優生学

Eugenics

☆ 優生学(Eugenics; 古代ギリシャ語 εύ̃ (eû) 「良い、健康な」と -γενής (genḗs) 「生まれる、存在する、成長する/成長した」に由来)は、 優生学(/juːˈdʒɛnɪks/ yoo-JEN-iks; from Ancient Greek εύ̃ (eû) 'good, well' and -γενής (genḗs) 'born, come into being, growing/grown')とは、ある人間集団の遺伝的質を改善することを目的とした信念と実践の体系である。 歴史的に、優生学者たちは劣っているとされる人々や集団の生殖能力を抑制したり、優れているとされる人々の生殖能力を促進したりすることで、さまざまな人 間の遺伝子頻度 優生学の現代史は19世紀後半に始まり、イギリスで優生学運動が盛んになり、その後、アメリカ、カナダ、オーストラリア、そしてヨーロッパ諸国(スウェー デンやドイツなど)を含む多くの国々に広がった。この時代には、政治的立場を問わず、多くの人々が優生学の考え方を支持した。その結果、多くの国が優生政 策を採用し、国民の遺伝的資質の向上を目指した。 優生学は進歩的な社会運動として始まったが、現代ではこの用語は科学的な人種差別(レイシズム)と 密接に関連している。 歴史的に、優生学の考え方は、遺伝的に望ましいとみなされた母親に対する出生前ケアから、不適格とみなされた人々に対する強制的な不妊手術や殺害まで、幅 広い行為を正当化するために用いられてきた。集団遺伝学者にとって、この用語には対立遺伝子頻度を変えることなく近親交配を回避することが含まれていた。 例えば、J. B J. B. S. ハルダネは「モーターバスは近親婚の村社会を分散させることで、強力な優生学的な手段となる」と記している。優生学として具体的に何が該当するのかについ ては、現在も議論が続いている。初期の優生学者の多くは、社会階級と強い相関関係にあることが多い測定された知能の要因を懸念していた(→以前の「優生学」ポータル)。

| Eugenics

(/juːˈdʒɛnɪks/ yoo-JEN-iks; from Ancient Greek εύ̃ (eû) 'good, well'

and -γενής (genḗs) 'born, come into being, growing/grown')[1] is a set

of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a

human population.[2][3][4] Historically, eugenicists have altered

various human gene frequencies by inhibiting the fertility of people

and groups purported to be inferior or promoting that of those

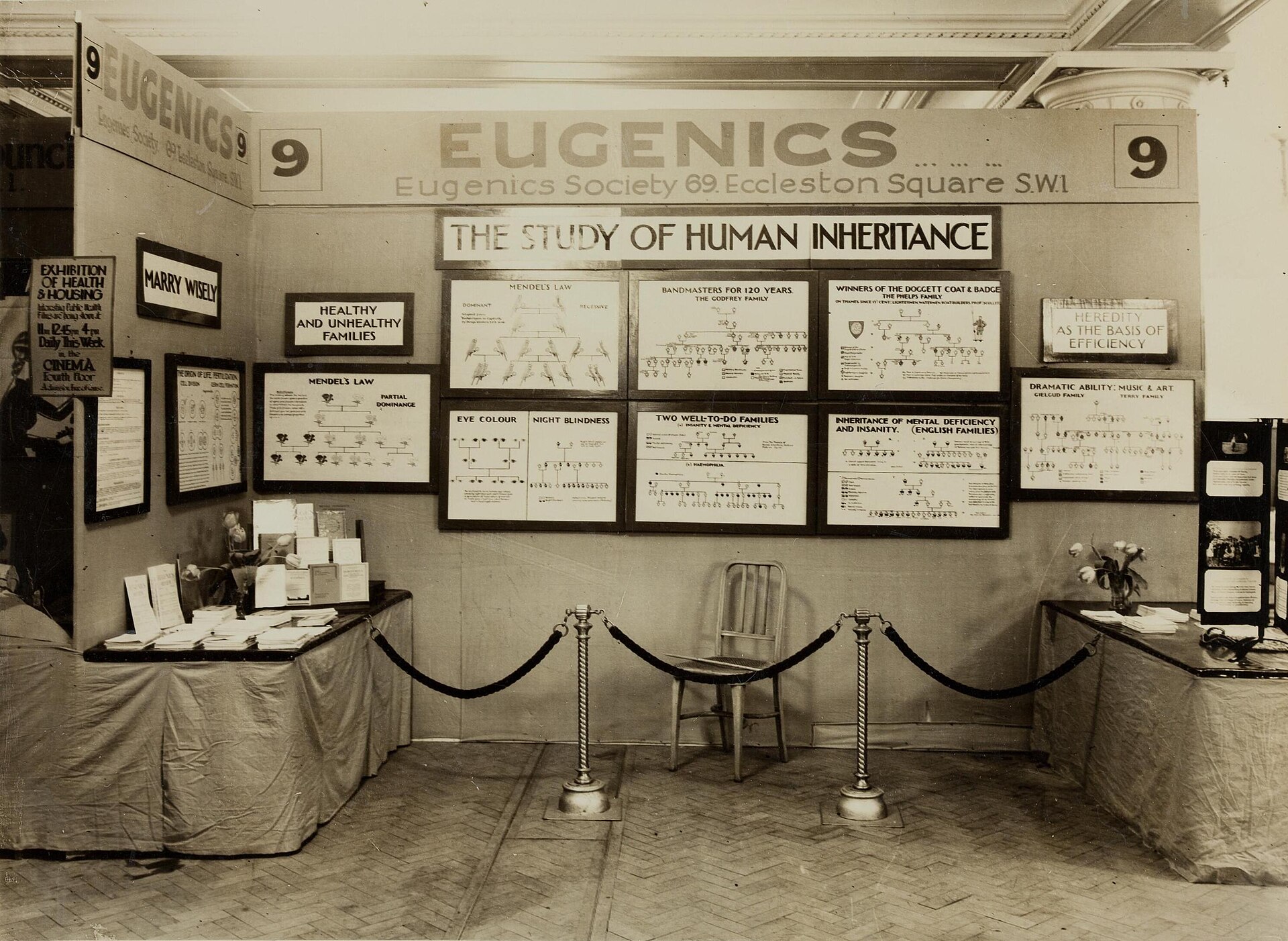

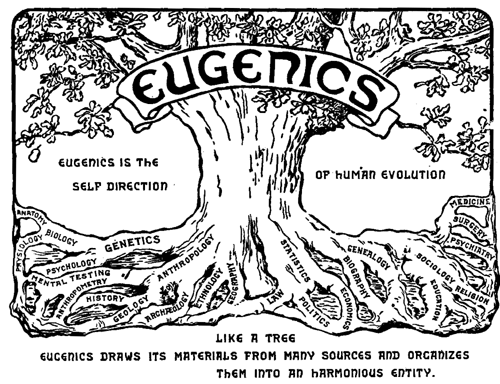

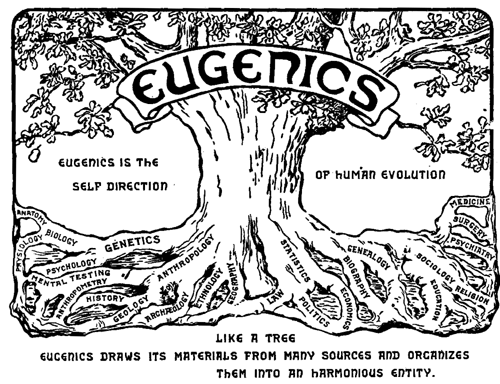

purported to be superior.[5] The contemporary history of eugenics began in the late 19th century, when a popular eugenics movement emerged in the United Kingdom,[6] and then spread to many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia,[7] and most European countries (e.g. Sweden and Germany). In this period, people from across the political spectrum espoused eugenic ideas. Consequently, many countries adopted eugenic policies, intended to improve the quality of their populations' genetic stock. While it originated as a progressive social movement,[8][9][10][11] in contemporary usage, the term is closely associated with scientific racism.[12] Historically, the idea of eugenics has been used to argue for a broad array of practices ranging from prenatal care for mothers deemed genetically desirable to the forced sterilization and murder of those deemed unfit.[5] To population geneticists, the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding without altering allele frequencies; for example, J. B. S. Haldane wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent."[13] Debate as to what exactly counts as eugenics continues today.[14] Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of measured intelligence that often correlated strongly with social class.  A 1930s exhibit by the Eugenics Society. Some of the signs read "Healthy and Unhealthy Families", "Heredity as the Basis of Efficiency" and "Marry Wisely" respectively |

優生学(Eugenics;

古代ギリシャ語 εύ̃ (eû) 「良い、健康な」と -γενής (genḗs)

「生まれる、存在する、成長する/成長した」に由来)[1]は、 優生学(/juːˈdʒɛnɪks/ yoo-JEN-iks; from

Ancient Greek εύ̃ (eû) 'good, well' and -γενής (genḗs) 'born, come into

being,

growing/grown')[1]とは、ある人間集団の遺伝的質を改善することを目的とした信念と実践の体系である。[2][3][4]

歴史的に、優生学者たちは劣っているとされる人々や集団の生殖能力を抑制したり、優れているとされる人々の生殖能力を促進したりすることで、さまざまな人

間の遺伝子頻度 優生学の現代史は19世紀後半に始まり、イギリスで優生学運動が盛んになり[6]、その後、アメリカ、カナダ、オーストラリア[7]、そしてヨーロッパ諸 国(スウェーデンやドイツなど)を含む多くの国々に広がった。この時代には、政治的立場を問わず、多くの人々が優生学の考え方を支持した。その結果、多く の国が優生政策を採用し、国民の遺伝的資質の向上を目指した。 優生学は進歩的な社会運動として始まったが[8][9][10][11]、現代ではこの用語は科学的な人種差別と密接に関連している[12]。 歴史的に、優生学の考え方は、遺伝的に望ましいとみなされた母親に対する出生前ケアから、不適格とみなされた人々に対する強制的な不妊手術や殺害まで、幅 広い行為を正当化するために用いられてきた。[5] 集団遺伝学者にとって、この用語には対立遺伝子頻度を変えることなく近親交配を回避することが含まれていた。例えば、J. B J. B. S. ハルダネは「モーターバスは近親婚の村社会を分散させることで、強力な優生学的な手段となる」と記している。[13] 優生学として具体的に何が該当するのかについては、現在も議論が続いている。[14] 初期の優生学者の多くは、社会階級と強い相関関係にあることが多い測定された知能の要因を懸念していた。  1930年代の優生学協会の展示。いくつかの標識にはそれぞれ「健康な家族と不健康な家族」、「効率性の基礎としての遺伝」、「賢く結婚しよう」と書かれている。 |

