ディ-オ あるいはバナナボートソング

Day-O, or The Banana Boat Song

[alternative] Harry

Belafonte - Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) (Live)

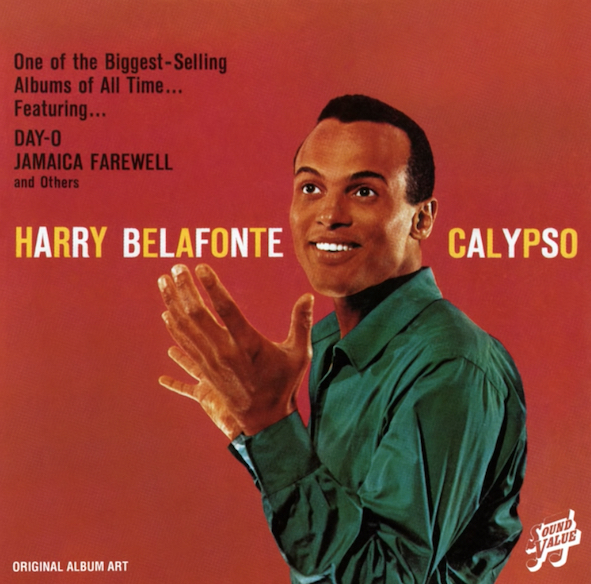

☆ 「Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)」は、ジャマイカの伝統的なフォークソングである。この曲はメントの影響を受けているが、一般的には、よりよく知られたカリプソ音楽の一例とし て分類されている。バナナを船に積み込む夜勤の港湾労働者の視点に立った、コール・アンド・レスポンスの労働歌である。歌詞の内容は、日が暮れてシフトが 終わり、家に帰るために自分の仕事を数えてほしいというものだ。最もよく知られたバージョンは、ジャマイカ系アメリカ人シンガーのハリー・ベラフォンテが1956年に発表したもの(原題は "Banana Boat (Day-O)")で、後に彼の代表曲のひとつとなった。ベラフォンテは2011年、PBS NewsHourのグウェン・イフィルとのインタビューで、「Day-O」を「植民地化された生活の中で、最も過酷な仕事をしている黒人についての、闘争 についての歌」と語っている。「私はその歌を、世界が愛するアンセムに磨き上げた」。

| "Day-O

(The Banana Boat Song)" is a traditional Jamaican folk song. The

song has mento influences, but it is commonly classified as an example

of the better known calypso music. It is a call and response work song, from the point of view of dock workers working the night shift loading bananas onto ships. The lyrics describe how daylight has come, their shift is over, and they want their work to be counted up so that they can go home. The best-known version was released by Jamaican-American singer Harry Belafonte in 1956 (originally titled "Banana Boat (Day-O)") and later became one of his signature songs. That same year the Tarriers released an alternative version that incorporated the chorus of another Jamaican call and response folk song, "Hill and Gully Rider". Both versions became simultaneously popular the following year, placing 5th and 6th on the 20 February 1957, US Top 40 Singles chart.[2] The Tarriers version was covered multiple times in 1956 and 1957, including by the Fontane Sisters, Sarah Vaughan, Steve Lawrence, and Shirley Bassey, all of whom charted in the top 40 in their respective countries.[3] Belafonte described "Day-O" as "a song about struggle, about black people in a colonized life doing the most grueling work," in a 2011 interview with Gwen Ifill on PBS NewsHour. "I took that song and honed it into an anthem that the world loved." |

「Day-O (The Banana Boat

Song)」は、ジャマイカの伝統的なフォークソングである。この曲はメント(mento)の影響を受けているが、一般的には、よりよく知られたカリプソ音楽の一例とし

て分類されている。 バナナを船に積み込む夜勤の港湾労働者の視点に立った、コール・アンド・レスポンスの労働歌である。歌詞の内容は、日が暮れてシフトが終わり、家に帰るた めに自分の仕事を数えてほしいというものだ。 最もよく知られたバージョンは、ジャマイカ系アメリカ人シンガーのハリー・ベラフォンテが1956年に発表したもの(原題は "Banana Boat (Day-O)")で、後に彼の代表曲のひとつとなった。同じ年、タリアーズが別のジャマイカのコール&レスポンス民謡「Hill and Gully Rider」のコーラスを取り入れた別バージョンを発表。タリアーズのヴァージョンは1956年と1957年に何度もカヴァーされ、その中にはフォンタ ン・シスターズ、サラ・ヴォーン、スティーヴ・ローレンス、シャーリー・バッシーも含まれており、彼らは皆それぞれの国でトップ40にチャートインした [3]。 ベラフォンテは2011年、PBS NewsHourのグウェン・イフィルとのインタビューで、「Day-O」を「植民地化された生活の中で、最も過酷な仕事をしている黒人についての、闘争 についての歌」と語っている。「私はその歌を、世界が愛するアンセムに磨き上げた」。 |

| History "The Banana Boat Song" likely originated around the beginning of the 20th century when the banana trade in Jamaica was growing. It was sung by Jamaican dockworkers, who typically worked at night to avoid the heat of the daytime sun. When daylight arrived, they knew that their boss would arrive to tally the bananas so they could go home.[4] The song was first recorded by Trinidadian singer Edric Connor and his band the Caribbeans on the 1952 album Songs from Jamaica; the song was called "Day Dah Light".[5] Belafonte based his version on Connor's 1952 and Louise Bennett's 1954 recordings.[6][7] In 1955, American singer-songwriters Lord Burgess and William Attaway wrote a version of the lyrics for The Colgate Comedy Hour, in which the song was performed by Harry Belafonte.[8] Belafonte recorded the song for RCA Victor and this is the version that is best known to listeners today, as it reached number five on the Billboard charts in 1957 and later became Belafonte's signature song. Side two of Belafonte's 1956 Calypso album opens with "Star O", a song referring to the day shift ending when the first star is seen in the sky. During recording, when asked for its title, Harry spells, "Day Done Light". Also in 1956, folk singer Bob Gibson, who had traveled to Jamaica and heard the song, taught his version to the folk band the Tarriers. They recorded a version of that song that incorporated the chorus of "Hill and Gully Rider", another Jamaican folk song. This release became their biggest hit, reaching number four on the pop charts, where it outperformed Belafonte's version. The Tarriers' version was recorded by the Fontane Sisters, Sarah Vaughan, and Steve Lawrence in 1956, all of whom charted in the US Top 40, and by Shirley Bassey in 1957, whose recording became a hit in the United Kingdom.[9] The Tarriers, or some subset of the three members of the group (Erik Darling, Bob Carey and Alan Arkin, later better known as an actor) are sometimes credited as the writers of the song. |

