 2015, p. 372. 24. Buchanan 2015, p. 25; Carrier 1998, p. 189; Kaufman 2004, p. 658; Smith 2018, p. 106. 25. Buchanan 2015, p. 25. 26. Buchanan 2015, p. 26. 27. Land 2011, pp. 171–172. 28. Land 2011, pp. 369–370. |

注 A. これらのカテゴリーは『千のプラトー』で展開されたものである。 引用 1. Demers 2006, p. 166. 2. Clark 2012, p. 199. 3. グッドマン 2010、100-102 ページ。 4. マルクラ 2006、38-42 ページ。 5. バザノ 2021、295 ページ、ブレナー 2021、42 ページ。 6. マーフィー 2015。 7. バザノ 2021、295 ページ、コロンバ 1991、13 ページ、ウィットロック 2020、517 ページ。 8. ウィットロック 2020、518、520 ページ。 9. ウィットロック 2020、517-518 ページ。 10. ウィットロック 2020、517 ページ。 11. ブレナー 2021、42 ページ。 12. スミス 2018、106-107 ページ。 13. フォックス 2011、361 ページ。 14. フォックス 2011、360-361 ページ。 15. グッドマン 2010、102 ページ。 16. マルクラ 2006、38 ページ。 17. マルクラ 2006、40 ページ。 18. マルクラ 2006、42 ページ。 19. ホランド 2008、76-77 ページ。 20. Albertsen & Diken 2006、231-232 ページ、Clark 2012、203 ページ。 21. Adkins 2015、102 ページ。 22. Adkins 2015、101-102 ページ。 23. レストン 2015, p. 372. 24. ブキャナン 2015, p. 25; キャリヤー 1998, p. 189; カウフマン 2004, p. 658; スミス 2018, p. 106. 25. ブキャナン 2015, p. 25. 26. ブキャナン 2015, p. 26。 27. ランド 2011, pp. 171–172。 28. ランド 2011, pp. 369–370。 |

| Bibliography Adkins, Brent (2015). Deleuze and Guattari's A thousand plateaus: A critical introduction and guide. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686452. Albertsen, Niels; Diken, Bülent (2006). "Society with/out organs". In Fuglsang, Martin; Sørensen, Bent Meier (eds.). Deleuze and the social. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748620920. Bazzano, Manu (3 July 2021). "The body-without-organs: A user's manual". European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling. 23 (3): 289–303. doi:10.1080/13642537.2021.1961833. S2CID 238794978. Brenner, Leon S. (2021). "Is the autistic body a body without organs?". In McLaughlin, Becky R.; Daffron, Eric (eds.). The body in theory: Essays after Lacan and Foucault. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9781476678559. Buchanan, Ian (2015). "The 'structural necessity' of the body without organs". In Buchanan, Ian; Matts, Tim; Tynan, Aidan (eds.). Deleuze and the schizoanalysis of literature. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781472529633. Carrier, Ronald M. (May 1998). "The ontological significance of Deleuze and Guattari's concept of the body without organs". Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology. 29 (2): 189–206. doi:10.1080/00071773.1998.11665445. Clark, Vanessa (16 April 2012). "Art practice as possible worlds". International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies. 3 (2–3): 198. doi:10.18357/ijcyfs32-3201210866. Colombat, André Pierre (1991). "A thousand trails to work with Deleuze". SubStance. 20 (3): 10–23. doi:10.2307/3685176. ISSN 0049-2426. JSTOR 3685176. Demers, Jason (August 2006). "Re-membering the body without organs". Angelaki. 11 (2): 153–168. doi:10.1080/09697250601029333. S2CID 144031891. Fox, Nick J (December 2011). "The ill-health assemblage: Beyond the body-with-organs" (PDF). Health Sociology Review. 20 (4): 359–371. doi:10.5172/hesr.2011.20.4.359. S2CID 144369239. Goodman, Steve (2010). Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01347-5. Holland, Eugene W. (2008). "Schizoanalysis, nomadology, fascism". In Buchanan, Ian; Thoburn, Nicholas (eds.). Deleuze and politics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748632879. Kaufman, Eleanor (2004). "Betraying well". Criticism. 46 (4): 651–659. doi:10.1353/crt.2005.0016. ISSN 0011-1589. JSTOR 23127250. S2CID 258105122. Land, Nick (2011). Brassier, Ray; Mackay, Robin (eds.). Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987-2007. MIT Press; Urbanomic. ISBN 9780955308789. Leston, Robert (2015). "Deleuze, Haraway, and the radical democracy of desire". Configurations. 23 (3): 355–376. doi:10.1353/con.2015.0023. S2CID 146714920. Markula, Pirkko (February 2006). "Deleuze and the body without organs: Disreading the fit feminine identity". Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 30 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1177/0193723505282469. S2CID 144934352. Murphy, Jay (2015). "The Artaud effect". CTheory (Theorizing 21C). Smith, Daniel (March 2018). "What is the body without organs? Machine and organism in Deleuze and Guattari". Continental Philosophy Review. 51 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1007/s11007-016-9406-0. S2CID 254800444. Whitlock, Matthew G. (2020). "The wrong side out with(out) God: An autopsy of the body without organs". Deleuze and Guattari Studies. 14 (3): 507–532. doi:10.3366/dlgs.2020.0414. S2CID 225487537. |

