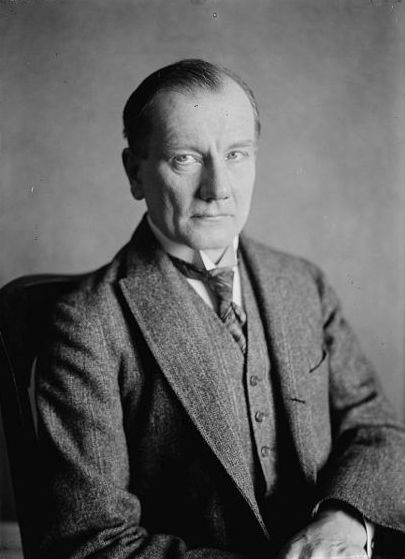

エルンスト・フォン・ドホナーニ

Ernst von Dohnányi, 1877-1960

Ernő

Dohnányi (1877 - 1960), a Hungarian conductor, composer, and pianist.

Published between ca. 1920 and ca. 1925

☆ エルンスト・フォン・ドホナーニ(ハンガリー語:Dohnányi Ernő、 [ˈɛrnøː ˈdohnaːɲi]、1877年7月27日 - 1960年2月9日)は、ハンガリーの作曲家、ピアニスト、指揮者。ほとんどの作曲作品にはドイツ語名の形式を使用している。[1]

作曲様式と作品

★作風は折衷的である。ハンガリーのさまざまな民族音楽の要素を取り入れているが、コダーイやバルトークの

ような愛国的な作曲家とは看做されていない。ドホナーニの創作姿勢は、ヨーロッパのクラシック音楽の強力な伝統に、より深く根ざしており、とりわけブラー

ムスの痕跡が歴然としている。いくつかの作品ではブラームス作品からフレーズを引用し、先輩作曲家への敬意を明らかに示しており、また有名なピアノ曲『演

奏会用練習曲集』作品28は、ショパンの練習曲よりもむしろブラームスのカプリッチョやインテルメッツォを模範としている。

★

しかしながら、他にもさまざまな影響を吸収し、成熟期の作風は、R.シュトラウスやマーラーの華麗なオーケストレーションや、レーガーの複雑な対位法様式

も採り入れている。渡米後の作品、たとえば最後の管弦楽曲となった『アメリカ狂詩曲』では、古いアメリカ民謡や、ジャズへの関心を窺がわせている。

★

『演奏会用練習曲』はゴドフスキやラフマニノフによってしばしば演奏・録音され、早くから有名であった。戦後のハンガリー政府は、初期の政権発足時に弾圧

したにもかかわらず、共産党独裁体制の末期に近づいてから、ブダペストの音楽出版社よりドホナーニのピアノ曲集を刊行した。

★ドホナーニは編曲も多く手掛けており、シューベルトの「高雅なワルツ」、ブラームスのワルツ集、「ジプシー風ロンド」、ヨハン・シュトラウス2世のワルツなどのピアノ独奏用編曲を残している。

| Ernst von

Dohnányi

(Hungarian: Dohnányi Ernő, [ˈɛrnøː ˈdohnaːɲi]; 27 July 1877 – 9

February 1960) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and conductor. He used

