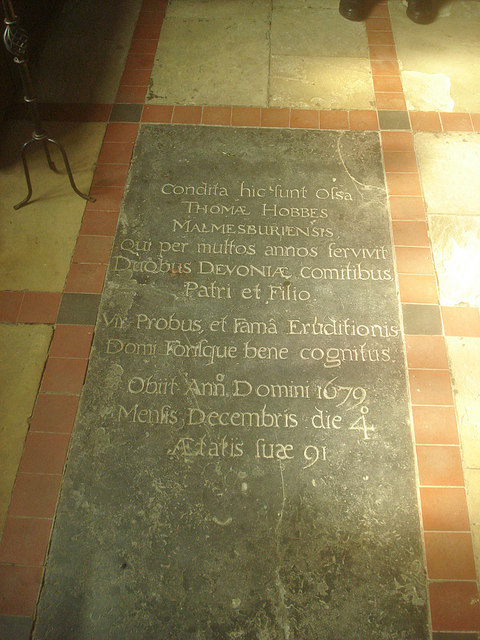

Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1679

トーマス・ホッブス

Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1679

トマス・ホッブズ(Thomas Hobbes、1588 年4月15日 - 1679年12月14日)はイギリスの哲学者。ホッブズは1651年に著した『リヴァイアサン』(Leviathan)で最もよく知られており、この本の 中で社会契約論の影響力のある定式化が説かれている。政治哲学に加えて、ホッブズは哲学全般だけでなく、歴史学、法学、幾何学、神学、倫理学など、多様な 分野に貢献した。彼は近代政治哲学の創始者の一人と考えられている。ホッブズはマルムズベリーで生まれ育ち、オックスフォード大学を経て1608年にケン ブリッジ大学を卒業。その後、キャベンディッシュ家の家庭教師となる。1641年にフランスからイギリスに戻ったホッブズは、1642年から1651年に かけて、議会派と王党派の間で起こったイギリス内戦の破壊と残虐さを目の当たりにし、『リヴァイアサン』における絶対君主による統治の主張に大きな影響を 与えた。リヴァイアサンは、社会契約論以外にも、自然状態(「万人の万人に対する戦争」)や自然法則といった考え方を広めた。リヴァイアサンの他の主な著 作には、三部作『De Cive』(1642年)、『De Corpore』(1655年)、『De Homine』(1658年)、遺作『Behemoth』(1681年)などがある。

★

| Thomas Hobbes

(/hɒbz/ HOBZ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English

philosopher. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, in which

he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory.[5] In

addition to political philosophy, Hobbes contributed to a diverse array

of other fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, theology,

and ethics, as well as philosophy in general. He is considered to be

one of the founders of modern political philosophy.[6][7] Hobbes was born and raised in Malmesbury and attended the University of Oxford before graduating from the University of Cambridge in 1608. He then became a tutor to the Cavendish family. After returning to England from France in 1641, Hobbes witnessed the destruction and brutality of the English Civil War from 1642 to 1651 between Parliamentarians and Royalists, which heavily influenced his advocacy for governance by an absolute sovereign in Leviathan. Aside from social contract theory, Leviathan also popularized ideas such as the state of nature ("war of all against all") and laws of nature. His other major works include the trilogy De Cive (1642), De Corpore (1655), and De Homine (1658) as well as the posthumous work Behemoth (1681). |

トマス・ホッブズ(Thomas Hobbes、/hɒ

HOBZ、1588年4月15日 -

1679年12月14日)はイギリスの哲学者。ホッブズは1651年に著した『リヴァイアサン』(Leviathan)で最もよく知られており、この本の

中で社会契約論の影響力のある定式化が説かれている[5]。政治哲学に加えて、ホッブズは哲学全般だけでなく、歴史学、法学、幾何学、神学、倫理学など、

多様な分野に貢献した。彼は近代政治哲学の創始者の一人と考えられている[6][7]。 ホッブズはマルムズベリーで生まれ育ち、オックスフォード大学を経て1608年にケンブリッジ大学を卒業。その後、キャベンディッシュ家の家庭教師とな る。1641年にフランスからイギリスに戻ったホッブズは、1642年から1651年にかけて、議会派と王党派の間で起こったイギリス内戦の破壊と残虐さ を目の当たりにし、『リヴァイアサン』における絶対君主による統治の主張に大きな影響を与えた。リヴァイアサンは、社会契約論以外にも、自然状態(「万人 の万人に対する戦争」)や自然法則といった考え方を広めた。 リヴァイアサンの他の主な著作には、三部作『De Cive』(1642年)、『De Corpore』(1655年)、『De Homine』(1658年)、遺作『Behemoth』(1681年)などがある。 |