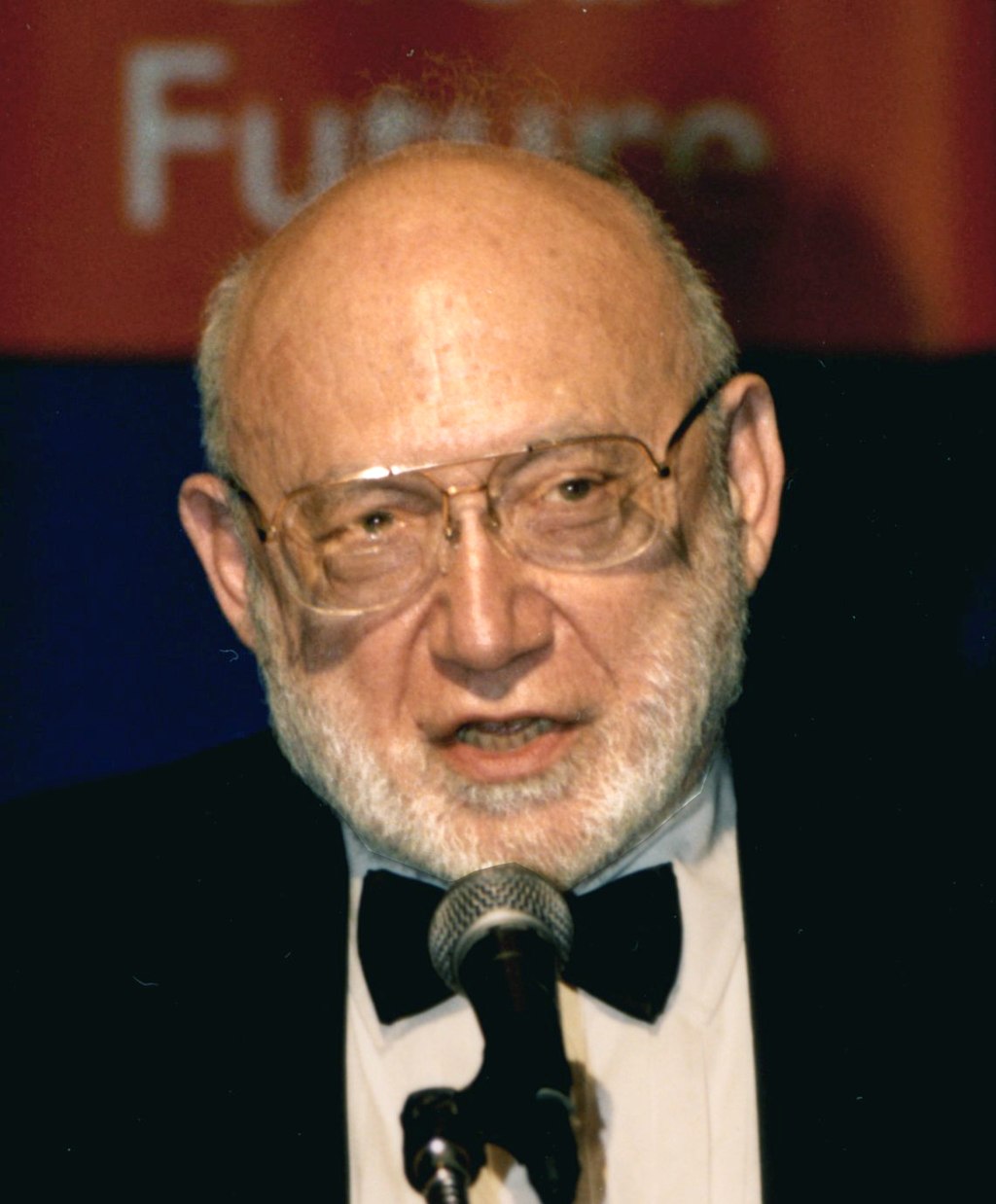

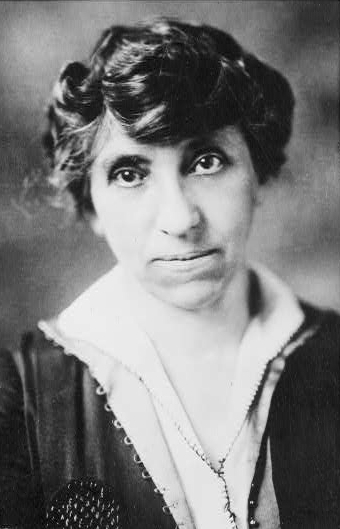

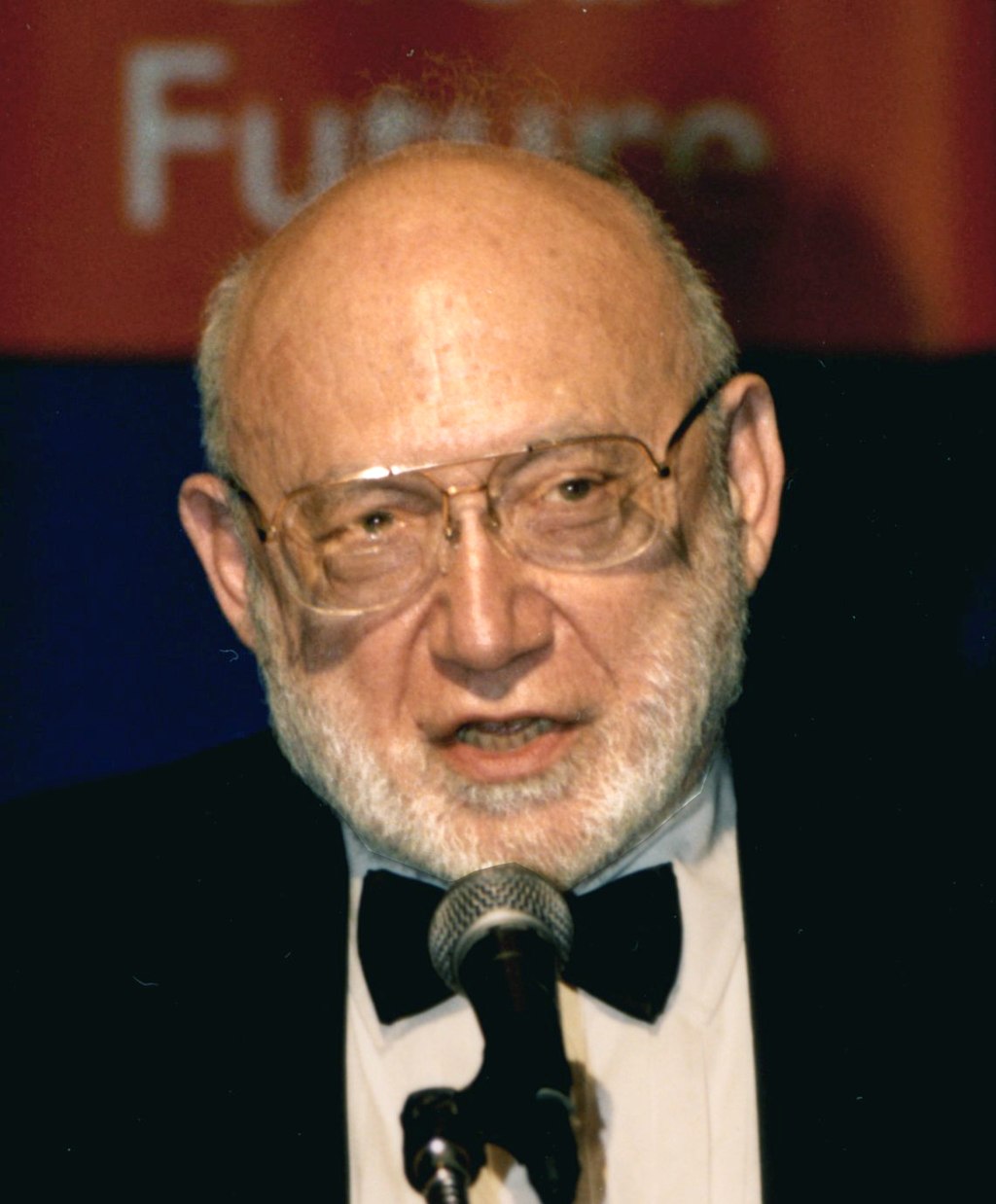

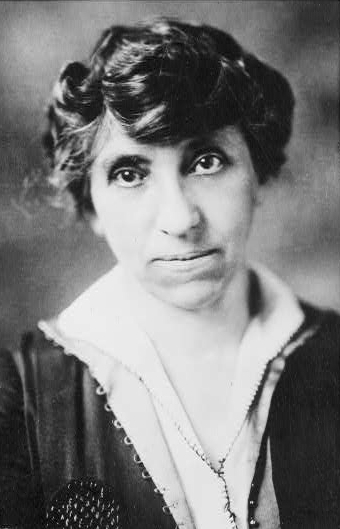

Common distinctions Lester Frank Ward wrote the early paper: "Eugenics, Euthenics and Eudemics", making yet further distinctions.[15]  Having presented papers at eugenics conferences alongside fellow Nobel prize winners in Physiology or Medicine, Hermann J. Muller and Francis Crick, as late as 1963[16] and equally concerned over the civilizational prospect of dysgenics,[17] Jewish geneticist Joshua Lederberg would nonetheless go on to coin the contrasting term Euphenics.[18] The aforementioned eugenic programs included both positive measures, such as encouraging individuals deemed particularly "fit" to reproduce, and negative measures, such as marriage prohibitions and forced sterilization of people deemed unfit for reproduction.[5][19][20]: 104–155 In other words, positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged, for example, the eminently intelligent, the healthy, and the successful. Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, in vitro fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning.[21] Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilization or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally "undesirable". This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning.[21] Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive; in Nazi Germany, for example, abortion was illegal for women deemed by the state to be fit.[22] As opposed to "euthenics" See also: Nature versus nurture controversy  Ellen Swallow Richards  Julia Clifford Lathrop Ellen Swallow Richards (left), the first female student and instructor at MIT was one of the first to use the term, while Julia Clifford Lathrop (right) continued to promote it in the form of an interdisciplinary academic program later to be mostly absorbed into the field of home economics Euthenics (/juːˈθɛnɪks/) is the study of improvement of human functioning and well-being by improvement of living conditions.[23] "Improvement" is conducted by altering external factors such as education and the controllable environments, including environmentalism, education regarding employment, home economics, sanitation, and housing, as well as the prevention and removal of contagious disease and parasites.[citation needed] In a New York Times article of May 23, 1926, Rose Field notes of the description, "the simplest [is] efficient living".[24] It is also described as "a right to environment",[25] commonly as dual to a "right of birth" that correspondingly falls under the purview of eugenics.[26] Euthenics is not normally interpreted to have anything to do with changing the composition of the human gene pool by definition, although everything that affects society has some effect on who reproduces and who does not.[27] The influential historian of education, Abraham Flexner questions its scientific value in stating: [T]he “science” is artificially pieced together of bits of mental hygiene, child guidance, nutrition, speech development and correction, family problems, wealth consumption, food preparation, household technology, and horticulture. A nursery school and a school for little children are also included. The institute is actually justified in an official publication by the profound question of a girl student who is reported as asking, “What is the connection of Shakespeare with having a baby?” The Vassar Institute of Euthenics bridges this gap![28] Eugenicist, Charles Benedict Davenport, noted in his article "Euthenics and Eugenics," found reprinted in the Popular Science Monthly: Thus the two schools of euthenics and eugenics stand opposed, each viewing the other unkindly. Against eugenics it is urged that it is a fatalistic doctrine and deprives life of the stimulus toward effort. Against euthenics the other side urges that it demands an endless amount of money to patch up conditions in the vain effort to get greater efficiency. Which of the two doctrines is true? The thoughtful mind must concede that, as is so often the case where doctrines are opposed, each view is partial, incomplete and really false. The truth does not exactly lie between the doctrines; it comprehends them both. [...] [I]n the generations to come, the teachings and practice of euthenics [...] [may] yield greater result because of the previous practice of the principles of eugenics.[29] Along similar lines famously argued psychologist and early intelligence researcher Edward L. Thorndike some two years later for an understanding that better integrates eugenic study: The more rational the race becomes, the better roads, ships, tools, machines, foods, medicines and the like it will produce to aid itself, though it will need them less. The more sagacious and just and humane the original nature that is bred into man, the better schools, laws, churches, traditions and customs it will fortify itself by. There is no so certain and economical a way to improve man's environment as to improve his nature.[30] |

一般的な区別 レスター・フランク・ウォードは初期の論文「優生学、優生主義、優生学」で、さらに区別を行っている。  1963年には、ノーベル生理学・医学賞受賞者のヘルマン・J・ミュラーやフランシス・クリックらとともに優生学の会議で論文を発表したユダヤ人の遺伝学 者ジョシュア・レダーバーグは、劣生学(dysgenics)の文明の見通しについて同様に懸念を示していたが[17]、対照的な用語であるユーフェクス (幸生学?)という造語を考案した[18]。 前述の優生学プログラムには、特に「適合」とみなされた個人の繁殖を奨励するといった積極的措置と、繁殖に適さないとみなされた人々に対する結婚禁止や強制不妊手術といった消極的措置の両方が含まれていた。[5][19][20]:104–155 つまり、ポジティブ優生学は、遺伝的に優れた人々、例えば、非常に聡明な人、健康な人、成功している人など、の繁殖を奨励することを目的としている。考え られるアプローチとしては、財政的・政治的な刺激策、特定の人口統計分析、体外受精、卵子移植、クローン技術などが含まれる。[21] ネガティブ優生学は、身体的、精神的、あるいは道徳的に「望ましくない」とみなされた人々を、断種や隔離によって排除することを目的としている。これには 中絶、不妊手術、その他の家族計画の方法が含まれる。[21] 優生学の積極的・消極的双方の側面は強制的なものでありうる。例えばナチス・ドイツでは、国家が適格とみなした女性の中絶は違法であった。[22] 「優生学」とは対照的に 関連項目: 環境 vs. 遺伝の論争  エレン・スワロー・リチャーズ  ジュリア・クリフォード・ラスロップ エレン・スワロー・リチャーズ(左)は、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)初の女子学生および講師であり、この用語を最初に使用した人物の一人であっ た。一方、ジュリア・クリフォード・ラスロップ(右)は、学際的な学術プログラムという形でこの概念を推進し続け、後にそれは主に家政学の分野に吸収され た ユートヘニクス(/juːˈθɛnɪks/)は、生活環境の改善による人間の機能と幸福の向上を研究する学問である。「改善」は、教育や制御可能な環境な どの外的要因を変化させることによって行われる。これには、環境保護、雇用に関する教育、家政学、公衆衛生、住宅、および伝染病や寄生虫の予防と駆除が含 まれる。 1926年5月23日付のニューヨーク・タイムズの記事で、ローズ・フィールドは「最も単純なものが最も効率的な生活である」と記している。[24] また、「環境に対する権利」とも表現され、[25] 一般的に「出生の権利」と対をなし、優生学の対象となる。[26] 優生学は、定義上、人間の遺伝子プールの構成を変えることとは通常関係がないと解釈されているが、社会に影響を与えるものはすべて、誰が繁殖し、誰が繁殖しないかに何らかの影響を与える。 教育史家として影響力のあるアブラハム・フレクスナーは、その科学的価値を疑問視し、次のように述べている。 「科学」は、精神衛生、児童指導、栄養、言語発達と矯正、家庭問題、富の消費、食品の調理、家庭技術、園芸といった分野の断片を人為的に組み合わせたもの である。保育園や幼児向け学校も含まれる。この研究所は、ある女子学生が「シェイクスピアと出産の関係とは何ですか?」と質問したという深い問いを公式出 版物で正当化している。ヴァッサー・ユーセティクス研究所がこのギャップを埋める![28] 優生学者チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポートは、記事「ユーセティクスと優生学」で、次のように述べている。 こうして、ユートニクスと優生学の2つの学派は対立し、それぞれが相手を不親切だと見なしている。優生学に対しては、それは宿命論的な教義であり、努力へ の刺激を奪うものだと主張されている。一方、ユートニクスに対しては、より高い効率性を求めて無駄な努力を続けるために、その状況を改善するために際限の ない金額が必要になると反対派は主張している。この2つの教義のうち、どちらが真実なのだろうか? 思慮深い人であれば、教義が対立する場合にはよくあることだが、それぞれの見解は部分的で不完全であり、実際には誤りであることを認めざるを得ないだろう。真実は、両者の教義のちょうど中間に位置するものではなく、両者を包括するものである。 [...] 今後、世代を経て、ユーセニクスの教えと実践は、[...] 以前の優生学の原則の実践により、より大きな成果をもたらすかもしれない。[29] 同様の論調で、著名な心理学者であり、初期の知能研究家であったエドワード・L・ソーンダイクは、優生学をより統合的に理解するために、2年ほど後に次のように主張した。 人種がより理性的になればなるほど、より良い道路、船、道具、機械、食品、医薬品などを生み出し、それらを必要とする機会も減るだろう。人間に育まれる本 来の性質がより賢明で公正かつ人道的なものであればあるほど、より良い学校、法律、教会、伝統、慣習によって自らを強化するだろう。人間の環境を改善する のにこれほど確実で経済的な方法はない。[30] |

