のうさんてきしぜん〈と〉しょさんてきしぜん、Natura naturans and Natura naturata

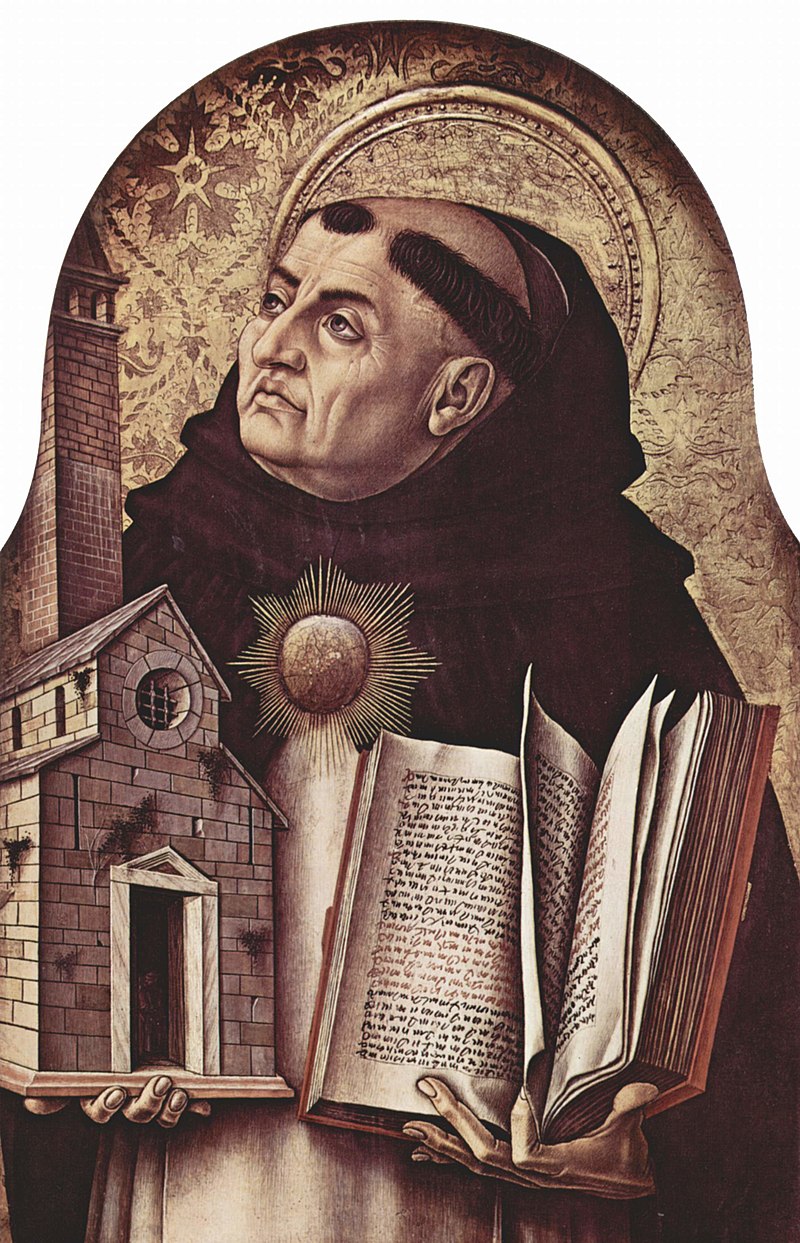

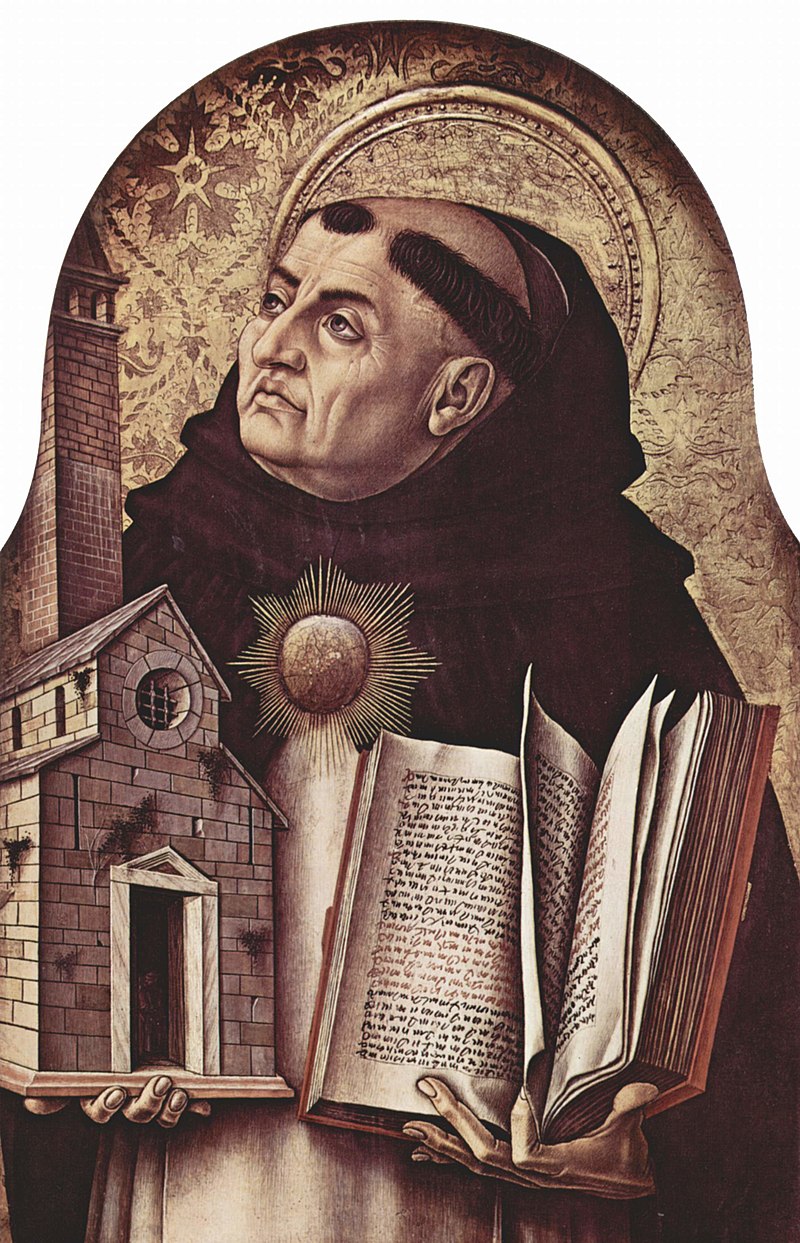

Albertus Magnus, O.P. (c. 1200–1280).

能産的自然と所産的自然

のうさんてきしぜん〈と〉しょさんてきしぜん、Natura naturans and Natura naturata

Albertus Magnus, O.P. (c. 1200–1280).

解説:池田光穂

西洋文明において、人間は自然——ギリシャ語のフュ シス、ラテン語のナトゥーラ——と闘い、自然を克服したという説明を、我々日本人は好む。そして、しばしば「自然と調和したり、対話する」日本的あるいは 東洋的自然観をもちだして、西洋の自然認識との「違い」を持ち出してなんとかそれを説明した気持ち(=理解する)になっている。だが、これはあまりにも西 洋における「自然認識」についての浅薄で一面的な見方である。西洋もまた(たぶん東洋や極東たる「日本」と同様な情熱をもって)「自然とは何か?」につい て深く、そして長期にわたって考えてきたのだ。

その例を、能産的自然(natura naturans)と所産的自然(natura naturata)という2つの自然概念から考察することは、大変興味深い。デカルトによると、神から人間に与えられた認識能力、すなわち「自然の光 (lumen naturale)」により、良識(ボン・サンス)を得ることができるという(『哲学原理』I-30)。この場合の自然は、人間に対峙し克服すべきもので はなく、むしろ逆に人間に与えられる恩寵の一種なのである。自然は、野生につながる野蛮で統御不能な超自然的な秩序であると同時に、人間を人間たらしめる 「理性の働き」でもある。この自然の力がもつ、相矛盾する考え——人間の認識を超える最後は人間に付与される超自然的で人間の能力を超える奇跡的な秩序形 成力と、人間の理性を含めたそのような自然の作用を理解しその帰結としての秩序を反省的に眺めることができる人間の能力——と、その理解が重要なテーマと して浮上してくるのだ。

