ピュロニズムあるいはフュロン主義

Pyrrhonism

☆ピュ ロニズム(Pyrrhonism)とは、古代ギリシャの哲学的懐疑 主義の一派で、ドグマを否定し、あらゆる信念の真偽に対する判断の停止を提唱する。紀元前1世紀にアエネシデムスによって創始され、紀元前4世紀にはピュ ローとフリウスのティモンの教えに触発されたと言われている。ピュロニズムは、紀元前2世紀末から3世紀初頭に書かれたセクストゥス・エンピリクスの現存 する著作によって今日最もよく知られている。ルネサンス期にセクストゥスの著作が出版されると、懐疑主義への関心が再燃し、宗教改革思想や近世哲学の発展 に大きな役割を果たした。

| Pyrrhonism is an

Ancient Greek school of philosophical skepticism which rejects dogma

and advocates the suspension of judgement over the truth of all

beliefs. It was founded by Aenesidemus in the first century BCE, and

said to have been inspired by the teachings of Pyrrho and Timon of

Phlius in the fourth century BCE. Pyrrhonism is best known today

through the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus, writing in the late

second century or early third century CE. The publication of Sextus'

works in the Renaissance ignited a revival of interest in Skepticism

and played a major role in Reformation thought and the development of

early modern philosophy. |

ピュロニズム(Pyrrhonism)とは、古代ギリシャの哲学的懐疑

主義の一派で、ドグマを否定し、あらゆる信念の真偽に対する判断の停止を提唱する。紀元前1世紀にアエネシデムスによって創始され、紀元前4世紀にはピュ

ローとフリウスのティモンの教えに触発されたと言われている。ピュロニズムは、紀元前2世紀末から3世紀初頭に書かれたセクストゥス・エンピリクスの現存

する著作によって今日最もよく知られている。ルネサンス期にセクストゥスの著作が出版されると、懐疑主義への関心が再燃し、宗教改革思想や近世哲学の発展

に大きな役割を果たした。 |

| History Pyrrhonism is named after Pyrrho of Elis, a Greek philosopher in the 4th century BCE who was credited by the later Pyrrhonists with forming the first comprehensive school of skeptical thought. However, ancient testimony about the philosophical beliefs of the historical Pyrrho is minimal, and often contradictory:[1] his teachings were recorded by his student Timon of Phlius, but those works have been lost, and only survive in fragments quoted by later authors, and based on testimonies of later authors such as Cicero, Pyrrho's own philosophy as recorded by Timon may have been much more dogmatic than that of the later school who bore his name.[1] While Pyrrhonism would become the dominant form of skepticism in the early Roman period, in the Hellenistic period, the Platonic Academy was the primary advocate of skepticism until the mid-first century BCE,[3] when Pyrrhonism as a philosophical school was founded by Aenesidemus.[1][4] |

歴史 ピュロニズムは、紀元前4世紀のギリシャの哲学者エリスのピュロ(Pyrho)にちなんで命名された。ピュロニズムは、懐疑思想の最初の包括的な学派を形 成したと後のピュロニストたちに信じられている。しかし、歴史上のピュローの哲学的信条に関する古代の証言はごくわずかであり、しばしば矛盾している。 [1]彼の教えは弟子のフリウスのティモンによって記録されているが、それらの著作は失われており、後世の著者が引用した断片が残っているだけである。ま た、キケロなどの後世の著者の証言によれば、ティモンによって記録されたピュロー自身の哲学は、彼の名を冠した後世の学派の哲学よりもはるかに独断的で あった可能性がある。 [1]ピュローニズムが初期ローマ時代において懐疑主義の支配的な形態となる一方で、ヘレニズム時代においては、前1世紀半ばに哲学学派としてのピュロー ニズムがアエネシデムスによって創設されるまで[3]、プラトン学派が懐疑主義の主要な提唱者であった[1][4]。 |

