懐疑主義

かいぎろん、懐疑論、 skepticism

☆ 「懐疑主義(かいぎしゅぎ、英語: skepticism)とは、基本的原理・認識に対して、その普遍妥当性、客観性ないし蓋然性を吟味し、根拠のないあらゆるドクサ(独断)を排除しようと する主義である。懐疑論(かいぎろん)とも呼ばれる」ウィキペディア日本語)。その反対語は「独断論・独断主義(Dogmatismus)」で「絶対的な 明証性をもつとされる基本的原理(ドグマ)を根底におき、そこから世界の構造を明らかにしようとする立場」である。(「哲学的懐疑主義」「ピュロニズムあるいはフュロン主義」は別稿で説明する)

以下では、★0)懐疑主義概説、★1)ヒュームの「連想の原理」、★2)哲学的懐疑主義、★3)セクストゥス・エンピリコス、★4)ピュロニズムあるいはフュロン主義、の順で説明する。そのうち、★2)と★4)は別項でも同様の説明をしている。

★ 英語のウィキペディア:0)懐疑主義概説

| Skepticism, also spelled scepticism in British English, is an attitude of doubt or suspicion toward claims of knowledge that are considered mere beliefs or doctrines. For example, a person who is skeptical of a government's claims about an ongoing war is doubting whether the claims are accurate. In such cases, skeptics usually recommend not disbelief but suspension of belief, i.e., maintaining a neutral attitude that neither confirms nor denies the claim. This attitude is often motivated by the impression that the available evidence is insufficient to support the claim. Formally, skepticism is a topic of interest in philosophy, especially epistemology. More informally, skepticism as an expression of doubt or suspicion can be applied to any topic, including politics, religion, and pseudoscience. It is often applied in limited areas such as morality (moral skepticism), atheism (skepticism about the existence of God), and the supernatural. Some theorists distinguish between “good” or moderate skepticism, which requires strong evidence before accepting a position, and “bad” or radical skepticism, which prefers to suspend judgment indefinitely. Philosophical skepticism is one important form of skepticism. Philosophical skepticism is one of the important forms of skepticism, denying knowledge claims that seem certain from the standpoint of common sense. The radical form of philosophical skepticism denies that “knowledge or rational belief is possible” and urges us to suspend judgment on many or all controversial matters. The more moderate form simply asserts that nothing is known with certainty, or that little or nothing is known about non-empirical matters, such as whether God exists, whether humans have free will, or whether there is an afterlife. In ancient philosophy, skepticism was understood as a way of life associated with inner peace. Skepticism has contributed to many important developments in science and philosophy. It has also influenced contemporary social movements. Religious skepticism advocates doubting basic religious principles such as immortality, providence, and revelation. Scientific skepticism advocates testing the reliability of beliefs by conducting systematic investigations using the scientific method and discovering empirical evidence. | 懐疑主義とは、イギリス英語ではscepticismとも表記され、単なる信念や教義とみなされる知識の主張に対する疑問の態度や疑念のことである。例えば、現在進行中の戦争に関する政府の主張に対して懐疑的な人は、その主張が正確であるかどうかを疑っていることになる。このような場合、懐疑論者は通常、不信ではなく信念の一時停止、つまり主張を肯定も否定もしない中立的な態度を保つことを推奨する。このような態度は多くの場合、入手可能な証拠がその主張を裏付けるには不十分であるという印象に突き動かされている。 形式的には、懐疑論は哲学、特に認識論において関心のあるテーマである。より非公式には、疑問や疑念の表現としての懐疑主義は、政治、宗教、疑似科学な ど、あらゆるトピックに適用できる。道徳(道徳的懐疑主義)、無神論(神の存在に対する懐疑主義)、超自然的なものなど、限定された領域で適用されること が多い。ある立場を受け入れる前に強力な証拠を求める「良い」懐疑主義や穏健な懐疑主義と、判断を無期限に保留したがる「悪い」懐疑主義や急進的な懐疑主義を区別する理論家もいる。 哲学的懐疑主義は懐疑主義の重要な形態の一つである。哲学的懐疑主義は、懐疑主義の重要な形態の一つであり、常識的な見地から確実と思われる知識の主張を 否定する。哲学的懐疑論の急進的な形態は、「知識や理性的な信念が可能である」ことを否定し、論争の的となる事柄の多くまたはすべてについて判断を保留す るよう促す。より穏健な形では、確実なことは何もわからない、あるいは、神が存在するかどうか、人間に自由意志があるかどうか、死後の世界があるかどうか など、経験的でない事柄についてはほとんど何もわからないと主張するだけである。古代の哲学では、懐疑主義は内なる平和と結びついた生き方として理解されていた。 懐疑主義は、科学や哲学における多くの重要な発展に寄与してきた。また、現代の社会運動にも影響を与えた。宗教的懐疑主義は、不死、摂理、啓示といった基本的な宗教的原理を疑うことを提唱している。科学的懐疑主義は、科学的方法を用いた体系的な調査を行い、経験的証拠を発見することによって、信念の信頼性を検証することを提唱している。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skepticism |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★1)ヒュームの「連想の原理」(→「ディヴィッド・ヒューム」)

David Hume's

Principles of association Regardless of how boundless it may seem, a person's imagination is confined to the mind's ability to recombine the information it has already acquired from the body's sensory experience (the ideas that have been derived from impressions). In addition, "as our imagination takes our most basic ideas and leads us to form new ones, it is directed by three principles of association, namely, resemblance, contiguity, and cause and effect":[74] The principle of resemblance refers to the tendency of ideas to become associated if the objects they represent resemble one another. For example, someone looking at an illustration of a flower can conceive an idea of the physical flower because the idea of the illustrated object is associated with the physical object's idea. The principle of contiguity describes the tendency of ideas to become associated if the objects they represent are near to each other in time or space, such as when the thought of a crayon in a box leads one to think of the crayon contiguous to it. The principle of cause and effect refers to the tendency of ideas to become associated if the objects they represent are causally related, which explains how remembering a broken window can make someone think of a ball that had caused the window to shatter. Hume elaborates more on the last principle, explaining that, when somebody observes that one object or event consistently produces the same object or event, that results in "an expectation that a particular event (a 'cause') will be followed by another event (an 'effect') previously and constantly associated with it".[75] Hume calls this principle custom, or habit, saying that "custom...renders our experience useful to us, and makes us expect, for the future, a similar train of events with those which have appeared in the past".[31] However, even though custom can serve as a guide in life, it still only represents an expectation. In other words:[76] Experience cannot establish a necessary connection between cause and effect, because we can imagine without contradiction a case where the cause does not produce its usual effect…the reason why we mistakenly infer that there is something in the cause that necessarily produces its effect is because our past experiences have habituated us to think in this way. Continuing this idea, Hume argues that "only in the pure realm of ideas, logic, and mathematics, not contingent on the direct sense awareness of reality, [can] causation safely…be applied—all other sciences are reduced to probability".[77][31] He uses this scepticism to reject metaphysics and many theological views on the basis that they are not grounded in fact and observations, and are therefore beyond the reach of human understanding. Induction and causation The cornerstone of Hume's epistemology is the problem of induction. This may be the area of Hume's thought where his scepticism about human powers of reason is most pronounced.[78] The problem revolves around the plausibility of inductive reasoning, that is, reasoning from the observed behaviour of objects to their behaviour when unobserved. As Hume wrote, induction concerns how things behave when they go "beyond the present testimony of the senses, or the records of our memory".[79] Hume argues that we tend to believe that things behave in a regular manner, meaning that patterns in the behaviour of objects seem to persist into the future, and throughout the unobserved present.[80] Hume's argument is that we cannot rationally justify the claim that nature will continue to be uniform, as justification comes in only two varieties—demonstrative reasoning and probable reasoning[iii]—and both of these are inadequate. With regard to demonstrative reasoning, Hume argues that the uniformity principle cannot be demonstrated, as it is "consistent and conceivable" that nature might stop being regular.[81] Turning to probable reasoning, Hume argues that we cannot hold that nature will continue to be uniform because it has been in the past. As this is using the very sort of reasoning (induction) that is under question, it would be circular reasoning.[82] Thus, no form of justification will rationally warrant our inductive inferences. Hume's solution to this problem is to argue that, rather than reason, natural instinct explains the human practice of making inductive inferences. He asserts that "Nature, by an absolute and uncontroulable [sic] necessity has determin'd us to judge as well as to breathe and feel." In 1985, and in agreement with Hume, John D. Kenyon writes:[83] Reason might manage to raise a doubt about the truth of a conclusion of natural inductive inference just for a moment ... but the sheer agreeableness of animal faith will protect us from excessive caution and sterile suspension of belief. Others, such as Charles Sanders Peirce, have demurred from Hume's solution,[84] while some, such as Kant and Karl Popper, have thought that Hume's analysis has "posed a most fundamental challenge to all human knowledge claims".[85] The notion of causation is closely linked to the problem of induction. According to Hume, we reason inductively by associating constantly conjoined events. It is the mental act of association that is the basis of our concept of causation. At least three interpretations of Hume's theory of causation are represented in the literature:[86] the logical positivist; the sceptical realist; and the quasi-realist. Hume acknowledged that there are events constantly unfolding, and humanity cannot guarantee that these events are caused by prior events or are independent instances. He opposed the widely accepted theory of causation that 'all events have a specific course or reason'. Therefore, Hume crafted his own theory of causation, formed through his empiricist and sceptic beliefs. He split causation into two realms: "All the objects of human reason or enquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds, to wit, Relations of Ideas, and Matters of Fact."[31] Relations of Ideas are a priori and represent universal bonds between ideas that mark the cornerstones of human thought. Matters of Fact are dependent on the observer and experience. They are often not universally held to be true among multiple persons. Hume was an Empiricist, meaning he believed "causes and effects are discoverable not by reason, but by experience".[31] He goes on to say that, even with the perspective of the past, humanity cannot dictate future events because thoughts of the past are limited, compared to the possibilities for the future. Hume's separation between Matters of Fact and Relations of Ideas is often referred to as "Hume's fork."[1] |

