フェラ・クティ

Fela Kuti, 1938-1997

☆ フェラ・アニクルアポ・クティ(Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti、1938年10月15日 - 1997年8月2日)はナイジェリアのミュージシャンであり政治活動家である。彼は、西アフリカ音楽とアメリカン・ファンクやジャズを融合させたナイジェ リアの音楽ジャンルであるアフロビート(Afrobeat)の主要な革新者とみなされている。[1] 人気絶頂期には、アフリカで最も「挑戦的でカリスマ性のある音楽パフォーマー」の一人と評された。[2] AllMusicは、彼を国際的に重要な「音楽的かつ社会政治的な声」と表現している。[3] クティはナイジェリアの女性人権活動家フンミライ・ランソメ・クティの息子であった。海外での初期の経験を経て、彼とバンドのアフリカ'70(ドラマー兼 音楽監督のトニー・アレンを擁する)は、1970年代にナイジェリアで一躍スターダムにのし上がった。その間、彼はナイジェリアの軍事政権の公然たる批判 者であり、標的でもあった。[3] 1970年、彼は軍事政権からの独立を宣言したカラクッタ共和国共同体を設立した。このコミューンは1978年の襲撃により破壊され、クティと彼の母親が 負傷した。[4] 1984年にはムハンマド・ブハリ政権により投獄されたが、20ヶ月後に釈放された。1980年代、1990年代を通じてレコーディングとパフォーマンス を続けた。1997年に死去して以来、彼の音楽の再発と編集は息子のフェミ・クティが監修している。

| Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì

(born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti; 15 October 1938 – 2

August 1997) was a Nigerian musician and political activist. He is

regarded as the principal innovator of Afrobeat, a Nigerian music genre

that combines West African music with American funk and jazz.[1] At the

height of his popularity, he was referred to as one of Africa's most

"challenging and charismatic music performers".[2] AllMusic described

him as "a musical and sociopolitical voice" of international

significance.[3] Kuti was the son of Nigerian women's rights activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. After early experiences abroad, he and his band Africa '70 (featuring drummer and musical director Tony Allen) shot to stardom in Nigeria during the 1970s, during which he was an outspoken critic and target of Nigeria's military juntas.[3] In 1970, he founded the Kalakuta Republic commune, which declared itself independent from military rule. The commune was destroyed in a 1978 raid that injured Kuti and his mother.[4] He was jailed by the government of Muhammadu Buhari in 1984, but released after 20 months. He continued to record and perform through the 1980s and 1990s. Since his death in 1997, reissues and compilations of his music have been overseen by his son, Femi Kuti.[3] |

フェラ・アニクルアポ・クティ(Olufela Olusegun

Oludotun Ransome-Kuti、1938年10月15日 -

1997年8月2日)はナイジェリアのミュージシャンであり政治活動家である。彼は、西アフリカ音楽とアメリカン・ファンクやジャズを融合させたナイジェ

リアの音楽ジャンルであるアフロビートの主要な革新者とみなされている。[1]

人気絶頂期には、アフリカで最も「挑戦的でカリスマ性のある音楽パフォーマー」の一人と評された。[2]

AllMusicは、彼を国際的に重要な「音楽的かつ社会政治的な声」と表現している。[3] クティはナイジェリアの女性人権活動家フンミライ・ランソメ・クティの息子であった。海外での初期の経験を経て、彼とバンドのアフリカ'70(ドラマー兼 音楽監督のトニー・アレンを擁する)は、1970年代にナイジェリアで一躍スターダムにのし上がった。その間、彼はナイジェリアの軍事政権の公然たる批判 者であり、標的でもあった。[3] 1970年、彼は軍事政権からの独立を宣言したカラクッタ共和国共同体を設立した。このコミューンは1978年の襲撃により破壊され、クティと彼の母親が 負傷した。[4] 1984年にはムハンマド・ブハリ政権により投獄されたが、20ヶ月後に釈放された。1980年代、1990年代を通じてレコーディングとパフォーマンス を続けた。1997年に死去して以来、彼の音楽の再発と編集は息子のフェミ・クティが監修している。 |

| Life and career Early life Reverend Israel and Chief Funmilayo seated, Dolu at back, Fela in the foreground and baby Beko, with Olikoye at right The Ransome-Kuti family c. 1940 Kuti[5] was born into the Ransome-Kuti family, an upper-middle-class family, on 15 October 1938, in Abeokuta, Colonial Nigeria.[6] His mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was an anti-colonial feminist, and his father, Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, was an Anglican minister, school principal, and the first president of the Nigeria Union of Teachers.[7] Kuti's parents both played active roles in the anti-colonial movement in Nigeria, most notably the Abeokuta Women's Riots which was led by his mother in 1946.[8] His brothers Beko Ransome-Kuti and Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, both medical doctors, were well known nationally.[4] Kuti is a cousin[9] to the writer and laureate Wole Soyinka, a Nobel Prize for Literature winner.[10] They are both descendants of Josiah Ransome-Kuti, who is Kuti's paternal grandfather and Soyinka's maternal great-grandfather.[11] Kuti attended Abeokuta Grammar School. In 1958, he was sent to London to study medicine but decided to study music instead at the Trinity College of Music, with the trumpet being his preferred instrument.[4] While there, he formed the band Koola Lobitos and played a fusion of jazz and highlife.[12] The ensemble would include members, Bayo Martins on drums and Wole Bucknor on piano.[13] In 1960, Kuti married his first wife, Remilekun (Remi) Taylor, with whom he had three children (Yeni, Femi, and Sola).[14] In 1963, Kuti moved back to the newly independent Federation of Nigeria, re-formed Koola Lobitos, and trained as a radio producer for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. He played for some time with Victor Olaiya and his All-Stars.[15] He called his style Afrobeat, a combination of Apala, funk, jazz, highlife, salsa, calypso, and traditional Yoruba music. In 1969, Kuti took the band to the United States and spent ten months in Los Angeles. While there, he discovered the Black Power movement through Sandra Smith (now known as Sandra Izsadore or Sandra Akanke Isidore),[16] a partisan of the Black Panther Party. This experience heavily influenced his music and political views.[17] He renamed the band Nigeria 70. Soon after, the Immigration and Naturalization Service was tipped off by a promoter that Kuti and his band were in the US without work permits. The band performed a quick recording session in Los Angeles that would later be released as The '69 Los Angeles Sessions.[18] |

人生とキャリア 幼少期 前列に座るイスラエル牧師とチーフ・ファンミライオ、後列にドルー、手前にフェラとベコ、右にオリコイエ ランサム=クティ一家、1940年頃 クティ[5]は、1938年10月15日、植民地時代のナイジェリアのアベオクタで、中流上流階級の家庭であるランサム=クティ家に生まれた。[6] 彼の母親、フンミラヨ・ランサム=クティは反植民地主義のフェミニストであり、父親のイスラエル・オルドトゥン・ランサム=クティは、 英国国教会の聖職者、学校の校長、そしてナイジェリア教員組合の初代会長であった。[7] クーティの両親はともにナイジェリアの反植民地運動で積極的な役割を果たし、特に1946年に母親が主導したアベオクタ女性暴動は有名である。[8] 兄弟のベコ・ランサム=クーティとオリコイェ・ランサム=クーティは ともに医師であるベコ・ランサム=クティとオリコイェ・ランサム=クティは、国民に広く知られていた。[4] クティはノーベル文学賞受賞作家であるウォーレ・ショインカの従兄弟である。[9] 2人はともにジョシア・ランサム=クティの子孫であり、ジョシアはクティの父方の祖父、ショインカの母方の曾祖父にあたる。[11] クティはアベオクタ・グラマースクールに通った。1958年、医学を学ぶためにロンドンに送られたが、代わりにトリニティ・カレッジ・オブ・ミュージック で音楽を学ぶことを決意し、トランペットを好んで演奏した。[4] 滞在中、クティはバンド「クーラ・ロビトス」を結成し、ジャズとハイライフの融合を演奏した。[12] このバンドには、ドラムのバイヨ・マーティンスとピアノのウォーレ・バックナーが参加していた。[13] 1960年、クーティは最初の妻レミレクン(レミ)・テイラーと結婚し、3人の子供(イェニ、フェミ、ソラ)をもうけた。[14] 1963年、クーティは新たに独立したナイジェリア連邦に戻り、クーラ・ロビトスを再結成し、ナイジェリア放送公社でラジオプロデューサーとしての訓練を 受けた。彼はしばらくの間、ビクター・オライヤと彼のオールスターズと共演した。[15] 彼は自身のスタイルをアフロビートと呼び、アパラ、ファンク、ジャズ、ハイライフ、サルサ、カリプソ、ヨルバの伝統音楽を融合させた。1969年、クティ はバンドを率いてアメリカ合衆国に渡り、ロサンゼルスで10か月を過ごした。滞在中、ブラックパンサー党の支持者であるサンドラ・スミス(現サンドラ・イ ズサドーレまたはサンドラ・アカンケ・イシドーレ)を通じてブラックパワー運動を知った。この経験は、彼の音楽と政治的見解に大きな影響を与えた。 [17] 彼はバンド名をNigeria 70に改名した。ほどなく、移民帰化局がプロモーターから、クティとバンドメンバーが就労許可証なしで米国に滞在しているとの情報を得た。バンドはロサン ゼルスで急遽レコーディング・セッションを行い、後に『The '69 Los Angeles Sessions』としてリリースされた。[18] |

