ドグマ

Dogma

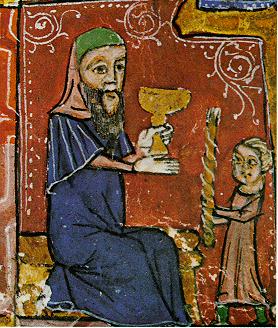

Observing the Havdalah ritual, 14th-century Spain

☆ ドグマ(あるいは教義)とは、最も広い意味では、改革の可能性のない、決定的な信念のことである。ユダヤ教、ローマカトリック、プロテスタント[1]、イ スラム教などの宗教の公式な原則や教義、ストア派などの哲学者や哲学派の立場、ファシズム、社会主義、進歩主義、自由主義、保守主義などの政治思想体系な どの形をとることがある[2]。[3] 蔑称的な意味では、教義とは、攻撃的な政治的利益や権威による決定などを指す[4][5]。より一般的には、その信奉者が合理的に議論することを望まない 強い信念に適用される。この態度は「教条的」または「教条主義」と呼ばれ、宗教に関する事柄を指すことが多いが、この蔑称的な意味は、宗教的信念に適用さ れる形式的な意味から大きく逸脱している。蔑称的な意味は、有神論的な態度に限定されず、政治的または哲学的な教条に対してもよく用いられる。

★ドグマ中心の言説構造をドグマチズム(独断論 dogmatism)という。ドグマチズムは、証拠や他者の意見を考慮せずに、原則を紛れもない真実として確立しようとする傾向のことである。

| Dogma, in its

broadest sense, is any belief held definitively and without the

possibility of reform. It may be in the form of an official system of

principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Judaism, Roman

Catholicism, Protestantism,[1] or Islam, the positions of a philosopher

or philosophical school, such as Stoicism, and political belief systems

such as fascism, socialism, progressivism, liberalism, and

conservatism.[2][3] In the pejorative sense, dogma refers to enforced decisions, such as those of aggressive political interests or authorities.[4][5] More generally, it is applied to some strong belief that its adherents are not willing to discuss rationally. This attitude is named as a dogmatic one, or dogmatism, and is often used to refer to matters related to religion, though this pejorative sense strays far from the formal sense in which it is applied to religious belief. The pejorative sense is not limited to theistic attitudes alone and is often used with respect to political or philosophical dogmas. |

ドグマとは、最も広い意味では、改革の可能性のない、決定的な信念のこ

とである。ユダヤ教、ローマカトリック、プロテスタント[1]、イスラム教などの宗教の公式な原則や教義、ストア派などの哲学者や哲学派の立場、ファシズ

ム、社会主義、進歩主義、自由主義、保守主義などの政治思想体系などの形をとることがある[2]。[3] 蔑称的な意味では、教義とは、攻撃的な政治的利益や権威による決定などを指す[4][5]。より一般的には、その信奉者が合理的に議論することを望まない 強い信念に適用される。この態度は「教条的」または「教条主義」と呼ばれ、宗教に関する事柄を指すことが多いが、この蔑称的な意味は、宗教的信念に適用さ れる形式的な意味から大きく逸脱している。蔑称的な意味は、有神論的な態度に限定されず、政治的または哲学的な教条に対してもよく用いられる。 |

| Etymology See also: Doxa The word dogma was adopted in the 17th century from Latin: dogma, lit. 'philosophical tenet or principle', derived from the Ancient Greek: δόγμα, romanized: dogma, lit. 'opinion, belief, judgement' from the Ancient Greek: δοκεῖ, romanized: dokeî, lit. 'it seems that...'. The plural is based on the Latin: dogmata, though dogmas may be more commonly used in English. |

語源 関連項目:ドクサ 「教義」という言葉は、17 世紀にラテン語の「dogma」から採用されました。これは、古代ギリシャ語の「δόγμα」に由来し、文字通り「哲学の教義や原則」を意味します。古代 ギリシャ語の「δοκεῖ」に由来し、文字通り「意見、信念、判断」を意味します。複数形はラテン語の dogmata に基づくが、英語では dogmas がより一般的に使用される。 |

| In philosophy Pyrrhonism In Pyrrhonism, "dogma" refers to assent to a proposition about a non-evident matter.[6] The main principle of Pyrrhonism is expressed by the word acatalepsia, which connotes the ability to withhold assent from doctrines regarding the truth of things in their own nature; against every statement its contradiction may be advanced with equal justification. Consequently, Pyrrhonists withhold assent with regard to non-evident propositions, i.e., dogmas.[7] Pyrrhonists argue that dogmatists, such as the Stoics, Epicureans, and Peripatetics, have failed to demonstrate that their doctrines regarding non-evident matters are true. |

