モダニズム

Modernism

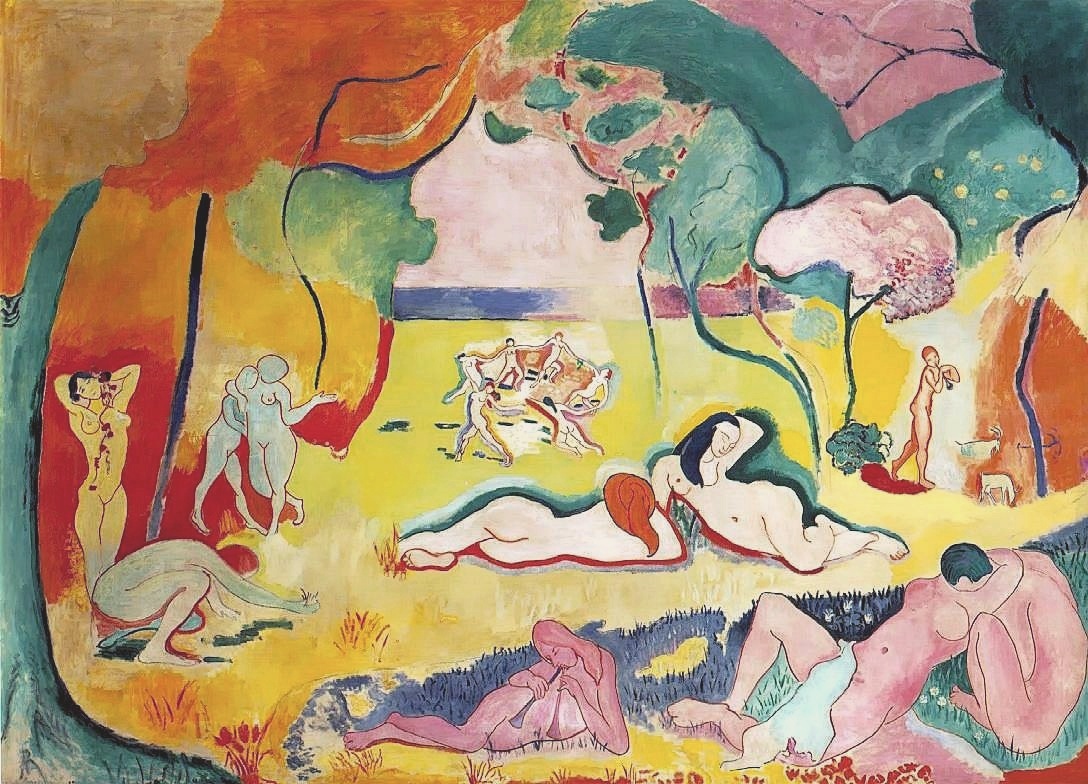

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo

Picasso, 1907, oil on canvas, 244 x 234 cm; arguably the first cubist

painting; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

☆ モダニズムとは、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて西洋社会が大き く変容したことから生まれた哲学、宗教、芸術運動である。この運動は、都市化、建築、新技術、戦争などの特徴を含む、新しく出現した産業世界を反映した芸 術、哲学、社会組織の新しい形態の創造への願望を反映している。芸術家たちは、彼らが時代遅れ、あるいは時代遅れと考えた伝統的な芸術の形式から離れよう とした。詩人エズラ・パウンドが1934年に発した「Make it New」という命令が、この運動のアプローチの試金石となった。

★ポストモダンにおける時間性を考えるヒント;

1)モダンという時間の中に「発展」という考え方がある

2)「発展」はつねに右肩あがりである

3)プレモダン→アーリーモダン→ミッドモダン→レイトモダン→ポストモダンという時間の進行のうち「アーリーモダン→ミッドモダン→レイトモダン」が、モダンという時間性である。

4)モダンというもの(概念)の中に完成という概念があるので、モダニストにとって、ポストモダンは、厄介な時間、新しい問題性が生じる時間、取り組まなければならない新しい(sui generis)課題があると考える。

| Modernism is a

philosophical, religious, and arts movement that arose from broad

transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new

forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the

newly emerging industrial world, including features such as

urbanization, architecture, new technologies, and war. Artists

attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they

considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction

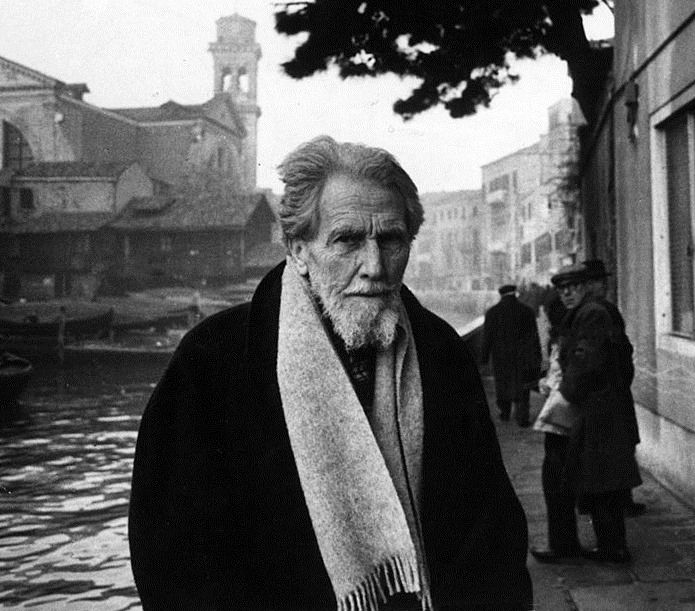

to "Make it New" was the touchstone of the movement's approach. Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream-of-consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, divisionist painting and modern architecture. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism[a][2][3] and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody.[b][c][4] Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and many modernists also rejected religious belief.[5][d] A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art.[7] While some scholars see modernism continuing into the 21st century, others see it evolving into late modernism or high modernism.[8] Postmodernism is a departure from modernism and rejects its basic assumptions.[9][10][11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modernism  Ezra Pound in Venice, 1963 |

モダニズムとは、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて西洋社会が大き

く変容したことから生まれた哲学、宗教、芸術運動である。この運動は、都市化、建築、新技術、戦争などの特徴を含む、新しく出現した産業世界を反映した芸

術、哲学、社会組織の新しい形態の創造への願望を反映している。芸術家たちは、彼らが時代遅れ、あるいは時代遅れと考えた伝統的な芸術の形式から離れよう

とした。詩人エズラ・パウンドが1934年に発した「Make it New」という命令が、この運動のアプローチの試金石となった。 モダニズムの革新には、抽象芸術、意識の流れの小説、モンタージュ映画、無調音楽や十二音音楽、分割主義の絵画、近代建築などがあった。モダニズムはリア リズムのイデオロギーを明確に否定し[a][2][3]、再演、取り込み、書き直し、再現、改訂、パロディを用いることによって過去の作品を利用した [b][c][4]。モダニズムは啓蒙思想の確実性も否定し、多くのモダニストは宗教的信仰も否定した。 [5][d]モダニズムの顕著な特徴は、芸術的および社会的伝統に関する自意識であり、それはしばしば、芸術作品を創作する際に使用されるプロセスや素材 に注目させる技法の使用とともに、形式の実験につながった[7]。 ポストモダニズムはモダニズムからの逸脱であり、その基本的な前提を否定している[9][10][11]。  エズラ・パウンド(ヴェニス, 1963) |

| Definition Some commentators define modernism as a mode of thinking—one or more philosophically defined characteristics, like self-consciousness or self-reference, that run across all the novelties in the arts and the disciplines.[12] More common, especially in the West, are those who see it as a socially progressive trend of thought that affirms the power of human beings to create, improve, and reshape their environment with the aid of practical experimentation, scientific knowledge, or technology.[e] From this perspective, modernism encouraged the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was holding back progress, and replacing it with new ways of reaching the same end. According to Roger Griffin, modernism can be defined as a broad cultural, social, or political initiative, sustained by the ethos of "the temporality of the new". Modernism sought to restore, Griffin writes, a "sense of sublime order and purpose to the contemporary world, thereby counteracting the (perceived) erosion of an overarching 'nomos', or 'sacred canopy', under the fragmenting and secularizing impact of modernity." Therefore, phenomena apparently unrelated to each other such as "Expressionism, Futurism, vitalism, Theosophy, psychoanalysis, nudism, eugenics, utopian town planning and architecture, modern dance, Bolshevism, organic nationalism – and even the cult of self-sacrifice that sustained the hecatomb of the First World War – disclose a common cause and psychological matrix in the fight against (perceived) decadence." All of them embody bids to access a "supra-personal experience of reality", in which individuals believed they could transcend their own mortality, and eventually that they had ceased to be victims of history to become instead its creators.[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modernism |

定義 モダニズムを、自己意識や自己言及のような、芸術や学問分野のあらゆる新しさを貫く、哲学的に定義された特徴、あるいはそれ以上の思考様式と定義する論者 もいる[12]。 より一般的なのは、特に西洋において、モダニズムを、実践的な実験や科学的知識、あるいは技術の助けを借りて、環境を創造し、改善し、再形成する人間の力 を肯定する、社会的に進歩的な思考傾向として捉える人々である。 [この観点から、モダニズムは商業から哲学に至るまで、存在のあらゆる側面の再検討を奨励し、進歩を妨げているものを見つけ出し、同じ目的に到達するため の新しい方法に置き換えることを目標とした。 ロジャー・グリフィンによれば、モダニズムとは、「新しいものの時間性」という倫理観に支えられた、広範な文化的、社会的、政治的イニシアチブと定義でき る。グリフィンは、モダニズムは「現代世界に崇高な秩序と目的の感覚を回復させることで、モダニティの断片化と世俗化の影響下で、包括的な『ノモス』、す なわち『聖なる天蓋』が侵食されている(と認識されている)ことに対抗しようとした」と書いている。したがって、「表現主義、未来派、活力主義、神智学、 精神分析、ヌーディズム、優生学、ユートピア的な都市計画や建築、モダンダンス、ボルシェヴィズム、有機的ナショナリズム、さらには第一次世界大戦の大惨 事を支えた自己犠牲のカルトなど、一見互いに無関係に見える現象は、(知覚された)退廃との闘いにおける共通の原因と心理的マトリックスを開示してい る」。それらはすべて、「超個人的な現実体験」にアクセスするための入札を具現化したものであり、そこでは個人は自らの死を超越し、最終的には歴史の犠牲 者であることをやめ、その代わりに歴史の創造者となることができると信じていた[14]。 |

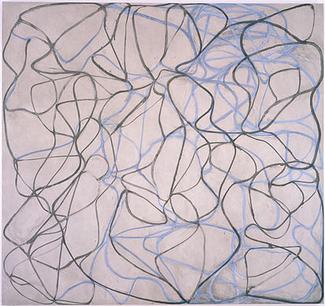

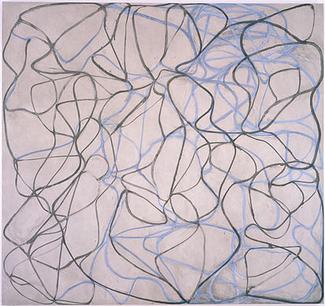

| Modernism, Romanticism,

Philosophy and Symbol Literary modernism is often summed up in a line from W. B. Yeats: "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold” (in 'The Second Coming').[15] Modernists often search for a metaphysical 'centre' but experience its collapse.[16] (Postmodernism, by way of contrast, celebrate that collapse, exposing the failure of metaphysics, for instance in Jacques Derrida's deconstruction of metaphysical claims.)[17] Philosophically, the collapse of metaphysics can be traced back to the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776), who argued that we never actually perceive one event causing another. We only experience the 'constant conjunction' of events, and do not perceive a metaphysical 'cause'. Similarly, Hume argues (without using the actual terms) that we never know the self as object, only the self as subject, and we are thus blind to our true natures.[18] More generally, if we only 'know' through sensory experience (seeing, touching, etc.), then we cannot 'know' or make metaphysical claims. Modernism is thus often driven emotionally by the desire for metaphysical truths, while understanding their impossibility. Modernist novels, for instance, feature characters like Marlow in Heart of Darkness or Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby who believe that they have encountered some great truth about nature or character, truths that the novels themselves treat ironically, offering more mundane explanations.[19] Similarly, many poems of Wallace Stevens struggle with the sense of nature's significance, falling under two headings: poems in which the speaker denies that nature has meaning, only for nature to loom up by the end of the poem; and poems in which the speaker claims nature has meaning, only for that meaning to collapse by the end of the poem. Modernism often rejects nineteenth century realism, if the latter is understood as focusing on the embodiment of meaning within a naturalistic representation. At the same time, some modernists aim at a more 'real' realism, one that is decentred. Picasso's proto-cubist painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon of 1907 (see picture above) does not present its subjects from a single point of view (that of a single viewer), but instead presents a flat, two-dimensional picture plane. 'The Poet' of 1911 is similarly decentred, presenting the body from every point of view. As the Peggy Guggenheim Collections website puts it, 'Picasso presents multiple views of each object, as if he had moved around it, and synthesizes them into a single compound image'.[20] Modernism, with its sense that 'things fall apart,' can be seen as the apotheosis of romanticism, if romanticism is the (often frustrated) quest for metaphysical truths about character, nature, God and meaning in the world.[21] Modernism often yearns for a romantic or metaphysical centre, but finds only its collapse. This distinction between modernism and romanticism extends to their respective treatments of 'symbol'. The romantics at times see an essential relation (the 'ground') between the symbol (the 'vehicle', in I.A. Richards's terms)[22] and its 'tenor' (its meaning)—for example in Coleridge's description of nature as 'that eternal language which thy God / Utters'.[23] But while nature and its symbols may be God's language, for some romantic theorists it remains inscrutable. As Goethe (not quite a romantic) said, 'the idea [or meaning] remains eternally and infinitely active and inaccessible in the image'.[24] This was extended in modernist theory which, drawing on its Symbolist precursors, often emphasises the inscrutability and failure of symbol and metaphor—for example in Stevens who seeks and fails to find meaning in nature, even if he at times seems to sense such a meaning. As such, symbolists and modernists at times adopt a mystical approach to suggest a non-rational sense of meaning.[25] For these reasons, modernist metaphors are often unnatural, as for instance in T.S. Eliot's description of an evening 'spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table'.[26] Similarly, in many later modernist poets nature is unnaturalised and at times mechanised, as for example in Stephen Oliver's image of the moon busily 'hoisting' itself into consciousness.[27] |

