エドワード・サピア

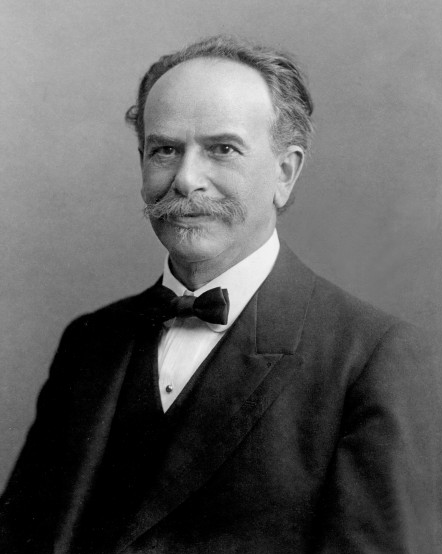

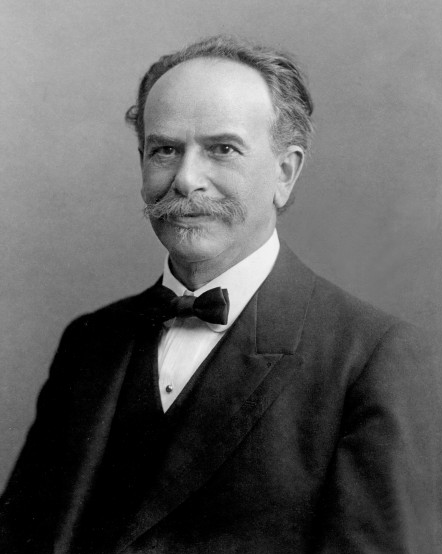

Edward Sapir (1884-1939)

☆ エドワード・サピア(/səˈp↪Ll_26Ar/; 1884年1月26日 - 1939年2月4日)はアメリカの人類学者・言語学者であり、アメリカにおける言語学の発展において最も重要な人物の一人と広く考えられている。

| Edward Sapir

(/səˈpɪər/; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American

anthropologist-linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most

important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics

in the United States.[1][2] Sapir was born in German Pomerania, in what is now northern Poland. His family emigrated to the United States of America when he was a child. He studied Germanic linguistics at Columbia, where he came under the influence of Franz Boas, who inspired him to work on Native American languages. While finishing his Ph.D. he went to California to work with Alfred Kroeber documenting the indigenous languages there. He was employed by the Geological Survey of Canada for fifteen years, where he came into his own as one of the most significant linguists in North America, the other being Leonard Bloomfield. He was offered a professorship at the University of Chicago, and stayed for several years continuing to work for the professionalization of the discipline of linguistics. By the end of his life he was professor of anthropology at Yale. Among his many students were the linguists Mary Haas and Morris Swadesh, and anthropologists such as Fred Eggan and Hortense Powdermaker. With his linguistic background, Sapir became the one student of Boas to develop most completely the relationship between linguistics and anthropology. Sapir studied the ways in which language and culture influence each other, and he was interested in the relation between linguistic differences, and differences in cultural world views. This part of his thinking was developed by his student Benjamin Lee Whorf into the principle of linguistic relativity or the "Sapir–Whorf" hypothesis. In anthropology Sapir is known as an early proponent of the importance of psychology to anthropology, maintaining that studying the nature of relationships between different individual personalities is important for the ways in which culture and society develop.[3] Among his major contributions to linguistics is his classification of Indigenous languages of the Americas, upon which he elaborated for most of his professional life. He played an important role in developing the modern concept of the phoneme, greatly advancing the understanding of phonology. Before Sapir it was generally considered impossible to apply the methods of historical linguistics to languages of indigenous peoples because they were believed to be more primitive than the Indo-European languages. Sapir was the first to prove that the methods of comparative linguistics were equally valid when applied to indigenous languages. In the 1929 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica he published what was then the most authoritative classification of Native American languages, and the first based on evidence from modern comparative linguistics. He was the first to produce evidence for the classification of the Algic, Uto-Aztecan, and Na-Dene languages. He proposed some language families that are not considered to have been adequately demonstrated, but which continue to generate investigation such as Hokan and Penutian. He specialized in the study of Athabascan languages, Chinookan languages, and Uto-Aztecan languages, producing important grammatical descriptions of Takelma, Wishram, Southern Paiute. Later in his career he also worked with Yiddish, Hebrew, and Chinese, as well as Germanic languages, and he also was invested in the development of an International Auxiliary Language. |

エドワード・サピア(/səˈp↪Ll_26Ar/;

1884年1月26日 -

1939年2月4日)はアメリカの人類学者・言語学者であり、アメリカにおける言語学の発展において最も重要な人物の一人と広く考えられている[1]

[2]。 サピアは現在のポーランド北部にあるドイツ領ポメラニアで生まれた。幼少時に家族でアメリカ合衆国に移住。コロンビア大学でゲルマン言語学を学び、そこで フランツ・ボースの影響を受け、アメリカ先住民の言語を研究するようになる。博士号を取得する間、カリフォルニアに行き、アルフレッド・クルーバーととも に現地の先住民の言語を記録する仕事をした。カナダ地質調査所(Geological Survey of Canada)に15年間勤務し、北米で最も重要な言語学者として頭角を現した。シカゴ大学の教授職のオファーを受け、数年間在籍し、言語学という学問の 専門化を目指した。晩年にはイェール大学で人類学の教授を務めた。彼の教え子には、言語学者のメアリー・ハースやモリス・スワデッシュ、人類学者のフレッ ド・エガンやホーテンス・パウダーメイカーなどがいる。 言語学的背景を持つサピアは、言語学と人類学の関係を最も完全に発展させたボースの弟子となった。サピアは言語と文化が互いに影響し合う方法を研究し、言 語の違いと文化的世界観の違いとの関係に興味を持った。彼の思考のこの部分は、弟子のベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフによって言語相対性の原理、あるいは 「サピア・ウォーフ」仮説へと発展した。人類学においては、サピアは人類学における心理学の重要性を早くから提唱した人物として知られており、異なる個人 のパーソナリティ間の関係の本質を研究することは、文化や社会が発展する方法にとって重要であると主張している[3]。 言語学への大きな貢献のひとつに、アメリカ大陸の先住民言語を分類したことが挙げられる。彼は音素の現代的な概念の開発において重要な役割を果たし、音韻 論の理解を大きく前進させた。 サピア以前は、先住民の言語はインド・ヨーロッパ語族よりも原始的であると考えられていたため、歴史言語学の手法を適用することは不可能と考えられてい た。サピアは、比較言語学の方法が先住民の言語に適用されても同様に有効であることを証明した最初の人物である。ブリタニカ百科事典の1929年版で、彼 は当時最も権威のあるアメリカ先住民の言語の分類を発表し、現代の比較言語学の証拠に基づいた最初の分類を発表した。彼はアルギック語、ウト・アステカ 語、ナ・デネ語の分類の証拠を初めて提示した。また、ホカン語やペヌティア語など、十分に実証されたとは考えられていないが、調査が続けられている言語族 をいくつか提唱した。 アサバスカン諸語、チヌーカン諸語、ウト・アステカ諸語の研究を専門とし、タケルマ語、ウィシュラム語、サザン・パイユート語の重要な文法記述を作成し た。その後、イディッシュ語、ヘブライ語、中国語、ゲルマン語の研究にも取り組み、国際補助語の開発にも力を注いだ。 |