| 1970s After Kuti and his band returned to Nigeria, the group was renamed (the) Africa '70 as lyrical themes changed from love to social issues.[12] He formed the Kalakuta Republic—a commune, recording studio, and home for many people connected to the band—which he later declared independent from the Nigerian state. Kuti set up a nightclub in the Empire Hotel. He first named the Afro-Spot and later the Afrika Shrine, where he performed regularly and officiated at personalised Yoruba traditional ceremonies in honor of his native ancestral faith. He also changed his name to Anikulapo (meaning "He who carries death in his pouch", with the interpretation: "I will be the master of my own destiny and will decide when it is time for death to take me").[4][19] He stopped using the hyphenated surname "Ransome" because he considered it a slave name.[20] Kuti's music was popular among the Nigerian public and Africans in general.[21] He decided to sing in Pidgin English so that individuals all over Africa could enjoy his music, where the local languages they speak are diverse and numerous. As popular as Kuti's music had become in Nigeria and elsewhere, it was unpopular with the ruling government, and raids on the Kalakuta Republic were frequent. During 1972, Ginger Baker recorded Stratavarious, with Kuti appearing alongside vocalist and guitarist Bobby Tench.[22] Around this time, Kuti became even more involved with the Yoruba religion.[2] In 1977, Kuti and Africa 70 released the album Zombie, which heavily criticized Nigerian soldiers, and used the zombie metaphor to describe the Nigerian military's methods. The album was a massive success and infuriated the government, who raided the Kalakuta Republic with 1,000 soldiers. During the raid, Kuti was severely beaten, and his elderly mother (the first woman to drive a car in Nigeria) was fatally injured after being thrown from a window.[4] The commune was burnt down, and Kuti's studio, instruments, and master tapes were destroyed. Kuti claimed that he would have been killed had it not been for a commanding officer's intervention as he was being beaten. Kuti's response to the attack was to deliver his mother's coffin to the Dodan Barracks in Lagos, General Olusegun Obasanjo's residence, and to write two songs, "Coffin for Head of State" and "Unknown Soldier," referencing the official inquiry that claimed an unknown soldier had destroyed the commune.[23] Kuti and his band took up residence in Crossroads Hotel after the Shrine had been destroyed along with the commune. In 1978, he married 27 women, many of whom were dancers, composers, and singers with whom he worked. The marriages served not only to mark the anniversary of the attack on the Kalakuta Republic but also to protect Kuti and his wives from authorities' false claims that Kuti was kidnapping women.[24] Later, he adopted a rotation system of maintaining 12 simultaneous wives.[25] There were also two concerts in the year: the first was in Accra, in which rioting broke out during the song "Zombie", which caused Kuti to be banned from entering Ghana; the second was after the Berlin Jazz Festival when most of Kuti's musicians deserted him due to rumours that he planned to use all of the proceeds to fund his presidential campaign. In 1978 Fela performed at the Berliner Jazztage in Berlin with his band Africa 70. Disappointed by their fees, Tony Allen, the band leader and almost all the musicians resigned.[26] Since then, Baryton player Lekan Animashaun became band leader and Fela created a new group named Egypt 80. In 1979, Kuti formed his political party, which he called Movement of the People (MOP), to "clean up society like a mop",[4] but it quickly became inactive due to his confrontations with the government of the day. MOP preached Nkrumahism and Africanism.[27][28] |

1970年代 クティとバンドがナイジェリアに戻った後、歌詞のテーマが恋愛から社会問題へと変化したため、グループは(ザ)アフリカ'70と改名された。[12] 彼は、バンドと関わりのある多くの人々のための共同体、レコーディングスタジオ、そして住居であるカラクタクタ共和国を設立し、後にナイジェリア政府から の独立を宣言した。 クティはエンパイア・ホテルにナイトクラブを開いた。当初はアフロ・スポット、後にアフリカ・シュラインと名付けたこのクラブで、彼は定期的にパフォーマ ンスを行い、自身の故郷の祖先崇拝に敬意を表して、ヨルバ族の伝統的な儀式を独自に執り行った。また、彼は自身の名前をアニクラポ(「ポーチに死を忍ばせ る者」という意味で、解釈としては「 「私は自分の運命の主人となり、死が訪れる時を自分で決める」という意味である)。[4][19] ハイフンで結ばれた名字「ランサム」は奴隷名であると考え、使用しなくなった。[20] クティの音楽はナイジェリア国民やアフリカ人一般に人気があった。[21] 彼は、アフリカ中の人々が彼の音楽を楽しめるように、ピジン・イングリッシュで歌うことにした。彼らが話す現地語は多様かつ多数である。クティの音楽はナ イジェリアやその他の地域で人気を博したが、支配政府には不評であり、カラクータ共和国への襲撃は頻繁に行われた。1972年、ジンジャー・ベイカーは 『ストラタヴァリウス』を録音し、クーティはボーカリスト兼ギタリストのボビー・テンチとともに参加した。[22] この頃、クーティはヨルバの宗教にさらに深く関わるようになった。[2] 1977年、クティとアフリカ70はアルバム『ゾンビ』を発表した。このアルバムはナイジェリアの兵士たちを痛烈に批判し、ゾンビの隠喩を用いてナイジェ リア軍のやり方を表現した。このアルバムは大成功を収めたが、政府を激怒させ、政府は1,000人の兵士を動員してカラクータ共和国を急襲した。襲撃の 際、クーティはひどく殴られ、高齢の母親(ナイジェリアで初めて車を運転した女性)は窓から投げ出されて致命傷を負った。[4] コミューンは焼き払われ、クーティのスタジオ、楽器、マスターテープは破壊された。クーティは、殴られている際に指揮官が介入しなければ自分は殺されてい ただろうと主張した。この襲撃事件に対するクーティの反応は、母親の棺をラゴスのオバサンジョ将軍の邸宅であるドダン・バラックスに運び、クーニャ・ フォー・ヘッド・オブ・ステイト(Coffin for Head of State)とアンノウン・ソルジャー(Unknown Soldier)という2曲の歌を作曲したことだった。この歌は、無名の兵士がコミューンを破壊したという公式調査に言及している。 クーニャと彼のバンドは、コミューンとともにシュラインが破壊された後、クロスローズ・ホテルに住み着いた。1978年、彼は27人の女性と結婚した。そ の多くはダンサー、作曲家、歌手であり、彼と仕事をした人々であった。この結婚は、カラクータ共和国への攻撃の記念日を祝うためだけでなく、当局がクー ティを女性誘拐犯であると主張するのを防ぐためでもあった。[24] その後、彼は12人の妻を同時に持つローテーション制を採用した。[25] その年には2回のコンサートがあった :1つ目はアクラで行われたもので、曲「ゾンビ」の演奏中に暴動が発生し、クティはガーナへの入国を禁止された。2つ目はベルリン・ジャズ・フェスティバ ルの後に行われたもので、クティが大統領選挙の資金調達のために収益のすべてを使うつもりだという噂が流れたため、彼のミュージシャンのほとんどが彼のも とを去った。 1978年、フェラは自身のバンド、アフリカ70を率いてベルリンのジャズフェスティバルに出演した。ギャラに失望したバンドリーダーのトニー・アレンを はじめ、ほとんどのミュージシャンが辞めてしまった。[26] それ以来、バリトン奏者のレカン・アニマショーンがバンドリーダーとなり、フェラはエジプト80という新しいグループを結成した。1979年、クティは 「モップのように社会をきれいにする」ために、人民運動(MOP)と呼ばれる自身の政治団体を結成したが、当時の政府との対立により、すぐに活動は停滞し た。MOPは、エンクルマ主義とアフリカ主義を説いていた。[27][28] |

