ベーラ・バルトーク

Béla Viktor János Bartók, 1881-1945

☆ ベラ・ヴィクトル・ヤーノシュ・バルトーク(/ˈbeɪlə ˈbɑːrtɒk/; ハンガリー語: [ˈbɒrtoːk ˈbeːlɒ]; 1881年3月25日 – 1945年9月26日)は、ハンガリーの作曲家、ピアニスト、民族音楽学者だった。彼は20世紀で最も重要な作曲家の1人とされ、フランツ・リストと共に ハンガリー最大の作曲家とされている[1]。主な作品には、オペラ『青ひげ公の城』、バレエ『奇跡のマンダリン』、弦楽のための音楽、打楽器とチェレスタ のための音楽、管弦楽のための協奏曲、6つの弦楽四重奏曲などがある。民謡(民俗音楽/フォーク・ミュージック)の収集と分析的研究を通じて、彼は比較音 楽学の創始者の一人となり、後に民族音楽学として知られるようになった。アンソニー・トマシーニによると、バルトークは「後世の作曲家たちに、あらゆる文 化の民謡や古典音楽の伝統を作品に取り入れる力を与えた」人物であり、「シェーンベルクの驚異的な表現手法に直面しても、調性、非伝統的な音階、無調の漂 流を融合させた独自の言語を築き上げた、圧倒的な現代主義者」だった。[2]

| Béla Viktor János Bartók

(/ˈbeɪlə ˈbɑːrtɒk/; Hungarian: [ˈbɒrtoːk ˈbeːlɒ]; 25 March 1881 – 26

September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and

ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers

of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as Hungary's

greatest composers.[1] Among his notable works are the opera

Bluebeard's Castle, the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin, Music for

Strings, Percussion and Celesta, the Concerto for Orchestra and six

string quartets. Through his collection and analytical study of folk

music, he was one of the founders of comparative musicology, which

later became known as ethnomusicology. Per Anthony Tommasini, Bartók

"has empowered generations of subsequent composers to incorporate folk

music and classical traditions from whatever culture into their works

and was "a formidable modernist who in the face of Schoenberg’s

breathtaking formulations showed another way, forging a language that

was an amalgam of tonality, unorthodox scales and atonal wanderings."[2] |

ベ

ラ・ヴィクトル・ヤーノシュ・バルトーク(/ˈbeɪlə ˈbɑːrtɒk/; ハンガリー語: [ˈbɒrtoːk ˈbeːlɒ];

1881年3月25日 –

1945年9月26日)は、ハンガリーの作曲家、ピアニスト、民族音楽学者だった。彼は20世紀で最も重要な作曲家の1人とされ、フランツ・リストと共に

ハンガリー最大の作曲家とされている[1]。主な作品には、オペラ『青ひげ公の城』、バレエ『奇跡のマンダリン』、弦楽のための音楽、打楽器とチェレスタ

のための音楽、管弦楽のための協奏曲、6つの弦楽四重奏曲などがある。民謡(民俗音楽/フォーク・ミュージック)の収集と分析的研究を通じて、彼は比較音

楽学の創始者の一人となり、後に民族音楽学として知られるようになった。アンソニー・トマシーニによると、バルトークは「後世の作曲家たちに、あらゆる文

化の民謡や古典音楽の伝統を作品に取り入れる力を与えた」人物であり、「シェーンベルクの驚異的な表現手法に直面しても、調性、非伝統的な音階、無調の漂

流を融合させた独自の言語を築き上げた、圧倒的な現代主義者」だった。[2] |

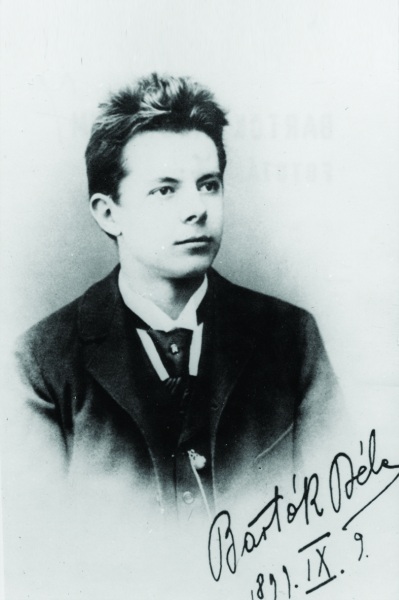

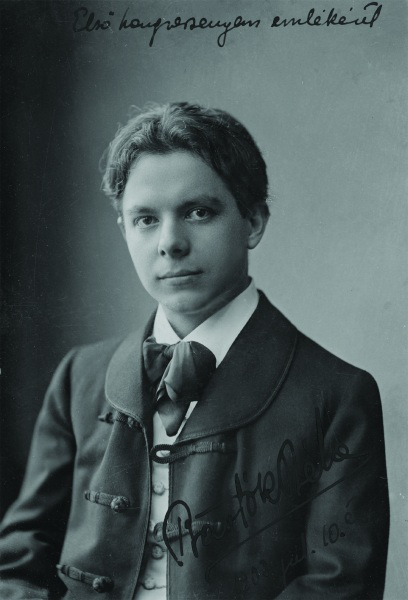

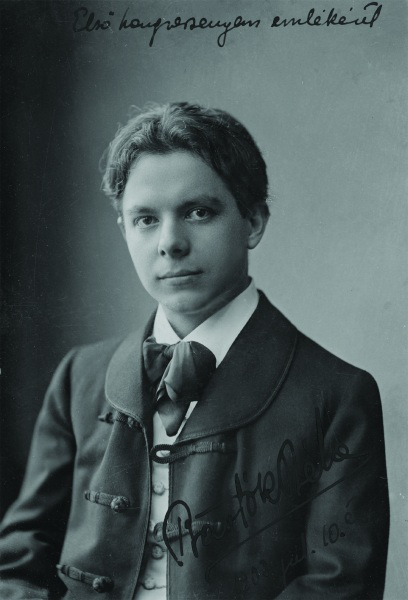

| Biography Childhood and early years (1881–1898) Bartók was born in the Banatian town of Nagyszentmiklós in the Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Sânnicolau Mare, Romania) on 25 March 1881.[3] On his father's side, the Bartók family was a Hungarian lower noble family, originating from Borsodszirák, Borsod.[4] His paternal grandmother was a Catholic of Bunjevci origin, but considered herself Hungarian.[5] Bartók's father (1855–1888) was also named Béla. Bartók's mother, Paula (née Voit) [hu] (1857–1939), spoke[6] Hungarian fluently.[7] A native of Turócszentmárton (present-day Martin, Slovakia),[8] she had German, Hungarian and Slovak or Polish ancestry. Béla displayed notable musical talent very early in life. According to his mother, he could distinguish between different dance rhythms that she played on the piano before he learned to speak in complete sentences.[9] By the age of four he was able to play 40 pieces on the piano, and his mother began formally teaching him the next year. In 1888, when he was seven, his father, the director of an agricultural school, died suddenly. His mother then took Béla and his sister, Erzsébet, to live in Nagyszőlős (present-day Vynohradiv, Ukraine) and then in Pressburg (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia). Béla gave his first public recital aged 11 in Nagyszőlős, to positive critical reception.[10][page needed] Among the pieces he played was his own first composition, written two years previously: a short piece called "The Course of the Danube".[11] Shortly thereafter, László Erkel accepted him as a pupil.[12] Early musical career (1899–1908)  Bartók's signature on his high-school-graduation photograph, dated 9 September 1899 From 1899 to 1903, Bartók studied piano under István Thomán, a former student of Franz Liszt, and composition under János Koessler at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest.[13] There he met Zoltán Kodály, who made a strong impression on him and became a lifelong friend and colleague.[14] In 1903, Bartók wrote his first major orchestral work, Kossuth, a symphonic poem that honored Lajos Kossuth, hero of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.[15] The music of Richard Strauss, whom he met in 1902 at the Budapest premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra, strongly influenced his early work.[16] When visiting a holiday resort in the summer of 1904, Bartók overheard a young nanny, Lidi Dósa from Kibéd in Transylvania, sing folk songs to the children in her care. This sparked his lifelong dedication to folk music.[17] Beginning in 1907, he came under the influence of French composer Claude Debussy, whose compositions Kodály had brought back from Paris. Bartók's large-scale orchestral works were still in the style of Johannes Brahms and Richard Strauss, but he wrote a number of small piano pieces which showed his growing interest in folk music. The first piece to show clear signs of this new interest is the String Quartet No. 1 in A minor (1908), which contains folk-like elements.[18] He began teaching as a piano professor at the Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest. This position freed him from touring Europe as a pianist. Among his notable students were Fritz Reiner, Sir Georg Solti, György Sándor, Ernő Balogh, Gisela Selden-Goth, and Lili Kraus. After Bartók moved to the United States, he taught Jack Beeson and Violet Archer. In 1908, Bartok and Kodály traveled into the countryside to collect and research old Magyar folk melodies. Their growing interest in folk music coincided with a contemporary social interest in traditional national culture. Magyar folk music had previously been categorised as Gypsy music. The classic example is Franz Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies for piano, which he based on popular art songs performed by Romani bands of the time. In contrast, Bartók and Kodály discovered that the old Magyar folk melodies were based on pentatonic scales, similar to those in Asian folk traditions, such as those of Central Asia, Anatolia and Siberia.[19] Bartók and Kodály set about incorporating elements of such Magyar peasant music into their compositions. They both frequently quoted folk song melodies verbatim and wrote pieces derived entirely from authentic songs. An example is Bartok's two volumes entitled For Children for solo piano, containing 80 folk tunes to which he wrote accompaniment. Bartók's style in his art music compositions was a synthesis of folk music, classicism, and modernism. His melodic and harmonic sense was influenced by the folk music of Hungary, Romania, and other nations. He was especially fond of the asymmetrical dance rhythms and pungent harmonies found in Bulgarian music. Most of his early compositions offer a blend of nationalist and late Romantic elements. |

略歴 幼少期と青年期 (1881年–1898年) バルトークは、1881年3月25日にハンガリー王国(現在のルーマニア、サンニコラウ・マレ)のバナティア地方にあるナジセントミクロスで生まれた。 [3] 父親の側のバルトーク家は、ボルショドのボルショドジラクを起源とするハンガリーの低貴族の家系だった。[4] 彼の父方の祖母は、ブンジェフチ出身のローマカトリック教徒だったが、自分はハンガリー人だと考えていた。[5] バルトークの父親(1855年~1888年)もベラという名前だった。バルトークの母親、ポーラ(旧姓ヴォイト)[hu](1857年~1939年)は、 ハンガリー語を流暢に話した[6]。[7] トルオツェントマールトン(現在のスロバキアのマーティン)出身[8] で、ドイツ、ハンガリー、スロバキア、ポーランドの血を引く。 ベラは幼い頃から卓越した音楽的才能を発揮していました。母親によると、彼は完全な文章を話すようになる前から、彼女がピアノで弾く異なるダンスのリズム を区別することができたそうです[9]。4歳になる頃には40曲のピアノ曲を弾けるようになり、翌年、母親から正式にピアノの指導を受け始めました。 1888年、7歳のとき、農業学校の校長だった父親が突然亡くなった。その後、母親はベラと妹のエルゼベットを連れて、ナジソルシュ(現在のウクライナの ヴィノグラディフ)に移住し、その後プレスブルク(現在のスロバキアのブラチスラヴァ)に移住した。ベラは11歳の時にナジショロスで最初の公開演奏会を 開き、批評家から好評を得た。[10][ページが必要] 彼が演奏した曲の中には、2年前に作曲した自身の最初の作品「ドナウ川の流路」という短い曲もあった。[11] その後まもなく、ラースロー・エルケルが彼を弟子として受け入れた。[12] 初期の音楽活動 (1899年–1908年)  1899年9月9日付けの高校卒業写真に書かれたバルトークの署名 1899年から1903年まで、バルトークはブダペストの王立音楽アカデミーで、フランツ・リストの弟子であるイシュトヴァーン・トマーンのもとでピアノ を、ヤーノシュ・コエッサーのもとで作曲を学んだ。[13] そこで彼は、彼に強い印象を与え、生涯の友人兼同僚となるゾルターン・コダーイと出会った。[14] 1903年、バルトークは最初の主要な管弦楽曲『コシュート』を作曲した。これは、1848年のハンガリー革命の英雄、ラヨシュ・コシュートを称える交響 詩である。[15] 1902年にブダペストでの『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』の初演で出会ったリヒャルト・シュトラウスの音楽は、彼の初期の作品に大きな影響を与えた。 [16] 1904年の夏、休暇地を訪れていたバルトークは、トランシルヴァニアのキベド出身で、子供たちに民謡を歌っていた若い乳母、リディ・ドーサの歌声を耳に した。これが、彼の一生を民謡に捧げるきっかけとなった。[17] 1907年から、彼はコダーイがパリから持ち帰った作曲家のクロード・ドビュッシーの影響を受けるようになった。バルトークの大規模な管弦楽作品は、まだ ヨハネス・ブラームスとリヒャルト・シュトラウスのスタイルを継承していたが、彼は民謡への関心が高まるにつれ、数多くの小規模なピアノ作品を書いた。こ の新しい興味を明確に示した最初の作品は、民謡的な要素を含む「弦楽四重奏曲第1番 ニ短調」(1908年)だ。[18] 彼はブダペストのリスト音楽院でピアノ教授として教鞭を執り始めた。この職は、ピアニストとしてヨーロッパをツアーする義務から彼を解放した。彼の著名な 生徒には、フリッツ・ライナー、サー・ゲオルグ・ショルティ、ゲオルグ・サンダー、エルノー・バログ、ギゼラ・ゼルデン=ゴット、リリ・クラウスなどがい る。バルトークがアメリカに移住した後、彼はジャック・ビーソンとバイオレット・アーチャーを指導した。 1908年、バルトークとコダーイは、古いマジャール民謡を収集・研究するために田舎を訪れました。彼らの民謡への関心の高まりは、伝統的な国民文化に対 する当時の社会的関心と一致していました。マジャール民謡は、それまではジプシー音楽に分類されていた。その典型的な例は、フランツ・リストが、当時のロ マ(ジプシー)のバンドが演奏していた民謡を基に作曲したピアノ曲「ハンガリー狂詩曲」だ。それに対して、バルトークとコダーイは、古いマジャール民謡 は、中央アジア、アナトリア、シベリアなどのアジアの民謡と同じような五音階に基づいていることを発見した[19]。 バルトークとコダーイは、このようなマジャール農民音楽の要素を自身の作曲に取り入れることに取り組んだ。彼らはともに、民謡のメロディをそのまま引用し たり、本物の歌から完全に派生した作品を書き下ろしたりした。例として、バルトークのピアノ独奏曲集『子供のために』の2巻があり、80の民謡に伴奏を付 けた作品が含まれている。バルトークの芸術音楽作曲のスタイルは、民謡、古典主義、そしてモダニズムを融合したものだった。彼の旋律と和声の感覚は、ハン ガリー、ルーマニア、その他の国の民謡の影響を受けている。彼は、ブルガリア音楽に見られる非対称の舞曲のリズムと刺激的な和声を特に好んだ。彼の初期の 作曲のほとんどは、ナショナリズムと後期ロマン主義の要素が融合したものとなっている。 |