参考文献 Adkins, Brent (2015). Deleuze and ガタリ's A thousand plateaus: A critical introduction and guide. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686452. Albertsen, Niels; Diken, Bülent (2006). 「器官のある/ない社会」. Fuglsang, Martin; Sørensen, Bent Meier (eds.) 編. 『ドゥルーズと社会』. エディンバラ大学出版局. ISBN 9780748620920. Bazzano, Manu (2021年7月3日). 「器官なき身体:ユーザーマニュアル」。European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling(ヨーロッパ心理療法・カウンセリングジャーナル)。23 (3): 289–303. doi:10.1080/13642537.2021.1961833. S2CID 238794978. ブレナー、レオン・S.(2021)。「自閉症の身体は器官なき身体か?」。マクラフリン、ベッキー・R.;ダフロン、エリック(編)。『理論における身 体:ラカンとフーコー以後のエッセイ』。ノースカロライナ州ジェファーソン:マクファーランド。ISBN 9781476678559。 ブキャナン、イアン(2015)。「器官なき身体の『構造的必然性』」。ブキャナン、イアン;マット、ティム;タイナン、エイダン(編)。『ドゥルーズと 文学のスキゾ分析』。ロンドン:ブルームズベリー。ISBN 9781472529633。 キャリヤー、ロナルド・M.(1998年5月)。「ドゥルーズとガタリの器官なき身体概念の存在論的意義」。『英国現象学会誌』。29巻2号: 189–206頁。doi:10.1080/00071773.1998.11665445。 クラーク、ヴァネッサ(2012年4月16日)。「可能世界としての芸術実践」。『国際児童・青少年・家族研究ジャーナル』。3巻2-3号:198頁。 doi:10.18357/ijcyfs32-3201210866。 コロンバ、アンドレ・ピエール(1991年)。「ドゥルーズと働く千の道」。『サブスタンス』。20巻3号:10–23頁。doi: 10.2307/3685176。ISSN 0049-2426。JSTOR 3685176。 デマーズ、ジェイソン (2006年8月)。「器官なき身体の再構成」。『アンジェラキ』。11巻2号:153–168頁。doi: 10.1080/09697250601029333。S2CID 144031891。 フォックス、ニック・J(2011年12月)。「健康不良の集合体:臓器のある身体を超えて」 (PDF). Health Sociology Review. 20 (4): 359–371. doi:10.5172/hesr.2011.20.4.359. S2CID 144369239. グッドマン、スティーブ (2010). ソニック・ウォーフェア:音、感情、そして恐怖の生態学。MIT Press。ISBN 978-0-262-01347-5。 Holland, Eugene W. (2008). 「スキゾ分析、ノマドロジー、ファシズム」 Buchanan, Ian; Thoburn, Nicholas (eds.) Deleuze and politics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748632879。 カウフマン、エレノア (2004)。「よく裏切る」。批評。46 (4): 651–659。doi:10.1353/crt.2005.0016。ISSN 0011-1589。JSTOR 23127250. S2CID 258105122. ランド、ニック(2011)。ブラッシエ、レイ;マッケイ、ロビン(編)。『牙あるイデア:1987-2007年 著作集』MITプレス;アーバノミック。ISBN 9780955308789。 レストン、ロバート(2015)。「ドゥルーズ、ハラウェイ、そして欲望の急進的民主主義」。『コンフィギュレーションズ』。23巻3号:355–376 頁。doi:10.1353/con.2015.0023。S2CID 146714920。 マルクラ、ピルッコ(2006年2月)。「ドゥルーズと器官なき身体:適合的な女性的アイデンティティの誤読」。Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 30 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1177/0193723505282469. S2CID 144934352. マーフィー、ジェイ(2015)。「アルトー効果」。CTheory(21世紀の理論化)。 スミス、ダニエル(2018年3月)。「器官なき身体とは何か?ドゥルーズとガタリにおける機械と有機体」。大陸哲学レビュー。51 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1007/s11007-016-9406-0. S2CID 254800444. ホイットロック、マシュー G. (2020). 「神を伴わない(あるいは伴わない)裏返し:器官なき身体の解剖」『ドゥルーズ・ガタリ研究』14巻3号:507–532頁。doi: 10.3366/dlgs.2020.0414。S2CID 225487537。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Body_without_organs |