歴史 「バナナ・ボートの歌」は、ジャマイカでバナナ貿易が盛んだった20世紀初頭頃に生まれたと思われる。この歌はジャマイカの港湾労働者たちによって歌われ たもので、彼らは通常、昼間の太陽の暑さを避けるために夜間に働いていた。昼間がやってくると、彼らはボスがバナナを集計しに来ることを知っていたので、 家に帰ることができた[4]。 この曲はトリニダードのシンガー、エドリック・コナーと彼のバンド、カリビーンズによって1952年のアルバム『Songs from Jamaica』で初めてレコーディングされた。 1955年、アメリカのシンガーソングライターであるロード・バージェスとウィリアム・アッタウェイは、コルゲート・コメディ・アワー(The Colgate Comedy Hour)のために歌詞を書き、その中でハリー・ベラフォンテがこの曲を演奏した[8]。ベラフォンテの1956年のカリプソ・アルバムのサイド2は 「Star O」で始まる。レコーディング中、タイトルを聞かれたハリーは "Day Done Light "と答えた。 また、1956年には、ジャマイカを旅してこの曲を聴いたフォーク・シンガーのボブ・ギブソンが、フォーク・バンドのタリアーズにそのヴァージョンを教え た。彼らは、同じくジャマイカのフォークソングである「Hill and Gully Rider」のコーラスを取り入れたヴァージョンをレコーディングした。このリリースは彼らの最大のヒットとなり、ポップ・チャートで4位を記録し、ベラ フォンテのヴァージョンを上回った。タリアーズのヴァージョンは、1956年にフォンタン・シスターズ、サラ・ヴォーン、スティーヴ・ローレンスによって レコーディングされ、いずれもアメリカのトップ40にチャートインした。 |

| Notable covers In 1980, Canadian children's singer Raffi covered the song, releasing on his album Baby Beluga.[citation needed] The Fontane Sisters recorded the Tarriers version in a recording of the song for Dot Records in 1956. It charted to number 13 in the US in 1957.[10] Sarah Vaughan and an orchestra conducted by David Carroll recorded a jazzy version for Mercury Records in 1956, credited to Darling, Carey, and Arkin of the Tarriers. It charted at number 19 on the US Top 40 charts in 1957.[3][10] Shirley Bassey recorded the Tarriers version in 1957 for 4 Star Records, which became her first single to chart in the U.K., peaking at number 8.[9] It later appeared on her 1959 album The Bewitching Miss Bassey.[citation needed] Steve Lawrence recorded the Tarriers version in 1957 for Coral Records, with a chorus and orchestra directed by Dick Jacobs. It peaked at number 18 on the US Top 40 charts that year.[10] |

著名なカヴァー 1980年、カナダの子供向け歌手ラフィがこの曲をカヴァーし、アルバム『ベイビー・ベルーガ』で発表した[要出典]。 フォンタン・シスターズは1956年にドット・レコードのためにタリアス・バージョンをレコーディングした。この曲は1957年に全米チャート13位を記 録した[10]。 サラ・ヴォーンとデヴィッド・キャロル指揮のオーケストラは1956年にマーキュリー・レコードにジャジーなヴァージョンを録音し、タリアーズのダーリ ン、キャリー、アーキンがクレジットされた。これは1957年の全米トップ40チャートで19位にチャートインした[3][10]。 シャーリー・バッシーは1957年に4スター・レコードでタリアーズのヴァージョンをレコーディングし、イギリスでチャートインした初のシングルとなり、 8位を記録した[9]。後に1959年のアルバム『The Bewitching Miss Bassey』に収録された[要出典]。 スティーヴ・ローレンスは1957年、コーラル・レコードのために、ディック・ジェイコブスの指揮によるコーラスとオーケストラでタリアス・ヴァージョン を録音した。同年の全米トップ40チャートで18位を記録した[10]。 |

| Parodies and alternate lyrics "Banana Boat (Day-O)", a parody by Stan Freberg and Billy May released in 1957 by Capitol Records, features ongoing disagreement between an enthusiastic Jamaican lead singer (played by Freberg) and a bongo-playing beatnik (played by Peter Leeds) who "don't dig loud noises" and has the catchphrase "You're too loud, man". When he hears the lyric about the "deadly black taranch-la" (actually the highly venomous Brazilian wandering spider, commonly dubbed "banana spider"), the beatnik protests, "No, man! Don't sing about spiders, I mean, oooo! like I don't dig spiders". Freberg's version was popular, reaching number 25 on the US Top 40 charts in 1957,[10] and received much radio airplay; Harry Belafonte reportedly disliked the parody.[11] Stan Freberg's version was the basis for the jingle for the TV advert for the UK chocolate bar Trio from the mid-1980s to the early to mid-1990s, the lyrics being, "Trio, Trio, I want a Trio and I want one now. Not one, not two, but three things in it; chocolatey biscuit and a toffee taste too." Dutch comedian André van Duin released his version in 1972 called Het bananenlied: the banana song. This song asks repetitively why bananas are bent. It reaches the conclusion that if the bananas weren't bent they wouldn't fit into their peels. German band Trio performed a parody with "Bommerlunder" (a German schnapps) substituted for the words "daylight come" in the 1980s. The Serbian comedy rock band the Kuguars, consisting of famous Serbian actors, covered the song in 1998, with lyrics in Serbian dedicated to the, at the time, Yugoslav national soccer team player Dejan "Dejo" Savićević. The song became a nationwide hit, and a promotional video for the song had been recorded. In their 1994 album, the comedy music group Grup Vitamin included a Turkish cover of the song parodying the macho culture in the country. In 1988–89, Belafonte's children, David and Gina, parodied the song in a commercial about the Oldsmobile Toronado Trofeo. (David was singing "Trofeo" in the same style as "Day-O" in the song). A 1991 Brazilian commercial used a parody of the song to promote their bubble gum brand "Bubbaloo Banana" with lyrics dedicated to the banana-flavoured candy A parody of this song was used in an E-Trade commercial that first aired on Super Bowl LII. Biscuit manufacturer Jacob's parodied the song in the 1980s for advertisements for the Trio biscuit bar, sung by an animated character called Suzy. Food manufacturer Kellogg's parodied the song in their 2001 television advertisement for their breakfast cereal Fruit 'n Fibre. For an ad campaign that started in 1991, now-defunct Seattle-based department store chain The Bon Marché used a version of the song with alternate lyrics in their commercials.[12] The Swedish humor show Rally, which aired between 1995 and 2002 in Sveriges Radio P3 made a version called "Hey Mr. Taliban", which speaks about Osama Bin Laden. The Rockin Roll Morning show on KOMP 92.3 created a flash video called Osama bin Laden Nowhere to run - nowhere to hide that features United States Secretary of State Colin Powell singing a parody of the song about Osama bin Laden getting bombed. In November 2019, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert modified the lyrics to make fun of Mike Pompeo, saying "Pompe-O, Pompe-O. Hearing come and I wanna go home."[13] |