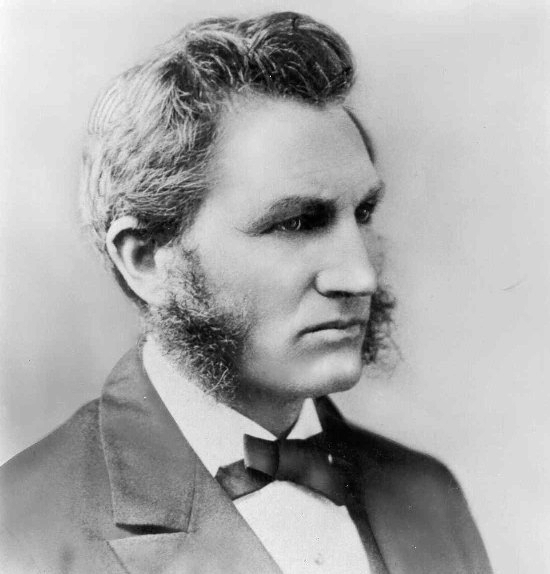

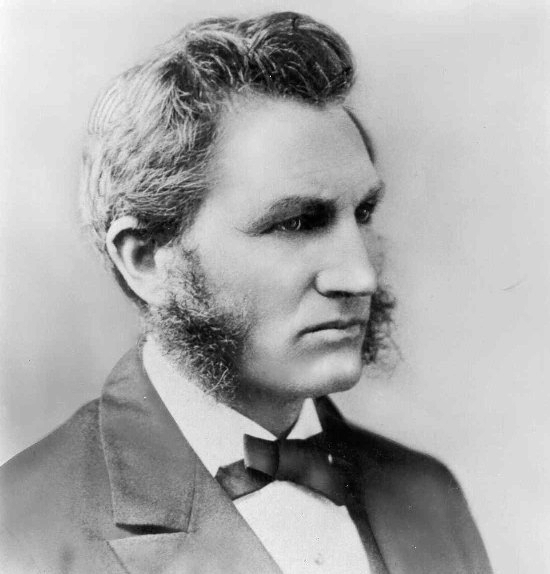

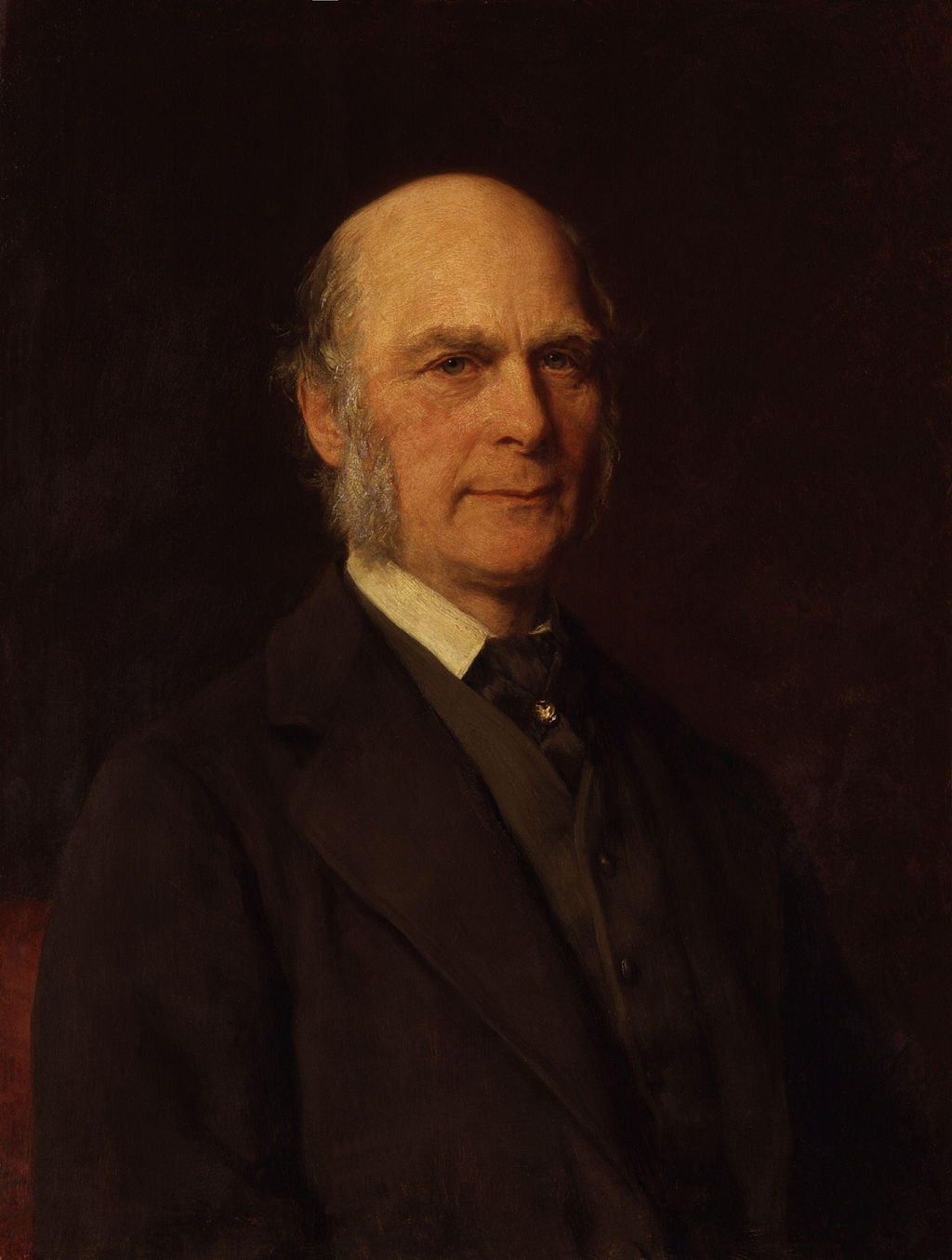

| Historical eugenics Main article: History of eugenics Ancient and medieval origins This section is an excerpt from History of eugenics § Ancient eugenics.[edit]  Giuseppe Diotti's The selection of the infant Spartans (1840) According to Plutarch, in Sparta, every proper citizen's child was inspected by their council of elders, the Gerousia, which determined whether or not the child was fit to live.[31] If the child was deemed incapable of living a Spartan life, the child was usually killed in a chasm near the Taygetus mountain known as the Apothetae.[32][33] Further trials intended to discern a child's fitness included bathing them in wine and exposing them to the elements to fend for themselves. To Sparta, this would ensure only the strongest survived and procreated.[34] And so selective infanticide seems to have been comparably widespread in Ancient Rome[35] as it had already long been in Athens.[36] Furthermore, according to Tacitus (c. 56 – c. 120), a Roman of the Imperial Period, the Germanic tribes of his day killed any member of their community they deemed cowardly, unwarlike or "stained with abominable vices", usually by drowning them in swamps.[37][38] The characteristic practice of selective infanticide in the Roman Empire did not subside until its Christianization, which however also mandated negative eugenics, e.g. by the council of Adge in 506, which forbade marriage between cousins.[39] For the parallel case of medieval China, as mediated by its meritocratic system of imperial examinations, a study analyzing genealogical records of 36,456 men from six Chinese lineages between 1350 and 1920 found that the literati (degree and office holders) had more than double the number of surviving sons compared to non-degree holders;[40] ceteris paribus indicating stable and persistent eugenic pressures towards the associated traits.[41] Academic origins See also: Galton Laboratory and Eugenics Record Office  Francis Galton (1822–1911) was a British polymath who coined the term "eugenics" The term eugenics and its modern field of study were first formulated by Francis Galton in 1883,[42][43][44][a] directly drawing on the recent work delineating natural selection by his half-cousin Charles Darwin.[46][47][48][b] He published his observations and conclusions chiefly in his influential book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Galton himself defined it as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations".[50] The first to systematically apply Darwinism theory to human relations, Galton believed that various desirable human qualities were also hereditary ones, although Darwin strongly disagreed with this elaboration of his theory.[51] And it should also be noted that many of the early geneticists were not themselves Darwinians.[48] Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from various sources.[52] Organizations were formed to win public support for and to sway opinion towards responsible eugenic values in parenthood, including the British Eugenics Education Society of 1907 and the American Eugenics Society of 1921. Both sought support from leading clergymen and modified their message to meet religious ideals.[53] In 1909, the Anglican clergymen William Inge and James Peile both wrote for the Eugenics Education Society. Inge was an invited speaker at the 1921 International Eugenics Conference, which was also endorsed by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York Patrick Joseph Hayes.[53] Three International Eugenics Conferences presented a global venue for eugenicists, with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York City. Eugenic policies in the United States were first implemented by state-level legislators in the early 1900s.[54] Eugenic policies also took root in France, Germany, and Great Britain.[55] Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in other countries including Belgium,[56] Brazil,[57] Canada,[58] Japan and Sweden. Frederick Osborn's 1937 journal article "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy" framed eugenics as a social philosophy—a philosophy with implications for social order.[59] That definition is not universally accepted. Osborn advocated for higher rates of sexual reproduction among people with desired traits ("positive eugenics") or reduced rates of sexual reproduction or sterilization of people with less-desired or undesired traits ("negative eugenics"). In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations.[60] Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics,[61] the Cold Spring Harbor Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution,[62] and the Eugenics Record Office.[63] Politically, the movement advocated measures such as sterilization laws.[64] In its moral dimension, eugenics rejected the doctrine that all human beings are born equal and redefined moral worth purely in terms of genetic fitness.[65] Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race" or "Aryan" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of "unfit" races.[66][67] Many leading British politicians subscribed to the theories of eugenics. Winston Churchill supported the British Eugenics Society and was an honorary vice president for the organization. Churchill believed that eugenics could solve "race deterioration" and reduce crime and poverty.[49][68][69] As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century, when it was practiced around the world and promoted by governments, institutions, and influential individuals. Many countries enacted[70] various eugenics policies, including: genetic screenings, birth control, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation and sequestering the mentally ill), compulsory sterilization, forced abortions or forced pregnancies, ultimately culminating in genocide. By 2014, gene selection (rather than "people selection") was made possible through advances in genome editing,[71] leading to what is sometimes called new eugenics, also known as "neo-eugenics", "consumer eugenics", or "liberal eugenics"; which focuses on individual freedom and allegedly pulls away from racism, sexism or a focus on intelligence.[72] Early opposition Early critics of the philosophy of eugenics included the American sociologist Lester Frank Ward,[73] the English writer G. K. Chesterton, and Scottish tuberculosis pioneer and author Halliday Sutherland.[c] Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics", Chesterton's 1917 book Eugenics and Other Evils,[75] and Franz Boas' 1916 article "Eugenics" (published in The Scientific Monthly)[76] were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing movement. Several biologists were also antagonistic to the eugenics movement, including Lancelot Hogben.[77] Other biologists who were themselves eugenicists, such as J. B. S. Haldane and R. A. Fisher, however, also expressed skepticism in the belief that sterilization of "defectives" (i.e. a purely negative eugenics) would lead to the disappearance of undesirable genetic traits.[78] Among institutions, the Catholic Church was an opponent of state-enforced sterilizations, but accepted isolating people with hereditary diseases so as not to let them reproduce.[79] Attempts by the Eugenics Education Society to persuade the British government to legalize voluntary sterilization were opposed by Catholics and by the Labour Party.[80] The American Eugenics Society initially gained some Catholic supporters, but Catholic support declined following the 1930 papal encyclical Casti connubii.[53] In this, Pope Pius XI explicitly condemned sterilization laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."[81] In fact, more generally, "[m]uch of the opposition to eugenics during that era, at least in Europe, came from the right."[20]: 36 The eugenicists' political successes in Germany and Scandinavia were not at all matched in such countries as Poland and Czechoslovakia, even though measures had been proposed there, largely because of the Catholic church's moderating influence.[82] |

歴史的優生学 詳細は「優生学の歴史」を参照 古代および中世の起源 このセクションは、「優生学の歴史 § 古代の優生学」からの抜粋である。[編集]  ジュゼッペ・ディオッティ著『幼児スパルタ人の選別』(1840年) プルタルコスによると、スパルタでは、すべての適正な市民の子供たちは、年長者評議会であるゲルシアによって検査され、その子供が生きるのにふさわしいか どうかを判断されていた。[31] 子供がスパルタ式の生活を送るのにふさわしくないと判断された場合、 その子供は通常、アポテタイとして知られるタイゲタス山の近くの裂け目で殺された。[32][33] 子供の適性を判断するためのさらなる試験には、子供をワインで沐浴させたり、子供自身で生き延びるために自然環境にさらすことも含まれていた。スパルタで は、この方法によって最も強い者が生き残り、子孫を残すことができると考えられていた。[34] 厳選的な幼児殺しは、古代ローマでも比較的広く行われていたようである。[35] すでにアテネでは長い間行われていたことである。[36] さらに、古代ローマ時代のローマ人であるタキトゥス(紀元前56年頃 - 120年頃)によると、彼の時代のゲルマン部族は、臆病で戦いを好まない、あるいは「忌まわしい悪徳に染まった」とみなした共同体内のメンバーを、通常は沼地に沈めることで殺害していたという。 ローマ帝国における特徴的な幼児殺しは、キリスト教化されるまで収まることはなかった。しかし、キリスト教化はネガティブな優生学も義務付けた。例えば、506年のアドゲ公会議では、従兄弟同士の結婚を禁じた。 中世中国における同様の事例については、その実力本位の科挙制度を媒介として、1350年から1920年の間に6つの中国系統から選ばれた36,456人 の男性の系図記録を分析した研究では、 学位取得者(学位および役職保有者)は、非取得者に比べて生存している息子の数が2倍以上であることが判明した。[40] 他の条件が同じ場合、これは関連する形質に対する安定した持続的な優生学的な圧力が存在することを示している。[41] 学問的起源 関連項目:ガルトン研究所および優生学記録室  フランシス・ガルトン(1822年-1911年)は、「優生学」という用語を考案したイギリスの博識家である。 優生学という用語と、その現代的な研究分野は、1883年にフランシス・ガルトンによって初めて提唱されたものであり[42][43][44][a]、彼 の異母従兄弟であるチャールズ・ダーウィンによる自然淘汰の研究を直接的に参照したものである[46][47][48][b]。ガルトンは、自身の観察結 果と結論を主に影響力のある著書『人間能力とその開発に関する研究』で発表した。ガルトン自身は「人類の管理下にあるあらゆる要因を研究し、それによって 将来の世代の人種的資質を向上させたり、低下させたりする」と定義した。[50] ダーウィニズム理論を人間関係に体系的に初めて適用したガルトンは、望ましい人間的資質は遺伝によるものだと考えていたが、ダーウィンは自身の理論のこの 展開に強く反対していた。[51] また、初期の遺伝学者の多くはダーウィニストではなかったことも指摘しておくべきである。[48] 優生学は多くの大学で学問分野となり、さまざまな資金源から資金援助を受けた。[52] 1907年の英国優生学教育協会や1921年の米国優生学協会など、優生学に基づく子育てに対する世論の支持を獲得し、世論を誘導するための組織が結成さ れた。両者とも、指導的な聖職者たちから支援を求め、宗教的理想に適うようメッセージを修正した。[53] 1909年には、英国国教会の聖職者であるウィリアム・インジとジェームズ・パイルの両者が優生学教育協会のために執筆した。インジは1921年の国際優 生学会議の招待講演者であり、この会議はニューヨークのローマ・カトリック大司教パトリック・ジョセフ・ヘイズからも支持されていた。[53] 国際優生学会議は、優生学者たちに世界的な場を提供し、1912年にはロンドンで、1921年と1932年にはニューヨーク市で会議が開催された。米国に おける優生政策は、1900年代初頭に州レベルの立法者によって初めて実施された。[54] 優生政策はフランス、ドイツ、英国でも根付いた。[55] その後、1920年代と1930年代には、ベルギー、ブラジル、カナダ、日本、スウェーデンを含む他の国々でも、特定の精神患者に対する不妊手術という優 生政策が実施された。 フレデリック・オズボーンの1937年の論文「優生哲学の発展」では、優生学を社会哲学、すなわち社会秩序に影響を与える哲学として位置づけた。[59] この定義は広く受け入れられているわけではない。オズボーンは、望ましい形質を持つ人々の間の性生殖率を高めること(「積極的優生学」)、または望ましく ない形質を持つ人々の性生殖率を低くすること、あるいは不妊手術を施すこと(「消極的優生学」)を提唱した。 優生学は多くの国々で実践されただけでなく、国際優生学連盟を通じて国際的に組織化された。[60] その科学的側面は、カイザー・ヴィルヘルム人類学・遺伝学・優生学研究所[61]、コールド・スプリング・ハーバーのカーネギー実験進化研究所[62]、 優生学記録室[63]などの研究機関を通じて継続された。政治的には、 この運動は、不妊手術法などの措置を提唱した。[64] 倫理的な観点では、優生学は「人間はみな平等に生まれてくる」という教義を否定し、純粋に遺伝的な適性という観点から道徳的価値を再定義した。[65] その人種差別的な要素には、純粋な「北方人種」または「アーリア人」の遺伝子プールを追求し、最終的に「不適格」な人種を排除することが含まれていた。 [66][67] 多くのイギリスの有力政治家が優生学の理論を支持した。ウィンストン・チャーチルは英国優生学協会を支援し、同協会の名誉副会長を務めた。チャーチルは優生学が「人種の劣化」を解決し、犯罪と貧困を減少させると信じていた。 社会運動として優生学は20世紀初頭に最も人気を博し、世界中で実践され、政府や機関、有力者によって推進された。多くの国々で、遺伝子検査、出生抑制、 出生率の差別的推進、結婚制限、隔離(人種隔離と精神障害者の隔離の両方)、強制不妊手術、強制中絶または強制妊娠など、さまざまな優生政策が施行され た。最終的には大量虐殺に至った。2014年までに、ゲノム編集の進歩により、遺伝子選択(「人選」ではなく)が可能になった。これは、時に「新優生学」 とも呼ばれるもので、「ネオ・優生学」、「消費者優生学」、または「リベラル優生学」とも呼ばれ、個人の自由を重視し、人種差別や性差別、あるいは知能重 視から離れるとされる。 初期の反対 優生学の哲学に対する初期の批判者には、アメリカの社会学者レスター・フランク・ウォード(Lester Frank Ward)[73]、イギリスの作家G. K. チェスタートン(G. K. Chesterton)、スコットランドの結核のパイオニアであり作家でもあるハリデイ・サザーランド(Halliday Sutherland)[c]などがいた。ウォードの1913年の論文「優生学、ユーセニクス、 Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics」、チェスタートンの1917年の著書『優生学とその他の諸悪』[75]、フランツ・ボアズの1916年の論文「優生学」(『月刊科学』 掲載)[76]は、急速に拡大するこの運動に対して、いずれも厳しい批判を展開した。 また、ランセロット・ホグベン(Lancelot Hogben)をはじめとする複数の生物学者も優生学運動に敵対的であった。[77] 一方、J. B. S. ハルデーンやR. A. フィッシャーといった優生学の信奉者であった生物学者たちは、欠陥者(すなわち純粋に否定的な優生学)の断種が望ましくない遺伝形質の消滅につながるとい う信念に懐疑的な見解を示していた。[78] 機関の中では、カトリック教会は国家による不妊手術の強制に反対していたが、遺伝性疾患を持つ人々を隔離して、彼らが子孫を残さないようにすることは容認 していた。[79]優生学教育協会による、英国政府に自発的不妊手術を合法化するよう説得する試みは、 カトリック教会や労働党から反対を受けた。[80] アメリカ優生学協会は当初、カトリック教会の支持を得たが、1930年の教皇回勅『カスティ・コンヌビ』(Casti connubii)以降、カトリック教会の支持は減少した。[53] この中で、教皇ピウス11世は、断種法を明確に非難した。「公の司法当局は、その国民の身体に対して直接的な権限を有していない。したがって、犯罪が起 こっておらず、重大な処罰に値する理由がない場合、優生学上の理由であろうとその他の理由であろうと、身体に直接的な危害を加えたり、身体の完全性を損な うようなことは決してできない」[81] 実際、より一般的に言えば、「少なくともヨーロッパでは、優生学に対する当時の反対意見の多くは右派から出ていた」[20]:36。ドイツやスカンジナビ ア諸国における優生学者たちの政治的成功は、カトリック教会の穏健な影響力により、ポーランドやチェコスロバキアなどの国々ではまったく見られなかった が、それらの国々でも措置が提案されていた。[82] |