★Les informations de sections

entières de cet article ne sont pas sourcées et les rares passages

sourcés sont étayés par des sources primaires et aucune source

secondaire de qualité.

[この記事のセクション全体の情報は出典が明記されておらず、出典が明記されているごく一部の箇所も、一次資料によって裏付けられており、質の高い二次資

料は一切使用されていない。]

★ 【日本語ウィキペディアの「器官なき身体」】★同じく「検証可能 な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか不十分」の評価

器 官なき身体(きかんなきしんたい、フランス語:corps sans organes)とはジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリがアントナン・アルトーの言葉をもとに自らの哲学的概念として展開した概念である。 ドゥルーズは『意味の論理学』[1]で、アントナン・アルトーの宇宙的身体と身体器官に関するテクストを分析・参照する中で、この用語を使い始めた。 1972年に刊行されたガタリとの初の共著『アンチ・オイディプス』[2]で本格的に論じられるようになった。 全体に対して部分の持つ自由さが顕揚される。器官とは、機能に基づく生命維持のための有機体の一部分であるが(モル的)、同時に有機体としてではなく無意 識における部分対象としてまったく別次元の存在(分子的)ともなる。 身体には有機体的サイクルとは別個の欲望する身体とでもいうべき「器官なき身体」が存在し、それにとって個体の生存を維持する諸器官は必要とされない。植 物における成長サイクルと生殖サイクルをたとえにすれば、人間にとっては生殖器という器官は性行動にとって結果として使われるものに過ぎず、五感、全身を 使って生殖活動があらゆる社交活動、創造活動へと広がってゆく。それは女性的な身体と言えるかもしれない。器官ある身体が、男性的身体、生存してゆく身 体、個体を形成する身体だとすれば、器官なき身体とは、女性的な、包み込む、癒しの身体、対象を欲望し、また生み出す身体ということがいえるかもしれな い。 引用の元になったアルトーの原文を読むと、アルトーの意図したものはむしろ、(男性器という)器官なき身体、という文脈であり、いわゆる去勢願望のことで ある。しかしD&Gはそれから文脈を広げて、いわゆる女性的な身体(いや、男性中心主義的「でない」身体)の文脈で使っている。(動物生成変化、女性生成 変化)。これは、日本において、蓮實重彦が再三、「性とは性器の体験ではない」「性器なき性交」という言葉を発することとほぼ同義に対応していると思われ る(→ドゥルーズのオカマを掘るの引用を参照【引用者】)。あらゆる官能的、芸術的な体験の中に、この「性器なき性交」とでも例えるしかないものが含まれ る。 「器官なき身体とは卵である」というD&Gの言葉も、そのことを表している。