| Philosophy The goal of Pyrrhonism is ataraxia,[5] an untroubled and tranquil condition of soul that results from a suspension of judgement, a mental rest owing to which we neither deny nor affirm anything. Pyrrhonists dispute that the dogmatists – which includes all of Pyrrhonism's rival philosophies – claim to have found truth regarding non-evident matters, and that these opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) are what prevent one from attaining eudaimonia. For any of these dogma, a Pyrrhonist makes arguments for and against such that the matter cannot be concluded, thus suspending judgement, and thereby inducing ataraxia. Pyrrhonists can be subdivided into those who are ephectic (engaged in suspension of judgment), aporetic (engaged in refutation)[6] or zetetic (engaged in seeking).[7] An ephectic merely suspends judgment on a matter, "balancing perceptions and thoughts against one another,"[8] It is a less aggressive form of skepticism, in that sometimes "suspension of judgment evidently just happens to the sceptic".[9] An aporetic skeptic, in contrast, works more actively towards their goal, engaging in the refutation of arguments in favor of various possible beliefs in order to reach aporia, an impasse, or state of perplexity,[10] which leads to suspension of judgement.[9] Finally, the zetetic claims to be continually searching for the truth but to have thus far been unable to find it, and thus continues to suspend belief while also searching for reason to cease the suspension of belief. Modes Although Pyrrhonism's objective is ataraxia, it is best known for its epistemological arguments. The core practice is through setting argument against argument. To aid in this, the Pyrrhonist philosophers Aenesidemus and Agrippa developed sets of stock arguments known as "modes" or "tropes." The ten modes of Aenesidemus Aenesidemus is considered the creator of the ten tropes of Aenesidemus (also known as the ten modes of Aenesidemus)—although whether he invented the tropes or just systematized them from prior Pyrrhonist works is unknown. The tropes represent reasons for suspension of judgment. These are as follows:[11] Different animals manifest different modes of perception; Similar differences are seen among individual men; For the same man, information perceived with the senses is self-contradictory Furthermore, it varies from time to time with physical changes In addition, this data differs according to local relations Objects are known only indirectly through the medium of air, moisture, etc. These objects are in a condition of perpetual change in colour, temperature, size and motion All perceptions are relative and interact one upon another Our impressions become less critical through repetition and custom All men are brought up with different beliefs, under different laws and social conditions According to Sextus, superordinate to these ten modes stand three other modes: that based on the subject who judges (modes 1, 2, 3 & 4), that based on the object judged (modes 7 & 10), that based on both subject who judges and object judged (modes 5, 6, 8 & 9), and superordinate to these three modes is the mode of relation.[12] The five modes of Agrippa These "tropes" or "modes" are given by Sextus Empiricus in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism. According to Sextus, they are attributed only "to the more recent skeptics" and it is by Diogenes Laërtius that we attribute them to Agrippa.[13] The five tropes of Agrippa are: Dissent – The uncertainty demonstrated by the differences of opinions among philosophers and people in general. Infinite regress – All proof rests on matters themselves in need of proof, and so on to infinity. Relation – All things are changed as their relations become changed, or, as we look upon them from different points of view. Assumption – The truth asserted is based on an unsupported assumption. Circularity – The truth asserted involves a circularity of proofs. According to the mode deriving from dispute, we find that undecidable dissension about the matter proposed has come about both in ordinary life and among philosophers. Because of this we are not able to choose or to rule out anything, and we end up with suspension of judgement. In the mode deriving from infinite regress, we say that what is brought forward as a source of conviction for the matter proposed itself needs another such source, which itself needs another, and so ad infinitum, so that we have no point from which to begin to establish anything, and suspension of judgement follows. In the mode deriving from relativity, as we said above, the existing object appears to be such-and-such relative to the subject judging and to the things observed together with it, but we suspend judgement on what it is like in its nature. We have the mode from hypothesis when the Dogmatists, being thrown back ad infinitum, begin from something which they do not establish but claim to assume simply and without proof in virtue of a concession. The reciprocal mode occurs when what ought to be confirmatory of the object under investigation needs to be made convincing by the object under investigation; then, being unable to take either in order to establish the other, we suspend judgement about both.[14] With reference to these five tropes, that the first and third are a short summary of the earlier Ten Modes of Aenesidemus.[13] The three additional ones show a progress in the Pyrrhonist system, building upon the objections derived from the fallibility of sense and opinion to more abstract and metaphysical grounds. According to Victor Brochard "the five tropes can be regarded as the most radical and most precise formulation of skepticism that has ever been given. In a sense, they are still irresistible today."[15] Criteria of action Pyrrhonist decision making is made according to what the Pyrrhonists describe as the criteria of action holding to the appearances, without beliefs in accord with the ordinary regimen of life based on: the guidance of nature, by which we are naturally capable of sensation and thought the compulsion of the passions by which hunger drives us to food and thirst makes us drink the handing down of customs and laws by which we accept that piety in the conduct of life is good and impiety bad instruction in techne[16] Skeptic sayings The Pyrrhonists devised several sayings (Greek ΦΩΝΩΝ) to help practitioners bring their minds to suspend judgment.[17] Among these are: Not more, nothing more (a saying attributed to Democritus[18]) Non-assertion (aphasia) Perhaps, it is possible, maybe I withhold assent I determine nothing (Montaigne created a variant of this as his own personal motto, "Que sais-je?" – "what do I know?") Everything is indeterminate Everything is non-apprehensible I do not apprehend To every argument an equal argument is opposed |