パロディと代替歌詞 「1957年にキャピトル・レコードからリリースされたスタン・フレバーグとビリー・メイによるパロディ「Banana Boat (Day-O)」は、フレバーグ扮する熱狂的なジャマイカ人リード・シンガーと、ピーター・リーズ扮するボンゴを弾くビートニクとの間の不和を描いてい る。彼が「致命的な黒いタランチュラ」(実際は猛毒を持つブラジルの徘徊蜘蛛で、通称「バナナグモ」)の歌詞を聞くと、ビートニクは抗議する!クモのこと を歌わないでくれ、つまり、クモは嫌いなんだ」。ハリー・ベラフォンテはこのパロディを嫌っていたと伝えられている[11]。スタン・フレバーグのバー ジョンは、1980年代半ばから1990年代前半から半ばにかけて、イギリスのチョコレート・バー「Trio」のテレビ広告のジングルのベースとなってお り、歌詞は「Trio, Trio, I want a Trio and I want one now. トリオ、トリオ、トリオが欲しい、今すぐ欲しい」という歌詞だった。 オランダのコメディアン、アンドレ・ファン・ドゥインは1972年に「Het bananenlied(バナナの歌)」というバージョンを発表した。この歌は、なぜバナナは曲がっているのかと繰り返し問いかける。バナナが曲がってい なければ、皮に収まらないという結論に達する。 ドイツのバンド、トリオは1980年代、「Bommerlunder」(ドイツのシュナップス)を「daylight come」の代わりに使ったパロディを披露した。 セルビアの有名俳優で構成されたセルビアのコメディ・ロックバンド、クグアルズは1998年、当時ユーゴスラビア代表のサッカー選手だったデヤン "デヨ "サヴィッチに捧げたセルビア語の歌詞でこの曲をカバーした。この曲は全国的なヒットとなり、プロモーション・ビデオも制作された。 1994年のアルバムでは、コメディ音楽グループ、グループ・ビタミンが、トルコのマッチョ文化をパロディにしたこの曲のトルコ語カヴァーを収録してい る。 1988年から89年にかけて、ベラフォンテの子供たち、デヴィッドとジーナは、オールズモビル・トロナド・トロフェオのコマーシャルでこの曲をパロディ にした。(デヴィッドはこの曲の中で「Trofeo」を「Day-O」と同じスタイルで歌っていた)。 1991年のブラジルのCMでは、バナナ味のキャンディに捧げた歌詞で、バブルガムのブランド「Bubbaloo Banana」の宣伝にこの曲のパロディが使われた。 スーパーボウルLIIで初めて放映されたEトレードのCMでも、この曲のパロディが使われた。 ビスケットメーカーのJacob'sは、1980年代にビスケットバー「Trio」の広告でこの曲をパロディ化し、スージーというアニメキャラクターが 歌った。 食品メーカーのケロッグは2001年、朝食用シリアル「フルーツン・ファイバー」のテレビ広告でこの歌をパロディにした。 1991年に始まった広告キャンペーンでは、今はなきシアトルに本拠を置く百貨店チェーン、ボン・マルシェが、歌詞を入れ替えたこの曲のヴァージョンをコ マーシャルに使用した[12]。 1995年から2002年にかけてSveriges Radio P3で放送されたスウェーデンのユーモア番組『Rally』は、オサマ・ビン・ラディンについて語った「Hey Mr.KOMP 92.3の番組『Rockin Roll Morning』は『Osama bin Laden Nowhere to run - nowhere to hide』というフラッシュビデオを作成し、コリン・パウエル米国務長官が爆撃を受けるオサマ・ビンラディンについてこの曲のパロディを歌うという内容 だった。 2019年11月、『ザ・レイト・ショー・ウィズ・スティーヴン・コルベア』は、マイク・ポンペオを揶揄するために歌詞を改変し、「ポンペオー、ポンペ オー。ヒアリングが来て、家に帰りたい」[13]。 |

| Samples and interpolations Chilean program 31 minutos used the song "Arwrarwrirwrarwro" by Bombi which was based on "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)".[14] Jason Derulo's song "Don't Wanna Go Home" heavily samples "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)".[15] Lil Wayne's song "6 Foot 7 Foot" samples and derives its title from "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)".[16] In media and politics The original 1956 Belafonte recording is heard in the 1988 film Beetlejuice in a dinner scene in which the guests are supernaturally compelled to dance along to the song by the film's protagonists.[17] It was sung by Beetlejuice and Lydia in the first episode of the television animated series, and it appeared in the Broadway musical adaptation.[18] In the TV series The Muppet Show season 3 episode 14, Harry Belafonte performs the song accompanied by Fozzie Bear and other muppets. Fozzie Bear requests to be a tally man as identified in the lyrics of the song. Harry Belafonte explains what a tally man is as he proceeds to sing with other muppets accompanying singing the song's answer. In the TV series Legends of Tomorrow season 2 episode 14 "Moonshot", the character Martin Stein abruptly starts singing the song to cause a distraction.[19] During the first leg of the thirty-second season of the American version of The Amazing Race, contestants had to play a section of the song on a steelpan during a Roadblock challenge.[20] In the Justin Trudeau blackface controversy, on September 18, 2019, Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada, admitted to singing "Day-O" while wearing blackface makeup and an afro wig at a talent show when he was in high school at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf.[21] |

