デジデリウス・エラスムス

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, 1466-1536

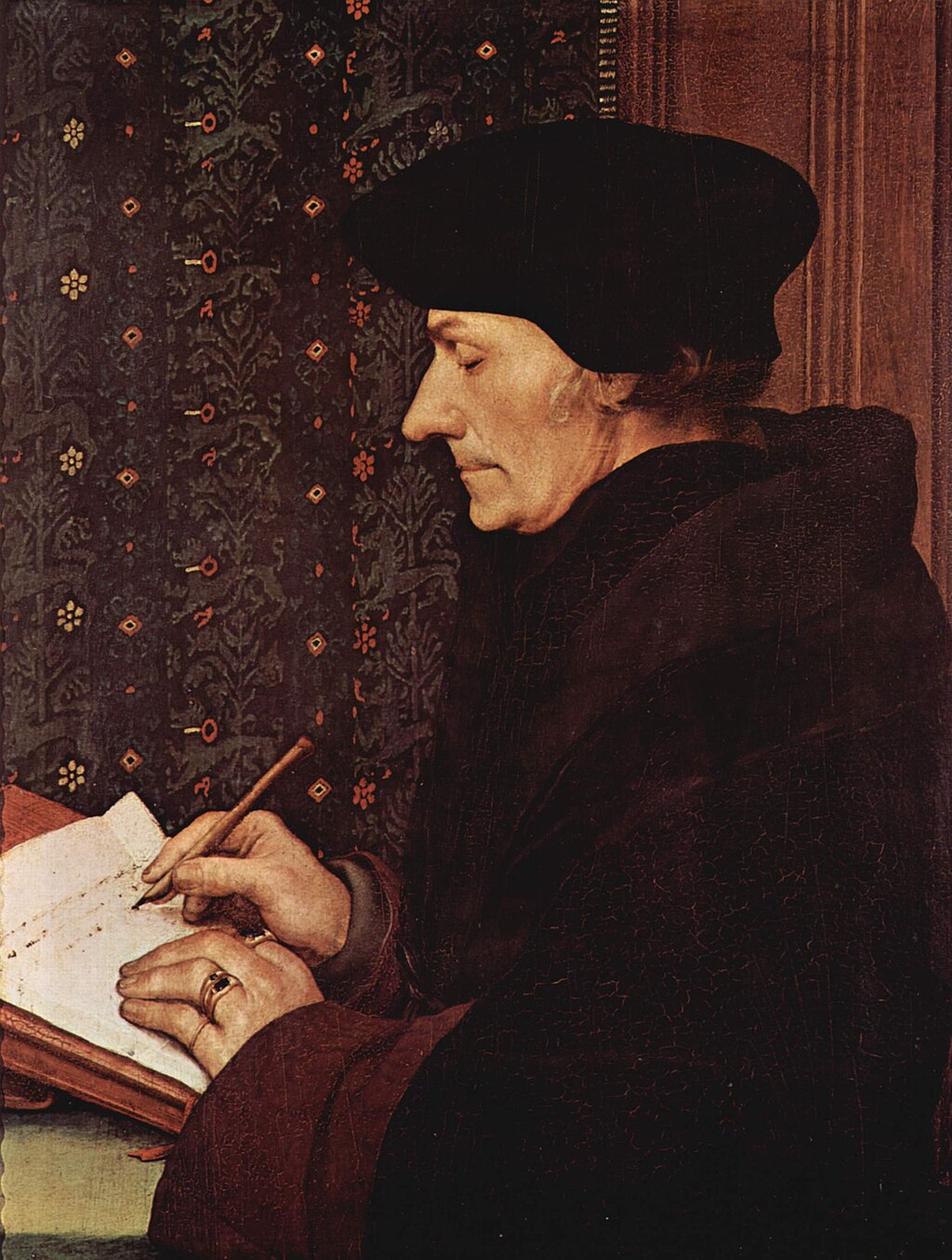

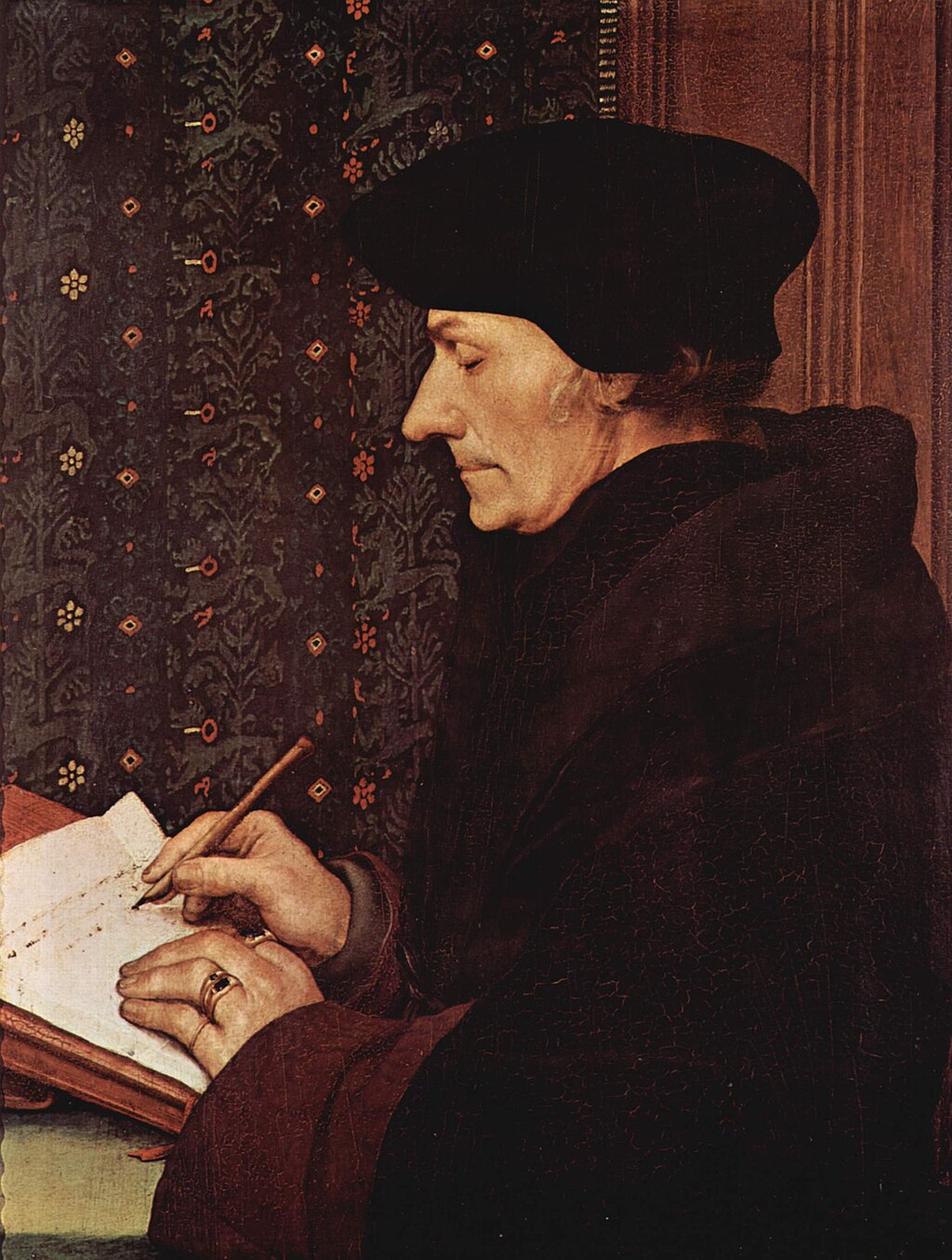

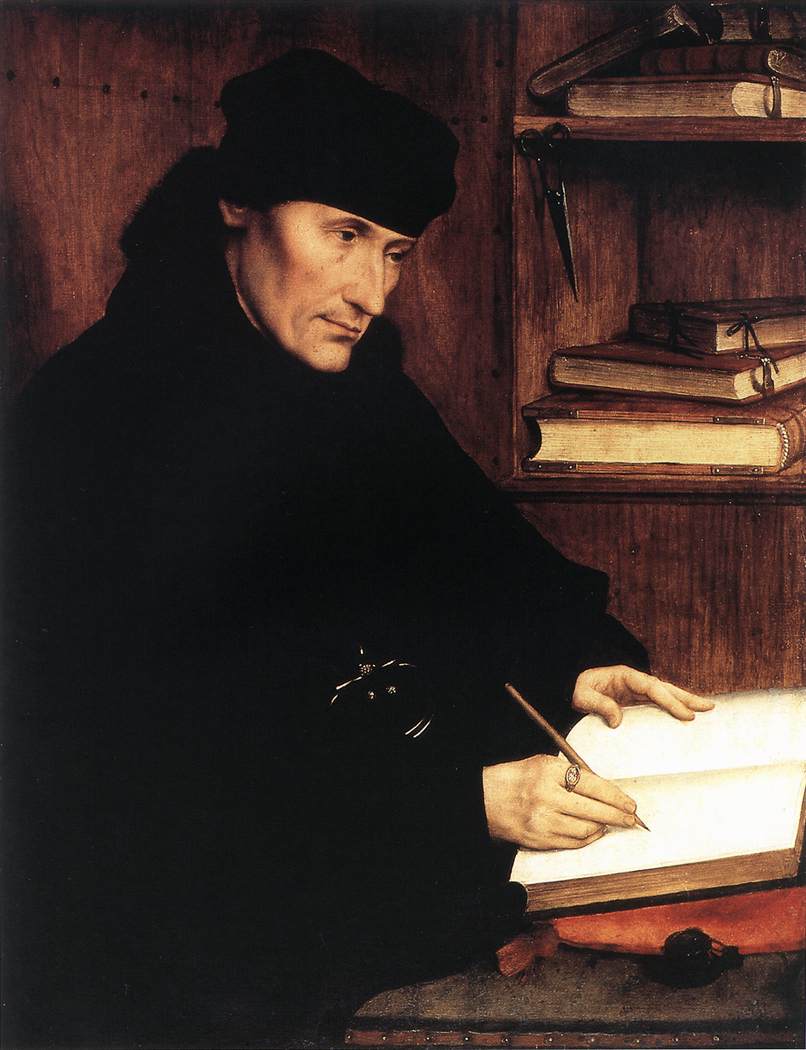

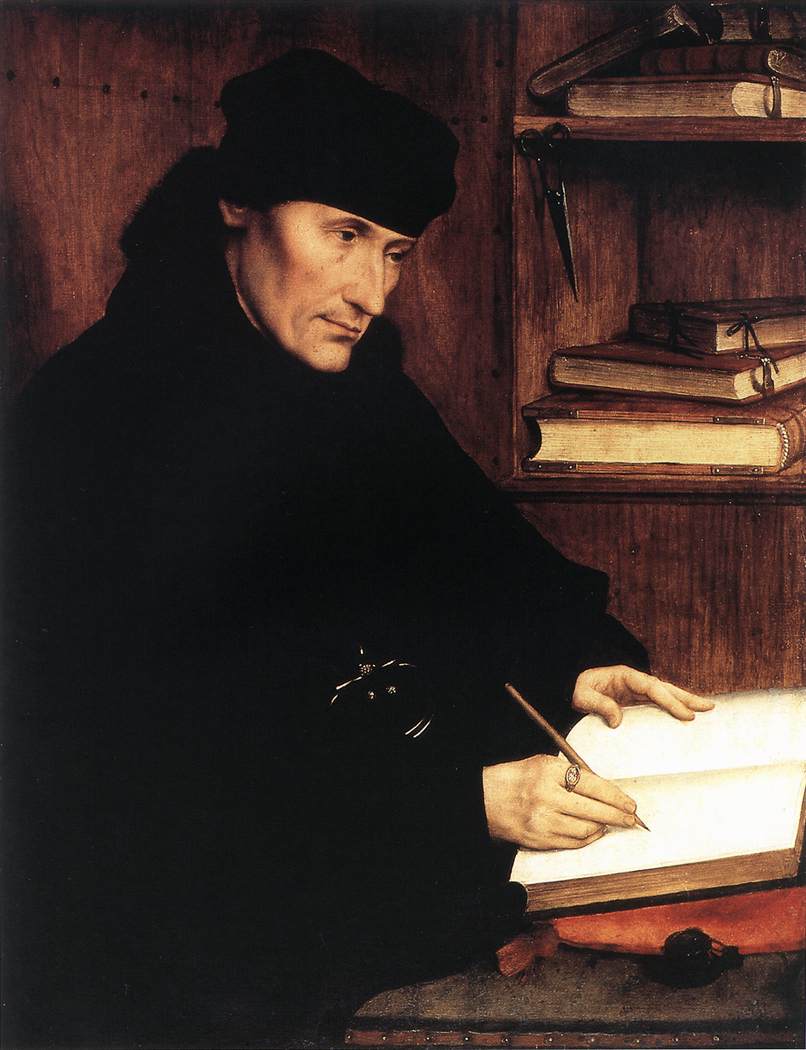

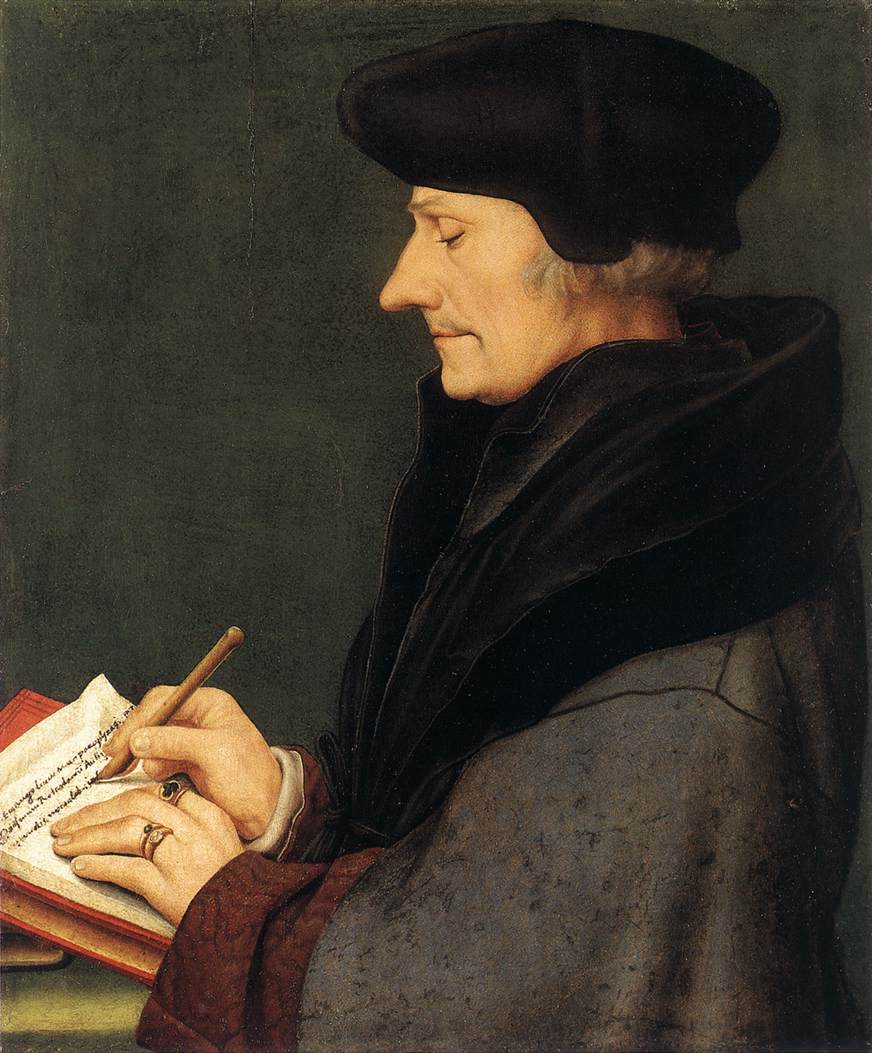

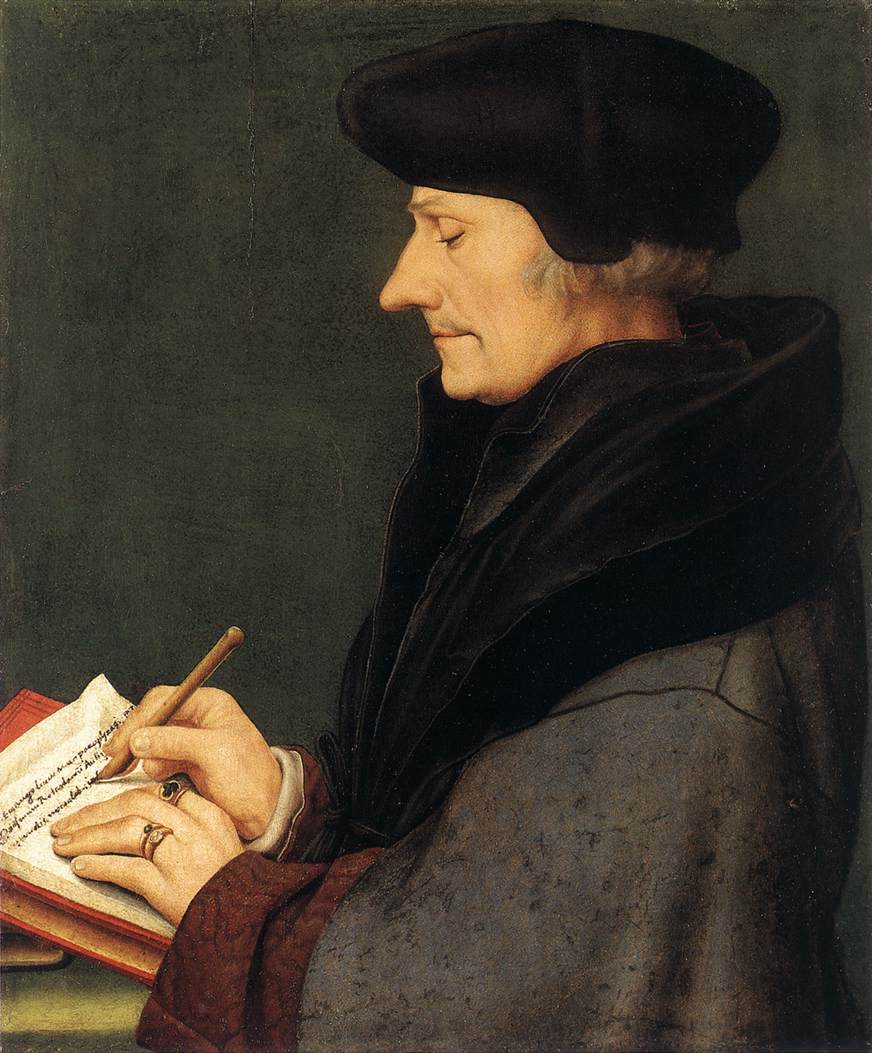

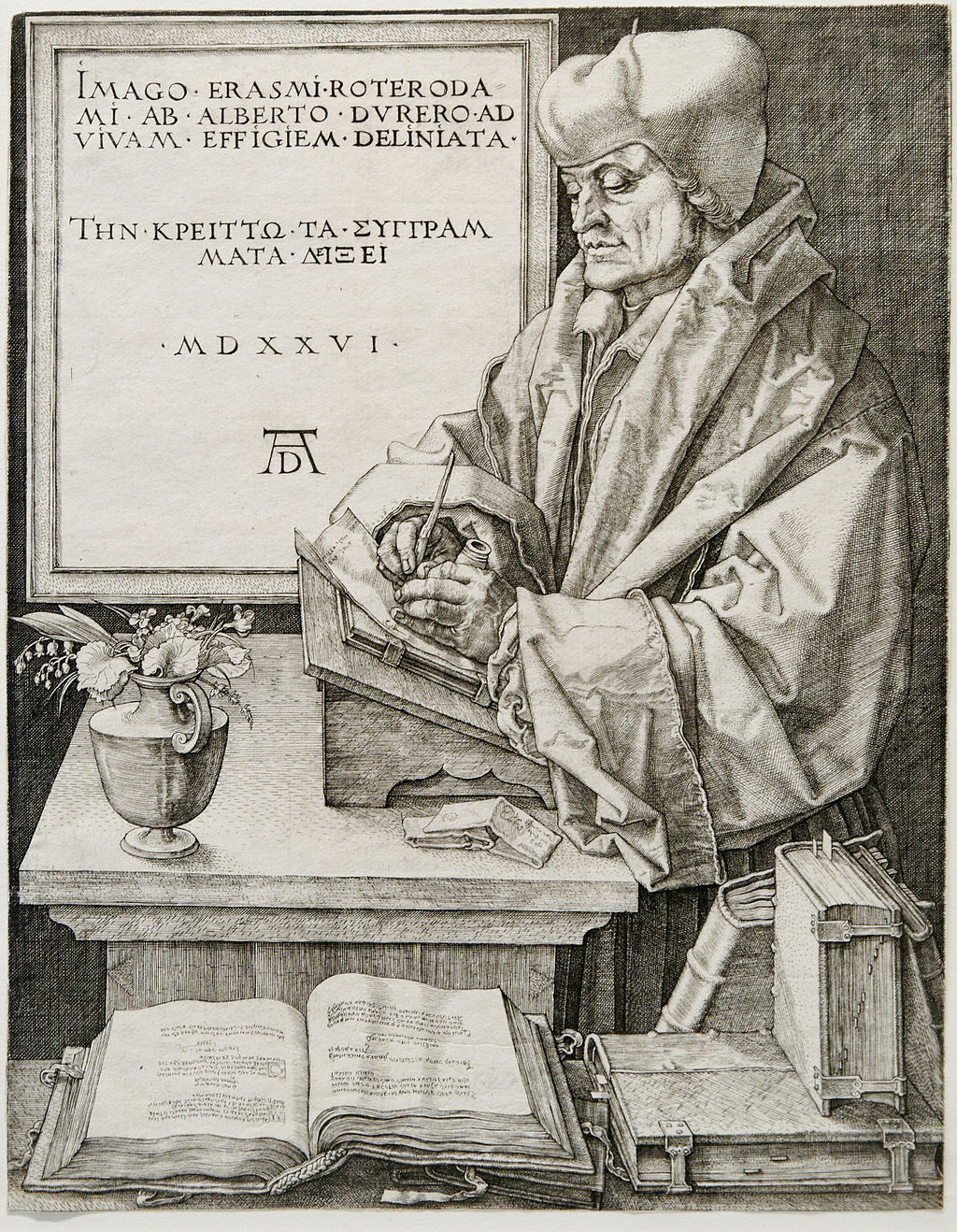

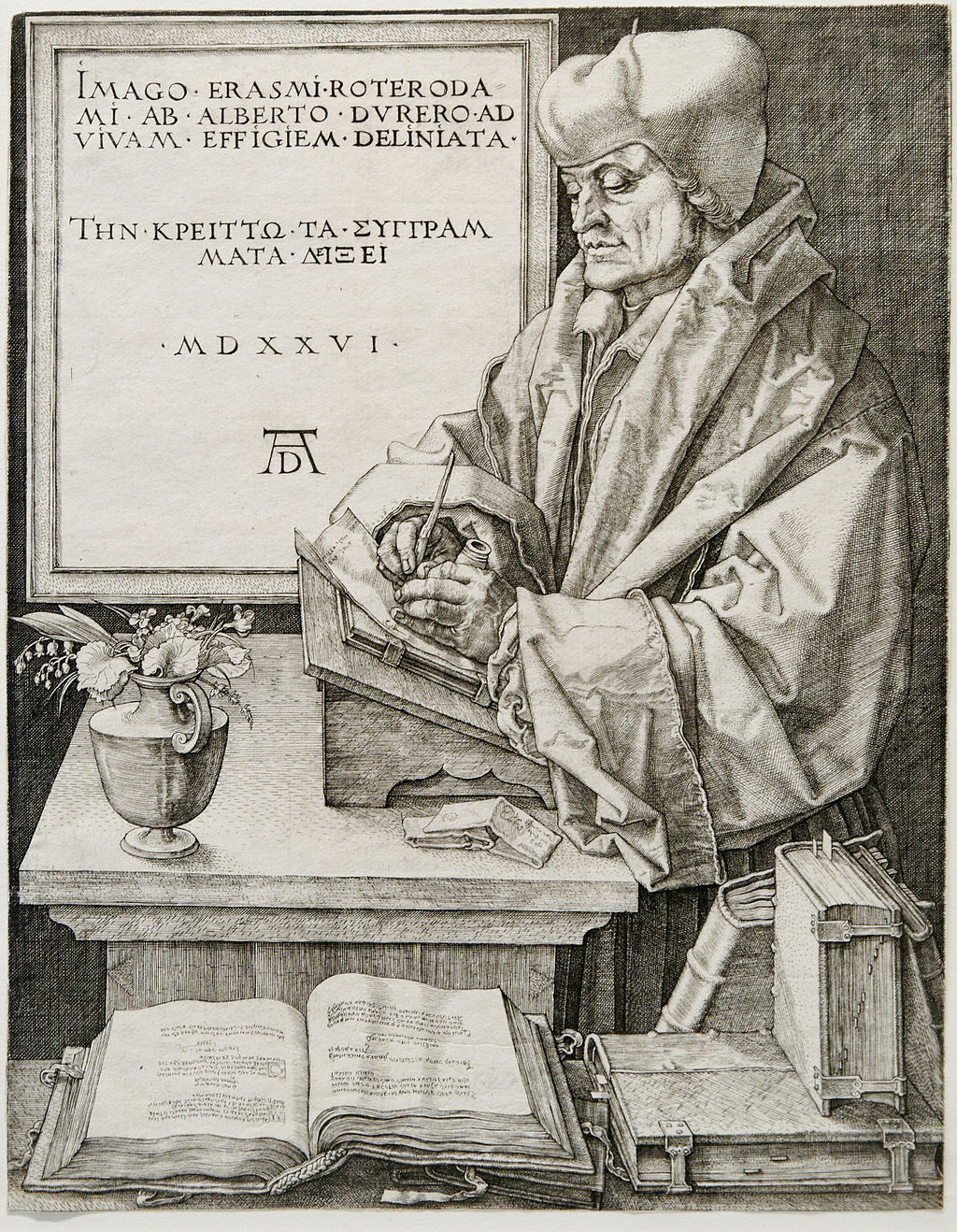

Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam with Renaissance Pilaster by Hans Holbein the Younger

