サイバーパンク

Cyberpunk, Cyber-Punk

解説:池田光穂

サイバーパンク(cyber-punk, cyberpunk)というのは、コンピュータあるいは自動制御の用語であるサイバー(cyber)[→サイバネティクス]と、非行少年や青二才をあらわ す俗語由来のパンク(punk)の合成語である。

これにより、サイバーパンクとは、 ネットワークコンピュータと主体的にリンケージのした人間主体ならびにヒューマノイド・エージェンシーのことをさすようになったとい われている。

ただし、このような定義は世間の常識を逸脱した過激なものであるので、このページ の読者は下記の解説をよく読んで、自分なりの定義を模索すべきだ(ウィキなどでは、この用語に思想や社会運動の意味を込めているが、現実社会とサイバーパ ンクの関係の可能性について穿った見方である)。

さてサイバー(cyber)が接頭辞となって英語に流布するようになったのは言うまでもなくN・ ウィーナーのサイバネティクス(cybernetics)であり、これは通 信と制御についての学問を彼が提唱した際に用いられた言葉だった(ウィーナー 1957)。サイバーの語源はギリシャ語の操舵手あるいは統治者(kuberne-te-s)に求められる。ウィーナーがなぜこのような造語をおこなった かというと、それは彼の「情報」の定義と密接に関係しているからである。

ウィーナーによる「情報」の定義とは、個体が外界に適応しようと行動したり、行動の結果を外界か らえる際に、個体が外界と交換するものの内容のことをさす。サイバーという用語が、後にcyberspace や cyberphobia(コンピュタ恐怖症)のようにインターネットやそれに繋がるコンピュータを明示するようになったのは、サイバーに行為主体(=操舵 手)としての意味を持たせようとしたウィーナーからみれば不本意であっただろう。

その意味で、奥出直人がサイバーパンクを「頭脳の構造を探るような高度なテクノロジーをマスター し、それを自分のためだけに使う連中」と説明した時、それは言葉が最初にもっていた意味を復活させたと言える(奥出 1990:158)。サイバーパンクはテクノロジーの発達(正確には変化)と切り離せない。つまり、サイバーパンクの定義は、テクノロジーと人間主体との 関係の変化により変容しうるということである。変容が終わった時、この言葉は廃語になる。

Social impact of Cyberpunk.

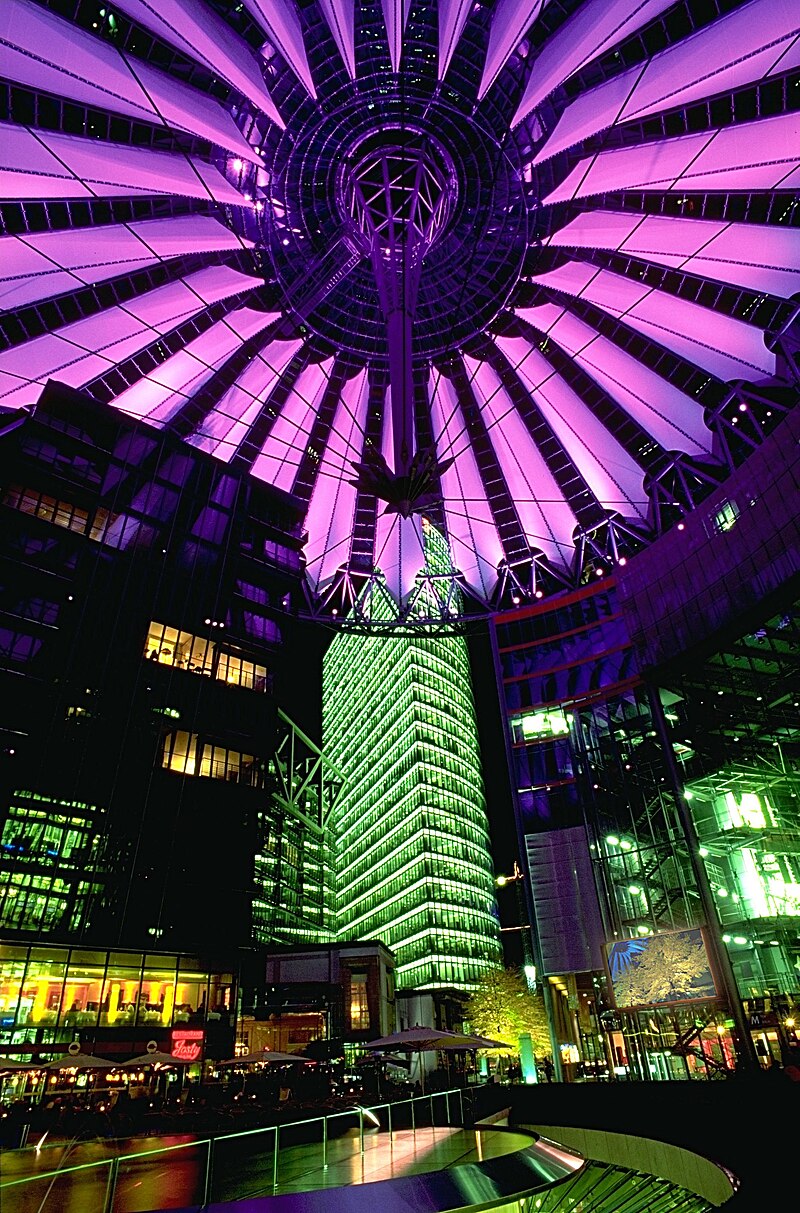

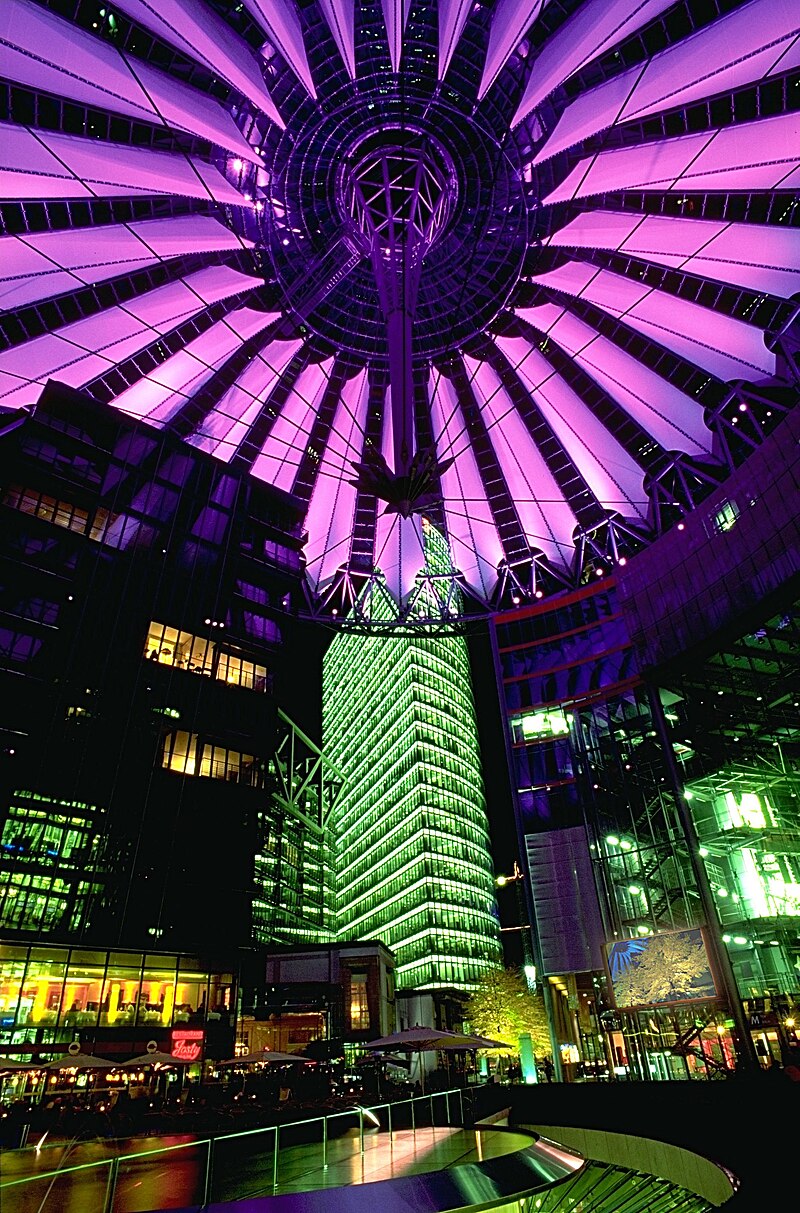

Art and architecture Berlin's Center Potsdamer Platz, opened in 2000, has been described as having a cyberpunk aesthetic. Writers David Suzuki and Holly Dressel describe the cafes, brand-name stores and video arcades of the Center Potsdamer Platz in the Potsdamer Platz public square of Berlin, Germany, as "a vision of a cyberpunk, corporate urban future".[118] |

芸術と建築 2000年にオープンしたベルリンのポツダム広場センターは、サイバーパンク的な美学を持つと評されている。 作家デイヴィッド・スズキとホリー・ドレッセルは、ドイツ・ベルリンのポツダム広場にある同センターのカフェ、ブランド店、ビデオゲームセンターを「サイバーパンク的な企業都市の未来像」と表現している。[118] |

| Society and counterculture Several subcultures have been inspired by cyberpunk fiction. These include the cyberdelic counter culture of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Cyberdelic, whose adherents referred to themselves as "cyberpunks", attempted to blend the psychedelic art and drug movement with the technology of cyberculture. Early adherents included Timothy Leary, Mark Frauenfelder and R. U. Sirius. The movement largely faded following the dot-com bubble implosion of 2000.[citation needed] Cybergoth is a fashion and dance subculture which draws its inspiration from cyberpunk fiction, as well as rave and Gothic subcultures. In addition, a distinct cyberpunk fashion of its own has emerged in recent years[when?] which rejects the raver and goth influences of cybergoth, and draws inspiration from urban street fashion, "post apocalypse", functional clothing, high tech sports wear, tactical uniform and multifunction. This fashion goes by names like "tech wear", "goth ninja" or "tech ninja".[citation needed] The Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, demolished in 1994, is often referenced as the model cyberpunk/dystopian slum as, given its poor living conditions at the time coupled with the city's political, physical, and economic isolation has caused many in academia to be fascinated by the ingenuity of its spawning.[119] |