★1)ヒュームの「連想の原理」(→「ディヴィッド・ヒューム」) 人の想像力は、いかに無限に見えるとしても、すでに身体の感覚から得た情報(印象から派生したアイデア)を再び組み合わせるという心の働きに限定される。 また、「想像力は、最も基本的な考えを取り出して新しい考えを形成するように導くとき、類似性、連続性、原因と結果という3つの連合の原理によって方向づ けられる」:[74]。 類似性の原理とは、表象する対象が互いに類似している場合に、観念が関連付けられるようになる傾向を指す。例えば、花のイラストを見ている人は、イラスト のオブジェクトのアイデアが物理的なオブジェクトのアイデアと関連付けられているため、物理的な花のアイデアを思い浮かべることができる。 連続性の原理とは、箱の中のクレヨンを考えると、それに隣接するクレヨンを考えるように、時間的・空間的に表象する対象が近接している場合、観念が関連付 けられる傾向を示すものである。 因果の原理とは、観念が表す対象が因果関係にある場合、観念は関連付けられる傾向があるというもので、割れた窓を思い出すと、窓を割る原因となったボール を思い浮かべることができることを説明している。 ヒュームは最後の原理をさらに詳しく説明し、ある物体や出来事が一貫して同じ物体や出来事を生み出すことを誰かが観察するとき、それは「ある特定の出来事 (『原因』)が、それに以前から絶えず関連している別の出来事(『結果』)に続くだろうという期待」に帰結すると説明する。 [75] ヒュームはこの原理を慣習(習慣)と呼び、「慣習は...我々の経験を我々にとって有益なものにし、過去に現れたものと同様の出来事の流れを将来に向けて 期待させる」[31]と言っている。 しかし、慣習が人生における指針として機能することができるとしても、それは依然として期待を表すに過ぎない。言い換えれば、[76]。 経験によって原因と結果の間の必要な関係を確立することはできない。なぜなら、原因がその通常の結果を生じない場合を矛盾なく想像することができるからで ある...我々が原因の中に必ずその結果を生じさせる何かがあると誤って推論するのは、過去の経験がこのように考えるように我々を習慣化させたからであ る」。 この考えを続けて、ヒュームは「現実の直接的な感覚的認識に左右されない純粋な思想、論理、数学の領域においてのみ、因果関係を安全に...適用すること ができる-他のすべての科学は確率に還元される」と論じている[77][31] 彼はこの懐疑論を使って、事実と観察に基づかないために人間の理解の範囲を超えるものとして形而上学と多くの神学的見解を否定している。 帰納と因果関係 ヒュームの認識論の礎は帰納の問題である。これはヒュームの思想の中で、人間の理性的な力に対する彼の懐疑が最も顕著に現れている領域かもしれない [78]。この問題は帰納的推論、つまり観察された物の振る舞いから観察されていない時の振る舞いへの推論の妥当性をめぐって展開される。ヒュームが書い たように、帰納は「感覚の現在の証言や記憶の記録を超えた」ときに物事がどのように振る舞うかに関係している[79]。ヒュームは、物事の振る舞いのパ ターンが未来にも、観察されていない現在にも持続するように見えることを意味し、私たちが規則正しく振る舞うことを信じる傾向があると論じている。 ヒュームの主張は、自然が均一であり続けるという主張を合理的に正当化することはできないということであり、正当化には実証的推論と確率的推論 [iii]という二つの種類しかなく、これらは両方とも不適切であるとしている。実証的推論に関してヒュームは、自然が規則的でなくなる可能性は「一貫性 があり考えられる」ので、一様性原理は実証できないと主張する[81]。これはまさに問題になっている推論(帰納)を用いているので、循環的な推論になっ てしまう[82]。したがって、どのような正当化も我々の帰納的推論を合理的に保証することはできない。 この問題に対するヒュームの解決策は、理性よりもむしろ自然の本能が人間が帰納的推論を行うことを説明すると主張することである。彼は、「自然は、絶対的 で制御不能な(中略)必然性によって、呼吸や感情と同様に判断するよう我々に命じている」と主張している。1985年、ヒュームと同意見であるジョン・ D・ケニヨンは次のように書いている[83]。 理性は自然な帰納推論の結論の真偽について一瞬でも疑念を生じさせることができるかもしれない......しかし、動物の信仰が持つ極めて同意しやすい性 質は、過度の警戒や不毛な信仰の停止から我々を守ってくれるだろう」。 チャールズ・サンダース・パースのような他の人々はヒュームの解決策に難色を示しており[84]、カントやカール・ポパーのような人々はヒュームの分析が 「すべての人間の知識の主張に対して最も根本的な挑戦を突きつけている」と考えている[85]。 因果関係の概念は帰納の問題と密接に関連している。ヒュームによれば、我々は常に結合された事象を関連付けることによって帰納的に推論する。それは因果関 係の概念の基礎となる連想の精神的行為である。ヒュームの因果論に対する文献上の解釈は少なくとも以下の3つである[86]。 論理実証主義者 懐疑的実在論者、および 準実現主義者である。 ヒュームは、絶えず展開する事象があり、人類はこれらの事象が先行する事象によって引き起こされたものであることや独立した事例であることを保証すること ができないことを認めていた。そして、「すべての出来事には特定の経過や理由がある」という、広く受け入れられている因果論に反対した。そこでヒューム は、経験主義と懐疑主義の信念から、独自の因果論を構築した。彼は因果関係を2つの領域に分けた。「人間の理性や探求の対象はすべて、当然ながら観念の関 係と事実の問題の2種類に分けられる」[31]。観念の関係は先験的であり、人間の思考の礎となる観念間の普遍的な結びつきを表している。事実の問題は、 観察者と経験に依存するものである。それらはしばしば複数の人物の間で普遍的に真であるとされるものではない。ヒュームは経験主義者であり、「原因と結果 は理性によってではなく、経験によって発見できる」と考えていた[31]。 彼はさらに、過去の視点を持ってしても、未来の可能性に比べて過去の思考は限られているため、人類は未来の出来事を指示することができないと述べている。 ヒュームの「事実の事柄」と「思考の関係」の分離は、しばしば「ヒュームのフォーク」と呼ばれる[1]。 |

| Philosophical

skepticism (UK spelling: scepticism; from Greek σκέψις skepsis,

"inquiry") is a family of philosophical views that question the

possibility of knowledge.[1][2] It differs from other forms of

skepticism in that it even rejects very plausible knowledge claims that

belong to basic common sense. Philosophical skeptics are often

classified into two general categories: Those who deny all possibility

of knowledge, and those who advocate for the suspension of judgment due

to the inadequacy of evidence.[3] This distinction is modeled after the

differences between the Academic skeptics and the Pyrrhonian skeptics

in ancient Greek philosophy. In the latter sense, skepticism is

understood as a way of life that helps the practitioner achieve inner

peace. Some types of philosophical skepticism reject all forms of

knowledge while others limit this rejection to certain fields, for

example, to knowledge about moral doctrines or about the external

world. Some theorists criticize philosophical skepticism based on the

claim that it is a self-refuting idea since its proponents seem to

claim to know that there is no knowledge. Other objections focus on its

implausibility and distance from regular life. Philosophical skepticism is a doubtful attitude toward commonly accepted knowledge claims. It is an important form of skepticism. Skepticism in general is a questioning attitude toward all kinds of knowledge claims. In this wide sense, it is quite common in everyday life: many people are ordinary skeptics about parapsychology or about astrology because they doubt the claims made by proponents of these fields.[4] But the same people are not skeptical about other knowledge claims like the ones found in regular school books. Philosophical skepticism differs from ordinary skepticism in that it even rejects knowledge claims that belong to basic common sense and seem to be very certain.[4] For this reason, it is sometimes referred to as radical doubt.[5] In some cases, it is even proclaimed that one does not know that "I have two hands" or that "the sun will come out tomorrow".[6][7] In this regard, philosophical skepticism is not a position commonly adopted by regular people in everyday life.[8][9] This denial of knowledge is usually associated with the demand that one should suspend one's beliefs about the doubted proposition. This means that one should neither believe nor disbelieve it but keep an open mind without committing oneself one way or the other.[10] Philosophical skepticism is often based on the idea that no matter how certain one is about a given belief, one could still be wrong about it.[11][7] From this observation, it is argued that the belief does not amount to knowledge. Philosophical skepticism follows from the consideration that this might be the case for most or all beliefs.[12] Because of its wide-ranging consequences, it is of central interest to theories of knowledge since it questions their very foundations.[10] According to some definitions, philosophical skepticism is not just the rejection of some forms of commonly accepted knowledge but the rejection of all forms of knowledge.[4][10][13] In this regard, we may have relatively secure beliefs in some cases but these beliefs never amount to knowledge. Weaker forms of philosophical skepticism restrict this rejection to specific fields, like the external world or moral doctrines. In some cases, knowledge per se is not rejected but it is still denied that one can ever be absolutely certain.[9][14] There are only few defenders of philosophical skepticism in the strong sense.[4] In this regard, it is much more commonly used as a theoretical tool to test theories.[5][4][12][15] On this view, it is a philosophical methodology that can be utilized to probe a theory to find its weak points, either to expose it or to modify it in order to arrive at a better version of it.[5] However, some theorists distinguish philosophical skepticism from methodological skepticism in that philosophical skepticism is an approach that questions the possibility of certainty in knowledge, whereas methodological skepticism is an approach that subjects all knowledge claims to scrutiny with the goal of sorting out true from false claims.[citation needed] Similarly, scientific skepticism differs from philosophical skepticism in that scientific skepticism is an epistemological position in which one questions the veracity of claims lacking empirical evidence. In practice, the term most commonly references the examination of claims and theories that appear to be pseudoscience, rather than the routine discussions and challenges among scientists.[16] In ancient philosophy, skepticism was seen not just as a theory about the existence of knowledge but as a way of life. This outlook is motivated by the idea that suspending one's judgment on all kinds of issues brings with it inner peace and thereby contributes to the skeptic's happiness.[14][17][18] |

哲学的懐疑主義(てつがくてきかいぎろん、英:

scepticism、ギリシャ語: σκέψις

skepsis、「探究」に由来)は、知識の可能性に疑問を呈する哲学的見解の一群である[1][2]。

基本的な常識に属する非常にもっともらしい知識の主張さえも否定するという点で、他の形態の懐疑論とは異なる。哲学的懐疑論者はしばしば2つの一般的なカ

テゴリーに分類される:

知識の可能性をすべて否定する人々と、証拠の不十分さによる判断の停止を主張する人々である。この区別は、古代ギリシャ哲学におけるアカデミック懐疑論者

とピュロニア懐疑論者の違いに倣ったものである[3]。後者の意味では、懐疑主義は、実践者が内なる平和を達成するのに役立つ生き方として理解されてい

る。哲学的懐疑主義には、あらゆる形式の知識を否定するものもあれば、この否定を特定の分野、例えば道徳的教義や外界に関する知識に限定するものもある。

哲学的懐疑主義を批判する理論家の中には、哲学的懐疑主義の支持者は知識がないことを知っていると主張しているように見えるため、哲学的懐疑主義は自己反

駁的な考えであるという主張に基づいている者もいる。他の反論は、その非現実性と日常生活からの距離に焦点を当てている。 哲学的懐疑主義とは、一般に受け入れられている知識の主張に対して疑念 を抱く態度のことである。懐疑主義の重要な一形態である。一般に懐疑主義とは、あらゆる知識の主張に対して疑問を呈する態度のことである。超心理学や占星 術については、多くの人がこれらの分野の支持者による主張を疑っているため、普通の懐疑主義者である。哲学的懐疑主義が普通の懐疑主義とは異なるのは、基 本的な常識に属し、非常に確かであると思われる知識の主張さえも拒絶するという点である。このため、それは時に急進的な疑念と呼ばれる。 [6][7]この点で、哲学的懐疑論は日常生活において一般的な人々が採用する立場ではない。 この知識の否定は通常、疑われる命題についての信念を一時停止すべきだという要求と関連している。哲学的懐疑論は、与えられた信念についてどれだけ確信が あ っても、それについて間違っている可能性もあるという考えに基づいてい ることが多い[11][7] 。哲学的懐疑論は、ほとんどの、あるいはすべての信念につい てそうであるかもしれないという考察から生まれたものである[12]。その広範な結 果から、懐疑論は知識理論の根幹を問うものであり、知識理論の中心的な関心事 となっている[10]。 ある定義によれば、哲学的懐疑主義とは、一般的に受け入れられている知識の ある形式を否定するだけではなく、あらゆる形式の知識を否定することであ る[4][10][13]。この点において、私たちは場合によっては比較的確実な信念を持 つかもしれないが、それらの信念は決して知識にはならない。哲学的懐疑論の弱い形態は、この拒絶を外界や道徳的教義のような特定の分野に限定している。場 合によっては、知識それ自体は否定されないが、それでも人が絶対的に確信できることは否定される[9][14]。 この観点から、懐疑論は理論を検証するための理論的ツールとしてより一般的に使用されている[5][4][12][15] 。 [しかし、哲学的懐疑主義と方法論的懐疑主義を区別する理論家もおり、哲学的懐疑主義が知識における確実性の可能性を問うアプローチであるのに対して、方 法論的懐疑主義は、真の主張と虚偽の主張を選別する目的で、すべての知識の主張を精査にかけるアプローチである[要出典]。同様に、科学的懐疑主義は哲学 的懐疑主義とは異なり、科学的懐疑主義は経験的証拠を欠く主張の信憑性を問う認識論的立場である。実際には、この用語は、科学者間の日常的な議論や挑戦よ りも、疑似科学と思われる主張や理論の検証を指すことが最も一般的である[16]。 古代の哲学では、懐疑主義は知識の存在に関する理論としてだけでなく、生き方として捉えられていた。このような考え方は、あらゆる問題に対する判断を保留 することが内なる平和をもたらし、それによって懐疑主義者の幸福に貢献するという考え方に動機づけられている[14][17][18]。 |