the German form of his name on most published compositions.[1] |

エルンスト・フォン・ドホナーニ(ハンガリー語:Dohnányi

Ernő、 [ˈɛrnøː ˈdohnaːɲi]、1877年7月27日 -

1960年2月9日)は、ハンガリーの作曲家、ピアニスト、指揮者。ほとんどの作曲作品にはドイツ語名の形式を使用している。[1] |

| Biography Dohnányi was born in Pozsony, Kingdom of Hungary (today Bratislava, Slovakia). Born into the old noble Dohnányi family, he was the son of Frigyes Dohnányi (1843–1909) and his wife, Ottilia Szlabey.[2] He first studied music with his father, a professor of mathematics and an amateur cellist, and then when he was eight years old, with Carl Forstner, organist at the local cathedral. In 1894 he moved to Budapest and enrolled in the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music, studying piano with István Thomán and composition with Hans von Koessler, a cousin of Max Reger.[3] István Thomán had been a favorite student of Franz Liszt, while Hans von Koessler was a devotee of Johannes Brahms's music. These two influences played an important part in Dohnányi's life: Liszt on his piano playing and Brahms on his compositions.[4] Dohnányi's first published work, his Piano Quintet in C minor, earned approval from Brahms, who promoted it in Vienna. Dohnányi did not study long at the Academy of Music: in June 1897 he sought to take the final exams right away, without completing his studies. Permission was granted, and a few days later he passed with high marks, as composer and pianist, graduating at less than 20 years of age.[4] After a few lessons with Eugen d'Albert, another student of Liszt, Dohnányi made his debut in Berlin in 1897 and was recognized at once as a performer of high merit. Similar success followed in Vienna and on a subsequent tour of Europe. He made his London debut at a Richter concert in Queen's Hall, with a notable performance of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4. He was among the first to conduct and popularize Bartók's more accessible music. During the 1898 season, Dohnányi visited the United States, where he gained a reputation playing Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4 for his American debut with the St. Louis Symphony. Unlike most famous pianists of the time, he did not limit himself to solo recitals and concertos, but also appeared in chamber music. In 1901 he completed his Symphony No. 1, his first orchestral work. Although he was heavily influenced by established contemporaries, notably Brahms, it displayed considerable technical skill in its own right.[5]  Ernst von Dohnányi, c. 1900 Dohnányi married Elisabeth "Elsa" Kunwald (also a pianist), and they had a son, Hans, in 1902. Hans was to be the father of the German politician Klaus von Dohnányi and of the conductor Christoph von Dohnányi, longtime Music Director of the Cleveland Orchestra. Hans distinguished himself as a leader of the anti-Nazi resistance in Germany and was ultimately executed in the final stages of World War II. In addition to Hans, Dohnányi and Elsa Kunwald also had a daughter, Greta.[6] Following an invitation by the violinist Joseph Joachim, a close friend of Brahms, Dohnányi taught at the Hochschule in Berlin from 1905 to 1915. There he wrote The Veil of Pierrette, Op. 18, and the Suite in F-sharp minor, Op. 19. Returning to Budapest, he appeared in a remarkable number of performances over the following decade, notably in the Beethoven sesquicentenial year of 1920/1921.[7] Before World War I broke out, Dohnányi met and fell in love with a German actress (also described as a singer),[8] Elsa Galafrés, who was married to the Polish Jewish violinist Bronisław Huberman. They could not yet marry as their spouses refused to divorce them, but nonetheless, Dohnányi and Elsa Galafrés had a son, Matthew, in January 1917. Both later gained the divorces they sought and were married in June 1919. Dohnányi also adopted Johannes, Elsa's son by Huberman.[9][10][11] During the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, Dohnányi was appointed Director of the Budapest Academy, but a few months later the new interim government replaced him with the prominent violinist Jenő Hubay after Dohnányi had refused to dismiss the pedagogue and composer Zoltán Kodály from the Academy for his supposedly leftist political position.[12] However in 1920, with Admiral Horthy becoming Regent of Hungary, Dohnányi was named Music Director of the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra and as such promoted the music of Béla Bartók,[citation needed] Zoltán Kodály, Leo Weiner and other contemporary Hungarian composers. That same 1920 season, he performed the complete piano works of Beethoven and recorded several of his works on the Ampico player-piano-roll apparatus. He gained renown as a teacher. His pupils included Andor Földes, Mischa Levitzki, Ervin Nyiregyházi, Géza Anda, Annie Fischer, Hope Squire, Helen Camille Stanley, Bertha Tideman-Wijers, Edward Kilenyi, Bálint Vázsonyi, Sir Georg Solti, Istvan Kantor, Georges Cziffra and Ľudovít Rajter (conductor and Dohnányi's godson). In 1933 he organized the first International Franz Liszt Piano Competition.[13] In 1937 Dohnányi met Ilona Zachár, who was married with two children. By this time, he had separated from his second wife Elsa Galafrés. He and Ilona travelled throughout Europe as husband and wife, but were not legally married until they settled in the United States. After Dohnányi's death, Ilona, in her biography, launched a campaign to quell his reputation as a Nazi sympathizer.[14] Peter Halász continued this in an article titled "Persecuted Musicians in Hungary between 1919–1945", which portrayed him as a "victim" of Nazism,[15] and by James Grymes, who in his book called Dohnányi saw him as "a forgotten hero of the Holocaust resistance".[16] In 1934 Dohnányi was once again appointed Director of the Budapest Academy of Music, a post he held until 1943. According to the 2015 entry on Dohnányi in New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "From 1939 much of [Dohnányi's] time was devoted to the fight against growing Nazi influences." By 1941 he had resigned his directorial post, rather than submit to the anti-Jewish legislation. In his orchestra, the Budapest Philharmonic [17] he managed to keep on all Jewish members until two months after the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944, when he disbanded the ensemble. In November 1944 he moved to Austria, a decision which drew criticism for many years.[why?] Musicologist James A. Grymes has defended Dohnányi's actions during the war, crediting his solidarity with Jewish colleagues and his actions to help some escape from Nazi-occupied countries.[18] From 1949, Dohnányi taught for ten years at the Florida State University School of Music in Tallahassee. He became an honorary member of the Epsilon Iota chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity there. He and his wife Ilona became American citizens in 1955.[19] |