| 1466 | デジデリウス・エラスムス

(Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus)ロッテルダムで生まれる。 |

| 1487 |

この年に流行した疾病で両親を亡くし

た。エラスムスと兄は後見人により共同生活兄弟団付属の寄宿学校に入れられ、「デヴォツィオ・モデルナ」(Devotio

Moderna:新しき信心)の教育を受けた。 |

| 1487 |

親族の意思に従ってデルフトに近いステ

インにあった聖アウグスチノ修道会の修道院に入る。『反蛮族論』の執筆 |

| 1492 |

司祭叙階を受けると、卓抜したラテン語

能力を認められてカンブレー (Cambray) の司教秘書に抜擢され、合法的に修道会を離れることができた。 |

| 1495 |

カンブレー司教の許しを得、神学博士号

の取得を目指してパリ大学へ入学し、モンテーギュ学寮に入った |

| 1496 |

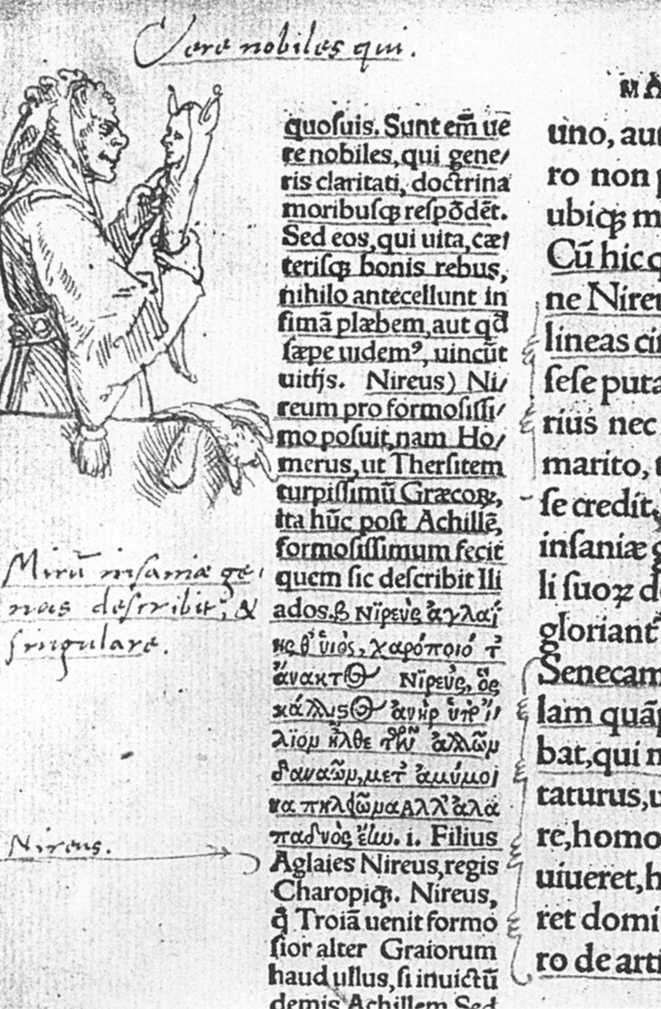

自らを「デジデリウス」と名乗るように

なり、『古典名句集』(Collectanea Adagiorum) を書き始める。貧しかったエラスムスはパリへ出てラテン語の個人教授を始めた。 |

| 1499 |

イングランドへ渡り、同地の上流社会に多くの知己を得た。人文主義者

ジョン・コレット (John

Colet)、終生の友となった政治家トマス・モア、若きヘンリー王子(後のヘンリー8

世)などと交わった。ジョン・コレットはエラスムスのギリシア語の

知識不足を指摘し、さらに研鑽を積むよう促す。エラスムスは聖書研究に着手し、キリスト教的著作を発表するようになる。 |

| 1500 |

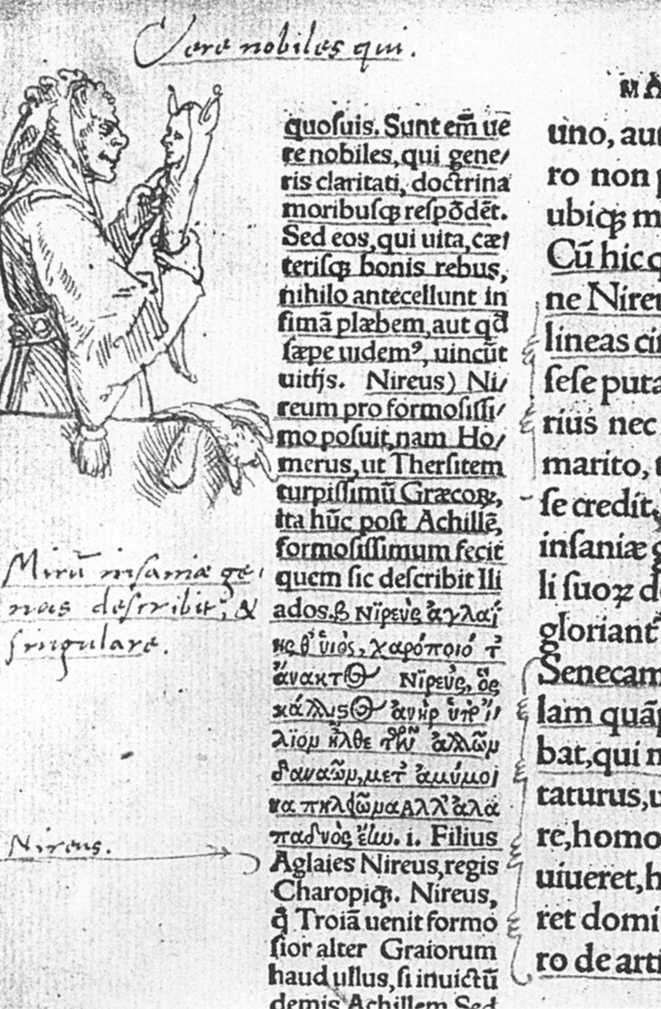

『古典名句集』 |

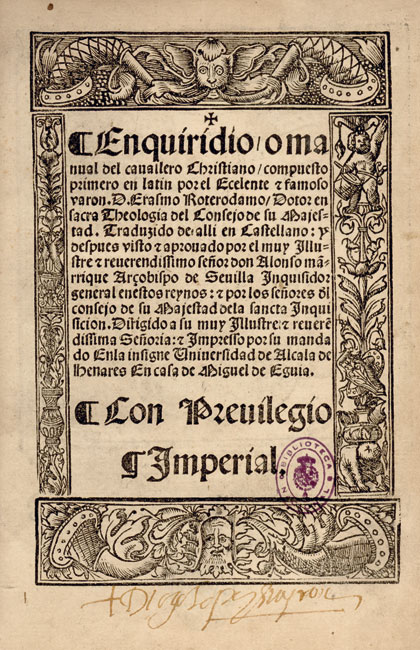

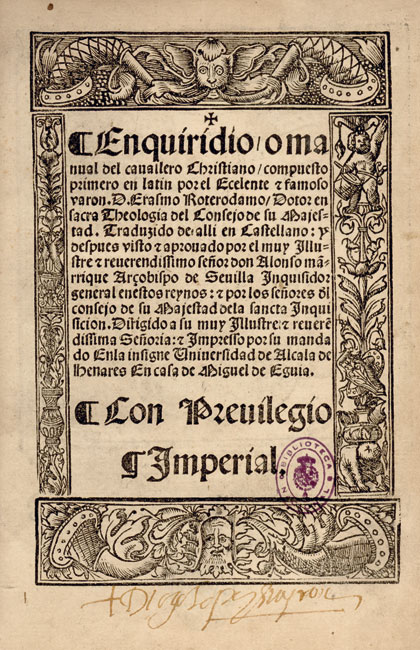

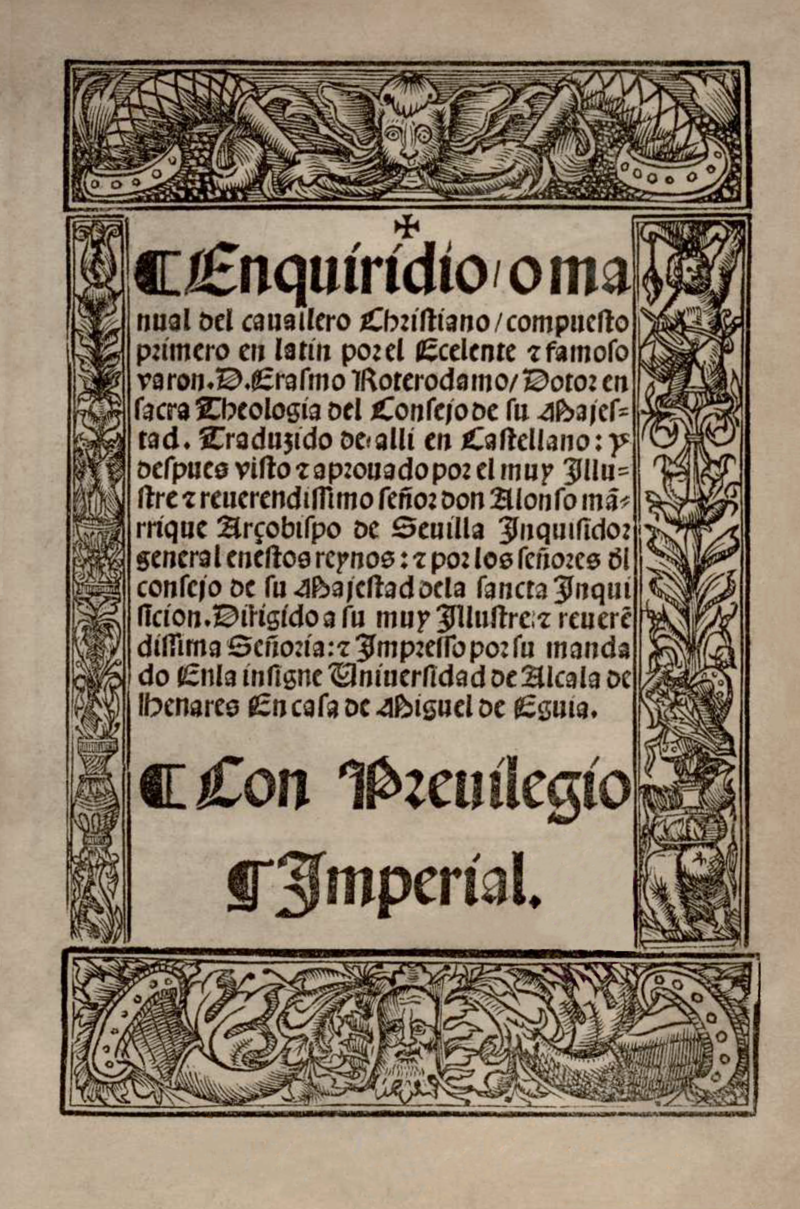