サンプルと挿入 チリの番組『31 minutos』では、"Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) "を基にしたボンビの曲 "Arwrarwrirwrarwro "が使われた[14]。 ジェイソン・デルーロの曲「Don't Wanna Go Home」は「Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)」を大きくサンプリングしている[15]。 リル・ウェインの曲 "6 Foot 7 Foot "は "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) "をサンプリングし、そのタイトルに由来している[16]。 メディアと政治において 1956年にベラフォンテが録音したオリジナルは、1988年の映画『ビートルジュース』で、主人公たちによってゲストたちが超自然的にこの曲に合わせて 踊らされるディナーのシーンで聴ける[17]。 テレビシリーズ『ザ・マペット・ショー』シーズン3エピソード14では、ハリー・ベラフォンテがフォジー・ベアや他のマペットを従えてこの曲を披露。フォ ジー・ベアはこの曲の歌詞にあるように、集計係になることを要求する。ハリー・ベラフォンテは、歌の答えを歌う他のマペットたちと一緒に歌いながら、タ リーマンとは何かを説明する。 TVシリーズ『レジェンド・オブ・トゥモロー』シーズン2エピソード14「Moonshot」では、登場人物のマーティン・スタインが突然この曲を歌い始 め、混乱を引き起こす[19]。 アメリカ版『アメイジング・レース』第30シーズンの第1レグでは、ロードブロックの挑戦中に出場者がスティールパンでこの曲の一部を演奏しなければなら なかった[20]。 ジャスティン・トルドーの黒塗り論争では、2019年9月18日、カナダのジャスティン・トルドー首相が、コレージュ・ジャン=ド=ブレブフの高校時代に タレントショーで黒塗りメイクとアフロかつらをつけながら「Day-O」を歌ったことを認めた[21]。 |

| Mento is a style of Jamaican

folk music that predates and has greatly influenced ska and reggae

music. It is a fusion of African rhythmic elements and European

elements, which reached peak popularity in the 1940s and 1950s.[2]

Mento typically features acoustic instruments, such as acoustic guitar,

banjo, hand drums, and the rhumba box — a large mbira in the shape of a

box that can be sat on while played. The rhumba box carries the bass

part of the music. Mento is often confused with calypso, a musical form from Trinidad and Tobago. Although the two share many similarities, they are separate and distinct musical forms. During the mid-20th century, mento was conflated with calypso, and mento was frequently referred to as calypso, kalypso and mento calypso.[3] Mento singers frequently used calypso songs and techniques. As in calypso, mento uses topical lyrics with a humorous slant, commenting on poverty and other social issues.[3] Sexual innuendo is also common. |

メント(Mento)は、スカやレゲエに先行して大きな影響を与えた

ジャマイカの民族音楽のスタイルである。アフリカのリズムの要素とヨーロッパの要素の融合であり、1940年代と1950年代に人気のピークを迎えた

[2]。メントは通常、アコースティックギター、バンジョー、ハンドドラム、ルンバボックス(演奏中に座ることができる箱の形をした大きなムビラ)などの

アコースティック楽器を特徴とする。ルンバ・ボックスは音楽の低音部を担う。 メントはしばしば、トリニダード・トバゴの音楽形態であるカリプソと混同される。両者には多くの共通点があるが、別個の音楽形態である。20世紀半ば、メ ントはカリプソと混同され、メントはしばしばカリプソ、カリプソ、メント・カリプソと呼ばれた[3]。カリプソと同様、メントはユーモアを交えた歌詞を使 い、貧困やその他の社会問題についてコメントする。 |