社会とカウンターカルチャー サイバーパンク小説に影響を受けたサブカルチャーがいくつか存在する。1980年代後半から1990年代初頭にかけてのサイバーデリック・カウンターカル チャーもその一つだ。サイバーデリックの信奉者たちは自らを「サイバーパンク」と呼び、サイケデリックアートやドラッグ運動をサイバーカルチャーの技術と 融合させようとした。初期の支持者にはティモシー・リアリー、マーク・フラウエンフェルダー、R・U・シリウスらがいた。この運動は2000年のドットコ ムバブル崩壊後にほぼ衰退した。 サイバーゴスは、サイバーパンク小説やレイヴ、ゴシック文化から影響を受けたファッション・ダンスサブカルチャーである。さらに近年[時期不明]、サイ バーゴスのレイバーやゴス的要素を排し、都市型ストリートファッション、「ポスト・アポカリプス」、機能性衣類、ハイテクスポーツウェア、タクティカルユ ニフォーム、多機能性を源泉とする独自のサイバーパンクファッションが台頭している。この潮流は「テックウェア」「ゴス・ニンジャ」「テック・ニンジャ」 などの名称で呼ばれる[出典必要]。 1994年に解体された香港の九龍城寨は、当時の劣悪な生活環境と政治的・物理的・経済的孤立が相まって、その独創性に学界の多くが魅了されたことから、サイバーパンク/ディストピア的なスラムの典型例としてしばしば言及される。[119] |

| Cyberpunk derivatives Main article: Cyberpunk derivatives As a wider variety of writers began to work with cyberpunk concepts, new subgenres of science fiction emerged, some of which could be considered as playing off the cyberpunk label, others which could be considered as legitimate explorations into newer territory. These focused on technology and its social effects in different ways. One prominent subgenre is "steampunk," which is set in an alternate history Victorian era that combines anachronistic technology with cyberpunk's bleak film noir world view. The term was originally coined around 1987 as a joke to describe some of the novels of Tim Powers, James P. Blaylock, and K.W. Jeter, but by the time Gibson and Sterling entered the subgenre with their collaborative novel The Difference Engine the term was being used earnestly as well.[120] Another subgenre is "biopunk" (cyberpunk themes dominated by biotechnology) from the early 1990s, a derivative style building on biotechnology rather than informational technology. In these stories, people are changed in some way not by mechanical means, but by genetic manipulation. |

サイバーパンクの派生作品 メイン記事: サイバーパンクの派生作品 より多様な作家がサイバーパンクの概念を取り入れるにつれ、SFの新たなサブジャンルが出現した。その中にはサイバーパンクのレッテルを利用したものと、 新たな領域への正当な探求と見なせるものがある。これらは技術とその社会的影響を異なる方法で焦点化した。代表的なサブジャンルの一つが「スチームパン ク」である。これは時代錯誤的な技術とサイバーパンクの陰鬱なフィルム・ノワール的世界観を組み合わせた、架空のヴィクトリア朝時代を舞台としている。こ の用語は1987年頃、ティム・パワーズ、ジェームズ・P・ブレイロック、K・W・ジーターの小説を冗談めかして表現するために生まれた。しかしギブソン とスターリングが共著『ディファレンス・エンジン』でこのサブジャンルに参入した頃には、真剣な意味でも使われるようになっていた。[120] 別のサブジャンルとして、1990年代初頭から登場した「バイオパンク」(バイオテクノロジーが支配的なサイバーパンクテーマ)がある。これは情報技術で はなくバイオテクノロジーを基盤とした派生スタイルだ。これらの物語では、人間は機械的な手段ではなく遺伝子操作によって何らかの形で変容する。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberpunk |

文学作品ではサイバースペースの中に自我が侵入するとまで表現される。そのためウィリアム・ギブ ソン(1948-)『ニューロマンサー』(1984)などのサイバーパンク小説が「技術的に増強された(technologically- enhanced)文化的諸体系において周縁化した人々※」を取り扱うと定義されていることは、サイバーパンクという概念が、人間のある種のカテゴリーを さすと同時に、そのような人びとが担ったり拘束されもする社会性=文化をも包摂する概念であることがわかる(Frank 1998)。フランクの解説にしたがうと、社会的に周辺化されている人々つまり弱者は、サイバースペースにおいては、現実社会における強者(=経済的、社 会的、権力的にパワーのある人のみならず、警察や司法、あるいはマフィア組織など裏社会の実力者を含む)に比肩するだけの力と機会をもちうるというレジス タンス小説としても、『ニューロマンサー』を理解することも可能である。

※原文は、Cyberpunk literature, in general, deals with marginalized people in technologically-enhanced cultural "systems".です(http://www.non.com/news.answers/cyberpunk-faq.html, March 7,2004)。

解説者による註釈

この文章における人間主体という用語は、近代合理主義が前提にする、一枚岩で合理的で主体と客体 の二分法をよく理解しそれを行動に反映させることができるような行為主体をモデルしている部分と、その自己意識はともかくとして、肌で境界づけられた身体 をもつ、単なる行為主体という意味をごっちゃにしています。サイバーパンクの定義は、マン=マシン・インターフェース(→ユーザーインターフェイス)の発達により、いかようにも変化しま すので、このような軟弱な定義づけの限界は目に見えてわかると思いますが、むしろ議論のたたき台としてご利用ください。

ちなみに、かつて、私がウィリアム・ギブスン(ギブソン)のインタビュー映像をみたときに彼がこ んなことをいっていたのを鮮烈に覚えている:「予防注射というのは、人類にとっての最初のサイ ボーグ化経験だったのさ」

| Cyberpunk is a

subgenre of science fiction set in a dystopian future. It is

characterized by its focus on a combination of "low-life and high

tech".[1] It features a range of futuristic technological and

scientific achievements, including artificial intelligence and

cyberware, which are juxtaposed with societal collapse, dystopia or

decay.[2] A significant portion of cyberpunk can be traced back to the

New Wave science fiction movement of the 1960s and 1970s. During this

period, prominent writers such as Philip K. Dick, Michael Moorcock,

Roger Zelazny, John Brunner, J. G. Ballard, Philip José Farmer and

Harlan Ellison explored the impact of technology, drug culture, and the

sexual revolution. These authors diverged from the utopian inclinations

prevalent in earlier science fiction. Comics exploring cyberpunk themes began appearing as early as Judge Dredd, first published in 1977.[3] Released in 1984, William Gibson's influential debut novel Neuromancer helped solidify cyberpunk as a genre, drawing influence from punk subculture and early hacker culture. Frank Miller's Ronin is an example of a cyberpunk graphic novel. Other influential cyberpunk writers included Bruce Sterling and Rudy Rucker. The Japanese cyberpunk subgenre began in 1982 with the debut of Katsuhiro Otomo's manga series Akira, with its 1988 anime film adaptation (also directed by Otomo) later popularizing the subgenre. Early films in the genre include Ridley Scott's 1982 film Blade Runner, one of several of Philip K. Dick's works that have been adapted into films (in this case, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). The "first cyberpunk television series"[4] was the TV series Max Headroom from 1987, playing in a futuristic dystopia ruled by an oligarchy of television networks, and where computer hacking played a central role in many story lines. The films Johnny Mnemonic (1995)[5] and New Rose Hotel (1998),[6][7] both based upon short stories by William Gibson, flopped commercially and critically, while Batman Beyond (1999–2001), The Matrix trilogy (1999–2003) and Judge Dredd (1995) were some of the most influential cyberpunk films. Newer cyberpunk media includes Tron: Legacy (2010), a sequel to the original Tron (1982); Blade Runner 2049 (2017), a sequel to the original 1982 film; Dredd (2012), which was not a sequel to the original movie; Ghost in the Shell (2017), a live-action adaptation of the original manga; Alita: Battle Angel (2019), based on the 1990s Japanese manga Battle Angel Alita; the 2018 Netflix TV series Altered Carbon, based on Richard K. Morgan's 2002 novel of the same name; and the video game Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) and original net animation (ONA) miniseries Cyberpunk: Edgerunners (2022), both based on R. Talsorian Games's 1988 tabletop role-playing game Cyberpunk. |

サイバーパンクは、ディストピア的な未来を舞台とするSFのサブジャン

ルだ。その特徴は「低俗さとハイテクの組み合わせ」に焦点を当てている点にある[1]。人工知能やサイバーウェアといった未来的な技術的・科学的成果が、

社会の崩壊やディストピア、衰退といった状況と並置されるのが特徴だ。[2]

サイバーパンクの大部分は、1960年代から1970年代にかけてのニューウェーブSF運動に起源を持つ。この時期、フィリップ・K・ディック、マイケ

ル・ムーアコック、ロジャー・ゼラズニー、ジョン・ブルナー、J・G・バラード、フィリップ・ホセ・ファーマー、ハーラン・エリソンといった著名な作家た

ちが、技術、ドラッグ文化、性革命の影響を探求した。これらの作家たちは、それ以前のSFに蔓延していたユートピア的傾向から離れていった。 サイバーパンクテーマを扱うコミックは、1977年に初出版された『ジャッジ・ドレッド』[3]に遡る。1984年に発表されたウィリアム・ギブソンの影 響力あるデビュー小説『ニューロマンサー』は、パンクサブカルチャーや初期ハッカー文化の影響を受けつつ、サイバーパンクをジャンルとして確立するのに貢 献した。フランク・ミラーの『ロニン』はサイバーパンク・グラフィックノベルの一例だ。ブルース・スターリングやルディ・ラッカーも影響力のあるサイバー パンク作家である。日本のサイバーパンク亜流は1982年、大友克洋の漫画シリーズ『AKIRA』のデビューで始まり、1988年のアニメ映画化(大友監 督)によって後にこの亜流が普及した。 このジャンルの初期映画には、リドリー・スコット監督の1982年作品『ブレードランナー』がある。これはフィリップ・K・ディックの作品を映画化した数 作品の一つであり(本作の場合は『アンドロイドは電気羊の夢を見るか?』が原作)、 「最初のサイバーパンクテレビシリーズ」[4]は1987年の『マックス・ヘッドルーム』である。テレビネットワークの寡頭支配下にある未来のディストピ アを舞台とし、多くのストーリーラインでコンピューターハッキングが中心的な役割を果たした。ウィリアム・ギブソンの短編小説を原作とする映画『ジョ ニー・ムネモニック』(1995年)[5]と『ニュー・ローズ・ホテル』(1998年)[6][7]は、商業的にも批評的にも失敗に終わった。一方、 『バットマン・ビヨンド』(1999年–2001年)、 『マトリックス』三部作(1999–2003)と『ジャッジ・ドレッド』(1995)は、最も影響力のあるサイバーパンク映画の一部だ。 より新しいサイバーパンクメディアには、オリジナル『トロン』(1982年)の続編『トロン: レガシー』(2010年)、オリジナル1982年作品の続編『ブレードランナー 2049』(2017年)、オリジナル映画の続編ではない『ドレッド』(2012年)、オリジナル漫画の実写化『ゴースト・イン・ザ・シェル』(2017 年)、 『アリータ: battler angel』(2019年)は1990年代の日本漫画『バトルエンジェル アリータ』を原作とする。2018年のNetflixテレビシリーズ『オルタード・カーボン』はリチャード・K・モーガンの2002年同名小説を原作とす る。またビデオゲーム『サイバーパンク2077』(2020年)とオリジナルネットアニメ(ONA)ミニシリーズ『サイバーパンク:エッジランナーズ』 (2022年)は、いずれもR.タルソリアン・ゲームズの1988年テーブルトップRPG『サイバーパンク』を原作とする。エッジランナーズ(2022 年)は、いずれもR.タルソリアン・ゲームズ社の1988年発売テーブルトップRPG『サイバーパンク』を原作としている。 |

| Background Lawrence Person has attempted to define the content and ethos of the cyberpunk literary movement stating: Classic cyberpunk characters were marginalized, alienated loners who lived on the edge of society in generally dystopic futures where daily life was impacted by rapid technological change, an ubiquitous datasphere of computerized information, and invasive modification of the human body. — Lawrence Person[8] Cyberpunk plots often involve conflict between artificial intelligence, hackers, and megacorporations, and tend to be set in a near-future Earth, rather than in the far-future settings or galactic vistas found in novels such as Isaac Asimov's Foundation or Frank Herbert's Dune.[9] The settings are usually post-industrial dystopias but tend to feature extraordinary cultural ferment and the use of technology in ways never anticipated by its original inventors ("the street finds its own uses for things").[10] Much of the genre's atmosphere echoes film noir, and written works in the genre often use techniques from detective fiction.[11] There are sources who view that cyberpunk has shifted from a literary movement to a mode of science fiction due to the limited number of writers and its transition to a more generalized cultural formation.[12][13][14] |