| Classification Skepticism can be classified according to its scope. Local skepticism involves being skeptical about particular areas of knowledge (e.g. moral skepticism, skepticism about the external world, or skepticism about other minds), whereas radical skepticism claims that one cannot know anything—including that one cannot know about knowing anything. Skepticism can also be classified according to its method. Western philosophy has two basic approaches to skepticism.[19] Cartesian skepticism—named somewhat misleadingly after René Descartes, who was not a skeptic but used some traditional skeptical arguments in his Meditations to help establish his rationalist approach to knowledge—attempts to show that any proposed knowledge claim can be doubted. Agrippan skepticism focuses on justification rather than the possibility of doubt. According to this view, none of the ways in which one might attempt to justify a claim are adequate. One can justify a claim based on other claims, but this leads to an infinite regress of justifications. One can use a dogmatic assertion, but this is not a justification. One can use circular reasoning, but this fails to justify the conclusion. Skeptical scenarios A skeptical scenario is a hypothetical situation which can be used in an argument for skepticism about a particular claim or class of claims. Usually the scenario posits the existence of a deceptive power that deceives our senses and undermines the justification of knowledge otherwise accepted as justified, and is proposed in order to call into question our ordinary claims to knowledge on the grounds that we cannot exclude the possibility of skeptical scenarios being true. Skeptical scenarios have received a great deal of attention in modern Western philosophy. The first major skeptical scenario in modern Western philosophy appears in René Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy. At the end of the first Meditation Descartes writes: "I will suppose... that some evil demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies to deceive me." The "evil demon problem", also known as "Descartes' evil demon", was first proposed by René Descartes. It invokes the possibility of a being who could deliberately mislead one into falsely believing everything that you take to be true. The "brain in a vat" hypothesis is cast in contemporary scientific terms. It supposes that one might be a disembodied brain kept alive in a vat and fed false sensory signals by a mad scientist. Further, it asserts that since a brain in a vat would have no way of knowing that it was a brain in a vat, you cannot prove that you are not a brain in a vat. The "dream argument", proposed by both René Descartes and Zhuangzi, supposes reality to be indistinguishable from a dream. The "five minute hypothesis", most notably proposed by Bertrand Russell, suggests that we cannot prove that the world was not created five minutes ago (along with false memories and false evidence suggesting that it was not only five minutes old). The "simulated reality hypothesis" or "Matrix hypothesis" suggests that everyone, or even the entire universe, might be inside a computer simulation or virtual reality. The "Solipsistic" theory that claims that knowledge of the world is an illusion of the Self. Epistemological skepticism Skepticism, as an epistemological view, calls into question whether knowledge is possible at all. This is distinct from other known skeptical practices, including Cartesian skepticism, as it targets knowledge in general instead of individual types of knowledge. Skeptics argue that belief in something does not justify an assertion of knowledge of it. In this, skeptics oppose foundationalism, which states that there are basic positions that are self-justified or beyond justification, without reference to others. (One example of such foundationalism may be found in Spinoza's Ethics.) The skeptical response to this can take several approaches. First, claiming that "basic positions" must exist amounts to the logical fallacy of argument from ignorance combined with the slippery slope.[citation needed] Among other arguments, skeptics use the Münchhausen trilemma and the problem of the criterion to claim that no certain belief can be achieved. This position is known as "global skepticism" or "radical skepticism." Foundationalists have used the same trilemma as a justification for demanding the validity of basic beliefs.[citation needed] Epistemological nihilism rejects the possibility of human knowledge, but not necessarily knowledge in general. There are two different categories of epistemological skepticism, which can be referred to as mitigated and unmitigated skepticism. The two forms are contrasting but are still true forms of skepticism. Mitigated skepticism does not accept "strong" or "strict" knowledge claims but does, however, approve specific weaker ones. These weaker claims can be assigned the title of "virtual knowledge", but must be to justified belief. Some mitigated skeptics are also fallibilists, arguing that knowledge does not require certainty. Mitigated skeptics hold that knowledge does not require certainty and that many beliefs are, in practice, certain to the point that they can be safely acted upon in order to live significant and meaningful lives. Unmitigated skepticism rejects both claims of virtual knowledge and strong knowledge.[20] Characterising knowledge as strong, weak, virtual or genuine can be determined differently depending on a person's viewpoint as well as their characterisation of knowledge. Unmitigated skeptics believe that objective truths are unknowable and that man should live in an isolated environment in order to win mental peace. This is because everything, according to them, is changing and relative. The refusal to make judgments is of uttermost importance since there is no knowledge; only probable opinions.[20] Criticism Philosophical skepticism has been criticized in various ways. Some criticisms see it as a self-refuting idea while others point out that it is implausible, psychologically impossible, or a pointless intellectual game. One of the strongest criticisms claims that philosophical skepticism is contradictory or self-refuting. This position is based on the idea that it not only rejects the existence of knowledge but seems to make knowledge claims itself at the same time.[9][21][22] For example, to claim that there is no knowledge seems to be itself a knowledge claim. This problem is particularly relevant for versions of philosophical skepticism that deny any form of knowledge. So the global skeptic denies that any claim is rationally justified but then goes on to provide arguments in an attempt to rationally justify their denial.[21] Some philosophical skeptics have responded to this objection by restricting the denial of knowledge to certain fields without denying the existence of knowledge in general. Another defense consists in understanding philosophical skepticism not as a theory but as a tool or a methodology. In this case, it may be used fruitfully to reject and improve philosophical systems despite its shortcomings as a theory.[9][15] Another criticism holds that philosophical skepticism is highly counterintuitive by pointing out how far removed it is from regular life.[8][9] For example, it seems very impractical, if not psychologically impossible, to suspend all beliefs at the same time. And even if it was possible, it would not be advisable since "the complete skeptic would wind up starving to death or walking into walls or out of windows".[9] This criticism can allow that there are some arguments that support philosophical skepticism. However, it has been claimed that they are not nearly strong enough to support such a radical conclusion.[8] Common-sense philosophers follow this line of thought by arguing that regular common-sense beliefs are much more reliable than the skeptics' intricate arguments.[8] George Edward Moore, for example, tried to refute skepticism about the existence of the external world, not by engaging with its complex arguments, but by using a simple observation: that he has two hands. For Moore, this observation is a reliable source of knowledge incompatible with external world skepticism since it entails that at least two physical objects exist.[23][8] A closely related objection sees philosophical skepticism as an "idle academic exercise" or a "waste of time".[10] This is often based on the idea that, because of its initial implausibility and distance from everyday life, it has little or no practical value.[9][15] In this regard, Arthur Schopenhauer compares the position of radical skepticism to a border fortress that is best ignored: it is impregnable but its garrison does not pose any threat since it never sets foot outside the fortress.[24] One defense of philosophical skepticism is that it has had important impacts on the history of philosophy at large and not just among skeptical philosophers. This is due to its critical attitude, which remains a constant challenge to the epistemic foundations of various philosophical theories. It has often provoked creative responses from other philosophers when trying to modify the affected theory to avoid the problem of skepticism.[9][14] According to Pierre Le Morvan, there are two very common negative responses to philosophical skepticism. The first understands it as a threat to all kinds of philosophical theories and strives to disprove it. According to the second, philosophical skepticism is a useless distraction and should better be avoided altogether. Le Morvan himself proposes a positive third alternative: to use it as a philosophical tool in a few selected cases to overcome prejudices and foster practical wisdom.[15] |

分類 懐疑主義はその範囲によって分類することができる。局所的懐疑主義では、知識の特定の領域(例えば、道徳的懐疑主義、外界に対する懐疑主義、他の心に対す る懐疑主義)に対して懐疑的であるのに対し、急進的懐疑主義では、人は何も知ることができないと主張する。 懐疑主義はまた、その方法によっても分類できる。ルネ・デカルトは懐疑論者ではなかったが、彼の『瞑想録』において、知識に対する合理主義的アプローチを 確立するために伝統的な懐疑論的議論を用いていた。アグリッパンの懐疑主義は、疑いの可能性よりもむしろ正当性に焦点を当てる。この考え方によれば、ある 主張を正当化しようとする方法はどれも適切ではない。他の主張に基づいて主張を正当化することはできるが、これは正当化の無限後退につながる。独断的な主 張を使うこともできるが、これは正当化ではない。循環推論を使うことはできるが、これは結論を正当化できない。 懐疑的シナリオ 懐疑的なシナリオとは、特定の主張または主張のクラスについて懐疑的であることを主張する際に使用できる仮定の状況である。通常、このシナリオは、私たち の感覚を欺き、正当なものとして受け入れられている知識の正当性を損なう欺瞞的な力の存在を仮定し、懐疑的なシナリオが真実である可能性を排除できないと いう理由で、知識に対する私たちの通常の主張に疑問を投げかけるために提案される。懐疑的なシナリオは、近代西洋哲学において多くの注目を集めてきた。 近代西洋哲学における最初の主要な懐疑的シナリオは、ルネ・デカルトの『第一哲学の瞑想』に登場する。デカルトは最初の「瞑想」の最後で、「私は...最 大限の力と狡猾さを持つ邪悪な悪魔が、私を欺くために全力を尽くしたと仮定する」と書いている。 邪悪な悪魔の問題」は「デカルトの邪悪な悪魔」とも呼ばれ、ルネ・デカルトによって初めて提唱された。これは、自分が真実だと信じていることすべてを、意 図的に誤信させる可能性のある存在を呼び起こすものである。 桶の中の脳」仮説は、現代の科学用語で表現されている。マッドサイエンティストによって虚偽の感覚信号を与えられ、桶の中で生かされている実体のない脳で ある可能性を仮定しているのだ。さらに、桶の中の脳は自分が桶の中の脳であることを知る術を持たないので、自分が桶の中の脳でないことを証明することはで きないと主張する。 ルネ・デカルトと荘子によって提唱された「夢論」は、現実は夢と区別がつかないとするものである。 バートランド・ラッセルが提唱したことで知られる「5分仮説」は、世界が5分前に創造されたものではないことを証明できないことを示唆する(5分前ではな いことを示唆する虚偽の記憶や虚偽の証拠とともに)。 シミュレーテッド・リアリティ仮説」あるいは「マトリックス仮説」は、すべての人、あるいは宇宙全体がコンピューターのシミュレーションや仮想現実の中に ある可能性を示唆している。 世界の知識は自己の幻想であると主張する「独我論」。 認識論的懐疑主義 認識論的な見方としての懐疑論は、知識がまったく可能かどうかを問うものである。これは、デカルト的懐疑主義を含む他の既知の懐疑的実践とは異なり、個々 のタイプの知識ではなく、一般的な知識を対象としている。 懐疑論者は、何かを信じることは、それに関する知識の主張を正当化するものではないと主張する。この点で、懐疑論者は、他のものを参照することなく、自己 正当化される、あるいは正当化を超える基本的な立場があるとする基礎主義に反対する。(スピノザの『倫理学(エチカ)』にそのような基礎主義の一例が見られる)これ に対する懐疑論者の反応は、いくつかのアプローチをとることができる。第一に、「基本的立場」が存在しなければならないと主張することは、無知からの議論 と滑りやすい坂道を組み合わせた論理的誤謬に相当する[要出典]。 懐疑論者は他の主張の中でも、ミュンヒハウゼンのトリレンマと基準の問題を用 いて、確実な信念は達成できないと主張する。この立場は "グローバル懐疑主義 "または "急進的懐疑主義 "として知られている。基礎主義者は同じトリレンマを、基本的信念の妥当性を要求する正当な理由と して用いている[citation needed]。認識論的ニヒリズムは人間の知識の可能性を否定す るが、必ずしも知識一般を否定するわけではない。 認識論的懐疑主義には2つの異なるカテゴリーがあり、緩和された懐疑主義(mitigated skepticism)と緩和されていない懐疑主義(unmitigated skepticism)と呼ばれることがある。この2つの形態は対照的であるが、懐疑主義の真の形態であることに変わりはない。緩和された懐疑主義は、 「強い」あるいは「厳格な」知識の主張は認めないが、特定の弱い主張は認める。これらの弱い主張には「仮想知識」の称号を与えることができるが、正当化さ れた信念でなければならない。緩和された懐疑論者の中には、知識は確実性を必要としないと主張する誤謬主義者もいる。緩和された懐疑論者は、知識は確実性 を必要とせず、多くの信念は、重要で意 味のある人生を送るために、安全に行動することができる程度には、実際 に確実であると主張する。未消化の懐疑主義者は、バーチャルな知識も強い知識も否定する[20]。疑いなき懐疑主義者は、客観的な真理は知ることができ ず、人間は精神的な平穏を得るために隔離された環境で生きるべきだと信じている。彼らによれば、すべては変化するものであり、相対的なものだからだ。知識 は存在せず、あるのは可能性のある意見だけであるため、判断を下すことを拒否することが最も重要である[20]。 批判 哲学的懐疑論は様々な形で批判されてきた。ある批判は懐疑主義を自己反駁的な考えと見なし、またある批判は懐疑主義があり得ない、心理学的に不可能であ る、あるいは無意味な知的ゲームであると指摘する。最も強い批判のひとつは、哲学的懐疑論は矛盾している、あるいは自己反駁的であるというものである。こ の立場は、知識の存在を否定するだけでなく、同時に知識の主張自体も行っているように見えるという考えに基づいている[9][21][22]。例えば、知 識が存在しないと主張すること自体が知識の主張であるように見える。この問題は、あらゆる形の知識を否定する哲学的懐疑主義のバージョンに特に関連してい る。そのため、グローバル懐疑論者は、あらゆる主張が合理的に正当化されることを否定するが、その後、その否定を合理的に正当化しようとする論拠を提供す ることになる。もう一つの抗弁は、哲学的懐疑主義を理論としてではなく、道具や方法論として理解することである。この場合、理論としての欠点があるにもか かわらず、哲学体系を否定し改善するために有益に使用される可能性がある[9][15]。 もう一つの批判は、哲学的懐疑論が通常の生活からいかにかけ離れているかを指摘することで、哲学的懐疑論が非常に直観に反しているとするものである[8] [9]。例えば、すべての信念を同時に中断することは、心理学的に不可能ではないにしても、非常に非現実的であるように思われる。また、仮にそれが可能で あったとしても、「完全な懐疑主義者は餓死するか、壁にぶつかったり窓から出たりする羽目になる」ので、お勧めできないだろう[9]。この批判は、哲学的 懐疑主義を支持する議論があることを認めることができる。例えば、ジョージ・エドワード・ムーアは、外界の存在に関する懐疑論に対して、その複雑な議論に 関与するのではなく、「自分には両手がある」という単純な観察を用いて反論しようとした。ムーアにとってこの観察は、少なくとも2つの物理的物体が存在す ることを伴うので、外界懐疑主義とは相容れない信頼できる知識の源である[23][8]。 これと密接に関連する反論は、哲学的懐疑主義を「学問的な空論」あるいは「時間の無駄」であると見なしている[10]。 [この点に関して、アーサー・ショーペンハウアーは急進的懐疑主義の立場を、無視するのが最も良い国境の要塞に例えている。これは、様々な哲学理論の認識 論的基礎に対する絶え間ない挑戦であり続けるその批判的態度によるものである。懐疑論の問題を回避するために、影響を受けた理論を修正しようとする際に、 他の哲学者たちから創造的な反応を引き起こすこともしばしばあった[9][14]。 ピエール・ル・モルヴァンによれば、哲学的懐疑論に対する否定的な反応には2つある。一つ目は、懐疑論をあらゆる哲学理論に対する脅威として理解し、その 反証に努めることである。もうひとつは、哲学的懐疑論は無用な気晴らしであり、完全に避けるべきだというものである。ル・モルヴァン自身は積極的な第三の 選択肢を提唱している。それは、偏見を克服し実践的な知恵を育むために、少数の選ばれたケースにおいて哲学的な道具として懐疑主義を用いるというものであ る[15]。 |