| 1504 |

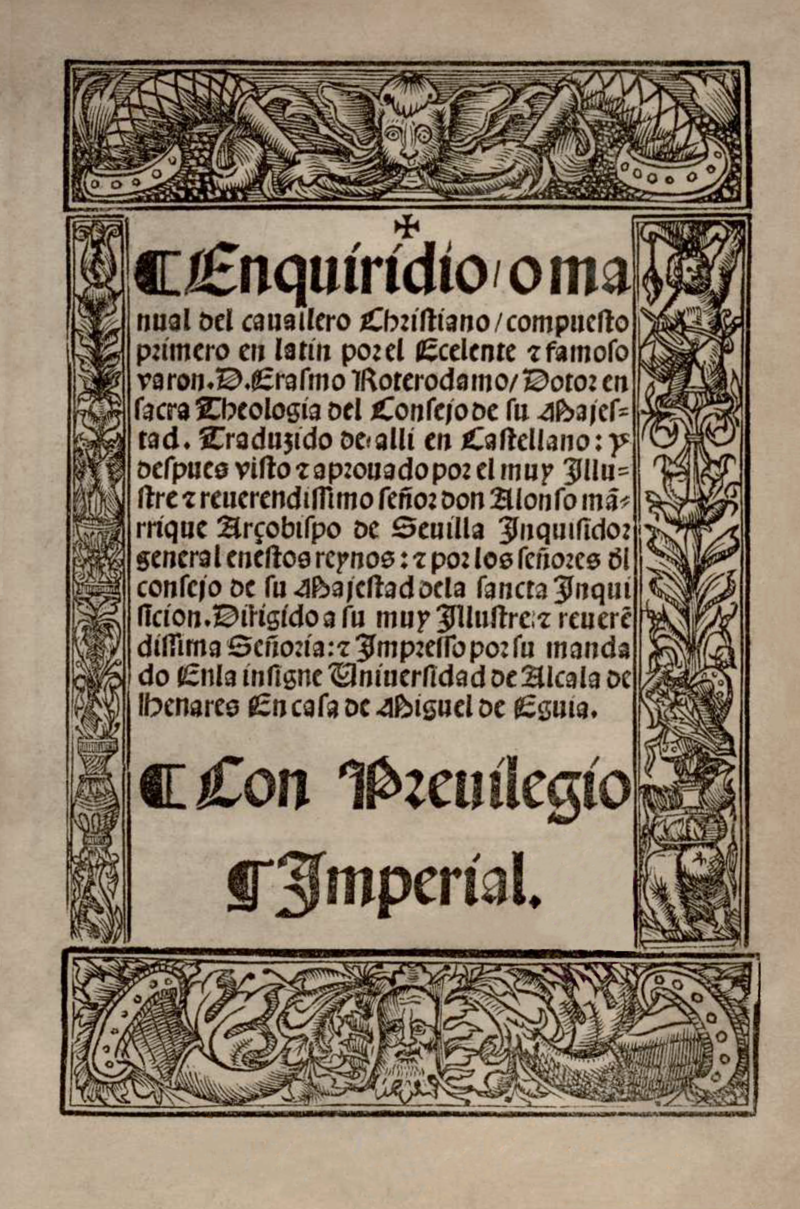

『エンキリディオン』。ルーヴァンでロレンツォ・ヴァッラの手による

『新約聖書註解』の写本を見出した |

| 1506 |

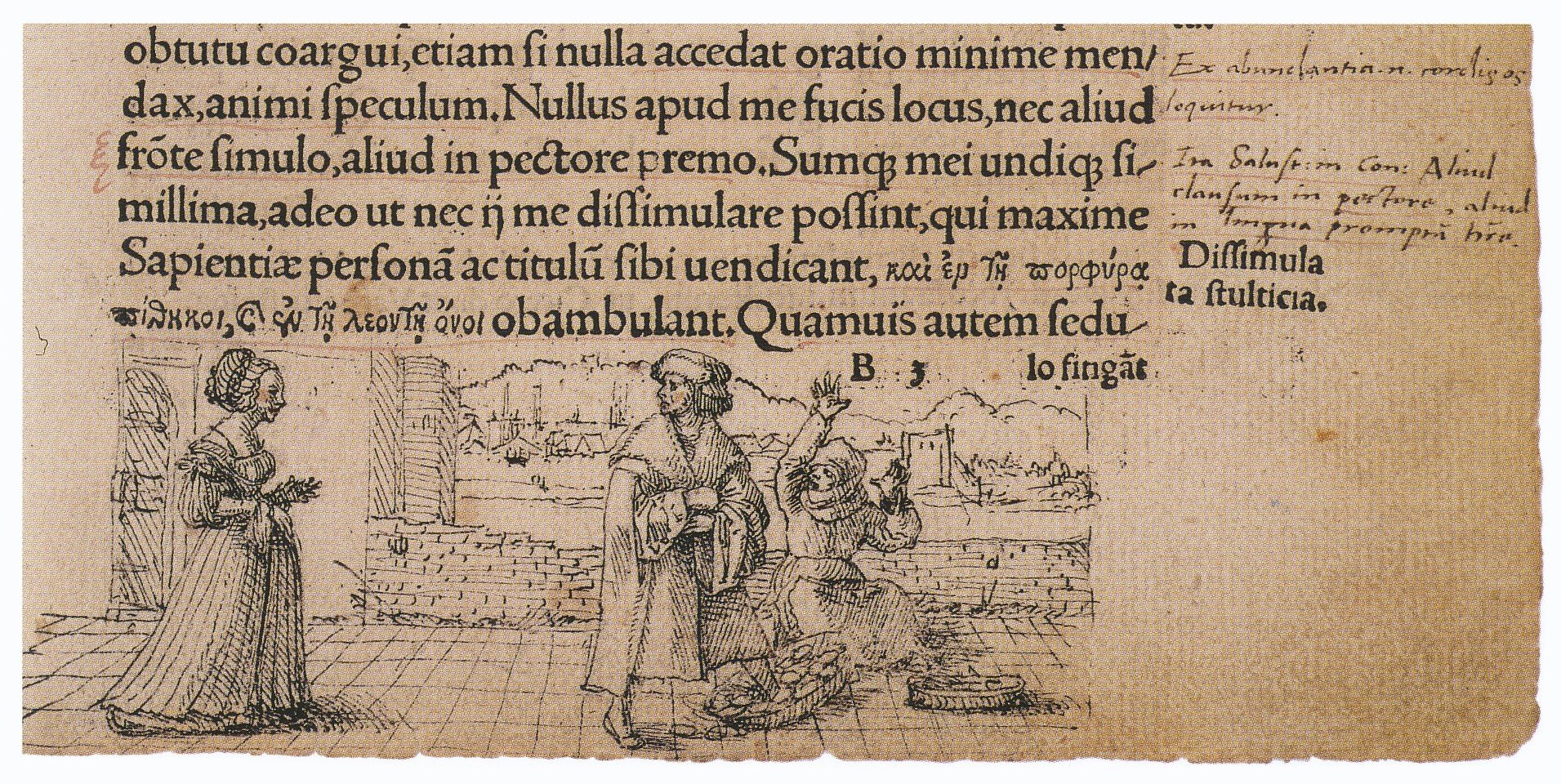

少年時代から憧れたイタリア行きを果たし、訪れたトリノ大学で神学博士

号を授与された。その後イギリスに向かうためアルプスを越えたが、その道中で『痴愚神礼賛』の構想を得た。1511同書が刊行。 |

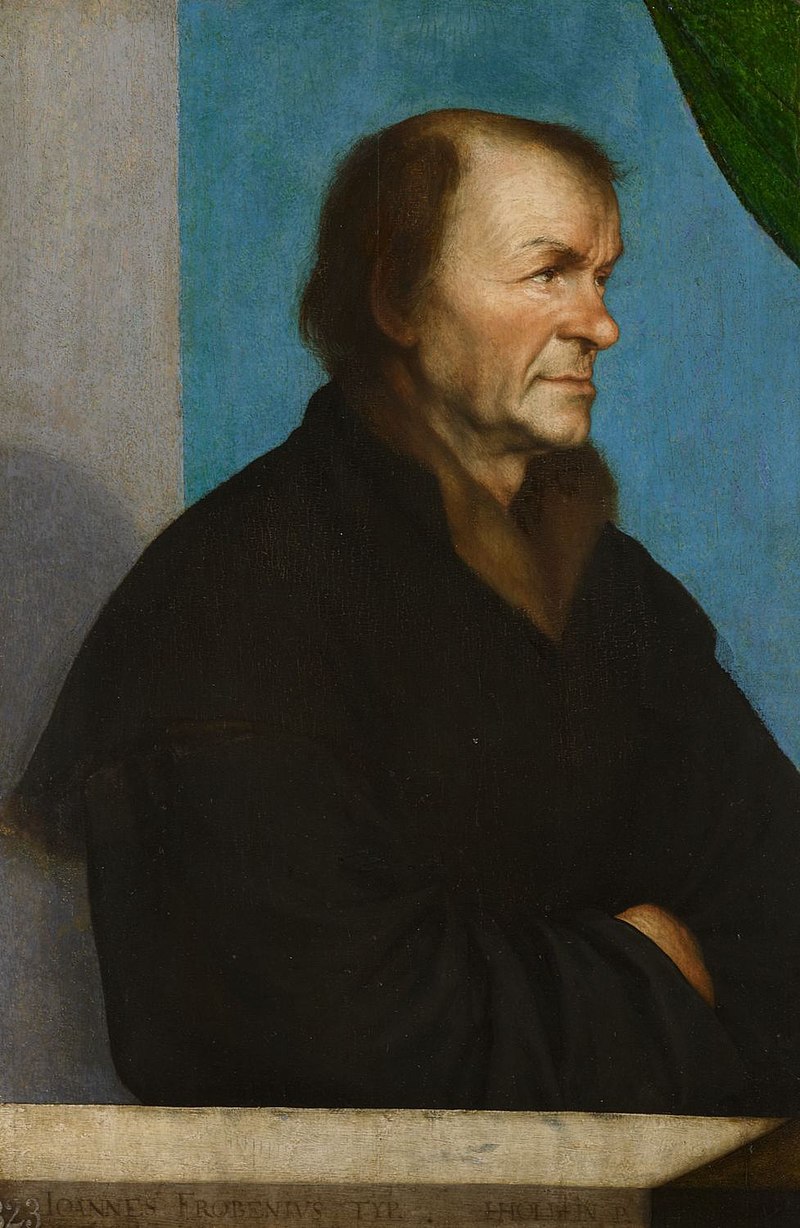

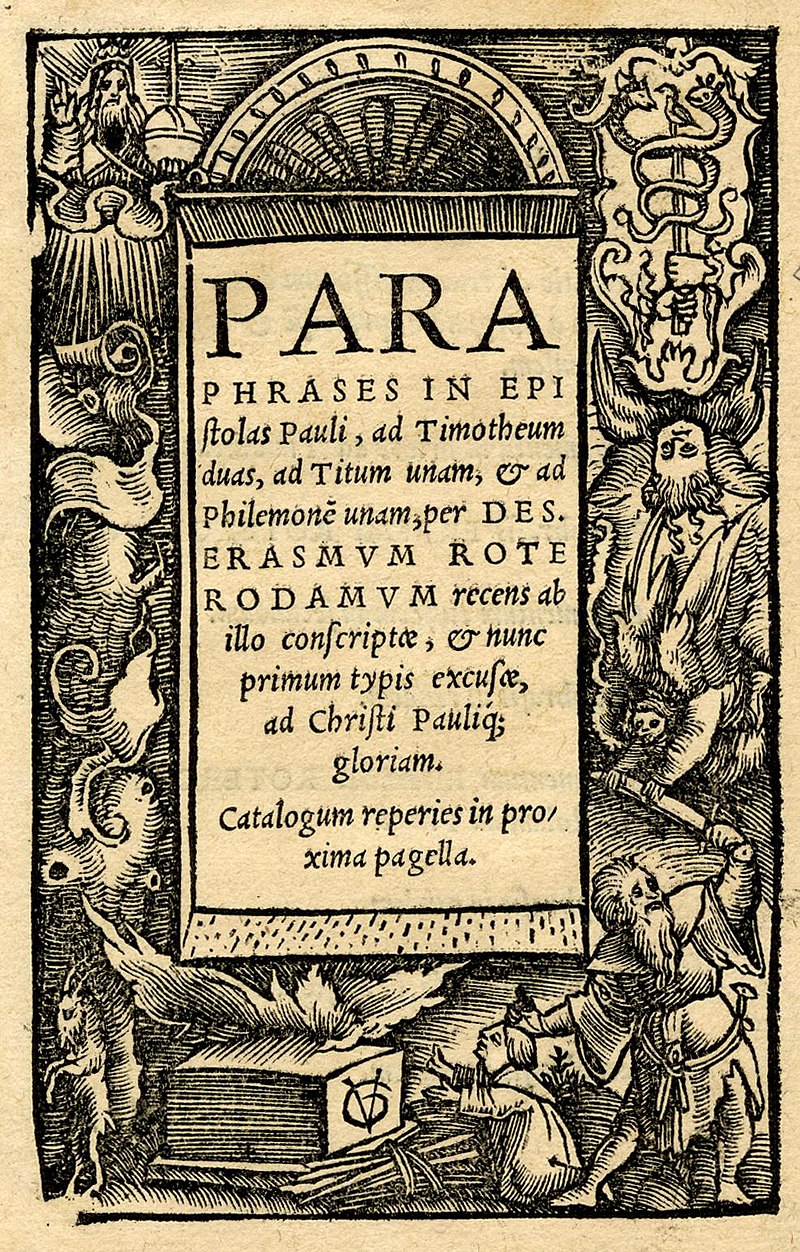

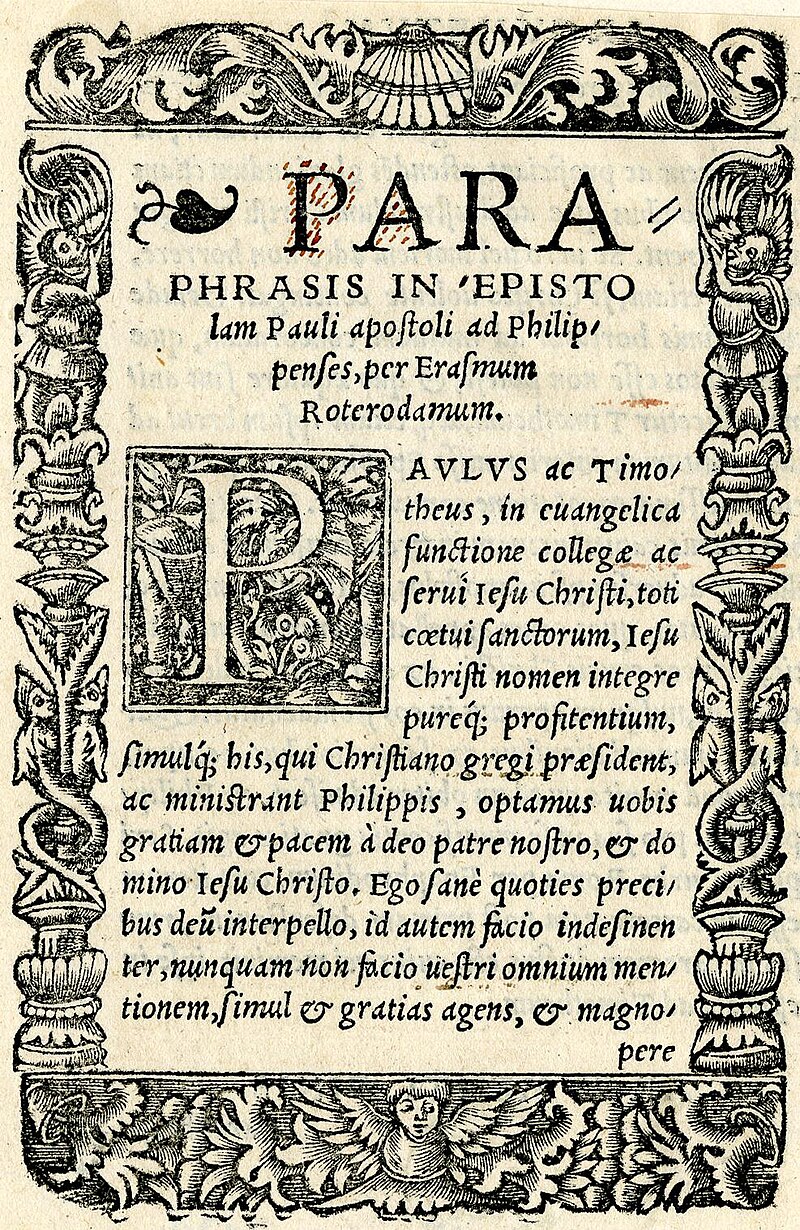

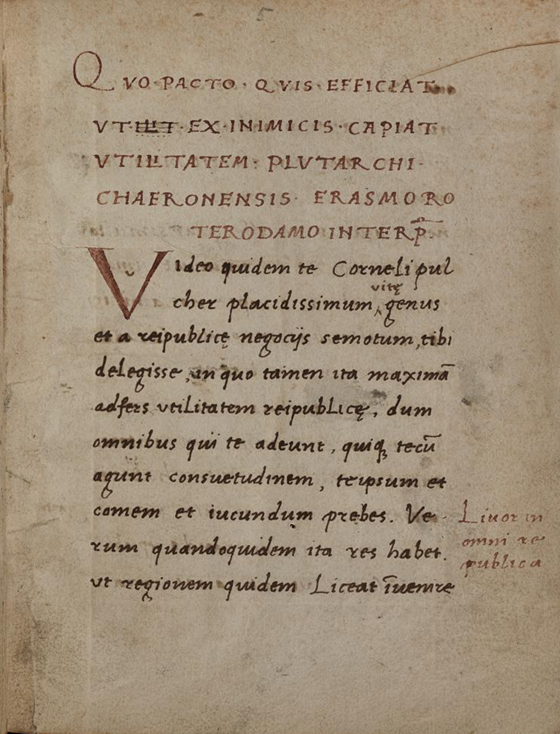

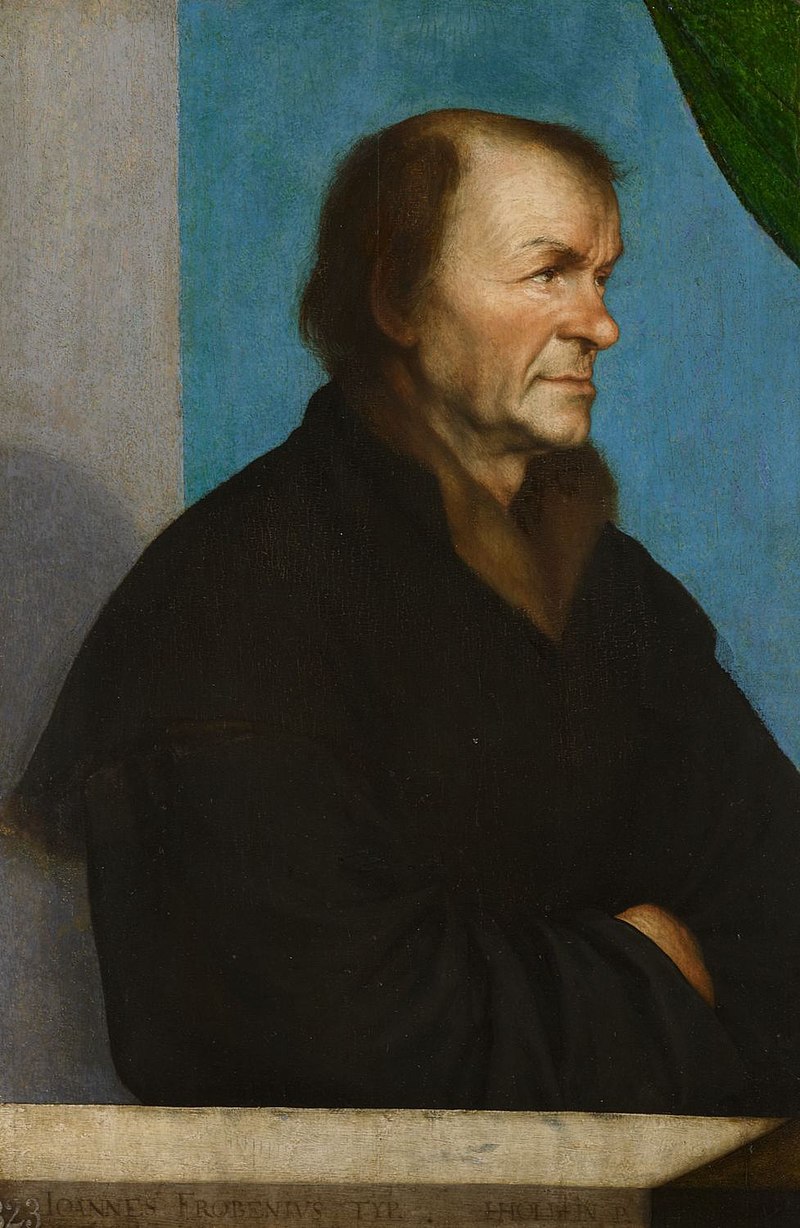

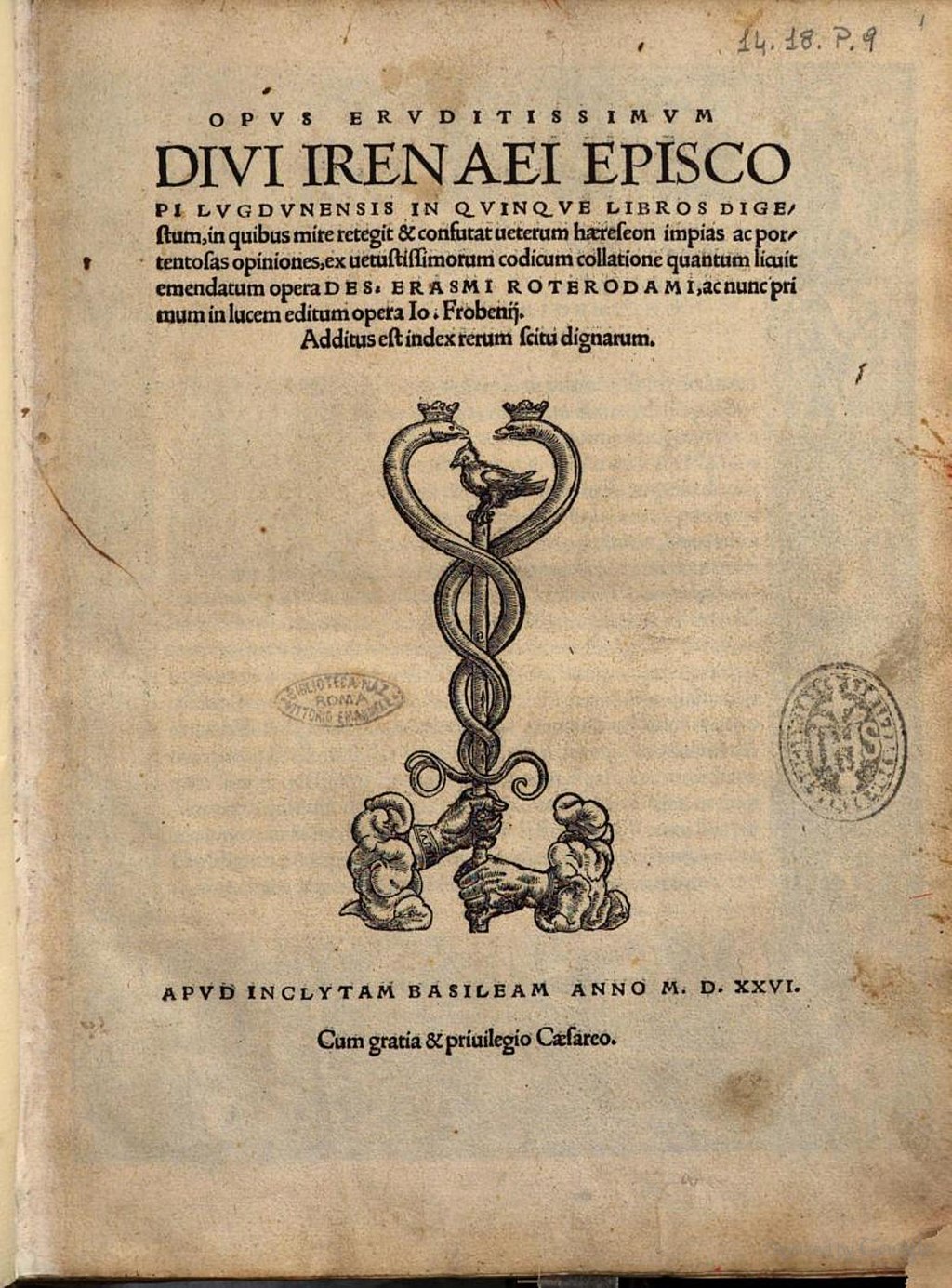

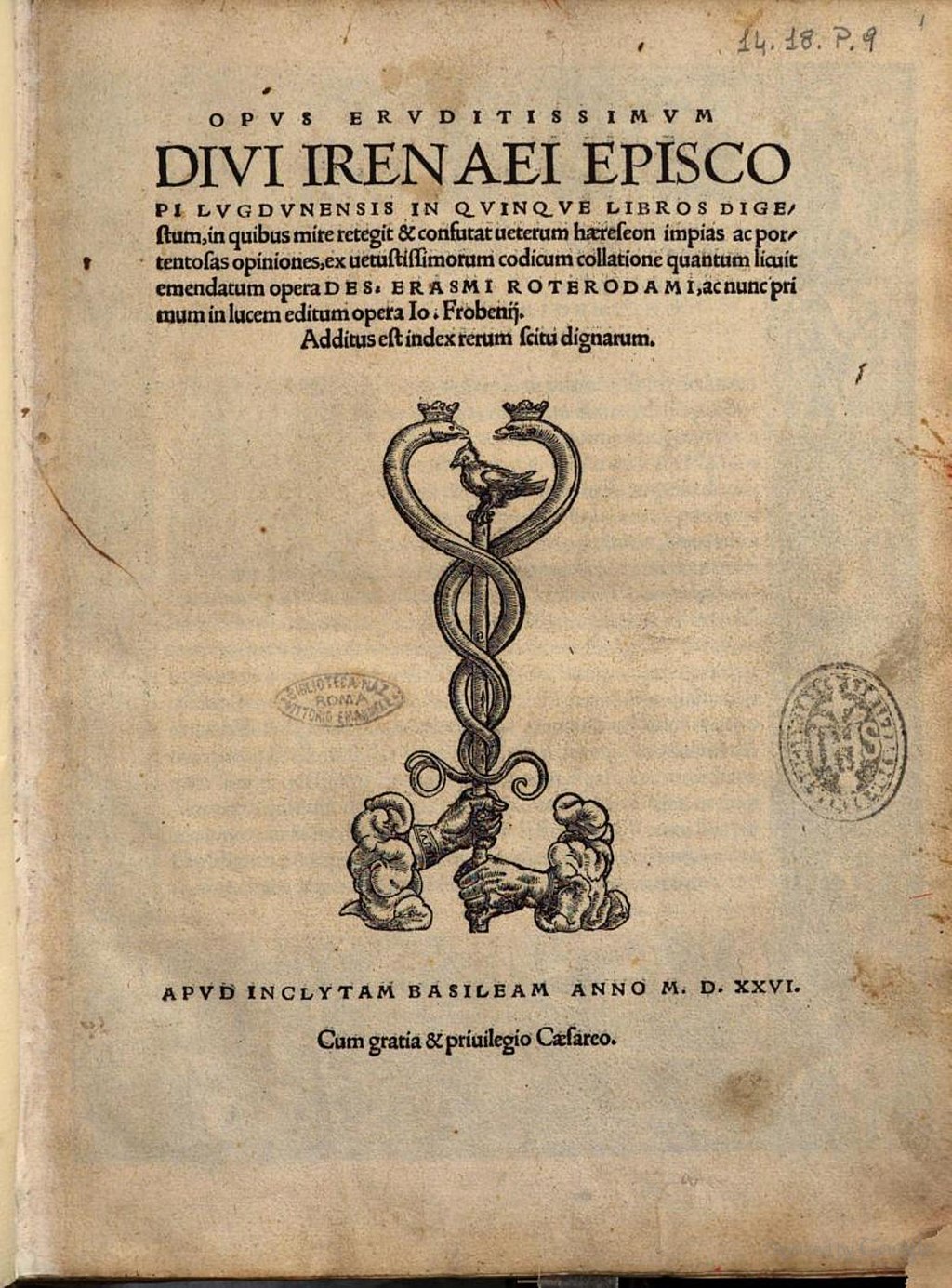

| 1514 |

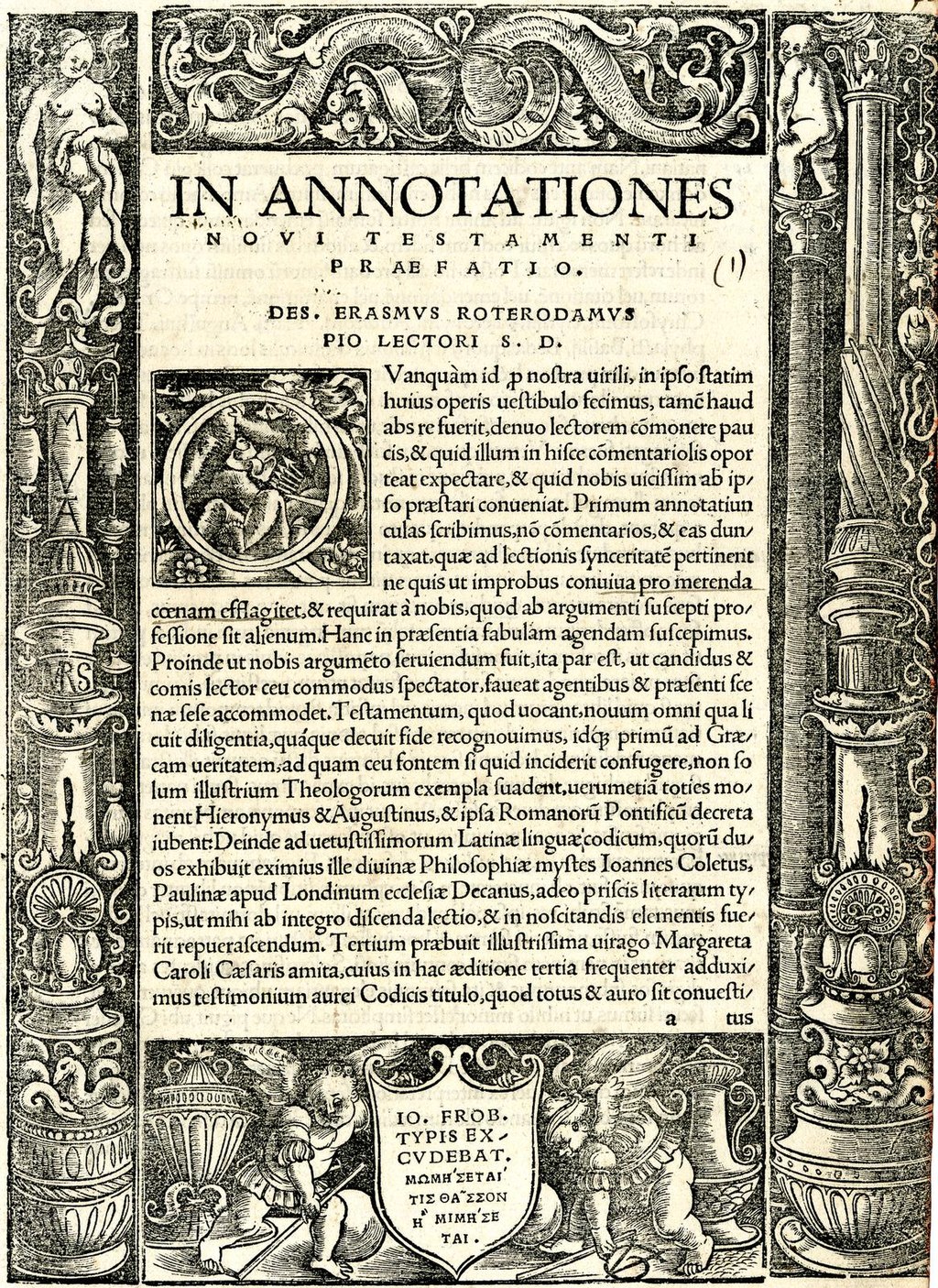

スイスのバーゼルに到着したエラスムスは書店店主ヨハン・フローベン

(Johan Froben) と知り合う。フローベンとエラスムスは意気投合し、以後のエラスムスの著作はフローベンの書店から出版されることになる |

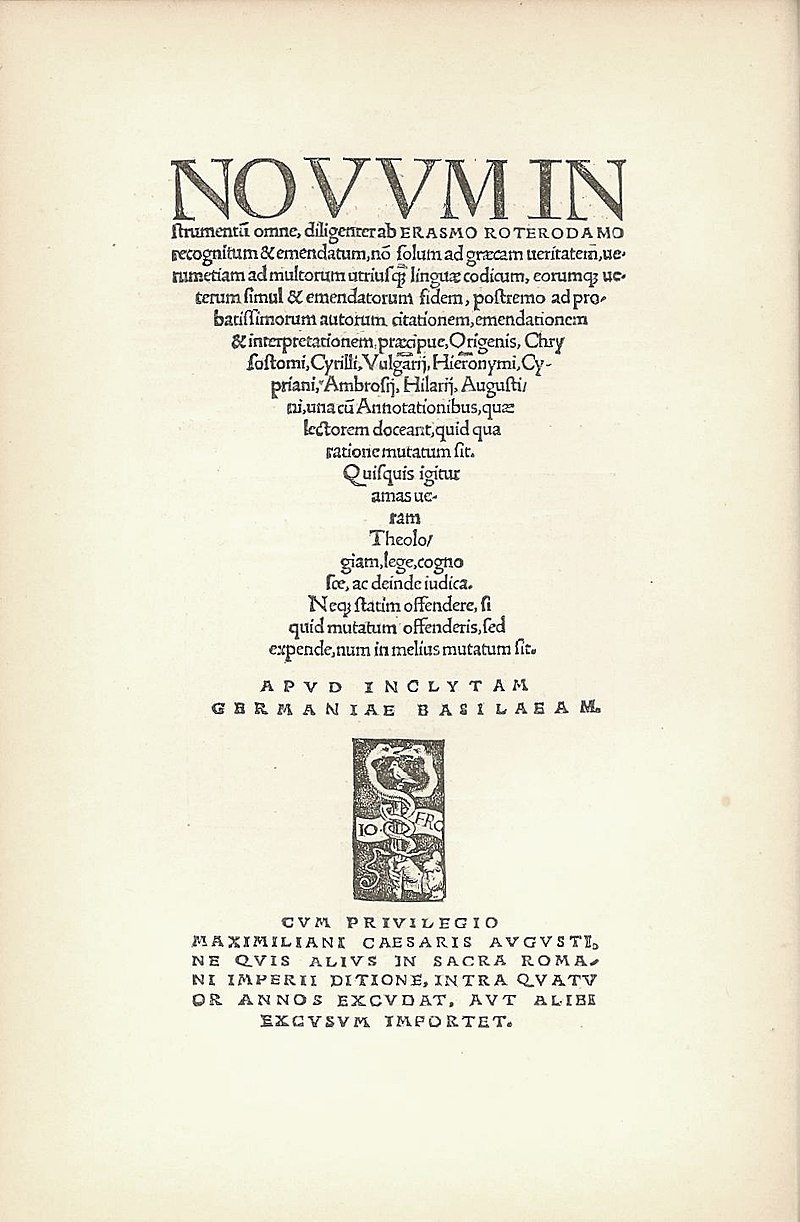

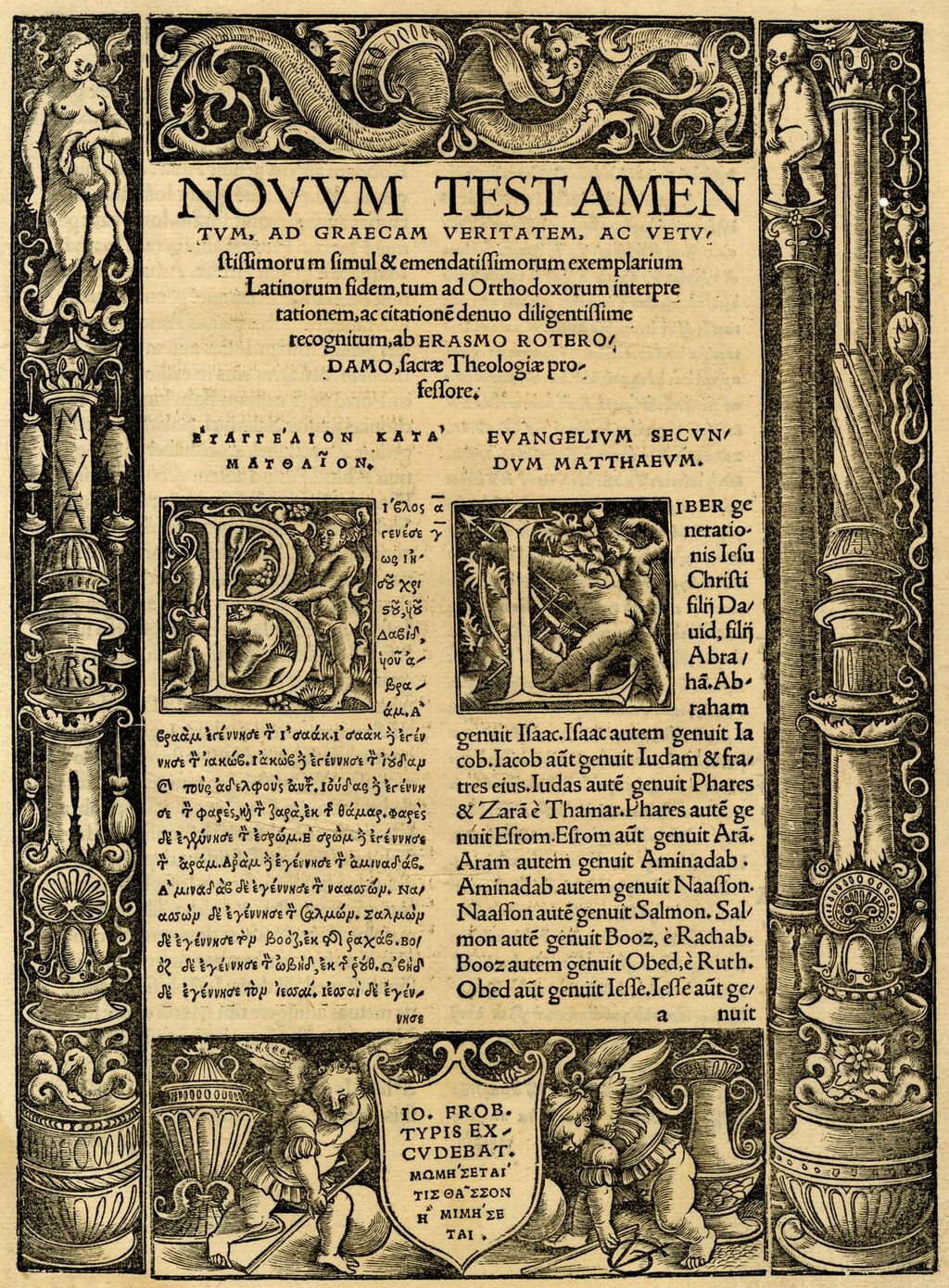

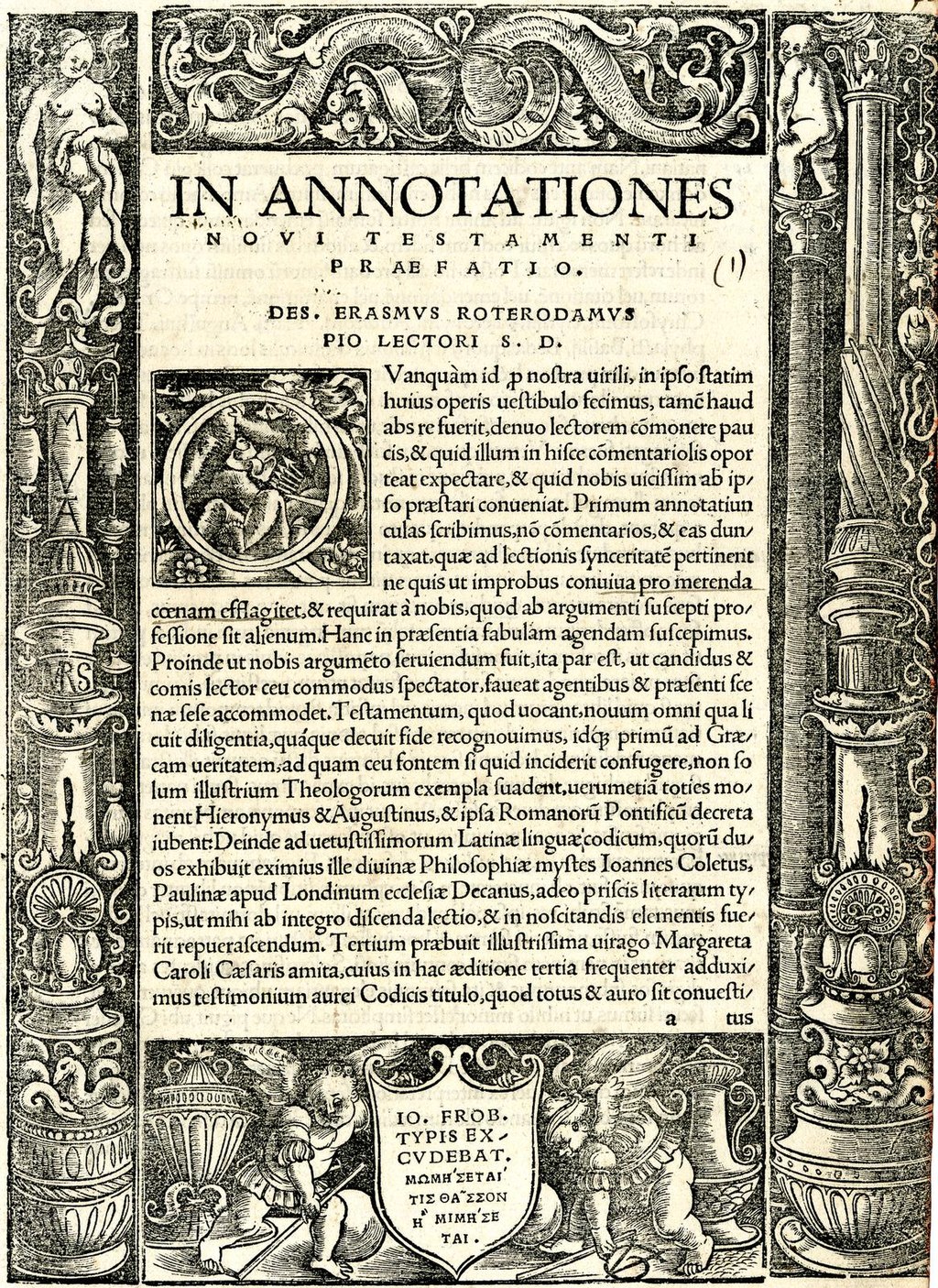

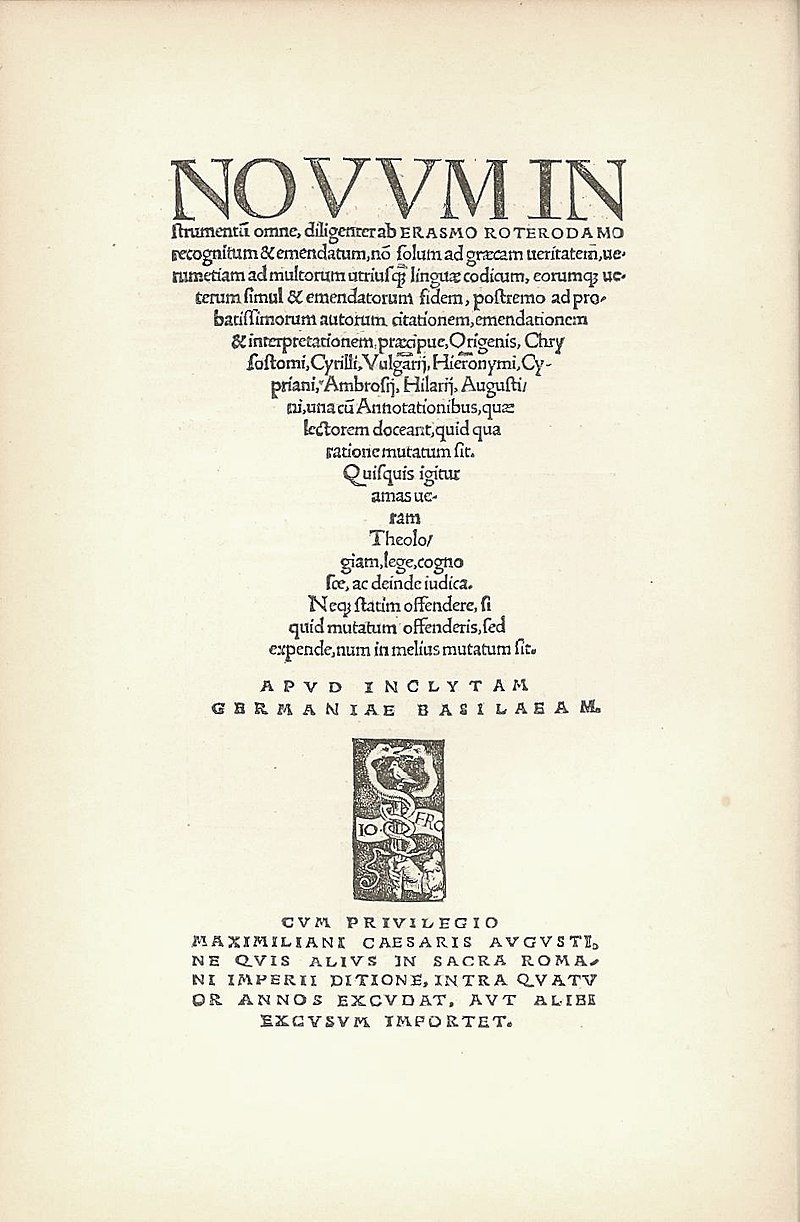

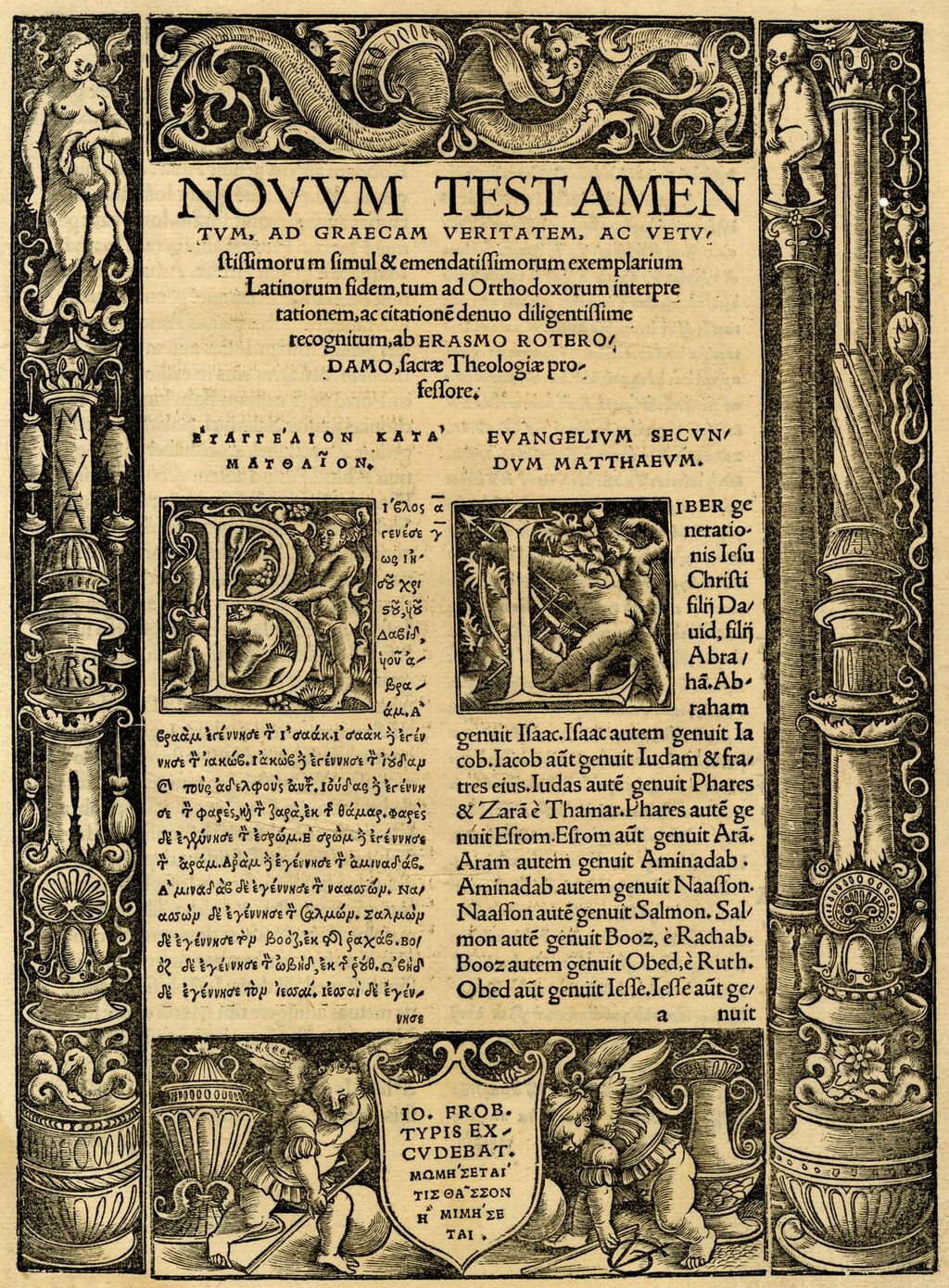

| 1516 |

『校訂版 新約聖書』(Novum Instrumentum)