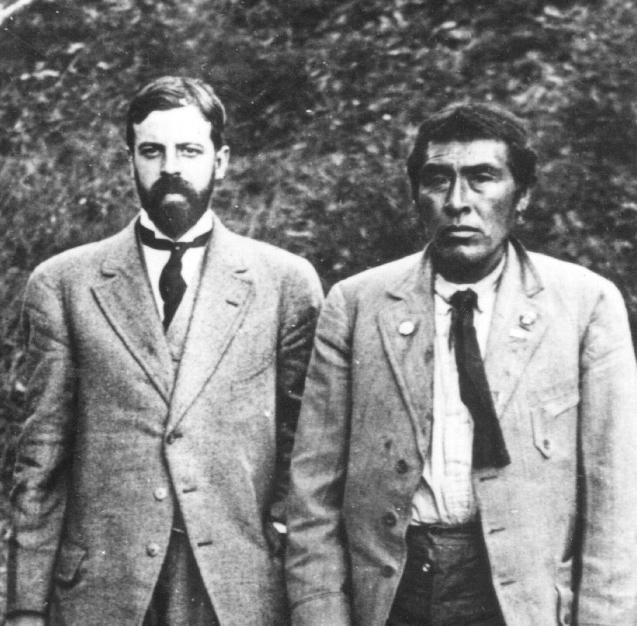

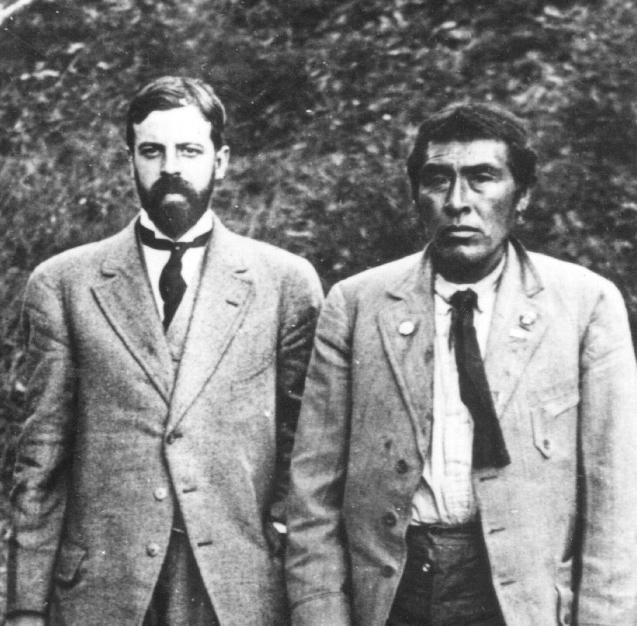

| Life Childhood and youth Sapir was born into a family of Lithuanian Jews in Lauenburg (now Lębork) in the Province of Pomerania where his father, Jacob David Sapir, worked as a cantor. The family was not Orthodox, and his father maintained his ties to Judaism through its music. The Sapir family did not stay long in Pomerania and never accepted German as a nationality. Edward Sapir's first language was Yiddish,[4] and later English. In 1888, when he was four years old, the family moved to Liverpool, England, and in 1890 to the United States, to Richmond, Virginia. Here Edward Sapir lost his younger brother Max to typhoid fever. His father had difficulty keeping a job in a synagogue and finally settled in New York on the Lower East Side, where the family lived in poverty. As Jacob Sapir could not provide for his family, Sapir's mother, Eva Seagal Sapir, opened a shop to supply the basic necessities. They formally divorced in 1910. After settling in New York, Edward Sapir was raised mostly by his mother, who stressed the importance of education for upward social mobility, and turned the family increasingly away from Judaism. Even though Eva Sapir was an important influence, Sapir received his lust for knowledge and interest in scholarship, aesthetics, and music from his father. At age 14 Sapir won a Pulitzer scholarship to the prestigious Horace Mann high school, but he chose not to attend the school which he found too posh, going instead to DeWitt Clinton High School,[5] and saving the scholarship money for his college education. Through the scholarship Sapir supplemented his mother's meager earnings.[4] Columbia Sapir entered Columbia in 1901, still paying with the Pulitzer scholarship. Columbia at this time was one of the few elite private universities that did not limit admission of Jewish applicants with implicit quotas around 12 percent—approximately 40% of incoming students at Columbia were Jewish.[6] Sapir earned both a B.A. (1904) and an M.A. (1905) in Germanic philology from Columbia, before embarking on his Ph.D. in Anthropology which he completed in 1909.[7] College  Columbia University library in 1903 Sapir emphasized language study in his college years at Columbia, studying Latin, Greek, and French for eight semesters. From his sophomore year he additionally began to focus on Germanic languages, completing coursework in Gothic, Old High German, Old Saxon, Icelandic, Dutch, Swedish, and Danish. Through Germanics professor William Carpenter, Sapir was exposed to methods of comparative linguistics that were being developed into a more scientific framework than the traditional philological approach. He also took courses in Sanskrit, and complemented his language studies by studying music in the department of the famous composer Edward MacDowell (though it is uncertain whether Sapir ever studied with MacDowell himself). In his last year in college Sapir enrolled in the course "Introduction to Anthropology", with Professor Livingston Farrand, who taught the Boas "four field" approach to anthropology. He also enrolled in an advanced anthropology seminar taught by Franz Boas, a course that would completely change the direction of his career.[8] Influence of Boas  Franz Boas Although still in college, Sapir was allowed to participate in the Boas graduate seminar on American Languages, which included translations of Native American and Inuit myths collected by Boas. In this way Sapir was introduced to Indigenous American languages while he kept working on his M.A. in Germanic linguistics. Robert Lowie later said that Sapir's fascination with indigenous languages stemmed from the seminar with Boas in which Boas used examples from Native American languages to disprove all of Sapir's common-sense assumptions about the basic nature of language. Sapir's 1905 Master's thesis was an analysis of Johann Gottfried Herder's Treatise on the Origin of Language, and included examples from Inuit and Native American languages, not at all familiar to a Germanicist. The thesis criticized Herder for retaining a Biblical chronology, too shallow to allow for the observable diversification of languages, but he also argued with Herder that all of the world's languages have equal aesthetic potentials and grammatical complexity. He ended the paper by calling for a "very extended study of all the various existing stocks of languages, in order to determine the most fundamental properties of language" – almost a program statement for the modern study of linguistic typology, and a very Boasian approach.[9] In 1906 he finished his coursework, having focused the last year on courses in anthropology and taking seminars such as Primitive Culture with Farrand, Ethnology with Boas, Archaeology and courses in Chinese language and culture with Berthold Laufer. He also maintained his Indo-European studies with courses in Celtic, Old Saxon, Swedish, and Sanskrit. Having finished his coursework, Sapir moved on to his doctoral fieldwork, spending several years in short-term appointments while working on his dissertation.[10] Early fieldwork  Tony Tillohash with family. Tillohash was Sapir's collaborator on the famous description of the Southern Paiute language Sapir's first fieldwork was on the Wishram Chinook language in the summer of 1905, funded by the Bureau of American Ethnology. This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau. Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas. In the summer of 1906 he worked on Takelma and Chasta Costa. Sapir's work on Takelma became his doctoral dissertation, which he defended in 1908. The dissertation foreshadowed several important trends in Sapir's work, particularly the careful attention to the intuition of native speakers regarding sound patterns that later would become the basis for Sapir's formulation of the phoneme.[11] In 1907–1908 Sapir was offered a position at the University of California at Berkeley, where Boas' first student Alfred Kroeber was the head of a project under the California state survey to document the Indigenous languages of California. Kroeber suggested that Sapir study the nearly extinct Yana language, and Sapir set to work. Sapir worked first with Betty Brown, one of the language's few remaining speakers. Later he began work with Sam Batwi, who spoke another dialect of Yana, but whose knowledge of Yana mythology was an important fount of knowledge. Sapir described the way in which the Yana language distinguishes grammatically and lexically between the speech of men and women.[12] The collaboration between Kroeber and Sapir was made difficult by the fact that Sapir largely followed his own interest in detailed linguistic description, ignoring the administrative pressures to which Kroeber was subject, among them the need for a speedy completion and a focus on the broader classification issues. In the end Sapir didn't finish the work during the allotted year, and Kroeber was unable to offer him a longer appointment. Disappointed at not being able to stay at Berkeley, Sapir devoted his best efforts to other work, and did not get around to preparing any of the Yana material for publication until 1910,[13] to Kroeber's deep disappointment.[14] Sapir ended up leaving California early to take up a fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught Ethnology and American Linguistics. At Pennsylvania he worked closely with another student of Boas, Frank Speck, and the two undertook work on Catawba in the summer of 1909.[15] Also in the summer of 1909, Sapir went to Utah with his student J. Alden Mason. Intending originally to work on Hopi, he studied the Southern Paiute language; he decided to work with Tony Tillohash, who proved to be the perfect informant. Tillohash's strong intuition about the sound patterns of his language led Sapir to propose that the phoneme is not just an abstraction existing at the structural level of language, but in fact has psychological reality for speakers. Tillohash became a good friend of Sapir, and visited him at his home in New York and Philadelphia. Sapir worked with his father to transcribe a number of Southern Paiute songs that Tillohash knew. This fruitful collaboration laid the ground work for the classical description of the Southern Paiute language published in 1930,[16] and enabled Sapir to produce conclusive evidence linking the Shoshonean languages to the Nahuan languages – establishing the Uto-Aztecan language family. Sapir's description of Southern Paiute is known by linguistics as "a model of analytical excellence".[17] At Pennsylvania, Sapir was urged to work at a quicker pace than he felt comfortable. His "Grammar of Southern Paiute" was supposed to be published in Boas' Handbook of American Indian Languages, and Boas urged him to complete a preliminary version while funding for the publication remained available, but Sapir did not want to compromise on quality, and in the end the Handbook had to go to press without Sapir's piece. Boas kept working to secure a stable appointment for his student, and by his recommendation Sapir ended up being hired by the Canadian Geological Survey, who wanted him to lead the institutionalization of anthropology in Canada.[18] Sapir, who by then had given up the hope of working at one of the few American research universities, accepted the appointment and moved to Ottawa. In Ottawa In the years 1910–25 Sapir established and directed the Anthropological Division in the Geological Survey of Canada in Ottawa. When he was hired, he was one of the first full-time anthropologists in Canada. He brought his parents with him to Ottawa, and also quickly established his own family, marrying Florence Delson, who also had Lithuanian Jewish roots. Neither the Sapirs nor the Delsons were in favor of the match. The Delsons, who hailed from the prestigious Jewish center of Vilna, considered the Sapirs to be rural upstarts and were less than impressed with Sapir's career in an unpronounceable academic field. Edward and Florence had three children together: Herbert Michael, Helen Ruth, and Philip.