1980s and beyond  Two of Kuti's sons are musicians: Femi and Seun. In 1980 Fela signed an exclusive management with French producer Martin Meissonnier who secured a record deal with Arista records London through A&R Tarquin Gotch. The first album came out in February 1981 under the title of "Black President" with the track "ITT" and on the B-Side "Colonial Mentality" and an edited version of "Sorrow Tears and Blood" (these two tracks recorded with Africa 70 and Tony Allen were unreleased in Europe).[29] Following the release, Fela performed his first European tour (4 concerts in a week) with a suite of 70 people. The tour starting in Paris on March 15, 1981, with a huge crowd estimated at 10000 people,[30] then Brussels, Wien and Strasbourg. "Black President was followed by another album was recorded in Paris in july 1981: "Original Sufferhead",[31] with "Power Show" on the B-side. Fela also recorded the track "Perambulator" in Paris. Arista gave his back freedom to Fela at the end of 1981.[32] French Filmmaker Jean Jacques Flori came to Lagos early 1982 to direct the now classic film "Music is a Weapon". The filmed was broadcast first on Antenne 2 (french TV in 1982). The film producer Stephane Tchalgaldjieff didn't like the film and decided to re edit it for an international release.[33] "V.I.P. (Vagabonds in Power)" and "Authority Stealing" were released in 1980, with the former being a live performance done in Berlin, West Germany. In 1983, Kuti nominated himself for president[4] in Nigeria's first elections in decades, but his candidature was refused. At this time, Kuti created a new band, Egypt 80, which reflected the view that Egyptian civilization, knowledge, philosophy, mathematics, and religious systems are African and must be claimed as such. Kuti stated in an interview: "Stressing the point that I have to make Africans aware of the fact that Egyptian civilization belongs to the African. So that was the reason why I changed the name of my band to Egypt 80."[34] Kuti continued to record albums and tour the country. He further infuriated the political establishment by implicating ITT Corporation's vice-president, Moshood Abiola, and Obasanjo in the popular 25-minute political screed entitled "I.T.T. (International Thief-Thief)".[4] In 1984, Muhammadu Buhari's government, of which Kuti was a vocal opponent, jailed him on a charge of currency smuggling. Amnesty International and others denounced the charges as politically motivated.[35] Amnesty designated him a prisoner of conscience,[36] and other human rights groups also took up his case. After 20 months, General Ibrahim Babangida released him from prison. On his release, Kuti divorced his 12 remaining wives, citing "marriage brings jealousy and selfishness" since his wives would regularly compete for superiority.[25][37] Kuti continued to release albums with Egypt 80 and toured in the United States and Europe while continuing to be politically active. In 1986, he performed in Giants Stadium in New Jersey as part of Amnesty International's A Conspiracy of Hope concert along with Bono, Carlos Santana, and the Neville Brothers. In 1989, Kuti and Egypt 80 released the anti-apartheid album Beasts of No Nation that depicted U.S. President Ronald Reagan, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and South African State President Pieter Willem Botha on its cover. The title of the composition evolved out of a statement by Botha: "This uprising [against the apartheid system] will bring out the beast in us."[4] Kuti's album output slowed in the 1990s, and eventually, he ceased releasing albums altogether. On 21 January 1993,[38] he and four members of Africa 70 were arrested and were later charged on 25 January for the murder of an electrician.[39] Rumours also speculated that he was suffering from an illness for which he was refusing treatment. However, there had been no confirmed statement from Kuti about this speculation. |

1980年代以降  クティの息子2人はミュージシャンである。フェミとスンだ。 1980年、フェラはフランスのプロデューサー、マーティン・メイソニエと専属マネジメント契約を結び、A&Rのタルキン・ゴッチを通じてアリス タ・レコード・ロンドンとレコード契約を結んだ。1981年2月、ファーストアルバム『Black President』がリリースされ、タイトルトラック「ITT」とB面の「Colonial Mentality」、そして「Sorrow Tears and Blood」の編集版が収録された (アフリカ70とトニー・アレンとの共演によるこの2曲はヨーロッパでは未発表だった)。[29] リリース後、フェラは70人編成のバンドを率いて初のヨーロッパ・ツアー(1週間に4回のコンサート)を行った。このツアーは1981年3月15日にパリ で始まり、1万人の観客が集まったと推定されている。[30]その後ブリュッセル、ウィーン、ストラスブールを回った。「ブラック・プレジデント」に続い て、1981年7月にパリで次のアルバムが録音された。「オリジナル・サファーヘッド」[31]のB面には「パワー・ショー」が収録されている。フェラは パリで「ペランブラトール」も録音した。1981年末、アリスタはフェラに自由を与えた。[32] 1982年初頭、フランスの映画製作者ジャン=ジャック・フロリがラゴスを訪れ、現在では古典となった映画『Music is a Weapon』の監督を務めた。この映画は、1982年のフランスTV局Antenne 2で初めて放送された。映画プロデューサーのステファン・チャルガルジエフは映画を気に入らず、国際的な公開に向けて再編集することを決めた。 「V.I.P. (Vagabonds in Power)」と「Authority Stealing」は1980年にリリースされ、前者は西ドイツのベルリンで行われたライブパフォーマンスである。 1983年、クティはナイジェリアで数十年ぶりに実施された選挙で大統領候補に自らを指名したが[4]、立候補は認められなかった。この時期、クティはエ ジプト文明、知識、哲学、数学、宗教体系はアフリカのものであり、アフリカのものであると主張すべきであるという見解を反映した新しいバンド、エジプト 80を結成した。クティはインタビューで次のように述べている。「エジプト文明はアフリカのものだという事実をアフリカ人に認識させる必要があるという点 を強調した。それが私がバンド名をエジプト80に変えた理由だ」[34] クティはアルバムの録音と国内ツアーを続けた。彼は、ITTコーポレーションの副社長モスフード・アビオラとオバサンジョを暗に非難した25分間の人気政 治的演説「I.T.T. (International Thief-Thief)」で、政治体制をさらに激怒させた。[4] 1984年、クティが公然と反対していたムハンマド・ブハリ政権は、通貨密輸の容疑で彼を投獄した。アムネスティ・インターナショナルやその他の団体は、 この告発は政治的な動機によるものだと非難した。[35] アムネスティは彼を良心の囚人と指定し、[36] 他の人権団体も彼の件を取り上げた。 20ヶ月後、イブラヒム・ババンギダ将軍が彼を釈放した。 釈放後、クティは残っていた12人の妻たちと離婚した。 彼は、妻たちが優位性を争うために定期的に競い合うため、「結婚は嫉妬と利己主義をもたらす」と述べた。[25][37] クティはエジプト80とともにアルバムをリリースし続け、政治的に活発な活動を続ける一方で、アメリカやヨーロッパでツアーを行った。1986年には、 ニュージャージー州のジャイアンツ・スタジアムで、ボノ、カルロス・サンタナ、ネヴィル・ブラザーズらとともにアムネスティ・インターナショナルの「希望 の陰謀」コンサートの一環としてパフォーマンスを行った。1989年、クーティとエジプト80は、反アパルトヘイトのアルバム『Beasts of No Nation』をリリースした。このアルバムのジャケットには、米国大統領ロナルド・レーガン、英国首相マーガレット・サッチャー、南アフリカ大統領ピ エール・ウィレム・ボタの肖像が描かれていた。この曲のタイトルは、ボタの「この蜂起(アパルトヘイト体制に対する)は、我々の中の野獣を引き出すだろ う」という発言から発展したものである。 クティのアルバムのリリースは1990年代に減少し、最終的には完全にリリースされなくなった。1993年1月21日、[38]アフリカ70の4人のメン バーとともに逮捕され、電気技師殺害容疑で1月25日に起訴された。[39]噂では、彼は治療を拒否している病気にかかっているとされていた。しかし、こ の憶測についてクーティが確認した声明は発表されていない。 |

| Death On 3 August 1997, Kuti's brother Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, already a prominent AIDS activist and former Minister of Health, announced that Kuti had died on the previous day from complications related to AIDS. Kuti had been an AIDS denialist,[40] and his widow maintained that he did not die of AIDS.[41][42] His youngest son Seun took the role of leading Kuti's former band Egypt 80. As of 2022, the band is still active, releasing music under the moniker Seun Kuti & Egypt 80.[43] |

死 1997年8月3日、すでに著名なエイズ活動家であり、元保健大臣でもあったクーティの兄弟オリコイェ・ランサム・クーティが、クーティが前日にエイズ関 連の合併症により死亡したと発表した。クティはエイズ否定論者であったが[40]、彼の未亡人は、彼はエイズで死んだのではないと主張している[41] [42]。彼の末息子であるSeunは、クティの元バンドであるエジプト80を率いる役割を引き継いだ。2022年現在、バンドはまだ活動しており、 Seun Kuti & Egypt 80という名義で音楽をリリースしている[43]。 |