★

器官のない身体[Corps-sans-organes]

(著者らはCsOと略称)は、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリが共同著作『アンチ・オイディプス』および『千の平原』で展開した

概念である。ジル・ドゥルーズは、すでに『プルーストと記号』(1964年)[1]

および『意味の論理』(1969年)でこの概念について触れていた。しかし、「器官のない身体」という表現は、フランスの詩人アントナン・アルトーが、特

に『神の裁きを終わらせるために』の中で最初に提唱したものである。

自らを「身体の反逆者」と呼ぶこの詩人は、解剖学的身体、つまり人間を閉じ込める「墓のような身体」に対して、彼が「原子的な身体」と呼ぶものを対置して

いる。したがって、彼にとっては「人間の解剖学を踊らせること」が重要であり、器官のない身体は、人間の再創造、すなわち彼が「創造されていない人間」と

呼ぶものに参加する身体行為である。

| Le

corps-sans-organes (abrégé en CsO par les auteurs) est un concept

développé par les philosophes français Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari

dans leurs œuvres communes : L'Anti-Œdipe et Mille Plateaux. Gilles

Deleuze en avait déjà dit quelques mots dans Proust et les signes

(1964)[1] et Logique du sens (1969). Cependant, l'expression de « corps

sans organes » a tout d'abord été formulée par le poète français

Antonin Artaud, notamment dans Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu. Le poète, qui se dit « insurgé du corps », oppose ce qu'il appelle parfois le corps « atomique » au corps anatomique, le corps-tombeau qui enferme les hommes ; il s'agit donc pour lui de « faire danser l'anatomie humaine », le corps sans organes étant un corps-acte qui participe ainsi d'une recréation de l'homme, ce qu'il nomme « l'Homme incréé ». |

器官のない身体[Corps-sans-organes]

(著者らはCsOと略称)は、フランスの哲学者ジル・

ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリが共同著作『アンチ・オイディプス』および『千の平原』で展開した概念である。ジル・ドゥルーズは、すでに『プルースト

と記号』(1964年)[1]

および『意味の論理』(1969年)でこの概念について触れていた。しかし、「器官のない身体」という表現は、フランスの詩人アントナン・アルトーが、特

に『神の裁きを終わらせるために』の中で最初に提唱したものである。 自らを「身体の反逆者」と呼ぶこの詩人は、解剖学的身体、つまり人間を閉じ込める「墓のような身体」に対して、彼が「原子的な身体」と呼ぶものを対置して いる。したがって、彼にとっては「人間の解剖学を踊らせること」が重要であり、器官のない身体は、人間の再創造、すなわち彼が「創造されていない人間」と 呼ぶものに参加する身体行為である。 |