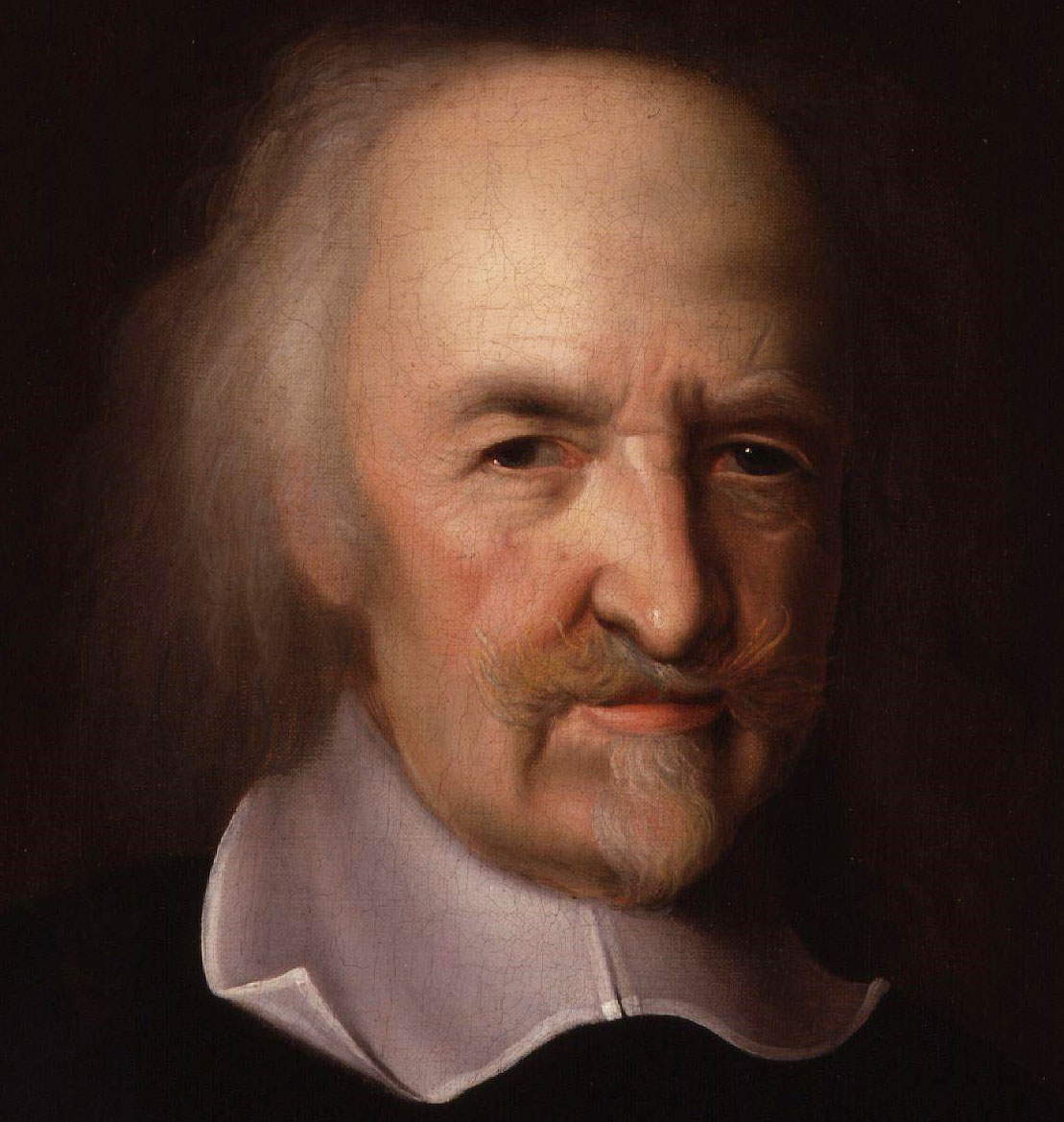

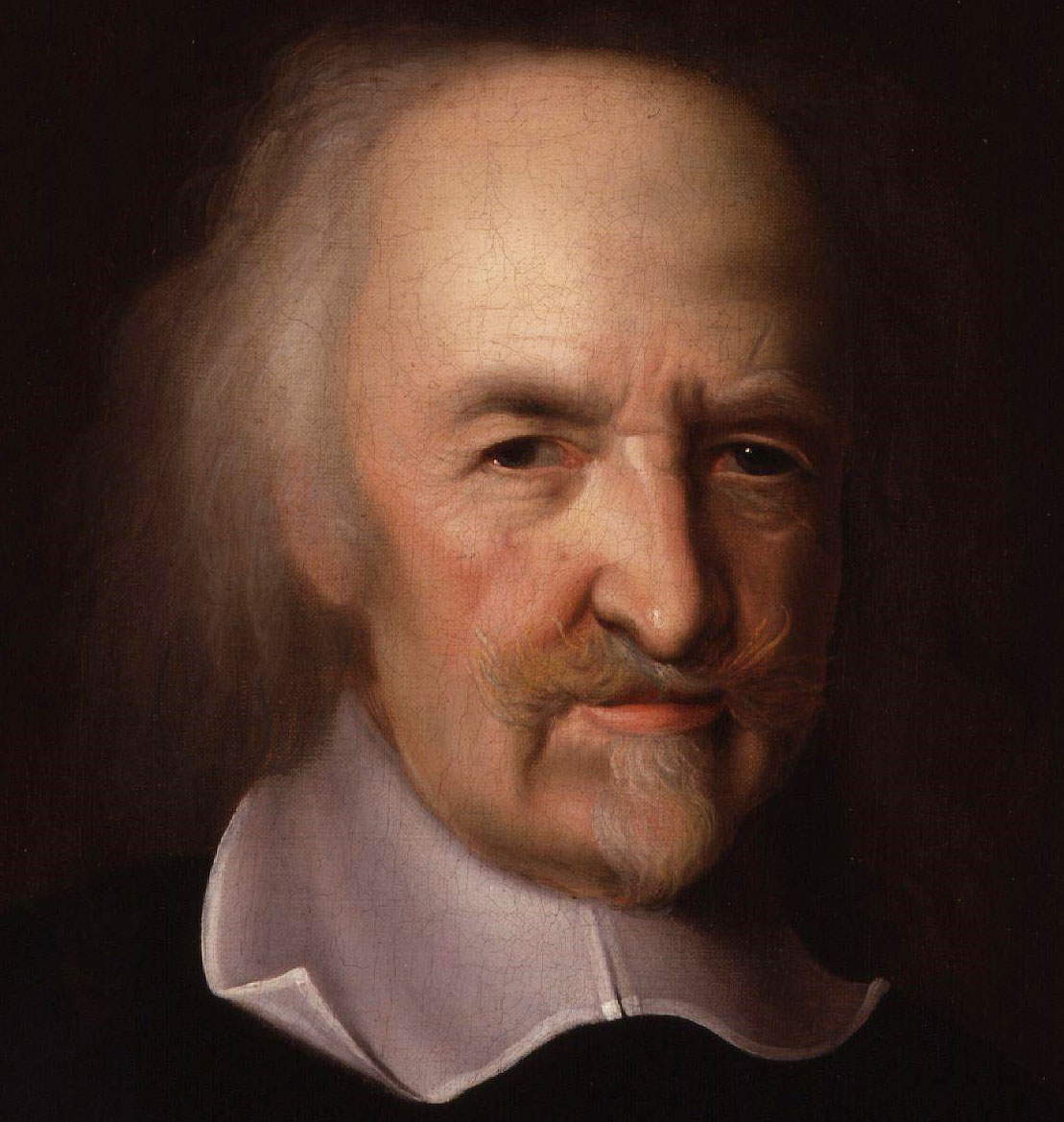

Skepticism in the seventeenth

century Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) During his long stay in Paris, Thomas Hobbes was actively involved in the circle of major skeptics like Gassendi and Mersenne who focus on the study of skepticism and epistemology. Unlike his fellow skeptic friends, Hobbes never treated skepticism as a main topic for discussion in his works. Nonetheless, Hobbes was still labeled as a religious skeptic by his contemporaries for raising doubts about Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch and his political and psychological explanation of the religions. Although Hobbes himself did not go further to challenge other religious principles, his suspicion for the Mosaic authorship did significant damage to the religious traditions and paved the way for later religious skeptics like Spinoza and Isaac La Peyrère to further question some of the fundamental beliefs of the Judeo-Christian religious system. Hobbes' answer to skepticism and epistemology was innovatively political: he believed that moral knowledge and religious knowledge were in their nature relative, and there was no absolute standard of truth governing them. As a result, it was out of political reasons that certain truth standards about religions and ethics were devised and established in order to form a functioning government and stable society.[3][42][43][44]  Baruch Spinoza and religious skepticism Baruch Spinoza was among the first European philosophers who were religious skeptics. He was quite familiar with the philosophy of Descartes and unprecedentedly extended the application of the Cartesian method to the religious context by analyzing religious texts with it. Spinoza sought to dispute the knowledge-claims of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic religious system by examining its two foundations: the Scripture and the Miracles. He claimed that all Cartesian knowledge, or the rational knowledge should be accessible to the entire population. Therefore, the Scriptures, aside from those by Jesus, should not be considered the secret knowledge attained from God but just the imagination of the prophets. The Scriptures, as a result of this claim, could not serve as a base for knowledge and were reduced to simple ancient historical texts. Moreover, Spinoza also rejected the possibility for the Miracles by simply asserting that people only considered them miraculous due to their lack of understanding of the nature. By rejecting the validity of the Scriptures and the Miracles, Spinoza demolished the foundation for religious knowledge-claim and established his understanding of the Cartesian knowledge as the sole authority of knowledge-claims. Despite being deeply skeptical of the religions, Spinoza was in fact exceedingly anti-skeptical towards reason and rationality. He steadfastly confirmed the legitimacy of reason by associating it with the acknowledgement of God, and thereby skepticism with the rational approach to knowledge was not due to problems with the rational knowledge but from the fundamental lack of understanding of God. Spinoza's religious skepticism and anti-skepticism with reason thus helped him transform epistemology by separating the theological knowledge-claims and the rational knowledge-claims.[3][45]  Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) Pierre Bayle was a French philosopher in the late 17th century that was described by Richard Popkin to be a "supersceptic" who carried out the sceptic tradition to the extreme. Bayle was born in a Calvinist family in Carla-Bayle, and during the early stage of his life, he converted into Catholicism before returning to Calvinism. This conversion between religions caused him to leave France for the more religiously tolerant Holland where he stayed and worked for the rest of his life.[3] Bayle believed that truth cannot be obtained through reason and that all human endeavor to acquire absolute knowledge would inevitably lead to failure. Bayle's main approach was highly skeptical and destructive: he sought to examine and analyze all existing theories in all fields of human knowledge in order to show the faults in their reasoning and thus the absurdity of the theories themselves. In his magnum opus, Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (Historical and Critical Dictionary), Bayle painstakingly identified the logical flaws in several works throughout the history in order to emphasize the absolute futility of rationality. Bayle's complete nullification of reason led him to conclude that faith is the final and only way to truth.[3][46][47] Bayle's real intention behind his extremely destructive works remained controversial. Some described him to be a Fideist, while others speculated him to be a secret Atheist. However, no matter what his original intention was, Bayle did cast significant influence on the upcoming Age of Enlightenment with his destruction of some of the most essential theological ideas and his justification of religious tolerance Atheism in his works.[3][46][47] |