背景 ローレンス・パーソンはサイバーパンク文学運動の内容と精神を定義しようと試み、次のように述べている: 古典的なサイバーパンクの登場人物は、社会のはずれで生きる疎外された孤独者だった。彼らが生きる近未来は概してディストピア的で、急速な技術革新、遍在 するコンピュータ化された情報圏、そして人体への侵襲的な改造が日常生活に影響を与えていた。 —ローレンス・パーソン[8] サイバーパンクの物語は、人工知能、ハッカー、巨大企業間の対立を頻繁に扱い、アイザック・アシモフの『ファウンデーション』やフランク・ハーバートの 『デューン』に見られるような遠い未来や銀河規模の舞台ではなく、近未来の地球を舞台とする傾向がある。[9] 舞台は通常ポスト産業社会のディストピアだが、並外れた文化的発酵と、技術が本来の発明者たちの予想をはるかに超えた形で利用される様子(「街は物事に独 自の用途を見出す」)が特徴的だ。[10] このジャンルの雰囲気の多くはフィルム・ノワールを彷彿とさせ、このジャンルの著作は探偵小説の手法を多用する。[11] サイバーパンクは、作家数が限られていることや、より一般的な文化的形成へと移行したことから、文学運動からSFの一形態へと変化したと見る見解もある。 [12][13][14] |

| History and origins The origins of cyberpunk are rooted in the New Wave science fiction movement of the 1960s and 1970s, where New Worlds, under the editorship of Michael Moorcock, began inviting and encouraging stories that examined new writing styles, techniques, and archetypes. Reacting to conventional storytelling, New Wave authors attempted to present a world where society coped with a constant upheaval of new technology and culture, generally with dystopian outcomes. Writers like Roger Zelazny, J. G. Ballard, Philip José Farmer, Samuel R. Delany, and Harlan Ellison often examined the impact of drug culture, technology, and the ongoing sexual revolution, drawing themes and influence from experimental literature of Beat Generation authors such as William S. Burroughs, and art movements like Dadaism.[15][16] Ballard, a notable critic of literary archetypes in science fiction, instead employs metaphysical and psychological concepts, seeking greater relevance to readers of the day. Ballard's work is considered have had a profound influence on cyberpunk's development,[17][better source needed] as evidenced by the term "Ballardian" becoming used to ascribe literary excellence amongst science fiction social circles.[18] Ballard, along with Zelazny and others continued the popular development of "realism" within the genre.[19] Delany's 1968 novel Nova, considered a forerunner of cyberpunk literature,[20] includes neural implants, a now popular cyberpunk trope for human computer interfaces.[21] Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, first published in 1968, shares common dystopian themes with later works by Gibson and Sterling, and is praised for its "realist" exploration of cybernetic and artificial intelligence ideas and ethics.[citation needed] |

歴史と起源 サイバーパンクの起源は、1960年代から1970年代にかけてのニューウェーブSF運動に根ざしている。マイケル・ムーアコックが編集長を務める 『ニュー・ワールド』誌が、新たな文体や技法、原型を探求する物語を積極的に募集し奨励したのだ。従来の物語形式への反動として、ニューウェーブ作家たち は、社会が絶え間なく押し寄せる新技術と文化の激変に対処する世界を提示しようとした。その結末は概してディストピア的なものだった。ロジャー・ゼラズ ニー、J・G・バラード、フィリップ・ホセ・ファーマー、サミュエル・R・ディレイニー、ハーラン・エリソンといった作家たちは、ドラッグ文化や技術、進 行中の性的革命の影響を頻繁に考察した。彼らはウィリアム・S・バロウズらビート・ジェネレーション作家たちの実験的文学や、ダダイズムのような芸術運動 からテーマや影響を引き出している[15]。[16] SFにおける文学的原型を鋭く批判したバラードは、代わりに形而上学的・心理学的概念を用い、当時の読者との関連性を高めようとした。バラードの作品はサ イバーパンクの発展に深い影響を与えたと考えられており[17][より良い出典が必要]、SF界隈で文学的卓越性を称える「バラード的」という用語が生ま れたことがその証左である。[18] バラードはゼラズニーらと共に、このジャンルにおける「リアリズム」の普及的発展を継続した。[19] デラニーの1968年小説『ノヴァ』はサイバーパンク文学の先駆者とされ[20]、神経インプラントを扱っている。これは現在では人間とコンピュータのイ ンターフェースとして人気のサイバーパンク的トロープである。[21] フィリップ・K・ディックの小説『アンドロイドは電気羊の夢を見るか?』は1968年に初版が刊行され、ギブソンやスターリングの後期作品と共通するディ ストピア的テーマを共有している。また、サイバネティクスや人工知能の思想・倫理を「リアリズム」的に探求した点で高く評価されている。[出典が必要] |

| Etymology The term "cyberpunk" first appeared as the title of a short story by Bruce Bethke, written in 1980 and published in Amazing Stories in 1983.[22][23] The name was picked up by Gardner Dozois, editor of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, and popularized in his editorials.[24][25] Bethke says he made two lists of words, one for technology, one for troublemakers, and experimented with combining them variously into compound words, consciously attempting to coin a term that encompassed both punk attitudes and high technology. He described the idea thus: The kids who trashed my computer; their kids were going to be Holy Terrors, combining the ethical vacuity of teenagers with a technical fluency we adults could only guess at. Further, the parents and other adult authority figures of the early 21st Century were going to be terribly ill-equipped to deal with the first generation of teenagers who grew up truly "speaking computer".[26] Afterward, Dozois began using this term in his own writing, most notably in a 1984 Washington Post article where he said "About the closest thing here to a self-willed esthetic 'school' would be the purveyors of bizarre hard-edged, high-tech stuff, who have on occasion been referred to as 'cyberpunks' — Sterling, Gibson, Shiner, Cadigan, Bear."[27] Also in 1984, William Gibson's novel Neuromancer was published, delivering a glimpse of a future encompassed by what became an archetype of cyberpunk "virtual reality", with the human mind being fed light-based worldscapes through a computer interface. Some, perhaps ironically including Bethke himself, argued at the time that the writers whose style Gibson's books epitomized should be called "Neuromantics", a pun on the name of the novel plus "New Romantics", a term used for a New Wave pop music movement that had just occurred in Britain, but this term did not catch on. Bethke later paraphrased Michael Swanwick's argument for the term: "the movement writers should properly be termed neuromantics, since so much of what they were doing was clearly imitating Neuromancer". Sterling was another writer who played a central role, often consciously, in the cyberpunk genre, variously seen as either keeping it on track, or distorting its natural path into a stagnant formula.[28] In 1986, he edited a volume of cyberpunk stories called Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology, an attempt to establish what cyberpunk was, from Sterling's perspective.[29] In the subsequent decade, the motifs of Gibson's Neuromancer became formulaic, climaxing in the satirical extremes of Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash in 1992. Bookending the cyberpunk era, Bethke himself published a novel in 1995 called Headcrash, like Snow Crash a satirical attack on the genre's excesses. Fittingly, it won an honor named after cyberpunk's spiritual founder, the Philip K. Dick Award. It satirized the genre in this way: ...full of young guys with no social lives, no sex lives and no hope of ever moving out of their mothers' basements ... They're total wankers and losers who indulge in Messianic fantasies about someday getting even with the world through almost-magical computer skills, but whose actual use of the Net amounts to dialing up the scatophilia forum and downloading a few disgusting pictures. You know, cyberpunks.[30] |

語源 「サイバーパンク」という用語は、ブルース・ベスケーが1980年に執筆し、1983年に『アメージング・ストーリーズ』誌に掲載した短編小説のタイトル として初めて登場した。[22][23] この名称は、アイザック・アシモフの『サイエンス・フィクション・マガジン』編集者であるガードナー・ドゾワによって採用され、彼の編集後記で広められ た。[24] [25] ベスケは、技術用語とトラブルメーカーを表す言葉をそれぞれリスト化し、それらを様々な形で組み合わせる実験を行ったと述べている。パンクの態度とハイテクノロジーの両方を包含する用語を意図的に造語しようとしたのだ。彼はその構想をこう説明している: 俺のコンピューターを壊したガキども。そのガキどもの子供たちは「聖なる恐怖」になるだろう。ティーンエイジャーの倫理観の欠如と、我々大人が想像すらで きない技術的流暢さを併せ持つ存在だ。さらに、21世紀初頭の親や他の大人権威者たちは、真に「コンピューターを話す」世代として育った最初のティーンエ イジャーたちに対処する手段を全く持っていないだろう。[26] その後ドゾワは自身の著作でこの用語を使い始め、特に1984年のワシントン・ポスト紙記事で「ここでの自己主張的な美的『流派』に最も近いのは、時に 『サイバーパンク』と呼ばれる奇妙な鋭利なハイテク作品を扱う連中だ——スターリング、ギブソン、シャイナー、ケイディガン、ベア」と記した。[27] 同じく1984年、ウィリアム・ギブソンの小説『ニューロマンサー』が刊行された。この作品は、後にサイバーパンクの典型となる「仮想現実」に包まれた未 来の一端を提示した。人間の精神がコンピュータインターフェースを通じて光で構成された世界景観を摂取する世界である。当時、皮肉にもベスケ自身を含む一 部の人々は、ギブソンの作品が象徴する作風を持つ作家たちを「ニューロマンティクス」と呼ぶべきだと主張した。これは小説のタイトルと、英国でちょうど起 こったニューウェーブ・ポップ音楽運動を指す「ニューロマンティクス」を掛けた言葉遊びである。しかしこの用語は定着しなかった。ベスケは後にマイケル・ スワンウィックのこの用語に関する主張を要約した:「この運動の作家たちはニューロマンティクスと呼ぶべきだ。彼らの作品の多くが明らかに『ニューロマン サー』を模倣していたからだ」。 スターリングもまた、サイバーパンクジャンルにおいて中心的な役割を果たした作家の一人である。その役割は、ジャンルを正しい軌道に乗せたとも、自然な発 展を停滞した定型へと歪めたとも、様々な見方がある。[28] 1986年、彼は『ミラーシェイズ:サイバーパンク・アンソロジー』と題した短編集を編集した。これはスターリングの視点からサイバーパンクの本質を確立 しようとする試みであった。[29] その後10年間で、ギブソンの『ニューロマンサー』のモチーフは定型化し、1992年のニール・スティーブンソンの『スノウ・クラッシュ』における風刺的な極端な表現で頂点に達した。 サイバーパンク時代の幕開けと終焉を象徴するように、ベスケー自身も1995年に『ヘッドクラッシュ』を発表した。これは『スノウ・クラッシュ』同様、 ジャンルの過剰さを風刺的に攻撃する作品である。ふさわしいことに、サイバーパンクの精神的創始者に因むフィリップ・K・ディック賞を受賞した。その風刺 はこうだ: …社会生活も性生活もなく、母親の地下室から一生出られない若者たちで溢れている…彼らは完全な自慰狂で負け犬だ。魔法のようなコンピューター技術でいつ か世界に復讐するという救世主的幻想に浸っているが、ネットの実利用はスカトロフォビア掲示板にダイヤルアップして、気持ち悪い画像を数枚ダウンロードす る程度だ。そう、サイバーパンクってやつさ。[30] |

| Style and ethos Primary figures in the cyberpunk movement include William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, Bruce Sterling, Bruce Bethke, Pat Cadigan, Rudy Rucker, and John Shirley. Philip K. Dick (author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, from which the film Blade Runner was adapted) is also seen by some as prefiguring the movement.[31] Blade Runner can be seen as a quintessential example of the cyberpunk style and theme.[9] Video games, board games, and tabletop role-playing games, such as Cyberpunk 2020 and Shadowrun, often feature storylines that are heavily influenced by cyberpunk writing and movies. Beginning in the early 1990s, some trends in fashion and music were also labeled as cyberpunk. Cyberpunk is also featured prominently in anime and manga (Japanese cyberpunk), with Akira, Ghost in the Shell and Cowboy Bebop being among the most notable.[32] |