文学的モダニズムはしばしばW・B・イェイツの一節に要約される:

モダニストはしばしば形而上学的な「中心」を探し求めるが、その崩壊を経験する[16](ポストモダニズムは対照的にその崩壊を賞賛し、例えばジャック・

デリダの形而上学的主張の脱構築において形而上学の失敗を暴露する)[17]。 哲学的には、形而上学の崩壊はスコットランドの哲学者デイヴィッド・ヒューム(1711-1776)まで遡ることができる。私たちは事象の「絶え間ない連 関」を経験するだけであり、形而上学的な「原因」を認識することはない。同様に、ヒュームは(実際の用語を使わずに)、私たちは客体としての自己を知るこ とはなく、主体としての自己を知るのみであり、したがって私たちは自分の本性について盲目であると主張している[18]。より一般的には、もし私たちが感 覚的経験(見る、触れるなど)を通してしか「知らない」のであれば、私たちは「知る」ことも、形而上学的な主張をすることもできない。 したがって、モダニズムはしばしば形而上学的真理への欲求によって感情的に駆り立てられるが、その一方でその不可能性を理解している。例えばモダニズム小 説には、『闇の奥』のマーロウや『華麗なるギャツビー』のニック・キャラウェイのように、自然や性格に関する偉大な真理に出会ったと信じる人物が登場す る。 [19]同様に、ウォレス・スティーヴンスの詩の多くは、自然の意義の感覚と格闘しており、2つの見出しに分類される。すなわち、話し手が自然が意味を持 つことを否定し、ただ詩の終わりには自然が迫ってくる詩と、話し手が自然が意味を持つと主張し、ただ詩の終わりにはその意味が崩れてしまう詩である。 モダニズムはしばしば19世紀のリアリズムを否定するが、もし後者が自然主義的表象の中での意味の体現に焦点を当てていると理解するならば。同時に、より 「リアル」なリアリズムを目指すモダニストもいる。ピカソのキュビズムの原型ともいえる1907年の「アヴィニョンの娘」(上の写真参照)は、主題を単一 の視点(一人の鑑賞者の視点)からではなく、平面的な二次元の画面を提示している。1911年の『詩人』も同様に、あらゆる視点から身体を提示し、デッサ ンされている。ペギー・グッゲンハイム・コレクションのウェブサイトが言うように、「ピカソは、あたかもその周囲を動き回ったかのように、各オブジェクト の複数の視点を提示し、それらをひとつの複合的なイメージに統合している」[20]。 ロマン主義が、人格、自然、神、そして世界における意味についての形而上学的真理を探求する(しばしば挫折する)ものであるとすれば、「物事はバラバラに なる」という感覚を持つモダニズムは、ロマン主義の神格化と見ることができる[21]。モダニズムはしばしば、ロマン主義的あるいは形而上学的な中心を熱 望するが、その崩壊しか見出せない。 モダニズムとロマン主義のこの区別は、それぞれの「象徴」の扱いにも及んでいる。ロマン主義者たちは時に、象徴(I.A.リチャーズの用語で言うところの 「乗り物」)[22]とその「テノール」(その意味)の間に本質的な関係(「根拠」)を見出す。ゲーテ(ロマン主義者とは言い難い)が言ったように、「イ デア(あるいは意味)はイメージの中で永遠に、無限に活動し、アクセスできないままである」[24]。このことはモダニズム理論においても拡張され、象徴 主義の前身を引きながら、象徴や比喩の不可解さや失敗を強調することが多い。このように、象徴主義者とモダニストは時として、意味の非合理的な感覚を示唆 するために神秘主義的なアプローチを採用する[25]。 このような理由から、モダニズムのメタファーはしばしば不自然であり、例えばT.S.エリオットの「空に向かって広がる夕方/テーブルの上で恍惚とする患 者のような」[26]のような描写がそうである。同様に、多くの後期モダニズムの詩人たちにおいては、自然は不自然化され、例えばスティーヴン・オリ ヴァーの、意識に向かって忙しく自らを「吊り上げる」月のイメージのように、時には機械化されている[27]。 |