哲学 ピロン主義(あるいはフィロニズム、懐疑主義) ピロン主義では、「教義」とは、明白ではない事柄に関する命題への同意を指す[6]。ピロン主義の主な原則は、アカタレプシアという言葉で表現され、物事 の本質に関する教義への同意を保留する能力、つまり、あらゆる主張に対して、その矛盾を同等の正当性をもって反論できることを意味する。したがって、ピロ ン主義者は、非自明な命題、すなわちドグマに対して同意を保留する。[7] ピロン主義者は、ストア派、エピクロス派、ペリパスト派などのドグマティストは、非自明な事柄に関する教義が真実であることを証明できなかったと主張する。 |

| In religion Christianity In Christianity, a dogma is a belief communicated by divine revelation and defined by the Church,[8] The organization's formal religious positions may be taught to new members or simply communicated to those who choose to become members. It is rare for agreement with an organization's formal positions to be a requirement for attendance, though membership may be required for some church activities.[8] In the narrower sense of the church's official interpretation of divine revelation,[9] theologians distinguish between defined and non-defined dogmas, the former being those set out by authoritative bodies such as the Roman Curia for the Catholic Church, the latter being those which are universally held but have not been officially defined, the nature of Christ as universal redeemer being an example.[10] The term originated in late ancient Greek philosophy legal usage, in which it meant a decree or command, and came to be used in the same sense in early Christian theology.[11] Protestants to differing degrees are less formal about doctrine, and often rely on denomination-specific beliefs, but seldom refer to these beliefs as dogmata. The first[citation needed] unofficial institution of dogma in the Christian church was by Saint Irenaeus in his Demonstration of Apostolic Teaching, which provides a 'manual of essentials' constituting the 'body of truth'. |

宗教 キリスト教 キリスト教において、教義とは、神の啓示によって伝えられ、教会によって定義された信仰のことである[8]。組織の正式な宗教的立場は、新しい会員に教え られる場合もあれば、会員になることを選択した者に単に伝えられる場合もある。組織の正式な立場に同意することが出席の要件となることはまれであるが、一 部の教会活動には会員資格が必要とされる場合もある。[8] 神の啓示に関する教会の公式な解釈のより狭い意味では[9]、神学者は、定義された教義と定義されていない教義を区別している。前者は、カトリック教会の ローマ教皇庁などの権威ある機関によって定められたものであり、後者は、普遍的に受け入れられているが、公式に定義されていないものである。キリストの普 遍的な救い主としての性質がその例だ。[10] この用語は、古代ギリシャ哲学の法的な用法で、法令や命令を意味し、初期のキリスト教神学でも同じ意味で用いられるようになった。[11] プロテスタントは、教義についてさまざまな程度において形式ばらない傾向があり、多くの場合、宗派特有の信仰に依存しているが、これらの信仰を教義と呼ぶ ことはほとんどない。キリスト教教会における教義の最初の[出典必要]非公式な制定は、聖イレーネウスが『使徒の教義の証明』において行ったもので、これ は「真実の体系」を構成する「必須事項の手引き」を提供している。 |

| Catholicism and Eastern Christianity Main article: Dogma in the Catholic Church For Catholicism and Eastern Christianity, the dogmata are contained in the Nicene Creed and the canon laws of two, three, seven, or twenty ecumenical councils (depending on whether one is Church of the East, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, or Roman Catholic). These tenets are summarized by John of Damascus in his Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, which is the third book of his main work, titled The Fount of Knowledge. In this book he takes a dual approach in explaining each article of the faith: one, directed at Christians, where he uses quotes from the Bible and, occasionally, from works of other Church Fathers, and the second, directed both at members of non-Christian religions and at atheists, for whom he employs Aristotelian logic and dialectics. The decisions of fourteen later councils that Catholics hold as dogmatic and a small number of decrees promulgated by popes exercising papal infallibility (for examples, see Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary) are considered as being a part of the Catholic Church's sacred body of dogma. |

カトリックと東方キリスト教 主な記事:カトリック教会の教義 カトリック教と東方キリスト教において、教義はニカイア信条と、2回、3回、7回、または20回の公会議(東方教会、東方正教会、東方正教会、またはロー マ・カトリック教会に属するかによって異なる)の教会法に収められている。これらの教義は、ヨハネス・ダマスカスによって『正統信仰の正確な説明』に要約 されており、これは彼の主要著作『知識の泉』の第3巻に収録されている。この書物において、彼は信仰の各条項を説明する際に二重のアプローチを採用してい る。一つはキリスト教徒を対象としたもので、聖書の引用や、時折他の教父の著作からの引用を用いる。もう一つは、非キリスト教徒や無神論者を対象としたも ので、アリストテレスの論理と弁証法を用いる。 カトリック教徒が教義として受け入れている14の後の公会議の決定と、教皇の教皇不可謬性に基づいて公布された少数の教令(例:無原罪の御宿り、マリアの被昇天)は、カトリック教会の聖なる教義体系の一部とされている。 |

| Judaism In the Jewish commentary tradition, dogma is a principle by which the Rabbanim can try the proofs of faith about the existence of God and truth;[12] dogma is what is necessarily true for rational thinking.[13] In Jewish Kabbalah, a dogma is an archetype of the Pardes or Torah Nistar, the secrets of Bible. In the relation between "logical thinking" and "rational Kabbalah" the "Partzuf" is the means to identify "dogma".[clarification needed] |