| Biography Early life Thomas Hobbes was born on 5 April 1588 (Old Style), in Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. Having been born prematurely when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, Hobbes later reported that "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear."[8] Hobbes had a brother, Edmund, about two years older, as well as a sister, Anne. Although Thomas Hobbes's childhood is unknown to a large extent, as is his mother's name,[9] it is known that Hobbes's father, Thomas Sr., was the vicar of both Charlton and Westport. Hobbes's father was uneducated, according to John Aubrey, Hobbes's biographer, and he "disesteemed learning."[10] Thomas Sr. was involved in a fight with the local clergy outside his church, forcing him to leave London. As a result, the family was left in the care of Thomas Sr.'s older brother, Francis, a wealthy glove manufacturer with no family of his own. |

略歴 生い立ち トマス・ホッブズは1588年4月5日(旧暦)、イングランドのウェストポート(現在はウィルトシャーのマルムズベリーの一部)で生まれた。スペイン艦隊 の侵攻を知った母親が早産したため、ホッブズは後に「私の母は双子を産んだ:私と恐怖を」[8]と報告している。 トマス・ホッブズの幼少期は母親の名前と同様に不明な点が多いが[9]、ホッブズの父トマス・シニアがチャールトンとウェストポートの牧師であったことは 知られている。ホッブズの伝記作家ジョン・オーブリーによれば、ホッブズの父親は無学で、「学問を軽んじていた」[10]。その結果、一家はトーマス・シ ニアの兄で裕福な手袋製造業者のフランシスに預けられることになり、フランシスは自分の家族を持たなかった。 |

|

Education Hobbes Jr. was educated at Westport church from age four, passed to the Malmesbury school, and then to a private school kept by a young man named Robert Latimer, a graduate of the University of Oxford.[11] Hobbes was a good pupil, and between 1601 and 1602 he went up to Magdalen Hall, the predecessor to Hertford College, Oxford, where he was taught scholastic logic and mathematics.[12][13][14] The principal, John Wilkinson, was a Puritan and had some influence on Hobbes. Before going up to Oxford, Hobbes translated Euripides' Medea from Greek into Latin verse.[10] At university, Thomas Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum as he was little attracted by the scholastic learning.[11] Leaving Oxford, Hobbes completed his B.A. degree by incorporation at St John's College, Cambridge, in 1608.[15] He was recommended by Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, as tutor to William, the son of William Cavendish,[11] Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl of Devonshire), and began a lifelong connection with that family.[16] William Cavendish was elevated to the peerage on his father's death in 1626, holding it for two years before his death in 1628. His son, also William, likewise became the 3rd Earl of Devonshire. Hobbes served as a tutor and secretary to both men. The 1st Earl's younger brother, Charles Cavendish, had two sons who were patrons of Hobbes. The elder son, William Cavendish, later 1st Duke of Newcastle, was a leading supporter of Charles I during the civil war personally financing an army for the king, having been governor to the Prince of Wales, Charles James, Duke of Cornwall. It was to this William Cavendish that Hobbes dedicated his Elements of Law.[10] Hobbes became a companion to the younger William Cavendish and they both took part in a grand tour of Europe between 1610 and 1615. Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during the tour, in contrast to the scholastic philosophy that he had learned in Oxford. In Venice, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, an associate of Paolo Sarpi, a Venetian scholar and statesman.[10] His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at a careful study of classic Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of which was, in 1628, his great translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War,[11] the first translation of that work into English from a Greek manuscript. It has been argued that three of the discourses in the 1620 publication known as Horae Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses also represent the work of Hobbes from this period.[17] Although he did associate with literary figures like Ben Jonson and briefly worked as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, translating several of his Essays into Latin,[10] he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629. In June 1628, his employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague, and his widow, the countess Christian, dismissed Hobbes.[18][19] |