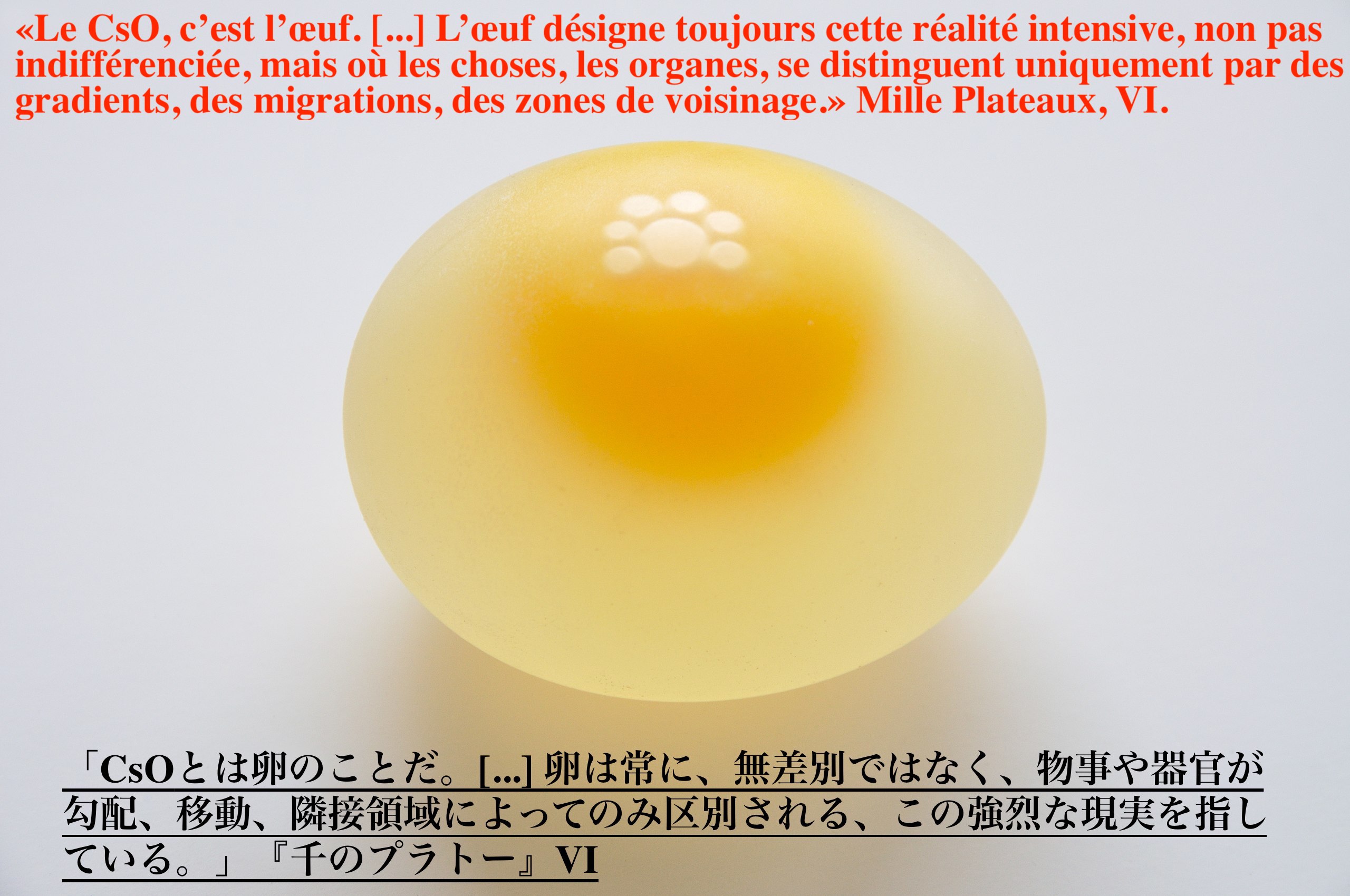

| «Le CsO, c’est l’œuf. [...]

L’œuf désigne toujours cette réalité intensive, non pas indifférenciée,

mais où les choses, les organes, se distinguent uniquement par des

gradients, des migrations, des zones de voisinage.» Mille Plateaux, VI. |

「CsOとは卵のことだ。[...]