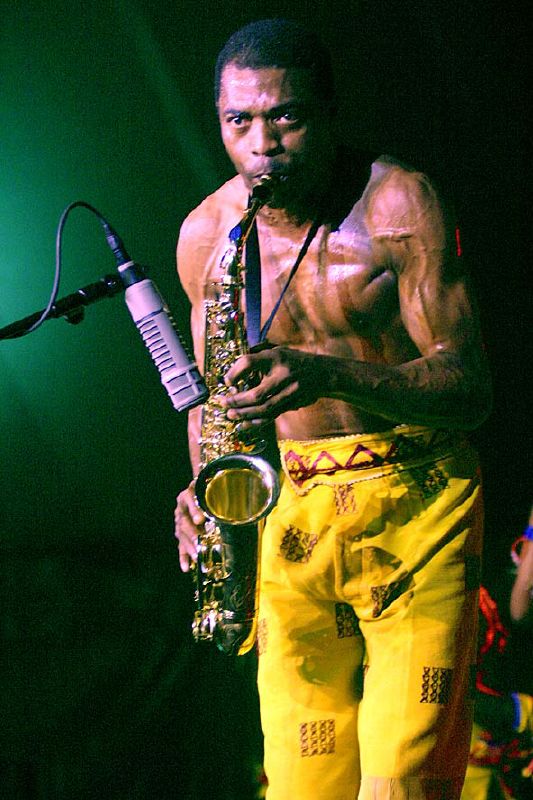

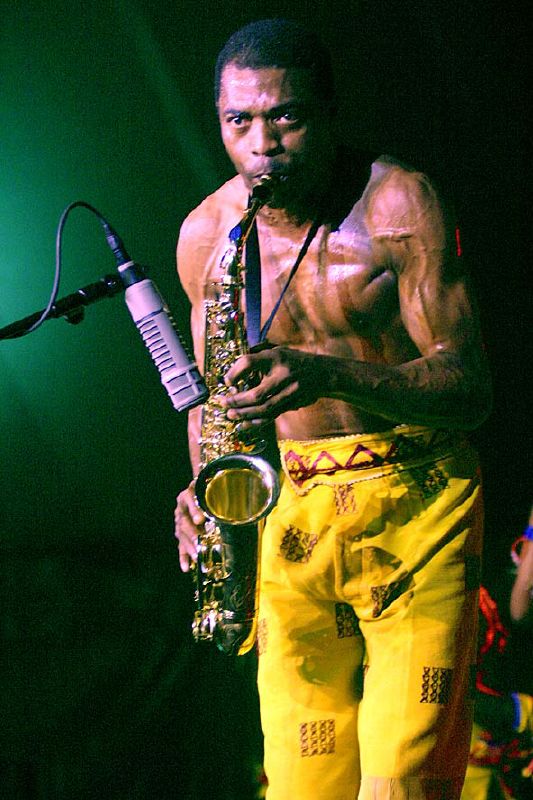

| Music Main article: Afrobeat James Brown was an important American influence on Kuti's musical style. Music Kuti's musical style is called Afrobeat.[44] It is a style he largely created, and is a complex fusion of jazz, funk, highlife, and traditional Nigerian and African chants and rhythms. It contains elements of psychedelic soul and has similarities to James Brown's music. Afrobeat also borrows heavily from the native "tinker pan".[45] Tony Allen, Kuti's drummer of twenty years, was instrumental in the creation of Afrobeat. Kuti once stated that "there would be no Afrobeat without Tony Allen".[46] Tony Allen's drumming notably makes sparing use of 2 & 4 backbeat style playing, instead opting for outlining the time in shuffling hard-bop fashion, while maintaining a strong downbeat. There are clear audible musical similarities between Kuti's compositions and the work of electric-era Miles Davis, Sly Stone and Afrofunk pioneer Orlando Julius. Kuti's band was notable for featuring two baritone saxophones when most groups only used one. This is a common technique in African and African-influenced musical styles and can be seen in funk and hip hop. His bands sometimes performed with two bassists at the same time both playing interlocking melodies and rhythms. There were always two or more guitarists. The electric West African style guitar in Afrobeat bands is a key part of the sound, and is used to give basic structure, playing a repeating chordal/melodic statement, riff, or groove. Some elements often present in Kuti's music are the call-and-response within the chorus and figurative but simple lyrics. His songs were also very long, at least 10–15 minutes in length, and many reached 20 or 30 minutes, while some unreleased tracks would last up to 45 minutes when performed live. Their length was one of many reasons that his music never reached a substantial degree of popularity outside Africa. His LP records frequently had one 30-minute track per side. Typically there is an "instrumental introduction" jam section of the song roughly 10–15 minutes long before Kuti starts singing the "main" part of the song, featuring his lyrics and singing, for another 10–15 minutes. On some recordings, his songs are divided into two parts: Part 1 being the instrumental, and Part 2 adding in vocals. Kuti's songs are mostly sung in Nigerian Pidgin English, although he also performed a few songs in the Yoruba language. His main instruments were the saxophone and the keyboards, but he also played the trumpet, electric guitar, and the occasional drum solo. Kuti refused to perform songs again after he had already recorded them, which hindered his popularity outside Africa[citation needed]. The subject of Kuti's songs tended to be very complex. They regularly challenged common received notions in the manner of political commentary through song. Many of his songs also expressed a form of parody and satire. The main theme he conveyed through his music was the search for justice through exploration of political and social topics that affected the common people.[47] |

音楽 詳細は「アフロビート」を参照 ジェームス・ブラウンは、クティの音楽スタイルに影響を与えた重要なアメリカのアーティストである。 音楽 クティの音楽スタイルはアフロビートと呼ばれる。[44] これは彼がほぼ作り出したスタイルであり、ジャズ、ファンク、ハイライフ、ナイジェリアやアフリカの伝統的なチャントやリズムの複雑な融合である。サイケ デリック・ソウルの要素を含み、ジェームス・ブラウンの音楽と類似している。また、アフロビートは土着の「ティンカーパン」からも多くを借用している。 [45] アフロビートの創出に重要な役割を果たしたのが、クーティの20年にわたるドラマー、トニー・アレンである。クーティはかつて「トニー・アレンなしのアフ ロビートはありえない」と述べたことがある。[46] トニー・アレンのドラムは、2&4の裏拍スタイルの演奏を控えめにし、代わりにハードバップ風のシャッフルで拍を強調する。クーティの作曲と、エレクト リック・ジャズ時代のマイルス・デイヴィス、スライ・ストーン、アフロファンクのパイオニアであるオーランド・ジュリアスの作品との間には、明らかな音楽 的類似性がある。 クーティのバンドは、ほとんどのグループが1人しか使わないバリトンサックスを2本使用することで知られていた。これはアフリカやアフリカの影響を受けた 音楽スタイルでは一般的なテクニックであり、ファンクやヒップホップでも見られる。彼のバンドでは、2人のベーシストが同時に演奏し、メロディとリズムを 交互に演奏することもあった。ギタリストは常に2人以上いた。 アフロビートのバンドでは、西アフリカのエレクトリック・スタイルのギターがサウンドの重要な要素であり、コード/メロディの繰り返し、リフ、グルーヴを 演奏し、基本的な構造を与えるために使用される。 クティの音楽にしばしば見られる要素として、コーラスにおけるコール・アンド・レスポンスや、比喩的だがシンプルな歌詞がある。彼の曲は非常に長く、少な くとも10~15分、20分や30分に及ぶものも多く、未発表曲の中にはライブで演奏されると45分に達するものもある。こうした長さが、彼の音楽がアフ リカ国外で大きな人気を得ることがなかった理由のひとつである。彼のLPレコードには、片面に30分の曲が1曲収録されていることが多かった。通常、ク ティが歌詞と歌で「メイン」パートを歌う前に、10~15分ほどの「インストゥルメンタル・イントロダクション」ジャム・セクションがあり、その後さらに 10~15分ほど歌う。一部の録音では、彼の歌は2つのパートに分けられている。パート1はインストゥルメンタル、パート2はボーカル付きである。 クティの歌は主にナイジェリア・ピジン・イングリッシュで歌われるが、ヨルバ語の歌もいくつかある。主な楽器はサックスとキーボードだが、トランペットや エレキギターも演奏し、ドラムソロも時折披露した。クティは一度録音した曲を再び演奏することは拒否したため、アフリカ以外の地域での人気は妨げられた [要出典]。 クティの歌の主題は非常に複雑である傾向があった。それらは、歌を通じた政治的論評という形で、一般的な既成概念に定期的に挑戦していた。彼の歌の多く は、パロディや風刺の一形態も表現していた。彼が音楽を通じて伝えた主なテーマは、一般市民に影響を与える政治的・社会的なトピックを探究することで正義 を追求することだった。 |

| Showmanship Kuti was known for his showmanship, and his concerts were often outlandish and wild. He referred to his stage act as the "Underground Spiritual Game". Many expected him to perform shows like those in the Western world, but during the 1980s, he was not interested in putting on a "show". His European performance was a representation of what was relevant at the time and his other inspirations.[2] He attempted to make a movie but lost all the materials to the fire that was set to his house by the military government in power.[48] He thought that art, and thus his own music, should have political meaning.[2] Kuti's concerts also regularly involved female singers and dancers, later dubbed as "Queens." The Queens were women who helped influence the popularization of his music. They were dressed colorfully and wore makeup all over their bodies that expressed their visual creativity. The singers of the group played a backup role for Kuti, usually echoing his words or humming along, while the dancers would put on a performance of an erotic manner. This began to spark controversy due to the nature of their involvement with Kuti's political tone, along with the reality that a lot of the women were young.[37] Kuti was part of an Afrocentric consciousness movement that was founded on and delivered through his music. In an interview included in Hank Bordowitz's Noise of the World, Kuti stated: Music is supposed to have an effect. If you're playing music and people don't feel something, you're not doing shit. That's what African music is about. When you hear something, you must move. I want to move people to dance, but also to think. Music wants to dictate a better life, against a bad life. When you're listening to something that depicts having a better life, and you're not having a better life, it must have an effect on you.[49] |