教育 ホッブズ・ジュニアは4歳からウェストポート教会で教育を受け、マルムズベリー校を経て、オックスフォード大学を卒業したロバート・ラティマーという青年 が経営する私塾に通った[11]。 [校長のジョン・ウィルキンソンはピューリタンで、ホッブズに影響を与えた。オックスフォードに上がる前、ホッブズはエウリピデスの『メデア』をギリシャ 語からラテン語に訳した[10]。 大学では、トマス・ホッブズは自分自身のカリキュラムに従ったようで、スコラ学にはほとんど魅力を感じなかった[11]。オックスフォードを去ったホッブ ズは、1608年にケンブリッジのセント・ジョンズ・カレッジで編入学により学士号を取得。 [15]マグダレン校での師であったジェームズ・ハッセー卿の推薦で、ハードウィック男爵(後のデヴォンシャー伯爵)ウィリアム・キャヴェンディッシュ [11]の息子ウィリアムの家庭教師となり、同家との生涯のつながりが始まった[16]。息子のウィリアムも同様に第3代デヴォンシャー伯爵となった。 ホッブズは二人の家庭教師や秘書を務めた。第1伯爵の弟チャールズ・キャベンディッシュには、ホッブズの後援者であった2人の息子がいた。長男のウィリア ム・キャヴェンディッシュ(後の第1代ニューカッスル公)は、内戦中、チャールズ1世の有力な支持者であり、コーンウォール公チャールズ・ジェームス・ ウェールズ皇太子の知事として、国王のために自ら軍に資金を提供した。ホッブズが『法の要素』[10]を献呈したのは、このウィリアム・キャヴェンディッ シュであった。 ホッブズは若きウィリアム・キャヴェンディッシュの伴侶となり、二人は1610年から1615年にかけてのヨーロッパ大旅行に参加した。ホッブズはこの旅 行で、オックスフォードで学んだスコラ哲学とは対照的に、ヨーロッパの科学的・批判的手法に触れた。ヴェネツィアでは、ホッブズはヴェネツィアの学者であ り政治家であったパオロ・サルピの同僚であったフルゲンツィオ・ミカンツィオと知り合いになった[10]。 当時のホッブズの学術的な努力は、古典的なギリシア語やラテン語の著者の入念な研究を目的としたものであり、その成果として1628年にトゥキュディデス の『ペロポネソス戦争史』を大々的に翻訳した[11]。Horae Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses』として知られる1620年の出版物に収録された3つの言説も、この時期のホッブズの著作であると論じられている[17]。 ホッブズはベン・ジョンソンのような文学者と交際し、短期間フランシス・ベーコンの助手として彼の『エッセイ』のいくつかをラテン語に翻訳していたが [10]、1629年以降になるまで哲学の分野に力を入れることはなかった。1628年6月、当時デヴォンシャー伯爵であった雇い主のキャヴェンディッ シュがペストで亡くなり、未亡人のクリスチャン伯爵夫人はホッブズを解雇した[18][19]。 |

|

In Paris (1629–1637) Hobbes soon (in 1629) found work as a tutor to Gervase Clifton, the son of Sir Gervase Clifton, 1st Baronet, mostly spent in Paris, until November 1630.[20] Thereafter, he again found work with the Cavendish family, tutoring William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, the eldest son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven years, as well as tutoring, he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy, awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Galileo Galilei in Florence while he was under house arrest upon condemnation, in 1636, and was later a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.[18] Hobbes's first area of study was an interest in the physical doctrine of motion and physical momentum. Despite his interest in this phenomenon, he disdained experimental work as in physics. He went on to conceive the system of thought to the elaboration of which he would devote his life. His scheme was first to work out, in a separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion, at least as motion or mechanical action was then understood. He then singled out Man from the realm of Nature and plants. Then, in another treatise, he showed what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions whereby Man came into relation with Man. Finally, he considered, in his crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued how this must be regulated if people were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery". Thus he proposed to unite the separate phenomena of Body, Man, and the State.[18] |