[19] Canada's Geological Survey As director of the Anthropological division of the Geological Survey of Canada, Sapir embarked on a project to document the Indigenous cultures and languages of Canada. His first fieldwork took him to Vancouver Island to work on the Nootka language. Apart from Sapir the division had two other staff members, Marius Barbeau and Harlan I. Smith. Sapir insisted that the discipline of linguistics was of integral importance for ethnographic description, arguing that just as nobody would dream of discussing the history of the Catholic Church without knowing Latin or study German folksongs without knowing German, so it made little sense to approach the study of Indigenous folklore without knowledge of the indigenous languages.[20] At this point the only Canadian first nation languages that were well known were Kwakiutl, described by Boas, Tshimshian and Haida. Sapir explicitly used the standard of documentation of European languages, to argue that the amassing knowledge of indigenous languages was of paramount importance. By introducing the high standards of Boasian anthropology, Sapir incited antagonism from those amateur ethnologists who felt that they had contributed important work. Unsatisfied with efforts by amateur and governmental anthropologists, Sapir worked to introduce an academic program of anthropology at one of the major universities, in order to professionalize the discipline.[21] Sapir enlisted the assistance of fellow Boasians: Frank Speck, Paul Radin and Alexander Goldenweiser, who with Barbeau worked on the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands: the Ojibwa, the Iroquois, the Huron and the Wyandot. Sapir initiated work on the Athabascan languages of the Mackenzie valley and the Yukon, but it proved too difficult to find adequate assistance, and he concentrated mainly on Nootka and the languages of the North West Coast.[22] During his time in Canada, together with Speck, Sapir also acted as an advocate for Indigenous rights, arguing publicly for introduction of better medical care for Indigenous communities, and assisting the Six Nation Iroquois in trying to recover eleven wampum belts that had been stolen from the reservation and were on display in the museum of the University of Pennsylvania. (The belts were finally returned to the Iroquois in 1988.) He also argued for the reversal of a Canadian law prohibiting the Potlatch ceremony of the West Coast tribes.[23] Work with Ishi  Alfred Kroeber and Ishi In 1915 Sapir returned to California, where his expertise on the Yana language made him urgently needed. Kroeber had come into contact with Ishi, the last native speaker of the Yahi language, closely related to Yana, and needed someone to document the language urgently. Ishi, who had grown up without contact with European-Americans, was monolingual in Yahi and was the last surviving member of his people. He had been adopted by the Kroebers, but had fallen ill with tuberculosis, and was not expected to live long. Sam Batwi, the speaker of Yana who had worked with Sapir, was unable to understand the Yahi variety, and Krober was convinced that only Sapir would be able to communicate with Ishi. Sapir traveled to San Francisco and worked with Ishi over the summer of 1915, having to invent new methods for working with a monolingual speaker. The information from Ishi was invaluable for understanding the relation between the different dialects of Yana. Ishi died of his illness in early 1916, and Kroeber partly blamed the exacting nature of working with Sapir for his failure to recover. Sapir described the work: "I think I may safely say that my work with Ishi is by far the most time-consuming and nerve-racking that I have ever undertaken. Ishi's imperturbable good humor alone made the work possible, though it also at times added to my exasperation".[24] Moving on  Margaret Mead decades after her affair with Sapir The First World War took its toll on the Canadian Geological Survey, cutting funding for anthropology and making the academic climate less agreeable. Sapir continued work on Athabascan, working with two speakers of the Alaskan languages Kutchin and Ingalik. Sapir was now more preoccupied with testing hypotheses about historical relationships between the Na-Dene languages than with documenting endangered languages, in effect becoming a theoretician.[25] He was also growing to feel isolated from his American colleagues. From 1912 Florence's health deteriorated due to a lung abscess, and a resulting depression. The Sapir household was largely run by Eva Sapir, who did not get along well with Florence, and this added to the strain on both Florence and Edward. Sapir's parents had by now divorced and his father seemed to develop psychosis, which made it necessary for him to leave Canada for Philadelphia, where Edward continued to support him financially. Florence was hospitalized for long periods both for her depressions and for the lung abscess, and she died in 1924 due to an infection following surgery, providing the final incentive for Sapir to leave Canada. When the University of Chicago offered him a position, he happily accepted. During his period in Canada, Sapir came into his own as the leading figure in linguistics in North America. Among his substantial publications from this period were his book on Time Perspective in the Aboriginal American Culture (1916), in which he laid out an approach to using historical linguistics to study the prehistory of Native American cultures. Particularly important for establishing him in the field was his seminal book Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech (1921), which was a layman's introduction to the discipline of linguistics as Sapir envisioned it. He also participated in the formulation of a report to the American Anthropological Association regarding the standardization of orthographic principles for writing Indigenous languages. While in Ottawa, he also collected and published French Canadian Folk Songs, and wrote a volume of his own poetry.[26] His interest in poetry led him to form a close friendship with another Boasian anthropologist and poet, Ruth Benedict. Sapir initially wrote to Benedict to commend her for her dissertation on "The Guardian Spirit", but soon realized that Benedict had published poetry pseudonymously. In their correspondence the two critiqued each other's work, both submitting to the same publishers, and both being rejected. They also were both interested in psychology and the relation between individual personalities and cultural patterns, and in their correspondences they frequently psychoanalyzed each other. However, Sapir often showed little understanding for Benedict's private thoughts and feelings[according to whom?], and particularly his conservative gender ideology[vague] jarred with Benedict's struggles as a female professional academic.[citation needed] Though they were very close friends for a while, it was ultimately the differences in worldview and personality that led their friendship to fray.[27] Before departing Canada, Sapir had a short affair with Margaret Mead, Benedict's protégé at Columbia. But Sapir's conservative ideas about marriage and the woman's role were anathema to Mead, as they had been to Benedict, and as Mead left to do field work in Samoa, the two separated permanently. Mead received news of Sapir's remarriage while still in Samoa, and burned their correspondence there on the beach.[28] Chicago years Settling in Chicago reinvigorated Sapir intellectually and personally. He socialized with intellectuals, gave lectures, participated in poetry and music clubs. His first graduate student at Chicago was Li Fang-Kuei.[29] The Sapir household continued to be managed largely by Grandmother Eva, until Sapir remarried in 1926. Sapir's second wife, Jean Victoria McClenaghan, was sixteen years younger than he. She had first met Sapir when a student in Ottawa, but had since also come to work at the University of Chicago's department of Juvenile Research. Their son Paul Edward Sapir was born in 1928.[30] Their other son J. David Sapir became a linguist and anthropologist specializing in West African Languages, especially Jola languages. Sapir also exerted influence through his membership in the Chicago School of Sociology, and his friendship with psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan. At Yale From 1931 until his death in 1939, Sapir taught at Yale University, where he became the head of the Department of Anthropology. He was invited to Yale to found an interdisciplinary program combining anthropology, linguistics and psychology, aimed at studying "the impact of culture on personality". While Sapir was explicitly given the task of founding a distinct anthropology department, this was not well received by the department of sociology who worked by William Graham Sumner's "Evolutionary sociology", which was anathema to Sapir's Boasian approach, nor by the two anthropologists of the Institute for Human Relations Clark Wissler and G. P. Murdock.[31] Sapir never thrived at Yale, where as one of only four Jewish faculty members out of 569 he was denied membership to the faculty club where the senior faculty discussed academic business.[32] At Yale, Sapir's graduate students included Morris Swadesh, Benjamin Lee Whorf, Mary Haas, Charles Hockett, and Harry Hoijer, several of whom he brought with him from Chicago.[33] Sapir came to regard a young Semiticist named Zellig Harris as his intellectual heir, although Harris was never a formal student of Sapir. (For a time he dated Sapir's daughter.)[34] In 1936 Sapir clashed with the Institute for Human Relations over the research proposal by anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker, who proposed a study of the black community of Indianola, Mississippi. Sapir argued that her research should be funded instead of the more sociological work of John Dollard. Sapir eventually lost the discussion and Powdermaker had to leave Yale.[31] During his tenure at Yale, Sapir was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[35] the United States National Academy of Sciences,[36] and the American Philosophical Society.[37] In the summer of 1937 while teaching at the Linguistic Institute of the Linguistic Society of America in Ann Arbor, Sapir began having problems with a heart condition that had been diagnosed a couple of years earlier.[38] In 1938, he had to take a leave from Yale, during which Benjamin Lee Whorf taught his courses and G. P. Murdock advised some of his students. After Sapir's death in 1939, G. P. Murdock became the chair of the anthropology department. Murdock, who despised the Boasian paradigm of cultural anthropology, dismantled most of Sapir's efforts to integrate anthropology, psychology, and linguistics.[39] |