ショーマンシップ クティは、そのショーマンシップで知られており、彼のコンサートは奇抜で荒々しいものだった。彼は自身のステージを「アンダーグラウンド・スピリチュア ル・ゲーム」と呼んでいた。多くの人々は、彼が西洋のショーのようなパフォーマンスを行うことを期待していたが、1980年代の彼は「ショー」を行うこと に興味を示さなかった。彼のヨーロッパでのパフォーマンスは、当時関連性のあるものや、その他のインスピレーションを表現したものだった。[2] 彼は映画制作を試みたが、軍事政権によって放火された自宅の火災で、すべての素材を失った。[48] 彼は芸術、そして自身の音楽には政治的な意味があるべきだと考えていた。[2] クティのコンサートには、後に「クイーンズ」と呼ばれるようになる女性歌手やダンサーも定期的に参加していた。クイーンズは、彼の音楽の普及に影響を与え た女性たちであった。彼女たちはカラフルな衣装を身にまとい、全身に化粧を施し、視覚的な創造性を表現していた。グループの歌手たちは、クティのバック アップ役として、通常は彼の言葉を繰り返したり、ハミングしたりしていた。一方、ダンサーたちはエロティックなパフォーマンスを披露していた。これは、彼 らのクティとの関わりが政治的な色合いを帯びていたこと、また、多くの女性が若かったという現実もあって、論争を引き起こすようになった。 クティは、自身の音楽を基盤とし、音楽を通じて発信するアフロセントリック(黒人中心主義)の意識改革運動の一翼を担っていた。ハンク・ボルドウィッツ著『Noise of the World』に掲載されたインタビューで、クティは次のように述べている。 音楽には影響力があるはずだ。音楽を演奏しているのに、人々が何も感じなければ、それは何の意味もない。それがアフリカ音楽の真髄だ。何かを聞いたら、人 は動かずにはいられない。私は人々を踊らせたいが、同時に考えさせたいとも思っている。音楽は、悪い生活に反対して、より良い生活を望んでいる。より良い 生活を描いた音楽を聴いているのに、より良い生活を送れていないとしたら、それは何らかの影響を与えているはずだ。 |

| Political views and activism Activism Kuti was highly engaged in political activism in Africa from the 1970s until his death. He criticized the corruption of Nigerian government officials and the mistreatment of Nigerian citizens. He spoke of colonialism as the root of the socio-economic and political problems that plagued the African people. Corruption was one of the worst political problems facing Africa in the 1970s and Nigeria was among the most corrupt countries. Its government rigged elections and performed coups that ultimately worsened poverty, economic inequality, unemployment, and political instability, further promoting corruption and crime. Kuti's protest songs covered themes inspired by the realities of corruption and socio-economic inequality in Africa. Kuti's political statements could be heard throughout Africa.[48] Kuti's open vocalization of the violent and oppressive regime controlling Nigeria did not come without consequence. He was arrested on over 200 different occasions and spent time in jail, including his longest stint of 20 months after his arrest in 1984. On top of jail time, the corrupt government sent soldiers to beat Kuti, his family and friends, and destroy wherever he lived and whatever instruments or recordings he had.[50][48] In the 1970s, Kuti began to run outspoken political columns in the advertising space of daily and weekly newspapers such as The Daily Times and The Punch, bypassing editorial censorship in Nigeria's predominantly state-controlled media.[51] Published throughout the 1970s and early 1980s under the title "Chief Priest Say", these columns were extensions of Kuti's famous Yabi Sessions—consciousness-raising word-sound rituals, with himself as chief priest, conducted at his Lagos nightclub. Organized around a militantly Afrocentric rendering of history and the essence of black beauty, "Chief Priest Say" focused on the role of cultural hegemony in the continuing subjugation of Africans. Kuti addressed many topics, from fierce denunciations of the Nigerian Government's criminal behavior, Islam and Christianity's exploitative nature, and evil multinational corporations; to deconstructions of Western medicine, Black Muslims, sex, pollution, and poverty. "Chief Priest Say" was eventually canceled by The Daily Times and The Punch. Many have speculated that the paper's editors were pressured to stop publication, including threats of violence.[52] |

政治的見解と政治活動 政治活動 クティは1970年代から亡くなるまで、アフリカの政治活動に深く関わっていた。彼はナイジェリア政府役人の汚職とナイジェリア国民への虐待を批判した。 彼は、アフリカの人々を苦しめる社会経済的および政治的問題の根源として植民地主義を挙げた。汚職は1970年代のアフリカが直面していた最悪の政治問題 のひとつであり、ナイジェリアはその中でも最も腐敗した国のひとつであった。その政府は不正選挙を行い、クーデターを起こし、最終的には貧困、経済的不平 等、失業、政治的不安定を悪化させ、汚職と犯罪をさらに助長した。クティの抗議歌は、アフリカにおける汚職と社会経済的不平等という現実からインスピレー ションを得たテーマを扱っていた。クティの政治的声明はアフリカ全土で聞かれた。 ナイジェリアを支配する暴力的で抑圧的な政権を公に批判したクーティは、当然ながらその代償を払うことになった。彼は200回以上も逮捕され、刑務所に収 監された。1984年の逮捕後、20ヶ月間という最長期間を刑務所で過ごした。刑務所での拘禁に加え、腐敗した政府はクーティや彼の家族、友人を兵士に暴 行させ、彼が住んでいた場所や所有していた楽器や録音物をすべて破壊した。 1970年代、クティはナイジェリアの国営メディアが編集の検閲を行う中、デイリー・タイムズやパンチといった日刊紙や週刊紙の広告スペースに、政治的な コラムを掲載し始めた。1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて「Chief Priest Say」というタイトルで掲載されたこれらのコラムは、ラゴスのナイトクラブで自らを司祭長として行われた、意識を高める言葉と音の儀式として有名なヤ ビ・セッションの延長線上にあるものであった。 「Chief Priest Say」は、攻撃的なまでにアフリカ中心主義的な歴史観と黒人の美の本質を軸に展開され、アフリカ人が今もなお従属的な立場に置かれていることにおける文 化的な覇権の役割に焦点を当てた。クティは、ナイジェリア政府の犯罪行為、イスラム教とキリスト教の搾取的な性質、悪の多国籍企業に対する激しい非難か ら、西洋医学、ブラック・ムスリム、セックス、汚染、貧困の分析まで、さまざまなトピックを取り上げた。「チーフ・プリースト・セイ」は最終的に、デイ リー・タイムズ紙とパンチ紙によって中止された。多くの人々は、暴力の脅威を含め、紙面の編集者が出版中止に圧力をかけられたのではないかと推測してい る。[52] |

| Political views "Imagine Che Guevara and Bob Marley rolled into one person and you get a sense of Nigerian musician and activist Fela Kuti." —Herald Sun, February 2011[53] Kuti's lyrics expressed his inner thoughts. His rise in popularity throughout the 1970s signalled a change in the relation between music as an art form and Nigerian socio-political discourse.[54] In 1984, he critiqued and insulted the authoritarian then-president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari.[55] "Beast of No Nation", one of his most popular songs, refers to Buhari as an "animal in a madman's body"; in Nigerian Pidgin: "No be outside Buhari dey ee / na craze man be dat / animal in craze man skini." Kuti strongly believed in Africa and always preached peace among its people. He thought the most important way for them to fight European cultural imperialism was to support traditional religions and lifestyles in their continent.[2] The American Black Power movement also influenced Kuti's political views; he supported Pan-Africanism and socialism and called for a united, democratic African republic.[56][57] African leaders he supported during his lifetime include Kwame Nkrumah and Thomas Sankara.[27] Kuti was a candid supporter of human rights, and many of his songs are direct attacks against dictatorships, specifically the militaristic governments of Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s. He also criticized fellow Africans (especially the upper class) for betraying traditional African culture. In 1978 Kuti became a polygamist when he simultaneously married 27 women.[58][59] The highly publicized wedding served many purposes: it marked the one-year anniversary of Kuti and his wives surviving the Nigerian government's attack on the Kalakuta Republic in 1977,[60] and also formalized Kuti's relationships with the women living with him; this legal status prevented the Nigerian government from raiding Kuti's compound on the grounds that Kuti had kidnapped the women.[60] Kuti also described polygamy as logical and convenient: "A man goes for many women in the first place. Like in Europe, when a man is married when the wife is sleeping, he goes out and sleeps around. He should bring the women in the house, man, to live with him, and stop running around the streets!"[61] Some characterize his views towards women as misogyny and typically cite songs like "Mattress" as further evidence.[62][63] In a more complex example, he mocks African women's aspiration to European standards of ladyhood while extolling the values of the market woman in "Lady".[63] However, Kuti also critiqued what he considered aberrant displays of African masculinity. In his songs "J.J.D. (Johnny Just Drop)" and "Gentleman", Kuti mocks African men's culturally and politically inappropriate adoption of European standards and declares himself "African man: Original".[60] Kuti was also an outspoken critic of the United States. At a meeting during his 1981 Amsterdam tour, he "complained about the psychological warfare that American organizations like ITT and the CIA waged against developing nations in terms of language". Because terms such as Third World, undeveloped, or non-aligned countries imply inferiority, Kuti felt they should not be used.[58] |