パリ時代(1629年-1637年) ホッブズは間もなく(1629年)、第1男爵サー・ゲルヴェーズ・クリフトンの息子であるゲルヴェーズ・クリフトンの家庭教師の仕事を見つけ、1630年 11月まで主にパリで過ごした[20]。その後7年間、家庭教師と並行して哲学の知識を深め、重要な哲学論争に対する好奇心を目覚めさせた。1636年に は、ガリレオ・ガリレイが断罪されて軟禁されている間にフィレンツェを訪れ、その後、マリン・メルセンヌが主催するパリの哲学グループの常連討論者となっ た[18]。 ホッブズの最初の研究分野は、運動と物理的運動量に関する物理学的教義への関心であった。この現象への関心にもかかわらず、彼は物理学のような実験的作業 を軽んじた。その後、ホッブズは生涯を捧げることになる思想体系を構想した。彼の構想は、まず別個の論文で、身体に関する体系的な教義を構築し、物理現象 がいかに普遍的に、少なくとも当時理解されていた運動や機械的作用の観点から説明可能であるかを示すことだった。そして、自然や植物の領域から人間を除外 した。そして別の論考で、感覚、知識、感情、情念といった、人間と人間との関係において特有の現象を生み出すのに、具体的にどのような身体運動が関わって いるかを示した。そして最後に、彼はその頂点に立つ論文で、人間がどのように社会に入るように動かされるかを考察し、人々が「残忍さと悲惨さ」に逆戻りし ないためには、これをどのように規制しなければならないかを論じた。こうして彼は、身体、人間、国家という別々の現象を統合することを提案した[18]。 |

|

In England (1637–1641) Hobbes came back home from Paris, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent, which disrupted him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan.[18] However, by the end of the Short Parliament in 1640, he had written a short treatise called The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic. It was not published and only circulated as a manuscript among his acquaintances. A pirated version, however, was published about ten years later. Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the sitting of the Short Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly mark the influences of the rising political crisis. Nevertheless, many (though not all) elements of Hobbes's political thought were unchanged between The Elements of Law and Leviathan, which demonstrates that the events of the English Civil War had little effect on his contractarian methodology. However, the arguments in Leviathan were modified from The Elements of Law when it came to the necessity of consent in creating political obligation: Hobbes wrote in The Elements of Law that Patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were. This was perhaps a reflection either of Hobbes's thoughts about the engagement controversy or of his reaction to treatises published by Patriarchalists, such as Sir Robert Filmer, between 1640 and 1651.[citation needed] When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was in disfavour due to the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris. He did not return for 11 years. In Paris, he rejoined the coterie around Mersenne and wrote a critique of the Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes, which was printed as third among the sets of "Objections" appended, with "Replies" from Descartes, in 1641. A different set of remarks on other works by Descartes succeeded only in ending all correspondence between the two.[21] Hobbes also extended his own works in a way, working on the third section, De Cive, which was finished in November 1641. Although it was initially only circulated privately, it was well received, and included lines of argumentation that were repeated a decade later in Leviathan. He then returned to hard work on the first two sections of his work and published little except a short treatise on optics (Tractatus opticus), included in the collection of scientific tracts published by Mersenne as Cogitata physico-mathematica in 1644. He built a good reputation in philosophic circles and in 1645 was chosen with Descartes, Gilles de Roberval and others to referee the controversy between John Pell and Longomontanus over the problem of squaring the circle.[21] |