人生 子供時代と青年時代 サピールは、ポメラニア州ラウエンブルク(現ルーブルク)のリトアニア系ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた。一家は正統派ではなく、父親は音楽を通じてユダヤ教と の絆を保っていた。サピル一家はポメラニアに長く留まることはなく、ドイツ語を国籍として受け入れることはなかった。エドワード・サピアの最初の言語はイ ディッシュ語で[4]、後に英語になった。1888年、エドワード・サピアが4歳のとき、一家はイギリスのリバプールに、1890年にはアメリカのヴァー ジニア州リッチモンドに引っ越した。エドワード・サピアはここで弟のマックスを腸チフスで亡くした。父親はシナゴーグで仕事を続けることが難しく、最終的 にニューヨークのロウアー・イースト・サイドに落ち着いた。ジェイコブ・サピールが家族を養うことができなかったため、サピールの母エヴァ・シーガル・サ ピールは、基本的な生活必需品を供給するために店を開いた。二人は1910年に正式に離婚した。エドワード・サピアーはニューヨークに定住した後、主に母 親によって育てられたが、母親は社会的地位向上のための教育の重要性を強調し、一家をユダヤ教からますます遠ざけていった。エヴァ・サピアの影響は大き かったが、サピアの知識欲と学問、美学、音楽への興味は父親から受け継いだ。14歳の時、サピールはピューリッツァーの奨学金を得て、名門ホレス・マン高 校に入学したが、あまりに高級なこの学校には行かず、代わりにデウィット・クリントン高校に進学し[5]、奨学金を大学進学のために貯めた。サピアは奨学 金を通じて母親のわずかな収入を補った[4]。 コロンビア大学 1901年、ピューリッツァー奨学金でコロンビア大学に入学。当時のコロンビア大学は、ユダヤ人志願者の入学を制限していない数少ないエリート私立大学の ひとつで、12パーセント前後の暗黙の枠があり、コロンビア大学の新入生の約40パーセントがユダヤ人であった[6]。 カレッジ  1903年のコロンビア大学図書館 コロンビア大学での大学時代、サピアは語学学習に力を入れ、ラテン語、ギリシャ語、フランス語を8学期学んだ。2年生からはさらにゲルマン語にも力を入れ 始め、ゴート語、古高ドイツ語、古サクソン語、アイスランド語、オランダ語、スウェーデン語、デンマーク語の授業を履修した。ゲルマン語学のウィリアム・ カーペンター教授を通じて、サピアは、従来の言語学的アプローチよりも科学的な枠組みへと発展しつつあった比較言語学の手法に触れた。サンスクリット語の 授業も受け、有名な作曲家エドワード・マクダウェルの学部で音楽を学び、語学の勉強を補った(ただし、サピア自身がマクダウェルに師事したかどうかは定か ではない)。大学最後の年、サピアは「人類学入門」というコースに入学し、人類学へのボアスの「4つのフィールド」アプローチを教えるリビングストン・ ファランド教授に師事した。彼はまた、フランツ・ボアスが教える上級人類学セミナーにも登録し、このコースは彼のキャリアの方向性を完全に変えることに なった[8]。 ボアズの影響  フランツ・ボアズ まだ大学在学中であったが、サピアはボアスのアメリカ言語学の大学院セミナーに参加することを許され、そこにはボアスが収集したアメリカ先住民やイヌイッ トの神話の翻訳も含まれていた。こうしてサピールは、ゲルマン言語学の修士号を取得しながら、アメリカ先住民の言語に触れることになった。ロバート・ロー ウィーは後に、サピアがアメリカ先住民の言語に魅了されたのは、ボアスとのセミナーがきっかけであり、ボアスはアメリカ先住民の言語の例を用いて、言語の 基本的性質に関するサピアの常識的な仮定をすべて反証したのだと述べている。サピアの1905年の修士論文は、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー (Johann Gottfried Herder)の『言語の起源に関する論考』を分析したもので、ゲルマン主義者にはまったくなじみのないイヌイット語やアメリカ先住民の言語の例も含まれ ていた。この論文では、ヘルダーが聖書的な年表を保持し、言語の観察可能な多様性を許容するにはあまりにも浅はかであると批判したが、彼はまた、世界のす べての言語が等しく美的な可能性と文法的な複雑性を持っているとヘルダーに反論した。彼は論文の最後に、「言語の最も基本的な特性を決定するために、現存 するすべての言語の様々なストックの非常に拡張された研究」を呼びかけており、これはほとんど現代の言語類型論の研究のためのプログラム声明であり、非常 にボアジアン的なアプローチであった[9]。 1906年、彼は最後の1年間を人類学のコースに集中し、ファーランドの原始文化、ボースの民族学、考古学、そしてベルトルド・ラウファーの中国語と中国 文化のコースなどのセミナーを受講し、コースワークを終えた。また、ケルト語、古サクソン語、スウェーデン語、サンスクリット語のコースでインド・ヨー ロッパ語の研究も続けた。コースワークを終えると、サピアは博士課程のフィールドワークに移り、数年間の短期滞在をしながら学位論文に取り組んだ [10]。 初期のフィールドワーク  トニー・ティロハシュと家族。ティロハシュはサピアの共同研究者であり、南パイユート語の記述で有名である。 サピアの最初のフィールドワークは1905年の夏、アメリカ民族学局の資金援助によるウィシュラム・チヌーク語の調査であった。ボースはサピアがアメリカ 民族学局のために民族学的情報を収集することに特に関心を持っていた。サピアはウィシュラム語のテキストを一冊集め、1909年に出版し、チヌーク語の音 体系についてボアスよりもはるかに洗練された理解を得ることに成功した。1906年の夏、彼はタケルマとチャスタ・コスタに取り組んだ。サピアのタケルマ に関する研究は彼の博士論文となり、1908年に提出された。この学位論文はサピアの研究におけるいくつかの重要な傾向を予感させるものであり、特に音の パターンに関する母語話者の直感に注意深く注意を払うことは、後にサピアの音素の定式化の基礎となるものであった[11]。 1907年から1908年にかけて、サピアはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校での職を得る。そこではボースの最初の教え子であったアルフレッド・クルー バーがカリフォルニア州調査の下でカリフォルニアの先住民言語を記録するプロジェクトの責任者であった。クローバーはサピアに、絶滅寸前のヤナ語を研究す るよう提案し、サピアは研究に着手した。サピアはまず、ヤナ語の数少ない残存話者の一人であるベティ・ブラウンと仕事をした。後に彼は、ヤナ語の別の方言 を話し、ヤナ神話に関する知識が重要な知識の源泉であったサム・バトウィと仕事を始めた。サピアは、ヤナ語が文法的にも語彙的にも男女の発話を区別する方 法を説明した[12]。 クルーバーとサピアの共同作業は、サピアが詳細な言語記述に対する自身の関心にほぼ従ったという事実によって困難なものとなった。結局、サピアは決められ た1年の間に研究を終えることができず、クルーバーは彼にもっと長い任期を与えることができなかった。 バークレーに留まることができなかったことに失望したサピアは、他の仕事に全力を注ぎ、1910年までヤナの資料を出版するための準備に取りかかることが できず、クルーバーは深く落胆した[13]。 サピールは結局、早々にカリフォルニアを去り、ペンシルベニア大学でフェローシップを受け、民族学とアメリカ言語学を教えた。ペンシルバニア大学では、 ボースのもう一人の教え子フランク・スペックと緊密に協力し、二人は1909年の夏にカタウバに関する研究を行った[15]。当初はホピ語を研究するつも りであったが、彼はサザン・パイユート語を研究し、完璧な情報提供者であることが判明したトニー・ティロハシュと仕事をすることにした。ティロハシュは彼 の言語の音パターンについて強い直感を持ち、サピアが音素は言語の構造レベルに存在する単なる抽象的なものではなく、実際には話者にとって心理的なリアリ ティを持つものであると提唱するきっかけとなった。 ティロハシュはサピアの親友となり、ニューヨークとフィラデルフィアの彼の家を訪れた。サピアは父親と協力して、ティロハシュが知っていたサザン・パイ ユートの歌を書き起こした。この実り多い共同作業は、1930年に発表されたサザン・パイユート語の古典的記述の基礎となり[16]、サピアがショショネ ア諸語とナフアン諸語を結びつける決定的な証拠を作成することを可能にした。サピアのサザン・パイユートに関する記述は、言語学では「卓越した分析モデ ル」として知られている[17]。 ペンシルバニアでは、サピアは自分が心地よいと感じるよりも早いペースで仕事をするように促された。彼の「サザン・パイユートの文法」はボースの『アメリ カ・インディアン言語ハンドブック』に掲載されることになっており、ボースは出版資金があるうちに予備版を完成させるよう促したが、サピアは品質に妥協し たくなかったため、結局ハンドブックはサピアの作品なしで出版されることになった。ボアスは教え子のために安定した職を確保する努力を続け、サピアは彼の 推薦でカナダ地質調査所に雇われることになった。 オタワにて 1910年から25年にかけて、サピールはオタワのカナダ地質調査所(Geological Survey of Canada)に人類学部門を設立し、指揮を執った。彼が雇われたとき、彼はカナダで最初の常勤人類学者の一人であった。彼は両親をオタワに呼び寄せ、リ トアニア系ユダヤ人にルーツを持つフローレンス・デルソンと結婚し、すぐに家庭を築いた。サピール家もデルソン家もこの結婚には賛成しなかった。デルソン 夫妻はヴィルナの名門ユダヤ人街出身で、サピア夫妻を田舎の成り上がり者とみなし、サピアが発音できない学問分野でキャリアを積んでいることにあまり感心 しなかった。エドワードとフローレンスには3人の子供がいた: ハーバート・マイケル、ヘレン・ルース、フィリップである[19]。 カナダ地質調査所 カナダ地質調査所の人類学部門の責任者として、サピアはカナダの先住民文化と言語を記録するプロジェクトに着手した。最初のフィールドワークはバンクー バー島でヌートカ語の研究に取り組んだ。