哲学 ピュロニズムの目標はアタラクシア[5]であり、判断の停止、つまり何も否定も肯定もしない精神的な休息から生じる、悩みのない静謐な魂の状態である。 ピュロニストたちは、ピュロニズムのすべての対立哲学を含むドグマティストたちが、自明でない事柄に関して真理を発見したと主張し、自明でない事柄に関す るこれらの意見(すなわちドグマ)こそが、人がエウダイモニアに到達するのを妨げるものであると主張する。ピュロニストは、これらのドグマについて、結論 が出ないような賛否両論を展開し、判断を保留し、アタラクシアを誘発する。 ピュロニストは、ephectic(判断の停止に従事する)、aporetic(反論に従事する)[6]、zetetic(探求に従事する)[7]のいず れかに細分化される。ephecticは単にある事柄に対する判断を停止し、「知覚と思考のバランスをとる」[8]。 [これとは対照的に、無神論的懐疑論者はより積極的に目標に向か い、判断の停止につながるアポリア(袋小路、当惑の状態)[10]に到達す るために、様々な可能性のある信念を支持する論証の反駁に従事する。 様式 ピュロニズムの目的はアタラクシアであるが、認識論的な議論で最もよく知られている。中心的な実践は、議論に議論をぶつけることである。これを助けるため に、ピュロニズムの哲学者アエネシデムスとアグリッパは、"モード "または "トロペ "として知られる論証のセットを開発した。 アエネシデムスの10のモード アエネシデムスは、アエネシデムスの10の論法(アエネシデムスの10のモードとも呼ばれる)の創始者と考えられているが、彼がこの論法を発明したのか、 それともピュロン派の先行著作から体系化したのかは不明である。この類型は判断を保留する理由を表している。それらは以下の通りである[11]。 動物によって知覚の様式は異なる; 同様の違いが個々の人間にも見られる; 同じ人間であっても、感覚によって知覚される情報は自己矛盾している。 さらに、それは身体的な変化によって時々刻々と変化する。 さらに、このデータは局所的な関係によって異なる。 物体は、空気や湿気などを媒介として間接的にしかわからない。 これらの物体は、色、温度、大きさ、動きにおいて、絶え間なく変化する状態にある。 すべての知覚は相対的であり、互いに影響し合っている。 私たちの印象は、繰り返しと習慣によって、あまり批判的にならなくなる。 人はみな、さまざまな法律や社会的条件のもとで、さまざまな信念をもって育つ セクストゥスによれば、これら10の態様の上位に、判断する主体に基づく態様(態様1、2、3、4)、判断される対象に基づく態様(態様7、10)、判断 する主体と判断される対象の両方に基づく態様(態様5、6、8、9)、そしてこれら3つの態様の上位に位置するのが関係の態様である[12]。 アグリッパの5つのモード これらの「様態」または「モード」は、セクストゥス・エンピリクスが『ピュロニズム概論』(Outlines of Pyrrhonism)の中で示している。セクストゥスによれば、それらは「より最近の懐疑論者にのみ」帰せられるものであり、アグリッパに帰せられるの はディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによるものである[13]: 異論 - 哲学者や一般の人々の意見の違いによって示される不確実性。 無限後退 - すべての証明は、証明の必要な事柄そのものにかかっており、無限に続く。 関係 - すべての物事は、その関係が変化するにつれて、あるいは異なる視点から見るにつれて変化する。 仮定 - 主張された真理は、裏付けのない仮定に基づいている。 循環性 - 主張される真理は、証明の循環性を伴う。 論争に由来する態様によれば、私たちは、提案された問題についての決定不可能な論争が、日常生活においても哲学者の間でも生じていることに気づく。そのた め、私たちは何かを選択することも排除することもできず、判断の停止に陥ってしまう。無限後退に由来する様式では、提案された事柄を納得させる源泉として 持ち出されたもの自体が、別のそのような源泉を必要とし、その源泉自体もまた別の源泉を必要とし、このように無限に続くので、何かを立証し始める時点がな くなり、判断の停止が続くと言う。相対性から派生する様式では、先に述べたように、現存する対象は、判断する主体や、それとともに観察されるものに対して 相対的にそのように見えるが、それが本質的にどのようなものであるかについては判断を保留する。ドグマティストたちが、無限に引き戻されながら、自分たち が立証することなく、譲歩のゆえに単純に、証明することなく仮定すると主張する何かから始めるとき、われわれは仮説からの様式を持つ。相互モードは、調査 対象の確証となるべきものが、調査対象によって説得力を与えられる必要があるときに生じる。 これらの5つの論法に関して、第1番目と第3番目は以前のアエネシデムスの10態様の短い要約であり[13]、追加された3つの論法はピュロニスト体系に おける進歩を示しており、感覚と意見の誤りから派生した反論をより抽象的で形而上学的な根拠へと発展させている。ヴィクトル・ブロシャールによれば、「5 つの主題は、懐疑主義を最も先鋭的かつ正確に定式化したものとみなすことができる。ある意味で、それらは今日でも抵抗できない」[15]。 行動の基準 ピュロニストによる意思決定は、ピュロニストが「見かけに従った行動の基準」と表現するものに従って行われる: 自然の導き。それによって、人間は生まれながらにして感覚と思考を持つことができる。 飢えが人を食べ物に向かわせ、喉の渇きが人を飲ませる、情念の強制。 習慣と掟の伝承。これによって私たちは、生活行為における敬虔さが善であり、不謹慎さが悪であることを受け入れる。 テクネ[16]の教え 懐疑主義者の格言 ピュロニストたちは、修行者たちの心を判断停止に導くために、いくつかの格言(ギリシャ語のΦΩΝΩΝ)を考案した[17]: それ以上でもそれ以上でもない(デモクリトスの格言[18])。 非主張(失語症) おそらく、それは可能である。 私は同意を保留する 私は何も決定しない(モンテーニュはこれを変形して、自身の座右の銘 "Que sais-je? "を作った。- 私は何を知っているのか?) すべては不確定である すべては理解できない 私は理解しない すべての議論には、同じ議論が対立する |