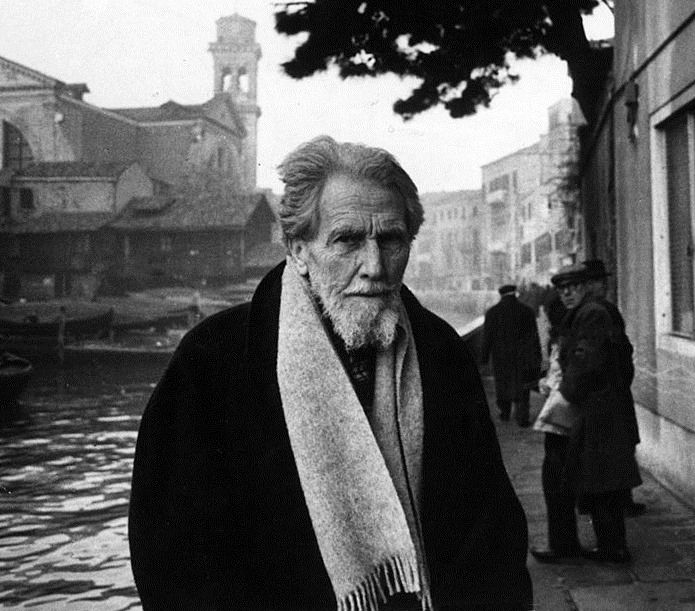

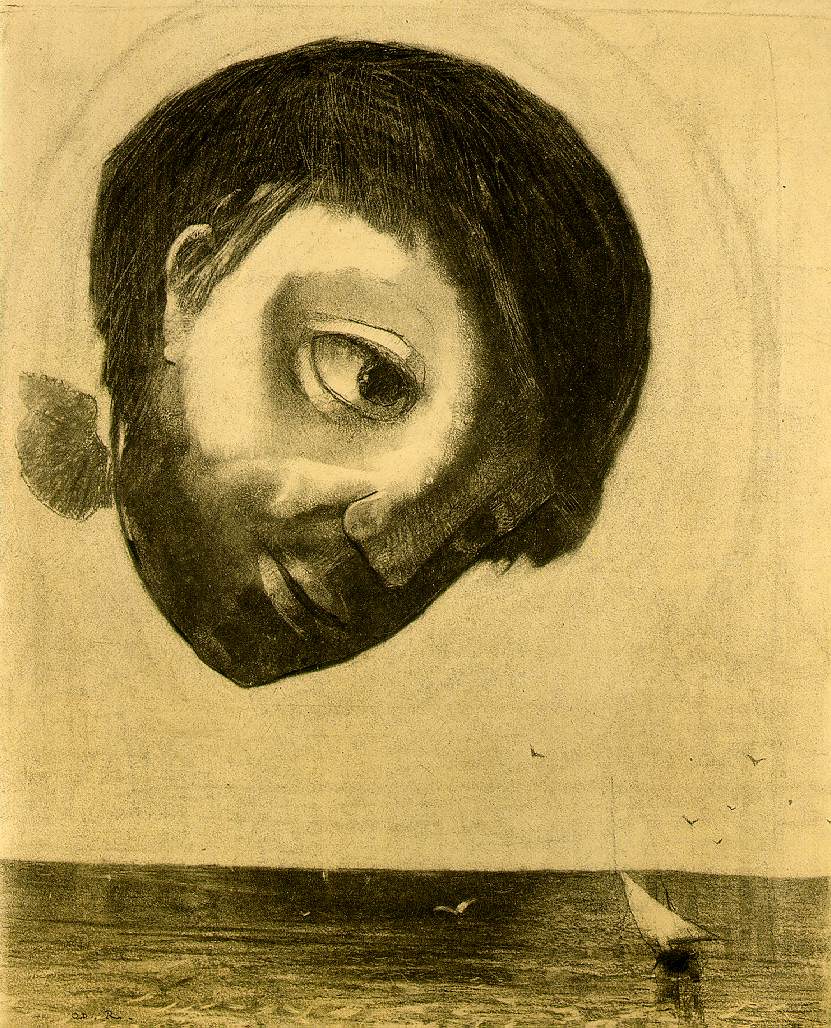

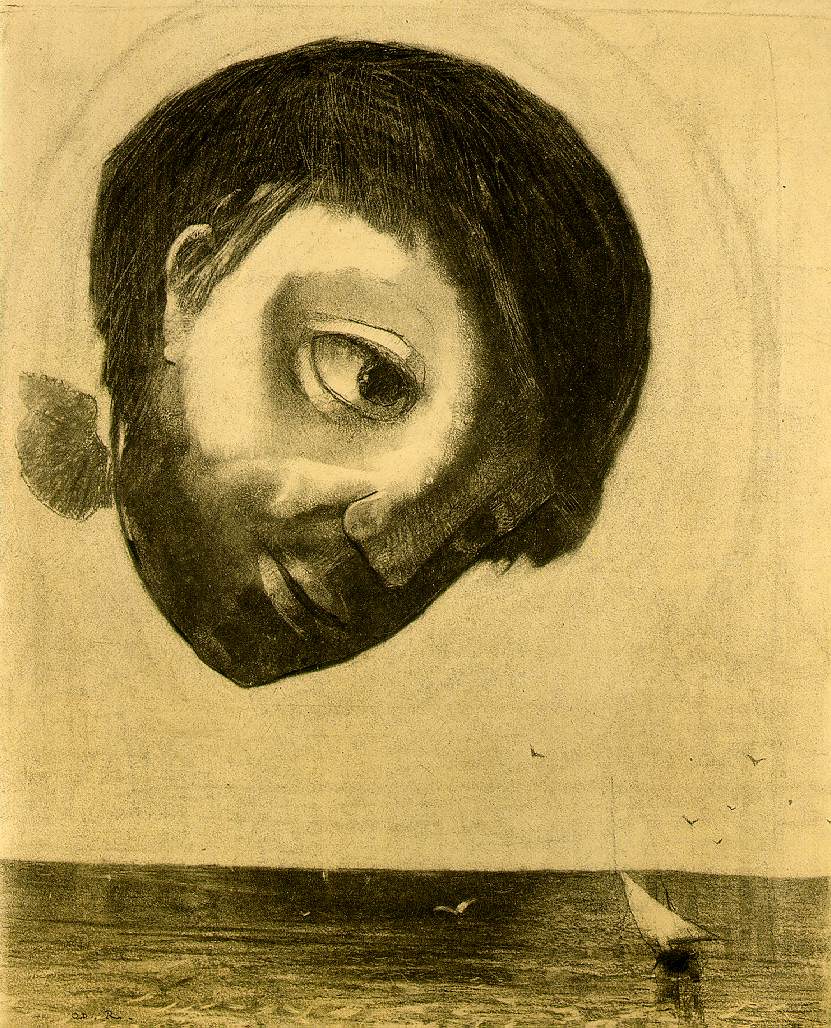

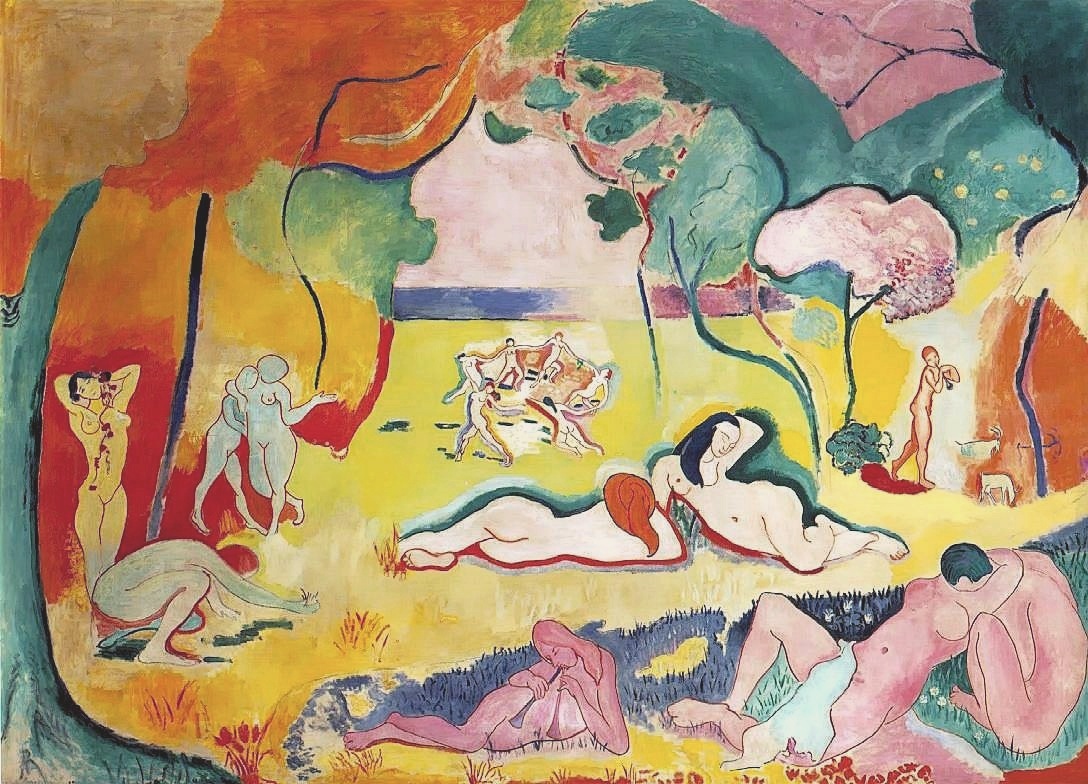

| Early history Origins  Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People, 1830, a Romantic work of art. According to a critic, modernism developed out of Romanticism's revolt against the effects of the Industrial Revolution and bourgeois values: "The ground motive of modernism, Graff asserts, was criticism of the nineteenth-century bourgeois social order and its world view [...] the modernists, carrying the torch of romanticism."[a][2][3] While J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), one of the greatest landscape painters of the 19th century, was a member of the Romantic movement, as "a pioneer in the study of light, colour, and atmosphere", he "anticipated the French Impressionists" and therefore modernism "in breaking down conventional formulas of representation; [though] unlike them, he believed that his works should always express significant historical, mythological, literary, or other narrative themes."[29]  A Realist portrait of Otto von Bismarck. Modernist artists largely rejected realism. The dominant trends of industrial Victorian England were opposed, from about 1850, by the English poets and painters that constituted the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, because of their "opposition to technical skill without inspiration."[30]: 815 They were influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had strong feelings about the role of art in helping to improve the lives of the urban working classes, in the rapidly expanding industrial cities of Britain.[30]: 816 Art critic Clement Greenberg describes the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as proto-Modernists: "There the proto-Modernists were, of all people, the pre-Raphaelites (and even before them, as proto-proto-Modernists, the German Nazarenes). The Pre-Raphaelites actually foreshadowed Manet (1832–1883), with whom Modernist painting most definitely begins. They acted on a dissatisfaction with painting as practiced in their time, holding that its realism wasn't truthful enough."[31] Rationalism has also had opponents in the philosophers Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)[32] and later Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), both of whom had significant influence on existentialism and nihilism.[33]: 120 However, the Industrial Revolution continued. Influential innovations included steam-powered industrialization, and especially the development of railways, starting in Britain in the 1830s,[34] and the subsequent advancements in physics, engineering, and architecture associated with this. A major 19th-century engineering achievement was The Crystal Palace, the huge cast-iron and plate glass exhibition hall built for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Glass and iron were used in a similar monumental style in the construction of major railway terminals in London, such as Paddington Station (1854)[35] and King's Cross station (1852).[36] These technological advances led to the building of later structures like the Brooklyn Bridge (1883) and the Eiffel Tower (1889). The latter broke all previous limitations on how tall man-made objects could be. These engineering marvels radically altered the 19th-century urban environment and the daily lives of people. The human experience of time itself was altered, with the development of the electric telegraph from 1837,[37] and the adoption of standard time by British railway companies from 1845, and in the rest of the world over the next fifty years.[38] Despite continuing technological advances, the idea that history and civilization were inherently progressive, and that progress was always good, came under increasing attack in the nineteenth century. Arguments arose that the values of the artist and those of society were not merely different, but that Society was antithetical to Progress, and could not move forward in its present form. Early in the century, the philosopher Schopenhauer (1788–1860) (The World as Will and Representation, 1819) had called into question the previous optimism, and his ideas had an important influence on later thinkers, including Nietzsche.[32] Two of the most significant thinkers of the mid nineteenth century were biologist Charles Darwin (1809–1882), author of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), and political scientist Karl Marx (1818–1883), author of Das Kapital (1867). Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection undermined religious certainty and the idea of human uniqueness. In particular, the notion that human beings were driven by the same impulses as "lower animals" proved to be difficult to reconcile with the idea of an ennobling spirituality.[39] Karl Marx argued that there were fundamental contradictions within the capitalist system, and that the workers were anything but free.[40]  Odilon Redon, Guardian Spirit of the Waters, 1878, charcoal on paper, Art Institute of Chicago The beginnings in the late nineteenth century Historians, and writers in different disciplines, have suggested various dates as starting points for modernism. Historian William Everdell, for example, has argued that modernism began in the 1870s, when metaphorical (or ontological) continuity began to yield to the discrete with mathematician Richard Dedekind's (1831–1916) Dedekind cut, and Ludwig Boltzmann's (1844–1906) statistical thermodynamics.[12] Everdell also thinks modernism in painting began in 1885–1886 with Seurat's Divisionism, the "dots" used to paint A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. On the other hand, visual art critic Clement Greenberg called Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) "the first real Modernist",[41] though he also wrote, "What can be safely called Modernism emerged in the middle of the last century—and rather locally, in France, with Baudelaire in literature and Manet in painting, and perhaps with Flaubert, too, in prose fiction. (It was a while later, and not so locally, that Modernism appeared in music and architecture)."[31] The poet Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), and Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary were both published in 1857. Baudelaire's essay "The Painter of Modern Life" (1863) inspired young artists to break away from tradition and innovate new ways of portraying their world in art. In the arts and letters, two important approaches developed separately in France, beginning in the 1860s. The first was Impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, but outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist paintings attempted to convey that human beings do not see objects, but instead see light itself. The school gathered adherents despite internal divisions among its leading practitioners, and became increasingly influential. Initially rejected from the most important commercial show of the time, the government-sponsored Paris Salon, the Impressionists organized yearly group exhibitions in commercial venues during the 1870s and 1880s, timing them to coincide with the official Salon. A significant event of 1863 was the Salon des Refusés, created by Emperor Napoleon III to display all of the paintings rejected by the Paris Salon. While most were in standard styles, but by inferior artists, the work of Manet attracted tremendous attention, and opened commercial doors to the movement. The second French school was Symbolism, which literary historians see beginning with Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), and including the later poets, Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) Une Saison en Enfer (A Season in Hell, 1873), Paul Verlaine (1844–1896), Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), and Paul Valéry (1871–1945). The symbolists "stressed the priority of suggestion and evocation over direct description and explicit analogy," and were especially interested in "the musical properties of language."[42] Cabaret, which gave birth to so many of the arts of modernism, including the immediate precursors of film, may be said to have begun in France in 1881 with the opening of the Black Cat in Montmartre, the beginning of the ironic monologue, and the founding of the Society of Incoherent Arts.[43]  Henri Matisse, Le bonheur de vivre, 1905–06, Barnes Foundation, Merion, PA. An early Fauvist masterpiece. Influential in the early days of modernism were the theories of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). Freud's first major work was Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer, 1895). Central to Freud's thinking is the idea "of the primacy of the unconscious mind in mental life," so that all subjective reality was based on the play of basic drives and instincts, through which the outside world was perceived. Freud's description of subjective states involved an unconscious mind full of primal impulses, and counterbalancing self-imposed restrictions derived from social values.[30]: 538  Henri Matisse, The Dance, 1910, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubist Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Henri Matisse's second version of The Dance signifies a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[44] Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) was another major precursor of modernism,[45] with a philosophy in which psychological drives, specifically the "will to power" (Wille zur Macht), was of central importance: "Nietzsche often identified life itself with 'will to power', that is, with an instinct for growth and durability."[46][47] Henri Bergson (1859–1941), on the other hand, emphasized the difference between scientific, clock time and the direct, subjective, human experience of time.[33]: 131 His work on time and consciousness "had a great influence on twentieth-century novelists," especially those modernists who used the stream of consciousness technique, such as Dorothy Richardson, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf (1882–1941).[48] Also important in Bergson's philosophy was the idea of élan vital, the life force, which "brings about the creative evolution of everything."[33]: 132 His philosophy also placed a high value on intuition, though without rejecting the importance of the intellect.[33]: 132 Important literary precursors of modernism were Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), who wrote the novels Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880);[49] Walt Whitman (1819–1892), who published the poetry collection Leaves of Grass (1855–1891); and August Strindberg (1849–1912), especially his later plays, including the trilogy To Damascus 1898–1901, A Dream Play (1902) and The Ghost Sonata (1907). Henry James has also been suggested as a significant precursor, in a work as early as The Portrait of a Lady (1881).[50] Out of the collision of ideals derived from Romanticism, and an attempt to find a way for knowledge to explain that which was as yet unknown, came the first wave of works in the first decade of the 20th century, which, while their authors considered them extensions of existing trends in art, broke the implicit contract with the general public that artists were the interpreters and representatives of bourgeois culture and ideas. These "Modernist" landmarks include the atonal ending of Arnold Schoenberg's Second String Quartet in 1908, the expressionist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky starting in 1903, and culminating with his first abstract painting and the founding of the Blue Rider group in Munich in 1911, and the rise of fauvism and the inventions of cubism from the studios of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and others, in the years between 1900 and 1910. |