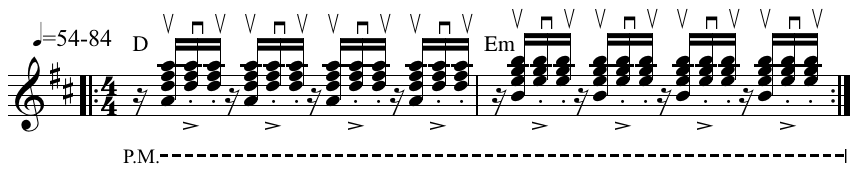

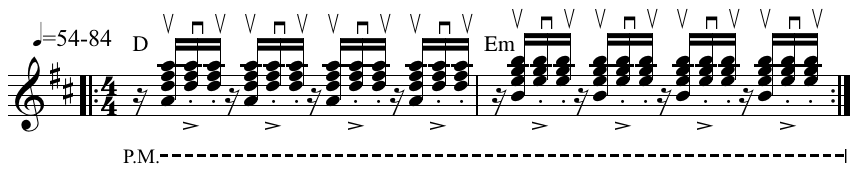

Mento rhythm using Sibelius 5. |

シベリウスの交響曲5番を使ったメントのリズム |

| History Mento draws on musical traditions brought by enslaved West Africa people.[3] Enslaved musicians were often required to play music for their masters and often rewarded for such skills.[3] The Africans created a creole music, incorporating such elements of these traditions, including quadrille, into their own folk music.[3][4] The Jamaican mento style has a long history of conflation with Trinidadian calypso. The lyrics of mento songs often deal with aspects of everyday life in a light-hearted and humorous way. Many comment on poverty, poor housing, and other social issues. Thinly veiled sexual references and innuendo are also common. Mento can be seen as a precursor of some of the movement motifs and themes dealing with such social issues found in modern dancehall. It became more popular in the late 1940s, with mento performances becoming a common aspect of dances, parties and other events in Jamaica.[4] The word mento is of uncertain etymology; it may be from an African language or Cuban Spanish; Rex Nettleford said the term was brought back from Cuba by Jamaicans returning from work there.[5] Supposedly, it derives from the Spanish verb mentar, "to mention, call out, name", because of the subtle ways that lyrics criticised people (whether fellow blacks, or the whites who were in charge).[6][7] Major 1950s mento recording artists include Louise Bennett, Count Lasher, Harold Richardson, Lord Flea, Lord Fly, Alerth Bedasse with Chin's Calypso Sextet, Laurel Aitken, Denzil Laing, Lord Composer, Lord Lebby, Lord Power, Hubert Porter, and Harry Belafonte, a New Yorker of Jamaican origin. His wildly popular hit records in 1956–1958, including "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)" and "Jamaica Farewell", were mento songs sold as calypso. Previously recorded Jamaican versions of many Belafonte's classic "calypso" hits can be heard on the Jamaica – Mento 1951–1958 CD released by Frémeaux & Associés in 2009.[8] Due in part to Belafonte's popularity, mento became widely conflated with calypso in the 1950s. In a 1957 interview for Calypso Star magazine, Lord Flea said: In Jamaica, we call our music 'mento' until very recently. Today, 'calypso' is beginning to be used for all kinds of West Indian music. This is because it's become so commercialized there. Some people like to think of West Indians as carefree natives who work and sing and play and laugh their lives away. But this isn't so. Most of the people there are hard working folks, and many of them are smart business men. If the tourists want 'calypso', that's what we sell them.[9] This was the golden age of mento, as records pressed by Stanley Motta, Ivan Chin, Ken Khouri and others brought the music to a new audience. In the 1960s it became overshadowed by ska and reggae. Mento is still played in Jamaica, especially in areas frequented by tourists. Lloyd Bradley, reggae historian and author of the seminal reggae book, Bass Culture, said that Lee "Scratch" Perry's seminal 1976 dub album, Super Ape, contained some of the purest mento influences he knew.[10] This style of music was revived in popularity by the Jolly Boys in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the release of four recordings on First Warning Records/Rykodisc and a tour that included the United States.[4] Stanley Beckford and Gilzene and the Blue Light Mento Band also revived rural mento in the 2000s. The mento dance is a Jamaican folk-form dance with acoustic guitar, banjo, hand drums and rhumba box. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mento https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day-O_(The_Banana_Boat_Song) |

歴史 メントは西アフリカの奴隷にされた人々によってもたらされた音楽の伝統を基にしている[3]。 奴隷にされた音楽家はしばしば主人のために音楽を演奏することを要求され、しばしばそのような技術に対して報酬を与えられていた[3]。 アフリカ人たちはクレオール音楽を創り出し、クアドリルを含むこれらの伝統の要素を自分たちの民族音楽に取り入れた[3][4]。 ジャマイカのメント・スタイルは、トリニダードのカリプソと混同されてきた長い歴史がある。メントの歌詞は、日常生活の一面を軽快かつユーモラスに扱って いることが多い。貧困、貧しい住宅、その他の社会問題についてコメントするものが多い。また、薄っすらとした性的な言及や陰口もよく見られる。メントは、 現代のダンスホールに見られる、そうした社会問題を扱ったムーブメントのモチーフやテーマの先駆けともいえる。1940年代後半に人気が高まり、メントの パフォーマンスはジャマイカのダンス、パーティー、その他のイベントでよく見られるようになった[4]。 レックス・ネトルフォードによると、この言葉はキューバでの仕事から戻ったジャマイカ人がキューバから持ち帰ったものだという。[5]おそらく、歌詞が微 妙な方法で人々(仲間の黒人であれ、責任者である白人であれ)を批判することから、スペイン語の動詞mentar「言及する、呼びかける、名指す」に由来 している[6][7]。 1950年代の主なメント・レコーディング・アーティストには、ルイーズ・ベネット、カウント・ラッシャー、ハロルド・リチャードソン、ロード・フリー、 ロード・フライ、チンズ・カリプソ・セクステットのアレス・ベダス、ローレル・エイトケン、デンジル・レイン、ロード・コンポーザー、ロード・レビー、 ロード・パワー、ヒューバート・ポーター、そしてジャマイカ出身のニューヨーカー、ハリー・ベラフォンテがいる。1956年から1958年にかけて、 「Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)」や「Jamaica Farewell」を含む彼の大人気ヒット・レコードは、カリプソとして販売されたメント・ソングだった。2009年にFrémeaux & AssociésからリリースされたCD『Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958』では、ベラフォンテの古典的な "カリプソ "ヒット曲のジャマイカン・ヴァージョンを聴くことができる[8]。 ベラフォンテの人気もあり、メントは1950年代にカリプソと広く混同されるようになった。1957年のカリプソ・スター誌のインタビューで、ロード・フ リー(Lord Flea)はこう語っている: ジャマイカでは、ごく最近まで自分たちの音楽を "メント "と呼んでいた。今日、"カリプソ "はあらゆる西インド音楽に使われ始めている。カリプソが商業化されたからだ。西インド人のことを、働き、歌い、遊び、人生を笑い飛ばすのんきな原住民だ と考えたがる人もいる。しかし、そうではない。西インド諸島の人々のほとんどは勤勉で、賢いビジネスマンも多い。観光客が "カリプソ "を欲しがれば、それを売るんだ」[9]。 スタンリー・モッタ、アイヴァン・チン、ケン・クーリらがプレスしたレコードがこの音楽を新しい聴衆に広めたことで、この時代はメントの黄金期となった。 1960年代にはスカやレゲエの影に隠れてしまった。今でもジャマイカでは、特に観光客がよく訪れる地域でメントが演奏されている。レゲエの歴史家であ り、代表的なレゲエ本『Bass Culture』の著者であるロイド・ブラッドリーは、リー・"スクラッチ"・ペリーの1976年の代表的なダブ・アルバム『Super Ape』には、彼が知る限り最も純粋なメントの影響が含まれていると述べている[10]。 [10]このスタイルの音楽は、1980年代後半から1990年代前半にかけて、ジョリー・ボーイズがファースト・ウォーニング・レコード/ライコディス クから4枚のレコーディングをリリースし、アメリカを含むツアーを行ったことで人気が復活した[4]。メント・ダンスとは、アコースティック・ギター、バ ンジョー、ハンド・ドラム、ルンバ・ボックスを使ったジャマイカのフォーク・フォームのダンスである。 |

| Day-o, day-ay-ay-o Daylight come and me wan' go home Day, me say day, me say day, me say day, me say day, me say day-ay-ay-o Daylight come and me wan' go home Work all night on a drink a rum (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Stack banana 'til the mornin' come (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Come, mister tally man, tally me banana (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Come, mister tally man, tally me banana (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Lift six foot, seven foot, eight foot, bunch (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Six foot, seven foot, eight foot, bunch (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Day, me say day-ay-ay-o (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Day, me say day, me say day, me say day, me say day, me say day (Daylight come and me wan' go home) A beautiful bunch of ripe banana (Daylight come and me wan' go home) Hide the deadly black tarantula (Daylight come and me wan' go home) https://genius.com/Harry-belafonte-day-o-banana-boat-song-lyrics |