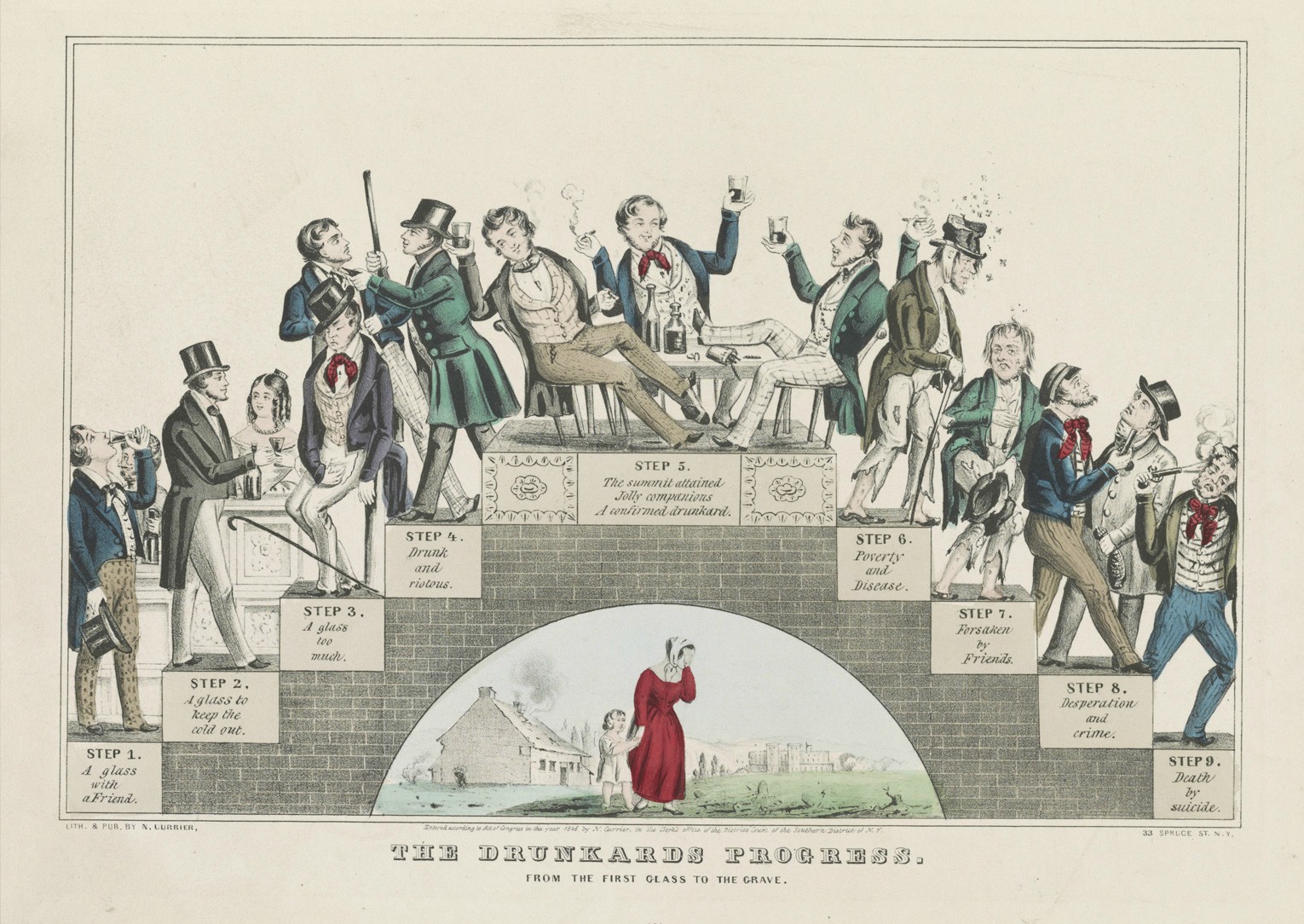

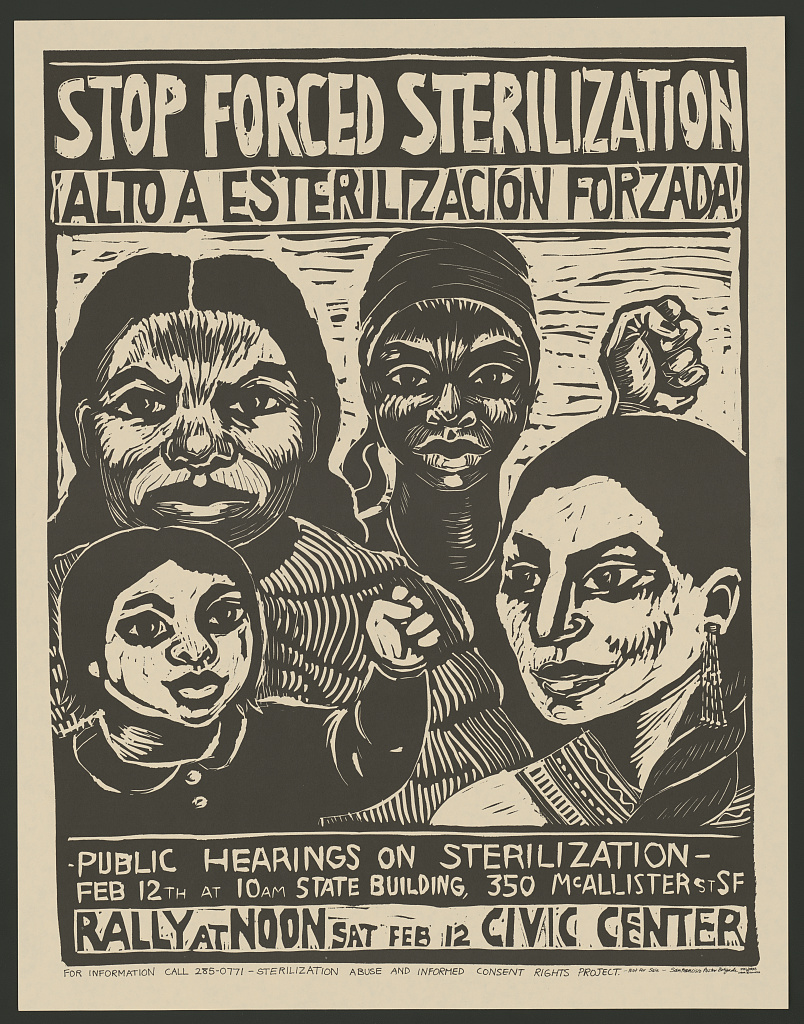

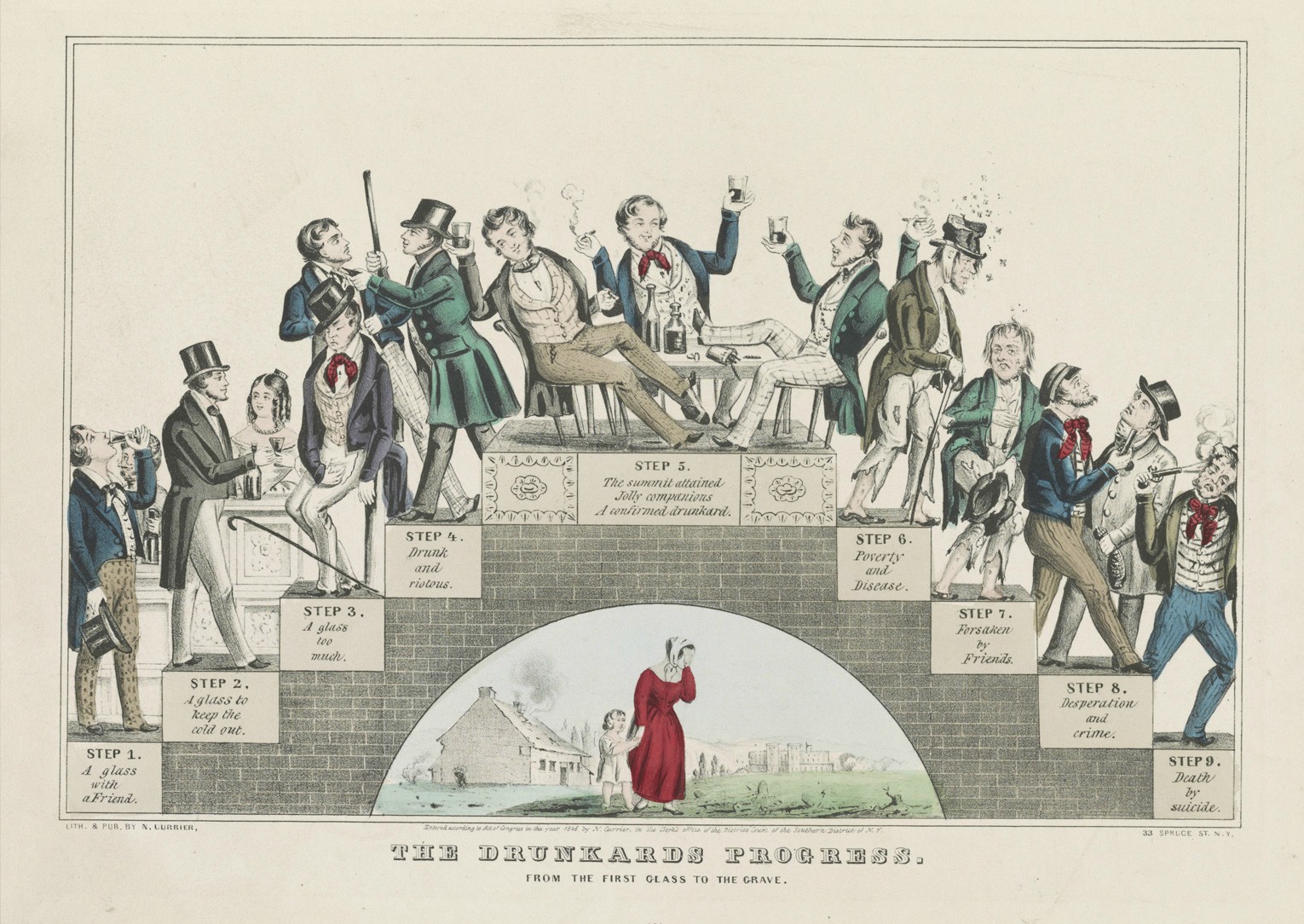

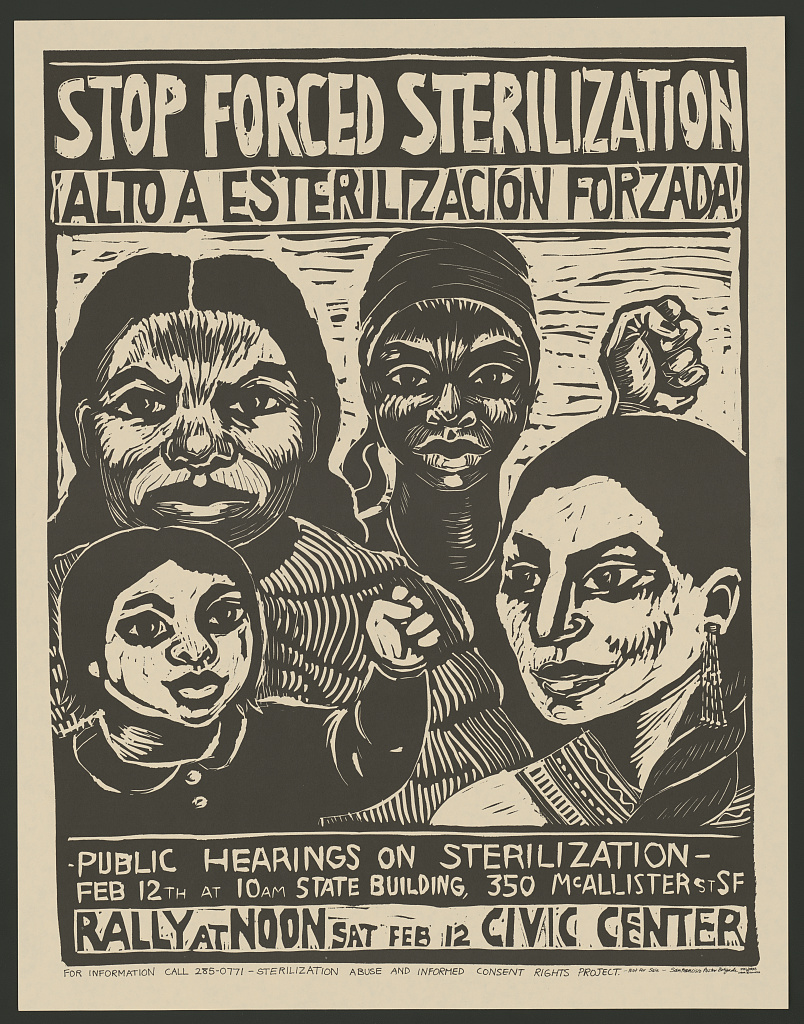

| Concerns over human devolution The Lamarckian backdrop "Any new set of conditions which renders a species' food and safety very easily obtained, seems to lead to degeneration" Ray Lankester (1880)[83] "We stand now in the midst of a severe mental epidemic; of a sort of black death of degeneration and hysteria, and it is natural that we should ask anxiously on all sides: 'What is to come next?" Max Simon Nordau (1892)[84]  Morel for one, clearly influenced by Lamarck, claimed that environmental factors such as drugs or alcohol would revert one's offspring to an evolutionarily more primitive stage.[85] The idea of progress was at once a social, political and scientific theory. The theory of evolution, as described in Darwin's The Origin of Species, provided for many social theorists the necessary scientific foundation for the idea of social and political progress. The terms evolution and progress were in fact often used interchangeably in the 19th century.[86] The rapid industrial, political and economic progress in 19th-century Europe and North America was, however, paralleled by a sustained discussion about increasing rates of crime, insanity, vagrancy, prostitution, and so forth. Confronted with this apparent paradox, evolutionary scientists, criminal anthropologists and psychiatrists postulated that civilization and scientific progress could be a cause of physical and social pathology as much as a defense against it.[87][page needed] According to the theory of degeneration, a host of individual and social pathologies in a finite network of diseases, disorders and moral habits could be explained by a biologically based affliction. The primary symptoms of the affliction were thought to be a weakening of the vital forces and willpower of its victim. In this way, a wide range of social and medical deviations, including crime, violence, alcoholism, prostitution, gambling, and pornography, could be explained by reference to a biological defect within the individual. The theory of degeneration was therefore predicated on evolutionary theory. The forces of degeneration opposed those of evolution, and those afflicted with degeneration were thought to represent a return to an earlier evolutionary stage. One of the earliest and most systematric approaches along such lines is that of Bénédict Morel, who wrote: "When under any kind of noxious influence an organism becomes debilitated, its successors will not resemble the healthy, normal type of the species, with capacities for development, but will form a new sub-species, which, like all others, possesses the capacity of transmitting to its offspring, in a continuously increasing degree, its peculiarities, these being morbid deviations from the normal form – gaps in development, malformations and infirmities"[88][d] Accordingly, degeneration theory owed more to Lamarckism than Darwinism, for only the former knew a "use it or lose it" lemma so characteristically intuitive as to enter the public[90] such as artistic imagination at the unprecedented scale that it did.[e] Dysgenics This section is an excerpt from Dysgenics.[edit] Dysgenics refers to any decrease in the prevalence of traits deemed to be either socially desirable or generally adaptive to their environment due to selective pressure disfavouring their reproduction.[92] In 1915 the term was used by David Starr Jordan to describe the supposed deleterious effects of modern warfare on group-level genetic fitness because of its tendency to kill physically healthy men while preserving the disabled at home.[93][94] Similar concerns had been raised by early eugenicists and social Darwinists during the 19th century, and continued to play a role in scientific and public policy debates throughout the 20th century.[95] More recent concerns about supposed dysgenic effects in human populations have been advanced by the controversial psychologist Richard Lynn, notably in his 1996 book Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations, which argued that a reduction in selection pressures and decreased infant mortality since the Industrial Revolution have resulted in an increased propagation of deleterious traits and genetic disorders.[96][97] Despite these concerns, genetic studies have shown no evidence for dysgenic effects in human populations.[96][98][99][100] Reviewing Lynn's book, the scholar John R. Wilmoth notes: "Overall, the most puzzling aspect of Lynn's alarmist position is that the deterioration of average intelligence predicted by the eugenicists has not occurred."[101] Compulsory sterilization This section is an excerpt from Compulsory sterilization.[edit]  Anglo-Spanish political poster Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done by surgical or chemical means. Purported justifications for compulsory sterilization have included population control, eugenics, limiting the spread of HIV, and ethnic genocide. Several countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century.[102] Although such programs have been made illegal in much of the world, instances of forced or coerced sterilizations still persist. Eugenic feminism This section is an excerpt from Eugenic feminism.[edit]  Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1904 Eugenic feminism was a current of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics.[103] Originally coined by the Lebanese-British physician and vocal eugenicist Caleb Saleeby,[104][105][106] the term has since been applied to summarize views held by prominent feminists of Great Britain and the United States. Some early suffragettes in Canada, especially a group known as The Famous Five, also pushed for various eugenic policies. Eugenic feminists argued that if women were provided with more rights and equality, the deteriorating characteristics of a given race could be averted. North American eugenics  American eugenicists generally pursued more public-facing work and accordingly became widely known for their racism in particular. Along these lines, they were often harshly criticized by their British counterparts.[107] This section is an excerpt from Eugenics in the United States.[edit] While its American practice was ostensibly about improving genetic quality, it has been argued that eugenics was more about preserving the position of the dominant groups in the population. Scholarly research has determined that people who found themselves targets of the eugenics movement were those who were seen as unfit for society—the poor, the disabled, the mentally ill, and specific communities of color—and a disproportionate number of those who fell victim to eugenicists' sterilization initiatives were women who were identified as African American, Asian American, or Native American.[108][109] As a result, the United States' eugenics movement is now generally associated with racist and nativist elements, as the movement was to some extent a reaction to demographic and population changes, as well as concerns over the economy and social well-being, rather than scientific genetics.[110][109] Eugenics in Mexico This section is an excerpt from Eugenics in Mexico.[edit] Following the Mexican Revolution, the eugenics movement gained prominence in Mexico. Seeking to change the genetic make-up of the country's population, proponents of eugenics in Mexico focused primarily on rebuilding the population, creating healthy citizens, and ameliorating the effects of perceived social ills such as alcoholism, prostitution, and venereal diseases. Mexican eugenics, at its height in the 1930s, influenced the state's health, education, and welfare policies.[111] Unlike in other countries, the eugenics movements in Latin America were largely founded on the idea of neo-Lamarckian eugenics.[112] Neo-Lamarckian eugenics stated that the outside effects experienced by an organism throughout its lifetime changed its genetics permanently, allowing the organism to pass acquired traits onto its offspring.[113] In the Neo-Lamarckian genetic framework, activities such as prostitution and alcoholism could result in the degeneration of future generations, amplifying fears about the effects of certain social ills. However, the supposed genetic malleability also offered hope to certain Latin American eugenicists, as social reform would have the ability to transform the population more permanently.[112] Nazism and the decline of eugenics See also: Nazi eugenic, Racial hygiene, Life unworthy of life, and Scientific racism  Schloss Hartheim, a former center for Nazi Germany's Aktion T4 campaign The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler had praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf in 1925 and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States once he took power.[114] Some common early 20th century eugenics methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals, and racial groups (such as the Roma and Jews in Nazi Germany) as "degenerate" or "unfit", and therefore led to segregation, institutionalization, sterilization, and even mass murder.[115] The Nazi policy of identifying German citizens deemed mentally or physically unfit and then systematically killing them with poison gas, referred to as the Aktion T4 campaign, is understood by historians to have paved the way for the Holocaust.[116][117][118] "All practices aimed at eugenics, any use of the human body or any of its parts for financial gain, and human cloning shall be prohibited." Hungarian Constitution[119] "Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority." The first and most fundamental article of German basic law[120] By the end of World War II, many eugenics laws were abandoned, having become associated with Nazi Germany.[121] H. G. Wells, who had called for "the sterilization of failures" in 1904,[122] stated in his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For? that among the human rights, which he believed should be available to all people, was "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment".[123] After World War II, the practice of "imposing measures intended to prevent births within [a national, ethnical, racial or religious] group" fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.[124] The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons".[125] |