英国時代(1637年-1641年) 1637年、パリから帰国したホッブズは、不平不満に苛まれるイギリスを目の当たりにし、彼の哲学的計画の秩序ある実行を妨げることになった[18]。し かし、1640年の短期議会が終わるまでに、彼は『自然法および政治法の要素』という短い論文を書き上げていた。これは出版されず、彼の知人の間で手稿と して流通しただけであった。しかし、約10年後に海賊版が出版された。法の要素』の大部分は、短命議会が開かれる前に書かれたと思われるが、政治的危機の 高まりの影響をはっきりと示す極論的な部分もある。とはいえ、ホッブズの政治思想の多くの要素(すべてではないが)は、『法の要素』と『リヴァイアサン』 の間で変わっておらず、イギリス内戦の出来事がホッブズの契約論的方法論にほとんど影響を与えなかったことを示している。しかし、『リヴァイアサン』にお ける議論は、政治的義務の発生における同意の必要性に関しては、『法の要素』から変更されている: ホッブズは『法の要素』の中で、愛国王国は必ずしも被支配者の同意によって形成されるものではないと書いたが、『リヴァイアサン』の中では同意によって形 成されると主張した。これはおそらく、婚約論争に対するホッブズの考え、あるいは1640年から1651年にかけてサー・ロバート・フィルマーなどの家父 長制論者が出版した論考に対するホッブズの反応のいずれかを反映したものであった[要出典]。 1640年11月、長議会が短議会を引き継ぐと、ホッブズは彼の論考の流通によって不利な立場に立たされたと感じ、パリに逃亡した。ホッブズは11年間帰 らなかった。パリでは、メルセンヌ周辺の同人たちに再び加わり、デカルトの『第一哲学瞑想録』に対する批評を書いた。この批評は、デカルトの「反論」とと もに1641年に印刷された。デカルトの他の著作に対する別の論考は、二人の間のやりとりをすべて終わらせることに成功した[21]。 ホッブズはまた、自身の著作をある意味で拡張し、1641年11月に完成した第三部『デ・シーヴ』に取り組んだ。当初は内々にしか配布されなかったが、好 評を博し、10年後の『リヴァイアサン』で繰り返される論旨が含まれていた。1644年にメルセンヌが『Cogitata physico-mathematica』として出版した科学論文集に収録された光学に関する短い論考(Tractatus opticus)以外はほとんど出版しなかった。1645年には、デカルト、ジル・ド・ロベルヴァルらとともに、円の二乗の問題をめぐるジョン・ペルとロ ンゴモンタヌスの論争の審判に選ばれた[21]。 |

|

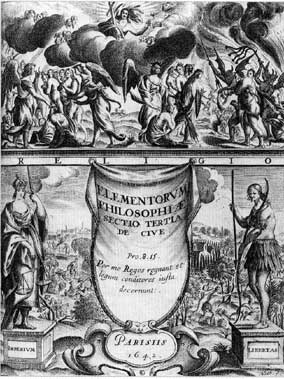

Civil War Period (1642–1651) The English Civil War began in 1642, and when the royalist cause began to decline in mid-1644, many royalists came to Paris and were known to Hobbes.[21] This revitalised Hobbes's political interests, and the De Cive was republished and more widely distributed. The printing began in 1646 by Samuel de Sorbiere through the Elsevier press in Amsterdam with a new preface and some new notes in reply to objections.[21] In 1647, Hobbes took up a position as mathematical instructor to the young Charles, Prince of Wales, who had come to Paris from Jersey around July. This engagement lasted until 1648 when Charles went to Holland.[21]  Frontispiece from De Cive (1642) The company of the exiled royalists led Hobbes to produce Leviathan, which set forth his theory of civil government in relation to the political crisis resulting from the war. Hobbes compared the State to a monster (leviathan) composed of men, created under pressure of human needs and dissolved by civil strife due to human passions. The work closed with a general "Review and Conclusion", in response to the war, which answered the question: Does a subject have the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect is irrevocably lost?[21] During the years of composing Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647, he suffered a near-fatal illness that disabled him for six months.[21] On recovering, he resumed his literary task and completed it by 1650. Meanwhile, a translation of De Cive was being produced; scholars disagree about whether it was Hobbes who translated it.[22] In 1650, a pirated edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic was published.[23] It was divided into two small volumes: Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie; and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick.[22] In 1651, the translation of De Cive was published under the title Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society.[24] Also, the printing of the greater work proceeded, and finally appeared in mid-1651, titled Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil. It had a famous title-page engraving depicting a crowned giant above the waist towering above hills overlooking a landscape, holding a sword and a crozier and made up of tiny human figures. The work had immediate impact.[22] Soon, Hobbes was more lauded and decried than any other thinker of his time.[22] The first effect of its publication was to sever his link with the exiled royalists, who might well have killed him.[22] The secularist spirit of his book greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics.[22] Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government for protection and fled back to London in winter 1651.[22] After his submission to the Council of State, he was allowed to subside into private life[22] in Fetter Lane.[citation needed] |