| Texts Except for the works of Sextus Empiricus, the texts of ancient Pyrrhonism have been lost. There is a summary of the Pyrrhonian Discourses by Aenesidemus, preserved by Photius, and a brief summary of Pyrrho's teaching by Aristocles, quoting Pyrrho's student Timon preserved by Eusebius: 'The things themselves are equally indifferent, and unstable, and indeterminate, and therefore neither our senses nor our opinions are either true or false. For this reason then we must not trust them, but be without opinions, and without bias, and without wavering, saying of every single thing that it no more is than is not, or both is and is not, or neither is nor is not.[19] |

テキスト セクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作を除いて、古代のピュローニズムのテキストは失われてしまった。Photiusによって保存されている AenesidemusによるPyrrhonian Discoursesの要約と、Eusebiusによって保存されているピュローの弟子Timonを引用したAristoclesによるピュローの教えの 簡単な要約がある: 物事そのものは等しく無関心であり、不安定であり、不確定である。したがって、我々の感覚も我々の意見も、真でも偽でもない。だからこそ、私たちはそれら を信用せず、意見を持たず、偏見を持たず、揺らぐことなく、あらゆる事物について、それはあるともないともいえず、あるともないともいえず、あるともない ともいえず、あるともないともいえないと言わなければならない」[19]。 |