卵は常に、無差別ではなく、物事や器官が勾配、移動、隣接領域によってのみ区別される、この強烈な現実を指している。」『千のプラトー』VI |

| Clarification du concept CsO Pour comprendre le CsO il est important de saisir la définition deleuzienne du désir. Dans L'Anti-Œdipe (1972), Deleuze et Guattari remettent en cause explicitement la conception psychanalytique du désir. Ce qui constitue le thème central de l'Anti-Œdipe, c'est que, pour Deleuze et Guattari, le désir n'est pas une scène de théâtre, mais une usine qui produit sans cesse, qui crée des agencements, qui est cause de déterritorialisation et de reterritorialisation, des agencements machiniques de choses, des machines désirantes. Le désir compris comme usine nous permet dès lors de concevoir les machines désirantes. Car dans la nature et dans tout corps il n'y a que des agencements machiniques, une multiplicité de machines, machine désirante, mais aussi machine-organe, machine-énergie, et des couples, accouplements de machines. Deleuze unit l'homme et la nature au travers d'un processus couplant les machines : « L'homme et la nature produisent l'un dans l'autre »— paradigme de la coextensivité du corps et de la nature, corps intensif, corps immanent traversé de seuils, de niveaux, de vecteurs, de gradients d'intensité. Le CsO est une production du désir, il s'oppose à l'organisme que nous font les machines désirantes. Le corps souffre de ne pas avoir d'autre organisation, ou pas d'organisation du tout... Le CsO est un corps sans image (« avant » la représentation organique), une anti-production, mais il est inévitable parce qu'il nous pénètre sans cesse, et sans cesse nous le pénétrons. Le CsO est un programme, une expérimentation et non un fantasme. Produit comme un tout à côté de parties auxquelles il s'ajoute, le CsO s'oppose à l'organisme. Car c'est par le corps, et par les organes, que le désir passe et non par l'organisme. Dans Francis Bacon : logique de la sensation (1981), Deleuze explique que « le corps sans organes se définit donc par un organe indéterminé, tandis que l’organisme se définit par des organes déterminés. » « Au lieu d’une bouche et d’un anus qui risquent tous deux de se détraquer, pourquoi n’aurait-on pas un seul orifice polyvalent pour l’alimentation et la défécation ? On pourrait murer la bouche et le nez combler l’estomac et creuser un trou d’aération directement dans les poumons — ce qui aurait dû être fait dès l’origine.[2] » Il y a de multiples possibilités du CsO selon les désirs, les êtres... Citons comme exemple le corps hypocondriaque, dont les organes se détruisent, ou le corps schizophrène, qui mène la lutte contre ses propres organes. Si Deleuze aime à prendre l'exemple du schizophrène, en citant notamment l'œuvre d'Antonin Artaud, il signale que le CsO peut aussi être « gaieté, extase, danse... » mais l'expérimentation n'est pas anodine, elle peut entraîner la mort. Il faut, par conséquent, être prudent même si l'expérimentation du CsO est une question de vie ou de mort. Car pour Deleuze il ne faut pas, comme le prétend la psychanalyse, retrouver notre « moi » mais aller au-delà. Deleuze dit, dans son Abécédaire, qu'« on ne délire pas sur papa-maman, on délire le monde ». Aussi précise-t-il dans Mille plateaux : « Remplacer l'anamnèse par l'oubli, l'interprétation par l'expérimentation. » Deleuze s'oppose à l'idée du désir perçu comme manque ou fantasme. Pour Deleuze, le grand livre sur le CsO est l'Éthique de Baruch Spinoza : les attributs, les substances, les intensités ignorent l'opposition de l'un et du multiple puisqu'il y a multiplicité de fusions, d'abouchemenents, de glissements : « Le corps n'est plus qu'un ensemble de clapets, sas, écluses, bols ou vases communicants[3] » Le CsO est comme un œuf sur lequel, et dans lequel, des intensités circulent, intensités qu'il produit et distribue dans un espace intensif, inétendu. |