略歴 ドホナーニは、ハンガリー王国(現在のスロバキア、ブラチスラヴァ)のポジョニで生まれた。由緒あるドホナーニ家の息子として、フリジェシュ・ドホナーニ (1843年~1909年)と妻オティリア・スラベイの間に生まれた。2] 彼は、数学の教授でありアマチュアチェロ奏者であった父親から音楽を学び、8歳のときに、地元の聖堂のオルガニスト、カール・フォルストナーに師事した。 1894年にブダペストに移り、ハンガリー王立国立音楽アカデミーに入学し、イシュトヴァーン・トマーヌにピアノを、マックス・レーガーのいとこであるハ ンス・フォン・ケスラーに作曲を学んだ。 イシュトヴァーン・トマーヌはフランツ・リストの愛弟子であり、ハンス・フォン・ケスラーはヨハネス・ブラームスの音楽の熱心な信奉者だった。この2人の 影響はドホナーニの人生に重要な役割を果たした:リストは彼のピアノ演奏に、ブラームスは彼の作曲に。[4] ドホナーニの最初の出版作品であるピアノ五重奏曲ハ短調はブラームスの賛同を得て、ウィーンで宣伝された。ドホナーニは音楽アカデミーでの勉強は長く続か なかった。1897年6月、彼は学業を修了せずに最終試験を受けることを希望した。許可が下り、数日後、作曲家兼ピアニストとして高得点で合格し、20歳 未満で卒業した。[4] リストのもう一人の弟子であるオイゲン・ダルベルトに数回レッスンを受けた後、ドホナーニは1897年にベルリンでデビューし、その卓越した演奏力で一躍 脚光を浴びた。ウィーン、そしてその後のヨーロッパツアーでも同様の成功を収めた。ロンドンデビューは、クイーンズ・ホールで開催されたリヒターコンサー トで、ベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第4番の演奏で注目を浴びた。彼は、バルトークのより親しみやすい音楽を指揮し、普及させた最初の指揮者の一人だっ た。 1898年のシーズン、ドホナーニはアメリカを訪れ、セントルイス交響楽団とのアメリカデビュー公演でベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第4番を演奏し、高い 評価を得た。当時の有名なピアニストの多くとは異なり、彼はソロリサイタルや協奏曲だけに留まらず、室内楽にも出演した。1901年に、彼は最初の管弦楽 作品である交響曲第1番を完成させた。彼はブラームスをはじめとする確立された同時代の作曲家に大きな影響を受けていたが、この作品には独自の技術的な巧 みさが顕著に表れていた。[5]  エルンスト・フォン・ドホナーニ、1900年頃 ドホナーニは、エリザベス・「エルザ」・クンヴァルト(ピアニスト)と結婚し、1902年に息子のハンスが生まれた。ハンスは、ドイツの政治家クラウス・ フォン・ドホナーニと、クリーブランド管弦楽団の音楽監督を長年務めた指揮者クリストフ・フォン・ドホナーニの父である。ハンスはドイツの反ナチス抵抗運 動の指導者として活躍したが、第二次世界大戦の終盤に処刑された。ドホナーニとエルザ・クンヴァルトには、ハンスの他にグレタという娘がいた。[6] ブラームスの親しい友人であったヴァイオリニスト、ヨーゼフ・ヨアヒム(Joseph Joachim)の招待を受けて、ドナニーは1905年から1915年までベルリン音楽大学(Hochschule)で教鞭を執った。そこで、彼は「ピエ ルレットのベール」作品18と「嬰ヘ短調組曲」作品19を作曲した。ブダペストに戻った彼は、1920年から1921年のベートーヴェン生誕150周年を 記念した演奏会を中心に、10年間に数多くの演奏会に出演した。 第一次世界大戦が勃発する前に、ドホナーニは、ポーランド系ユダヤ人のヴァイオリニスト、ブロニスワフ・フーバーマンと結婚していたドイツの女優(歌手と も呼ばれる)エルザ・ガラフレスと出会い、恋に落ちた。