初期の歴史 起源  ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワの「民衆を率いる自由」1830年、ロマン主義の作品. ある批評家によれば、モダニズムは産業革命の影響とブルジョワ的価値観に対するロマン主義の反乱から発展した: 「モダニズムの根本的な動機は、19世紀のブルジョア社会秩序とその世界観に対する批判であったとグラフは主張する。19世紀最大の風景画家の一人である ターナー(1775-1851)は、「光、色彩、大気の研究の先駆者」としてロマン主義運動の一員であったが、彼は「従来の表現形式を打破するという点 で、フランスの印象派を先取りし」、ひいてはモダニズムを先取りした[29]。  オットー・フォン・ビスマルクのリアリズム肖像画。モダニズムの芸術家たちは写実主義を大きく否定した。 工業化されたヴィクトリア朝イングランドの支配的な傾向に対して、1850年頃からラファエル前派を構成するイギリスの詩人や画家たちは、「インスピレー ションを伴わない技術的な技巧に反対」していた[30]。 「彼らは美術批評家ジョン・ラスキン(1819-1900)の著作に影響を受けており、彼は急速に拡大するイギリスの工業都市において、都市労働者階級の 生活向上に役立つ芸術の役割について強い感情を抱いていた[30]: 816 美術批評家クレメント・グリーンバーグは、ラファエル前派同胞団をプロト・モダニストと評している: 「そこでのプロト・モダニストとは、他でもない、ラファエル前派であった(そしてさらにその前のプロト・プロト・モダニストとしては、ドイツのナザレ派で あった)。ラファエル前派は、実はマネ(1832-1883)の前身であり、モダニズム絵画はマネから始まる。ラファエル前派は、当時行われていた絵画に 対する不満から行動し、その写実主義が真実味に欠けるとしていた: 120 しかし、産業革命は続いた。影響力のある技術革新としては、蒸気を動力とする工業化、特に1830年代にイギリスで始まった鉄道の発達[34]、それに伴 う物理学、工学、建築学の進歩が挙げられる。19世紀の主要な工学的業績は、1851年にロンドンで開催された万国博覧会のために建設された巨大な鋳鉄と 板ガラスの展示ホールであるクリスタル・パレスであった。ガラスと鉄は、パディントン駅(1854年)[35]やキングス・クロス駅(1852年)といっ たロンドンの主要な鉄道ターミナルの建設においても、同様の記念碑的スタイルで使用された[36]。エッフェル塔は、人工物の高さに関するそれまでの制限 をすべて打ち破った。これらの工学的驚異は、19世紀の都市環境と人々の日常生活を根本的に変えた。1837年からの電気電信の開発[37]、1845年 からのイギリスの鉄道会社による標準時の採用、そしてその後の50年間にわたる世界の他の地域での標準時の採用によって、人間の時間体験そのものが変化し た[38]。 技術の進歩が続いていたにもかかわらず、歴史と文明は本質的に進歩的であり、進歩は常に善であるという考え方は、19世紀になるとますます攻撃されるよう になった。芸術家の価値観と社会の価値観は単に異なっているだけでなく、社会は進歩とは相反するものであり、現在の形では前進できないという主張が生まれ た。世紀初頭、哲学者ショーペンハウアー(1788-1860)(『意志と表象としての世界』1819年)はそれまでの楽観主義に疑問を投げかけ、彼の考 えはニーチェを含む後の思想家たちに重要な影響を与えた。 [32]19世紀半ばの最も重要な2人の思想家は、『自然淘汰による種の起源』(1859年)の著者である生物学者チャールズ・ダーウィン(1809- 1882年)と、『資本論』(1867年)の著者である政治学者カール・マルクス(1818-1883年)であった。ダーウィンの自然淘汰による進化論 は、宗教的な確信と人間の独自性という考えを根底から覆した。特に、人間は「下等動物」と同じ衝動に突き動かされているという考え方は、崇高な精神性の考 え方と調和させることが困難であることが判明した[39]。カール・マルクスは、資本主義システムの中には根本的な矛盾があり、労働者は自由であるとは言 えないと主張した[40]。  オディロン・ルドン《水の守護霊》1878年、紙に木炭、シカゴ美術館蔵 19世紀後半の始まり 歴史家やさまざまな分野の作家は、モダニズムの出発点としてさまざまな時期を提示してきた。例えば、歴史家のウィリアム・エヴァーデルは、数学者リチャー ド・デデキント(1831-1916)のデデキント・カットやルートヴィヒ・ボルツマン(1844-1906)の統計熱力学によって、隠喩的な(あるいは 存在論的な)連続性が離散的なものに屈し始めた1870年代にモダニズムが始まったと主張している。 [12] エヴァーデルはまた、絵画におけるモダニズムは、1885年から1886年にかけて、スーラが『ラ・グランド・ジャット島の日曜日の午後』を描くために用 いた「点」による分割主義から始まったと考えている。一方、視覚芸術批評家のクレメント・グリーンバーグは、イマニュエル・カント(1724-1804) を「最初の真のモダニスト」と呼んだが[41]、彼はまた、「モダニズムと安全に呼べるものは、前世紀の中頃に、むしろフランスで、文学のボードレールや 絵画のマネ、そしておそらく散文小説のフローベールによって出現した。(詩人ボードレールの『悪の華』(Les Fleurs du mal)とフローベールの小説『ボヴァリー夫人』(Madame Bovary)はともに1857年に出版された。ボードレールのエッセイ『現代生活の画家』(1863年)は、若い芸術家たちに伝統から脱却し、芸術で自 分たちの世界を描く新しい方法を革新するよう促した。 芸術と文字の分野では、1860年代からフランスで2つの重要なアプローチが別々に発展した。ひとつは印象派で、当初はアトリエではなく屋外(en plein air)での制作に重点を置いていた。印象派の絵画は、人間が物を見るのではなく、光そのものを見ていることを伝えようとした。この一派は、主要な画家た ちの内部分裂にもかかわらず支持者を集め、影響力を増していった。当初、政府主催のパリ・サロンという当時最も重要な商業的展覧会から退けられていた印象 派は、1870年代から1880年代にかけて、公式のサロンと時期を合わせ、商業的な会場で毎年グループ展を開催した。1863年の重要なイベントは、皇 帝ナポレオン3世がパリ・サロンで却下された絵画を展示するために創設した「拒絶のサロン」だった。ほとんどの作品は標準的なスタイルであったが、劣った 画家たちによるものであったが、マネの作品は大きな注目を集め、この運動への商業的な扉を開いた。第二のフランス派は象徴主義で、文学史家はシャルル・ ボードレール(1821-1867)に始まり、アルチュール・ランボー(1854-1891)『地獄の季節』(1873)、ポール・ヴェルレーヌ (1844-1896)、ステファン・マラルメ(1842-1898)、ポール・ヴァレリー(1871-1945)ら後期の詩人を含むと見ている。象徴主 義者たちは「直接的な描写や明示的な類推よりも暗示や喚起の優先を強調」し、特に「言語の音楽的特性」に関心を寄せていた[42]。 キャバレーは、モンマルトルの黒猫の開店、皮肉な一人芝居の始まり、支離滅裂な芸術協会の設立とともに、1881年にフランスで始まったと言えるかもしれ ない[43]。  アンリ・マティス《Le bonheur de vivre》1905-06年、バーンズ財団、ペンシルベニア州メリオン。フォーヴィスム初期の傑作。 モダニズムの初期に影響を与えたのは、ジークムント・フロイト(1856-1939)の理論である。フロイトの最初の主著は『ヒステリー研究』(ヨーゼ フ・ブロイヤーとの共著、1895年)である。フロイトの考え方の中心は、「精神生活における無意識の優位性」という考え方であり、すべての主観的現実は 基本的な衝動と本能の戯れに基づいており、それを通して外界が知覚されるというものであった。フロイトの主観的状態に関する記述は、原始的な衝動に満ちた 無意識の心と、社会的価値観に由来する自己に課された制限の均衡をとることとを含んでいた[30]: 538  アンリ・マティス《ダンス》1910年、エルミタージュ美術館、サンクトペテルブルク、ロシア。20世紀初頭、アンリ・マティスをはじめ、キュービズム以 前のジョルジュ・ブラック、アンドレ・ドラン、ラウル・デュフィ、モーリス・ド・ヴラマンクら数人の若い芸術家たちは、批評家たちがフォーヴィスムと呼ん だ「野性的」で多色的、表現力豊かな風景画や人物画でパリ画壇に革命を起こした。アンリ・マティスの『ダンス』の第2版は、彼のキャリアと近代絵画の発展 における重要なポイントを意味する[44]。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェ(1844-1900)は、モダニズムのもう一人の主要な先駆者であり[45]、心理的衝動、特に「力への意志」(Wille zur Macht)が中心的な重要性を持つ哲学者であった: ニーチェはしばしば生そのものを「力への意志」、つまり成長と耐久性への本能と同一視していた」[46][47]。一方、アンリ・ベルクソン(1859- 1941)は科学的な時計の時間と直接的で主観的な人間の時間体験との違いを強調していた[33]: 131 時間と意識に関する彼の研究は「20世紀の小説家たち、特にドロシー・リチャードソン、ジェイムズ・ジョイス、ヴァージニア・ウルフ(1882- 1941)といった意識の流れの技法を用いたモダニストたちに大きな影響を与えた」[48]: 132 彼の哲学はまた、知性の重要性を否定することなく、直観に高い価値を置いていた[33]: 132 モダニズムの重要な文学的先駆者は、小説『罪と罰』(1866年)と『カラマーゾフの兄弟』(1880年)を書いたフョードル・ドストエフスキー (1821-1881年)である; [49]詩集『草の葉』(1855-1891)を出版したウォルト・ホイットマン(1819-1892)、アウグスト・ストリンドベリ(1849- 1912)、特に『ダマスカスへ』(1898-1901)、『夢の劇』(1902)、『ゴースト・ソナタ』(1907)の三部作を含む晩年の戯曲。ヘン リー・ジェイムズもまた、『ある貴婦人の肖像』(1881年)という初期の作品において、重要な先駆者として示唆されている[50]。 ロマン主義から派生した理想と、まだ未知であったものを説明する知識を見出そうとする試みの衝突から、20世紀の最初の10年間に最初の作品の波が押し寄 せた。これらの作品は、作者たちが既存の芸術の傾向の延長線上にあると考える一方で、芸術家はブルジョア文化や思想の解釈者であり代表者であるという一般 大衆との暗黙の契約を破った。これらの「モダニズム」のランドマークには、1908年のアーノルド・シェーンベルクの弦楽四重奏曲第2番の無調の終結、 1903年に始まったワシリー・カンディンスキーの表現主義絵画、1911年の彼の最初の抽象絵画とミュンヘンでの「青い騎手」グループの創設に至るま で、1900年から1910年にかけてのアンリ・マティス、パブロ・ピカソ、ジョルジュ・ブラックらのアトリエからのフォーヴィスムの台頭とキュビスムの 発明が含まれる。 |