今道友信からの引用:「恩寵をラテン語ではグラー ティア(gratia)というので、中世のトマス・アクィナス(Thomas Aquinas, ca. 1225-1274)の思想の要約として、しばしば "Gratia naturam non tollit, sed eam perficit"=恩寵は自然を破壊せずこれを完成する、という文章が引用される。これが神としての超自然と人間を含めての自然一般との 関係をあらわし ている。動物はこのナトゥーラすなわち自然の世界にとどまるが、人間はとくに、それを超える営みをすることができる」(今道友信『自然哲学序説』p.19, 講談社学術文庫、1993年)。

能産的自然(蘭:natuurende Natuur)スピノザ『神・人間および人間の幸福に関する短論文』第1部第8章

所産的自然(蘭:genatuurde Natuur)スピノザ『神・人間および人間の幸福に関する短論文』第1部第9章

ルネサンスの自然哲学の考え方の中には、すでにこの 自然は二重の位置を与えれていて、自然に対する神の調停機能の理解として、神は「能産的自然(natura naturans)」、現象世界は「所産的自然(natura naturata)」と捉えて、この矛盾の一致を、神において認識するというものがある。知恵ある無知という考え方を提示したニコラウス・ クザーヌスがそ の例であるが、この用語を明確に区分し、能産的自然に神の位置をあてはめたのはスピノザだという。しかし、この2つの用語の最初の提唱者は、ヴィンデルバ ンドによるとアヴェロイズム(Averroism、アイブン・ルシュド=アヴェロエス ( Averroes, 1126-1198)中世の偉大なアリストテレス註釈者による哲学や思想)に由来するものだという。

| "The original ground of all things, the deity, must therefore lie beyond Being and knowledge; it is above reason, above Being; it has no determination or quality, it is "Nothing." But this" deity" (of negative theology) reveals itself in the triune God, and the God who is and knows creates' out of nothing the creatures whose Ideas he knows within himself; for this knowing is his creating. This process of self-revelation belongs to the essence of the deity; it is hence a timeless necessity, and no ac.t of will in the proper sense of the word is required for God to produce the world. The deity, as productive or generative essence, as "un-natured Nature" [or Nature that has not yet taken on a nature], is real or actual only by knowing and unfolding itself in God and the world as produced reality, as natured Nature. God creates all-said Nicolaus Cusanus -- that is to say, he is all. And on the other hand, according to Eckhart, all things have essence or substance only in so far as they are themselves God; whatever else appears in them as phenomena, their determination in space and time, their" here" and" now" (" Hie" und "Nu," hic et nunc with Thomas), is nothing"(Wildelband 1901:335-336). | 万物の根源である「神」は、存在と知識を超えて存在しなければならず、 理性の上、存在の上にあり、決定や質を持たず、「無」である。しかし、この(否定神学の)"神 "は三位一体の神の中に姿を現し、存在し知っている神は、自らの内にその考えを知っている被造物を無から創り出します;この知ることが彼の創造だからで す。この自己啓示の過程は神の本質に属するものであり、それゆえ、それは時を超えた必然であり、神が世界を生み出すためには、正しい意味での意志の働きは 必要ない。生産的あるいは生成的な本質としての神、「自然でない自然」[あるいはまだ自然を獲得していない自然]としての神は、神と生産された現実として の世界、自然である自然の中で自らを知り、展開することによってのみ、現実あるいは実在となるのである。神はすべてを創造する--とニコラウス・クザーヌ スは言ったが、それはつまり、神がすべてであるということである。一方、エックハルトによれば、万物は、それ自体が神である限りにおいてのみ本質あるいは 実体を持つ。現象としての万物、空間と時間におけるその決定、それらの「ここ」と「今」(トーマスでは「Hie」 und 「Nu」、hic et nunc)に現れる他のものは、何もない」(ヴィルダーバンド 1901:335-336) 。 |

| "The more... in the system of Averroes, matter was regarded as eternally in motion within itself, and as actuated by unity of life, the less could the moving Form be separated from it realiter, and thus the same divine All-being appeared on the one hand as Form and moving force (natura naturans), and on the other hand as matter, as "moved world (natura naturata)."(Wildelband 1901:338). | アヴェロエスの体系において、物質がそれ自身の内部で永遠に運動し、生