内戦期 (1642-1651) 1642年にイングランド内戦が始まり、1644年半ばに王党派が衰退し始めると、多くの王党派がパリを訪れ、ホッブズの知るところとなった[21]。印 刷は1646年にサミュエル・ド・ソルビエールによってアムステルダムのエルゼヴィア印刷所を通じて開始され、新しい序文と反論に対するいくつかの新しい 注釈が加えられた[21]。 1647年、ホッブズは、7月頃にジャージー島からパリにやってきた若きチャールズ皇太子の数学指導教官の職に就いた。この職はチャールズがオランダに渡 る1648年まで続いた[21]。  『デ・シーヴ』(1642年)の扉絵 追放された王党派の仲間たちによって、ホッブズは『リヴァイアサン』を著すことになる。ホッブズは国家を人間からなる怪物(リヴァイアサン)になぞらえ、 人間の必要性に迫られて創造され、人間の情念による内紛によって解消されるとした。この作品は、戦争に対応した「総説と結論」で幕を閉じ、次の問いに答え ている: 臣民は、かつての主権者の保護する力が回復不能なまでに失われたとき、忠誠を変更する権利を有するのか? リヴァイアサン』の執筆期間中、ホッブズはパリかパリ近郊に滞在していた。1647年、ホッブズは瀕死の重傷を負い、6ヶ月間動けなくなったが[21]、 回復してからは執筆を再開し、1650年までに完成させた。その間、『デ・シーヴ』の翻訳が作られていたが、それを翻訳したのがホッブズであったかどうか については学者の間でも意見が分かれている[22]。 1650年、『自然法および政治法の要素』の海賊版が出版された[23]: 人間の本性、あるいは政治の基本的要素』と『政治的身体、あるいは道徳的、政治的な法の要素』である[22]。 1651年、『デ・シーヴ』の翻訳が『政府と社会に関する哲学的初歩』というタイトルで出版された[24]。また、より大きな著作の印刷が進められ、最終 的に1651年半ばに『リヴァイアサン』(Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil)というタイトルで出版された。有名なタイトルページのエングレーヴィングには、風景を見下ろす丘の上にそびえ立つ腰より上の王冠をかぶった巨 人が、剣と矛を持ち、小さな人影で構成されている様子が描かれていた。ホッブズの著作の世俗主義的な精神は、英国国教会とフランスのカトリック教徒の双方 を大いに怒らせた。 [22]ホッブズは革命的なイギリス政府に保護を求め、1651年の冬にロンドンに逃げ帰った[22]。 |