スタイルと精神 サイバーパンク運動の主要な人物には、ウィリアム・ギブソン、ニール・スティーブンソン、ブルース・スターリング、ブルース・ベスケー、パット・キャディ ガン、ルディ・ラッカー、ジョン・シャーリーらがいる。フィリップ・K・ディック(映画『ブレードランナー』の原作『アンドロイドは電気羊の夢を見る か?』の著者)も、この運動を予見した人物と見なされることがある。[31] 『ブレードランナー』はサイバーパンクのスタイルとテーマの典型例と言える。[9] ビデオゲーム、ボードゲーム、テーブルトップRPG(例:『サイバーパンク2020』や『シャドウラン』)は、サイバーパンクの小説や映画の影響を強く受 けたストーリーラインを頻繁に採用している。1990年代初頭からは、ファッションや音楽のいくつかの潮流もサイバーパンクと称されるようになった。サイ バーパンクはアニメやマンガ(日本のサイバーパンク)でも顕著に扱われており、『AKIRA』『攻殻機動隊』『カウボーイビバップ』などが最も著名な例で ある。[32] |

| Setting Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan (the latter image depicts Shibuya Crossing). Life in Kowloon Walled City has often inspired the dystopian identity in modern media works. Cyberpunk writers tend to use elements from crime fiction—particularly hardboiled detective fiction and film noir—and postmodernist prose to describe an often nihilistic underground side of an electronic society. The genre's vision of a troubled future is often called the antithesis of the generally utopian visions of the future popular in the 1940s and 1950s. Gibson defined cyberpunk's antipathy towards utopian science fiction in his 1981 short story "The Gernsback Continuum", which pokes fun at and, to a certain extent, condemns utopian science fiction.[33][34][35] In some cyberpunk writing, much of the action takes place online, in cyberspace, blurring the line between actual and virtual reality.[36] A typical trope in such work is a direct connection between the human brain and computer systems. Cyberpunk settings are dystopias with corruption, computers, and computer networks. The economic and technological state of Japan is a regular theme in the cyberpunk literature of the 1980s. Of Japan's influence on the genre, William Gibson said, "Modern Japan simply was cyberpunk."[37] Cyberpunk is often set in urbanized, artificial landscapes, and "city lights, receding" was used by Gibson as one of the genre's first metaphors for cyberspace and virtual reality.[38] The cityscapes of Hong Kong[39] has had major influences in the urban backgrounds, ambiance and settings in many cyberpunk works such as Blade Runner and Shadowrun. Ridley Scott envisioned the landscape of cyberpunk Los Angeles in Blade Runner to be "Hong Kong on a very bad day".[40] The streetscapes of the Ghost in the Shell film were based on Hong Kong. Its director Mamoru Oshii felt that Hong Kong's strange and chaotic streets where "old and new exist in confusing relationships" fit the theme of the film well.[39] Hong Kong's Kowloon Walled City is particularly notable for its disorganized hyper-urbanization and breakdown in traditional urban planning to be an inspiration to cyberpunk landscapes. During the British rule of Hong Kong, it was an area neglected by both the British and Qing administrations, embodying elements of liberalism in a dystopian context. Portrayals of East Asia and Asians in Western cyberpunk have been criticized as Orientalist and promoting racist tropes playing on American and European fears of East Asian dominance;[41][42] this has been referred to as "techno-Orientalism".[43] Society and government Cyberpunk can be intended to disquiet readers and call them to action. It often expresses a sense of rebellion, suggesting that one could describe it as a type of cultural revolution in science fiction. In the words of author and critic David Brin: ...a closer look [at cyberpunk authors] reveals that they nearly always portray future societies in which governments have become wimpy and pathetic ...Popular science fiction tales by Gibson, Williams, Cadigan and others do depict Orwellian accumulations of power in the next century, but nearly always clutched in the secretive hands of a wealthy or corporate elite.[44] Cyberpunk stories have also been seen as fictional forecasts of the evolution of the Internet. The earliest descriptions of a global communications network came long before the World Wide Web entered popular awareness, though not before traditional science-fiction writers such as Arthur C. Clarke and some social commentators such as James Burke began predicting that such networks would eventually form.[45] Some observers cite that cyberpunk tends to marginalize sectors of society such as women and people of colour. It is claimed that, for instance, cyberpunk depicts fantasies that ultimately empower masculinity using fragmentary and decentered aesthetic that culminate in a masculine genre populated by male outlaws.[46] Critics also note the absence of any reference to Africa or black characters in the quintessential cyberpunk film Blade Runner,[12] while other films reinforce stereotypes.[47] |

設定 日本、東京都渋谷区(後者の画像は渋谷スクランブル交差点を描いている)。 九龍城寨での生活は、現代メディア作品におけるディストピア的なアイデンティティの源泉となってきた。 サイバーパンクの作家たちは、犯罪小説(特にハードボイルド探偵小説やフィルム・ノワール)の要素とポストモダニズム的な散文を用いて、電子社会の虚無的 な地下世界を描写する傾向がある。このジャンルが描く問題を抱えた未来像は、1940~50年代に流行したユートピア的な未来像の対極とよく呼ばれる。ギ ブソンは1981年の短編『ガーンズバック・コンティニュアム』で、ユートピアSFへの反感を定義した。この作品はユートピアSFを嘲笑し、ある程度非難 している。[33][34][35] サイバーパンク作品では、物語の多くがオンライン上、つまりサイバースペースで展開され、現実と仮想現実の境界が曖昧になる。[36] このような作品に典型的なトロープは、人間の脳とコンピュータシステムの直接接続である。サイバーパンクの舞台は、腐敗とコンピュータ、そしてコンピュー タネットワークが蔓延するディストピアだ。 1980年代のサイバーパンク文学では、日本の経済・技術的状況が頻繁にテーマとなる。このジャンルへの日本の影響について、ウィリアム・ギブソンは「現 代の日本そのものがサイバーパンクだった」と述べている[37]。サイバーパンクは都市化された人工景観を舞台とする場合が多く、ギブソンは「遠ざかる都 市の灯り」をサイバースペースと仮想現実を表す最初の比喩の一つとして用いた。[38] 香港の都市景観[39]は、『ブレードランナー』や『シャドウラン』など多くのサイバーパンク作品の都市背景、雰囲気、設定に大きな影響を与えた。リド リー・スコットは『ブレードランナー』におけるサイバーパンク・ロサンゼルスの景観を「最悪の日の香港」と表現した。[40] 映画『攻殻機動隊』の街並みは香港を基にしている。監督の押井守は「新旧が入り乱れる」香港の混沌とした街並みが作品のテーマに合致すると感じた [39]。特に九龍城砦は、無秩序な超都市化と伝統的都市計画の崩壊が顕著で、サイバーパンク的景観の源泉となった。香港が英国の統治下にあった時代、こ の地域は英国と清の両政府から放置され、ディストピア的な文脈における自由主義的要素を体現していた。西洋のサイバーパンクにおける東アジアとアジア人の 描写は、オリエンタリズム的であり、東アジアの支配に対する欧米の恐怖心を煽る人種差別的な定型表現を助長していると批判されてきた[41][42]。こ れは「テクノ・オリエンタリズム」と呼ばれている。[43] 社会と政府 サイバーパンクは読者に不安を抱かせ、行動を促す意図を持つ。しばしば反逆の感覚を表現し、SFにおける一種の文化革命と形容できる。作家兼評論家デイヴィッド・ブリンの言葉を借りれば: ...(サイバーパンク作家たちを)よく見ると、彼らが描く未来社会では政府が弱腰で哀れな存在になっていることがほぼ常だ...ギブソン、ウィリアム ズ、ケイディガンらによる人気SF作品は確かに次世紀におけるオーウェル的な権力集中を描いているが、その権力はほぼ例外なく富裕層や企業エリートの秘密 主義的な手に握られている。[44] サイバーパンク作品はインターネットの進化を予見したフィクションとも見なされてきた。世界規模通信ネットワークの初期描写は、ワールドワイドウェブが一 般に認知されるはるか以前から存在した。ただしアーサー・C・クラークのような伝統的SF作家やジェームズ・バークのような社会評論家が、こうしたネット ワークの出現を予測し始めた時期よりは後である。[45] 一部の観察者は、サイバーパンクが女性や有色人種といった社会層を周縁化する傾向があると指摘する。例えば、サイバーパンクは断片的で脱中心的な美学を用 い、最終的に男性性を強化する幻想を描いていると主張される。それは男性的なアウトローが占める男性的なジャンルへと集約されるのだ[46]。批評家たち はまた、典型的なサイバーパンク映画『ブレードランナー』においてアフリカや黒人キャラクターへの言及が全くないことを指摘する[12]。一方で他の映画 は固定観念を強化している[47]。 |

| Media Literature See also: List of cyberpunk works § Print media, and Cyborgs in fiction Minnesota writer Bruce Bethke coined the term in 1983 for his short story "Cyberpunk", which was published in an issue of Amazing Science Fiction Stories.[48] The term was quickly appropriated as a label to be applied to the works of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Pat Cadigan and others. Of these, Sterling became the movement's chief ideologue, thanks to his fanzine Cheap Truth. John Shirley wrote articles on Sterling and Rucker's significance.[49] John Brunner's 1975 novel The Shockwave Rider is considered by many[who?] to be the first cyberpunk novel with many of the tropes commonly associated with the genre, some five years before the term was popularized by Dozois.[50] William Gibson with his novel Neuromancer (1984) is arguably the most famous writer connected with the term cyberpunk. He emphasized style, a fascination with surfaces, and atmosphere over traditional science-fiction tropes. Regarded as ground-breaking and sometimes as "the archetypal cyberpunk work",[8] Neuromancer was awarded the Hugo, Nebula, and Philip K. Dick Awards. Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) followed after Gibson's popular debut novel. According to the Jargon File, "Gibson's near-total ignorance of computers and the present-day hacker culture enabled him to speculate about the role of computers and hackers in the future in ways hackers have since found both irritatingly naïve and tremendously stimulating."[51] Early on, cyberpunk was hailed as a radical departure from science-fiction standards and a new manifestation of vitality.[52] Shortly thereafter, some critics arose to challenge its status as a revolutionary movement. These critics said that the science fiction New Wave of the 1960s was much more innovative as far as narrative techniques and styles were concerned.[53] While Neuromancer's narrator may have had an unusual "voice" for science fiction, much older examples can be found: Gibson's narrative voice, for example, resembles that of an updated Raymond Chandler, as in his novel The Big Sleep (1939).[52] Others noted that almost all traits claimed to be uniquely cyberpunk could in fact be found in older writers' works—often citing J. G. Ballard, Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Stanisław Lem, Samuel R. Delany, and even William S. Burroughs.[52] For example, Philip K. Dick's works contain recurring themes of social decay, artificial intelligence, paranoia, and blurred lines between objective and subjective realities.[54] The influential cyberpunk movie Blade Runner (1982) is based on his book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.[55] Humans linked to machines are found in Pohl and Kornbluth's Wolfbane (1959) and Roger Zelazny's Creatures of Light and Darkness (1968).[citation needed] In 1994, scholar Brian Stonehill suggested that Thomas Pynchon's 1973 novel Gravity's Rainbow "not only curses but precurses what we now glibly dub cyberspace."[56] Other important predecessors include Alfred Bester's two most celebrated novels, The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination,[57] as well as Vernor Vinge's novella True Names.[58] |