この部門にはサピアの他にマリウス・バルボーとハーラン・I・スミスの2人のスタッフがいた。サピアは、ラテン語 を知らずにカトリック教会の歴史を論じたり、ドイツ語を知らずにドイツのフォークソングを研究したりする人がいないように、先住民の言語の知識なしに先住 民のフォークロアの研究に取り組むことはほとんど意味がないと主張し、言語学という学問分野は民族誌の記述にとって不可欠な重要性を持つと主張した [20]。 この時点で、カナダの先住民の言語としてよく知られていたのは、ボアスが記述したクワキウトル語、ツィムシャン語、ハイダ語だけであった。サピアはヨー ロッパ言語の文書化の基準を明確に利用し、先住民の言語の知識を蓄積することが最も重要であると主張した。ボアス人類学の高い水準を紹介することで、サピ アは自分たちが重要な仕事に貢献していると感じていたアマチュア民族学者たちの反感を買った。アマチュアや政府の人類学者の努力に満足できなかったサピア は、この学問を専門化するために、主要な大学のひとつに人類学の学術プログラムを導入することに取り組んだ[21]。 サピアはボアジアンの仲間に協力を求めた: フランク・スペック、ポール・ラディン、アレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザーは、バルボーとともに東部森林地帯の人々、すなわちオジブワ族、イロコイ族、 ヒューロン族、ワイアンドット族の研究に取り組んだ。サピールはマッケンジー渓谷とユーコンのアサバスカン諸語の研究に着手したが、適切な助力を得ること が困難であることが判明し、彼は主にヌートカ語と北西海岸の諸言語に集中した[22]。 カナダ滞在中、サピアはスペックとともに先住民の権利擁護者としても活動し、先住民コミュニティにより良い医療を導入するよう公に主張し、保留地から盗ま れペンシルベニア大学の博物館に展示されていた11個のワンパンベルトを取り戻そうとする6ネーション・イロコイ族を支援した。(彼はまた、西海岸部族の ポトラッチ儀式を禁止するカナダの法律を撤回するよう主張した[23]。 イシとの仕事  アルフレッド・クローバーとイシ 1915年、サピアはカリフォルニアに戻り、ヤナ語に関する彼の専門知識が緊急に必要とされた。クローバーは、ヤナに近縁のヤヒ語の最後のネイティブス ピーカーであるイシと接触し、この言語を緊急に文書化する人材を必要としていた。ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人と接触することなく育ったイシは、ヤヒ語を単独で 話し、彼の民族の最後の生き残りだった。彼はクローバー家の養子となったが、結核で倒れ、長くは生きられないと思われていた。サピアーと一緒に働いていた ヤナ語を話すサム・バトウィはヤヒ族の言葉を理解することができず、クローバーはサピアーだけがイシとコミュニケーションできると確信した。サピールはサ ンフランシスコに渡り、1915年の夏にかけてイシと仕事をした。イシからの情報は、ヤナの異なる方言の関係を理解する上で貴重なものだった。イシは 1916年初めに病気で亡くなったが、クローバーはサピアとの共同作業の厳しさのせいで、イシが回復しなかったことを一部非難した。サピアはこの仕事につ いてこう語っている: 「イシとの仕事は、私がこれまでに引き受けた仕事の中で、最も時間がかかり、神経をすり減らすものであった。イシは平静を装ってユーモアを振りまいてくれ ただけで、この仕事が可能になったが、それが私の苛立ちに拍車をかけることもあった」[24]。 次のステップへ  サピアとの関係から数十年後のマーガレット・ミード 第一次世界大戦はカナダ地質調査所にも打撃を与え、人類学への資金が削減され、学問的風土は好ましくないものとなった。サピアはアサバスカン語の研究を続 け、アラスカ語のクッチンとインガリクの2人の話者と仕事をした。サピアは、絶滅の危機に瀕した言語を記録することよりも、ナ・デネ諸語間の歴史的関係に 関する仮説を検証することに夢中になり、事実上、理論家になりつつあった[25]。1912年以降、フローレンスは肺膿瘍のために健康状態が悪化し、その 結果うつ病になった。サピアの家庭は主にエヴァ・サピアが切り盛りしていたが、彼女はフローレンスと仲が悪く、これがフローレンスとエドワードの両方に負 担をかけることになった。サピアの両親は離婚し、父親は精神病を発症したようで、カナダを離れてフィラデルフィアに向かう必要があった。フローレンスはう つ病と肺膿瘍のために長期入院し、1924年に手術後の感染症で亡くなった。シカゴ大学から職を与えられると、彼は喜んでそれを引き受けた。 カナダ滞在中、サピアは北米における言語学の第一人者として頭角を現した。この時期の主な著書に『アボリジニ・アメリカン文化における時間遠近法』 (1916年)があり、歴史言語学を使ってアメリカ先住民の先史文化を研究するアプローチを確立した。この分野での彼の地位を確立するために特に重要だっ たのは、彼の代表的な著書『言語』である: An Introduction to the Study of Speech (1921)は、サピアが思い描く言語学という学問分野への入門書であった。また、アメリカ人類学会に提出した、先住民の言語を表記するための正書法の標 準化に関する報告書の作成にも参加した。 オタワ滞在中、彼はまたフランス系カナダ人の民謡を集めて出版し、自作の詩を1巻書いた[26]。詩への関心から、彼は同じくボアジア系の人類学者で詩人 のルース・ベネディクトと親交を結ぶ。サピアは当初、ベネディクトの「守護霊」に関する論文を称賛するために手紙を書いたが、すぐにベネディクトが偽名で 詩を発表していることに気づいた。文通の中で二人は互いの作品を批評し合い、同じ出版社に投稿し、ともに断られた。また、ふたりは心理学や、個人の人格と 文化的パターンとの関係にも関心があり、文通の中でしばしば互いを精神分析した。しかし、サピアはしばしばベネディクトの私的な考えや感情にほとんど理解 を示さず[誰によれば]、特に彼の保守的なジェンダー思想[曖昧]は、ベネディクトの女性職業学者としての葛藤と軋轢を生んだ[要出典]。しばらくの間、 二人は非常に親しい友人であったが、最終的に二人の友情にほころびが生じたのは、世界観や性格の違いであった[27]。 カナダを発つ前、サピアはコロンビア大学でベネディクトの弟子であったマーガレット・ミードと短期間の不倫関係にあった。しかし、結婚と女性の役割に関す るサピアの保守的な考え方は、ベネディクトにとってそうであったように、ミードにとっても忌まわしいものであり、ミードがサモアでのフィールドワークに出 発すると、2人は永久に別れることになった。ミードはまだサモアにいるときにサピアの再婚の知らせを受け、二人の書簡を浜辺で燃やした[28]。 シカゴ時代 シカゴに定住したサピアは、知的にも個人的にも活力を取り戻した。彼は知識人と交際し、講演を行い、詩や音楽のクラブに参加した。1926年にサピアが再 婚するまで、サピアの家庭は主に祖母エヴァによって管理され続けた[29]。サピアの2番目の妻、ジャン・ヴィクトリア・マクレナガンは彼より16歳年下 だった。彼女はオタワの学生時代にサピールに初めて会ったが、その後シカゴ大学の少年研究学部でも働くようになった。1928年に息子のポール・エドワー ド・サピアが生まれた[30]。もう一人の息子のJ・デイヴィッド・サピアは、西アフリカの言語、特にジョラ語を専門とする言語学者・人類学者となった。 サピアはまた、シカゴ社会学会の会員であり、心理学者ハリー・スタック・サリバンとの友情を通じて影響力を行使した。 エール大学にて 1931年から1939年に亡くなるまで、サピアはイェール大学で教鞭をとり、人類学部長となった。彼は人類学、言語学、心理学を組み合わせた学際的プロ グラムを設立するためにイェール大学に招かれ、「文化が人格に与える影響」を研究することを目的とした。サピアが明確に人類学部の創設を任された一方で、 これはウィリアム・グラハム・サムナーの「進化社会学」によって活動していた社会学部や、人間関係研究所の2人の人類学者クラーク・ウィスラーとG. サピアがイェール大学で成功することはなく、569名の教授陣のうち4名しかいなかったユダヤ人教授陣の一人として、上級教授陣が学問的な議論をするファ カルティクラブへの入会を拒否されていた[32]。 イェール大学では、サピアの大学院生にはモリス・スワデッシュ、ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフ、メアリー・ハース、チャールズ・ホケット、ハリー・ホイ ジャーなどがおり、そのうちの何人かはシカゴから連れてきたものであった[33]。サピアはゼリグ・ハリスという若いセム語学者を自分の知的後継者とみな すようになったが、ハリスはサピアの正式な生徒ではなかった。(1936年、サピアはミシシッピ州インディアノーラの黒人コミュニティの研究を提案した人 類学者ホーテンス・パウダーメイカーの研究提案をめぐって人間関係研究所と衝突。サピアは、ジョン・ダラードのより社会学的な研究ではなく、彼女の研究に 資金を提供すべきだと主張した。結局サピアはこの議論に敗れ、パウダーメーカーはイェール大学を去ることになった[31]。 イェール大学在職中、サピアはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミー、[35]アメリカ合衆国科学アカデミー、[36]アメリカ哲学協会に選出された[37]。 1937年の夏、アナーバーにあるアメリカ言語学会の言語学研究所で教鞭をとっていたサピアは、その数年前に診断されていた心臓の病気に悩まされるように なる[38]。 1938年にはイェール大学を休学せざるを得なくなり、その間、ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフが講義を担当し、G.P.マードックが何人かの学生に助言を 与える。1939年のサピアの死後、G.P.マードックは人類学部の学長に就任。文化人類学のボアジアン・パラダイムを軽蔑していたマードックは、人類 学、心理学、言語学を統合しようとしたサピアの努力のほとんどを解体した[39]。 |