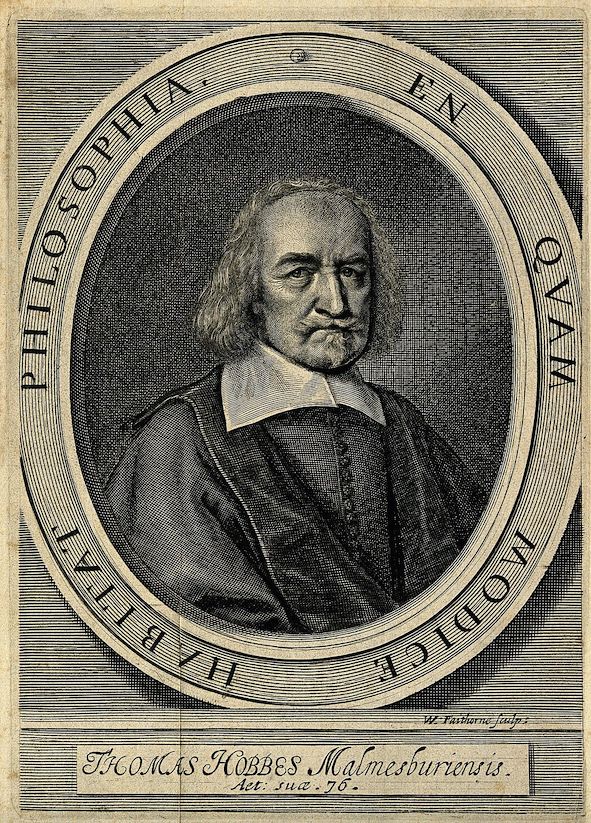

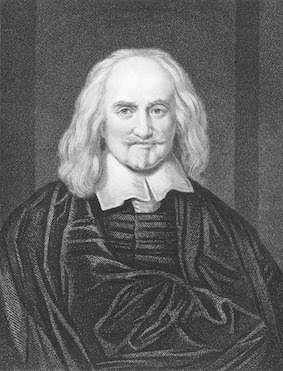

Later life Thomas Hobbes. Line engraving by William Faithorne, 1668 In 1658, Hobbes published the final section of his philosophical system, completing the scheme he had planned more than 20 years before. De Homine consisted for the most part of an elaborate theory of vision. The remainder of the treatise dealt cursorily with some of the topics more fully treated in the Human Nature and the Leviathan. In addition to publishing some controversial writings on mathematics, including disciplines like geometry, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works.[22] From the time of the Restoration, he acquired a new prominence; "Hobbism" became a byword for all that respectable society ought to denounce. The young king, Hobbes's former pupil, now Charles II, remembered Hobbes and called him to the court to grant him a pension of £100.[25] The king was important in protecting Hobbes when, in 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and profaneness. That same year, on 17 October 1666, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred "should be empowered to receive information touching such books as tend to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan."[26] Hobbes was terrified at the prospect of being labelled a heretic, and proceeded to burn some of his compromising papers. At the same time, he examined the actual state of the law of heresy. The results of his investigation were first announced in three short Dialogues added as an Appendix to his Latin translation of Leviathan, published in Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes aimed to show that, since the High Court of Commission had been put down, there remained no court of heresy at all to which he was amenable, and that nothing could be heresy except opposing the Nicene Creed, which, he maintained, Leviathan did not do.[27] The only consequence that came of the bill was that Hobbes could never thereafter publish anything in England on subjects relating to human conduct. The 1668 edition of his works was printed in Amsterdam because he could not obtain the censor's licence for its publication in England. Other writings were not made public until after his death, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662. For some time, Hobbes was not even allowed to respond, whatever his enemies tried. Despite this, his reputation abroad was formidable.[27] Hobbes spent the last four or five years of his life with his patron, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire, at the family's Chatsworth House estate. He had been a friend of the family since 1608 when he first tutored an earlier William Cavendish.[28] After Hobbes's death, many of his manuscripts would be found at Chatsworth House.[29] His final works were an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into "rugged" English rhymes that in 1673 led to a complete translation of both Iliad and Odyssey in 1675.[27] |

その後の人生 トマス・ホッブズ ウィリアム・フェイスーンによる線刻画、1668年 1658年、ホッブズは哲学体系の最終章を発表し、20年以上前に計画していた計画を完成させた。De Homine』の大部分は、精巧な視覚論で構成されていた。残りの部分は、『人間本性』や『リヴァイアサン』でより詳細に扱われているいくつかのテーマに ついて、ざっと扱ったものであった。幾何学のような学問を含む数学に関するいくつかの論議を呼ぶ著作を発表することに加えて、ホッブズは哲学的著作も発表 し続けた[22]。 王政復古の頃から、ホッブズは新たな脚光を浴びるようになり、「ホッブズ主義」は立派な社会が糾弾すべきすべてのものの代名詞となった。ホッブズのかつて の弟子であった若き国王チャールズ2世は、ホッブズを覚えており、宮廷に呼んで100ポンドの年金を与えた[25]。 1666年、下院が無神論と不敬罪に反対する法案を提出したとき、国王はホッブズを保護するために重要な役割を果たした。同年、1666年10月17日、 法案が付託された委員会は、「無神論、冒涜、不敬につながるような書物...特に...『リヴァイアサン』と呼ばれるホッブズ氏の書物...に関する情報 を受け取る権限を与えられるべきである」[26]と命じられた。同時に、彼は異端法の実態を調査した。調査の結果は、1668年にアムステルダムで出版さ れた『リヴァイアサン』のラテン語訳の付録として加えられた3つの短い対話篇で初めて発表された。この付録の中でホッブズは、高等法院が廃止された以上、 自分が従順とする異端法廷がまったく残っていないこと、ニカイア信条に反対すること以外は異端となりえないこと、そしてリヴァイアサンはそれを行っていな いと主張したことを示すことを目的とした[27]。 この法案によってもたらされた唯一の結果は、ホッブズが以後イングランドで人間の行為に関する題材を出版することができなくなったことであった。彼の著作 の1668年版はアムステルダムで印刷されたが、それはイングランドで出版するための検閲官の許可を得ることができなかったからである。1640年から 1662年にかけてのイングランドの内戦の原因や、内戦を遂行するための助言と策略の歴史』(Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by the carried carried on the year 1640 to the year 1662)など、他の著作は彼の死後まで公開されなかった。ホッブズはしばらくの間、敵が何を試みても反論することさえ許されなかった。にもかかわらず、 彼の海外での評判はすこぶる高かった[27]。 ホッブズは人生の最後の4、5年を、彼のパトロンであったデヴォンシャー公爵ウィリアム・キャヴェンディッシュとともに、同家のチャッツワース・ハウスで 過ごした。ホッブズの死後、彼の手稿の多くはチャッツワース・ハウスで発見されることになる[29]。 彼の最後の作品は、1672年のラテン語詩による自伝と、1673年に『オデュッセイア』4巻を「荒々しい」英語韻文に翻訳したもので、1675年には 『イーリアス』と『オデュッセイア』の全訳につながった[27]。 |