政治的見解 「チェ・ゲバラとボブ・マーリーを一人の人間に重ね合わせたような感覚が、ナイジェリアのミュージシャンであり活動家でもあるフェラ・クティにはある。」 —ヘラルド・サン、2011年2月[53] クティの歌詞は自身の内なる思いを表現した。1970年代を通じて人気が高まったことは、芸術としての音楽とナイジェリアの社会政治的言説との関係の変化 を意味した。[54] 1984年、彼は ナイジェリア連邦共和国の大統領であったムハンマド・ブハリを批判し侮辱した。[55] 彼の最も人気のある曲のひとつである「Beast of No Nation」では、ブハリを「狂人の体をした動物」と表現している。ナイジェリア・ピジン語で「No be outside Buhari dey ee / na craze man be dat / animal in craze man skini.」と歌っている。クティはアフリカを強く信じており、常にアフリカの人々の間に平和を説いていた。ヨーロッパの文化帝国主義に対抗する最も重 要な手段は、アフリカ大陸の伝統宗教と生活様式を支持することであると彼は考えていた。[2] アメリカのブラックパワー運動もまた、クティの政治的見解に影響を与えた。彼は汎アフリカ主義と社会主義を支持し、統一された民主的なアフリカ共和国を呼 びかけた。[56][57] 彼が生涯を通じて支援したアフリカの指導者にはクワメ・エンクルマやトーマス・サンカラなどがいる。[27] クーティは率直に人権を支持し、彼の歌の多くは独裁政権、特に1970年代と1980年代のナイジェリアの軍事政権に対する直接的な攻撃となっている。ま た、彼は伝統的なアフリカ文化を裏切った同胞のアフリカ人(特に上流階級)を批判した。 1978年、クティは27人の女性と同時に結婚し、一夫多妻制となった。[58][59] この結婚式は多くの目的を果たした。1977年のカラクータ共和国に対するナイジェリア政府の攻撃をクティと彼の妻たちが生き延びた1周年を記念したもの であり [60] また、クティと同居する女性たちとの関係を正式なものとした。この法的地位により、クティが女性たちを誘拐したという理由でナイジェリア政府がクティの屋 敷を急襲することを阻止することができた。[60] クティはまた、一夫多妻制を論理的かつ都合の良いものだと説明した。「そもそも男は多くの女を求めるものだ。ヨーロッパのように、男が妻と結婚していると きに妻が寝ている間に、男は外に出て他の女と寝る。男は女たちを家に連れてきて、一緒に暮らすべきだ。そして、街中をうろつくのはやめるべきだ!」 [61] 彼の女性に対する見方を女性嫌悪と評する者もおり、その典型的な例として「マットレス」のような歌を挙げる者もいる。[62][63] より複雑な例では、彼は「レディ」の中で市場の女性の価値を称賛しながら、アフリカの女性がヨーロッパの女性像に憧れることを嘲笑している。[63] しかし、クティはアフリカの男性らしさの異常な表れとみなしたものについても批判した。彼の歌「J.J.D. (ジョニー・ジャスト・ドロップ)」と「ジェントルマン」では、クティはアフリカの男性がヨーロッパの基準を文化的に、政治的に不適切に採用していること を嘲笑し、自らを「アフリカの男:オリジナル」と宣言している。オリジナル」と宣言した。[60] クティは米国の批判者としても知られていた。1981年のアムステルダム・ツアー中の会合で、彼は「ITTやCIAといった米国の組織が発展途上国に対し て言語面で仕掛ける心理戦について不満を述べた。第三世界、未開発、非同盟国といった言葉は劣等感を意味するため、それらの言葉を使うべきではないとク ティは感じていた。[58] |

Legacy The New Afrika Shrine, Lagos Kuti is remembered as an influential icon who voiced his opinions on matters that affected the nation through his music. Since 1998, the Felabration festival, an idea pioneered by his daughter Yeni Kuti,[64] is held each year at the New Afrika Shrine to celebrate the life of this music legend and his birthday. Since Kuti's death in 1997, there has been a revival of his influence in music and popular culture, culminating in another re-release of his catalog controlled by UMG, Broadway, and off-Broadway shows, and new bands, such as Antibalas, who carry the Afrobeat banner to a new generation of listeners. In 1999, Universal Music France, under Francis Kertekian, remastered the 45 albums that it owned and released them on 26 compact discs. These titles were licensed globally, except in Nigeria and Japan, where other companies owned Kuti's music. In 2005, the American operations of UMG licensed all of its world-music titles to the UK-based label Wrasse Records, which repackaged the same 26 discs for distribution in the United States (where they replaced the titles issues by MCA) and the UK. In 2009, Universal created a new deal for the US and Europe, with Knitting Factory Records and PIAS respectively, which included the release of the Broadway cast recording of the musical Fela! In 2013, FKO Ltd., the entity that owned the rights to all of Kuti's compositions, was acquired by BMG Rights Management. In 2003, the Black President exhibition debuted at the New Museum for Contemporary Art, New York, and featured concerts, symposia, films, and 39 international artists' works.[65][58][66] American singer Bilal recorded a remake of Kuti's 1977 song "Sorrow Tears and Blood" for his second album, Love for Sale, featuring a guest rap by Common. Bilal cited Kuti's mix of jazz and folk tastes as an influence on his music.[67] The 2007 film The Visitor, directed by Thomas McCarthy, depicted a disconnected professor (Richard Jenkins) who wanted to play the djembe; he learns from a young Syrian (Haaz Sleiman) who tells the professor he will never truly understand African music unless he listens to Fela. The film features clips of Kuti's "Open and Close" and "Je'nwi Temi (Don't Gag Me)". |

遺産 ラゴスのニュー・アフリカ・シュライン クーティは、音楽を通じて国民に影響を与える事柄について意見を表明した影響力のある象徴的人物として記憶されている。1998年より、彼の娘イェニ・ クーティが発案したフェスティバル「フェラブレーション」が、この音楽界の伝説的人物の生涯と誕生日を祝うために、毎年ニュー・アフリカ・シュラインで開 催されている。1997年のクティの死後、彼の音楽や大衆文化への影響力が復活し、UMG、ブロードウェイ、オフ・ブロードウェイのショー、そしてアン ティバラスなどの新しいバンドが、彼のカタログを再リリースし、アフロビートの旗を新しい世代のリスナーに掲げている。 1999年には、フランシス・ケルテキアン率いるユニバーサル・ミュージック・フランスが、同社が所有する45枚のアルバムをリマスターし、26枚のCD としてリリースした。これらのタイトルは、クーティの音楽を他の企業が所有しているナイジェリアと日本を除く全世界でライセンスされた。2005年には、 UMGの米国事業部門が、ワールドミュージックの全タイトルを英国のレーベル、Wrasse Recordsにライセンス供与し、Wrasse Recordsは同じ26枚のディスクを再パッケージ化して、米国(MCAから発売されていたタイトルに代わるもの)と英国で流通させた。2009年には ユニバーサルは、米国ではKnitting Factory Records、欧州ではPIASとそれぞれ新たな契約を結び、ミュージカル『フェラ!』のブロードウェイ・キャスト・レコーディングのリリースもその中 に含まれていた。2013年、クティの全作曲の権利を所有していたFKO Ltd.はBMG Rights Managementに買収された。 2003年には、ニューヨークのニュー・ミュージアム・フォー・コンテンポラリー・アートで「ブラック・プレジデント」展が開催され、コンサート、シンポジウム、映画、39人の国際的なアーティストの作品が展示された。 アメリカの歌手ビラルは、1977年のクーティの楽曲「Sorrow Tears and Blood」を自身の2枚目のアルバム『Love for Sale』のためにリメイクし、ゲストラッパーのコモンをフィーチャーした。ビラルは、クーティのジャズとフォークのテイストをミックスした音楽が自身の 音楽に影響を与えたと述べている。 2007年の映画『訪問者』はトーマス・マッカーシー監督による作品で、ジャンベを演奏したいと思っている、孤立した大学教授(リチャード・ジェンキン ス)を描いている。彼はシリア人の青年(ハーズ・スレイマン)から、フェラの音楽を聴かない限り、アフリカ音楽を本当に理解することはできないと教えられ る。この映画には、クティの「Open and Close」と「Je'nwi Temi (Don't Gag Me)」のクリップがフィーチャーされている。 |

The Afrobeat band Antibalas in 2005 In 2008, an off-Broadway production about Kuti's life, entitled Fela! and inspired by the 1982 biography Fela, Fela! This Bitch of a Life by Carlos Moore,[68][69] began with a collaborative workshop between the Afrobeat band Antibalas and Tony award-winner Bill T. Jones. The production was a massive success, and sold-out performances during its run and gained critical acclaim. On 22 November 2009, Fela! began a run on Broadway at the Eugene O'Neill Theatre. Jim Lewis helped co-write the script (along with Jones) and obtained producer backing from Jay-Z and Will Smith, among others. On 4 May 2010, Fela! was nominated for 11 Tony Awards, including Best Musical, Best Book of a Musical, Best Direction of a Musical for Bill T. Jones, Best Leading Actor in a Musical for Sahr Ngaujah, and Best Featured Actress in a Musical for Lillias White.[70] In 2011, the London production of Fela! (staged at the Royal National Theatre) was filmed.[58] On 11 June 2012, it was announced that Fela! would return to Broadway for 32 performances.[71] On 18 August 2009, DJ J.Period released a free mixtape to the general public, entitled The Messengers. It is a collaboration with Somali-born hip-hop artist K'naan paying tribute to Kuti, Bob Marley, and Bob Dylan. Two months later, Knitting Factory Records began re-releasing the 45 titles controlled by UMG, starting with yet another re-release in the US of the compilation The Best of the Black President, which was completed and released in 2013.[72] Fela Son of Kuti: The Fall of Kalakuta is a stage play written by Onyekaba Cornel Best in 2010. It has had triumphant acclaim as part of that year's Felabration and returned in 2014 at the National Theatre and Freedom Park in Lagos. The play deals with events in a hideout, a day after the fall of Kalakuta. The full-length documentary film Finding Fela, directed by Alex Gibney, premiered at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. |