命の統一によって作動していると見なされれば見なされるほど、動く形はそこから分離されなくなり、したがって同じ神の万物は、一方では形と動く力

(natura naturans)として、他方では物質として、「動く世界(natura naturata)」として現れた」(ウイルデルバンド

1901:338).... |

| "The conceptions which lie at the basis of this unfolding of the metaphysical fantasy in Bruno had their source in the main "in Nicolaus Cusanus, whose teachings had been preserved by Charles Bouille, though in his exposition they had to some degree lost their vivid freshness. Just this the Nolan knew how to restore. He not only raised the principle of the coincidentia oppositorum to the artistic reconciliation of contrasts, to the harmonious total action of opposing partial forces in the divine primitive essence, but above all he gave to the conceptions of the infinite and the finite a far wider reaching significance. As regards the deity and its relation to the world, the Neo-Platonic relations are essentially retained. God himself, as the unity exalted above all opposites, cannot be apprehended through any finite attribute or qualification, and therefore is unknowable in his own proper essence (negative theology) ; but at the same time he is still thought as the inexhaustible, infinite world-force, as the natura naturans, which in eternal change forms, and "unfolds" itself purposefully and in conformity with law, into the natura naturata."(Wildelband 1901:368). | 「ブルーノにおける形而上学的幻想の展開の根底にある概念は、シャル

ル・ブイユによって保存されたニコラウス・クサヌスにその源を発しているが、彼の解説によって、その鮮明さはいくらか失われていた。しかし、ノーランはこ

れを回復する方法を知っていた。ノーランは、「対立する一致」の原理を、対照の芸術的な調和、神の原初的な本質における対立する部分的な力の調和的な全体

作用にまで高めただけでなく、何よりも無限と有限の概念に、はるかに広い範囲の意味を与えたのである。神とその世界との関係については、新プラトン主義の

関係が基本的に維持されている。神自身は、すべての対立物の上に高められた統一体として、いかなる有限の属性や資格によっても理解されることはなく、した

がって彼自身の本来の本質において知ることができない(否定神学)。しかし同時に彼は、永遠の変化においてそれ自身を形成し、目的を持って、法則に適合し

てナチュラータへと「展開」するナチュラ ナチュランとして、無尽蔵で無限の世界力として依然として考えられている」(ウイルスバンド

1901:368).... |

| "Hence Spinoza can say also that' God consists of countless attributes, or Deus SIVE omnia ejus attributa. (*) * Which, however, is in nowise to be interpreted as if the attributes were self-subsistent prime realities and "God" only the collective name for them (as K. Thomas supposed, Sp. als Metaphysiker, Konigsberg, 1840). Such a crassly nominalistic cap-stone would press the whole system out of joint. | したがってスピノザは、「神は無数の属性からなる」、すなわち

Deus SIVE omnia ejus attributa

とも言うことができた。(しかし、このことは、あたかも属性が自存する素粒子であり、「神」はその総称に過ぎないかのように解釈してはならない(K.

Thomas, Sp. als Metaphysiker, Konigsberg,

1840の考え)。このような粗雑な名辞主義的な定石は、システム全体を破綻させることになる。 |

| And the same relation is afterwards repeated between the attributes and the modes. Every attribute, because it expresses the infinite essence of God in a definite manner, is again infinite in its own way; but it does not exist otherwise than with and in its countless modifications. God then exists only in things as their universal essence, and they only in him as the modes of his reality., In this sense , Spinoza adopts from Nicolaus Cusanus and Giordano Bruno the expressions natura naturans and natura naturata. God is Nature: as the universal world-essence, he is the natura naturans ; as sum-total of the individual things in which this essence exists modified, he is the natura naturata. If in this connection the natura naturans is called occasionally also the efficient cause of things, this creative force must not be thought as something distinct from its workings; this cause exists nowhere but in its workings. This is Spinoza's complete and unreserved pantheism."(Wildelband 1901:409). | そして、属性と様態の間でも同じ関係が繰り返される。あらゆる属性は、

神の無限の本質を明確な方法で表現しているので、それ自体もまた無限である。しかし、それは、その無数の修正とともに、またその修正の中でしか存在しない

のである。この意味でスピノザはニコラウス・クザーヌスやジョルダーノ・ブルーノからナトゥーラ・ナトゥーラスとナトゥーラ・ナトゥラータという表現を採

用している。神は自然である:普遍的な世界本質として、彼はナトゥーラ・ナトゥーランスであり、この本質が修正されて存在する個々のものの総体として、彼

はナトゥーラ・ナトゥーラタである。この関連で、ナチュラ

ナチュランが時折、物事の効率的原因とも呼ばれる場合、この創造力は、その働きとは異なるものと考えてはならない、この原因は、その働きの中以外のどこに

も存在しない。これがスピノザの完全無欠の汎神論である」(ウイルデルバンド 1901:409). |

| "There was a long Western lineage for variants of the doublet natura naturans / natura naturata, a lineage adverted to in Spinoza's remark(quoted in paragraph [b] below) that even the Thomists speak of God as natura naturans. (St. Thomas himself had remarked more cautiously that "certain ones" employed this terminology, thus establishing his own critical distance from it.) Much more to the point for Spinoza's adoption of this pairing, however, was its presence in the textbooks of Heereboord and other current authors studied at Leiden and elsewhere"(Collins 1984:46). | 「natura naturans / natura