メディア 文学 関連項目: サイバーパンク作品一覧 § 印刷媒体、および フィクションにおけるサイボーグ ミネソタ州の作家ブルース・ベスケが1983年、短編小説『サイバーパンク』でこの用語を考案した。同作は『アメージング・サイエンス・フィクション・ス トーリーズ』誌に掲載された[48]。この用語はすぐにウィリアム・ギブソン、ブルース・スターリング、パット・キャディガンらの作品に適用されるラベル として定着した。この中でスターリングは、自身のファンジン『チープ・トゥルース』を通じて、この運動の主要な思想家となった。ジョン・シャーリーはス ターリングとラッカーの重要性について論じた[49]。ジョン・ブルナーの1975年の小説『衝撃波の騎手』は、ドゾワによって用語が普及する約5年前か ら、このジャンルに共通する多くのトロープを備えた最初のサイバーパンク小説であると多くの者[誰?]によって考えられている。[50] ウィリアム・ギブソンは、小説『ニューロマンサー』(1984年)でサイバーパンクという用語と最も深く結びついた作家と言える。彼は従来のSFの定型よ りも、スタイルや表層への執着、雰囲気を重視した。『ニューロマンサー』は画期的であり、「サイバーパンクの原型となる作品」とも評され[8]、ヒュー ゴー賞、ネビュラ賞、フィリップ・K・ディック賞を受賞した。デビュー作の成功後、1986年に『カウント・ゼロ』、1988年に『モナ・リザ・オーバー ドライブ』を発表した。『ジャルゴン・ファイル』によれば、「ギブソンのコンピュータと現代ハッカー文化に対するほぼ完全な無知が、ハッカーたちが後に 『苛立たしいほど素朴でありながら非常に刺激的』と評する未来像を構想する原動力となった」[51]。 初期のサイバーパンクは、SFの常識からの急進的な脱却と新たな活力の現れとして称賛された[52]。しかし間もなく、革命的運動としての地位に異議を唱 える批評家が現れた。彼らは1960年代のSFニューウェーブの方が、物語技法やスタイルにおいてはるかに革新的だったと主張した。[53] 『ニューロマンサー』の語り手がSFとしては異例の「声」を持っていたとしても、はるかに古い例は存在する。例えばギブソンの語り口は、レイモンド・チャ ンドラーの小説『大いなる眠り』(1939年)を現代風に更新したようなものだ。[52] また、サイバーパンク特有とされる特徴のほとんどは、実際には過去の作家たちの作品に見出せると指摘する者もいた。J・G・バラード、フィリップ・K・ ディック、ハーラン・エリソン、スタニスワフ・レム、サミュエル・R・ディレイニー、さらにはウィリアム・S・バロウズの名がしばしば挙げられた [52]。例えばフィリップ・K・ディックの作品には、社会の衰退、人工知能、パラノイア、客観的現実と主観的現実の境界の曖昧化といったテーマが繰り返 し登場する。[54] 影響力のあるサイバーパンク映画『ブレードランナー』(1982年)は、彼の小説『アンドロイドは電気羊の夢を見るか?』を原作としている。[55] 人間と機械の接続は、ポールとコーンブルースの『ウルフベイン』(1959年)やロジャー・ゼラズニーの『光と闇の生き物たち』(1968年)にも見られ る。[出典必要] 1994年、学者ブライアン・ストーンヒルはトマス・ピンチョンの1973年の小説『重力虹』について「現代で軽々しくサイバースペースと呼ぶものを単に 呪うだけでなく、その前兆を示している」と指摘した。[56] その他の重要な先駆作には、アルフレッド・ベスターの最も評価の高い二作『破壊された男』と『星は我が宿り処』[57]、そしてヴァーナー・ヴィンジの中 編小説『真の名』が含まれる。[58] |

| Reception and impact Science-fiction writer David Brin describes cyberpunk as "the finest free promotion campaign ever waged on behalf of science fiction". It may not have attracted the "real punks", but it did ensnare many new readers, and it provided the sort of movement that postmodern literary critics found alluring. Cyberpunk made science fiction more attractive to academics, argues Brin; in addition, it made science fiction more profitable to Hollywood and to the visual arts generally. Although the "self-important rhetoric and whines of persecution" on the part of cyberpunk fans were irritating at worst and humorous at best, Brin declares that the "rebels did shake things up. We owe them a debt."[59] Fredric Jameson considers cyberpunk the "supreme literary expression if not of postmodernism, then of late capitalism itself".[60] Cyberpunk further inspired many later writers to incorporate cyberpunk ideas into their own works,[citation needed] such as George Alec Effinger's When Gravity Fails. Wired magazine, created by Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe, mixes new technology, art, literature, and current topics in order to interest today's cyberpunk fans, which Paula Yoo claims "proves that hardcore hackers, multimedia junkies, cyberpunks and cellular freaks are poised to take over the world".[61] |

受容と影響 SF作家デイヴィッド・ブリンはサイバーパンクを「SFのために展開された史上最高の無料宣伝キャンペーン」と評している。本物のパンク層を惹きつけられ なかったかもしれないが、多くの新規読者を獲得し、ポストモダン文学批評家が魅了されるような運動を生み出したのだ。ブリンによれば、サイバーパンクは SFを学界にとってより魅力的にした。加えて、ハリウッドや視覚芸術全般にとってSFをより収益性の高いものにした。サイバーパンクファンの「自己重要感 を伴うレトリックや迫害への愚痴」は最悪の場合苛立たしく、最良の場合でも滑稽だったが、ブリンは「反逆者たちは確かに物事を揺さぶった。我々は彼らに借 りを負っている」と宣言している[59]。 フレデリック・ジェイムソンはサイバーパンクを「ポストモダニズムそのものではなくても、後期資本主義そのものの最高の文学的表現」と見なしている。[60] サイバーパンクはさらに多くの後続作家に影響を与え、自らの作品にサイバーパンクの思想を取り入れるよう促した[出典必要]。例えばジョージ・アレック・ エフィンガーの『重力が失われたとき』がそうだ。ルイ・ロセットとジェーン・メトカーフが創刊した『ワイアード』誌は、新技術・芸術・文学・時事問題を融 合させ、現代のサイバーパンク愛好家の関心を引く。ポーラ・ユーによれば、これは「ハードコアなハッカー、マルチメディア中毒者、サイバーパンク、携帯電 話マニアが世界を掌握しようとしている証拠だ」[61]。 |

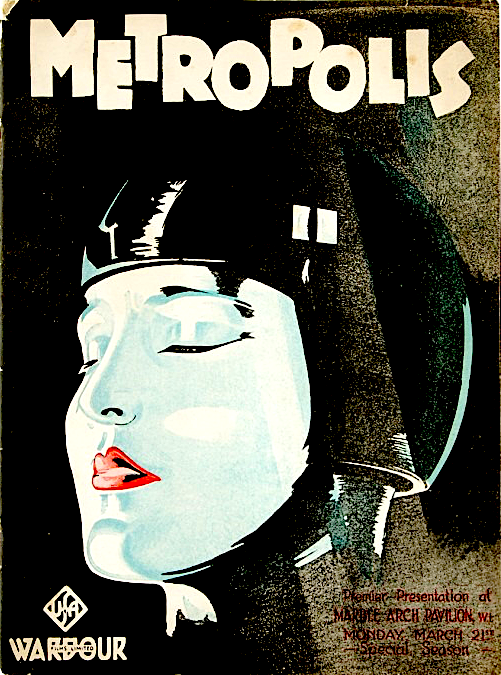

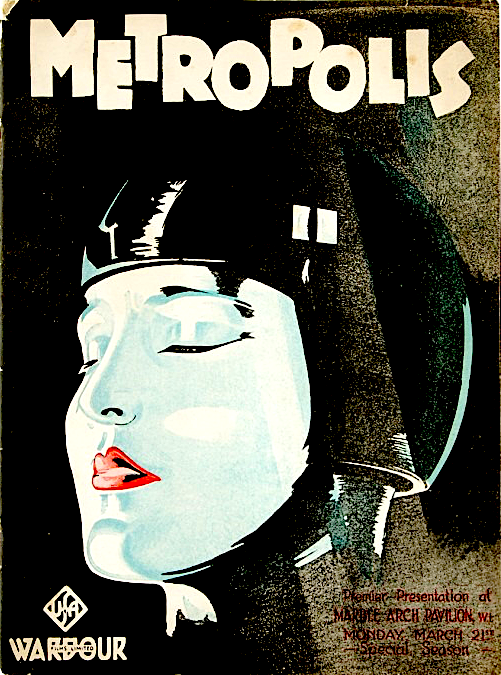

| Film and television See also: List of cyberpunk works § Films, List of cyberpunk works § Television and Web Series, and Japanese cyberpunk  Metropolis, one of the earliest cyberpunk films ever made.[62][63] The film Blade Runner (1982) is set in 2019 in a dystopian future in which manufactured beings called replicants are slaves used on space colonies and are legal prey on Earth to various bounty hunters who "retire" (kill) them. Although Blade Runner was largely unsuccessful in its first theatrical release, it found a viewership in the home video market and became a cult film.[64] Since the movie omits the religious and mythical elements of Dick's original novel (e.g. empathy boxes and Wilbur Mercer), it falls more strictly within the cyberpunk genre than the novel does. William Gibson later revealed that upon first viewing the film, he was surprised at how the look of this film matched his vision for Neuromancer, a book he was then working on. The film's tone has since been the staple of many cyberpunk movies, such as The Matrix trilogy (1999–2003), which uses a wide variety of cyberpunk elements.[65] A sequel to Blade Runner was released in 2017. The TV series Max Headroom (1987) is an iconic cyberpunk work, taking place in a futuristic dystopia ruled by an oligarchy of television networks. Computer hacking played a central role in many of the story lines. Max Headroom has been called "the first cyberpunk television series".[4] The number of films in the genre has grown steadily since Blade Runner. Several of Philip K. Dick's works have been adapted to the silver screen. The films Johnny Mnemonic[5] (1995) and New Rose Hotel[6][7] (1998), both based on short stories by William Gibson, flopped commercially and critically. Other cyberpunk films include RoboCop (1987), Total Recall (1990), Hardware (1990), The Lawnmower Man (1992), 12 Monkeys (1995), Hackers (1995), and Strange Days (1995). Some cyberpunk films have been described as tech-noir, a hybrid genre combining neo-noir and science fiction or cyberpunk. |