彼らの配偶者が離婚を拒否したため、彼らはまだ結婚できなかったが、ドホナーニとエルサ・ガラフレ スは1917年1月に息子マシューをもうけた。両者は後に離婚を成立させ、1919年6月に結婚した。ドホナーニはまた、エルサとフーベルマンの息子ヨハ ネスを養子にした。[9][10][11] 1919年の短命なハンガリー・ソビエト共和国時代、ドホナーニはブダペスト音楽アカデミーの院長に任命されたが、数ヶ月後、ドホナーニが、左派政治の立 場を理由に、教育者であり作曲家のゾルターン・コダーイをアカデミーから解雇することを拒否したため、新暫定政府は彼を著名なヴァイオリニスト、イェー ノ・フバイに交代させた。[12] しかし、1920年にホルティ提督がハンガリー摂政に就任すると、ドホナーニはブダペスト・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の音楽監督に任命され、ベラ・バル トーク[出典必要]、ゾルターン・コダーイ、レオ・ヴァイナーをはじめとする現代ハンガリー作曲家の音楽を推進した。同じ 1920 年のシーズン、彼はベートーヴェンのピアノ作品全曲を演奏し、そのうちのいくつかをアンピコ・プレイヤー・ピアノ・ロール装置で録音した。彼は教師として も名声を博した。彼の弟子には、アンドール・フォルデス、ミシャ・レヴィツキー、エルヴィン・ニレギハージ、ゲザ・アンダ、アニエ・フィッシャー、ホー プ・スクワイア、ヘレン・カミーユ・スタンリー、ベルタ・ティデマン=ヴィイェルス、エドワード・キレニ、バルイント・ヴァズォーニ、サー・ジョージ・ソ ルティ、イシュトヴァーン・カンター、ジョルジュ・チフラ、ルドヴィット・ラジェル(指揮者でドホナーニの養子)などがいた。1933年に、彼は最初の国 際フランツ・リスト・ピアノコンクールを主催した。[13] 1937年、ドホナーニは2人の子供を持つイロナ・ザカールと出会った。この頃、彼は2番目の妻エルザ・ガラフレスと別居していた。2人は夫と妻として ヨーロッパ中を旅したが、米国に定住するまで法的に結婚はしなかった。ドホナーニの死後、イロナは自伝の中で、彼がナチス支持者だったという評判を覆す キャンペーンを展開した。[14] ピーター・ハラーシュは、彼をナチズムの「犠牲者」として描いた「1919年から1945年のハンガリーにおける迫害された音楽家たち」という記事でこれ を継続し、ジェームズ・グライムズも、彼の著書でドホナーニを「ホロコースト抵抗運動の忘れられた英雄」と表現した。[16] 1934年、ドホナーニは再びブダペスト音楽アカデミーのディレクターに任命され、1943年までその職を務めた。2015年の『ニューグローヴ音楽事 典』のドホナーニの項目によると、「1939年以降、ドホナーニの時間の多くは、拡大するナチスの影響力との闘いに費やされた」とされている。1941年 までに、彼は反ユダヤ法に従うことを拒否し、ディレクターの職を辞任した。彼のオーケストラ、ブダペスト・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団[17]では、 1944年3月のドイツのハンガリー侵攻から2ヶ月後まで、すべてのユダヤ人メンバーを雇用し続けたが、その後、楽団を解散させた。1944年11月、彼 はオーストリアに移住したが、この決断は長年批判の対象となった。[なぜ?] 音楽学者ジェームズ・A・グリムズは、ドホナーニの戦争中の行動を擁護し、ユダヤ人同僚との連帯と、ナチス占領下から逃れるのを助けた行動を評価してい る。[18] 1949 年から、ドホナーニはタラハシーのフロリダ州立大学音楽学部で 10 年間教鞭をとった。そこで、ファイ・ミュー・アルファ・シンフォニア友愛会のイプシロン・イオタ支部名誉会員になった。1955 年、妻イロナとともにアメリカ国籍を取得した。[19] |