と9巻からなる『ヒエロニムス著作集』は学識者の間で高く評価され、人文主義者としてのエラスムスの評価を決定付ける。ブルゴーニュ公シャルル(後のカー

ル5世)の名誉参議官に任命 |

| 1517 |

聖アウグスチノ修道会員マルティン・ルターが発表した『95ヶ条の論

題』 |

| 1521 |

1521年にルーヴァン大学を去り、バーゼルへ移った。のちにバーゼル

で宗教改革が進展するとそれに耐えられずフライブルクへ移った。 |

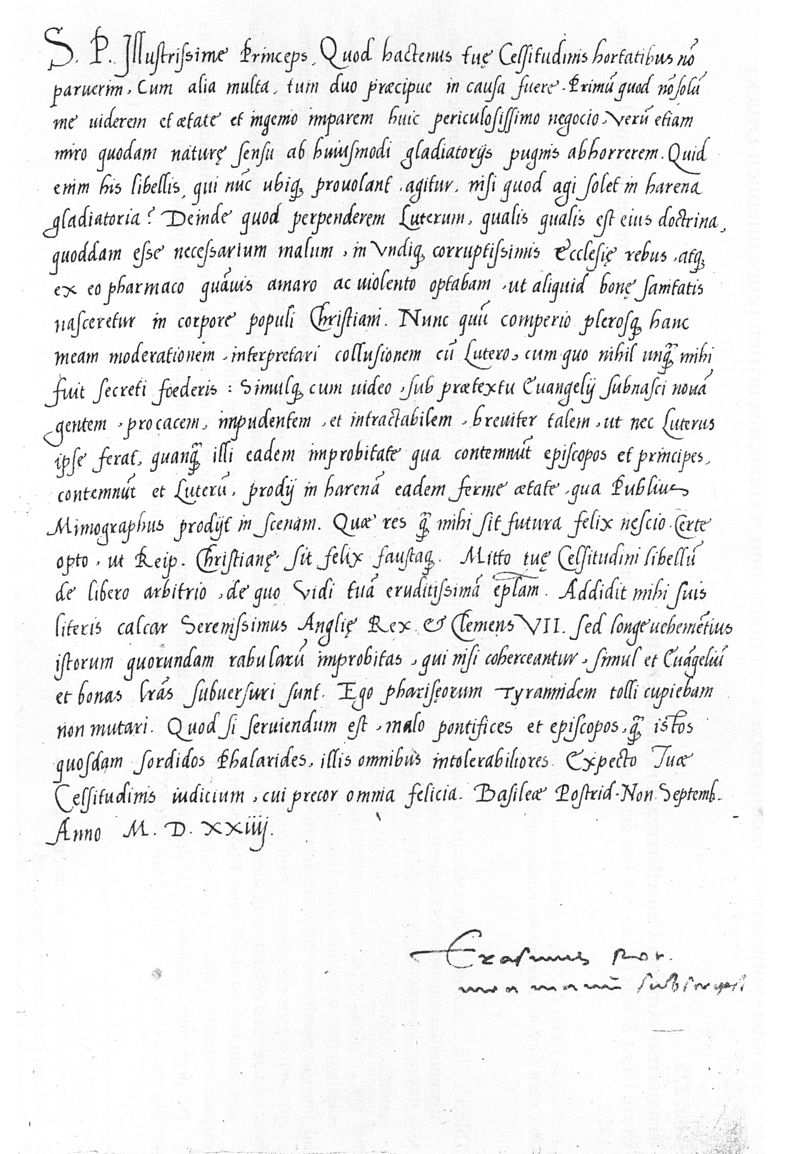

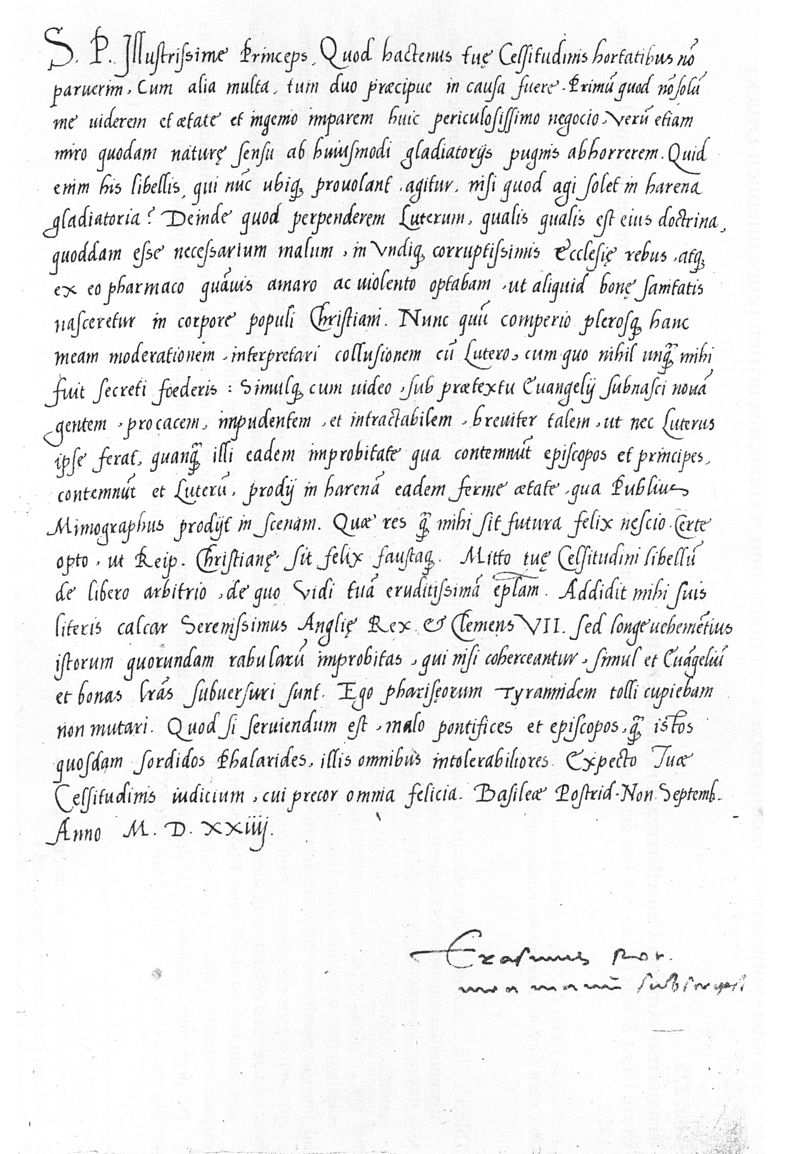

| 1524 | ヘンリー8世の考えとトマス・モアの書簡に触発され、エラスムスは カトリック教会内で古代から議論が続けられてきた自由意志の問題についての著作『自 由意志論』(De lebero Arbitrio, 1524年)を執筆した。自由意志の問題はルター思想の骨子であったため、ルターはこれを看過できず、対抗する形で『奴隷意志論』(De servo Arbitrio) を発表。 |

| 1526 | エラスムスはさらにそれに対する『反論』 (Hyperaspistes, 1526年)を著しているが、結局これを最後にエラスムスは泥沼化したルター問題から手を引いた |

| 1535 |

再びバーゼルに戻る |

| 1536 |

1536年7月12日にバーゼルで死去 |

Portrait

of Erasmus of Rotterdam (1523) by Hans Holbein the Younger

デジデリウス・エラスムス・ロテロダムス(Desiderius

Erasmus Roterodamus /ˌdɛzɪˈɪəriəs ɪˈ; Dutch: [ˌdeˈˈDʌdeˈ [ˌdeˈ

eˈˈ];

英語: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus; 1466年10月28日頃 -

1536年7月12日)は、オランダのキリスト教人文主義者、カトリック神学者、教育学者、風刺家、哲学者: 1466年10月28日頃 -

1536年7月12日)は、オランダのキリスト教人文主義者、カトリック神学者、教育者、風刺家、哲学者。膨大な数の翻訳、著書、エッセイ、祈り、書簡を

通して、北方ルネサンス期の最も影響力のある思想家の一人であり、オランダ文化および西洋文化の主要人物の一人とみなされている[2][3]。

古典研究における重要な人物であり、自然なラテン語の文体で、のびのびとした文章を書いた。カトリックの司祭として人文主義的なテクストを開発し、重要な

新約聖書のラテン語版とギリシア語版を作成した。また、『自由意志について』、『愚行礼賛』、『キリスト教騎士の手引書』、『子供の礼節について』、『コ

ピア』などの著作もある: その他多くの著作がある。

エラスムスは、ヨーロッパの宗教改革の高まりを背景に生きた。彼は聖書的人文主義神学を展開し、その中で寛容、和合、無関心な事柄に対する自由な思考を提

唱した。彼は生涯カトリック教会の信徒であり、教会の内部からの改革に尽力した。彼は、マルティン・ルターやジョン・カルヴァンといった著名な改革者たち

が単子論の教義を支持して否定した、伝統的な教義である相乗論を推進した。彼の中道的なアプローチは、両陣営の党派を失望させ、さらには怒らせた。

エラスムスの約70年間は、4つの時期に分けることができる。

第一に、孤児となり困窮していた中世オランダの子供時代;

第二に、カノン(一種の半修道士)、書記官、司祭、落ちこぼれで病弱な大学生、詩人志望者、家庭教師としての苦闘の日々;

第三に、1499年にイギリスの改革派サークル、次いでフランスの急進派フランシスコ会士ジャン・ヴィトリエ(またはヴォワリエ)、そして後にヴェネツィ アのギリシャ語圏のアルディン新アカデミーと接触した後、ますます集中し、文学的生産性を高めていった、華やかではあったが放浪的な時期。

第四に、『新約聖書』を著し、ルター派への反発を強めながら、ヨーロッパ思想に多大な影響を及ぼした、より安定し落ち着いた最後の黒い森の時代である。

| Desiderius Erasmus

Roterodamus (/ˌdɛzɪˈdɪəriəs ɪˈræzməs/; Dutch: [ˌdeːziˈdeːriʏs

eˈrɑsmʏs]; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus; 28 October c.1466

– 12 July 1536) was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic theologian,

educationalist, satirist, and philosopher. Through his vast number of

translations, books, essays, prayers and letters, he is considered one

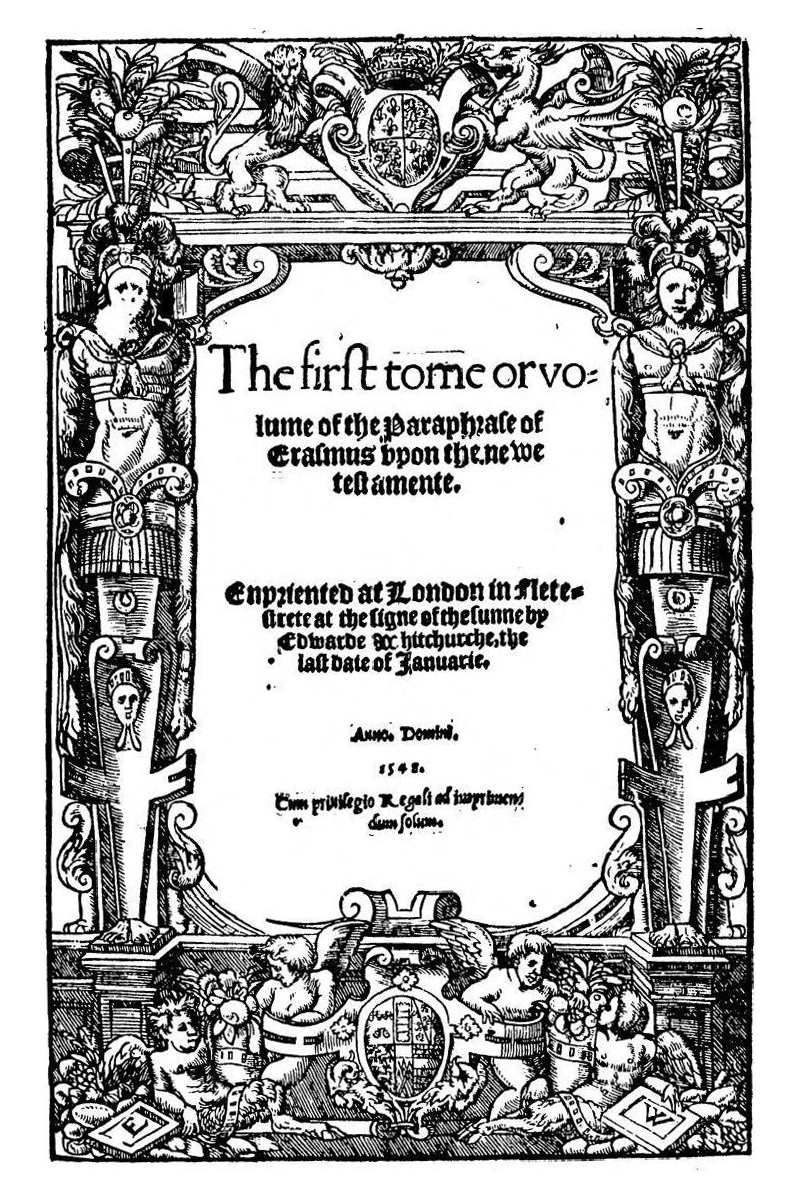

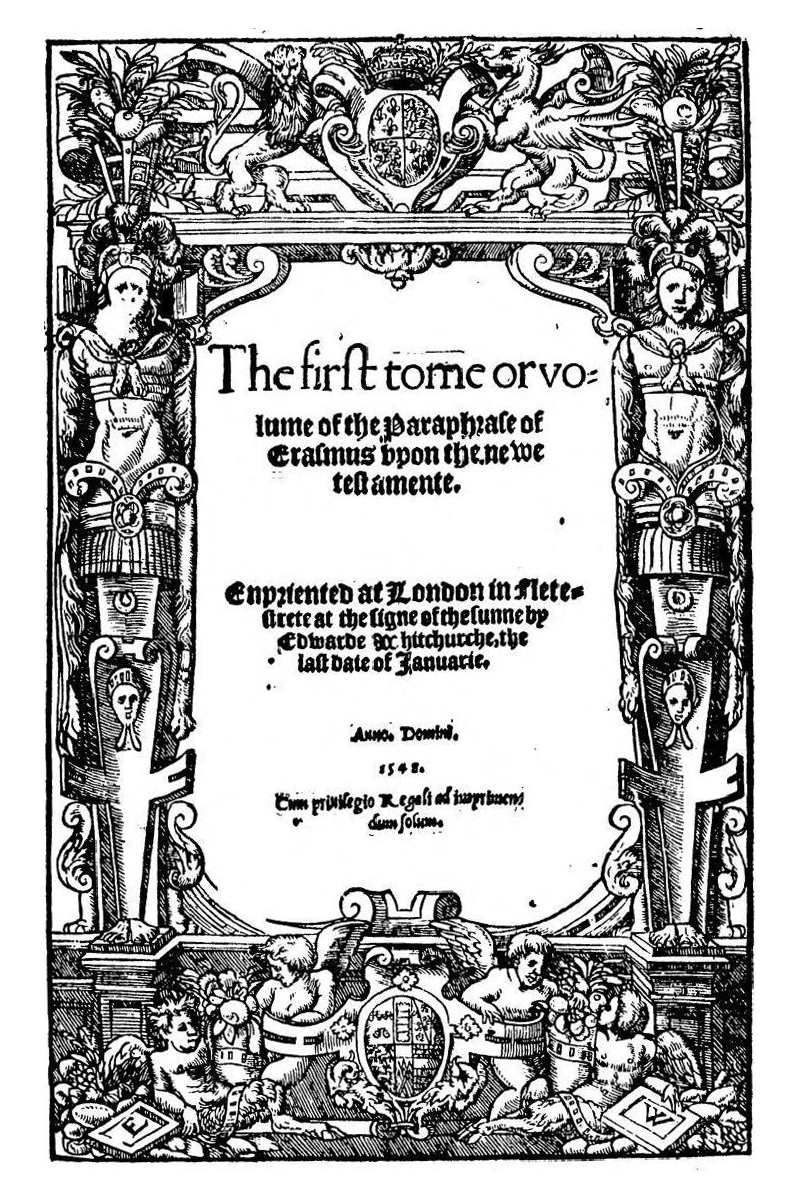

of the most influential thinkers of the Northern Renaissance and one of

the major figures of Dutch and Western culture.[2][3] He was an important figure in classical scholarship who wrote in a spontaneous, copious and natural Latin style. As a Catholic priest developing humanist techniques for working on texts, he prepared important new Latin and Greek editions of the New Testament, which raised questions that would be influential in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. He also wrote On Free Will, The Praise of Folly, Handbook of a Christian Knight, On Civility in Children, Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style and many other works. Erasmus lived against the backdrop of the growing European religious Reformation. He developed a biblical humanistic theology in which he advocated tolerance, concord and free thinking on matters of indifference. He remained a member of the Catholic Church all his life, remaining committed to reforming the Church from within. He promoted the traditional doctrine of synergism, which some prominent Reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin rejected in favor of the doctrine of monergism. His middle-road approach disappointed, and even angered, partisans in both camps. |

デジデリウス・エラスムス・ロテロダムス(Desiderius

Erasmus Roterodamus /ˌdɛzɪˈɪəriəs ɪˈ; Dutch: [ˌdeˈˈDʌdeˈ [ˌdeˈ

eˈˈ];

英語: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus; 1466年10月28日頃 -

1536年7月12日)は、オランダのキリスト教人文主義者、カトリック神学者、教育学者、風刺家、哲学者: 1466年10月28日頃 -

1536年7月12日)は、オランダのキリスト教人文主義者、カトリック神学者、教育者、風刺家、哲学者。膨大な数の翻訳、著書、エッセイ、祈り、書簡を

通して、北方ルネサンス期の最も影響力のある思想家の一人であり、オランダ文化および西洋文化の主要人物の一人とみなされている[2][3]。 古典研究における重要な人物であり、自然なラテン語の文体で、のびのびとした文章を書いた。カトリックの司祭として人文主義的なテクストを開発し、重要な 新約聖書のラテン語版とギリシア語版を作成した。また、『自由意志について』、『愚行礼賛』、『キリスト教騎士の手引書』、『子供の礼節について』、『コ ピア』などの著作もある: その他多くの著作がある。 エラスムスは、ヨーロッパの宗教改革の高まりを背景に生きた。彼は聖書的人文主義神学を展開し、その中で寛容、和合、無関心な事柄に対する自由な思考を提 唱した。彼は生涯カトリック教会の信徒であり、教会の内部からの改革に尽力した。彼は、マルティン・ルターやジョン・カルヴァンといった著名な改革者たち が単子論の教義を支持して否定した、伝統的な教義である相乗論を推進した。彼の中道的なアプローチは、両陣営の党派を失望させ、さらには怒らせた。 |

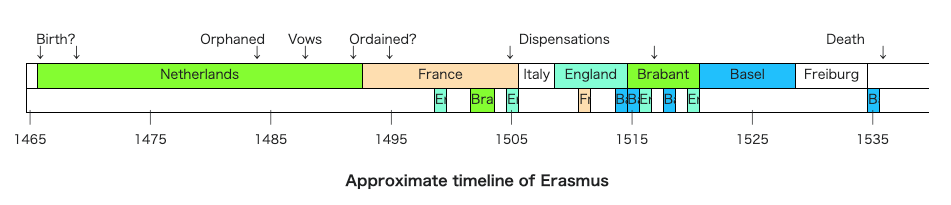

| Biography Erasmus's almost 70 years can be divided into four quarters. First was his medieval Dutch childhood, ending with his being orphaned and impoverished; second, his struggling years as a canon (a kind of semi-monk), a clerk, a priest, a failing and sickly university student, a would-be poet, and a tutor; third, his flourishing but peripatetic years of increasing focus and literary productivity following his 1499 contact with a reformist English circle, then with radical French Franciscan Jean Vitrier (or Voirier) and later with the Greek-speaking Aldine New Academy in Venice; and fourth, his final more secure and settled Black Forest years as a prime influencer of European thought through his New Testament and increasing opposition to Lutheranism. |

バイオグラフィー エラスムスの約70年間は、4つの時期に分けることができる。 第一に、孤児となり困窮していた中世オランダの子供時代; 第二に、カノン(一種の半修道士)、書記官、司祭、落ちこぼれで病弱な大学生、詩人志望者、家庭教師としての苦闘の日々; 第三に、1499年にイギリスの改革派サークル、次いでフランスの急進派フランシスコ会士ジャン・ヴィトリエ(またはヴォワリエ)、そして後にヴェネツィ アのギリシャ語圏のアルディン新アカデミーと接触した後、ますます集中し、文学的生産性を高めていった、華やかではあったが放浪的な時期。 第四に、『新約聖書』を著し、ルター派への反発を強めながら、ヨーロッパ思想に多大な影響を及ぼした、より安定し落ち着いた最後の黒い森の時代である。 |