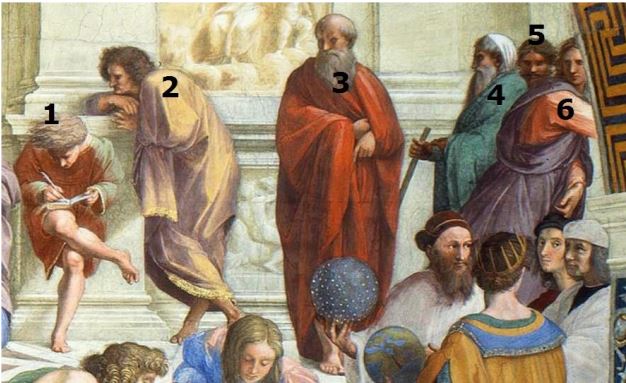

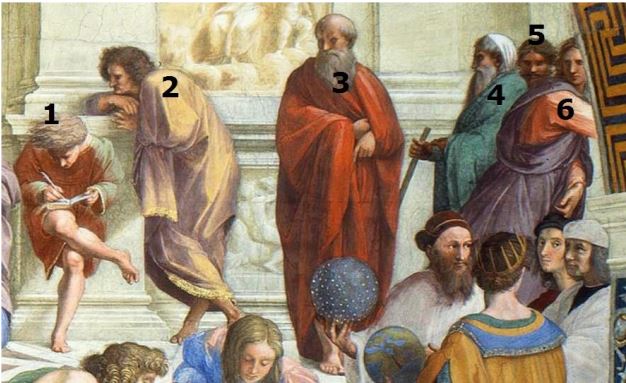

| Influence In Ancient Greek philosophy  Skeptics in Raphael's School of Athens painting. Pyrrho is #4 and Timon #5 Pyrrhonism is often contrasted with Academic skepticism, a similar but distinct form of Hellenistic philosophical skepticism.[9][20][21] While early Academic skepticism was influenced in part by Pyrrho,[22] it grew more and more dogmatic until Aenesidemus broke with the Academics to revive Pyrrhonism in the first century BCE, denouncing the Academy as "Stoics fighting against Stoics.[23]" Some later Pyrrhonists, such as Sextus Empiricus, go so far as to claim that Pyrrhonists are the only real skeptics, dividing all philosophy into the dogmatists, the Academics, and the skeptics.[20] Dogmatists claim to have knowledge, Academic skeptics claim that knowledge is impossible, while Pyrrhonists assent to neither proposition, suspending judgment on both.[9][20][24] The second century Roman historian Aulus Gellius describes the distinction as "...the Academics apprehend (in some sense) the very fact that nothing can be apprehended, and they determine (in some sense) that nothing can be determined, whereas the Pyrrhonists assert that not even that seems to be true, since nothing seems to be true.[25][21]" Sextus Empiricus also said that the Pyrrhonist school influenced and had substantial overlap with the Empiric school of medicine, but that Pyrrhonism had more in common with the Methodic school in that it "follow[s] the appearances and take[s] from these whatever seems expedient."[26] Although Julian the Apostate[27] mentions that Pyrrhonism had died out at the time of his writings, other writers mention the existence of later Pyrrhonists. Pseudo-Clement, writing around the same time (c. 300-320 CE) mentions Pyrrhonists in his Homilies[28] and Agathias even reports a Pyrrhonist named Uranius as late as the middle of the 6th century CE.[29] Similarities between Pyrrhonism and Indian philosophy  Nagarjuna, a Madhyamaka Buddhist philosopher whose skeptical arguments are similar to those preserved in the work of Sextus Empiricus According to Diogenes Laërtius, Pyrrho was said to have traveled to India with Alexander the Great's army where Pyrrho was said to have studied with the magi and the gymnosophists,[30] and where he may have been influenced by Buddhist teachings,[31] most particularly the three marks of existence.[32] Scholars who argue for such influence mention the fact that even the ancient author Diogenesis Laërtius states as much, when he wrote that Pyrrho “foregathered with the Indian Gymnosophists and with the Magi. This led him to adopt a most noble philosophy."[31] According to Christopher I. Beckwith's analysis of the Aristocles Passage, adiaphora (anatta), astathmēta (dukkha), and anepikrita (anicca) are strikingly similar to the Buddhist three marks of existence,[32] indicating that Pyrrho's teaching is based on Buddhism. Beckwith contends that the 18 months Pyrrho spent in India were long enough to learn a foreign language, and that the key innovative tenets of Pyrrho's skepticism were only found in Indian philosophy at the time and not in Greece.[33] Other similarities between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism include a version of the tetralemma among the Pyrrhonist maxims, and more significantly, the idea of suspension of judgement and how that can lead to peace and liberation, ataraxia in Pyrrhonism and nirvana in Buddhism.[34][35] Furthermore, Buddhist philosopher Jan Westerhoff says "many of Nāgārjuna's arguments concerning causation bear strong similarities to classical sceptical arguments as presented in the third book of Sextus Empiricus's Outlines of Pyrrhonism,"[36] and Thomas McEvilley suspects that Nagarjuna may have been influenced by Greek Pyrrhonist texts imported into India.[37] McEvilley argues for mutual iteration in the Buddhist logico-epistemological traditions between Pyrrhonism and Madhyamika: An extraordinary similarity, that has long been noticed, between Pyrrhonism and Mādhyamika is the formula known in connection with Buddhism as the fourfold negation (Catuṣkoṭi) and which in Pyrrhonic form might be called the fourfold indeterminacy.[38] McEvilley also notes a correspondence between the Pyrrhonist and Madhyamaka views about truth, comparing Sextus' account[39] of two criteria regarding truth, one which judges between reality and unreality, and another which we use as a guide in everyday life. By the first criteria, nothing is either true or false, but by the second, information from the senses may be considered either true or false for practical purposes. As Edward Conze[40] has noted, this is similar to the Madhyamika Two Truths doctrine, a distinction between "Absolute truth" (paramārthasatya), "the knowledge of the real as it is without any distortion,"[41] and "Truth so-called" (saṃvṛti satya), "truth as conventionally believed in common parlance.