| In the United States, he

continued to compose and became interested in American folk music. His

last orchestral work (except for a 1957 revision of the Symphony No. 2)

was American Rhapsody (1953), written for the sesquicentennial of Ohio

University and including folk material, for example, "Turkey in the

Straw", "On Top of Old Smokey" and "I am a poor wayfaring stranger".[19] His last public performance, on January 30, 1960, was at Florida State University, conducting the university orchestra in Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4, with his doctoral student, Edward R. Thaden, as soloist. After the performance, Dohnányi traveled to New York City to record some Beethoven piano sonatas and shorter piano pieces for Everest Records.[19] He had previously recorded a Mozart concerto in the early 1930s in Hungary (No. 17, in G major, K. 453, playing and conducting the Budapest Philharmonic),and also his own Variations on a Nursery Tune, the second movement of his Ruralia hungarica (Gypsy Andante), and a few solo works (but no Beethoven sonatas) on 78 rpm.[citation needed] He had also recorded various other works, including Beethoven's Tempest Sonata and Haydn's F minor Variations, on early mono LPs. Dohnányi died of pneumonia on 9 February 1960, in New York City, ten days after his final performance, and was buried in Tallahassee, Florida, where he had taught at the university for ten years.[19]  Dohnányi's gravesite at Roselawn Cemetery, Tallahassee, Florida |

アメリカでは作曲活動を続け、アメリカのフォークミュージックに興味を

持つようになった。彼の最後の管弦楽作品(1957年の交響曲第2番の改訂版を除く)は、オハイオ大学創立150周年を記念して作曲された『アメリカン・

ラプソディ』(1953年)で、例えば「ターキー・イン・ザ・ストロー」「オン・トップ・オブ・オールド・スモーキー」「アイ・アム・ア・プア・ウェイ

ファリング・ストレンジャー」などのフォーク音楽の素材を採り入れている。[19] 1960年1月30日、フロリダ州立大学で、博士課程の学生であるエドワード・R・サデンをソリストに迎え、ベートーヴェンのピアノ協奏曲第4番を指揮し て、最後の公の演奏を行った。演奏後、ドホナーニはニューヨーク市を訪れ、エベレスト・レコードのためにベートーヴェンのピアノソナタと短編のピアノ曲を 録音した。[19] 彼は1930年代初頭にハンガリーでモーツァルトの協奏曲(第17番、ニ長調、K. 453、ブダペスト・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団を指揮し演奏)を録音しており、また自身の「子守歌の変奏曲」(『ルラリア・ハンガリカ』の第2楽章「ジプ シー・アンダンテ」)と数曲のソロ作品(ただしベートーヴェンのソナタは含まれない)を78回転レコードで録音していた。[出典必要] 彼はまた、ベートーヴェンの『テンペスト・ソナタ』やハイドンの『F短調変奏曲』を含む、さまざまな作品を初期のモノラルLPに録音していた。 ドホナーニは、最後の公演から 10 日後の 1960 年 2 月 9 日、ニューヨーク市で肺炎により死去し、10 年間教鞭をとったフロリダ州タラハシーに埋葬された。  フロリダ州タラハシーのローズローン墓地にあるドホナーニの墓 |

| Influence and legacy The BBC issued an LP recording taken from one of his last concerts, heard in 1959 at Florida State University, in which he played Beethoven's piano sonata Op. 31 No. 1 and Schubert's piano sonata D. 894. The Testament label has reissued the recital on CD in a set that also includes three of the pianist's own short pieces that he played there as encores, a short recital of his works that he played at the 1956 Edinburgh Festival, and a few that were broadcast on the BBC in 1936. Dohnányi's three volumes of Daily Finger Exercises for the Advanced Pianist were published by Mills Music in 1962. The Warren D. Allen Music Library at Florida State University's College of Music holds a large archive of Dohnányi's papers, manuscripts and related materials. The Hungarian government posthumously awarded him its highest civilian honor, the Kossuth Prize, in 1990.[20] An International Ernst von Dohnányi Festival was held at Florida State University in 2002. The LSU professor Milton Hallman was a student of his and in 1987 recorded a CD called Works For Piano containing some of Dohnányi's most notable music. |