人類の退化に対する懸念 ラマルク主義的な背景 「種の食料や安全が非常に容易に得られるような新たな状況は、退化につながると思われる」 レイ・ランケスター(1880年)[83] 「我々は今、深刻な精神的な流行病の真っ只中にいる。退化とヒステリーという黒死病のような流行病だ。そして、あらゆる方面で不安に駆られて『次に何が起こるのか?』と問うのは当然である」 マックス・シモン・ノルダウ(1892年)[84]  モレルは明らかにラマルクの影響を受けており、薬物やアルコールなどの環境要因が、進化論的により原始的な段階へと子孫を後退させる可能性があると主張した。[85] 進歩という概念は、社会、政治、科学の理論であった。 ダーウィンの『種の起源』で述べられた進化論は、多くの社会理論家たちに、社会と政治の進歩という概念に必要な科学的基盤を提供した。 実際、進化と進歩という用語は19世紀にはしばしば互換的に使用されていた。 しかし、19世紀のヨーロッパと北アメリカにおける急速な産業、政治、経済の進歩は、犯罪、狂気、浮浪、売春などの増加率に関する持続的な議論と並行して いた。この明白な矛盾に直面し、進化論の科学者、犯罪人類学者、精神科医は、文明と科学の進歩が、それに対する防御としてだけでなく、身体的および社会的 病理の原因にもなり得ると仮定した。 退化論によれば、病気、障害、道徳的習慣の有限のネットワークにおける個人および社会病理学の多くは、生物学的な苦悩によって説明できる。その苦悩の主な 症状は、犠牲者の生命力と意志力の弱体化であると考えられていた。このように、犯罪、暴力、アルコール依存症、売春、ギャンブル、ポルノグラフィーなど、 幅広い社会的な逸脱や医学的な逸脱は、個人の生物学的欠陥に言及することで説明できる。したがって退行論は進化論を前提としていた。退行の力は進化の力に 逆らうものであり、退行に苦しむ人々は進化の前の段階に戻ったと考えられた。この路線に沿った最も初期かつ最も体系的なアプローチの一つは、ベネディク ト・モレルのものだ。彼は次のように書いている。 「有害な影響下で生物が衰弱した場合、その生物の後継者は、発育能力を備えた健康で正常な種のタイプとは似ても似つかず、新たな亜種を形成する。この亜種 は、他の亜種と同様に、その特異性を子孫に絶え間なく増大する形で伝達する能力を備えている。この特異性とは、正常な形態からの病的逸脱であり、発育不 全、奇形、虚弱である」[88][d] したがって、退化論はダーウィニズムよりもラマルク主義の影響を強く受けており、後者だけが「使わなければ失う」という特徴的な直観的要素を一般の人々にも理解できるほどに知っていた。[90] 芸術的想像力のような前例のない規模で人々の心に入り込んだのである。[e] ディジネティクス このセクションは『Dysgenics』からの抜粋である。 Dysgenics』とは、社会的に望ましい、あるいは環境に一般的に適応しているとみなされる形質の有病率が、その再生産を不利にする選択圧力によって減少することを指す。 1915年、デイヴィッド・スター・ジョーダンは、この用語を、身体的に健康な男性を殺す傾向があり、障害者を自宅で保護する傾向があることから、集団レ ベルの遺伝的適応力に対する近代戦争の有害な影響を説明するのに使用した。[93][94] 類似の懸念は、19世紀の初期優生学者や社会ダーウィニストによって提起されていたが、20世紀を通じて科学や公共政策の議論において引き続き役割を果た してきた。[95] 人間集団における劣性遺伝的影響に関する最近の懸念は、物議を醸した心理学者リチャード・リンによって提起された。特に、1996年の著書 『Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations』では、産業革命以降の選択圧力の減少と乳児死亡率の低下が有害な形質と遺伝性疾患の伝播増加につながったと主張している。 こうした懸念にもかかわらず、遺伝学の研究では、人類集団における劣性遺伝の影響を示す証拠は見つかっていない。[96][98][99][100] リンの著書を検証した学者ジョン・R・ウィルモスは、「全体として、優生学者が予測した平均的な知能の低下が起こっていないことが、リンの警鐘的な主張の 最も不可解な点である」と指摘している。[101] 強制不妊手術 このセクションは、強制不妊手術からの抜粋である。[編集]  アメリカのスペイン系の政治ポスター 強制不妊手術は、強制不妊手術または強制的不妊手術とも呼ばれ、特定の人々を政府の命令で不本意に不妊にするあらゆるプログラムを指す。不妊手術は、個人の生殖能力を奪うもので、通常は外科的または化学的手段によって行われる。 強制不妊手術の正当化の理由として、人口抑制、優生学、HIVの蔓延の抑制、民族の大量虐殺などが挙げられてきた。 20世紀初頭には、いくつかの国で不妊手術プログラムが実施された。[102] このようなプログラムは世界の大半で違法とされているが、強制または強要による不妊手術は今もなお行われている。 優生学派フェミニズム この節は「優生学派フェミニズム」からの抜粋である。[編集]  1904年、自身の研究室にてマリー・ストープス 優生フェミニズムは、優生学と重なる部分のある女性参政権運動の潮流であった。[103] この用語は、レバノン系イギリス人の医師で著名な優生学者であったケイレブ・サリビーによって最初に用いられたが、[104][105][106] それ以来、イギリスやアメリカ合衆国の著名なフェミニストの主張を要約する際に用いられるようになった。カナダの初期の女性参政権運動家たち、特に 「Famous Five」として知られるグループも、さまざまな優生政策を推進した。 優生主義的フェミニストたちは、女性にさらなる権利と平等が与えられれば、特定の民族の劣化する特性を回避できると主張した。 北アメリカの優生学  アメリカの優生学者は一般的に、より公的な活動に従事し、特に人種差別主義者として広く知られるようになった。この点において、彼らはしばしばイギリスの同業者から厳しい批判を受けた。[107] このセクションは、アメリカにおける優生学からの抜粋である。[編集] アメリカの優生学は、表向きには遺伝的資質の改善を目的としていたが、優生学はむしろ人口における支配的集団の地位を維持することに重点が置かれていたと いう主張がある。学術研究では、優生学運動の標的となったのは、社会に適さないと見なされた人々、すなわち貧困層、障害者、精神疾患患者、特定の有色人種 コミュニティであり、優生学者による不妊手術の犠牲者の多くは、アフリカ系アメリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人、またはアメリカ先住民と特定された女性であっ たことが判明している。その結果、米国の優生学運動は、現在では一般的に人種差別主義や排外主義の要素と関連付けられている。この運動はある程度、科学的 遺伝学というよりも、人口統計や人口の変化、経済や社会福祉への懸念への反応であったからだ。 メキシコにおける優生学 このセクションは、メキシコにおける優生学からの抜粋である。 メキシコ革命の後、メキシコでは優生学運動が盛んになった。メキシコにおける優生学の推進者たちは、同国の人口の遺伝的構成を変えることを目指し、人口の 再構築、健康な国民の創出、アルコール依存症、売春、性病などの社会悪と見なされる問題の改善に主に焦点を当てた。メキシコの優生学は1930年代に最盛 期を迎え、同国の保健、教育、福祉政策に影響を与えた。[111] 他の国々とは異なり、ラテンアメリカにおける優生学運動は、新ラマルク主義優生学の考え方に大きく基づいていた。[112] 新ラマルク主義優生学は、生物が生涯にわたって経験する外的影響がその生物の 遺伝子を恒久的に変化させ、生物が獲得した形質を子孫に受け継がせることができると主張した。[113] 新ラマルク主義の遺伝的枠組みでは、売春やアルコール依存症などの活動が次世代の退化につながる可能性があり、特定の社会悪の影響に対する懸念を拡大させ た。しかし、遺伝子の可塑性という想定は、社会改革が人口をより恒久的に変える能力を持つという点で、特定のラテンアメリカの優生学者たちに希望をもたら した。[112] ナチズムと優生学の衰退 関連項目:ナチス優生学、人種衛生学、生命に値しない生命、科学的人種主義  ナチス・ドイツの「T4作戦」の拠点であったハルトハイム城 優生学の科学的評価は1930年代に低下し始め、エルンスト・ルディンが優生学をナチス・ドイツの人種政策の正当化に利用した時期である。アドルフ・ヒト ラーは1925年に『我が闘争』の中で優生学の考え方を賞賛し、取り入れ、政権を握ると、アメリカ合衆国で先鞭のついた「欠陥者」の不妊手術に関する優生 学の法律を模倣した。[114] 20世紀初頭の一般的な優生学の手法には、貧困層、精神疾患患者、盲人、聾唖者、発達障害者、不特定多数の女性、同性愛者、人種的集団(ナチス・ドイツに おけるロマやユダヤ人など)を含む個人とその家族を特定し、分類することが含まれていた。ナチス・ドイツにおけるロマやユダヤ人などの集団を「退廃的」あ るいは「不適格」と見なし、隔離、施設収容、断種、さらには大量殺人に至らしめた。[115] ナチスは、ドイツ国民の中で精神または肉体的に不適格とみなされた人々を特定し、計画的に毒ガスで殺害する政策をとり、これは「T4作戦」と呼ばれた。こ の政策は、ホロコーストへの道を開いたと歴史家によって理解されている。[116][117][118] 「優生学を目的としたあらゆる行為、金銭的利益を得るための人体またはその一部の使用、および人間のクローニングは、すべて禁止される」 ハンガリー憲法[119] 「人間の尊厳は不可侵である。これを尊重し、保護することは、国家権力の義務である」 ドイツ基本法の第1条および最も基本的な条項[120] 第二次世界大戦の終結までに、多くの優生学関連の法律はナチス・ドイツと関連付けられるようになり、放棄された。[121] 1904年に「不適格者の不妊手術」を呼びかけていたH.G.ウェルズは、1940年の著書『人間が持つ権利: すなわち、彼が万人に与えられるべきだと考えていた人権の中には、「身体の切断、不妊手術、拷問、あらゆる体罰の禁止」も含まれていた。[123]第二次 世界大戦後、「国家、民族、人種、宗教上の)集団内での出生を防止する目的の措置を課す」行為は、 宗教的]集団内での出生を防止する措置」は、ジェノサイドの防止および処罰に関する条約で定められた新たな国際犯罪であるジェノサイドの定義に該当する。 [124] 欧州連合の基本権憲章も「優生学的な実践、特に人選を目的としたものの禁止」を宣言している。[125] |

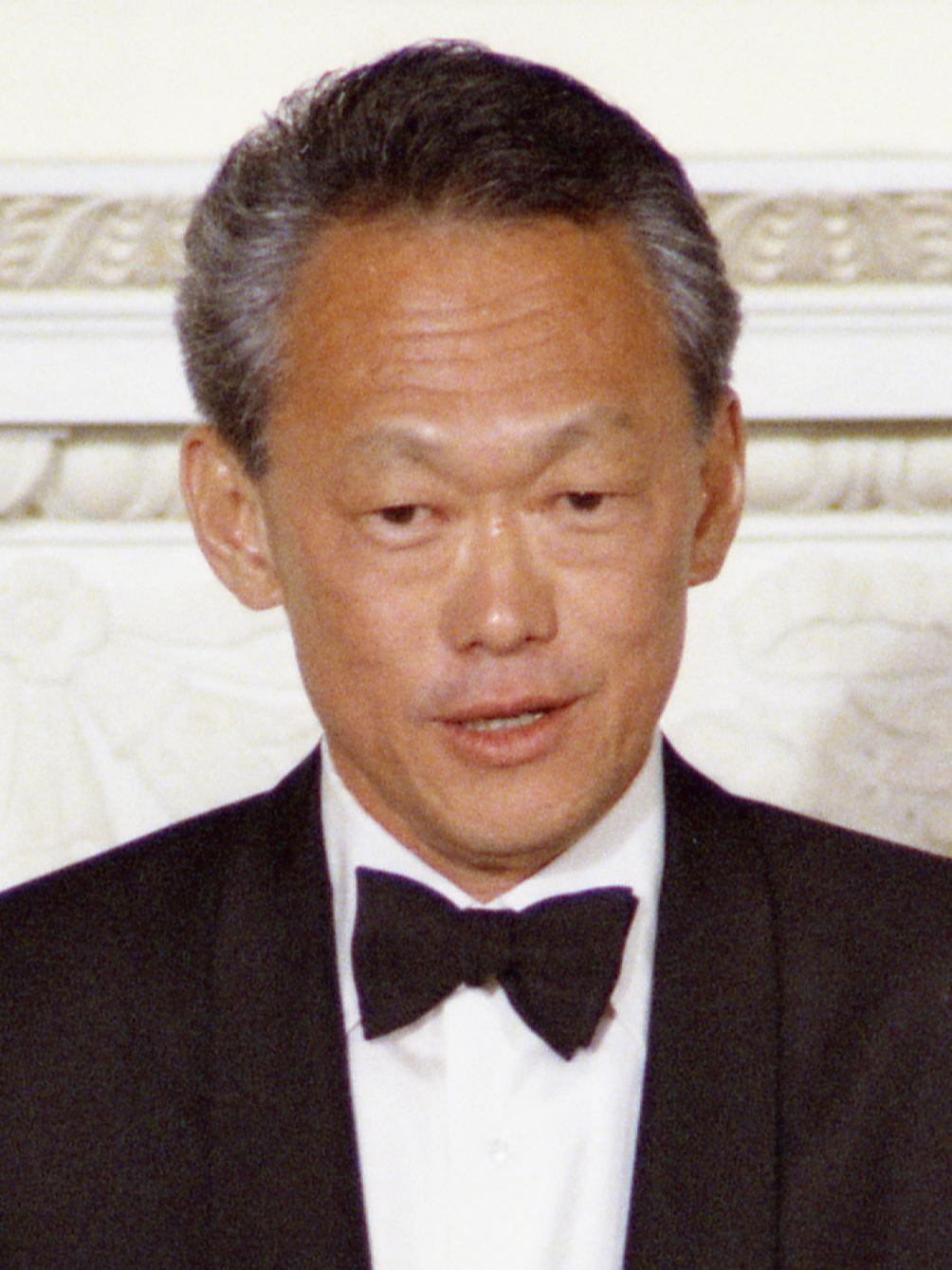

| Modern eugenics See also: New eugenics Developments in genetic, genomic, and reproductive technologies at the beginning of the 21st century have raised numerous questions regarding the ethical status of eugenics, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in the subject. Some, such as UC Berkeley sociologist Troy Duster, have argued that modern genetics is a back door to eugenics.[126] This view was shared by then-White House Assistant Director for Forensic Sciences, Tania Simoncelli, who stated in a 2003 publication by the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College that advances in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are moving society to a "new era of eugenics", and that, unlike the Nazi eugenics, modern eugenics is consumer driven and market based, "where children are increasingly regarded as made-to-order consumer products".[127] In a similar spirit, the United Nations' International Bioethics Committee wrote that the ethical problems of human genetic engineering should not be confused with the ethical problems of the 20th century eugenics movements. However, it is still problematic because it challenges the idea of human equality and opens up new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who do not want, or cannot afford, the technology.[128] Before any of these technological breakthroughs, however, prenatal screening has long been called by some a contemporary and highly prevalent form of eugenics because it may lead to selective abortions of fetuses with undesirable traits.[129] In Singapore Main article: Population control in Singapore  Lee Kuan Yew at a state dinner held in his honor, 1975 Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of Singapore, actively promoted eugenics as late as 1983.[130] In 1984, Singapore began providing financial incentives to highly educated women to encourage them to have more children. For this purpose was introduced the "Graduate Mother Scheme" that incentivized graduate women to get married as much as the rest of their populace.[131] The incentives were extremely unpopular and regarded as eugenic, and were seen as discriminatory towards Singapore's non-Chinese ethnic population. In 1985, the incentives were partly abandoned as ineffective, while the government matchmaking agency, the Social Development Network, remains active.[132][133][134] |

現代の優生学 関連情報: 新優生学 21世紀初頭における遺伝学、ゲノム学、生殖工学の進歩により、優生学の倫理的立場に関する多くの疑問が提起され、事実上、このテーマへの関心が再び高 まった。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の社会学者トロイ・ダスター(Troy Duster)のように、現代の遺伝学は優生学への裏口であると主張する者もいる。[126] この見解は、当時ホワイトハウスの法科学担当次官であったタニア・シモンチェリ(Tania Simoncelli)も共有しており、彼女は2003年にハンプシャー・カレッジの人口開発プログラムが発表した論文の中で、着床前遺伝子診断 (PGD)の進歩は社会を「優生学の新時代」へと導いていると述べ、 。ナチスの優生学とは異なり、現代の優生学は消費者主導で市場ベースであり、「子供はますます注文生産の消費財とみなされるようになってきている」と述べ ている。[127] 同様の考えに基づき、国連の国際生命倫理委員会は、ヒト遺伝子操作の倫理的問題は20世紀の優生学運動の倫理的問題と混同すべきではないと記している。し かし、それは依然として問題である。なぜなら、人間の平等という概念に疑問を投げかけ、その技術を望まない、あるいはその技術を利用する余裕のない人々に 対して、新たな形の差別や汚名を招くからである。[128] しかし、こうした技術的進歩の前に、望ましくない形質を持つ胎児の選択的中絶につながる可能性があるとして、出生前スクリーニングは、一部の人々から、現 代の優生学の非常に一般的な形態であると長らく呼ばれてきた。[129] シンガポールでは 詳細は「シンガポールの人口抑制」を参照  1975年、リー・クアンユーの名誉晩餐会にて シンガポールの建国の父であるリー・クアンユーは、1983年まで優生学を積極的に推進していた。[130] 1984年、シンガポールは高学歴の女性に対して、より多くの子供を産むよう奨励する金銭的インセンティブの提供を開始した。この目的のために「既卒女性 制度」が導入され、既卒女性が他の国民と同様に結婚するよう奨励された。[131] この奨励策は極めて不評で、優生学的なものとみなされ、シンガポールの非中国系民族に対する差別的措置と見なされた。1985年には、そのインセンティブ は効果がないとして一部廃止されたが、政府の仲介機関であるソーシャル・ディベロップメント・ネットワークは現在も活動している。[132][133] [134] |