2005年のアフロビートバンド、アンティバルサ 2008年、クティの生涯を描いたオフブロードウェイの作品『フェラ!』が、1982年の伝記『フェラ!このクソったれ人生』を原作として制作された。こ の作品は、アフロビートバンドのアンティバルサとトニー賞受賞者ビル・T・ジョーンズのコラボレーションによるワークショップから始まった。この作品は大 成功を収め、公演期間中は完売となり、批評家からも高い評価を受けた。2009年11月22日、ブロードウェイのユージン・オニール劇場で『フェラ!』の 公演が始まった。ジム・ルイスは脚本の共同執筆を手伝い(ジョーンズと共に)、ジェイ・Zとウィル・スミスなどからプロデューサーとしての支援を得た。 2010年5月4日、Fela!はトニー賞で11部門にノミネートされた。その中には、ミュージカル作品賞、ミュージカル脚本賞、ビル・T・ジョーンズの ミュージカル演出賞、サー・ンガウジャのミュージカル主演男優賞、リリアス・ホワイトのミュージカル助演女優賞が含まれていた イアス・ホワイトが受賞した。[70] 2011年には、ロンドンで上演された『フェラ!』(ロイヤル・ナショナル・シアターで上演)が映画化された。[58] 2012年6月11日、ブロードウェイで32公演が行われることが発表された。 2009年8月18日、DJ J.Periodは一般向けに無料ミックステープ『The Messengers』をリリースした。これはソマリア生まれのヒップホップアーティスト、K'naanとのコラボレーションで、クーティ、ボブ・マー リー、ボブ・ディランに捧げた作品である。 2ヶ月後、Knitting Factory Recordsは、UMGが管理する45タイトルの再リリースを開始し、2013年に完成・リリースされたコンピレーション『The Best of the Black President』の米国での再リリースから始まった。 フェラ・クティの息子:カラクータの崩壊』は、2010年にオニェカバ・コーネル・ベストが執筆した舞台劇である。この作品は、その年のフェラブレーショ ンの一環として大成功を収め、2014年にはラゴスの国立劇場とフリーダムパークで再演された。この舞台劇は、カラクータ崩壊の翌日の隠れ家での出来事を 描いている。 アレックス・ギブニー監督による長編ドキュメンタリー映画『フェラを探して』は、2014年のサンダンス映画祭で初公開された。 |

| A biographical film by Focus

Features, directed by Steve McQueen and written by Biyi Bandele, was

rumoured to be in production in 2010, with Chiwetel Ejiofor in the lead

role.[73] However, by 2014, the proposal was no longer produced under

Focus Features, and while he maintained his role as the main writer,

McQueen was replaced by Andrew Dosunmu as the director. McQueen told

The Hollywood Reporter that the film was "dead".[74] The 2019 documentary film My Friend Fela (Meu amigo Fela) by Joel Zito Araújo, explores the complexity of Kuti's life "through the eyes and conversations" of his biographer Carlos Moore.[75] The collaborative jazz/afrobeat album Rejoice by Tony Allen and Hugh Masekela, released in 2020, includes the track "Never (Lagos Never Gonna Be the Same)", a tribute to Kuti, through whom Allen and Masekela first met in the 1970s.[76][77] Kuti's songs "Zombie" & "Sorrow Tears and Blood" has appeared in the video game Grand Theft Auto: IV, and he was posthumously nominated to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2021.[78] In 2021, Hulu released a six-episode documentary miniseries, McCartney 3,2,1, in which Paul McCartney is quoted as saying of a visit to see Fela Kuti at the African Shrine, Kuti's club outside of Lagos, in the early 1970s: "The music was so incredible that I wept. Hearing that was one of the greatest music moments of my life."[79] On 1 November 2021, a blue plaque was unveiled by the Nubian Jak Community Trust at 12 Stanlake Road, Shepherd's Bush, where Kuti first lived when he came to London in 1958 and was studying music at Trinity College.[80][81] The event included tributes from Kuti's daughter Shalewa Ransome-Kuti, Resonance FM broadcaster Debbie Golt, Kuti's former manager Rikki Stein, cover artist Lemi Ghariokwu, and others.[82][83][84] In 2022, Kuti was inducted into the Black Music & Entertainment Walk of Fame.[85] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Kuti at number 188 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[86] |

2010年には、フォーカス・フィーチャーズによる伝記映画が制作中で

あるという噂があり、主演はチウェテール・エジフォーであった。[73]

しかし、2014年までにフォーカス・フィーチャーズによる制作は中止となり、マックイーンはメインの脚本家としての役割を維持したが、監督はアンド

リュー・ドスナムに交代した。マックイーンは『ハリウッド・レポーター』誌に、この映画は「死んだ」と語った。[74] 2019年のドキュメンタリー映画『マイ・フレンド・フェラ(原題:Meu amigo Fela)』は、ジョエル・ジト・アラウージョ監督が、伝記作家カルロス・ムーアの「目と会話」を通して、クティの複雑な人生を掘り下げている。[75] 2020年にリリースされたトニー・アレンとヒュー・マセケラによるコラボレーション・ジャズ/アフロビート・アルバム『Rejoice』には、クティへ のトリビュート曲「Never (Lagos Never Gonna Be the Same)」が収録されており、この曲を通じてアレンとマセケラは1970年代に初めて出会った。 クティの楽曲「ゾンビ」と「悲しみと涙と血」はビデオゲーム『グランド・セフト・オートIV』に登場しており、2021年に死後、ロックの殿堂入り候補に選ばれた。 2021年、Huluは6話構成のドキュメンタリー・ミニシリーズ『McCartney 3,2,1』を公開し、ポール・マッカートニーが1970年代初頭にフェラ・クティのラゴス郊外にあるクラブ「アフリカン・シュライン」を訪れた際のこと を「あまりにも素晴らしい音楽で、涙が出た。あれは人生で最高の音楽体験のひとつだった」と語っていると引用している。 2021年11月1日、1958年にロンドンに渡りトリニティ・カレッジで音楽を学んでいた頃に初めて暮らしたシェパーズ・ブッシュのスタンレイク・ロー ド12番地で、ヌビア・ジャック・コミュニティ・トラストによりブルー・プラークが除幕された。[80][8 1] このイベントには、クーティの娘シャレワ・ランサム=クーティ、レゾナンスFMのDJデビー・ゴルト、クーティの元マネージャーのリッキー・スタイン、カ バーアーティストのレミ・ガリオクウなどから追悼の言葉が寄せられた。 2022年、クティはブラック・ミュージック&エンターテイメント・ウォーク・オブ・フェーム入りを果たした。[85] 2023年、ローリング・ストーン誌は、クティを「史上最高のシンガー200人」の188位に選出した。[86] |

| Discography Main article: Fela Kuti discography With Africa 70 Fela Fela Fela (1970) Live! (with Ginger Baker) (1971) Fela's London Scene (1971) Why Black Man Dey Suffer (1971) Open & Close (1971) Na Poi (1971) Shakara (1972) Roforofo Fight (1972) Afrodisiac (1973) Gentleman (1973) Alagbon Close (1974) Noise for Vendor Mouth (1975) Confusion (1975) Everything Scatter (1975) Expensive Shit (1975) He Miss Road (1975) Unnecessary Begging (1976) Kalakuta Show (1976) Upside Down (1976) Ikoyi Blindness (1976) Before I Jump Like Monkey Give Me Banana (1976) Excuse-O (1976) Yellow Fever (1976) Zombie (1977) Stalemate (1977) No Agreement (1977) Sorrow Tears and Blood (1977) J.J.D. (Johnny Just Drop!!) (1977) Shuffering and Shmiling (1978) Unknown Soldier (1979) V.I.P. (Vagabonds in Power) (1979) I.T.T. (International Thief Thief) (1980) Music of Many Colours (1980) (with Roy Ayers) Authority Stealing (1980) Coffin for Head of State (1981) I Go Shout Plenty!!! (1986, recorded in 1976) With Egypt 80 Original Sufferhead (1981) Perambulator (1983) Live in Amsterdam (1983) Army Arrangement (1985) Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense (1986) Beasts of No Nation (1989) Confusion Break Bones (1990) O.D.O.O. (Overtake Don Overtake Overtake) (1990) Underground System (1992) Live in Detroit 1986 (2010) Compilations The Best Best of Fela Kuti (1999) The Underground Spiritual Game (2004) Lagos Baby 1963 to 1969 (2008) The Best of the Black President 2 (2013) Filmography Arena - Fela Kuti: Father of Afrobeat,2020 Plimsoll MamaPut Film for BBC My Friend Fela, 2019, Joel Zito Araújo (Casa de Criação Cinema) Finding Fela, 2014, Alex Gibney and Jack Gulick (Jigsaw Productions) Femi Kuti — Live at the Shrine, 2005, recorded live in Lagos, Nigeria (Palm Pictures) Fela Live! Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and the Egypt '80 Band, 1984, recorded live at Glastonbury, England (Yazoo) Fela Kuti: Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense & Berliner Jazztage '78 (Double Feature), 1984 (Lorber Films) Fela in Concert, 1981 (VIEW) Music Is the Weapon, 1982, Stéphane Tchalgadjieff and Jean-Jacques Flori (Universal Music) |