影響と遺産 BBC は、1959年にフロリダ州立大学で行われた彼の最後のコンサートの録音から、ベートーヴェンのピアノソナタ Op. 31 No. 1 とシューベルトのピアノソナタ D. 894 を収録した LP を発売した。テスタメント・レーベルは、このリサイタルをCDで再発し、セットには彼がその場でアンコールとして演奏した自身の短編作品3曲、1956年 のエディンバラ・フェスティバルで演奏した自身の作品のリサイタル、および1936年にBBCで放送された数曲も収録されている。 ドホナーニの3巻からなる『上級ピアニストのための毎日の指練習曲』は、1962年にミルズ・ミュージックから出版された。 フロリダ州立大学音楽学部ウォーレン・D・アレン音楽図書館には、ドホナーニの論文、原稿、関連資料の膨大なアーカイブが保管されている。 1990年、ハンガリー政府は、ドホナーニに最高位の民間人栄誉であるコシュート賞を死後授与した。 2002年、フロリダ州立大学で「国際エルンスト・ドホナーニ・フェスティバル」が開催された。LSU の教授であるミルトン・ホールマンは、ドホナーニの弟子であり、1987年にドホナーニの最も著名な楽曲を収録した CD「Works For Piano」を録音した。 |

| Compositions Dohnányi's composing style was personal, but very conservative. His music largely subscribes to the Romantic idiom. Although he used elements of Hungarian folk music, he is not seen to draw on folk traditions in the way that Bartók or Kodály do. Some characterize his style as traditional mainstream Euro-Germanic in the Brahmsian manner (structurally more than in the way the music actually sounds) rather than specifically Hungarian, while others hear very little of Brahms in his music. The very best of his works may be his Serenade in C major for string trio, Op. 10 (1902) and Variations on a Nursery Tune for piano and orchestra, Op. 25 (1914). His Second symphony is a major work which he composed during the Second World War. It is uncharacteristically sombre, notably in the third movement, which is grotesque and dissonant. Stage Der Schleier der Pierrette (The Veil of Pierrette), Mime in three parts (Libretto after Arthur Schnitzler), Op. 18 (1909) Tante Simona (Aunt Simona), Comic Opera in one act (Libretto by Victor Heindl), Op. 20 (1912) A vajda tornya (The Tower of the Voivod), Romantic Opera in three acts (Libretto by Viktor Lányi, after Hans Heinz Ewers and Marc Henry), Op. 30 (1922) A tenor (The Tenor), Comic Opera in three acts (Libretto by Ernő Góth and Carl Sternheim, after Bürger Schippel by Carl Sternheim), Op. 34 (1927) Choral Szegedi mise (Szeged Mass, also Missa in Dedicatione Ecclesiae), Op. 35 (1930) Cantus vitae, Symphonic Cantata, Op. 38 (1941) Stabat mater, Op. 46 (1953) Orchestral Symphony in F major (1896, unpublished) - Hungarian King's Prize in 1897[4] Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 9 (1901) Suite in F-sharp minor, Op. 19 (1909) Ünnepi nyitány (Festival Overture), Op. 31 (1923) Ruralia hungarica (based on Hungarian folk tunes), Op. 32b (1924) Szimfonikus percek (Symphonic Minutes), Op. 36 (1933) Symphony No. 2 in E major, Op. 40 (1945, revised 1954-7) [21] American Rhapsody, Op. 47 (1953) Solo instrument and orchestra Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 5 (1898) (the opening theme was inspired by Brahms's Symphony No. 1) Konzertstück (Concertpiece) in D major for cello and orchestra, Op. 12 (1904) Variations on a Nursery Tune (Variationen über ein Kinderlied) for piano and orchestra, Op. 25 (1914) Violin Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 27 (1915) Piano Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 42 (1947) Violin Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 43 (1950) Concertino for harp and chamber orchestra, Op. 45 (1952) Chamber and instrumental String Quartet in D minor, 1893 (unpublished, manuscript at British Library) (Grymes, Ernst von Dohnányi: A Bio-bibliography, p. 32) String Sextet in B♭ major, 1893 (revised 1896, revised and premiered 1898. Recorded on Hungaroton, 2006.) (Grymes, p. 32) Minuet for String Quartet, 1894 (Grymes, p. 32. Manuscript at the National Széchényi Library) Piano Quartet in F♯ minor, (1894) Piano Quintet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 1 (1895) String Quartet No. 1 in A major, Op. 7 (1899) Sonata in B♭ minor for cello and piano, Op. 8 (1899) |Serenade in C major for string trio, Op. 10 (1902) String Quartet No. 2 in D♭ major, Op. 15 (1906) Sonata in C♯ minor for violin and piano, Op. 21 (1912) Piano Quintet No. 2 in E♭ minor, Op. 26 (1914) String Quartet No. 3 in A minor, Op. 33 (1926) Sextet in C major for piano, strings and winds, Op. 37 (1935) Aria for flute and piano, Op 48, No. 1 (1958) Passacaglia for solo flute, Op. 48, No. 2 (1959) Piano Four Pieces, Op. 2 (1897, pub. 1905) Waltzes in F♯ minor for four hands, Op. 3 (1897) Variations and Fugue on a Theme of E[mma].G[ruber]., Op. 4 (1897) Gavotte and Musette (WoO, 1898) Albumblatt (WoO, 1899) Passacaglia in E♭ minor, Op. 6 (1899) Four Rhapsodies, Op. 11 (1903) Winterreigen, Op. 13 (1905) Humoresque in the form of a Suite, Op. 17 (1907) Three Pieces, Op. 23 (1912) Fugue in D minor for left hand (WoO, 1913) Suite in A minor "Suite in the Old Style", Op. 24 (1913) Six Concert Etudes, Op. 28 (1916) Variations on a Hungarian Folksong, Op. 29 (1917) Pastorale on a Hungarian Christmas Song (WoO, 1920) Valses nobles, concert arrangement for piano (after Schubert, D. 969) (WoO, 1920) Ruralia hungarica, Op. 32a (1923) Waltz for Piano from Delibes' "Coppelia" (WoO, 1925) Six Pieces, Op. 41 (1945) Waltz Suite, for two pianos, Op. 39a (1945), Limping Waltz for solo piano, Op. 39b (1947) Three Singular Pieces, Op. 44 (1951) Twelve Short Studies for the Advanced Pianist (1951) |