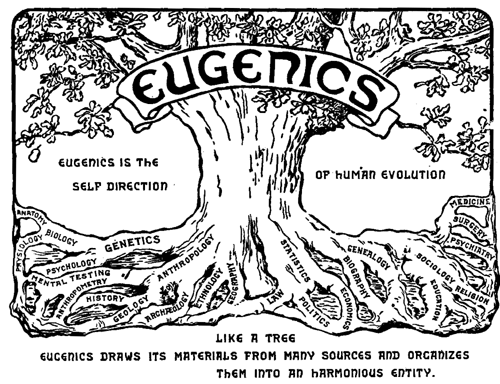

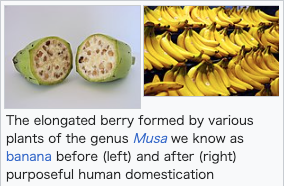

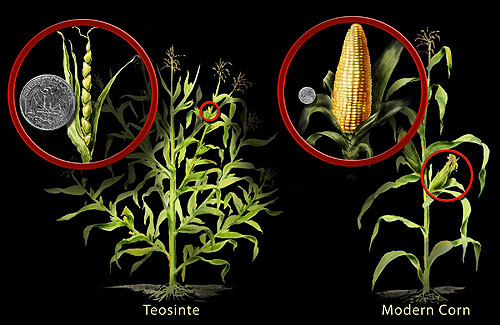

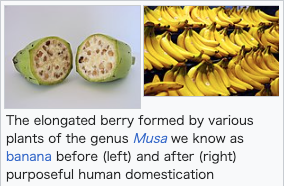

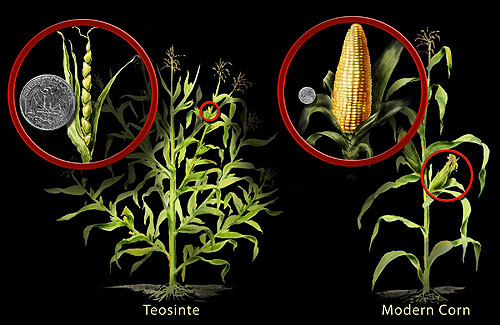

| Contested scientific status Further information: Sociobiology § Reception, and Criticism of evolutionary psychology  In the decades after World War II, the term "eugenics" had taken on a negative connotation and as a result, the use of it became increasingly unpopular within the scientific community. Many organizations and journals that had their origins in the eugenics movement began to distance themselves from the philosophy which spawned it, as when Eugenics Quarterly was renamed Social Biology in 1969 One general concern that many bring to the table, is that the reduced genetic diversity some argue to be a likely feature of long-term, species-wide eugenics plans,[135] could eventually result in inbreeding depression,[135] increased spread of infectious disease,[136][137] and decreased resilience to changes in the environment.[138][page needed] Arguments for scientific validity See also: Selective breeding, De novo domestication, List of domesticated animals, List of domesticated plants, and Self-domestication  Inside a wild banana Supermarket bananas The elongated berry formed by various plants of the genus Musa we know as banana before (left) and after (right) purposeful human domestication  Teosinte (left) was cultivated and eventually evolved into modern corn (right). In his original lecture "Darwinism, Medical Progress and Eugenics", Karl Pearson claimed that everything concerning eugenics fell into the field of medicine.[139] Similarly apologetic, Czech-American Aleš Hrdlička, head of the American Anthropological Association from 1925 to 1926 and "perhaps the leading physical anthropologist in the country at the time"[140] posited that its' ultimate aim "is that it may, on the basis of accumulated knowledge and together with other branches of research, show the tendencies of the actual and future evolution of man, and aid in its possible regulation or improvement. The growing science of eugenics will essentially become applied anthropology."[141] More recently, prominent evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins stated of the matter: The spectre of Hitler has led some scientists to stray from "ought" to "is" and deny that breeding for human qualities is even possible. But if you can breed cattle for milk yield, horses for running speed, and dogs for herding skill, why on Earth should it be impossible to breed humans for mathematical, musical or athletic ability? Objections such as "these are not one-dimensional abilities" apply equally to cows, horses and dogs and never stopped anybody in practice. I wonder whether, some 60 years after Hitler's death, we might at least venture to ask what the moral difference is between breeding for musical ability and forcing a child to take music lessons.[142] Scientifically possible and already well-established, heterozygote carrier testing is used in the prevention of autosomal recessive disorders, allowing couples to determine if they are at risk of passing various hereditary defects onto a future child.[143][144] There are various examples of eugenic acts that managed to lower the prevalence of recessive diseases, although not negatively affecting the heterozygote carriers of those diseases themselves. The elevated prevalence of various genetically transmitted diseases among Ashkenazi Jew populations (e.g. per Tay–Sachs, cystic fibrosis, Canavan's disease and Gaucher's disease), has been markedly decreased in more recent cohorts by the widespread adoption of genetic screening[145] (cf. also Dor Yeshorim). Objections to scientific validity Amanda Caleb, Professor of Medical Humanities at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, says "Eugenic laws and policies are now understood as part of a specious devotion to a pseudoscience that actively dehumanizes to support political agendas and not true science or medicine."[146] The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based on genetic inheritance was made in 1915 by Thomas Hunt Morgan. He demonstrated the event of genetic mutation occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with white eyes from a family with red eyes,[49]: 336–337 demonstrating that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance.[49]: 336–337 [clarification needed] Additionally, Morgan criticized the view that certain traits, such as intelligence and criminality, were hereditary because these traits were subjective.[147][f] Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences multiple, seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits, an example being phenylketonuria, which is a human disease that affects multiple systems but is caused by one gene defect.[150] Andrzej Pękalski, from the University of Wroclaw, argues that eugenics can cause harmful loss of genetic diversity if a eugenics program selects a pleiotropic gene that could possibly be associated with a positive trait. Pękalski uses the example of a coercive government eugenics program that prohibits people with myopia from breeding but has the unintended consequence of also selecting against high intelligence since the two go together.[151] While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology, at this point there is no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some conditions such as sickle-cell disease and cystic fibrosis respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual, so eliminating these genes is undesirable in places where such diseases are common.[138] Such cases in which, furthermore, even individual organisms' massive suffering or even death due to the odd 25 percent of homozygotes ineliminable by natural section under a Mendelian pattern of inheritance may be justified for the greater ecological good that is conspecifics incur a greater so-called heterozygote advantage in turn.[152] Edwin Black, journalist, historian, and author of War Against the Weak, argues that eugenics is often deemed a pseudoscience because what is defined as a genetic improvement of a desired trait is a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined through objective scientific inquiry.[2] Indeed, the most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. Historically, this aspect of eugenics is often considered to be tainted with scientific racism and pseudoscience.[2][153]  Logo from the Second International Eugenics Conference, 1921. The bottom text reads: "Like A Tree, Eugenics Draws Its Materials From Many Sources And Organizes Them Into An Harmonious Entity" (such sources, i.e. roots, purportedly including e.g. genetics, physiology, mental testing, anthropology, statistics, medicine, politics and sociology)[154] Regarding the lasting controversy above, himself citing recent scholarship,[155][156] historian of science Aaron Gillette notes that: Others take a more nuanced view. They recognize that there was a wide variety of eugenic theories, some of which were much less race- or class-based than others. Eugenicists might also give greater or lesser acknowledgment to the role that environment played in shaping human behavior. In some cases, eugenics was almost imperceptibly intertwined with health care, child care, birth control, and sex education issues. In this sense, eugenics has been called, "a 'modern' way of talking about social problems in biologizing terms".'[157]: 11 Indeed, granting that the historical phenomenon of eugenics was that of a pseudoscience, Gilette further notes that this derived chiefly from its being "an epiphenomenon of a number of sciences, which all intersected at the claim that it was possible to consciously guide human evolution."[157]: 2 |

科学上の地位をめぐる論争 詳細情報:社会生物学 § 進化心理学の受容と批判  第二次世界大戦後の数十年間、「優生学」という用語は否定的な意味合いを持つようになり、その結果、科学界ではその使用が次第に不評となった。優生学運動 に起源を持つ多くの組織や学術誌は、1969年に『優生学季刊誌』が『社会生物学』に改名されたように、その運動を生み出した哲学から距離を置くように なった 多くの人が抱く一般的な懸念として、長期的な種全体の優生計画の特徴として、遺伝的多様性の低下が挙げられるが、これは最終的に近親交配による弱体化、感染症の蔓延、環境変化への耐性の低下につながる可能性がある。 科学的妥当性に関する議論 関連項目:品種改良、デノボ・ドメスティケーション、家畜化された動物一覧、家畜化された植物一覧、自己家畜化  野生のバナナの内側 スーパーマーケットのバナナ バナナとして知られる様々なバショウ属の植物が形成する細長い実。左は人間による意図的な家畜化の前、右は後  テオシント(左)は栽培され、やがて現代のトウモロコシ(右)へと進化していった。 カール・ピアソンは、当初の講演「ダーウィニズム、医学の進歩と優生学」において、優生学に関するものはすべて医学の分野に属すると主張した。[139] 同様に弁明的なチェコ系アメリカ人のアレシュ・フリドリチカは、1925年から1926年までアメリカ人類学会の会長を務め、 「おそらく当時アメリカで最も著名な自然人類学者」[140]であった彼は、優生学の究極の目的は「蓄積された知識に基づいて、他の研究分野と協力しなが ら、人類の現在および将来の進化の傾向を明らかにし、その制御や改善を可能にすることである。発展する優生学は、本質的には応用人類学となるだろう」 [141]と主張した。 最近では、著名な進化生物学者リチャード・ドーキンスがこの問題について次のように述べている。 ヒトラーの亡霊が一部の科学者を「~すべき」から「~している」へと迷わせ、人間としての資質を育てることなど不可能であると否定するに至らせた。しか し、乳量を増やすために牛を品種改良したり、走るスピードを上げるために馬を品種改良したり、牧畜の能力を高めるために犬を品種改良したりできるのに、な ぜ数学や音楽、運動能力を高めるために人間を品種改良することが不可能であると言えるのか? 「これらは単一の能力ではない」というような反対意見は、牛や馬、犬にも同様に当てはまるものであり、実際にそれを理由に誰かがそれをやめることは決して ない。 ヒトラーの死後60年が経った今、音楽的能力を育てることと、子供に音楽のレッスンを受けさせることの間に、道徳的な違いが何なのか、少なくとも尋ねてみることはできるのではないだろうか。 科学的に可能であり、すでに確立されているヘテロ接合体の保因者検査は、常染色体劣性遺伝疾患の予防に用いられ、夫婦が将来生まれてくる子供にさまざまな 遺伝的欠陥が遺伝するリスクがあるかどうかを判断することができる。[143][144] 劣性遺伝疾患の有病率を低下させることに成功した優生学的な行為の例は数多くあるが、それらの疾患のヘテロ接合体の保因者自身に悪影響を及ぼすことはな い。アシュケナージ系ユダヤ人集団における様々な遺伝性疾患(例えばテイ・サックス病、嚢胞性線維症、カナバン病、ゴーシェ病など)の有病率の上昇は、遺 伝子スクリーニングの普及により、より最近の集団では著しく減少している[145](Dor Yeshorimも参照)。 科学的妥当性に対する異論 ゲイシンガー・コモンウェルス医学部の医療人文学教授であるアマンダ・カレブは、「優生法や優生政策は、政治的アジェンダを支持するために人々を積極的に 非人間化する疑似科学への見せかけの献身の一部であり、真の科学や医学ではないと理解されるようになった」と述べている[146]。 遺伝的継承に基づく従来の優生学に対する最初の大きな挑戦は、1915年にトーマス・ハント・モーガンによってなされた。彼は、赤い目の家系から白目の ショウジョウバエ(Drosophila melanogaster)が孵化したという発見をめぐり、遺伝的変異が継承とは無関係に起こることを実証した。遺伝子変異は遺伝とは無関係に起こること を証明した。[49]: 336–337 [要出典] さらに、モーガンは、知能や犯罪性などの形質は主観的なものであるため、それらが遺伝的であるという見解を批判した。[147][f] 多面的作用は、ある遺伝子が複数の、一見無関係な表現型の形質に影響を及ぼす場合に起こる。その例として、複数の器官に影響を及ぼすものの、1つの遺伝子 の欠陥によって引き起こされるヒトの疾患であるフェニルケトン尿症がある。[150] ヴロツワフ大学のAndrzej Pękalskiは、優生学プログラムが、おそらくは肯定的な形質と関連する可能性のある多面的作用遺伝子を選択した場合、優生学は遺伝的多様性の有害な 損失を引き起こす可能性があると主張している。Pękalskiは、近視の人が子孫を残すことを禁止する強制的な政府の優生学プログラムを例に挙げている が、近視と高い知能は関連しているため、意図せぬ結果として高い知能も排除してしまうというものである。[151] 遺伝学の科学は、特定の特性や状態を特定し理解する方法をますます提供するようになってきているが、人間の遺伝学、文化、心理学の複雑さを考えると、現時 点では、最終的に望ましい、あるいは望ましくない特性を決定する客観的な手段について合意が得られているわけではない。鎌状赤血球病や嚢胞性線維症などの 状態は、劣性対立遺伝子のコピーが個体の遺伝子型に1つ含まれている場合、それぞれマラリアに対する免疫やコレラに対する抵抗力となるため、これらの遺伝 子を排除することは、これらの病気が多い地域では望ましくない。[138] さらに、 メンデルの遺伝パターンでは自然に切断できないホモ接合体の25%という異常な割合によって、個々の生物が多大な苦痛を被ったり、死に至るような場合で も、同種生物がより大きな生態学的利益を得るために、いわゆるヘテロ接合体の優位性が生じることは正当化されるかもしれない。 ジャーナリスト、歴史家であり、『弱者に対する戦争』の著者であるエドウィン・ブラックは、優生学が疑似科学とみなされることが多いのは、望ましい形質の 遺伝的改善と定義されるものが、客観的な科学的調査によって決定できる問題ではなく、むしろ文化的な選択であるためだと主張している。[2] 実際、優生学で最も論争の的となってきたのは、人間の遺伝子プールの「改善」の定義、つまり、有益な特性とは何か、欠陥とは何かという点である。歴史的 に、優生学のこの側面はしばしば科学的根拠のない人種差別とみなされてきた。[2][153]  1921年の第2回国際優生学会議のロゴ。下部のテキストには「優生学は、木のように、多くの情報源から材料を集め、それらを調和のとれた一つのものとし てまとめる」(そのような情報源には、遺伝学、生理学、精神テスト、人類学、統計学、医学、政治学、社会学などがある)と書かれている。 上記の永続的な論争について、科学史家のアーロン・ギレットは、最近の研究を引用しながら、次のように述べている。 他の人々は、より微妙な見方をしている。彼らは、優生学には多種多様な理論があり、その中には人種や階級に基づくものよりもはるかに少ないものもあること を認識している。優生学者たちは、人間の行動形成における環境の役割についても、程度の差こそあれ、一定の評価を下していた可能性がある。優生学は、医 療、育児、避妊、性教育の問題とほとんど気づかれないほどに絡み合っていた場合もあった。この意味で、優生学は「生物学用語で社会問題を語る『近代的な』 方法」と呼ばれてきた。[157]: 11 実際、優生学という歴史的現象が疑似科学であったとすれば、ギレットはさらに、その主な原因は「人間の進化を意識的に導くことが可能であるという主張に、多くの科学が交差する副次的な現象」であったことにあると指摘している。[157]: 2 |