[41][42]  Map of Alexander the Great's empire and the route he and Pyrrho took to India However, other scholars, such as Stephen Batchelor[43] and Charles Goodman[44] question Beckwith's conclusions about the degree of Buddhist influence on Pyrrho. Conversely, while critical of Beckwith's ideas, Kuzminsky sees credibility in the hypothesis that Pyrrho was influenced by Buddhism, even if it cannot be safely ascertained with our current information.[31] While discussing Christopher Beckwith's claims in Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, Jerker Blomqvist states that: On the other hand, certain elements that are generally regarded as essential features of Buddhism are entirely absent from ancient Pyrrhonism/scepticism. The concepts of good and bad karma must have been an impossibility in the Pyrrhonist universe, if "things" were ἀδιάφορα, 'without a logical self-identity', and, consequently, could not be differentiated from each other by labels such as 'good' and 'bad' or 'just' and 'unjust'. A doctrine of rebirth, reminiscent of the Buddhist one though favored by Plato and Pythagoras, was totally alien to the Pyrrhonists. The ἀταραξία, 'undisturbedness', that the Pyrrhonists promised their followers, may have a superficial resemblance to the Buddhist nirvana, but ἀταραξία, unlike nirvana, did not involve a liberation from a cycle of reincarnation; rather, it was a mode of life in this world, blessed with μετριοπάθεια, 'moderation of feeling' or 'moderate suffering', not with the absence of any variety of pain. Kuzminski, whom Beckwith hails as a precursor of his, had largely ignored the problem with this disparity between Buddhism and Pyrrhonism.[45] Ajñana, which upheld radical skepticism, may have been a more powerful influence on Pyrrho than Buddhism. The Buddhists referred to Ajñana's adherents as Amarāvikkhepikas or "eel-wrigglers", due to their refusal to commit to a single doctrine.[46] Scholars including Barua, Jayatilleke, and Flintoff, contend that Pyrrho was influenced by, or at the very least agreed with, Indian skepticism rather than Buddhism or Jainism, based on the fact that he valued ataraxia, which can be translated as "freedom from worry".[47][48][49] Jayatilleke, in particular, contends that Pyrrho may have been influenced by the first three schools of Ajñana, since they too valued freedom from worry.[50] Modern  Balance scales in equal balance are a modern symbol of Pyrrhonism The recovery and publication of the works of Sextus Empiricus, particularly a widely influential translation by Henri Estienne published in 1562,[51] ignited a revival of interest in Pyrrhonism.[51] Philosophers of the time used his works to source their arguments on how to deal with the religious issues of their day. Major philosophers such as Michel de Montaigne, Marin Mersenne, and Pierre Gassendi later drew on the model of Pyrrhonism outlined in Sextus Empiricus' works for their own arguments. This resurgence of Pyrrhonism has sometimes been called the beginning of modern philosophy.[51] Montaigne adopted the image of a balance scale for his motto,[52] which became a modern symbol of Pyrrhonism.[citation needed] It has also been suggested that Pyrrhonism provided the skeptical underpinnings that René Descartes drew from in developing his influential method of Cartesian doubt and the associated turn of early modern philosophy towards epistemology.[51] In the 18th century, David Hume was also considerably influenced by Pyrrhonism, using "Pyrrhonism" as a synonym for "skepticism."[53][better source needed].  Nietzsche was critical of Pyrrhonian ephectics. Friedrich Nietzsche, however, criticized the "ephetics" of the Pyrrhonists as a flaw of early philosophers, who he characterized as "shy little blunderer[s] and milquetoast[s] with crooked legs" prone to overindulging "his doubting drive, his negating drive, his wait-and-see ('ephectic') drive, his analytical drive, his exploring, searching, venturing drive, his comparing, balancing drive, his will to neutrality and objectivity, his will to every sine ira et studio: have we already grasped that for the longest time they all went against the first demands of morality and conscience?"[54] Contemporary Fallibilism is a modern, fundamental perspective of the scientific method, as put forth by Karl Popper and Charles Sanders Peirce, that all knowledge is, at best, an approximation, and that any scientist always must stipulate this in her or his research and findings. It is, in effect, a modernized extension of Pyrrhonism.[55] Indeed, historic Pyrrhonists sometimes are described by modern authors as fallibilists and modern fallibilists sometimes are described as Pyrrhonists.[56] The term "neo-Pyrrhonism" is used to refer to modern Pyrrhonists such as Benson Mates and Robert Fogelin.[57][58] |