ユダヤ教 ユダヤ教の注釈の伝統では、教義とは、ラバニムが神の存在や真実に関する信仰の証明を試すための原則である[12]。教義とは、合理的な思考にとって必然 的に真実であるものである[13]。ユダヤ教のカバラでは、教義とは、パルデスまたはトーラー・ニスター、すなわち聖書の秘密の原型である。「論理的思 考」と「合理的なカバラ」の関係において、「パルツフ」は「教義」を特定する手段である。[説明が必要] |

| Buddhism Main article: View (Buddhism) View or position (Sanskrit: दृष्टि, romanized: dṛṣṭi; Pali: diṭṭhi) is a central idea in Buddhism that corresponds with the Western notion of dogma.[14] In Buddhist thought, a view is not a simple, abstract collection of propositions, but a charged interpretation of experience which intensely shapes and affects thought, sensation, and action.[15] Having the proper mental attitude toward views is therefore considered an integral part of the Buddhist path, as sometimes correct views need to be put into practice and incorrect views abandoned, while at other times all views are seen as obstacles to enlightenment.[16] |

仏教 主な記事:見解(仏教 見解または立場(サンスクリット語:दृष्टि、ローマ字表記:dṛṣṭi、パーリ語:diṭṭhi)は、西洋の教義の概念に相当する、仏教の中心的な 考えだ。[14] 仏教の思想において、見解は単純な抽象的な命題の集合ではなく、思考、感覚、行動を強く形作り、影響を与える経験の解釈である。[15] したがって、見解に対して適切な精神態度を持つことは、仏教の道において不可欠な部分とみなされている。なぜなら、正しい見解を実践し、誤った見解を放棄 する必要がある場合もある一方、すべての見解が悟りの障害と見なされる場合もあるからである。[16] |

| Islam In the context of Islam, dogma is best translated as عقيدة (ʿAqīda). ʿAqīda refers to the core tenets of Islamic belief, such as faith in Allah, the prophets, the afterlife, and other essential doctrines. It is a fundamental aspect of Islamic theology, and different Islamic schools (e.g., Ashʿarī, Māturīdī, and Salafī) have varying interpretations of ʿAqīda while agreeing on its foundational principles. |

イスラム教 イスラム教の文脈において、教義は「عقيدة(ʿAqīda)」と訳すのが最も適切です。 ʿAqīda は、アッラー、預言者、来世、その他の重要な教義に対する信仰など、イスラム教の信仰の核心となる教義を指します。これはイスラム神学の基本的な側面であ り、異なるイスラム教派(アシュアリー派、マトゥリーディ派、サラフィー派など)は、その基本原則については一致していますが、ʿAqīda の解釈はさまざまです。 |

| Axiom – Statement that is taken to be true Central dogma of molecular biology – Explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system Doctrine#Religious usage – Codification of beliefs Dogmatic theology – Theology of theoretical official truths Escalation of commitment – A human behavior pattern in which the participant takes on increasingly greater risk Faith – Confidence or trust, often characterized as without evidence Pseudoskepticism – Position that appears to be skeptic but is actually dogmatic Standard social science model – Alleged model of social science thought |

公理 – 真であるとみなされる命題 分子生物学の中心的教義 – 生物系における遺伝情報の流れの説明 教義#宗教的用法 – 信仰の体系化 教義神学 – 理論的な公式の真理に関する神学 コミットメントのエスカレーション – 参加者がますます大きなリスクを負うようになる人間の行動パターン 信仰 – 証拠がないにもかかわらず、確信や信頼を持つこと 疑似懐疑主義 – 懐疑的であるように見えるが、実際には教条的な立場 標準的社会科学モデル – 社会科学の思考のモデルとされるもの |

| Bibliography Blackburn, Simon (2016). "Dogma". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873530-4. Fuller, Paul (2005). The Notion of Diṭṭhi in Theravāda Buddhism: The Point of View (PDF). Routledge. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. McKim, D.K. (2001). "Dogma". In Elwell, Walter A. (ed.). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2075-9. O'Collins, Gerald (1983). "Dogma". In Richardson, Alan; Bowden, John (eds.). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22748-7. Stanglin, K.D. (2009). "Dogma". In Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.). Global Dictionary of Theology: A Resource for the Worldwide Church. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-7811-6. |

参考文献 ブラックバーン、サイモン (2016). 「ドグマ」. オックスフォード哲学辞典. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-873530-4. フラー、ポール (2005). 上座部仏教におけるディッティの概念:視点 (PDF). ルーテル. 2015年2月26日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。 マッキム、D.K. (2001). 「教義」 『福音主義神学辞典』 ウォルター・A・エルウェル編。ベイカー・アカデミック。ISBN 978-0-8010-2075-9。 オコリンズ、ジェラルド(1983)。「教義」。リチャードソン、アラン;ボウデン、ジョン(編)。『ウェストミンスターキリスト教神学辞典』。ウェストミンスター・ジョン・ノックス・プレス。ISBN 978-0-664-22748-7。 スタンギン、K.D.(2009)。「教義」。ディルネス、ウィリアム・A.、カールカイネン、ヴェリ・マッティ(編)。『世界神学辞典:世界教会向けリソース』。インターバーシティ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-8308-7811-6。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dogma |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099