| Middle years and career (1909–1939) Personal life In 1909, at the age of 28, Bartók married Márta Ziegler (1893–1967), aged 16. Their son, Béla Bartók III [hu], was born the next year. After nearly 15 years together, Bartók divorced Márta in June 1923. Two months after his divorce, he married Ditta Pásztory (1903–1982), a piano student, ten days after proposing to her. She was aged 19, he 42. Their son, Péter [hu], was born in 1924.[20] Raised as a Catholic, by his early adulthood Bartók had become an atheist. He later became attracted to Unitarianism and publicly converted to the Unitarian faith in 1916. Although Bartók was not conventionally religious, according to his son Béla Bartók III, "he was a nature lover: he always mentioned the miraculous order of nature with great reverence". As an adult, Béla III later became lay president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church.[21] Opera In 1911, Bartók wrote what was to be his only opera, Bluebeard's Castle, dedicated to Márta. In creating Bluebeard's Castle, Bartók uses symbolism to show parallels between unconscious motivation and fate. The opera in showing fate has a strong interaction between the characters and gives the idea that people are not able to control what the outcome will be.[22] He entered it for a prize by the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, but they rejected his work as not fit for the stage.[23] In 1917 Bartók revised the score for the 1918 première and rewrote the ending. Following the 1919 revolution, in which he actively participated, he was pressured by the Horthy regime to remove the name of librettist Béla Balázs from the opera, as Balázs was of Jewish origin, was blacklisted, and had left the country for Vienna. Bluebeard's Castle received only one revival, in 1936, before Bartók emigrated. For the remainder of his life, although devoted to Hungary, its people and its culture, he never felt much loyalty to the government or its official establishments.[citation needed] |

中年の時代とキャリア (1909年~1939年) 私生活 1909年、28歳のバルトークは16歳のマルタ・ツィーグラー (1893年~1967年) と結婚した。翌年、息子のベラ・バルトーク3世 [hu] が生まれた。15年近くの結婚生活の後、バルトークは1923年6月にマルタと離婚した。離婚から2ヶ月後、彼はピアノの生徒だったディッタ・パストル (1903–1982)にプロポーズし、10日後に結婚した。彼女は19歳、彼は42歳だった。彼らの息子、ペテル [hu] は1924年に生まれた。[20] カトリック教徒として育てられたが、成人期には無神論者となった。のちにユニテリアン主義に惹かれ、1916年に公にユニテリアン教に改宗した。バルトー クは伝統的な宗教観は持たなかったが、息子のベラ・バルトーク3世によると、「彼は自然愛好家であり、自然の奇跡的な秩序を常に深い敬意を持って語ってい た」という。成人後、ベラ3世はハンガリーユニテリアン教会の信徒会長に就任した。[21] オペラ 1911年、バルトークは、マルタに捧げた唯一のオペラ「青ひげ公の城」を作曲した。「青ひげ公の城」では、バルトークは象徴性を用いて、無意識の動機と 運命の類似点を表現している。このオペラでは、運命が表現されており、登場人物たちの相互作用が強く、人民は結果をコントロールすることはできないという 考えが示されている[22]。彼はこの作品をハンガリー美術委員会の賞に応募したが、舞台には不適切として却下された[23]。1917年、バルトークは 1918年の初演に向けて楽譜を改訂し、結末を書き直した。1919年の革命に積極的に参加した後、彼はホルティ政権から、リブレット作家ベラ・バラージ の名前をオペラから削除するよう圧力を受けた。バラージはユダヤ系で、黒リストに載せられ、ウィーンに逃れていたからだ。『青ひげの城』は、バルトークが 移住する前の1936年に一度だけ再演された。彼は生涯、ハンガリーとその人民、文化に献身しましたが、政府や公的機関に対してあまり忠誠心を抱くことは なかったようです。 |

Folk music and composition Béla Bartók using a phonograph to record Slovak folk songs sung by peasants in Zobordarázs[24] (Slovak: Dražovce, today part of Nitra, Slovakia) After his disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission competition, Bartók wrote little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on collecting and arranging folk music. He found the phonograph an essential tool for collecting folk music for its accuracy, objectivity, and manipulability.[25] He collected first in the Carpathian Basin (then the Kingdom of Hungary), where he notated Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, and Bulgarian folk music. The developmental breakthrough for Bartok arrived when he collaboratively collected folk music with Zoltán Kodály through the medium of a phonomotor, on which they studied classification possibilities (for individual folk songs) and recorded hundreds of cylinders. Bartok's compositional command of folk elements is expressed in such an authentic and undiluted a manner because of the scales, sounds, and rhythms that were so much a part of his native Hungary that he automatically saw music in these terms.[26] He also collected in Moldavia, Wallachia, and (in 1913) Algeria. The outbreak of World War I forced him to stop the expeditions, but he returned to composing with a ballet called The Wooden Prince (1914–1916) and the String Quartet No. 2 in (1915–1917), both influenced by Debussy. Bartók's score for The Miraculous Mandarin, another ballet, was influenced by Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and Richard Strauss. Though started in 1918, the story's sexual content kept it from being performed until 1926. He next wrote his two violin sonatas (written in 1921 and 1922, respectively), which are among his most harmonically and structurally complex pieces.[27] In March 1927, he visited Barcelona and performed the Rhapsody for piano Sz. 26 with the Orquestra Pau Casals at the Gran Teatre del Liceu.[28] During the same stay, he attended a concert by the Cobla Barcelona [ca] at the Palau de la Música Catalana.[28] According to the critic Joan Llongueras i Badia [ca], "he was very interested in the sardanas, above all, the freshness, spontaneity and life of our music [...] he wanted to know the mechanism of the tenoras and the tibles, and requested data on the composition of the cobla and extension and characteristics of each instrument".[28] In 1927–1928, Bartók wrote his Third and Fourth String Quartets, after which his compositions demonstrated his mature style. Notable examples of this period are Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) and Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939). The Fifth String Quartet was composed in 1934, and the Sixth String Quartet (his last) in 1939. In 1936 he travelled to Turkey to collect and study Turkish folk music. He worked in collaboration with Turkish composer Ahmet Adnan Saygun mostly around Adana.[29][30] |

民謡と作曲 ベラ・バルトークが、ゾボルダラス(スロバキア語:ドラゾフツェ、現在はスロバキアのニトラの一部)の農民たちが歌うスロバキア民謡を蓄音機で録音しているところ[24] 美術委員会コンクールでの失望後、バルトークは2、3年間ほとんど作曲せず、民謡の収集と編曲に専念した。彼は、民謡の収集にフォノグラフが不可欠なツー ルだと考え、その正確性、客観性、操作性の高さを評価した[25]。彼はまずカルパティア盆地(当時のハンガリー王国)で収集を開始し、ハンガリー、スロ バキア、ルーマニア、ブルガリアの民謡を楽譜に記した。バルトークの作曲における画期的な進展は、ゾルターン・コダーイと共同で、フォノモーターという装 置を用いて民謡を収集し、個々の民謡の分類可能性を研究し、数百本のシリンダーを録音した際に訪れた。バルトークの作曲における民謡要素の掌握が、これほ ど本物で純粋な形で表現されているのは、彼の故郷ハンガリーで深く根付いた音階、音色、リズムが、彼にとって音楽そのものとして自然に感じられていたから だよ。[26] 彼はモルダヴィア、ワラキア、そして1913年にはアルジェリアでも収集を行った。第一次世界大戦の勃発により、彼は調査を中断せざるを得なかったが、デ ビュッシーの影響を受けたバレエ『木製の王子』(1914–1916)と弦楽四重奏曲第2番(1915–1917)の作曲に戻った。 バルトークの別のバレエ『奇跡のマンダリン』の楽譜は、イゴール・ストラヴィンスキー、アーノルド・シェーンベルク、リヒャルト・シュトラウスに影響を受 けている。1918年に作曲が開始されたが、その性的内容のため、1926年まで上演されなかった。次に、彼は2つのヴァイオリンソナタ(それぞれ 1921年と1922年に作曲)を作曲した。これらは、彼の作品の中でも最も調和と構造が複雑な作品のひとつだ[27]。 1927年3月、彼はバルセロナを訪れ、グラン・テアトロ・デル・リセウで、オルケストラ・パウ・カザルスとピアノのための狂詩曲 Sz. 26 を演奏した[28]。同じ滞在中に、彼はカタルーニャ音楽堂でコブラ・バルセロナ [ca] のコンサートを聴いた。[28] 批評家のジョアン・ロンゲラス・イ・バディア [ca] によると、「彼はサルダーナに非常に興味を示し、特に私たちの音楽の清新さ、即興性、生命力に魅了された [...] テノラとティブレの仕組みを知りたがり、コブラの編成や各楽器の特性に関する資料を請求した」と述べている。[28] 1927年から1928年にかけて、バルトークは第3弦楽四重奏曲と第4弦楽四重奏曲を作曲し、その後、彼の作曲は成熟したスタイルを示した。この時代の 代表作には、『弦楽のための音楽、打楽器とチェレスタのための音楽』(1936年)と『弦楽オーケストラのためのディヴェルティメント』(1939年)が ある。第5弦楽四重奏曲は1934年に、第6弦楽四重奏曲(最後の作品)は1939年に作曲された。1936年、トルコ民謡の収集と研究のためトルコを訪 れ、主にアダナ周辺でトルコ人作曲家アフメト・アドナン・サユンと共同作業を行った。[29][30] |