映画とテレビ 関連項目:サイバーパンク作品一覧 § 映画、サイバーパンク作品一覧 § テレビ・ウェブシリーズ、日本のサイバーパンク  『メトロポリス』は、史上最も初期のサイバーパンク映画の一つである。[62] [63] 映画『ブレードランナー』(1982年)は2019年を舞台とするディストピア的な未来を描いている。そこではレプリカントと呼ばれる人工生命体が宇宙コ ロニーで奴隷として使われ、地球上では様々な賞金稼ぎにとって合法的な獲物となっている。彼らは「引退」(殺害)されるのだ。ブレードランナーは劇場公開 時にはほとんど成功しなかったが、ホームビデオ市場で観客を獲得し、カルト映画となった。[64] この映画はディック原作の宗教的・神話的要素(共感ボックスやウィルバー・マーサーなど)を省略しているため、小説よりも厳密にサイバーパンクジャンルに 分類される。ウィリアム・ギブソンは後に、本作を初めて観た際、当時執筆中だった『ニューロマンサー』のイメージと映像が驚くほど一致していたと明かして いる。この映画のトーンはその後、数多くのサイバーパンク映画の基本となった。例えば『マトリックス』三部作(1999-2003)は多様なサイバーパン ク要素を採用している。[65] 『ブレードランナー』の続編は2017年に公開された。 テレビシリーズ『マックス・ヘッドルーム』(1987年)は象徴的なサイバーパンク作品であり、テレビネットワークの寡頭支配下にある未来のディストピア を舞台としている。コンピュータハッキングが多くのストーリーラインで中心的な役割を果たした。『マックス・ヘッドルーム』は「最初のサイバーパンクテレ ビシリーズ」と呼ばれている。[4] このジャンルの映画数は『ブレードランナー』以降着実に増加している。フィリップ・K・ディックの作品のいくつかは銀幕に翻案された。ウィリアム・ギブソ ンの短編小説を基にした映画『ジョニー・ムネモニック』[5](1995年)と『ニュー・ローズ・ホテル』[6][7](1998年)は、商業的にも批評 的にも失敗に終わった。その他のサイバーパンク映画には『ロボコップ』(1987年)、『トータル・リコール』(1990年)、『ハードウェア』 (1990年)、『ザ・ローンモアー・マン』(1992年)、『12モンキーズ』(1995年)、『ハッカーズ』(1995年)、『ストレンジ・デイズ』 (1995年)などがある。一部のサイバーパンク映画は、ネオノワールとSFあるいはサイバーパンクを融合したハイブリッドジャンルである「テックノワー ル」と評されている。 |

| Anime and manga Main article: Japanese cyberpunk See also: List of cyberpunk works § Animation, and List of cyberpunk works § Graphic novels and comics The Japanese cyberpunk subgenre began in 1982 with the debut of Katsuhiro Otomo's manga series Akira, with its 1988 anime film adaptation, which Otomo directed, later popularizing the subgenre. Akira inspired a wave of Japanese cyberpunk works, including manga and anime series such as Ghost in the Shell, Battle Angel Alita, and Cowboy Bebop.[66] Other early Japanese cyberpunk works include the 1982 film Burst City, and the 1989 film Tetsuo: The Iron Man. According to Paul Gravett, when Akira began to be published, cyberpunk literature had not yet been translated into Japanese, Otomo has distinct inspirations such as Mitsuteru Yokoyama's manga series Tetsujin 28-go (1956–1966) and Moebius.[67] In contrast to Western cyberpunk which has roots in New Wave science fiction literature, Japanese cyberpunk has roots in underground music culture, specifically the Japanese punk subculture that arose from the Japanese punk music scene in the 1970s. The filmmaker Sogo Ishii introduced this subculture to Japanese cinema with the punk film Panic High School (1978) and the punk biker film Crazy Thunder Road (1980), both portraying the rebellion and anarchy associated with punk, and the latter featuring a punk biker gang aesthetic. Ishii's punk films paved the way for Otomo's seminal cyberpunk work Akira.[68] Cyberpunk themes are widely visible in anime and manga. In Japan, where cosplay is popular and not only teenagers display such fashion styles, cyberpunk has been accepted and its influence is widespread. William Gibson's Neuromancer, whose influence dominated the early cyberpunk movement, was also set in Chiba, one of Japan's largest industrial areas, although at the time of writing the novel Gibson did not know the location of Chiba and had no idea how perfectly it fit his vision in some ways. The exposure to cyberpunk ideas and fiction in the 1980s has allowed it to seep into the Japanese culture. Cyberpunk anime and manga draw upon a futuristic vision which has elements in common with Western science fiction and therefore have received wide international acceptance outside Japan. "The conceptualization involved in cyberpunk is more of forging ahead, looking at the new global culture. It is a culture that does not exist right now, so the Japanese concept of a cyberpunk future, seems just as valid as a Western one, especially as Western cyberpunk often incorporates many Japanese elements."[69] William Gibson is now a frequent visitor to Japan, and he came to see that many of his visions of Japan have become a reality: Modern Japan simply was cyberpunk. The Japanese themselves knew it and delighted in it. I remember my first glimpse of Shibuya, when one of the young Tokyo journalists who had taken me there, his face drenched with the light of a thousand media-suns—all that towering, animated crawl of commercial information—said, "You see? You see? It is Blade Runner town." And it was. It so evidently was.[37] |

アニメとマンガ メイン記事: 日本のサイバーパンク 関連項目: サイバーパンク作品一覧 § アニメーション、および サイバーパンク作品一覧 § グラフィックノベルとコミック 日本のサイバーパンクサブジャンルは、1982年に大友克洋の漫画シリーズ『AKIRA』がデビューしたことで始まった。1988年には大友自身が監督し たアニメ映画化作品が制作され、このサブジャンルを広く普及させた。『AKIRA』は『攻殻機動隊』『バートン・エンジェル・アリタ』『カウボーイビバッ プ』などの漫画・アニメシリーズを含む、日本のサイバーパンク作品の波を巻き起こした。その他の初期の日本のサイバーパンク作品には、1982年の映画 『バースト・シティ』や1989年の映画『鉄男』がある。 ポール・グラベットによれば、『AKIRA』の連載開始当時、サイバーパンク文学はまだ日本語に翻訳されていなかった。大友は横山光輝の漫画『鉄人28号』(1956-1966年)やメビウスなど、明確な影響源を持っている。[67] 西洋のサイバーパンクがニューウェーブSF文学に起源を持つ一方、日本のサイバーパンクはアンダーグラウンド音楽文化、特に1970年代の日本のパンク音 楽シーンから生まれた日本のパンクサブカルチャーに起源を持つ。映画監督・石井聰俑はパンク映画『パニック・ハイスクール』(1978年)とパンク・バイ カー映画『クレイジー・サンダーロード』(1980年)でこのサブカルチャーを日本映画に導入した。両作ともパンクにまつわる反逆と無秩序を描き、後者は パンク・バイカーギャングの美学を特徴としている。石井のパンク映画は大友の画期的なサイバーパンク作品『AKIRA』への道を開いた。[68] サイバーパンクのテーマはアニメやマンガに広く見られる。コスプレが流行し、若者だけでなく様々な世代がそのようなファッションスタイルを身につける日本 では、サイバーパンクは受け入れられ、その影響は広範に及んでいる。初期サイバーパンク運動に決定的な影響を与えたウィリアム・ギブソンの『ニューロマン サー』も、日本の主要工業地帯である千葉を舞台としている。ただし小説執筆当時、ギブソンは千葉の場所を知らず、その場所が自身の構想にどれほど完璧に合 致するかも全く認識していなかった。1980年代におけるサイバーパンク思想やフィクションへの接触が、日本文化への浸透を可能にしたのである。 サイバーパンクアニメやマンガは、西洋のSFと共通要素を持つ未来像を基にしているため、日本国外でも広く受け入れられている。「サイバーパンクにおける 概念化は、むしろ新たなグローバル文化を見据えて前進する姿勢だ。それは現時点では存在しない文化であるため、日本のサイバーパンク的未来像は西洋のもの と同様に妥当性を持つ。特に西洋のサイバーパンクは多くの日本的要素を取り込んでいるからだ」[69]ウィリアム・ギブソンは現在、頻繁に日本を訪れてい る。彼は自らの描いた日本の未来像の多くが現実となったことを目の当たりにしたのだ: 現代の日本はまさにサイバーパンクだった。日本人自身もそれを自覚し、楽しんでいた。初めて渋谷を見た時のことを覚えている。私を案内した東京の若い ジャーナリストが、メディアの太陽が千個も降り注ぐような光に顔を照らしながら――あの高くそびえ立つ、動く商業情報の流れを見ながら――言ったのだ。 「ほら? ほら? これがブレードランナーの街だ」と。そしてそれは確かにそうだった。あまりにも明白にそうだったのだ。[37] |