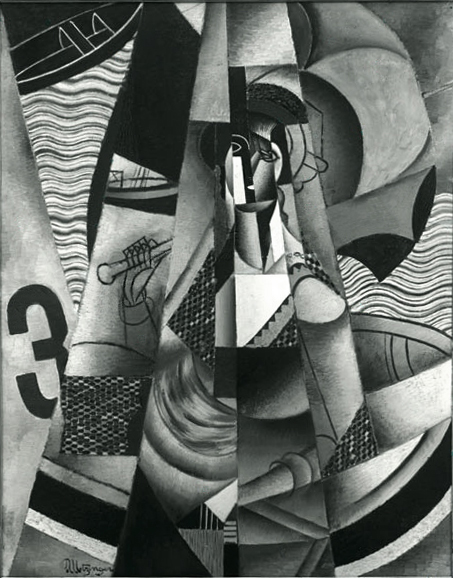

Main period, 1900-1930; 1930-1945 Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, Mill Run, Pennsylvania (1937). Fallingwater was one of Wright's most famous private residences (completed 1937). Early 20th century to 1930  Palais Stoclet (1905–1911) by modernist architect Josef Hoffmann  Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, Art Institute of Chicago An important aspect of modernism is how it relates to tradition through its adoption of techniques like reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[b][c]  Piet Mondrian, View from the Dunes with Beach and Piers, Domburg, 1909, oil and pencil on cardboard, Museum of Modern Art, New York City  The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS) is Spain's national museum of 20th-century art, located in Madrid. The photo shows the old building with the addition of one of the contemporary glass towers to the exterior by Ian Ritchie Architects with the closeup of the modern art tower. T. S. Eliot made significant comments on the relation of the artist to tradition, including: "[W]e shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of [a poet's] work, may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously."[53] However, the relationship of Modernism with tradition was complex, as literary scholar Peter Childs indicates: "There were paradoxical if not opposed trends towards revolutionary and reactionary positions, fear of the new and delight at the disappearance of the old, nihilism and fanatical enthusiasm, creativity and despair."[4] An example of how Modernist art can be both revolutionary and yet be related to past tradition, is the music of the composer Arnold Schoenberg. On the one hand Schoenberg rejected traditional tonal harmony, the hierarchical system of organizing works of music that had guided music making for at least a century and a half. He believed he had discovered a wholly new way of organizing sound, based in the use of twelve-note rows. Yet while this was indeed wholly new, its origins can be traced back in the work of earlier composers, such as Franz Liszt,[54] Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and Max Reger.[55][56] Schoenberg also wrote tonal music throughout his career. In the world of art, in the first decade of the 20th century, young painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were causing a shock with their rejection of traditional perspective as the means of structuring paintings,[57][58] though the impressionist Monet had already been innovative in his use of perspective.[59] In 1907, as Picasso was painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Oskar Kokoschka was writing Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer, Hope of Women), the first Expressionist play (produced with scandal in 1909), and Arnold Schoenberg was composing his String Quartet No.2 in F sharp minor (1908), his first composition without a tonal centre. A primary influence that led to Cubism was the representation of three-dimensional form in the late works of Paul Cézanne, which were displayed in a retrospective at the 1907 Salon d'Automne.[60] In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassembled in an abstracted form; instead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts the subject from a multitude of viewpoints to represent the subject in a greater context.[61] Cubism was brought to the attention of the general public for the first time in 1911 at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris (held 21 April – 13 June). Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Roger de La Fresnaye were shown together in Room 41, provoking a 'scandal' out of which Cubism emerged and spread throughout Paris and beyond. Also in 1911, Kandinsky painted Bild mit Kreis (Picture with a Circle), which he later called the first abstract painting.[62]: 167 In 1912, Metzinger and Gleizes wrote the first (and only) major Cubist manifesto, Du "Cubisme", published in time for the Salon de la Section d'Or, the largest Cubist exhibition to date. In 1912 Metzinger painted and exhibited his enchanting La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a Horse) and Danseuse au Café (Dancer in a Café). Albert Gleizes painted and exhibited his Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) and his monumental Le Dépiquage des Moissons (Harvest Threshing). This work, along with La Ville de Paris (City of Paris) by Robert Delaunay, was the largest and most ambitious Cubist painting undertaken during the pre-War Cubist period.[63] In 1905, a group of four German artists, led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, formed Die Brücke (the Bridge) in the city of Dresden. This was arguably the founding organization for the German Expressionist movement, though they did not use the word itself. A few years later, in 1911, a like-minded group of young artists formed Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Munich. The name came from Wassily Kandinsky's Der Blaue Reiter painting of 1903. Among their members were Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and August Macke. However, the term "Expressionism" did not firmly establish itself until 1913.[62]: 274 Though initially mainly a German artistic movement,[f] most predominant in painting, poetry and the theatre between 1910 and 1930, most precursors of the movement were not German. Furthermore, there have been expressionist writers of prose fiction, as well as non-German speaking expressionist writers, and, while the movement had declined in Germany with the rise of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, there were subsequent expressionist works.  Portrait of Eduard Kosmack (1910) by Egon Schiele  Le Corbusier, The Villa Savoye in Poissy (1928–1931) Expressionism is notoriously difficult to define, in part because it "overlapped with other major 'isms' of the modernist period: with Futurism, Vorticism, Cubism, Surrealism and Dada."[66] Richard Murphy also comments: "the search for an all-inclusive definition is problematic to the extent that the most challenging expressionists" such as the novelist Franz Kafka, poet Gottfried Benn, and novelist Alfred Döblin were simultaneously the most vociferous anti-expressionists.[67]: 43 What, however, can be said, is that it was a movement that developed in the early 20th century mainly in Germany in reaction to the dehumanizing effect of industrialization and the growth of cities, and that "one of the central means by which expressionism identifies itself as an avant-garde movement, and by which it marks its distance to traditions and the cultural institution as a whole is through its relationship to realism and the dominant conventions of representation."[67]: 43 More explicitly: that the expressionists rejected the ideology of realism.[67]: 43–48 [68] There was a concentrated Expressionist movement in early 20th century German theatre, of which Georg Kaiser and Ernst Toller were the most famous playwrights. Other notable Expressionist dramatists included Reinhard Sorge, Walter Hasenclever, Hans Henny Jahnn, and Arnolt Bronnen. They looked back to Swedish playwright August Strindberg and German actor and dramatist Frank Wedekind as precursors of their dramaturgical experiments. Oskar Kokoschka's Murderer, the Hope of Women was the first fully Expressionist work for the theatre, which opened on 4 July 1909 in Vienna.[69] The extreme simplification of characters to mythic types, choral effects, declamatory dialogue and heightened intensity would become characteristic of later Expressionist plays. The first full-length Expressionist play was The Son by Walter Hasenclever, which was published in 1914 and first performed in 1916.[70] Futurism is yet another modernist movement.[71] In 1909, the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro published F. T. Marinetti's first manifesto. Soon afterwards a group of painters (Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini) co-signed the Futurist Manifesto. Modeled on Marx and Engels' famous "Communist Manifesto" (1848), such manifestoes put forward ideas that were meant to provoke and to gather followers. However, arguments in favor of geometric or purely abstract painting were, at this time, largely confined to "little magazines" which had only tiny circulations. Modernist primitivism and pessimism were controversial, and the mainstream in the first decade of the 20th century was still inclined towards a faith in progress and liberal optimism.  Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm (57.5 in × 44.9 in), exhibited at Moderni Umeni, S.V.U. Mánes, Prague, 1914, acquired in 1916 by Georg Muche at the Galerie Der Sturm, confiscated by the Nazis circa 1936–1937, displayed at the Degenerate Art show in Munich, and missing ever since.[72] Abstract artists, taking as their examples the impressionists, as well as Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Edvard Munch (1863–1944), began with the assumption that color and shape, not the depiction of the natural world, formed the essential characteristics of art.[73] Western art had been, from the Renaissance up to the middle of the 19th century, underpinned by the logic of perspective and an attempt to reproduce an illusion of visible reality. The arts of cultures other than the European had become accessible and showed alternative ways of describing visual experience to the artist. By the end of the 19th century many artists felt a need to create a new kind of art which would encompass the fundamental changes taking place in technology, science and philosophy. The sources from which individual artists drew their theoretical arguments were diverse, and reflected the social and intellectual preoccupations in all areas of Western culture at that time.[74] Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich all believed in redefining art as the arrangement of pure color. The use of photography, which had rendered much of the representational function of visual art obsolete, strongly affected this aspect of modernism.[75] Modernist architects and designers, such as Frank Lloyd Wright[76] and Le Corbusier,[77] believed that new technology rendered old styles of building obsolete. Le Corbusier thought that buildings should function as "machines for living in", analogous to cars, which he saw as machines for traveling in.[78] Just as cars had replaced the horse, so modernist design should reject the old styles and structures inherited from Ancient Greece or from the Middle Ages. Following this machine aesthetic, modernist designers typically rejected decorative motifs in design, preferring to emphasize the materials used and pure geometrical forms.[79] The skyscraper is the archetypal modernist building, and the Wainwright Building, a 10-story office building built 1890–91, in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, is among the first skyscrapers in the world.[80] Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building in New York (1956–1958) is often regarded as the pinnacle of this modernist high-rise architecture.[81] Many aspects of modernist design still persist within the mainstream of contemporary architecture, though previous dogmatism has given way to a more playful use of decoration, historical quotation, and spatial drama.  André Masson, Pedestal Table in the Studio 1922, early example of Surrealism In 1913—which was the year of philosopher Edmund Husserl's Ideas, physicist Niels Bohr's quantized atom, Ezra Pound's founding of imagism, the Armory Show in New York, and in Saint Petersburg the "first futurist opera", Mikhail Matyushin's Victory over the Sun—another Russian composer, Igor Stravinsky, composed The Rite of Spring, a ballet that depicts human sacrifice, and has a musical score full of dissonance and primitive rhythm. This caused uproar on its first performance in Paris. At this time though modernism was still "progressive", increasingly it saw traditional forms and traditional social arrangements as hindering progress, and was recasting the artist as a revolutionary, engaged in overthrowing rather than enlightening society. Also in 1913 a less violent event occurred in France with the publication of the first volume of Marcel Proust's important novel sequence À la recherche du temps perdu (1913–1927) (In Search of Lost Time). This is often presented as an early example of a writer using the stream-of-consciousness technique, but Robert Humphrey comments that Proust "is concerned only with the reminiscent aspect of consciousness" and that he "was deliberately recapturing the past for the purpose of communicating; hence he did not write a stream-of-consciousness novel."[82] Stream of consciousness was an important modernist literary innovation, and it has been suggested that Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931) was the first to make full use of it in his short story "Leutnant Gustl" ("None but the Brave") (1900).[83] Dorothy Richardson was the first English writer to use it, in the early volumes of her novel sequence Pilgrimage (1915–1967).[g] The other modernist novelists that are associated with the use of this narrative technique include James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) and Italo Svevo in La coscienza di Zeno (1923).[85] However, with the coming of the Great War of 1914–1918 and the Russian Revolution of 1917, the world was drastically changed and doubt cast on the beliefs and institutions of the past. The failure of the previous status quo seemed self-evident to a generation that had seen millions die fighting over scraps of earth: prior to 1914 it had been argued that no one would fight such a war, since the cost was too high. The birth of a machine age which had made major changes in the conditions of daily life in the 19th century now had radically changed the nature of warfare. The traumatic nature of recent experience altered basic assumptions, and realistic depiction of life in the arts seemed inadequate when faced with the fantastically surreal nature of trench warfare. The view that mankind was making steady moral progress now seemed ridiculous in the face of the senseless slaughter, described in works such as Erich Maria Remarque's novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1929). Therefore, modernism's view of reality, which had been a minority taste before the war, became more generally accepted in the 1920s. In literature and visual art some modernists sought to defy expectations mainly in order to make their art more vivid, or to force the audience to take the trouble to question their own preconceptions. This aspect of modernism has often seemed a reaction to consumer culture, which developed in Europe and North America in the late 19th century. Whereas most manufacturers try to make products that will be marketable by appealing to preferences and prejudices, high modernists rejected such consumerist attitudes in order to undermine conventional thinking. The art critic Clement Greenberg expounded this theory of modernism in his essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch.[86] Greenberg labeled the products of consumer culture "kitsch", because their design aimed simply to have maximum appeal, with any difficult features removed. For Greenberg, modernism thus formed a reaction against the development of such examples of modern consumer culture as commercial popular music, Hollywood, and advertising. Greenberg associated this with the revolutionary rejection of capitalism. Some modernists saw themselves as part of a revolutionary culture that included political revolution. In Russia after the 1917 Revolution there was indeed initially a burgeoning of avant-garde cultural activity, which included Russian Futurism. However others rejected conventional politics as well as artistic conventions, believing that a revolution of political consciousness had greater importance than a change in political structures. But many modernists saw themselves as apolitical. Others, such as T. S. Eliot, rejected mass popular culture from a conservative position. Some even argue that modernism in literature and art functioned to sustain an elite culture which excluded the majority of the population.[86] Surrealism, which originated in the early 1920s, came to be regarded by the public as the most extreme form of modernism, or "the avant-garde of Modernism".[87] The word "surrealist" was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire and first appeared in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias, which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917. Major surrealists include Paul Éluard, Robert Desnos,[88] Max Ernst, Hans Arp, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, Joan Miró, and Marcel Duchamp.[89] By 1930, Modernism had won a place in the establishment, including the political and artistic establishment, although by this time Modernism itself had changed. Modernism continues: 1930–1945 Modernism continued to evolve during the 1930s. Between 1930 and 1932 composer Arnold Schoenberg worked on Moses und Aron, one of the first operas to make use of the twelve-tone technique,[90] Pablo Picasso painted in 1937 Guernica, his cubist condemnation of fascism, while in 1939 James Joyce pushed the boundaries of the modern novel further with Finnegans Wake. Also by 1930 Modernism began to influence mainstream culture, so that, for example, The New Yorker magazine began publishing work, influenced by Modernism, by young writers and humorists like Dorothy Parker,[91] Robert Benchley, E. B. White, S. J. Perelman, and James Thurber, amongst others.[92] Perelman is highly regarded for his humorous short stories that he published in magazines in the 1930s and 1940s, most often in The New Yorker, which are considered to be the first examples of surrealist humor in America.[93] Modern ideas in art also began to appear more frequently in commercials and logos, an early example of which, from 1916, is the famous London Underground logo designed by Edward Johnston.[94] One of the most visible changes of this period was the adoption of new technologies into daily life of ordinary people in Western Europe and North America. Electricity, the telephone, the radio, the automobile—and the need to work with them, repair them and live with them—created social change. The kind of disruptive moment that only a few knew in the 1880s became a common occurrence. For example, the speed of communication reserved for the stock brokers of 1890 became part of family life, at least in middle class North America. Associated with urbanization and changing social mores also came smaller families and changed relationships between parents and their children.  London Underground logo designed by Edward Johnston. This is the modern version (with minor modifications) of one that was first used in 1916. Another strong influence at this time was Marxism. After the generally primitivistic/irrationalist aspect of pre-World War I Modernism (which for many modernists precluded any attachment to merely political solutions) and the neoclassicism of the 1920s (as represented most famously by T. S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky—which rejected popular solutions to modern problems), the rise of fascism, the Great Depression, and the march to war helped to radicalise a generation. Bertolt Brecht, W. H. Auden, André Breton, Louis Aragon and the philosophers Antonio Gramsci and Walter Benjamin are perhaps the most famous exemplars of this Modernist form of Marxism. There were, however, also modernists explicitly of 'the right', including Salvador Dalí, Wyndham Lewis, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, the Dutch author Menno ter Braak and others.[95] Significant Modernist literary works continued to be created in the 1920s and 1930s, including further novels by Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, Robert Musil, and Dorothy Richardson. The American Modernist dramatist Eugene O'Neill's career began in 1914, but his major works appeared in the 1920s, 1930s and early 1940s. Two other significant Modernist dramatists writing in the 1920s and 1930s were Bertolt Brecht and Federico García Lorca. D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover was privately published in 1928, while another important landmark for the history of the modern novel came with the publication of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury in 1929. In the 1930s, in addition to further major works by Faulkner, Samuel Beckett published his first major work, the novel Murphy (1938). Then in 1939 James Joyce's Finnegans Wake appeared. This is written in a largely idiosyncratic language, consisting of a mixture of standard English lexical items and neologistic multilingual puns and portmanteau words, which attempts to recreate the experience of sleep and dreams.[96] In poetry T. S. Eliot, E. E. Cummings, and Wallace Stevens were writing from the 1920s until the 1950s. While Modernist poetry in English is often viewed as an American phenomenon, with leading exponents including Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, H.D., and Louis Zukofsky, there were important British Modernist poets, including David Jones, Hugh MacDiarmid, Basil Bunting, and W. H. Auden. European Modernist poets include Federico García Lorca, Anna Akhmatova, Constantine Cavafy, and Paul Valéry. James Joyce statue on North Earl Street, Dublin, by Marjorie FitzGibbon The Modernist movement continued during this period in Soviet Russia. In 1930 composer Dimitri Shostakovich's (1906–1975) opera The Nose was premiered, in which he uses a montage of different styles, including folk music, popular song and atonality. Amongst his influences was Alban Berg's (1885–1935) opera Wozzeck (1925), which "had made a tremendous impression on Shostakovich when it was staged in Leningrad."[97] However, from 1932 Socialist realism began to oust Modernism in the Soviet Union,[98] and in 1936 Shostakovich was attacked and forced to withdraw his 4th Symphony.[99] Alban Berg wrote another significant, though incomplete, Modernist opera, Lulu, which premiered in 1937. Berg's Violin Concerto was first performed in 1935. Like Shostakovich, other composers faced difficulties in this period. In Germany Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) was forced to flee to the U.S. when Hitler came to power in 1933, because of his Modernist atonal style as well as his Jewish ancestry.[100] His major works from this period are a Violin Concerto, Op. 36 (1934/36), and a Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942). Schoenberg also wrote tonal music in this period with the Suite for Strings in G major (1935) and the Chamber Symphony No. 2 in E♭ minor, Op. 38 (begun in 1906, completed in 1939).[100] During this time Hungarian Modernist Béla Bartók (1881–1945) produced a number of major works, including Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) and the Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939), String Quartet No. 5 (1934), and No. 6 (his last, 1939). But he too left for the US in 1940, because of the rise of fascism in Hungary.[100] Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) continued writing in his neoclassical style during the 1930s and 1940s, writing works like the Symphony of Psalms (1930), Symphony in C (1940) and Symphony in Three Movements (1945). He also emigrated to the US because of World War II. Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992), however, served in the French army during the war and was imprisoned at Stalag VIII-A by the Germans, where he composed his famous Quatuor pour la fin du temps ("Quartet for the End of Time"). The quartet was first performed in January 1941 to an audience of prisoners and prison guards.[101] In painting, during the 1920s and the 1930s and the Great Depression, modernism was defined by Surrealism, late Cubism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, German Expressionism, and Modernist and masterful color painters like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard as well as the abstractions of artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky which characterized the European art scene. In Germany, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz and others politicized their paintings, foreshadowing the coming of World War II, while in America, modernism is seen in the form of American Scene painting and the social realism and regionalism movements that contained both political and social commentary dominated the art world. Artists like Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, George Tooker, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh, and others became prominent. Modernism is defined in Latin America by painters Joaquín Torres-García from Uruguay and Rufino Tamayo from Mexico, while the muralist movement with Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Pedro Nel Gómez and Santiago Martínez Delgado, and Symbolist paintings by Frida Kahlo, began a renaissance of the arts for the region, characterized by a freer use of color and an emphasis on political messages. Diego Rivera is perhaps best known by the public world for his 1933 mural, Man at the Crossroads, in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. When his patron Nelson Rockefeller discovered that the mural included a portrait of Vladimir Lenin and other communist imagery, he fired Rivera, and the unfinished work was eventually destroyed by Rockefeller's staff. Frida Kahlo's works are often characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her paintings' bright colors and dramatic symbolism. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work as well; she combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition, which were often bloody and violent. Frida Kahlo's Symbolist works relate strongly to Surrealism and to the magic realism movement in literature. Political activism was an important piece of David Siqueiros' life, and frequently inspired him to set aside his artistic career. His art was deeply rooted in the Mexican Revolution. The period from the 1920s to the 1950s is known as the Mexican Renaissance, and Siqueiros was active in the attempt to create an art that was at once Mexican and universal. The young Jackson Pollock attended the workshop and helped build floats for the parade. During the 1930s radical leftist politics characterized many of the artists connected to Surrealism, including Pablo Picasso.[102] On 26 April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the Basque town of Gernika was bombed by Nazi Germany's Luftwaffe. The Germans were attacking to support the efforts of Francisco Franco to overthrow the Basque government and the Spanish Republican government. Pablo Picasso painted his mural-sized Guernica to commemorate the horrors of the bombing. During the Great Depression of the 1930s and through the years of World War II, American art was characterized by social realism and American Scene painting, in the work of Grant Wood, Edward Hopper, Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, and several others. Nighthawks (1942) is a painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people sitting in a downtown diner late at night. It is not only Hopper's most famous painting, but one of the most recognizable in American art. The scene was inspired by a diner in Greenwich Village. Hopper began painting it immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After this event there was a large feeling of gloominess over the country, a feeling that is portrayed in the painting. The urban street is empty outside the diner, and inside none of the three patrons is apparently looking or talking to the others but instead is lost in their own thoughts. This portrayal of modern urban life as empty or lonely is a common theme throughout Hopper's work. American Gothic is a painting by Grant Wood from 1930. Portraying a pitchfork-holding farmer and a younger woman in front of a house of Carpenter Gothic style, it is one of the most familiar images in 20th-century American art. Art critics had favorable opinions about the painting; like Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley, they assumed the painting was meant to be a satire of rural small-town life. It was thus seen as part of the trend towards increasingly critical depictions of rural America, along the lines of Sherwood Anderson's 1919 Winesburg, Ohio, Sinclair Lewis's 1920 Main Street, and Carl Van Vechten's The Tattooed Countess in literature.[103] However, with the onset of the Great Depression, the painting came to be seen as a depiction of steadfast American pioneer spirit. The situation for artists in Europe during the 1930s deteriorated rapidly as the Nazis' power in Germany and across Eastern Europe increased. Degenerate art was a term adopted by the Nazi regime in Germany for virtually all modern art. Such art was banned on the grounds that it was un-German or Jewish Bolshevist in nature, and those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions. These included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce art entirely. Degenerate Art was also the title of an exhibition, mounted by the Nazis in Munich in 1937. The climate became so hostile for artists and art associated with modernism and abstraction that many left for the Americas. German artist Max Beckmann and scores of others fled Europe for New York. In New York City a new generation of young and exciting Modernist painters led by Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and others were just beginning to come of age. Arshile Gorky's portrait of someone who might be Willem de Kooning is an example of the evolution of abstract expressionism from the context of figure painting, cubism and surrealism. Along with his friends de Kooning and John D. Graham, Gorky created biomorphically shaped and abstracted figurative compositions that by the 1940s evolved into totally abstract paintings. Gorky's work seems to be a careful analysis of memory, emotion and shape, using line and color to express feeling and nature. |