naturata という二重引用符の変種には長い西洋の系譜があり、スピノザがトマス派でさえ神を natura naturans

として語っている(下記 [b]

項で引用)ことに言及されている系譜である。(聖トマス自身は、「ある種の者たち」がこの用語を用いていることをより慎重に指摘し、この用語との批判的距

離を確立している)。しかし、スピノザがこの対を採用したのは、ライデンや他の場所で研究されたヘレボルドや他の現役作家の教科書にこの対が存在したこと

がはるかに重要だった」(Collins 1984:46)。 |

| "As far as the pair itself is concerned, Spinoza wants to use it to mark a distinction that never breaks up into a disruption of the unity of nature. The usage of natura naturans / natura naturata signifies most basically an active coupling or knitting together of all the components in nature. Hence it corresponds to the primary, most adequate sense of "the whole of nature." Something would be lacking in the wholeness of nature were only one member of the relationship present. It is this active intrinsic componency that prevents a shredding of nature's integrity. The latter admits of differentiation but not of a one-sided rendering absolute of either the naturing or the natured principle"(Collins 1984:46-47). | 「スピノザはこのペアを、自然の統一を乱すことのない区別を示すために

使いたいと考えています。natura naturans / natura naturata

の用法は、最も基本的には、自然におけるすべての構成要素の能動的な結合または結びつきを意味する。したがって、それは "自然の全体

"の第一の、最も適切な意味に対応する。もし、ある構成要素だけが存在していたら、自然の全体性において何かが欠けてしまうだろう。自然の完全性が寸断さ

れるのを防ぐのは、この積極的な内在的構成要素性である。後者は分化を認めるが、自然化する原理と自然化される原理のどちらかを一方的に絶対化することは

できない」(Collins 1984:46-47)。 |

| 以下は、Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Baruch Spinoza より、なお引用文(翻訳)のIp, I は『倫理学』からの引用 | |

| "There are, Spinoza insists, two sides of Nature. First, there is the active, productive aspect of the universe—God and his attributes, from which all else follows. This is what Spinoza, employing the same terms he used in the Short Treatise, calls Natura naturans, “naturing Nature”. Strictly speaking, this is identical with God. The other aspect of the universe is that which is produced and sustained by the active aspect, Natura naturata, “natured Nature”. | 「スピノザは自然には2つの側面があると主張する。第一に、宇宙の活動

的で生産的な側面、すなわち神とその属性があり、そこから他のすべてが導かれる。スピノザは『小論』で使われたのと同じ用語を用いて、これを「ナトゥー

ラ・ナトゥーラス」(「生れる自然」)と呼んでいる。厳密には、これは神と同一である。宇宙のもう一つの側面は、能動的な側面によって生み出され維持され

るもので、ナトゥーラ・ナトゥラータ、「ナチュラートする自然」である。 |

| By Natura naturata I understand whatever follows from the necessity of God's nature, or from any of God's attributes, i.e., all the modes of God's attributes insofar as they are considered as things that are in God, and can neither be nor be conceived without God. (Ip29s). | ナトゥーラ・ナトゥラータとは、神の本性の必然性から、あるいは神の属

性のいずれかから生じるもの、すなわち、それらが神の中にあるものとして考えられる限りにおいて、神の属性のすべての様式であり、神なしでは存在も発想も

できないものであることを、私は理解する。(Ip29s)である。 |

| There is some debate in the literature about whether God is also to be identified with Natura naturata. Be that as it may, Spinoza's fundamental insight in Book One is that Nature is an indivisible, uncaused, substantial whole—in fact, it is the only substantial whole. Outside of Nature, there is nothing, and everything that exists is a part of Nature and is brought into being by Nature with a deterministic necessity. This unified, unique, productive, necessary being just is what is meant by ‘God’. Because of the necessity inherent in Nature, there is no teleology in the universe. Nature does not act for any ends, and things do not exist for any set purposes. There are no “final causes” (to use the common Aristotelian phrase). God does not “do” things for the sake of anything else. The order of things just follows from God's essences with an inviolable determinism. All talk of God's purposes, intentions, goals, preferences or aims is just an anthropomorphizing fiction. | 文献上では、神もまたナチュラータと同定されるべきかどうかという議論