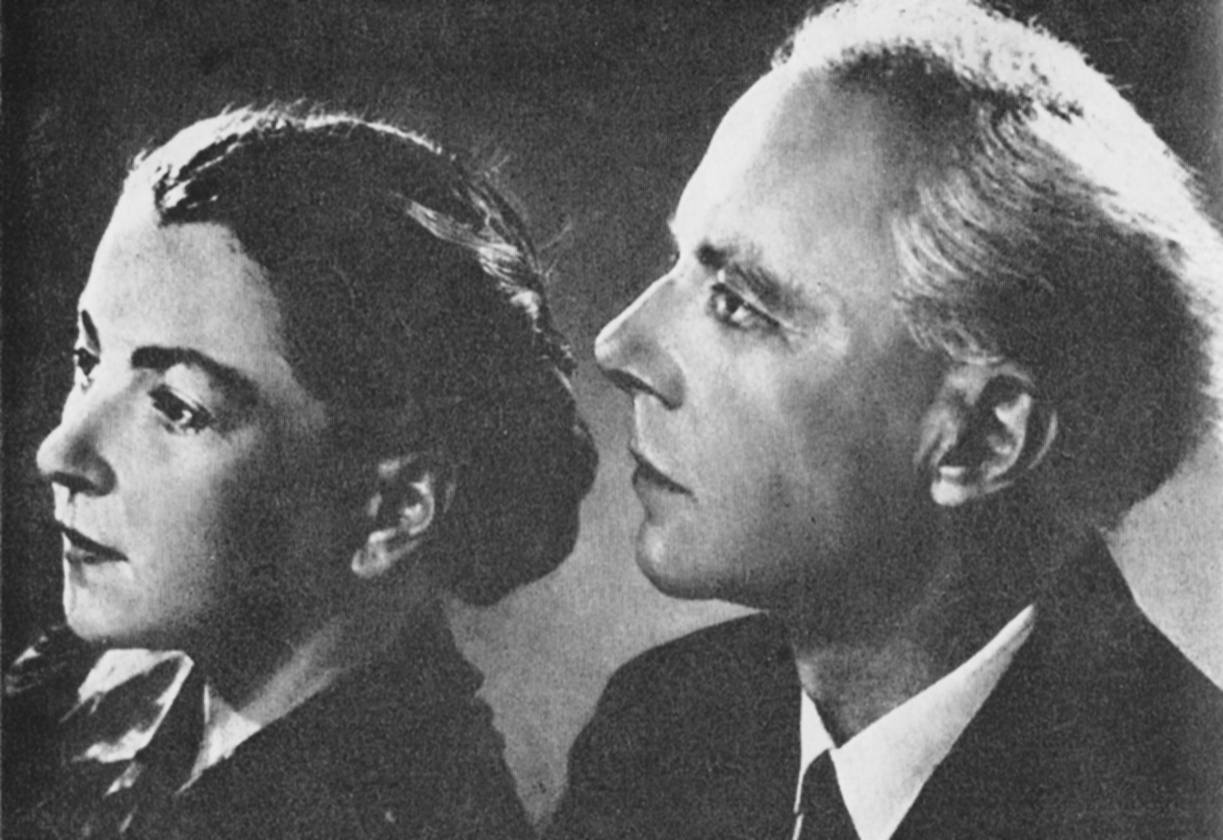

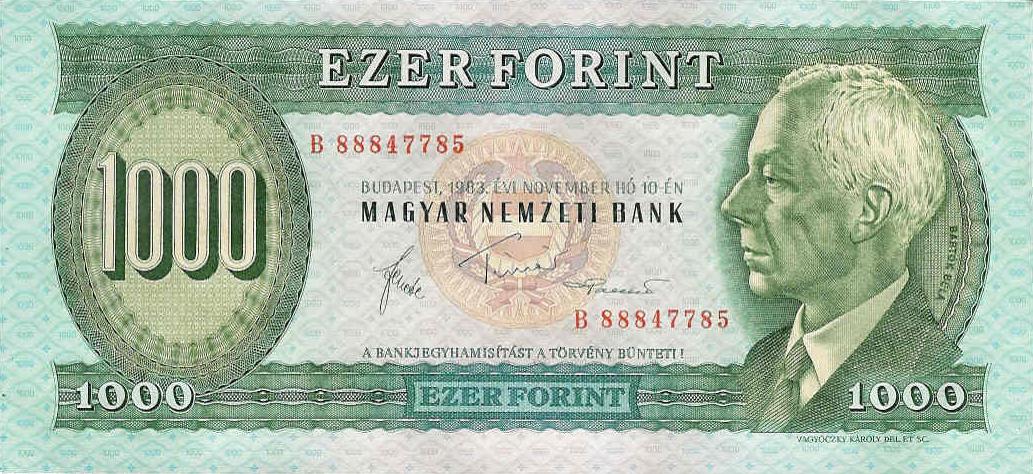

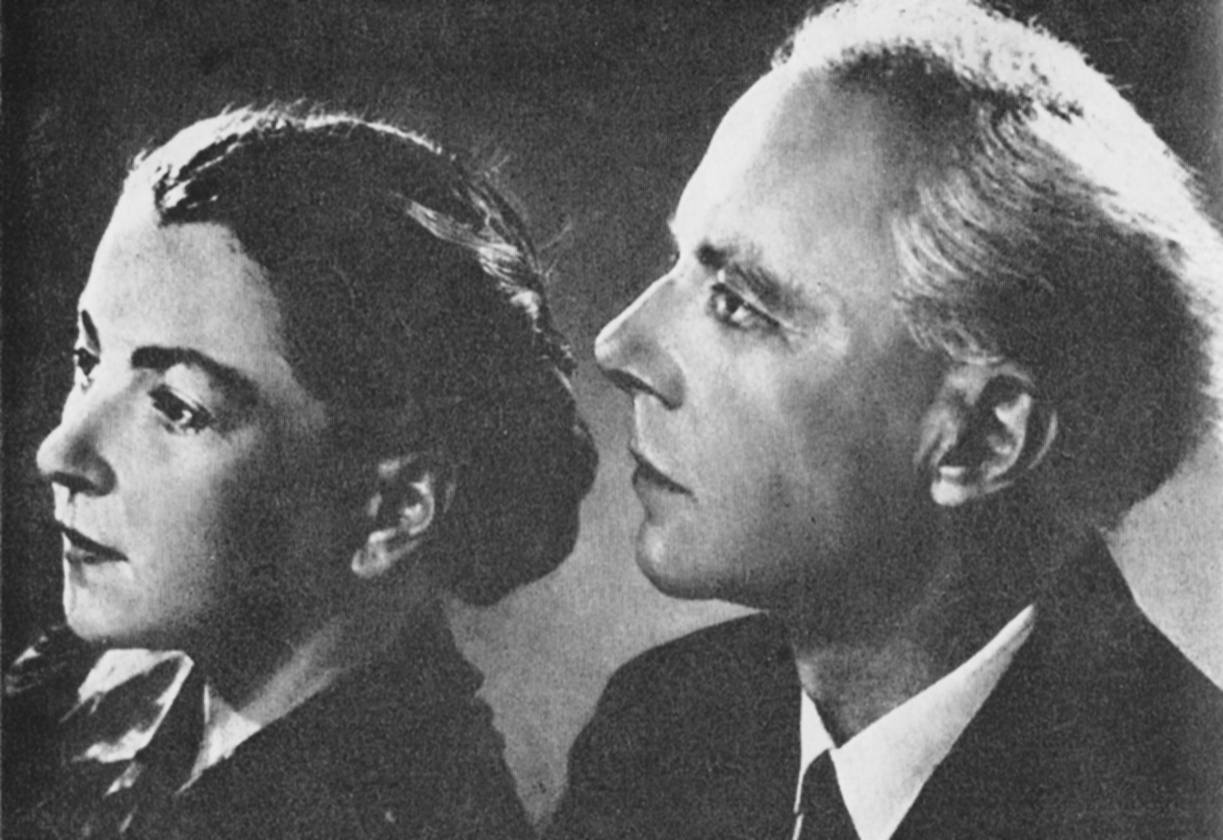

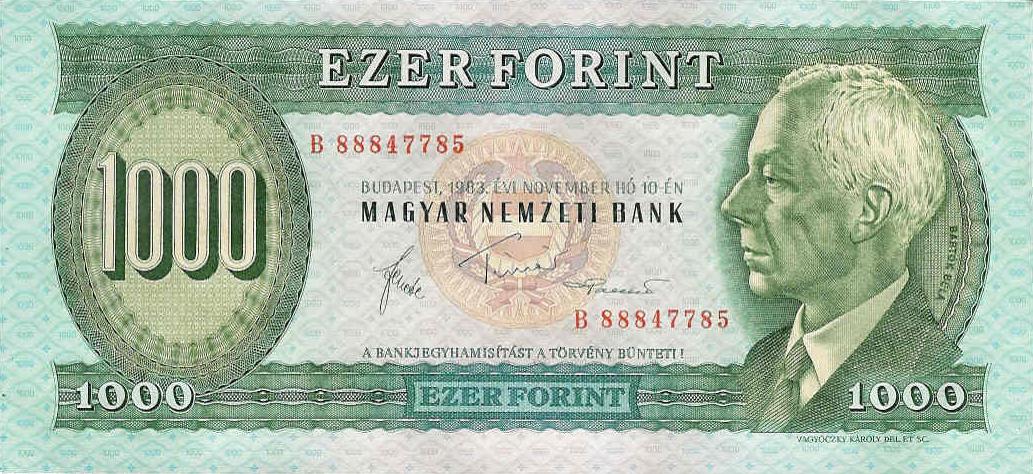

World War II and final years (1940–1945) Bartok and Pásztory In 1940, as the European political situation worsened after the outbreak of World War II, Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary. He strongly opposed the Nazis and Hungary's alliance with Germany and the Axis powers under the Tripartite Pact. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Bartók refused to give concerts in Germany and broke away from his publisher there. His anti-fascist political views caused him a great deal of trouble with the establishment in Hungary. In his will recorded on 4 October 1940, he requested that no square or street be named after him until the Budapest squares Oktogon and Kodály körönd, or in fact any square or street in Hungary, no longer bore the names of Mussolini or Hitler, as they did at the time he wrote his will.[31] Having first sent his manuscripts out of the country, Bartók reluctantly emigrated to the US with his wife, Ditta Pásztory, in October 1940. They settled in New York City after arriving on the night of 29–30 October by a steamer from Lisbon. After joining them in 1942, their younger son Péter Bartók enlisted in the United States Navy, where he served in the Pacific during the remainder of the war and later settled in Florida, where he became a recording and sound engineer. His elder son by his first marriage, Béla Bartók III, remained in Hungary and later worked as a railroad official until his retirement in the early 1980s. Although he became an American citizen in 1945 shortly before his death,[32] Bartók never felt fully at home in the United States. He initially found it difficult to compose in his new surroundings. Although he was well known in America as a pianist, ethnomusicologist and teacher, he was not well known as a composer. There was little American interest in his music during his final years. He and his wife Ditta gave some concerts, but demand for them was low.[33] Bartók, who had made some recordings in Hungary, also recorded for Columbia Records after he came to the US; many of these recordings (some with Bartók's own spoken introductions) were later issued on LP and CD.[34][35][36][37][38][39][40] Bartók was supported by a $3000-yearly research fellowship from Columbia University for several years (more than $50,000 in 2024 dollars).[41] He and Ditta worked on a large collection of Serbian and Croatian folk songs in Columbia's libraries. Bartók's economic difficulties during his first years in America were mitigated by publication royalties, teaching and performance tours. While his finances were always precarious, he did not live and die in poverty as was the common myth. He had enough friends and supporters to ensure that there was sufficient money and work available for him to live on. Bartók was a proud man and did not easily accept charity. Despite being short on cash at times, he often refused money that his friends offered him out of their own pockets. Although he was not a member of the ASCAP, the society paid for any medical care he needed during his last two years, to which Bartók reluctantly agreed. According to Edward Jablonski's 1963 article, "At no time during Bartók's American years did his income amount to less than $4,000 a year" (about $70,000 in 2024 dollars).[42] The first symptoms of his health problems began late in 1940, when his right shoulder began to show signs of stiffening. In 1942, symptoms increased and he started having bouts of fever. Bartók's illness was at first thought to be a recurrence of the tuberculosis he had experienced as a young man, and one of his doctors in New York was Edgar Mayer, director of Will Rogers Memorial Hospital in Saranac Lake, but medical examinations found no underlying disease. Finally, in April 1944, leukemia was diagnosed, but by this time, little could be done.[43] As his body slowly failed, Bartók found more creative energy and produced a final set of masterpieces, partly thanks to the violinist Joseph Szigeti and the conductor Fritz Reiner (Reiner had been Bartók's friend and champion since his days as Bartók's student at the Royal Academy). Bartók's last work might well have been the String Quartet No. 6 but for Serge Koussevitzky's commission for the Concerto for Orchestra. Koussevitsky's Boston Symphony Orchestra premiered the work in December 1944 to highly positive reviews. The Concerto for Orchestra quickly became Bartók's most popular work, although he did not live to see its full impact.[44] In 1944, he was also commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin to write a Sonata for Solo Violin. In 1945, Bartók composed his Piano Concerto No. 3, a graceful and almost neo-classical work, as a surprise 42nd birthday present for Ditta, but he died just over a month before her birthday, with the scoring not quite finished. He had also sketched his Viola Concerto, but had barely started the scoring at his death, leaving completed only the viola part and sketches of the orchestral part.  Béla Bartók's portrait on 1000 Hungarian forint banknote (printed between 1983 and 1992; no longer in circulation) Béla Bartók died at age 64 in a hospital in New York City from complications of leukemia (specifically, of secondary polycythemia) on 26 September 1945. His funeral was attended by only ten people. Aside from his widow and their son, other attendees included György Sándor.[45] Bartók's body was initially interred in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. During the final year of communist Hungary in the late 1980s, the Hungarian government, along with his two sons, Béla III and Péter, requested that his remains be exhumed and transferred back to Budapest for burial, where Hungary arranged a state funeral for him on 7 July 1988. He was re-interred at Budapest's Farkasréti Cemetery, next to the remains of Ditta, who died in 1982, one year after what would have been Béla Bartók's 100th birthday.[46] The two unfinished works were later completed by his pupil Tibor Serly. György Sándor was the soloist in the first performance of the Third Piano Concerto on 8 February 1946. Ditta Pásztory-Bartók later played and recorded it. The Viola Concerto was revised and published in the 1990s by Bartók's son; this version may be closer to what Bartók intended.[47] Concurrently, Peter Bartók, in association with Argentine musician Nelson Dellamaggiore, worked to reprint and revise past editions of the Third Piano Concerto.[48] |