影響 古代ギリシャ哲学  ラファエロの「アテネの学校」に描かれた懐疑論者たち。ピュローは4番、ティモンは5番。 ピュローニズムはしばしばヘレニズム哲学の懐疑主義の類似した、しかし別個の形式であるアカデミズム懐疑主義と対比される[9][20][21]。初期の アカデミズム懐疑主義はピュローの影響を一部受けていたが[22]、前1世紀にアエネシデムスがアカデミズムを「ストア派と戦うストア派」[23]として 非難し、ピュローニズムを復活させるためにアカデミズムと決別するまで、それはますます教条的になっていった。後世のピュローニストの中には、セクストゥ ス・エンピリクスのように、ピュローニストだけが真の懐疑論者であると主張し、すべての哲学を教条主義者、学問主義者、懐疑論者に分けている者もいる。 [9][20][24]2世紀のローマの歴史家アウルス・ゲリウスはこの区別を「...アカデミズム派は(ある意味で)何も理解できないという事実そのも のを理解し、(ある意味で)何も決定できないということを決定する。 セクストゥス・エンピリクスもまた、ピュロニスト学派はエンピリック学派の医学に影響を与え、それと実質的に重なる部分があったが、ピュロニズムは「外見 に従い、都合のよさそうなものは何でもそこから取る」という点で、メソドリック学派と共通点が多かったと述べている[26]。 背教者ユリアヌス[27]は、彼の著作が書かれた時点でピュロニズムは消滅していたと述べているが、他の著者は後世のピュロニストの存在に言及している。 同時期(紀元300年頃~320年頃)に書かれた偽クレメンスは、その『論説』の中でピュロニア主義者について言及しており[28]、アガティアスは紀元 6世紀中頃にはウラニウスというピュロニア主義者を報告している[29]。 ピュロニズムとインド哲学の類似性  マディヤマカ仏教の哲学者であるナーガールジュナの懐疑論は、セクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作に残されているものと類似している。 ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによれば、ピュローはアレクサンダー大王の軍隊とともにインドに渡り、そこでピュローは魔術師や体操術師とともに学んだとさ れ[30]、仏教の教え、特に存在の3つの印[31]に影響を受けた可能性がある。 [32] そのような影響を主張する学者たちは、古代の著者ディオゲネシス・ラエルティウスでさえ、ピュローが「インドのジムノソフィストやマギと集った。このこと が彼に最も崇高な哲学を採用させた」[31]。 クリストファー・I・ベックウィズによる『アリストクレスの一節』の分析によれば、アディアフォラ(anatta)、アスタスメータ(dukkha)、ア ネピクリタ(anicca)は仏教の存在の三徴と驚くほど似ており[32]、ピュローの教えが仏教に基づいていることを示している。ベックウィズは、ピュ ローがインドで過ごした18ヶ月は外国語を学ぶのに十分な期間であり、ピュローの懐疑論の重要な革新的教義は当時のインド哲学にしかなく、ギリシャにはな かったと主張している[33]。 [33]ピュローニズムと仏教の他の類似点としては、ピュローニズムの格言の中に四連荘厳のバージョンがあり、より重要な点として、判断の停止と、それが どのように平和と解脱、ピュローニズムにおけるアタラクシアと仏教における涅槃につながるかという考え方がある[34][35]。 さらに仏教哲学者のヤン・ウェスターホフは、「因果関係に関するナーガールジュナの議論の多くは、セクストゥス・エンピリクスの『ピュロニズム概論』の第 3巻に提示されている古典的な懐疑論と強い類似性を持っている」と述べており[36]、トーマス・マッケヴィリーは、ナーガールジュナがインドに輸入され たギリシアのピュロニズムのテキストの影響を受けたのではないかと疑っている[37]。 [マッケビリーは、ピュロン主義とマディヤミカの間の仏教論理学・認識論の伝統における相互反復を論じている: ピュロニズムとマディヤミカの間には、仏教との関連で四重否定(Catuṣkoṭi)として知られ、ピュロニズム的な形式では四重不確定性 (fourfold indeterminacy)と呼ばれるかもしれない公式があり、長い間注目されてきた驚くべき類似性がある」[38]。 マッケヴィリーはまた、真理に関する2つの基準、1つは現実と非現実を判断する基準であり、もう1つは日常生活において指針として用いる基準であるという セクストゥスの説明[39]を比較しながら、真理に関するピュロロン派とマディヤマカの見解の間に対応関係があることを指摘している。第一の基準では、何 事も真か偽かのいずれでもないが、第二の基準では、感覚からの情報は実用的な目的のために真か偽かのいずれかと見なされることがある。エドワード・コン ツェ[40]が指摘しているように、これはマディヤミカの「二つの真理」の教義に類似しており、「絶対的な真理」(paramārthasatya)、 「いかなる歪みもないありのままの現実の知識」[41]と「いわゆる真理」(saṃvṛti satya)、「一般的な言い回しで慣習的に信じられている真理」[41][42]との区別である。  アレキサンダー大王の帝国地図と、彼とピュローがインドに向かったルート しかし、スティーヴン・バチェラー[43]やチャールズ・グッドマン[44]のような他の学者は、ピューロに対する仏教の影響の度合いに関するベックウィ ズの結論に疑問を呈している。逆に、クズミンスキーはベックウィズの考えに批判的である一方で、ピュローが仏教の影響を受けていたという仮説には、現在の 情報では安全に確認できないとしても信憑性があると見ている[31]。 