| Influence Akira (1982 manga) and its 1988 anime film adaptation have influenced numerous works in animation, comics, film, music, television and video games.[70][71] Akira has been cited as a major influence on Hollywood films such as The Matrix,[72] Chronicle,[73] Looper,[74] Midnight Special, and Inception,[70] as well as cyberpunk-influenced video games such as Hideo Kojima's Snatcher[75] and Metal Gear Solid,[66] Valve's Half-Life series[76][77] and Dontnod Entertainment's Remember Me.[78] Akira has also influenced the work of musicians such as Kanye West, who paid homage to Akira in the "Stronger" music video,[70] and Lupe Fiasco, whose album Tetsuo & Youth is named after Tetsuo Shima.[79] The popular bike from the film, Kaneda's Motorbike, appears in Steven Spielberg's film Ready Player One,[80] and CD Projekt's video game Cyberpunk 2077.[81] An interpretation of digital rain, similar to the images used in Ghost in the Shell and later in The Matrix Ghost in the Shell (1995) influenced a number of prominent filmmakers, most notably the Wachowskis in The Matrix (1999) and its sequels.[82] The Matrix series took several concepts from the film, including the Matrix digital rain, which was inspired by the opening credits of Ghost in the Shell and a sushi magazine the wife of the senior designer of the animation, Simon Witheley, had in the kitchen at the time,[83] and the way characters access the Matrix through holes in the back of their necks.[84] Other parallels have been drawn to James Cameron's Avatar, Steven Spielberg's A.I. Artificial Intelligence, and Jonathan Mostow's Surrogates.[84] James Cameron cited Ghost in the Shell as a source of inspiration,[85] citing it as an influence on Avatar.[86] The original video animation Megazone 23 (1985) has a number of similarities to The Matrix.[87] Battle Angel Alita (1990) has had a notable influence on filmmaker James Cameron, who was planning to adapt it into a film since 2000. It was an influence on his TV series Dark Angel, and he is the producer of the 2019 film adaptation Alita: Battle Angel.[88] Comics In 1975, artist Moebius collaborated with writer Dan O'Bannon on a story called The Long Tomorrow, published in the French magazine Métal Hurlant. One of the first works featuring elements now seen as exemplifying cyberpunk, it combined influences from film noir and hardboiled crime fiction with a distant sci-fi environment.[89] Author William Gibson stated that Moebius' artwork for the series, along with other visuals from Métal Hurlant, strongly influenced his 1984 novel Neuromancer.[90] The series had a far-reaching impact in the cyberpunk genre,[91] being cited as an influence on Ridley Scott's Alien (1979) and Blade Runner.[92] Moebius expanded upon The Long Tomorrow's aesthetic with The Incal, a graphic novel collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky published from 1980 to 1988. The story centers around the exploits of a detective named John Difool in various science fiction settings, and while not confined to the tropes of cyberpunk, it features many elements of the genre.[93] Moebius was one of the designers of Tron (1982), a movie that shows a world inside a computer.[94] Concurrently with many other foundational cyberpunk works, DC Comics published Frank Miller's six-issue miniseries Rōnin from 1983 to 1984. The series, incorporating aspects of Samurai culture, martial arts films and manga, is set in a dystopian near-future New York. It explores the link between an ancient Japanese warrior and the apocalyptic, crumbling cityscape he finds himself in. The comic also bears several similarities to Akira,[95] with highly powerful telepaths playing central roles, as well as sharing many key visuals.[96] Rōnin would go on to influence many later works, including Samurai Jack[97] and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,[98] as well as video games such as Cyberpunk 2077.[99] Two years later, Miller himself would incorporate several toned-down elements of Rōnin into his acclaimed 1986 miniseries The Dark Knight Returns, in which a retired Bruce Wayne once again takes up the mantle of Batman in a Gotham that is increasingly becoming more dystopian.[100] Paul Pope's Batman: Year 100, published in 2006, also exhibits several traits typical of cyberpunk fiction, such as a rebel protagonist opposing a future authoritarian state, and a distinct retrofuturist aesthetic that makes callbacks to both The Dark Knight Returns and Batman's original appearances in the 1940s.[101] |

影響 『AKIRA』(1982年漫画)とその1988年のアニメ映画化作品は、アニメーション、コミック、映画、音楽、テレビ、ビデオゲームなど数多くの作品 に影響を与えた。[70][71] 『マトリックス』[72]、『クロニクル』[73]、『ルーパー』[74]、『ミッドナイト・スペシャル』、『インセプション』[70]といったハリウッ ド映画や、小島秀夫の『スナッチャー』[75]や『メタルギアソリッド』 [66] バルブの『ハーフライフ』シリーズ[76][77]、ドンノッド・エンターテインメントの『リメンバー・ミー』[78]などにも影響を与えている。 『AKIRA』はミュージシャンの作品にも影響を及ぼしており、カニエ・ウェストは「ストロンガー」のミュージックビデオで『AKIRA』へのオマージュ を捧げ[70]、ルペ・フィアスコはアルバム『鉄雄&ユース』のタイトルを島鉄雄に因んで名付けた。[79] 映画に登場する人気のバイク「金田のマシン」は、スティーヴン・スピルバーグ監督の映画『レディ・プレイヤー1』[80]や、CD Projektのビデオゲーム『サイバーパンク2077』[81]にも登場している。 デジタルレインの解釈は、『攻殻機動隊』や後に『マトリックス』で使用された映像と類似している 『攻殻機動隊』(1995年)は数多くの著名な映画製作者に影響を与えた。特にウォシャウスキー兄弟の『マトリックス』(1999年)とその続編が顕著で ある。[82] 『マトリックス』シリーズは本作から複数の概念を借用している。例えばマトリックスのデジタルレインは、『攻殻機動隊』のオープニングクレジットと、当時 アニメーション上級デザイナーのサイモン・ウィズリーの妻が台所に置いていた寿司雑誌から着想を得た[83]。またキャラクターが首の後ろの穴からマト リックスにアクセスする手法も同様である。[84] 他にもジェームズ・キャメロンの『アバター』、スティーヴン・スピルバーグの『A.I.』ジョナサン・モストウの『サロゲート』との類似点が指摘されてい る。[84] ジェームズ・キャメロンは『攻殻機動隊』をインスピレーションの源として挙げ、[85] 『アバター』への影響を認めている。[86] オリジナルビデオアニメ『メガゾーン23』(1985年)は『マトリックス』と多くの類似点を持つ[87]。『バトル・エンジェル アリタ』(1990年)は映画監督ジェームズ・キャメロンに顕著な影響を与え、彼は2000年から映画化を計画していた。この作品は彼のテレビシリーズ 『ダーク・エンジェル』に影響を与え、彼は2019年の映画化作品『アリータ: バトル・エンジェル』のプロデューサーを務めた。[88] コミック 1975年、アーティストのメビウスは作家ダン・オバノンと共同で『ロング・トゥモロー』という物語を制作し、フランスの雑誌『メタル・ユルラン』に掲載 した。後にサイバーパンクの典型と見なされる要素を初めて取り入れた作品の一つであり、フィルム・ノワールやハードボイルド犯罪小説の影響と、遠い未来の SF的環境を融合させていた。[89] 作家ウィリアム・ギブソンは、モービウスの本シリーズにおけるアートワークや『メタル・ユルラン』の他のビジュアルが、自身の1984年の小説『ニューロ マンサー』に強く影響を与えたと述べている。[90] 本シリーズはサイバーパンクジャンルに広範な影響を与え[91]、リドリー・スコットの『エイリアン』(1979年)や『ブレードランナー』への影響源と して引用されている。[92] メビウスは『ロング・トゥモロー』の美学を、アレハンドロ・ホドロフスキーとの共同グラフィックノベル『インカル』(1980-1988年刊行)で発展さ せた。物語はジョン・ディフールという探偵の活躍を様々なSF設定で描くもので、サイバーパンクの定型に限定されないが、同ジャンルの要素を多く含む。 [93] モービウスは映画『トロン』(1982年)のデザイン担当者の一人だった。この作品はコンピューター内部の世界を描いている。 [94] 他の多くのサイバーパンク作品と同時期に、DCコミックスはフランク・ミラーの6号連続ミニシリーズ『ローニン』を1983年から1984年にかけて刊行 した。このシリーズは、侍文化、武術映画、マンガの要素を取り入れ、ディストピア的な近未来のニューヨークを舞台としている。古代日本の戦士と、彼が身を 置く終末的で崩壊しつつある都市景観との繋がりを探求している。このコミックは『AKIRA』[95]とも幾つかの類似点があり、強力なテレパシー能力者 が中心的な役割を果たすほか、多くの重要なビジュアルを共有している。[96] 『ローニン』は後に『サムライジャック』[97]や『ティーンエイジ・ミュータント・ニンジャ・タートルズ』[98]をはじめ、ビデオゲーム『サイバーパ ンク2077』など多くの作品に影響を与えた。[99] 2年後、ミラー自身は『浪人』の幾つかの要素を緩和して、1986年に発表された高評価のミニシリーズ『ダークナイト・リターンズ』に組み込んだ。この作 品では、引退したブルース・ウェインが、ますますディストピア化していくゴッサムで再びバットマンの役割を担う。[100] ポール・ポープの『バットマン:イヤー100』(2006年刊)もまた、反体制の主人公が未来の権威主義国家に立ち向かうといったサイバーパンク小説の典 型的な特徴や、『ダークナイト・リターンズ』と1940年代のバットマン初登場作の両方を想起させる独特のレトロフューチャリスティックな美学を示してい る。[101] |

| Video games See also: List of cyberpunk works § Video games, and List of cyberpunk works § Role-playing games There are many cyberpunk video games. Popular series include the Megami Tensei series, Kojima's Snatcher and Metal Gear series, Deus Ex series, Syndicate series, and System Shock and its sequel. Other games, like Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, and the Matrix series, are based upon genre movies, or role-playing games (for instance the various Shadowrun games). Several RPGs called Cyberpunk exist: Cyberpunk, Cyberpunk 2020, Cyberpunk v3.0 and Cyberpunk Red written by Mike Pondsmith and published by R. Talsorian Games, and GURPS Cyberpunk, published by Steve Jackson Games as a module of the GURPS family of RPGs. Cyberpunk 2020 was designed with the settings of William Gibson's writings in mind, and to some extent with his approval,[102] unlike the approach taken by FASA in producing the transgenre Shadowrun game and its various sequels, which mixes cyberpunk with fantasy elements such as magic and fantasy races such as orcs and elves. Both are set in the near future, in a world where cybernetics are prominent. Iron Crown Enterprises released an RPG named Cyberspace, which was out of print for several years until recently being re-released in online PDF form. CD Projekt Red released Cyberpunk 2077, a cyberpunk open world first-person shooter/role-playing video game (RPG) based on the tabletop RPG Cyberpunk 2020, on December 10, 2020.[103][104][105] In 1990, in a convergence of cyberpunk art and reality, the United States Secret Service raided Steve Jackson Games's headquarters and confiscated all their computers. Officials denied that the target had been the GURPS Cyberpunk sourcebook, but Jackson later wrote that he and his colleagues "were never able to secure the return of the complete manuscript; [...] The Secret Service at first flatly refused to return anything – then agreed to let us copy files, but when we got to their office, restricted us to one set of out-of-date files – then agreed to make copies for us, but said "tomorrow" every day from March 4 to March 26. On March 26 we received a set of disks which purported to be our files, but the material was late, incomplete and well-nigh useless."[106] Steve Jackson Games won a lawsuit against the Secret Service, aided by the new Electronic Frontier Foundation. This event has achieved a sort of notoriety, which has extended to the book itself as well. All published editions of GURPS Cyberpunk have a tagline on the front cover, which reads "The book that was seized by the U.S. Secret Service!" Inside, the book provides a summary of the raid and its aftermath. Cyberpunk has also inspired several tabletop, miniature and board games such as Necromunda by Games Workshop. Netrunner is a collectible card game introduced in 1996, based on the Cyberpunk 2020 role-playing game. Tokyo NOVA, debuting in 1993, is a cyberpunk role-playing game that uses playing cards instead of dice. Music See also: List of cyberpunk works § Music Much of the industrial/dance heavy "Cyberpunk"—recorded in Billy Idol's Macintosh-run studio—revolves around Idol's theme of the common man rising up to fight against a faceless, soulless, corporate world. —Julie Romandetta[107] Invariably the origin of cyberpunk music lies in the synthesizer-heavy scores of cyberpunk films such as Escape from New York (1981) and Blade Runner (1982).[108] Some musicians and acts have been classified as cyberpunk due to their aesthetic style and musical content. Often dealing with dystopian visions of the future or biomechanical themes, some fit more squarely in the category than others. Bands whose music has been classified as cyberpunk include Psydoll,[109] Front Line Assembly,[110] Clock DVA,[111]Angelspit[112] and Sigue Sigue Sputnik.[113] Some musicians not normally associated with cyberpunk have at times been inspired to create concept albums exploring such themes. Albums such as the British musician and songwriter Gary Numan's Replicas, The Pleasure Principle and Telekon were heavily inspired by the works of Philip K. Dick. Kraftwerk's The Man-Machine and Computer World albums both explored the theme of humanity becoming dependent on technology. Nine Inch Nails' concept album Year Zero also fits into this category. Fear Factory concept albums are heavily based upon future dystopia, cybernetics, clash between man and machines, virtual worlds. Billy Idol's Cyberpunk drew heavily from cyberpunk literature and the cyberdelic counter culture in its creation. 1. Outside, a cyberpunk narrative fueled concept album by David Bowie, was warmly met by critics upon its release in 1995. Many musicians have also taken inspiration from specific cyberpunk works or authors, including Sonic Youth, whose albums Sister and Daydream Nation take influence from the works of Philip K. Dick and William Gibson respectively. Madonna's 2001 Drowned World Tour opened with a cyberpunk section, where costumes, asethetics and stage props were used to accentuate the dystopian nature of the theatrical concert.[citation needed] Lady Gaga used a cyberpunk-persona and visual style for her sixth studio album Chromatica (2020).[114][115] Vaporwave and synthwave are also influenced by cyberpunk. The former has been inspired by one of the messages of cyberpunk and is interpreted as a dystopian[116] critique of capitalism[117] in the vein of cyberpunk and the latter is more surface-level, inspired only by the aesthetic of cyberpunk as a nostalgic retrofuturistic revival of aspects of cyberpunk's origins. |