主要な時期(1900〜1930年;1930年〜1945年) フランク・ロイド・ライト《フォーリングウォーター》(ペンシルベニア州ミル・ラン、1937年)。フォーリングウォーターは、ライトの最も有名な個人邸 宅のひとつ(1937年完成)。 20世紀初頭~1930年  モダニズム建築家ヨーゼフ・ホフマンによるストクレ宮(1905年~1911年  パブロ・ピカソ《ダニエル=ヘンリー・カーンヴァイラーの肖像》1910年、シカゴ美術館蔵 モダニズムの重要な側面は、新しい形式における再演、取り込み、書き換え、再現、改訂、パロディといった技法の採用を通じて、伝統とどのように関わるかと いうことである[b][c]。  ピエト・モンドリアン《砂丘からの眺めと浜辺と桟橋、ドンブルグ》1909年、油彩、鉛筆、厚紙、ニューヨーク近代美術館蔵  国立レイナ・ソフィア美術館(MNCARS)は、マドリードにあるスペインの国立20世紀美術館。写真は、イアン・リッチー・アーキテクツによる現代的な ガラスタワーのひとつを外観に加えた旧館と、現代美術タワーのクローズアップ。 T. S.エリオットは、芸術家と伝統との関係について、次のような重要なコメントを残している: 「詩人の)作品の最良の部分だけでなく、最も個性的な部分は、死んだ詩人、つまり彼の祖先が最も力強くその不滅性を主張している部分であることがよくあ る」[53] しかし、文学者ピーター・チャイルズが示すように、モダニズムと伝統の関係は複雑であった: 「革命的な立場と反動的な立場、新しいものへの恐怖と古いものの消滅への喜び、ニヒリズムと狂信的な熱狂、創造性と絶望など、対立的ではないにせよ逆説的 な傾向があった」[4]。 モダニズム芸術がいかに革命的でありながら、過去の伝統と関係しうるかを示す例として、作曲家アーノルド・シェーンベルクの音楽が挙げられる。一方で シェーンベルクは、少なくとも1世紀半にわたって音楽制作を導いてきた伝統的な調性和声、つまり音楽作品を組織する階層的なシステムを否定した。彼は、 12音列を使ったまったく新しい音の構成法を発見したと信じていた。しかし、これは確かに全く新しいものではあったが、その起源は、フランツ・リスト [54]、リヒャルト・ワーグナー、グスタフ・マーラー、リヒャルト・シュトラウス、マックス・レーガーといった、それ以前の作曲家の作品にまで遡ること ができる。 美術の世界では、20世紀の最初の10年間、パブロ・ピカソやアンリ・マティスといった若い画家たちが、絵画を構成する手段としての伝統的な遠近法を否定 して衝撃を与えていた[57][58]。 [1907年、ピカソが『レ・ドゥモワゼル・ダヴィニヨン』を描いていた頃、オスカー・ココシュカは表現主義初の戯曲『殺人者、女たちの希望』 (Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen)を書いており(1909年にスキャンダルで上演)、アーノルド・シェーンベルクは弦楽四重奏曲第2番嬰ヘ短調(1908年)を作曲してい た。嬰ヘ短調、1908年)を作曲していた。 キュービズムにつながる主な影響は、1907年のサロン・ドートンヌでの回顧展で展示されたポール・セザンヌの晩年の作品における三次元的な形の表現で あった[60]。 [60]キュビズムの作品では、対象物は分析され、分解され、抽象化された形で再構築される。対象物を一つの視点から描くのではなく、画家は対象をより大 きな文脈で表現するために多数の視点から描く。[61] キュビズムは1911年、パリのサロン・デ・アンデパンダン(4月21日~6月13日開催)で初めて一般大衆の注目を集めた。ジャン・メッツィンガー、ア ルベール・グライーズ、アンリ・ル・フォコニエ、ロベール・ドローネ、フェルナン・レジェ、ロジェ・ド・ラ・フレネが41号室で一堂に会し、「スキャンダ ル」を引き起こした。また1911年、カンディンスキーは後に最初の抽象絵画と呼ばれる《円のある絵》を描いた[62]: 167 1912年、メッツィンガーとグライズは、最初の(そして唯一の)主要なキュビズム宣言書『キュビスム』を執筆。1912年、メッツィンガーは魅惑的な 《馬を連れた女》と《カフェの踊り子》を描き、展示した。アルベール・グライズは、『水浴女たち』(Les Baigneuses)と記念碑的な『収穫の脱穀』(Le Dépiquage des Moissons)を描き、展示した。この作品は、ロベール・ドローネイの『パリの街』(La Ville de Paris)と共に、戦前のキュビズム時代に描かれたキュビズム絵画の中で最大かつ最も野心的なものであった[63]。 1905年、エルンスト・ルートヴィヒ・キルヒナーに率いられた4人のドイツ人芸術家のグループは、ドレスデンの街で「橋(Die Brücke)」を結成した。これは間違いなくドイツ表現主義運動の創始組織であったが、彼らはこの言葉自体は使わなかった。数年後の1911年、志を同 じくする若い芸術家たちがミュンヘンで「青い騎手」を結成した。この名前は、ワシリー・カンディンスキーが1903年に描いた「青い騎手」に由来する。メ ンバーの中には、カンディンスキー、フランツ・マルク、パウル・クレー、アウグスト・マッケらがいた。しかし、「表現主義」という言葉が定着したのは 1913年のことである[62]: 274当初は主にドイツの芸術運動であり、1910年から1930年にかけて絵画、詩、演劇において最も優勢であったが[f]、この運動の前駆者のほとん どはドイツ人ではなかった。さらに、散文小説の表現主義作家やドイツ語圏以外の表現主義作家も存在し、ドイツでは1930年代にアドルフ・ヒトラーが台頭 して運動は衰退したが、その後の表現主義作品も存在した。  エゴン・シーレ作『エドゥアルド・コスマックの肖像』(1910年  ル・コルビュジエ『ポワシーのサヴォワ邸』(1928-1931年) 表現主義は、「未来派、ヴォルティズム、キュビスム、シュルレアリスム、ダダなど、モダニズム期の他の主要な "イズム "と重なっていた」[66]こともあり、定義が難しいことで知られている: 小説家フランツ・カフカ、詩人ゴットフリート・ベン、小説家アルフレッド・デブリンのような「最も挑戦的な表現主義者」が、同時に最も声高な反表現主義者 であったという点で、包括的な定義の探求には問題がある」[67]: 43 しかし言えることは、表現主義が20世紀初頭に主にドイツで、工業化と都市の発展による非人間的な影響への反動として発展した運動であり、「表現主義が自 らをアヴァンギャルド運動として識別し、伝統や文化制度全体との距離を示す中心的な手段のひとつは、リアリズムや支配的な表現の慣習との関係を通じてであ る」ということである[67]: 43 より明確には、表現主義者たちはリアリズムのイデオロギーを否定していた: ゲオルク・カイザーとエルンスト・トラーが最も有名な劇作家である。他の著名 な表現主義劇作家には、ラインハルト・ゾルゲ、ヴァルター・ハーゼンクレーヴァー、ハンス・ヘニー・ヤーン、アーノルト・ブロンネンらがいた。彼らは、ス ウェーデンの劇作家アウグスト・ストリンドベリやドイツの俳優兼劇作家フランク・ヴェーデキントを、演劇的実験の先駆者として振り返った。1909年7月 4日にウィーンで初演されたオスカー・ココシュカの『殺人者、女たちの希望』は、劇場のための最初の完全な表現主義作品であった[69]。登場人物を神話 的なタイプに極端に単純化し、合唱的な効果、宣言的な台詞、激しさを増した演出は、後の表現主義劇の特徴となる。最初の長編表現主義戯曲は、1914年に 出版され、1916年に初演されたヴァルター・ハーセンスレーヴァーの『息子』である[70]。 未来派はまた別のモダニズム運動である[71]。1909年、パリの新聞『ル・フィガロ』がF・T・マリネッティの最初のマニフェストを掲載。その直後、 画家のグループ(ジャコモ・バッラ、ウンベルト・ボッチョーニ、カルロ・カッラ、ルイジ・ルッソロ、ジーノ・セヴェリーニ)が未来派宣言に共同署名した。 マルクスとエンゲルスの有名な「共産党宣言」(1848年)に倣い、このようなマニフェストは、フォロワーを刺激し、集めることを意図したアイデアを提唱 する。しかし、幾何学的な絵画や純粋な抽象絵画を支持する主張は、この当時、部数の少ない「小さな雑誌」に限られていた。モダニズムのプリミティヴィズム とペシミズムは物議を醸し、20世紀最初の10年の主流はまだ進歩信仰とリベラルな楽観主義に傾いていた。  Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm (57.5 × 44.9 in), S.V.U. Mánes, Prague, Moderni Umeni, S.V.U. Mánes, Prague, 1914で展示され、1916年にGalerie Der SturmでGeorg Mucheによって入手され、1936年から1937年頃にナチスによって没収され、ミュンヘンの退廃芸術展で展示され、それ以来行方不明になっている [72]。 抽象芸術家たちは、印象派やポール・セザンヌ(1839-1906)、エドヴァルド・ムンク(1863-1944)を手本とし、自然界の描写ではなく、色 と形が芸術の本質的な特徴を形成するという仮定から出発した[73]。ルネサンスから19世紀半ばまでの西洋美術は、遠近法の論理に支えられ、目に見える 現実の幻想を再現しようとする試みによって支えられていた。ヨーロッパ以外の文化の芸術は身近なものとなり、芸術家にとって視覚的経験を描写する代替的な 方法を示すようになった。19世紀末には、多くの芸術家が、技術、科学、哲学の根本的な変化を包含する新しい芸術を創造する必要性を感じていた。ワシ リー・カンディンスキー、ピエト・モンドリアン、カジミール・マレーヴィチは、純粋な色彩の配置として芸術を再定義することを信条としていた。視覚芸術の 具象的機能の多くを時代遅れにしていた写真の使用は、モダニズムのこの側面に強く影響を与えた[75]。 フランク・ロイド・ライト[76]やル・コルビュジエ[77]のようなモダニズムの建築家やデザイナーは、新しい技術が古い建築様式を時代遅れにすると信 じていた。ル・コルビュジエは、建物は「住むための機械」として機能すべきであり、それは自動車になぞらえられ、自動車は移動するための機械であると考え た[78]。自動車が馬に取って代わったように、モダニズムのデザインは古代ギリシャや中世から受け継いだ古い様式や構造を否定すべきであった。超高層ビ ルは典型的なモダニズム建築であり、1890年から91年にかけてアメリカ合衆国ミズーリ州セントルイスに建設された10階建てのオフィスビル、ウェイン ライトビルは世界初の超高層ビルのひとつである。 [80]ルートヴィヒ・ミース・ファン・デル・ローエのニューヨークのシーグラム・ビルディング(1956-1958)は、しばしばこのモダニズム高層建 築の頂点と見なされている[81]。モダニズム・デザインの多くの側面は、現代建築の主流の中でまだ存続しているが、以前の独断主義は、装飾、歴史的引 用、空間ドラマをより遊び心に満ちた使い方に道を譲っている。  アンドレ・マッソン《アトリエの台座テーブル》1922年、シュルレアリスムの初期例 1913年といえば、哲学者エドムント・フッサールの「イデア」、物理学者ニールス・ボーアの量子化原子、エズラ・パウンドのイマジズム創始、ニューヨー クのアーモリーショー、サンクトペテルブルクでの「最初の未来派オペラ」ミハイル・マチューシンの「太陽の勝利」があった年である。これはパリでの初演時 に騒動を引き起こした。この頃、モダニズムはまだ「進歩的」であったが、伝統的な形式や伝統的な社会体制が進歩を妨げていると考えるようになり、芸術家を 革命家として捉え直し、社会を啓蒙するのではなく転覆させることに従事していた。また1913年には、マルセル・プルーストの重要な小説群『失われた時を 求めて』(À la recherche du temps perdu、1913-1927)の第1巻が出版され、フランスではそれほど暴力的ではない出来事が起こった。これはしばしば、意識の流れの技法を用いた 作家の初期の例として紹介されるが、ロバート・ハンフリーは、プルーストは「意識の回想的側面にのみ関心を抱いており」、「コミュニケーションを目的とし て意図的に過去を捉え直していたのであり、それゆえ彼は意識の流れの小説を書いていない」とコメントしている[82]。 意識の流れはモダニズム文学の重要な革新であり、アーサー・シュニッツラー(1862-1931)が短編小説『ロイトナント・グストル』(『勇者以外誰も いない』)(1900年)で初めてそれを駆使したと示唆されている。 [ドロシー・リチャードソンは、彼女の小説『巡礼』(1915-1967)の初期の巻で、これを使用した最初のイギリス人作家であった。 しかし、1914年から1918年にかけての第一次世界大戦と1917年のロシア革命が起こると、世界は大きく変わり、過去の信念や制度に疑念が投げかけ られた。1914年以前は、そのような戦争はコストがかかりすぎるため、誰も戦わないと論じられていた。19世紀に日常生活の状況に大きな変化をもたらし た機械時代の誕生は、今や戦争の本質を根本的に変えてしまった。最近の体験のトラウマ的な性質は基本的な前提を変え、芸術における現実的な生活描写は、塹 壕戦の幻想的で超現実的な性質に直面したときには不十分なものに思えた。エーリッヒ・マリア・レマルクの小説『西部戦線異状なし』(1929年)などに描 かれた無分別な殺戮を前にすると、人類が道徳的に着実に進歩しているという見方は滑稽に思えた。そのため、戦前は少数派だったモダニズムの現実観が、 1920年代にはより一般的に受け入れられるようになった。 文学や視覚芸術において、一部のモダニストたちは、主に自分たちの芸術をより鮮烈なものにするため、あるいは観客に自分たちの先入観を疑う手間を強いるた めに、期待に逆らおうとした。モダニズムのこうした側面は、19世紀後半にヨーロッパと北米で発展した消費文化への反動と思われがちだ。多くのメーカー が、嗜好や偏見に訴えかけることで市場性のある製品を作ろうとするのに対し、ハイ・モダニストたちは、従来の考え方を根底から覆すために、そのような消費 者主義的な態度を否定した。美術批評家のクレメント・グリーンバーグは、そのエッセイ『アヴァンギャルドとキッチュ』の中で、このモダニズム論を展開して いる[86]。グリーンバーグは、消費者文化の製品に「キッチュ」というレッテルを貼った。グリーンバーグにとってモダニズムは、商業的なポピュラー音 楽、ハリウッド、広告といった現代の消費文化の発展に対する反動であった。グリーンバーグはこのことを、資本主義に対する革命的な拒絶と結びつけた。 モダニストの中には、自分たちが政治革命を含む革命文化の一部であると考える者もいた。1917年革命後のロシアでは、確かに当初、ロシア未来派を含む前 衛的な文化活動が急成長した。しかし、政治構造の変化よりも政治意識の革命の方が重要であると考え、従来の政治や芸術の常識を否定した人々もいた。しか し、モダニストの多くは自分たちを政治的な存在ではないと考えた。また、T・S・エリオットのように、保守的な立場から大衆文化を否定する者もいた。文学 や芸術におけるモダニズムは、人口の大多数を排除するエリート文化を維持するために機能していたと主張する者さえいる[86]。 