デイ・オ、デイ・ア・イ・オ 日が暮れて 家路につく デイ、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う 日が暮れて 家路につく 一晩中ラム酒を飲んで (日が暮れて 家路につく) 朝が来るまでバナナを積み重ねる (日が暮れて 家路につく) 集計係のおじさん バナナを集計してくれ (日が暮れたら 家に帰ろう) 集計係のお兄さん バナナを数えてちょうだい (日が暮れて 家路につく) 6フィート7フィート8フィート束を持ち上げる (日が暮れて 家路につく) 6フィート、7フィート、8フィート、バンチ (日が暮れて 家路につく) デイ、僕はデイと言う (日が暮れて 家路につく) デイ、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う、僕はデイと言う (日が暮れて 家路につく) 熟れたバナナの美しい房 (日が暮れて 家路につく) 凶暴な黒いタランチュラを隠して (日が暮れて 家路につく) 原詩の出典 https://genius.com/Harry-belafonte-day-o-banana-boat-song-lyrics |

| A work song is a

piece of music closely connected to a form of work, either sung while

conducting a task (usually to coordinate timing) or a song linked to a

task that might be a connected narrative, description, or protest song.

An example is "I've Been Working on the Railroad". |

作業歌とは、作業の形態と密接に結びついた楽曲のことで、作業を行いな

がら(通常はタイミングを合わせるために)歌われるもの、あるいは作業と結びついた歌で、物語や説明、抗議歌のようなものである。例えば、"I've

Been Working on the Railroad "がある。 |

| Definitions and categories Records of work songs are as old as historical records, and anthropological evidence suggests that most agrarian societies tend to have them.[1] Most modern commentators on work songs have included both songs sung while working as well as songs about work since the two categories are seen as interconnected.[2] Norm Cohen divided collected work songs into domestic, agricultural or pastoral, sea shanties, African-American work songs, songs and chants of direction, and street cries.[3] Ted Gioia further divided agricultural and pastoral songs into hunting, cultivation and herding songs, and highlighted the industrial or proto-industrial songs of cloth workers (see Waulking song), factory workers, seamen, longshoremen, mechanics, plumbers, electricians, lumberjacks, cowboys and miners. He also added prisoner songs and modern work songs.[1] |

定義とカテゴリー 作業歌の記録は歴史的な記録と同じくらい古く、人類学的な証拠によると、ほとんどの農耕社会には作業歌が存在する傾向がある。現代の作業歌の解説者の多く は、作業歌は作業中に歌われる歌と作業に関する歌の両方を含んでいる。 [2]ノーム・コーエンは、収集されたワークソングを、家庭の歌、農業や牧畜の歌、海のシャンティ、アフリカ系アメリカ人のワークソング、方向性を示す歌 や唱歌、街頭の叫び声に分類した[3]。テッド・ジョイアはさらに、農業や牧畜の歌を狩猟、耕作、牧畜の歌に分類し、布地労働者(Waulking songを参照)、工場労働者、船乗り、港湾労働者、整備士、配管工、電気技師、木こり、カウボーイ、鉱夫の工業的または原工業的な歌に注目した。また、 囚人の歌や近代的な労働歌も追加された[1]。 |

| African-American work songs Further information: African-American music § 18th century, and Field holler African-American work songs originally developed in the era of slavery, between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Because they were part of an almost entirely oral culture, they had no fixed form and only began to be recorded as the era of slavery came to an end after 1865. Slave Songs of the United States was the first collection of African-American "slave songs." It was published in 1867 by William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison.[8] Though this text included many songs by slaves, other texts have also been published that include work songs. Many songs sung by slaves have their origins in African song traditions, and may have been sung to remind the Africans of home, while others were instituted by the captors to raise morale and keep Africans working in rhythm.[9] They have also been seen as a means of withstanding hardship and expressing anger and frustration through creativity or covert verbal opposition.[10] Similarly, work songs have been used as a form of rebellion and resistance.[11] Specifically, African-American women work songs have a particular history and center on resistance and self-care.[12] Work songs helped to pass down information about the lived experience of enslaved people to their communities and families.[12] A common feature of African-American songs was the call-and-response format, where a leader would sing a verse or verses and the others would respond with a chorus. This came from African traditions of agricultural work song and found its way into the spirituals that developed once Africans in bondage began to convert to Christianity and from there to both gospel music and the blues. The call and response format showcases the ways in which work songs foster dialogue. The importance of dialogue is illuminated in many African-American traditions and continues on to the present day.[12] Particular to the African call and response tradition is the overlapping of the call and response.[13] The leader's part might overlap with the response, thus creating a unique collaborative sound. Similarly, African-American folk and traditional music focuses on polyphony rather than a melody with a harmony.[13] Often, there will be multiple rhythmic patterns used in the same song "resulting in a counterpoint of rhythms."[13] The focus on polyphony also allows for improvisation, a component that is crucial to African-American work songs.[13] As scholar Tilford Brooks writes, "improvisation is utilized extensively in Black folk songs, and it is an essential element especially in songs that employ the call-and-response pattern."[13] Brooks also notes that often in a work song, "the leader has license to improvise on the melody in [their] call, while the response usually repeats its basic melody line without change."[13] Also evident were field hollers, shouts, and moans, which may have been originally designed for different bands or individuals to locate each other and narrative songs that used folk tales and folk motifs, often making use of homemade instruments.[14] In early African captivity drums were used to provide rhythm, but they were banned in later years because of the fear that Africans would use them to communicate in a rebellion; nevertheless, Africans managed to generate percussion and percussive sounds, using other instruments or their own bodies.[15] In the 1950s, there are very few examples of work songs linked to cotton picking.[16] Corn, however, was a very common subject of work songs on a typical plantation. Because the crop was the main component of most Africans' diet,[citation needed] they would often sing about it regardless of whether it was being harvested. Often, communities in the south would hold "corn-shucking jubilees," during which an entire community of planters would gather on one plantation. The planters would bring their harvests, as well as their enslaved workers, and work such as shucking corn, rolling logs, or threshing rice would be done, accompanied by the singing of Africans doing work. The following is an example of a song Africans would sing as they approached one of these festivals. It is from ex bonded African William Wells Brown's memoir " My Southern Home." All them pretty gals will be there, Shuck that corn before you eat; They will fix it for us rare, Shuck that corn before you eat. I know that supper will be big, Shuck that corn before you eat; I think I smell a fine roast pig, Shuck that corn before you eat. — Slaves in the Antebellum South These long, mournful, antiphonal songs accompanied the work on cotton plantations, under the driver's lash. — Tony Palmer, All You Need is Love: The Story of Popular Music.[17] Work songs were used by African-American railroad work crews in the southern United States before modern machinery became available in the 1960s. Anne Kimzey of the Alabama Center For Traditional Culture writes: "All-black gandy dancer crews used songs and chants as tools to help accomplish specific tasks and to send coded messages to each other so as not to be understood by the foreman and others. The lead singer, or caller, would chant to his crew, for example, to realign a rail to a certain position. His purpose was to uplift his crew, both physically and emotionally, while seeing to the coordination of the work at hand. It took a skilled, sensitive caller to raise the right chant to fit the task at hand and the mood of the men. Using tonal boundaries and melodic style typical of the blues, each caller had his own signature. The effectiveness of a caller to move his men has been likened to how a preacher can move a congregation."[18] Another common type of African-American work song was the "boat song." Sung by slaves who had the job of rowing, this type of work song is characterized by "plaintive, melancholy singing." These songs were not somber because the work was more troublesome than the work of harvesting crops. Rather, they were low-spirited so that they could maintain the slow, steady tempo needed for rowing. In this way, work songs followed the African tradition, emphasizing the importance of activities being accompanied by the appropriate song.[19] The historian Sylviane Diouf and ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik identify Islamic music as an influence on field holler music.[20][21] Diouf notes a striking resemblance between the Islamic call to prayer (originating from Bilal ibn Rabah, a famous Abyssinian African Muslim in the early 7th century) and 19th-century field holler music, noting that both have similar lyrics praising God, melody, note changes, "words that seem to quiver and shake" in the vocal cords, dramatic changes in musical scales, and nasal intonation. She attributes the origins of field holler music to African Muslim slaves who accounted for an estimated 30% of African slaves in America. According to Kubik, "the vocal style of many blues singers using melisma, wavy intonation, and so forth is a heritage of that large region of West Africa that had been in contact with the Arabic-Islamic world of the Maghreb since the seventh and eighth centuries."[20][21] There was particularly a significant trans-Saharan cross-fertilization between the musical traditions of the Maghreb and the Sahel.[21] |