17世紀の懐疑主義 トマス・ホッブズ(1588-1679) トマス・ホッブズはパリに長く滞在し、ガサンディやメルセンヌのような懐疑主義や認識論の研究に重点を置く主要な懐疑論者のサークルに積極的に参加した。 懐疑論者の仲間たちとは異なり、ホッブズは懐疑論を著作の主要なテーマとして扱うことはなかった。とはいえ、ホッブズは、モザイクによる五書への疑念や、 宗教の政治的・心理学的説明によって、同時代の人々から宗教懐疑論者のレッテルを貼られていた。ホッブズ自身はそれ以上他の宗教的原則に挑戦することはな かったが、モザイクの作者に対する彼の疑念は宗教的伝統に大きなダメージを与え、スピノザやイサク・ラ・ペイエールといった後の宗教懐疑論者がユダヤ・キ リスト教宗教体系の基本的信念のいくつかにさらに疑問を投げかける道を開いた。懐疑論と認識論に対するホッブズの答えは、革新的な政治的なものだった。彼 は、道徳的知識と宗教的知識は本質的に相対的なものであり、それらを支配する絶対的な真理基準は存在しないと考えた。その結果、政府と安定した社会を形成 するために、宗教と倫理に関する一定の真理基準が考案され、確立されたのは政治的理由からであった[3][42][43][44]。  バルーフ・スピノザと宗教的懐疑主義 バルーフ・スピノザは宗教懐疑主義者であった最初のヨーロッパの哲学者の一人である。彼はデカルトの哲学に精通しており、デカルトの方法を宗教的文脈に適 用し、宗教的テクストを分析するという前例のないことを行った。スピノザは、ユダヤ教・キリスト教・イスラム教の宗教体系の二つの基盤である「聖典」と 「奇蹟」を検証することで、その知識主張に異議を唱えようとした。スピノザは、デカルト的な知識、すなわち理性的な知識は、すべての人がアクセスできるべ きだと主張した。したがって、イエスによるものは別として、聖典は神から得た秘密の知識ではなく、預言者の想像に過ぎないと考えるべきである。このような 主張の結果、聖典は知識の基盤としての役割を果たせず、単なる古代の歴史的テキストに矮小化された。さらにスピノザは、人々が奇跡を奇跡的なものと考えた のは、自然を理解していなかったからに他ならないと主張し、奇跡の可能性を否定した。聖典と奇跡の妥当性を否定することで、スピノザは宗教的知識主張の基 盤を破壊し、知識主張の唯一の権威としてのデカルト的知識の理解を確立したのである。宗教に深く懐疑的であったにもかかわらず、スピノザは理性と合理性に 対しては極めて反懐疑的であった。彼は理性を神の承認と結びつけることによって、理性の正当性を確固として確認したのであり、それゆえ理性的な知へのアプ ローチに対する懐疑は、理性的な知の問題ではなく、神に対する根本的な理解の欠如に起因するものであった。スピノザの宗教的懐疑主義と理性による反懐疑主 義は、このように神学的知識主張と理性的知識主張を分離することによって認識論を変革するのに役立った[3][45]。  ピエール・バイル(1647年-1706年) ピエール・バユは17世紀後半のフランスの哲学者であり、リチャード・ポプキンは懐疑主義の伝統を極限まで貫いた「超懐疑主義者」であると評している。ベ イユはカルラ=ベイユのカルヴァン派の家庭に生まれ、人生の初期にカトリックに改宗し、その後カルヴァン派に戻った。この宗教間の転向により、彼はフラン スを離れ、より宗教的に寛容なオランダに移り、そこで生涯を過ごした[3]。 ベイユは、真理は理性によって得られるものではなく、絶対的な知識を得ようとする人間の努力は必然的に失敗に終わると考えていた。ベイユの主なアプローチ は、非常に懐疑的で破壊的なものであった。彼は、人間の知識のあらゆる分野において、既存のあらゆる理論を検証・分析し、その推論の欠点、ひいては理論そ のものの不合理さを示そうとした。大著『歴史批評辞典』(Dictionnaire Historique et Critique)の中で、ベイユは、合理性の絶対的な無益さを強調するために、歴史上のいくつかの作品の論理的欠陥を丹念に指摘した。バイユは理性を完 全に無効化することで、信仰こそが真理への最終的かつ唯一の道であると結論づけた[3][46][47]。 極めて破壊的な著作の背後にあるベイユの真意は依然として議論の的となっていた。ある者は彼をフィディストであると評し、またある者は隠れ無神論者である と推測した。しかし、その真意がどのようなものであったにせよ、ベイユはその著作の中で最も本質的な神学思想のいくつかを破壊し、宗教的寛容無神論を正当 化したことで、来るべき啓蒙の時代に大きな影響を与えた[3][46][47]。 |

Skepticism in the Age of

Enlightenment David Hume was among the most influential proponents of philosophical skepticism during the Age of Enlightenment and one of the most notable voices of the Scottish Enlightenment and British Empiricism.[48][49] He especially espoused skepticism regarding inductive reasoning, and questioned what the foundation of morality was, creating the is–ought problem. His approach to skepticism is considered even more radical than that of Descartes.[according to whom?] Hume argued that any coherent idea must be either a mental copy of an impression (a direct sensory perception) or copies of multiple impressions innovatively combined. Since certain human activities like religion, superstition, and metaphysics are not premised on any actual sense-impressions, their claims to knowledge are logically unjustified. Furthermore, Hume even demonstrates that science is merely a psychological phenomenon based on the association of ideas: often, specifically, an assumption of cause-and-effect relationships that is itself not grounded in any sense-impressions. Thus, even scientific knowledge is logically unjustified, being not actually objective or provable but, rather, mere conjecture flimsily based on our minds perceiving regular correlations between distinct events. Hume thus falls into extreme skepticism regarding the possibility of any certain knowledge. Ultimately, he offers that, at best, a science of human nature is the "only solid foundation for the other sciences".[50]  Kant Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to provide a ground for empirical science against David Hume's skeptical treatment of the notion of cause and effect. Hume (1711–1776) argued that for the notion of cause and effect no analysis is possible which is also acceptable to the empiricist program primarily outlined by John Locke (1632–1704).[51] But, Kant's attempt to give a ground to knowledge in the empirical sciences at the same time cut off the possibility of knowledge of any other knowledge, especially what Kant called "metaphysical knowledge". So, for Kant, empirical science was legitimate, but metaphysics and philosophy was mostly illegitimate. The most important exception to this demarcation of the legitimate from the illegitimate was ethics, the principles of which Kant argued can be known by pure reason without appeal to the principles required for empirical knowledge. Thus, with respect to metaphysics and philosophy in general (ethics being the exception), Kant was a skeptic. This skepticism as well as the explicit skepticism of G. E. Schulze[52] gave rise to a robust discussion of skepticism in German idealistic philosophy, especially by Hegel.[53] Kant's idea was that the real world (the noumenon or thing-in-itself) was inaccessible to human reason (though the empirical world of nature can be known to human understanding) and therefore we can never know anything about the ultimate reality of the world. Hegel argued against Kant that although Kant was right that using what Hegel called "finite" concepts of "the understanding" precluded knowledge of reality, we were not constrained to use only "finite" concepts and could actually acquire knowledge of reality using "infinite concepts" that arise from self-consciousness.[54] Skepticism in the 20th century and contemporary philosophy G. E. Moore famously presented the "Here is one hand" argument against skepticism in his 1925 paper, "A Defence of Common Sense".[1] Moore claimed that he could prove that the external world exists by simply presenting the following argument while holding up his hands: "Here is one hand; here is another hand; therefore, there are at least two objects; therefore, external-world skepticism fails". His argument was developed for the purpose of vindicating common sense and refuting skepticism.[1] Ludwig Wittgenstein later argued in his On Certainty (posthumously published in 1969) that Moore's argument rested on the way that ordinary language is used, rather than on anything about knowledge.[55] In contemporary philosophy, Richard Popkin was a particularly influential scholar on the topic of skepticism. His account of the history of skepticism given in The History of Scepticism from Savonarola to Bayle (first edition published as The History of Scepticism From Erasmus to Descartes) was accepted as the standard for contemporary scholarship in the area for decades after its release in 1960.[56] Barry Stroud also published a number of works on philosophical skepticism, most notably his 1984 monograph, The Significance of Philosophical Scepticism.[57] From the mid-1990s, Stroud, alongside Richard Fumerton, put forward influential anti-externalist arguments in favour of a position called "metaepistemological scepticism".[58] Other contemporary philosophers known for their work on skepticism include James Pryor, Keith DeRose, and Peter Klein.[1] |

啓蒙時代の懐疑主義 デイヴィッド・ヒュームは啓蒙時代における哲学的懐疑主義の最も影響力のある支持者の一人であり、スコットランド啓蒙主義とイギリス経験主義の最も注目す べき声の一人であった[48][49]。 彼は特に帰納的推論に関する懐疑主義を支持し、道徳の基礎が何であるかに疑問を投げかけ、is-ought問題を生み出した。彼の懐疑主義へのアプローチ はデカルトよりもさらに急進的であると考えられている。 ヒュームは、あらゆる首尾一貫した考えは、印象(直接的な感覚的知覚)の精神的コピーか、革新的に組み合わされた複数の印象のコピーのどちらかでなければ ならないと主張した。宗教、迷信、形而上学のようなある種の人間の営みは、実際の感覚的印象を前提としていないので、知識に対するそれらの主張は論理的に 正当化されない。さらにヒュームは、科学は単に観念の結びつきに基づく心理学的現象にすぎず、具体的には、それ自体がいかなる感覚的印象にも基づかない因 果関係の仮定にすぎないことさえ示している。したがって、科学的な知識でさえ論理的に正当化されない。客観的でも証明可能でもなく、むしろ、異なる事象の 間に規則的な相関関係を知覚する私たちの心に基づいて、単なる憶測を薄っぺらくしているにすぎないのである。こうしてヒュームは、確実な知識の可能性につ いて極端な懐疑論に陥る。最終的に彼は、せいぜい人間性の科学が「他の諸科学のための唯一の堅固な基礎」であると提唱している[50]。  カント イマヌエル・カント(1724-1804)は、原因と結果の概念に懐疑的なデイヴィッド・ヒューム(1711-1776)に対して、経験科学の根拠を提供 しようとした。ヒューム(1711-1776)は、原因と結果の概念については分析が不可能であると主張したが、これはジョン・ロック(1632- 1704)によって主に概説された経験主義的プログラムにも受け入れられるものであった[51]。しかし、経験科学における知識に根拠を与えようとするカ ントの試みは、同時に他の知識、特にカントが「形而上学的知識」と呼んだものについての知識の可能性を断ち切るものであった。つまり、カントにとって経験 科学は正当なものであったが、形而上学や哲学はほとんど非合法なものであった。この合法と非合法の区分の最も重要な例外は倫理学であり、その原理は経験的 知識に必要な原理に訴えることなく純粋理性によって知ることができるとカントは主張した。このように、形而上学と哲学全般(倫理学は例外)に関して、カン トは懐疑論者であった。この懐疑論とG・E・シュルツ[52]の明確な懐疑論は、ドイツ観念論哲学、特にヘーゲル[53]による懐疑論に関する強固な議論 を生んだ。カントの考えは、現実世界(ヌーメノンまたは事物自体)は人間の理性にはアクセス不可能であり(経験的な自然界は人間の理解によって知ることが できるが)、したがって世界の究極的な実在については何も知ることができないというものであった。ヘーゲルはカントに対して、ヘーゲルが「理解」の「有 限」概念と呼ぶものを使用することが現実の知識を妨げるという点ではカントは正しかったが、我々は「有限」概念のみを使用することに束縛されることはな く、実際には自己意識から生じる「無限概念」を使用して現実の知識を獲得することができると主張していた[54]。 20世紀における懐疑主義と現代哲学 G.E.ムーアは1925年の論文『常識の擁護』において懐疑論に対して「ここに片手がある」という議論を提示したことで有名である[1]。ムーアは、両 手を掲げながら次のような議論を提示するだけで、外界が存在することを証明できると主張した: 「ここに1つの手があり、ここにもう1つの手がある。したがって、少なくとも2つの対象が存在し、したがって外界懐疑論は失敗する」。彼の議論は常識を正 当化し、懐疑主義を反駁する目的で展開された[1]。後にルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインは『確かさについて』(1969年に死後に出版)の中で、 ムーアの議論は知識に関することではなく、通常の言語の使われ方にかかっていると主張した[55]。 現代哲学において、リチャード・ポプキンは懐疑主義のトピックにおいて特に影響力のある学者であった。バリー・ストラウドもまた哲学的懐疑主義に関する多 くの著作を発表しており、特に1984年の単行本『哲学的懐疑主義の意義』は有名である。 [57]1990年代半ばからストラウドは、リチャード・フマートンとともに、「メタ認識論的懐疑主義」と呼ばれる立場を支持する反外在主義的な議論を提 唱し、影響力を持つようになった[58]。懐疑主義に関する研究で知られる他の現代哲学者には、ジェームズ・プライヤー、キース・デローズ、ピーター・ク ラインなどがいる[1]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_skepticism |