1920年代初頭に生まれたシュルレアリスムは、モダニズムの最も極端な形態、あるいは「モダニズムの前衛」と世間からみなされるようになった[87]。 シュルレアリスト」という言葉はギョーム・アポリネールによって作られ、1903年に書かれ、1917年に初演された彼の戯曲『ティレジアスの夢』の序文 に初めて登場した。主なシュルレアリストには、ポール・エリュアール、ロベール・デスノス、マックス・エルンスト、ハンス・アルプ、アントナン・アル トー、レイモン・クノー、ジョアン・ミロ、マルセル・デュシャンなどがいる[89]。 1930年までに、モダニズムは政治的、芸術的エスタブリッシュメントを含むエスタブリッシュメントの中で地位を獲得したが、この頃にはモダニズムそのも のが変化していた。 モダニズムは続く: 1930-1945 モダニズムは1930年代も進化を続けた。1930年から1932年にかけて、作曲家アーノルド・シェーンベルクは、十二音技法を用いた最初のオペラのひ とつである『モーゼとアロン』に取り組み[90]、パブロ・ピカソは、1937年にファシズムをキュービズムで非難した『ゲルニカ』を描き、1939年に はジェイムズ・ジョイスが『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』で近代小説の境界をさらに押し広げた。また、1930年までにはモダニズムが文化の主流に影響を及ぼ し始め、例えば『ニューヨーカー』誌はモダニズムの影響を受けたドロシー・パーカー、[91] ロバート・ベンチリー、E・B・ホワイト、S・J・ペレルマン、ジェームズ・サーバーなどの若手作家やユーモア作家の作品を掲載し始めた。 [ペレルマンは、1930年代から1940年代にかけて雑誌に発表したユーモラスな短編小説で高く評価されており、中でも『ニューヨーカー』誌に掲載され ることが多く、アメリカにおけるシュルレアリスム的ユーモアの最初の例と考えられている[93]。芸術におけるモダンなアイデアも、コマーシャルやロゴに 頻繁に登場するようになり、その初期の例として、1916年にエドワード・ジョンストンがデザインした有名なロンドンの地下鉄のロゴが挙げられる [94]。 この時代の最も目に見える変化のひとつは、西ヨーロッパと北米の一般庶民の日常生活に新しい技術が取り入れられたことである。電気、電話、ラジオ、自動 車、そしてそれらを使って仕事をし、修理し、生活する必要性が、社会に変化をもたらした。1880年代にはごく一部の人しか知らなかったような破壊的な瞬 間が、日常茶飯事となった。たとえば、1890年には株式ブローカーにしか許されなかったコミュニケーションのスピードが、少なくとも北米の中流階級では 家庭生活の一部となった。都市化と社会風俗の変化に伴い、家族の人数も減り、親子関係も変化した。  エドワード・ジョンストンがデザインしたロンドン地下鉄のロゴ。1916年に初めて使用されたものの現代版(若干の修正あり)。 この時期、もうひとつ強い影響を受けたのがマルクス主義だった。第一次世界大戦前のモダニズム(多くのモダニストにとって、単なる政治的解決策への執着を 排除していた)や1920年代の新古典主義(T・S・エリオットやイーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーに代表されるように、現代的な問題に対する大衆的な解決策 を否定していた)は、概して原始主義的/非合理主義的な側面を持っていた。ベルトルト・ブレヒト、W・H・オーデン、アンドレ・ブルトン、ルイ・アラゴ ン、そして哲学者のアントニオ・グラムシとヴァルター・ベンヤミンが、マルクス主義のモダニズムの最も有名な模範であろう。しかし、サルバドール・ダリ、 ウィンダム・ルイス、T・S・エリオット、エズラ・パウンド、オランダの作家メンノ・テル・ブラックなど、明確に「右派」のモダニストもいた[95]。 マルセル・プルースト、ヴァージニア・ウルフ、ロバート・ムージル、ドロシー・リチャードソンによる小説など、1920年代から1930年代にかけても重 要なモダニズム文学作品が創作され続けた。アメリカのモダニズム劇作家ユージン・オニールのキャリアは1914年に始まったが、代表作は1920年代、 1930年代、1940年代初頭に登場した。1920年代と1930年代に書かれた他の2人の重要なモダニズム劇作家は、ベルトルト・ブレヒトとフェデリ コ・ガルシア・ロルカである。D.H.ロレンスの『チャタレイ夫人の恋人』は1928年に私家出版され、1929年にウィリアム・フォークナーの『音と怒 り』が出版されたのも、近代小説史にとって重要な画期的出来事だった。1930年代には、フォークナーのさらなる大作に加え、サミュエル・ベケットが初の 大作となる小説『マーフィー』(1938年)を発表。そして1939年、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』が発表された。この作品は、標 準的な英語の語彙項目と新語的な多言語のダジャレやポルトマントー語の混合からなる、主に特異な言語で書かれており、睡眠や夢の経験を再現しようと試みて いる[96]。詩においては、T・S・エリオット、E・E・カミングス、ウォレス・スティーヴンスが1920年代から1950年代まで執筆していた。英語 におけるモダニズム詩は、エズラ・パウンド、T.S.エリオット、マリアンヌ・ムーア、ウィリアム・カルロス・ウィリアムズ、H.D.、ルイス・ズコフス キーなどの代表的な表現者を含むアメリカの現象と見なされることが多いが、デイヴィッド・ジョーンズ、ヒュー・マクダイアミッド、バジル・バンティング、 W.H.オーデンなどの重要なイギリスのモダニズム詩人もいた。ヨーロッパのモダニズム詩人には、フェデリコ・ガルシア・ロルカ、アンナ・アフマートワ、 コンスタンティン・カヴァフィ、ポール・ヴァレリーなどがいる。 【省略】 ダブリン、ノース・アール・ストリートのジェイムズ・ジョイス像(マージョリー・フィッツギボン作 この時期、ソビエト・ロシアではモダニズム運動が続いていた。1930年、作曲家ディミトリ・ショスタコーヴィチ(1906~1975)のオペラ『鼻』が 初演され、彼は民族音楽、ポピュラーソング、無調など、さまざまなスタイルのモンタージュを用いた。彼の影響の中には、アルバン・ベルク(1885- 1935)のオペラ『ヴォツェック』(1925)があり、「レニングラードで上演されたとき、ショスタコーヴィチに多大な印象を与えた」[97]。しか し、1932年からソ連では社会主義リアリズムがモダニズムを追放し始め[98]、1936年にショスタコーヴィチは攻撃され、交響曲第4番を撤回させら れた[99]。ベルクのヴァイオリン協奏曲は1935年に初演された。ショスタコーヴィチと同様、この時期、他の作曲家たちも困難に直面した。 ドイツでは、アルノルト・シェーンベルク(1874~1951)が、1933年にヒトラーが政権を握ると、そのモダニズム的な無調の作風とユダヤ人の先祖 を理由に、アメリカへの亡命を余儀なくされた[100]。この時期の主な作品は、ヴァイオリン協奏曲作品36(1934/36)とピアノ協奏曲作品42 (1942)である。シェーンベルクはこの時期、弦楽のための組曲ト長調(1935年)や室内交響曲第2番変ホ短調作品38(1906年着手、1939年 完成)といった調性音楽も書いている。 [100]この時期、ハンガリーのモダニスト、ベラ・バルトーク(1881~1945)は、「弦楽器、打楽器とチェレスタのための音楽」(1936)、 「弦楽オーケストラのためのディヴェルティメント」(1939)、「弦楽四重奏曲第5番」(1934)、「第6番」(最後の作品、1939)など、数多く の大作を残した。イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキー(1882-1971)は、1930年代から1940年代にかけても新古典主義のスタイルで作曲を続け、交 響詩篇(1930)、交響曲ハ長調(1940)、交響曲三楽章(1945)といった作品を書いた。また、第二次世界大戦のためアメリカに移住した。しか し、オリヴィエ・メシアン(1908-1992)は戦時中フランス軍に従軍し、ドイツ軍によってシュターラークVIII-Aに収監され、そこで有名な《時 の終わりのための四重奏曲》を作曲した。この四重奏曲は1941年1月に囚人と看守の聴衆を前に初演された[101]。 絵画においては、1920年代から1930年代、そして世界恐慌の時代にかけて、モダニズムはシュルレアリスム、後期キュビスム、バウハウス、デ・ステイ ル、ダダ、ドイツ表現主義、そしてアンリ・マティスやピエール・ボナールのようなモダニストで優れた色彩の画家たち、さらにはピエト・モンドリアンやワシ リー・カンディンスキーのような抽象画によって定義され、ヨーロッパのアートシーンを特徴づけた。ドイツでは、マックス・ベックマン、オットー・ディック ス、ジョージ・グロッシュらが、第二次世界大戦の到来を予感させる政治的な絵画を制作し、アメリカでは、モダニズムはアメリカ風景画の形で見られ、政治 的・社会的な批評を含む社会的リアリズム運動や地域主義運動が美術界を席巻した。ベン・シャーン、トーマス・ハート・ベントン、グラント・ウッド、ジョー ジ・トゥーカー、ジョン・ステュアート・カリー、レジナルド・マーシュなどの芸術家が著名になった。ラテンアメリカでは、ウルグアイの画家ホアキン・トー レス=ガルシアとメキシコのルフィノ・タマヨによってモダニズムが定義され、ディエゴ・リベラ、ダビド・シケイロス、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ペド ロ・ネル・ゴメス、サンティアゴ・マルティネス・デルガドによる壁画運動、フリーダ・カーロによる象徴主義の絵画が、より自由な色使いと政治的メッセージ の強調を特徴とするこの地域の芸術のルネサンスを始めた。 ディエゴ・リベラは、ロックフェラー・センターのRCAビルのロビーにある1933年の壁画『十字路の男』で、おそらく世間一般に最もよく知られている。 彼のパトロンであったネルソン・ロックフェラーは、この壁画にウラジーミル・レーニンの肖像やその他の共産主義的なイメージが含まれていることを知ると、 リベラを解雇し、未完成の作品は最終的にロックフェラーのスタッフによって破壊された。フリーダ・カーロの作品の特徴は、しばしばその峻烈な痛みの描写に ある。カーロはメキシコの土着文化に深く影響を受けており、それは彼女の絵画の鮮やかな色彩と劇的な象徴主義に表れている。キリスト教やユダヤ教のテーマ もしばしば彼女の作品に描かれている。彼女は、しばしば血なまぐさく暴力的であった古典的な宗教的メキシコの伝統の要素を組み合わせたのである。フリー ダ・カーロの象徴主義の作品は、シュルレアリスムや文学におけるマジック・リアリズム運動と強く関連している。 政治活動はダビッド・シケイロスの人生の重要な一部であり、芸術家としてのキャリアを脇に置くよう、たびたび彼を鼓舞した。彼の芸術はメキシコ革命に深く 根ざしていた。1920年代から1950年代にかけての時代はメキシコ・ルネッサンスと呼ばれ、シケイロスはメキシコ的でありながら普遍的な芸術を創造し ようと積極的に活動した。若き日のジャクソン・ポロックもワークショップに参加し、パレードの山車作りを手伝った。 1930年代には、パブロ・ピカソをはじめ、シュルレアリスムにつながる芸術家の多くが急進的な左翼政治を特徴としていた[102]。スペイン内戦中の 1937年4月26日、バスクの町ゲルニカがナチス・ドイツ空軍の爆撃を受けた。ドイツ軍は、バスク政府とスペイン共和国政府を転覆させようとするフラン シスコ・フランコの努力を支援するために攻撃していた。パブロ・ピカソはこの爆撃の恐怖を記念して、壁画サイズのゲルニカを描いた。 1930年代の世界恐慌から第二次世界大戦にかけて、アメリカ美術はグラント・ウッド、エドワード・ホッパー、ベン・シャーン、トーマス・ハート・ベント ン、その他数人の作品に見られる社会的リアリズムとアメリカ風景画を特徴とした。ナイトホークス』(1942年)はエドワード・ホッパーの作品で、深夜の ダウンタウンのダイナーに座る人々を描いている。ホッパーの最も有名な絵であるだけでなく、アメリカ美術の中で最もよく知られた絵のひとつである。この シーンは、グリニッジ・ヴィレッジのダイナーから着想を得た。ホッパーがこの絵を描き始めたのは、真珠湾攻撃の直後だった。この出来事の後、この国には大 きな暗澹たる気分が広がっていたが、それはこの絵にも描かれている。ダイナーの外には誰もいない都会の通り、店内では3人の常連客の誰も他の客に目もくれ ず、会話もなく、それぞれの思索に耽っているようだ。このように現代の都市生活を空虚なもの、孤独なものとして描くことは、ホッパーの作品に共通するテー マである。 アメリカン・ゴシック』はグラント・ウッドが1930年に描いた作品だ。カーペンター・ゴシック様式の家の前で投石器を持つ農夫と若い女性を描いたこの作 品は、20世紀アメリカ美術の中で最も親しまれているイメージのひとつである。美術批評家たちは、ガートルード・スタインやクリストファー・モーリーのよ うに、この絵が田舎の小さな町の生活を風刺していると考え、好意的に評価した。そのため、シャーウッド・アンダーソンの『オハイオ州ワインズバーグ』 (1919年)、シンクレア・ルイスの『メイン・ストリート』(1920年)、カール・ヴァン・ヴェヒテンの『刺青をした伯爵夫人』(文学)のように、ア メリカの田舎を批判的に描く傾向が強まる中で、この絵もその流れの一部と見なされた[103]。しかし、世界恐慌が始まると、この絵はアメリカの揺るぎな い開拓者精神を描いたものと見なされるようになった。 1930年代のヨーロッパでは、ナチスがドイツと東ヨーロッパ全域で勢力を拡大するにつれて、芸術家を取り巻く状況は急速に悪化した。退廃芸術とは、ドイ ツのナチス政権が事実上すべての現代美術に対して採用した言葉である。そのような芸術は、ドイツ的でない、あるいはユダヤ人ボリシェヴィスト的であるとい う理由で禁止され、退廃芸術家と認定された者は制裁の対象となった。このような制裁には、教職から解雇されること、展示や販売を禁止されること、場合に よっては芸術作品の制作を全面的に禁止されることなどが含まれた。1937年にナチスがミュンヘンで開催した展覧会のタイトルも「退廃芸術」だった。モダ ニズムや抽象主義に関連する芸術家や芸術を敵視する風潮が強まり、多くの芸術家がアメリカ大陸へと去っていった。ドイツ人画家のマックス・ベックマンをは じめ、多くの芸術家たちがヨーロッパからニューヨークへと向かった。ニューヨークでは、アルシール・ゴーリキーやウィレム・デ・クーニングらに代表され る、若く刺激的なモダニズムの画家たちが新時代を迎えようとしていた。 アルシール・ゴーリキーが描いたウィレム・デ・クーニングと思われる人物の肖像画は、人物画、キュビスム、シュルレアリスムの文脈から抽象表現主義が進化 した一例である。ゴーリキーは、友人であったデ・クーニングやジョン・D・グラハムとともに、生物的な形をした抽象化された具象画を制作し、1940年代 には完全に抽象化された絵画へと発展させた。ゴーリキーの作品は、記憶、感情、形を注意深く分析し、線と色を使って感情や自然を表現しているようだ。 |