CsOの概念の明確化 CsOを理解するには、ドゥルーズの欲望の定義を理解することが重要だ。『アンチ・エディプス』(1972年)の中で、ドゥルーズとガタリは、精神分析学 的な欲望の概念を明確に疑問視している。アンチ・エディプス』の中心的なテーマは、ドゥルーズとガタリにとって、欲望は劇場の舞台ではなく、絶え間なく生 産し、配置を生み出し、脱領域化と再領域化、物事の機械的配置、欲望の機械を引き起こす工場であるということだ。欲望を工場として理解することで、欲望の 機械を構想することができる。なぜなら、自然やあらゆる身体には、機械的な配置、つまり、欲望の機械だけでなく、器官としての機械、エネルギーとしての機 械、そして機械の組み合わせや結合といった、多様な機械しか存在しないからだ。ドゥルーズは、機械を結合するプロセスを通じて人間と自然を結びつける。 「人間と自然は互いに生み出す」― 身体と自然の共存性のパラダイム、強度のある身体、閾値、レベル、ベクトル、強度の勾配が貫く内在的な身体。 CsO は欲望の産物であり、欲望を持つ機械が私たちに作り出す有機体とは対立する。身体は、他の組織を持たないこと、あるいはまったく組織を持たないことに苦し む... CsO はイメージのない身体(有機的表現の「前」の段階)であり、反生産物であるが、それは私たちに絶えず浸透し、私たちも絶えず CsO に浸透するため、避けられないものである。CsO はプログラムであり、実験であり、幻想ではない。部分に加えて全体として生成される CsO は、有機体に反対する。なぜなら、欲望は有機体ではなく、身体と器官を通して通るからだ。 『フランシス・ベーコン:感覚の論理』(1981)の中で、 ドゥルーズは、「器官のない身体は、不確定な器官によって定義されるのに対し、有機体は確定した器官によって定義される」と説明している。「口と肛門はど ちらも故障する危険性がある。それならば、食事と排便のための多機能な開口部を一つだけ設けてはどうだろうか?口と鼻を塞ぎ、胃を埋め、肺に直接通気孔を 開けることができる。これは当初から行われるべきだったことだ」[2]と述べている。 CsOには、欲望や存在に応じてさまざまな可能性がある。例えば、臓器が破壊される心気症の体、あるいは自身の臓器と闘う統合失調症の体などが挙げられ る。ドゥルーズは、アントナン・アルトーの作品を引用して統合失調症の例を好んで取り上げるが、CsO は「陽気さ、恍惚、ダンス... 」ともなり得るが、その実験は軽々しいものではなく、死に至ることもある。したがって、CsOの実験は生死にかかわる問題であるにもかかわらず、慎重であ る必要がある。なぜなら、ドゥルーズにとって、精神分析が主張するように「自我」を取り戻すことではなく、それを超えることが重要だからだ。ドゥルーズ は、その『アルファベット順の辞書』の中で、「パパやママについて妄想するのではなく、世界について妄想する」と述べている。また、『千のプラトー』の中 で、「回顧を忘却に、解釈を実験に置き換える」と明確に述べている。ドゥルーズは、欠乏や幻想として認識される欲望という概念に反対している。 ドゥルーズにとって、CsOに関する偉大な書物はバルーク・スピノザの『倫理学』である。属性、物質、強度は、融合、合流、滑りの多様性があるため、単数 と複数の対立を無視する。「身体はもはや、弁、水門、水門、ボウル、または連通容器の集合体に過ぎない」[3] 」 CsOは、その上、そしてその内部で強度が循環する卵のようなものだ。その強度は、CsOが、広がりのない、強度のある空間で生み出し、分配するものであ る。 |

| Références 1. Deleuze 1998, p. 218. 2. William Burroughs, Le Festin nu 3. Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, Mille Plateaux, p. 189 |