第二次世界大戦と晩年(1940年~1945年) バルトークとパストーリ 1940年、第二次世界大戦の勃発によりヨーロッパの政治情勢が悪化する中、バルトークはハンガリーからの脱出をますます強く考えるようになった。彼はナ チスと、三国同盟の下でドイツおよび枢軸国と同盟を結んだハンガリーに強く反対していた。1933年にナチスが政権を握った後、バルトークはドイツでのコ ンサートを拒否し、ドイツの出版社との関係を断ち切った。彼の反ファシスト的な政治的立場は、ハンガリーの支配層から大きな迫害を受けた。1940年10 月4日に記録された遺言で、彼は、ブダペストのオクトゴン広場とコダーイ・コーロンド広場、またはハンガリー国内のいかなる広場や道路にも、ムッソリーニ やヒトラーの名前が付けられている限り、自身の名前を付けることを拒否した。[31] 手稿を国外に送った後、バルトークは1940年10月、妻のディッタ・パストルと共にやむを得ずアメリカに移民した。彼らはリスボンから出航した蒸気船で 10月29日から30日にかけてニューヨークに到着し、同市に定住した。1942年に彼らに合流した彼らの次男ペテル・バルトークはアメリカ海軍に入隊 し、戦争終結まで太平洋戦線で従軍し、後にフロリダに定住して録音・音響エンジニアとなった。最初の結婚での長男ベラ・バルトーク3世はハンガリーに残 り、1980年代初頭の退職まで鉄道職員として働いた。 1945年に死去する直前にアメリカ市民権を取得したものの[32]、バルトークはアメリカで完全に居心地の良さを感じなかった。新しい環境で作曲するこ とは当初困難だった。アメリカではピアニスト、民族音楽学者、教師として知られていたが、作曲家としてはほとんど知られていなかった。彼の晩年、アメリカ での彼の音楽への関心はほとんどなかった。彼と妻のディッタはいくつかのコンサートを開催したが、需要は低かった[33]。ハンガリーでいくつかの録音を 残していたバルトークは、アメリカに移住後、コロンビア・レコードで録音を行った。これらの録音の多く(一部はバルトーク自身の口頭解説付き)は、後に LPとCDでリリースされた[34][35][36][37][38][39][40]。 バルトークは、コロンビア大学から年間 3000 ドル(2024 年のドルで 5 万ドル以上)の研究助成金を数年間受けた。[41] 彼とディッタは、コロンビア大学の図書館で、セルビアとクロアチアの民謡の大規模な収集作業に取り組んだ。アメリカでの最初の数年間、バルトークは経済的 に困難な状況にあったが、出版の印税、教鞭、演奏ツアーによってその苦境は緩和された。彼の財政は常に不安定だったが、一般的な伝説のように貧困の中で生 きたり死んだりはしなかった。彼には十分な友人や支援者がおり、生活するための十分な資金と仕事があった。バルトークは誇り高い人物であり、慈善を容易に 受け入れることはなかった。現金に困った時期もあったが、友人たちが自腹で差し出した金銭を断ることも多かった。彼はASCAPの会員ではなかったが、最 後の2年間、必要な医療費は同団体が負担し、バルトークは渋々同意した。エドワード・ジャブロンスキーの 1963 年の記事によると、「バルトークがアメリカで過ごした期間、彼の年収が 4,000 ドル(2024 年のドルでおよそ 70,000 ドル)を下回ったことはなかった」とのことです。[42]彼の健康問題の最初の症状は 1940 年後半、右肩にこわばりの兆候が現れたことから始まりました。1942年に症状が悪化し、発熱の発作が起こるようになった。バルトークの病気は当初、若き 日に罹った結核の再発と診断され、ニューヨークの医師の一人はサラナックレイクにあるウィル・ロジャース記念病院の院長エドガー・メイヤーだったが、医学 的検査では根本的な病気は見つからなかった。1944年4月、ついに白血病と診断されたが、その時点ではほとんど手立てはなかった。[43] 体が徐々に衰えていく中、バルトークはより創造的なエネルギーを見出し、ヴァイオリニストのジョセフ・シゲティと指揮者のフリッツ・ライナー(ライナー は、バルトークが王立アカデミーの学生だった頃から友人であり、彼の支援者だった)の協力もあり、最後の傑作をいくつか生み出した。バルトークの最後の作 品は、セルゲイ・クーセヴィツキーの委嘱による「管弦楽のための協奏曲」でなければ、おそらく「弦楽四重奏曲第6番」だったかもしれない。クーセヴィツ キーのボストン交響楽団は、1944年12月にこの作品を初演し、高い評価を受けた。管弦楽のための協奏曲は、バルトークの最も人気のある作品となった が、彼はその全貌を目にすることはなかった。[44] 1944年には、イェフディ・メニューインからソロ・ヴァイオリンのためのソナタの委嘱を受けた。1945年、バルトークはディッタの42歳の誕生日プレ ゼントとして、優雅でほぼ新古典主義的な作品であるピアノ協奏曲第3番を作曲したが、彼女の誕生日の1ヶ月余り前に死去し、楽譜は未完成のままだった。ま た、ヴィオラ協奏曲もスケッチしていたが、死の時には楽譜の書き始めにすぎず、ヴィオラパートとオーケストラパートのスケッチしか完成していなかった。  1000 ハンガリー・フォリント紙幣に描かれたベラ・バルトークの肖像(1983年から1992年に印刷、現在は流通していない) 1945年9月26日、ベラ・バルトークは、白血病(具体的には、二次性多血症)の合併症により、ニューヨーク市の病院で64歳の生涯を閉じた。彼の葬儀には、10人の人民しか参列しなかった。彼の未亡人と息子たち、そして、ジェルジ・サンドールが参列した。 バルトークの遺体は当初、ニューヨーク州ハートスデールのフェルンクリフ墓地に埋葬された。1980年代後半の共産主義ハンガリー最後の年、ハンガリー政 府と彼の2人の息子、ベラ3世とペテルは、遺体を発掘しブダペストに移送して再埋葬するよう要請した。ハンガリーは1988年7月7日に彼のために国葬を 執り行った。彼はブダペストのファルカシュレティ墓地に再埋葬され、1982年に死去したディッタの遺体の隣に眠っている。ディッタは、ベラ・バルトーク の100回目の誕生日である前年死去していた。[46] 2つの未完成作品は、後に彼の弟子であるティボール・セルリによって完成された。1946年2月8日に開催された第3番のピアノ協奏曲の初演では、ジェル ジ・サンドールがソリストを務めた。ディッタ・パストルィ=バルトークは後にこの作品を演奏し、録音した。ヴィオラ協奏曲は、バルトークの息子によって 1990年代に改訂され出版された。この版は、バルトークの意図に近づいている可能性がある。[47] 同時期に、ピーター・バルトークはアルゼンチンの音楽家ネルソン・デラマッジョレと協力し、第3ピアノ協奏曲の過去の版の再版と改訂に取り組んだ。 [48] |

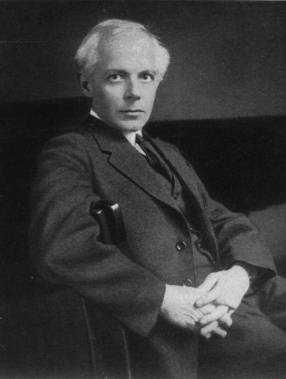

| Music Further information: List of compositions by Béla Bartók Bartók's music reflects two trends that dramatically changed the sound of music in the 20th century: the breakdown of the diatonic system of harmony that had served composers for the previous two hundred years;[49] and the revival of nationalism as a source for musical inspiration, a trend that began with Mikhail Glinka and Antonín Dvořák in the last half of the 19th century.[50] In his search for new forms of tonality, Bartók turned to Hungarian folk music, as well as to other folk music of the Carpathian Basin and even of Algeria and Turkey; in so doing he became influential in that stream of modernism which used indigenous music and techniques.[51] One characteristic style of music is his Night music, which he used mostly in slow movements of multi-movement ensemble or orchestral compositions in his mature period. It is characterised by "eerie dissonances providing a backdrop to sounds of nature and lonely melodies".[52] An example is the third movement (Adagio) of his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. His music can be grouped roughly in accordance with the different periods in his life. Early years (1890–1902)  Bartók in 1903 The works of Bartók's youth were written in a classical and early romantic style touched with influences of popular and romani music.[53][page needed] Between 1890 and 1894 (9 to 13 years of age) he wrote 31 piano pieces.[1][54] Although most of these were simple dance pieces, in these early works Bartók began to tackle some more advanced forms, as in his ten-part programmatic A Duna folyása ("The Course of the Danube", 1890–1894), which he played in his first public recital in 1892.[55] In Catholic grammar school Bartók took to studying the scores of composers "from Bach to Wagner",[56] his compositions then advancing in style and taking on similarities to Schumann and Brahms.[57] Following his matriculation into the Budapest Academy in 1890 he composed very little, though he began to work on exercises in orchestration and familiarized himself thoroughly with the operas of Wagner.[58] In 1902 his creative energies were revitalized by the discovery of the music of Richard Strauss, whose tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra, according to Bartók, "stimulated the greatest enthusiasm in me; at last I saw the way that lay before me". Bartók also owned the score to A Hero's Life, which he transcribed for the piano and committed to memory.[59] |

音楽 詳細情報:ベラ・バルトークの作曲作品一覧 バルトークの音楽は、20 世紀の音楽の響きを劇的に変えた 2 つの傾向を反映している。1 つは、200 年以上にわたって作曲家に利用されてきた全音階による和声体系の崩壊[49]、もう 1 つは、19 世紀後半にミハイル・グリンカとアントニン・ドヴォルザークによって始まった、音楽のインスピレーションの源としてのナショナリズムの復活だ。[50] 新しい調性の形態を探求する中で、バルトークはハンガリーの民謡だけでなく、カルパティア盆地の他の民謡、さらにはアルジェリアやトルコの民謡にも目を向 けた。これにより、彼は先住民の音楽と技法を採用したモダニズムの潮流に大きな影響を与えた。[51] 彼の音楽の特徴的なスタイルのひとつは「夜想曲」で、これは主に、成熟期の多楽章からなるアンサンブルやオーケストラ作曲の緩徐楽章で使用されている。こ のスタイルは、「不気味な不協和音が、自然の音や孤独なメロディーを背景として流れている」ことが特徴だ[52]。その例としては、弦楽、打楽器、チェレ スタのための音楽の第3楽章(アダージョ)が挙げられる。彼の音楽は、その生涯の異なる時期に応じて大まかに分類することができる。 初期(1890年~1902年)  1903年のバルトーク バルトークの若き頃の作品は、古典的かつ初期ロマン派のスタイルで、民謡やロマ音楽の影響を受けている。[53][ページが必要] 1890年から1894年(9歳から13歳)にかけて、彼は31曲のピアノ曲を作曲した。[1][54] これらのほとんどは単純な舞曲だったが、これらの初期作品において、バルトークはより高度な形式に挑戦し始めた。例えば、10楽章からなるプログラム音楽 『ドナウ川の流転』(1890–1894)は、1892年の最初の公開演奏会で演奏された。[55] カトリックの文法学校で、バルトークは「バッハからワーグナーまで」の作曲家の楽譜を研究し始め、その作曲スタイルは進化し、シューマンやブラームスに似 た特徴を帯びるようになった。[57] 1890年にブダペスト音楽アカデミーに入学した後、彼はほとんど作曲をしなかったが、管弦楽法の実習に取り組み、ワーグナーのオペラを徹底的に研究し た。[58] 1902年、リヒャルト・シュトラウスの音楽を発見したことで創造力が再燃し、シュトラウスの交響詩『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』について、バルトー クは「私の中に最大の熱意を刺激した。ついに私の前に広がる道が見えた」と述べた。バルトークは『英雄の生涯』の楽譜を所有し、ピアノ用に編曲し、暗譜し た。[59] |