|

Sextus Empiricus (Greek: Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, Sextos Empeirikos; fl. mid-late 2nd century AD) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician with Roman citizenship. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and because of the arguments they contain against the other Hellenistic philosophies, they are also a major source of information about those philosophies. |

セクストゥス・エンピリコス(ギリシャ語: Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, Sextos Empeirikos; 2世紀半ばから後半)は、ギリシャのピュロン派の哲学者であり、ローマ市民権を持つエンピリス派の医師である。彼の哲学的著作は、古代ギリシア・ローマの ピュロン主義に関する現存する最も完全な記述であり、他のヘレニズム哲学に対する反論を含んでいるため、それらの哲学に関する主要な情報源でもある。 |

| Life Little is known about Sextus Empiricus. He likely lived in Alexandria, Rome, or Athens.[1] His Roman name, Sextus, implies he was a Roman citizen.[2] The Suda, a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia, states that he was the same person as Sextus of Chaeronea,[3] as do other pre-modern sources, but this identification is commonly doubted.[4] In his medical work, as reflected by his name, tradition maintains that he belonged to the Empiric school in which Pyrrhonism was popular. However, at least twice in his writings, Sextus seems to place himself closer to the Methodic school. |

人生 セクストゥス・エンピリカスについてはほとんど知られていない。10世紀のビザンチン百科事典である『スダ』には、他の前近代史料と同様に、彼がチャエロ ネアのセクストゥスと同一人物であると記されているが[3]、この同一性については一般に疑問視されている[4]。しかし、セクストゥスは著作の中で少な くとも2回、自らを方法学派に近い位置に置いているようである。 |

| Philosophy Main article: Pyrrhonism As a skeptic, Sextus Empiricus raised concerns which applied to all types of knowledge. He doubted the validity of induction[5] long before its best known critic David Hume, and raised the regress argument against all forms of reasoning: Those who claim for themselves to judge the truth are bound to possess a criterion of truth. This criterion, then, either is without a judge's approval or has been approved. But if it is without approval, whence comes it that it is trustworthy? For no matter of dispute is to be trusted without judging. And, if it has been approved, that which approves it, in turn, either has been approved or has not been approved, and so on ad infinitum.[6] This view is known as Pyrrhonian skepticism, which Sextus differentiated from Academic skepticism as practiced by Carneades which, according to Sextus, denies the possibility of knowledge altogether, something that Sextus criticized as being an affirmative belief. Instead, Sextus advocates simply giving up belief; in other words, suspending judgment (epoché) about whether or not anything is knowable.[7] Only by suspending judgment can we attain a state of ataraxia (roughly, 'peace of mind'). There is some debate as to the extent to which Sextus advocated the suspension of judgement. According to Myles Burnyeat,[8] Jonathan Barnes,[9] and Benson Mates,[10] Sextus advises that we should suspend judgment about virtually all beliefs; that is to say, we should neither affirm any belief as true nor deny any belief as false, since we may live without any beliefs, acting by habit. Michael Frede, however, defends a different interpretation,[11] according to which Sextus does allow beliefs, so long as they are not derived by reason, philosophy or speculation; a skeptic may, for example, accept common opinions in the skeptic's society. The important difference between the skeptic and the dogmatist is that the skeptic does not hold his beliefs as a result of rigorous philosophical investigation. |

哲学 主な記事 ピュロニズム 懐疑論者であったセクストゥス・エンピリクスは、あらゆる種類の知識に適用される懸念を提起した。彼は帰納法[5]の最も有名な批判者であるデイヴィッド・ヒュームよりもずっと前に帰納法の有効性を疑い、あらゆる推論に対して逆行論を提起した: 真理を判断することを自ら主張する者は、真理の基準を持っているはずである。この基準は、裁判官の承認がないか、承認されているかのどちらかである。しか し、もしそれが承認されていないのであれば、どうしてそれが信頼に足るということになるのか。いかなる争点も、判断なしに信用されることはないからであ る。また、それが承認されたものであるならば、それを承認するものは、承認されたものであるか、承認されていないものであるかのいずれかであり、無限に続 く[6]。 この見解はピュロニア的懐疑主義として知られており、セクストゥスはカルネアデスが実践した学術的懐疑主義とは区別していた。カルネアデスは、セクストゥ スによれば、知識の可能性を完全に否定しており、セクストゥスは肯定的信念であると批判していた。その代わりに、セクストゥスは単に信じることを放棄する こと、言い換えれば、何事も知ることができるかどうかについての判断(エポケー)を保留することを提唱している[7]。判断を保留することによってのみ、 私たちはアタラクシア(おおよそ「心の平安」)の状態に到達することができる。 セクストゥスがどの程度まで判断の停止を唱えたかについては議論がある。マイルス・バーニェート、[8] ジョナサン・バーンズ、[9] ベンソン・メイツ[10] によれば、セクストゥスは、事実上すべての信念につい て判断を保留すべきだと助言している。しかしミヒャエル・フレデは別の解釈を擁護しており[11]、それによると、セクストゥスは理性、哲学、思索によっ て導き出されたものでない限り、信念を認めている。懐疑論者と独断論者の重要な違いは、懐疑論者は自分の信念を厳密な哲学的調査の結果として持っているわ けではないということである。 |

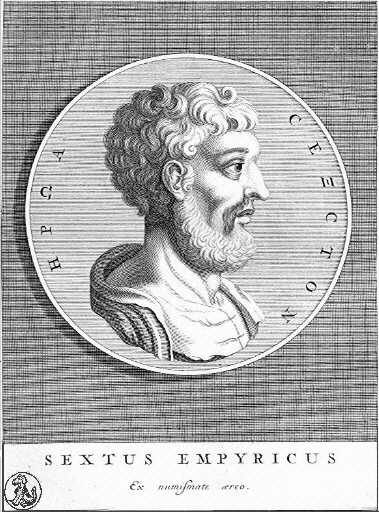

| Writings Diogenes Laërtius[12] and the Suda[3] report that Sextus Empiricus wrote ten books on Pyrrhonism. The Suda also says Sextus wrote a book Ethica. Sextus Empiricus's three surviving works are the Outlines of Pyrrhonism (Πυῤῥώνειοι ὑποτυπώσεις, Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseis, thus commonly abbreviated PH), and two distinct works preserved under the same title, Adversus Mathematicos (Πρὸς μαθηματικούς, Pros mathematikous, commonly abbreviated "AM" or "M" and known as Against Those in the Disciplines, or Against the Mathematicians). Adversus Mathematicos is incomplete as the text references parts that are not in the surviving text. Adversus Mathematicos also includes mentions of three other works which did not survive: Medical Commentaries (AD I 202) Empirical Commentaries (AM I 62) Commentaries on the Soul which includes a discussion of the Pythagoreans' metaphysical theory of numbers (AD IV 284) and shows that the soul is nothing (AM VI 55)[13] The surviving first six books of Adversus Mathematicos are commonly known as Against the Professors. Each book also has a traditional title;[14] although none of these titles except Pros mathematikous and Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseis are found in the manuscripts. Adversus Mathematicos I–VI is sometimes distinguished from Adversus Mathematicos VII–XI by using another title, Against the Dogmatists (Πρὸς δογματικούς, Pros dogmatikous) and then the remaining books are numbered as I–II, III–IV, and V, despite the fact that it is commonly inferred that what we have is just part of a larger work whose beginning is missing and it is unknown how much of the total work has been lost. The supposed general title of this partially lost work is Skeptical Treatises' (Σκεπτικὰ Ὑπομνήματα/Skeptika Hypomnēmata).[15] |

著作 ディオゲネス・ラエルティウス[12]と『スダ』[3]は、セクストゥス・エンピリクスがピュロニズムについて10冊の本を書いたと報告している。また、 SudaはSextusがEthicaという本を書いたと述べている。現存するセクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作は、『ピュロニズム概説』 (Πυῤῥώνειοις, Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseis, したがって一般にはPHと略される)と、同じ題名で保存されている2つの著作である、 Adversus Mathematicos (Πρὸς μαθηματικούς, Pros mathematikous, 一般に「AM」または「M」と略され、「学問に携わる者に反対する」または「数学者に反対する」として知られる)。アドヴァーサス・マテマティコス』は、 現存するテキストにない部分を参照しているため、不完全なものである。Adversus Mathematicos』には、現存しない他の3つの著作についても言及されている: 『医学注解』(AD I 202) 経験的注解(AM I 62) ピュタゴラス派の形而上学的数論(AD IV 284)の議論を含み、魂が無であることを示す『魂の注解』(AM VI 55)[13] 。 現存する『数学的逆説』の最初の6冊は、一般に『教授たちに対して』として知られている。各書には伝統的な題名もあるが[14]、写本には『Pros mathematikous』と『Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseis』以外の題名は見当たらない。 Adversus Mathematicos I-VI』は、『Adversus Mathematicos VII-XI』とは別の題名『Against the Dogmatists』(Πρὸς δογματικούς, Pros dogmatikous)を用いて区別されることもあり、残りの書物には『I-II』『III-IV』『V』と番号が振られている。この部分的に失われた 著作の一般的なタイトルは『懐疑論』(Σκεπτικὰ Ὑπομνήματα/Skeptika Hypomnēmata)とされている[15]。 |

|

|

| Legacy An influential Latin translation of Sextus's Outlines was published by Henricus Stephanus in Geneva in 1562,[16] and this was followed by a complete Latin Sextus with Gentian Hervet as translator in 1569.[17] Petrus and Jacobus Chouet published the Greek text for the first time in 1621. Stephanus did not publish it with his Latin translation either in 1562 or in 1569, nor was it published in the reprint of the latter in 1619. Sextus's Outlines were widely read in Europe during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and had a profound effect on Michel de Montaigne, David Hume and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, among many others. Another source for the circulation of Sextus's ideas was Pierre Bayle's Dictionary. The legacy of Pyrrhonism is described in Richard Popkin's The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Descartes and High Road to Pyrrhonism. The transmission of Sextus's manuscripts through antiquity and the Middle Ages is reconstructed by Luciano Floridi's Sextus Empiricus, The Recovery and Transmission of Pyrrhonism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). Since the Renaissance, French philosophy has been continuously influenced by Sextus: Montaigne in the 16th century, Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Pierre-Daniel Huet and François de La Mothe Le Vayer in the 17th century, many of the "Philosophes", and in recent times controversial figures such as Michel Onfray, in a direct line of filiation between Sextus' radical skepticism and secular or even radical atheism.[18] |