アフリカ系アメリカ人のワークソング さらなる情報 アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽§18世紀、フィールド・ホラー アフリカ系アメリカ人のワーク・ソングは、もともと奴隷制度の時代、17世紀から19世紀にかけて発展した。ほぼ完全に口承文化の一部であったため、定 まった形式を持たず、1865年以降に奴隷制の時代が終わると、初めて記録されるようになった。Slave Songs of the United States』は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の「奴隷の歌」の最初のコレクションである。ウィリアム・フランシス・アレン、チャールズ・ピカード・ウェア、 ルーシー・マッキム・ギャリソンによって1867年に出版された[8]。このテキストには奴隷による歌が多く含まれているが、労働歌を含む他のテキストも 出版されている。奴隷によって歌われた歌の多くはアフリカの歌の伝統に起源を持ち、アフリカ人に故郷を思い出させるために歌われた可能性がある一方で、他 の歌は捕虜によって士気を高め、アフリカ人をリズムよく働かせるために制定された可能性がある[9]。 [特に、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性のワークソングは特別な歴史があり、抵抗と自己ケアを中心に据えている[12]。 ワークソングは、奴隷にされた人々の生きた経験に関する情報をコミュニティや家族に伝えるのに役立った[12]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の歌の共通の特徴は、コールアンドレスポンス形式である。これはアフリカの伝統的な農作業歌から生まれたもので、奴隷状態にあったア フリカ人がキリスト教に改宗し始めると、スピリチュアル・ソングへと発展し、そこからゴスペルやブルースへとつながっていった。コール・アンド・レスポン スの形式は、ワーク・ソングが対話を促進する方法を示している。アフリカのコール&レスポンスの伝統に特有なのは、コールとレスポンスが重なることである [13]。同様に、アフリカ系アメリカ人のフォークや伝統音楽は、ハーモニーを持つメロディよりもポリフォニーに重点を置いている[13]。多くの場合、 同じ曲の中で複数のリズムパターンが使用され、「リズムの対位法をもたらす」[13]。 [13]学者のティルフォード・ブルックスが書いているように、「即興は黒人フォークソングで広範囲に利用されており、特にコールアンドレスポンスのパ ターンを採用した曲では不可欠な要素である」[13]。 「また、野太い声、叫び声、うめき声も明らかであり、これらはもともと異なるバンドや個人が互いの位置を確認するために考案されたものであった可能性があ る。 [14]。初期のアフリカ人の捕虜生活ではドラムがリズムを提供するために使用されていたが、後年にはアフリカ人が反乱の際にコミュニケーションに使用す ることを恐れて禁止された。それでもアフリカ人は他の楽器や自分の体を使用して、打楽器やパーカッシブな音を生み出すことに成功していた[15]。 しかしトウモロコシは、典型的なプランテーションでは作業歌の題材として非常に一般的であった。この作物はほとんどのアフリカ人の食生活の主要な構成要素 であったため[要出典]、収穫の有無にかかわらず、彼らはしばしばその作物について歌った。南部のコミュニティではしばしば「コーン・シャッキング・ジュ ビリー」が開催され、プランターのコミュニティ全体が1つのプランテーションに集まった。プランターたちは収穫物や奴隷労働者を持ち寄り、トウモロコシの 殻むき、丸太の転がし、稲の脱穀などの作業を、仕事をするアフリカ人たちの歌声とともに行った。以下は、アフリカ人がこうした祭りに近づくと歌う歌の一例 である。元保釈金付きアフリカ人のウィリアム・ウェルズ・ブラウンの回想録 "My Southern Home "から。 かわいい女の子たちがみんなそこにいるさ、 食べる前にとうもろこしの殻をむいてね; 彼らは私たちのためにレアに直してくれる、 食べる前にトウモロコシをしゃぶれ。 晩餐は豪華なものになるさ、 食べる前に、そのとうもろこしをしゃくりなさい; 立派な豚の丸焼きの匂いがする、 食べる前に、そのトウモロコシをしゃくりなさい。 - 前世紀南部の奴隷たち 綿花プランテーションで、運転手に鞭打たれながら働く奴隷たちは、哀愁を帯びた長い賛美歌を口ずさんでいた。 - トニー・パーマー『All You Need is Love: ポピュラー音楽の物語』[17]。 1960年代に近代的な機械が利用できるようになる以前、アメリカ南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人の鉄道作業員によって、作業歌が使われていた。アラバマ伝統 文化センター(Alabama Center For Traditional Culture)のアン・キムジー(Anne Kimzey)は次のように書いている。「黒人ガンディ・ダンサーの乗組員たちは、歌や詠唱を、特定の作業を達成するための道具として、また現場監督など に理解されないように互いに暗号化されたメッセージを送るために使っていた。リード・シンガー(コーラー)は、例えばレールを特定の位置に整列させるよう にクルーに詠唱する。彼の目的は、肉体的にも精神的にも乗組員を高揚させ、同時に目の前の作業の調整を見守ることだった。手元の作業と乗組員の気分に合っ た適切な詠唱を上げるには、熟練した繊細なコーラーが必要だった。ブルースに典型的な音色の境界線とメロディーを使い、コーラーはそれぞれ独自の特徴を 持っていた。部下を動かすコーラーの効果は、説教者が会衆を動かす方法に例えられてきた」[18]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の作業歌のもう一つの一般的なタイプは、"ボートソング "であった。ボートを漕ぐ仕事をしていた奴隷たちによって歌われたこのタイプの作業歌の特徴は、"悲しげで哀愁を帯びた歌唱 "である。これらの歌は、農作物を収穫する仕事よりも厄介な仕事だからということで、物悲しいものではなかった。むしろ、櫓を漕ぐのに必要なゆっくりとし たテンポを維持するために、低調な歌だったのだ。このように、作業歌はアフリカの伝統に従ったものであり、活動が適切な歌とともに行われることの重要性を 強調していた[19]。 歴史家のシルヴィアン・ディウフや民族音楽学者のゲルハルト・クービックは、イスラム音楽がフィールドホラーミュージックに影響を与えたと指摘している [20][21]。 [20][21]ディウフは、イスラム教の祈りの呼びかけ(7世紀初頭の有名なアビシニア系アフリカ人イスラム教徒であるビラル・イブン・ラバに由来)と 19世紀の野次馬音楽との間に顕著な類似点があると指摘し、両者には神を賛美する歌詞、メロディ、音符の変化、声帯の「震え、揺れ動くような言葉」、音階 の劇的な変化、鼻音のイントネーションなどが類似していると指摘している。彼女は、フィールドホラーミュージックの起源は、アメリカにいたアフリカ人奴隷 の30%を占めていたと推定されるアフリカ系イスラム教徒の奴隷たちであるとしている。クビックによれば、「メリスマや波打つようなイントネーションなど を用いた多くのブルース・シンガーのヴォーカル・スタイルは、7世紀から8世紀にかけてマグレブのアラビア語・イスラーム世界と接触していた西アフリカの 広大な地域の遺産である」[20][21]。特にマグレブとサヘルの音楽的伝統の間には、サハラ砂漠を越えた大きな相互肥沃化があった[21]。 |