| New influences (1903–1911) Under the influence of Strauss, Bartók composed in 1903 Kossuth, a symphonic poem in ten tableaux on the subject of the 1848 Hungarian war of independence, reflecting the composers growing interest in musical nationalism.[60] A year later he renewed his opus numbers with the Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra serving as Opus 1. Driven by nationalistic fervor and a desire to transcend the influence of prior composers, Bartók began a lifelong devotion to folk music, which was sparked by his overhearing nanny Lidi Dósa's singing of Transylvanian folk songs at a Hungarian resort in 1904.[61] Bartók began to collect Magyar peasant melodies, later extending to the folk music of other peoples of the Carpathian Basin, Slovaks, Romanians, Rusyns, Serbs and Croatians.[62] He used fewer and fewer romantic elements, in favour of an idiom that embodied folk music as intrinsic and essential to its style. Later in life he commented on the incorporation of folk and art music:[63] The question is, what are the ways in which peasant music is taken over and becomes transmuted into modern music? We may, for instance, take over a peasant melody unchanged or only slightly varied, write an accompaniment to it and possibly some opening and concluding phrases. This kind of work would show a certain analogy with Bach's treatment of chorales. ... Another method ... is the following: the composer does not make use of a real peasant melody but invents his own imitation of such melodies. There is no true difference between this method and the one described above. ... There is yet a third way ... Neither peasant melodies nor imitations of peasant melodies can be found in his music, but it is pervaded by the atmosphere of peasant music. In this case we may say, he has completely absorbed the idiom of peasant music which has become his musical mother tongue. Bartók became first acquainted with Debussy's music in 1907 and regarded his music highly. In an interview in 1939 Bartók said:[64] Debussy's great service to music was to reawaken among all musicians an awareness of harmony and its possibilities. In that, he was just as important as Beethoven, who revealed to us the possibilities of progressive form, or as Bach, who showed us the transcendent significance of counterpoint. Now, what I am always asking myself is this: is it possible to make a synthesis of these three great masters, a living synthesis that will be valid for our time? Debussy's influence is present in the Fourteen Bagatelles (1908). These made Ferruccio Busoni exclaim: "At last something truly new!"[65] Until 1911, Bartók composed widely differing works which ranged from adherence to romantic style, to folk song arrangements and to his modernist opera Bluebeard's Castle. The negative reception of his work led him to focus on folk music research after 1911 and abandon composition with the exception of folk music arrangements.[66][67] Inspiration and experimentation (1916–1921) His pessimistic attitude towards composing was lifted by the stormy and inspiring contact with Klára Gombossy in the summer of 1915.[68] This interesting episode in Bartók's life remained hidden until it was researched by Denijs Dille between 1979 and 1989.[69] Bartók started composing again, including the Suite for piano opus 14 (1916), and The Miraculous Mandarin (1919)[70] and he completed The Wooden Prince (1917).[71] Bartók felt the result of World War I as a personal tragedy.[72] Many regions he loved were severed from Hungary: Transylvania, the Banat (where he was born), and Bratislava (Pozsony, where his mother had lived). Additionally, the political relations between Hungary and other successor states to the Austro-Hungarian empire prohibited his folk music research outside of Hungary.[73] Bartók also wrote the noteworthy Eight Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs in 1920 and the sunny Dance Suite in 1923, the year of his second marriage. "Synthesis of East and West" (1926–1945) In 1926, Bartók needed a significant piece for piano and orchestra with which he could tour in Europe and America. He was particularly inspired by American composer Henry Cowell's controversial use of intense tone clusters on the piano while touring western Europe. Bartók happened to be present at one of these concerts and (to avoid causing offence) later requested Cowell's permission to use his technique, which Cowell granted. In the preparation for writing his first Piano Concerto, he wrote his Sonata, Out of Doors, and Nine Little Pieces, all for solo piano, and all of which prominently utilize clusters.[74] He increasingly found his own voice in his maturity. The style of his last period – named "Synthesis of East and West"[75] – is hard to define let alone to put under one term. In his mature period, Bartók wrote relatively few works but most of them are large-scale compositions for large settings. Only his voice works have programmatic titles and his late works often adhere to classical forms. Among Bartók's most important works are the six string quartets (1909, 1917, 1927, 1928, 1934, and 1939), the Cantata Profana (1930), which Bartók declared was the work he felt and professed to be his most personal "credo",[76] the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936),[1] the Concerto for Orchestra (1943) and the Third Piano Concerto (1945).[77][page needed] He made a lasting contribution to the literature for younger students: for his son Péter's music lessons, he composed Mikrokosmos, a six-volume collection of graded piano pieces.[1] |

新しい影響(1903年~1911年 シュトラウスの影響を受けて、バルトークは1903年に、1848年のハンガリー独立戦争を題材にした10つの場面からなる交響詩「コシュート」を作曲 し、音楽におけるナショナリズムへの関心の高まりを反映した。[60] 1年後、彼は作品番号を刷新し、「ピアノとオーケストラのための狂詩曲」を作品1とした。ナショナリストとしての熱意と、先人の作曲家の影響を超えたいと いう願望に駆り立てられたバルトークは、1904年にハンガリーのリゾート地で乳母のリディ・ドサが歌うトランシルヴァニアの民謡を耳にしたことをきっか けに、民謡に生涯を捧げるようになった。[61] バルトークは、マジャール人の農民の民謡の収集を始め、後にカルパティア盆地の他の民族、スロバキア人、ルーマニア人、ルシン人、セルビア人、クロアチア 人の民謡にもその範囲を広げた。[62] 彼は、そのスタイルに本質的かつ不可欠な要素として民謡を体現する表現を好んで、ロマン主義的な要素をますます少なくしていった。晩年、彼は民謡と芸術音 楽の融合について次のように述べている。[63] 問題は、農民の音楽がどのように取り入れられ、現代音楽に変容するのかということだ。例えば、農民のメロディをそのまま、またはわずかに変えて取り入れ、 それに伴奏を付け、場合によっては冒頭と結尾のフレーズを付けることができる。この種の作品は、バッハのコラールへの扱いに一定の類似性を見出すことがで きる。... 別の方法としては、作曲家が実際の農民の旋律を使用せず、そのような旋律を模倣して独自に創作する方法がある。この方法は、上記の方法と本質的に何の違い もない。...さらに 3 つめの方法もある。彼の音楽には、農民の旋律も農民の旋律の模倣も一切見られないが、農民の音楽のような雰囲気が全体に漂っている。この場合、彼は農民音 楽の表現を完全に吸収し、それを自分の音楽の母語としたと言えるだろう。 バルトークは 1907 年にドビュッシーの音楽と初めて出会い、その音楽を高く評価した。1939 年のインタビューで、バルトークは次のように述べている。[64] ドビュッシーの音楽に対する大きな功績は、すべての音楽家に和声とその可能性に対する認識を再び目覚めさせたことだ。その点で、彼は、進歩的な形式の可能 性を私たちに明らかにしたベートーヴェンや、対位法の超越的な意義を私たちに示したバッハと同じくらい重要だった。今、私が常に自問しているのは、この3 人の偉大な巨匠たちを、私たちの時代にも通用する生きた総合として統合することは可能か、ということだ。 ドビュッシーの影響は、「14の小品」(1908年)にも見られる。この作品について、フェルッチョ・ブゾーニは「ついに真に新しいものが登場した!」と 絶賛した[65]。1911年まで、バルトークは、ロマン主義のスタイルに忠実な作品から、民謡の編曲、そしてモダニズムのオペラ『青ひげ公の城』に至る まで、非常に多様な作品を作曲した。彼の作品は否定的な評価を受けたため、1911年以降、彼は民謡の研究に専念し、民謡の編曲以外の作曲は断念した [66][67]。 インスピレーションと実験(1916年–1921年) 作曲に対する悲観的な態度は、1915年の夏にクララ・ゴンボッシーとの激動で刺激的な出会いによって解消された。[68] バートークの生涯におけるこの興味深いエピソードは、1979年から1989年にデニース・ディルによって研究されるまで知られていなかった。[69] バルトークは作曲活動を再開し、ピアノ組曲作品14(1916年)、『奇跡のマンダリン』(1919年)[70] を作曲し、『木製の王子』(1917年)を完成させた。[71] バルトークは、第一次世界大戦の結末を個人的な悲劇として受け止めた。[72] 彼が愛した多くの地域がハンガリーから切り離された。トランシルヴァニア、バナト(彼の故郷)、ブラチスラヴァ(ポジョニ、彼の母親が住んでいた場所)。 さらに、オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国から独立した諸国との政治関係により、ハンガリー国外での民謡研究が禁止された。[73] バルトークは1920年に注目すべき『ハンガリー民謡による8つの即興曲』を、1923年に明るい『ダンス組曲』を作曲した。この年は彼の二度目の結婚の 年だった。 「東洋と西洋の融合」(1926年~1945年) 1926年、バルトークは、ヨーロッパとアメリカをツアーするために、ピアノとオーケストラのための重要な楽曲を必要としていた。彼は、西ヨーロッパをツ アーしていたアメリカの作曲家、ヘンリー・カウエルが、ピアノで強烈な音群を駆使した物議を醸した演奏に特に感銘を受けた。バルトークは偶然そのコンサー トに attendance し、(不快な思いをさせないため)後にカウエルにその技法の使用許可を求め、カウエルはこれを許可した。最初のピアノ協奏曲の作曲準備中に、彼はソロピア ノのための『ソナタ』『屋外で』『九つの小品』を書き、いずれもクラスターを特徴的に使用している。[74] 彼は成熟期に自らの表現方法を次第に見出していった。彼の最後の時期のスタイル——「東と西の融合」[75]と名付けられた——は、定義するどころか、一 つの用語で括ることも難しい。成熟期には比較的少ない作品しか残していないが、そのほとんどが大規模な編成のための大規模な作品だ。声楽作品のみがプログ ラム的なタイトルを持ち、晩年の作品は古典的な形式に忠実なものが多く見られる。 バルトークの最も重要な作品としては、6つの弦楽四重奏曲(1909年、1917年、1927年、1928年、1934年、1939年)、バルトークが 「自分の最も個人的な信条」と公言した『カンタータ・プロファナ』(1930年)、『弦楽のための音楽、 打楽器とチェレスタのための音楽(1936年)、[1] 管弦楽のための協奏曲(1943年)、第3番ピアノ協奏曲(1945年)がある。[77][ページ番号必要] 彼は若い学生のための音楽教育に永続的な貢献をした。息子のペーテルのための音楽レッスン用に、6巻からなる段階別ピアノ曲集『ミクロコスモス』を作曲し た。[1] |

Musical analysis Béla Bartók memorial plaque in Baja, Hungary Paul Wilson lists as the most prominent characteristics of Bartók's music from late 1920s onwards the influence of the Carpathian basin and European art music, and his changing attitude toward (and use of) tonality, but without the use of the traditional harmonic functions associated with major and minor scales.[78] Although Bartók claimed in his writings that his music was always tonal, he rarely used the chords or scales normally associated with tonality, and so the descriptive resources of tonal theory are of limited use. George Perle (1955) and Elliott Antokoletz (1984) focus on his alternative methods of signaling tonal centers, via axes of inversional symmetry. Others view Bartók's axes of symmetry in terms of atonal analytic protocols. Richard Cohn (1988) argues that inversional symmetry is often a byproduct of another atonal procedure, the formation of chords from transpositionally related dyads. Atonal pitch-class theory also furnishes resources for exploring polymodal chromaticism, projected sets, privileged patterns, and large set types used as source sets such as the equal tempered twelve tone aggregate, octatonic scale (and alpha chord), the diatonic and heptatonia secunda seven-note scales, and less often the whole tone scale and the primary pentatonic collection.[79] He rarely used the simple aggregate actively to shape musical structure, though there are notable examples such as the second theme from the first movement of his Second Violin Concerto, of which he commented that he "wanted to show Schoenberg that one can use all twelve tones and still remain tonal".[80] More thoroughly, in the first eight measures of the last movement of his Second Quartet, all notes gradually gather with the twelfth (G♭) sounding for the first time on the last beat of measure 8, marking the end of the first section. The aggregate is partitioned in the opening of the Third String Quartet with C♯–D–D♯–E in the accompaniment (strings) while the remaining pitch classes are used in the melody (violin 1) and more often as 7–35 (diatonic or "white-key" collection) and 5–35 (pentatonic or "black-key" collection) such as in no. 6 of the Eight Improvisations. There, the primary theme is on the black keys in the left hand, while the right accompanies with triads from the white keys. In measures 50–51 in the third movement of the Fourth Quartet, the first violin and cello play black-key chords, while the second violin and viola play stepwise diatonic lines.[81] On the other hand, from as early as the Suite for piano, Op. 14 (1914), he occasionally employed a form of serialism based on compound interval cycles, some of which are maximally distributed, multi-aggregate cycles.[82][83] Ernő Lendvai analyses Bartók's works as being based on two opposing tonal systems, that of the acoustic scale and the axis system, as well as using the golden section as a structural principle.[84] Milton Babbitt, in his 1949 review of Bartók's string quartets, criticized Bartók for using tonality and non-tonal methods unique to each piece. Babbitt noted that "Bartók's solution was a specific one, it cannot be duplicated".[85] Bartók's use of "two organizational principles"—tonality for large scale relationships and the piece-specific method for moment to moment thematic elements—was a problem for Babbitt, who worried that the "highly attenuated tonality" requires extreme non-harmonic methods to create a feeling of closure.[86] |