| Anthropological thought Sapir's anthropological thought has been described as isolated within the field of anthropology in his own days. Instead of searching for the ways in which culture influences human behavior, Sapir was interested in understanding how cultural patterns themselves were shaped by the composition of individual personalities that make up a society. This made Sapir cultivate an interest in individual psychology and his view of culture was more psychological than many of his contemporaries.[40][41] It has been suggested that there is a close relation between Sapir's literary interests and his anthropological thought. His literary theory saw individual aesthetic sensibilities and creativity to interact with learned cultural traditions to produce unique and new poetic forms, echoing the way that he also saw individuals and cultural patterns to dialectically influence each other.[42] |

人類学的思想 サピアの人類学的思想は、当時の人類学の分野では孤立していたと言われている。サピアは、文化が人間の行動にどのような影響を与えるかを探るのではなく、 文化パターンそのものが、社会を構成する個々の人格の構成によってどのように形成されるかを理解することに関心を持った。サピアの文学的関心と彼の人類学 的思想との間には密接な関係があることが示唆されている[40][41]。彼の文学理論では、個人の美的感覚や創造性が学習された文化的伝統と相互作用し てユニークで新しい詩的形式を生み出すと見ており、それは彼が個人と文化的パターンが弁証法的に影響し合うと見ていたことと呼応している[42]。 |