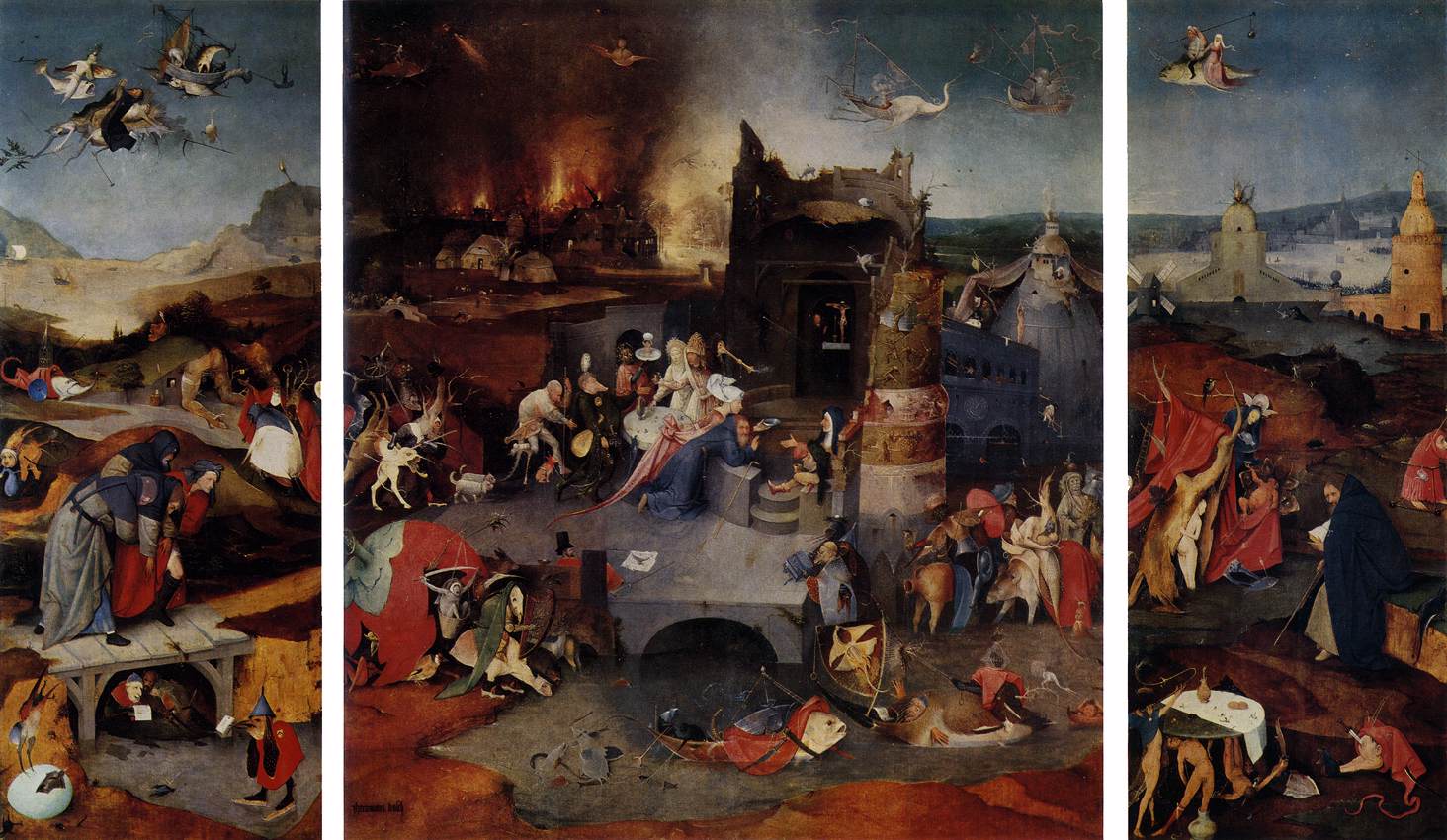

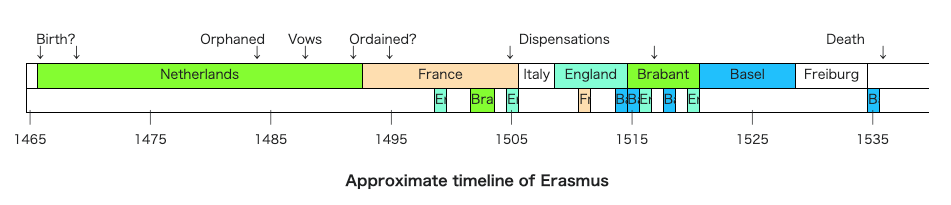

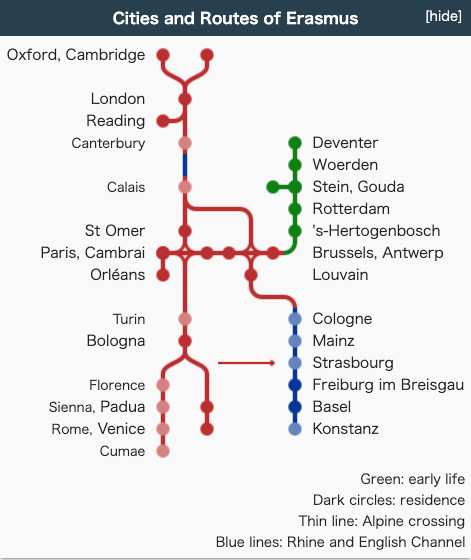

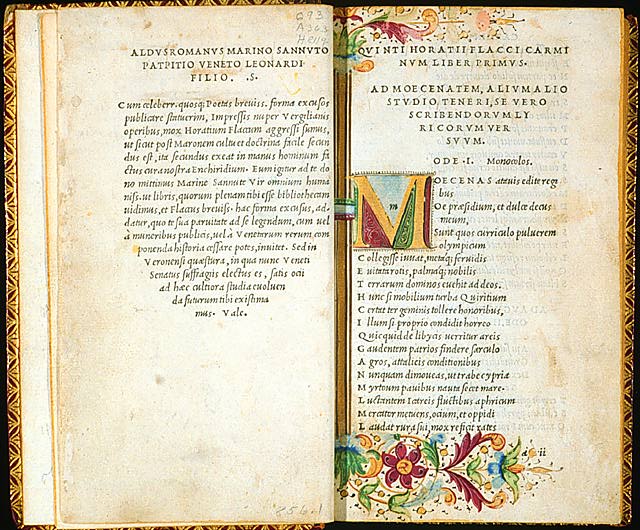

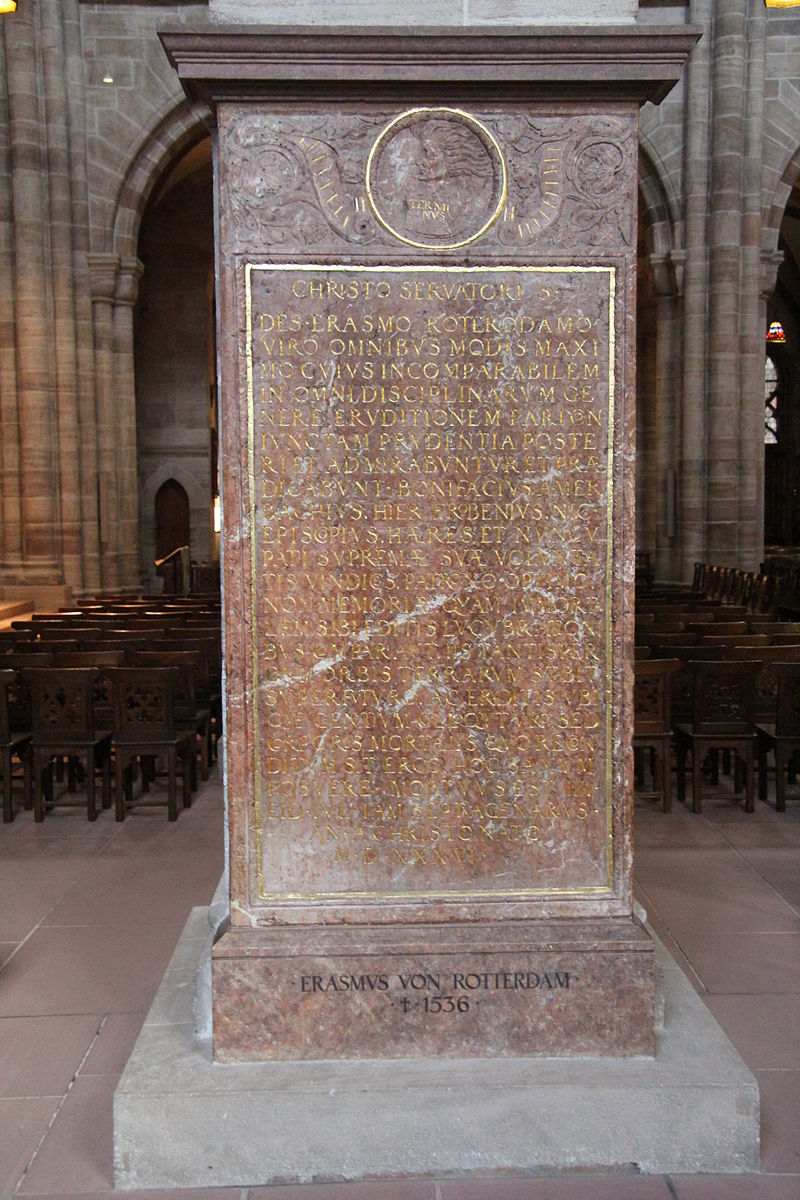

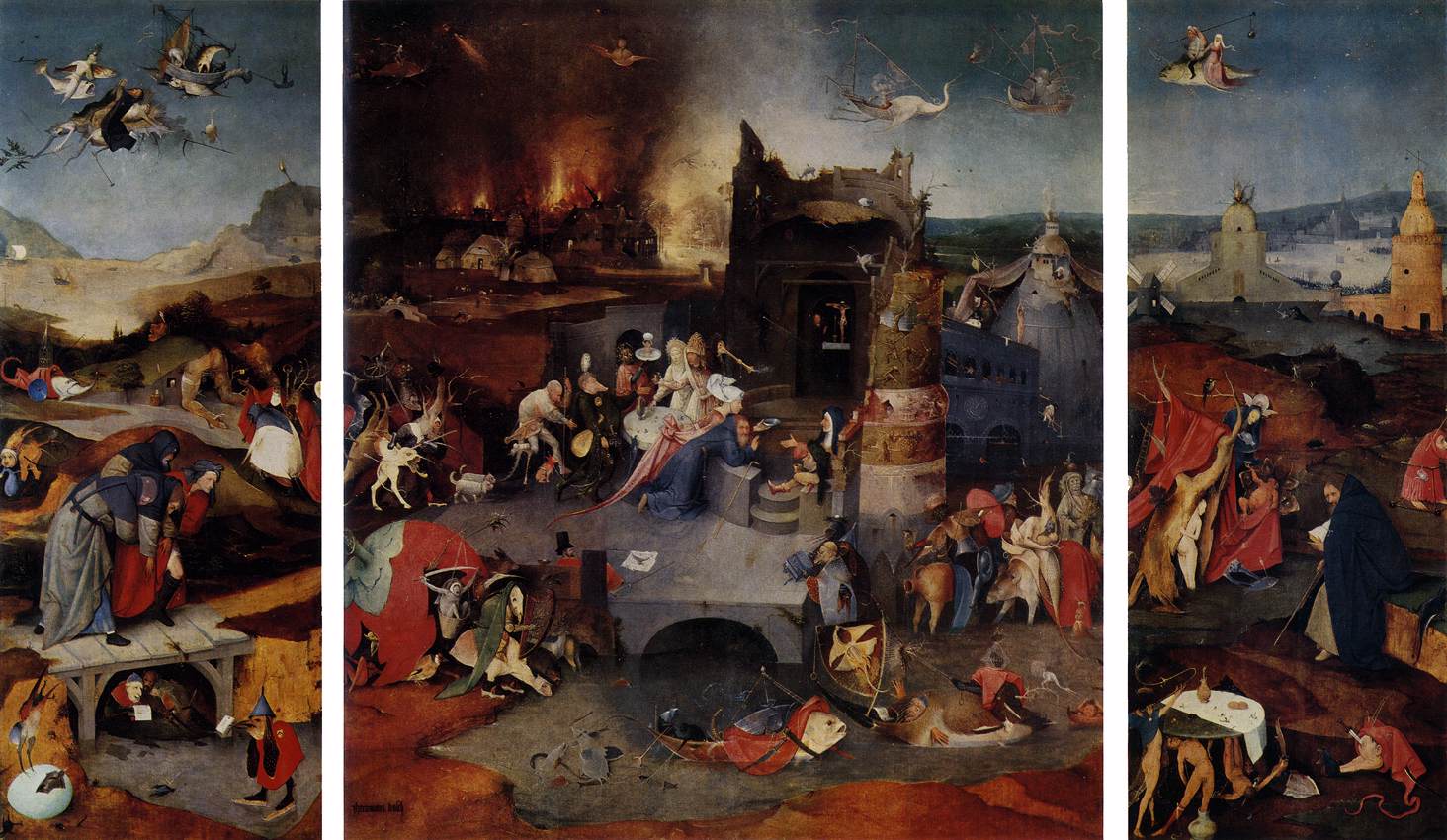

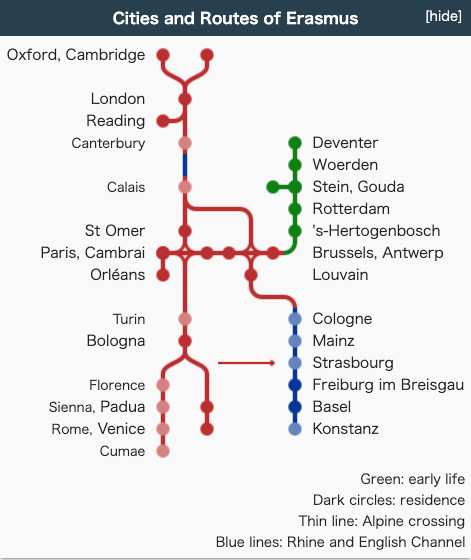

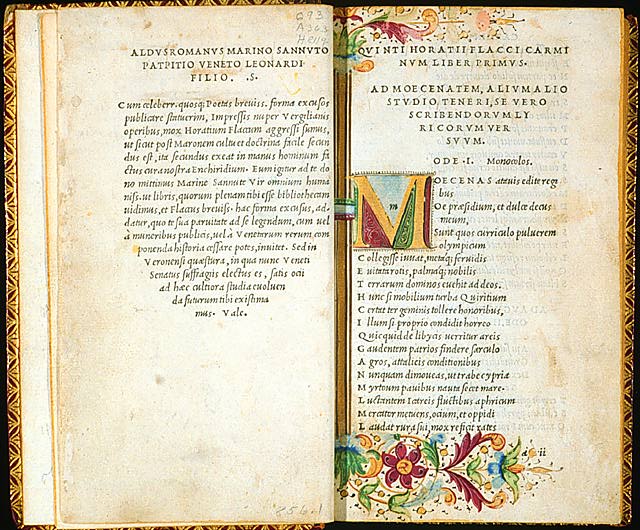

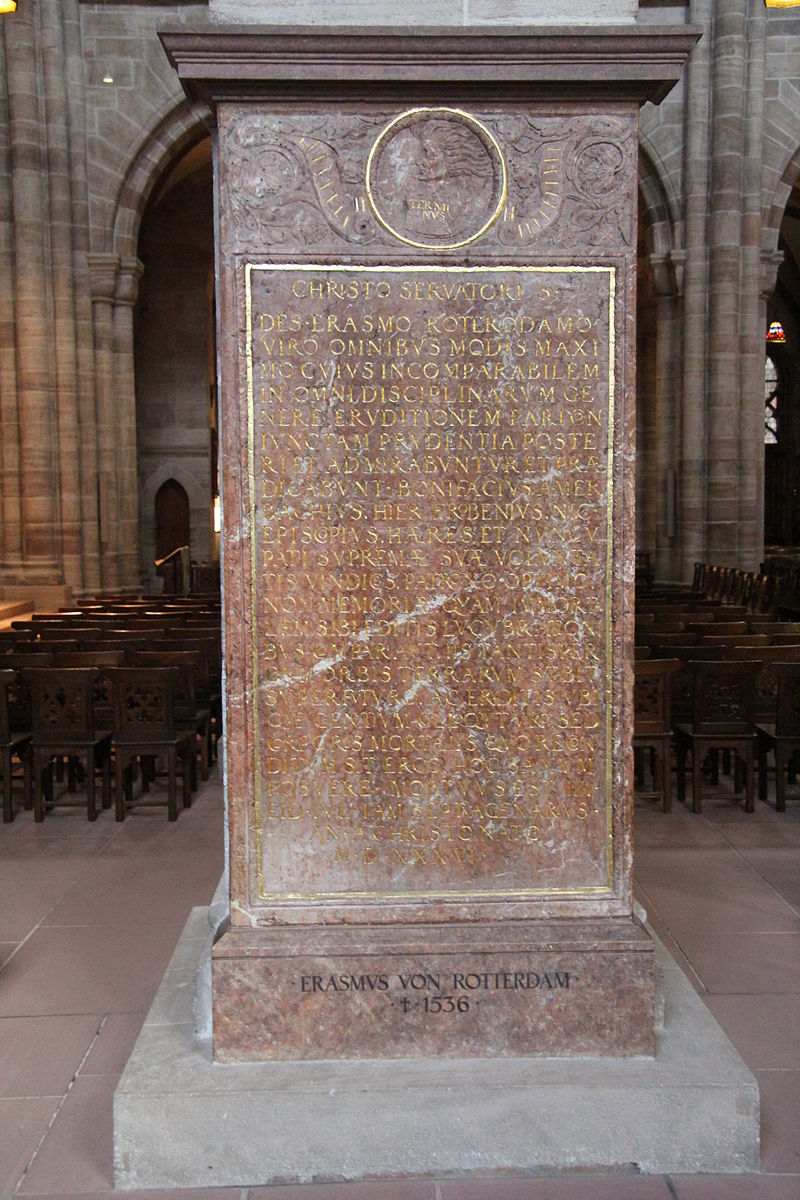

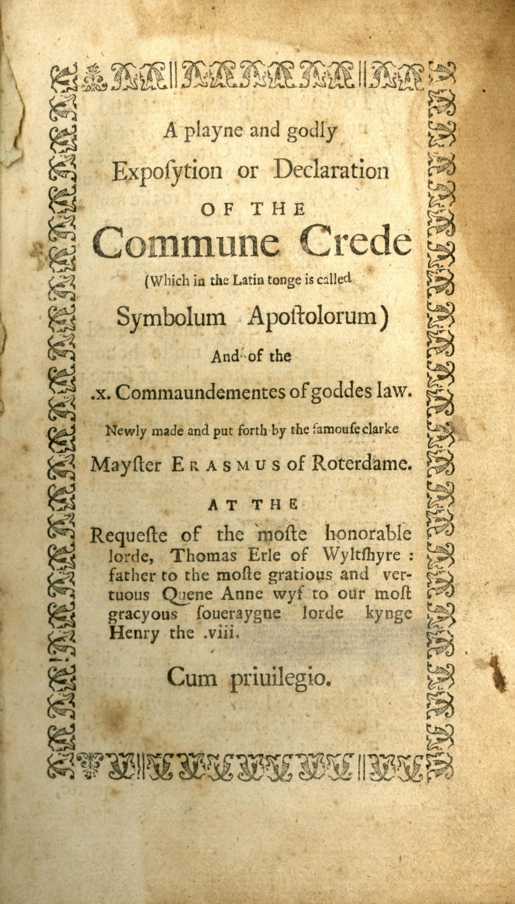

Early life Statue of Erasmus in Rotterdam. Gilded bronze statue by Hendrick de Keyser (1622), replacing a stone (1557), and a wooden (1549). Desiderius Erasmus is reported to have been born in Rotterdam on 27 or 28 October ("the vigil of Simon and Jude")[4] in the late-1460s. He was named[note 1] after Erasmus of Formiae, whom Erasmus' father Gerard (Gerardus Helye)[5] personally favored.[6][7] Although associated closely with Rotterdam, he lived there for only four years, never to return afterwards. The year of Erasmus' birth is unclear: in later life he calculated his age as if born in 1466, but frequently his remembered age at major events actually implies 1469.[8][9]: 8 (This article currently gives 1466 as the birth year.[10][11] To handle this disagreement, ages are given first based on 1469, then in parentheses based on 1466: e.g., "20 (or 23)".) Furthermore, many details of his early life must be gleaned from a fictionalized third-person account he wrote in 1516 (published in 1529) in a letter to a fictitious Papal secretary, Lambertus Grunnius ("Mr. Grunt").[12] His parents could not be legally married: his father, Gerard, was a Catholic priest[13] who may have spent up to six years in the 1450s or 60s in Italy as a scribe and scholar.[14]: 196 His mother was Margaretha Rogerius (Latinized form of Dutch surname Rutgers),[15] the daughter of a doctor from Zevenbergen. She may have been Gerard's housekeeper.[13][16] Although he was born out of wedlock, Erasmus was cared for by his parents, with a loving household and the best education, until their early deaths from the bubonic plague in 1483. His only sibling Peter might have been born in 1463, and some writers suggest Margaret was a widow and Peter was the half-brother of Erasmus; Erasmus on the other side called him his brother.[9] There were legal and social restrictions on the careers and opportunities open to the children of unwed parents. Erasmus' own story, in the possibly forged 1524 Compendium vitae Erasmi was along the lines that his parents were engaged, with the formal marriage blocked by his relatives (presumably a young widow or unmarried mother with a child was not an advantageous match); his father went to Italy to study Latin and Greek, and the relatives mislead Gerard that Margaretha had died, on which news grieving Gerard romantically took Holy Orders, only to find on his return that Margaretha was alive; many scholars dispute this account.[17]: 89 In 1471 his father became the vice-curate of the small town of Woerden (where young Erasmus may have attended the local vernacular school to learn to read and write) and in 1476 was promoted to the vice-curate of Gouda.[5] Erasmus was given the highest education available to a young man of his day, in a series of monastic or semi-monastic schools. In 1476, at the age of 6 (or 9), his family moved to Gouda and he started at the school of Mr Pieter Winckel,[5] who later became his guardian (and, perhaps, diverted Erasmus and Peter's inheritance.) (Historians who date his birth in 1466 have Erasmus in Utrecht at the choir school at this period.[18]) In 1478, at the age of 9 (or 12), he and his older brother Peter were sent to one of the best Latin schools in the Netherlands, located at Deventer and owned by the chapter clergy of the Lebuïnuskerk (St. Lebuin's Church).[10] Towards the end of his stay there the curriculum was renewed by the new principal of the school, Alexander Hegius, a correspondent of pioneering rhetorician Rudolphus Agricola. For the first time in Europe north of the Alps, Greek was taught at a lower level than a university[19] and this is where he began learning it.[20] His education there ended when plague struck the city about 1483,[21] and his mother, who had moved to provide a home for her sons, died from the infection. Following the death of his parents and 20 students at his school[9] he moved back to his patria (Rotterdam?)[5] where he was supported by Berthe de Heyden,[22] a compassionate widow.[9]  Hieronymous Bosch, Temptation of St Anthony, triptych (c. 1501), painted in 's-Hertogenbosch, later owned by friend Damião de Gois In 1484, around the age 14 (or 17), he and his brother went to a cheaper[23] grammar school or seminary at 's-Hertogenbosch run by the Brethren of the Common Life:[24][note 2] Erasmus' Epistle to Grunnius satirizes them as the "Collationary Brethren"[12] who select and sort boys for monkhood. He was exposed there to the Devotio moderna movement and the Brethren's famous book The Imitation of Christ but resented the harsh rules and strict methods of the religious brothers and educators.[10] The two brothers made an agreement that they would resist the clergy but attend the university;[22] Erasmus longed to study in Italy, the birthplace of Latin, and have a degree from an Italian university.[8]: 804 Instead, Peter left for the Augustinian canonry in Stein, which left Erasmus feeling betrayed.[22] Around this time he wrote forlornly to his friend Elizabeth de Heyden "Shipwrecked am I, and lost, 'mid waters chill'."[9] He suffered Quartan fever for over a year. Eventually Erasmus moved to the same abbey as a postulant in or before 1487,[5] around the age of 16 (or 19.)[note 3] Vows, ordination and canonry experience  Bust by Hildo Krop (1950) in Gouda, where Erasmus spent his youth Poverty[25] had forced Erasmus into the consecrated life, entering the novitiate in 1487[26] at the canonry at rural Stein, very near Gouda, South Holland: the Chapter of Sion community largely borrowed its rule from the larger monkish Congregation of Windesheim.[note 4] In 1488–1490, the surrounding region was plundered badly by armies fighting the Jonker Fransen war of succession and then suffered a famine.[8]: 759 Erasmus professed his vows as a Canon Regular of St. Augustine[note 5] there in late 1488 at age 19 (or 22).[26] Historian Fr. Aiden Gasquet later wrote: "One thing, however, would seem to be quite clear; he could never have had any vocation for the religious life. His whole subsequent history shows this unmistakeably."[30] According to one Catholic biographer, Erasmus had a spiritual awakening at the monastery.[31] Certain abuses in religious orders were among the chief objects of his later calls to reform the Western Church from within, particularly coerced or tricked recruitment of immature boys (the fictionalized account in the Letter to Grunnius calls them "victims of Dominic and Francis and Benedict"): Erasmus felt he had belonged to this class, joining "voluntarily but not freely" and so considered himself, if not morally bound by his vows, certainly legally, socially and honour- bound to keep them, yet to look for his true vocation.[27]: 439 While at Stein, 18-(or 21-)year-old Erasmus fell in unrequited love, forming what he called a "passionate attachment" (Latin: fervidos amores), with a fellow canon, Servatius Rogerus,[note 6] and wrote a series of love letters[note 7][33] in which he called Rogerus "half my soul",[note 8] writing that "it was not for the sake of reward or out of a desire for any favour that I have wooed you both unhappily and relentlessly. What is it then? Why, that you love him who loves you."[34][note 9] This correspondence contrasts with the generally detached and much more restrained attitude he usually showed in his later life, though he had a capacity to form and maintain deep male friendships,[note 10] such as with More, Colet, and Ammonio.[note 11] No mentions or sexual accusations were ever made of Erasmus during his lifetime. His works notably praise moderate sexual desire in marriage between men and women.[35] Circle of Latin Secretaries Juan de Vergara • Pietro Carmeliano[36] • Guillaume Budé • Pietro Bembo • Jacopo Sadoleto • Richard Pace • Andrea Ammonio • Hieronymus Emser • Cornelius Grapheus • Johannes Secundus • Juan de Valdés, Alfonso de Valdés • Peter Vannes • Gentian Hervetus • Jan Łaski • Lambert Grunnius (fictitious)[12]: 337 Latin Secretaries became a significant part of Erasmus' later network of correspondents and friends.[note 12] In 1493, his Prior arranged for him to leave the Stein house[38] and take up the post of Latin Secretary to the ambitious Bishop of Cambrai, Henry of Bergen, on account of his great skill in Latin and his reputation as a man of letters.[39][note 13] He was ordained to the Catholic priesthood either on 25 April 1492,[25] or 25 April 1495, at age 25 (or 28.)[note 14] Either way, he did not actively work as a choir priest for very long,[41] though his many works on confession and penance suggests experience of dispensing them. From 1500, he avoided returning to the canonry at Stein even insisting the diet and hours would kill him,[note 15] though he did stay with other Augustinian communities and at monasteries of other orders in his travels. Rogerus, who became prior at Stein in 1504, and Erasmus corresponded over the years, with Rogerus demanding Erasmus return after his studies were complete. Nevertheless, the library of the canonry[note 16] ended up with by far the largest collection of Erasmus' publications in the Gouda region.[42] In 1505 Pope Julius II granted a dispensation from the vow of poverty to the extent of allowing Erasmus to hold certain benefices, and from the control and habit of his order, though he remained a priest and, formally, an Augustinian canon regular[note 17] the rest his life.[27] In 1517 Pope Leo X granted legal dispensations for Erasmus' defects of natality[note 18] and confirmed the previous dispensation, allowing the 48-(or 51-)year-old his independence[43] but still, as a canon, capable of holding office as a prior or abbot.[27] ↓Birth? ↓Orphaned ↓Vows ↓Ordained? ↓Dispensations ↓ ↓Death ↓ ↓ Netherlands France Italy England Brabant Basel Freiburg England Brabant England France Basel Basel England Basel England Basel │ 1465 │ 1475 │ 1485 │ 1495 │ 1505 │ 1515 │ 1525 │ 1535  Approximate timeline of Erasmus Many of Erasmus' convictions seem to spring from his early biography: esteem for the married state and appropriate marriages, support for priestly marriage, concern for improving marriage prospects for females, opposition to inconsiderate rules notably institutional dietary rules, a desire to make education engaging for the participants, interest in classical languages, horror of poverty and spiritual hopelessness, distaste for friars begging when they could study or work, unwillingness to be in the control of authorities, laicism, the need for those in authority to act in the best interest of their charges, a prizing of mercy and peace, an anger over unnecessary war especially between avaricious princes, an awareness of mortality, etc. Travels Cities and Routes of Erasmus Oxford, Cambridge London Reading Canterbury Deventer Woerden Calais Stein, Gouda Rotterdam St Omer 's-Hertogenbosch Paris, Cambrai Brussels, Antwerp Orléans Louvain Turin Cologne Bologna Mainz Strasbourg Florence Freiburg im Breisgau Sienna, Padua Basel Rome, Venice Konstanz Cumae Green: early life Dark circles: residence Thin line: Alpine crossing Blue lines: Rhine and English Channel Erasmus traveled widely and regularly, for reasons of poverty, "escape" from his Stein canonry (to Cambrai), education (to Paris, Turin), escape from the sweating sickness plague (to Orléans), employment (to England), searching libraries for manuscripts, writing (Brabant), royal counsel (Cologne), patronage, tutoring and chaperoning (North Italy), networking (Rome), seeing books through printing in person (Paris, Venice, Louvain, Basel), and avoiding the persecution of religious fanatics (to Freiburg.) He enjoyed horseback riding[44]  Paris In 1495 with Bishop Henry's consent and a stipend, Erasmus went on to study at the University of Paris in the Collège de Montaigu, a centre of reforming zeal,[note 19] under the direction of the ascetic Jan Standonck, of whose rigors he complained.[45] The university was then the chief seat of Scholastic learning but already coming under the influence of Renaissance humanism.[46] For instance, Erasmus became an intimate friend of an Italian humanist Publio Fausto Andrelini, poet and "professor of humanity" in Paris.[47] During this time, Erasmus developed a deep aversion to exclusive or excessive Aristotelianism and Scholasticism[48] and started finding work as a tutor/chaperone to visiting English and Scottish aristocrats. England English circle.[49] Thomas More • John Colet • Thomas Linacre • William Grocyn • William Lily • Andrea Ammonio • Juan Luis Vives • Cuthbert Tunstall • Henry Bullock • Thomas Lupset • Richard Foxe • Christopher Urswick • Robert Aldrich • Richard Whitford • Lorenzo Campeggio • Richard Reynolds • Polydore Vergil Patrons: William Blount • William Warham • John Fisher • John Longland • Margaret Beaufort • Catherine of Aragon "I can truly say that no place in the world has given me so many friends—true, learned, helpful, and illustrious friends—as the single city of London." Letter to Colet, 1509[30] Erasmus stayed in England at least three times.[note 20] In between he had periods studying in Paris, Orléans, Leuven and other cities.  Erasmus by Hans Holbein the Younger. Louvre, Paris. First visit - 1499-1500 In 1499 he was invited to England by William Blount, 4th Baron Mountjoy, who offered to accompany him on his trip to England.[50] His time in England was fruitful in the making of lifelong friendships with the leaders of English thought in the days of King Henry VIII. During his first visit to England in 1499, he studied or taught at the University of Oxford. Erasmus was particularly impressed by the Bible teaching of John Colet, who pursued a style more akin to the church fathers than the Scholastics. Through the influence of the humanist John Colet, his interests turned towards theology.[50] Other distinctive features of Colet's thought that may have influenced Erasmus are his pacifism,[51] reform-mindedness,[52] anti-Scholasticism and pastoral esteem for the sacrament of Confession.[53]: 94 This prompted him, upon his return from England to Paris, to intensively study the Greek language, which would enable him to study theology on a more profound level.[54]: 518 Erasmus also became fast friends with Thomas More, a young law student considering becoming a monk, whose thought (e.g., on conscience and equity) had been influenced by 14th century French theologian Jean Gerson,[55][56] and whose intellect had been developed by his powerful patron Cardinal John Morton (d. 1500) who had famously attempted reforms of English monasteries.[57] Erasmus left London with a full purse from his generous friends, to allow him to complete his studies. However, he had been provided with bad legal advice by his friends: the English Customs officials confiscated all the gold and silver, leaving him with nothing except a night fever that lasted several months. Second visit - 1505-1506  Sir Thomas More, by Hans Holbein the Younger For Erasmus' second visit, he spent over a year staying at recently married Thomas More's house, now a lawyer and Member of Parliament, honing his translation skills.[49] Erasmus preferred to live the life of an independent scholar and made a conscious effort to avoid any actions or formal ties that might inhibit his individual freedom.[58] In England Erasmus was approached with prominent offices but he declined them all, until the King himself offered his support.[58] He was inclined, but eventually did not accept and longed for a stay in Italy.[58] Third visit - 1510-1515 In 1510, Erasmus arrived at More's bustling house, was parked in bed to recover from his recurrent illness, and wrote The Praise of Folly, which was to be a best-seller. More was at that time the undersheriff of the City of London. After his glorious reception in Italy, Erasmus had returned broke and jobless,[note 21] with strained relations with former friends and benefactors on the continent, and he regretted leaving Italy, despite being horrified by papal warfare. There is a gap in his usually voluminous correspondence: his so-called "two lost years", perhaps due to self-censorship of dangerous or disgruntled opinions;[note 11] he shared lodgings with his friend Andrea Ammonio (Latin secretary to Mountjoy, and the next year, to Henry VIII) provided at the London Austin Friars' compound, skipping out after a disagreement with the friars over rent that caused bad blood.[note 22] He assisted his friend John Colet by authoring Greek textbooks and securing members of staff for the newly established St Paul's School[60] and was in contact when Colet gave his notorious 1512 Convocation sermon which called for a reformation of ecclesiastical affairs.[61]: 230–250 At Colet's instigation, Erasmus started work on De copia. In 1511, the University of Cambridge's Chancellor John Fisher arranged for Erasmus to be the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity, though Erasmus turned down the option of spending the rest of his life as a professor there. He studied and taught Greek and researched and lectured on Jerome.[49][note 23] Erasmus mainly stayed at Queens' College while lecturing at the university,[63] between 1511 and 1515.[note 24] Erasmus' rooms were located in the "I" staircase of Old Court.[64] Despite a chronic shortage of money, he succeeded in mastering Greek by an intensive, day-and-night study of three years, taught by Thomas Linacre, continuously begging in letters that his friends send him books and money for teachers.