音楽分析 ハンガリー、バジャにあるベラ・バルトークの記念碑 ポール・ウィルソンは、1920年代後半以降のバルトークの音楽の特徴として、カルパティア盆地とヨーロッパの芸術音楽の影響、そして調性に対する彼の態 度の変化(および調性の使用)を挙げていますが、長調や短調に関連する伝統的な和声機能は使用していないと述べています[78]。 バルトークは、自分の音楽は常に調性音楽であると著作で主張しているが、通常、調性に関連付けられる和音や音階をほとんど使用していないため、調性理論の 記述的資源は限られたものとなっている。ジョージ・パール(1955)とエリオット・アントコレッツ(1984)は、反転対称軸による調性中心を示す彼の 代替手法に焦点を当てている。他の研究者は、バルトークの対称軸を無調分析のプロトコルとして捉えている。リチャード・コーン(1988)は、反転対称性 は、別の無調の手法、すなわち転位関係にある 2 音から和音を形成する手法の副産物であることが多いと主張している。無調音階理論は、多モードの色彩主義、投影集合、特権パターン、および等音程 12 音集合、オクタトニック音階(およびアルファコード)、全音階および 7 音階、そしてあまり使用されない全音階および一次五音階コレクションなどのソースセットとして使用される大規模な集合タイプを探求するためのリソースも提 供している。 彼は、単純な集合体を音楽構造を形成するために積極的に使用することはほとんどなかったが、第2ヴァイオリン協奏曲の第1楽章の第2主題など、注目すべき 例がある。彼はこの作品について、「シェーンベルクに、12音すべてを使用しても調性を保つことができることを示したかった」とコメントしている。 [80] より徹底的に、第2弦楽四重奏曲の最終楽章の最初の8小節では、すべての音が徐々に集まり、12番目の音(G♭)が8小節目の最後の拍で初めて鳴り、第1 部の終わりを告げる。この集合体は、第3弦楽四重奏曲の冒頭で、伴奏(弦楽器)にC♯–D–D♯–Eが用いられ、残りの音高クラスはメロディ(第1ヴァイ オリン)に用いられ、より頻繁に7–35(ダイアトニックまたは「白鍵」集合)と5–35(ペンタトニックまたは「黒鍵」集合)として用いられる。例え ば、 6のように、より頻繁に使用されている。そこでは、主要テーマは左手の黒鍵で奏でられ、右手の伴奏は白鍵の三和音で伴奏している。第4弦楽四重奏曲の第3 楽章の50–51小節では、第1ヴァイオリンとチェロが黒鍵の和音を奏で、第2ヴァイオリンとヴィオラが段階的なダイアトニックな旋律を奏でている。 [81] 一方、ピアノ組曲、作品 14(1914)からは、複合音程サイクルに基づく一連の形式を時折採用しており、その一部は、最大限に分散された、複数の集合サイクルとなっている [82][83]。エルノ・レンドヴァイは、バルトークの作品は、音響音階と軸システムという 2 つの対立する調性体系に基づいており、黄金比を構造原理として用いていると分析している[84]。 ミルトン・バビットは、1949 年にバルトークの弦楽四重奏曲を批評し、各作品に固有の調性および非調性手法を使用していることを批判した。バビットは「バルトークの解決策は特定のもの です。それは再現できません」と指摘している。[85] バルトークの「2つの組織原理」——大規模な関係には調性、瞬間的な主題要素には作品固有の方法——は、バビットにとって問題だった。彼は「高度に希薄化 された調性」が、閉塞感を創出するために極端な非和声的手法が必要だと懸念していた。[86] |

| Catalogues The cataloguing of Bartók's works is somewhat complex. Bartók assigned opus numbers to his works three times, the last of these series ending with the Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1, Op. 21 in 1921. He ended this practice because of the difficulty of distinguishing between original works and ethnographic arrangements, and between major and minor works. Since his death, three attempts—two full and one partial—have been made at cataloguing. The first, and still most widely used, is András Szőllősy's chronological Sz. numbers, from 1 to 121. Denijs Dille [nl] subsequently reorganised the juvenilia (Sz. 1–25) thematically, as DD numbers 1 to 77. The most recent catalogue is that of László Somfai; this is a chronological index with works identified by BB numbers 1 to 129, incorporating corrections based on the Béla Bartók Thematic Catalogue. On 1 January 2016, Bartók's works entered the public domain in the European Union.[87] Discography Together with his like-minded contemporary Zoltán Kodály, Bartók embarked on an extensive programme of field research to capture the folk and peasant melodies of Magyar, Slovak and Romanian language territories.[62] At first they transcribed the melodies by hand, but later they began to use a phonomotor, a wax cylinder recording machine invented by Thomas Edison.[88] Compilations of Bartók's field recordings, interviews, and original piano playing have been released over the years, largely by the Hungarian record label Hungaroton: ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 1994. Bartók at the Piano. Hungaroton 12326. 6-CD set. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 1995a. Bartók Plays Bartók – Bartók at the Piano 1929–41. Pearl 9166. CD recording. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 1995b. Bartók Recordings from Private Collections. Hungaroton 12334. CD recording. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 2003. Bartók Plays Bartók. Pearl 179. CD recording. Bartók, Béla. 2003. Bartók Sonata for 2 Pianos & Percussion, Suite for 2 Pianos. Apex 0927-49569-2. CD recording. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 2007. Bartók: Contrasts, Mikrokosmos. Membran/Documents 223546. CD recording. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 2008. Bartók Plays Bartók. Urania 340. CD recording. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 2016. Bartók the Pianist. Hungaroton HCD32790-91. Two CDs. Works by Bartók, Domenico Scarlatti, Zoltán Kodály, and Franz Liszt. A compilation of field recordings and transcriptions for two violas was also recently released by Tantara Records in 2014.[89] On 18 March 2016 Decca Classics released Béla Bartók: The Complete Works, the first ever complete compilation of all of Bartók's compositions, including new recordings of never-before-recorded early piano and vocal works. However, none of the composer's own performances are included in this 32-disc set.[90] |

カタログ バルトークの作品の分類は、やや複雑だ。バルトークは、3度にわたり作品に作品番号を付け、その最後のシリーズは、1921年の「ヴァイオリンとピアノの ためのソナタ第1番 Op.21」で終わっている。彼は、原作と民族音楽のアレンジ、そして主要作品とマイナー作品との区別が難しいため、この慣習をやめた。彼の死後、3つの カタログ化試みがなされた。最初のものは、現在最も広く使用されているアンドラーシュ・ソローシの年代順のSz.番号(1から121)だ。その後、デニー ス・ディル[nl]が若年期の作品(Sz. 1–25)をテーマ別に再編成し、DD番号1から77とした。最新の目録は、ラースロー・ソンファイによるもので、ベラ・バルトークのテーマ別目録に基づ く修正を取り入れた、1 から 129 までの BB 番号による年代順の索引だ。 2016年1月1日、バルトークの作品は、欧州連合でパブリックドメインとなった。[87] ディスコグラフィ バルトークは、同時代の同志であるゾルターン・コダーイと共に、マジャール語、スロバキア語、ルーマニア語圏の民謡と農民のメロディを収集する大規模な フィールド調査を開始した。[62] 当初は手書きでメロディを転写していたが、後にトーマス・エジソンが発明した蝋管録音機「フォノモーター」を使用するようになった。[88] バルトークのフィールド録音、インタビュー、オリジナルのピアノ演奏を収録したコンピレーションアルバムが、主にハンガリーのレコードレーベル、ハンガロ トンから長年にわたってリリースされている。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。1994年。Bartók at the Piano。ハンガロトン 12326。6枚組CD。 ‹TfM参照›バルトーク、ベラ。1995a. 『バルトークがバルトークを演奏 – バルトークのピアノ演奏 1929–41』。パール 9166。CD録音。 ‹TfM参照›バルトーク、ベラ。1995b. 『バルトークの私蔵録音集』。ハンガロトン 12334。CD録音。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。2003。バルトークがバルトークを演奏。パール 179。CD録音。 バルトーク、ベラ。2003。バルトーク:2台のピアノと打楽器のためのソナタ、2台のピアノのための組曲。アペックス 0927-49569-2。CD録音。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。2007年。バルトーク:コントラスト、ミクロコスモス。メンブレン/ドキュメンツ 223546。CD録音。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。2008年。バルトークがバルトークを演奏。ウラニア 340。CD録音。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。2016年。バルトーク・ザ・ピアニスト。ハンガロトン HCD32790-91。2枚組CD。バルトーク、ドメニコ・スカルラッティ、ゾルタン・コダーイ、フランツ・リストの作品。 2014年には、2台のヴィオラのためのフィールド録音と編曲集が、タンタラ・レコードからリリースされた。[89] 2016年3月18日、デッカ・クラシックスは、これまで録音されたことのない初期のピアノ作品や声楽作品を含む、バルトークの作曲全曲を初めて完全収録 した『Béla Bartók: The Complete Works』をリリースした。ただし、この32枚組のアルバムには、作曲者自身の演奏は収録されていない。[90] |