ビデオゲーム 関連項目: サイバーパンク作品一覧 § ビデオゲーム、および サイバーパンク作品一覧 § ロールプレイングゲーム サイバーパンクをテーマにしたビデオゲームは数多く存在する。人気シリーズには『女神転生』シリーズ、小島秀夫の『スナッチャー』及び『メタルギア』シ リーズ、『デウスエクス』シリーズ、『シンジケート』シリーズ、『システムショック』とその続編などがある。その他にも『ブレードランナー』、『攻殻機動 隊』、『マトリックス』シリーズといった映画を原作とした作品や、ロールプレイングゲーム(例えば各種『シャドウラン』ゲームなど)も存在する。 『サイバーパンク』という名のRPGが複数存在する:マイク・ポンドスミスが執筆しR.タルソリアン・ゲームズが発行した『サイバーパンク』『サイバーパ ンク2020』『サイバーパンクv3.0』『サイバーパンク・レッド』、そしてスティーブ・ジャクソン・ゲームズがGURPS RPGシリーズのモジュールとして発行した『GURPS サイバーパンク』である。『サイバーパンク2020』はウィリアム・ギブソンの著作の世界観を念頭に設計され、ある程度彼の承認を得ていた[102]。こ れはFASAが制作したトランスジャンル作品『シャドウラン』とその続編群のアプローチとは異なる。後者はサイバーパンクに魔法やオーク・エルフといった ファンタジー種族といった要素を混ぜている。両者とも近未来を舞台とし、サイバネティクスが顕著な世界観を持つ。アイアン・クラウン・エンタープライズは 『サイバースペース』というRPGを発売したが、数年間絶版状態だった後、最近オンラインPDF形式で再発売された。CD Projekt Redは2020年12月10日、テーブルトップRPG『サイバーパンク2020』を基にしたサイバーパンク系オープンワールドFPS/RPG『サイバー パンク2077』を発売した[103][104]。[105] 1990年、サイバーパンク芸術と現実が交錯する中、アメリカ合衆国シークレットサービスがスティーブ・ジャクソン・ゲームズ本社を急襲し、全コンピュー ターを押収した。当局は標的が『GURPS サイバーパンク』ソースブックではなかったと否定したが、ジャクソンは後に「完全な原稿の返還を確約できなかった」と記している。[...] 秘密捜査局は当初、一切の返還を断固拒否した。その後、ファイルのコピーを許可すると言いながら、実際に事務所に行くと、古いファイルの一式しか渡さな かった。さらにコピーを作成すると言いながら、3月4日から26日まで毎日「明日」と言い続けた。3月26日、我々のファイルと称するディスク一式を受け 取ったが、内容は遅れており、不完全で、ほぼ無用の長物だった。」[106] スティーブ・ジャクソン・ゲームズは、新たに設立された電子フロンティア財団の支援を得て、シークレットサービスに対する訴訟に勝訴した。この事件は一種 の悪名を得て、その悪名は書籍自体にも及んでいる。GURPSサイバーパンクの全出版版には表紙に「米国シークレットサービスに押収された本!」という キャッチコピーが記載されている。内部では、押収事件とその余波の概要が説明されている。 サイバーパンクはまた、ゲームズワークショップの『ネクロムンダ』など、複数のテーブルトップゲーム、ミニチュアゲーム、ボードゲームに影響を与えた。 1996年に発表されたコレクティブルカードゲーム『ネットランナー』は、サイバーパンク2020ロールプレイングゲームを基にしている。1993年にデ ビューした『東京ノヴァ』は、サイバーパンクロールプレイングゲームであり、ダイスの代わりにトランプを使用する。 音楽 関連項目: サイバーパンク作品一覧 § 音楽 ビリー・アイドルのマッキントッシュ製スタジオで録音された、インダストリアル/ダンス色の強い「サイバーパンク」の多くは、アイドルが掲げる「無名の魂なき企業世界に立ち向かう庶民」というテーマを中心に展開している。 —ジュリー・ロマンデッタ [107] サイバーパンク音楽の起源は、必ずと言っていいほど『ニューヨーク1997』(1981年)や『ブレードランナー』(1982年)といったサイバーパンク 映画のシンセサイザー主体のサウンドトラックにある。[108] 一部のミュージシャンやグループは、その美的スタイルや音楽的内容からサイバーパンクに分類されてきた。未来のディストピア的ビジョンや生体機械的テーマ を扱うことが多く、他よりも明確にこのカテゴリーに当てはまる者もいる。サイバーパンクと分類される音楽を手がけるバンドには、サイドール[109]、フ ロント・ライン・アセンブリー[110]、クロックDVA[111]、エンジェルスピット[112]、シグ・シグ・スプートニクなどがいる。[113] 通常サイバーパンクと関連付けられないミュージシャンも、こうしたテーマを探求するコンセプトアルバム制作にインスピレーションを得ることがある。英国の ミュージシャン兼ソングライター、ゲイリー・ニューマンの『レプリカズ』『ザ・プレジャー・プリンシプル』『テレコン』といったアルバムは、フィリップ・ K・ディックの作品から強い影響を受けている。クラフトワークの『ザ・マン・マシン』と『コンピュータ・ワールド』の両アルバムは、人類が技術に依存する ようになるというテーマを探求した。ナイン・インチ・ネイルズのコンセプトアルバム『イヤー・ゼロ』もこのカテゴリーに当てはまる。フィア・ファクトリー のコンセプトアルバムは、未来のディストピア、サイバネティクス、人間と機械の衝突、仮想世界などを強く基調としている。 ビリー・アイドルの『サイバーパンク』は、制作過程でサイバーパンク文学とサイバーデリックなカウンターカルチャーから大きく影響を受けた。1. デイヴィッド・ボウイのコンセプトアルバム『アウトサイド』は、サイバーパンク的な物語性で構成され、1995年のリリース時に批評家から好評を得た。多 くのミュージシャンも特定のサイバーパンク作品や作家から着想を得ており、ソニック・ユースのアルバム『シスター』と『デイドリーム・ネイション』はそれ ぞれフィリップ・K・ディックとウィリアム・ギブソンの作品に影響を受けている。マドンナの2001年『ドローン・ワールド・ツアー』は、衣装・美学・舞 台装置を用いて演劇的コンサートのディストピア的性質を強調したサイバーパンク・セクションで幕を開けた。レディー・ガガは6作目のスタジオアルバム『ク ロマティカ』(2020年)でサイバーパンク的なペルソナとビジュアルスタイルを採用した。 ヴェイパーウェイブとシンセウェーブもサイバーパンクの影響を受けている。前者はサイバーパンクのメッセージの一つに触発され、サイバーパンクの流れをく む資本主義へのディストピア的批判と解釈される。後者はより表層的で、サイバーパンクの起源の側面をノスタルジックなレトロフューチャリスティックな復興 として、その美学のみに触発されている。 |

| Social impact |

Social impactはこのページの上部に移転している |

| Registered trademark status In the United States, the term "Cyberpunk" is a registered trademark owned by CD Projekt SA who obtained it from the previous owner R. Talsorian Games Inc. who originally registered it for its tabletop role-playing game.[121] R. Talsorian Games currently used the trademark under license from CD Projekt SA for the tabletop role-playing game.[122] Within the European Union, the "Cyberpunk" trademark is owned by two parties: CD Projekt SA for "games and online gaming services"[123] (particularly for the video game adaptation of the former) and by Sony Music for use outside games.[124] |

登録商標の地位 米国において、「サイバーパンク」という用語はCD Projekt SAが所有する登録商標である。同社は、元所有者であるR. Talsorian Games Inc.からこの商標を取得した。同社は当初、自社のテーブルトップロールプレイングゲームのためにこの商標を登録していた。[121] R. Talsorian Gamesは現在、CD Projekt SAからのライセンスに基づき、テーブルトップロールプレイングゲームにおいてこの商標を使用している。[122] 欧州連合内では、「サイバーパンク」商標は二つの当事者が所有している。CD Projekt SAが「ゲーム及びオンラインゲームサービス」[123](特に前者のビデオゲーム化作品)について、ソニー・ミュージックがゲーム以外の用途について所有している。[124] |

| Corporate warfare Cyborg Digital dystopia Postcyberpunk Posthumanization Steampunk Solarpunk Utopian and dystopian fiction |

企業戦争 サイボーグ デジタルディストピア ポストサイバーパンク ポストヒューマニゼーション スチームパンク ソーラーパンク ユートピアとディストピア小説 |

| Further reading Bould, Mark (2005). "Cyberpunk". A Companion to Science Fiction. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 217–231. doi:10.1002/9780470997055.ch15. ISBN 978-0-470-99705-5. O'Connell, Hugh Charles (2022). "Cyberpunk". In O'Donnell, Patrick; Burn, Stephen J.; Larkin, Lesley (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Fiction 1980–2020. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1002/9781119431732.ecaf0155. ISBN 978-1-119-43173-2. McFarlane Anna; Schmeink Lars; Murphy Graham, eds. (2019). The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351139885. ISBN 9781351139885. Murphy Graham; Schmeink Lars, eds. (2018). Cyberpunk and visual culture (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138062917. |

参考文献 Bould, Mark (2005). 「サイバーパンク」. 『サイエンスフィクション事典』. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 217–231. doi:10.1002/9780470997055.ch15. ISBN 978-0-470-99705-5. オコネル、ヒュー・チャールズ(2022)。「サイバーパンク」。オドネル、パトリック;バーン、スティーブン・J.;ラーキン、レスリー(編)。『現代 アメリカ小説事典 1980–2020』。ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ。pp. 1–11。doi:10.1002/9781119431732.ecaf0155。ISBN 978-1-119-43173-2。 マクファーレン・アンナ、シュメインク・ラース、マーフィー・グラハム編(2019)。『サイバーパンク文化のラウトレッジ・コンパニオン』(第 1 版)。ニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ。doi:10.4324/9781351139885。ISBN 9781351139885。 マーフィー、グラハム、シュメインク、ラース編(2018)。『サイバーパンクと視覚文化』(第 1 版)。ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ。ISBN 9781138062917。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberpunk |

文献

サイト内リンク

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099