[65] Erasmus suffered from poor health and was especially concerned with heating, clean air, ventilation, draughts, fresh food and unspoiled wine: he complained about the draughtiness of English buildings.[66] He complained that Queens' College could not supply him with enough decent wine[note 25] (wine was the Renaissance medicine for gallstones, from which Erasmus suffered).[67] As Queens' was an unusually humanist-leaning institution in the 16th century, Queens' College Old Library still houses many first editions of Erasmus's publications, many of which were acquired during that period by bequest or purchase, including Erasmus's New Testament translation, which is signed by friend and Polish religious reformer Jan Łaski.[68] By this time More was a judge on the poorman's equity court (Master of Requests) and a Privy Counsellor. France and Brabant French circle Jean Vitrier (or Vourier) • Jacob/James Batt • Publio Fausto Andrelini • Josse Bade • Louis de Berquin • Robert Fisher • Richard Whitford • Guillaume Budé • Thomas Grey • Hector Boece • Robert Gaguin Opponents: Noël Béda Patrons: Bishop Henry of Bergen,Thomas Grey, Lady of Veere Following his first trip to England, Erasmus returned first to poverty in Paris, where he started to compile the Adagio for his students, then to Orleans to escape the plague, and then to semi-monastic life, scholarly studies and writing in France, notably at the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Bertin at St Omer (1501,1502) where he wrote the initial version of the Enchiridion (Handbook of the Christian Knight.) A particular influence was his encounter in 1501 with Jean (Jehan) Vitrier, a radical Franciscan who consolidated Erasmus' thoughts against excessive valorization of monasticism,[53]: 94, 95 ceremonialism[note 26] and fasting[note 27] in a kind of conversion experience,[14]: 213, 219 and introduced him to Origen.[70] In 1502, Erasmus went to Brabant, ultimately to the university at Louvain, then back to Paris in 1504. Italy Italian circle Aldus Manutius • Giulio Camillo • Alexander Stewart • Pietro Bembo • Bombasius • Marcus Musurus • Janus Lascaris • Giles of Viterbo • Egnazio • Germain de Brie • Ferry Carondelet • Urbano Valeriani • Tommaso Inghiram • Carteromachus Opponents: Aleander, Alberto Pío, Sepúlveda Patrons: Popes Leo X, Adrian VI, Clement VII, Paul III, King James IV In 1506 he was able to accompany and tutor the sons of the personal physician of the English King through Italy to Bologna.[58] His discovery en route of Lorenzo Valla's New Testament Notes was a major event in his career and prompted Erasmus to study the New Testament using philology.[71] In 1506 they passed through Turin and he arranged to be awarded the degree of Doctor of Sacred Theology (Sacra Theologia)[72]: 638 from the University of Turin per saltum[58] at age 37 (or 40.) Erasmus stayed tutoring in Bologna for a year; in the Winter, Erasmus was present when Pope Julius II entered victorious into the conquered Bologna which he had besieged before.[58]  Book printed and illuminated at Aldine press, Venice (1501), Horace, Works Erasmus traveled on to Venice, working on an expanded version of his Adagia at the Aldine Press of the famous printer Aldus Manutius, advised him which manuscripts to publish,[73] and was an honorary member of the graecophone Aldine "New Academy" (Greek: Neakadêmia (Νεακαδημία)).[74] From Aldus he learned the in-person workflow that made him productive at Froben: making last-minute changes, and immediately checking and correcting printed page proofs as soon as the ink had dried. Aldus wrote that Erasmus could do twice as much work in a given time as any other man he had ever met.[30] In 1507, according to his letters, he studied advanced Greek in Padua with the Venetian natural philosopher, Giulio Camillo.[75] He found employment tutoring and escorting Scottish nobleman Alexander Stewart, the 24-year old Archbishop of St Andrews, through Padua, Florence, and Siena[note 28] Erasmus made it to Rome in 1509, visiting some notable libraries and cardinals, but having a less active association with Italian scholars than might have been expected. In 1510, William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Mountjoy lured him back to England, now under its new humanist king, paying £10 journey money.[77] On his trip back over the Alps, down the Rhein, to England, Erasmus mentally composed The Praise of Folly. Brabant (Flanders) Burgundy/Louvain circle Adrian of Utrecht • Pieter Gillis • Martin Dorp • Hieronymus van Busleyden • Albrecht Dürer • Dirk Martens • Nicolas Cleynaerts • Cornelius Grapheus Opponents: Latomus • Edward Lee • Ulrich von Hutten • Nicolaas Baechem (Egmondanus) Patrons: Charles V His residence at Leuven, where he lectured at the University, exposed Erasmus to much criticism from those ascetics, academics and clerics hostile to the principles of literary and religious reform to which he was devoting his life.[78] In 1514, en route to Basel, he made the acquaintance of Hermannus Buschius, Ulrich von Hutten and Johann Reuchlin who introduced him to the Hebrew language in Mainz.[79] In 1514, he suffered a fall from his horse and injured his back.  Quinten Massijs - Portrait of Peter Gillis or Gilles (1517), half of a diptych with portrait of Erasmus below, painted as a gift from them for Thomas More.[80] Erasmus may have made several other short visits to England or English territory while living in Brabant.[49] Happily for Erasmus, More and Tunstall were posted in Brussels or Antwerp on government missions around 1516, More for six months, Tunstall for longer. Their circle include Pieter Gillis of Antwerp, in whose house Thomas More's wrote Utopia (pub. 1516) with Erasmus' encouragement,[note 29] Erasmus editing and perhaps even contributing fragments.[82] However, in 1517, his great friend Ammonio died in England of the Sweating Sickness. Erasmus had accepted an honorary position as a Councillor to Charles V with an annuity of 200 guilders,[83] and tutored his brother, the teenage future Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand of Hapsburg. At this time he wrote The Education of a Christian Prince (Institutio principis Christiani). In 1517, he supported the foundation at the university of the Collegium Trilingue for the study of Hebrew, Latin, and Greek[84]: s1.14.14 —after the model of Cisneros' College of the Three Languages at the University of Alcalá—financed by his late friend Hieronymus van Busleyden's will.[85]  Field of the Cloth of Gold, w. Henry VIII (British - prev. attrib. Hans Holbein the Younger) In 1520 he was present at the Field of the Cloth of Gold with Guillaume Budé, probably his last meetings with Thomas More[86] and William Warham. His friends and former students and old correspondents were the incoming political elite, and he had risen with them.[note 30] He stayed in various locations including Anderlecht (near Brussels) in the Summer of 1521.[87] Basel Swiss circle[88]: 56, 63 Johannes Froben • Hieronymus Froben • Beatus Rhenanus • Bonifacius Amerbach • Bruno Amerbach • Hans Holbein the Younger • Simon Grynaeus • Sebastian Brandt • Wolfgang Capito • Damião de Góis • Gilbert Cousin • Jakob Näf • Augustinus Marius Opponents: Œcolampadius Patrons: Antoine I. de Vergy, Christoph von Utenheim  Desiderius Erasmus dictating to his ammenuensis Gilbert Cousin or Cognatus. From a book by Cousin, and itself claimed to be based on fresco in Cousin's house in Nozeroy, Burgundy. Engraving possibly by fr:Claude Luc. From 1514, Erasmus regularly traveled to Basel to coordinate the printing of his books with Froben. He developed a lasting association with the great Basel publisher Johann Froben and later his son Hieronymus Froben (Eramus' godson) who together published over 200 works with Erasmus,[89] working with expert scholar-correctors who went on to illustrious careers.[88] His initial interest in Froben's operation was aroused by his discovery of the printer's folio edition of the Adagiorum Chiliades tres (Adagia) (1513).[90] Froben's work was notable for using the new Roman type (rather than blackletter) and Aldine-like Italic and Greek fonts, as well as elegant layouts using borders and fancy capitals;[88]: 59 Hans Holbein (the Younger) cut several woodblock capitals for Erasmus' editions. The printing of many his books was supervised by his Alsatian friend, the Greek scholar Beatus Rhenanus.[note 31] In 1521 he settled in Basel.[91] He was weary of the controversies and hostility at Louvain, and feared being dragged further into the Lutheran controversy.[92] He agreed to be the Froben press' literary superintendent writing dedications and prefaces[30] for an annuity and profit share.[62] Apart from Froben's production team, he had his own household[note 32]with a formidable housekeeper, stable of horses, and up to eight boarders or paid servants: who acted as assistants, correctors, amanuenses, dining companions, international couriers, and carers.[94] It was his habit to sit at times by a ground-floor window, to make it easier to see and be seen by strolling humanists for chatting.[95] In collaboration with Froben and his team, the scope and ambition of Erasmus' Annotations, Erasmus' long-researched project of philological notes of the New Testament along the lines of Valla's Adnotations, had grown to also include a lightly revised Latin Vulgate, then the Greek text, then several edifying essays on methodology, then a highly revised Vulgate—all bundled as his Novum testamentum omne and pirated individually throughout Europe— then finally his amplified Paraphrases.  Pope Adrian VI (1522-1523) In 1522, Erasmus' compatriot, former teacher (c. 1502) and friend from University of Louvain unexpectedly became Pope Adrian VI,[note 33] after having served as Regent (and/or Grand Inquisitor) of Spain for six years. Like Erasmus and Luther, he had been influenced by the Brethren of the Common Life. He tried to entice Erasmus to Rome. His reforms of the Roman Curia which he hoped would meet the objections of many Lutherans were stymied (party because the Holy See was broke), though re-worked at the Council of Trent, and he died in 1523.[97] As the popular and nationalist responses to Luther gathered momentum, the social disorders, which Erasmus dreaded and Luther disassociated himself from, began to appear, including the German Peasants' War (1524–1525), the Anabaptist insurrections in Germany and in the Low Countries, iconoclasm, and the radicalisation of peasants across Europe. If these were the outcomes of reform, Erasmus was thankful that he had kept out of it. Yet he was ever more bitterly accused of having started the whole "tragedy" (as Erasmus dubbed the matter).[note 34] In 1523, he provided financial support to the impoverished and disgraced former Latin Secretary of Antwerp Cornelius Grapheus, on his release from the newly introduced Inquisition.[98]: 558 In 1525, a former student of Erasmus who had served at Erasmus' father's former church at Woerden, Jan de Bakker (Pistorius) was the first priest to be executed as a heretic in the Netherlands. In 1529, his French translator and friend Louis de Berquin was burnt in Paris, following his condemnation as an anti-Rome heretic by the Sorbonne theologians. Freiburg  Portrait of Damião de Góis by Albrecht Dürer Following iconoclastic rioting in 1529 led by Œcolampadius his former assistant,[note 35] the city of Basel definitely adopted the Reformation, and banned the Catholic mass on April 1, 1529.[99] Erasmus left Basel on the 13 April 1529 and departed by ship to the Catholic university town of Freiburg im Breisgau to be under the protection of his former student, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria,[14]: 210 staying for two years on the top floor of the Whale House,[100] then buying and refurbishing a house of his own,[note 36] where he took in scholar/assistants as table-boarders[101] such as Cornelius Grapheus' friend Damião de Góis, some of them fleeing persecution. Despite increasing frailty[note 37] Erasmus continued to work productively, notably on a new magnum opus, his manual on preaching Ecclesiastes, and his small book on preparing for death. His boarder for five months, the Portuguese scholar/diplomat Damião de Góis,[98] worked on his lobbying on the plight of the Sámi in Sweden and the Ethiopian church, and stimulated[103]: 82 Erasmus' increasing awareness of foreign missions.[note 38] There are no extant letters between More and Erasmus from the start of More's period as Chancellor until his resignation (1529–1523), almost to the day. Erasmus wrote several important non-political works under the surprising patronage of Thomas Bolyn: his Ennaratio triplex in Psalmum XXII or Triple Commentary on Psalm 23 (1529); his catechism to counter Luther Explanatio Symboli or A Playne and Godly Exposition or Declaration of the Commune Crede (1533) which sold out in three hours at the Frankfurt Book Fair, and Praeparatio ad mortem or Preparation for Death (1534) which would be one of Erasmus' most popular and most hijacked works.[105][note 39] Fates of Friends  William Warham (c.1450–1532), Archbishop of Canterbury, after Hans Holbein  Cuthbert Tunstall (1474–1559), Bishop of Durham In the 1530s, life became more dangerous for Spanish Erasmians when Erasmus' protector, the Inquisitor General Alonso Manrique de Lara fell out of favour with the royal court and lost power within his own organization to friar-theologians. In 1532 Erasmus' friend, conversos Juan de Vergara (Cisneros' Latin secretary who had worked on the Complutensian Polyglot and published Stunica's criticism of Erasmus,) was arrested by the Spanish Inquisition and had to be ransomed from them by the humanist Archbishop of Toledo Alonso III Fonseca, also a correspondent of Erasmus', who had previously rescued Ignatius of Loyola from them.[106]: 80 There was a generational change in the Catholic hierarchy. In 1530, the reforming French bishop Guillaume Briçonnet died. In 1532 his beloved long-time mentor English Primate Warham died of old age,[note 40] as did reforming cardinal Giles of Viterbo and Swiss bishop Hugo von Hohenlandenberg. In 1534 his distrusted protector Clement IV died, his recent Italian ally Cardinal Cajetan died, and his old ally Cardinal Campeggio retired. As more friends died (in 1533, his friend Pieter Gillis; in 1534, William Blount; in early 1536, Catherine of Aragon;) and as Luther and some Lutherans and some powerful Catholic theologians renewed their personal attacks on Erasmus, his letters are increasingly focused on concerns on the status of friendships and safety as he considered moving from bland Freiburg despite his health.[note 41] In 1535, Erasmus' friends Thomas More, Bishop John Fisher and Brigittine Richard Reynolds[note 42] were executed as pro-Rome traitors by Henry VIII, who Erasmus and More had first met as a boy. Despite illness Erasmus wrote the first biography of More (and Fisher), the short, anonymous Expositio Fidelis, which Froben published, at the instigation of de Góis.[98] After Erasmus' time, numerous of Erasmus' translators later met similar fates at the hands of Anglican, Catholic and Reformed sectarians and autocrats: including Margaret Pole, William Tyndale, Michael Servetus. Others, such as Charles V's Latin secretary Juan de Valdés, fled and died in self-exile. Erasmus' friend and collaborator Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall eventually died in prison under Elizabeth I for refusing the Oath of Supremacy. Erasmus' correspondent Bishop Stephen Gardiner, who he had known as a teenaged student in Paris and Cambridge,[108] was later imprisoned in the Tower of London for five years under Edward VI for impeding Protestantism.[note 43] Damião de Góis was tried before the Portuguese Inquisition at age 72,[98] detained almost incommunicado, finally exiled to a monastery, and on release perhaps murdered.[110] His amanuensis Gilbert Cousin died in prison at age 66, shortly after being arrested on the personal order of Pope Pius V.[94] Death in Basel  Epitaph for Erasmus in the Basel Minster When his strength began to fail, he finally decided to accept an invitation by Queen Mary of Hungary, Regent of the Netherlands (sister of his former student Archduke Ferdinand I and Emperor Charles V), to move from Freiburg to Brabant. In 1535, he moved back to the Froben compound in Basel in preparation (Œcolampadius having died, and private practice of his religion now possible) and saw his last major works such as Ecclesiastes through publication, though he grew more frail. On July 12, 1536, he died at an attack of dysentery.[111] He had remained loyal to Roman Catholicism,[112] but biographers have disagreed whether to treat him as an insider or an outsider.[note 44] He may not have received or had the opportunity to receive the last rites of the Catholic Church;[note 45] the contemporary reports of his death do not mention whether he asked for a Catholic priest or not,[note 46] if any were secretly or privately in Basel. His last words, as recorded by his friend and biographer Beatus Rhenanus, were apparently "Dear God" (Dutch: Lieve God).[114] He was buried with great ceremony in the Basel Minster (the former cathedral). The Protestant city authorities remarkably allowed his funeral to be an ecumenical Catholic requiem Mass.[115] As his heir he instated Bonifacius Amerbach to give seed money[note 47] to students and the needy;[note 48] he had received a dispensation to make a will rather than have his wealth revert to his order, the Chapter of Sion, and had long pre-sold most of his personal library of almost 500 books to Jan Łaski.[116][117] One of the eventual recipients was the impoverished Protestant humanist Sebastian Castellio, who had fled from Geneva to Basel, who subsequently translated the Bible into Latin and French, and who worked for the repair of the breach and divide of Christianity in its Catholic, Anabaptist, and Protestant branches.[118] |