| Statues and other memorials |

(省略) |

| Sources ‹See TfM›Antokoletz, Elliott. 1984. The Music of Béla Bartók: A Study of Tonality and Progression in Twentieth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04604-7. ‹See TfM›Babbitt, Milton. 1949. "The String Quartets of Bartók". Musical Quarterly 35 (July): 377–85. Reprinted in The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt, edited by Stephen Peles, with Stephen Dembski, Andrew Mead, and Joseph N. Straus, 1–9. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-691-08966-9. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 1948. Levelek, fényképek, kéziratok, kották. [Letters, photographs, manuscripts, scores], ed. János Demény, 2 vols. A Muvészeti Tanács könyvei, 1.–2. sz. Budapest: Magyar Muvészeti Tanács. English edition, as Béla Bartók: Letters, translated by Péter Balabán and István Farkas; translation revised by Elisabeth West and Colin Mason (London: Faber and Faber Ltd.; New York: St. Martin's Press, 1971). ISBN 978-0-571-09638-1 ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 1976. Essays, selected and edited by Benjamin Suchoff. The New York Bartók Archive Studies in Musicology, No. 8. London: Faber & Faber; New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-571-10120-7. ‹See TfM›Bartók, Béla. 2018. Romanian Folk Dances (Sheet music), London: Chester Music. Bartók: Complete Works. Decca Records. 2016. OCLC 945742125. ‹See TfM›Botstein, Leon. [n.d.] "Modernism", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 29 April 2008), (subscription access). ‹See TfM›Chalmers, Kenneth. 1995. Béla Bartók. 20th-Century Composers. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3164-0 (pbk). Citron, Pierre (1963). Bartok. Paris: Editions du Seuil. OCLC 1577771. ‹See TfM›Cohn, Richard, 1988. "Inversional Symmetry and Transpositional Combination in Bartók." Music Theory Spectrum 10:19–42. ‹See TfM›Cooper, David. 2015. Béla Bartók. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21307-2. de Toth, June (1999). "Béla Bartók: A Biography". Béla Bartók: Solo Piano Works (liner notes). Béla Bartók. Eroica Classical Recordings. OCLC 29737219. JDT 3136. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007. ‹See TfM›Dicaire, David. 2010. The Early Years of Folk Music: Fifty Founders of the Tradition. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5737-3. ‹See TfM›Dille, Denijs. 1990. Béla Bartók: Regard sur le Passé. (French, no English version available). Namur: Presses universitaires de Namur. ISBN 978-2-87037-168-8, 978-2-87037-168-8. ‹See TfM›Einstein, Alfred. 1947. Music in the Romantic Era. New York: W. W. Norton. ‹See TfM›Fisk, Josiah (ed.). 1997. Composers on Music: Eight Centuries of Writings: A New and Expanded Revision of Morgenstern's Classic Anthology. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-279-6. ‹See TfM›Gagné, Nicole V. 2012. Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music. Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6765-9. ‹See TfM›Getting, Peter. 2020. Zomieral s pocitom, že jeho práca bola daromná. Našťastie nebula. Bartók zanechal monumentálne dielo. SME.sk (accessed 9 May 2020). ‹See TfM›Gillies, Malcolm (ed.). 1990. Bartók Remembered. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14243-9 (cased) ISBN 978-0-571-14244-6 (pbk). ‹See TfM›Gillies, Malcolm (ed.). 1993. The Bartók Companion. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-15330-5 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-571-15331-2 (pbk); New York: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-931340-74-1. ‹See TfM›Gillies, Malcolm. 2001. "Béla Bartók". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers. Also in Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 23 May 2006), (subscription access). ‹See TfM›Gollin, Edward. 2007. "Multi-Aggregate Cycles and Multi-Aggregate Serial Techniques in the Music of Béla Bartók". Music Theory Spectrum 29, no. 2 (Fall): 143–76. ‹See TfM›Griffiths, Paul. 1978. A Concise History of Modern Music. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20164-0. ‹See TfM›Griffiths, Paul. 1988. Bartók. London: JM Dent & Sons Ltd. ‹See TfM›Hooker, Lynn. 2001. "The Political and Cultural Climate in Hungary at the Turn of the Twentieth Century". In The Cambridge Companion to Bartók, edited by Amanda Bayley, 7–23. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66010-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-521-66958-0 (pbk). ‹See TfM›Hughes, Peter. 2001. "Béla Bartók" in Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. [n.p.]: Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Archive from 7 December 2013 (accessed 24 October 2017). ‹See TfM›Hughes, Peter. 2007. "Béla Bartók: Composer (1881–1945)". In Notable American Unitarians 1936–1961, edited by Herbert Vetter, 21–22. Cambridge: Harvard Square Library. ISBN 978-0-615-14784-0. ‹See TfM›Jones, Tom. 2012. "See Béla Bartók". Tired of London, Tired of Life blog site (8 October) (accessed 4 July 2014). ‹See TfM›Kory, Agnes. 2007. "Kodály, Bartók, and Fiddle Music in Bartók's Compositions". Béla Bartók Centre for Musicianship website (accessed 27 September 2018). ‹See TfM›Lendvai, Ernő. 1971. Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music, introduced by Alan Bush. London: Kahn & Averill. ISBN 978-0-900707-04-9 OCLC 240301. ‹See TfM›Martins, José António Oliveira. 2006. "Dasian, Guidonian, and Affinity Spaces in Twentieth-century Music". Ph.D. diss. Chicago: University of Chicago. ‹See TfM›Matthews, Peter. 2012. "Bartók in New York". Feast of Music website (accessed 26 September 2018).[unreliable source?] ‹See TfM›Maurice, Donald. 2004. Bartók's Viola Concerto: The Remarkable Story of His Swansong. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195348118 (accessed 19 October 2017) ‹See TfM›Moreux, Serge. 1953. Béla Bartók, translated G. S. Fraser and Erik de Mauny. London: The Harvill Press. ‹See TfM›Moreux. 1974. Béla Bartók, translated G. S. Fraser and Erik de Mauny, with a preface by Arthur Honegger. Partial reprint of Moreux (1953). New York: Vienna House. ‹See TfM›Móser, Zoltán. 2006a. "Szavak, feliratok, kivonatok". Tiszatáj 60, no. 3 (March): 41–45. ‹See TfM›Özgentürk, Nebil. 2008. Türkiye'nin Hatıra Defteri, episode 3. Istanbul: Bir Yudum İnsan Prodüksiyon LTD. ȘTİ. Turkish CNN television documentary series. ‹See TfM›Perle, George. 1955. "Symmetrical Formations in the String Quartets of Béla Bartók". Music Review 16, no. 4 (November 1955). Reprinted in The Right Notes: Twenty-Three Selected Essays by George Perle on Twentieth-Century Music, foreword by Oliver Knussen, introduction by David Headlam, 189–205. Monographs in Musicology. Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-0-945193-37-1. ‹See TfM›Rockwell, John. 1982. "Kodaly Was More Than a Composer". The New York Times (12 December). ‹See TfM›Rodda, Richard E. 1990–2018. "String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Op. 7/Sz 40: About the Work". The Kennedy Center website (accessed 27 September 2018). ‹See TfM›Schneider, David E. 2006. Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality. California Studies in 20th-Century Music 5. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24503-7. ‹See TfM›Sipos, János (ed.). 2000. In the Wake of Bartók in Anatolia 1: Collection Near Adana. Budapest: Ethnofon Records. ‹See TfM›Somfai, László. 1996. Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources. Ernest Bloch Lectures in Music 9. Berkeley : University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08485-8. ‹See TfM›Stevens, Halsey. 1964. The Life and Music of Béla Bartók, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ASIN: B000NZ54ZS ‹See TfM›Stevens, Halsey. 1993. The Life and Music of Béla Bartók, third edition, prepared by Malcolm Gillies. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198163497. ‹See TfM›Stevens, Halsey. 2018. "Béla Bartók: Hungarian Composer". Encyclopædia Britannica online (accessed 27 September 2018). ‹See TfM›Suchoff, Benjamin. 2001 Béla Bartók: Life and Work. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4076-8 – via Google Books. (2001) (accessed 29 July 2019). ‹See TfM›Szabolcsi, Bence. 1974. "Bartók Béla: Cantata profana". In Miért szép századunk zenéje? (Why is the music of the Twentieth century so beautiful?), edited by György Kroó, [page needed]. Budapest: Gondolat ISBN 978-963-280-015-8 ‹See TfM›Szekernyés János. 2017. "Bartókék Nagyszentmiklóson" [Bartók in Nagyszentmiklós]. Művelődés 70 (July) (accessed 10 March 2019). ‹See TfM›Tudzin, Jessica Taylor. 2010. "Schooled in Bartók". Bohemian Ink blog site (2 August) (accessed 4 July 2014). Voices From The Past: Béla Bartók's 44 Duos & Original Field Recordings. Tantara Records. 2014. OCLC 868907693. Wilhelm, Kurt (1989). Richard Strauss: An intimate Portrait. London: Thames and Hudson. ‹See TfM›Wilson, Paul. 1992. The Music of Béla Bartók. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05111-7. |

出典 ‹TfM を参照›Antokoletz, Elliott. 1984. The Music of Béla Bartók: A Study of Tonality and Progression in Twentieth-Century Music. バークレーおよびロサンゼルス: カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 978-0-520-04604-7。 ‹TfM 参照›バビット、ミルトン。1949 年。「The String Quartets of Bartók」 Musical Quarterly 35 (7 月): 377–85。The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt、スティーブン・ペレス、スティーブン・デムスキー、アンドルー・ミード、ジョセフ・N・ストラウス編、1–9 に再掲載。プリンストン: プリンストン大学出版局、2003 年。ISBN 978-0-691-08966-9。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。1948年。Levelek, fényképek, kéziratok, kották. [手紙、写真、原稿、楽譜]、編者:János Demény、2巻。A Muvészeti Tanács könyvei, 1.–2. sz. ブダペスト: Magyar Muvészeti Tanács。英語版は、ペテル・バラバンとイシュトヴァーン・ファルカシュによる翻訳、エリザベス・ウェストとコリン・メイソンによる翻訳の改訂版とし て、ベラ・バルトーク『Letters』として出版されている(ロンドン:Faber and Faber Ltd.、ニューヨーク:St. Martin's Press、1971年)。ISBN 978-0-571-09638-1 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。1976年。エッセイ、ベンジャミン・サコフによる選択・編集。The New York Bartók Archive Studies in Musicology、No. 8。ロンドン:Faber & Faber、ニューヨーク:St. Martin's Press。ISBN 978-0-571-10120-7。 ‹TfMを参照›バルトーク、ベラ。2018年。ルーマニアの民謡(楽譜)、ロンドン:チェスター・ミュージック。 バルトーク:全集。デッカ・レコード。2016年。OCLC 945742125。 ‹TfM 参照› ボットスタイン、レオン。[発行年不明] 「モダニズム」、Grove Music Online、L. メイシー編(2008年4月29日アクセス)、(購読アクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›Chalmers, Kenneth. 1995. Béla Bartók. 20th-Century Composers. ロンドン: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3164-0 (pbk). Citron, Pierre (1963). Bartok. パリ: Editions du Seuil. OCLC 1577771. ‹TfM を参照›Cohn, Richard, 1988. 「Inversional Symmetry and Transpositional Combination in Bartók」 Music Theory Spectrum 10:19–42. ‹TfM を参照›クーパー、デビッド。2015年。ベラ・バルトーク。ニューヘイブンおよびロンドン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-300-21307-2。 デ・トス、ジューン (1999). 「ベラ・バルトーク:伝記」. ベラ・バルトーク:ソロ・ピアノ作品 (ライナーノーツ). ベラ・バルトーク. エロイカ・クラシック・レコーディングス. OCLC 29737219. JDT 3136. 2007年4月8日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年4月14日に取得。 ‹TfMを参照›ディケール, デビッド. 2010. フォークミュージックの初期: 伝統の50人の創始者. ジェファーソン, N.C.: マクファーランド. ISBN 978-0-7864-5737-3. ‹TfMを参照›ディル、デニイス。1990年。『ベラ・バルトーク:過去への回顧』 (フランス語、英語版は未出版)。ナミュール:プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・ナミュール。ISBN 978-2-87037-168-8、978-2-87037-168-8。 ‹TfMを参照›アインシュタイン、アルフレッド。1947年。『ロマン派時代の音楽』。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン。 ‹TfMを参照›フィスク、ジョサイア(編)。1997年。『作曲家たちの音楽論:8世紀にわたる著作集:モーゲンシュテルンの古典的アンソロジーの新装増補版』。ボストン:ノースイースタン大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-55553-279-6。 ‹TfMを参照›Gagné, Nicole V. 2012. Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music. Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts. メリーランド州ラナム:スケアクロウ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-8108-6765-9。 ‹TfMを参照›ゲッティング、ピーター。2020. Zomieral s pocitom, že jeho práca bola daromná. Našťastie nebula. Bartók zanechal monumentálne dielo. SME.sk (2020年5月9日にアクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›ギリーズ、マルコム(編)。1990. 『バルトークを偲ぶ』。ロンドン:ファーバー。ISBN 978-0-571-14243-9(ハードカバー) ISBN 978-0-571-14244-6(ペーパーバック)。 ‹TfMを参照›ギリーズ、マルコム(編)。1993. 『バルトーク・コンパニオン』 ロンドン:Faber。ISBN 978-0-571-15330-5(ハードカバー)、ISBN 978-0-571-15331-2(ペーパーバック);ニューヨーク:Hal Leonard。ISBN 978-0-931340-74-1。 ‹TfMを参照›Gillies, Malcolm. 2001. 「Béla Bartók」. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, スタンリー・サディ、ジョン・ティレル編. ロンドン: マクミラン・パブリッシャーズ. また、Grove Music Online, L. Macy 編 (2006年5月23日アクセス), (購読アクセス). ‹TfMを参照›Gollin, Edward. 2007. 「Multi-Aggregate Cycles and Multi-Aggregate Serial Techniques in the Music of Béla Bartók」. Music Theory Spectrum 29, no. 2 (Fall): 143–76. ‹TfMを参照›Griffiths, Paul. 1978. A Concise History of Modern Music. ロンドン:テムズ・アンド・ハドソン。ISBN 978-0-500-20164-0。 ‹TfMを参照›グリフィス、ポール。1988年。バルトーク。ロンドン:JM Dent & Sons Ltd. ‹TfMを参照›フッカー、リン。2001年。「20世紀初頭のハンガリーの政治的・文化的状況」。『The Cambridge Companion to Bartók』アマンダ・ベイリー編、7-23 ページ。ケンブリッジ・コンパニオンズ・トゥ・ミュージック。ケンブリッジおよびニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-66010-5 (ハードカバー)、ISBN 978-0-521-66958-0 (ペーパーバック)。 ‹TfMを参照›ヒューズ、ピーター。2001年。「ベラ・バルトーク」『ユニテリアンおよびユニバーサル主義者伝記事典』。[n.p.]:ユニテリアン・ユニバーサル主義歴史協会。2013年12月7日アーカイブ(2017年10月24日アクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›ヒューズ、ピーター。2007年。「ベラ・バルトーク:作曲家(1881-1945)」。『著名なアメリカユニテリアン 1936-1961』ハーバート・ヴェッター編、21-22。ケンブリッジ:ハーバード・スクエア・ライブラリー。ISBN 978-0-615-14784-0。 ‹TfMを参照›ジョーンズ、トム。2012年。「ベラ・バルトークを参照」。Tired of London, Tired of Life ブログサイト(10月8日)(2014年7月4日アクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›コーリー、アグネス。2007年。「コダーイ、バルトーク、そしてバルトークの作曲におけるフィドル音楽」。ベラ・バルトーク音楽センターウェブサイト(2018年9月27日アクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›Lendvai, Ernő. 1971. Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music, introduced by Alan Bush. London: Kahn & Averill. ISBN 978-0-900707-04-9 OCLC 240301. ‹TfMを参照›Martins, José António Oliveira. 2006. 「20 世紀の音楽におけるダシアン、ギド、アフィニティ空間」. 博士論文. シカゴ: シカゴ大学. ‹TfMを参照›Matthews, Peter. 2012. 「ニューヨークのバルトーク」. Feast of Music ウェブサイト(2018年9月26日アクセス)。[信頼性の低い情報源?] ‹TfMを参照›Maurice, Donald. 2004. Bartók's Viola Concerto: The Remarkable Story of His Swansong. オックスフォードおよびニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 9780195348118 (2017年10月19日アクセス) ‹TfMを参照›モルー、セルジュ。1953年。ベラ・バルトーク、G. S. フレイザーとエリック・ド・マニー訳。ロンドン:ハーヴィル・プレス。 ‹TfMを参照›モルー。1974年。ベラ・バルトーク、G. S. フレイザーとエリック・ド・マニー訳、アーサー・オネゲル序文。Moreux (1953) の部分再版。ニューヨーク:Vienna House。 ‹TfMを参照›Móser, Zoltán. 2006a. 「Szavak, feliratok, kivonatok」. Tiszatáj 60, no. 3 (3月): 41–45. ‹TfMを参照›Özgentürk, Nebil. 2008. Türkiye'nin Hatıra Defteri、エピソード 3。イスタンブール:Bir Yudum İnsan Prodüksiyon LTD. ȘTİ。トルコ CNN テレビドキュメンタリーシリーズ。 ‹TfM を参照›Perle, George. 1955. 「Symmetrical Formations in the String Quartets of Béla Bartók」。Music Review 16、第 4 号(1955 年 11 月)。The Right Notes に再掲載。ジョージ・パールによる20世紀音楽に関する23の選集、オリバー・クヌッセンによる序文、デイビッド・ヘッドラムによる序文、 189–205。音楽学モノグラフ。ニューヨーク州スタイベサント:ペンドラゴン・プレス。ISBN 978-0-945193-37-1。 ‹TfMを参照›ロックウェル、ジョン。1982。「コダーイは作曲家以上の存在だった」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ(12月12日)。 ‹TfMを参照›ロダ、リチャード・E。1990–2018。「弦楽四重奏曲第1番イ短調、作品7/Sz 40:作品について」。ケネディ・センターウェブサイト(2018年9月27日アクセス)。 ‹TfMを参照›シュナイダー、デビッド・E. 2006. バルトーク、ハンガリー、そして伝統の再生:現代性と国民性の交差点におけるケーススタディ。20 世紀の音楽に関するカリフォルニア研究 5。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 978-0-520-24503-7。 ‹TfMを参照›シポス、ヤノシュ(編)。2000年。『In the Wake of Bartók in Anatolia 1: Collection Near Adana』。ブダペスト:Ethnofon Records。 ‹TfMを参照›ソンファイ、ラースロー。1996年。『Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources』。 |