遺産 1562年、ジュネーヴでヘンリクス・ステファヌス(Henricus Stephanus)によりセクストゥス概論のラテン語訳が出版され[16]、1569年にはジェンティアン・エルヴェ(Gentian Hervet)を訳者とする完全なラテン語版セクストゥスが出版された[17]。ステファヌスは1562年にも1569年にもラテン語訳と一緒に出版して おらず、1619年の後者の再版にも掲載されていない。 セクストゥスの『概説』は16、17、18世紀のヨーロッパで広く読まれ、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘル ム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルなどに多大な影響を与えた。セクストゥスの思想が広まったもうひとつの源は、ピエール・バイルの『辞典』である。ピュロニズム の遺産については、リチャード・ポプキンの『エラスムスからデカルトまでの懐疑主義の歴史』(The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Descartes)と『ピュロニズムへの王道』(High Road to Pyrrhonism)で述べられている。古代と中世を通じたセクストゥスの写本の伝播については、ルチアーノ・フローリディ著『セクストゥス・エンピリ クス、ピュロニズムの回復と伝播』(オックスフォード大学出版局、2002年)が再構築している。ルネサンス以来、フランス哲学はセクストゥスの影響を受 け続けてきた: 16世紀のモンテーニュ、17世紀のデカルト、ブレーズ・パスカル、ピエール=ダニエル・ユエ、フランソワ・ド・ラ・モテ・ル・ヴェイエ、多くの「哲学者 たち」、そして近年ではミシェル・オンフレイのような物議を醸す人物が、セクストゥスの急進的懐疑主義と世俗的、あるいは急進的な無神論との間に直接的な 関係を築いている[18]。 |

| Works Translations Old complete translation in four volumes Sextus Empiricus, Sextus Empiricus I: Outlines of Pyrrhonism. R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1933/2000). ISBN 0-674-99301-2 Sextus Empiricus, Sextus Empiricus II: Against the Logicians. R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1935/1997). ISBN 0-674-99321-7 Sextus Empiricus, Sextus Empiricus III: Against the Physicists, Against the Ethicists. R.G. Bury (trans.) Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1936/1997. ISBN 0-674-99344-6 Sextus Empiricus, Sextus Empiricus IV: Against the Professors. R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1949/2000). ISBN 0-674-99420-5 New partial translations Sextus Empiricus, Against the Grammarians (Adversos Mathematicos I) David Blank (trans.) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-824470-3 Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians (Adversos Mathematicos IV) Lorenzo Corti (trans.) Leiden: Brill, 2024. ISBN 978-90-04-67949-8 Sextus Empiricus, Against those in the Disciplines (Adversos Mathematicos I-VI). Richard Bett (trans.) (New York: Oxford University Press 2018). ISBN 9780198712701 Sextus Empiricus, Against the Logicians. (Adversus Mathematicos VII and VIII). Richard Bett (trans.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-53195-0 Sextus Empiricus, Against the Physicists (Adversus Mathematicos IX and X). Richard Bett (trans.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 0-521-51391-X Sextus Empiricus, Against the Ethicists (Adversus Mathematicos XI). Richard Bett (trans.) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000). ISBN 0-19-825097-5 Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Scepticism. Julia Annas and Jonathan Barnes (trans.) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. 2000). ISBN 0-521-77809-3 Sextus Empiricus, The Skeptic Way: Sextus Empiricus's Outlines of Pyrrhonism. Benson Mates (trans.) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-509213-9 Sextus Empiricus, Selections from the Major Writings on Skepticism Man and God. Sanford G. Etheridge (trans.) Indianapolis: Hackett, 1985. ISBN 0-87220-006-X French translations Sextus Empiricus, Contre les Professeurs (the first six treatises), Greek text and French Translation, under the editorship of Pierre Pellegrin (Paris: Seuil-Points, 2002). ISBN 2-02-048521-4 Sextus Empirucis, Esquisses Pyrrhoniennes, Greek text and French Translation, under the editorship of Pierre Pellegrin (Paris: Seuil-Points, 1997). Old editions Sexti Empirici Adversus mathematicos, hoc est, adversus eos qui profitentur disciplinas, Gentiano Herveto Aurelio interprete, Parisiis, M. Javenem, 1569 (Vicifons). |

作品紹介 翻訳 旧全訳 全4巻 セクストゥス・エンピリカス、セクストゥス・エンピリカス I: ピュロニズムの概説。R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1933/2000). ISBN 0-674-99301-2 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『セクストゥス・エンピリカスII:論理学者に抗して』。R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1935/1997). ISBN 0-674-99321-7 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『セクストゥス・エンピリカスIII 物理学者、倫理学者への反論』(ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州、ハーバード大学出版部、1935年/1997年 R.G. Bury (trans.) Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1936/1997. ISBN 0-674-99344-6 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『セクストゥス・エンピリカスIV:教授たちに抗して』。R.G. Bury (trans.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1949/2000). ISBN 0-674-99420-5 新しい部分訳 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『文法学者たちに反論する』(Adversos Mathematicos I) デイヴィッド・ブランク(訳)オックスフォード: クラレンドン・プレス, 1998. ISBN 0-19-824470-3 Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians (Adversos Mathematicos IV) Lorenzo Corti (trans.) Leiden: Brill, 2024. ISBN 978-90-04-67949-8 セクストゥス・エンピリクス『学問の徒に反対する』(Adversos Mathematicos I-VI)。Richard Bett (trans.) (New York: Oxford University Press 2018). ISBN 9780198712701 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『論理学者に反論する。(Adversus Mathematicos VII and VIII)。Richard Bett (trans.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-53195-0 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『物理学者に対する反論』(数学的反論IXとX)。Richard Bett (trans.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 0-521-51391-x セクストゥス・エンピリカス『倫理主義者に抗して』(Adversus Mathematicos XI)。Richard Bett (trans.) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000). ISBN 0-19-825097-5 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『懐疑論概説』。Julia Annas and Jonathan Barnes (trans.) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. 2000). ISBN 0-521-77809-3 Sextus Empiricus, The Skeptic Way: セクストゥス・エンピリクス『ピュロニズム概説』。Benson Mates (trans.) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-509213-9 セクストゥス・エンピリカス『懐疑論人間と神』主要著作選集. Sanford G. Etheridge (trans.) Indianapolis: Hackett, 1985. ISBN 0-87220-006-x フランス語訳 Sextus Empiricus, Contre les Professeurs (the first six treatises), ギリシア語テキストとフランス語訳、Pierre Pellegrin編 (Paris: Seuil-Points, 2002). ISBN 2-02-048521-4 Sextus Empirucis, Esquisses Pyrrhoniennes, ギリシア語テキストとフランス語訳、Pierre Pellegrin編集 (Paris: Seuil-Points, 1997). 旧版 Sexti Empirici Adversus mathematicos, hoc est, adversus eos qui profitentur disciplinas, Gentiano Herveto Aurelio interprete, Parisiis, M. Javenem, 1569 (Vicifons). |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sextus_Empiricus |

|

| Pyrrhonism |

|

★ ピロニズ/ピュロニズム(Pyrrhonism)(→「ピュロニズムあるいはフュロン主義」)

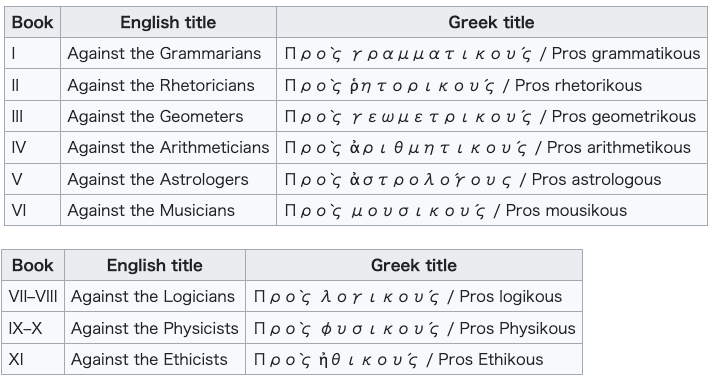

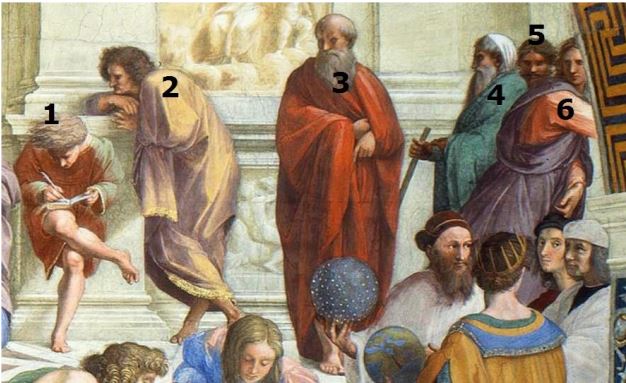

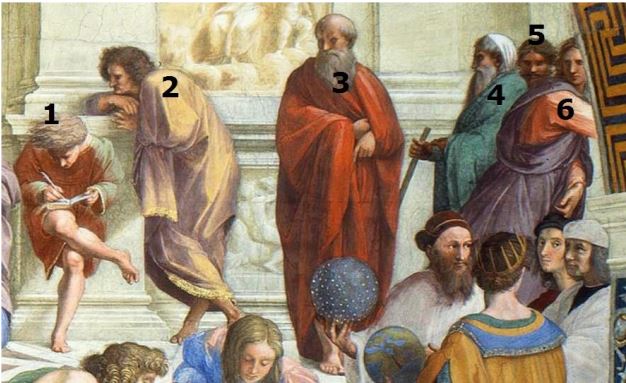

Skeptics in Raphael's School of Athens painting. Pyrrho is #4 and Timon #5 Pyrrhonism is an Ancient Greek school of philosophical skepticism which rejects dogma and advocates the suspension of judgement over the truth of all beliefs. It was founded by Aenesidemus in the first century BCE, and said to have been inspired by the teachings of Pyrrho and Timon of Phlius in the fourth century BCE.[1] Pyrrhonism is best known today through the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus, writing in the late second century or early third century CE.[2] The publication of Sextus' works in the Renaissance ignited a revival of interest in Skepticism and played a major role in Reformation thought and the development of early modern philosophy. |

ラファエロの「アテネの学校」に描かれた懐疑論者たち。ピュローは4番、ティモンは5番。 ピュ ロニズム(Pyrrhonism)とは、古代ギリシャの哲学的懐疑主義の一派で、ドグマを否定し、あらゆる信念の真偽に対する判断の停止を提唱する。紀元 前1世紀にアエネシデムスによって創始され、紀元前4世紀にはピュローとフリウスのティモンの教えに触発されたと言われている。ピュロニズムは、紀元前2 世紀後半から3世紀初頭に書かれたセクストゥス・エンピリクスの現存する著作によって今日最もよく知られている。ルネサンス期にセクストゥスの著作が出版 されると、懐疑主義への関心が再燃し、宗教改革思想や近世哲学の発展に大きな役割を果たした。 |

| History Pyrrhonism is named after Pyrrho of Elis, a Greek philosopher in the 4th century BCE who was credited by the later Pyrrhonists with forming the first comprehensive school of skeptical thought. However, ancient testimony about the philosophical beliefs of the historical Pyrrho is minimal, and often contradictory:[1] his teachings were recorded by his student Timon of Phlius, but those works have been lost, and only survive in fragments quoted by later authors, and based on testimonies of later authors such as Cicero, Pyrrho's own philosophy as recorded by Timon may have been much more dogmatic than that of the later school who bore his name.[1] While Pyrrhonism would become the dominant form of skepticism in the early Roman period, in the Hellenistic period, the Platonic Academy was the primary advocate of skepticism until the mid-first century BCE,[3] when Pyrrhonism as a philosophical school was founded by Aenesidemus.[1][4] |