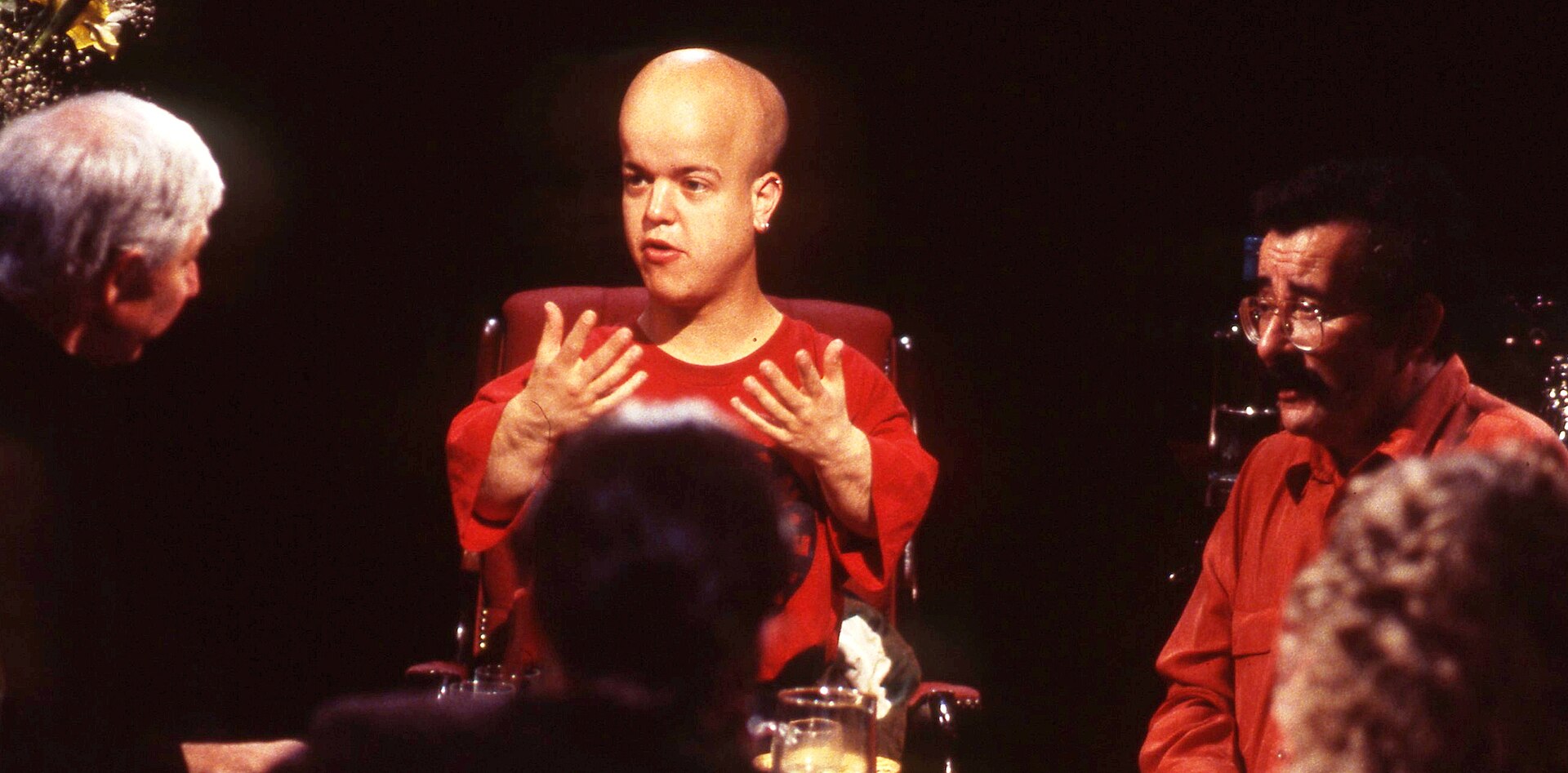

| Contested ethical status Contemporary ethical opposition See also: Larry Arnhart, Leon Kass, and Preimplantation genetic diagnosis § Religious objections  Noted critic of eugenics,[158][159] Thomas Shakespeare (middle) appearing on TV show in 1994 In a book directly addressed at socialist eugenicist J.B.S. Haldane and his once-influential Daedalus, Betrand Russell, had one serious objection of his own: eugenic policies might simply end up being used to reproduce existing power relations “rather than to make men happy.”[160] Environmental ethicist Bill McKibben argued against germinal choice technology and other advanced biotechnological strategies for human enhancement. He writes that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging, maximum life span and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome with technology. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, he argues, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using Ming China, Tokugawa Japan and the contemporary Amish as examples.[161] The threat of perfection This section is an excerpt from Bioconservatism § Michael Sandel.[edit] Michael J. Sandel is an American political philosopher and a prominent bioconservative. His article and subsequent book, both titled The Case Against Perfection,[162][163] concern the moral permissibility of genetic engineering or genome editing. Sandel compares genetic and non-genetic forms of enhancement pointing to the fact that much of non-genetic alteration has largely the same effect as genetic engineering. SAT tutors or study drugs such as Ritalin can have similar effects as minor tampering with natural born intelligence. Sandel uses such examples to argue that the most important moral issue with genetic engineering is not that the consequences of manipulating human nature will undermine human agency but the perfectionist aspiration behind such a drive to mastery. For Sandel, "the deepest moral objection to enhancement lies less in the perfection it seeks than in the human disposition it expresses and promotes.”[163] For example, the parental desire for a child to be of a certain genetic quality is incompatible with the special kind of unconditional love parents should have for their children. He writes “[t]o appreciate children as gifts is to accept them as they come, not as objects of our design or products of our will or instruments of our ambition.”[163]  Michael Sandel in 2012 Sandel insists that consequentialist arguments overlook the principle issue of whether bioenhancement should be aspired to at all. He is attributed with the view that human augmentation should be avoided as it expresses an excessive desire to change oneself and 'become masters of our nature.'[164] For example, in the field of cognitive enhancement, he argues that moral question we should be concerned with is not the consequences of inequality of access to such technology in possibly creating two classes of humans but whether we should aspire to such enhancement at all. Similarly, he has argued that the ethical problem with genetic engineering is not that it undermines the child's autonomy, as this claim "wrongly implies that absent a designing parent, children are free to choose their characteristics for themselves."[162] Rather, he sees enhancement as hubristic, taking nature into our own hands: pursuing the fixity of enhancement is an instance of vanity.[165] Sandel also criticizes the argument that a genetically engineered athlete would have an unfair advantage over his unenhanced competitors, suggesting that it has always been the case that some athletes are better endowed genetically than others.[162] In short, Sandel argues that the real ethical problems with genetic engineering concern its effects on humility, responsibility and solidarity.[162] Contemporary ethical advocacy See also: Perfectionism (philosophy) and Peter Sloterdijk § Reprogenetics dispute "If the use of cochlear implants means that there are fewer Deaf people, is this ‘genocide’? Does our acceptance of prenatal diagnosis and selective abortion mean that we are ‘drifting toward a eugenic resurgence that differs only superficially from earlier patterns’. [...] [This] overlooks the crucial fact that cochlear implants do not have victims." Australian bioethicist Peter Singer (2003),[166] some of whose own relatives were killed in the Holocaust.[167] Some, for example Nathaniel C. Comfort of Johns Hopkins University, claim that the change from state-led reproductive-genetic decision-making to individual choice has moderated the worst abuses of eugenics by transferring the decision-making process from the state to patients and their families.[168] Comfort suggests that "the eugenic impulse drives us to eliminate disease, live longer and healthier, with greater intelligence, and a better adjustment to the conditions of society; and the health benefits, the intellectual thrill and the profits of genetic bio-medicine are too great for us to do otherwise."[169] Others, such as bioethicist Stephen Wilkinson of Keele University and Honorary Research Fellow Eve Garrard at the University of Manchester, claim that some aspects of modern genetics can be classified as eugenics, but that this classification does not inherently make modern genetics immoral.[170] In their book published in 2000, From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice, bioethicists Allen Buchanan, Dan Brock, Norman Daniels and Daniel Wikler argued that liberal societies have an obligation to encourage as wide an adoption of eugenic enhancement technologies as possible (so long as such policies do not infringe on individuals' reproductive rights or exert undue pressures on prospective parents to use these technologies) in order to maximize public health and minimize the inequalities that may result from both natural genetic endowments and unequal access to genetic enhancements.[20] In his book A Theory of Justice (1971), American philosopher John Rawls argued that "[o]ver time a society is to take steps to preserve the general level of natural abilities and to prevent the diffusion of serious defects".[171] The original position, a hypothetical situation developed by Rawls, has been used as an argument for negative eugenics.[172][173] Accordingly, some morally support germline editing precisely because of its capacity to (re)distribute such Rawlsian primary goods.[174][175] Status quo bias and the reversal test Main article: Status quo bias Bostrom and Ord introduced the reversal test to provide an answer to the question of how one can, given that humans might suffer from irrational status quo bias, distinguish between valid criticisms of a proposed increase in some human trait and criticisms merely motivated by resistance to change.[176] The reversal test attempts to do this by asking whether it would be a good thing if the trait was decreased: An example given is that if someone objects that an increase in intelligence would be a bad thing due to more dangerous weapons being made etc., the objector to that position would then ask "Shouldn't we decrease intelligence then?" "Reversal Test: When a proposal to change a certain parameter is thought to have bad overall consequences, consider a change to the same parameter in the opposite direction. If this is also thought to have bad overall consequences, then the onus is on those who reach these conclusions to explain why our position cannot be improved through changes to this parameter. If they are unable to do so, then we have reason to suspect that they suffer from status quo bias." (p. 664)[176] Ideally the test will help reveal whether status quo bias is an important causal factor in the initial judgement. A similar thought experiment in regards to dampening traumatic memories was described by Adam J. Kolber, imagining whether aliens naturally resistant to traumatic memories should adopt traumatic "memory enhancement".[177] The "trip to reality" rebuttal to Nozick's experience machine thought experiment (where one's entire current life is shown to be a simulation and one is offered to return to reality) can also be seen as a form of reversal test.[178] The utilitarian perspective of Procreative Beneficence See also: Eradication of suffering  Bioethicist and former PHD student of Peter Singer's, Julian Savulescu in 2015 Savulescu coined the phrase procreative beneficence. It is the controversial[179][180][vague] moral obligation, rather than mere permission, of parents in a position to select their children, for instance through preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and subsequent embryo selection or selective termination, to favor those expected to have the best possible life.[181][182][183] An argument[vague] in favor of this principle is that traits (such as empathy, memory, etc.) are "all-purpose means" in the sense of being instrumental in realizing whatever life plans the child may come to have.[184] Philosopher Walter Veit has argued that because there is no intrinsic moral difference between "creating" and "choosing" a life, eugenics becomes a natural consequence of procreative beneficence.[179] Similar positions were also taken by John Harris, Robert Ranisch and Ben Saunders respectively.[185][186][187] Transhuman perspectives The term directed evolution is used within the transhumanist community to refer to the idea of applying the principles of directed evolution and experimental evolution to the control of human evolution.[188] Law professor Maxwell Mehlman has said that "for transhumanists, directed evolution is likened to the Holy Grail".[188] Riccardo Campa of the IEET wrote that "self-directed evolution" can be coupled with many different political, philosophical, and religious views within the transhumanist movement.[189] Problematizing the therapy-enhancement distinction This section is an excerpt from Philosophy of medicine § Demarcating therapy.[edit]  Leg prostheses may allow double-amputee Paralympic sprinters to run faster than their Olympic counterparts[190] Self-described opponents of historical eugenics first and foremost,[g] are known to insist on a particularly stringent treatment-enhancement distinction (sometimes also called divide or gap). This distinction, naturally, "draws a line between services or interventions meant to prevent or cure (or otherwise ameliorate) conditions that we view as diseases or disabilities and interventions that improve a condition that we view as a normal function or feature of members of our species".[193] And yet the adequacy of such a dichotomy is highly contested in modern scholarly bioethics. One simple counterargument is that it has already long been ignored throughout various contemporary fields of scientific study and practice such as "preventive medicine, palliative care, obstetrics, sports medicine, plastic surgery, contraceptive devices, fertility treatments, cosmetic dental procedures, and much else".[194] This is one way of conducting ostensively what has been coined the "moral continuum argument" by some of its critics.[195][h] Granting these assertions' validity, one may, once more, call this first and foremost a moral collapse of the therapy–enhancement distinction. Without such a clear divide, restorative medicine and exploratory eugenics also invariably become harder to distinguish;[i] and accordingly might one explain the matter's relevance to ongoing transhumanist discourse. |

論争の的となった倫理的立場 現代の倫理的反対 関連項目:ラリー・アーナート、レオン・カス、着床前遺伝子診断 § 宗教的反対  優生学の著名な批判者であるトーマス・シェイクスピア(中央)は、1994年のテレビ番組に出演した 社会主義優生学者J.B.S.ハルダーンと、かつて影響力を持っていたベイトランド・ラッセルの『ダイダロス』に直接的に言及した著書の中で、ラッセル は、優生政策は単に「人間を幸せにするため」ではなく、既存の権力関係を再生産するために利用されるだけかもしれないという重大な異論を唱えている。 環境倫理学者のビル・マッキベンは、胚選択技術やその他の人間能力強化のための先進的バイオテクノロジー戦略に反対している。彼は、老化に対する脆弱性、 寿命の限界、身体能力や認知能力に対する生物学的制約など、人間に共通する限界を克服しようとして、人間(あるいはその子供)の根本的な側面を改変するこ とは道徳的に間違っていると主張している。このような操作によって「改善」しようとする試みは、人間にとって意味のある選択を経験する上で必要な文脈を提 供する限界を取り除くことになる。このような限界がテクノロジーによって克服できるような世界では、人間の生命はもはや意味のあるものとは見なされないだ ろうと彼は主張する。 明らかに治療目的で生殖細胞選択技術を用いるという目標でさえ、放棄すべきであると彼は主張する。なぜなら、それは認知能力などを改変したいという誘惑を 必然的に生み出すからだ。 明の中国、徳川時代の日本、現代のアーミッシュを例に挙げ、特定のテクノロジーを放棄することで社会が恩恵を受ける可能性があると彼は主張する。 [161] 完璧さの脅威 このセクションは、バイオコンサバティヴィズム § マイケル・サンデルからの抜粋である。 マイケル・J・サンデルは、アメリカの政治哲学者であり、著名なバイオコンサバティヴィストである。彼の論文とそれに続く著書は、どちらも『完璧さへの反 対論』というタイトルであり、遺伝子操作やゲノム編集の道徳的許容性について論じている。サンドルは、遺伝子操作と非遺伝子操作による強化を比較し、非遺 伝子操作による変化の多くは遺伝子操作とほぼ同じ効果をもたらすという事実を指摘している。家庭教師やリタリンなどの学習用薬剤は、生まれながらの知能を わずかに改変するのと同様の効果をもたらす可能性がある。サンデルは、このような例を挙げて、遺伝子操作に関する最も重要な道徳的問題は、人間性を操作し た結果、人間の行動力が損なわれることではなく、そのような支配への欲求の背後にある完璧主義的な願望であると主張している。サンデルにとって、「強化に 対する最も深い道徳的異議は、その完璧さにあるのではなく、それが表現し、推進する人間の性質にある」[163]。例えば、子供が特定の遺伝的資質を持つ ことを望む親の気持ちは、親が子供に対して持つべき無条件の愛とは相容れない。彼は「子どもを贈り物として評価することは、子どもをありのままに受け入れ ることであり、自分の設計したものや自分の意志の産物、あるいは自分の野望の道具として受け入れることではない」と書いている。[163]  2012年のマイケル・サンデル サンデルは、結果論的な議論は、バイオエンハンスメントを追求すべきかどうかという根本的な問題を見落としていると主張している。人間拡張は、自己を変え たいという過剰な願望や「自然の支配者になりたい」という願望の表れであるため、回避すべきだという見解を彼が述べているとされる。[164] たとえば、認知機能拡張の分野では、そうした技術へのアクセスに不平等が生じ、人間が2つの階級に分かれる可能性があることによる結果ではなく、そうした 拡張を望むかどうかということが、私たちが懸念すべき道徳的な問題であると彼は主張している。同様に、遺伝子操作の倫理的問題は、子供の自主性を損なうこ とではなく、この主張は「設計者の親が不在であれば、子供は自分自身で自由に特性を選択できる」と「誤って暗示している」と彼は主張している。[162] むしろ、彼は強化を傲慢な行為であり、自然を我々の手で操作することであると見なしている。強化の固定化を追求することは、 。 また、サンドエルは、遺伝子操作されたアスリートが、強化されていない競合相手に対して不公平な優位性を持つという主張を批判し、一部のアスリートは遺伝 的に他の人よりも恵まれているという状況は常に存在してきたと指摘している。[162] つまり、サンデルは、遺伝子操作の真の倫理的問題は、謙虚さ、責任、連帯への影響に関するものであると主張している。[162] 現代の倫理的主張 関連項目: 完全主義 (哲学) および ピーター・スローターダイク § 生殖遺伝学論争 「人工内耳の使用によってろう者が減るのであれば、これは『大量虐殺』なのか?出生前診断や選択的中絶を容認することは、我々が『表面的には以前のパター ンと異なる優生学の復活へと向かっている』ことを意味するのか?」オーストラリアの生命倫理学者ピーター・シンガー(2003年)[166]は、自身の親 族の一部がホロコーストで命を落としている。 オーストラリアの生命倫理学者ピーター・シンガー(2003年)[166]は、自身の親族の一部がホロコーストで命を落としている[167]。 例えばジョンズ・ホプキンス大学のナサニエル・C・コンフォートは、生殖遺伝に関する意思決定を国家主導から個人の選択に変更することで、意思決定プロセ スを国家から患者とその家族に移行させ、優生学の最悪の悪用を緩和したと主張している。[168] コンフォートは、「優生学的な衝動は、病気を排除し、より長く健康に生き、より高い知性を持ち、社会の状況にうまく適応することを私たちに促している。。 健康上の利益、知的な興奮、遺伝子バイオ医療の利益は、そうしないにはあまりにも大きい」と主張している。[169] キール大学の生命倫理学者スティーブン・ウィルキンソンやマンチェスター大学の名誉研究員イヴ・ギャラードなどの専門家は、現代の遺伝学の一部は優生学に 分類できるが、この分類は本質的に現代の遺伝学を不道徳にするものではないと主張している。[170] 2000年に出版された著書『偶然から選択へ: 遺伝学と正義』の中で、生命倫理学者のアレン・ブキャナン、ダン・ブロック、ノーマン・ダニエルズ、ダニエル・ウィックラーは、自由主義社会には、公衆衛 生を最大限に高め、自然遺伝的素質や遺伝子強化への不平等なアクセスから生じる可能性のある不平等を最小限に抑えるために、優生強化技術を可能な限り広く 採用するよう奨励する義務がある(ただし、そのような政策が個人の生殖権を侵害したり、これらの技術を使用するよう見込みのある親に不当な圧力をかけるも のでない限り)と主張した。 アメリカの哲学者ジョン・ロールズは著書『正義論』(1971年)の中で、「社会は時間をかけて、自然能力の一般的な水準を維持し、深刻な欠陥の拡散を防 ぐための措置を講じるべきである」と主張している。[171] ロールズが仮想した状況である「原初状態」は、 ローウェルズが考案した仮想の状況は、ネガティブ優生学の論拠として用いられてきた。[172][173] それゆえ、ローウェルズの「原初財」を(再)分配する能力があるという理由で、生殖細胞系列編集を道徳的に支持する者もいる。[174][175] 現状維持バイアスと反転テスト 詳細は「現状維持バイアス」を参照 ボストロムとオードは、人間が非合理的な現状維持バイアスに苦しむ可能性があることを踏まえ、提案されたある人間的特性の増加に対する妥当な批判と、単に 変化への抵抗感から生じる批判とを区別する方法を提示するために、反転テストを導入した。反転テストでは、その特性が減少した場合にそれが良いことである かどうかを問うことで、これを試みる。例えば、知能の向上はより危険な武器の製造につながるなど、悪いことであると誰かが反対した場合、その反対者は「そ れなら知能を低下させるべきではないか」と問うことになる。 「逆転テスト:あるパラメータの変更が全体として悪い結果をもたらすと思われる場合、同じパラメータを反対方向に変更することを検討する。もし、それに よっても全体的な結果が悪くなると考えられる場合、その結論に達した人々は、なぜこのパラメータの変更によって我々の立場が改善されないのかを説明しなけ ればならない。もし彼らがそれを説明できない場合、彼らが現状維持バイアスに苦しんでいると疑う理由がある。」(p. 664)[176] 理想的には、このテストによって、現状維持バイアスが最初の判断における重要な因果要因であるかどうかが明らかになる。 心的外傷の記憶を弱めることに関する同様の思考実験は、アダム・J・コルバーによって説明されており、心的外傷の記憶に自然に耐性のある宇宙人が心的外傷 の「記憶強化」を採用すべきかどうかを想像している。[177] ノジックの経験マシン思考実験(現在の生活全体がシミュレーションであることが示され、現実に戻ることを提案される)に対する「現実への旅」という反論 も、逆転テストの一形態と見なすことができる。[178] 生殖的慈悲の功利主義的観点 参照:苦痛の根絶  2015年、生命倫理学者でピーター・シンガーの元博士課程学生であるジュリアン・サヴレスキュ サヴァレスキュは「生殖的慈悲」という語を造語した。これは、単なる許可ではなく、たとえば着床前遺伝子診断(PGD)やその後の胚の選択、あるいは選択 的中絶によって、最良の人生を送ることが期待される子供を選ぶ立場にある親の道徳的義務であるとされ、議論を呼んでいる[179][180][曖昧さ回 避]。 この原則を支持する主張[曖昧]は、特性(共感、記憶力など)は、子供が将来持つかもしれない人生設計の実現に役立つという意味で「万能の手段」であるというものである。 哲学者のウォルター・ヴァイトは、「人生を『創造』すること」と「人生を『選択』すること」の間に本質的な道徳的違いはないため、優生学は生殖に関する慈 悲深い行為の自然な帰結であると主張している。[179] 同様の立場は、ジョン・ハリス、ロバート・ラニッシュ、ベン・サンダースによってそれぞれ取られている。[185][186][187] トランスヒューマニズムの視点 トランスヒューマニストのコミュニティでは、方向づけられた進化という用語が、方向づけられた進化と実験的進化の原理を人間の進化の制御に適用するという 考え方を指して用いられている。[188] 法学教授のマクスウェル・メイルマンは、「トランスヒューマニストにとって、方向づけられた進化は聖杯のようなものだ」と述べている。[188] IEETのリカルド・カンパは、「自己方向づけ進化」はトランスヒューマニスト運動における多くの異なる政治的、哲学的、宗教的見解と結びつく可能性があると述べている。[189] 治療強化の区別を問題視する このセクションは、医学哲学 § 治療の区別からの抜粋である。[編集]  義足は、両下肢切断のパラリンピック短距離走選手がオリンピック選手よりも速く走ることを可能にするかもしれない[190]。 歴史的優生学の自称反対派は、何よりもまず、とりわけ厳格な治療強化の区別(時に「差異」または「ギャップ」とも呼ばれる)を主張することが知られている [g]。この区別は当然、「疾病や障害と見なされる状態を予防または治療(または改善)することを目的としたサービスや介入と、正常な機能または人類の特 性と見なされる状態を改善する介入との間に線を引く」ものである。[193] しかし、このような二分法の妥当性については、現代の学術的な生命倫理の分野で激しい論争が繰り広げられている。単純な反論のひとつは、すでに「予防医 学、緩和ケア、産科、スポーツ医学、形成外科、避妊器具、不妊治療、美容歯科治療、その他多数」といった現代のさまざまな科学的研究や実践の分野で、長い 間無視されてきたというものである。[194] これは、一部の批判者によって「道徳的連続性論」と名付けられたものを表向きに行うひとつの方法である。[195][h] これらの主張の妥当性を認めるならば、これは第一に、治療と強化の区別という道徳的な崩壊であると言うことができる。このような明確な区別がなければ、再 生医療と探求的優生学も常に区別が難しくなる。[i] したがって、この問題は現在進行中のトランスヒューマニストの議論に関連していると説明できるかもしれない。 |