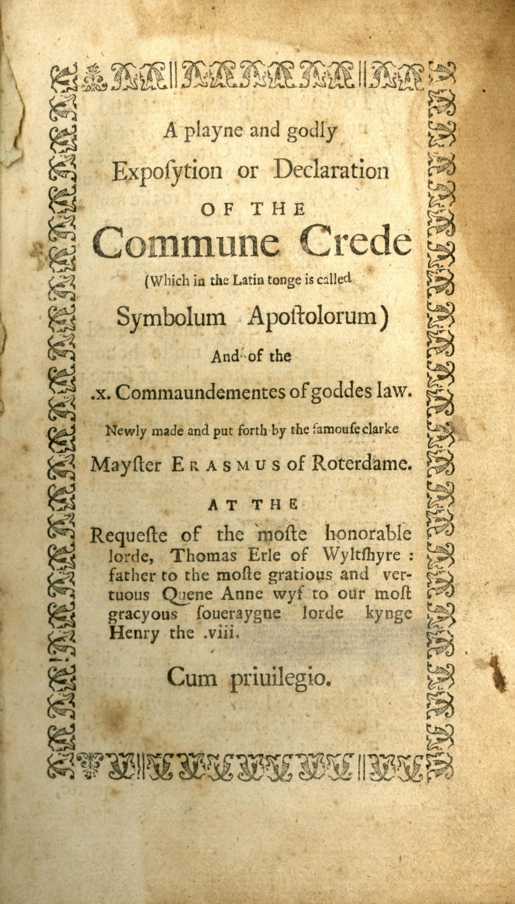

生い立ち ロッテルダムにあるエラスムス像。石像(1557年)、木像(1549年)に代わるヘンドリック・デ・カイザー作の金メッキブロンズ像(1622年)。 デジデリウス・エラスムスは、1460年代後半の10月27日か28日(「シモンとユダの夜」)[4]にロッテルダムで生まれたと伝えられている。名前 は、エラスムスの父ゲラルト(Gerardus Helye)[5]が個人的に好意を寄せていたフォルミアエのエラスムスにちなんで付けられた[注釈 1]。 エラスムスの生年ははっきりしない。後年、彼は1466年生まれとして年齢を計算したが、主要な出来事における彼の記憶年齢は実際には1469年を意味す ることが多い[8][9]: 8 (この記事では現在1466年を生年としている[10][11]。この不一致を扱うため、年齢はまず1469年に基づいて与えられ、次に1466年に基づ いて括弧書きで与えられている:例えば「20(または23)」)。さらに、彼の生い立ちの多くの詳細は、1516年に彼が架空の教皇庁書記官ランベルトゥ ス・グルニウス(「グラント氏」)に宛てた手紙の中で書いた架空の三人称の記述(1529年に出版)から得なければならない[12]。 父ジェラールはカトリックの司祭で[13]、1450年代から60年代にかけて6年間、書記や学者としてイタリアに滞在していた可能性がある[14]: 196 母親はゼーヴェンバーゲン出身の医師の娘マルガレータ・ロジェリウス(オランダ姓ルトガースのラテン語化)[15]。エラスムスは婚外子であったが、 1483年に両親がペストで早くに亡くなるまで、愛情深い家庭と最良の教育によって養育された。マーガレットは未亡人で、ピーターはエラスムスの腹違いの 兄であったとする作家もいる[9]。 エラスムス自身は、1524年の『Compendium vitae Erasmi』の中で、両親は婚約していたが、親族によって正式な結婚は阻止された(おそらく若い未亡人や未婚の子持ちの母親は有利な結婚相手ではなかっ た)、父親はラテン語とギリシア語を勉強するためにイタリアに行き、親族はマルガレータが亡くなったとジェラルドに誤解させ、悲嘆に暮れるジェラルドはロ マンチックに聖職に就いたが、帰国後にマルガレータが生きていたことを知ったという筋書きであった。 [17]: 89 1471年、父親は小さな町ヴォールデンの副教皇となり(幼いエラスムスは読み書きを学ぶために地元の方言学校に通っていたと思われる)、1476年には ゴーダの副教皇に昇格した[5]。 エラスムスは、修道院や半修道院のような学校で、当時の若者にとって最高の教育を受けた。1476年、6歳(または9歳)で家族はゴーダに移り住み、ピー テル・ヴィンケル氏[5]の学校に通い始めるが、彼は後にエラスムスの後見人となる(そしておそらく、エラスムスとピーテルの遺産を横流しした) (1466年に生まれたとする歴史家は、この時期、エラスムスはユトレヒトの聖歌隊学校にいたとする[18])。 1478年、9歳(または12歳)のエラスムスは、兄のピーターとともに、オランダで最も優れたラテン語学校のひとつ、デヴェンターにあるレビュイヌス教 会(Lebuïnuskerk)[10]の支部聖職者が所有するラテン語学校に送られた。アルプス以北のヨーロッパで初めてギリシア語が大学よりも低いレ ベルで教えられるようになり[19]、そこで彼はギリシア語を学び始めた[20]。1483年頃、ペストが街を襲い[21]、息子たちに家を与えるために 引っ越していた母親が感染症で亡くなったため、そこでの教育は終わった。両親と学校の20人の生徒[9]の死後、彼は故郷(ロッテルダム?)[5]に戻 り、そこで慈愛に満ちた未亡人ベルト・デ・ヘイデン[22]に支えられた[9]。  ヒエロニマス・ボス《聖アントニウスの誘惑》三幅対(1501年頃)、ヘルトーヘンボスで描かれ、後に友人のダミアン・デ・ゴイスが所有。 1484年、14歳(または17歳)の頃、彼は弟とともに、共同生活の兄弟たち[24][注釈 2]が運営する、's-ヘルトーヘンボッシュの安価な[23]文法学校または神学校に通った。エラスムスは、そこでデヴォティオ・モデルナ運動やブレザレ ンたちの名著『キリストの模倣』に触れるが、修道兄弟や教育者たちの厳しい規則や厳格なやり方に憤慨する[10]。2人の兄弟は、聖職者には抵抗するが大 学には通うという協定を結ぶ[22]。 [8]: 804 代わりに、ピーターはシュタインのアウグスティヌス派のカノン会修道院に向かったため、エラスムスは裏切られたと感じた[22]。この頃、エラスムスは友 人のエリザベス・デ・ヘイデンに「私は難破し、"冷たい水の中で "道に迷っている」と寂しげに書き送っている[9]。やがてエラスムスは1487年以前、16歳(または19歳)[5]の頃にポスチュアントとして同じ修 道院に移った[注釈 3]。 誓願、叙階、カノナリーの経験  エラスムスが青年期を過ごしたゴーダでのヒルド・クロップ作の胸像(1950年) 貧しさ[25]のためにエラスムスは奉献生活に入ることを余儀なくされ、1487年[26]、南ホラント州ゴーダにほど近いシュタインにある修道院で修練 院に入った。1488年から1490年にかけて、周辺地域はヨンカー・フランセン継承戦争を戦う軍隊によってひどい略奪を受け、その後飢饉に見舞われた。 [8]: 759年、エラスムスは1488年末に19歳(あるいは22歳)で聖アウグスティヌス修道会正教会士[注釈 5]として誓願を立てた[26]。エラスムスは修道院で精神的に目覚めたのである」[31]。 修道会におけるある種の虐待は、後に彼が西方教会を内部から改革しようと呼びかけた主な対象のひとつであり、特に未成熟の少年たちを強制的に、あるいは騙 して勧誘していた(『グルニウスへの手紙』の架空の記述では、彼らを「ドミニコとフランシスコとベネディクトの犠牲者」と呼んでいる): エラスムスは、自分がこのような階層に属していると感じ、「自発的に、しかし自由には」入信しなかったので、道徳的に誓願に縛られていないとしても、法 的、社会的、名誉的に誓願を守る義務があることは確かであり、自分の真の召命を探す義務があると考えた[27]: 439 スタイン在学中、18歳(あるいは21歳)のエラスムスは、同じカノンであったセルヴァティウス・ロジェルスと、彼が「熱烈な愛」(ラテン語: fervidos amores)と呼ぶ片思いをし[註6]、一連の恋文[註7][33]を書き、その中でロジェルスを「私の魂の半分」と呼び[註8]、「私があなた方を不 幸にも執拗に口説いたのは、報酬のためでも、好意のためでもありません。では何なのか?この書簡は、モア、コレット、アンモニオなど[注釈 10]、深い男同士の友情を築き、維持する能力を持っていたとはいえ、後世のエラスムスが通常見せる、一般的に冷淡ではるかに抑制された態度とは対照的で ある[注釈 11]。エラスムスが生前に言及されたり性的な非難を受けたりしたことはない。彼の著作では、男女間の結婚生活における適度な性欲を賞賛するものが目立つ [35]。 ラテン秘書のサークル フアン・デ・ベルガラ - ピエトロ・カルメリアーノ[36] - ギョーム・ブデ - ピエトロ・ベンボ - ヤコポ・サドレト - リチャード・パーチェ - アンドレア・アンモニオ - ヒエロニムス・エムサー - コルネリウス・グラフェウス - ヨハネス・セクンドゥス - フアン・デ・バルデス、アルフォンソ・デ・バルデス - ペーテル・ヴァネス - ゲンチアン・ヘルヴェトゥス - ヤン・ワスキ - ランベルト・グルニウス(架空)[12]: 337 ラテン語の秘書は、後にエラスムスの文通相手や友人のネットワークの重要な一部となった[注釈 12]。 1493年、修道院長はエラスムスがシュタイン家を去り[38]、野心的なカンブライ司教ベルゲンのラテン語秘書となるよう取り計らった。 1492年4月25日[25]、あるいは1495年4月25日、25歳(あるいは28歳)でカトリック司祭に叙階された[14]。 1500年以降、彼は食事と時間によって命を落とすと主張してシュタインのカノン座に戻ることを避けたが[註 15]、他のアウグスチノ会の共同体や他の修道会の修道院に滞在した。1504年にシュタインの修道院長に就任したロジェルスとエラスムスは何年にもわ たって文通を続け、ロジェルスはエラスムスが学業を終えた後に戻ることを要求した。それにもかかわらず、カノナリーの図書館[注釈 16]には、ゴーダ地方でエラスムスの出版物が圧倒的に多く収蔵されることになった[42]。 1505年、教皇ユリウス2世は、エラスムスが特定の聖職に就くことを認める程度に清貧の誓願から免除し、修道会の統制と習慣から免除することを認めた が、彼は司祭であり、形式的にはアウグスチノ会の正教会司祭[注釈 17]であり続けた。 [27] 1517年、教皇レオ10世はエラスムスの生まれつきの欠点[注釈 18]に対して法的な免除を与え、48歳(または51歳)のエラスムスの独立を認め[43]、それでもなおカノンとして司祭や修道院長の職に就くことを認 めた[27]。 ↓出生? ↓孤児 ↓誓願 ↓出家? ↓処分 ↓ ↓死 ↓ ↓ オランダ フランス イタリア イングランド ブラバント バーゼル フライブルク イギリス ブラバント イングランド フランス バーゼル バーゼル イングランド バーゼル イギリス バーゼル │ 1465 │ 1475 │ 1485 │ 1495 │ 1505 │ 1515 │ 1525 │ 1535  エラスムスのおおよその年表(図をクリック) エラスムスの信念の多くは、初期の伝記から生まれたようだ: 既婚状態と適切な結婚への尊敬、司祭の結婚への支持、女性の結婚の可能性を高めることへの関心、思いやりのない規則への反対、特に制度上の食事規則、教育 を参加者にとって魅力的なものにしたいという願望、古典的言語への関心、貧困と精神的絶望への恐怖、 勉強や仕事ができるのに物乞いをする修道士への嫌悪感、権力者の支配下に置かれることへの不本意さ、信心深さ、権力者が自分の担当者の最善の利益のために 行動する必要性、慈悲と平和の尊さ、不必要な戦争、特に欲深い王侯間の戦争への怒り、死への意識など。 旅行記 エラスムスの都市とルート オックスフォード、ケンブリッジ ロンドン 読書 カンタベリー ヴェルデン カレー シュタイン、ゴーダ ロッテルダム サン・オメル ヘルトーゲンボッシュ パリ、カンブレー ブリュッセル、アントワープ オルレアン ルーバン トリノ ケルン ボローニャ マインツ ストラスブール フィレンツェ フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウ シエナ パドヴァ バーゼル ローマ、ヴェネツィア コンスタンツ クマエ 緑: 初期の生活 濃い丸:居住地 細い線 アルプス越え 青い線 ライン川とイギリス海峡 エラスムスは、貧しさ、シュタインのカノン職からの「逃亡」(カンブライへ)、教育(パリ、トリノへ)、発汗病ペストからの逃亡(オルレアンへ)、就職 (イングランドへ)、写本のための図書館探しなどの理由で、広く定期的に旅をした、 執筆(ブラバント)、王室顧問(ケルン)、後援、家庭教師、付き添い(北イタリア)、人脈作り(ローマ)、印刷を通して本を直接見る(パリ、ヴェネツィ ア、ルーヴァン、バーゼル)、宗教狂信者の迫害を避ける(フライブルクへ)。 乗馬を楽しんだ[44]。  パリ 1495年、ヘンリー司教の同意と俸給を得て、エラスムスはパリ大学のコレージュ・ド・モンタイグで学ぶことになるが、ここは改革熱の中心地であった[注 19]。 [例えば、エラスムスは、詩人でありパリの「人間性教授」であったイタリアの人文主義者パブリオ・ファウスト・アンドレリーニと親しい友人となった [47]。 この時期、エラスムスは排他的あるいは過剰なアリストテレス主義やスコラ哲学を深く嫌うようになり[48]、イギリスやスコットランドの貴族を訪問する際 の家庭教師や付き添いとしての仕事を見つけるようになる。 イングランド イングランドのサークル[49]。 トマス・モア - ジョン・コレット - トーマス・リナクル - ウィリアム・グローシン - ウィリアム・リリー - アンドレア・アンモニオ - ファン・ルイス・ヴィヴェス - カスバート・タンストール - ヘンリー・ブロック - トーマス・ルプセット - リチャード・フォックス - クリストファー・アーズウィック - ロバート・アルドリッチ - リチャード・ウィットフォード - ロレンツォ・カンペッジョ - リチャード・レイノルズ - ポリドール・ヴェルジル パトロン ウィリアム・ブラウント、ウィリアム・ウォーハム、ジョン・フィッシャー、ジョン・ロングランド、マーガレット・ボーフォート、キャサリン・オブ・アラゴ ン "ロンドンの街ほど、真の友人、学識ある友人、親切な友人、名高い友人を多く与えてくれた場所は、世界中どこを探してもない。" コレットへの手紙、1509年[30]。 その間、パリ、オルレアン、ルーヴェン、その他の都市に留学した時期もあった[註 20]。  ハンス・ホルベイン作『エラスムス』。パリ、ルーヴル。 最初の訪問 - 1499年から1500年 1499年、第4代マウントジョイ男爵ウィリアム・ブラウントに招かれ、イングランドへの旅に同行することになった[50]。イングランドでの生活は、ヘ ンリー8世時代のイギリス思想の指導者たちと生涯の友好関係を築く上で実り多いものとなった。 1499年に初めてイギリスを訪れたエラスムスは、オックスフォード大学で学んだり教鞭をとったりした。エラスムスは、スコラ学者よりも教父に近いスタイ ルを追求したジョン・コレットの聖書教育に特に感銘を受けた。人文主義者ジョン・コレットの影響により、彼の関心は神学へと向けられていった[50]。エ ラスムスに影響を与えたと思われるコレットの思想の他の特徴としては、平和主義、改革志向、反スコラ学主義、告解の秘跡に対する司牧的尊重[53]などが 挙げられる[94]。 このため、イギリスからパリに戻ったエラスムスは、ギリシャ語を集中的に学び、神学をより深いレベルで研究するようになった[54]: 518 エラスムスはまた、修道士になろうと考えていた若い法学生トマス・モアと急接近し、その思想(良心と衡平性など)は14世紀のフランスの神学者ジャン・ ジェルソンの影響を受けており[55][56]、その知性はイギリスの修道院の改革を試みたことで有名な彼の強力なパトロンであったジョン・モートン枢機 卿(1500年没)によって培われていた[57]。 エラスムスは、寛大な友人たちから学業を全うするための資金を満額もらってロンドンを後にした。しかし、友人たちから間違った法的助言を受けたエラスムス は、イギリスの税関職員に金銀を没収され、数ヶ月続いた夜間発熱以外に何も残らなかった。 二度目の訪問 - 1505年から1506年  ハンス・ホルベイン作「トマス・モア卿 エラスムスの2度目の訪問では、結婚したばかりのトマス・モアの家に1年以上滞在し、翻訳の腕を磨いた。 エラスムスは独立した学者としての生活を好み、個人の自由を阻害するような行動や形式的な結びつきを避けるよう意識的に努力した[58]。 イギリスではエラスムスは著名な役職を打診されたが、国王自身が支援を申し出るまですべて断った[58]。 彼はその気になったが、結局受け入れず、イタリアでの滞在を切望した[58]。 3度目の訪問 - 1510年-1515年 1510年、エラスムスはモアの賑やかな家に到着し、再発した病気を治すためにベッドに寝かされ、ベストセラーとなる『愚行礼賛』を執筆した。モアは当 時、ロンドン市の下屋長だった。 イタリアでの輝かしい歓待の後、エラスムスは無一文で職もなく[注釈 21]、大陸のかつての友人や恩人との関係もぎくしゃくしたまま帰国し、ローマ教皇の戦乱に怯えながらもイタリアを去ることを後悔していた。いわゆる「失 われた2年間」は、おそらく危険な意見や不満な意見を自粛したためであろう[注釈 11]。彼は友人のアンドレア・アンモニオ(マウントジョイのラテン語秘書、翌年はヘンリー8世のラテン語秘書)とロンドンのオースティン修道士の屋敷に 下宿していたが、家賃をめぐって修道士たちと意見が対立し、悪仲になったため、下宿を飛び出した[注釈 22]。 友人であったジョン・コレットを助け、ギリシア語の教科書を執筆したり、新しく設立されたセント・ポール・スクールのスタッフを確保したりした[60]。 コレットが1512年に悪名高い招集説教を行い、教会問題の改革を訴えた際にも連絡を取り合っていた[61]: 230-250 コレットの勧めで、エラスムスは『デ・コピア』の執筆を開始した。 1511年、ケンブリッジ大学のジョン・フィッシャー総長の計らいで、エラスムスはレディ・マーガレット神学教授となる。彼はギリシャ語を学び、教え、 ジェロームについて研究し、講義を行った[49][注 23]。 1511年から1515年にかけて、エラスムスは主にクイーンズ・カレッジに滞在しながら講義を行った[63]。エラスムスの部屋はオールド・コートの 「I」階段にあった[64]。慢性的な資金不足にもかかわらず、彼はトマス・リナクルの指導のもと、3年間昼夜を問わない集中的な学習によってギリシア語 を習得することに成功した。 エラスムスは不健康に悩まされ、特に暖房、きれいな空気、換気、隙間風、新鮮な食べ物、汚れのないワインに気を配り、イギリスの建物の風通しの悪さに不満 を漏らしていた[66]。 彼はクイーンズ・カレッジが十分なワイン[注釈 25]を供給してくれないことに不満を漏らしていた(ワインはエラスムスが苦しんでいた胆石のルネサンス時代の薬であった)。 [67] クイーンズ・カレッジ旧図書館には、16世紀には珍しくヒューマニズムに傾倒した教育機関であったため、エラスムスの出版物の初版本が数多く所蔵されてい る。その多くは、遺贈や購入によってこの時期に入手されたもので、友人でありポーランドの宗教改革者であったヤン・ワスキの署名が入ったエラスムスの新約 聖書の翻訳もそのひとつである[68]。 この頃、モアはポーマンの衡平法判事(Master of Requests)であり、枢密顧問官でもあった。 フランスとブラバント フランスのサークル ジャン・ヴィトリエ(またはヴーリエ) - ヤコブ/ジェームズ・バット - プブリオ・ファウスト・アンドレリーニ - ジョッセ・バデ - ルイ・ド・ベルカン - ロバート・フィッシャー - リチャード・ウィットフォード - ギヨーム・ブデ - トーマス・グレイ - ヘクトール・ボース - ロバート・ガギャン 対戦相手 ノエル・ベダ パトロン ベルゲン司教アンリ、トーマス・グレイ、ヴェール夫人 最初のイギリス旅行の後、エラスムスはまずパリの貧困に戻り、そこで生徒のために『アダージョ』の編纂を始め、ペストから逃れるためにオルレアンへ、そし てフランスでの半修道院生活、学術研究、執筆活動、特にサン・オーメルのサン・ベルタンベネディクト会修道院(1501,1502年)で『エンチリディオ ン(キリスト教騎士の手引書)』の初版を執筆した。 特に影響を受けたのは、1501年に急進的なフランシスコ会士であったジャン(ジェハン)・ヴィトリエとの出会いであり、彼は一種の回心体験[14]: 213, 219において修道制[53]: 94, 95の儀式主義[注釈 26]と断食[注釈 27]の過剰な価値化に反対するエラスムスの考えを統合し、オリゲンに彼を紹介した[70]。 1502年、エラスムスはブラバントへ行き、最終的にはルーヴァンの大学へ、そして1504年にはパリへ戻った。 イタリア イタリアのサークル アルドゥス・マヌティウス - ジュリオ・カミッロ - アレクサンダー・スチュワート - ピエトロ・ベンボ - ボンバシウス - マルクス・ムスルス - ヤヌス・ラスカリス - ヴィテルボのジャイルズ - エグナツィオ - ジェルマン・ド・ブリエ - フェリー・カロンデレ - ウルバノ・ヴァレリアーニ - トマソ・インギラム - カーターマカス 対戦相手 アレアンデル、アルベルト・ピオ、セパルベダ パトロン 教皇レオ10世、アドリアヌス6世、クレメンス7世、パウロ3世、ジェームズ4世 1506年、イギリス国王の主治医の息子たちに同行して、イタリアからボローニャまで家庭教師をすることができた[58]。 その途中、ロレンツォ・ヴァッラの『新約聖書注』を発見したことは、彼のキャリアにおいて大きな出来事であり、エラスムスが言語学を使って新約聖書を研究 するきっかけとなった[71]。 1506年、二人はトリノを通過し、エラスムスは37歳(または40歳)でトリノ大学から聖なる神学博士の学位(Sacra Theologia)[72]: 638を授与された。  ヴェネツィアのアルディン印刷所で印刷され、彩色された本(1501年)、『ホレス著作集』。 エラスムスはヴェネツィアに渡り、有名な印刷業者アルドゥス・マヌティウスのアルディン印刷所で『アダージア』の増補版に取り組み、どの原稿を出版すべき かを助言し[73]、グラコフォンのアルディン「新アカデミー」(ギリシア語: Neakadêmia (Νεακαδημία) )の名誉会員となった。 [74] 彼はアルドゥスから、土壇場で変更を加えたり、インクが乾くとすぐに印刷された校正刷りをチェックして修正したりするという、フローベンで生産性を高めた 対面式のワークフローを学んだ。アルドゥスは、エラスムスはこれまで会ったどの人物よりも、与えられた時間に2倍の仕事をこなすことができたと書いている [30]。 1507年、彼の手紙によれば、彼はパドヴァでヴェネツィアの自然哲学者ジュリオ・カミッロのもとで高度なギリシア語を学んだ[75]。彼はパドヴァ、 フィレンツェ、シエナ[注釈 28]を巡り、24歳のセント・アンドリュース大司教であったスコットランドの貴族アレクサンダー・スチュワートの家庭教師とエスコートの仕事を見つけ た。 1510年、カンタベリー大主教ウィリアム・ウォーハムとマウントジョイ卿は、10ポンドの旅費を支払って、エラスムスを新しい人文主義者の国王の下にあ るイングランドに誘い戻した[77]。 ブラバント(フランドル) ブルゴーニュ/ルーヴァン圏 ユトレヒトのアドリアン - ピーテル・ギリス - マルティン・ドルプ - ヒエロニムス・ファン・ブスレーデン - アルブレヒト・デューラー - ディルク・マルテンス - ニコラ・クレイナールツ - コルネリウス・グラフェウス 対戦相手 ラトムス - エドワード・リー - ウルリッヒ・フォン・ハッテン - ニコラース・ベーケム(エグモンダヌス) パトロン シャルル5世 1514年、バーゼルに向かう途中、ヘルマヌス・ブスキウス、ウルリッヒ・フォン・ハッテン、ヨハン・ロイクリンの知遇を得、マインツでヘブライ語を学ぶ [79]。  Quinten Massijs - Portrait of Peter Gillis or Gilles (1517), 二部作の半分で、下にエラスムスの肖像が描かれている。 49]エラスムスにとって幸運なことに、モアとタンストールは1516年頃に政府の使節団としてブリュッセルかアントワープに赴任し、モアは6ヶ月間、タ ンストールはそれ以上の期間赴任した。彼らの仲間にはアントワープのピーテル・ギリスがおり、その家でトマス・モアはエラスムスの勧めで『ユートピア』 (1516年出版)を執筆し、エラスムスは編集を担当し、おそらく断片を寄稿した[82]。 エラスムスは、200ギルダー[83]の年金を支給されるチャールズ5世の参事官という名誉職を引き受け、彼の弟である10代の後の神聖ローマ皇帝ハプス ブルク家のフェルディナントの家庭教師をしていた。この頃、『キリスト教王子の教育』(Institutio principis Christiani)を著した。 1517年、亡き友人ヒエロニムス・ファン・ブスレーデンの遺言により、ヘブライ語、ラテン語、ギリシア語を学ぶためのコレギウム・トリリンゲ[84]: s1.14.14の設立を支援。  ヘンリー8世作《黄金布の野原》(イギリス - 若きハンス・ホルベインの旧作) 1520年、彼はギヨーム・ブデとともに「黄金布の野原」に立ち会ったが、これはおそらくトマス・モア[86]やウィリアム・ウォーハムとの最後の出会い であった。彼の友人やかつての教え子、古い文通相手は次期政治エリートであり、彼は彼らとともに出世していた[注釈 30]。 1521年の夏にはアンデルレヒト(ブリュッセル近郊)など様々な場所に滞在した[87]。 バーゼル スイス・サークル[88]: 56, 63 ヨハネス・フローベン - ヒエロニムス・フローベン - ベアトゥス・レーナヌス - ボニファシウス・アメルバッハ - ブルーノ・アメルバッハ - 若きハンス・ホルバイン - シモン・グリネウス - セバスチャン・ブラント - ヴォルフガング・カピート - ダミアン・デ・ゴイス - ギルバート・カズン - ヤコブ・ネフ - アウグスティヌス・マリウス 対戦相手 ウコランパディウス パトロン アントワーヌ1世ド・ヴェルジ、クリストフ・フォン・ウテンハイム  デジデリウス・エラスムスが、アンメヌエンシスであるギルバート・クーシンまたはコグナトゥスに口述したもの。ブルゴーニュのノゼロイにあるクーザンの家 のフレスコ画に基づくとされる。おそらくクロード・リュック(fr:Claude Luc)によるエングレーヴィング。 1514年以降、エラスムスは定期的にバーゼルを訪れ、フローベンと本の印刷を調整した。バーゼルの偉大な出版人ヨハン・フローベンと、後にその息子ヒエ ロニムス・フローベン(エラスムスの名付け子)と永続的な関係を築き、エラスムスとともに200以上の著作を出版し[89]、輝かしいキャリアを歩んだ専 門の学者・校訂者たちと仕事をした[88]。 フロベンの仕事は、(ブラックレターではなく)新しいローマン体、アルダイン風のイタリック体やギリシア体、そして縁取りや派手な大文字を使ったエレガン トなレイアウトで知られていた[88]: 59 ハンス・ホルバイン(若)は、エラスムス版のためにいくつかの木版画の大文字を制作した。彼の多くの著書の印刷は、アルザス人の友人であるギリシア人学者 ベアトゥス・レナヌスによって監督された[注釈 31]。 1521年、彼はバーゼルに定住し[91]、ルーヴァンでの論争や敵対関係に疲れ果て、ルター派の論争にこれ以上引きずり込まれることを恐れていた [92]。 年金と利益の分け前を得るために、献辞や序文[30]を書くフローベン印刷所の文芸監督者となることに同意した。 [62]フローベンの制作チームとは別に、彼は自分の家庭[注釈 32]を持ち、手強い家政婦、馬小屋、8人までの下宿人や有給の使用人を抱えていた。 フロベンと彼のチームとの共同作業により、エラスムスの『注釈』の範囲と野心は、ヴァッラの『注釈』に沿った新約聖書の文献学的注釈というエラスムスの長 年の研究プロジェクトであったが、軽く改訂されたラテン語のヴルガータ、次にギリシャ語のテキスト、次に方法論に関するいくつかの有益なエッセイ、次に高 度に改訂されたヴルガータ-これらはすべて彼の『Novum testamentum omne』として束ねられ、ヨーロッパ中で個別に海賊版化された-、そして最後に彼の増幅されたパラフレーズを含むまでに成長した。  教皇アドリアヌス6世 (1522-1523) 1522年、エラスムスの同胞であり、ルーヴァン大学時代の恩師(1502年頃)であり友人であったアドリアヌス6世が、6年間スペインの摂政(および/ または大審問官)を務めた後、思いがけず教皇となった[注 33]。エラスムスやルターと同様、彼は「共同生活の兄弟たち」の影響を受けていた。彼はエラスムスをローマに誘おうとした。多くのルター派の反対を満た すことを期待した彼のローマ教皇庁改革は、トレント公会議で練り直されたものの(教皇庁が破産したため)頓挫し、1523年に死去した[97]。 ルターに対する民衆や民族主義者の反応が勢いを増すにつれ、エラスムスが恐れ、ルターが自らを切り離した社会的な混乱が現れ始めた。これらが改革の成果だ とすれば、エラスムスは自分が改革に関与しなかったことに感謝していた。しかし、この「悲劇」(エラスムスはこの問題をこう呼んだ)を引き起こしたのは自 分であるとして、エラスムスはますます激しく非難されるようになった[注釈 34]。 1523年、新たに導入された異端審問から釈放された、困窮し失脚したアントワープの元ラテン語長官コルネリウス・グラフェウスに財政援助を行った [98]: 558 1525年、エラスムスの元教え子で、エラスムスの父の教会であったヴォールデンの教会で奉仕していたヤン・デ・バッカー(ピストリウス)が、オランダで 異端者として処刑された最初の司祭となる。1529年、彼のフランスの翻訳者であり友人でもあったルイ・ド・ベルカンは、ソルボンヌ大学の神学者たちに よって反ローマ派の異端者として断罪された後、パリで火刑に処された。 フライブルク  ダミアン・デ・ゴイスの肖像(アルブレヒト・デューラー作) 1529年、エラスムスの元助手であったウトコランパディウスが率いるイコノクラスティックな暴動の後[注釈 35]、バーゼル市は宗教改革を確実に採用し、1529年4月1日にカトリックのミサを禁止した。 [99] エラスムスは1529年4月13日にバーゼルを離れ、かつての教え子であったオーストリアのフェルディナント大公[14]の庇護のもと、カトリックの大学 都市フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウへと船で向かった: 210はクジラの家の最上階に2年間滞在し[100]、その後自分の家を買って改装し[注釈 36]、コルネリウス・グラフェウスの友人ダミアン・デ・ゴイスのような学者やアシスタントを食客として受け入れた[101]。 エラスムスは、虚弱[註 37]であったにもかかわらず、新しい大著『伝道の書』や『死の準備』など、生産的な仕事を続けていた。5ヶ月の間、彼の下宿人であったポルトガルの学者 /外交官であったダミアン・デ・ゴイス[98]は、スウェーデンのサーメ人の苦境とエチオピアの教会に関するロビー活動に取り組み、海外宣教に対するエラ スムスの意識の高まりを刺激した[103][注釈 38]。 モアが総長として就任してから辞任するまで(1529-1523年)、モアとエラスムスの間の書簡はほとんど現存していない。エラスムスは、トマス・ボリ ンの驚くべき庇護のもとで、詩篇23篇の三重注解(Ennaratio triplex in Psalmum XXII)(1529年)、フランクフルトのブックフェアで3時間で完売したルターに対抗するためのカテキズム(Explanatio Symboli)、戯曲的で神々しい説明またはコミューン・クレデの宣言(A Playne and Godly Exposition or Declaration of the Commune Crede)(1533年)、そしてエラスムスの最も人気があり、最も乗っ取られた作品のひとつとなる死の準備(Praeparatio ad mortem)(1534年)など、政治以外の重要な作品をいくつか書いた。 [105][注釈 39]がある。 友人たちの運命  ウィリアム・ウォーハム(1450年頃-1532年)、カンタベリー大司教、ハンス・ホルベインによる。  カスバート・タンストール(1474-1559)、ダラム司教 1530年代、エラスムスの庇護者であった奉行総長アロンソ・マンリケ・デ・ララが王宮の寵愛を受けなくなり、自身の組織内でも修道士神学者たちに権力を 奪われたことで、スペインのエラスムス派の生活はより危険なものとなった。1532年、エラスムスの友人であった会話者フアン・デ・ベルガラ(シスネロス のラテン語秘書で、コンプルテンシアン・ポリグロットに取り組み、ストゥニカのエラスムス批判を出版した)はスペイン異端審問所に逮捕され、トレドの人文 主義者アロンソ3世フォンセカ大司教(エラスムスの文通相手でもあり、以前ロヨラのイグナチオを異端審問所から救い出した人物)によって身柄を確保された [106]: 80。 カトリックの階層にも世代交代があった。1530年、改革派のフランス人司教ギヨーム・ブリゾネが死去。1532年、彼の敬愛する長年の指導者であったイ ギリス人主教ウォーラムが老衰で亡くなり[注釈 40]、改革派のヴィテルボ枢機卿ジャイルズやスイス人主教フーゴ・フォン・ホーエンランデンベルクも亡くなった。1534年には、不信を抱いていた庇護 者クレメンス4世が亡くなり、最近の盟友であったイタリアのカジェタン枢機卿が亡くなり、古くからの盟友であったカンペッジョ枢機卿が引退した。 さらに多くの友人が亡くなり(1533年、友人のピーテル・ギリス、1534年、ウィリアム・ブラウント、1536年初頭、アラゴンのカトリーヌ)、ル ターや一部のルター派、一部の有力なカトリック神学者たちがエラスムスに対する個人的な攻撃を再開したため、彼の書簡は、健康であるにもかかわらず、当た り障りのないフライブルクからの移住を検討する中で、友人関係の状況や安全に関する懸念にますます焦点が当てられるようになった[注釈 41]。 1535年、エラスムスの友人であったトマス・モア、司教ジョン・フィッシャー、ブリジット派のリチャード・レイノルズ[注釈 42]が、親ローマ派の反逆者としてヘンリー8世によって処刑された。病気にもかかわらず、エラスムスはモア(とフィッシャー)の最初の伝記 『Expositio Fidelis』を匿名で執筆し、デ・ゴイスの勧めでフローベンが出版した[98]。 エラスムスの時代以降も、マーガレット・ポール、ウィリアム・ティンデール、マイケル・セルヴェトゥスなど、多くのエラスムスの翻訳者たちが聖公会、カト リック、改革派の宗派や独裁者の手によって同様の運命をたどった。また、シャルル5世のラテン語秘書フアン・デ・バルデスのように、逃亡し、亡命先で亡く なった者もいた。 エラスムスの友人であり協力者であったカスバート・タンストール司教は、エリザベス1世の下、覇権の誓いを拒否した罪で獄死した。エラスムスの文通相手で あったスティーヴン・ガーディナー司教は、10代の学生時代にパリとケンブリッジで知り合ったが[108]、後にエドワード6世の下でプロテスタンティズ ムを阻害したとしてロンドン塔に5年間投獄された。 [註43] ダミアン・デ・ゴイスは72歳のときにポルトガルの異端審問にかけられ[98]、ほとんど隔離された状態で拘留され、最終的に修道院に追放され、釈放され た後におそらく殺害された[110]。 アマニエのギルバート・クーザンは教皇ピウス5世の個人的な命令で逮捕された直後、66歳で獄死した[94]。 バーゼルでの死  バーゼルのミンストルにあるエラスムスの墓碑銘 体力が衰え始めた頃、彼はついにオランダ摂政のハンガリー王妃メアリー(かつての教え子であるフェルディナント1世と皇帝シャルル5世の妹)の招待を受 け、フライブルクからブラバントへ移ることを決めた。1535年、彼はバーゼルのフローベンの屋敷に戻り、準備に取りかかった(ウコランパディウスが死去 し、彼の宗教の個人的な実践が可能になった)。1536年7月12日、赤痢の発作で死去した[111]。 彼はローマ・カトリックに忠誠を誓っていたが[112]、伝記作家たちは彼をインサイダーとして扱うかアウトサイダーとして扱うかで意見が分かれている [注釈 44]。 彼はカトリック教会の最後の儀式を受けなかったかもしれないし、受ける機会がなかったかもしれない[注 45]。彼の死に関する同時代の報告書には、彼がカトリック司祭を求めたかどうか、バーゼルに密かにあるいは個人的に司祭がいたのかどうか[注 46]については触れられていない。 彼の友人で伝記作家のベアトゥス・レナヌスによって記録された彼の最後の言葉は、「親愛なる神よ」(オランダ語:Lieve God)であったようだ[114]。プロテスタントの市当局は、彼の葬儀をエキュメニカルなカトリックのレクイエム・ミサとすることを見事に許可した [115]。 相続人としては、ボニファティウス・アマーバッハを任命し、学生や困窮者に種銭[注釈 47]を与えた。[注釈 48]彼は、自分の財産が自分の修道会であるシオン会に戻るよりも、遺言書を作成する方が良いという免除を受けており、500冊近い個人蔵書のほとんどを ヤン・ワスキに事前に売却していた。 [116][117]最終的な受取人の一人は、ジュネーヴからバーゼルに逃れてきた貧しいプロテスタントの人文主義者セバスチャン・カステリオであり、彼 はその後聖書をラテン語とフランス語に翻訳し、カトリック、アナバプティスト、プロテスタントにおけるキリスト教の分裂と分裂の修復のために働いた [118]。 |