| Further reading ‹See TfM›"Polereczky család". Arcanum.hu website (accessed 30 December 2019). Bartók, Béla. 1976. "The Influence of Peasant Music on Modern Music (1931)". In Béla Bartók Essays, edited by Benjamin Suchoff, 340–44. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-10120-7 OCLC 60900461 Bartók, Béla. 1981. The Hungarian Folk Song Archived 4 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine, second English edition, edited by Benjamin Suchoff, translated by Michel D. Calvocoressi, with annotations by Zoltán Kodály. The New York Bartók Archive Studies in Musicology 13. Albany: State University of New York Press. Bartók, Peter. 2002. "My Father". Homosassa, Florida, Bartók Records (ISBN 978-0-9641961-2-4). Bayley, Amanda (ed.). 2001. The Cambridge Companion to Bartók Archived 4 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66010-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-521-66958-0 (pbk). Bónis, Ferenc. 2006. Élet-képek: Bartók Béla Archived 4 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó: Vávi Kft., Alföldi Nyomda Zrt. ISBN 978-963-506-649-0. Boys, Henry. 1945. "Béla Bartók 1881–1945". The Musical Times 86, no. 1233 (November): 329–31. Cohn, Richard, 1992. "Bartók's Octatonic Strategies: A Motivic Approach." Journal of the American Musicological Society 44 Czeizel, Endre. 1992. Családfa: honnan jövünk, mik vagyunk, hová megyünk? [Budapest]: Kossuth Könyvkiadó. ISBN 978-963-09-3569-2 Decca. 2016. "Béla Bartók: Complete Works: Int. Release 18 Mar. 2016: 32 CDs, 0289 478 9311 0 Archived 20 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Welcome to Decca Classics: Catalogue, www.deccaclassics.com (accessed 19 August 2016). Fassett, Agatha, 1958. The Naked Face of Genius: Béla Bartók's American Years. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Jyrkiäinen, Reijo. 2012. "Form, Monothematicism, Variation and Symmetry in Béla Bartók's String Quartets". Ph.D. diss. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-10-8040-1 (Abstract). Kárpáti, János. 1975. Bartók's String Quartets, translated by Fred MacNicol. Budapest: Corvina Press. Kasparov, Andrey. 2000. "Third Piano Concerto in the Revised 1994 Edition: Newly Discovered Corrections by the Composer". Hungarian Music Quarterly 11, nos. 3–4:2–11. Leafstedt, Carl S. 1999. Inside Bluebeard's Castle. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510999-3 Lendvai, Ernő. 1972. "Einführung in die Formen- und Harmoniewelt Bartóks" (1953). In his Béla Bartók: Weg und Werk, edited by Bence Szabolcsi, 105–49. Kassel: Bärenreiter. Loxdale, Hugh D., and Adalbert Balog. 2009. "Béla Bartók: Musician, Musicologist, Composer, and Entomologist!." Antenna – Bulletin of the Royal Entomological Society of London 33, no. 4:175–82. Maconie, Robin. 2005. Other Planets: The Music of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Lanham, MD, Toronto, Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5356-0. Martins, José Oliveira. 2015. "Bartók's Polymodality: the Dasian and other Affinity Spaces". Journal of Music Theory 59, no. 2 (October): 273–320. Móser, Zoltán. 2006b. "Bartók-õsök Gömörben". Honismeret: A Honismereti Szövetség folyóirata [permanent dead link] 34, no. 2 (April): 9–11. Nelson, David Taylor (2012). "Béla Bartók: The Father of Ethnomusicology", Musical Offerings: Vol. 3: No. 2, Article 2. Archived 6 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Sluder, Claude K. 1994. "Revised Bartók Composition Highlights Pro Musica Concert". The Republic (16 February). Smith, Erik. 1965. A discussion between István Kertész and the producer. DECCA Records (liner notes for Bluebeard's Castle). Somfai, László. 1981. Tizennyolc Bartók-tanulmány [Eighteen Bartók Studies]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó. ISBN 978-963-330-370-2. Wells, John C. 1990. "Bartók", in Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 63. Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-05383-0 |

さらに読む ‹TfMを参照›「Polereczky család」。Arcanum.hu ウェブサイト(2019年12月30日アクセス)。 バルトーク、ベラ。1976年。「農民音楽が現代音楽に与えた影響(1931年)」。ベラ・バルトークエッセイ、ベンジャミン・サコフ編、340-44 ページ。ロンドン:Faber & Faber。ISBN 978-0-571-10120-7 OCLC 60900461 バルトーク、ベラ。1981年。『ハンガリーの民謡』 2023年10月4日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、第2版、ベンジャミン・サコフ編、ミシェル・D・カルヴォコレッシ訳、ゾルタン・コダーイ注釈。 ニューヨーク・バルトーク・アーカイブ音楽学研究 13。アルバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。 バルトーク、ピーター。2002年。「My Father」。フロリダ州ホモサッサ、バルトーク・レコード(ISBN 978-0-9641961-2-4)。 ベイリー、アマンダ(編)。2001. 『The Cambridge Companion to Bartók』ウェイバックマシンに2023年10月4日にアーカイブ。ケンブリッジ・カンパニオンズ・トゥ・ミュージック。ケンブリッジおよびニュー ヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-66010-5(ハードカバー);ISBN 978-0-521-66958-0(ペーパーバック)。 ボニス、フェレンツ。2006年。『エレット・ケペク:バルトーク・ベラ』 Archived 4 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine。ブダペスト:Balassi Kiadó: Vávi Kft., Alföldi Nyomda Zrt. ISBN 978-963-506-649-0。 Boys, Henry. 1945. 「Béla Bartók 1881–1945」. The Musical Times 86, no. 1233 (November): 329–31. Cohn, Richard, 1992. 「Bartók's Octatonic Strategies: A Motivic Approach」. Journal of the American Musicological Society 44 チェイゼル、エンドレ。1992年。『Családfa: honnan jövünk, mik vagyunk, hová megyünk?』 [ブダペスト]:Kossuth Könyvkiadó。ISBN 978-963-09-3569-2 デッカ. 2016. 「ベラ・バルトーク:全作品:国際リリース 2016年3月18日:32枚組CD、0289 478 9311 0 2016年8月20日にウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ」. デッカ・クラシックへようこそ:カタログ, www.deccaclassics.com (2016年8月19日にアクセス). ファセット、アガサ、1958年。『天才の素顔:ベラ・バルトークのアメリカ時代』。ボストン:Houghton Mifflin。 Jyrkiäinen, Reijo. 2012. 「ベラ・バルトークの弦楽四重奏曲における形式、単主題主義、変奏、対称性」. 博士論文. ヘルシンキ: ヘルシンキ大学. ISBN 978-952-10-8040-1 (要約). カルパティ、ヤノシュ。1975年。バルトークの弦楽四重奏曲、フレッド・マクニコル訳。ブダペスト:コルヴィナ・プレス。 カスパロフ、アンドレイ。2000年。「1994年改訂版の第3番ピアノ協奏曲:作曲家による新たに発見された訂正」。ハンガリアン・ミュージック・クォータリー 11、3–4号:2–11。 リーフステッド、カール・S. 1999. 『青ひげの城の内部』. ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-510999-3 レンドヴァイ、エルノー。1972年。「Einführung in die Formen- und Harmoniewelt Bartóks」(1953年)。ベラ・バルトーク:Weg und Werk(ベレンツィ・サボルチ編)105-49。カッセル:ベーレンライター。 ロックスデール、ヒュー・D.、およびアダルベルト・バログ。2009年。「ベラ・バルトーク:音楽家、音楽学者、作曲家、そして昆虫学者!」『アンテナ – ロイヤル昆虫学会ロンドン支部会報』33、第4号:175–82。 マコニー、ロビン。2005年。『Other Planets: The Music of Karlheinz Stockhausen』 (他の惑星:カールハインツ・シュトックハウゼンの音楽)。メリーランド州ラナム、トロント、オックスフォード:The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5356-0。 マルティンス、ホセ・オリベイラ。2015年。「バルトークの多様性:ダシアンとその他の親和性空間」。Journal of Music Theory 59, no. 2 (October): 273–320. Móser, Zoltán. 2006b. 「Bartók-õsök Gömörben」 Honismeret: A Honismereti Szövetség folyóirata [永久リンク切れ] 34, no. 2 (April): 9–11. ネルソン, デビッド・テイラー (2012). 「ベラ・バルトーク: 民族音楽学の父」, ミュージカル・オファリングス: 第3巻 第2号, 記事2. 2013年12月6日にウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ スルーダー, クレオド・K. 1994. 「改訂されたバルトークの作曲ハイライト プロ・ムジカ・コンサート」. ザ・リパブリック (2月16日). スミス、エリック。1965. イシュトヴァーン・ケルテスとプロデューサーの討論。DECCA Records(『青ひげ公の城』のライナーノーツ)。 ソムファイ、ラースロー。1981. Tizennyolc Bartók-tanulmány [18のバルトーク研究]。ブダペスト:Zeneműkiadó。ISBN 978-963-330-370-2。 ウェルズ、ジョン・C. 1990. 「バルトーク」、『ロングマン発音辞典』、63ページ。ハーロウ、イギリス:ロングマン。ISBN 978-0-582-05383-0 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B%C3%A9la_Bart%C3%B3k |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