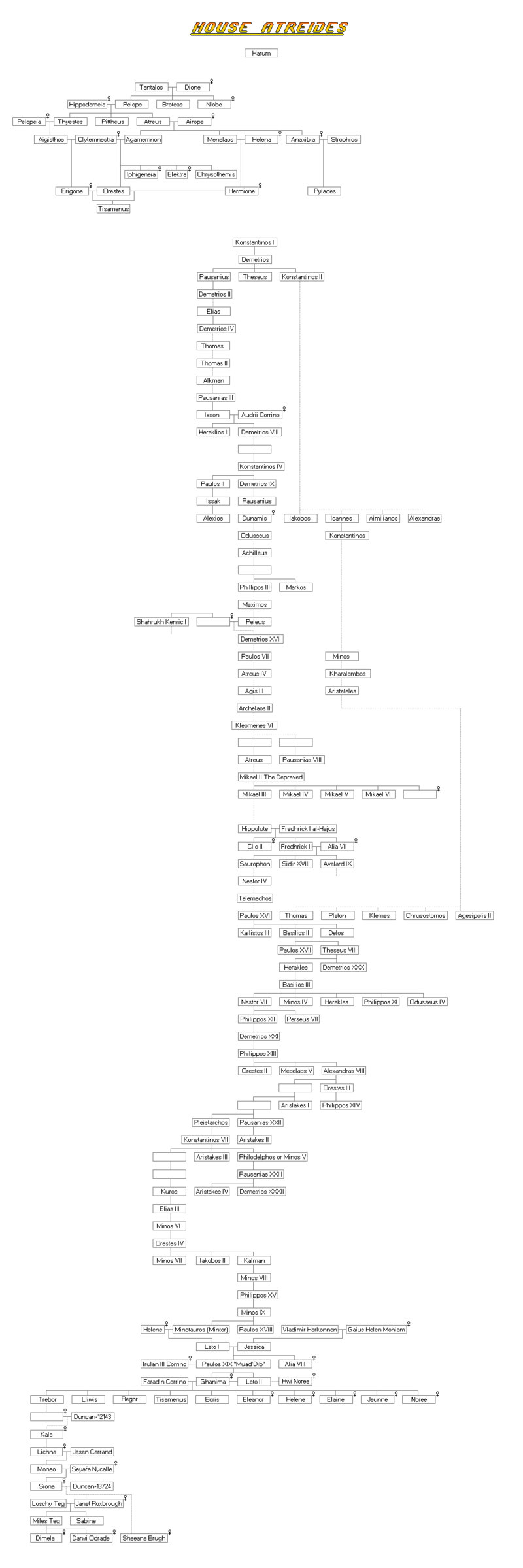

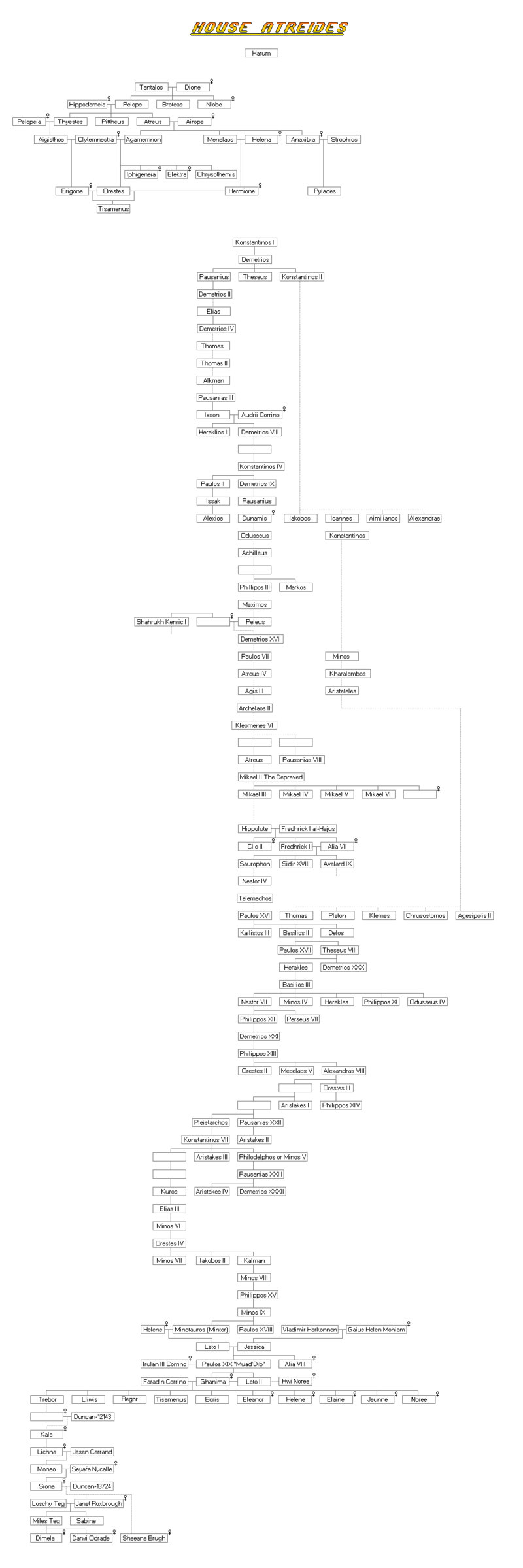

| In science fiction See also: Speculative evolution, Evolution in fiction, and Genetics in fiction  Incomplete pedigree chart of House Atreides from which one half of the Kwisatz Haderach had been strategically bred  In the movie, "Gattaca" also refers to the futuristic building complex that hosts the astronauts for an ongoing space colonization program The novel Brave New World by the English author Aldous Huxley (1931), is a dystopian social science fiction novel which is set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy. Various works by the author Robert A. Heinlein mention the Howard Foundation, a group which attempts to improve human longevity through selective breeding. Among Frank Herbert's other works, the Dune series, starting with the eponymous 1965 novel, describes selective breeding by a powerful sisterhood, the Bene Gesserit, to produce a supernormal male being, the Kwisatz Haderach.[199] The Star Trek franchise features a race of genetically engineered humans which is known as "Augments", the most notable of them is Khan Noonien Singh. These "supermen" were the cause of the Eugenics Wars, a dark period in Earth's fictional history, before they were deposed and exiled. They appear in many of the franchise's story arcs, most frequently, they appear as villains.[200][j] The film Gattaca (1997) provides a fictional example of a dystopian society that uses eugenics to decide what people are capable of and their place in the world. The title alludes to the letters G, A, T and C, the four nucleobases of DNA, and depicts the possible consequences of genetic discrimination in the present societal framework. Relegated to the role of a cleaner owing to his genetically projected death at age 32 due to a heart condition (being told: "The only way you'll see the inside of a spaceship is if you were cleaning it”), the protagonist observes enhanced astronauts as they are demonstrating their superhuman athleticism. Nonetheless, against mere uniformity being the movies key theme, it may be highlighted[203] that it also includes a twelve fingered concert pianist nonetheless taken to be highly esteemed. Even though it was not a box office success, it was critically acclaimed and it is said to have crystallized the debate over human genetic engineering[k] in the public consciousness.[204][205][l] As to its accuracy, its production company, Sony Pictures, consulted with a gene therapy researcher and prominent critic of eugenics known to have stated that "[w]e should not step over the line that delineates treatment from enhancement",[208] W. French Anderson, to ensure that the portrayal of science was realistic. Disputing their sucess in this mission, Philim Yam of Scientific American called the film "science bashing" and Nature's Kevin Davies called it a "surprisingly pedestrian affair", while molecular biologist Lee Silver described its extreme determinism as "a straw man".[209][210][m] In an even more pointed critique, in his 2018 book Blueprint, the behavioral geneticist Robert Plomin writes that while Gattaca warned of the dangers of genetic information being used by a totalitarian state, genetic testing could also favor better meritocracy in democratic societies which already administer a variety of standardized tests to select people for education and employment. He suggests that polygenic scores might supplement testing in a manner that is essentially free of biases.[212] Along similar lines, in the 2004 book Citizen Cyborg,[211] democratic transhumanist James Hughes had already argued against what he considers to be "professional fearmongers",[211]: xiii stating of the movie's premises: Astronaut training programs are entirely justified in attempting to screen out people with heart problems for safety reasons; In the United States, people are already being screened by insurance companies on the basis of their propensities to disease, for actuarial purposes; Rather than banning genetic testing or genetic enhancement, society should simply develop genetic information privacy laws, such as the U.S. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, that allow justified forms of genetic testing and data aggregation, but forbid those that are judged to result in genetic discrimination. Enforcing these would not be very hard once a system for reporting and penalties is in place.[211]: 146-7 |

SF 関連項目: 推測上の進化、フィクションにおける進化、フィクションにおける遺伝学  クウィサッツ・ハダラックの血統図の半分が戦略的に繁殖されたアトレイデス家の不完全な家系図  映画『ガタカ』では、進行中の宇宙植民地化計画に参加する宇宙飛行士たちが滞在する未来的な複合施設についても言及されている 小説『すばらしい新世界』(1931年)は、イギリスの作家オルダス・ハクスリーによるディストピアの社会科学小説であり、未来世界「ワールド・ステート」を舞台としている。この世界では、環境が操作され、知能に基づく社会階層が形成されている。 ロバート・A・ハインラインの作品では、人類の長寿化を目的とした選択交配を行うハワード財団について言及されている。 フランク・ハーバートの他の作品では、1965年の同名小説から始まる『デューン』シリーズで、強力な姉妹団であるベネ・ゲセルートが、超常的な男性であるクィサッツ・ハダラクを生み出すための選択交配について描かれている。 スタートレックシリーズでは、オーグメントと呼ばれる遺伝子操作された人類が登場する。その中でも最も有名なのはカーン・ヌニエン・シンである。これらの 「超人」は、追放される前の優生戦争と呼ばれる地球の架空の歴史における暗黒時代を引き起こした。彼らはシリーズの多くのストーリーに登場し、最も頻繁に 悪役として登場する。[200][j] 映画『ガタカ』(1997年)は、優生学によって人間の能力や社会での地位を決定するディストピア社会の架空の例を示している。タイトルは、DNAの4つ の核酸塩基であるG、A、T、Cを暗示しており、現在の社会構造における遺伝子差別の結果として起こりうることを描いている。心臓疾患により32歳で遺伝 的に死ぬことが予測されたため清掃員の仕事に甘んじる主人公(「宇宙船の内部を見ることができるのは、掃除をしている場合だけだ」と言われる)は、超人的 な運動能力を発揮する強化された宇宙飛行士たちのデモンストレーションを見学する。しかし、単一性こそが映画の主要テーマであるにもかかわらず、十二指腸 のコンサートピアニストが非常に高く評価されている点も強調されている[203]。興行的には成功しなかったものの、批評家からは高い評価を受け、人間の 遺伝子操作に関する議論を一般の人々の意識に定着させたと言われている[204][205][l]。その正確性については、制作会社であるソニー・ピク チャーズは 、科学の描写が現実的であることを確実にするため、遺伝子治療の研究者であり優生学の著名な批判者として知られ、「『治療』と『強化』を区別する一線を踏 み越えてはならない」と述べたことがある[208]W・フレンチ・アンダーソンに相談した。この使命における彼らの成功を否定する意見として、サイエン ティフィック・アメリカのフィル・ヤムは映画を「科学バッシング」と呼び、ネイチャーのケビン・デイヴィスは「驚くほど平凡な出来事」と評した。一方、分 子生物学者のリー・シルバーは、その極端な決定論を「藁人形」と表現した。[209][210][m] さらに鋭い批判として、行動遺伝学者のロバート・プロミンは2018年の著書『Blueprint』で、ガタカは全体主義国家による遺伝子情報の利用の危 険性を警告したが、遺伝子検査はすでに教育や雇用に際して様々な標準テストを実施している民主的社会において、より優れた能力主義を促進する可能性もある と書いている。彼は、多因子遺伝子スコアが、本質的に偏りのない方法でテストを補完できる可能性があると示唆している。[212] 同様の論調で、2004年の著書『Citizen Cyborg』[211]の中で、民主的なトランスヒューマニストであるジェームズ・ヒューズは、彼が「プロの恐怖をあおる人々」とみなす人々に対してす でに反論しており[211]:xiii、映画の前提について次のように述べている。 宇宙飛行士の訓練プログラムは、安全上の理由から心臓に問題のある人々を排除しようとする試みは完全に正当化される。 米国では、保険会社はすでに保険数理上の目的で、病気の傾向に基づいて人々を選別している。 遺伝子検査や遺伝子強化を禁止するのではなく、社会は単に、正当な遺伝子検査やデータ収集を許可し、遺伝子差別につながると判断されたものを禁じる、米国 遺伝情報差別禁止法のような遺伝情報プライバシー法を整備すべきである。報告と罰則のシステムが整備されれば、これらの施行はそれほど難しくないだろう。 [211]:146-7 |

| Ableism – Discrimination on grounds of disability Bioconservatism – Cautious stance towards modifying human nature Culling – Process of segregating organisms in biology Dor Yeshorim – Jewish genetic screening organization Dysgenics – Decrease in genetic traits deemed desirable Eugenic feminism – Areas of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics Genetic engineering – Manipulation of an organism's genome Genetic enhancement – Technologies to genetically improve human bodies Hereditarianism – View that genetics plays a major role in determining human behavior Heritability of IQ – Percent of variation in Iq scores in a given population associated with genetic variation New eugenics – Liberal use of reprogenetics in human enhancement Mendelian traits in humans Simple Mendelian genetics in humans Moral enhancement – Use of biotechnology to improve one's character Project Prevention – American non-profit organization Social Darwinism – Group of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices Wrongful life – Civil law action which alleges that a defendant has wrongfully caused a child to be born |

アビリズム(Ableism) – 障害を理由とする差別 バイオコンサバティズム(Bioconservatism) – 人間の性質を改変することに対する慎重な姿勢 カリング(Culling) – 生物学における生物の選別 ドール・イェシロム(Dor Yeshorim) – ユダヤ人の遺伝子スクリーニング機関 ディゼンジクス(Dysgenics) – 望ましいとされる遺伝形質の減少 優生フェミニズム(Eugenic feminism) – 優生学と重なる女性の参政権運動の分野 遺伝子工学(Genetic engineering) – 生物のゲノムの操作 遺伝子強化 – 人体を遺伝的に改善する技術 遺伝説 – 遺伝子が人間の行動を決定する上で主要な役割を果たしているという見解 IQの遺伝率 – 特定の集団におけるIQスコアの変動の割合で、遺伝的変異に関連する ニュー・ユージェニックス – ヒューマン・エンハンスメントにおける生殖遺伝学の自由な利用 人間のメンデル形質 人間の単純なメンデル遺伝学 モラル・エンハンスメント – バイオテクノロジーを利用して人格を向上させること プロジェクト・プレベンション – アメリカの非営利団体 社会ダーウィニズム – 疑似科学的な理論と社会実践のグループ 不当な生命 – 被告が不当に子供を産ませたとして民事訴訟を起こすこと |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugenics |

ク

レジット:「優生学」(旧ページは「優生学:ポータル」とし移転しました」)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