参考文献 1. Deleuze 1998, p. 218. 2. William Burroughs, Le Festin nu 3. Gilles Deleuze et ガタリ, Mille Plateaux, p. 189 |

| Bibliographie Gilles Deleuze, Proust et les signes, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, coll. « Quadrige », 1998 (1re éd. 1964), 224 p. (ISBN 2130478581) Gilles Deleuze, Logique du sens, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1969, 392 p. (ISBN 2707301523) Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, L'Anti-Œdipe : Capitalisme et schizophrénie, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1972, 494 p. (ISBN 2-7073-0067-5) Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, Mille Plateaux : Capitalisme et schizophrénie 2, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1980, 645 p. (ISBN 2-7073-0307-0) Gilles Deleuze, « Le corps sans organes et la figure de Bacon », dans Francis Bacon. Logique de la sensation, Paris, Seuil, coll. « L'ordre philosophique », 2002 (1re éd. 1981) (EAN 9782020500142), p. 47-52. Arnaud Villani, « Corps sans organes », dans Robert Sasso (dir.) et Arnaud Villani (dir.), Le Vocabulaire de Gilles Deleuze, Nice, Centre de Recherches en Histoire des Idées, coll. « Les Cahiers de Noesis » (no 3), 2003, p. 62-66. Gilles Deleuze et Claire Parnet, Dialogues, Paris, Flammarion, coll. « Champs », 2004 (1re éd. 1995), 187 p. (ISBN 2-08-081343-9) Évelyne Grossman, Le corps de l'informe, textes réunis et présentés par Évelyne Grossman, Textuel, no 42, Paris 7 - Denis Diderot - revue de l'UFR, 2002, 224 p. Florence Andoka, « Machine désirante et subjectivité dans 'L'Anti-Œdipe de Deleuze et Guattari », Philosophique, Annales littéraires de l'Université de Franche-Comté, vol. 15, 12, p. 85-94 (lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 7 avril 2023). Serge Agnessan, Corps sans organes, Éditions Poètes de brousse, Montréal, 2022, 82 p. Articles connexes Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu d'Antonin Artaud Conatus |

参考文献 ジル・ドゥルーズ、『プルーストと記号』、パリ、プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、シリーズ「クアドリジ」、1998年(初版1964年)、 224ページ(ISBN 2130478581) ジル・ドゥルーズ、『意味の論理』、パリ、 ミニュイ出版社、「批評」シリーズ、1969年、392ページ(ISBN 2707301523) ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリ、『アンチ・エディプス:資本主義と統合失調症』、パリ、ミニュイ出版社、「批評」シリーズ、1972年、494 ページ (ISBN 2-7073-0067-5) ジル・ドゥルーズ、フェリックス・ガタリ著、『千のプラトー:資本主義と統合失調症 2』、パリ、ミニュイ社、「批評」シリーズ、1980年、645ページ。(ISBN 2-7073-0307-0) ジル・ドゥルーズ、「器官のない身体とベーコンの姿」、フランシス・ベーコン『感覚の論理』、パリ、セイル社、「哲学の秩序」シリーズ、2002年(初版 1981年)(EAN 9782020500142)、47-52ページ。 アルノー・ヴィラーニ、「器官のない身体」、ロベール・サッソ(編)、アルノー・ヴィラーニ(編)、『ジル・ドゥルーズの語彙集』、ニース、思想史研究セ ンター、「レ・カヒエ・ド・ノエシス」シリーズ(第3号)、2003年、62-66ページ。 ジル・ドゥルーズとクレール・パルネ、『対話』パリ、フラマリオン、コレクション「シャン」、2004年(初版1995年)、187ページ(ISBN 2-08-081343-9)。 エヴリーヌ・グロスマン、『形のない身体』、エヴリーヌ・グロスマンによるテキストの編集・紹介、Textuel、第42号、パリ7区 - デニス・ディドロ - UFR誌、2002年、224ページ。 フローレンス・アンドカ、「ドゥルーズとガタリの『アンチ・エディプス』における欲望の機械と主観性」、Philosophique、フランシュ・コンテ 大学文学年報、第15巻、12、85-94ページ(オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]、2023年4月7日アクセス)。 セルジュ・アグネサン、『器官のない身体』、Éditions Poètes de brousse、モントリオール、2022年、82ページ。 関連記事 アントナン・アルトーの『神の裁きを終わらせるために』 コナトゥス |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corps-sans-organes |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099