| Breadth of languages studied Sapir's special focus among American languages was in the Athabaskan languages, a family which especially fascinated him. In a private letter, he wrote: "Dene is probably the son-of-a-bitchiest language in America to actually know...most fascinating of all languages ever invented."[43] Sapir also studied the languages and cultures of Wishram Chinook, Navajo, Nootka, Colorado River Numic, Takelma, and Yana. His research on Southern Paiute, in collaboration with consultant Tony Tillohash, led to a 1933 article which would become influential in the characterization of the phoneme.[44] Although noted for his work on American linguistics, Sapir wrote prolifically in linguistics in general. His book Language provides everything from a grammar-typological classification of languages (with examples ranging from Chinese to Nootka) to speculation on the phenomenon of language drift,[45] and the arbitrariness of associations between language, race, and culture. Sapir was also a pioneer in Yiddish studies (his first language) in the United States (cf. Notes on Judeo-German phonology, 1915). Sapir was active in the international auxiliary language movement. In his paper "The Function of an International Auxiliary Language", he argued for the benefits of a regular grammar and advocated a critical focus on the fundamentals of language, unbiased by the idiosyncrasies of national languages, in the choice of an international auxiliary language. He was the first Research Director of the International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA), which presented the Interlingua conference in 1951. He directed the Association from 1930 to 1931, and was a member of its Consultative Counsel for Linguistic Research from 1927 to 1938.[46] Sapir consulted with Alice Vanderbilt Morris to develop the research program of IALA.[47] |