歴史 ピュロニズムは、紀元前4世紀のギリシャの哲学者エリスのピュロ(Pyrho)にちなんで命名された。ピュロニズムは、懐疑思想の最初の包括的な学派を形 成したと後のピュロニストたちに信じられている。しかし、歴史上のピュローの哲学的信条に関する古代の証言はごくわずかであり、しばしば矛盾している。 [1]彼の教えは弟子のフリウスのティモンによって記録されているが、それらの著作は失われており、後世の著者が引用した断片が残っているだけである。ま た、キケロなどの後世の著者の証言によれば、ティモンによって記録されたピュロー自身の哲学は、彼の名を冠した後世の学派の哲学よりもはるかに独断的で あった可能性がある。 [1]ピュローニズムが初期ローマ時代において懐疑主義の支配的な形態となる一方で、ヘレニズム時代においては、前1世紀半ばに哲学学派としてのピュロー ニズムがアエネシデムスによって創設されるまで[3]、プラトン学派が懐疑主義の主要な提唱者であった[1][4]。 |

| Philosophy The goal of Pyrrhonism is ataraxia,[5] an untroubled and tranquil condition of soul that results from a suspension of judgement, a mental rest owing to which we neither deny nor affirm anything. Pyrrhonists dispute that the dogmatists – which includes all of Pyrrhonism's rival philosophies – claim to have found truth regarding non-evident matters, and that these opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) are what prevent one from attaining eudaimonia. For any of these dogmas, a Pyrrhonist makes arguments for and against such that the matter cannot be concluded, thus suspending judgement, and thereby inducing ataraxia. Pyrrhonists can be subdivided into those who are ephectic (engaged in suspension of judgment), aporetic (engaged in refutation)[6] or zetetic (engaged in seeking).[7] An ephectic merely suspends judgment on a matter, "balancing perceptions and thoughts against one another,"[8] It is a less aggressive form of skepticism, in that sometimes "suspension of judgment evidently just happens to the sceptic".[9] An aporetic skeptic, in contrast, works more actively towards their goal, engaging in the refutation of arguments in favor of various possible beliefs in order to reach aporia, an impasse, or state of perplexity,[10] which leads to suspension of judgement.[9] Finally, the zetetic claims to be continually searching for the truth but to have thus far been unable to find it, and thus continues to suspend belief while also searching for reason to cease the suspension of belief. Modes Although Pyrrhonism's objective is ataraxia, it is best known for its epistemological arguments. The core practice is through setting argument against argument. To aid in this, the Pyrrhonist philosophers Aenesidemus and Agrippa developed sets of stock arguments known as "modes" or "tropes." The ten modes of Aenesidemus Aenesidemus is considered the creator of the ten tropes of Aenesidemus (also known as the ten modes of Aenesidemus)—although whether he invented the tropes or just systematized them from prior Pyrrhonist works is unknown. The tropes represent reasons for suspension of judgment. These are as follows:[11] Different animals manifest different modes of perception; Similar differences are seen among individual men; For the same man, information perceived with the senses is self-contradictory Furthermore, it varies from time to time with physical changes In addition, this data differs according to local relations Objects are known only indirectly through the medium of air, moisture, etc. These objects are in a condition of perpetual change in colour, temperature, size and motion All perceptions are relative and interact one upon another Our impressions become less critical through repetition and custom All men are brought up with different beliefs, under different laws and social conditions According to Sextus, superordinate to these ten modes stand three other modes: that based on the subject who judges (modes 1, 2, 3 & 4), that based on the object judged (modes 7 & 10), that based on both subject who judges and object judged (modes 5, 6, 8 & 9), and superordinate to these three modes is the mode of relation.[12] The five modes of Agrippa These "tropes" or "modes" are given by Sextus Empiricus in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism. According to Sextus, they are attributed only "to the more recent skeptics" and it is by Diogenes Laërtius that we attribute them to Agrippa.[13] The five tropes of Agrippa are: Dissent – The uncertainty demonstrated by the differences of opinions among philosophers and people in general. Infinite regress – All proof rests on matters themselves in need of proof, and so on to infinity. Relation – All things are changed as their relations become changed, or, as we look upon them from different points of view. Assumption – The truth asserted is based on an unsupported assumption. Circularity – The truth asserted involves a circularity of proofs. According to the mode deriving from dispute, we find that undecidable dissension about the matter proposed has come about both in ordinary life and among philosophers. Because of this we are not able to choose or to rule out anything, and we end up with suspension of judgement. In the mode deriving from infinite regress, we say that what is brought forward as a source of conviction for the matter proposed itself needs another such source, which itself needs another, and so ad infinitum, so that we have no point from which to begin to establish anything, and suspension of judgement follows. In the mode deriving from relativity, as we said above, the existing object appears to be such-and-such relative to the subject judging and to the things observed together with it, but we suspend judgement on what it is like in its nature. We have the mode from hypothesis when the Dogmatists, being thrown back ad infinitum, begin from something which they do not establish but claim to assume simply and without proof in virtue of a concession. The reciprocal mode occurs when what ought to be confirmatory of the object under investigation needs to be made convincing by the object under investigation; then, being unable to take either in order to establish the other, we suspend judgement about both.[14] With reference to these five tropes, that the first and third are a short summary of the earlier Ten Modes of Aenesidemus.[13] The three additional ones show a progress in the Pyrrhonist system, building upon the objections derived from the fallibility of sense and opinion to more abstract and metaphysical grounds. According to Victor Brochard "the five tropes can be regarded as the most radical and most precise formulation of skepticism that has ever been given. In a sense, they are still irresistible today."[15] Criteria of action Pyrrhonist decision making is made according to what the Pyrrhonists describe as the criteria of action holding to the appearances, without beliefs in accord with the ordinary regimen of life based on: the guidance of nature, by which we are naturally capable of sensation and thought the compulsion of the passions by which hunger drives us to food and thirst makes us drink the handing down of customs and laws by which we accept that piety in the conduct of life is good and impiety bad instruction in techne[16] Skeptic sayings The Pyrrhonists devised several sayings (Greek ΦΩΝΩΝ) to help practitioners bring their minds to suspend judgment.[17] Among these are: Not more, nothing more (a saying attributed to Democritus[18]) Non-assertion (aphasia) Perhaps, it is possible, maybe I withhold assent I determine nothing (Montaigne created a variant of this as his own personal motto, "Que sais-je?" – "what do I know?") Everything is indeterminate Everything is non-apprehensible I do not apprehend To every argument an equal argument is opposed |

哲学 ピュロニズムの目標はアタラクシア[5]であり、判断の停止、つまり何も否定も肯定もしない精神的な休息から生じる、悩みのない静謐な魂の状態である。 ピュロニストたちは、ピュロニズムと対立するすべての哲学を含むドグマティストたちが、自明でない事柄に関して真理を発見したと主張し、自明でない事柄に 関するこれらの意見(すなわちドグマ)が、人がエウダイモニアに到達するのを妨げるものであると主張する。ピュローニストは、これらのドグマについて、結 論が出ないような賛否両論を展開し、判断を保留して、アタラクシアを誘発する。 ピュロニストは、判断の一時停止に従事するエフェクティック(ephectic)、反論に従事するアポレティック(aporetic)[6]、探求に従事 するゼテティック(zetetic)に細分化される[7]。エフェクティック(ephectic)は、単にある問題に対する判断を一時停止し、「知覚と思 考のバランスをとる」[8]。 [これとは対照的に、無神論的懐疑論者はより積極的に目標に向か い、判断の停止につながるアポリア(袋小路、当惑の状態)[10]に到達す るために、様々な可能性のある信念を支持する論証の反駁に従事する。 様式 ピュロニズムの目的はアタラクシアであるが、認識論的な議論で最もよく知られている。中心的な実践は、議論に議論をぶつけることである。これを助けるため に、ピュロニズムの哲学者アエネシデムスとアグリッパは、「モード 」または 「トロペ 」として知られる論証のセットを開発した。 アエネシデムスの10のモード アエネシデムスは、アエネシデムスの10の論法(アエネシデムスの10のモードとも呼ばれる)の創始者と考えられているが、彼がこの論法を発明したのか、 それともピュロン派の先行著作から体系化したのかは不明である。この類型は判断を保留する理由を表している。それらは以下の通りである[11]。 動物によって知覚の様式は異なる; 同様の違いが個々の人間にも見られる; 同じ人間であっても、感覚によって知覚される情報は自己矛盾している。 さらに、それは身体的な変化によって時々刻々と変化する。 さらに、このデータは局所的な関係によって異なる。 物体は、空気や湿気などを媒介として間接的にしかわからない。 これらの物体は、色、温度、大きさ、動きにおいて、絶え間なく変化する状態にある。 すべての知覚は相対的であり、互いに影響し合っている。 私たちの印象は、繰り返しと習慣によって、あまり批判的にならなくなる。 人はみな、さまざまな法律や社会的条件のもとで、さまざまな信念をもって育つ セクストゥスによれば、これら10の態様の上位に、判断する主体に基づく態様(態様1、2、3、4)、判断される対象に基づく態様(態様7、10)、判断 する主体と判断される対象の両方に基づく態様(態様5、6、8、9)、そしてこれら3つの態様の上位に位置するのが関係の態様である[12]。 アグリッパの5つのモード これらの「様態」または「モード」は、セクストゥス・エンピリクスが『ピュロニズム概論』(Outlines of Pyrrhonism)の中で示している。セクストゥスによれば、それらは「より最近の懐疑論者にのみ」帰せられるものであり、アグリッパに帰せられるの はディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによるものである[13]: 異論 - 哲学者や一般の人々の意見の違いによって示される不確実性。 無限後退 - すべての証明は、証明の必要な事柄そのものにかかっており、無限に続く。 関係 - すべての物事は、その関係が変化するにつれて、あるいは異なる視点から見るにつれて変化する。 仮定 - 主張された真理は、裏付けのない仮定に基づいている。 循環性 - 主張される真理は、証明の循環性を伴う。 論争に由来する態様によれば、私たちは、提案された問題についての決定不可能な論争が、日常生活においても哲学者の間でも生じていることに気づく。そのた め、私たちは何かを選択することも排除することもできず、判断の停止に陥ってしまう。無限後退に由来する様式では、提案された事柄を納得させる源泉として 持ち出されたもの自体が、別のそのような源泉を必要とし、その源泉自体もまた別の源泉を必要とし、このように無限に続くので、何かを立証し始める時点がな くなり、判断の停止が続くと言う。相対性から派生する様式では、先に述べたように、現存する対象は、判断する主体や、それとともに観察されるものに対して 相対的にそのように見えるが、それが本質的にどのようなものであるかについては判断を保留する。ドグマティストたちが、無限に引き戻されながら、自分たち が立証することなく、譲歩のゆえに単純に、証明することなく仮定すると主張する何かから始めるとき、われわれは仮説からの様式を持つ。相互モードは、調査 対象の確証となるべきものが、調査対象によって説得力を与えられる必要があるときに生じる。 これらの5つの論法に関して、第1番目と第3番目は以前のアエネシデムスの10態様の短い要約であり[13]、追加された3つの論法はピュロニスト体系に おける進歩を示しており、感覚と意見の誤りから派生した反論をより抽象的で形而上学的な根拠へと発展させている。ヴィクトル・ブロシャールによれば、「5 つの主題は、懐疑主義を最も先鋭的かつ正確に定式化したものとみなすことができる。ある意味で、それらは今日でも抵抗できない」[15]。 行動の基準 ピュロニストによる意思決定は、ピュロニストが「見かけに従った行動の基準」と表現するものに従って行われる: 自然の導き。それによって、人間は生まれながらにして感覚と思考を持つことができる。 飢えが人を食べ物に向かわせ、喉の渇きが人を飲ませる、情念の強制。 習慣と掟の伝承。これによって私たちは、生活行為における敬虔さが善であり、不謹慎さが悪であることを受け入れる。 テクネ[16]の教え 懐疑主義者の格言 ピュロニストたちは、修行者たちの心を判断停止に導くために、いくつかの格言(ギリシャ語のΦΩΝΩΝ)を考案した[17]: それ以上でもそれ以上でもない(デモクリトスの格言[18])。 非主張(失語症) おそらく、それは可能である。 私は同意を保留する 私は何も決定しない(モンテーニュはこれを変形して、自身の座右の銘 「Que sais-je? 」を作った。- 私は何を知っているのか?) すべては不確定である すべては理解できない 私は理解しない すべての議論には、同じ議論が対立する |

| Texts Except for the works of Sextus Empiricus, the texts of ancient Pyrrhonism have been lost. There is a summary of the Pyrrhonian Discourses by Aenesidemus, preserved by Photius, and a brief summary of Pyrrho's teaching by Aristocles, quoting Pyrrho's student Timon preserved by Eusebius: 'The things themselves are equally indifferent, and unstable, and indeterminate, and therefore neither our senses nor our opinions are either true or false. For this reason then we must not trust them, but be without opinions, and without bias, and without wavering, saying of every single thing that it no more is than is not, or both is and is not, or neither is nor is not.[19] |

テキスト セクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作を除いて、古代のピュローニズムのテキストは失われてしまった。Photiusによって保存されている AenesidemusによるPyrrhonian Discoursesの要約と、Eusebiusによって保存されているピュローの弟子Timonを引用したAristoclesによるピュローの教えの 簡単な要約がある: 物事そのものは等しく無関心であり、不安定であり、不確定である。したがって、我々の感覚も我々の意見も、真でも偽でもない。だからこそ、私たちはそれら を信用せず、意見を持たず、偏見を持たず、揺らぐことなく、あらゆる事物について、それはあるともないともいえず、あるともないともいえず、あるともない ともいえず、あるともないともいえないと言わなければならない」[19]。 |