作曲 ドホナーニの作曲スタイルは個性的だが、非常に保守的だった。彼の音楽は、主にロマン派の表現手法を採用している。ハンガリーの民謡の要素も取り入れてい るが、バルトークやコダーイのように民謡の伝統を直接的に活用しているとは見られない。彼のスタイルを、ブラームス流の伝統的な主流のユーロ・ゲルマン的 (構造的には音楽の実際の音色よりも)と特徴付ける人もいれば、彼の音楽にブラームスの影響をほとんど感じないという人もいます。彼の最高傑作は、弦楽三 重奏のためのセレナーデ ニ長調 作品10(1902年)と、ピアノと管弦楽のための子守歌の変奏曲 作品25(1914年)かもしれない。彼の第2交響曲は、第二次世界大戦中に作曲された主要作品だ。これは彼らしくない暗く、特に第3楽章はグロテスクで 不協和音に満ちている。 舞台 『ピエルレットのベール』(3幕のミーム、アーサー・シュニッツラーの台本による)、作品18(1909年) 『タンテ・シモーナ』(1幕の喜歌劇、ヴィクター・ハインドルの台本による)、作品20(1912年) 『ヴォイヴォドの塔』(A vajda tornya)、3幕のロマンティック・オペラ(ヴィクトル・ラニによる台本、ハンス・ハインツ・エwersとマルク・ヘンリー原作)、作品30 (1922年) 『テノール』(3幕の喜歌劇、台本:エルノー・ゴートとカール・シュテルンハイム、カール・シュテルンハイムの『Bürger Schippel』に基づく)、作品34(1927年) 合唱 『セゲドのミサ』(『セゲドのミサ』、または『教会奉献ミサ』)、作品35(1930年) カンツス・ヴィターエ、交響的カンタータ、作品38(1941年) スタバト・マーテル、作品46(1953年) 管弦楽 交響曲第1番 ヘ長調(1896年、未発表) - 1897年ハンガリー国王賞[4] 交響曲第1番 ニ短調、作品9(1901年) 組曲 嬰ヘ短調、作品19(1909年) Ünnepi nyitány(祝祭序曲)、作品31(1923年) 『ルラリア・ハンガリカ』(ハンガリーの民謡に基づく)、作品32b(1924年) 『シンフォニック・ミニッツ』、作品36(1933年) 交響曲第2番 ホ長調、作品40(1945年、1954-7年改訂)[21] アメリカン・ラプソディ、作品47(1953年) 独奏楽器と管弦楽 ピアノ協奏曲第1番 ホ短調、作品5(1898年)(冒頭のテーマはブラームスの交響曲第1番から着想) コンツェルトシュトゥック(Concertpiece) チェロと管弦楽のためのニ長調、作品12(1904年) 子守歌による変奏曲(Variationen über ein Kinderlied)ピアノと管弦楽のための、作品25(1914年) ヴァイオリン協奏曲第1番 ニ短調、作品27(1915年) ピアノ協奏曲第2番 ロ短調、作品42(1947年) ヴァイオリン協奏曲第 2 番 ハ短調 Op. 43 (1950) ハープと室内オーケストラのためのコンチェルティーノ Op. 45 (1952) 室内楽および器楽曲 弦楽四重奏曲 ニ短調、1893 年(未発表、大英図書館に楽譜が所蔵) (Grymes, Ernst von Dohnányi: A Bio-bibliography、32 ページ) 弦楽六重奏曲 B♭長調、1893年(1896年に改訂、1898年に改訂、初演。2006年にハンガロトンから録音) (Grymes、32ページ 弦楽四重奏曲のためのメヌエット、1894年(Grymes、32ページ。