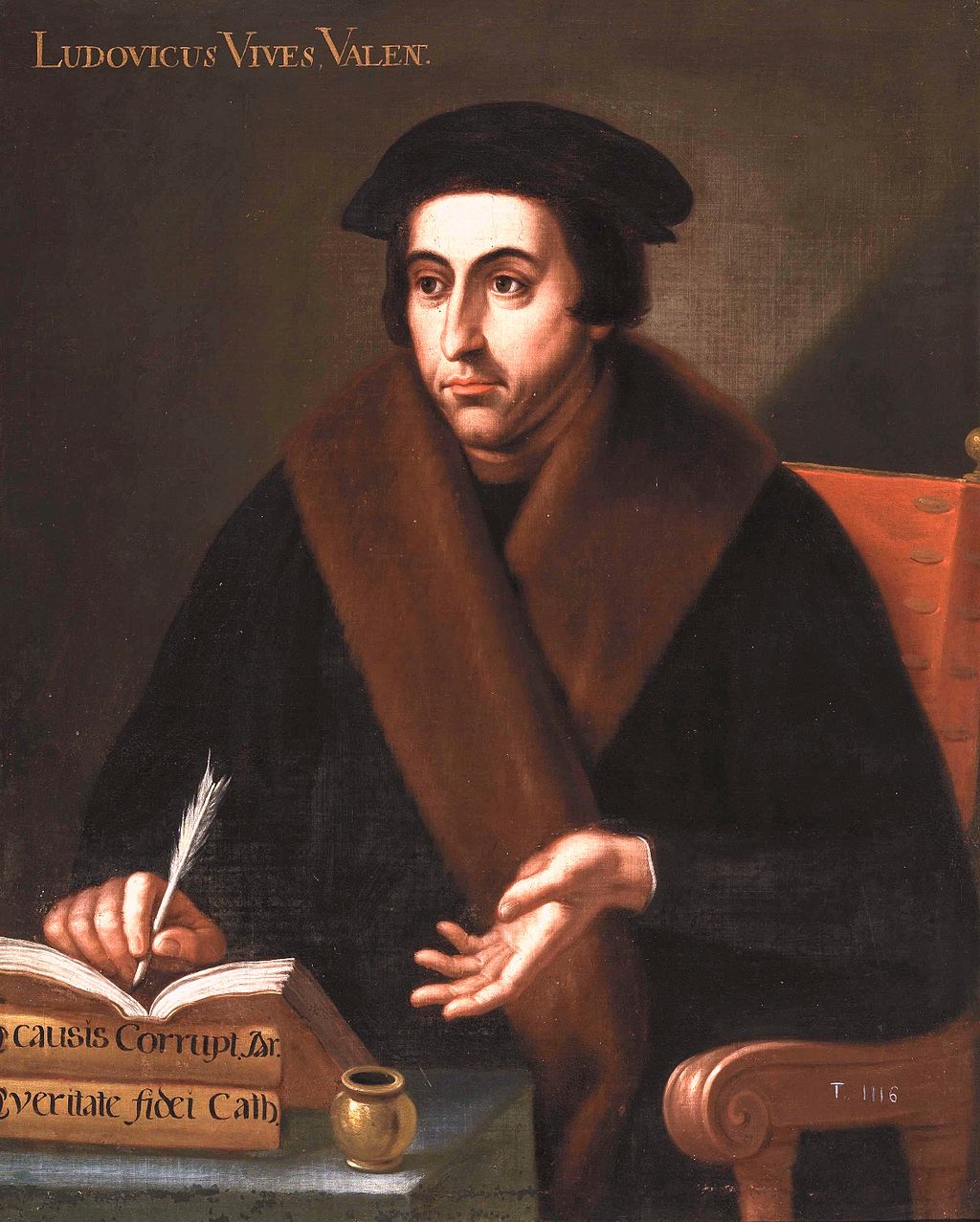

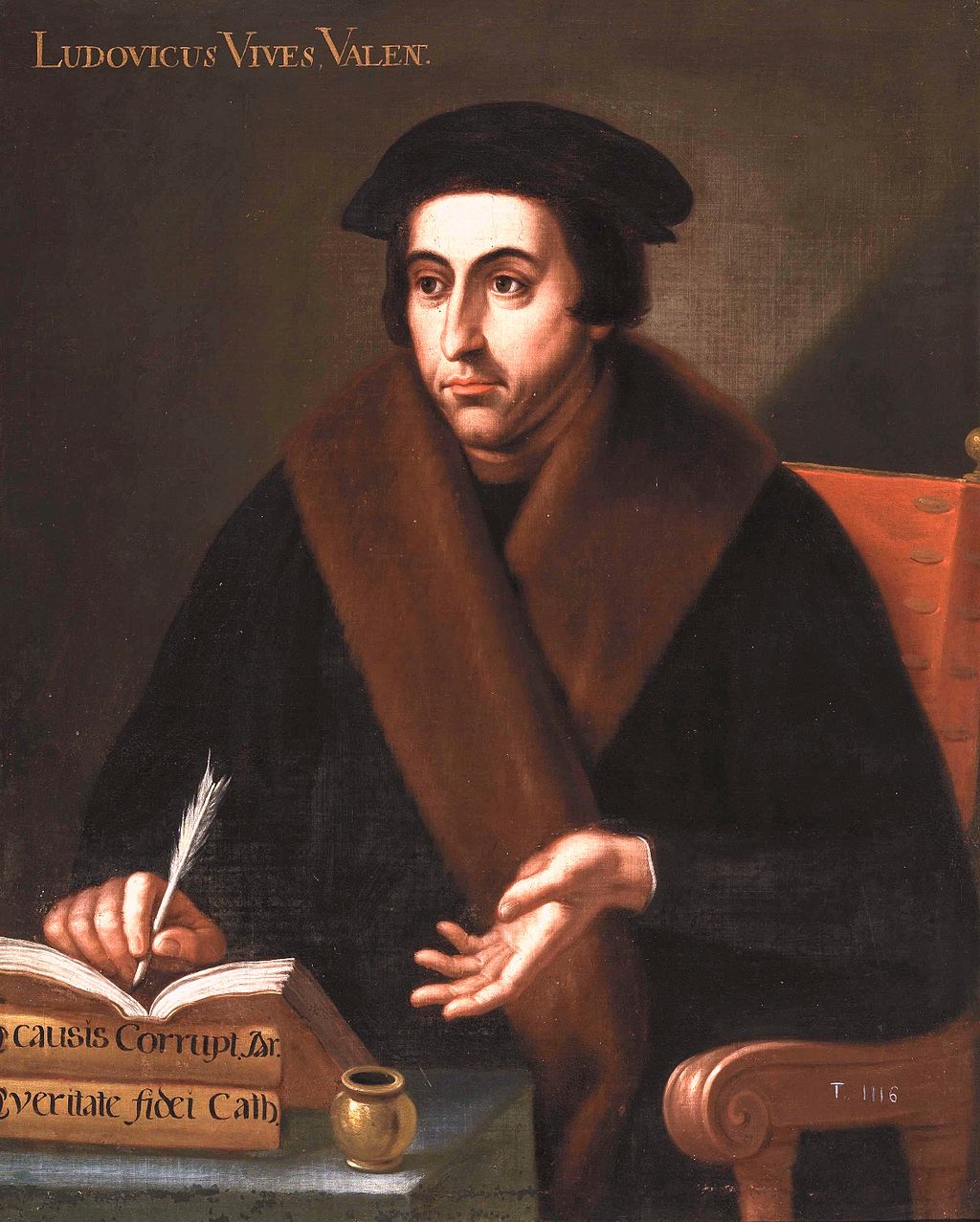

| Thought and views Erasmus had a distinctive manner of thinking, a Catholic historian suggests: one that is capacious in its perception, agile in its judgments, and unsettling in its irony with "a deep and abiding commitment to human flourishing"[119] "In all spheres, his outlook was essentially pastoral."[14]: 225 Erasmus has been called a seminal rather than a consistent or systematic thinker,[120] notably averse to over-extending from the specific to the general; who nevertheless should be taken very seriously as a pastoral[note 49] and rhetorical theologian, with a philological and historical approach—rather than a metaphysical approach—to interpreting Scripture[122][note 50] and interested in the literal and tropological senses.[14]: 145 French theologian Louis Bouyer commented "Erasmus was to be one of those who can get no edification from exegesis where they suspect some misinterpretation."[123] A theologian has written of "Erasmus’ preparedness completely to satisfy no-one but himself."[124] He has been called moderate, judicious and constructive even when being critical or when mocking extremes.[125][note 51] Pacifism Peace, peaceableness and peacemaking, in all spheres from the domestic to the religious to the political, were central distinctives of Erasmus' writing on Christian living and his mystical theology:[126] "the sum and summary of our religion is peace and unanimity" [note 52] At the Nativity of Jesus "the angels sang not the glories of war, nor a song of triumph, but a hymn of peace.":[127] He (Christ) conquered by gentleness; He conquered by kindness; he conquered by truth itself — Method of True Theology, 4 [note 53]: 570 Erasmus was not an absolute Pacifist but promoted political Pacificism and religious Irenicism.[128] Notable writings on irenicism include de Concordia, On the War with the Turks, The Education of a Christian Prince, On Restoring the Concord of the Church, and The Complaint of Peace. Erasmus' ecclesiology of peacemaking held that the church authorities had a divine mandate to settle religious disputes,[note 54] in an as non-excluding way as possible, including by the preferably-minimal development of doctrine. In the latter, Lady Peace insists on peace as the crux of Christian life and for understanding Christ: I give you my peace, I leave you my peace" (John 14:27). You hear what he leaves his people? Not horses, bodyguards, empire or riches – none of these. What then? He gives peace, leaves peace – peace with friends, peace with enemies. — The Complaint of Peace[129] A historian has called him "The 16th Century's Pioneer of Peace Education and a Culture of Peace".[note 55] War See also: Erasmus § The Complaint of Peace (1517) Erasmus had experienced war as a child and was particularly concerned about wars between Christian kings, who should be brothers and not start wars; a theme in his book The Education of a Christian Prince. His Adages included "War is sweet to those who have never tasted it" (Dulce bellum inexpertis from Pindar's Greek.)[note 56] He promoted and was present at the Field of Cloth of Gold,[131] and his wide-ranging correspondence frequently related to issues of peacemaking.[note 57] He saw a key role of the Church in peacemaking by arbitration,[133] and the office of the Pope was necessary to reign in tyrannical princes and bishops.[30]: 195 He questioned the practical usefulness and abuses[note 58] of Just War theory, further limiting it to feasible defensive actions with popular support and that "war should never be undertaken unless, as a last resort, it cannot be avoided."[134] In his Adages he discusses (common translation) "A disadvantageous peace is better than a just war", which owes to Cicero and John Colet's "Better an unjust peace than the justest war." Erasmus was extremely critical of the warlike way of important European princes of his era, including some princes of the church.[note 59] He described these princes as corrupt and greedy. Erasmus believed that these princes "collude in a game, of which the outcome is to exhaust and oppress the commonwealth".[84]: s1.7.4 He spoke more freely about this matter in letters sent to his friends like Thomas More, Beatus Rhenanus and Adrianus Barlandus: a particular target of his criticisms was the Emperor Maximilian I, whom Erasmus blamed for allegedly preventing the Netherlands from signing a peace treaty with Guelders[135] and other schemes to cause wars in order to extract money from his subjects.[note 60] One of his approaches was to send, and publish, congratulatory and lionizing letters to princes who, though in a position of strength, negotiated peace with neighbours: such as to King Sigismund I the Old of Poland in 1527.[103]: 75 Christian religious toleration  Portrait of Erasmus, after Quinten Massijs (1517) He referred to his irenical disposition in the Preface to On Free Will as a secret inclination of nature that would make him even prefer the views of the Sceptics over intolerant assertions, though he sharply distinguished adiaphora from what was uncontentiously explicit in the New Testament or absolutely mandated by Church teaching.[136] Concord demanded unity and assent: Erasmus was anti-sectarian[note 61] as well as non-sectarian.[137] To follow the law of love, our intellects must be humble and friendly when making any assertions: he called contention "earthly, beastly, demonic"[138]: 739 and a good-enough reason to reject a teacher or their followers. In Melancthon's view, Erasmus taught charity not faith.[139]: 10 Certain works of Erasmus laid a foundation for religious toleration of private opinions and ecumenism. For example, in De libero arbitrio, opposing certain views of Martin Luther, Erasmus noted that religious disputants should be temperate in their language, "because in this way the truth, which is often lost amidst too much wrangling may be more surely perceived." Gary Remer writes, "Like Cicero, Erasmus concludes that truth is furthered by a more harmonious relationship between interlocutors."[140] Erasmus' pacificism included a particular dislike for sedition, which caused warfare: It was the duty of the leaders of this (reforming) movement, if Christ was their goal, to refrain not only from vice, but even from every appearance of evil; and to offer not the slightest stumbling block to the Gospel, studiously avoiding even practices which, although allowed, are yet not expedient. Above all they should have guarded against all sedition. — Letter to Martin Bucer[141] Erasmus had been involved in early attempts to protect Luther and his sympathisers from charges of heresy. Erasmus wrote Inquisitio de fide to limit what should be considered heresy to fractiously agitating against essential doctrines (e.g., those of the Creed), with malice and persistence. As with St Theodore the Studite,[142] Erasmus was against the death penalty merely for private or peaceable heresy, or for dissent on non-essentials: "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."[143] The Church has the duty to protect believers and convert or heal heretics; he invoked Jesus' parable of the wheat and tares.[14]: 200 Nevertheless, he allowed the death penalty against violent seditionists, to prevent bloodshed and war: he allowed that the state has the right to execute those who are a necessary danger to public order—whether heretic or orthodox—but noted (e.g., to fr:Noël Béda) that Augustine had been against the execution of even violent Donatists: Johannes Trapman states that Erasmus' endorsement of suppression of the Anabaptists springs from their refusal to heed magistrates and the criminal violence of the Münster rebellion not because of their heretical views on baptism.[144] Despite these concessions to state power, he suggested that religious persecution could still be challenged as inexpedient (ineffective).[145] In a letter to Cardial Lorenzo Campeggio, Erasmus lobbied diplomatically for toleration: "If the sects could be tolerated under certain conditions (as the Bohemians pretend), it would, I admit, be a grievous misfortune, but one more endurable than war."[citation needed] Jews and Turks While the focus of most of his writing was about peace within Christendom with a sole focus on Europe until his last decade, he was involved in the public policy debate on war with the Ottoman Empire, which was then invading Western Europe, notably in his book On the war against the Turks (1530), with Pope Leo X promoting going on the offensive with a new crusade.[note 62] Erasmus re-worked Luther's rhetoric that the invading Turks represent God's judgment of decadent Christendom, but without Luther's fatalism: Erasmus not only accused Western leaders of kingdom-threatening hypocrisy, he proposed a remedy: anti-expansionist moral reforms by Europe's disunited leaders as a necessary unitive political step before aggressive warfare against the Ottoman threat, reforms which might themselves, if sincere, prevent both the internecine and foreign warfare.[103]  Juan Luis Vives In common with his times,[146] Erasmus regarded the Jewish and Islamic religions as Christian heresies rather than separate religions, using the inclusive term half-Christian for the latter. However, there is a wide range of scholarly opinion on the extent and nature of antisemitic and anti-Moslem prejudice in his writings: Erasmus scholar Shimon Markish wrote that the charge of antisemitism could not be sustained in Erasmus' public writings,[147] however historian Nathan Ron has found his writing to be harsh and racial in its implications, with contempt and hostility to Islam.[148] Biographer James Tracy sees an anti-semitic edge in Erasmus' comments against Johannes Pfefferkorn in the Ruechlin affair, which expresses Erasmus' general "suspicion of those who, behind the scenes, manipulate influence and opinion for nefarious ends."[note 63] Erasmus was not vehemently antisemitic in the way of the later post-Catholic Martin Luther; it was not a topic or theme of his public writing. Erasmus claimed not to be personally xenophobic: "For I am of such a nature that I could love even a Jew, were he a pleasant companion and did not spew out blasphemy against Christ"[note 64] however Markish suggests that it is probable Erasmus never actually encountered a (practicing) Jew.[149][note 65] Unusually for a Christian theologian of any time, he perceived and championed strong Hellenistic rather than exclusively Hebraic influences on the intellectual milieux of Jesus, Paul and the early church.[note 66] Interpretation caveats: analogy, irony, foils The picture is complicated because when Erasmus wrote of Judaism, he frequently was not referring to contemporary Jews but allegorically, by analogy with Second Temple Judaism, to Christians of his time who mistakenly promoted external ritualism over interior piety,[note 67] notably in the monastic lifestyle.[note 68] Erasmus' pervasive anti-ceremonialism treated the early Church debates on circumcision, food and special days as manifestations of cultural chauvinism, a general human characteristic, by the initial Jewish Christians.[note 69] Erasmus often wrote in a highly ironical idiom,[119] especially in his letters,[note 70] which makes them prone to different interpretations when taken literally rather than ironically.[note 71] Erasmus chided Ulrich von Hutten's claims that Erasmus was a Lutheran, saying that von Hutten had not detected the irony in Erasmus' public letters enough.[95]: 27 Terence J. Martin identifies an "Erasmian pattern" that the supposed (by the reader) otherness (of Jews, Turks, Lapplanders, Indians, and even women and heretics) "provides a foil against which the failures of Christian culture can be exposed and criticized."[152] In de bello Turcico, Erasmus allegorizes that we should "kill the Turk, not the man."[note 72] On the subject of slavery, Erasmus characteristically treated it in passing when dealing with tyranny: Christians were not allowed to be tyrants, which slave-owning required, but especially not to be the masters of other Christians.[153] Erasmus had various other piecemeal arguments against slavery: for example, that it was not legitimate to have slaves taken in an unjust war, but it was not a subject that occupied him. Domestic and community peace Further information: § On the Institution of Christian Marriage (1526) Further information: Pre-Tridentine Mass § Vernacular and laity in the medieval and Reformation eras Erasmus' emphasis on peacemaking reflects a typical pre-occupation of medieval lay spirituality as historian John Bossy (as summarized by Eamon Duffy) puts it: "medieval Christianity had been fundamentally concerned with the creation and maintenance of peace in a violent world. “Christianity” in medieval Europe denoted neither an ideology nor an institution, but a community of believers whose religious ideal—constantly aspired to if seldom attained—was peace and mutual love."[154] In marriage, Erasmus' two significant innovations, according to historian Nathan Ron, were that "matrimony can and should be a joyous bond, and that this goal can be achieved by a relationship between spouses based on mutuality, conversation, and persuasion."[155]: 4:43 |

思想と見解 あるカトリック史家は、エラスムスには独特の思考様式があったと指摘する。それは、「人間の繁栄に対する深く変わらぬコミットメント」[119]をもっ て、広い認識力、機敏な判断力、不穏な皮肉[119]を持つものであり、「あらゆる領域において、彼の見通しは本質的に司牧的であった」[14]: 225。 エラスムスは、一貫した、あるいは体系的な思想家というよりは、むしろ精液的な思想家と呼ばれており[120]、特に特定のものから一般的なものへと拡張 しすぎることを嫌っていた。それにもかかわらず、聖書の解釈に対して形而上学的なアプローチというよりはむしろ言語学的・歴史学的なアプローチを持ち [122][注釈 50]、文字通りの意味とトロポロジー的な意味に関心を持つ牧会的[注釈 49]かつ修辞学的な神学者として、非常に真剣に受け止めるべきである[14]: 145 フランスの神学者ルイ・ブイエは「エラスムスは、誤訳を疑うような釈義からは何の啓発も得られない人々の一人であった」とコメントしている[123]。 ある神学者は「エラスムスは自分以外の誰も満足させることができないことを覚悟していた」と書いている[124]。彼は批判的であったり、極端なものを嘲 笑するときでさえ、穏健で、判断力があり、建設的であると呼ばれている[125][注釈 51]。 平和主義 家庭的なものから宗教的なもの、政治的なものまで、あらゆる領域における平和、平和主義、平和創造は、キリスト教的生活に関するエラスムスの著作と神秘主 義神学の中心的な特徴であった。 彼(キリスト)は優しさによって征服し、優しさによって征服し、真理そのものによって征服した。 - 真の神学の方法』4 [注 53]: 570 エラスムスは絶対的平和主義者ではなかったが、政治的太平洋主義と宗教的イレニシズムを推進した[128]。イレニシズムに関する著名な著作には、『デ・ コンコルディア』、『トルコとの戦争について』、『キリスト教王子の教育』、『教会のコンコルドの回復について』、『平和の不満』などがある。エラスムス の平和創造に関する教会論は、教会当局には宗教的紛争を解決する神の使命があるとし[注 54]、教義をできれば最小限に発展させるなど、できるだけ排除しない方法で解決することを求めた。 後者において、平和婦人は、キリスト教生活の核心として、またキリストを理解するための平和を主張している: わたしはあなたがたにわたしの平和を与え、わたしの平和をあなたがたに残す」(ヨハネ14:27)。私の平和を与え、私の平和を残す」(ヨハネ14: 27)。馬でも、護衛でも、帝国でも、富でもない。では何なのか?彼は平和を与え、平和を残す-友との平和、敵との平和。 - 平和への不満[129] ある歴史家は彼を「16世紀の平和教育と平和文化の先駆者」と呼んだ[注釈 55]。 戦争 も参照: エラスムス§『平和の訴え』(1517年) エラスムスは幼い頃に戦争を経験し、特にキリスト教国王同士の戦争に懸念を抱いていた。彼の格言には「戦争は味わったことのない者にとっては甘いものであ る」(ピンダルのギリシャ語からDulce bellum inexpertis)などがある[注 56]。 彼は「金の布の野原」を推進し、その場に立ち会った[131]。彼の幅広い書簡はしばしば平和構築の問題に関連していた[注釈 57]。彼は仲裁による平和構築において教会が重要な役割を果たすと考えており[133]、教皇の地位は専制的な王侯や司教を統治するために必要であった [30]: 195 彼は正義の戦争理論の実際的な有用性と濫用[注 58]に疑問を呈し、さらに人民の支持を得た実現可能な防衛行動に限定し、「戦争は、最後の手段として、それを避けることができない場合を除き、決して引 き受けるべきでない」とした[134]。彼の格言の中で(一般的な訳語)"A disadvantageous peace is better than a just war"(不利な平和は正義の戦争にまさる)について論じており、これはキケロとジョン・コレットの "Better an unjust peace than the justest war "に負っている。 エラスムスは、教会の諸侯を含む同時代のヨーロッパの重要な諸侯の戦争的なやり方を非常に批判していた[注 59]。エラスムスは、これらの諸侯は「ゲームに結託しており、その結果は連邦を疲弊させ、抑圧することである」と考えていた[84]: s1.7。 4 彼はトマス・モア、ベアトゥス・レナヌス、アドリアヌス・バーランドゥスといった友人たちに送った書簡の中で、この問題についてより自由に語っていた。特 に批判の対象となったのは皇帝マクシミリアン1世であり、エラスムスはオランダがゲルダース[135]と和平条約を結ぶのを妨げたとされることや、臣民か ら金を引き出すために戦争を引き起こそうとするその他の企てを非難していた[注釈 60]。 エラスムスのアプローチのひとつは、1527年にポーランド王ジギスムント1世に宛てた手紙のように、強大な立場にありながら隣国と和平交渉を行った諸侯 に祝賀や讃美の手紙を送り、それを公表することであった[103]。 キリスト教の宗教的寛容  クインテン・マサイス(?)によるエラスムスの肖像画(1517年) エラスムスは、『自由意志について』の序文で、不寛容な主張よりも懐疑主義者の見解を好むような本性のひそかな傾きとして、自分のアイレン主義的な性格に ついて言及しているが、彼はアディアフォラと、新約聖書の中で議論の余地のないほど明示されているもの、あるいは教会の教えによって絶対的に義務づけられ ているものとを峻別していた[136]: エラスムスは反宗教主義者[注釈 61]であると同時に非宗教主義者であった[137]。 愛の法則に従うためには、私たちの知性はいかなる主張をするときにも謙虚で友好的でなければならない:彼は論争を「地上の、獣のような、悪魔のような」 [138]:739と呼び、教師やその信者を拒絶する十分な理由とした。メランクトンの見解では、エラスムスは信仰ではなく慈愛を教えていた[139]: 10 エラスムスのある著作は、私見に対する宗教的寛容とエキュメニズムの基礎を築いた。例えば、マルティン・ルターのある見解に反対した『De libero arbitrio』において、エラスムスは宗教論争者は言葉を慎むべきであると述べている。ゲーリー・レマーは、「キケロと同様に、エラスムスも、真理は 対話者間のより調和的な関係によって促進されると結論づけている」[140]と書いている。 エラスムスの平和主義には、戦争を引き起こす扇動に対する特別な嫌悪が含まれていた: キリストが彼らの目標であるならば、この(改革)運動の指導者たちの義務は、悪を慎むだけでなく、あらゆる悪の外観さえも慎むことであった。とりわけ、彼 らはあらゆる扇動から身を守るべきである。 - マルティン・ブッカーへの手紙[141]。 エラスムスは、ルターとその同調者を異端容疑から守ろうとする初期の試みに関わっていた。エラスムスは『Inquisitio de fide』を書き、異端とみなされるべきものを、悪意と執着をもって、本質的な教義(たとえば信条の教義)に対して分裂的に扇動することに限定した。聖テ オドール修道士[142]と同様に、エラスムスは、単に私的な異端や平和的な異端、あるいは本質的でない異端に対する死刑に反対していた: 「教会は信者を保護し、異端者を改宗させたり治癒したりする義務がある。 とはいえ、流血や戦争を防ぐために、暴力的な扇動者に対しては死刑を認めた。異端であろうと正統派であろうと、公序良俗に必要な危険をもたらす者を国家が 処刑する権利は認めるが、アウグスティヌスは暴力的なドナティストでさえも処刑することに反対していたことを(例えば、ノエル・ベダに対して)指摘した: ヨハネス・トラップマンは、エラスムスがアナバプテスト派の弾圧を支持したのは、彼らが洗礼に関する異端的な見解のためではなく、彼らが判事に従うことを 拒否したことと、ミュンスターの反乱の犯罪的暴力に起因すると述べている[144]。こうした国家権力への譲歩にもかかわらず、彼は宗教的迫害が依然とし て不都合(効果がない)として異議を唱えられる可能性があることを示唆していた[145]。 カーディアル・ロレンツォ・カンペッジョに宛てた手紙の中で、エラスムスは寛容を外交的に働きかけた: 「もし(ボヘミア人が装っているように)一定の条件のもとで諸宗派が容認されるのであれば、それは痛ましい不幸であることは認めますが、戦争よりは耐えら れるものです」[要出典]。 ユダヤ人とトルコ人 エラスムスは、晩年の10年間まで、キリスト教圏内の平和に焦点を当て、ヨーロッパにのみ焦点を当てていたが、当時西ヨーロッパに侵攻していたオスマン帝 国との戦争に関する公の政策論争に関与しており、特に『トルコとの戦争について』(1530年)では、教皇レオ10世が新たな十字軍による攻勢を推進して いた[注釈 62]。 エラスムスは、侵入してくるトルコ人が退廃したキリスト教に対する神の裁きを象徴しているというルターのレトリックを、ルターの宿命論抜きで再構築した: エラスムスは、西欧の指導者たちの王国を脅かす偽善を非難しただけでなく、オスマン帝国の脅威に対する積極的な戦争の前に必要な統一的な政治的ステップと して、ヨーロッパの分裂した指導者たちによる反拡大主義的な道徳的改革を、それ自体が、誠実であれば、内戦と外戦の両方を防ぐかもしれない改革として、救 済策を提案した[103]。  フアン・ルイス・ビベス 当時と同様に[146]、エラスムスはユダヤ教とイスラム教を別個の宗教というよりもむしろキリスト教の異端とみなし、後者にはハーフ・クリスチャンとい う包括的な用語を用いた。しかし、エラスムスの著作に見られる反ユダヤ的、反モスレム的偏見の程度や性質については、学者によってさまざまな見解がある: エラスムスの研究者であるシモン・マルキシュは、エラスムスの公的な著作において反ユダヤ主義を主張することはできないと書いているが[147]、歴史家 のネイサン・ロンは、エラスムスの著作は辛辣で人種差別的な意味合いが強く、イスラム教を侮蔑し敵視していると指摘している[148]。 [148] 伝記作家のジェームス・トレーシーは、エラスムスのリューヒリン事件におけるヨハネス・プフェフェルコルンに対する発言に反ユダヤ主義的な側面があると見 ており、これはエラスムスの一般的な「陰で影響力と世論を操り、邪悪な目的を達成しようとする者に対する疑念」[注釈 63]を表現している。 エラスムスは、後のポスト・カトリックのマルティン・ルターのように激しく反ユダヤ主義者というわけではなく、それは彼の公的な著作の話題やテーマではな かった。エラスムスは個人的には排外主義者ではないと主張している。「私はユダヤ人であっても、その人が愉快な仲間であり、キリストに対する冒涜を吐き出 さなければ、愛することができるような性質だからである」[注釈 64]が、マーキッシュはエラスムスが実際に(実践的な)ユダヤ人に出会ったことはない可能性が高いと指摘している[149][注釈 65]。 当時のキリスト教神学者としては珍しく、彼はイエス、パウロ、そして初代教会の知的環境において、ヘブライ的な影響というよりもむしろヘレニズム的な影響 を強く受け、それを支持していた[注 66]。 解釈の注意点:類推、皮肉、箔 エラスムスがユダヤ教について書いたとき、彼はしばしば現代のユダヤ人についてではなく、第二神殿ユダヤ教との類推によって、特に修道生活において、内面 的な敬虔さよりも外面的な儀式主義[注釈 67]を誤って推進した当時のキリスト教徒について寓意的に言及していたため、その図式は複雑であった[注釈 68] 。 エラスムスはしばしば非常に皮肉な慣用句で書いており[119]、特に書簡においては[注釈 70]、そのため皮肉的にではなく文字通りに解釈すると異なる解釈がなされやすい[注釈 71]。 エラスムスはウルリッヒ・フォン・ハッテンがエラスムスはルター派であったと主張していることを非難し、フォン・ハッテンがエラスムスの公の書簡における 皮肉を十分に見抜いていなかったと述べている[95]: 27。 テレンス・J・マーティンは、(読者が)想定する他者性(ユダヤ人、トルコ人、ラップランド人、インド人、さらには女性や異端者)が「キリスト教文化の失 敗を暴露し批判するための箔を提供する」という「エラスムス的パターン」を特定している[152]。 de bello Turcicoにおいて、エラスムスは「人間ではなくトルコ人を殺すべきである」と寓意している[注釈 72]。 奴隷制については、エラスムスは専制政治を扱う際に、一応の扱いをするのが特徴的であった: エラスムスは奴隷制に反対する様々な断片的な議論を持っていた。例えば、不当な戦争で奴隷を連行することは正当ではないというような議論であった。 国内と地域社会の平和 さらなる情報 § キリスト教の結婚制度について (1526) さらに詳しい情報 三位一体以前のミサ § 中世と宗教改革の時代における言語と信徒 エラスムスが平和創造を強調したのは、歴史家ジョン・ボッシー(イーモン・ダフィーの要約)が言うように、中世の信徒霊性の典型的な先入観を反映してい る: 「中世キリスト教は、暴力的な世界における平和の創造と維持に基本的な関心を持っていた。「中世ヨーロッパにおける "キリスト教 "は、イデオロギーでも制度でもなく、信者の共同体を示していた。 歴史家ネイサン・ロンによれば、結婚におけるエラスムスの2つの重要な革新は、「結婚は喜びの絆でありうるし、そうあるべきであり、この目標は相互性、会 話、説得に基づく配偶者間の関係によって達成されうる」ということであった[155]: 4:43 |