がある。それはともかく、第1巻におけるスピノザの基本的な洞察は、自然は不可分で、原因のない、実質的な全体である-実際、それは唯一の実質的な全体で

ある-というものである。自然の外には何もなく、存在するすべてのものは自然の一部であり、自然によって決定論的必然性を持って生み出される。この統一さ

れた、ユニークな、生産的な、必要な存在とは、まさに「神」を意味するものです。自然に内在する必然性のために、宇宙には目的論が存在しない。自然はいか

なる目的のためにも行動せず、物事は定められた目的のために存在するのではありません。アリストテレスの言葉を借りれば、「最終原因」は存在しないので

す。神は他の何かのために物事を「行う」ことはない。物事の秩序は、神の本質から不可侵の決定論で導かれるだけである。神の目的、意図、目標、好み、狙い

などの話はすべて擬人化されたフィクションに過ぎない。 |

| All the prejudices I here undertake to expose depend on this one: that men commonly suppose that all natural things act, as men do, on account of an end; indeed, they maintain as certain that God himself directs all things to some certain end, for they say that God has made all things for man, and man that he might worship God. (I, Appendix) | 私がここで暴露しようとするすべての偏見は、この一つに依存している:

人は一般的に、すべての自然物は、人のように、ある目的のために行動すると考える。実際、彼らは、神自身がすべてのものをある特定の目的のために指示して

いると確信し、神が万物を人間のために作り、人間が神を崇拝するようにしたと言う。(一、付録) |

| "Natural law[-> Natural Law] (Latin: ius naturale, lex naturalis) is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independent of positive law (the enacted laws of a state or society).[2] According to natural law theory, all people have inherent rights, conferred not by act of legislation but by "God, nature, or reason."[3] Natural law theory can also refer to "theories of ethics, theories of politics, theories of civil law, and theories of religious morality."[4]"- Thomas Aquinas, a Catholic philosopher of the Middle Ages, revived and developed the concept of natural law from ancient Greek philosophy, - Natural law. | "自然法[-> Natural Law] (Latin:

ius naturale, lex naturalis) , 自然法とは、人

間の本性をよく観察した上で、実定法(国家や社会が制定した法律)とは無関係に推論・適用できる人間本来の価値観に基づく法体系である。自然法論によれ

ば、すべての人は、立法行為ではなく、"神、自然、理性

"によって付与された固有の権利を有するとされる。自然法論は、「倫理学、政治学、民法、宗教道徳の理論」を指すこともある |

source: http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13964-spinoza-baruch-benedict-de-spinoza

知力と重力、ふたりは仲良し

重力の虹ならぬ、虹の重力。恩寵か必然の負債かどう

かはわからないが、地球の生命体に重力という賜物がある。ホモ・サピエンスにとっての知力と同じようなもの。知力は我々の人生を豊かにすると同様に荒廃も

させる。平和に協力するゲームに参加するし、裏で亡き者にする欲望したい誘惑も知力が給備する。スピノザの神(自然)と同じようなものか?呪ってもいけな

いし、また有難がっても愚か。

●The Origine of Natural Law

【再掲】"Natural law[->

Natural

Law]

(Latin: ius naturale, lex naturalis) "-

Thomas Aquinas, a

Catholic philosopher of the Middle Ages, revived and developed the

concept of natural law from ancient Greek philosophy, - Natural law.

【翻訳】"自然法[-> Natural Law] (Latin: ius naturale, lex naturalis)

自然法とは、人間の本性をよく観察した上で、実定法(国家や社会が制定した法律)とは無関係に推論・適用できる人間本来の価値観に基づく法体系である。自

然法論によれば、すべての人は、立法行為ではなく、"神、自然、理性

"によって付与された固有の権利を有するとされる。自然法論は、「倫理学、政治学、民法、宗教道徳の理論」を指すこともある。

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Thomas

Aquinas, by Carlo Crivelli (1430-1495)

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099