|

ハリー・ベラフォンテと日本での受容 ハリー・ベラフォンテ(Harry Belafonte、1927年3月1日 - 2023年4月25日)は、アメリカ合衆国の歌手、俳優、社会活動家。「バナナ・ボート」などのヒット曲やアフリカ支援のチャリティソング「ウィ・アー・ ザ・ワールド」の制作にも携わる[1]。「USAフォー・アフリカ」の提唱者として知られる。 ニューヨーク市ハーレム生まれ。父親は仏領マルティニーク系黒人、母はジャマイカ系である。1956年に「バナナ・ボート」が世界的な大ヒットとなり、ア ルバム『カリプソ』も当時としては珍しいミリオンセラーを記録し、一躍スターとなった[2]。 「バナナ・ボート」はジャマイカの労働者がバナナを船に積み込むときに歌う労働歌を元に作られた曲で、"Day-o, Day-ay-ay-o ・・・ Day, me say day, me say day, me say day Me say day, me say day-ay-ay-o・・・"。という掛け声が特徴的。この掛け声の語感のコミカルさから、日本でも浜村美智子や江利チエミのカバーバージョンがヒット した。またその後も「マティルダ」や「ダニー・ボーイ」などの世界的なヒット曲を連発した。 ベラフォンテのコンサートを観た三島由紀夫は、「ベラフォンテがどんなにすばらしかは、舞台を見なければ、本当のところはわからない。ここには熱帯の太陽 があり、カリブ海の貿易風があり、ドレイたちの悲痛な歴史があり、力と陽気さと同時に繊細さと悲哀があり、素朴な人間の魂のありのままの表示がある。そし て舞台の上のベラフォンテは、まさしく太陽のやうにかがやいてゐる。(中略)歌はれる歌には、リフレインが多い。全編ほとんどリフレインといふやうな歌が ある。これは民謡的特色だが、同時に呪術的特色でもある。わづかなバリエーションを伴ひながら『夏はもうあらかた過ぎた』(ダーン・レイド・アラウンド) とか『夜ごと日の沈むとき』(スザンヌ)とかいふ詩句が、彼の甘いしはがれた声で、何度となくくりかへされると、われわれは、ベラフォンテの特色である、 暗い粘つこい叙情の中へ、だんだんにひき入れられる。声が褐色の幅広いリボンのやうにひらめく。われわれは、もうその声のほかには、世界中に何も聞かない のである。(中略)(私は)『バナナ・ボート』や、たのしい『ラ・バンバ』をことに愛する」[3]と、その歌声を絶賛した。 2023年4月25日、うっ血性心不全のため、マンハッタン・アッパーウエストサイドにある自宅にて死去、96歳没[2][4]。 https://x.gd/ERLP8 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