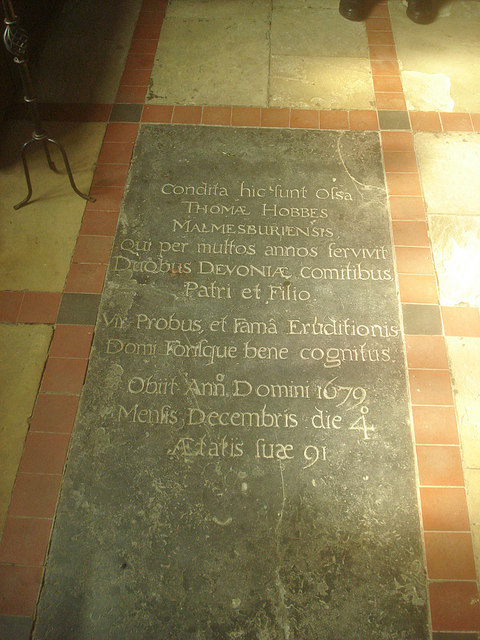

Death Tomb of Thomas Hobbes in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire In October 1679 Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, and then a paralytic stroke, from which he died on 4 December 1679, aged 91,[27][30] at Hardwick Hall, owned by the Cavendish family.[29] His last words were said to have been "A great leap in the dark", uttered in his final conscious moments.[31] His body was interred in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire.[32] |

死 ダービーシャー州オルト・ハックノールの洗礼者ヨハネ教会にあるトマス・ホッブズの墓 1679年10月、ホッブズは膀胱を患い、その後麻痺性脳卒中を起こし、1679年12月4日、キャヴェンディッシュ家が所有するハードウィック・ホール で91歳で死去した[27][30]。 彼の最期の言葉は「暗闇の中での大跳躍」であったと言われており、最後の意識の瞬間に発せられたものであった[31]。 彼の遺体はダービーシャーのオルト・ハックノールの洗礼者聖ヨハネ教会に埋葬された[32]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hobbes |

★トーマス・ホッブス(続き)

ルネ・デ カルト、トーマス・ホッブス、そしてバルー フ(あるいはベネディト)・スピノザの3名(とりわけ前2者)は、17世紀の政治思想や(宗教から世俗への)政治思想における啓蒙哲学の影響を考 えるため の重大な思想家たちです。この3人を同時にならべて年譜にしたのが、このページです。ただし、彼ら(ホッブス+デカルト)より四半世紀以上後代のスピノザ の人生については、ユダヤ人コミュニティからの破門という事情を考えて、同じように並べるのは憚られますが、逆に、彼(スピノザ)は、より根本的 に人間中 心主義の哲学のアイディアをもたらしたという意味で、やはり同列にとりあげ、比較してみると興味深いとおもった次第です——そのためスピノザの年譜は不正 確で、その後の改訂は「スピノザの人生と作品」でおこなっています。

啓蒙は、かく のごとく、人間の自由の不可分でこのましいものだが、それを遂行するためには、啓蒙君主のも とで自由を享受する臣民には、次のようなことが言われなければならない:「好きなだけ、何事についても議論しなさい、ただし(君主に)服従せよ」。そのよ うな逆説が、共和状態の市民の自由には課される。また、精神を多少なりとも制約するほうが精神の自由についてのその能力を発揮するような自由の余地がうま れる。これもまた、啓蒙の逆説である。自由に行動する能力が高まると、統治の原則にまでおよんでゆく。統治者はもはや機械ではない、人間(市民)をそれに ふさわしく処遇することが、自らにとっても有益であることを理解するようになる(→「啓蒙とはなに か?」)。(→「 ホッブス・デカルト・スピノザ」)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