原稿はセーチェーニ国立図書館に所蔵) ピアノ四重奏曲 変ホ長調(1894年) ピアノ五重奏曲第1番 ヘ短調、作品1(1895年) 弦楽四重奏曲第1番 イ長調、作品7(1899年) チェロとピアノのためのソナタ 変ホ短調、作品8(1899年) |弦楽三重奏曲 作品10(1902年) 弦楽四重奏曲第2番 変ニ長調、作品15(1906年) ヴァイオリンとピアノのためのソナタ 作品21(1912年) ピアノ五重奏曲第2番 変ホ短調、作品26 (1914) 弦楽四重奏曲第3番 イ短調 Op. 33 (1926) ピアノ、弦楽器、管楽器のための六重奏曲 ハ長調 Op. 37 (1935) フルートとピアノのためのアリア Op. 48, No. 1 (1958) パッサカリア ソロ・フルートのための、作品48、第2番 (1959) ピアノ 4つの小品、作品2 (1897、1905年出版) 4手のためのワルツ、作品3 (1897) E[mma].G[ruber]の主題による変奏曲とフーガ、作品4(1897年) ガヴォットとムゼット(WoO、1898年) アルバム葉(WoO、1899年) 変ロ短調のパッサカリア、作品6(1899年) 4つの狂詩曲、作品11(1903年) ウィンターリーゲン、作品13(1905年) 組曲形式のユーモレスク、作品17(1907年) 3つの小品、作品23(1912年) 左手のためのフーガ、作品13(WoO、1913年) 組曲 イ短調「古風な組曲」、作品24(1913年) 6つのコンチェルト・エチュード、作品28(1916年) ハンガリー民謡による変奏曲、作品29(1917年) ハンガリー民謡による牧歌(WoO、1920年) 『貴族のワルツ』、ピアノのためのコンサート編曲(シューベルトのD. 969による)(WoO、1920年) 『ハンガリーの田園風景』、作品32a(1923年) デリブの『コッペリア』からのピアノのためのワルツ(WoO、1925年) 6つの小品、作品41(1945年) ワルツ組曲、2台のピアノのための、作品39a(1945年) 跛行するワルツ、ピアノ独奏のための、作品39b(1947年) 3つの特異な小品、作品44(1951年) 上級ピアニストのための12の短い練習曲(1951年) |

| Sources Carnes, Mark Christopher, ed. (2002). American National Biography: Supplement 2. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522202-9. Dohnányi, Ilona von (2002). James A. Grymes (ed.). Ernst von Dohnányi: A Song of Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34103-5. Grymes, James A., ed. (2005). Perspectives on Ernst von Dohnányi. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810851252. Retrieved 2014-01-20. Kusz, Veronika (2020). A Wayfaring Stranger: Ernst von Dohnányi's American Years, 1949–1960. California Studies in 20th-Century Music. Vol. 25. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520301832. |

|

| Further reading William Lines Hubbard et al., eds., The American History and Encyclopedia of Music, vol. 1 (London: Irving Squire, 1908), pp. 183–184 available online |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_von_Dohn%C3%A1nyi |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