|

| Selected publications Books Sapir, Edward (1907). Herder's "Ursprung der Sprache". Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ASIN: B0006CWB2W. Sapir, Edward (1908). "On the etymology of Sanskrit asru, Avestan asru, Greek dakru". In Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji (ed.). Spiegel memorial volume. Papers on Iranian subjects written by various scholars in honour of the late Dr. Frederic Spiegel. Bombay: British India Press. pp. 156–159. Sapir, Edward; Curtin, Jeremiah (1909). Wishram texts, together with Wasco tales and myths. E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-0-404-58152-7. ASIN: B000855RIW. Sapir, Edward (1910). Yana Texts. Berkeley University Press. ISBN 978-1-177-11286-4. Sapir, Edward (1915). A sketch of the social organization of the Nass River Indians. Ottawa: Government Printing Office. Sapir, Edward (1915). Noun reduplication in Comox, a Salish language of Vancouver island. Ottawa: Government Printing Office. Sapir, Edward (1916). Time Perspective in Aboriginal American Culture, A Study in Method. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau. Sapir, Edward (1917). Dreams and Gibes. Boston: The Gorham Press. ISBN 978-0-548-56941-2. Sapir, Edward (1921). Language: An introduction to the study of speech. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. ISBN 978-4-87187-529-5. ASIN: B000NGWX8I. Sapir, Edward; Swadesh, Morris (1939). Nootka Texts: Tales and ethnological narratives, with grammatical notes and lexical materials. Philadelphia: Linguistic Society of America. ISBN 978-0-404-11893-8. ASIN: B000EB54JC. Sapir, Edward (1949). Mandelbaum, David (ed.). Selected writings in language, culture and personality. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01115-1. ASIN: B000PX25CS. Sapir, Edward; Irvine, Judith (2002). The psychology of culture: A course of lectures. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017282-9. Essays and articles Sapir, Edward (1907). "Preliminary report on the language and mythology of the Upper Chinook". American Anthropologist. 9 (3): 533–544. doi:10.1525/aa.1907.9.3.02a00100. Kroeber, Alfred Louis; Waterman, Thomas Talbot; Sapir, Edward; Sparkman, Philip Stedman (January–March 1908). "Notes on California folk-lore". Journal of American Folklore. 21 (80): 35–42. doi:10.2307/534527. hdl:2027/uc1.31822005860226. JSTOR 534527. Sapir, Edward (1910). "Some fundamental characteristics of the Ute language". Science. 31 (792): 350–352. doi:10.1126/science.31.792.350. PMID 17738737. Sapir, Edward (1911). "Some aspects of Nootka language and culture". American Anthropologist. 13: 15–28. doi:10.1525/aa.1911.13.1.02a00030. Sapir, Edward (1911). "The problem of noun incorporation in American languages". American Anthropologist. 13 (2): 250–282. doi:10.1525/aa.1911.13.2.02a00060. S2CID 162838136. Sapir, E. (1913). "Southern Paiute and Nahuatl, a study in Uto-Aztekan" (PDF). Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 10 (2): 379–425. doi:10.3406/jsa.1913.2866.[permanent dead link] Sapir, E. (1915). "Abnormal Types of Speech in Nootka" (PDF). Memoir (Geological Survey of Canada). 62. doi:10.4095/103492. hdl:2027/uc1.32106013085003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-08. Sapir, E. (1915). "Noun Reduplication in Comox, a Salish Language of Vancouver Island" (PDF). Memoir (Geological Survey of Canada). 63. doi:10.4095/103493. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t1td9v139. S2CID 126745281. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-08. Sapir, E. (1915). "A Sketch of the Social Organization of the Nass River Indians" (PDF). Museum Bulletin (Geological Survey of Canada). 19. doi:10.4095/104974. hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t0qr4xq6w. S2CID 131590414. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-08. Sapir, Edward (1915). "The Na-dene languages: a preliminary report". American Anthropologist. 17 (3): 765–773. doi:10.1525/aa.1915.17.3.02a00080. Sapir, E. (1916). "Time Perspective in Aboriginal American culture: A Study in Method" (PDF). Memoir (Geological Survey of Canada). 90. doi:10.4095/103486. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t4xh0677f. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-08. Sapir, Edward (1917). "Do we need a superorganic?". American Anthropologist. 19 (3): 441–447. doi:10.1525/aa.1917.19.3.02a00150. Sapir, E. (1923). "Prefatory note" (PDF). Museum Bulletin (Geological Survey of Canada). 37: iii. doi:10.4095/104978. hdl:2027/uc1.31822007179245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-08. Sapir, Edward (1924). "The grammarian and his language". The American Mercury (1): 149–155. Sapir, Edward (1924). "Culture, Genuine and Spurious". The American Journal of Sociology. 29 (4): 401–429. doi:10.1086/213616. S2CID 145455225. Sapir, Edward (1925). "Memorandum on the problem of an international auxiliary language". The Romanic Review (16): 244–256. Sapir, Edward (1925). "Sound patterns in language". Language. 1 (2): 37–51. doi:10.2307/409004. JSTOR 409004. Sapir, Edward (1931). "The function of an international auxiliary language". Romanic Review (11): 4–15. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Sapir, Edward (1936). "Internal linguistic evidence suggestive of the Northern origin of the Navaho". American Anthropologist. 38 (2): 224–235. doi:10.1525/aa.1936.38.2.02a00040. Sapir, Edward (1944). "Grading: a study in semantics". Philosophy of Science. 11 (2): 93–116. doi:10.1086/286828. S2CID 120492809. Sapir, Edward (1947). "The relation of American Indian linguistics to general linguistics". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 3 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.3.1.3628530. S2CID 61608089. Biographies Koerner, E. F. K.; Koerner, Konrad (1985). Edward Sapir: Appraisals of his life and work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-4518-2. Cowan, William; Foster, Michael K.; Koerner, Konrad (1986). New perspectives in language, culture, and personality: Proceedings of the Edward Sapir Centenary Conference (Ottawa, 1–3 October 1984). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-4522-9. Darnell, Regna (1989). Edward Sapir: linguist, anthropologist, humanist. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06678-6. Sapir, Edward; Bright, William (1992). Southern Paiute and Ute: linguistics and ethnography. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013543-5. Sapir, Edward; Darnell, Regna; Irvine, Judith T.; Handler, Richard (1999). The collected works of Edward Sapir: culture. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-012639-6. Correspondence Sapir, Edward; Kroeber, Alfred L.; Golla (ed.), Victor (1984). "The Sapir–Kroeber correspondence: Letters between Edward Sapir and A.L. Kroeber 1905–1925" (PDF). Reports from the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages. 6: 1–509. {{cite journal}}: |last3= has generic name (help) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Sapir |

+++

| 1884 ドイツ、ポメラニア州ローエンブル

グのユダヤ人 家族(父親はラビ)に生まれる(1月26日) 1889 アメリカへ移住、ニューヨークで少年時代をおく る 1900 コロンビア大学入学(16歳) 1904 コロンビア大学卒業、大学院に進学し、ゲルマン 語とセム語を専攻(同時期フランツ・ボアズに師事) 1905 初の調査旅行、ウィシュラム・インディアンの言 語調査、ゲルマン語研究で修士号 1906 UCバークレー校に新設された人類学部に助手と して赴任、この頃オレゴン州タケルマ・インディアン研究(タケルマ語文法は博士論文となる) 1908 バークレーでテニュアが得られずペンシルバニア 大学フェロー、パイウート語研究 1909 ペンシルバニア大学人類学部講師、博士号(コロ ンビア大学) 1910 カナダ国立博物館地質調査部に人類学課主任、オ タワ在住(〜1925)、フローレンス・デルソンと結婚 1921 『言語——ことばの研究入門』出版(37 歳) 1924 フローレンス死亡 Culture, Genuine and Spurious, 1924 Racial Superiority, 1924 1925 シカゴ大学人類学部准教授 1926 ジーン・マクレナガンと結婚 1927 シカゴ大学教授 The Unconscious Patterning of Behavior in Society, 1927 1931 イエール大学人類学部学部長。国立研究協議会・ 心理学・人類学部門議長「パーソナリティと文化に関する委員会」 1932 「文化がパーソナリティにおよぼす影響につい て」国際セミナー Cultural Anthropology and Psychiatry, 1932 1933 アメリカ言語学会会長 1934 アメリカ学士院会員 The Emergence of the Concept of Personality in a Study of Culture, 1934 Personality, in Encyclopedia of Social Science ,1934 1937 持病の心臓病悪化 The Contribution of Psychiatry to an Understanding of Behavior in Society, 1937 1938 アメリカ人類学会会長 1939 心臓病で死亡(2月4日、享年55歳) 1983 S・マレー『社会科学の集団形成』(1983)から の引用 「シカゴ学派がサピアの影響をあまり受けていないというこ とは、歴史的な謎である。サピアがシカゴの社会学者たちと良好な関係にあったこと、同化に対するシカゴ学派の一般的枠内でのことではあるが英語以外の言語 で書かれたアメリカ人の日記に関するロバート・パークの労作に示されている言語に対する関心、ならびにG・H・ミードの社会哲学において言語に認められた 重要性といったことを考えあわせると、何らかの形の社会言語学があの時点で生起しなかったのは意外というほかはない」(ヴァンカン、1999:171から の引用)Yves Winkin, Les Moments et Leurs Hommes. |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