クリストファー・ベックウィズの主張を『ギリシアの仏陀』で論じている: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia』の中で、クリストファー・ベックウィズの主張を論じながら、イェルカー・ブロムクヴィストは次のように述べている: 他方、一般に仏教の本質的な特徴と見なされているある要素は、古代のピュローニズム/懐疑主義にはまったく見られない。もし「物事」がἀδιάφορα、 「論理的な自己同一性を持たない」ものであり、その結果、「善」と「悪」、「正義」と「不義」といったラベルによって互いに区別することができないのであ れば、善悪のカルマという概念はピュロニズムの世界では不可能であったに違いない。プラトンやピュタゴラスが好んだとはいえ、仏教を彷彿とさせる再生の教 義は、ピュロニストにとってはまったく異質なものであった。ピュロニストたちが信奉者に約束したἀταραξία は、仏教の涅槃と表面的には似ているかもしれないが、ἀταραξία は涅槃とは異なり、輪廻転生のサイクルからの解放を意味しない; むしろそれは、μετριοπάθεια、「中庸の感情」あるいは「中庸の苦しみ」に祝福された現世の生活様式であって、さまざまな苦痛がないわけではな い。クズミンスキーはベックウィズの先駆者であるが、仏教とピュロン教の間のこの不一致の問題をほとんど無視していた[45]。 急進的な懐疑主義を支持するアジュニャーナは、仏教よりもピュローに強い影響を与えたかもしれない。バルア、ジャヤティレケ、フリントフなどの学者は、 ピューロは仏教やジャイナ教よりもむしろインドの懐疑主義の影響を受けていた、あるいは少なくともそれに賛同していたと主張している。 [47][48][49]特にジャヤティレケは、ピュローはアジュニャーナの最初の3つの学派の影響を受けている可能性があると主張している。 近代  ピュローニズムの現代的な象徴である均等なバランスの天秤 セクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作、特に1562年に出版されたアンリ・エスティエンヌによる広く影響力のある翻訳[51]が回収・出版されたことで、 ピュロニズムへの関心が再び高まった。 当時の哲学者たちは、当時の宗教的問題にどのように対処すべきかについて、彼の著作を論拠としていた。ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ、マリン・メルセンヌ、 ピエール・ガッサンディといった主要な哲学者たちは、後にセクストゥス・エンピリクスの著作に概説されているピュロニズムのモデルを自らの議論のために利 用した。このピュロニズムの復活は近代哲学の始まりと呼ばれることもある[51]。モンテーニュは自身のモットーに天秤秤のイメージを採用し[52]、 ピュロニズムの近代的なシンボルとなった。 [18世紀にはデイヴィッド・ヒュームもピュロニズムの影響をかなり受けており、「懐疑主義」の同義語として「ピュロニズム」を使用していた[53][要 出典]。  ニーチェはピュロン派の予言的態度に批判的であった。 しかし、フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、ピュロン派の「エフェティシズム」を初期の哲学者の欠点として批判していた、 否定衝動、様子見(「エフェクティック」)衝動、分析衝動、探求・探索・冒険衝動、比較・均衡衝動、中立性・客観性への意志、あらゆるシネイラとスタジオ への意志: 長い間、それらはすべて道徳と良心の最初の要求に反していたことを、われわれはすでに理解しているのだろうか? "[54] 現代 Fallibilismとは、カール・ポパーとチャールズ・サンダース・パイアースが提唱した科学的手法の現代的で基本的な観点であり、すべての知識はせ いぜい近似値であり、いかなる科学者もその研究や発見において常にこのことを規定しなければならないというものである。実際、歴史的なピュロニストたち は、現代の著者たちによってフォリビリスト(fallibilist)と表現されることがあり、現代のフォリビリストたちはピュロニストと表現されること がある[56]。 ネオ・ピュロニズム」という用語は、ベンソン・メイツやロバート・フォゲリンのような現代のピュロニストを指すのに用いられる[57][58]。 |

| Ajñana Apophasis Apophatic theology Cognitive closure (philosophy) Cratylism De Docta Ignorantia Defeatism Quietism Buddhism and the Roman world Greco-Buddhism Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations E-Prime Nassim Nicholas Taleb Trivialism The Hedgehog and the Fox List of unsolved problems in philosophy |

アジュニャーナ アポファシス アポファシス神学 認知的閉鎖(哲学) クラティリズム デ・ドクタ・イグノランティア 敗北主義 静寂主義 仏教とローマ世界 ギリシャ仏教 古代ギリシャと古代インドの関係 Eプライム ナシーム・ニコラス・タレブ 些細なこと ハリネズミとキツネ 哲学における未解決問題のリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrrhonism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