ディスコグラフィー 詳細はフェラ・クティのディスコグラフィーを参照 アフリカ70と共に フェラ・フェラ・フェラ(1970年 ライヴ! (ジンジャー・ベイカーとの共演)(1971年 フェラのロンドン・シーン(1971年 なぜ黒人は苦しまなければならないのか(1971年 オープン&クローズ(1971年 ナ・ポイ(1971年 Shakara (1972) Roforofo Fight (1972) Afrodisiac (1973) Gentleman (1973) Alagbon Close (1974) Noise for Vendor Mouth (1975) Confusion (1975) Everything Scatter (1975) Expensive Shit (1975) He Miss Road (1975) Unnecessary Begging (1976) Kalakuta Show (1976) Upside Down (1976) Ikoyi Blindness (1976) Before I Jump Like Monkey Give Me Banana (1976) Excuse-O (1976) Yellow Fever (1976) ゾンビ (1977) 膠着状態 (1977) 合意なし (1977) 悲しみと涙と血 (1977) J.J.D. (ジョニー・ジャスト・ドロップ!!) (1977) 苦悩と微笑 (1978) アンノウン・ソルジャー (1979) V.I.P. (Vagabonds in Power) (1979) I.T.T. (International Thief Thief) (1980) ミュージック・オブ・メニー・カラーズ (1980) (with Roy Ayers) オーソリティ・スティーリング (1980) コフィン・フォー・ザ・ヘッド・オブ・ステイト (1981) I Go Shout Plenty!!! (1986, recorded in 1976) With Egypt 80 Original Sufferhead (1981) Perambulator (1983) Live in Amsterdam (1983) Army Arrangement (1985) Teacher Don't Teach Me Nonsense (1986) Beasts of No Nation (1989) コンフュージョン・ブレイク・ボーンズ (1990) O.D.O.O. (Overtake Don Overtake Overtake) (1990) アンダーグラウンド・システム (1992) ライブ・イン・デトロイト1986 (2010) コンピレーション ザ・ベスト・ベスト・オブ・フェラ・クティ (1999) ザ・アンダーグラウンド・スピリチュアル・ゲーム (2004) ラゴス・ベイビー 1963年から1969年 (2008) ブラック・プレジデント ザ・ベスト・オブ・ザ・ベスト 2 (2013) フィルモグラフィー アリーナ - フェラ・クティ:アフロビートの父、2020年 プリムソル・ママ、BBCのための映画 マイ・フレンド・フェラ、2019年、ジョエル・ジト・アラウージョ(Casa de Criação Cinema) フェラを探して(Finding Fela)、2014年、アレックス・ギブニーとジャック・グリック(ジグソー・プロダクションズ) フェミ・クティ - ライブ・アット・ザ・シュライン(Femi Kuti — Live at the Shrine)、2005年、ナイジェリアのラゴスでライブ録音(パーム・ピクチャーズ) フェラ・ライブ!(Fela Live!)フェラ・アニクラポ・クティ・アンド・ザ・エジプト'80バンド(Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and the Egypt '80 Band)、1984年、イギリスのグラストンベリーでライブ録音(ヤズー) フェラ・クティ:教師はくだらないことを教えるな&ベルリン・ジャズ・フェスティバル'78(2本立て)、1984年(Lorber Films) フェラ・イン・コンサート、1981年(VIEW) 音楽は武器だ、1982年、ステファン・チャルガジェフとジャン=ジャック・フロリ(ユニバーサル・ミュージック) |

| Further reading Alimi, Shina; Anthony, Iroju Opeyemi (15 September 2013). "No agreement today, no agreement tomorrow: Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and human rights activism in Nigeria" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 6 (4): 74–95. Gale A356354162. Bordowitz, Hank (2004). Noise of the World:Non-Western Musicians In Their Own Words. Soft Skull Press. Canada. Chude, Olisaemeka (11 November 2015), "Let's keep felabrating" Archived 31 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ayiba magazine Idowu, Mabinuori Kayode (2002). Fela, le Combattant. Le Castor Astral. France. Moore, Carlos (1982). Fela, Fela! This Bitch of a Life. Allison & Busby. UK. (Authorised biography). New edition Chicago Review Press, 2009 (with Introduction by Margaret Busby and foreword by Gilberto Gil); Nigerian edition Cassava Republic Press (with Prologue by Lindsay Barrett). Ogunyemi, Christopher Babatunde (2 October 2021). "Fela Kuti's Black consciousness: African cosmology and the re-configuration of Blackness in 'colonial mentality'". African Identities. 19 (4): 487–501. doi:10.1080/14725843.2020.1803793. S2CID 225491880. Olorunyomi, Sola (2002). Afrobeat: Fela and the Imagined Continent. Africa World Press. USA. Olaniyan, Tejumola (2004). Arrest the Music! Fela and his Rebel Art and Politics. Indiana University Press. USA. Schoonmaker, Trevor, ed. (2003). Fela: From West Africa to West Broadway. Palgrave Macmillan. USA. Schoonmaker, Trevor, ed. (2003). Black President: The Art & Legacy of Fela Anikulapo Kuti. New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. ISBN 0-915557-87-8. Sithole, Tendayi (July 2012). "Fela Kuti and the oppositional lyrical power". Muziki. 9 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/18125980.2012.737101. S2CID 142993486. Stewart, Alexander (2013). "Make It Funky: Fela Kuti, James Brown and the Invention of Afrobeat". American Studies. 52 (4): 99–118. doi:10.1353/ams.2013.0124. JSTOR 24589271. S2CID 145682238. Gale A426625632 Project MUSE 528297 ProQuest 1498087584.[permanent dead link] Veal, Michael E. (1997). Fela: The Life of an African Musical Icon. Temple University Press. USA. Wilmer, Val (September 2011), "Fela Kuti in London", in The Wire, No. 331. |

さらに読む Alimi, Shina; Anthony, Iroju Opeyemi (2013年9月15日). 「No agreement today, no agreement tomorrow: Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and human rights activism in Nigeria」 (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 6 (4): 74–95. Gale A356354162. Bordowitz, Hank (2004). Noise of the World: Non-Western Musicians In Their Own Words. Soft Skull Press. カナダ. Chude, Olisaemeka (2015年11月11日), 「Let's keep felabrating」 Archived 31 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ayiba magazine Idowu, Mabinuori Kayode (2002). Fela, le Combattant. Le Castor Astral. France. ムーア、カルロス(1982年)。フェラ、フェラ!このクソったれ人生。アリソン&バスビー。英国。(公認伝記)。新版シカゴレビュープレス、2009年 (マーガレット・バスビーによる序文とジルベルト・ジルによる序文付き)、ナイジェリア版キャッサバ・リパブリック・プレス(リンゼイ・バレットによるプ ロローグ付き)。 オグンイェミ、クリストファー・ババトゥンデ(2021年10月2日)。「フェラ・クティのブラック・コンシャスネス:アフリカの宇宙論と『植民地主義的 メンタリティ』におけるブラックネス再構成」『African Identities』第19巻第4号、2021年10月2日、487-501頁。doi: 10.1080/14725843.2020.1803793。S2CID 225491880。 オロルンヨミ、ソラ(2002年)。 アフロビート:フェラと想像上の大陸。 アフリカ・ワールド・プレス。 米国。 オラニヤン、テジュモラ(2004年)。 音楽を逮捕せよ! フェラと彼の反逆の芸術と政治。 インディアナ大学出版。 米国。 シューンメーカー、トレバー編(2003年)。 フェラ:西アフリカからウェストブロードウェイまで。 パルグレーブ・マクミラン。 米国。 Schoonmaker, Trevor, ed. (2003). Black President: The Art & Legacy of Fela Anikulapo Kuti. New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. ISBN 0-915557-87-8. Sithole, Tendayi (2012年7月). 「Fela Kuti and the oppositional lyrical power」. Muziki. 9 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/18125980.2012.737101. S2CID 142993486. スチュワート、アレクサンダー(2013年)。「ファンキーにしよう:フェラ・クティ、ジェームス・ブラウンとアフロビートの発明」。アメリカ研究。52 (4):99-118。doi:10.1353/ams.2013.0124。S2CID 145682238. Gale A426625632 Project MUSE 528297 ProQuest 1498087584.[permanent dead link] Veal, Michael E. (1997). Fela: The Life of an African Musical Icon. Temple University Press. USA. Wilmer, Val (September 2011), 「Fela Kuti in London」, in The Wire, No. 331. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fela_Kuti | |

| Fela Kuti自伝 / カルロス・ムーア著 ; 菊池淳子訳, KEN BOOKS , 2013 FELAは生涯、自由であることを求め生きた。その混沌の奥底から生まれた超普遍的グルーヴ、FELAの音楽、FELAの芸術。私たちは今、彼の存在をど う受けとめればいいのか。そこから何を想像することができるのだろうか。生きること自体が闘いであり、アートそのものだった偉大な「兄弟」による自伝。 アファ・オジョ 雨の女神 アビク、俺は二度生まれた 三千発のおしおき お袋、フンミラヨ ようこそ、俺の人生!さらば、親父 親友、フェラ J・K・ブライマー 故郷を遠く離れて レミ、美しき最初の妻 ハイライフ・ジャズからアフロ・ビートへ 摩天楼で見失ったもの、見つけたもの〔ほか〕 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